December 30, 2014

Amsterdam: Lohengrin Lite

At times in my past encounters, Mr. Audi has summoned forth interpretive results of unearthly beauty and unerring emotional resonance. His successes are among my most memorable opera-going experiences. At other times, Pierre’s over-thinking of subtext has muddied the plot and defused the emotional core of the musico-dramatic source material.

His ambitious Lohengrin for the Netherlands Opera manages moments of haunting beauty, it is true, but random choices of distracting symbols and inexplicable stage movement draw the viewer out of the artistic illusion with alarming regularity.

I quite admired almost all of Jannis Kounellis’ imposing, brooding set design. The cavernous stage of the Muziekthater can be a big space to fill, but Mr. Kounellis has crafted an overwhelming, four story, floor-to-ceiling structure for Act I, that featured seated rows of countless stoic choristers, presiding like unyielding magistrates over a life-or-death trial in a colosseum.

Act II opened up quite a bit, first with an austere balcony for Elsa stage right, then with a more claustrophobic set of receding walls with restricted entrances that nonetheless provided concentrated focal points. For the bridal chamber, Kounellis provided a mysterious set of dark panels that were punctuated with (presumably swan) feathers. Illuminating and apt.

Angelo Figus contributed a wide-ranging, fantastical costume design, with attire often larger than life, bulky, and well, it has to be said, misshapen. The splendid sculpted voluminous capes for the men at the start of Two were replaced by curious white body ‘wraps’ that were unshapely and unflattering. Lohengrin himself appeared not unlike like he was wearing a sculpture of a swan. Best look of the night: Ortrud looked hip and stylish in a red-lined black vamp dress and blond wig. Runner up: the gorgeous visual moment when Elsa was ceremoniously topped with her bridal veil.

All of these visual components were tellingly lit by Jean Kalman. The harsh cross lighting was complemented by well-chosen specials and warm tints at critical dramatic revelations. The separate areas for the conspirators and Elsa in Act II were especially well considered. Mr. Kalman could only do so much however, and his gamely rendered, glowing backlighting effect for the arrival of the swan could not compensate for the fact a train-car full of oars (not a swan) slowly rolled across the stage from left to right as the hero’s voice sounded from off stage left. (See ‘distracting symbols,’ above.)

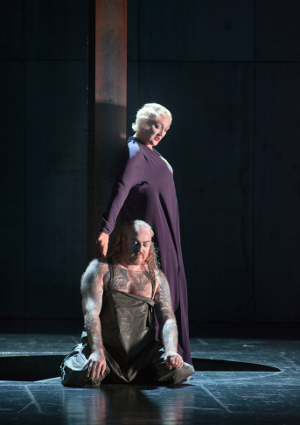

Michaela Schuster as Otrud and Evgeny Nikitin as Friedrich von Telramund

Michaela Schuster as Otrud and Evgeny Nikitin as Friedrich von Telramund

Audi did manage to provide plenty of ideas to chew on. After an opening act that seemed almost Konzertant, replete with semaphoric gestures and ritual choreographic movement, the director infused the rest of the night with more teeming movement that pulsated and morphed with dramatic purpose. The original primitive ritual posturing in which all men had weapons (clubs, staves, knives, pipes), relaxed into more naturalistic interaction to good effect.

The musical achievements were largely impressive. In the first third, the performance was characterized by a rather diffuse sound and lack of forward motion. No import. No inherent burning fire. But as of Act Two, conductor Marc Albrecht seems to have found his muse and from that point on the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra achieved a translucent vibrance and a thrilling sense of ensemble. Ching-Lien Wu’s meticulously prepared chorus went from strength to strength all night long.

The towering vocal performance of the night was the white-hot Ortrud from the laser-toned Michaela Schuster. Ms. Schuster poured out phrase after phrase that etched in the memory as among the finest I have yet heard in this role. The potent Michaela not only sang her socks off, but maybe also sang off the ceiling paint, and she alone was worth the price of admission.

Juliane Banse had most of the assets required as Elsa, including a warm and pulsing soprano that is very sympathetic. But if the occasional smudged phrases and splayed tone are any indication, the part may at this point be a size “just” too large for her inherently lyric soprano. It cannot be denied that her duo scene with Ortrud was arguably the highlight of the evening.

The reliable bass-baritone Günther Groissböck was plagued by an uncharacteristically unfocussed top at the start, but then settled down to regale us with his usual impressive, warm, and powerful vocal presence. Evgeny Nikitin, as an ersatz tattooed biker, was a stolid Freidrich von Telramund. Mr. Nikitin seemed hell bent on pulverizing top notes and ended up barely hanging onto sustained upper phrases with somewhat wooly, straight tone. But, when he sang softer, lo, Evgeny demonstrated a baritone of great beauty and control. More of that, please, sir!

Still, the opera is not named Ortrud, nor Elsa, nor Telramund. The actual title role found Nikolai Schukoff, and his slim tenor, lacking. Mr. Schukoff is handsome and stage-savvy. He has admirable innate musical sensibilities. What he does not have, and cannot suggest, is a heroic voice. Being over-parted, Nikolai resorted to trying to ride the orchestra by manufacturing a pointed, almost pinched delivery, but there was no disguising the fact that there simply was no substantial presence in his smallish instrument. When the opera is called Lohengrin, and that title role calls for a Wagnerian heroic tenor, that shortcoming is a serious limitation.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Heinrich der Vogler: Günther Groissböck; Lohengrin: Nikolai Schukoff; Elsa von Brabant: Juliane Banse; Freidrich von Telramund: Evgeny Nikitin; Ortrud: Michaela Schuster; Der Heerrufer des Königs: Bastiaan Everink; Conductor: Marc Albrecht; Director: Pierre Audi; Set Design: Jannis Kounellis; Costume Design: Angelo Figus; Lighting Design: Jean Kalman; Chorus Master: Ching-Lien Wu.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/lohengrin0078.png

image_description=Juliane Banse as Elsa von Brabant and Nikolai Schukoff as Lohengrin with Koor van De Nationale Opera [Photo by Ruth Walz]

product=yes

product_title=Amsterdam: Lohengrin Lite

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Juliane Banse as Elsa von Brabant and Nikolai Schukoff as Lohengrin with Koor van De Nationale Opera

Photos by Ruth Walz

December 26, 2014

Fidelio, Manitoba Opera

And it is a mystery why it’s taken this long to see the German composer’s sole opera with its message of hope never more sorely needed than today. Kudos to MO’sGeneral Director/CEO Larry Desrochers, who also directed the 150-minute production (sung in German with English surtitles) for choosing this opera that also commemorates the historic opening of Winnipeg’s Canadian Museum for Human Rights — the first national museum built outside the country’s capital Ottawa.

Desrochers’ vision transplants French librettist Jean-Nicolas Bouilly’s original story to 1989 Cold War Germany, circa the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall which lent its own contemporary relevance.

Maestro Tyrone Paterson led the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra throughout Beethoven’s uplifting score. Set/costume designer Sheldon Johnson’s towering pockmarked grey prison walls; industrial hanging lights and two carbon copy office desks further infused the opera’s visual world with stark, regimented order. Bill Williams’ razor sharp lighting design helped mitigate the production’s overly monochromatic feel - not helped by drab, prisonesque costumes — with effects such as shafts of cold light in Act II’s dungeon scene as penetrating as search lights.

Saskatchewan-born soprano Ileana Montalbetti in her company debut as protagonist Leonore proved well worth the wait. Her chameleonic ability to morph between manly Fidelio and devoted wife Leonore is as remarkable as her strong, effortless voice and dramatic skills. Her powerhouse ‘big moment’ aria“Abscheulicher, wo eilst du hin" in which she resolutely vows to save her husband easily deserved one of the first bravas of the night.

Canadian tenor David Pomeroy compelled in his role debut as shackled political prisoner Florestan, his dramatic voice first heard as a bellowing cry of human suffering during his Act II opening recitative/aria “Gott! welch' unkel hier! In des Lebens Frühlingstagen.” His keen acting skills perfectly balanced both worlds of struggle and strength; not inspiring pity but true compassion as he collapsed in chains until finally rescued by Leonore.

Critically acclaimed bass-baritone Kristopher Irmiter portrayed the villainous Don Pizarro with swaggering menace. His initial, less-is-more delivery finally exploded during aria “Ha! welch ein Augenblick!" in which he vows to murder his nemesis Florestan, likewise effectively pulling the puppet strings of American bass Valerian Ruminski in his role as jailer Rocco.

Ileana Montalbetti as Fidelio and David Pomeroy as Florestan with the Manitoba Opera Chorus

Ileana Montalbetti as Fidelio and David Pomeroy as Florestan with the Manitoba Opera Chorus

Charismatic Winnipeg-born soprano Lara Secord-Haid also made an impressive MO debut as teenaged character Marzelline, blindly in love with Fidelio as she thwarted Irish-Canadian tenor Michael Colvin’s Jacquino’s romantic advances during duet “Jetzt, Schätzchen, jetzt sind wir allein.” The rising star’s crystal clear voice easily soared to the top of her range during " O wär ich schon mit dir vereint,” wholly convincing as a fickle young girl in love.Bass-baritone David Watson imbued his benevolent government official Don Fernando, who frees all prisoners including his longtime friend Florestan, with his customary gravitas.

Admittedly, the dynamic between the lead couple did not always ring true. Although Fidelio is ostensibly an opera of ideas, at its core it remains a deeply abiding love story. After Leonore finally saves her husband, she ecstatically sings of “indescribable joy” — albeit across the stage. After being separated for two years, wouldn’t she immediately rush into his arms? This emotional disconnect became the production’s only flaw.

Nevertheless, all was quickly forgiven during the climactic finale where the stage floods with scores of real-life heroes and heroines — former refugees now making their home in Winnipeg — who all carry within themselves their own true life Fidelio opera. Their dignified presence as the MO Chorus (prepared by Tadeusz Biernacki)sings, “God tests us but does not desert us” moved many in the opening night crowd to tears that became the crux of the entire production. There could be no more intensely raw, authentic moment on any stage, operatic or theatrical alike in our city all season long, with the powerful image not soon easily forgotten.

Holly Harris

image=http://www.operatoday.com/_RWT7796.png image_description=leana Montalbetti as Fidelio, Kristopher Irmiter as Pizarro, and David Pomeroy as Florestan [Photo by R. Tinker] product=yes product_title=Fidelio, Manitoba Opera product_by=A review by Holly Harris product_id=Above: leana Montalbetti as Fidelio, Kristopher Irmiter as Pizarro, and David Pomeroy as FlorestanPhotos by R. Tinker

December 22, 2014

The Hilliard Ensemble: Farewell Concert at Wigmore Hall

While countertenor David James is the sole survivor from the original four-man line-up, the current quartet of James, tenors Rogers Covey-Crump and Steven Harrold, and baritone Gordon Jones have been singing together since 1998, and this Farewell Concert at the Wigmore Hall — an occasion for both poignancy and celebration — confirmed that they are bowing out while still at the top.

Performing music from Pérotin to Pärt, from anonymous medieval carols to Roger Marsh’s 2013 Poor Yorick, the Hilliards gave a masterclass in musical and textual precision; not for nothing are they named after the Elizabethan miniaturist, Nicholas Hilliard, whose attention to pictorial detail they have ever aimed to replicate in musical contexts. But, more remarkable even than the accuracy and clarity — every word perfectly enunciated — was the innate, shared musicality of the four singers; the rises and falls, ebbs and flows were instinctively felt and mesmerising in their assured simplicity and directness. It is this ‘oneness’ that produces such pure, entrancing vocal beauty.

In a recent Guardian article, Gordon Jones remarked that the programme for the group’s Farewell Concert was ‘a bit unstructured — that’s unusual for us. But taken together it represents much that has been important to us, and to the people who have been close to us and who will be in the audience. We were also keen to include a few pieces written for us by composers who will also be in attendance’. The programme may have been eclectic but during this valedictory evening it was the Hilliards’ ability to reveal the modernity of Pérotin’s plainsong, with its complex rhythms and striking dissonances, and to make music from the twenty-first century speak with the sincerity and openness of Gregorian chant which underlined the ensemble’s range and accomplishment.

We began, fittingly, with the first-known notated composition for four voices, Pérotin’sViderunt Omnes, a Christmas gradual: the lowest voice — the cantus firmus — presents that original plainchant in extremely long notes, while the other voices blossom in elaborate melismatic polyphony.A remarkably poised balance was achieved between the elongated syllables of the bass and the complex decorative counterpoint above; and there was a wonderful clarity with each resolution of the increasing dissonance before the change from one syllable of the text to the next, creating a sense of spiritual affirmation. Indeed, the short text announces that God has arrived in ‘All the ends of the world’ and the Lord has ‘declared his salvation’, and there was a spirit of exultation in the buoyant rhythms and driving imitative points. Interestingly, the clashing overtones foreshadowed the ‘tintinnabulation’ of Arvo Pärt, heard later in the evening.

The Hilliards have commissioned many new compositions, adding greatly to the richness of the repertoire for four high male voices. During a 1995 residency at the summer school which they established, Piers Hellawell offered the group settings of passages from Nicholas Hilliard’s The Art of Limning, published in 1570, which explore the expressive nature of colour. The text of ‘True beautie’ strives to capture the power of colour to make objects appear transparent, a power evoked by the Hilliards’ ravishing tone; the scrupulously rendered interweaving melodies of ‘Saphire’ were a musical match for the power of the painter, a ‘cunning artificer’, who ‘helpeth nature and addeth beauty’.

In contrast to such intricacy, the music of Arvo Pärt offered simple artlessness. Pärt’s And One of the Pharisees, a setting of a long-text from the gospel of Luke for baritone, tenor and countertenor, contrasted homophonic, monosyllabic chanting recounting the parable of Christ’s forgiveness of a sinful woman with the freer solo-voice direct speech of Christ and the Pharisee.Most Holy Mother of God, for 4 voices, composed for the group in 2003, their thirtieth year, is a repetitive plea to the Blessed Virgin to ‘save us’. In both works, the Hilliards captured the intense liturgical candour of Pärt’s minimalist idiom, while in the Most Holy Mother they use the tensions in the syncopated opening motif to create energy and momentum within the meditative medium.

In December 2013, celebrating their 40th anniversary, the ensemble premiered Roger Marsh’s Poor Yorick, a setting of the description of the death of Yorick from Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy. Here they presented the long central section of the three-part work, ‘Death of Yorick’, Rogers Covey-Crump singing affectingly as the dying Yorick while Gordon Jones assumed the role of Eugenius, whose tearful addresses to his dying friend at times took a wry turn, as with the consolation, ‘I declare I know not, Yorick, how to part with thee, and would gladly flatter my hopes … that there is still enough left of thee to make a bishop, and that I may live to see it’. The Hilliards enjoyed the humour and the theatricality of the work, expressed through Marsh’s rich harmonies.

But, it was in the earlier repertoire that the singers excelled, elevating seemingly simple compositions such as‘There is no rose’, ‘Lullay, lullow’ and ‘Ecce quod natura’ — anonymous carols for two and three voices — to high musical stature. Most striking of all was the eloquence of ‘Ah, gentle Jesu’ by Sheryngham, a composer about whose life and work nothing is known. A candid dialogue between the crucified Christ (two low voices) and a remorseful sinner (two high voices), this work was beautifully soft and warm.

The Farewell concluded with ‘Excursion into the Mountains’ from the austere music drama I went to the house but did not enter by Heiner Goebbels, a mediation on the passing of life which was commissioned by the Hilliards and first performed in 2008. ‘Excursion in the Mountains’ presents a complete short story by Kafka in which a writer reflects on the negatives and absences in his life, desiring the freedom of the mountains where ‘throats become free!’ The spirited music ironically contrasts with the quizzical text, and the work ended, appropriately, with the jovial exclamation: ‘It’s a wonder that we don’t burst into song.’

Jones, in the afore-mentioned interview, remarked prior to the event, ‘As we approach the final performance I’ve really no idea how we will feel on the night. We’ve sung more than 100 concerts around the world this year, and throughout, we’ve resisted as strongly as we could calling it a “farewell tour”. That would have seemed so maudlin and mawkish … I just hope we can get through everything — some of the pieces are quite tricky — especially if it turns out to be a bit of a Kleenex evening.’

In fact, this was not an evening for tears, just gladness and joy that we have had the opportunity to experience such wonderful music-making, a mood perfectly captured by the single encore which tenderly slipped away into the silence, the Scottish song, ‘Remember Me My Dear’.

Claire Seymour

Performers and programme:

The Hilliard Ensemble: David James countertenor, Rogers Covey-Crump tenor, Steven Harrold tenor, Gordon Jones baritone. Wigmore Hall, London, Saturday 20 th December 2014.

Pérotin — Viderunt omnes; Piers Hellawell — ‘True beautie’, ‘Saphire’; Arvo Pärt — And One of the Pharisees; Roger Marsh — ‘Death of Yorick’; Sheryngham — ‘Ah, gentle Jesu’; Arvo Pärt — Most Holy Mother of God; Anonymous — ‘There is no rose’, ‘Marvel not Joseph’, ‘Lullay, lullow’; 15th-century English carol — ‘Ecce quod natura’; Heiner Goebbels, ‘Excursion in the Mountains’.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/TheHilliardEnsemble%20%288%29.png image_description=The Hilliard Ensemble [Photo by Marco Borggreve] product=yes product_title=The Hilliard Ensemble: Farewell Concert at Wigmore Hall product_id=A review by Claire Seymour product_by=Above: The Hilliard Ensemble [Photo by Marco Borggreve]Fidelio opens new season at La Scala

It would be hard to imagine a musician today who is more politically active than Daniel Barenboim. As just one example, the success he has achieved since 1999 with his West-Eastern Divan Orchestra (comprising young Israeli, Palestinian and Arab musicians) is living proof that Art can prevail when politicians continuously fail. That said, it is hardly surprising that Maestro Barenboim made his farewell as Musical Director of La Scala with Beethoven’s only opera, which like the last movement of the 9th Symphony, extols the eternal values of brotherhood, peace, tolerance and freedom.

Barenboim’s personal connection to this opera is almost palpable and as Musical Director, he must have approved the choice of English director Deborah Warner to follow in the footsteps of Otto Schenk, Giorgio Strehler and Werner Herzog in bringing Fidelio to the Scala stage. The contemporary and perhaps deliberately location-neutral stage setting by Chloe Obolensky (a large, drab, cement-columned, ghetto-esque courtyard — curiously without any visible cells) encouraged the universal themes of the dramaturgy to resonate with a 21st century audience almost inured to brutality and injustice. Certainly Madame Warner brought out consistently fine acting from all protagonists, but as in many modern adaptations, there were some serious inconsistencies between text and direction. When Leonore asks Rocco to let the prisoners out for some fresh air because the weather is so wonderful (Heute ist das Wetter so schön) the semi-subterranean West Side Story-ish cement space was still so gloomy there was hardly any light at all. Gott, welch Dunkel hier indeed. Much more difficult to understand was the final scene when the prisoners were freed as the result of a massive break-in rescue mission led by rather motley, hard-hatted urban guerrillas and not as Rocco states, due to a general pardon by the King. ( Der Minister hat eine Liste aller Gefangenen…alle sollen ihm vorgeführt werden.) To fit her crypto-Che Guevara liberation concept, Madame Warner cut from the dialogue Rocco’s specific instruction to Jacquino to free the prisoners (öffnet die oberen Gefängnisse! ) which was a bit naughty. If regal clemency was good enough for Beethoven, Sonnleithner & Treitschke, why not for Warner? Similarly, after Don Fernando praises the virtues of liberty, love and brotherhood ( Tyrannenstrenge sei mir fern. Es sucht der Bruder seine Bruder und kann er helfen, hilft er gern) instead of Don Pizzaro being led off to an uncertain fate, a very loud gun shot is heard. Summary execution is hardly in the spirit of brotherly compassion. Finally, when all are extolling the praises of Leonore’s extraordinary devotion and courage (Stimm in unsern Jubel ein! Nie wird es zu hoch besungen, Retterinn des Gatten sein !) Madame Warner has Marzelline sulking prominently at the front of the stage then engaging in some superfluous business with Jacquino before giving him a kiss and running off. The domestic trivialities and petty adolescent infatuations of Act 1 have been completely subsumed in Act II by issues of momentous universal truth and importance. It is no time to worry about the selfish disappointments of a miffed teenager. This part of the direction was both irritating, distracting and absolutely unnecessary. Furthermore, the general confusion and chaos of the final staging marred what was otherwise exemplary singing by the chorus.

Klaus Florian Vogt as Florestan, Peter Mattei as Don Fernando and Kwangchul Youn as Rocco

Klaus Florian Vogt as Florestan, Peter Mattei as Don Fernando and Kwangchul Youn as Rocco

As mentioned, the acting by all singers was outstanding and even more impressive in close-up focus on the subsequent RAI broadcast. Florian Hoffmann as Jacquino was a very credible frustrated teenager in jeans, hoodie and white T-shirt which read ‘WOW!’ His appealing light tenor was slightly overpowered by the orchestra in the opening duet with Marzelline and following ensembles, but on the whole this was a very convincing performance. As the object of his unrequited affection, the Marzelline of Mojca Erdmann was very well acted and sung. A highly attractive stage appearance and agreeable vocal colour made Jacquino’s ardour entirely understandable. Although the voice seemed to spread occasionally when forte in the upper register, her Act I aria ‘O wär ich schon mit dir vereint’ was charmingly sung and her cantilena in the sublime ‘ Mir ist so wunderbar’ quartet was extremely well balanced with the other singers. Falk Struckmann has been snarling Don Pizzaro for quite a long time but apart from a rather silly and spivvy Mafioso-style suit, his interpretation seemed fresh and suitably fiendish. His astonishment at finding out that Fidelio was actually a woman (sein Weib?) in the great confrontation scene in Act II was utterly convincing. The Don Fernando of Peter Mattei was mellifluously sung as ever, although his appearance was entirely without gravitas and he looked more like a smug property developer bringing news of a successful rental assistance plan to under-privileged tenants than a compassionate Minister of State rejoicing in the honour of freeing political prisoners. As Rocco, the Korean bass Kwangchul Youn enjoyed a big success with the audience. Certainly an Asian physiognomy would have been somewhat unlikely as a State gaoler in 18th century Spain, but in this location-ambiguous production, it didn’t jar at all. Possessing a very appealing warm baritone timbre and singing (and speaking) with perfect German diction, this was a performance full of personality, humour, subtlety and musical insight which fully deserved the accolades he received from the notoriously picky Scala pubblico. Florestan was sung by Klaus Florian Vogt. Whilst not having the meaty macho tenor klang of Jon Vickers or James King, this Florestan’s more lyric timbre worked extremely well and projected effortlessly over the orchestra from the opening impassioned G natural on ‘Gott’, through themerciless tessitura of theO namenlose Freude duet to the concluding Wer ein solches Weib. The luke-warm response he received during the curtain-calls was difficult to fathom. The standout performance was unquestionably that of Anja Kampe as Leonore. Like Falk Struckmann, Madame Kampe is no stranger to her role, but managed to infuse the part with such spontaneous emotion and total commitment, it was an absolute triumph. Combining the intelligence and dramatic insight of Hildegard Behrens with the vocal technical assurance of Birgit Nilsson, this was in all respects an extremely fine interpretation. Despite a slightly shaky exposed top Bb on Tödt’ erst sein Weib! there were wonderfully powerful low C# chest notes (wie Meereswogen) in the Abscheulicher! recitative, beautiful dulcet piano word-colouring on Farbenbogen, a vibrato-free perfectly pitched top B natural on erreichen and impressive accuracy and clarity during the fioratura and leaps in der treue Gattenliebe. Bravissima Anja!

Florian Hoffmann as Jacquino, Mojca Erdmann as Marzelline, Anja Kampe as Leonore, Klaus Florian Vogt as Florestan and Peter Mattei as Don Fernando

Florian Hoffmann as Jacquino, Mojca Erdmann as Marzelline, Anja Kampe as Leonore, Klaus Florian Vogt as Florestan and Peter Mattei as Don Fernando

The greatest ovation of the evening however was for conductor Daniel Barenboim and the La Scala orchestra. The maestro opted for the less familiar but longer and more symphonic Leonore Overture No. 2 in C Major to start the performance over the usual E Major alternative. This meant cutting the even more dramatic Leonore Overture No. 3, usually included by conductors such as von Karajan and Bernstein and played in most German houses during the scene change just before the Act II finale. Barenboim’s conducting was so full of nuance, unforced rubati and meticulous attention to the composer’s markings it is difficult to single out specific sections of the partitura for particular praise. Every crescendo and diminuendo, from the strings and winds in the sixth measure of the overture to each sfp, sf and marcato in the tremendous conclusion of Retterin des Gattin sein were played with flawless precision and clarity. This was not just a reading of rhythmic and dynamic exactitude but of gorgeous orchestral colouring as well — the opening cello passage to Mir ist so wunderbar and the soaring oboe solo in Leonore’s Welch ein Augenblick being just two examples. The performance was a worthy Abschiedsgeschenk from a maestro who has not always enjoyed the approbation of the mercurial Milanese, some of whom still squawk about the Simon Boccanegra fiasco in 2010. Whether the same fondness will be felt for Deborah Warner’s production remains to be seen.

The audience at this, the fourth performance, was not quite as enthusiastic as at the premiere and there were no ovations after the overture or arias. Perhaps they confused Fidelio with Parsifal. Local press reported the applause at the opening night curtain went for 15 minutes. One can imagine that having paid over US$3,000 a ticket, the chic prima rappresentazione crowd was determined to have a good time.

Jonathan Sutherland

Cast and production information:

Fernando: Peter Mattei, Don Pizzaro: Falk Struckmann, Florestan: Klaus Florian Vogt, Leonore: Anja Kampe, Rocco: Kwangchul Youn, Marzelline: Mojca Erdmann, Jacquino: Florian Hoffmann, Erster Gefangener: Oreste Cosimo, Zweiter Gefangener: Devis Longo. Conductor: Daniel Barenboim, Director: Deborah Warner, Set and Costume Design: Chloe Obolensky, Chorus Master: Bruno Casoni Don. Teatro alla Scala Milano 16th December 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mojca%20Erdmann%20%28Marzelline%29%20Florian%20Hoffmann%20%28Jacquino%29%20.png image_description=Mojca Erdmann as Marzelline and Florian Hoffmann as Jaquino [Photo courtesy of Ufficio Stampa Teatro alla Scala] product=yes product_title=Fidelio opens new season at La Scala product_by=A review by Jonathan Sutherland product_id=Above: Mojca Erdmann as Marzelline and Florian Hoffmann as JaquinoPhotos courtesy of Ufficio Stampa Teatro alla Scala

December 21, 2014

Mahler Songs: Christian Gerhaher, Wigmore Hall

His "O du, mein holder Abendstern" was so sublimely beautiful that it seemed to come from beyond the realms of reality. Wolfram is not so much a character in an opera as an almost divine symbol of Knightly Virtue. But does the idealized perfection of Wartburg triumph over Venusberg? Tannhäuser didn't think so, and Elisabeth chooses Tannhäuser.

Pertinent thoughts with a significant bearing on Mahler performance practice. Gerhaher began with Mahler's Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen. Far too much emphasis is placed on their autobiographical content. Like a Geselle, Mahler is learning his craft, through well-made "apprentice miniatures" that will form the basis of his symphonies from the first to the fourth, with echoes beyond He was experimenting with the aesthetic of Des Knaben Wunderhorn, the collection of poems and ballads compiled from oral tradition by Achim von Armin and Clemens Brentano in 1805. The folk origins of this collection are significant, for they embodied early 19th century Romantic attitudes, not authentic "folk" tradition so much as reworkings by intellectuals for the fast-growing urban middle class. Mahler wasn't writing fake folk song but songs as themes that will later be developed in sophisticated abstract form.

Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen isn't a song cycle so much as a series of stand-alone songs, each of which illustrates an emotional state, from the energetic "Ging heut' Morgen übers Feld " to the scherzo-like psychosis of "Ich hab'ein glühend Messer". A certain amount of detachment on the part of singer and pianist is reasonable, but Gerhaher and Huber didn't engage with the emotional changes. Gerhaher's pace was fractionally too slow, not perhaps enough for most to notice, but enough to keep voice and piano out of synch. Huber jumped in too forcefully.

A selection of songs based on Das Knaben Wunderhorn followed, including early songs from the Lieder und Gesänge,aus der Jugendzeit. Songs about children, but songs with a macabre twist, reflecting a very different attitude to youth than we hold today. After Bruno Bettelheim, we can't take fairy tales at surface value. Even the lyrical "Zu Strassburg auf der Schanz" describes a soldier who deserts his post and is executed. "Das irdische Leben" could deal with child abuse, or the fate of unrecognized talent, but by its very nature, it should express something Mahler returns to the theme in later works, so it must have had more meaning for him than Gerhaher and Huber brought to it on this occasion. Possibly Gerhaher wasn't well as he mopped his brow a lot, which is perfectly acceptable, especially at this time of the year. But no matter how beautiful a singer's instrument might be, artistry resides in the way it is played. To paraphrase Mahler himself, "the music lies not in the notes" but in the communication of ideas.

Kindertotenlieder marks a transition in Mahler's music leading away from the world of Wunderhorn towards more conceptual horizons. In many ways, this group of songs resembles a five-movement symphony, integrated by recurring motifs of dark and light, rising to a transcendent finale, where the storm is vanquished, and the children "vom Gottes Hand bedeckt". In its own way not so very different from the redemption and transfiguration that marks works like Das Lied von der Erde. To reach this resolution, however, the poet has had to undergo extreme desolation. Friedrich Rückert knew about death and anguish. In "Wenn dein Mütterlein" , he refers to gazing, not at the mother's face, but closer to the ground, where children should be. It's detail that could probably come only from lived experience. Dignity is in order, and restraint, but emotional truth is of the essence. As Tannhäuser might have said, good singing isn't everything.

For an encore, Gerhaer and Huber offered a piano version of Urlicht from Mahler's Symphony no 2. "Der Mensch liegt in größter Pein!" .He is so rejected that even the angels want to turn him away. but that only strengthens his resolve. "Ich bin von Gott und will wieder zu Gott!". At last, Gerhaher's voice took on more colour and more definition. An excellent encore. If only the rest of the recital had been as good.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Gerhaher.png

image_description=Christian Gerhaher [Photo by Jim Rakete for SonyClassical]

product=yes

product_title= Gustav Mahler Songs:Christian Gerhaher, Gerold Huber, Wigmore Hall, London 17th December 2014 London

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Christian Gerhaher [Photo by Jim Rakete for SonyClassical]

December 19, 2014

Modernity vanquished? Verdi Un ballo in maschera, Royal Opera House, London

On the surface, this new production appears quaint and undemanding. It uses painted flats, for example, pulled back and forth across, as in toy theatre. The scenes painted on them are vaguely generic, depicting neither Boston nor Stockholm, where the tale supposedly takes place. Instead, we focus on Verdi, and on theatre practices of the past. In other words, opera as the art of illusion, not an attempt to replicate reality. Take this production too literally and you'll miss the wit and intelligence behind it.

Although the designs may seem retro, it is as conceptually radical as any minimalist "modern" production. What it demonstrates is that good opera lies not in external decoration but in creative imagination.

This Un ballo in m,aschera also works extremely well because it places full focus on the singing. The drama unfolds through a series of showpieces, providing the singers with opportunities to display their skills. It's perfect for artists like Joseph Calleja and Dmitri Hvorostovsky, both of them highly charismatic personalities. They created Riccardo and Renato as convincing characters, but, perhaps even more unusually, ctreated a powerful dynmaic between themselves as artists.The bond between them felt personal and energizing, and went far further than good singing. They seemed to be challenging each other with evident glee. One star turn after another, carried off with exuberance. Calleja's natural warmth suffused his portrayal of Riccardo, adding elements of good nature and good humour, which go a long way in overcoming the weaknesses in the plot. Calleja doesn't need to act in a naturalistic fashion: he makes you feel that under the costume beats the heart of a sturdy, ardent Maltese tenor.

This is very much a "singer's opera" so the other parts are also strongly cast. Liudmyla Monastyrska. sang Amelia, over whom Riccardo and Renato fall out. There isn't much character development for the part in the libretto, so Monastyrska fills it out with the feminine timbre of her singing. Serena Gamberoni, as Oscar, Riccardo's page, was impressive. She replaced Rosemary Joshua, who is unwell, but has put her own individual stamp on the role, When Gamberoni sings the "laughter" passages, her voice sparkles with agility and energy. Anatoli Sivko sang Samuel and Jihoon Kim sang Tom. It's interesting how little background detail the score gives about the parts, but Siv ko and Kim sang with such clear conviction that the roles had genuine conviction. They felt like parrallel versions of Renato and Riccardo. Marianne Cornetti sings Ulrica, a delicious part that must be fun to sing. .

Katharina Thoma directed Richard Strauss Ariadne auf Naxos for Glyndebourne in 2013. Read my analysis here. On a superficial level, this Un ballo in maschera and Ariadne auf Naxos might seem very different, but Thoma is far too adept to be doing a sudden change of style. Ariadne auf Naxos is a satire on the making of an opera, juxtaposing the "reality" of the players and the opera they are contracted to take part in. In Un ballo in maschera, Thoma balances the "reality" of cast and staging with the way they are used to create performance. The acting is stylised by modern standards, but that fits the meticulously archaic use of stage equipment. At one point, stagehands fold up the flats we've just been admiring: art and artifice at once.

This studied theatricality pays off brilliantly in the scene where Amelia goes to the graveyard to consult Ulrica, the soothsayer. This is a glorious bit of Gothic High Camp, with graves, urns, weeping willows and statues that come alive to dance. Verdi's libretto was an adaptation of a play by Eugene Scribe. Hence the similarity to Scribe's libretto for Meyerbeer Robert le Diable. Horror movies entertain when they're so bad, they're good. Part of the fun is the frisson of implausibility. After the performance, I bumped into someone whose taste in opera is impeccable. He was delighted: "Funny, yet not offensive". Thoma's Un ballo in maschera is a lot more subversive - and thoughtful - than meets the eye. Audiences who hate anything modern on principle will love this production, but will its subtle satire be lost on other audiences?

Anne Ozorio

image=

image_description=

product=yes

product_title= Giuseppi Verdi : Un ballo in maschera, Royal O[pera House, London

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=

December 18, 2014

A Shakespearean Songbook

By Matthew Gurewitsch [WSJ, 12 December 2014]

While he lived, the schoolmaster’s son Franz Schubert made no great splash in the world. Intimates called him Schwammerl, or Mushroom, supposedly because he was small and round. His occasional travels never took him more than 200 miles from his native Vienna. Before his death, much of his music was played only at private gatherings or not at all. Yet the catalog of symphonies, piano sonatas, chamber music and sacred works he brought forth in his brief 31 years—four years fewer than Mozart’s, 26 fewer than Beethoven’s—places him well and truly in the company of the immortals. Arguably most impressive of all is his legacy of song, inexhaustible in its Shakespearean variety, upward of 700 items, each, to the mind of Graham Johnson, “a law unto itself.”

December 15, 2014

La Traviata in Ljubljana Slovenia

After a series of directional disasters throughout the Balkans, it was refreshing to find a production which was neither ridiculous, irrelevant or doggedly self-serving. Director Lutz Hochstraate and set designer Rudolf Rischer combined to make a credible interpretation of this overly familiar opera which has certainly suffered more than its fair share of production atrocities. Huge floor to ceiling doors worked well to delineate different scenes and provide multiple entry points for soloists and chorus. Set properties were minimal and uncluttered. The use of enormous silhouettes/shadow figures on a rear scrim to represent the passing Carnival in Act III was particularly effective.

Musically things were more or less in competent hands although the small-ish pit presented certain problems, especially in the reduced string section which numbered only 16 first and second violins. Other than the opening to Aida, it is hard to think of another Verdi opera where the high strings are so exposed as in the Preludio (and later introduction to Act III) in La Traviata. The ppp markings requiring the barest whisper of a melodic line makes these measures acoustically easier in smaller houses, but the most minute flaws are cruelly apparent, and in the Slovenian National Theatre uneven string tone and intonation imprecision were evident at the outset. Czech conductor and Janaček specialist Jaroslav Kyslink maintained a brisk pace throughout, although a little more attention to fermate, rubati and a wider breadth of tempi would have been preferable. He certainly kept the reduced Verdian orchestra from overpowering the singers, but in such a small house (530 seats) one would have expected better projection from the stage.

The large corowas vocally impressive although the Italian diction should have been clearer. This could be due to the fact that many operas in Ljubljana (and all buffo repertoire) are still sung in Slovenian. Although the ensemble singing was strong, the comprimario roles were for the most part disappointing. Gastone (Rusmir Redžić); Douphol (Anton Habjan); the Marchese (Juan Vasle) and Giuseppe (Edvard Strah) sang adequately but without distinction. The Flora of Galja Gorčeva had reasonable stage presence but very poor diction. Annina was more sympathetically sung and acted by Galja Gorčeva. The most impressive of the smaller roles was the Dr. Grenvil of young Slovenian bass-baritone Rok Bavčar who in the limited amount he has to sing, displayed a warm timbre and commendable phrasing. He may have been better cast as Père Germont. This role was interpreted by Ivan Andres Arnšek who was regrettably dramatically and vocally unconvincing - perhaps too affable for one of the most hypocritical if not despicable characters Francesco Piave adapted from Dumas’ roman. His physical appearance, despite a shock of grey hair, suggested more Alfredo’s older brother and the addition of a walking stick was more a hindrance than a dramatic asset as he forgot to use it most of the time. Mr Arnšek’s voice was not disagreeable but lacked depth and resonance and his dramatic denunciation of Alfredo at the beginning of the Act II Sc. ii finale (Di sprezzo degno) had no gravitas or impact at all.

Alfredo was performed by Alijaž Farasin. While he sang the notes (except the Act II O mio rimorso cabaletta) there was something rather bland about his performance. Dei miei bollenti spiriti was about as boiling as a plate of cold bucatini. This was no passionate young man hopelessly in love with a seductive courtesan, but a rather pedestrian provincial out of his emotional depth. A slightly nasal timbre marred the ideal lyricism of the role, although he was more effective expressing rage in Act II Sc. ii Ah, comprendo! basta, basta. One certainly missed the impassioned exuberance of Rolando Villazón, Jonas Kaufmann or Joseph Calleja.

The greatest interest of the evening was the unscheduled Violetta of Russian soprano Natalia Ushakova. This is a singer who is currently singing everything from the Königin der Nacht and Manon Lescaut to Salomé. It is hard to define exactly what kind of soprano she is, which in a sense is helpful in an opera which requires at least three different kinds of voices for the lead role. Although enjoying frequent collaboration with Plácido Domingo and apparent success at La Scala with Mimi, Covent Garden with Amelia (Simon Boccanegra) and Violetta in Vienna, from this performance it is hard to understand how she has achieved such accolades. With such great interpreters of the role as Ileana Cotrubaş, Teresa Stratas, Angela Gheorghiu, Natalie Dessay and Renée Fleming still in recent memory, Violetta is a role which should not be attempted lightly. Apart from a rather irritating habit of squinting like a Smiley icon when taking high notes, Madame Ushakova’s voice is definitely uneven. While the F minor semiquavers at the beginning of Ah, fors'è lui in Act I were crisply detached as marked, the A natural at the end of addio del passato in Act III perfectly pitched without any annoying vibrato and her mezzavoce in dite alla giovine in Act II Sc.i the most moving singing of the evening, there were numerous intonation problems and awkward portamenti throughout her performance. Sheseemed to have no trill technique at all, which was especially noticeable on the Db, Ab and F’s on Ora son forte in the closing duet with Alfredo. The fioratura in the Act I Sempre libera lacked ease and elegance (definitely no Joan Sutherland) especially in the unaccompanied semiquaver ornamentation on ‘ah’ preceding the tempo change to allegro on follie, follie. Similarly, the fioratura on gioir was rushed and poorly defined. The top Db immediately before the allegro brillante change was dangerously unfocussed. It is hard to imagine this soprano coping with the high F’s in Der Hölle Rache. Although having formidable projection, the wrenching Amami, Alfredo, quant'io t'amo phrase in Act II Sc.iwas surprisinglylacking in vocal power and dramatic conviction. This Violetta’s stage presence was also a long way from that of the Alexandre Dumas’ seductive dame aux camélias. More cheerful babushka than sophisticated femme fatale, there was a contadina quality about her persona which might have appealed to the provincial in Alfredo but certainly not the worldly Baron Douphol. All in all, a rather mixed bag from Madame Ushakova. The enthusiastic audience gave the performance a very warm reception and a number of curtain calls. But Ljubljana is still a long way from La Scala.

Jonathan Sutherland

Cast and production information:

La Traviata Slovenian National Theatre Ljubljana 5th December 2014 Conductor: Jaroslav Kyzlink, Director: Lutz Hochstraate, Set design: Rudolf Rischer, Costume Design: Bettina Richter, Choreography: Ivo Kosi Violetta Valery: Natalia Ushakova, Flora: Galja Gorčeva, Annina: Dunja Spruk, Alfrredo Germont: Alijaž Farasin, George Germont: Ivan Andres Arnšek, Gaston: Rusmir Redžić, Baron Douphol: Anton Habjan, Marchese d’Obigny: Juan Vasle, Dr. Grenvil: Rok Bavčar, Giuseppe: Edvard Strah

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Alija%C5%BE%20Farasin%20%28Alfredo%29%20Natalia%20Ushakova%20%28Violetta%29%20Act%20I.png image_description=A scene from Act I of La Traviata [Photo by Darja Štravs Tisu courtesy of Slovenian National Theatre Ljubljana] product=yes product_title=La Traviata in Ljubljana Slovenia product_by=A review by Jonathan Sutherland product_id=Above: A scene from Act I of La Traviata [Photo by Darja Štravs Tisu courtesy of Slovenian National Theatre Ljubljana]Otello in Bucharest — Moor’s the pity

Known to European opera-goers for her work in Frankfurt (and also the less than triumphant Lulu in Salzburg four years ago) Madame Nemirova’s conception of Otello for Bucharest was a single idée fixe. As Sherlock Holmes might have put it: ‘The Case of the Incriminating Handkerchief’. The fazzoletto in question took on such overwhelming significance at one point during the superb concertante ensemble E un dì sul mio sorriso in Act III, the sky was literally snowing with ragged pieces of white cloth which were certainly a far cry from the fine cambric (un tessuto trapunto a fior e più sottil d’un velo) specified in the text. The ubiquitous hanky first made a surprise appearance falling from the sky during Otello’s Già nella notte densa scena making no sense of his statement to Iago in Act II that he gave it to Desdemona when they first met (il fazzoletto ch’io le diedi, pegno primo d’amor).

The single stage set design by Viorica Petrovici was a steeply raked stone-stepped ersatz piazza with two ugly metal balconies/fire escapes, metal railings and a Giacometti-esque tree at the back. It would appear that the Venetian Republic’saccounting departmentweren’t wasting any money on lavish quarters for their gubernatorial representatives. Not only was Desdemona deprived of her prie-dieu, she didn’t get a bedroom — or even a bed. The Salce salce aria in Act IV was sung à la Manon Lescaut outside among the detritus of fallen fazzoletti left over from the previous act. The staging was also a long way from 15th century Cyprus. It was possibly intended to be contemporary Lampedusa or even somewhere in Sicily as there seemed to be an abundance of persecuted Albanian refugee types mixed with the odd Mafiosi and carabinieri.

Otello was rescued from the storm in a rubber dinghy but the leone di San Marco’s entrance and triumphant Esultate! was made nowhere near the stage or dinghy but from the stage-right parterre loge with Desdemona at his side — presumably an unscripted stowaway. The rubber dinghy turns into ‘The Love Boat’ as the locus of Otello and Desdemona’s conjugal bliss at the end of Act I. It seems the Venetians, at least in warmer Cyprus, were keen on al fresco fornication. The drunken brawl between Cassio and Montano in Act I was not fought with the customary swords but with street-gang style broken bottles. Unfortunately the bottles were plastic which made Montano’s serious wounding unlikely and Otello’s imperious command to Abbasso le spade! rather hyperbolic. Caporegimento Iago’s dramatic Act II scena and aria Credo in un Dio crudel was sung sitting on the edge of the stage with his legs hanging over the orchestra pit and the house-lights turned on, presumably to indicate the veracity of his Machiavelli/mafioso mentality or perhaps to keep the audience from dozing off. This was hardly likely given the violent blasts from the brass section of the orchestra. Instead of receiving tributes of flowers from the Cypriot children in Act II ( T’offriamo il giglio, soave stel) Desdemona gives the kiddies small sheets of paper to make paper planes. The projectiles then waft through the air portending the appearance of the flying fazzoletti in the next Act. In keeping with the conceit of a Sicilian setting and cosa nostra traditions, at the end of the great Act II duet Sì, pel ciel marmoreo guiro, Otello and Iago cut themselves across the chest and then embrace to seal the deal with a blood pact of homicidal corpuscles. Perhaps confusing Otello with Pagliacci, Madame Nemirova has Otello paint black war-paint splodges and stripes on his very white face during his Act III aria Dio! mi potevi, despite the fact that Otello’s natural blackness is frequently referred to in the libretto (ho sul viso quest’atro tenebror). The end result is a rather pasty, chubby-grubby, non-descript, ineffectual individual with a kink for Goth. The important official ducal document ordering Otello’s return to Venice (una pergamena avvoltata) was a miserable scrap of paper Lodovico’s cleaning lady might have used for a laundry list. Obviously there was also no ducal seal for Otello to kiss (Io bacio il segno della Sovrana Maestà). The final soi disant coup de théâtre was during Otello’s dying moments whenIago appears in the stage-right box and turns to the audience as if rendering judgment on his successful machinations. Mephistopheles meets Simon Cowell.

Mercifully the musical side of the performance was vastly less irritating. The coro trained by 86 year old chorus master Stelian Olariu was consistently impressive, paid scrupulous attention to the dynamic markings of the score and sang with impeccable diction. Fortunately they also somehow managed to get through Act III without the blizzard of falling handkerchiefs clogging their throats. There were a few synchronization problems with the orchestra in the Act II cross rhythm ensemble with children’s choir (T’offriamo il giglio, soave stel) and later in the animando sempre poco a poco conclusion to Act III beginning with Desdemona’s ed or, l’angoscia in viso. One suspects this was more to do with poor ensemble control from the podium than choral lassitude.

Adrian Morar conducted with unspectacular dependability, although his reading tended to lack breadth and the orchestral balance was often unsatisfactory, particularly in most of the woodwind section, which seemed incapable of playing anything less than mezzo-forte. There was no organ for the ominous pedal which underpins the opening Una vela! Una vela! chorus and other instrumentation was either omitted or reduced. With a total of only 22 first and second violins, the soaring string sound which is necessary to balance the formidable orchestration for brass and percussion was generally absent. While for most of the score the flutes had the requisite dolce timbre, bassoons were almost always too loud and the cor anglais solo passages in Salce salce were jarringly intrusive (the scores indicates nothing louder than piano and more often pianissimo). There were intonation and rhythmic inconsistencies with the double basses in the long F Minor solo poco piu mosso passage preceding Otello’s entrance in Act IV although there was some particularly lyrical and sensitive cello playing during the introduction to the Già nella notte densa duet in Act I. Horns were raspy (not such a bad thing) but often made slightly imprecise and wobbly entries.

Of the principle singers Cassio, Desdemona and especially Iago, were more than satisfactory. The Cassio of Liviu Indricău had credible stage presence, a clearly focused voice in all ranges and an excellent bright ringing top. His singing of Miracolo vago dell’aspo e dell’ago in the Act II duet with Iago displayed sound legato and an attractive cantilena. Iulia Isaev as Desdemona was clearly the crowd favourite and received a standing ovation at the final curtain calls. Looking rather like Karita Mattila with blond hair and voluptuous bosom, she sang with commendable fidelity to the score and sensitivity to the exceptionally poetic libretto. Her long set piece ‘Salce salce’ in Act IV was well paced, displayed a warm legato and an ability to shape the long Verdian vocal line. The Ab at the end of the final arpeggio was a tad rushed but showed a Tebaldi-like vibrato- free top which was particularly agreeable. If there was any criticism it was a slight lack of power in the big ensembles, but there are not many Mirella Freni’s out there who can ratchet up the fortissimi to soar over massed chorus, soloists and orchestra. The Iago of Valentin Vasiliu showed complete commitment to the role, both vocally and dramatically. With a combination of the snarling marcato of Leo Nucci and the insinuating lyricism of Piero Cappuccilli, Mr Vasiliu is a first-rate baritone with strong projection and measured mezzopiano. His Italian diction was also excellent. Of the smaller roles, the Emilia of Sorana Negrea was dramatically convincing but a little under-voiced, especially in the important confrontation with Otello at the end of Act IV. The Lodovico of Marius Boloş was vocally weak and dramatically implausible as the Emissary of the Doge and Senate of Venice. His appearance in an ill-fitting tuxedo merely enforced a total lack of gravitas. It was hard to find anything to admire about the Otello of guest artist Daniel Magdal. Yes, he could certainly belt out top Gs, As and Bb’s but that was all. There was no legato technique and his phrasing, if it existed at all, was invariably clipped short. Chest and low register notes were lacking in vocus, parlando passages were perfunctory and any attempt at piano disappeared down his doublet. Unfortunately Mr Magdal’s physical appearance matched his vocal shortcomings. Instead of the utterly dominating physical stage presence one experienced with James McCracken, Jon Vickers or Plácido Domingo as the intimidating intemperate warrior, all we had was a pale, paunchy, pouting, petit-bourgeois with a leather fetish. Considering the quality of the other protagonists, this irksome production deserved a much better title-role tenor.

Jonathan Sutherland

Cast and production information:

Otello: Daniel Magdal, Iago: Valentin Vasiliu, Cassio: Liviu Indricău, Roderigo: Valentin Racoveanu, Lodovico: Marius Boloş, Montano: Iustinian Zetea, Araldo: Dan Indricău, Desdemona: Iulia Isaev, Emilia: Sorana Negrea. Romanian National Opera Bucharest 27th November 2014 Conductor: Adrian Morar, Direction: Vera Nemirova, Stage design: Viorica Petrovici, Chorus Master: Stelian Olariu, Choreography: Smaranda Morgovan.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Daniel%20Magdal%20%28Otello%29%20%20%26%20Valentin%20Vasiliu%20%28Iago%29.png image_description=Daniel Magdal as Otello and Valentin Vasiliu as Iago [Photo by Gin Photo courtesy of the Romanian National Opera Bucharest] product=yes product_title=Otello in Bucharest — Moor’s the pity product_by=A review by Jonathan Sutherland product_id=Above: Daniel Magdal as Otello and Valentin Vasiliu as IagoPhotos by Gin Photo courtesy of the Romanian National Opera Bucharest

Il trovatore at Lyric Opera of Chicago

The title character Manrico is sung by Yonghoon Lee, his beloved Leonora by Amber Wagner. Mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe takes the role of the gypsy Azucena, mother of the troubadour Manrico, while baritone Quinn Kelsey sings the Conte di Luna. Ferrando, in the service of the Count, is performed by bass Andrea Silvestrelli. The Lyric Opera Orchestra is conducted by Ascher Fisch and the Chorus is prepared by Michael Black. In charge of both directing the revival and the choreography is Leah Hausmann.

It is the words of Ferrando with which the action commences, as he cries out

“All’erta, all’erta!” [“Look sharp!”] to his assembled men while encouraging them to remain attentive at the night-watch. The current Conte remains near the house of his beloved Leonora at times throughout the night. Mr. Silvestrelli’s rising pitch on “Trovador” underscores a serious rivalry between the troubadour and the Count, since both men hope to secure the affections of Leonora. In his performance of “Abbitta zingara” [“a despicable gypsy crone”] Silvestrelli narrates the background of the elder Conte di Luna’s misfortunes with a captivating sense of musical line. The rapid, tripping notes of this aria were produced with clarity and decorative touches, so that the entire vocal line was vividly audible. In the second part of his aria Silvestrelli warns the collected men-at-arms with a lighter tone and even greater flexibility in the runs and trills. Establishing dramatic parallels at “al inferno” [“to hell”], the men of the Lyric Opera Chorus join in the wish to see the old gypsy’s daughter Azucena condemned to burn just as her mother.

Quinn Kelsey

Quinn Kelsey

After this exciting opening scene Leonora’s entrance communicates an emotional state with softer yet equally moving vocal gestures. Ms. Wagner as Leonora emerges to look into the nocturnal garden, during a scene where she is accompanied by her attendant Inez, sung in this production by mezzo-soprano J’nai Bridges. Wagner’s conception of “Tacea la notte” [“The serene night was silent”] shows a mature approach to the scene and following cabaletta, in which vocal decoration enhances the urgency of her character’s emotions. When she describes to Inez the first meeting with her unidentified admirer, Wagner declaims “al vincitor” [“onto the victor”] with a pure, rising pitch to recall the recipient of the crown after a recent tournament. At the same time, in her aria Wagner’s binding of individual verses creates a smooth yet growing intensity. Exciting top notes are combined with an effective slide toward the close of the piece. Ms. Bridges acts as an ideal foil to her mistress with deeply moving low notes in her appeal to reject the continued appearances of the mysterious troubadour. Wagner’s performance of the cabaletta “Di tale amor” [“With such love”], in which she rebuffs Inez’s appeal, shows a solid command of range with middle and low pitches being used impressively.

In the following three scenes of the first act the two male principals establish their vocal and dramatic presence. Mr. Kelsey’s Conte, at first alone in the garden, trembles with positive anticipation in the hope of glimpsing Leonora. The Conte’s manner is transformed into rage when he recognizes the voice of the troubadour Manrico. Kelsey’s shift in vocal color and intonation illuminates the text as well as his character’s volatile personality. His tender words “l’amorosa fiamma” [“flame of love”] disappear believably into the rage of “Io tremo” [“I seethe”] and “O gelosia!” [“Ah, jealousy!”], when Manrico’s song is heard. Kelsey’s physical involvement underlines his masterful projection of contradictory emotions when he encounters Leonora in the moonlit scene. Mr. Lee settled into Manrico’s serenade from offstage after several pinched forte notes. His entrance is greeted, of course, with relief by Leonora and even greater rage by the Conte. During the ensuing trio, before an expected sword fight concludes the act, all three principals sing with exciting commitment. Kelsey stands out especially for his vocal embellishments as a further expression of fury. Concerning the production, some of the dramatic blocking at this point could be adjusted in order to render the stage action even more credible.

Quin Kelsey, Yonghoon Lee and Amber Wagner

Quin Kelsey, Yonghoon Lee and Amber Wagner

In the second act as here depicted the Anvil Chorus is a gritty, muscular assembly of workers. In Azucena’s extended aria and soliloquy “Stride la vampa!” [“The flame crackles!”] Ms. Blythe relates the burning of her mother at times with dramatic high pitches, at others with piano tenderness. Blythe inhabits the role of Azucena completely as she narrates her own determination to avenge the execution of her mother. Cries, laughter, and lyrical melodies as well as outbursts are combined into a seamless evocation of the gypsy’s persona. When she sings here together with Lee’s Manrico, Blythe maintains her line of character while also issuing warnings and urgent appeals for her son’s safety. In the concluding scene of Act Two Manrico has left the gypsy camp, despite Azucena’s council, in order to engage in battle and to prevent Leonora from entering a convent. The Conte arrives simultaneously at the convent with the intention of abducting his beloved. As he waits in the company of Ferrando outside the convent the Conte sings “Il balen del suo sorriso” [“The flashing of her smile”], reflecting on his continued infatuation with Leonora. The showpiece aria for baritone is precisely that in Kelsey’s performance: diction is superbly maintained so that individual elements are clearly audible while also yielding to interpretive emphasis. The “stella” [“star”], with which his beloved compares, is intoned with a poignant top note, lines incorporating decoration or trills are sung with lightness to balance the emotional involvement. Toward the close, Kelsey’s rendition of “tempesta” truly reflects the storm that rages in the heart of the Conte. Manrico’s appearance to save Leonora from abduction is swift and here deftly staged. As the heroine is whisked off by the troubadour, Wagner’s final note expresses the shock and elation at being saved, at least for the interim.

The brief third act shows Lee’s Manrico, in his first aria, to his best. In his song to Leonora, “Ah sì, ben mio” [“Ah yes, my love”] Lee controls volume and stays evenly on pitch while incorporating the embellishments and piano lines that make this aria into a true song of love. Once he hears that Azucena is imprisoned and awaits execution, Lee standing amidst the supporting chorus sings the famous “Di quella pira” [“Of that pyre”]. Here Lee’s high notes were fully in place, yet his middle and lower registers were ineffectively veiled.

In Act Four Leonora is called upon to express her character’s resolve in a series of arias and ensembles. In the first of these, “D’amor sull’ali rosee” [“On the rose-colored wings of love”], Leonora sings of her attempts to console and to free Manrico who has been imprisoned by the Conte. Wagner’s approach to this aria is very well executed, her descents to low pitches emerging as naturally as the requisite trills and top notes. The subsequent duet during which Leonora offers herself to the Conte while attempting to free Manrico [“Mira di acerbe lagrime” [“O look, of bitter tears”] is performed by Wagner and Kelsey with a number of bel canto touches in a further exchange of contradictory emotions.

The final duet between Azucena and Manrico shows Lee comforting Blythe’s gypsy in a touching scene before the violent conclusion of the opera. Lee sings here with assured legato to dispel his mother’s fears of the pyre. As a pendant to this scene between mother and son, the final dramatic outburst revealing the fraternal relationship of Manrico and the Conte becomes all the more shocking.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/02_Stephanie_Blythe_TROVATORE_DSC_3098_cMichael_Brosilow.png

image_description=Stephanie Blythe [Photo by Michael Brosilow]

product=yes

product_title=Il trovatore at Lyric Opera of Chicago

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=Above: Stephanie Blythe

Photos by Michael Brosilow

Schubert’s Winterreise by Matthias Goerne

While there is little of the angst-ridden word-painting of Ian Bostridge, there is an unwavering attention to the meaning and expressive qualities of the text — as one might expect from a native speaker — and some surprising heightening and emphasis at times. Similarly, while Goerne does not adopt the sustained, penetrating intensity of a singer such as Mark Padmore, there is a growing sense of urgency which is all the more compelling because of the contrast created between the swift opening and the increasing violence of the final songs.

Goerne and his pianist, Christoph Eschenbach, are not melodramatic, but they are direct. Eschenbach plays with flexibility and responsiveness; the accompaniment is prominent, an equal partner on this journey through the austere winter landscape. And, however troubled the melancholy traveller becomes, the beauty of Goerne’s tone is never marred; the beguilingly sweet tone lures us into the bleak land, and we join the wanderer’s mesmerising descent into terror and isolation.

‘Gute Nacht’ begins purposefully, with a surprisingly brisk tread; Goerne’s voice is full of rich colours and the prominent piano accents in the ‘between-phrase’ motifs convey animation. But, with the shift to the major tonality at ‘Will dich im Traum nicht stören,/ Wär’ Schad’ um deine Ruh’ (I will not disturb you as you dream, It would be a shame to spoil your rest) there is a sudden withdrawal and wistfulness, an indication of the wide dramatic range and vocal control which will characterise the whole cycle. Typical too is the subtlety of Eschenbach’s response to the text, as the accompaniment to each stanza paints a slightly different hue.

A forceful and assertive ‘Die Wetterfahne’ follows, full of striking dramatic contrasts: crisp piano motifs convey the anger of the wind, but there is quiet introspection with the line, ‘Der Wind spielt drinnen mit den Herzen,/ Wie auf dem Dach, nur nicht so laut’ (Inside the wind is playing with hearts, As on the roof, only less loudly), before a tempestuous close. Eschenbach’s sensitivity gives expressive nuance to the piano introduction of ‘Gefrorne Tränen’ and in this song Goerne’s voice wells with directness and vulnerability: ‘Ob es mir denn entgangen,/ Daß ich geweinet hab?’ (Have I, then, not noticed That I have been weeping?). The ardency and focused tone powerfully evoke the passionate heat of his tears, that would melt ‘All the ice of winter’.

‘Der Lindenbaum’ is one of the highlights of the first part of the cycle and epitomises the performers’ intelligent musicianship. The opening is theatrical, the crescendo and culminating quaver chords quite brutal; the effect is to infer the realms of emotion that lay beneath the contained lyricism of the baritone’s beautiful utterance. Here Goerne colours the words wonderfully, heightening the rise to ‘ihm’ in the line ‘Es zog in Freud’ und Leide Zu ihm mich immer fort’ (In joy and sorrow I was ever drawn to it), and effecting a tender transition to the major mode, his tone full and earnest as the branches rustle and beckon: ‘Come to me, friend, Here you will find rest.’ But, there is movement as the chilling wind sweeps on, and the piano triplet semiquavers are unrelenting and cold. A telling diminuendo and pause precede the voice’s entry for the final stanza and there is a sudden and powerful sense of lassitude: ‘Nun bin ich manche Stunde Entfernt von jenem Ort,/ Und immer hör’ ich’s rauschen: Du fändest Ruhe dort!’ (Now I am many hours’ journey from that place; yet I still hear the rustling: ‘There you would find rest.’). Goerne’s rising fourth in the repeated last phrase is laden with weariness.

‘Wasserflut’ marks a tightening of the emotional screw, the tension between the voice’s triplets and the piano’s dotted rhythms creating a dragging sense of labouring onwards, as the singer’s tears fall in the snow. Goerne’s baritone burns with ferocity as the ice breaks into pieces: ‘Und das Eis zerspringt in Schollen,/ Und der weiche Schnee zerrinnt.’ And, in the second stanza his pushes so far that he almost loses control of the intonation. Now we understand the depths of the wanderer’s unrest. The mental schism widens in the succeeding songs, conveyed by gestures such as the pause before the final verse of ‘Auf dem Flusse’, before the voice surges forward in a desperate bid to restore the singer’s sense of self: ‘Mein Herz, in diesem Bache/ Erkennst du nun dein Bild? (My heart, do you now recognize/Your image in this brook?).

Eschenbach remains an attentive partner. In ‘Ruckblick’ the troubling juxtaposition of fire and ice in the text prickles in the oscillating triplet semiquavers of the piano introduction; and in ‘Irrlicht’ the piano’s triplet motif is surprisingly hard and insistent, its repeated note followed by an accusing rise. In contrast, Goerne’s sixth and octave leaps are beautifully mellifluous, the richly decorative melody suave and lyrical. The final stanza is strikingly assertive but drifts into pensiveness at the close.

The dynamic and expressive contrasts of ‘Rast’ are so great that we begin to fear for soul and mind of protagonist; might we too be sucked into his darkness. The folksiness of ‘Frühlingstraum’ is bitter-sweet and the song is never allowed to settle, the schnell episode rushing forward with restlessness and haste: such contrasts between wistfulness and pain are disturbing, and the Eschenbach’s final broken arpeggio is full of poignancy.

Goerne’s forceful repeating cry, ‘Mein Herz’, in ‘Die Post’ rings out above Eschenbach’s light- of-foot gallop, but the vigour of this song dissipates in the ensuing ‘Der greise Kopf’. The very slow tempo intensifies the morose pessimism of the text and establishes a mood of disillusionment and exhaustion, of body and soul, which is perfectly captured in Goerne’s lyrical falling phrases, with their almost painfully lovely mordants. The wanderer stares at the road ahead, and at the vista of his own life, and the immensity of blackness before him is powerfully portrayed by the piano’s whispered final phrase which sinks gracefully into silent pathos. Eschenbach’s crisp off-beat semiquavers in ‘Die Krähe’, high above the baritone, evoke the predatory crow, etched in the sky, circling slowly, while the rhythmic imbalances of ‘Letzte Hoffnung’ further restrain the forward momentum. Goerne suggests the faltering of the wanderer, both literal and metaphysical, as he stretches the pulse, even though the vocal line is smooth and unbroken. There is tension at the top of the challenging closing phrase, ‘Wein’ auf meiner Hoffnung Grab’ (And weep on the grave of my hopes), but never strain.

As we move through the final songs Goerne’s baritone becomes fuller and the range of expression broadens. ‘Täuschung’ conveys dreamy preoccupation but the comforts of delusion are swiftly erased in ‘Der Wegweiser’ where Goerne’s monotone is solemn and morose, mimicked by the deathly tread of the accompaniment with its eerie chromatic bass line. The low repetitions of the final stanza, ‘Einen Weiser seh’ ich stehen’ (I see a signpost standing) are ominous.

In ‘Das Wirthaus’, the traveller stops beside a graveyard and longs for rest but, turned away from the tavern, is forced to go onwards. Goerne and Eschenbach adopt what some may find an excessively slow tempo, but it does establish a funereal lethargy; it is dignity rather than irony that is brought to the fore here, and the piano’s full chords take on an ecclesiastical colour, fading gently at the close. After the angry defiance of ‘Mut!’, ‘Die Nebensonnen’ is almost unearthly in its still beauty: again the tempo is very slow and Goerne’s narrow melody circles as if entranced. The human presence of the hurdy-gurdy man in ‘Der Leiermann’ brings no consolation; the quiet phrases are drained of emotion, yet powerfully suggestive of resignation borne of despair.

The tone of the ending is desolate but powerful: Romantic Sehnsucht has been translated into a very modern disorientation and loneliness.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Matthias%20Goerne%20and%20Christoph%20Eschenbach%20-%20Schubert%20Winterreise%20D%20911%20-%20Artwork.png image_description=Harmonia Mundi HMC902107 [CD] product=yes product_title=Schubert: Winterreise D.911 product_by=Matthias Goerne, baritone; Christoph Eschenbach, piano. product_id=Harmonia Mundi HMC902107 [CD] price=$14.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=1529073December 13, 2014

daggers are a thane’s best friend

By John Yohalem [Parterre Box, 12 December 2014]

A Birnam Wood of Macbeths and Ladys has come traipsing through New York this year. Dell’ Arte Opera staged Verdi’s early masterpiece last Summer, and the Met revived its grandiose production of the work back in the Fall. The Met followed that up with a splendid revival of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. And now the Manhattan School of Music’s Opera Theater program (through Sunday) is giving performances of Ernest Bloch’s opera of the same (only to be whispered) name.

December 11, 2014

Mary, Queen of Heaven, Wigmore Hall

In the late-medieval period, Christian thinking centred on the belief that the surest route to eternal peace was through the agency of the Blessed Virgin. Choral music repeatedly invoked her aid; in the Eton Choirbook she is frequently beseeched and, indeed, Eton College had been founded by Henry VI in 1440 as ‘The King’s College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor’. Yet, Tudor dynastic politics was never wholly absent from either the religious or cultural life of the age, as The Cardinall’s Musick under the direction of Andrew Carwood intriguingly revealed.

Fayrfax was one of the most pre-eminent English musicians of the early-sixteenth century, holding many important positions during the kingship of Henry VII and the early reign of Henry VIII. A member of the Chapel Royal, he accompanied Henry VIII to the Field of Cloth of Gold in 1520. Subsequently, his talents have perhaps been undervalued: he has been seen as a musical ‘conservative’, emulating the style and methods of Dunstable at a time when Flemish musicians such as Josquin de Près were experimenting with new complex polyphonic techniques.

Fayrfax’s Mass, O quam glorifica, is one of most complex masses of the period, and the Gloria opened the evening’s performance. The mass was probably written as part of Fayrfax’s doctorate submission to the University of Cambridge c.1502, and was thus designed to show off the Fayrfax’s technical skill and musical invention — as well as his mastery of the perceived intellectual foundations of the art of composition, such as the mathematical patterns which underpin the formal structure and metrical arrangements.

The ten singers of The Cardinall’s Musick gave a polished and purposeful account, Fayrfax’s fluent note-against-note counterpoint and conjunct melodies, with only occasional dissonance, resulting in a mellifluous mass of sound. Great dignity was evoked, and interest generated, by the perpetual re-voicings and re-positionings of Fayrfax’s expansive chords of full harmony. Moreover, just as the textural patterns were handled very expressively, so the metrical complications — the mixed meters, irregular phrase lengths and complex syncopations — were pointedly and judiciously articulated.

Interestingly, The Cardinall’s Musick presented not a perfectly blended sound but one in which individual voices retained their distinct timbre and character; such individualism is perhaps at odds with the contemporary ‘spirit’ of the age, but it is an approach which — complemented by Carwood’s subtle changes of tempo and slight rubatos — nevertheless helped to highlight and shape the points of imitation, and it brought animation and colour to the textures.

Fayrfax’s beautiful melodic writing was noteworthy in the simple motet Ave lumen gratiae (Hail light of grace), a litany of praise in which each line begins with the uplifting address, ‘Ave’. But, it was the five-part motet, Eterne laudis lilium, which brought the full vocal voices together for the concluding work of the programme, which most was most compelling and also most strange. After a hymn of praise to the Blessed Virgin, there follows a genealogy of the Holy Family, tracing the female lineage from Mary to St. Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist. The two sections announcing the list of names, pairing the tenor first with the treble and then with the bass, were excitedly swept aside by imitative entries for all five voices when ‘Elizabeth’ was announced. Records show that on 28 March 1502, Fayrfax received twenty shillings from Elizabeth of York, the consort of Henry VII and mother of Henry VIII, for setting ‘an anthem of oure Lady and St Elizabeth’. Clearly this motet was intended as a tribute to Queen Elizabeth of York who was mortally ill at the of the work’s composition — indeed, the first letter of each line forms an acrostic reading ELISABETH REGINA ANGLIE — and here the repetitions of the Queen’s name were finely and expressively sung.