March 30, 2014

Five Young Singers Named Winners in the Final Round of the 2014 Met National Council Auditions

The Metropolitan Opera [30 March 2014]

After a months-long series of competitions at the district, regional, and national levels, a panel of judges has named five young singers the winners of the 2014 National Council Auditions, the nation’s most prestigious vocal competition. Each winner, who performed two arias onstage at the Metropolitan Opera this afternoon with conductor Marco Armiliato and the Met’s orchestra, will receive a $15,000 cash prize and the prestige and exposure that come with winning a competition that has launched the careers of many of opera’s biggest stars.

ROH presents Cavalli’s L’Ormindo at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, London

Hurrah for the Royal Opera’s latest and most innovative Baroque production. Inside this gorgeous gem of a theatre, the Shakespeare’s Globe’s new indoor space known as the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, Kasper Holten and his team have created a mini masterpiece of baroque performance with Cavalli’s L’Ormindo.

Aided and abetted by a superb team of young singers and Christian Curnyn’s top-of-the range period musicians Holten has given us — some might say at last — hope for the future. Now Londoners have a truly special place within which to enjoy baroque opera and period theatre which does not intimidate with either size or brutal modern architecture. Seating just 340, and open since the beginning of the year, the Playhouse, snuggled alongside its famous larger sister the Globe, has been described as “an archetype, rather than a replica, of a specific Jacobean indoor theatre”. Inside, lit only with beeswax candles, the audience is immediately immersed in the drama seated as many are within yards of the performers, others just a little higher in the galleries surrounding the proscenium-less stage. With Cavalli’s little known L’Ormindo (last seen in London in 1967) which opened on Friday night to a packed house, the Playhouse has announced its arrival on the baroque opera scene with a flourish of shameless extravagance, saucy wit and sublime musicianship.

Ed Lyon as Amidas and Susanna Hurrell as Erisbe

Ed Lyon as Amidas and Susanna Hurrell as Erisbe

Cavalli’s work may be little known today — his La Calisto being perhaps most frequently performed — but this near-contemporary of Monteverdi was highly successful in his day and a master of his craft. He had to be: no composer working for either aristocratic patron or the new breed of fickle theatre owner at that time could get away with second best. From palace drawing room to the streets inside weeks was not uncommon. His work may have gone out of fashion for a few hundred years but perhaps its felicitous mix of eroticism, money, fame and fortune now rings a topical bell? With L’Ormindo we have the usual baroque pot of swirling royal love affairs, spurned fiancées, cross-dressed nurses, bawdy comedy, magical allegorical figures, and lower-class confidants who use the audience as sounding boards for their musings on the baser problems of life and love. What we also got however was real international-standard production values: fabulous costumes by Anja Vang Kragh (whose Dior/McCartney pedigree is easy to appreciate), a raft of some of the best young singers available today, clever stage direction which used the unique size and shape of the space to best advantage, a marvellously witty English translation by Christopher Cowell and an 8 piece band of seasoned period performance experts (the continuo group, led by Curnyn, of harpsichord, baroque harp and theorbo deserve special mention).

Rachel Kelly as Mirinda

Rachel Kelly as Mirinda

The nine singers, some taking two roles, were without exception terrific. Rehearsals must have been sufficient as they moved gracefully and expertly around the ever-present hazard of the real candle flames at both head and foot height (this writer not being alone in holding their breath from time to time as huge dresses, swirling capes and feathers came within millimetres of conflagration). But it was the excellence and intelligence of their singing and acting which supported the whole edifice around them; seldom does one get the chance to enjoy an opera where one can honestly say there was no weak link. Each deserves detailed praise and description, but suffice to say that if forced to choose just two, the names of Sam Boden (high tenor) as Ormindo, and Rachel Kelly (mezzo soprano) as Mirinda might just be them. Boden displayed a beautiful limpid tone and line totally in keeping with his character and Kelly a warm yet lively mezzo with which she also managed crisp diction — an important facet of performance in English with no surtitles. Of the smaller roles, mention must be made of James Laing (countertenor) as the page Nerillus/Cupid for both his elegant even tone and apparent insouciance as he hung suspended in pink and gold tutu from the flies. Such gentle guying of baroque opera’s traditions was part of the humour inherent in this production.

It seems that Kasper Holten in his relatively new position of Director of Opera at Covent Garden has at last turned the tide and found imaginative ways to support the continued flourishing of “old” opera. By working with innovative partners such as the Globe and Curnyn’s Early Opera group, he has done what many before him failed to do: spark new life into old magic. Long may we enjoy the fruits of his labours.

Sue Loder

The ROH/Shakespeare’s Globe production of Cavalli’s L’Ormindo continues on 28th, 29th March and 1 st, 2nd, 4th, 5th, 8th, 9th, 11th and 12th April at 7.30pm. Returns only at time of writing. BBC Radio 3 will broadcast the opera on the 5th April at 7.30pm.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ORMINDO%20SC1_7580.png image_description=Samuel Boden as Ormindo [Photo by Stephen Cummiskey] product=yes product_title=ROH presents Cavalli’s L’Ormindo at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, London product_by=A review by Sue Loder product_id=Above: Samuel Boden as OrmindoPhotos © Stephen Cummiskey

March 27, 2014

Harrison Birtwistle, Elliott Carter, Wigmore Hall, London

So it was that Birtwistle bookended the evening. The first piece was his Fantasia upon all the notes (2012), commissioned by the present ensemble and premiered at the Wigmore Hall in March 2012. Scored for flute, clarinet, harp (the sound of the harp, although not omnipresent, was a Theseus-thread through the evening) and string quartet, the score breathed out a lyric expansiveness, its long lines fully honoured here and leading to a frenetic climax before the piece effectively disintegrated. The basis for the composition (“all the notes”) is the shifting scales of the harp, dependent on the pedals used. In this way, the harp, by no means soloistic, subtly guides the harmonic language of the piece. It was a fine example of the composer's subtle practices, and was beautifully and sensitively delivered here by members of the Nash Ensemble.

Carter and Birtwistle are of course linked by age as well as the complexities of their music (although the manifestations of those complexities are, of course, very different). There were two Carter pieces in the first half: Enchanted Preludes of 1988 and Esprit Rude/Esprit Doux of some 22 years previous. The first, Enchanted Preludes, is scored for flute and cello, here played by Philippa Davies and Adrian Brendel, respectively. It was a virtuoso performance of a sophisticated piece. Both players demonstrated superb control of their instruments in a piece that demonstrates, concisely, Carter's strengths of a consistent harmonic language and a superb ear for detail. If Esprit Rude/Esprit Doux for flute and clarinet (Davies again, this time with Richard Hosford on clarinet) was not quite as fine a piece, not as sure of itself, it nevertheless evinced a great sense of dialogue.

The Adams was the odd man out. Somehow Shaker Loops, in its chamber version for seven strings, felt rather roughly 'inserted' in deference to the American side of the concert series. It was a fabulous performance: perfectly graduated crescendi and a real sense of determination. But the piece felt over-long and frankly bloated, and was firmly compositionally outgunned by its companion pieces.

Elliott Carter's Mosaic of 2004 (for flute, oboe, clarinet, harp, string trio and double-bass) began the second half. The harp part is virtuosic but in the pre-concert talk Birtwistle had contrasted Carter's treatment of the instrument to his own: Carter does not let the instrument resonate (and therefore, by implication, be true to its own nature). The complex pedal work is impressive indeed as a performance act and one does have to wonder if this aspect is part of the piece's basis, just as the viola is asked to be contra-itself and be very forceful; very un-viola-like perhaps. It is an interesting piece, certainly, but it was overshadowed to no small extent by the piece that most people had surely come to hear, Birtwistle's recent The Moth Requiem (2012).

The BBC Singers were on absolute top form for the demands of this work, which sets a number of Latin names of butterflies interspersed into the poem “A Literalist” by Robin Blaser from his larger work The Moth Poem. The poem concerns a moth trapped in the body of a piano and which could be heard in contact with the strings. It is a lovely idea, and masterfully realised. The scoring is for 12 singers, 3 harps and alto flute. In fact Birtwistle uses the three harps as one “meta-instrument”, as he explained in his characteristically dry-witted pre-performance event. Birtwistle's years of experience enabled him to weave an intoxicating sonic tapestry. The fragmenting of texture and musical material in the work's final stages is impeccably timed. This is nothing short of a masterpiece.

Running through the concert was the sure direction of Nicholas Kok, whose clarity as a conductor was a model of its kind. A remarkable evening.

Colin Clarke

image=http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Harrison_Birtwistle.jpg/256px-Harrison_Birtwistle.jpg

image_description=Harrison Birtwistle

product=yes

product_title= Harrison Birtwistle :Fantasia upon all the notes (2012). The Moth Requiem (2012), Elliott Carter :Enchanted Preludes (1988). Esprit Rude/Esprit Doux (1964). Mosaic (2004), John Adams : Shaker Loops. The Nash Ensemble; BBC Singers, Nicholas Kok

Wigmore Hall, 26th March 2014

product_by=A review by Colin Clarke

product_id=Above: Harrison Birtwistle by MITO Settembre Musica (Wikicommons Images)

Requiem for a Lost Opera Company

After Gioachino Rossini's death in 1868, Giuseppe Verdi suggested that a group of then-famous Italian composers collaborate on a requiem in Rossini's honor to be played on the first anniversary of his death. Verdi wrote the final Libera me and was frustrated when the work was not performed. Six years later, he put his composition to use in a Mass that honored another man whom he greatly admired, Italian poet and novelist Alessandro Manzoni. The first performance of the Manzoni Requiem took place at the church of St. Mark in Milan on May 22, 1874, the first anniversary of the writer’s death. The piece lends itself much more to the concert stage than to the church, however, and it is most often played in theaters and opera houses.

On Wednesday, March 19, 2014, General Director Ian Campbell of San Diego Opera announced that the company would go out of business at the end of this season. The next day the company performed their long-planned Verdi Requiem with a stellar cast including soprano Krassimira Stoyanova, mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe, tenor Piotr Beczala, and bass Ferruccio Furlanetto. They and the San Diego Master Chorale combined with the San Diego Opera chorus sang to the accompaniment of the San Diego Symphony conducted by Massimo Zanetti. The seats went on sale in the fall and by Christmas the house was completely sold out. However, on the day of the performance the mood was funereal.

Opening with muted cello sounds, the beginning of the Mass indicated the sorrowful mood of both musicians and audience. Maestro Zanetti had a tremendous range of dynamics and the following Dies Irae came in with thunderous drum beats. Blythe sang of judgment with a tapestry of tonal color and was joined by Beczala and Stoyanova in the description of the disparity between the power of God and the human condition. Beczala’s Ingemisco was a thing of great lyrical beauty that became one or the crown jewels of this performance. Furlanetto sang of the damned being consigned to the flames of Hell and Stoyanova sang the Libera Me with a radiance that transcended the darkness of the surrounding aura. Eventually, the chorus returned to the day of wrath and of tears, which this certainly was for its members. Perhaps it was their outrage at being dismissed with little regard for their devotion to the company that made the orchestra and chorus sing and play with every fibre of their bodies. Together with the internationally known soloists, they made this a Verdi Requiem never to be forgotten by anyone who was in the Civic Theater that night.

Maria Nockin

Cast:

Soprano, Krassimira Stoyanova; Mezzo-soprano, Stephanie Blythe; Tenor, Piotr Beczala; Bass, Ferruccio Furlanetto; Conductor, Massimo Zanetti.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Manzoni.gif

image_description=Portrait of Alessandro Manzoni by Francesco Hayez [Source: Wikipedia]

product=yes

product_title= Requiem for a Lost Opera Company

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Portrait of Alessandro Manzoni by Francesco Hayez [Source: Wikipedia]

March 21, 2014

The Met’s Werther a tasty mix of singing, staging, acting and orchestral splendor

Massenet’s Werther is a soufflé. If all the ingredients — sets, direction, singing, conducting — are perfectly blended, it will stand up just fine. But if anything is amiss, it will collapse.

Fortunately all the ingredients were tastily in place in the Met’s new production that featured the overdue house debut of mezzo Sophie Koch as Charlotte and tenor-du-jour Jonas Kaufmann as Werther, all blended by British director Richard Eyre and conductor Alain Altinoglu.

Based on Goethe’s 1774 novel The Sorrows of Young Werther, this is, at heart, a two-character opera. The melancholy (or simply depressed) poet Werther is besotted by the virtuous Charlotte, who is betrothed to the dull Albert. Charlotte is quietly passionate about Werther, but she won’t yield to him or to her own desires because she promised her dying mother she would marry Albert.

Despairing, Werther leaves her, then returns on Christmas Eve, is rejected (after a single passionate kiss), borrows Albert’s pistols, retreats to his garret, and commits suicide. The distraught Charlotte runs to the garret, arrives too late to save him and, in this production, contemplates using the pistol on herself as the stage lights dim.

Excerpt from Werther's aria from Act I of Massenet’s opera. Jonas Kaufmann (Werther). Production: Richard Eyre. Conductor: Alain Altinoglu. 2013-14 season. Video courtesy of the Metropolitan OperaAll the important action is between these two. Charlotte’s teenage sister Sophie flits in and out of the opera exhibiting her own crush on Werther and adding some light-hearted relief. Charlotte’s father, siblings, husband and some townspeople make appearances, but they provide little more than dramatic and musical padding.

It is hard to imagine two performers more persuasive in these roles than Koch and Kaufmann. Eyre has directed them to accentuate their differences. She is cool, distant, and manipulative. He is manic, ardent, and menacing. She is costumed elegantly in late 19th century fashions. He is, at first, quite proper in a floor-length dark formal coat with a white waistcoat, tie or scarf. But as his mental state deteriorates, so does the outfit.

Eyre has provided a wealth of directorial touches to keep this melodrama afloat. Although only married to Albert for three months, Charlotte, in her body language, makes it clear that the relationship is joyless for her. She sits rigidly near him on a bench, just far enough to signal her emotional distance. Sophie exhibits her attraction to Werther by rubbing up against him on that same bench, only to see Werther jump away as if stuck by a hatpin. When Werther shoots himself, great globs of blood not only cover his white blouse, but also splatter the wall behind him and stain the bed coverings.

Excerpt from Werther's aria from Act III of Massenet's opera. Jonas Kaufmann (Werther), Sophie Koch (Charlotte). Production: Richard Eyre. Conductor: Alain Altinoglu. 2013-14 season. Video courtesy of the Metropolitan OperaSpecial praise goes to Video Designer Wendall K. Harrington for projections that were constantly imaginative. Flocks of ravens roosted in trees when Charlotte’s mother was buried in a pantomime during the overture. The snow at the winter burial scene visually melted into a verdant spring filled with images of leafy trees. When Charlotte and Werther were dancing at a ball between Acts One and Two (which is when they fall in love), projections created the illusion they were whirling around the dance floor. Charlotte ran through a video of city streets and a snowstorm to reach Werther’s garret.

Equally impressive were the set designs of Rob Howell. Act One opens outside Charlotte’s house in a lush, pastoral setting complete with little walking bridges and gentle hills. Act Two is a quaint town square with benches and a shaded table. Act Three is a dramatic library and music room in Albert’s house, where Charlotte reads Werther’s crazed love letters, and where he confronts her and threatens suicide. Act Four, Werther’s garret, first appears at the back of the Act Three set as a distant box within the stage picture. Imperceptibly the garret moves forward and replaces the Act Three set, concentrating the audience’s attention on his suicide in this small space, which is now at the center of the stage.

These visual elements are essential to the audience’s appreciation of this opera because Massenet is no tunesmith. Just when the action begs for a melody from an Offenbach or Gounod, Massenet fails to deliver. Yes, there are some celebrated arias — Werther’s Invocation to nature in Act One, his Lied to Ossian in Act Three, Charlotte’s letter scene in Act Three — but even these, to my ears, lack a distinctive melodic profile.

Excerpt from Charlotte's aria from Act III of Massenet's "Werther." Sophie Koch (Charlotte), Lisette Oropesa (Sophie). Production: Richard Eyre. Conductor: Alain Altinoglu. Video courtesy of the Metropolitan OperaAs critic and musicologist Rodney Milnes writes in The New Grove, Werther is a “through composed conversation piece.” Massenet is a colorist with the ability to match any mood or action in the orchestral writing. He provides a river of perfumed music that is always beguiling but hard to remember. His writing for woodwinds is magical. The overall tint of the orchestral writing is dark, as befits the subject. It’s masterful in its way, but faceless.

Without choruses or familiar arias, the opera will only work if the audience is totally invested in the fates of the two main characters — and this the Met production achieved.

Koch and Kaufmann have sung these roles in major houses all over the world. The music is clearly in their bones, and throats.

In this run of performances, Koch joined the group of golden age mezzos currently at the Met: Joyce DiDonato, Susan Graham, Stephanie Blythe and others. She has a voice that easily carries throughout the large auditorium. She is always on pitch. The sound is pleasing in all its registers. She demonstrated enormous volume in her farewell cry to her sister in Act Three, and tenderness in ministering to her younger siblings in Act One. She was thoroughly convincing in the Act Three letter scene as she re-reads Werther’s desperate pleas and realizes he has settled on suicide. Emotionally she held herself in reserve (no doubt at Eyre’s urging) until she cradled the dying Werther in Act Four. She is a tall and handsome woman who acts in a modern style. No diva antics for her. She is more an Eboli than a Carmen in temperament. Her voice may lack the sort of immediately identifiable characteristics of the stentorian Blythe, but Koch is a true artist nonetheless.

At first I thought Kaufmann was too much the heldentenor for the tormented poet, more a Tannhäuser than Werther. But the Met’s program note makes clear that the role was created in 1892 by Ernest Van Dyck, who also sang Lohengrin and Parsifal. So Kaufmann’s often ringing and aggressive tone must have been what Massenet wanted. Kaufmann has a well-controlled head voice to complement his golden top notes. At times I thought I was listening to a voice that would be more congenial as Samson (in the Saint-Saëns opera) but it worked, particularly in his lengthy demise in Act Four.

(According to both The New York Times and my friends in Syracuse, New York and Portland, Maine who were watching the live HD relay in movie theaters, the audio cut out for seven minutes of Werther’s death scene, causing much annoyance and yielding refunds. The Met blamed satellite problems.)

Baritone David Bizic was convincing as both a hearty Albert and then an aggrieved Albert, once he suspects his wife still loves Werther. He managed the transition from one to the other in just a few notes with a hardening of his voice as he willingly gave his pistols to Werther.

Soprano Lisette Oropesa was a sparkling Sophie, at her best when trying to cheer up her sister with an aria about birds. Jonathan Summers was a bit underpowered as Charlotte’s widowed father.

Conductor Alain Altinoglu seems to be a natural Massenet conductor. He kept the perfumed waters rolling, building tension along the way, relaxing where possible, and delivering an emotional conclusion. The Met Orchestra responded well to his leadership. He should have a bright future in the house.

This was the last performance of the season for Werther. Surely the Met will bring it back, and I urge you to see it, even if Kaufmann and Koch do not repeat their roles. Eyre’s overall conception, Harrington’s projections, and the Met Orchestra’s playing are worth the hefty price of admission.

David Rubin

CNY Café Momus

This review first appeared at CNY Café Momus.. It is reprinted with the permission of the author

image=http://www.operatoday.com/wertpd_3097a.png image_description=Jonas Kaufmann as the title character and Sophie Koch as Charlotte [Photo by Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera] product=yes product_title=The Met’s Werther a tasty mix of singing, staging, acting and orchestral splendor product_by=A review by David Rubin product_id=Above: Jonas Kaufmann as the title character and Sophie Koch as Charlotte [Photo by Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera]March 20, 2014

San Diego Opera Will Shut its Doors

By Maria Nockin [Opera Today, 20 March 2014]

After forty-nine years of delivering fine performances, usually with outstanding casts, San Diego Opera will shut down permanently on June 30, 2014. The population of the city has changed markedly and the opera has had increasingly greater difficulty attracting donations. As with most opera companies, ticket sales for the company’s performances could only cover half the cost of its productions.

The rest of the money had to be made up by donations and they simply were not forthcoming. The opera’s board of directors, many of them large donors, voted thirty-three to one in favor of discontinuing operations. We can only hope that eventually another company will bring opera to San Diegans.

March 19, 2014

Chicago’s New Barber of Seville

Happily, Lyric Opera of Chicago’s delightful new Barber fulfills both vocal and technical expectations with a bright and lively conception. Figaro is sung by Nathan Gunn, Isabel Leonard makes her house debut as Rosina, and Alek Shrader performs Count Almaviva, a role for which he is justly celebrated on operatic stages throughout the United States and Europe. Further artists featured in this notable cast include Alessandro Corbelli as Dr. Bartolo, the guardian of Rosina, Kyle Ketelsen as Don Basilio the music master, and Tracy Cantin as the maid Berta; Will Liverman sings Fiorello and John Irvin performs the part of the sergeant. Michele Mariotti makes his Chicago conducting debut leading these performances. Director of this new production is Rob Ashford, with sets and costumes by Scott Pask and Catherine Zuber respectively. Michael Black prepared the Lyric Opera Chorus.

During the overture to the opera a scrim covers the stage with sketches of three coifed heads representing the Count, Rosina, and presumably the resourceful and ever-present Barber. Mr. Mariotti had the overture played with a light touch so that the strings were a subtle lead to the other forces in the orchestra. One could also hear clearly the plucking of individual string chords at appropriate moments, just as levels of volume rose and sank in anticipation of modulations in forthcoming scenes of the opera. During the second part of the overture repeats were played with variations and justified emphases. As the first scene of the opera begins, the chorus of musicians moves from one side of Dr. Bartolo’s house to the other, their team-like comical gestures matching the swell of the music in this production. While their leader Fiorello has tried to rally both discipline and quiet the Count clutches at the wall of the building in which his beloved Rosina lives under the tutelage of Bartolo. Mr. Shrader’s Almaviva repeats the calls for quiet with a truly soft emphasis on “Piano!” His movements and facial expressions indicate an anticipation scarcely kept in check. In Almaviva’s song at daybreak performed beneath Rosina’s balcony, “Ecco ridente in cielo” [“Look on the smiling sky”], Shrader expresses his ardor with an exuberant trill on “la bella aurora” [“the beautiful dawn”]. The tenor’s range was shown effectively with a full descent at “Sorgi ancora” [“still not arisen”], rising decorations on “vieni bell’ idol mio” [“Come, my treasured one”], and a cry of anguish at “Oh, Dio” to express the futile pain of waiting. As tempos and emotional commitment accelerated Shrader incorporated distinctive and well-chosen embellishments into the second part of his serenade. The tenor draws on a full range of technique and vocal color, just as his acting matched communicative gesture to his chosen vocal expression. As such, Almaviva’s palpable frustration at not knowing whether he has been heard by Rosina is displayed by Shrader in athletic poses and believable grimaces. Although forced to conceal himself at the arrival of the barber Figaro, this Almaviva’s presence is undiminished. Mr. Gunn’s Figaro has the requisite mobility and vocal energy to entertain and to suggest a resourceful fellow for those in need of his help. Gunn’s practiced declamation was equivalent to his character Figaro’s vocal runs in the “Largo al factotum” [“Make way for the factotum”]. At times in this famous aria the vocal projection was subject to an overly enthusiastic orchestral volume. The following interaction between Almaviva and Figaro was staged cleverly and with ample movement proceeding toward the ensuing musical numbers. Rosina appears on the balcony and drops her note to Almaviva; Bartolo warns his charge against suspicious contact and departs on an errand. At this point the Count sings his next serenade and identifies himself falsely as Lindoro, so that he might attract Rosina’s love on his own account and not because of wealth and title [“Si il mio nome saper voi bramate” (“If you wish to know my name”)]. During the first part of Almaviva’s song Shrader’s assured legato and fluid vocal runs prompt the expected encouragement of Rosina from her balcony that he should continue. Almaviva’s excitement at this response included here decorative top notes inserted at “fida e costante” [“faithful and true”] and a further trill toward the close. Only a sudden distraction inside the house prevents the young couple from further communication. Count Almaviva depends on Figaro’s resourceful scheme, that he take on the disguise of a soldier, in order to gain entry to the house and to see Rosina. The duet between Shrader and Gunn concluding this scene is vocally exciting and physically entertaining as they dance together while celebrating the pact.

The second substantial part of Act One features Rosina as a committed participant in any future attempt to meet her “Lindoro.” Ms. Leonard’s “Una voce poco fa” [“A voice I just heard”] is skillfully sung with decorations taken on rising lines, excellent runs, and application of rubato at textually appropriate moments toward the close. The start of her collusion with Figaro is matched now by Dr. Bartolo’s conspiratorial dealings with Basilio. The latter recommends defamation of the Count, whom he identifies as Rosina’s suitor. Mr. Ketelsen’s performance in the role of Basilio is notable for his vocal accomplishments while staying within character in the aria “La calumnia.,” directed toward Count Almaviva. Ketelsen’s physical gestures suggest a doddering teacher yet his voice blooms in enthusiastic might with rich bass notes on “Leggermente” and truly explosive pitches on “colpo di cannone” [“Outbursts from a cannon”]. Accomplished decoration concluded the piece by an artist whom one hopes to hear in additional bel canto roles. Once the doctor and music teacher depart, Rosina and Figaro are able to continue their mutual revelations. In their duet “Dunque io son” [“Then it is I”] both characters reflect on Lindoro’s emotional promise and the need for caution because of Bartolo’s own plans. In this duet Leonard and Gunn sing with even greater invention than earlier as though illustrating their crafty approach with vocal embellishments. When Mr. Corbelli as Bartolo enumerates his suspicions to Rosina, the aria “A un dottor della mia sorte” [“For a doctor of my standing”] is performed as more than a simple character piece. Corbelli truly inhabits the role of Dr. Bartolo, his sense of vocal line and sustained pitches giving emphasis to the fulminating ire expressed in the text. When the housemaid Berta enters to respond to pounding at the door, Ms. Cantin stumbles about with her laundry-basket while uttering believable cries of impatience. Her role as performed in the finale of Act One is crucial as a vocal anchor bringing to a crescendo the disparate arguments and colors. Almaviva is admitted as disguised, his feigned inebriation causing disagreement with Bartolo and relief for Rosina. Just as the household characters and guest are joined by Basilio and Figaro, the resulting ensemble sparkles with full yet disciplined Rossinian frenzy. In response to Shrader’s impressive high pitch on “In arresto? Io?” [“Arrested ? I?”], and his revelation to the official in charge, the police recognize the identity of the drunken soldier and refuse to detain him. All the principals participate in, with Ms. Cantin’s forte notes propelling forward, a commentary on the mental confusion in which they are trapped as the act concludes. (“Mi par d’esser con la testa in un’orrida fucina” [“My head seems to be in a fiery smithy”].

In the house of Bartolo at the start of Act Two the doctor has scarcely recovered from the confusing interruption of the inebriated soldier when Count Almaviva arrives in his second disguise, Don Alonso, professor of music and alleged pupil of Basilio. He purports to take the place of his ill teacher and proceeds with a music lesson for Rosina. Leornard performs the noted aria, “Contro un cor che accende amore” [“Against a heart inflamed with love”] as a clever response to the advances of her eager suitor, while also preserving its opportunities for vocal embellishments as a set piece. At the entrance of a seemingly healthy Basilio, a quick ruse must be invented to dispose of the real music master. When the conspirators attempt to convince Basilio of his dreadful appearance, Mr. Ketelsen asks, “Sono giallo come un morto?” [“I am yellow as a corpse?”] with deep sustained pitches making “un morto” shudderingly possible. Once he has left after a spirited performance of the “Buona sera” ensemble and agreement by Rosina to meet her lover at midnight, Berta is left alone to comment on the unabated frenzy of this household. Cantin’s performance of Berta’s solo “Il vecchiotto cerca moglie” [“The old man seeks a wife”] shows an assured and comic approach including effective chest tones, a superb diminuendo in the repeat, and inventive decorations taken at the close.

The ultimate appearance of Rosina’s “Lindoro” and Figaro at midnight prompts the blissful admission that Lindoro and Almaviva are indeed one and the same individual. Rosina’s relief at not having been deceived in her devotions as well as Almaviva’s boundless joy at winning his suit result in the extended duet in which Leonard and Shrader complement each other delightfully. At one last attempt by Dr. Bartolo to apprehend the presumed scoundrel Almaviva’s proclaimed identity and revelatory aria, “Cessa di più resistere” [“Cease any further resisance”] put an end to such challenging opposition. Mr. Shrader’s ornamentation and sheer vocal facility in this piece are flawless, matched in excitement by the following, more rapid “Ah il più lieto, il più felice” [“The blithest, the happiest”] describing his ardor for the love now granted. Almaviva’s final word “felicità” accentuates the happy spirit which invests this model new production of Rossini’s masterpiece.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/11_Alek_Shrader_Isabel_Leonard_BARBER_OF_SEVILLE_DR2_2519_cDan_Rest.png image_description=Alek Shrader and Isabel Leonard in Rossini’s “The Barber of Seville” at Lyric Opera. Photo: Dan Rest product=yes product_title=Chicago’s New Barber of Seville product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino product_id=Above: Alek Shrader and Isabel Leonard in Rossini’s “The Barber of Seville” at Lyric Opera. [Photo by Dan Rest]Lucia in LA: A Performance to Remember

In 1835 Gaetano Donizetti composed his drama tragico Lucia di Lammermoor to a libretto by Salvadore Cammarano. He based upon Sir Walter Scott's 1819 historical novel The Bride of Lammermoor. Scott based his plot on a seventeenth century incident that took place between Janet Dalrymple and her lover, Archibald, the third Lord Rutherfurd. The Dalrymple family, who lived in in the Lammermuir Hills of south-east Scotland, objected to the match because Rutherfurd was poor and supported King Charles II. The Dalrymples, who were staunch Whigs, preferred a constitutional monarchy to absolute rule.

An impassive Janet married her family’s choice, Sir David Dunbar of Baldoon Castle, on August 24, 1669. Not long after the couple retired, screaming was heard from their room. When the family forced the door open, they found David bleeding from stab wounds. Janet was trying to hide in a corner and she had blood on her nightgown. We only know that she appeared to be insane and died two weeks later. Scott had once been in love with a lady who jilted him for a richer man, so his novel may have reflected a personal emotional response.

On March 15, 2014, Los Angeles Opera presented Elkhanah Pulitzer’s production of the opera, which she set in 1885 when women were beginning to be recognized as persons separate from their fathers, brothers and husbands. At that time many European countries were beginning to allow women to own property, obtain higher education, and choose their husbands. An 1882 Swedish law granted women the right to choose their own marriage partners. Women in Scotland could have known what rights might soon be theirs.

Edgardo, Saimir Pirgu, finds that Lucia, Albina Shagimuratova, is marrying Arturo, Vladimir Dmitruk

Edgardo, Saimir Pirgu, finds that Lucia, Albina Shagimuratova, is marrying Arturo, Vladimir Dmitruk

Carolina Angulo’s scenery for Pulitzer’s production was totally unembellished except for a few neon strips, and it became a background for Duane Schuler’s lighting and Wendall K. Harrington’s fascinating projections that realized much of what was being sung in the libretto. Christine Crook’s stylized costumes were equally lacking in detail, but they served to set the time of the action in the past.

Soprano Albina Shagimuratova portrayed a troubled Lucia who had hallucinations from the beginning. An accomplished virtuoso, she created a real character and sang the coloratura trills and cadenzas of the Mad Scene with freshness and verve. Commanding the stage as her passionate lover Edgardo, tenor Saimir Pirgu sang with great beauty of tone and a variety of sound colors. He was already a fine tenor when he first came to LA to sing Rinuccio in the company’s 2008 Gianni Schicchi, but he has since become one of the world’s most important interpreters of lyric tenor roles. Even with the inclusion of an extra scene in this production, he sounded as fresh at the end of the opera as he did when it began.

Baritone Stephen Powell who impressed the San Diego audience in Pagliacci, was thoroughly confrontational as Lucia’s bully of a brother, Enrico. His evenly focused stentorian tones let you know that he would have his way, no matter what the consequences. As the Calvinist preacher, Raimondo, James Cresswell was the sanest of the principal characters, but his version of religion was no help to the heroine. Vocally, his range was even from top to bottom as he sang Donizetti’s difficult music.

I hope this cast will record the opera. This sextet, in particular, with six equally strong wonderful voices, deserves to have a wider hearing. Vladimir Dmitruk, the Arturo, will probably make a good career in the future and D’Ana Lombard, the Alisa, may go on to more important roles. Joshua Guerrero, who had already been spotted as a new talent when he sang in last year’s Evening of Zarzuela and Latin American Music, was a committed Normanno.

Enrico, Stephen Powell, and Lucia, Albina Shagimuratova

Enrico, Stephen Powell, and Lucia, Albina Shagimuratova

This was a complete rendition of the opera that opened up the usual cuts. The inclusion of the Wolf’s Crag Scene brought some music to the stage that many operagoers might never have heard sung live before. It also added to the audience’s knowledge of Edgardo’s character. Although the movements of members of Grant Gershon’s chorus were stylized, they added greatly to dramatic tension of each of the scenes in which they appeared with their strong, well-harmonized singing.

James Conlon brought us not only the complete Lucia, he performed it for us the way Donizetti originally conceived it. That included Thomas Bloch’s exquisite playing of the glass harmonica as the accompaniment to Lucia’s madness. The instrument is composed of numerous blown crystal glass bowls fitted into one another but not touching. They are held in place by a horizontal rod. The diameter of each bowl determines its note and a pedal controls the rotation of all so that the player can rub their edges with wet fingers as the bowls turn.

Maestro Conlon gave his audience dramatic climaxes as well as long lyrical lines while supporting the singers by keeping the decibel level low enough for them to be heard with ease. This was an extraordinary rendition of this well known opera that many in the audience will remember for years to come.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Normanno, Joshua Guerrero; Enrico, Stephen Powell; Raimondo, James Creswell; Lucia, Albina Shagimuratova; Alisa, D’Ana Lombard; Edgardo, Saimir Pirgu; Arturo, Vladimir Dmitruk; Conductor, James Conlon; Director Elkhanah Pulitzer; Projection and Scenic Designer, Wendall K. Harrington; Scenery Designer, Carolina Angulo; Costume Designer, Christine Crook; Lighting Designer, Duane Schuler; Chorus Master, Grant Gershon; Movement, Kitty McNamee.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/LdL5SHAG%20MAD018.png

image_description=Albina Shagimuratova as Lucia in Mad Scene [Photo by Robert Millard]

product=yes

product_title=Lucia in LA: A Performance to Remember

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Albina Shagimuratova as Lucia in Mad Scene

Photos by Robert Millard

San Diego Opera Presents an All Star Ballo in Maschera

In 1857, the Teatro San Carlo in Naples commissioned Giuseppe Verdi to write an opera. He first intended the work to be his King Lear, but that could not be ready in time for the 1858 Carnival Season. Later, he and his librettist Antonio Somma decided to base an Italian opera on Eugène Scribe’s French libretto for Daniel Auber's Gustave III, ou Le bal masqué. Scribe wrote about the 1792 assassination of King Gustav III of Sweden who was shot while attending a masked ball. Censors in Italy, however, had serious objections. Verdi and Somma made changes, only to be refused a second time. In his libretto, Scribe had kept the historical figures of Gustav and the fortune-teller, but added the character of Amelia and her romance with the king.

On January 14, 1858, several Italians attempted to assassinate Emperor Napoleon III in Paris. After that, censors absolutely forbade the opera to show the murder of a monarch. They told Verdi and Somma to make further changes. Verdi was so angry that he broke his contract. The management of San Carlo sued him and he countersued. After some months, when the legal issues were resolved, Verdi was free to present the libretto and musical outline of the work to the Rome Opera. Since censors demanded further changes, they moved the site of the action to Boston during the British colonial period.

Tenor Piotr Beczala (Gustav III) and mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe (Madame Arvidson).

Tenor Piotr Beczala (Gustav III) and mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe (Madame Arvidson).

On February 17, 1859, The Teatro Apollo in Rome premiered Un ballo in maschera (A Masked Ball). Not until the twentieth century was the site of the action moved back to Sweden. Now the baritone is called Count Anckarström after the actual killer who was beheaded for his crime.

On March 11, 2014, San Diego Opera presented Verdi’s A Masked Ball in a traditional production by Leslie Koenig. She used wonderfully ornate older scenery that formed an excellent background for John Conklin’s soft colored costumes and Gary Marder’s well-planned lighting designs. Metropolitan Opera star tenor Piotr Beczala was Gustav III, the king of Sweden. It’s a long role and there were a few rough-edged tones in his first aria, but after that he gave a radiant performance. His duet with Krassimira Stoyanova, the Amelia, and his final aria were superbly sung. Stoyanova's lustrous voice blended well with Beczala's and she gave an insightful portrayal of his troubled but innocent love interest.

Greek baritone Aris Argiris is new to San Diego. With his performance of Count Anckarström, he established himself as a fine singing actor with a stentorian voice and a commanding presence. His scene with Amelia made sparks fly across the orchestra pit. Stephanie Blythe has an incredible voice with a distinctive sound and a huge range of tone colors, all of which she used as Madame Arvidson, the mysterious fortune-teller.

Act 3 finale

Act 3 finale

The trouser role of Oscar requires a coloratura soprano to provide a bit of comic relief in the midst of this dark, tragic story. Kathleen Kim’s bright sound and jaunty stance provided just the right touch for the part. Joseph Hu was thoroughly amusing as an infirm High Judge. Dark voiced Kevin Langan and Ashraf Sewailam were impressively menacing as Counts Ribbing and Horn.

Chorus Master Charles F. Prestinari’s singers represented townspeople of various professions and they sang together in solid harmonies. Conductor Massimo Zanetti made a most auspicious debut and proved that the orchestra can be part of the drama. He brought the orchestra up to fortissimo on some occasions when there was no singing and kept it down to a reasonable level when soloists had to be heard above it.

Maria Nockin

____________________________________

Cast and Production Information:

Count Ribbing, Kevin Langan; Count Horn, Ashraf Sewailam; High Judge and Amelia’s Servant, Joseph Hu; Gustav III, Piotr Beczala; Count Anckarström, Aris Argiris; Amelia Anckarström, Krassimira Stoyanova; Madame Arvidson, Stephanie Blythe; Oscar, Kathleen Kim; Conductor, Massimo Zanetti; Director, Lesley Koenig; Costume Designer, John Conklin; Chorus Master, Charles F. Prestinari; Lighting Design, Gary Marder; Choreographer, Kenneth Von Heidecke

image=http://www.operatoday.com/BAL1_1560a-L.png

image_description=Baritone Aris Argiris (Count Anckarstrom) and soprano Krassimira Stoyanova (Amelia) in San Diego Opera's A MASKED BALL. March, 2014. [Photo copyright Ken Howard]

product=yes

product_title=San Diego Opera Presents an All Star Ballo in Maschera

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Baritone Aris Argiris (Count Anckarstrom) and soprano Krassimira Stoyanova (Amelia) in San Diego Opera's A MASKED BALL. March, 2014.

Photos © Ken Howard

Anne Schwanewilms, Wigmore Hall

As in their December 2011 recital at the Wigmore Hall, Schwanewilms and pianist Charles Spencer chose to open both halves of the evening with songs from Mahler’s Des Knaben Wunderhorn — indeed they repeated the previous programme almost in its entirety, deviating only at the end when three songs by Richard Strauss replaced Mahler’s five Rückert Lieder. But, who minds such replication when the singing is so refined, the artistry so expressive and the partnership between soprano and accompanist so finely attuned.

Schwanewilms can command the world’s grandest operatic stages: her voice is luxurious and immense, and her sense of character and situation discerning and adroit. Indeed, commenting upon her recent Metropolitan Opera appearance as the Empress in Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten, one critic observed ‘Schwanewilms was still a powerful presence even when she was silent’. But, she always tailors the expanse and colour of her voice, and the articulation of the text, to the poetic or dramatic situation. Pianist Roger Vignoles has suggested that ‘to enter the world of Mahler’s Wunderhorn songs is like opening a picture book. Each page gives us another character, another fairy tale, another episode, whether happy or tragic, in the tale of human existence’, and here Schwanewilms put her protean naturalism to superb effect in Mahler’s enchanting songs, by turns wryly comic and sweetly pastoral.

Bird-song pre-dominated. In ‘Um schlimme Kinder artig zu machen’ (How to make naughty children behave), Spencer’s dry staccato and droll rubatos introduced Schwanewilms’ nonchalant presentation of the folky ballad, the ringing cuckoo-calls amusingly onomatopoeic. Sadly, the cuckoo met his demise in the following song, ‘Ablösung in Sommer’ (The changing of the summer guard), exhausted by his own lusty singing, to be replaced by the nightingale; this shift from the rustic clowning of the preceding song to transcendent lyricism was perfectly represented by the soprano’s silky tone, crystalline at the top, and Spencer’s intricate embellishments.

In ‘Ich ging mit Lust’ (I walked joyfully) the simple sweetness of the rising phrases blossomed to acquire an ecstatic sheen as Schwanewilms conveyed the pure delight inspired by ‘Die kleinen Waldvögelein im grünen Wald!’ (those woodland birds in the green wood!). Changes of key and texture were thoughtfully nuanced, the curving rhapsodic phrases uplifting, and the ending poignant — ‘Wo ist dein Herzliebster geblieben?’ (Where is your sweetheart now?). Spencer effectively pointed the piquant harmonies and twists in ‘Verlorne Müh’ (Wasted effort), and Schwanewilms proved equally convincing as both the crafty flirtatious shepherdess who attempts to entice her ‘laddie’ and the stubbornly unyielding shepherd boy himself — mulishly flinging his final refusal at the enamoured lass, ‘Ich mag es halt nit!’ (I’ll have none of it).

The later sequence of Wunderhorn songs plumbed deeper emotions, beginning with ‘Scheiden und Meiden’ (Farewell and parting). Schwanewilms bloomed gloriously through the impassioned departure depicted in the first stanza, while the rich hues of her lower register cast a more ominous shadow over the second stanza, with its allusions to darkness and death: ‘Es scheidet da Kind schon in der Wieg!’ (The child departs in the cradle even!). The closing leave-takings — ‘Ade! Ade!’ — expressed first urgent desire and then resigned acceptance.

‘Rheinlegendchen’ (Little Rhine legend) span a charmingly innocent narrative, the piano interludes playing their part in conveying imagery and feeling. ‘Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen’ (Where the splendid trumpets sound) was one of the highlights of the Mahler lieder, beautifully poetic as the soprano first enriched her tone, ‘Das Mädchen stand auf, und ließ ihn ein’ (The girl arose and let him in), and then retreated, the ethereally floating phrase, ‘Willkommen, lieber Knabe mein’ (O welcome, dearest love of mine), suggesting the fragility of the wondrous, longed-for moment. Schwanewilms bestowed a warmth upon the soldier’s admission that he must soon depart, before Spencer’s alert ‘trumpet-calls’ (reminding us that in these songs Mahler conjures on the piano the diverse instrumental colours of the original orchestral scoring) whisked him away to war.

We began where we started, with a singing competition between the cuckoo and nightingale, ‘Lob des hohen Verstandes’ (In praise of high intellect) with Schwanewilms once more relishing the opportunity to imitate the musical calling cards of the natural world.

Between the two Mahler sequences, songs by Lizst encouraged both singer and accompanist to expand their expressive range. In ‘Oh! Quand je dors’ (Ah, while I sleep) Schwanewilms demonstrated her thrilling power and consummate control, swelling and then retreating to an exquisite pianissimo with absolute assurance, and subtly modifying the colour of the final held note to underscore the change from major to minor tonality: ‘Soudain mon âme/ S’éveillera!’ (at once my soul/will wake!) Three songs from ‘Lieder aus Schillers Wilhelm Tell’ followed. ‘Der Fischerknabe’ (The fisherboy) was notable for the weightless, gliding rise in the closing line, ‘Ich locke den Schläfer,/ Ich zieh ihn herein’ (I lure the slumberer/ and drag him down), the transparent piano postlude underpinning the melodic paradox. Similarly, in ‘Die Hirt’ (The shepherd) and ‘Der Alpenjäger’ (The alpine hunstman), Spencer’s part in the communicating the narrative was not inconsiderable.

Closing the first half, an impassioned rendition of ‘Loreley’ showcased Schwanewilms’ ability to effortlessly modulate the mood and the extraordinary power and flexibility of her voice across an astonishing range. The tone was sumptuous, the legato seamless, and the complex architecture ofo the song skilfully crafted.

One of the finest Straussian’s performing on the operatic stage today, Schwanewilm offered three of the composer’s songs to conclude. The melodic lines of ‘Die Nacht’ were imbued with energy, painting a vivid portrait of darkness as it extinguishes and steals the lights of the world — ironically, the soprano’s own voice reverberated with the flowers’ colours and the river’s silvery gloss which the nocturnal visitant plunders. Spencer’s urgent, climbing lines and heavy accompanimental rhythms brought a sense of desperation to the closing verses of ‘Geduld’ (Patience). The concluding ‘Allerseelen’ (All Souls’ Day) was laden with nostalgia, most especially in the intense repetitions of longing (‘Gib mir nur einen deiner süßen Blicke’, (give me but one of your sweet glances)) and the rapture of the final cry, ‘Komm’ an mein Herz, daß ich dich wieder habe’ (come to my heart and so be mine again).

Schwanewilms knows and understands these songs, but the delivery retains a freshness which is entrancing. Quite simply, one cannot imagine anyone singing them better.

Claire Seymour

Programme:

Mahler — From Des Knaben Wunderhorn: ‘Um schlimme Kinder artig zu machen’; ‘Ablösung im Sommer’; ‘Ich ging mit Lust’; ‘Verlorne Müh’; ‘Scheiden und Meiden’; ‘Rheinlegendchen’; ‘Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen’; ‘Lob des hohen Verstandes’. Liszt — ‘Oh! quand je dors’; ‘Lieder aus Schillers Wilhelm Tell’; ‘Die Loreley’. Richard Strauss: ‘Die Nacht’; ‘Geduld’; ‘Allerseelen’. Anne Schwanewilms, soprano; Charles Spencer, piano. Wigmore Hall, London, 13 March 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/A_Schwanewilms_%28c%29_Javier_del_Real_WEB.png image_description=Anne Schwanewilms [Photo by Javier del Real] product=yes product_title=Anne Schwanewilms, Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Anne Schwanewilms [Photo by Javier del Real]Die Frau ohne Schatten, Royal Opera

Dread memories of Christof Loy (Tristan and Lulu, here in London, still more his unspeakable Salzburg travesty of Die Frau) made me wonder afterward whether I had shown undue clemency, but no: almost two days later, I am still reeling from the impact of so extraordinary a performance, one which no house in the world could conceivably improve upon, and which I doubt could even be matched. For whilst Claus Guth’s production had many virtues, which I shall come to a little later, it was Strauss’s astonishing, still widely misunderstood, score which, rightly, had pride of place. If any performance, anywhere in the world, does more for his cause in this anniversary year, I think I shall find myself in need of a new vocabulary of superlatives.

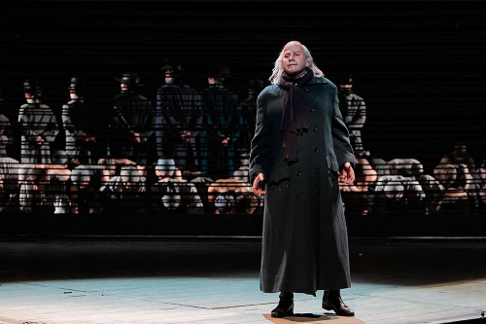

Johan Reuter as Barak and Elena Pankratova as Barak’s Wife

Johan Reuter as Barak and Elena Pankratova as Barak’s Wife

Above all, I must commend Semyon Bychkov and the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. The very first time I heard this work was in 2001, the final outing of John Cox’s Royal Opera production, with celebrated designs by David Hockney; Christoph von Dohnányi’s conducting of the orchestra remains one of the finest I have heard of a Strauss opera. Then, I found myself lost in admiration both for his and for this orchestra’s achievement. Bychkov proved himself every inch Dohnányi’s equal; indeed, I am not entirely sure that he was not surpassed. No matter: it is not a competition. Bychkov’s command of the orchestra was nothing short of awe-inspiring. If in retrospect, the first act seemed seemed a little on the expository side, then that is surely a reflection of Strauss’s writing. Patiently building up not only the dramatic tension but the motivic material from which the score would truly, ravishingly blossom, Bychkov showed himself possessed in equal measure of an ear for colour so acute as almost to rival Boulez — now imagine a FroSch from him! — with the deepest of structural understanding. Horizontal and vertical presentation of the score offered in conjunction with voices and staging a three-, even four- dimensional performance to rival that one sees in one’s mind when hearing Karl Böhm on CD. And if the Covent Garden did not sound quite with Böhm’s Viennese sweetness, it had phantasmagorical qualities all of its own: the refreshment of a true rival rather than the flattery of imitation. More than once, I found myself thinking, doubtless heretically: Klangfarbenmelodie! Strauss’s uncomprehending disdain for the ‘atonal’ Schoenberg notwithstanding, we did not stand so very far from the world of the latter’s op.16 Orchestral Pieces. Bychkov’s ear for combining musico-dramatical tension in the combination of sonority and harmonic tension ensured that we must think of him as not only an excellent, but a great Straussian.

And then — the singing! That earlier Covent Garden performance had also marked my first encounter with Johan Botha. He proved at least as remarkable more than twelve years on. This Emperor, as mellifluous as he was vocally powerful, sounded every inch a Siegfried, and a golden age Siegfried at that. (If indeed such an age ever really existed.) Emily Magee had a few moments of relative infallibility, but by any reasonable standards, her Empress was an impressive achievement, all the more so given the wholehearted dramatic commitment offered in conjunction with the purely vocal. Elena Pankratova was making her Royal Opera debut as Barak’s Wife; hochdramtisch singing of the highest order was to be savoured here, her climaxes at the end of the first and second acts sending shivers down the spine. If Johan Reuter’s Barak at first sounded a little plain, that may as much have been character-portrayal as anything else; his performance grew into something genuinely moving, testament to the potential greatness of, as it were, Everyman (to borrow from Hofmannsthal’s future). As for Michaela Schuster’s Nurse, her offerng of musical and dramatic malevolence — tonality on less the pre- than the post-Schoenbergian brink, though never beyond it — would have been an object lesson in itself, even had it not been heightened by such stage presence and intelligence. Smaller roles were almost all impressively handled, David Butt Philip’s attractively voiced Apparition perhaps especially worthy of note. The only disappointment was the tremulous Falcon of Anush Hovhannisyan. Renato Balsadonna’s Royal Opera Chorus was, as expected, excellent throughout.

Elena Pankratova as Barak’s Wife; Michaela Schuster as Nurse and Emily Magee as Empress

Elena Pankratova as Barak’s Wife; Michaela Schuster as Nurse and Emily Magee as Empress

Guth’s staging, first seen at La Scala in 2012, presents the Empress in a sanatorium, Christian Schmidt’s stylish designs highly evocative of the time of composition. Our heroine is, one might say, hysterical in every sense. To begin with, she — and we — are somewhat unclear concerning the boundaries of reality and dream. Is Freud being channelled or satirised? Unclear, and all the better for it, which renders the very ending, in which it appears ‘all to have been a dream’ something of a disappointment. That said, much of what we see in between is riveting. With the best will in the world, some of Hofmannsthal’s symbolism upon symbolism — The Magic Flute really is best left alone — can seem unnecessary; it certainly seemed — and seems — to do so to Strauss. Yet the poet’s idea of transformation gains a fair hearing, or rather viewing, and there is a proper sense of the mythological, even the fantastical, to the dreamed world we enter, never more so than at the spectacular close to the second act, Olaf Winter’s lighting crucial here, and the craggy opening of the third. Those problematical echoes of Tamino and Pamina’s trials are presented with greater visual conviction than I can previously recall — and indeed greater conviction than one often sees in productions of the ‘original’. The sheer weirdness but also menacing sense of judgement emanating from a courtroom of strange creatures close to the end not only testifies to imagination and its possibilities but also to the misogynistic pro-natalism, from which, try as we might, we cannot ultimately rescue the opera. By contrast, Loy in Salzburg arrogantly declared that the work did not interest him and made not even the slightest attempt to deal with it. It was the sort of thing that might appeal to those who do not care for Strauss, or indeed Hofmannsthal, in the first place, though even they would most likely have been bored to tears with the banal ‘alternative’ narrative presented. Guth, for the most part, successfully treads a tightrope between presentation and interpretation.

A good staging then, and a truly outstanding musical performance. My first act upon returning home was to visit the Royal Opera House website, to buy myself another ticket. Hear this if you can. The performance on 29 March will be broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 at 5.45 p.m.

Mark Berry

Cast and production information:

Nurse: Michaela Schuster; Spirit Messenger: Ashley Holland; Emperor: Johan Botha; Empress: Emily Magee; Voice of the Falcon: Anush Hovhannisyan; The One-Eyed: Adrian Clarke; The One-Armed: Jeremy White; The Hunchback: Hubert Francis; Barak’s Wife: Elena Pankratova; Barak: Johan Reuter; Serving Maids: Kathy Batho, Emma Smith, Andrea Hazell; Apparition of a Youth: David Butt Philip; Voices of Unborn Children: Ana James, Kiandra Howarth, Andrea Hazell, Nadezhda Karyazina, Cari Searle, Amy Catt; Night-Watchmen: Michel de Souza, Jihoon Kim, Adrian Clarke Voice from Above: Catherine Carby; Guardian of the Threshold: Dušica Bijelić. Director: Claus Guth; Designs: Christian Schmidt; Lighting: Olaf Winter; Video: Andi A. Müller; Associate Director: Aglaja Nicolet; Dramaturge: Ronny Dietrich; Royal Opera Chorus (chorus master: Renato Balsadonna)/Orchestra of the Royal Opera House/Semyon Bychkov (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Friday 14 March 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/140311_1111.png image_description=Emily Magee as Empress [Photo © ROH / Clive Barda] product=yes product_title=Die Frau ohne Schatten, Royal Opera product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Emily Magee as EmpressPhotos © ROH / Clive Barda

March 13, 2014

Jean-Paul Scarpitta in Montpellier

Jean-Paul Scarpitta however wanted to talk about his battles, a situation he has not yet spoken about publicly. As the luncheon meeting progressed the battles, the man and his Mozart trilogy merged into a single philosophy created of quite complex components.

It all starts with composer René Koering who brought Jean-Paul Scarpitta to Montpellier in 2001 for a small mise en scène of Saint-Saêns’ Carnival of the Animals. Koering who had a long standing programming connection with Radio France founded the Festival de Radio France et de Montpellier Languedoc-Roussillon in 1985. Always a forum for rare music and performances, in the first decade of the next century this superb summer festival was especially noted for reviving forgotten operas from the early twentieth century.

In 1990 Koering became the director of the Opéra Orchestre National de Montpellier (OONM), bringing the ideals of the festival into the daily musical life of Montpellier — a broad program of symphonic and chamber music, original productions of rare and standard opera at ticket prices that encourage filled halls (top prices even in 2014 are but 32 euros for concerts and 65 euros for operas plus there are substantial discounts for subscribers and those under 27 years of age).

Montpellier’s 250,000 residents are part of an urban area that counts 550,000 inhabitants, making it the fourteenth largest metropolitan area in France. Its Opéra however is one of only five regional companies (with Bordeaux, Nancy, Lyon, and Strasbourg) that are designated as national, denoting a stature more or less akin to the Opéra National de Paris.

Jean-Paul Scarpitta returned to the festival in 2004 to stage Kodály’s singspiel Háry Jànos. But with a twist. Scarpitta brought his friend Gérard Depardieu with him to narrate Kodaly’s tale about a country bumpkin who arrives in Vienna. Scarpitta’s first steps as a metteur en scène had been back in 1997 for Stravinsky’s A Soldier’s Tale at Paris’ Théâtre des Champs-Élysées with Depardieu as the soldier. I asked how he knew Depardieu. Scarpitta said that he had gone backstage after a performance to introduce himself. Responding to my un-asked question Scarpitta said that you accept your friends as they are.

Conductor Ricardo Muti has been an important force in Scarpitta’s artistic life for the past 20 years. I asked how he came to know the famous maestro. Scarpitta said he introduced himself going backstage after a performance, greatly moved by the music.

Jean-Paul Scarpitta [Source: Wikipedia]

Jean-Paul Scarpitta [Source: Wikipedia]

Scarpitta confessed that he needs to admire. An adolescent, his greatest admiration was of ballerina Ghislaine Thesmar who later became a star at the Paris Opera Ballet in the 1970‘s, and a frequent guest star at the New York City Ballet as well. Scarpitta told me how he, a student of art history, followed her to New York with his camera, documenting her work with George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. Another photographic adventure as well helped propel the young Scarpitta to recognition in Parisian artistic circles — he compiled an exhibition of 50 years of fashion photography in Vogue magazine, an exhibition that toured the world.

I neglected to ask what repertoire Muti conducted the night Scarpitta met the maestro. Maybe it was Mozart, a composer Muti became close to in his forty year association with the Vienna Philharmonic. The Italian conductor is famous for his strongly personal Mozart, fusing intelligence, elegance and wit, attributes that as well extend to the stagings of the Mozart/DaPonte trilogy by Jean-Paul Scarpitta.

For Scarpitta art is line and form and tone, in music, dance and photography. But above all else Scarpitta insists that it is heart. Scarpitta announced to me that we are all Don Giovanni.

Those many years ago Muti told Scarpitta that he needed a theater where he would make his own art. Scarpitta’s was appointed general director of the OONM in 2011, fulfilling finally Muti’s assertion. That same year Muti invited Scarpitta to stage Nabucco in Rome. The production became famous not because of Scarpitta’s staging but because at the premiere Muti laid down his baton after the "Va pensiero" chorus to speak to the audience about the Berlusconi budget cuts to the arts, quoting a line from the chorus, “Oh mia patria, sì bella e perduta (lost).”

Muti then invited the public to sing along in a repeat of the famous chorus. Learn the words before you attend Nabucco at the Chorégies d’Orange this summer where "Va pensiero" has always been a singalong. It will again be staged by Scarpitta.

And, quid pro quo, Scarpitta invited Muti’s daughter Chiara to Montpellier to stage Orfeo ed Euridice this past fall (yes, the Italian, not the French version), her debut as an opera director.

Enter another of the forces in Scarpitta’s artistic life: Georges Frêche, mayor of Montpellier from 1977 until 2004 when he became president of the Montpellier agglomeration and then president of the conseil régional de Languedoc-Rossillon until his death in October 2010. This remarkable man, prominent in the Socialist Party his entire life, gave Montpellier its current look, initiating major urbanization projects that have made Montpellier a model for the world. Among the most significant is a huge central plaza, the Place Comédie and Esplanade, with the fine old (1888) 1200 seat Opéra Comédie at one extreme and the ultra-modern, 2000 seat Théâtre Berlioz at the other. Scarpitta deems this expanse of enlightened urbanization a sleeping beauty, begging to be artistically fulfilled.

Evidently a passionate proponent of the arts Georges Frêche was also an advocate of making the arts accessible to a large public. He had his disciple in René Koering whom he advanced to Superintendent of Music for Montpellier in 2000. A golden era ensued that ultimately gave Jean Paul Scarpitta his theater, among many other accomplishments. Scarpitta staged the world premiere of Pergolesi’s never before performed Salustia, Hindemith’s lurid Sancta Susanna, Honneger’s Joan of Arc at the Stake, plus Offenbach’s never finished La Haine (here completed by composer Koering) with Depardieu and another of Scapitta’s fascinations, actress Fanny Ardant.

Koering named Scarpitta to “artist-in-residence” at OONM for 2006/07 thus signaling to the honorable Frêche that Scarpitta was artistically and politically his obvious successor. Scarpitta had moved in the François Mitterrand circles in Paris in the 1980’s (as did Françoise Sagan who became, by the way, an intimate friend of Scarpitta). Interestingly Mitterrand, France’s first socialist president, always kept his distance from Frêche who had been a fervent Maoist in the 1960’s and remained ever since a firebrand politician.

The death of Frêche in 2010 upended and ended the office of Superintendent of Music, its finances were made public (Montpellier’s daily newspaper Midi Libre reported that Koering had awarded himself an annual salary of 294,000 euros), its considerable deficits were questioned, and furthermore France’s Ministry of Culture had descended from Paris to insist that something be done about the quality of the chorus — not up to the standard of an opéra national!

Koering, then 70 years old, his artistic and political accomplishment enormous, stepped aside a year before his contract expired to make way for new energy — a team headed by Jean-Paul Scarpitta.

Rare and forgotten repertory has all but disappeared from Scarpitta’s personal theater, replaced by the grand repertory of heroines who are victims — Carmen, Manon, Violetta and particularly Mimi whom Scarpitta deems a saint who gains the veneration of all those who surround her. As a stage director Scarpitta describes his approach as instinctual rather than conceptual, allowing him to juxtapose the redemptive process effected by the sacrifices of these operatic heroines with his fascination for Baudelaire, a poet whose name he often mentioned during our lunch. In fact Baudelaire’s search in Les Fleurs du Mal for sublime beauty in crude reality is exactly matched in these four operas.

Scarpitta originally staged Mozart’s Don Giovanni in 2007 with France’s famed Le Concert Spiritual in the pit, this esteemed Baroque ensemble then in residence in Koering’s Montpellier. Most striking was the youth of the cast, and beyond that the perfection of the casting, each character beautifully defined physically, well endowed vocally and musically finished. The key to the staging was the hysterical laughter of Don Giovanni that ended the first act — a young man very unsure of himself, Scarpitta explained when I asked about the laughter. The uncertainties of youth were very present and made potent by fine singing. The death of the Don was but the catalyst of the consequent tragedies felt in all these young lives.

Les Noces de Figaro took us to another plain, that of luxury and elegance. Scarpitta’s friend, famous couturier Jean Paul Gaultier created the costumes that clothed the perfect cast. Again the crème de la crème of young singers who could have been cast because their bodies made high fashion design look like such, or these singers could have been cast because they were capable of highly refined lyricism. Scarpitta’s staging too was all about elegance, that restrained beauty inherent in minimal movement (this included several quite graceful full body falls). In spite of Figaro assuming the fetal position during Marcellina’s aria Mozart’s humanity was the casualty of the production.

Jean Paul Gaultier and Jean-Paul Scarpitta are both directors of the Carla Bruni-Sarkozy Foundation, an activity very much on Scarpitta’s mind. The foundation offers educational opportunities to academically talented, under-privileged youth, and stresses that the grants are made to youth both on the political right and left. In 2007 Scarpitta was one of 150 French intellectuals who signed a letter supporting Socialist Party candidate Ségolène Royal in her bid for the presidency of France won by Nicolas Sarkozy. On the other hand Scarpitta was one of 20 prominent French artists who signed a letter supporting Sarkozy in the 2012 presidential election.

As for nearly all the operas he has staged for Montpellier Scarpitta designed the set for Cosi fan tutte — a green floor and a blue wall. That is all. There is however no minimalism whatsoever in the pit. Conductors for the trilogy have been as young and talented as the cast. For Cosi it was English conductor Alexander Shelley who brought remarkable musical depth to this problematic Mozart opera. In fact this conductor made time stand still — the opera was not about its silly story, it was about the voices of youth, and Scarpitta’s staging left no emotive pulse of the music without an empathetic position. The splendid young cast abstractly danced to the music of this conductor.

Le Figaro rightly discerned that there was no humor in this Cosi, and went on to find a complete absence of stage direction in Scarpitta’s stripped down production, adding that the voices of the Fiordiligi and Dorabella were splendid if you did not have to look at the stage, and that the Despina was the only dramatically alive character on the stage. Le Monde rightly discerned that this was a staging of a légèreté galante (galant lightness), but meant that such an approach is hardly the current and appropriate politic for Cosi. And furthermore that the cast was uniformly mediocre, especially the Despina. Well, except the Dorabella who was magnificent, not to mention the equally wonderful violas of the orchestra, alto voices evidently on this critic’s mind.

An internet blogger correctly attributed Scarpitta’s dramaturgy to Robert Wilson (or “Bob” as he is known in France) and to Giorgio Strehler, suggesting that it is mere imitation. The venerated Italian metteur en scène Strehler was the first of Scarpitta’s theatrical fascinations, and through ballerina Ghislaine Thesmar he wangled an introduction. He then became part of Strehler’s Parisian cadre, observing this great director at work.

The European operatic avant garde has long been smitten with Texan Robert Wilson (Scarpitta now has Wilson’s, that is Bob’s gifted lighting designer Urs Schönebaum as part of his creative team). If Scarpitta’s stagings are homages to these two theatrical geniuses they are as well his homages to opera’s grand repertoire. This is Scarpitta’s style, based on his greatest need — to admire. This operatic minimalism, seen through Baudelaire’s filter of evil flowers gives Scarpitta his unique, and original directorial voice.

Scarpitta has not had good press, for example the Montpellier daily Midi Libre blindly repeated assertions by the chorus that he does not read music. I asked if he in fact does not read music. Of course he does, and plays the piano, one of the passions of his early youth. He does not read orchestral score, nor do I, nor I imagine do most of the choristers.

The Scarpitta artistic vision for Montpellier, and some of the guest conductors, like Riccardo Muti, and designers like Schönebaum have placed great pressures on the OONM salaires — the chorus, orchestra and the stagehands, the workers in the artistic trenches of the opera company. After the comfortable satisfactions of the Koering years they have not liked the Scarpitta challenges and have effected his removal from the direction of OONM.

Scarpitta has one final staging in his contract, Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle that will occur in fall 2014. Don Giovanni and Barbe-bleue are two masculine operatic signposts that hold great interest for Scarpitta. Like Giovanni, Barbe-bleue dares to show his inner self, his solitude, his sorrows, his difficulties with relationships. Scarpitta believes that the blood on Bartok’s stage is actually that of Bluebeard, oozing more each and every day. There is no doubt that it is Scarpitta’s blood to be spilled all over the stage this fall. And I believe he will have enjoyed every minute of his combats montpelliérains.

Scarpitta wishes his successor, Valérie Chevalier, success. He recognizes her very great experience will be quite useful as she confronts the enormous financial, artistic and political challenges facing OONM. In the wake of the Scarpitta difficulties for this current season the Regional Council, a supporter of Scarpitta, had diminished its contribution by 5 million euros (Georges Frêche had taken it to 9,5 million so it became 4 million). The president of the Montpellier agglomeration, Jean Pierre Moure, who removed Scarpitta from the OONM direction, stepped in with an additional 5 million to restore the budget to 24,000,000 euros. President Moure has made himself a very important patron of and participant in the affairs of the OONM.

It was a tense lunch at the Jardin des Cinq Sens, a Relais et Chateaux with its Michelin starred restaurant, Scarpitta’s residence when in Montpellier. He was on edge knowing that he is raw meat for journalists. I could not find a way to put him at ease and we never really connected during those two and one half hours. Well, maybe at the end we did — when we stood up he used his napkin to brush off the breadcrumbs that had fallen onto my shirtfront.

We met again after the late afternoon symphony concert at the Théâtre Berlioz. Young Alexander Shelley of the Scarpitta Cosi had conducted, slowly, very slowly Franck’s Symphony in D minor, and the principal cellist of the Orchestre National de Montpellier, Alexandre Dmitriev had performed Henri Dutilleux’s Tout un monde lointain, the title a verse from Baudelaire’s La Chevelure, and each of its five movements prescribed with verses pulled from Les Fleurs du Mal. Seated within sight of Scarpitta we could see he was transfixed (the man sitting next to me went to sleep). It was also quite apparent that some sections of the orchestra are in need of modernization.

No longer on edge, and walking on air after the Dutilleux, Scarpitta kissed the hand of my wife and recalled his trip through San Francisco, how he had admired the city on his way to Napa to visit his friend — yes, you guessed it — Francis Ford Coppola.

Michael Milenski

Michael Milenski resides in San Francisco in spring and fall, and in the south of France in winter and summer. His reviews of the Scarpitta Mozart/DaPonte operas are on Opera Today. This essay was compiled from articles in the French press, a lengthy statement by Jean-Paul Scarpitta on the website of the Carlo Bruni-Sarkozy Foundation, general information found on the web, and of course from his conversations with Mr. Scarpitta.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Scarpitta_Color.png

image_description=Jean-Paul Scarpitta [Photo by Marc Ginot / Opéra national de Montpellier]

product=yes

product_title=Jean-Paul Scarpitta in Montpellier

product_by=An interview by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Jean-Paul Scarpitta [Photo by Marc Ginot / Opéra national de Montpellier]

March 12, 2014

Interview: Tenor Saimir Pirgu — From Albania to Italy to LA

When legendary tenor Luciano Pavarotti was at a spa, he asked for a singer to come and perform for him. My teacher suggested that I sing for him. Pavarotti liked me so much that he became my mentor. That was the luckiest moment of my life! I was nineteen when I started working with him.