October 28, 2012

La bohème on Tour, WNO, Oxford

As such, larger companies tend to err on the side of caution when creating new productions. Puccini’s La bohème is quite tightly constructed, and it doesn’t take easily to deconstruction or redefinition; the most directors tend to do is to move the period of the action from the mid-1800’s of the original. Annabel Arden’s new production for Welsh National Opera concentrates on telling the story in a clear, direct manner and illuminating the relationships between the characters with telling details. The production was new in June 2012, but WNO has revived it for their autumn tour; as a number of the original cast are in this revival it feels more like an extension of the original run.

I caught it on Thursday 25 October at the New Theatre, in Oxford. The New Theatre was originally a 1930’s cinema, and though the theatre takes large scale musical shows, there seems to be no pit, The WNO orchestra played from the floor of the stalls, which did seem to affect balance slightly though conductor Simon Phillippo did his best to keep the orchestra down and the singers were never overwhelmed. Phillippo is a WNO staff conductor who has taken over from Carlo Rizzi for this revival.

Arden and her designer Stephen Brimson Lewis have set the opera in the Paris of the early 20th century. These Bohemians are some of the young artists who flocked to Paris in these years, Les Annees Folles. The advantage of this is that we no longer have to think of the men as students. Though WNO’s singers were all young, this relieved the men of some of the more embarrassing antics which can mar acts 1 and 3. Here the men were skittish, but believable.

The setting for act 1 was rather cool. The set was a fixed structure, with a ramp at the back and doors on from the sides, all in metal. For act 1 these were disguised by translucent drops which depicted a Parisian roof-scape (in white), along with projections to add atmosphere. The flat had no walls, which combined with the translucent nature of the drops, meant that Arden could create some magical effects. The moment when Marcello (David Kempster), Colline (Piotr Lempa) and Schaunard (Daniel Grice) appear in the street and shout up to Rodolfo (Alex Vicens) and Mimi (Giselle Allen) was magical.

For act 2, the entire setting was in the open air, with waiters coming and going through the big metal doors at the side of stage. Projections on the back enlivened things, adding detail to what could have been a stark setting. I felt that Arden’s handling of the crowds in the busier parts of the scene seemed a little stilted, as if she was feeling constrained by the need to make a busy stage out of not quite enough people. She relied quite heavily on the excellent childrens chorus and on Michael Clifton-Thompson’s Parpignal (in a monkey mask!) to create movement. But from the moment when Musetta (Kate Valentine) struck up the waltz song, it was spell-binding. It seemed that Arden was best at illuminating individual details in the opera.

Michael Clifton-Thompson as Parpignol with cast

Michael Clifton-Thompson as Parpignol with cast

During this scene, the playing of the time period was, I think, a little heavy handed with one woman dressed as a man, another looking like Gertrude Stein or Frida Kahlo and two men in drag. Perhaps Paris was really like this at that time, but it felt a bit over done.

For act 3 the set was reduced to its simple basics, forming a bleak cold backdrop to the action. In the final act, though we were back in the flat, there were no drops of streetscapes, everything was bleaker, cooler, simpler; a rather elegant use of naturalism and stylisation to aid the story telling.

Spanish tenor Alex Vicens was in the original production but his Mimi, Giselle Allen, was new for this revival. Vicens has an appealing stage manner, his Rodolfo was endearing and involving in ways that do not always happen. Vicens had a tendency to semaphore with his hands, a habit that the director had clearly not been able to break him of, but he conveyed Rodolfo’s charm. You could understand why Mimi might fall for him. It has to be admitted that Vicens voice was a bit dry at the top, so that the famous moments in act 1 did not flower, quite the way they should have done. But Vicens was ardent and intense, shaping the music nicely.

Giselle Allen did not seem entirely comfortable in act 1 either. She and Vicens generated real tension and real attraction during their scene, the action was dramatically believable but musically it did not quite blossom. In fact, their strongest moment musically was act 3; this seemed to suit Allen’s voice best and their duet was heart breaking both dramatically and musically. I did wonder whether Allen’s repertoire might suggest her moving in a rather more dramatic direction. She is not the most Italianate of singers, but applied real intelligence to the role and was always a delight dramatically.

The strength of Arden’s production was in the little naturalistic details which she illuminated the action. In the wrong hands this would seem fussy, but here it helped made sense of the plot. And the act 4 death scene for Mimi was one of the most moving, least stagey that I have ever come across; a testament both to Arden and to Vicens and Allen.

Of course, this attention to detail helped make the most of the role of the other Bohemians. David Kempster’s Marcello came over as the lynchpin of the action. Kempster and Arden made the role of Marcello seem stronger and more important than is sometimes the case. The on-off romance of Marcello with Kate Valentine’s Musetta was a serious counter-poise to Rodolfo and Mimi rather than a side show. Valentine’s account of Musetta’s waltz in act 2 was a delight, but Arden developed it into a real dramatic moment as well. Kempster was serious and intense and you really felt for him.

One of the virtues of the production was that, at the end you were aware of the different characters reactions to Mimi’s death and came away with the feeling that none of their lives would quite be the same again.

Piotr Lempa was slightly dry voiced as Colline but his aria to his coat was touching. Daniel Grice had lovely swagger as Schaunard, complete with long hair and velvet suit. For once the hi-jinks in act 4 didn’t feel forced.

Martin Lloyd made a gross Alcindoro, perhaps too highly caricatured. Laurence Cole and Stephen Wells were the customs officials in act 3.

Simon Phillippo conducted with care and efficiency. His speeds kept things moving, without seeming rushed. But occasionally I wanted him to stretch things out, to dwell a little more. This is a case of styles of rubato, enjoying things without dwelling on them too much. But Phillippo drew fine playing from his orchestra and supported the singers admirably.

Arden has concentrated on the details in Puccini’s opera, telling the story with clarity and applying directorial gloss with subtlety. Perhaps there is scope for an edgier reading of the opera, but that would then not be the popular vehicle which the WNO needs for touring. Because this was popular, the house applauded warmly and I overheard many discussions about the opera as I walked to the station.

Robert Hugill

Click here for a photo gallery, together with video and audio presentations of this production.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Boheme_WNO_2012_06.gif

image_description=Kate Valentine as Musetta, Gary Griffiths as Schaunard and David Soar as Colline [Photo by Catherine Ashmore courtesy of Welsh National Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Giacomo Puccini : La bohème

product_by=Marcello: David Kempster; Rodolfo: Alex Vicens; Colline: Piotr Lempa; Schaunard: Daniel Grice; Benoit: Howard Kirk; Mimi: Giselle Allen; Parpignol: Michael Clifton-Thompson; Alcindoro: Martin Lloyd; Musetta: Kate Valentine; Customs Official: Laurence Cole; Customs Sergeant: Stephen Wells. Chorus and Orchestra of Welsh National Opera. Conductor: Simon Phillippo. Director: Annabel Arden. Designer: Stephen Brimson Lewis.

Thursday, October 25 2012, New Theatre, Oxford

product_id=Above: Kate Valentine as Musetta, Gary Griffiths as Schaunard and David Soar as Colline

Photos by Catherine Ashmore courtesy of Welsh National Opera

October 27, 2012

A New Production of Elektra at Lyric Opera of Chicago

Christine Goerke, in her debut with this company, delivered a relentless yet at the same time lyrical performance, one in which Elektra’s early delusions are transformed by the character’s determination to see her plan for revenge ultimately realized. Her sister Chrysothemis is sung by soprano Emily Magee, their mother Klytmämnestra by mezzo-soprano Jill Grove, Orest by bass-baritone Alan Held, and Aegisth by tenor Roger Honeywell. Sir Andrew Davis conducts these performances which open Lyric Opera’s fifty-eighth season.

At the sound of the distinctive opening chords the stage depicts a servants’ courtyard at center with, at left, a stairwell leading up to a stone edifice tilted menacingly. The doorway at the top of the stairwell emits a reddish glow. During the opening dialogue of the maids Elektra is visible from time to time caught up in gestures of emotional distress coupled with sounds akin to laughter. In her defense of Elektra’s nobility of spirit the fifth maid, sung and declaimed here with admirable attention to diction by Tracy Cantin, communicates further the tension that accompanies Elektra’s dilemma. Once the maids have retreated indoors Elektra occupies the stage alone and delivers her opening monologue. From the start Ms. Goerke uses her dramatic and vocal powers to portray a character obsessed with the dimensions of past injustice and future vengeance. Goerke’s calls to her father Agamemnon, coupled with a narration of his slaughter, are delivered with an impressive and secure range. In her erratic memory this Elektra intones the dramatic low pitches of “Sie schlugen dich im Bade tot” [“They murdered you in the bath”] in flashes with tender appeals phrased piano for Agamemnon in spirit again to reveal himself [“Zeig dich deinem Kind” (“Appear before your child”)]. As the orchestra swells gradually toward the close of Elektra’s extended monologue Goerke’s voice rises in believable excitement at the thought of a triumphal dance. In her plan for sibling cooperation she envisions the “Purpurgezelte” [“pavilions of purple”] that will be erected upon the successful revenge taken for Agamemnon’s death. Here Goerke’s forte notes matched the orchestral power and were integrated into a seamless portrayal of distress and vision. The final appeal to “Agamemnon,” just as at the start of the scene, suggests here through audible symmetry a barely contained simmer of emotional fury which is still to be unleashed.

Jill Grove [Photo by Dario Acosta courtesy of IMG Artists]

Jill Grove [Photo by Dario Acosta courtesy of IMG Artists]

At the entrance of Chrysothemis in the following scene Goerke injects a palpable scorn into her greeting, “Was willst du, Tochter meiner Mutter?” [“What do you seek, daughter of my mother?”]. In their interaction and frenzied discussion of Klytmämnestra’s plan to imprison Elektra, Ms. Magee creates an emotionally complex figure. Her Chrysothemis attempts to warn Elektra yet also unleashes lyrical pleas to be allowed to live as a woman and to ignore the past. Once her feelings become charged to the point of declaring, “Viel lieber tot als leben und nicht leben,” [“So much better to be dead rather than to live and not live”], Magee’s yearning vocal line rises exquisitely in contrast to Elektra’s present starkness.

In the following scene Chrysothemis runs off to allow the inevitable confrontation between Klytmämnestra and Elektra. Jill Grove shows herself to be an equal partner in this vocal and dramatic confrontation, as her Klytmämnestra derides the “paralysis” [“gelähmt sein”] of her own strength when confronted by her daughter. In her address to Elektra the rising notes on “Habt ihr gehört? Habt ihr verstanden?” [“Did you hear? Did you understand?”] flow into a solid and chilling contralto pitch on “Ich will nicht mehr hören” [“I do not wish to hear any more”], both establishing the dread that she herself feels and can likewise inspire in others. The revelation that a sacrifice must be made to halt Klytmämnestra’s nightmares leads to Elektra’s triumphant announcement that the Queen herself must die as this “Opfer.” Grove uses appropriately melodramatic gestures to register the Queen’s horror until a servant provides her with the information that her feared son Orest has died before returning to the court. As she regains her composure Grove’s Klytmämnestra retreats with her retinue while delivering exultant cries of relief.

When Chrysothemis announces this very information to Elektra in their following exchange Goerke’s repetition of “Es ist nicht wahr” [“It is not true”] communicates her frustration in acidic tones. Elektra reveals to Chrysothemis that she has hidden the axe used in Agamemnon’s murder and the sisters must now wield it in lieu of Orest. The accompanying duet between Goerke and Magee stands out as a lyrical showpiece of this production as their voices blend and move apart in rhythmic succession. At the ultimate refusal of Chrysothemis to participate in the vengeance and her flight into the house, Elektra is left in grim resolve to dig for the buried axe herself.

As Elektra continues to search for the hidden weapon, a shadow appears on the back and side walls of the stage. The stranger [“Was willst du, fremder Mensch?” (“What do you seek, stranger?”)] identifies himself as a former companion of Orest who has come to deliver personally the news of his death to the Queen. In the scene of recognition Orest is able first to appreciate the identity of his sister through conversation despite her degraded state. Mr. Held portrays the stranger convincingly with questioning tones of respect, until the moment of recognition when his resonant voice blooms into the role of the heroic brother with a determined mission. In like manner, Goerke’s dramatic cry of recognition at the identification of her brother is softened as she sings piano with distended notes of relief and love. Despite their ecstatic reunion they are reminded of the task as Orest enters the palace. Only Elektra’s despair at having forgotten to provide Orest with the axe breaks the awful tension sustained in the orchestral accompaniment. The screams of Klytmämnestra are followed soon by the arrival in the courtyard of a drunken Aegisth. Elektra assures him passage into the house and to the same fate as that met by her mother. At the appearance of Chrysothemis in the courtyard and her joyous declaration of “Gut sind die Götter” [“The gods are benevolent”], Elektra begins her dance of celebration predicted earlier in her dramatic monologue. The continued emotional strain has, however, snapped and Elektra falls down lifeless to the horror of her sister. The final cries by Chrysothemis of “Orest!” bring about the crashing chords of resolution. The production of Elektra by Lyric Opera of Chicago with its superb cast as well as musical leadership by Sir Andrew Davis will remain as a testament to the innovation and greatness of Strauss’s music.

Salvatore Calomino

Click here for cast and production information.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Christine_Goerke_-_Photo_by_Christian_Steiner_2c_%282%29.png image_description=Christine Goerke [Photo by Christian Steiner courtesy of IMG Artists] product=yes product_title=A New Production of Elektra at Lyric Opera of Chicago product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino product_id=Above: Christine Goerke [Photo by Christian Steiner courtesy of IMG Artists]Amsterdam’s Skin Show

This was amply evidenced by the striking new production of Written on Skin, from composer George Benjamin and librettist Martin Crimp. There is nothing “easy” about this enigmatic work, and yet it is richly rewarding for those who are willing to revel in its intriguing complexities.

The piece is based on a 12th century Occitan legend (oh that again!) but is framed by 21st-century “spiritual” sensibilities as it considers the dynamics of co-dependent personal relationships, life-changing decisions, and mind-altering entanglements. The slender plot concerns a ruthless, rich lord who brutally controls his childishly obedient young wife Agnes. The brute commissions an artist (The Boy) who he welcomes into his house to complete a book of “illuminations” (text and illustrations on parchment = skin). The despot wishes to have his political prowess and domestic “bliss” immortalized in flattering terms.

Instead, the creation of the book incites his wife’s rebellion, which manifests itself in her seduction of the artist. The wife then exploits her intimacy with the visitor and coerces his alteration of the book’s content to expose her husband with truthful revelations of his despicable character and deplorable misdeeds. When the artist candidly (foolishly) documents his passionate affair with the wife, the cuckold stabs him, cuts out his heart and serves it to his unsuspecting wife for dinner. When she is informed of what she is ingesting, she defiantly keeps eating and praising its flavorful taste.

As the husband makes to stab his wife, she runs up the tower and hurls herself off of it, remaining suspended in mid-drop, hovering in one final “illustration” that leaves her between heaven and earth. This slowly unfolding, nay churning of the emotional sub-text makes Pelléas seem a model of cogent expeditiousness. Factor in a trio of 21st century “angels” who periodically offer such contemporary commentary as “erase the Saturday car-park from the market place,” and you have a richly enigmatic, Pinter-esque concoction. And perhaps its vague juxtaposition of images is its greatest asset since it not only commands our rapt attention, but encourages us to speculate. I was riveted by the performance from first to last.

This was owing in no small part to Mr. Benjamin’s hauntingly beautiful score, with its layers of orchestral colors and unusually grateful vocal writing. The composer also presided on the podium, eliciting thrilling results from the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra. The group met every challenge of this opaque work’s masterful orchestrations. Although there are many influences evident in the musical results (Britten, Messiaen, Berg, among others), Benjamin has found his own style, and his own palette of effects, one that includes vocal lines meant to please the ear, and not just the intellect, as in many another contemporary opera.

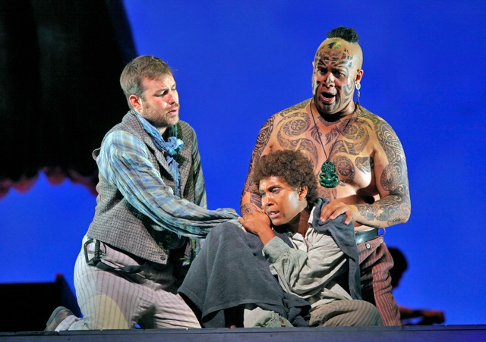

Christopher Purves as The Protector, Bejun Mehta as Boy and Elin Rombo as Agnès

Christopher Purves as The Protector, Bejun Mehta as Boy and Elin Rombo as Agnès

The singers were uniformly first-rate, starting with Christopher Purves who scored a tour-de-force with his nuanced impersonation of the Protector. Mr. Purves is possessed of a powerful, incisive bass-baritone that was supremely well-controlled. Even when his character was called upon to snarl or bark musical statements, Mr. Purves kept his instrument focused and refined. He was also capable of meaningful introspective musings, and colored his voice with menace for bone-chilling, sinister insinuations.

Bejun Mehta proves yet again why he is numbered among the top echelon of current day counter-tenors. From his first long sustained note that slowly built in volume, he regaled us with beautifully modulated singing that had all the richness of a resonant viola. Mr. Mehta not only has uncommonly fine diction, but also has an unusually wide range of colors in his warmly ingratiating instrument. Bejun found a perfectly judged obscurity as the Boy, with his physical abandon Flower-Child-like in its naiveté. After his demise, the Boy returns as an Angel, an apt metaphor since Mehta sang like an angel all night long.

Lovely Elin Rombo scored all the right dramatic beats as the dominated wife. Her reliable, gleaming soprano was used with great skill and absolute service to the writing, and Ms. Rombo was equally effective whether whispering hushed exchanges, wringing out every bit of pathos from arching flights above the staff, or forcefully propositioning her pliable house guest. Her cool, even vocal delivery after she learns what (or rather whom) she is ‘eating’ was a model of control.

Victoria Simmonds was a firm-voiced Marie (Agnes’s sister) and she made a substantial contribution to the ensemble as Angel 2. Allan Clayton was quite fine as Marie’s husband John, and his suave tenor made a memorable impression as Angel 3. Although not credited, the concentrated work of several added supers was important to the milieu of the concept.

And the production’s “concept” provided quite a massive, spectacular architectural setting that was at once solidly realistic, and nebulously spiritual. The brilliance of the visual realization was that it managed to suggest a green room, wings, a fly loft and stage performance space while at the same time suggesting limbo, heaven, and most certainly, hell. A sturdy two story structure, the ground floor left contained a period drawing room out of some austere Dutch Masters painting flanked far left by a moody grove of trees. Through the room’s stage right door was a brilliantly white “green” room, or waiting room, or dressing room, or…well your take is as good as mine.

Bejun Mehta as Angel 1, Victoria Simmonds as Angel 2 and Allan Clayton as Angel 3

Bejun Mehta as Angel 1, Victoria Simmonds as Angel 2 and Allan Clayton as Angel 3

Upstairs, the trees have burrowed upward through the left floor, a dated ante room center has a window that opens on the great outdoors, and a white ‘office’ on right suggests a corporate nerve center as easily as it implies ‘heaven.’ The married pair are clad in time neutral interpretations of medieval garb while the Angels trade off contemporary business wear for their period attire as required. Vicki Mortimer’s thought-provoking set and wholly appropriate costumes were masterfully lit by Jon Clark, whose brooding color choices were integrated into a lighting design which perfectly balanced tight specialty spots, moody washes, looming shadows, and pointed brilliance.

Best of all, director Katie Mitchell was able to knit together the many (deliberately) disparate dramatic conventions into a convincing, unified whole. Mr. Crimp’s libretto is an especial challenge since characters often speak of themselves in the third person, and recite stage directions even as they perform them. It is to Ms. Mitchell’s great credit that far from distancing us from the soul of the tale, her stagecraft intrigues us, envelopes us, consumes us.

When characters are emotionally spent at the end of selected scenes, they shrink or collapse into the waiting arms of the omnipresent stage hands/angels/supers, to be comforted even as they are moved around like another stage property to be re-set in its proper place. I cannot remember the last time I have been so engaged by such overt theatricality from both writers and producers. Katie has also managed to draw incisive, highly charged character relationships from her cast, and the whole is meticulously paced, blocked, and coached.

I shall not soon forget the coup de theatre at opera’s end as the misused wife flees her murderous spouse up a white staircase extending into the loft, running to leap to her death, pursued by the rest of the cast, all in excruciatingly. Slow. Motion. Ironically, this is one of the few instances where the production fails the script since it calls for her to leap but be suspended mid-air, but then who has ever seen Brűnnhilde ride Grane onto the pyre? (So there.) Never you mind, it is spell-binding nonetheless.

Written on Skin was that all-too-rare treat, a compelling new piece of writing that spoke with its own affecting voice, performed by a peerless cast and band, matched by an enthralling stage production that served to make for a potent evening of musical drama. Here’s wishing it many more successful first nights and an enduring presence in the repertoire.

James Sohre

Production

The Protector: Christopher Purves; Agnes: Elin Rombo; Angel 1/Boy: Bejun Mehta; Angel 2/Marie: Victoria Simmonds; Angel 3/John: Allan Clayton; Composer: George Benjamin; Libretto: Martin Crimp; Conductor: George Benjamin; Director: Katie Mitchell; Set and Costume Design Vicki Mortimer; Lighting Design: Jon Clark; Netherland Chamber Orchestra

Co-production with Festival Aix-en-Provence, Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Teatro dei Maggio Musicale Florence, and Théâtre du Capitole Toulouse

image=http://www.operatoday.com/writtenonskin0187.png

image_description=Bejun Mehta as Boy and Christopher Purves as The Protector [Photo by Ruth Walz courtesy of De Nederlandse Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Amsterdam’s Skin Show

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Bejun Mehta as Boy and Christopher Purves as The Protector

Photos by Ruth Walz courtesy of De Nederlandse Opera

Lohengrin in San Francisco

Lohengrin like never before. It was an orgy of orchestral colors, an adventure in sonic discovery, the absolute summit of virtuosic orchestral delivery. Maestro Nicola Luisotti attacked and conquered Lohengrin.

There. That’s done. What’s left now that it’s all over?

No longer mythic Germanic lore, this tale seemed to be an episode from, say, Ceausescu’s already mythic Romania, where books were torn from library shelves to burn to make electricity to light the libraries. Though in the emptied library in which all this took magic took place there was not enough juice to illuminate all the grandiose (Romanian socialist moderne) light sources. Well, save in the last scene when Lohengrin finally was going to save the masses. But bowed out.

The masses were magnificent socialists, eighty mighty workers (plus a few sword and standard bearers) who whispered in shimmering sounds and roared in full, transparent tones. But with such idealistic and obviously pleasurable glory in their sonority, and willing unity in their regimentation (yes, this multitude of virtuosic choristers was happily organized in lines and blocks) that they hardly needed to be saved from such perfection — to cede such artistry to mere Western materialism would be tragic indeed.

Meanwhile Icelandic bass Kristinn Sigmundsson in socialist general regalia was instructed to walk downstage center and be the embattled king Heinrich. Mr. Sigmundsson, once an estimable artist, here was perfect as crumbling, ineffective power. Baritone Brian Mulligan, a San Francisco Opera fixture, was Heinrich’s prissy acolyte, a welcomed vocal contrast to his superior. Mr. Mulligan is a richly voiced singer who complemented the maestro’s musical textures while overwhelming the import of this mere herald.

American tenor Brandon Jovanovich was the Lohengrin, a role debut. He apparently has a new voice teacher as the perfectly reasonable tenor we heard a few years ago as Luigi in Il Tabarro has been transformed into a trumpet. While he has not yet mastered the subtlety of tone of a fine trumpeter he does have a surprising variety of volume if not color, though his first and last words in the opera were delivered in a tentative half voice that was cause for concern. Even with its moments of real beauty the sharpness of his tone worked with the costuming of this production to make him look and sound gawky. Though this maybe helped establish the assumed caricatural intent of this conception of Lohengrin.

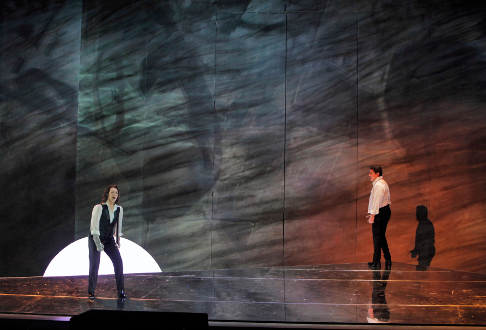

Brandon Jovanovich as Lohengrin and Camilla Nylund as Elsa von Brabant

Brandon Jovanovich as Lohengrin and Camilla Nylund as Elsa von Brabant

Of the five principals the Elsa of Finnish soprano Camilla Nylund realized the most successful character. Elsa herself is a lost soul, and Mlle. Nylund though looking like a well-kept Romanian apparatchik had no idea how to be one. The purity of her voice and the innocence of her presence served her well, though in the bigger moments her voice could not ride the the maestro’s mighty crests, as could, for example, the out-of-scale voice of Mr. Jovanovich.

German bass-baritone Gerd Grochowski seemed over parted as Telramund, diminishing the stature of evil in Wagner’s struggle to overcome baser levels of humanity. Mr. Grochowski’s fine baritone and interesting persona are more at home in roles that are more lyric and perhaps more complex psychologically. He lacks the inherent vocal color and physical force to personify an uncontrolled thirst for power, willing to say or do anything to get it. Reduced to a whimpering wimp in this production there was little for all those arcane powers of the Holy Grail to overcome.

Joining her homeless husband as Ortrud, the bag lady was German mezzo Petra Lang. Mme. Lang did not seem to be in good voice, her final curse thinly delivered, again underlining the opera’s need to endow evil with enough stature to be worth overcoming. As it was the famous pollution of socialist industry managed to create quite atmospheric lighting for Ortrud’s scenes brainwashing Telramund and deceiving Elsa, convincingly delivered by Mme. Lang.

A scene from Act I

A scene from Act I

The production by British director Daniel Slater and British designer Robert Innes Hopkins is from Geneva (2008) and was already in close-by Houston (2009). It apparently has the intention to remove all magic from Wagner’s tale where swans ferry supernatural knights back and forth from an imaginary mountain. The musical moments for these arrivals and departures are truly momentous, even in ordinary circumstances, but here the workers and apparatchiks stare always forward only to discover and not seem to care that the bus terminal was behind them.

The production could not support the musical values imposed by Mo. Luisotti. Magic, and a lot of it was sorely needed to give place and meaning to this mountain of sound.

Michael Milenski

Program

Lohengrin: Brandon Jovanovich; Elsa von Brabant: Camilla Nylund; Ortrud: Petra Lang; Friedrich von Telramund: Gerd Grochowski; Heinrich der Vogler: Kristinn Sigmundsson; King’s Herald: Brian Mulligan. San Francisco Opera Chorus and Orchestra. Conductor: Nicola Luisotti; Stage Director: Daniel Slater; Production Designer: Robert Innes Hopkins; Lighting Designer: Simon Mills. War Memorial Opera House, October 24, 2012.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/10--Lohengrin.png

image_description=Petra Lang as Ortrud and Gerd Grochowski as Friedrich von Telramund [Photo by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Lohengrin in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Petra Lang as Ortrud and Gerd Grochowski as Friedrich von Telramund

Photos by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera

October 24, 2012

Parsifal bears its own Cross

As such, it is no wonder that it has yielded some of Germany’s most seminal and controversial stagings of the past decade. The late Christoph Schlingensief brought giant, rotting bunnies to Bayreuth in 2004, the original stage to which Wagner consecrated the work in 1882—leaving New Yorker critic Alex Ross “ready to hurl,” as he so candidly put it—while Stefan Herheim’s 2008 deconstructionist production for the ‘Green Hill’ becomes an allegory for German history, traveling through the world wars of the twentieth century and into the bureaucratic Federal Republic of Bonn.

Philipp Stötzl, in his new staging for the Deutsche Oper (seen at its premiere on October 21), has opted for a more conventional yet equally radical concept that foregrounds explicitly Christian imagery. The director, who worked in film before making several successful forays into opera, casts the story as a series of tableaux vivants set in a rocky mountainous region that could easily be Nazareth (sets co-designed with Conrad Moritz Reinhardt). The curtains open during the overture to a realist portrait of Jesus on the cross, surrounded by nomads and a Roman soldier. Self-flogging and fake blood abound as the procession continues, with Amfortas carrying his own cross in the final scene.

In a genius stroke that counters the lengthy nature of the opening act, Gurnemanz’s narrations about Amfortas’ seduction by Kundry and the Last Supper are depicted on the rocks in flashbacks. Parsifal, appearing in a modern black suit and tie, descends upon the scene as if walking across a film set, an effect which is accentuated by conspicuous fluorescent lighting on all sides (Ulrich Niepel). Klingsor’s magic garden is fashioned as a Mayan cave of sorts, with Native American-inspired garb for the warlock and semi-nude floral get-ups for the flower maidens (costumes by Kathi Maurer), while the final act returns to a rocky, post-apocalyptic no man’s last featuring modern-day dress and a single streetlamp under which Parsifal is anointed by a blindly fervent crowd.

Matti Salminen as Gurnemanz and Klaus Florian Vogt as Parsifal with chorus

Matti Salminen as Gurnemanz and Klaus Florian Vogt as Parsifal with chorus

Stötzl’s episodes were for the most part expertly coordinated with the music, such as when Parsifal lunges his spear toward Amfortas’ wound, only to have the ruler grab it in an act of suicide (a gesture borrowed from Schlingensief). The director’s still lives, at their best, served to illustrate Wagner’s proto-cinematic qualities (theories point to the composer’s use of Leitmotifs and underscoring, techniques which were picked up by Hollywood starting in the silent film era, as well as the darkened theatre and continental seating in Bayreuth). The surging Liebesmahl (love feast) motif of the overture against the crucifixion scene captured the essence of Wagner’s spirit, a cry for redemption and a manic belief in the power of art to transform the senses.

Other scenes, such as the slow-moving mass of bodies wielding swords in the orchestral postlude of the final act, were nearly comical in their kitsch factor. The final act proved most perplexing in its chronological jump and aesthetic abstraction, failing to fully explain Parsifal’s anachronistic presence in the rest of the opera. It was also not clear whether the reverential raising of hands toward the grail in the final scene, including the shaking and collapsing of a man in zeal, was meant to be tongue-in-cheek. If Stötzl hoped to include an element of social critique, it was lost in the religious pageant.

Evelyn Herlitzius, as Kundry and Thomas Jesatko as Klingsor with dancers

Evelyn Herlitzius, as Kundry and Thomas Jesatko as Klingsor with dancers

Nonetheless, his characters emerged in immediately human strokes. Klaus Florian Vogt, slowly overtaking Jonas Kaufmann as today’s most coveted Wagnerian tenor, conveyed Parsifal’s selfless naiveté with clarion tones and an unforced thespian presence. Although his high lying timbre may not conform to the vision of many seasoned Wagnerians, his sharp musicianship and natural appeal surely compensate. The baritone Thomas Johannes Mayer gave a wrenching delivery in the role of Amfortas, evoking his existential struggle without chewing the scenery and phrasing with great sensitivity.

The dark voice of veteran bass Matti Saliminen may have developed a slightly gravely quality, but he was unquestionably authoritative as the knight Gurnemanz, winning thunderous applause. Evelyn Herlitzius incarnated the wandering heathen Kundry with seductive tones, grounding large melodic leaps with a burnished low range. She was in particularly fine voice for her narrative to Parsifal, “Ich sah das Kind,” about seeing him as a baby in his mother’s arms. The bass Albert Pesendorfer was rich voiced and commanding as Amfortas’ father Titurel, and Thomas Jesatko a magnetic Klingsor. Comprimario roles were strongly cast, with Burkhard Ulrich and Tobias Kehrer standing out as the First and Second Knights of the Grail. The chorus of the Deutsche Oper brought a characteristic blend of elegant lyricism and homogeneity of tone.

Thomas J. Mayer as Amfortas and Evelyn Herlitzius as Kundry with chorus

Thomas J. Mayer as Amfortas and Evelyn Herlitzius as Kundry with chorus

Donald Runnicles, now entering his fourth season as music director of the Deutsche Oper, led the orchestra in a smooth, strong-willed reading that did not always brim with tremendous pathos but did full justice to the soaring lines of Wagner’s score. The horns and trumpets were in top form through chromatic motifs, and although the strings’ gleaming tone did not always make its way into the transcendent, there was little doubt of the orchestra’s authentic connection to this tradition. With so many subversive productions circulating as we approach the eve of Wagner’s bicentenary in 2013, perhaps there is no need to fight the inevitable weight of history.

Rebecca Schmid

Click here for cast and production information.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Parsifal_DO_05.jpg image_description=Evelyn Herlitzius as Kundry and Klaus Florian Vogt as Parsifal [Photo © Matthias Baus] product=yes product_title=Parsifal bears its own Cross product_by=A review by Rebecca Schmid product_id=Above: Evelyn Herlitzius as Kundry and Klaus Florian Vogt as ParsifalAll photos © Matthias Baus

October 23, 2012

Don Giovanni at ENO

In 2010, it registered as the worst staging I had ever seen: a fiercely contested category, when one considers that it includes Francesca Zambello’s mindless farrago across Covent Garden at the Royal Opera — now, may the Commendatore be thanked, consigned to the flames of Hell. (Kasper Holten, Director of Opera, is said to have insisted, having viewed it in horror, that the sets be destroyed, lest it never return.) There were grounds for the odd glimmer of hope; Norris was said to have revised the production in the face of its well-nigh universal mauling from critics and other audience members alike. Yet the marketing did little to allay one’s fears, especially when reading the bizarre description on ENO’s website of a ‘riveting romp [that] follows the last twenty-four hours in the life of the legendary Lothario’. Something really ought to be done about whomever is involved in publicising productions; for, irrespective of the quality of what we see on stage, they more often than not end up sounding merely ludicrous: in this case, more Carry On Seville than one of the greatest musical dramas in the repertory. Even if one were willing thus to disparage Da Ponte — and I am certainly not — does Mozart’s re-telling of the Fall in any sense characterised by the phrase ‘riveting romp’?

Iain Patterson as Don Giovanni and Darren Jeffery as Leporello

Iain Patterson as Don Giovanni and Darren Jeffery as Leporello

How, then, had Norris’s revisions turned out? Early on, I felt there was a degree of improvement. The weird obsession with electricity — certainly not of the musical variety — had gone, but not to be replaced by anything else. Certain but only certain of the most bizarre impositions had gone, or been weeded out, yet not always thoroughly enough. For instance, there was a strange remnant of the already strange moment when, towards the end of the Act Two sextet, people began to strip off, when Don Ottavio — an ‘uptight fiancé’, according to the company website — carefully removed his shoes and socks. No one reacted, and a few minutes later — I think, during Donna Anna’a ‘Non mi dir’ — he put them back on again. Otherwise, the hideous sets and other designs remain as they were, though one might claim a degree of contemporary ‘relevance’ in that Don Giovanni’s dated ‘leisure wear’ now brings with it unfortunate resonances of the late Jimmy Saville. Alas, nothing is made of the similarity. The flat designed as if by a teenage girl, full of hearts and pink balloons, remains; as does the building that resembles a community centre. Leporello still appears to be a tramp. There are no discernible attempts to reflect Da Ponte’s, let alone Mozart’s, careful societal distinctions and there is no sign whatsoever that anyone has understood that Don Giovanni is a religious drama or it is nothing. Norris has clearly opted for ‘nothing’.

There is, believe it or not, a villain perhaps more pernicious still. Jeremy Sams’s dreadful, attention-seeking English translation does its best to live up to the ‘riveting romp’ description. A few, very loud, members of the audience did their best to disrupt what little ‘action’ there was by laughing uproariously after every single line: the very instance of a rhyme is intrinsically hilarious to some, it would seem. A catalogue of Sams’s sins — sin has gone by the board in the drama itself — would take far longer than Leporello’s aria. But I no more understand why the countries in that aria should be transformed into months — ‘ma in Ispagna’ becomes ‘March and April’ — than I do why Zerlina was singing about owning a pharmacy in ‘Vedrai carino,’ or whatever it became in this ‘version’. It is barely a translation, but nor is it any sense a reimagination along the brilliant lines of the recent gay Don Giovanni at Heaven; it merely caters towards those with no more elevated thoughts than Zerlina going down on her knees, about which we are informed time and time again, lest anyone should have missed such ‘humour’. The lack of respect accorded to Da Ponte borders upon the sickening.

Edward Gardner led a watered-down Harnoncourt-style performance. At first it might even have seemed exciting, but it soon became wearing, mistaking the aggressively loud for the dramatically potent. Where was the repose, let alone the well-nigh unbearable beauty, in Mozart’s score? A peculiar ‘version’ was employed, in that Elvira retained both her arias, whereas Ottavio only had his in the first act. On stage, Prague remains preferable every time, despite the painful musical losses its adoption entails; sadly, few conductors seem to bother.

Iain Paterson remains bizarrely miscast in the title role, entirely bereft of charisma. Darren Jeffery’s Leporello was bluff and dull in tone. (How one longed for Erwin Schrott — in either role, or both!) Katherine Broderick was too often shrill and squally as Donna Anna, and her stage presence was less then convincing, shuffling on and off, without so much as a hint of seria imperiousness. Her ‘uptight fiancé’ was sung well enough, by Ben Johnson, though to my ears, his instrument is too much of an ‘English tenor’ to sound at home in Mozart. Sarah Redgwick’s Elvira was probably the best of the bunch, perhaps alongside Matthew Best’s Commendatore, but anyone would have struggled in this production, with these words. Elvira more or less managed to seem a credible character, thanks to Redgwick’s impressive acting skills, quite an achievement in the circumstances. Sarah Tynan made little impression either way as Zerlina, though she had far more of a voice than the dry-, even feeble-toned Masetto of John Molloy: surely another instance of miscasting.

ENO had a viscerally exciting production, genuinely daring, almost worthy of Giovanni’s kinetic energy. It seems quite incomprehensible why anyone should have elected to ditch the coke-fuelled orgiastic extravagance of Calixto Bieito — now there is a properly Catholic sensibility — for Rufus Norris. whose lukewarm response at the curtain calls was more genuinely amusing than anything we had seen or heard on stage. Maybe the contraceptive imagery was judicious after all.

Mark Berry

Cast and Production:

Don Giovanni: Iain Paterson; Leporello: Darren Jeffery; Donna Anna: Katherine Broderick; Don Ottavio: Ben Johnson; Donna Elvira: Sarah Redwick; Commendatore: Matthew Best; Zerlina: Sarah Tynan; Masetto: John Molloy. Director: Rufus Norris; Set designs: Ian MacNeil; Costumes: Nicky Gillibrand; Lighting: Paul Anderson; Movement: Jonathan Lunn; Projections: Finn Ross. Orchestra and Chorus of the English National Opera (chorus master: Martin Fitzpatrick)/Edward Gardner (conductor). The Coliseum, London, Wednesday 17 October

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Don-Giovanni01.gif image_description=Iain Patterson as Don Giovanni and Sarah Redgwick as Donna Elvira [Photo by Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of English National Opera] product=yes product_title=Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Il dissoluto punito, ossia Don Giovanni (KV 527) product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Iain Patterson as Don Giovanni and Sarah Redgwick as Donna ElviraPhotos by Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of English National Opera

October 21, 2012

Mozart and Salieri — Young Artists at the Royal Opera House

Salieri is jealous because Mozart makes composing look easy. He poisons Mozart but weeps, since he’s reading the score for the Requiem, presumably overwhelmed by its beauty. We know the plot is fiction, but the text is by Alexander Pushkin, who lifts it above maudlin melodrama. Salieri can kill Mozart but he can’t kill his art. In destroying his rival, Salieri has compromised his integrity. “Can crime and genius go together?” he asks himself, and consoles himself with the thought that Michelangelo killed his model for the crucified Christ to get a better likeness for death. Does art justify murder? Pushkin and Rimsky-Korsakov possibly knew the tale was untrue, making Salieri’s excuse highly ironic.

Mozart and Salieri is unusual. The part of Salieri so dominates the work that it is more psychodrama than opera. Mozart and Salieri barely interact. Mozart isn’t a character so much as the embodiment of music. The real protagonists here are Salieri and the orchestra. At critical moments, Rimsky-Korsakov adds apposite musical quotations. Moments of Cherubino’s “Voi che sapete” convey Mozart’s youthful impudence. Fortepiano melodies are played, and shrouded figures sing excerpts from Mozart’s Requiem. References to Salieri’s opera Tarare and to Beaumarchais and Haydn are embedded into text and orchestration, expanding Salieri’s monologue. He can “hear” but he can’t create like Mozart can. The Southbank Sinfonia was conducted by Paul Wingfield, with Michele Gamba playing the keyboard Mozart is seen playing invisibly on stage, his hands lit with golden light. A magical moment.

Ashley Riches sang the demanding role of Salieri. His experience and skill come over well, even though he’s been a member of the Jette Parker Young Artists programme for barely a month. Later this year, he’ll be singing parts in The Royal Opera House Robert le Diable, Don Carlo and La rondine, and covering the title role in Eugene Onegin. In this opera, Mozart isn’t given much to sing, and the range in the part is limited, but Pablo Bemsch developed the role purposefully through his acting. Salieri thinks Mozart is skittish: Bemsch with sheer personality shows that Mozart is a stronger character than Salieri could ever fathom. Bemsch is a second-year Young Artist and has been heard extensively. He’s covering Lensky in February 2013.

The Jette Parker Young Artists Programme isn’t just for singers but focuses on theatre skills. This production was one of the most sophisticated I’ve seen for a group with these relatively limited resources. Sophie Mosberger and Pedro Ribeiro designed an elegantly simple set, which suggested that Salieri, despite his wealth and status, was a fundamentally isolated man. The little puppet figure buffeted by figures in the darkness suggested that both Mozart and Salieri were victims of forces greater than themselves. Exquisite lighting by Warren Letton, colours changing as mysteriously as the music. A stunning finale, where the dark figures singing excerpts from the Requiem move around lighted candles. Since financial problems will haunt the opera world for a long time to come, this restrained but poetic minimalism may be the way ahead. This production was intelligently thought through, and musically sensitive.

Before Rimsky-Korsakov’s Mozart and Salieri, we heard Mozart’s Bastien and Bastienne, written when the composer was twelve years old. It’s a slight piece about a courtship between shepherd and shepherdess. Staging this literally would expose its weaknesses. Ribeiro and Mosberger set the Singspiele in a vaguely industrial landscape, which added much needed good humour and gave the singers more material with which to develop character. The trouble is, neither Bastien or Bastienne are much more than stereotypes. David Butt Philip, another new Young Artist, generates interest with his voice though the part is shallow. Dušica Bijelić sings sweetly but needs to project more forcefully. Jihoon Kim made a much more convincing portrayal of Colas, the wise older man who sorts things out. He was a striking Hector’s Ghost in the Royal Opera House Les Troyens in June 2012, and will be singing in several ROH productions in the 2012/13 season.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Wolfgang-amadeus-mozart_2.gif

image_description=The Boy Mozart [Source: Wikipedia]

product=yes

product_title=Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart : Bastien and Bateinne, Nikolia Rimsky-Korsakov, Mozart and Salieri

product_by=Bastien and Bastienne : Colas: Jihoon Kim, Bastien: David Butt Philip, Bastienne : Dušica Bijelić, Factory Owner's wife : Justina Gringyte, Conductor : Michele Gamba, Continuo : Paul Wingfield, Mozart and Salieri : Salieri : Ashley Riches, Mozart : Pablo Bemsch, Conductor : Paul Wingfield, Keyboard : Michele Gamba, South Bank Sinfonia, Chorus : Dušica Bijelić, Justina Gringyte, Hanna Hipp, David Butt Philip, Michel de Souza, Jihoon Kim

Linbury Studio Theatre, Royal Opera House, London, Wales, 17th October, 2012

product_id= Above: The Boy Mozart [Source: Wikipedia]

October 20, 2012

Where the Wild Things Are, LA Philharmonic

Sendak’s original book has been around for a long time. Published in 1963, it was immediately criticized by child psychologists for arousing possibly traumatic wild animal feelings within children, and set off a great public debate on the subject. By 1979 however, the work had not only become a canon of children’s literature, but the Opéra National in Brussels commissioned Knussen to compose a work based on the story, in celebration of UNESCO’s International Year of the Child. The opera premiered there in 1980. But Knussen didn’t complete the work to his satisfaction until 1984. This version of the score, with costumes designed by Sendak, was performed in London by the Glyndebourne Touring Opera, that same year.

For anyone, who may not know the story, it’s about a boy named Max, whom we meet when he is wearing his wolf suit, bushy tale and all, and hammering away at everything that annoys him — causing such havoc at home that his mother calls him a “wilde chaya”, Yiddish for wild animal. Max repeats these Yiddish words to himself in an ongoing frenzy, when his mother orders him to bed without dinner. Miraculously, his room is transformed into a jungle and Max sets off on a long sail into a land full of wild animals who at first threaten him, then crown him their King, which occasion is celebrated with a wild “rumpus.” (Such a 1960s word!) Suddenly hungry, Max begins longing for home, and wonders whether he’ll find any food there. Sure enough, back in his own bedroom, after his return sail, he finds his supper — still hot.

In Jones’ restrained but elegant production, Sendak’s own illustrations are projected on a large screen and animated on a offstage keyboard by Jones. Max, the only live character on stage, except for the momentary appearance of his mother, interacts with the projections. Figures representing Max’s family in their ordinary clothes, are silhouetted behind an offstage screen, from where they sing and act their wild animal parts. A small orchestra is clearly visible performing this marvelously orchestrated score. Added to its usual ranks are a tinkling two handed piano part, a rumbling contra bassoon and among too many other percussion instruments to list, clogs, sizzle cymbals, a spring coil, and “balloon with pin.”

The opera has had many stagings — three new ones just this year in Germany and Holland. But my guess is that charming and inventive as other productions may be, Jones’ vision, which uses Sendak’s own cross-hatched drawings of sharp clawed, fuzzy footed beasts, with facial expressions that only he could create, offers a simplicity and kind of purity that no other will match.

The cast was headed by Claire Booth, a slight, vivacious soprano, with voice enough to rise over the orchestral rumblings and energy enough to rumpus for forty minutes. Booth, as well as the rest of the cast, sang the production’s premier last June at the Aldeburgh Music Festival. They will repeat their performances in November at London’s Barbican Hall.

Along with the brief opera, the orchestra performed Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite, accompanied by Jones’ more traditional silhouettes projected as though in a story book. Though Ravel’s work is a ballet, which implies constant movement to the music, Jones’ projections were fairly still, but added an interesting dimension to the orchestral story-telling. The star of this performance was the orchestra and the wonderful variations of sound it produced within its subdued, but silken rendering of the French score.

The Disney Concert Hall is not an ideal venue for producing opera. When a side of the orchestral space is used for staging, as it was here, the audience seated above that space, cannot see what is happening directly below them. I sat above the screen behind which the Max’s silhouetted family was acting and singing, and didn’t know that they were there until they came out for their curtain call. I hope some way can be found to improve sight lines for producing the expanded repertory including staged vocal works that the Orchestra is planning to offer in the Hall.

Estelle Gilson

Production:

Max:Claire Booth; Mama/Female Wild Thing:Susan Bickley; Moyshe/Wild Thing with Beard:Christopher Lemmings; Aaron/Wild Thing with Horns:Jonathan Gunthorpe; Emil/Rooster Wild Thing:Graeme Broadbent; Bernard/Bull Wild Thing:Graeme Danby; Tzippy:Charlotte McDougal. Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. Conductor: Gustavo Dudamel. Director, Designer and Video Artist: Netia Jones. Lighting Design: Ian Scott.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/WTWTA_2.gif image_description=Where the Wild Things Are [Image courtesy of LA Philharmonic] product=yes product_title=Where the Wild Things Are, LA Philharmonic product_by=A review by Estelle Gilson product_id=Images courtesy of LA PhilharmonicOctober 19, 2012

To Rome With Love: A Woody Allen film

Cut to a hospital somewhere in Italy — an anxiety-ridden voice is heard recounting, to anyone within earshot, of how he’d dreamt about this happening, that the shirt he wore for this performance — a present from his mother-in-law — was now ruined, and that the soprano probably put her boy toy supernumerary up to taking him out. And finally, “Is the doctor Jewish, you know cause, cause…I’d prefer if he were kosher since, since I had a club sandwich today and, and, that’ll kind of balance things out.”

Some of you might recognize part of the above as non-fiction. In1995, tenor Fabio Armiliato went through the ordeal of hospitalization and recovery after this exact unfortunate improvisation became part of a production of Tosca. The rest of this, to the best of my knowledge, is fiction, dialogue invented by me as an ode to the painfully self-examining and incessantly loquacious director’s filmmaking style. There need no longer be a wondering of how Allen might handle the subject of opera in film.

Checking out reviews of To Rome With Love (in theaters as of June 22), two stood out for their specific contrasts. One was a rave, from a publication not solely specializing in classical music, but from an opera newsy. The less complimenting piece centered on Allen’s relationship to the arts and how that influenced the construct of the film. The rave set aside particular positive attention for an opera singer by the name Armiliato. To Rome With Love, then, is a convergence of Allen and opera, as it is a convergence of Allen and Armiliato and their two characters.

Fabio is one of two Armiliatos to leave an imprint in opera today. Marco is a conductor that has had great success leading major orchestras at major theaters, through major opera assignments the world over. Fabio’s career has progressed so that he has become one of the premiere exponents of the dramatic repertory. Aside from a Tosca experience (and a Carmen one involving a sword and an Armiliato extremity) that would be difficult to make up, there is little indication why he would appear in Allen’s film. It turns out that Armiliato is a natural in Allen’s nearly probable satirical environment; I appear to have enjoyed Armiliato more than the reviewer that appraised his presence “charming.”

F. Armiliato singing at ‘red-carpet’ event promoting To Rome With LoveGenoese Armiliato plays Giancarlo, the owner of a funerary home shoppe in a strip mall. He is what you’d expect from a caricature of this persona and as the film gets underway, Armiliato gets lost in it. He is sullen and dry and flat, that is until he cleanses off embalming fluid and rigor mortis at the end of the work day and produces those big, operatically-trained sounds of Armiliato’s in the shower.

Setting the character’s temperament aside, Armiliato is warm and appears comfortable on camera. He also has a way with playing the ridiculous smoothly, and with having humor and irony fade into one another. If Allen has a gift for writing in absurdities that are nevertheless easy for actors to identify with, opera singer Armiliato seemed to easily find that place in the “filmy” climate. In opera, Armiliato’s reception steers sharply in the direction of physique (“tall, dark and handsome”), presence (“animal-like magnetism”) and greater still towards his voice — style and taste. Of his dramatics on stage, the general consensus is, well, quiet. This is a good thing in opera. It worked to an advantage in To Rome With Love.

There is nothing left to be desired from this soundtrack (per Armiliato) stacked up against the best recorded material of Del Monaco. The miking and its exposure tells us more about what Armiliato does vocally. It is a hearty, if a bit thick, and well-supported sound that rises fully through the range. It is singing that sets itself apart in knowing the music and for a strong sense of the style (mostly versimo). On the opera stage, Armiliato’s tone sounds like it falls short of the pitch in the very lower parts of the range but the middle and high range singing, squillante e potente, is from a voice opera-special and movie-star handsome.

This absolutely startles (even if your expecting it) and begins Allen’s character’s mind to churn when he visits his daughter (played by Alison Pill) and her boyfriend (played Flavio Parenti) — son of mortician. Allen’s character (Jerry) is a bit change of pace for him. He still has lots to say, and says it with the tense and torn interlocution that we’ve come to expect. But the direction of the message is “out of character.”

As a more careful than wise elder-statesman (a funny turn in it’s own right), he is less believable pinning the label of communist revolutionary on his daughter’s beau. As a cutting-edge opera-director, the kind that seeks to reinvent, update and upset all things traditional in opera, he is at least theoretically more in his element. The story doesn’t play like it’s about him anyway, or even like the ideas are bounced off him as happens in Allen’s early works.

The convergence of opera and Allen in film is poetic for the director, a convergence of fortune and the fantastic: an extraordinary talent (Ginacarlo’s) that only surfaces in the shower and a director (Jerry), in an outside-imposed professional asylum, that has no qualms about fitting this into the plot twist of Pagliacci in a major opera house. But before anyone is aware of the limitations of this talent, Jerry seeks the advice of others. The first to object is Michelangelo (Giancarlo’s son), with loud warnings of his father becoming a product, a cog and bourgeois puppet. His son sees him as fine as he is.

Giancarlo strongly agrees at first. And before you know it, the film turns to an audition, with presumably opera-elites in jury. Here we get to probably the funniest moment with regards to singing in the film. “Nessun Dorma” is already going badly, hacked up, strained high notes, no signs of the enormously gifted voice heard coming from the shower of the Giancarlo home. Then, the final note arrives. In mid-scream, Armiliato contorts his face to match, sticking-out his tongue in, possibly, a last ditch effort to loosen his voice. Or, possibly, Armiliato is sticking it out at us, the audience.

Allen’s To Rome With Love goes only so much farther into opera than many a film, and other parts of the ensemble set pieces that are the director’s forte also play to the world of opera, to love, infatuation, and the fickle nature and folly of fame.

Judy Davis (Phyllis) is again an Allen wife, less frustrated by the predicaments he has for her this time around. Roberto Benigni (Leopoldo) is a nobody who has celebrity suddenly thrust on him for no apparent reason. A young man (played by Alessandro Tiberi) loses his girlfriend (played by Alessandra Mastronardi) but gains Penelope Cruz (Anna), a lady-of-the-night that knocks on the wrong hotel door (“sono tutta tua,” she says to him, things have been paid for). This leads to some of the best comedic moments of the film. Jesse Eisenberg, Greta Gerwig, and Ellen Page (young Jack, Sally, and Monica) help Alec Baldwin (older Jack) relive an after-college year in Italy, with Baldwin meeting that younger Jack struggling to make sense of the world.

To open and close the film, this world is directed by a polizia (Pierluigi Marchionne). From the pedestal of a traffic circle in “every street” Rome, this character muses to the audience of the events and world that pass around, this world where Allen, opera, and Armiliato, meet.

Robert Carreras

Click here for additional information regarding this film.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/To_Rome_poster.gif image_description=To Rome With Love Poster product=yes product_title=To Rome With Love: A Woody Allen film product_by=A review by Robert Carreras product_id=Above: To Rome With Love PosterLucia di Lammermoor at Arizona Opera

The daughter of the famous Italian tenor and cellist, Nicola Tacchinardi, Fanny began working on her vocal technique in childhood. Eventually she became associated with the music of bel canto composers, such as Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini, and the young Verdi. In 1832, she made her stage debut at Livorno and she soon appeared in major Italian cities singing major roles in operas such as Tancredi, La gazza ladra, Il pirata, and L’elisir d’amore.

When Donizetti heard her in 1833, he described her voice as “rather cold, but quite accurate and perfectly in tune.” He chose her to create title roles in three of his operas: Rosmonda d’Inghilterra, Pia de’ Tolomei, and Lucia di Lammermoor. Her voice has elsewhere been described as sweet and light with a brilliant upper register. We know that she had remarkable agility and that she could sing a given aria several times in succession, each time with a different cadenza. It seems that she caused an unfortunate dispute during the rehearsals for the Lucia premiere. Donizetti wrote that she made a fuss, which terrified tenor Gilbert Duprez, because she wanted the last scene of the opera to be sung by the soprano, not the tenor.

Gilbert Duprez (1806-1896), the French tenor famous for pioneering the delivery of an operatic high C from the chest, created the role of Edgardo in Lucia. Having made his debut as Count Almaviva in Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia in Paris in 1825, a few years later he decided to try his luck in Italy. There, the operatic scene was more active and he found work even though he preferred to sing operas in which there were few elaborate coloratura passages. In 1831, Duprez took part in the first Italian performance of Rossini’s Guglielmo Tell and, for the first time during the performance of an opera, he sang a high C full voice, not in the so-called falsetto register as was usual at that time. After that, his success was assured in Italy. By 1835, when he sang Edgardo at the world premiere of Lucia di Lammermoor at the San Carlo Opera House in Naples, his reputation was well established. He also sang leading roles in other Donizetti premieres such as La favorite, Les Martyrs, and Dom Sébastien. In 1851, he made his last public appearance as Edgardo at the Théâtre des Italiens in Paris. By that time his high C from the chest had become a standard feature of operatic singing. His legacy was the tenore di forza, a direct ancestor of today’s dramatic tenor.

Domenico Cosselli (1801-1855) was an Italian bass-baritone most often associated with the florid singing of Rossini’s operas. For Donizetti, however, he created: Olivo in Olivo e Pasquale, Azzo in Parisina, and Enrico in Lucia di Lammermoor. He was one of the first singers to make the transition from the old concept of a bass to what we know today as a baritone, a voice type that in 1835 was still in its infancy. He gave the role of Enrico a new dimension that looked forward to the idea of the Verdi baritone.

On Saturday evening October 13, Arizona Opera presented Lucia di Lammermoor in a traditional production with sets by Robert R. O’Hearn that was originally seen at Florida Grand Opera. Fenlon Lamb, who has sung mezzo-soprano roles on the opera stage, directed it in Arizona. She told Lucia’s sad tale in a most realistic manner. Some might have questioned her use of an actress to embody the ghost that Lucia says she sees at the fountain, but it did underline the young woman’s desperate mental state. The attractive, detailed costumes from A.T. Jones and Sons were correct for the time and place. Douglas Provost’s evocative lighting added much to the show’s gothic ambience.

The Lucia was Stacy Tappan, who sang one of the Rhine Maidens in the recent Los Angeles Ring of the Nibelungen. Hers is a substantial lyric coloratura voice and she has the technical resources to follow in the steps of singers like Tacchinardi Persiani. Joseph Wolverton was a romantic Edgardo who sang with a secure line. The surprise of the evening was the Enrico of Mark Walters. He sang his first scene aria, “Cruda, funesta smania”, with powerful low tones and thrilling top notes. Jordan Bisch, who has a dark, dense voice, made an auspicious debut as Raimondo, the minister who tries to make peace between the families. Samuel Levine was an appropriately smarmy Normanno and Laura Wilde a dramatic Alisa. David Margulis, whom I last heard as an apprentice at Santa Fe Opera, was a radiant voiced Arturo who held his own in the beautifully sung sextet. The chorus is most important in this opera and, thanks to the hard work of Henri Venanzi, Arizona Opera has a truly first class choral group. They acted individually and sang their harmonies with exquisite precision. Steven White conducted at a brisk pace, never letting the tension sag in the least. He shaped the orchestral sound so as to bring out every color and detail of Donizetti’s magnificent score. This was a fine performance and an auspicious opening for Arizona Opera’s 2012-2013 season.

Maria Nockin

Cast:

Lucia: Stacy Tappan; Edgardo: Joseph Wolverton; Enrico: Mark Walters; Raimondo: Jordan Bisch; Normanno: Samuel Levine; Arturo: David Margulis; Alisa: Laura Wilde; Conductor: Steven White; Director: Fenlon Lamb; Chorus Master: Henri Venanzi; Set Designer: Robert R. O’Hearn; Costumes: A.T. Jones and Sons; Lighting Design: Douglas Provost.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/TAPPAN.gif image_description=Stacy Tappan product=yes product_title=Lucia di Lammermoor at Arizona Opera product_by=A review by Maria Nockin product_id=Above: Stacy Tappan (Lucia)October 18, 2012

Schumann: Under the influence

In an explicatory note, Biss declares his intention to move Schumann from the sidelines — admired, says Biss, only for a remarkably small number of his works — to the centre-stage, as a “vital, riveting creative force”. Each of Biss’s four programmes endeavours to show Schumann’s relationship to both past and present, pairing his works with those of an influential predecessor and a composer of the future whose music “without him would not have been possible”.

Poetic and musical links were forged in this recital, with Schubert’s settings of Heine, from the song cycle Schwanengesang, preceding a performance of Schumann’s Dichterliebe, the composer’s self-constructed sequence of poems by Heine written to honour and celebrate his love for his beloved Clara. Tenor Mark Padmore was a serious and moving interpreter, although his meticulous pronunciation did not quite embrace the sensuousness of Heine’s texts. The result was a reading which conveyed the extremes — desolate depths and ephemeral lightness — but did not always capture the ‘in-between’ realms of earthly passion and natural human feeling.

After a turbulent ‘Der Atlas’, where Biss’s tempestuous opening evoked the bitter fury of Atlas, who must bear the whole world’s sorrow, Schubert‘s Ihr bild’ (‘Her picture’) established an eerie pathos during the sparse opening, the singular line shaped with insight and effect, before blooming to simple joy: “A wonderful smile played/ about her lips”. The dark intensity of the concluding despairing cry, “I have lost you!”, was transmuted into a casual, balladeer-like air in ‘Das Fischermädschen’ (‘The fishermaiden’), Biss’s subtle rubatos urging the compound rhythms to a gentle pianissimo close. ‘Die Stadt’ was pure Gothic melodrama, Padmore final utterances laden with resentment and regret. The slow tempo of the final song, ‘Der Doppelgänger’ (‘The wraith’) enhanced the mood of fearful oppression and inner torment.

Padmore’s Dichterliebe was characterised by melodic eloquence and expressive earnestness. His affecting whisper, “Doch wenn du sprichst: Ich liebe dich”, in ‘Wenn ich in deine Augen seh’ (‘When I look into your eyes’) was disturbingly pathetic and wretched. In contrast, ‘Im Rhein, im heiligen Strome’ (‘In the Rhine, the holy river’) juxtaposed majesty with still quietude. The tenor’s deep register in ‘Ich grolle nicht’ (‘I bear no grudge’) was a little obscured by the piano accompaniment but Padmore made much of the text in the concluding verse, as the poet-narrator witnesses “the serpent gnawing your heart”, and the passionate intensity of the accelerating piano postlude, running headlong into the subsequent ‘Und wüßten’s die Blumen’ (‘If the little flowers knew’) was thrilling. Indeed, the links and juxtapositions in the narrative structure were effectively defined, as when the hard disillusionment at the close of ‘Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen’ (‘A boy loves a girl’) — which began with a poignant silence — hastened into the shifting colours of ‘Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen’ (‘One bright summer morning’).

Biss was an alert and energised accompanist, underpinning ‘Die Rose, die Lilie, die Taube’ (‘Rose, lily, dove’) with an airy, springy buoyancy, while the trailing arpeggios of ‘Hör’ ich das Liedchen klingen were clear and delicate, perfectly evoking the speaker’s dissolving tears in the piano postlude. In ‘Aus alten Märchen’ (‘A white hand beckons’) Biss’s staccato dotted rhythms conjured an elfin sprightliness; the performers used the slower tempo of the final two verses to convey the unattainability of the singer’s dream.

In the closing song, ‘Die alten, bösen Lieder’ (‘The bad old songs’), Padmore adopted a powerful and rhetorical theatricality, culminating in an anguished fall, coloured by diminished harmony: “Die sollen den Sarg fortragen,/ Und senken in’s Meer hinab;” They shall bear the coffin away,/ and sink it deep into the sea;”).

Preceding the Heine sequences, soprano Camilla Tilling gave an exciting performance of Alban Berg’s early songs, Sieben frühe Lieder. Tilling appreciated the luxuriousness and sensuality of these diverse songs, warming and brightening her tone at emotional highpoints — as in the opening ‘Nacht’ (‘Night’) which creeps in with gentle gracefulness and blossoms to convey the singer’s awe as “Weites Wundererland ist aufgetan” (“A vast wonderland opens up”). Similarly, in the Brahmsian ‘Die Nachtigall’ (‘The Nightingale’) the “sweet sound of her echoing song” resonated sonorously around the hall. Tilling’s tone acquired a glossy sheen in ‘Schilflied’ (‘Reed song’) to suggest the enlivening effect of the poet’s inner thoughts, while in ‘Liebesode’ (‘Ode to love’) she called on more burnished colours to complement the piano’s chromatic harmonies and portray the ecstatic dreams of the sleeping lovers.

Biss began the recital with a wonderfully imaginative performance of Schumann’s Gesänge der Frühe, responsive to the diverse moods of the individual movements — from the poetic simplicity of the exquisite voicing in ‘Im ruhigen tempo’ to the hymn-like tranquillity of ‘Im Anfange ruhiges’. Biss’s ability to use texture and timbre to communicate meaning was impressive: the rhythmic propulsion of ‘Belebt, nicht zu rasch, the minor key cascades and understated rubatos of ‘Bewegt’ and the final airy chord of ‘Lebhaft’ spoke directly, with immediacy and emotion.

Claire Seymour

Performers

Camilla Tilling, soprano; Mark Padmore, tenor; Jonathan Biss, piano. Wigmore Hall, London, Thursday 11 October 2012.

Programme

Schumann: Gesänge der Frühe Op.133

Berg: Sieben frühe Lieder

Schubert: Heine Lieder from Schwanengesang D957

Schumann: Dichterliebe Op.48

October 17, 2012

Albert Herring at Covent Garden

A director has to make us laugh while also finding the darker kernel encased in an outer shell of light-hearted satire; to enjoy and celebrate its somewhat localised, even cliquish, nature, while also recognising the continuing relevance and wider frame of reference of its themes and inferences.

Composed for the newly formed English Opera Group and first performed at Glyndebourne in 1947, the opera can seem on the surface to be a comic companion piece to The Rape of Lucretia. When Albert Herring opened the inaugural Aldeburgh Festival in 1948, the Suffolk audience must have been aware that small towns and villages around Aldeburgh, and their inhabitants, had come in for a sharp, somewhat patronising, satirical critique.

The local benefactress, Lady Billows, (modelled, according to Britten’s sister, Beth, on her mother-in-law!) has offered a prize of £25 to be given to a ‘May Queen’ as an encouragement to virtue. In the absence of a suitably chaste maiden, Albert Herring is nominated ‘May King’, to the delight of his overbearing, domineering mother. At the crowning ceremony two young lovers, Sid and Nancy, lace Albert’s lemonade with rum; called upon to give a speech he can only hiccough drunkenly, and he flees. When Albert’s orange-blossom crown is later discovered in the gutter, muddy and squashed, the worst is assumed. But, the community’s collective outpouring of grief is interrupted when Albert creeps nonchalantly back in. He explains that he has merely been enjoying experiences that have been denied him in the past and, derisively rejecting his crown, announces his new spirit of self-assertion.

In his ‘Director’s Notes’, Christopher Rolls maintains, “The key thing about Herring is that it is very, very funny. Funny because it’s full of absurd situations and recognisable characters.” That may be so, but without careful direction the somewhat dated humour can quickly slide into stereotype and caricature — what Ronald Duncan described as “church-bazaar parochialism” — and the localisms and provincialisms of Eric Crozier’s rather prosaic libretto can seem old-fashioned, even dull. To impose an overly serious sophistication on the work would undermine the animated light-heartedness of the drama; but, there must be some acknowledgement of the complex dialogues which the opera conducts: between innocence and experience, repression and liberation, subjugation and self-determination.

The black-box stage of the Linbury Theatre necessitates imaginative and economical designing, and Neil Irish’s ‘caged’ set neatly served for all three of the opera’s locations — the May Day committee room, the Herring’s greengrocer shop and the crowning banquet itself — while cleverly conveying the oppression and containment experienced not just by the brow-beaten Albert, but by all members of the Loxford community who are under Lady Billows’ domination.

Rosie Aldridge as Florence Pike, Jennifer Rhys-Davies as Lady Billows and Anna-Clare Monk as Miss Wordsworth

Rosie Aldridge as Florence Pike, Jennifer Rhys-Davies as Lady Billows and Anna-Clare Monk as Miss Wordsworth

Albert is literally imprisoned within his mother’s shop and metaphorically oppressed by the labels imposed upon him by Loxford society. Visually, the grid-like trellis which scaled three walls also offered plenty of opportunities for surreptitious surveillance, and glimpses of the world on the other side of the bars were a reminder of Albert’s confinement and a symbol of his yearning for release. Guy Hoare’s subtle and imaginative lighting added much, as shadows surreptitiously deepened and were alleviated, reflecting the emotional swings of the drama.

At the start of Act 1, the inhabitants of Loxford assemble in turn, and the ETO cast immediately and deftly established clear-cut characterisation. Delivering, without exception, Crozier’s unassuming text in an unaffected manner, they achieved a balance between pastiche and realism, using exaggeration and over-emphasis intelligently and sparingly.

Taking her instructions from the imperious Lady Billows, the be-trousered (a hint of lesbianism?) Rosie Aldridge was a thoughtful, composed Florence, diligently noting in flexible recitative the methods she must use to gather evidence of moral corruption among the young in Loxford, while allowing her voice to bloom in more lyrical passages to suggest a latent awareness of her employer’s intolerance and narrow-mindedness.