February 24, 2014

Turandot, Royal Opera

The field may be fiercely contested, and I should hesitate to award first place to any one contender, but is there a more brazenly offensive opera to modern sensibilities than Turandot? Its racism and misogyny are far from unique, though they are experienced here in a form so extreme that even the dullest of listeners could hardly fail to notice them. The particular offensiveness goes far beyond that, however. Michael Tanner, writing in The Spectator upon this production’s previous outing of the season, went so far as to describe it as ‘an irredeemable work, a terrible end to a career that had included three indisputable masterpieces and three less evident ones, counting Il Trittico as one.’ The real problem is the plot itself. Again to quote Tanner, only summarizing what happens yet in reality twisting the knife by having the plot speak for itself, ‘once Liù has killed herself because she can’t stand any more pain, Calaf forgets about her, and about his frail old father Timur who just disappears, and turns all his attention on Turandot.’ It is repellent, and it is well-nigh impossible to imagine someone possessed of a smidgeon of humanity feeling otherwise.

And yet, its repellent quality fascinates, on account of Puccini’s manipulative genius. There is nothing beneath the surface, but what a surface! What Tanner rightly condemns as a ‘void’ draws one in to its nothingness and achieves if not nihilistic intent then certainly representation and experience of the work’s nihilistic essence. It is not entirely different from much Strauss in that respect, though the sadism is Puccini’s own: how he revels once again in the torture as much as the vile sacrifice itself! A ‘successful’ performance is therefore a problematical concept indeed. Should the work simply be portrayed for what it is? Or should it be confronted, questioned, in some sense ‘dealt with’?

Alfred Kim as Calaf, Matthew Rose as Timur and Ailyn Perez as Liù

Alfred Kim as Calaf, Matthew Rose as Timur and Ailyn Perez as Liù

The Royal Opera opted for the former, at least in terms of the umpteenth revival of Andrei Serban’s production, first seen in 1984. Andrew Sinclair’s revival direction seemed tighter than it had in September of last year, though I think that may have been in large part a matter of greater musical — in particular, orchestral — dynamism, sharpening the cruel edges of the work. Yes, there is something of an effort — which again, came across more strongly than last time around — to present the performance with the idea of ‘staging’ to the forefront. It comes perilously close to being lost, however, by the exuberant success of the execution, not least Kate Flatt’s choreography. ‘About staging’ turns into ‘mere staging’. Likewise the Orientalism of Sally Jacobs’s designs. Surely by 2014, we need to inject a measure of irony, or indeed violence. I had a nasty feeling that many of those in the audience wildly applauding had not so much as registered the attendant problems: an urgent need for any responsible new production.

The orchestra was on magnificent form throughout. Nicola Luisotti not only revelled in the score’s phantasmagorical harmonies and sonorities but also imparted a startling symphonic continuity not only to each act but to the work as a whole. Puccini’s surface and that void beneath could hardly have been more brilliantly — in more than one sense — evoked. This Puccini, quite rightly, sounded more than ever a brother of Strauss, not least in his twin descent from Wagner’s invention and disavowal of Wagner’s moral intent. Such made the echoes and/or presentiments of Schoenberg — not only the avant-gardism of Pierrot lunaire, but also the wondrous late Romanticism of Gurrelieder — sound all the more painful, given the strenuous moralism of the Austrian composer, as fervent an admirer of Puccini as Puccini was of him. Luisotti had done for the most part a decent job with Don Giovanni, but he was clearly more in his element here. If only the staging had questioned the work as the fine musical performance necessarily did.

David Butt Philip as Pang, Grant Doyle as Ping and Luis Gomes as Pong

David Butt Philip as Pang, Grant Doyle as Ping and Luis Gomes as Pong

Iréne Theorin did what she had to do in the truly repugnant title role. Steel and sheer vocal strength were allied to a subtler-than-usual command of dynamic contrast. Alfred Kim might have offered more in terms of subtlety, especially during that aria, which sounded too much like an aria, however much responsibility Puccini must also bear for that. But otherwise, his was a formidable, untiring performance. Liù once again fared very well in indeed in terms of casting, Ailyn Pérez offering a moving portrayal — again, may Puccini’s manipulations be cursed! — in which musical and dramatic imperatives were as one. There are greater opportunities for vocal shading, and of course for sympathy, than with the Princess; Perez undoubtedly took them all. Matthew Rose made for a noble Timur, whilst the unbearably irritating trio of Ping, Pong, and Pang received uncommonly excellent performances, again as laudable in stage as in musical terms, from Grant Doyle, David Butt Philip, and Luis Gomes. Renato Balsadonna’s chorus and extra chorus showed themselves the orchestra’s equals in excellence.

Wagner feared that excellent performances of Tristan would be his ruin; audiences would not be able to take them. In a very different sense, one might say the same of this ‘irredeemable’ work; at least unless a director has the courage more directly to confront its horrors.

Mark Berry

Cast and production information:

Mandarin: Ashley Riches; Liù: Ailyn Pérez; Timur: Matthew Rose; Calaf: Alfred Kim; Ping: Grant Doyle; Pang: David Butt Philip; Pong: Luis Gomes; Turandot: Iréne Theorin; Emperor Altoum: Alasdair Elliott; Soprano soli — Marianne Cotterill, Anne Osborne. Director: Andrei Serban; Andrew Sinclair (revival director); Sally Jacobs (designs); F. Mitchell Dana (lighting); Kate Flatt (choreography); Tatiana Novaes Coelho (choreologist). Royal Opera Chorus and Extra Chorus (chorus master: Renato Balsadonna)/Orchestra of the Royal Opera House/Nicola Luisotti (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Thursday 20 February 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Turandot-14-02-14-ROH-1776.gif image_description=Irene Theorin as Turnadot [Photo © ROH / Tristram Kenton] product=yes product_title=Turandot, Royal Opera product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Irene Theorin as TurnadotPhotos © ROH / Tristram Kenton

Carmen in Bilbao

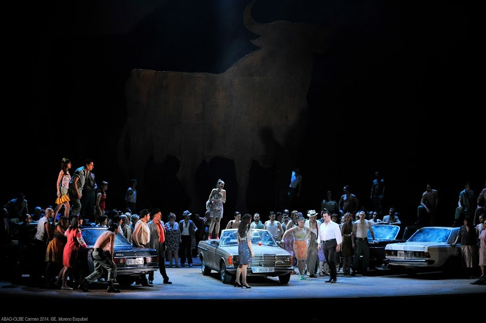

The Calixto Bieito Carmen is old news, this edition having already taken place in Barcelona, Venice and Torino, though a Bieito Carmen has been around on advanced European operatic stages since 1999. It was never headline news, finding instead this extraordinary stage director in a rather subdued state. Yes, there was fellatio, pissing, nudity, gang rape, child abuse and true brutality. Yes, Mercedes was Lilas Pastia’s middle-aged wife, and yes, Don Jose was really annoyed by an insistent Micaëla who sang her pretty song and then gave Carmen the “up-yours.”

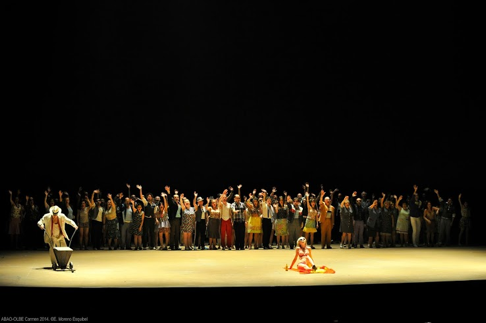

Bieito creates a world that puts you on edge, here it was Spain with the cut-out bulls on the hilltops, gypsies in dilapidated cars, freaked out youth, blinding beaches and lurid tourism, and of course bull rings. But finally Bieito’s bull ring was only a chalk-line circle laid down by Lilas Pastia in which the raw power of Carmen’s indifference was pitted against the impotent supplications of Jose. Murdered, Jose dragged Carmen out of the circle — like a dead bull.

Movement is violent and often sudden in this and all Bieito worlds. There were very limited moments of dialogue but many additions of crowd noise and shouts, and punctuations of imposed silence broken by frenetic crowd clamor. The quintet was splendidly staged catching the lightening speed of the music in fast, demonstrative movement, and the trio was deadpan, the cards read on the hood of a car with no sense of doom, Carmen indifferent to her fate.

Act III. Escamillo in white shirt. Photo by E. Moreno Esquibel

Act III. Escamillo in white shirt. Photo by E. Moreno Esquibel

There was no set. A simple cyclorama against which there was first a flag pole and a phone booth, then a car and a Christmas tree, then eight cars and a gigantic cut out bull and finally nothing except a beach with a marked out chalk ring.

All this might seem a recipe for a dynamite Carmen, but this does not seem to be Bieito’s intention. This tale of Jose’s infatuation disappeared into this cosmos of marginal life in Spain and became unimportant, its emotions melted into the morass of a much bigger and equally violent, emotionally raw world.

With some setbacks along the way Bilbao's Amigos de la Ópera managed a cast responsive to the needs of both Bizet and Bieito. The Carmen announced in the publicity was Sonia Ganassi who withdrew because of illness, young Italian mezzo Giuseppina Piunti came to replace her. However she could not do this second performance (of five) thus this performance fell to the cover Carmen. Ana Ibarra is a young Spanish artist, not a Carmen by nature or physique but a very fine singer, and with obviously limited rehearsal attention she still gave a quite credible performance, greatly appreciated by the audience.

Lilas Pastia marking bull ring circle and sunbather. Photo by E. Moreno Esquibel

Lilas Pastia marking bull ring circle and sunbather. Photo by E. Moreno Esquibel

Venezuelan tenor Aquiles Machado is in his vocal prime, and gave a beautifully sung performance. His Flower Song was the hit of the evening, the high notes squarely placed and exciting. Mr. Machado projects an affecting presence, and could perhaps be a moving Jose in a heated or even warmer production. Quick on his feet he was able to have a real looking knife fight with Escamillo, leaping from roof to roof of a line of cars. He was equaled in agility by seasoned Spanish baritone Carlos Alvaro! This esteemed singer brought a sharp Italianate edge to the role, making Escamillo a powerful and dangerous presence with real bullfighter voiced coglioni if not with physique or stance.

Micaëla was sung by Valencia born soprano Maite Alberola who brought a brightness of voice that has made her a fine traviata though she did not move with a natural agility in the wonderfully tacky clothing that was her costume. With the resources of a traviata voice (a brilliant top and a warm middle voice) she found unusual and very welcome vocal excitement in her aria.

French maestro Jean Yves Ossonce provided a generally idiomatic reading, giving the principals solid understanding for their arias — a faster than usual “Je dis,” a louder than usual "La fleur que tu m'avais jetée," as examples. The quintet was masterfully held together and the big chorus scenes were unleashed with sonic abandon — the Euskadiko Orkestra Sinfonikoa gave it their all.

The support roles — Frasquita, Mercedes, Remendado, Dancairo, Zuniga and Morales — were of proper age, voice, and experience (i.e. gratefully not pieced together from a young artist program). The Mercedes of Basque mezzo Itxaro Mentxaka was especially interesting as the middle aged wife of Lilas Pastia, the Zuniga of Italian Federico Sacchi stood out as a real sleaze, his brutally murdered body an unforgettable image.

Bilbao is about architecture, as you know. There is an old (nineteenth century), imposing opera house said to be an imitation of Paris’ Garnier that is no longer used. The Asociación Bilbaina de Amigos de la Ópera now produces its operas in the theater of the Palacio Euskalduna, Bilbao’s conference center that opened in 1999. Designed by architects Federico Soriano and Dolores Palacios it is supposed to be like a vessel permanently under construction (it stands on a dock of the former Euskalduna Shipyard). It received the 2001 Enric Miralles award at the 6th Biennial of Spanish Architecture.

However striking the architecture may be, and the public areas are of interest if a bit hard to navigate, the hall itself reveals the lack of interest architects in general seem to have for opera. If these two architects had ever been to an opera they would know that an auditorium is a dark place to sit while you observe a performance, that no prime seating space should be sacrificed to some questionable geometric design whims, that every seat should be as close as possible to the stage (the upper reaches of this theater are unbelievably remote), and finally, actually first of all, that the sound in the hall is of utmost importance (the cavernous depths of this theater create a hollow “cavernous” sound).

Ignoring these completely obvious requirements for the auditorium one can only imagine the ignorance these architects will have exercised in designing the stage (here too wide), wings and dressing rooms. Is there no prize for bad theater architecture. There is a stupendous amount of it worldwide that could compete for being the absolute stupidest.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Carmen: Ana Ibarra; Don José: Aquiles Machado; Escamillo: Carlos Álvarez; Micaëla: Maite Alberola; Mercedes: Itxaro Mentxaka; Frasquita: Elena Sancho Pereg; Le Remendado: Vicenç Esteve; Le Dancaïre: Damián del Castillo; Zuniga: Federico Sacchi; Moralès: Giovanni Guagliardo; Lilas Pastia (actor): Abdelazir El Mountassir. Euskadiko Orkestra Sinfonikoa, Coro de Opera de Bilbao. Conductor: Jean Yves Ossonce; Mise en scène: Calixto Bieito; Scenery: Alfons Flores; Costumes: Mercé Paloma; Lighting: Alberto Rodriguez. Palacio Euskalduna, Bilbao, February 18, 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Carmen_BilbaoOT1.png

image_description=Carmen Act I

product=yes

product_title=Carmen in Bilbao

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Carmen in Act I [Photo by E. Moreno Esquibel]

La Favorite in Toulouse

The news though is actually Chinese tenor Yijie Shi who assumed the beautiful young woman who had knelt next to him at the famous shrine Santiago de Campostela was pure. She was not.

Never mind that Donizetti’s la favorite was not French. Named Léonor di Guzman she was in historical fact the mistress of no less than Alfonso XI, the king of Castille who is famous for driving the Moors out of Andalusia in the mid fourteenth century. History is often reinvented in opera plots to make passions more real than facts, thus according to Donizetti’s librettists it was the lovesick novice monk Fernand, (tenor Shi) who actually led the Spanish armies to these important victories under Alfonso’s flag.

All Fernand wanted in return was the hand of the beautiful and pure woman he had prayed with. Alfonso however was a cunning thinker who did not want to give up his mistress, not to mention that his courtiers detested the upstart Fernand as well. Add to this mess a meddlesome priest of proto-inquisitor zeal and you can see that there was a lot to sing about.

Donizetti’s French masterpiece was in the hands of Italian conductor Antonello Allemandi. This maestro, a bel canto specialist, captured the fire and intensity of the passions from the get-go, making the overture a superbly eloquent transition to a musical world based on beautiful lines and colors that elaborate distress and make it compellingly elegant. Mo. Allemandi demonstrated a full authority over the stage for the musically complex scenes, and in the arias and duets he demonstrated his confidence in the artistry of distraught singers by establishing ample tempos to support their soaring vocal lines while he concentrated on pulling every possible nuance from the pit players.

The great climaxes of the quintets and sextets with chorus achieved emotional releases that equaled those of the later Romantic masters while remaining specifically bel canto.

Shanghai born tenor Yijie Shi, a protogé of the Pesaro Rossini Festival, made a startling first impression, standing in shirtsleeves among a disciplined formation of hooded monks. He did not cut a figure that would lead soldiers into battle though he did finally become the smitten, naive and always confused young lover who basks in the pleasure of his feelings. After an extended apprenticeship in Pesaro he is now a finished performer, more at home in the bel canto repertory than in Rossini. His voice is purely Italianate, and his French was splendid. By the end of the performance it was certain that Mr. Shi now owns this role, singing it and acting it with true bel canto abandon.

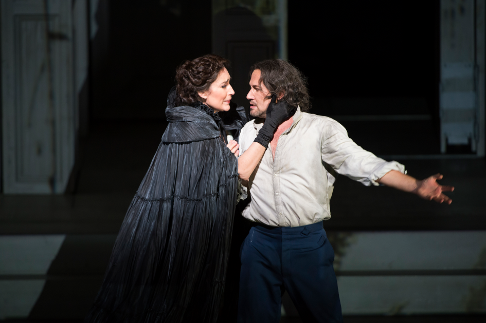

Kate Aldridge as Léonor, Yijie Shi as Fernand. Photo by Patrice Nin

Kate Aldridge as Léonor, Yijie Shi as Fernand. Photo by Patrice Nin

If the tenor has the most to sing in La Favorite, the heroine is burdened with the need to exemplify the magnetism that would pull a young monk from his vows of chastity while bemoaning her situation — as mistress to the king she cannot and never will be wife to any man. American mezzo-soprano Kate Aldridge, a seasoned bel canto artist, did not succeed, lacking at this point in her career the warmth of voice and charm of youth to bring Leonora emotionally alive. Her most effective if inappropriate vocal moments occurred when she used the chest voice that has made her a very fine Carmen.

The opera was conceived in French for the Paris Opera (not the Théâtre-Italien where Donizetti’s Italian operas were performed) as a vehicle for the mistress of the director of the opera. In the style of French grand opera the heroine is a dramatically complex role for mezzo soprano. Léonora is subdued and discretely nuanced in her only aria and in her scenes with Fernand and Alfonso. The opera is in the four act grand opera form, though the traditional ballet was missing in Toulouse.

Alfonso was sung by French baritone Lodovic Tézier. Of clear, sterling colored voice Mr. Térzier is an ideal Donizetti villain, well able to convincingly rage, manipulate and deceive without sacrificing beauty of tone and grace of execution. Italian bass Giovanni Furlanetto as the father superior Balthazar produced a rich and smooth basso cantante though he did not convey a force of personality that could make him a convincing spiritual father to Fernand or an imposing accuser to Alfonso. The role of Inès was charmingly performed by Marie-Bénédicte Souquet.

Lodovic Tézier as Alphonse XI. Photo by Patrice Nin

Lodovic Tézier as Alphonse XI. Photo by Patrice Nin

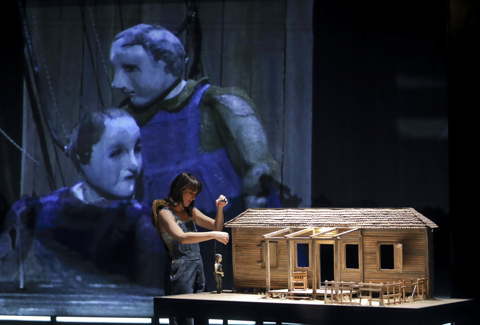

The new production, by Vincent Boussard and his designers Vincent Lemaire (scenery) and Christian Lacroix (costumes), was in minimal terms. The mists and spirituality of Santiago de Campostela were conveyed in mirrored stage walls, fogs and lights with a backdrop of abstracted soaring arches, the sumptuousness of Seville’s Alcazar was effected in emerald greens, graced by parading, lifelike peacocks on the arms of courtiers. The mirrored side walls descended opening balconies on either side from where courtiers would learn all court happenings.

Costumes were abstracted into colors rather than shapes taking us into a musical space rather than a specific historical moment. The single prop, excepting the peacocks, was an illuminated suitcase Fernand took with him into his worldly adventures and returned with to take finally his vows. Metteur en scéne Boussard is a master of staging musically rather than dramatically, moving his chorus as a structural musical force and his principals as moments of music, finding extended periods of poetry rendered in classical sculptural poses.

It was a splendid afternoon of beautifully staged bel canto transformed into great music. This production can be watched on CultureBox of France Télévision through August 15, 2014: La Favorite

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Léonor de Guzman: Kate Aldrich; Fernand: Yijie Shi; Alphonse XI: Ludovic Tézier: Balthazar: Giovanni Furlanetto; Don Gaspar: Alain Gabriel; Inès: Marie-Bénédicte Souquet; Chorus and Orchestra of the Théâtre du Capitole. Conductor: Antonello Allemandi: Mise en scène: Vincent Boussard; Scenery: Vincent Lemaire; Costumes: Christian Lacroix; Lighting: Guido Levi. Théâtre du Capitole, Toulouse, February 16, 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Favorite_ToulouseOT1.png

image_description=Giovanni Furlanetto as Balthazar, Yijie Shi as Fernand [Photo by Patrice Nin]

product=yes

product_title=La Favorite in Toulouse

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Giovanni Furlanetto as Balthazar, Yijie Shi as Fernand [Photo by Patrice Nin]

February 22, 2014

Benjamin Britten: Paul Bunyan

He went to America, I think it was ‘38, early ‘39, and I went soon after. I think it wouldn’t be too much oversimplifying the situation to say that many of us young people at the time felt that Europe was more or less finished … I went to America and felt that I would make my future there.’ (Letters from a Life, vol.1, eds. Mitchell and Reed, p.619).

Premiered in May 1941 in the Brander Matthews Hall at Columbia University, Paul Bunyan — the ‘choral operetta’ that Britten and Auden created on the quintessentially American theme of the legend of the eponymous pioneering lumberjack — might be seen as a naïve attempt to beguile: an offering intended to confirm their artistic credentials for American citizenship. But it also hinted at the challenges ahead for a nation built upon a Dream, as its people learn that they must balance individual choice with the need to tolerate ‘difference’ and protect the ‘outsider’.

Piotr Lempa (Ben Benny) and Stuart Haycock (Sam Sharkey)

Piotr Lempa (Ben Benny) and Stuart Haycock (Sam Sharkey)

It is a challenge to make something coherent of a work which offers both an uplifting parable and symbolic inferences; both light-hearted Broadway gags and more biting Thirties’ socialism. Britten’s score is an appealing medley of deft pastiches — blues quartet, country and western ballad, jazz lament, Gilbert and Sullivan comedy — each idiom following the next in quick succession, with the odd extravagant Donizettian-duet thrown into the mix; but the narrative thread is rather weak and the allegory at times ambiguous.

For this ETO production, director Liam Steel and set/costume designer Anna Fleischle opted to keep things fairly simple, housing all the action in an orthodox Loggers’ Cabin, and moving swiftly between the multifarious numbers in the manner of a slick Broadway musical. Even the Western Union Boy (tenor Matt R. J. Ward) was keen to get into the act, excitedly executing a polished table-top routine that would not have shamed Fred Astaire.

Singing the limpid, swinging motif that is one of the few uniting elements of the score, the unison chorus seemed a little slow to get going; but maybe this is the point — for the soporific way of life of the ‘Old Trees’ (represented by tall timbers of wood), before man’s arrival on earth, is overturned in this opening ensemble by the ambition and energy of the impatient ‘Young Trees’ (shorter burgeoning planks). In full voice by the end of the number, the ETO chorus was impressively resonant, foreshadowing an even more resplendent pinnacle, ‘O great day of discovery’, in Act 2.

Steel has decided to capitalise upon the fact that, while there is not much of a narrative thread, there are lots of terrific individual musical numbers in which Britten shows off his prowess as a master of pastiche and parody. The choreography was slick, particularly given the limits of the stage space; this is a genuine ‘company’ work, with the soloists coming forth from the chorus, and the ensemble numbers were the highpoint. Especially notable were the lumberjacks’ chorus in Act 1 in Act 1 — which utilised many a hackneyed Broadway gag to cheerful effect — the Quartet of Swedes, and the loggers’ hyperbolic, competitive rivalry for Tiny’s attention.

One of the challenges for a director is how to present the oversized eponymous hero who never actually appears on stage. Paul Bunyan is less a ‘character’ than an embodiment of man’s glorious spirit of conquest; but he is a static element in the drama and presents difficulties with regard to the integration of his projected, disembodied voice with the drama seen on stage. Steel had an ingenuous solution: as the tale of his birth and life was told by the collective gathering, Bunyan’s growth — from ‘six inches’, he gained ‘346 pounds every week’ and ‘grew so fast, by the time he was eight/ He was at tall as the Empire State’ — was illustrated by the ascending top hat of Uncle Sam which, bedecked with red and blue band, was lifted ever higher by successive members of the company, a metaphor for Bunyan and a personification of the emergent nation. Subsequently, the awe-struck loggers addressed their champion with gazes striving upwards, a rickety ladder adorned with a bedraggled Star-Spangled Banner pointing to a distant pinnacle of aspiration. Bunyan’s words were intoned sonorously but without sententiousness by Damian Lewis.

Company members

Company members

Tenor Mark Wilde skilfully conveyed the reflective introspection of Johnny Inkslinger, the brooding ‘book keeper’, using a tender voice and expressive nuance most sensitively. In his big Act 1 number, ‘Inkslinger’s Song’, in which the troubled outsider reflects on the irreconcilable gap between the simplicity of nature and the complexity of human culture, Wilde’s tone and projection grew in a controlled fashion as the melody expanded from recitative-like declamation to arioso outpouring. Although he was at times a little pushed at the top, Wilde created a convincingly rounded character, a man capable of complexity of feeling. Seated on a bunk, alone in the cabin, in Inkslinger’s ‘Regret’, his despair in the face of the conflict between hope and misfortune was poignant in its simplicity of articulation.

Elsewhere there was indulgent exuberance. Crooning an Italianate ‘Cooks’ duet’, bass Piotr Lempa (Ben Benny) and tenor Stuart Haycock (Sam Sharkey) were deliciously camp. They made sure that we were aware that Auden’s slick satire on vulgarity of an advertising culture which plays upon our insecurities — ‘The Best People are crazy about soups! … Beans are all the rage among the Higher Income Groups!’ — is just as apt now as in the 1930s.

The animal roles, cast for female voices, provide a welcome complement to the rugged male voices that predominate, and Abigail Kelly, as the dog Fido, and Amy J. Payne and Emma Watkinson, as the felines Moppet and Poppet, were both alluring of voice and edgy of character: when feisty Fido joined the courtesan cats in a piquant denouncement of social ills in the Act 2 ‘Litany’, their appeal ‘Save animals and men’, made an impact. As the loafer-flapping Geese, a form of life half-way between the trees and mankind, Lorna Bridge, Annabel Mountford and Hannah Sawle also sang with vocal precision and dramatic impact.

Many of these characters in this nascent nature are not only searching for their future paths but also for their inner selves. Tenor Ashley Catling revealed a thoughtfulness hidden by the logger’s brawn in Slim’s Song, as he lamented, ‘I must hunt my shadow/ And the self I lack’. Baritone Wyn Pencarreg was splendid as the bewildered foreman Hel Helson, a dull dunderhead who is bewildered by life’s turns and tribulations. Pencarreg blindly blustered in ‘The Mocking of Hel Helson’, brutally asserting ‘versions’ of his self — ‘Helson the Brave, the Fair, the Wise …’ — but also winning our sympathy.

Helsons’s violent, futile assault on Bunyan is juxtaposed with the love duet of Slim and Tiny, the latter role sung with sweet clarity and warmth by mezzo soprano Caryl Hughes. Steel placed the frolicking lovers and the felled logger on top and lower bunk respectively, surrounded by a chorus by turns mournful then scornful — a delightful comic juxtaposition.

One detail which failed to convince was the sharing of the Narrator’s ballads between Inkslinger and the company. It’s true that by allowing the members of the collective to take successive lines of the guitar-accompanied ballads, Steel allowed them to tell their own tale; but, the balladeer can lend a useful ironic distance and serve as narrative link between the essentially stand-alone numbers. And, Inkslinger himself is at one remove from the collective, a man of words and thoughts, reflecting on his actions and motives, achievements and future paths, much like Auden himself at this time; he is decidedly not one of the herd.

In the rather dry acoustic of the Linbury Studio Theatre, Britten’s economical woodwind-based orchestration provided a fitting commentary on the vocal numbers; this was especially so in Inskslinger’s numbers. The ETO orchestra was placed behind the back wall of the cabin, but the woodwind pierced through crisp and clear, although some of the string resonance was sacrificed. Conductor Philip Sunderland kept things moving along with many a well-judged tempo: the jazz-inspired ‘Quartet of the Defeated’ was aptly funereal.

There are dark undertones in this operetta, though: ‘Inkslinger’s Song’ concludes with an outpouring of the social conscience of the 1930s: ‘Oh, but where are the beautiful places/ Where what you begin you complete,/ Where the joy shine out of men’ faces,/ And all get sufficient to eat?’. For all its virtues, Steel’s rather homespun reading didn’t always capture this aspect. Indeed, Paul Bunyan’s ‘Goodnight’ which closes Act 1 (a passage which was added by Britten during revisions to the score in 1974) put me in mind of the 1970s television show The Waltons — as darkness fell and the lapping dog quietened, I half expected to hear ‘G’night John-Boy’ echoing from the loggers’ bunks!

Mark Wilde (Johnny Inkslinger)

Mark Wilde (Johnny Inkslinger)

One of the side-effects of the almost relentlessly up-beat feeling was that moments of stillness and import did not always make their full impact. One of the most powerful musico-dramatic moments comes in the opening scene when ‘the whole pattern of life is altered’ and ‘the moon turns blue’: the logger who enthusiastically slapped blue paint on the cog-wheel perched high up the cabin wall raised a wry titter, but I’m not sure that this really captured the romance of Britten’s ethereal ‘gamelan’ colours and harmonies.

Similarly, at the end, Bunyan’s final words to the emergent nation were somewhat lost, as the party-goers began clearing up the debris of the celebration. Perhaps Steel was making a subtle point: Bunyan says, ‘America is what you do/ America is I and you, /America is what you choose to make it’, but these Americans did not listen and failed to recognise their responsibilities, individual and collective. In the closing moments, Steel attempted to add some political depth to the production. If the action had already suggested that the American Dream was flawed at the start, then the future certainly did not look good for these loggers, judging by the contents of the wicker basket left by Bunyan for the loggers, like a prophesy to be resignedly accepted or actively resisted. Bent intently, and to the incredulity of the onlookers, Inkslinger withdrew first a pistol, then a lurid Guantanamo jumpsuit, followed by an overly large Bible (presaging the influence of the Christian Right?), a shabby copy of Playboy, some fast food wrappers, a lap-top, a periwig and noose. This chain of emblems of the institutions of state and finance spoke powerfully. The final image of black soprano Abigail Kelly, draped with a crumpled Stars and Stripes, was a poignant one.

Claire Seymour

English Touring Opera’s productions of King Priam, Paul Bunyan and The Magic Flute continue at the Linbury Studio Theatre until 22nd February and then tour until 31st May. See www.englishtouringopera.org.uk for further details.

Cast and production information:

Paul Bunyan, Damian Lewis; Jonny Inkslinger, Mark Wilde; Hel Helson, Wyn Pencarreg; Tiny, Caryl Hughes; Hot Biscuit Slim, Ashley Catling; Sam Sharkey/Andy Anderson, Stuart Haycock; Ben Benny, Piotr Lempa; Fido, Abigail Kelly; Moppet, Amy J Payne; Poppet/Moon, Emma Watkinson; Western Union Boy, Matt R J Ward; John Shears/Blues Singer, Adam Tunnicliffe; Cross Crosshaulson/Farmer Matthew Sprange; Blues Singer/Crony, Johnny Herford; Blues Singer/Crony, Henry Manning; Jen Jenson/Crony, Maciek O’Shea; Pete Peterson, Simon Gfeller; Goose/Wind, Hannah Sawle; Goose, Lorna Bridge; Goose/Heron, Annabel Mountford; Blues Singer/Squirrel, Helen Johnson; Beetle, Susan Moore; Young Tree/Boy, Emily-Jane Thomas; Conductor, Philip Sunderland; Director, Liam Steel; Designer, Anna Fleischle; Lighting Designer, Guy Hoare; Assistant Director, Dafydd Hall Williams. Linbury Studio Theatre, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Wednesday 19th February 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ETO_PaulBunyan_2649.gif image_description=Ashley Catling (Hot Biscuit Slim) and Caryl Hughes (Tiny). [Photo by Richard Hubert Smith courtesy English Touring Opera] product=yes product_title=Benjamin Britten: Paul Bunyan product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Ashley Catling (Hot Biscuit Slim) and Caryl Hughes (Tiny).Photos © Richard Hubert Smith courtesy English Touring Opera

February 20, 2014

Tippett’s King Priam

But Tippett’s powerfully gritty work has failed to find the place in the repertoire that it deserves, so it was welcome news that English Touring Opera were opening their Spring tour with James Conway’s new production of the opera. I attended the opening performance on 13 February 2014 at Covent Garden’s Linbury Studio Theatre. Michael Rosewell conducted a new reduced orchestration by Iain Farrington, James Conway directed with designs by Anna Fleischle. Roderick Earle sang King Priam with Laure Meloy as Hecuba, Grant Doyle as Hector, Camilla Roberts as Andromache, Nicholas Sharratt as Paris, Niamh Kelly as Helen, Charne Rochford as Achilles, Adrian Dwyer as Hermes and a cast including Andrew Slater, Clarissa Meek, Stuart Haycock, Johnny Herford, Henry Manning and Piotr Lempa.

The size of the cast, perhaps, gives a hint as to why the opera is not revived more often. Covent Garden last performed it in 1985 (when the original Sam Wanamaker production was revived and taken to the Herod Atticus Theatre in Athens). Opera North’s 1991 production was given by ENO in 1991, the last time the opera was staged in London, though we had a concert performance at the Proms in 2003.

![ETO_KingPriam_8094.gif [Photo © Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of English Touring Opera]](http://www.operatoday.com/ETO_KingPriam_8094.gif) Niamh Kelly (Helen)

Niamh Kelly (Helen)

Anna Fleischle’s set was a single unit concrete bunker-like structure which gave flexibility to the acting area by including a high level walk way at the back. The centre of the stage was taken by a small podium with a large metallic structure which double as a number of things. The playing space was highly effectively organised, but seemed to lack the space which Tippett’s opera demands. Partly this was because of the decision to put the orchestra on-stage behind the singers and hidden by a scrim. This decision was taken partly because of worries about balance problems at the Linbury Theatre (I understand for the remainder of the tour the orchestra will be in the pit), but it did give the overall production a claustrophobic feel. James Conway seems to have deliberately played this up, with the chorus often crowding onto the stage.

The decision to put the orchestra behind the singers was, I think, a fatal one. Far too often the bodies of the singers muffled the orchestra. The brass was rarely thrilling; the fanfares at the opening sounded too distant and the war music for Achilles at the end of Act two simply did not register strongly enough — it certainly wasn’t threatening and the brass was at times overwhelmed by the chorus. There is a lot of fine detail in Tippett’s score, each major character is doubled by a solo instrument and whilst these were played effectively some of the detail was blunted.

![ETO_KingPriam_0512.gif [Photo © Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of English Touring Opera]](http://www.operatoday.com/ETO_KingPriam_0512.gif) Nicholas Sharratt (Paris), Grant Doyle (Hector) and Roderick Earle (Priam)

Nicholas Sharratt (Paris), Grant Doyle (Hector) and Roderick Earle (Priam)

Conway and Fleischle seemed to take similar mis-steps with the costumes. I can understand the wish to avoid classical Greek costumes. Fleischle seems to have combined elements of Middle-Eastern dress, notably the rich fabrics with other more tribal elements. Feathers played a big part in the look of the production, with lots used in head-dresses as well as in collars and cloaks. Individual pieces were stunning, and the work which went into the head-dresses for the three goddesses (Hera, Athene and Helen) in the judgement scene were individually brilliant. But the overall effect was fussy and busy, and I particularly disliked the animal skull based crowns for Priam and Hecuba. Conway and Fleischle seemed to have explicitly reacted against the clean lines of Tippett’s score, and produced something deliberately at odds with it. Whereas Conway’s admirable productions of Handel operas are stripped down clean lines, allowing the music to speak, here he and Fleischle seemed to be doing their best to compete.

Within these confines there were some stunning performances from the singers. Whilst Conway’s production does not get the opera quite right, there was enough to enjoy and react positively when there were so many fine individual performances.

Roderick Earle gave a towering performance as Priam. Tippett’s vocal writing in the opera is mainly declamatory and I felt that Earle took time to settle, but Tippett gives the character a series of strong monologues which help to clarify things. The scene when Priam goes to beg Achilles for Hector’s body was particularly powerful. Earle gave a fine account of Priam’s final disintegration and it wasn’t his fault that the staging here seemed to be too fussy and miss the point a bit.

![ETO_KingPriam_8063.gif [Photo © Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of English Touring Opera]](http://www.operatoday.com/ETO_KingPriam_8063.gif) Left: Laure Meloy (Hecuba). Centre, foreground: Camilla Roberts (Andromache).

Left: Laure Meloy (Hecuba). Centre, foreground: Camilla Roberts (Andromache).

Laure Meloy made a strong, passionate Hecuba. The first Hecuba was the fine dramatic soprano Marie Collier and Meloy here brought a vividly passionate warmth to the role. Grant Doyle was brightly enthusiastic Hector, neatly differentiating the young man of the early scenes from the later seasoned veteran. He gave a nicely enthusiastic gung-ho feel to the role, making Hector’s bravado believable. Camilla Roberts was wonderfully tragic and passionate as his wife (the part was created by Josephine Veasey who was a fine Didon in Berlioz’s Trojan opera) In the lovely scene in act two when each of the Trojan women gets a solo moment, Roberts brought forth a stream of lyrical passion and intensity. Tippett’s writing for the three leading Trojan women is interesting as he very much eschews the high upper soprano register, no lyric coloratura here, instead creating three rich warm, believable and highly differentiated women. Something which the casting and the singers brought out admirably.

The young Paris was played by a treble, Thomas Delgado-Little, who projected the not uncomplicated lines with security and accuracy. Nicholas Sharratt brought something of this youthful enthusiasm to his portrayal of Paris as an adult, managing to overcome an unfortunate costume involving a pair of orange loon pants! Sharratt gave the feeling that Paris had never quite grown up, and sang Paris’s music with a vividness and a nice bright sense of line. His Helen was the mysterious Niamh Kelly, who brought out the full complexity of Helen’s unknowable character, making her tantalisingly mysterious.

Charne Rochford, who has given fine performances as Luigi (Il Tabarro) and Adorno (Simon Boccanegra) for ETO, was not ideal as Achilles. He brought passionate intensity and striking vibrancy of voice to Achilles songs in act two, where Tippett give just a guitar accompaniment. But what is needed here is lyric clarity and beauty of line. Robert Tear was a notable exponent of the role and it was originally sung by Richard Lewis, both tenors capable of combining power with lyric intensity and a sense of line. Rochford was on securer ground in Achilles’s more dramatic moments. He and Piotr Lempa made convincing work of Achilles and Patroclus’s short scene together, and Lempa made you regret that the role of Patroclus is so short.

![ETO_KingPriam_7891.gif [Photo © Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of English Touring Opera]](http://www.operatoday.com/ETO_KingPriam_7891.gif) Upstage: Nicholas Sharratt (Paris) and Niamh Kelly (Helen)

Upstage: Nicholas Sharratt (Paris) and Niamh Kelly (Helen)

Perhaps one of ETO’s problems was that the casting of King Priam requires three significant tenors, so it is with relief that I can report Adrian Dwyer more than entirely admirable in the high tenor part of Hermes, the divine messenger. His solo paen to the power of music in the middle of act three was a notable moment.

Andrew Slater brought his familiar vibrant dramatic intensity to the role of the Old Man. He, Clarissa Meek as the Nurse, and Adam Tunniclife as the Young Guard, made a very strong chorus as they repeatedly stepped out of their roles and discussed the action. Mediating between the ancient characters and our present day. Here Conway’s handling was pitch perfect and their scenes were some of the strongest in the opera.

The smaller roles were all well taken with Stuart Haycock, Johnny Herford and Henry Manning as Hunters as well as singing in the ensembles.

The orchestra under Michael Rosewell played admirably, and there were some lovely moments. The score is one of Tippett’s most seductive, and it is elegant in its spareness. Iain Farrington’s orchestration seemed to preserve the score’s richness and elegance, would that we could have heard it better.

This is one of those productions which will probably develop as it tours and it would certainly be worth dropping in to the Cambridge Arts Theatre in May to catch the final performances. Certainly playing the production in more open, less confined theatres than the bunker-like Linbury Theatre will be an improvement. But ETO are to be congratulated for even attempting such a feat and I urge everyone to take the opportunity to see Tippett’s operatic masterpiece.

Robert Hugill

Cast and production information:

King Priam: Roderick Earle, Hecuba: Laure Meloy, Hector:Grant Doyle, Andromache: Camilla Roberts, Paris:Nicholas Sharratt, Helen: Niamh Kelly, Achilles: Charne Rochford, Hermes: Adrian Dwyer, Old Man: Andrew Slater, Nurse: Clarissa Meek, Young Soldier: Stuart Haycock, Hunter: Johnny Herford, Hunter: Henry Manning, Hunter: Piotr Lempa.

Click here for another perspective from Mark Berry.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ETO_KingPriam_8036.gif image_description=L-R: Nicholas Sharratt (Paris), Grant Doyle (Hector), Roderick Earle (Priam), Simon Gfeller (Chorus), Johnny Herford (Chorus), Adrian Dwyer (Hermes), Charne Rochford (Achilles), Andrew Slater (Old Man). [Photo by Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of English Touring Opera] product=yes product_title=Tippett’s King Priam product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id=Above: L-R: Nicholas Sharratt (Paris), Grant Doyle (Hector), Roderick Earle (Priam), Simon Gfeller (Chorus), Johnny Herford (Chorus), Adrian Dwyer (Hermes), Charne Rochford (Achilles) and Andrew Slater (Old Man).Photos © Richard Hubert Smith courtesy of English Touring Opera

February 19, 2014

Die Fledermaus in Chicago

The production of Die Fledermaus is owned by the San Francisco Opera and received its first Chicago viewing in this series of performances starting in December and lasting until the latter part of January. The two female leads, Rosalinde von Eisenstein and her maid Adele, were sung by Juliane Banse and Daniela Fally respectively, the former making her American operatic debut and the latter her American stage debut. Tenor Michael Spyres, whose role of Alfred sings the opening number of the score, made his Chicago Lyric Opera debut in this production. Baritone Adrian Eröd likewise sang for the first time in this house as Dr. Falke, the friend of Gabriel von Eisenstein, husband of Rosalinde. Bo Skovhus reprised the role of Gabriel which he had sung here several years earlier. David Cangelosi portrayed his lawyer Dr. Blind and Andrew Shore was Frank, the prison warden. Yet a final significant role debut was the Prince Orlovsky sung by Emily Fons. The Lyric Opera Orchestra was conducted by Ward Stare.

Daniela Fally as Adele and Bo Skovhus as Eisenstein. Act 1

Daniela Fally as Adele and Bo Skovhus as Eisenstein. Act 1

During the overture a facsimile of a Fledermaus audience-program from an 1874 performance of the opera at the Theater an der Wien was projected onto a screen covering the stage. The varied and distinct melodic parts that make up the overture were held together nicely under Mr. Stare’s direction. At the start of Act One the first two characters, both distracted by personal concerns, pursue their ambitions with vocal determination until their paths invariably cross. Alfred, the former admirer of Rosalinde von Eisenstein, sings an ardently loud serenade to honor the now married woman of the house. At the same time, the chambermaid Adele has received a note from her sister Ida, member of the corps du ballet, including an invitation to “ein grand Souper” [“exclusive late-night reception”] for which Adele must secure time off. These separate aspirations from the start of the musical drama run predictably awry and contribute with delightful symmetry to the complications of not only the first but also the following two acts. Mr. Spyres’s Alfred is appropriately passionate in his vocalism, to the extent that his eager devotion leans cleverly on the edge of several pitches in rapturous expression. Because his singing continues to hinder the maid Adele’s concentration, she orders Alfred from the premises but not before Rosalinde recognizes the voice of her former suitor. The ensuing dialogue as depicted by Ms. Banse and Ms. Nally, in which Adele pleads in vain for time to visit her “arme Tante” [“poor aunt”], is well acted and reflects their social differences by means of cleverly articulated German. After Alfred returns briefly to seek a hearing from Rosalinde, the final conflict is introduced. Gabriel arrives from court with his lawyer Dr. Blind. In the trio between husband, wife, and lawyer Gabriel’s impending prison sentence is approached with mutual accusations of guilt. Each of the principal singers matched well the brisk tempos encouraged by Mr. Stare, as each participated in the physical histrionics of ejecting Dr. Blind. His place is taken almost immediately by the entrance of Dr. Falke, an old friend of Gabriel who tenders an invitation to the very souper for which Adele has attempted to secure time away. In the role of Falke Mr. Eröd is ideally cast, his lyrical line projecting effortlessly and again showing an idiomatic sense of the text both spoken and sung. He convinces Gabriel easily to accept the invitation to Orlovsky’s souper and effectively to commence his prison sentence on the following morning. After his transformation into evening clothes and into a much more cheerful mood, Gabriel departs for the souper under the pretext of beginning his imprisonment. Ms. Banse assumes an appropriate state of confusion as she grants Adele the desired free evening, bids farewell to her husband, and faces again the presence of an importunate Alfred. Mr. Spyres’s toast to love [“Trinke Liebchen, trinke schnell” (“Drink, my darling, drink quickly”)] - performed with gusto and scrupulous diction - attempts to reverse the despondent mood of Rosalinde. When Frank the warden arrives to escort Gabriel to jail, the absence of her true husband leaves Rosalinde no choice but to proclaim that her present suitor “Kann nur allein der Gatte sein” [“can be none other than my husband”]. As such, he is escorted to jail in Gabriel’s stead.

The sentiment expressed by Alfred in his recurring lyrics at the close of the first act, “Glücklich ist, wer vergisst, was doch nicht zu ändern ist” [“Happy the one who forgets what cannot in any case be changed”] seems to haunt the atmosphere of the souper in Act Two. To be sure, Orlovsky’s dictum, that every guest must engage in pleasure or be cast out from the festivity, contributes to the frenzied amusement. In this role Ms. Fons used her extensive range remarkably by combining dramatic top notes with an extended lower register in both dialogue and sung passages. After Gabriel’s amusing exchange with the Prince, he recognizes Adele wearing one of his wife’s evening gowns. In response to her employer’s confrontation Adele’s self-defense is delightfully expressed in the laughing song “Mein Herr Marquis.” In this showpiece Fally showed herself to be the equal of the challenging vocal line, as she touched on high pitches and skittered through rapid passages as skillfully as her physical gestures during dance movements taken together with the male chorus. Additional guests arrive in disguise at Orlovsky’s fête, among these the warden Frank and Rosalinde assuming the identity of a Hungarian countess who is given the privilege of “Maskenfreiheit” [“right to wear a mask”] to protect her identity. After an amusing exchange with Skovhus, in which he loses his watch in attempting to seduce her, Banse sings the Hungarian czárdás to defend the nationality of her assumed character. Banse’s forte emphases and determined expression convince the others to accept her authenticity. Equally impressive is Falke’s encouragement for all to join in friendship, “Brüderlein und Schwesterlein,” [“Brother dear and sister dear”]. Here Eröd sang with excellent legato, carefully placed rubato on the title words, and an idiomatic sense of textual emphasis. The following ballets enliven the scene of the party until Gabriel leaves in haste to proceed to the jail.

In Act Three the expected comedy of the jail scene of Die Fledermaus is indeed featured, yet the humor remained tastefully above the level of burlesque. Frank returns to assume his post as warden, while the effect of champagne hinders his full concentration. Adele’s aria, “Spiel’ ich die Unschuld vom Lande” [“If I play the naïve maid from the country”], is sung touchingly by Fally in the reprise of which the soprano added well-chosen embellishments. The progressive unmasking of characters and their admissions of assumed identity leads naturally to a balanced ending yet leaves open the likely repeat of such an evening. In this respect, Lyric Opera of Chicago has captured the atmosphere of Strauss’s Vienna with a cast of singers and actors that make it come to life.

Salvatore Calomino

Click here for audio commentary courtesy of Lyric Opera of Chicago.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Act3_DanRest1.gif image_description=Michael Spyres as Alfred, Bo Skovhus as Eisenstein and Juliane Banse as Rosalinde. Act 3. [Photo by Dan Rest] product=yes product_title=Die Fledermaus in Chicago product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino product_id=Above: Michael Spyres as Alfred, Bo Skovhus as Eisenstein and Juliane Banse as Rosalinde. Act 3Photos by Dan Rest

February 16, 2014

Rigoletto, ENO

Having taken the plunge, the ENO management have entrusted the task to director Christopher Alden. One cannot say they weren’t warned: his ‘nineteenth-century gentleman’s club’ up-date of the opera was castigated when first seen in Chicago in 2000, subsequently given a make-over and a kiss-of-life in Toronto in 2011, but no more favourably received. Perhaps Alden is right to say that we are all conservative conformists, too short-sighted and timid to appreciate the ‘edginess’ of his conception, but having witnessed the resurrection of his concept at ENO, I would prefer to conclude that Alden’s reading is illogical and inconsistent, sacrificing character to situation and equilibrium to momentarily pleasing but superficial flourishes.

Having recently placed the foppish aristocrats who populate Strauss’s Der Fledermaus on the Freudian couch, Alden seems to be taking the same approach here; Rigoletto spends an inordinate amount of time sitting on a plush chair positioned on the extreme front-right of the stage, lost in reverie, while a black-gowned, Mrs Danver-like phantom sweeps a black-veil curtain back and forth across the stage. Is Rigoletto asleep? Is what unfolds before us a recurring nightmare? Is the action a flashback, a memory? It’s not really clear; indeed, there are rather too many confusing, unanswered questions.

What is Rigoletto about? The director tells us that he has been concerned to illuminate the power of the ‘patriarchal nineteenth-century male’ whose ruthless exercise of authority results in the ‘subjugation of women’. A valid point in relation to the Duke, certainly: but surely not one which is appropriate with regard to Rigoletto, who idealises his beloved, departed wife and worships his daughter, caring more for her than for his own soul?

The jester’s grievances arise from class and ‘difference’; ridiculed and reviled he hates the Duke and the courtiers for their aristocratic hauteur, and his fellow man in general as he does not share Rigoletto’s malformation and affliction. Reflecting Rigoletto’s sense of class injustice, Alden and his designer, Michael Levine, certainly gives us a sumptuous setting, replacing the Mantuan court with a gentleman’s gaming club of Verdi’s own epoch. Gleaming wood-panelled walls, a majestic coffered ceiling, luxurious loungers, handsome oriental rugs, fragrant palms - the setting presents a fitting depiction of masculine domination, presumption, and clubby fraternity. Yet, presumably women would be absent from such a machismo domain? So, how are we to explain the presence of Giovanna, Gilda’s nurse, who is apparently acting as a pimp for the ‘genteel’ affiliates and who, insouciantly casting aside Gilda’s confidences, allows herself to be seduced by the Duke?

Moreover, how can this single room represent ‘both sides of Rigoletto’s life’ if, as Alden asserts, his tragic error is that he believes he ‘can neatly divide himself into [these] two separate compartments’? How also can it evoke the furtive domains of abduction, subterfuge and murder, which are equally important in the opera? The libretto distinguishes the various locale: opulent royal court, Rigoletto’s humble abode, Sparafucile’s scrubby inn. Alden commits a really shocking betrayal of musical form and meaning in the final Act, where Sparafucile and Maddalena lurk within the seedy bar plotting murder while Gilda and Rigoletto crouch outside in the darkness, alone, betrayed, disillusioned. This spatial division is embedded in the form of the quartet, and underscores the poignancy of the discovery of the treachery. To present all participants within a single space severely undermines the musical and dramatic potency of Verdi’s score.

In addition, we need to see Rigoletto’s private world in order to understand his humanity. Alden suggests that the jester’s sequestered domain reveals his schizophrenia, that he is ‘sweetly sentimental in his desire to keep his daughter pure and uncorrupted by the outside world’. But, surely we are meant to believe that Rigoletto’s love for his daughter is genuine rather than sentimentally self-deceptive. Physically and mentally deformed, his one redeeming quality is his filial devotion … otherwise, what is the tragedy? Moreover, Alden thrusts Gilda into the public sphere; in this production, there is no protected space where she is sheltered by fatherly concern - contradicting his observation that the women are all ‘locked safely away at home’. If that is the case, who then is the crazed banshee in white petticoat flailing and wailing amid the patriarchal associates?

More than this, the characters, dressed identically, are hard to distinguish. The men wear tuxedos; the women black. Even Rigoletto dons evening dress, and his ‘fool’s cap’ is passed among the company. Alden suggests that the opera critiques the ‘abuses of monarchy’: ‘It is a nightmare about an all-powerful and irresponsible ruler’. Too true: Hugo’s Le roi s’amuse ran into problems with the censors precisely because it seemed to portray the cynical immorality of a monarch. But, such a dismissive disregard relies on absolute power. What is there here to distinguish the Duke from his fellow club members? He brandishes a sword in ‘Questa o quella’ - a phallic flourish or a moment of Giovanni-esque defiance? Is it the Duke’s way with the women - he is according to Alden a ‘personification of unbridled libido’ - that ordains him unqualified power? And, if so, what are we to make of the fact that Sparafucile and his sister Maddalena seem to be engaged in an incestuous relationship?

Worn out by these unfathomable and irritating details, one feels strangely detached from the events playing before one’s eyes. Thank heavens, therefore, for a superb cast of soloists. As the eponymous anti-hero, Hawaiian baritone Quinn Kelsey was stunning. He brought a conversational naturalness to the jester’s outburst and intimacies, fully appreciating the psychological depth and complexity of his character - regardless of the staging, his Rigoletto was not ‘all-powerful and irresponsible’ but rather a flawed man governed by a virulent desire for vengeance and retribution, his sense of triumph tragically undermined by the desecration and loss of his only love. The jester’s long Act 2 recitativo accompagnato, in which he bitterly compares himself with the assassin, was a portrait of chastened self-awareness combined with passionate self-pity. Kelsey injected both defiance and lamentation into the conversational lines, reaching out to the audience and for the first time winning our sympathy. Elsewhere - as when the courtiers called for vengeance at the end of the first scene - Rigoletto’s long-smouldering hatred was conveyed by a well-judged roughness in the voice which suggested a fateful grievance against the world and an internalised torture.

Barry Bank carried off the Duke’s superficial gallantry with cynical ease and complacent grace. The top notes glided; the tone rang brightly. He sounded almost too good to be true; it was no wonder the unworldly Gilda was enrapt.

Peter Rose’s Sparafucile was an embodiment of dark menace. His cavernous bass suggested a man who knows he is damned but who, like an East-End gangster, adheres to a mysterious but steadfast code of honour. Rose cautiously negotiated his contract with the equally villainous jester, as if feeling through the darkness of a moral quagmire.

As Gilda, Anna Christy brought an alluring richness but not the necessary naivety to the role. The tone was appealing and the coloratura accurate and florid, richly expressive of her love for her father. But Christy lacked the tender, childlike simplicity of one who does not even know her father’s name. ‘Caro nome’, in which Gilda reflects on the name of the one who has first awoken her to love, was vocally accomplished but did not always match superlative technique with psychological expression.

Justina Gringyte (Maddalena), Diana Montague (Giovanna) and David Stout (Monterone) made strong contributions also. The male chorus remained on-stage throughout and sang virulently; but their sexual voyeurism, the lynching of Monterone, and their indulgence is outlandish sexual display when Gilda was murdered seemed oddly out-of-place in a gentleman’s club - especially when, in the latter instance, moments before they had been sedately reading the newspapers …

Overall, a major problem was that despite the tense and visceral musical fabric drawn from the orchestra by conductor Graeme Jenkins, the dramatic momentum was weak. Too often Rigoletto was to be found asleep in the chair and the scene changes were clunky. Thus, there was a noticeable hiatus between the two scenes of Act 1: we stared at gauzy black curtain while furniture was shifted noisily shifted beyond. Moreover, too often innermost conversations were presented in a dislocated manner. For example, when Gilda and Rigoletto conversed earnestly and intimately they were placed at opposing extremes of the fore-stage, facing the audience. If they cannot connect with each other, how can we emphasise with their tragedy?

In Verdi’s score, after the conventional operatic ‘last breaths’, Gilda is granted a conventional ‘resurrection’: the nineteenth-century heroine’s standard final words of forgiveness and self-condemnation. Verdi’s opera must close with Rigoletto’s wild cry of grief and despair: ‘The curse is fulfilled.’ But, Alden’s Gilda rises like an angel and floats towards a glaring light, presumably to join her mother in the afterlife. Alden declares that Rigoletto is an ‘incendiary work’; but, here he unequivocally quenches the fire. The cold brightness that illuminates Gilda’s final steps ‘blinds’ us - the black veil that has separated us from the action has smothered the flame of sympathy too.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Duke of Mantua, Barry Banks; Rigoletto, Quinn Kelsey; Gilda, Anna Christy; Sparafucile, Peter Rose; Maddalena, Justine Gringyte; Giovanna, Diana Montague; Count Monterone, David Stout; Marullo, George Humphreys; Borsa, Anthony Gregory; Count Ceprano, Barnaby Rea; Countess Ceprano, Susan Rann; Page, Joanne Appleby; Usher, Paul Sheehan; Conductor, Graeme Jenkins; Director, Christopher Alden; Designer, Michael Levine; Lighting Designer, Duane Schuler; Orchestra and Chorus of English National Opera. English National Opera, London Coliseum, Thursday 13th February 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/5051.png image_description=Anna Christy and Quinn Kelsey [Photo by Alastair Muir] product=yes product_title=Rigoletto, ENO product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Anna Christy and Quinn Kelsey [Photo © Alastair Muir]John Dowland: In Darkness

‘Semper Dowland Semper Dolens’ (Always Dowland, always sad); such was the motto of the Elizabethan lutenist, poet, diplomat — and possibly spy — John Dowland. And, certainly there was much darkness and despair as tenor Ian Bostridge, lutenist Elizabeth Kenny and the viol consort Fretwork interwove a selection of the composer’s sorrowful songs with a sequence of instrumental pavans and galliards. The prevailing mood was one of melancholy, but a melancholy of a poetic kind: not a sickness of the mind which consumes and destroys, but rather a meditative profundity inspiring creative outpouring.

‘Modern’ misery might be an oppressive, existential sadness — as Susan Sontag declared, ‘Depression is melancholy, minus its charm’ — but scholars have characterised the Renaissance as a ‘golden age’ of melancholy, when an excess of black bile was both a physical illness to be treated by the idiosyncratic methods of contemporary medics, and a conduit to the imperial majesty of the human mind. As humanists began translating ancient Greek texts, they discovered the Aristotelian notion of melancholic brilliance: the belief that those inclined to melancholy often display a genius which set them apart. Similarly, the Romantics eulogised melancholy as an essential element of the sublime and glorified the sadness that would bring insight and reveal truth.

It is this exaltation of melancholy that one finds in Dowland. The songs have a fairly limited melodic range and this, coupled with the absence of fioriture, directs the listener’s attention the poetry itself. Given this emphasis on the text, one can think of few singers more suited to interpret and convey the nuances of Dowland’s suggestive, often ambiguous lines than Ian Bostridge, a master words-smith. Yet, scale is important. Elizabethans would surely be surprised, if not shocked, by the much larger, more ambient voices of modern singers; in the past the lines would have been gently recounted, the message more important than the melody. There is a danger that undue emphasis and underscoring might distort rather than illuminate.

The simplicity of the songs must speak for itself, the harmonic and imitative details almost imperceptibly adding meaning. Although there were moments where the poet-singer persona was imbued with a more Romantic sensibility than might have been desirable, Bostridge by and large negotiated this danger, using expressive accents and textual emphasis judiciously. Moreover, the unfailingly true intonation communicated the sentiments of the texts with absolute sincerity.

Keen to maximise the unprecedented success of his First Book of Songs, printed in 1597, Dowland arranged them to be performed by whatever domestic forces might be available. The softly unrolling ‘Flow My Tears’ was accompanied by the full ensemble, Bostridge’s low register perhaps a little unfocused, insufficiently distinct against the regularity of the viol timbre. But, the tenor’s alertness to every opportunity for subtle stresses which can underline both meaning and form was immediately apparent, the two verbs — ‘Down vain lights, shine you no more’ — establishing a more insistent voice after the forlorn opening stanza. No occasion for variety was neglected: the lightness and energy of the following stanza, and the more restless movement in the viol lines, evoked agitation, to be replaced by the poignant reticence of the subsequent announcement, ‘since hope is gone’. The final stanza was a microcosm of the virtues of the whole programme: dynamic variety — the forte challenge to the ‘shadows that in darkness dwell’ giving way to pianissimo resignation; exquisite harmonic inflection, with false relations lightly underscored; and poised conclusions, the lute’s cadential ornamentation delicately adorning the bitter-sweet tierce de Picardie.

In ‘Can she excuse my wrongs’, Bostridge’s clear diction highlighted the rhythmic elasticity of the accompaniment, which developed further in the intricate in-between verse commentaries. ‘Come Again’ found the tenor accompanied solely by Kenny’s lute. Bostridge built the rising sequence, ‘To see, to hear, to touch, to kiss, to die’, with urgency, blooming on the final syllable; in contrast, in the subsequent verse the recognition that the lover’s hopes are futile, ‘I die/ In endless pain and endless misery’, was darkened by a richly toned decorative turn on the final word.

Kenny also accompanied ‘Sorrow stay’, but this short song is no simple strophic song with accompaniment, but rather seems to anticipate Romantic lieder, the lute promoted from an accompanying role engaging in idiomatic dialogue with the voice, to an equal partner. The instrumental harmonies and melodic motifs are as significant as the voice in conveying meaning. Such interplay deepened the self-castigating misery of the poet-singer’s opening cry to Sorrow, ‘lend repentant tears/ To a woeful wretched wight’; similarly, the lagging delay of the final falling couplet enhanced the sense of the protagonist’s struggle and defeat: ‘down, down I fall/ And arise I never shall.’ At the repeat, Bostridge held the pinnacle, ‘arise’, for just a moment before sinking again into doleful submission.

‘My thoughts are winged with hopes’ offered some respite from the gloom, the more sanguine sentiments conveyed by a sense of movement through the phrases, and the lively trochaic emphases in the viol accompaniment. With one bass viol and the tenor viol silent, the airier texture complemented the optimism of the text.

But, this lighter mood did not last long, for in Dowland’s masterpiece, ‘In darkness let me dwell’, the tenor’s veiled lower register and seamless phrases, supported by bass viol and lute, took us to the abyss. Bostridge exploited the experimental harmonic colouring of the words, almost sneering the phrase ‘My music hellish jarring sounds’ and employing a nasal bitterness and chromatic slide to convey angry despair: ‘wedded to my woes,/ And bedded to my tomb’. The sudden assertiveness of the appeal for death was startling; in the final reprise of opening phrase, the lute gradually expired, leaving just a scarcely audible voice before that too faded inconclusively into the silence. This was a breath-taking display of insight coupled with musicality and technical skill.

After these dark hues, ‘Time Stands Still’ drew forth a sweeter tone, while the enclosing shapes of the long melodic lines conveyed a quietude and motionlessness which was only briefly disturbed by the lute’s energetic flourish introducing the more purposeful declaration, ‘If bloudlesse envie say, dutie hath no desert’. Tempo and textures were used expressively in ‘If my complaint’. The sprightliness suggested the singer’s pained sense of injustice, while the viols’ inter-verse elaboration might have been a riposte from she, or he, who stands accused — for this song may be as much an appeal to a negligent patron as an indifferent beloved.

In ‘I say my lady weep’ Bostridge used a sotto voce to moving effect. Indeed, tears - ‘Lachrimae’ — were in many ways Dowland’s catchword. He even signed his name ‘Jo. Dowlandi de Lachrimae’. In between the songs, Fretwork presented seven ‘Lachrimæ’ pavans, each defined by a preceding adjective — old tears, old tears renewed, sad tears, lovers’ tears — with characteristic discipline and refinement. The harmonic subtleties of ‘Lachrimæ Gementes’ (groaning tears) cultivated an almost trance-like self-absorption; similarly, the chromatic complexities of the more homophonic ‘Lachrimæ Verae’ (true tears), and the easing of the tempo at the close, were deeply expressive.

There were also galliards and pavans whose titles and dedications give us an indication of the various societies in which Dowland moved; from the Earl of Essex to Digory Piper, a Cornish pirate! Though each dance was consummately delivered, at times I found the musical interest in the middle and lower voices was sacrificed to homogeneity, or overwhelmed by the consistent emphasis given to the upper line of Asako Morikawa’s viola da gamba.

In the instrumental numbers there was a general problem of balance, with Kenny’s lute often absorbed into the uniform viol texture, and clearly audible only at the decorative cadences. However, the busy, more vigorous passages of the ‘The King of Denmark’s Galliard’ did create a more spacious foundation for the lute’s intricate passagework.

Kenny’s performance of ‘Forlorn Hope Fancy’ made one lament that the programme included only one work for solo lute; the drooping chromatic scale with which the piece commences was expertly shaped, initiating contrapuntal lines of textural clarity and variety. Synchronised and broken chords eloquently punctuated the running melodic lines, the latter assuming ever-more complex questing patterns. Kenny’s technical virtuosity was complemented by expressive articulacy; concluding with a rhetorical flourish, this ‘Fancy’ spoke as directly and movingly as any of Dowland’s songs.

While Fretwork performed these pavans and galliards, Bostridge remained seated, centre-stage, like a brooding Hamlet: ‘How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable / Seem to me all the uses of this world!’ There was, however, some lightening of the mood at the close, the mild, carefree nimbleness of ‘M. Henry Noell his Galiard’ and the brightly soaring high vocal lines of the final song, ‘Shall I strive with words to move’, bringing a freshness to alleviate the melancholy.

As Richard Boothby reminded us in his programme article, a sonnet by one of Dowland’s contemporary poets, Richard Barnfield, praised the composer, ‘whose heavenly touch / Upon the lute doth ravish human sense’. On this occasion, in the words of Dowland himself, ‘Sorrow was there made fair’.

Claire Seymour

Performers:

Ian Bostridge tenor, Elizabeth Kenny lute, Fretwork: Asako Morikawa, Reiko Ichise, William Hunt, Richard Tunnicliffe, Richard Boothby, viols. King’s Place, London, Wednesday, 12th February 2014.

Programme:

Flow my tears; Lachrimæ Antiquæ Novæ; The King of Denmark’s Galliard; Can she excuse my wrongs/The Earle of Essex Galliard; Lachrimæ Gementes; Forlorn Hope Fancy; Come Again, sweet love doth now invite; Sorrow stay!; M. John Langton’s Pavan; My thoughts are winged with hope; Lachrimæ Tristes; In darkness let me dwell; Lachrimæ Coactæ; Time stands still; If my complaints/ Captaine Digory Piper, his Galliard 4.00; Lachrimæ Amantis; If floods of tears; Lachrimæ Veræ; I saw my lady weep; M. Henry Noell his Galliard; Shall I strive with words

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Woman_Lute-Vermeer.png image_description=Woman with a Lute by Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) [Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art] product=yes product_title=John Dowland: In Darkness product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Woman with a Lute by Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) [Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art]February 11, 2014

Lucia di Lammermoor in Marseille

Not that there was not some good singing, namely Czech soprano Zuzana Markova as Lucia. Originally the Lucia of the relief cast (taking two of the six performances) this beautiful young singer was advanced into the primary cast when illness forced the first Lucia to cancel. Of secure technique, solid musicianship and a voice in its youthful bloom Mlle. Markova did hold the stage the entire evening, lacking only a diva presence to achieve a convincing bel canto performance. This talented young artist is in dire need of coaching — not only how a real diva artist might act this demanding role but also how a real diva might act.

Certainly Mlle. Markova was not in a position to pull diva antics, like refusing to wear the costumes designed for Lucia by Opéra de Marseille house designer Katia Duflot. A bona fide diva would know that if the audience was baffled by the gravity defying design of her bare shoulder red gown, it was probably not paying attention to her performance. Never mind that the red gown did not finally reveal a topless Mlle. Markova, the bare shoulder white gown of the wedding scene all but revealed everything. Mlle. Markova’s lovely young breasts simply upstaged her beautiful young voice.

Giuseppe Gipali as Edgardo, Zuzana Markova as Lucia. Photo by Christian Dresse

Giuseppe Gipali as Edgardo, Zuzana Markova as Lucia. Photo by Christian Dresse

On the other hand Lucia's brother Enrico sung by French baritone Marc Barrard was visually choked by the high collar Mme. Duflot engineered for his first act costume. Our sympathy for his strangled sound was however unfounded as his later costume with unbuttoned shirt allowed plenty of breathing room. We discovered that his voice is unfocused and sounds very worn, or perhaps making a bel canto sound is simply foreign to his voice. If the program booklet biography is at all complete this role may have been his first venture into this repertory.

Giuseppe Gipali was the Edgardo. This Albanian tenor turned bel canto into can belto in vocal tones and shapes that were stylistically appropriate if monochromatic and unvaryingly forte. Mr. Gipali is not an affecting performer, his eyes never on the person (Lucia) he was singing to, instead his face was always outward, performing directly to the audience. His final scene — his suicide — was in fact splendidly sung, lacking any hint of sincerity of emotion that could bring this famous opera to its hyper-Romantic conclusion.

And finally Polish bass Wojtek Smilek was Raimondo, the Calvinist priest. Mr. Smilek is an important local resource, frequently appearing in Marseille, nearby cities and in Paris. He sings just about every smaller principal bass role you can think of. Unfortunately Raimondo is a big role, with lots of exposed singing. While Mr. Smilek is a fine singer he does not have the warmth of tone required for basso cantante roles nor the smoothness of line that can make him a lyric bass.

Lucia di Lammermoor is a numbers opera, one big aria or duet after another, embellished by chorus interjections that change circumstances to motivate even more beautiful singing — there is simply a huge amount of a very particular style of solo singing. This opera must be carefully cast. It was not.

The Sextet. Photo by Christian Dresse

The Sextet. Photo by Christian Dresse

The pit was overseen by French conductor Alain Guingal who responsibly sustained the proceedings but supplied no stylistic flourish to make this evening musically vibrant. While the big harp obligato in the first act was magnificently played the flute duet with Lucia’s mad scene was rendered with contours and colors that went too far beyond those offered by Mlle. Markova.

The new production was staged by French theater director Fréderic Bélier-Garcia. He is the absolute master of staging operas that are strings of numbers, finding natural seeming motion for his singers while they perform lengthy arias about how they feel. Here he exploited a new trick by sometimes taking his singers to the extreme sides of the stage to stand against the wide soft black false proscenium, removing the singer from all scenic context. With absolutely glorious lighting by designer Roberto Venturi the singers were suddenly stripped of everything except voice and artistry —what greater effect could be created for the supreme moments of bel canto opera!

The physical production was designed by Jacques Gabel, a frequent collaborator of Mr. Bélier-Garcia. The design was minimal, two scrims on which various forest shapes were projected, a platform that was sometime a ramp and sometime a pier, like on a lake, and (of course) a chandelier. The sensuous stained glass Jesus figure on a panel flown in for the Enrico/Edgardo meeting is hard to explain, as are the brilliant northern light colors that embellished the scrims from time to time. But not as hard to explain as the costumes described above that just did not seem to belong in a drafty old Scottish castle.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Lucia: Zuzana Markova; Alisa: Lucie Roche; Enrico: Marc Barrard; Edgardo: Giuseppe Gipali; Raimondo: Wojtek Smilek; Arturo: Stanislas de Barbeyrac; Normanno: Marc Larcher. Orchestra and Chorus of the Opéra de Marseille. Conductor: Alain Guingal; Mise en scène: Frédéric Bélier-Garcia; Scenery: Jacques Gabel; Costumes: Katia Duflot; Lighting: Roberto Venturi. Opéra de Marseille, February 6, 2014

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lucia_Marseille1.png

image_description=Lucia and Enrico in Marseille Lucia

product=yes

product_title=Lucia di Lammermoor in Marseille

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski