October 31, 2011

German tenor thrills Met audience in solo recital

By Mike Silverman [AP, 31 October 2011]

He’s already thrilled Metropolitan Opera audiences with his exceptional vocal powers in such large-scale works as Puccini’s “Tosca,’’ Bizet’s “Carmen’’ and Wagner’s “Die Walkuere.’’

October 27, 2011

Renée Fleming and Dmitri Hvorostovsky: A Musical Odyssey in St. Petersburg

Would it really have been unacceptable to call the program “A Musical Travelogue in St. Petersburg”? There are no adventures with sirens or one-eyed giants, nor is there any sense of homecoming and redemption. Instead, soprano Fleming (Hvorostovsky apparently otherwise engaged) walks through some of the more appealing tourist locations of the city, in three segments that take up about 20 minutes of the main program’s 90-minute running time. At least Decca provides an additional four musical selections for the DVD release.

Putting aside persnickety complaints about language, the DVD is very enjoyable. It gets off to a great start by skipping introductions and immediately joining Renée and Dmitri in front of the State Hermitage orchestra and conductor Constantine Orbelian. Credits roll as the singers launch into the fourth act duet of Il Trovatore’s Leonora and Di Luna. Other than Violetta and Desdemona, Verdi hasn’t played a big part in Ms. Fleming’s career, so it’s fairly surprising how well she does in this scene. Hvorostovsky has sung the Count many times, and in this smaller hall, he is able to bring all of his skill to the performance without having to push as he would in a larger venue. Next, after 10 minutes of Renée guiding us through the Winter Palace, we return to the concert and an extended scene from Simon Boccanegra. A briefer travelogue is followed by several Russian songs, with Olga Kern at the piano. This is Hvorostovsky’s home territory, of course, and he shines; Ms. Fleming looks and sounds ravishing.

Another travelogue section precedes the return of the orchestra for selections from three Tchaikovsky operas, listed in the booklet as Pique Dame, Oprichnik, and the reliable Eugene Onegin. Hvorostovsky sings Yeletzki’s aria handsomely as expected, and the rare opera’s aria for Renée is quite beautiful. Then the pair performs the final scene of Onegin with a potent mixture of elegance and dramatic force.

The bonus tracks are all worthy and undoubtedly only edited out of the main program only for reasons of timing (the main program was offered on PBS in the Great Performances series). Dmitri sings Hamlet’s drinking song from the Ambroise Thomas opera and a rare and very entertaining Anton Rubinstein number. Ms. Fleming gives us her creamy “Casta Diva” and Lisa’s first act aria from Pique Dame.

The Decca set has rudimentary packaging, but the performance itself is classy, and as the travelogue sections are separately tracked, they can easily be skipped on repeat viewings. If one doesn't expect the rollicking adventure of a true odyssey, this set should prove to be high-quality musical entertainment.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/0743383.png

image_description=Decca 0440 074 3383 6 GH [DVD]

product=yes

product_title=Renée Fleming and Dmitri Hvorostovsky: A Musical Odyssey in St. Petersburg

product_by=Renée Fleming, soprano. Dmitri Hvorostovsky, baritone. State Hermitage Orchestra. Conductor: Constantine Orbelian. Directed for video by Brian Large.

product_id=Decca 0440 074 3383 6 GH [DVD]

price=$27.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=509305

Pavarotti at the Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan has recently re-released on DVD the 1978 telecast of Pavarotti’s first Cavaradossi at the Metropolitan. The greater testimony to the ongoing fame of this tenor is a separate Decca release, in tandem with the Metropolitan Opera, called “Bravo Pavarotti.” Only a singer who has reached a very rare level of popularity gets the distinction (if that’s the word) of an entire DVD devoted to clips of aria performances from various telecasts, with absolutely no other content. Decca and the Metropolitan clearly believe there is a market out there, an audience that wants a disc they can put on whenever they just want to bathe in the warm beautify of Pavarotti’s tone and his joyful stage presence.

The DVD consists of 14 excerpts from Pavarotti’s repertoire at the Metropolitan — entirely Italian: Verdi, Donizetti, Puccini and Leoncavallo, with the interesting addition of his restrained but effective appearance in Mozart’s Idomeneo. The video quality varies, with some of the older clips lacking vibrancy, but Pavarotti’s connection to the audience can be felt at almost every moment. Indeed, part of the length of this relatively short DVD (about 90 minutes) comes from extended shots of the tenor, arms wide, eyes initially closed, basking in the extended ovations he came to expect. Are these performances flawless? Of course not. The high notes of both Che gelida manina and La donna è mobile both show his technical skill, as in both cases the note is initially not there for him. Pavarotti adjusts and holds on, where a lesser sing might have cut the note short.

Although not the most convincing actor, these clips do show him as an engaged performer — but then most of these are from his golden middle period, before he began to earn himself a reputation for carelessness and indifference. The close-ups are fascinating, however, for that face, so joyful and alive during the ovations, is a true singer’s mask when vocalizing. Pavarotti’s eyes focus on some distant spot, as he produces his sound and prepares for whatever musical challenge the next phrase may bring. The most illustrative — and amusing — example of this is the Rigoletto quartet, which Pavarotti sings with the Maddelena of Isola Jones, a strikingly beautiful woman with ample — and exposed — cleavage. While singing, Pavarotti is entirely professional, but when he has the chance, he can’t help but very realistically portray the Duke’s leering enjoyment of his evening’s conquest.

So is “Bravo Pavarotti” for anyone but the most diehard Pavarotti fan? Probably not. The brief booklet essay merely runs through some basic information on each performance, and otherwise there is nothing in the package that one couldn’t put together for oneself fairly easily.

That complete 1978 Tosca is a different matter. Conducted with fervor by a very young James Conlon, this Tosca is a handsome example of the Met at its tasteful, traditional best. This is the Tito Gobbi production, and among the three excellent bonus features is a conversation between this performance’s Scarpia, Cornell MacNeil, and Gobbi. We also get a chance to watch James Levine and Conlon try to outdo each other in insightful comments about Puccini’s score. The best of the three is a short rehearsal sequence with Conlon and a pianist leading Shirley Verrett, the Tosca, and Pavarotti through the act three duet. Conlon proves himself to be calm and psychologically astute, as he supports a somewhat needy Verrett and keeps Pavarotti from getting bored.

Pavarotti is in glorious voice throughout (the two big arias are part of the Bravo Pavarotti set), and MacNeil, though late in his career, has the experience and craftsmanship to keep mostly disguised the voice’s tendency to sag in pitch. Verrett, in unappealing light make-up, offers little that is original in her Tosca, but she inhabits the role with grace and passion. Extended passages start to show some stress on her voice (she was known primarily for mezzo repertory), but she has enough of a success to earn a shower of torn program confetti at curtain call.

Tosca was always planned to be the opera Pavarotti would perform in for his final complete performance at the Metropolitan. A year or two before that happened, Pavarotti had to cancel a run. He was replaced in one performance at the last moment by a very young Salvatore Licitra, who earned glowing reviews that suggested he might be the “next Pavarotti.” Alas, Licitra’s career, while substantial, did not support that characterization, and even more sadly, Licitra died this year in an accident. Other singers may come along and be alarmed to find themselves declared “the next Pavarotti,” but everyone knows there will be no such singer. And with Decca holding onto its legacy of recorded Pavarotti performances, we won’t be without the real Pavarotti anyway.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/0743410.png

image_description=Decca 0440 074 3410 9 DH [DVD]

product=yes

product_title=Giacomo Puccini: Tosca

product_by=Tosca: Shirley Verrett; Cavaradossi: Luciano Pavarotti; Scarpia: Cornell MacNeil. The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Conductor: James Conlon. Director: Tito Gobbi. Metropolitan Opera, December 1978.

product_id=Decca 0440 074 3410 9 DH [DVD]

price=$24.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=9762&name_role1=1&comp_id=2345&genre=33&bcorder=195&name_id=53434&name_role=3

Bravo Pavarotti: Luciano Pavarotti’s Greatest Performances at the Metropolitan Opera

Various artists

Decca DVD B0014805-09

Tosca

Music: Giacomo Puccini

Libretto: Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica

Metropolitan Opera, December 1978

Director: Tito Gobbi

The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra

Conductor: James Conlon

Tosca: Shirley Verrett

Cavaradossi: Luciano Pavarotti

Scarpia: Cornell MacNeil

Decca DVD B0014793-09

Carmen returns to the Opéra Comique

After all, any conductor who doesn’t follow the practice would seem to be tagged as “historically ignorant.”

At its start some decades ago, the “HIP” movement focused on baroque and early classical era music. It has since branched out, and that branch is impressively extended with the recent DVD of Sir John Eliot Gardiner conducting his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique at the Opéra Comique in an historically informed performance of Georges Bizet’s Carmen. Besides employing instruments of the era, this production aims for authenticity from the ground up — or “the stage” up. For Carmen debuted at the Opéra Comique, infamously receiving a less than ideal reception that many conjecture added to the stress which culminated in the composer’s early death from heart disease. Stage director Adrian Noble strives to freshen the action while keeping to a libretto-bound conception of the story and characters. This is still, therefore, a Carmen who sits with legs splayed, and who sashays with one hand on a hip. That said, Noble does have his Don José plant a kiss on Micaela in act one that goes beyond the usual pallid interaction.

Set and costume designer Mark Thompson, however, seems of two minds. The costumes are very traditional, though nicely done — almost everything is in a spectrum of light beige through dark brown, and the clothes look truly worn. In so many a Carmen, everyone looks as if the local dry cleaner is working overtime. Thompson’s uniset, however, surely looks nothing like whatever the Opéra Comique used in 1875. Act three, for example, gives only the barest indication of a mountain pass. Instead, we have a sort of elevated walkway at the rear which slopes to stage level, and a circular platform just off mid-stage. Apparently the cigarette factory is subterranean, as the girls take their break by clambering out of the platform. For act 4, Noble and Thompson clear the stage for the intense action of the last scene.

There are moments in the recorded performance where one can almost imagine, however, that one is watching — if not the authentic first performance — something rawer and more authentic than many another recorded Carmen. Sir John and the artistic team use an edited version of the score (by one Richard Lanhman-Smith) that has spoken dialogue, as Bizet originally intended. And under Noble’s direction, a committed cast delivers strong performances — honest and stripped-down to essentials. Anna Caterina Antonacci’s Carmen has already been recorded in an acclaimed Covent Garden performance opposite Jonas Kaufmann. Her comfort in the role allows her to perform even the most stereotypical gestures and movements with relaxed conviction. Oddly, the only times that her singing reflects any discomfort with the role is at the higher range — which one might think unusual for a singer with a career as a soprano. Perhaps in adjusting her voice for the reliance on the middle range, Antonacci loses a bit of security at the top. It’s a very minor compromise in an otherwise strong performance.

Her Don José does a fine job right up until his big second act aria and continues to be fine thereafter. But Andrew Richards is not able to deliver the “Flower Song” with the security and confidence the moment requires. It’s all the more unfortunate as his Don José is so believable — a man of modest attraction, overwhelmed by the chance to share the passion of Carmen, and then devastated when it is withdrawn. The supporting cast makes more routine impressions, with Anne-Catherine Gillet giving us a Micaela even mousier than usual, and Nicolas Cavallier too smug for his own good as Escamillo.

As for Gardiner and his orchestra, they often play fast, as one might expect, and there are patches of roughness than either attest to the authenticity of the performance or suggest a deaf ear to musical sophistication — depending on one’s attitude towards HIP. Gardiner’s most regrettable choice is the Nehru jacket. Un-HIP.

The packaging is remarkably handsome but not without compromises. Your reviewer prefers removable booklets to one bound to the spine. The two discs are visually nearly identical, with text almost impossible to read. Figuring out how to dislodge the discs from the casing also took more of your reviewer’s ingenuity than he would have liked. The bonus feature is a rather routine 20 minute set of interviews, but as the booklet has nothing but credits and synopsis, anyone wanting a little more insight into the performance will have to view it.

Not a “hip” Carmen, then, but this HIP Carmen does have historical appeal and a strong performance of the title role.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/FRA_Carmen.png image_description=FRA Musica FRA 004 product=yes product_title=Georges Bizet: Carmen product_by=Carmen: Anna Caterina Antonacci; Don José: Andrew Richards; Escamillo: Nicolas Cavallier. Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique. The Monteverdi Choir. Director: Adrian Noble. Conductor: Sir John Eliot Gardiner. Opéra Comique, June 2009. product_id=FRA Musica FRA 004 [2DVDs] price=$37.49 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=1141&name_role1=1&comp_id=479&genre=33&bcorder=195&label_id=12271Béatrice et Bénédict, Opera Boston

It is a question that Berlioz, to his frustration, never quite answered. In his youth, bel canto held the stage, and the tone was set by Rossini and Bellini; by his maturity, grand opera and its rather different conventions had taken over. How was a composer of the highest aspirations to structure a work that was to give rein to experience and perception? The reliable but chilly structures of the Baroque and the da capo aria, with its implied assurance that the world was to return to the given social order, just as the singer was bound to return to the first melody, were not going to prove satisfactory; the very different example of the opera-comique in France, with its bumptious mixture of popular entertainment and cultivated composition was, for a composer like Berlioz, little inspiration. The failures of Schubert’s Fierrabras and Schumann’s Genoveva as dramatic vehicles functioned as a kind of warning, and the silence of Brahms — his profound disinterest in writing for the stage — was instructive. Only Weber’s Freischutz, and, to a lesser extent, his Euryanthe and Oberon, established and retained places on the international stage, and in the allegiances of popular and learned auditors.

By the time Berlioz wrote Béatrice et Bénédict, he had endured a lifetime of frustration and misunderstanding in opera. No composer has ever loved drama more, or more instinctively, than Berlioz, yet he had the greatest difficulties — many self-imposed — in creating vehicles that played as drama. Benvenuto Cellini is a mess of color and action; La Damnation de Faust, despite recent efforts by the Metropolitan Opera, is almost inert dramatically; Les Troyens is a magnificent masterpiece, but long, unwieldy, and intermittently static. Beatrice and Benedict, which he wrote in the early 1860s, is an odd creation by almost any standard. The story, extracted by Berlioz himself from Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, is a light, almost eventless romantic comedy. The heart of Much Ado is a fundamentally misogynistic tale of deception and wronged virtue: Claudio is suborned by Don John into believing that his betrothed, Hero, has been untrue to him. These unhappy lovers, on their winding way back to the altar, are accompanied by the low-comedy antics of the local constabulary, and, most of all, by Hero’s cousin Beatrice and Claudio’s boon companion, Benedick, whose repeated slanging matches signal, to everyone but themselves, a deep underlying sexual tension and romantic affection. These two have long since crowded the disquieting principal plot, which is a story only an academic could love — as long ago as the 1630s, King Charles I titled his copy of the play Beatrice and Benedict. Berlioz simply discards all the pesky business — gone Don John, gone denunciations at the altar, gone Dogberry and the antics of the police; welcome a slight and forgettable bit of new business with a newly-devised character, the music-master Somarone (“Big Ass”). The trouble here is that without even a hint of shadow — all Claudio and Hero do is to egg their friends on, while the nuptials approach — there is very little narrative drive. It does not come as much of a surprise to learn that Berlioz planned the work as a one-act opera, and extended it; the music of the two-act version is consistently rewarding, but dramatically almost as inert as his Faust. Berlioz’s thinking here is orchestral, and almost symphonic — Béatrice et Bénédict is, arguably, a symphony or tone poem on themes from Shakespeare, with voices. As such, it is among Berlioz’s most appealing works: the duet-nocturne that closes the first Act, perfectly performed by Opera Boston, is arguably one of the most beautiful episodes in all of opera.

Julie Boulianne as Béatrice and Sean Panikkar as Bénédict [Photo courtesy of Opera Boston]

Julie Boulianne as Béatrice and Sean Panikkar as Bénédict [Photo courtesy of Opera Boston]

For all his superior mastery of more complex forms and ideas, Beethoven, Berlioz’s great musical model, could only wish he had written ten more beautiful minutes. Opera Boston, a laudable champion of the neglected and under-heard in opera, has essayed a fluent, elegant staging of Berlioz’s last stage work. The setting is still Sicily — or, that sort of neverland Shakespeare always evokes in his comedies — but resituated in a high-toned 1950s, complete with puffed skirts, bobs, and up-dos — you almost expect a poodle-skirt to sashay in. Designer Robert Perdziola’s set design is equally stylish — the capolavoro is perhaps the lifting of set’s back wall, mottle-painted to suggest aging stucco, to reveal a heart-stopping night sky and distant harbor. As Beatrice, Julie Boulianne has a fine mezzo-soprano voice, a little hard-toned in the upper reaches; Sean Panikkar as Benedict lacked a little polish and finish in tone. Heather Buck’s Hero was excellent at the top and bottom of her register, but a little elusive at times in the middle. Kelley O’Connor as Ursule almost stole the evening, with an arresting, dark-colored low-mezzo voice. Gil Rose’s orchestra offered a seamless and idiomatic reading of Berlioz’s tuneful score. Director David Kneuss, a long-time advocate of the work, decided on an odd hybridization of languages and styles — the sung score was heard in Berlioz’s French, the dialogue in English, in an adaptation that mixed Shakespeare, Berlioz’s own additions for the French-language premere in 1863, and what was apparently some of Kneuss’ own work. Although the result was not as jarring as might have been feared, why not go all the way in any one of these directions? Shakespeare, with minimal alterations? modern English for everything? French for all? Kneuss also did not entirely solve Berlioz’s dramaturgical problems, perhaps a thankless task on the best of days. Principals and chorus were frequently perfectly stationary in moments that, musically and dramatically, suggest movement (the opening of Act I; the drinking song in Act II) — but then, to be fair, Berlioz always had peculiar ideas about what constituted a party.

Finale [Photo courtesy of Opera Boston]

Finale [Photo courtesy of Opera Boston]

Beatrice and Benedict was not quite his last work — the Memoirs were to follow — but is arguably his last musical work of any importance. Like Verdi long after him, he said farewell to the stage, and to some degree to music, with comedy — and comedy from Shakespeare, at that. He lacked Verdi’s Boito — he had no librettist of genius to help shape the drama, and provide a loving but stern pair of eyes to look over the work. Why this work — and why this curious selection from Much Ado? Shakespeare had long been both his inspiration and his undoing; it was through Shakespeare that he found himself as a composer of genius, and it was through Shakespeare that he met Harriet Smithson, the English actress he loved and married. Their relationship declined into mutual loathing and recrimination — but in this bagatelle on Shakespearean themes, we see a merrily quarrelling couple, Beatrice and Benedict, whose loving combat never degrades into hatred. They are Hector and Harriet, without the depredations of age or misfortune. When it premiered, Verdi’s Forza del Destino opened in Imperial Russia; Offenbach’s Belle Helene was in preparation, and Meyerbeer’s Africaine was being completed; most of all, Wagner’s Walkure had just appeared at Bayreuth. Aesthetics very different from Berlioz’s, although perhaps similar in ambition, had arisen; yet this last and most polished and mature work from the pen of Berlioz deserved and deserves to be heard. Opera Boston’s commendable production, with its polished style and fine young singers, goes a long way toward keeping Berlioz’s music fresh and living for contemporary audiences.

Graham Christian

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Much_Ado_Quarto.png image_description=Title page of the first quarto of Much Ado About Nothing by Shakespeare [Source: Wikipedia] product=yes product_title=Hector Berlioz: Béatrice et Bénédict product_by=Click here for cast and production information. product_id=Above: Title page of the first quarto of Much Ado About Nothing by Shakespeare [Source: Wikipedia]October 26, 2011

Don Giovanni, Metropolitan Opera

Supposedly, when the opera was performed the following evening, the ink was still wet on the pages.

Barbara Frittoli as Donna Elvira

Barbara Frittoli as Donna Elvira

The finished product is a marvel of composition. After the opening, two ferocious minor chords, what follows is a depiction of hell: the perfect beginning to an opera whose full title is Don Giovanni, or The Punished Miscreant. When the Met’s new principal conductor, Fabio Luisi, conducted the new production of Don Giovanni on Saturday, October 22nd, he executed the beginning minor chords of the overture with startling accuracy. However, in the following section, in which Mozart depicts hell, he seemed a tad lackluster. Unfortunately, this was a sad harbinger of what was to come, not just from the pit, but from the stage as well.

So what went wrong? My diagnosis is that the Met’s new production, directed by acclaimed Broadway director Michael Grandage, fell victim to the politics of the Peter Gelb regime. As a director who is unfamiliar to opera, Grandage fits well into Gelb’s scheme of operatic rejuvenation, for the purposes of demonstrating to the public that “opera is not just great music, but great theater as well.” To be fair, Mr. Grandage’s work can be breathtaking. A recent Broadway run of Hamlet, starring Jude Law, was a wonderful night at the theater. Unfortunately, Mr. Grandage’s productions function mainly as vehicles for the performers. Had Hamlet not starred the dynamic Mr. Law, it might have come up flat. This is what happened here.

Marina Rebeka as Donna Anna

Marina Rebeka as Donna Anna

The real problem with this production, therefore, can be seen as a trick of fate. Under normal circumstances, the title rascal would have been played by baritone Mariusz Kwiecien and James Levine would have been in the pit. As it happened, both Mr. Kwiecien and Mr. Levine were indisposed, so the Finnish baritone Peter Mattei had to be pulled from The Barber of Seville where he was singing Figaro, and Fabio Luisi stepped in, yet again at the last minute, for Mr. Levine.

While an amazing Figaro, Mr. Mattei’s Giovanni was a caricature of the great villain. To be sure, Don Giovanni is an opera buffa, but it is less a bubbling comedy, like Rossini’s Barber, and more a dark comedy with far-reaching political undertones. The oversexed nobleman of the title is supposed to make you laugh, but each laugh is supposed to hurt. Mattei’s Giovanni lacked the essential component of volatility that Mozart so desperately wanted. That said, he sang well. His “Deh vieni alla finestra” was a joy to hear, but despite the masterful singing, this aria, just like the majority of the performance, lacked emotional substance.

As Leporello, Luca Pisaroni was magnificent. He played Giovanni’s servant as a sardonic commentator on the action. His performance as the valet made me hope that he would one day attempt the Don himself. Among the men, other standouts include Ramón Vargas, who gave a wonderfully sung and surprisingly masterful performance as Don Ottavio. He was far from the epitome of inactivity of other productions. Joshua Bloom gave an excellent turn as Masetto, and Štefan Kocán was a marvelously unstable and threatening Commendatore.

Of the three women, Mojca Erdmann was a stylish Zerlina. She certainly has the technique to sing Mozart, however her character portrayal of the wily peasant girl was a little flat. The highlight of her performance was “Vedrai carino.” It showcased her ability as an actress while at the same time making one wish the rest of her performance could have been as good. Marina Rebeka was a thrilling Donna Anna. The highlight of her performance was “Or sai che l’onore.” It is customary to portray Donna Anna as a strong character, only limited by the accident of being born a woman. However, here she didn’t just scold Don Ottavio. Had the aria been longer, she might have eaten him alive.

Mojca Erdmann as Zerlina and Joshua Bloom as Masetto

Mojca Erdmann as Zerlina and Joshua Bloom as Masetto

The crowning achievement of this performance was Barbara Frittoli. For better or worse, she became the focal point of the opera. She took a well-known facet of the character, her ambivalent mix of revulsion and love for Giovanni, and explored it to the utmost degree. Unlike other Elviras, who between acts one and two seem to magically change from loathing to adoration for the Don, both facets of her character were present from the beginning.

Critics have maligned this production for its set, which consists of a wall of decrepit-looking shuttered balconies. They scoff at its so-called “Advent calendar” design. In my opinion, the design is not the flaw here. What is an issue is the blocking. Throughout the opera, certain characters on the ground interact with those standing on balconies. This creates an uncomfortable lack of chemistry in an opera that is supposed to sizzle with eroticism. Yet even when all the characters are standing together on the ground, there was confusion in their interactions. For instance, Donna Anna was not present for Don Ottavio’s rendition of “Il mio Tesoro.” As a consequence, Mr. Vargas had to sing of his love for Donna Anna to everyone else but Donna Anna.

Instead, Mr. Vargas focused on Donna Elvira. While this strengthened the idea that Elvira is engaged in a neverending search for love, this directorial faux pas made me wonder if Elvira was really the title character of this production. There were some instances of genius. Don Giovanni removed Zerlina’s veil just before “La ci darem la mano.” A subconscious nod toward his desire to take her virginity, perhaps? Also, Elvira was ravished on the dining room table by a Giovanni who was literally blinded to fate during his last meal on Earth.

Luca Pisaroni as Leporello, Barbara Frittoli as Donna Elvira, Ramón Vargas as Don Ottavio, Peter Mattei as Don Giovanni, and Marina Rebeka as Donna Anna

Luca Pisaroni as Leporello, Barbara Frittoli as Donna Elvira, Ramón Vargas as Don Ottavio, Peter Mattei as Don Giovanni, and Marina Rebeka as Donna Anna

However, such inspiration was fleeting. At the end, when all the characters sing of their need to put their lives back in order, I was left wondering, “Was there any real threat to begin with?” The desire to reinvigorate the public’s interest in opera with ubertheatrical productions is a noble endeavor, but if the performance doesn’t at least acknowledge what originally excited the composer, how can we be sure a modern day public will be interested?

Gregory Moomjy

image=http://www.operatoday.com/GIOVANNI-Pisaroni-Mattei6582.png image_description=Luca Pisaroni as Leporello and Peter Mattei as Don Giovanni [Photo by Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera] product=yes product_title=W. A. Mozart: Don Giovanni product_by=Donna Anna: Marina Rebeka; Donna Elvira: Barbara Frittoli; Zerlina: Mojca Erdmann; Don Ottavio: Ramón Vargas; Don Giovanni: Peter Mattei; Leporello: Luca Pisaroni; Masetto: Joshua Bloom; The Commendatore: Stefan Kocán. The Metropolitan Opera. Conductor: Fabio Luisi. product_id=Above: Luca Pisaroni as Leporello and Peter Mattei as Don GiovanniPhotos by Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera

Delayed by Injury, Giovanni Still Arrives

By Anthony Tommasini [NY Times, 26 October 2011]

The Polish baritone Mariusz Kwiecien looked nimble on his feet, sang robustly and threw himself into the title role of Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” at the Metropolitan Opera on Tuesday night in the new production by the director Michael Grandage. Whatever one’s take on Mr. Kwiecien’s portrayal of a role he considers his calling card, his performance was a triumph of physical rehabilitation and artistic determination.

A Portrait of Manon — Young Artrists at the Royal Opera House

All members of the Royal Opera House Young Artists scheme are professionals, not students, and have extensive experience even before they come, as former Young Artist Simona Mihai put it “to be polished like gemstones”. Graduates of the scheme include Marina Poplavskaya, Jacques Imbrailo and Ekaterina Gubernova.

Most of the Young Artists are singers, but the scheme also covers other aspects of opera-making. The singers, directors and conductors in the scheme created this special performance of Massenet Le Portrait de Manon and Berlioz Les Nuits d'été to demonstrate their skills.

Pablo Bemsch

Pablo Bemsch

Massenet composed Le Portrait de Manon in 1894 as a one-act sequel to Manon. It is an excellent choice, coming after the Royal Opera House productions of Manon and Cendrillon. Knowing the background is valuable, as Le Portrait de Manon is essentially an epilogue to Manon. However, this Young Artists production was good enough that it could stand on its own.

Des Grieux (Zhengzhong Zhou) has grown old and bitter, so trapped in his grief that he's irritated when his lively young nephew Jean (Hanna Hipp) falls in love and wants to marry. The set (Sophie Mosberger) is very well designed, emphasizing Des Grieux's isolation, despite the trappings of wealth. There's a long rumination, in which Des Grieux sings about his past. Zhengzhong Zhou worked two years in France, and sang Valentin in Gounod's Faust earlier this month, so although he's only 27, he characterized Des Grieux's personality with emotional depth. His makeup was so well done, he looked as mature as he sounded. Pablo Bemsch, as Tiberge, Des Grieux's friend, was also very convincing, extending our sympathy with the predicament. Des Grieux isn't being unreasonable when he opposes Jean's marriage: perhaps he doesn't want the young man to be hurt as he was.

Zhengzhong Zhou as Des Grieux and Hannah Hipp as Jean

Zhengzhong Zhou as Des Grieux and Hannah Hipp as Jean

Love and youth will triumph, after all, as this is opera. Hanna Hipp is one of this year's new members of the Young Artists scheme, but she impressed greatly even as a student several years ago at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. Here she's a vivacious young scamp in trousers. Maybe Des Grieux is right, Jean's too young to be tied down. But Hipp and Aurore (Susana Gaspar) are spirited, and their confidence in their roles makes the resolution inevitable. Stunned by Aurore's appearance, dressed as Manon, Des Grieux remembers and relents. If Manon the opera is tragic, Le Portrait de Manon is an invigorating romp, and in this performance, deftly executed.

Berlioz’s Les Nuits d'été is a song cycle, and even in the 1856 orchestral transcription heard here, doesn't transfer easily to the stage. In theory, there's no reason why not, and the undercurrent of dream unifies the group of songs. While the staging for Le Portrait de Manon was concise, enhancing, adding to meaning, the staging for Les Nuits d'été was clumsy. One bed might have sufficed. These songs express states of mind, not different characters.

Hannah Hipp as Jean, Pablo Bemsch as Tiberge and Susana Gaspar as Aurore

Hannah Hipp as Jean, Pablo Bemsch as Tiberge and Susana Gaspar as Aurore

Pablo Bensch had been interesting as Tiberge earlier, so I was looking forward to his Villanelle. Unfortunately orchestra and singer weren't properly aligned, the winds entering insensitively, throwing the vocal line off kilter. Fortunately, Bemsch was better supported in Au Cimitiere. Hanna Hipp and Susana Gaspar sang the other songs. The balance was good, making a case for mixed voices. Berlioz sanctioned this, but it's usually impractical in recital — another good reason for paying attention to Young Artists Events, where repertoire is often approached in interesting ways.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/JPYA_LES-NUITS-DETE-01.gif image_description=Hannah Hipp [Photo © The Royal Opera / Richard Hubert Smith] product=yes product_title=Jules Massenet: Le Portrait de Manon; Hector Berlioz: Les Nuits d’été product_by=Aurore: Susana Gaspar; Jean: Hanna Hipp; Tiberge: Pablo Bemsch; Des Grieux: Zhengzhong Zhou. Conductor: Geoffrey Paterson (Le Portrait de Manoin). Volker Krafft (Les Nuits d’été). South Bank Sinfonia. Director: Pedro Ribeiro. Designer: Sophie Mosberger. Lighting: Warren Letton. Movement: Mandy Demetriou. Royal Opera House Jette Parker Young Artists, Linbury Studio Theatre, 18th October 2011. product_id=Above: Hannah HippPhotos © The Royal Opera / Richard Hubert Smith

Don Giovanni in San Francisco

San Francisco Opera unveiled a new Don Giovanni just now in nearly direct competition with the new Giovanni from the Met (you can see it soon on Live in HD). Of course the Met has avoided an American take on this old story as well, preferring to impose still more British artistic imperialism on Americans.

Marco Vinco as Leporello and Serena Farnocchia as Donna Elvira

Marco Vinco as Leporello and Serena Farnocchia as Donna Elvira

The SFO Giovanni is all about egoism, and we are not talking just about the libidinous Don. We are of course talking about SFO music director Nicola Luisotti. Like the Don, this maestro is much larger than life, and equally astonishing in his powers. But the Luisotti Don Giovanni is not about sex as it is for most stage directors, it is about how Luisotti can take you to the brink of lyric orgasm and hold you there longer than maybe you ever thought possible.

Of course the maestro did need some collaborators to support his lyric blowout, specifically a general director willing to suspend artistic judgement and engage a stage director who is at home on secondary Italian stages where standards are parochial to say the least. One Gabriele Lavia was Luisotti’s collaborator for his Salome in Bologna shortly after the San Francisco one (if in Bologna it was orchestrally more brilliant the staging was even cornier than in San Francisco).

The comedy of Mozart’s sublime tragicommedia in San Francisco was watching Sig. Lavia keep the maestro’s singers on a plain about 4 feet wide across the stage apron where no one could escape the maestro’s thrall. And still tell the story. It sometimes worked, sort of, belying the not-too-distant link of Mozartian dramaturgy to the linear and static placement of singers for Baroque opera seria.

Shawn Mathey as Don Ottavio and Ellie Dehn as Donna Anna

Shawn Mathey as Don Ottavio and Ellie Dehn as Donna Anna

General Director Gockley as well engaged a small scale, very Italiate diva, the splendid Serena Farnocchia whose bright lyric voice is on the small side for Donna Elvira, and light enough to negotiate, almost, Elvira’s very difficult music at the speed of light. The maestro succeeded in upstaging Sig.ra Farnocchia’s “Mi tradi” with a hyper emotional orchestral accompaniment to its recit (grotesque heaving).

Donna Anna was the American soprano Ellie Dehn who had made little impression as the Figaro Countess last fall. But she glowed vocally as a retiring Donna Anna, her just ample enough voice blended perfectly in ensembles, having shown with hanging beauty and fine musicianship in her first act aria "Or sai chi l'onore.” American tenor Shawn Mathey was Don Ottavio, but not the usual impotent one. Turning the tables he was the singer with the coglioni rather than the usual Giovanni heroines. Both Don Ottavio arias were blockbusters, exposing forceful, detached tones in quick passages and fioratura, and letting tone and feeling explode in lyric passages. Both Ms. Dehn and Mr. Mathey managed a synergy with the maestro to sublime effect.

Kate Lindsey as Zerlina

Kate Lindsey as Zerlina

Ignoring all potential complexities of relationship to his master, Italian bass Marco Vinco made Leporello a cute, almost expendable character, needed but not wanted. Though he, like most all Leporellos earned the biggest ovation. Like Leporello, Zerlina and Masetto were needed only for the maestro’s beautifully wrought ensembles, but not much more. Zerlina was ably and musically sung by Kate Lindsey, Adler Fellow Ryan Kuster made a cute Masetto.

San Francisco regular, bass baritone Lucas Meachem filled the shoes of Don Giovanni with aplomb and even charm. Mozart did not endow his most loved character with arias of consequence, and a stage director must dig way beneath the surface to intuit any complexity of personality, obviously not the scope of this production. But the Don is always big, and he lets it all hang out in his explosion at the end of the first act. Needless to say this was the meat of the maestro who turned it into an absolute frenzy. Mr. Meachem could not possibly compete, though he gave it a good try. The real Don would have thrown this maestro the very graphic up-yours gesture and walked off the stage.

From the downbeat of the overture Mo. Luisotti stated that this Mozart opera was an orchestral and musical process, its very sound groaning with importance, reminding us that the maestro has made his orchestra into one of the world’s fine pit ensembles. The beginning foretold the absolutely literal ending with the Commendatore, ably delivered by bass Morris Robinson, wreaking his vengeance on the Don in gigantic symphonic terms. We discovered last fall that after the maestro’s over-the-top musical dénouement in The Marriage of Figaro that he could not touch the quiet Mozartian humanity that ends Figaro. And here he does not even look for Mozart’s humanity, ending Giovanni with the Don’s noisy descent into hell rather than letting the quietly splendid Prague sextet wipe up the mess.

It was a fun evening. However Mozart and San Francisco might equally enjoy a bit of operatic integrity.

Michael Milenski

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DG--Don.gif

image_description=Lucas Meacham as Don Giovanni [Photo by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

product=yes

product_title=W. A. Mozart: Don Giovanni

product_by=Donna Anna: Ellie Dehn; Donna Elvira: Serena Farnocchia; Leporello: Marco Vinco; Don Giovanni: Lucas Meacham; Don Ottavio: Shawn Mathey; Zerlina: Kate Lindsey; Masetto: Ryan Kuster; The Commendatore: Morris Robinson. War Memorial Opera House. San Francisco Opera Orchestra and Chorus. Conductor: Nicola Luisotti. Stage Director; Gabriele Lavia; Set Designer: Alessandro Camera; Costume Designer: Andrea Viotti; Lighting Designer: Christopher Maravich. (10/18/2011). Photos by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera.

product_id=Above: Lucas Meacham as Don Giovanni

Photos by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera

October 24, 2011

Oedipe, La Monnaie, Brussels

By Francis Carlin [Financial Times, 24 October 2011]

Oratorio or opera? Enescu’s only work for the stage is such a fascinating score that the question seems of secondary importance. First performed at the Paris Opera in 1936 and very rarely heard since, Oedipe is Enescu’s musical testament, a richly harmonised compendium of tradition and modernity.

Der fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera

When this production of Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer premiered at the Royal Opera House in February 2009, (review here), Bryn Terfel was its raison d’être. His absence was sorely felt, even by those who aren’t usually seduced by his charms. In this revival, the draw was Jeffrey Tate’s return to Covent Garden after nearly 20 years.

Minimal stagings can work when they highlight meaning and music. Tim Albery’s production (designed by Michael Levine) is a blank canvas, which styles The Flying Dutchman rather than suggests much about who he is. No portrait of any kind in sight. Instead, a toy boat. The boat itself is wonderfully staged, and it’s a masterstroke to see real water on stage, lit so its reflection shines magically into the auditorium. But it doesn’t convey the wildness of the open ocean, nor the turbulent psychic storm around which this opera predicates.

Perhaps Albery’s interpretation is that the opera predicates on Senta and her frustratons, the Dutchman being a projection of her fantasies. Anja Kempe’s Senta was extremely impressive in 2009. Then, she was a perfect foil to Terfel’s solid, taciturn Dutchman. Kempe’s energy created Senta as driven to extremes to escape what to her might have seemed mind numbing conformity. The Dutchman is her ticket out of town, rather than a cursed soul. It’s a valid interpretation, given Albery’s factory staging of the spinning scene, and marginal references to the haunted ship. The concept is worth exploring, though here it’s rather too simplistic. Senta’s not Tosca. Wildness is tricky to sing into this part, and occasionally Kempe relied more on forcefulness than finesse. Nonetheless, she can do it well, and should settle further into the run.

Egils Silins was a late replacement for Falk Struckmann as The Dutchman. This was his Covent Garden debut, and possibly his highest profile performance to date. Although his voice isn’t particularly distinctive, he’s secure vocally and does seem to have a feel for the part. In a production where the singer has more to work with and is less exposed, he’d make a bigger impact. Part of this stems from Albery’s approach, where the Dutchman is reduced to little more than Senta’s dreams. It takes an unusually powerful and charismatic singer to counterbalance these limitations.

Stephen Milling’s Daland was forcefully secure, even too noble, given that the character has an unpleasant streak of venality, which would work well in Albery’s concept, but wasn’t developed. Still, it’s enough that he sang well. Endrik Wottrich’s Erik had problems with pitch and intonation, but was reasonably well acted. Clare Shearer’s Mary was excellent — no fault of hers that the role here was a cipher.

The role of Steersman is much bigger, and critical to the plot, for the Steersman is guides the ship into the distance. Both Senta and the Steersman dream, but Senta can’t think past the present. John Tessier has to sing suspended up a rope ladder, but hasn’t quite the character to make the part as compelling as it might be. But then many productions don’t make enough of the role, and this production doesn’t, either. It’s odd, given Albery’s interest in images of conformity as the Steersman is part of the crew. As always, the Royal Opera House choruses sing and move perfectly. The vocal battle between the Dutchman’s crew and Daland’s crew isn’t quite as horrific as it might be, but the “Steuermann, laß die Wacht!” refrain was sung with such jaunty zest that it left no doubt that these sailors and their families had no time for spooks and neurosis.

Egils Silins as Der Holländer, Anja Kampe as Senta and Stephen Milling as Daland

Egils Silins as Der Holländer, Anja Kampe as Senta and Stephen Milling as Daland

And so to Jeffrey Tate’s long awaited return to London. Fortunately Albery did not stage the protracted Overture, so we could concentrate on the orchestra. Tate’s pace was electric, injecting the malevolent atmosphere the staging tried so hard to suppress. The energy dissipated at other points, which was a kindness to the singers, who didn’t have to compete, and to Albery’s staging, which was so much at odds with the demonic, elemental fury in the music. When the Dutchman’s crew descend back into the bowels of their ship, Tate lets the orchestra burst forth again. They’re back on the ocean again, metaphorically defying storms and tribulations.

For more details, please see the Royal Opera House website.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Dutchman_ROH_03.gif image_description=Egils Silins as Der Holländer and Anja Kampe as Senta [Photo by Mike Hoban courtesy of The Royal Opera House] product=yes product_title=Richard Wagner: Der fliegende Holländer product_by=Daland: Stephen Milling; Steersman: John Tessier; The Dutchman: Egils Silins; Senat: Anja Kempe; Mary: Claire Shearer; Erik: Endrik Wottrich Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House. Chorus Director: Renato Balsadonna. Conductor: effrey Tate. Director: Tim Albery. Set designs: Michael Levine. Costumes: Constance Hoffman. Lighting: David Finn. Movement: Philippe Giradeau. Royal Opera House, London, 18th October 2011. product_id=Above: Egils Silins as Der Holländer and Anja Kampe as SentaPhotos by Mike Hoban courtesy of The Royal Opera House

October 23, 2011

Renata Pokupić, Wigmore Hall

Ranging far from the coloratura repertoire with which she has primarily made her name in the opera house, Pokupić was perhaps more comfortable with the impassioned folk sentiments of Dvořák’s Cigánské melodie (Gypsy Songs) and the flamboyance of Weill’s songs from Marie Galante than with the poised control of Schubert’s late lieder or the expressive nuances of Enescu’s settings of Clément Marot; but, supported by the typically accomplished accompaniments of Roger Vignoles, she presented an engaging sequence of song to a receptive audience.

The opening four Schubert songs, all composed during the last two or three years of the composer’s death in 1828, reveal the extraordinary diversity that Schubert achieved within the small form. Drawn and translated by Edward von Bauemfeld from Shakespeare’s The Two Gentlemen of Verona, ‘An Silvia’ is a sweet serenade to the eponymous protagonist. Adopting a tender, reflective tone Popukić revealed flashes of glimmering brightness, as the narrator remarked nature’s adoration of Silvia’s powers – “the wide fields praise her” and “Her gentle child-like charm refreshes”. Unfortunately, ‘Im Abendrot’ (‘Sunset glow’) and ‘Die Junge Nonne’ (‘The young nun’) were marred by some insecure intonation and melodic uncertainty; Popukić particularly struggled to control sustained pitches and confined melodic contours. Moreover, though the larger dramatic canvas of the final song suited the mezzo soprano’s temperament, a fittingly vigorous outburst as the nun rejoices in her transfiguring love for her God – “The loving bride awaits the bridegroom,/purified by testing fire -/ wedded to eternal love” – revealed plenty of power and fire, but also some unpleasant pushing of the voice at the expressive climax.

Roger Vignoles is a master of the judicious accompaniment, creating consistent, understated textures from which significant bass figures, telling melodic motifs and pointed expressive gestures sleekly arise to effortlessly assert themselves and then surreptitiously fade, always in expressive service of the text or diplomatically responding to the singer’s needs. This was most powerfully evident in the Schubert songs. Thus, the gentle ‘strumming’ of ‘An Silvia’ was momentarily enlivened by melodic echoes of, and dialogue with, the voice, all the while underpinned by the springing dotted rhythms of the leaping bass. And, appreciative of the way these ‘miniature’ forms can contain significant emotional depths and range, and alert to the overall structure and drama, he expertly controlled the rubato and brief but affective alternation of major and minor tonalities in the penultimate stanza of ‘Im Frühling’, restoring the settled ambience at the close. Sweeping, arpeggiated chords radiated the warm, golden gleam of the glowing sun in ‘Im Abendrot’, then gave way to the ‘raging storm’ – conveyed by an energised, oscillating bass, trembling beneath clanging treble cloister bells – in ‘Die junge Nonne’.

A more centred vocal line, amid adventurous harmonic progressions, was achieved in the ardent ‘Estrene à Anne’ (‘A gift for Anne’), which began the sequence of five songs from the Romanian George Enescu’s Sept Chanson de Clément Marot. Popukić effectively negotiated the rather archaic French texts and demonstrated much feeling for textual meaning and nuance, particularly in ‘Languir me fais’ (‘You make me pine’), where Vignoles’ elegant piano introduction adeptly established the reflective mood. She enjoyed the wit of ‘Aux damoyselles paresseuses d’escrit à leurs amys’ (‘To young ladies too lazy to write to their friends’), pianist and singer crafting an adroitly calculated, insouciant reading. Popukić’s delightfully rich lower register was much in evidence in ‘Changeons propos, c’est trop chanté d’amours’ (‘Let’s change the subject, enough of lauding love’), an unsentimental drinking song which galloped and then collapsed in a inebriated conclusion in praise of liquor and its celebrants, Bacchus and Silenus, who: “drank standing bolt upright;/ then he would dance,/ and bruise himself/ his nose was as red as a cherry;/ Many are those descended from his race.”

The second half of the recital found Popukić in her more natural element, whether embodying the bohemian personae of Dvořák’s folk songs, which tell of the joys and hardships of gypsy life, or enjoying the cabaret lilt of Weill’s songs for Jacques Déval’s play, Marie Galante. Popukić proved herself capable of shaping and controlling wide-ranging melodic arcs and leaping between registers, and of communicating extremes and contrasts of emotion, in the Cigánské melodie. An intense gravity characterised ‘My song resounds with love to me again’, as the narrator experiences both joy and loss, “when I am glad that, freed from misery/ my brother dies”; and deep melancholy underpinned ‘And the wood’s silent all around’, despite the warm major harmonies. Similarly, the arching melodic phrases of ‘Songs my mother taught me’, beautifully fashioned by Popukić with lustrous tone and enriched by the piano’s decorative ornamental motifs and propelling syncopations, presented a poignant blend of contradictory sentiments. A wilder more festive mood was created in the following two dances, ‘The strings are tuned, my lad’, and ‘Wide sleeves and loose trousers’, as Popukić at last fully relaxed, relishing the nonchalant fluctuations of pace and the unrestrained celebrations of freedom and music.

In Weill’s tango-inspired ‘Youkali’, Popukić unleashed a sultry low register and suave lyricism, saving a dulcet floating colour for the closing phrase as the narrator reflects that, whatever tedium we must endure in life, the human soul seeks escape, “oblivion everywhere”: “to find the mystery,/ where our dreams are buried/ in some Youkali.” The melodramatic grotesquery of ‘Le grand Lustucru’ (‘The Great Bogeyman’) and the extravagant dramatic sentiments of ‘J’attends un navire’ (‘I wait for a ship’) allowed Popukić to indulge her theatrical instincts, bringing the recital to an energetic and highly entertaining conclusion.

Claire Seymour

Programme:

Franz Schubert: ‘An Silvia’ D891; ‘Im Frühling’

D882; ‘Im Abendrot’ D799; ‘Die junge Nonne’ D828.

George Enescu: Songs from Sept chanson de Clément Marot Op.15

Antonín Dvořák: Cigánské melodie (Gypsy Songs) Op.55

Kurt Weill: Songs from Marie Galante

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Pokupic.png image_description=Renata Pokupić [Photo by Chris Gloag courtesy of Intermusica] product=yes product_title=Renata Pokupić, Wigmore Hall product_by=Mezzo-soprano: Renata Pokupić; Piano: Roger Vignoles. Wigmore Hall, London, Monday 17th October 2011. product_id=Above: Renata Pokupić [Photo by Chris Gloag courtesy of Intermusica]Intertwining facets of Italian High Baroque

Judith, Esther, Delilah, Bathsheba, Mary Magdalen, Saint Cecilia, Saint Agatha and their companions were the favorite heroines of those stories, inasmuch their feminine charms, and their dangerous influence on men’s behavior, were often graphically described in the librettos.

Manuscript title page of Oratorio di Giuditta © Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

Manuscript title page of Oratorio di Giuditta © Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

La vedova generosa [The Generous Widow] is the recently identified subtitle for Giuditta, one among the several dozens oratorios written by the Rimini-born composer Antonio Draghi (1634/35-1700) for the Habsburg imperial court at Vienna. One may scent therein a tribute to Draghi’s generous employer, the empress dowager Eleonora Gonzaga, whose musical household in Vienna was second only to that of her stepson, the music-avid (and amateur composer) emperor Leopold I. Both Eleonora and Leopold were devout Roman Catholics, much Italianate in their taste for music drama. Besides opera proper, they invested a good amount of their time and financial resources on oratorios, a musical entertainment originally devised by St. Philip Neri to keep people off the dangerous enticements of secular theaters, but soon transformed into a “perfect spiritual melodrama”, as abate Arcangelo Spagna, a theorist, put it in 1706.

Thus the subject of Judith, the ‘generous’ Jewish widow who delivered her people from the Assyrian chieftain Holofernes by means of unorthodox sexual warfare, could not escape Eleonora’s attention, nor the one of an ambitious court composer. Just months after the premiere performance, which arguably took place some time between Lent 1668 and Lent 1669, Draghi was promoted from the Empress’ to the Emperor’s service, with a substantial raise in his salary.

Rimini, Ensemble Seicentonovecento in Draghi’s Giuditta [Photo by Fabiana Rossi]

Rimini, Ensemble Seicentonovecento in Draghi’s Giuditta [Photo by Fabiana Rossi]

So much for the historic background. As to the music itself, Draghi’s Giuditta stands mid-way between the earlier, Cavalli-style, Venetian opera and the progressive Neapolitan school launched by Alessandro Scarlatti during the following decade. The prevailing syllabic recitative is largely peppered with elaborate florid passages, and most cadenzas soar to eloquent ariosos in triple time, sometimes with a dance-like lilt. Although just two numbers are formally labeled “aria” in the manuscript score, there are actually a few more. While only the final ensemble for the four soloists (Judith, her maid Abra, Holofernes and the Narrator) brings the caption “da capo”, two arias for Abra - somewhat of a comic character - are clearly set in the the ‘modern’ ternary form A-B-A`, a daring experiment for the times. However, the centerpiece is a long and articulate conversation scene between Holofernes and Judith, totalling nearly one fourth of the entire work. It’s a red-hot skirmish between the lusty chieftain and his would-be victim; the former voicing his desire enhanced by heavy drunkennes, the latter pretending to reciprocate but determined to cut his head as soon as he falls asleep.

Every manner of compositional devices are employed here, from secco recitative, through arioso, to outright aria (particularly compelling is “In dolce calma” for Holofernes, accompanied by a pair of gambas). Minutes before accomplishing her brave deed, Judith fulfills the dearest expectation of any early opera-goer: a lament on a descending chromatic tetrachord, the time-honored emblem for grief and supplication (“Pietà Signor”).

Such a precious rediscovery was presented in Draghi’s native city as a special project within the 62.nd installment of the Sagra Musicale Malatestiana, a major festival series attracting visitors from several countries. For the third year in a row, Italian and Austrian institutions joined forces to celebrate Draghi, hitherto an injustly neglected composer of the Baroque era. Contrary to the current fade for oratorios, the Rome-based Ensemble Seicentonovecento led by Flavio Colusso didn’t arrange a fully staged production. The venue, a large 18th-century Jesuit church in downtown Rimini, offered visual attractions enough. No props, very few movements from the singers, and passages from period sermons delivered by actress Silvia De Palma shaped the performance as close as possible to the original conditions: half private entertainment, albeit in fashionable court circles, and half act of religious worship. Of course, most credit for the success goes to the music department. A scanty yet energetic ensemble of two violins, theorbo, organ and harpsichord accompanied a quartet of vocal soloists conversant both with the dramatic subtleties of recitar cantando and the virtuosic coloratura of late 17th-century bel canto. Two recognized specialists as sopranos Gemma Bertagnolli (Giuditta) and Elena Cecchi Fedi (Abra) were complemented by the up-and-coming bass Luigi De Donato (Oloferne) and by the male alto Antonio Giovannini, a beginner who seems poised for great things.

Robert Wilson’s fans use to maintain that he deepens and actualizes the dramaturgy of those operas he happens to stage. In my opinion, either is hardly true, as the Texan director’s strategy apparently aims at sucking the life out of any particular opera, freezing down its dramaturgy deep below the zero point in the pursue of such ritual impassiveness as it was probably the case with the original Greek tragedy - and still is with the Byzantine church liturgy, the Japanese Nô, India’s Katakhali or Stockhausen’s Licht cycle. To be sure, all these theatrical or quasi-theatrical genres are indented in a respectable religious vision where issues of style, symbols and formality are paramount, but actualization is obviously ruled out, while deepths of emotion (if any) are the individual elaboration of their devout attenders. Whether about Parsifal or Aida, Gluck’s French Orphée or his Monteverdi forerunner Orfeo, each of Wilson’s productions closely resembles but Wilson, just as any Mass resembles another Mass, leaving aside such local details as the language of the sung texts and the music accompanying them.

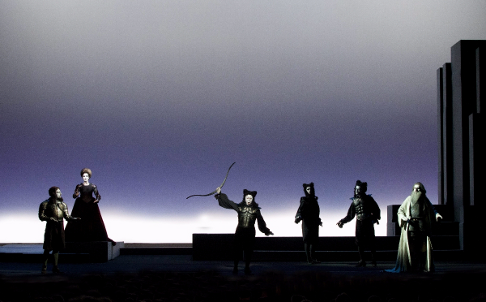

The present Ritorno di Ulisse - being the middle panel of a Monteverdi/Wilson trilogy scheduled by La Scala in co-production with the Paris Opéra between 2009 and 2013 - sticks to the trend: neither reconstruction nor deconstruction of the Classic, rather an embalming of it as in a classy funeral parlour. In the Prologue, the curtain rises on a backdrop mirroring Poussin’s Le Printemps, an Arcadian landscape inhabited by cute Disney-esque animals and mimes embodying Love, Fortune, Time and Human Frailty; too bad that the corresponding singers are plunged in the pit to the disadvantage of audibility. The core action revolves within hollow spaces ‘representing’ the sea or the Olympus, while the royal palace at Ithaca, where Penelope is detained in self-imprisonment, is aptly surrounded with menacing black slates.

The Bow Contest scene [Photo by Lucie Jansch]

The Bow Contest scene [Photo by Lucie Jansch]

Deities and human beings, the powerful and the destitutes, the goodies and the villains, look equally unimpassioned and hieratic; static figures striking enigmatic poses with their white-gloved hands and their pale, heavily made-up, faces. Most of them, enclosed in Baroque parade armours, are donning lofty wigs or feathered bonnets. A déjà vu from the court pageants at Paris and Vienna during the mid 1600s, thus leaving the timeline near the 1640 premiere of the opera. What else? Colour-coded lighting schemes and sparse but effective props: Ulysse’s bow, the skeleton of a ship bottom, a Greek idol on a column.

Deaf to the minimal-chic mermaids of Wilson’s staging, Rinaldo Alessandrini offered a vibrant rendering of the score, despite the many uncertainties surrounding the actual completness of the unique Vienna manuscript (the critical edition he lately prepared for Bärenreiter underwent a few cuts as well as some educated guesses about the instrumental colours). The continuo players of his Concerto Italiano added authentic flare to a selection of strings from the Scala pit orchestra. Thus Monteverdi’s explicit concern for "affetti" (human passions) revived from Wilson's ritual fridge, also thanks to a company of all-Italian voices where Sara Mingardo and Furio Zanasi, both accomplished artists beyond strict specialist boundaries, towered as Penelope and Ulisse. Luca Dordolo made a graceful Eumete, Marianna Pizzolato a convincing Ericlea, Leonardo Cortellazzi’s Telemaco soared as the performance progressed. Among the double-bill cameos, basses Salvo Vitale and Luigi De Donato displayed remarkable panache. I only wonder what happened to brave Monica Bacelli, who for one time left aside her favorite breeches roles. Her Melanto, although allowed to display more acting liveliness than any other character in the show, betrayed an alarming vocal disarray. Hopefully just an off night.

Carlo Vitali

Cast Lists

Antonio Draghi: Oratorio di Giuditta (1668, libretto by anonymous)

Giuditta: Gemma Bertagnolli; Abra: Elena Cecchi Fedi; Testo [The Narrator]: Antonio Giovannini; Oloferne: Luigi De Donato. Ensemble Seicentonovecento (on period instruments). Flavio Colusso, conductor. Chiesa del Suffragio, Rimini, Italy. Performance of 20 September 2011.

Claudio Monteverdi: Il ritorno di Ulisse in patria (1640, libretto by Giacomo Badoaro)

Ulisse: Furio Zanasi; Penelope: Sara Mingardo; Eumete: Luca Dordolo; Telemaco: Leonardo Cortellazzi; Fortuna/Melanto: Monica Bacelli; Il Tempo/Nettuno: Luigi De Donato; a.o. Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala, with continuo elements from Concerto Italiano. Robert Wilson, director. Rinaldo Alessandrini, conductor. Teatro alla Scala, Milan, Italy. Performance of 28 September 2011.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Penelope.png image_description=Sara Mingardo as Penelope [Photo by Lucie Jansch ] product=yes product_title=Antonio Draghi: Oratorio di GiudittaClaudio Monteverdi: Il ritorno di Ulisse in patria product_by=See body of review for cast lists product_id=Above: Sara Mingardo as Penelope [Photo by Lucie Jansch ]

October 20, 2011

Opera North's Queen of Spades - in pictures

[Guardian, 20 October 2011]

Neil Bartlett's new production of Tchaikovsky's great opera of gambling, of secrets, of love and death opens at Opera North on 20 October. We asked Bartlett - making his operatic debut - to pick his key moments from the production and tell us about them

October 12, 2011

Britten’s War Requiem, London

The final words of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem are words of peace and hope, but recent and on-going conflicts in Rwanda, Liberia, Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya suggest that although almost fifty years have passed since the work was first performed, to celebrate the rebuilding and re-consecration in May 1962 of the bomb-blasted Coventry Cathedral, the sentiments of Wilfred Owen, voiced in the epigraph, have lost none of their impact or relevance: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity. All a poet can do today is warn.”

Much of the power of the work lies in its innate contrasts. Owen’s dark, distressing war poems form a counterpoint to the consolations of the requiem mass, and the interweaving of secular and sacred, vernacular and Vulgate, is often challenging, surprising and deeply ironic. A resonant, full orchestral clamour contrasts with delicate, finely fashioned chamber sonorities; soloists and chorus intertwine and counterpoise. Brightness interrupts the darkness, and is then once more overwhelmed by horror and terror.

Conductor Gianandrea Noseda, deputising for the indisposed Sir Colin Davis, was ever alert to such contrasts. Thus, in the opening ‘Requiem aeternam’, the lustre of high trebles of Eltham College Choir – placed distantly, as Britten requested, in the gallery – thrillingly broke through the solemn, funereal tolling of the orchestral accompaniment; similarly, the gentle phrasing of the women’s voices in the choral ‘Recordare’ was abruptly and dramatically superseded by the energetic, bellicose assertions of the men’s ‘Confutatis maledictis’. Elsewhere, the very quietness was itself imbued with ominous, discomforting resonances: the whispered conclusion to the fugal ‘Quam olim Abrahae’, following the terror of the lines, ‘the old man would not so, but slew his son, – And half the seed of Europe one by one’, was spine-chilling. Throughout the London Symphony Chorus were on fine form, enunciating the text clearly and attentive to all the significance musical details.

A cast of impressive soloists had been assembled. Ian Bostridge may have more than fifty performances of the War Requiem behind him but he is clearly not about to let any element of routine enter into his interpretation. In a recent interview he asked, “Which war, whose Requiem?” and his intense engagement with this question underpinned a remarkably committed performance, one which judiciously conveyed every nuance and inflection of the text. Never afraid to use the grain and catches of the voice to highlight the bitterness and ugliness expressed by Owen, Bostridge is totally attuned to the musical and poetic expression, uniting the power of both in his delivery. He produced a disturbing vehemence in ‘What passing bells for these who die as cattle?’ but created an exquisite, poised stillness in the ‘Agnus Dei’.

Baritone Simon Keenlyside was less overtly dramatic but he provided an effective base or grounding for the more extrovert tenor. Singing with sincerity and considerable beauty of tone, Keenlyside communicated authoritatively, especially in ‘Be slowly lifted up, thou long back arm’. In their duet passages, as the men sing with ironic cheerfulness of death, or chillingly relate the story of Abraham and Isaac, both singers displayed an admirable feeling for the text. Every word pulsed with meaning and import, especially in the final extract from Owen’s ‘Strange Meeting’.

The solo soprano is separated from the two male soloists, musically and textually, and here Slovenian Sabina Cvilak was spatially distanced too, placed in the choir. Singing the Latin text, ‘Liber scriptus’, which sets out day of judgement, Cvilak was perhaps a little too placid, not making full use of her undoubted rich tone, although the declamatory phrases of the ‘Sanctus’ were well-shaped and she displayed a pure tone and a well-supported pianissimo.

The players of the London Symphony Orchestra were on tremendous form, guided skilfully by Noseda who illuminated all the details of the score. Noseda’s control of the musico-dramatic form was exemplary and his galvanising of his forces in the big moments superb: thus the chilling distant fanfares which herald the outbreak of violent combat at the start of the ‘Dies Irae’ built to an explosive force. The full fury of the orchestral forces were sparingly employed and the turbulent outbursts perfectly judged, as in the frighteningly precipitous ‘Libera me’ in which the stifled percussion eventually detonated in a terrifying climax with the entry of the organ. In contrast, Noseda paced the more grave moments with controlled deliberation. The chamber ensemble which virtuosically accompanies the songs sensitively supported the intimate drama and dialogue of Owen’s verses.

In a recent essay in the Guardian newspaper, Bostridge wrote that, “The War Requiem is a masterpiece of the deepest emotional and moral depth. It is also an enormous contraption of musical ingenuity”. This was a purposeful and impressively crafted performance, one which powerfully expounded the human truths and elemental emotions exposed by Britten and by Owen; time does not lessen their importance or impact.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Wilfred_Owen_2.gif image_description=Wilfred Owen product=yes product_title=Benjamin Britten: War Requiem product_by=Sabina Cvilak, soprano; Ian Bostridge, tenor; Simon Keenlyside, bass. Conductor: Gianandrea Noseda. London Symphony Orchestra. London Symphony Chorus. Eltham College Choir Trebles. Barbican Hall, London, 9th October 2011. product_id=Above: Wilfred OwenThreepenny Opera, Brooklyn

Should I wait before citing the superb performers with their rictus-expressions and balletic, Dr. Caligari-meets-Charlie Chaplin slapstick, the exquisite stage pictures and the orchestrated horselaughs, burps and farts that emerged from the orchestra, the tidily synchronized sound effects of a cane whipping through the air or a curtain pulled on its links, the nasty ancient jokes that seemed to hit targets as new as this morning on Wall Street right in the gold? For me, no lover of Wilson’s glacial opera stagings (Lohengrin, Einstein on the Beach), Threepenny went by as swiftly as a smutty shaggy dog joke with many a guffaw before the punchline, and I’d gladly see it again. No; I think I’ll start with my interpretation of the piece and its place in “operatic” history. Reviews of the performers will be the punchline.

The Beggar’s Opera, the Gay-Pepusch satire on opera seria as practiced (most notably by Handel) in London in 1728, tickled many a funnybone of its time with the princes and sultans and enchantresses of opera transformed into pimps, thieves, con-men and ladies of dubious repute. The dialogue was underworld slang and the tunes were pop songs of the day. Handel’s operatic reputation took ages to recover, and the threat of satire was always a-lurk in London thereafter for any artist taken too seriously. But the audiences who laughed were not the beggars or street people John Gay depicted on stage: They were the same middle and upper classes who had admired the no longer chic Handel.

Precisely two centuries later, in 1928 in Weimar Berlin, that hotbed of cynicism, social criticism and moral decay, Beggar’s Opera was reborn. Kurt Weill, a trained symphonist with an interest in jazz, and the Leftist playwright Bertolt Brecht transformed the London beggars into the dregs of Dreigroschenoper, satirizing the self-devouring of capitalist excess in a fable that epitomized their time and place. It also made a star of Weill’s lover, Lotte Lenya. An appropriately gritty film from 1931 survives, and a couple of the songs (“Mack the Knife,” “Pirate Jenny”) are standards. The only artistic interpretation of the Weimar era that is better known, at least in this country, is Kander and Ebb’s Cabaret, whose songs and personalities are prettified versions of the ones that shocked (and delighted) Berlin. Not coincidentally, the original Cabaret also starred Lenya.

Lenya’s participation in the “opera” is significant. Her voice may have been trained, but she was by no stretch of the imagination an opera singer. That was more than okay for the parts she sang; they are hardly bel canto roles. And throughout the Robert Wilson production, recently given at the Brooklyn Academy of Music opera house, I found myself wondering if the Brecht-Weill piece is an opera at all (most of it is spoken dialogue), and marveling at how the cast, none of them singing in an operatic manner, used their voices, cracked, exaggerated, twisted, sneering, insinuating, whining, caricatures in both dialogue and song, to express the antisocial, anti-sentimental story they had to tell. Threepenny Opera may be an anti-opera, but it is certainly music drama and vocal theater, thrilling, mythic, in your face.

No small part of the shock and the humor of the original Beggars’ Opera was provided by the contrast of its characters and their motivations—as well as their manner of singing—with the highfalutin pleasures of Handelian opera. Trained voices and their exquisite display were hardly the point of the songs of vengeance and sex and the lust for gold. The outrageous conclusion, with Macheath obliged (because it’s an opera) to live happily ever after with two girls who hate each other in order to suit the Handelian lieto final, undermined the aristocratic operatic morals. It was a dose of naturalism (then an unknown bird on the stage) to cure if not hack to death the artifice of the reigning form. Hacking actual reigning monarchs came a bit later.

Ruth Glöss as the Old Prostitute, Stefan Kurt as Macheath and Angela Winkler as Jenny

Ruth Glöss as the Old Prostitute, Stefan Kurt as Macheath and Angela Winkler as Jenny

Over the centuries, each new theatrical step towards the “natural” has made the artificial seem more formal, more distant (Handel and his contemporaries were no longer performed) until a new sort of naturalism reigned. On the spoken stage, Scribe abandoned the royal court for the bourgeois drawing room, then Ibsen and Chekhov began to talk of things unfit for the drawing room ideal. To sum up this acceptable standard of “naturalism,” Brecht and Weill (and not only they) invaded the lowest reaches of society, with music of a studied grossness. Once naturalism has reached this extreme (and movies had created another revolution), their chic and their ability to shock soon vanished as well. Even before the triumph of the modern style of Regie-theater, Dreigroschenoper and its Brecht-Weill successors (Happy End, Mahagonny, Seven Deadly Sins) helped to invent a new theater that could only be absorbed and defused by presentation in a new artificial style. This was the occasion of Richard Foreman’s vividly formal production of Threepenny Opera with Raul Julia at the Beaumont Theater (a hit), of the John Dexter version on Broadway with Sting and Maureen McGovern (a flop), and—now—of the Robert Wilson interpretation come to New York.

Wilson, like Foreman, has his own style of artifice, imposed to some extent on every work he encounters: Philip Glass’s Einstein on the Beach, Wagner’s Lohengrin and Parsifal, Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, the Stein-Thomson Four Saints in Three Acts. His encounters with the slow movement and slowly gathering message of Wagner’s dramas might have seemed a perfect fit on paper; in practice, even with performers like Ben Heppner and Karita Mattila, there was a steady seepage of dramatic excitement. At the New York premiere of Einstein, more of the audience was outside the theater, talking about the production (scathingly or otherwise), than remained inside, enduring it.

In contrast, Weill and Brecht have a very swift-moving theater, a theater that holds our attention with much activity, roundabout schemes and betrayals, slowing down barely at all for sarcastic songful commentary and reflection on the action. This, set against typically Wilsonian bars of light (for the shelves in Peachum’s pawnshop or the rafters in Macheath’s garret or the bars on his prison cell) and enacted with a set of formalized emaciated staggers, sexy swivels, dancing wobbles and leaning crowds, has us riveted, paying determined attention to the stories being enacted. The acting is anything but natural, is cartoonish and expressionistic at once, to the extent that the most vulgar gestures are as polite as silhouettes, the most monstrous jokes evoke giggles. These people are not real, and for once none of them attempt to be. Lucy Brown reacts to Mack’s betrayal with a face like Munch’s The Scream. Celia Peachum rolls her considerable bulk about in a parody of both aging sexuality and desperate petit-bourgeois propriety. Mack himself never changes his grin, whether he is seducing, betraying, murdering or being betrayed. The skull-like Tiger Brown indicates only with a voiced jowlishness his regret at stiffing his old friend. Jenny seems too battered by years as a whore to have any emotion left whether selling her lover to his enemies or rescuing him. It’s a puppet show, a carnival Faust for open-mouthed children, and when real issues like corporate wealth and its exploitation of poverty come up—as the subjects did, to much delighted laughter during performances while the Occupy Wall Street movement camped out not two miles to the west of BAM—it is perhaps to show us how close our lives have become to caricature, to send up the whole notion of a “naturalistic” theater that dares to ignore our current crisis.