November 29, 2013

Early Opera Company: Acis and Galatea

This vibrant, stylish performance by the Early Opera Company, under the direction of Christian Curnyn, left us in no doubt as to why it was one of the few of Handel’s large-scale works to remain popular after the composer’s death. As the drama swiftly unfolded, the stream of glorious melodies rang forth one after the other, spanning the full dramatic gamut from elation to despair, from fury to resignation.

The first performance of the work in 1718 was a private one, at James Brydges’ elegant house, Cannons, where Handel had been fortunate to gain employment following the closure of the King’s Theatre in 1717. Described as a ‘masque’, Acis and Galatea is typical of the short works on pastoral or mythological subjects which represented a home-grown ‘rejoinder’ in the face of the increasing public taste for Italian opera during the early eighteenth century.

The libretto — which was probably co-authored by John Gay, Alexander Pope and John Hughes — is drawn from Dryden’s translation of the thirteenth book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which appeared in London in 1717. It depicts a romance which unites earthly and immortal realms. The sea nymph Galatea is pining for her beloved, Acis; unbeknown to her, the young shepherd is simultaneously searching for her, anxious to be reunited with his cherished Galatea. The rational, worldly-wise Damon warns Acis that he is neglecting his duties, but the impetuous shepherd heeds not his friend, and eventually the lovers are reunited. However, the arrival of the love-struck monster Polyphemus soon spoils the celebrations, for the giant demands that Galatea transfer her affections to himself; when she refuses and Acis rises in fury against the giant, Polyphemus crushes Acis to death under a boulder. Distraught, Galatea is reminded of her divine powers: she transforms the dead Acis into a stream, thus granting him immortality.

Christian Curnyn launched into the overture with verve, the dynamic, animated playing of the instrumentalists setting the high standard of playing that was sustained throughout the evening and establishing a gripping dramatic momentum. Ensemble was exemplary, and the stylish execution, full of intensity but always elegant, was impressive, as the players painted an Arcadian scene.

The influence of Purcell, especially Dido and Aeneas, is evident in the way in which the chorus is intimately involved in the drama. On the rather crowded Wigmore Hall platform, the five singers were seated behind the instrumentalists, forming a well-blended chorus from which they emerged to take their solo roles, thereby both participating in and reflecting on the action.

The opening chorus instituted the mood of Arcadian serenity, the five voices intermingling with ease and simplicity, initially creating a sense of breadth, before the introduction of some relaxed counterpoint and points of imitation. In contrast, ‘Wretched lovers!’, which commences Act 2 was full of foreboding, and in the unaccompanied lament, ‘Mourn all ye muses’, sung over the body of the slain Acis, the consort of voices was touching but not sentimental, particularly at the line, ‘The gentle Acis is no more’.

The soloists were uniformly excellent.

As Galatea, Sophie Bevan produced a luscious Italianate cantilena, her gorgeous tone resonating sensuously throughout the hall. In ‘Hush ye pretty warbling choir’, her nimble vocal line melded sweetly with the sopranino recorder and upper strings. Handel’s technical challenges presented no problem for Bevan: trills were neat, ornaments not excessive. The recitative which precedes her aria of mourning, ‘Heart, the seat of soft desire’, was poignant, and her subsequent earnest command, ‘Rock, thy hollow womb disclose! The bubbling fountain!’ consoling; while the line ‘Lo! it flows’, suggested a touchingly hesitant joy. In this final aria, the sparkling treble recorders of Ian Wilson and Hannah McLaughin, accompanied by mellifluous, undulating strings, wonderfully evoked the magic of the fountain into which Acis has metamorphosed.

Robert Murray demonstrated a lovely sense of line as Acis. He made much of what is essential quite a weak role dramatically, combining passion and lyricism, both assertive and elegant. ‘Where shall I seek the maiden fair?’ was full of the naïve haste of youth; in the second Act, Murray skilfully suggested the shepherd’s growing emotional maturity, shaping the dynamic rises in ‘Love sounds th'alarm’ with intelligence and craftsmanship. His penetrating melody was gratifyingly complemented by Katharina Spreckelsen superb oboe playing.

As Damon, Samuel Boden’s graceful, light tenor provided a pleasing contrast to Murray’s more ardent tone. Boden captured well Damon’s composure and wisdom; ‘Consider, fond Shepard’, in which he attempts to quell Acis’s jealous anger had elegance and presence. Boden sang with sweet, refined tone, especially in an eloquent ‘Consider, fond shepherd’. ‘Would you gain the tender creature’ — an appeal to Polyphemus to essay a gentler line of seduction — would surely have charmed anyone but this unfeeling brute.

To lose one villain was unfortunate, but to lose two could have been potentially disastrous, had Matthew Rose not been available to step into the breach when first Derek Welton, and then his replacement Ashley Riches, were unable to perform the role of Polyphemus. From his first utterance, ‘I rage, I melt, I burn’, Rose filled the auditorium with a rich and profoundly satisfying sound.

Both fearsome and grotesque, in this opening accompanied recitative and throughout the opera he conveyed the essential complexity of the role: are we supposed to laugh at the lovelorn ogre whose gauche compliments and endearments fail to impress, or to protest at his vicious, petulant cruelty which shatters the lovers’ harmony? Probably both; and, in the following aria, ‘O ruddier than the cherry’, Rose conveyed the immensity of the Cyclopean monster’s burning love for Galatea and his fiery hatred for Acis.

Ian Wilson’s delightfully sprightly recorder obbligato reminded us of Ovid’s humorous depiction of Polyphemus as a ferocious goliath who plays an outsized set of shepherd’s pipes! Polyphemus is the dramatic catalyst, disrupting the Elysian bliss, and Rose’s ferocious interjections in the peaceful duet, ‘The flocks shall leave the mountains’, brutally shattered the lovers’ calm avowals of constancy and steadfastness. Curnyn and his performers were justifiably radiant as they acknowledged the appreciative and heartfelt applause. This was a fantastic, engaging performance with not a single weak link. A fabulous evening.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Robert Murray, tenor (as Acis); Sophie Bevan, soprano (as Galatea); Samuel Boden, tenor (as Damon); Matthew Rose, baritone (as Polyphemus); David de Winter, tenor (as Coridon); Christian Curnyn, director, harpsichord. Wigmore Hall, London, 27th November 2013.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sophie_Bevan_Ahlburg.gif image_description=Sophie Bevan [Photo © Sussie Ahlburg] product=yes product_title=Early Opera Company: Acis and Galatea product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Sophie Bevan [Photo © Sussie Ahlburg]November 27, 2013

Werner Güra Lieder recital, Wigmore Hall

The poems are united into a coherent whole by their varied presentations of the theme of love, as expressed through imagery of the natural world, and by the continuity of the musical form - each song moving to the next without a break, creating an integrated, progressive structure.

Güra, accompanied by his frequent partner, pianist Christoph Berner, is an affable, relaxed performer. He did not sing from memory, but was poised and by no means bound to the score. Yet, despite his unperturbed manner, clean delivery and good projection, the opening songs of Beethoven’s cycle were not fully assured. The tone was somewhat unfocused, the intonation occasionally imprecise, especially as he moved to a higher register, and at times he struggling to sustain a smooth melodic line. There was certainly a clear response to the text of the opening song, ‘Auf dem Hügel sitz ich’ (I sit on the hill): ‘Wo ich dich, Geliebte, fand’ (where, my love, I first found you) was sweetly floated, there was urgency in the line, ‘Weit bin ich von dir geschieden’ (Now I’m far from you), and a sensitive rubato elongated ‘Die dir klagen meine Pein!’ ([songs] that speak to you of my distress). But, Güra’s diction was not always as crisp as might have been expected from a native German speaker. Berner effectively shaped the inter-verse commentaries, finding a range of colours and moods.

The eerie monotone in the middle of the subsequent song, ‘Wo die Berge so blau’ (Where the blue mountains) was more steady, however; hushed and full of longing, the tenor’s whispered phrases preceded the fresh energy and accelerando which embodied the poet-speaker’s rising passion at the close of the song.

Berner’s dancing triplet semiquavers captured the lightness of the airborne clouds in ‘Leichte Segler in den Höhen’ (Light clouds sailing on high); and, the performers controlled the varying tempi effectively to convey both the fleetness of the soft west winds and the rippling brook and the mournful lassitude of the poet’s melancholy.

The ornamental flourishes in the accompaniment to ‘Es kehret der Maien’ were similarly buoyant and playful, crisply articulating the babblings of the brook and the dips and arcs of the swallow’s sweeping flight. But, here and in the following song, ‘Nimm sie hin den, diese Lieder’ (Accept, then, these songs), Güra’s intonation was again a little wayward, and while in the baritonal region the tone was pleasing, focused and warm, as the voice moved across registers the fluency of the melodic lines was sometimes disrupted by changes of tonal colour, the tendency to over-emphasise particular words, and by occasionally uneven breath control.

Things settled down a bit in the following sequence of individual Beethoven songs. Güra captured some of the simple lyricism of ‘An die Hoffnung’ (Op.32, To Hope), particularly in the final stanza, the minor 6th rising delicately and poignantly as the poet-speaker describes the upward gaze of the protagonist who, in the twilight of his days, glances up and sees the gleam of celestial comforts. It was a pity, therefore, that too often the ends of phrases were ‘thrown away’, rather than carefully shaped. The lower register of ‘Lied aus der Ferne’ (Song from afar) suited Güra, and the opening had an fitting earnestness and presence, which built slowly through the song erupting in a passionate, impetuous outburst at the close, as the poet-speaker calls to his beloved to make of his home a temple of rapture, ‘die Göttin sei du!’ (and be its goddess!).

The drooping appoggiaturas of ‘Resignation’ were tenderly outlined. This song was a highlight of the first half, the urgency of the dramatic pounding chords between the two verses, contrasting vocal dynamics and strange intervallic leaps conveying the intensity of the self-consuming flame, and culminating in commanding repetitions, ‘lisch aus’(go out, my light!). In ‘Adelaide’ Güra demonstrated his dramatic insight and sense of theatre, the voice never overwhelmed by the formidable energy of the piano part. The folky brightness of ‘Der Kuß’ brought the Beethoven sequence to a carefree, light-hearted close; Güra at last settled fully into the song, and showed that he can spin a tale, producing an air of muted surprise - ‘Ich wagt es doch und küßte sie’ (But I dared and kissed her) - comically mimicking Chloe’s disgruntled scream, and insouciantly relishing the cheek of his actions in the pianissimo repetitions of ‘Doch’: ‘Doch lange hinterher’ - she screamed, ‘but not until long after’!

Things were more even and assured after the interval. In Henri Duparc’s ‘Phidylé’, Güra captured the calm melancholy of Leconte de Lisle’s verse, the air of restraint in the vocal line conveying the hesitant but burgeoning sensuality of the lover who watches the sleeping Phidylé and anticipates her awakening. Berner’s opening chords were tranquil, almost hypnotic; Introspection returned in ‘Ich wandelte unter den Bäumen’ as Güra enriched his tone to suggest the headiness of the fragrant breeze and flowers. In a touching rendition of ‘Chanson Triste’ (Song of Sadness) the performers made much of the contrasts between high and low registers, and engaged in complex counterpoint and conversation, embodying the interchanges between man and nature, between the lover and moon. A tender head voice, ill-fitting in the Beethoven songs, here perfectly captured the poet-speaker’s fragile hopes, ‘Que peut-être je guérirai’ (that perhaps I shall be healed). After the incisive rhythms of ‘The manoir de Rosamonde’, ‘Extase’ (Rapture) vividly but gracefully conveyed the eroticism of Jean Lahor’s text.

In Schumann’s Liederkreis (Op.24) Güra was more responsive to the meaning of the texts (Heine) than he had been earlier in the evening. ‘Morgens steh' ich auf und frage’ (Every morning I wake and ask) began purposefully, before drifting to a more wistful air of reverie. ‘Ich wandelte unter den Bäumen’ was similarly introspective; Güra displayed the ability to modulate his tone engagingly, lightening his voice when the poet-speaker’s old dreams returned to disturb his grief -‘Da kam da alte Träumem’ - and employing a darker, veiled quality to express the sadness and solitude of the final line, ‘Ich aber niemandem trau’ (I trust no one).

The fragmented, stabbing chords of the piano accompaniment in ‘Lieb Liebchen, leg’s Händchen’ (Lay you hand on my heart, my love) grimly suggested both the lover’s heart beat and the hammering of the coffin-maker. There was an airy eeriness about the final stanza culminating in an effectively fragmented, tense close, ‘Damit ich balde schlafen kann’ (so that I soon might sleep). The rocking rhythms of ‘Schöne Wiege meiner Leiden’ (Lovely cradle of my sorrows) and the strange harmonies of the central verses suggested a mind propelled to madness; a weary stillness marked the final stanza, Berner’s eloquent postlude depicting the fatal resignation of the text.

In contrast, ‘Warte, warte, wilder Schiffmann’ (Wait, O wait, wild sailor) opened with a wild cry, establishing a restless, almost violent mood that was enhanced by the piano’s pounding octaves. Ominous chords opened the final song, ‘Anfangs wollt’ ich fast verzagen’ (At first I almost lost heart), but the poet’s fear that he ‘could not bear it’ gave way to a tentative hope - ‘Und ich hab’es doch getragen’ (and yet I have borne it -), before expectancy diffused into ambiguity and elusiveness.

Güra and Berner performed with a directness which was much appreciated by the Wigmore Hall audience. But, there are a few technical matters to be considered if the full emotional impact of these lieder is to be expressed and experienced.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Werner_Gura.gif

image_description=Werner Güra

product=yes

product_title=Werner Güra, Christoph Berner, Wigmore Hall, London 19th November 2013

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Werner Güra

November 22, 2013

Porgy and Bess in San Francisco

Yet Porgy and Bess has survived through all this! Well, more or less, and even so it again proves itself an operatic masterpiece of the American century.

All the above titles and qualifiers played at New York’s Richard Rogers Theater for nine months in 2012 and began a national tour in San Francisco this November 10 at the Golden Gate Theatre (a barn of an old theater in San Francisco’s, uhm, colorful Tenderloin). It travels on to Los Angeles and to cities in Florida and Ohio.

This Porgy and Bess has new punch indeed. The draconian control over the opera by the Gershwin Estate evidently continues (note the registered trademark logos), here manifest in the Gershwin Estate’s choice of Broadway director Diane Paulus (Hair) to consider perspectives that heretofore have remained buried in its characters and therefore to renew the piece.

The musical adaptation by Diedre L. Murray (Running Man) is always in the Gershwin spirit if not to its letter. For starters Jake sang the second verse of Clara’s “Summertime.” It went from there to music you think you have never heard before. As well the recasting of the story by playwright Suzan-Lori Parks (Topdog/Underdog) may have made some of the old music seem like new music.

Moving from the pit of an opera house to the pit of a vaudeville theater necessitates much reduced orchestration — five woodwinds and six brass (both with an impressive array of instruments to be blown), nine strings, and a keyboard. The percussion battery, somehow manipulated by one player, includes just about anything you can think of to hit or ring.

Additional transformation from opera house to theater is the addition of sound reinforcement. Here Acme Sound Partners (Hair, A Chorus Line) keeps the sound at reasonable levels and the balance of voice to pit at someone’s idea of perfection. Though the wall of sound is quite flat the skilled players in the orchestra wail the great pieces we know so well, and with the percussion battery and digital sound technology create a hurricane that is positively awesome.

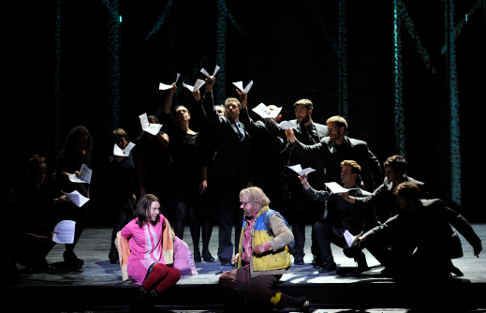

The national cast of THE GERSHWINS' PORGY AND BESS. Photo by Michael J. Lutch

The national cast of THE GERSHWINS' PORGY AND BESS. Photo by Michael J. Lutch

What makes this production of Porgy and Bess become a fine piece of theatrical art is the minimalism of its staging — only a raked stage platform, an abstract ramshackle back wall, a sky scrim for the picnic, a border to make an interior, a hanging lamp to swing in the storm. There are but twenty-two total inhabitants of Catfish Row, and two policemen. These minimal physical and human resources focused our responses onto the opera’s human tragedies through the joys and sorrows we could clearly perceive on each and every face and body on the stage.

The choreography, by Ronald K. Brown too was minimal, just enough to make it a “show” with a few snappy moves by the bodies that could, and even some surprising, acrobatic moves (the four fishermen being fish) by bodies you were sure could not — there were no skinny chorus boys and girls here.

Unlike the broader and deeper exploration of the human spirit that may occur on the opera stage the Broadway musical heads for always direct emotions. Suzan-Lori Parks has Bess deeply in love with Porgy. Clara hands her baby to Bess who becomes its surrogate mother. A dose of happy dust in a weak moment forces Mariah, the matriarch of Catfish Row to expel Bess, who, devastated, has no where to go but New York. Porgy then seems to be going somewhere too, transfixed by love.

It all works and it is all opera, meaning big stories, big emotions, big music, because of the splendid performances of Alicia Hall Moran as Bess, Nathaniel Stampley as Porgy and Alvin Crawford as Crown. Mlle. Moran plays a weak and strong Bess, warm and fun, above all honest. Bess is complex and of course since it is a musical she is very appealing. Mr. Stampley makes Porgy a simple, warm and open spirit, charismatic and quite handsome. Mr. Crawford is a towering, muscular force, dumb and selfish though he too is good underneath it all. All ably vocally negotiated their numbers, especially Mlle. Moran in an appropriately husky mezzo.

Opera audiences will surely savor the pleasures of this smart production, tightly conceived and very well directed. One can wish for such stagecraft on opera house stages where production values on the level of this Porgy and Bess are very rare, too rare indeed.

For comparison with an opera house production please see Porgy and Bess at San Francisco Opera.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Porgy: Nathaniel Stampley; Bess: Alicia Hall Moran; Clara: Sumayya Ali; Jake: David Hughey; Mariah: Danielle Lee Greaves; Sporting Life: Kingsley Leggs; Mingo: Kent Overshown; Serena: Denisha Ballew; Robbins: James Earl Jones II; Crown: Alvin Crawford; Detective: Dan Barnhill; Policeman: Fred Rose; Strawberry Woman: Sarita Rachelle Lilly; Honey Man; Chauncey Packer; Crab Man; Dwelvan David. Conductor: Dale Rieling. American Repertory Theater production. Book adaptation: Suzan-Lori Parks; Musical score adaptation: Diedre L. Murray; Stage Director: Diane Paulus; Choreography: Ronald K. Brown; Set Design: Riccardo Hernandez; Costume Design: ESosa; Lighting Design: Christopher Akerlind. Golden Gate Theater, San Francisco. November 20, 2013.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Porgy_SHNSF3.png

image_description=Porgy and Bess in the National Company of "The Gershwins' Porgy and Bess [Photo by Michael J. Lutch]

product=yes

product_title=Porgy and Bess in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Alicia Hall Moran as Bess, Nathaniel Stampley as Porgy in the National Company of "The Gershwins' Porgy and Bess" [Photo by Michael J. Lutch]

November 19, 2013

Arizona Opera Presents a Fine Flying Dutchman

On November 15, 2013, Arizona Opera celebrated Richard Wagner’s two hundredth birthday with a new production of his first success, The Flying Dutchman (Der Fliegende Holländer). Wagner was inspired to write this opera after he fled from Riga where his creditors were hot on his trail. While conducting at the court theater there, he and his first wife, Minna, had run up huge debts. When he lost the job, there was no way he could pay. The court confiscated their passports but they escaped the debt collectors by illegally crossing the border into Prussia. There they boarded a ship for an eight-day passage to London. They encountered terrible storms and high winds which forced their sailing ship to endure a three-week rollercoaster ride as its captain sought shelter along the coast of Norway. The stormy seas made the composer think of Nordic legends, one of which was the story of the Dutchman who could only return to land once in seven years.

Later he wrote: "The voyage through the Norwegian reefs made a wonderful impression on my imagination; the legend of The Flying Dutchman, which the sailors verified, took on a distinctive, strange coloring that only my sea adventures could have given it.” Several of Wagner’s protagonists were men who lived outside of society. Not only does the Dutchman materialize out of the ether, so does Lohengrin. The Dutchman is a wanderer and so are Siegmund, Tannhäuser, and Wotan. The Flying Dutchman was a seminal opera for him.

This opera requires a large orchestra that would not fit in the Phoenix Symphony Hall pit. Since Arizona Opera wanted to use the full complement of musicians, the players were at the back of the stage and the action was mounted on flooring built over the orchestra pit. It brought the singers much closer to the audience and all the overtones and colors in their voices were easily heard. Director Bernard Uzan gave us a realistic interpretation of the story while Peter Dean Beck’s platforms and props made it come to life with the help of this most capable cast. Most of the scenery consisted of Douglas Provost’s visually piquant projections, which included nautical images by Gustave Doré, one of Wagner’s favorite artists. The projection seen upon entry contained portraits of Wagner and Doré.

With the stage in this arrangement, there could be no curtain, so after the overture, Daland, Raymond Aceto, strode onstage from the wings to ask the Steersman to take the next watch. Aceto has a magnificent bass sound and it was all the more evident with him in front of the orchestra. For the Steersman, Christian Reinert, it was not a good thing. He had trouble reaching his high notes and there was no orchestral cover to hide any of it.

Baritone Mark Delavan was a passionate Dutchman whose cavernous voice surged out over the audience with tonal opulence. A powerful Senta, Lori Phillips’ bright sound energized the text and made her rendition exciting. She is just beginning to emerge as a true dramatic soprano but she is already singing with a distinctively colored sound. It has been many years since a soprano brought as much exhilaration to this role as Phillips did on Saturday night.

Corey Bix was a credible Eric who would have made Senta a good husband had she not been infatuated with the Dutchman and his legend. Young artist program member, Beth Lytwynec showed her ability as a character actress with her portrayal of Senta's work supervisor, Mary, as an old woman. Her singing showed her sonorous, youthful voice, however. Henri Venanzi’s chorus was relegated to a slightly raised area behind the orchestra so they could not move about freely. Although they did perform some dance movements, they made their part clear with robust singing. Conductor Joseph Resigno's lyrical interpretation of this early Wagner score brought out its relationship to the nineteenth century operas that preceded it. His players responded with an exciting rendition that helped make this one of the best performances heard recently at Arizona Opera.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

The Dutchman, Mark Delavan; Daland, Ramond Aceto; Senta, Lori Phillips; Erik, Corey BIx; Steersman, Christian Reinert; Mary, Beth Lytwynec; Director, Bernard Uzan; Conductor, Joseph Resigno; Chorus Master, Henri Venanzi; Lighting and Projection Design, Douglas Provost; Scenery and Props, Peter Dean Beck.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/1465328_551487128254068_170.gif

image_description=Flying Dutchman [Photo by Tim Trumble Photo]

product=yes

product_title=Arizona Opera Presents a Fine Flying Dutchman

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Photos by Tim Trumble Photo

November 18, 2013

The Rape of Lucretia, Glyndebourne Touring Opera

Fiona Shaw’s new production of Britten’s problematic second opera, The Rape of Lucretia, doesn’t quite succeed in answering St Augustine’s question, but it does powerfully communicate the work’s troubling dramatic power and relevance.

This Britten centenary year has brought forth a chest of treasures, familiar and rare. Amid the countless offerings, at home and abroad, of the operatic favourites - from Peter Grimes to Death in Venice - we have enjoyed several renditions of the Canticles and Church Parables, performances of Paul Bunyan and Owen Wingrave, and innumerable masterpieces of the chamber repertoire: ranging from the abstractions of Our Hunting Fathers to balletic presentations of Phaedra, with scarcely a song or chamber work neglected, including Britten’s juvenilia.

But, Lucretia is a tricky one. Even the television opera, Owen Wingrave - which can sit uncomfortably in a theatrical context and presents characters with whom it is hard to empathise - communicates its ‘meaning’ more directly: whether we consider it a ghost story, anti-war manifesto or psycho-sexual drama, Wingrave is obviously ‘about’ something. But, Lucretia’s ‘message’ is equivocal and elusive; and, this is not wholly the fault of Ronald Duncan’s dreadfully verbose libretto - how, for example, is a composer supposed to respond to lines such as ‘and always he’d pay his way/ With the prodigious liberality/ Of self-coined obsequious flattery’?

Part of the problem lies in the tale itself. In the Roman account, there are no ambiguities: Lucretia kills herself for socio-political reasons - her husband’s power, social status and honour depend upon her virtue. In Shakespeare’s poetic narrative, Lucrece exhibits a guilt which is laden with Christian misogyny: she is beautiful, and her loveliness and purity has provoked Tarquin’s natural, masculine sexuality - so it’s her fault, like Eve, and the least she can do for the sake of everyone else is finish things off quickly.

Britten’s opera shifts between the two positions. We begin in a Roman military camp beside the Tiber, the formal device of the Male and Female chorus distancing us from the action in the manner of Greek tragedy. Indulging in crude banter, the boisterous soldiers praise Lucretia’s steadfastness and goodness, and the Male Chorus acknowledges, ‘Collatinus is politically astute to choose a virtuous wife./ Collatinus shines bright from Lucretia’s fame’.

However, contradicting this ‘historical’ focus, in their first lines the Choruses announce, ‘We’ll view these human passions and these years/ Through eyes which once have wept with Christ’s own tears’, establishing a specifically Christian perspective, one confirmed in Lucretia’s dying words, ‘See, how my wanton blood/ Washes my shame away!’ And, then there is the Christian epilogue which offers salvation to the participants’ despairing cry, ‘Is this all?’: ‘Jesus Christ. He is all! He is all!’ It’s all rather confusing.

Fiona Shaw and her design team (sets Michael Levine, lighting Paul Anderson, costume Nicky Gillibrand) opt for desolation with scarce hint of salvation. A bleak, raked stage, covered with earth overlain with a grubby black cloth, is dimly lit. Throughout the opera, the characters struggle to climb this incline, a physical manifestation of their worldly troubles and inner torments, and turn from us to peer into the delicate blue light which glows from afar - an elusive emblem of hope perhaps, but ever unattainable.

The cloth is raised with a single, central pole to form a dingy encampment. Drunken soldiers squat in the dark corners of the crowded tent, their fatigues reminding us that war, with its suffering and atrocities, is not merely an historical phenomenon. The Male and Female Choruses, dressed in dull 1940s clothing, are our conduit, via WWII, to this former era. In the libretto, the house curtain rises to show the Chorus ‘reading from books’; but Shaw literally digs her way back into antiquity, the Male Chorus scrabbling in a muddy pit from which Lucretia is later unearthed. Similarly, Collatinus’s house is an archaeological site, its perimeter marked by excavators’ tape, only a few foundation stones and rubble indicating its inner dimensions.

The gloom is ubiquitous, a cross-shaped standard lap providing weak illumination. Only at the start of Act 2, when Lucretia lies asleep, dreaming ‘the sunken treasures of heavy sleep’, does Anderson shine a gleaming white spotlight on her resting form, the sudden contrast powerfully evoking the purity of one who is ‘as light as a lily that floats upon a lake’. However, the glistening transparency proves poignantly fragile and defenceless against Tarquinius’ lust - ‘Loveliness like this is never chaste; If not enjoyed, it is just waste!’ Shaw shows us, explicitly and indisputably, how Tarquinius is driven to destroy the very beauty that he desires, Lucretia’s defilement taking place amid the earth and gravel of a dark, Hadean pit. At the end, it is from this pit that severed limbs and a head are unearthed; the Choruses’ closing religious consolations are bitterly unconvincing.

On 15th November, the young cast were on fine form. Andrew Dickinson and Kate Valentine were outstanding as the Male and Female Chorus respectively, engaging our interest and our feelings as they related and participated in the unfolding tragedy. Dickinson articulated Duncan’s literary turgidities with clarity and fluency, his delivery natural and unmannered but the sentiments heartfelt. Valentine sang with generous tone and warmth, always relaxed, blending beautifully with Dickinson in the duet refrain which punctuates the opera. The lullaby which the Female Chorus sings over Lucretia’s sleeping form was elegant and touching, enhanced by some exquisite playing by alto flute, bass clarinet and horn.

Britten and Duncan originally conceived the Choruses as commentators, relating a tale from the annals of Roman history (as the curtain falls on Act 1, they ‘pick up their books and continue reading’). At times, Shaw’s Choruses adopted a similarly distanced viewpoint but elsewhere they travelled back through time, and engaged and interacted with the past. So, as Dickinson related the account of Tarquinius’s nocturnal journey to Rome, his precipitous flight was mimed in the background while the Female Chorus tried to intercept and deter the dissolute Roman ruler as he recklessly lamed his horse and plunged into the Tiber, propelled by jealousy and lust. Such interaction added immediacy and deepened our empathy. The occurrences of the distant past have been undergone by many since: during WWII and in the present day. Shaw shows us that the story the Choruses tell, is their tale too; but, it does seem a step too far to suggest an intimate sexual attraction between the two Choruses …

The role of Lucretia was originally written for Kathleen Ferrier; Claudia Huckle may not possess a voice of such ample fullness, but after a slightly hesitant start she produced an intense and affecting performance. She acted with intelligence and commitment. A voice that initially embodied lightness and composure, transmuted after her violation to darker tones conveying vulnerability and self-castigation. Her confession was rich, mobile and expressive, her exposure unveiling a troubling guilt as Tarquinius’s desire became her crime. Huckle’s Lucretia is no artificial idol; rather she is a real, flesh-and-blood woman, shocked and destroyed by her own unbidden passions.

Duncan’s libretto depicts the rigid divisions in Roman society between male and female groups. Here, the Etruscan soldiers were crude, misogynistic competitors, convincingly brazen and coarse. In contrast, Ellie Laugharne’s lively, bright Lucia and Catherine Wyn-Rogers pure-toned Bianca suggested honest, uncomplicated friendship and love within the female domain.

Oliver Dunn revealed an appealing baritone and sure dramatic instincts as Junius. David Soar presented a well-rounded Collatinus, his strident Act 1 soliloquy on ‘love’ giving way to tender and profound sincerity following Lucretia’s confession, supported by rising woodwind and harp accompaniment gently intimating hope; ironically his forgiveness merely exacerbated Lucretia’s remorse.

As Tarquinius, Duncan Rock was fittingly assertive and muscular, although his aggression and brashness was modulated by moments of lyricism. Enraged by taunts and boasts, stirred by Lucretia’s beauty and virtue, his passionate outburst before his assault was poetic and ecstatic.

After the rape, Rock sadly conveyed a sense of his own loss - ‘Though I have won/ I’m lost./ Give me my soul/ Again/ In your veins sleep/ My rest.’; his Tarquinius was to be both censured and pitied.

Britten’s score is sparse, fitting for the post-war cultural climate when the work was composed, and ideal for our own ‘age of austerity’. In contrast to the drab bleakness on stage, the twelve instrumentalists conducted by Jack Ridley responded wonderfully to the transparent lucidities of Britten’s scoring. As Tarquinius crept through Lucretia’s house, the percussion’s nervous motifs skilfully depicted the explosive tension within the assailant. There was some enchantingly sensitive playing from harpist Sue Blair, and Alan Darbyshire’s silky cor anglais melody, above unsettling off-beat bass quavers, deepened the poignancy of Lucretia’s entrance preceding her confession.

In an article, ‘The Problems of a Librettist: Is Opera Emotionally Immature?’, Duncan suggested that the opera continued the dramatization of the conflict between the individual and society begun in Peter Grimes: ‘the individual is personified by Lucretia whose virtuous personality is persecuted, raped, by Tarquinius, who symbolises Society’. A more abstract reading might propose that the opera explores relationships between desire and violence, love and sin: after Lucretia’s death, the whole cast cry: ‘How is it possible that she/ Being so pure should die!’

But, for all the digging and delving, Fiona Shaw doesn’t find historical or philosophical ‘truth’: Lucretia’s suicide is presented more as a personal purgation than a social sacrifice, but the intimations of her guilt are neither confirmed nor eradicated. The Christian epilogue does not provide a redemptive framework: we do not equate Lucretia’s suffering with Christ’s crucifixion. But, this doesn’t matter. Shaw offers an intensely moving spectacle. As Lucretia herself says: ‘What I have spoken never can be forgotten.’

Claire Seymour

Glyndebourne Touring Opera will perform in Milton Keynes 19-23 November, Plymouth 24-30 November and Stoke-on-Trent 11/14 December.

Listen to the Rape of Lucretia podcast

Cast and production information:

Male Chorus, Andrew Dickinson; Female Chorus, Kate Valentine; Collatinus, David Soar; Junius, Oliver Dunn; Tarquinius, Duncan Rock; Lucretia, Claudia Huckle; Bianca, Catherine Wyn-Rogers; Lucia Ellie Laugharne; Director, Fiona Shaw; Conductor, Jack Ridley; Set Designer, Michael Levine; Lighting Designer, Paul Anderson; Costume Designer, Nicky Gillibrand; The Glyndebourne Tour Orchestra. Glyndebourne Touring Opera. The Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury, Friday 15th November, 2013.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/RapeofLucretia_2501.gif image_description =Scene from The Rape of Lucretia [Photo by Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of Glyndebourne Touring Opera] product=yes product_title=The Rape of Lucretia, Glyndebourne Touring Opera product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Scene from The Rape of LucretiaPhotos by Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of Glyndebourne Touring Opera

November 17, 2013

The Barber of Seville in San Francisco

It is the staging of Spanish stage director Emilio Sagi (pronounced saw-he) that has many of the ideas he first explored at Madrid’s Teatro Real in a big production that then traveled to Los Angeles, both cities likely harbors for its witty and affectionate quoting of classic hispanic flamenco postures. This San Francisco Barber is a slimmed down, re-elaborated version of the original Sagi conception that will soon be shared with the Lithuanian National Opera.

There was much to like on opening night, notably the polished performances of Count Almaviva and his future countess, characters also known as Lindoro sung by Mexican tenor Janvier Camarena and Rosina sung by American mezzo-soprano Isabel Leonard.

Mr. Camarena provided the high points of the evening, accompanying himself on the guitar for the serenade with virtuoso plucking technique, acting the music teacher with the skill of a sure comedian. To top it off he gave us the rare “Cessa di più risistere” later known and now better known as “Non piu mesta” from La cenerentola in a dazzling display of fioratura and high notes that brought the house down.

Mlle. Leonard, if not of pure hispanic origin (her mother was Argentine) even so matched Mr. Camarena’s latin excitement and brilliant singing with a presence that exuded refined fun and projected mature vocal and histrionic confidence — a poised Rosina who knew what she wanted and how to get it. Once a student at the Joffrey Ballet School she was well prepared to snap out flamenco poses that easily outclassed those of the official ballerinas.

There were moments of fine, idiomatic conducting. Italian conductor Giuseppe Finzi effectively captured the ephemeral Rossini ethos from time to time (the joy and blatant fun of singing difficult, florid music with aplomb), particularly in his support of the arias of these two singers. As well the maestro often caught the transparent rhythms of the big ensembles where three to six complex and sometimes more vocal lines compete with complete musical ease, conviction and wit.

The set, designed by Spaniard Llorenç Corbella, is quite different from the Madrid production. Here it is essentially a narrow, diagonally raked platform thrusting upstage, with an adjacent abstract black area (no scenery) accessible to various contraptions on wheels and lots of choristers. At best the set worked well, the rake providing a dynamic line on which the principals moved up and down, on and off, the black area serving as a space to stage business that elaborates the various musical numbers.

Besides the witty gloss of the flamenco poses, the Sagi production was embellished with lots of spoke wheel vehicles (bicycle like) that gave a sense of lightness and fleetness to the staging that flouted period (century or decade). The costumes as well were embellished with witty abstractions of Sevillian decorations that had little to do with period and everything to do taking costumes onto an abstract musical level.

Various human bodies and objects crawled out from under the raked platform and props flew down from above from time to time to further negate any sense of real time or real space. Barber’s various numbers were arbitrarily placed on the ramp or in the black space and finally everything more or less disappeared anyway to reveal a night sky filled with fireworks (projected). In short director Sagi and his designer Corbella concocted a heady framework for the music of Rossini’s masterpiece. It would have been truly brilliant had it gotten off the ground.

Lucas Meachem as Figaro, Janvier Camarena as Almaviva, Alessandro Corbelli as Bartolo, Andrea Silvestrelli as Basilio, Catherine Cook as Berta, Isabel Leonard as Rosina [Photo by Cory Weaver]

Lucas Meachem as Figaro, Janvier Camarena as Almaviva, Alessandro Corbelli as Bartolo, Andrea Silvestrelli as Basilio, Catherine Cook as Berta, Isabel Leonard as Rosina [Photo by Cory Weaver]

Unfortunately stage director Sagi was more interested in exploring these interesting theatrical ideas than in staging his singers. This lack of a unified and focused dramatic intelligence resulted in the feeling that Rossini’s headstrong characters were arbitrarily walking through the classic comedic process rather than bringing it to life.

A plodding succession of the events of the story we know so well resulted. This sense was exacerbated in the pit. While conductor Finzi did have his truly splendid moments, and there many of them he could not impose a larger musical unity over an act or the evening, evidenced by the overture that ignited no excitement whatsoever. There was a sense of relief when nine dancers appeared to maybe add some life with a bit of abstracted flamenco movement. Alas the choreography was clumsy and meaningless, later met with feelings of dread whenever the dancing became lengthy.

A.J. Glueckert as Ambrogio, Catherine Cook as Berta [Photo by Cory Weaver]

A.J. Glueckert as Ambrogio, Catherine Cook as Berta [Photo by Cory Weaver]

Catherine Cook was the Berta who was as lightheaded as Rosina was weighty minded. She made her aria another of the evening’s high points with the help of her adoring Ambrogio, Adler Fellow A.J. Glueckert who shined as a silent, physical performance artist given he has hardly anything to sing. Bass baritone Hadleigh Adams brought snap and flair to the brief role of the Officer, not allowing his few moments on stage to go unnoticed.

Andrea Silvestrelli brought the considerable panache he provides Rigoletto’s Sparafucile to the role of Basilio. This major role stood out as miscast, and as a vocal misfit into Rossini’s vocal and musical textures. Much the same can be said of the Figaro of Lucas Meachem who confused bellowing with singing and strutting with acting. Italian bass baritone Alessandro Corbelli is a small scale if accomplished Bartolo who here disappeared into the melée rather than making himself the cause of it all.

Of the many, many Barbiere productions encountered over the years, this one stacks up among the best. Its glaring flaws could have easily been overcome with more careful casting, conducting, lighting and directing.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Figaro: Lucas Meachem; Rosina: Isabel Leonard; Count Almaviva: Javier Camarena; Doctor Bartolo: Alessandro Corbelli; Don Basilio: Andrea Silvestrelli; Berta: Catherine Cook; Ambrogio: A.J. Glueckert; Fiorello: Ao Li; An Officer: Hadleigh Adams; Notary: Andrew Truett. San Francisco Opera Chorus and Orchestra. Conductor: Giuseppe Finzi. Stage director: Emilio Sagi; Set Designer: Llorenc Corbella; Costume Designer: Pepa Ojanguren; Lighting Designer: Gary Marder; Choreographer: Nuria Castejón. San Francisco War Memorial Opera House. November 13, 2013.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/BarberSF_Top.png

image_description=Rosina and Lindoro in Il barbiere di Siviglia [Photo by Cory Weaver]

product=yes

product_title=The Barber of Seville in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Rosina and Lindoro in Il barbiere di Siviglia [Photos by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

November 11, 2013

Britten’s Atmospheric War Requiem, London

The sense of occasion was overwhelming.

The vast auditorium was packed, and the arena area where Prommers throng in summer, was filled with seats. Before the performance began, the house lights were turned, not onto the stage but onto the audience. It was a moment of sheer theatre, but utterly appropriate, for everyone in the building must have known, or know of someone affected by the barbarity of war. No-one could remain unmoved. Wilfred Owen wrote about the First World War, and Britten wrote to commemorate peace after the Second World War. But the world is still wracked by conflict. Wars of attrition continue, millions of people still suffer. Turning the spotlight on the audience reminded us that Remembrance is more than "Lest we forget" but also implies moral obligation.

How amazing it must have been for the performers to look onto the Royal Albert Hall and see the lights shining on thousands of faces! This was infinitely more a communal experience than just a musical event. The lines between performance and reception blurred. Normal measure of performance were largely irrelevant. We were all participating in something much greater than ourselves.

Because the War Requiem was commissioned to mark the rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral, it has become associated with vast venues and ostentatious displays of public piety. Although it's written for some 300 performers, at the really critical moments, Britten silences the tumult. Britten was essentially a private man, not given to big public gestures of emotion. The heart of the piece is the twelve member ensemble that accompanies the two male soloists. The choruses and the female soloist sing in Latin, and sing words that would fit neatly into any standard Requiem Mass. Significantly, Britten sets the key texts in English, using the words of Wilfred Owen, who wrote from personal experience. Owen does not celebrate public victory : quite the opposite. He fought bravely, but eschewed formal religion. Britten doesn't quote the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac, but Wifred Owen's Parable of the Old Men and the Young, with its reference to the wilful slaying, not sanctioned by God, of "half the seed of Europe, one by one"

"Move him into the sun" sings the tenor (Allan Clayton). The quote is from a poem titled Futility. A corpse lies on snowbound ground. The soprano and choruses sing "Lachrymosa", of tears and the conventional expression of sorrow. The music is beautiful, but Owen, and Britten are having none of this. "O what made fatuous sunbeams toil, to break earth's sleep at all"? Unlike seeds in the soil, the dead don't re-sprout. In the Sanctus, the choirs sing "Hosanna in excelcis". But Britten has the baritone (Roderick Williams) sing, quite pointedly "Mine ancient scars should not be gloried. Nor my titanic tears, the seas, be dried". Britten's War Requiem isn't designed to comfort, as much as to provoke.

Bychkov places the chamber ensemble to his immediate left, "the heart side" in theatre parlance.The instrumentation mimics that of a large orchestra - five strings, four winds, horn, harp and percussion - but the individual voices are heard clearly : It's another indication of Britten's "inner" programme.

"Lbera me, Domine" the soprano (Sabina Cvilak) sings, haloed by the chorus. "Tremens factus sum ego" (I tremble and fear) The orchestra screams, cymbals crashing, suggesting the chaos of battle. Bychkov's definition of horns, trumpets and trombones was specially good, emphasizing military conflict. But Britten deliberately shifts focus. To minimal accompaniment the tenor sings ""Strange friend, I said, here is no cause to mourn". Tenor and baritone face each other in a strange No Man's Land where nations do not fight. There are no "Germans" or "British" here but two human beings, man to man. Their voices blend. "Let us sleep now", singing in unity. They are turning away from the vast forces around them. Perhaps Britten recognized that social forces dominate over the private. The War Requiem ends on a wave of uplifting glory, sending the audience out into the world feeling the better for having been part of the experience.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/WWI.png

image_description=A World War I battle scene [Source: US Army]

product=yes

product_title=Britten’s Atmospheric War Requiem, London

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: A World War I battle scene [Source: US Army]

November 9, 2013

Barbican Britten

However, Robert Tear, John Vickers, Philip Langridge and others established themselves as worthy and independent heirs, forging interpretations which were original, insightful and distinctive. Today we are fortunate to have a stellar crop of tenors who bring unique and fresh insights to Britten’s music, but it is a rare combination of cerebral insight and visceral but controlled passion which characterises Ian Bostridge’s responses and which makes his performances so captivating.

Written for the 1936 Norwich Festival, Britten’s orchestral song cycle Our Hunting Fathers certainly demands of its soloist both intellectual perspicacity and emotional immersion, two erudite, philosophical poems by W.H. Auden — Britten’s perennial collaborator during the 1930s — framing three energised Anglo-Saxon texts, the latter modernised by Auden. As Britten anticipated, the first performance, by the LPO and soloist Sophie Wyss, was not well-received: superficially the poetry examines man’s relationship with the animal kingdom, but there exists a both a political dimension and a less obvious sexual sub-text which the local audience were slow to perceive or appreciate, Auden’s complex imagery and verbal dexterity proving overly recondite.

This performance by Ian Bostridge, accompanied by the Britten Sinfonia conducted by Paul Daniel, brought clarity and focus to the superficially obscure poetry, brilliantly conveying the musical structure which unites the diversity of styles required to communicate the varied sentiments of the texts.

In the opening recitative of the ‘Prologue’, marked sempre ad lib., Bostridge’s tone was restrained, perfectly emulating the parsonical mood of the words; the dry orchestral accompaniment facilitated the supremacy of the vocal line. Daniel encouraged the woodwind — who played superbly throughout the evening — in their interjections which contrast with the sustained string chords, casting light on significant lines of text: ‘the poles between which our desire unceasingly is discharged.’ At the image of the ‘extraordinary compulsion of the deluge and earthquake’, Bostridge’s rising minor ninths were deeply poignant, the sustained ppp string chord with trilling side drum and snares surging to an explosive fff.

‘Rats Away!’ is an anonymous medieval text which depicts animals as vermin, the primarily wind-based orchestration and scurrying musical material presenting an unsentimental, hard-edged world.

Bostridge’s virtuosic dexterity was evident in his florid melismatic variant of the opening orchestral gestures; he projected the scalic figure, ‘Rats!’, with clarity and precision combined with cadenza-like energy — aspiring with propulsive vigour towards the climactic, sustained high A — while Daniel drew forth a shrill timbre from the tremolando strings and flutter-tonguing woodwind. A contrasting mood was established in the central section, the voice articulating a sort of invocatory prayer in discourse with a legato solo viola (Clare Finnimore); here, Bostridge shaped the passage with consummate control, incisively accenting the leaping octaves which announce the names of the Evangelists and driving towards the intervallic expansiveness of the climactic phrase, ‘That these names were utter’d in’. The insistent repetitions of the three-note ‘Rats!’ motif in the recapitulation were terrifyingly dynamic, and the tenor’s final throw-away ‘Amen’, dropping from high decorative exclamations to a low D, after a laden pause, sardonically emphasised the satirical nature of the religious statements in the text — a cynicism which was further confirmed by the motivic continuations of the unison strings, which Daniel guided into ambiguous dissolution.

In ‘Messalina’ we move from public to private domains, as the singer mourns the loss of his pet monkey. Bostridge’s drooping lament, ‘Ay, ay me, alas, heigh ho!’, richly resonated with the hollowness of the divided strings’ opening 5ths, the singer’s glissandi falling 7ths both musically precise and ardently expressive. The narrative lines, ‘Thus doth Messalina go/ Up and down the house a-cry’, possessed a folk-like naivety, as the solo woodwind melodies intertwined with the voice. The elaborate, melismatic cries of ‘Fie!’ were electrifying: Bostridge was not afraid to push his voice to the limits through the tumbling major/minor thirds, the quiet registral expanse of soaring molto espressivo e vibrato strings above deep tuba and trombone expressed both the wide scope of emotions experienced and the chasm of grief. The tenor’s stabbing crotchets, ‘Fie!’, dissipated into despair and some beautiful solos from horn, bassoon and alto saxophone, the latter lyrically played by Christian Forshaw, led us without pause into Britten’s setting of Thomas Ravenscroft’s ‘Dance of Death’ — ‘Hawking for the Partridge’.

The tenor’s initial roll call of predators — ‘Beauty, Timble, Trover, Damsel’ — was savage, the tight tarantella rhythm a parody of the traditional hunting song. Bostridge whistled through his teeth, the repeated rising 9th, ‘Whurrrrret!’, penetrating and discomforting; indeed, the sense of a self-gratifying pleasure in violence is given an ominous twist in the subsequent passage, where the isolation and repetition of the words ‘Travel Jew’ portentously equates the ritual killing of animals with the ‘Jew-hunting’ perpetrated by Nazi Germany — as ever, Bostridge was alert to every nuance and inference of the text, and to the musical opportunities for its expression. Daniel drew forth the multitude of onomatopoeic motifs — the woodwinds’ staccato flurry of feathers, the horn’s rasping glissandi of alarm — creating a mood of terror and hysteria.

The conductor sustained the insistent rhythms of the ‘Dance of Death’ in the concluding ‘Epilogue and Funeral March’; the ostinato xylophone soullessly suggested man’s inability to break out of the endless cycle of cruelty and despair. This movement possesses a disturbing tension and ambiguity, and Bostridge and Daniel made much of the contrasts between Auden’s two stanzas, exploiting Britten’s interjections and imitative sounds.

Auden’s first stanza describes the traditional self-assurance of man, who pities the animals’ undirected innocence and whose own love, the driving power which motivates the individual, is tempered by reason. However, in the second stanza Auden proposes a ‘modern’ view of a love which leads to guilt and self-regard, adapting lines from Lenin to ask us to imagine a man who has modified his ‘southern gestures’ and makes it his ambition only ‘To hunger, work illegally,/ And be anonymous?’

Bostridge’s extended melisma, contrasting powerfully with the composure of the preceding syllabic lines, was finely crafted: initially restrained — recalling the opening of the ‘Prologue’ — then flowering exquisitely into an impassioned arioso. In the concluding funeral march, Daniel fashioned a controlled disintegration, as the bass faded away leaving hard col legno and pizzicato strings to offer the final inconclusive, pessimistic utterances.

Elsewhere in the programme the prodigious talents of the Britten Sinfonia — individually and collectively — were much on display. A pacy reading of Britten’s arrangement of Purcell’s Chacony in G Minor allowed the strings to demonstrate their responsive appreciation of the composer’s rhythmic vitality and impulsiveness, as well as their feeling for colour and dynamic range. Daniel’s flexible, free direction suggested that he is a dancer manqué, so lithe and unconstrained were his gestures.

Young pianist, Lara Melda — the winner of the BBC Young Musician of the Year competition in 2010 — was a dazzling soloist in Britten’s Young Apollo (for piano, string quartet and string orchestra), sparkling through the rising scales in scintillating fashion above gleaming, brilliant strings. Her reading was full of the bright optimism of youth; fittingly, for the work was first performed in Toronto in 1939 with the 25-year-old composer himself at the keyboard.

Tippett’s Fantasia concertante on a theme of Corelli was engagingly theatrical, the textures rich and the elaborate ornamentations lavishly conveyed. Soloists Thomas Gould (violin), Miranda Dale (violin) and Caroline Dearnley (cello) were superb, Gould in particular galvanising all the instrumentalists to offer an uplifting, deeply committed performance.

Britten’s Suite on English Folk Tunes bears the sub-title ‘A Time There Was’ — an allusion to Thomas Hardy’s Winter Words — and the inscription, ‘lovingly and reverently dedicate to the memory of Percy Grainger’. At first glance, it might be felt that Britten and Grainger have little in common, but a penetratingly creative engagement with English folk-song links the two disparate personalities, and in this performance Daniel demonstrated a discerning appreciation of the relationship between the simple, straightforward folk-song melodies and the, at times, disruptive accompaniments. The final movement, a setting of ‘Lord Melbourne’ which was collected by Grainger, was imbued with a draining dejection, redolent of Hardy’s verse.

Claire Seymour

‘Barbican Britten’ continues until 24th November — see www.barbican.org.uk for further details.

Programme and performers:

Henry Purcell, arr. Benjamin Britten, Chacony in G Minor; Benjamin Britten, Young Apollo Op.16; Michael Tippett,Fantasia concertante on a theme of Corelli; Benjamin Britten, Our Hunting Fathers, Op.8; Benjamin Britten, Suite on English Folk Tunes (A Time There Was). Ian Bostridge, tenor; Lara Melda, piano; Paul Daniel, conductor; Britten Sinfonia. Barbican Centre, London, Friday 8th November 2013.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Britten-Sinfonia.png image_description=Britten Sinfonia product=yes product_title=Barbican Britten product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Britten SinfoniaNovember 8, 2013

Exaudi: O tenebroso giorno — Gesualdo then and now

Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa, was the warp between which the weft threads of modernism were woven. Madrigalist, mannerist and master of harmonic ingenuity, the patrician composer’s contributions to the genre are remarkable for their harmonic capriciousness and volatility. Much is often made of the fact that one can add ‘murderer’ to the alliterative inventory of the composer’s roles, his violent despatch of his faithless wife and her lover earning him notoriety in the annals of music history; and, while such vengeful acts were in fact common in Renaissance Italian courts — indeed, the contemporary code of honour practically demanded them — it is perhaps not too fanciful to imagine that something of Gesualdo’s brooding, melancholic temperament is evident in the turbulent harmonic daring of his madrigals.

It has been suggested that Gesualdo’s harmonic adventurousness was inspired by his visits to Ferrara from 1594, where he was able to experiment upon the archicembalo with six keyboards that had been constructed by the court maestro Nicola Vicentino. But, it is just as likely that overhearing the vocal ensemble that Vicentino had trained in secrecy, in order to put into practice his own experimental theories of music, was the major influence in the formation of Gesualdo’s idiosyncratic idiom.

Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa [Source: Wikipedia]

Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa [Source: Wikipedia]

Writing of a new edition of the madrigals published in1962, the musicologist Denis Stevens declared, ‘Five fine soloists, each with perfect intonation, not too much vibrato, and a really controlled line, would bring … [the] splendid pieces in this book to life’. ‘Dolcissima mia vita’ (Sweetness life of mine) immediately asserted the composer’s highly personal vein of chromatic irregularity, and five members of Exaudi , although they took a few minutes to settle, certainly brought vitality to the contrapuntal lines, ‘Credete forse che’l bel foco ond’ardo’ (Can you believe the fire that now scorches me), triggered by a buoyant countertenor line sung by Tom Williams.

The sliding chromatic resolutions of ‘Deh, come invan sospiro’ (Ah! How I sigh in vain) demonstrated the composer’s skill in expressing the struggle between violent, conflicting emotions, while the closing repetitions of ‘divenga morte’ (life for me has become death) spanned a spectrum of colours and moods, both rich and shadowy. In ‘Tu piangi, o Filli mia’ (You weep, O my Phyllis), the five voices blended agreeably; in an energetic rendition, the strong communication between the members of the quintet was evident in the vivid sectional contrasts that were achieved.

Gesualdo’s almost hypersensitive response to lyric emotions is unfailingly astonishing, as the individual vocal lines veer in unexpected directions, the linear discourses producing a questing, searching mood as dissonances are suspended and resolutions delayed. In ‘Itene, o miei sospiri’ (Go now, o my sighs) the sheer force of the harmonic energy was remarkable, building from the initial direct command, ‘Itene’, to the rich contrapuntal interweaving of the climax, before the relaxation of the concluding homophonic thirds. The deep register of the opening of ‘O tenebroso giorno’ (O dark day) was forbiddingly sombre, before the more uplifting harmonies of ‘Quando lieto ritorno/ Farai dinanzi a quella/Che è più d’ogni altra bella’ (When will you happily/ return to that beauty’s side/ who is more beautiful than any other) created a flowing lightness. The voices negotiated the unusual, challenging intervals of the melodic lines with pinpoint accuracy, and the final phrase possessed a pure air of expansiveness: ‘Che con suoi sguardi morte e vita appaga?’ (whose gaze satisfies both death and life?’).

The rich open vowel sounds of ‘O dolorosa gioia’ (Oh dolorous joy), sung with lustrous timbre, opened the second half of the recital; the five vocalists enjoyed the harmonic paradoxes used to convey the oxymoronic verse — unexpectedly easeful major harmonies suggest ‘soave dolore’ (sweet suffering), for example. The final line, ‘Poichè sì docle mi fa morto e vivo’ (for so sweetly it makes me feel both dead and alive) had both immediacy and aloofness. The fitful changes of mood of the brief ‘Moro, lasso’ (I die, alas), were powerfully communicated, the despairing cry, ‘Ahi, che m’ancide e non vuo!’ (oh, kills me and will not help me!), full of rhetorical directness.

Two madrigals à 6 brought the sequence to a close: ‘Tenebrae factae sunt’ (Darkness covered the earth) had both solemn depth and warmth, while the incessant suspensions and twists of ‘Caligaverunt oculi mei’ (My eyes are dimmed), particularly in the final homophonic section, were meticulously precise and moving.

Interspersed between the Renaissance treasures were four contemporary works; the present in conversation with the past. (The Gesualdo works were performed without conductor, while director James Weeks led the new madrigals). Stefano Gervanosi’s ‘Amore l’alma m’allaccia’ (Tasso, Love tightens my soul), for SSATB, was immensely challenging with its dense, iridescent sonorities and textures, the accumulating harmonic tension provocatively evoking the pain of ‘dolci aspre catene’ (sweet bitter chains). Repetition of miniature motifs built to an imitative frenzy, and the singers demonstrated rhythmic precision and expert ensemble in the more airy, fragmented closing section, the brief vocal snatches intimating the erotic tensions of the text.

Exaudi performed Michael Finnissy’s Sesto Libro di Carlo Gesualdo I in October 2012; at that time, I remarked the way the composer ‘exploited the sinuous false relations, suspensions and dissonances of the sixteenth-century idiom … explicitly intertwining elements of Gesualdo’s original with Finnissy’s own elaborations and developments’. Here, three later songs from the set were presented. The transparent texture of the 2-voice opening to III, ‘Beltà poi che t’assenti’ (My beauty, since you are gone) was enriched by piquant close dissonances, while the sustained lamenting lines of the end were affectingly shaped. IV, ‘Quel ‘no’ crudel che la mia speme ancise’ (That cruel ‘no’ which killed my hope), presented copious challenges for the two sopranos and for conductor, Weeks, whose broad loops emphatically marked the points of coincidence amid the free rhapsodic sweeps of the vocal lines, with their eerie glissandi and ululations. As the voices moved apart in register, the interplay between the burnished lower voice and the soaring high soprano effectively conveyed love’s power to ‘vince ogni core’ (conquer all hearts). A denser texture characterised VI, ‘Resta di darmi noia’ (Cease to give me annoyance), the five voices vividly articulating the opening text in homophonous broken rhythms; above a bed of sustained chords, tenor and soprano engaged in a veritable vocal battle of passion and bitterness: ‘Morta è per me la gioia,/ Onde sperar non lice/ D’esser mai più felice’ (For me all joy is dead, nor can I ever hope again to find happiness).

Christopher Fox’s ‘suo tormento’ (His torment) is a setting of an extract from Dante’s ‘Inferno’ Canto X, although as the composer’s programme note explained: ‘Dante’s text … is used only as a sound-source and in the score the source-word for each sound is given [in square brackets] to indicate how the underlaid letters should sound. The text is ‘read’ outwards from the centre … reading, as it were, into both past and future — and the music should sound like a doomed attempt to be understood.’ Certainly, the broken phrases expressed a sense of frustrated attempts to see and comprehend and a vexing impotence. Two shorts settings of Antonio Gramsci followed, the words set in more conventional fashion. ‘figura’, ‘hoketus’ and ‘kanon’ from Johannes Schöllhorn’s Madrigali a Dio (texts by Pier Paolo Pasolini) was the last of the modern offerings. Set for 6 voices these madrigals are cerebral works, ‘figura’ opening with a wave-like drone, with the voices freely and linearly interacting with each other in complex just intonation. ‘hoketus’ was energised and unpredictable, meaning conveyed by sound rather than sense, whirling glissandi and introverted ‘chattering’ representing ‘una sola/ Parola, una sola/ Parola ripete pazzamente’ (a single word, a single word madly repeats). The stratospheric soprano in ‘kanon’ was effortlessly delivered by Juliet Fraser, above an energetic counterpoint of male voices. Needless to say, these works demanded enormous precision of rhythm and pitch, perfect ensemble as well as vocal confidence; the members of Exaudi exhibited all these qualities in abundance.

I’ve previously expressed reservations, and I’m still not convinced, that director James Weeks’ inter-madrigal commentaries, though direct and engaging, are truly necessary or beneficial: for they weaken the continuity of the musical dialogue between past and present, a musical conversation which would be stronger if fluid and uninterrupted by the spoken word. But, in the final reckoning the music spoke for itself: the noble humanistic spirit of the Renaissance madrigal, underpinned by the potency of intense vocal expression, is alive and well.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

James Weeks, director; Juliet Fraser, Amanda Morrison, soprano; Lucy Goddard, mezzo-soprano; Tom Williams, countertenor; Stephen Jeffes, Jonathan Bungard, tenor; Jonathan Saunders, Simon Whiteley, bass. Wigmore Hall, London, Wednesday 6th November 2013.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/exaudi9a.gif

image_description=Exaudi Vocal Ensemble

product=yes

product_title=Exaudi: O tenebroso giorno — Gesualdo then and now

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Exaudi Vocal Ensemble

The Magic Flute, ENO, London

Simon McBurney's production is audacious but absolutely true to Mozart's cheeky, irreverent generosity of spirit. Tamino and Papageno find Enlightenment (and the girls of their dreams) because they dare face the tests before them. Each takes the journey in his own way: the saga transcends time and place. From Greek myth to Parsifal, even to Star Wars, the allegory refreshes itself in endless retelling. It is a universal voyage of self-discovery.

Ben Johnson as Tamino

Ben Johnson as Tamino

Simon McBurney and Complicité create dazzlingly imaginative theatre. Their A Dog's Heart was astonishingly vivid. The opera was a mess but the staging turned it into art. With Mozart, McBurney has infinitely better music, and rises to the challenge. As we hear the Overture, we see a hand write words in chalk on a blackboard. As the opera evolves we learn its significance. Words communicate. We see images of books on shelves, and up to the moment mobile devices. The stage above the stage is a laptop or Notebook. It's suspended on wires from the roof and looks dangerously fragile, but that in itself has meaning. Finn Ross's' video projections are among the best in the business, and extremely well integrated into the drama. Technology may change the ways we express ourselves, but if we don't communicate, or refuse to engage with each other, we're lost. At the end, chalk figures proclaim "WISDOM LOVE". Simple and austere but all the more powerful for that.

Ben Johnson as Tamino (foreground), Rosie Aldridge, Eleanor Dennis, Clare Presland (L-R background) as the Three Ladies

Ben Johnson as Tamino (foreground), Rosie Aldridge, Eleanor Dennis, Clare Presland (L-R background) as the Three Ladies

Technology changes in theatre, too. Film and computer-generated images break down physical restraints of production and free imaginative possibilities. The Magic Flute IS magic after all, not realism. It cries for cosmic flights of fantasy. McBurney's designer, Michael Levine, gives us the night sky in all its glory : myriad sparkling stars in the firmament. The Queen of the Night (Cornelia Götz) in this production isn't spectacular but the forces she commands most certainly are. Extra-terrestrial sound effects amplify the sense of cosmic spaciousness. Off-stage noises are a natural part of staging. Here they rumble at the edge of consciousness. Gergely Madaras seems spurred to conduct with strong, dramatic flair. This highlighted the quiet moments when the Flute (Katie Bedfiord) emerged. The flute felt all the more magical and fragile. The Flute is more than an instrument. It is fundamental to the meaning of the opera. Like Papageno's bells, it evokes something pure, primeval and plaintive. McBurney's staging was musically as well as visually astute. The "birds" that fly in these woods were pieces of paper fluttering like the pages of books. Like the Flute and the bells, economy of gesture expresses deeper meaning.

This staging is beautiful, revealing its charms obliquely, much as the Singspiel tradition is more subtle than later forms of grand opera, and McBurney respects the vibe. The scene where Tamino and Pamina float, apparently suspended in space, surrounded by "birds" is magical. The English dialogue is genuinely witty. Papageno (Roland Wood) quaffs a bottle of Chateauneuf du papageno!

Roland Wood as Papageno and Devon Guthrie as Pamina

Roland Wood as Papageno and Devon Guthrie as Pamina

The singing and acting were also above average for the ENO, hamstrung as it is by the need to do operas in a language other than those for which they were written. This cast delivered with panache, communicating their enthusiasm with style and wit, obliterating the lumpen ENO Die Fledermaus, killed not by the staging but by the performance.

Ben Johnson sang Tamino. He has stage presence..He even looks right, and creates a Tamino with personality, doggedly battling the situation he's in. His firm, assertive singing showed that Tamino is not a spoiled princeling but a man of character and resolve who can face what Sarastro, and the world, throws at him.

Roland Wood sang Papageno, ostensibly the lesser, low-born character in the opera but fundamental to its meaning. Princes abound in classical art, but Mozart gives us Everyman as non-hero in a strikingly modern way. From Papageno we can trace a line through to Siegfried and even to Wozzeck, a role taken by many good Papagenos, and one which Wood is surely destined for. The Papageno songs are harder to carry off than they seem because a singer has to express the role's innate nobility while acting the inept Fool. Spontaneous applause after the Papageno/Papagena duet., and very well deserved indeed. I didn't like the fake provincial accent and Little Britain connotations which English theatre is obsessed with, but Roland Wood's personality shines through the disguise.

Mary Bevan as Papagena and Roland Wood as Papageno

Mary Bevan as Papagena and Roland Wood as Papageno

Mozart's arias for Sarastro are so resoundingly written that they evoke the idea of Sarastro as a figure beyond time, an acolyte, perhaps, of Egyptian gods. James Cresswell sang the part well, though he didn't quite suggest the complexity of the character: Sarastro has very dark sides. He's an unforgiving judge rather than a father figure. Cornelia Götz sang The Queen of the Night. Here, she's no Darth Vader vamp, as in some stagings, but a surprisingly vulnerable woman. Her Ladies (Eleanor Dennis, Clare Presland, Rosie Aldridge) extend her part. Monostratos (Brian Galliford) conveys the Alberich-like animalism, suggesting that he's a dark cousin of Papageno, gone bad.

Devon Guthrie sang a lovely Tamina and Mary Bevan a spirited, lyrical Papagena. The Three Spirits were Alessio D'Andrea, Finlay A'Court and Alex Karlsson, costumed as ancients, whose Norn-like purpose they serve.

This Magic Flute might confound those who want their Mozart vacuous, but those who truly love the opera will get a lot from this highly individual, perceptive approach.

For more details check the ENO website

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ENO_MF_07.png

image_description=Cornelia Götz as The Queen of the Night [Photo by Robbie Jack courtesy of English National Opera]

product=yes

product_title=The Magic Flute, ENO, London

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Cornelia Götz as The Queen of the Night

Photos by Robbie Jack courtesy of English National Opera

Britten, Danced.

Britten's Phaedra was made to be moved to. Maze-like, recurring patterns, mirror images. The orchestration is bizarre. It's scored for percussion and harpsichord, with small string ensemble and soprano, Its textures are stark and stylized, with the directness of Greek or Roman art: no fancy background decoration. Percussion and harpsichord? The timpani and metallic instruments add a raw edge, militaristic perhaps, or maybe ceremonial. Phaedra, after all, is a queen and she takes her regal responsibilities seriously. Britten's cycle feels like state treason, (which of course it is). Against the grim percussion, the harpsichord struggles, the thinness of its tone perfectly portrays Phaedra's vulnerability. Harpsichords are percussion instruments too, and Britten makes no pretence at writing anything harmonic or baroque.

Britten's nine songs evolve like tableaux, each a stage in Phaedra's journey from her wedding day to her death. Phaedra's feelings are not love, but a curse. "I faced my flaming executioner Aphrodite, my mother's murderer". Phaedra's mother was Pasiphaë, who slept with the bull and died giving birth to The Minotaur. Kinky. Britten sets the vocal part in a combination of long, soaring arcs and short staccato interspersed with tense silence. "I could not breath or speak", she sings , describing the compulsion that overwhelms her. She rasps, "Love. Love. Love" heavy and hollow like ostinato, against wildly turbulent, twisting discords, marked by high, screaming strings. "Alone" she suddenly shouts : no adornment, no softening. Indeed, by this stage words are bursting out almost randomly, without any attempt to civilize feelings into conventional form.

"Death to the unhappy is no catastrophe" she intones. At last the strings rise in a sort of elegaic anthem, almost recognizably melodic, but quickly surge into a whirring, rushing torrent. "Chills already dark along by boiling veins" Phaedra faces death heroically. In the end, a solo cello plays a sweet, lyrical passage : Phaedra is no more.

The Britten Sinfonia were shrouded in darkness: an atmospheric touch. The music seemed to materialize out of nowhere, like the mysterious workings of Fate that have cursed Phaedra. The dancers of the Richard Alston Dance Company appeared in strict formation: disciplined, unsentimental, like a Greek chorus. Costumes (Fotini Dimou) glowed scarlet like blood, purple like Phoenician royal. Hippolytus (Ihsaan de Banya) dances among his friends. He's magnificent - so muscular, so lithe, so physical. Phaedra (Allison Cook) is smitten. Because the music moves in tableaux, there are opportunities for different ensembles. Pekka Kuuisto's violin was particularly evocative, suggesting sensual, but sinister curves. Kuuisto's strong, charismatic personality makes an impact even when he's in the background. The dancers weaved languidly when he played, then snapped into fierce angular stances, as stylized and unyielding as the music itself. Alston also made more of the role of Theseus (James Muller) and Oenone (Nancy Nerantzi), fleshing out the drama as counterparts to Phaedra and Hippolytus.