January 31, 2014

Peter Grimes, ENO

However, this revival of David Alden’s exceptional 2009 production of Peter Grimes at ENO makes one wonder if, in future, tenors will be similarly measured against Stuart Skelton’s heart-rending Peter Grimes, for the Australian tenor here re-visits a role which in recent years he has increasingly made his own.

The question has so often been: visionary dreamer or brutal realist? Skelton’s Peter Grimes is both. He makes the ruthless fisherman’s dreams seem rational and attainable, and yet, simultaneously, poignantly deluded, forever to remain tauntingly out of reach. This Grimes is a divided man: ruthless and defiant, and tragically vulnerable. Determined to challenge and transcend the monstrous hypocrisy of the ludicrous but venomous inhabitants of The Borough, he remains pitifully subject to their warped morality and materialism. Skelton’s Grimes has a poignant humanity which is magnified by the ugly depravity of the Borough’s cast of grotesques.

Alden updates George Crabbe’s eighteenth-century milieu to the time of the opera’s composition — Britten made the first sketches of the opera aboard the Axel Johnson liner as he headed back to Britain in 1942, having spent three years in America, to the disapproval of many in his homeland. And, as the back wall tilts to spew the parade of outlandish odd-balls into the court-room, one is reminded of other, more recent oppressive, maniacal regimes.

A severe, sharply angled barn (set design by Paul Steinberg) serves as court room, workplace and public house, its sloping walls swivelling to transform into shore-side promenade, storm-struck exterior and Grimes’s cliff-top hut.

Rebecca de Pont Daves as Auntie, Mary Bevan as Second Niece, Elza ven den Heever as Ellen Orford and Rhian Lois as First Niece

Rebecca de Pont Daves as Auntie, Mary Bevan as Second Niece, Elza ven den Heever as Ellen Orford and Rhian Lois as First Niece

Despite the nautical buoy which looms at the right of the stage, some might lament the absence a tangible sea — the providential force in the lives of the community, both provider and destroyer. However, Adam Silverman’s terrific lighting renders the shimmers and storms of the ocean ever-present; at times the sheen of sun on water makes the back-stage gleam, the boundaries between land and ocean dangerously ambiguous. As the sea tempest approaches the coast, the radiance which filters through the tall windows of the wharf, as the day’s catch is cleaned and gutted, assumes first a fragile hint of grey and then a lowering dark intensity, revealing the vulnerability of those whose lives depend upon the whims of an indifferent natural world. When the lightning eventually releases its electric might, there is a sense of both welcome release and defenceless exposure.

Silverman’s illuminating glare is like a beam of truth. There is no hiding the ugly bruise which stains the apprentice’s shoulder, or the community’s vicious sadism. Particularly effective are the dark, towering silhouettes which hover in the background, shadows which suggest other lives and other selves — paths which might be taken but which remain forever out of reach. Thus, as Ellen urges Grimes’s young apprentice to enjoy the warm Sunday morning sunshine, they are taunted by both the Borough’s hypocritical hymn-singing and their own looming profiles. Nowhere is this more affecting that in Grimes’s Act 2 ‘mad scene’, where Skelton’s hulking contour forms multiple distant yet threatening doppelgängers, a symbol of his fractured self, taunting the disintegrating fisherman with past deeds and abandoned hopes. When Skelton shuffles off at the close, to take his boat on one last, fatal mission, one feels that he is escaping from himself as much as fleeing from the merciless Borough posse.

Skelton’s Grimes combines both gentleness and aggression, and he seems uneasy with either,; he is comfortable only when at work, fishing net in hand, at peace only when cradled by the ocean’s embrace. At the end of the Prologue duet, sung tenderly and with absolute technical assurance by Skelton and Elza Van den Heever (as Ellen Orford), the fisherman reaches out to take Ellen’s hand, before brusquely shoving her aside, unable to cast off his self-conscious pride, accept her affection and expose himself to love’s uncertainties.

Emotionally illiterate, this Grimes is similarly unaware of his physical might. Skelton welcomes the new apprentice who will help him ‘fish the sea dry’ and earn sufficient wealth to conquer the Borough’s scorn; but as he hoists the boy aloft, whirling him back to his hut, it is clear that he does not appreciate the danger that his muscular power and verbal suppression pose to the child. The apprentice — whose silent suffering is sensitively played by Timothy Kirrage — cowers in the bare hut in soundless misery and terror; but, his cliff-top fall is unequivocally an accident. As the rope which supports the boy snakes through Grimes’s fingers, his distress is palpable and it is concern, as well as the Borough’s hunting cries, that sends him scurrying desperately after the boy. When the mob arrive they find an empty shack and leave. But then, a stark, eerie vertical light illumines the cliff down which the boy has tumbled, at the bottom of which Grimes hunches, cradling the dead child in his arms. It is a heart-breaking moment. The villagers have sneered at Grimes — ‘call that a home’ — at end of Act 1; but, it is only home he knows and can offer.

Felicity Palmer as Mrs Sedley

Felicity Palmer as Mrs Sedley

Skelton squeezes every emotion from Britten’s score. ‘What harbour shelters peace?’ is both yearning and despairing, as Grimes’s hopes turn to angry desolation. At the conclusion of Act 1, he furiously ropes himself to the wall to confront the coming maelstrom. Like Lear, out-facing the raging winds and drenching downpour, Grimes both defies and invites the storm. Grimes and the storm are as one; as Balstrode says, ‘This storm is useful, you can speak your mind … There is grandeur in a gale of wind to free confession, set a conscience free’.

Yet, when Grimes attempts to share his vision with those sheltering in Auntie’s tavern, he is met with incredulity, confusion and disdain. Skelton’s voice was almost inaudible at the start of ‘Great Bear and Pleiades’, but the fragility possessed great presence, each repeated E gaining in intensity and assuming a new hue, before fading with the falling melody into poignant stillness — the arc of the phrases like the eternal ebb and flow of the waves, or the transient glimmer of a distant star. Out-voiced by the pub-goers’ shanty, ‘Old Joe has gone fishing’, Skelton lumbers despairingly among the raucous revellers, a lone soul among the massed ranks of oppression and repression.

But, this is no one-man show; the cast is uniformly strong. While some of the principals are returning to re-visit their roles from 2009, two newcomers to the production play Grimes’s confidantes, Ellen Orford and Balstrode. Iain Paterson’s Balstrode is an imposing stage presence. Commanding of voice, and with characteristically excellent diction, Paterson is by turns a noble, authoritative figure among the Borough, then a weary sea-dog, limping stoically, seemingly worn down by Grimes’s own disaffection. Balstrode is not spared Grimes’s aggression, and Paterson uses his dark-toned, smooth bass-baritone to convey the old sailor’s shock and disappointment.

South African Elza van den Heever is superb as Ellen, her glowing mezzo soprano expressing both compassion and resigned realism. Van den Heever began tenderly, but later demonstrated considerable dramatic power and emotional sincerity. The meditative trio which closes Act 2 Scene 1, for Ellen, Auntie and the two Nieces, was wonderfully moving, a moment of repose and respite from the braying calls of the Borough, as the villagers march out, seeking Grimes, to the vicious beat of Hobson’s drum.

Rebecca de Pont Davies was a charismatic Auntie, mischievously swapping pin-striped suit for a floor-length sabre, the warmth of her middle register charming pub-goers and audience alike. As her Nieces, ENO Harewood Artists Rhian Lois and Mary Bevan brought a sparkling vocal brightness to their rather dark portrayal with its lingering suggestions of child abuse and exploitation.

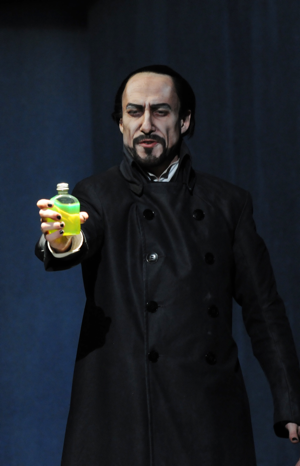

Leigh Melrose reprised his role as Ned Keene, a pill-pushing, mustard-suited spiv, singing with compelling clarity; Matthew Best returned to the role of Swallow, his forceful pronouncements in the opening court scene drawing us immediately into the conflict. Felicity Palmer conveyed both the preposterousness and pathos of Mrs Sedley, while the Bob Boles of Michael Colvin was convincingly and absurdly sanctimonious.

Matthew Best as Swallow, Rhian Lois as First Niece and Leigh Melrose as Ned Keene

Matthew Best as Swallow, Rhian Lois as First Niece and Leigh Melrose as Ned Keene

The ENO chorus was on excellent form too; after a slightly untidy start in the Prologue, the precision of the ensemble was impressive in the subsequent set-pieces, and the power of their massed voices was chillingly resonant in the climactic posse scene.

Guiding all with characteristic assurance and powerful dramatic drive, conductor Edward Gardner yet again demonstrated an innate appreciation of Britten’s musico-dramatic structure and idiom. In the first of the instrumental interludes, the crystalline etching of flute, clarinet, violins, violas and harp alternated with majestic, dissonant surges from the timpani and brass; in the storm interlude the profound hammering of timpani and pizzicato double bass exploded beneath the chromatic whirling above.

My only doubt about Gardner’s authoritative reading concerns some of the tempi, which were often daringly slow, especially in the final act. The pauses between the posse’s hysterical cries, ‘Peter Grimes!’, were so extended that there was a risk of the tension breaking. Similarly, Skelton’s final monologue was audaciously drawn out; certainly, Grimes’s mental and physical dissolution was conveyed, but perhaps some of his self-consuming bitterness and fury was lost.

And, I’m not sure that the ending captures entirely the right note. In the last scene of the opera, Britten instructs that the women of the Borough should carry bundles of fishing nets down to the shore, as they sing of ‘the cold beginning of another day’. The implication is that, as Swallow spies ‘a boat, sinking out at sea’, the fisher-folk refuse to recognise their role in the tragedy that has ensued, and remain indifferent to Grimes’s anguish and death, unconcernedly resuming the routines of daily life. However, Alden’s Borough do not refuse to acknowledge the terrible events they have instigated; rather, they face the audience, unmoving, slowly declaiming the final scalic arcs, as if Grimes’s death has drained them of their own life-force.

Alden’s Borough is suffocating and stultifying; the director offers no open vistas to dilute the poison of hypocritical self-righteousness which poisons its inhabitants, just tantalising glimpses of the freedom and expanse of the sea which will ultimately salve and bless Grimes. Although the transvestism and sexual perversities of the Moot Hall party are somewhat anachronistic, they are a powerful reminder of the self-destructive force of perverted moralising. And, of the fragile defences of those who resist, who dare to be different, dare to dream.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Peter Grimes, Stuart Skelton; Ellen Orford, Elza van den Heever, Captain Balstrode, Iain Paterson; Auntie, Rebecca de Pont Davies; First niece, Rhian Lois; Second niece, Mary Bevan; Bob Boles, Michael Colvin; Swallow, Matthew Best; Mrs Sedley, Felicity Palmer; Reverend Horace Adams, Timothy Robinson; Ned Keene, Leigh Melrose; Hobson, Matthew Trevino; Apprentice, Timothy Kirrage; Doctor Crabbe, Ben Craze; Conductor, Edward Gardner; Director, David Alden; Assistant Director, Ian Rutherford; Set Designer, Paul Steinberg; Costume Director, Brigitte Reifenstuel; Movement Director, Maxine Braham; Lighting Designer, Adam Silverman; Orchestra and Chorus of English National Opera. English National Opera, London Coliseum, Wednesday 29th January 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ENO%20Peter%20Grimes%202014%2C%20Elza%20van%20den%20Heever%2C%20Stuart%20Skelton%20%28c%29%20Robert%20Workman.png image_description=Elza van den Heever as Ellen Orford and Stuart Skelton as Peter Grimes [Photo by Robert Workman courtesy of English National Opera] product=yes product_title=Peter Grimes, ENO product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Elza van den Heever as Ellen Orford and Stuart Skelton as Peter GrimesPhotos by Robert Workman courtesy of English National Opera

January 30, 2014

Puccini’s La bohème at Arizona Opera

Giacomo Puccini and Ruggiero Leoncavallo both wrote operas based on Henri Murger’s Scènes de la Vie de Bohème, but their operas are very different. Not only does each tell different parts of Murger’s wide ranging Scènes, Puccini and his librettists, Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, changed much of the story. For one thing, they made Mimì more faithful to Rodolfo, and thus much more acceptable to a bourgeois audience. The distribution of voices is also quite different. In the Puccini Mimì and Musetta are sopranos; Rodolfo is a tenor and Marcello a baritone. In the Leoncavallo, Mimì is a soprano, Musetta a mezzo, Rodolfo a baritone, and Marcello a tenor.

The Puccini opera starts with the men in their garret, but Leoncavallo puts the whole group in the Café Momus where they attempt to “dine and dash” because they have no money. His Act II opens on the repossession of Musetta’s property because her ex-lover is refusing to pay her debts. By Act III, Musetta, who had again taken up with Marcello, is leaving him because she is tired of poverty. She knows that Mimì is living with a nobleman and she hopes to do that too. Mimì returns to Rodolfo in the final act, but she is very ill. She dies as the bells chime for Christmas day. Although it might be fun to see the Leoncavallo opera someday, it is easy to see why Puccini’s story, even without his exquisite music, makes it the more popular work.

On January 25, 2014, Arizona Opera presented Candace Evans's production of Puccini’s La bohème with exciting young artists Zach Borichevsky and Corinne Winters as a romantic Rodolfo and his charming but not-so-innocent Mimì. Evans gave us a realistic interpretation of the libretto staged on sets by Peter Dean Beck. The first and fourth acts took place in a frigid attic room that radiated its cold out into the audience. A dual level set provided adequate space for the joyous outdoor Christmas Eve scene that formed the opera’s second act. It was a perfect background for Andrea Shokery’s grand entrance as the flirtatious Musetta. She sang her coquettish waltz song with dulcet tones, all the time trying to rekindle the interest her old lover, Marcello. When her shoe began to pinch her foot, she asked her escort, Alcindoro, to help her remove it. As he pulled off the shoe she pulled up her several skirts, to his embarrassment and the amusement of the audience.

As Marcello, baritone Daniel Teadt still loved her despite her acerbic personality, and he was happy to take her into his arms. Puccini never gave the lovesick Marcello an aria but Teadt had some beautifully lyric moments in Act III. Chris Carr was a gregarious Schaunard and Thomas Hammons made the most of his two character roles, Benoit, the ineffectual landlord, and Alcindoro, the old dandy who gave up a great deal of dignity to have a beautiful young woman on his arm. Young artist program member Calvin Griffin acquitted himself well as the intellectual Colline. Together, these artists evoked great depth of emotion with their ability to color their tones and act with their voices. Although the story of this opera is sad, Henri Venanzi’s choristers made the second act a pleasant interlude in Mimì’s inevitable decline. At the end, Rodolfo was the last to realize she has died, but when he finally did it was heartbreaking. Joel Revzen led the Arizona Opera Orchestra in a lucid reading of the score that brought out to poignancy of the story. This was a fine performance of the Puccini masterwork and the exquisite playing of the orchestra was a large part of it.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Rodolfo, Zach Borichevsky; Mimì. Corinne Winters; Musetta, Andrea Shokery; Marcello, Daniel Teadt; Collie, Calvin Griffin; Schaunard, Chris Carr; Benoit/Alcindoro, Thomas Hammons; Parpignol, Dennis Tamblyn; Conductor, Joel Revzen; Director Candace Evans; Chorus Master, Henri Venanzi; Scenic Designer, Peter Dean Beck; Costumes, A. T, Jones and Sons; Lighting, Douglas Provost.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Boheme%2011.png

image_description=Act II of La bohème [Photo courtesy of Arizona Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Puccini’s La bohème at Arizona Opera

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: A scene from Act II of La bohème [Photo courtesy of Arizona Opera]

January 25, 2014

Francesco Bartolomeo Conti: L’Issipile

The dramma per musica was premiered at the Imperial Court Theatre in Vienna during the Carnival of 1732, but was not a great success, and was granted only three performances; perhaps, if the cast of Baroque specialists and instrumentalists presenting the opera at the Wigmore Hall on Wednesday evening had been on duty on 7th February 1732, the story might have been different … for this outstanding and utterly absorbing performance by La Nuova Musica and a stellar set of soloists made for a thrilling musical evening.

Metastasio’s opera seria combines two Classical myths: that of Jason and the Argonauts and the tale of the rebellion by the women of Lemnos. Perhaps the violent nature of the subject — the vengeful slaughter of the men of Lemnos — was off-putting for early-eighteenth-century audiences and the Viennese court.

The action unfolds on the island of Lemnos, in the Aegean Sea. The soldiers of Lemnos have won their battle on the neighbouring island, Thrace, but attracted by the wealth and beauty of their enemy’s women, they have delayed their return home. Eventually their King, Thoas, eager to attend the wedding of his daughter, Issipile, to Giasone (Jason), convinces them to wend their way homeward; but, their irate, vengeful wives have hatched a terrible plot to kill their husbands upon their arrival, using the distractions of the festival of Bacchus to mask their vicious intent. Issipile tries to warn her father; she hides him and tells the other women that he has already been killed. This action, however, causes her to be rejected twice: first, by Jason who condemns this act of patricide, and then by the Lemnos women, when they discover the truth.

Eurynome, the leader of the women, is especially angered, as her son, Learchus, has previously been spurned by Issipile and forced to flee from Lemnos following a failed attempt to abduct her; it is rumoured that in desperation he has killed himself in exile. In fact, he has become a pirate and, hearing of Jason’s return, Learchus travels to Lemnos and hides in the palace, planning a second kidnap attempt. However, Issipile’s goodness wins through in the end: the virtuous are saved, the evil punished, the lovers married and Lemnos restored to peace.

An inconsequential tale, but one which inspired Conti to compose substantial arias of great power and passion, interspersed within lengthy, varied recitatives, many of which are accompagnato. High voices dominate and the six roles form effective pairs, the female roles being particularly strongly characterised.

Soprano Lucy Crowe infused Issipile’s virtuosic arias with both intensity and delicacy — often, paradoxically, simultaneously — capturing both the tenderness of her filial devotion and the ache of marital passion. The long aria which closes the first act exemplified the way that Crowe employed both penetration and sweetness — top Cs floated effortlessly, the vocal acrobatics were effortlessly agile — to portray the self-doubt which tinges the heroine’s virtue; the vocal delights were enhanced by striking variations of tempo, stirring harmonies and inventive motifs from the violins.

Crowe was perfectly complemented by the sentimental warmth of tone of soprano Rebecca Bottone, as Rodope. The lyricism and clarity of Bottone’s recitatives was deeply communicative. The Act 1 aria, in which Issipile’s confidante gives the villainous Learchus a lesson in moral philosophy, combined seriousness of intent with a persuasively seductive, luxurious tone. The sequential interplay between voice and strings, and the beautiful, rich earnestness of the soprano’s lower register in the da capo repeat, was profoundly moving; surely such musical reflections and exhortations would deflect a jealous blackguard from his evil ways…

Learchus is an anti-hero of Iago-like proportions. His intrigues and machinations were superbly rendered by countertenor Flavio Ferri-Benedetti; his relentless evil — conveyed by stunning vocal leaps from crystalline heights to resonant depths — was riveting, while his conceited pouting and strutting, embellished with tightly pulsating trills, entertained. The final scene in which Learchus, mid-way through his assassination-abduction mission, recognises his own erroneousness and imprudence and stabs himself in self-chastising remorse, was gripping. (Ferri-Benedetti is clearly the man to go to if you want to learn about Conti: currently completing a doctoral thesis on Metastasian heroines, the countertenor both prepared the edition of the score and provided the English translation of the libretto which was projected onto the wall of the Wigmore Hall cupola.)

And, what a treat for the audience to have two countertenors of such star quality to beguile them. The devil may have all the best tunes, but Lawrence Zazzo, as Giasone, equalled Ferri-Benedetti in the posing and strutting department. Zazzo’s recitatives were particularly fluent and flexible, and he used elegance and graceful evenness of phrase to convey Giasone’s essential honesty and righteousness.

John Mark Ainsley’s unfailingly beautiful, well-centred tone embodied the dignity and fair-mindedness of Thoas, as well as the sincerity and depth of his love for his daughter. His life may have been in danger, but Thoas never wavered, exuding calm composure and confident nobility throughout. Mark Ainsley encompassed the extraordinarily wide range with ease; the melodic arcs were wonderful spun, underpinned in Thoas’s second aria by dense but delicate contrapuntal lines of the strings, the minor tonality adding to the poignancy.

Diana Montague’s resentful Eurynome equalled Thoas in dramatic stature and musical characterisation; her arias were characterised by excellent diction and vocal refinement combined with rhetorical impact. The fury of her Act 1 aria, emphasised by the agitated accompaniment, gave way to more tragic sensibilities at the start of Act 2, guiding the audience to recognise Eurynome’s misfortune as well as her bitterness.

The fourteen instrumentalists of La Nuova Musica, led from the harpsichord by founder and director David Bates, produced playing of fleetness, vivacity and charm. The Sinfonia epitomised the perfectly synchronised panache of the strings’ Italianate lines, and the striking contrasts of dynamics suggested the surprising twists and turns of the drama to follow. In the complex arias, oboe (Leo Duarte) and bassoon (Rebecca Hammond) added colour to the tutti sections; the more contrapuntal accompaniments were incisively articulated. Conti’s recitative is fast-moving, Metastasio’s lines often shared between characters; Bates unfailingly created forward motion and excitement in these exchanges, which the soloists delivered with naturalness and spontaneity. Sudden harmonic swerves and interruptions were emphasised but never mannered.

Concert performance this may have been, but the drama was transfixing. The three hours whizzed by. One longs for a recording.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

La Nuova Musica. David Bates, director; Lucy Crowe, soprano (Issipile); John Mark Ainsley, tenor (Thoas), Lawrence Zazzo, countertenor (Giasone); Flavio Ferri-Benedetti, countertenor (Learchus); Diana Montague, mezzo-soprano (Eurynome); Rebecca Bottone, soprano (Rodope). Wigmore Hall, London, 22nd January 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/3513.png image_description=Lucy Crowe [Photo © Harmonia Mundi USA Marco Borgreve] product=yes product_title=Francesco Bartolomeo Conti: L’Issipile product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Lucy Crowe [Photo © Harmonia Mundi USA Marco Borgreve]January 24, 2014

Christoph Prégardien, Wigmore Hall

He and Michael Gees gave a recital at the Wigmore Hall, London, which showed how vigorous the Lieder tradition continues to be. Prégardien and Gees created a programme that illuminated the liveliness of the Romantic imagination. Nature spirits abound, and fairy tales and ghostly figures of legend. Lulled into fantasy, one might miss the hints of danger that lurk behind these charming dreamscapes. The Romantics were intrigued by the subconcious long before the language of psychology was coined.

The recital began with one of the most lyrical songs in the whole Lieder repertoire, Carl Loewe's Der Nöck (Op129/2 1857) to a poem by August Kopisch. A Nix, a male water sprite who plays his harp by a wild waterfall. Its waves hang suspended in mid air, the vapours forming a rainbow halo around the Nix. Circular figures in the piano part suggest tumbling waters. Prégardien breathed into the long vowel sounds so they rolled beautifully We could hear what the text means when it refers to a nightingale, silenced in awe. Suddenly the magic is broken when humans draw near. The waves roar, the trees stand tall, and the nightingale flees, until it's safe for the Nöck to reveal himself again. Prégardien and Gees paired Loewe's song with Franz Schubert.s Der Zwerg (D771, 1822) to a poem by Matthäus von Collin. A queen and a dwarf are alone on a boat on a lake. Love, murder and possible suicide haunt the idyll. The Id is released, violently, in a blissful setting.

Franz Liszt's Es war ein König in Thule> (S278/2 1856) sets a poem from Goethe's Faust. Schubert's setting is more folkloric, reflecting the innocence of Gretchen who sings in the saga. Liszt's setting is more elaborate. Lovely, falling diminuendos describe the way the King drinks one last time from his chalice, before throwing it "hinunter in die Flut". Perhaps the queen who gave him the chalice was herself a nature spirit who lived beneath the lake? Prégardien intoned the line "Trank nie einen Tropfen mehr" solemnly : the King has died.

Prégardien has championed the songs of Franz Lachner (1803-1890), who knew Schubert, Loewe, Schumann and Wagner, and worked in court circles in Munich, where he knew only too well what the Romantic imagination could do to real kings like Ludwig II. Lachner's Die Meerfrau was written in Vienna, comes from early in his career and sets a poem by Heinrich Heine. A water spirit appears and drags a mortal to a watery grave. The song comes from Lachner's magnum opus, Sängerfahrt op 33 (1831) where the are numerous songs on similar themes of supernatural seduction and death. Ironically, Lachner wrote the collection on the eve of his own marriage, dedicating it to his bride. One wonders what modern psychoanalysts might make of that. Prégardien and Gees also performed Lachner's Ein Traumbild from the same collection. Tjhe final strophe is particularly luscious: The cock crows at dawn, and the vampire seductress flees.

Prégardien and Gees also performed Liszt's Die Loreley (S273/2 1854-9), whose long prelude contains the Tristan motif in germ, before it was developed by Wagner. As Richard Stokes writes in his programme notes, it "begins with a leap of a diminished seventh : the voice however begins with a fourth ...and then soars a sixth - identical in harmonic terms with the piano's diminished sevenths". In the context of these feverish succubi, Hugo Wolf's Ritter Kurts Brautfahrt (1888) made an interesting contrast. On the way to his wedding, the Knight meets many temptations that almost throw him off course, including a mystery nursemaid who claims that her charge is his child. Yet it's quite a cheery song with cryptic in-jokes that refer to the music of Wolf's friend, the composer Karl Goldmark, who lent Wolf money, knowing he wouldn't be repaid.

Prégardien's unique timbre and ability to float legato has inspired several composers, most notably Wilhelm Killmayer (b 1927). Killmayer's Hölderlin Lieder were written for Peter Schreier and are, I think, the most exquisite songs of the last half of the last century. Prégardien has recorded them too. Killmayer wrote his Heine Lieder for Prégardien, setting 35 songs by Heine. Killmayer's songs don't imitate Schumann's. They engage with the meaning of Heine's texts in a highly original style, with pauses, and piano resonances that float in the air. The effect resembles speech, yet also inner contemplation. Killmayer revisits the poets of the past, and writes music for them in a new, refreshing way.

In this Wigmore Hall recital, Prégardien and Gees performed Killmayer's Schön-Rohtraut (2004). The poem is Eduard Mörike, from 1838. Rohtraut is King Ringang's daughter. She doesn't spin or sew, but hunts annd fishes like a man. Mörike was inspired by the strange sound of the names, which he found in an ancient book, but the princess could be a reincarnation of the wild and elusive "Peregrina" who might have led Mörike astray. The lines are simple and repetitive, which suits Killmayer's abstract, almost zen-like purity. As Rohtraut leads the boy into the woods, his excitement mounts. Killmayer's delicate, fluttering note sequences suggest a heart beating with nervous anticipation. We feel we are at one with the boy, as enthralled as he.

Michael Gees is himself a composer, and Prégardien has performed and recorded his songs several times. This time, we heard Gees's Der Zauberlehrling (2005) where he sets Goethe's poem about the sorcerer's apprentice who uses magic to wash the floor and conjures up a flood. Gees setting is delightful. Rolling, rumbling figures to suggest the rising waters, and a stiff march to suggest the legions of broomsticks. Syncopated rhythms and zany downbeats, used with great flair. The audience burst into spontaneous applause. Gees and Prégardien were taken by surprise. Gees was thrilled, and beamed with happiness. It's heart warming to see a composer get respect like that.

The recital ended with old favourites like Loewe's Edward (Op1/11818) Tom der Reimer (Op 135a 1860), Schumann's Belsazar (Op57 1840) and Wolf's Der Feuerreiter (1888). Schubert's Erlkönig made a rousing encore, Since Prégardien and Gees had done Loewe's Erlkönig (Op 1/23 1818) earlier in the evening, it was good to reflect on the differences between the two settings. Loewe's real answer to Schubert's Erlkönig is his Herr Oluf, which is another song of prenuptial anxiety, murder and mayhem, . Prégardien and Gees could be doing recitals like this over and over and not exhaust the Lieder repertoire.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/CP_2.png

image_description=Christoph Prégardien [Photo © Marco Borggreve]

product=yes

product_title=Schubert, Schumann, Loewe, Lachner, Liszt, Gees, Killmayer, Wold : Christoph Ptrégardien, Michael Gees, Wigmore Hall, 22nd January 2014

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Christoph Prégardien [Photo © Marco Borggreve]

January 23, 2014

Parsifal, Chicago

At the same time a group of youths is awakened and encouraged by Gurnemanz in their prayers of devotion. This daily routine of the Grail community is staged with somber dignity before the King Amfortas is carried onstage in the midst of renewed and heightened suffering. The sudden arrival of Kundry, credited with access to magical powers, gives temporary hope as she beings a balsam with the potential of healing. When the King is brought to his bath Gurnemanz narrates the background of all that has transpired in this community of religious and worldly aspirations. Before the title character makes his first appearance the figures and events listed have created an atmosphere at once stagnant and yet somehow prepared for resolution. In the role of Gurnemanz Kwangchul Youn makes his Chicago Lyric debut. Kundry is also a house debut role for Daveda Karanas. Amfortas is sung by Thomas Hampson. Knights and esquires of the Grail are portrayed by John Irvin, Richard Ollarsaba, Angela Mannino, J’nai Bridges, Matthew DiBattista, and Adam Bonanni. Sir Andrew Davis conducts the Lyric Opera Orchestra and Chorus.

The intrusion of Parsifal, sung by Paul Groves in his role debut, was staged with appropriate surprise and confusion generated among members of the Grail community and by the title character himself. Just as the isolated Grail inhabitants recognize Parsifal’s violent deed in killing a wild swan, the protagonist understands his own actions as a natural response to his surroundings (“Gewiß! Im Fluge treffe ich, was fliegt!” [“Of course! I shoot down in flight whatever has wings!”]). The musical and dramatic depiction of these introductory scenes catches the spirit of Wagner’s score and text while yielding an individual approach to the current Lyric Opera production. In his admonishments to the Grail knights and attendants Mr. Youn uses his rich bass voice with remarkable facility. Lines such as “Sorgt für das Bad!” (“Prepare the bath!”) and “Der König stöhnt!” (“The king is groaning!”) are intoned with a sense of authority combined with underlying compassion. Forte pitches were sung as natural extensions of the vocal line and Youn’s intonation showed a deep understanding of the communicated text. At times the pronunciation of unstressed final syllables was overly exact, a tendency which detracted only slightly from an otherwise exemplary Gurnemanz. The fluttering character of Kundry is captured aptly in Ms. Karanas’s approach. She used her secure and extensive vocal range in such lines as, “nur Ruhe will ich … Schlafen! - oh, daß mich keiner wecke! Nein! Nicht schlafen! - Grausen faßt mich!” (“I simply wish to rest … to sleep! Oh, let no one awaken me! But no, not sleep! - Fear takes hold of me!”) in order to emphasize the ambiguity inherent in Kundry’s persona. In the role of Amfortas, as a means to communicating without doubt the King’s suffering Mr. Hampson emoted in an interpretation that should have depended more on a sung line if it were to remain lyrically and dramatically credible. The Parsifal of Mr. Groves is sung with a warm tone suggesting innocence and identification with his mother, important for her descent from the family of the Grail. Decorations performed by Groves on the line “Im Walde und auf wilder Aue waren wir heim” [“We made our home in the forest and on the open meadow”] indicate his identification with kinship and defense of his upbringing until the present. The trio of Gurnemanz, Kundry, and Parsifal interacts with progressing revelations concerning the youth and the atmosphere into which he was destined to find himself. Youn’s character becomes gradually paternal as he recognizes Parsifal’s heritage and attempts to guide him toward the Grail’s true essence. [“nun laß zum frommen Mahle mich dich geleiten” (“now let me lead you toward the sacred repast”)]. After a procession of knights has passed, the King is once again brought in to experience the presence of the Grail at the sacred hour [“hoch steht die Sonne” (“the sun stands now at its height in the sky”)]. In response to Amfortas and his emotional cries of “Wehe!” in this production, Parsifal moves slightly closer to the suffering victim, yet only as a demonstration of curiosity. The collected knights of the Grail, here very well prepared in their diction and controlled projection, recite the invitation “Nehmet vom Brod … Nehmet vom Wein” [“Partake of the bread … Partake of the wine”] before the prostrate Amfortas is removed on his pallet. In the final image before the act’s end Youn as Gurnemanz reacts with appropriate derision over Parsifal’s inaction [“Du bist doch eben nur ein Tor” (“You are nothing but a simple fool”)], as he commands the youth to leave.

The realm of Klingsor in Act Two illuminates the ambivalent character of Kundry and makes further apparent, as if from a distance, the failings in the present generations of the Grail. This act also prepares the audience to experience the resolution of such deficiencies through Parsifal as protagonist during the final act. As such, the trio of performers in Act Two is vital to the continued development of Wagner’s aesthetic. Ms. Karanas and Mr. Groves, joined by the Klingsor of baritone Tómas Tómasson, made of this act a model of vocal and dramatic excitement. Klingsor is dressed in this production in a variegated red costume with the same hue painted onto his face. He is further positioned in a stylized neon structure, also in red, which emits smoke from the tower at his commands. As Tómasson proclaimed “Die Zeit ist da!” and “Herauf zu mir!” [“The time has come!” and “I summon you up to assist me!”] the stage was set for Parsifal’s arrival and Kundry’s obedient responses. Tómasson’s interpretation of the sorcerer is impressive for his vibrant, dramatic vocalism as well as his physical involvement in Klingsor’s demands. His performance of Klingsor’s laugh is equally chilling as he witnesses Parsifal’s approach and describes the hero’s searching glances into the magical garden [“Wie stolz er nun steht auf der Zinne!” (“How proudly he is standing there on the parapet!”)] After Klingsor’s interaction with Kundry, he conjures the flower-maidens to tempt Parsifal. This scene was effectively staged with costumes and movements even overdone in some respects. Kundry’s subsequent attempts to seduce Parsifal and her further revelations concerning his heritage and mother Herzeleide were delivered by Karanas with superb control, especially in the upper register. Groves’ Parsifal truly came into his own in this act, as he unleashed dramatic pitches on “Die Klage” (“The lament”) and a moving legato approach to “Erlösungswonne” (“joy of redemption”).

In a fitting preparation for the resolution of Act Three the production stages clearly the demise of Klingsor and his realm via his own spear. Parsifal catches the weapon to put an end to this magical and destructive kingdom. With this spear and resolve to atone for his own failings Groves as Parsifal proceeds to seek out the Grail as Act three develops. His ultimate healing of Amfortas’s interminable cries of “Wehe!” with the application of the spear, now transformed in its effect, elevates both the kingdom of the Grail and Parsifal’s own position in this production’s unforgettable transformation.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Parsifal_3_Chicago.gif image_description=Paul Groves as Parsifal. Act 1. [Photo by Dan Rest] product=yes product_title=Parsifal, Chicago product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino product_id=Above: Paul Groves as Parsifal. Act 1. [Photo by Dan Rest]January 22, 2014

La traviata, Chicago

The title role was sung by Marina Rebeka in her company debut; Joseph Calleja repeated his success as Alfredo Germont; the father of Alfredo, Giorgio Germont, was performed by baritone Quinn Kelsey. The Lyric Opera Orchestra and Chorus were conducted by Massimo Zanetti.

The first and final acts of Verdi’s opera were united in the visual depiction of Violetta Valery’s domain, while the atmosphere attendant on both depictions showed a considerable difference. During the overture to the opera the audience was able to witness, through a film-like curtain suspended before the stage, the protagonist Violetta helped by her maid as she stepped into a ball-gown and train. As the strings played their achingly wistful melody during the overture Violetta donned both feathers and wings to prepare herself further for the festive party in her home. This element of belle époque artifice continued throughout the production lending a credible tone to the celebratory scenes in the later acts.

From her first lines of invitation, “Flora, amici …” and “Miei cari, sedete …” [“Flora, my friends …” and “My dear friends, please be seated”], Ms. Rebeka had full command of Violetta’s role. She sings with a comfortable approach to the character’s shifting vocal lines, uses decoration judiciously, and remains involved in the stage action as hostess at her salon. At Alfredo Germont’s introduction Mr. Calleja assumes a tentative yet searching approach, so that the audience is able to sense his vivid interest not only in the setting but also in its hostess. Calleja’s admirable line and embellishments in the “Brindisi” [“Libiamo” (“Drink”)] are models of bel canto Verdian singing. Individual notes are projected clearly, just as the intensity and color of Calleja’s decorations emphasize an involvement progressing beyond infatuation. When he responds to Violetta’s questions concerning this passionate interest, Calleja introduces his self-defense with a suspenseful diminuendo before describing his unexpected love already for the duration of a year. With a seamless flow of legato expression Calleja outlines his character’s emotional struggle as summarized finally with a tear-laden effect on “Croce e delizia” [“Cross and ecstasy”]. Rebeka’s response is equally moving while she pronounces “un cosi eroico amore” [“such an heroic love”] with a rising line of decoration. During their rapid exchange of plans to meet again when the flower has withered, both principals sang “domani” [“tomorrow”] in piano intimacy. As a means to depicting their growing, shared love, this hushed glance into the characters’ feeling enhanced for the audience the resolve expressed in the duet as concluded.

During an introspective solo, when left alone to ponder the changes affecting her current state, Violetta doubts at first the possibility of authentic love. In the first part of her aria, “Ah, fors’è lui” [“Ah, perhaps he is the one”], Rebeka uses her skills to sing and modulate from soft to loud as though involved in an emphatic conversation with her heart. The incomprehensible, or “misterioso,” is sung by Rebeka softly and in awe, whereas her voice blooms in volume under the weight of the “croce.” During the ensuing “Sempre libera” [“Forever free”] the rapid runs were executed cleanly and forte notes were taken as pure, lyrical cries of emotion. Rebeka succeeds at integrating this showpiece aria smoothly into the drama while at the same time leaving a strong impression of her bel canto approach. Toward the close of the act Calleja’s repeated offstage appeals of “Croce” extended the emotional web for both protagonists even further.

At the start of Act Two Alfredo, while alone, muses on his happiness in the soliloquy “Lunge da lei per me” [“When she is far away”]. Calleja’s breath control and embellishments on “il passato” and “Io vivo quasi in ciel” [“the past” and “I seem to live in heaven”] underline his dream-like state before the rude awakening of Violetta’s financial sacrifice, about which he learns unexpectedly from Annina. In his aria of response, “Oh mio rimorso! Oh, infamia!” [“Oh remorse! Oh infamy!”], Alfredo is indeed jolted into recognizing his position. Calleja performs this aria with true emotional vigor and takes the repeat with the effect of emphasizing his resolve. Act Two of La traviata belongs, of course, just as much to Giorgio Germont, the father of Alfredo. Mr. Kelsey demonstrates a solid command of this role, his exciting baritone drawing on resonant shades of nuance especially during his introductory scene with Violetta. When making an appeal to his son’s lover Kelsey includes individual decoration to enhance the spirit of his request. His sense of rubato was effective in “genitor” [“father”] just as was the embellishment with which he sang “L’angiol consolatore” [“Consoling angel”]. As if in response to this moving portrayal of paternal need, Rebeka’s Violetta sang “Dite alla giovane” [“Tell your daughter”] with a decidedly slow tempo, so that each word was pronounced in fulfillment of her proposed actions. Both singers were then united in a rising line on “sacrifizio” as Violetta subsequently promised to leave Alfredo.

The following scene of Act Two showed Kelsey just as much to advantage. His performance of “Di Provenza il mar” [“From Provence … the sea”], addressed to a disconsolate Alfredo, was noteworthy for its disciplined approach to phrasing. The aria was performed in its uncut form, so that the audience was privileged to hear a polished performance of a baritone staple which is so often trimmed in other productions. Toward the close of this scene the orchestra, perhaps out of sympathy with the anguish expressed between father and son, played its accompaniment too loudly. In the final part of Act Two, at the salon of Flora, the costumed dancers and additional performers fit well into the overall setting of the party. After the intimate duet between Alfredo and Violetta - leading to anger, misunderstanding, and his public denunciation - Germont père returns and participates in a final ensemble. Here Kelsey’s superb legato could be traced throughout the group, while Rebeka performed her part with searing top notes as she lay on her side. Calleja’s lines “rimorso io n’ho” [“I am sick with remorse”], with equally notable projection, remained the dominant impression at the close of the ensemble.

Act Three is staged at first through the same curtain as at the start of Act One, yet now Violetta lies ill and weak as attended by Annina. After Dr. Grenvil hints discretely that Violetta has only several hours to live, the maidservant is sent off to perform errands. When left alone Violetta sings “Addio, del passato” [“Farewell … of the past”], which Rebeka performed with multiple high notes shading to diminuendo. Her vision of “La tomba ai mortali” [“The tomb for us mortals”], as expressed in this performance, was clearly visible to the protagonist despite a letter announcing the imminent arrival of Alfredo. Although he arrives shortly before Violetta succumbs, their final duet, “Parigi, o cara” [“From Paris, dear”] remains ironically also a vision. The tragedy of her death renders this final lyrical happiness, with Calleja’s leading lines answered touchingly by Rebeka’s sustained responses, a poignant conclusion to this excellent new production of Verdi’s masterpiece.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/traviata-1-TR.gif image_description=Marina Rebeka as Violetta, Act 1. [Photo by Todd Rosenberg Photography] product=yes product_title=La traviata, Chicago product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino product_id=Above: Marina Rebeka as Violetta, Act 1. [Photo by Todd Rosenberg Photography]Gluck: Orpheus and Eurydice

Presenting Gluck’s opera, Orpheus and Eurydice, EPOC invite you to metamorphose from passive onlooker to active participant, joining Orpheus as he journeys to the underworld to rescue his treasured Eurydice.

Led by Artistic Director, Mark Tinkler, The English Pocket Opera Company — now 20-years-old —has for the last 10 years been dedicated to creative educational projects with children young people, ranging from primary school children to undergraduates. Previous years have seen Hamlet, Don Giovanni, Dream (based on Purcell’s The Faerie Queen, a version of The Ring, Bluebeard’s and Hansel and Gretel performed in a variety of venues, from the Brady Centre in Tower Hamlets to The Cochrane Theatre.

The company produces what it describes as ‘Opera for, by and with children’. Feedback from participants and teachers has been extraordinarily positive, even eulogistic. And, the statistics too are impressive. In 2012, up to 50,000 children drawn from 250 schools in 2012 benefitted from the company’s multidisciplinary programmes; this year’s four-phase project exploring Christoph Willibald Gluck’s opera, Orpheus and Eurydice, will involve over 10,000 children from 55 schools, as well as talented designers studying the BA in Performance Design and Practice at Central St Martins (part of the University of the Arts London), amateur singers and musicians, along with some professional singers, musicians and theatre practitioners.

In many ways — in this anniversary year — Gluck’s ‘reform’ opera is a good choice for this ambulatory project: Gluck’s story is told simply and with clarity, a result of the composer’s aspirations to replace the obscure, complex plots of opera seria with a ‘noble simplicity’ — it’s a tale which is easy to follow while perambulating!

Summoned to our feet by Orpheus (Paul Featherstone) in fairground fashion — ‘Roll up, roll up, for the greatest story ever told!’ — we followed the hero, accompanied by accordion player, fiddler and assorted furry-masked creature, to the opening location. The performance begins, not with the solemn, grief-laden chorus of nymphs and shepherds but with the wedding banquet of Orpheus and Eurydice (Pamela Hay) which, somewhat wryly, takes place in the college canteen (design, Maddy Rita Faye). A trellis table is adorned with goblets, victuals and floral bouquets, around which twirl and spiral the newly-weds and assorted animal guests, occasionally sweeping members of the audience into their festive dance. A piano or keyboard is stationed at each venue; in this opening scene, Music Director and pianist Philip Voldman — who played with unflappable composure and fluency throughout —strikes up, not Gluck’s elegant measures, but the mesmerising melody of Papageno’s ‘Das klinget so herrlich’, which rings out, calming the beasts and reminding us of another operatic rescue mission in which the hero must stoically undergo trials and tribulations in order for his beloved to be restored to his arms.

Fatally bitten by a serpent, Eurydice is carried by Orpheus to her grave. Recorded music bridges the gap between some locations, and the transitions between live and recorded sound are smooth and natural. Denise Dumitrescu’s designs turn the CSM Studio Theatre into a Classical funeral vault; burnished gold, circular pillars of ruffled cloth ripple from ceiling to floor, enclosing distraught mourners, as the funeral chorus provide a dignified accompaniment to the noble grace of the setting. As the delicate columns tumble gracefully to the floor, and Orpheus lunges fruitlessly into the airy space, loss and absence are poignantly emphasised. Again, the onlookers are drawn into the action, beckoned to strew white lilies on Eurydice’s grave, as Orpheus desperately seeks his lost love through the mists of cloth which drape the entrance to the underworld.

Vivian Lu’s striking, expressionistic tree turns a corner of the Theatre Bar into the wood in which Orpheus becomes increasingly distressed — haunted obsessively by the vision and voice of his dead wife. From here, we progress to the banks of the Styx where Amor (Joanne Foote) appears, to instruct Orpheus to travel to Hades in order to plead with the Furies for Eurydice to be spared. In an appropriately bare, starkly lit corner, designer Anastasia Glazova’s white screens are opened to reveal Amor crouching in a bubble wrap cage; the bubble wrap is torn down to form a Styxian carpet leading us to Hell (the Platform Theatre Orchestra Pit) — although as we trod the watery path, paying the beastly Charon by dropping badges into his mouth, the percussive popping produced a rather unfortunate, glib sound effect.

But, the motion of descent is persuasive; the rickety stairs leading to the bowels of the pit emphasise the precariousness and risks of Orpheus’s venture, and the dense smoke which swirled in around us in the gloom — perhaps too dense? — evoked the mists which obscure his understanding and his progress. A discarded shopping trolley, filled with detritus and diabolic emblems (design Lucia Riley) is a fitting emblem of misery and despair. Three Furies (Isabella Van Braeckel, Joanna Foote and Eimear Monaghan) angrily storm through the darkness, accompanied by dramatic choral interjections from above, until quelled by the sweetness of Orpheus’s lyre — evoked by the resonant pizzicati of Sivan Traub’s violin — they agree to help return Eurydice to him.

Ascending to the Theatre Stage, the audience find themselves in the Elysium Fields of the versatile Van Braeckel and Monaghan, a shimmering paradise of reflecting white discs strung from knotted ropes, the floor ornamented with black, circular mats decorated with silvery spirals; the scene is illuminated by an evocative amber and chartreuse glow. The unveiling of a hideous skeleton when Orpheus contravenes his promise not to look back at Euridice is a striking coup de theatre. Drawn to the front of the stage, we witnessed Orpheus submit to suicidal thoughts in the Theatre Auditorium which is transformed by Mathias Krajewski into Orpheus’s homeland. A wig-wam of thin threads furnishes him with a hang-man’s rope until his grief so moves the Gods that they allow Eurydice to return to the mortal world, weaving and gliding through the audience to re-join her husband.

For the happy conclusion, the jubilant characters and chorus assemble in the Theatre Bar for a celebratory home-coming. Robin Soutar’s pillar-box red Punch and Judy booth restores the sardonic, burlesque air of the opening scene, as the dignified strains of Gluck give way to the more riotous tones of Offenbach’s ‘Infernal Galop’.

Performance standards were high, especially considering that most of the participants are amateurs performers. As Eurydice, soprano Pamela Hay revealed a glittering upper register and strong, varied characterisation, capable of capturing both the intensity and insouciance that the different settings require. The sweetness of her tone and elegance of phrase garnered much pity for Eurydice. Joanna Foote was similarly affecting as Amor: her arias were well-crafted and stylish. The chorus sang with good intonation and a well-blended, balanced sound.

As Orpheus, Paul Featherstone was committed and impassioned, and he did much to involve the audience in the drama and to encourage their sympathetic engagement with the protagonists’ fates. But, sadly, poor intonation, some heavy-handed shaping of the melodic phrases, a rough-edged tone and an undeviating dynamic level — forte — made this role a weak link in the performance. There were moments of tenderness, but these were not sustained, and the big numbers — ‘Chiamo il mio ben’, Che farò senza Euridice?’ — lacked the necessary mellifluousness and lyricism.

The designs were fresh and interesting; these young, up-and-coming students approached the work without preconceptions about what opera design ‘should’ be, and there were some imaginative and striking visual images and effects. Occasionally elements of the venue were a little distracting — signs and notices, stairways and lighting drawing our focus away from the moral dignity of the mythological journey; and, occasionally unsuspecting art students going about their business were startled to find themselves part of an operatic liberation assignment, their passage barred by an assortment of blessed spirits or demons! But, the imbibers in the Theatre Bar seemed pleasantly amused by the arrival of the pantomime-esque road-show at the close.

It seems incredible that all this is achieved on a shoe-string budget; EPOC relies on box office receipts and students have to fund their own materials for sets and costumes. It is not just a ‘worthy’ venture but a worthwhile and artistically rewarding one too.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

This ‘promenade’ version of Gluck’s opera is ‘Phase 2’ of EPOC’s project, following on from Phase 1 ‘Opera Blocks’, an interactive presentation in primary schools unpacking the work, and opera in general. Next comes a performance at the Royal Albert Hall on 17 March involving choirs representing all 55 schools in the borough of Camden accompanied by the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment; Phase 4 will conclude the project, during which EPOC will work with schools to create their own versions of Orpheus and Eurydice — writing arias, choruses, building and designing sets and costumes, before performing their devised works to parents.

Orpheus, Paul Featherstone; Eurydice, Pamela Hay; Amor, Joanna Foote; Animals at Wedding Feast Vivian Lu (Rhinoceros), Anastasia Glazova (Monkey), Eimear Monaghan; (Rabbit), Joanna Foote (Snake); Mourners at Funeral Isabella Van Braeckel, Laureline Garcia, Jess Milton, Krishna Menon, Marlene Binder, Chuck Blue Lowry; Priest at Funeral, Robin Soutar; Charon, Minshin Yano; 3 Moirai (Furies) Isabella Van Braeckel (Atropos), Joanna Foote (Lachesis), Eimear Monaghan (Clotho); Blessed Spirits Joanna Foote (sung), Maddy Rita Faye, Lucia Riley; Director, Mark Tinkler; Music Director, Philip Voldman; Lighting Design. Alex Hopkins, Fridthjofur Thorsteinsson; Set Design, Maddy Rita Faye, Denisa Dumitrescu, Vivian Lu, Anastasia Glazova, Lucia Riley, Isabella Van Braeckel, Eimear Monaghan, Mathias Krajewski, Robin Soutar; Costume Design. Robin Soutar (Orpheus), Denisa Dumitrescu (Eurydice), Anastasia Glazova, (Amor), Mathias Krajewski (Amor Sc6, Olympian Gods), Maddy Rita Faye (‘Animals’ at Wedding Feast), Denisa Dumitrescu (Mourners and Priest at Funeral), Lucia Riley (Charon & 3 Moirai), Isabella Van Braeckel, Eimear Monaghan (Blessed Spirits and Eurydice puppet); Violin, Sivan Traub; Stage Manager, Heather Young; Lighting Assistant, Aubrey Tait. Platform Theatre, Central St Martin’s, London, Tuesday, 21st January, 2014

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Orpheus_SpencerStanhope.gif image_description=Orpheus and Eurydice on the Banks of the Styx (1878) by John Roddam Spencer Stanhope product=yes product_title=Gluck: Orpheus and Eurydice product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Orpheus and Eurydice on the Banks of the Styx (1878) by John Roddam Spencer StanhopeGerald Finley: Winterreise

The youthfulness of the protagonist may be best evoked by the high plangent quality of the tenor voice; moreover, Schubert was himself a tenor and it was in this register that the songs were first performed by the composer in an intimate salon before an audience of his closest friends. His choice of keys might also suggest that it was the tenorial range and timbre that he had in mind.

However, shortly before he died, Schubert’s close friend, the Austrian baritone Johann Michael Vogl, who was then in his fifties, performed the cycle for the composer. The expressive variety and range of the baritone voice can offer fresh insights and communicate powerfully; it is now as common for Winterreise to be performed by baritones, and on this occasion Canadian bass-baritone Gerald Finley added his name to the list of those seeking to make this cycle his own.

Accompanied by pianist Julius Drake, Finley’s reading is one which combines poise and eloquence with bleakness and resignation. Solemn, restrained and dignified, there are none of the flourishes and angst-ridden gestures which have sometimes charged other interpretations; but, the protagonist’s suffering is never in doubt — indeed, the darkness of the register adding to the air of solemn woe.

The performers took a little time to settle into the dramatic and emotional setting of Wilhelm Müller’s poem. The clarity which marked Drake’s gentle introductory chords and ornaments in ‘Gute Nachte’ (Good night) was characteristic of the way the accompaniment gestures were meticulously ‘picked out’ throughout the cycle, expressive details and embellishments enriching the narrative. But, despite the contrasts between Finley’s veiled pianissimo suggesting the delicately shifting moonlight shadows which keep the traveller company and the angry explosion of frustration at the start of the third stanza, the song felt a little ‘four-square’, the piano’s onward tread relentless, the only rhythmic rubato the slight pause before the change to the major mode for the last stanza. Similarly, while Finley’s articulation of the German was exemplary, in these opening songs at times the texts were almost a little too clearly enunciated, lacking a conversational ease and naturalness.

‘Die Wetterfahne’ (The weather-vane) had more assertive energy, climaxing in the angry repetitions ‘Was fragen sie nach meinen Schmerzen?’ (What is my torment to them?) and the accumulating haste of the final line. After this outburst, the piano’s dry staccato crotchets at the start of ‘Gefrorne Tränen’ (Frozen Tears) were disturbingly cool, the sparse texture and low register adding to the sense a heart chilled and numb. Finley’s impassioned timbre in the final stanza hinted at the fierce heat encased within the outer shell, but the piano’s parched closing motifs suggested both tentative steps upon the ice without and the heart’s struggle to escape the numbness.

This battle with deadening dejection continued in ‘Erstarrung’ (Numbness), where Drake’s agitated, turbulent accompaniment contrasted with the intense focus of the vocal line: the repeated line ‘Mit meinen heißen Tränen’(with my hot tears) was particularly unsettling.

By the time we reached ‘Der Lindenbaum’ (The linden tree), pianist and singer were into their stride. The rhetoric of the piano introduction established a narrative air, and Finley’s beautiful melodic lines and excellent diction made for exquisite story-telling. At times during the recital I found the pace a little too slow, overly grave and ponderous; but here the forward momentum and occasionally foreboding tone created a sense of driving inevitability. The nuances at the opening of ‘Wasserflut’ (Waterfall) — the slight delays in Drake’s introduction, the melancholy of the falling octaves which end the vocal lines and point the rhymes, and the deflections and shifts in the harmony — were wonderfully expressive. Finley skilfully controlled his vocal power to convey concentrated yearning and anguish.

In ‘Auf dem Flusse’ the juxtaposition of the Finley’s dark low voice and the distinctly articulated repeated quavers and triplets of Drake’s accompaniment created a thrilling tension which erupted in the final stanza, the baritonal forceful resonance revealing the protagonist’s inner schisms: ‘Mein Herz, in diesem Bache/ Erkennst du nun dein Bild?’ (My heart, do you now see your own likeness in this stream?) The volatile surges of ‘Rückblick’ and the violent pounding in the bass developed this mood of conflict and confrontation. Here, Finley found great variety of colour, the voice unfailingly mellifluous and the final line infused with sweet wistfulness.

After a short pause, the magical lightness of Finley’s higher register and the mischievous rubatos and accelerations in Drake’s accompaniment were as enchanting as the will-o’-the-wisp of which Finley sang. As in so many of the songs, the performers demonstrated an intelligent grasp not just of the overall structure of the cycle, but also of the miniature architecture of each individual song. Here, the repetition of the final line reinforced the protagonist’s despondancy: ‘Jedes Leiden auch sein Grab’ (every sorrow will find its grave).

The unaffected ease of ‘Fruhlingstraum’ (Dream of spring) brought freshness, and suggested genuinely happier times. The singer’s gifts as a communicator came to the fore: first we had the startling drama of the crowing cock which awakens the dreamer, the piano’s stridency depicting the shriek of the ravens; then the trance-like reticence of the dreamy reflections of the half-awake protagonist as he gazes at the patterns on the window panes and slips into reverie. ‘Einsamkeit’ reached expressive heights, the repetitions of the final line laden with pain. Drake set a crisp pace in ‘Die Post’ (The mail-coach); the subtle pause before the shift to the minor key was wonderful.

A slow tempo was adopted for ‘Der greise Kopf’ (The hoary head). This, together with the eloquence of the falling melodic phrases and dry accompaniment chords, established an aptly despairing mood — a real sense of inner despair and horror; but, I did feel that some of the tempi in the cycle’s closing songs were a little on the ponderous side, and the long pause that Finley, understandably, took before ‘Im Dorfe’ (In the village), regrettably halted the dramatic and emotional impetus. ‘Die Krähe’ (The crow) was more abandoned and the piano’s fragmented opening in ‘Letze Hoffnung’ (Last hope) was fittingly unsettling. This approach — the accompaniment ‘niggling’ at the singer in an understated but disquieting manner — continued in ‘Im Dorfe’, the trilling motifs indicating the cruel disillusionment that the slumbers will experience when daylight returns and reality inevitably quashes their dreams. Similarly, Drake’s skipping compound rhythms in ‘Täuschung’ (Delusion) seemed to mock the singer as he followed the dancing, ‘friendly’ light.

The bass line of the piano introduction to ‘Der Wegweiser’ (The signpost) possessed a gentle mournfulness which was extended by the quiet modulation to the major mode in the second stanza, the tender beauty of Finley’s pianissimo, the deadening evenness of the monotone repetitions of the last line — ‘Die nock Keiner ging zurück’ (from which no man has ever returned) — and by the wearying rallentando of the piano’s closing cadence.

‘Das Wirthaus’ was similarly drained of forward propulsion, although the rising intensity and focus of the close anticipated the impetuousness of ‘Mut!’ (Courage!). I thought the decision to run straight on into ‘Die Nebensonnen’ (Phantom suns) was a misjudgement. It is just at that point in the cycle where the re-ordering of Müller’s original sequence has such a striking effect: the optimism of ‘Mut!’ at this point of the cycle is almost a bizarre parody, even surreal, and, following this breathless impulsiveness, the shock of the return to the dark resonances of ‘Die Nebelsonnen’ is enhanced by a moment of dazed silence, however brief.

The last song, ‘Die Leiermann’ (The organ-grinder) was a superb study in weariness and dejection, but ultimately not in hopelessness, the final lines pressing forward, the wayfarer not yet defeated.

Finley did not so much embody the protagonist, experiencing and depicting his suffering in the present; rather, he seemed an elder man re-living a journey made in the impetuousness of youth. There was a sense of wearily and painfully returning to past experiences; experiences which have been revisited in memory many times before, so that the twists and turns of the emotional journey are etched in the singer’s conscience and body, unavoidable, inerasable.

Claire Seymour

Gerald Finley and Julius Drake will release a new recording of Winterreise (Hyperion) in March 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Finley_67.gif image_description=Gerald Finley [Photo by Sim Canetty-Clarke] product=yes product_title=Gerald Finley: Winterreise product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Gerald Finley [Photo by Sim Canetty-Clarke]Jules Massenet: Manon, ROH

Like Carmen before her, Manon leads men to steal, cheat and murder; but in Massenet’s opéra comique, the sweet sensuous of the score, and in particular the affecting beauty of the ‘innocent’ heroine’s music, might convince us that the worst thing she is ‘guilty’ of is a slight flightiness.

Laurent Pelly’s 2010 production, receiving its first revival here (revival director, Christian Räth), was designed with a particular Manon in mind - star diva Anna Netrebko, whose performances were lauded for their passionate fervour and luscious tone, and for the sparkling ‘chemistry’ between Netrebko’s Manon and her Des Grieux, Vittorio Grigolo. Ermonela Jaho, who made such a stirring debut at Covent Garden in 2008, as Violetta (again, stepping into Netrebko’s shoes, when the latter was indisposed), took a little time to warm up; in the opening act, her characterisation seemed to me rather unsubstantial, as she flitted about the central, open expanse of Chantal Thomas’s Amiens square, swirling and dancing light-heartedly. She certainly did not look as if she was unduly threatened or cowered by the looming walls of the convent to which her family have sent her - because she is too fond of a good time.

Jaho’s tone is attractive but, initially at least, was not sufficiently full of bloom to communicate engagingly with the audience, and the lower range lacked weight and focus; moreover, an overly broad vibrato and some rather indistinct French led to a sense of nebulousness. She brought greater variety of colour and more commitment to subsequent acts; ‘Adieu, notre petite table’ was a touching farewell to the humble, honest home life she has shared with Des Grieux; and Jaho sparkled disarmingly in Act 3, the high roulades of ‘Je marche sur tous les chemins’ and ‘Obéissons quand leur voix appelle’ secure and conveying her frivolous delight and youthful superficiality.

American tenor Matthew Polenzani was a physically striking and vocally compelling Chevalier des Grieux. His powerful lyric tenor was soulful and touching; the ravishing whispered high pianissimos of his Act 2 aria, ‘En fermant les yeux’, suggested the fragility of his dreams for their future happiness. ‘Ah! Fuyez, douce image’, as the Abbé relives his memories with Manon, expressed both integrity and vulnerability; it was the highlight of the night. Polenzani has an exemplary grasp of the French idiom; the smooth legato, the sinuousness phrasing, and the sheer beauty of sound combined to create a dramatically convincing and musically enthralling performance. He deserved his considerable approbation.

Audun Iversen’s Lescaut was fittingly rumbustious, swaggering arrogantly and singing with vigour and vitality. As Guillot de Morfontaine, French tenor Christophe Mortagne was superb, reprising the role in which he made his ROH debut in 2010: by turns deluded roué and bitter fool, his strong acting was complemented by characterful singing. Alastair Miles and William Shimell offered strong support as the aging Count des Grieux and the self-important De Brétigny respectively.

Matthew Polenzani as Chevalier Des Grieux and Audun Iversen as Lescaut

Matthew Polenzani as Chevalier Des Grieux and Audun Iversen as Lescaut

Simona Mihai recreated her 2010 role as Pousette and was joined by two Jette Parker Young Artists, Rachel Kelly (Javotte) and Nadezhda Karyazina (Rosette). The perky trio sang crisply and brightly, their stage movements neatly executed and well-timed.

Pelly’s production is all about shifting perspectives and angles. Although the action has consciously been shifted from the France of Louis XV to La Belle Époque, in fact it tends towards abstraction, specificity of costume and period being less important than the inferences of the design. In Act 1 a steep staircase rises precipitously to the town houses perched precariously atop the convent walls (the stonework has all the solidity and appeal of a self-assembly furniture kit from MUJI); the stairway swings through 180⁰ for Act 2, forming a rickety gang-plank to the lovers’ garret apartment. The purple-grey Paris skyline shimmers charmingly in the hinterland, but the zig-zagging incline of the staircase embodies the obstacles in their path to future happiness.

Two crooked raked passageways, bordered by ugly metal railings, straddle the breadth of La Cours-la-Reine; the restriction on free movement that this imposes makes for a few choreographic challenges - the scene is really just an excuse for the opéra-comique’s obligatory ballet divertissement - but these are surmounted through some complex manoeuvring of personnel. There are some visual mishaps though. What is the point of the hazy ferris wheel flickering in the distance? And, what is the large round orange object centre-backdrop? Similarly, in scene 2 the dull green monochrome of the gaming room of the Hôtel de Transylvanie evokes severe asceticism rather than rakish hedonism.

In Act 4, the pillars in the vestry of the seminary at Saint-Sulpice list alarming askew, mirrored by Des Grieux’s austere iron-framed bed in the smaller chamber seen to the left; indicative of the way Abbé des Grieux’s faith is about to lurch out of kilter. Having behaved shockingly and with impunity throughout the opera, insouciantly offending bourgeois sensibilities and mores, in the final act Manon’s sins come home to roost and our heroine expires on road to Le Havre; Thomas’s angles have now sharpened to an infinity point, a row of street lights leading the eye to the horizon, the bleakness of the landscape (effectively lit by Joël Adam) inferring the desolate future.

Matthew Polenzani as Chevalier Des Grieux and Ermonela Jaho as Manon Lescaut

Matthew Polenzani as Chevalier Des Grieux and Ermonela Jaho as Manon Lescaut

The chorus were on good form. The choreography (Lionel Hoche) is at times quite complex, requiring precision and nimbleness, and the large crowd scenes were slick. In the Hôtel de Transylvanie the bareness of the set, while unappealing to the eye, did at least allow for some complicated drills. Dressed in a shocking pink, sleeveless gown (a jarring clash with the deadening green walls), Manon presents a show routine reminiscent of Madonna’s video for Material Girl (itself a wry take-off of Marilyn Monroe’s Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend) -an allusion which was presumably intended to highlight the topicality of a tale which tells of a young woman’s desire for wealth and material comfort at the expense of love and relationships.

It’s a long show, at four hours, and at times I felt that conductor Emmanuel Villaume might have moved things along more swiftly. But the ROH Orchestra played with conviction and idiomatic style, the searing act climaxes giving depth and credibility to the emotions depicted on stage.

Overall, Pelly and Thomas tell the story clearly but they don’t quite fully engage our sympathy for the protagonists; the production needs a bit of a pick-me-up - perhaps things will swing along with more passion and pace as the run proceeds.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Manon Lescaut, Ermonela Jaho; Lescaut, Audun Iversen; Chevalier des Grieux, Matthew Polenzani; Le Comte des Grieux, Alastair Miles; Guillot de Morfontaine, Christophe Mortagne; De Brétigny, William Shimell; Poussette, Simona Mihai; Javotte, Rachel Kelly; Rosette, Nadezhda Karyazina; Innkeeper, Lynton Black; Guard 1, Elliot Goldie; Guard 2, Donaldson Bell; Director, Laurent Pelly. Conductor, Emmanuel Villaume; Dramaturg, Agathe Mélinand; Set designs, Chantal Thomas; Costume designs, Laurent Pelly and Jean-Jacques Delmotte; Lighting design, Joël Adam; Choreography, Lionel Hoche; Royal Opera Chorus; Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Tuesday 14th January, 2014.

This is a co-production with The Metropolitan Opera, New York, La Scala, Milan, and Théâtre du Capitole, Toulouse. The run continues until 4 February. Mexican soprano Ailyn Pérez will sing Manon on 31 January and 4 February.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/MANON_RO_873A.gif image_description=Ermonela Jaho as Manon Lescaut [Photo by ROH/Bill Cooper] product=yes product_title=Jules Massenet Manon, Royal Opera House, London product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Ermonela Jaho as Manon LescautPhotos by ROH/Bill Cooper

Songlives: Johannes Brahms

Taking us along these autobiographical paths were bass-baritone Hanno Müller-Brachmann and, standing in for the indisposed Bernada Fink, soprano Ann Murray. Both singers adopted a wonderfully sincere and direct approach: nothing was exaggerated or overstated but the vocal lines were allowed to blossom in response to heightened emotion or drama in an unaffected but thoughtful and well-considered fashion.

Müller-Brachmann commenced ‘The early years’ with the unusually brief ‘Heimkehr’ (Homecoming). Described by Susan Youens in her detailed programme notes as ’21 bars of agitated, rapturous emotion’, the song presents an impetuous lover’s appeal to the natural world not to come to an apocalyptic end until he has hastened to his beloved’s side! Despite its brevity, the song enabled Müller-Brachmann to exhibit the admirable qualities which would be on display throughout the evening: a powerful intensity matched by an eloquent and controlled delivery, the text crystal clear, the dramatic and emotional focus encapsulated without undue exaggeration. ‘Die Überläufer’ (The deserter) revealed the bass-baritone’s full, burnished lower register, complementing the darkly erotic imagery of the anonymous text; as the poet-narrator expresses wonder ‘Daß mein Schatz so falsch könnt’ sein’ (that my darling could be so false) a delicate enhancement of ‘so falsch könnt’ neatly conveyed the protagonist’s anguish.

In this part of the programme, Murray and Müller-Brachmann alternated, Murray’s renditions of ‘In der Fremde’ (In a foreign land) and ‘Liebestreu’ (True love) interwoven between the bass-baritone’s numbers. In the former, Murray displayed a serene composure and sweet pianissimo to evoke the wistfulness of Eichendorff’s text; the glowing lustre of the voice may be more restrained than of former years, but there is no doubting the expressive beauty of the soprano’s innately well-crafted melodic lines. At the piano, Martineau contributed enormously to the communicative power of these songs: in ‘Liebstrau’, as so often throughout the evening, the engaging interplay between voice and accompaniment, and the particularly impressive clarity of the left hand figures and counter-melodies, was notable.

‘New Paths’ was the title of an article published by Robert Schumann in October 1853 in which he expressed his admiration for the music of the then 20-year-old Brahms. Müller-Brachmann’s ‘Ständchen’ (Serenade) combined a gentle vocal restraint with tight rhythms in the accompaniment and very effective use of rubato, especially in the piano postlude, creating both lightness of spirit and depth of feeling. The forward momentum quickened in ‘Der Ganz zum Lieben’ (The walk to the beloved), the lilting motifs sweeping onwards as the lover hurried towards his loved one’s home, before another could steal her love. In contrast, the initial focused tranquillity of Murray’s ‘An eine Äolsharfe’ gave way to moments of dramatic intensity, the recitative-like vocal melody of the opening expanding lyrically above a bed of rich major harmonies. The performers’ appreciation of the spacious structure of this song, the first of Brahms’ truly ambitious songs, was impressive.