March 31, 2012

Elmer Gantry the Opera

His best novels came relatively early, a string of successes climaxing with the Nobel Prize for literature — the first won by an American — after Dodsworth. He continued to produce novels until his death a couple decades later; they are mostly forgotten, and even his best work merits little discussion today. His themes of the banality and hypocrisy of American middle class mores haven’t exactly lost their relevance, but they seem obvious and forced. It’s interesting that, according to Richard Dyer’s excellent booklet essay, the inspiration for composer Robert Aldridge and librettist Herschel Garfein’s operatic adaptation of Elmer Gantry came while watching the 1960 film version. The cinematic version, with its Academy Award-winning performance in the lead by Burt Lancaster, at least retains Technicolor vividness.

The story of Elmer Gantry has a picaresque quality, as we follow a brash young athlete who, almost by accident, finds himself on the path to becoming a successful Evangelist, all the while pursuing his own need for female companionship and ego-building applause. The rather labored ironic ending finds Gantry leaving behind, if not in the dust then in the ashes of a fire, those who had helped him reach his goals, and moving onto to a vaguely “New Age” type religious re-birth. In another booklet essay, Leann Davis Alspaugh quotes the great line from H. L. Mencken that “deep within the heart of every evangelist lies the wreck of a car salesman.” Those relatively few pithy words put across the thrust of Elmer Gantry, at least as an opera. Over two hours of accomplished, professional composition and literary adaptation belabors the point at excessive length.

However, there is much to commend in the work of Aldridge and Garfein. In particular, Aldridge finds ways to use creative orchestration to give momentum and a sense of variety to a score that mostly builds upon the comparatively unsophisticated sounds of gospel music. There are hints of Copland from time to time, or perhaps one of Virgil Thompson’s documentary film scores. The problem is that when it comes time for an aria, that inspiring breath of original melodic inspiration that is found in the great operas of the standard repertory evades Aldridge. Nevertheless, when a booklet essay writer notes that the opera has already found a niche for itself at American music colleges as a fine piece to stage for aspiring singers, it’s clear that the sheer craftsmanship of Elmer Gantry the opera has earned it a kind of success.

Composer Robert Aldridge and librettist Herschel Garfein [Photo by Jane Kung]

Composer Robert Aldridge and librettist Herschel Garfein [Photo by Jane Kung]

The Naxos recording, made before an enthusiastic live audience, benefits from the strong leadership of conductor William Boggs over the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra and the Florentine Opera Chorus. In the title role, Keith Phares offers the kind of smooth baritone reminiscent of Nathan Gunn — a handsome sound without much character. In the somewhat superfluous role of Gantry’s best friend Frank, Vale Rideout strains a bit at the high end. Patricia Risley sings the lead female role of Sister Falconer, a female evangelist who is actually more interesting as a character than Gantry. Like Phares, Risley’s seems to have adopted a vocal production arguably closer to Broadway than to an opera stage, and a little more thrust and edge would have been good. In the role of a pathetic husband that Gantry cuckolds, Frank Kelley gets a manic mad scene that should go over very well for budding character tenors looking for competition pieces in English.

Naxos manages to provide a slim booklet with informative essays, production stills, and the libretto in English. On the debit side, Naxos doesn’t provide much tracking, with the long act one, for example, on CD 1 with only 6 tracks. Although your reviewer will reserve judgment on whether Elmer Gantry the opera belongs in a CD series called “American Opera Classics,” it is an honest and finely assembled piece that makes a strong case for itself. The same cannot necessarily be said for many American operas of the last decades with higher profiles.

Chris Mullins

[Editor’s Note: Elmer Gantry received two Grammy Awards for Best Contemporary Classical Composition and Best Engineered Album, Classical at the 54th Annual Grammy Awards (2011)]

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Elmer_Ganrty.gif image_description=Naxos 8.669032-33 product=yes product_title=Robert Livingston Aldridge: Elmer Gantry product_by=Gantry: Keith Phares; Sister Falconer: Patricia Risley; Frank: Vale Rideout; Eddie: Frank Kelley; Lulu: Heather Buck. Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra and Florentine Opera Chorus. Conductor: William Boggs. product_id=Naxos 8.669032-33 [2CDs] price=$15.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?ordertag=Comprecom172-587476&album_id=588343 Elmer Gantry Music: Robert Aldridge Libretto: Herschel Garfein Naxos CD 8.669032-33Gerald Barry: The Importance of Being Earnest

The decision to set a play as well-known as The Importance of Being Earnest cannot have been easy, surely, given the famous nature of the text. Was it intimidating? Or stimulating? ”It was hard and strange to begin and a joy after.When I began I wondered how to manage famous lines like “A man who marries without knowing Bunbury has a very tedious time of it.”I decided to treat them as Chorales sung by a choir, like in the St Matthew Passion, or like slogans held up by protestors. But having used the choir for about 90 seconds, I saw the text more clearly and dispensed with them. That’s why they only appear in Act 1 and never again.They are prerecorded and come across like messages from the Gods.”

I notice, in connection with this, that you famously set another famous text, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, for English National Orchestra. “Yes it’s a wonderful text as well. It’s at Wilde’s level. It also is structurally sound and has a wonderful directness. No false note there.” The work (The Importance of Being Earnest) was written in 2009/10, I believe, and the Los Angeles performance was a great success. There is a delicious sense of humour running through your writing (the glissando-like up and down runs of the opening of act 3, for example), and a lightness of touch, both in the handling of the material itself as well as in the scoring. This is perhaps not associated too often with ‘modern’ music…I ask how Finnissy brought about the musical equivalent to Wilde’s absurdist text?. “Well, I’ve always loved Wilde’s ecstatic sense of nonsense — like Alice in Wonderland in a way. In Wilde there’s a dark uncaring humour, complete disregard for convention, delight in lying — and that’s my home.I don’t know if it’s an Irish thing or not — all I know is, it’s all I know.”

You have Thomas Adès conducting the Barbican performance (as he did, of course, the Los Angeles one). How does it feel to have another composer conducting your work? Is it true (in Adès’ case) that this brings extra insights (people frequently say that about Boulez, for example).

“When Tom is conducting I feel completely safe. In fact, when it’s a project initiated (I nearly said ignited — but it’s a good word) by him, it calls forth from me an extra energy. There’s a thing of entrails in operation when Tom is involved. He’s inspiring. He was born that way.”

There is a lyricism as well as bold humour here too in the music. As he re-read the play in preparation for the composition of this work, what were Barry’s reactions? What kind of processes did these reactions go through to find their way to the finished score?. “Well, various things presented themselves. For instance, both Lady Bracknell and Miss Prism are Germanophiles, so I made them composers. They both get to sing their own settings of Schiller’s Ode to Joy, and when Lady Bracknell gets carried away, she naturally breaks into German. By the third act, Lady Bracknell is more unhinged. She can focus, and ask questions, but if the answers are more than her brain can bear, she ignores them and goes on to something else.

“When Miss Prism is asked to identify the handbag, she goes into a withdrawn state of inspection, naturally humming the German national anthem as she does so, because Germany is crucial to her and Lady Bracknell.”

I comment that actors often say that comedy is one of the hardest parts of their art; would you say the same is true, musically, too? That, especially creating humour under a modernist aesthetic, is a challenge indeed? “It isn’t a challenge at all. I never think of being funny and never set out to be. I never think of aesthetics, or of anything at all. I just act. My body acts, my nervous system. Things just happen. When the audience laughed in LA I was startled to begin with — thrown. I know that sounds odd. I used to laugh alone at what I’d done. But it never occurred to me that my solitary laughter would become a public thing.

“In the scene in Act 2 between Cecily and Gwendolen, where they hurl insults at one another, 40 dinner plates are broken. I thought, apart from killing someone, what’s a good expression of anger?. And, of course, breaking things is one. So that’s how that came about. And because viciousness and fascism are one, I use hobnailed marching jack boots as well. And as I felt more was needed, I have the girls shoot one another at the end of the scene. Having done so they just go on to have afternoon tea, because they are as The Undead.” I comment that Barry is good at comedy, though: the LA Times blog (Culture Monster) called your second opera, The Triumph of Beauty and Deceit, written for Channel Four TV, “Non-stop nuttiness”…

“People who don’t know one another have said that kind of thing for decades so it must be true” comes the reply. Talking of which, I can’t help wondering about how US audiences coped with a dialogue about cucumber sandwiches…especially one set to angular dodecaphony…

“As far as I remember, even though I cut about two thirds of the play, I didn’t cut any reference to food and eating. And there are a lot of those in the original. So in my version they loom even larger. The men are as interested in food as they are in the women. There’s a strange moment when Cecily meets Algernon for the first time in Act 2, and out of the blue he says, “I am hungry”. The stage directions says “They pass into the house.” It’s eerie. You don’t quite know what might happen. I love the moment in Act 1 when Lady Bracknell says “I had some crumpets with Lady Harbury, who seems to be living entirely for pleasure now”, and the orchestra is suddenly hushed and dark. There is something unspeakable there.”

Regarding Barry’s musical language, I point out that although he uses twelve-tone techniques, this seems to be but one part of his armoury. There’s no mistaking the modernism of the keyboard opening — and how it incorporates Auld Lang Syne is delightful (as well as the comedy of the line “I don’t play accurately”...) The compositional challenge, it strikes me, is how to incorporate the variety of techniques you use into a coherent musico-dramatic whole. How did he craft this?

“I play that solo myself. It’s really hard and I don’t play it accurately! I was glad to be in one piece by the end. I was barely hanging on. I recorded it in one take the night before I went to LA for the premiere and got into a panic because I thought I wouldn’t make it because I hadn’t trained enough. I wasn’t fit at all. That solo was commissioned by my friend Betty Freeman before she died. I miss her and think of her a lot.

“I have a weird piano technique. I studied with an old lady in the west of Ireland, and then I met another old lady who was a pupil of Alfred Cortot’s so I received Cortot’s spirit from her hands! I use “Auld Lang Syne” like I might use a cup to drink out of. In the opera it’s an object surrounded by a whirling parallel world removed from it. They move together but have nothing to do with one another. The tune is the basis of the love duet between Jack and Gwendolen, and the duet between Jack and Algernon, and is usually used by the butlers Lane and Merriman to announce people. So it’s a structural pillar of a kind. About incorporating varieties of techniques or musics. These are really no more than a mirror to the circus of life. They work in the way we ourselves feel, see, hear, myriad things all the time which have no obvious connection. They are life.

“There are various kinds of musics used in Earnest — in that I think of musical history as mine, and roam in it where I will. But in the use of those musics there is an underlying reason each time. Instead of the so-called serial music after the beginning of the opera, I had originally written profound (of course!) music and when I put it together with the text, it sounded fake. And when I substituted the ‘fake’ serial music, it sounded funny and original. I think the reason is something like this: Wilde’s text is fantastically artificial, and when I went into overdrive to match it with similar originality, it was too heartfelt and became mawkish/sentimental. It betrayed Wilde’s text — making it ordinary. The tension disappeared. When I matched Wilde’s artificiality, with highly ‘contrived’ serialism, both were at home with one another, and there was no false note. One was as fake (artificial) as the other. They were happily surreal together.

“Maybe it’s that Wilde + Conventional Emotion is less good than Wilde + Artifice. And considering that there is so much deceit in the play, and his own life being filled with it, my fake serialism was truer to his world of fakery.”

I hear quite a lot of Straninskian sonorities and gestures in this work, too (the repeated note gesture heard at various points, including punctuating the patter-setting setting of the Ode to Joy, seems a case in point). Am I right in identifying this influence, and if so can you outline why he is important to you? Can you identify any other influences or references in your score? “You could be right in mentioning Stravinsky. I love him obviously. Who doesn’t?. But I don’t think about that when I’m writing. If by chance I regurgitated one of his atmospheres and did it honourably, I would be happy.” This is Barry’s fifth opera — and I assume not his last, given Earnest’s success. How does he see opera, as an art-form? An arena in which to explore a multitude of emotions (comedy, in this instance?). A still-vibrant art-form? “Opera is what it always was and will be. Nothing is ever in crisis. The only things that are ever in crisis are the people who use the forms. If there’s ever any weakness in anything, it’s the author’s fault. People who speak of the death of things talk rubbish. Everything remains the same. Everything is always the same. Nothing changes. All there are, are different levels of imagination, and that has always been the case. There is no advance imaginatively from Piero della Francesca to Wagner. They are both at the highest level and are therefore both the same. That’s all that matters. Any other considerations are footnotes.” I notice Barry created the libretto himself, taking Wilde as your starting point of course. But he had to make cuts, obviously — how hard was this, given the strength of Wilde’s play as an entity in itself? What did you cut, and why?

“I cut two thirds of the text. But I would say, that if you’d never read the play before, and read my remaining third, you wouldn’t know anything was missing. It shows how strong Wilde’s structure is. The play’s bones are unshatterable. My version is an X-ray of it.I enter into the play’s madness in varying degrees throughout. One of them is where Dr Chasuble says “Everything is quite ready for the christenings”. Instead of Wilde’s text in response to Chasuble, the whole cast respond with repeated vocal glissandi. They are like a menagerie, animals who cry out, beyond words.”

And finally, did Barry fashion any of the various vocal parts with specific singers in mind? “I did think of Barbara Hannigan — it’s rare that I don’t think of her!. Because she has a glorious high D, I gave her one as a present for her last note in the opera.”

For more details please see here.

The Birmingham premiere will take place on 28th April at the Symphony Hall, Birmingham.Colin Stuart Clarke

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Barry_Ades.gif image_description=Gerald Barry and Thomas Adès [Photo courtesy of Faith Wilson] product=yes product_title=Gerald Barry: The Importance of Being Earnest product_by=By Colin Stuart Clarke product_id=Above: Gerald Barry and Thomas Adès [Photo courtesy of Faith Wilson]March 28, 2012

Historical Performances from Covent Garden: Barbiere, La traviata and Tosca

ICA Classics appears to be a label dedicated to in-house tapes of live Covent Garden performances of the mid-to-late Fifties. Of the three sets reviewed here, all share constricted audio that mutes the orchestra but gives voices — at least the stronger ones — satisfactory prominence. Tape hiss, while audible, will not bother any but the most sensitive after a short period of adjustment. The question becomes then — how many “carats” can be ascribed for these nuggets from one of opera’s supposed Golden Ages?

The most fun comes with the 1960 Il Barbiere di Siviglia, with conductor Carlo Maria Giulini leading a tastefully raucous performance. The audience takes longer than the singers to warm up, by the time act one concludes, the stage action has broken through any stereotypical British reserve, and the extended bouts of laughter will make most any listener impatient to know what was happening on stage. Rolando Panerai sings a youthful, confident Figaro, but most of the laughter seems centered around the Bartolo of Fernando Corena. Luigi Alva offers a stylish Conte d’Almaviva, and for some of us, it’s nice to end this opera without the extended aria Rossini cut and later used in Cenerentola. Juan Diego Florez fires up standing ovations with this piece when he takes on the role, but it is narratively redundant and shifts the focus away from what should be an ensemble finale. Teresa Berganza made Rosina a specialty. There is much evidence here of the special quality she brought to the role — feminine and feisty — but either the stage action placed her further from the source microphone or the quality of her voice was not as susceptible to off-stage miking. Her vocal effect is dimmed by a recessed quality.

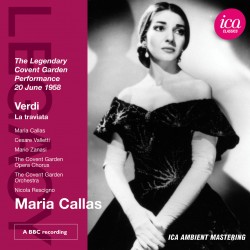

A couple of years before that 1960 performance Maria Callas made a notable appearance as Violetta in Verdi’s La Traviata. Although still in her mid-30s, 1958 finds Callas in variable voice. The middle still has warmth and agility, but the top is awkwardly approached and often unpleasant, although Callas holds onto high notes as if hoping the quality will improve through sheer determination. Act three comes off best, as she doesn’t have to extend upwards as much. Then again, it may have been an off-night for everyone. The stylish light tenor Cesare Valletti starts off “Un di felice” as if unsure of the key, and then seems to struggle with conductor Nicola Rescigno over tempo. He improves as the night progresses, but this is probably not a performance he would have wanted a permanent record of. Mario Zanasi is a competent Germont, not much more. This is a document for Callas-philes.

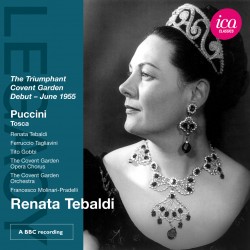

And for those still adhering to a supposed “Callas vs. Tebaldi” fan feud, the 1955 Tosca finds Tebaldi in glorious voice. Although the great soprano tends to let the sheer beauty and size of her voice carry much of the characterization, she does offer some moments of personal insight, including a spookily whispered repetition of “Mori!” at Scarpia’s death, and a sudden scream as her own final leap. For Cavaradossi Ferruccio Tagliavini pushes his voice forward, perhaps to match Tebaldi. While retaining his individual sound, Tagliavini stays at one emotional pitch, even in his act three showpiece. The biggest and saddest surprise is the Scarpia of Tito Gobbi. This is a role with which he will forever be identified, but as recorded here, he sounds dry all night, shouting for effect. One grows eager for Tosca to get her revenge. Conductor Franceso Molinari-Pradelli supports Puccini and the singers well, including a soprano “boy shepherd” in act three who sounds exactly like a mature soprano.

ICA Classics provides a brief booklet note that gives some basic details about the run of performances from which the recordings are drawn. Unsurprisingly, those commentators find each performance to be a long-lost gem. At budget price, there’s not much risk for the curious fan who would like to close his or her eyes, hop in an imaginary time machine and imagine themselves in London for these performances. Of the three, only the Barbiere gets a recommendation here.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ICA_5046.PNG image_description=ICA Classics ICAC 5046 product=yes product_title=Gioachino Rossini: Il barbiere di Siviglia product_by=Figaro: Rolando Panerai; Rosina: Teresa Berganza; Count Almaviva: Luigi Alva; Dr Bartolo: Fernando Corena; Don Basilio: Ivo Vinco; Fiorello: Ronald Lewis; Berta: Josephine Veasey; Un Ufficiale: Robert Bowman. The Covent Garden Chorus (Chorus Master: Douglas Robinson). The Covent Garden Orchestra. Conductor: Carlo Maria Giulini. Royal Opera House, London, 21 May 1960. product_id=ICA Classics ICAC 5046 [2CDs] price=$22.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=654196

ENO announces Mini Operas: A Worldwide Online Talent Search to Inspire People to Create Opera

ENO Press Release [27 March 2012]

ENO announces Mini Operas, a world-wide, online search for composers, writers and film makers that will seek out emerging opera talent of the future from across the world. Three competitions to find future stars of all the components of creating an opera will be launched online allowing everyone to submit entries for one or more categories…

[Note: Follow the ENO Mini Operas program at http://twitter.com/#!/minioperas]

March 27, 2012

La forza del destino by Chelsea Opera Group

This fuels Chelsea Opera Group productions with the kind of commitment you get from true devotees who love what they’re doing. Founded by David Cairns, they produced Berlioz Les Troyens and even Benevenuto Cellini in the 1960’s, conducted by Colin Davis, closely associated with them since their inception. London would not be what it is without the Chelsea Opera Group ethos and its audiences.

Starting this year’s season at London’s South Bank, the Chelsea Opera Group presented Giuseppe Verdi’s La forza del destino, in the 1862 St Petersburg version rather than the more familiar 1869 Milan version. Chelsea Opera did La forza del destino previously in 1959, 1966 and 1986. Some patrons have heard them all. Last year, there was an excellent production in Paris, with Violeta Urmana, Marcelo Àlvarez and Kwangchul Youn. The Chelsea Opera budget can’t scale such stellar heights but compensates with verve. Gweneth-Ann Jeffers, Peter Auty and Brindley Sherratt gave performances so passionate that they filled the Queen Elizabeth Hall so effectively there was no need for staging. Jeffers and Auty sang these roles at Opera Holland Park in 2010.

In La forza del destino, Jeffers is a force of nature, expressing levels of Leonora’s personality hinted at in the score. Leonora is virginal but passionate. She’s planning to elope to South America, sacrificing her status for an outsider whose ancestors are descended from the god of the Sun (ie Incas). Leonora’s father is a bigot, and her brother equally rigid, but Leonora has greater depth of personality. Jeffers smoulders, caressing the low tessitura, soaring to crescendi and extended high passages. Forceful voice, well applied technique. Jeffers is a born diva, but her powers come from within, fuelled by intelligence and understanding of how music shapes role. Leonora is resourceful — who would chose to be a hermit in a monastery — but she can’t escape Fate. If Fate can destroy someone as strong as Jeffers’s Leonora, there’s no hope for anyone else. Verdi’s “Fate” motif flows throughout the music, sometimes seductive and subtle, but relentless. It surges in the big strings sections, weighted down by celli and basses. But when Jeffers sings Leonora the crucial aria “Pace, Pace”, she’s accompanied by harps, for she’s alone with God. Dramatic sopranos like Gweneth-Ann Jeffers are rare — why don’t we hear her more often in this country? She’s a resource we should appreciate.

Don Alvaro is a long and taxing part, but without staging, the voice is more exposed and has to carry the drama. Peter Auty was more impressive than he was two years ago. In this performance there’s an aria cut from later editions, which commands, as the notes say, “high tessitura and neurotic tension”. Auty threw himself into the spirit, singing with a heroism that captures Don Alvaro’s personality. No matter how hard Don Alvaro tries, Fate will destroy him. Dying early is no escape. Pehaps Don Alvaro will suffer more if he has to find redemption. Certainly, Verdi’s emphasis on spiritual rigour is blunted if Don Alvaro simply drops dead. The role isn’t meant to be easy, and Auty understood the poignancy, rewarded by audience applause. Auty’s young, by no means a bland “English tenor” and has a lot of potential.

The plot pivots around Leonora and Don Alvaro but Verdi expands the idea of Fate in many ways. Don Carlo (Robert Poulton) doesn’t think, or even feel much love for his sister. He’s programmed like an automaton, a manifestation of Fate as obsessive compulsive non-empathy. The part’s against Poulton, though he sings well. But Don Carlo is killed because he doesn’t even question things. Significantly, Verdi writes other characters to extend the concept of Fate. He didn’t write Preziosilla (Antonia Sotgiu) simply for colour. She’s not “gypsy slut” but represents something much more sinister. She is much more Mefistofele than Carmen, for she goads the soldiers on. “Rataplan, Rataplan” can be macabre, a Dance of Death, but here it was genteel, the COG Chorus and The Imperial Male Voice Choir singing with enthusiasm, taken in by Fate in the guise of provocateur.

Significantly, Verdi develops the monastic roles. The peasants suffer poverty and war, yet do nothing to change their fate. Fra Melitone (Donald Maxwell) has some insight, but rails at the peasants for being poor because they have too many children. (Celibates don’t understand). Melitone is also the gatekeeper and rule enforcer, a benign version of Don Carlo. Maxwell’s too nice to be nasty, but creates the comic aspects of the part very well. Il Padre Guardiano (Brindley Sherratt) on the other hand is a figure as powerful as Leonora herself, with dispassionate objectivity.

“Charity” he keeps telling Fra Melitone, meaning charitable feelings not free food. This kind of charity is exactly what Don Carlo and his father don’t understand. So they become tools of fate and die without having learned anything about life. Sherratt’s Guardiano is magnificent, utterly authoritative. Perhaps he realizes that Padre Guardiano is the voice of God, or at least, some superior, all-merciful being who might have to the power to thwart Fate. Notice how Verdi writes the part for the same voice type as the the Marchese di Calatrava (Richard Wiegold). The two men are polar opposites. Sherratt sings with such resonance that you sense the character’s emotional and spiritual depth. No wonder Leonora confides in him. Moreover, he breaks rules, letting her into the monastery. In the ending where Don Alvaro doesn’t die, Padre Guardino plays a pivotal role, implying that there are other values than revenge and pig headedness. Everyone dies in the end, but if you live properly, Fate doesn’t win. Leonora has learned this, which is why she finds a kind of apotheosis in death. God has shown her mercy.

Minor roles add spark to any opera, but much depends on who is singing them. I’m certainly looking forward to hearing Paul Curievici (Trabucco) again. He’s so involved with the opera that his face expresses what’s going on even when he’s just listening. Intuitive expressiveness like this is a gift that can’t be taught. This is the sign of someone who really act, from his soul outwards. He’s extremely young, so another talent to listen out for. I last heard him in the GSMD Poulenc Dialogues des Carmelites. In La forza del destino, he gets to sing a lot more, and does that well, too.

Robert Newton conducted the Chelsea Opera Orchestra and Deborah Miles-Johnson was chorus master. Three more Chelsea Opera Productions coming up this year — Donizetti Maria Padilla on 27 May, Massenet Don Quichotte on 25 November conducted by ROH chorus master, Renato Balsadonna. More details on the COG website.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Verdi_standing.gif image_description=Verdi standing product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: La Forza del Destino product_by=Il Marchese di Calatrava: Richard Wiegold; Donna Leonore di Vargas: Gweneth-Ann Jeffers; Curra: Patrizia Dina; Don Alvaro: Peter Auty; Un Alcade: Joihn Brice; Don Carlo di Vargas: Robert Poulton; Mastro Trabuco: Paul Curievici; Preziosilla: Antonia Sotgiu; Fra Melitone: Donald Maxwell; Il Padre Guardiano: Brindley Sherratt; The Doctor: Christopher Childs Santos. The Chelsea Opera Group Orchestra and Chorus. The Imperial Male Voice Chorus. Conductor: Robin Newton. Chorus master: Deborah Miles-Johnson. Queen Elizabeh Hall, South Bank, London, 25th March 2012. product_id=Above: Giuseppe VerdiMarch 24, 2012

Lucia and the glass harmonica

Unless…the conductor follows the fashion of adhering to the composer’s original thought and employing a glass harmonica in place of the flute. And that occurs more and more often. Two pieces of evidence here: a 2006 Bergamo Musica Festival production, and perhaps more surprisingly, the 2010 Mariinksy Theater recording. In both cases, the glass harmonica definitely adds to the creepy atmosphere of the scene. The Mariinsky recording offers a sharper aural picture, and the glass harmonicist etches a very clean line of echoing response to soprano Natalie Dessay. The glass harmonica counterpart in the Bergamo recording seems to be caught further from the microphones, slightly dulling the intended effect.

However, in most other respects the Bergamo version scores points over the Mariinsky. Some might have wondered if the starry names associated with the Mariinksy would mean a rival to the opera’s best recorded versions might be appearing. Such is not the case. Conductor Valery Gergiev has a broad symphonic repertoire, but his leadership of Italian opera has received mixed notices. Here, he sustains a poised reading, with no errant tempos or capricious highlighting of stray orchestral detail. Ultimately, however, the reading is a bit dull. More of that Gergiev idiosyncrasy might have helped. The supporting cast is mostly Russian (or at least house singers of the Mariinsky). The heavy tones of Vladislav Sulimsky’s Enrico and Ilya Bannik’s Raimondo blur the characters and veer toward cartoonish villainy.

Gergiev has two superstars as his leads. Lucia is a Natalie Dessay specialty, but this recording almost clinically details the wear and stresses on her instrument from her most recent vocal crisis. The voice is intact, but the suppleness is gone, and high notes fly uncomfortably close to screech territory. Surprisingly, Piotr Bezcala also seems to be in less than ideal voice, with his long final scene occasionally rushed and forced. Both have behind them many finer performances in these roles.

The recordings coming from the Mariinksy label benefit from handsome art design and traditionally generous booklets.

The Naxos, on the other hand, has a thin booklet and nothing else (this is the audio version of a performance also available from Naxos on DVD). The live production was nothing special to look at, and the audio version allows listeners to focus on what an idiomatic conductor and orchestra can provide, as well as the less starry but very capable cast.

Luca Grassi as Enrico and Enrico Giuseppe Iori as Raimondo both possess the right sound for their roles. As Edgardo, the Naxos offers Roberto De Blasio, a rising tenor who has started to pick up a few Metropolitan Opera assignments in the last season. He has just the right weight for the role - masculine, yet limber. In the years since this 2006 recording, he has hopefully brought some more distinctive coloring to his singing. In the title role, Désirée Rancatore puts on a high note display, with crisp coloratura. The middle voice, however, sags under a loose vibrato. Dessay may sound exhausted in her mad scene (not inappropriate), but Rancatore exhausts her listeners in hers, with more of an assault on the scene than an interpretation.

If neither of these versions comes anywhere close the best of the many available recordings of Lucia, the Naxos still deserves the edge for its fluency and old-fashioned commitment.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/MAR0512.gif image_description=Mariinsky MAR0512 [2CDs] product=yes product_title=Gaetano Donizetti: Lucia di Lammermoor product_by=Natalie Dessay: Lucia; Vladislav Sulimsky: Enrico; Piotr Beczala: Edgardo; Dmitry Voropaev: Arturo; Ilya Bannik: Raimondo; Sergei Skorokhodov: Normanno. Sascha Reckert, Glass Harmonica. Mariinsky Orchestra and Chorus. Valery Gergiev, conductor. Recorded in the Mariinsky Concert Hall, St Petersburg, 12-16 September 2010. product_id=Mariinsky MAR0512 [2CDs] price=$31.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=3144&name_role1=1&comp_id=901&genre=33&bcorder=195&label_id=11847 Lucia di Lammermoor Music: Gaetano Donizetti Libretto: Salvatore Cammarano Mariinsky Theater - 2010 Orchestra and Chorus of the Mariinsky Theater Conductor: Valery Gergiev Lucia: Natalie Dessay Edgardo: Piotr Beczala Enrico: Vladislav Sulimsky Raimondo: Ilya Bannik Mariinsky CD MAR0512 Bergamo Musica Festival - 2006 Orchestra and Chorus of the Bergamo Musica festival Conductor: Antonino Fogliani Lucia: Désirée Rancatore Edgardo: Roberto De Biasio Enrico: Luca Grassi Raimondo: Enrico Giuseppe Iori Naxos CD 8.660255-56

Florian Boesch at Wigmore Hall

This was a wholly original, perceptive reading, informed by great insight. In Die schöne Müllerin the brook speaks through the piano. A brook flows forth with force. This isn’t a pretty little Bachlein, even if the protagonist is fooled. It powers a large commercial millwheel. This master miller employs many staff, and the brook keeps them all in work. The millwheel crushes grain into flour. The brook also controls the miller lad’s mind and crushes him with overwhelming force.

From the outset, it was clear that Malcolm Martineau understood why Schubert wrote such pounding, repetitive rhythms into the piano part. They are so shocking tthat most pianists soften them to make them more “musical”, but when they’re heard with this force, you realize that the brook is a personality. That’s certainly how the miller’s lad sees it. “Vom Wasser haben wir’s gelent, vom Wasser”. Right from the start, he’s doing what the brook tells him. The energy in the piano part is compulsive rather than merely compelling, so Martineau’s approach is psychologically right. The poem, too, reflects this hard-driven quality, with words repeated at the end of sentences, for emphasis. Boesch sings them purposefully, “Das Wandern”, ““Das Wasser” and “und wandern” yet again. Piano and voice in harmony, but it’s the unison of goosestep march.

Also perceptive was the way Boesch and Martineau revealed the jarring contrasts between each song. The hard-driven march gives way to more seductive rolling patterns, then voice and piano diverge. The miller has spotted the mill. Boesch’s voice warms with hope, “War es also gemeint?”, but Martneau’s dark pedaling tells us no. “Am Feierabend” is often sung gemütlich, for the miller’s lad now feels part of a community.. But the imagery includes the millwheel, still grinding when the workers are at rest. Martineau is ferocious, for the brook is, and will become ever more jealous. Later, the young miller will obey, but for the moment, he’s still contemplating love. Significantly, the voice is relatively unaccompanied at the start of “Der Neugierige”, and Boesch’s voice finds lyrical stillness. But the brook attacks again in “Ungeduld”, with its manic pace. Seldom have these mood swings seemed so bi-polar. In “Mein!” Boesch sings as if he’s won the girl. Martineau’s playing reminds us that the brook might think quite something else. Emphatic, brutal last note, no quibbling.

Many years ago, Matthias Goerne’s first recording of Die schöne Müllerin revealed the young miller as emotionally disturbed, living in schizoid fantasy. It’s a perfectly valid interpretation, though Goerne was to adopt a more conventional but superlative approach in his recording with Christoph Eschenbach. Boesch, however, makes the young miller sympathetic. Because it’s easier to identify with a miller created with such warmth, the brook’s vindictive pursuit seems all the more tragic. Boesch’s rich timbre and faint Austrian burr makes him plausibly masculine, so the rivalry between the miller and the huntsman isn’t entirely one-sided. No less than six songs in this 20 song cycle deal with the miller, the huntsman and the girl, with music and the colour green and all that signifies. The songs were performed without a break, since they’re a last interlude, when the miller still inhabits the real world.

With the minor key “Trockne Blumen”, the young miller enters the death zone. Boesch sings quietly but it’s an unnatural calm. His last cry “Der Mai ist kommen, der Winter is aus!” was a last backwards look at happier times. Martineau makes the last chords resonate into silence. The miller will not live to see Spring. The brook now “speaks” through the text, as well as through the piano. Miller and brook are becoming one again, the miller’s soul absorbed by the brook. This is surreal, even by the Gothic norms of Romantic poetry. Boesch makes interesting connections. His hands may clasp involuntarily, but the stillness of his singing suggests quasi-religious sacrifice. Did the poet Wilhelm Müller think of pre-Christian fertility rites, or to primeval myths of female water spirits luring men to their doom? It hardly matters. Boesch’s eerie calm is disconcerting. It’s as if the miller is willingly hypnotized.

The last song, “Das Baches Weigenlied” is a lullaby but most certainly not serene or comforting. Rolling rhythms again, but now the piano part falls into gentle repose. The brook is now speaking through the voice part and through the miller. It’s not the miller who is now at peace. He’s dead. The brook has consumed him and no longer needs to rage. Schubert sets the song lyrically, but it’s the culmination of a nightmare, straight out of the aesthetic that gave rise to Erlkönig (and indeed to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein) As I’ve said many times before, only the shallow hear shallow in Schubert, but it needs to be said if we are to learn from him. This recital shows us what real Lieder singing is about. It’s uncompromising psychological truth.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/BOESCH-2_credit_wiener-konz.gif image_description=Florian Boesch © Wiener Konzerthaus / Lukas Beck product=yes product_title=Franz Schubert: Die schöne Müllerin product_by=Florian Boesch, baritone; Malcom Martineau, piano. Wigmore Hall, London, 21 March 2012. product_id=Above: Florian Boesch © Wiener Konzerthaus / Lukas BeckRoyal Opera House 2012-13 season

Opera exercises many different feelings, Holten explained. As a young boy in Copenhagen, it opened out vast new horizons for him. Through opera, we engage with the drama of being human. Running an opera house is more than just business. Its “product” is creativity. If opera houses scale back and play safe, they lose the vision that makes opera thrilling in the first place. Holten’s strategy for straitened times is daring. Grow the audience from strength, giving patrons something to get excited about, whether they’re new to the genre or not.

Six new opera productions, higher profile revivals and an ambitious programme of external events that will expand the reach of the Royal Opera House far beyond Covent Garden. More live HD broadcasts, so ROH premieres can reach wider audiences. More links with smaller, independent companies. Even an experimental pricing structure. The whole atmosphere is a buzz, reflecting Holten’s dual responsibilities as manager and as creative artist.

Obviously the big Wagner Ring will dominate the autumn season. It’s sold out, despite sky-high prices, but Wagner’s anniversary is most definitely a special occasion. This production is aimed at a more general audience than a core of Wagner aficionados. Bryn Terfel, Susan Bullock and other stars ensure its success. This is a new Keith Warner production, conducted by Antonio Pappano. Wagner is always interesting and the sheer sense of occasion is part of the attraction. It takes the Met to really wreck the Ring. The ROH Ring should keep the house afloat for years.

In December, Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Robert Le Diable makes its first London appearance since around 1890. Once, Robert Le Diable was un succès fou, a sensation to which all Europe flocked, for it marked a new style in French opera. Heinrich Heine attended, incorporating it into his poetry “Es ist ein großes Zauberstück, Voll Teufelslust und Liebe”. Some of the arias are very well known, since Joan Sutherland was very fond of them. So hearing it in context is a great opportunity. There’s a renaissance in 19th century French opera, and the ROH has been on the crest, with Massenet, Berlioz and Gounod. The cast is superb. Brian Hymel who so impressed as the Prince in Rusalka, will be singing with Diana Damrau, Marina Poplavskaya, John Relyea and Jean-François Borras. This repertoire diverges from the Italianate style so fashionable at present, so it’s good news for opera adventurers exploring “new” perspectives.

Benjamin Britten’s centenary falls in November 2013, so the eyes of the world will be on how Britain honours the greatest opera composer it has produced. Britten often visited the ROH (he used to eat at Bertorelli’s) but he wasn’t really part of the ROH in-crowd then. So it’s good that the Royal Opera House is giving him his due, and with a twist Britten would have appreciated. Had the ROH been boring and played safe, we’d get another Peter Grimes. Instead, Holten has chosen the extremely rare Gloriana, which even Britten true believers don’t know well. This is thrilling, as Gloriana is problematic to stage, for Britten experiments with Elizabethan form. There’s only one recording (dull) but there is an Opus Arte DVD with Opera North (brilliant) that treats the work in cinematic style, which is an excellent solution (review here). It would be hard to top that, but the Royal Opera House has resources few other have, and Richard Jones as director could make it work. Strong British cast:: Susan Bullock, Kate Royal, Toby Spence, Mark Stone and other stalwarts, conducted by Paul Daniel. Definitely a “historic event”.

Three of the most important British composers are highlighted this year. Britten, Harrison Birtwistle and George Benjamin, “The 3 B’s” quips Holten. Perhaps the most significant British opera in recent years, Harrison Birtwistle’s The Minotaur, is revived at last in January. Get to this, since the DVD is inertly filmed, something I hope Holten will address at some stage, since film is the next frontier in bringing opera to audiences outside the house. Like any other part of staging it needs to be done well. John Tomlinson, Christine Rice, Andrew Watts and Johan Reuter return, and Alan Oke sings the part created by Philip Langridge.

George Benjamin’s first full scale opera, Written on the Skin, premieres March 8 2013. This is a very important occasion indeed, and will be heard in eight European cities. Benjamin’s not a fast writer, but painstakingly scrupulous, and this is his most ambitious large work to date. The libretto is by Martin Crimp, with whom Benjamin created the masterpiece Into the Little Hill. Read more about that here. The plot’s dramatic. A rich man hires an artist to illuminate a manuscript. The rich man kills the artist when the latter falls in love wuth the former’s wife and has him baked into a pie and served for dinner. Barbara Hannigan sings the wife, which means the part will be fiendishly inventive and demanding. That’s Hannigan’s specialty (read about her singing Boulez here on this site). Obviously a countertenor role to match, this time Bejun Mehta. Benjamin is a quintessentially European composer, so it’s good that Written on the Skin will be broadcast live, internationally in HD.

The Royal Opera House has always been good for Verdi. The new season brings a Verdi Immersion, three operas in succession, a sort of Verdi Ring, since his anniversary coincides with Wagner’s. The series starts, appropriately, with Nabucco, in a new production by Daniele Abbado and Alison Chitty. Plácido Domingo and Leo Nucci alternate Nabucco. Domingo’s presence alone will make this an attraction. He’s an icon as much as a singer. Acting isn’t affected by age. Domingo can project character, which is what this role needs. Since it’s Nabucco, the Royal Opera House chorus will be in their element. and they’re so good they could carry the show. Nabucco is followed by Don Carlos in May and Simon Boccanegra i in June/July. Although the latter are revivals, if they’re worth doing, they’re worth doing well, so the ROH is are injecting high-quality standards worthy of the best new productions. Antonio Pappano is taking over the conducting and Verdi is his specialty. Absolutely top quality singers — Harteros, Kaufmann, Kwiecień, Furlanetto, Halvarson, Hampson. Even if you’ve seen these umpteen times before, this time they will sound fresh.

It’s good that the Royal Opera House has in Holten a director who is a hands-on theatre person, because that ensures he’s on the ball as an artist. February brings his first ROH production, Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin. Partly Russian cast with Simon Keenlyside for popular appeal. Robin Ticciati, the new incumbent at Glyndebourne, conducts. Since the ROH will be working more with other houses like the innovative Music Theatre Wales, what might this signify, if it means anything at all? Chances are that this time the audience won’t mindlessly applaud the scenery as they did at the recent ENO production, but instead pay attention to the music.

Also an indicator of new creative times is Gioachino Rossini La Donna del Lago in May, a new production directed by John Fulljames, Associate Director This is significant because it was to have been a co-production, but the Royal Opera House pulled out and created their own. This is radical, but it’s much better to do good work than regurgitate a turkey. Operas have a long run in time, so it’s a wonder this doesn’t happen more often and save more reputations, time and money. Holten describes Fulljames as the ROH “dramaturge”, an artistic philosopher with very strong theatre skills, as anyone familiar with his work over the years will recognize. Fulljames’s new production was put together efficiently, using pre-existing technical resources for new purposes. This isn’t recycling, but resourcefulness, as it takes a genuinely creative mind to work round difficulties. Much trickier than working from a blank canvas. Perhaps this is a good way forward at a time of budget restraint? The cast includes Joyce DiDonato, Juan Diego Flórez, specialists in this repertoire, so for singing alone, this new La Donna del Lago will be intriguing.

For more information please see the Royal Opera House website

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Royal_Opera_House_with_ballerina.gif image_description=Royal Opera House and Ballerina [Source: Wikipedia] product=yes product_title=Royal Opera House 2012-13 season product_by=By Anne Ozorio product_id=Above: The Royal Opera House, Bow Street frontage, with the statue of Dame Ninette de Valois in the foreground [Source: Wikipedia]A Child of Our Time, Barbican Hall

At a little more than an hour long, Tippett’s 1939-41 oratorio might have been thought to make for short measure by itself, though I for one should much prefer to leave wanting more rather than to regret the inclusion of padding. In any case, the companion piece was certainly not padding on this occasion; we were treated to the London premiere of Hugh Wood’s delightful second violin concerto, written between 2002 and 2004, and reviewed in 2008 (premiered by Alexandra Wood, the Milton Keynes City Orchestra, and Sian Edwards in 2009). Cast in the ‘traditional’ three movements, ‘marked ‘Allegro appassionata e energico’, ‘Larghetto, calmo,’ and ‘Vivacissimo’, this proved to be a concerto worthy of any soloist’s — and orchestra’s — attention, and received committed performances from all concerned. Sir Andrew Davis is an old Wood hand, having recorded the composer’s Symphony and Scenes from Comus for NMC. His direction of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, also featured on that recording, seemed authoritative, rhythms tight and colours boldly portrayed. Likewise the contribution of Anthony Marwood impressed. His is not a ‘big’ violin tone, or at least it was not on this occasion, but his shaping of Wood’s lines and his irreproachable intonation — there are a lot of tricky yet always idiomatic double-stopping passages here — served the composer well. What struck me most forcefully about the work were the powerful echoes of Berg: to have as a kinsman, if not a model, the composer of the greatest of all twentieth-century violin concertos is not necessarily a bad thing. I assume that the harmonic relationship between the two works must be deliberate. Certainly the way Wood’s themes construct themselves — at least quasi-serially, by the sound of it — has strong parallels in the work of his august predecessor. Even the solo violin theme which enters in the second bar (a rising figure of semiquavers, G-B-E-flat-F-sharp-B-flat-D-F-A, which then continues to soar above the orchestra in lyrical crotchet triplets) seems to harness the spirit if not the letter of Berg’s example. The transformative technique to which the themes are subjected, and through which they are developed, may ultimately have its roots in Liszt, even Beethoven, but it sounds very much Wood’s own. I wondered also whether , especially in the rondo-like finale, there was something of a homage to Prokofiev, though this may have been nothing more than unwitting correspondence; whatever the truth of that, the woodblocks and other lively, rhythmic untuned percussion gave a hint of the Russian composer’s second concerto. (Wood in his programme note pointed to a ‘Spanish’ tinge, ‘prompted by Alexandra Wood’s playing of Sarasate).

A Child of Our Time had the second half to itself. Davis and the BBC SO again have a good track-record in the composer’s music, if not quite so extensive as the conductor’s namesake, Sir Colin. Marking both the increasingly traumatic turn of events in the 1930s — in particular, Kristallnacht and the 1938 assassination of a Nazi diplomat by a Jewish boy, composition beginning the day after war was declared — and the composer’s undertaking of Jungian analysis, this oratorio attempts to address the political by virtue of a turn to the psychoanalytical. That ultimately remains for me a problematical turn, though there can be no doubting the composer’s sincerity. Is it really enough in the Part Two scena — there are three parts, echoing Handel’s Messiah — for the Narrator’s ‘He shoots the official’ to be responded to with the mezzo’s ‘But he shoots only his dark brother’? It might well be the case that the fate of the boy whose tale is told obliquely can provide no answers, but do political atrocities really permit of a solution in which all we need to do is to master our dark unconscious?

At any rate, the oratorio received a fine performance. Its opening orchestral bars evoked a melancholy as ‘English’, if distinctively so, as the music of many of Tippett’s countrymen, up to and including Birtwistle, yet with its own harmonic and melodic inspiration. Are there in the music and the storytelling hints of Weill too, or does that merely reflect common influences? The BBC SO’s contribution impressed greatly, whether in the instrumental interludes — Tippett’s inspiration here Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis — or the more grandly orchestral passages, the opening to the Third Part rhythmically tight and implacable, not least thanks to Davis’s direction. The first interlude, with its trio of two solo flutes and solo viola against a softly singing cello section was powerfully matched by the third part ‘Preludium’, almost neo-Baroque, in which two flutes and solo oboe prepared us for the final peroration, chaste yet without Stravinskian coldness. Choral singing was excellent throughout, the BBC Symphony Chorus as ever well trained by Stephen Jackson, yet with an emotional as well as a musical weight necessary to convey Tippett’s pain and transformation. Strength in anger — ‘A Spiritual of Anger’ — was powerfully conveyed in ‘Go down Moses’, though the intonation of Matthew Rose’s bass contributions was not always spot on. Nicole Cabell and the chorus provided what is perhaps the most magical moment. An exquisitely floated and shaded — with fulsome, though never excessive vibrato — soprano solo, ‘How can I cherish my man in such days…?’ persisted whilst the chorus movingly ‘stole in’ beneath, with the spiritual ‘Steal away’. The use of five spirituals, clearly echoing Bach’s Passion chorales, seems to me not without its problems; simplification of harmonic language at times sounds a little abrupt. Yet again, compositional sincerity tends to win out over such doubts. Karen Cargill, whilst definitely a mezzo, brought a welcome hint of the traditional oratorio contralto too to numbers such as ‘Man has measured the heavens with a telescope’. I was less sure about John Mark Ainsley’s contributions, sometimes both lachrymose and underpowered, struggling to be heard above the orchestra. (It should however be noted that he was a late replacement for an indisposed Toby Spence.) This may be a problematic work, then, but it received for the most part powerful, enlightened advocacy.

Mark Berry

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tippett.gif image_description=Sir Michael Tippett product=yes product_title=Hugh Wood: Violin Concerto no.2, op.50; Sir Michael Tippett: A Child of Our Time product_by=Anthony Marwood (violin); Nicole Cabell (soprano); Karen Cargill (mezzo-soprano); John Mark Ainsley (tenor); Matthew Rose (bass); BBC Symphony Chorus (chorus master: Stephen Jackson); BBC Symphony Orchestra/Sir Andrew Davis (conductor). Barbican Hall, London, Friday 23 March 2012. product_id=Above: Sir Michael TippettMarch 22, 2012

Albert Herring, LA

The British composer was born on November 22nd 1913 — St. Cecelia’s day, in the seaside town of Lowestoft. Before we go any further, I think you ought to know that Lowestoft’s chief export was herring.

Janis Kelly as Lady Billows

Janis Kelly as Lady Billows

Though Britten is generally known to the operatic public for somber operatic works — the tragedies Peter Grimes and Billy Budd — he also had a lively, if far less frequently displayed musical sense of humor. In 1941,while living in the United States, he wrote the comical Paul Bunyon to a libretto by W.S. Auden. He returned to England in 1942, where Albert Herring premiered at Glyndebourne in 1947. Britten’s most concentrated piece of musical hilarity can be found in his 1960 A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Its Pyramus and Thisbe scene is a bright and brilliant take of 19th century Italian opera.

Albert Herring is based on a story called Le Rosier de Mme. Husson by French author Guy de Maupassant. The tale was suggested to Britten by librettist, Eric Crozier, then a member of Britten’s coterie. The story is set in Gisor, a French town in Normandy, socially structured much like towns of England’s Suffolk County, assuring that the transfer of locale was easily worked out. Its title can be loosely translated as Mme. Husson’s Rose King.

The essence of the French story’s plot and that of the opera are essentially the same. Both describe the eternal societal urge of small town’s upper crust to make its lower crust behave better. Though their endings and styles are far different — Crozier insisted the libretto have some kind of rhyming scheme — both plans for betterment go awry.

Lady Billows, the formidable doyenne of the fictitious British town of Loxford, is distressed by the number of illegitimate births, and decides to find, crown and reward a virtuous May Queen. When the girls suggested by the school teacher, the mayor, the police superintendent and the vicar are found wanting by Lady Billows’ equally formidable housekeeper, Florence Pike, the group decides to crown a May King. He is Albert Herring, a virginal boy who works in his widowed mother’s greengrocer’s shop. Poor, protesting Albert is decked out for the celebration in a white-as-a-swan suit and white hat decorated with orange blossoms. Sitting nearby, his mother glows with pride and waits impatiently to get the award money in her hands. But Albert’s friend Sid and Sid’s girl Nancy, hoping to loosen him up, spike his lemonade with rum. No sooner are the celebrations over when Albert disappears.

Liam Bonner as Sid; Daniela Mack as Nancy

Liam Bonner as Sid; Daniela Mack as Nancy

There is a huge search for the boy. A clue is found – a filthy orange blossom wreath. It is brought to the greengrocer’s home, laid to rest in the center of the table, and mourned by all in a masterful piece of music, an elegiac threnody, as if it were the boy himself. Albert’s sudden appearance in his sullied white suit seems almost unwelcome, but returns us to comedy as each person in turn interrogates him. His vice-laden adventures shock everyone but Sid and Nancy. And in conclusion, after everyone leaves, he tells his mother he’s keeping his money, and (horrors!) to mind her own business.

The Los Angeles Opera production, directed by Paul Curran was created for Santa Fe Opera, whose theater is open to the setting sun and other elements of nature. Differences in the set and lighting required for the enclosed Los Angeles theater, enhanced and intensified elements of the production. Subtle changes in the direction added to the comedy. Considering that Britten wrote the work as a chamber opera, it played well in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. Under James Conlon’s direction, the thirteen very individualistic characters on the stage, and the thirteen very precise musicians in the pit evoked the humor and pathos of Albert’s story. Maestro Conlon’s appreciation of the opera — he considers it one of the five great comic operas in the repertory — clarified elements of Britten’s scoring of the work; for example, the differences between the pompous music of the Lady Billows and town’s elite, and the rhythms of Albert and its shop keepers. Conlon also made sure, in word during his pre-performance talk, and in music when on the podium, that his audience heard Britten’s musical jest: the love potion theme from Tristan and Isolde as the rum was poured into Albert’s glass. Why not? This is the drink that will change his life forever.

Richard Bernstein as Superintendent Budd; Alek Shrader as Albert Herring; Janis Kelly as Lady Billows; Jonathan Michie as Mr. Gedge, the Vicar; Robert McPherson as Mr. Upfold, the Mayor; Ronnita Nicole Miller as Florence Pike; Stacey Tappan as Miss Wordsworth

Richard Bernstein as Superintendent Budd; Alek Shrader as Albert Herring; Janis Kelly as Lady Billows; Jonathan Michie as Mr. Gedge, the Vicar; Robert McPherson as Mr. Upfold, the Mayor; Ronnita Nicole Miller as Florence Pike; Stacey Tappan as Miss Wordsworth

Every member of the cast with the exception of Stacey Tappan, Richard Bernstein and Caleb Glickman was making an LA opera debut in his production. Baritone Jonathan Michie, properly fussy as the Vicar, and lyric tenor Alek Shrader, charming as Albert, had appeared in their roles in Santa Fe. Shrader, who has been singing in Europe recently, will debut at the Met later this year. Janis Kelly’s interpretation of the officious Lady Billows left nothing to be desired vocally. She did however lack avoirdupois. One imagines her ladyship to be more generously proportioned. Christine Brewer, a more ample soprano and veteran of the Santa Fe production, sang the last two performances. Mezzo Ronnita Nicole Miller, a singer I have enjoyed in the past, played Florence Pike with great comic timing. Liam Bonner and Daniela Mack as Sid and Nancy, were charmingly carefree lovers, and Jane Bunnell struck the proper notes musically as well as theatrically, as the properly proud and distressed mother who knows a quid when she sees one.

Rarely does one wonder what will happen to the characters in an opera after the final curtain. Most often, all the ones we care about are dead. At the conclusion of Albert Herring, however, every Loxford resident we’ve met will go on living. One can’t help wondering about Albert’s future in the town. Mme Husson’s May King became the sobriquet for the Gisor’s town drunk.

Estelle Gilson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/alh2098.gif image_description=Alek Shrader as Albert Herring, with Daniela Mack as Nancy and Liam Bonner as Sid [Photo by Robert Millard for LA Opera] product=yes product_title=Benjamin Britten: Albert Herring product_by=Lady Billows: Janis Kelly/Christine Brewer; Florence Pike: Ronnita Nicole Miller; Miss Wordsworth, head teacher: Stacey Tappan; Mr. Gedge, the Vicar:Jonathan Michie; Mr. Upfold, the Mayor: Robert McPherson; Police Superintendent Budd: Richard Bernstein; Emmie, Village Child: Erin Sanzero; Cis, Village Child: Jamie-Rose Guarrine; Harry, Village Child: Caleb Glickman; Sid, a butcher’s assistant: Liam Bonner; Albert Herring: Alek Shrader; Nancy, from the Bakery: Daniela Mack; Mrs. Herring, Albert’s Mother: Jane Funnel. Conductor: James Conlon. Director: Paul Curran. Scenic and Costume Designer: Kevin Knight. Lighting Designer: Rick Fisher. product_id=Above: Alek Shrader as Albert Herring, with Daniela Mack as Nancy and Liam Bonner as SidPhotos by Robert Millard for LA Opera

March 19, 2012

Metropolitan Opera National Council Grand Finals Concert

There are a variety of organizations that use different methods to ensure that the next generation of singers is equipped with the experience they need to have a fruitful career in an extremely competitive environment.

Last year, for instance, Juliard’s opera department teamed up with the Met for their first annual co-production. In this case, Smetna’s The Bartered Bride allowed young singers to acquire stage experience as well as to work with big name officials such as James Levine. Other organizations such as Virginia’s Wolf Trap Opera Company dedicate themselves to cultivating new singers by designing entire seasons around them.

Still, the most popular method is the Evergreen Vocal Competition. The Met’s National Council Auditions are a fine example of such a vocal competition. Each March, less than ten finalists, selected from across America, are flown to New York for a concert, hosted by a famous singer and conducted by a well-known conductor. The concert also includes a surprise guest. The event, open to the public, is designed in such a way as to grant participants an invaluable experience while at the same time allowing the audience a sneak peek at upcoming talent. For the five chosen winners, the prize is $15,000 each and the opportunity to join in the Met’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program.

This year, the Grand Finals Concert of the National Council Auditions took place on Sunday, March 18th. It was hosted by bass-baritone Eric Owens, who has been making waves in the role of Albrecht in the Met’s new Robert Lepage Ring cycle. Owens also fulfilled the role of guest artist. The five winners were baritone Anthony Clark Evans, tenor Matthew Grills, mezzo-soprano Margaret Mezzacappa, soprano Janai Brugger, and countertenor Andrey Nemzer. The Metropolitan Opera orchestra was led adroitly by Andrew Davis.

All the participants, regardless of whether they won or lost, should congratulate themselves on making the concert an extremely close competition. In past years, there were clearly defined winners and losers. This wasn’t the case this year. Anthony Clark Evans sang magnificently. Both his arias, “Si puo? Si puo?” from Pagliacci, and “Hai gia vinta la causa,” from Le Nozze di Figaro, proved that despite the lack of such baritones as Sherrill Milnes, true Italianate singing is thankfully not dead. Although, it must be said that his portrayal of the angry yet risible count in the latter case came up a little short.

Despite the extraneous vibrato in her rendition of “O ma lyre immortelle,” from Gounod’s Sappho, Margaret Mezzacappa was able to showcase her warm chest tones. Also, her rendition of “Hence, Iris, hence away!” from Handel’s Semele, showcased her adaptability with baroque ornamentation. Countertenor Andrey Nemzer showcased his ability as a fine-singing actor in Giulio Cesare’s “Domero la tua firezza,” while his interpretation of “Ratmir’s Aria,” from Glinka’s Ruslan and Lyudmila, was an utter joy to hear.

Soprano Janai Brugger, a crowd favorite, is clearly someone to watch. In both her arias, the famous “Depuis le jour,” from Louise, and Die Zauberflote’s “Ach, ich fuhl’s,” demonstrated warm tone and command of legato and ornamentation. The highlight of Matthew Grills’ two performances was the always-popular, “Ah! mes amis!” from La Fille Du Regiment. It was eye-opening; so many tenors go for the champagne aspect of the aria, a la Pavarotti, but his interpretation had a more day-dreamlike quality. His Tonio was definitely thrilled with his amorous success, but was lost in daydreams of love, as opposed to pouring forth ebullient expressions of joy.

The joy of this concert was that so many of those who didn’t win deserved compensations for their performances. Soprano Lauren Snouffer sang excellently in her second aria, “Air du Feu,” from Ravel’s L’Enfant et les Sortileges. However, I was very impressed with her ability to handle the seemingly endless recitative of “Padre, germani, addio!” from Mozart’s Idomeneo. Kevin Ray proved himself versatile, both as a Helden tenor in “Ein Schwert verhiess mir der Vater,” from Walküre, and as an Italianate singer in “Durch die Walder,” from Weber’s Der Freischutz.

Michael Sumuel was a superb actor in Leporello’s catalogue aria, yet he was also moving in Aleko’s cavatina from Rachmaninoff’s Aleko. Despite the concert’s short duration, Andrew Davis and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra can congratulate themselves on splendidly navigating a wide range of repertoire that extended from Handel to John Adams, and along the way, incorporated seldom-performed composers such as Rachmaninoff and Weber. Eric Owens sang splendidly in King Philip’s showpiece, “Ella giammai m’amo,” from Verdi’s Don Carlo. His adept ability at phrasing was especially noteworthy during the repetitions of “Amore, per me non ha” (She never loved me).

Lastly, the audience was blessed with an appearance by Peter Gelb as Eric Owens was getting ready to sing. As he spoke, he reminded the audience that even if a certain singer didn’t win, it did not mean that they would not be seen again on the Metropolitan Opera stage. After all, it is important to keep in mind that such singers as Richard Tucker, Patricia Racette, and Joyce DiDonato did not win. Still, I am happy to say that all of them deserved to be there, regardless of whether or not they won. I look forward to seeing them all on the Met stage again.

Greg Moomjy

image=http://www.operatoday.com/2012Winners.gif image_description=Left to Right: 2012 National Council Audition Winners Andrey Nemzer, Margaret Mezzacappa, Janai Brugger, Matthew Grills, and Anthony Clark Evans. [Photo by Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera] product=yes product_title=Metropolitan Opera National Council Grand Finals Concert product_by=By Greg Moomjy product_id=Above: Left to Right: 2012 National Council Audition Winners Andrey Nemzer, Margaret Mezzacappa, Janai Brugger, Matthew Grills, and Anthony Clark Evans. [Photo by Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera]Levine conducts at the Metropolitan Opera: 1978 to 2006

Drama aplenty may occur within the Metropolitan’s offices or rehearsal rooms, but the only drama presented to the public stays within the confines of the stage action dictated by opera librettos. Appointed to the title of Music Director in 1976, Levine can look back on decades at the Metropolitan that stand as a singular achievement. That achievement will not be threatened by the sad turn that Levine’s ongoing health problems took last year, which forced him to withdraw from the rest of the current season and for all scheduled performances in the 2012-2013 season as well. For now, he retains the title of Music Director. The time is coming, however, when the Metropolitan Opera will have to transition to a new musical and artistic leader.

Whenever that may happen, Levine’s legacy will remain available for viewing, as not long into his tenure the Metropolitan began its famous “Live from Lincoln Center” telecasts, most of which are now available on DVD. And of course Peter Gelb, the current General Manager, initiated the Metropolitan Opera “HD Live” series of movie casts in 2006, with Levine conducting the premiere performance of an English adaptation of Mozart’s The Magic Flute. Viewing two of the late 1970’s telecasts (Verdi's Otello and the reliable Cav/Pag pairing), then a late 1990s’ performance of Andrea Chénier, and ending with that 2006 Magic Flute, one can see the effects of time on Levine’s physical self, but the aesthetic impression is of an ageless artistic entity, disciplined and steadfast in adherence to core musical values.

The Otello DVD alone could serve to establish the reasons for Levine’s artistic reputation. The orchestral performance powers ahead but retains tension in the quieter moments. Levine’s simultaneously manages to support the three leads, all great singers but none without flaws. The titanic Otello of Jon Vickers touches greatness, even though the tenor on that evening has occasional bouts with hoarseness. Cornell MacNeil, the Iago, finds a good match between the malevolent character and the less attractive — to avoid saying “ugly” — side of his vocal production. Renata Scotto is in fine voice as Desdemona, with only brief premonitions of the barbed-wire tightness that her top would exhibit too often thereafter. All flaws fall away in the performance’s best moments, including a devastating act four.

Considering his reputation today for tackiness and ostentation, some viewers may be surprised by the atmospheric, restrained settings director Franco Zefferelli provided. This is work that Zefferelli can be proud of - resolutely traditional but dynamic and dramatically concise. Those who followed the Metropolitan Opera in the late decades of the 20th century will be thrilled to hear Peter Allen announce the casts at the curtain calls after each act. Sony Music, which distributes these DVDs (except for the Giordano, which comes from Decca) for the Metropolitan Opera, provides no special features and only rudimentary booklets.

Zefferelli also produced the pairing of Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana and Leoncavallo's Pagliacci, also recorded in 1978. Almost as restrained in effect as the Otello, these operas benefit from Zefferelli’s eye for settings that can serve the larger scenes but also focus in on smaller spaces for the more intimate moments. The Cav set has the town square one would expect, but the Pagliacci somewhat strangely seems to be set in some sort of desert. The arid landscape and looming sky of the backdrop bring a sense of a dark dream to the action. As transferred to DVD, both this performance and that of the Otello suffer from murky, dark visuals.

In Italian repertory, Levine’s impeccable control may strike some as fussiness, but both these scores benefit greatly from the attention to detail and apt tempo choices. Plácido Domingo takes both leads. Despite his handsome presence, he doesn’t project Turiddu’s hyper masculinity all that well nor Canio’s borderline psychosis. Domingo reaches a higher level in the confrontation with the fierce Santuzza of Tatiana Troyanos. The rest of the Cav cast works at a lower level, especially the generic Alfio of Vern Shinall and the cheesy Lola of Isola Jones (who does, one must admit, smashingly look the part).

In the Pag, Domingo works with the affecting Nedda of Teresa Stratas, who should have fought her director when he asked her to dance and sing for most of her solo scene, affecting her breath support. Sherill Milnes looms ominously as Tonio (and of course loses his final line to the tenor). The dull Silvio of Allan Monk does drain away some of the show’s impact.

Moving ahead almost two decades for the Andrea Chénier of Giordano, Levine in 1997 may physically show the effects of the advancing years, but his leadership of the orchestra in a score than can come across as overblown and even pedestrian in places retains the positive attributes of the earlier performances. Here he has Luciano Pavarotti as his tenor lead, beefing up his sound fairly successfully and caught in relatively good shape. The TV director’s close-ups do the tenor and his heavy make-up no favors. Maria Guleghina’s Maddalena won’t please those who love the great Italian sopranos who have taken on this role; Guleghina tends to let the sheer physical force of her voice do a lot of the work, and an aria like “La momma morta” could use more delicacy. Juan Pons does his expected good work as Carlo, and the opera still manages to build up a good head of steam for its roof-rattling closing duet.

The production of Nicolas Joël shows one of the Metropolitan’s early efforts to update its production style. Joël melds some traditional tableaus with prop abstractions, especially in the suitably ominous finale.

By 2006, the Metropolitan had started not only to invite some of Europe’s top directors but also to reach out to top directors of “straight” American theater. Julie Taymor’s The Magic Flute, featuring her trademark puppetry and clever stage effects, was such a hit that the Met commissioned an English adaptation to a slightly abridged score, as a “Magic Flute for families". It still runs almost two hours, but it’s a fast, fun time, and Levine conducts Mozart with a lovely blend of taste and energy. The cast looks great, but none of them - with one possible exception - really exhibits the sheer atavistic star power that the Metropolitan Opera audiences have come to expect. Matthew Polenzani is a pleasant but anodyne Tamino, and his Pamina, Ying Huang, lacks personality. Taymor gives the Queen of the Night a spectacular costume, which helps Erika Miklósa make more of an impression that she otherwise might. Nathan Gunn clowns it up as Papageno, but his effort shows. Only René Pape commands the screen, but his accented English seems to be slightly handicapping his usual power. The English translation, by J. D. McClatchy, will be most successful for those who like cutesy puns and comic anachronisms.

Fans of Levine will want all of these; for those who may respect him but don’t necessarily count themselves as collectors, the Otello would be the indispensable selection.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sony_Otello.gif image_description=Sony 791012 [DVD] product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Otello product_by=Otello: Jon Vickers; Desdemona: Renata Scotto; Iago: Cornell MacNeil. Metropolitan Opera. Conductor: James Levine. product_id=Sony 791012 [DVD] price=$17.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=595627&album_group=2 Conductor: James Levine The Metropolitan Opera and Orchestra Otello Music: Giuseppe Verdi Libretto: Arrigo Boito Otello: Jon Vickers Desdemona: Renata Scotto Iago: Cornell MacNeil September 25, 1978 performance Sony Music DVD 88697 91012 9 Cavalleria Rusticana/Pagliacci Cavalleria Rusticana Music: Pietro Mascagni Libretto: G. Targioni-Tozzetti and G. Menasci Santuzza: Tatiana Troyanos Turiddu: Plácido Domingo Pagliacci Music and libretto: Ruggero Leoncavallo Tonio: Sherill Milnes Canio: Plácido Domingo Nedda: Teresa Stratas April 5, 1978 performance Sony Music DVD 88697 91008 9 Andrea Chénier Music: Umberto Giordano Libretto: Luigi Illica Gérard: Juan Pons Maddalena: Maria Guleghina Chénier: Luciano Pavarotti 1997 performance Decca DVD B0016111-09 The Magic Flute Music: Wolfgang Mozart Libretto: Emanuel Schikaneder English adaptation: J. D. McClatchy Tamino: Matthew Polenzani Papageno: Nathan Gunn Queen of the Night: Erika Miklósa Pamina: Ying Huang Sarastro: René Pape December 2006 performance Sony Music DVD 88697 91013 9

Don Pasquale, San Diego

So here it is once again at San Diego Opera in its “spaghetti western” guise — the David Gately production that the opera company premiered in 2002. Happily for the opera company’s patrons it signals the end of their mourning period for poor, demented Salome and for the unfortunate crew in Moby-Dick. There’s nothing but rollicking operatic fun ahead for them.

Danielle de Niese as Norina

Danielle de Niese as Norina

Not having previously seen this production, the Western “shtick” promotions for the work - ladies in corsets and cowboys in bubble baths — stirred old puritanical impulses and elicited my deepest fears. Of course transpositions of time and place are common in opera productions. In fact it happened to this very opera, Don Pasquale, just a few years after its 1843 premiere at the Italian Theater in Paris. Donizetti and his librettist Giovanni Ruffini had set the work in contemporary time. “But,” says the old Grove Dictionary of Music, “the singers and audiences considered there was a little absurdity in prima donna, baritone and basso wearing the dress of every day life; and it was usual for the sake of picturesqueness in costume to put back the time of the incidents to the 18th century.”

I needn’t have worried about sinful excess. As in that early Don Pasquale, picturesqueness in costume and sets is primarily what this clever production is about. Six-guns and horses notwithstanding, the most admirable element of Gately’s production is the restraint he showed in not allowing wild West gags and horseplay to overpower the essential commedia dell’ arte formula at the heart of this opera buffa.

Charles Castronovo as Ernesto

Charles Castronovo as Ernesto