November 30, 2015

Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg in San Francisco

Verdi looks ahead, Wagner looks back. It is hard to tell if the current production of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnburg on the War Memorial stage looks forward or backward. Happily it is a return to an international production standard, increasingly rare at SFO, with British stage director David McVicar’s 2011 Glyndebourne version of Wagner’s masterpiece.

The conceit of the production seems to be that there are no cuts whatsoever to Wagner’s score. This resulted in an evening of five hours and forty minutes. Knowingly conducted by Mark Elder it did feel somewhat briefer than that, maybe like just about five hours. Still it was a long, very long evening.

This excellent conductor, once the music director of English National Opera, gave a firm, powerful and satisfying traditional hand to the famous overture, a tone that dissolved into a convincing lyricism that prevailed for the duration.

The David McVicar production was all about home-spun tradition, in fact the most moving moments of this lovely, emotional evening were Hans Sach’s admonition to Walther that he respect artistic tradition and Walther’s acquiescence to such respect.

As Wagner intended the philosophical and artistic meat of the opera was the shoemaker Hans Sachs. The real i.e. historical Hans Sachs shoemaker lived to the ripe old Renaissance age of 82, and there are those of us who remember the silver haired Hans Sachs of the four [!] SFO Meistersinger productions between 1959 and 1971. Just now the youthfulness of 43 year-old British baritone James Rutherford — an accomplished artist of wide expressive range — seemed at odds with the gravity we wanted and needed to award Hans Sachs for the first two acts.

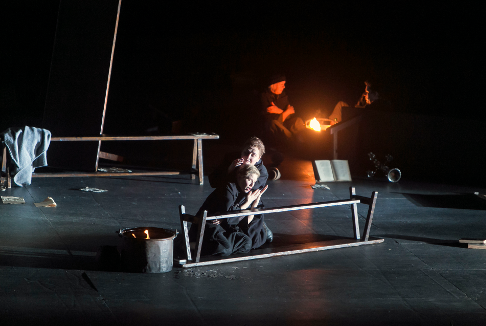

The Act III quintet

The Act III quintet

But with Hans Sachs extended soliloquy that dominates the first scene of the third act we entered into a real and tortured, not yet age-resigned psyche. As Hans Sachs uncovered and contemplated a portrait of his dead wife and child his conflicts gained an apparent philosophical realness that took us to the elusive, profound plane Wagner wished to achieve. This high minded angst then dissolved into the famous quintet, the love triangle (Sachs, Eva and Walther) holding hands with the lesser beings (David and Lene) in a simple, soft lyricism that forsook the musical gravity that should illuminate this magnificent moment and make it magical.

Ain Anger as Pogner, Rachel Willis-Sorensen as Eva, Brandon Jovanovich as Walther, James Rutherford as Sachs

Ain Anger as Pogner, Rachel Willis-Sorensen as Eva, Brandon Jovanovich as Walther, James Rutherford as Sachs

The McVicar production and the Mark Elder orchestra more than anything else worked to demystify Wagnerian thought and to quell Wagnerian rhetoric. Further example were the phenomenal complexities of mid-summer night riot chorus graphically reduced to a few dancers and children cavorting across the front of the stage, and as more example, the phenomenal choral complexities of the mid-summer day celebration graphically defined by three jugglers on stilts — fortunately the solidity of the musical preparation was not compromised by the fragility of the precarious balancing and juggling.

Director David McVicar’s slick stagecraft was always supported by conductor Mark Elder’s direct lyricism. As intended on the stage and from the pit the result was anything but intimidating and this despite the extraordinary length that was so wittily and unnecessarily imposed.

The production discretely toyed with Beckmesser, revealing but not dwelling on the famous anti-semitic polemic inherent to this opera. Here Beckmesser was superbly enacted by German baritone Martin Gantner who towed a very fine line between ridicule and caricature. Distinctly costumed in all-black he somehow evoked our sympathy within the larger warmth of the production. However at the end Beckmesser the Jew was left seated at the extreme edge of the stage, far from and pointedly exiled from the Wagnerian reconciliation of art and love.

San Francisco Opera’s casting perhaps inadvertently supported the home-spun nature of the production as it unfolded on the War Memorial stage. With the exception of the two baritones it was unpretentiously cast. Montana tenor Brandon Jovanovich was a vulnerable Walther whose prize song (“Morgenlich leuchtend im rosigen Schein") was just persuasive enough. Eva was sung by recent Houston Opera Studio graduate Rachel Willis-Sorensen whose tone I found shrill and whose vocal strength was not sufficient to hold together the quintet (not all my friends agree with me). Alek Shrader was vocally miscast though an exquisitely charming David while Sasha Cooke as Magdalene was vocally splendid. German bass Ain Anger as Eva’s father Veit Pogner added a further homey touch, his first act monologue shakily delivered.

It is a very great pleasure to hear San Francisco Opera’s fine orchestra and chorus in service to a fine conductor and a solid production.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Hans Sachs: James Rutherford; Walther von Stolzing: Brandon Jovanovich; Eva: Rachel Willis-Sorensen; Magdalene: Sasha Cooke; David: Alek Shrader; Sixtus Beckmesser: Martin Gantner; Veit Pogner: Ain Anger; Fritz Kothner: Philip Horst; Kunz Vogelgesang: AJ Glueckert; Balthasar Zorn: Joel Sorensen; Augustin Moser: Corey Bix; Ulrich Eisslinger: Joseph Hu; Konrad Nachtigall: Sam Handley; Hans Schwarz: Anthony Reed; Hermann Ortel: Edward Nelson; A night watchman: Andrea Silvestrelli; Hans Foltz; Matthew Stump; An apprentice: Laurel Porter. Chorus and Orchestra of the San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Sir Mark Elder; Production: Sir David McVicar; Revival Co-Directors: Marie Lambert and Ian Rutherford; Production Designer: Vicki Mortimer; Lighting Designer: Paule Constable; Choreography: Andrew George. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, November 24, 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Meistersinger_SF1.png

image_description=San Francisco Opera Chorus, Act 1 [Photo by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=San Francisco Opera Chorus, Act 1 [All photos by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

Le Nozze di Figaro, Manitoba Opera

However, it does make for a terrific night of madcapopera buffa as proven during Manitoba Opera’s 2015/16 season-opener of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro ( The Marriage of Figaro).

Last staged by the 43-year old company in 2006, the four-act opera buffa based on Lorenzo Da Ponte’s Italian libretto is regarded among the top 10 operas performed worldwide. The three-hour plus production directed by MO newcomer Brent Krysa featured the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra led by Tadeusz Biernacki (who also prepared the Manitoba Opera Chorus), as well as a dream team of accomplished Winnipeg-born sopranos.

The first of those is Andriana Chuchman, whose skyrocketing career has already taken her to the Metropolitan Opera house as well as seeing her gracing the stage with fabled Spanish tenor Plácido Domingo during her LA Opera debut this fall. An equally compelling actor who last appeared on the MO stage in 2011, Chuchman crafted a radiant Susanna with her Act III aria “Deh, vieni, non tardar” particularly showcasing her luminous, soaring vocals.

Charismatic local soprano Lara Ciekiewicz continues to prove her gifts as a natural stage chameleon, able to crack viewers up one moment with her razor sharp comic timing before breaking their hearts the next with her soulful performances — such as her MO debut as slave girl Liù in Turandot last April. Her two solos as the Countess Almaviva: “Porgi, Amor,” matched only by her later mesmerizing “Dove sono I bei momenti” did the latter, as she revealed the complex emotional underbelly of her deeply conflicted, all-too-human character.

Canadian bass-baritone Daniel Okulitch likewise dazzled with his swaggering portrayal of the skirt chasing Count who petulantly stomps his feet and wields large axes. His robust vocals, as displayed during his Act III recitative and aria “Hai già vinta la causa! ... Vedrò, mentr'io sospiro,” added brooding gravitas to the comic froth. His truly touching finale “Contessa perdono!” added its own grace note to the entire show.

Kudos to veteran mezzo-soprano Donnalynn Grills, grappling with real-life illness as housekeeper Marcellina. Singing mostly sotto voce, Grills’ strong acting chops helped sell her character for all she’s worth, aided by simpatico sidekicks Dr. Bartolo (baritone Peter McGillivray) and Don Basilio (tenor David Menzies) who valiantly rallied by her side in support.

Canadian bass-baritone Gordon Bintner (MO debut) created a convincing Figaro, including his “Non piu andrai farfollone amoroso” sung with military precision, with his portrayal noticeably growing more confident throughout the performance. He also received the night’s biggest guffaws after leaping into Grills’ waiting lap as his long-lost mother, later tossing off his tongue-twisting “Aprite un po’ quegli occhi” that earned cries of bravo.

Mezzo-soprano Alicia Woynarski (MO debut) created an admirably convincing male persona in the trouser role of page Cherubino, despite suffering minor intonation issues during “Non so piu cosa son.” Her later “Voi che sa pate” fared better, although her lovesick character mooning for women could have gone much further.

A highlight proved to be seeing now Toronto-based colouratura soprano Anne-Marie MacIntosh, a recent graduate from the University of Manitoba’s Desautels Faculty of Music marking her impressive MO debut as Barbarina. This rising star made every minute of her relatively short stage time count, including delivering a riveting “L'ho perduta, me meschina” under a starry night sky.

The stylish, albeit decidedly traditional production included ornate period costumes and effective sets originally created for Pacific Opera Victoria and Calgary Opera. Revolving mirrored door panels spun throughout the production at strategic moments captured designer Bill Williams’ flashing shards of light, adding to the overall, crazy funhouse atmosphere that’s a bit like love itself.

Holly Harris

image=http://www.operatoday.com/_RWT2708.png image_description=Andriana Chuchman as Susanna and Gordon Bintner as Figaro [Photo by R. Tinker] product=yes product_title=Le Nozze di Figaro, Manitoba Opera product_by=A review by Holly Harris product_id=Above: Andriana Chuchman as Susanna and Gordon Bintner as FigaroPhotos by R. Tinker

Arizona Opera Presents Florencia in el Amazonas

Co-commissioned by Houston Grand Opera (HGO), Los Angeles Opera, and Seattle Opera, Florencia premiered on October 25, 1996. Since then, HGO has remounted it and Los Angeles Opera has staged it twice. The Opera de Bellas Artes in México City, as well as Seattle Opera and numerous other U.S. companies have each performed it once.

Daniel Catán composed a melodic score that brings modern tonal music to a fresh group of operagoers who attend the theater for the enjoyment of newly wrought melodies. Part of the inspiration for this story is Magic Realism, a literary style popularized by Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez. The opera’s librettist, Marcela Fuentes-Berain, who studied with Garcia Márquez, imbued her work with elements of the style, which includes the appearance of river spirits and, at the finale, a magnificently colored butterfly. On November 13, 2015, Director Joshua Borths brought Magic Realism to life in the Arizona Opera production designed by Douglas Provost and Peter Nolle.

The lush, neo-Romantic colorations of Catán's orchestration reflect his impressions of the river’s unique sounds. Although his vocal lines recall early Puccini, Catán’s many-layered orchestral sonorities are reminiscent of the complexities heard in music by Richard Strauss, Heitor Villa-Lobos and the French Impressionists. Catán wrote that the greatest of his debts was having learnt that the originality of an opera need not involve the rejection of tradition but the assimilation of it. As a result, he wanted his twenty-first century opera to be a continuation of opera’s melodic tradition. In Phoenix, conductor Joseph Mechavich led a well-constructed and exciting performance of this lush, complex score.

The opera’s title character, Florencia, is a mature singer who returns home to the Amazon after years of success abroad. The music of this dramatic role requires a voice with the spin and polish of youth, however. Although Sandra Lopez was not the quintessential Florencia, she portrayed the role with passion and sang with a strong, resonant voice. Luis Alejandro Orozco was Riolobo, a member of the crew on the ship taking Florencia and several music lovers up the Amazon. Orozco’s charisma and smooth singing introduced the river’s magical world and he told the story with excellent diction. Imbued with the magic of the waters, River Spirits danced Molly Lajoie’s inventive choreography as they appeared and disappeared from its mists.

Susannah Biller was Rosalba, a young woman whose main interest was in documenting Florencia’s biography. Biller’s silvery tones acquired a luminous quality when her character fell in love with the Captain’s nephew, Arcadio, sung by the robust-voiced Andrew Bidlack. His ringing, lyrical tones blended beautifully with the clarity of Biller’s notes. Levi Hernandez and Adriana Zabala portrayed Paula and Alvaro, a couple who had begun to fall out of love. The river worked its magic, however and, as their voices began to blend, they rediscovered the love that had once bound them together. It was the ship’s Captain who led all these passengers on their trip into the life-changing mysteries of the river. Lyric bass baritone Calvin Griffin sang the role with a smooth dark voice as he commanded his beleaguered ship. It was a treat to see this lush, green opera in desert-dry Arizona! I hope Florencia in el Amazonas will make the rounds of many more regional opera companies. I know I would like to see it again in the near future.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Florencia Grimaldi, Sandra Lopez; Riolobo, Luis Alejandro Orozco; Rosalba, Susannah Biller; Arcadio, Andrew Bidlack; Paula, Adriana Zabala, Alvaro, Levi Hernandez; Capitán, Calvin Griffin; Conductor, Joseph Mechavich; Director, Joseph Borths; Lighting Designer, Douglas Provost; Scenic Designers, Douglas Provost, Peter Nolle; Costume Designer, Adriana Diaz; Chorus Master Henri Venanzi; Choreographer, Molly Lajoie.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Florencia%2001.png

image_description=A scene from Florencia in el Amazonas [Photo by Tim Trumble]

product=yes

product_title=Arizona Opera Presents Florencia in el Amazonas

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: A scene from Florencia in el Amazonas [Photo by Tim Trumble]

Viva la Mamma!: A Fun Evening at POP

His librettist, Domenico Gilardoni, adapted the libretto from two plays by Antonio Simone Sografi. In 1827, Donizetti and Gilardoni originally based a one-act farce on Le convenienze teatrali for the Teatro Nuovo in Naples. Revising it for performance at the Teatro alla Cannobiana in Milan in 1831, they expanded the work to two acts by adding recitatives and other material based on Le inconvenienze teatrali.

Not many opera composers have been able to write both comedy and tragedy successfully. Donizetti was one of the few. He embodied his musical jokes in his imitations of music by Rossini, Bellini, and Mozart. His Rossini-inspired passages got faster and louder while his faux Bellini melodies were stretched to almost impossible lengths. Donizetti wrote such convincing music in Mozart’s style that people often wonder which opera he took it from.

Le convenienze ed inconvenienze teatrali, or Viva la Mamma, is supposed to take place in a provincial theater. For the Pacific Opera Project (POP) presentation on November 19, 2015, the intimate table settings of the Highland Park Ebell Club provided the correct sized hall but not the provincial atmosphere. Ebell was the perfect hall for a modern version Donizetti comedy updated by Josh Shaw, POP’s director, scenic designer, and supertitles translator.

As Mamma, baritone Ryan Thorn was the star of the show with far more forceful diva antics than any leading soprano would dare. Thorn had a stentorian baritone voice and a charismatic presence that gave him control of the stage and everyone on it. No mere artist was going to upstage this theatrical “mamma” and from the black and blue marks on her daughter, the audience knew she did not accept defeat often at home. Soprano Amy Lawrence who exhibited strong, well placed high notes was Mamma’s long suffering daughter, Luigia Castragatti, (cat castrator). Perhaps we will hear more of her in the future.

Sung by Katherine Giaquinto, Prima Donna Daria Garbinati sings beautifully, but this character has florid coloratura where her brain should be. When her husband, baritone Don Procolo, sung by Carl King, trys to plead her cause, he only causes more friction. Eventually the Don has to replace the foreign born tenor, Guglielmo Hollerachevogelfänger-Lopez (Revengeofhellbirdcatcher-Lopez) who was portrayed with great enthusiasm by Kyle Patterson.

While Maestro Stephen Karr was actually conducting the orchestra, bass-baritone Scott Levin was playing the part of Conductor Biscroma Strappaviscere (bowel ripper) on stage. Thus two conductors were working within sight of each other. Phil Mayer was a business like Impressario, Eleen Hsu-Wentlandt an amusing Pippetto and Matthew Welch gave a sparkling account of librettist Salsapariglia’s lines. With Viva La Mamma, Pacific Opera Project ended its 2015 season in a blaze of glory.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Mamma Agata, Ryan Thorn; The Prima donna, Katherine Giaquinto; Biscroma Strappaviscere, Scott Levin; Don Procolo, Carl King; Luigia Castragatti, Amy Lawrence; The Impresario, Phil Mayer; Cesare Salsapariglia, Matthew Welch; Guglielmo Hollerachevogelfänger-Lopez, Kyle Patterson; Pippetto, Eileen Hsu-Wendtland; Conductor, Stephen Karr; Director, Scenic Designer and Supertitles Translator, Josh Shaw; Costume Designer, Maggie Green.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Viva_la_mamma.png

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Viva la Mamma!: A Fun Evening at POP

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Viva la mamma! [Photo courtesy of Pacific Opera Project]

LA Opera Norma: A Feast for the Ears

The Teatro alla Scala in Milan gave the first performance in 1831, on the day after Christmas. The role of Norma was written for Giuditta Pasta who regularly sang leading bel canto roles in London, Paris, Milan and Naples between 1824 and 1837. Besides Norma, Pasta created the title role in Donizetti’s Anna Bolena and Amina in Bellini’s La sonambula. Maria Callas, the most famous bel canto diva of the twentieth century, portrayed Norma in eighty-nine performances with important opera companies around the world.

On Saturday evening, November 21, 2015, Los Angeles Opera premiered Vincenzo Bellini’s Norma in a production by Anne Bogart that was originally seen at the Washington National Opera. It featured a severely raked minimal set by Neil Patel and colorful, luxurious costumes by James Schuette. Like many operas of the bel canto era, Norma is more about singing than acting and LAO assembled an outstanding cast that easily handled Bellini’s difficult music.

Angela Meade was the Druid priestess and dedicated virgin who had secretly borne two children to her Roman lover. Meade sang her music in the grand style of this seminal opera. Despite an occasional shrill high note, her singing grew in authority, confidence and effect as the voice warmed and her “Casta Diva” was emotionally and dramatically eloquent. Although not much action was played out on stage, this Norma always used her vocal resources to express the drama.

Bellini used simple technical methods of instrumentation, together with long melodies bolstered by conventional harmony, to produce the passionate emotional qualities of the score. Casting some of the finest singers performing today, Bogart relied on their ability to act with their voices and she allowed them to put the story of the love triangle across the footlights with their vocal colorations. She showed the Gauls’ dislike of Roman occupation by her treatment of Grant Gershon’s chorus, members of which sang their melodic and rhythmic lines with gusto.

The most beautiful voice in the performance belonged to debutante mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton who sang a creamy-smooth Adalgisa. It’s unfortunate that her character has no aria, but Barton showed her virtuosity in a most exquisite rendering of the duet “Mira o Norma.” Also debuting that night, tenor Russell Thomas was Pollione, the Roman proconsul in Gaul. Because Pollione has betrayed Norma with Adalgisa it is an ungrateful part, but Thomas sang it with a powerful dark voice that he used in fine bel canto style. Morris Robinson’s Oroveso commanded the stage and provided all the breadth, dignity and ocean-deep sonority that Bellini's music demanded.

Two members of the Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program sang the parts of Flavio and Clotilde. Rafael Moras and Lacey Jo Benter showed great promise and proved they can hold the stage with the best singers of our age. Choreographer Barney O’Hanlon’s dancers reminded us that the piece takes place in a Druid stronghold and they added to its religious aspect. James Conlon’s masterly conducting grounded and emphasized the beauty of the singing. His translucent interpretation reminded listeners of the numerous simple but original strokes of genius to be found in Bellini's instrumentation. Sometimes opera is great theater, at other times it is simply incredible singing. Los Angeles Opera’s Norma was a feast for the ears.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Conductor, James Conlon; Director, Anne Bogart; Set Designer, Neil Patel; Costume Designer, James Schuette; Lighting Designer, Duane Schuler; Chorus Director, Grant Gershon; Choreographer, Barney O’Hanlon; Oroveso, Morris Robinson; Pollione, Russell Thomas; Flavio, Rafael Moras; Norma, Angela Meade; Adalgisa, Jamie Barton; Clotilde, Lacey Jo Benter.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/NORM1_0240p.png

image_description=Jamie Barton as Adalgisa in LA Opera's 2015 production of "Norma." (Photo: Ken Howard)

product=yes

product_title=LA Opera Norma: A Feast for the Ears

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Jamie Barton as Adalgisa [Photo by Ken Howard]

Alban Berg’s Wozzeck at Lyric Opera of Chicago

Just such an effort is part of the current season at Lyric Opera of Chicago as led by its music director Sir Andrew Davis and in a production designed by Sir David McVicar. The roles of Wozzeck and Marie are performed by Tomasz Konieczny and Angela Denoke, both making significant debuts in this house. Gerhard Siegel and Brindley Sherratt sing the Captain and the Doctor, roles of authority in Wozzeck’s tormented life. Andres, friend of Wozzeck, and Margret, the neighbor of Marie, are portrayed by David Portillo and Jill Grove; Stefan Vinke is cast as the Drum Major. The roles of the apprentices are taken by Bradley Smoak and Anthony Clark Evans, a Soldier by Alec Carlson, and the Fool by Brenton Ryan. Messrs. Siegel, Vinke, Carlson, and Ryan are singing in their house debuts. Vicki Mortimer and Paule Constable are the Set and Costume as well as the Lighting Designers in this new production. Michael Black has prepared the Chorus and Josephine Lee the Children’s Chorus.

Angela Denoke and Zachary Uzarraga

Angela Denoke and Zachary Uzarraga

Before the start of the first scene a raised platform bearing the memorial likeness of a soldier is visible above the central back part of the stage. An outstretched arm protrudes here from a prostrate figure, just as a sword and helmet are perched atop. This image bears directly on Wozzeck’s lowly position within the military and also reflects McVicar’s dating of the action during a period showing the effects of the First World War. Scenic divisions within each of the three acts are ingeniously marked by a white half-curtain, manipulated to open or close rapidly from behind by stage hands. As the curtain is withdrawn to reveal the first scene with a focus on Wozzeck and his Captain, Siegel cries out with high pitches on the “Ewigkeit” [“eternity”] which he fears will intrude on his mundane existence. Konieczny’s Wozzeck proceeds to shave the Captain while responding in steady, deep tones of respect, “Jawohl, Herr Hauptmann.” [“Yes indeed, Captain”]. Yet this acquiescence soon shifts to reveal an underlying resentful tension. When the Captain chides Wozzeck for acting immorally by fathering an illegitimate child, the responding vocal line and its delivery changes. Low pitches by Konieczny on “Lasset die Kleinen zu mir kommen” [“Suffer the little children to come unto Me”] have a more ominous ring; Wozzeck’s attempts to defend himself before the Captain, “Wir arme Leut’!” [“We poor folk!”] show still the controlled resentment of societal oppression. Konieczky’s remarkably attentive delivery highlights “Tugend/tugendsam” [“Virtue/virtuous”], aspects of moral behavior which his standing is not privileged to enjoy. The statement by this Wozzeck concludes with an extended and onomatopoetic emphasis on “donnern” in the phrase, “Wenn wir in den Himmel kämen, so müßten wir donnern helfen” [“If we arrived in heaven, we would have to help produce thunder”]. Once the half-curtain is pulled across this scene, as though affecting a shutter in an early film, the orchestral postlude, with its emphases here on brass and percussion, underlines the confrontational repression just related. A subsequent opening of the half-curtain reveals in the second scene Wozzeck and his friend/fellow-soldier Andres cutting and gathering sticks on a field at some distance from the village or barracks. It is in this scene that Wozzeck first appears as one possessed in contrast to the simplistic nature of Andres singing a folk-tune. Indeed the musical title given by Berg to this scene, “Rhapsodie,” emphasizes the growing, unavoidable gap between Wozzeck and his intimates. While Mr. Portillo’s Andres sings liltingly the traditional “Das ist die schöne Jägerei” [“A hunter bold I’d like to be”] and encourages Wozzeck “Sing lieber mit” [“Just sing along”] to forget his visions, the latter accelerate throughout the scene. Just as the mushrooms “nachwachsen” [“are growing”] with a pitch expressing horror before their spread, Konieczny stamps and sings “es wandert was mit uns da unten!” [“There’s something following us down there”] with deepened color. The “rhapsody” concludes with a simply delivered comment on nature’s sudden silence, “als wäre die Welt tot” [“as though the world were dead”].

The following scene introduces Marie and her child by Wozzeck, a segment again defined by Berg with musical types, “Militärmarsch” and “Wiegenlied” [“Lullaby”]. Ms. Denoke’s Marie defines the character as both protective mother and sensual woman in a convincing summation. Her fascination with the passing military band led by the Drum Major prompts her to sing unabashedly, “Soldaten sind schöne Burschen!” [“Soldiers are handsome fellows!”] with a melting tone of expectation. After her verbal confrontation with the neighbor Margret, replete with mutual accusations, Marie adapts her voice to the lullaby. Here Denoke produces one of the most striking images of this production. The lyrical transformation of her character, with soft, high pitches on “Sing ich die ganze Nacht” [“Though I sing the night through”] is accompanied by her tender gesture of a cradling embrace as she lies down with the child. Her sense of temporary peace is interrupted by Wozzeck, who comes to tell her that he is on the track of his visions, yet they are still “finster” [“dark”]. When he refuses to stay and spend time with the child, Marie concludes resignedly “Er schnappt noch über mit den Gedanken!” [“He’s going crazy with his ideas!”]. In an echo of Konieczny’s earlier soliloquy, Denoke declares “Wir arme Leut’” [“We poor folk”] while she releases a chilling, low pitch on “Es schauert mich …” [“It makes me shiver in fear …”].

In the following scene with the Doctor the medical assistants place Wozzeck in a chair behind a giant magnifying glass, so that his enlarged image is displayed for the audience’s speculation. Mr. Sherratt expresses the Doctor’s irritation and self-important pronouncements on Wozzeck as a test-case with emphases on high pitches and sibilants in “ärgern” and “ungesund.” When Wozzeck asks about the formations of mushrooms he has observed, the Doctor identifies triumphantly “eine köstliche aberratio mentalis partialis” [“a splendid aberratio mentalis partialis”] in his patient’s psyche. Wozzeck is assured now of an additional “Groschen” in pay because of his cooperation; as a consequence, his attention migrates to Marie whom he hopes to support and whose name Konieczny repeats in hushed introspection. In the final brief scene of the act, marked “Andante affettuoso,” Marie’s liaison with the Drum Major begins the ultimate challenge in Wozzeck’s humiliation. Despite the lyrical emphases in Denoke’s protest, “Rühr’ mich nicht an!” [“Don’t touch me!”], Marie leads the Drum Major behind the half-curtain into her dwelling. With true resignation Denoke declares, “Meinetwegen, es ist alles eins!” [“Oh, what difference does it make to me!”]; their physical union is seen as two shadow-figures behind the curtain.

The five scenes of Act Two, described by Berg as a “Symphony in Five Movements,” intensify Wozzeck’s interaction with the characters introduced in Act One. As though a continuation of the preceding act, Marie sits here in the first scene with the child at her feet. As she admires the gift of earrings from the Drum Major, Marie encourages he boy to sleep and leave her to her reveries as one of the beautiful “Madamen.” Denoke’s frustrated demeanor with her child indicates her character’s slide into self-interest, indeed magnified by a defensive pose at Wozzeck’s reappearance. Now it is Wozzeck who shows concern for the boy as he watches the child sweat in his sleep. After surrendering his meager pay, Wozzeck departs. Denoke’s heartfelt lament, “Ich bin doch ein schlecht’ Mensch! Ich könnt mich erstechen!” [“I’m a horrible person! I could stab myself to death!”], replete with self-recrimination, is a soul-wrenching premonition of the dramatic progression to the end. As the Doctor and Captain dispute in a subsequent scene, Wozzeck appears and is led by their insinuations to the full realization of Marie’s actions. His confrontation with Marie illustrates now the violence to which personal and societal pressure have driven him. In response to Marie’s “Was hast, Franz?” [“What’s the matter, Franz?”], delivered by Denoke with a full reserve of mock innocence, Konieczny’s surly accusations nearly lead him to strike her. Marie’s declaration, that she should prefer to be stabbed, reveals both to Wozzeck and to the audience a possible end to the tension. The following scene at a public house merely strengthens Wozzeck’s resolve, when he sees Marie dancing with the Drum Major. Denoke’s cries of “Immer zu!” [“On and on!”] suggest complete abandon and the likely transfer of her emotions. The climax of this triangle occurs in the barracks at the return of the Drum Major and his challenge of Wozzeck. After their struggle and Wozzeck’s defeat, the other soldiers present watch, yet each returns to sleep. Konieczny’s intonation of “Einer nach dem Andern!” [“One after the other!”] indicates Wozzeck’s resignation at being left - simply - alone.

At the start of Act Three Marie reads the Biblical passage of the woman taken in adultery. Denoke’s clear, high pitches on “Herr Gott” are followed by corresponding low pitches of self-disgust. She clutches the child now, as in Act One, in her attempt to rebuild an emotional web which has become shattered. The interweaving of Biblical lines with a folk-song on an orphaned child are here especially touching in performance. Wozzeck comes to take Marie for a final walk. As the stage rear turns red, he stabs her. When Wozzeck returns to the public house to participate in a dance, Konieczny seems, for the moment, carefree. He drinks, carouses, and dances with gusto in his facial expressions. As soon as blood is noticed on his person, Wozzeck realizes he must return to the scene of Marie’s murder and hide the knife. The sense of guilt now washes over him, as the water into which he casts the knife seems to be blood; he wanders further and drowns. Marie’s earlier premonition of an orphaned child is realized in the final scene. Her son sings “Hopp hopp” while he rides his hobby-horse, at first in the company of other children, and then alone on the stage. The melodic line ends abruptly, just as life has ended for Marie and Wozzeck. Lyric Opera of Chicago has met the challenge of Berg’s score in a riveting production that will long be remembered.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Gerhard%20Siegel_Tomasz%20Konieczny_WOZZECK_F2A5470_c.Cory%20Weaver.png

image_description=Gerhard Siegel and Tomasz Konieczny [Photo by Cory Weaver]

product=yes

product_title=Alban Berg’s Wozzeck at Lyric Opera of Chicago

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=Above: Gerhard Siegel and Tomasz Konieczny

Photos by Cory Weaver

A Prize-Winning Rediscovery from 1840s Paris (and 1830s Egypt)

Over the past few decades, it has been brought back to the concert hall—and introduced to the recording studio—by prominent and adventuresome conductors. The recording reviewed below is only the second that the complete work has ever received. On 18 November 2015, it was awarded the Grand Prix du Disque from the Académie Charles Cros, in the category “Redécouverte du répertoire” (that is: for rediscovering an important work from the past).

I wrote a mostly glowing review of this recording for American Record Guide (July/August 2015). It is reprinted below (with kind permission of ARG), lightly expanded and updated.

* * *

Félicien David (1810-76) was one of the most admired French composers of his day. He was particularly known for his songs and for Le désert. The latter, a fascinating 49-minute-long work for voices and orchestra, is performed (twice!) on the CD set here reviewed.

In the past three decades, a number of David’s works have received first recordings, including all his piano trios and string quartets, his brass nonet, and some of his twenty-four one-movement pieces for string quintet (with double-bass). Within the past year, two separate discs have surveyed his songs. A recent 2-CD set (on Naxos) makes a strong case for David’s imaginative comic opera Lalla-Roukh, whose plot unfurls in northern India and Uzbekistan.

A recording of his only grand opera, Herculanum (just released by Ediciones Singulares) features major singers, including Véronique Gens and Karine Deshayes. (The first stage production of Herculanum in nearly a century and a half will occur at Wexford Festival Opera, in Ireland, during October-November 2016.) Forthcoming are yet more first recordings, including Christophe Colomb, a work that reenacts and celebrates Columbus’s first voyage to America. Most of these recordings (including the present one) were made possible to a large extent by the scholarly efforts—and with the financial assistance—of the Centre de musique romantique française (located at the Palazetto Bru Zane, in Venice), which is directed by the astute and indefatigable musicologist Alexandre Dratwicki.

The various recordings mentioned above, like the live performances upon which some of them were based, have been greeted with delight by listeners and reviewers. Maybe I should say “with surprised delight.” Most of us tend to assume that, if music that was composed 170 years ago has gone unrecorded until now, the composer must be at fault. But Félicien David’s strong melodies, imaginative instrumental writing, and often endearingly innocent tone are helping to make his compositions welcome again.

Le désert and the aforementioned Christophe Colomb are works in a genre that David invented: the ode-symphonie. An ode-symphonie consists of a series of symphonic movements and vocal numbers, all linked by a narration in spoken verse. It was intended to be performed “in concert” (that is: without costumes, sets, or on-stage action). We might describe an ode-symphonie as a secular oratorio but with poetic spoken recitations added.

At its premiere in Paris (December 1844), Le désert was hailed as a masterpiece by Berlioz and other critics. Berlioz soon conducted Le désert himself, and the work went on to be performed and published (often in translation) across Europe and in the United States. Though the genre was short-lived, late echoes of it are perhaps found in such well-known works with narrator (in French: récitant) as Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex and Honegger’s Le roi David.

Le désert describes the progress of a caravan in an unidentified Arabic-speaking land. In part 1 of the work, the endless sands are pictured in slow string chords, the travelers sing their joy at being out under the open sky, but then are hit by a blinding sandstorm. In part 2, they pitch their tents for the night and entertain themselves and each other with love songs and with another choral declaration of freedom from urban constraints.

Two orchestral movements within Part II require a bit of explanation. The first, an energetic and emphatic movement entitled “Fantasia arabe,” presumably represents a shooting competition by men on horseback. (During the nineteenth century, this sort of equestrian event was widely known in Arabic-speaking lands as a fantasia.) The second, entitled “Danse des almées,” presumably encourages the listener to imagine the supple movements of some dancing women. (No females, by the way, sing in Le désert: the chorus is all-male.) The work’s third and final section begins with an orchestral evocation of a sunrise; a muezzin then calls the faithful to worship; and, finally, the travelers resume their journey across the trackless dunes.

David had spent the years 1833-35 in Egypt and other nearby lands. Le désert makes use of some general impressions that he had brought back with him to France and also incorporates specific tunes and dance rhythms (notably in one of the tenor solos in Part 2, entitled “Rêverie du soir,” and in the aforementioned “Fantasia arabe”) that he had transcribed while living and traveling in the region.

Le désert went largely unperformed from the late nineteenth century to the late twentieth. One exception: a wonderful early twentieth-century recording exists of David’s version of the muezzin call, sung—in Arabic, as the score prescribes—by Eugène de Creus. (The long-held chords, originally in the strings, were here arranged for a mixed ensemble that the acoustic microphone could capture better.) Since the 1960s, David’s Le désert has been revived in performance at least five times that I know of. One of those performances—in Berlin, 1989—got recorded by Capriccio and is still available on that label. It can also be heard in its entirety on YouTube.

The recording here reviewed was made in May 2014 at a performance in Paris (at the Cité de la Musique), with some inserts from a one-hour touch-up recording session. (Major excerpts from it can be heard on YouTube, but the complete performance is only available as a commercial CD or download.) The performance, beautifully recorded, proves once again that the work’s wildfire success during the nineteenth century was no aberration: the music is full of novelty (considering its date: 1844) and has a satisfying shape, thanks to the composer but also to Auguste Colin, the skillful author of the spoken and sung verses.

The performance is mostly enchanting. Conductor Laurence Equilbey chooses appropriate tempos and encourages the chorus and orchestra to phrase more sensitively than their counterparts did in the 1989 Capriccio recording. I enjoyed various subtle shifts of tempo, some unwritten crescendos and decrescendos, and a few slight adjustments of rhythm to create a more overtly “Middle Eastern” effect. The superb male chorus is from Accentus, a choral ensemble of which Equilbey is music director and with which she has made numerous recordings. The wind solos are exquisitely turned.

Of the three solo vocal numbers, the longest two, “Hymne à la nuit” and “Rêverie du soir,” are sung by tenor Cyrille Dubois. Dubois’s vocal technique is typically French, he clearly understands every word he is singing, he keeps the vibrato under exquisite control, and he can file the voice down to a near-whisper while keeping the breath supported. (In the 1989 recording—the one that is on YouTube, complete—the Italian tenor sings all three numbers, healthily but with little nuance.) The third solo, a short but crucial “Chant du muezzin,” is here performed—over the aforementioned long-held string chords—by American tenor Zachary Wilder, who stepped in on short notice when the singer originally hired had to cancel. Wilder performs this muezzin call (using—like de Creus in the century-old recording mentioned above—the Arabic words) with alert rhythmic sense and clear coloratura. Wilder has been widely admired for his early-music performances under such conductors as William Christie and Christophe Rousset. His sweet, flexible voice adapts perfectly to this very different purpose. (Full disclosure: he was a student in an undergraduate music-history class that I taught at the Eastman School a decade or so ago. But I can take no credit for his remarkable artistry.)

I said the new CD set is “mostly enchanting.” The one slight disappointment, for me, is the spoken narration. Winling speaks gently, in a private, reflective voice that would surely not carry without a microphone, whereas the narrator in the 1989 Berlin performance used a fuller dynamic range. The majesty and terror of nature—repeatedly invoked by the chorus and orchestra—are better matched by a narrator declaiming with full breath. Winling’s quiet understatement makes him sound emotionally distant from the events he is describing, or regretful, or even pained.

The conductor and record label have decided to offer the work twice, for the price of a single CD: one disk has the performance without narration, the other with it. Anybody who dislikes Winling’s untheatrical manner—or who prefers not to have to listen to speech between musical numbers and “over” purely orchestral passages—can simply use the other disk, containing the un-narrated version. There is, to my know ledge, no historical precedent for performing Le désert without its spoken verses. I was prepared to hate the result but found that the music held up well on its own. I suspect that Equilbey may have here paved the way for future performances of Le désert without strophes déclamées, just as orchestras generally perform Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra without its original pedagogical chatter and sometimes even offer Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf minus the storyteller.

The importance of Le désert has been recognized by noted music historians, including Richard Taruskin ( Oxford History of Western Music, vol. 3, pp. 386-92) and Robert Laudon (in his path-breaking book The Dramatic Symphony, published in 2012 by Pendragon). Its influence is undeniable: not just on French composers, such as Bizet, Delibes, and Massenet, but also on Verdi (the opening of Attila; the ballet music he added for the Paris production of Otello), Grieg (“Morning Mood,” from Peer Gynt), and Borodin ( In the Steppes of Central Asia). Even apart from its historical importance, David’s appealing work rewards close listening and study. The full score is scheduled to be reprinted soon by Musikproduktion Jürgen Höflich (Munich). The piano-vocal score can still be found in music libraries around the world. Who knows?—some enterprising choral conductor may soon be bringing the work to a concert hall near you.

One final grumble: the booklet’s (uncredited) translation of the poetic texts could have been a bit more precise. “Une amante” is not just any “lover” but a female one. “Les solitudes profondes” is bizarrely translated as “my vast wastes” (without any indication of who “my” might refer to); the phrase actually means something like “the endless empty spaces [all around our caravan].” And, to the four helpful footnotes, a fifth could have been added, indicating that the phrase “mon bien-aimé”—though masculine—refers most likely to a female beloved. The French phrase here was presumably Auguste Colin’s attempt at reflecting a centuries-old tradition, in Arabic and Ottoman poetry alike, by which a poet used a masculine-gender word to protect the identity of the woman whom he was praising and also to protect himself from accusations of expending too much time and attention on affairs of the heart instead of on such manly pursuits as religious devotion, scholarly study, productive labor, or patriotic soldiering. Recent scholars—such as Walter G. Andrews, in the richly documented book Ottoman Poetry, pp. 14-16—do allow that, at least in certain poems, the term “beloved” did refer to a man (perhaps a younger one than the poet). Still, there is no evidence in writings about Le désert, whether by David or by Berlioz or other contemporaries who wrote about the work, that a homoerotic subtext was in any way intended—or even noticed as possible—in this particular tenor solo.

Ralph P. Locke

Ralph Locke is Professor Emeritus of Musicology at the Eastman School of Music. His most recent books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart . He is also the founding editor of Eastman Studies in Music, a book series published by University of Rochester Press.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/006063.png image_description=Felicien David: Le Desert (Naïve V5405) product=yes product_title=Félicien David: Le désert, “ode-symphonie.” product_by=Cyrille Dubois and Zachary Wilder, tenors; Jean-Marie Winling, speaker; Accentus [choral group], Orchestre de chambre de Paris/Laurence Equilbey. product_id=Naïve V5405 [2CDs] price=$17.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=1735617November 29, 2015

Florilegium at Wigmore Hall

The work of these three composers may be less familiar to listeners, but Florilegium revealed the musical sophistication — under the increasing influence of the Italian style — and emotional range of this music which was composed during the second half of the seventeenth century.

Franz Tunder was born in Lübeck, a town whose most well-known musical inhabitant is probably Tunder’s son-in-law, Dietrich Buxtehude. Buxtehude succeeded Tunder as organist of St. Mary’s Church where he developed the renowned free concerts, ‘Abendmusiken’, which his father-in-law had founded and which continued for several hundred years. Few compositions by Franz Tunder have survived: just fourteen works for organ and seventeen vocal works, plus an instrumental sinfonia to a motet. It is thought that the vocal compositions were not intended for performance in church — as such works had no place in the liturgy followed at Lübeck — and were instead composed for the evening concerts at St. Mary’s. They are evenly divided between works with German texts and those that set Latin devotional texts, and it was two of the latter that we heard here.

The motets ‘Da mihi, Domine’ (Give me wisdom, Lord) and ‘O Jesu dulcissime’ (O sweet Jesus) might in fact be termed ‘sacred concertos’, formed as they are of short movements for voice and obbligato instruments. The text of ‘Da mihi Domine’ consists of two responds for matins, the first recalling verses from Chapter 9 of the Book of Wisdom, and the second ‘Ne derelinquas me’ (Do not forsake me) bearing similarities to verses 1 and 3 of Ecclesiasticus Chapter 23. There was a gentle intimacy about this performance by Roderick Williams and six members of Florilegium (Catherine Martin and Jean Paterson [violin], Ylvali Zilliacus [viola], Reiko Ichise [viola da gamba], Jennifer Morsches [cello] and Terence Charlston [chamber organ]), but also a convincing progression through the short movements and increasing sense of urgency and triumph.

There is an Italian influence evident in Tunder’s work: the late German composer, singer and music theorist, Johann Mattheson, reported in 1740 that Tunder had studied with Frescobaldi when he was in Florence from 1627 to 1630. In the opening Sinfonia the instrumental lines entwined like voices in a Monteverdi madrigal. Though marked ‘Adagio’, the movement had a flowing two- then three-beats-per-bar impetus which made Tunder’s unusual use of rests effective, the silences never staying the momentum of the phrases. The first vocal passage, with organ accompaniment, lay quite low for Williams but the tone was full and focused, and as the phrases rose and become more florid the baritone imbued the melismatic appeals to the Lord, and the large vocal leaps, with grandeur and nobility. Imitative rhythms between the voice and organ bass line created propulsion, and this section led fluently into the more dance-like triple time section which follows. After the commanding pronouncement of the imperative ‘Mitte, mitte’, Williams displayed impressive control in the movement’s long vocal lines, the rising scalic motifs transferring seamlessly between the strings and voice. Similarly, there was rhetorical power during the section which sets the second text, as Williams repeated his calls to the ‘father and ruler of my life’, ‘domine pater’; and vitality was injected by the dotted rhythms of the alternating interpolations of the strings and voice, an interplay which became increasingly complex — and saw the return of the expressive rests of the opening — in the concluding sections of the motet.

‘O Jesu dulcissime’ is scored for bass voice, two violins, and continuo — the latter provided here by organ and viola da gamba. In the brisk Sinfonia, the close thirds of the violins were plangent and swelled expressively; after Williams’ solo entry his vocal line was embraced by the string lines and subsumed into the continuity of the ongoing step-wise phrases. While there were moments when the violins almost over-powered the vocal line, with the phrase ‘Quod per sacramentum tuum’ (What is your secret), the melody became more decorative, allowing Williams’ baritone to bloom, exhibiting precision and evenness during the melismatic runs. After the ‘mystery’ of the earlier sections, the fluid passagework created a spirit of ecstatic joy which flourished in the buoyant ‘Amen’ which concludes the work.

Bohemian-born Heinrich Biber spent most of his life in Salzburg where he was recognized as one of the finest violinists of his generation; as a composer, he is best known for his series of dazzling, virtuosic violin sonatas, titled the ‘Mystery’ or ‘Rosary’ sonatas. But, Biber also wrote ‘programme’ music, including the ‘Night Watchman’ Serenade for five instruments and bass voice, so-called because its fifth movement, Ciacona (which follows four instrumental movements, Serenada, Adagio, Allamanda and Aria). In this Ciacona, a ‘Night Watchman’ enters, to the pizzicato accompaniment of the upper strings whose players mimic lutenists by placing their instruments under their arms. As the watchman creeps through the streets he recites his nocturnal cry: ‘Lost ihr Herr’n und last euch sag’n’ (Listen folk and mark the hour,/ The bell strikes nine (ten) within the tower,/ All’s safe and all’s well,/ And praise to God the Father and to Our Lady).

There was some vigorous rhythmic articulation and exaggerated dynamic contrasts in the opening Serenada, while the Adagio was richer and warmer in tone; the cadences of the Allamanda were attractively decorated by organist Terence Charlston, whose chromatic bass line was relaxed and created an easy flow. Williams entered the platform from the stage-right rear door, effected a slow circumambulation of the stage, before exiting left; the textual enunciation of this night-time messenger was aptly crisp and the tone clarion. Strong accents restored rhythmic vitality during the Gavotte, and were complemented by fast bow strokes and rapid trills in the Retirada.

The vocal items were interspersed with instrumental works. The concert opened with Buxtehude’s Sonata in C BuxWV266 (for 2 violins, viola da gamba and organ) in which the somewhat reedy timbre of the Adagio was supersede by a brightness and lucidity in the Allegro. Leader Catherine Martin was unflustered by the bravura passagework of the Adagio and the ceaseless triplets of the Presto, and the ensemble made expressive use of the passages in the minor tonalities, shifts of tempo and changes of texture culminating in the solid harmonic progressions of the final Lento. Flautist and Florilegium director Ashley Solomon joined the instrumentalists to perform J.S. Bach’s Trio Sonata in G Minor BWV 1038 and Georg Philipp Telemann’s Concert in D TWV51: D2, his wooden flute adding a warm glow to the ensemble’s colour, as Charlston’s harpsichord gave freshness and light. The withdrawn pathos and veiled melancholy of the Adagio of Bach’s Sonata was particularly touching, and the phrases and cadences were beautifully tapered.

If these works demonstrated the increasing sophistication of the Austro-German Baroque style, and also the link between the early Baroque style and the later Baroque composers such as J.S. Bach, the concluding performance of Bach’s solo cantata ‘Ich habe genug’ left no doubt that Bach’s works were the crowning pinnacle.

From the start Williams, performing from memory, established a devotional mood, one of stillness, intimacy and consolation, spinning wonderfully long lines with superb breath control as he sang of contempt for worldly life and a yearning for death and the life beyond. In the first Aria, Alexandra Bellamy’s oboe sang assuredly and lyrically; the string lines were smoothly articulated, carrying the oboe on its ornamented journey. And while the instrumental dissonances were never exaggerated, the chromaticisms and decorations spoke of the pain suffered in the world, while Williams’ vocal line conveyed noble forbearance, as he used the consonant ‘h’ expressively in the eponymous utterance, ‘Ich habe genug’, (It is enough) to complement the violins’ melodic mordant. The tempo was relaxed but controlled; indeed, the whole cantata possessed an intensity which was never mannered but suggested fervent introspection. The Recitativo was muscular but relaxed, the penultimate textual line, ‘Mit Freuden sagt ich’ (With joy I say to you), powerful and direct, particularly after the gentle yearning of the first Aria. Williams ‘crept’ into the subsequent Aria, ‘Schlummert ein. Ihr matten Augen’ (Close in sleep, you weary eyes), and the lyricism of the vocal line in this section was greatly affecting; a more forthright tone, however, was appropriate for the assertion, ‘Welt, ich bleibe nicht mehr hier’ (World, I shall dwell no longer here) — such sensitivity to the text and its meaning was impressive throughout. The flowing semiquavers of the final Vivace Aria, ‘Ich freue mich auf meinen Tod’ (I look forward to my death), were a graceful stream, elegant and clear — and, paradoxically, life-affirming.

Claire Seymour

Performers and programme:

Florilegium: Ashley Solomon, director. Roderick Williams, baritone

Buxtehude: Sonata in C BuxWV266; Tunder: ‘Da mihi Domine’; Biber Serenada a 5 “Der Nachtwächter”; Tunder:’ O Jesu dulcissime’; J.S. Bach: Trio Sonata in G major BWV1038; Teleman: Concerto in D for flute, violin and strings TWV51:D2; J.S. Bach: ‘Ich habe genug’ BWV82. Wigmore Hall, London, Wednesday, 25th November 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Roderick-Williams.png image_description=Roderick Williams product=yes product_title=Florilegium at Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Roderick WilliamsLeoncavallo’s Zazà by Opera Rara

Ruggero Leoncavallo’s eponymous opera lives by its heroine. Tackling this exhausting, and perilous, role at the Barbican Hall, Argentinian soprano Ermonela Jaho gave an absolutely fabulous performance, her range, warmth and total commitment ensuring that the hooker’s heart of gold shone winningly.

This concert performance of Leoncavallo’s Zazà by Opera Rara with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, saw the company make its maiden venture into verismo waters. Written in 1900, eight years after I Pagliacci, and first performed at the Teatro Lirico di Milano conducted by Toscanini, Zazà was initially a huge popular success. In the 20 years following its première, the opera received over 50 new productions in opera houses around the world and the title role became a show-case for a number of prima donnas, including Rosina Storchio (who created the role), Emma Carelli and Geraldine Farrar. The latter even selected it for her farewell performance at the Metropolitan Opera in 1922.

At the time of the premiere of Zazà, things must have looked auspicious for Leoncavallo. His career seemed to be on a roll: the acclaim received by his two previous operas, I Pagliacci (1892) and La Bohème (1897), suggested he was enjoying a golden streak. Now, though, Zazà — along with the almost all of Leoncavallo’s twenty or so operas and operettas — has fallen out of the repertoire. Pagliacci alone assures the longevity of the composer’s name, and even that opera rarely stands alone but is ‘coupled’, as ‘Pag’ to Mascagni’s ‘Cav’.

The libretto of Zazà is based upon a highly successful play by Pierre Breton and Charles Simon, written in 1898 for the flamboyant actress, Gabrielle Rejane. The action takes place in contemporary Saint-Étienne and Paris, and takes us back-stage at a seedy music-hall where we follow the emotional breakdown of the chanteuse Zazà when she discovers that the man whom she loves is already married.

The tale is predictably tawdry and trashy but it has a surprising, if somewhat syrupy, ending. The fêted cabaret star Zazà wins a bet with the journalist Bussy that she can seduce one of the frequent visitors to the theatre, Milio Dufresne — an international businessman on the prowl for a casual fling — even though he seems indifferent to her charms. Zazà’s fellow singer Cascart, smitten and rejected by the diva, reveals to the now infatuated Zazà that Milio is having an affair. Cascart and Anaide, the singer’s alcoholic mother, try to persuade her to leave Milio but Zazà refuses and determines to travel to Paris to confront him. Milio is in fact married and has a young daughter, Totò (an affectionate diminutive for Antonietta). When Zazà meets Totò she is overcome by, and identifies with, the child’s vulnerability, and recalls the unhappiness of her own childhood which she is anxious to spare Totò. Showing respectful deference to Madame Dufresne, whose essential goodness she recognises, Zazà returns to Saint-Etienne. When Milio follows her, the low-born courtesan — now a sadder but sager woman — surprises us, and perhaps herself, by demonstrating greater moral integrity than the high-born gentleman, and in so doing she exposes the cad’s callousness.

Leoncavallo’s score is a riot of vivid colour, bursting with infectious dance tunes and inventive musico-dramatic flourishes. It moves fluently between arioso and aria, the big numbers emerging naturally from the ebb and flow of the protagonists’ exchanges. Maurizio Benini encouraged the BBC Symphony Orchestra to relish the Italianate lusciousness and allowed us to appreciate Leoncavallo’s gift for orchestration. But, with the large orchestra — which included a ‘cabaret band’ placed stage left during Act 1 — pushed right to the fore of the stage, and Benini disinclined to restrain his players’ vitality, the singers were sometimes overpowered in the more conversational episodes, especially during the first Act when it was initially quite difficult to ascertain who was who in busy cabaret scenes. However, amid the Puccini-esque scraps and fragments, some terrific tunes emerge from the melodic cul-de-sacs, including one soaring upwelling of sentimentality that serves as a sort of leitmotif for Zazà's love, and Benini ensured that the lyric high-points packed their punch.

The orchestral theatricality was not always matched by the ‘staging’, though it’s hard to know what stage director Susannah Waters should have done given that the small front strip of stage available for the singers was strewn with music stands, and most of the cast, wearing modern evening dress, were pretty bound to their scores. There was some atmospheric lighting, the dazzling pinks of night-time revelry giving way to the cool green of morning sobriety, and some distinguishing of the setting — the cabaret band were replaced by a single piano in Dufresne’s apartment, upon which Totò does her daily practice. But only Jaho truly ‘lived’ her part, unstintingly using her voice, face and body to convey Zazà’s self-consuming passions and sentiments. The opera has only one off-stage women’s chorus — sung attractively by the ladies of the BBC Singers; it therefore seemed unnecessary to seat a full chorus behind the orchestra for the duration of the evening when for the most part they had little more to do than applaud the charming ‘Kiss Duet’ with which Zazà and Cascart entertain the night-club clientele. Totò is a spoken role and Leoncavallo supplies just light orchestral support for her dialogue, but while Julia Ferri’s enunciation of the lines was touching in its directness and openness, the over-amplification and wide reverberation surreally disembodied her voice from the dainty figure we saw before us.

But such minor misgivings were swept aside by Jaho’s incredible commitment and vocal allure. She ran the emotional gamut from predatory sensuality to euphoric happiness to anguished sorrow, utterly convincing us and drawing us into her tragic journey. The lower-lying passages may sometimes have made less impact, and occasionally Jaho strayed sharp at the top, but who cares when one is enveloped by surging, supply lyrical outpourings that are by turns glossily luxurious and exquisitely delicate.

A scheduled replacement for the indisposed Nicola Alaimo, Stephen Gaertner was excellent as Cascart, the rejected lover whose indignant vexation is out-weighted by his undiminished love. Gaertner was rare among the cast in singing securely off the score. He was commanding in his big arias, his rich, dark baritone rising powerfully above the orchestral roar; and his nuanced and expressive phrasing made for convincing interaction with Jaho in their duets. Cascart’s Act 4 show-stopper, ‘Zaza, piccola zingara’, was one of the high-lights of the evening.

As Dufresne, Riccardo Massi revealed a strong upper register capable of carrying a clear line, and the tenor’s phrasing was unfailingly intelligent and sensitive. But, I found his lower voice a little withheld and he had a tendency, initially at least, to approach notes from below. Massi cut an elegant figure but didn’t make much effort to ‘act’; that is, until Dufresne’s self-justifying Act 4 aria when Massi convincingly revealed the shallowness and self-pity of this bounder’s grumbles about the complexities of his messy romantic predicament. His lack of remorse was worthy of a Pinkerton.

A strong cast filled the smaller roles, with Nicky Spence (the impresario, Courtois) and Kathryn Rudge (Natalia, Zazà’s maid) making a particularly strong impression. Moving from the ranks of the BBC Singers, and stepping in at 24-hours’ notice to fill the indisposed Patricia Bardon’s shoes, Rebecca Lodge used her bright mezzo effectively to convey the boisterousness of the boozy Anaide, Zazà’s mother. Soprano Helen Neeves was a dignified Mme Dufresne, and as Floriana (a singer), Fflur Wyn sparkled in her Act 1 aria.

Perhaps a fully staged production is necessary to do justice to Zazà’s melodramatic excesses — although a concert performance at least spares us a mawkish ending. On this occasion, Jaho almost single-handedly provided passion and theatre sufficient to convince us of the veracity of the drama. At the close she seemed, understandably, drained somewhat dazed. She had powerfully engaged us all in Zazà’s agonising predicament and utterly deserved the admiring and affectionate adulation bestowed.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Zazà — Ermonela Jaho, Milio Dufresne — Riccardo Massi, Cascart — Stephen Gaertner, Anaide — Rebecca Lodge, Bussy — David Stout, Natalia — Kathryn Rudge, Floriana — Fflur Wyn, Courtois — Nicky Spence, Signora Dufresne — Helen Neeves, Duclou (a stage manager) — Simon Thorpe, Augusto (a waiter) — Christopher Turner, Il Signore — Robert Anthony Gardiner, Marco (the Dufrenes’ butler) — Edward Goater, Totò — Julia Ferri (spoken role); Susannah Waters — director, Maurizo Benini — conductor, BBC Symphony Orchestra, BBC Singers. Barbican Hall, London, Friday, 27 November 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/u16PlGcrfoprht0C0ldIMluFR4ejd-HXuX9ouIU3no8%2C39FMt4iQ5QQ3luLEq8IEsd4S_e8SUi5we0eDYat_unc%2CxcsXQeZ2AE2DqrL47mw4DxW6p5rv1UqsA1xQQCOds64%2CVCeD35cQ7PmFBaI7s1_uxLztKxBvjFYX5xN5w0KsFsU%2CNKLltOxZFltZzHDVh1znzZm2cZKTSs-bwpKuysLLaio%2Ce.png image_description=Riccardo Massi and Ermonela Jaho [Photo by Russell Duncan] product=yes product_title=Leoncavallo’s Zazà by Opera Rara product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Riccardo Massi and Ermonela Jaho [Photo by Russell Duncan]November 27, 2015

L'ospedale - an anonymous opera rediscovered

What is astonishing about this anonymous opera, which was rediscovered in the Marciana Library in 2003 by musicologist Naomi Matsumoto and superbly presented here by Solomon’s Knot baroque collective, is that Abati’s biting invective is so strikingly modern, and topical. With NHS junior doctors set to go on strike three times next month, issues such as the state funding of the health service, doctors’ pay and working hours, and patient waiting times have never been more hotly disputed in the UK. Moreover, the creeping privatisation, fragmentation and destabilisation of the NHS, in the guise of euphemistically termed ‘efficiency savings’, has brought the ‘profitability’ debate to the fore, and left many fearing that those unable to pay for healthcare will be vulnerable to growing health inequality. As Abati’s libretto asks, ‘Who can find a cure for poverty and desperation?’

The action takes place in an ospedale, a type of charitable institution which in seventeenth-century Italy formed part of the ‘welfare system’: ospedali were usually attached to churches, and they housed and treated those with ailments and social conditions that made them undesirable to the rest of society - such as lepers, syphilitics, abandoned children and orphans, prostitutes and the homeless. (Fittingly, one role of the ospedali was to educate their patients, and this involved musical education; musical ensembles, cori, were formed and these gave performances designed to raise funds and attract sponsors, with the result that in the in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the grandest of the ospedali were at the core of Venetian culture.)

In Abati’s shabby ospedale, four patients languish amid squalor, seeking cures for their varied ailments: unrequited love, professional disappointment, mental deficiency and poverty. (It says much for the potency of the purse in quelling the wealthy hypochondriac’s neurosis that it is only the last of these four ailments which proves truly incurable.) They await the arrival of a new doctor whose medications and remedies will, they hope, restore them to health; but the charlatan’s idiosyncratic treatments have unexpected and unwished-for side-effects, and the sufferers risk losing more than their money.

This is Solomon’s Knot’s first fully staged production. Director James Hurley’s staging updates the action to the present, as immediately confirmed by a supplementary Prologue in which we seem to be eavesdropping on a disingenuous circumlocution by the Minister for Health to the House of Commons, as he justifies the need, in this age of austerity, for reductions to the health budget, and calls for greater efficiency within the NHS as well as an enlarged role for the ‘Big Society’ in order to alleviate the potentially adverse effects of the government’s reforms. (The Minister returns in an Epilogue, to announce his resignation in the light of the first-rate achievements of professional medics.)

The production was sung in Italian with English surtitles, and I found myself wishing that my own Italian was less rudimentary so that I might have a better appreciation of how far the double (even triple), entendres were evidence of Amati’s wit, or were the result of the ‘transcriptions, translations and workshop projects’ which Solomon’s Knot have undertaken during the past two years to bring the opera ‘back to life’. Either way, the satire was certainly au courant, the gags inventive, and the polemic provocative.

Wilton’s Music Hall was the perfect venue. Situated in the historic East End, it is the world’s oldest music hall. For many decades the Hall has been afflicted with damp and dereliction; a flyer for a 1997 production of The Wasteland, directed by Deborah Warner and performed by Fiona Shaw, advised mid-winter visitors to the unheated hall to ‘please dress warmly’, to which a journalist added ‘wear hard hats’. But, despite the welcome completion in September this year of long-running renovations, the makeover has retained the genuine historic fabric and, sitting in the dimly lit, smoke-filled hall (lighting by Ben Pickersgill) it was easy to imagine oneself in an insalubrious infirmary - historic or modern. Rachel Szmukler’s set consisted of a curtained hospital bed, towering piles of orange garbage bags containing medical waste (and new ‘inmates’’ personal belongings), and a trolley laden with urine samples. The harsh glare of strip lights and a glowing vending machine - peddling sugar foodstuffs unlikely to nourish the needy - spread an unforgiving glare. Performing in the round can have its pitfalls though, and while the sight-lines from my seat were superb, others seated on the opposite side of the arena may have found the frequent drawing of the curtain around the operating couch to be frustratingly obstructive.

The quack doctor - actually the disguised Minister for Health, undertaking secret scrutiny of his ailing health care system - attends to the four patients in turn. Rebecca Moon light, clear soprano conveyed profound depths of passion during Innamorato’s melodramatic tale of unreciprocated lesbian desire (presumably the role was originally sung by a castrato?); her lovelorn lament matched Monteverdi for rhetorical urgency, but the doctor was not touched by her distress, basically advising that she should ‘get over it’. Overlooked for career advancement, Cortigiano may be suffering from work-related stress, but tenor Thomas Herford did not let the City boy’s anxieties infect his own lyrical elegance. Countertenor Michal Czerniawski’s Matto was the embodiment of hyper-manic instability, fluctuating between insight and insanity, the latter moments enhanced by some inane shrieking. Nicholas Merryweather displayed characteristic dramatic confidence and vocal sureness as Povero, whose inability to pay the doctor’s fees exposes the latter’s avarice. Merryweather’s well-centred baritone made for a pleasing contrast with Czerniawski, and provided a strong foundation in the lively ensembles. As the fraudulent physician, Jonathan Sells showed considerable comic nous, while Lucy Page demonstrated a crystalline soprano as the put-upon hospital orderly, Forestiero.

The score alternates arias - madrigals, laments, balletti - arioso, ensembles and spoken dialogue, and is melodious, briskly energetic and inventive. To the mix were added two madrigals by Gesualdo, whose bitter-sweet dissonances and chromatic lamentations perfectly complemented the mood of emotional disturbance and anguish. James Halliday drew superb playing from the small instrumental ensemble: rhythmically alert, vigorous and colourful.

Music, medicine and madness are a potent mix. Indeed, my guest for the evening was a retired psychiatrist who has just published a study of operatic heroes who might be considered to exhibit a range of personality disorders (and who, ironically, undertook his training at the nearby London Hospital). This production by Solomon’s Knot perfectly balanced satire and silliness; it was an earnest critique of the medical profession, historic and modern, and also exuberant fun. It took risks, and while not all of them came off, it communicated directly and with thought-provoking candour.

Claire Seymour

Forestiero - Lucy Page, Povero - Nicholas Merryweather, Matto - Michal Czerniawski, Innamorato -Rebecca Moon, Cortigiano - Thomas Herford, Medico - Jonathan Sells; Director - James Hurley, Musical Director - James Halliday, Designer - Rachel Szmukler, Lighting Designer - Ben Pickersgill.

image=

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=L’Ospedale (libretto, Antonio Abati), Wilton’s Music Hall, London

Wednesday 17th November 2015

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=

Šimon Voseček : Biedermann and the Arsonists

The words of the Chorus of Firemen and the images of a burning citadel which open Independent Opera’s production of Šimon Voseček’s opera, Biedermann and the Arsonists - receiving its UK premiere at Sadler’s Wells, following the premiere of the 90-minute opera at Neue Oper Wien in 2013 - are disturbingly close to the bone, in the light of recent terrorist atrocities in Paris and the IS attack upon Russian Airbus A321-200.

The opera sets Swiss playwright Max Frisch’s Biedermann und die Brandstifter, which was written for radio in 1953 and adapted for the theatre five years later. David Pountney has provided a new English translation, though as Voseček has noted, ‘[t]he piece is already written as if it were a libretto - it was hardly necessary to do anything to it’; thus, except for the excision of the prologue, epilogue and one character, a ‘Dr of Philosophy’, Pountney has made few significant changes. The play reflects Frisch’s contempt for Europe’s lack of vision or moral cowardice when faced with the rise of Nazism in the 1930s, and the continent’s similarly complacent response to the annexation of Czechoslovakia in 1948. And, despite the Kremlin’s announcement this week that Russian President Vladimir Putin and his French counterpart, François Hollande, have spoken by telephone and agreed to coordinate military attacks in Syria, it is hard not to see parallels between the West’s recent unwillingness to acknowledge, confront and challenge the threat from radical Islam.

Gottlieb Beidermann (whose name implies ‘Everyman’) is a bourgeois businessman who has made his fortune peddling fake hair lotion. His town has a problem: arsonists are burning down its houses. Biedermann thinks the perpetrators should be lynched. But, when two homeless strangers - a brutish former jailbird turned wrestler and a slick head waiter - knock on his door, and weasel and wangle their way into his home, taking residence in the attic, Beidermann, inhibited by middle-class guilt, pushes aside his suspicions that his lodgers are the fire-raisers in the vain hope that politeness and courtesy will keep the threat they pose at bay. His pyromaniac tenants subsequently fill his garret with barrels of petrol but he turns a blind eye to their evil intent, failing to recognise that his wilful ignorance implicates him in their destructiveness. The ineffectualness of denial and self-deception as a strategy for self-protection is overtly confirmed when Beidermann literally becomes their accomplice, handing them the very match that they use to turn his own home into an inferno.

The director of this production, which celebrates Independent Opera’s 10th anniversary, is twenty-five year old Max Hoehn - the recipient of Independent Opera at Sadler’s Wells 2015 Director Fellowship: the first competition of its kind for opera directors in the UK, offering a young director the chance to stage a chamber-scale piece in London with resources comparable to those of the main UK companies.

Frisch assigns no designated time or place to the action, and Hoehn and his designer Jemima Robinson set the drama in the present. Inside Beidermann’s chic abode, the minimalist décor, unread books and token art, decorative candelabras and domestic maid, confirm his wealth, status and pseudo-culture. Amid such comfort, Biedermann enjoys his cigars and the wine flows copiously. The split-level set frames a modish dining room with a bathroom stage-right (where the characters take refuge as the tension escalates) and an attic stage-left, where the barrels of petrol are stored. The domestic realism is tempered by the surreal glow of lurid greens and pinks, and the blinding flashes of search-lights and red hazard beacons.

Frisch employs a Chorus of Fireman, which functions to some degree in the manner of a Greek chorus, describing and commenting on action which takes place off-stage. Adam Sullivan, Johnny Herford and Bradley Travis sang with precision, forming a well-coordinated ensemble, but also distinguishing the fire-fighters as individuals. Lodged in a pillar-box red, children’s-book fire engine, these ‘officers of order’ were portraits of inanity, the cartoonish stylisation of their movements, together with the juxtaposition of overly grave recitation and hysterical falsetto heightening their idiocy. The angel-wings they sport on their high-vis uniforms might infer that they guard the town with religious zeal, but while their role is to protect the population, the images of blazing buildings and their ‘Keystone Cops’ style clock-working suggested that, though they are preparing for the worst, they are doing little to stop it happening. They repeatedly warn and observe: ‘We are ready!’ But, they do nothing but wait, strewing the set with yellow ‘Do not cross’ fire-tape and danger signs, and tying themselves in knots with a snaking red fire-hose.

There are obvious echoes of Brecht’s alienation techniques in Frisch’s use of the Chorus, but, as Hoehn shows, the Swiss playwright is not as didactic as Brecht.