June 30, 2014

Ariadne auf Naxos, Royal Opera

Unimpressed by the librettist’s pretentiousness, Strauss replied that as a ‘superficial musician’ he couldn’t understand Hofmannsthal’s complex symbolism concerning the nature of Ariadne's salvation and transformation, and that the audience was likely to share his bafflement.

Hofmannsthal is certainly equivocal about why the interaction between the two seemingly incompatible philosophies of art and life presented in Ariadne auf Naxos results in the transfiguration of Ariadne as she lies in Bacchus’ arms at the end of the work. And, Christof Loy’s 2002 production doesn’t really address the opera’s theoretical conundrums; but, in the hands of a superlative cast, it does offer visual and musical sumptuousness and gratification. Back in 2002, the production marked both the re-opening of the Royal Opera House after a major refurbishment and the arrival of Antonio Pappano as musical director. The adventurousness of the striking coup de theatre at the start of the Prologue is an apt symbol of the aspiration and confidence which Pappano has brought to the House, and twelve years on this second revival retains its classiness and ambition.

Ariadne, daughter of Minos, the King of Crete, has helped her Athenian lover Theseus slay the Minotaur and escape from the labyrinth. However, upon their arrival on the island of Naxos, Theseus deserts his saviour and Ariadne languishes alone until Bacchus arrives, having fleed from Circe’s evil clutches. The grieving Princess mistakes Bacchus for Hermes, the messenger of Death, while he believes she is an enchantress — although this time he is happy to submit to her magic.

Jane Archibald as Zerbinetta and Ruxandra Donose as the Composer

Jane Archibald as Zerbinetta and Ruxandra Donose as the Composer

This is the subject of the after-dinner Opera commissioned by the ‘richest man in Vienna’ which forms Strauss’s second ‘Act’. It is preceded by a Prologue in which we see the Composer learn, with dismay and impassioned disbelief, that his noble opera seria is to be performed ‘simultaneously’ with the dances and distractions of a commedia dell’arte troupe. Consoled by his Music Master, he is forced to make sacrilegious cuts to his score while the comedians and dancers delight in devising the intrusive diversions.

Designer Herbert Murauer opening set is the entrance salon of an affluent mansion: it’s glossy and sleek, but also soulless. His Lordship’s money can buy anything, except sensibility; served by a haughty Major Domo (an imperious Christoph Quest) who can bark out orders but is denied the language of music, the master commissions masterpieces but rates fireworks about art.

Murauer swiftly takes us from the clinical vestibule into more creative, if somewhat chaotic, realms, the whole set magically rising as we descend into the cellar where the artists are at work. The transformation is slick, but it’s a pity that a 40-minute interval is necessary to dismantle the complex machinery that it necessitates and to assemble the Poussin-esque set for the ensuing Opera. Moreover, although the candle-lit emeralds and aquamarines of the ‘island’ are an effective representation of seventeenth-century taste (Jennifer Tipton’s lighting design is particularly atmospheric and emphasises the ‘artifice’ which is such a significant element of Strauss’s dialectic), the classical French Baroque landscape mural has little in common with the modern-period Prologue and there are scant directorial connections between the two parts of the opera. Costumes are similarly confusing: Ariadne dons mourning black, the nymphs and spirits sport eighteenth-century dress (one looks suspiciously like Mozart) and Zerbinetta — her stilletto boots and skimpy dress sluttishly flirtatious — is accompanied by a cast of entertainers dressed respectively in combat gear, a shiny shellsuit, tartan and rockers’ black leather. Ariadne’s cave is a dressing table perhaps to suggest that, peering into the mirror, she is consumed by her own solipsism?

But, things cannot fail to please with Karita Matilla taking the title role for the first time. Wittily self-parodic as the Prima Donna in the Prologue, she tranforms into a ‘real’ diva for the Opera proper, rapturous of voice and expertly balancing nobility with excess. Matilla’s soprano possesses a powerful Straussian lustre, easily capable of soaring over the orchestra, and she sings her long monologues with heartful commitment. But, she also finds variety of colour: recalling her happiness with Theseus in ‘Ein schönes war’ her tone is bright and joyful. And, Matilla demonstrates a strong lower range, particularly when she sings of the ‘Realm of Death’, building this monologue to an ecstatic climax.

Matilla commands the stage but the other principals are no less satisfying. Ruxandre Donose’s Composer was overflowing with adolescent fervour and idealism. Her smooth mezzo is perfect for Strauss’s flowing arioso melodies, and her outburst that ‘Musik ist eine heilige Kunst’ (music is a holy art) was full of elevated feeling and conviction. Donose made engaging use of a wide dynamic range and was totally convincing in her interaction with Jane Archibald’s Zerbinetta. The latter has all the necessary vocal weapons in her arsenal and she had no trouble whizzing nimbly through the coloratura tricks of ‘Großmächtige Prinzessin’ and sustaining a reliable high F. Archibald’s tone is silvery and even in the stratosphere retains its sweetness. She had a good stab at capturing Zerbinetta’s less-than-innocent coquetry and effervescence; and one could forgive the Composer for submitting to the charms of her Prologue number, ‘Ein Augenblick ist wenig’. But, she didn’t have quite enough stage presence or depth of characterisation for this production — a touch more of Despina needed, perhaps?

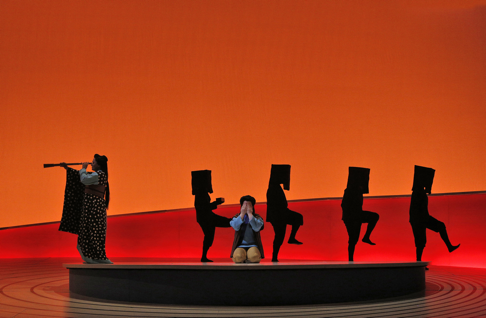

Kiandra Howarth as Echo, Wynne Evans as Scaramuccio, Paul Schweinester as Brighella, Karita Mattila as Ariadne, Jane Archibald as Zerbinetta and Jeremy White as Truffaldino

Kiandra Howarth as Echo, Wynne Evans as Scaramuccio, Paul Schweinester as Brighella, Karita Mattila as Ariadne, Jane Archibald as Zerbinetta and Jeremy White as Truffaldino

Roberto Saccà tenor doesn’t have quite enough dramatic energy or openness at the top for the demanding role of Bacchus — it is after all the voice that frees Ariadne from her torment and pain — but in many other ways he acquitted himself well and had the stamina to cope with the unforgiving challenges, and tessitura, of the part. There were some deft comic touches during the tomfoolery of the Prologue, and his overall performance was robust, maintaining focus through to the final duet.

Thomas Allen was typically dependable as the rather frazzled Music Master, the diction superb as always. Ed Lyons had all the high notes, including a secure top B, and delivered the preening Dancing Master’s comic lines with waggishness. Baritone Marcus Werber sang Harlequin’s song with a pleasing cantilena and strong high notes. Tenor Wynne Evans was a powerful Scaramuccio, while Truffaldin was sung with smooth lyricism by bass Jeremy White. Paul Schweinester used his flexible tenor well in the role of Brighella. However, as the commedia dell’arte troupe insinuate themselves into the Opera, choreographer Beate Vollack’s routines at times verged on slapstick and the pantomimesque steps of ‘Die Dame gibt mis trübem Sinn’ — danced in an attempt to cheer up the gloomy Princess — were tiresome.

Echo (Kiandra Howarth), Naiad (Sofia Fomina) and Dryad (Karen Cargill) blended beautifully, especially in their trio commenting on Ariadne’s grief. Howarth’s pure, youthful soprano is just right for Echo’s simple imitations; Cargill’s mezzo is fittingly dark and rich. In the smaller roles of the Lackey, Officer and Wig-maker, Jihoon Kim, David Butt Philip and Ashley Riches, respectively, all performed well.

Supportive of his singers throughout, Pappano brought a surprising mix of luxuriousness and lucidity — there were some very effective pianissimi — to Strauss’s richly textured score. Solos from clarinet, horn, flute and bassoon were beautifully executed in sentimental dialogue with the vocal lines; and the string playing in the overture to the Opera was sorrowful and affecting. The conductor paced the drama with mastery, especially the final duet, controlling the ever-accumulating waves of sound with fine judgment. In Pappano’s hands, Romanticism and Classicism were perfectly blended.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Ariadne/The Prima Donna, Karita Mattila; Bacchus/The Tenor, Roberto Saccà; Zerbinetta, Jane Archibald; The Composer, Ruxandra Donose; Harlequin, Markus Werba; A Music Master, Thomas Allen; Dancing Master, Ed Lyon; Wig Maker, Ashley Riches; Lackey, Jihoon Kim; Scaramuccio, Wynne Evans; Brighella, Paul Schweinester; Truffaldino, Jeremy White; Officer, David Butt Philip; Naiad, Sofia Fomina; Dryad, Karen Cargill; Echo, Kiandra Howarth; Major Domo, Christoph Quest; Director, Christof Loy; Conductor, Antonio Pappano; Designs, Herbert Murauer; Lighting, Jennifer Tipton; Choreography, Beate Vollack; Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Wednesday 25th June 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/2662ashm_1020.gif image_description=Karita Mattila as Ariadne [Photo © ROH/ Catherine Ashmore] product=yes product_title=Ariadne auf Naxos, Royal Opera product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Karita Mattila as AriadnePhotos © ROH/ Catherine Ashmore

June 27, 2014

Leoš Janáček : The Cunning Little Vixen, Garsington Opera at Wormsley

In a letter to Kamila Stösslová dated the 10th of February that year he writes wistfully “I have begun writing The Cunning Little Vixen. A merry thing with a sad end: I am taking up a place at that sad end myself ……and I so belong there”.

It is tempting to see a connection between the opera’s composition and the purchase of his country home in Hukvaldy “beyond the stream, great forests” which he began to regard as something of a retirement home. The opera is one of those works, earthy, especially in this translation, and yet all the more affecting for containing a profound truth. Humans and animals alike inhabit the forest, we share the same emotions, we live briefly, all too soon we die but the forest lives on. As in that wonderful epilogue to Das Lied von der Erde, “The beloved earth everywhere blossoms and greens in springtime anew. Everywhere and forever the distances brighten blue”. The Forester’s ecstatic farewell at the opera’s close touches similar emotions, albeit refracted through Janáček’s unique prism.

Of course Cunning Little Vixen can also be taken as entertainment pure and simple with its hilarious scenes in the local pub with the repressed minister, the even more repressed schoolmaster and the almost equally repressed Forester getting as we would say in Scotland “fou and unca happy” (ie ‘smashed), then at the Forester’s hut with the hens, the cock - here summarily ‘bobbited’ on stage by the Vixen - and the dog Lapak, and last but not least the rapturous (and extremely funny) courtship and mating of Vixen Long Ears with the Fox and other scenes in the forest. For that reason it is ideal summer opera - Glyndebourne did it recently - although, given the overt but scarcely suppressed sexual longing of nearly all the characters, it is a moot point - unlike, say, Hansel & Gretel- whether it would ever be suitable for children. However, it is certainly a ‘feel-good’ opera - at least until the Vixen is shot by the macho poacher Harasta who, as we hear from subsequent conversation in the pub, will shortly marry the local object of desire, Terynka, who will be wearing a new fox fur muff for the occasion. At that point the plot darkens.

Given Janáček’s own unconsummated passion over many years for Kamila Stösslová, it is hard not to see the main character’s emotions as at least partly autobiographical. Thankfully Janáček’s relationship with Kamila seems to have remained entirely proper. Had it been otherwise we should probably never have had that magnificent flow of late masterpieces. Ironically I knew an old Czech gentleman in Malta called Jaroslav who had fallen in love with a married woman across a crowded theatre in Prague in the 1920’s and whose unrequited passion for her lasted till his death some 50 years later. He produced an epic love poem in her honour running to over 100 pages which he would read to his friends with tears streaming down his face.

This, the final opera in Garsington’s current season of three operas, is an undoubted delight and there are no obvious weak links in the substantial cast, Claire Booth consistently excellent as the Vixen and the stentorian Grant Doyle impressive as the Forester. The Cunning Little Vixen has a large cast of other animals - the frog, the grasshopper, the badger, the hens (excellent in their movements) as well as those already mentioned and assorted humans of whom both Timothy Robinson’s sad schoolmaster and Henry Waddington’s priest both deserve special mention. So too does Victoria Simmonds characterful fox.

That said, there have to be a number of minor reservations about the production itself. With its rural setting Garsington should be an ideal location for Cunning Little Vixen (the sliding doors behind the stage open onto woods beyond, surely a perfect backdrop for the forest scenes but, unlike Vert-Vert, this was not used).The interior scenes in the inn had a set that looked uncomfortably like Laura Ashley wallpaper from the 1960’s - one could see what the designer had in mind since this had to double as the forest glade when the set worked (on several occasions it jammed and the stage staff had difficulty moving it). Nor were the Vixen’s nonchalant movements entirely convincingly foxy (I speak from experience as we have a vixen which regularly uses our back garden and has even joined us for lunch on sunny days, sitting on the roof of our garden shed and eyeing us up curiously as we eat; she either moves very cautiously or trots along quite rapidly).

For the most part Garry Walker and the orchestra had the score’s measure, refusing to jolly it along too quickly and allowing its moments of wonder and ‘wood magic’ to emerge naturally; however, there were some occasions where the music cried out for greater weight and intensity, notably that glorious pantheistic epilogue where the Forester, alone in the forest, reflects on his lost youth and his loveless marriage and - when he sees a fox cub resembling the young vixen - wonders if he should take it home with him.

A postscript. Given the awful story of the tenor at the Met who took a heart attack some years ago during a performance of The Makropoulos Case and fell from a ladder, it was interesting to see boys/cubs clambering up and down ladders without helmets, body harnesses and carabiners. Fortunately the ubiquitous Health & Safety’s writ does not seem to have reached Garsington. After all, boys will be boys and we all survived falling out of the odd tree. Long may it continue. Viva la liberta!

Douglas Cooksey

The Cunning Little Vixen

Music Leos Janáček

Libretto Leos Janáček based on the novel Liska Bystrouska by Rudolf Tesnohlidek,

Forester:: Grant Doyle, Forester’s wife : Lucy Schaufer, Schoolmaster \: Timothy Robinson, Priest :Henry Waddington, Harašta : Joshua Bloom, Pásek (innkeeper) : Aaron Cawley, Pásek’s wife : Helen Anne Gregory, Pepík : William Gardner, Frantík : Theo Lally, Young Vixen Bystrouška : Alexandra Persinaru, Vixen Bystrouška : Claire Booth, Fox : Victoria Simmonds, Cricket: Isaac Flanagan, Grasshopper : Sophie Thomson, Frog : Gabriel Kuti, Mosquito : Richard Dowling, Lapák a dog: Anna Harvey

Cock : Alice Rose Privett, Chocholka a hen : Katherine Crompton, Badger :Bragi Jonnson, Woodpecker : Marta Fontanals-Simmons, Owl : Grace Durham, Jay : Elizabeth Karani, Vixen dancer :Chiara Vinci, Forester dancer :Jamie Higgins,

Conductor :Garry Walker, Director : Daniel Slater, Designer : Robert Innes Hopkins,

Lighting Designer : Tim Mascall, Choreographer: Maxine Braham, Assistant conductor Holly Mathieson, Garsington Opera Orchestra

mage=h

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Leos Janáček The Cunning Little Vixen, Garsington Opera at Wormsley, 25th June 2014

product_by=A review by Douglas Cooksey

product_id=

June 26, 2014

La Traviata in Marseille

Maybe because it had a bad reputation as a betrayal of Alexander Dumas fils’ novel La Dame aux Camélias and maybe because local critics had already objected to its jumpy motifs and its vulgar rhythms. Once on the stage of Marseille’s venerable Opéra (1787) however it has become, with Rigotetto, Marseille’s most performed opera.

These June performances were sold out three months in advance — one wonders what foresight will have informed the Marseillais that this was a Traviata not to miss?

Alexander Dumas fils too might have been pleased. His 20 year-old Marguerite, renamed Violetta in the opera was very young as well, and very beautiful. The honesty and ironic innocence that Dumas finds in his ill-starred prostitute radiated from young Czech soprano Zuzana Marková in her role debut.

Act I, Gaston, Alfredo, Le Marquis, Violetta, Flora.

Act I, Gaston, Alfredo, Le Marquis, Violetta, Flora.

Mlle. Marková may have been a somewhat tentative Lucia last winter in Marseille, but as Violetta she moved with new found grace and delivered a deeply studied performance with complete mastery and conviction. She is a remarkable technician in the first flower of beautiful, clear, coloratura voice. The E-flat taken in “Sempre libera” rang with silvery confidence, the mid-voice of the second act and death shone with strength and warmth.

It was a sterling performance allowed by remarkable conducting, that of Stuttgart formed young Korean maestra Eun Sun Kim (it is already an established career with credits at English National Opera, Frankfurt Opera, Vienna Volksoper). The maestra is clearly of a new generation of conductors who feel tempos in a minimalist sense — slower macro-pulses offering sound spaces where immediate depths may be probed. Musical energy is discovered by the exploration of this microcosmos rather than in energy found by forcing brute speed and sudden braking.

This musicianship allows for the lyric expansion inherent in bel canto and here it laid bare the roots of the mid-period Verdi in this rapidly disappearing style. Mlle. Marková exposed bel canto’s purity of melodic intention by stylishly suspending her musical lines, plus she exploited these long, carefully sculpted melodic contours in lovely pianissimos and full fortes, and with beautiful vocal colors.

The conducting of Eun Sun Kim well served the artistry of Canadian baritone Jean-François Lapoint as Giorgio Germont. Mr. Lapoint who counts both Pelleas and Golaud among his roles is primarily known in the French repertory. He brought a projection of text from these roles, and a delicacy of delivery that created an unusual depth of personality and musical presence to Germont. The absence of an Italianate color and inflection, and an inborn leading-man presence were overcome here by the convincing sense of bel canto that he and Mlle. Eun achieved (Mr. Lapointe also counts Donizetti’s Alphonse XI [La Favorite] among his roles).

Zuzana Marková as Violetta, Jean François Lapointe as Giorgio Germont

Zuzana Marková as Violetta, Jean François Lapointe as Giorgio Germont

It was a new production, the work of Renée Auphan, the former general director of Marseille Opera (perhaps accounting for the care in its casting). In her program notes she cautions us not to think too much about the Dumas novel, that that demi-monde is far removed from our experience. She asks us instead to focus on Verdi’s universal humanity.

But the characters in her staging are very much those of Dumas, starting with the youth of Mlle. Marková (if not the brattish confidence of Dumas’ Marguerite) and the forty-some age of the has-been prostitute Flora. Her Act III party admitted the startling vulgarity of the demi-monde as described by Dumas. French mezzo Sophie Pondijiclis made this role vividly real, a revelation. French mezzo Christine Tocci played Annina, here transformed from Verdi’s dramatic utility into Dumas’ Nanine, a factotum confidante, possibly a lover of Marguerite, not a chamber maid. Costumed in male styled trousers and top, with a bright smile and strong voice Mlle. Tocci was constantly at Violetta’s side, a vivid, voiceless presence in Act I.

Act II begins with Alfredo’s outpouring of contentment, the emotion ironically compromised by the presence of Dr. Grenvil, who sits writing something, perhaps a prescription, while Alfredo sings the opening of "dei miei bollenti spiriti" to him. The doctor then departs, imparting a perfunctory gesture of professional sympathy to Alfredo. Romanian tenor Teodor Ilincâl made Dumas’ obsessive Armand quite real as Verdi’s Alfredo. Mr. Ilincâl is a strong voiced, Faustian tenor who well embodied Dumas and Verdi’s single minded and selfishly Romantic lover. Verdi simply does not award him the delicacy or complexity of feeling that he lavished on Violetta and Germont.

Mme. Auphan is wise to suggest that we not dwell on Dumas. But understanding the detail of her mise en scène together with the exemplary casting and the musical depth of the conducting explains why this staging brought unexpected vitality to this old warhorse. It was not a moving Traviata so much as it was an almost clinically musical and dramatic examination of this masterpiece. And finally it was mesmerizing art.

The new production provided an unobtrusive, standard mid-nineteenth century setting designed by Marseille born Christine Marest, a veteran of the late 20th century avant garde. The scenery, beautifully lighted by photographer Roberto Venturi, was a stage box that easily transformed its feeling from salon to an intimate, emotional interior space most notably in the “sempre libera.” In Dumas novel this scene takes place in Marguerite’s boudoir, in the Auphan production the lights of the salon are softened into dim, candle light, and just as in the Dumas novel Alfredo is present, making this scene an operatic pas de deux, Violetta voicing her conflicts while Alfredo crumples a white camellia.

There were performances on six consecutive days, thus there were two casts. Jean-François Lapointe however unexpectedly sang all performances (and was still in fine form at the fifth performance). Intelligence from the pressroom indicates that the alternate cast was quite impressive — Romanian soprano Mihaela Marcu as Violetta and Turkish tenor Bülent Bezdüz as Alfredo.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Violetta: Zuzana Marková; Flora: Sophie Pondjiclis; Annina: Christine Tocci; Alfredo Germont: Teodor Ilincäi; Giorgio Germont: Jean-François Lapointe; Le Baron: Jean-Marie Delpas; Le Marquis: Christophe Gay; Le Docteur: Alain Herriau; Gaston de Letorières: Carl Ghazarossian; Giuseppe: Camille Tresmontant. Chorus and Orchestra of the Opéra de Marseille. Conductor: Eun Sun Kim; Stage Director: Renée Auphan; Scenic Designer: Christine Marest; Costume Designer: Katia Duflot; Lighting Designer: Roberto Venturi. Opéra de Marseille, June 21, 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Traviata_MRS1OT.png

product=yes

product_title=La Traviata in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Zuzana Marková as Violetta, Teodor Illingäi as Alfredo [Photos by Christian Dresse, courtesy of Opéra de Marseille)]

June 25, 2014

Opera Radio

|

||||

| Radio Stephansdom (Vienna) | ||||

|

|

|||

| BR-Klassik (Munich) | Radio Classique (Paris) | |||

June 23, 2014

Dallas Opera Teams with San Diego Opera

By Mark Lowry [TheaterJones, 20 June 2014]

The Dallas Opera's previously announced world premiere of Great Scott in 2015 will now be co-produced with the recently saved San Diego Opera.

[More . . . .]

Madama Butterfly in San Francisco

It was an Italian opera, the abstract visual images of a Japanese born American and an American fable that converged magically into artistic totality.

The 2006 production itself (design and staging), is from Opera Omaha. It has since traveled to Madison, Dayton, Vancouver, Honolulu, Atlanta, Philadelphia and Charlotte. It would hold the stage in any opera house in the opera world. It is a masterpiece.

The sets and costumes are by Omaha based ceramic artist Jun Kaneko who collaborated with stage director Leslie Swackhamer, a professor at Sam Houston State University (Houston) whose theatrical roots are in Seattle, to create this unique production.

Jun Kaneko works primarily in repeated patterns in two dimensional clay, a visual process that brilliantly found its way into Puccini’s verismo — the abstracted, multi-colored umbrellas of the wedding guests was the kaleidoscope of village life, the sliding panel of black and white squares meant the house. Screens flew in and out on which repeating, jagged lines of growing tension were drawn. These were but some of the patterns that multiplied the joyous and horrific emotional obsessions that are at the base of verismo.

Act I, Patricia Racette as Butterfly. Photo by Cory Weaver.

Act I, Patricia Racette as Butterfly. Photo by Cory Weaver.

Kaneko creates abstract location (background) in giant swaths of solid color — a golden yellow for the marriage, this color carried through the opera by the golden trousers of Trouble, reds and blues for the American presence, and finally brilliant red for blood, in a dripping image that mirrored the neck seppuku committed by the Butterfly standing just below. These were some of the colors that conveyed the powerfully contrasting forces of verismo.

San Francisco Opera’s Nicola Luisotti was in the pit. This powerful musical presence usually dominates the War Memorial stage. However here the tyrannical maestro met his match — the evolving visual statements riveted our eyes to the stage, diva Patricia captivated our emotions. The maestro did no more than hold us in thrall to this masterwork. It was what great operatic conducting can be. And very seldom is.

Act II vigil. Photo by Cory Weaver.

Act II vigil. Photo by Cory Weaver.

This was the performance in its finest moments.

Soprano Patricia Racette no longer has the bloom of voice to create the Act I Butterfly or to deliver a resplendent “un bel di.” But she has gained vocal force and darker colors to execute with soul-wrenching power the words that take her gently and brutally to sacrifice and suicide.

Patricia Racette’s Butterfly has been legend for many years. It is a role she is not likely to keep in her voice much longer.

Mezzo soprano Elizabeth DeShong portrayed a Suzuki that could easily become legendary as well. She possesses a lyric mezzo voice in full flower, and a presence that offers an expanded dimension of character for roles like Suzuki and Cenerentola (her Glyndebourne debut) and trouser roles like Hansel (Chicago) and Maffio Orsini (ENO and SFO).

Baritone Brian Mulligan made an adequate Sharpless but did not resonate with the stature of the Racette Butterfly. The Pinkerton was tenor Brian Jagde, a recent Adler Fellow who does not have the refinement necessary to appear on a major stage (the War Memorial claims it is). It was a raw performance, made embarrassing by the strutting onto the stage apron (and even upon the prompter box) to attempt to impress us with his high notes. This young tenor will perform Pinkerton at Covent Garden, casting that is surely manifestation of artistic anti-Americanism. Current Adler Fellow Julius Ahn is not a big enough performer to fill the Goro pants in a major production.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Cio-Cio-San: Patricia Racette; Lt. B.F. Pinkerton: Brian Jagde; Suzuki: Elizabeth DeShong; Sharpless: Brian Mulligan; Goro: Julius Ahn; Kate Pinkerton: Jacqueline Piccolino; Prince Yamadori: Efrain Solis; The Bonze: Morris Robinson; Commissioner: Hadleigh Adams. Chorus and Orchestra of San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Nicola Luisotti; Stage Director; Leslie Swackhamer; Production Designer: Jun Kaneko; Lighting Designer: Gary Marder. War Memorial Opera House, June 15, 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Butterfly_SF3OT.png

product=yes

product_title=Madama Butterfly in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Patricia Racette as Butterfly, Brian Jagde as Pinkerson [Photo by Cory Weaver]

Luca Francesconi : Quartett, Linbury Studio Theatre, London

When visiting a new country, it helps to know its language and customs. Francesconi's music may seem strange, but that doesn't make it invalid. Francesconi's music is modern but connects deeply to European culture.

Quartett might seem gruesome but no more so than the original story, which was written in 1782. In Choderlos de Laclos's Les Liaisons damgereuses Valmont and Merteuil play kinky mind games. They manipulate other people , and pride themselves on their cynical lack of emotional engagement. They're specially drawn to good people like Madame de Tourvel, because they get a special kick from destroying genuinely good and sincere people. The original book is so well known that it should be part of basic education, but there's also a summary on Wikipedia and a Meryl Streep movie.

Francesconi's setting, based on a play by Heiner Mueller, predicates on the idea that Merteuil and Valmont are alone in an apocalyptic wasteland. It doesn't really matter what disaster has befallen them, save that they've lost the wealth and privileges that let them get away with so much for so long. Perhaps they're in Purgatory, forced to face the consequences of what they have done. Can there be any greater hell for two people who have escaped responsibility for their actions because of their social status.

At first we see a woman ( Kirsten Chávez) in the tatters of an 18th century noblewoman's gown, her corset still tightly laced. Despite what's around her all she can think of is sex. "The skin remembers touch", she groans, "whether hand or claw". At least she's facing one aspect of her depravity. Significantly, the word "Tourvel" intrudes on her consciousness. Tourvel, the virtuous wife Merteuil challenged Valmont to seduce. Tourvel gave into Valmont out of warped Christian generosity because she thought her love might redeem him: the complete opposite of Merteuil Thus Meretuil is obsessed with her memory

The book, Les Liaisons damgereuses is a collection of letters, reputedly exchanged by Merteuil and Valmont as they plot their stratagems and taunt one another. In a modern novel, we read multiple points of view, and the author's commentary. In letter-novels we have only the letter writers' perspective: we have to guess between the lines how other people feel. The structure of Francesconi's Quartett replicates this anomie, so fundamental to the emotional disengagement Merteuil and Valmont seek to achieve.

The epistolary nature of the original also influences Francesconi's dramatic form. Miniature scenes progress seamlessly, ideas and persona changing back and forth. The vocal lines are arch, like the tone in the letters. In the opera, Leigh Melrose sings great falsetto! Valmont and Merteuil act out different scenarios, like method actors, trying to find their way into an experience. They switch rapidly between personas, sometimes reversing parts. Fransceoni's mentor was the late Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, whose influence can be heard in Francesconi's use of spatial relationships and electronic sound. Sometimes the singers stand silent, listening to recordings of their own voices singing other parts, making them reflect. . Perhaps that's why the opera is called "Quartett", though there are only two players. It may also refer to the chamber music upon which Francesconi's reputation was built, where players interact with each other in intricate formation.

Andrew Gourlay conducted the London Sinfonietta. This isn't easy music to play although it's so atmospheric that it sets the background to the story. The orchestra murmurs comment, and screams in frustration, suggesting the unseen voices of people whom Valmont and Merteuil block out of their consciences. Quartett is much more sophisticated and satisfying than much of what the London Sinfonietta has been doing in recent years.

Gradually Valmont and Merteuil get deeper into the wider implications of what they have done. Valmont and Merteuil think of Cécile, the young virgin straight from convent whom Valmont seduced, and ruminate on the idea of sin and the church, They ponder the irony that the parts they pollute once gave them life. In the book, Valmont is thrown off his scams because he developed genuine feelings for Tourvel. Merteuil had to acknowledge that she had feelings for him under her tough exterior. Perhaps, as Valmont sings, they'll get together in hell. Thus he willingly drinks poison and dies, while Merteuil is left alone, waiting.

John Fulljames's staging highlights the psychic dislocation. Soutra Gilmour's simple panels of fabric hang down from the ceiling, giving a vertical dimension to the horizontal stage. With intelligent lighting (the wonderful Bruno Poet) the fabric can resemble torn lace, or mountains, or reversed, black flames reaching upwards from Hell. Sounds Intermedia mixed the electronics. Ravi Deepres created the video projections. Mark Stone and Angelica Voje sing in the second cast.

Please also read ">Susana Malkki on Francesconi . She conducted Quartett in Milan and Amsterdam.

Anne Ozorio

mage=h

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Luca Francesconi : Quartett, Linbury Studio Theare, Royal Opera |House, London 19th June 2014

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=

June 20, 2014

June 19, 2014

Puccini Manon Lescaut, Royal Opera House, London

When Antonio Pappano is fired with the passion he feels for this music, few other conductors even come close. He' was phenomenal. He took risks with depth and colour, which pay off magnificently. He wasn't afraid of the way the music at times veers towards extremes of vulgarity, expressing the greed and nastiness of nearly every character in the plot. In this score, there's no room for polite timidity. Themes of freedom occur throughout this opera, which Pappano delineates with great verve. Yet there's discipline in Pappano's conducting. His firm, unsentimental mastery keeps the orchestral playing tight. Manon may lose control of her life, but Pappano keeps firm a moral compass. In the Intermezzo, this tension between escape and entrapment was particularly vivid. No need for staging. Instead, Puccini's quotation from Prévost's text was projected, austerely, onto the curtain.

Kristine Opolais created a Manon that will define her career for years to come, and become a benchmark against which future Manon will be compared. Her voice has a lucid sweetness that expresses Manon's beauty, but her technique is so solid that she can also suggest the ruthlessness so fundamental to the role. The Act Two passages she sings cover a huge range of emotions, which Opolais defines with absolute clarity. In every nuance, Opolais makes us feel what Manon might feel, so intimately that one almost feels as if we were intruding on Manon's emotional privacy. It's not "easy listening" but exceptionally poignant.

In the final scene, Puccini specifies darkness and cold, undulating terrain and a bleak horizon. There are no deserts around New Orleans, which is on a delta. Opolais lies, literally "at the end of the road", suspended in mid-air devoid of every comfort. Then Opolais sings, transforming Manon from a dying wretch in a dirty dress through the sheer beauty and dignity of her singing. "Sei tu, sei tu che piangi?", she started, building up to the haunted "Sola, perduta, abbandonata, in landa desolata. Orror!"". The glory of Opolais's singing seemed to make Manon shine from within, as if she had at last found the true light of love. I was so moved I was shaking. Anyone who couldn't be touched by this scene and by Opolais must have concrete in their arteries, instead of blood.

Opolais and Jonas Kaufmann are so ideally cast. Their presence might push up the cost of tickets, but think in terms of investment. These performances will be talked about for decades to come. Kaufmann's deliciously dark-hued timbre makes him a perfect Italianate hero. On the first night, in the First Act, some minor tightness in his voice dulled his singing somewhat, but he's absolutely worth listening to even when he's not in top form. In the love duets, his interaction with Opolais was so good one could forgive him anything. By the crucially important last scene, his voice was ringing out true and clean again - a heroic act of artistry much appreciated by those who value singing. He'll get better as the run progresses.

Manon Lescaut is very much an ensemble piece although the two principals attract most attention. Christopher Maltman sang Lescaut, Manon's corrupt brother. Lescaut is low down and dirty, a calculating chancer with no scruples who'll gladly set upon his friends if it suits him. Maltman's gutsy energy infused his singing with earthy brio, completely in character. Maurizio Muraro sang an unusually well-defined Geronte, who exudes slime and malevolent power. How that voice spits menace!

The lesser parts were also extremely well delivered. The Sergeant is a more significant role than many assume it to be. Jihoon Kim sang it with more personality than it usually gets. he makes the role feel like a Geronte who hasn't made enough money to kick people around, but would if he could. Significantly Puccini places the part in context of the female prisoners who are Manon manquées.Benjamin Hulett sang Edmondo, Nigel Cliffe the Innkeeper, Nadezhda Karyazina the Musician, Robert Burt the Dance master, Luis Gomes the lamplighter and Jeremy White the Naval Captain. Good work all round. Although attention focuses on overall staging, the director's input in defining roles should never be underestimated. Jonathan Kent's Personenregie was exceptionally accurate.

This production attracted controversy even before the performances began. However, it is in fact remarkably close to Puccini's fundamental vision. Those who hate "modern" on principle often do so without context or understanding. So what if the coach at Amiens is a car? How else do rich people travel? So what if Manon wears pink? Puccini's Manon Lescaut hasn't been seen at the Royal Opera House for 30 years, but Massenet's Manon is regularly revived. So Londoners are more familiar with Manon than with Manon Lescaut. Yet the two operas are radically different. Mix them up and you've got problems. In Massenet, Manon and Des Grieux have a love nest in a garret. But Puccini goes straight past to Geronte's mansion and to the sordid business of sex and money.All the more respect to Puccini's prescience. Anyone who is shocked by the this production needs to go to the score and read it carefully.

Geronte thinks he's an artist. Because he thinks he owns Manon - so he uses her as a canvas to act out his fantasies. Jonathan Kent isn't making this up. Read the score. One minute Manon is in her boudoir, putting on makeup, talking to her brother. Next minute, musicians pour in and the have to be shooed out. Then, "Geronte fa cenno agli amici di tirarsi in disparte e di sedersi. Durante il ballo alcuni servi girano portando cioccolata e rinfresch"i. Geronte beckons to friends to stand on the sidelines and sit. During the dance some servos are bringing chocolate and refreshments). The guests know that Manon sleeps with Geronte. They have come in order to be titillated. It's not the dancing they've come to admire. They're pervs. Geronte is showing off, letting his pals know what a catch Manon is. Hence the dancing: a physical activity that predicates on the body and the poses a body can be forced into "Tutta la vostra personcina,or s'avanzi! Cosi!... lo vi scongiuro" sings the Dancing master. But he has no illusions. "...a tempo!", he sings, pointing out quite explicitly that her talents do not include dance. "Dancing is a serious matter!" he says, in exasperation. But the audience don't care about dancing. They've come to gape at Manon. There's nothing romantic in this. Geronte is a creep who exploits women. It's an 18th century live sex show. Geronte's parading his pet animal.

So Manon concurs? So many vulnerable women get caught up in the sick game, for whatever reason. The love scene that follows, between Opolais and Kaufmann, is all the morer magical because we've seen the brutality Manon endured to win her jewels. Perhaps we also feel (at least I did) some sympathy for Manon's materialistic little soul. She knows that money buys a kind of freedom.When news of Mark Anthony Turnage's commission for Anna Nicole first emerged, some were surprised. Others said "Manon Lescaut". The story, unfortunately, is universal..At first I couldn't understand what the film crew and lighting booms meant but I think they suggest the way every society exploits women and treats them as objects for gratification. Later, the lighting booms close down like prison bars. Some of the women being transported are hard cases but others are women who've fallen into bad situations, but are equally condemned. Far from being sexist, this production addresses something universal and very present about society. I'm still not sure about the giant billboard "Naiveté" but there is no law that says we have to get every detail at once. Perhaps Kent is connecting to advertising images and popular media, which is fair enough.

People wail about "trusting the composer". But it is they who don't trust the composer. Any decent opera can inspire so much in so many. No-one owns the copyright on interpretation. But the booing mob don't permit anyone else to have an opinion and insist on forcing their own on others who might be trying to engage more deeply. It's time, I think, to call the bluff on booers. They don't actually care about opera. Like Geronte, they're into control, not art..

Anne Ozorio

mage=h

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Giacomo Puccini : Manon Lescaut, Royal Opera |House, London 17th June 2014

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=

June 18, 2014

The Pearl Fishers, ENO

Certainly, the opera is more than a one-hit wonder, and its celebrated ‘lollipop’, the tenor-baritone duet ‘Au fond du temple saint’, is one of many melodic gems in a sumptuous score.

It’s what holding them together that’s the problem. Cormon and Carré’s flimsy tale of the forbidden love of two best friends for one High Priestess suffers from one-dimensional characterisation and a generous dose of the nineteenth-century French obsession with ‘the Orient’ — the armchair traveller hoping for an authentic Eastern sojourn has to wade through such nonsense as the notion of the ancient Ceylonese venerating Hindu gods with European music.

Woolcock’s solution is a visual one; and in places it works. Designer Dick Bird’s opening image of elegant divers swooping and plunging with astonishingly balletic grace to scoop pearls from the ocean bed is arresting (although it was a pity that conductor Jean-Luc Tingaud did not coax a similarly exotic aural kaleidoscope from the pit during the rather lacklustre overture). Later, billowing silk evokes the ebbing moonlit waves, and these swell in the storm sequence into a raging video tsunami which surges and heaves, threatening to over-spill into the auditorium.

John Tessier as Nadir, Sophie Bevan as Leïla and George von Bergen as Zurga

John Tessier as Nadir, Sophie Bevan as Leïla and George von Bergen as Zurga

Jen Schriever’s lighting enhances the fantasy: the colours evoke the opulent emeralds and aquamarines of the omnipresent waters, and the burnished ochres and oranges of the tropical sun. The change from day to night — as the dockside dwellings fade into shadow, beneath the glint and shimmer of distant hillside lights — is magical.

In an attempt to inject some realism into the orientalist schmaltz, Woolcock and Bird transfer the action to modern Sri Lanka and construct a chaotic shanty-town of corrugated shacks, the barbed wire and concrete jumble suggesting an ideological slant relating to global warming and/or western commercial exploitation. I wondered for a moment whether the be-suited Westerners wandering through the hovels were corrupt pearl-factory owners, but as they disappeared after the opening act I assume they were simply goggle-eyed tourists.

While these are worthy touches, they are not sustained; static mise en scènerather than enlivening dramatic threads. Kevin Pollard’s costumes lean towards cliché and, more importantly, Woolcock offers the cast almost no direction. It doesn’t matter what they are singing or in what context — making eternal vows of loyalty, swearing undying devotion, threatening revenge — there is scarcely any physical or visual interaction between the principals who stand, sit or lie stock still, facing the audience. Only in the fight sequence between Leila and Zurga in Act 3 is there any sense of choreographed dynamism.

One problem is that the set is cramped; there is just room enough for the chorus to assemble collectively amid the staggering lean-tos and for the principals to walk to the front of the stage, or climb the side-stairs. The result is that the ENO chorus looks rather ‘amateur’, although after a slightly hesitant start, they are on cracking musical form. ‘Brahma divin Brahma!’ at the close of Act 2 was fervent and resounding.

A scene from The Pearl Fishers

A scene from The Pearl Fishers

A pre-curtain announcement warned us that Sophie Bevan was suffering from a virus but it didn’t seem to affect her performance as the High Priestess Leila too adversely, although perhaps there was initially a sense that she was saving her brightest sparkle for the big moments. ‘Comme autrefois dans la nuit sombre’, when Leila reflects on her past secret assignations with Nadir, was persuasive and charming, and Bevan bloomed in the lovers’ passionate Act 2 duet. In Act 3, despite being thrown around by an enraged, vengeful Zurga, her voice was characteristically accurate and vivid.

As Nadir, John Tessier made good use of his attractive tenor in his Act 1 aria ‘Je crois entendre encore’: the phrasing was flexible, the tone appealing and the upper register unforced as Tessier conveyed both Nadir’s rapturous devotion and his essential honour. But, his voice is quite light-weight and he didn’t quite have the resonance to carry the long, arching lines in the duet with George von Bergen’s Zurga. Von Bergen had more punch and power, and his diction was superb; the Act 3 aria ‘L’orage est calmé’ was full of feeling as Zurga expresses his remorse for his angry condemnation of Nadir. But, both men needed more variety of colour to compensate for the lack of psychological complexity provided by the librettists. Barnaby Rea was a full-voiced Nourabad but his dreadful costume was a hindrance to any notable dramatic impact.

After their uninspiring start, the ENO instrumentalists shone in some exquisite solos, with horn and flute particularly impressive, but Tinguad never quite drew playing of sufficient lyric passion from his players. Martin Fitzpatrick’s rather staid translation added scant fire or frisson to the mix.

Dissatisfaction with the ending — Bizet’s own and that of the critics — resulted in various versions and no clear picture of the composer’s preferred form. Woolcock leaves us with the depressing image of suffering children being carried from the all-consuming flames of the burning ghat, the pyre ignited by Zurga in order to facilitate the lovers’ escape; a somewhat dispiriting end given the selfless nature of Zurga’s sacrifice.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Leïla, Sophie Bevan; Nadir, John Tessier; Zurga, George von Bergen; Nourabad, Barnaby Rea; Director, Penny Woolcock; Conductor, Jean-Luc Tingaud; Set Designer, Dick Bird; Costume Designer, Kevin Pollard; Lighting Designer, Jen Schriever; Video Designer, 59 Productions Ltd; Choreographer, Andrew Dawson; Translator, Martin Fitzpatrick. English National Opera, London Coliseum, Monday 16th June 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ENO_PF_01.gif image_description=ENO The Pearl Fishers, Sophie Bevan [Photo by ENO/Mike Hoban] product=yes product_title=The Pearl Fishers, ENO product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Sophie Bevan as LeïlaPhotos © ENO/Mike Hoban

June 17, 2014

The Metropolitan Opera to cancel its Live in HD transmission of John Adams’s The Death of Klinghoffer scheduled for this fall

New York, NY (June 17, 2014 ) — After an outpouring of concern that its plans to transmit John Adams’s opera The Death of Klinghoffer might be used to fan global anti-Semitism, the Metropolitan Opera announced the decision today to cancel its Live in HD transmission, scheduled for November 15, 2014. The opera, which premiered in 1991, is about the 1985 hijacking of the Achille Lauro cruise ship and the murder of one of its Jewish passengers, Leon Klinghoffer, at the hands of Palestinian terrorists.

“I’m convinced that the opera is not anti-Semitic,” said the Met’s General Manager, Peter Gelb. “But I’ve also become convinced that there is genuine concern in the international Jewish community that the live transmission of The Death of Klinghoffer would be inappropriate at this time of rising anti-Semitism, particularly in Europe.” The final decision was made after a series of discussions between Mr. Gelb and Abraham Foxman, National Director of the Anti-Defamation League, representing the wishes of the Klinghoffer daughters.

In recent seasons, the Metropolitan Opera has championed contemporary operatic masterpieces as part of its ongoing efforts to keep opera artistically current. Previously, the Met has presented John Adams’s other two major operas, Doctor Atomic (in 2008) and Nixon in China (in 2011). “John Adams is one of America’s greatest composers and The Death of Klinghoffer is one of his greatest works,” said Gelb. The Met will go forward with its stage presentation of The Death of Klinghoffer in its scheduled run of eight performances from October 20 to November 15. In deference to the daughters of Leon and Marilyn Klinghoffer, the Met has agreed to include a message from them both in the Met’s Playbill and on its website.

In recent years, The Death of Klinghoffer has been presented without incident at The Juilliard School (2009), the Opera Theatre of St. Louis (2011), and as recently as this March in Long Beach, California. The Met’s new production was first seen in London at the English National Opera in 2012, and received widespread critical acclaim.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/lacombe_10100_x3z5831_c2.gif image_description=Peter Gelb [Photo by Brigitte Lacombe] product=yes product_title=The Metropolitan Opera to cancel its Live in HD transmission of John Adams’s The Death of Klinghoffer scheduled for this fall product_by=From The Metropolitan Opera product_id=Above: Peter Gelb [Photo by Brigitte Lacombe]June 16, 2014

Britten: Owen Wingrave, Aldeburgh Music Festival

Indeed, the protection of innocence and the condemnation of cruelty runs through nearly all Britten's work, powerfully informing his whole creative persona. Owen Wingrave is critical to any real appreciation of what Britten stood for.

The Aldeburgh Music Festival and the Britten-Pears Foundation are wise to stage Owen Wingrave again, in the same place where the composer conducted the first public performance back in 1970. In 1914, men marched to war because they were led to believe that they were fighting "the war to end all wars". One hundred years later, those who believe in military solutions seem to have learned nothing from a century of almost incessant warfare. More than ever, we need Owen Wingrave and Britten's passionate opposition to mindless conformity.

Owen Wingrave was commissioned for television. Nearly a quarter of a million people watched it when it was first broadcast by the BBC in 1972, reaching audiences far beyond any opera house. That in itself is a statement about its significance. Composers wrote for film almost as soon as technology added sound to movies. Britten enjoyed going to the cinema, and spent his war years working for the GPO Film Unit. In Owen Wingrave, music and an understanding of film technique go together. The abstraction of music can be expressed through devices like split frames and juxtaposed images. On the physical stage, such things aren't easy to carry off. At Aldeburgh, director Neil Bartlett has chosen a minimalist set, enhanced by dramatic light effects (Ian Scott). This reflects the austerity in the music, which in turn reflects the stark moral situation Owen is faced with. "Listen to the house!" the female singers repeat, their lines intertwining, as if a knot - or noose - were being drawn tight. For the house does speak - "creaks and rustles, groans and moans" .The oppressiveness is almost palpable. "The "boom of the cannonade", created by percussion and low brass is so sinister that we could be hearing a thousand years of ghosts marching relentlessly towards death. The spirit of Paramore looms so large in the music that we don't need to see the house to feel its malign presence. Better the dark shadows and spartan set, so our imaginations can conjure up unseen images of horror.

In the original film, portraits of Wingraves past line the walls, menacingly, and come alive, leaping at Owen, like the present members of his family scold him, singly and in unison. On film, that's plausible, on stage it would be contrived. Bartlett, and choreographer and movement director Struan Leslie, use a group of young soldiers as a silent chorus. They operate in tight formation, as befits soldiers, but their movements also reflect figures in the music: a very subtle effect, which justifies their value in the production. They're also useful for technical reasons - they move such furniture as there is on the bare stage, "building" the haunted room by reversing the panels that serve as walls. Most perceptive of all, the soldiers are young, inspiring more sympathy than if they mere replicas of wizened old Wingraves, ghosts perhaps of young men sent to early deaths. Victims and perpetrators, harnessed together in perpetuity, like the ghosts in the haunted room, like Owen and Paramore.

The stark staging has a further advantage in that it throws extra focus on the singers and on the Britten-Pears Orchestra, conducted by Mark Wigglesworth, designated Music Director at the ENO when Edward Gardner moves on. Britten, Nagano and Richard Hickox hover over Wigglesworth, but he gives a good account of the music, stressing the clarity of the writing for solo instruments versus larger groups. Excellent experience for the young players in this orchestra, many of whom will go on to play in larger ensembles.

Ross Ramgobin sings Owen. Again, one retains memories of Gerald Finley and above all, Jacques Imbrailo, who created the part ten years ago when he was still a member of the Jette Parker Young Artists programme at the Royal Opera House. Imbrailo is perhaps the ideal Owen, since his voice shimmers with preternatural purity, but Ramgobin does well against such competition, which says a lot in his favour. Ramgobin's voice is agile and light, with a much more convincingly youthful timbre than Benjamin Luxon and Peter Coleman-Wright.

Susan Bullock sings Miss Jane Wingrave. The part contains sharp edges, to emphasize the character's sterile frustration. Bullock creates the effect of strangled tension without tightening throat or chest, but articulates her words with rapier-sharp diction. Catherine Backhouse sings a pert Kate, and Janis Kelly sings her mother Mrs Julian. Isaiah Bell sang Lechmere unusually well, his voice adding colours to the part, which could otherwise be interpreted as bland and callow. A singer to watch. Jonathan Summers sings Spencer Coyle and Samantha Crawford sings his wife, artfully suggesting the dynamic between the couple, where he controls and she is left to flutter prettily, but bleakly along. Richard Berkeley-Steele sang General Sir Philip Wingrave and James Way sang the Ballad singer, again with more personality (a good thing) than the part might otherwise attract.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/22/Benjamin_Britten%2C_London_Records_1968_publicity_photo_for_Wikipedia_crop.jpg?uselang=en-gb

image_description=Benjamin Britten at Aldeburgh, 1968, photographer Hans Wild

product=yes

product_title=Britten: Owen Wingrave, Aldeburgh Music Festival

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Benjamin Britten at Aldeburgh, 1968 [Photo by Hans Wild]

June 13, 2014

Show Boat in San Francisco

Critical consensus seems to be that Jerome Kern’s Show Boat was acceptable in San Francisco’s 3200 seat War Memorial (and at Chicago’s 3500 seat Lyric Opera). This acceptance has come at a price — sophisticated electronic amplification of voices and the imposition of a scale of production that well exceeds the stature of the piece.

At the press conference before this San Francisco run of performances (the production has already been seen in Washington D.C. and Chicago) there were three primary rationales offered for presenting Show Boat on a grand opera stage.

The first rationale is that if operettas such as, and specifically mentioned, Die Fledermaus, La Périchole and Die Lustige Witwe are firmly established in the international operatic repertory, why not an American operetta (you must first of all consider Show Boat an operetta and that is a complicated rationale). Note that La Périchole has never been on the War Memorial stage, nor has any other Offenbach operetta. What small amount of dialogue that has occurred in SFO productions of Die Fledermaus and Die Lustige Witwe productions has used the natural acoustic of the opera house. No singing voices have been amplified.

The second rationale is that given the demise of American light opera companies it becomes the responsibility of American grand opera companies to preserve the American Musical Theater heritage. Note that most of the musicals that comprise this current popular theater heritage occurred before the advent of sound reinforcement.

The by now classic American musicals were staged in theaters adapted to acoustical voice projection (recall the focused nasal sound of spoken dialogue delivered in earlier times that projected easily to the last rows of a vaudeville “opera house”). If American grand opera companies feel compelled to step outside their mission of producing opera they should at least move from opera houses to appropriately sized theaters where acoustic voices are possible.

The third rationale is that Show Boat dared introduce racial issues into popular theater. The presence of this stain on our national history evidently elevates the importance of Show Boat, and imposes a moral duty on grand opera companies to remind us that we have sins to expiate. Maybe like American imperialism in Madama Butterfly, and narrow, what we now call Victorian mores like in La Traviata. Opera can make it painfully pleasurable to go through this cathartic process.

Angela Renée Simpson as Queenie, Morris Robinson as Joe. Photo by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera

Upon a bit of consideration however the racial issues addressed in Show Boat are more about problems white skinned people encounter than the inequalities encountered by black skinned people. The blacks in Show Boat contentedly remain the underclass throughout the story (white girl gets rich and may or may not take back her no-good husband) and these blacks seemed happy to represent little more than caricatures of what whites wanted blacks to be back in 1927. It was surprising to see contemporary black skinned people willing to accept this assignment.

Finally Show Boat was a sing along. The songs are immortal it seems, or at least inescapable to those of us who grew up in mid-century America — songs sort of like “Di Provenza il mar” and “Un bel dì” for the current opera crowd. However after we have hummed along with a Verdi and Puccini aria there remains so much more to invade our souls than a few more catchy songs.

Many contented critics did finally confess the triviality, read poverty of the story once it was revealed in the second act. Other contented critics admitted that the razzle dazzle of the production numbers was pale imitation of what should occur in a real Broadway show.

Patricia Racette as Julie. Photo by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera

The San Francisco cast included opera soprano Heidi Stober who achieved a sufficient level of sparkle as Magnolia. Opera diva soprano Patricia Racette brought some presence but little tone to the role of Julie, opera baritone Michael Todd Simpson as Magnolia’s gambler husband Ravenal was highly miked making his voice sound like a musical comedy voice, a voice that seemed quite tired by end of the second act. Operatic bass Morris Robinson made appropriate bass sounds as Joe who sings “Old Man River” over and over again.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Magnolia Hawks: Heidi Stober; Gaylord Ravenal: Michael Todd Simpson; Cap’n Andy Hawks: Bill Irwin; Julie la Verne: Patricia Racette; Queenie: Angela Renée Simpson; Party Ann Hawks: Harriet Harris; Ellie Mae Chipley: Kirsten Wyatt; Joe: Morris Robinson; Frank Schultz: John Bolton; Mrs. Obrien: Sharon McNight; et al. San Francisco Opera Orchestra and Chorus. Conductor: John DeMain. Stage Director: Francesca Zambello; Set Designer: Peter Davison; Costume Designer: Paul Tazewell; Lighting Designer: Mark McCullough; Sound Designer: Tod Nixon; Choreographer: Michele Lynch. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, June 3, 2014

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ShowBoat_SF1OT.png

image_description=ShowBoat

product=yes

product_title=Show Boat in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Heidi Stober as Magnolia, Michael Todd Simpson as Ravenal [Photo by Cory Weaver, San Francisco Opera]

Anna Prohaska, one of Europe’s most promising sopranos

She is also releasing her third recording, “Behind the Lines” with Deutsche Grammophon.

Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites is intense, but Sister Constance is resolutely cheerful. What part does a character like that have in this opera? “The superficial answer would be: every tragic, complex opera needs comic relief. She is the sprightly, busy young novice, always a bit late with finishing her chores because she frequently drifts off into pastoral memories of her Breton village. But Bernados and Poulenc give her character a unique twist. She has an obsession with death, in fact with dying young and — as she insists to poor, already traumatized Blanche — dying with her fellow novice. This is when you start questioning — which one of the two is actually psychotic? Isn’t it absolutely natural and understandable for Blanche to be terrified, as an aristocrat during the Reign of Terror? Has Constance in fact lost her mind? She seems such a bouncy, life-affirming character, but at the same time she is seemingly impatient to get to ‘the other side’, the ‘better place’. But here we enter deeply theological territory! “

How does a sweet girl like that face death? It’s much more demanding role than some realize.

“This is the tricky part about the role. It’s not actually that hard to play a fanatic, a visionary. It’s fun to switch from banal banter to fanatical glares to illuminated, vocational moments. It’s more of a tightrope dance towards the end of the opera, where Constance faces her execution, stripped of her habit, where you have to try and find the human being that has the instinct to survive, and to show her inner battle without pushing the boundaries of the ensemble and this timeless production with its sparse aesthetics”.

Miss Prohaska’s voice is distinctive. What operatic roles does she enjoy most, and why?

“I have a lot of friends who play certain instruments and complain about the limitations of their repertoire, and say that that they envy us singers for the sheer amount of marvellous music that has been written for the human voice. We, on the other hand, have to listen to our bodies and damp our enthusiasm for roles that might be too dramatic or too light or too high or too low, even if the greatest maestro tries to convince you that you would be ‘phenomenal’. But isn’t it fabulous that we are so spoilt for choice as singers? Our repertoire is vast and theoretically everyone can pick and chose what suits them best. I must admit, I do have a strong penchant for melancholy music, for the dramatic. But that doesn’t mean I’m dying to sing Tosca. I can find these sentiments in Handel, in Pamina, which I sang for the first time this season, or Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier, which can have an immense emotional scope. In my opinion, you have to let a character grow in your mind first to help you falling into the trap of cliché — along with working with a good director of course! At the moment the early baroque composers, especially Cavalli, fascinate me. But one of my greatest loves will always be Henry Purcell. To sing Dido — one of the most perfect pieces of music theatre ever — on a concert tour this year with MusicAEterna was such a privilege and felt so right at the same time”.

Her repertoire is remarkably adventurous, and she sounds comfortable in many different styles, from Baroque to Hanns Eisler. Her recording and recital programmes are exceptionally well chosen.

“Funny — I subconsciously avoided Eisler for a long time. Probably because I went to the former East Berlin Hanns Eisler Music Academy. Wouldn’t it be a shame if we singers didn’t make use of the wide scope of what composers have left us and are still writing for us? With recital programmes I tend to make brainstorming lists over the years, where I collect songs I have either heard in concert or on recordings, or which I have stumbled upon reading a score. I group them according to topics. To give the programme a shape, I try to narrow down the topic more than the periods of music, because it interests me to find the differences and similarities between songs with similar themes from different musical periods. It’s tied very closely to the songs’ poetry, of course, and I sometimes search for poems first and find really interesting settings. In the end, the precept should be that it’s good music and that the final sequence has to ‘click’. There I try to trust my dramaturgical instincts.”

At the Royal Opera House, Miss Prohaska is singing for Sir Simon Rattle. Based in Berlin, she’s sung with the Berliner Philharmoniker many times. She also sang frequently with Claudio Abbado, Daniel Barenboim and many others.

“Sir Simon is simply a dream to work with. On the podium he manages to incorporate a paradox: the reliability and support of the classic ‘Kapellmeister’ and the inspired and innovative risk taker. He has this intellectual knowledge of the repertoire and the arts in general but is anything but a snob. When I took over a concert of Webern songs when I was 25 — my first regular concert series with the Berliner Philharmonic — I was terribly nervous before the first rehearsal. The first thing Simon said to me in front of the orchestra was ‘Thank you Anna, for taking over so short notice. We really appreciate that.’ I can tell you - you get spoilt by that sort of treatment! “

“I learned a great deal from working with Claudio Abbado, and it was a huge privilege to be part of his musical world for a short time while he was still with us. I would rather say though that the conductor and arranger Eberhard Kloke has been my mentor, opening up my ears and mind to the far corners of the repertoire from an early age on, and my voice teacher Brenda Mitchell taught me how to sing it healthily! Daniel Barenboim has had a huge part in my musical development since I started working with him at the Berlin State Opera when I was 23. Back then I was offered my contract as an ensemble member in the wake of learning the middle-sized role of Frasquita (Carmen) overnight. The morning of the performance — I had hardly slept due to cramming the French text into my head all night I wanted the musical rehearsal with Daniel to be perfect. So I sang from the score. He snatched it out of my hand, threw it on the floor and shouted ‘Are you using this tonight on stage as well?!’ He can be intimidating, and pushes you to your limits. But if you beat your inner demons of fear in these situations, there’s very little that can frighten you afterwards. “

“Contrasting colour and intention within a piece plays a major role in Daniel’s music making: ‘The colour between the first and the second phrase has to be so different, you need a visa to go across’, he would say. Last November I gave my first Lieder recital with him in Berlin. For me, it was so natural and on the other hand miraculous how we seem to have become musical partners, the way he listens to my ideas, the way we can discuss interpretation or simply make music spontaneously on stage.”

The renowned conductor, Felix Prohaska was Anna Prohaska’s grandfather. With that background, when did she realize she’d be a singer?

“My mother tells me that I could sing before I could talk. Apparently certain atonal scales were coming from my cot when I was nine months old, after I had been infused by my English grandmother’s nursery songs. I sang at family parties from the age of six, in church and school choirs from my early teens onwards, and professionally have worked as a soloist since I was 16. It all seems it was written in the stars. But there were times where I was toying with becoming an archaeologist or an art historian — like my uncle and aunt. These are still passions of mine. Whenever I go to a town in Italy it’s — ‘how many Roman ruins, churches and museums can I cram into one day?’ up to the point where I’m nearly fainting and need to find a ciabatta as soon as possible to stuff my face with, so I can move on! I feel quite sad not to have been able to work with or be taught by my grandfather. He also must have been a fabulous accompanist. Yet through working on Schubert songs with my father Andreas — who was also a singer before he became an opera director — I think quite a bit of Felix’s knowledge has been passed on to me.”

With a voice as pure and versatile as hers, Miss Prohaska could do a lot. What does she plan for in the near future ?

“Thank you ever so much! I would hate to develop a wobble or breathy sound, or any other irreparable damage to my cords because I didn’t have the willpower to say no to unsuitable roles or a cluttered schedule. Of course the offers of Verdi’s Violetta, Berg’s Lulu or Mozart’s Konstanze dangle in front of you like Tantalus’s fruit, and perhaps (or even probably) my voice will develop into that direction. But for now I am thrilled and fulfilled to sing my current repertory. I would be so thrilled to expand my baroque repertoire to sing Cleopatra in Handel’s Giulio Cesare, or Cavalli’s Calisto. And having sung Yniold in Pelléas et Mélisande when I was 17, I’d love to sing Mélisande.”

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Anna_Prohaska-2798-480.gif image_description=Anna Prohaska [Photo by Patrick Walter] product=yes product_title=Anna Prohaska, one of Europe’s most promising sopranos product_by=An interview by Anne Ozorio product_id=Above: Anna Prohaska [Photo by Patrick Walter]June 12, 2014

La Traviata in San Francisco

And unwelcomed. Take for instance the 2009 San Francisco installment which was the 2006 art deco version imported from L.A. Opera directed by Marta Domingo. Violetta, a flapper, arrived at the party in a Rolls Royce during the overture, and it was downhill from there even though the soprano was Anna Netrebko.

Just now in San Francisco there was a welcome surprise, and that was Verdi’s orchestral score made vividly present in moods and colors, rushes and hesitations, pianos and fortes, well, pianissimos and fortissimos. It was the high octane conducting of Nicola Luisotti that made Verdi’s first truly masterful score the star of the show. The pit was the sentient center of Verdi’s personal and deeply felt domestic tragedy.

Never mind that this intense emotional focus emanating from the seemingly inspired musicianship of a superb orchestra revealed Francesco Maria Piave’s (and one assumes Verdi’s) dramatic structure to be truly clumsy. Or that Luisotti’s ultimate acceleration missed the emotional beats of the opera’s final moments — the blow of the intense release was summarily trampled over — a not atypical Luisotti conclusion.

La Traviata, Act I. Photo by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera

The reliable 1987 (twenty-seven years ago) San Francisco Opera production by John Copley was back on stage. It is definitely mid-nineteenth century in concept as required by Verdi, glowing in warm colors (the splendid lighting designed by Gary Marder). The wash of colors, the swish of lavish gowns, the brilliant red flash of the flamenco dancer, the weight of nineteenth century architecture were however at odds with the detail and precision emerging from the Luisotti pit, and the emotional depth of the score itself.

The cast was decidedly low octane, and intimidated by the conductor. The stage action by the principals was kept downstage center, looking not at each other while singing to one another but presentational, addressing the audience and most importantly remaining able to have direct eye contact with the conductor.

Soprano Nicole Cabell replaced the originally announced Bulgarian soprano Sonya Yoncheva as Violetta. Mlle. Cabell has previously proven herself a fine bel canto singer in San Francisco (Giulietta in Bellini’s I Capuleti ed i Montecchi) in an integrated production (musical and production elements were compatible). A fine singer and artist, here undirected, she struggled to dominate the stage as required of Violetta, and did not possess an energy or brilliance of tone to bring Violetta to vibrant life. She opted out of the optional E-flat in “Sempre Libera.”

Albanian tenor Saimir Pirgu has also proven himself in San Francisco as a bel canto singer (Tebaldo in Bellini’s I Capuleti ed i Montecchi). A fine singer and artist, vocally he cannot make the leap from easily fulfilling the demands of well-directed bel canto to the specific vocal and histrionic requirements of proto-realism roles (a larger, warmer voice and presence) or the higher powered vocal demands of mid- and late Verdi theater.

Nicole Cabell as Traviata, Vladimir Stoyanov as Germont. Photo by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera

Bulgarian baritone Vladimir Stoyanov sang Germont. This esteemed artist possesses a quite beautiful voice, and more than Mlle. Cabell or Mr. Pirgu fulfilled the Luisotti musical vision. Yet he too seemed a too small vocal and histrionic presence on the War Memorial stage.

Conductor Nicola Luisotti brings very specific and very powerful musicianship to opera. San Francisco Opera has yet to build a production around his unique talent. One hopes this may one day happen.

Luisotti conducts the first six performances (through June 29). The remaining four July performances, including the July 5 performance beamed directly onto the gigantic scoreboard of AT&T Park (home of the Giants), have a different cast of principals and a different conductor. Opera-at-the-Ball Park is not to be missed. It may be the Traviata you want to see.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Violetta Valéry: Nicole Cabell; Alfredo Germont: Saimir Pirgu; Giorgio Germont: Vladimir Stoyanov; Flora Bervoix: Zanda Svede; Gastone: Daniel Montenegro; Baron Douphol: Dale Travis; Marquis D’Obigny: Hadleigh Adams; Doctor Grenvil: Andrew Craig Brown; Annina: Erin Johnson; Giuseppe: Christopher Jackson. Chorus and Orchestra of San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Nicola Luisotti. Original stage director: John Copley; Stage director: Laurie Feldman; Set design: John Conklin; Costume design: David Walker; Lighting design: Gary Marder; Choreographer: Yaelisa. San Francisco War Memorial Opera House, June 11, 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Traviata_SF1OT.png

image_description=Traviata

product=yes

product_title=La Traviata in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Nicole Cabell as Violetta Valéry, Saimir Pirgu as Alfredo Germont [Photo by Cory Weaver, San Francisco Opera]

A Digital Orchestra for Opera? Purists Take (and Play) Offense

By Michael Cooper [NY Times, 11 June 2014]

Nothing about Wagner’s epic “Ring” cycle is small in scale, but when a would-be impresario came up with the idea of staging it in West Hartford, Conn., he envisioned replacing its massive orchestral forces with the digital sounds of sampled instruments.

[More....]

June 11, 2014

Opera Las Vegas Presents Stellar Barber of Seville

Daniel Sutin, who sang the title role, held the audience in thrall as he described his activities with strong burnished bronzed tones in his “Largo al factotum.” As the beautiful and not-quite-so-meek Rosina, Renée Tatum sang with true bel canto tone, excellent taste, and fine musicianship.

Pierre Caron de Beaumarchais wrote his play, The Barber of Seville, in 1773, but could not get it publicly performed until two years later, because its politics offended French nobility. In the meantime it was often read privately read at artistic salons. Thus, when its content was becoming known without public performance, the authorities decided that they might as well allow it to be staged.