July 31, 2011

Die Liebe der Danae, Bard Summerstage

Consequently, organizations such Bard Summerstage, which have these tenets incorporated into their mission, serve an invaluable purpose.

The opera portion of this year’s festival, saw the U.S. premier of Richard Strauss’s forgotten gem Die Liebe der Danae. At first glance, Bard’s decision to present this opera may seem a bit strange. After all, Strauss is a very well-represented late Romantic composer. Yet, on closer inspection, one realizes that Strauss, like Jean Sibelius, who co-shares the spotlight of this festival, fell out of favor with the 20th century public, who viewed his unabashed tonality as antique. To be sure, there are moments in Strauss’s music that are atonal, but as far as operas go, people were more interested in the shock value of Salome than in the lyricism of Die Liebe der Danae.

Despite occasional blemishes, the cast and production team managed to present the opera in such a way that made a compelling case for Strauss’s unapologetic melodies, as well as the composer’s penchant for utilizing even the most omnipresent of mythic gods.

Under the direction of Leon Botstein, the American Symphony Orchestra exhibited both the lyricism and the humor of the score. While it is wonderful to see a new side of a revered composer, it is also enjoyable to revel in what he is already known for. In this case, I would have liked to see more of a balance between the humor and lyricism in Act I, but Botstein improved in that regard as the opera progressed.

The cast was headed by Meagan Miller, who has previously won the National Council Auditions of the Metropolitan Opera. Her voice was powerful, yet also extremely lyrical. For those used to other sopranos such as Lauren Flanigan, the deep timbre of her voice may, at first, be disconcerting, but there were times throughout the performance, when during a lyrical passage, the audience was simply spellbound. As Midas, Roger Honeywell was stunning. Especially noteworthy was his Act I entrance, which put the difficulty of the role on par with Verdi’s Otello. There were times when he seemed to lose stamina, but those moments were few, and he quickly recovered. Of mention were Jud Perry, who played Mercury, and Aurora Sein Perry, Camille Zamora, Jamie Van Eyck, and Rebecca Ringle, who played Semele, Europa, Alcmene, and Leda, respectively. They brought a comic element to the opera which was much appreciated. Although the four women required time to warm up as an ensemble, they managed to create spotless psychological portrayals on the individual level, and by the end, they worked as a cohesive group.

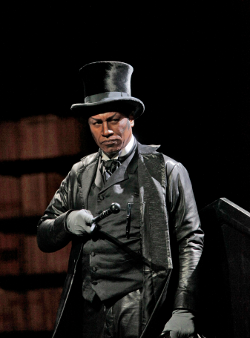

It must be said that, as Jupiter, Carsten Wittmoser was a bit lackluster. However, he too improved by the last act. Still, it has been said that Jupiter was a complex character, on par with Der Rosenkavalier’s Maria Theresa, and Wittmoser missed many opportunities to demonstrate the complexities of this most-human king of the gods.

Overall the production was impeccable and visually compelling. The chorus sang strongly and portrayed the greedy inhabitants of Eos in a way that strengthened Kevin Newbury’s modern adaptation, which set the story in post-recession America. The physical aspects of the production were stirring. The stage pictures Newbury created demonstrated both the appeal and severity of wealth, a point so crucial to the story. Additionally, there were moments that were both comic, yet touching. Such was the case when, in Act III, Danae put her suitcases in the beat up jalopy that would her car in the decidedly unwealthy life she chose with her beloved Midas.

Bard Summerstage deserves credit for a job well done for successfully resurrecting an incredibly powerful 20th century work. Die Liebe der Danae is proof positive. While Strauss’s music may be lyrical, it is richly enduring. Tastes may change, but the humanity of Strauss’s music doesn’t.

Gregory Moomjy

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DanaeJanGossaert.gif image_description=Danae by Jan Mabuse (aka Jan Gossaert) product=yes product_title=Richard Strauss: Die Liebe der Danae product_by=Danae: Meagan Miller; Jupiter: Carsten Wittmoser; Midas: Roger Honeywell; Xanthe: Sarah Jane McMahon; Pollux: Dennis Petersen; Merkur: Jud Perry; Semele: Aurora Sein Perry; Europa: Camille Zamora; Alcmene: Jamie Van Eyck; Leda: Rebecca Ringle. American Symphony Orchestra. Conducted by Leon Botstein, music director. Directed by Kevin Newbury. Set Design by Rafael Viñoly and Mimi Lien. Costumes by Jessica Jahn. Lighting by D. M. Wood. product_id=Above: Danae by Jan Mabuse (aka Jan Gossaert)Rodelinda Triumphs at Iford Opera

Nobility in love and war — ideas fully understood in all of their ramifications in the season of 1724-25 when Handel wrote this marvellous music to match the libretto of Nicola Haym — are the cornerstones of this opera’s appeal and a wise director understands this. This time in Handel’s career — around his 40th birthday — was one of the most fertile in his life. Within just 14 months he had composed not only Rodelinda, but also Giulio Cesare and Tamerlano. All are great operas, and it’s no surprise to see all three regularly performed by the top opera houses around the world today. So, with a huge emotional canvas to explore with Rodelinda, how did the small but ambitious Iford Opera fare with this tale set in about 500 AD, in what is now northern Italy?

Brilliantly is the answer. At Iford’s Friday night first performance the full house of some 90 people were treated to what must be one of the most riveting and persuasive productions of this opera in the UK in the last decade - and all the more remarkable given the comparative youthfulness of the singers and constraints of this miniature faux-Italiante cloister performance space. And for once it was the whole artistic team working together to bring Handel’s great music to life: design, direction, music and voice. The opera, as is usual at Iford, is sung in English, and the young singers all had excellent diction — far better in fact than many of their more illustrious seniors working today.

The plot is (for opera seria) fairly straightforward: Rodelinda is Queen of Lombardy, her husband Bertarido is a king apparently defeated and killed by the usurper Grimoaldo who, not content with just the kingdom, also wants Rodelinda’s love as well. The Queen resists his blandishments, and of course pretty soon Bertarido does return and sets in motion the power-play between Good and Evil. Or at least, so it seems. There is more to this story than that of course and, gradually, through a series of passionate and soul-searching arias from all the protagonists we come to understand better the dilemmas of royal blood (or just power) and those who aspire to it.

Director Martin Constantine and designer Mark Friend have worked wonders with Christian Curnyn’s Early Opera Company to make the most of Iford’s “in the square” performance space and the usefully compressed and claustrophobic nature of this opera’s plot, based as it is inside the royal palace throughout, was ideal for their purposes. The focus of all the action is an all-purpose central table in, on, and around which everything revolves. Props are confined to clever use of paper : as screens, drapes, photocopied prints of family life before the troubles, and the odd knife here and there. Costumes were drab modern, with little to differentiate master from servant. As the EOC’s stylish period band of 13 musicians began the Overture the audience were bemused by large paper screens apparently blocking their view of the “stage” area but as the music came to an end hooded and cloaked men silently entered from different directions and dramatically tore into the screens and destroyed them: the throne of Bertarido had been usurped, Grimoaldo was now in power with Rodelinda and her son Flavio at his mercy, and let the action commence.

Owen Willetts as Unulfo

Owen Willetts as Unulfo

Here, from the very first notes of Rodelinda’s lament for her lost husband, it is immediately obvious that soprano Gillian Ramm is the real deal as a Handelian heroine. Her voice is warm, well-projected and secure of technique with a sumptuous gleaming top that she uses with musicality and confidence. As the evening progressed she showed some lovely colours in the slow airs and nicely appropriate ornamentation — her “Return, my dearest love” was intelligently phrased and limpidly sung, although a little more light and shade in dynamics could have improved the overall effect even more.

She was quickly joined by tenor Nathan Vale as the usurper Grimoaldo and baritone Jonathan Brown as his treacherous, ambitious henchman Garibaldo. Vale is well known in UK Handelian circles — a previous winner of the Handel Singing Prize in London — and his voice and acting have both developed well since then. His tenor is now best described as a strong lyric -although in this role only the delightfully lilting “Happy shepherd boy” near the end of the final Act allows him to show his more lyrical qualities. His obvious command of Handelian idiom coupled well with some detailed acting of this complex character who is torn between right and wrong throughout; some initial tightness at the top of his range soon disappeared and he gave a memorable performance.

He was matched both vocally and dramatically by Brown as the scheming Garibaldo — this part is so easily reduced to cardboard-cutout villainy that it was a revelation to see and hear Brown discovering the nuances of Handel’s scoring for this unpleasant character. His baritone is not of the chocolate-smooth variety but it is flexible, expressive and commanding without resorting to the baritone “bark” one sometimes hears. A very polished performance.

As Rodelinda’s husband and king of Lombardy, Bertarido is the typical Handelian hero in all his complexity. Sung here by the rising British countertenor James Laing, we were treated to some sensitive and perceptive music-making which brought the character’s emotional journey very close to home — his duet with Ramm in “I embrace you” was a highlight for them both. As Bertarido descends into depression and despair towards the end of the first half his singing was simply heart-rending and his acting totally committed. Laing’s voice is sweet, supple, light and flexible but not large; having heard him sing Vivaldi at Garsington recently I was surprised to find him a little lacking in projection here. He was tiring by the end after an all-guns-blazing “Live tyrant” and perhaps was not one hundred per cent fit on this night.

The other male “good guy” of the opera is Bertarido’s servant/assistant Unulfo who epitomises the ideals of loyalty, strength of character, courage beyond the call etc. He is not an out and out hero: he is the little guy, the ignored chap in the corner, the one who sees everything and says little. As such, it’s a gift for any singing actor and although shorn of two arias early in the opera in this production, young Owen Willetts made the most of it and in doing so displayed an astonishing countertenor voice that lingers in the memory. His voice is dark, dark, and darker with a power and projection that reminded me of early Derek Lee Ragin or perhaps Bejun Mehta, which is all the more surprising given his English choral scholar background. His expressive features and obvious facility for dramatic expression when intelligently directed complete the picture, and if he lacks heroic inches there’s plenty else to compensate.

The final character completing this intense cauldron of power and passion is that of the wronged, vengeful Eduige, sister of Bertarido and focus of Garibaldo’s ambition and lust. Irish mezzo soprano Doreen Curran is an accomplished actress and threw herself into this role with a full, flexible mezzo which she used with dramatic flair. The voice is rich and warm in the middle with some golden tones at the top and her scenes with Brown were thrillingly intense, although perhaps there was scope for more ornamentation in her da capos, particularly in her early “vendetta” aria. Again, as with all these singers, her diction was superb.

A word must be said about the mute role of the boy Flavio, played on first night by the very young actor Yves Morris. He stayed in character throughout his scenes (which were long and intense) and gave a very promising performance, whatever his future holds.

Curnyn’s Early Opera orchestra is now one of the best small period bands around and their contribution to the production cannot be underestimated; driving, supporting and colouring the drama at every turn with some skilled and responsive playing. Some minor tuning problems in the strings half way through were quickly sorted and the thirteen players received their fair share of what was a prolonged and very enthusiastic ovation for this terrific Rodelinda. Handel opera is so often these days second-guessed by ego-driven directors and stage producers; Iford Arts can be congratulated on producing a modern version that stayed true to the essence of England’s greatest composer.

Sue Loder

Handel’s Rodelinda continues at Iford Opera, Bradford on Avon, England on August 2nd, 3rd, 5th 6th and 9th. A few tickets remain at time of writing. See www.ifordarts.co.uk

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rodelinda_Iford_01.gif image_description=Gillian Ramm as Rodelinda and James Laing as Bertarido [Photo courtesy of Iford Arts] product=yes product_title=G. F. Handel: Rodelinda product_by=Rodelinda: Gillian Ramm; Bertarido: James Laing; Grimoaldo: Nathan Vale; Garibaldo: Jonathan Brown; Eduige: Doreen Curran; Unulfo: Owen Willetts; Flavio: Alex Surtees/Yves Morris. Director: Martin Constantine. Designer: Mark Friend. Conductor: Christian Curnyn. Music: Orchestra of the Early Opera Company. product_id=Above: Gillian Ramm as Rodelinda and James Laing as BertaridoPhotos courtesy of Iford Arts

July 29, 2011

Rigoletto, Opera Holland Park

Tom Scutt’s clever set is economical and theatrically effective. Two rusty, corrugated iron freight units, helpfully labelled ‘Italia’ in case we are in any doubt of the location, may not immediately be visually appealing; but, spun and disrobed to reveal first a bordello bondage cage à la Berlusconi, then Rigoletto’s meek abode, next Sparafucile’s seedy bar which is itself transformed into the assassin’s gruesome abattoir, they prove efficient and engaging.

They also neatly contain the various locations but also allow for some pointed juxtapositions between interiors and exteriors, thereby enhancing tragic ironies. Thus, as Gilda promises her father that her love was only for him and for God, we see the Duke persuading Giovanna to allow him admittance to the young innocent’s sparse bedroom, foreshadowing the subsequent seduction. Similarly, we witness the plotting of Gilda’s abductors as she sleeps unknowingly within. Moreover, Gilda’s own ascent to the roof-top, effectively indicates her desire for freedom from her father’s jealous, selfish oppression. Most powerfully, in the Act 3 quartet, Gilda and Rigoletto cower in the gloom without, overhearing the Duke’s flirtations with Maddalena within — the contrasting sentiments which animate the four characters convincingly revealed and fully intelligible.

Jaewoo Kim as Duke and Patricia Orr as Maddalena

Jaewoo Kim as Duke and Patricia Orr as Maddalena

Director Lindsay Posner has updated the action to an unspecified modern era — Jonathan Miller’s Mafioso motifs, all sinister dark glasses and slick suits, retain their influence. But, despite the success of Miller’s seminal production, there remain some problems with such an updating. The opening ball scene may be suitably colourful — red velvet-clad hussies slinkily gyrating and twisting between the black-masked tuxedoes, and the piquant dances and carefree gaiety ticking the debauchery box — but the overall impression is not really the ‘kingdom of pleasure’ of which the revellers boast.

And, bunga-bunga parties don’t generally employ a ‘court jester’. Thus Rigoletto’s appearance, clutching a cane walking stick, afflicted by a small hunch, and sporting a ‘buffone’ ti-shirt seems a little out of kilter.

Similarly, it’s customarily necessary for the audience to imagine Gilda as much younger than the average prima donna in the role: but here, it is hard to believe that the tomboy-ish naïf in hoodie and leggings knows nothing at all of life or love, or even her father’s name. Moreover, for one so innocent, Gilda’s maidenly resistance gives way with remarkable rapidly under the pressure of the Duke’s passionate wiles. Surely the florid coloratura of one so pure should not be accompanied by sexual shivering and writhing among the tousled sheets?

Bewitched by her aristocratic wooer, Gilda delivers ‘Caro nome’ clutching a pillow in a dancing embrace, while her hairbrush is fashioned into a wannabe’s microphone — all that is missing is some air-guitar strumming and strutting; not bad for a girl who leaves the house only to go to church, and who — judging by the paucity of her decrepit surroundings (certainly her home is humble, but is it really a hovel?) - is not in possession of even a transistor radio.

Perhaps such criticisms are unfair, for elsewhere, Posner demonstrates a notable attention to detail, resulting in an imaginative reinterpretation of familiar moments. Thus, we witness Gilda’s suicidal lunging for Sparafucile’s knife intent, despite her beloved’s infidelities, on self-sacrifice to save the Duke. And, the bar-TV screen, showing Seria A is interrupted by Pavarotti’s rendering of ‘La donna è mobile’, itself swiftly silenced by some speedy zapping by the Duke, neatly timed to coincide with the score.

And, there is much fine singing. As the Mantuan Duke, Korean-born Australian tenor Jaewoo Kim is perhaps somewhat miscast. Solid and reliable, he never looked completely comfortable as the smarmy charmer, or sufficiently predatory as the celebrant of promiscuity in ‘Questa o quella’. A rather tentative host in the opening party scene, the Duke’s dishevelled appearance in boxer shorts after his assignation with Maddelena hardly presents him as a louche libertine. Though accurate and secure of intonation, Kim lacks a true lyric quality and the requisite warm palette of colours, and his voice was somewhat hard and inflexible, particularly at top. Without sufficient musical and theatrical presence to command the stage, the Duke was at times unfortunately overshadowed, as in his agitated Act 2 aria when he laments the loss of the girl who has become the lodestar of his life — never convincing sentiments at the best of times.

Verdi’s jester is not a benign joker, rather a bitter, cruel man who, warped by his physical deformity, is selfish and abusive. But he is also a portrait of psychological and physical suffering and thus his physical deformities must be made clear if he is to be more than a mischievous imp, and if his paranoia and resulting spiteful vindictiveness are to be understood and forgiven. In his donkey jacket and Viking helmet, Robert Poulton’s scarcely inhibited ‘hunchback’ has to work hard to win our sympathy. But, Poulton proves himself eminently able to deal with the vocal demands and stamina of this challenging role; particularly impressive were the long recitatives, such as that which follows his first encounter with Sparafucile. His vengeful anger and bitterness were always clear, and he worked hard to arouse our sympathy in the duets with Gilda, producing a pleasing cantabile in ‘Piangi, fanciulla’.

Robert Poulton as Rigoletto

Robert Poulton as Rigoletto

Julia Sporsén, as Gilda, was a real revelation, displaying superb clarity and projection, her tone pure and effortlessly pleasing; she revelled in the bright coloratura and the simple childlike lyricism with equal aplomb — although, as ever, it proved difficult to reconcile the showy bravura with trusting simplicity. Sporsén may have lacked a genuine pianissimo but she demonstrated true tenderness in the opera’s final moments, and more than compensated for a lack of dynamic range with a soaring, gilded soprano as she appealed to Heaven for pity. Posner’s ‘masterstroke’ was saved for this final duet: for, instead of a momentary miracle recovery in father’s arms, summoning just enough strength to tell her heart-broken, frenzied father how she deceived him, this Gilda has already joined her mother in Heaven - an angelic voice, aloft, real or imagined, while the hunchback, clutching a body-bag, laments his misguided love and irredeemable loss. For once, no suspension of disbelief was required, and the distance both literal and metaphorical between father and daughter was touchingly rendered.

Graeme Broadbent’s Sparafucile radiated stentorian menace; his cavernous bass conveyed the emotionless amorality of the aproned butcher, who sharpened his knives like a demon barber. As Monterone, William Robert Allenby struck a dignified figure, his brooding, powerful bass-baritone suitably aggrieved.

In the other minor roles, a leather-clad Patricia Orr was a lively Maddalena, while Laura Wood’s Giovanna smuggled the Duke under Gilda’s dressing table with perfect timing. The chorus sung with secure ensemble.

Conductor Stuart Stratford was consistently alert to the musical details, coaxing beautiful solo playing from his principal cello, clarinet and oboe. After a solemn opening (perhaps the horns might have provided a touch more menace), he skilfully controlled the subtle shifts of pace, volleying rhythmic rises, and swelling instrumental furies followed by anxious descents, which characterise Verdi’s melodramatic score.

The venue itself provided the icing on the cake, as the darkening sky cast natural shadows heralding the approach of the louring storm and soughing wind, and signalled the unavoidable fulfilment of Monterone’s curse.

Overall, OHP served up a truly enjoyable evening of much fine musicianship and, despite a few false notes, some genuinely fresh theatrical insights.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rigo-207-1.gif image_description=Robert Poulton as Rigoletto and Julia Sporsén as Gilda. [Photo by Fritz Curzon.courtesy of Opera Holland Park] product=yes product_title=Verdi: Rigoletto product_by=Rigoletto: Robert Poulton; Gilda: Julia Sporsén; Duke : Jaewoo Kim; Sparafucile: Graeme Broadbent; Maddalena: Patricia Orr; Count Ceprano: Simon Wilding; Monterone: William Robert Allenby; Marullo: John Lofthouse; Borsa: Neal Cooper; Countess Ceprano: Anna Patalong; Giovanna: Laura Woods; Court Usher: Mark Spyropoulos; Page: Nicola Wydenbach; Conductor: Stuart Stratford; Director : Lindsay Posner. Designer: Tom Scutt. Lighting Designer: Philip Gladwell. Choreographer: Nikki Woollaston. Opera Holland Park, Tuesday, 26th July 2011. product_id=Above: Robert Poulton as Rigoletto and Julia Sporsén as GildaAll photos by Fritz Curzon.courtesy of Opera Holland Park

July 28, 2011

Boston Midsummer Opera’s Italian Girl in Algiers

Undertaken in response to a desperate plea from the Teatro San Benedetto in Venice to fill a gap in the spring schedule, Rossini’s opera was completed in an astonishing twenty-seven days. It was the work of a young man — it could be argued that all of Rossini’s operas are the works of a young man, since he retired from the theater at thirty-eight — but by no means an inexperienced one: La scala di seta, La pietra del paragone, and Tancredi were already behind him. The impress of Mozart’s most ebullient moments is still heavy on the very young Rossini, but this is a kind of Mozart in constant and barely controlled agitation: not for Rossini the long lyrical lines of his friend in later life, Vincenzo Bellini. The libretto, which had already been set by Luigi Mosca just a few years earlier, is a farcical continuation of the European fascination with Turkish, and more broadly Middle Eastern, themes and ideas: the dauntless Isabella, fortuitously shipwrecked in Algiers, chances upon her lost lover, now enslaved, and contrives to free herself and him, while making a fool of the Bey Mustafa.

Director Minter and designer Dobay have resituated the piece in the present day, in a place more or less like the U.A. E. (so much for Algiers!), which has made an uneasy compromise with Western culture — the Bey and his wives in more or less traditionally Arab garb, while the Bey’s henchmen wear shirts and trousers. The dazzling single set suggested the jewel-toned interiors of a palace, with easy access to a stylized dock, while cinnamon-colored silhouettes suggested the towers of the city beyond and around the action; it made the best of the stage, urging the cast forward toward the audience. It seems to have been, if one reads the notes, the intention of both the music director and the stage director to bring an undercurrent of real danger to the proceedings (Barbary pirates! Sexism!), but happily this ambition had faded out within half an hour. For all that we know about Rossini’s flexibility in supplying new arias for new cities or singers, his dramaturgy at its best proceeds with ironclad determination: Rossini’s unstoppable music and the dramatic flow it illustrates tell us insistently that this is a farce, not a melodrama. There is no way to confuse Italiana with The Death of Klinghoffer. Mustafa is not menacing: he’s infantile; he’s been declawed by the end of the first act.

As the richly characterized Isabella, the fourth of the flexible roles for the low-meezo voice Rossini cherished (but not the last: Rosina and Angelina were to follow) Eddy sang with notable accuracy, and her remarkable beauty was underscored by her comic flair. Downs must be one of the younger and better-looking Mustafas on record. There was a certain active tone in his voice which, while a benefit to lyrical singing, slightly blurred some of his passage-work. As the hapless Lindoro, Williams sang well, very much in the manner of the Irish tenor, with that high and forward placement. Kravitz’s Taddeo was an agreeable goof, while Jakubiak, in the rather thankless role of the rejected wife, acquitted herself well, despite passing pitch inaccuracies in the first act. BMO reduced Rossini’s male double-chorus to four voices — the Bey’s muscle — which made sense dramaturgically, but effectively reduced the piece to a chamber opera. Wyner’s orchestra played with a clean accuracy, although the singers were occasionally tempted to get ahead of her.

(L-R) Sandra Piques Eddy as Isabella, Sara Jakubiak as Elvira, and Eric Downs as Mustafa

(L-R) Sandra Piques Eddy as Isabella, Sara Jakubiak as Elvira, and Eric Downs as Mustafa

One of the challenges of Angelo Anelli’s quite serviceable libretto is the nature of Isabella’s relationship with the men in her life. Who is Taddeo (Kravitz) — cast-off lover? Failed suitor? Is he an old man, a pantalone, or just a luckless young or middle-aged one? One has the notion that Anelli never quite decided, and the age-old uncertainty hovers over this production as it does over most. How can Lindoro (Williams), passive in his captivity while awaiting his Isabella, seem more than effete? It is remarkably difficult to bring Lindoro into focus, and almost impossible, dramaturgically, to bring them into focus together. The comedy is almost reducible to a contest of wills between the spirited Isabella and the schoolyard-bully Mustafa. As the conductor’s notes rightly point out, it is a specimen also of the then-popular “rescue” opera. She fails to mention, however, its striking resemblance to the greatest “rescue” opera, which similarly features a surprising female rescuer: Fidelio, the first version of which predated Italiana by eight years, and the final version of which followed it by only a year. These operas, like the contemporary writings of Madame de Stael and Mary Wollstonecraft, ask: what is the capacity of a woman? In Rossini’s works, the woman steadily loses power, until she is a sinner (Semiramide), and then hardly more than a cipher (Comte Ory; Guillaume Tell).

(L-R) Bradley Williams as Lindoro, Eric Downs as Mustafa, and David Kravitz as Taddeo

(L-R) Bradley Williams as Lindoro, Eric Downs as Mustafa, and David Kravitz as Taddeo

We have little trouble now in agreeing with the very young Rossini on the joys of seeing a woman exert all the force of her beauty and wit — but what of the mode alla Turca? Minter’s version, which connects the dots between the Turkish threat circa 1800 and today’s oil magnates with shady “shipping” practices, hardly diminishes the cultural chauvinism of the original, and concludes in the same place. It is just more fun, according to Anelli and Rossini, to be Italian than anything else, and Isabella and her friends want nothing better than to be back home, where women are free; Minter’s production, which concludes with the Bey’s thugs converted to pseudo-Italian clothing (to the point of waving little Italian flags), ready to expatriate, and the Bey himself, as well as his wife, in semi-Western garb, tacitly agrees with them, cultural anxiety notwithstanding. Still, Boston Midsummer Opera delivers a Rossini production of great verve and clarity — a real summer pleasure.

Graham Christian

image=http://www.operatoday.com/IGIA-2.gif image_description=Sandra Piques Eddy is Isabella [Photo by Chris McKenzie courtesy of Boston Midsummer Opera] product=yes product_title=Gioacchino Rossini: The Italian Girl in Algiers (L’Italiana in Algeri) product_by=Isabella: Sandra Piques Eddy; Lindoro: Bradley Williams; Taddeo: David Kravitz; Mustafa: Eric Downs; Elvira: Sara Jakubiak; Zulman: Julia Mintzer; Ali: David Lara. Vocal Quartet/Chorus: Sean Lair, Michael Kuhn, Stephen Humeston, Joshua Taylor. Music Director and Conductor: Susan Davenny Wyner; Stage Director: Drew Minter; Scenic Designer: Stephen Dobay. Tsai Performance Center, Boston, 27, 29, 31 July 2011. product_id=Above: Sandra Piques Eddy as IsabellaAll photos by Chris McKenzie courtesy of Boston Midsummer Opera

July 27, 2011

Rigoletto, Miami Lyric Opera

Wanton rankling may start off with high ratings and a spike in tickets sales but can easily degenerate into opprobrium and murk an artistic work’s essence. The opera Verdi and Piave set out to complete for Teatro La Fenice was on course for such an ignoble providence were it not for the duo’s imagination, and discretion. La maledizione was the working title for the opera almost cursed with the sort of attention that would dull its artistic merits.

Distilled from a Victor Hugo play with a checkered performance past, the opera would meet with its own curses before its premiere in 1851. The play (Le roi s’amuse) and the opera (Rigoletto) revolve around such a curse, something Miami Lyric Opera Director Raffaele Cardone reminded of when he addressed the audience pre-performance on opening night June 23rd. Placing the context of Rigoletto directly on, and finding its dramatic pole in, the curse teased the imagination as to what was to come, holding out the suspense of the grist for Rigoletto’s mill: La maledizione.

This performance marks a whole new set of standards for MLO. Sets (designed by Carlos Arditti), still on the main backdrops, were more suggestive of the piece (in this case, 16th century Mantova) and redolent of specific scenes: there were columns and archways at the party and a nicely lit (in blue) background, the alley where the sanction was dealt was as an hallucination - a dark and muggy picture; Rigoletto’s domicile was depicted by a patently different scene (turning a bit cheeky when a flimsy wall shook terribly as the jester set the ladder on it). The curtain rose for the final time to a tavern that any assassin might find a suitable safe house.

Artistic expression and sensibility in staging too have improved for the small company. A soft screen hazed the view of the opening scene, the ballroom at the Ducal palace; courtiers held their dance poses for the length of the overture. Movement in the room thereafter was well-planned, with varied exchanges as members of the court came in contact with each other. Blocking and shifting of positions was thoughtful too for the Act Three gathering of Gilda’s abductors. Adequate effects (strobes/lighting by Kevin Roman) in that final scene at the tavern saw to a turbulent tempest.

Musically, including in the singing, those heading the company have much to be pleased with. Conductor Doris Lang Kosloff and players seemed to work well together, resulting in nice string articulation (with fine violins in Cortigliani), sweet flute phrasing (in the work’s echoed themes) and well-modulated dynamics. Miguel A. Raymat beat clear, accurate, and powerful sounds on the kettle drum, supporting the overture, the storm, and the finale.

Cuban baritone Nelson Martinez first appeared with MLO in a Gala concert in the spring of 2007; Martinez sang a Rigoletto later that same season. With the company he as appeared as Rossini’s Figaro, Escamillo, and Giorgio Germont. Locally, Martinez is considered a tested talent; his proved to be the most schooled voice — technically and stylistically — in this cast. As far as size (and heartiness) and the ease of its use in high tessitura, Martinez’s voice does well by Verdi. It is hard to forget the force of the high note he held out to close ‘Pari siamo’.

MLO went out of town for the Gilda. Gina Galati is an American soprano that has studied in a Verdian Academy at Bussetto; she has the voice — its flutter fitting for ‘Caro nome’ — and looks of a soubrette. This was Galati’s first singing engagement with MLO; she shared Gilda with local Susana Diaz (the Gilda on June 25th). As the cad, the vehicle through which Verdi’s opera gets interesting, the Duke of Mantua, Aurelio Dominguez had some laudable moments in this tricky role and his first outing with MLO (two other tenors sang on subsequent performance evenings). The difficult recitative and aria that opens Act Two, where the Duke implores the heavens over the snatching of Gilda, was a triumph for the tenor. Dominguez ducked few obstacles, meeting Galati for the high note in their duet.

MLO returnee Diego Baner made a fine Sparafucile vocally — the rapid vibrato of his bass an interesting change of pace. On the stage, Baner distracted with his tendency to look downward. Graduating from the Florida Grand Opera chorus to a critical role here, Monterone, Cuban bass-baritone Armando Naranjo clearly understands the importance of the curse; Naranjo communicated anger with constant fervor in his singing. Lisseth Jimenez was a saucy Maddalena of darkish tone and Jesse Vargas and Mathew Caines did good work in their brief moments as Borsa and Marullo. Ketty Delgado (Giovanna) and Erica Williams (Paggio) appeared for the first time with MLO.

Pablo Hernandez (Chorus Master) did not put his group to work for the storm and the singers were musically rough here and there (in the second act, the men were at odds over entrances and the text). In the case of costumes, Pamela De Vercelly is credited for colorful work. Vercelly will not be faulted for hosiery (a few with Swiss cheesy wear) unflattering to male cast members whose best features are not their legs. One could be cursed with much worse.

La maledizione would also be a dummy title meant to throw authorities off the scent of Verdi and Piave and their busy redactions of Hugo’s Le roi s’amuse. Hugo encountered trouble mounting the play in France due to its content and the opera was meeting with similar obstructions in Italy some twenty years later. As it went, La maledizione went through a number of textual alterations as Verdi and Piave tried to satisfy censors that feared the reprisal of royals over their less than stately depiction. La maledizione wound up retaining its place in the story; the hunchback also remained and was renamed, as was the opera, Rigoletto.

Robert Carreras

image=http://www.operatoday.com/RigolettoMLOMartinezGalati.gif image_description=Nelson Martinez as Rigoletto and Gina Galati as Gilda [Photo courtesy of Miami Lyric Opera] product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Rigoletto product_by=Rigoletto: Nelson Martinez; Gilda: Gina Galati/Susana Diaz; Duke of Mantua: Aurelio Dominguez/Eduardo Calcano/Luis Riopedre; Sparafucile Diego Baner; Maddalena: Lissette Gimenez; Monterone: Armando Naranjo/Ismael Gonzalez; Borsa: Jesse Vargas; Marullo: Matthew Caines; Giovanna: Ketty Delgado; Ceprano: Ismael Gonzalez/Armando Naranjo; Contessa: Daisy Su; Paggio: Erica Williams; Usciere: Eric Dobkin/Jesus Gonzalez. Conductor: Doris Lang Kosloff. Chorus Master Pablo Hernandez. Costumes: Pamela De Vercelly. Stage: Val Medina. Lighting: Kevin Roman. Sets: Carlos Arditti. product_id=Above: Nelson Martinez as Rigoletto and Gina Galati as Gilda [Photo courtesy of Miami Lyric Opera]July 26, 2011

Verdi’s Requiem, BBC Proms

But following this sacred premiere, the work went on to have 3 further performances at La Scala and Verdi then took it on tour round theatrical venues in Europe. So from the word go, the piece has been poised between the sacred and the secular. It is this which gives the piece some of its fascination and difficulty. Verdi’s writing mixes operatic elements with some which are more sacred. For soloists he calls for 4 experienced Verdians, but then he writes unaccompanied ensemble passages for them which are some way from what he would have written in an opera.

At the BBC Proms on Sunday 24th July, Semyon Bychkov conducted BBC forces in a very large scale performance. There were 3 choirs (BBC Symphony Chorus, BBC National Chorus of Wales and the London Philharmonic Choir) with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and a quartet of soloists all with strong Verdian credentials (Marina Poplavskaya, Mariana Pentcheva, Joseph Calleja and Ferrucio Furlanetto). The three choirs numbered around 450 singers and the orchestra was similarly large scale, complete with a cimbasso on the brass bass line (instead of the modern tuba or euphonium)

This issue of size is an interesting one, which can also be traced back to Verdi’s original performances. Though the 1874 performances at La Scala used a choir of 120, when Verdi took the work on tour round Europe his attitude seems to have been flexible. So that whilst he performed the piece in Paris at the Opéra-Comique (not a large theatre), in London it was performed at the Royal Albert Hall in 1875 with huge forces. Clearly Verdi was not dogmatic about the forces involved, so we should not be either. Instead we can sit back and revel in the sheer sound that Bychkov conjured from his Proms forces.

The opening demonstrated what a wonderful sound can be created by a disciplined large choir singing in hushed tones. Though big in scale, this wasn’t a driven or a bombastic performance, Bychkov drew some beautifully quiet and detailed singing from his choristers. The difficulty of combining 450 singers in such a space should not be underestimated and it is to the three choirs’ credit that their choristers combined in such a powerful and disciplined fashion.

All was not quiet, of course. Come the ‘Dies Irae’ then all hell was let loose in appropriate fashion. Here we were able to take stock of Bychkov’s flexible tempi. He did not drive the piece forward manically, but let it expand at a rate suitable for the Albert Hall’s problematic acoustic. The ‘Dies Irae’ was not the fastest performance that I have experienced, but even when letting the music breathe Bychkov kept up the power and momentum in an impressive fashion.

The chorus’s big solo moment, of course, comes in the ‘Sanctus’ where they perform without the soloists. Here we got some beautifully detailed singing, and fine dancing tone.

The soloists were an interesting bunch, each with a distinctive and particular voice. Mezzo-soprano Pentcheva was a last-minute replacement for Sonia Ganassi. Pentcheva has proven Verdi credentials; her voice combines a distinctive dark hued lower register with a flexible upper, capable of some lovely quiet singing. She has a strong vibrato which might not be to everyone’s taste. She proved tasteful and flexible in her singing and brought some great beauty to her quiet moments, along with vivid projection of words.

Calleja sang the tenor part with full tone and a fine sense of line; he brought a fine sense of quiet rapture to the ‘Hostias’. Perhaps he missed the more bravura elements of the part, but he was a fine ensemble singer contributing intelligently to the many concerted solo moments. Ferrucio Furlanetto brought a world-weary grandeur to the bass part; lacking the ultimate in power, he showed commitment and discipline along with a fine sense of line.

Finally, of course, we come to the soprano; whilst all the soloists have their moments, Verdi’s use of the soprano in the final ‘Libera me’ ensures that it is the soprano who we remember best. Poplavskaya brought her familiar plangent tones and beautifully expressive line to the role, singing with a commitment which suggested she was living the part rather than just singing a soprano solo. She floated some supremely lovely lines during the piece, but these were always intelligently placed and not just vocalism for its own sake. In the ‘Libera me’ she took the drama to the point where she was in danger of becoming manner, but the ‘Requiem’ section where she sang just accompanied by the unaccompanied choir was simply beautiful. Though I must admit to having a slight reservation, Poplavskaya’s quiet plangency threatened to push the notes below pitch, but this was a small point in what was a very fine performance.

The soloists are more than just 4 individuals, Verdi asks them to sing in ensemble rather a lot and to do so unaccompanied. Poplavskaya, Pentcheva, Calleja and Furlanetto patently listened to each other and though their voices were very different, created a real ensemble. Most people who have heard the Requiem quite a few times have stories about the intonation problems in these ensemble passages. But not here. And in the ‘Agnus Dei ‘Poplavskaya and Pentcheva sang in octaves in a way which, whilst not quite of one voice, came pretty close.

The BBC Symphony Orchestra provided sterling support and some brilliant playing. Granted their string tone does not approach the vibrancy of the best bands in this music, but they brought commitment, intelligence and delicacy.

Bychkov controlled all in a way which allowed the detail of the work to be felt without compromising the big moments. This was certainly a performance of contrasts. Inevitably some detail gets lost in the Albert Hall, but Bychkov brought out much that was finely wrought, then contrasted it with some spectacularly loud moments. The ‘Dies Irae’ and the ‘Tuba Mirum’ are not the be all and end all of a performance of Verdi’s Requiem; here these big moments were big indeed but contrasted with some moments of nicely quiet intensity.

Robert Hugill

image=http://www.operatoday.com/poplavskaya_marina.gif image_description=Marina Poplavskaya [Photo courtesy of Zemsky Green Artist Management] product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Requiem product_by=Marina Poplavskaya, soprano; Mariana Pentcheva, mezzo-soprano; Joseph Calleja, tenor; Ferruccio Furlanetto, bass. BBC Symphony Chorus. BBC National Chorus of Wales. London Philharmonic Choir. BBC Symphony Orchestra. Semyon Bychkov, conductor. product_id=Above: Marina Poplavskaya [Photo courtesy of Zemsky Green Artist Management]July 25, 2011

Placido Domingo announces Operalia winners in Moscow

[LA Times, 25 July 2011]

The annual Operalia competition, held this year in Moscow, concluded Sunday with a ceremony led by the organization's founder, Plácido Domingo. The first-prize winners were American tenor René Barbera and South African soprano Pretty Yende.

July 22, 2011

G. F. Handel: Athalia

Music composed by G. F. Handel. Libretto by Samuel Humphreys, after Athalie by Jean Racine (1691).

First performance: Oxford 1733

Athalia Killing the Royal Children [Source: sang sabda]

Athalia Killing the Royal Children [Source: sang sabda]

| Principal Performers: | |

| Athalia, Baalite Queen of Judah and Daughter of Jezebel | Soprano |

| Josabeth, Wife of Joad | Soprano |

| Joas, King of Judah | Boy Soprano |

| Joad, High Priest | Alto |

| Mathan, Priest of Baal, formerly a Jewish Priest | Tenor |

| Abner, Captain of the Jewish Forces | Bass |

From Second Kings 11 (KJV):

1And when Athaliah the mother of Ahaziah saw that her son was dead, she arose and destroyed all the seed royal. 2But Jehosheba, the daughter of king Joram, sister of Ahaziah, took Joash the son of Ahaziah, and stole him from among the king’s sons which were slain; and they hid him, even him and his nurse, in the bedchamber from Athaliah, so that he was not slain. 3And he was with her hid in the house of the LORD six years. And Athaliah did reign over the land.

4And the seventh year Jehoiada sent and fetched the rulers over hundreds, with the captains and the guard, and brought them to him into the house of the LORD, and made a covenant with them, and took an oath of them in the house of the LORD, and shewed them the king’s son. 5And he commanded them, saying, This is the thing that ye shall do; A third part of you that enter in on the sabbath shall even be keepers of the watch of the king’s house; 6And a third part shall be at the gate of Sur; and a third part at the gate behind the guard: so shall ye keep the watch of the house, that it be not broken down. 7And two parts of all you that go forth on the sabbath, even they shall keep the watch of the house of the LORD about the king. 8And ye shall compass the king round about, every man with his weapons in his hand: and he that cometh within the ranges, let him be slain: and be ye with the king as he goeth out and as he cometh in.

9And the captains over the hundreds did according to all things that Jehoiada the priest commanded: and they took every man his men that were to come in on the sabbath, with them that should go out on the sabbath, and came to Jehoiada the priest. 10And to the captains over hundreds did the priest give king David’s spears and shields, that were in the temple of the LORD. 11And the guard stood, every man with his weapons in his hand, round about the king, from the right corner of the temple to the left corner of the temple, along by the altar and the temple. 12And he brought forth the king’s son, and put the crown upon him, and gave him the testimony; and they made him king, and anointed him; and they clapped their hands, and said, God save the king.

13And when Athaliah heard the noise of the guard and of the people, she came to the people into the temple of the LORD. 14And when she looked, behold, the king stood by a pillar, as the manner was, and the princes and the trumpeters by the king, and all the people of the land rejoiced, and blew with trumpets: and Athaliah rent her clothes, and cried, Treason, Treason. 15But Jehoiada the priest commanded the captains of the hundreds, the officers of the host, and said unto them, Have her forth without the ranges: and him that followeth her kill with the sword. For the priest had said, Let her not be slain in the house of the LORD. 16And they laid hands on her; and she went by the way by the which the horses came into the king’s house: and there was she slain.

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Athalia_Dore.gif image_description=Death of Athaliah. Engraving by Gustave Doré (1832-1883) audio=yes first_audio_name=G. F. Handel: Athalia first_audio_link=http://www.sarastro.info/music/handel/athalia/Athalia_Koln.mp3 product=yes product_title=G. F. Handel: Athalia product_by=Athalia: Simone Kermes; Josabeth: Sarah Fox: Joas: Johannette Zomer: Joad: Iestyn Davies: Mathan: James Gilchrist; Abner: Neal Davies. Balthasar-Neumann-Chor. Concerto Köln. Director: Ivor Bolton. Live performance, 24 May 2009, Kölner Philharmonie. product_id=Above: Death of Athaliah. Engraving by Gustave Doré (1832-1883)Strauss Joins Sibelius’s Vacation

By Peter G. Davis [NY Times, 22 July 2011]

HOW, you may ask, does an opera by Richard Strauss find its way into a music festival devoted largely to the world of Jean Sibelius? This great Finnish composer is the focal point of this year’s SummerScape extravaganza now under way at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y., and an important operatic novelty is invariably a highlight of the festival. But Sibelius never wrote an opera of any size or substance. To include one by Strauss — even a relative rarity like “Die Liebe der Danae,” which receives what is said to be its first fully staged performance in the New York region on Friday evening — seems a bit of a stretch.

The Sopranos — Dissecting opera’s fervent fans

Herr Engels and his wife were enjoying retirement with a cultural event every single night, whether that be opera or the symphony or theater or a gallery opening; tonight, he had set his sights on me and wanted my opinion. I had one — small and squalid and intense as it was — but while Herr Engels had been steeped in culture, I had merely dipped a toe in. I had seen my first opera for the first time less than a year before, and he was asking for me to report on what I had seen. I didn’t have the language for it yet, not even a basic vocabulary. I started to list the Berlin operas I had seen — Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges, Braunfels’s Jeanne d’Arc, Wagner’s Rienzi…

“Ah, the Rienzi. How was that?”

I mistakenly believed that he was asking because he had not seen that production. I started to explain how they changed the setting of Rome to a unspecified totalitarian space, how the staging was interesting, the clever ways they used Wagner’s overly long musical interludes and ballet sections. “I liked it,” I finally declared.

Herr Engels paused, brushed nonexistent crumbs off of the table, and simply said, “No. We did not care for it.”

Despite the shame he afflicted on me, Herr Engels would prove to be a rather benign, and even generous, version of a type I’ve since grown to know well. You know the opera fanatic even if you have never attended an opera performance in your life. He or she knows every performance, every singer, every composer, every conductor. The critics… phooey, they know nothing, but the fanatic holds the key to opera knowledge and enjoyment. Only they truly understand the art, and only they truly appreciate the art.

In The Opera Fanatic: Ethnography of an Obsession, Claudio E. Benzecry identifies four distinct types of the obsessed attendee: There’s the hero, who believes he is keeping the opera house open and the art itself alive and vital. There’s the addict, who is willing to sacrifice his families, friends, lovers, money, and sanity to attend multiple performances of the same opera, to listen to the records and attend lectures and travel to distant theaters. There’s the nostalgic, for whom everything was better when it was sung by Maria Callas, or Joan Sutherland, or back in 1965, or back when people took pride in knowing about opera. Then there’s the pilgrim, the devoted subject who treats the opera house as a religious temple.

Mostly what I was thinking while reading The Opera Fanatic was, “Phew. At least I haven’t fallen so far.” And yet while my passion may be new, as I continued reading, I realized that patterns were emerging. I was showing signs. My trip to visit Mad King Ludwig’s castle in Bavaria with its rooms decorated in loving tribute to Wagner could be mistaken for a pilgrimage — as could my trips to the opera houses of Vienna and Budapest and Odessa. My obsessive shopping sprees for tickets and my insistence that I always reserve the same seat might be the behavior of the Addict. Yes, I didn’t have a favorite diva and was more interested in the stories of the composers and the libretto writers, that didn’t make it any less annoying that I insisted on telling everyone the story of Boito’s Mefistofele, which may have been a masterpiece — and my favorite opera — but also destroyed his career.

Take the “opera” out of The Opera Fanatic, and there are still recognizable templates at play. And you may indeed want to remove “opera” to get a better look, as it can be very difficult for outsiders to see the appeal. Opera is often dismissed as a dead art form, as an elitist plaything of the wealthy and the out-of-touch. Wayne Koestenbaum spends a lot of time in The Queen’s Throat: Opera, Homosexuality, and the Mystery of Desire trying to make opera a gay thing. While the wealthy do remain patrons of the opera houses, statistically speaking, the average opera viewer is much more…normal. On paper at least. Benzecry — who treated the Teatro Colón like a mysterious village and reported back on the inhabitants’ behavior as an anthropologist would — found that the most devoted of its guests are middle class, many the children of immigrants, and, statistically, don’t lean more straight or gay than the outside world. So when you do remove the opera, you find that the addicts share much in common — probably to their protestations and their horror — with people who get obsessed about other things, whether that be comic books or Lord of the Rings or certain pop musicians or television shows.

I have gone to science-fiction conventions. I have waited in line for a Tori Amos concert. I have dated a comic book collector and a music critic. Yet I have always been on the outside of fan culture, never obsessive enough about any one topic to be seen as anything but a poseur by the true fans. They are always all too happy to explain to me why I am wrong about my opinion of TV’s Game of Thrones or how this Amos tour is overwhelmingly inferior to the second leg of her 1994 shows, which of course I did not see. Herr Engels was simply a better dressed and much more polite psychopomp to my latest adventure in fandom, but there are certainly equivalents in every fan culture I’ve encountered. There have certainly been those who wanted to hold my head underwater because I balked at the engulfing qualities of these passions, all the time and travel and schooling and money involved, and I was thus found unworthy of the objects of their love.

And it is love. Not in that “Oh, I love chocolate cake” kind of way, but in the way one falls in love with a paramour. Both Benzecry and Koestenbaum write about the difficulty fans have in sustaining a romantic relationship that doesn’t revolve around a shared opera obsession (it’s no coincidence that this is also the stereotype of nearly every fan culture). It’s as if these fans accidentally fell in love not with a human being but on opera, like a deluded gosling who imprinted on a sheepdog rather than its own mother. Koestenbaum writes, “The taste for opera is seen not only as compensation for lost love objects, but as the very catalyst of loss. The opera queen is lonely because he listens to opera: Opera isolates him from the sexual marketplace.” And opera feeds the fan like a lover, providing an emotional experience on par with romance, with all of the ecstasy and disappointment and anger and joy and everything in between. It’s no wonder a father in Opera Fanatic tries to curb his daughter’s growing interest in the Colón. He would like her to get married and not become one of the distinguished older women Benzecry interviews, who starts crying as she explains just how much the opera has meant to her. Of the dozens of opera fanatics he speaks to, he reports that fewer “than a third live with a permanent partner.”

What remains elusive in both books is the identification of the mechanism in these people that chose opera. Koestenbaum tries so hard to tie opera to his homosexuality, making metaphors about the closet and the voice and gay identification with the diva, that the reader is left with no option but not to believe him. It begins to sound like a pathological belief system. (I came across my copy of his book at the used bookstore, and I could read not only the text but the previous owner’s increasing frustration with Koestenbaum’s certainty. Next to yet another of the writer’s line insisting opera is the territory solely of the gays — “Opera’s apparent distance from contemporary life made it a refuge for gays, who were creations of modern sexual systems, and yet whom society could not acknowledge or accommodate” — my co-reader scrawled in an exasperated, “This is crazy!”) Koestenbaum and Benzecry’s interviewees all have their theories and their origin stories — family members who played operas on the phonograph, a waltz randomly heard on the radio, a lover who took them to the opera for the first time — but there’s no specific reason why it was opera, and not, say, an episode of Star Trek, which has also been the territory of the unacknowledged and the unaccommodated, that set their particular souls alight. But that’s love for you. The more we love someone who hurts us and obsesses us and sets us afire, the more we try to find justification for that love in our past.

As for me, I couldn’t really tell you. Something must have been in alignment the night I saw the Prokofiev with my friend Veda. I’m trying to keep a rein on it, although I’m aware the alabaster bust of Wagner that sits glaring at me as I sleep is probably not doing much for my bedroom karma. Love remains a powerful and destructive force that some of us need to hold at bay, to fight our fates. As Koestenbaum flipped through a collection of opera records in his friend’s garage, he said, “Why don’t you bring the records into the house? This is a terrific collection!” His friend replied, “You don’t know what would happen. You have no idea what would happen.” • 12 July 2011

Jessa Crispin

This review first appeared in The Smart Set. It is reprinted with the permission of the author.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/9780226043425.gif image_description=The Opera Fanatic product=yes product_title=Claudio E. Benzecry: The Opera Fanatic — Ethnography of an Obsession product_by=Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011 product_id=ISBN: 9780226043425 price=$29.00 product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/0226043428

Mignon and Saul at Buxton Opera Festival

The first three operatic productions, Donizetti’s Maria di Rohan, Handel’s Saul and Thomas’s Mignon, were all Festival Productions, an impressive achievement for Greenwood as he hands over the reigns to incoming director, Stephen Barlow.

Drawn from Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre, the libretto of Mignon was rendered by Michel Carré and Jules Barbier into a comic drama, mingling improbable absurdities with touching tenderness.

Lothario, a wealthy gentleman, has lost his mind after the death of his wife and the abduction of his daughter, Sperata, whom he desperately seeks. Kidnapped by the cruel Jarno, the leader of a vagrant band of entertainers, she now appears as his ‘star turn’, Mignon, a mysterious, androgynous dancer. Rescued by the altruistic Wilhelm, Mignon falls in love with her saviour, but he has eyes only for Philine, the dazzling leading lady of a flamboyant troupe of theatrical players. Inexplicably drawn to Mignon, Lothario wishes to support her; but she yearns to be with Wilhelm who reluctantly agrees to let her travel with him, disguised as his male servant. Conflicts increase: Frederick and Wilhelm fight for Philine’s love, while Mignon’s jealous hatred of Philine grows. Driven to the edge of madness she agrees to salvage Philine’s bouquet from a burning theatre, an act of selflessness which spurs Wilhelm to his second chivalrous rescue mission, and awakens his ardent passion for Mignon. However, further unfortunate misunderstandings delay the happy resolution. It is not until Lothario surprisingly declares that the house where Mignon has been recovering belongs to him that her memory of past people and places returns; a box of treasures — a child’s doll and prayer book — sparks the realisation that she is in fact Sperata, his long lost daughter.

In effect, Mignon presents a sort of sub-Puccinian melodrama: the shady unemployed theatrical entertainers possess little of the aesthetic ardency of the Parisian Bohemians; Mignon herself lacks Mimi’s tragic grandeur. However, the characters are appealing and their dilemmas engaging; moreover, the tale offered Thomas much potential for both potent expression and sweet lyricism, and is a work of much musical charm and grace. As Andrew Lamb notes in his programme essay, Mignon, which marked Thomas’s return to composition after a spell as an academic, became the composer’s most successful work, greatly esteemed in its day and performed more than 1500 times from its premiere in 1866 and 1919, after which the forms and idioms it celebrated fell from fashion.

Wendy Dawn Thompson as Mignon and Ryan MacPherson as Wilhelm

Wendy Dawn Thompson as Mignon and Ryan MacPherson as Wilhelm

Director Annilese Miskimmon has adopted a suitably light touch, updating the action to the 1920s, and delighting in the frivolity and sparkle. Her playful approach is complemented by Nicky Shaw’s economical but visually appealing sets; director and designer work well together to introduce some neat dramatic touches. Thus the opening post-theatre party scene sets off with a swing of energy and jollity, dressing room doors dancing gaily to and fro, as a flurry of acrobats, ventriloquists, escapologists, magicians and dancers whizz and whirl across the stage. The limited space is efficiently deployed: at the end of Act 1, the stage is enveloped in murky smoke to transport us to a dusty, crowded railway station, an illuminated sign pointing the way to the platforms; and the burning theatre, engulfed by flames ignited by an increasingly vengeful and raving Lothario, is effectively realised.

As Wilhelm, American tenor Ryan MacPherson was dramatically credible — a handsome Hollywood matinee idol - and displayed a truly pleasing voice across the registers. His fairly light tenor was initially a little grainy when pushing at the top, but as he relaxed he produced a richer, fuller sound, particularly in the closing trio.

Despite some adroit gymnastic feats, as she deftly squeezed herself into the laundry box in which she is imprisoned by the dastardly Jarno, Wendy Dawn Thompson took a little time to warm up vocally and establish her character. But, her Act 2 aria ‘Connais-tu le pays’ revealed a glowing, rich mezzo tone which conveyed Mignon’s innocence and integrity, developing a deeper psychology as her confusion and suffering are revealed.

Baritone Russell Smythe was a rather jaded Lothario. He had some not insignificant intonation problems, although these lessened as he settled into the role; but he did not find a way to effect a transition between Lothario’s introverted suffering and his aggrieved public outbursts, and Smythe’s tendency to bellow to convey both anger and despair reduced our sympathy for the bereaved and lonely man.

Gillian Keith as Philine and Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks as Laerte

Gillian Keith as Philine and Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks as Laerte

Indian tenor Amar Muchhaka was a likeable Frederick, but the star of the show was undoubtedly, and fittingly, Gillian Keith as the dazzling diva, Philine. Keith relished the giddy theatricality of her show-stopping Polonaise and despatched the coloratura of ‘Je suis Tytania’ with aplomb. Her dressing-room door appropriately sported a glittering star; and it was no surprise that her excessive luggage required the heft of several strapping chaps to hoist it onto the departing train.

Opera enthusiasts can take an infinite number of improbabilities and coincidences in their stride, but there is an innate problem with Mignon in that the plot does not successfully combine or integrate the comic and tragic strands. Occasionally these sat uncomfortably alongside each other. Thus, the ‘play-within-a-play’ performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream — during which the simple-minded rustics dotingly worship Tytania as she is born aloft upon a crescent moon — was effectively presented (mechanical malfunction adding a further piquant touch), but it was then a rather abrupt switch to Mignon’s increasing distress and despair as she embarked upon a suicide dash into the flames.

Despite this, and the libretto’s somewhat uneven dispersal of dramatic events, energetic conducting by Andrew Greenwood drew lively playing from the Northern Chamber Orchestra and kept the show moving swiftly on to its happy, if slightly implausible, resolution.

Similar imaginative leaps were demanded of the audience by Olivia Fuchs’ production of Handel’s Saul the following evening. In a programme article Fuchs notes that Charles Jennens’ libretto, based on the first book of Samuel, reflects some of the social and political events of the day, and that the challenge is to “[find] another context closer to our own experience that reflects the universal concerns of nationhood, power and its subsequent abuse”. Fuchs thus updates the biblical action to post-WW2: Saul is a physically commanding but psychologically insecure US president and Daniel a dashing young pilot, fresh from heroic exploits which, judging from the exploding mushroom cloud in the opening visual sequence, presumably included dropping the nuclear bomb on Hiroshima.

Jonathan Best as Saul

Jonathan Best as Saul

While, generally, attention to detail is a good thing, it is possible to be overly specific and precise. Certainly Saul, composed shortly after the Glorious Revolution, raises questions about leadership, the legitimacy of rule and dynastic succession, and explores the effects of power upon the individual and the community. Such abstract concepts translate with relevance to our own age, but Fuchs’ declaration that Saul “shows us the way a nation establishes itself as a superpower, how it justifies war as a means of defence and a way of establishing national identity” seems to be taking things a bit too far. By pinpointing particular moments in twentieth-century history with such precision, Fuchs and designer Yannis Thavoris try to create parallels that are not always credible or sustainable: the victory chorus which opens Act 1 is now a VJ parade, the subsequent conflict with the Philistines becomes the Korean war (making nonsense of the text — who are the ‘Uncircumcised’ in 1950?), and Daniel only narrowly avoids a ‘Lewinsky moment’ in the Oval Office in Act 2!

Another problem, inherent in the genre, is what to do with the chorus. In opera seria, the ‘chorus’ was not a separate entity but simply an ensemble for the soloists, usually performed as a tableau at the start or end of each act before the sequence of individual da capo arias; but in his oratorios, Handel uses the chorus as a sort of Greek chorus which comments on the action as it develops and provides a moral benchmark for the audience. The difficulty in a dramatic staging of the work is therefore how to integrate the chorus plausibly in the action. Choreographer Clare Whistler certainly tried to suggest the chorus’ unity of thought and judgement, ritualistically assembling the members in sequence, using imitation and repetition of movement to indicate collective judgements and beliefs. Yet, there was frequently too much fuss and busyness: umbrellas were certainly requisite outside the house during an unseasonable wet week, but were they really essential as a prop for a well-drilled choral routine? The ‘meaning’ of such gestures, like the twisting hand movements that opened Act 2, was often obscure or plain daft (were the chorus’ lime green hands supposed to indicate Saul’s envy which the people condemn?). Moreover, they distracted both the chorus from watching the beat, and the audience from focusing on what was otherwise some fine ensemble singing.

Jonathan Best was strong in the title role, conveying the paranoia and jealous anguish of the eponymous ruler with intelligence and conviction. Robert Murray presented a thoughtful portrait, musically focused and dramatically engaging; but as Saul’s two daughters, Merab and Michal, Elizabeth Atherton and Ruby Hughes respectively made less dramatic impact and Hughes’ projection was rather weak at times. Most impressive of the cast was Anne Marie Gibbons, a stunning David, who used her burnished lower register to convey significant emotional depth as the young man experiences fresh hopes, passions and fears. One wonders, though, despite Gibbons’ beautiful legato line and sensitive decorative embellishments, whether the role should not really be taken by a countertenor, as Handel envisaged. In a silent role, as the Witch of Endor, Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks was dramatically effective (he was similarly assured in the small role of Laerte in Mignon the previous evening).

Jonathan Best as Saul, Robert Murray as Jonathan, Anne Marie Gibbons as David, with the Festival chorus

Jonathan Best as Saul, Robert Murray as Jonathan, Anne Marie Gibbons as David, with the Festival chorus

Conducting the Orchestra of the Sixteen, Harry Christophers established a lively momentum in Act 1 but, while alert to the musical details, he was not entirely successful in sustaining dramatic urgency, particularly through the series of slow arias in Act 3. One innate problem is that the musical involvement of David actually decreases in inverse proportion to his dramatic significance and growing power. And, Christophers wasn’t helped by the frequent hiatuses necessitated by numerous scene changes, including one (presumably unintentional) long pause between the scenes of the final act, which destroyed the musical and dramatic impetus.

In addition to the in-house productions and operas presented by visiting companies, the Festival offers a Literary Series, walks, a vibrant Fringe scene, and a concert programme, Mainly Music. On Tuesday 18th July the Frith Piano Quartet were on fine form in a recital of both well-known and unfamiliar chamber music by Dvořák. Taking advantage of the presence of a harmonium in the Pavilion Arts Centre, they began with the seldom performed Five Bagatelles, Op.47, Alistair Young’s warm harmonium tones blending sympathetically with the folk-inspired melodies of the strings, which are developed in variation form through a range of tempi and moods. Young was replaced by pianist Benjamin Frith in Dvořák’s second Piano Quartet in E-flat Op.87. The precision of the ensemble, led confidently and with stylistic panache by Robert Heard, was impressive: the instrumentalists responded sensitively as individual lines rose and fell within the energetic textures, Frith’s vigorous piano motifs never over-shadowing the strings. Louise Williams enjoyed the opportunities afforded by the composer to display her rich viola tone, while ‘cellist Richard Jenkinson provided strong rhythmic impetus, his athletic and precise pizzicato particularly note-worthy.

The 2012 Festival promises more such delights, with a programme scheduled to include more Handel, Strauss’s Intermezzo and Sibelius’s The Maiden in the Tower.

Claire Seymour

Cast Lists:

Mignon

Mignon: Wendy Dawn Thompson; Philine: Gillian Keith; Wilhelm: Ryan MacPherson; Lothario: Russell Smythe; Laerte: Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks; Jerno: Mark Holland; Frederick: Amar Muchhala. Conductor: Andrew Greenwood. Director: Annilese Miskimmon. Designer: Nicky Shaw. Lighting: John Bishop. Buxton Opera Festival 2011, Saturday 16th July 2011.

Saul

Saul: Jonathan Best; Jonathan: Robert Murray; David: Anne Marie Gibbons; Merab: Elizabeth Atherton; Michal: Ruby Hughes; Witch of Endor: Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks; Ghost of Samuel: Andrew Slater; High Priest: Andrew Mackenzie-Wicks; Doeg: Philip Gault. Conductor: Harry Christophers. Director: Olivia Fuchs. Designer: Yannis Thavoris. Choreographer: Clare Whistler. Lighting designerJohn Bishop. Buxton Opera Festival 2011, Sunday 17th July 2011.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/mignon_gillian-keith-276.gif image_description=Gillian Keith as Philine [Photo by Robert Workman courtesy of Buxton Opera Festival] product=yes product_title=Ambroise Thomas: Mignon; Georg Frederic Handel: Saul product_by=See body of review for cast lists. product_id=Above: Gillian Keith as PhilineAll photos by Robert Workman courtesy of Buxton Opera Festival

July 21, 2011

Sciarrino: Luci Mie Traditrici

by Andrew Clements [Guardian, 21 July 2011]

Sciarrino's opera may be only a little over a decade old, yet this is already the third version of Luci Mie Traditrici, and the second on the Stradivarius label, to appear on disc. Unlike its predecessors, though, this recording comes from stage performances - at last year's Montepulciano festival - and has a dimension of vivid theatricality that makes the others seem strait-laced in comparison.

Inside a Master Class: Breathe, Punctuate, Forget Led Zeppelin

By Erik Piepenburg [NY Times, 21 July 2011]

IN the Terrence McNally play “Master Class,” the opera diva Maria Callas (played by Tyne Daly) understands pedagogy to mean wiping the floor with young students’ ambitions.

“Try isn’t good enough,” Callas scolds. “Do.”

July 19, 2011

Opera in Contract Spat

By Erica Orden [WSJ, 19 July 2011]

Unions representing New York City Opera performers have questioned whether the company's intention to vacate its home at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts is prudent. Now they are questioning whether it's legal.

Havergal Brian’s “Gothic” Symphony

Havergal Brian (1876-1972) is a cult figure in British music who attracts an intense following, even though his music is rarely performed and existing recordings are of not of the highest standards. He’s better known by reputation than by listening experience. Indeed, it’s this very air of exclusivity that’s part of his appeal. BBC Prom 4 was a historic watershed in Brian reception, because it gave Brian maximum possible publicity, and the best performance to date.

This was a truly spectacular, extravagant event. Brian’s “Gothic” Symphony is apparently in the Guinness Book of Records for being the biggest symphony ever written, and only the BBC Proms can provide the resources to do it justice. Thus, this Prom was a once-in-a-lifetime experience, a historic occasion that wasn’t to be missed. It was a form of total theatre that will be remembered for decades.

One third of the massive Royal Albert Hall was reserved to accommodate the sheer number of performers, almost a thousand in all. Nine choruses, no less, visually impressive, especially the women’s choir in lavender, and the children’s choirs in white. Two main orchestras, the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and the BBC Concert Orchestra. Two “timpani orchestras”, as opposed to “symphony orchestras”, positioned at the sides of the auditorium, between the choristers and audience. Those sitting near them may be deaf for days. And, like a Colossus above them all, the mighty Royal Albert Hall Willis organ, with its 9,997 pipes and 149 stops, the largest in Europe.

Martyn Brabbins conducted the gargantuan forces with aplomb. He’s braved the dense jungle of this score like a fearless explorer mapping unknown territory. He’s clearly prepared the work thoroughly, searching out the main features in this bewildering terrain. Brian’s “Gothic” is a strange Leviathan which has defeated the best efforts of many, so Brabbins deserves a medal for persistence and dedication.

Brabbins focuses on the many details which build up to form the dense undergrowth. A flurry of harps, for example, and a bizarre chorus of xylophones, springing out unexpectedly, like exotic birds startled into flight. The whole symphony seems to be built from details like this, an accumulation whose object is to amass as many pieces as possible — not a jigsaw, for the ideas don’t really cohere. So Brabbins’s carefully thought out detail brings out the endless proliferation that gives this symphony its charm.

Brian was a self-taught, almost eccentric character who wasn’t particularly bothered by the practicalities of performance. There are many ideas in this symphony, but they are briefly glimpsed and don’t develop. On paper, they may look good, but they don’t necessarily make much sense in practical performance. For example, the timpani orchestras, backed by very loud brass. At first they call out to each other across the expanse of the auditorium. Then one falls more or less silent thereafter.

Brian’s Gothic has been compared to Mahler’s Eighth Symphony, on the basis that the latter was marketed as the “symphony of a thousand”, but the comparison is nonsense. The label was a PR ruse. Mahler’s focus was on spiritual meaning. Although Mahler’s structure is unorthodox, there’s a powerful trajectory that pulls it forward. The inspiration behind Brian’s symphony isn’t consistent. Liturgical texts are used, but the thrust isn’t particularly spiritual. Brian is certainly ambitious, quoting Goethe’s Faust on his title page, (“Whoever strives with all his might, that man we can redeem”), but the energy dissipates.

For example, in the final movement, the ‘Te ergo quaesumus’, Alastair Miles intones lines that waver upwards and down, perhaps in homage to Orthodox chant, but the orchestra then plays a parody of jazz swing. Sometimes contrasts have reason, but in this symphony they seem to exist for variety’s sake. When Susan Gritton sings ‘Judex crederis esse venturus’ from way up in the rafters, it’s a truly sublime moment — magnificent singing, magnificently theatrical. But the rest of the movement consists of that 4-word sentence alone, and it’s quickly dispensed with in favour of meaningless extended vocalise. In all three major Proms concerts so far (Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass and Rossini’s William Tell) the tenor parts have been fiendishly difficult. Peter Auty deserves recognition for valour, since he surmounted Brian’s extreme demands for his part. Christine Rice sang part well, but Brian leaves the part curiously underwritten.

This performance of Brian’s “Gothic” symphony was hugely enjoyable because it worked remarkably well as theatre. Brian himself may not have anticipated the concept of sonic architecture quite in the way that others — including Stockhausen, whom Brabbins also conducts well — but the BBC Proms and the Royal Albert Hall can work wonders. Brabbins and his multitude deserve a great deal of credit, but so too, do the organizers who made this possible in the first place — a thousand performers and a huge array of instruments. Moving this army must have been a logistic nightmare. Many of these choirs are major names on the choral scene, and were brought in from all over the country.