July 26, 2010

Santa Fe’s Mixed Dreams

They tend, thus, to be simplistic and easily understood by children. They also tend to be tricky sources for writing effective opera.

When used as the text for an opera, which sometimes can be effectively done, as in Engelbert Humperdinck’s wonderful Hansel and Gretel, it is the musical score that makes the work successful. All the blank spaces are filled in and emotion is established by the music. If this does not happen — trouble.

Trouble is what Santa Fe Opera had plenty of in mounting the never-before-staged 1978 opera, Life is a Dream, by (now retired) Amherst professor of music, composer Lewis Spratlan. The composer was on hand in Santa Fe for the opera’s rehearsal period and generously conducted symposia and gave interviews, and he let it be known that we were all in for a treat with Life is a Dream.

In a way, we were. Visually! The set is a most ingenious array of lighted barrier gates — think of the ‘arms’ that descend over a road at railroad crossings. A score of such members, fitted out with incandescent light tubes, would swing down or up from stage right and left, on visible ‘gears,’ comic strip version, providing all sorts of moods and meanings. We were in a forest so they were tree limbs; our characters were in danger so they could hide behind the barriers and be safe, we needed a ceiling, so all the light-arms ascended to the top of the stage and formed a pleasing ‘ceiling’ and source of light for the action below. If we needed a mood change, the tubes of warm light could grow cooler, or less or more intense. It was tremendously impressive and innovative, and my hat is off to scenic designer David Korins and lighting designer Japhy Weidman, as well as over-all stage director Kevin Newbury, who enjoyed nothing less than a triumph with their concept of mis-en-scène.

The evening also benefitted from Jessica Jahn’s elegant formal costumes of, I suppose, the era of the opera’s dramatic source, Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s 16th Century play, La Vida es Sueño (libretto adaptation by James Maraniss). A major stage element was a curiously Dada-esque (think Marcel Duchamps) ‘tower’ that rose from the stage floor, all round and mechanical and metallic with strong doors that contained the wild and dangerous son of King Basilio who had to be exiled to a forest, kept from society, and from endangering the King. The tall tower, on occasion, would move lower into the stage floor and become a throne, with amusing rather faux-Land of Oz lighting, and sometimes it would disappear entirely to make room for the King’s court. It was all great visual fun. Bravo!

John Cheek as King Basilio and Chorus

John Cheek as King Basilio and Chorus

Meanwhile, back at the forest, the wild and crazy boy, Segismundo, is now a grown up Prince, though he does not know it. But the King, old and near death, is having second thoughts, and risks bringing the boy in from the cold to test him out as a functioning Heir (though the ambitious Duke Astolfo aspires to the throne). Alas, young Seggie does not pass the test, for he throws an unsatisfactory servant off a balcony in to the sea, and engages in further unpleasantness. Back he goes to the tower in the forest — where a few more things happen, and whether dreaming or not dreaming, the Prince vows to behave himself and be a good monarch, while all rejoice. Yep, a happy ending. Interestingly enough, vocal music is abandoned for the final climactic lines of the play/opera and the words are clearly spoken by our reformed hero, a quite clever device for they could be heard and understood.

Now we come full circle: Spratlan’s opera did not convince me for several reasons, quite aside from the simplistic tale whence it springs. First among the problems is a cerebral, if sometimes witty, score that bears no lyric material whatsoever. Virtually all vocal writing is spiky, cruelly high and low and vehement and loud, and for Prince Segismundo, especially, it requires huge reserves of power and range that no tenor since Lauritz Melchior could possess. None of the singers, even in the few potentially romantic moments between the tenor Prince and his soprano would-be girlfriends, held any emotional warmth.

Roger Honeywell as Segismundo and Carin Gilfry as Estrella

Roger Honeywell as Segismundo and Carin Gilfry as Estrella

Most people, this one included, go to the opera to be entertained and moved, touched by emotion, which may be resolved or left unresolved, but there needs to be a lyric line and reach of voice that conjures up human feelings, in a compound of words and music, that make for lyric drama. Even the astringency of a masterwork such as Alban Berg’s Wozzeck, for all its sharp-edged atonality offers a strong core of emotion (and tonality). Mr. Spratlin’s sometimes-tonal score is marvelous in its use of wood winds, its musical tropes and schemes that sometimes even comment upon and illustrate words or situations on the stage; but it offers precious little ‘singing’ music, with a dry result that fails in the end to capture our sympathy. Now and again one can be reminded of the music for Façade of William Walton, or patches of Britten or Barber operas. If only Dream gave us a few touches of emotion as does Barber’s Knoxville, Summer 1915, we would have something to take home. But Mr. Spratlan has chosen to remain in the classroom instead.

Roger Honeywell as Segismundo and Ellie Dehn as Rosaura

Roger Honeywell as Segismundo and Ellie Dehn as Rosaura

Let’s end on a positive note: In addition to providing a memorable

production for the world premiere run of Life is a Dream, Santa Fe

Opera assembled a remarkable and I might say brave cast that achieved miracles.

The complex music must be very difficult to learn (if the King had his eye on

conductor Leonard Slatkin at all times, who can blame him?), and it is surely

hard to sing. The cast, all of them, turned in remarkably accomplished

performances.

Tenor Roger Honeywell exceeded himself in the high-and-loud role of the toubled Prince, and I hope his voice benefits from a lot of rest between shows, for he is sorely taxed by the exploitative, even anti-vocal writing. James Maddalena and Craig Verm, baritones, were effective as the Prince’s mentor and rival, respectively, Verm displaying an unusually attractive vocal gift. Keith Jameson as the court’s jester Clarin had to sing, juggle, play tricks and be ever-present all evening, and he excelled, as did the beautiful soprano of Ellie Dehn. Her music, of all, allowed a few moments of dulcet tone, which she had in abundance. Bass John Cheek sounded old, noble and wobbly, which was appropriate as the weakening King, while Carin Gilfrey, Darik Knutsen, Thomas Forde and Heath Hubert were up to the demands of their supporting roles.

Musical director Leonard Slatkin, a sometimes controversial figure in operatic conducting, proved exactly right for the Spratlan score, handling it with seeming ease and expert efficiency.

James A. Van Sant © 2010

image=http://www.operatoday.com/_MG_8479.png image_description=Roger Honeywell (Segismundo) & John Cheek (King Basilio) [Photo by Ken Howard courtesy of Santa Fe Opera] product=yes product_title=Lewis Spratlan: Life is a Dream product_by=King Basilio: John Cheek; Segismundo: Roger Honeywell; Clotaldo: James Maddalena; Rosaura: Ellie Dehn. Conductor: Leonard Slatkin. Director: Kevin Newbury. Scenic Designer: David Korins. Costume Designer: Jessica Jahn. Lighting Designer: Japhy Weideman. product_id=Above: Roger Honeywell as Segismundo and John Cheek as King BasilioAll photos by Ken Howard courtesy of Santa Fe Opera

George Benjamin: Into the Little Hill, Linbury, London

This revival, at the Linbury Studio Theatre at the Royal Opera House, London, confirmed its place as a cornerstone of modern British repertoire.

It’s very loosely based on the fairy tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin, where a conformist community rat on the piper who rids them of vermin. So he takes their children into a “little hill”. The one act opera is disturbing because it treats the story as nightmare.

Into the Little Hill operates on many different levels at once. There’s a political element.The mob violently demand the extermination of all rats, and the Minister sells his principles for votes. There’s a suggestion that the rats aren’t rats but other humans. As the Child says, they wear clothes and carry suitcases — an echo of the Holocaust? There’s social commentary, and the spectre of child abduction, all the more disturbing as the father is implicated.

Nightmares are powerful because they reveal themselves through portents, subliminally working on the subconscious. This is a work that defies classification. Quite likely Benjamin and his librettist Martin Crimp can’t explain its full portent, because it operates on the unconscious, on a subliminal level which cold logic cannot reach. That’s why it’s endlessly intriguing. Perhaps the way to get into Into the Little Hill is to let your intuition lead you.

The Minister’s Child appears to her mother in a chink of light.”Come home” says the mother. No, says the child, “Our home is under the earth. With the angel under the earth” What can that mean, no-one knows. But as the child says “The deeper we burrow, the brighter his music burns”. “Can’t you see?” cries the child. The child sees, because it doesn’t carry the millstone of received wisdom.

Into the Little Hill operates like a half-remembered dream, flotsam flowing out of the unconscious, to be processed in the listeners mind. Rats invade the town, eating grain and concrete, destroying the foundations of social order, Later, the children disappear into the bowels of the earth. “We’re burrowing” sings the child, “streams of hot metal, ribbons of magnesium, particles of light”.

A “man with no eyes, no nose, no ears” materializes in the Minister’s little daughter’s bedroom. He invades the sanctuary, mysteriously, disturbingly.. He is powerful because he can breach all defences, even the Minister’s office. “With music I can reach right in /march slaves to the factory/ or patiently unravel the clouds” Sinister as he is, he’s morally neutral — “The choice is yours” he says to the Minister.

The whole opera pivots on ideas of dissimulation, concealment, crawling into dark recesses. Nothing is safe. So the music here is cloaked in disguise. You hear something eerie, or harps or bells. Sure enough, there’s a cimbalom right in the heart of the orchestra. You hear something tense, tinny and shrill: it’s a banjo, and conventional strings being played like banjos, strings plucked high up the shaft, not bowed. Much emphasis on low-toned instruments like bass flute and bass clarinet, whose sensuous, seductive themes weave through the piece like a narcotic night-blooming flower.

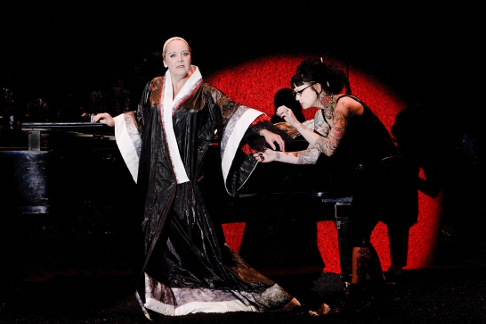

Susan Bickley and Claire Booth sing. The parts aren’t defined, as such. Their voices interchange, with each other and with the “voices” in the orchestra, adding to the unsettling, dream-like effect. Bickley and Booth are the foremost interpreters of modern music in this country. They are superb. Good as the recording on Nimbus is, the singers there don’t come close to Bickley and Booth, who have lived this piece for some time. If Bickley, Booth and the London Sinfonietta record this, their version will be the one to get.

Their expertise matters, because this singing has to be approached with an almost intuitive understanding of how the vocal parts interact with the music. Both are attuned to the inner logic of the piece, so the ever-changing balance flows seamlessly. Although the text is conversational, the syntax is surreal. At several points, Booth has to “sing” at such a high pitch she’s almost inaudible. It takes physical effort. She braces herself, so as not to strain her voice beyond the limits. Humans might not hear such pitches, but rats can.

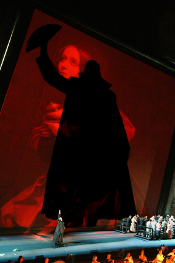

The staging, by The Opera Group, (director, John Fulljames), fits the music and the semi-narrative. The Man with no Face operates through music : the London Sinfonietta play on stage, behind a gauze curtain, vaguely visible behind the action, very much part of the concept as the orchestra is so important in this opera. The stage is dominated by a huge circular frame. “I can make rats drop from the rim of the world” says the man with no eyes. “But the world, says the minister, is round”. “The world — says the man — is the shape my music makes it.”

Susan Bickley [Photo by Robert Workman]

Susan Bickley [Photo by Robert Workman]

The floor is scattered with black, soft objects. When I attended the performance at Aldeburgh in June, I was close enough to touch and smell the acrid stench of rubber. It’s a striking extra dimension. By the time the production reached London the smell was almost gone. It was less oppressive, but gone too was the extra element of menace. Like music, smell can’t be seen but it operates on the mind.

Into the Little Hill was preceded by Luciano Berio’s Recital 1, It’s a tour de force, testing a singer’s full range. It’s a stream of consciousness monologue. Susan Bickley was magnificent, singing for nearly 45 minutes. Snatches of Lieder and Opera rise to the surface, receding as her mind moves on to other things. It’s tragic, for the singer is desolate, looking back on a lifetime of loneliness.

Since Berio wrote it for Cathy Berberian long after their marriage ended, it’s bittersweet, but also strangely affectionate. The interplay between singer and orchestra reflects the interplay between composer and muse. Many in-jokes, such as when Bickley sings “A composer is socially embarrassing when he tries to speak”. But that’s the whole point, for Berio speaks through the orchestration, The piece is an elaborate puzzle-game, tightly scored with intricate key changes and modulations.

Berio plays with illusion. At one stage, members of the orchestra emerge to share space with Bickley. They start to play, but the sounds are grotesquely distorted. Then they exchange instruments. What do these musicians normally play? This was the London Sinfonietta, Britain’s best contemporary music orchestra, an ensemble of virtuosi. Berio is having a laugh, for the rest of the piece is so sophisticated that bad players would be completely lost.

Bickley leans towards the audience, trying to get them to respond to her directly. I very nearly did. Berio and Berberian would have been thrilled, for part of the concept behind this piece is the relationship between illusion and reality. “Isn’t all life there?”, declaims Bickley, with a diva-like sweep of her arms.

For more information please see the Royal Opera House site here.

Anne Ozorio

Cast:

George Benjamin: Into the Little Hill (Martin Crimp: libretto)

Susan Bickley, mezzo-soprano; Claire Booth, soprano. London Sinfonietta. Frank Ollu: conductor.

Luciano Berio: Recital 1

Susan Bickley: The Singer; John Constable: The Accompanist; Nina Kate: The Dresser. The Opera Group. John Fulljames: Director. Soutra Gilmour: Set and Costume Designer. Jon Clark: Lighting.

Linbury Studio Theatre, Royal Opera House, London. 23rd July 2010

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ITLH064.png

image_description=Claire Booth (lying) and Susan Bickley (standing) [Photo by Alaistair Muir courtesy of The Royal Opera]

product=yes

product_title=George Benjamin: Into the Little Hill

product_by=The Royal Opera

product_id=Above: Claire Booth (lying) and Susan Bickley (standing) [Photo by Alaistair Muir courtesy of The Royal Opera]

July 25, 2010

Overdue Debut for Composer and Exiled Prince

By Anthony Tommasini [NY Times, 25 July 2010]

SANTA FE, N.M. — When an opera company presents a world premiere by a living composer, the opera in question usually represents the composer’s current style and approach. This was not the case on Saturday night for the absurdly overdue premiere of Lewis Spratlan’s “Life Is a Dream” here at the Santa Fe Opera.

July 22, 2010

Hoffmann Takes A Hit In Santa Fe

While gifted with some lovely melodic writing and opportunities for grand operatic singing, the story of a depressed alcoholic poet (“he never drinks water,” one line has it), and his tales of futile amorous adventure often seem over-stuffed with dialogue and redundant action. This opera is expensive and difficult to produce, and in the end bears only a negative message.

Just what Hoffmann’s message is has long been a subject of discussion. My view is that once the pretty surface of melody and musical charm is peeled back, below lies only vegetable cellulose, or nothing much. Some will argue that romantic fantasy is at the core of the piece; others find 19th century existential angst; Richard Wagner condemned it for a lack of “moral” value. I would tend to express it more in terms of the bad psychology of a neurotically disturbed man who through the confusions of alcohol and dissipation dooms his own romantic ambitions. However any of that may be, it is best to take Hoffmann as an exercise in visual pleasure and melodic delight — if there are singers and producers to make it happen, and a producer and music director to give it a light and stylish touch.

Erin Wall as Antonia

Erin Wall as Antonia

In Santa Fe Opera’s heavy-handed production, the show turned out to be

badly cast and suffocatingly over-produced. None of the singers was adequate to

the task at hand; the voices were minor or flawed. The leading tenor, Paul

Groves, the key figure in the opera, who looked and played well, seemed to have

no upper register and was often short on volume. Professional that he is,

Groves soldiered through, but he was far from the real thing, in this most

lyrical of big French tenor parts.

Canadian soprano Erin Wall assumed the neigh-impossible task of singing the three major soprano roles the opera requires, the coloratura doll of Act I, Olympia, the lyric soprano of Act II, Antonia and the soprano or mezzo part of the Venetian courtesan, Giulietta, in Act III. She did not have the light agility or highest tones required by Olympia, as Santa Fe’s management must surely have known, and thus it seems a decision was made to turn her Olympia into Gilbert & Sullivan camp — if she did not have the clean runs or pin-point high notes, well mark it up to technical difficulties in her manufacturer Spalanzani’s design. All in good fun? Ho hum. In later acts Wall fared better, and demonstrated a solid top, through high-C, as Antonia though not much tonal allure or play of color; her voice seemed to thicken under pressure, which was much of the time. As an actress Wall was never more than bland.

Kate Lindsey as Nicklausse, Wayne Tigges as Councilor Lindorf and Students

Kate Lindsey as Nicklausse, Wayne Tigges as Councilor Lindorf and Students

The only other singer I will address now is the bass-baritone Wayne Tigges,

a last minute replacement for an ailing colleague in the all-consuming and

vocally demanding roles of Offenbach’s four villains, who are in every

scene, with much to sing, and comprise the engine that drives the thrust of

“evil” though the show — that is quite aside from demon rum.

Tigges proved a boy sent to do a man’s job, and while earnest and

hard-working he did not have the magnetic personality or force or maturity of

voice to claim the part. He needs coaching in menace with John Malcovich.

With an inadequate tenor and bass, and soprano who was short on stage charisma and vocal interest, Offenbach’s score was not well-served. I have to say, and am sorry to do so, that Stephen Lord, music director of Opera Theatre of St. Louis, was a cut-and-dried conductor in the pit. While his orchestra played well enough, far too often Maestro Lord’s direction lacked vitality, dragged where it should have sparkled, left dead moments and, in general, lacked shape, flow and accent. Disappointing.

Now we come to Santa Fe’s stage producer, one of the most famous bad-boys of opera, Christopher Alden — who fully lived up to his reputation. I am going to keep this short — who needs a list of horrors? Alden’s direction was everywhere fussy and mannered, secondary characters moved in slow motion, slithered across the stage floor, pranced about their heads in picture frames, joined hands in a merry trio of dancing — and so on, endlessly. In the final moments of Act II, gilded high-style Second Empire opera boxes emerged from stage right holding an audience eager to applaud the diva Antonia, who had expired moments before. Ah so! We were watching a play within a play (who knew?) — and the Second Act, which Offenbach had already provided with an unnecessary anti-climax following Antonia’s death, offered yet another development as Antonia arose from the dead and took her bows. Now, let’s see, where did that plot go?

Paul Groves as Hoffmann, Kate Lindsey as Nicklausse, Wayne Tigges as Captain Dapertutto, Erin Wall as Giulietta, David Cangelosi as Pitichinaccio and Darik Knutsen as Peter Schlémil (standing)

Paul Groves as Hoffmann, Kate Lindsey as Nicklausse, Wayne Tigges as Captain Dapertutto, Erin Wall as Giulietta, David Cangelosi as Pitichinaccio and Darik Knutsen as Peter Schlémil (standing)

Costumes? Elegant, lavish with Victorian flounces, bustles and ruffles everywhere. Set? Not bad, actually: it all transpired in Luther’s Tavern, a high handsome room with five massive beams across the ceiling, a dark wood dado around the room and white plastered walls that showed off various plaques and hangings. Platforms with minimal trappings for scenes following the Tavern’s opening one (the Kleinsach scene), were brought in and out; they proved effective, and in the Venetian scene featured a massive painting in the style of Turner depicting the grand canal. It worked!

Maybe we will write more about all this later in the season; these things have a way of ripening, and several of the secondary players deserve attention for some were excellent. For now SFO’s Tales of Hoffmann is a game hardly worth the candle.

© 2010 James A. Van Sant/Santa Fe

Click here for a contrary opinion.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/_MG_0429.gif image_description=Paul Groves (Hoffmann) and Erin Wall (Giulietta) [Photo by Ken Howard courtesy of Santa Fe Opera] product=yes product_title=Jacques Offenbach: Tales of Hoffmann product_by=Stella / Olympia: Erin Wall; Antonia / Giulietta: Erin Wall; Nicklausse: Kate Lindsey; Voice of Antonia's Mother: Jill Grove; Hoffmann: Paul Groves; Spalanzani: Mark Schowalter; Lindorf / Coppelius: Wayne Tigges; Dr. Miracle / Dapertutto: Wayne Tigges; Andres / Cochenille: David Cangelosi; Frantz / Pittichinaccio: David Cangelosi; Crespel / Luther: Harold Wilson. Conductor: Stephen Lord. Director: Christopher Alden. Scenic Designer: Allen Moyer. Costume Designer: Constance Hoffman. Lighting Designer: Pat Collins. product_id=Above: Paul Groves as Hoffmann and Erin Wall as GiuliettaAll photos by Ken Howard courtesy of Santa Fe Opera

The Adventures of Pinocchio

Subsequently a few U.S. companies have piloted Flight (if you will) to stage including Opera Theater of St. Louis and Boston Lyric Opera. Other than that, Dove is a fairly unknown name here.

A viewing of one of his more recent efforts, The Adventures of Pinocchio, in its premiere run from the Opera North company in 2007, doesn’t offer evidence that Dove’s work is set to make a breakthrough here in the U.S. However, his score to Alasdair Middleton’s libretto exhibits a formidable level of professionalism and orchestral imagination (did your reviewer hear a banjo at one point?). Combined with a playful and creative staging by Martin Donovan (with sets and costumes by Francis O-Connor), the resulting work seems made for DVD — especially as captured in the crisp and detailed picture of a Blu-Ray set.

That said, an opera being “made for DVD” shouldn’t be mistaken for unreserved praise. If Dove’s music were removed or reduced to soundtrack status, this production would probably be just as charming and entertaining. Dove can create superficially appealing music, but it comes off as derivative. Bits reminiscent of Britten, Sondheim, and especially Janáček (think Cunning Little Vixen) pop up frequently, and one delightful scene for the Ape-Judge has a swaggering tune like something from Prokofiev. There’s a fine line between revealing one’s influences and using them as the foundation for one’s own work, and Dove resides in the latter part. With no keen musical identity of his own, the score can’t establish itself as central to the work’s value as a truly first-rate operatic score should.

Middleton’s libretto certainly gives Dove ample opportunity to show off the composer’s range of influences. As stated over and over again in the bonus feature interviews of composer, librettist, conductor and director, this opera more closely follows the original source material of Carlo Collodi’s novel than the more famous Walt Disney cartoon chose to do. Written serially, Collodi’s novel is a picaresque, episodic and fantastic in invention. This requires a huge cast, with several singers taking on more than one role. If any one scene fails to grasp a viewer’s attention, that viewer need not grow too impatient, for another and quite different scene will be up shortly. There is no narrative arc to speak of - Pinocchio actually “learns” his lesson about being a bad boy by the end of act one, but he has to learn it all over again, and again and again, in act two, before the curtain can finally come down. The tone throughout veers between a light-hearted playfulness that children will enjoy to a darker-hued vision that will keep an adult’s interest. The nearest point of comparison seems to be Humperdinck’s Hansel und Gretel — among that greater opera’s many virtues, it is much briefer. The Adventures of Pinocchio runs to around two and a half hours.

The title role goes to a mezzo, here in the person of Victoria Simmonds. Her pleasant voice retains a high degree of femininity, although her acting is boyish enough. O’Connor’s ingenious costume makes Simmonds into a cartoonish yet believable figure. The huge supporting cast features many amusing caricatures, with Mark White’s Cat and James Laing’s Fox, two con artist animals, making particularly strong impressions. Established baritone Jonathan Summers seems oddly strained by Gepetto’s music, and no emotional connection really happens between him and the boy of wood, sapping the ending of any resonance. Mary Palzas apparently has a substantial career as a dramatic soprano in the UK. In the key role of The Blue Fairy, she has a strong stage presence but the voice has a lot more edge than one might think a Fairy would possess.

David Parry and the Opera North orchestra do well by Dove’s eclectic score. As operatic entertainment The Adventures of Pinocchio, while overlong, offers much, but it falls short of being an authentic accomplishment. Should composer Dove move beyond his influences, he may well yet prove to a major voice.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/OABD7019D.gif image_description=Jonathan Dove: The Adventures of Pinocchio product=yes product_title=Jonathan Dove: The Adventures of Pinocchio (Libretto by Alasdair Middleton) product_by=Pinocchio: Victoria Simmonds; Geppetto: Jonathan Summers; The Blue Fairy: Mary Plazas; Cricket / Parrot: Rebecca Bottone; Puppeteer / Ape-Judge / Ringmaster: Graeme Broadbent; Lampwick: Allan Clayton; Cat: Mark Wilde; Fox / Coachman: James Laing; Pigeon / Snail: Carole Wilson. Opera North Chorus and Orchestra. David Parry, conductor. Martin Duncan, stage director. Recorded live at Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, on 29 February and 1 March 2008. product_id=Opus Arte OABD7019D [Blu-Ray DVD] price=$30.99 product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/B001OA071WTolomeo, New York

By George Loomis [Financial Times, 22 July 2010]

Glimmerglass Opera has a notable record of performing Handel, but its productions have sometimes emphasised cuteness over emotional substance.

Opera Star to Try Some Musical-Theater Gunplay

By Daniel J. Wakin [NY Times, 22 July 2010]

Deborah Voigt, a leading dramatic soprano known for portraying Strauss and Wagner heroines, will be packing heat next summer in the title role of “Annie Get Your Gun” at the Glimmerglass Opera Festival.

July 21, 2010

Pity the Supplicant, Beware the Gatekeeper

By Anthony Tommasini [NY Times, 21 July 2010]

Anyone who has waited in line at the post office or tried to get some officious bureaucrat to process an application will respond to the central dilemma of “La Porta Della Legge,” the Italian composer Salvatore Sciarrino’s latest opera, which had its North American premiere courtesy of the Lincoln Center Festival on Tuesday night at John Jay College.

Angela Meade's Norma at Caramoor

Though none of these ladies lived long enough to record her art, Andrew Porter, in a pre-performance talk at Caramoor, quoted several critics of the era to show that each Norma was controversial—what delighted one writer was insufficient for another.

Lilli Lehmann, the Met’s first Norma (singing it in German), made the famous comment that Norma took more out of her than all three of Wagner’s Brünnhildes—a quote misconstrued by many an impresario to imply that any natural Brünnhilde was also a Norma. (The Met tried to persuade Kirsten Flagstad to take it over from Ponselle, but she had more sense than they did.) More to the point, perhaps, is that the first Norma, Pasta, was also Bellini’s first Sonnambula, a far gentler, more sentimental sort of role—Norma must rage, but she also feels the pangs of rejected love, of deep maternal love and of women’s friendship. Wagner admired Bellini extravagantly and loved Norma—he had coached Lehmann’s mother in the role for a benefit performance he conducted. From Bellini, in part, Wagner learned the way a melody could be extended to express lingering emotional truths, one emotion drifting into others. Too, there is more than a touch of Greek tragedy to Norma, with its fierceness of feeling beneath simplicity of action, and Wagner took much of his method of dramatic construction from Greek sources.

Angela Meade (Norma) and Keri Alkema (Adalgisa)

Angela Meade (Norma) and Keri Alkema (Adalgisa)

What Lehmann probably meant by her bon mot is that the vocal line in

Wagner’s Ring is part of many concurrent lines of sound, that

the voice fades out of and into the overall texture, and the orchestra will

carry the score if the voice fades. In Bellini, the singer has no place to

hide—the orchestration is delicate (a lot of pizzicato) and subservient

to the singer, who must create the statements, tensions and confrontations of

the role. If you run out of breath in Bellini, everyone in the house will know

it. For this among other reasons, perfect Normas are rare to unheard-of. In a

saner age, singers used to respect its complexities and seldom attempted it

without justification. In the entire twentieth century, by general consensus,

there were only two nearly perfect Normas, at least outside Italy: Rosa

Ponselle and Maria Callas. After Callas’s era, Joan Sutherland and

Montserrat Caballé both sang vocally sumptuous Normas that left something to be

desired in characterization. Unfortunately, they made the opera sound so easy

to sing, in their very different personal styles, that many ambitious sopranos

after them decided to tackle it, only to crash and burn. I haven’t heard

a competent Norma since Sutherland and Caballé laid down their verbena

wreaths—or I hadn’t until last Friday.

Norma is a seeress who has betrayed her gods and her country out of love for an enemy seducer. Sworn to virginity, she has borne her lover two children and repressed calls for a national uprising. When she learns he loves another priestess, her jealous rage almost inspires her to murder her children à la Medea or to command a nationwide massacre. Failing that, she could have her rival burned in front of her lover’s eyes—she considers this—or she can face the truth and her own corruption. Who is the traitor? “Son io,” she sings—unaccompanied, a moment of stark drama—“’Tis I”—adding, “Prepare the fire.” Surely Wagner was inspired by the gorgeous finale, the melody rising, falling, evolving, sweeping us along, the lovers marching through an angry throng to fiery doom, and that it was not in the back of his mind as he completed Götterdämmerung.

Angela Meade is 32. Her voice is large, beautiful and carefully trained. Her theatrical temperament is on the cautious side but her instincts are good and she has applied herself to the dramatic side of things. She made her stage debut at the Met two years ago in Verdi’s Ernani, replacing an ailing Sondra Radvanovsky, and though a bit uncertain on stage and understandably wary in early scenes, she had the goods for a thrilling final act. Last year, at Caramoor, Will Crutchfield persuaded her to undertake the title role in Rossini’s Semiramide, one of the mightier benchmarks for a dramatic coloratura. Again she made a slow start and her acting was stiff, but the entire second act (an endurance contest for all four leads) was edge-of-the-seat stuff. This year, therefore, Maestro Crutchfield resolved to showcase her in two performances of Norma. Those, we sighed, whom the Gods would destroy, they first tempt to appear as Norma.

Angela Meade (Norma), Keri Alkema (Adalgisa) and Emmanuel di Villarosa (Pollione) with Will Crutchfield (conducting)

Angela Meade (Norma), Keri Alkema (Adalgisa) and Emmanuel di Villarosa (Pollione) with Will Crutchfield (conducting)

From the first performance came joyous reports; I attended the second and happily confirm them: Meade is a far more than respectable Norma. For a first attempt, this was exceptional bel canto singing and operatic acting.

Meade’s voice possesses some of Sutherland’s metallic power in her upper range, including a clarion high D she brought forth to end the great Act I trio, and she shares Sutherland’s cleanness of attack if not her unwavering breath control. Some of her highest notes and ornaments, however, are not quite so easy or even, especially in soft singing, where she sometimes resorted to head voice. She ornaments with taste and the head-voice notes are pretty, but this altered register implies she is ducking away from full-force singing. Her chest voice, in contrast, is superbly produced and of great beauty and evenness, reminding me of Tebaldi, who also sang dramatic coloratura roles early in her career. This argues that bel canto roles will not be Meade’s meat forever, but that when the highest notes fade, she could have an important career in the lirico-spinto repertory of Verdi and Puccini that currently lacks an ideal interpreter. Perhaps best of all, Meade knows how to present her dramatic ideas forcefully, jabbing with a sudden attack (as Norma, so often angry, must do) or turning reflective with a creamy legato.

In looks, though on the plump side, Meade moves well and holds herself with dignity. She evinces a dramatic as well as a musical intelligence, and these combined with the sheer loveliness of her singing to bring the house to its feet at Caramoor. We were all eager to hear her again in any number of roles. To achieve such an impression with Norma, the most unconquerable of heroines, is itself a major achievement.

Her Adalgisa, Keri Alkema, sang with a dark, sensuous contrast to Meade’s brighter sound. During their duets, the two ladies mingled their voices to sublime effect, blending colors and ornaments deliciously.

The evening’s Pollione, Emmanuel di Villarosa, announced he was performing with a cold and at first sounded that way, intonation faulty, high phrases brought down an octave to avoid cracking. He nonetheless made a sturdy, ardent figure and had warmed up by the great trio to carry his full dramatic weight. His change of heart in the final scene (a weakness of the libretto) seemed perfectly credible. Daniel Mobbs sang Norma’s father, Oroveso, impressively, and the Orchestra of St. Luke’s muddled through punishing humidity that hampered taut string playing.

For many of us, it was as genuine a Norma as we could have hoped for after so many mediocre imitations. I almost envied the younger generation who were hearing this superb score for the first time and hearing it done so well.

Sadly, traffic jams getting out of New York on a Friday evening kept me from attending the pre-opera concert of some of Wagner’s bel canto works, excerpts from Das Liebesverbot (his “Bellini” opera) and other items, sung by younger members of the Crutchfield program, but I got back to Caramoor on Sunday afternoon for a concert of Chopin and Schumann chamber music (this year marks the bicentennial of both gentlemen) with, set among the cellos like a jewel of great price, Sasha Cooke performing Schumann’s Frauenliebe und Leben.

As a rule, I am reluctant to hear yet another soprano take on this too-familiar song cycle, Schumann’s idealization of the adoration of his new bride, Clara—a loving but far more sophisticated and complex woman than is the narrator of these poems. (In this the era of gay marriage, which male singer will be the first to tackle it? Actually, Matthias Goerne has already done so.) But Sasha Cooke is more than capable of making clichés new. Her voice is an ample, generous mezzo of great size and appeal, clear and precise at “chamber” level, then effortlessly soaring to fill Caramoor’s enormous tent at the more delirious moments of the score. Her diction is exceptional, her dramatic gifts considerable—she tells the story and seems to inhabit the naïve narrator. In the music of Frauenliebe, a very simple woman expresses with her voice an emotional commitment deeper than words, and Cooke seemed to be living each layer of meaning, the notes swelling as her heart sought words.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/20100710Caramoor_3442.gif image_description=Angela Meade, soprano, performs the roll of Norma in Bellini's Norma a Bel Canto at Caramoor performance in the Venetian Theater at Caramoor in Katonah New York on July 10, 2010..(photo by Gabe Palacio) product=yes product_title=Norma, Sasha Cooke at Caramoor product_by=Norma: Angela Meade; Adalgisa: Keri Alkema; Pollione: Emmanuel di Villarosa; Oroveso: Daniel Mobbs. Orchestra of St. Luke’s conducted by Will Crutchfield. Caramoor International Music Festival. Performance of July 16. Chamber Music at Caramoor, featuring Sasha Cooke, performance of July 18. product_id=Above: Angela Meade performing the role of NormaAll photos by Gabe Palacio

Cosima Wagner — The Lady of Bayreuth

Famous as the wife of the pianist-conductor Hans von Bülow, who ran off to marry the composer Richard Wagner, Cosima was the daughter of Franz Liszt and eventually the matriarch who forged her last husband’s legacy at Bayreuth. Hilmes begins his study of Cosima in the present at the annual Bayreuth Festival, which continues to attract audiences. In explaining his interest in Cosima, Hilmes identifies his sources (pp. 349-50), which are in this case voluminous and extend beyond the woman’s diaries, which have already been published in German and English translation. This is an account of an exceptional woman, who transformed conventional widowhood into a living monument to her husband’s memory and also shaped music performance internationally through her development of the Festival at Bayreuth.

Hilmes divides his work into chapters that cover Cosima’s life logically, started with her early life as the illegitimate daughter of Liszt and the French author Marie d’Agoult. He follows with an account of Cosima’s relationship with Liszt’s one-time student Hans von Bülow, which ultimately resulted in what Hilmes calls a marriage of convenience. Here Hilmes is good to show the misunderstandings that have emerged over the years, and to allow some of the documents to speak for themselves, which emerges neatly in his coverage of an episode in which Bülow encountered Cosima with Wagner on the street (pp. 58-59), a scene which has a different character depending on whom one reads. Hilmes’ approach opens the door to a fresh account of Cosima’s affair with Wagner, her divorce from Bülow, and her eventual marriage with Wagner. This portion of the book is of interest for the subtext that emerges in the section headings. Since Bülow conducted the premiere of Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde, the presence of that title as a subhead (p. 77) offers a useful point of reference. Likewise, other references to literature and other topics emerges as with “Human, All Too Human” (p. 112) and others. Despite the subtle references, Hilmes is nowhere arch or judgmental. He discusses the sense of guilt Cosmia felt in the way she treated Bülow sensitively. Elsewhere Hilmes shows how active a role Cosima played in Wagner’s life, and this anticipates the role she would take in shaping Bayreuth as an institution later in her own life.

The account of Cosima’s life with Wagner is lively and engaging. The freshness with which Hilmes approaches the episode invites an investigation of the sources and also a rereading of those famous diaries of Cosima in light of the perspectives that are found here. Wagner’s death is depicted with proper reverence, yet shown to be the turning point in what emerges as a kind of musical cult (p. 158), as Cosima identifies herself almost entirely with Wagner and also their home — she even uses Wahnfried as an eponym in correspondence with her daughter Daniela. This is a fascinating aspect of Cosima’s life, and it merits attention in Hilmes treatment of it. In turn, it sets the stage for the international attention that reaches Bayreuth and the role that the Festival takes in shaping German culture. The question of antisemitism emerges in this book, and its treatment is appropriately open; elsewhere Hitler’s relationship with Wagner’s music comes into play, as does the ways in which Cosima shaped the future of Bayreuth as she approached her later years. Hilmes discusses Siegfried Wagner sufficiently and also treats some of the family relationships with a deft hand. As found in other books, the Wagners are a subject that merit separate treatment, and Hilmes offers a nice balance in discussing the family matters, while always retaining the focus on Cosima as his subject.

Part of the attraction of this biography is the lively style the Stewart Spencer brings to the translation. It reads well, and flows with a natural, authorial sense of the language. Spencer seems as engaged in the subject as the author, and that is due to his own work on Wagner and his music. For these and other reasons, this biography has much to recommend for those interested in Cosima and her hand in shaping one of the important institutions in German music in the last century.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Cosima_Wagner.gif

image_description=Cosima Wagner — The Lady of Bayreuth

product=yes

product_title=Cosima Wagner — The Lady of Bayreuth

product_by=By Oliver Hilmes; Translated by Stewart Spencer. Yale University Press, 2010.

product_id=ISBN: 9780300152159

price=$26.40

product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/0300152159

July 20, 2010

Simon Boccanegra at the Proms

But, the ovation which greeted the conclusion of this semi-staged performance of Verdi’s dark, brooding Simon Boccanegra was wholly justified — for once the reality more than lived up to the hype.

Of course, the anticipation — with Proms managers predicting queues for Arena day tickets stretching into Hyde Park — was largely for Plácido Domingo, returning to the stage just a few months after treatment for cancer, in his new guise as a baritone.

Domingo may profess that his decision to abandon his place as one of the ‘Three Tenors’ was not merely one of expediency but driven by a life-long desire to sing one of Verdi’s greatest roles, the 14th-century Genoan patriarch, Simon Boccanegra. In fact, for some time Domingo has been uncomfortable at the upper end of his tenor range; indeed, he has of late asked conductors to transpose roles downwards. But, his voice has always been characterised by a dusky, baritonal colour, and here he seemed liberated, relishing the soaring lines of the role, while elsewhere adopting an appropriately weary tone. While dramatically this captured the complexities and contrasts of this imperfect man — a ruthless, swashbuckling pirate reluctantly recruited as leader of a warring community of aristocrats and plebeians — musically it turned the role upside down: for the low, conversational phrases sounded effortful while the tense melodic peaks projected with ease. For Domingo’s baritone is a fairly light voice, lacking a genuine heft, and some might prefer a more burnished tone, particularly in the lower register where Domingo used his chest to strengthen and reinforce the sound. However, one can overlook such matters when presented with such a convincing characterisation, for Domingo truly embodied the tragic grandeur and dignity of the careworn ruler.

A flop at its premiere in 1857 — and performed here in the revised 1881 version — Simon Boccanegra remains one of Verdi’s most convoluted plots. There are several tangled strands, characters have multiple names and identities, and it would be a fruitless endeavour to attempt to unravel the complications. However, while this performance may have been only semi-staged, there are other ways of conveying the emotional meaning of the music than busy stage action and clever directorial tricks. Domingo perfectly communicated the trauma and torment of the troubled Doge; and especially impressive was the relationship he forged with Amelia, sung by Russian soprano Maria Poplavskaya, in their tender reconciliation scenes. Poplavskaya’s opening aria was pitch-perfect and serene, and although at times her soprano lacked the necessary shimmer, she successfully conveyed both the vulnerability and feistiness of Amelia, as she stands up to her domineering father.

But this performance was not just about Domingo and the superb ensemble cast was inspired by the occasion, the company and by Verdi’s music. Singing the role of Adorno, tenor Joseph Calleja almost stole the show; Calleja has a secure Verdian technique, strong in tone and projection, subtle in dramatic nuance. His Act 2 aria was electrifyingly ardent and justly inspired the loudest applause of the night. There were rumours that Ferruccio Furlanetto might be indisposed but such fears proved unfounded, and he was a typically imposing and dignified Jacopo Fiesco, his gleaming, sonorous bass easily filling the cavernous auditorium. Bass-baritone Jonathan Summers, completing the cast as Paolo, lacked tonal brightness and stamina but was dramatically effective as the Iago-lile villain, oozing menace.

Truly at home in this repertoire, Antonio Pappano commanded the orchestra of the Royal Opera House with a blend of passionate abandon and absolute control, delighting in Verdi’s instrumental tapestry and drawing musical pictures of great feeling and finesse. The ensembles, especially the Act 2 trio and the Council Chamber scene, were particularly well-shaped. Pappano’s players rose to the occasion, producing committed and superlative playing with a genuinely Verdian tinta.

Plácido Domingo has had a long, varied and illustrious career, as tenor, conductor, artistic director (at the Los Angeles Opera and the Washington National Opera), always seeking out new musical experiences and personal challenges, and this clearly continues. In 1959, aged just 18-years-old, he auditioned for the National Opera in Mexico City as a baritone, and was told by the impressed jury that he was not really a baritone and should be tackling tenor roles — so began a celebrated and distinguished career. Now things have come full circle. But one can’t help feeling that the auditioning panel was in fact correct — Domingo was and is a tenor: the overall colour and bright ‘edge’ of his voice remain those of a tenor regardless of the register. However, whether this ‘project’ is a personal indulgence or a brave experiment, it is one which is fully justified by the musical outcome. Domingo told one recent interviewer, “After Boccanegra … I will probably say Amen.” Simon Boccanegra may spend the second half of the opera melodiously dying a drawn-out death by poisoning but, fortunately, Domingo does not yet sound ready to stop.

Claire Seymour

Click here for audio clips of this performance.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Domingo_Boccanegra_ROH_2010.gif image_description=Plácido Domingo as Simon Boccanegra [Photo by Catherine Ashmore courtesy of The Royal Opera] product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Simon Boccanegra product_by=Simon Boccanegra: Plácido Domingo; Amelia: Marina Poplavskaya; Gabriele Adorno: Joseph Calleja; Jacopo Fiesco: Ferruccio Furlanetto; Paolo Albiani: Jonathan Summers; Pietro: Lukas Jakobski. Conductor: Antonio Pappano. Royal Opera Chorus. Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Director: Elijah Moshinsky. Costume Designer: Peter J. Hall. Royal Albert Hall, London. Sunday 18th July 2010. product_id=Above: Plácido Domingo as Simon Boccanegra [Photo by Catherine Ashmore courtesy of The Royal Opera]Opera’s Brigadoon — OTSL’s 2010 Season of the Sublime

For just over a month, Opera Theatre of St. Louis turns the gardens on the campus of Webster University into a paradise for opera-lovers, a place where musical integrity and dramatic innovation both bloom apparently overnight.

The 2010 season opened with a production of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro which played to the company’s strengths — namely, gifted young singers singing in the vernacular of their audience in an intimate setting. In James Robinson’s appealing and generally well-cast staging, the domestic dysfunction within the Almaviva estate illustrated the larger social concern of violence between the upper and lower classes. The clever new translation by Andrew Porter contained several genuinely funny moments and the singers put the text across well.

Jamie Van Eyck as Cherubino

Jamie Van Eyck as Cherubino

Heading the talented cast was Christopher Feigum as Figaro. Judging by his

successes in the past two seasons, Feigum was born to play this character. Not

only was his barber canny as well as caring, he also communicated the sense of

masculine competition between servant and master in both “Se vuol

ballare” and an intense stare-off with the Count leading into the wedding

procession.

Edward Parks as the Count and Amanda Majeski as the Countess

Edward Parks as the Count and Amanda Majeski as the Countess

The counterpart of Figaro’s tension with the Count should be physical

chemistry with his bride-to-be. As her elegant and moving performance in the

role of Marie Antoinette in John Corigliano’s The Ghosts of

Versailles illustrated, Maria Kanyova is an extremely compelling singer

and actress. She is not, however, a born soubrette and it was disappointing to

see her in a role that did not showcase her talents as well as triumphs of

seasons past. Her Susanna seemed worried too often and acted as Figaro’s

magician’s assistant than his equal partner. Still, the final phrases of

“Deh, vieni” were enchanting and I look forward to hearing Kanyova

again.

In the roles of the Count and Countess Almaviva, Edward Parks and Amanda Majeski were as well-suited to their respective parts as they were well-matched as a couple. Parks imbued his Almaviva with a vanity that complemented his violent tendencies and the moment he took to compose himself after “Hai già vinta la causa” was perfection. As his wife, Majeski conveyed preternatural musical maturity with her carefully molded phrases and exquisite control over her voice. Her face was as lovely and expressive as her singing and one could almost see the memory of young Almaviva serenading his Rosina cross her face as she listened to Cherubino’s canzonetta.

Jamie Barton as Marcellina, Maria Kanyova as Susanna, Christopher Feigum as Figaro, and Matthew Lau as Doctor Bartolo

Jamie Barton as Marcellina, Maria Kanyova as Susanna, Christopher Feigum as Figaro, and Matthew Lau as Doctor Bartolo

As the page, Jamie Van Eyck delivered said canzonetta with hormonally charged urgency. Also among the excellent supporting cast were Jamie Barton, Matthew Lau, and Matthew DiBattista. The trio took evident (and infectious) pleasure at being onstage both individually and as a group. Bradley Smoak was rather young for the role of Antonio, but his transformation from inept drunkard to the persnickety Floor Manager he played in Peter Ash’s The Golden Ticket was impressive. As his daughter, Elizabeth Zharoff showed much promise, even if her Barbarina came across as more dull-witted than young. John Matthew Myers delivered one of the evening’s best punchlines as a deadpan Don Curzio.

For the first half of the opera, a large crack in the wall and floor physically represented the discord within the household. Bruno Schwengl provided charming sets and costumes, with the exception of a singularly ugly garden for Act IV. Both lighting by Christopher Akerlind and choreography by Seán Curran were exquisite. Stephen Lord, a relatively last minute replacement for Timothy Long, presided over members of the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra with his signature confidence and zest. The company’s Artistic Director James Robinson created several moments of amusing and innovative theater including staging during the iconic overture, a haircut given to Cherubino during “Non più andrai,” antics with a dress form, and multiple pairs of roving hands. The only moment that fell flat was the large tree that literally fell to the ground during the opera’s final moments.

As Madame Larina says in David Lloyd-Jones’ translation of Eugene Onegin, in real life there are no heroes or heroines. If that is true, then the opera is where we go to find them. As Tatyana in Kevin Newbury’s production of the Tchaikovsky opera for OTSL, Dina Kuznetsova performed with the vocal and dramatic presence of a true heroine. However, when we first encounter the character, Tatyana is a dreamy and impressionable girl. It was difficult to hear Kuznetsova’s full, womanly voice and remember she is an ingénue, especially as the mature Tatyana appeared in the opening moments of this staging, gazing upon a portrait of her younger self from the summer she met Onegin. This early revelation robbed the audience of the Pygmalion moment in Act III, when Tatyana has established herself in St. Petersburg as a woman of significant reserve and social standing.

Because the staging focused so much upon Tatyana, the role of Eugene Onegin seemed strangely underdeveloped. Little was done to answer the perturbing questions about Onegin’s nature and, as his primary characteristic appeared to be moral ambivalence, it was easy to feel ambivalent about the man himself. In the title role, Christopher Margiera’s fine singing and strong musical presence were best utilized in moments of ensemble, such as the gorgeous quartet in Act I. As Tatyana’s sister Olga, Lindsay Ammann was appropriately kittenish and her fair coloring contrasted beautifully with Kuznetsova’s dark hair. In the role of Olga’s paramour Vladimir Lensky, Sean Panikkar sang with an ardency and tenderness that left you wishing you were Olga (at least for the first act). His aria comprised of some of the most musically satisfying moments of the entire season.

Sean Panikkar as Lensky and Lindsay Ammann as Olga

Sean Panikkar as Lensky and Lindsay Ammann as Olga

In the supporting roles of Madame Larina and Filipyevna, Gloria Parker and

Susan Shafer each performed with a winning mixture of strength and softness.

Andrew Drost’s Monsieur Triquet was a perfect complement to his turn as

Augustus Gloop in The Golden Ticket. For both roles, Drost drew on his

considerable musical finesse and physical elegance to great comic effect.

Christian Van Horn, an OTSL favorite, was a young but dignified Prince

Gremin.

As the first peasant, Jeffrey Hill led a chorus of very well-prepared, organized, and happy peasants. In particular, the girlishness of the women’s chorus was used effectively to underscore Tatyana’s brooding nature. Conductor David Agler led the cast and orchestra in a performance memorable for its musical integrity from start to finish.

The sparse wooden sets designed by Allen Moyer, although attractive, did little to illustrate the scope of the Larin estate or to differentiate between the provincial and St. Petersburg interiors. That said, the minimalist horizontality provided a perfect frame for the bleak moments of Lensky’s aria and the subsequent duel. Moreover, the transition from exterior to interior for the party scene was a little piece of theatrical magic. Martin Pakledinaz’s handsome costumes were enhanced by Tom Watson’s especially naturalistic and effective hair and makeup.

To the company’s credit, it is nearly impossible to assess two of the four festival productions without considering the other two. Each staging complements the others and the young artists (both onstage and off) benefit from this cross-pollination as much as the company’s devoted followers. By the end of the season, it is hard to imagine the gardens empty and the theater fallen silent. Then, like Brigadoon, it all is gone. Luckily for us, we don’t have to wait 200 years for the next season of enchantment.

Alison Moritz

Marriage of Figaro

Figaro, servant to Almaviva: Christopher Feigum; Susanna, Rosina's maid and Figaro's intended bride: Maria Kanyova; Doctor Bartolo: Matthew Lau; Marcellina, his housekeeper: Jamie Barton; Cherubino, page to the Countess: Jamie Van Eyck; Count Almaviva: Edward Parks; Don Basilio, music master to the household: Matthew DiBattista; Rosina, Countess Almaviva: Amanda Majeski; Antonio, gardener and uncle to Susanna: Bradley Smoak; Don Curzio, lawyer: John Matthew Myers; Barbarina, Antonio's daughter: Elizabeth Zharoff; Two peasant girls: Rebecca Nathanson and Irene Snyder. Conductor: Timothy Long, Gregory Ritchey (June 16); Stage Director: James Robinson. Set and Costume Designer: Bruno Schwengl. Choreographer: Seán Curran. Lighting Designer: Christopher Akerlind.

Eugene Onegin

Tatiana, daughter of Madame Larina: Dina Kuznetsova: Olga, her sister; Lindsay Ammann: Madame Larina; Gloria Parker; Filipyevna, the family’s old nurse: Susan Shafer; A Young Peasant: Jeffrey Hill; Vladimir Lensky, a poet: Sean Panikkar; Eugene Onegin, a friend of Lensky: Christopher Magiera; A Captain: Adrian Rosas; Monsieur Triquet, an old friend of the Larina family: Andrew Drost: Zaretsky, a retired officer: Aubrey Allicock; Guillot, Onegin’s valet: Nick Fitzer; Prince Gremin: Oren Gradus. Conductor: David Agler. Stage Director: Kevin Newbury. Set Designer: Allen Moyer. Costume Designer: Martin Pakledinaz. Choreographer: Seán Curran. Lighting Designer: Christopher Akerlind.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/11Onegin01.png image_description=Dina Kuznetsova as Tatiana and Christopher Magiera as Onegin [Photo by Ken Howard courtesy of Opera Theatre of Saint Louis] product=yes product_title=Opera’s Brigadoon — OTSL’s 2010 Season of the Sublime product_by= product_id=Above: Dina Kuznetsova as Tatiana and Christopher Magiera as OneginAll photos by Ken Howard courtesy of Opera Theatre of Saint Louis

July 19, 2010

Meistersinger at the Proms

Bryn Terfel sings his first Hans Sachs this season. Anything Terfel appears in will elicit ecstatic praise because he’s a national hero. He’s iconic, but you don’t have to be Welsh or British to adore him. His sheer presence made Prom 2 unmissable, even for those new to Wagner. A good introduction to the composer and his music.

Terfel was, of course, magnificent. Hans Sachs is an ideal vehicle for his talents. Terfel’s forceful timbre suits the “public” Hans Sachs, revered Meistersinger and shaper of public opinion. The Meistersingers represent civic pride and power: Wagnerian singing is often cursed by “park and bark”. Fortunately Terfel realizes that there’s a lot more to Sachs than public persona. Sachs is a poet after all, and a shoemaker — solitary professions, unlike being a Town Clerk. Notice how Wagner keeps Sachs in relative reserve until Act One, Scene Three.

Terfel’s finest moments thus came in moments where Sachs is on his own, in his workshop, relating to others one to one. “Was duftet doch der Flieder” let Terfel sing quietly. Declamation isn’t Sachs’s style. Terfel’s “Wahn! Wahn! Überall Wahn!” could have had more world-weary pathos, and more delicacy on words like “Der Flieder”. The Elder tree after all, is critical to the whole opera, for it means new growth, just as Walther von Stoltzing brings new ideas to the Meistersingers. Johannesnacht is Hans Sachs’s name-day, to men of his time a potent symbol. But perhaps I quibble, because the Proms reaches mass audiences. Better that Terfel inspires audiences to listen more and discover Wagner in their own time.

Terfel looks the part, physically overwhelming Christopher Purves’s Beckmesser. Terfel’s a big man, but he’s nimble on his feet when he has to be, dancing a merry jig around Purves. What a good idea to incorporate this detail from the full staging into concert performance! It’s invigorating. Sachs may be old, but he’s on the ball. That’s why he sees Walther’s potential.

This Beckmesser, though, easily stands muster against Terfel’s Sachs. Christopher Purves has a real gift for character singing. He moves about in quick, tense gestures, which amplify the acid-brightness of his singing. Beckmesser isn’t an outsider, he’s a Meistersinger and civic leader, an “insider” if there ever was one, obsessed with rules and status and keeping newcomers out. Purves’s Beckmesser is a fool, but too cheerful to be evil. His “songs” are done as amusing parody rather than grotesque. The harpist who really plays the tune of the lute make it sound quite beautiful in a quirky way.

There’s also a lot more to Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg than the nationalistic overtones shamelessly hijacked by the Third Reich. So much for their “respect” for Wagner. “Die heil’gen Deutsche Kunst” meant something completely different to Hans Sachs, living as he did during the Reformation, when Germany was being torn apart in the struggle between Lutheran (German) and Catholic (Foreign) values. That’s why Sachs was interested in German identity.

Wagner was doing a Luther, too, trying to develop a new kind of music theatre, based on German tradition, as opposed to French and Italian opera. Germany didn’t exist as nation-state until 1871 — several years after Meistersinger was written. It was a concept with many positive aspects, supported by many for its modernizing potential. This makes the rise of the Third Reich even more troubling, for it is a paradigm of society.

Prom 2 Meistersinger reflected Sachs’s concept of Germania, not Hitler’s. In the WNO production, images of German cultural heroes through the ages are projected onto the stage, reminding us that “holy German art” goes back a thousand years and has produced men like Bach and Goethe. And Art is holy because of what it is, ultimately greater than nations.

Walther von Stoltzing is the real outsider in Nuremberg, having learned singing from nature, from birds in the woods (though he read Vogelweide, showing that he, too, knows tradition).. He’s an aristocrat but significantly declassé, a wanderer like Wagner himself. Because Germany was fragmented until very recently, Germany was full of wanderers, especially after the Thirty Years and Napoleonic wars. Wanderers recur throughout the Romantic genre. Stolzing symbolizes the new.

Raymond Very’s Walther is good, though not transcendentally luminous. The Prize Song is ravishingly beautiful, but Wagner shows how it develops through experience. Walther’s first effort isn’t great, but he meets Eva,. His art is created through love. When Very sings the words “Eva im Paradies”, his voice expands warmly, expressively.

Amanda Roocroft’s voice has mellowed and rounded out well. Even if she isn’t an ingénue, her Eva is very well realized. This must be one of the crowning moments in her career, immeasurably better than when I last heard her sing Eva nearly ten years ago. She was spirited, her voice agile and bright. Die Pognerin is too big a role for a babe, which makes casting tricky. Roocroft convinces through her voice. Arguably, Eva doesn’t have to be a teen. Magdelena (Anna Burford) is older than David, but she appreciates Walther before he does.

The real discovery in this production is Andrew Tortise’s David. He’s wonderful. Tortise’s huge Act One Scene one arias are a tour de force, but Tortise sustains the inner logic through the different stages, pacing himself carefully. On top of this, he acts well, too, a fresher, more impudent Walther in the making. It’s an intelligent characterization, because under the comic surface of the role, David is a powerful figure. Wagner doesn’t write so much for the role for nothing. Like Walther, David is part of the future. Tortise has impressed me several times before in minor parts. Now, with this superb David, Tortise is the future, too.

Brindley Sherratt’s Pogner is authoritative as befits someone of his experience and stage personality. Pogner is a more troubling figure than most productions express, because Sherratt makes him sound so firm. Why is he giving his daughter away, against her will, ostensibly for the sake of art? Can people be traded for abstract ideas? Therein lies one of the dark secrets in this opera.

If art must be controlled through guilds and conformist rules, is it art? Are rules a means of suppression, or bulwarks against dissolution. Implicitly, in the background lurks the idea of a world in constant transition, where standing still means falling back. Perhaps this is why Meistersinger attracts the Far Right, though there’s a lot in it to appeal to the Far Left as well. This set of Meistersingers sang pleasantly, but only Sherratt’s Pogner hinted at more unpleasant levels.

Also very impressive was David Soar’s Nightwatchman — definitely a singer to listen out for.

The Chorus and Orchestra of Welsh National Orchestra, conducted by Lothar Koenigs, supported the performance solidly. Any performance at the Proms generates its own excitement, which creates an aura of wonder that’s hard to resist. I had a good time, though on purely musical terms this Prom wasn’t a match for other great Meistersingers, though it will be fondly remembered by English-speaking audiences. Nonetheless, the Proms aren’t about perfection. They’re there to get people stimulated, so they have a good time and go on to hear more. Beckmesser values don’t apply.

The Proms are the “Biggest music Festival in the World”, now in its 116th season. BBC Proms 2010 can be heard live, and internationally broadcast live, online and on demand. Please follow this link for more information.

Anne Ozorio

Click here to listen to audio clips of this performance.

Click here for Jim Sohre’s review of this production performed at Cardiff.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Meistersinger_Act3.png

image_description=Act III from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Ferdinand Leeke)

product=yes

product_title=Richard Wagner: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

product_by=Walther von Stolzing: Raymond Very; Eva: Amanda Roocroft; Magdalene: Anna Burford; David: Andrew Tortise; Hans Sachs: Bryn Terfel; Sixtus Beckmesser: Christopher Purves; Veit Pogner: Brindley Sherratt; Fritz Kothner: Simon Thorpe; Kunz Vogelgesang: Geraint Dodd; Konrad Nachtigall: David Stout; Ulrich Eisslinger: Andrew Rees; Herman Ortel: Owen Webb; Balthasar Zorn: Rhys Meirion; Augustin Moser: Stephen Rooke; Hans Folz: Arwel Huw Morgan; Hans Schwarz: Paul Hodges; Nightwatchman: David Soar. Conductor: Lothar Koenigs. Prom 2, BBC Proms 2010. Royal Albert Hall, London. 17th July 2010.

product_id=Above: Act III from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Ferdinand Leeke)

July 18, 2010

Paul Groves shines in dizzying take on 'Tales'

By James M. Keller [The New Mexican, 18 July 2010]

With his new production of Jacques Offenbach's The Tales of Hoffmann, unveiled Saturday night at Santa Fe Opera, director Christopher Alden did not merely lay an egg; he laid a supersized soufflé that over the course of three and a quarter hours collapsed under its own weight.

Mahler’s 8th at Royal Albert Hall

Yet this First Night of the Proms underwhelmed to an extent that surprised, a state of affairs for which responsibility lay squarely at the door of the conductor, Jiři Bělohlávek. Whatever the strengths of the present Principal Conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra may be, they always seemed unlikely to lie in Mahler, and so it proved. Should a performance of this work turn out to be merely a pleasant enough experience, something has clearly gone awry. It was not even wrong-headed enough to interest in the sense that, say, Sir Georg Solti’s relentlessly hard-driven, unabashedly operatic recording might, although, almost paradoxically, in its soft-grained way, it perhaps stood closer to such a reading than to probing renditions by the likes of Jascha Horenstein, Dmitri Mitropoulos, Pierre Boulez, or Michael Gielen.

My first impression was favourable, Bělohlávek rendering Mahler’s counterpoint surprisingly clear, apparently placing the work in the tradition of the composer’s fifth symphony. Doubts soon set in, however. The first ‘slower’ section set the pace, or lack of it, for its successors. Mahler writes, following his a tempo indication, ‘Etwas (aber unmerklich) gemäßigter; immer sehr fließend.’ Instead of relative moderation and care always to flow, the music almost ground to a halt. This is not simply a matter of tempo, of course; vitality was lacking. Returning to the comparison with Solti, the solo quintet sounded too ‘operatic’, in an almost Italianate sense: Mahler for those who prefer Verdi, albeit without fire. Bělohlávek guided a clear enough course through the first movement, but the reading was very four-square, lacking in dynamism, and ultimately quite debilitating in terms of its sectional approach. The work’s structure needs to be brought out, but just as important to that is the unity of the movement and indeed of the symphony as a whole. And so, the ‘Accende…’ music, exciting in itself, did not seem to come from anywhere. Moreover, the orchestra was underpowered — indeed, surprisingly small: just sixteen first violins down to eight double basses. The strings, especially during the first part, often sounded scrawny and there were uncomfortably shrill moments from the woodwind. There was, however, some splendid duo work towards the end of the movement from the kettledrums, and the presence of the Royal Albert Hall organ (Malcolm Hicks) was throughout impressive, almost violently so at times. Choral singing was here and elsewhere very fine indeed, undoubtedly the saving grace of the performance. Applause marred the conclusion of this first part.

The opening of the second part flowed but lacked mystery — at least until the sounding of beautifully grave horns, followed by shimmering violins: a passage to savour. The brass section was resplendent, yet it was impossible to overlook the general lack of depth to string tone. Mahler’s music needs to resound as if hailing from the bowels of the earth, not as if it were a thin layer of turf lain on the surface. Matters improved, however, once the chorus re-entered, and the echo effect was unusually impressive: not easy, with these forces. Hanno Müller-Brachmann was a typically thoughtful, beautiful-toned Pater Ecstaticus, and Tomasz Konieczny more or less followed suit, if hardly de profundis, as Pater Profundus. Stephanie Blythe stood out amongst the female soloists: a mezzo, but with hints of an earth-mother contralto. Stefan Vinke was a very late substitute for the indisposed Nikolai Schukoff as Doctor Marianus. He sounded a little nervous to start with, but grew into the part, though without the virility that so impressed me when I saw him in Leipzig as Lohengrin and Parsifal. (Doubtless the size of the hall has something to do with it too, but if ever there were a Royal Albert Hall work, it must be this.) Twyla Robinson improved dramatically as Una Poenitentium, the words of her first stanza indistinct, diction much superior thereafter, and with a glorious tone in conclusion: ‘Vergönne mir, ihn zu belehren, noch blendet ihn der neue Tag!’ Choral singing was once again of a very high standard; I was especially taken by the lovely tone of the Chorus of Blessed Boys as they circled (at least in one’s imagination).

The conductor, however, continued to let the side down. Thematic links with the first part were clearly brought out, but that was one of the interpretation’s few virtues. (In any case, the connections are pretty difficult to miss!) Orchestral heft was simply lacking; for much of the time, Bělohlávek sounded as though he would have been more at home with Mendelssohn or, at a push, Schumann. The latter’s Scenes from Goethe’s Faust might have responded better to such treatment, though I fear that that work would have lacked fire too. Slow passages dragged and accelerations sounded arbitrary. There were some beautiful instrumental moments, for instance the sound of strings, harps, and harmonium as Mater Gloriosa floated into view, but again this was too much of a slow section in itself, preceded by an inordinately distended and downright sentimentalised ‘Jungfrau, rein im schönsten Sinne…’ from Doctor Marianus and chorus. It was again the latter that shone in the final Chorus Mysticus: beautifully sung, but that is not nearly enough. A performance of this work that fails to grab one by the scruff of one’s neck is barely a performance at all.

Mark Berry

Click here to listen to this performance.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/gustav_mahler.png image_description=Gustav Mahler product=yes product_title=Gustav Mahler: Symphony no.8 in E-flat major product_by=Mardi Byers (soprano, Magna Peccatrix); Twyla Robinson (soprano, Una Poenitentium); Malin Christensson (soprano, Mater Gloriosa); Stephanie Blythe (mezzo-soprano, Mulier Samaritana); Kelley O’Connor (mezzo-soprano, Maria Aegyptica); Stefan Vinke (tenor, Doctor Marianus); Hanno Müller-Brachmann (bass-baritone, Pater Ecstaticus); Tomasz Konieczny (bass, Pater Profundus). Choristers of St Paul’s Cathedral (chorus-master: Andrew Carwood); Choristers of Westminster Abbey (chorus-master: James O’Donnell); Choristers of Westminster Cathedral (chorus-master: Martin Baker); BBC Symphony Chorus (chorus-master: Stephen Jackson); Crouch End Festival Chorus (chorus-master: David Temple); Sydney Philharmonia Choirs (chorus-master: Brett Weymark); BBC Symphony Orchestra; Jiři Bělohlávek (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, Friday 16 July 2010. product_id=Above: Gustav MahlerDarkness Visible: Dowland and beyond

Taking the music of the enigmatic and complex figure, John Dowland — lutenist, actor, Elizabethan diplomat and suspected spy — as its starting point and impetus, the programme explored some of the many transformations of Dowland, revealing the performers’ innate understanding of the myriad ways in which words and music ‘speak’ to their audiences.

Even the most simple and ‘straightforward’ of Dowland’s own lute songs and airs are rarely without courtly sophistication and ironic conceits, and while the opening song, ‘Away with these self-loving lads’, relates a folky narrative reminiscent of pastoral comedy, the alternations between music and declamation, forward momentum and dramatic pause, reminded us of the theatrical context of many of the first performances of these songs. ‘O sweet woods’ demonstrated the creamy lyricism of Padmore’s tenor, floating and ethereal in the higher registers, firm and centred, even warmly earthy in the lower regions. A rhythmic strength and flexible control of tempo was apparent in ‘Come again, sweet love doth now invite’.

Political intrigue — shrouded in a coded language of betrayals and reprisals — underpins Dowland’s ‘If my complaints could passions move’, as a melancholy lover’s abstract address to an absent Love, masks a very specific entreaty to Elizabeth I on behalf of Dowland’s patron, the Earl of Essex, for an end to exile and a re-admittance to the court and to the Queen’s heart. Employing ornament both for exquisite melodic effect and to highlight textual nuance, Padmore’s earnest entreaty, ‘Yet thou dost hope when I despair,/ And when I hope, thou mak’st me hope in vain’, would surely have moved any regal sensibility; while an unaffected lightness added a gentle poignancy to the avowal, ‘That I do live, it I thy pow’r:/ That I desire it is thy worth’.

Britten drew upon this melody in his Lachrymae for solo viola; after much fragmentation and development, the theme is sonorously sounded in the piano bass in the final moments, establishing a destination for the unfulfilled searching of the preceding bars. Widely regarded as one of the foremost viola players in the world, Lawrence Power created an heightened intimacy which recalled the contexts of the original Elizabethan performances. With melancholy tenderness, Power conveyed the restless tension at the heart of Britten’s lament, the veiled ending astonishing for its delicate restraint.

Returning to Dowland himself, Kenny’s and Padmore’s powerful rendition of the mournful, solipsistic ‘In darkness let me dwell’, brought the first part of this concert to a close; but no focus or intensity were lost during the interval, as proceedings recommenced seamlessly, opening with Thomas Adès’ piano work, Darknesse visible, a reinterpretation of Milton’s poem, played with supreme musicianship by Andrew West. West appreciated both the architectural lucidity of Adès’ eerie composition — creating exquisite spatial forms from the contrasting registers and textures of the weaving contrapuntal lines — and its troubled beauty, placing just the right emphasis on pungent dissonances and the interplay of sound and silence, anger and restraint.