March 31, 2015

Fedora in Genoa

If the operas of Giacomo Puccini are the standard bearers for operatic verismo, the stories of Giovanni Verga hold that place in literature. And there was the Casa Sonzogno [an Italian opera publishing house destroyed by a WWII bomb] that sponsored the famous 1888 competition in which Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana (libretto on a story by Verga) took first place and became the emblematic moment of verismo.

A now forgotten opera by Umberto Giordano, Mala Vita (An Unhappy Life) took sixth place (out of 73 entries) in that competition. Mala Vita is the grizzly tale of a tuberculosis stricken prostitute and was in fact performed in 1890. Note that Puccini’s La boheme premiered in 1896.

Meanwhile in those same years Giordano saw the famed French tragedienne Sarah Bernhardt as Fédora and Puccini saw la Bernhardt as La Tosca, eponymous plays by Victorien Sardou. This facile playwright gave the public what it wanted — intense moments for dramatic outbursts against a colorful historical backdrop, with no demand that the public wade through motivations or contexts.

The operas Fedora (1898) and Tosca (1900) are very similar pieces. Both are three brief acts, both are about a powerful female in a politically volatile climate, both end in suicide. But where Puccini lyrically expands the personalities of his protagonists into rich, post romantic music, Giordano stays very close to the action making his story an intense, fast moving single action. Lyric moments are brief and fiery, generally less than a couple of minutes, the music looking forward to the more direct, minimalist tendencies of twentieth century music drama.

The new production of Fedora in Genoa attempts to bring historical depth to the Sardou play. Stage director Rosetta Cucchi and her set designer Tiziano Santi created a huge, full stage window looking upstage onto an imaginary plain where actions went well beyond the direct, let us say brutal happenings taking place downstage — Fedora’s mortally wounded fiance is brought on stage to die (Act 1), Fedora falls in love with the murderer and betrays him to the police (Act II), Fedora regrets this and kills herself (Act III).

The contexts for these acts played out in this imaginary space were visually splendid if rather confusing. There were battle fields that made us think of the of the 1916 revolution far more than remind us of the the specific context of Sardou’s play — the 1881 assassination of Alexander II. This impression was reinforced by a tableau portrait by costumed supernumeraries of the Czar’s family that made us think of the 1918 murders of the Romanov family. [See lead photo.]

To complicate these contexts the whole opera was played as a flashback — a duplicate Loris (as the by now very aged assassin of Fedora’s fiance) sat on the stage apron for the entire opera (including intermissions) only to walk into the imaginary plain in the final moments of the opera for a brief encounter/recognition of a young goatherd, perhaps the youngest son of the assassinated Ivan the Terrible. Or what?

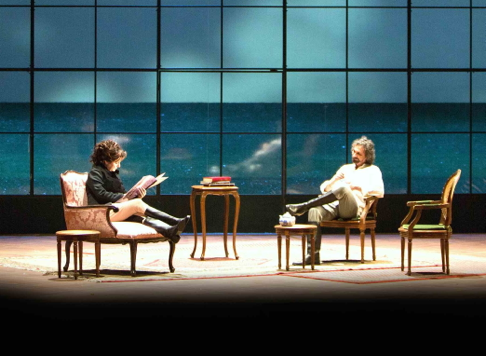

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, Fabio Armiliato as Loris, Act III

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, Fabio Armiliato as Loris, Act III

Of course none of this really mattered because Giordano’s opera is about the immediate passions of a rich Russian aristocrat, the widow Fedora. Fedora was sung by 56 year-old diva Daniela Dessi. Loris, the assassin of her fiancé and a suspected nihilist, was sung by 59 year-old Fabio Armiliato (both ages determined by birth dates found on the internet). These two formidable artists are partners in real life. Both were in good voice, but voices no longer capable of carving Giordano’s unique vocal exclamations in easy tones, relying instead large, uncolored wooden sounds. It was obvious that both artists knew well and once embodied the vocalism and the musicality of the style, and that they were working hard and honestly to achieve it again. The result was compromised.

Fedora’s friend Olga was enacted by Russian soubrette Daria Kovalenko, ably creating the intended overbearing presence of such a Slavic personality. Pianist (in real life) Siriio Restani, the Carlo Felice house pianist, had his moment in the spotlight giving the Act II solo concert against which Fedora and Loris declare their love in a precious scene that would find itself perfectly at home in the shallow sensualism and sensationalsim of Italian decadentismo, a parallel style to gritty verismo.

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, male supporting cast

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, male supporting cast

The myriad of smaller roles were executed with typical Italian panache.

The greater impact of the evening was lost by a late start for the brief first act, explained somewhat by an announcement about some casting problem, then there was an overly long first intermission. After the brief second act there was a very extended intermission (one can assume there was some backstage drama, left unexplained). The orchestra players became impatient and began stamping their feet, and finally we were given the brief third act. The far less-than-sold-out house gave la Dessi a huge ovation.

The pit at the Teatro Carlo Felice does not offer a great presence to an orchestra. None the less it was obvious that we were in fine musical hands. Young conductor Valerio Galli, already a verismo specialist, made the most of Giordano’s sophisticated score over this too long evening.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Fedora: Daniela Dessì; Loris: Fabio Armiliato; De Siriex: Alfonso Antoniozzi; Olga: Daria Kovalenko; Dimitri: Margherita Rotondi; Desiré: Manuel Pierattelli; Il Barone Rouvel: Alessandro Fantoni; Cirillo: Luigi Roni; Boroff: Claudio Ottino; Gretch: Roberto Maietta; Lorek: Davide Mura; Nicola: Matteo Armanino; Sergio: Pasquale Graziano; Michele: Roberto Conti; Boleslao Lazinski: Sirio Restani. Chorus and Orchestra of Teatro Carlo Felice. Conductor: Valerio Galli; Metteur en scène: Rosetta Cucchi; Set Design: Tiziano Santi; Costumes: Claudia Pernigotti; Lighting: Luciano Novelli. Teatro Carlo Felice, Genoa, March 25, 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Fedora_Genoa1.png

image_description=Daniela Dessi as Fedora, Act II [Photo courtesy of Teatro San Carlo]

product=yes

product_title=Fedora in Genoa

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Daniela Dessi as Fedora, Act II

Photos courtesy of the Teatro San Carlo

March 30, 2015

The Marriage of Figaro, LA Opera

Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais wrote Le Mariage de Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) as a sequel to his Le Barbier de Seville, (The Barber of Seville). In his preface to the play, the author notes that it was the Prince of Conti who requested him to continue the story. Figaro, who actually represents the author, advocates revolution much more avidly in the play than in the opera. The play’s Paris premiere on April 27, 1784 was an enormous success. It ran for sixty-eight consecutive performances, earning higher box-office receipts than any other eighteenth century French play. Sources say that the author donated his profit to charity. The first English production opened late that same year and ran into early 1785.

Renee Rapier as Cherubino and Guanqun Yu as the Countess

Renee Rapier as Cherubino and Guanqun Yu as the Countess

Beaumarchais was a great deal more than just a playwright; he was also an arms dealer who was active in both the French and American Revolutions. Before 1778, when France officially entered the American war, the writer saw to the delivery of munitions, money and supplies to the colonists. The Central Intelligence Agency still has a file on him that was not declassified until 1993. It can be seen here.

On March 26, 2015, Los Angeles Opera presented Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro), the libretto of which writer Lorenzo da Ponte based on Beaumarchais’ Le Mariage de Figaro. The Ian Judge production featured jewel-colored box sets by Tim Goodchild that threw the voices out into the hall. Only for the finale did the set open up on to a garden that filled the whole stage and at the very end featured actual fireworks. The eclectic costume designs by Deidre Clancy did not set the action in any particular era.

Roberto Tagliavini was a magnificent Figaro who commanded the stage while out manouvering the Count. Tagliavini has a stentorian bass baritone voice with a robust delivery. He is a valuable asset to the company, as is Operalia winner Guanqun Yu who sang the Countess. She sang with radiant, creamy tones and impressive technical ability including an exquisite trill. As the Count, Ryan McKinny was a strict taskmaster who thought no underling should notice his foibles. He sang with dark, vigorous sounds. Pretty Yende was a piquant Susanna who paced herself well for this long role. She sang her last act aria with floods of lustrous tone. Renée Rapier’s Cherubino was a bubbly teenager who kept the action moving swiftly. His girlfriend, Barbarina, portrayed by So Young Park, sang her aria with radiant silvery tones. I understand she will sing the Queen of the Night next year.

Robert Brubaker as Don Basilio, Lucy Schaufer as Marcellina and Kristinn Sigmundsson as Doctor Bartolo

Robert Brubaker as Don Basilio, Lucy Schaufer as Marcellina and Kristinn Sigmundsson as Doctor Bartolo

Bass Kristinn Sigmundsson was a lawyerly but lovable Dr. Bartolo who sang his patter with speed and accuracy. As Marcellina, who was once his lover, Lucy Schaufer was the embodiment of a difficult 1950s superdiva, and she sang at least as well. Joel Sorensen was a wonderfully amusing notary, Philip Cokorinos a convincing drunk, and Robert Brubaker a malicious Don Basilio. Chorus Director Grant Gershon’s singers sang with clear diction as they communicated Mozart’s subtle nuances.

One of the best reasons for attending opera in Los Angeles is the conducting of James Conlon. His Mozart is always magical and this performance was no exception. His tempi were fresh and his interpretation revealed sonorities that are occasionally missed. Los Angeles Opera brought us a fabulous cast and they sang one of the best renditions of The Marriage of Figaro that I have head in quite a few years.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Figaro, Roberto Tagliavini; Susanna, Pretty Yende; Count Almaviva, Ryan McKinny; Countess Almaviva, Guanqun Yu; Cherubino, Renée Rapier; Doctor Bartolo, Kristinn Sigmundsson; Marcellina, Lucy Schaufer; Don Basilio, Robert Brubaker; Don Curzio, Joel Sorensen; Barbarina, So Young Park; Antonio, Philip Cokorinos; Conductor, James Conlon; Director, Ian Judge; Scenery Designer, Tim Goodchild; Costume Designer, Deirdre Clancy; Lighting Designer, Mark Doubleday; Chorus Director, Grant Gershon; Original Choreographer, Sergio Trujillo; Choreographer, Chad Everett Allen.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Figaro_002-Pb.png

image_description=Roberto Tagliavini as Figaro and Pretty Yende as Susanna [Photo: Craig T. Mathew / LA Opera]

product=yes

product_title=The Marriage of Figaro, LA Opera

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Roberto Tagliavini as Figaro and Pretty Yende as Susanna

Photos: Craig T. Mathew / LA Opera

March 29, 2015

Beyond Falstaff in ‘Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor’: Otto Nicolai’s Revolutionary ‘Wives’

By John R Severn [Music & Letters, February 2015]

This article explores how Otto Nicolai and Salomon Hermann von Mosenthal’s Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (Berlin, 1849) might contribute to an alternative reception history of Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor, in which the play’s unusual features—in particular the central role it gives to female agency, family life, and the natural world—are positively valued.

Scheherazade.2: Violin, cimbalom and female empowerment star in John Adams’ new work

By Rebecca Lentjes [Bachtrack, 28 March 2015]

John Adams has been known to draw inspiration from American writers—Walt Whitman, E. Annie Proulx—for his works, but his most recent composition, Scheherazade.2, is presented as a musical sequel of sorts to the sprawling Middle Eastern collection One Thousand and One Nights. Mr Adams explained at the piece’s world première on Thursday…

The Tempest Songbook, Gotham Chamber Opera

A co-production with The Martha Graham Dance Company, the evening’s program was directed and choreographed by Luca Veggetti. The narrative of The Tempest is so deliberately surrealistic that I found the resistance of narrative in the program engaging, rather than the reverse. To this Shakespeare aficionado, the interpolations by Dryden sounded strange, but it was these interpolations that much of the 1712 incidental music, attributed to Henry Purcell, was designed to set. The Purcell and Kaija Saariaho‘s 2004 Tempest Songbook for soprano, baritone and period instrument ensemble intertwined in fascinating ways. In this version, it was receiving its world premiere, and I loved the textures of harpsichord, recorder, and archlute (archlute!) in Saariaho’s unconventional harmonies. It was at Saariaho’s suggestion that the two pieces appeared thus interwoven, and the dialogue between them was musically rich and intellectually stimulating.

The creative set design was by Jean-Baptiste Barrière. It seems almost a misnomer to call it minimalist, so richly multivalent was the globe that hung elegantly suspended by ropes reminiscent of the fated ship’s rigging. Light projections onto it were skillfully used to evoke globes of the kind so beloved at the courts of early modern Europe, with seas and continents shifting under maps of the zodiac, charts of the stars. Images of the singers and dancers also often appeared there, mirroring and amplifying the action on the stage. The music of Purcell and Saariaho appeared in alternate sections throughout most of the evening, with a suite of Saariaho’s songs in the second half of the hour-long program, which was performed without intermission. From a fairly straightforward presentation of the initial scenes of The Tempest, with the panic and anger of the Bosun, and the terror and sorrow of Miranda, the structure became increasingly impressionistic, with Saariaho’s music allowing Ariel and Caliban (for instance) much more time than the source material gives them.

Eight musicians of the Gotham Chamber Opera orchestra played with admirable verve and versatility under the leadership of Neal Goren. Transitions between the baroque and the contemporary never felt rough or forced. I enjoyed not only the brio with which they handled the moods of the Purcell, from ceremonial to cheerful, but the skill with which they explored the rich and varied textures of the Saariaho. This was especially notable in the Bosun’s Lament, where the orchestra musicians echoed the “Roaring, shrieking, howling” of the spirits described by the increasingly desperate seaman. As we moved to Prospero’s isle, the dancers began to take turns in center stage, sometimes mirroring the movements of the singers, sometimes giving bodily expression (with skill that took my breath away) to the emotions they voiced. In acting for Ariel and Caliban, respectively, Peiju Chien-Pott and Abdiel Jacobsen gave performances of extraordinary intensity.

Soprano Jennifer Zetlan and bass-baritone Thomas Richards faced the challenges not only of singing music in two very different styles, but of voicing a diverse array of characters: Prospero and Miranda; Ariel and Caliban; the bosun and the god of the sea. Zetlan handled the vocal lines and the emotional arc of Miranda’s Lament (Saariaho) well, but it was as the sprite Ariel that she really shone, both in the magnificent self-declaration (combining several of the speeches to Prospero) and the exquisite “Full fathom five...”, which was the penultimate section of the program. This was my first time hearing Thomas Richards, and I was very favorably impressed both by his stage presence and by his full-voiced, plangent singing. He sang both the Saariaho and the Purcell with great expressivity. My Musicologist Roommate, who accompanied me, wanted more ornamentation, but Richards made very fine use of vocal coloring. Saariaho’s setting of Caliban’s Dream I thought especially lovely. In a traditional production of Shakespeare’s play, the optimistic concluding ensemble (recording here) would seem strangely inopportune, but here, it seemed only fitting. The program will be given two more performances in this run, and could provide an interesting addition to the repertoire of small companies.

This review first appeared at Opera Obsession. It is reprinted with permission of the author.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/2015-2728_0289.png image_description=Scene from The Tempest Songbook [Photo by Julieta Cervantes] product=yes product_title=Henry Purcell/Kaija Saariaho: The Tempest Songbook product_by= product_id=Above: Scene from The Tempest SongbookPhotos by Julieta Cervantes

March 26, 2015

San Diego Opera presents Adams’ Riveting Nixon in China

Director Peter Sellars first suggested the idea for the opera to Adams and eventually convinced him that the piece would be viable despite a lack of action. Alice Goodman then did considerable research into United States President Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China. Adams, interested in myths and their origins, thought that the opera could show the original history behind Nixon’s mythic visit. He and Sellars wanted a heroic baritone to play the role of Nixon. For this, his first opera, Adams’ usual minimalist music also shows the influence of Wagner and Stravinsky along with jazz and big band sounds. It’s a fascinating mix that we don’t always hear in his later works.

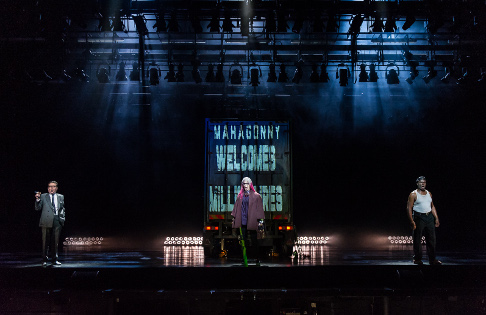

Franco Pomponi as Richard Nixon, Chen-ye Yuan as Chou En-Lai, and Chad Shelton as Mao Tse-Tung

Franco Pomponi as Richard Nixon, Chen-ye Yuan as Chou En-Lai, and Chad Shelton as Mao Tse-Tung

San Diego Opera staged Nixon in China on March 17, 2015, in a production by James Robinson with interesting sets by Allen Moyer suggesting 1970s television. James Schuette added authentic costuming from the era. Adams has chosen to have the singing amplified in his operas so there was a sound designer, Brian Mohr. There was considerable ballet in this opera and choreographer Seán Curran, along with principal dancers Julio Cantano-Yee and Khamla Somphanh, made it a most welcome and integral part of the show. Loved the dancers as whirling waiters at the banquet.

Franco Pomponi was a more than life sized Richard Nixon who sang his lines with the robust heroic sound Adams originally envisioned. Chen-ye Yuan was an officious Chou En-Lai and Chad Shelton was an elderly but still mentally capable Mao Tse-Tung. Sarah Castle, Buffy Baggott and Jennifer DeDominici comprised the trio of dissonant secretaries who always surrounded Mao. Although women had lesser roles in the actual visit, they had major parts in the opera. Kathleen Kim was a fabulous Madame Mao who sang one of the most difficult coloratura arias ever written as though it was an easy tune. With the simple costume of a Chinese working woman, she showed her artistry with filigrees of sound. As Pat Nixon, lustrous voiced Maria Kanyova was the girl next door who dearly loved the husband with whom she was swept up into history. Always a wonderful character actor, Patrick Carfizzi made Henry Kissinger as interesting and cantankerous as he was during the seventies.

(L-R) Sarah Castle as the 1st Secretary to Mao, Buffy Baggott as the 2nd Secretary to Mao, Jennifer DeDominici as the 3rd Secretary to Mao, and Patrick Carfizzi as Henry Kissinger

(L-R) Sarah Castle as the 1st Secretary to Mao, Buffy Baggott as the 2nd Secretary to Mao, Jennifer DeDominici as the 3rd Secretary to Mao, and Patrick Carfizzi as Henry Kissinger

Charles Prestinari’s San Diego Opera Chorus provided an excellent rhythmic and harmonic background for the historic scenes found in Adams’ mythic piece. It was the excellent work of conductor Joseph Mechavich that held stage and pit together and made this piece come alive for the San Diego audience. I hope the new San Diego Opera will give us more contemporary opera and allow us to see new pieces as they begin to enter the repertoire.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Chou En-Lai, Chen-Ye Yuan; Richard Nixon, Franco Pomponi; Henry Kissinger, Patrick Carfizzi; Mao Tse-Tung, Chad Shelton; Secretaries to Mao: Sarah Castle, Buffy Baggott, Jennifer DeDominici; Pat Nixon, Maria Kanyova; Madame Mao, Kathleen Kim; Conductor, Joseph Mechavich; Production, Houston Grand Opera; Director, James Robinson; Set Designer, Allen Moyer; Costume Designer, James Schuette; Lighting Designer, Paul Palazzo; Sound Designer, Brian Mohr; Choreographer, Seán Curran; Chorus Master, Charles Prestinari.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/NIX_0296a.png

image_description=Franco Pomponi as Richard Nixon and soprano Maria Kanyova as Pat Nixon [Photo by Ken Howard]

product=yes

product_title=San Diego Opera presents Adams’ Riveting Nixon in China

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Franco Pomponi as Richard Nixon and soprano Maria Kanyova as Pat Nixon

Photos by Ken Howard

Ars Minerva presents Castrovillari’s La Cleopatra in San Francisco

Ars Minerva is a new San Francisco based company that is presenting the Carnival Series Project: music that was played during the seventeenth century Venetian season of Carnevale, the name of which means goodbye to meat. This time of year culminated in Martedi Grasso (Mardi Gras/Fat Tuesday) the day before Ash Wednesday, which begins the penitential season of Lent. Carnevale di Venezia was famous not only for its music but also for its elaborate masks, facsimiles of which were on view in the lobby of the Marines Memorial Theater at La Cleopatra.

On March 14 and 15, 2015, Céline Ricci directed the up-to-date, realistic action of Castrovillari’s timeless opera. I saw the matinee performance on the fifteenth. The stage design by Matthew Holmes consisted of necessary pieces of furniture and a screen on which scenic elements were projected as though reflected in an imaginary pool. Together with Brian Poedy’s lighting, each scene was effectively put in its correct setting. Ricci was a glorious Queen Cleopatra whose regal persona turned romantic when she was with Marc Antonio. Vocally, she endowed her music with a wide variety of colors while conveying every emotional expression from protestations of love to death threats.

In this piece, Marc Antonio, sung with a secure line by countertenor Randall Scotting, was a straying husband whose wife, Ottavia, was anything but a wilting flower. Nell Snaidas sang Ottavia with power and passion as she tried to persuade a servant to kill the queen. Igor Viera, dressed in rough clothing and a grass hat, sang Clisterno with a robust sound. Together with Michael Desnoyers as the smart-mouthed, cross dressing elderly servant, Filenia, he brought moments of comic relief to this otherwise dramatic story.

Jennifer Ellis Kampani sang Coriaspe with sumptuous tones and iridescent waves of musical color. Hers is a voice from which I hope to hear a great deal more. Molly Mahoney was a mellifluous Arsinoe and Spencer Dodd sang with burnished tones in the dual roles of Dolabella and Arante.

The Marines Memorial Theater is not overly big and Derek Tam’s Baroque players filled the space with gorgeous sound. Tam played the harpsichord and conducted. Adam Cockerham played theorbo and guitar. Gretchen Claassen played cello, while Natalie Carducci and Laura Rubinstein-Salzedo played first and second violins. It was a great treat to hear this beautiful, well-composed opera that has been unjustly forgotten for so long. Thank you, Céline Ricci, for bringing it to us.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Cleopatra, Céline Ricci; Marc Antonio, Randall Scotting; Ottavia, Nell Snaidas; Coriaspe, Jennifer Ellis Kampani; Arsinoe, Molly Mahoney; Filenia, Michael Desnoyers; Clisterno, Igor Viera; Dolabella/Ariante, Spencer Dodd; Augusto, Anders Froelich; Domitio, James Hogan; Director, Céline Ricci; Video Stage Design, Matthew Holmes, Lighting Design, Brian Poedy; Conductor, Derek Tam; Theorbo and Guitar, Adam Cockerham; Cello, Gretchen Claassen; Violin I, Natalie Carducci; Violin II, Laura Rubinstein-Salzedo.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/La_Cleopatra.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Ars Minerva presents Castrovillari’s La Cleopatra in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=

World Premiere of Jennifer Higdon’s opera Cold Mountain at Santa Fe Opera this August

Jennifer Higdon’s first opera, Cold Mountain, premieres at The Santa Fe Opera on August 1, 2015 and runs until August 22. In addition, Opera Philadelphia recently announced that they will give the East Coast premiere of Cold Mountain during their 2015-16 season. This Monday at 7:30 p.m., the Guggenheim Museum in New York will host a special event: Higdon, author Charles Frazier, stage director Leonard Foglia and librettist Gene Scheer will discuss the new opera, and Cold Mountain cast members Isabel Leonard, Emily Fons, Jay Hunter Morris, Kevin Burdette, and Roger Honeywell will perform musical selections. For more information, click here .

Cold Mountain takes an American story as its subject—the desertion of Confederate soldier W.P. Inman to return to his love in the mountains of North Carolina during the Civil War. Based on Charles Frazier's best-selling novel, which was turned into an award-winning movie, it features a libretto by Gene Scheer ( Moby-Dick; An American Tragedy), recounting Inman's dangerous odyssey, trekking across North Carolina back to Cold Mountain. This Santa Fe Opera, Opera Philadelphia, and Minnesota Opera co-commission stars Nathan Gunn as the soldier Inman, Isabel Leonard as his lover, Ada, and Jay Hunter Morris as the villainous Teague in both Santa Fe and Philadelphia.

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize in Music for her Violin Concerto and one of America’s most-performed composers, Jennifer Higdon taught herself the flute at the age of 15 and began to compose at 21. Of the 50 recordings of her work, Percussion Concerto, Higdon: Concerto for Orchestra/City Scape, Strange Imaginary Animals, and Transmigration have all won Grammy Awards. Her work blue cathedral has been performed more than 500 times since its premiere in 2000. Higdon also teaches composition at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia.

"I didn't realize that I would be carrying these characters in my head and heart for about two and a half years,” Higdon told NPR Music . “But in many ways, living inside the opera, which it felt like I did, was not like anything I've ever experienced before. The entire group stayed with me day and night. I've been pretty absent from the present-day world for quite some time. That type of concentrated creativity has been amazing to experience.”

“I think Cold Mountain is going to be the great American operatic work,” said Gunn. “The music is beautiful and amazingly dramatic in scope.”

“Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain is a beautiful story filled with history, love, fear, and courage,” said Leonard. “Jennifer Higdon and Gene Scheer have now turned that story into an incredible musical journey and I cannot wait to share it with the people of Santa Fe and Philadelphia.”

“The greatest moments, for me, are when I get to sing new music,” said Hunter Morris. “I love stepping into the character and stepping into the voice for the first time.”

The

Guggenheim

March 30, 2015

Santa

Fe Opera

August 1, 5, 14, 17, 22, 2015

Opera

Philadelphia

February 5, 7, 10, 12, 14, 2016

Copyright © 2015 First Chair Promotion, All rights reserved.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Higdon-Slight-Smile.png image_description=Jennifer Higdon [Photo by J. Henry Fair] product=yes product_title=World Premiere of Jennifer Higdon’s opera Cold Mountain at Santa Fe Opera this August product_by=First Chair Promotion Press Release product_id=Above: Jennifer Higdon [Photo by J. Henry Fair]An Ideal Cast in Chicago’s Tannhäuser

The Chicago performances include Johan Botha as Tannhäuser, Amber Wagner in the role of Elisabeth, Gerald Finley as Wolfram von Eschenbach, Michaela Schuster as Venus, and John Relyea as Landgraf Hermann. Also participating in these performances are Jesse Donner as Walter, Daniel Sutin as Biterolf, Angela Mannino as the Shepherd, Corey Bix as Heinrich, and Richard Wiegold as Reinmar. Sir Andrew Davis conducts the Lyric Opera Orchestra and Michael Black has prepared the chorus, both groups here performing at the level of a festival. The production is directed by Tim Albery. Messrs. Bix, Wiegold, and Albery are in their debut season at Lyric Opera.

Gerald Finley as Wolfram, Johan Botha as Tannhäuser, and Amber Wagner as Elisabeth

Gerald Finley as Wolfram, Johan Botha as Tannhäuser, and Amber Wagner as Elisabeth

Staging the Venusberg scene is a perennial challenge to dramatic credibility. The current production makes a valiant effort to capture the spirit of music and drama, while matching a modernist updating in dress and stage props. After an impressive performance of the overture’s opening with the horns squarely on pitch and sensitive playing by the violas, the viewer notes a straight-back chair positioned at stage front on the right-hand side. Seated in the chair, dressed in a contemporary suit, is Tannhäuser. From the darkened stage recesses a figure emerges, and a miniature theater-frame with curtain descends onto the main stage, just as the Venusberg music intensifies. As the curtain in this stage-upon-a-stage opens, Venus - draped in a black evening dress - appears at its center. Dressed likewise as a match to the principals in style and formality, the male and female dancers participating in the bacchanal populate the center stage around a longish table. The choreographed motions suggest the physical pleasure to which Tannhäuser has committed himself after his departure from the society of the court. The dancers fulfill here Wagner’s textual summary of undulating movement interspersed with the sirens’ chorus of “Naht euch dem Strande” [“Draw near to the shore”]. Once the pair is alone, Venus questions the grounds for Tannhäuser’s distraction; his reveries simply recall images of nature which are now banned from his experience. In this response Mr. Botha’s recitation signals the tedium of his present, timeless state with drawn-out emphasis on “Tage, Monde …” [“Days, months …”]. In reaction to Ms. Schuster’s expressive “Ergreife Deine Harfe” [“Seize your harp”], Botha begins his praise of Venus [“Dir töne Lob” (“Praise be to you”)] with a lilting and embellished line. Yet in the midst of his love-song Botha’s tone changes effectively with the realization that he is a “Sterblicher” [“mortal”]. After Venus’s offended reaction Tannhäuser repeats both his praise and his appeal to leave her realm. Botha’s lyrical decorations on the line “nach unsrer Vöglein liebem Sange” [“for the sweet song of our beloved birds”] in describing the homeland build the grounds for his repeated declarations on “Freiheit” and “Laß mich ziehn!” [“Freedom” “Let me depart!”]. Resulting from his final dramatic statement, “Mein Heil liegt in Maria” [“My salvation remains with Mary”], delivered by Botha with exciting forte pitches, Tannhäuser is released from the control of Venus and returns to his origins.

Once Tannhäuser is anchored in a familiar landscape, his sense of sinfulness is enhanced. He sees a shepherd beneath a tree, located here toward the rear of the stage, and soon the latter’s song, “Frau Holda,” celebrates the return of pleasant weather. As the shepherd Angela Mannino sings with bright, unforced line, executing lovely decoration on “strahlte” to emphasize the play of the sun’s rays in “da strahlte warm die Sonne” [“and the sun began to shine warmly”]. A troop of pilgrims sings of its devotional passage just as the shepherd wishes them Godspeed to Rome. As an observer Tannhäuser is struck by their piety and laments his guilt even more intensely. In the balance of Act I the remaining male characters of the opera are introduced. The identity of the isolated penitent is first questioned by Landgraf Hermann, then immediately recognized by Wolfram. Messrs. Relyea and Finley inhabit these roles seamlessly. After individual welcoming words the knights and singers encourage Tannhäuser collectively to remain in their midst. Wolfram’s appeal, “Bleib bei Elisabeth!” [“Stay for the sake of Elisabeth!”] turns the tide in the returning knight’s resolve. While elaborating on this statement, Finley’s Wolfram sings a lush melodic passage recalling the effect of Tannhäuser’s departure on Elisabeth. Beginning with thoughts confined to individual verses [“Als du in kühnem Sange uns besrittest” (“When you in daring song did strive with us”)], Finley’s application of legato and transition builds as he proclaims, “O kehr zurück, du kühner Sänger” [“O return to us, you bold singer”]. The palpable effect of these lines, echoed by Relyea’s Landgraf, show Tannhäuser proclaiming his determination to remain in this company at the close of the act.

Act II introduces from its start the heroine Elisabeth. The interior of the palace whose hall she addresses in “Dich teure Halle” [“You, beloved hall”] suffers from neglect. By showing a state of decay, the set seems to externalize the inner ruin of Elisabeth’s and the court’s temperament. Ms. Wagner sings her opening aria with a commitment and power that bodes well for her assumption of yet additional roles in the dramatic-lyric repertoire. Wagner’s believable emphasis in her middle and lower registers to describe the effects of Tannhäuser’s earlier departure [“aus düstrem Traum” (“from gloomy dreams”)] transformed into a joyful declaration of welcome, squarely on pitch, in the repeat of “Sei mir gegrüßt!” [“Be greeted by me!”]. The subsequent duet with Tannhäuser, as they celebrate their reunion in the hall, shows both voices in elevated, forte excitement [“Gepriesen sei die Stunde!” (“Praised be the hour!”)], yet also woven together in emotional harmony.

An orchestral interlude heralds the arrival of guests who will observe the singers perform at the festivity. The latter are addressed directly by the Landgraf [“Ihr lieben Sänger” (“You dear singers”)] when he encourages each to describe while singing “der Liebe Wesen” [“the nature of love”]. Relyea’s diction and sense of communicating the text are exemplary in this extended depiction of the singers’ task. The first to sing is Wolfram in an address which shows Finley lingering convincingly on “die Seele” [“the soul”] and “der Liebe reinstes Wesen” [“love’s purest essence”], as he emphasizes the spirituality of love. Tannhäuser’s demur at this characterization of love is contradicted roundly by Walter von der Vogelweide. Mr. Donner’s Walter is sung with full, nicely rounded voice, laying emphasis on “die Tugend wahr” [“true virtue”] and decorating skillfully the “Inbrunst” [“fervor”] which he derides Tannhäuser for lacking. That very spirituality is flaunted in Botha’s resounding subsequent paean to sensual love. The court’s shocked denunciation of Tannhäuser is interrupted passionately by Elisabeth. Ms. Wagner’s recitation of this monologue contains striking shifts between describing Tannhäuser’s fall and her own sense of inner piety. As she reminds the others that “auch für ihn einst der Erlöser litt” [“the Redeemer suffered once for him as well”], Ms. Wagner leads the assembled members of the court to encourage forgiveness and repentance. In the final ensemble before Tannhäuser leaves on a pilgrimage - tellingly to Rome, as an echo of Act I - individual voices blend here yet are also perceived distinctly in a plea for a potential miracle.

The final act of Tannhäuser continues the passage to that very miracle, yet only after the demonstration of true sacrifice. Elisabeth’s prayer near the start of the act is achingly delivered by Ms. Wagner, as she begs the Virgin Mary to be taken from this earth as a means to atone “für seine Schuld” [“for his transgression”]. Wolfram’s response, when his attempts to follow her to the palace are gently rebuffed, is the prayer to the evening star to accompany Elisabeth in her journey heavenward. Finley’s performance of this piece, “O du, mein holder Abendstern,” is justly lauded, and here his singing matches the wistful yearning of the production’s movements. His voice quivers with devotion, as he graces the words “ein sel’ger Engel dort zu werden” [“to become a blessed angel there”] with fervent embellishment. Tannhäuser’s return signals his final confrontation with the character Wolfram. Botha details with dramatic gesture the rejection of his entreaties at Rome and his determination to return to Venus. In the struggle over the fate of Tannhäuser’s soul, Finley and Botha act with urgency to the point of the chorus announcing Elisabeth’s sacrifice. As the penitent now begs a departed Elisabeth to pray for him, the miracle of the pope’s staff is revealed. The final scenes in these performances are not simply a denouement but rather a convincing resolution of love’s dilemma.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/17_Corey_Bix_Johan_Botha_Richard_Wiegold_Jesse_Donner_TANNHAUSER_LYR150204_611_cTodd_Rosenberg.png

image_description=Johan Botha as Tannhäuser [Photo © Todd Rosenberg]

product=yes

product_title=An Ideal Cast in Chicago’s Tannhäuser

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=Above: Johan Botha as Tannhäuser

Photos © Todd Rosenberg

March 22, 2015

Winners of the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions Announced

New York, NY (March 22, 2015) — After a months-long series of competitions at the district, regional, and national levels, five young singers have been named the winners of the nation’s most prestigious vocal competition, the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions. Each winner receives a $15,000 cash prize and the prestige and exposure that come with winning the competition that launched the careers of many of opera’s biggest stars.

This year’s winners are Nicholas Brownlee, bass-baritone (Western Region: Mobile, Alabama); Marina Costa-Jackson, soprano (Middle Atlantic Region: Salt Lake City, Utah); Joseph Dennis, tenor (Eastern Region: McKinney, Texas); Reginald Smith, Jr., baritone (Southeast Region: Atlanta, Georgia); and Virginie Verrez, mezzo-soprano (Eastern Region: Brive La Gaillarde, France, currently living in New York, New York).

Earlier this afternoon, nine finalists performed on the Met stage in the final phase of the competition. Each sang two arias with the Met orchestra, led by the company’s Principal Conductor, Fabio Luisi. The audience for the Grand Finals Concert included artistic directors of leading opera companies, artist managers, important teachers and coaches, music critics, and many other industry professionals with the potential to play an influential role in the career of a young singer.

The Met Auditions, currently in their 62nd year, were the public’s first introduction to many of today’s best-known stars, including Renée Fleming, Susan Graham, Thomas Hampson, Eric Owens, Sondra Radvanovsky, Frederica von Stade, and Deborah Voigt. Recent winners who have gone on to embark on major operatic careers include Paul Appleby, Jamie Barton, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Michael Fabiano, Lisette Oropesa, Susanna Phillips, Alek Shrader, and Amber Wagner. 126 singers who participated in the National Council process early in their careers are on the Met’s roster in the current season.

The Grand Finals Concert was hosted by current Met star Angela Meade, who first came to prominence in 2007 as a winner of the National Council Auditions. Meade sang “Ebben?…Ne andrò lontana” from Catalani’s La Wally and “Casta Diva” from Bellini’s Norma while the judges deliberated. The concert was recorded for broadcast at a later date on public radio stations across the United States.

The remaining four finalistsJared Bybee, baritone (Middle Atlantic Region: Modesto, California); Allegra De Vita, mezzo-soprano (New England Region: Trumbull, Connecticut); Kathryn Henry, soprano (Upper Midwest Region: Sheboygan, Wisconsin); and Deniz Uzun, mezzo-soprano (Central Region: Mannheim, Germany, currently living in Bloomington, Indiana)—each received a cash prize of $5,000.

The regional and district-level auditions, held across the U.S. and Canada, are sponsored by the Metropolitan Opera National Council and administered by National Council members and hundreds of volunteers from across the country. Given the reach of the auditions, the number of applicants, and the program’s long tradition, the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions are considered the most prestigious competition for singers seeking to launch an operatic career.

Nicholas Brownlee

Bass-Baritone (Mobile, Alabama)

Age 25

In the 2015-16 season, Nicholas Brownlee will be returning for his second year as a Domingo Colburn Stein Young Artist at Los Angeles Opera, where he will be heard as Colline in La Bohème, the Speaker in Die Zauberflöte, the Bonze in Madama Butterfly, and the Gardener in Jake Heggie’s Moby-Dick. Next season also includes his Atlanta Opera debut as Colline. He will also be returning for his second season at Santa Fe Opera this summer as the First Soldier in Salome. This season he made debuts with the Los Angeles Philharmonic as the bass soloist in the Beethoven Choral Fantasy, as well as London’s Barbican Centre in performances of Unsuk Chin’s Alice in Wonderland, co-produced with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. He is a First Place winner of the Palm Springs Opera Guild Competition as well as a national semi-finalist in the 2011 Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions. Western Region.

Marina Costa-Jackson

Soprano (Salt Lake City, Utah)

Age 27

Marina Costa-Jackson is a third-year resident artist at the Academy of Vocal Arts in Philadelphia, where she is heard this season as Mimì inLa Bohème and as Marguerite in Faust. In Philadelphia, she has also sung Lisa in The Queen of Spades and Amelia in Un Ballo in Maschera. She appeared at Madison Square Garden last year with Andrea Bocelli and has recently returned from a concert tour in Russia with Dmitri Hvorostovsky’s “Dmitri and Friends”. She received first prize in the Giulio Gari Foundation, was a second place winner with the Marcello Giordani Foundation, a finalist in the International Hans Gabor Belvedere Competition, and an award winner with the Opera Index, Licia Albanese-Puccini Foundation, Mario Lanza Institute, Sergio Franchi Music Foundation, and George London Foundation. She will make her professional debut next season with Michigan Opera Theater as Musetta in La Bohème. Middle Atlantic Region.

Joseph Dennis

Tenor (McKinney, Texas)

Age 30

In 2013 Joseph Dennis appeared with the Santa Fe Opera as Giuseppe in La Traviata and last summer returned to that company for the title role in the American premiere of Huang Ruo’s Dr. Sun Yat-Sen. This season he sings Števa in Jen˚ufa with Des Moines Metro Opera. He has also appeared with the Palm Beach Opera as Malcolm in Macbeth and in productions of Il Barbiere di Siviglia and Les Contes d’Hoffmann. He pursued theater studies at Collin College and vocal performance at Stephen F. Austin State University, where his roles include Elder Gleaton in Carlisle Floyd’s Susannah, Kaspar in Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors, Alfred inDie Fledermaus, and Gastone in La Traviata. At the University of Oklahoma he sang Pylades in Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride and Fenton in Falstaff. This fall he joins the ensemble of the Vienna State Opera. Eastern Region.

Reginald Smith, Jr.

Baritone (Atlanta, Georgia)

Age 26

Reginald Smith, Jr. is a studio artist with the Houston Grand Opera and his operatic repertoire includes the title role of Falstaff, Germont inLa Traviata, Marullo in Rigoletto, the Speaker in Die Zauberflöte, Dr. Falke in Die Fledermaus, and Figaro in Le Nozze di Figaro. On the concert stage he has appeared with the Houston Symphony Orchestra, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Lexington Philharmonic, Kentucky Symphony Orchestra, Owensboro Symphony Orchestra, Johnson City Symphony, the Evansville Symphony Orchestra, and the Cincinnati Pops. He has been a reward recipient in the George London Foundation Competition, Dallas Opera Guild Vocal Competition, and received first place in the Orpheus Vocal Competition and National Opera Society Competition. This summer he joins the Wolf Trap Opera as a Filene Young Artist where he will sing Count Almaviva in Le Nozze di Figaro. Southeast Region.

Virginie Verrez

Mezzo-soprano (Brive La Gallarde, France)

Age 26

Virginie Verrez received her bachelor of music degree from the Juilliard School where she is continuing her music studies on a Kovner Fellowship. Last month at Juilliard she sang Clytemnestre in Gluck’s Iphigenie en Aulide as part of the Met+Juilliard program. She has previously sung Beatrice in Wolf-Ferrari’s Donne Curiose, Zenobia in Handel’s Radamisto, and Junon in Charpentier’s Acteon at Juilliard, and additional performances include Lola in Cavalleria Rusticana with Avignon Opera and Mercédès in Carmen with Wolf Trap Opera. In 2014 she was a soloist in Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with the Philadelphia Orchestra and made her Carnegie Hall debut in Bruckner’s Te Deum. She is a prize winner of the Opera Index Competition, McCammon Competition, Licia Albanese-Puccini Foundation, and Gerda Lissner Foundation. This fall she will become a member of the Metropolitan Opera’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program. Eastern Region.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Met_audition_winners.png image_description=2015 National Council Winners: (from l to r) Reginald Smith, Jr., Virginie Verrez, Joseph Dennis, Marina Costa-Jackson, Nicholas Brownlee [Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera] product=yes product_title=Winners of the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions Announced product_by= product_id=Above: 2015 National Council Winners: (from l to r) Reginald Smith, Jr., Virginie Verrez, Joseph Dennis, Marina Costa-Jackson, Nicholas BrownleePhoto courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera

A Chat with Julia Noulin-Mérat

She is the Associate Producer for Boston Lyric Opera and the Director of Design and Production for Boston’s Guerilla Opera. She is also the resident set designer for the New York’s Attic Theatre Company. Some of her designs include: Bluebeard’s Castle for Opera Omaha, Xerxes for the Connecticut Early Music Festival, and Madama Butterfly for El Paso Opera. Her engagements for the 2015-2016 season are with Nationale Reisopera, Gotham Chamber Opera, Boston Lyric Opera, and Castleton Festival.

Today she drops by for an interview with our Maria Nockin.

MN: Julia, how do you come to have three citizenships?

JNM: My dad is Canadian and my mom is French. Thus, I was born with both of those. Since I went to graduate school in the United States, I became an American citizen. Some things have changed since Nine-Eleven. You used to have to relinquish your Canadian citizenship before becoming an American. Now you don’t have to do that anymore.

MN: Where did you grow up?

JNM: I grew up a little bit everywhere! First, I lived in Montreal, then in Paris. I’ve also lived in Belgium. My dad worked in research for a pharmaceutical company, so we traveled a great deal, but I went back to Montreal to do my undergraduate work at Concordia University. Originally, I wanted to be a physician and I began to study for it, but I got the design bug. I don’t regret it. I’m lucky to have discovered what I like to do at such a young age. A friend of mine who lived in my dorm said: “Julia, you are always at the theater or at the museum. You have art hanging in your room. Don’t you think you should do something that pertains to the theater? “ When I said I’m not a performer, he replied that there are other aspects of theater. Eventually, I did an internship in set design and I fell in love with the work.

A scene from L’Enfant et les Sortileges – Boston Conservatory [Photo by Julia Noulin-Mérat]

A scene from L’Enfant et les Sortileges – Boston Conservatory [Photo by Julia Noulin-Mérat]

MN: What is your mission as a designer?

JNM: I want to make sure that the entire evening’s presentation is an event for the audience from when the doors open until they close. I want every performance to be as engaging and as exciting as possible. Opera in particular requires all the art forms to come together. In it there is not only singing and orchestral music, but also dancing and visual art. Although I am in the performing arts world, I feel like a visual artist. Many times people forget that.

When I was an undergraduate, I took a fabulous class called Performance for Designers. In it, they made us wear tight corsets and the highest possible heels. We had to perform on a raked stage on which normal chairs would topple over. That definitely made us think about whether or not performers could work comfortably within our designs. Some years later, one of my own students wanted his audience to sit on Astroturf. The next week that class sat on it. After twenty minutes some of them asked to return to the chairs. I told them that if they want the audience to sit on it for three hours, they could do it for the length of the class. Three years after that, I met a carpenter on a show who told me that her boyfriend still spoke of my “Astroturf class”.

A scene from La traviata – Boston Lyric Opera [Photo by Aram Boghosian]

A scene from La traviata – Boston Lyric Opera [Photo by Aram Boghosian]

MN: Did you get any significant insight from a teacher or mentor?

JNM: John Conklin is a colleague and a mentor that I met through Boston Lyric Opera. I have worked with him for almost four years. He is an incredibly talented artist and I get a thrill out of everything we work on together. He always approaches an opera with totally fresh eyes. I find it inspiring to see this man who has been in the business for many years rediscover each work that he approaches. If I can do a mere half of what he does, I will be immensely happy.

MN: What productions have you done with him?

JNM: With Boston Lyric Opera, he’s designed Rigoletto that also went to Opera Omaha and Atlanta Opera. Right now we are gearing up for next season, which includes La Bohème, Werther and The Merry Widow. I designed a set for La Traviata alone, too, but it is amazing to have John to bounce ideas off of.

One of the reasons I chose Boston University for graduate school was its Opera Institute. It was very important for me to attend a design school that had a close relationship with an opera department. A program with no opera would have been a waste of time for me. My relationships with singers would not be the same if I had gone to a school where students only designed for the theater. In Boston, I worked with the amazing Sharon Daniels who taught me what to worry about and how to deal with singers. The Institute had guest directors, as well. That helped me learn to deal with different working styles and enabled me to form important relationships. One of the directors I met in grad school was Nathan Troup who staged Francesco Cavalli’s La Calisto for Simpson College in January 2015. We’ve been working together for nine years now and have done over fifteen new productions.

Since I was in Boston, which is a composer’s town, I became connected with Guerilla Opera. I have been working with that company since its second year when it had musicians but no one working in production. Say It Ain’t So, Joe, was an opera about Sarah Palin and Joe Biden that I did with them. I really got the contemporary opera bug working with those people. All their pieces are commissioned, and I find it fascinating to work with composers and librettists as well as singers. With Guerilla Opera, a designer gets to work with creators from the beginning of their labors. The company has a residency at the Boston Conservatory and a little fifty-five-seat black box theater where we get to try all sorts of things.

Last year I worked on composer Ken Ueno’s chamber opera, Gallo, which features a soprano in a box filled with Cheerios and a countertenor in a chicken suit. The little rings made sounds but we figured out how to get around that. Unfortunately, many other companies don’t have a lot of resources or time to allow you to experiment. I love working where I can try all kinds of new ideas.

A scene from La Calisto – Simpson College [Photo by Luke Behaunek]

A scene from La Calisto – Simpson College [Photo by Luke Behaunek]

MN: What is your production of La Calisto like?

JNM: Our La Calisto is set in the glamorous era of the 1920s. All the gods have human characteristics and there is a great deal of gender bending. We set the action in a train station that becomes a nightclub. When the opera was performed at the Simpson College Theater, we placed Maestro Bernard McDonald’s orchestra in the center of the stage so that the musicians could be seen playing their period instruments. They were part of the nightclub, which was fun, too.

MN: What do you see yourself doing five or ten years from now?

JNM: I also have a degree in arts administration so I would like to be artistic director or advisor for a company, but I still want to design for other companies internationally. Next year I will do a show with Reisopera in co-production with Gotham Chamber Opera in Amsterdam and this summer I am going to the Castleton Festival.

MN: How do we assure the continuance of opera for generations to come?

JNM: There have been quite a few articles written saying that opera is dead in Boston. After reading three of them I became more than a little annoyed. I refuse to believe that opera is a dying art form. Although my studio is in New York, I have very close ties to Boston. I remembered that there was a New York Opera Party that brought all the city’s functioning companies together after the New York City Opera closed. Boston, too, needed to celebrate opera as a living art form. Last year I reached out to the artistic directors of its many companies and we had an exciting celebration with each company performing a song. Thus, we celebrated our rich and vast diversity within the opera world.

A scene from Bluebeard’s Castle – Opera Omaha [Photo by Jim Scholz]

A scene from Bluebeard’s Castle – Opera Omaha [Photo by Jim Scholz]

MN: What do you like best about designing for opera in the United States?

JNM: Many people have asked me why I live in the States and not in Europe. I believe that opera in the United States is on the verge of something very exciting. I think the art will reinvent itself because of its financial challenges. That scene will be very exciting for those of us who work in it.

When I did a Madama Butterfly in El Paso Texas I encountered a most amazing opera audience. The opera house is close to the border with Mexico. Standing in front of it I could watch the patrons walking across to the United States in their fancy opera clothes. I just loved seeing that.

MN: What kind of modern technology do you find most helpful?

JNM: I use every kind of technology that is available to me and appropriate to the piece. I love experimenting, too, but I know designers have to be careful that technology does not become a distraction. It has to help move the story along. When La Calisto was first staged, it had every possible bit of technology, but since then it has also been staged for smaller companies. Often they have lower budgets and we have to produce the same effects without using expensive tools. I do some shows on very large budgets and others on very tiny budgets. It’s the projects themselves and the possible collaborations with other artists that have to interest me, not the money involved.

Some aspects of opera in the United States are new already. I don’t think we could have had an Opera America Conference discussing site specific performance fifteen years ago. Boston Lyric and Long Beach Opera for example both perform in sites other than theaters. Seats have to be accessible and comfortable and site-specific opera is not necessarily cheap, either. We don’t have the usual theater infrastructure, so we have to make everything we need and we have to worry about sound balance. I love doing it, however, because it is an exciting challenge.

MN: Do you teach?

JNM: I would like to teach more and transmit the approaches that I have developed and the “Opera World” that I love to the next generation. However, I travel a lot and to be fair to my students, I only give guest lectures and take interns for the moment.

MN: What do you like best about designing?

JNM: I love making the audience an integral part of the show. We must remember that when most operas were new, the art and the chandeliers in the opera houses were new, too. I like to immerse the audience in the world of the opera being played. One way of doing that is by inviting artists to do installations in or around the theater. When I did Bluebeard’s Castle at Opera Omaha we had three hundred twenty doors on stage as well as a very large orchestra. The castle wrapped around the orchestra so that it appeared to be inside the building.

Opera Omaha General Director Roger Weitz brings his audience many new ways to look at opera, including new singers and new directors. Happily, he has an audience that accepts new ideas. Of course, he also stages wonderful traditional performances. Most importantly, his audience trusts him to bring them quality shows. The relationship a company has with its audience really helps the art form grow. I should also point out that the kind of brand building based on the artistic product and achievements such as producer Beth Morrison’s successes in New York, Los Angeles, and elsewhere, brings engaged audiences to the theater.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Julia_Noulin-Merat.png image_description=Julia Noulin-Mérat [Photo © Steven Meyer] product=yes product_title=A Chat with Julia Noulin-Mérat product_by=An interview by Maria Nockin product_id=Above: Julia Noulin-Mérat [Photo © Steven Meyer]Madame Butterfly, Royal Opera

If Puccini’s aim was — in keeping with verismo ideology — to portray the grim reality of contemporary life then the story of Cio-Cio-San’s exploitation, abandonment and self-sacrifice must have seemed a fitting tale. John Luther Long’s eponymous short story — which since its 1904 publication has spawned many a Butterfly-derivation — was based on a real-life incident: here, then, was the opportunity for the composer to depict the catastrophic actualities of cultural and sexual exploitation amid human suffering, gritty pragmatism and stoic self-sacrifice in back-street Nagasaki.

However, Puccini was evidently more interested in verismo settings than its aesthetics and philosophies: perhaps the only ‘genuine’ verismo operas are Il Tabarro and Tosca, for even in La Bohème the emphasis is more on the captivating bohemian milieu than the sordid quotidian affairs of the common man and woman. The garrets of the nineteenth-century Quartier Latin may have posed as present-day normality but in fact they were just as remote and picturesque as the faraway harbour-shores of Nagasaki.

Brian Jagde as Lieutenant B.F. Pinkerton and Kristine Opolais as Cio-Cio-San

Brian Jagde as Lieutenant B.F. Pinkerton and Kristine Opolais as Cio-Cio-San

Thus, Madame Butterfly is less an exposure of racial, financial and sexual abuse than a tale of love, sacrifice and redemption — and one not so far from the ideals of German Romanticism. Puccini may have called Madame Butterfly a ‘tragedia giapponese’ but it is not Japanese in any naturalistic sense: indeed the French term Japonisme might be nearer to the mark, referring as it does to the mania for the East which followed the end of Japanese isolation from the West in 1854. In the pavilions of the world fairs held in Paris during the late-nineteenth century, the Occident discovered the Orient through displays of the latter’s art, plays and music — and it devoured what it saw.

This infatuation is thrillingly reflected in Christian Fenouillat’s subtle but penetrating set designs and the wildly glowing colours of Christophe Forey’s lighting scheme: Puccini’s orientalism is exotic mystery rather than naturalistic misery. So, Fenouillat presents us with a room whoseshoji screens decorously rise and slide to reveal glimpses of Nagasaki — a pale view of the hills — or an ornamental shūyū, the blue-pink mist which hazily bathes the ornamental garden making a fairy-tale of Butterfly’s entrance. These screens allow rays of yellow-green or orange light to slide across the set floor, emphasising the unfamiliar perspective of the world we view. It will not reveal all its secrets or admit interlopers: Kate Pinkerton appears first as a silhouette, ominous and alien, through the dividing screen. And, the flat backgrounds cut off figures and sakura trees at the edge of the frame; this is an asymmetrical world of juxtaposed angles, layers and colours. Japanese cherry blossom trees are traditionally associated with clouds, because of their weightless flowery mass, and when the ephemeral petals tumble to the floor at the end of Act 3, illumined by a ghostly moon-glow, the death of Butterfly’s airy dreams is painfully apparent.

All this beauty and symbolism might be mere superficial satisfaction for one’s sensibilities, if it were not for the dramatic insight and vocal distinction of Latvian soprano Kristine Opolais who truly appreciates, and communicates, that Butterfly’s tragedy is a personal one not a cultural one. Opolais may not convince as an ingénue or a teenage Geisha: she is too tall and her voice too sophisticated and knowingly mature to encapsulate the girlish immaturities of a giggling fifteen-year-old. But, her Butterfly is a ‘real’ woman of disturbing integrity and resolution, and this steely determination is gradually revealed by Opolais to be an unwavering willpower and honesty which will eventually destroy both herself and Pinkerton.

Gabriele Viviani as Sharpless

Gabriele Viviani as Sharpless

Opolais’s spinto glistens like gossamer thread but has an underlying strength; she sang with such seductive lyricism that, for once, one might empathise with Pinkerton’s infatuation. Her voice is not huge, though, and there were some places where it was overshadowed by the orchestral fabric; but, in the end-of-Act 1 love duet Opolais used a powerful chest voice to convey the shockingly deep passion which lays beneath her docile purity and the demure civilities of her culture.

In Act 2 she laid bare Butterfly’s emotional unpredictability: her haughty sulkiness when admonished or guided by Suzuki; her youthful excitability which irrepressibly bursts out, interrupting Sharpless’s reading of Pinkerton’s letter; her fiery anger when the US consul dares to suggest that she may never see Pinkerton again. In a pre-production interview in the Daily Telegraph Opolais said of the role: ‘Just to sing it with a good voice is not enough, it asks tears from your soul. I am very emotional on stage and the music is so tender that I suffer for real when I am singing it.’ This was nowhere more evident than in ‘Un bel dì’ where the wistful honesty of her singing totally explicitly and uncompromisingly revealed her despair.

Leiser and Caurier manage to keep their production on the right side of sentimentality, but here it was Opolais who imbued it with true tragic authority. It was a pity then that her final death throes were exaggerated and unconvincing: Butterfly’s destiny has been foreshadowed, for example in her prostrate figure at the close of Act 1, and once the ornate tantō has done its fatal work, one might have hoped for a less melodramatic physical collapse to convey Butterfly’s ultimately destructive passivity.

Opolais is well-partnered by Brian Jagde’s Pinkerton. The American tenor’s interpretation of the Yankee Lieutenant as an insensitive young buck whose crime is carelessness rather than malice is convincing, even if it doesn’t allow for much emotional range. Jadge’s tenor is bright and powerful, and although there were a few over-reaching rasps in Act 1, his aria, ‘Addio fiorito asil’, was deeply moving, full of shame and sorrow.

The rest of the cast were solid but somewhat overshadowed by Opolais’s intensity. Albanian mezzo-soprano Enkelejda Shkosa was a feisty Suzuki, strong and rich of voice, and Jeremy White’s white-faced Bonze cursed chillingly. Gabriele Viviani made a fairly bland impact as Sharpless, but Carlo Bosi’s Goro was wily and snakily persistent and the Italian tenor grabbed his dramatic moments.

The single performer who matched Opolais’s fearless commitment was conductor Nicola Luisottiwho drew incredible incisive playing from the pit, alternating searing, fervent climaxes — the instrumental introduction did not waste any time in setting out Luisotti’s intentions — with moments of pristine tenderness. Together with Opolais, Luisotti conveyed an essential truth: that Butterfly’s tragedy is not caused by external forces of pillage and corruption but derives from within, from her own misplaced love.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Cio-Cio-San, Kristine Opolais; Pinkerton, Brian Jagde; Sharpless, Gabriele Viviani; Goro, Carlo Bosi; Suzuki, Enkelejda Shkosa; Bonze, Jeremy White; Yamadori, Yuriy Yurchuk; Imperial Commissioner Samuel Dale Johnson; Kate Pinkerton, Anush Hovhannisyan; Conductor, Nicola Luisotti; Directors Moshe Leiser and Patrice Caurier; Set designs, Christian Fenouillat; Costume designs, Agostino Cavalca; Lighting design, Christophe Forey; Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Friday 20th March 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/%C2%A9BC20150317_Madama_Butterfly_RO_817%20ENKELEJDA%20SHKOSA%20AS%20SUZUKI%2C%20KRISTINE%20OPOLAIS%20AS%20CIO-CIO-SAN%20%28C%29%20ROH.%20PHOTOGRAPHER%20BILL%20COOPER.png image_description=Enkelejda Shkosa as Suzuki and Kristine Opolais as Cio-Cio-San [Photo © ROH. Photographer Bill Cooper. product=yes product_title=Giacomo Puccini: Madame Butterfly product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Enkelejda Shkosa as Suzuki and Kristine Opolais as Cio-Cio-SanPhotos © ROH. Photographer Bill Cooper.

March 21, 2015

Tosca in Marseille

The recent, misguided Pierre Audi production at the Opéra de Paris is an example. Despite its slick “look” it was no more than the emperor in new clothes. But maybe you made your way to Marseille last week where the new production (sets/costumes/stage direction) by Louis Désiré restored your faith in revisionist productions. And in Tosca.

It was not a cast of singers in Marseille that limited its sights to the verismo thrills perpetrated by larger than life opera singers and effect mongering conductors. It was a cast that immersed itself in a revision of Tosca. No longer a mere showpiece for powerful singers of powerful personality the opera had become true theater where every word was eloquent and every gesture carved — a revisionist Tosca if there ever was one.

Director Désiré imagined Puccini’s “shabby little shocker” in a shadowy atmosphere that bespoke the prevailing dangerous political climate in which corrupt power, jealousy and unfettered lust exploded into lurid happenings. The production was in fact a study in chiaroscuro — fields of darkness with shafts of yellow light at the precise moments when emotions flared.

Lighting the singers will have been a monumental task, not only for the very accomplished lighting designer Patrick Méeüs, but also for the actors to learn where and when to move into and out of the shafts of light (note that Mr. Méeüs primarily designs lighting for dance where directional lighting techniques are highly developed).

Marseille born Louis Désiré maybe began his career as a costume designer or maybe as a set designer (the program bio is unclear). As both he is known to American audiences as a collaborator of American director Francesco Negrin (Werther in San Francisco and Rinaldo in Chicago).

Adina Aaron as Tosca, Giorgio Berrugi as Cavaradossi, Carlos Almaguer as Scarpia

Adina Aaron as Tosca, Giorgio Berrugi as Cavaradossi, Carlos Almaguer as Scarpia

As the sole metteur en scène of this Tosca he created stage pictures that are the highly charged personal moments of Mannerist painting — to be clear, it is the moment he captures, not the action. In fact his staging is two dimensional tableaux, occurring with few exceptions within the proscenium frame. He uses clever techniques to reduce this larger frame — for example Scarpia’s Act II table is a long black quadrangle box extending across half the stage, when actors move behind it there lower bodies are hidden, thus a sort close-up is effected.

The large proscenium frame of course was completely filled for the Scarpia “Te Deum.” There was no procession, only Scarpia standing downstage center holding one of the roses Tosca had placed on the altar to the Virgin Mary. Behind him in two straight, across the stage lines were 48 black cossack covered Opéra de Marseille choristers whose arms rose in celestial rapture to Scarpia’s sexual raptures. It was good, very, very good.

Scarpia’s apartment boasted a small balcony on the side where Tosca escaped to sing her “Vissi d’arte” in a shaft of light, her lower body hidden by the railing. These tableau moments told the sordid tale from beginning to end in a seemingly inexhaustible catalogue of Mannerist inspired poses, epitomized by the execution — Cavaradossi was alone downstage center, the revolving stage had removed the shooters from the frame, Tosca was hidden behind a wall).

American soprano Adina Aaron, dressed the entire opera in an unadorned straight line gold gown (like a shaft of light), created an exotic presence for the actress Floria Tosca, her dark hued voice producing a lovely, burnished spinto tone, her less-than-full-throated high climaxes absorbed into the musicality of her character. She closed Act II sitting alone down stage center, flanked by two candles to speak Tosca’s “davanti lui tutta Roma tremava.” Delivered with resigned irony the tableau was simply an ironic statement of the line we had been waiting for.

Italian tenor Giorgio Berrugi sang Cavaradossi with exquisite musicality, all famous Italian tenor mannerisms firmly present but impeccably integrated musically. His ease of vocal production in this spinto role made his character about musical line, integrating his music into Puccini’s high octane drama in a flow that supported Mr. Désiré’s flow of tableaux. Of very great pleasure was the dramatic and musical authenticity of his rolled “r”‘s, creating unexpected ornamentation.

Mexican baritone Carlos Almaguer roared with unfettered gusto, as must every Scarpia. In this staging he is not asked to be emotionally complex but simply to reign as the perpetrator of the darkness of Napoleonic political atmospheres. Here he did not complicate his basically gruff delivery with nuance, nor did he attempt to assume an out-sized presence. He underscored director Désiré’s Tosca as a straight forward, uncomplicated recounting of the facts of the story. That he waited until the final curtain calls to take his bow assured the dramatic integrity of the production.

Of note as well was the excellent Angelotti of French bass Antoine Garcin, for once a consul of the fallen Italian republic who showed requisite age and stature.

Italian conductor Fabrizio Maria Carminati sacrificed the showy, obvious effects of this warhorse opera to the far more subtle demands of the production. It is the mark of a real opera conductor to integrate the score into the production. We can be very grateful to Mo. Carminati for the unobtrusive and very able contribution of the pit.

As metteur en scène Mr. Désiré both designs and stages Carmen for the Chorégies d’Orange this summer, with lighting by Patrick Méeüs. Not to be missed (cherries-atop-the-cake: Kate Aldridge as Carmen, Jonas Kaufmann as Jose).

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Floria Tosca: Adina Aaron: Mario Cavaradossi: Giorgio Berrugi; Scarpia: Carlos Almaguer; Le Sacristain: Jacques Calatayud; Angelotti: Antoine Garcin; Spoletta: Loïc Felix; Sciarrone: Jean-Marie Delpas; Le Pâtre: Jessica Murrolo. Orchestre et Chœur de l'Opéra de Marseille. Conductor: Fabrizio Maria Carminati; Mise en scène / Décors / Costumes; Louis Désiré; Lighting: Patrick Méeüs. Opéra de Marseille, March 18, 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tosca_Marseille1.png

image_description=Photo by Christian Dresse courtesy of the Opéra de Marseille

product=yes

product_title=Tosca in Marseille

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Adina Aaron as Tosca, Giorgio Berrugi as Cavaradossi

Photos by Christian Dresse courtesy of the Opéra de Marseille

March 20, 2015

Poetry beyond words — Nash Ensemble, Wigmore Hall

Ostensibly, the concert featured some of the best modern British composers, plus Elliott Carter, an honorary Brit, since his music has been so passionately championed in this country.

But a deeper perusal of the programme revealed even greater depths.. “Poetry beyond Words” I thought, since most of the pieces transformed their original sources in text and visual images into exquisitely original works of art. Lieder ohne Worte: an affirmation of the life force that is creativity.

Simon Holt’s Shadow Realm (1983) gets its title from a poem by Magnus Enzensberger (a favourite of Hans Werner Henze). “.....for a while/ i step out of my shadow/for a while.....”. Holt’s music penetrates the elusive mysteries of the text, going beyond the words to express its spirit. It’s structured in two halves, “shadowing” one another, but scored for an unusual combination of clarinet, harp and cello, creating a three-way conversation, creating a further shadow around the duality of its conception. It’s a miniature, only eight minutes long, but its concision is so elegant that it puts to shame many works which drown in verbose meandering. Holt was only 25 when it was written: a remarkable original achievement by a composer whose self-effacing manner belies a mind of great originality. It says much about the Nash Ensemble that they commissioned it, long before Holt became famous.

The poems of Lorine Neidecker (1903-1970) pack intense meaning into fragmentary, haiku-like lines, some of which don’t even follow grammatical syntax. But therein lies their beauty. Harrison Birtwistle’s Nine Settings of Lorine Niedecker (1998-2000), another Nash commission, distills each poem with a kind of almost homeopathic concentration, communicating the spirit of the poems, far more creatively than mere word-painting. Claire Booth sings arching lines which reach upwards and outwards, sustaining the legato, while the cello weaves around, without interruption, coming into its own only when the voice falls silent, like an elusive echo, Eventually, the poems seem to move away, beyond human hearing. The music gradually slows down, voice and cello retreating together with melancholy “footsteps”, each note expressed with solemn dignity. Birtwistle recognizes the fundamental structure of Niedecker’s text, but emphasizing syllables and single words, rather than phrases. “ thru bird/start, wing/drip, weed/drift”, though in the text the words are joined. Perhaps this captures the sense of water, dripping quietly in some vast stillness. Yet it’s also typically Birtwistlean puzzle-making, creating patterns within patterns, layers within layers. Beautiful moments linger in the memory, like the “You, ah you, of mourning doves”, where the poet plays with the word “you”, which sounds like dove call yet also evokes human meaning, while the composer, for once, infuses the word “mourning” drawing its resonance out, like the cooing of the bird.

One of the great joys of Julian Anderson’s music is that he’s an extraordinarily visual composer. Graphic images inspire his music and enrich its interpretation. His Alhambra Fantasy (2000) was stimulated by Islamic architecture, The Book of Hours (2005) by the miniatures in Les Trés riches heures du Duc de Berry, and even Symphony (2003), despite its non-committal title, owes much to the paintings of Sibelius’s friend, Axel Gallen-Kallela. Yet again, the Nash Ensemble recognized his unique gift almost from the start. Poetry Nearing Silence (1997) was inspired by The Heart of a Humument, a book of paintings by Tom Phillips, where random words from an obscure novel were picked at random, then adventurously illustrated.

Just as Phillips transforms words into visuals, Anderson transforms ideas into abstract music. Eight highly individual segments unfold over 12 minutes. Each has a title, borrowed from the book, though the settings as such aren’t literal. In the third segment “my future as the star in a film of my room”, one of the violinists plays percussion (a ratchet), which whirrs like the cranking of an old-fashioned camera. In the Wigmore Hall, the sound is decidedly disturbing, but that’s perhaps Anderson’s intention : we can’t take what we hear for granted. In theory, the segments travel round Europe - Vienna, Bohemia, Carpathia, Paris. Far away landscapes of the imagination: perhaps we hear references to Janáček’s Sinfonietta, crazily buoyant but cheerful. The Nash play at being folk musicians, imitating alphorns and shepherd’s pipes. Everything in joyous transformation! Gradually, the clarinet (Richard Hosford) draws things together, as silence descends. Although Anderson doesn’t employ voice in this piece, it feels like song, because the orchestration has such personality.