August 31, 2010

Scottish Opera may survive and thrive as a smaller and leaner part-time company

By Alan Rodger [Herald Scotland, 31 August 2010]

Michael Tumelty’s trenchant criticism of the decision to reduce the orchestra of Scottish Opera to half-time working is high on anger and suggestions of mischief (“Hang your head in shame, Scottish Opera, you are a disgrace to the nation”, Herald Arts, August 28).

August 30, 2010

Salzburger Festspiele: Triumph jenseits von Dur und Moll

Walter Weidringer [Die Presse, 30 August 2010]

Die Berliner Philharmoniker unter Simon Rattle triumphierten mit Schönberg, Webern und Berg. Mit solch beredtem Ausdruck erfüllten die Berliner auch die bewegenden Totenklagen von Weberns.

Krisen und Triumphe: Jonas Kaufmann erinnert sich

[Focus, 30 August 2010]

Dies war der Fall nach seinem Debüt an der legendären New Yorker Metropolitan Opera in La Traviata im Februar 2006. Die Erinnerungen daran (Meinen die wirklich mich?) lässt ihn an die Anfänge seiner Karriere in Deutschland in der Provinz, aber auch an persönliche Krisen zurückdenken. Aber wenn eine große alte Dame der Opernkunst wie Christa Ludwig meint, nachdem sie Kaufmann zum ersten Mal gehört hat, das ist ganz große Kunst, dann lässt das aufhorchen.

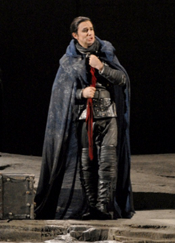

Puccini’s Edgar at the Teatro Regio Torino

But opera companies have another strategy as well — to resurrect/rehabilitate forgotten works of proven masters. For Giacomo Puccini, the main beneficiary among his lesser-known operas has been La Rondine, a slight work with a mostly gorgeous score that has enjoyed a growing number of performances in recent years. Puccini’s extremely negative recorded comments on his first full-length opera, Edgar, seem to have kept the inquisitive away. The chief revelation of this 2008 Teatro Regio Torino staging of the full four-act Edgar is how right Puccini was to dismiss the work as hopeless. That does not mean, however, that the resulting DVD isn’t of interest. With strong male leads and a colorful, handsome staging by Lorenzo Mariani (with costumes and sets by Maurizio Balò), this Edgar makes for a mostly entertaining show.

After the initial failure of Edgar, Puccini convinced his publisher to find him another librettist than Ferdinado Fontana, indicating the theatrical sharpness that would guide the creation of the composer’s masterpieces to come. For Fontana, as judged by Edgar, was a hopeless librettist — narratively sluggish and prone to lumbering attempts at flights of poetry that never leave the ground. The opera’s basic story bears a strong resemblance to that of Wagner’s Tannhäuser — a young man can’t choose between a woman who excites him physically (Tigrana) and a more innocent woman who touches his heart (Fidelia). Fontana attempts a sort of love rectangle with the addition of Frank, another admirer of Fidelia who ends the opera at Edgar’s side, helping to restore Edgar’s reputation after his dalliance with Tigrana and flight to the army has led him to fake his own death. The story veers between being oppressively obvious and elliptically obscure. Later Puccini works would show the composer comfortable with sharp changes of mood and place between acts that require an audience to “catch up” with the story. That strategy doesn’t work here because the characters in Edgar, hobbled by Fontana’s verse, haven’t made a claim on the audience’s involvement.

José Cura’s portrayal of Edgar gains strength as the character darkens; the callow youth of the opening scene doesn’t fit him as well. The voice is as idiosyncratic as ever, with lines of forceful energy interspersed by unfortunate growls and yelps for high notes. A less charismatic tenor might sing the entire role better, but really only a stage animal like Cura has a chance of making the character believable at all. Cura is well-partnered in several key scenes by Marco Vratogna’s Frank, a very masculine and credible rival and, later, friend of the hero. Frank has a brief solo early on and not much of interest to sing after that, but Vratogna manages to hold his own anyway.

The two key female roles are less happily cast. Julia Gertseva has no choice but to ham up the overtly sexual, murderously jealous Tigrana. She is at least fun to watch and sings with attractive tone. As Fidelia, Amarilli Nizza never recovers from a long opening scene where her soprano sounds overly mature and strained. She does somewhat better in the last act, but her character’s passivity has long wore out her welcome by then.

Although the full blossoming of Puccini’s melodic talent was yet to come, much enjoyable music can be found in the score. Unfortunately, conductor Yoram David and the Torino forces sound tentative and undernourished. Be prepared, by the way, in the fourth act (discarded fairly early on by Puccini) to hear a great deal of the last act duet between Tosca and Cavaradossi.

Strangely, Richard Eckstein’s booklet essay ends abruptly with an ellipsis. Before that sudden conclusion, the writer covers the errant history of the opera satisfactorily. The Blu-Ray edition does a great job of presenting the bold colors and designs of the set and costumes. Only historical accuracy can explain the bizarre helmet of crow feathers Vratogna’s Frank and other soldiers have to sport in the third act.

Put the disc in your player expecting no more than some occasional patches of fine music and a great deal of insight into the early stages of Puccini’s career, and this Edgar will justify its existence.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/101378.gif

image_description=Giacomo Puccini: Edgar

product=yes

product_title=Giacomo Puccini: Edgar

product_by=Edgar: José Cura; Fidelia: Amarilli Nizza; Tigrana: Julia Gertseva; Frank: Marco Vratogna; Gualtiero: Carlo Cigni. Conservatorio “Giuseppe Verdi” di Torino Boys’ Choir. Torino Teatro Regio Boys’ Choir. Torino Teatro Regio Chorus and Orchestra Yoram David, conductor. Lorenzo Mariani, stage director. Maurizio Balò, set and costume design. Christian Pinaud, light design. Recorded live from the Teatro Regio Torino, 2008.

product_id=ArtHaus 101378 [Blu-Ray]

price=$32.99

product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/B002JP9HIU

August 29, 2010

Brahms: Lieder

Her sense of style is apparent from the start of the recording, with a spirited reading of “Bei dir sind meine Gedanken,” and Vignoles sensitive accompaniment supports Fink well. The nuances of musical phrasing fit well into the poetic lines, as it should be, and that, perhaps is one of the best things to say about this recording of range of Brahms’s Lieder. The “Sapphische Ode” is telling for the understated simplicity Fink offers in allowing the lines to emerge effortlessly, and with that the accompaniment comes to the fore readily. This is chamber music in the best sense, as one player hands off the line to the other, with Fink’s phrases intersecting with Vignoles, and Vignoles leading nicely to the continuation of the vocal line.

Such interplay is particularly noticeable in “Von ewiger Liebe,” with its two-part structure juxtaposing the somber opening with the affirming conclusion, a transformation that is supported by the metric change, from 3 / 4 to 6 / 8. The valediction at the conclusion suggests the kind of intensity Mahler would create in his setting of Rückert’s “Um Mitternacht.” This calls to mind the more sustained mood of this song, which Fink and Vignoles deliver with conviction, The rhythmic interplay and the vocal inflection combine well in the execution of this piece, along with the other songs in the selection.

The pieces are from various sets of Lieder that Brahms composed at various times in his career, and this results in a useful overview of the composer’s efforts in this genre. At the same time, the in wide selection requires the performers to be sensitive to the details that set the pieces apart from each other, and they meet that challenge well. The early “Liebestreu” from his Opus 3 set is effective, as are later compositions, such as “Der Jäger” (Op. 95) and “Das Mädchen spricht” (Op. 107). Throughout the recording Vignoles offers a solid and nuanced accompaniment that not only supports Fink, but also suggests the kind of partnership essential to Lieder and particularly necessary in the contributions of Brahms. The other choices from Brahms’ approximately 200 Lieder include some pieces that are heard less often, yet fit Fink’s voice quite well, like “Der Gang zum Liebchen,” while the familiar ones, like Brahms’s famous lullaby, “Wiegenlied,” is fresh and fitting, especially as the final selection on the CD.

In this Harmonia Mundi recording, the sound is sympathetic to the repertoire, with a warm resonance that lets the voice and piano work well. The result is an exemplary studio recording of Lieder which, at the same time, offer the immediate sound associated with live recitals. In addition, the booklet that accompanies the recording is conceived well, with the full texts and translations of each of the Lieder complemented with a brief essay by Walter Rösler. These elements of the CD support the excellent performances found in this recording my mezzo-soprano Bernarda Fink and pianist Roger Vignoles.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Fink_Brahms.gif

image_description=Brahms: Lieder

product=yes

product_title=Brahms: Lieder

product_by=Bernarda Fink, mezzo-soprano. Roger Vignoles, piano.

product_id=Harmonia Mundi 901926 [CD]

price=$21.98

product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/B000L439ZI

Prom 51, Royal Albert Hall, London Tête à Tête Festival, Riverside Studios, London Così fan tutte, Village Underground, London

By Anna Picard [The Independent, 29 August 2010]

Gothic sensibility permeated the Royal Albert Hall on Monday evening: euphoric, melancholic, sun-dazzled and moon-drunk.

BBC Prom 54; La fanciulla del West; Joyce DiDonato; Simon Keenlyside; Kronos Quartet

By Fiona Maddocks [The Guardian, 29 August 2010]

Driven and obsessive, drawing on 1970s jazz funk, soul and gospel, Mark-Anthony Turnage's new BBC Proms commission Hammered Out burst noisily upon the world at Thursday's world premiere conducted by David Robertson. A scrunchy havoc of whip, sleigh bells, saxophones, bass guitar, as well as the full forces of the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the Nibelung note of a household hammer for good measure, bashed, danced and whirled through this 15-minute non-stop toccata.

David McVicar’s Salome

To the left is a large manhole cover, under which Jochanaan fulminates; to the right is a spiral staircase, lit by a harsh moon.

It is easy to see why the director, David McVicar, would be attracted to this rehistoricizing. Suddenly the little ghost-waltz that accompanies Salome near her entrance (“Ich will nicht hineingehn”) becomes something like diegetic music; the extreme cruelty of much of the action becomes institutionalized as state policy; and we may recall, with a slight shiver, that Strauss’s only recordings as a opera conductor are of fragments from two 1942 performances of Salome. On the other hand, the opera’s treatment of the disputatious Jews is unsympathetic, and the Nietzschean Strauss said that he regarded Jochanaan in particular as a clown; so McVicar skirts a dangerous area of interpretation, in which the Jews of the Third Reich might seem to deserve what they get. Possibly McVicar tried to avoid this by playing down the comedy of the disputation-fugue: the Jews look at one another like mildly peeved intellectuals.

Wilde regarded Salome and John the Baptist as occult twins, and even contemplated a sequel in which Salome, still alive after being crushed by the soldiers’ shields, put on a hair-shirt and started to preach the gospel of Jesus in the wilderness; eventually she would make her way to France and fall through the frozen Rhône—the ice would refreeze leaving only her head visible. Nadja Michael’s Salome is hectoring, brutal, unseductive—she is a sexual being only through sadism. She doesn’t cajole Narraboth into opening the cistern: she browbeats him, and even pushes him to the floor when he capitulates. Michael raves powerfully throughout the opera, and sings powerfully too, though she doesn’t always hit the correct notes, and there’s a distracting warble in her voice, almost the warble of 1940s pop singers.

Michael Volle’s Jochanaan is everything you could want: shirtless, dressed in a long drab Jewish coat with a phallic belt-dangle, he is a potent lunatic, uncontrolled in his gestures as he reels across the stage, but superbly controlled in his voice. When he sings of Herodias’ lovers—the young Egyptians in their delicate linen and hyacinth stones and golden shields and gigantic bodies—he writhes on the floor, as if he were caught up in some sexual trance at the thought of these beautiful young foreigners. This is how the production emphasizes the way in which Jochanaan and Salome are doubles: they are both obsessive-compulsives, obsessive-convulsives, mad with lust.

The unhappy aspect of this production is the Herod of Thomas Moser. Moser can make a handsome sound, but he’s a somewhat listless presence, loud but bland. Philippe Jordan, the brilliant conductor, makes the opera move like the wind (as all Strauss opera, particularly the schmaltzy ones, should move) except when Moser sings: then momentum is lost, perhaps owing to Moser’s flaccid, rhythmically inexact phrasing. His one impressive scene is a silent one, during Salome’s dance, here staged as a black-out scene in which Herod and Salome play together with a Salome-shaped doll, a dress-maker’s dummy, a large dressing-mirror, and a long rack of dresses—it’s a lovely conceit, as Salome enters Herod’s fantasy-world of fetishes and idols, deflections of sexuality onto dead images. Wilde’s Salome was never anything much more than an image in a mirror: “She is like the shadow of a white rose in a mirror of silver,” Narraboth says, and in her dance she dances her way right into the glass that she, in some sense, never left.

Daniel Albright

image=http://www.operatoday.com/OABD7069D.gif image_description=Richard Strauss: Salome product=yes product_title=Richard Strauss: Salome product_by=Salome: Nadja Michael; Herodias: Michaela Schuster; Herod: Thomas Moser; Narraboth: Joseph Kaiser; Jokanaan: Michael Volle. The Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Philippe Jordan, conductor. David McVicar, stage director. Recorded live at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden on 3, 6, and 8 March, 2008. product_id=Opus Arte OABD7069D [Blu-Ray] price=$35.99 product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/B003LRQ0ZSAt Bard Festival, placing Berg at center of modern musical Vienna

By Jeremy Eichler [Boston Globe, 29 August 2010]

ANNANDALE-ON-HUDSON, N.Y. — The year in the photo is 1920. The great Viennese composer Alban Berg, 35 years old, stands at an open window of his Vienna home, gazing directly out at the camera yet also somehow beyond it. His face conceals like a mask. The breakthrough triumph of his first opera, “Wozzeck,’’ is five years in the unknowable future. We sense perhaps an air of reserved confidence, perhaps a tint of melancholy. But there is more to this picture.

August 28, 2010

Multimedia Opera Production to Debut at Roosevelt University

Chicago, IL, August 28, 2010 --(PR.com)-- On October 22, Roosevelt University will host a multimedia opera production composed and produced by Kyong Mee Choi, assistant professor of music composition in the university’s music conservatory and recipient of the prestigious Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship. The opera will be held at Ganz Hall, Roosevelt University, 430 S. Michigan Ave., at 7:30 p.m.

Opera San Jose plans 'gigantic' production for West Coast premiere of 'Anna Karenina'

By Richard Scheinin [San Jose Mercury News, 28 August 2010]

Future operatic soprano Jasmina Halimic discovered Leo Tolstoy's "Anna Karenina" as a schoolgirl in Bosnia. But it wasn't until years later -- after moving to the United States in 1994 -- that she really got it: Tolstoy's masterpiece became an Oprah's Book Club selection in 2004, and Halimic reread it while studying music in Indiana.

August 27, 2010

La fanciulla del West/L’Heure espagnole, Usher Hall, Edinburgh

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 27 August 2010]

By choosing Oceans Apart for his 2010 theme, Edinburgh International Festival director Jonathan Mills opened up fertile avenues for exploration in spoken theatre and classical music, while leaving little room for manoeuvre in opera. The obvious choice was Puccini’s wild west thriller La fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West). Premiered in New York 100 years ago and never previously heard in Scotland, it conjures a picture of the New World that, though seen through the eyes of a composer who had never experienced it, effectively captures the values of a frontier community.

Us and them is the cultural problem, not Pomp and Circumstance

By Lynsey Hanley [The Guardian, 27 August 2010]

There are more ways of divvying people up than according to how much money they've got. A survey this week by Reader's Digest concluded that a large proportion of Britain is culturally impoverished, with one-third of those surveyed never having listened to classical music and three-quarters unable to identify Edward Elgar as the composer of Pomp and Circumstance.

How we learned to start worrying and love Mahler

By Jessica Duchen [The Independent, 27 August 2010]

On Gustav Mahler's 11th birthday, the story goes, a family friend asked what he wanted to be when he grew up. "Jesus Christ," said the lad. To the astonished "Why?" he replied: "Because I want to suffer for other people."

Rolando's musical passion for home

[BBC, 27 August 2010]

The celebrated tenor Rolando Villazon is renowned for his exuberance when it comes to his beloved opera but he's equally passionate about the music of his Mexican homeland.

August 26, 2010

HGO to produce Wagner's massive Ring Cycle

By Everett Evans [Houston Chronicle, 26 August 2010]

Siegfried, Brünnhilde, Wotan and company are heading for Houston, as Houston Grand Opera prepares to tackle the Mount Everest of opera, Richard Wagner's monumental Ring Cycle.

Classique, opéra, danse : les temps forts de l'automne

Christian Merlin [Le Figaro, 26 August 2010]

L'Opéra de Paris lance sa rentrée en douceur, avec trois reprises de productions anciennes ( Le Vaisseau fantôme, de Wagner, L'Italienne à Alger, de Rossini, Eugène Onéguine, de Tchaïkovski): sans l'attrait de la nouveauté, on ira surtout pour les distributions, avec notamment la brillante Vivica Genaux dans les vocalises rossiniennes et l'immense Ludovic Tézier en Onéguine.

Unlocking the Mystery of Honegger

By Leslie Sprout [NY Times, 26 August 2010]

Arthur Honegger’s “Chant de Libération” was not a piece I intended to consult during a research trip to Paris in June 2009. Like others who knew of it, I thought the score was lost. Honegger had composed this song for baritone, chorus and orchestra in secret during the German occupation of France. Its only known trace was a tantalizing description of its October 1944 premiere in liberated Paris: a “triumph” by a “musician of the Resistance,” the music critic Maurice Brillant wrote.

The Sixteen/Christophers, Usher Hall, Edinburgh

By Rowena Smith [The Guardian, 26 August 2010]

The festival's New World theme has already offered up one baroque representation of the Aztec emperor Montezuma in Graun's opera seria - here it presented another in the form of Purcell's music for The Indian Queen. Dramatically, the play from which the music was taken seems to have been an unwieldy work. The outline synopsis runs to seven pages in the concert programme and contains more twists, turns, and complicated relationships than an entire basket of Handel operas - not in themselves known for either their concision or their plot rationality.

August 25, 2010

Mostly Mozart finale, Avery Fisher Hall, New York

By Martin Bernheimer [Financial Times, 25 August 2010]

The Mostly Mozart Festival ended on Friday with an only Mozart concert. It may have promised a bit more than it delivered, but it did end in a reasonable blaze of grandeur.

Opera Lover Targets Young Patrons With $25 Seats

By Erica Orden [WSJ, 25 August 2010]

At 80 years old, Agnes Varis is trying to make opera audiences younger. "Your average opera-goer cannot be 65—give me break," said Ms. Varis. "You're not going to keep an opera house alive with that."

August 24, 2010

Aspen makes Corigliano’s Ghosts classic

The Met production journeyed to the Chicago Lyric — and then the work disappeared. Happily, Ghosts returned to life a year ago when John David Earnest’ s revised and trimmed-down version was premiered by the St. Louis Opera Theater and then exported to Ireland for the festive opening of a new house in Wexford.

Still scored, however, for 60 singers and a full-sized orchestra, the demands made by Ghosts places the work beyond the reach of many professional companies, while making it a field day for student opera enterprises. Northwestern University staged the work last season, and a third totally new production by the Aspen Opera Theatre Center brought down the certain on the 63rd season of one of the nation’s major summer festivals late in August. Edward Berkeley, Juilliard mentor who has directed the Aspen Center for three decades, built the 2011 season around the figure of Figaro. Ghosts was preceded by both Rossini’s Barber of Seville and Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro, the first two parts of Pierre Beaumarchais’ 18th-century account of the Almavivas. (Northwestern staged the same “trilogy” during its past season.)

“Ghosts fits a festival well,” said Berkeley, who directed the production, seen on August 19 in Aspen’s historic Wheeler Opera House. “And in this context it gave students a look at how different composers treat the same group of characters.” “It also gave our audience a chance to compare how they have used the same material.”

Although the reduced version — with a single intermission it runs slightly less than three hours — contains enough plot and calls for singers sufficient for three operas, the Aspen staging made clear that Ghosts is a success now worthy of entering the standard repertory. The central figure of the story is Marie Antoinette, who 200 years after she was beheaded in the French Revolution, wants to return to life. In an opera-within-an opera the story moves back to 1793 and offers a complex picture of the Almaviva family, familiar from Rossini and Mozart.

For the libretto William M. Hoffman relied heavily on The Guilty Mother, the third part of Beaumarchais’s Figaro trilogy. But instead of merely re-writing the story Beaumarchais, author the original, becomes the central figure of Ghosts — author, director and major figure of the inner opera, in which he and the late Empress fall in love. Although it is still more opera than can be absorbed in a single performance, Ghosts is now effective and often moving theater. (Small wonder that one heard voices in the Aspen audience express the wish to see the work again.)

Top vocal honors in Aspen went to South-African soprano Golda Schultz, now a student at Juilliard, who sang Rosina. Her tender duet with Korean mezzo Chorong Kim, now — as Beaumarchais tells it — the loving father of Léon, was the highlight of the Aspen staging. As Beaumarchais, the man who makes everything move in Ghosts, tall and lean bass-baritone Andreas Aroditis, a further Juilliard student, was amazingly adept and versatile. Christin Wismann, cover for the role in St. Louis and a member of the supporting cast in Wexford, was a delicately tragic Marie Antoinette, an ideal object for Beaumarchais’ affection. As ill-intentioned Begéarss Julius Ahn, a regular with Boston Lyric Opera, was delightfully malicious in his Aspen debut. David Williams, a recent studio artist with Berlin’s Komische Oper, left one with a strong desire to hear him as the “real” Figaro, the role that he sang with such professional aplomb in the Aspen Ghosts. And Aspen provided him with a vivacious Susanna in Kim Sogioka, a mezzo with impressive credentials in the oratorio world. Tenor Michael Kelly, highly regarded as a song recitalist, sang an aristocratic — if dissolute — Count Almaviva, while Lauren Snouffer was thoroughly engaging as his illegitimate daughter Florestine.

Major credit for the success of Aspen’s Ghosts goes, however, to Michael Christie, who conducted both the St. Louis and Wexford performances of the revised score. Still in his mid-’30s Christie, now music director of the Phoenix Symphony, began his career as assistant to Franz Welser-Möst at the Zurich Opera. Earlier in the summer he identified himself as a future Wagnerian of promise in a concert with Jane Eaglen at the Colorado Music Festival in Boulder.

Conducting an orchestra that overflowed into the Wheeler Green Room, Christie’s total command of the score was impressive; he further showed that rare balance of concern for both singers and ensemble under his command. Handsome — and ghost-like — sets were by John Kasarda; lavish period costumes were the work of Marina Reti.

Finally, Ghosts could profit from further reduction. If excised, the entire scene built around Samira, the hoochie-cochie dancer at the Turkish embassy bash, would not be missed — even if this was the role on which Marilyn Horne squandered her talent at the Met.

Wes Blomster

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Figaro.gif image_description=Sketch of Figaro by Marina Reti courtesy of the Aspen Opera Theater Center product=yes product_title=John Corigliano: Ghosts of Versailles product_by=Aspen Music Festival 2010 product_id=Photos by Alex Irvin courtesy of Aspen Opera Theater CenterLes Enfants Terribles

By Andrew Clements [The Guardian, 24 August 2010]

In the 1990s, Philip Glass composed a trilogy of music-theatre pieces based on films by Jean Cocteau. His remarkable reworking of La Belle et la Bête was brought to London by the composer's own ensemble soon after the premiere, while the first and most conventional of the three, Orphée, was seen at the Linbury theatre five years ago. But Les Enfants Terribles, completed in 1996, has had to wait for its British premiere, impressively staged by the Volta theatre company as the last event in this year's Grimeborn season, east London's alternative summer opera festival.

A Globe-Spanning Musical Feast

By George Loomis [NY Times, 24 August 2010]

EDINBURGH — The Edinburgh International Festival has gone multicultural. In a sense, when the offerings of a festival number well over 100 and embrace opera, dance, drama, concerts and other categories, it might be hard not to. But the festival’s theme this summer, “oceans apart,” seeks to connect continents, and in a four-day visit, one could experience a number of events that did just that.

Jean Sibelius: Kullervo, Op. 7.

Derived from Finnish mythology, the movements depict major events in the life of the hero Kullervo and found in the epic the Kalevala. This five-movement works opens with an instrumental piece that sets the stage for idiom Sibelius would explore in the work, and the reading by conductor Ari Rasilainen is convincing. The breadth of timbre, the pacing of rhythm and the placement of the percussive accents at the dramatically appropriate points support the structure of the movement. The second movement is a depiction of Kullervo’s youth and is reminiscent structurally of a Scherzo. In this movement the chordal figures in the low brass evoke well an important element of the style associated with Sibelius’s mature symphonies. At the same time, some of the colors are typical of Sibelius, the extended lines in the clarinet interacting with strings and other sections of the orchestra.

In the third movement Sibelius leave Kullervo’s story to the suggestions of instrumental writing, but incorporates voices to clarify the narrative. Kullervo’s story resembles that of Siegmund and Sieglinde in Wagner's Die Walküre, except for its tragic consequences in the Kalevala when the hero realizes that he seduced his sister. His sister commits suicide, and Kullervo resolves to become a warrior, where he meets his own tragic fate. Here the male chorus relates the lays of the Kalevala with excellent diction, which sets up the exchanges between the solo voices that convey the dialogue between Kullervo and his sister. Sibelius punctuates the choral sections with appropriate figures in the orchestra, and Rasilainen does well to allow the forces to render the sometimes dense score with admirable clarity

Of the two soloists, Juha Uusitalo should be familiar to audiences from his recent international performances, including Wotan in Zubin Mehta’s recent Ring cycle in Barcelona (released on Blu-Ray). This recording of Kullervo captures Uusitalo at an earlier point in this career, since it is based on performances given between 13 and 15 December 2005. Uusitalo is persuasive here, with his sonorous voice emerging clearly; soprano Satu Vihavainen likewise delivered a fine performance, with those voices prominent in the third movement, where Sibelius used voices to bring out the dramatic core of Kullervo’s story. Voices are absent from the fourth movement, and Rasilainen does well here bring out the evocative music to continue Sibelius’s narrative as envision in this score. The chorus is part of the final movement, which depicts the Kullervo’s death, and the text serves as a fine valediction of the Finnish hero.

This is a work that reveals much about Sibelius’s development as a symphonist and at the same time stands well on its own merits through Rasilainen’s compelling interpretation. While Sibelius is known better for his instrumental symphonies, that should not detract from the merits of the Kullervo Symphony or the symphonic poems that include voice.

This fine CPO recording includes the texts and translations of the vocal music, and the Karin Kempken’s notes offer some good background on this fine work by Sibelius. The sound is clear and rich, without excesses that detract from the nicely voiced chords. Not the first recording of this important work, this release is a solid contribution to the discography of Sibelius.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kullervo_CPO.gif

image_description=Jean Sibelius: Kullervo, Op. 7

product=yes

product_title=Jean Sibelius: Kullervo, Op. 7

product_by=Satu Vihavainen, soprano, Juha Uusitalo, bass-baritone, KYL Male chorus, Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz, Ari Rasilainen, conductor.

product_id=CPO 777 196-2 [SACD]

price=$16.99

product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/B000IY0616

Glimmerglass Rarities Out-Score Hall of Famer

Handel’s little-performed Tolomeo was treated to an endlessly witty, constantly surprising — aw hell, let me say it — smasheroo production by the one of opera’s most imaginative directors, Chas Rader-Shieber. Sometimes he can be a bit too imaginative, it is true, as in St. Louis’s fussy Una Cosa Rara, where he seemed to be mistrustful of the material and hence created endless distraction from it.

Not so here, where Mr. R-S’s inventions not only underscored the characters’ emotional states and complemented the dramatic situation, but masterfully fleshed out a very very very (did I say ‘very’?) lean plot, rife with convoluted masquerades. Purists will carp that this serious (seriously boring?) dramatic material is not the basis for humorous interpretation. I say Chas has upended the static piece to its own benefit, and thrown the heart-aching moments into even higher relief.

Anthony Roth Costanzo as Tolomeo and Julie Boulianne as Elisa [Photo by Karli Cadel courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

Anthony Roth Costanzo as Tolomeo and Julie Boulianne as Elisa [Photo by Karli Cadel courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

That Glimmerglass has been challenged by the financial climate is evidenced

by the pleading recorded pre-show announcement in which music director David

Angus not only silences cellphones but solicits donations. Practically,

enforced austerity required that all the operas share the same basic scenic

environment, a big textured gray box in which doors, windows and structural

elements could be swapped out. In the case of Tolomeo set designer

Donald Eastman and the director turned this into a springboard for simple, well

chosen visual delights.

At rise, Tolomeo sings of the sea, but is contemplating the waters…in a fishbowl on a stand. As he sings of maritime perils, a stuffed shark descend from the flies. The director concocts a true star entrance for our hero by having him crouched behind the bowl, face distorted by the water until a musical swell occasions his standing upright so we can take full measure of our leading man. The shipwrecked Alessandro staggers on with half of a ‘destroyed’ toy boat in each hand, before he faints as the plot requires. Boat pieces get passed to Tolomeo and, in short order, to Elisa who takes charge of the situation by fusing the halves back together, re-appearing with the boat as an adornment incorporated into her wild henna wig (the excellent hair and make-up were by Anne Ford-Coates). This is not only clever entertainment, but underscored Elisa’s character in her entrance aria.

Carefully selected set pieces from an upper crust home of Handel’s time provided apt images and visual clarity: a richly set dining table; an armoire that contained appropriately changing images and, in one goof, a piece of colorful topiary that got unceremoniously schlepped out to decorate/punctuate a ‘garden’ moment; and a bed-cum-funeral-bier for Tolomeo. Chas added three extras to the ensemble in the form of mute, slightly doddering old men (Desmond V. and Julian A. Gialanella, Jack Loewenguth) who were almost omnipresent as they constantly adapted the environment by moving around various furniture elements. I will not soon forget the image of the ‘dying’ Tolomeo in his great aria, being drawn to, and languishing on the constantly circling bed. The image of serene repose achieved as the supers inched it into its final resting place just as the music concluded was stunning.

The lustful sexiness was heightened, too, with more leering machinations than on an average episode of The Bachelorette. The inspired finale found everyone getting prepped for a good tumble by stripping down to their skivvies, with even the villainous Araspe suddenly redeemed as he is overtaken by randy urges to shuck his red suit and join the partying. There were so many telling moments that it is impossible to include them all, but surely one of the loveliest effects was the placement of ordinary (period) oscillating room fans down stage to create the ‘breeze’ of which Seleuce sings, and which carried her scattered white tissue paper messages about the playing space. This theme was carried through with a small shower of red tissue paper as Tolomeo subsequently sings of his longing, and shortly thereafter, a cascading profusion of red from the flies as accompaniment to Seleuce’s haunting aria.

Joélle Harvey as Seleuce and Steven LaBrie as Araspe [Photo by Karli Cadel courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

Joélle Harvey as Seleuce and Steven LaBrie as Araspe [Photo by Karli Cadel courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

Lest I imply that clever effects were all there was, Mr.Rader-Shieber also showed a deft hand at creating meaningful subtext for his performers, and he beautifully judged interaction between the characters. It did not hurt that he had a superlative lot of singers at his disposal.

It is so gratifying to see how counter tenor Anthony Roth Costanzo has developed in only the two years since his Nireno in Julius Caesar here. Already then an artist of great promise, Mr. Costanzo had matured into an assured star on the verge of a major international career. He is possessed of an exceptionally clear, incisive timbre and his sure-fire, take-no-prisoners way with even the trickiest coloratura was thrilling. He does not shy away from some aggressively butch singing in the lower register, but it is in the upper reaches that he truly shines. His nuanced, deeply felt reading of his death aria held us spell bound. Although slight of stature, he nevertheless commands the stage with his committed physicality.

Joélle Harvey, too, has progressed remarkably since last I encountered her in Orpheus in the Underworld. On this occasion she was giving the kind of controlled, ethereal, affecting performance that had the intermission crowd asking “who is that fabulous soprano?” She has a limpid and technically secure lyric instrument which gives over easily to the plangent outpourings Handel asks of her. Ms. Harvey’s spot-on performance was the heart of the production, the emotional rock that grounded the proceedings. The celebrated echo section and duet with Tolomeo was a standout. although in one of the show’s only minor miscalculations, I wished the supers had butted out for the duration of that gorgeous set piece so we could have just reveled in its musical perfection.

I quite liked Julie Boulianne in last year’s Cenerentola but nothing about that performance prepared me for the brilliance of her Elisa. Ms. Boulianne still displayed a bit of covered vocal production and (just) decent fioriture in her first appearance, but immediately thereafter she caught fire and lavished us with sizzling vocal pyrotechnics all night. Moreover, she displayed a fiery and comically savvy stage presence throughout, greatly assisted by a wonderfully daffy costume — part tutu, part vamp, all Lady Gaga — from the talented costume designer Andrea Hood. Ms. Hood scored big with all of her ingenious creations, but Seleuce’s distressed, wilting, catty-wompers hoop skirt also greatly illuminated the character. And while I am on ‘illumination,’ Kelley Rourke’s diverse lighting design perfectly enhanced the scenic effects.

Young American Artists Steven LaBrie and Karin Mushegain more than held their own up against these three masterful portrayals. As the evil Araspe, Mr. LaBrie cut a handsome figure and is possessed of a ringing, rich lyric baritone. His assured portrayal never descended into cliche and he mined much humor from his chicanery. Ms. Mushegain has an ideal, dusky mezzo for the trousers role of Alessandro, and she reveled in her florid singing. Her stage demeanor was sympathetic and appealing.

The musical proceedings were masterfully helmed by conductor Christian Curnyn, who brought out much subtlety in Handel’s writing, phrased with his soloists as one, and displayed admirable pacing and theatrical drive. He was ably abetted by the sensitive playing from Ruth Berry (Continuo), Michael Leopold (Theorbo) and especially David Moody (Harpsichord).

Tolomeo was truly ‘Festival’ opera, a performance and production that would be at home on any world stage. Very close behind was a wholly engaging new production of Copland’s The Tender Land. If the all-Young Artist cast is any gauge, the future of operatic singing is very, very bright.

L to R: Joseph Barron as Grandpa Moss, Mark Diamond as Top and Andrew Stenson as Martin in The Tender Land [Photo by Karli Cadel courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

L to R: Joseph Barron as Grandpa Moss, Mark Diamond as Top and Andrew Stenson as Martin in The Tender Land [Photo by Karli Cadel courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

Let us immediately discount the fact that for the several character roles, the apprentices are simply and unavoidably too young. That said, I found Stephanie Foley Davis not only able to suggest a couple of decades of life experiences as Ma Moss, but also to sing it with a knowing richness of tone and musical authority that belie her years. This was a secure and memorable role assumption. Almost as successful was Joseph Barron in the (let’s face it) unsympathetic role of Grandpa Moss. Although the company wisely eschewed cheesy age make-up, the burly Mr. Barron nevertheless conveyed ample gravitas and seniority, and used his secure, authoritative bass-baritone to good effect. Mr. Splinters made the most of his crucial moments thanks to the pleasing baritone of Chris Lysack. In the small role of Beth Moss, Rebecca Jo Loeb made a fine impression with her totally committed, always consistent take on the young girl.

The Tender Land is Laurie’s journey of course, and who wouldn’t want to to make the trip with immensely gifted young soprano Lindsay Russell. Ms. Russell has all the goods for this deceptively simple role. She has the ‘heart’ in her ample lyric voice for the simple longings of “The World So Wide”, to be sure. But she also has the ‘ping’ and the moxie for the determined pronouncements in the opera’s climactic scena. Her instrument is uniform throughout, her musicianship is natural and clean, and her technique easily accommodates the often angular Copland writing. If she does not yet float a pianissimo quite as effortlessly as Dawn or Renee, rest assured, she will. Lindsay Russell is poised on the fast track to the major league.

Andrew Stenson’s pleasing tenor has just enough heft for the under-written role of the drifter Martin. He did all that was required dramatically, although somehow I felt there was more complexity to the role than could be found in Mr. Stenson’s hale-fellow-well-met approach. Still, it is not every day we enjoy a young artist with such a beautiful tone and with a reliable technique that is hooked up so well.

Stephanie Foley Davis as Ma Moss and Chris Lysack as Mr. Splinters (right) in The Tender Land [Photo by Claire McAdams courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

Stephanie Foley Davis as Ma Moss and Chris Lysack as Mr. Splinters (right) in The Tender Land [Photo by Claire McAdams courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

My bet on The-One-To-Watch is young Mark Diamond whose virile, buzzy baritone brought his every phrase as Top to vivid life, and whose intense, prowling stage demeanor was marked by a concentrated arc of dramatic conviction. From the moment Mr. Diamond appeared he commanded attention and admiration. Watch for him soon at an opera house near you.

Conductor Stewart Robinson not only conveyed his affection for the score in his pre-show talk, but more important he conducted it lovingly in the pit. The orchestra responded with secure, vibrant, sensitive Copland of the highest order. The Maestro ably supported his young artists, and he shepherded the great ensembles with elan that was tempered by clean control. I confess I am a sap for the unfolding tune and steady crescendo of “The Promise of Living” and the addition of the chorus to the soloists (with the Copland estate’s permission) was an affecting choice that should become the ‘standard.’ Most impressively, Robinson also guided the assembled forces through a tight and propulsive reading of “Stomp Your Foot”, never missing a beat even though the actors were simultaneously cleanly executing some simple but effective (and uncredited) choreography.

L to R: Rebecca Jo Loeb as Beth Moss, Lindsay Russell as Laurie Moss and Stephanie Foley Davis as Ma Moss in The Tender Land [Photo by Claire McAdams courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

L to R: Rebecca Jo Loeb as Beth Moss, Lindsay Russell as Laurie Moss and Stephanie Foley Davis as Ma Moss in The Tender Land [Photo by Claire McAdams courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

Perhaps the dance steps were just another part of the successful staging devised by director Tazewell Thompson, who served the naïveté of the homey story and the folksiness of the score with the creation of uncomplicated, straight-forward, clean-as-a whistle blocking that made for charming stage pictures as well as well-pointed confrontations. The ‘basic box’ set was somewhat adorned by the addition of two white clapboard walls fronting the sides and a ladder propped up stage right that afforded some use of levels as Top and others variously scrambled up and down. Otherwise, well-chosen set pieces and props, and imaginative directorial re-definitions of the playing space provided all that was required for The Tender Land to make its gentle points.

Smaller companies are usually at a disadvantage taking on a bread-and-butter staple such as Tosca. First of all, it is the stomping ground for very the biggest stars. We cannot help but come to the piece with echos of Caballe and Verrett and Nilsson and Pavarotti and Domingo and Milnes and MacNeill in our ears. On top of that, we have the ‘real-famous-Roman-sites’ visuals of Zeffirelli and Visconti and Pizzi in our eyes. And then there are the over-sized passions of the story and the thundering musical punctuations required from the sizable orchestration. Is there any opera in the repertoire that is laden with quite so many expectations? Given all that, it surprising that the competent Glimmerglass production succeeds as well as it does.

Adam Diegel as Cavaradossi and Lise Lindstrom in the title role of Tosca [Photo by Karli Cadel courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

Adam Diegel as Cavaradossi and Lise Lindstrom in the title role of Tosca [Photo by Karli Cadel courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

Certainly, Lise Lindstrom is a polished singer who has a good touch of steel

in her well-schooled soprano, which is admirably ‘present’ at all

extremes of the range. Ms. Lindstrom also commands some of the most secure,

laser-like high notes I have ever heard. She never

misses…B-flat…B…C…she could probably keep zinging

them out to the point only dogs can hear. What Lise does not yet have is an

Italianate delivery, rather seeming to be a very admirable Straussian caught in

the wrong opera. Nor is she helped by Matthew Pachtman’s beautifully

tailored but wrong-headed 1920’s gowns in silver, white and black. I

mean, Floria is not a black-grey kinda gal. She (and the production) cried out

for color, not only to mirror the seething emotional situations but also to

evoke the turmoil of a politically unsettled Rome. The diva would never ever

wear a white evening gown to sing a cantata in a chapel. Never. Here, Mr.

Eastman’s multi-use sets showed their limitations, functional to a point

but evoking neither time nor place, although Jeff Harris’s varied

lighting made some amends.

I wanted to love Adam Diegel’s Cavaradossi as much as the rest of the public seemed to, for his is an often thrilling pushed lyric sound with spinto leanings. However, I confess I feared for him in a way that I feared for Carrerras when I heard him do it — thrilling yes, but at his limit and, it turned out, at his peril. Mr. Diegel has a troubling way of often clinging hard to a forte sustained top note and releasing it with a slight catch that veers just sharp of the pitch. I couldn’t help but think he is just getting through it…for now. “E Lucevan le Stelle” was arguably his best moment all night, his soft singing heartfelt (albeit crooned) and his final descending anguished portamento enthusiastically over-stated enough to give Franco Corelli pause. But effective? You betcha.

Lester Lynch as Scarpia and Glimmerglass Opera Chorus Member Paul Griswold in Tosca [Photo by Claire McAdams courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

Lester Lynch as Scarpia and Glimmerglass Opera Chorus Member Paul Griswold in Tosca [Photo by Claire McAdams courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]

It was booming baritone Lester Lynch who served notice that he is now in consideration for admittance to the Scarpia Preferred Pantheon. Mr. Lynch sang much of the night with exceptionally controlled suavity and mellifluous rolling tone, but when he needed to pour it on he had the Puccinian fire power and the dramatic heat to raise the hair on the back of your neck. And ‘heat’ was otherwise sorely missing from the night’s activities. Much of the blame must be placed on Ned Canty’s generalized direction. In a scenario where the action springs from jealousy, sexual attraction, manipulation, and political intrigue, the characters too seldom even looked at each other. As our hero and heroine sung much of their first encounter straight out to the audience side by side or separated, they could as easily have been Rodolfo and Mimi, so non-specific were their dramatic intentions, so unremarkable the communication of their needs and opinions.

David Angus did not bring much more to the mix by way of support from the pit, the orchestra sounding reduced in size and with a significant lack of presence in the lower voices. The opening chords didn’t thunder, the unison horns at the top of Three sounded puny (and punky), and little refined orchestral detail made it as far as my seat. You know who did fare very well indeed? The Young American Artists! Again. Although they were appearing in roles always played by seasoned older comprimarios, Robert Kerr was a splendid Sacristan, Aaron Sorenson an orotund Angelotti, Zachary Nelson a solid Sciarrone, and Dominick Rodriguez offered the best-sung Spoleto of my experience. Xi Wang intoned the Shepherd with her lovely (if too womanly) soprano.

James Sohre

Cast Lists

Tolomeo — Tolomeo: Anthony Roth Costanzo; Allessandro: Karin Mushegain; Elisa: Julie Boulianne; Seleuce: Joélle Harvey; Araspe: Steven LaBrie; Supernumeraries: Desmond V. Gialanella, Julian A. Gialanella, Jack Loewenguth. Continuo, Baroque Cello: Ruth Berry. Theorbo and archlute: Michael Leopold. Harpsichord: David Moody. Conductor: Christian Curnyn. Director: Chas Rader-Shieber. Set Design: Donald Eastman. Costume Design: Andrea Hood. Lighting Design: Robert Wierzel. Hair and Make-up: Anne Ford-Coates.

The Tender Land — Beth Moss: Rebecca Jo Loeb; Ma Moss: Stephanie Foley Davis; Mr. Splinters: Chris Lysack; Laurie Moss: Lindsay Russell; Top: Mark Diamond; Martin: Andrew Stenson; Grandpa Moss: Joseph Barron; Mrs. Jenks: Jamilyn Manning-White; Mr. Jenks: Will Liverman. Conductor: Stewart Robinson. Director: Tazewell Thompson. Set Design: Donald Eastman. Costume Design: Andrea Hood. Lighting Design: Robert Wierzel. Hair & Make-up: Anne Ford-Coates.

Tosca — Cesare Angelotti: Aaron Sorenson; Sacristan: Robert Kerr; Mario Cavaradossi: Adam Diegel; Floria Tosca: Lise Lindstrom; Baron Scarpia: Lester Lynch; Spoletta: Dominick Rodriguez; Sciarrone: Zachary Nelson; Shepherd: Xi Wang; Jailer: Jonathon Lasch. Conductor: David Angus. Director: Ned Canty. Set Design: Donald Eastman. Costume Design: Matthew Pachtman. Lighting Design: Jeff Harris. Hair & Make-up: Anne Ford-Coates.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tolomeo-Press-CMcAdams-006.gif image_description=Joélle Harvey as Seleuce [Photo by Claire McAdams/Glimmerglass Opera] product=yes product_title=Glimmerglass Rarities Out-Score Hall of Famer product_by= product_id=Above: Joélle Harvey as Seleuce (Tolomeo) [Photo by Claire McAdams courtesy of Glimmerglass Opera]Naxos founder Klaus Heymann on what lies ahead for classical recordings

[The Gramophone, 24 August 2010]

Gramophone met up with Klaus Heymann, founder of Naxos, to find out his views of the future of the classical recording business and the role Naxos will play in it.

Robert Baksa — An Interview by Tom Moore

He is a long time resident of New York, where he was born, but due to childhood asthma, spent much of his childhood in Arizona. The last decade has seen numerous CDs dedicated exclusively to his work, including a 2003 disc including the three sonatas for flute and piano performed by Katherine Fink and Elizabeth DiFelice, and a 2009 disc by the Heim duo with Christine Bock of chamber music for flute, viola and guitar. We spoke by telephone on March 9, 2010.

TM: Where were you born and raised? Was your family musical?

RB: I was born in New York City. My family had just come over from Hungary about four years before I was born. My mother was actually an American citizen, because she was born in Ohio. The rest of her family was waiting to gain citizenship, and the grandmother decided that she was ready to die, and the family had to go back to Hungary, because Grandmother wanted to see her grandchildren. As it turned out she lasted another five years, and by that time the war had broken out and nobody could get out of the country. My mother grew up in Hungary, and as long as she could go back to the US before she was eighteen, she would retain her citizenship, which is what actually happened.

With regard to musicality, my mother wanted very much to study music when she was a child but she was so nearsighted that she could not see the music with a violin under her chin. She was also a wonderful artist — she wanted to be an artist, but her mother died when she was only eleven or twelve and in rural Hungary she had no choice but to leave school and take care of the kids. Her two older brothers were trained as violinists, and in fact when the whole family came to the United States they had a Hungarian Gypsy orchestra, which I have a very clear memory of when we were still in New York.

I was very precocious — my mother told me that I started to talk when I was nine months old. One of the first things I ever asked for was the Widdavals (the Merry Widow Waltz). Music really excited me. The recorded music that my parents brought over from Hungary was the classics — I remember Brahms symphonies, excerpts from Johann Strauss operas. That was very early in my life. I got excited by music, and would jump and dance around the room. Unfortunately, I was asthmatic. One of the first things that the doctors said to my parents was “Get a piano and sit this kid down”. So at a very early age I was working on the piano. I remember that I would bring my little friends in and make them sit down while I improvised pieces for them. The whole idea of creating music came very, very early for me. My piano teacher was driven to distraction because I would never play the lessons the way that they were written, especially if there was a dissonant passing tone. I would get outraged, and say “this is wrong!” and refuse to play the music as it was written.

The asthma was pretty serious, and they told my parents that if they didn’t move me to a drier climate I might not survive. We packed up when I was about four or five, and moved to Arizona, so I grew up in Tucson.

TM: Please say a little more about the family in Hungary. Where was the family from?

RB: It may have been Gyor. I have never been to Hungary, and don’t know too much about it, because once we had moved to Arizona, the whole milieu of the family and friends who were Hungarian disappeared from our lives. My father, I think, was born in Nyregyhaza. He and my mother met via correspondence. She went back to Hungary after they had corresponded for a while, and they actually only met on the day that they were married. His biggest gift was antique repairing. When we moved to Arizona, where people didn’t have antiques at that time, that was a big disadvantage for us. We didn’t even get a piano there until I was eleven or twelve, so I didn’t have the chance to develop into a good pianist as far as technique was concerned. I did play well enough, and worked my way through college as a dance band pianist. I even did a short gig as a cocktail pianist once I was out of college, but basically my training through junior high, high school and college was as a violinist. However, I really didn’t like the instrument, and when I came back to New York on my own, in my early twenties, I just put the instrument aside, and with very few exceptions, never played again. I was convinced that everybody in New York was practically a Heifetz, so I didn’t want to compete with that. I could probably have made a good living as a pit violinist for the Broadway shows, but it was a decision I made, and that was the end of it.

TM: Was the family Jewish?

RB: No — as a matter of fact, my great-grandfather was a Hapsburg duke who also happened to be a Catholic priest, so we are all illegitimate.

TM: A very complicated story…I asked since there were many Jews who had to leave Hungary at that time.

RB: We had many Hungarians who came to visit us in Tucson at the time of uprisings in the 50s. I think anybody who could get out of Hungary did so, Jewish or not. When my mother came back to the USA in order to retain her citizenship, she was working as a domestic servant, and there was an older Jewish couple — he was a chef, and she was a chief pastry chef — who worked in various resorts around the country. They took her in as a kind of daughter, and they were the only grandparents that we ever knew, since our actual grandparents had died long before we were born. So I have always had an affinity with Jewish people, but am not Jewish.

TM: Please talk about your days playing for dances.

RB: I was a scrawny kid, with thick, thick glasses, about as geeky as anyone could be, I wasn’t cool, but they always hired me to play the dance jobs, so I must have been doing something right. I am not very fond of jazz, and people tell me that all it would take would be to spend more time with it. But having worked my way through college as essentially a jazz pianist, I can attest to the fact that it didn’t work. I am very involved with putting down the right notes in a composition. Jazz has so much to do with the energy of the performer, a lot more to do with the energy of the performer than with getting the notes right. All of these improvisational things can be interesting, but not if you are involved with writing the right notes. What I admire is a composer who can write a few simple notes, and it just takes the top of your head off. I got to know the music of Chopin when I was in my early teens, about the time that we got a piano in Arizona, and having heard it on recordings, I went to the music store to look at the sheet music. I would think “Is that all it is?” I couldn’t quite figure out what made it so wonderful. It seemed to have little to do with those notes, and something to do with Chopin having put those notes down, whatever it was that came out of his personality.

TM: What you said about not playing the notes on the page at your lessons is a story that I have heard from numerous other composers. You were a working musician by the time you were in your teens. At what point did you decide that you were a composer?

RB: When we got a piano, I simply bought music paper and started to write music. At the same time, I was studying in school to be a commercial artist. Throughout my years of high school there was a definite pull in one direction or another. As a matter of fact, I had a series of cartoons published on a weekly basis in the Arizona Star, and people would say, “Is that your dad that does the cartoons?”, and I would cheerfully say “No, that’s me!” That was a real decision for me to make — which one would win out. I always loved music more than art, but I had a feeling that perhaps I wouldn’t be able to make a living as a composer…very prophetic! I pushed the art for a while, but by the end of high school I realized that my heart really was in music.

At that time, the music that attracted me was by a man named Leroy Anderson. People don’t often remember who he is, though they still play and sing his Sleighride at Christmas time. I did a lot of short novelty piano pieces in that style. I was also very interested in film music, especially music for the big biblical spectaculars, because they had such lush, brilliant orchestration. This was all before I had had any kind of training as a composer. When I went to college I became friends with the guy who was the filmmaker at the film bureau of the University of Arizona. He gave me the chance to score a bunch of documentaries that he was making. We would record most of them with the University Orchestra, and so I had considerable opportunities to learn orchestration in a “hands-on” way by writing for film, which was invaluable. While I was still in high school, the musical director for a big spectacular called Cinerama Holiday came to Tucson because he was doing a big documentary about Arizona. He gave me a little bit of money and asked me to write a short theme, which would be performed by the school orchestra in the film. Just by chance, while we were rehearsing or recording it, Ferdie Grofe was in the audience. Not so many people know his Grand Canyon Suite anymore, but it was wonderfully popular. He said “I was dozing off, and I heard your music!” He was really quite taken with it. Unfortunately, they didn’t use it in the final cut of the film. This was in the late fifties.

When I got the chance to do those documentaries, I sent one of my film scores to Miklos Rozsa in Hollywood. One of my favorites among his scores was Quo Vadis. He was most complimentary. He wrote me back that the music was “extraordinarily well-written and well-suited to the subject matter.” It seemed as though it would be a good opportunity to go to Hollywood and study with him. We corresponded for a while, but when I went to Hollywood to visit an aunt, he was in Europe and I couldn’t reach him. Somehow the idea of going to the West Coast got put aside. I thought the best place for a serious career would be the East Coast. In 1961 I went to New York after having been in Tanglewood for the summer.

TM: How was Tanglewood in 1961?

RB: I think that I was very intimidated by the whole experience, because there were not a whole lot of heavies in the musical world who had come to Arizona where I had studied. Most of the other students at Tanglewood had studied with important composers at important eastern conservatories. Because of the way the curriculum at the U of Arizona was structured, I was an education major — I think everybody had to be. I got a degree in composition, but only a bachelor’s degree. The first teacher that I studied with there was a man named Robert McBride. If you look very hard you might find a piece of his recorded somewhere. He was a big, folksy man — very laid-back. During the time I studied with him, he might have made a few suggestions, but mostly he said “All right. Go on with this now.” The other man that I studied with, who was the orchestra director at the time, Henry Johnson, was someone whom I had a lot of respect for. I was always under his elbow because I was the section leader of the second violins. But we argued all the time about composition. He would say “this is not consistent”, and I would say “Yes, it’s consistent”. I was never an easy student — I always had my own ideas.

When I went to Tanglewood, I had hoped that I would study with Copland, because Copland had been out in Arizona, and was in fact instrumental in getting me to Tanglewood, but I was assigned to Lukas Foss instead. Unfortunately Foss and I just had a basic personality conflict. I couldn’t write anything during the six weeks that I was there. I first played him a piano sonatina, which is a small work. All he had to say was that I didn’t used enough of the keyboard at the higher end. I thought to myself “I know that it’s there — if I want to use it, I’ll use it….” He also said “You are obviously very fond of Ravel”, and I was not fond of Ravel. So for me he had two strikes against him from the start. Foss was the best-known teacher that I ever had, but I don’t think I gained anything from studying with him. You have to be more willing to listen to somebody else than I was at the time. Or if I had felt more compatible with him it might have been a different experience.

One of the things that has struck me in thinking about what has happened with me over the years is that there seems to have been a certain pressure from teachers to expand one’s language, be more experimental, try new things. When I left Tanglewood, and moved back to New York, I wrote a large string piece, a piece which I am very proud of to this day. Unfortunately, it has never been performed. Stokowski was interested in the piece but he died before he could schedule it. I sent it to Copland, and he simply wrote it off — he said “this is irrelevant”. This is not the way to treat a creative person, I feel, especially since I have always demonstrated a certain technical level in my work. I have a letter somewhere from Ned Rorem where he says “Obviously you have technique to burn.” Copland, before he stopped writing, was getting into more dissonant music, and trying all kinds of systems. The big problem for me is that I have never liked that music, I don’t respond to that music. I listen to these pieces again and again, thinking that something will finally grab me and interest me — and it doesn’t happen.

When I was in college, I took out the scores, and listened to all the Bartok string quartets, and was blown away by them. But I found, later in my life, that the more I heard them, the less I found them satisfying. I know that many people might think that is a sacrilegious thing to say. But I find those pieces ugly, I find very little beauty in them, and I don’t see the point in forcing myself to write in a way that is incompatible with what I like to hear and with what I like to write.

After that wonderful compliment I got from Rozsa, I sent him some of my chamber music, but he had lost interest in me. Today, a lot of people are going back to tonality and seeing what they can come up with, as a natural expression of what they want to say. I was doing that all along. I tried once to write a twelve-tone piece, but when I took out all the notes that I absolutely hated, it was in G minor….the handwriting was on the wall.

My experience of music is not only intellectual. I love things that are cleanly written — with lots of correlation between every part in the accompaniment, the inner voices, the melodies — but beyond that, it has got to have an emotional impact other than angst which is all I get from atonal music. One of the things that has always surprised me when I talk about it to other people in the field is that when I hear very, very dissonant music, with no resolutions, my stomach tightens up. It’s a visceral experience for me. I don’t understand how people can sit at a concert or in front of a speaker, and not be affected like that. We know that the whole universe is nothing but vibrations. The strongest vibrations of the overtone series produce the triad. If you have very dissonant music, what you have is very jumbled vibrations hitting the ear. Beyond a certain point, it becomes noise. This has always been very immediate for me, and I get less and less patient with music that doesn’t pay attention to that reality.

In the 1930s, when he wrote all those sonatas, Hindemith’s music became much more harmonious and lyrical. He still used his system, but the music became more transparent and less dissonant. After Salome and Elektra, Strauss started to write music that just melts you when hear it. Here were two master technicians, who came upon the idea that one doesn’t have to “push the envelope” all the time contrary to what everyone else was promoting.

TM: Could you talk about a piece of chamber music from your production that comes from this period in the early 1960s?

RB: When I got back to New York, I did not have a piano for a long time. I had to sneak into a local church to use the piano (because I have always written at the piano, at least to start a piece). I wrote a lot of small choral pieces, and a lot of songs. I wanted to go back to school, because I only had the bachelor’s degree but there was no money for that. I had done chamber music in college, but with the exception of one piece, those are forgotten items which I have either lost or discarded by now.

I don’t feel that I really started to write my mature works until about 1970, 1972. Within a few years, I wrote the Oboe Quintet, which is still very much on the boards and the Octet for Woodwinds which has been very popular. Many people have criticized me over the years for being too backward-looking, but I have three pieces which I wrote as a teenager which are still published and still being performed. That says something. Arthur Cohen, who used to head Carl Fischer, used to say that he expected a good choral work to have a five-year shelf life, but the choral pieces that I wrote in the sixties are still selling. Choral music is not doing so well these days, because people will buy a single copy and make photocopies, and the number of choruses has certainly diminished, but I have several things that have continued to sell for forty years. In the song area, people say that they are always hearing my songs in recital (another problem, because students go to the library and photocopy one song). There’s a lot of music out there being done all the time. This is very different from composers in the university system, with their comfortable pensions, which makes it very easy for them to be in line for grants, commissions, and awards. It’s very frustrating for me, because my music doesn’t sound difficult. It’s easy to understand, and the effect may be that not too much is happening. But when a performer starts working on it, he realizes that it’s not easy music at all. My Bagatelles, which I was just going to show a pianist friend — have pages that are thick with notes. One reviewer compared them to Bach inventions. If you give a piece like that to someone who has to listen to forty-seven entries for a contest, it may not make much of an impression on the first hearing. But there won’t be a second hearing, because they have got too much to go through. So I’ve had bad luck with the contest business.

TM: But you have had good luck with performers who pick up the score and continue into the piece.

RB: Yes, there are many performers who have been very supportive over the years. Oddly, some of them did not like my stuff when they first heard it. Always a mystery to me.

I made my living as a music copyist in New York for about forty years. That has gone by the wayside, since now every composer has their own software on their computer. Every once in a while I will still pick up a job. Because of the fact that I had been an art student, I had a wonderful hand for copying, and that was very valuable to me for a long time. Once I switched over to doing it on the computer, I would never pick up a pen again. What a boon that was!

TM: Perhaps you would like to say a little about your operas.

RB: In about 1967 I wanted to do an opera. When I was in college, I had a book called Fifteen American One-Act Plays, and one of the pieces in there was a play by Edna St. Vincent Millay called Aria da Capo, which is not very often done. I think it’s kind of an awkward play in a way, but it certainly cried out for music. So that was my first opera. I entered it in a contest for one-act operas for children. It wasn’t necessarily a play for children, but it was a chance to perhaps get somewhere with it. I didn’t win the first prize, only the second, largely, I’m sure, because there is a double murder in it. But it did get the attention of the Metropolitan Opera Studio which was connected to the big house. They had a stable of young singers who would do performances in the schools. I don’t recall if they did anything from the winning opera, but they did parts of my Aria da Capo, and the singers liked it so much that they went to the director of the studio and said “Why don’t we commission this guy?” That was exciting. My eyes were full of lots of zeros after the dollar sign. I got a call from the director who said “Well, Mr. Baksa, the Lincoln Center committee doesn’t know who you are, so they have given a commission to someone better known than you. But if you will accept five hundred dollars, we will give you a commission as well.” That’s how I came to write Red Carnations. Unfortunately they only did a few performances before the new regime came in and got rid of the Studio. The Studio no longer exists.

I decided that I needed to orchestrate the new piece. At first they had told me they wanted a few instruments, but once I started the piece, they said, no, no, no, just piano, so I had to go back and redo it with piano accompaniment. My mother managed to find a little money, which allowed me to take the time to orchestrate the piece.

A friend of mine who was a manager for singers said “Let’s show Aria da Capo to David Lloyd”, Lloyd was a prominent American Tenor who was at the time the director of the Lake George Opera. David got excited, and said “we’ll do it this summer.” But that was a problem because the season had already been programmed, and so I actually only got one performance of it, as a part of a gala. But I said, OK, let’s go with this, because they always brought a new work into Manhattan, at Hunter College. Unfortunately, Hunter disbanded their program, and it never came into New York.

I heard about a contest, which was looking for entries, and I entered the score and waited and waited. After a year, I called, and learned that the conductor/adjudicator had lost the score, so I never was part of the contest. This was some kind of good luck, right?

By this time I had become friends with Richard Woitach, who was one of the assistant conductors at the Met, and one of their best coaches, too. He was working at the Academy of Vocal Arts in Philadelphia, and suggested that we do a performance there, with piano, not a fully-staged performance, more of a reading, but it was staged. They loved it so much so that they performed it again in the spring of the next year. I had hoped that they would do a full performance, staged at the Walnut St. Theater, but it never went anywhere.

Many of the people that I showed Aria da Capo to didn’t want to take a chance, because it was a one-acter, and calling for at least a thirty-piece orchestra. About this time many arts organizations were beginning to find fundraising more difficult. I had already added a prologue to the work and decided to reorchestrate it for a chamber group. I was able to complete that about a year ago. Now it has eleven instruments in the orchestra, and five characters, so it should be an evening of opera suitable for smaller companies.

Next chapter: For the opera that the Met commissioned, Red Carnations, I went back to the book with the one-act plays. I found a little throwaway play about a couple that meet at a costume party, and make plans to meet at a city park. But they are not sure that they are going to recognize each other — that’s where you get the “red carnations”. I had orchestrated it for a chamber group. At the time I had been doing copying of a Haydn opera for Michael Feldman and the St. Luke’s orchestra. Michael liked the piece and agreed to do the premiere of the orchestrated version. The Orchestra of St. Luke’s used to rehearse in downtown Manhattan, in St. Luke’s Church, which is where they got their name. They found that the kids from the school next door would come into the rehearsals and sit entranced. Michael decided to form an organization called The Children’s Free Opera of New York to showcase this opera that I had written, and they did it twenty-five or thirty times, would take it out to various places in the city, or to Town Hall, and would bus kids in. About the same time there was a small opera company in Baltimore, the Minnikin Opera, which toured it as an introduction to opera for two years. Unfortunately the publisher who was handling the piece went belly-up. For a number of years I had no representation for Red Carnations at all. I was able, because I had already formed my own publishing company, to take everything back, and make a deal with the Theodore Presser Company, and since that time the work has been used by the Dallas Opera as an introduction to opera. Santa Fe used it for their apprentice tours as well, There were also some smaller companies which presented it as part of their regular seasons. But I really haven’t had anyone pushing on the work, which is a shame, because you can do it easily with piano, and the kids and adults love it. When I met my singers at a recent production in Hudson, the tenor said “You write so beautifully for voice”. It’s been a frustration that I haven’t had an agent to help get this piece produced more often.

When I came to New York I showed a bunch of my work to someone who was very important at Boosey and Hawkes, and he engineered a couple of careers for fledgling opera composers, some of whom became rather well-known. He said to the management of Boosey, “Let’s take this guy on — I think he is going to be a comer”, but within a few weeks he left Boosey, and we were never with the same house again, so I never had that somebody who would be really pushing my work. So much of what happens with new music comes through your university position, or the teachers that you have worked with, who probably sit on the boards for prizes or foundations. Anybody can say they are a good composer. We need to have another voice singing our praises.

TM: You mentioned the new CD with several of your works, including Celestials.

RB: Some time ago Bret and Annette Heim recorded Celestials and contacted me. We kept in touch. Since I am not a guitarist, I am always happy to an instrumentalist check over what I have done, since writing for guitar is no easy matter. After some time Bret said “We’d like to do a whole album of your work”, since by that point they had also performed the Sonata for Flute and Guitar. So they made a second recording of Celestials along with two sonatas for guitar and Journeys which they commissioned. This last piece added viola to the flute and guitar duo. The first recording they did of Celestials was wonderful but having lived with the piece for some time, the second is even more beautiful…even more of a living thing.

TM: You seem to have knack for writing for woodwinds, which might be connected to the fact you write so well for the voice.

RB: I try to write music for an instrument that makes it sound good.

TM: That does what it does, rather than what it doesn’t do.

RB: If the performer doesn’t sound good, it doesn’t reflect well on me. But I do seem to have a knack since I have had instrumentalists come up to me and assume that I play their instrument. There was a piece for piano and three winds performed and the oboist said to me “You’re an oboist, aren’t you?” And I’m not. I did have a couple of weeks on almost every instrument when I was in college, but I also make an effort to learn what every instrument does well, and I think that makes a big difference.

TM: I am reminded of the great Telemann, not sufficiently regarded by those who are Bach-worshippers, who made a point of knowing what an instrument did well, and writing for its assets.

RB: I am just getting to know Telemann…of course he was terribly well-known in his day.