April 29, 2015

Hercules vs Vampires: Film Becomes Opera!

Composer Patrick Morganelli was already a Bava fan when Opera Theater Oregon chose him to create music for a live performance featuring a Bava film. The first version of Hercules vs Vampires premiered in May 2010. For the accomplished singers of L A Opera’s Young Artist Program in 2015, Morganelli reworked the vocal parts and made them more technically demanding.

In the early sixties, Italian film director Mario Bava was making pictures with male body builders whose well oiled physiques appeared spectacular on the screen. Composer Patrick Morganelli was already one of Bava’s fans in 2009 when Opera Theater Oregon (OTO), a small but adventurous company based in Portland chose him to create music for a live performance featuring a Bava film. The first version of Hercules vs Vampires premiered at OTO in May 2010. For the more accomplished singers of L A Opera’s Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program, Morganelli reworked the vocal parts and made them more technically demanding.

Because each utterance has to fit into the time that the filmed character is seen saying it, the number of words in the libretto had to be cut by about two-thirds. Still, the libretto text had to convey the same meaning as the spoken dialogue, so Morganelli, who did this work himself, had a time-consuming job. Conductor Christopher Allen, an alumnus of the LA Opera Young Artist Program, saw to it that the music fit the filmed speeches. Because of the format, he was not able to allow the singers to hold the notes on which their voices sounded best for even a beat longer than what was written in the score.

Reg Park as Hercules

Reg Park as Hercules

In the story, Hercules’s sweetheart, Dianara, was the rightful queen of Acalia, but her evil uncle, Lycos, put a spell on her and stole her throne. Hercules consulted an oracle that told him a magic stone from Hades would free her. He would also need a golden apple to assure his safe return to earth. Boiling lava and a powerful storm at sea tested Hercules and his friend, Theseus, who were played on the screen by Reg Park and George Ardisson. When they arrived at Acalia, they found it in chaos. One reason for the trouble was that Persephone, the daughter of Pluto, had fallen in love with Theseus and overstayed the time she was allowed to visit earth. Theseus loved her and fought with Hercules but when she realized she was the cause of trouble, she went back to Pluto’s realm.

Lycos wanted to drink all of Dianara’s blood but Hercules saved her only to find himself besieged by the undead in every imaginable form. This fight music is some of Morganelli’s best and I imagine it could be made into a short orchestral piece that could stand alone.

Morganelli said he differentiated between music for Hades and Earth. Earth was more accessible and impressionistic, while Hades was described by hard-edged and atonal phrases. Thus, Summer Hassan as Dianara sang more lyrical music than Vanessa Becerra as Zarathusa and Medea. It was Becerra’s pure toned, clean coloratura that made her stand out as an artist to watch for in the future, however.

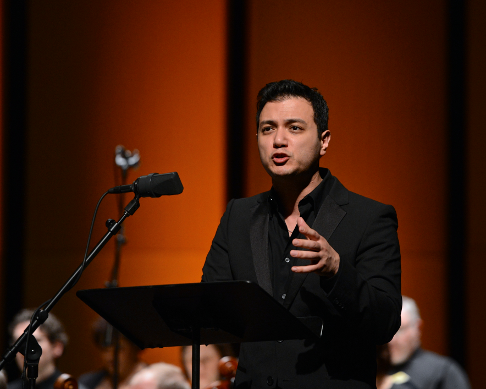

At first I wondered why Hercules was a baritone instead of a heldentenor. Then I heard Kihun Yoon! He had the virile, resonant tones needed for a strongman. As Theseus, Frederick Ballentine sang with burnished bronze sounds that portrayed Hercules’s more romantic friend. Mezzo-soprano Lacey-Jo Benter sang passionately with a particularly opulent middle register that offered a pleasant contrast to the two sopranos.

Nicolas Brownlee was a malevolent Lycos whose evil was apparent to the audience long before it was to Hercules. Bass-baritone Craig Colclough’s vigorous, dark-voiced characterizations of Procrustes and the God of Evil completed the opposition to Hercules and Dianara. Maestro Allen held his twenty-six-player orchestra in a tight mold because of film timings, but he also drew translucent and harmonically effective music from them. This was a most intriguing experiment that might well be tried with another film. It will be interesting to see what happens with this brand new genre in the future.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Lycos, Nicholas Brownlee; Henchman/Kyros/Peasant, Brenton Ryan; Hercules, Kihun Yoon; Dianara/Hesperide/Peasant/City Woman, Summer Hassan; Medea/Zarathusa/Chained Woman/Helena, Vanessa Becerra; Theseus, Frederick Ballentine; Telemachus/City Man/Palace Attendant, Rafael Moras; Procrustes/God of Evil, Craig Colclough; Conductor, Christopher Allen.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/regparkhercules.png

image_description=Reg Park as Hercules

product=yes

product_title=Hercules vs Vampires: Film Becomes Opera!

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Reg Park as Hercules

April 26, 2015

Kathleen Ferrier Awards, Wigmore Hall

The competition was inaugurated in 1956, three years after the untimely death of the great English contralto, with the aim of honouring Ferrier’s memory by encouraging and supporting — in the words of this year’s jury chairman, Graham Johnson — ‘open-hearted and communicative vocal talent, promising young singers who somehow or other bore the Ferrier stamp while in no sense being imitators’. Held annually, it was originally restricted to singers from the Empire and Commonwealth but is now open to any singer under the age of 29 who has studied for at least one year in the UK or Republic of Ireland.

Preliminary rounds require candidates to demonstrate their accomplishment in song and opera, in varied languages, and to perform music written in the past and during the last fifty years. In the Final, they are required to present at least one English song and to balance song and opera in a recital lasting not more than 20 minutes.

Programming is, therefore, crucial. And, this is where the sole male competitor came unstuck. Hungarian tenor Gyula Rab demonstrated a strong, handsome voice in his final item, ‘Ecco, ridente in cielo’ from Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia, with pleasing Italianate colouring, but this was preceded by two rather leaden Liszt songs from Tre sonetti di Petrarca in which, despite communicating well with accompanist Paul McKenzie, the 28-year-old Rab sounded under pressure and strained at the top. More problematic still was Britten’s arrangement of Purcell’s ‘Sweeter than roses’. Rab worked hard — but therein lay the problem, for the result was cumbersome and overly weighty, lacking the necessary elasticity and cleanness which the idiom requires. Rab could not hide his own disappointment with his performance but he can take heart that he has an exciting summer ahead: he returns to the Glyndebourne Festival, where he was a Chorus member in 2013, for Carmen and Poliuto, taking the role of A Christian and understudying Nearco in the latter.

That left five sopranos to battle it out. Soraya Mafi had the difficult task of opening the evening. The 26-year-old graduated from the Royal College of Music’s International Opera School in 2014 and makes her debut with ENO in The Pirates of Penzance later this month, but that did not stop the nerves kicking in and Mafi seemed somewhat disengaged in Mozart’s ‘L’amerò sarò costante’ from Il re pastore; despite the warm shine and stylish decorations she did not consistently communicate the heartfelt sincerity of Aminta’s devotions. However, in Hugo Wolf’s ‘Er ist’s’ from the Mörike-Liederbuch Mafi’s soprano bloomed thrillingly to announce the arrival of spring, and the fine-spun phrases of Julius Harrison’s ‘Philomel’ were crystalline above accompanist Ian Tindale’s magical rippling accompaniment. Tindale, who conjured tremendous energy in the Wolf song and whose introduction to Liszt’s ‘Oh! Quand je dors’ was wonderfully eloquent, was the deserving recipient of the Accompanist’s Prize. In the Liszt song, Mafi again demonstrated impressive technical control and powerful projection while in her final item, Strauss’s ‘Frühlingsstimmen’, her bright gleam came into its own as she raced through the glittery roulades with stylish panache.

Suzanne Fischer, a 27-year-old Britten-Pears Young Artist, brought drama to ‘Villes’, the first of three songs from Britten’s Les Illuminations, but found the rapidly enunciated text a challenge too far, though in the song’s less hasty final episode she revealed an appealing lower register. The third song of Britten’s cycle, ‘Phase and Antique’, was more composed, but Fischer had not quite mastered the interpretative demands. She began her programme with Constanze’s ‘Ach, ich liebte’ from Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail, in which a variety of vocal colours persuasively conveyed emotion, while Schubert’s ‘Suleika II’ saw both Fischer and her accompanist Nicholas Fletcher scale the virtuosic challenges impressively, demonstrating clarity of line and considerable dexterity respectively. Fischer was a suave and confident Musetta in ‘Quando m’en vo soletta’ from La bohème, her waltzing phrases blending coquettish charm and tenderness.

Given the predominance of soprano voices, the decision by 24-year-old Gemma Lois Summerfield to open her programme with two less familiar songs by Sibelius was a welcome one. In ‘Diamanten på Marssnön’ (A diamond on the March snow) her rich velvety tone was alluringly set against Sebastian Wybrew’s sparkling accompaniment. Summerfield shaped the phrases with assurance and control. To my uneducated ears, her Finnish sounded idiomatic and in ‘Flickan kom ifrån sin älsklings möte’ she told related the tale of the girl who, returning from meeting her lover, must confront her angry mother most engagingly. Similarly, each verse of Mendelssohn’s strophic ‘Hexenlied’ was nuanced as she whipped through the imagery of broomsticks, goats, dragons and Beelzebub. Here, and in Copland’s ‘Heart! We will forget him!’ from 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, Summerfield moved with effortless legato between registers, her lovely burnished lower voice complemented by a glossy top. Frau Fluth’s monologue from Nicolai’s Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor was stunningly capricious and sparkling — a highlight of the evening.

Alice Privett, a 27-year-old graduate of the Royal Academy of Music, opened the post-interval sequence with Massenet’s ‘Je suis encore tout étourdie’; she got confidently into her stride and made a good effort to convey Manon’s confusion when she meets Lescaut as she journeys to the convent, without really capturing the young girl’s naïve vulnerability. Likewise, the hymnal lyricism of ‘O waly, waly’ (arranged Britten) eluded Privett and her pianist Chad Vindin. In Messiaen’s ‘L’amour de piroutcha’ from the song cycle Harawi, however, they found their niche and showed great composure, Privett’s silky phrasing supported by Vindin’s subtly understated accompaniment, conveying the song’s strange mystical quality. Handel’s ‘Let the bright seraphim’ had a brassy brightness and allowed Privett to show off her breath control and neat trills.

Prunier’s aria ‘Chi il bel sogno’ from Puccini’s La rondine was the wonderfully persuasive opening item in the final programme of the evening, presented by the Armenian soprano Tereza Gevorgyan. The 27-year-old is currently studying at the National Opera Studio — supported by Opera North, the Amar-Franses and Foster-Jenkins Trust and Opera Les Azuriales — and in this impressively assured rendition (accompanied by Fletcher, who did double duty during the evening) Gevorgyan employed judicious rubato and produced a lovely vocal sheen. Manon’s ‘Je marche sur tous les chemins’ (Massenet) was dazzling as Gevorgyan span the vocal line ravishingly. Here, and in ‘How fair this spot’ by Rachmaninov and Tchaikovsky’s ‘Tell me, what in the shade of the branches’, she showed that she has tremendous stage presence. Bridge’s ‘Love went a-riding’ was an exciting rip-roaring close.

The panel of judges awarded Second Prize to Mafi, while Summerfield — the youngest competitor — swept the board taking both the Song Prize, for her interpretation of Sibelius, and First Prize. I’d have had a hard time picking a winner from this impressive line-up.

Claire Seymour

Artists and programmes:

Soraya Mafi (soprano), Ian Tindle (piano): Mozart ‘L’amerò sarò costante’, Wolf ‘‘Er ist’s’, Harrison ‘Philomel’, Liszt ‘Oh! Quands je dors’, J. Strauss ‘Frühlingsstimmen Waltz’.

Suzanne Fletcher (soprano), Nicholas Fletcher (piano): Mozart ‘Ach, ich liebte’, Britten ‘Villes’, ‘Phrase and Antique’, Schubert ‘Suleika II’, Puccini ‘Quando m’en vo soletta’, Bridge ‘Love went a-riding’.

Gemma Lois Summerfield (soprano), Sebastien Wybrew (piano): Sibelius ‘Diamanten på Marssnön’ and ‘Flickan kom ifrån sin älsklings möte’, Mendelssohn ‘Hexenlied’, Duparc ‘Chanson triste’, Copland ‘Heart! We will forget him’, Nicolai ‘Nun eilt herbei’.

Alice Privett (soprano), Chad Vindin (piano): Massenet ‘Je suis encore’, Britten ‘O waly waly’, Messiaen ‘L’amour de piroutcha’, Handel ‘Let the bright seraphim’.

Gyula Rab (tenor), Paul McKenzie (piano): Liszt ‘Benedetto sia ‘l giorno’ and ‘I’vidi in terra angelici costumi’, Britten/Purcell ‘Sweeter than roses’, Rossini ‘Ecco ridente e celo’.

Tereza Gevorgyan (soprano), Nicholas Fletcher (piano): Puccini ‘Chi il bel sorgno’, Massenet ‘Je marche sur tous les chemins’, Rachmaninov ‘How fair this spot’ (Zdes’ khorosho), Tchaikovsky ‘Tell me, what in the shade of the branches?’, Bridge ‘Love went a-riding’.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/gemmaloissummerfield.png image_description=Gemma Lois Summerfeld product=yes product_title=Kathleen Ferrier Awards, Wigmore Hall product_by=By Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Gemma Lois SummerfeldThree Tales, Imax Cinema, Science Museum, London

By David Cheal [FT, 24 April 2015]

Steve Reich and Beryl Korot tackle hubris with 2002 ‘video opera’ about science and technology

April 21, 2015

Die beste hochdramatische Sopranistin der Gegenwart

By Manuel Brug [Die Welt]

Sie entäußert sich auf der Bühne, gibt perfekt eine vollkommen gestörte Frau, die moderne Mörderin: Die Schwedin Nina Stemme ist die ideale Heroine. Zu Hause mag sie das komplette Gegenteil.

“Tarquin” an der Berliner Staatsoper: Vom Werden eines Diktators

By Benedikt von Bernstorff [Der Tagesspiegel]

Ernst Krenek hat seine Kammeroper „Tarquin“ 1940 im US-Exil geschrieben, nach der Uraufführung 1950 präsentiert die Werkstatt der Staatsoper im Schillertheater erst die dritte Produktion des Werks. Dabei beweist Krenek, dass sich mit der Zwölftontechnik der Schönberg-Schule effektvolles Musiktheater schreiben lässt. Die Partitur ist für zwei Klaviere, Geige, Klarinette, Trompete und Schlagzeug instrumentiert, die musikalische Dramaturgie suggestiv, tonale Anklänge und ein leitmotivisch eingesetztes Thema mit Sehnsuchtsintervall und Rosenkavalier-Appeal erleichtern den Zugang.

Moses und Aron, Komische Oper Berlin

By Shirley Apthorp [FT, 21 April 2015]

Holocaust references are a delicate matter on any stage, but a defensible choice in a production of Arnold Schoenberg’s monolithic Moses und Aron. Here, the mountain that Moses descends is a vast pile of Jewish corpses.

April 19, 2015

Death Clown for Cutie (Cav and Pag at the Met)

By Micaela [Likely Impossibilities, 19 April 2015]

Men are sensitive and easily injured souls, as ten minutes in any internet comment section would tell you. Such is also the gist of Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana and Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci, the august double bill of verismo which presents us twice with the even more august situation of baritones interfering with soprano-tenor relationships and it all getting very bloody. In the Met's new production, Fabio Luisi makes these high octane scores sound quite classy, but otherwise the two diverge: a dreary, clunky Cav is followed by a fun and punchy Pag. Oh, one other thing in common: for better and for worse, Marcelo Alvarez is the tenor. I shouldn't be putting that last, which might give you an idea of what is going on here.

April 16, 2015

Green: Mélodies françaises sur des poèmes de Verlaine

“Et leur chanson se mêle au clair de lune.” Coutertenor Philippe Jaroussky sings these words, which translate to “and their song mingles with the moonlight,” no fewer than three times on his new recording, Green: Mélodies françaises sur des poèmes de Verlaine. The strongest aspect of the ambitious and rewarding CD is its offering of multiple composers’ interpretations of the symbolist poetry of Paul Verlaine, such as his 1869 Clair de lune. Jaroussky sings versions of this song by Claude Debussy, Gabriel Fauré, and Jozef Zygmunt Szulc, all three of which feature vocal and instrumental melodies wending around each other, worrying yet hopeful, and evoking the “birds dreaming in the trees” and the “fountains sobbing with ecstasy.” The Debussy version, transcribed for the Quatour Ebène by Jérôme Ducros, features a cello swirling around and under the piano and voice. Debussy set several Verlaine poems to music, beginning at age 19, and his symbolist approach is here made palpable as Jaroussky’s plush vowels ebb and flow like the moonlight’s reflection in receding waves and ripples of water. All three works were composed around the turn of the twentieth century, and are set to the same three stanzas of poetry, yet Jaroussky brings out the three contrasting compositional interpretations with poise.

These differing versions of Clair de lune are only three of the 43 songs on Jaroussky’s recent recording, the first since his 2009 Opium, which also tackled the broad range in French song, and which also co-starred Ducros as his tireless pianist-accompanist. These mélodies françaises are not meant for countertenor, but Jaroussky states that “this repertoire has always been a secret passion of mine” and wonders, “why not venture into other musical worlds if we feel they are suited to our voices?” He carefully selected a wide range of examples, including not just multiple musicalizations of the same texts and imagery (as with Clair de lune), but also varying genres and even eras, with the composers’ death dates ranging from 1894 (Emmanual Chabrier) to 2001 (Charles Trenet). The overwhelming number of songs at first seems to be arranged in a haphazard order before one realizes that Jaroussky is simply giving us the fullest and richest portrait of Verlaine’s poetry. Despite sharing similar literary inclinations, the composers’ soundscapes range from the romantic to the modernistic to the chanson -esque, and the recording jumps along in an unpredictable sequence, from the melancholy to the jolly to the impressionistic. Jaroussky and Ducros, occasionally joined by the Quatour Ebène as well, prove skillful in navigating the range in sounds, though the numerous (nine of the 43) songs by Debussy are the most vivid, and vividly-conveyed.

Debussy, the symbolist composer who was so drawn to Verlaine from such a young age, also composed music for Green, the title song of the recording and another poem weighing heavy with symbolism, as in lines like “the morning wind freezes on my forehead”. Caplet, mostly known now as an orchestrator of Debussy, filled his own setting of Green with staggered, staggering melodies and a disjointed musing between the piano and voice. All three—Debussy’s and Caplet’s as well as Fauré’s version—ripple throughout with widening, broadening strokes of sound and color. Despite being the title song, however, Green is not the most frequently-interpreted: La lune blanche andIl pleure dans mon coeur are represented no fewer than four times each on Jaroussky’s recording. Charles Koechlin’s rendition of Il pleure dans mon coeur skates the edge of melodrama, with curious chords popping in and preventing excessive trudgery, while Florent Schmitt’s Il pleure dans mon coeur is a bit simpler and more consoling. Yet again, though, the Debussy and Fauré versions are truly vivid and the most expertly-delivered by Jaroussky and Ducros. The melancholy mood is felt rather than told, with the piano notes dissolving into tears in the rippling symbolism of Debussy’s version, and the piano notes descending to a final chord of discontented sleep in Fauré’s.

The chansons offer a breath of fresh air from these distressing examples or the more romantic sounds of composers like Poldowski and Massenet. Slightly more upbeat songs like Charles Trenet’s Verlaine (Chanson d’automne) and Georges Brassens’s Colombine provide a glimpse of an entirely different genre of mélodies françaises. Trenet’s Verlaine, in contrast with Debussy’s symbolist Verlaine who swirls with colors and emotions, is a real treat. Jaroussky’s voice melts over the dancing strings and piano like chocolate sauce over a sundae, with the staccato piano note at the end as the cherry on top. Other songs from later composers, like the two interpretations of Un grand sommeil noir—one by Arthur Honegger, the other by Edgard Varèse—contribute their own unique arrangement of vowels, colors, and accompaniments, such as the spidery piano part climbing and limping its way through Honegger’s Un grand sommeil noir. With such breadth in theme and mood, the recording is clearly a labor of love, and Jaroussky and Ducros bring sensitivity to each track. Just as each of the composers crafted their own shade of Green, so the countertenor here has created an entirely new take on the poetry of Verlaine, and one that leaves a distinct impression upon each listening.

Rebecca S. Lentjes

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Green.png image_description=Green: Mélodies françaises sur des poèmes de Verlaine product=yes product_title=Green: Mélodies françaises sur des poèmes de Verlaine product_by= Philippe Jaroussky, countertenor; Jerome Ducros, piano. product_id=Erato 2564616693 [2CDs] price=$17.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=1673292J. C. Bach: Adriano in Siria

The series will incorporate 250th anniversary performances of all Mozart’s important compositions, as well as works by his contemporaries. The journey has begun with an exploration of Mozart’s childhood visit to London in 1764-65 and a performance of Johann Christian Bach’s Adriano in Siria — the first staging since the original production 250 years ago (although a concert performance was given at the Camden Festival in March 1982 by the BBC Concert Orchestra under Sir Charles Mackerras, and several of the opera’s arias, most notably the celebrated ‘Cara la dolce fiamma’, have survived in the repertory).

Classical Opera have presented many fine performances on the concert platform of repertory from the late-eighteenth century and have made a number of excellent recordings of lesser-known works — among them Mozart’s Die Schuldigkeit des Ersten Gebots and Apollo and Hyacinth, and Arne’s Artaxerxes. But, it is good to see the company putting opera where it truly belongs, on the stage, and even better to have the opportunity to see and hear a work by a composer whose music is seldom performed today but who was known during his day throughout Europe as the ‘London Bach’.

Invited to write two operas for the King’s Theatre Haymarket, J. S. Bach’s eleventh surviving son arrived in the city in 1762 as a 26-year-old and stayed for the rest of his life. Two years later, the 9-year-old Mozart came to London with his family for a visit that was to last for 15 months. Adriano in Siria was presented during the 1764-65 season. Classical Opera’s founder, Ian Page argues that Mozart almost certainly attended at least one performance of this work and held the opera and its composer in high regard. London audiences were less enthusiastic though, and after seven performances it was withdrawn and never revived. In a recent Guardian article, Page cites an amusing letter written by an ‘anonymous footman’ at the King’s Theatre to The Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, which records that ‘the extraordinary merit of Mr Bach’s Adriano in Siria could not rescue it from the vengeance of these destroyers; it was doomed to oblivion as soon as it was presented: and why? Because forsooth Mr Bach did not breathe Italian air as soon as he was born. All but the Italians acknowledged the beauties of Mr Bach’s operas; and none but the Italians could have been capable of smothering so elegant a production’. ‘Extraordinary merit’ is indeed apt praise, based on this performance in the Britten Theatre at the Royal College of Music.

First set by Antonio Caldara in 1732, Pietro Metastasio’s libretto subsequently served more than 60 composers. It presents a fictional account involving Emperor Hadrian and King Osroes I of Parthia, during the former’s time as ruler of Syria. Adriano is a flawed figure: infatuated with one of his prisoners — Emirena, the Parthian princess who loves Farnaspe — he rejects his own betrothed, Sabina (who is secretly admired by Aquilio). The enraged King Osroa attempts to kill Adriano, first by burning down the citadel, then by disguising himself as a Roman soldier and stabbing him; both efforts are unsuccessful and when Farnaspe, who is suspected of arson, is discovered by Adriano fleeing with Emirena and holding Osroa’s sword, all three find themselves back in prison. The Parthians suffer yet more wretchedness at the hands of the barbarous Emperor, but eventually, Adriano’s better instincts surface — perhaps he is inspired by the nobler example set by his citizens, who demonstrate loyalty and integrity in adversity. In a hasty lieto fine, Osroa is spared death and restored to the throne, Aquilio is forgiven, and the pairs of lovers suitably matched up. (Perhaps the political dimensions of such a tale, probably designed by Metastasio to please the absolutist authorities in contemporary European city states, did not go down well in late-eighteenth-century London?)

The structure follows the typical opera seria pattern of three acts built from scenes of recitative (some of which was abbreviated in this performance) followed by a solo exit aria, and director Thomas Guthrie has had to work hard to overcome the resulting static quality — with some success. Most imaginative are the transformations from exterior to interior which are effected during the long da capo arias, often triggered by the change of mood in an aria’s contrasting middle section. Particularly striking was the descent of the black backdrop during Osroa’s first aria, in which he laments his daughter’s imprisonment and swears defiance and vengeance; the transmutation from sky-blue expanse to dark inner chamber was suggestive of the shadows in Osroa’s heart and made his aria intimate and affecting, despite his wild fury. Less successful were the attempts to indicate the unfolding ‘action’ as the soloists performed their arias at the front or side of the stage. Against a sky streaked with fiery red, at the rear of the stage Romans raced back and forth to save the burning citadel; Adriano’s henchmen stomped about seeking rebellious Parthians; in the more serene moments, actors swooped and fluttered paper birds. But, such to-ing and fro-ing distracted from the affekts being articulated by the protagonists at these moments, as if the narrative conveyed through the recitative was being noisily shoe-horned into the arias themselves. Moreover, while there was a sensible concern to show the brutality of Adriano and his regime, the rough-treatment dispensed by the Roman soldiers was often at odds with the exquisite grace of the score.

Rhys Jarman’s designs were simple and beautiful. A few plinths and costumes — the latter reminiscent of the luxurious decadence of Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s depictions of the Roman Empire — were all that were needed to establish the epoch. Lighting designer Katharine Williams employed the expansive back-drop as a canvas — bare expect for a few suggestive silhouettes of columns and topiary — on which to unfold a gradually metamorphosing palette (also evocative of Alma-Tadema) to match the sung emotions.

The cast were uniformly strong. As Adriano, mezzo-soprano Rowan Hellier was appropriately restless and headstrong. Though a little uncertain in her opening aria, she gained in confidence and the lovely richness of her tone gave stature to the Emperor despite his fickle caprices, while in higher registers her voice shone beautifully. The other castrato role, Farnaspe, was taken by soprano Erica Eloff (given Page’s commitment to period performance, why no countertenors?). Eloff struggled with the virtuosity of her first aria, ‘Disperato in mar turbato’; in the higher-lying runs her voice seemed unsupported. But, there is no doubting the exquisite beauty of her tone and in the expressive phrasing of ‘Cara la dolce fiamma’ Eloff demonstrated considerable musicality and sensitive appreciation of the style. It was a highlight of the evening, alongside Emirena’s ‘Deh lascia, o ciel pietoso’. In the latter role, soprano Ellie Laugharne was also challenged by some of the more taxing coloratura but her singing persuasively communicated character and feeling. As Sabina, Filipa van Eck sang accurately and vivaciously but her resonant, burnished soprano was rather odds with the others voices and with the eighteenth-century aesthetic.

Stuart Jackson’s Osroa was a commanding presence; although not possessing a huge voice, Jackson used his alluring tenor, and the text, to convey the King’s integrity in his two arias. Tenor Nick Pritchard performed Aquilio’s Act 3 aria, in which he admires the manipulative cunning of his efforts to win Sabina, which considerable confidence and skill. It was worth waiting for.

The Orchestra of Classical Opera, under Page’s baton, were stylish and charismatic. In particular, Page brought to the fore Bach’s inventive and captivating writing for the woodwind; there were some lovely clarinet solos and one could almost imagine the excitement of the young Mozart upon hearing the wonderfully warm blend of groupings of clarinets, horns and bassoons.

Page suggests that J. C. Bach was arguably the biggest influence on the young Mozart’s burgeoning compositional voice. Indeed, Mozart travelled to Paris in 1778 where he again encountered Bach and attended a performance of Bach’s opera, Amadis de Gaul. Mozart wrote to his father: ‘Mr. Bach from London has been here for the last fortnight. … You can easily imagine his delight and mine at meeting again; perhaps his delight may not have been quite as sincere as mine —but one must admit that he is an honorable man and willing to do justice to others. I love him (as you know) and respect him with all my heart; and as for him, there is no doubt but that he has praised me warmly, not only to my face, but to others, also, and in all seriousness — not in the exaggerated manner which some affect.’ (27 August 1778)

Whatever the degree of his influence upon the young Mozart, J. C. Bach — described by one London contemporary as a ‘second Handel’ — contributed many individual numbers for inclusion in operas by other composers and produced 14 operas of his own. It would be good to hear more of them.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Adriano — Rowan Hellier, Osroa — Stuart Jackson, Emirena — Ellie Laugharne, Fasnaspe — Erica Eloff, Aquilio — Nick Pritchard, Sabina — Filipa van Eck, Actors — Leiran Gibson, Victoria Haynes, Lauren Okadigbo (Sabina’s lady-in-waiting), Sandro Piccirilli, Daniel Swan (Adriano’s attendant), Lotte Tickner (Emirena’s lady-in-waiting); Conductor — Ian Page, Director — Thomas Guthrie, Designer — Rhys Jarman, Lighting — Katharine Williams, The Orchestra of Classical Opera. Britten Theatre, Royal College of Music, London, Tuesday 14 th April 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rowan_Hellier.png image_description=Rowan Hellier [Photo by andystaplesphotography.com courtesy of Rayfield Allied] product=yes product_title=J. C. Bach: Adriano in Siria product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Rowan Hellier [Photo by andystaplesphotography.com courtesy of Rayfield Allied]April 15, 2015

Bethan Langford, Wigmore Hall

The foundation has diverse and commendable aims, from encouraging and supporting young musicians on the threshold of their careers, to initiating educational programmes for school children from underprivileged backgrounds, to performing public recitals at two London hospitals and working with patients on their wards.

Concordia also provide public concerts at prestigious venues across London, and this Annual Prize Winners Concert at the Wigmore Hall, in association with the Worshipful Company of Musicians, was one such occasion. British mezzo-soprano Bethan Langford added the Concordia Founder’s Prize to a long list of awards that she has received in recent years. A student on the Opera Course at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, Langford is the recipient of the School’s Susan Longford Prize, the Paul Hamburger lieder prize and the Violette Szabo award for English song. She also won the 2013 John Fussell Award and is a Samling Scholar, and is a recipient of the Elizabeth Eagle-Bott Award for visually impaired musicians from the RNIB. Langford was accompanied here by pianist Ben-San Lau, winner of the Concordia Foundation’s Serena Nevill Prize.

Langford and Lau’s first sequence of songs juxtaposed the serene and spiritual with the rumbustious and rollicking. Charles Ives’s ‘Songs my mother taught me’ was written in 1895, fifteen years after Dvořák’s more famous setting, which we would hear later in the evening. Langford was focused and direct, the tone open and well-rounded. The steadiness of line, despite the low tessitura and long phrases, was impressive and typical of the considerable composure and maturity that she displayed throughout the recital. Lau complemented the softly rising arcs in the voice with delicately oscillating octaves above a low intoning drone in the bass, and the subtle shifting of the harmonies and musical layers in the piano against the gentle vocal melody created a spaciousness and timelessness.

Herbert Howell’s ‘King David’ followed. This is one of Howell’s finest songs, and one of many settings that he made of poetry by his friend Walter de la Mare. Here Langford was a clear and unaffected storyteller: she used the rhythmic flexibilities of the score and her alluring tone to imbue the tale of King David’s sorrow with passion and sincerity, building an operatic ‘scena’ of great intensity. The richness and power of the vocal line communicated the anguish that haunted the King’s heart despite the soothing pleasures of the playing of one hundred harps. Yet, there was gentleness and poignancy too, as the King wanders in his garden and is uplifted by the innocent song of the nightingale, even though this little bird — like Hardy’s darkling thrush — is oblivious to his dark feelings: ‘Tell me, thou little bird that singest,/ Who taught my grief to thee?’ Lau’s delicate traceries and arpeggios gave voice to the bird’s melancholy utterances, and the piano postlude evoked the elegiac loveliness of the Georgian poets.

The darkness was more overt in two songs from Benjamin Britten’s A Charm of Lullabies, a collection of five lullabies which the composer wrote for the mezzo-soprano Nancy Evans. ‘A Cradle Song’, a setting of Blake, began with a languidly swinging bass line from Lau but the entry of the voice’s entreaty, ‘Sleep, sleep, beauty bright’, quelled the forward movement. For much of the song, the vocal line was richly expressive and exploratory. The dreaminess culminated in the beautifully quiet reprise of the opening vocal melody, the piano’s final gestures luring us into slumber. We quickly awoke, though, with the alarming admonishment which opens ‘A Charm’: ‘Quiet!’ Langford amusingly captured the exasperation of the mother whose child will not sleep, although the imploring tone of the final requests, ‘Quiet, sleep!’, suggested deeper unrest. Lau negotiated the busy piano part with accomplishment. We then returned to Ives for a flamboyant rendering of ‘The Circus Band’; Langford achieved a thrilling brightness at the top and demonstrated impressive vocal agility, while Lau did a sterling job of evoking the prancing horses and blasting trombones. As those waiting in Main Street for the arrival of the circus declare, ‘Oh! Aint it a grand and glorious noise!’

Next, the duo looked back to the art songs of the nineteenth century, beginning with Schubert’s ‘Der blinde Knabe’ (The blind boy). Initially I found Lau’s accompaniment — rippling right-hand figuration and a two-quaver staccato interjection in the left hand — a little intrusive; but, this was a rare occasion in this performance where Lau was not wonderfully supportive and sensitive, and Schubert’s writing does make considerable demands on the pianist with its rhythmic stumblings and uncertainties. Colley Cibber’s poem (translated into German by Jacob Nicolaus de Jachelutta Craigher) of childhood tragedy — in which the blind boy asks of the sighted, ‘O ye love ones, tell me some day/ What is this thing called light?’ — might lead the listener to expect gushing Victorian sentimentality. But, Schubert’s setting conveys not pathos but endurance, emphasizing the essential inner strength of the child. In the halting opening phrases, Langford created an air of wonder and mystery, while the movement to the minor key in the fourth stanza — ‘In truth I know not your delights/ And yet ’tis not my fault/ In suffering of it I’m glad/ With patience I endure’ — was haunting, but gentle and lacking self-pity. The return to the major key at the close — ‘I am as happy as a King,/ though still a poor blind boy (‘ein armer blinder Knab’) brought stillness and peace.

Two of Antonín Dvořák’s Gypsy Songs (Zigeunermelodien) followed. ‘Songs my mother taught me’ (Když mne stará matka zpívat, zpívat ucívala) was a highlight of the evening, Lau establishing a beguiling lilt and Langford employing a beautiful mezza voce to convey the singer’s sadness and hope. She made a good attempt at the Czech too. ‘Give a hawk a fine cage’ (Dejte klec jestrábu ze zlata ryzého) brought the sequence to a rousing, rhetorical close.

After the interval, Langford and Lau visited Mahler’s Der Knaben Wunderhorn. The vocal characterisation was strong in ‘Trost im Unglück’ (Solace in Misfortune), as Langford captured the petulant feistiness of the hussar’s paramour. In ‘Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen’ (Where the fair trumpet sounds) — another dialogue between a young girl and her lover, but one which intimates both erotic passion and loss — the full richness of the mezzo-soprano’s voice blossomed charismatically, in lush phrases which were focused and accurate. Lau’s figures summoned up the bugles and drums of the battleground, and these military gestures contrasted poignantly with the tenderness of the lovers’ intimated, ambiguous encounter.

In three of Poulenc’s 1948 Calligrammes (a collection of settings of Apollinaire, whose subtitle ‘Poèmes de la Paix et de la Guerre’ reveals the sufferings of war to be its subject), Langford’s French diction was less clear. But, in the brief ‘Il pleut’ she gave her voice a sheen which pierced through the piano’s ‘rain’ (the cascades match Apollinaire’s visual ‘picture’, for the typography of the poem mimics the slants of falling rain). Here, Lau once again made the difficult figuration sound effortless. ‘Aussi bien que les cigales’ (As well as the cicadas) was notable for its rhetorical bravura and effulgent energy. To conclude the vocal sequence Langford and Lau selected Richard Rodney Bennett’s ‘Tango’, from The History of the Thé Dansant, composed in 1994 and based on the popular dances of the 1920s. Its combination of exuberance and lyricism was a charming conclusion to the vocal items in the programme.

Closing each half of the recital, the Ducasse Trio — winners of the Concordia’s Barthel Prize — presented works for piano, clarinet and violin by Ives, Khachaturian and Bartók. Violinist Charlotte Maclet assuredly conjured different worlds, from the reserved serenity of Ives to the brashness of Bartók’s scordatura exclamations. In the latter composer’s Contrasts, Maclet’s strong tone and virtuosity communicated Bartók’s passion for the music of his native Hungary, and helped to make the challenging score persuasive and engaging. There was much fluid, agile playing from clarinettist William Duncombe in Khachaturian’s Trio and pianist Fiachra Garvey was ever responsive to his fellow musicians. It was good to have an opportunity to hear these seldom performed chamber works.

As they gathered on stage together at the end of the evening, the performers’ enjoyment and pride was evident and infectious.

Claire Seymour

Performers and programme:

Bethan Langford mezzo-soprano, Ben-San Lau piano, Ducasse Trio (Charlotte Maclet violin, William Duncombe clarinet, Fiachra Garvey piano). Wigmore Hall, London, Monday 13th April 2015.

Charles Ives: ‘Songs my mother taught me’; Herbert Howells: ‘King David’; Benjamin Britten: A Charm of Lullabies Op.41 (‘A Cradle Song’, ‘A Charm’); Charles Ives: ‘The Circus Band’; Franz Schubert: ‘Der blinde Knabe’ D833; Antonín Dvořák’s Gypsy Songs (Zigeunermelodien) Op. 55 (No.4 ‘Songs my mother taught me’ (Když mne stará matka zpívat, zpívat ucívala), No.7 ‘Give a hawk a fine cage’ (Dejte klec jestrábu ze zlata ryzého); Charles Ives: Largo for Violin, Clarinet and Piano; Aram Khachaturian: Trio for clarinet, violin and piano; Gustav Mahler: Des Knaben Wunderhorn (‘Trost im Unglück’, ‘Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen’); Francis Poulenc: Calligrammes (No.4 ‘Il pleut’, No.5 ‘La Grâce exilée’, No.6 ‘Aussi bien que les cigales’; Richard Rodney Bennett: A History of the Thé Dansant (No.3 Tango); Béla Bartók: Contrasts Sz.111.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bethan_Langford2.png image_description=Bethan Langford [Source: http://www.bethanlangford.com/] product=yes product_title=Bethan Langford, Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Bethan Langford [Source: Bethan Langford]April 14, 2015

A broken heart in a bloodstained nightgown

By Phillip Larrimore [14 April 2015, The Charlotte Observer]

Opera Carolina’s production of “Lucia di Lammermoor” at Belk Theater is elegantly set, handsomely lit, fleetly conducted, and sung with high virtuosity, especially among the principals.

Tansy Davies: Between Worlds (world premiere)

This co-commission from ENO and the Barbican seems, alas, founded upon a bad idea. One can make an opera out of almost anything, of course, but that does not mean that some subject matter is no more or no less suitable than any other. The problem with the highly fashionable — at least in some quarters — tendency to base operas upon recent(-ish) news stories is that, all too easily, their ‘documentary’ as opposed to artistic quality becomes the issue at stake. In the case of the bombing of the Twin Towers, there is also the question of attempting to put oneself beyond criticism, or at least of appearing to do so, by dealing with such portentous subject matter. Or, in the opposite case, of creating a controversy, when someone objects to the choice of subject matter.

But the problem lies more with the specific choices of Nick Drake’s libretto: which, frankly, is dire. What are we told? That some people, with differing personalities and differing personal and financial circumstances, went to work one day, not knowing what was to happen, and never came back. Not much more than that, really. As a friend said to me after the event, there is a reason why disaster films tend not to deal with actual disasters, but will have at least someone surviving. What is an undeniable tragedy in ‘real life’ does not necessarily transfer so well to tragedy on stage. Moreover, the banality of the words — which will doubtless be justified as ‘realistic’ — irritates and, worse than that, bores. There is a limit to how many times anyone wants to hear ‘What the fuck?’ repeated on stage. Snatches of ‘real-life’, if fictional, conversation, are heard from the chorus as well as the ‘characters’, presumably a nod to the celebrated telephone messages left by victims. What on earth the ‘Shaman’ character is doing is anyone’s guess. I assume he in some sense signifies Fate; to start with, I wondered whether we might have a guest appearance from Stockhausen; alas not. Anyway, he spouts gibberish, which at least offers verbal and indeed musical variety, which to some extent is taken up by other members of the cast, especially the Janitor. Then he disappears. That sits very oddly with the work’s ‘realism’, and not productively so. Might it not have been more interesting to deal with the creators of what Stockhausen so memorably called Lucifer’s greatest work of art? Or, better still, to create a more finely balanced, fictional story?

Tansy Davies’s score is better than that. I suppose one would describe it as ‘eclectic’. There is nothing wrong with that; indeed, as Hans Werner Henze put it, writing about The Bassarids, ‘with Goethe under my pillow, I’m not going to lose any sleep about the possibility of being accused of eclecticism. Goethe’s definition ran: “An eclectic … is anyone who, from that which surrounds him, takes what corresponds to his nature.” If you wanted to do so, you could count Bach, Mozart, Verdi, Wagner, Mahler, and Stravinsky as eclectics.’ What I missed, though, was any real sense of musical characterisation, or indeed of sympathy for voices. The score is atmospheric, and has a nice enough line in impending doom, ‘darkening’ in almost traditional ‘operatic’ style, but it tends more towards background, like a good film score, rather than participating in and creating the drama. That, at any rate, was my impression from a first hearing. Rightly or wrongly, music seemed subordinated not so much to ‘drama’, as to subject matter.

Deborah Warner’s production plays things pretty straight. What to do with the actual moments of impact? Stylisation is not a bad solution, so we see pieces of paper fall from the ceiling. Having a Mother sit at the front of the stage, looking ‘soulfully’ into the distance, at the close, risks bathos; but perhaps that is in the libretto. It does no particular harm. Insofar as I could discern, the ENO Orchestra and Chorus were very well prepared, incisively conducted by Gerry Cornelius. The cast is called upon more obviously to act than to display great vocal prowess, but its members all did what was asked of them. Andrew Watts’s counter-tenor Shaman stood out, but then, as mentioned, the role puzzling fizzled out. Susan Bickley’s talents seemed wasted, but as usual, impressed.

So then, I was happy to have gone, but cannot imagine rushing back. Apologists for new (alleged) conceptions of opera would ask where the problem was with that. Must everything, or indeed anything today, be a masterpiece? Well, clearly not everything will be, but I am not sure that I am willing to ditch the work concept or even the ‘masterpiece concept’ so emphatically, quite yet. Besides, this is clearly intended as a ‘work’, not as a ‘happening’, or some such alternative. ENO deserves credit for supporting and performing the work. Perhaps next time around, it will be luckier with respect to the outcome; this was, after all, the company that commissioned The Mask of Orpheus.

Mark Berry

Cast and production information:

Shaman: Andrew Watts; Janitor: Eric Greene; Younger Woman: Rhian Lois; Realtor: Clare Presland; Younger Man: William Morgan; Older Man: Phillip Rhodes; Mother: Susan Bickley; Lover: Sarah Champion; Babysitter: Claire Egan; Wife: Susan Young; Security Guard: Ronald Samm; Firefighter 1: Philip Sheffield; Firefighter 2: Rodney Earl Clarke; Sister: Niamh Kelly; Child: Edward Green. Director: Deborah Warner; Set designs: Michael Levine; Costumes: Brigitte Reiffenstuel; Lighting: Jean Kalman; Video: Tal Yarden; Choreography: Kim Brandstrup. Orchestra of the English National Opera/ Chorus of the English National Opera (chorus master: Stephen Higgins)/Gerry Cornelius (conductor). Barbican Theatre, London, Saturday 11 April 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tansy_Davies.png image_description=Tansy Davies [Photo by Rikard Österlund] product=yes product_title=Tansy Davies: Between Worlds (world premiere) product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Tansy Davies [Photo by Rikard Österlund]April 13, 2015

Arizona Opera Ends Season in Fine Style with Fille du Régiment

While in Paris working on the French versions of his other operas, Gaetano Donizetti took some time to write an opéra-comique, La Fille du Régiment (The Daughter of the Regiment). Its French text is by Jean-François Bayard, a nephew of the famous librettist Eugène Scribe, and the prolific but rather old fashioned Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges.

After its premiere at the Opéra-Comique on February 11, 1840, Marie-Julie Halligner, who sang the Marquise of Berkenfeld, said that the performance was "a barely averted disaster" because the tenor was frequently off pitch. French critic and composer Hector Berlioz claimed that the new work could not be taken seriously, but in all probability his opinion was colored by jealousy. During a single year, Donizetti had two works performed at the Opéra, two at the Théâtre de la Renaissance, two at the Opéra-Comique, and one at the Théâtre-Italien.

La Fille du Régiment soon became popular at the Opéra-Comique and it achieved its thousandth performance within seventy years. One of the reasons for its success was the aria that defeated the premiere’s tenor, Mécène Marié de l'Isle. "Ah! Mes amis, quel jour de fête!” ("Ah, my friends, what an exciting day"), is best known for containing nine high Cs.

David Portillo as Tonio, Susannah Biller as Marie with Regiment including Stefano De Peppo as Sergeant Sulpice

David Portillo as Tonio, Susannah Biller as Marie with Regiment including Stefano De Peppo as Sergeant Sulpice

On March 7, 1843, the first American performance of Fille took place at the Théâtre d'Orléans in New Orleans. It was so successful there that the company brought the opera to New York City where it was highly praised by local newspapers. As time went on, artists such as Jenny Lind, Henriette Sontag, Adelina Patti, Lily Pons, and Joan Sutherland enjoyed singing the role of Marie.

On April 10, 2015, Arizona Opera finished its season with La Fille du Régiment at Phoenix Symphony Hall. A passionate Marie, Susannah Biller was a veritable energizer bunny onstage. Her voice is bright and flexible with a good bloom on top and a tiny bit of steel in it. Having created an exciting character, she sang with agility as well as passion.

Tenor David Portillo, who has a beautiful lyric sound, had no difficulty reaching the nine high Cs in the famous aria. As lively and buoyant as Biller, bass Stefano de Peppo was a nimble, hilariously funny Sergeant Sulpice who sang with a colorful, robust voice. Donizetti did not often write major roles for lower women’s voices but the comedic Marquise of Berkenfeld is an exception. Mezzo Margaret Gawrysiak played her part broadly and showed her true vocal ability in her aria, “Pour une Femme de mon Nom” (“For a Woman with my Name”).

Arizona Opera Young Artist Program member Calvin Griffin has become a valuable member of the company. A lithe and limber comedian, he made an attentive Hortensius. Chris Carr was an amusing corporal while actress Didi Conn was an entertaining Duchess of Krakenthorpe. Like many other operas of this era, Fille has a great deal of choral music. Henri Venanzi’s singers conveyed in idiomatic French style and grace.

Right from the opening notes of the overture, the audience knew that conductor Keitaro Harada was putting his individual stamp on this piece. He combined Donizetti’s delightful melodies with dramatic musical coherence. His dynamic range was huge and he kept the playing transparent so that listeners heard all the melodic strands in the fabric of the score. This was one of the best shows of the year at Arizona Opera and it leaves us waiting with bated breath for next season. Personally, I can’t wait for Emmerich Kálmán’s operetta, Arizona Lady, a piece that has never before been seen in Arizona.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Marie, Susannah Biller; Tonio, David Portillo; Sergeant Sulpice, Stefano De Peppo; The Marquise, Margaret Gawrysiak; Hortensius, Calvin Griffin; Corporal, Chris Carr; Duchess of Krakenthorpe, Didi Conn; Notary, Ian Christiansen; Peasant, Justin Carpenter; Conductor, Keitaro Harada; Stage Director, John de los Santos; Scenic Design, Boyd Ostroff; Lighting Designer, Douglas Provost; Chorus Master, Henri Venanzi; Dancers, Phoenix Ballet; Supertitles, Keith Wolfe.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DofR%20BILLER%20N%20DE%20PEPPO%20snd%207.png

image_description=Susannah Biller as Marie and Stefano De Peppo as Sergeant Sulpice [Photo by Tim Trumble for Arizona Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Arizona Opera Ends Season in Fine Style with Fille du Régiment

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Susannah Biller as Marie and Stefano De Peppo as Sergeant Sulpice

Photos by Tim Trumble for Arizona Opera

Il turco in Italia, Royal Opera

Add to that Romani’s profusion of mad-cap motion and Rossini’s tuneful, if largely indistinctive, musical fun and what’s not to like?

So, why did I find myself yawning rather than guffawing during this first night of the run? Things certainly unfolded efficiently enough, from Fenouillat’s sliding flats to Alessandro Corbelli’s wry patter. Yet, some of the paint’s brilliance has faded and Corbelli, while still the master buffo caricato, was not always focused of voice and at times seemed to be going through the theatrical motions. The ensemble was good and the farce fluent: three of the cast — Corbelli, Thomas Allen and Ildebrando D’Arcangelo have sung in every performance of this production, while Barry Banks was the original Don Narciso and Aleksandra Kurzak sang Fiorilli for the first revival in 2010, so one would expect the slapstick to be slick. Indeed, Don Geronio (Corbelli) and Selim (D’Arcangelo) conclude their tussle by trapping a waiter between two chairs with the grace and precision of Royal Ballet principals (Movement Director, Leah Hausman).

Conductor Evelino Pidò draw some charming playing from the ROH orchestra and created a good balance between stage and pit. There was strong singing too from the ROH chorus: the women were a sharp band of pick-pockets and the men looked glitzy in their blue wigs and ball-gowns. But, despite the incessant on-stage commotion, it all felt rather perfunctory and dramatically sluggish. There was plenty of laughter around me but, unfathomably, that seemed to be prompted by the unembellished surtitles rather than anything happening on stage.

Aleksandra Kurzak as Fiorilla, Ildebrando D’Arcangelo as Selim, and Rachel Kelly as Zaida

Aleksandra Kurzak as Fiorilla, Ildebrando D’Arcangelo as Selim, and Rachel Kelly as Zaida

The 1950s and 60s have been fertile decades of late for opera directors seeking a piquant period-update. And, it seems appropriate for Caurier and Leiser to recreate an era which saw a revival of interest in Il Turco, starting with Maria Callas’s 1950 performance in Rome at the Teatro Eliseo and the 1955 La Scala production of the opera, which had been absent from that house’s stage for 130 years.

The directors give us every cliché in the book, from Narciso’s greased Elvis-quiff to a superfluity of vintage vehicles: one scene assembles a taxi, a Fiat 500 and a Vespa. This is a simple, carefree world where everyone is rich and happy, and the sun always shines. No wonder that the arrival of a Turk — atop the prow of his luxury yacht — creates such excitement amongst these urbane Italians. If one were tempted to detect a touch of xenophobia in Romani’s libretto, Caurier and Leiser certainly don’t cast even the slightest glance in the direction of UKIP.

It’s probably not the directors’ fault if things feel rather insubstantial — the text and score are frivolous froth. But, during the evening’s longeurs — particularly in Act 2 — I found myself musing on tangential matters. Last year, an exhibition at the Estorick Collection in London presented photographs of the era of Italy’s ‘economic miracle’; of Brigitte Bardot indolently sipping champagne, and Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor idling on the deck of their yacht. But, Fellini’s film, which is repeatedly referenced in the programme, was not a celebration of a hedonistic golden age, rather a critique of it: the title is highly ironic. And, the parallels with post-Berlusconi Italy are not particularly heartening. Those living in the Roma camps of southern Italy face bitter discrimination; a few years ago, the Guardian reported that photographs had emerged of a beach in Naples where two young Roma gypsy girls had drowned, while just feet away from them a carefree couple enjoy a leisurely picnic.

If I’m straying from the point, it’s because I spent much of the evening struggling to find the ‘point’ of this production; but this was undoubtedly futile, for there isn’t one … and, indeed, why should there be more to Rossini’s opera than harmless fun under an azure sky? Those around me evidently enjoyed themselves.

Barry Banks as Don Narciso, Thomas Allen as Prosdocimo, and Rachel Kelly as Zaida

Barry Banks as Don Narciso, Thomas Allen as Prosdocimo, and Rachel Kelly as Zaida

One of Rossini’s earliest comic farces, Il Turco in Italia was first performed in 1814 at La Scala. The score is busy and bustling, but largely unmemorable; Rossini makes little attempt to use his music to characterise and it often feels oddly disconnected from the text. But, then, the ‘text’ is ‘made up’ as it goes along … for the Poet, Prosdocimo, struggling in the mires of writer’s block, has arrived at a gypsy encampment hoping to find inspiration for his new opera libretto among the everyday happenings of the common folk. As so, our opera unfolds before us … except that the common folk prove more unpredictable that the Poet anticipated and re-write the scenes that he has penned for them. The result is an intrigue that would be a serious contender for the ‘most confusing plot in opera’ prize.

But, here goes … we are in Naples. A Turkish prince, Pasha Selim, wanders into a beach-side gypsy camping ground, irritated because his favourite amour has escaped from the harem and confused because he finds that on this foreign soil he cannot simply buy himself another wife if he wants one. But, things soon look up: Fiorilla — the flighty, flirtatious wife of put-upon Don Geronio — is happy to take Selim's mind off his troubles … if she can squeeze him in between assignations with her lover Narciso. Prosdocimo is relieved to find the elusive plot for his new opera buffa among these tangles of romantic philandering and marital suffering. The action occasionally veers in tragic directions, but the Poet successfully engineers a happy ending. At the close repentance is sworn, forgiveness is dispensed, and the various couples are reunited, leaving a lonesome Narciso to nurse his wounded pride and heart.

As the abused Geronio, Corbelli once again showed us how buffo should blend buffoonery and pathos, whether tangling with the fronds of a palm tree or fighting strands of spaghetti. This was a theatrical masterclass even if at times Corbelli’s singing was rather unfocussed, particularly in the more florid passages. The influence of Così fan tutte on Rossini’s opera can be strongly felt (Mozart’s opera had been staged at La Scala shortly before Il Turco was premiered) and as the stylishly white-suited Prosdocimo, Thomas Allen essentially reprised his inimitable Don Alfonso, confidently manipulating the action with suavity and wit. There isn’t much of a voice left, but Allen can still effortlessly command the stage.

Barry Banks, attired in garish yellow denim and sporting an unattractive beard, sounded a bit strained in Narciso’s show-piece aria but established a good rapport with Corbelli, the two rivals brought together by Fiorilla’s perfidies. Polish soprano Aleksandra Kurzakreturned to the role of Fiorilla and perted, pouted and strutted with aplomb. She showed vocal athleticism, although some of the coloratura was ragged at the top, and I didn’t always find her tone attractive — it was rather too ‘edgy’ when in the stratosphere and Kurzak didn’t capture the vulnerability with should show through Fiorilla’s narcissism in her soul-searching aria of repentance, ‘Squallida veste, e bruna d’affanno e pentimento’, as she reflects on her love for the three men and her anguish at being torn between them. There was more warmth, however, in her final reconciliation duet with Geronio.

There were no doubts about Ildebrando d’Arcangelo, though; he was as sumptuous of voice as he was alluring of appearance. His bass was velvety and dark, wonderfully conveying the exoticism of the strange and foreign. D’Arcangelo’s virtuosic arias were technically precise but also full of colour and character, and his duets with Corbelli and Fiorilla were the highlights of the evening.

Two Jette Parker Young Artists were given their chance to shine. As Zaida, Irish mezzo-soprano Rachel Kelly impressed, competing feistily with Fiorilla for Selim’s attention and affection. When I heard Kelly last year, in the role of Mirinda in the ROH’s production of L’Ormindo at the Globe Theatre, I remarked the ‘rich sensuality’ of her voice, and this glowing warmth was much in evidence again. Portuguese tenor Luis Gomes had little to do as Albazar but acquitted himself well.

This was a good ensemble performance. If you like a dash of Pirandello spiced with Goldoni, then you’ll enjoy.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Fiorilla — Aleksandra Kurzak, Selim — Ildebrando D'Arcangelo, Don Geronio — Alessandro Corbelli, Don Narciso — Barry Banks, Prosdocimo — Thomas Allen, Zaida — Rachel Kelly, Albazar — Luis Gomes; Conductor — Evelino Pidó, Directors — Moshe Leiser and Patrice Caurier, Associate Director — Richard Gerard Jones, Set Designs — Christian Fenouillat, Costume Designs — Agostino Cavalca, Lighting Design — Christophe Forey, Movement Director — Leah Hausman, Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Saturday 11th April 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Il%20Turco%20In%20Italia-ROH-623%20ALEKSANDRA%20KURZAK%20AS%20FIORILLA%20%C2%A9%20ROH.%20PHOTOGRAPHER%20TRISTRAM%20KENTON.png image_description=Aleksandra Kurzak as Fiorilla [Photo © ROH. Photographer: Tristram Kenton] product=yes product_title= Gioacchino Rossini : Il turco in Italia, Royal Opera House, London, 11th April 2015 product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Aleksandra Kurzak as FiorillaPhotos © ROH. Photographer: Tristram Kenton

April 12, 2015

The Siege of Calais

——

The Wild Man of the West Indies

This is committed programming, but characteristic of a company which in 2014 won an Outstanding Achievement in Opera Olivier Award for their ‘brave and challenging’ productions of Michael Tippett’s King Priam and Benjamin Britten’s Paul Bunyan that year.

The Siege of Calais was premiered at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples in 1836, the forty-ninth of Donizetti’s operas to be performed during his lifetime. After its initial run of thirty-six performances it was unheard until Opera Rara’s acclaimed 1990 recording under David Parry, with Della Jones, Nuccio Focile and Christian du Plessis in the leading roles.

Salvatore’s Cammarano’s libretto is unusual in that it is idealistic heroism rather than passionate romance which is at the heart of the drama. The opera presents an account of the 1346 Siege of Calais mainly from the perspective of the city’s Mayor, Eustachio, and his son Aurelio. Eustachio defies his besiegers, quells unrest among the French citizens, and uncovers and overcomes a rebellion led by an English spy. Word arrives that the English King will spare the town if six of its finest citizens are offered up for the humiliation of a public execution. Donizetti was not fully satisfied with the dramatic construction of his opera. There is also a third act, often omitted even during the original run, in which the focus shifts to the English camp where King Edward III entertains Isabella, his queen. (Presumably the incorporated dances were intended to entertain French audiences.) In this longer version, the English monarchs, though initially unrelenting, are ultimately swayed by the honour and selflessness of the French victims and free them, to general rejoicing.

Director James Conway follows the convention of omitting this final act (although he assimilates some of the Act 3 music into the earlier scenes — King Edward’s aria to rally the troops, for example). However, even without this last-act switch from tragedy to celebration, Cammarano’s libretto doesn’t quite come off. There is a basic tension — will the burghers of Calais resist or submit to the pitiless English blockaders? Yet, within this general narrative, the ups and downs flip repeatedly from melodrama to anti-climax, with little forward movement. So, for example, we move from the initial scene outside the city wall, to a powerful duet for Eustachio, the Calais Mayor, and his daughter-in-law Eleonora, who despair the loss of Aurelio whom they fear has selflessly sacrificed himself in an attempt to gain food for his new-born son (his daring deeds are depicted by Conway during the overture). But, their lamentations are unexpectedly interrupted by the jolly arrival of Giovanni D’Aire with news that Aurelio has survived after all, a rapid change of tone which makes their grief seem superfluous and excessive, and their joy at Aurelio’s endurance somewhat trite.

The inadequacies of the drama are exacerbated by Conway’s very restrained direction. The protagonists do little more than stand and deliver, and the choreography of the choruses is particularly unanimated. Eustachio — evidently suffering from a damaged ankle — sings several of his key proclamations seated on an upturned bucket. The characters play ‘parcel the parcel’ with the ‘baby’, rather indifferent to the grey bundle which they unceremoniously pass between them. And, the suffering French burghers seem occasionally to forget the severity of their injuries, throwing sticks and supports aside to leap and gambol at moments of excitement and elation. A bandage and bruise do not an invalid make.

Things are not helped by the fact that Donizetti’s score occasionally reverts to ‘rum-ti-tum’ banality at moments of emotional catharsis. That said, there are also places, particularly in the act-ending ensembles, where the music does express powerful human feelings and psychological depth. And, Samal Blak’s designs, though fairly minimal (just a broken sewage pipe and some mangled hanging bundles) certainly convey the bleakness and misery of war. Conway and Blak choose not to offer a realistic presentation of the historic events of the Hundred Years War. Instead we have an unspecified time and place; perhaps the siege of St Petersburg, or even more topical conflicts in Bosnia, Serbia, former Soviet states and Syria, are suggested. The lighting design of Mark Howard is effective too: particularly expressive was the gradual move from the deep blue of midnight to the vibrant red of the dawn executions.

What makes this production come alive is the consistently strong singing of the cast who are unswerving in their commitment to the score, and none more so than baritone Craig Smith as Eustachio. His opening solo, a well-developed recitative-arioso, had a Verdian intensity and Smith demonstrated stamina and accuracy — and a lovely smooth lower register — throughout his honest depiction of man wracked by personal love and public responsibility. Soprano Paula Sides sang the rather undeveloped role of Eleonora, Aurelia’s wife, with beautiful tone and shining vibrancy at the emotional climaxes. She inspired genuine pathos, especially in her prayer over the sleeping Aurelio, which opens Act 2. Her heartfelt invocation awoke the dreaming Aurelio, triggering a sumptuous duet with the voices soaring and dipping in adjacent thirds and sixths; this was plush and thrilling singing.

The trouser-role of Aurelio was magnificently performed by mezzo-soprano Catherine Carby. She made an exceptional impact across a wide range, leaping athletically between registers, and her low voice was stirring and firm, of penetrating richness. Donizetti’s score is, for once, virtuosity-lite, but in its more florid passages Carby used the flamboyant gestures to make a striking dramatic impression: Aurelio’s account of his terrifying dream was especially moving. Sincerity and passion were the touch-words here; and Carby blended as effortlessly with Sides’ Eleonora in their Act 2 duet as she did with the five French victims in the ensemble which ends the act.

As Edoardo, the English King, Grant Doyle demonstrated fine bel canto characteristics, although Edmondo (a strong, bright Ronan Busfield) looked somewhat disconcerted to find himself first dragged into a blithe dance by his King, as the latter anticipates overcoming the obstacles to his glory, then menacingly threatened with a sharp tweak of the ear.

Unusually, Donizetti’s emphasis is on the ensembles — which may have accounted for the opera’s lack of popularity following the first Naples’ performances — and the whole cast and chorus obliged with invigorating singing. In the minor roles Andrew Glover (Giovanni D’Aire), Matthew Stiff (Pietro de Wisants), Matt R J Ward (Giacomo de Wisants), Jan Capiński (Armando) and Peter Braithwaite (a Stranger) all acquitted themselves admirably. The Octet at the close of Act 1 was superb; similarly moving was Act 2 close as the citizens fought for the honour to die to spare their fellow men. The orchestral score is interesting and Jeremy Silver conducted with energy, whipping the action along; if there was occasionally some waywardness in the choral numbers it was quickly remedied. The overture was notable for some lovely horn and woodwind solos.

Donizetti's Il furioso all'isola di San Domingo, retitled by ETO as the more ‘catchy’ The Wild Man of the West Indies, is even more of a rarity. First heard in Rome in 1833, the opera has a libretto by Jacopo Ferretti which is based upon an episode from Part 1 of Cervante’s Don Quixote. The action centres on the mad ravings of a Spanish gentleman, Cardenio, who has sought refuge on a Caribbean island following his wife’s infidelities with own brother, Fernando. The plantation manager, Bartolomeo, orders Cardenio to be detained but Marcello, Bartolomeo’s daughter, urges her father to show compassion. A monstrous storm wrecks a ship and washes up both Eleonora, the unfaithful wife, and Fernando; both are seeking forgiveness and reconciliation.

Donna Bateman as Marcella and chorus in The Wild Man of the West Indies (Il furioso all'isola di San Domingo) [Photo by Richard Hubert Smith]

Donna Bateman as Marcella and chorus in The Wild Man of the West Indies (Il furioso all'isola di San Domingo) [Photo by Richard Hubert Smith]

Act 1 is promising and establishes a compelling dramatic direction, but the second act does little but eke out a prolonged reunion, offering copious backstory, a ludicrous suicide attempt, a momentary blindness, and some unconvincing volte-face. The result is that the characters largely fail to engage our sympathy: moreover, Ferdinand, Bartolomeo and the latter’s slave, Kaidamà, have little to do in Act 2 exacerbating the dramatic imbalance. Again, high seriousness and comedy sit rather uncomfortably side by side. Donizetti had completed L’elisir d’amore in the previous year and there are several suggestions of recycling in this score, not least in Eleonora’s final cavatina and cabaletta ‘ Che dalla gioia’ (What extreme happiness) which, as the joy bursts from the heart of the pardoned wife, has more than a touch of Adina about it.

Florençe de Maré’s set is beguiling, though. A huge curve — arching wood encrusted with shimmering greens and blues — evokes both Hokusai’s ‘Great Wave off Kanagawa’ and a ship’s bow; enclosing a trapdoor through which madman and slave can surface and be banished, after the storm it becomes a visual emblem of the damage done by the sea tempest. Chained buoys suggest the quayside setting and remind us of other chains and enslavements. All is beautifully lit by Mark Howland: glowing emeralds and aquamarines evoke the rainbow glints of sun on sea, while the moonlit scenes are etiolated and eerie. The cirrus clouds beyond metamorphose magically from calm sky-blue wisps to blood-red inflected sweeps.

As the Wild Man, Craig Smith once again put in a sterling performance: aggrieved and wronged, he prowled and lurched around the isle, while retaining a core of noble dignity. If Smith lacked a little stamina in the second act, this was understandable given his efforts of the previous evening. His madman is part-Prospero, without Shakespeare’s magic, part-Robinson Crusoe, without his Man Friday. As Kaidamà, Barotolomeo’s slave, Peter Braithwaite does a good job of suggesting the latter though. Braithwaite impressed with his alert acting as the ‘English spy’ in The Siege of Calais, and here he married an appreciation of the slave’s essential worthiness with an appropriate dash of comic levity. He also articulated the Italian text well too, among two casts where serviceable pronunciation was more common.

Sally Silver sang with lustrous tone as Eleonora, negotiating the runs fluently, although she was occasionally a little constrained at the very top. She and Smith have to carry the dramatic and emotional burdens of Act 2, and Silver acted convincingly. Once an overly rapid vibrato had settled down, tenor Nicholas Sharratt was a confident Fernando with forceful projection: he hit the high notes too, but the tightness and thin tone suggested that he was pushing quite a way beyond his comfort zone. Njabulo Madlala had considerable poise as Bartolomeo, and mezzo-soprano Emma Watkinson (standing in for the indisposed Donna Bateman) sparkled as Marcella.

The chorus were once again in fine voice, but there was some silly prancing around at the start of Act 2 which made a rather jarring preface to the grand reconciliation scene. Jeremy Silver led another sure performance in the pit.

In what seems almost an ‘apologia’ in the programme booklet, Conway argues for the opera’s affinity with Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale and Cymbeline, while Khan — in discussion with Aidan McQuade, Director of Anti-Slavery International — suggests that slavery is, if indirectly, the driving force of the plot. But, Donizetti was no William Wilberforce. More convincing is Conway’s explanation that the repertoire presented on this tour was selected because the operas were works which ETO could ‘have a good chance of doing well, and which might move people who are open to feeling and thinking’. On the basis of the musical successes evident in these two performances, which show us that there is more to Donizetti that we might imagine, I’d agree with that.

Claire Seymour

The Siege of Calais : Eustachio — Craig Smith, Aurelio — Catherine Carby, Eleonora — Paula Sides, Giovanni d’Aire — Andrew Glover, Petrio de Wisants — Matthew Stiff, Giocomo de Wisants — Matt R J Ward, Armando — Jan Capiński, A Stranger — Peter Braithwaite; Conductor — Jeremy Silver, Director — James Conway, Designer — Samal Blak, Lighting Designer — Mark Howland, Chorus and Orchestra of English Touring Opera (leader Richard George).

The Wild Man of the West Indies : Cardenio — Craig Smith, Bartolomeo — Njabulo Madlala, Marcella — Emma Watkinson, Kaidamà — Peter Braithwaite, Eleonora — Sally Silver, Fernando — Nicholas Sharratt; Conductor — Jeremy Silver, Director — Iqbal Khan, Designer — Florençe de Maré, Lighting Designer — Mark Howland, Chorus and Orchestra of English Touring Opera (leader Richard George).

Everyman Theatre, Cheltenham, Wednesday 8th and Thursday 9th April 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/WJK_5317.png image_description=Paula Sides as Eleonora and Craig Smith as Eustachio in The Siege of Calais [Photo by Bill Knight] product=yes product_title=Donizetti: The Siege of Calais and The Wild Man of the West Indies product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Paula Sides as Eleonora and Craig Smith as Eustachio in The Siege of Calais [Photo by Bill Knight]April 7, 2015

Voices in space: Meredith Monk & friends construct musical cathedrals at 50-year anniversary concert

By Rebecca Lentjes [bachtrack, 5 April 2015]

“The rhythm of words takes away from my sense of rhythm,” Meredith Monk explained after a riveting performance of her piece Things Heaven and Hell by the Young People’s Chorus of New York City. The third part of Ms. Monk’s 1992 work Three Heavens and Hells, this piece was one of only a handful to incorporate real words in the entirety of the four-and-a-half hour Meredith Monk & Friends celebration at Carnegie’s Zankel Hall last weekend.

April 3, 2015

The Met’s Lucia di Lammermoor

There’s lots of life left in Mary Zimmerman’s handsomely staged and remarkably fresh Metropolitan Opera production of Lucia di Lammermoor, which debuted in 2007 with Natalie Dessay in the title role and has been reprised here several times since.

There’s lots of life, too, in the voice of Albina Shagimuratova — the title character in the company’s 2015 reprisal that opened March 16.

From a purely visual perspective, Shagimuratova may not get everyone’s vote for the most persuasive Lucia to have populated a Zimmerman production — which besides Dessay has included Annick Massis, Diana Damrau and Anna Netrebko. Nor is Shagimuratova likely to win any awards for best actor. But if the Russian soprano does not entirely look the part of the fragile vulnerable tragic heroine, she sure does sound it. Of the three Zimmerman Lucias I’ve heard to-date (Dessay, Netrebko and Shagimuratova), none has surpassed the sheer beauty and agility of the latter’s dramatic coloratura soprano.

Donizetti's opera, a perennial favorite since its Neapolitan premiere in 1835, is loosely based on Walter Scott’s The Bride of Lammermoor — the historical novelist's 1819 tale of a feuding pair of Scottish noble families, the Ravenswoods and the Lammermoors. (Zimmerman moves the setting a couple of hundred years forward to the Victorian Era.)

Joseph Calleja as Edgardo

Joseph Calleja as Edgardo