February 29, 2016

Khovanshchina at Dutch National Opera convinces musically, less so theatrically

Modest Mussorgsky’s byzantine Khovanshchina fictionalises historical power struggles from which Tsar Peter, later the Great, emerges as the victor. Its plot, a series of episodic scenes, centres around Prince Ivan Khovansky’s attempt to topple the Romanovs and put his son Andrey on the throne. His muscle are the Streltsy, elite guardsmen who have degenerated into a drunken, plundering menace. The Khovanskys oppose the progressive movement, represented by Prince Vasily Golitsin, who supports Peter’s reforms towards a Westernised Russia. As leader of the Old Believers, the enigmatic Dosifey also opposes religious and political reform, but abhors the Streltsy’s excesses. Inhabiting an ambiguous moral landscape, these characters’ motivations are often clouded, making them both intriguing and difficult to fathom.

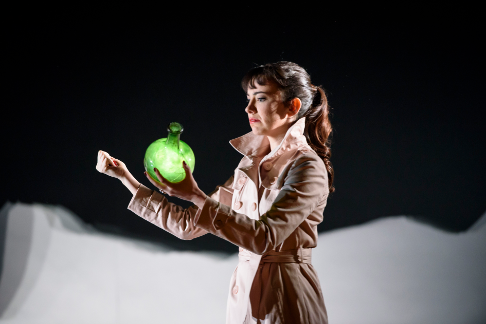

Director Christof Loy’s production opens with a tableau vivant of a painting by Vasily Surikov called the Morning of the Streltsy’s Execution (1881), which depicts Peter’s barbaric annihilation of the insurgent militia, an event that occurred outside the opera’s time frame. Saturated in golden light, as in the original, the figures in the painting doff their historical costumes and become our contemporaries. The golden light ebbs away and returns only when the painting is pieced together again at the end. The concept lucidly connects the 17th century to our time, but relies heavily on strong singing actors. Once the painting dissolves, the sets consist of starkly lit monochrome walls, and three hours is a long time to be looking at vacant walls.

Anita Rachvelishvili (Marfa), Maxim Aksenov (Vorst Andrej Chovanski), Koor van De Nationale Opera [Photo by Monika Rittershaus]

Anita Rachvelishvili (Marfa), Maxim Aksenov (Vorst Andrej Chovanski), Koor van De Nationale Opera [Photo by Monika Rittershaus]

Burdened with sustaining dramatic interest, not all the singers met the challenge. It was the insistent surge in the orchestra, who poured out delicate and mysterious tinctures, which unfailingly kept up the tension. Conductor Ingo Metzmacher beautifully captured both the heady Eastern perfume and the groundswell of ancient tides in Dmitri Shostakovich’s orchestration of the score, which Mussorgsky left unfinished. A reinforced brass section provided excellent military display. In the stupendous choral scenes, the Dutch National Chorus was on its best form when mixed. All-male numbers lacked a Slavic full-toned bass and the women’s chorus entertaining Khovansky was marred by strident top notes. In their best scenes, however, most notably as the Old Believers, the chorus matched the orchestra in highly evocative soundscapes.

Transplanting the action to the present worked only partially. Khovansky’s harem as a nightclub, where underage sex slaves are coerced into a clumsy Dance of the Persian Slaves, was compellingly disturbing. On the other hand, a group of supposedly illiterate office workers bullying a Scribe, portrayed with avid self-importance and reedy tenor by Andrey Popov, into reading them a notice board, is the kind of incongruence that causes a mental short circuit. Some symbols remained unclear, maybe on purpose. Did the pigtailed little girl instrumental in Khovansky’s assassination personify Russia’s innocence?

The cast was more satisfying than the staging. Well-sung supporting roles included the orotund-voiced, boisterous soldiers of Vitali Roznyko and Sulkhan Jaiani. Acting credibly as the drunken Strelets Kuzka, Vasily Efimov wielded a puzzling tenor, with a breathless, small middle range and brawny loud notes. Bass Dimitry Ivashchenko, announced as suffering from a cold, sang Ivan Khovansky full-bodiedly and securely, but needed to tread carefully, sacrificing a degree of expression. As his son Andrey, tenor Maxim Aksenov started out with faltering pitch, but improved later on. Orlin Anastassov gave a frustrating performance as the sect leader Dosifey. His luxurious bass fitted the role like a glove, but he alternated splendid singing and vivid moments with gurgled vocalism and monotony. In the end, his Dosifey lacked the dark charisma that would persuade his disciples to commit mass suicide.

Bass Gábor Bretz’s first appearance as the pro-Romanov nobleman Shaklovity was vocally prepossessing but rather featureless. Fortunately, he caught dramatic fire in his great aria bemoaning Russia’s suffering. The other incendiary performances came from tenor Kurt Streit as the agitated Golitsin, his bleached high notes registering rising panic, and the three women. Svetlana Ignatovich left a radiant impression in the short role of Emma. Some shrillness in her high notes suited the character, who was being set upon by the lecherous Andrey. Olga Savova was equally arresting as the judgmental Susanna. Her confrontation with fellow Old Believer Marfa was a theatrical peak. In fact, every scene with Anita Rachvelishvili in it set off the dramatic seismograph. Her fascinating Marfa was complex in voice and action, and completely mesmerising, longing for Andrey in gorgeous mezza voce, and terrifying Golitsin in her quaking fortune-telling scene. With her voluptuous contralto base from which her voice curls smokily up the scale, Ms Rachvelishvili was born to sing this role. Whether she stood in front of a black or white wall, when she sang the whole stage was aswirl with colour.

Jenny Camilleri

Cast and production information:

Prince Ivan Khovansky— Dimitry Ivashchenko, Prince Andrey Khovansky — Maxim Aksenov, Prince Vasily Golitsin — Kurt Streit, Boyar Fyodor Shaklovity — Gábor Bretz, Dosifey — Orlin Anastassov, Marfa — Anita Rachvelishvili, Emma — Svetlana Ignatovich, Susanna — Olga Savova, Scribe — Andrey Popov , Kuzka — Vasily Efimov, Varsonofiev — Roger Smeets, Streshnev — Morschi Franz, First Strelets — Vitali Roznyko, Second Strelets — Sulkhan Jaiani, Prince Golitsin’s Servant — Richard Prada, Principal Dancer — Gyorgy Puchalski, Conductor — Ingo Metzmacher, Director — Christof Loy, Set Designer — Johannes Leiacker, Costume Designer — Ursula Renzenbrink, Lighting Designer — Reinhard Traub, Choreographer — Thomas Wilhelm, Dramaturge — Katja Hagedorn, Dutch National Opera Choir, New Amsterdam Children’s Choir, Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra. Seen at Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam, Saturday, 27th February 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/dno_chovansjts-_a4-300dpi.png image_description=Photo by Petrovsky & Ramone product=yes product_title=Khovanshchina at Dutch National Opera convinces musically, less so theatrically product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Above photo by Petrovsky & RamoneSophie Bevan, Wigmore Hall

The programme was clearly selected to show-case the qualities and strengths of soprano Sophie Bevan. And, her vocal assets were immediately evident in the opening work, Bach’s Falsche Welt, dir trau ich nicht! (False world, I do not trust you! (1726)). The fine definition of her phrasing, her evenness across the range, and the directness of Bevan’s stage manner made for an immediate and captivating opening recitative, which presents a sombre response to the Pharisees’ intention to trick Jesus, who has been preaching against them, into betraying himself.

From the assertive falling sixth and tight rhythm of the opening accusation, ‘Falsche Welt’, Bevan responded to every nuance in the text and score, avoiding extravagant gesture and letting the inherently dramatic music do the work. Vocal leaps were clean and the tuning of the biting chromatic twists was spot on. The richness that was evident in the anger conveyed here was strengthened in the confident assertions of the following aria, ‘Immerlin, immerlin’ (No matter); the repetitions of the short motif, ‘immerlin’, danced lightly and the rapid running passages — in which Bevan was partnered by an agile bass line — were gracefully nimble. In the central section, in which celebrates the singer’s faith in God’s friendship despite the falsity of the earthly world, Bevan revealed a plusher, fuller tone.

The triple-time second aria offered a calm contrast, ‘Ich halt es mit dem lieben Gott’ (I put my faith in God; as the singer spurns the world and joins with God, the oboes added to the lilting sweetness and composure, while the off-beat interjections of bassoon and bass helped to maintain rhythmic tension. Bevan’s singing was bright and joyful, endearingly candid and unfussy.

The opening sinfonia of the cantata is an adaptation of Brandenburg Concerto 1, and director John Butt and the players of Dunedin began in ebullient fashion, the musical arguments thrown buoyantly between the instrumental voices, with the pungent horns warmly supplementing the racing semiquavers of the violins and oboes. The players’ dynamism and clarity complemented the freshness of Bevan’s singing, although in the chorale — which was originally scored for four voices — single-handedly she could not quite match the strength of the horns.

Handel’s Alpestre monte (Alpine mountain) — written during the composer’s Italian ‘apprenticeship’ and after a perilous journey through the Alps — is perhaps more explicitly dramatic, but also quite madrigalian and cinematic. The opening recitative describes a Gothic terrain — ‘Triste albergo d’orror,/ Nido di fere,/ Fra l’ombre cupe e nere’ (sad refuge of fear, lair of wild beasts in the gloomy shadows) — and the chromatic contortions of the vocal line, atmospheric string playing and low vocal register created a sinister, twisted mood. There was further expressive sentiment from the strings in the following aria, ‘Is so ben ch’il Vostro orrore’ (I know well that the horror you inspire), and a stunning pianissimo which conveyed the potency of the pathetic fallacy (‘As in this surrounding gloom, so my heart is surrounded by shadows, horrible and fierce ghosts’).

Bevan treated the text luxuriantly in the recitatives, underscoring the tragic intensity of a love that is so fierce, ‘Al fin perdei me stesso,/ E il cor perdel’ (I ended up losing myself and losing my heart). And, in the final aria (‘Almen dopo il fato’) she made used of copious vocal light and shade, blending beautifully with the two violins, and imbuing the falling lines with poignancy. The soprano also appreciated — as is not always the case with soloists at the Wigmore Hall — how to modify her voice for the size and acoustic of the venue; and in so doing, she proved herself to be a real ‘singing actress’.

Handel’s Gloria HWV deest was the final vocal item. It’s a work which was only fairly recently identified as a Handel work, when in 2001 Professor Hans Joachim Marx’s research — while preparing a new edition of Handel’s Latin church music — led him to deduce that Handel was indeed the composer. It’s virtuosic in the extreme; but Bevan sang rings round the solo part — her technical arsenal enabled her to despatch ornate melisma, long-breathed phrases, rapid repetitions and octave transferences with ease. She also enjoyed the musical rhetoric: the suspensions and sequences that entwine with the vocal lines were teasingly articulated. The vocal delivery implied an insouciance which cheekily contradicted the sincerity of the text! — most especially when the ‘Amen’, switching to a duple metre, took off precipitously, and joyously.

The players of Dunedin also got their chance to shine, in instrumental works woven between the vocal items. Bach’s Fourth Brandenburg Concerto was rhythmically alert (hemiolas rarely sound this theatrical!), airy of texture, the phrasing by turns punchy and warmly rounded. Cecilia Bernardini’s solo violin phrases were elegantly shaped, while the recorder solos of Catherine Latham and Pamela Thorby had great character. My only query was whether Butt needed to work quite so hard, cueing all and sundry, and maintaining a dynamic presence throughout, when his players seemed to have an innate appreciation of the festive spirit which he sought to capture? Contrast, vibrancy and revelry were also features of Handel’s Concerto Grosso in Bb Op.3 No.2 (though why were the two oboes hidden away behind the string ripieno?).

In 2013 Bevan was awarded the ‘Young Singer’ award at the inaugural 2013 International Opera Awards. This was an enchanting performance which confirmed her vocal stature and maturity, and her stage presence.

Claire Seymour

Performers and programme:

Dunedin Consort: John Butt — director/harpsichord, Sophie Bevan — soprano, Cecilia Bernardini — violin, Pamela Thorby & Catherine Latham — recorder

J.S. Bach — Cantata: Falsche Welt, dir trau ich nicht BWV52, Brandenburg Concerto No.4 in G major BWV1049; Handel — Cantata:Alpestre monte HWV81, Concerto Grosso in B flat major Op.3 No.2 HWV313, Gloria HWV deest. Wigmore Hall, London, Friday 26 th February 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sophie_Bevan.png image_description=Sophie Bevan product=yes product_title=Sophie Bevan, Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Sophie BevanExtraordinary Pelléas et Mélisande

How unique was this performance? Well, if you missed this Pelléas et Mélisande, you missed the only production of the work in a major American house in the past two years. And none is projected here through 2018.

Pelléas et Mélisande is based on a play of the same name by Belgian born, Maurice Maeterlinck. It was first performed in 1893. Maeterlinck, a prolific and popular writer in his day, was a symbolist, as were many of France's greatest poets of the age including Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Verlaine and Rimbaud. These symbolist poets, who believed that music was the most direct route to the emotions, strove to write musical verse- and in fact their poetry inspired not only Debussy, but composers - Gounod, Ravel, Fauré and others - to create a new and enchanting age of French art songs, known as Mélodie What does symbolism in an opera look like?

Well, an outline of the story will help. Of course, there will be a love triangle. But the first thing to note in this opera is that first person we see and hear in the opening scene is a man, who, like Dante, in the first lines of the Inferno, suddenly realizes that smack in the middle of his life, he is lost in dark woods. This is Prince Golaud, who immediately hears weeping and encounters another lost person - Mélisande, a beautiful maiden with cascading golden hair. She has just dropped a jeweled crown, which an unknown “he” had given her, into a nearby pond. Still weeping, she tells Golaud that everyone in the distant land she came from has hurt her in some way. She refuses his offer to retrieve the crown, by threatening to leap into the water herself, if he does so. Golaud, who is widowed, eventually marries Melisande. The pair return to Golaud's homeland, Allemonde, where Mélisande, who has still not told Golaud anything about her past, will meet his mother, Geneviève, his blind grandfather King Arkel, his little son, Yniold and his younger half brother, Pelléas. Allemonde is a land of despair, poverty and famine. The castle is surrounded by dark gardens and endless forests, though the sea is visible from a nearby coast. Within the castle itself, Pelléas' father lies seriously ill. He will recover, but the mysterious young woman with cascading golden tresses will not bring hoped for joy and light to the castle. Its gloom will devour her.

Symbolism? Whereas Golaud and the young lovers, Pelléas and Mélisande suffer through experiences that every other operatic love triangle suffers: love, lost love, unrequited love, hate, rage, fear, betrayal - what makes this trio unique is that none of them seems to know where they are, who they are, what they want. They do not understand themselves, and certainly not each other, but seem suspended in some floating space. However, the chracters in this opera have some strangely interrelated characteristics. Whereas King Arkel is blind, Mélisande's eyes are never closed unless she's sleeping. In an early encounter Pelléas takes Mélisande to the once miraculous Fountain of the Blind, no longer valued because Arkel has lost his sight. The ability and inability “to see” in all its meanings is of primary concern to both Maeterlinck and Debussy. The word yeux, eyes is spoken nineteen times in this libretto, aveugle, blind, nine times.

And we come across strangely related interactions. In a rendezvous with Pelléas, Mélisande drops the gold wedding ring Golaud had given her into a deep well. At that very moment Golaud is thrown from his horse and injured.

Maeterlinck had an oft quoted credo “Art always works by detour and never acts directly. “ Apparently, the musical detour to Mélisande, a woman with no known background, proved puzzling to Debussy, who wrote to a friend of the difficulty of creating music from “nothingness”. Fortunately, he succeeded. Perhaps he had learned of a scholar's view of Maeterlinck's work, which asserts that Mélisande had been one of Bluebeard's wives, who escaped with a detested crown.

The Los Angeles Philharmonic has been daring in its attempts to present opera and other important vocal works in its theatrically-challenged space. Whereas the Mozart/Daponte operas sometimes seemed shoehorned into inadequate space, this Pelléas et Mélisande with a larger cast than Cosi fan tutte, was enhanced by the thoughtful restraints of its semi- staged concert presentation - which allowed the orchestra - the musical heart and voice of the opera - to carry Debussy's sensual score to the audience's heart.

The production, conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen and directed by David Edwards, was previously presented in London's Royal Festival Hall in 2014 with the same superb baritone leads. High baritone, Stéphane Degout was an ardent Pelléas and bass baritone, Laurent Naouri ranged superbly through Golaud's towering rages and sorrowful regrets. Camilla Trilling was a clear voiced, vulnerable Mélisande, soprano Chloé Briot, a captivating Yniold. Well known veteran artists, Dame Felicity Palmer and Sir Willard White, sang Geneviève and Arkel, respectively.

Director David Edwards added static nude blindfolded figures at the rear of Disney Hall to reflect the often voiced concerns about blindness, as well as to symbolize the devastation of the land. They enhanced both the depth of the stage and depth of despair in Allemonde and its castle.

But it was Eka-Pekka Salonen's command of the orchestra that illuminated the brilliance and mystery of this opera in new ways. It seemed as though Salonen was making a point of keeping an almost audible beat going beneath the restless wash of orchestral colors. Salonen, who has spoken of his love for this score, added a narrator to both productions, who read text drawn from Maeterlinck's writing. I'm not sure the words were helpful, but actress, Kate Burton's narration acted as a kind of frame, that helped set the tale unfolding behind her, in a land of make believe.

Estelle Gilson

Cast and production information:

Pelléas: Stephan Degout; Mélisande: Camilla Tilling; Golaud: Laurent Naouri; Arkel: Willard White; Geneviève: Felicity Palmer; Yniold: Chloé Briot; Physician: Nicholas Brownlee; Narrator: Kate Burton; Conductor: Esa-Pekka Salonen; Director: David Edwards; Lighting designer: Colin Grenfell.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Camilla_Tilling.png image_description=Camilla Tilling [Photo courtesy of Harrison Parrott] product=yes product_title=Extraordinary Pelléas et Mélisande product_by=Estelle Gilson product_id=Camilla Tilling [Photo courtesy of Harrison Parrott]Fascinating Magic Flute in Los Angeles

A singspiel (sing play) is a work made up of arias, duets, ensembles, and spoken dialogue. Kosky describes the Flute as a “mix of fantasy, surrealism, magic, and deeply touching human emotions.”

Thus, Kosky, Andrade, and Barritt condensed the Magic Flute’s dialogue and turned it into silent film intertitles. The result was the Kosky/Andrade/Barritt Magic Flute seen at Los Angeles opera in 2013 and again this year. In the Kosky production, the cast sings the musical numbers while the audience reads spoken dialogue on silent-movie-type screens and pianist Peter Walsh plays excerpts from Mozart’s C Minor and D Minor Fantasies. It is, without a doubt, one of the most imaginative productions of the work this critic has seen in more than fifty years of opera going.

At the performance at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on February 20, 2016, director Kosky gave Papageno an amusing cat that followed his every move while barely controllable vicious dogs led Monastatos about. Other animals were also ingeniously animated. Esther Bialas dressed The Three Ladies in Roaring Twenties costumes. When they punished Papageno for lying, the audience saw an enlarged picture of his constantly moving mouth.

Conductor James Conlon’s tempi were often fast but they always fit the twists and turns of the story and at times he gave us serenity. Always aware of the singers’ needs, he gave this performance clearly balanced sonorities in a vigorous, evocative rendition of Mozart’s singspiel.

Ben Bliss, a recent alumnus of the Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program (YAP), was an elegant, silken voiced Tamino with golden top notes. A new artist, he was a perfect young lover who sang his first aria, "Dies Bildnis is bezaubernd schön," (This portrait is enchantingly beautiful) with a resonant, virile sound. Bliss is a tenor to watch. Marita Sølberg was a suave, feminine, Pamina who sang with vocal refinement and admirable phrasing.

As Papageno, Jonathan Michie offered an appealing dramatic impersonation that was both amusing and touching. Whether bragging, longing for a lover or merely calling for a good meal, Michie’s irrepressible bird catcher offered delightful comedy that always held the audience’s interest. Watching him made the audience understand why Emanuel Schikaneder, the librettist, wrote the role for himself.

Soprano So Young Park (YAP) sang the Queen of the Night with considerable verve and fine enunciation. She had the twinkling staccati as well as a smooth Mozartean line that the role calls for. William Schwinghammer was somewhat underpowered Sarastro but he created a visually authoritative character.

As the Three Ladies, Stacey Tappan, Summer Hassan (YAP), and Peabody Southwell were endearing flappers who formed an idyllic trio. Program member Vanessa Becerra was an expressive Papagena, while fellow member Brenton Ryan created a refined, evil characterization as Monostatos. Frederick Ballentine (YAP) was a sturdy First Armored Mann and bass-baritone Nicholas Brownlee (YAP) was a resonant Speaker and Second Armored Man.

The Los Angeles Children’s chorus provided three treble soloists who sang well and handled themselves adroitly. Grant Gershon directed the Los Angeles Opera Chorus as they added their graceful harmony to this most interesting production which captured the wonder and fantasy of Mozart’s last opera.

Maria Nockin

Posted by maria_n at 12:33 PM

February 24, 2016

Theatre of the Ayre, Wigmore Hall

Noting in his Preface to Harmonia Sacra (1688/93) that the ‘youthful and gay’ had already been entertained with a ‘variety of rare compositions’, the entrepreneurial Henry Playford addressed his new publication to: ‘others, who are no less musical though they are more devout.’ For these ‘pious persons’, who are excellent judges of both music and wit, divine hymns are the ‘most proper entertainment’, one which ‘warms and actuates all the powers of the soul and fills the mind with the brightest and most ravishing contemplations’.

The devotional songs presented here certainly foregrounded the misery of the penitential and the blisses of spiritual consolation which might be attained through devotion — a fitting focus, perhaps, for the current liturgical season. In addition to Psalm texts, there were settings penned by persons whom Playford describes as ‘eminent both for learning and piety’ and who include William Fuller, Bishop of Lincoln, and poet George Herbert.

While the lion’s share of the programme was de devoted to Purcell, whose dominant presence would surely have made the collection more attractive to potential purchasers, there were contributions by Purcell’s English contemporaries, John Blow and Pelham Humfrey, whose collaborative ‘Hark how the wakeful cheerful cock’ opened the programme, seguing from the brief canon ‘Laudate Dominum’ to which the five soloists had processed onto the platform.

The dialogue, begun by Humfrey and completed by Blow, between two penitents was spirited and theatrical: as awareness of their sins mounted so did their misery, and soprano Sophie Daneman and tenor Nicholas Mulroy joined in lamentation — ‘Since then the cause of both our grief’s the same,/ Mix we our tears for grief let’s die,/ But first our dirge let’s sing, or cry:’ — the enriched accompaniment, as theorbo was joined by viola da gamba and harpsichord, ironically deepening the sweetness of their miserere.

Pepys may have described Humfrey as a man ‘full of form and confidence and vanity’, but the anthem ‘Lord! I have sinned’ suggests that his self-assurance may have been justified, for he was clearly skilful in using flamboyant musical gesture to express sombre contrition. The Italianate idiom — drooping chromaticism, angular melodic shapes and poignant dissonances — was delivered with madrigalian vivacity by Daneman, accompanied by organ and viola da gamba, but while the soprano’s phrases were expressive, the line and tuning were not consistently controlled. In particular, I found Daneman’s tendency to slide through the chromatic sighs to be excessive; the sentiments she seemed sought are already present in the music and need no exaggerated articulation.

There was even more Italianate virtuosity to enjoy in soprano Katherine Watson’s witty and technically assured performance of Giacomo Carissimi’s dramatic motet ‘Lucifer Caelestis olim’, which enacts Lucifer’s fall from grace. Watson was equally convincing as the imperious narrator, the boastful Lucifer and when she was when delivering God’s condemnation, perhaps not surprising as the two dramatic figures are, ironically, not distinguished in terms of musical style. Lucifer’s deluded bragging — ‘O me felice, o me beatum coelestis gloriae decoratum!’ (O how happy am I, blessed and adorned with the glory of heaven!) — was delivered in nimble coloratura with a bright edge at the top and real strength in the lower register.

John Blow brought Mulroy and bass Matthew Brook together in two rich duets. ‘Help, Father Abraham!: The dialogue of Dives and Abraham’ showcased the agility and diverse hues of Mulroy’s bright tenor as he pleaded for Brook’s Abraham to show pity, while Brook demonstrated rhetorical presence — ‘What son of Hell and darkness dare molest/ This blessed saint, scarce warm yet on my breast?’, he thundered — and control of vocal nuance. In ‘Enough my muse, of early things’, it was Mulroy’s registral range which was noteworthy, as he rose from low depths to a fervent upper register, calling upon his muse to take up its lute and play ‘Happy mournful stories, The lamentable glories of the crucify’d King’. There was striking urgency as the two voices blended in thirds, and melismas were delivered with sharp musical and textual clarity.

But, this was really Purcell’s evening. Many of the Purcell’s devotional songs survive only in manuscript, and so Playford’s publication is a valuable one; the songs are some of the less familiar works among the composer’s output but also some of the finest. On his title pages to the two volumes of Harmonia Sacra, Playford noted that the continuo part should be played by ‘theorbo-lute, bass-viol, harpsichord, or organ’ and that was the ensemble gathered here, supplemented by two violins, as ‘domestic’ representatives of the renowned Twenty-Four Violins of the Chapel Royal. Brook was joined by the violins, viola da gamba and organ in Purcell’s ‘My song shall be of the loving kindness of the Lord’, and the instrumentalists provided a rich-textured symphony between the arioso and recitative passages of Brook’s intense but lyrical solo; there was some delightful interplay and dialogue between voice and instrumentalists, and Watson, Mulroy and countertenor Robin Blaze gradual heightened the exaltation of the choral Hallelujah. Brook’s performance of ‘In the black dismal dungeon of despair’ was a highlight of the evening: to the sparse accompaniment of theorbo, the bass wrought meaning from every detail of the text — for example, opening the vowels of the title line to convey the depths of suffering, or the rolling of the ‘r’ in ‘certain horrid judgement’ — and music. Here, too, the unsurpassed naturalness of Purcell’s text setting was evident, in the short-long sprung rhythms (‘Lost to all hope of Liberty,/ Hence ne-ver to remove’) which punched home meaning, and in the melismatic flourishes which reified emotion — ‘Being guilty of so long, so great neglect’. This was a masterly rendition, sustained to the final perfectly executed trill.

Contrasting trios of voices were presented in and ’I was glad when they said unto me’ (ATB) and ‘In guilty night: Saul and the witch of Endor’ (STB). In the latter, the voices moved with freedom from ensemble blend to solo prominence and build the drama with urgency. The chromatic piquancy conveying his ‘sore distress’, Mulroy’s Saul hurried fearfully through his imploration, ‘For pity’s sake tell me, what shall I do?’ but Brook’s Samuel was implacable in his magisterial authority: ‘At thou forlorn of God and com’st to me?’ Daneman was a lively witch, but at times I thought that, determined to impress upon us the passion of Purcell’s declamatory idiom, she sacrificed beauty of tone and precision for dramatic effect. In ‘I was glad’, the interjection of the two violins rivalled the voices for rhetorical impact.

The two female voices spoke with a pleasingly unified timbre at the close of Purcell’s ‘Jehovah quam multi sunt hostes’; Watson demonstrated a burnished lower range at the start of ‘With sick and famished eyes’, and again negotiated the dissonances and disjunctions of the more Italianate passages skilfully, though the virtuosity did occasionally detract from the clarity of the diction.

In the concluding items, and with the metaphorical setting of the sun, we moved closer to spiritual consolation and rest, with two ‘Evening Hymns’. The first, to an anonymous text, was warmly delivered by Mulroy and Brook, and again the interaction between instrumental and vocal bass parts brought expressive richness to the close, ‘By sleeping, how it is to die’. Robin Blaze performed Purcell’s long-lined melodic setting of Bishop Fuller’s more well-known text with gentle understatement, accompanied by Kenny’s thoughtful theorbo. Thomas Tallis’ hymn, ‘All praise to thee my God this night’, the textures engagingly varied for each verse, brought the evening to a soothing close.

The continuo ensemble also performed three trio sonatas by Purcell, with expertise and musicality. The unanimity of articulation and expression of violinists Rodolfo Richter and Jane Gordon was remarkable, and Alison McGillivray’s viola da gamba provided a lyrical even-toned bass, while Robert Howard was an alert and crisp contributor at the keyboard and organ. The increasingly complex and deeply compelling accumulations and variations of the Chacony of the Trio Sonata No.6 in G Minor (Z807) almost stole the show.

Claire Seymour

Performers and programme:

Theatre of the Ayre: Rodolfo Richter violin, Jane Gordon violin, Alison McGillivray viola da gamba, Robert Howarth organ, Sophie Daneman soprano, Katherine Watson soprano, Robin Blaze countertenor, Nicholas Mulroy tenor, Matthew Brook baritone, Elizabeth Kenny director, theorbo.

Anon — Canon a 3 Laudate Dominum; John Blow — ‘Hark how the wakeful cheerful cock’; Henry Purcell — ‘My song shall be alway of the loving kindness of the Lord’ Z31, Trio Sonata in Three Parts No. 10 in A major Z799; John Blow — ‘Enough, my muse, of earthly things’; Henry Purcell — ‘In the black, dismal dungeon of despair’ Z190, Trio Sonata in Three Parts No. 11 in F minor Z800, ‘In Guilty Night’ (Saul and the Witch of Endor) Z134, ‘I was glad when they said unto me’ Z19, Jehova, quam multi sunt hostes’ Z135; Giacomo Carissimi: ‘Lucifer, caelestis olim’; Henry Purcell — ‘Trio Sonata in Four Parts No. 6 in G minor’ Z807; Pelham Humfrey — ‘Lord, I have sinned’; John Blow — ‘Help, Father Abraham’; Henry Purcell — ‘With sick and famish’d eyes’ Z200, ‘Now that the sun hath veiled his light’ (An Evening Hymn on a Ground) Z193, Trio Sonata in Four Parts No. 10 in D major Z811, ‘The Night is come’ (An Evening Hymn) Z77; Thomas Tallis — ‘All praise to thee my God this night’.

Wigmore Hall, London, Tuesday 23rd February 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Elizabeth%20Kenny.png image_description=Elizabeth Kenny product=yes product_title=Theatre of the Ayre, Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Elizabeth KennyFebruary 22, 2016

HOT Dream in Honolulu

Director Henry G. Akina has skillfully crafted an unfussy, straight forward, tightly organized production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, that offered few surprises but ample delights. Mr. Akina’s clarity of story-telling is a welcome asset, and he moves his performers around like the seasoned pro he is, with utmost clarity of purpose.

Mortals, gods, and rude mechanicals alike are well-characterized here, not only as definitive, identifiable groups, but also as highly individualized components in the story. Some whimsical touches drew audible audience appreciation, whether it was Tytania playfully wriggling her behind onto a hammock; Puck’s astonishing defiance of gravity with weightless leaps and jetées; or Lysander’s and Demetrius’ use of Helena as a human rope for an amorous tug-of-war.

Peter Dean Beck’s set design was highly efficient: a workable center stage unit set of platforms and stairs that provided an ideal environment for varied scenes and locales. This unit was beautifully framed by a diaphanous “forest” of legs and borders on which were projected a spectacular series of images, masterfully designed by Adam Larsen. The constantly modulating, universal woods changed seasons, changed climates, and conveyed a well-calibrated sense of the passing of seasons. The ‘autumn’ leaves falling as the lovers transitioned was a feat of potent and moving imagery.

Mr. Beck complemented Mr. Larsen’s projections with a carefully considered lighting design: atmospheric, moody, and always well-judged. The simple addition of a set of “tree trunks” (in the form of stylized drapes that flew in and out) was all that was needed to complete the magical playing space. That said, I do wish that actors hadn’t kept bumping into those fabric “trees” causing them to jiggle. There was a cleverly crafted hammock for the Fairy Queen, and a simple workbench on saw horses was smoothly schlepped in and out by the rude mechanicals. In total, Beck contributed a practical environment of scenery and lighting that was admirable for its visual economy.

Helen E. Rodgers has contributed a commendable cornucopia of fantastical costumes with her inspired design, aptly defining each divergent group, while simultaneously dressing each individual in apparel distinctive to their function in the story. Rick Jarvie’s and Sue Sittko Schaefer's imaginative, spot-on wig and make-up design was a critical component in the success of the production, enhancing the performers in making their full effect.

Best of all, singing was of a uniformly high standard throughout. As Lysander, John Bellemer displayed a compact, pliant, gleaming lyric tenor. He was well complemented by Joshua Jeremiah as Demtetrius, whose warmly appealing, burnished baritone was wedded to exceptional diction. Both cut strapping romantic figures.

Rachelle Durkin was a commanding presence as a delightfully daffy Helena. Her accurate, laser-focused coloratura was counter balanced by evenly produced melismas, vocally a cross between a tuneful yapping poodle and a mournful lovesick spaniel. All that was wanting tonally was perhaps a bit more womanly allure. Claire Shackleton’s smooth, ripe mezzo gifted the role of Hermia with a luxurious lower-middle and an effortlessly floated top. These four lovers triumphed in the great Act Three quartet, their fresh, youthful instruments soaring, aching, and tumbling over each other in heartfelt, overlapping phrases. It proved to be the heart of the show and the unequivocal triumph of the evening.

Anne-Carolyn Bird and Daniel Brubeck were flawlessly paired as Tytania and Oberon, regal, statuesque, and, oh yeah, sexy. Ms. Bird’s silvery, shimmering soprano shows off a solid technique, alluring tonal beauty, and supreme clarity. Her lovely appearance and regal carriage served the role well. Mr. Brubeck’s appealing, mellifluous countertenor was freely produced and it dripped with class, both in richness of sound and in delivery. There could have occasionally been a bit more point in the lower register, but his elegant singing, lanky demeanor and ethereal movement made for a fine Fairy King.

Paul T. Mitri was near perfection as Puck. While this spoken role is greatly truncated in the libretto adaptation, Mr. Mitri made every syllable count and he accurately spoke his lines in synch with the musical stings. Moreover, he was a wiry larger-than-life omnipresence owing to an energetic, super human physicalization that leapt and tumbled and bounced and vaulted and floated like an Energizer Bunny on Red Bull channeling Roger Rabbit. A star turn, indeed, Paul.

Nathan Stark made an auspicious role debut as an uncommonly fine Bottom. His stage demeanor was by turns pompous, genial, blustering, and endearing and he captured every bit of the part’s humor, especially when portraying the overwrought Pyramus. His well-schooled bass-baritone has a steely thrust, and its easy amplitude allowed it to ring out in the house. Mr. Stark’s authoritative impersonation made us love to be annoyed by this meddlesome tinker. His loose-limbed antics as the ass were the perfect partner to Tytania’s ‘gaga’ spooning, but did the director have to let the “soundly sleeping” couple visibly get up and casually exit the stage halfway through Act II?

Buzz Tennent’s stolid, resonant baritone showed great nuance and musicality as Quince/Prologue, missing only a bit of incisive bite when the orchestration thickened around him. Leon Williams (Starveling/Moonshine) is a local favorite and it is easy to see why since he is a natural stage creature and has a rich, rolling baritone, seamlessly deployed. Kyle Erdos-Knapp’s sweet, honeyed tenor was a perfect fit for the beardless, just-post-pubescent Flute/Thysbe. As the latter “damsel” Mr. Erdos-Knapp flounced and minced around the stage with great abandon, and his melodramatic stage movements nailed every laugh.

Tyler Simpson was a definite asset to the proceedings, his bass a pleasing addition as Snug/Lion. The dual roles of Snout/Wall were in the capable care of tenor Nathan Munson, whose steady and secure comprimario singing was infused with engaging personality. Mr. Akina was especially successful in bonding this diverse band of singing comics into a finely tuned ensemble with well-judged focus and unity of purpose. Great team players, all.

Even the very smallest roles were splendidly cast. As Theseus and Hippolyta, Jamie Offenbach and Katharine Goeldner come onstage very late in the evening, but when they did it was no holds barred. Mr. Offenbach has a height and noble bearing that warrant attention, and his penetrating, dark baritone scored with the riveting outpouring of every phrase. Ms. Goeldner’s imposing, evenly produced mezzo similarly weighted each pronouncement, making her every measure a joy to hear. It is not often two performers can come in at the 11th hour with such brief opportunity, and momentarily take over the show, but that’s just what they did, brilliantly. They left us wanting more. Much more.

Rounding out the cast was a simply stunning group of children as the fairy chorus, easily the equal of any youth group I have yet heard in any opera. Their accurate ensemble singing was surpassed only by the high quality of the four young soloists. They were consummate professionals throughout, executing their varied choral positions beautifully, always mindful of the dramatic pacing, and completely focused on the task at hand.

Benjamin Britten was a master of orchestration. He explored endless variety of effects, combined sounds in unique and challenging ways, and demanded virtuosic playing that stretches a band to its limit and provides no hiding place. Even a highly skilled orchestra that plays together almost daily is challenged by A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The ethereal banks of shimmering strings, the unsettling portamenti, the chattering and skittering winds, the relentless shifting percussive effects, and the angular (dare I say, ungrateful?) arpeggiated “fanfares” in the brass are just a few of the daunting requirements.

If the result in the pit was not always idiomatically seamless, this was nonetheless a very fine, accomplished effort thanks to the inspired conducting of William Lacey. Maestro Lacey is a real find, and I always had the secure feeling that he knew how to confidently draw the very best from his players and his cast. He found just the right arc for each Act (not to mention the entire evening), and while he could certainly whip up a wickedly frenzied mosaic of sound when required, his greatest achievement may have been in allowing just the right amount of serenity to inform the introspective stretches, allowing them to “breathe.” He partnered the singers expertly, wrung every bit of color out of the score, and summoned up the comedic elements with gusto. Mr. Lacey would seem to have a great future and boy, do we need him!

If there are easier ‘sells’ than this operatic rarity, the Tuesday night audience didn’t seem to know or care, responding with unbridled enthusiasm. The overall charm and accessibility of HOT’s winningly executed production wrapped the rapt crowd in a joyous artistic embrace. Dreamy, indeed.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Puck: Paul T. Mitri; Tytania: Anne-Carolyn Bird; Oberon: Daniel Brubeck; Lysander: John Bellemer; Hermia: Claire Shackleton; Demetrius: Joshua Jeremiah; Helena: Rachelle Durkin; Quince/Prologue: Buz Tennent; Snug/Lion: Tyler Simpson; Starveling/Moonshine: Leon Williams; Flute/Thisbe: Kyle Erdos-Knapp; Snout/Wall: Nathan Munson; Bottom/Pyramus: Nathan Stark; Theseus: Jamie Offenbach; Hippolyta: Katharine Goeldner; Conductor: William Lacey; Director: Henry G. Akina; Set and Lighting Design: Peter Dean Beck; Costume Design: Helen E. Rodgers; Wig and Make-up Design: Rick Jarvie and Sue Sittko Schaefer; Projections Design: Adam Larsen. Hawaii Opera Theatre, 16 February 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/12716350_10153473662502712_656306428577071032_o.png image_description=[Photo by David Takagi] product=yes product_title=HOT Dream in Honolulu product_by=A review by James Sohre product_id=Photos by David TakagiFebruary 19, 2016

Arizona Opera Presents an Interesting Carmen

Because the subject matter was considered vulgar and inappropriate for the Comique’s family-oriented audience, it was not well received. The opera’s depiction of lawlessness and immorality broke new ground in French opera. Carmen would later be considered the bridge between opéra-comique and the verismo style of late nineteenth century Italian opera.

Although Carmen was not revived in Paris until 1883, productions outside of France drew large audiences before that and the opera was soon on its way to becoming the immensely popular work it is today. According to Operabase, Carmen is now the world’s second most popular opera. The only opera that is more popular than Carmen is Verdi’s La traviata.

On February 5, 2016, Arizona Opera presented Carmen in an updated but otherwise traditionally realistic production directed by Tara Faircloth. Douglas Provost’s functional set allowed the story to unfold in a straightforward manner.

Daniela Mack and Adam Diegel as Carmen and Don José.

Daniela Mack and Adam Diegel as Carmen and Don José.

As Carmen, Daniela Mack sang her lines with an exquisite palette of colorations and smooth dynamic range. A singer with dark hued sultry tones, she also had a fine sense of French style. Her personality could have been more fiery and her acting more intense in the dramatic scenes, but she did keep all eyes upon her when she sang. Her renditions of the Habañera and Seguidilla established her passionate nature and the deviousness of her character and she continued to emphasize Carmen’s fickleness as the plot unfolded. Her Chanson Bohème showed her love of unrestricted freedom and her Card Song proved her belief in the power of fate.

Adam Diegel was a rough-edged and dramatic Don José whose burnished, virile sound rang free throughout the auditorium. He delivered his lines with dramatic conviction and his acting conveyed considerable emotional impact. The Micaëla, Karin Wolverton was a great deal more than a simple country girl who wanted to marry a soldier. A brave and feisty young woman, she readily faced the dangers of looking for her boy friend among a band of soldiers and searching for him at night at an international border crossing. Best of all, Wolverton sang with silvery tones that blossomed into exquisite top notes.

Daniela Mack and Joseph Lattanzi as Carmen and Morales

Daniela Mack and Joseph Lattanzi as Carmen and Morales

Calvin Griffin as Zuniga and Joseph Lattanzi as Morales contributed effective portraits as two of the coarse, unrefined soldiers. Ryan Kuster gave a strong impression as the handsome and charismatic celebrity, Escamillo. The difficult tessitura of the Toreador Song seemed easy for him as he sang it to his fans at Lillas Pastia’s Tavern. Amy Mahoney and Alyssa Martin as Frasquita and Mércèdes, Joseph Lattanzi and Andrew Penning as El Dancaïro and El Remendado handled their assignments with alacrity. Together with Mack as Carmen the group gave a strong rendition of the tricky Quintet.

Henri Venanzi’s chorus was well prepared and sang in fine French style, but they tended to move as a group rather than as individuals. Conductor Keitaro Harada gave a balanced reading of the score that had a lucidity of musical detail and a good helping of emotional tension. He gave every phrase its proper shape and drew especially fine playing from the orchestra in the delightful entr'acte that opens the third act.

Audiences never seem to tire of Carmen and it always seems to retain its power to quicken the pulse. The many bows and the standing ovation that greeted Arizona Opera’s fine cast at the end of this performance only serve as a reminder of the opera's well deserved place in the repertoire.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Carmen, Daniela Mack; Don José, Adam Diegel; Escamillo, Ryan Kuster; Micaela, Karen Wolverton; Morales/El Dancaïro, Joseph Lattanzi; El Remendado, Andrew Penning; Frasquita, Amy Mahoney; Mércèdes, Alyssa Martin; Zuniga, Calvin Griffin; Conductor, Keitaro Harada; Director, Tara Faircloth; Lighting and Scenic Director, Douglas Provost; Projection Designer, S. Katy Tucker; Chorus Master, Henri Venanzi; Fight Director, Andrea Robertson.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Carmen%2035.png

image_description=Daniela Mack as Carmen [Photo by Tim Trumble]

product=yes

product_title=Arizona Opera Presents an Interesting Carmen

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Daniela Mack as Carmen

Photos by Tim Trumble

L'Aiglon in Marseille

All this would probably remain a footnote to history except Marseille born playwright Edmond Rostand (author of the famous Cyrano de Bergerac) wrote a six act play (1900) that wrung hearts in beautiful alexandrine verse about this young man who was deluded into believing he could restore the Bonapartists to France. The fabled Austrian diplomat Metternich who in fact had engineered the marriage, raison d’état, that begot the Aiglon was now a formidable counterforce for raisons d’état — not to mention his young age and fragile health.

Films based on the Rostand play were made in 1913, 1921 and 1931. In 1936 composers Jacques Ibert and Arthur Honeger joined forces to create an opera (joint compositions a practice Ibert in particular pursued it seems). The libretto was created by the prolific Henri Cain (many operas for Massenet as example) based on the Rostand play, then ruthlessly modified by the composers.

Stéphanie D'Oustrac as Napoleon II reinventing the Battle of Wagram

Stéphanie D'Oustrac as Napoleon II reinventing the Battle of Wagram

Ibert composed acts I and V, Honegger wrote II, III and IV, acts I, III and V are based largely on Viennese walzes much in keeping with the boulevard musical popular in Paris between the world wars. Honegger proves himself again a formidable dramatic composer in Acts II and particularly in Act IV which was an evocation of the stunning victory of Napoleon I at the battle of Wagram. Ibert interspersed some lovely airs in Act I and engineered a lovely, touching death in Act V. Both composers created sophisticated music easily accessible to a broad, early mid-twentieth century Parisian public.

The first and biggest problem of the evening was that the program booklet proclaimed no historical context for the opera. Most of us were in the dark, after all the happenings are a minor footnote to history. The program contained only the biographies of the artists plus self-congratulatory notes by the stage director. A “synopsis” stated only that the story is the pathetic attempt to restore Napoleon II as emperor of France. Period. With absolutely no context provided we were forced to keep our eyes glued on the supertitles, deciphering the alexandrines as best we could to create the story that was unfolding way down there on the stage.

And in fact it is a good story, well told by messieurs Ibert and Honegger.

Among other problems of the evening was the Aiglon herself, Stéphanie D’Oustrac who was suffering from a bad cold. In spite of this Mme. D’Oustrac managed a total performance, creating the youth, vulnerability, idealism, naïveté and delusion of the 21 year-old soldier in often very beautiful voice, and even in the passages in which she was vocally restrained the poetic voice of the Aiglon was never lost. It was a tour de force performance by a very special artist.

The remainder of the cast did not achieve the stature sufficient to support such a performance. There were those who were viable and those who were not, those who could sing and those who could not, those who were too young or too old for their roles. In particular the role of Flambeau, the faithful footman who naively deludes the young soldier, demanded an artist of accomplishment and stature. Such an artist was not provided.

Franco Pomponi as Metternich

Franco Pomponi as Metternich

This was a remount of a 2004 Marseille production by the metteur en scène team Moshe Leiser and Patrice Caurier. It is typical of their style which is quite spare but very precise both in decor and by focus of light — characters are placed in specific shafts, lines and pools of light for specific and powerful moments of revelation. It can be very effective. The remount by former Marseille Opera directeur général Renée Auphan did not effect the style, hampered by poor casting as well as by attempting to recreate such a precise production so long after it was fresh.

If anything went right it was the pit! Conductor Jean-Yves Ossonce coaxed the Marseille orchestra to beautiful playing, capturing the spirit of the waltzes, the sweetness of the airs, and the dramatic force and colors of the Honegger acts. The pit did indeed make a fine recommendation for this piece to find its way occasionally onto repertory starved, adventurous stages around the world.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

L’Aiglon: Stéphanie D’Oustrac; Thérèse de Lorget: Ludivine Gombert; Marie Louise: Bénédicte Rousseno; La Comtesse Camerata: Sandrine Eyglier; Fanny Elssler: Laurence Janot; Isabelle, le Manteau vénitien: Caroline Gea; Flambeau Marc Barrard; Le Prince Metternich: Franco Pomponi; Le Maréchal Marmont: Antoine Garcin; Frédéric de Gentz: Yves Coudray; L’Attaché militaire français: Éric Vignau; Le Chevalier de Prokesch-Osten: Yann Toussaint; Arlequin: Anas Seguin; Polichinelle, un Matassin: Camille Tresmontant; Un Gilles: Frédéric Leroy. Chorus and Orchestra of the Opera de Marseille. Conductor: Jean-Yves Ossance; Production: Patrice Caurier and Moshe Leiser; Metteur en scène: Renée Auphan; Décors: Christian Fenouillat; Costumes Agostino Cavalca; Lumières: Olivier Modol d'après original lighting designer Christophe Forey. The Opéra de Marseille, February 16, 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Aiglon_Marseille1.png

product=yes

product_title=L’Aiglon in Marseille

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Stéphanie D’Oustrac as Napoleon II [All photos courtesy of the Opéra de Marseille]

February 18, 2016

Norma , ENO

English National Opera's first ever production of Bellini's Norma opened at the London Coliseum on 17 February 2016 at a time when the company is particularly in the spotlight. The production was originally seen at Opera North in 2012. Christopher Alden directed, with designs by Charles Edwards. The young American soprano Marjorie Owens sang Norma, with Peter Auty as Pollione, Jennifer Holloway as Adalgisa and James Creswell as Oroveso. Stephen Lord, the music director of Opera Theatre Saint Louis, conducted.

The challenge for any director is to find a setting for Bellini's opera which provides the right dramatic intensity of the struggle between Gauls and Romans (one that with the benefit of hindsight we know to be doomed), without the possibly risible elements that arise from doing it in togas. Christopher Alden's production seemed to be based in a 19th century Amish-like sect of wood workers and foresters, with the 'Romans' marked out as capitalist exploiters; both Peter Auty's Pollione and Adrian Dwyer's Flavio were dressed in smart 19th century frock coats and top hats in marked contrast to the backwoods 'Gauls'. Charles Edwards set was an impressive yet simple wood clad box (admirably assisting the singers), with a huge tree trunk into which the 'Druids' carved runic like figures and which, thanks to a system of pulleys, was raised and lowered. This formed the centre-piece of the 'Gauls' cult which seemed to involve imbibing narcotic fumes to induce a trance. For my taste, Alden was a little too interested in the minutiae of the cult, with a great deal of business around the tree, the narcotics, a bible like book and a significant use of axes. And visually the beauties of the set did not carry over into the depressingly sludge coloured costuming

I think the production would have been stronger if it had been more abstract, but Christopher Alden's productions are rarely discreet. This was full of his usual trademarks including extremes of behaviour, a mistrust of the stage directions which was almost wilful and a sense of expressionist drama which, at its best, can heighten the musical experience. At the London Coliseum we have recently seen and heard how Christopher Alden's approach can work wonders with composers like Janacek, but I was less convinced by his taking this approach to Bellini. Too often the stylised behaviour and intense violence on stage seemed at odds to the music in a way which was distracting rather than producing creative dialogue.

Peter Auty, Jennifer Holloway, Marjorie Owens, Eleanor Inglis and Adrian Dwyer

Peter Auty, Jennifer Holloway, Marjorie Owens, Eleanor Inglis and Adrian Dwyer

As Norma, Marjorie Owens displayed a big, bright voice with an admirable freedom throughout the range, with only a hint of tightness at the very top which is entirely attributable to the effects of a prominent first night. She is a soprano in the mould of Jane Eaglen (whom I heard as Norma with Scottish Opera), and Rita Hunter (whom I only heard on record in the role). Currently she is singing the title roles in Aida and Strauss's Ariadne auf Naxos, plus jugend-dramatisch roles such as Senta (Der fliegende Hollander).

Norma is a big sing and the soprano is rarely off the stage and much of the drama is developed in a series of duets and trios. But the challenge for a soprano like Owens is not just the stamina required but to be able to sing the fioriture cleanly, evenly and expressively. Owens managed this with creditable honours. Her opening cavatina and cabaletta (which starts with the famous 'Casta diva') showed that Owens could spin a strong line which was not a little elegant and combine power with a sense of the shape of Bellini's music. Perhaps the passage-work was not quite pin-point but it was damn fine.

Another challenge of this role is to marry up the music and text with an intensity of purpose (something which Callas demonstrated brilliantly). Owens showed that she could do this, here scene where she contemplates killing her children was viscerally intense with every note counting, despite some ludicrous axe waving which was required of her by Alden. Elsewhere, I sometimes felt that a care for the beauty of line took precedence, and wanted her to perform with a bit more risk and a bit more bite. She enunciated George Hall's new translation admirably, but could have relished the text more. All in all this was a notable assumption and a performance which will certainly deepen and develop.

Jennifer Holloway is a lyric mezzo-soprano who has been seen at the London Coliseum as Musetta (La Boheme) and Orlovsky (Die Fledermaus). Not a bel canto specialist, she brought a lyric warmth to the role of Adalgisa and a nice intensity which chimed in with Alden's production. She managed to create a sense of youth without seeming too Mumsy yet not compromising the warmth of her tone. Not all the passage-work was free from smudging, but she combined well with Marjorie Owens in the duets. At the moment some bits seemed a little careful, but there were enough moments of magic to make me suspect that this partnership will flourish.

Peter Auty's Pollione was more of an archetype than a real person. Both Auty and Dwyer spent far more time on stage than Bellini might have expected, providing angry, casually exploitative presences. Unfortunately rather than seeming threatening, much of this verged on risible posturing. Auty sang Pollione nobly and strongly, providing a firmness of purpose in the great trio (with Owens and Holloway) which concluded Act One. Yet it was a performance which did not quite spark to anger, and the final denouement with Owens seem solidly creditable, but lacking just that edge of intensity.

James Creswell was an incisive and commanding Oroveso, dominating his fellow 'Gauls' yet singing with a sense of shape and purpose. Valerie Reid as Clotilde was certainly not the callow girl that Clotilde usually is, and Reid brought a wonderfully fierce intensity to her portrayal. Adrian Dwyer as Flavio sang his duet with Auty's Pollione with fine style, so it was a shame that he was disembowelled by the 'Gauls' for his pains! Felix Warren and Samuel Murray were Norma’s rather intense two children.

The chorus were on stunning form and were rightly applauded at the end. They brought a strength and intensity to the choruses which is necessary to make the 'Gauls' believable in their anger, the chorus also brought a sense of belief in the production so that they invested Alden's detailed action with real purpose.

This was a big boned, traditional performance, with Stephen Lord conducting an up front, sometimes loud, account of the score. There was no hint of period style (such as Charles Mackerras might have brought to the performance) and no thought at re-thinking the voice types and relationships such as happened at Cecilia Bartoli's Salzburg performances of the opera. Within these parameters, Lord and the orchestra were were fine accompanists of the singers, and brought out the marches in stirring fashion.

George Hall's admirably straightforward translation was clear and direct, though it did not quite get rid of that sense of strangeness at hearing Bellini in English. And the performance made me realise quite how intimately Bellini's music is bound up into the sound and the poetics of the Italian libretto.

I do not wish to decry the performances at the London Coliseum, and I realise that the exigencies of casting particularly in English make the perfect cast difficult to achieve. But at a time when English National Opera is under such close scrutiny, and at time when there is a sense of questioning as to exactly what the company is for, it was a shame that three of the leading roles in the opera were cast with Americans.

It was wonderful to see bel canto back at the London Coliseum, the serious operas of Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti are no where near frequent enough visitors. I do hope that this production of Norma returns soon as I feel that it has the potential to grow and develop.

Robert Hugill

Cast and production information:

Marjorie Owens: Norma, Peter Auty: Pollione, Jennifer Holloway:

Adalgisa, James Creswell: Oroveso, Valerie Reid: Clotidle, Adrian Dwyer:

Flavio, Felix Warren and Samuel Murray: Norma’s children. Director:

Christopher Alden, Set Designer: Charles Edwards, Costume designer: Sue

Willmington, Lighting Designer: Adam Silverman. Conductor: Stephen Lord

English National Opera at the London Coliseum, 17 February 2015.

Photos by Alastair Muir

Schubert: The Complete Songs

The songs were grouped by poet, and we began with settings of six poems by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe — a poet who preferred composers to take a direct approach to setting his poems: that is, to retain the structure of his texts and avoid overly fancy and heavy piano accompaniments.

Schubert often treats his poets’ work with much greater freedom, digression and complexity than Goethe desired, but the single-strophe songs offered here revealed the composer’s ability to turn these brief texts into spell-binding musical miniatures. Johnson’s chords rippled gently at the start of ‘Meeres Stille’ (Calm sea), delicately supporting the carefully unfolding tenor melody. Bostridge imbued the simple line with great profundity: the openness of the vowels, ‘Glatte Fläche’ (glassy surface), permitted a momentary flash of brightness, before the dark descent into ‘deadly silence’. The extreme slowness of ‘Wandrers Nachtlied I’ (Wanderer’s night-song) established an expressive intensity which strengthened into rhetoric with the troubled question, ‘Was soll all der Schmerz und Lust?’ (What use is all this joy and pain?). If Bostridge did not quite control the first high, quiet floating reply, ‘Süßer Friede!’ (Sweet peace!), the enriched repetition was warmly persuasive, but the consolations of this song were cruelly swept aside by ‘Wonne der Wehmut’ (Delight in sadness), where Bostridge coloured his voice with a slightly harder ‘edge’ to convey the poet-speaker’s self-consoling melancholy. Goethe’s six-line poem equates ‘eternal’ (ewigen) love with ‘unhappy’ (unglücklicher) love — a simple alteration in the two final lines (which repeat the opening lines) confirms the Romantic conceit — and Bostridge, ever alert to textual nuance, made much of the agonised dissonance, aided by Johnson’s biting accent, to convey the speaker’s pain; a pain, which was subsumed and embraced in the consonant repetitions of Schubert’s closing phrase, ‘Trocknet nicht’ (Grow not dry).

The tempo of ‘An den Mond’ was slower than my recollections of other performances by Bostridge of this song; I thought that it made the opening more tense with anticipation, and it also made for greater contrast with the subsequent forward momentum, ‘Fließe, Fließem lieber Fluß!’ (Flow, flow on, beloved river!), which was aided by Johnson’s even, undulating quavers. ‘Jägers Abendlied’ (Huntsman’s evening song) and ‘An Schwager Kronos’ (To Coachman Chronos) were marvellously intense counterparts to the single-strophe songs, though — uncharacteristically — the text of the former was distinctly approximate in places. There was imprecision, too, in the booming piano octaves which open the latter, and while the wide, glorious vistas opened magically as the horseman crested the hill, I’d have liked more staccato definition in the pounding accompaniment triplets.

Now largely forgotten as a poet, Johann Baptist Mayrhofer had a considerable influence on Schubert’s musical and personal development, and the composer set 47 songs and two operas to Mayrhofer’s texts. The poet was described by Johannes Brahms as the ‘ernsthafteste’ (most serious) of Schubert’s friends, and it was no surprise that the ten settings which followed took us into more complex and, at times, obscure psychological and mythological realms, in which pain and passion combined in an ambiguous communion.

The strange harmonic lurches of and shifts of tempo of ‘Atys’ are deliberately destabilising, and Bostridge’s telling of the tale of this self-castrating fertility deity’s tragic end was disturbing. (In Mayrhofer’s version of the myth, as the cymbals announce the arrival of his beloved goddess, the unrequited Atys throws himself from a cliff in the forest in a fit of mad frenzy. The tenor, too, staggered (alarmingly at times) as if pierced by the speaker’s pain. Here was the instinctive appreciation of the text’s nuances that we are so used to from Bostridge; the smallest details — a slight injection of intensity at the end of the first stanza was all that was needed to convey the fervour of Atys’ yearning for his homeland — made their mark. And, Johnson was an equally vivid story-teller: the softness of the major-key conclusion to this first stanza was quickly quelled by the darkness of the minor tonality, and the dryness of the punched chords at the start of Atys’ own account of his rage testified to the ferocity of his pent-up fury. The long piano postlude was a superb musical narrative. In ‘Der zürnenden Diana’ (To Diana in her wrath), however, the accompaniment at times overwhelmed the voice and again I found the thick-textured repeating chords occasionally uneven. But the duplicitous goddess’s image, which gladdens Actaeon’s heart even as he dies, was conjured by a beautiful lucidity of texture and smooth but penetrating vocal phrasing, making the hit of the arrow — which seemed almost literally to fell Bostridge — even more acute.

Bostridge’s ability to employ his extensive technical capacities to diverse expressive effect was ever evident. There was not a single song that did not have something to surprise us, or command our attention. The strength of line in ‘An die Freunde’ (To my friends) was noteworthy, emphasising the power of human love — ‘Das freut euch, Guten, freuet euch;/ Die alles is dem Toten gleich’ (rejoice, good friends, rejoice; all this is nothing to the dead) — particularly after the Gothic eeriness of the piano’s chromatic tread at the start. The high-lying melody of ‘Abendstern’ (Evening star) was sweetly and surely phrased, the major-minor alternations bittersweet, as the poet-speaker’s apostrophe to the lovely celestial light paradoxically conveyed his own terrestrial alienation. ‘Einsamkeit’ (Solitude) was, quite simply, breath-taking in its dramatic and musical range, and its philosophical insight.

While some of the Mayrhofer settings are well-known, it was good to hear some unfamiliar songs too: ‘Wie Ulfru fischt’ (Ulfru fishing) presented another indistinct protagonist who longs for refuge from man’s insecurities, dilemmas and disappointments — expressed by the furious unrelenting quavers of the accompaniment and the determined onward march of the vocal line — and whose surprising identification with the fish whom he hunts leads him to long to share the blithe tranquillity of the fishes’ sanctuary. The entry of the voice in ‘Freiwilliges Versinken’ (Voluntary oblivion) — on a weak beat and into cloudy harmonic territory, amid piano inner-voice trills — was wrong-footing. Here, the power of Bostridge’s lower register together with the fragmentation of the vocal line created a hypnotic sense of disintegration, while the intimations of release suggested by the concluding hints of major tonality, and the tenor’s wonderfully controlled upwards appoggiatura, spilled into, and were extended by, Johnson’s expressive piano postlude. ‘Auflösug’ (Dissolution) was an apocalyptic whirlwind — again, there was a danger that the voice might be overshadowed by the piano’s tumult — in which the poet-speaker longs for the world to dissolve in self-consuming exhilaration. But, there were surprises here, too, in the astonishing final line in which the low tenor phrase was subsumed within the piano’s shimmering ‘ätherischen Chöre’ (ethereal choirs).

The final sequence of six songs was devoted to settings of Ernst Konrad Friedrich Schulze. ‘Die liebliche Stern’ (The lovely star) was sung with dulcet beauty; in contrast, in ‘Tiefes Leid’ (Deep sorrow) Bostridge turned a burning, accusative gaze upon the audience, pulling the slow pulse this way and that to embody the poet-speaker’s own mental anguish — ‘Ich bin von aller Ruh gechieden,/ Ich treib’ umher auf wilder Flut;’ (I have lost all peace of mind and drift on wild waters), and retreating into introspection in the whispered lines, ‘Nicht weck’ ich sie mit meinen Schritten/ In ihrer dunlen Einsamkeit.’ (I shall not wake them with my footsteps in their dark solitude.) In ‘Lebensmut’ (Courage for living), despite the piano’s heroic summons, Bostridge seemed overcome by weariness as the poet-speaker faced the sapping struggles of life; leaning onto and into the piano (in which he had placed a score) it seemed that the tenor might succumb to the disillusionment and collapse which baits the speaker. Both ‘Im Walde’ (In the forest) and ‘Auf der Brücke’ (On the bridge) were characterised by strong unity of interpretation. Finally, after the dreamy delusions of ‘In Frühling’ (In Spring), the final song, ‘Über Wildemann (Above Wildemann), concluded our journey. The sublime mountain landscape (Wildemann is a small town in the Harz highlands) with its roaring winds, rushing rivers and verdant meadows offered tempting consolation to the tormented poet-speaker in the central major-key verses, but at the final reckoning there was only alienation, as the final verse drove onwards with grim obsessiveness.

Claire Seymour

Performers and programme:

Ian Bostridge, tenor; Graham Johnson, piano.

Meeres Stille, Wandrers Nachtlied I, An den Mond, Wonne der Wehmut, Jägers Abendlied, An Schwager Kronos; Geheimnis, Wie Ulfru fischt, Atys, Einsamkeit, An die Freunde, Freiwilliges Versinken, Der zürnenden Diana, Abendstern, Auflösung, Gondelfahrer; Im Walde, Der liebliche Stern, Auf der Brücke, Tiefes Lied, Lebensmut, Im Frühling, Über Wildemann. Wigmore Hall, London, Tuesday 16th February 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Franz-Schubert.png image_description=Franz Schubert product=yes product_title=Schubert: The Complete Songs product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Franz SchubertFebruary 17, 2016

M is for Man, Music and Mystery

Characteristically cerebral yet playful, the film opens with a logo, ‘Not Mozart’, and a Magritte-like image of Mozart’s familiar silhouette, complete with periwig, minus his visage. The subsequent video-collage constructs the ‘man’ and ‘musician’ through the parts, and absences, which form the whole.

The Barbican Centre’s celebration of the music Louis Andriessen, takes its title from Greenaway. This series of performances and events, by the Britten Sinfonia and BBC Symphony Orchestra, similarly places side-by-side the eclectic influences - Bach, Stravinsky, Mondrian, Dante - from which Andriessen has drawn inspiration and reveals the composer’s distinctive musical voice.

In La Passione, Andriessen’s 2002 song-cycle on texts by the Italian poet Dino Campana (1885-1932), the two soloists, singer and violinist, are both accomplices and adversaries. Though stylistically and formally the work has more in common with Stravinsky than with Bach, there is a nod in the direction of the latter’s Passions in the quasi-obbligato function of the violin part, which, in Andriessen’s words, ‘shadows the voice in a diabolic way, exploring the threatening nature of much of the poetry, like the world of a Bosch painting’.

Britten Sinfonia [Photo by Harry Rankin]

Britten Sinfonia [Photo by Harry Rankin]

The work was composed for, and inspired by, Andriessen’s oft and close collaborator Italian mezzo soprano Cristina Zavalloni and violinist Monica Germino; the latter was indisposed on this occasion, but her replacement, Frederieke Saeijs, playing with considerable virtuosity and composure, was as immersed in Campana’s surreal hinterland as Zavalloni. Standing to left and right of the tightly arranged ensemble, the (amplified) soloists dramatized the poet’s mental anguish - Campana was troubled by mental health problems and spent the last 14 years of his life in a psychiatric clinic near Florence - Saeijs embodying a demonic presence in the poet-speaker’s mind. Campana’s strange symbolist texts depict an autobiographical ‘journey’ - physical and spiritual - from Marradi, through Bologna, Genova and on to Argentina. Zavalloni conveyed the terrors and travails of his quest for an ‘eternal moment’ which will bring peace, with visceral engagement, entering the poet’s fantastical, sometimes gruesome, dream-collage, with total commitment: indeed, some may have found her flinching, swaying, kneeling and hand-gesturing to be distracting.

Zavanolli did not neglect the lyricism in the pain, the sweetness in despair, and demonstrated enormous vocal versatility; if at times there were shrieks or sobs, and some problems with tuning at the top, then this did not seem out of keeping with the nature of the work. The mezzo soprano’s constantly changing vocal colour captured the full range of the text’s emotions, from ennui to elation, hallucination to pained lucidity. She relished the vocal glissandi and negotiated Andriessen’s awkward intervallic leaps, which convey the emotional instability which both disturbs and defines the poet-speaker, with unnerving ease.

Biting, angular brass fanfares herald the first song, ‘Una Canzone Si Rompe’ (A Song Breaks) - and the brass form a stable core in the instrumental sound-world, against the shifting colours of synthesisers, guitars, pianos, cimbalom, woodwind, strings and percussion. Zavalloni was a theatrical presence from the first, lured into the emotional drama by the orchestra’s persuasive syncopations. ‘La Sera di Fiera’ (The Evening of the Fair) was assertive but the singer slipped into more lyrical reverie with a memory, ‘Era la notte/ Di fiera della perfida Babele’ (It was the night of the fair perfidious Babel), and span a beguiling tale whose bizarre visions of ‘grotesque whistling’, ‘angelic little bells’, prostitutes’ cries and ‘pantomimes of Ophelia’ accrued a frightening, propelling energy. The entry of the violin, slow-moving and shrouded in dissonant harmonic arguments, exposed the poet-speaker’s vulnerability, which comes from absence of love: ‘Eppure il cuore porta del dolore:/ Lasciano il cuore mio di porta in porta.’ Campana infused the swelling final syllable with all the ‘pain’ which leaves ‘my heart in portal after portal’.

The wild vigour of Saeijs’ cadenza-like outburst - fiercely punched out low tones batting with the raging of the upper strings - embodied the ‘horned black form’ which haunts the following song, ‘Una Forma Nera Cornuta’, the searing strength of the violin tone calling forth an orchestra tumult. Saeijs was an eerie interloper in ‘O Satana’ (O Satan). Zavanolli addressed her antagonist with oratorical power, before the voice withdrew, sapped of its strength, and - with a vocal slide that signalled the poet-speaker’s desperation and defencelessness - called on the dark presence to ‘take pity on my long suffering!’

‘Sul Treno in Corsa’ (On the Moving Train) began with a nightmarish melange of jerking lurches and piercing whistles, before the rhythms acquired coherence and urgency: ‘la corsa penetrava, penetrava con la velocita di una cataclisma’ (the motion penetrated, penetrated with the speed of a cataclysm). Zavanolli literally squared up to her alter ego, asking ‘era la morte?/ Od era la vita?’ (was it death? Or was it life?) The final song, ‘Il Russo’ (The Russian) gave a bleak answer. The text depicts the execution of an unnamed Russian soldier. The crystalline, high violin line - almost vibrato-less, its intensity formed by the purity of tone and the focus of the bowed strokes - the juxtaposition of high and low wind, and the infiltration of an array of percussive knocks and pluckings by the violins, electric and bass guitars, and cimbalom, recreated the harrowing landscape, literal and figurative, of WW1. Saeijs, at first soaring confidently then challenging with vicious pizzicatos, baited the singer. But, an ‘eternal moment’, if not peace, was intimated in stillness of the poet-speaker’s realisation, ‘il Russo era stato ucciso’ (the Russian had been killed).

Conductor Clark Rundell was an unobtrusive yet reassuring presence, guiding the performers fluently through the contrasting songs, which flowed as an organic, single-movement entity. The Britten Sinfonia demonstrated unflagging energy as they surged through the hurtling, insistent - at times astringent - lines of Andriessen’s score.