November 28, 2011

François Couperin by Florilegium, Wigmore Hall

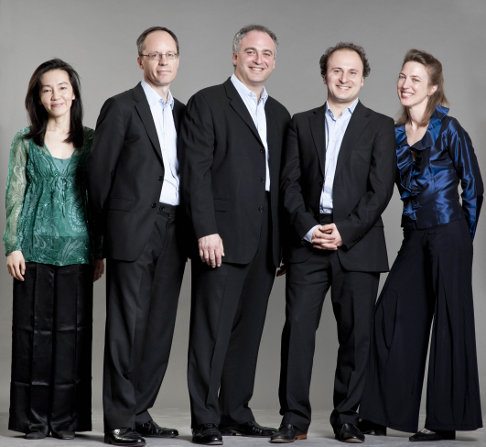

These qualities were affectingly demonstrated during this wonderfully tender performance by Florilegum of secular instrumental and sacred vocal music, compositions which unite the best of contemporary French and Italian conventions.

Couperin was born in 1688 in Paris, the son of Charles Couperin, the organist St Gervais in Paris. On his father’s premature death, the organist position passed to Lalande, but François, an early musical genius, was already deputising for Lalande at the age of ten, and on his 18th birthday he officially inherited his father’s previous position. Lalande praised the young man’s innovative 1690 collection of Pièces d’orgue as “worthy of being given to the public” and helped to establish him as a Court organist in 1693. In 1700 Couperin acquired the younger D’Anglebert’s position as harpsichordist at Versailles.

He amassed a notable quantity of superlative harpsichord pieces, which began appearing in elegantly engraved editions in 1713, following other noteworthy collections by Rameau and Dandrieu; but, ever the individualist, Couperin chose to group his pièces into ordres rather than suites, and relied much less on dance movements than his contemporaries, preferring the freer and more evocative pièces de caractère.

In his publications of the early 1720s he offered a wide variety of ways in which the French and Italian styles might be united. As Richard Langham Smith’s eloquent, informative programme notes state, the works grouped under the title of Les Nations were “written in the style of Corelli”; the composer had been “charmed by the sonatas of Corelli, whose works I shall love as long as I shall live, just as I do the works of Monsieur de Lully”.

Les Nations is the title under which Couperin published a collection of four large-scale sonatas; Florilegum presented two – the earliest of the ordres composed for chamber consort – La Françoise and L’Espagnole. Director Ashley Solomon, fellow traverse flautist Andrew Crawford, and violinists Bojan Cici and Tuomo Suni were expressively supported by Emilia Benjamin’s viola da gamba, David Miller’s theorbo and the delectable harpsichord playing of Terence Charistan. The ensemble relished Couperin’s luscious timbres and colours, responding naturally to the considerable rhetoric of the small dance forms, exploiting contrast and delighting in the piquant expressive dissonances.

In the slower, more intricate movements, as in the ‘Sarabande’ of L’Espagnole, the meticulous attention to ornament and detail was impressive, although such details were never allowed to disrupt the graceful melodic line. String and woodwind articulation in the more energetic dances was bracingly crisp and fresh; repetitions were constantly re-invigorated. Rapid passage work in ‘La Gigue’ from La Françoise was sharply articulated. Despite the fact that these interpretations were clearly honed to perfection, there was a surprising sense of spontaneity, as if the reading was unfolding in real time.

Florilegium [Photo by Amit Lennon]

Florilegium [Photo by Amit Lennon]

The instrumentalists were joined by sopranos Dame Emma Kirkby and Elin Manahan Thomas in Couperin’s captivating Leçons de Ténèbres, extremely beautiful and genuinely spiritual music for ecclesiastical use. Couperin’s interest in the Italian style, as represented by Carissimi and Charpentier, influenced his sacred vocal music, particularly his motets, versets and leçons de ténèbres, and the result of this stylistic diffusion is enchantingly presented in the Leçons.

In the Tenebrae service, psalms are sung, interspersed with the text from the Lamentations of Jeremiah. In Couperin’s setting we are aware of delicate and deliberate crafting: each of the responsaries is preceded by a huge musical ‘capital letter’ much like the way the first letter of a Hebrew psalm is set to a long melisma – as Langham Smith describes “a musical equivalent to an ornamented manuscript with elaborately gilded capital letters.”

The two soloists brought their own strengths to the delivery of the text. Thomas, alert and energised, using the voice to thrill and excite; Kirkby effortlessly shaped individual phrases into affecting larger units, creating heart-rending melodic shapes and inflecting the text with human sentiment. Soaring melodic arches and effortlessly gilded ornaments evoked cathedral realms. For Kirkby aficionados, vocal purity and beauty is taken for granted, but she also exhibited a real sense of the architectural splendour of these pieces.

Thomas’s pronunciation of the Latin text was idiomatically French in inflection, as it would have been performed at the time. Her ornamentation was superb; she produced a shimmering beauty which invigorated the sacred text with exotic nuance. In the third lesson, the intertwined soaring voices evoked aspiring gothic cathedral arches. The accompaniment was flexible and alert, sensitive to nuance and creating a real sense of intimacy. The repeated refrain, “Jerusalem, Jerusalem, convertere ad Dominium Deum tuum”, (Jerusalem, return thee to the Lord, thy God) both united the various lessons, and provided variety and gradation.

These are pieces of heavenly exquisiteness, designed to inspire piety through their sheer beauty. Whatever one’s religious allegiances and affiliations, this recital inspired ‘devotion’ through the performers’ absolute commitment to magnificent splendour and nuanced, expressive inflection, perfectly assimilating the sacred and the secular.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Couperin.png image_description=François Couperin product=yes product_title=François Couperin: Sonata from Premier Ordre: La Françoise ‘Les Nations’; Première Leçon de ténèbres pour le mercredi Saint; Deuxième Leçon de ténèbres pour le mercredi Saint; Suite from Premier Ordre: La Françoise ‘Les Nations’; Sonata from Premier Ordre: L’Espagnole ’Les Nations’; Troisième Leçon de ténèbres pour le mercredi Saint; Suite from Premier Ordre: L’Espagnole ‘Les Nations’. product_by=Dame Emma Kirkby, soprano; Elin Manahan Thomas, soprano. Florilegium. Ashley Solomon. director. Wigmore Hall, London, Thursday 24 November, 2011. product_id=Above: François CouperinNovember 27, 2011

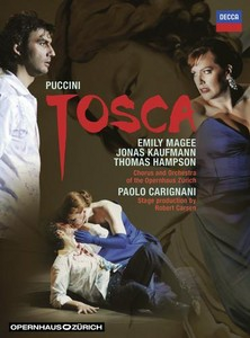

Tosca, ENO

Malfitano’s staging makes a refreshing change both from the likes of the floundering first-time spoken theatre and film directors often recently engaged by the company, and from the ludicrous, dramatically-null vulgarity of the Zeffirelli brigade. It doubtless helps to have someone at the directorial helm who knows the work from the inside, having sung the title-role a good many times herself. There is nothing here — with the possible exception of the third act — to frighten self-appointed ‘traditionalists’, although in such repertoire and with respect the audiences it tends to attract, I cannot help but wish that someone would occasionally shock the horses. (Just imagine what Calixto Bieito might make of Tosca!) Despite the sometimes bizarre specificity of the libretto, there seems to me no reason why intelligent relocation or abstraction could not work: the opera is not in any meaningful sense ‘about’ the experience of the French Revolution in Rome. Malfitano, however, elects successfully to retain the settings and for the most part the attitudes of the work’s creators, respecting as do they the classical unities.

The first act is therefore set in S.Andrea della Valle at noon, convincingly represented in realistic fashion by Frank Philipp Schlössmann’s designs. The force of Cavaradossi’s painting registers straightforwardly, but none the worse for that. One strongly feels the menace of the Church as pillar of the (re-)established order at the entrance of clergy and acolytes for the “Te Deum”. (I cannot help but find the anti-clericalism shallow, verging on the puerile, but that is no fault of the production.) Likewise, the second act is set at evening in Scarpia’s quarters in the Palazzo Farnese, furnished as one might expect, though without excess. The third act therefore comes as a bit of a surprise, at least in terms of designs . Doubtless taking as its cue references in words and stage directions to the stars, perhaps even those to the saints in heaven, we see the skies as if from a space ship, though something akin to the battlements is still present. It did not bother me in the slightest, though nor, by the same token, did I find the image revelatory. Throughout, Malfitano’s direction of the characters on stage proves quietly accomplished, providing neither mishaps nor particular flashes of revelation. I do not mean to imply that it is dull, for it is not, but nor does this in any sense approach reinterpretation, for which many will doubtless be relieved. If I found the final melodrama as difficult to take as ever, a not-entirely-fitting conclusion to so well-crafted a score, then clearly I am in the minority; rightly or wrongly, it receives faithful treatment here.

Stephen Lord’s conducting was impressive. Lord is not a conductor I have previously heard, but I should certainly be interested to do so again. Despite the occasional instance of perhaps driving the score a little hard, the full yet variegated sound conjured from the orchestra was as fine as I have heard at the Coliseum for quite some time. Alert to Puccini’s Wagnerisms without overplaying them, there was a fine continuity to Lord’s traversal of the score, which here in both harmony and orchestration at times sounded, to its great benefit, appreciably more modernistic than one often hears. It was not for nothing that both Schoenberg and Berg were admirers. Even Mahler, in his scathing description of a Meistermachwerk, acknowledged the skill of orchestration — an undoubted advance upon so many of Puccini’s Italian forebears — though added that any cobbler nowadays could merely ‘orchestrate to perfection’.

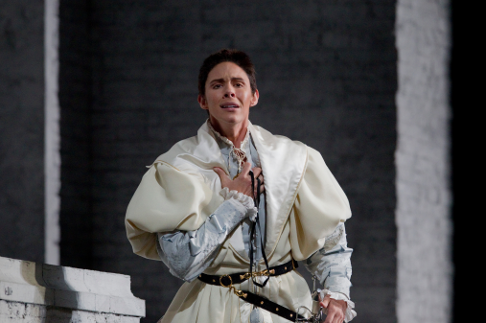

Anthony Michaels-Moore as Scarpia

Anthony Michaels-Moore as Scarpia

If the singing did not truly scaled the heights, it was professionally despatched. No one is going to replicate Callas, and Claire Rutter wisely did not attempt to try: hers was an intelligent enough stage portrayal, a little lacking in charisma perhaps, likewise in creation of the diva-status of Floria Tosca as singer, but, despite occasional weakness in sustaining her line, there was nothing grievous to worry about. Gwyn Hughes-Jones’s Cavaradossi was not entirely free of crooning tendencies, nor did it revel in subtleties, but it was well enough sung, and would doubtless have sounded better in Italian. Anthony Michaels-Moore seemed to experience vocal difficulties in the first act but his Scarpia sharpened up in the second, albeit without ever quite capturing the sheer danger and malevolence of the most notable interpreters. The smaller parts were all well taken. Choral singing, not always the strongest point recently at the Coliseum, was similarly accomplished.

Mark Berry

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tosca_2011_Claire_Rutter_Gwyn_Hughes_Jones_4_Credit_Mike_Hoban.png image_description=Claire Rutter as Tosca and Gwyn Hughes Jones as Cavaradossi [Photo by Mike Hoban courtesy of English National Opera] product=yes product_title=Giacomo Puccini: Tosca product_by=Floria Tosca: Claire Rutter; Mario Cavaradossi: Gwyn Hughes Jones; Baron Scarpia: Anthony Michaels-Moore; Cesare Angelotti: Matthew Hargreaves; Sacristan: Henry Waddington; Spoletta: Scott Davies; Sciarrone: Graeme Danby; Gaoler: Christopher Ross; Shepherd-boy: Jacob Ramsay-Patel. Director: Catherine Malfitano; Set designs: Frank Schloessmann; Costumes: Gideon Davey; Lighting: David Martin Jacques and Kevin Sleep. Chorus of the English National Opera (chorus master: Nicholas Chalmers); Orchestra of the English National Opera; Stephen Lord (conductor). Coliseum, London, Saturday 26 November 2011. product_id=Above: Claire Rutter as Tosca and Gwyn Hughes Jones as CavaradossiiPhotos by Mike Hoban courtesy of English National Opera

Piotr Beczala

Richard Eyre’s production premiered in 1994 and has been revived many times. Indeed, there are three different runs this year alone, with three different casts. Two DVDs are available, one conducted by Georg Solti, and another released this year with Renée Fleming, Joseph Calleja and Thomas Hampson. It’s a hardy perennial. Must the role be daunting to take on?

Piotr Beczala flashes a brilliant smile. He loves this staging and is delighted to be taking part. “The winds of time are blowing away the good Zefferelli and Schenk productions. It’s a pity in my opinion, but you have to live with it”. So he’ll be singing with special pleasure because it’s a historic production. In the second act, Alfredo and Violetta are in the country house. “It’s so beautiful, the colours are lovely pastels, and the dimensions of the set put attention on the singers. Productions like this give the singers a chance to tell the story. It’s not just the directors”.

This is Beczala’s ninth Alfredo since 1993, so the part is close to his heart. So it’s an advantage that he’s coming to the Eyre staging he likes so much, for he will be singing with fresh enthusiasm. “There is no such thing as routine in this business”, he says, “We start every performance like it’s completely new. Every performance has new ideas because the singers and conductor are different”. Dynamic relationships change. “Of course it’s more or less the same, but every time the tension between performers is new. That is what we transport to the public even if they’ve seen the staging many times”.

“Absolutely”, he adds, “because the words I’m singing express something I feel at that very moment. We have to learn to be the character together with the other characters. Every Violetta is different, and you have to work with the person who is singing the part. So the connection on stage is unique, and we create an experience. We communicate to the public the beauty of the opera”.

“So even though we know every note, we have lots of time to prepare. So we talk and work out in rehearsal what kind of energy to use in each scene so we create a unique picture in each production”.

In one season in 2010, Beczala sang Roméo in three different productions of Gounod Roméo et Juliette. At the Staatsoper in Vienna, he sang with Anna Netrebko, at the Royal Opera House in London with Nino Machaidze and at the Met in New York with Hei-kyung Hong (replacing Angela Gheorghiu). “Twenty four or twenty five performances, but never the same. It gave me the chance to really develop the role in different ways and get it 'in my throat'".

“Alfredo is not as easy a role as people might think. Any student can skip the high C’s but the really important challenge is to show how Alfredo’s character is changing. At first he’s naïve, but in the final act, he’s mature and adult confronted by Violetta’s death. This production is moving because it’s so realistic. Blood on the pillows!”

“Alfredo is struggling not to be like his father. Young people need to break from family tradition and make their own mistakes and learn responsibility. Alfredo wants to save Violetta because he thinks that the power of his love can change things. But life is brutal, it never works out as simple as that. We were talking in rehearsal about why Violetta needed a big country house. Why not rent a smaller place so the money would last longer ? She’s not like Manon, who was rich but can live simply when she needs to. Maybe in the back of her mind, Violetta needs champagne and caviar”.

Beczala looks amazingly young, even close-up, a great advantage for a singer who specializes in lyric Romantic heroes. But he greatly reveres the heritage of the past. He recalls wearing a costume which had been used by Nicolai Gedda. “It was very special, like the ghost of the past passing on energy”

“All my heroes are in the past”, he adds, “like Fritz Wunderlich, or Jussi Björling”. Beczala is a friend of Eva Wunderlich. “We talk about him a lot. I do a lot of the same repertoire that he did, like Tamino and Belmonte”.

“I was listening to Tito Schipa yesterday, singing the Siciliano from Cavalleria rusticana from 1913. It’s amazing how beautifully he sings. He used his voice intelligently. Singers like he and Caruso had to create the personality, the phrasing. No models. It’s good that we have so many wonderful recordings, but it’s also a handicap because we also have to create. Technique is always changing. Caruso was the first who sang with versimo fire “ but he didn’t overdo it. Too much verismich is histrionics, not real emotions and real singing”.

Beczala beams happily. “One of my dreams is to take my colleagues from today back to, say, 1907, to a studio and sing arias with very old microphones. Nowadays there is so much pressure from the media to create ’stars’, but I’m more interested in creating the characters through music”.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/beczala_3.png

image_description=Piotr Beczala [Photo by Kurt Pinter]

product=yes

product_title=Piotr Beczala — An Interview

product_by=By Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Piotr Beczala [Photo by Kurt Pinter]

November 25, 2011

Saul, Barbican Hall

Charles Jennens compilation, based on biblical sources, created a powerful structure which enabled Handel to create a work which became the first of his English music dramas. The work was performed at the Barbican on Tuesday 21st November by The Sixteen under conductor Harry Christophers, in a concert performance which brought out the essential drama of the piece.

The title role is a remarkable portrait of a conflicted personality, and Handel emphasised this by reducing the characters arias and concentrating on recitative (both secco and accompanied). This means that it can be tricky role to bring off, fatally easy to under play in a concert performance. Peter Purves brought both Handelian bravura and drama to the role, no only acting but reacting, his performance continuing when others were performing, so that Purves showed Saul’s furious reaction to the Israelites praise for David. Purves is perhaps not the tidiest Handelian singer and he did have a tendency to distort the vocal line for expressive purposes. But this was a performance where music and drama went grippingly hand in hand.

The role of David was written for a woman to sing, but in recent years there has been a tendency for it to be sung by counter-tenors. Sarah Connolly demonstrated that in the right hands, the richness, depth and flexibility of a female mezzo-soprano voice can work wonders in the role. Though known for her Handel roles, Connolly’s voice has developed into quite a big instrument. Here she gave a finely moulded, intelligent performance of great beauty.

Robert Murray made an affable Jonathan, with a nicely turned phrase but not quite the purity of line that I would have liked. More importantly, I didn’t feel that there was much drama in the relationship between Murray’s Jonathan and Connolly’s David, though Murray’s individual contributions were finely done.

The drama isn’t perfect, Jennens libretto spends a little too much time on Saul’s daughters Merab and Michal. Elizabeth Atherton as Merab didn’t display quite such a firm line as I would have liked; but the role is a gift for an actress and Atherton displayed a nice line in temperament as the haughty Merab. Joelle Harvey was sweet as Michal, but the role doesn’t really call for much more. Harvey and Connolly duetted delightfully, but even they couldn’t quite convince that two duets in Act 2 is one duet too many.

But Act 2 closed in dramatic fashion with Purves’s powerful delivery of Saul’s accompagnato and a strong closing chorus, ‘O fatal consequence’. The drama continued to be vividly played in the final act, with Christophers encouraging the orchestra to bring out the rawness of Handel’s wonderful scene with the Witch of Endor. All closing with a strongly felt final Elegy.

The smaller roles (of which there are quite a few) were all taken by members of the Sixteen choir, with Jeremy Budd as an edgy, mysterious Witch of Endor, Mark Dobell as the High Priest, Stuart Young as an eerie Ghost of Samuel, Ben Davies as Does, Eamonn Dougan as a strongly characterised Abner and Tom Raskin as the unfortunate Amelkite killed by David at the end. All were strong and more than a credit to the group. Dobell did not always manage to make the rather prosy part of the High Priest interesting, but he was certainly had a good go.

The work was not strictly staged, and everyone sang from scores, but some thought had been put into elements of staging, entrances and exits so that the results contributed immensely to the feeling of drama. Though we had the libretto, diction was uniformly excellent and you hardly needed the words.

The 18 person choir (male altos, female sopranos) brought conviction and enthusiasm to their usually polished delivery. The chorus is called on to sometimes embody the Israelite people and sometimes simply comment; in whichever role the Sixteen was dramatically involved.

Handel’s orchestra is quite a large one, he uses trumpets, trombones and kettledrums. The work has a number of symphonies, describing off-stage action such as battles and funeral corteges so that Handel gives the orchestra a number of solo moments, with some lovely playing from harpist Frances Kelly; Handel also used a Carillon/Glockenspiel to great effect. The Sixteen Orchestra was clearly enthused by the work and by Christophers direction as they played with infection conviction. Christophers went for a rather rich continuo sound, using harp, theorbo, harpsichord and organ as part of the continuo group, which is understandable given the breadth of Handel’s orchestration in the piece. It was performed in Anthony Hicks’s edition.

Christophers ran each act without breaks, so that we had chance to feel how the drama flowed. He encouraged both cast and orchestra to produce vividly dramatic performances and the results were immensely engaging. There is a recording coming out next year and I look forward to it.

Robert Hugill

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Handel_NPG_mw02875.gif image_description=George Frideric Handel by Francis Kyte (1742) [Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery] product=yes product_title=G. F. Handel: Saul product_by=David: Sarah Connolly; Saul: Christopher Purves; Jonathan: Robert Murray; Merab: Elizabeth Atherton; Michal: Joelle Harvey; Witch of Endor: Jeremy Budd; High Priest: Mark Dobell; Ghost of Samuel: Stuart Young; Doeg: Ben Davies; Abner: Eamonn Dougan; Amalekite: Tom Raskin. The Sixteen Choir and Orchestra. Conductor: Harry Christophers. Barbican Hall, London, Tuesday, 22nd November 2011. product_id=Above: George Frideric Handel by Francis Kyte (1742) [Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery]Xerxes in San Francisco

It was a fine evening in the War Memorial Opera House, a rare visit by one of opera’s greatest dramatists, G.F. Handel now 326 years-old. San Francisco Opera welcomed his 273 years-old Xerxes with a production that is 26 years-old.

Sonia Prina as Amastris

Sonia Prina as Amastris

While the mushy acoustic of San Francisco’s venerable opera house is not kind to the linear detail and sculptural shapes of Baroque opera an exemplary cast overcame this handicap with the help of the English National Opera production directed by Nicholas Hytner and designed by David Fielding — purely and simply a classic.

The Handel revival has been going on quite a while now, in fact nearly one hundred years though not so many of his operas find their way onto the big stages to play for broader audiences. That may be the reason that when the populist and always lively ENO took on Xerxes for the Handel 1985 anniversary it choose to play up the comic elements of this opera seria, in fact to make it an outright comedy, trappings it wears quite naturally.

Impeccable comic timing and deadpan humor rarely describe performances by mezzo-soprano Susan Graham (whose roles at SFO include Iphigénie, Ariodante and Sister Helen [Dead Man Walking]). As the Persian king Serse (Xerxes) these attributes are as appropriate as the more usual phrases like impeccable musicianship and superb delivery. Her trouser acting technique does not attempt masculinity leaving us gratefully unconfused in the usual gender confusion.

Wayne Tigges as Ariodates

Wayne Tigges as Ariodates

Almost the same things can be said about countertenor David Daniels who was her/his (Serse’s) rival in love, though in the case of Mr. Daniels the gender confusion became a part of the comedy with his maleness exaggerated by the addition of a beard — all the while singing in a male voice in a female register. Mr. Daniels has a quite beautiful falsetto that is evenly colored throughout his range, and exposes his mastery of Baroque style with every note.

To a man all the other pro- and antagonists were scene stealers. Heidi Stober and Lisette Oropesa were the sisters, Atalanta and Romilda, very lyric singers and beguiling actresses, complemented by the delightfully outraged Sonia Prina as Serse’s forgotten fiance Amastris, now disguised as a soldier. She earned a huge ovation for her dynamite, end of first act explosion “Saprà delle mie offese, ben vendicarsi il cor.”

Well, to a man it was hopeless, tormented love finally resolved by the dumb coyness of lovesick Serse aided by the very real charm of the servant Elviro sung by baritone Michael Samuel and by the pomposity of the general Ariodates adroitly served up by bass Wayne Tigges.

The greatest pleasure of the evening was however the finished staging accomplished by stage director Michael Walling. Its imposed precise movements were confidently executed by the cast. This finish alone allowed the comedy to shine as well as to expose gracefully the considerable personal charms of the seven principals. Not to mention the huge presence of 24 choristers (but only two brief choruses) and 17 tireless supernumeraries as the very slightly defined Persian society (disguised in period European dress) — totally gray, shadowy, barely visible gentle commentators on the shenanigans of Handel’s brightly dressed lovers — that added very welcome action and context to the countless arias.

David Fielding’s set on which Serse and Ariodates plot their invasion of Europe was a Baroque room with a garden superimposed (recognizing that Xerxes is really a pastorale) with a back wall that flew out to reveal some witty Middle Eastern vistas and side panels that opened to admit some monumental Persian sculpture in museum cases. Together with the cheap lawn chairs and newspapers there was plenty of nifty confusion of time and place to complement the amusing gender confusions mixed up in the silly romantic convolutions.

Lisette Oropesa as Romilda, Michael Sumuel as Elviro and David Daniels as Arsamenes

Lisette Oropesa as Romilda, Michael Sumuel as Elviro and David Daniels as Arsamenes

Conductor Patrick Summers allowed all this to happen without imposing musical extravagances, choosing instead to indulge in his sympathy for the needs of his singers. There was no real attempt or for that matter possibility or even need to create a Baroque sound in the vast expanse of the War memorial.

This production from twenty-six years ago reflects the tastes and challenges of that time, a particularly innovative period at the ENO. A new production now of this problematic opera might attempt to underscore the depth of emotion in its exposition of these tragic (genuinely unhappy) stories. The feelings are musically quite real. The heady humor of the Hytner production kept us outside and above the much of the potential musical depth and maybe some of the pleasures of this Handel score.

Michael Milenski

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Daniels_Graham_Xerxes.gif image_description=David Daniels as Arsamenes and Susan Graham as Xerxes [Photo by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera] product=yes product_title=G. F. Handel: Xerxes product_by=Xerxes: Susan Graham; Romilda: Lisette Oropesa; Arsamenes: David Daniels; Atalanta: Heidi Stober; Amastris: Sonia Prina; Ariodates: Wayne Tigges; Elviro: Michael Sumuel. San Francisco Opera Chorus and Orchestra. Conductor: Patrick Summers; Production: Nicholas Hytner; Revival Director: Michael Walling; Production Designer: David Fielding; Lighting Designer: Paul Pyant. (11/16/2011) product_id=Above: David Daniels as Arsamenes and Susan Graham as XerxesPhotos by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera

November 23, 2011

The Queen of Spades, Opera North

The experience marked me for life. I have never doubted since that Wozzeck is one of the greatest operas ever written, nor have I doubted that opera, whatever the disappointments one may experience in practice, can at its best prove at least as potent a form of drama as any other. It is many years now since I heard a performance from the company, though I have received very good reports from those who have, often comparing its offerings favourably with those on offer from the two principal London houses. I was therefore delighted to have opportunity to see and to hear for myself in Opera North’s first visit to the Barbican Theatre. (More are planned.) The timing was interesting too, affording comparison with Eugene Onegin across town at the Coliseum. Claire Seymour, writing for this site, enjoyed Deborah Warner’s staging much more than I did (click here).

First impressions of Neil Bartlett’s production were preferable to those of Warner’s Met-bound anodyne crowd-pleaser. There is, at least to begin with, no evident point of view expressed; straightforward storytelling seems the order of the day. By the same token, however, that does not come across as a deliberate policy to play safe, even to condescend. The setting is where it ‘should’ be; costumes are of the period; there is neither jarring nor particular elucidation. It would have been bizarre and not just unwelcome if the audience had followed the practice of a segment of that for Onegin and had drowned out the music by applauding Kandis Cook’s serviceable sets; they simply did their job without ostentation and without sentimental emphasis upon petit bourgeois conceptions of the ‘beautiful’. However, I said ‘first impressions’ above, because there is one aspect of Bartlett’s staging that might distress the literal-minded. It seemed interesting to me, yet arguably out of place in a production that offered nothing more of the same, rather as if the concept had wandered in from elsewhere. I speak of Bartlett’s treatment of the Countess, who emerges a sex-crazed vamp: she certainly would have captured attention in her scarlet gown even if she had not been played by Dame Josephine Barstow. Fitting or not, it was at least an idea, which was more than could be said for anything Warner mustered. The Personenregie, however, was considerably less skilled, or at least its execution was. And If Catherine the Great made her appearance, I am afraid I missed it.

The real problems, though, lay in the musical performances, and above all with Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts’s Hermann. It did not sound as though this were an off-day, more a matter of having taken on a task that lay far beyond what the voice was incapable of delivering. It would be a matter of taste rather than judgement whether the shouting or tuning proved more painful. This, I am sad to say, constituted some of the most troubling professional singing I have heard; indeed, most student or other amateur performances are executed at a much higher level. He improved slightly during the third act, though he continued to croon in a manner that might have been thought excessive for a West End musical. Some smaller roles were no less approximate and crude, though, by the same token, some proved much better. William Dazeley’s Yeletsky impressed, as did the Tomsky of Jonathan Summers. Perhaps best of all was Alexandra Sherman’s Pauline. Hers was that rare thing: a true contralto. Moreover, she could use it to properly dramatic ends, the song, ‘Podrugi milïye,’ musically shaped and genuinely moving. Orla Boylan’s Lisa had its moments, but sometimes found herself all over the place in terms both of (melo-)drama and of intonation.

The chorus had clearly been well trained by Timothy Burke, and generally acquitted itself well, most of all in the third act, when, despite the translation, choral sound came across as more plausibly Russian than elsewhere. (The translation itself veered between embarrassing couplets and the merely prosaic; in that respect, Martin Pickard’s work recalled what we heard from him for Onegin.) Barstow, as the reader may have guessed, stole the show. Though her tuning was a little awry upon her entrance, and some might have queried the preponderance of quasi-spoken, parlando style, she can still hold a stage. One longed for more, wishing that her palpable commitment had rubbed off on others.

Richard Farnes proved intermittently impressive. There was certainly dramatic drive, sensitivity too, to his conducting. Yet, whilst there were moments in which the orchestra sounded to have just the right Tchaikovsky sound - the opening of the third act, for instance - there were other passages in which the score veered awkwardly between dark, would-be Wagnerism and soft-centred Puccini. A greater body of strings would have assisted: though what was mustered played well, the lack of heft was apparent throughout. Characterful woodwind was offset by variable brass, sometimes blaring, sometimes surprisingly tentative. (Placing outside the pit, at the edge of the stage, doubtless did not help.)

It was just about worth it for the Countess, then, but Opera North’s outing to London proved for the most part a damp squib. And it is surely a little too easy to say that the problem may have lain in staging so ambitious a work. After all, it was Wozzeck, no less, that made such an impression upon me in Sheffield. The stage director of that searing, life-changing Wozzeck? Ironically, one Deborah Warner…

Mark Berry

Click here for a photo gallery and other production information.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tchaikovsky_portrait.png image_description=Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky by Nikolay Kuznetsov [Source: Wikipedia] product=yes product_title=Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: The Queen of Spades, op.68 product_by=Lisa: Orla Boylan; Countess: Dame Josephine Barstow; Hermann: Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts; Count Tomsky, Pluto: Jonathan Summers; Prince Yeletsky: William Dazeley; Pauline, Daphnis: Alexandra Sherman; Governess: Fiona Kimm; Chekalinsky: Daniel Norman; Sourin: Julian Tovey; Masha: Gillene Herbert; Chaplitsky: David Llewellyn; Narumov: Dean Robinson; Master of Ceremonies: Paul Rendall; Chloë: Miranda Bevin. Director: Neil Bartlett (director). Designs: Kandis Cook. Lighting: Chris Davey. Choreography: Leah Hausman. Chorus of Opera North (chorus master: Timothy Burke). Orchestra of Opera North. Richard Farnes (conductor). Barbican Theatre, London, Tuesday, 22 November 2011. product_id=Above: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky by Nikolay Kuznetsov [Source: Wikipedia]November 22, 2011

Hugh the Drover Over the Pub

The Rocky element may seem the least likely, but in fact Hugh the Drover grew out of Vaughan Williams’s wish “to set a prize fight to music.” One possibility he considered was an opera based on George Borrow’s strange, atmospheric Bildungsroman, Lavengro (1851), which contains what used to be one of the most famous fights in English literature. Such an opera may have had the dramatic profundity to establish a place in the English repertoire, but unfortunately it was never written. Instead, Vaughan Williams set a rather trite libretto by Harold Child (1869-1945), a writer and theatre critic with no previous experience of writing librettos. Child arranged a story (suggested in good part by the composer) in which there is a prize fight between love rivals. There is evidence that Vaughan Williams was unhappy with Child’s unrealistic rendering of country life, and his thoughts about his librettist’s talents are succinctly revealed in his immediate conversion to the idea of Literaturoper (his next opera, Sir John in Love, takes a libretto directly from Shakespeare no less). In 1942 he pointedly omitted Hugh from a list of his operas with “good libretti.”

Nevertheless, Child’s libretto is not quite the hopeless thing it is sometimes represented as. It tells a simple story of love-at-first-sight set in a Cotswold market town (inspired by Northleach, Gloucestershire) at the time of the Napoleonic wars. Mary, daughter of the village constable, is being pressed into an unwilling marriage with the wealthy but brutal John the butcher. When Hugh the drover appears and offers her the chance to escape to a life of heavily romanticised wandering she unhesitatingly declares a willingness to become his bride. Immediately afterwards John offers to fight anyone for twenty pounds, Hugh takes him on, says he is fighting for Mary, and in proper Rocky fashion comes from behind to win triumphantly. But then John denounces Hugh as a French spy, the villagers turn on him (a slight pre-echo of Peter Grimes), and he is placed in the stocks. Mary is loyal to her man, and when his innocence is proved they set off almost immediately to follow the droving life together. The main idea may have come from J. M. Synge’s first play, In the Shadow of the Glen (1903), where an unnamed tramp persuades an unhappily married woman to embark on some romanticised tramping with him (“you'll be hearing the herons crying out over the black lakes”).

Vaughan Williams set Hugh and Mary’s story to the most gloriously tuneful music possible. Hugh the Drover has the same sort of melodic richness as Cavalleria Rusticana, and as with Mascagni’s masterpiece much of it appears to be constructed from the very stuff of popular song. The analogy can be taken further, too: both these operas of high passions in country places have an unpretentious, spontaneous, youthful freshness about them (though Vaughan Williams was no youth when he wrote Hugh); and both include extensive choral music to construct a musical portrait of a community, the values of which have a significant bearing on the foregrounded action. What is most surprising, though, is that Vaughan Williams wrote some passionate, thrilling vocal lines for Hugh and Mary that would by no means be out of place in Cavalleria.

But while Mascagni’s opera conquered the world and came to define the very idea of “popular opera,” Hugh the Drover signally failed. Written between 1910 and 1914, no production could be arranged before the First World War erupted. After the war Vaughan Williams tinkered with it, and for unexplained reasons there was no production until 1924, when the British National Opera Company gave three performances at the end of their season. Since then there have been a considerable number of productions, nearly all of them in Britain, but it has been shunned by the big companies and come nowhere near to being a standard repertoire work.

It would be unfair to blame this wholly on the libretto. Hugh the Drover gives out mixed messages about what it wants to be, unlike Ethel Smyth’s closely contemporary The Boatswain’s Mate (1916), which similarly set out to be a “popular opera” and enjoyed vastly more success (it was in the repertory of the Old Vic in the 1920s). The Boatswain’s Mate, too, is a story of country life with music that often seems close to popular song. But Smyth, who prepared her own libretto, created far more believable characters and even when they sing in an obviously “operatic” fashion the dramatic illusion is maintained that they are ordinary people inhabiting their ordinary culture (just as in Albert Herring, say). By contrast, Hugh and Mary are not remotely credible as real country folk and their vision of marriage is purely fantastical. They are operatic lovers, as much Italian as British, and in their passion seem to enter a world of “high” culture remote from the popular culture of the village around them.

Should Hugh the Drover, then, be produced as a folksy village piece, or as a stirring, “operatic” love story, a sort of English verismo? Uncertainty has been fatal to the opera’s success. Big companies have no doubt correctly concluded that serious productions emphasising the more operatic qualities would get a thorough mauling from the professional critics (whose taste for British opera seldom ventures back further than Britten). The thinness of the story, the lack of psychological interest, and the clunky poetry of the libretto, too often unintentionally funny, would all be exposed. On the other hand, the size of the opera, and the musical demands it makes, have been major discouragements to the amateur and semi-professional companies who might be attracted to its more folksy, fun-filled side, and who could give it the sort of down to earth treatment as unpretentious entertainment that the story is best designed to support.

It would perhaps be a slight exaggeration to suggest that all the problems surrounding Hugh the Drover have been solved at a stroke by Hampstead Garden Opera, but it is close to the truth. Their production feels absolutely right. It has been made possible by a new reduced version of the score for chamber orchestra prepared by Oliver-John Ruthven; it’s pleasing to note that this was undertaken “with permission, encouragement and generous support from the Vaughan Williams Charitable Trust” and is now available to hire. At the small Upstairs at the Gatehouse theatre the musicians are unobtrusively tucked away to one side of the performance space, the rest of which is transformed into a Georgian town square. The audience is essentially in the imagined town, which comes across as the sort of charming vision of English country life in yesteryear in which we all like to believe. The theatre itself is famously above a pub, drinks can be taken upstairs, hardly anyone bothers to dress up, and the simplicity of it all is perfectly suited to the imagined world of Hugh the Drover, which could easily appear absurdly quaint framed by an elaborate proscenium arch.

The secret of Hampstead Garden Opera’s success, I think, is that they concentrate simply on the entertainment value of the opera. They neither attempt to dignify it with a serious treatment, nor trace some meaning in it that simply isn’t there, nor, heaven forbid, try to make it “relevant.” They do not send it up, but they “sub-reference” the audience, to use Charles Lamb’s term, just enough to say “look, this is all tremendous fun, and we’re really enjoying ourselves.” This palpable sense of enjoyment conveyed by the singers, combined with the sheer immediacy of the production, was tremendously infectious, and it is hard to imagine anyone with a taste for musical theatre, of whatever stamp, not enjoying this production. Indeed for anyone who’s “afraid of opera” but likes other kinds of musical theatre, this Hugh the Drover can be recommended as an irresistible introduction to the art form. Peter Grimes can wait till later.

The openness of the production to the pure pleasure of the work was not at the expense of any significant compromise in musical values. Zachary Devin and Phillipa Murray were superb as Hugh and Mary, both singing in the strong, impassioned but unshowy way that Vaughan Williams would have wanted. The supporting roles were sung in character very ably, and the chorus sang their socks off whenever they had the chance. Oliver-John Ruthven conducted himself, providing a spirited and faultless accompaniment to the proceedings; some subtleties in the full score were doubtless sacrificed in the rearrangement, but I can’t say I noticed, and I doubt anyone else did either.

Altogether, while I can imagine technically more polished versions of Hugh the Drover, I find it hard to imagine a better one, and now that it has been adjusted to the needs of smaller companies and venues I hope it will become more widely recognised for what it is: not a great opera, but great operatic entertainment, with melodies that lodge themselves in your head for days.

David Chandler

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Hugh_Drover_2627.gif image_description=Philippa Murray as Mary and Zachary Devin as Hugh the Drover [Photo by Laurent Compagnon courtesy of Hampstead Garden Opera] product=yes product_title=Ralph Vaughan Williams: Hugh the Drover product_by=Hugh the Drover: Zachary Devin; Mary: Phillipa Murray; John the Butcher: David Roberts; Aunt Jane: Charlotte King; The Showman / Sergeant: James Williams; The Constable: Ian Helm; The Turnkey: Nick Whitfield; The Ballad Seller: Robert Davis. Hampstead Garden Opera and the Dionysus Ensemble. Music Director / Conductor: Oliver-John Ruthven. Production Director: Angela Hardcastle. Set and Costume Designer: Charlie Tymms. Upstairs at the Gatehouse, Highgate, London, 12 November 2011 (matinee). product_id=Above: Philippa Murray as Mary and Zachary Devin as Hugh the Drover [Photo by Laurent Compagnon courtesy of Hampstead Garden Opera]

November 20, 2011

Turandot in San Francisco

Well, almost a new cast. The slave girl Liu of Leah Crocetto was a hold over from the October cast though her performance in these new circumstances seemed more vibrant and vivid. No longer dwarfed by larger than life colleagues, it was far bigger than before and this time it truly mesmerized the opera house — her prayer and supplication, then her suicide came in limpid pianissimi, in rich forti, the youth and freshness of her voice embodied the purity and innocence of maidenhood.

Susan Foster was both the new Turandot and a new Turandot — not the icy, unattainable princess but the vulnerable, neurotic maiden, a Turandot very rarely revealed. Now she was a human scaled, twisted rival of the pure and gentle Liu. To be sure Mme. Foster could not be the icy Turandot if she wanted to. She does not possess the steely, dramatic voice nor the mythic persona to engage in a shouting match with her suitor Calaf. But she does have an engaging dramatic voice with volume aplenty when she needs it, and a personal softness that shone beautifully in her touching revelation that Calaf’s name was in fact “love.”

Walter Fraccaro as Calaf and Susan Foster as Turandot

Walter Fraccaro as Calaf and Susan Foster as Turandot

Calaf too, tenor Walter Fraccaro, had a softness and vulnerability that brought a very human dimension to his “Nessun dorma” that beguiled the opera house with its intimacy and earned him one of its all time biggest ovations. His Calaf was a young warrior who was perhaps as neurotic as Turandot, both of them equating love, or let us just say sex — there is that kiss — with death. Mr. Fraccaro did have the heft and volume in secure, supple voice to assault Turandot in his second act answers to her riddles.

Bass Christian Van Horn brought physical stature (he’s tall) and volume to Timur, confidently anchoring the narrative relationships of the opera’s’ protagonists. The Hockney production does not offer this personage opportunity to expand emotionally.

San Francisco Opera Resident Conductor Giuseppi Finzi allowed Puccini’s score to rise naturally from the pit, with tempos that encouraged its huge sonic scope to saturate the War Memorial Opera house. It is a great big opera that gives the San Francisco Opera chorus and orchestra opportunity to strut their stuff as two of the world’s fine ensembles.

The musical flow revealed this young conductor’s understanding of Puccini’s story. He did not sacrifice this newly discovered delicate humanity to dramatic and musical effect — this score’s fatal temptation. But what the young maestro could not do was drive the Alfano duet that ends the opera to the musical coherency that his predecessor Nicola Luisotti miraculously achieved, nor bring point and edge to the machinations of Ping, Pang and Pong.

Walter Fraccaro as Calaf, Leah Crocetto as Liù and Christian Van Horn as Timur

Walter Fraccaro as Calaf, Leah Crocetto as Liù and Christian Van Horn as Timur

The Hockney production is saturated with Chinese reds and fantastical shapes that evoke much more than illustrate a sense of Oriental splendor. Hockney thinks two dimensionally, i.e. the proscenium opening is a canvas, thus we are presented with a succession of paintings. This places his characters on the canvas, or rather it freezes them onto the canvas. There is little movement, and virtually no dramatic reality, i.e. characters do not speak to each other — conversations are a visual, public presentation. Puccini’s Turandot offered this formidable visual artist unique opportunity to create a masterpiece.

Michael Milenski

image=http://www.operatoday.com/turandot003.png

image_description=Susan Foster as Turandot [Photo by D. Ross Cameron/San Francisco Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Giacomo Puccini: Turandot

product_by=Turandot: Susan Foster; Calaf: Walter Fraccaro; Liù: Leah Crocetto; Timur: Christian Van Horn; Ping: Hyung Yun; Pang: Greg Fedderly; Pong: Daniel Montenegro; Emperor Altoum: Joseph Frank; A Mandarin: Ryan Kuster. San Francisco Opera Orchestra and Chorus. Conductor: Giuseppe Finzi; Stage Director: Garnett Bruce; Set Designer: David Hockney; Costume Designer: Ian Falconer; Lighting Designer: Christopher Maravich. Performance of 18 November 2011.

product_id=Above: Susan Foster as Turandot

Photos by D. Ross Cameron/San Francisco Opera

November 18, 2011

Lucia di Lammermoor, Chicago

In the performance seen René Barbera replaced the indisposed tenor Giuseppe Filianoti in the lead role of Lucia’s lover Edgardo. Baritone Quinn Kelsey sang the role of Lucia’s brother Lord Enrico Ashton and bass-baritone Christian Van Horn the role of Raimondo. By coincidence in this performance all four lead roles were assumed by past or current members of the Ryan Opera Center. The Lyric Opera Orchestra and Chorus were conducted by Massimo Zanetti in his debut season.

During the overture soft light shone through a blue scrim which returned and was varied at select points during the subsequent scenes. The woodwinds contributed notably to a generally well led performance of the overture, although the percussion was at times overly loud and pauses could be better seamed together. The male voices in the initial scene created a strong impression, one which remained consistent throughout the performance. As Normanno sung with urgent appeal by baritone Paul Scholten leads a search party to find Edgardo of Ravenswood, the male chorus members and Enrico join the group. In his aria and cabaletta Quinn Kelsey gave a nuanced and authoritative performance, clearly defining the venal character of Lucia’s brother. “Cruda, funesta smania” was sung with a true sense of line and color to emphasize words such as “horribile.” The cabaletta “La pietade in suo favore” proceeded naturally with well chosen vocal decoration, pitches sung flat to give additional emphasis, and effective top notes. The voice of Mr. Van Horn, so vital later in these performances, added here to the ensemble with chorus where his impressive range gave memorable support to the effect of the group.

In the second scene of Act One Lucia and Edgardo make their initial impressions, the heroine appearing before being joined by her outlawed suitor. As she relates to her confidante Alisa the tale of violence between lovers in an earlier generation of the Ravenswood clan, Lucia sings “Regnava nel silenzio” and claims to have seen the spirit of the dead girl at the fountain. As the narrative unfolds Ms. Phillips characterizes Lucia’s emotions by modulating her voice between full and hushed. In the second half of the scene showcasing the cabaletta “Quando rapito in estasi” Phillips drew on especially secure vocal decoration, as she negotiated the aria with all the repeats taken. Barbera’s Edgardo blended well with Phillips in their subsequent duet, his voice taking on a more declamatory tone when he sang solo lines. The exchange of rings and promise of future letters was sworn by both singers with lyrically believable tenderness.

The second act of this production was performed after the first without pause. Although the scene now changes to the interior of Enrico’s study, a stylized tree from the previous act staged outdoors can now be seen as through a window. The emotions attendant on that earlier scene drift into a conflict accelerating between Lucia and her brother: he insists in the confrontation here depicted that she marry Arturo Bucklaw in order to save the Ashton family. Both singers showed a skilled application of bel canto technique in their interaction, just as their dramatic outbursts were vocally in character. Once Enrico leaves her alone, Lucia is comforted and advised by Raimondo. Surely a highlight of this production was Mr. Van Horn’s performance of the aria “Ah, cedi, cedi,” a piece which has so often been cut from stagings of Lucia. Here Raimondo relies on humane persuasion and a tone of religious authority to convince Lucia that she should follow Enrico’s suggestion. Van Horn’s sonorous line and excellent low notes were matched in his cabaletta by a lightness and rhythmic sensitivity where noticeable articulation led to an impressively dramatic close. In the final scene of Act Two with all the principals on the stage the bridal couple is prepared for the wedding ceremony in festive attire. In assuming the role of Arturo Bucklaw Bernard Holcomb brought a good sense of diction and legato phrasing to his lines. Once the true beloved Edgardo reappeared, the sextet was performed with uniform commitment and individual voices soaring at appropriate moments. As Edgardo cursed Lucia’s perfidy the act concluded in a well staged ensemble. Van Horn’s thrilling calls of “Pace” sounded ever more futile as the enmity between Enrico and Edgardo predominated to the close.

Lyric Opera’s production of Lucia includes the scene outside the tower of Wolf’s Crag and hence divides Act Three into a trio of significant parts. In the first of these identified traditionally with the location Edgardo and Enrico confront each other on the grounds of the Ravenswood family estate. As they sang the duet (“Qui del padre ancora respira”) both Kelsey and Barbera chose decoration judiciously and allowed their characters to be defined by dramatic technique and a firm sense of legato. The growing rage between the two men and their assignation for a duel in the final scene helped clarify the plot and presents strong arguments for including the scene regularly in stagings of the opera. In the second scene the two major arias were sung with a memorable sense of integration into the dramatic flow. During the wedding festivities Raimondo bursts in to announce that Lucia has murdered her husband Arturo (“Dalle stanze ove Lucia”). Van Horn’s intonation in the aria expressed his horror at the discovery, just as his delivery of “infelice” followed by splendid top notes communicated Lucia’s state of madness to the revelers. When the heroine appears at the top of a precipitous staircase to sing the mad scene (“Il dolce suono”) Ms. Phillips acted and sang as one possessed. The effect of her fluid, secure delivery of the runs, trills, and roulades in this vocal challenge gave her Lucia the freedom to express visions and emotions in movement as well. Her ghostly singing of high notes pianissimo, punctuated with pitches delivered and held flat to enhance the sense of instability, added to this interpretation of a complex mental state. In the final scene of the opera Edgardo awaits Lucia’s brother in order to fight the duel that was agreed upon in the first part of this act. Mr. Barbera’s stylish delivery of the famous tenor aria (“Fra poco a me ricovero”) showed a supple approach with a welcome ring to high notes, as he ended the piece by taking the opportunity for introspective singing piano. When he realizes that Lucia has died and witnesses her funeral procession, Barbera inflected his cabaletta with wrenching emotion before stabbing himself to join his beloved in death.

Salvatore Calomino

Click here for a photo gallery and other information regarding this production.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lucia_Chicago_01.gif image_description=Susanna Phillips as Lucia and Giuseppe Filianoti as Edgardo [Photo by Dan Rest] product=yes product_title=Gaetano Donizetti: Lucia di Lammermoor product_by=Click here for cast and other information. product_id=Above: Susanna Phillips as Lucia and Giuseppe Filianoti as Edgardo [Photo by Dan Rest]November 17, 2011

Tricks and Treats, New World Symphony

To this listener, Brewer deserves the designation of Mastersinger, a small group and curious breed that occasionally contains in it a top lieder singer.

Lied is, in all cultures where “high-art” literature is transmuted into compilations of songs, made for the interpreter, for storytellers. Singers enter the culture of lied knowing full well it demands total subservience to telling the tale. As it is with the best of lieder interpreters (Dietrich Fischer Dieskau and Christa Ludwig come to mind), Christine Brewer has a knack for this music that is partly inborn.

Lied history takes more formal shape in the 19 th century with the works of German composers; most prolific in the style was Franz Schubert; working in the style through the turn of the 20 th century was Hugo Wolf. Composers often set their lieder to a theme in a series, or cycle. The lieder singer is faced with the test of becoming as much a part of the background as they can possibly muster, coming in and out of the foreground to serve the music as indicated and in setting the poetry in high relief. The lieder singer further sets the tone for the theme and carries it through the cycle.

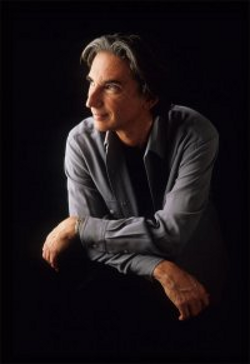

Michael Tilson Thomas [Photo by Chris Wahlberg]

Michael Tilson Thomas [Photo by Chris Wahlberg]

Brewer makes this look easy. No one can qualify the Illinois native’s German as anything but romantic. She gets right to vowels, hanging on ever so lightly, giving consonants that snap that settles on the ear. Brewer exercises a judicious mix of vibrato treatments over a warm stream of sound and a tonal quality similar to Jessye Norman’s, with a more forward placement. The lower register is remarkably secure and round, climbing as that one proverbial “column of sound,” a sound that was born to soar. She reaches high-note territory (E, F and G) with ease; yet she builds phrases with sincerity and depth, which takes a tremendous amount of discipline. This is what she does; and it makes Brewer all the more special.

Billed as an evening of “Tricks and Treats,” New World Symphony (NWS) and Artistic Director Michael Tilson Thomas hosted Brewer at the Knight Concert Hall on October 29th. The vocal portion of the concert consisted of Richard Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder, what amounts to a serenade the composer created to the poems of his muse at the time, Mathilde Wesendonck, who is described as “one of the most significant women in Wagner’s life” in the program notes.

Even when Christine Brewer could let loose through Wagner’s five lied, she drew out plaintive tones that were an integral part of the story, saving her considerable powers for the articulation of German. Such was the case for “Der Engel,” where vocal control goes a long way in conveying how the selflessness of angels fills the hollowness of human existence. Brewer sang phrases that left one breathless, literally and figuratively.

Internal suffering was in full effect in “Im Treibhaus — Studie zu Tristan und Isolde,” where Brewer, Tilson Thomas and orchestra teamed for a moment of otherworldly waves of music, with violins playing off of one another in a way rarely heard. Brewer held a certain musical line while drafting steamy tones over the phrase “Malet Zeichen in die Luft,” where Wagner speaks to the horticulture of supernatural dispositions, asking nature to disclose its wonders.

“Schmerzen” brings more opportunity for vocal muscle, right from the first notes of the vocal line. Here still, Brewer created tones that came across as gentle acceptance of nature’s abiding relationship between life and death.

A conducting “Golden Age” for these times surely comes in the presence of Michael Tilson Thomas. He deserves the appellation Musikmeister. In NWS — America’s only full-time orchestral academy — he has a splendidly boundless and stimulating canvas with which to put to use and to share his inestimable experience and multitudinous skills. Michael Tilson Thomas and Christine Brewer are, individually, artists that bring a certain magic to everything they do. Together, Tilson Thomas and Brewer cause all aspects of a musical show to come into phase.

Tilson Thomas’ dancing with the New World Symphony is unison personified. In “Schmerzen,” where the descending scale of forte strings and winds calls for sudden passion and intra-instrument matching, the sound entered as if warmed up from a few bars back. The NWS conductor carries instrumentalists along with him — wrist rolls move bows and sway woodwinds; he revved up the baton to urge tempi, and brought horn players to the balls of their feet. It all happened at once. Tilson Thomas steps in the direction of a section, calling on them to build sound space, gesturing directions with his left hand, and pointing to have players attend to specific features. Thomas’ communication with Brewer was intense. He sought out her inflections and movements signaling different moods and changes in musical design.

The concert opened with Richard Strauss’ Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks and ended, after the Wagner lied, with Johannes Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C minor. Strauss’ tone poem is an excellent vehicle to show off NWS. Its light beginning and exposed horn and long staccato violin stretches — all the way through the build up and Strauss’ playful winds and wide use of the percussion family — were played with nice contrasts, zinging accuracy and stamina to spare.

NWS showed versatility, power and pathos beyond their years in Merry Pranks and especially in the Brahms. The second movement was guided by Tilson Thomas as a soft hymn with hanging phrases of elegance and downward spins taken with care for keeping a joined soundscape. Improbable as it is, instrumentalists managed the most organic playing in the most demanding of Brahms’ orchestral drawings, the final movement. NWS took its shifts from driving chords to lush orchestral effects, creating a tightly held story right through to the ceremonial finish.

“Golden Age” or no, any night like this — pairing starry singer and starry conductor with a very hungry group of instrumentalists — ranks up there with any of the most vaunted classical musical moments, anywhere, anytime.

Robert Carreras

For more information about New World Symphony check www.nws.edu

image=http://www.operatoday.com/BrewerPhotoChristianSteiner.png image_description=Christine Brewer [Photo by Christian Steiner] product=yes product_title=Richard Strauss: Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks, Op. 28; Richard Wagner: Wesendonck Lieder (orch. Felix Mottl); Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68. product_by=Christine Brewer, soprano. New World Symphony. Michael Tilson Thomas, conductor. Adrienne Arsht Center, Knight Concert Hall, Saturday, 29 October 2011. product_id=Above: Christine Brewer [Photo by Christian Steiner]November 15, 2011

Eugene Onegin, ENO

Fittingly for a work drawn from Pushkin’s verse novel, Warner’s vision is literary in its inspiration. Moving the action forward fifty years, from Pushkin’s 1840s to the late-nineteenth century, the director and her designer, Tom Pye, conjure a moving picture of Chekovian ‘twilight moods’. The pace is gently controlled; beautifully rendered natural scene drops unfold, like pages of a book, as we move through the chapters of the protagonists’ lives. The visual detail and accuracy of observation recalls Chekhov’s stylised blend of realism and romance.

Pye’s designs are sumptuous and surprising. The imposing ballroom columns of the third act, through which polonaising couples burst, justly won an instantaneous gasp of applause; cleverly, as the suppressed emotions of the social interior are exchanged for the freedom of the natural exterior, the splendid pillars become terrace colonnades – their majesty emphasising the tragic frailty of the protagonists. Most impressive was the silvery lakeside expanse of the second act, all glistening ice, wintry branches and shimmering mist – perfectly capturing the frozen emotions of the duellists who are alienated by jealousy, pride and convention.

The only puzzle was the vast barn of act one, which replaced the usual winter dacha. It was not clear why members of the fairly wealthy Larin family slept in what looked like an outbuilding. And, such an immense expense, stretching into the wings and up to the flies, was not the ideal location for Tatiana’s letter scene, which requires a sense of intimacy and constraint. Jean Kalman’s striking lighting did help: violent shadows loomed ominously behind the tormented heroine, and the gleaming sunrise which heralded the end of the act was almost painful in its gradually deepening intensity. The designs were complemented by Chloe Obolensky’s detailed naturalistic costumes.

Of the strong cast assembled, it was Toby Spence, as a fervently passionately Lensky who shone brightest. A sustained and utterly convincing dramatic interpretation was matched by a faultless vocal performance. In particular, in his act 2 aria preceding the duel, Spence delivered an exquisite pianissimo passage of reflection, poignantly recognising and regretting that even genuine fraternal love could not prevent pointless annihilation of life. The tensions and antagonisms between Lensky and Onegin were visually suggested by the taut diagonal line that the men formed as they ranged their rifles, Lensky sited to the rear of the stage, already receding from life. Warner’s attention to detail was impressive in this scene; telling touches, such as Onegin’s removal of his hat, subtly shaped the audience’s response.

Amanda Echalaz as Tatiana and Claudia Huckle as Olga

Amanda Echalaz as Tatiana and Claudia Huckle as Olga

Lensky’s romantic ardour was such that it is hard to imagine how he could have formed such a strong friendship with the coolly aloof Onegin of Audun Iversen! It is a role that the Norwegian baritone has tackled to acclaim several times before; in this production, his Onegin is not a dastardly villain but wavers between blunt honesty and immature self-indulgence. He is bored by and frustrated with stifling social conventions. Although a little constrained to begin, by the final act Iversen’s beautiful mellow tone, with its rich low notes and free, relaxed in upper register, went some way to winning the audience’s sympathy for this flawed dreamer.

Having recently taken audiences by storm as Tosca at both of London’s main houses, Amanda Echalaz’s Tatiana was a little disappointing. There is no doubting the wonderful strength and depth of her voice, and her secure chest notes are impressive. Tatiana’s elegiac passion was powerfully conveyed. But, Echalaz’s tone was rather one-dimensional. She has admirable stamina and there was lots of power, but not much light and shade. There were some moments of gleam, but on the whole both more radiance and more fragility were required in order to convey Tatiana’s tragic vulnerability and emotional frailty. There were some intonation problems too, particularly a tendency for the fortissimos to stray sharpwards.

Auden Iversen as Onegin and Amanda Echalaz as Tatiana

Auden Iversen as Onegin and Amanda Echalaz as Tatiana

The principals were well supported by the minor roles. Diana Montague (Larina) and Catherine Wyn-Rogers (Filippyevna) were superb, while Claudia Huckle was a lively, impassioned Olga. Brindley Sherratt, who impressed in ENO’s recent Simon Boccanegra, displayed gravitas and honesty as the elderly Gremin. In the cameo role of Monsieur Triquet, Adrian Thompson almost stole the show!

The thunder of the enlarged chorus in the climactic moments was rich and thrilling, although they were a little untidy at times. The stage was crowded, with children and dancers adding to the maelstrom. Kim Brandstrup’s choreography combined stylised realisation of Russian peasant culture enriched with modernist gesture; both in the opening act and the later ballroom the dances served to establish cultural mannerisms and social hierarchies.

Claudia Huckle as Olga and Toby Spence as Lensky

Claudia Huckle as Olga and Toby Spence as Lensky

Edward Gardner conducted with consummate appreciation of the spirit and pace of the opera: he and Warner allow space for emotive silences, most tellingly in letter scene. Pauses between scenes and acts suggest that while life hangs suspended, later everything will inevitably change. Sudden surges of rapturous orchestral outpouring are contained within controlled musical forms, as the repressed souls fleetingly give vent to romantic yearnings. Gardner’s attention to detail is masterly. Nothing is over-stated. Tchaikovsky’s score is not so interested in external worlds but in the characters’ inner development, just as in Chekhov’s plays the poetic power is hidden beneath surfaces, and so reveals the true depths of human experience.

Martin Pickard’s translation is rather mundane at times although he captures some of the original’s lyricism in the set pieces. Pushkin’s tale may be a fairly clichéd account of unrequited love, missed opportunities and the conflict between passion and convention, but it is a tale with which all can surely identify. If despair and hopelessness dominate, there is still radiance amid the torture. From quiet beginnings, Warner allows huge human passions to emerge. She simply lets the music tell its story.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Onegin_ENO_2011_02.gif image_description=Amanda Echalaz as Tatiana [Photo by Neil Libbert courtesy of English National Opera] product=yes product_title=Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Eugene Onegin product_by=Eugene Onegin: Audun Iversen; Vladimir Lensky: Toby Spence; Tatiana: Amanda Echalaz; Olga: Claudia Huckle; Filippyevna: Catherine Wyn-Rogers; Monsieur Triquet: Adrian Thompson; Madame Larina: Diana Montague; Zaretsky: David Stout; Prince Gremin: Brindley Sherratt; A Captain: Paul Napier-Burrows; Peasant Singer: David Newman. Director: Deborah Warner. Conductor: Edward Gardner. Orchestra of English National Opera. Set designer: Tom Pye. Lighting designer: Jean Kalman. Costume: Chloe Obolensky. Choreographer: Kim Brandstrup. English National Opera, Coliseum, London, Saturday 12th November 2011. product_id=Above: Amanda Echalaz as TatianaPhotos by Neil Libbert courtesy of English National Opera

November 14, 2011

Dark Sisters, New York

An operatic treatment was sure to appear in due course, but due course in opera-land usually takes at least a generation. Not this time! Young Nico Muhly’s Dark Sisters, about five wives of a polygamous “prophet” who has been accused of abusing his twenty-odd children, had its premiere this month in a visually and aurally sumptuous production by Gotham Chamber Opera and Music-Theatre Group that will travel in June to its co-producer, the Opera Company of Philadelphia.

Caitlyn Lynch as Eliza and Kristina Bachrach as Lucinda

Caitlyn Lynch as Eliza and Kristina Bachrach as Lucinda

Having no previous acquaintance with Muhly’s music, I was tremendously impressed by his skill at writing for both chamber orchestra (13 musicians) and voice. First of all, he can write for the voice, in a sensuous, gratifying way that suits the voices doing the singing. It might be called an instrumental manner: Voices, solo or in combinations in various ranges echo or mimic the way he pairs unusual combinations of instruments to shade or emphasize a line of text or an unexpressed emotion, a violin with an English horn or a flute with celesta. There are striking effects that support a scene or a moment more subtly than the high melodramatic manner opera is used to. To a scenario with very little stage action, Muhly brings vivid musical activity, interesting even when its working out is not what the listener might have expected.

For one striking example, Act I closes with the Prophet choosing to spend the night not with one of the four biddable wives who yearn for nothing else, but with Eliza (Caitlin Lynch), the wife for whom the assault of the outside world and the taking of her daughter, Lucinda, has crystallized years of disaffection. Though she is submissive in word and gesture, Eliza’s disgust at the Prophet’s marital rape—her memories of her wedding night at sixteen, her escape into fantasies (which, it is implied, have been getting her by for years)—are indicated by a subtle agitation, ripples of percussion and harp, that express her state of mind with perfect economy, and the repulsive occasion is staged with spare good taste. Compare the perfervid scenes of sexual violation in Floyd’s Susannah, Loesser’s Most Happy Fella, Ginastera’s Beatrix Cenci, Britten’s Lucretia. Britten is one of Muhly’s obvious models; so is Samuel Barber—I departed humming Vanessa’s “In stillness, in silence, I have waited for you.” But Muhly’s music could not be mistaken for either Britten or Barber; it is too lush for the former, less melodically giving than the latter.

Impressed as I was by the aural textures and the skillful mood painting of Dark Sisters, I felt distanced, confused, by Muhly’s tonal but astringent melodic language, so ambitiously displayed. There seemed, at least at first hearing, too eager a sidestep from the easily caught phrase. When not harmonizing, too many of the vocal lines sounded like recitative sung with feeling. The varieties of sound and the sheer gorgeousness of the women’s voices led us eagerly from place to place, but this aversion to anything simple or basic made the traditional hymn tune “Abide with Me,” when it turned up in the final scene, unduly attractive, a relief for the ear kept on edge. Perhaps that was the intention, the composer’s riff on our preference for neater drama and more melodiously appealing characters—his modern twist on the adage that the Devil gets the best tunes. For by this time the plot of this very internal opera had taken some curious turns, one (Eliza’s flight), foreshadowed and satisfying, others not so easy to parse. The ending is ambiguous rather than self-righteous or pat; we are satisfied and unsettled at the same time.

Left to right: Jennifer Zetlan as Zina, Margaret Lattimore as Presendia, Caitlin Lynch as Eliza, Jennifer Check as Almera and Eve Gigliotti as Ruth

Left to right: Jennifer Zetlan as Zina, Margaret Lattimore as Presendia, Caitlin Lynch as Eliza, Jennifer Check as Almera and Eve Gigliotti as Ruth

As the opera begins, the women mourn for their children, seized by state authorities, and from their interwoven mourning individual natures gradually announce themselves. Their husband, the Prophet, flees to the desert—seeking communion with God’s messengers, he says—and their discontent is left to seethe and bicker and recall the past without him. Ruth has lost her children because the Prophet would not permit doctors to come from outside. Zina is proud of her new sewing machine, the Prophet’s gift; Presendia resents that gift and takes her own refuge in art. They pine for their husband and resent him; they accept the restrictions of their life, the only life they know, but rebellion simmers. And Eliza, who does not enjoy her husband’s attentions as the others do, is horrified when she discovers he has promised her fifteen-year-old daughter to an elderly friend. In Act II, on an amusing, not too forced parody of a TV news show, a self-important newscaster who clearly regards the wives as freaks, puts them on screen to discuss their polygamous plight. The women refuse to condemn their own distinctive lives. Presendia points out: “It’s not a compound; it’s a ranch … our home! … This is America! … In some states they let men marry other men!” But Eliza, as we knew she would, seizes the opportunity to escape.

Stephen Karam’s libretto is spare on action. Instead, he presents the internal drama of the female protagonists, glancing on all the expected themes with a blessedly light touch that Muhly has matched: There is just enough conflict between the wives, not too much; there is just enough sermonizing, not too much. Nor does Karam oversimplify the issue of what such women are to do with themselves if they do break free: Where would they go? How are they to live? It’s no simple matter, and Karam does not brush it off or assume that we will take a certain side (though of course, most of us sophisticated, secular opera-goers will).

This is one of the epic stories of our time, and not just for child brides on a Southwestern ranch. At adolescence, in many societies, girls are given to older husbands to forge alliances while boys are often “excommunicated,” banished friendless and unprepared to the world they have been raised to distrust. Similar tales come from other traditional societies in revolutionary times: the Hasidic Jews, the Reservation Indians, or the youth of cultures where women are veiled or circumcised and daughters ill-educated, not daring not protest traditional decisions. Raised to believe the outside world is hostile and sexually exploitive (and isn’t it?), they must choose between a known space with dependable family love and finding the courage to give it all up for the terrifying unknown. For most individuals so trapped, this is neither a simple nor an obvious choice. To Karam and Muhly’s great credit, in boiling such matters down to a 100-minute operatic presentation, they never suggest that the solutions are simple, obvious or predetermined; they do not slight the attractions to remain or those of departure. Dark Sisters is not a snide fable; it is a sincere effort to get under the human skin of the problem.

Kevin Burdette as Prophet/News Anchor

Kevin Burdette as Prophet/News Anchor

The production design (director Rebecca Taichman, sets and video by 59 Productions, lighting by Donald Holder) might be a textbook for the latest in multi-media opera (projections, double screens, films within films, lighting in back, in front, all around), but who ever designed a textbook this beautiful? The gray lives of the women on their ranch are expressed by their white, nightgown-ish dresses set between red-brown desert sands and blazing skies, and their visions of star-filled nights and cloudy, alluring paradises glow.