July 31, 2014

Rameau Grand Motets, BBC Proms

Perfection, as one would expect from arguably the finest Rameau interpreters in the business, and that's saying a lot, given the exceptionally high quality of French baroque performance in the last 40 years.

Even more meaningfully, this perfection was mixed with joy and humour. This was an hommage to Rameau, whose 250th anniversary we celebrate, But for us in the audience, it was also an hommage to William Christie, who founded Les Arts Florissants in 1979. Christie and the generations of artists he has inspired blend new scholarly research with musical intelligence.

In his lifetime, Rameau was something of a radical. Christie and modern baroque specialists present Rameau's music as vinrantly as it might have been when was still new. Deus noster refugium (1713) (God is our refuge) begins in relatively conventional mode, suitable for decorous church performance. Then a wilder, almost dance-like mood takes over, ushered in by "footsteps"in the vocal line, where each syllable is deliberately defined. The voices sing with firm conviction, while the forces around them are in tumult. With a little imagination, we can hear, as Lindsay Kemp describes in his programme notes, "''mountains' cast into the sea (bursts of tremolos and rushing scales in the strings, stoically resisted by firmly regular crotchets in the three solo voices; swelling waters (smooth but restless choral writing over forward-driving strings); and finally streams that 'filled the city of God with joy' a gigue-like aria for soprano with solo violin".

Quam dilecta tabernacula (1713-15?) (How lovely is thy dwelling place) allows Rameau to write elaboately decorative fugal patterns. Rameau, the master of technical form, also manages to evoke the beauty of the outdoors. The piece begins with very high soprano, accompanied by delicate winds : pastoral, sensual and mysteriously unearthly. The choruses introduce a livelier mood, which might suggest fecundity and vigorous growth. The soprano solo is balanced by a tenor solo, then later by baritone. Elegant design, reminiscent of baroque gardens, laid out in tight formation. When the soloists sing in ensemble, and later with full chorus, the voices entwine gracefully.

The version of In convertendo Dominus (Psalm 126, When the Lord turned again the Captivity of Zion) only now exists in a revision made for Holy Week in 1751. The piece begins with a wonderful part for very high tenor, presaging the passion later French opera would have for the voice type. Do we owe Enée and Robert le Diable to Rameau? Reinoud Van Mechelen's voice rang nicely, joined by the other five soloists in merry, lilting chorus that suggests laughter. The bass Cyril Costanzo's art was enhanced by whip-like flourishes of brass and wind. Even lovelier, the well decorated soprano passages, which lead into a beautiful blending of solo voices and orchestra. A pause: and then the exquisite chorus. "They that go out weeping....shall come back in exultation, carrying their sheaves with them. Christie balances the voices so finely that one really hears "sheaves", united and golden.

If these Grand Motets weren't enough, Christie continued with so many encores that the BBC schedule was thrown off kilter, and only one can be heard on rebroadcast. Haha! I thought, admiring Christie's bravado. Since I'd come for the music (and for Les Arts Flo) I was glad I could stay, and not worry about mundane things like missing the last bus. "Hahahahahaha " went the chorus in the excerpt from Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville's In exitu Israel (1753) on exactly the same subject. A brilliant choice! Just as in Rameaus In convertendo Dominus, the Hebrews are laughing because they've been freed. Rameau's laughter is more subtle, Mondonville's more crude, "crowd pleasing" to the point of being coarse. Christie is making a point. Mondonville was more fashionable at the time, but as we know now, Rameau has had the last laugh.

Christie continued with an extract from Rameau's Castor et Pollux which was used with words of the, Kyrie Eléison for Rameau's funeral Mass. The opera and its successors meant a lot to the composer, and to Christie, who conducted Hippolyte et Aricie at Glyndebourne last year (read my review HERE). Christie is no fool. Respect his choices. He knows baroque style better than most, and chose as director Jonathan Kent, with whom he created the magnificent Glyndebourne Purcell The Fairy Queen. "If it's good enough for Bill Christie", my companion said, "It's good enough for me". At the interval at Glyndebourne we bumped into Christie himself, and told him. He beamed with delight, his eyes twinkling. "That's what I like", he grinned.

Christie and Les Arts Florissantes ended with an excerpt from Les Indes Galantes, their greatest hit, which revolutionized public perceptions of the genre. The baroque era was audacious, given to extravagant, crazy extremes. People embraced the new world outside Europe, and delighted in exotic fantasy. Po-faced litera;ism is an aberration of late 20th century culture, dominated by TV. To really appreciate baroque style, it helps to understand the period. "You have to steep yourself in historical, performance practice", says Christie. "it has to become completely natural and spontaneous. If the public starts to become aware of the archaeological aspects, then we've failed. I think one of the reasons we've had success in Les Arts Florissants is because we've become completely instinctive". This fabulous Prom unleashed the joy, energy and wit in the style. Christie makes Rameau, and the spirit of his age, come alive.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rameau.png

image_description=Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) by Guillaume Philippe Benoist [Source: WikiMedia]

product=yes

product_title= Jean-Philippe Rameau, Grand Motets, William Christie, Les Arts Florissant, BBC Prom 17, Royal Albert Hall, London 29h July 2014

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) by Guillaume Philippe Benoist [Source: WikiMedia]

July 28, 2014

Adriana Lecouvreur, Opera Holland Park

Director Martin Lloyd Evans re-located the work to the mid 20th century and designer Jamie Vartan provided some stylish 1930's style costumes. Cheryl Barker sang the title role, with Peter Auty as Maurizio, Tiziana Carraro as the Princess de Bouillon, Richard Burkhard as Michonnet, Simon Wilding as the Prince de Bouillon, Ian Beadle as Quinault, Peter Davoren as Poisson, Maud Miller as Mlle Jouvenot, Chloe Hinton as Mlle Dangeville and Robert Burt as Abbe de Choiseul, with dancers from English National Ballet. Manlio Benzi conducted The City of London Sinfonia.

Director Martin Lloyd Evans re-located the work to the mid 20th century and designer Jamie Vartan provided some stylish 1930's style costumes. Cheryl Barker sang the title role, with Peter Auty as Maurizio, Tiziana Carraro as the Princess de Bouillon, Richard Burkhard as Michonnet, Simon Wilding as the Prince de Bouillon, Ian Beadle as Quinault, Peter Davoren as Poisson, Maud Miller as Mlle Jouvenot, Chloe Hinton as Mlle Dangeville and Robert Burt as Abbe de Choiseul, with dancers from English National Ballet. Manlio Benzi conductied The City of London Sinfonia.

Jamie Vartan's sets made imaginative use of the remaining facade of Holland Park House, which was bombed in 1940. The play in Act One took place inside the house with a caravan for Adriana and sundry back stage detritus and spare scenery. These were re-purposed in Act Two to create the stylish modern villa. Act three took place outside Holland Park House, now standing in for the Prince's mansion with the framework of the caravan creating a pavilion, with act four returning to Adriana's caravan, this time revealing a stylish 1930's style wooden interior. Vartan's costumes were stylishly in period with an eye for the niceties; though Adriana was always beautifully dressed, there was just the gentlest hint that her taste was a little bit common compared to the Princess who was very soignée all in white in act two and all in black in act three.

It is a tricky opera to bring off. The opera requires a real diva of temperament in the title role, one who has the capability to sing the long lyric vocal line but who also has some bite. Iit doesn't help that there is also a slightly barmy plot, which no amount of tinkering can remedy. To Martin Lloyd-Evans's credit he didn't try, but presented the act two shenanigans with dramatic commitment, imagination, and a nice element of humour (though no-one giggled thank goodness).

Cheryl Barker made a stylish and glamorous Adriana, bringing a convincing theatricality to the spoken sections and a wonderful sense of spite in the act three extract from Phédre. Her act one solo had a lovely lyric beauty, and a sense of intimacy apt to the humble surroundings (a caravan!). What seemed slightly worrying was that, though poised, her relationship with Peter Auty's ardent Maurizio seemed a little cool a little too perfect (more Joan Crawford than Bette Davis). But Barker's Adriana really came into focus in the last act. Not with the great solo poveri fiori which was finely done indeed, but with the solo where she tells Maurizio that she will not marry him, that for her the crown will be one of laurel leaves. Barker's Adriana was first and foremost and actress and you sense that despite her distress in act four, she would have returned to work because acting was the most important thing in her life. It was a performance which grew on me and in the final act displayed intense power, theatricality and, yes, diva-dom.

Peter Auty made a wonderfully passionate Maurizio, completely believable in the intensity of his passion and the way he was able to distribute his favours equally between two women (Adriana and the Princesse de Bouillon). Perhaps Auty does not have quite and ideally open Italianate sound, it seems a little covered. But his tenor has great freedom and a lovely evenness over the range. And a consistent ability to project Cilea's vocal lines with convincing passion and vibrancy.

Prncesse de Bouillon is a gift of a role, and Tiziana Carraro did not disappoint. She was vibrantly passionate in act two with a thrillingly intense scene with Auty, and then in the subsequent intrigue brought off hiding in a broom cupboard under a sheet with great aplomb. In Act Three, the atmosphere fairly crackled and Carraro's body language was vivid even when she wasn't singing.

Richard Burkhard was profoundly touching as the stage manager Michonnet, very moving in the way he portrayed his unspoken love for Adriana. In many ways Burkhard was the linchpin of the production, the subtly drawn sane man around whom all the mayhem happened. Burkhard gave Michonnet a sympathetically intent feel and to a certain extent rather stole the show with his detailed yet finely sung and understated performance.

The four actors, Quinault, Posson, Mlle Jouvenot and Mlle Dangeville were played four of Opera Holland Park's previous Christine Collins Young Artists, Ian Beadle, Peter Davoren, Maud Miller and Chloe Hinton. They formed charming foursome, always popping up together and combining joy with style and a certain element of fun. Robert Burt made a delightful Abbe de Chazeuil. into everything and far too fond of the young ladies. Whilst Simon Wilding was a fine upstanding Prince de Bouillon.

James Streeter provided the choreography for the highly effective ballet in act three which was danced by principals from the English National Ballet.

Cilea makes great use of the orchestra in the opera, with quite a number of orchestral interludes and the City of London Sinfonia did not disappoint, combining passion and suaveness in their performance. Manlio Benzi conducted with a clear feel for Cilea's idiom. It is easy both to over heat and to undercook the music, and Benzi walked a stylish line between the two, giving us a finely drawn but dramatic performance.

Despite some initial reservations, this was a highly effective and dramatic performance which came together in a powerful conclusion in the last act.

Robert Hugill

Cast and production information:

Adriana: Cheryl Barker, Maurizio: Peter Auty, Princess de Bouillon: Tizian Carraro, Michonnet: Richard Burkhard, Prince de Bouillon: Simon Wilding, Quinault: Ian Beadle, Poisson: Peter Davoren, Mlle Jouvenot: Maude Miller, Mlle Dangeville: Chloe Hinton, Abbe de Chazeuil: Robert Burt, Chorus of Opera Holland Park, Dancers from English National Ballet, City of London Sinfonia, Director: Martin Lloyd Evans, Designer: Jamie Vartan, Lighting: Colin Grenfel, Choreography: James Streeter, Conductor: Manlio Benzi

Opera Holland Park, London 26 July 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/adriana_1.png

image_description=Adriana Lecouvreur [Image courtesy of Opera Holland Park]

product=yes

product_title=Francesco Cilea: Adriana Lecouvreur

product_by=A review by Robert Hugill

product_id=Above: Adriana Lecouvreur [Image courtesy of Opera Holland Park]

July 27, 2014

Back to the Beginnings: Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria at Iford Opera.

The world of commercial public opera had only just dawned with the opening of the Teatro San Cassiano in Venice in 1637 and for the first time opera became open to all who could afford a ticket, rather than beholden to the patronage of generous princes. Monteverdi took full advantage of the new stage and at the age of 73 brought all his experience of more than 30 years of opera-writing since his ground-breaking L’Orfeo (what a pity we have lost all those works) to the creation of two of his greatest pieces, Ulysses and then his final masterpiece, Poppea.

As was the fashion, the “new” opera of the 1640s celebrated the precedence of the text over the music. It was said that music served to illustrate and therefore followed the text of the drama in every way, allowing the musicians to fill in the chords between the vocal and bass lines as they wished. More complete orchestration, it was thought, should be confined to musical interludes and aria-type passages. This theory has, it must be admitted, caused many of today’s early musicians many headaches!

At Iford, director Justin Way and conductor Christian Curnyn have sensibly foregone the usual “Prologue” as the original libretto by Badoaro established the fact that humans are just playthings at the mercy of the gods - Time, Fortune and Love .However, after this he also leaps into the story of our hero near the end of his trials and travels, and so we join the story as Penelope weeps and waits for her husband to return, pestered by ambitious suitors, whilst Ulysses is washed up on the shores of Ithaca unaware that the goddess Minerva has an idea......

Elisabeth Cragg as Minerva

Elisabeth Cragg as Minerva

This Iford Opera production, sung in English, made the most of the tiny space with a vaguely “ancient/mythological” blue flooring design and subdued (and occasionally wayward) lighting. Costumes were also vaguely modern with more than a touch of the dressing-up box, but did little to disturb the intense drama of the piece. A production which served rather than inspired.

However, it was, rightly, the music and the drama which stayed with the audience as we departed into a ridiculously warm and starlit night in the depths of the Wiltshire countryside. Curnyn’s group of eight superb early instrument specialists - with himself at the harpsichord almost part of the drama from time to time - drew us into this time-warp of sound with grace, style and (even more difficult on a sultry evening) amazingly good tuning.

Jonathan McGovern as Ulysses and Rowan Hellier as Penelope

Jonathan McGovern as Ulysses and Rowan Hellier as Penelope

Of the 12 young singers there can only be praise, and they kept up Iford’s reputation for high quality vocalism. The restricted acting space requires complete immersion in the role as there is literally nowhere to hide when so close to the audience and as actors some were better than others. Here experience tended to tell: standouts had to be Rowan Hellier as a noble, plangent Penelope with rich mezzo tones throughout; Jonathan McGovern as the wandering hero Ulysses who brought a powerful tenor which also could spin a line with ease, and Daniel Auchincloss as the faithful servant/shepherd Eumaeus, who’s early music experience, high tenor and appealing stage presence made themselves felt. Among the more minor roles, the resonant snarling bass of Callum Thorpe as one of the nicely-delineated three suitors was memorable.

Monteverdi is not an “easy” option for any summer festival opera series and Iford Opera is to be congratulated for finding exactly the right mix of musicians and singers to convince and perhaps convert those for whom this was a first experience of how it all started so very long ago.

Sue Loder

Click here for cast and production information.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ulysses_Iford3.png

image_description=Photo by Rob Cole courtesy of Iford Arts

product=yes

product_title=Claudio Monteverdi: The Return of Ulysses

product_by=A review by Sue Loder

product_id=Photos © Rob Cole courtesy of Iford Arts

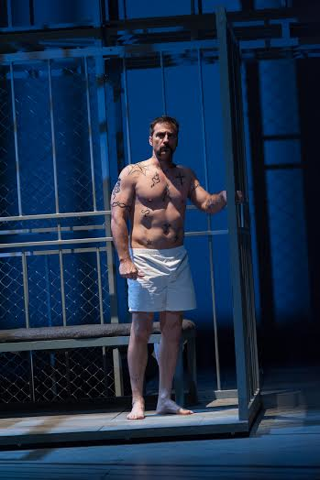

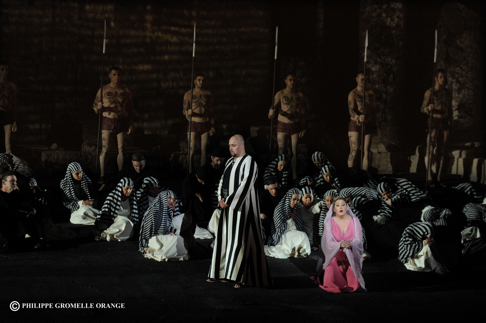

Schoenberg : Moses und Aron, Welsh National Opera, London

It is a sad state of affairs when a season that includes both Boulevard Solitude and Moses und Aron is considered exceptional, but it is - and is all the more so when one contrasts such seriousness of purpose with the endless revivals of La traviata which, Die Frau ohne Schatten notwithstanding, seem to occupy so much of the Royal Opera’s effort. That said, if the Royal Opera has not undertaken what would be only its second ever staging of Schoenberg’s masterpiece - the first and last was in 1965, long before most of us were born! - then at least it has engaged in a very welcome ‘WNO at the Royal Opera House’ relationship, in which we in London shall have the opportunity to see some of the fruits of the more adventurous company’s endeavours.

All of that would be more or less in vain, were the results not to attain the excellence Schoenberg demands. They were, in pretty much every respect, any of the doubtless inevitable shortcomings being of relatively minor importance. This was probably the finest work I have yet heard from Lothar Koenigs - to whose partnership with David Pountney we clearly owe many thanks. There can be no faking the necessary depth of musical understanding in this score, any more than there can be in Wagner or Brahms (or, indeed, anything that matters). Koenigs’s textual clarity and clarity of purpose not only enabled the drama to develop; they were in good part the Wagnerian embodiment, even representation, of the musical drama - not the least here of Schoenberg’s dialectics. There were occasional slips by the WNO Orchestra, but in no sense did they detract from a wholehearted contribution, which might have suggested that the work had been in its repertoire for years. (Recent Wagner, Berg, and indeed Henze will have done no harm, but even so…)

Perhaps the most exceptional work of all - though opera is, or at least should be, one of the supreme elevations of collaboration over miserable, bourgeois ‘competition’ - came from the WNO Chorus. In an interview to accompany Pierre Boulez’s second recording of Moses, Schoenberg’s great - alongside the very different Michael Gielen, his greatest? - interpreter and critic remarked: ‘People always say that it’s not an opera but an oratorio, which Schoenberg later turned into an opera. That interested me, because I disagree with it. The chorus, for example, is the most important character in the opera. It’s like a chameleon, speaking for or against, sometimes even internally divided or emphatic in its support of one particular party; it is angry, it is docile, it comments on the action.’ Musically and dramatically - indeed, quite rightly there seemed little distinction to be made - the chorus succeeded in fulfilling Boulez’s and Schoenberg’s expectations. Whether en masse, soloistically, or at various stages of in between, whether singing, speaking or at various stages of in between, Schoenberg’s highly charged and often ravishingly beautiful choral writing - I was often set thinking of his psalm settings - were faithfully, viscerally communicated. And of course, communication, both its necessity and its impossibility, is very much the thing in this of all operas; or rather, it is one of the things, all of them, like the score itself derived entirely from a single row, proceeding from the necessity and impossibility of representing the Almighty Himself. If indeed that is who He is, for at least at times, an element of doubt should and did set in, with respect to whether Moses is on the wrong track all together. This is and was a drama, not a tract.

I had my moments of doubt concerning the production too. Jossi Wieler and Sergio Morabito, as revived - very well, insofar as I could tell - by Jörg Behr present the entirety of the action in a single, courtroom venue. Law is of course a concern of the drama in several respects, the law-giving properties of the twelve-note method involved in a complicated, dramatically generative relationship with Mosaic law and the law of Creation itself. Moreover, as Aron points out to Moses, the Tables of the Law are ‘images also, just part of the whole idea’. That said, the idea or ideas of law do not seem to be especially emphasised, and - without wishing for some entirely impractical as well as undesirable Cecil B. de Mille Biblical ‘epic’ presentation, which would make only too clear the truth of Adorno’s charge that grand opera prepared the way for popular cinema - it is difficult to feel, at least at first, that there is not an element of dramatic constriction in the monothematic scenic realisation. (I am not entirely sure what was meant by the description of having been ‘based on an original design by Anna Viebrock’, given that no further design work was credited.)

And yet, so long as one is prepared to do some thinking - and anyone who is not should be allowed anywhere near this opera - it is perfectly possible to glean a great deal; what appears to be constriction was in some sense also mental liberation, which again is one of the crucial dialectics at work in the drama itself, concerned as it and indeed all modern philosophy are with the Kantian antinomy between freedom and determinism. Not only can the courtroom - if indeed that is what it was - readily convert itself, sometimes with a little scenic rearrangement but above all through the engagement of our minds, into a venue for political and/or religious activity or, through Aron’s manipulative-representational skills, into a cinema, upon which the crowd can watch the orgy, as we watch the crowd. We, the receptive and creative audience - at least, that is what we should be - have to employ our minds to represent what the Israelites were seeing, and thus to engage in that very necessity and impossibility of representation of which Moses and Aron spoke and sang. That is not to say, of course, that we should never see what goes on; Reto Nickler’s excellent Vienna production (available on DVD, under the inspired musical direction of Daniele Gatti, with the Vienna orchestra playing this music as only it can) shows what can be done with modern communicative messages of advertising and pornography. But what first seems as though it may simply be a cowardly - or even financially necessary - abdication of responsibility is revealed to be something much more interesting and, at some level, even provocatively Schoenbergian.

John Tomlinson’s assumption of the title role was predictably imposing. There was a good deal of what Gary Tomlinson has called the ‘Michelangesque terribilità’ of Schoenberg’s flawed hero, though I could not help but feel that the melodrama was overdone in the final scene. Still, the tragic grandeur, very much in the line of Wotan, of Tomlinson’s Moses was unquestionable. Although he seemed to have tired a little in the first half of the second act, Rainer Trost’s Aron proved a fine foil. I am not sure I have heard so clear a contrast between Sprechstimme and sinuous twelve-note bel canto (with a good deal of Siegfried et al. thrown in). Spatial matters played their role in the first act; placing on stage heightened the unbridgeable contrast between the two characters competing on unequal yet still justified terms. (One should never fall into the trap of saying that Moses is right and Aron is wrong; Schoenberg tilts the scales but remains some way from upending them, and there are certainly occasions when Moses is shown to be unambiguously, even unimaginatively in the wrong.)

Were I to proceed to hymn musico-dramatic excellence in the smaller roles, I should probably find myself simply repeating the cast list. However, I shall, in the spirit of the work, attempt the impossible, and single out Richard Wiegold’s stentorian Priest, the exemplarily alert contributions of Daniel Grice and Alexander Sprague, and the - literally - unearthly beauty summoned up by the chorus of six solo voices: Fiona Harrison, Amanda Baldwin, Sian Meinir, Peter Wilman, Alastair Moore, and Laurence Cole. For a work that struggles, like Aquinas, with a theological via negative, there was a great deal to be positive and thankful about. Three cheers to WNO!

Mark Berry

Cast and production information:

Moses: Sir John Tomlinson; Aron: Rainer Trost; A Young Maiden, First Naked Virgin: Elizabeth Atherton; A Youth: Alexander Sprague; Another Man, An Ephraimite: Daniel Grice; A Priest: Richard Wiegold; First Elder: Julian Boyce; Second Elder: Laurence Cole; Third Elder: Alastair Moore; Sick Woman, Fourth Naked Virgin: Rebecca Alonwy-Jones; Naked Youth: Edmond Choo; Second Naked Virgin: Fiona Harrison; Third Naked Virgin: Louise Ratcliffe; Chorus of six solo voices: Fiona Harrison, Amanda Baldwin, Sian Meinir, Peter Wilman, Alastair Moore, Laurence Cole. Jossi Wieler and Sergio Morabito (directors); Jörg Behr (revival director); Anna Viebrock (original designs); Tim Mitchell (lighting). Chorus and Extra Chorus of Welsh National Opera (chorus master: Stephen Harris)/Orchestra of Welsh National Opera/Lothar Koenigs (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Friday 25 July 2014.

mage=

image_description=

product=yes

product_title= Arnold Schoenberg : Moses und Aron, Welsh National Opera, Royal Opera House, London 25th July 2014

product_by=A review by Mark Berry

product_id=

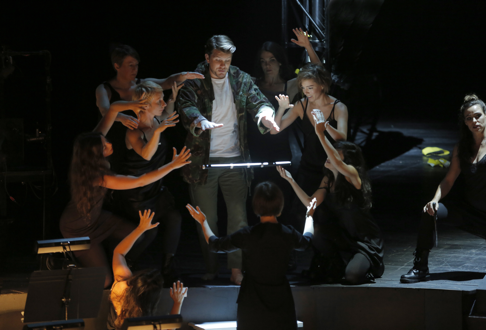

Count Ory, Dead Man Walking

and La traviata in Des Moines

The astonishing young tenor Taylor Stayton anchored the overall vocal excellence with an effortless traversal of the title role. Time was when the vocal demands of this opus limited any production attempts to the occasional appearance of someone like Rockwell Blake who could make at least a decent stab at the Count. These days, high-flying tenors seem to be turning up with happy regularity, and with his performance here, Mr. Stayton has announced that he is deserving to be numbered on the short list of Rossini all-stars.

The voice has it all: flexibility, endurance, beauty of tone, generosity of substance, and stratospheric range. Moreover, Taylor cuts a handsome figure on the stage, appealing, spontaneous, and boyishly athletic (witness a surprising - planned - fall into a clean somersault when he got tangled in his newly-donned hermit robes). He has already appeared at such top tier houses as the Met, and will undoubtedly become a regular fixture there and elsewhere. JDF should be very very nervous!

Sydney Mancasola (Countess), Taylor Stayton (Ory) Stephanie Lauricella (Isolier)

Sydney Mancasola (Countess), Taylor Stayton (Ory) Stephanie Lauricella (Isolier)

Every inch his equal, rising star Sydney Mancasola offered cascades of spot-on vocalizing as the Countess Adele. The silvery soprano seemed to gain in heft after her spectacularly sung entrance aria, and her immaculate coloratura was matched by her poised stage presence. In addition to meeting every challenge of some of Rossini’s most difficult ornamentations, Ms. Mancasola admirably acted with her voice which, in a comedy, is to say she found myriad ways to be funny. The inspired, heaving sobs that she injected into her “weeping” moments were worthy of Carol Burnett. This was just one of many memorable vocal effects. Having recently seen the uniquely gifted Cecilia Bartoli in this punishing role, I can say that Ms. Mancasola found an equally effective vocal identity as Adele, and lavished the part with dazzling pyrotechnics.

As the page Isolier, Stephanie Lauricella was a delectable puppy dog, believably boyish, and possessed of a robust mezzo that nonetheless had amazing dexterity, sort of an impish Cherubino on uppers. She strode around the space with understated masculinity, modulated her “handsome” putty face into an endless variety of fretting takes and wide-eyed surprises, and milked being a woman-playing-a-man-playing-a-woman for all it was worth. Best of all, Ms. Lauricella was up to the same high standards as her co-stars, making the well known bedroom trio an unfolding delight, musically and comically.

Iowan Wayne Tigges made a welcome debut here on home turf with a big voiced at-but-not-over the top traversal of the Tutor. Mr. Tigges seemed to roll up Mustafa, Bartolo, and Basilio, chewed on them for a bit, and then spit out a characterization of laser-beam intensity, his imposing bass bouncing happily through the house. But Mr. Tigges’ voice was not just imposing. When called upon, he could vocally dance around rapid-fire patter with the fleet-footed skill of a prize fighter. Stephen Labrie also had good luck with the featured role of Raimbaud, his full-bodied baritone proving to have warm appeal. He tickled us with his assured drinking song, although when he pressed the patter too hard, he occasionally got ahead of the beat. Since his voice carries well in the house, I would urge him to put a little less effort into “selling” those effects. Margaret Lattimore was luxury casting as Ragonde, her plummy mezzo as rich as chocolate mousse. An added bonus is that Ms. Lattimore has perfectly tuned comic timing and her many subtle bits of registering dismay never failed to elicit a laugh.

Chorus Master Lisa Hasson’s well-schooled ensemble proved to be such an important element that there is no doubt it was another major ‘character’ in the successful telling of the story. Well-choreographed movement, including a meticulous execution of the sewing scene with goofy synchronized, audible stabs at the embroidery hoops, just kept growing in effect and finally all this precision gave way to great abandon in the drunken nun scene.

Howard Tsvi Kaplan’s lavish, colorful costumes would not be out of place in Once Upon a Mattress, and I enjoyed set designer R. Keith Brumley’s Disney-inspired castle and drawbridge, and the too too pretty, have-a-nice-day sun, that got comically clouded with a cut-out whenever someone had the sadz. Barry Steele’s clever lighting conspired gleefully with all the visual shenanigans. The effect of the massive bed rising from the depths of the apron was well-calculated (does even fracking go as deep as that trap?).

If you were seated on the front side of the thrust stage, the direction and blocking was quite inventive, but I may not have been as happy to see the show from the sides. Most of the communication to the audience was played straight out. Still, David Gately devised fresh and funny business, crafted varied movement, and infused the final bedroom trio with a tasteful physicality.

In the pit, Maestro Dean Williamson’s orchestra was, well, why beat around the bush, just about as good as it gets. The scattered effects of the prelude were well judged and the rhythmic control and overall crescendo effects were meticulously coordinated so as to sound spontaneous and inevitable. I actually may have erred in comparing this to Pesaro. Based on my one experience with that annual Rossini Festival, this Le Comte Ory was far superior. Italy may have something they could learn from Indianola.

Everyone involved with the powerhouse production of Dead Man Walking covered themselves in glory. This was music- and theatre-making of the highest order.

Composer Jake Heggie has made the pivotal role of Sister Helen Prejean a huge ‘sing.’ It ranges from simple, floated folk tunes, to urgent conversational exchanges, to pointed wisecracks, to punishing emotional outbursts, to stinging dramatic force required at both extremes of the range. Librettist Terence McNally has compounded the challenge by scripting a torturous emotional journey that requires elements of extreme restraint, steady growth to understanding, and utter abandon to a raw transformation and spiritual bonding. In Elise Quagliata, the creators may have found their most powerful Helen yet.

Her luminous voice made every moment count, with a powerful, tireless mezzo displaying a rich, amiable tone of unbelievable stamina. Ms. Quagliata could hurl out climax after climax, one topping the other for searing intensity, then just as easily she could turn on a dime and scale back to a haunting whisper. The palette of vocal color Elise brought to the drama was staggering, from the sunlit joy of the opening scene to the final unaccompanied lines, mere wisps laced with unconditional love after Joe’s execution. This was great vocalism with limp, effortless delivery that was always deployed in committed service to the character. Truly memorable.

David Adam Moore as Joseph de Rocher

David Adam Moore as Joseph de Rocher

As the murderer Joseph de Rocher, David Adam Moore is also now surely without equal in this part. Mr. Moore discovered every possibility to transform this character who has committed a despicable crime into a complex entity that was dramatically and musically compelling. It did not hurt that he possesses a gorgeous, forceful baritone with a sound technique that not only served the spirited (often coarse) declamations well, but also facilitated heart-rending messa da voce effects. The baritone took us on a fascinating aural and physical voyage to repentance. When he finally broke down and confessed, it was cataclysmic, a life changing moment for both character and audience. As the repentant killer, he tore us apart in his final moments. David was physically perfect for de Rocher, theatrically affecting, musically impeccable, and fully deserving of the most vociferous and robust ovation of the entire festival.

After her merry hijinks in the Rossini, the versatile Margaret Lattimore was back as Joe’s grieving mother. On this occasion, Ms. Lattimore brought seamless beauty to her singing, and elicited wondrous empathy for her plight. Although appearing as simple, unaffected, and homey as a Wal-Mart shopper, she engendered a noble strength of character. Her steadfast dedication to all her sons’ well-being informed the piece, and made us seriously question whether it is moral to kill a killer who is also a big brother, loving son, and troubled child of God. As the unsympathetic and garrulous prison chaplain, Stephen Sanders put his steely, forthright tenor to good purpose in portraying an unyielding personality. Kyle Albertson found a good solution to make the Warden three-dimensional by alternating his stern, firm-voiced statements with mellifluous phrases as appropriate.

Wayne Tigges also did a remarkable about face from daffy Rossini business, to contribute a superb turn as the father who retreats from his vengeful feelings into a miasma of doubt and spiritual indecision. His nuanced singing was another highlight of the day. Karen Slack (Sister Rose) captured the audience with a spinning, thrilling top voice that soared above the staff. Ms. Slack’s distinguished work in the extended, sonorous duet with Helen, served notice that she is an artist we will definitely want to hear again (and again).

The final ensemble

The final ensemble

R. Keith Brumley has designed a scenic environment that is sparse, fragmentary, and so highly effective that you almost didn’t notice it. Set changes were accomplished with speed and minimal effort. Barry Steele provided a moody, often stark lighting design with many splendid effects, like the blood red wash as the execution party sway-marched to the chamber. Fort Worth Opera’s simple costume plot did all that was needed. That company also furnished an integral sound design that brought the piece to a chilling conclusion with the whooshing release of poisonous liquids and the beating heart monitor that pierced the theatre until it beat no more.

Conductor David Neely led an immaculate reading of this challenging score. From the meandering phrases of the opening prelude, through the tense confrontations that proliferate the piece, to the gut-wrenching anguish of the many extended ariosos and ensemble, Maestro Neely allowed the score to unfold with both sensitivity and tension. Arguably the most profound and forceful musical moment was the slow, forceful unfolding of the “Our Father” peppered with cries of “Dead Man Walking” by the whole company as the tension built to the unavoidable moment of punishment. The orchestra has never sounded more committed, singly and in ensemble.

Director Kristine Mcintyre not only honed dramatic moments of unerring dramatic accuracy, but also mined every ounce of humor in the work, striking a powerful balance. She managed to help each performer find a sympathetic core to the character. Finally, the venue itself was perhaps the most perfect space imaginable to invest the work with such soul-stirring impact. Unlike proscenium productions, where we are observers from the other side of the pit, in this thrust arrangement we became full participants in the drama. When de Rocher was strapped to the table, suggesting the crucifix, and Helen was onstage reaching out to him from across the divide, we were inexorably drawn into the act of witnessing the loss of a life. As her final unaccompanied hymn tune faded and the lights all went to black, in that moment before we dared break the silence with applause, someone a couple of rows behind me broke out in heaving sobs. I cannot imagine a more powerful production of this engrossing opera.

The new staging of La Traviata included a deluxe physical production, world famous music, an expansive and extravagant concept, unique staging features, and in the Everest of female Verdi roles, a stunning new soprano to cheer to the rafters. Caitlyn Lynch regaled us with a polished, creamy tone of spun gold.

Caitlyn Lynhc (Violetta) and Diego Silva (Alfredo)

Caitlyn Lynhc (Violetta) and Diego Silva (Alfredo)

Fussbudgety operaphiles often like to opine a fine Violetta needs to be Joan Sutherland in Act I, Birgit Nilsson in Act II, Montserrat Caballe in Act III and Beverly Sills in Act IV. Granted, this role is a varied, complicated, fascinating piece of vocal writing, and Mr. Verdi has given Violetta several musical ‘personalities’ to cope with. And Ms. Lynch decidedly showed she had the goods to bring all the requisite big moments to fruition.

Indeed, she proved capable of accurate, playful coloratura; could summon a spinto-ish heft throughout many a rangy phrase; floated high notes with great delicacy; and is blessed with a lovely face and figure. Caitlyn is relatively new to this complex heroine, arguably Verdi’s greatest, but she clearly has abundant stage savvy, has all the notes in her voice, and she concentrates mightily on singing it conscientiously with utmost attention to detail. Time and further outings in the part will no doubt afford this gifted soprano the opportunity to build on this solid beginning and invite more spontaneity. If there is one quality I would urge her to explore, it is a poignant fragility that is not yet readily present in her impersonation. Such emotional investment begins to inform her “Addio dal passato” when she starts to find the right balance of sound technique and touching dramatic intention.

Diego Silva’s medium-sized tenor has a somewhat fast vibrato that found his Alfredo at his best in Act III when he could let it all out. Elsewhere he gambled on crooning his way through too many tender phrases, injecting breathiness to suggest sincerity. As long as Mr. Silva kept the voice hooked up he made a decent impression, but when he let his focus wander, got off the line and went diffuse, he tended to flat especially on descending phrases. Still, he is nice-looking, sincere, and has good musical instincts.

Todd Thomas has a substantial baritone and is capable of a big, imposing sound. Perhaps a bit too imposing. He almost overstated his first entrance, and verged on a caricature of paternal anger that made him come off as a little unhinged. He settled down after a few phrases but never quite found the empathy and conflicted tenderness in the part. Mr. Thomas’ requested embrace of Violetta came off as perfunctory, but so was his relationship with his son. His technique is rock solid, and he seems to be capable of far more sensitive vocalism. Perhaps it was a directorial choice, but he just did not seem spiritually connected to anyone’s plight, even his own.

Ashley Dixon, a smoky-toned Flora, commanded our interest. Luis Orozco, a lanky, egotistic Duphol showed off a solid bass and no nonsense delivery. Brenton Ryan was an appealing Gastone, making the most of his stage time and displaying a pleasantly refined lyric tenor. Tom Dillon seemed luxury casting as Dr. Grenvil, singing with a beautiful, orotund, sympathetic bass.

"Libiamo"

"Libiamo"

As we entered the theatre, a hologram-like projection of a ghostly woman in a wedding dress floated across the black scrim from stage right to disappear stage left, only to keep re-appearing in an endless loop. This was powerful imagery that foretold the journey we were about to undertake. Robert Little’s expansive set design suggested luxury with judicious choices. The ballroom was created with layers of gilt doors and arches that gave great depth to the stage. Here and throughout the evening, the rich look was augmented by gorgeous period costumes from A.T. Jone and Jones, Inc., that were lavish and eye-catching. An expert make up and hair design from Joanne Weaver completed the perfect picture.

The bucolic atmosphere in Act II was also pleasing if arguably a bit too sprawling. Act III gave us a dazzling red Moorish framework. Lisa Hasson’s excellent chorus was well used, first as the wiggling naughty gypsy girls, then as the stalwart toreros with one bullfighter and a boy in a bull mask cavorting, all the while conveying the idea of slightly salacious party games. The gaming table was effectively situated up left but somehow it seemed too inconsequential in size. Kyle Lang’s fluid choreography contributed mightily to the success of the party scenes.

The placement of the giant deathbed on the thrust was a good choice, and the black scrim behind it eventually revealed a row of buildings on the street outside. I quite liked the touch of seeing the singing revelers momentarily people that boulevard, and appreciated the visual of Alfredo standing with his back to us, looking up at Violetta’s window.

Lillian Groag’s direction was chockfull of such imaginative considerations. Her blocking, especially group scenes, used the entire space well with a focus that was beautifully judged so we always knew right where to look. Minor characters were unusually well-developed and sustained. I wish that the three principals had found more sub-text to play so that they might have ignited some real sparks and generated some needed heat. This was exacerbated in the garden scene where the gap between Violetta and Germont was sometimes too great, the crosses too big, the moves occasionally unmotivated.

David Neely led the score with predicable stylistic flair and once past a somewhat scratchy prelude, the sounds emanating from the pit were assured and purposeful. The company has assembled a technically first-rate, beautifully sung mounting of this timeless classic. I only wish they had also found the heart of it.

James Sohre

Le Comte Ory

Le Comte Ory: Taylor Stayton; Comtesse Adele: Sydney Mancasola; Isolier: Stephanie Lauricella; Raimbaud: Stephen Labrie; Ragonde: Margaret Lattimore; Tutor: Wayne Tigges; Alice: Abigail Paschke; Conductor: Dean Williamson; Director: David Gately; Set Design: R. Keith Brumley; Lighting Design: Barry Steele; Costume Design: Howard Tsvi Kaplan; Make Up and Hair Design: Joanne Weaver (for Elsen and Associates, Inc.); Chorus Master: Lisa Hasson

Dead Man Walking

Sister Helen Prejean: Elise Quagliata; Joseph de Rocher: David Adam Moore; Mrs. Patrick de Rocher: Margaret Lattimore; Sister Rose: Karen Slack; George Benton: Kyle Albertson; Father Greenville: Stephen Sanders; Kitty Hart: Kimberly Roberts; Owen Hart: Wayne Tigges; Jade Boucher: Mary Creswell; Howard Boucher: Edwin Griffith; Motorcycle Cop: Kenneth Stavert; Older Brother: Benjamin Schaefer; Younger Brother: Lucas Knoll; Sister Catherine: Nataly Wickham; Sister Lilliane: Stephanie Schoenhofer; Prison Guard 1: Casey Yeargain; Prison Guard 2: Zachary Ballard; Teenage Girl: Madison Densmore; Teenage Boy: Brad Jahner; Anthony de Rocher: Brendan Dunphy; Jimmy: Pierce Mansfield; Conductor: David Neely; Director: Kristine Mcintyre; Set Design: R. Keith Brumley; Lighting Design: Barry Steele; Costumes and Sound provided by Fort Worth Opera; Make Up and Hair Design: Joanne Weaver (for Elsen and Associates, Inc.); Chorus Master: Lisa Hasson

La Traviata

Violetta Valery: Caitlyn Lynch; Flora Bervoix: Ashley Dixon; Annina: Rebecca Krynksi; Alfredo Germont: Diego Silva; Giorgio Germont: Todd Thomas; Gastone: Brenton Ryan; Baron Duphol: Luis Orozco; Marchese D’Obigny: Nickoli Strommer; Doctor Grenvil: Tony Dillon; Flora’s Sevant: Brad Barron; Giuseppe: Joshua Wheeker; Conductor: David Neely; Director: Lillian Groag; Choreographer: Kyle Lang; Set Design: Robert Little; Lighting Design: Barry Steele; Make Up and Hair Design: Joanne Weaver (for Elsen and Associates, Inc.); Costumes from A.T. Jones and Jones, Inc., Baltimore; Chorus Master: Lisa Hasson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ory_Sohre2.png

product=yes

product_title=Count Ory in Des Moines

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Taylor Stayton as Ory and the "nuns" [All photos courtesy of Des Moines Metro Opera]

July 26, 2014

Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass, BBC Proms

During the rehearsals for the premiere - just 3 for the orchestra and one 3-hour rehearsal for the whole ensemble - the composer made many changes, and such alterations continued so that by the time of the only other performance during Janáček’s lifetime, in Prague in April 1928, many of the instrumental (especially brass) lines had been doubled, complex rhythmic patterns had been ‘ironed-out’ (the Kyrie was originally in 5/4 time), a passage for 3 off-stage clarinets had been cut along with music for 3 sets of pedal timpani, and choral passages were also excised.

Were these changes a result of practical expediency? Too few rehearsals to work out solutions to performance problems; sopranos who could not sustain the high Bbs in the original ending to the Sanctus; instrumental players who found the unconventional, asymmetrical cross rhythms unfathomable in the Kyrie? Too few bars, perhaps, for the clarinettists to get off stage! Or, do they reflect Janáček’s revised, and final, musical judgement? For example, the composer added brass to the ending of the Sinfonietta for the reason that it was not possible to create the necessary climaxes without additional forces, and the same decision may have been taken in the case of the Mass.

Pre-occupied immediately afterwards with the composition of From the House of the Dead, Janáček reputedly declared that he was not inclined to concern himself with the score of the Glagolitic Mass. So, are the difficulties of the original performances still problems today? And, which version of the work best represents the composer’s intentions?

There are no unequivocal answers to these questions, but at the Royal Albert Hall we were offered the opportunity to hear the ‘raw’ Glagolitic Mass - startlingly imaginative, defiantly rhetorical, unquestionably ‘modern’ - when a reconstruction of the original 1926 score by Janáček scholar Paul Wingfield was performed by the London Symphony Chorus and Orchestra under the baton of Valery Gergiev.

This was certainly a rousing rendition, as Gergiev drew energised, committed playing and singing from the forces massed before him, and created expectancy and excitement from the alternations of brass, chorus and vocal soloists. The fanfares of the Intrada were vibrant and invigorating, while in the instrumental Uvod Gergiev allowed air between the varied instrumental voices.

The entry of the chorus in the Kyrie (Gospodi pomiluj) had the quiet simplicity of an unaffected prayer and this mood of sincere devotion was given added fervour by the entry of soprano Mlada Khudoley whose breath-taking power and projection did not in any way diminish the sumptuous beauty of her soaring lines. In common with all the soloists, Khudoley genuinely and fully appreciated the composer’s unique ‘operatic’ idiom.

In the Gloria (Slava) the chorus reached ecstatic heights, while the long Credo (Věruju) allowed Gergiev to find a diversity of moods and colours: the vocal solos and choral interjections were impassioned - tenor Mikhail Vekua’s proclamations shook the RAH rafters - but there was also some consoling sweetness during the gentle orchestral interlude. The Agnus Dei (Agneče Božij) was dark of hue, a moment of deep reflection before Thomas Trotter’s invigorated organ solo in which flamboyant technical proficiency was blended with a sense of the composer’s vehemence and zeal.

Janáček wrote: ‘I hear in the tenor solo a kind of high priest, in the soprano solo a maiden angel, in the chorus our people. The candles are high fir trees in the wood, lit up by stars; and somewhere in the ritual see a vision of the princely St Wenceslas. And the language is that of the missionaries Cyril and Methodius.’ Gergiev and the LSO and Chorus were true to this pantheistic spirit.

Barry Douglas first came to prominence in 1986 when he won the Tchaikovsky Competition. Currently mid-way through a monumental project to record the complete works for solo piano of both Brahms and Schubert, in the first half of the programme Douglas performed Brahms’s First Piano Concerto - and there was something of the introspection of the solo piano music about Douglas’s first entry, which was resigned and consciously removed from the orchestral tumult. This deliberation, focus and intense concentration contrasted markedly with the forthright vigour and rhetoric that Gergiev encouraged from the LSO in the dramatic orchestral opening passage.

Perhaps it was just where I was seated, or maybe the RAH acoustic is not suited to the symphonic blend of soloist and orchestra which Brahms crafts, but I found the LSO’s playing disappointingly heavy, the rhythms lacking bite, the textures dense, especially in the third movement Rondo. Conducting without a baton, Gergiev fluttered his hands and fingers incessantly but there was little that flickered lightly in the orchestral sound that these twitchings brought forth.

That’s not to say that there was not some fine instrumental playing. In the second movement, the clarinets and oboes played with poetry and pathos, and the demanding writing for horns and timpani was executed with great accomplishment throughout. But, I found myself focusing on Douglas’s solo voice: the warmth of the hymn-like chordal second subject in the first movement was wonderfully soothing and throughout Douglas’s virtuosity was wonderfully integrated within the eloquent communication of the spirit of Brahms’ music.

Claire Seymour

All BBC Proms can be heard online, internationally for 30 days after broadcast

Cast and production information:

Barry Douglas, piano. Mlada Khudoley, soprano; Yulia Mattochkina, mezzo soprano; Mikhail Vekua, tenor; Yuri Vorobiev, bass; Thomas Trotter, organ; Valery Gergiev, conductor; London Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Chorus.

mage=

image_description=

product=yes

product_title= Leos Janáček : Glagolitic Mass, Brahms : Piano Concerto no 1, BBC Prom 9 Royal Albert Hall, London, 24th July 2014

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=

Donizetti and Mozart, Jette Parker Young Artists Royal Opera House, London

We began with the first act of Donizetti’s La favorite, a fairly flimsy love triangle which tangentially evokes the struggles between state and church in fourteen-century Spain during the Moorish invasions of that time. Fernand, a monk, forgoes his holy vows in order to pursue his, as yet unidentified, beloved - he turns out to be Léonor the ‘favourite’ mistress of the King of Castile Alfonso XI. In Act 1 we see Fernand, warned by his Father Superior Balthazar of the dangers which will ensue if his denies his sacred vocation and enters the ‘seas of life’, travel (blindfolded) to the island of Leon, where he is met by Léonor’s companion, Inès. A passionate reunion ensues: Fernand’s hopes are first dashed - when Léonor declares that they must never meet again - and then given fresh impetus, when he learns that she has given him a commission in the army.

Australian director Greg Eldridge, also a JPYA (the scheme supports stage directors, conductors, répétiteurs, music staff as well as singers) took a sensibly minimal, abstract approach - recesses and shadows to suggest monastic cloisters, a floaty white drape to evoke an island ambience - using the deep colours Edward Armitage’s lighting design and Natalia Stewart’s period costumes to suggest tempestuous emotions and unpredictable hazards. During the overture, the blood-red glow transmuted first to a cooler aquamarine, then dimmed to ominous black; the outcome of risks taken in the name of desire were clearly signposted by the encompassing darkness and by the lyric passion summoned from the Welsh National Opera Orchestra by conductor Paul Wingfield. The orchestral lines were vigorous and clearly defined, although perhaps Wingfield did give his forthright brass section a little too much of a free rein.

The chorus of monks processed earnestly (movement director, Jo Meredith) establishing a suitably devout context for Fernand’s rebellious outburst. And, as the wayward, strong-willed monk, tenor Luis Gomes demonstrated a fine, elegant line, with a sure sense of the structure of the lyrical phrases. At the top, and at points of heightened drama as when Fernand rejoices in the promotion which he hopes will elevate him nearer to his beloved’s social position, there was some tightness; but there was also much musicality and a convincing sense of character and dramatic engagement. South Korean bass Jihoon Kim - Jette Parker Principal Artist - was solemn and imperious as the naysaying Balthazar, using his large grave bass to convey the onerous weight of blessed duty and sacrifice; at times the tone was a little unfocused, but overall the performance was persuasive.

As Inès, Armenian soprano Anush Hovhannisyan alternated warmth and refinement in her aria with the chorus, and the sound was appealing. Most impressive of all was Russian mezzo-soprano Nadezhda Karyazina whose full upper bloom and lower opulence were beguiling as Léonor.

As if a pairing of Donizetti and Mozart was not enough, Puccini was thrown in to the mix after the interval, when John Copley’s set for La bohème served as the stage for the first act of Così fan tutte. The cast might have been forgiven the odd identity crisis: one blink and Ashley’s Riches’ Don Alfonso might morph into Scarpia. But, Eldridge fashioned some neat comic touches, as when Ferrando and Guglielmo searched the wardrobes of Mimi and Marcello for their Albanian disguises. The overture was rather over-populated though, as chorus-members trundled through a vibrant café, distracting from the grace of the playing which conductor Michele Gamba coaxed in the pit. (Perhaps, as the Act 1 chorus was cut, this was just to give the monks and island belles from the first half something to do?)

Of the cast, Riches and Australian soprano Kiandra Howarth stood out. Riches has a strong stage present and excellent sense of wit, timing and gesture to add to his firm bass. Howarth didn’t quite have the evenness across the range required for a truly masterful ‘Come scoglio’ but at the top she shone and her sense of Mozartian idiom, and parody, was excellent.

Rachel Kelly has a lovely mezzo, sweet-toned and agile but very centred, which made Dorabella’s ‘Smanie implacabili’ a winning number, despite its mock-hysterics. Serbian soprano Dušica Bijelić took the role of Despina and acted engagingly although she did not always project with Mozartian clarity and lightness.

British tenor David Butt Philip (Ferrando) and Brazilian baritone Michel de Souza (Guglielmo) were a fine comic duo. Although he started his musical life as a baritone, Butt Philip sang without strain at the top and with elegance. De Souza was given Guglielmo’s ‘"Rivolgete a lui lo sguardo"’ to demonstrate his talents.

The roll call of JPYA alumni is impressive. And, with the announcement that Jihoon Kim will become a Principal Artist with the Royal Opera next season, and that five new participants (who were selected from almost 400 applicants drawn from 58 nations) will join the Programme from September 2014 - Australians Lauren Fagan (soprano), Samuel Johnson (baritone) and Samuel Sekker (tenor); British bass James Platt; bass-baritone Yuriy Yurchuk from the Ukraine - it is clear that the JPYA Programme continues to make a significant and highly valuable contribution to the development of the careers of young singers and opera professionals, and to the musical life of the capital and beyond.

Claire Seymour

La favorite: Inès, Anush Hovhannisyan; Léonor, Nadezhda Karyazina; Fernand, Luis Gomes;

Balthazar. Jihoon Kim.

Così fan tutte: Despina, Dušica Bijelić; Fiordiligi, Kiandra Howarth; Dorabella, Rachel Kelly; Ferrando, David Butt Philip; Guglielmo, Michel de Souza; Don Alfonso, Ashley Riches.

Stage director, Greg Eldridge; Conductor (La favorite) Paul Wingfield, (Così fan tutte) Michele Gamba, Welsh National Opera Orchestra; Continuo (Così fan tutte), David Syrus.

mage=

image_description=

product=yes

product_title= Donizetti: La favourite, Mozart Così fan tutte, Jette Parker Young Artists Summer Gala, Royal Opera House, London 20th July 2014

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=

Glyndebourne's Strauss Der Rosenkavalier, BBC Proms

Semi-staged it might have been but it’s amazing how a stretch-limo of a chaise-longue and some atmospheric lighting can translate you from a hot night in modern-day South Kensington to the rococo opulence of fin de siècle Vienna or a slightly surreal 1960s locale.

Jones and his designer Paul Steinberg left their eye-straining patterned wallpaper at Glyndebourne, but the glowing colours of the illuminated strip which bordered the raised platform were a subtle replacement. Much can be communicated with a simple visual image and, as ever in Jones’s productions, the details here were telling. In Act 1 Baron Ochs and Mariandel sit at opposite ends of the cream couch, Ochs’ misapprehension that he is wooing a potential sexual conquest comically emphasised by the literal gap between the eager wooer and the disguised Octavian. Subsequently, when Octavian and the Marschallin resume this position, the space between assumes a tragic resonance, intimating not delusion but as yet unvoiced self-knowledge and foreshadowings of estrangement.

We move from the Marchallin’s levee to Faninel’s art deco palace in Act 2, his brightly coloured illuminated name replacing the patterns of Act 1, and the cream chaise-longue supplanted by a crimson velvet couch. Movements and transitions throughout the evening were unfussy; and Sarah Fahie, the semi-staging and movement director, made effective use of the auditorium, placing the off-stage band in the Gallery during Ochs’ failed seduction of Mariandel in Act III.

Kate Royal was a graceful, poised Marschallin, both vocally and dramatically. Her soprano is not excessively opulent but it is clear and silky, and her singing was unfailingly accurate and intelligently phrased. While Royal didn’t quite plumb the Marschallin’s emotional depths, there were many moments of dramatic insight. After the busy opening scenes, I was quite disarmed when, gazing in the mirror at her freshly arranged coiffeur, Royal reflected, ‘"Mein lieber Hippolyte,/ heut haben Sie ein altes Weib aus mir gemacht"’ (My dear Hippolyte, today you’ve made me into an old woman’); the change of colour and vocal shadows, as if she were singing to herself, seemed to confirm the Marschallin’s essential isolation from the vulgar business proceeding around her.

When the Marschallin pondered the passing of time at the end of Act 1, Royal’s monologues were again marked by self-composure and were quietly reflective; she let the music speak for itself and her discreet approach was all the more effective for Octavian’s boisterous, naive interjections: ‘Nicht heut, nicht morgen! Ich hab’ dich lieb. … Wenn’s so einen Tage geben muss, ich denk’ ihn nicht!’ (Not today, no tomorrow! I love you! … If such a day there must be, I’ll not think of it!)

There was poignancy too: at the end of Act I, turning away from the Hall into a world of private musing, Royal curled elegantly on the chaise-longue, watched over by a portrait of Freud (and the bust of Henry Wood), and her self-containment was underpinned by conductor Robin Ticciati’s gentle musical direction - three carefully place pizzicati, followed by the merest delay before the horns’ final muted chord. Yet, while it is easy for us to pity the Marschallin, after the glorious riches of the Act III trio Royal’s slightly impatient final renunciation, ‘Ja, ja’, made us think again.

Tara Erraught’s Octavian was superbly sung and acted: particularly impressive was her meticulous attention to the dramatic inferences and details - Erraught even altered her accent, to considerable comic effect, when disguised as Mariandel. In the opening scenes, this Octavian was by turns ardent and tender, petulant and exuberant, stubborn and emollient; and Erraught’s focused, bright, strong sound conveyed the confidence of youth and intimated the man Octavian will become. Erraught’s mezzo swelled glossily, blooming into the auditorium, as Octavian, inflamed with adolescent self-assurance, craved both Love and his beloved Bichette: ‘Ja, ist Sie da? Dann will ich Sie halter, dass Si emir nicht wieder entkommt!’ (Is she really here? I will hold her lest she escapes me again!) This was the performance of the evening.

With Teodora Gheorghiu indisposed, soprano Louise Alder donned Sophie’s fairy-princess finery and endured being flung about like a stiff marionette, prinked and preened to debutante perfection. I recently reviewed Alder at the Wigmore Hall and remarked that she was a ‘name to watch … remarkably assured … [with] an alluring voice characterised by lyrical charm and astonishing power, particularly at the top; and her vocal prowess was complemented by a sure sense of poetic meaning and musical poetry’. These qualities were certainly in evidence, but we had to wait a little time for Alder to truly shine.

Ticciati paced the presentation of the rose scene perfectly. Octavian’s entry was arresting, full of expectation and a sense of occasion; standing side by side, facing towards the Hall, the young lovers-to-be intimated both the formality of the ceremony and their own nervousness; then, as they turned to face each other, Erraught wonderfully conveyed the moment that Cupid punctured Octavian’s heart, swaying gently inwards as if lured by a hypnotic blend of the silver rose’s heady scent and the image of perfection before him.

Alder’s floating gossamer arcs were flawlessly tuned and delicately placed, but I did not like her tendency to swell through the note, from fragile transparency to momentary gleam and back again, and would have preferred a more even line. But, she quickly settled and gained in confidence, and post-presentation both Alder and Erraught displayed an openness of tone which underscored the candour of their exchanges, ‘Wird Sie das Mannsbild da heiraten, ma cousine? … Nicht um die Welt!’ (Are you going to marry that fellow, ma cousine? … Not for all the world!). Ever feistier, the voice increasingly focused, Alder established a strong stage presence, flinging off her silver slippers and removing her ghastly flounces to be draped by Marianne in a simple white dressing-gown; her true heart liberated from the trappings of formal courtship.

Lars Woldt was also unavailable and Franz Hawlata stepped effortlessly into Baron Ochs’s alpine leather boots. Hawlata possesses natural comic timing which, after the clumsy staircase tumble of his initial entry, relied here on understatement rather than bombast; he (and Jones) realise that actions are funnier if not played for laughs; as a consequence, convinced of the Baron’s utter lack of self-knowledge and thus too of his honesty, we were prompted to veer between aversion and sympathy for the hapless suitor. In a neat touch, at the end of Act 2 a flunkey unfolded a concertinaed portrait gallery of potential mistresses (something mid-way between a set of Renaissance miniatures and an internet dating site roll call), and Ochs’s transparent misconceptions prompted an affectionate snigger. Hawlata has a lovely, appealing tone, and his voice was, aptly, by turns flexible and sturdy; he was also the best of the cast in communicating the text, and many moments were enhanced by this clarity - as in, for example, the end-of-Act 2 exchanges with Helene Schneiderman’s excellent Annina.

There was much to admire, too, elsewhere, Michael Kraus’s finely sung Faninal being a notable highlight. As the Italian Singer, the idiomatic, virile tone of tenor Andrej Dunaev impressively filled the Hall, and there strong performances from Christopher Gillett (Valzacchi), Miranda Keys (Marianne) and Gwynne Howell (the Notary).

Under the baton of Robin Ticciati, the London Philharmonic Orchestra produced playing as elegant as the vocal performances. Ticciati’s conducting was unfussy but precise and sensitive to the singers. There was no bombast - I had to listen hard during the overture to hear the sexually-charged yelp from the horns - and one might have desired more indulgent sensuousness. But, Ticciati was alert to the way that the orchestral colours guide us across the spectrum of emotional highs and lows: there was much beauty in the fluttering of harps, celeste and flute during the presentation of the rose, but also timbral darkness. The tempi were well-judged, especially the Act III trio.

This was a delightful evening. The comedy was gentle - a wry chuckle rather than a belly-laugh - but not a moment passed without something for the ear or eye to enjoy.

Claire Seymour

Kate Royal, soprano (Marschallin); Tara Erraught, mezzo-soprano (Octavian); Franz Hawlata, bass (Baron Ochs); Louise Alder, soprano (Sophie); Michael Kraus, baritone (Herr von Faninal); Miranda Keys, soprano (Marianne); Christopher Gillett, tenor (Valzacchi); Helene Schneiderman, mezzo-soprano (Annina); Gwynne Howell, bass (Notary); Andrej Dunaev, tenor (Italian Singer); Robert Wörle tenor (Innkeeper); Scott Conner, bass (Police Inspector); Robin Ticciati, conductor; Sarah Fahie, semi-stage/movement director; London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Claire Seymour

All BBC Proms are available on-line, internationally for 30 days after broadcasr

image=

image_description=

product=yes

product_tRicahrd Strauss : Der Rosenkavlier, BBC Prom 6, Royal Albert Hall, London, 22nd July 2014

product_by=A review by Claire seymour

product_id=

July 22, 2014

Il turco in Italia at the Aix Festival

A revitalized Rossini world has emerged over the past several decades, the difficult if astonishing tragedies find occasional productions, the famous comedies find ever tighter mise en scènes, and singers have reached for an ever more refined Rossini technique and style. So when a conductor comes along who can enter the Rossini ethos, and this is not often, a sort of operatic nirvana can be achieved.

Director Alden’s Turco at the Long Beach Opera is remembered as one of these rare operatic moments. While the musical resources of a small opera company are limited, and American operatic resources twenty years ago were more enthusiastic than accomplished the Long Beach Turco succeeded not because of conducting but because of the staging. Alden’s heroine, trapped in her drab existence, found escape in the movies (like many of us in the 1950’s), and imagined herself swept of her feet by a handsome guy in a white suit with an accent. Finally, of course, real life prevailed and real love won the hearts of everyone.

This simple concept anchored three hours of singing, and made the very high artifice itself of the brilliant Rossini style the emotional crux of this fantasy of fulfillment.

Twenty years later Alden has now envisioned Rossini’s comic masterpiece as an intellectual game, much like Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author. Alden has made Rossini’s playwright Prosdocimo the protagonist of the opera, not just a benevolent facilitator of an intrigue about to happen (librettist Felice Romani had enriched a commonplace operatic comedy with the conceit of an author looking for a story). Alden’s Prosdocimo is an omnipresent troublemaker in perpetual conflict with his characters.

Prosdocimo possesses a Pirandello era (or so) typewriter on which he actually performs the Rossini score — clackity clack, clackity clack — in lively sync with the sounds coming from the pit. Well, until the heroine Fiorella grabs the typewriter to write her own script for a while. Alden makes his concept work flawlessly, with business between the author and his characters happening every second. Few if any moments are spared for us to savor the human dimensions of the story while we admire this interplay of wills.

Cecelia Hall as Zaida, Olga Peretyatko as Fiorella. Set design by Andrew Lieberman

Cecelia Hall as Zaida, Olga Peretyatko as Fiorella. Set design by Andrew Lieberman

Alden and his set designer Andrew Lieberman know that less can be more, therefore they endeavored to keep the surroundings as simple as possible. The set is a floor that is stuck upon what would be the back wall of the stage climbing onto what would be the ceiling — a mind-boggling vaulted floor. It is the floor of an unidentified room, maybe the floor of the Korean evangelical church the pair used for their Berlin Aida a few years back. There was a church basement coffee urn in one corner of the Aix set, a reference certainly foreign to the French audience.

Alden furthered his early-twentieth-century-theater concept with an extravagant overlay of theatrical tricks discovered by Pirandello’s contemporary Bertolt Brecht. The staging was indeed an amusing primer in Brecht's so-called Epic Theater, notably the half curtain, here movie palace green with a gold fringe. Set and costume changes were Brechtian a vista — we got to see a few of France’s intrepid intermittants actually at work (these are seasonal theatrical technicians about to loose their favored unemployment compensation who had gone on strike to prevent the premiere of Il turco from occurring as scheduled). All this Epic Theater served as smart business to intensify the mind games.

Lighting designer Adam Silverman provided an initial blast of stark white light emanating from a stage-wide hanging line of institutional lights, then at times he used only a part of the line to indicate a reduced acting area within the extreme width of the Archevêché theater. As well much use was made of exaggerated side lighting (a side wall deftly slide back to admit this strong yellow gold light), not to mention changing the color of the huge back wall floor to rose or light green from time to time, and the surprising moment when a strip, stage wide, of lights embedded into the floor burst into in brilliant upward light. Like the staging and the design, the lighting too was virtuoso.

The prow pole of a classic sailing ship, replete with the sumptuous breasts of its carved female figurehead, was the Brechtian image for the Selim (the Turco). He was Romanian bass Adrian Sampetrean who was purely and simply machismo incarnate. Vocally he delivered raging coloratura cleanly and in full voice and displayed a confidence of character that was appropriately intimidating. Russian soprano Olga Peretytko, a regular at the Pesaro Rossini Festival, made a cheap and sassy Fiorella, well able to delightfully embody the caricature of a tacky Hollywood sex queen. Unfortunately by this penultimate performance (a run of seven) she was unable to find the vocal brilliance and stability that would equal her exquisitely defined character.

American soprano Cecelia Hall was Zaida, the Turco’s original love now in competition with Fiorella, She was costumed, like the Turco (whose only Turkish mark was a beaded fez), in homely, 30’s or 40’s drab everyday western clothes. The costume designer was Kaye Voyce, like Lieberman and Silverman, a frequent Alden collaborator. She managed a huge variety of vividly defined costumes — gypsy-like skirts for the six women extras who accompanied the drab Zaida (so we would know she is a gypsy even though she was not dressed like one), not to forget the transparent, filmy, fancy ball gowns the eighteen male choristers donned to create the masquerade party.

All this theatrical brilliance on the stage would have been more effective and more meaningful had there been a brilliant Rossini pit. As it was there were Les Musiciens du Louvre Grenoble, an original instrument orchestra (instruments of the time a piece was composed) founded 30 years ago by its now famous conductor Marc Minkowski. Perhaps, though doubtfully, a Rossini orchestra actually sounded like a wheezy reed organ, but this is not the sound needed to support a conceptually and theatrically complex contemporary opera production.

Conductor Minkowski never reached the Rossini boil that propels the listener into musical euphoria. The only true Rossini moment of the evening was achieved by tenor Lawrence Brownlee who gamely portrayed Don Narciso (an additional suitor of Fiorella) as an trench coat covered spastic. He lay in front of the half curtain and delivered “Tu seconda il mio disegno” in high style to earn the biggest, and the only real ovation of the evening.

Italian buffo Pietro Spagnoli ably fulfilled the task of bringing Alden’s high energy Prosdocimo to life for the duration of the long evening, and baritone Alessandro Corbelli found his match as the duped, defeated Don Geronio, the long-suffering husband of Fiorella.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Selim: Adrian Sâmpetrean; Fiorilla: Olga Peretyatko; Don Geronio: Alessandro Corbelli; Narciso: Lawrence Brownlee; Prosdocimo: Pietro Spagnoli; Zaida: Cecelia Hall; Albazar: Juan Sancho. Chœur: Ensemble vocal Aedes; Orchestre: Les Musiciens du Louvre Grenoble. Conductor: Marc Minkowski; Mise en scène: Christopher Alden; Décors: Andrew Lieberman; Costumes: Kaye Voyce; Lumière: Adam Silverman. Théâtre du l’Archevêché, Aix-en-Provence, July 19, 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Turco_Aix1.png

product=yes

product_title=Il turco in Italia at the Aix Festival

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Alessandro Corbelli as Don Geronio, Olga Peretyatko as Fiorella [Photos by Patrick Berger, courtesy of the Aix Festival]

July 20, 2014

First Night of the BBC Proms : Elgar The Kingdom

Elgar dreamed of writing a trilogy of oratorios examining the nature of Christianity as Jesus taught his followers, using the grand context of the Edwardian taste. In The Apostles, Jesus sets out his beliefs in simple, human terms. Judas doubts him and is confounded. In The Kingdom, the focus is more diffuse. The disciples are many and their story unfolds through a series of tableaux, impressive set pieces, but with less obvious human drama. The final, part would hase been titled "The Last Judgement", when World and Time are destroyed and the faithful of all ages are raised from the dead, joining Jesus in Eternity. The sheer audacity of that vision may have stymied Elgar, much in the way that Sibelius's dreams for his eighth symphony inhibited realization. Fragments of The Last Judgement made their way into drafts for what was to be Elgar's third and final symphony, which we now know in Anthony Payne's performing version. There could be many reasons why Elgar didn't proceed, but he may well have intuited the contradiction between simple faith and extravagant gesture.

In his excellent programme notes, Stephen Johnson describes The Kingdom "as a kind of symphonic 'slow movement", a pause between two much more monumental pillars. It doesn't exist on its own out of context, and can't really be judged as a stand-alone. Elgar's creative output declined after the First World War. Since we know the wars that followed, listening to this piece is even more poignant. The Kingdom is a fragment of a confident but doomed past. I also like The Kingdom because, like The Apostles, it portrays Jesus and his followers are down-to-earth ordinary men and women encountering events normal comprehension. They're not pious saints but simple folk with fears and insecurities, saved by faith.

Andrew Davis conducted the Prelude with sober dignity. The disciples are starting a journey that continues 2000 years later. Davis's tempi were unhurried, with just enough liveliness to suggest the excitement of hopes to come. There are familiar themes from The Apostles here, and lyrical passages, which Davis conducted with particular finesse. I watched his hands sculpt curving shapes, and the BBC Symphony Orchestra responded well. Nice bright horns, seductive lower winds. The long pauses with which Davis marked the different parts of the piece serve a purpose, but tended to break the flow. However, Davis masterfully contrasted extreme of volume and relative quietness, giving dramatic structure.