February 28, 2015

Eine florentinische Tragödie and I pagliacci in Monte-Carlo

These brief operas have interesting points of convergence, both are love triangles with older men and younger wives. both have physically unattractive protagonists, both are set in Italy. The librettos for both were written in the early 1890’s. And both are just plain ugly stories.

Nonetheless there are striking, irreconcilable differences that prevent them from creating a soul satisfying evening of opera. I pagliacci (1893) is one of the masterpieces of the startling new verismo movement in Italy. A Florentine Tragedy (1917) came 25 years later, captive of the psychological and musical complexities of the collapsing Viennese cultural hegemony. Simply said I pagliacci remains a fresh, new piece and A Florentine Tragedy rests a derivative attempt to revive lost musical enthusiasms. Namely and unabashedly the scandalous excitement created by Salome, Electra and Rosenkavalier.

Barbara Haveman as Bianca, Carsten Wittmoser as Simone, Zoran Todorovich as Guido

Barbara Haveman as Bianca, Carsten Wittmoser as Simone, Zoran Todorovich as Guido

Zemlinsky’s rendering of Oscar Wilde’s sick little tale was simply Zemlinsky getting even with Gustav Mahler for being more attractive to Alma Mahler than he was. And, well, making an opera about Alma Mahler’s affair with the architect Walter Gropius while she was married to Mahler. It is a very personal, vindictive work.

It began the evening. When it was over the audience could not get to the bar fast enough.

Metteur en scène Daniel Benoin would have nothing to do with Zemlinsky’s monumental (triple or quadruple winds, six horns, huge percussion battery) pettiness and therefore set out to find a less gossipy context for this sordid tale. He moved the action from 16th century Florence to the Italy just a bit after 1917 and the emergence of Fascism. Simone (the older husband) exits his shop from time to time, passing the Black Shirt recruiters visible though the huge shop windows. For the dénouement he returns to his shop in full Blackshirt garb (he strangles young, old-order rich Guido). Simone and his young wife Bianca reconcile and the strong, new Italy is born!

The Zemlinsky opera is enormously enriched by this concept, given that Zemlinsky’s music does not really allow us to enter into the psyches of his actors (as, for example, Strauss had) but instead keeps us enthralled in the web of subterfuges Simone is creating to murder Guido. Director Benoin allowed that we might participate in politically powerful propaganda that can possibly be found in, or matched by the music rather than in the petty jealousies that are not musically supported.

The inherent irony of decadent music of a collapsing empire building a strong new political order did not trouble Mr. Benoin who was having fun with his designers. Set designer Rudy Sabounghi created a richly traditional Florentine shop, gorgeous in scope and detail, the exposition of luxury fabrics though was limited to sample books [!], but at last yards and yards of real fabric fell from the rafters, some of which Simone used to strangle Guido.

Nathalie Bérard-Benoin created costumes that were flagrantly and effectively at odds with the period details of the set, Simone in a monochrome rose modern suit, shirt and tie, Guido in a darker rose suit, shirt and tie. Bianca was in a Klimt inspired beaded dress and wigged firmly into the dying pre-fascist era.

It was a solid, sophisticated and amusing production richly conducted by Pinchas Steinberg who was unwilling to sacrifice the humors of Zemlinsky’s huge orchestrations when the singers were unable to sustain needed and appropriate volumes of sound. It was an orchestral, not a singerly event.

María José Siri as Nedda, Leo Nucci as Tonio

María José Siri as Nedda, Leo Nucci as Tonio

The exact opposite may be said of I pagliacci. It was very nearly a dream cast of singers who kept the audience in their seats applauding long after Canio had slaughtered Nedda. The pagliacci were opera stars baritone Leo Nucci and the estimable tenor Marcelo Álvarez, the Nedda was Argentine soprano María José Siri who thrilled us with the shimmering edge to her youthful tone. Silvio was Chinese born, Covent Garden trained baritone Zhengzhong Zhou whose exceedingly beautiful voice made the love duet with Nedda a meltingly beautiful few minutes. Peppe was carefully and charmingly etched by Italian tenor Enrico Casari. While conductor Steinberg did not fully capture the intense dramas of verismo he did give these superb singers tempos on which its lyricism could gracefully soar.

In fact the lighter weight and easier movements of Leoncavallo’s vocal lines felt much more at home in tenor Álvarez‘ voice than does Puccini’s Cavaradossi, surely this excellent artist's signature role (recently sung at the Bastille). Baritone Leo Nucci is a nimble 72 years of age (he wanted us to know this by effecting a heel clicking jump now and again). He is in good voice and is still a viable Tonio. Soprano Siri, a Tosca in her own right (Vienna and Berlin), is young enough to be believable as a real Nedda and sufficiently experienced in the grand repertoire to bring real diva style to her portrayal.

The common element to both short operas was designer, Monaco native Rudy Sabounghi (director Benoin did his own lighting, Pagliacci was lighted by Laurant Castaingt). Sabounghi with Swiss metteur en scène Allex Aguilera had us see through the back wall of a stage in order to create the conceit that we too are the actors since we feel what they feel — I pagliacci plays very heavily with the metaphor of theater.

It got even more complicated. The pagliacci started out as circus clowns, drumming up business for the upcoming performance, their public were country folk on the way to church. Though by the time of the performance of the play within the opera Tonio and Canio had dressed themselves in everyday clothes as they were dealing with their real, off-stage passions. Conversely the country folk now had transformed themselves into commedia dell’arte costumes, like the actors on the stage should have been costumed. This audience then was seated on the stage directly mirroring the Salle Garnier audience, thus it was they who were dealing with theatrical passions. We, the Salle Garner audience, were dealing with the real passions. Verismo indeed.

It all more or less worked in its weird way. Most of all it gave us something to get our minds around. Neither of the stagings found the essences of these strange little operas, nor were they looking for the them. It was a high-level, challenging and ultimately satisfying evening of opera.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

A Florentine Tragedy Guido Bardi: Zoran Todorovich; Simone: Carsten Wittmoser; Bianca: Barbara Haveman. Mise en scène et lumières: Daniel Benoin; Décors: Rudy Sabounghi; Costumes: Nathalie Bérard-Benoin. I pagliacci Canio: Marcelo Álvarez; Nedda: María José Siri; Tonio: Leo Nucci; Beppe: Enrico Casari; Silvio: ZhengZhong Zhou. Mise en scène: Allex Aguilera; Décors Rudy Sabounghi; Costumes: Jorge Jara; Lumières: Laurent Castaingt. Chorus of the Opéra de Monte-Carlo, Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte-Carlo. Conductor: Pinchas Steinberg. Salle Garnier, Monte-Carlo, Monaco, February 25, 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Pagliacci_Monaco1.png

product=yes

product_title=A Florentine Tragedy and I pagliacci in Monte-Carlo

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: María José Siri as Nedda, Marcelo Álvarez as Canio [All photos copyright Opéra de Monte-Carlo]

February 27, 2015

Carmen, Pacific Symphony

Prosper Mérimée serialized his novella, Carmen, in the Revue des deux Mondes in 1845. It came out in book form the next year. The author said his inspiration was a tale the Countess of Montijo told him when he visited Spain in 1830. He said, “It was about that ruffian from Málaga who had killed his mistress.” Then he added: “As I have been studying the Gypsies for some time, I made my heroine a Gypsy." Mérimée may also have been influenced by Alexander Pushkin’s narrative poem The Gypsies, a work Mérimée translated into French.

The novella is very different from the opera. The book tells of José Lizarrabengoa, a Basque hidalgo from Navarre, whereas the opera is about the Gypsy, Carmen. Micaëla, Frasquita, and Mercédès do not appear in the novella. Le Dancaïre, is only a minor character in the story, while Le Remendado is killed by Carmen's husband one page after his introduction. Escamillo, whom Mérimée calls Lucas, is seen only in the bullring. Only one major facet of the story is true of both novella and opera: José is fatally attracted to Carmen.

Gypsy Dance: Amanda Opusynski, Milena Kitic and Sarah Larsen with dancers

Gypsy Dance: Amanda Opusynski, Milena Kitic and Sarah Larsen with dancers

On February 19, 2015, Pacific Symphony presented its annual performance of a semi-staged opera. This year’s presentation at the Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa, California, featured Georges Bizet’s Carmen. Director Dean Anthony used the front of the stage and a few solid set pieces by Scenic Designer Matt Scarpino to depict the opera’s various scenes. Of course, Kathryn Wilson’s well-coordinated costumes and the ambience created by Kathy Pryzgoda’s lighting added a great deal to the cast’s ability to tell the story.

Milena Kitic, who has sung Carmen with opera companies around the world including the Metropolitan Opera and Opera Pacific, was an energetic Gypsy whose rich, lustrous golden tones soared over the orchestra and into the excellent acoustics of the 2000 seat hall. Tenor Andrew Richards was an outstanding Don José who mastered both the dramatic and the lyrical aspects of his role. The score of Carmen calls for substantial orchestral power and Richards’ voice sailed over it with ease. The surprise was that he was able to scale it down to the sweetest of pianissimos for the final notes of the “Flower Song”.

The Violetta in Pacific Symphony’s performance of La Traviata, Elizabeth Caballero, was a thoughtful Micaëla who made the audience realize what a good life José would have had if he married her. A versatile lyric soprano, she sang with strength when it was called for and with limpid, radiant tones in more lyrical moments. Konstantin Smoriginas swaggered into Lillas Pastia’s café as the reigning bullfighter and sang his “Toreador Song” with resonant, robust sounds. He seemed to be having fun with the role and the part fit him perfectly.

Soprano Amanda Opuszynski and mezzo-soprano Sarah Larsen portrayed Carmen’s friends, Frasquita and Mercédès. Since Carmen and Mercédès had lower voices, it was up to Frasquita to sing the high notes and Opuszynski came through with flying colors. Larsen’s bronzed tones provided colorful harmony. As Moralès and Zuniga, Keith Harris and Andew Gangstad were credible soldiers who sang with dark tonal colors. Harris also portrayed Le Dancaïre, who together with Jonathan Blalock as Le Remendado, added to the dramatic coherence of the gang of smugglers.

Currently, Music Director Carl St. Clair is marking his twenty-fifth season with Pacific Symphony. He has guided its growth and it is now the largest Symphony Orchestra to have been formed in the United States during the past fifty years. Before he came to Costa Mesa, much of his background was in opera which he still conducts magnificently. His tempi were incisive and he brought an infectious verve to Carmen’s unforgettable melodies. It would be wonderful to hear him conduct more opera in the near future. We know that Pacific Symphony will do another opera next year. I for one very much look forward to it.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Carmen, Milena Kitic; Don José, Andrew Richards; Micaëla, Elizabeth Caballero; Escamillo, Konstantin Smoriginas; Mercédès, Sarah Larsen; Frasquita, Amanda Opuszynski; Zuniga, Andrew Gangstad; Moralès/Le Dancaïre, Keith Harris; Le Remendado, Jonathan Blalock; Conductor, Carl St. Clair; Director Dean Anthony; Scenic Designer, Matt Scarpino; Lighting Designer, Kathy Pryzgoda; Costume Coordinator, Kathryn Wilson.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/190CARMEN%201465__n.png

image_description=Mercédès, Sarah Larsen; Carmen, Milena Kitic; Frasquita, Amanda Opuszynski; Le Remendado, Jonathan Blalock; Le Dancaïre, Keith Harris.

product=yes

product_title=Carmen, Pacific Symphony

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Mercédès, Sarah Larsen; Carmen, Milena Kitic; Frasquita, Amanda Opuszynski; Le Remendado, Jonathan Blalock; Le Dancaïre, Keith Harris.

February 26, 2015

The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, ENO

Above all, I am thinking of Nikolaus Lehnhoff’s production of Parsifal, sadly revived but once, with estimable conducting from ENO’s soon-to-be Music Director, Mark Wigglesworth, and a fine cast (bar an unfortunate Kundry). The contrast with the Royal Opera’s recent Parsifal — a production that appeared to offer a bizarre tribute to Jimmy Savile, a Music Director quite out of his depth, and a tenor whose replacement with a pneumatic drill would have been more or less universally welcomed — was telling. Here, a Meistersinger production originally seen in Cardiff again proved preferable to Covent Garden’s most recent offering (an especially sad state of affairs at the sometime house of Bernard Haitink). If we quietly leave to one side the most extravagant claims heard over the past fortnight — surely more a consequence of sympathy with and support for ENO in the face of financial and managerial difficulties than of properly critical reception — this proved something to be cherished, something of which ENO could justly be proud: a good, and in many respects very good, company performance.

Edward Gardner’s conducting certainly marked an advance upon his 2012 Flying Dutchman. One would hardly expect someone conducting The Mastersingers for the first time to give a performance at the level of a Haitink or a Thielemann, let alone the greatest conductors of the past; nor did he. Yet, once we were past a fitful first-act Prelude — I began to wonder whether we were in for a Harnoncourt-lite assault upon Wagner! — Gardner’s reading permitted the score to flow as it should. (I shudder in horror when I recall Antonio Pappano’s hackwork — a generous description — at Covent Garden.) If there was rarely the orchestral weight, the grounding in the bass, that Wagner’s work ideally requires, relative lightness of touch was perhaps no bad thing for lighter voices than one would generally encounter. Moreover, Gardner seemed surer as time went on: not an unusual thing in this score, for even so fine a Wagnerian such as Daniele Gatti gave a similar impression a year-and-a-half ago in Salzburg, coming ‘into focus’ more strongly as the work progressed. Moreover, orchestral playing, considered simply in itself, was excellent throughout; a larger body of strings would have been welcome, but one cannot have everything. The ENO Chorus, clearly well trained by Martin Fitzpatrick, offered sterling service in the best sense: weighty where required, yet anything but undifferentiated. Orchestra and chorus alike have prospered under Gardner’s leadership; they are treasures the company and country at large have the strongest of obligations to protect.

What of Richard Jones’s production? Clearly, to anyone familiar with the work of Stefan Herheim, or, from an earlier generation, say,Harry Kupfer and Götz Friedrich, there has again been an excess of extravagant praise. The production rarely gets in the way: certainly a cause for celebration. Yet, by the same token, it has nothing in particular to add to our understanding, however diverting the ‘spot the German artist on the stage curtain’ might be. (I could not help but smile at the mischievous inclusion of Frank Castorf.) A predictably post-modern mix of nineteenth- and sixteenth(?)-century costume could have been used to say something interesting about Wagner’s donning earlier, anachronistic garb (that is, Bach rather than something ‘authentic’). It would need to have been more sharply defined and directed, though; here, it remains on the level of the mildly confusing, or at least incoherent. One has a sense of community, but it is difficult to discern much in the way of the darker side of the work — without which, the light makes less impression, just as its ‘secondary’ diatonicism remains predicated, both immediately and more reflectively, upon the chromaticism of Tristan. I can see why Jones might have opted — at least that is what I think he was doing — to present Hans Sachs as suffering from bipolar disorder, doing an irritatingly silly dance at one point, prior to slumping into depression. Had that been a personal illustration of the Schopenhauerian Wahn afflicting the world more generally, it would have worked a great deal better, though, than an all-too-simple explanation for Sachs’s mood-swings. The translation, similarly mistaking the personal for the metaphysical, certainly did not help: ‘Mad! Mad! Everyone’s mad!’ for ‘Wahn! Wahn! Überall Wahn!’ If that were misleading, though, far worse was the bizarre reference to ‘ancient Rome’ instead of the Holy Roman Empire in Sachs’s final peroration, rendering his warnings meaningless and merely absurd. There is enough uninformed misunderstanding of this scene as it is, largely born, it seems, by Anglophone audiences being unable or unwilling to read what Wagner actually wrote; further confusion such as that is anything but helpful.

Jones certainly did score, though, in his adroit direction of the cast on stage, although much of that credit should certainly go directly to members of that cast. Andrew Shore’s Beckmesser was an unalloyed joy, treading the difficult line between comedy and dignity as surely as anyone was is likely to see today. His diction was beyond reproach, seamless integration of Wort und Ton almost having one forget the problems of translation. James Creswell’s rich bass similarly impressed, having one wish that Pogner’s role might be considerably expanded. David Stout’s Kothner elicited a not dissimilar reaction from this listener. Iain Paterson’s voice is less ideally suited to his role, that of Sachs, but there was no doubting his commitment to role and performance, the thoughtfulness of which offered many compensations. The other Masters and Nicholas Crawley’s sumptuously-clad Night Watchmen were an impressive bunch too. I wondered whether, to begin with, Gwyn Hughes Jones’s Walther was a little too Italianate in style; that is doubtless more a matter of taste than anything else, though, and either the performance or my ears adjusted — or both. He certainly went from strength to strength in the second and third acts, experiencing no difficulties whatsoever in making himself heard above the rest of the ensemble, without any recourse to barking. Nicky Spence’s characterful David — it would, admittedly, be an odd David who was not characterful! — struggled a little with his higher notes in the first act, but, like the cast as a whole, offered a portrayal considerably more than the sum of its parts. I was less keen on Rachel Nicholls’s somewhat harsh-toned Eva, having the distinct impression that her voice was being forced, perhaps on account of the size of the theatre. (But then, Wagner tends to be performed in larger theatres.) Madeleine Shaw’s Magdalene was straightforwardly a joy to hear, as impressive in its way as the assumptions of Shore and Creswell. Again, it was difficult not to wish for more.

So, despite certain reservations, this was a Meistersinger to be reckoned with. On a number of occasions, especially during the third act, work and performance brought a lump to my throat, even once a tear to my eye. That, surely, is the acid test — and it was readily passed.

Mark Berry

Cast and production information:

Walther: Gwyn Hughes Jones; Eva: Rachel Nicholls; Magdalene: Madeleine Shaw; David: Nicky Spence; Hans Sachs: Iain Paterson; Sixtus Beckmesser: Andrew Shore; Veit Pogner: James Creswell; Fritz Kothner: David Stout; Kunz Vogelgesang: Peter van Hulle; Konrad Nachtigall: Quentin Hayes; Ulrich Eisslinger: Timothy Robinson; Hermann Ortel: Nicholas Folwell; Balthasar Zorn: Richard Roberts; Augustin Moser: Stephen Rooke; Hans Folz: Roderick Earle; Hans Schwarz: Jonathan Lemalu; Night Watchman: Nicholas Crawley. Director: Richard Jones; Set designs: Paul Steinberg; Costumes: Buki Schiff; Lighting: Mimi Jordan Sherrin; Choreography: Lucy Burge. Chorus (chorus master: Martin Fitzpatrick) and Orchestra of the English National Opera/Edward Gardner (conductor). The Coliseum, London, Saturday 21 February 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/eno-mastersingers-rachel-nicholls-and-iain-paterson-c-catherine-ashmore.png image_description=Rachel Nicholls as Eva and Iain Paterson as Hans Sachs [Photo by Catherine Ashmore] product=yes product_title=The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, ENO product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Rachel Nicholls as Eva and Iain Paterson as Hans Sachs [Photo by Catherine Ashmore]February 24, 2015

San Diego Opera presents an excellent Don Giovanni

Muni designed the simple sets, directed the concentrated action and translated da Ponte’s text into interesting supertitles. In this production, Ildebrando D’Arcangelo’s Don was a bon vivant as well as a womanizer who sang with consistently satisfying resonant, polished tones.

Lorenzo da Ponte wrote the libretto for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni, basing his text on various legends about the famous Spanish seducer. Evidence suggests that the first fully dramatized version of the story was by a monk, Tirso de Molina (1579-1648), who published El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra (‘The Trickster of Seville and the Stone Guest’) in 1630. Readers may remember that da Ponte was once ordained as a priest. De Molina’s Don goes to Hell as does the title character of José Espronceda's 1840 poem El estudiante de Salamanca (‘The Student of Salamanca’), but some versions of the legend end differently. The protagonist in José Zorrilla's 1844 play Don Juan Tenorio, receives a divine pardon.

Ildebrando D’Arcangelo as Don Giovanni and Myrtò Papatanasiu as Donna Elvira

Ildebrando D’Arcangelo as Don Giovanni and Myrtò Papatanasiu as Donna Elvira

On Friday February 20, 2015, San Diego Opera presented Mozart’s Don Giovanni in a production by Nicholas Muni originally seen at Cincinnati Opera. Muni designed the simple sets, directed the concentrated action and translated da Ponte’s text into interesting supertitles. In this production, Ildebrando D’Arcangelo’s Don was a bon vivant as well as a womanizer who sang with consistently satisfying resonant, polished tones. A congenial Don, many in the audience would have preferred to sit down and have a beer with him rather than see him dragged off to eternal damnation.

In this opera many of the characters are conflicted. Often, they sing one idea while their music plays another. That gives the artist a great deal of room for characterization and many of them made fine portrayals. Especially believable was the Leporello of Ashraf Sewailam. Not only did he sing well, he never stopped moving. While his Catalog Aria thoroughly offended Donna Elvira, it fascinated the audience who gave it a well-deserved hand of applause. What is most amazing is that Sewailam was a last minute substitute. He is a most valuable artist indeed.

We will never know whether Donna Anna wanted to get away from the Don as she says, or if she secretly wanted to enjoy his advances as her music suggests. Ellie Dehn registered a wide range of emotional shifts with great delicacy while singing with glinting sonorities. As her fiancé Don Ottavio, Paul Appleby sang with radiant tones spun out in a stunningly beautiful legato. He is definitely a young singer to watch.

Myrtò Papatanasiu was a feisty Donna Elvira who thought she could change the Don’s ways. Like many women before and since, she found it could not be done, but she learned her lesson while singing with honeyed tones. Emily Fons and Kristopher Irmiter were most believable as Zerlina and her bridegroom, Masetto. Fons, who was a member of the young artist program at the Lyric Opera of Chicago from 2010 to 2012, seems to be at the onset of a most impressive career. Her singing was an iridescent wave of vocal color as she captured her character’s delicious moments of indecision. Kristopher Irmiter was a bold peasant who had to deal with the fact that a nobleman like the Don could kill him with impunity. Bass Reinhard Hagen sang the Commendatore’s low notes with thrust as he energized their text with conviction.

Chorus Master Charles Prestinari’s chorus sang in subtle harmonies and imbued the text with nuanced emotions. Dorothy Randall's alert and stylish playing made the recitatives a joy to hear. Although conductor Daniele Callegari seemed to have a rather loose concept of the architecture of the opera, he held stage and pit together while allowing the singers enough room to breathe and emote. The resurrected San Diego Opera certainly put together a hit with this performance of the Mozart masterwork.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Leporello, Ashraf Sewailam; Don Giovanni, IldebrandoD’Arcangelo; Donna Anna, Ellie Dehn; Commendatore, Reinhard Hagen; Don Ottavio, Paul Appleby; Donna Elvira, Myrtò Papatanasiu; Zerlina, Emily Fons; Masetto, Kristopher Irmiter; Conductor, Daniele Callegari; Director, Set Designer, Paul Muni; Costume Designer, David Burdick; Lighting Designer, Thomas C. Hase; Chorus Master, Charles Prestinari.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/_b5a9C%20Weaver%20SDO%20697.png

image_description=Asraf Sewailam as Leporello and Myrtò Papatanasiu as Donna Elvira [Photo by Cory Weaver]

product=yes

product_title=San Diego Opera presents an excellent Don Giovanni

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Asraf Sewailam as Leporello and Myrtò Papatanasiu as Donna Elvira

Photos by Cory Weaver

Tosca at Chicago Lyric

The first roster features Tatiana Serjan as Floria Tosca the singer, Brian Jagde as her lover Mario Cavaradossi, Evgeny Nikitin as Baron Scarpia, Richard Ollarsaba as Cesare Angelotti, and Dale Travis as the Sacristan. The roles of Spoleta, Sciarrone, the shepherd, and the jailer are taken by Rodell Rosel, Bradley Smoak, Annie Wagner, and Anthony Clark Evans respectively. Dmitri Jurowski conducts the Lyric Opera Orchesta and Michael Black has prepared the Lyric Opera Chorus. For this version of Caird’s production Bunny Christie collaborates as scenic and costume designer. Serjan, Jagde, Nikitin, Wagner, Jurowski, and Christie are all in their debut seasons at Lyric Opera.

After the familiar opening chords of Act I, Angelotti — who has escaped from imprisonment — seeks refuge in the Church of Sant’ Andrea della Valle. Mr. Ollarsaba commences the action in this production by pulling aside a white sheet stained red, which had covered the stage, and which apparently indicated the violence associated with this version of the opera’s setting. Ollarsaba integrates his lines well into a depiction of Angelotti’s desperate yet successful search for the key to a temporary hiding place in the church. At his entrance Mr. Travis inhabits the role of the sacristan comfortably, fretting while keeping order yet good-naturedly accepting his duties. When Cavaradossi enters and asks after the sacristan’s actions [“Che fai?”], an innocent moment of interrupted prayer leads to a flood of lyrical sentiment. Already from those initial spoken words Mr. Jagde creates an earnest, believable hero. Once he climbs a steep scaffold to survey his painted work thus far, Jagde’s performance of “Recondita armonia” [“Oh, hidden harmony”] establishes his as a significant tenor voice not only for Puccini but also for other major composers as well. When singing in this aria of the “azzurro … occhio” [“blue eyes”] in his painted creation, he compares these to the “occhio nero” [“black eyes”] of his dear Tosca. At his moment Jagde’s voice takes on an Italianate warmth emphasizing both the artist’s inspiration and the lover’s devotion. In the concluding soliloquy to art his voice at first blooms with absolute control over pitch and forte volume, then ends the aria with an effectively shaded diminuendo on “Tosca, sei tu!” [“Tosca, it is you!”].

Brian Jagde as Cavaradossi and Tatiana Serjan as Tosca

Brian Jagde as Cavaradossi and Tatiana Serjan as Tosca

A reunion with Angelotti, who emerges very briefly from hiding in the side chapel, is interrupted by Tosca’s calls to open the locked gate of the church. From the point of Ms. Serjan’s entrance it is clear that the Floria Tosca of this production fulfills a specific interpretation of the title character. Rather than relying solely on the persona of a singer celebrated throughout Rome, Mr. Caird’s Tosca projects a coarser image in keeping with the rural origins of the heroine in Vittorio Sardou’s play. Such depiction is apparent here in Tosca’s dress and movements, just as Serjan sings her lines at first with the intonation of an unsophisticated maiden. The attempt to fit this mold does not always suit Serjan’s voice. When she sings in full voice in keeping with the score, top notes seem occasionally uncontrolled as though the preceding interpretive model were thwarting vocal transitions. It is also at this point of the music-drama that Caird introduces a “spirit character” as a “child Madonna” or “ghost of Tosca’s innocence,” as explained in the program insert with the director’s note, “A New View of Tosca.” This “view” would have the heroine, and the audience, reflect on her past and youth at moments of religious fervor or crisis. The “child Madonna” disappears after Tosca’s prayer in front of the Virgin and thus allows for the moving love duet between the principals. Here Jagde again delivered an impressive flow of lyricism in both dialogue and the duet. When he claims to have painted the Marchesa Attavanti without being observed by her, the lines “Non visto, la ritrassi” were sufficiently expressive to convince any Tosca of his faithfulness. Jagde’s sense of legato throughout the duet is a noticeable asset, so that the words “Floria, t’amo” blend naturally with the surrounding attributes in his recitation.

When Tosca leaves for an engagement, Cavaradossi and Angelotti are able to devise a strategy for eventual escape from the menacing henchmen of the police chief. At the mention of the notorious official, Jagde colors the name Scarpia with a truly deprecating snarl. Cannon shots signal the imminent presence of the police, and both men flee from the church. The sacristan reappears and is surprised to find the interior deserted; soon he is surrounded by singing and dancing children, performed here by the Chicago Children’s Choir. Jubilation at the news of Napolean’s defeat comes to a halt with the entrance of Baron Scarpia. From the first Mr. Nikitin seems understated in the role, at times singing flat from the pitch. When Tosca reappears in search of her lover, Nikitin warms to the role. He sings his final “Va Tosca,” alternating with the clergy reciting the Te Deum, in rising, declarative notes. The orchestra under Jurowski’s lead captured especially the dramatic highlights at the close of the act.

Evgeny Nikitin as Scarpia and Tatiana Serjan as Tosca

Evgeny Nikitin as Scarpia and Tatiana Serjan as Tosca

The interior of Act II in this production is described by its director as “a war-damaged renaissance ballroom,” suggestive of time periods later than that indicated by Puccini in his text. Scarpia’s lair seems to conceal a plan for his own subsequent survival during this period of political uncertainty. Given that directorial lead, the introspective recitations of Nikitin’s Scarpia at the start of the act match a calculating portrayal of the chief policeman. He hurls questions at Cavaradossi who has now been detained by the police and is kept in the presence of its chief authority. In this exchange Nikitin and Jagde spar believably for verbal control until the arrival of Tosca. Despite subsequent repeated torture offstage, Cavaradossi remains steadfast and warns Tosca not to reveal the hiding place of Angelotti. Yet in order to spare her lover further pain Tosca relents, allowing Scarpia to send his men in search of the prisoner. When a sudden announcement declares that Napolean has won in the battle at Marengo, Cavaradossi sings his paean to liberty beginning with the famous “Vittoria! Vittoria!” The forte pitches are here exact, and Jagde sustains these for an exciting delivery. When Scarpia and Tosca are left alone, the woman realizes that she must consent to the baron’s “altra mercede” [“other recompense”] in order to save her imprisoned lover. Before the violent conclusion, Tosca sings the summary of her life “Vissi d’arte” [“I lived for art”]. In this aria Serjan demonstrates the necessary control and vocal range to render the piece beautifully effective. Her final line of prayer in the aria, “Perche me ne rimuneri cosi?” [“Why do you repay me thus?”] is an especially touching display of emotional innocence. In the final moment of the scene Tosca’s violent act against Scarpia is here accompanied by the reappearance of the “child Madonna,” hence adding supplementary comment on the murder.

Act III will again incorporate the “child Madonna” at the opera’s close but first the figure appears as the young shepherd, and sings the latter’s aria at daybreak. A dead body, in dress reminiscent of Angelotti’s earlier costume, is hoisted up and remains hanging throughout the following scenes of the opera. The stars are visible through a large open window at the back of the stage. In the second scene Cavaradossi writes his letter of farewell to Tosca and muses on their love, now almost vanished. The mood is appropriately wistful and tragic, while the oboe introduction to the aria “E lucevan le stelle” [“And the stars were shining”] could be played more subtly. Jagde’s performance of this piece shows a careful sense of transition in volume matching the import of individual lines of text. His conclusion on “tanto la vita” [“life so much”] emphasizes the bared irony of treasuring love in the final moments of life. Of course, Tosca arrives almost immediately with information on the safe passage granted, Scarpia’s murder, and the plan for a mock execution. In their duet both Serjan and Jagde bloom in unforced glory to celebrate the renewed possibility of their love. The ultimate tragedy of this duet is borne out by the firing squad’s mechanical execution of Cavaradossi. When Tosca realizes her threatened position and final choice to evade the police, she looks one more time at the “child Madonna” before her leap from the window. This directorial hesitation is explained as a means to timing the suicide in tandem with the opera’s final chords, yet the implied delay leads to a possible question of Tosca’s resolve. New productions of standard opera will always provide interpretive possibilities and insights not before realized concerning an iconic score. In this production the opportunity to hear singing in keeping with the spirit of the work, especially that of Mr. Jagde, remains its principal advantage.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/13_Tatiana_Serjan_TOSCA_LYR150121_498_cTodd_Rosenberg.png

image_description=Tatiana Serjan as Tosca [Photo by Todd Rosenberg]

product=yes

product_title=Puccini’s Tosca at Lyric Opera of Chicago

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=Above: Tatiana Serjan as Tosca

Photos © Todd Rosenberg

February 17, 2015

Spring Gala: Cream of the Crop!

Monday, March 30, 2015, 7pm

Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall

Hear the stars of tomorrow today in a spectacular gala evening celebrating New York Festival of Song's Emerging Artists programs! Over the past decade, NYFOS has taken a growing interest in mentoring, coaching, and nurturing some of the most promising young vocalists of our era. Many opera programs exist for young artists but there are very few that focus only on the art of song. It is the most exposed and direct kind of performing—no costumes of make-up to mask one's vulnerability—just the musicianship, intelligence, and honesty of the singer. Over 100 young talents have participated in NYFOS residencies and some of our most distinguished alumni will appear in the gala, including Paul Appleby, John Brancy, Julia Bullock, Theo Lebow and Annie Rosen.

February 16, 2015

Henri Dutilleux: Correspondances

Following its brief, opening Rilke (in translation) setting, ‘Gong’, ‘Danse cosmique’ offered Barbara Hannigan greater dramatic possibilities, well taken. The Philharmonia under Esa-Pekka Salonen provided vivid, often pictorial playing. Singer and orchestra proved tender indeed during the treatment of ‘solitude’ in the oddly-chosen extract from a letter from Aleksandr Solzhenitzyn to Mstislav Rostropovich and Galina Vishnevskaya. Hannigan’s closing repetitions of ‘toujours’ faded away nicely, as did the orchestra. ‘Gong II’ provided something a little more labyrinthine, even perhaps Bergian, although Pli selon pli this certainly is not. The closing ‘De Vincent á Théo’ brought beguiling sonorities and, in Hannigan’s performance, a stunning vocal climax.

Mitsuko Uchida joined the orchestra for Ravel’s G major Concerto. There were a few occasions when I wondered whether the Philharmonia had had enough rehearsal here, lapses in ensemble uncharacteristic for both orchestra and conductor. Otherwise, Salonen proved general cool but not cold, even though a little more freedom at times might not have gone amiss. Uchida’s playing was a model of clarity, energy, an of course grace. It is all too easy to make Mozartian comparisons here, but they did not seem especially relevant; this was Ravel, and sounded like it. Uchida’s second-movement cantilena was beautifully judged, a product of harmonic understanding as much as her melodic voicing itself. Woodwind solos were exquisitely voiced, with just the right degree of general orchestral languor. The scampering energy of the finale was occasionally hampered by a couple more lapses in ensemble, but the ‘sense’ of the music was there, especially in Salonen’s building of tension. Uchida’s choice of encore was inspired: the second of Schoenberg’s Six Little Piano Pieces, op.19, that repeated major third, G-B, making its point of continuity.

L’Enfant et les sortilèges followed the interval. Salonen’s tendency, especially at the start, was towards fleetness of tempo; there was certainly no hint of sentimentality. Indeed, a keen sense of forward motion was maintained throughout the performance. The action took place on a ‘stage’ surrounding the stage proper, a resourceful semi-staging giving all that we really needed, not least thanks to imaginative animation (for instance, the confusion of the clock) and atmospheric lighting. There was great character and chemistry to be experienced between the singers, François Piolino often stealing the show, whether by himself or in his interactions with others. Chloé Briot presented a convincingly boyish Child, never forgetting - nor did the performers as a whole - that this is not really a children’s opera at all, but an opera about that most adult of preoccupations, childhood. Hannigan, when she reappeared, now as the Princess, was very much a woman in a man’s creation of a supposed child’s world. Scenes were very sharply defined as almost self-contained units; Salonen seemed, at least to my ears, to perceive Ravel’s opera almost as a cinematic dream-sequence. Certain figures reminded us of the sound-world of the piano concerto, but there was no mistaking the heady atmosphere of the night.

Mark Berry

Programme and performers:

Henri Dutilleux and Maurice Ravel: Correspondances; Piano Concerto in G major; L’Enfant et les Sortilèges. Barbara Hannigan (soprano, Princess);Dame Mitsuko Uchida (piano);Chloé Briot (Child); Elodie Méchain: Mother, Chinese Cup, Dragonfly;Andrea Hill: Louis XV Armchair, Shepherd, White Cat, Squirrel; Omo Bello: Shepherdess, Bat, Owl;Sabine Devieilhe: Fire, Nightingale;Jean-Sébastien Bou: Grandfather Clock;François Piolino: Teapot, Arithmetic, Frog; Nicola Courjal: Armchair, Tree.Director: Irina Brown; Movement: Quinny Sacks; Designs: Ruth Sutcliffe; Lighting: Kevin Treacy; Video: Louis Price. Philharmonia Voices (director: Aidan Oliver)/Philharmonia Orchestra /Esa-Pekka Salonen (conductor). Royal Festival Hall, London, Thursday 12 February 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Barbara%20Hannigan%202%20%C2%A9%20Raphael%20Brand.png image_description=Barbara Hannigan [Photo by Raphael Brand] product=yes product_title=Henri Dutilleux: Correspondances product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Barbara Hannigan [Photo by Raphael Brand]February 15, 2015

Get out of the goove! Now Radio 1 bans Madonna, 56, for being 'irrelevant and old' for its teenage listeners

By Chris Hastings [Daily Mail, 14 February 2015]

She has dominated the airwaves during 30 years as a chart-topper, but now Radio 1 has decided that Madonna is an immaterial girl and just too old for its teenage listeners.

Despite her determined efforts to look - and sound - youthful, the 56-year-old has been dropped from the station’s playlist that determines which songs are played by DJs during the day.

LA Opera Revives The Ghosts of Versailles

The composer started to set Caron de Beaumarchais’ third book, La Mère Coupable (‘The Guilty Mother’) but he and librettist William M. Hoffmann could not complete their work in the allotted three years. Actually, writing The Ghosts of Versailles took seven years and the Met did not premiere it until December 19, 1991. It was a major success, however, and the company revived it for the 1994-1995 season.

On February 7, 2015, Los Angeles Opera mounted a monumental production of The Ghosts of Versailles. The work, which composer Corigliano calls a grand opera buffa, opens after the deaths of many of its characters. Costume designer Linda Cho clothed the singers in detailed soft colored eighteenth century costumes. Because many people had been beheaded she wrapped the heads of dancers in black. Director Darko Tresnjak made sense of the opera’s complicated story and enabled his singers to create realistic characters. Scenic Designer Alexander Dodge gave us a fabulous illusion of the palace at Versailles and accommodated some short opera-within-an-opera scenes on the set.

Christopher Maltman as Beaumarchais with Guanqun Yu as Rosina and Renée Rapier as Cherubino

Christopher Maltman as Beaumarchais with Guanqun Yu as Rosina and Renée Rapier as Cherubino

Some characters, of course, came directly from the Mozart and Rossini operas. Tenor Joshua Guerrero was a handsome, robust voiced Count Almaviva. Mezzo-soprano Lucy Schaufer was an amusing Susanna who sang a charming duet with soprano Guanqun Yu as Rosina. Following the story line of La Mère Coupable in which Rosina has an affair with Cherubino, Yu sang a delightful duet with mezzo Renée Rapier as well. Rosina’s son and Almaviva’s daughter, Leon and Florestine, portrayed by Brenton Ryan and Stacey Tappan, sang with honeyed tones. For their pieces, Corigliano’s music had a Mozartian sound and included some quotations from the characters’ original music.

For scenes with ghosts, he offered much more modern sounds. Patricia Racette was a plaintive Marie Antoinette and Kristinn Sigmundsson a stentorian Louis XVI. Lucas Meachem was an energetic and sonorous Figaro who never tired despite the length of his role. Christopher Maltman, inhabited his role as Beaumarchais with conviction as he cared for the doomed queen. There were two fascinating cameos in the first act. Patti LuPone enchanted the audience as Turkish dancer, Samira, who enters on a pink elephant. Victoria Livengood sang a faux Wagner aria with gusto, only to end with a pie to her face. Later she was a sophisticated woman with an enormous hat.

The villain, Bégearss, sung by tenor Robert Brubaker, pretends to befriend the nobility, but in reality he is an unscrupulous double agent. In Act II he is first seen abusing his servant, Wilhelm, played by the amusing Joel Sorensen. Later he leads a mob that raids the Count’s ball in an effort to secure the queen’s most valuable necklace. In the end, Figaro and Susanna leave in a hot air balloon as Beaumarchais regains the necklace for Marie Antoinette who chooses to go to her execution rather than change history.

This buffa opera offered aerialists and other circus acts, enchanting dances, and precise choral ensembles. Aaron Rhyne’s projections created varied ambiances and York Kennedy’s lighting made everything come to life. Under Grant Gershon’s direction, the chorus sang with harmonic precision while acting as individuals. James Conlon held the entire enterprise together with flexible rhythms and dramatic tension that never lagged. Ghosts is a truly enthralling opera that deserves to be seen and heard more often. This was, indeed, an extraordinary evening.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Almaviva, Joshua Guerrero; Rosina, Guanqun Yu; Susanna, Lucy Schaufer; Figaro, Lucas Meachem; Cherubino, Renée Rapier; Florestine, Stacey Tappan; Léon, Brenton Ryan; Bégearss, Robert Brubaker; Samira, Patti LuPone; Suleyman Pasha, Philip Cokorinos; Wilhelm, Joel Sorensen; English Ambassador, Museop Kim. Beaumarchais, Christopher Maltman; Marie Antoinette, Patricia Racette; Woman in a Hat, Wagnerian soprano, Victoria Livengood; Louis XVI, Kristinn Sigmundsson; Marquis, Scott Scully; Three Gossips: So Young Park, Vanessa Becerra, Peabody Southwell; Four Aristocrats: Summer Hassan, Lacey Jo Benter, Frederick Ballentine, Patrick Blackwell; Conductor, James Conlon; Director, Darko Tresnjak; Chorus Director, Grant Gershon; Choreographer Peggy Hickey; Costume Designer, Linda Cho; Scenic Designer, Alexander Dodge; Lighting Designer, York Kennedy; Projection Designer, Aaron Rhyne.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/046-P%20Ghosts%20Samira%20bigger.png

image_description=Scene at the Turkish Embassy (Act I) [Photo by Craig Matthew]

product=yes

product_title=LA Opera Revives The Ghosts of Versailles

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Scene at the Turkish Embassy (Act I)

Photos by Craig Matthew

Syracuse Opera’s ‘A Little Night Music’ a little too lean

By David Abrams [CNY Café Momus, 6 February 2015]

There’s little point in arguing whether Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music is, at its core, a musical or an operetta. It could be either, depending on the resources put into the production effort. Syracuse Opera chose to trumpet the work as “operetta,” not musical theater, during the weeks leading up to Friday’s premiere. And that label calls into question the company’s use of a chamber-sized pit orchestra.

February 12, 2015

La Traviata, ENO

Ben Johnson and Anthony Michaels Moore repeated their performances as Alfredo and Giorgio Germont and the smaller cast members were the same. The production was revived by Mika Blauensteiner who was the assistant director on the original production. The biggest changes were that the conductor was now Roland Böer, and the title role was sung by the American soprano Elizabeth Zharoff.

Konwitschny’s view of the opera is stripped down, anti-romantic and not a little dystopic. The opera is cut so that it plays for just under two hours, without an interval. The biggest loss is the party entertainment in Act 2, scene 2, but throughout Konwitschny has tightened the focus of the work so that Violetta and Alfredo are even more the focus of attention. The advantage of losing the intervals is the concentration of focus, and the way the ends of scenes bled into the next notably the prone party guests from act two, scene two, crawling away from Violetta at the opening of act three.

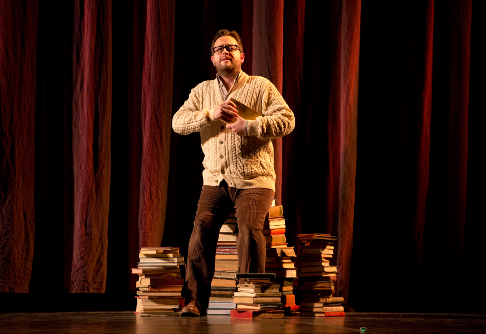

And the whole piece plays out against sets of red curtains, effectively this opera is set in the theatre. As the action progresses, curtains are opened so that more of upstage is revealed, till the very end when on a bare stage Elizabeth Zharoff’s Violetta walked through the final curtain (an elegant metaphor, or a corny gag depending on your point of view). There are no props beyond a chair and pile of books, no stage setting, no frippery, no big frocks. The focus is on Violetta, and Zharoff was on-stage virtually the whole time.

Ben Johnson as Alfredo

Ben Johnson as Alfredo

Konwitschny’s Violetta is a woman who seems to be acting all the time. Only at the very end does she take her wig off (a different one in each scene) to reveal her natural hair; her treatment by the Doctor (Martin Lamb) seems to involve considerable amounts of drugs &mdash: is she ill, or does she have a serious habit? She dies alone, on-stage, with the remaining cast members Anthony Michaels Moore, Martin Lamb, Valerie Reed (Annina) and Ben Johnson in the auditorium. So the focus is very much on the singer. In the 2013 production, Corinne Winters made a coruscating impression as Violetta, and if Zharoff did not quite match those memories she certainly took control of the role and blasted us with emotion.

Zharoff has a surprising sounding voice. Looking through her resume she sings lyric roles with quite a bit of coloratura, offering Violetta, Marguerite (Faust), Pamina, and Constanze. But in the theatre her voice creates a big, vibrant impression partly because she has a significant and constant vibrato. I have to confess that I rather prefer a cleaner voice in this repertoire, but Zharoff made it work. She was adept at thinning her voice out at the top and producing a fragility which was essential to her portrayal. The fioriture in act one’s Sempre libera were confidently done, she was expressive and there was never a sense of having to simply ‘get through’ the act. But with such a vibrato laden tone, inevitably the passagework does get occluded somewhat. This was a performance which grew. I felt that Zharoff was still finding her feet in act one, and there were tuning problems which will disappear. Dite alla giovine was beautifully crafted, but it was the final act which really moved, On a bare stage, with the action focussed on Violetta alone, Zharoff really held the stage and we appreciated the full emotional depth of her high-wattage account of the role.

Ben Johnson’s voice seems to have developed an even finer expressive sheen to it than before, this was one of the most beautifully crafted accounts of the role of Alfredo that I have heard. To a certain extent the timbre was at odds with the visual image, of the cardigan wearing nerd. But the very self-absorbed nature of this Alfredo certainly gets over some of the plots more ridiculous corners, you could well believe Ben Johnson’s Alfredo not noticing obvious things like Violetta selling up. My emphasis on the beauty of timbre should not blind you to the emotional depth of Johnson’s performance too. At the moment you are still aware of Johnson’s careful control, you never felt he was in danger of letting go the way the greatest exponents of this role have done. But Johnson’s achievement as young artist is superb and I look forward to hearing more of him in this repertoire (he will be singing Carlo in Verdi’s Giovanna d’Arco at this year’s Buxton Festival).

Matthew Hargreaves as the Baron, Elizabeth Zharoff as Violetta, and Ben Johnson as Alfredo

Matthew Hargreaves as the Baron, Elizabeth Zharoff as Violetta, and Ben Johnson as Alfredo

Anthony Michaels Moore offered one of the most beautifully sung accounts of the role of Giorgio Germont that I have ever heard. Ramrod stiff of back, and clearly unable to communicate properly with his children, this was less of an ogre than a highly inhibited man. Sometimes I wished for a performance that was more rough-hewn, but listening to Michaels Moore’s sense of control and intelligent understanding of Verdi’s vocal line was a joy in itself. For much of his scene with Zharoff in act two, I had my eyes closed. Konwitschny brings Giorgio on with a young girl, the daughter to whom Giorgio refers, and too often during the Violetta/Giorgio duet it was the young girl who was the focus of attention. I felt I was being manipulated and did not like it. This is particularly true when, after getting worked up Giorgio strikes the girl. An act which leads directly to Violetta’s giving an and Dite all giovine, but surely a falsification of the emotional core of the scene.

The smaller characters were all strongly etched, even through the cuts. Matthew Hargreaves made a strong Baron and very much a nasty piece of work, Clare Presland was a party-girl Flora and Valerie Reid was a capable and sympathetic Annina.

Seeing the production again, it struck me how hard edged everything is. None of the subsidiary characters are likeable and the party scenes are positively toxic, why would anyone put up with these friends. They make Ben Johnson’s nerdish and inhibited Alfredo look positively normal. What also struck me this time was the sense of being manipulated; as the production has become more familiar I could sense more the way Konwitschny was arranging things so that we had to react in a certain way.

The production was sung in Martin Fitzpatrick’s modern sounding translation, and diction was excellent.

Conductor Roland Böer is music director of Cantiere Internazionale d’Arte in Montepulciano. He conducted a finely controlled account of the score. His tempi were on the moderate to fast side, and this was very modern Verdi without any of the sort of indulgence we might sometimes expect. Böer did allow room for the singers, and his tempi were not overly rigid, but his relaxations and rubatos were relatively small scale. He avoided being overly brisk, but I did want him to linger a little more, to love the music a bit more. That said, he drew a very finely expressive performance from the orchestra with some lovely spun out lines.

This is not a neutral production of the opera (but then no production is), and it certainly explores the sorts of contemporary issues which interested Verdi. The composer wanted La Traviata to be a contemporary opera, something that can get lost in a big frock production. Konwitschny’s approach raises all sorts of issues about what it is to be true to the composer’s intentions. But he places a lot of responsibility on his cast and here, the revival cast were on fine form and created a thrilling evening of musical theatre that left you going home wondering and thoughtful (as well as humming Sempre libera).

Robert Hugill

Cast and production information:

Violetta: Elizabeth Zharoff, Alfredo: Ben Johnson, Giorgio: Anthony Michaels Moore, Flora: Clare Presland, Gason: Paul Hopwood, Baron: Mathew Hargreaves, Marquis: Charles Johnson, Doctor: Martin Lamb, Annina: Valerie Reed, Servant: David Newman, Messenger: Paul Sheehan, Girl: Aven Alqahdi/Emily Speed. Director: Peter Konwitschny, Revival Director: Mika Blauensteiner, Designer: Johannes Leiacker, Lighting designer: Joachim Klein, Translation: Martin Fitzpatrick. Conductor: Roland Böer. English National Opera, London Coliseum, 2nd February 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ENO%20La%20traviata%202015%2C%20Elizabeth%20Zharoff%203%20%28c%29%20Donald%20Cooper.png image_description=Elizabeth Zharoff as Violetta [Photo by Donald Cooper courtesy of English National Opera] product=yes product_title=La Traviata, ENO product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id=Above: Elizabeth Zharoff as ViolettaPhotos by Donald Cooper courtesy of English National Opera

February 8, 2015

Idomeneo in Lyon

Totally confused by the Uzi bearing thugs [sigh] that herded distressed costumes on and off the stage, and, well, by the mezzo-soprano in concert dress standing extreme stage right (singing Idamante while voiceless mezzo-soprano Kate Aldrich walked the role on the stage) luckily I found the insert in the program book at the intermission that would enlighten me. The Opéra de Lyon had come to a belated conclusion that this new production by German director Martin Kušej (koooo-shy) might not make any sense.

Mr. Kušej’s dramaturg, Olaf A. Schmitt, explained that Idomeneo lives in fear of the future established by the diminished chords of his Act II aria “Fuor del mar.” Furthermore that the D major tonality of this aria was the same as the first chords of the overture thereby establishing Idomeneo as the sovereign. The aria is old-fashioned, the da capo form, and this proves that Idomeneo is captive of an out-of-date, unchangeable system.

To make a long story short, Idamante is also captive, both the old and new sovereigns hold their repressive power by embracing and exploiting a religious system. This is proven because D major is obviously Idomeneo’s tyranny, and then this tonality is adopted by Idamante in his supplications to be sacrificed to the gods in order to save his people.

This rationale seems to have been constructed so that in the dénouement of the opera the resignation of Idomeneo may occur with him alone on the stage. He is writhing in emotional agony in what must now be a prison (the set was a revolving platform of repeating doors). He in fact has lost his power, and there has been no sacrifice. Furthermore the old, unchangeable order remains. The final celebratory chorus is grimly sung by drably dressed (old “Eastern-bloc”) choristers. At least they were not playing with the little fishes that had earlier served to demonstrate calmed waters.

This sea monster of the first act gave way to the playful little fishes of the second act mentioned above

This sea monster of the first act gave way to the playful little fishes of the second act mentioned above

Did I get this right? More or less?

Well, it might have worked, and in fact the final Idomeneo scene was a powerful coup de théâtre that might have been convincing theater had the Opéra de Lyon provided a persuasive cast of singers, and more than perfunctory conducting.

As it was the voiceless Kate Aldrich was the only convincing presence on the stage, this fine artist here acted this travesty role with surprising masculine force (she physically attacked Idomeneo when she wanted him to do her bidding — note how this supports Mr. Kušej’s concept).

Mme. Aldrich in fact had the flu and could not sing (the flu had been passed around the cast, evidently you never knew who would be down for which performance). Her words were beautifully sung by Russian mezzo Margarita Gritskova who sometimes could not help becoming dramatically involved (musically). But we needed the artistic maturity of la Aldrich to make Idamante alive.

The balance of the cast, all fine singers, did not have the force of character or the physical presences to make a convincing case for this off-the-wall, politically naive, theatrically forced concept. It was a long, very long evening.

We can only shutter at our premonitions of what Mr. Kušej and Mr. Schmitt may attempt with Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail at the Aix Festival this coming summer.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Idoménée: Lothar Odinius; Idamante: Kate Aldrich; Ilia: Elena Galitskaya; Electre: Ingela Brimbert; Arbace: Julien Behr; Voix de Neptune: Lukas Jakobski. Orchestre et Choeurs de l’Opéra de Lyon. Conductor: Gérard Korsten; Mise en scène: Martin Kušej; Collaborateur artistique à la mise en scène: Herbert Stöger; Dramaturgie: Olaf Schmitt; Décors: Annette Murschetz; Costumes: Heide Kastler; Lumières: Reinhard Traub. Opéra Nouvel, Lyon, February 1, 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Idomeneo_Lyon1.png

product=yes

product_title=Idomeneo in Lyon

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above:Elena Galitskaya as Ilia, Kate Aldrich as Idamante [all photos copyright by Jean-Pierre Maurin, courtesy of the Opéra de Lyon]

Der fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera

However, when it comes to productions, I cannot help but think that it increasingly obscures rather than aids understanding. Where, after all, has the production been in the mean time? Hades?

More to the point, though, I think we tend to underestimate, at least in many cases, the role of the revival director. (The often problematical ‘repertory system employed in many German theatres is a different matter; I am thinking here of theatres operating according to what is essentially a stagione principle.) In this particular case, Daniel Dooner seemed to make a better job of ‘reviving’ Tim Albery’s production of The Flying Dutchman than Albery had made of presenting it in the first place. Or was it a matter of a better-adjusted cast? The one does not exclude the other, of course; indeed, the two are not unlikely to have been related.

Adrianne Pieczonka as Senta

Adrianne Pieczonka as Senta

The 2009 ‘premiere’ had greatly disappointed, eschewing Wagner’s interest in myth for a form of dreary realism, quite out of place and seemingly determined — understandably, I suppose, given its misguided premise — to downplay the figure of the Dutchman as much as possible. It did not make sense and it did not involve. The irritants have not entirely gone away, especially during the third act, in which the drunken antics of the townsfolk — here, it must be admitted, very well portrayed by the chorus and Ed Lyon’s Steersman — still seem to be far too much ‘the point’. But they are counterbalanced and, on occasion, supplanted by a stronger sense of the Dutchman’s plight and its consequences. ‘Revival’ seems something of a misnomer for a hugely beneficial shift of emphasis, unless we mean that the work itself experiences something of a revival — which, I think, it does, at least vis-à-vis its outing six years ago.

Bryn Terfel’s performance certainly seems less ‘revived’ than brought to life for the first time. In 2009, he had disappointed perhaps even more than the production. There were still occasional unwelcome tendencies towards crooning, especially towards the end of his first-act monologue. They were occasional, though, and Terfel followed up his excellent Proms Walküre Wotan — almost certainly the best thing I have heard him sing — with a world-weary Dutchman who, moments of tiredness aside, yet had powers of something mysterious in reserve for when the moment called. This time the words were not only crystal-clear- always a formidable weapon in Terfel’s armoury — but invested with a true sense of dramatic meaning.

Adrianne Pieczonka’s Senta was at least his equal in terms of dramatic commitment; arguably, this thrilling, unmistakeably womanly performance went still further. I say ‘womanly’ since this was a reading that seemed thoroughly in keeping with a recent, welcome understanding of Wagner’s earlier heroines to be more than virginal male projections. Peter Rose made the most of Daland’s character: venal, yes, but also looking to the future for his daughter as well as himself. Michael König offered an alert Erik, Catherine Wyn-Rogers a properly maternal Mary. Often threatening to steal the show was Lyon’s Steersman, as fine a portrayal as I can recall: an everyman, perhaps, but one with agency, for which verbal and musical acuity alike should be thanked.

Ed Lyon as the Steersman

Ed Lyon as the Steersman

Andris Nelsons’s conducting for the most part brought out the best from the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. However, the interpretation as a whole did not seem quite to have settled; I strongly suspect that subsequent performances will impress more. The Flying Dutchman is a difficult work to bring off; despite fashionable claims for overplaying its (alleged) antecedents, it really works best as a whole when viewed, as Wagner would later do so, in the light of his subsequent musico-dramatic theories. Senta’s Ballad may not originally have been its dramatic kernel, but it has become so. Nelsons sometimes seemed unclear which way to tilt, especially during a drawn-out Overture, whose extremes of tempo threatened to negate any sense of unity. There were sluggish passages elsewhere: not hugely drawn out, but enough to make one wonder where the music was heading. The third act emerged tightest, and may well be a pointer to what audiences will hear later in the run. Choral singing was not entirely free of blurred edges, but there was much to admire, and again, I suspect that slight shortcomings will soon be overcome. This remained an impressive ‘revival’, all the more so, given its manifest superiority to the production’s first outing.

Mark Berry

Cast and production information:

The Dutchman: Bryn Terfel; Senta: Adrianne Pieczonka; Daland: Peter Rose; Erik: Michael König; Mary: Catherine Wyn-Rogers; Steersman: Ed Lyon. Director: Tim Albery: Revival director: Daniel Dooner; Set Designs: Michael Levine; Costumes: Constance Hoffmann; Lighting: David Finn. Chorus of the Royal Opera House (chorus master: Renato Balsadonna)/Orchestra of the Royal Opera House/Andris Nelsons (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Thursday 5 February 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/150202_0043%20hollander-Edit%20adj%20BRYN%20TERFEL%20AS%20THE%20DUTCHMAN%20%28C%29%20ROH.%20PHOTOGRAPHER%20CLIVE%20BARDA.png

image_description=Bryn Terfel as the Dutchman [Photo ROH/Clive Barda]

product=yes,

product_title=Richard Wagner: Der fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera, London, 5th February 2015

product_by=A review by Mark Berry

product_id=Above: Bryn Terfel as the Dutchman

Photos © ROH. Photographer: Clive Barda.

Iphigénie en Tauride in Geneva

(The Metropolitan and Seattle operas production directed by Stephen Wadsworth made it to Live in HD in 2011, and Robert Carsen’s 2006/2007 production was seen in San Francisco and Chicago.)

Gluck’s 1779 opera is a strange work, its libretto based on the 1757 tragedy of the same name by Claude Guimond de la Touche who had lifted entire sections of his play from earlier opera librettos based on Euripides’ tragedy Iphigenia in Taurus. La Touche was a Jesuit for 14 years, but left the order to be a full-time poet.

Gluck’s French operas are through-composed solemn events, well respected in the troubled times that lead to the French revolution. But Gretry’s comic operas of the same moment with spoken dialogues and pretty airs were far more pleasurable to audiences. Maybe some of Gretry’s easy sentimentality made its way into Gluck’s tragedy in the questionable relationship between Oreste and his companion Pylade. The 1997 Glimmerglass production simply made them lovers.

If the Carsen production was dismissed as euro-trash by a critic on Resmusica* (blood covered walls, all actors in black tunics), and the Wadsworth production according to the critic on The Classical Review seemed fearful that its audience might be bored (hyper-ventilating ballets) the new Geneva production hits the nerve center of the opera by listening to the music. The production hears its solemnity, participates in its individual dramas, and illustrates its pantomimes — there is not a single second when the stage action departs from the absolute directness of the storytelling. The Gluck genius was to make music drama, and it was pure in Geneva.

Alexey Tikhomirov as Thoas and male chorus puppets

Alexey Tikhomirov as Thoas and male chorus puppets

Gluck’s rediscovered tragic unities are relentlessly upheld in this production staged by German born, culturally French informed stage director Lukas Hemleb and Berlin born, European and American formed sculptor Alexander Polzin. There was no ballet. Instead every principal actor had his double. A life-size puppet. Every blacked-out chorister, forty of them, held his life-size, black puppet. The set, astounding in scope, was a heavy Greek theater made of huge cut stones. It too had its double, an equal construction that had been yanked from the earth, suspended above the stage for the final scenes of the opera.

The concept was to step back from action, to allow the actors react to the story and to themselves as the story unfolded. Body movement was abstractly linear, the movement of mechanically motivated limbs. The results were constructions of motion that mirrored the brutal melodic lines of this morbid tale, and the abruptness of harmonic and theatrical structure, The actors were the music, and it was always a theater, theater itself, that we saw, and felt, from within and from without.

For the third act there was no set, only a bowl in the middle of the stage into which plummeted bits of the presumed dead Oreste. Oreste was Italian baritone Bruno Taddia who in the second act had fallen away from his puppet double onto the forestage to deliver, alone, his agonized recitative “Dieux protecteurs de ces affreux rivages!” In the emotional immediacy, rare in Gluck, of this outburst he became his puppet, moving in jerks and spasms as if operated by an exterior force. This force was Gluck’s music and the tragic muse.

Bruno Taddia as Oreste, Steve Davislim as Pylade, their puppet doubles

Bruno Taddia as Oreste, Steve Davislim as Pylade, their puppet doubles

Mr. Taddia gave an over-the-top performance in warm, secure voice. His extreme performance was matched to a much lesser degree by the Iphigénie of Italian soprano Anna Caterina Antonacci (remember that this was a Maria Callas role so the stakes are already impossibly high). Her physical involvement was gratefully more measured (much more) than that of Mr. Taddia, her voice securely if not easily or opulently carved Gluck’s emotional recitative “Je cede à vos désirs” and air “D’une image, hélas, trop chérie!”

Oreste’s companion Pylade was sung by Australian tenor Steve Davislim. At the final performance, perhaps exhausted from the run of six performances this fine artist was unable to take his air “Divinité des grandes âmes” to its melodic heights, though it was otherwise sung in beautiful voice. Pylade, unlike Oreste and Iphégenie is tormented only by human love (for Oreste), and not by divine forces.

As the tyrant king Thoas bass Alexey Tikhomirov threatened appropriately if without distinction compared to the powerful performances of Iphigénie, Oreste and Pylade.

The proceedings were presided over by Dresden born conductor Hartmut Haenchen, who magnificently managed the score, integrating its orchestral, choral, balletic and solo voices into the tragedia messa in musica that Gluck imagined. It must be said that one did not hear the orchestra separately from seeing the stage. Gesamtkunstwerk indeed.

Michael Milenski

*"Euro-trash" was the term used by Resmusica, a French language website.

Casts and production information:

Iphigénie: Anna Caterina Antonacci; Oreste: Bruno Taddia; Pylade: Steve Davislim; Thoas: Alexey Tikhomirov; Diane: Julienne Walker; Un Scythe: Michel de Souza; 1ère Prêtresse: Mi-Young Kim; 2ème Prêtresse: Marianne Dellacasagrande; Une femme grecque: Cristiana Presutti; Le Ministre du sanctuaire: Wolfgang Barta. Chœur du Grand Théâtre de Genève, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. Conductor: Hartmut Haenchen;

Mise en scène: Lukas Hemleb; Décors: Alexander Polzin; Costumes: Andrea Schmidt-Futterer; Lumières: Marion Hewlett; Collaboration chorégraphique: Joanna O’Keeffe. Grand Théâtre de Genève, February 4, 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Iphigenie_Geneva1.png

product=yes

product_title=Iphigénie en Tauride in Geneva

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Anna Caterina Antonacci as Iphigénie, her puppet double, female chorister puppet [all photos copyright Carole Parodi, courtesy of the Grand Théâtre de Genève]

February 6, 2015

Tristan et Isolde in Toulouse

But ten years later, 1952, Kirsten Flagstad sang Isolde in Toulouse, in German of course. The then director of the opera, tenor Louis Izar was a celebrated Ring Mime, and the then mayor of Toulouse, Raymond Badiou himself was big friends with Wieland Wagner. Toulouse had become known as Bayreuth-sur-Garonne (the river that passes through Toulouse).

Tristan und Isolde however disappeared from the Theatre du Capitole after the 1972 production (Herbert Becker and Klara Barlow), not to reappear until 2007 in a production by Nicholas Joël, remounted just now with American tenor Robert Dean Smith as Tristan and Portuguese soprano Elisabete Matos as Isolde. At the first intermission a tall gentleman strode through the bar loudly proclaiming in hoch British that it was “better than Bayreuth.”

Elisabete Matos as Isolde

Elisabete Matos as Isolde

Most of us have not been to Bayreuth so we cannot know, but it was indeed certain that this Tristan was already an ultimate experience, and that was well before the Tristan delirium that was the musically shattering climax of the performance. The conductor was 62 year old, Leipzig born conductor Claus Peter Flor, known in the U.S. as the guest conductor of the Dallas Symphony (1999-2008). While no stranger to the opera pit his program booklet biography reveals him to be primarily an orchestral conductor.

The maestro concentrated his attention on the famed Toulouse orchestra, here strings 12/12/10/8/6, triple winds but 6 horns, with the full backstage complement of 6 horns and 3 each trumpets and trombones. There were two harps for the mesmerizingly beautiful second act love tryst, Brangäne gorgeously intoning her admonitions. The exquisite minor third trills of the clarinets had already laid the foundations for Wagner’s eternally quivering passions.

If seventy six orchestra players and two heroic voices can be said to whisper this was the intimacy of the second act. In fact the first act as well was developed in personal rather than mythical voices, the oboes, flutes and English horn working to color Isolde’s despair, Brangäne’s (in black spectacles) deception, and Tristan’s indifference. The first act love duet was surprise more than passion, preparing us for the musico-psychological treatise on nineteenth Romantic century love that was the second and third acts.

Metteur en scène Nicholas Joël hovered between the real and the magical, his production sometimes staged and sometimes semi-staged. Wagner’s first act sailors were 8 supernumeraries [figurants] (the chorus was hidden) in formal concert dress (tails) who reappeared at the end of the opera as King Mark’s soldiers. The second act swords drawn, Melot’s thrust was symbolically received, Tristan fell, isolated on the other side of the stage. At the end of the opera Kurvenal’s thrust was symbolic, not actually touching the jealous traitor, Tristan’s friend Melot.

Elisabete Matos as Isolde, Robert Dean Smith as Tristan

Elisabete Matos as Isolde, Robert Dean Smith as Tristan

Finally Tristan lying dead, Isolde rose, walked down stage center (the soldiers, the dead Kurvenal and Melot as well as King Mark had all slipped off stage). This was the liebestod for the brilliant-red gowned Isolde, in concert now. It was, as intended, a panegyric to love. It was not the end of an opera.

The coup de théâtre occurred at the beginning of the third act. The curtain rose on the wounded Tristan hanging over the front point of the now sharply elevated triangular center platform (the stage set was three platforms that in the first act had moved up and down as the wave motions of the sea). Arms and head dangling into the emptiness high above the orchestra pit Tristan remained there for maybe ten minutes (through the English horn solo and Kurvenal’s scene with the shepherd).

He awoke to deliver his great mad scene, always perched on this point, and somehow balanced philosophy with emotional rawness, rationality with irrationality. It was in this delirium that the maestro let loose with the great (and here the biggest) orchestral climaxes of the entire opera. It was the cerebral drama of this extended tract that made the Joël concept of Tristan become the masterpiece Tristan und Isolde is said to be — we both understood and felt love as if we were a Romantic poet.

Robert Dean Smith is of strong, secure and virile voice, his dramatic and musical intelligence apparent, well able to effect the considerable challenges of this mise en scène. He has already established himself as one of the important Tristans of our day on the world’s important stages. Elisabete Matos has performed Isolde once before, in 2011 at Barcelona’s Liceu. In the prime of voice she is able to soar to and beyond the enormous climaxes never compromising her richly colored sound. Her familiarity with the great Verdi dramatic soprano roles lies under her Isolde, the liebestod far more intimate and personal than heroic. The vast emotional vistas and philosophic scope of this production were perfectly realized in her performance.

German mezzo-soprano Daniela Sindram well fulfilled the requirements of this production, her Brangäne a very present figure in Wagner’s conceptual preparations. Costumed in white German baritone Stefan Heidemann made a very present Kurvenal, his rather loud, darkly colored voice a welcomed contrast to the refined Heldon tenor tone of Robert Dean Smith. German bass Hans-Peter König was a perfunctory King Mark.

Conductor Claus Peter Flor created this remarkable musical vision that fulfilled the complex theatrical vision of Nicholas Joël. The stage and pit were remarkably synchronized, the maestro focused on his orchestra, the stage very sure of itself.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Tristan: Robert Dean Smith; Isolde: Elisabete Matos; King Mark: Hans-Peter Koenig; Kurwenal: Stefan Heidemann; Melot: Thomas Dolié; Brangaene: Daniela Sindram; Un Jeune matelot / Un Berger: Paul Kaufmann; Un Pilote: Jean-Luc Antoine. Choeur du Capitole, Orchestre national du Capitole. Conductor: Claus Peter Flor; Mise en scène: Nicolas Joel; Scenery and costumes: Andreas Reinhardt; Lighting: Vinicio Cheli. Théâtre du Capitole, Toulouse, February 1, 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tristan_Toulouse1.png

product=yes

product_title=Tristan und Isolde in Toulouse

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Robert Dean Smith as Tristan, Elisabete Matos as Isolde [all photos copyright Patrice Nin, courtesy of the Théâtre du Capitole]

February 5, 2015

Arizona Opera presents Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin