August 30, 2015

Santa Fe: Secondary Mozart in First Rate Staging

Assuredly, there was nothing phony about Santa Fe Opera’s total commitment to quality in producing this lesser Mozart opus. There is nothing really wrong with the writing to be sure, but neither is there the brilliance of his masterpieces yet to come. Still, second tier Mozart is arguably better than first rate Soler, or Salieri.

The production itself could hardly have been bettered, however, and if this meticulously performed Finta didn’t stir you, it probably never will. This was stagecraft and music making as good as it gets. The starry cast was under the inspired baton of conductor Harry Bicket.

Maestro Bicket is celebrated for his especial skills in this type of repertoire and he led a vivid, urgent reading of great variety and color. His attention to detail drew committed playing from the exceptional orchestra, and impassioned, heartfelt vocalizing from his singers.

William Burden is one of the finest lyric tenors in the business, and one of the busiest. I know of no one else who can survey such a wide range of roles from Baroque to Contemporary with such assurance. As the Podestà (Magistrate), Mr. Burden has ample opportunity to show his full bag of tricks which includes honeyed tone, supple technique, and dead accurate melismas. A consummate actor, he always, always sings with utter conviction and understanding of the drama. This was but another outstanding portrayal from this treasurable tenor.

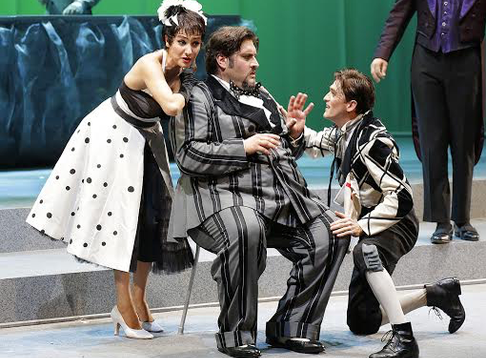

Susanna Phillips as Arminda and Joel Prieto as Count Belfiore

Susanna Phillips as Arminda and Joel Prieto as Count Belfiore

I first encountered soprano Heidi Stober at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis where I thought she was remarkably fine. In the intervening years, Ms. Stober has grown even more and on this occasion, her Sandrina was individualized, poignant, musically faultless, and fully realized as a wonderfully complex character. She did not sing the part so much as inhabit it. Her poised, warm instrument had enormous appeal.

Providing welcome balance, Laura Tatulescu combined sass and pointed singing to create an edgy, confrontational impression as the sharp-tongued Serpetta. It is to her credit and skillful technique that Ms. Tatulescu is able to craft a personality that is acerbic, without the vocals turning acidic. Her clear, rhythmically assured singing was a pleasure and she clearly relished her comic opportunities and wrung every bit of firebrand potential out of the role.

Joshua Hopkins is a suave performer, with a rich, manly baritone, evenly produced with a suggestion of plush velvet. His Nardo was a perfect foil for Serpetta and they created real sparks between them. Mr. Hopkins knows how to command the stage and his physical presence was as handsome as his vocalizing. Cecelia Hall effected just the right hangdog look to engage our sympathies as Ramiro, and her creamy singing was vibrant and characterful. Even in such a less developed role, Ms. Hall more than held her own in this polished ensemble.

Susanna Phillips took obvious delight in playing Arminda, the opera’s Queen of Mean. She found ample excuses to unleash pointed phrases styled with laser-like accuracy. Yet she resisted delving into caricature, and she also lavished us with singing of amplitude and richness. Ms. Phillips’ disciplined vocal portrayal was nevertheless wedded to a sense of spontaneity thanks to her canny acting.

Joshua Hopkins as Nardo and Laura Tatulescu as Serpetta

Joshua Hopkins as Nardo and Laura Tatulescu as Serpetta

Rounding out that cast as Count Belfiore, Joel Prieto offered witty, fluid phrases that were well served by his congenial tenor. Mr. Prieto, too, had a good sense of fun and a loose, easy stage presence. His flexible technique and appealing bright timbre suited the role, although there may be more to be mined in the complicated Count.

Tim Albery has directed with simplicity and clarity. His fluid movement of the actors was highly effective, and the shifting pairings-up, and squarings-off of the cast were brilliant. The whole evening played out as a balletic cat and mouse game with roles, and advantage of positions, in constant flux.

Hildegard Bechler has certainly done her part to ensure the evening’s success with a set design that is at once functional, mysterious, bare bones, and profound. There is an arching wall stage left that is impeccably detailed with an ornate tromp l’oeil recreation of a period palace hall. Chairs with upholstered seats stand against the wall, while a large dining room table sits center stage. This functions as occasional meeting place where character some together, or as a barrier, keeping characters apart.

About two thirds of the stage is covered with lush green Astroturf-as-carpeting, abutted by the requisite garden which takes up the down left area. The rust and yellow flowers (many planted by Sandrina in Act One) are a beautiful balance as they encroach on the formal interior. The dining table is replaced in Act Two by a chaise lounge, which got cleverly incorporated into the staging.

The ensemble

The ensemble

Jon Morrell created totally apt costumes that aided greatly in the characterizations, black and severe for the servants (including the phony farmerette), and sumptuous for the nobles. The incorporation of floral images in such things as Arminda’s dress and the tablecloth only added to the cheeky visuals. Thomas C. Hase’s slowly unfolding lighting effects were mesmerizing. The extremely deliberate cross fade from sunny exterior to moody interior in the first act was stunning.

Every element of La finta giardiniera was committed to showing that this talented group absolutely believed in the worth of this piece. And damn, if ultimately they didn’t succeed in making me believe in it, too!

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Sandrina: Heidi Stober; Serpetta: Laura Tatulescu; Ramiro: Cecelia Hall; The Podesta: William Burden; Nardo: Joshua Hopkins; Arminda: Susanna Phillips; Count Belfiore: Joel Prieto; Conductor: Harry Bicket; Director: Tim Albery; Set Design: Hildegard Bechler; Costume Design: Jon Morrell; Lighting Design: Thomas C. Hase.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/6-Heidi-Stober-%28Sandrina%29-and-William-Burden-%28Podesta%29-in-%E2%80%98La-Finta-Giardiniera.%E2%80%99-Photo-%C2%A9-Ken-Howard-for-Santa-Fe-Opera%2C-2015.png

image_description=Heidi Stober as Sandrina and William Burden as the Podesta [Photo by Ken Howard]

product=yes

product_title=Santa Fe: Secondary Mozart in First Rate Staging

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Heidi Stober as Sandrina and William Burden as Podesta

Photos by Ken Howard

Regimented Daughter in Santa Fe

After a sparkling, infectious overture, expertly led by Speranza Scappucci, a Les Miz style barricade rotates to reveal the choristers, not in colorful folk costumes, but in severely styled black funeral wear (think: Amish look).

Belying the set-up of the sprightly overture, director Ned Canty got things off to a rather somber start, more William Tell than Donizetti’s comic opus. After this stolid beginning, Mr. Canty seemed to have second thoughts, and in short order the tale gets liberally peppered with the usual (and some unusual) shameless jokes and inspired (and some uninspired) physical comedic schtick, and then some. Canty wrote the English dialogue with the music sung in the original French.

Allen Moyer’s sets and costumes were quite witty and adaptable. The barricade of Act I yields furniture and props that cleverly get plucked off the pile, and there are ample levels to create interesting stage pictures. The ornate false proscenium, hunter green with panels painted with Tyrolean scenes, created a sense of place and established a highly theatrical style. A stylish carriage conveys the Marquise on- and off-stage. The Berkenfeld manse of Act II is sumptuous inside and out, its exterior paraphrasing Linderhof. Rick Fisher’s efficient lighting design was up to his usual high standard.

After the drab opening attire, Mr. Moyer’s costumes add color little by little, first with red and blue uniform jackets, then with Tonio’s red and black Trachten, later with lavish party gowns. Marie’s over-the-top pink dress for the Lesson Scene was a riot of invention and that scene crackled with good humor. And then the director seemed to change his mind again with the mood becoming soul-searching, earnest, and well, a bit ponderous. By the time he changed his mind yet again with the interpolated and extraneous announcement of silly German names and titles of all of the party guests, the Duchess of Krakenthorp was thoroughly pre-empted and upstaged.

Alek Shrader as Tonio, Anna Christy as Marie and Kevin Burdette as Sulpice-Pingot

Alek Shrader as Tonio, Anna Christy as Marie and Kevin Burdette as Sulpice-Pingot

By that point, the return to frivolity was too little too late. Self-indulgence marred Act II with too many lilies being gilded with too much “added material,” too much deference to the (secondary character) Marquise’s “feelings,” and too little regard for pacing in what is, after all, a pretty slight comedy. By removing non-essential business, tightening the repetitious dialogue, keeping the focus on Marie-Tonio, and urging the pace along, about ten minutes could be taken off the second act and the show would be even better than the audience already thinks it is.

Whatever the (only) occasional longueurs of the staging, Maestra Scappucci snapped the proceedings back into focus every time her authoritative baton came down, eliciting a reading of the score that was characterized by audacious spontaneity, effervescence and a keen sense of style. The conductor not only admirably partnered her singers with breadth and flexibility on poignant arias, but also took firm control over such tricky allegro passages as that breathless account of the Act II trio Tous les trois réunis. Clearly, the talented Speranza Scappucci is a podium star on the rise.

A lot is asked of the four principles in carrying The Daughter on their backs, and they did not disappoint. The great Beverly Sills once described the vivandière Marie as “Lucille Ball with high notes.” Just as we all loved Lucy, we were enchanted by pretty, perky and petite Anna Christy who proved a natural as the canteen girl, a supposed orphan who has been “adopted” by the 21st Regiment.

Ms. Christy takes the stage as an unapologetic tomboy and shows off awesome comic timing. Adding to the appeal, she also has a finely spun, meticulously schooled, silvery soprano of great agility and admirable range. While she offers sparkling vocalizing throughout the evening, it is in the slower arias that she finds the most personalized tone and most engaging pathos. If I had one wish for Anna, it might be to eliminate a few of the held notes in alt. The couple of thrilling successes were offset by a few that wanted to splay. When you are as accomplished as this, when we are already eating out of your hand, when we wouldn’t miss the additional stratospheric notes, why take chances? That minor quibble aside, Anna Christy is giving a wholly accomplished star performance.

Phyllis Pancella as the Marquise of Berkenfeld and Alek Shrader as Tonio

Phyllis Pancella as the Marquise of Berkenfeld and Alek Shrader as Tonio

Alek Shrader is easily the funniest Tonio of my experience. From his first entrance, picture postcard handsome in his Tyrolean get-up, he immediately betrays a puppy dog eagerness and gangliness that is consistently appealing. His physical comedy was superb. When he tried to be Joe Cool, listening to Marie’s story, he kept feigning casual positions that were impossible to maintain, with one of these finding him clinging to the barricade and dangling like a dyspeptic monkey.

Mr. Shrader’s singing was assured and correct, although the tone has taken on a slightly veiled quality since last I heard him. He has a fine sense of legato, to be sure, and he injects personality and purpose into all he sings. The very top notes thin out a mite these days, and while he certainly had the goods for “Mes amis,” he lacked that final ounce of real distinction. Like his co-star, he scored decisively in such touching moments as Pour me rapprocher de Marie, in which his beautiful instrument, comfortable tessitura, and heartfelt intent magically merged.

As Sergeant Sulpice, it was hard to believe that Kevin Burdette was the same performer who was so serious and compelling in Cold Mountain some days prior. Here, he was all loose limbs and German-challenged orator, a marriage of Dick Van Dyke and Mr. Magoo. Forget about solar panels, Mr. Burdette generates enough energy to power greater Santa Fe. That he also sang with a direct, polished delivery was icing on the pratfall.

Far from the usual dotty Marquise de Berkenfeld, Phyllis Pancella offered a glamorous and elegant interpretation. If her ripe mezzo has gained a more mature sheen over the years, she remains a very gifted singer. Her craft is on full display as she deftly utilizes a change of registers to underscore comic shifts in her musical lines. Moreover, she proved herself once again to be a fine comedienne, delivering her lines with an endearing self-importance, while mugging with a vaudevillian’s understated expertise.

Judith Christin as the Duchess of Krakenthorp

Judith Christin as the Duchess of Krakenthorp

The accomplished singer Judith Christin seemed wasted as the Duchess of Krakenthorp. Heavily made up in clown white greasepaint and overstated features, got up in an over-the-top silvery-white gown, and topped with an ostentatious wig, when Ms. Christin spoke in her distinctive contralto and rasped an exhortation with a heavy German accent, she could have been a man in drag. She did all that was asked of her with conviction to be sure, but I for one wish more had been asked.

Apprentice Calvin Griffin offered an imposing, handsome presence and sang with an assured bass-baritone as the servant Hortensius. Susanne Sheston had the chorus singing with gusto and personality. Seán Curran crafted some delightful, natural choreography, especially the Regiment’s fist pounding “salute” that delectably recalled the hand jive.

All in all, this Daughter had quite a successful romp across the SFO stage, but when she got too regimented and moody I just wish someone had told her to lighten back up.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Hortensius: Calvin Griffin; Marquise of Berkenfeld: Phyllis Pancella; Peasant: Jack Swanson; Sergeant Sulpice Pingot: Kevin Burdette; Marie: Anna Christy; Tonio: Alek Shrader; Corporal: Adrian Smith; Duchess of Krakenthorp: Judith Christin; Notary: Jorell Williams; Conductor: Speranza Scappucci; Director: Ned Canty; Set and Costume Design: Allen Moyer; Lighting Design: Rick Fisher; Choreographer: Seán Curran; Chorus Master: Susanne Sheston; English Dialogue: Ned Canty.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/21-Anna-Christy-%28Marie%29-in-%27The-Daughter-of-the-Regiment.%27-Photo-%28c%29-Ken-Howard-for-The-Santa-Fe-Opera%2C-2015.png

image_description=Anna Christy as Marie

product=yes

product_title=Regimented Daughter in Santa Fe

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Anna Christy as Marie

Photos by Ken Howard

Santa Fe’s Celebratory Jester

Like SFO itself, the Verdi opus proved to be evergreen.

This was owing in no small part to a high-powered cast that would be at home on any world stage. In the title role, Quinn Kelsey served notice that he surely has few contemporary equals in this demanding part. Mr. Kelsey dominated the proceedings from his first appearance, not only with a hulking physical presence but also with a superlative baritone that had urgency and menace.

His measured, sarcastic barbs were served up with a honeyed malice, and his introspective musings had a possessed, haunting humanity. In the duets with his daughter, his opulent legato conveyed a depth of feeling not often captured by other interpreters. His was a top tier performance of one of the greatest baritone roles in the canon.

Bruce Sledge as the Duke of Mantua and Georgia Jarman as Gilda

Bruce Sledge as the Duke of Mantua and Georgia Jarman as Gilda

As Gilda, Georgia Jarman matched him in every respect, displaying a sizable lyric soprano, capable of great nuance and color. The hints of gold in her upper register conveyed a youthful, infatuated girl in her first scene, while the touch of tremulous intensity in lower ranges communicated her conflicted disobedience of her father’s wishes.

After the Duke rapes Gilda, Ms. Jarman infused the sound with a touching despair, then maintained a firm resolve to the end. Her delicate, ethereal singing in the final bars was not meant for mere human ears; it was ravishing and heartbreaking.

Bruce Sledge brings such a secure lyric tenor to the Duke of Mantua, so lovingly produced that you could almost be seduced that he is not a shitheel. Mr. Sledge has all the notes in his arsenal and then some, and he sings the famous arias and the treacherous quartet with abandon. His acting and vocal coloring are a bit generalized but he is never unengaged. Time and experience will allow this talented singer to find his own unique qualities that he can bring to the role.

Apprentice Peixin Chen was sonorous and unctuous as the villainous Sparafucile. His rich, dark bass poured forth effortlessly, and he had a fine stage presence. As his sister (and murderous cohort) Maddalena, Nicole Piccolomini pinned our ears back with a steely mezzo of substantial size and import. Although not announced as indisposed, there seemed to be hints of a troubling rasp to some attacked phrases. Still, Ms. Piccolomini gave an assured performance.

Robert Pomakov was a coiled spring of a Monterone, his thunderous bass frightening in its intensity. Young artist Jarrett Ott took advantage of every note the master wrote for Marullo and sang with a solid, attractive baritone. Shabnam Kalbasi similarly imbued Countess Ceprano’s critical phrases with poised, attractive singing. Anne Marie Stanley made much out of Giovanna with sassy, classy vocalizing and a well-rounded characterization.

Nicole Piccolomini as Maddalena

Nicole Piccolomini as Maddalena

From Jader Bignamini’s first downbeat, the conductor led a propulsive, taut reading weighted with dramatic conviction. The foreshadowing of the curse in the prelude has never seemed so urgent. Maestro Bignamini crafts a thrilling dramatic arc to the familiar score that not only moves forward inexorably but also takes time to relish subtleties in the diverse emotional journeys of the characters. Susanne Sheston has the marvelous chorus trained to a fare-thee-well.

The physical production could hardly have been better. Adrian Linford does double duty as Set and Costume Designer and excels at both. The production has been placed in the time of its composition. To solve the challenge of the multiple settings required within the limits of the SFO stage, Mr. Linford has crafted a marvel of a rotating structure that is a veritable kaleidoscopic collage of stairs and colonnades and fences and windows and chambers, all slightly askew, and all multi-functional. The colors, textures and architectural fragments skillfully evoke Mantua.

Mr. Linford’s costumes are very inventive, especially for the jester, decked out in a large overcoat, with a Charlie Chaplin hat, thick orthopedic shoe on one foot, and a false vest front that Gilda helps him change out during their first duet. Courtiers look sufficiently wealthy but with a patina of debauchery. The women are mostly got up (or not clothed much at all) as lurid, willing and available sex objects. Giovanna is an abused maid who has a visible syphilis scar on her pallid face.

This is a crumbling, decadent environment, tellingly lit with a twilight-of-the-gods finality by Rick Fisher. Within this effective visual environment, Director Lee Blakely directs a straight forward, no-nonsense telling of the tragedy that is breathtaking in its accurate simplicity. Mr. Blakely has crafted an evening of movement and interaction that is always true to the story and that clarifies the shifting dynamics of mood and character development. His use of the many available levels creates visual interest and variety. When he does inject some innovative sub-text, it pays handsome dividends.

Quinn Kelsey as Rigoletto and Georgia Jarman as Gilda

Quinn Kelsey as Rigoletto and Georgia Jarman as Gilda

The usually forgettable maid Giovanna is a case in point. Blakely’s take is that she is a spectral, unhappy (perhaps abused) creature, who appears to be starving. Her complicity in tricking Rigoletto is born of revenge, and after Rigoletto sinks to his knees with the realization that his daughter has been kidnaped, she spits on him as she stalks off. It is such attention to detail, and commitment to honest interplay that makes this a near perfect “Rigoletto,” shattering in its cumulative effect.

I can’t think of a better two-thousandth milestone present than this fine evening of opera with the company operating on all cylinders at its very best.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Duke of Mantua: Bruce Sledge; Borsa: Adrian Kramer; Countess Ceprano: Shabnam Kalbasi; Rigoletto: Quinn Kelsey; Marullo: Jarett Ott; Count Ceprano: Calvin Griffin; Count Monterone: Robert Pomakov; Sparafucile: Peixin Chen; Gilda: Georgia Jarman; Giovanna: Anne Marie Stanley; Monterone’s Daughter: Andrea Nunez; Court Usher: Michael Adams; Maddalena: Nicole Piccolomini; Conductor: Jader Bignamini; Director: Lee Blakeley; Set and Costume Design: Adrian Linford; Lighting Design: Rick Fisher; Choreographer: Nicola Bowie; Chorus Master: Susanne Sheston.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/19-Quinn-Kelsey-%28Rigoletto%29-in-%27Rigoletto.%27-Photo-%28c%29-Ken-Howard-for-The-Santa-Fe-Opera%2C-2015.png

image_description=Quinn Kelsey as Rigoletto [Photo by Ken Howard]

product=yes

product_title=Santa Fe’s Celebratory Jester

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above Quinn Kelsey as Rigoletto

Photos by Ken Howard

Sibelius Kullervo, BBC Proms, London

Sakari Oramo considers Kullervo “a masterpiece”, and, at Prom 58 at the Royal Albert Hall, London, conducted it with such conviction that there can be little doubt about its unique place in Sibelius’s output, and indeed in music history.

Kullervo is such a remarkable work, so shockingly original that Paavo Berglund revisited it fifteen years after his original recording. Neeme Järvi brought yet more new insights. There have been many other performances since, but Sakari Oramo creates an interpretation of great depth and perceptiveness.

From a hushed opening, the Allegro Moderato grew with ever increasing impatience, as if it were an Overture to an opera, for a quasi-opera this is. One cannot underestimate the impact of Wagner and his “forest murmurs”, though even at this early stage in his career, Sibelius was iconoclastic, deliberately seeking a new sound world. Unlike Wagner who re-imagined Norse legend, Sibelius heard living oral tradition at first hand. Kullervo comes alive with the rhythms of the Kalevala, with its strange, primitive pulse and shamanistic repetitions. Hence the short, sharp intervals in the brass and winds, and the driving pizzicato in the strings, creating a sense of tense, ritualized movement. Even to our ears accustomed to Stravinsky, Bartók and Janáček, Kullervo still sounds raw and primeval. Yet it was written twenty-one years before The Rite of Spring

I’ve often wondered if Sibelius himself realized how daring Kullervo was and, being a worrier, pulled back, as he might have pulled back from the enormity of his conception for the Eighth? Once, Sibelius performance history presented the composer in sub-Tchaikovsky terms, which really doesn’t do the composer justice. Kullervo resets the balance so we can think ahead to the Fifth and Seventh Symphonies and their audacity and inventiveness It is, unequivocally new and individual, the mark of a true genius.

In Kullervo, we can hear the origins of tone poems like Nightride into Sunrise and Lemminkäinen Suite. and reflect that the tone poems are much darker than mere portraits of Nature and myth. Thus the lucid detail of Oramo’s conductng, which emphasizes the sophistication that lies beneath the ostensible savagery in the piece. It’s not simply a folk tale for grand orchestra but an experimental approach to dynamics and relationships. The contrast between emotional extremes and the tight, staccato-like intervals creates abstract narrative tension. Oramo makes the orchestra “sing” as if we’re hearing Kullervo’s nervous heartbeat, pulsating with frustration.

Kullervo is also a musical act of defiance, written as it was at a time when Finland was resisting efforts by Russia to curb its freedoms. This adds context to the figure of Kullervo himself, a child born into suffering. One can appreciate Kullervo without knowing the Kalevala, but it does enhance meaning. Runes XXXI to XXXVI give Kullervo’s background. He’s cruelly mistreated by an uncle who stole his patrimony. He’s tortured and sold into slavery. When he meets the maiden, he rapes her because he wants what she represents, yet, raised in cruelty, he doesn’t have what we might call “social skills”. Dreams of his long-lost mother have kept him going , so when he discovers that the woman he has violated is his sister, he suffers such guilt that he must offer his own life in appeasement.

Johanna Rusanen-Kartano sang Kullervo’s sister. She’s a very good dramatic soprano, with the intensity to remind us that the girl, too, has had a traumatic past, lost in the woods while hunting for berries. Her story is as tragic as her brother’s. Rusanen-Kartano’s lines were rapid-fire tongue twisters, delivered with absolute precison and bite. Later her lines curve sensuously,but even in these beautiful moments, she retained a mysterious quality as if the girl had been led into the forest by evil spirits, represented perhaps in the clarinets and pumping woodwind around her. Waltteri Torikka sang the baritone part. He didn’t have quite the assurance of, say, Jorma Hynninen, but he can express the vulnerability that lurks behind Kullervo’s brutishness. If his voice didn’t project well, live, in the cavern that is the Royal Albert Hall it sounded better on broadcast. There’s potential in this voice.

In Kullervo, the choir (the Polytech Choir augmented by the men of the BBC Symphony Chorus) operate like a Greek Chorus commenting on proceedings and adding ballast to the orchestra. These choral parts are difficult, for the lines flow with little pause for breath, relentlessly moving the action forward. The Finnish language, too, poses problems. Every vowel sound must be articulated, and there are vowel sounds one after another in succesion, cut across with stinging sibillants. “Kullervo, Kalevon poika, sinisukka äijön lapsi,”. For the Polytech Choir from Helsinki, the lines flow seamlessly, yet are energized by high testosterone punchiness. We can hear the fast-moving sleigh, complete with bells as it rushes “noilla Väinön kankahilla, ammoin raatuilla ahoilla”. Yet these rhythms also suggest violence, the relentless course of fate, and lets face it a fairly explicit description of sex. I was fascinated by the way the choir varied their emphases, dropped to whispers and rose to full volume, and the variety of subtle expression.

In London, we hear the BBC Symphony Orchestra all the time, so we take them for granted, and forget how good they really are. The Alla marcia (Kellervo goes to war) isn’t difficult for players with these technical skills, but they played with energy and vigour. Oramo marked the end of the battle with a long silence, soon the voices of the male choirs returned, ghost-like. Muted large brass, tuba and trumpets muffled, bassoons sighing, clarinets rising like smoke on a battlefield. While Kullervo begins characterized by hard, angular sounds, and breaking off painfully into silence, the final movement, Kullervo’s Death, is an andante. The timpani were beaten in slow march, placed at a distance from the rest of the percussion, cradling the orchestra, perhaps, in the kind of embrace Kullervo never knew. Sibelius didn’t set the last lines of Rune XXXVI but he and his audiences would have known the moral with which the saga ends. It is a warning that children should not be abused or mistreated.

Starting with a very good En Saga (Op 9, 1892 rev 1902), this was by far the most-focused and well performed Sibelius this season, making up for a patchy, and diisappointing symphonic cycle in earlier Proms. .

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kullervo-Goes-to-War-Akseli-Gallen-Kallela.png

image_description='Kullervo Goes to War' by Akseli Gallen-Kallela

product=yes

product_title=Sibelius Kullervo, BBC Proms, London

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: 'Kullervo Goes to War' by Akseli Gallen-Kallela

August 28, 2015

Aïda at Aspen

The title role was taken by the young American soprano Tamara Wilson, who received accolades as a replacement Aïda at the MET last December. Wilson’s cool and silvery soprano reminds one of great interwar Aïda’s—Elizabeth Rethberg comes to mind—rather than Leontyne Price, Maria Callas, Renata Tebaldi or other postwar singers who have led us to expect broad warm, darkly golden-toned voices in this role. (Wilson even looks a bit like something out of an early 20th century photograph—which I mean as a compliment.) Wilson’s voice is so perfectly focused that at pianissimo it can easily fill even an acoustically problematic space such as Aspen’s large tent, yet it can also swell to a thrilling forte, and beyond to fortissimo—all without spoiling the timbre or line. The technical difficulties of the role—including the dolce high c in “O Patria Mia,” which only a few singers per generation can really sing as written—pose for her no problem. Her clear diction, subtle inflection and musical intelligence, combined with an ability to act with her face, added up to coherent musical-dramatic characterization of the title character: more girlish and vulnerable than one generally sees. As she ages, the voice may fill out further, particularly at the bottom. If so, Wilson may become an Aïda for the ages.

As Ramfis, Morris Robinson commanded the stage even when sharing it with one hundred others. His thundering cries of “Guerra!” rang above the first scene concertante finale, his sonorous bass floated just audible above the opening chorus of the second scene, his subsequent high f at “Folgore morte” was firm, and so on through the night. He acted equally well: his looming presence added an ominous element to the Egyptian priesthood and his quick glances signaled that he was on to Radamès and Aïda long before anyone else. Diction is the only area in which Robinson could improve, but this former all-American football player who began singing opera seriously only at 30, is already more than repaying the early faith of the Met and other companies.

At least at this stage in his career, Brian Mulligan wisely rejects the gruff bluster with which most baritones approach Amonasro in favor of scrupulous and sensitive attention to the score. His approach was evident from his opening declaration (“suo padre!”). Most baritones announce their belated presence with a ringing forte at this point, which makes some dramatic sense for a king in disguise. Yet Mulligan sang it as Verdi plainly wrote it in the score: forte at first, but with a lovely, almost reflective, decrescendo. Elsewhere Mulligan’s scrupulousness and sensitivity paid dividends as well, particularly in the Act III duet with Aïda. Here again we may have the makings of a heavyweight Verdi greatness.

The fourth young singer, tenor Issachah Savage, clearly possesses that rare operatic gift: a near-ideal natural instrument to sing Radamès. He possesses bronze-hued grandeur for the heroic passages and a sweetly mixed timbre for the more intimate ones. Though he has been singing this role for several years, however, nervousness seemed to undermine his big moments. He cut off many extended and exposed phrases, sagged flat and dropped a line in “Celeste Aïda,” and failed to produce a clear tone on both the final A of Act 3 and the penultimate pianissimo B-flat of Act 4. Still, this young Philadelphian is a singer to watch; he may yet achieve historical greatness in spinto and dramatic roles.

The fifth lead singer, Mezzo Michelle DeYoung, was by far the most experienced and best-known singer on stage. She is a consummate professional. The voice is even and smooth from top to bottom and the diction clear. She looks the part and she has clearly thought out the musical-dramatic effects she seeks at every point: her portrayal of Amneris is more sympathetic than the scenery-chewing norm. Yet in the end one wonders if this is really the right role for someone without the requisite chesty mezzo power and steely edge of a classic Verdi mezzo, particularly at the extremes of the voice. She simply failed to command the stage at Amneris’s grandest moments: the Act II duet and, above all, the end of the Judgment Scene, where the ultimate high A is made to ring out more powerfully and longer than the strict four beats in Verdi’s score.

As for the smaller roles, Pureum Jo delivered the Sacerdotessa’s exotic lines smoothly but (whether due to placement or intent) too loudly: the temple priestess’s voice is supposed to emerge mysteriously and exotically from somewhere in the darkness of a vast temple, which is why Verdi marked it to be subtle and soft, even though off-stage. Bass Matthew Treviño and tenor Landon Shaw II used strident declamation, good diction and excellent acting—not to mention the appearance of handsome young mafiosi—to make the most of their cameos as the King and the Messenger.

Given that they (I am told) less than a week and few rehearsals, the Aspen Festival Orchestra under Robert Spano performed with remarkable fluidity, accuracy and idiomatic style. To be sure, the orchestra contains ringers, such as Elaine Douvas (Principal Oboe of the Metropolitan Opera) and David Halen (Concertmaster of the St. Louis Symphony), who can handle this material in their sleep. But it also includes top students and young professionals, who acquitted themselves impressively. (No lack of a younger generation among orchestral musicians, evidently!) Only the triumphal trumpets in the higher key struggled. The chorus sang lustily, but also with subtlety when it mattered most. Spano directed well, only occasionally proceeding with excessive caution. By necessity, a semi-staged production will emphasize the intimate aspects of this opera, which took place within a hollow cloth pyramid, open on the side facing the audience. It made for an adequate, though not impressive, set. Comic relief was provided in the Triumphal Scene by permitting a half dozen very large white balloons bounce around the audience, as the principals—still inhabiting the world of 5000 years ago—watched bemused from the stage.

Andrew Moravcsik

image=http://www.operatoday.com/tamara-wilson-279-edit.png image_description=Tamara Wilson [Photo by Aaron Gang courtesy of Columbia Artists Management Inc.] product=yes product_title=Aïda at Aspen product_by=A review by Andrew Moravcsik product_id=Above: Tamara Wilson [Photo by Aaron Gang courtesy of Columbia Artists Management Inc.]Prom 53: Shostakovich — Orango

Flags were fluttering feverishly in the Arena and Gallery; the orchestra sported festive red sashes and the conductor had swapped his tuxedo for a lurid orange ti-shirt print-stamped with a hammer-and-sickle and an outsize portrait of Stalin; jazz mingled with brassy fanfares — and I was sure at one point that I heard a snatch of ‘Rule, Britannia!’. Had the ‘Last Night’ come early? No, we were being invited to embrace the bizarre and grotesque world of Dmitri Shostakovich’s unfinished (1932) opera, Orango.

Having just read Joanna Burke’s wide-ranging and thought-provoking investigation into What It Means to Be Human (Virago, 2011) — following Bourke’s arguments down the scientific, ethical and political byways of speciesism, xenografts and cross-transplantation — it seemed fitting to find myself watching the Prologue of an opera by Shostakovich in which the protagonist is a half-man/half-ape hybrid — the result of a grotesque medical experiment — who now resides in a Moscow circus and who is brought before the jeering crowds so that they can marvel at his dexterity with knife and fork, the civilised manner in which he blows his nose and yawns, and his musical prowess at the piano keyboard.

Orango was commissioned by the Bolshoi Theatre in 1932 to celebrate the 15th anniversary of the October Revolution, and the creators were given a broad theme to motivate them: ‘growth during revolution and socialist construction’. But, rather than producing a straightforward warning against the dangers of Western capitalism, Shostakovich and his collaborators devised a biting satire — recalling Mikhail Bulgakov’s allegorical novel Heart of a Dog — on the Communist Revolution’s attempt to radically transform mankind, and on the utopian science of the 1920s. One of the sources of inspiration for Shostakovich and his librettists, Aleksey Tolstoy (the ‘Red Count’) and Alexander Starchakov (who was arrested and executed by Stalin in 1937), was probably the work of the Russian biologist, Ilya Ivanovich Ivanov who attempted the hybridization of humans and other primates, chiefly chimpanzees. Shostakovich is reported to have visited Ivanov’s primate research station in Sukhumi while holidaying near the Black Sea.

Originally planned as a three-act opera, only the Prologue survives (though who knows what may subsequently turn up in the recouped refuse …). The manuscript was found by Russian musicologist Olga Digonskaya — who had been working with Irina Shostakovich, the composer's third wife and widow, on Shostakovich's catalogue — in the Glinka State Central Museum of Musical Culture, Moscow in December 2004. Digonskaya discovered a cardboard file containing some hundreds of pages of musical sketches and scores in Shostakovich’s hand. The story goes that a composer friend bribed Shostakovich’s housemaid to salvage the contents of his waste bin, thereby saving potential compositional gems from the garbage, and that some of this ‘rescued rubbish’ made its way into the Glinka Museum: among the ‘detritus’ were 13 pages of Orango — about 35 minutes of music. A piano score was published in 2010, with a scholarly introduction by Digonskaya, and this was later orchestrated by Gerard McBurney.

From these beginnings Finnish conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen has consistently championed Orango, giving the premiere of the Prologue in Los Angeles in December 2011 (with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and staged by Peter Sellars; a live recording was released by Deutsche Grammophon in 2012), bringing it to Europe in May 2013 (with the Philharmonia Orchestra at the Festival Hall London), and taking the opera back home to Russia in April 2014, where he conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the Yurlov Russian State Academic Choir in a concert at Moscow’s Conservatory, as part of the International Rostropovich Festival.

In the Prologue, the Master of Ceremonies recounts Orango’s tale before the crowds at the Palace of Soviets, Stalin’s monumental but ultimately unrealized skyscraper — just one of the busy projections beneath and around the RAH organ balcony (stage/video design, Louis Price) which accompanied the performance. The MC relates how, after serving heroically in World War I and finding riches as an anti-communist journalist and newspaper mogul, Orango went bankrupt in an international financial meltdown and, as his behaviour was becoming increasingly simian and brutal, has been sold to the Soviet Circus. Hearing this news, and dissatisfied with the entertainment offered by a famous Russian ballerina, the impatient and increasingly bacchanalian crowds demand that Orango be brought before them. The man-primate is duly paraded but he becomes agitated and aggressive when he espies a young woman with red hair, Suzanna (who was to have been revealed later in the opera as his ex-wife). Another ballet display sends Orango wild with exasperation — ‘I’m suffocating, suffocating under this animal skin’ (here, Orango and the ballerina had a face-off over an outsized red Kalashnikov) — and the show is stopped, as the embryologist, his daughter and a foreign journalist all make claims to have a connection with Orango. The Prologue concludes with the crowd’s hysterical chant, ‘Laugh! Laugh!’, as the ape-man struggles for breath.

The Philharmonia Voices enthusiastically launched proceedings with a choral anthem celebrating the ‘freedoms’ of the new Soviet ages, with the miseries of pre-Revolution misery, their voices gusty, their copies of Pravda thrust heartily aloft. Later they would waft sunflowers and punch the air with similar panache.

As the Master of Ceremonies charged with entertaining the crowd of bored Foreigners — alien capitalists from the West — bass Denis Beganski was nattily dressed in blue silk but slightly woolly of voice, although his patter song eulogizing the miracles of the new Soviet economy went with a swing. Faced with the Foreigners’ demands for ‘something more interesting’, the MC summoned ‘the USSR’s most famous ballerina’, Nastya Terpsikhorova (Rosie Kay) whose ‘Dance of Peace’ was tidily executed. Dressed in a furry costume that looked decidedly itchy, tenor Ivan Novoselev effectively conveyed Orango’s unpredictability and the pathos of his situation. Dmitro Kolyeushko acted well as the Zoologist, more interested in his bananas than in the beast with whose care he is entrusted. As Suzanna, Natalia Pavlova was vocally strong and dramatically engaging. The ‘Foreign Visitors to Moscow’ looked like a strange troupe of grotesques but made consistently sure, if fairly minor, individual contributions.

Salonen and the Philharmonia had great fun with this outrageous and uproarious score. There was much impressive playing from the brass, percussion, bassoons and flutes in particular. Characteristically, there’s a lot of self-quotation — with music from The Bolt, Hypothetically Murdered and Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District among the many Shostakovich works making an appearance. It’s also an eclectic mix of idioms: a potpourri of can-cans, cabaret and children’s nursery songs — a veritable Orango-Tango mélange. But, we were never permitted to forget that Shostakovich’s satire is serious stuff: the musical mix may be wild, but there’s a grim blackness too. If the musicians’ approach was fearless, then we were reminded by this focused, intense performance that at this stage in his career Shostakovich was similarly daring; in music, as in life.

The 1932 commission was not delivered to deadline, and the opera was apparently abandoned: perhaps Shostakovich was distracted by his concurrent work on the scores of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk and the Fourth Symphony, or perhaps the creators recognised that their sharp lampooning of Social Realist ideology and spectacle would not go down very well with Stalin’s cronies in the Kremlin. Acts 1 to 3 would have told, in flashback, the full story of Orango’s life from his creation to his arrival in the USSR; all we have is this zany preface — which in fact suggests that considerable work would have been needed to tighten up the dramatic structure. These ‘opening’ 40 minutes are rather aimless: Orango’s story was to have been told in flashback in the following three acts, but on the evidence of the Prologue the overall result might well have been chaotic rather than coherent. The Prologue is certainly ‘all action’; and, in this staging the performers used the whole space of the auditorium, entering by various stairways and parading the aisles. But while the score repeatedly tickles — and electrifies — the ear, the hypermania serves little purpose and the cast have nothing much to actually ‘do’, resulting on this occasion in several long ‘freeze-frames’ as the soloists stood stock still during long orchestral episodes.

But, the orchestral fireworks and madcap energy of Orango enlivened a Prom whose first half never quite came alight. Salonen certainly didn’t hold back in Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin, a one-act ‘pantomime’ which presents a lurid tale of prostitution, embezzlement and murder. Trombone glissandi, pounding timpani, rhapsodic clarinet curls and scales, and shining horn outbursts all contributed to a beguilingly vibrant canvas. But, while there was much impressive instrumental playing, the rhythms — for example in the fugal section over a bass ostinato, as the Mandarin chases the young dancer — didn’t quite feel sufficiently ‘tight’. And, if the waltzes needed more seductive sheen, the violent episodes needed a more incisive edge.

I found David Fray’s performance of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.24 in C minor distinctly underwhelming. Every phrase was careful, thoughtful and beautiful; but Fray — seated on a standard RAH chair, rather than a piano stool, and his back bent alarmingly, so as to make one fear for the curvature of his spine — seemed to be playing to himself, rather than to Hall. The orchestral accompaniment was stodgy at times, lacked bite and vigour, and felt bass-heavy — something that was certainly not true of the Shostakovich after the interval, where the violins had bite and sparkle in equal measure. Perhaps this was a ‘dark’ prelude to Shostakovich’s sardonic bleakness? But, if so, it was brusquely swept aside by the bitter energy of Orango’s disturbing truths.

Claire Seymour

Click here for a broadcast of this performance.

Programme:

Bartók — The Miraculous Mandarin; Mozart — Piano Concerto No.24 in C minor K.491; Shostakovich — Orango, Prologue (orch. G. McBurney)

Performers:

David Fray — piano

Cast (Orango):

French Visitors to Moscow

Armand Fleury (a French embryologist) — Alexander Shagun, tenor; Renée (his daughter) — Natalia Yakimova, mezzo-soprano; Foreigner 1 — Vladimir Babokin, tenor; Foreigner 2 — Oleg Losev, tenor; Paul Mâche (a French reporter) — Alexander Trofimov, tenor; Susanna (Orango’s Parisian socialite wife) — Natalia Pavlova, soprano.Soviet Citizens

Bass (Commissar) — Yuri Yevchuk, bass; Guard — Lev Elgardt, bass; Master of Ceremonies — Denis Beganski, bass-baritone; Nastya Terpsikhorova (a dancer) — Rosie Kay, dancer; Zoologist — Dmitry Kolyeushko, tenor; Orango — Ivan Novoselov, baritone.

Esa-Pekka Salonen — conductor. Irina Brown — stage director. Louise Price — stage/video designer. Rosie Kay — movement director. Sades Robinson — costume supervisor. Steph Blythman — alterations/dresser. Bernie Davis — lighting design. Philharmonia Orchestra. Philharmonia Voices (lower voices).

Royal Albert Hall, London. Monday 24 August 2015.

Click here for additional information.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/salonen_esa_pekka.png image_description=Esa-Pekka Salonen / © Katja Tähjä product=yes product_title=Prom 53: Shostakovich — Orango product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Esa-Pekka Salonen / © Katja TähjäWritten on Skin at Lincoln Center

How was I to know that the critics and audiences (not just in Aix, but on a dozen other stages since) would acclaim the new work, George Benjamin’s Written on Skin, as the greatest opera written in the past half century?

Recently I had a chance to partially redress the error by attending the US stage premiere of the same production, with two-thirds of the same cast, at the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Center on August 13, where Benjamin is composer-in-residence. The opera is everything it is cracked up to be. It is a masterpiece that will surely be performed and appreciated a century from now.

Martin Crimp’s dark libretto, fifteen scenes in an intense 90 minutes with no intermission, is a sophisticated meditation on the story of Adam and Eve. Though characters simultaneously adopt multiple temporal and narrative perspectives in a post-modern manner—for example, by having characters speak about themselves in the third person, and angels serve as both narrators and characters—the basic plot rests on the oldest and simplest of operatic plot devices: the love triangle.

In the Dark Ages, a wealthy older man, the Protector, has a younger wife, Agnès. He invites a Boy, an angel in disguise, to come live with them in order to create an illuminated manuscript. The Boy’s efforts fascinate both man and wife: the former because it offers religious knowledge and the latter because it offers carnal knowledge. The Protector eventually learns that the Boy is teaching Agnès to be erotically self-aware: it hardly matters whether this occurs through an actual affair, pornographic suggestion, or both; or whether the angel seduces the woman, vice versa, or both. The love triangle becomes modestly homosexual as well as heterosexual, since the Protector also appears attracted to the Boy, albeit far more ambivalently than his wife.

Eventually the Protector can no longer bear such threats to the established moral order. He kills the Boy, rips out his heart, cooks it, and—in what he believes to be the ultimate reassertion of paternal authority—orders Agnès to eat it. She obeys, but in a deeper sense defies her husband by proclaiming that she will always love the “salty and sweet” taste of the Boy’s heart. Then, in a final Pyrrhic victory over her husband, she takes her own life by throwing herself from an upper balcony. These proceedings are intermittently narrated by observing angels, who also enter and exit the scene as minor characters. We do not, for example, witness Agnès’s final fall. Rather, in the final bars of the opera, the Boy (restored to angelic form) narrates the vision of her floating body, surrounded by three angels, as if it were the conclusion of his illuminated manuscript.

If the basic purpose of an operatic libretto is to create moments of tension and resolution that spark dramatic excitement, provoke human sympathy and, above all, fuel musical elaboration, Crimp succeeds brilliantly. Angels and manuscripts may seem abstract, intellectual and fussy, but they are in the end just plot devices. The essential action remains visceral and concrete, focused on three sympathetically and convincingly human characters. Throughout, the text remains complex and evocative, yet extremely terse and surprisingly intelligible, even when sung primarily by extremely high voices.

One cannot imagine three more committed singers in the leads. Two of them—Barbara Hannigan as Agnès and Christopher Purves as The Protector—created their roles. Hannigan may well be the greatest singing actress on the operatic stage today, not something often said of a specialist in the contemporary lyric coloratura soprano repertoire. Yet she possesses an instrument of clear tone and, above all, uncannily perfect intonation, which she employs in an uncompromisingly rigorous, musical, passionate and intelligent way. She is a compelling physical character on stage, further enhanced by her clear diction. She rises to the big moments, such as the stunning final portion of the second section of the opera. Overall, this is a riveting portrayal of a woman transformed by knowledge from timidity through passion to resistance.

Christopher Purves is an equally dramatic Protector, believably gruff, clever and strong. From a musical perspective, however, I felt at times that the role was being growled rather than sung, and was less technically solid than it might have been, particularly at the extremes of the vocal range. (This was true also vis-à-vis tapes of his previous performances, so perhaps indisposition played a role.) As this opera enters the canon, perhaps future baritones will approach the role differently. One can imagine a great Verdian with warmth yet steel and darkness in the voice bringing out a different side of what is latent in this tortured character.

Countertenor Tim Mead sang sweetly as the Boy. Some critics disparaged his diction, but I found him quite intelligible. Yet his voice seems to me more boyish than manly, too much of a soprano and not quite enough of an alto, and thus less compelling as the instrument of Agnès’ sexual awakening. Bajun Mehta, who created this role in Aix and sang it in a number of revivals, offers much more vocal and dramatic menace, as befits the equivalent of the Snake in the Garden of Eden. The other angels were strong, particularly Victoria Simmonds who doubled as Marie.

This set of performance revived the production directed by Katie Mitchell, seen originally at the Aix premiere. In general, the stage action was exceptionally persuasive and enhanced core themes of the plot—in part due to the excellent singing actors—while the set design sometimes tipped over into the fussy and unnecessarily self-important mannerisms of modern Regietheater. As is quite the rage in Europe these days, Vicki Mortimer’s sets employ a “Hollywood Squares” design: the stage is divided into boxes with different scenes. Most of the action takes place in the largest rectangle to the lower right: here is the medieval world of the main plot, where Jon Clark’s brilliantly subtle lighting shifts highlighted shifts in mood and perspective. (Trees trunks growing through the floor do, however, suggest further symbolic meanings.) Two boxes to the left, one above the other, are reserved for the observing angels, who are high-tech spirits with computers and Ikea office furniture. To the far right is a narrow stairwell used only by Agnès in the opera’s final moments, as she climbs to her death. And to the upper right is a dark room full of trees that the main characters shun: is this the Garden of Eden, from which all the characters are irremediably estranged? One wonders whether that is the ideal place to which Agnès seeks ultimately to return, or the purgatory from which she seeks to escape.

Engaging though its libretto, singing and staging may be, Written on Skin will enter the operatic canon above all due to its superb orchestral score. Benjamin’s writing is pleasantly free of the kitschy and monotonous devices that weigh down most contemporary opera. It is not an “easy listening” score in which intermittent atonal flourishes separate numbers derived from jazz, pop, traditional American or ethnic Chinese riffs. Nor is it a minimalist opera, in which miniscule bits of musical material are stretched to the breaking point on the rack of repetition. This is music that stands on its own: it is thickly textured and finely crafted, acknowledging yet transcending the past. Not since Britten has anyone written for operatic orchestra with such sensuous beauty, emotional impact, compositional rigor and mature self-restraint.

To be sure, gestures from 20th century modernist opera permeate Written in Skin. Benjamin’s restrained orchestration and way with words remind one of Debussy and Britten. The technique of presenting mythology simultaneously from the perspective of a narrator and a participant recalls not only Britten Rape of Lucretia, but also Stravinsky’s Odepus Rex. As the mind of the Protector unravels, tutti orchestral chords and whining woodwinds recall famous passages from Berg’s Wozzeck—though Benjaminhas purged all of that opera’s overt Romanticism. At various points, specific harmonies and timbres evoke Bartók, Kodály, Janáček, Ligeti, Birtwistle, Stockhausen and a long French tradition ending with Benjamin’s own teacher Messiaen.

Yet Written in Skin is no pastiche. Just as Mozart drew on Haydn, Gluck, Bach and others to forge his own distinct style, Benjamin has done so to craft a coherent 21st century musical language modern-day Mozartian in its spare, elegant beauty. A detailed analysis of Benjamin’s use of color, rhythm and harmony is a task better left to future dissertation writers—or at least those with access to an orchestral score—but here are a few impressions. Though most of the music is understated, Benjamin achieves an exceptional range of orchestral color, deployed with utmost refinement. While he realizes of this color through the use of unusual, often neo-medieval instruments—gamba, (faux) mandolins, glass harmonica and a wide range of percussion—generally he employs conventional, but spare and wide-ranging instrumentation. The most common texture involves simple, often open string intervals punctuated by brief melodic fragments in the woodwinds and muted brass, especially trumpets. The bottom of the orchestra (notably bass clarinet and double basses with a downward extension) is exceptionally active, at times lending the music an ominous quality without overweighting it. Much of the music seems to float in space, enveloping the singers, or is sensuous and serpentine, wrapping itself around them. One particularly effective example is the duet between the Agnès and the Boy, whose voices intertwine suggestively with orchestral lines. While Benjamin is often compared to Debussy, his music generally has more rhythmic impulse than Pelleas, yet without either a repetitive beat or obvious popular music reference. This highly atmospheric music effectively magnifies the shifting psychological moods of the singers, and the effect induced on a sympathetic listener can range from extreme beauty to heart-wrenching poignancy to repugnance. Occasionally the entire orchestra erupts in a jagged, harsh fortissimo, highlighted with piccolo and high flutes, but such passages rarely last. This varied orchestral texture, I find, comes through much more compellingly live than on the many video and audio versions that have circulated.

The Mahler Chamber Orchestra premiered this work at Aix. This is the second time in a month I have heard this group, and both times I have come away thinking there are no better chamber players anywhere in the world. Though atonal, Benjamin’s intervals seem so perfectly judged that they benefit from the spot-on intonation and subtle timbre such expert musicians provide. New York Philharmonic conductor Alan Gilbert conductor led, tempering firm precision with gentle sympathy.

Andrew Moravcsik

Cast and production information:

Christopher Purves, The Protector ; Barbara Hannigan, Agnès ; Tim Mead, Angel 1/The Boy; Victoria Simmonds, Angel 2/Marie ; Robert Murray, Angel 3/John ; David Alexander Parker, Laura Harling, Peter Hobday, and Sarah Northgraves, Angel Archivists.

Mahler Chamber Orchestra. Alan Gilbert, conductor. Katie Mitchell, director. Martin Crimp, text Vicki Mortimer, scenic and costume design. Jon Clark, lighting design.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/WoS.png image_description=Scene from Written on Skin [Photo courtesy of Barbara Hannigan] product=yes product_title=Written on Skin at Lincoln Center product_by=A review by Andrew Moravcsik product_id=Above: Scene from Written on Skin [Photo courtesy of Barbara Hannigan]La Púrpura de la Rosa

For those versed in Golden Age Spanish literature the name Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600-1681) will of course be familiar, but Calderón lovers and even connoisseurs are likely to raise an eyebrow at seeing the man who penned La Vida es Sueño (“Life is a Dream”), a philosophical tragicomedy solidly established in the canon of Western drama, become an opera librettist (English readers are invited to imagine Shakespeare or a quasi-Shakespeare writing an opera libretto to experience an analogous sense of puzzlement at the sight of the program). The conundrum, as Louise K. Stein explains in her excellent PR entry in mundoclasico.com (the introduction to her PR critical edition for Iberautor Promociones Culturales), goes back to 1659, when Calderón was indeed commissioned the libretto for Philip IV's court celebration of the Peace of the Pyrenees and worked together with Juan Hidalgo (1614-1685), the first person who set music to the text. All this happened in Madrid (Spain). To get to 1701 and Lima we need to go through several revivals of the opera (1679, 1690, and 1694, according to Stein) and the commission of the opera’s production by the Viceroy of Peru (probably in view of its success) to commemorate the 18th birthday of King Philip V and first anniversary of his succession to the throne. The composer of the Lima performance was Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco (1644-1728), born in Spain and later a resident of today’s Peru for several decades, a musician who, according to Stein, might have been a pupil of Hidalgo (it’s not clear from Stein’s entry what exactly motivated a fresh composer and thus score for the Lima performance, but apparently Torrejón left intact much of Hidalgo’s original music, so credit should be given to both for the final score).

The play and music themselves deserve more commentary that we can provide here (the reader is invited to consult Stein’s article for supplementary information). A highly allegorical text, PR tells the story of the love between Venus (Roman goddess of love) and Adonis (a handsome youth), which prompts the jealousy of Venus’ lover Mars (Roman god of war), and his attempt at revenge. At the end Mars partially succeeds, as Adonis is killed by a boar made vicious by Mars’ aids, which prompts Venus’ despair at the sight of his lover’s blood, none other than the “púrpura” of the opera’s title:

Belona:

y así, ¿para qué has de ver

que humana púrpura corre?

Todas:

Tanto, que de ella animadas,

cada flor es un Adonis

[Belona: And so, why do you want to see / / how human blood is running?

All: So much blood, that enlivened by it, / / every flower is an Adonis]

(PR, v. 1356-1359)

In between, characters like Jealousy, Disillusion, Fear, or Anger, among others, have tried to impart Mars a few lessons of prudential wisdom, apparently to no avail; in the end love triumphs and Jupiter elevates Venus and Adonis to Mount Olympus. The story, surprising for the candid celebration of erotic love in such a religious-minded author as Calderón, is accompanied by music that incorporates Latin American melodies and rhythms into an overall European dramatic and harmonic structure, with which one can establish useful comparisons with Renaissance or baroque composers such as Cabezón, Frescobaldi, Scarlatti, or Couperin. The opera itself (that is, the story and the music) can helpfully be compared with Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas and Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo.

As for the performance, Le Château de la Voix deserves credit on various grounds. First for its choice of a little-known opera that showcases a strong and interesting tradition not seldom ignored in histories of classical music, i.e. the Spanish (a fortiori, the colonial Spanish). Second for having assembled a highly efficient orchestra composed of faculty members of the University of Illinois School of Music (continuo group of harpsichord, viola de gamba, guitars, lutes, and harp). Finally, for having coached a diverse group of young vocal performers whose lack of expertise was amply made up for by their enthusiasm and attunement to the intricacies of the Spanish baroque not unusually convoluted ways of expressing artistic emotion.

A final linguistic note: the Real Academia Española dictionary accepts “púrpura” as “human blood” (7 th entry; poetical use), but in current Spanish the word routinely means “purple” (the color) or, alternatively and more technically, “purple dye murex” (a particular variety of medium-size sea snail), which is the 1st entry given by the RAE. So much as an indication that for Spanish speakers (at any rate present-day ones) the expression “la púrpura de la rosa” still retains its original Baroque qualities.

Iker Garcia

Additional information:

Music by Tomás de Torrejon y Velasco (1644-1728)

Libretto by Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600-1681)

Saturday August 1 (7:30pm), Sunday August 2 (3pm), 2015, Smith Hall, University

of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Le Château de la Voix (summer vocal Academy) accompanied by a period instrument orchestra

Click here for additional photos.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/10372919_343272459172398_3909360755917125068_o.png image_description=Dominique Daye Lim, Lila Powell and Emalie Huber [Photo courtesy of Le Château de la Voix] product=yes product_title=La Púrpura de la Rosa (“The Blood of the Rose”) product_by=A review by Iker Garcia product_id=Above: Dominique Daye Lim, Lila Powell and Emalie Huber [Photo courtesy of Le Château de la Voix]August 23, 2015

Pesaro’s Rossini Festival 2015

Though these dates encompass the well known Rossini comedies, both L’inganno felice and La gazza ladra are not comedies but semi-serious operas. La gazzetta, beyond comedy, is just plain farce. Rossini then established himself firmly in Naples where he wrote his great tragedies (though few of today’s opera goers can name more than one or two). Once in Paris he did finally write one last comedy (Le conte Ory in 1828).

Many of us with serious Rossini addictions make an annual pilgrimage to Pesaro where at times we do achieve Rossini nirvana. Such was not the case this August, though there were hints of the great Rossini in L’inganno felice.

The leaky, forlorn Adriatic Arena (home of Pesaro’s famed basketball team) also serves each summer as one of the world’s most interesting and exciting opera houses. This summer the opera installed in this vast space was La gazza ladra or in English The Thieving Magpie, a remount of the 2007 Pesaro production by Damiano Michieletto of recent Covent Garden Guillaume Tell booing fame whose Sigismondo (2010) in Pesaro was soundly booed as well — of course there were vocal protestations at his bows on the opening night of this La gazza ladra.

Stage director Michieletto’s conceit is that Rossini’s opera is a dream fantasy of an adolescent girl. She arranges a few small white tubes on the floor, fashions a sort of swing from some hanging cloth, climbs on and swings about the stage for a while. While it is obvious she is going to be the magpie it is not obvious what the 15 tubes are — cigarettes or tampon cases were overheard intermission interpretations. The tubes were then scenically amplified to provide the huge and only scenic elements.

Principal Gazza ladra singers in ensemble scene, with magpie in center (in white shorts)

Principal Gazza ladra singers in ensemble scene, with magpie in center (in white shorts)

Whatever they might be (for Michieletto they are probably only white tubes) their geometrical arrangements on the stage were Michieletto’s idea of minimalism, as were the costumes, the heroine in a bright green dress the entire evening, the chorus women first in identical brilliant red dresses, then for the execution in identical taupe toned dresses as examples. The chorus was staged in geometric lines or blocks executing geometrically repetitive movements. Five storm troupers made a straight line tableau across the front of the stage displaying their Uzis horizontally over their heads for the execution of the simple peasant girl.

Michieletto is not a musical stage director, insisting that his adolescent magpie-girl intrude, clumsily choreographed, among the singers at the very moments it was possible that Rossini lyricism might take flight. La gazza ladra is mature Rossini, and that means that there is a big cast and abundant ensembles of magnificent musical architecture. This director is oblivious of these structures, placing his five, six or seven singers (and chorus) in arbitrary geometric patterns instead of allowing musical imperatives to determine how, when and where the components move. The famed crescendo of intensities of these fabulous ensembles were therefore intentionally thwarted.

The Rossini Festival has engaged Mr. Michieletto to stage a new La donna del lago for next summer. Go figure.

La gazza ladra is a semi-seria opera — a servant girl of a tenant farmer will marry the farmer’s son but not before it is determined who stole the silver spoon. Meanwhile the servant girl is assumed to have been the thief and has been condemned to death. It is absolute farce endowed with powerful emotional moments that require important musical involvement — its obvious dramaturgical and musical challenges are daunting.

The musical direction of this avowed Rossini masterpiece was entrusted to veteran conductor Donato Renzetti. Mo. Renzetti’s big Rossini period (in Pesaro and elsewhere) was in the early 1980’s. There has been much refinement in the musical understanding of Rossini in the last 30 years that has well surpassed the slow and heavy realization that this maestro imposes. It may well have comfortably accommodated the needs and expectations of the singers of previous generations but it does not support current musical practice. This was evidenced by repeated musical misunderstandings of the orchestra players and some of the singers, i.e. they felt and expected a celerity that was intentionally and forcefully squashed.

Alex Esposito as Fernando, Nino Machaidze as Ninetta

Alex Esposito as Fernando, Nino Machaidze as Ninetta

The role of the servant girl Ninetta was given to Georgian soprano Nino Machaidze. This artist, much beloved by Los Angeles audiences (Gounod’s Juliet as well as Traviata and Boheme) was the perfect, unrepentant Fiorella in L.A Opera’s production of Il turco in Italia, her hard-edged, brilliant coloratura dramatically convincing. Mme. Machaidze does not possess a sweet voice nor does she project a sweet personality that could embody the simple Ninetta. She is all diva business, and she does it very well, but these attributes do not make her a Rossini artist.

There was one fine Rossini artist in the cast, Alex Esposito who sang Ninetta’s father Fernando Villabella. This esteemed bass exudes character and executes thrilling coloratura. Pesaro audiences are famous for extended applause given well performed arias (or scenes). Mr. Esposito’s second act aria was the sole recipient of such appreciation for the entire four hour duration of the performance.

Principals singers of La gazzetta

Principals singers of La gazzetta

La gazzetta or in English The Newspaper was on stage at the 800 seat, horseshoe Teatro Rossini the second night (of the second cycle). This opera was a contractual obligation for Napoli’s Teatro dei Fiorentini (FYI it is now a bingo palace) where audiences loved to be entertained. Rossini lifted some of La gazzetta’s major pieces from his masterwork Il turco in Italia (1814), and composed fine new material as well that found its way a few months later into his masterwork La Cenerentola.

La gazzetta is not a masterwork. A simple enough story (albeit three pages of synopsis needed): a silly father places an ad in the Gazette of Paris offering his daughter in marriage. She however loves the innkeeper. It is a three hour mess that finally gets cleared up at a costume party. As the libretto is based on a play by famed 18th century playwright Carlo Goldoni there is a lot of lively repartee that leaves us non-Italians (there are a lot of us and we come from around the globe) at a disadvantage — plus the supertitles are way above the stage and in 18th century Italian.

None the less there was a lot to look at on the stage, too much, but the story was easy to follow. We just missed the Goldoni wit that we knew was there and way above us. Rossini is performance art, this piece dominated by an electric performance by dead ringer Rossini look-alike Nicola Alaimo (a Metropolitan Opera Falstaff as well as a famed Guillaume Tell) as Don Pomponio, the silly father.

José Maria lo Monaco as Madama La Rose, Nicola Alaimo as Don Pomponio, Ernesto Lama as Tommasino

José Maria lo Monaco as Madama La Rose, Nicola Alaimo as Don Pomponio, Ernesto Lama as Tommasino

Stage director Marco Carniti gave Don Pomponio a side-kick servant mime he named Tommasino who seconded Don Pomponio’s decisions, argued with them, insisted that Don Pomponio’s wishes be carried out, and suffered Don Pomponio’s frustrations by repeated beatings. Neopolitan actor Ernesta Lama however was not a mute mime as he could not help himself from speaking out from time to time. It was pure comic delight. Stage director Carniti gave this physical theater performer much activity, and it was thoroughly musical, his physical intrusions into the arias and ensembles fully consistent with Rossini’s musical architecture (unlike the arbitrary Magpie intrusions in La gazza ladra).

Marco Carniti and his designer Manuela Gasperoni created a stage box fully enclosed by translucent plastic strips that easily absorbed projected colored light when not serving as a silhouette surface. Much of the mise en scène was in black and white, the costumes by Maria Filippi (a Franco Zeffirelli collaborator as well) were primarily in black and white but sometimes with bright color accents. This high design concept supported endless production numbers (like 1950’s American film musicals), including highly choreographed movement of the abstracted set pieces and much movement by four fine supernumeraries.

It was all too much for the simplistic wit of farce, and at the same time it was very well done and musically solid.

Hasmik Torosyan as Lisetta, Vito Priante as Filippo

Hasmik Torosyan as Lisetta, Vito Priante as Filippo

The singing was of good level, notably the silly father’s daughter Lisetta, sung by young Armenian soprano Hasmik Torosyan who last summer was a participant in the festival’s young artists program, the Accademia Rossiniana. The innkeeper Filippo was sung by Vito Priante who with Nicola Alaimo were the two fully accomplished performers of the evening, Mr. Priante offering delightful coloratura dressed as a Turkish suitor in the masquerade.

Conductor Enrique Mazzola provided an unobtrusive, fully idiomatic orchestral basis, but the wit and charm of Rossini’s orchestrations were overwhelmed by the production.

Principal singers of L'inganno felice

Principal singers of L'inganno felice

A Graham Vick production is always news, even moreso because this L’inganno felice was the revival of his 1994 Pesaro production for the Teatro Rossini, staged before he had become one of the world’s most admired and adventurous stage directors. In recent years he has reappeared at Pesaro with Mosé in Egitto (2011) and Guillaume Tell (2013) — both mise en scènes are masterpieces.

L’inganno felice is a simple, sentimental farce, the oft-used situation of a foundling baby, but here beautiful young woman, having been washed up on a shore. Here the shore was near a remote mine somewhere. A kindly old miner protects her and engineers a safe return to her beloved husband by tricking the very evil suitor she had rejected.

Vick and his designer Richard Hudson (most famous for The Lion King [1988], but on the other hand famous for this winter's Graham Vick production of Götterdämmerung at Palermo’s Teatro Massimo) imagined one grand diminution of light over the one and one half hours of the opera’s only act. The production’s original lighting designer Matthew Richardson returned to once again effect this spectacular light show — high noon becomes late afternoon then early evening, finally night falls to give cover for the deception. Meanwhile a miniature steamship traverses the far away, endless horizon for the duration of the action.

The set is an enormous curved white cyclorama with some Japanese looking gray splotches as clouds. There was a hole for the mine, a bench on the right indicating a house just offstage. When Nisa’s long lost husband, Bertrando happens to happen by he erects a tent on the other side of the stage. The stage floor is in cinematic detail, a realistic slope complete with struggling shrubs.

However Bertrando and his soldiers are straight out of nineteenth century operetta, Bertrando with grandiose epaulettes. Greek tenor Vassilis Kavayas, a recent Rossini Academician, brought ultimate snap and sparkle to his character as did his snappy soldiers to their marching entrances and exits.

Giulio Mastrototaro as Ormondo (blue uniform), Vassilis Kavayas as Bertrando, Mariangela Sicilia as Isabella, Carlo Lepore as Tarabotto, plus soldiers and supernumeraries

Giulio Mastrototaro as Ormondo (blue uniform), Vassilis Kavayas as Bertrando, Mariangela Sicilia as Isabella, Carlo Lepore as Tarabotto, plus soldiers and supernumeraries

The realistically costumed rustic miner Tarabotto was sung by veteran basso-buffo Carlo Lepore whose accomplished presence anchored the young cast. Also simply costumed in rags was Nisa, sung by ingenue soprano Mariangela Sicilia, a recent Rossini Academician as well. She began the evening with a splendidly sung contemplation of a tiny necklace pendent portrait of her long lost husband. Most of her remaining music required sustained singing but as the evening progressed her intonation seriously deteriorated.

Young Italian baritone Davide Luciano brought seriously snappy buffo to his role, Batone, an ardent, if not too bright sergeant. He had much to sing, and did a convincing and charmingly energetic performance that made you wish his coloratura was just a bit sharper. As it was the high point of the evening was the extended duet Batone sings with the miner Tarabotto where Tarabotto induces him into the deception. This duet and Alex Esposito’s aria “Eterni Dei, che sento!” in La gazza ladra were the two high points of all three operas of the festival)

With his eclectic set and his spotty cast Graham Vick’s palate had a bit of everything to work with. It was all masterfully laid out in low key, absolutely unpretentious terms, allowing us to enjoy all these wonderful performances without critical prejudice — though may we believe that back in 1994 perhaps the Vick production had considerable artistic prétention.

Great Rossini begins in the pit. The conductor was a thirty-four year old Russian, Denis Vlasenko, still another of the evening’s former Rossini Academicians. While Pesaro’s Orchestra Sinfonica G. Rossini lacks the finesse of the Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna (in the pit for La gazza ladra and La gazzetta) this young maestro still was able to create an estimable Rossini elation from time to time, the Rossini high that brings us back to Pesaro year after year.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information