October 31, 2013

Wexford Festival 2013

Doomed love and desperation inevitably drive many of the operatic protagonists to commit tragic acts, but, alleviating the despair, one man’s determination to be married results in a mad-cap dash around Paris in search of a Florentine straw hat.

The real ‘find’ of this Festival is undoubtedly Jacopo Foroni’s Cristina, Regina di Svezia, (seen on 25th October) first performed in 1849 and rarely heard since. Foroni was of Veronese birth but spent most of his working life in Sweden, introducing the Swedes to the latest works by Bellini, Donizetti and Verdi, before his own untimely death in 1849 during a cholera epidemic. On the evidence offered by Stephen Medcalf’s outstanding production of Cristina, Foroni was just as blessed with melodic and orchestrational gifts as were his better-known Italian compatriots.

Cristina was presumably intended to endear him to audiences in his newly chosen land. Set in the Tre Kronor castle in Stockholm, the opera presents the historic events leading to the abdication of Queen Cristina of Sweden in 1654, and depicts a knotted web of unrequited and frustrated love.

Cast of Cristina, regina di Svezia

Cast of Cristina, regina di Svezia

The Lord High Chancellor, Axel Oxenstjerna, accompanied by his son, Erik, has brokered a peace treaty to end the Thirty Years’ War, and at a public celebration of peace, Cristina rewards her loyal servant by announcing that Erik is to be given the hand of Maria Eufrosina, the Queen’s cousin, in marriage. Maria and her beloved Gabriele de la Gardie are less than delighted with this arrangement, but when Gabriele, who is himself the object of the Queen’s affections, suggests that they should elope, Maria desists, reminding Gabriele of the loss of honour that such an act would occasion. Maria’s hopeless weeping is interrupted by the Queen’s arrival; despatching Maria before the latter can explain the cause of her tears, Cristina then tells Gabriele of her hopes that they can rules Sweden together; she is unaware that Arnold Messenius and his son, Johan, are secretly plotting to overthrow her.

At the wedding, Maria is unable to go through with the ceremony and confesses that she loves another; when pressured by the Queen, she identifies her beloved as Gabriele. Furious, Cristina vows that Gabriele will be exiled; Messenius and his son now hope to recruit Gabriele to their seditious cause.

Meanwhile, Carlo Gustavo, Cristina’s cousin and the heir to the throne, has heard of the planned treachery and arrives on the island of Öland to infiltrate the conspirators, who now include Gabriele. Axel urges Cristina to accept Gustavo’s love and rule with him, but the Queen has become despondent and tells Axel of her wish to renounce the throne. When the rebels storm the castle, Gustavo declares that he will defend Cristina; subsequently, Gabriele, Messenius and Johan, are brought before Cristina who condemns the traitors, including Gabriele, to death. She tells Gustavo of her plan to abdicate in his favour and live the rest of her life in Italy; he tries to discourage her, and of his wish that they should marry and rule together, but she is adamant.

In the Grand Council chamber, the intriguers are sentenced, but as they are led away to their execution Cristina enters and publically forgives Gabriele, declaring that he may now marry Maria. She announces her own abdication, and places the crown on the reluctant Gustavo’s head. The people swear allegiance to their new monarch.

The life of the real Cristina was certainly filled with events of operatic proportions: thrust into public office from a tender age, following the death in battle of her father, Gustavus Adolphus II, when she was just six years old, she was a strong monarch but an unconventional one. By no means a beauty, and with a hunger for culture and learning considered ‘unfeminine’ during this period, she was stubbornly nonconformist; she refused to marry, dressed in a masculine fashion and indulged her interests in religion, alchemy and science. When she abdicated in 1654 she stunned her country by renouncing her father’s Lutheran faith and converting to Catholicism; however, Cristina did not lose her appetite for power and prestige, attempting to become Queen of Naples in 1656 (she made sure that the man who betrayed her plans was executed), and later seeking the Polish throne.

Eleanor Lyons, Fillipo Adami and Owen Gilhooly in Il Cappello di paglia di Firenzie

Eleanor Lyons, Fillipo Adami and Owen Gilhooly in Il Cappello di paglia di Firenzie

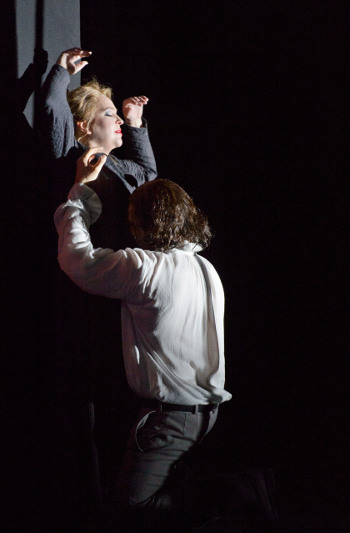

Foroni’s Cristina is less petulant and extreme - the unruly hair, men’s shoes and epicurean habits are not in evidence - and the focus of Giovanni Carlo Casanova’s libretto is on the loneliness which arises from the burdens of public duty. Indeed, the principals all suffer this inner tussle between personal fulfilment and honourable obligations; thus, during the opening moments of the overture, the passionate embrace of Maria (Lucia Cirillo) and Gabriele (John Bellemer) is interrupted by the arrival of stern officials, and all stiffly assume their places upon imposingly straight-backed Rennie Mackintosh chairs, facing the screen that will shortly announce the momentous political events. Medcalf and his designer, Jamie Vartan, have transferred the action to London during the 1930s, a time when such emotional conflicts would certainly have been recognised by a nation whose monarch had recently put love before duty, thrusting a reluctant sibling onto the throne.

Film sequences during the opening act effectively showcase the parallels. First we have Neville Chamberlain waving the Munich Agreement before grateful crowds; then, reversing the historical chronology, the coronation of George VI. The decision to replace seventeenth-century Swedish court life with a more familiar era, and one characterised by formality and decorum, also allows for some superb tableaux - and for some striking Downton Abbey-style costumes. Thus, the curtain rises on an impressively attired chorus of noblemen, soldiers, officials and servants, frozen for the briefest moment before the whirling celebration of peace ensues. Similarly cinematic effects are strikingly deployed in the wedding scene where Maria’s emotional disintegration is charted by a series of flash bulb freeze-frames which shockingly capture her growing despair. Only the archive film of bombing raid fires, shown in the moments preceding the storming of the castle, seemed a little too lengthy.

Vartan’s sets are engaging and ingenuous. After the imperious ceremony of the opening scenes, Act 2 finds Cristina in her private chambers, reflecting on the futility and destructiveness of power, and the art deco panelling, furniture and globe economically whisk us to a 1930s interior. Later, as she determines her future, and that of her nation, we see the Queen seated in her office, raised aloft, thereby emphasising her distance from her subjects and her emotional isolation.

Claudia Boyle and Fillipo Adami in Il Cappello di paglia di Firenze

Claudia Boyle and Fillipo Adami in Il Cappello di paglia di Firenze

In many years of visiting Wexford, I don’t think I have ever heard the Wexford Festival Chorus sound better; Foroni’s choruses combine Verdian vigour with occasional contrapuntal complexity, and the massed voices were on top form, producing a rich Italianate tone and singing with total commitment. Paula O’Reilly’s choreography is excellent, making full use of the stage, and the numerous personnel moved with fluency and naturalness. The arrival of Gustavo at the start of Act 2, his parachute descent wittily foreshadowed by some historical war footage, is a masterstroke which drew a gasp of praise. Moreover, the brooding red haze of Paul Keogan’s lighting design throughout the conspirators’ scene looks ahead ominously to the rebellious invasion of the Queen’s castle.

Foroni offers the singers some wonderful cantabile melodies and the cast relished them. As Maria, mezzo soprano Lucia Cirillo displayed a sumptuous tone and crafted beautifully balanced phrases. John Bellemer, who impressed as Sali in Medcalf’s production of A Village Romeo and Juliet at last year’s Festival, was similarly convincing as the impetuous, fervent Gabriele; as he sang of his love for Maria, his tenor was focused and intense, full of drama and feeling. Russian baritone, Igor Golovatenko was a strong Gustavo, resonantly exhibiting his love and loyalty for his Queen. (I had a small misgiving about the final tableau, however; would the steadfast Gustavo, however reluctantly endowed with royalty, immediately overturn Cristina’s last act of clemency and execute the pardoned conspirators - who had, after all, wished to promote Gustavo himself to the throne?)

Bass Thomas Faulkner and tenor Daniel Szeili acquitted themselves well as Messenius father and son respectively; Szeili displayed a tenor voice of great tenderness in a final aria of remorse which was truly moving. As Erik, Irish tenor Patrick Hyland showed great promise. David Stout’s Axel was particularly impressive during his Act 2 interview with Cristina, his well-rounded bass-baritone earnestly pleading with his Queen to marry Gustavo and remain monarch.

In the title role, Australian soprano Helena Dix demonstrated enormous stamina and impressive vocal power and accuracy. Dix has a silky lyric tone and she soared effortlessly in the large choral scenes. But, while her voice has much nobility and poise, I felt that Dix would have benefited from greater direction, for her posture and movements were not always sufficiently ‘regal’; she presided with formality and pomp during the public ceremonial scenes, but was less persuasive during the more personal interactions with her subjects. Dix’s costumes did not help imbue her with imperial majesty. When all around her were attired in elegant evening dress or impeccable uniforms, the Queen was initially robed in a black tent-like gown reminiscent of Queen Victoria’s mourning attire topped off with a blue sash, rather like a pageant princess. Even allowing for insomnia and workaholic restlessness, it is surely unlikely that Cristina would conduct her private meetings in silk pyjamas? And, in the final Act, her dull brown fitted suit and Hartmann suitcase suggested that the Queen had fallen far following her abjuration of the throne. A pity, when there were copious visual delights all around her, and Dix’s own singing won her a greatly deserved ovation.

Conductor Andrew Greenwood had the full measure of the score, ensuring that Foroni’s varied orchestral colours were clearly heard and appreciated, and shaping the surges and lulls with passion and perceptiveness.

With such riches on offer, one wonders why Cristina was not more of a hit? Presumably the Swedes were none too thrilled to be reminded of a monarch who had rejected her people and their faith, while it seems the Italians did not take to Cristina all that warmly either. Hopefully this convincing, imaginative Wexford’s production will put an end to the unjust neglect that Foroni’s terrific opera has endured.

Desire and duty did battle once more in a double bill (27th October) which reminded us of Jules Massenet’s skills as a melodist and also revealed a starker, more brutal idiom than we might expect from this most lyrical of composers.

Scene from Thérèse

Scene from Thérèse

Set in Revolutionary France, during the Terror of 1793-94, Thérèse (1907) is a melodrama which pits public against private, loyalty against love. As with Foroni’s Cristina, the eponymous heroine is based on a historical figure, in this case, Lucille Desmoulins who was executed in 1793, eight days after her husband, Camille. In Jules Claretie’s libretto, Thérèse finds herself torn between her allegiance to her husband, André Thorel - a Girondist and man of the people - and her passion for her aristocratic lover, Armand, Marquis de Clerval, who has fled to escape the Revolution. Thorel, the former childhood companion of Armand (his father was the Marquis’ steward), has purchased the Clerval chateau in order that it may one day be returned to his friend. When Armand reappears, still deeply in love with Thérèse, she is torn between her amorous feelings and her fidelity to her marriage vows.

André offers Armand protection within the chateau, and then provides him with a letter of safe passage so that he can escape the revolutionary horror. Emotions rise both in the house and on the streets, and Armand realises that he must leave. As her husband fights at the barricades with the Girondists, Thérèse initially agrees to flee with Armand, but on hearing that André has been captured and is to be executed, she recognises her true duty and cries, ‘Vive la roi!’ Arrested by the incensed Revolutionaries, she is taken to the guillotine, to die by her husband’s side.

In true verismo fashion, the plot is taut and intense: the conflicts are clearly drawn, the emotions pure and deep. The Director-Designer team of Renaud Doucet and André Barbe offer a marked twist though: we enter the eighteenth-century revolutionary world through a painterly frame, as curators and conservators in a starkly lit museum restoration workshop, scientifically preserve and renovate ‘the past’ as depicted by the works of art. ‘Stepping out’ of the paintings, the figures from history re-live their former experiences, their desperate emotions and suffering presenting a destabilising contrast to the clinical detachment of the modern scholars as they go about their task of historical reconstruction and repair. This schism between the emotional experience of those in the foreground and the cerebral intellect of those glimpsed beyond is one of the strengths of the concept, and it is enhanced by Paul Keoghan’s arresting lighting designs, the glacial cool of the workshop strip-lights replaced, for example, by a nostalgic yellow glow as Armand and Thérèse recollect their former love. Similarly, the vibrant colours and luxurious fabrics of the eighteenth-century attire contrast robustly with the clinical uniforms and workday attire of the present.

Yet, there are aspects of the staging that are less effective. The interactions between the figures from the past and present at the start of the opera are somewhat confusing and, having immersed ourselves in Thérèse’s fate it is disconcerting to be yanked back to the present when she is carried off to the scaffold not by the Revolutionaries but by technicians in white lab coats. Barbe and Doucet declare their intention to ‘explore the influence of painting on life’, but Thérèse is about life, not art. The strongest juxtaposition in the opera is between the inner life of the private heart and the external world of public politics and strife; it is an opposition which is embedded in the score and one which this production does not make sufficiently evident.

Brian Mulligan and Nora Sourouzian in Thérèse

Brian Mulligan and Nora Sourouzian in Thérèse

At the heart of the score are the passionate exchanges of Thérèse and Arnaud, and French-Canadian mezzo soprano Nora Sourouzian and French tenor Philippe Do prove that they possess the stylishness, lyricism and sensitivity to convey the poetry of these scenes most beautifully. Do has both the strength, though the voice is never forced, to bring a fierce ardour to the passionate high-points and a floating mezza voce which can modulate the emotional fire with sensitivity and lightness. Thérèse’s Act 2 aria, ‘Jour de juin, jour d’été’ was deliciously sweet and exquisitely phrased. Brian Mulligan, as André, made a considerable impact, demonstrating fine stage presence and singing with an open, burnished tone. Damien Pass was very competent in the small role of Morel.

The four principals showed their fortitude and versatility when they returned for the second half of the double bill: La Navarraise, another opera in which the personal and political intertwine, and one which at times seems more characteristic of Mascagni than Massenet.

First performed at Covent Garden in June 1894, La Navarraise is based on a short story,La Cigarette, by Claretie, which the author adapted, in collaboration with Henri Cain. Anita, a poor girl from Navarre, and Araquil, a soldier in the Spanish civil war, are in love but are forbidden to marry by Remigio, Araquil’s wealthy father, unless Anita pays a dowry of two thousand duros. The commander Garrido learns that his friend has been killed by the enemy commander, Zuccaraga, and declares his hatred for the latter; Anita proposes that she will kill Zuccaraga for a sum of two thousand duros, and although he is suspicious of her motives, Garrido agrees. As she approaches the enemy camp, protected by her statue of the Virgin Mary, Anita is observed by the soldier Ramon, who, assuming that Anita is a spy, tells Araquil; the latter fears that she has is visiting a secret lover. Having killed Zuccaraga, Anita runs through the gunfire and collects her reward from Garrido, who makes her swear not tell anyone of her deed.

Araquil, who has been mortally wounded during his search for Anita, demands to know where she has been, but her oath prevents her from speaking out and all she can do is show him the money in the hope that the realisation that they can now marry will quell his anger. Araquil, however, assumes she has prostituted herself, which she vehemently denies. As Remigio arrives with a doctor to tend his son, bells are heard in the distance, and Remigio explains that they are tolling for the assassinated Zuccaraga. Finally understanding the truth, Araquil dies. Anita becomes hysterical, wildly speaking of her forthcoming marriage which she thinks the bells foretell. Desperately seeking a knife with which to commit suicide, she realises that she lost it at the murder scene; all she has is her statue of the Holy Virgin. Before the horrified onlookers she erupts in crazed laughter and falls senseless, as Garrido laments ‘La folie’, the poor mad child.

Nora Sourouzian and Phillipe Do in La Navarraise

Nora Sourouzian and Phillipe Do in La Navarraise

Doucet and Barbe once again filter the tale through art, transforming the museum workshop to the Atelier des Grande-Augustins where Picasso painted Guernica. Created in response to the bombing of Guernica, a Basque village in northern Spain, by German and Italian warplanes at the behest of the Spanish Nationalist forces in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War, Guernica does indeed provide fitting visual frame for Massenet’s opera, for both works show the violence and chaos of war, and the suffering that it inflicts upon the innocent.

The stage is a collage of out-sized fragments from the painting: the wide-eyed bull; the horse falling in agony, a spear in its side piercing a gaping wound; a human skull and other dismembered body parts; a stigma; flames. Above, the projection of a gilded eighteenth-century chandelier has been replaced by a blazing light bulb in the shape of an evil eye.

The stage space is in fact so cluttered with these artistic fragments that there is hardly room to move, and the personnel are confined to a narrow strip at the front of the stage. The coral, dusty pink and cinnamon hues of the costumes and lighting summon up the rugged mountainous terrain of the region, but overall the ambience feels rather too static and confined.

The singing was, however, as committed as before the interval, with Do and Sourouzian once more a formidable duo, as Araquil and La Navarraise. Sourouzian’s lustrous high register was in evidence, in her Act 1 lament that she will not be able to marry her beloved Araquil; and she had real presence in the fiery outbursts which result in her mad demise. Do, too, showed his resourcefulness, creating a sincere portrait of a man of great strengths and all too human weaknesses; his final words, ‘the price of blood! how horrible!’, as Araquil realises the terrible lengths to which Anita has gone to secure his love, were chilling. Damien Pass was imposing as Remigio, while Brian Mulligan was a credible Garrido.

In the pit, Carlos Izcaray conducted with control, verve and attention to detail; the lyrical stream of melody - there was some lovely solo cello playing - was complemented by timbral bite and dynamic punch.

The third of the Festival’s trio of offerings provided some light relief from the afflictions of social responsibility and unfulfilled love. The Italian composer, conductor, pianist and academic Nino Rota is best known for his film scores, notably for the films of Fellini, Visconti, Zeffirelli, and for the first two films of Francis Ford Coppola's Godfather trilogy. Extraordinarily prolific, in addition to his considerable body of film work, Rota composed ballets, orchestral, choral and chamber works, and ten operas, one of which, Il Cappello Di Paglia Di Firenze (1955), director Andrea Cigni presents this year at Wexford (seen 26th October).

The libretto, adapted by Rota and his mother, Ernesta, from a vaudeville by Eugène Labiche and Marc-Antoine-Amédée Michel, Un chapeau de paille d’Italie, and which had been filmed in 1928, has a plot which makes the last act of Figaro seem the epitome of clarity and good sense.

On the morning that Fadinard is to be married to Elena, his horse eats a straw hat which belongs to a woman who has evaded the jealous watch of her vicious husband in order to rendezvous with her soldier lover. Confronted with Anaide (distraught - she cannot return home without her hat) and Emilio (her threatening and protective paramour), Fadinard realises he must find a replacement hat, and so sets of on a zany chase across Paris on a mad hatter treasure hunt, dragging deaf uncle, bumptious father-in-law, Nonancourt, and troupe of inebriated wedding guests behind him. Sent by the milliner to the Baronessa di Champigny’s residence, he is mistaken for a violin virtuoso; the Baroness has given the hat to her friend, the wife of Beaupertuis - Anaide - and so, unwittingly, Fadinard is thrown into the enemy’s den. While it rains champagne, the wedding partygoers are happy to party where their dancing shoes whisk them; but when it really rains misery sets in, especially when they are arrested for trespass.

Scene from La Navarraise

Scene from La Navarraise

Just when all seems lost - when faced with a cancelled marriage, a husband’s pistol and a prison cell - Fadinand is saved by deaf uncle Vézinet’s announcement that his wedding give is a Florentine straw hat - the perfect substitute for Elena’s chomped bonnet, and just what is needed to convince Beaupertuis that she is a wrongly accused innocent. The wedding of Fadinand and Elena can go ahead - and we hope that their future matrimony is not marred by further millinery machinations.

Director Andrea Cigni and Designer Lorenzo Cutùli present us with a front-drop carte postale dated 18th September 1958 which when raised reveals a sloped postage stamp stage, embraced by an assemblage of film and theatre posters which reference aspects of the farce to come: Halle Chapeaux, L’Infidèle by Sheridan and Scott, Chansons sous la pluie, Follies, High Society, Gaines’ Scandale, Revel: Parapluie. All very eye-catching but not much assistance in creating actual locales for the itinerant hat hunters.

Rota’s score is pure opera buffa - referencing the originals, Rossini and Donizetti, and throwing some sardonic twentieth-century spice à la Prokofiev and Stravinsky. Musical quotations and self-quotations abound, the orchestration is sassy, and it all zips along frothily if rather superficially - indeed, one feels that a lot of rhythmic energy is expended with little forward motion.

The problem with this production is that in aiming to make us laugh through caricature, exaggeration and improbability, Cigni gets bogged down in stylisation and extravagance, and things grind to a halt. The tilted stage platform, while allowing for the suggestion of different floors within Fadinand’s house, doesn’t help matters: the slick physical interchanges that farce requires are simply not possible when the chorus is trying to dance on a postage stamp, or principals are negotiating awkward trapdoors. To compensate for the actual lack of physical movement, we have flashing lights and outsized platters of fruit and cupcakes, but this is not sufficient reparation for the lack of a real belly laugh.

That said, Cigni does effectively convey the sense of movement around the city, but he has to take the chorus off the stage and deposit them in the aisles to do so … the rain-soaked, champagne-sozzled revellers made a pitiful trek through the auditorium, prior to the incarceration which would end their carousing. The female chorus excelled, both as hat-sewing seamstresses and resilient socialites.

Conductor Sergio Alapont failed to set things afire - though reliable, there was a lack of lightness and vivacity in the pit - but the singers did their best, although they did not look as if they were having much more fun than we were. Stepping into Fadinand’s shoes at the eleventh hour, tenor Filippo Adami revealed a clear, generous voice and a sure sense of comic timing. Slight of stature, Adami possesses significant stage presence; he played a noteworthy part in keeping the show rolling. His Elena, Irish soprano Claudia Boyle, was all glittery insouciance, prepared to tolerate her groom’s inexplicable goings-on with scarcely a complaint. Australian soprano Eleanor Lyons sparkled with faux naivety as Anaide, while Owen Gilhooly made a strong impression as Emilio, managing to be both menacing and sympathetic at the same time.

In the cameo role of Uncle Vézinet, tenor Aled Hall equipped himself well and exhibited a warm baritone and much dramatic wit; Salvatore Salvaggio’s Nonancourt was rather ponderous - his complaints about his pinching footwear and repeated cries, ‘It’s all off!’, did little to hasten the action forward. Filippo Fontana, as the bitter Beaupertuis, stayed the right side of parody and his focused bass baritone brought some depth to the role; Turkish mezzo soprano Asude Karayavuz enjoyed her turn as the outlandish Baronessa di Champigny, exhibiting a full, rounded tone and endearing comic waggishness.

In addition to the three main house productions, Wexford offered its usual diet of peripheral treats. Of the Short Works, Roberto Recchia’s L’elisir d’amore (26th October) was the most ingenious, transferring the action to a modern-day Irish Karaoke bar - one of the virtues of which was to provide a naturalistic raison d’être for surtitles! The PR media show, complete with Twitter links, which accompanied Dulcamara’s sales pitch was a scream - the only down side was that it distracted from Thomas Faulkner’s accomplished singing. Jennifer Davis relaxed into the role of Adina, singing accurately and with character; and while Patrick Hyland may not yet have the Italianate silkiness which ‘Una furtiva lagrima’ demands, his gentle, sensitive articulation was both intelligent and touching. Ian Beadle was an ostentatious Belcore, and Hannah Sawle produced an appealingly flirtatious lightness as Gianetta. After a slightly weighty start, Musical Director Richard Barker kept things flying along at the keyboard, although at over 90 minutes this was hardly a ‘short’ work.

In 2010, Richard Wargo’s Winners was staged in Wexford, and now we had the opportunity to hear the second part of the musical adaptation of Brian Friel’s two-parter, Losers. Set in the 1960s in the town of Ballymore, County Tyrone, Losers is a deliciously wry send up of religious fanatic fervour and the private destruction it wreaks - was it a coincidence that the premiere (27th October) coincided with the Festival Mass service …? Wargo employs an ear-pleasing idiom mingling Bernstein-like lyricism, the fluency of popular song and Britten-esque timbres (the women’s prayer recalls the soothing textures of the female quartet in The Rape of Lucretia). As the frustrated Hanna Wilson-Tracy, whose duty to mother and church must come before her natural affection for Andy Tracy (Nicholas Morris), Cátia Moresco aroused pity and affection, her heart-warming tone blending touchingly with Morris’s emotive baritone. Eleanor Lyons displayed musical precision and dramatic wit as the oppressive matriarch, Mrs Wilson; Kristin Finnegan and Chloe Morgan made up the fine cast, as the devout Kate Cassidy and her rebellious daughter Cissy, respectively, in a production which inspired mischievous laughs and resigned sighs alike.

Michael Balfe’s The Sleeping Queen was the most excitedly anticipated but perhaps the least satisfying musically of the three Short Works, despite the appealing designs of Sarah Bacon - all orange trees and trellised patios - and the atmospheric lighting of Pip Walsh. There was some fine singing from the young cast, not least from Johane Ansell as the Queen’s maid, Maria Dolores, and tenor Ronan Busfield as the love interest, Philippe D’Aguilar.

Lunchtime recitals in St Iglesias Church provided further musical sustenance. On 25th October Asude Karayavuz, accompanied by Andrea Grant, showed that she would make a fine Carmen, lustrous of tone and teasing of demeanour. In two arias by Massenet she revealed a sultry lower register and excellent French diction, later put to good use in Carmen’s Habanera and Seguidilla. Karayavuz’ Mediterranean sensibility was tapped in songs by Manuel de Falla, which she endowed with a folky silkiness and rueful melancholy. Damien Pass roved far and wide on 26th October, from Britten folk settings to authoritative readings of Vaughan Williams’ Songs of Travel, from Duparc’s settings of Baudelaire to Waltzing Mathilda. Pass’s diction was exemplary, in whatever language, and his tone striking - he is not afraid to indulge a whispered piano and can spin a narrative thread most effectively.

Claire Seymour

Casts and production information:

Nino Rota: Il Capello Di Paglia Di Firenza

Fadinard, Filippo Adami; Nonancourt, SalvatoreSalvaggio; Beaupertuis, Filippo Fontana; Lo zio Vézinet, Aled Hall; Emilio, Owen Gilhooly; Felicelen, Leonel Pinheiro; Elena, Claudia Boyle; Anaide, Eleanor Lyons; La Baronessa di Champigny, Asude Karayavuz; Achille di Rosalba, Leonel Pinheiro; La modista, Samantha Hay; Un caporale delle guardie, Nicholas Morris; Una guardia, Ronan Busfield; Minardi, Feilmidh Nunan; Minardi’s Pianist, Richard Barker; conductor, Sergio Alapont; director, Andrea Cigni; assistant director, Roberto Catalano; designer, Lorenzo Cutúli; lighting designer, Paul Keogan.

Jules Massenet: Il Thérèse

Thérèse, Nora Souzouzian; Armand de Clerval, Philippe Do; André Thorel Brian Mulligan; Morel, Damien Pass; Un Officier municipal, Jamie Rock; Un Officer, Raffaele d’Ascanio; Un autre Officier, Padraic Rowan; Une Voix d’Homme, Koji Terada; Une Voix de Femme, Christina Gill.

La Navarraise

Anita, Nora Sourouzian; Araquil, Philippe Do; Garrido, Brian Mulligan; Remigio, Damien Pass; Ramon, Peter Davouren; Bustamente, Koji Terada; Un Soldat, Joe Morgan. Conductor, Carlos Lzcaray; director, Renaud Doucet; assistant director, Sophie Motley; designer, André Barbe; lighting designer, Paul Keogan.

Jacopi Foroni: Cristina

Cristina, Helena Dix; Maria Eufrosina, Lucia Cirillo; Axel Oxenstjerna, David Stout; Erik Oxenstjerna, Patrick Hyland; Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie, John Bellemer; Carlo Gustavo, Igor Golovatenko; Arnold Messenius, Thomas Faulkner; Johan Messenius, Daniel Szeili; Un Pescatore, Joe Morgan; Voce Interna, Hannah Sawle; conductor, Andrew Greenwood; director, Stephen Medcalf; assistant director, Conor Hanratty; set designer, Jamie Vartan; lighting director, Paul Keogan; choreographer, Paula O’Reilly.

Wexford Festival Opera, 23rd October - 3rd November 2013

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Cristina_01.gif image_description=Helena Dix as Cristina [Photo by Clive Barda] product=yes product_title=Wexford Festival 2013 product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Helena Dix as CristinaPhotos by Clive Barda

October 29, 2013

Florilegium, Wigmore Hall

‘Vergnügte Ruh, beliebte Seelenlust’ (Delightful rest, beloved pleasure of the soul) was composed by Bach for performance in St Thomas’s Church, Leipzig, on the sixth Sunday after Trinity and was first heard on 28 July 1726. The text speaks of the desire to lead a virtuous in order to enter Heaven. The opening aria, with its lilting, flowing rhythms, was endowed with a tender, pastoral mood, the oboe d’amore (Alexandra Bellamy) blending soothingly with the strings and organ. Robin Blaze’s pure, even vocal line complemented the instrumental timbre and his delivery was confident and focused, although the text was not always enunciated with absolute clarity. Blaze spun sustained legato lines, particularly in the piano passages, but at times I found the countertenor’s tendency to heighten a particular word or phrase with a sudden crescendo or dynamic emphasis created an overly stark contrast of tone and diminished the effect of the effortlessly unfolding melodic contours.

Expressive contrasts of this nature were, however, put to good use in the following recitative, ‘Die Welt, das Sündenhaus’ (The world, that house of sin), which paints a picture of a sinful earth in league with the devil. Blaze almost snarled as he presented a vision of man who ‘sucht durch Hass und Neid/ Des Satans Bild an sich zu tragen’ (seeks through hate and spite/ The devil’s image e’er to cherish), while his humble address, ‘Gerechter Gott, wie weit ist doch der Mensch von dir entfernet’ (O righteous God, how far in truth is man from thee divided), was hushed and distant, aptly conveying meekness and regret.

The second aria, ‘Wie jammern mich doch die verkehrten Herzen’ (What sorrow fills me for these wayward spirits) opened with a dry preface, indicative of the speaker’s grief for the ‘wayward spirits’ who have ignored the Word of God. With the continuo line silent, Blaze struggled at times to blend with the rather sparse, and unusual, instrumental texture of two-part organ (now taking an obliggato role) with violins and violas in unison; in the lower pitched passages the countertenor sometimes lacked impact, although Blaze demonstrated virtuosic agility in the more florid passage work.

The following recitative, ‘Wer sollte sich demnach/ Wohl hier zu leben wünschen’ (Who shall, therefore, desire to live in this existence) was dark and eerie; the still chords of the strings and continuo plunged to a lower register to haunting effect, while the strings brought bright movement to the singer’s earnest plea, ‘bei Gott zu leben,/ Der selbst die Liebe heißt’ ([my heart] seeks alone with God its dwelling,/ Who is himself called love).

The rather bleak text of the final aria, ‘Mir ekelt mehr zu leben’ (I am sick to death of living), was mitigated by the glowing warmth of the oboe d’amore and the delicate traceries of the organ’s florid ornamentation (played with assurance by Terence Charlston) which together beautiful embodied the comforts and glory of Heaven. Blaze’s vocal phrases were impassioned but controlled, the lines graceful and flowing, the text imbued with meaning without recourse to melodrama.

Pergolesi’s ‘Salve Regina’ — originally in C Minor for soprano but later adapted for countertenor in F Minor — was composed during the last years of the composer’s short life, when he was in the employ of the Duke of Maddaloni. Suffering from tuberculosis, Pergolesi at times withdrew to a Franciscan monastery in Pozzuoli, Naples, and the ‘Salve Regina’ was written during the composer’s final retreat.

Here, Robin Blaze adopted a more theatrical mode, bringing greater urgency to the text which eulogises the Virgin Mary in a series of contrasting movements. Following a plangent string introduction, the singer issued resonant entreaties to the Virgin, to cast her blessing and mercy on the ‘poor banished children of Eve’ who languish on earth. Blaze’s elongated lyrical lines were deeply expressive of the mourning of mankind, ‘in hac lacrimarum valle’ (weeping in this valley of tears). He brought initially a surprising vigour to his plea, ‘Et Jesum, benedictum fructum ventis tui’ (show unto us the blessed fruit of thy womb, Jesus), then allowed the melody to evolve with poise and sweetness.

A heartfelt cry, ‘O clemens’, opened the final aria, as Blaze conveyed the sincere and solemn emotions of the text, before a final whispered declaration of reverence. Overall, this was a well-considered interpretation, one which balanced dramatic intensity with elegant grace, and which revealed Blaze’s wide-ranging technical expertise.

The vocal items were nested within various instrumental works. In the opening item, Telemann’s Overture in A Minor for Recorder and strings, director Ashley Solomon used an engagingly wide range of dynamics and impressively shaped crescendos to draw in the listener; the melodic lines had an extensive fluidity, while the ‘Air à Italien’ benefited from some markedly vigorous accents from the cello which acted as a springboard for the dance.

Throughout the evening, the instrumental support from the members of Florilegium was unfailingly sensitive and idiomatic: textures were homogenous and mellifluous, and a shared awareness of stylistically appropriate ‘good taste’ was ever-present. What was perhaps lacking was a dash of the spontaneous or unpredictable, and, at times, greater rhythmic verve and vigour — although Jennifer Morsches’ pizzicato cello utterances did much to brighten and enliven. That said, the facility and virtuosity of all, and the sweetness of tone — invigorated with occasional harmonic piquancy — ensured the audience’s considered and appreciative attentiveness. The running semiquavers of Handel’s Sonata in Bb for solo violin and strings were injected with drama. And, the Andante of Telemann’s Concerto in E for flute, oboe d’amore, viola d’amore and strings possessed a beautifully airy weightlessness, while the subsequent Allegro showcased the expressive presence and eloquence of Alexandra Bellamy’s oboe d’amore playing.

Claire Seymour

Programme and performers:

Telemann — Suite in A minor TWV55:A3; J.S. Bach — Cantata BWV170 ‘Vergnügte Ruh, beliebte Seelenlust’; Handel — Sonata a 5 in Bb HWV288; Pergolesi — Salve Regina in F minor; Telemann — Concerto in E for flute, oboe d’amore and viola d’amore TWV53:E1

Florilegium — Ashley Solomon (Director), flute/recorder; Robin Blaze, countertenor; Alexandra Bellamy, oboe d’amore; Bojan Cicic, violin 1/viola d’amore; Sophie Barber, violin 2; Magdalena Loth-Hill, violin 3; Malgorzata Ziemkiewicz, viola; Jennifer Morsches, cello; Carina Cosgrave, bass; Terence Charlston, harpsichord/chamber organ. Robin Blaze, countertenor. Wigmore Hall, London, Wednesday 23rd October 2013.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Florilegium.png image_description=Florilegium product=yes product_title=Florilegium, Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: FlorilegiumOctober 26, 2013

Iain Bell’s A Harlot’s Progress, An Opera to be Reckoned With

By José Mª Irurzun [Seen & Heard International, 24 October 2013]

Attending the world premiere of an opera is always a special occasion, and even more so if it is the first opera by its composer. If one adds to all this the fact that the venue is the Theater an der Wien, whose history is filled with premieres of musical masterpieces, the cup of interest cannot be more full of curiosity and expectations.

Old gods awaken

[Alex Ross: The Rest Is Noise, 25 October 2013]

Angela Meade and Jamie Barton both delivered tremendous performances in last night's Norma at the Met, causing some old-school pandemonium in the house. Meade sang with a degree of dramatic involvement that I hadn't yet seen from this greatly gifted soprano.

breaking baden

By John Yohalem [Parterre Box, 26 October 2013]

Baden-Baden 1927 is the title Gotham Chamber Opera has given to its evening of four brief operas that premiered together at a festival in, yes, Baden-Baden on July 17, 1927.

Soaring Into San Francisco: Greer Grimsley as The Flying Dutchman

San Francisco Classical Voice

Greer Grimsley returns to San Francisco Opera this week to sing the title role of The Flying Dutchman. Grimsley, a bass-baritone who made his company debut in 2002 as Scarpia in Tosca, returned as Monterone in the company’s 2006 Rigoletto and as Jokanaan in the 2009 Salome.

21 Reasons You Should Book for An Evening With Stuart Skelton & Friends in Celebration of ENO

Prima La Musica [7 October 2013]

Read about the concert here, and about Stuart's reasons for making it happen here. If you've already booked, then I salute you! If you haven't, and you're in London and free this Thursday, this is my shameless attempt to change your plans.

Of chaste divas and broken legato

Likely Impossibilitiess [13 October 2013]

I went to see Norma at the Met on Thursday in part because, I confess, I had never seen Norma.

Grumbles over Scala's New MD Designate, Mutiny on the High Cs

Opera Chic [23 October 2013]

It wouldn't be La Scala without cries of dissension, but when Corriere della Sera last week outed Riccardo Chailly as La Scala's incoming MD (for an outward-bound Barneboim), the orchestra's grumbles out-grumbled everyone.

October 24, 2013

Der Fliegende Holländer in San Francisco

That is more or less what happened last night at San Francisco Opera. Though the forces for Der Fliegende Holländer are relatively modest — three principal singers live the drama, three more offer background story; orchestrally there are but double winds, (except triple trombones and five horns). San Francisco Opera beefed up its chorus to a grandiose seventy-eight, after all it is a Wagner anniversary, and there were a few extra strings as well.

But Der Fliegende Holländer is the inauguration of Wagner’s uniquely fertile exploration of redemption through love, and it is emblematic of the tragic idealism that exponentially enriches nineteenth century art. It is conceptually and philosophically big art.

San Francisco Opera partnered with the Opéra Royal de Wallonie (a province of Belgium), that has a sizable presence in French provincial opera for this new production of Dutchman conceived by French/Romanian director Petrika Ionesco. Mr. Ionesco is known to San Francisco audiences for the Théâtre du Châtelet (Paris) staging of Cyrano de Bergerac seen two years ago at the War Memorial — a swashbuckling, cinematic conception that made the most of a slight opera for a broad audience. Mr. Ionesco has staged both Aida and Nabucco at the 80,000 seat Stadt de France and Continents on Parade at EuroDisney.

For those of us who did not see the Vaisseau Fantôme in Liège accounts say it began with Senta alone on stage in a cemetery (Senta does not appear in the libretto until the second act) and ended with Senta freezing to death among the same tombstones — the opera became Senta’s dream (Senta works in a factory that makes clothing and sails for sailors thus in her dream piles of cloth had become tombstones by means of tricky lighting).

In Liège the Dutchman flew onto Daland’s ship attached to a huge anchor to seek protection from the opening storm. Then there was some sort of science fiction action that accompanied the Dutchman to a fantasy place of skeletons and cloaks where he tells his tale of woe. The production was said to have been tuned to appeal to a broad public, maybe becoming a bit like a Stephen King novel.

Greer Grimsley as the Dutchman

Greer Grimsley as the Dutchman

Strange to say it was not until the production was actually onstage at War Memorial that the current artistic politic of San Francisco’s opera house determined that the production did not conform. Mr. Ionesco and his ideas were dismissed. A fast attempt was made to re-stage the opera by summarizing the action. Senta still began the opera alone on stage but there were no tombstones, and finally she leapt to her death from the remnant of a raised hatch from the Act I ship (though there was no idea where she landed as by that point we had no idea where we were). But it did not seem to be freezing and there was not a tombstone in sight. All this was hardly Ionesco’s adolescent dream, in fact it was simply a walk through of the libretto.

The Dutchman walked on and off the stage from downstage right or left with absolutely no visual magic or fanfare even though he is a phantom hero. He stood totally alone in front of the red lighted fantasy space to deliver his extended monologue as best he could. The considerable snowfall in Act I and the clumsy every-once-in-a-while projections of icebergs that could have dramaturgically motivated a death by freezing remained unexplained, arbitrary atmospheres.

It would have been heroic salvation had conductor Patrick Summers been able to redeem this fiasco through enthralling music. This was not the case, the maestro sought always a richness of orchestral description and color rather than a realization of music drama. Tempos were generally relaxed rather than charged with meaning, apparent first in the leaden overture, and burdensome particularly in the Dutchman monologue and the big Senta ballad. The maestro’s tempos never discovered the joys of a good wind nor found the terrors of a great storm, both stupendous expressive moments in Wagner’s first masterwork.

Mo. Summers is however particularly attuned to his singers, and some very fine, if meaningless performances resulted, most notably the Dutchman himself, enacted by American bass baritone Greer Grimsley. We can assume that the character Mr. Grimsley portrayed on the stage was created for the Ionesco production. The Dutchman was a suffering, vulnerable human man that Grimsley brilliantly portrayed both physically and vocally. He possesses a quite beautiful voice that he colored in many tonalities to fill his monologues with precise and genuine information and feeling.

Summers offered the same support to the Steersman, beautifully sung, and made real by Adler Fellow, tenor A.J. Glueckert. Welsh tenor Ian Storey created an Eric, Senta’s intended, who came across as more threatening than hurt. With a presence more Tristan than as a Hanseatic lad he sang Wagner’s quite felt music beautifully, perhaps too much so for the Ionesco character. His too frequent use of sotto voce was bothersome. Conductor Summers gave Senta’s father Daland the gruffness inherent to Icelandic bass Kristinn Sigmundsson’s persona and voice, a gruffness that resonated as well in the truly plodding tempos the maestro imposed on the dances that begin the third act.

Ian Storey as Eric, Lise Lindstrom as Senta

Ian Storey as Eric, Lise Lindstrom as Senta

Originally German soprano Petra Maria Schnitzer was cast as Senta. She was replaced by American (San Francisco) soprano Lise Lindstrom who is a fine singer well suited to the Turandot role she frequently sings on the major stages. Hers is not a voice of youthful sweetness or lyricism that might make Senta a mythical nineteenth century angel of death, but it did serve to portray Ionesco’s neurotically obsessed young woman. Intelligence gathered while the elevator descended to subterranean parking levels reveals that some of us thought she stole the show.

Hopefully such events as this Dutchman are once in a century.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Dutchman: Greer Grimsley; Senta: Lise Lindstrom; Erik: Ian Storey; Daland: Kristinn Sigmundsson; Steersman: A.J. Glueckert; Mary: Erin Johnson. Chorus and Orchestra of the San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Patrick Summers; Director/Set Designer: Petrika Ionesco; Costume Designer: Lili Kendaka; Lighting Designer: Gary Marder; Projection Designer: S. Katy Tucker. War Memorial Opera House, October 22, 2013.

EXTENDED

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Dutchman1_SFOT.png

image_description=The Dutchman and Senta at San Francisco Opera [Photo by Cory Weaver]

product=yes

product_title=Der Fliegende Holländer at San Francisco Opera

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above:The Dutchman and Senta at San Francisco Opera

Photos © Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera

October 23, 2013

Mark-Anthony Turnage, Greek

Anna Nicole, came this reminder — both sad and hopeful- that Mark-Anthony Turnage was once capable of writing urgent, exciting music theatre. Indeed, from this composer I have heard nothing finer, perhaps nothing to match, this, his first opera, to Steven Berkoff’s libretto after his own Oedipal play, Greek. Adverse circumstances notwithstanding, this performance and production from Music Theatre Wales offered everything one could reasonably hope for, and more. Marcus Farnsworth, who had been ailing on the first night, had awoken with no voice, to be replaced by an heroic combination of the flown-in-from-Berlin-that-afternoon Alastair Shelton-Smith to sing the part on stage and Michael McCarthy to act, to mime the sung passages, and to deliver the spoken text. If anything, the practice added to the feeling of alienation, social and theatrical, but it would have come to nothing without such committed performances. From the word go, or rather a somewhat bluer word than that, when McCarthy hastened toward the stage, scarily impersonating an irate member of the audience hurling abuse at the audience, he inhabited the role visually and gesturally. His own production frames the performance convincingly, offering a return into the audience as Eddy is rejected by his family, those who supposedly love him unable to stomach his desire to ‘climb back inside my mum’. Shelton-Smith’s assuredly protean yet deeply felt vocal performance fully deserved the rapturous reception it received from audience and fellow cast-members alike, and would have done so even if it had not been for the particular circumstances.

But the other performances were equally assured. Sally Silver and Louise Winter proved as versatile in vocal as in acting terms, their combination as lesbian separatist sphinx being sleazy and savagely humorous in equal measure. Gwion Thomas was just as impressive in the other male roles, the sad would-be patriarch as much as the brutal police chief. The Music Theatre Wales Ensemble under Michael Rafferty played Turnage’s score as to the manner born: angry and soulful, biting and tender, urgent and yet offering oases for reflection. Whether called upon to play in conventional terms, to shout, to stamp, or even to strike a pose, there could be no gainsaying the level of artistry on offer from players and conductor alike.

McCarthy’s production places the work firmly in the tradition of music theatre — doubtless partly out of necessity, but, unlike in the opera, virtue certainly arises out of fate. Props are minimal but used to full effect, the cast in proper post-Brechtian fashion undertaking the stage business too. Video projections of key words, not least Berkoff’s inevitable ‘Motherfucker’, heightens both drama and alienation. But perhaps the principal virtue is that of allowing the anger of Berkoff and Turnage’s drama to unfold, within an intelligent yet far from attention-seeking frame. The transposition of the Oedipus myth to 1980s London now seems both of its time and yet relevant to ours. It works as a far more daring version of the original EastEnders might have done, yet with injection of magic realism. Both Berkoff’s ear for language — the ability to forge a stylised ‘vernacular’, which yet can occasionally shift into knowingly would-be Shakespearean poetry — and Turnage’s response and intensification, whether his pounding protest rhythms or the jazzy seduction of his beloved saxophone, work just as McCarthy’s staging does: they grip and yet they will also, if not always, distance. Above all, one continues to feel and indeed to reiterate the anger felt by outcasts in the brutal Britain of Margaret Thatcher. Incest offers not only its own story, but stands or can come to stand also for other forms of social and sexual exclusion. Hearing of the plague, one can think of it as Thatcherism and the ignorant, hypocritical right-wing populism that continues to infest political discourse, or one can turn it round and view it as the guardians of morality most certainly would have done at the time of the 1988 premiere, as the fruits of sexual ‘deviance’: the tragedy of HIV/AIDS.

That space to think, to interpret is not the least of the work’s virtues, fully realised in performance. Its musical lineage is distinguished; on this occasion, those coming to mind included Stravinsky, Andriessen, magical shards of Knussen, and, alongside the music theatre of the Manchester School, that of Henze too, especially the angry social protest of Natascha Ungeheuer. But it is its own work, now with its own performance tradition, of which Music Theatre Wales’s contribution is heartily to be welcomed.

Mark Berry

Cast and production information:

Eddy: Alastair Shelton-Smith/Michael McCarthy; Eddy’s Mum/Waitress/Sphinx: Sally Silver; Eddy’s Sister/Waitress who becomes Eddy’s Wife/Sphinx: Louise Winter; Dad/Café Manager/Chief of Police: Gwion Thomas. Director: Michael McCarthy; Designs: Simon Banham; Lighting: Ace McCarron, Jon Turtle. The Music Theatre Wales Ensemble/Michael Rafferty (conductor). Linbury Studio Theatre, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Tuesday 22 October 2013.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Turnage.png image_description=Mark-Anthony Turnage [Photo by Philip Gatward] product=yes product_title=Mark-Anthony Turnage, Greek product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Mark-Anthony Turnage [Photo by Philip Gatward]Armide, Amsterdam

Luckily, at its heart we were privileged to have a soprano with true star quality, the radiant Karina Gauvin. Ms. Gauvin has a well-deserved reputation for pre-eminence in this Fach and it is easy to see why. Her lustrous, honeyed instrument is wedded to a refined technique that handily surmounts any obstacle the composer has invented. Well-colored dramatic outbursts? Check. Clean trills and coloratura with inner life? Check.

Check. Melting cantilenas, supreme arching legato phrases, rich chest voice? Check. Check. And Check.

And while she commands the style with precision and authenticity, Karina avoids the pitfalls of preciousness and correctness that can sometimes handicap such period efforts. Her Armide was a living, breathing, emoting woman that happened to flawlessly represent her story in Gluck’s musical vocabulary. Hers was a towering achievement.

Karina Gauvin as Armide and Frédéric Antoun as Renaud

Karina Gauvin as Armide and Frédéric Antoun as Renaud

She was well-matched by Frédéric Antoun as the dashing Renaud who is the object of her conflicted love-hate musings. Mr. Antoun’s lightly veiled, medium weight, freely produced tenor is an exact match for the role. The tonal production is well-connected from low to (very) high and he rides the breath with ease. He delivers yummy, haunting phrases when in love, and colors his declarations with appropriate scorn when freed from the spell. Although Ms. Gauvin’s vocal presence was marginally more forthcoming, the two partnered each other well in the extended duets,

As Armide’s confidantes, Karin Strobos (Phénice) and Ana Quintans (Sidonie) set off sparks with their assured, bravura delivery. Ms. Strobos’ youthful mezzo was cleanly produced with a hint of darkness, and her spunky stage presence enlivened every scene she was in. Ms. Quintans’ accurate soprano brought a welcome soubrette-ish brightness to the proceedings. This worked exceedingly well for her as Sidonie, but she was cast in multiple roles to include Naiad, Shepherdess (where her bright delivery worked), as well as the Demon in the Figure of Mélisse (where it worked less well, a bit more vocal heft being ideal).

Henk Neven drew a good distinction between his dual roles as the tormented Aronte and the swaggering Ubalde. As the latter, he provided some of the evening’s best French, revealing a creamy baritone that was robust at full voice and meltingly effective in half voice. Alas, Sébastein Droy could not match this double duty feat as Artémidore and the Danish Knight. His muffled tenor seemed short on top, and he kept the volume knob turned to mezzo forte either by choice or of necessity. As Hidraot, Andrew Foster-Williams’ good dramatic intent and hectoring delivery could not quite compensate for a somewhat woolly bass-baritone.

I have always loved the generous artist Diana Montague, but here she seemed miscast as Hate. Her beautiful styling, freely produced mezzo, and innate musicality were everywhere in evidence but the role seemed to require singer capable of a searing Cossotto tirade rather than a controlled lyrical reprimand. Francesca Russo Ermolli made a lovely impression late in the piece as Pleasure, her poised, pure tone gently beguiling us.

Ivor Bolton has few equals in this repertoire and he drew forth thrilling sounds from his band of instrumentalists. Whether as a tightly knit ensemble or featured in remarkable solos, this was a first class effort from the pit (the principal flute was just remarkable all night long). Nicholas Jenkins chorus was no less exciting, and their dramatic commitment was awesome, yes that’s the word. Nonetheless there were a couple of instances when chorus and orchestra were internally together, but there was a split second disparity between stage and pit. This was also true with Act IV, when Ubalde and the Danish Kinight seemed periodically, stubbornly out of sync. Since the musical perfection was ninety-nine per cent a given, I can only imagine there was an acoustic issue with the wide-open setting and its lack of reflective surfaces, the manic staging that was imposed on the piece, the upstage placement of the performers, or all three.

Hysterical (or at times sardonic) laughter, swords hurled to the ground, pregnant pauses, manic splashing in a pond. . .do these jump to mind when contemplating Gluck’s Armide? Because they evidently did to director Barrie Kosky. Katrin Lea Tag has designed a basic setting of a wide swath of lumpy turf that fills the center two thirds of the apron with a rather scruffy tree sprouting stage right. Armide, clad in a simple, wholly unremarkable black dress spends so much time posed by that single set piece, I half expected her to channel Lady Bird Johnson and urge us to “plant a tree, a shrub, a bush. . .”

Sébastien Droy as Le Chevalier Danois and Frédéric Antoun as Renaud

Sébastien Droy as Le Chevalier Danois and Frédéric Antoun as Renaud

Renaud’s enchantment is a curious ‘affair’ indeed. He ends his first solo asleep face down by the tree, so Armide becomes smitten with him solely from regarding his firm, um, torso, as she clings to the tree in perhaps too phallic a manner. As he became bewitched, they did a slooooooo-moooooo pas de deux that found them stroking faces, hair and arms over and over and over again. And over. Again. Then as the piece ended to deafening silence, they slunk to the right proscenium (presumably to stroke it) as Mr. Bolton waited and waited. And. Waited.

The Maestro’s body language suggested he got either amused or irritated that musical set pieces excellently performed got no applause, but truth to tell there was not one visual “button” to prompt a response. Two weeks prior, I was privileged to see a brand new opera that got frequent applause because the creative team (and composer) cued us when a section was finished. The repeated uses of long pauses was a considerable miscalculation, sapping the musical impetus, and distorting the shape. I mean these were long enough pauses to make Harold Pinter yell “get on with it!” Since there is no compensating dramatic revelation, I would urge eliminating them.

Ms. Tag’s setting eventually reveals the entire stage, with a large rectangular pool of water, and a scattering of trees. This had promise, perhaps only because this garden was a relief from the bleak desert. There was certainly little to fault with Franck Evin’s brilliant (pun intended) lighting design. Mr. Evin used harsh down- and cross-lighting to fine purpose and selectively added in color filters that enhanced the mood and emotion. The only mis-step was that Renaud sang much of one solo entirely in the dark while Mr. Kosky chose to illuminate extras who were noisily splashing in the pond behind.

This manic frolicking in the water was used on many occasions perhaps to distract us from the fact that the principals were not very well-directed and their character relationships were not well-developed. At one point, Armide’s two confidantes kick up water tirelessly while poor Ms. Gauvin tries gamely to sing over it. Another moment found the chorus clumped together slogging en masse through the pond from stage left to right while jerking their heads like pigeons on acid. Oh, and when in doubt of how to show actors are dramatically involved, make them throw swords clanking to the ground. No kidding, the metal met the road this way countless times over the long-ish evening.

Ms. Tag the set designer made a better presentation than Ms. Tag the costume designer. It is not her fault that her set was frequently ill-used. But it is her fault that the disparate assortment of clothing made little sense nor a unified statement. Some of it, like the schmatte foisted on Sidonie, looked like it might be beachwear covered by a weird wrap. Hidraot was attired in a paraphrase of kilts. Or was it a plaid 1950’s girl’s tartan skirt? At least the two knights looked like knights and Renaud looked heroic. What was up with bare-chested Aronte and the clinging white pants with a blood stain suggesting his manhood had been cut off? The fact that he a) was still singing baritone and b) was filling out the revealing trousers quite well thank you, suggested that Mrs. Aronte is/was a lucky woman.

Frédéric Antoun as Renaud

Frédéric Antoun as Renaud

One scene that almost worked in spite of itself was Hate’s entrance. With much laying on of mist after a rainstorm upstage, a group of male choristers crept on and pinned Armide onto her back on a hillock. Clad in ominous black period suits, with neck ruffs and sort of Baron von Richthofen aviator skull caps, eventually the men hold her legs spread, and she gives birth to Hate with Ms. Montague crawling into view from a trap door under her skirts. Quite a stunning, wow moment. But then the female chorus rushed on dressed identically in straight blond wigs, neon pink (sort of) business suits, and black vinyl boots. And the entire chorus twitched like they were choreographed by St. Vitus. I can only applaud their dedication and hard work even as I scratch my head as to how such a great moment was just thrown away with undisciplined excess.

When not splashing or twitching, characters engaged in inappropriate laughter. Armide is first made to cackle in anticipation of snaring Renaud, who ultimately laughs at Armide when he rejects her. There is choral laughter a number of times, perhaps most memorably when an effigy of Armide is hung by the neck and sent swinging near the end of Act I. Maybe they are tickled because it looks like an effect purchased at a Down in the Valley fire sale? This dummy gets swung back into action in Act II by which time we could have all used a good laugh.

In furthering the belief that nothing exceeds like excess, there is an endless rain of confetti late in the first half that starts out being quite dazzling and goes on until we are good and tired of it. But why stop? The second half begins with an endless rain of pink and red confetti, that outlives the Energizer Bunny. The lovely waltz late in the evening is not treated to proper ballet, but rather finds the cast paired off, slow-dancing in the pond like last call at the Junior prom. And when the music ends, they forget to tell the cast who keep swaying for another 30 seconds, well, just because they can.

In a final cynical decision, the production brings an old naked couple into the scene, I guess to nail home the idea to Renaud that this is what relationships will lead to, sagging bits and bobs and disorientation. By the time the glorious Ms. Gauvin gets stranded motionless on a dune, with all other distractions stilled, beautifully interpreting her final aria almost motionless as in a concert, I was thinking, “a concert. . .gee. . .if only.”

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Armide: Karina Gauvin; Hidraot: Andrew Foster-Williams; Renaud: Frédéric Antoun; Artémidore/Danish Knight: Sébastein Droy; Ubalde/Aronte: Henk Neven; Sidonie/Nayad/Shepherdess/Demon in the figure of Mélisse: Ana Quintans; Phénice: Karin Strobos; Hate: Diana Montague; A Pleasure: Francesca Russo Ermolli; Conductor: Ivor Bolton; Director: Barrie Kosky; Set and Costume Design: Katrin Lea Tag; Lighting Design: Franck Evin; Chorus Master: Nicholas Jenkins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/armide_172.png

image_description=Diana Montague as La Haine and Karina Gauvin as Armide [Photo by Monika Rittershaus courtesy of De Nederlandse Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Armide, Amsterdam

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Diana Montague as La Haine and Karina Gauvin as Armide

Photos by Monika Rittershaus courtesy of De Nederlandse Opera

London’s Vespers Ring the Right Bells

Much of this is owing to director Stefan Herheim’s growing reputation as a fascinating stage director, and the fact that this marked his debut in the UK, a country that has taught the world a thing or two about great theatre. Mr. Herheim’s riveting staging was indeed cause for celebration, but first it must be said that conductor Antonio Pappano arguably eclipsed every other achievement with so exceptional a reading of Verdi’s least appreciated mature opera.

“Passionate.” “Heartfelt.” “Electrifying.” These seem to be puny adjectives indeed to summarize Pappano’s achievement. “Definitive” might be the word. If the superlative ROH orchestra seemed to be on fire the whole night, it was Maestro Pappano who struck the match. Not only was his well-shaped performance idiomatically apt, characterized by breadth and power, but also his consummate uses of accelerando and rubato, at one with the singers, lent spontaneity and inevitability to the music-making that made us feel as if we were hearing it for the first time. The thundering ovation the orchestra and conductor received at curtain call was testament from an audience that knew they had just been gifted with a very special night at the opera.

Micahel Volle as Montfort and Bryan Hymel as Henri

Micahel Volle as Montfort and Bryan Hymel as Henri

Les vêpres siciliennes is probably no one’s favorite Verdi. In spite of some glorious stretches, there are segments that are reminiscent of more successful prior Verdi, or portents of even better Verdi to come. When we encounter this piece at all it is usually in its Italian version (I Vespri Siciliani). Well, what a difference the language makes. Every principal artist is here flattered by the French pronunciation, which favors a slight cover and softness (over the brighter Italianate delivery). And what a privilege that we have a cast that can so memorably deliver the goods.

Pride of place must go to Michael Volle’s exquisitely wrought Guy de Monfort. Having greatly admired Mr. Volle in German opera, nothing about his prior achievements prepared me for the depth and power of the impression he made in this role. The language suits his mellow (yet substantial) baritone to a “T” and he explores and deploys an entire range of colors and emotions from the very bottom of the role to the extreme top. There was not a note he produced that was not fraught with great detail, no phrase that was not informed with emotional nuance. He did not so much sing the part, as live it, and Michael quite simply stole the show. Nor was he alone in his success.

Brian Hymel has come a long long way since I first admired his promising Faust at Santa Fe. His mastery of French styling is evidenced by his triumphs in ever more challenging assignments on world stages (to include ROH). Mr. Hymel seems to have become something of a ‘local hero’ owing to his having saved a production or two by stepping in on short notice. But just being ‘available’ would not be enough in these heady surroundings. His utterly secure, freely produced top gleams and sails into the house with power and brilliance. He has learned well to use forward placement and pure, limp production to make the voice meaty in the lower passages. With skill and artistry the tenor has grown into ‘the‘ leading exponent currently performing this repertoire.

As a lovely Hélène, Lianna Haroutounian filled in for the previously announced Marina Poplavskaya (who was ill). Ms. Haroutounian is the real deal, a true spinto voice that can meet all the Verdian demands, and boy do we need her now! Her shimmering, golden tone could serve up melting phrases and anguished outbursts alike. The glowing top register was complemented by a middle with good presence, and a ringing chest voice.

If the soprano fudged a little with her opening coloratura, and dragged the “Bolero” ever so slightly to negotiate the tricky leaps and turns, many another great interpreter has similarly negotiated these challenges. A major emerging talent, we will be proud to say we knew her ‘when.’

Erwin Schrott as Procida

Erwin Schrott as Procida

As Jean Procida, Erwin Schrott often effects a big, take-no-prisoners vocal delivery which makes for good theatre, to be sure, but also invites uneven vocal production. While I admired his overall performance and enjoyed many statements and phrases, Mr. Schrott did not always succeed in marrying up his placement and his intent. “Et toi Palerme” was wonderfully varied, but the well-intended ebb and flow nonetheless exposed the singer’s somewhat weak legato. He was on firmer footing when his genial bass was more conversational in delivery, although I would urge him to moderate his dramatic instincts to pulverize climactic notes which can veer a mite off pitch. Still, Schrott is a mesmerizing performer and he wins the Nathan Gunn Award for getting to display his well-toned pecs in the prison scene.

As one would expect at Covent Garden, all of the minor roles were polished and poised, but I particularly enjoyed Jihoon Kim as Robert. This promising young singer is a Jette Parker Principal artist, and ROH is right to place such confidence in him and to nurture a performer of such accomplishment and real individuality. His rolling, dark bass surely has a bright future.

So what of the ‘controversial’ Stefan Herheim, whose leadership caused so much speculation, anticipation, and in some quarters, concern? In general terms, I find Mr. Herheim to be a serious director who does clean work. Not for him the easy way out. Everything he undertakes is thoroughly considered and consistent to itself. Many times this works brilliantly (the landmark Bayreuth Parsifal) and occasionally mis-fires (Brussel’s Rusalka-as-Belgian-streetwalker). Happily, Les vêpres siciliennes finds the heralded innovator at the top of his game.

Since the piece is somewhat weakly plotted, Herheim brilliantly approached it as a fantasy rather than a realistic history, paraphrasing the story within a meaningful context. The creative team re-imagined the setting in 1855 within the very ornate theatre that hosted the work’s Parisian premiere. His research led him to discover that not only were ballerinas idealized as the standard of contemporary feminine beauty, but they were also frequently reduced to being courtesans as male opportunists abused them to their own pleasurable ends. This concept further focuses on the theme of patrons who have the social and financial standing to use, and abuse art.

This ingeniously allows the entire piece to be set within the theatre, on- and back-stage, encompassing the auditorium itself. The ‘audience’ is at times viewing the story of the French occupation on the stage, and at times participating in the telling of it. Philipp Fürhofer’s monumental set design consists of ever-changing deconstructed components which include a massive gold proscenium arch, gilded ceiling appointments, three tiers of audience boxes, a huge mirrored wall complete with ballet barre, separate red and black grand drapes, and a gorgeous foyer wall with a painting of Etna erupting.

Bryan Hymel as Henri and Lianna Hartoutounian as Helene

Bryan Hymel as Henri and Lianna Hartoutounian as Helene

Mr. Fürhofer has concocted effective traffic patterns for keeping these elements in motion, with changes fluidly executed by the ROH backstage team. As large and handsome as the structures are, they are often used quite simply to achieve maximum effect. For example, the three tiers of boxes reverse to expose the stairs, which suggests the prison by simple addition of an executioner’s chopping block and straw. The mirrors separate to create entryways, and then recede to give way to the entire company performing ‘on stage’ as the elite watch from their boxes. The chopping block gets re-purposed as a wedding altar with the addition of candles that also get placed along the apron, creating footlights. The scenic invention was matched by Anders Poll’s meticulous lighting design. Not only did he isolate moments and soloists to fine effect but his washes and color choices created the right atmosphere, moving playfully between fantasy and reality. The garish illumination of the real audience in the score’s final moments was meant to beg the question: were we in any way complicit in using art to selfish ends?

The choice of period provided a fertile starting point for Gesine Völlm’s gorgeous costume designs. The elegant evening wear extended to Hélène’s resplendent sequined gowns. By contrast, the ‘actors’ performing the tale of the French-Italian conflict for the glitterati were decked out in a riot of colorful peasant folk costumes. With all this technical excellence in his arsenal, Mr. Herheim has crafted a wondrous re-telling of the story.

The overture is staged, opening with ballerinas in repose, in traditional white tutus. Seated in a chair down right, Procida is the ballet master, who rouses his charges to do their daily barre work. This serene, methodical fantasy milieu soon gives way to the intrusion of militiamen, who terrorize the women. Monfort brutally rapes one of the ballerinas, prompting three dancers to appear in black tutus, one injured, one pregnant, and one bearing a babe in arms. Soon, the young boy (Henri) appears who is the product of Monfort’s lust.

Herheim effectively uses the boy as a recurring visual, to include reappearing to be confronted by Monfort during his great aria, then as an axe-wielding executioner, and finally as a winged cupid in the wedding. The director has found considerable wit in this gloomy tale, witness the scene in which Monfort incites conspirators to battle and they respond by doing ballet barre work, daggers in hand.

There is also ingenious interweaving of dance throughout, which admirably unites and furthers the concept. Choreographer André de Jong has commendably utilized his corps in a tantalizing blend of modern story-telling served up through a traditional dance ‘vocabulary.’ The lovely use of the ballerinas to frame Procida for his great aria was but one of several thoroughly bewitching moments.

In addition to careful planning and well-judged artistic decisions, Mr. Herheim’s greatest strength may be his uncanny ability to inspire his actors to truthful, deeply felt performances of great specificity. His collaboration with Mr. Schrott to create a fey, yet feral ballet master of a Procida was genius. The emotional journey that Henri and Monfort took in their extended duet was stunning in its rich detail, only to be surpassed by the ensuing tenor-soprano duet. What volumes it spoke as the duo confronted each other while circling the chopping block that awaited them.

And what a coup de theatre lay in wait in the last scene! Fantasy finally morphs into phantasmagoria and Procida appears in drag (no kidding!), his gown paraphrasing the soprano’s first act black number, but here the underskirt is sparkling with red sequins. When he/she plucks up the French flag off the ground and begins massacring people by spearing them with the pole, insanity rules, art is used and abused, the Sicilians have been sacrificed, and the on-stage audience has been sated.

When normalcy returns, Monfort returns, no one is really dead (just ‘used’ for effect), curtain calls are posed, and then . . .well, you’ll have to see for yourself, if you can score a ticket. Stefan Herheim continues to impress, enrich, invent, delight, and mature as a pre-eminent director of our time, and we are all the better for it.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Thibault: Neal Cooper; Robert: Jihoon Kim; Le Sire de Béthune: Jean Teitgen; Le Comte de Vaudemont: Jeremy White; Daniéli: Nicolas Darmanin; La Duchesse Hélène: Lianna Haroutounian; Ninetta: Michelle Daly; Guy de Monfort: Michael Volle; Henri: Bryan Hymel; Jean Procida: Erwin Schrott; Mainfroid: Jung Soo Yun; Conductor: Antonio Pappano; Director: Stefan Herheim; Set Design: Philipp Fürhofer; Costume Design: Gesine Völlm; Lighting Design: Anders

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Vepres_RO_663.png

image_description=Erwin Schrott as Procida and Lianna Haroutounian as Helene [Photo © ROH / Bill Cooper]

product=yes

product_title=London’s Vespers Ring the Right Bells

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Erwin Schrott as Procida and Lianna Haroutounian as Helene

Photos © ROH / Bill Cooper

Verdi’s Otello at Lyric Opera of Chicago

The cast for the first performance included Johan Botha as Otello, Ana María Martínez as Desdemona, both Falk Struckmann and Todd Thomas singing the role of Iago, the former withdrawing because of indisposition after Act I. This performance also featured the American debut of tenor Antonio Poli as Cassio, John Irvin as Roderigo, Julie Anne Miller as Emilia, Evan Boyer as Lodovico, Anthony Clark Evans as Montano, and Richard Ollarsaba as a herald. The production was originally directed by Sir Peter Hall; the present revival is directed by Ashley Dean. Bertrand de Billy makes his Lyric Opera debut conducting these performances, and Michael Black is officially Chorus Master with the start of the current season.

Johan Botha as Otello and Falk Struckmann as Iago

Johan Botha as Otello and Falk Struckmann as Iago