November 30, 2014

Making a Note of It

By Eric Felten [WSJ, 28 November 2014]

In our age of easy playback, it’s hard to imagine how ephemeral music once was.

November 28, 2014

Florencia in el Amazonas Makes Triumphant Return to LA

The production made a strong impression on members of the audience as they entered the theater. On the curtain was a scene showing the Amazon and its surrounding jungle. In projections by S. Katy Tucker, fish were seen swimming in the river while flocks of tropical birds and swarms of multicolored butterflies periodically flew between the trees.

Florencia in el Amazonas is a contemporary opera by Daniel Catán (1949-2011) that was first seen at Houston Grand Opera on October 25, 1996. The libretto by Marcela Fuentes-Berain has some elements of Gabriel García Márquez’s style of magic realism but the story is her creation. The first Spanish-language opera to be staged by major United States opera companies, Florencia was commissioned for Houston, Los Angeles, and Seattle. It was last performed in Los Angeles in 1997. Houston revived it in 2001. Since then, there has been a performance somewhere in the western world every year or two. Restaged by original stage director, Francesca Zambello, Washington National Opera performed it most successfully last September and it will be at Nashville Opera early next year.

On November 22, 2014, Los Angeles Opera staged Zambello’s updated version. The production made a strong impression on members of the audience as they entered the theater. On the curtain was a scene showing the Amazon and its surrounding jungle. In projections by S. Katy Tucker, fish were seen swimming in the river while flocks of tropical birds and swarms of multicolored butterflies periodically flew between the trees.

All the scenery was animated!

With the lyricism of Catan’s melodic score, the story's magic realism came to life as Robert Israel’s stark but functional ship began its trip. Although his neo-romantic vocal lines are somewhat related to the music of early twentieth century Italian composers, Catan’s atmospheric orchestration is uniquely his own. Best of all, his music pleases the twenty-first century opera audience. Florencia calls to mind the natural beauty of the Amazon, especially the way conductor Grant Gershon pealed back layer after layer of the translucent score to expose its gorgeous sonorities. I wish Gershon had been a little more careful of his smaller voiced singers, but his rendition of the accompaniment was one of the best aspects of the evening.

Set in the early twentieth century, an older couple, Paula and Álvaro, Nancy Fabiola Herrera and Gordon Hawkins, needed to breathe some new life into their marriage. Herrera had a great deal of color in her dramatic-timbred voice and it came through the orchestration with creamy tones. Hawkins sang with a stentorian sound as he tried to make peace with her. New lovers, Rosalba and Arcadio, Lisette Oropesa and Arturo Chacón-Cruz, began to realize that their love could be real. Oropesa sang with spinning silvery tones that rang to the rafters, while Chacón-Cruz’s top notes oozed power and virility.

Verónica Villarroel was a strong voiced Florencia Grimaldi. She lived the part of the famous opera singer as she traveled with them towards the legendary opera house in the Brazilian rain forest city of Manaus. Bass-baritone David Pittsinger was an efficient ship's captain. Dancers realizing Eric Sean Fogel's balletic choreography symbolized the river’s mystical creatures. When a storm stopped the ship’s progress, river spirit Riolobo, sung by energetic baritone José Carbó, pleaded with the river gods. I have wanted to see this opera ever since I reviewed the recording many years ago. On Saturday evening, both my eyes and my ears were delighted by the performance. I would love to see it again and I hope my readers around the world will get that chance.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Riolobo, José Carbó; Rosalba, Lisette Oropesa; Paula, Nancy Fabiola Herrera; Alvaro, Gordon Hawkins; The Captain, David Pittsinger; Florencia Grimaldi, Verónica Villaroel; Arcadio, Arturo Chacón-Cruz; Conductor and Chorus Director, Grant Gershon; Director, Francesca Zambello; Scenery Designer, Robert Israel; Costume Designer, Catherine Zuber; Lighting Designer, Mark McCullough; Projection Designer, S. Katy Tucker; Choreographer, Eric Sean Fogel.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/14290-603-PR.png

image_description=Verónica Villarroel as Florencia Grimaldi [Photo by Craig T. Mathew /LA Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Florencia in el Amazonas Makes Triumphant Return to LA

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Verónica Villarroel as Florencia Grimaldi [Photo by Craig T. Mathew /LA Opera]

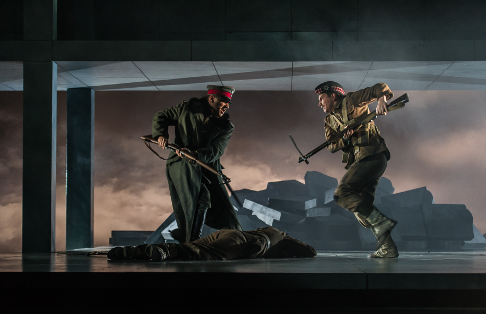

John Adams: The Gospel According to the Other Mary

Designed as a companion piece to their ‘nativity oratorio’, El Niño, which was premiered in 2000, The Gospel lies somewhere between an opera and a concert work; it was presented in concert form in May 2012 by the Los Angeles Philharmonic under Gustavo Dudamel, these performers subsequently travelling to the Barbican Centre in March 2013 for the semi-staged European premiere of the work. This ENO production is billed as the ‘world staged premiere’.

The Gospel presents the story of the Passion through the eyes of those whose tales are usually unheard: Mary Magadalen, her sister Martha and their brother Lazarus. Jesus’s words are quoted by others but Christ himself is neither seen nor heard.

Sellars’ libretto is a mélange: a patchwork of excerpts from the Old and New Testaments mingled with literary and philosophical writings from past and present, including texts and poems of a spiritual leaning by Hildegard of Bingen, Louise Erdrich, Primo Levi, Rosario Castellanos, June Jordan and Rubén Darío. Mary and Martha, as they become increasingly engaged in the fight for justice and social change, also recite the journals of the activist and pacifist, Dorothy Day, who founded the Catholic Worker Movement. Often texts are overlain, a soloist declaiming modern poetry while the chorus chant Hildegard of Bingen, for example. Indeed, the interweaving of eras is central to the creators’ endeavour, in the words of Sellars, to ‘set the passion story in the eternal present, in the tradition of sacred art’.

Thus, we move between biblical archetypes and present-day realism, the ‘timelessness’ of the former contrasting with the immediacy of contemporary social and political events such as the Arab Spring. Mary has become a human rights campaigner, fighting for the poor; she and Martha run a hostel for homeless women, the latter spurred in her mission by her own experiences of paternal abuse. Later, Mary and Martha join César Chávez on his 1000-mile march during the United Far Workers’ protest of 1975. In this way, the emotional journey of The Passion, from black despair to hope and promise, is re-enacted in our time.

George Tsypin’s set designs are simple but striking, allowing for fluid transitions between time and place. The rusts and ochres of open stage suggest a desert landscape – Syria? Iraq? – while the barbed wire perimeter fences which loom left and right intimate a prison (search lights beam down aggressively). Or perhaps, the wire is just an emblem of ‘pain’: for the action opens with a female drug addict beating her head against the metal bars, and Mary bewails, ‘they shall be afraid: pangs and sorrows shall take hold of them; they shall be in pain as a woman that travaileth’. On the back wall, a hand stretches out through the misty textures, reminiscent of religious iconography. It could be the hand of Christ, or that of a modern-day beggar. Subsequently, stricken torsos similarly evoke the pain of medieval Crucifixion images and the suffering of the hungry, afflicted and tormented in the present day.

There are few props and they too straddle different times and places: large cardboard boxes serve variously as ‘blankets’ for the homeless, as an altar table, and as Lazarus’s tomb. James F. Ingalls’ lighting design stuns us with stark blocks of complementary colour, black grid lines again conjuring grim institutional anonymity and restriction.

The principals gave totally committed performances, bringing real human anguish and visceral suffering to the biblical roles. Irish mezzo soprano Patricia Bardon demonstrated her huge versatility, presenting an introverted and dignified Mary, but one also whose emotions at times cannot be contained, bursting out in a wild maelstrom of fury. Bardon gave a strikingly vociferous rendition of Erdrich’s poem ‘Mary Magdalene’; but she also conveyed Mary’s inner grace, and, during an erotic dance with a ‘flex dancer’ identified only as ‘Banks’ (in the programme he is assigned the role of the Angel Gabriel), a contrasting seductiveness. Indeed, Banks’s gliding, waving and twitching, throughout the performance, was the most mesmerising element of the evening.

Meredith Arwady used the considerable depth and reach of her low contralto register to convey Martha’s resolute core, her dark tone and huge vocal power making a tremendous dramatic impact. The role of Lazarus was performed by tenor Russell Thomas, whose heroic tone did not preclude sweetness. On his end of Act 1 ‘aria’, the Passover scene, Thomas sang Primo Levi’s poetry with searing passion and steadfastness: ‘Tell me: how is this night different/ From all other nights?/ How, tell me, is this Passover/ Different from other Passovers?’ As the emotional temperature rose and Thomas’s ardency grew still further, the scene took on an almost Broadway-esque breadth and lyricism, although any hint of kitsch was swept away by grating orchestral postlude in which shrieking brass chords punctured through throbbing strings.

A trio of countertenors – Daniel Bubeck, Brian Cummings and Nathan Medley – are cast as ‘Seraphim’ and take on the narrative role played by the Evangelist in Bach’s Passions: they often sing as a trio and here the intensity of the blend timbres evoked an ecclesiastical purity which contrasted strikingly with the grittiness of the surrounding context.

Movement and dance play a large part. Sellars indulges in his trademark choreography of abstract gesturing for the chorus, while Mary and Lazarus have avatars in the form of two dancers; two further dances depict the Virgin Mary and embody abstract feelings and spiritual events, such as the raising of Lazarus from the dead. The ENO chorus, dressed in motley coloured shirts and overalls (costumes, Gabriel Berry), gave a sterling performance. From the first they were a thrillingly animated mass, crying out a prophecy from Isaiah, ‘Howl ye; for the day of the Lord is at hand’ with vigour and ferocity, and they sustained this concentration throughout the performance.

Portuguese conductor Joana Carneiro led the ENO Orchestra with precision and panache. Under her dynamic but economic baton, the orchestra gave a masterly account of the score. Carneiro’s every gesture was well-defined and clear of purpose, and her confidence and control inspired some wonderful instrumental playing.

The problem with The Gospel is that Sellars, in his desire to blend spiritual reflection with political activism, has not yet recognised that less can be more. I found that the constant bombardment of overt political and philosophical ‘messages’ distanced me from the characters and events, and weakened my empathy – which can hardly have been the intended effect. But, the muscular melodic lines, strident timbres and unexpectedly piquant harmonies and progressions of Adams’ score, particularly in the second Act, make one sit up and listen. There is a percussive acerbity to much of the score, the cimbalom featuring heavily alongside side and bass drums, three tam-tams, tuned gongs, chimes, almglocken and glockenspiel. A bass guitar lends an unsettling modern beat. And at the centre of the opera is a ‘Golgotha scene’ of tremendous power and imagination: exploiting the lowest resonances of the basses, bassoons, bass guitar and gongs, Adams suggests a bottom-less well of sound, and through this boom a clarinet wails like a siren. The music seems energised by the need to move between worlds; it never settles, responding continually to situation and sentiment, and thereby guiding the listener through the complex psychological landscape and ever-shifting points-of-view. It’s a shame that Sellars did not fully exploit the considerable dramatic potential of Adams’ language and form, both of which mark a significant move away from the repetitions and transitions of the minimalist idiom more typical of the composer.

I confess to some scepticism when I entered the Coliseum, but I left the auditorium, if not unequivocally convinced, then certainly intrigued and moved.

Claire Seymour

Cast: Mary Magdalene, Patricia Bardon; Martha her sister, Meredith Arwady; Lazarus their brother, Russell Thomas; Seraphim, Daniel Bubeck, Brian Cummings and Nathan Medley.

Dancers: Angel Gabriel, Banks; Mary, Stephanie Berge; Mary, Mother of Jesus, Ingrid Mackinnon; Lazarus, Parinay Mehra.

Director, Peter Sellars; Conductor, Joana Carneiro; Set designer, George Tsypin; Costume designer, Gabriel Berry; Lighting designer, James F. Ingalls; Sound designer, Mark Gray; English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ENO%20GATTOM%20Stephanie%20Berge%2C%20Patricia%20Bardon%204%20%28l-r%29%20%28c%29%20Richard%20Hubert%20Smith.png image_description=Stephanie Berge and Patricia Bardon [Photo by Richard Hubert Smith] product=yes product_title=John Adams: The Gospel According to the Other Mary product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Stephanie Berge and Patricia Bardon [Photo by Richard Hubert Smith]A new Yevgeny Onegin in Zagreb — Prince Gremin’s Fabulous Pool Party

Certainly inspired opera directors such as Giorgio Strehler or Jean-Pierre Ponnelle could add impressive psychological and visual insight into much of the standard operatic repertoire. But when far less gifted directors, usually with a background in theatre or film rather than music, decide to impose their idiosyncratic, self-serving and often gratuitously gimmicky interpretations on an undeserving libretto, the results are usually either embarrassing (Christoph Schlingensief) or downright offensive (Hans Neuenfels). Polish director Michał Znaniecki falls somewhere between the two.

Based on the premise that Alexander Pushkin’s complex character of Yevgeny Onegin undergoes a complete transformation after killing his friend Lensky in a duel and then through the realization that he has fallen hopelessly in love with the once rejected Tatyana, Mr Znaniecki uses the metaphor of melting ice. Given the grim bleakness of the Russian climate, there is nothing too objectionable about that. The problem is that the icy stylized birch forest/cage of Act I starts melting in Act II and by Act III, the majority of the stage is covered with so much water it turns into a very large wading pond. Either there are serious leakage problems with the roof of Prince Gremin’s palace in St Petersburg or he has changed from being an army general to a Imperial navy admiral who enjoys the sound of waves lapping in his own ballroom.

Mr. Znaniecki also designed the costumes, which were much more successful although one suspects he must own shares in the local Zagreb dry-cleaners as every character in Act III, from dancers to chorus to principal protagonists ends up so completely drenched that huge scale costume cleaning on a nightly basis must be required. Definitely a wardrobe department’s ultimate nightmare. Only Prince Gremin escapes soggy trouser legs and wet socks by being confined to a wheel chair, which on the other hand severely limits the dramatic opportunities for movement during his splendid aria.

The dancers clearly had problems during the opening Act III polonaise and subsequent ecossaise due to the slippery floor lying below several centimeters of water. Flippers or synchronized swimming might have been a better option.

Another novelty was that although Tchaikovsky and Shilovsky stipulated that the opera was in seven scenes, Mr Znaniecki preferred only six. Act I Sc. ii set in Tatyana’s bedroom also becomes Act I Sc. iii enabling the local peasant maidens to traipse about their mistress’ boudoir as well as allowing Onegin, a total stranger, to wander in and sit quite nonchalantly on her bed.

Even by the usual standards of loose bucolic morals, such a liberty would never have been countenanced in 1820s aristocratic Russian society. At first it seemed as though Tatyana was dreaming Onegin’s reply to her garrulous letter (not a bad idea at all) but as subsequent stage direction proved, this was not the case.

The introduction of a very prominent pool (that word again) table in Madame Larina’s ballroom at the opening of Act II was another production quirk. Triquet climbs onto it to deliver his name-day encomium to Tatyana and also has her dragged up to join him. At the end of the fawning couplets, he proceeds to grope her. Hardly correct social decorum befitting an aristocratic soirée.

The billiard cues provide props for the initial confrontation between Onegin and Lensky. It all seems a bit gimmicky and the pool table severely limits the space available for dancers and chorus (which was consistently impressive) during the opening waltz and mazurka.

The only truly convincing production idea was in Act III when the chorus of Prince Gremin’s vapid socialite guests stand behind a clear plastic scrim menacingly beckoning Onegin, who is on the other side, to join their superficial flashy-splashy world. Maybe he would prefer to change into a wet-suit first.

Mr Znaniecki staged a very similar watery production of Yevgeny Onegin in Bilbao in 2011 for which he was awarded the Premios Foundation Teatro Campoamor Líricos for the best new production in Spain. One shudders to contemplate what the other productions must have been like. Two performances on 18th and 20th November were heard for the most part with alternating casts.

Of the recurring interpreters the Larina of Želika Martić was vocally competent but rather vulgar in characterization (although a rural landowner she is cousin to a princess in St Petersburg, so is hardly a bumpkin). Jelena Kordić sang a suitably perky and coquettish Olga without displaying any outstanding mezzo soprano qualities.

The Lensky of Domagoj Dorotić was somewhat variable but on the whole quite impressive, especially at the second performance. Unfortunately his Act I arioso declaring his passionate love to Olga was both vocally tentative and dramatically distant without any sense of ardor at all. He could have been reading the weather report from Rostov. On the other hand, Lensky’s celebrated Act II aria ‘Kuda, kuda’ was sung with sensitivity, elegant legato, commendable mezzavoce and a finely controlled piano. Dorotić also displayed a surprising ringing upper register tone on the G# at measure 102 and on the Ab in the andante mosso change at 111. It was no surprise that at both performances he received the loudest applause from the audience. Different singers sang the other roles.

The Filipjevna of Jelena Kordić was more successful in chest notes and projection than Branka Sekulić Ćopo. It’s a shame her short scena before Tatyana’s Letter aria was delivered at the front of the stage in virtual darkness.

Although both tended to drag the tempo, Ladislav Vrgoć was vocally a more secure Triquet than Mario Bokun and the Prince Gremin of Ivica Čikeš far more impressive than Luciano Batinić. Mr Čikeš has a truly powerful and resonant bass voice with admirable diction and projection. It was all the more surprising that his Bb at measure 38 on ‘счастье’ (and again during the da capo at 130) was alarmingly below pitch.

The Tatyana of Valentina Fijačko, although a tad matronly, was more successful than Adela Golac Rilović. Neither interpreter of the role was exactly outstanding although Miss Fijačko managed the pivotal Letter scene relatively well, especially pleasing with her word colouring of ‘whispered words of hope’ (слова надежды мне шепнул). Both sopranos seemed to have problems with the F natural opening of the wistful Db major theme at measures 195 and 211 and resorted to slight upward sliding to find the note. One certainly misses the effortless cantilena of Mirella Freni, Anna Tomowa-Sintow, Anna Samuil or even Kiri te Kanawa at such moments.

In the title role shared by Ljubmir Puškarić and Robert Kolar, the latter was vocally and dramatically more convincing, but neither performance could be described as really memorable. The legato phrasing of both baritones was often lacking although the more declamatory passages were usually better sung. Interestingly neither braved the optional high piano F natural at the end of Onegin’s Act I aria which Peter Mattei’s performance of the role in Salzburg in 2007 made so affecting. It is also musically a much more satisfactory way of concluding the scena.

The real delight of these performances however was the conducting of veteran Croatian maestro Nikša Bareza. This is a conductor who has directed inter alia, Götterdämmerung, Fidelio, Tosca, Il Trovatore and Andrea Chenier at La Scala and whose impressive credentials include the Deutsche Oper in Berlin, the Hamburg Staatsoper, the Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich, and the Kirov Theatre in St. Petersburg. He also speaks fluent Russian, which was of immense help in supporting the singers in a Tchaikovsky opera - not to mention the fact that this was also the 6th production of the work he has led.

Similar to Wagner and Richard Strauss the orchestration in Yevgeny Onegin plays an absolutely paramount role. Part instrumental Greek chorus, part musical mirroring of the characters’ innermost thoughts and motivations and part reflection of the composer’s own angst and conflicting emotions at the time, this is a partitura so full of constantly shifting shadings, subtle rubati and emphatic rhythms, kaleidoscopic harmonics and minute inflections it covers every possible facet of orchestral expression. La tristesse Russe permeates almost every page of the score.

From the rousing brilliance of the Act III polonaise to the tender melancholy of the clarinet obbligato in Lensky’s aria, the plaintive violin phrases during Gremin’s aria, and the explosive fortissimo in the short orchestral passage towards the end of Tatyana’s letter scena (bars 270-293), maestro Bareza’s command of every nuance of this exceedingly complex score was unequivocally masterful.

Bareza: dix points, Znaniecki: zero.

Jonathan Sutherland

Cast and production information:

Conductor: Nikša Bareza. Direction and Costume Design: Michał Znaniecki. Set Design: Luigi Scoglio. Choreography: Diana Theocharidou. Larina: Želja Martić. Tatyana: Valentina Fijačko/Adela Golac Rilović. Olga: Jelena Kordić. Filipjevna: Branka Sekulić Ćopo/ Neda Martić. Yevgeny Onegin: Ljubmir Puškarić /Robert Kolar. Vladimir Lensky: Domagoj Dorotić. Prince Gremin: Ivica Čikeš/Luciano Batinić. Triquet: Ladislav Vrgoć /Mario Bokun. Photo credits: Mara Bratoš courtesy of the Croatian National Theatre Zagreb. Croatian National Theatre, Zagreb, 18th & 20th November 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Martina%20Menegoni%2C%20Stjepan%20Franetovi%C4%87.png image_description=Martina Menegoni and Stjepan Franetović product=yes product_title=A new Yevgeny Oneginin Zagreb — Prince Gremin’s Fabulous Pool Party product_by=A review by Jonathan Sutherland product_id=Above: Martina Menegoni and Stjepan FranetovićNovember 22, 2014

Nabucco in Novi Sad

Mercifully not. The straightforward reliable staging by Dejan Miladinović and effective costume designs by Jasna Petrović Badjarević were neither intrusive nor distracting. Despite having been first seen as long ago as 1983 when the opera was sung in Serbian, the production looked surprisingly fresh and functional.

A particularly pleasing production idea was during the Act III duet between Nabucco and Abigaille when the demonic anti-heroine destroys evidence of her low birth (Il foglio menzogner!). Instead of tearing up the incriminating document as indicated in the libretto, she smashes a clay tablet which is both historically much more accurate as paper didn’t exist in 6th century BC Babylon. This made a wonderful dramatic impact as the pieces shattered all over the stage. Another visual success was the enormous 5 metre long regal mantle Abigaille wears to ascend the throne which covered the entire flight of steps.

Due to earlier cuts (since restored) the opera was performed in three acts instead of the libretto’s stipulated four with Act II extending to the end of the Deh perdona, deh perdona duet between Abigaille and Nabucco. This meant that instead of the Va pensiero chorus almost ending Act III, it opened the last act of this three part version straight after the interval, which was dramatically much less effective.

Not just because of the justifiably celebrated Va pensiero chorus, Nabucco is an opera where the coro plays a major dramatic and musical role and in this regard the Novi Sad singers certainly didn’t disappoint. An impressive chorus of roughly 70 singers paid commendable attention to Verdi’s dynamics and markings. As with many large ensembles, there were one or two glitches in the presto concertante sections, especially the spirited Come notte a sol fulgente chorus with Zaccaria in Act I, Oh fuggite il maledetto that closes the ‘Jerusalem’ part of the opera and S'appressan gl'istanti d'un'ira fatale in Act II. The slower ensembles usually had better synchronization with the orchestra, especially Non far che i tuoi figli divengano preda at the end of the opening scena.

The famous Va pensiero chorus lost a lot of its customary impact due to the fact that the very young conductor Aleksandar Kojić (aged 30) chose a much more brisk tempo than one is accustomed to hearing. After all, it is marked largo in the partitura. The desperate longing for a patria perduta expressed so plaintively in the text and score was sadly missing. This was a supersonic Concorde flight on golden wings. Che peccato.

Such haste was even more curious as Kojić’s tempi for the rest of the performance were generally uncontroversial. Although coordination between pit and stage was occasionally a little fraught, this was by no means a shabby performance on the podium. String playing was generally acceptable, especially the cantabile cello introduction to Zaccaria’s recitative and Prigheria Vieni, o Levita! in Act II. There was some nice solo flute playing before Abigaille’s Anch'io dischiuso un giorno aria in Act II and again in Nabucco’s Dio di Giuda aria in Act IV. Less successful was the syncopated quaver horn punctuation in Va pensiero which was unduly heavy and had slight intonation problems.

Intonation problems would be a kind understatement to describe the performance of the Abigaille Valentina Milenković. Having had some kind of vocal crisis a few years ago, Madame Milenković essentially retired from the operatic stage and only sang an occasional Lisa in Pique Dame and Leonora in Il Trovatore but for some inexplicable reason chose to make her most recent comeback in one of the most diabolical roles Verdi ever inflicted on a soprano.

There was no coloratura, no mezzavoce, no chest notes, no lower register, no breath control, no phrasing, no piano technique - just an indescribably awful shriek at the very top of the range. The only identifiable aspect of her voice was a vibrato so wide the miserable Hebrews could have walked through it to freedom. Every ensemble was marred by her appalling screeching. In the Act II opening scena Anch'io dischiuso un giorno there was just a horrible whining, rasping noise. Diction and phrasing were a total blur. One wished the flute obbligato had continued without the vocal part.

But much worse was to come. The great cabaletta Salgo già del trono aurato was something that would have made Florence Foster Jenkins sound like Joan Sutherland. The fioratura was mush, the scale passages a murky blur, intonation seemed to cover about 3 semitones at once, the wide vibrato and wobble were totally out of control and mid-register notes inaudible. The top C at l'umil schiava a supplicar had your suffering reviewer groping for the earplugs. Perhaps Madame Milenković should consider La Duchesse du Crakentorp in La Fille du Regiment as her next comeback role.

The demanding and dramatically vital role of Zaccaria was sung by the Serbian bass Goran Krneta bravely trying to cope with a ridiculous Santa Claus beard. Despite having solid low notes, good projection and a dependable middle voice, his upper register needs a lot of work. Under any kind of pressure it tightened badly and made a rather unpleasant pinched sound. Intonation problems were noticeable in the Act IV à capella scena with chorus and Immenso Jeovha chi non ti sente was noticeably below pitch. Regrettably for the drama, Zaccaria’s important confrontations with Nabucco had little anthemic impact or emotive power. Oh trema insano! Questa è di Dio la stanza! at the end of Act I was particularly lame.

The role of Ismaele was sung by another young Serbian singer, Nenad Čiča. Certainly it is not the greatest role Verdi ever created for tenor, although its vocal importance in the ensembles is significant. Mr Čiča was clearly very nervous throughout and as a result, his voice often became badly constricted, especially in the upper register. Acting was definitely not his strong point either. His reaction to the fury of the Levites in Act II when he is ostracized for protecting Fenene from Zaccaria’s intended slaughter (Il maledetto non ha fratelli) was about as bland as if he had misplaced his breakfast bagel.

The object of Ismaele’s passion and obstinence, Fenene, was sung by a mature Serbian mezzo Violeta Srećković. She had a reasonable mezzovoce but nothing remarkable. Her important but musically underwhelming scena in Act IV (Oh dischiuso è il firmamento) was acceptable in the middle range but like Goran Krneta, very tight in the upper register. The High Priest of Baal sung by young Serbian bass Željko Andrić was a bit hooty in projection but vocally and dramatically reasonably effective. His scena Eccelsa donna, che d'Assiria il fato Reggi, le preci ascolta in Act III was more than satisfactory. The lesser roles of Anna (an older well-focused singer called Laura Pavlović) and Abdallo (Igor Ksionžik) were competently sung by the former and forgettably managed by the latter. It was more a case of small role, small voice. Basta.

The performer with anything but a small voice was the Nabucco of Dragutin Matić. Still only 33 years old, he first studied in Belgrade then in Würzburg Germany under the celebrated soprano Cheryl Studer. The grueling tessitura of the role is in many ways similar to that of Abigaille in that the demands Verdi places on this new kind of ‘high baritone’ are formidable in the extreme. Dragutin Matić has the robust masculine vocal colour of Matteo Manuguerra, the warm rounded mezzovoce tones of Piero Cappuccilli and the ringing top register of Renato Bruson. It was not surprising to learn he started his singing career as a tenor. There was real power in S'oda or me! Babilonesi without losing any intonation or musicality and the explosive line non son più re, son Dio!! was delivered with terrifying force and menace. Nabucco’s prayer to the God of the Hebrews to save Fenene (Dio di Giuda! l'ara e il tempio) and following cabaletta O prodi miei, seguitemi concluding with Di mia corona al sol in Act IV were unquestionably the musical highlights of the evening.

At the curtain calls Matić was loudly applauded by the audience which numbered only a handful of people. In fact the whole performance felt more like a closed Sitzprobe. Apparently the explanation for the extremely low attendance (despite seat prices ranging from €3 to €6.5) is that the production has been in the repertoire for over 30 years and locals are not particularly interested in seeing it again. Certainly once word got out that Valentina Milenković was appearing to crucify the role of Abigaille, only musical masochists or those expecting to experience a Balkan version of Florence Foster Jenkins were prepared to endure such a bizarre night at the opera. The Marx Brothers would have loved it — Verdi less so.

Jonathan Sutherland

image=http://www.operatoday.com/nabuko-005.png image_description=A scene from Nabucco [Photo courtesy of Serbian National Theatre, Novi Sad] product=yes product_title=Nabucco in Novi Sad product_by=A review by Jonathan Sutherland product_id=Above: A scene from Nabucco [Photo courtesy of Serbian National Theatre, Novi Sad]La Bohème in San Francisco

Mr. Caird is a very skilled director of theater and music theater. He is well credentialed in opera in Britain with productions at Welsh National Opera, his U.S. opera credits are productions at Houston Opera that have or will tour to other U.S. opera houses. Let us not overlook the Siefried and Roy show in Las Vegas (1991-2004).

Mr. Caird has created a slick, intelligent and successful production of La bohème. Typical of theater directors staging opera he has endeavored to keep the dramatic pace of the opera moving along, accelerating pace whenever possible. Scene changes are quick, intermissions are short, bows are choreographed. This with the apparent assumption that theater audiences need to keep their minds involved and music theater audiences need to keep the beat.

The opera audience has been conditioned over the past 300 years to stop time, to forget the story and sink into the elaboration of an emotion. So maybe for some of us in the War Memorial this Boheme seemed rushed and over-produced, even seemed condescending with lighting effects that were too obvious (as if we were incapable of feeling the music without its help).

Not even Rodolfo’s final cries were left as pure emotion — as the curtain fell on the dead Mimi he we see him transform the moment into words. We needed not feel the tragedy of this moment because it had become mere art — a tricky conceit. Maybe this Boheme was not for us, but for a music theater audience.

Michael Fabiano as Rodolfo, Alexia Voulgaridou as Mimi

Michael Fabiano as Rodolfo, Alexia Voulgaridou as Mimi

Mr. Caird’s astutely perceived La bohème as four character sketches — the garret, the cafe, the square, and the death. In fact Marcello, an artist as well, is busily sketching the dead Mimi when the curtain falls. Each setting is created by a collage of canvas paintings (images of rooms and buildings). The colors and costumes were in the warm palate of late nineteenth century naturalistic painting. Scene changes were a vista, stagehands visible in a slick bow to Brechtian dogma (with no hint of advocacy). It was meant to please a broad audience and it did.

Finally though none of this mattered. The November 19 performance was memorable because of riveting performances by American tenor Michael Fabiano as Rodolfo and Russian baritone Alexey Markov as Marcello. Tenor Fabiano boasts the clean musicianship of his American training, and an innate sense of Italian line unaffected by mannerism. He made Puccini into heroic bel canto that fully satisfies verismo. Mr. Fabiano is a natural actor, his moves at once incorporating the physicality of singing with the emotive enthusiasms of a young poet.

Michael Fabiano as Rodolfo, Alexey Markov as Marcello

Though of Russian formation much the same can be said of baritone Markov whose Slavic colored voice added an international exoticism to this young painter as well as specific flavor to the Parisian ambiance. Both Fabiano and Markov have strong, focused, beautiful voices that sailed across the orchestra. These artists in fact provided the musical determination for the performance far more than did the leadership, or lack of, from the pit.

The November 19 Mimi was Greek soprano Alexia Voulgaridou. The internet offers no birthday for Ms. Voulgaridou and it would not matter except that her voice betrayed the mannerisms of a singer no longer in the bloom of youth, or in bloom at all, and you wondered why she was cast as Mimi. Was it the spate of Toscas she undertook in 2013 (even though Tosca and Mimi are completely different voices)? But these Toscas seem to have worn her out and have encouraged her to fall back on generic (stock) opera singer moves and gestures.

The November 19 Musetta was former Adler Fellow Nadine Sierra. She was a far more youthful Musetta than you would expect to see on a major stage, and of much lighter voice (she is a lyric coloratura). This fine young artist made Musetta memorable, her coquettishness absolutely convincing while she carved out director Caird’s imaginative new antics to “Quando men vo soletta per la via.” These antics however forced an unnaturally slow tempo that would challenge even a much larger voice.

On November 20 the Mimi was former Adler Fellow Leah Crocetto. She sings beautifully, but physically she is not appropriate to embody a consumptive heroine. You wondered why she was cast. Italian tenor Giorgio Berrugi sang Rodolfo. This young tenor with a good sound has unfortunately absorbed many mannerisms that associate him with proverbial Italian provincial opera. Soprano Ellie Dehn sang Musetta. She is a San Francisco Mozart heroine (Countess, Donna Anna, Fiordiligi) who could not possibly make the transition from stately womanhood to this coquettish character role. San Francisco Opera regular, baritone Brian Mulligan was Marcello, a fish-out-of-water as well.

Colline, Schaunard, and Benoit/Alcindoro were the same singers for both casts. Christian van Horn is San Francisco Opera’s catch all bass, one night Alidoro in Cenerentola, the next two nights Colline, then back to Alidoro. While a competent performer he does not approach the depths of character that these smaller but crucially important roles require.

The conductor was San Francisco Opera’s resident conductor Giuseppe Finzi. With the help of messieurs Fabiano and Markov he carried off November 19 honorably. On November 20 he could not bring the cast to musical cohesion. At both performances I longed for a conductor who felt verismo, not simply a maestro to accompany, or try to, the singers. Follow this link for an account of a performance by such a maestro: La bohème at San Francisco Opera.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Mimì: Alexia Voulgaridou; Rodolfo: Michael Fabiano; Musetta: Nadine Sierra; Marcello: Alexdy Markov; Colline: Christian van Horn; Schaunard: Hadleigh Adams; Benoit/Alcindoro: Dale Travis. Alternate cast: Mimì: Leah Crocetto; Rodolfo: Giorgio Berrugi; Musetta: Ellie Dehn; Marcello: Brian Mulligan. San Francisco Opera Chorus and Orchestra. Conductor: Giuseppe Finzi. Stage Director: John Caird; Production Designer: David Farley; Lighting Designer: Michael James Clark. War Memorial Opera House, November 19/20, 2014. Seats row M).

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Boheme_SF2.png

product=yes

product_title=La bohème in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above:Nadine Sierra as Musetta [All photos by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

November 21, 2014

Radvanovsky Sings Recital in Los Angeles

On November 8, 2014, the recitalist was soprano Sondra Radvanovsky who was familiar to the Los Angeles audience because of her acclaimed performances of Tosca and Suor Angelica.

Accompanied by her long time collaborator, virtuoso pianist Anthony Manoli, she sang a challenging but not overly imaginative program of arias and songs in Italian, Russian, French, and English. Opening with a carefully crafted version of Ludwig van Beethoven’s early Ah Perfido, she showed her ability to handle both the declamatory and decorative aspects of this concert aria.

She followed it with three short songs by the composer for whose music she is best known, Giuseppe Verdi. He wrote the first two, In solitaria stanza (In a Lonely Room), and Perduta ho la pace (I Have Lost My Peace), before the premiere of his first opera, Oberto. The final song, Stornello (Italian Street Song), dates from the same year as his opera, La forza del destino. Although the songs are not major musical works, they are precursors of Verdi’s later operas and with each short piece Radvanovsky showed her ability to put a story across.

The most interesting pieces on this program were four enchanting but rarely sung romances by Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninov: A Dream, Oh, Never Sing to Me Again, How Fair this Spot, and Spring Waters. I hope someday she will sing a whole evening of Russian songs. Rachmaninov and other major Russian composers wrote many wonderful pieces that are seldom performed.

To complete the first part of her recital Radvanovsky, whose forte is opera rather than song, regaled her adoring crowd with “Pace, pace mio Dio” from La forza del destino. She had a magnificent command of dynamics and during this and several of her other arias she showed that she could take her sound down to a pianissimo and then gradually increase it until it became a full fledged fortissimo. (The technical term for it is messa di voce).

Radvanovsky, who had worn a form fitting dark gold taffeta for the first half, returned in bright green silk after the intermission to sing a trio of songs by Henri Duparc: Chanson Triste (Sad Song), Extase (Ecstasy), and Au pays où se fait le guerre (To the Country Where War is Waged). Here and in her rendition of the aria that followed them, "Pleurez, Pleurez mes jeux" (Cry, Cry my Eyes) from Jules Massenet’s Le Cid, she showed her mastery of the French idiom as well as her ability to convey the beauty of sadness and tragic memories.

The soprano sometimes spoke to the audience and at this point she brought her fans back from the contemplation of tragedy with three lighter but thoroughly charming American songs by Aaron Copland: Simple Gifts, Long Time Ago, and At the River. For the finale, Radvanovsky sang a rousing, virtuosic performance of the Bolero from Verdi’s I vespri Siciliani (The Sicilian Vespers). She sang that her senses were intoxicated. She was right, her audience was drunk on fine art as they listened to her encores: "Io son l'umile ancella" (I am the Humble Handmaiden) from Cilea's Adriana Lecouvreur, "I Could Have Danced All Night" from Loewe's My Fair Lady, "Vissi d'arte" ( I Live for Art) from Puccini's Tosca and "O mio babbino caro" (Oh, My Dearest Daddy) from Puccini's Gianni Schicchi.

Both Radvanovsky and Manoli gave bravura performances and their audience would have listened to them all night if they had continued to perform. Although the house was not much more than half full, this was a happy audience that can be counted upon to come out for more fine recitals at the Dorothy Chandler.

Maria Nockin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/LAO-Radvanovsky.png

image_description=Sondra Radvanovsky

product=yes

product_title=Radvanovsky Sings Recital in Los Angeles

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Sondra Radvanovsky

L’elisir d’amore, Royal Opera

Pelly’s production has much to commend it: capriciousness, irony, tenderness and realism. On this occasion, it was the appearance of Bryn Terfel in his first essay at the role of the fraudulent doctor, Dulcamara, that accounted for the heightened air of expectancy; an anticipation that was further whipped up by the placard-strewn front-drop advertising Dulcamara’s fabled elixirs: ‘Costipazione’, ‘Impotenza’, ‘smettere di fumare’ — you name it, Dulcamara’s tonics truly offer a universal cure.

Terfel’s Dulcamara was less sleazy smooth-operator and more grimy grease-ball. He certainly didn’t intend to waste any time flattering and charming the yokels, and there was no attempt to feign affability or hide his deception, from the villagers or us. So what if the publicity posters on the van are peeling and the fireworks fizzle out? Aided by a couple of brutes, who drive the tatty truck and pick the peasants’ pocket, this Dulcamara is a brisk operator. In ‘Udite, udite, o rustici’ Terfel seemed almost impatient to swindle the peasants, grab the money and make a swift getaway; no matter if Nemorino, desperate for a second dose of the magic draught, was hazardously hanging on to the bull bars.

In Act 1 Terfel’s delivery was precise and vocally powerfully — adding to the quack’s aggressive gruffness — but somewhat, and surprisingly, dramatically low-key. And, despite having swapped his grubby lab-overalls for soiled red velvet, in honour of the pre-nuptial celebrations, ‘Io son ricco e tu sei bella’ was similarly under-played, with none of the hamminess that we might have expected from Terfel. The ‘wandering hands’, however, that drew an irritated ‘Silenzio!’ from groom-to-be Belcore, were a hint of the mischief to come. For in his Act 2 duet with Adina, ‘Quanto amore ed io spietata’, seemingly astonished by the miraculous transformation of Nemorino’s fortunes in love and luck which his elixir has effected, Dulcamara determined to down a large swig himself. The result was a delightfully light-footed leap, a twang of the braces, a wiggle of the bum and a wicked twinkle in the eye; beckoned off-stage by a teasing Adina, Dulcamara at last showed his charisma and appeal. Returning for the final chorus laden with crates of ‘curative’ Bordeaux, Dulcamara was full of boasts that he could boost not just the villagers’ amorous fortunes but their purses too: they had but to swallow his syrup and romance and riches were theirs! Clutching the cash, Terfel was the epitome of charming chicanery, not quite able to believe his own luck or his ‘powers’!

But, despite his winning appeal this Dulcamara was not the ‘star’ of the show; those honours went to tenor Vittorio Grigolo whose Nemorino wore his warm heart on his stripy sleeve and sang with an ardency and allure that ultimately even Adina could not resist. From his opening tumble down set designer Chantal Thomas’s towering pyramid of hay bales, Grigolo buzzed with life and optimism. His voice was as agile as his boogieing, the phrases swooping and swooning with Italianate suavity. But, Grigolo can do tenderness as well as urgency, and he combined these sentiments with striking expressive beauty in a performance of ‘Una furtiva lagrima’ which brought the house down. Nemorino’s anguish was all the more moving for its juxtaposition with the preceding high jinks of ‘Quanto amore’, but Grigolo pushed on through the second verse, the faster-than-usual tempo ratcheting up the torment, before the wonderfully wilting sighs of the close struck every listener’s heart, including Lucy Crowe’s previously impervious Adina.

Crowe sang with characteristic lucidity, accuracy and sparkle at the top; but, she didn’t quite have the fullness of tone across the whole tessitura of the role or the variety of vocal colour to capture Adina’s changeability and multifariousness — at times, vocally, she seemed rather too ‘angelic’. Crowe did work hard dramatically: perched aloft on the haystack, preening her nails under a scarlet parasol, sunning herself behind outsize scarlet shades, Crowe was a pretty picture of Beckham-esque aloofness, seemingly indifferent to Nemorino’s doting. But, despite all the hip-wriggling and posturing, she showed us Adina’s self-awareness too. Festooned with premature confetti, she might smile for the wedding photographer, but elsewhere she was quick to elude Belcore’s clutches and embraces, her grimaces and hand-wringing revealing her distaste and disquiet.

Adina’s reservations were certainly understandable, for Levente Molnár’s swaggering, baton-swinging Belcore was the embodiment of misogynistic machismo. Slapping his thigh to summon his soon-to-be bride to his lap, Belcore then preceded to bounce his ‘prized possession’ up and down with un-rhythmic oafishness. The Romanian strutted and squared up, and used his powerful baritone most effectively, to suggest Belcore’s burly brutishness and masculine over-confidence. Australian soprano Kiandra Howarth, a Jette Parker Young Artist, was a bright and feisty Gianetta, showing strong stage presence in this minor role.

After a fairly lacklustre overture, conductor Daniele Rustioni drew some characterful playing from the ROH Orchestra — the woodwind solos were particularly jaunty. Towards the close the tempi were a touch impetuous, and at times he pulled ahead of his singers, but on the whole Rustioni ensured a good balance between stage and pit. The ROH Chorus were well-marshalled; if some of their gestures were rather stylised this only served to illustrate the villagers’ lack of imagination and credulity.

Pelly’s production is busy and bustling — the zippy dog is back and raises a chuckle as he races like quicksilver across the stage. But, it is the sorrowful stillness of Nemorino’s lament that truly hits the target. If the mid-November gloom is lowering your spirits and a pick-me-up is needed, then this show is the potion for you.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Adina, Lucy Crowe; Nemorino, Vittorio Grigolo; Dulcamara, Bryn Terfel ; Belcore, Levente Molnár; Giannetta,Kiandra Howarth; Director,Laurent Pelly; Revival director, Daniel Dooner; Conductor, Daniele Rustioni; Set designs, Chantal Thomas; Costume designs,Laurent Pelly; Associate costume designer, Donate Marchand; Lighting design, Joël Adam; Orchestra of the Royal Opera House; Royal Opera Chorus. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Tuesday 18th November 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/C31B9394%20-%20VITTORIO%20GRIGOLO%20AS%20NEMORINO%2C%20LUCY%20CROWE%20AS%20ADINA%20%C2%A9%20ROH%2C%20PHOTOGRAPH%20BY%20MARK%20DOUET.png image_description=Vittorio Grigolo as Nemorino and Lucy Crowe as Adina [Photo by Mark Douet © ROH] product=yes product_title=L’elisir d’amore, Royal Opera product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Vittorio Grigolo as Nemorino and Lucy Crowe as Adina [Photo by Mark Douet © ROH]November 20, 2014

Samling Showcase, Wigmore Hall

For this delightful programme of song, five of the outstanding young musicians who have been nurtured by the organisation came together with Samling’s patron, Sir Thomas Allen, and pianist Malcolm Martineau, for an evening of individual and collective music-making which certainly reached inspired heights of excellence and pleasure.

Mezzo-soprano Rachel Kelly was given the tough task of opening this annual Showcase, the first half of which explored the song repertoire of the mid-nineteenth to early-twentieth centuries; and she added to the challenge by beginning with Richard Strauss’s ‘Ruhe, Meine Seele!’ (Rest my soul), its slow, mysteriously unfolding opening requiring considerable composure and control. Kelly’s warm-toned soprano was co well-centred, and the ambiguous chromatic progressions skilfully negotiated, although as the song progressed she adopted a wider vibrato which — while it enriched the timbre, without disturbing the intonation — I found a little distracting. She used the rising register towards the close of the song to inject a note of anger and the heightened drama was enhanced by pianist James Sherlock’s impassioned accompanying gestures. This air of turbulence continued in the second of Strauss’s Op.21 songs, ‘Cäcilie’, which was composed on 9th September 1894, the day before his marriage to the soprano Pauline de Ahna. Here, Kelly showed that she has a powerful upper register (perhaps even overly forceful at times) to match her rich low resonance.

Fervent Strauss was followed by Verdian joyful doting, as tenor Joshua Owen Mills presented a vibrant rendition of Fenton’s ‘Dal labbro il canto estasiato vola’ (From my lips, a song of ecstasy flies) from Falstaff, in which the enamoured Fenton arrives at the oak tree and sings of his happiness. Accompanied by Malcolm Martineau, Owen Mills displayed a fine Italianate ring which perfectly complemented the textual sonnet’s many references to music and singing. The tenor balanced a bright gleam with tenderness. Fenton’s final line (Lips that are kissed lose none of their allure) drew forth onto the platform soprano Lucy Hall, his Nannetta, who responded warmly: ‘Indeed, they renew it, like the moon’. Hall then transported us to late nineteenth-century France, with Debussy’s ‘La Romance d’Ariel’. The lucidity of Sherlock’s piano introduction was bewitching and Hall showed plenty of courage in tackling the stratospheric surprises that Debussy throws in, although the intonation sometimes wandered at the top. And, if the tone was not always sufficiently silky, there was plenty of dramatic feeling and Hall demonstrated an innate, sure sense of phrase structure. She was more at home in the ensuing number, Poulenc’s ‘Le petit garçon trop bien portant’ (The too-healthy little boy) in which her voice took on a more soubrette-ish quality which successfully conveyed the song’s dry humour.

A ‘double duet’ followed — Schumann’s ‘Blaue Augen hat das Mädchen’ (The girl has blue eyes) from the Spanische Liebeslieder — in which Owen Mills’ buoyant tenor blended beautifully with Ross Ramgobin’s burnished baritone to convey the exuberance of youthful joy and love; pianists Sherlock and Martineau enjoyed the spritely rhythms of the accompaniment. Ramgobin has an elegant, full baritone and his rendition of ‘Wandrers Nachtlied I’ (Wanderer’s nightsong I), the first of three songs by Schubert, had a gentle ease and well-shaped sense of line. In ‘Am Strome’ (By the river), a subtle employment of rubato and tender diminuendo in the final verse movingly conveyed the protagonist’s yearning ‘for kinder shores’, while Sherlock’s short piano postlude offered some a hint of warmth and consolation. ‘Sehnsucht’ (Longing) was underpinned by the quiet but troubled throbbing of the repeating piano motif, the vocal line once again communicating clear emotions and meaning, thanks to Ramgobin’s astute appreciation of structure and line.

After these performances by the Samling scholars, it was Sir Thomas Allen’s own turn to take to the platform in four songs from Arthur Somervell’s infrequently heard narrative song-cycle, Maud, which is based upon Tennyson’s eponymous monodrama. Allen’s tone was varied, by turns shadowy and light, in response to the textual sentiments, and while the intonation was not always absolutely true at the top of the voice, the baritone’s power to move remains undiminished, and he conjured a sentimental mood, especially in the final song, ‘O that ‘twere possible’, whose very brevity enhanced the pathos. Allen was joined by Rachel Kelly in the final item of the first half, two duet arrangements from Mahler’s Des Knaben Wunderhorn. ‘Verlorne Müh’ (Wasted effort) raised a wry smile, as Allen’s dismissed Kelly’s romantic pleading, ‘Närrisches Dinterie,/ Ich geh dir halt nit’ (Foolish girl,/ I’ll not go with you); Sherlock’s accompaniment deepened the caricature, as Kelly’s wheedling and luring became ever more brazen and Allen’s brush-offs increasingly brusque. ‘Trost im Unglück’ (Consolation in sorrow), in which a hussar and his beloved engage in a noisy, belligerent exchange, brought the first half to a close in fractious fashion!

If there had been a slight sense of nervous excitement in the initial sequence of songs, the mood relaxed after the interval. Owen Mills rose to the challenges of Liszt’s dramatic ‘Benedetto sia ‘l giorno’ (Blessed be the day) and the composer’s more reflective ‘I’ vidi in terra angelici costumi’ (I beheld on earth angelic grace) from Tre Sonetti di Petrarca, and if sometimes the voice was a little tight in the fortissimo passages at the top, the tenor displayed a pleasing light head voice; the conclusion to the latter song evoked a mood of quiet reverie, which was enhanced further by Sherlock’s tender rippling postlude chords. Ramgobin’s performance of Wagner’s ‘Wie Todesahnung … O du ein holder Abendstern’ from Tannhäuser was one of the highlights of the evening, full of colour and interest, and sung with a warm, honeyed tone.

Joined by Owen Mills (as Count Belfiore), Lucy Hall was a beguiling Marchioness Violante Onesti (disguised as the gardener, Sandrina) in ‘Dove mai son!’ (Wherever can I be!) from La finta giardiniera, her voice blooming beautifully. The virtuosic runs of Rossini’s ‘Bel raggio lusinghier’ from Semiramide caused Rachel Kelly no problem, as she demonstrated great flexibility and striking power, although at times there was a flinty edge to the tone. Expressive recitative and an eloquent piano introduction by Martineau preceded Hall’s sorrowful ‘Oh! quante volte’ (Oh! how much time) from Bellini’s I Capuleti e i Monthecchi, which was notable for the soprano’s soft tone and pliant phrasing. To conclude, all four singers came together for a spirited performance of the final quartet from Rigoletto, ‘Bella figlia dell’amore’, in which the intricacy of the varied musical perspectives and changing relationships was masterfully crafted. Bernstein’s ‘Make Our Garden Grow’ was a stirring, radiant encore to a rousing evening of shared music-making.

Claire Seymour

Performers and programme:

Samling Scholars: Lucy Hall soprano, Rachel Kelly mezzo-soprano, Joshua Owen Mills tenor, Ross Ramgobin baritone, James Sherlock piano; Sir Thomas Allen baritone; Malcolm Martineau piano.

Richard Strauss: ‘Ruhe, meine Seele’, ‘Cäcilie’; Verdi: ‘Dal labbro il canto estasiato vola’ from Falstaff, ‘Bella figlia dell’amore’ from Rigoletto; Debussy, ‘La Romance d’Ariel’; Poulenc, ‘Le petit garçon trop’ bien portant’; Schumann ‘Blaue Augen hat das Mädchen’ from Spanische Liebeslieder; Schubert, ‘Wandrers Nachtlied I’, ‘Am Strome’, ‘Sehnsucht’ ; Arthur Somervell, Four Songs from Maud; Mahler. ‘Verlorne Müh’, ‘Trost im Unglück’ from Des Knaben Wunderhorn; Liszt, ‘Benedetto sia ‘l giorno’, ‘I’ vidi in terra angelici costumi’ from Tre Sonetti di Petrarca; Wagner, ‘Wie Todesahnung … O du ein holder Abendstern’ from Tannhäuser; Mozart, ‘Dove mai son!’ from La finta giardiniera; Rossini, ‘Bel raggio lusinghier’ from Semiramide; Bellini, ‘Oh! quante volte’ from I Capuleti e i Monthecchi. Wigmore Hall, London, Wednesday 12th November 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Thomas_Allen_1318.png image_description=Sir Thomas Allen [Photo by Sussie Ahlburg courtesy of Askonas Holt] product=yes product_title=Samling Showcase product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Sir Thomas Allen [Photo by Sussie Ahlburg courtesy of Askonas Holt]November 19, 2014

La cenerentola in San Francisco

It was a rare evening, very rare, at San Francisco Opera when everything, almost everything, went together perfectly.

La cenerentola is Rossini’s most complex, and certainly greatest comedy. The competition is stiff indeed — L’italiana in Algeri (1812), Il turco in Italia (1814) and Il barbiere di Siviglia (1816). What separates Cenerentola (1817) and puts it way out front is the sheer size and number of its ensembles, big concerted pieces with four, five and six-voices, sometimes with chorus as well. These are the hallmarks of the great tragedies that begin with Otello (1816), the opera composed by Rossini immediately before Cenerentola.

Both Armida (1817), the tragedy written immediately after, and Cenerentola end with a huge showpiece aria for the prima donna. These years are the mature Rossini who demands big, virtuoso singers, like Cenerentola whose bravura alone must be sufficient to close the show and bring the audience to a level of delirium that made Rossini the most famous opera composer in the world.

Virtuoso singing and the sculpting of the highly sophisticated musical architecture of the arias and ensembles are the challenges of this great comedy, both challenges well met just now in San Francisco.

Conductor Jesús López-Cobos made a wunderkind debut at San Francisco Opera in 1972 at the age of thirty-two, and returned for the fall 1974 season, again for more of the big Verdi repertoire. Now, after an absence of forty years, he is back on the podium, a master of what some of us believe to be the epitome of what opera can be — the mature Rossini! The Rossini ethos is also the most delicate of all the great composers and it is sublime when it is revealed. This is very rare.

Conductor López-Cobos immediately took Rossini’s overture to the lightest boil. It was the bubbling of the tiny drops of the finest mineral water and the fleetness of a long distance runner, and it kept us there for the duration. In a Rossini tragedy the delight would be the suspension of time into pure lyricism (you forget to breathe), and the sheer joy of releasing emotion, tragic though it may be. In a comedy, you found a smile on your face, your foot marking the beat. Sheer delight. In Rossini, comedy or tragedy, it is the same music and the same joy of making that music.

The Lópes-Cobos tempos and his flights of Rossini’s sophisticated instrumentation were never indulged for effect. For example the patter pieces (when a male voice breaks into rapid words) did not so much amaze us with lightning speed as they amused us with rhythmic words. The ensembles never lost their individual voices by accelerandos intended to drive us to musical fulfillment, instead we remained immersed in the complexities of the ensembles. It was measured conducting that at once reconciled Rossini with his music and Rossini with the singers provided by San Francisco Opera.

Efrain Solís as Dandini, René Barbera as Don Ramiro

Efrain Solís as Dandini, René Barbera as Don Ramiro

An announcement was made that French mezzo soprano Karine Deshayes was not feeling well and would not be at her best. As it was Mlle. Desayes displayed a reserved temperament and presence that left Cenerentola colorless for most of the evening. In the spectacular finale to the opera, “Non piu mesta” she did vocally approach the needed Rossini vocal excitement if not the personality. Had she not been indisposed perhaps her high notes would have been integrated into the smoother sounds of her lower voice.

Cenerentola’s father, Don Magnifico, was sung by Spanish bass-baritone Carlos Chausson. A seasoned interpreter of Rossini roles he was perfection itself in the delivery of this role as generic buffo. Bass-baritone Christian Van Horn, perfunctorily and colorlessly (fault of the staging) enacted Alidoro, the facilitator of the familiar story.

Production by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle

Production by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle

Young Texan tenor René Barbera made a splendid prince aka Don Ramiro in beautiful, smooth voice throughout the role’s very high tessitura. He delivered his big second act cabelletta “Si, ritrovarla io giuro” with the voice and personality that have made him the winner of vocal competitions and with high C’s to spare.

Among San Francisco’s great treasures are the Adlers. These young singers are usually the messengers and maids in the grand repertoire, and sometimes are over-parted in important roles. In this Cenerentola production they were utter perfection as Dandini and the ugly step sisters Clorinda and Tisbe. Both Maria Valdes and Zanda Svede made these minor roles (only Clorinda has a very brief aria) into scene stealing roles with the help of their stage director, Gregory Fortner.

But the biggest star of the evening (and it was a stiff competition) was California baritone Efrain Solis as the prince’s servant Dandini. This young singer exuded the charm, pent-up fun and exuberant singing that will make him a Rossini star. The cherry-atop-the-cake was the physical resemblance of Dandini, the servant, to Don Ramiro, the prince whom he was impersonating.

In its heyday San Francisco Opera not only discovered Jesus Lopez-Cobos but also Jean Pierre Ponnelle, a young French scenographer who revolutionized San Francisco’s idea of what opera production could be. This brilliant designer turned stage director created this production of La cenerentola for San Francisco Opera back in 1969 — forty-five years ago! Its black and white, pencil drawn filigree and apparent architecture (cross-section of a multi-storied house) make it both storybook and physically tangible. It is self-consciously old and that alone made it new back in the ’60’s. More importantly its decor is integrated into action — the actors climb throughout the set — it was opera as scenographic action, not just singing.

The limitation of the Ponnelle set is however its symmetry, and it is stifling. The larger Rossini repertory was just being re-discovered back then. Since then Rossini performance practice has evolved to understand and embrace the structural complexity of these works. A mise-en-scène now must incorporate the musical score as a physical and intellectual component of the staging. This can be accomplished by imposing concept and shape as powerful as the music — strength of concept is no longer perceptible in this antique production.

Jean-Pierre Ponnelle who died in 1988 has long since not been a part of his production. It has been staged in recent revivals by Gregory Fortner who has staged this gifted cast in San Francisco as well. One assumes he kept the basic outlines of the original staging, respecting the symmetry of the set. He certainly will have added clever schtick to keep the action energized and to showcase his performers.

It is time to memorialize the Ponnelle production in photographs and move on to productions consistent with current performance practice.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Cenerentola: Karine Deshayes; Don Ramiro: René Barbera; Dandini: Efrain Solis; Don Magnifico: Carlos Chausson; Alidoro: Christian Van Horn; Clorinda: Maria Valdes; Tisbe: Zanda Svede. San Francisco Opera Chorus and Orchestra. Conductor: Jésus López-Cobos. Production: Jean-Pierre Ponnelle; Stage Director: Gregory Fortner; Lighting Designer: Gary Marder. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, November 13, 2014. Seats: 11th row house left.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Cenerentola_SF1.png

product=yes

product_title=La Cenerentola in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above:Clorinda and Tisbe, the Ugly Sisters [All photos by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

Rameau: Maître à danser — William Christie, Barbican London

Maître à danser, not master of the dance but a master to be danced to: there's a difference. Rameau's music takes its very pulse from dance. Hearing it choreographed connects the movement in the music to the exuberant physical expressiveness that is dance.

Furthermore, the very structure of Rameau's music is influenced by the intricate patterns of dance. Rameau was a music theorist as well as a composer, his nephew was Didérot, the encyclopédiste, so this precise orderliness is fundamental to his idiom. Think about baroque gardens, where the abundance of nature is channelled into formal parterres, though woodlands flourish beyond, and birds fly freely.This tension between nature and artifice livens the spirit : gods mix with mortals, improbable plots seem perfectly plausible.

In these miniatures, one hears The Full Rameau. "You don't have to wade through a prologue, five acts and a postlude", as Christie has quipped. With dancers, the music becomes even more vivid. Sophie Daneman directed. She's a very good singer, specializing in the baroque and in Lieder. She's worked with Christie before. On this evidence, she's a very good director, too.

Christie and Les Arts Florissants presented two miniatures, Daphnis et Églé (1753) and La naissance d'Osiris. (1754). both were written as private entertainments for Louis XV and his court at Fontainebleau, after days spent out in the forests hunting for game. The context is relevant. these pieces also commemorate the birth of two royal princes. The Barbican stage was lit beautifully,suggesting candlelight in a darkend room, creating the right hushed tone of reverence. The King wanted to be amused. The show had to flatter his image of power. Both pieces present Happy Peasants, acting out simple, innocent lives, thanks to the benevolence of their King. When the second infant prince grew up, he was crowned Louis XVI and built Le petit Trianon, to act out pastoral idylls.

There's so little drama in Daphnis et Églé that its basically a masque for dancing, Daphnis (Reinoud Van Mechelen) and Églé (Élodie Fonnard), shepherd and shepherdess, are friends who gradually fall in love over a sequence of 16 tableaux. Daphnis flirts with a stranger, singing a lovely air. Églé drags him away. Dancers supply interest in the absence of plot. Each of these vignettes represent a different type of dance. Françoise Denieau choreographed. Fans of early dance will enthuse about the finer details. I enjoyed the diversity and intricate formations, charmed by the natural precision of the dancers. It felt like hearing the score come alive. Van Mechelen and Fonnard are familiar names on the French baroque circuit. Fonnard's particularly pert and dramatic and Van Mechelen has good stage presence. The first performance of this piece in 1753 flopped, apparently because the singers were duds. Fonnard and Van Mechelen most certainly are not.

Daphnis et Églé works well when its slender charms aren't overwhelmed by excess opulence. Daneman's staging reflects this innocence, A simple cloth is held up on sticks to suggest peasant theatre. Alain Blanchot's costumes (organic dyed fabric?) show the shepherds and shepherdesses in what would have been normal 18th century costume for their class, ie "modern" for the time. Daneman has worked with Christie since their first Hippolyte et Aricie together some 20 years ago.

La naissance d'Osiris is altogether more substantial. This time the French shepherds and shepherdesses congregate around an Egyptian temple (not literally depicted), worshipping Jupiter, much in the way paintings of this period showed European landscapes populated with Europeans and semi-naked figures from Classical Antiquity. There;s a particularly beautiful part for musette (baroque bagpipes). The player gets to walk around the stage, among the dancers, just as at a peasant celebration. The idyll is shattered with a violent thunderstorm, the full force of Les Arts Florissants unleashed in splendid fury. Great lighting effects (Christoph Naillet). From up in the gods in the Barbican balcony, Pierre Bessière's Jupiter fulminates. He will save the people by giving them his hero son, danced by a lithe young male dancer. Although the monarchy didn't know what was to come later, we can appreciate how poignant these pieces are because we do.

Since La naissance d'Osiris was written to mark the birth of Louis XV's second son (the future Louis XVI) the allusion is audacious. The king of the Gods rules with divine authority, like an absolute monarch. The people know their place. The piece is political power game, Fonnard sang Cupid, with simple wings stuck to her back - sweetly naive, but firmed by Fonnard's feisty singing. Sean Clayton sang A Shepherd and Arnaud Richard sang the High Priest. Eventually Jupiter takes his leave, and the Three Graces dance a lively trio.

Although Rameau's music had to be written to please a royal patron, at heart its gentle good humour and humanity triumph. We in the modern audience were able to experience Rameau presented with great depth and sensitivity.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Maitre.png

image_description=Scene from Maître à danser [Photo © Philippe Deival]

product=yes

product_title=Rameau: Maître à danser — William Christie, Barbican London

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Scene from Maître à danser [Photo © Philippe Deival]

November 11, 2014

November 10, 2014

The Met mounts a well sung but dramatically unconvincing ‘Carmen’

Operagoers have long grown accustomed to sacrificing dramatic integrity for a rewarding musical experience. Joan Sutherland was in her ‘60s when she sang Gilda in scenes from Verdi’s Rigoletto at a Met Gala concert in 1987. Her singing brought the house down, though it’s unlikely that anyone in the theater believed this could be the title character’s teenage daughter.

In today’s era of the Met’s high definition simulcasting, it’s growing increasingly difficult for the company to conduct business as usual. Intense visual scrutiny of the cameras pressure performers to act as credibly as they sing, and to look the part of the characters they portray. Music may still rule in opera, but in Peter Gelb’s brave new world of simulcasting, seeing is believing.

Casting the full-figured Anita Rachvelishvili as the iconic temptress Carmen in the Met’s Nov. 1 HD simulcast did not do much to enhance the dramatic integrity of the story. The Georgian mezzo-soprano has the voice for the role, to be sure — with a handsome middle range and sufficient weight in her pedal tones to add chills down the spine when she flips the fortune card and reads aloud, “La mort!” What was lacking in Rachvelishvili’s performance was the raw sexual magnetism required to bring the character Carmen to life.

When Richard Eyre’s production first ran in 2009, the sultry siren Elīna Garanĉa played the title role. Here, both singing and looks were equally convincing. Granted, Garanĉa’s unforgettable portrayal is a tough act to follow. But even ignoring the inevitable comparisons to the prior production, there was simply too little in Rachvelishvili’s performance to convey her character’s wild, dangerous and sexually alluring side.

The Habanera (sung sweetly though hardly seductively) fell flat, while the Seguidilla generated insufficient heat to make plausible Don José’s complicity in Carmen’s escape — for which he risks imprisonment. Nor was there sufficient electricity in Rachvelishvili’s dance sequence during the supposedly eroticTriangle Song at Lillas Pastia’s Tavern. As the pace of the music reached boiling point, I was sure she'd climb onto one of the tables and dance, as had Garanĉa. She did not. The little dancing we did see from her (on terra firma) would not likely have gotten her past the first round of Dancing With The Stars.

Ultimately, theater audiences across 69 countries had to be content with Rachvelishvili’s formidable vocal effort — a pleasure, indeed, but one perhaps better suited to radio broadcast than visual simulcast.

Aleksandrs Antonenko’s Don José, a bit stiff throughout the first act, grew increasingly convincing as the obsessed lover, driven to extremes over his ill-fated passion for Carmen.

In José we must sense the ambivalence of a once-proud soldier who is faced with a choice between a safe but boring life (with plain-Jane Micaëla) and an exciting but dangerous life (with by the gypsy Carmen). When he does not choose wisely, José must be seen as a pathetic loser whose self-respect begins to dwindle away — much like the money of an inveterate gambler at the dice tables. In short, José's life has gone to craps. Antonenko made this breakdown believable, and by the end of the third act he morphs into a fanatical, menacing stalker.

As a singer, Antonenko gave two performances: the one in the first half of the opera, where his voice lacked subtlety and he frequently clipped the ends of his phrases to wet his lips (such as in the first act duet with Micaëla); and the second half, where he found his voice in all its glory and used his strong spinto tenor to add body to the emotional outbursts. I shall remember him for the latter.

Simulcast viewers who missed the opportunity to hear Anita Hartig as Mimi in La Bohème last April (she took ill and had to be replaced) got their chance to hear the Romanian soprano play José's steadfast fiancée, Micaëla.

Hartig’s exquisite delivery of her signature Act Three aria Je dis que rien ne m'épouvante, sung as her character makes a last ditch attempt to free José from the grip of the deadly Carmen, was the singular most moving number in the production. Hartig's tender lyric soprano captured all the nuances of expression Bizet has to offer in this work. Her breathtaking decrescendo on the aria's final words, protégez moi, Seigneur (Protect me, O Lord), brought a lump to my throat. The profuse applause from the Met Opera audience at the end of the number said it all.

As the flamboyant toreador, a handsome and self-assured Ildar Abdrazakov at once captured the testosterone-charged persona of Escamillo — in looks as well as voice. Abdrazakov's Toreador Song at Lillas Pastia’s Tavern in Act Two was the highlight of an otherwise unspectacular first half of the performance. Though he tended to cheat the aria's sharply dotted-rhythms in favor of easier-to-sing triplets, Abdrazakov delivered his signature aria with a deep and meaty bass-baritone that made the listener sit up and take notice.

Keith Miller, reprising his role of Zuniga from the company's 2009 production, is an excellent actor whose dynamic onstage demeanor injects anima into the roles roles he portrays. Using his firm bass-baritone and strong visual presence, Miller crafted a strongly believable (and downright sleezy) captain of the guard.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a better pair of supporting singer-actors than soprano Kiri Deonarine (Frasquita) and mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson Cano (Mercédès), as Carmen's colorful gypsy cohorts.

The dynamic duo performed exceptionally well in their ensemble numbers, such as the quick-tongued, rapid patter-like dialogue of the delightful quintet Nous avons en tête une affaire — which they articulated with great clarity of diction. (Abdrazakov could have learned much from the pair's precision singing in the crisply dotted-rhythmic figures here.) But the true tour de force came in the charming Fortune-Telling Duet from Act Three, where the gypsies playfully coax the cards into "revealing" their future lovers and destinies. This number was not only sung beautifully, but provided a captivating visual experience.

Eyre’s production team, spearheaded by Set Designer Rob Howell, once again used a rotating stage (a technique that now bears Eyre's signature). This proved useful in making smooth transitions between scenes and augmented the look and scope of the crowd scenes — such as in the public square during Act One. In fact, almost everything in this production was staged effectively. I especially enjoyed the scene where the cigarette girls disembark en mass from the factory, gushing forth as would water from an open spigot.