February 29, 2012

Simon Boccanegra, LA

The production, like the fall’s Eugene Onegin, was not only a first for the company, but happily, starring the company’s director, Plácido Domingo, an even greater artistic success; proving that baritones can be thrilling too.

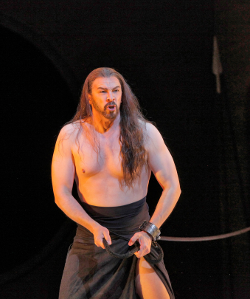

Vitalij Kowaljow as Fiesco

Vitalij Kowaljow as Fiesco

Verdi wrote Simon Boccanegra in 1857. Its libretto is based on a play by Antonio Garcia Guttiérrez, which in turn was based on the life of the Genoese plebeian, who was elected first Doge of Genoa in 1339. Verdi’s opera was not well received. However, nearly twenty-five years later the composer revised its music and used a new libretto created by Arrigo Boito. Boito, a writer and genius of another cut, had already composed Mefistofeles, his only opera. Subsequently he wrote the librettos for Verdi’s last and greatest works, Otello and Falstaff.

Simon Boccanegra’s story involves complicated personal and political intrigues. Like Verdi’s other political operas, Macbeth, for example, it is a dark work whose plot is not driven by romantic love. Five of its six major roles are for male voices. Two duets between bass and baritone are extraordinarily powerful. Like Macbeth, even the revised Simon Boccanegra has never achieved the popularity of other Verdi operas. However, it’s a favorite of mine. Its darkness comes not merely from the essentially male cast, its nasty intrigues, or its minimal romance. Musical darkness pervades the entire work from its key signatures, to its melodic lines, to its orchestration. Heartbreak and sorrow permeate the soul of Simon Boccanegra. And Verdi knew that soul intimately. Like Boccanegra, Verdi had lost a wife and daughters almost on the eve of his ascent to power and fame.

Simon Boccanegra begins with a prologue in which the major characters are introduced. Boccanegra is a young corsair, who is inveigled to accept the newly created post of Doge of Genoa by his manipulative power hungry friend, Paolo. We meet Fiesco, the father of Maria, the young woman Boccanegra loves, who has borne his daughter out of wedlock. Fiesco will forgive Boccanegra for this sin, if the corsair can produce that child. But he cannot. He tells Fiesco that little girl has disappeared. Moments later (and we are still in the prologue) just as Boccanegra discovers that Maria is dead, a joyous crowd arrives to declare him the newly elected Doge.

Ana María Martínez as Amelia

Ana María Martínez as Amelia

The first act begins 25 years later. Now Boccanegra and his daughter, Amelia discover each other. Unhappily, Amelia is in love with a tenor named Adorno. who along with Fiesco and Paolo, each for his own reasons, have united as sworn enemies of Boccanegra. The dramatic highlight of Simon Boccanegra is the magnificent Council Chamber scene with its thundering confrontation between Boccanegra and Paolo. Later, Paolo poisons the Doge. Nevertheless, the opera concludes with just punishment and reconciliation. Paolo is executed. Boccanegra tells Fiesco that Amelia is his granddaughter, and in an extraordinarily moving duet, the two old men, Boccanegra and Fiesco are reconciled. Amelia and Adorno marry. Adorno becomes the new Doge of Genoa. And the dying Boccanegra will find his Maria in heaven. If you can get to the pre-opera talk, Maestro Conlon does a marvelous job of unraveling this sleeve of tsouris, and with music, no less!

The darkness of its preceding scenes make our introduction to Amelia, with its brief moment of joy and high notes the only truly bright moment of the work. Interestingly in Amelia’s first aria of love and longing,”Come in quest’ora bruna” sung as she awaits Adorno, Verdi harks back to the rolling oom pah pah bass of his earlier operas. James Conlon warned his audience that they would cry at the recognition scene and sure enough, I did. But I don’t at every performance of this opera. As I said, sometimes everything seems to go right. And this scene certainly did that Sunday afternoon.

The very strong cast of male singers led by Domingo made this possible. The knock on the state of 71-year old singer’s Boccanegra: that his voice is not deep enough for the role, and raspy besides, may be true, but for the performance I saw, all that was irrelevant. With a dark wig and slimming costume, he strode and sang vigorously as the young Boccanegra. As the gray haired Doge, he was a commanding presence. Domingo has always been an excellent actor, and is unsurpassed in the subtleties his voice whether as tenor or baritone, can express in dramatic roles. The Ukrainian bass Vitalij Kowaljow, who sang Fiesco was a joy to hear if like me you thrill to clear, legato bass singing and long held last low notes. Baritone Paolo Gavanelli and bass Robert Pomakov were equally compelling. Stefano Secco, making his LA debut as Adorno, has a bright tenor voice and happily, his Italian could be understood. Anne María Martínez, a Grammy winner for an album she recorded with Domingo, has a rich lyric voice and produced a genuine trill. Kudos for the chorus, which has a large role in the opera. Maestro James Conlon, who confessed a particular affection for this opera, kept a limpid performance rolling at a brisk tempo.

Plácido Domingo (right) as Simon Boccanegra, with Stefano Secco (left) as Gabriele Adorno

Plácido Domingo (right) as Simon Boccanegra, with Stefano Secco (left) as Gabriele Adorno

Well, maybe there were two things that weren’t so right: the lighting and the sets created originally by lighting designer Duane Schuler and Michael Yeargan, respectively, for Covent Garden. They seem to have taken the “darkness” of the opera too literally. Both the prologue and final scene were entirely too dim and shadowed. During the prologue it was sometimes difficult to know who was singing. And I found the depth of the sets troubling. Both the prologue, which takes place in a public square and the Council chamber scene, which employ large choruses, were set on comparatively shallow sets, whereas the intimate scenes: the love scene, the recognition scene and Boccanegra’s death were performed with open depths behind them.

But these are quibbles. A great opera, whether joyous or sorrowful, is foremost about music that enters one’s heart and moves it. And Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra does just that.

Estelle Gilson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/sbc5086.gif image_description=Plácido Domingo as Simon Boccanegra [Photo by Robert Millard courtesy of Los Angeles Opera] product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Simon Boccanegra product_by=Simon Boccanegra: Plácido Domingo; Amelia: Ana María Martínez; Jacopo Fiesco: Vitalij Kowaljow; Gabriele Adorno: Stefano Secco; Paolo Albiani: Paolo Gavanelli; Pietro: Roberto Pomakov. Conductor: James Conlon. Director: Elijah Moshinsky. Set Designer: Michael Yeargan. Costume Designer: Peter J. Hall. Lighting Designer: Duane Schuler. product_id=Above: Plácido Domingo as Simon BoccanegraPhotos by Robert Millard courtesy of Los Angeles Opera

Barcelona Restores Cuts

By Frank Cadenhead [Opera Today, 29 February 2012]

Barcelona’s opera, the Gran Teatre del Liceu , has reversed course and restored cuts in the current season made earlier this month. Earlier this month, In response to government cuts in subsidies, the director general Joan Francesco Marco announced closures of the house between March 20 and April 10 and between June 5 and July 8.

Gran Teatre del Liceu Reverses Course

Earlier this month, In response to government cuts in subsidies, the director general Joan Francesco Marco announced closures of the house between March 20 and April 10 and between June 5 and July 8.

The closures were widely criticized in the local press and the staff planned a strike during the run of Puccini’s La bohème which opens this Friday. The labor unions have made some compromises, however, and the budget gap of €3.7 million seems to have been largely closed with these new agreements. Staff reductions and other measures to meet the reduced subsidies are still under review.

The double-bill of Zemlinsky’s operas, The Dwarf and A Florentine Tragedy and the run of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande will be performed as scheduled.

Frank Cadenhead

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Liceu_logo.gif image_description=Gran Teatre del Liceu logo product=yes product_title=Gran Teatre del Liceu Reverses Course product_by=By Frank CadenheadFebruary 28, 2012

Rusalka, Royal Opera

Agnes Zwierko as Ježibaba and Camilla Nylund as Rusalka

Agnes Zwierko as Ježibaba and Camilla Nylund as Rusalka

That is not to say that any production meeting with hostility qualifies as interesting; some, of course, are simply not very good, or worse. Yet, it seems that only the most vapid, unchallenging — and yes, I realise that the word ‘challenging’ is a red rag to self-appointed ‘traditionalist’ bulls — of productions will garner approval from the ranks of the petite bourgeoisie. The boorish behaviour of those who booed this Rusalka equates more or less precisely to the sort of antics they would condemn if they occurred on the street — the work of ‘hoodlums’, the ‘lower classes’, the ‘uneducated’, ‘rioters’, ‘immigrants’, et al. — yet somehow unwillingness or inability to think, the fascistic refusal to consider an alternative point of view, the threat of mob violence, becomes perfectly acceptable when one has paid the asking price for what they consider to be their rightful ‘entertainment’. They would no more bother to understand, to explore, to question, Rusalka were it depicted in the most ‘traditional’ of fashions, of course, but they explode at the mere suggestion that a work and a performance might ask something of them. For, as John Stuart Mill famously noted, ‘Although it is not true that all conservatives are stupid people, it is true that most stupid people are conservative.’ Wagner’s ‘emotionalisation of the intellect’ — ‘emotionalisation’, not abdication! — remains as foreign a country to them as it did to the Jockey Club thugs who prevented Tannhäuser from being performed in Paris; at least one might claim that the latter were having to deal with challenging ‘new music’, Zukunftsmuik, even. Here they were faced with an opera by Dvořák, first performed in 1901, in a staging that would barely raise an eyebrow in most German house or festivals. (The production, by Jossi Wieler and Sergio Morabito, hails initially from the Salzburg Festival.) It would be interesting to know how many of those booing had selfishly, uncomprehendingly disrupted a recent Marriage of Figaro in the same house by erupting into laughter at the very moment Count Almaviva sought forgiveness from the Countess. (There was also, bizarrely, to be heard at the opening of the third act a shouted call from a member of the audience for a ‘free’ Quebec.)

Scene from Rusalka

Scene from Rusalka

What, then, was it that incurred the wrath of the Tunbridge Wells beau monde? I can only assume that it was for the most part Barbara Ehnes’s sets, since the stage direction (presumably a good part of it from revival director, Samantha Seymour) was more often that not quite in harmony with the urgings and suggestions of Dvořák’s score. (The hostile rarely if ever listen to the music; at best, they follow the surtitles and bridle at deviations from what they imagine the stage directions might have been.) Even modern dress is mixed with a sense of the magical, the environment of Ježibaba the witch a case in point. There is even a cat, played both in giant form by Claire Talbot, and in real form, by — a cat, ‘Girlie’. What is real, and what is not? Collision between spirit and human worlds is compellingly brought to life, the devils and demons of a heathen past, including Slavonic river spirits (rusalki) come to tempt, to question, to lay bare the delusions of moralistic, bigoted modernity. Just as modern ‘love’ and marriage’ quickly boil down to money and power, so Vodník the water goblin finds his tawdry place of temptation whilst issuing his moralistic warnings. (Did the audience see itself reflected in the mirror? Perhaps, though I doubt that it even bothered to think that far.) Our ideas of Nature having been hopelessly compromised by what we have become, we ‘naturally’ see the world of rusalki from within the comforts of our hypocritical bordello. Who is exploiting whom, and who is ‘impure’? The souls of women who have committed suicide and of stillborn children — there are various accounts of who the rusalki actually are — or those who shun them in life and in death? Wieler and Morabito do not offer agitprop; rather they allow us to ask these questions of the work, and of ourselves. But equally importantly, they permit a sense of wonder to suffuse what remains very much a fairy tale, realism coexisting with, being corrected by, something older, more mysterious, more dangerous, and perhaps ultimately liberating. Chris Kondek’s video designs, not unlike the hydroelectric dam of Patrice Chéreau’s ‘Centenary’ Ring, both suggest Nature and through their necessary technological apparatus remind us of our distance from any supposed ‘Golden Age’, just as the opening scene will inevitably suggest to us Alberich, the Rhinemaidens, and the power of the erotic. (Wagner used the term liebesgelüste.)

Bryan Hymel as Prince and Petra Lang as Foreign Princess

Bryan Hymel as Prince and Petra Lang as Foreign Princess

Musical performances were equally strong, in many respects signalling a triumph for Covent Garden. First and foremost should be mentioned Yannick Nézet-Séguin, making his Royal Opera debut. The orchestra played for him as if for an old friend, offering a luscious, long-breathed Romanticism that made it sound a match — as, on its best days, it is — for any orchestra in the world. Magic was certainly to be heard: the sound of Dvořák’s harps again took me back to Das Rheingold — and to Bernard Haitink’s tenure at the house. Ominous fate was brought into being with similar conviction and communicative skill. Above all, Nézet-Séguin conveyed both a necessary sense of direction and a love for the score’s particular glories. If there are times when Dvořák might benefit from a little more, at least, of Janáček’s extraordinary dramatic concision, it would take a harder heart than mine to eschew the luxuriance on offer both in score and performance. Crucially, staging and performance interacted so that the contrast between worlds on stage intensified that in the pit, and vice versa.

Camilla Nylund shone in the title role. At times, especially during the first act, one might have wondered whether her voice would prove to have the necessary heft, but it did, and Nylund proved herself an accomplished actress into the bargain. Bryan Hymel may not be the most exciting of singers; the voice is not especially variegated. However, he proved dependable, and often a great deal more, the final duet as moving as one could reasonably expect. Alan Held was everything a Vodník should be: baleful, threatening, sincere, and yet perhaps not quite. The Spirit of the Lake may well have his own agenda — and certainly did here. Agnes Zwierko played the witch Ježibaba with wit, menace, and a fine sense of hypocrisy that brought the closed environments of Janáček’s dramas to mind. The four Jette Parker Young Artists participating, nymphs Anna Devin, Madeleine Perard, and Justina Gringyte, and Huntsman Daniel Grice all acquitted themselves with glowing colours. Indeed, Grice’s solo, enveloped by miraculous Freischütz-like horns from the orchestra, movingly evoked a world of lost or never-existent woodland innocence. Last but not least, Petra Lang’s Foreign Princess emerged, like Wagner’s Ortrud, as in some respects the most truthful, as well as the most devious, character of all. Splendidly sung and acted, Lang’s was a performance truly to savour. But then, this was a performance as a whole that was far more than the sum of its parts, a triumphant return to form for Covent Garden with its first ever staging of the work.

Mark Berry

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rusalka_ROH_2012_01.gif image_description=Camilla Nylund as Rusalka [Photo by Clive Barda/ROH] product=yes product_title=Antonín Dvořák: Rusalka product_by=Rusalka: Camilla Nylund; Foreign Princess: Petra Lang; Prince: Bryan Hymel; Ježibaba: Agnes Zwierko; Vodník: Alan Held; Huntsman: Daniel Grice; Gamekeeper: Gyula Orendt; Kitchen Boy: Ilse Eerens; Wood Nymphs: Anna Devin, Justina Gringyte, Madeleine Pierard; Mourek: Claire Talbot. Directors: Jossi Wieler, Sergio Morabito; Revival Director: Samantha Seymour; Set Designs: Barbara Ehnes; Costumes: Anja Rabes; Lighting: Olaf Freese; Video Designs: Chris Kondek; Choreography: Altea Garrido. Royal Opera Chorus (chorus master: Renato Balsadonna); Orchestra of the Royal Opera House/ Yannick Nézet-Seguin (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Monday 27 February 2012. product_id=Above: Camilla Nylund as RusalkaPhotos by Clive Barda/ROH

Beatrice and Benedict at the Wales Millennium Centre

Throughout his career Berlioz had a rather distinctive way with the form of a piece, so it is perhaps inevitable that an opéra comique written by him would not be straightforward. Beatrice and Benedict is his final dramatic work, a piece that is small scale partly because Berlioz’s health would not allow him to write anything bigger and partly because that was what was suitable for a summer entertainment at the spa of Baden-Baden. Stagings of the piece are relatively rare so it was with great pleasure that I anticipated WNO’s performance of the opera, doubly so as it was to be a revival of Elijah Moshinsky’s 1994 production, beautifully designed by Michael Yeargan (sets) and Dona Granata (costumes).

Robin Tritschler as Benedict

Robin Tritschler as Benedict

The work was performed in English with spoken dialogue adapted from Shakespeare’s play by Elijah Moshinsky and revival director Robin Tebbutt. Now the British, as a rule, are not very good at opéra comique, something awful seems to happen when the works cross the channel — Offenbach turns into G & S and anything more serious gets just plain embarrassing. Recent performances of the opera in London have tended to be concerts, in which the dialogue was either spoken by actors or replaced by a spoken narration, neither solution very satisfactory. With Beatrice and Benedict the problem is worse because people insist on trying to turn the piece back into a musical version of Much Ado About Nothing rather than sticking with a French opéra comique. In Cardiff we had dialogue cut to the bone, but spoken in a language which veered awkwardly between direct quotation from Shakespeare and more modern idiom.

I had heard wonderful reports of the original 1994 production Elijah Moshinsky production, but somehow the magic does not seems to have survived. The set looked lovely, ravishing in fact, with Paul Woodfield now in charge of Howard Harrison’s original lighting plot. But the set was designed for the far smaller stage of the New Theatre in Cardiff. And its rigidly architectural form meant that not only did the set look narrow, but sight lines were not ideal; it is a shame that somehow it could not have been opened up somewhat. The setting was 19th century Sicily, with the ladies in big crinoline dresses and an architectural loggia doing admirable service for all scenes in the opera.

Musically we got off to a good start with a sparkling account of the overture under Michael Hofstetter. The spoken dialogue got off to a bad start with Michael Clifton-Thompson’s Leonato having to deliver his lines with his back to the audience.

Gary Griffiths as Claudio and Piotr Lempa as Don Pedro

Gary Griffiths as Claudio and Piotr Lempa as Don Pedro

Sarah Fulgoni’s Beatrice looked lovely and she spoke her dialogue quite aptly. But there was something of a mis-match between her nice, well-modulated speaking voice and the incredibly richly upholstered tones of her mezzo-soprano voice. Here was a Beatrice who, though intelligent and musical, simply failed to sound like the sharp-witted Beatrice that we expect. There were moments of great beauty, particularly in Beatrice’s long solo in Act 2 when she comes to accept that she loves Benedict, but the as a whole the character failed to take off. Perhaps, this is partly because there was simply too little spark between Fulgoni and Robin Tritschler’s Benedict.

If Fulgoni’s voice seemed overly rich for her role, Tritschler’s lyric tenor seemed in danger of being too light for Benedict. Under pressure his voice seemed to turn a trifle too reedy and you wondered whether this was ideal repertoire for him. He encompassed Benedict’s solos melodiously and was and entirely willing and capable actor. But the essential spark was not there, his relationship with Beatrice just didn’t crackle with energy the way it should.

Both Fulgoni and Tritschler were entirely capable, but unfortunately Donald Maxwell as Somarone gave us an object lesson in how to take control of the stage whether speaking or singing. Somarone the learned music master can be a rather tedious character and Maxwell did rather over do things by including topical references into his speeches. But as a demonstration of how to capture the attention of an audience, he could not be faulted.

Laura Mitchell as Hero

Laura Mitchell as Hero

Laura Mitchell and Gary Griffiths played Hero and Claudio. Unfortunately in the opera Claudio is reduced to a cipher and as there is no one to impede their love, Hero has only to be delightfully in love. This Mitchell did beautifully, looking and sounding ravishing. She and Anna Burford as Ursula brought Act 1 to a ravishing close with their duet; one of the moments when music, drama and visuals came together in a moment of perfection which gave a hint at the pleasure the production must have given when new.

The role of Don Pedro is musically very small, but the character is quite a player in the spoken dialogue; Piotr Lempa, the only non-native English speaker in the cast, coped brilliantly nevertheless.

Under Michael Hofstetter the orchestra gave a sympathetic account of Berlioz’s score. Hofstetter’s biography in the programme book described him as a baroque specialist though he seems to have been venturing into wider water recently, with productions including Tristan und Isolde, and conducted Beatrice and Benedict at Houston Grand Opera in 2008.

This was one of the evenings in the theatre which does not quite catch fire, though nothing really goes wrong either. As Beatrice and Benedict is revived so rarely, I did so want it to be so much more; that said there were many incidental beauties along the way.

Robert Hugill

Click here for a photo gallery of this production.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/BB_WNO_14.gif image_description=Sara Fulgoni as Beatrice [Photo by Johan Persson courtesy of Welsh National Opera] product=yes product_title=Hector Berlioz: Beatrice and Benedict product_by=Beatrice: Sara Fulgoni; Benedict: Robin Tritschler; Don Pedro: Piotr Lempa; Leonato: Michael Clifton-Thompson; Hero: Laura Mitchell; Claudio: Gary Griffiths; Ursula: Anna Burford; Somarone: Donald Maxwell; Messenger: Stephen Wells. Housekeeper: Helen Greenaway. Orchestra and Chorus of Welsh National Opera. Conductor: Michael Hofstetter. Director: Elijah Moshinsky. Revival Director: Robin Tebbutt. Designer: Michael Yeargan. Costume Designer: Dona Granata. Lighting Designer: Howard Harrison. Lighting realised by: Paul Woodfield. Welsh National Opera, Wales Millenium Centre, 26th February 2012. product_id=Above: Sara Fulgoni as BeatricePhotos by Johan Persson courtesy of Welsh National Opera

February 27, 2012

The Opera House that Almost Wasn’t — Le Palais Garnier in Paris

Non-aficionados of the opera are familiar with the 1,900 plus-seat landmark theater. Tourists are in awe by its fine example of Beaux-Arts. The Palais Garnier is a prime stop on numerous sightseeing tours.

Chandelier at the Palais Garnier [Photo by Minor Keys]

Chandelier at the Palais Garnier [Photo by Minor Keys]

Even those who never visited the “City of Light” are acquainted with the Palais Garnier through Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera, written in 1910.

Leroux was a frequent visitor and explored the backstage areas and inner sanctions. One tragedy aided in his literary work, and Leroux took poetic license in his novel, when a portion of a chandelier fell and killed one of the opera patrons.

The Palais Garnier has gone through several name changes since its opening. Many simply refer to it as the Paris Opéra.

The Palais Garnier’s history began as part of the great improvement projects instrumented by Napoleon III and Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Napoleon III formulated a competition in search of an architect to design the structure to rival any of the existing opera houses in Italy.

The Grand Stair [Photo by Steven Zucker]

The Grand Stair [Photo by Steven Zucker]

Charles Garnier, a relatively unknown with limited on-hands experience, was awarded the project in 1860. Construction was disrupted by various incidences, including the back up of water from the aquifer, lack of funding, the Franco-Prussian War and the demise of Napoleon III’s Empire.

The incomplete structure was used in part as a storage warehouse for food supplies. Residents wanted it to be demolished since it represented a fallen empire.

Garnier persevered and continued by utilizing new techniques to architecture design. He disliked metal but knew he needed to use these materials in the building’s construction. However, he carefully concealed the metal from view. For cost saving measures, he used the innovative “gilding effect” to replace traditional gold leaves.

When finally launched 15 years later, Fromental Halévy’s La Juive was the inaugural production on January 5th, 1875 . Audiences noted all the ornamental detailing, including sculptures the renowned composers ablaze in bronze and paintings illustrating musical symbols. Equally compelling, the Grand Staircase, which leads into the multi-level theater, is a show-stopping feature measured by its marble of various hues.

The Grand Stair from Below [Photo by Steven Zucker]

The Grand Stair from Below [Photo by Steven Zucker]

At the entrance, immense mirrors allow patrons to become a part of the building’s interior décor. The vast and richly decorated foyers set the audience’s stage with pleasing scenes to stroll through during intermission.

The fortitude of creativity Charles Garnier shown in his design of the Palais Garnier served as a prototype for other worldwide structures. Examples include The Juliusz Slowacki Theatre in Krakow, Theatro Municipal do Rio de Janeiro, The Jefferson Building in Washington D.C., and National Opera House of Ukraine in Kiev.

Charles Garnier’s ultimate determination was to make the Palais Garnier a palace. Unquestionably he succeeded in his goal.

Veronica Shine

Planning a Visit:

The Palais Garnier is located on 281 Rue Saint-Denis in the district known as the Place de l’Opéra in the 9th arrondissement.

If driving, there is parking at Place Vendôme.

The venue is best reached via Paris’s fine public transportation.

By Métro: Board line nos. 3, 7, 8 to station Opéra

By RER: The regional “A” train closest station is Auber

By Bus: Ride any bus numbered 20, 21, 22, 27, 29, 42, 52, 53, 66, 6 8, 81, 95 directly to the Palais Garnier

The schedule for performances and events are at the Opéra national de Paris’ web site, which also provides a virtual tour of Palais Garnier. Additional nformation on performances and tours is available at the Palais Garnier’s box office, which is open Monday to Saturday from 10:30am to 6:30pm.

Find accommodations near the Palais Garnier at Parishotels.net or search for something with more elbow room with a holiday apartment at holidayapartments.net.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Palais_Garnier.gif image_description=Facade of Le Palais Garnier product=yes= product_title=The Opera House that Almost Wasn’t — Le Palais Garnier in Paris product_by=By Veronica Shine product_id=Above: Facade of Le Palais GarnierMahler: Symphony No. 9

The nature of the work itself requires the sophisticated engineering found with this release, which allows the subtleties to be heard clearly throughout, from the thing, soft textures at the opening of the first movement to the raucous tutti passages in the Rondo-Burleske. Along with the finesse implicit in the dynamic levels, the ambiance conveys the concerts which are the basis of this release, with the tension and dynamism of the performances. This is an interpretation which contributes to the existing discography of the Ninth Symphony because of the details that Gergiev brings to his reading of this important work from the early twentieth century.

As far as timings are concerned, the proportions match convention, with the first movement, 27:02; the second, 15:10; the third, 12:35; and the Finale, 24:24. The entire work is available on a single disc, packaged nicely with concise liner notes by Stephen Johnson. As useful as the essay is, the performance begs the question of Gergiev’s perspectives on this score. His interpretation of the first movement makes the structure palpable, without sacrificing expression. In this recording the opening measures are nicely detached, an approach that allows the motive to stand out when it recurs. At the same time, the clarity of the string textures is reproduced clearly in this recording, such that the middle voices emerge with ease. The brass are similarly articulate in this movement. The horns are prominent where required, and fit well into the timbres Mahler scored so precisely.

Gergiev’s tempos are spacious, with his pacing supporting both the thematic content and structure. The details are present without slavish adherence to the letter of the score. Gergiev offers an aggressive interpretation of this consummate work of Mahler’s symphonic oeuvre. In balancing the rich romantic sounds of the first movement with the chamber-music-like sonorities it also contains, Gergiev creates a dynamic in which the timbre is as expressive an element of the thematic material. The Coda of the first movement is eloquent in the way the music dissolves into the sonorities with which the structure concludes.

Tempo is critical for the second movement, where Gergiev’s master of the piece is apparent from the start. If Mahler is the master of transition, as one commentator once stated, Gergiev has mastered this aspect of the second movement in allowing the various sections of the piece flow together naturally. Nothing is out of place here, but presented as logically as it is performed with expression. In this performance the middle section is memorably impetuous, such that it sets up the reprise of the opening material effectively.

With the Rondo-Burleske, Gergiev offers an energetic reading of the score. The irony that Mahler composed in this piece is apparent in the style he used in this performance. Beyond the mastery of transitions, Gergiev offers a sense of continuity that allows the ideas to flow convincingly between the individual phrases to create well-articulated passages that bring to musical narrative to an exciting, if breathless conclusion.

Yet in bringing the Ninth to its conclusion, the final movement has the breadth it deserves. While never allowing the movement to languish, Gergiev’s interpretation is particularly moving. As with the first movement, the Finale dissolves into the individual sounds that Mahler used in the concluding section. The interpretation is profound, not maudlin, with the gravity of the Finale balancing the sonata form of the first movement in a recording that elicits repeated hearings. This is a fine performance, which enhances the contributions Gergiev has already made to the Mahler discography with his other releases on LSO Live.

Jim Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/LSO_0668.gif image_description=LSO Live 668 product=yes product_title=Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 9 product_by=London Symphony Orchestra. Valery Gergiev, conductor. product_id=LSO Live 668 [SACD] price=$16.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=7537&name_role1=1&comp_id=1807&genre=66&bcorder=195&name_id=56888&name_role=3John Adams — Death of Klinghoffer, London

Press reports suggested mass protests against John Adams’s The Death of Klinghoffer at the ENO. But there was just one polite demonstrator, who’d left by the end of the evening. Perhaps he saw the show. The subject is emotive, and important, but Adams’s treatment is not incendiary. It’s the nature of his music. Repetitive, ruminative cadences, which suggest contemplation rather than imposed narrative. Perhaps it’s the very anti-drama in this music that provokes response.

Sidney Outlaw as Rambo

Sidney Outlaw as Rambo

Adams's abstracted cadences evoke blurred boundaries: endless waves on the sea, the whirr of a ship’s engine, the slow ticking away of time. Unfortunately, this music also evokes tedium. Facts about the hijack of the Achille Lauro are projected onto the stage to keep us alert, but the music is saying something else altogether. Furthermore, Adams sets text counter-intuitively, so syntax is distorted in favour of unsettling stresses in places that would not occur in speech. Because our brains don’t process language in this way, meaning is sacrificed. It’s not good when you have to concentrate on sub-titles to figure out what’s being sung. Alice Goodman’s libretto has been criticized for being opaque, but it closely reflects Adams’s musical technique. Images are blurred and shift shape. In the opening Chorus, it’s deliberately unclear who the protagonist is. Is she a young woman in love or an old woman awaiting death? Or both? It’s immaterial. She’s a composite of millions who have been exiled throughout history. When music and text are both this oblique, the thrust of the drama is lost. Perhaps Adams wants us to savour each moment in detail, as we savour life itself, knowing it won’t last, but the cumulative effect of the First Act is soporific.

Things pick up in the Second Act, when Adams frees himself from earnest pseudo-documentary. Up to this point the action has mainly been in choruses. Now we have individuals with whom we can identify. Some of the words they sing come from transcripts made at the time, others are imaginative creations. It doesn’t matter. In these arias there’s dramatic reality. Leon Klinghoffer is presented as a likeable hero, and at last the opera has human focus. Alan Opie sings Klinghoffer so he comes over as a strong, reasonable man of authority, establishing a moral compass. The Aria of the Falling Body anchors Adams’s wavering oscillations with emotional truth.

Christopher Magiera as the Captain and Richard Burkhard as Mamoud

Christopher Magiera as the Captain and Richard Burkhard as Mamoud

Michaela Martens' arias as Marilyn Klinghoffer are tours de force, the last adding bite. The Captain (Christopher Magiera) handled the situation with cool headed professionalism. offering his own life to save his passengers, but Adams and Goodman don’t dilute the focus from Klinghoffer to make the Captain a hero. Mrs Klinghoffer, in her grief, can’t understand why her husband was killed without her knowing. It’s a thoughtful detail to include in the opera since in these situations no-one knows everything all the time. Fine vignettes too from Lucy Schaufer (The Swiss Grandmother), Clare Presland (The Palestinian Mother) and Kate Miller Heidke (The British Dancing Girl), so clueless that she doesn’t comprehend the enormity of what’s happening. In a much needed twist of humour, Adams adds snatches of pop music around the part.

Baldur Brönimann conducted the orchestra so details surfaced tellingly from the amorphous textures. He’s a specialist in modern repertoire and understands how the genre operates. This music is not an undifferentiated mass.

The staging, however, was much less sensitive. Directed by Tom Morris with designs by Tom Pye, it tried to give shape to Adams’s oblique non-forms by over emphasizing the literal, perhaps to create the sensationalism Adams and Goodman avoid. The dance sequences are awful, completely at odds with the story. This is not a game. It is more than just a struggle over a country, it’s part of the eternal struggle between haves and have-nots. In this production, the Palestinians raise their fists in the classic gesture of the oppressed. For a moment it looks like a Nazi salute. What the hijackers did was evil, but it does not follow that the poor should not act, whoever they might be. The scenes where Finn Ross’s video projections fill the stage are far more effective, and being semi-abstract, are more faithful to Adams’s idiom.

The Death of Klinghoffer has its longueurs but it’s an important statement. Twenty five years after the Achille Lauro hijacking, terrorism is, if anything, more widespread and more savage than ever before. Twin Towers, the school in Beslan, the cinema in Moscow, and Utøya. Is there something to be learned from The Death of Klinghoffer? Many thanks to the ENO for giving us a chance to hear for ourselves.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Klinghoffer_ENO_01.gif image_description=Alan Opie as Klinghoffer and Michaela Martens as Marilyn Klinghoffer [Photo © Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of English National Opera] product=yes product_title=John Adams: The Death of Klinghoffer product_by=Klinghoffer: Alan Opie; Captain: Christopher Magiera; Marilyn Klinghoffer: Michaela Martens; Molqi: Edwin Vega; Rambo: Sidney Outlaw; Mamoud: Richard Burkhard; Austrian Woman: Kathryn Harries; First Officer: James Cleverton; Swiss Grandmother: Lucy Schaufer; Palestinian Woman: Clare Presland; British Dancing Girl: Kate Miller-Heidke. Chorus of the English National Opera. Chorus Master: Francine Merry. Orchestra of the English National Opera. Conductor: Baldur Brönimann. Director: Tom Morris. Designs: Tom Pye. Video Projections: Finn Ross. Costumes: Laura Hopkins. Lighting: Jean Kalman. Choreographer: Arthur Pita. English National Opera. The Coliseum. London, 25th February 2012. product_id=Above: Alan Opie as Klinghoffer and Michaela Martens as Marilyn KlinghofferPhotos © Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of English National Opera

“Figures from the Antique”, Wigmore Hall

One mild criticism levelled at Bostridge in the past has been that his repertoire range is rather limited, but this recital series is convincingly dispelling that censure; here, an intriguing assemblage of chamber cantatas proved that he is as comfortable, and accomplished, in styles as disparate as baroque seria and French mélodie.

Bostridge was partnered by the Austrian soprano, Angelika Kirchschlager, and, opening the recital with Handel’s O numi eterni, she immediately established her striking dramatic presence, launching with unrestrained emotional force into an anguished account of the rape and suicide of Lucrezia. La Lucrezia is a truly ‘operatic’ work. Except for the admixture of recitative and aria, it has very little resemblance to the standard Baroque cantata; rather it is a complex scena in a multifaceted and unique form. Such complexity is integral to the development of Lucrezia’s agonising responses: pain, fury, doubt, resignation and revenge. Kirchschlager maximised the transitions — often unpredictable and unsettling — from recitative to aria, powerfully revealing the volatility and extremity of Lucrezia’s emotional states. Histrionic outbursts characterised by abrupt, jarring shifts of register were juxtaposed with calmer episodes where a reflective ‘cello accompaniment (sensitively played by Jonathan Manson of the English Concert) intimated the underlying sadness beneath the outpourings of aggressive vengeance. With a wild energy, Kirchschlager absolutely inhabited Lucrezia’s destabilised, damaged psyche. Yet, while not lacking in dramatic impact, her projection of the text was less impressive; and, it was a pity that her performance was so bound to the score throughout.

In contrast, Bostridge’s rendering of Alessandro Scarlatti’s Io son Neron, l’imperator del mondo was most definitely ‘off the book’. Bostridge’s unmannered delivery — and the intermingling of flamboyant posturing and imperious flourishes with traces of ironic insinuation — revealed a dramatic and emotional range far beyond the internalised, tormented modes with which he established his reputation. In the first aria, in which a supercilious Nero challenges even the gods, Bostridge demonstrated both vocal strength and flexibility as he arrogantly declared, “I want Jove to tremble before the magnificence of my presence”. With fitting irony, the rejections of the notion of compassion in the second aria draw forth the tenor’s most beautiful, seductive tone. The recitatives conveyed the tempestuousness of the deluded, unbalanced emperor, demonstrating his extreme cruelty and his delight in the suffering and slaughter he causes. The last aria 'Veder chi pena' is set as a tarantella, a southern Italian folk dance, and Bostridge enjoyed the paradox that this light-hearted form is in fact the ultimate demonstration of Nero's malignity as he sings: "To watch those that suffer and sigh is my heart's desire, evil since birth.”

The ‘modern’ half of the recital began with Eric Satie's little known “La Mort de Socrate”, a quiet, reflective account of the great Greek philosopher’s final moments before he is poisoned. Impressively performing the ceaselessly unfolding declamation from memory, Bostridge demonstrated his profound musical intelligence, appreciating both the understated manner and charm of the early twentieth-century French idiom and the underlying sincerity and affectivity of the sentiments expressed. With poise and elegance he related the French text — fragments from Plato’s Dialogues translated by Victor Cousin — his even tone and graceful delivery unaffectedly revealing its simple poignancy. Bostridge’s reading was sympathetically supported by some accomplished playing by the Aurora Orchestra, conducted by Nicholas Collon, who drew sharply defined textures from his ensemble.

Kirchschlager closed the recital with an impassioned performance of Benjamin Britten’s late masterwork, Phaedra, a ‘dramatic cantata’ written for Janet Baker. In contrast to the tragic nobility with which Baker reportedly imbued the role, Kirchschlager went for an unrelenting, full-throttle approach; and while she undoubtedly conveyed the neuroses and instability of Theseus’s unfaithful wife, by emphasising Phaedra’s sexuality and fickleness she neglected the quieter, internalised guilt and remorse that Britten’s music suggests. Certainly, in the ‘Presto to Hippolytus’ Britten sets explicitly sexual imagery from Robert Lowell’s translation of Racine: “Look, this monster ravenous/ For her execution, will not flinch,/ I want your sword’s spasmodic final inch.” And here Kirchschlager’s dazzling timbre together with striking rhythmic incisiveness from the instrumentalists of the Aurora Orchestra powerfully conveyed her adulterous lust and intimated her insanity.

But, Britten’s music is never frantic; the heights of Phaedra’s obsession are depicted by a chilling passage for stratospheric strings accompanied by untuned percussive strikes which suggest a pulsing, diminishing heartbeat, both serenely beautiful and poignantly prophetic of her imminent death. In the final ‘Adagio to Theseus’, Phaedra shows calm acceptance of her fate — “A cold composure I have never know/ Gives me a moment’s pause.” — her resignation underpinned by the orchestra’s gradual modulation towards C Major harmony and ‘resolution’. Superb instrumental playing — cellist Oliver Coates deserves especial mention — brought some emotional variety to the performance, to counter Kirchschlager’s remarkable but unremitting frenzy.

Claire Seymour

Programme:

Handel: O numi eterni (La Lucrezia) HWV145

Corelli: La Follia for violin and string ensemble

Scarlatti: Io son Neron, l’imperator del mondo

Satie: “The Death of Socrates” from Socrate

Britten: Phaedra Op.93

image=http://www.operatoday.com/socrates.gif image_description=The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David product=yes product_title=“Figures from the Antique” product_by=Angelika Kirchschlager, mezzo-soprano; Ian Bostridge, tenor. Aurora Orchestra. Nicholas Collon, conductor. The English Concert. Laurence Cummings, director and, harpsichord. Nadja Zwiener, solo violin. Wigmore Hall, London, Monday, 20th February 2012. product_id=Above: The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis DavidFebruary 26, 2012

Bryan Hymel, Rusalka’s Prince

“It’s a role that’s been good to me,” he says. He made his European debut in the role at Wexford Festival Opera in 2007. After an extended period working in Europe, it brought him back to the United States where he performed it with the Boston Lyric Opera three seasons ago. Now he’s singing the Prince again at the Royal Opera House. This is high profile, since it is the first ever full staging of the opera. Previously, it was heard only in concert performance.

This Royal Opera House Rusalka will be conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin, making his long-awaited debut at Covent Garden. Hymel is thrilled. “Yannick is a singer himself, he grew up in the choral tradition and was chorus master in Montréal before he made his name conducting. He’s just as at home with singers as he is with the orchestra”. Some conductors leave acting to the director,. “But Yannick understands. For him, the music is so important that he doesn’t want anything to get in the way of it.” In this production, the Foreign Prince is characterized as childish and nervous, which is valid. “But Yannick said to me, don’t let it get into your body. You know you can sing it, so you owe it to yourself to sing it well”. Hymel beams. “Few conductors have that spark of inspiration. I love it that he stands up for you as a singer, and is on the side of the music”.

This production is directed by Jossi Wieler and Sergio Morabito, and premiered in Salzburg. “Modern productions can be fine”, says Hymel, “but this one is very physical. It’s not easy on the body, It’s tricky to sing lying on your back, and there’s a lot of rolling about. You get beat up and knocked around, but you still have to sing beautifully”.

“Rusalka is a very dark story. Dvořák really wanted to delve the depths and shadowy aspects. Lots of low brass and ominous music that probe beyond a fairy tale”. Rusalki are water spirits, exquisitely alluring. but not wholesome. “Rusalka’s own music is so sweet that you can’t help falling in love with her. Here she has a little fish tail.” Hymel smiles and “acts” Rusalka’s movements, “So sweet and innocent. But Rusalki in general? Stay away!”

What drew Hymel to The Foreign Prince? “The music, of course. Wexford was my opportunity to get to know it well. I’d sung German and Russian, but singing in Czech was a bit intimidating. No Czech coach in Philadelphia, where I was studying then, and the coach I located in New York was flying all round the world. So I found a score with the text partly transliterated and listened to the Ben Heppner recording, while getting my mouth round those diacritics. Now Czech comes easily to Hymel, who also sings Janáček.

The Prince’s music is really very beautiful. In this production, the Prince gets a chance to be a romantic hero at the end of the First Act, but after that characterwise, things go downhill. He gets frustrated which you can understand because Rusalka cannot speak or communicate, but the way he drops her is cruel. Yet he’s not that childish, and in the end he takes responsibility for his previous impatience. He asks for that last kiss knowing that it will kill him. There won’t be any Happily Ever After. Psychologically, it’s very deep”.

Hymel has an affinity for lyrical roles like Enée in Berlioz Les Troyennes, which he sang with The Nederlandse Opera in Amsterdam. “Enée sits a half, even a full step higher than the Foreign Prince. It’s deceptive because it goes from A natural and A flat, and then in the last scene, after you’ve been singing your voice out, there’s a high C, not an easy C because of where it lies, and was written for a specific type of voice we don’t often hear these days”

Gounod Faust is another favorite.”The range is fantastic. Last summer I sang ten performances at the Santa Fe Opera conducted by Frederic Chaslin and directed by Stephen Lawless. The part is high, but with weight and you have to sing Faust as an old man and then young again with wonderful lines in the arias and duets.” Hymel is singing Faust again in Baltimore in April.

Don José in Bizet’s Carmen holds several special memories. When Hymel sang it at the Royal Opera House in 2010, he met the Greek soprano Irini Kyriakidou, a colleague of Aris Agiris, the Escamillo. They married and make a lovely couple. She’s recently made her Royal Opera House debut as Zerlina. Then, last year in Munich, when Hymel was singing in Nabucco, Jonas Kaufmann cancelled Don José at the last moment and Hymel stepped in. “It was fun but daunting. I heard the Intendant go in front of the curtain and make the announcement that Jonas would not be there. The audience started shouting and there I was, thinking, Oh gosh, this is Jonas’s home town and I have to face that crowd! But they were appreciative, and I was relieved”.

“I think there could be a renaissance in French grand opera, just like there was a renaissance in Rossini ten years or so ago, when it had been basically Il Barbiere de Seviglia.When singers like Juan Diego Flores and Lawrence Brownlee who can sing them properly, we can hear why the operas were good in the first place. There are all these wonderful operas like Benevenuto Cellini and Les Huguenots. What a great time it must have been them, with composers writing for so many different voice types. Nowadays, we’re “Italian heavy” as Hymel puts it, but there’s so much more to the tenor range,

“They say that between age 30 and 35 the voice is in transition”, says Hymel, who is 32, “And I can really feel it filling out in a good way. It’s not like when you’re 13 and it drops overnight It’s a gradual process. The more music I do, the more it stretches me. I had to sing La Traviata in Houston when the Alfredo pulled out. After the Prince and Faust, “Libiamo, Libiamo” was different. But it’s good. It’s like when you go to the gym, you don’t do the same exercise all the time because your body needs to adapt. Ultimately, that’s what makes you stronger”. Rusalka runs for six performances at the Royal Opera House from 27th February. Please see the Royal Opera House website for more.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bryan_Hymel.gif image_description=Brian Hymel product=yes product_title=Brian Hymel, Rusalka’s Foreign Prince product_by=By Anne Ozorio product_id=Above: Brian HymelFebruary 24, 2012

Moby-Dick, San Diego

Its libretto is taut and clear, its music accessible and appealing, and its visual effects spectacular and breathtaking. If you can get to see this production, do not miss it.

Moby-Dick, first performed by the Dallas Opera company in 2010, was jointly commissioned by Dallas, San Francisco, San Diego and Calgary Operas and the State Opera of South Australia. Calgary and South Australia have already seen it. The San Diego production marks its West Coast premier. San Francisco will see it this fall.

Melville was an author obsessed with telling what he considered the whole truth about everything. “Taking a book off the brain is akin to the ticklish and dangerous business of taking an old painting off a panel — you have to scrape off the whole brain in order to get at it with due safety,” he wrote while at work on Moby-Dick. Its main characters’ histories and emotional stories, its metaphorical, symbolic meanings were buried deep in over seven hundred pages of side tales and expository material. Heggie and librettist Gene Scheer miraculously reduced this leviathan work to two dramatic acts. Working with director and dramaturg Leonard Foglia and a visual production team, they shaped the material into an opera in which words, music and extraordinary visual effects flow together seamlessly.

The ingenious sets and projections begin during the overture and take us from the starry heaven to the deck of the Pequod just as the curtain rises. As the story rolls on we see the crew climbing the rigging, the ship jibing, a boy flailing in hostile seas, harpooners leaping in and falling out of small boats. Amazingly there is singing going on all the time.

Sheer’s libretto effectively captures the essence of human longings and love through poetic language and occasional patterns of rhyme. He centered the plot in two struggles as seen through two sets of relationships. The core of Moby-Dick is the moral and ethical struggle between the mad Captain Ahab ruthlessly pursing the white whale, and Starbuck, his principled first mate, who tries vainly to become the unhearing Ahab’s voice of conscience. We learn the yearning of the fearful young seaman called Greenhorn, who knows little of life and less about sailing, through his interaction with Queequeg, the self-contained aborigine harpooner, who befriends him. Then there is the cabin boy, Pip, loved by all, who sings, dances, plays his tambourine, and goes mad. The large crew provides an impressive male chorus.

Conductor Joseph Mechavich, replacing San Diego’s principal conductor, Karen Keltner, who became ill just before rehearsals were to begin, led an assured performance. Mechavich had conducted the work in Calgary. Tenor Jay Hunter Morris who had sung Captain Ahab in Australia was literally dropped into costume overnight after a run of Siegfrieds at the Met, when Ben Heppner left after the first performance. Stomping around on his peg leg, Morris handled the role’s high tessitura effortlessly. His second act duet with the excellent Morgan Smith, a veteran Starbuck, new to San Diego, was memorable. Jonathan Boyd, new to both San Diego and the role, was a sweet voiced Greenhorn, perfectly paired with the Queegueg of bass Jonathan Lemalu, another Moby Dick veteran, debuting in San Diego. The duet in which the two, high in the rigging, dream of a peaceful future on Queegueg’s island, is almost a love song. Soprano Talise Trevigne’s rich soprano, coupled with her agility and charm made one feel for the unfortunate Pip.

Jake Heggie is a composer known for his songs as well as operas. He not only writes movingly for the voice, but commands a rich and colorful orchestral palette, and has an enormous lyric gift. Extraordinarily for a newly heard work, a friend and I left the opera house singing snatches of its oft repeating orchestral themes. Is this good or bad? Will this score with its movie-music edge and oft repeated theme, survive? I have no doubt that the opera’s prelude and sea music will someday become a Moby-Dick suite, much like Sea Interludes taken from Britten’s Peter Grimes. There is much in this work both literally and musically of Britten’s Billy Budd (also based on a Melville novel). Musical references to Puccini, Bernstein, even Copland and Philip Glass have all been noted in Heggie’s score. But it is Heggie’s score alone that will determine the place of Moby Dick in the operatic repertoire.

I’d like to think that Moby-Dick will long be a part of the American operatic scene. But I worry how it will fare if and when less expensive productions cannot do justice to the visual aspects of the production. Will the music and story hold up?

The first act of the opera is spell binding as the visuals and story lines unfold before us. The second act, while visually brilliant, and offering two lyrical duets, is somewhat static, as we await the predictable conclusion. The Pequod is destroyed, the crew is lost at sea. We are astounded by the speed and brilliance of the scene, by the powerful rhythms and clashing dissonances of the sea, but we are not deeply moved. We have witnessed a huge tragedy, good people have died, but there is no single character aboard the Pequod whose fate moves us to tears; no Peter Grimes, Billy Budd, nor even the murderous barge captain, Michele in Il Tabarro.

Make no mistake, this was a thrilling evening of opera, greeted enthusiastically by a grateful audience. I left the theater feeling that American composers, writers and visual artists will keep opera alive throughout this still new century. .

Kudos to the San Diego opera company for having brought this work to its stage. Though not privy to the company’s internal workings, I know that aside from raising $2,398,956 required for artists, crews, sets, and everything else, its General and Artistic Director Ian Campbell and staff had to replace his conductor once and his star tenor, twice. So I’m grateful that Mr. Campbell too seems to have been a bit obsessed with finding Moby-Dick.

Estelle Gilson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Photografeo-035large-file.gif image_description=Jay Hunter Morris as Captain Ahab [Photo by Photografeo courtesy of San Diego Opera] product=yes product_title=Jake Heggie: Moby-Dick product_by=Queegueg:Jonathan Lemalu; Greenhorn:Johnathan Boyd; Starbuck:Morgan Smith; Pip:Talise Ttrevigne; Captain Ahab:Jay Hunter Morris; Conductor: Joseph Mechavich; Director and Dramaturg:Leonard Foglia; Librettist:Gene Scheer; Scenic Designer:Robert Brill; Costume Designer: Jane Greenwood; Lighting Designer:Donald Holder; Projection Designer:Elaine J. McCarthy. product_id=Above: Jay Hunter Morris as Captain Ahab [Photo by Photografeo courtesy of San Diego Opera]Fleming in Strauss’s Capriccio

None come to mind. But Richard Strauss twice stopped the progress of heavily scored recitative in his own operas to bring on caricatures of Italian opera singers for light-hearted relief. In Der Rosenkavalier the Marschallin is entertained in her boudoir by the “Italian singer,” a tenor who belts out what, ironically, is probably the best known aria from any Strauss opera, “Di rigori armato.” Then in Capriccio, Die Grafin, as elegant and aristocratic as her operatic predecessor, also finds such amusement, this time with the “Italian Singers,” a tenor and a soprano whose music mocks the “high note” obsession of Italian opera. It’s almost as if Strauss might have wondered if audiences might grow restless in the middle of an intermission-less two and a half hours of a barely dramatic debate over whether music or literature is the highest art. The buffo treatment afforded the Italian Singers might make such audiences recoil from wishing they could slip out of a Capriccio performance for some time with Il Trovatore.

Capriccio is a late work of Strauss, and as with the Vier Letzte Lieder and Metamorphosen, the score’s greatest music, in the final scene, is duskily lit with the glowing colors of a dying sunset. In the preceding two hours, Strauss weaves parodies of 18th century music along with his own craftsman-like ability to keep the musical motor running without ever seeming to arrive anywhere. The characters have no history or interior life to propel the action, such as it is. A musician, Flamand, and a poet, Olivier, compete for the patronage and romantic attention of Die Grafin. La Roche, a theater director, is putting on an entertainment for her, which will feature a self-infatuated actress (Clarion) as well as the two Italian Singers. As the theatrical endeavor proceeds, a rhetorical argument takes the place of any narrative drive — is it music or literature that is man’s highest artistic achievement? In her long closing soliloquy, Die Grafin evades a final answer, but the dominance of Strauss’s score seems to complete the response for her.

Capriccio will never be a mainstay of the operatic repertory, but it is the most frequently performed of any of the operas from the latter stage of Strauss’s career. It offers a great leading role for a soprano, who gets to be the focus of attention for most of the evening and who, at its close, has the stage to herself. In this Metropolitan Live HD performance from April 2011, Renée Fleming meets every vocal requirement of the role; not unexpectedly, as her credentials in Strauss have long been validated. What she can’t quite do is to suggest the depths of intelligence or sensuality that the other characters claim to see in Die Grafin. Peter Rose, a notable Baron Ochs, makes the most of his big scene as La Roche. Sarah Connolly gives the outrageous Clarion a good try, without quite seeming comfortable in the role. Joseph Kaiser as Flamand and Russell Braun as Olivier can’t escape the bland confines of their under-characterized roles. Barry Banks and Olga Makarina are very funny as the Italian Singers and also notably un-Italian.

Conducting Capriccio must be a treat, with its small ensembles built into the framework of larger orchestral set-pieces. Andrew Davis leads the Metropolitan Opera forces in a detailed, buffed performance. The John Cox production harmlessly updates the action, which is hardly historically relevant to begin with. Robert Perdziola’s costumes and Mauro Pagano’s sets complement the elegance and handsomeness of the work.

As strong as this performance is, anyone who loves this opera must also seek out a San Francisco Opera performance with Kiri te Kanawa and Tatiana Troyanos, both of whom simply outclass their talented peers in the more recent production.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Decca_0743454_DVD.gif image_description=Richard Strauss: Capriccio product=yes product_title=Richard Strauss: Capriccio product_by=Die Gräfin: Renée Fleming; Flamand: Joseph Kaiser; Olivier: Russell Braun; La Roche: Peter Rose; Clairon: Sarah Connolly. The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Conductor: Andrew Davis. product_id=Decca 0440 074 3454 3 DH [2DVDs] price=$37.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=654100&album_group=2

Michael Spyres — A Fool for Love

As he launched into the first cut, “Ah! mes amis” (Daughter of the Regiment) I found his sweet tone reminiscent of Javier Camarena, the poised musical line similar to Lawrence Brownlee’s, and the panache comparable to Juan Diego Florez. Not a bad triple threat combination there! And a very ballsy selection to start with since bel canto poster boy JDF not only had a very recent blockbuster success with Daughter in every major house and on DVD, but we also still have over-sized memories of the legendary Pav in the part.

Spyres seems to have a bit more heft going on than his immediate contemporaries, and while he squarely nails the requisite high C’s he doesn’t quite manage the varied colors and sassy ‘tude at the top that others bring to the part. Still, while his core voice may not exactly ‘live’ up there, he zings out the money notes with accuracy and skill. As he progresses directly to “Here I stand” (The Rake’s Progress), we immediately hear a more weighted quality, slightly rounder, discernibly fuller. If richness at the very top eludes him by a hair, he makes as much musical sense of the piece as anyone I have heard, keeping the angular dips and leaps admriably connected and focussed. The penultimate held note (“Ride”) is thrilling, gleaming, substantial. Moreover, Mr. Spyres has impeccable diction, and a dash of wit as he speaks “I wish I had money” as the tag.

As the tenor then segues into “Cessa di piu resistere” (The Barber of Seville), I am beginning to get the idea that he is looking to show his full aresenal, with sharp contrasts between the selections. Here, Michael utilizes a light-voiced approach for the most part, and scales back considerably to negotiate the fiendishly tricky, awkward, melismatic writing. His take-no-prisoners approach to Rossini and Donizetti, while commendable, makes him pull back on the very top notes, keeping everything very focused so that color and variety are somewhat slighted. In the stretto section where things get rhytmically heated, some of the fireworks are fudged ever so slightly. Spyres did astonish with a few very solid descents to the depths of his range and he has an unusually responsive lower middle.

The pendulum swings back to more full-bodied singing with “Una furtive lagrima” (L’elisir d’amore), in which he once again rounds the tone, lets it turn over, and brings it more into the speaking mask. He makes this aria anything but an old chestnut, lavishing it with creamy lines in which everything is solidly hooked up. This was excpetional vocalism, incorporating a masterful melding of the registers. For the first time, the voice seemed to have significant presence and power, so it made me curious just how much size he can convey in the house. With “Il Mio Tesoro” (Don Giovanni), Mr. Spyres seems to be affecting a “Mozart” style which came off a little bloodless compared to his other, more theatrically realized set pieces. There was absoltuely nothing wrong with it but he seemed a bit removed for the first time, when lo, he rallied for a solidly realized finish. I wish he could inform the first nine tenths of that piece with his final personalized commitment.

As for “Je crois entendre encore” (The Pearl Fishers) and “Pourquoi me reveiller” (Werther), based on this recorded evidence, Michale Spyres seems born to sing these French roles. He commands a well-controlled ‘messa di voce’ and an understanding of ‘voix mixte’ that are suavely deployed and exceptionally pleasing. In both, Spyres keeps the forward motion going with intensity and introspection. In the Werther he starts off with a slightly darkened tone and sober coloring that serve him quite well. By now I am seriously beginning to think his strong suit is not the florid singing (which seems more a party piece, just cuz he can do it). Both French pieces draw forth all his best instincts and elicit his most sonorous vocal approach. It would be a real pleasures to hear him in either of these roles.

Speaking of party pieces, I am not sure I have ever encountered the Italian Tenor’s solo from Der Rosenkavalier (“Di rigori armato il seno”) on a recital disc although plenty of star tenors have taken their turn at it on stage (fond memories here of Pavarotti at the Met during the “Luciano” season). Mr. Spyres sings it with a surging sense of line and an easy squillo that could be a preview of his own star turn in this role some day. I wondered what anyone could bring to “Che gelida manina” (La Boheme) that was fresh? How about simply an absolutely fresh new voice that is possessed of a solid technique. He convinces me even more with this aria that such roles are his eventual forte. He knows what he is singing and conveys it with directness, not as easy as it sounds. Michael unearths absolute truthfulness in the uncomplicated poet’s exposition.

Inviting another comparison with Florez, “La Donna e mobile” (Rigoletto) is a piece that JDF does most usually only in recital and it does push the brilliant Peruvian’s outer limits. But no such limitation exists for Spyres who delivers all the goods with bravado. Many a lyric tenor has come to grief over Edgardo (Lucia di Lammermoor) in general and “Fra poco a me ricovero” in particular. Spyres suggests a decent amount of gravitas and summons up a burnished tone for the long recit intro, then he doles out good but rather generic vocal lines in the wide-ranging aria. I wonder if he might discover the same wonderful variety that he brought to the recit and carry it forward into the aria?

“Kuda, kuda” (Lenksy’s aria, Eugene Onegin) is similarly characterized by a gorgeous tone but seems to lack a specifitiy evident elsewhere. He may speak Russian like a native for all I know but he finds less individualized drama in the text on this piece, which is well coached but not just yet his own. (When it is vocalized this well, and is so well-intended, am I just carping?) The reliable Moscow Chamber Orchestra really shines here under Constantine Orbelian’s efficient and supportive baton. The final selection “E la solita storia” (L’Arlesiana - Cilea) also really showcases Spyres interpretive gifts. The haunting, well-calculated musical build wedded to a splendid display of well accented parlando segued easily into beautiful arching lines.

This young tenor really knows where the music and the story are going, with each tale having a beginning, middle and end. He appears to be a conscientious and intelligent interpreter, coloring and tailoring his instrument and technique to make each genre as stylistically pure as possible. While he does tend to slightly cover or brighten top notes as needed for the varying demands, his is a reliable, freely-produced, imminently enjoyable timbre.

As for the structuring of the program, in the liner notes Michael makes a case for the sequence of the arias, selected to document a man’s life journey from first love to love lost. I do appreciate the thought that went into the content and the ordering of the pieces, but this is not after all Frauenliebe und -leben which is composed specifically with such a journey in mind. Rather it is more jukebox concertizing no better or worse than the shoe-horned songs of Mamma Mia! and the like. There is such a change in demeanor, such a departure of styles from one selection to the next that it just doesn’t communicate that this is one man on one journey. Admiring the scholarship, I demur that it does not play out to its intended effect. And really, with such diverse and wondrously effective singing on display, who cares?

As if a “Bonus” were needed, an encore of Dein ist mein ganzes Herz caps the disc, complete with dreamy, oozing, honeyed lines that drip Viennese enchantment, and featuring the very best climactic top notes of the compilation, ringing, forward and free.

Michael Spyres is on the fast track to being ‘the’ versatile, in-demand, go-to tenor in several different fachs. He promises much and, as evidenced by this debut solo effort, is already delivering handsomely on that potential.

James Sohre

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Delos-DE-3414-2.gif image_description=A Fool for Love product=yes product_title=A Fool for Love product_by=Michael Spyres, tenor. Moscow Chamber Orchestra. Conductor: Constantine Orbelian. product_id=Delos DE 3414 [CD] price=$17.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=202951&name_role1=2&bcorder=2&label_id=1073La clemenza di Tito — Barbican

After writing three great Italian operas which advanced the genre immensely, Mozart turned his attention elsewhere. In his final year he wrote two last operas, which not only contrast with each other but with the three Da Ponte operas which precede them. His singspiel Die Zauberflöte has long been accepted on operatic stages, but La clemenza di Tito has only relatively recently come to acceptance as being stage-worthy.

Somehow, Mozart’s reverting to an opera seria libretto based on Metastasio seemed a step backwards; compared to the three Da Ponte operas, La clemenza di Tito can seem static and actionless. It is in fact an opera which requires the right performers, and at the Barbican on Wednesday 22nd February, the Deutscher Kammerphiharmonie Bremen, under conductor Louis Langrée presented the opera in concert, with a cast who seemed to understand Mozart’s late, austere masterpiece, and vividly brought it to life.

Of course, the piece isn’t strictly an opera seria; the libretto was re-written for Mozart by Caterino Mazzola the Dresden court librettist. Mazzola reduced the number of acts to two and introduced trios, duets and ensembles, giving a greater role to the chorus and creating the Act 1 choral finale. (In fact there is a Gluck setting of the original libretto and I have long thought that it would be illuminating to hear the two side by side in concert.) But Mozart kept a number of opera seria elements in his setting, notably the use of long, highly serious arias; this of course was helped by the fact that one of the arias was a pre-existing concert aria which Mozart included, thus facilitating the speeding writing of the piece. He also relished the way the drama turns slowly, that we get to examine the major characters in detail, emotion by emotion, Affekt by Affekt.

The subtlety which Mozart and Mazzola brought to the piece is demonstrated by their Act 1 trio for Vitellia, Publio and Annio, inserted at the point where Tito has decided to make Vitellia his bride. This could easily have been an aria for Vitellia as she agonises over the fact that it is too late to call back Sesto from his plot; instead Mozart and Mazzola counterpoint this with Publio and Annio’s reactions, naturally they assume that Vitellia is imply overcome by the enormity of the honour of being made Caesar’s wife.

The concert performance at the Barbican was the third stop in a four city tour (Dortmund, Bremen, London, Paris) so that the performance was well bedded in. Though scores were used by the singers, some seemed to ignore them entirely and others were hardly bound to them. In fact this was a highly dramatic presentation. Chief amongst this was the Tito of Michael Schade. Schade used the recitatives in a vivid way, sometimes distorting the line for emphasis. His Tito was no compliant dummy, but a highly emotional and at times over-wrought man; in fact Schade was one of the most extrovert Tito’s I have ever seen, a highly involved and strongly projected performance. This was combined with some very fine Mozart singing, with a clear sense of line combined with dramatic thrust. This made Tito much more of a major player in the drama, rather than a passive ruler to whom things happened as has often been the case with other tenors in this role. Though I have to say that sometimes I thought that Schade went it little too far, with over emphatic dramatics which a good director would surely have taken in hand (there was no director credited in the programme).

Alice Coote’s Sesto was no less dramatic, but all the more compelling for being a far less histrionic performance. Coote’s Sesto was firmly rooted in the music, in the long statuesque arias which Mozart wrote for the character. The great showpiece “Parto, parto” was superbly done, finely accompanied by the solo bassett clarinet from the orchestra. But Sesto’s big accompagnato at the opening of Act 2 also showed a great artist at work, combining musical values with profound drama. Coote is highly experienced in baroque opera seria and so you felt that her performance in this, the last opera seria, was inflected by Mozart’s reflection of the past. Coote’s Sesto reflected both Mozart’s other writing for mezzo-soprano, but also earlier Handelian roles.

She was ably partnered by the Vitellia of Malin Hartelius. Vitellia is a curious role; written for a soprano, it includes the aria, “Non piu di fiori”, which may originally have been concert aria for a distinctly lower voice. This gives the part quite a wide range and its tessitura is such that mezzo-sopranos such as Janet Baker and Della Jones have played with role and on stage it can often be performed by a dramatic soprano (Julia Varady has recorded the role). Malin Hartelius has a rather lighter voice than these; her CV includes recent highlights such as Fiordiligi, Leila (Le Pecheurs de Perles) and her first Marschallin. She played Vitellia as more overtly sexy and rather less the scheming bitch; Hartelius brought a sexual charge to a lot of Vitellia’s music, here was a woman who lived in a man’s world by trading on her female wiles and charms. The relative lightness of Hartelius’s voice meant that we got a nice flexibility in the vocal line, which was a great treat. (Here was a Vitellia more closely related to Fiordiligi than is sometimes the case). She approached the top of her voice with caution, but nothing was announced regarding indisposition. In “Non piu di fiori” she approached the low notes bravely, making the effort seem part and parcel of a fine performance; again the obliggato was played finely by the orchestra’s clarinettist, this time on a bassett horn, thus giving the aria its distinctive tint.

Coote and Hartelius developed a strongly co-dependent relationship which was all too believable and became the strong engine of the drama around which the other roles circulated. Luckily the cast formed a strong ensemble, so that Coote and Hartelius did not overbalance the drama.

Christina Daletska displayed a lighter, brighter voice than Coote, so that her Annio was clearly related to Cherubino, though a Cherubino now grown up and willing to challenge authority. Daletska gave a seriously fine account of Annio’s aria “Tu fosti tradito” when he stands up to Tito after the discovery of Sesto’s involvement in the plot against Tito.

Rosa Feola was an entirely admirable Servilia, giving a performance that combined charm with a certain interesting dramatic edge. She left you wishing that Mozart had written more for this character.

Brindley Sherratt was Publio, the commander of the Praetorian Guards; a role entirely without aria, but one which has an important part to play in the drama and in the ensembles. Sherratt discharged his duty entirely admirably and convincingly, bringing a nicely dramatic firmness of line to the role.

Of course, one major aspect of any performance ofLa clemenza di Tito is the recitative. There’s a lot of it and it’s not all by Mozart; one of his pupils wrote it under his supervision. The cast gave us quite a full version, accompanied by Raphael Alpermann’s lively fortepiano. The result was fleet and dramatic, keeping the action moving and making us aware that it really was drama.

The Deutscher Kammerchor provided the choral moments with nicely turned phrases. They were not on stage all the time, so their entrances and exits were a little distracting, but once present their singing was of a high order.

Conductor Louis Langrée drew a fluent and at times speedy account of the music from the Deustche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen. But Langrée’s concern for lively expressiveness seemed at times to be at the expense of cohesiveness of ensemble. Still, he got a vivid and involving performance from everyone and above all made us believe in La clemenza di Tito as drama, rather than a museum curiosity.

Robert Hugill

Click here for the programme of this production.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Canaletto_Arch_Titus.gif image_description=The Arch of Titus by Canaletto product=yes product_title=W. A. Mozart: La clemenza di Titlo product_by=Tito: Michael Schade; Sesto: Alice Coote; Servilia: Rosa Feola; Vitellia: Malin Hartelius; Annio: Christina Daletska; Publio: Brindley Sherratt. Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen. Deutscher Kammerchor. Conductor: Louis Langrée. Barbican Hall, London, 22nd February 2012. product_id=Above: The Arch of Titus by CanalettoAmsterdam’s Invisible, Risible Kitezh