January 29, 2015

Katia Kabanova in Toulon

It is true that the Káťa Kabanová libretto is closer to The Makropoulos Affair and From the House of the Dead, sharing the brittle dramatic structures of these works and revealing the growing selfishness and emotional pessimism of the sixty-seven year old composer. But musically Káťa Kabanová seems spoken in the same voice that sings the emotional idealism of Jenůfa. Herein lies the challenge of producing Káťa Kabanová — it must hover between hope and hopelessness.

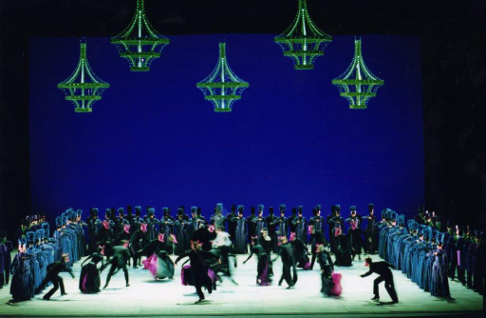

The Opéra de Toulon has just now presented this Janáček masterwork for the first time ever. It is a new production shared with the Opéra d’Avignon, thoughtfully and carefully directed by Nadine Duffaut. The set is by Emmanuelle Favre, a designer often utilized in the south of France, notably Orange, Marseille and Toulouse. Mme. Favre works in bold strokes, in big shapes and with few colors. Her décors are impressive, expressive and beautiful. As is the set for Káťa Kabanová.

Set design by Emmanuelle Favre, costume design by Danièle Barraud

Set design by Emmanuelle Favre, costume design by Danièle Barraud

The stage was a huge white box, a full stage platform with period furniture on it hovered high above the stage floor, descending to create an interior or to provide shelter from the storm. The side walls were mirrorized making occasional flashes of the brightly colored costumes, like the sonic flashes of Janáček’s nervous orchestra. The Volga was a pool of real water, its splashes the visual echos of nerves on edge.

Family and business are the crushing forces in Káťa Kabanová. They are embodied in this suspended platform, and in the very presence of Kabanicha, the mother of Katia’s husband, sung by mezzo-soprano Marie-Ange Todorovitch. Mme. Todorovitch too is often on the stages in the south of France. She is a force of nature, her voice powerful, her presence riveting. Director Duffaut ended the opera with la Todorovitch standing front and center, triumphant in five intense beams of white light.

Sébastien Lemoine as Kouliguine, Christina Carvin as Katia

Sébastien Lemoine as Kouliguine, Christina Carvin as Katia

The drowned Katia lies behind her. Portraying Katia is a vocal and dramatic tour de force, riding the cusp at all times between hope and despair. Franco-allemande soprano Christina Carvin possesses the idea colors — the slavic warmth of tone, a maturity of tone that forebodes, and a freshness of sound that breathes life. Mlle. Carvin made a powerful Katia. This young artist now sings regularly at the Vienna Staatsoper.

Katia’s young lover Boris was sung by Czech tenor Ladislav Elgr with sufficient vocal prowess to indulge in the manic love fantasies of Katia, but never to allow his character to lose its sense of defeat. In the beautifully directed scene when Katia publicly admits her infidelity he hovered in the background, then fled, and after his final moments with Katia near the end of the opera he simply evaporated.

The complementing personalities of Janáček’s slavic world, named below, were perfectly cast, notably Icelandic tenor Elmar Gilbertsson who sang Kudriach, some of it while riding the obligatory Jenůfa bicycle, and some of it skipping stones across the pool of water.

If this fine effort by the Opéra de Toulon did not create the full impact of Janacek’s brief opera it came close. While the tempos effected by Australian conductor Alexander Briger seemed appropriate and easily managed by the singers, the sounds coming from the pit sometimes seemed labored. It was apparent that the maestro was working closely with the orchestra but even so the boil of Janáček’s orchestral continuum did not always take flight.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Katia: Christina Carvin; Boris: Ladislav Elgr; Kabanicha: Marie-Ange Todorovitch; Dikoy: Mikhail Kolelishvili; Tichon: Zwetan Michailov; Varvara: Valentine Lemercier; Kudriach: Elmar Gilbertsson; Kouliguine: Sébastien Lemoine; Glasa: Caroline Meng. Chorus and orchestra of the Opéra de Toulon. Conductor: Alexander Briger; Mise en scène: Nadine Duffaut; Décors: Emmanuelle Favre; Costumes: Danièle Barraud; Lumières: Jacques Chatelet. Opéra de Toulon, March 27, 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kabanova_Toulon1.png

product=yes

product_title=Kat'a Kabanova in Toulon

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: (left to right) Mikhail Kolelishvili as Dikoï, Ange-Marie Todorovitch as Kabanicha, Christina Carvin as Katia, Ladislav Elgr (behind) as Boris, Zwetan Michailov as Tikhon [all photos copyright Frédéric Stéphan, courtesy of the Opéra de Toulon]

Peter Grimes in Nice

A new production of Peter Grimes is always news, in fact any production of this first Britten operatic masterpiece beckons travel from afar. Nice Opera artistic director (since 2012) Marc Adam was the metteur en scène for this new production for which he has collaborated with born-in-Algiers, raised-in-Nice, Juilliard School trained conductor Bruno Ferrandis. Mr. Adam previously collaborated with Mo. Ferrandis for a Wozzeck (Gurlitt) at the Opera de Rouen in 1997.

Much of Bruno Ferrandis’s career has transpired in Canada and the U.S. He is currently the music director of the Santa Rosa (California) Symphony.

Mr. Adam assembled an excellent cast. English tenor Johyn Graham Hall as Peter Grimes possesses an appropriate voice for Britten heros, not the dramatic tenor often associated with Grimes, but the lighter, character voice that characterizes the Aschenbach of Death in Venice, another of Mr. Hall’s Britten roles. Mr. Hall has an affecting presence and the vocal stamina to have seen the role through this production’s expressionist requirements.

Fabienne Jost as Ellen (left lower corner)

Fabienne Jost as Ellen (left lower corner)

French soprano Fabienne Jost sang Ellen. An ensemble singer at the Berne Opera and previously at German theaters, she offered a purity of voice and a musicality supported by fine technique that made this Ellen very pleasurable, in fact memorable.

Swallow was effectively portrayed by Marseille born, veteran bass-baritone André Cognet. French baritone Vincent Le Texier did not find the humanity of, or any softness for Balstrode, often barking his lines rather than singing. We were left unfulfilled by his character. Among the well cast smaller roles Marseille born tenor Edward Mout was especially effective as Bob Boles, all these rustic characters linguistically colored by carefully produced English sounds.

Among the more effective moments of the production were the black and white projections on the scrim covered proscenium that occurred during Peter Grimes’ famous orchestral sea interludes (of course Britten purists would have preferred no visual distraction from the sounds of these magnificent pieces). At times the images were the boiling sea, as well there were affective moments when the costumed actors were seen in pantomime through the foggy images. Puzzling however was the ascent to Grime’s cottage, rendered in images of industrial steel construction (the back side of the semicircular set unit was Grimes' hut).

Set design was entrusted to Roy Spahn who works primarily in German theaters. It was a strange semicircular multi-level abstraction of windows placed on a revolving stage. Installation of the revolving stage evidently necessitated a raised stage platform (about 60 cm [2‘] high) that was faced with incongruous black and white squares that looked a bit like Halloween decorations. The floor of the stage was not visible from the seats in the orchestra.

A further complication of the raised platform was the necessity to raise the conductor’s podium to give him view of the stage. This seemed to separate the maestro from his orchestra with the resulting impression that the orchestra was at adrift and rudderless, eviscerating the complex, ambiguous, sensual, cruel, tender, passive musico-dramatic world that is genius of Benjamin Britten. From time to time the maestro did take his eyes off the stage and engage the orchestra. These moments supplied brief impressions that the Orchestre Philharmonique de Nice was capable of creating the magic of the Britten score when asked.

It was perhaps an artistic choice of the director and conductor to strip the opera of its colors, moods and ambiguities, and focus the drama on the words and outward behavior of its actors. While this did create a theatrical atmosphere, often of great intensity, it stripped the opera of its emotional focus, rendering its protagonist as mentally unbalanced rather than as a complex human character adrift in a threatening natural world and outside an alien and uncomprehending human world.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Peter Grimes: John Graham Hall; Ellen Orford: Fabienne Jost; Balstrode: Vincent Le Texier; Tantine: Manuela Bress; Première nièce: Hélène Le Corre; Deuxième nièce; Anne Ellersiek; Bob Boles: Edward Mout; Swallow: André Cognet; Mrs Sedley: Sophie Fournier; Le recteur: Frédéric Diquero; Ned Keene: Bernard Imbert; Hobson: Thomas Dear. Orchestre Philharmonique de Nice; Choeur de l’Opéra de Nice. Conductor: Bruno Ferrandis; Mise en scène: Marc Adam; Décors: Roy Spahn; Costumes: Pierre Albert; Lumières: Hervé Gary; Chorégraphie: Pascale Chevreton. Opéra de Nice, January 24, 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Grimes_Nice1.png

product=yes

product_title=Peter Grimes in Nice

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: André Cognet as Swallow, John Graham Hall as Peter Grimes [all photos copyright Dominique Jaussein, courtesy of the Opéra de Nice]

January 27, 2015

A Definitive New Callas

By Michael Shae [The New York Review of Books, 24 January 2015]

Maria Callas converted me to opera. I am sure I am not unique in this, except in the particulars. In my early college years I immersed myself in recordings of the nineteenth-century symphonic repertory—Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Bruckner, the Russians—but for a long time I refused to listen to opera, would listen to an overture and then rush to change the record before the singing started. Then one day my roommate put Callas’s 1953 Tosca on the turntable and dropped the needle onto “Vissi d’arte.” I had no idea what she was singing, but near the conclusion of that imploring aria, as she comes to the end of the arching wordless phrase that soars from an A down slightly to a G, there is an audible intake of breath. She gasps—or is it a sob?

Guillaume Tell in Monaco

There was the usual automotive hardware in front of Monte-Carlo’s magical opera house. The peasants were all on the stage of the Salle Garnier, an embarrassment of riches, most notably Nicola Alaimo as Guillaume Tell and Celso Abelo as the lovesick Arnoldo. In fact the entire cast beginning with Mekeldi Atxalandabso as Reudi whose hymn to Swizerland “Accour dans ma nacelle” that opens the opera upheld the high level of singing that defined the evening, Basque tenor Atxalandabaso’s warm and easy high “c”’s only the first of the many vocal pleasures of the evening.

Music director of the Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte-Carlo Gianluca Gelmetti presided over his orchestra for this occasion, an opera he conducted twenty-years ago (1995) at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro to enormous critical acclaim. Much has transpired in his career since 1995. He is now famous for the Italian post-Romantic repertory perhaps explaining the massive sonic scope he found in the Rossini score for the Salle Garnier, and the warmth of tone he infused into the orchestral sound firmly persuading us that Guillaume Tell was a new, sentimental Rossini, and a unique Rossini — it is the last of the Rossini operatic oeuvres.

Before all else Rossini’s Guillaume Tell is French grand opéra as its extended dramatic recitatives attest, though Rossini could not keep himself from breaking into some coloratura from time to time, a lapse effortlessly and beautifully absorbed into the musical flow by the maestro. Rossini discovered the pleasures of the rich French low mezzo-soprano voice in Hedwedge, the wife of Guillaume, dissolving this voice into a sublime trio with Guillaume’s soprano son, Jemmy and Mathilde, his savior, with its intricacies rendered by the maestro in rich delicacy. Though Gelmetti had already pummeled us with the fiery Rossini we know so well when Guillaume and Walter Furst shamed Arnold into fighting for his fatherland.

Nicola Alaimo as Guillaume Tell, Nicholas Cavallier as Walter Furst, Celso Abelo as Arnold.

Nicola Alaimo as Guillaume Tell, Nicholas Cavallier as Walter Furst, Celso Abelo as Arnold.

There was the spectacle of typical grand opéra, the maestro endowing the classic Rossini storm with truly terrifying proportions (even though it was the same storm we know from the Roman comedies). And there were the magnificent complexities of the Rossini ensembles we know from the later Naples tragedies, the defiance of the peasants to the strength of the Hapsburgs magnified by Gelmetti in the repeating brass motifs in the orchestra, each time louder until it could not become louder. But it did, shattering the acoustic of the Salle Garnier.

At last Rossini resolved the opera’s conflicts into a huge, uncharacteristically pastoral ensemble evoking the beautiful cello elegy of the overture with its singing oboe echoed by flute — the majestic serenity of the Alps’ mountain valleys restored. But only for a short while, the peasants finally rushed forward shouting “liberté, liberté!” as loud as they possibly could.

One could not help recalling that it was in 1910 when the Monegasque Revolution forced the prince of Monaco, until then an absolute ruler, to proclaim a constitution.

What we missed in Monaco were the ballets, an economy that saved us one and one half hours of time, compacting the above musical riches of the opera into a brief three hours twenty minutes. Other less obvious economies took their toll as well, rendering the storytelling sometimes oblique and other times incomprehensible. The adage that the full ballets are integral to the dramatic integrity of Guillaume Tell was again proven in Monaco.

Décors by Eric Chevalier, Costumes by Françoise Raybaud

Décors by Eric Chevalier, Costumes by Françoise Raybaud

Monaco-born Jean-Louis Grinda, the metteur en scène (and general director of Opéra Monte-Carlo) knows that the complex musico-dramatic structures of the Rossini tragedies resonate in abstract formulae, either conceptual (like the museum dioramas of the 2013 Pesaro production) or in the physical architecture of the set itself. In this new production Grinda’s designer, Eric Chevalier, evokes the Helvetic mountainous setting in hazy images projected onto an imprisoning box structure of small repeating panels that open and close, the back wall of which disappeared into the brilliant dawn-of-freedom light. Costumer Françoise Raybaud provided threatening teutonic patterns of the late nineteenth century for the Hapsburg characters.

Movement for the chorus action was in purely geometric terms — lines and circles. Images were few, simple and powerful. Guillaume Tell himself pulled a plow, like a beast, across the stage during the opening chorus (a shocking and confusing image), there were two dance pantomime sequences in which a ballerina and a ballerino were attached to one another in a kiss (like two animals stuck together in the mating act — another shocking and confusing image) — choreography by Eugénie Andrin. Arias and duets were delivered standing front and center, as in concert format. Grinda provided a basic context and basic movements for the opera, but did little to illuminate the story evidently relying on the genius of Rossini and the brilliance of the performances to fire the evening.

And that they did.

Italian baritone Nicola Alaimo is a gigantic figure, appropriate to a mythic hero of William Tell proportion. His voice and presence are warm, powerful and encompassing, in short he is a convincing Guillaume Tell. His antagonist Gessler, the Hapsburg governor, was sung by French bass Nicholas Courjal in threatening, black toned vocal color, with a vividly present figure. Spanish tenor Celso Abelo as the fickle tenor Arnold had high “c”’s to spare, squarely hit and held rather then finding place in the musical flow. Just when you thought no human could have the stamina to hit another, he hit the final one of his showpiece aria and held it forever. Mr. Abelo is an accomplished Rossini performer.

Annick Massis as Mathilde, Élodie Méchain as Hedwidge

Annick Massis as Mathilde, Élodie Méchain as Hedwidge

French soprano Annick Massis was Mathilde, a role that only sometimes requires the Isabella Colbran dramatic coloratura model of Rossini tragedies. Mlle. Massis indeed well held the stage as Hapsburg aristocracy, riding crop in hand, though her showpiece arias were powerful her coloratura was not convincing and her high notes were of a spread tone that defied identifying any one individual note. French contralto Elodie Méchain sang Guillaume Tell’s wife Hedwidge to absolute perfection, and Russian soprano Julia Novakova as his son Jemmy provided the appropriate upper edge to the ensemble textures.

The only disappointment of the evening was the staging (lack of) for the arrow and apple.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Guillaume Tell: Nicola Alaimo; Hedwige: Elodie Méchain; Jemmy: Julia Novikova; Arnold: Celso Albelo; Melchtal: Patrick Bolleire; Walter Furst: Nicolas Cavallier; Gessler: Nicolas Courjal; Mathilde: Annick Massis; Rodolphe: Alain Gabriel; Leuthold: Philippe Ermelier; Reudi; Mikeldi Atxalandabaso. Chorus of the Opéra de Monte-Carlo. Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte-Carlo. Direction musicale: Gianluigi Gelmetti; Mise en scène: Jean-Louis Grinda; Décors: Éric Chevalier; Costumes: Françoise Raybaud; Lumières: Laurent Castaingt; Chorégraphie: Eugénie Andrin. Salle Garnier, Monte-Carlo, January 25, 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tell_Monaco1.png

product=yes

product_title=Guillaume Tell in Monte-Carlo

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Nicola Adaimo as Guillaume Tell, Celso Abelo as Arnold [All photos copyright Opéra de Monte-Carlo]

January 26, 2015

alt folks at home

By John Yohalem [Parterre Box, 25 January 2015]

Operamission, a scrappy little company that performs music from all sorts of eras and styles in venues all over town, is in fact its Kapellmeisterin, Jennifer Peterson. Her latest brainstorm was to give A Countertenor Cabaret, starring no fewer than 14 of these once-rare songbirds, in the cabaret space of the Duplex on Sheridan Square, and to live-stream the entire event, with translations of the remarkably varied musical fare.

LA Opera Presents Figaro 90210

The updating was only evident in the text. None of the music was changed, although Los Angeles Opera cut a good bit of it for the performances at the Barnsdall Gallery Theatre. On opening night, January 16, 2015, stage director Melissa Crespo told the story of undocumented workers in today’s California caught in the same situations that librettist DaPonte and author Caron de Beaumarchais wrote about over 200 years before. Just as in the original, the servant who had to be clever in order to keep his job also learned how to outwit his master.

In the Guerrerio version, Count and Countess Almaviva became the wealthy Mr. and Mrs. Conti. As a child, Figaro was found in a Rosarito bar wearing a Dodgers cap inscribed with the words Baby America. Thus, he insisted that American parents left him there. Susana was an undocumented worker from Mexico whom Mr. Conti threatened with deportation if she did not sleep with him. The most interesting character was the youngster that Guerrerio created to replace Cherubino: Bernard Curson, known as hip-hop artist Lil' B-Man. This scruffy teenager was in love with every woman on the property while singing Mozart, but with Bradon McDonald’s imaginative costuming, tenor Orson Van Gay II appeared to be a wild eyed rapper.

José Adán Pérez and Maria Elena Altany as Figaro and Susana

José Adán Pérez and Maria Elena Altany as Figaro and Susana

José Adán Pérez was an endearing Figaro whose antics seemed entire logical, but vocally he was no match for Craig Colclough who sang a memorable rendition of Mr. Conti's music. Maria Elena Altany was a charming Susana who sang with a small but untiring voice. As Roxanne Conti, Greta Baldwin was a cool beauty with a soaring, creamy sound. Many characters were changed visually, but they all had to sing their usual lines in the ensembles.

Don Curzio became Bernard’s mother, Donna Curson, who tried hard to chaperone her son and young Barbara Conti. Amber Mercomes was an efficient Donna and Hayden Eberhart a delightfully gothic Barbara. Basilio, the dancing master, became Basel, an amusing English teacher who wore pink shoes. Tenor Haqumai Waring Sharpe played him to the hilt while singing with exemplary diction.

Miki Yamashita as businesswoman Soon-Yi Nam was the modern Marcellina who had brought Susana across the border. As Babayan, her enforcer, F. Scott Levin sang Bartolo’s quick and demanding patter with aplomb. Eventually, they admit to being the parents who left baby Figaro in Rosarito. As with the original opera, everything worked out perfectly in the end. Roxanne Conti forgave her philandering husband and Figaro, now a citizen, was able to marry Susana and keep her from being deported.

Performed in a three hundred-seat hall, Figaro 90210 was accompanied by piano, two violins, cello, bass and guitar. Conductor Douglas Kinney Frost brought out all the memorable melodies in the original score and after the first few minutes the listener was no longer conscious of the size of the orchestra. This was a very different version of the Mozart-DaPonte masterpiece, but it worked well in Southern California. The audience loved it and at least one extra performance has had to be scheduled.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Figaro, José Adán Pérez; Susana, Maria Elena Altany; Paul Conti, Craig Colclough; Roxanne Conti, Greta Baldwin; Barbara Conti, Hayden Eberhart; Donna Curson, Amber Mercomes; Bernard Curson, aka Lil' B-Man, Orson Van Gay II; Soon-Yi Nam, Miki Yamashita; Babayan, E. Scott Levin; Basel, Haqumai Waring Sharpe; Atzuko, David Castillo; Conductor, David Kinney Frost; Director Melissa Crespo; Scenery Designer, Sibyl Wickersheimer; Costume Designer, Bradon McDonald; Projection and Lighting Designer, Tom Ontiveros.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Figaro90210_BG_610_2607pub.png

image_description=Craig Colclough as Mr Conti with Maria Elena Altany as Susana [Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Opera]

product=yes

product_title=LA Opera Presents Figaro 90210

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Craig Colclough as Mr Conti with Maria Elena Altany as Susana

Photos courtesy of Los Angeles Opera

Tristan und Isolde at the Wiener Staatsoper

In 1862 the Imperial Hofoper orchestra in Vienna spent nearly 18 months and over 70 rehearsals trying to work out how to play the score of Tristan und Isolde before finally giving up and declaring the opera un-performable. Fortunately in the intervening years, what is arguably the finest opera orchestra in the world has overcome its initial trepidation and since 1883 under such great conductors as Gustav Mahler, Herbert von Karajan, Karl Böhm and Carlos Kleiber, the orchester der Wiener Staasoper has become almost the definitive interpreter of this extraordinary, ground-breaking, kaleidoscopic, indescribably complex and fathomless partitura.

Taking over from the ignominiously departed former Generalmusikdirektor Franz Welser-Möst, maestro Peter Schneider (who first conducted the opera in Vienna some 25 years ago and has been the regular Tristan dirigent in Bayreuth since 2008) is certainly no stranger to the score. Rather like other dependable Staatsoper routiniers of the past such as Horst Stein or Berislav Klobučar, there were generally no nasty surprises in tempo or tonal balance and the Vienna orchestra was able to display its prodigious skills to the utmost. Whilst the incandescent, almost manic passion of Bernstein or Kleiber is definitely not part of Schneider’s conducting persona, from the sublime cello ‘ blickmotiv’ at measure 18 in the Einleitung to themusically orgasmic soaring first-violin crescendo passages begining at Hellend, schallend during Isolde’s monumental Verklärung, the Vienna strings demonstrated their unique honey-toned quality which is justifiably legendary. The brass and wind sections were no less impressive and even the maudlin and slightly loopy cor anglais solo starting at measure 9 in Act III Sc. 1 was played with meticulous attention to the endless minutae of the score. It is hard to think of an operaticpartitura (especially one lasting more than 4 hours) which is so suffused with varying shades of crescendo-diminuendo/sff/spp markings , finelynuanced rubati and ceaseless subtle tempo changes and the Vienna orchestra seemed to strive to perfect each one in proving that their predecessors 160 years ago were wrong.

Albert Dohmen as King Mark and Gabriel Bermúdez as Melot

Albert Dohmen as King Mark and Gabriel Bermúdez as Melot

Sadly perfection is not the word which springs to mind when considering David McVicar’s production which was first staged here in 2013 with Peter Seiffert and Nina Stemme in the titles roles. The stage design by Robert Jones got off to a good start with Tristan’s ship looking rather ominous and skeleton-like but also practical as it rotated on the stage to accomodate the small scene changes in Act I. A large moon which rises during the Einleitung changed colour according to shifts in the drama and created a suitably spooky atmosphere. Energetic choreography for sailors by Andrew George was also effective. But then things started to run aground. Isolde’s apartment in King Marke’s castle in Act II was hardly a Cornish Schloss Neuschwanstein. Wagner’s description of a garden with high trees (Garten mit hohen Bäumen) was replaced with a rather Spartan stepped-terrace dominated by an enormous phallic obelisk penetrating a wooden nest-cum-wicker doughnut. No prizes for guessing the symbolism here. There was so little direction in the immensely long duet in Act II Sc. 2 which ends with the rapturous Ohne Nennen, ohne Trennen, the performance could have been in concert version. Continuing the downhill slide, by Act III Tristan’s ancestral castle in Brittany was nothing more than a pile of rocks - quite a difference frommerely untended and overgrown (schadhaft und bewachsen)as stated in the libretto - and his bed of recuperation was a cross between a wooden deck-chair from Anything Goes and an uncomfortable chaise-longue with a crucifix-contoured back. Isolde’s ecstatic concluding Verklärung was sung to an empty stage (if one ignores the dead bodies of Tristan, Melot and Kurwenal laying around) despite her singing Seht ihr’s, Freunde at measure 5. At the end of the scena, instead of collapsing insensate over Tristan’s body as Wagner required and the union, even in death, of the two illicit lovers being graciously blessed by König Marke (Isolde sinkt, wie verklärt…sanft auf Tristans Leiche. Marke segnet die Leichen), Isolde just walks away - presumably to find more höchste Lust back in Ireland.

Of the singers, only the Tristan of reliable war-horse Peter Seiffert (his debut in Vienna was in 1984) remained from the original cast of two years ago. Herr Seiffert still has all the notes and the tortuous high tessitura of the role held no terrors whatsoever. His lengthy scena with Kurwenal in Act III Sc. 1 was powerfully sung with a true Heldentenorklang (especially the top ff Ab and A natural on Sehnsucht nicht) whilethe more lyrical mezzavoce passages in Dünkt dich das were elegantly phrased. Unfortunately there is something inescapably unconvincing about Kammersänger Seiffert’s extremely large stage appearance. There was none of the emotional intensity of Jon Vickers or the sheer sexiness of Peter Hofmann. Belonging more to the older ‘stand up and sing’ school, this interpretation was a long way from the all-conquering hero (dem Helden ohne Gleiche) and even further from the personification of Schopenhaurian Die Welt als Wille philosophy which had such a profound influence on Wagner in the conception of this tradition-shattering Handlung.

Following a long list of Swedish dramatic sopranos bringing distinction to the role of Isolde (eg. in Vienna alone Catarina Ligenza, Berit Lindholm and Nina Stemme — not to mention the incomparable Birgit Nilsson) Iréne Theorin had a lot of hard acts to follow. Having previously sung the role in Bayreuth in 2012 (again under Peter Schneider) and recently Brünnhilde (Götterdämmerung) at La Scala under Barenboim, Madame Theorin has impressive credentials. Prowling around the deck of Tristan’s ship in Act I like an exotic caged animal, she certainly looked convincing and her fury in Entartet Geschlecht…Zerschlag es dies trotzige Schiff was quite terrifying. At the outset there was a troubling wobble in the voice, especially in the middle register but as the opera progressed, a less woolly and better articulated sound prevailed. There were consistent problems with poor diction however which did not improve. This is a soprano who is also singing Venus in Vienna so her vocal range is formidable. The high B naturals on geb er es preis and mir lacht in Act I Sc. 3 had a true Nilsson-esque ping and the celebrated Mild und leise was as memorable for its restraint as the bravura top G sharps. The final pp F sharp on Lust was especially well taken.

Making her Staatsoper debut as Brangäne, Tanja Ariane Baumgarnter was under-voiced and dramatically far too passive for such a pivotal role. Considering this part has been performed in Vienna by such powerful singers as Ruth Hesse and Marjana Lipovšek (even Christa Ludwig), this was an unsatisfactory substitute for the production’s original Brangäne of Janina Baechle. König Marke was well sung by experienced bass (and regular Wotan) Albert Dohmen who looked like an Old Testament prophet in drag but showed exceptional dignity and real sadness when confronted with proof of Tristan’s treachery in Act II Sc. 3 (warum so sehrend, Unseliger, dort nun mich verwunden?) The smaller roles of Melot (young Spanish baritone Gabriel Bermúdez); Ein Hirt (Carlos Osuna); der Steuermann (Il Hong) and Stimme eines jungen Seemans (Jason Bridges) were all competently sung with some very credible acting from señor Bermúdez. The most impressive performance of the evening however came from Polish baritone Tomasz Konieczy as Kurwenal who seems to be making quite a career in Vienna, singing five roles in the 2014-15 season. Despite David McVicker’s odd direction of Kurwenal being drunk in Act I, he still managed to display an extremely impressive projection, a bright, forward placed warm timbre and a ringing top register (essential to the tessitura of the role) with an excellent stage presence. The extremities of range inDas sage sie in Act Iwere mastered with not only outstanding vocalization but delicious malice as he deliberately enflamed Isolde’s ire. His interaction with Tristan in Act III Sc. 1, especially at selig sollst gesunden was beautifully phrased, while the top F natural on Ehren Tristan mein Held had a real clarion quality. It would seem that Mariusz Kwiecień has a serious rival in the top Polish baritone stakes.

Apart from one brave booer, audience reaction to the performance was wildly enthusiastic. Epic Wagner evenings usually attract a different kind of opera goer and there was far less Prada and black-tie and much more parka and pullovers than is customary in this grandest of grand opera houses. An eclectic crowd ranging from incredibly serious Wagner-nerd types in the Stehplätzeto inscrutable Viennese in the loges mixed with a surprisingly large number of baffled, if not wretchedly bored-looking Asian tourists. Five hours of Wagner for any operatic neophyte is a big ask. It seems the Wiener Staatsoper has become just another 5-Star TripAdvisor attraction in the Austrian capital and ticket sales are over 99.6%. Whether a less discriminating audience is having an effect on the overall quality of performances is a contentious issue but certainly to maintain absolute excellence in a repertoire of 49 operas with 6 new productions over a 10 month period is an almost impossible task. Adequate rehearsal time, especially for revivals, is clearly a major logistical problem. Fortunately the orchester der Wiener Staasoper is more likely to rise to the occasion than many of the singers on the roster, even if it occasionally takes them 20 years to learn the score.

Jonathan Sutherland

Cast and production information:

Tristan: Peter Seiffert, König Marke: Albert Dohmen, Isolde: Iréne Theorin, Kurwenal: Tomasz Konieczy, Melot: Gabriel Bermúdez, Brangäne: Tanja Ariane Baumgarnter, Shepherd: Carlos Osuna, Steersman: Il Hon, Young sailor: Jason Bridges. Conductor: Peter Schneider, Director: David McVicar, Set Designer: Robert Jones, Lighting Designer: Paule Constable, Chorus Master: Martin Schebesta, Choreography: Andrew George. Wiener Staatsoper, 14th January 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Peter%20Seiffert%20as%20Tristan%20and%20Ir%C3%A9ne%20Theorin%20as%20Isolde.png image_description=Peter Seiffert as Tristan and Iréne Theorin as Isolde [Photo by Wiener Staatsoper/Michael Poehn] product=yes product_title=Tristan und Isolde at the Wiener Staatsoper product_by=A review by Jonathan Sutherland product_id=Above: Peter Seiffert as Tristan and Iréne Theorin as IsoldePhotos by Wiener Staatsoper/Michael Poehn

January 22, 2015

Songs of Night and Travel, Wigmore Hall

All of which featured in this interesting programme of nineteen- and early-twentieth-century song — some familiar, some rare — given by countertenor Christopher Ainslie, pianist James Baillieu and violist Gary Pomeroy (all of South African origin) at the Wigmore Hall.

Christopher Ainslie’s biographical note in the programme booklet reports that his future engagements this season include Gluck’s Orfeo at Opera de Lyon, and Handel’s Agrippina in Göttingen and Saul at Glyndebourne. This is the sort of repertoire which has won Ainslie deserved renown and seen him lauded as ‘A rock star of Baroque opera’ (New York Times); and, his technically masterful and vocally powerful performances have made one critic ‘keen to hear him in Britten and other florid roles, ancient and modern’ ( Seen & Heard). But, herein lays a problem which presumably this recital was intended to address: how is a countertenor to break the chains that bind him to roles from the Classical or mythic past, or to demonstrate that his voice can embody through its power and agility more than just majesty or ethereality, mystery or purity. Can the countertenor voice express the rich and diverse range of human emotions so characteristic of the texts of nineteenth-century lieder, for example?

This performance did not offer a definitive answer. There was much to admire. Ainslie has a pure, focused tone which he can darken and brighten at will. His delivery is controlled: his sustained notes are smooth and even, while runs and leaps demonstrate the nimbleness and suppleness of his powerful countertenor. There was nothing in this recital that was not poised, elegant and beautiful. But, at times Ainslie lacked the variety of tonal colour, the expressive nuance and sense of vocal freedom, and the innate responsiveness to textual meaning and the very sounds of the words, which is needed to fully or convincingly capture and convey the essence of ‘meaning’.

Ainslie started hesitatingly and did not seem comfortable in the first song, Ivor Gurney’s ‘Sleep’. The opening invocation, ‘Come, Sleep’, while crisply delivered, lacked warmth, and the cold, somewhat glassy tone did not seem fitting for an appeal for soothing solace from the day’s cares: ‘with thy sweet deceiving/ Lock me in delight awhile’. Pianist James Baillieu did imbue his oscillating semiquavers with some assuaging softness and sentiment, but Gurney’s wonderful climactic melody, ‘O let my joys have some abiding’, was strangely unmoving. However, the purity and stillness of Ainslie’s delivery was perfect for Roger Quilter’s ‘The Night Piece’ — one of the six songs of the cycle To Julia (Op.8, 1905), settings of poems from Robert Herrick’s vast collection, Hesperides (1648). The performers were alert to the imagery of the opening stanzas, the piano’s staccato quavers suggesting the ‘shooting stars’ and ‘sparks of fire’, the latter growing in intensity through the voice’s dotted-rhythm melisma. Ainslie’s concluding lines were impassioned and seductive — ‘And when I shall meet/ Thy silvery feet/ My soul I’ll pour into thee’ — while Baillieu’s accelerating close suggested that Julia had indeed been won.

Two songs by Schubert, ‘Nacht und Träume’ D.827 (Night and dreams) and ‘Die Sterne’ D.939 (The stars) were perhaps the least successful items of the evening. Though Ainslie found a legato translucence to depict the moonlight of the ‘Holy night’ in the former song, floating high above the dark, dreamy piano semiquaver accompaniment, and enriched his tone at the end of ‘Die Sterne’ to suggest the intensity of the stars’ shining blessing which links heaven and earth, in neither lied did he use the text expressively, in ways which might give greater character to the vocal phrases. Mendelssohn’s ‘Nachtlied’ Op.71 No.6 was more dramatic and penetrating. Begun in 1845 but not completed until 1847, the song was perhaps the composer’s way of coming to terms with his beloved sister Fanny’s death in May of that year. Here, the opening verses were touchingly introspective, the rising question, ‘Where now is … the sweet light of the loved one’s eyes?’ (‘Der Liebsten süßer Augenschein’) indicative of the protagonist’s love and pain. Baillieu pushed the tempo forward in the final stanza and the glowing vigour of the voice conjured the ‘cascade of bright sound’ which pours forth from the nightingale, conjoined with and consoling the poet-speaker.

Ainslie related the narrative clearly in Hugo Wolf’s quirky ‘Storchenbotschaft’ (1888) (Stork-tidings) but more animation was needed to capture the parodic irony of Mörike’s version of the folk legend that storks carry new babies to expectant parents. Baillieu’s twisting chromatic wriggles added humour, though, and the piano’s over-the-top postlude was fittingly riotous, as the new father greets the arrival of twins. The highlight of the first half was Richard Strauss’s ‘Nacht’ Op.10 No.3 (1885): again Baillieu contributed greatly to the power of the song, his opening pianissimo quavers delicately evoking the Night who ‘slips softly from the trees’, the repeated notes in the inner voices expressively nuanced. Here, too, Ainslie was more attentive to the text: the silver from the river and the gold of the cathedral’s roof gleamed in the penultimate verse, while a sense of mystery pervaded the final stanza depicting the plundered bush. The plunging octave of the final line, ‘O die Nacht, mir bangt, sie stehle Dich mir auch’ (Ah the night, I fear, will steal you too from me), was beautifully clear and deeply sensitive.

Either side of the interval, Ainslie was joined by viola player Gary Pomeroy, who had already demonstrated his relaxed expressive style in Frank Bridge’s elegiac Pensiero (1905) and stormy Allegro appassionato (1908) for viola and piano. In ‘Gestille Sehnsucht’ (Assuaged longing), the first of Brahms’s Two Songs Op.91, the warm viola counter-melodies and motifs blended attractively with Ainslie’s countertenor, highlighting the ‘soft voices’ of the birds and the stirring ‘desires’ of the poet-speaker. The double-stopped final cadence powerfully intimated the consummation of the singer’s longing. ‘Geistliches Wiegenlied’ (Sacred lullaby) played to Ainslie’s strengths, displaying his sweet tone and vocal power, the latter most dramatically when the mother rebukes the raging wind for disturbing her sleeping child. Bridge’s Three songs with viola (1906-7) were not published until 1982 but judging from this splendid performance these settings, which share the theme of death, deserve to be more often heard in the concert hall. The trio brought forth the individual character of each song: the dissonant, mournful passions of ‘Far, far from each other’ (Matthew Arnold), the angry sense of loss and confusion in ‘Where is it that our soul doth go?’ (Heinrich Heine), and the consolation offered by the Romantic sublime in ‘Music when soft voices die’ (Percy Bysshe Shelley). Baillieu’s whispering, brushing chords in the latter were magical.

Vaughan Williams’ Songs of Travel concluded the recital. The opening song, ‘The vagabond’, set off at a vigorous pace which established an energy and onward motion which was sustained through the cycle. ‘Let beauty awake’ would have benefited from greater tonal variety, while ‘The roadside fire’ and ‘Whither must I wander?’ require a stronger folk-like robustness; but Ainslie once again exploited his ethereal tone and vocal control in ‘In dreams’, while Baillieu’s wonderful introduction made palpable the eponymous ‘infinite shining heavens’ of the following song. Best of all was ‘Youth and love’, in which the phrases flowed with mesmerising fluidity and freshness. The return of the vagabond’s stoic tread marked the end of the cycle; if Ainslie had not quite managed to inhabit the journeymen’s shoes, he had told his story engagingly.

Claire Seymour

Performers and programme:

Christopher Ainslie — countertenor, James Baillieu — piano, Gary Pomeroy — viola.

Songs of Night and Travel : Gurney — ‘Sleep’; Quilter, ‘The Night Piece’; Schubert — ‘Nacht und Träume’ D.827, ‘Die Sterne’ D.939; Mendelssohn — ‘Nachtlied’ Op.71 No.6; Richard Strauss — ‘Die Nacht’ Op.10 No.3; Hugo Wolf — ‘Storchenbotschaft’; Bridge — Pensiero, Allegro appassionato; Brahms — Two songs with viola Op.91; Anonymous — ‘I’m just a poor wayfaring stranger’; Bridge — Three songs with viola; Vaughan Williams — Songs of Travel. Wigmore Hall, London, Wednesday 21st January 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Christopher_Ainslie_-_new_photo_1_credit_Denis_Jouglet.png image_description=Christopher Ainslie [Photo by Denis Jouglet] product=yes product_title=Songs of Night and Travel, Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Christopher Ainslie [Photo by Denis Jouglet]January 21, 2015

Andrea Chénier, Royal Opera

“It’s more of an opera”, said a lady, making a long pause, “…… than Fedora.” That said, it’s so full of catchy tunes and star turns that it would make a great feel-good West End musical. Basically, it’s a pot boiler even by opera standards. Had it been written 30 years later it would have been a Hollywood extravaganza, complete with dancing girls. But gosh, is it fun in its own camp way!

Jonas Kaufmann redeems the opera altogether, and raises it to an altogether higher level of power and dignity .The part is ideal for his rich, Italianate timbre with its hints of mystery and sensuality. Technically, the Big Numbers in Andrea Chénier aren’t nearly as brilliant or as beautiful as those in, say, Manon Lescaut, but they provides moments of display stunning even the least musical members of the audience. Fortunately, Kaufmann is a genuine artist, who doesn’t do things just for show. He creates the part with his singing, suggesting much more depth and complexity than the composer might have dared to imagine. This Andrea Chénier is a bad boy, a rock star, an outsider who writes poetry in an age of violence, yet he has the finesse to entrance a posh girl like Maddalena di Coigny. . After that “Un dì all’azzurro spazio” I was smitten, too.

Rosalind Plowright as Contessa Di Coigny, Eva-Maria Westbroek as Maddalena Di Coigny and Denyce Graves as Bersi

Rosalind Plowright as Contessa Di Coigny, Eva-Maria Westbroek as Maddalena Di Coigny and Denyce Graves as Bersi

Slight as Luigi Illica’s libretto may be, the story deals with cataclysmic events. The French Revolution was such a watershed in world history that it creates a powerful backdrop that it saves the opera from itself. Because know what the story, we can fill in the emotional extremes without much effort, but singing this impassioned helps a lot. Eva-Maria Westbroek is a house favourite because she makes all her roles feel personal: her Maddalena seems full-hearted and full-throated even before she dresses up for the ball. Westbroek brings out the feisty woman behind the fancy veneer. Giordano may emphasize the love story, but the French Revolution happened for very serious reasons.

Elegant as the Ancien Régime might have been, it was a system based on inequality and the abuse of wealth. Carlo Gérard (Željko Lučić) rages against the cruelty that has worn his father down. Lučić’s singing was so intense that he made it clear, that, for all the prettified décor of this set (designed by Robert Jones), the past was a hideous sham. The pastoral dance shows the rich pretending to be the peasants whom they exploit: dance is a metaphor for regimented group-think. The servants have lovely costumes (Jenny Tiramani) but these are uniforms, only prettier than prisoners or soldiers might expect. It’s also not for nothing that Bersi (Denyce Graves) is black.

Željko Lučić as Carlo Gérard and Elena Zilio as Madelon

Željko Lučić as Carlo Gérard and Elena Zilio as Madelon

This production is visually stunning — chandeliers in the middle of the field of vision, roccoco mirrors, colour co-ordinated designer clothes even for the mob in the court room. So much for the ideals which Chénier stood for. This Andrea Chénier is most certainly “Regie” because every production, no matter how banal, is a form of interpretation. David McVicar “decorates” but misinterprets meaning. The Revolution happened because, for a moment, people realized that superficial appearances deceive. It says much about modern society that people nowadays treasure trappings over truth. A man behind me kept talking loudly, bursting into insincere autopilot bravos and bragging about himself. Never before have I experienced behaviour as bad as that, especially not at ROH. If he really did know opera as well as he claimed to, surely he might have noticed that the implicit values of Andrea Chénier are quite the opposite?

Fortunately, Željko Lučić sang with such dignified fervour that those who go to opera to listen would have appreciated the depths inherent in the drama which this staging did so much to nullify. Kaufmann gets star billing, for good reason, but Lučić reached the true emotional depths. A big cast, young singers as impressive as the older ones.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/%C2%A9BC20150117_AndreaChenier_RO_241%20%20JONAS%20KAUFMANN%20AS%20ANDREA%20CH%C3%89NIER%20%28C%29%20ROH.%20PHOTOGRAPHER%20BILL%20COOPER.png image_description=Jonas Kaufmann as Andrea Chénier [Photo © ROH. Photographer Bill Cooper] product=yes product_title=Umberto Giordano: Andrea Chénier, Royal Opera House, London, 20th February 2015 product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio product_id=Above: Jonas Kaufmann as Andrea ChénierPhotos © ROH. Photographer Bill Cooper

January 20, 2015

The Met’s ‘La Traviata’ lean on glamour, rich in insight

By David Abrams [CNY Café Momus, 17 January 2015]

Beyond the austere set and surreal visuals, Willy Decker’s controversial 2010 Met production probes deeply into the heroine’s psyche.

Yevgeny Onegin in Warsaw

For some strange reason Tchaikovsky’s Yevgeny Onegin has recently been subject to the same directional quirks and aberrations that used to be reserved almost exclusively for the works of Wagner. Carrying on the bad old traditions of German directors such as Harry Kupfer and Hans Neunenfels, most of the recent culprits seem to have sprung from Poland. There was Michał Znaniecki’s aquatic staging in Bilbao and Zagreb; Krzysztow Warlikowski’s ‘Brokeback Mountain’ Yev-gay-ny in Munich (which certainly outraged the good Catholic burghers of Bayern) and pre-dating them all, Mariusz Treliński’s visually exciting but seriously flawed interpretation for the Polish National Opera in Warsaw in co-production with the Palacio de las Artes Reina Sofía in Valencia.

Mr Treliński’s most obvious and definitely annoying directional digression was the introduction of a non-speaking, omnipresent, white-clad, walking-stick-wielding spectral character listed in the programme as ‘O***’ (definitely not ‘O’ for Onassis). This repellent, diabolical, bald-headed ogre seemed at times to be a benign version of an old Onegin as a passive observer of past events (similar to Kasper Holten’s recent concept for Covent Garden) and at others, a truly Mephistophelian figure stage-managing every detail of the drama with absolute and brutal malevolence. Mariusz Treliński is a celebrated Polish film director and now Artistic Director of the Polish National Opera. Somehow he seems to see no problem in the ambiguity of the soi disant ‘superfluous man’ character as both passive observer and aggressive avatar puppeteer. At the opening of Act 2 O*** wears a large Anubis-like face mask and forces Tatyana to put on a black blindfold before leading her to the ball. Portents of death abound, either psychological or corporeal. He then puts the same blindfold on Lenski and dances with him too — clear inspiration for Krzysztow Warlikowski and the ‘Brokeback Mountain’ Onegin boys in Munich. O*** is positively vulture-like when he thrusts a sheet of paper at Tatyana in the Letter Scene and terrorizes her into completing the missive. Her important psychological state of nervous introspection, adolescent insecurity and romantic impetuosity are completely subsumed by this gratuitous distraction.

Irina Mataeva as Tatyana

Irina Mataeva as Tatyana

On the other hand, if ever there was an obvious corporate sponsorship nexus between an opera production and a famous logo, it was Treliński’s apple-laden images. Steve Jobs would have loved it. While Andrea Breth converted the Salzburg stage into a giant wheat field and Robert Carsen turned the Metropolitan’s mis-en-scène into a carpet of dead leaves, in this Polish version we had apples, apples, and more apples. A huge apple tree silhouette dominates the rear of he stage; an enormous pile of apples covers a refectory table in the first scene when Madame Larina and Filipjevna are supposed to be making jam (apple sauce?); O*** picks up an apple in the very first bars of the score; Onegin aggressively munches one and at the conclusion of the opera, a veritable harvest of (rotten?) apples roll towards the front of the stage. The autumnal demise of Onegin’s character with Granny Smith symbolism. The installation of a catwalk around the orchestra pit brought a lot of the drama very close to the audience but also created a certain cheap Victorian music-hall effect. Robert Carsen used the same idea in a recent production of Die Zauberflöte in Baden-Baden but Schikaneder and Mozartian Singspiel and are a very different box of apples to Aleksandr Pushkin and Tchaikovsky. Outstanding lighting by Felice Ross created several superb visual images of Boris Kudlićka’s staging, such as Tatyana laying prostrate in the shadows of bleak white birch trees at the end of Act I Sc.1. As a Pole creating a production for a Polish staging, it was also rather brave of Mr Treliński to have Emil Weslowski’s choreography of the Act III Polonaise as a series of incredibly slow stylized robotic steps rather than the usual swirling energy of such a powerful dance. It seemed to work. A sense of fatalistic inevitability predominates this staging, with or without O***, and is certainly appropriate to Aleksandr Pushkin’s characterizations or indeed early 19th century country life in Russia in general.

The singing was for the most part more than satisfactory. In the title role, Polish baritone Artur Ruciński was vocally impressive and dramatically credible even if the cold, contemptuous arrogance of Peter Mattei in Salzburg or Dmitri Hvorostovsky at the Met was absent. This meant his emotional collapse in Act III when finally rejected by Tatyana was demonstrably less empathetic, although his anguish was certainly very well acted — so much so that the audience broke into applause before the opera had actually ended. Although the voice was occasionally a little fuzzy, slightly pushed and sometimes lacking in clear focus, his Act I Когда бы жизнь домашним кругом aria was mellifluously sung and displayed a fine legato and agreeable rich timbre, especially in the upper-middle register. In opting for the concluding high F on мечты нежней,he sang it forte instead of piano as indicated in the score, but a solid ringing top is clearly one of Mr Ruciński’s strongest vocal attributes.Irina Mataeva’s interpretation of Tatyana had an Ophelia-ish quality about it which verged on the wide-eyed mystical if not slightly demented, especially in the first two acts. There were some intonation problems in the upper register and a rather intrusive wide vibrato which contradicted the innocence and youth of the character so well captured by Tatyanas such as Ileana Cotrubuş in the past or Anna Samuil in more recent productions. While the Act I Letter Scene was seriously marred by the distracting intrusion of O*** who alternated between a cruel, homicidal stalker and a tender Onegin with the speed of a Rossinian hemidemisemiquaver (guardian angel or wily temptor?) Miss Mataeva’s top Bbs were not particularly clean and the final Ab on вверяю! waspushed and not very pleasant.

Ballroom Scene, Act II

Ballroom Scene, Act II

Preening across the stage in Act III in a Schiaparelli pink cocktail frock, she looked like Audrey Hepburn in ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ — complete with cigarette holder. Fortunately by the second scene her singing of Онегин! Я тогда моложе had a much improved vocal assurance and the lower tessitura seemed more comfortable, not withstanding the persistent vibrato. Even the final powerful fff B natural on проща! was well taken.Despite showing surprising sexuality with Lensky, the Olga of Karolina Sikora, was dramatically rather bland, vocally underpowered and burdened with an unattractive wobble. Ewa Marciniec’s Larina was the same without the vibrato — or the sex. As Lensky, Ukrainian tenor du jour sensation Pavlo Tolstoy sang with restrained elegance, a warm forward dulcet timbre and excellent Alfredo Krause-like phrasing. His Я люблю вас люблю вас Ольга ardent outburst to Olga in Act I was passionate without being vulgar; the beginning of the Act II Sc.1 finale ensembleВашем доме! had a really beautiful tender mezza-voce cantilena andKuda,kuda in Act II was movingly sung without being saccharine. His upper register, especially on the top Ab in the ff andante mosso change on Желанный друг was perfectly focused and the whole scena was commendable for consistently fine intonation and bright, Italianate vocal colouring. Of the smaller roles, the Triquet of Tomasz Piluchowski was vocally undistinguished and had serious tempo coordination problems with the orchestra in his Act II encomium to Tatyana. Anna Lubanska’s Filipjevna was a real delight. Possessing a Regina Resnik-esque rich, plummy lower register and deep chest notes, she was also dramatically an ideal incarnation of the devoted babushka. As Prince Gremin, Aleksander Teliga lacked stage presence but made up for it with fine, well-articulated singing and an outstanding lower register. The final low Gb’s at счастье had impressive strength and projection.

The orchestra was capably led by Andriy Yurkevych. There was some fine string playing (e.g. the cello opening to Act II Sc.2 and the introduction to Kuda kuda); excellent brass (eg. the piano horn solo quaver phrases beginning at measure 187 in Tatyana’s Letter Scene); delicately balanced winds (especially the cheeky scale passage exchange between flute, oboe and clarinet in Act I at measure 152 and during the echoed major fifth piano quavers between flute, clarinet (and horn) beginning at the andante change at measure 47 in Tatyana’s Letter scene. There was also some very sensitive clarinet solos in Kuda, kuda. Unfortunately it seemed that maestro Yurkevych was a little too concerned with not overpowering the singers in this huge theatre, which should not have been a concern. When freed from such constraints, such as in the ff orchestral tutti at bars 270-293 of Tatyana’s Letter scene and the Act III opening Polonaise, the orchestra played with powerful precision and commendable attention to the markings of the score.

It will be interesting to see how Mr Treliński’s forthcoming unusual double-bill of Iolanta and Bluebeard’s Castle (the first co-production between the Polish National Opera and the Metropolitan Opera in New York) will be received by operatically conservative Manhattanites. Hopefully the Polish pippins will not be too bruised by the real Big Apple.

Jonathan Sutherland

Cast and production information:

Larina: Ewa Marciniec, Tatyana: Irina Mataeva, Olga: Karolina Sikora, Filipjevna: Anna Lubańska, Yevgeny Onegin: Artur Ruciński, Lensky: Pavlo Tolstoy, Prince Gremin: Aleksander Teliga, Triquet: Tomasz Piluchowski, O***: Emil Wesołowski. Conductor: Andriy Yurkevch, Director: Mariusz Treliński, Set Design: Boris Kudliča, Costumes: Joanna Klimas, Lighting: Felice Ross, Choreography: Emil Wesołowski. Polish National Opera, Teatr Wielki, Warsaw, 11th January 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Irina%20Mataeva%20as%20Tatyana%20and%20Emil%20Weso%C3%AAowski%20as%20O.png image_description=Irina Mataeva as Tatyana and Emil Wesołowski as O*** [Photo © Teatr Wielki — Opera Narodowa/Stefan Okołowicz] product=yes product_title=Yevgeny Onegin in Warsaw product_by=A review by Jonathan Sutherland product_id=Above: Irina Mataeva as Tatyana and Emil Wesołowski as O***Photos © Teatr Wielki — Opera Narodowa/Stefan Okołowicz

January 19, 2015

La belle au bois dormant, Théâtre de l’Athénée, Paris

By Francis Carlin [FT, 19 January 2015]

Ottorino Respighi (1879–1936) was Italy’s answer to Ravel as far as orchestration is concerned and best known for a trio of tone poems on Rome. He also completed nine operas, none of them on today’s performance radar.

January 17, 2015

Why bother?

With news that The Metropolitan Opera is having financial problems -- again -- now a dispute is brewing over the assets of the defunct New York City Opera with a view to reviving the company. Why bother?

January 16, 2015

Les Contes d’Hoffmann, Metropolitan Opera, New York

By Martin Bernheimer [FT, 14 January 2015]

Bartlett Sher’s interpretation of Les Contes d’Hoffmann was a mess at its Met premiere back in 2009. The sets, designed by Michael Yeargan, looked gaudy, the narrative seemed confused, and the stage remained chronically overpopulated.

Orfeo at the Roundhouse, Royal Opera

Just as things were at the first performance of Monteverdi’s Orfeo on 24 February 1607, in the exquisite apartments of the Gonzaga Palace in Mantua; except that we are at the Roundhouse in Camden, ducal regalia has been replaced by slick business suits and clerical attire, and those sitting in judgement upon the unfortunate pre-nuptial couple, Orfeo and Euridice, are not the Gods and Spirits of classical antiquity but black-cloaked representatives of modern civic and ecclesiastical institutions.

The ‘first opera’, the first time opera has been staged at the Roundhouse, an experienced theatre director’s first essay into opera, and the Royal Opera House’s first production of Orfeo: this quartet of inaugurations made for an auspicious occasion, with added interest offered by the involvement of a chorus comprising students from the Vocal Department of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, and dancing ‘nymphs and shepherds’ drawn from East London Dance. And, indeed, there was much to appreciate and enjoy at this opening night of director Michael Boyd’s production of Monteverdi’s favola in musica: but, there was also a sense that perhaps the opportunities afforded by the distinctive qualities of the venue and the rich variety of the personnel had not been grasped with quite the innovative spirit shown by Monteverdi himself four hundred years ago.

Rachel Kelly as Prosperina and Callum Thorpe as Pluto

Rachel Kelly as Prosperina and Callum Thorpe as Pluto

There’s certainly nothing wrong with the up-dating; the mythological heroes of early opera certainly served the rhetoric of propaganda expounded by the courtly centres of Europe, and director Michael Boyd’s concept of the conflict between individual creativity and self-expression (Euridice and Orfeo are clothed in white, albeit increasingly besmirched and charred as the opera progresses) and a Hadean, oppressive state that quells imaginative freedom is surely topical. Dressed in grey prisoners’ jumpsuits, the nymphs and shepherds are initially manacled, their fetters released so that they may celebrate the forthcoming matrimony as ordered by a Pastor (who has dropped his bucolic ‘al’); Pluto and Proserpina are chic oligarchs, Charon has an entourage of ‘heavies’.

And, Boyd tells his story simply and clearly, while Tom Piper’s designs are straightforward and minimal - the bare, circular stage is adorned with nothing more than fluttering emerald crêpe streamers to evoke Elysium. Disappointingly prosaic perhaps, but maybe there was concern that the in-the-round acoustic might be less than helpful or flattering (as it is, modest amplification is employed), and that complexities of staging would further hinder the singers’ projection and communication?

The libretto is full of references to both singing and dancing - this was, after all, the first time that a drama had been entirely sung by its protagonists and Monteverdi and his librettist, Alessandro Striggio, were perhaps anxious to persuade a potentially sceptical audience that what they were watching was entirely credible. Thus, movement plays a big part in Boyd’s production, and the madrigals, canzoni and balletti, with their tripping, dance-like rhythms are neatly choreographed. But, other than the set-piece dances, the production is frequently under-directed: so, in place of inherent dramatic movement which explicates the relationships between the protagonists and complements the musical narrative, we have superimposed movement - contemporary dance and circus acrobatics. Certainly, the young dancers of East London Dance are talented and often wonderfully expressive: their swirling evocation of the River Styx is entrancing, and the graceful cartwheels and ebullient somersaults with which they rejoice the imminent wedding delightfully embody the freshness and joy of a pastoral paradise. But elsewhere their physical exuberance seems at odds with the musical discourse and can be distracting, both visually and aurally. For example, the dancer’s presentation of Orfeo’s grief at the news of Euridice’s death certainly suggests a tortured soul writhing in anguish, but it also overpowers the vocal expression and diverts our attention from the essence of the opera: that is, the power of musical rhetoric.

Christopher Lowrey as Third Pastor, Gyula Orendt as Orfeo, Mary Bevan as Euridice and Anthony Gregory as First Pastor

Christopher Lowrey as Third Pastor, Gyula Orendt as Orfeo, Mary Bevan as Euridice and Anthony Gregory as First Pastor

Boyd does conjure some striking visual images. In the Prologue, La Musica (Mary Bevan, who also sings the role of Euridice) is unshackled and as she begins her strophic introduction to Orfeo’s tale, the tragic protagonist (Gyula Orendt) is carried in, borne aloft like a victim of crucifixion, so that she might clasp him in her arms - thereby foreshadowing the close of the opera, when the sorrowful Orfeo cradles his ‘lost’ beloved. Similarly, the lovers’ reluctance to part so that Euridice may prepare for the wedding is suggested by the chain of hands which stretches from Orfeo at the centre of the stage along the raised entrance platform: the outstretched arms prefigure the final dramatic image of Orfeo’s futile grasping for his beloved’s lifeless hand as he is raised heavenwards.

On the whole, and fittingly, in the absence of anything more than rudimentary stage action, it is the singers who must communicate the drama, and the cast are uniformly excellent. Mary Bevan sings with control and purity, suggesting the innate grace and goodness of Euridice, while Susan Bickley as her friend Silvia (Monteverdi’s Messenger) imbues this minor role with intensity and character. Callum Thorpe’s even bass-baritone conveys Pluto’s cool self-assurance and he is ably partnered by mezzo-soprano Rachel Kelly’s gleaming Prosperpina. As Charon, James Platt uses his strong bass-baritone to suggest Charon’s menacing obduracy. Tenors Anthony Gregory and Alexander Sprague blend beautifully with Christopher Lowrey’s warm, appealing countertenor, and all three Pastors communicate the drama powerfully.

As the only non-native speaker in the cast, Hungarian baritone Orendt isn’t always successful in his enunciation of Don Paterson’s new translation which tells the story plainly, without fussy conceits and with some effective and unobtrusive use of rhyme. But, Orendt’s commitment to the role is absolute and unceasing, and he sings with ardour and directness - even when hovering upside down from a harness, demonstrating a physical litheness and strength to equal his vocal flexibility. The arioso of ‘Possente Spirto’, the spiritual centre of the opera, gradually increased in persuasive fervour and demonstrated the considerable extent of Orendt’s vocal and musical resources; it was a pity, therefore, that his lyre - embodied by the two obbligato violins whose decorations embrace Orfeo’s appeals - was not given more prominence, for the violins’ elaborate ornamentations surely encapsulate La Musica’s opening assertion that she can charm mortal hearing and thus inspire human souls to attain the sonorous harmony of heavenly concord.

The nine postgraduate singers from the Guildhall vocal department acquit themselves well as the chorus but they and the musicians of the Early Opera Company - who play superbly under the direction of Christopher Moulds - feel a little removed from the drama, nested as they are at the rear of the large circular stage.

Boyd has relied on his dancers to recreate the excitement and anticipation which must have been experienced by the members of the Accademia degli Invaghiti in February 1607, but in so doing he somewhat neglects the musico-dramatic core of the opera. The final image of the anguished Orfeo, suspended between heaven and earth, is striking and moving. But the human and spiritual love which is embodied in Monteverdi’s score has been overshadowed by the visual and the physical. One might wish that Boyd had more consistently conjured the spirit of La Musica’s opening words: ‘I am Music, who with sweet melody know how to calm every troubled heart, and now with noble anger, now with love can inflame the most frozen minds.’

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Orfeo - Gyula Orendt, Euridice/La Musica - Mary Bevan; Silvia (Messenger) - Susan Bickley, First Pastor - Anthony Gregory, Seconda Pastor/Apollo - Alexander Sprague, Third Pastor/Hope - Christopher Lowrey, Charon - James Platt, Pluto - Callum Thorpe, Proserpina - Rachel Kelly, Nymph - Susanna Hurrell; Director - Michael Boyd, Conductor - Christopher Moulds, Set Designer - Tom Piper, Lighting Designer - Jean Kalman, Sound designer - Sound Intermedia, Movement Director - Liz Ranken, Circus Director - Lina Johansson, Orchestra of the Early Opera Company, Vocal Department of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, East London Dance. Royal Opera House, Roundhouse Camden, Tuesday 13th January 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/PR8A7945%20ORFEO%20-%20GYULA%20ORENDT%20AS%20ORFEO%2C%20MARY%20BEVAN%20AS%20EURIDICE%20%28C%29%20ROH-ROUNDHOUSE.%20PHOTOGRAPHER%20STEPHEN%20CUMMISKEY.png image_description=Gyula Orendt as Orfeo and Mary Bevan as Euridice [Photo by Stephen Cummiskey] product=yes product_title=Orfeo at the Roundhouse, Royal Opera product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Gyula Orendt as Orfeo and Mary Bevan as EuridicePhotos by Stephen Cummiskey

January 7, 2015

Idomeneo in Montpellier

A legacy of ousted Montpellier general director Jean Paul Scarpitta, the staging of Mozart’s first operatic masterpiece remained entrusted to Scarpitta’s assistant Jean-Yves Courrégelongue. Both Scarpitta and Courrégelongue are stage directors whose artistic formations were with Robert Wilson. Both have developed strongly individual voices, Wilsonesque only in so much as they both cultivate an extreme minimalism. Of these two Montpellier directors Courrégelongue is more imagistic, Scarpitta is more satiric.

Courrégelongue and his designer Mathieu Lorryy-Dupuy used a chair, a curtain, a table and a swimming pool to bring alive Mozart’s tale of sacrifice. This was not to update an ancient story’s Baroque retelling so much as it was to purge a Mozart masterpiece of extraneous, misleading detail (the trappings of an anachronistic opera seria for example) and to make it what it is — a dramatic action in music, and nothing more.

And yes, there was still the spectacle that is so strikingly created in Mozart’s score. It was squarely minimalist where less is more — an all the more terrifying appearance of the beast of the deep in the symbolic form of a sacrificial table exploding in white light. High tension had already been created in the blackouts that exploded into the sudden appearances of Idomeneo and later the crowds of terrified Cretans.

Courrégelongue hit sacrifice hard, depriving the opera of its obligatory happy ending. Elettra not only longed for death, she sacrificed herself to the love of Ilia and Idamante holding the sacrificial knife and disappearing through the crowd into swimming pool.

At last the gods having been appeased and the crowd having cleared the pool of detritus (plastic bags, old tires, etc.) deposited by the storms, Elettra’s body, victim of the opera’s emotional storms, was retrieved and laid out to Mozart’s orchestral epilogue. The sacrifice we had fought all evening had become real, it was a sacrifice more real to us than the averted opéra seria mythological filicide. And it was pure Mozart.

In Idomeneo the young Mozart had made an immensely powerful opéra seria, and here we discovered a hidden depth of humanity to surprisingly illuminate this masterpiece. It was fully realized musically in Montpellier by French conductor Sébastien Rouland whose considerable career seems to be centered in big house productions of Baroque repertory (contemporary perspectives, not historical re-creations).

Mo. Roulard brings bite and high drama to Mozart, suppressing the neo-classicism (balance of tension and relaxation) that informs the symphonic Mozart and his soon-to-come comedies. The appropriate (reduced) forces from the Orchestre National de Montpellier eagerly responded to the maestro’s demand for edgy tone and sharply defined shapes. The orchestra melted into transparent pianissimos for the prayer of Idomeneo creating transcendent musical magic, then roared with frustration in Electra’s final aria. Rare sonorities of orchestration sang out, most notably the fine horn quartet.

Anna Manske as Idamante, Marion Tassou as Ilia

Anna Manske as Idamante, Marion Tassou as Ilia

Mo. Roulard’s tempi were at once dramatically pointed and solidly within reach of the young cast. The three women were well matched in vocal color and accomplishment. Ilia was sung by French soprano Marion Tassou with beguiling purity of tone, Idamante was sung by Austrian mezzo Anna Manske who found a charming male/female compromise, and Elettra was sung by Swiss soprano Clémence Tilquin who raged with conviction in her aria begging for death. Robert Wilson costumer Yashi (single name) provided a simple dress for Illia, a shapely male business suit for Adamante and a slinky pants suit for Elettra, simple attire that spoke volumes about character.

The male voices were under par for a Montpellier Mozart opera, all over-parted, i.e. either unable to fulfill Mozart’s vocal demands or too inexperienced to be convincing, or both. An announcement was made that American tenor Brendan Tuohy as Idomeneo was “soufrant” and would not be at his best. While an appropriately imposing figure as Idomeneo his lack of experience to take on a major role on an important stage was glaring.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Idomeneo: Brendan Tuohy; Ilia: Marion Tassou; Idamante: Anna Manske; Elettra: Clémence Tilquin; Arbace: Antonio Figueroa; Nepture priest: Nikola Todorovitch; Neptune: Jean-vincent Blot. Chorus and orchestra of the Opéra Orchestre national Montpellier. Conductor: Sébastion Rouland; Mise en scène: Jean-Yves Courrégelongue; Scenery: Matthieu Lorry-Dupuy; Costumes: Yashi; Lighting: John Torres. Opéra Commedie, Montpellier. January 4, 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Idomeneo_Montpellier1.png

product=yes

product_title=Idomeneo in Montpellier

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Clémence Tilquin as Elettra [all photos copyright Marc Ginot, courtesy of the Opéra de Montpellier]

January 6, 2015

The Biggest Music Comeback of 2014: Vinyl Records

By Neil Shah [WSJ, 11 December 2014]

Nearly eight million old-fashioned vinyl records have been sold this year, up 49% from the same period last year, industry data show. Younger people, especially indie-rock fans, are buying records in greater numbers, attracted to the perceived superior sound quality of vinyl and the ritual of putting needle to groove.

January 5, 2015

L’elisir d’amore in Marseille

The Opéra de Marseille revived the 2004 Toulouse production of L'elisir d'amore as its holiday season confection. And quite a confection it is. Former Nicholas Joël assistant Arnaud Bernard and his designer William Orlandi envisioned Donizetti’s hyper sentimental story as a series of early twentieth century photographs (a sepia tinged silver color palate), and took the concept a step further by constructing a stage that was a series of shutters (complex flats that moved somewhat like the shutter of a still image mechanical camera).

There were complicated, sometimes amazing scenic moves, that included a disintegrated figuration of the shutter flats when we learned that Nemorino had become rich. Of course there were many visually splendid freezes, some self consciously posed for an on-stage old fashioned larger-than-life prop camera.

Set and costume design by William Orlandi

Set and costume design by William Orlandi

Yes, of course there were period bicycles that circled the stage (including a precarious ride by the diva), and there was was the antique automobile that brought on Dulcamara, an absolutely splendid car by an unidentified luxury maker that had been structurally reinforced to permit actors to climb all over it (Nemorino was exceptionally agile), and yes, of course there was the miniature model of the car as well, parked upstage with its tiny highlights on to oversee the consummation of the story (that Adina and Nemorino do in fact love one another).

Bel canto operas are indeed about singing, and Elisir is a series of arias, duets and trios that easily convince you, at least for the moment, that this opera must be the epitome of the style. Metteur en scène Arnaud Bernard’s snap shot concept at best set the stage for the singers to present themselves in specific musical moments to be remembered (i.e. visual moments where the bel canto could really rip). At worst the complex staging overwhelmed if not ignored Donizetti’s easy, satisfying sentimentalism.

The singers therefore had the challenge to live up to the production. Nemorino, Italian tenor Paolo Fanale, came the closest. While Mr. Fanale may not possess the sweetness of voice or character to be the ultimate Nemorino, he does possess the artistry to have delivered an absolutely exquisite “Una furtive lagrima,” the highpoint of the performance well recognized by the audience. This fine artist gamely executed the considerable antics required by the stage director.

Paolo Fanale as Nemorino, Inva Mula as Adina

Paolo Fanale as Nemorino, Inva Mula as Adina

Veteran soprano Inva Mula who recently sang Desdemona both in Marseille and at the Chorégies d’Orange competently managed the vocal and histrionic demands of Adina (as she had in San Francisco Opera’s 2008 Elisir when she had had to find her way through middle American cornfields in some heavy handed Americana). Her impressive vocal technique served her well though it revealed the strains of maturity when she did not secure satisfying pitch for her high notes, and it came across as mere competence in Adina’s spectacular “Prendi, per me sei libero,” not the joyous exuberance of singing so many notes so fast.

Argentine baritone Armando Noguera sang Sargent Belcore, late in the evening displaying some lovely coloratura in an otherwise underweight performance. The same may be said of the Dulcamara of Italian baritone Paolo Bordogna, a veteran of many roles at Pesaro’s Rossini Festival who well displayed his fine buffo instincts but who was dwarfed by his automobile and his magician costume. Gianetta was nicely sung by French soprano Jennifer Michel, evidently cast because she could sing the role rather than create the character.

It was not clear what was going on in the pit. Italian conductor Roberto Rizzi Brignoli seemed to be trying to conduct Donizetti’s opera while the stage was laboring to do Mr. Bernard’s production. The stage seemed to have the upper hand, after all it took a lot to execute all those antics — and while the shutters moved flawlessly they might not have. There was little synchrony between the pit and stage, and there seemed to be little synchrony between conductor and the orchestra players, who seemed reluctant or maybe technically unable to enter the bel canto spirit.

Finally Mo. Rizzi Brignoli and tenor hit it off magnificently in “Una furtiva lagrima,” and the maestro seemed at last to capture the spirit of Donizetti with his orchestra. Any hope for synchrony with the stage remained futile.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information: