April 29, 2016

A Conversation with Sir Nicholas Jackson

Indeed, the ‘Fireside Pantomime’ indulges in fiancé-swapping and satirical scepticism about love and faithfulness which would not be out of place in Così fan tutte.

So, we should not be surprised that Sir Nicholas Jackson — composer, organist and harpsichord — has recognised in the text’s wit, burlesque, swift character-sketching and dramatic vignettes, the perfect ingredients for an opera. (In fact, Thackeray’s satire had previously caught the attention of the English pianist, conductor and composer Ethel Leginska, who conducted the premiere of her second opera, The Rose and the Ring (1932) in Los Angeles on 23 February 1957, though I could find no evidence of the work having been performed subsequently.) Sir Nicholas’s The Rose and the Ring will receive its first performance at the Drapers’ Hall in the City of London on 4th May.

Charterhouse

Charterhouse

In conversation, Sir Nicholas explained that the origins of the project lay in coincidental but fortunate happenstance. Sir Nicholas’s grandfather, the nineteenth-century architect Sir T.G. Jackson — responsible for landmarks such as the Bridge of Sighs in Oxford and Radley Chapel — had known Thackeray’s daughter, and when rummaging through some books that he had inherited, Sir Nicholas came upon a copy of The Rose and the Ring and was instantly struck by its irresistible charm. Having recently made an arrangement for wind quintet and harpsichord of a sonata by Domenico Scarlatti, it seemed to Sir Nicholas that the juxtaposition of the rhetoric of eighteenth-century musical virtuosity and nineteenth-century literary enchant would have piquant, invigorating results. So, he set about identifying sonatas by Scarlatti that might be appropriate for adaptation and orchestration.

As an internationally renowned harpsichordist, Sir Nicholas has had a long association with Scarlatti; he has performed and recorded about 40 of the composer’s 555 sonatas and is familiar with many more of Scarlatti’s works for keyboard. This suggests that selecting the specific sonatas apt for transformation would have been a straightforward task; but, Sir Nicholas explained that, although he initially had strong and clear views about which sonatas would ‘work’, he repeatedly found that his expectations were mistaken.

The prevailing binary form sonatas proved less suitable than some of the less well-known longer works and it took some time to determine those ripe for adaptation. One imagines that the compositional complexity of the works might also present problems, but listening to the afore-mentioned Sextet ( Nimbus NI6301) I found the conversational character of Sir Nicholas’s arrangement inherently dramatic, as the woodwind instruments first punctuated the cadences of the keyboard’s intricate lines, then nonchalantly ran away with the melodic threads, spinning their own elaborations — mimicking Scarlatti’s own unconventional voice-leading. The nasal quality of the deep bassoon offered a characterful bass, and I was reminded that despite the apparent simplicity and limitation of Scarlatti’s resources, the composer employed an extended compass and mined a variety of sonorities and textures. The Rose and the Ring will employ both woodwind and strings, arranged antiphonally, thereby enhancing the dialogic nature of the score.

The swiftness and athleticism of Scarlatti’s music would seem to endow it with inherent dramatic properties but a high proportion of Scarlatti sonatas are fast and Sir Nicholas explained that this presents the singers with several challenges, not least fitting in the text. In addition, the original keys have been preserved with the result that at times the vocal lines lie quite high. But, listening to the Sextet it seems to me that Scarlatti’s use of repetition and rhetorical pauses, allied with harmonic audacity and far-flung modulations will prove a perfect match for the ingenious twists and turns of Thackeray’s absurd plot.

Indeed, as Sir Nicholas recalled, the esteemed Scarlatti scholar Ralph Kirkpatrick remarked that ‘[Scarlatti] has captured the click of castanets, the strumming of guitars, the thud of muffled drums, the harsh bitter wail of gypsy lament, the overwhelming gaiety of the village band, and above all the wiry tension of the Spanish dance’, adding that the composer’s music ranges ‘the courtly to the savage, from an almost saccharine urbanity to an acrid violence. Its gaiety is all the more intense for an undertone of tragedy. Its moments of meditative melancholy are at times overwhelmed by a surge of extrovert operatic passion’.

In preparing the libretto, Sir Nicholas endeavoured to retain as much of Thackeray’s text as possible. To assist an audience possibly unfamiliar with the tale, Sir Nicholas’s wife has ‘coloured’ several of the drawings with which Thackeray — who had once intended a career as an illustrator and who contributed regularly to Punch — had himself illustrated his novel, and these will be projected during the performance. In addition, some of the 24 scenes will be linked by narration, delivered by the actor Tim Pigott-Smith.

The cast of exciting young singers comprises several graduates of the International Opera School at the Royal College of Music, including 2012 Kathleen Ferrier Award finalist soprano Robyn Parton —the current holder of the Helen Clarke Award from Garsington Opera, who in September 2015 made her main stage debut as Barbarina in the ROH’s Le nozze di Figaro; bass-baritone Edward Grint, a London Handel Competition finalist in 2014, and Scottish mezzo-soprano; and, Katie Coventry, who is currently training at the International Opera School with Tim Evan-Jones. They are joined by fellow RCM graduates tenors Peter Aisher and William Morgan (the latter is National Opera Studio young artist in 2015-16) and Scottish-Iranian bass-baritone Michael Mofidian, who is studying at the Royal Academy of Music.

The singers will be accompanied by Concertante of London, the baroque ensemble which is led by violinist Madeleine Easton and of which Sir Nicholas is director. Indeed, the instrumentalists (who will perform on modern instruments) form a body of players with considerable experience of performing Sir Nicholas’s reconstructions and arrangements, having previously presented his ‘completion’ of William Lawes’ masqueThe Triumph of Peace and his realisation of Bach’s Musical Offering for four players ( SOMMCD 077).

Following the Drapers’ Hall performance, The Rose and the Ring will receive a public performance on 5th May at The Charterhouse — and it will undoubtedly be a ‘merrier’ occasion than Thackeray’s own ‘first night’ at the school in 1822, when he encountered ‘hard bed, hard words, strange boys bullying, and laughing, and jarring you with their hateful merriment’. Following the Charterhouse performance, the proceeds of which are being donated to the Charterhouse Charity ( Suttons Hospital) , the cast will gather on 7th May to record the work for release later in the year.

The Rose and the Ring is not Sir Nicholas’s first opera. In 1995 The Reluctant Highwayman was performed at Broomhill; subsequently revised, the three-act work employs similar forces to The Ring and the Rose. Excerpts have been recorded ( Nimbus NI6301) and Sir Nicholas hopes that the opera might be recorded in its entirety in the future.

But, before that we have the premiere of The Rose and the Ring to look forward to, and I anticipate an entertaining and thought-provoking evening in which social short-comings and human vanity are set alongside the sorrows attendant on love, and presented in striking music which is both elegant lavish.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Jackson-Nicholas-01.png image_description=Sir Nicholas Jackson product=yes product_title=A Conversation with Sir Nicholas Jackson product_by=An interview by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Sir Nicholas JacksonPacific Opera Project Recreates Mozart and Salieri Contest

The contest was part of the celebration of the marriage of the emperor’s sister, Christine Marie, to the Governor General of the Netherlands. After dinner with incidental music by Salieri, singers and instrumental musicians performed operas by unnamed composers. After the first show, the audience turned their chairs around to watch the second performance at the opposite end of the hall.

On April 17, 2016, Pacific Opera Project (POP) created the same atmosphere for its performance of the same operas, Mozart’s The Impressario (Der Schauspieldirektor) and Salieri’s Prima la Musica e Poi le Parole (First the Music and Then the Words) at the recital-sized hall of the South Pasadena Library. Since The Impressario’s original text contained jokes that were popular in the 1780s, POP presented it in English with an updated topical libretto by Josh and Kelsey Shaw. POP presented the Salieri work in the original Italian text by Giovanni Casti along with projected supertitles. For both operas, Maestro Stephen Karr led the chamber orchestra in an expert accompaniment that gave the singers the leeway they needed to sing their music with elegant phrasing while creating believable characters on the stage.

Baritone Andy Papas was a feisty Impressario whose acting set a high standard for the rest of the cast. As The Poet, Alex Boyd created a convincing character and intoned his topical material with a memorable baritone sound. The tenor voice and comedic talent of Christopher Anderson West added to the setting of the stage for the appearances of competing sopranos. Called Mesdames Herz and Silberklang in 1786, famous sopranos Caterina Cavalieri and the composer’s sister-in-law, Aloysia Weber, sang those roles in the Mozart entry. POP called the sopranos Everly Squills and Meryll Shrills. Karen Hogle-Brown sang Squills with the creamy tones of her smooth lyric soprano voice while Brooke deRosa sang Shrills with exquisite coloratura technique.

After a short intermission, members of the audience drank refreshments and turned their chairs around to see the second opera staged at the other end of the auditorium. As with the first presentation, Maggie Green designed the attractive and sometimes amusing costumes.

In Prima la Musica, Count Opizio contracted the composer and poet to write a new opera. When the curtain opens it has to be finished in four days. The composer has already written the score, but the poet has not been able to produce a useable text. Andy Papas was a credible composer who could not get his poet to produce a libretto. As The Poet, Alex Boyd made us understand his frustration as he sang with stentorian tones. Francesco Benucci created the role of The Poet for Salieri and, a few months later, the title role in The Marriage of Figaro for Mozart. I’d like to hear Boyd as Figaro, too.

Nancy Storace, the first Eleonora, was also the first Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro. In the POP performance, popular soprano Tracy Cox sang Eleonora, the prima donna hired by the Count. Cox is an artist who will probably be seen performing with larger companies in the near future and she was a perfect fit for this diva role. Her tones were full and round, her articulation clear and her technique unmarred by the slightest flaw. As Tonina, the comedic singer with whom The Poet had a relationship, Justine Aronson used a variety of expressive devices to create her character while singing with clarity of tone.

Pacific Opera Project always presents extraordinary new artists to savor and interesting musical works to contemplate. This was but one example of their presentation. After their summer hiatus, they will be doing Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio and Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress. I, for one, don’t want to miss them.

Maria Nockin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Double%20Bill%20Press%2011.png

image_description=Photo by Martha Benedict

product=yes

product_title=Pacific Opera Project Recreates Mozart and Salieri Contest

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above photo by Martha Benedict

Powerful chemistry in La Cenerentola in Cologne

On the way back from a semi-staged production of Rossini’s La Cenerentola the driver told me it might not be until 2020 until the site is built. But with two auditoriums in the Staatenhaus, Oper Köln has a very lively production slate. You could easily spend several days here enjoying opera.

Alexander Soddy led the Gürzenich Orchester Köln with amicable enthusiasm. Among comedic timing from the woodwind instruments especially the bassoons popped. The conductor encouraged his strings into a sweeping momentum during Rossini’s frenzied passages. Most of the time he balanced his musicians, the men of the Chor Opera Köln, and soloists with great results. However, in several moments the stepsisters and even in a few instances Don Ramiro were barely audible.

Debuting in these roles and repulsive in full force, Judith Thielsen (Tisbe) and Dongmin Lee (Clorinde) perfectly irritated as the stepsisters: their voices deliberately unpleasant and annoying. They gave the audience plenty of reason to smirk at them. Add to that their nauseatingly pink and green gowns, and they convincingly filled their parts. Carlo Lepore as Don Magnifico belted out his passages with great indignation. Andrei Bondarenko charmed as Dandini, while he vocally impressed with his stamina and musicality in “Come un’ape ne’ giorni d’aprile”.

As he rolled in on a skateboard, sunglasses and all, Scala’s Don Ramiro was more charming than a Disney prince. His regal voice had moments of glory with his great range. Outside of his interactions with Angelina, his highpoint solo occurred in the second act in “Si, ritrovarla io giuro”, where he revealed the powerful reach and flexibility of his voice, as well as his softer side during the subdued passages.

His chemistry with Adriana Bastidas Gamboa could be felt deeply. Indeed they captivated with their duets. While she initially came across a bit stiff in her modesty as Angelina, she lit up in her interaction with Scala. Intense romance brewed between them, as the two looked each other in the eyes. So convincing, it almost felt a bit voyeuristic to watch. You just wanted to leave these two lovers!

While Bastidas Gamboa did not really persuade as Angelina in Act I, she enchanted in her elegant gown suggesting pure virtue in the second act. Was her singing meant to be so different before and after her metamorphosis? In any case, her passionate duets with Scala were the vocal highlights of the evening. Perhaps stimulated by her chemistry with Scala, but Bastidas Gamboa fearlessly produced Rossini’s vocal acrobatics in “Nacqui all’affanno ... Non piu mesta” and received quite the ovation.

There were some cleverly staged bits. The Staatenhaus’s unflattering stagehand uniforms foreshadow Angelina and Don Ramiro’s destiny when they meet in the first act. And the two singers still managed to look good in them. Later, the gowns added fairytale splendor to the scenes. The men in the choir actively made expressive faces in reaction to the minimal acting on stage. Their mimicry amplified the tone of each scene.

This La Cenerentola was a pleasing engagement with swooning romantic moments as well as laugh-at comedy from the stepsisters and stepfather. The audience enjoyed the evening with plenty of chuckles, encouraging with applause and intermittent bravas for the soloists. The sassy elderly dames next to me surprised me with their clear joy.

Green, purple, blue, and orange, Nicol Hungsberg’s atmospheric lighting with its rich colours complemented Rossini’s vibrant score. The enthusiastic audience response throughout also generated a very warm ambience. The encouragingly high number of young folks surprised and suggested the future of opera is far from dead.

While the Staatenhaus is far from inviting, even a bit chilling, this La Cenerentola in Köln certainly lit up the auditorium, especially for a mere concert.

David Pinedo

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Reunited.png image_description=Scene from La Cenerentola [Photo by Klaus Lefebvre] product=yes product_title=Powerful chemistry in La Cenerentola in Cologne product_by=A review by David Pinedo product_id=Above: Scene from La Cenerentola [Photo by Klaus Lefebvre]April 28, 2016

Tannhäuser: Royal Opera House, London

True, Opera North will bring its concert Ring to the South Bank, but that is a somewhat different matter. Comparisons with serious houses, let alone serious cities, are not encouraging, especially if one widens the comparison to nineteenth-century Italian composers. Quite why is anyone’s guess; the composer is anything but unpopular. More to the point, Wagner and Mozart should stand at the heart of any opera house’s repertory. They can hardly do so if they are so rarely performed.

I mention that not only because it is very important in itself, but because it has serious implications for orchestras. What used to be Bernard Haitink’s orchestra has had a rougher time of things since his departure. Whilst a great conductor - Semyon Bychkov, for instance, in the first run of this production, or more recently, in Die Frau ohne Schatten - can still summon truly great things from the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, its day-to-day experience of core German repertory is fading. Here, under Hartmut Haenchen, there were no particular upsets, but there were only hints at what the orchestra has been capable of, and still might be. Haenchen’s conducting had its moments, but it was the heavenly lengths, and how they might fit together, that were lacking. A penny-plain opening to the Overture suggested ‘authenticist’ tendencies, as if Haenchen would rather be conducting the Dresden Tannhäuser, albeit conducting it a little like ‘period’ Mendelssohn. When it came to the music written for Paris, he seemed to linger and to rush, somewhat arbitrarily. There is stylistic ‘incongruity’, yes, if we want to call it that, but should we not be making something of that, even making it into a virtue?

I suspect that Haenchen’s tempi were, on balance, considerably quicker than Bychkov’s; that was certainly not how it felt, especially in the Venusberg, whose pleasures seemed at times interminable (in the wrong sense). Indeed, the exchanges between Tannhäuser and Venus often sounded alarmingly perfunctory, robbed not only of orchestral ‘cushioning’, but of the direction that Wagner’s orchestra-as-Greek Chorus, even at this stage in his career, offers. Of Beethoven, at least as Wagner would have understood him, there was little: perhaps there was, however, of fashionable, ‘period’ Beethoven-cut-down-to-size. Compared to the most recent other Tannhäuser I had heard, superlatively conducted by Daniel Barenboim in Berlin, this was disappointing.

Disappointing in that very important respect, anyway. There was much more to savour vocally. Peter Seiffert gave a strange performance in the title role: it came and went, seemingly without reason, sometimes, especially in the first act, alarmingly out of tune, at other times spot on, always tireless, even when, understandably, his voice acquired something of an edge in parts of the Rome Narration (movingly despatched). Emma Bell was a wonderful Elisabeth; I do not think I have heard anything finer from her. Sincere but certainly not bland, this Elisabeth’s vocal qualities were subtle yet, where necessary (and it often is!), powerful. Sophie Koch’s Venus was ravishingly sung, words and music in excellent, dramatically productive, balance. Christian Gerhaher’s Wolfram is a known quantity to many of us, of course, but no less welcome was it for that. The startling, almost indecent, yet utterly sincere, beauty of Gerhaher’s delivery was once again something for all to remember. There was no need to force the performance; he could draw us in so as to hear a pin drop. Phrasing was just as exemplary. Ed Lyon’s sweetly-sung, dramatically-committed Walther was another pleasure; if only he had had more to sing. Thank goodness, at least, Walther’s solo, only cut from Paris because the tenor could not sing it, was restored. Stephen Milling's sonorous Landgrave was, quite rightly, especially acclaimed by the audience. Young Raphael Janssens acquitted himself well as the Shepherd Boy. So did the chorus (and extra chorus) of Renato Balsadonna, although I think there was greater precision, and perhaps greater weight, under Bychkov in 2010.

Tim Albery’s production does not seem to have changed very much. The Venusberg scene is strongest, the ballet well choreographed by Jasmin Vardimon. It might have been a little raunchier - Wagner’s music here is, after all, the supreme musical manifestation of desperately trying and failing to achieve sexual climax - but it works well enough. The sense of the Royal Opera House being on stage is interesting in this opera. In a work whose central event is a song contest, who is performing, and why? Alas, nothing is really followed through, so that one cannot even really tell whether such metatheatrical possibilities are intended. We end up with little more than a mild compendium of clichés. One bizarre exception is the appearance of cowbells - there is, frankly, little to see - when Tannhäuser first returns to ‘normality’. Their lack of coordination would have been irritating in Mahler, but here, in Tannhäuser? If I had been Haenchen, or the house, I should have put a stop to it. This was not some interesting musical recomposition; it was just a bit of a mess. The war-torn (Balkan?) setting of the second act I presume to have taken its cue from the Landgrave’s ‘Wenn unser Schwert in blutig ernstern Kämpfen stritt für des deutschen Reiches Majestät’. It would be a stretch, however, to say that post-war deprivation was what Tannhäuser might really be ‘about’, at least without some further work on the director’s part. Albery seems content to let Michael Levine’s set designs do the work for him, which of course they cannot. The third act carries on in much the same way. Very much worth hearing for most of the singing, then, but a restricted view would not penalise you unduly.

Mark Berry

Cast and production information:

Tannhäuser: Peter Seiffert; Elisabeth: Emma Bell; Venus: Sophie Koch; Wolfram von Eschenbach: Christian Gerhaher; Hermann, Landgrave of Thuringia - Stephen Milling; Biterolf: Michael Kraus; Walther von der Vogelweide: Ed Lyon; Heinrich der Schreiber: Samuel Sakker; Reimar von Zweter: Jeremy White; Shepherd Boy: Raphael Janssens; Elisabeth’s Attendants: Kiera Lyness, Deborah Peake-Jones, Louise Armit, Kate McCarney. Tim Albery (director); Jasmin Vardimon (choreography, Venusberg scene); Michael Levine (set designs); Jon Morrell (costumes); David Finn (lighting); Maxime Braham (movement). Royal Opera Chorus and Extra Chorus (chorus master: Renato Balsadonna); Orchestra of the Royal Opera House/Hartmut Haenchen (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Tuesday 26 April 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tannhauser_ROH.png

image_description=Tannhäuser by Tim Albery

product=yes

product_title=Tannhäuser: Royal Opera House, London

product_by=A review by Mark Berry

product_id=Above image by Tim Albery

April 25, 2016

The Golden Cockerel in Düsseldorf

In these times of political madness, the new production of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Golden Cockerel (zoloty petushok) by Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf arrives as a refreshingly funny opera. Dmitry Bertman brings this political farce and sex comedy in a delightfully over-the-top staging that made for a highly entertaining and musically engaging production. If you happen to be in the area, it is definitely worth a trip to Düsseldorf, as it’s also scheduled for next season.

The opera is based on a poem by Pushkin, whom Rimsky-Korsakov greatly admired. Tsar Dodon convinces himself his neighboring country Shemakha will attack. He summons an Astrologer, who gives him a golden cockerel to advise him. The bird reveals the Tsarita of Shemakha desires expansion. The Tsar sends his two sons into battle, but they come out defeated. Although in the original libretto they die, Bertman keeps the opera light on drama and high on comedy, so the sons return at the end.

The second act takes place in Shemakha. To avoid conflict, the Tsarita seduces the Tsar and tricks him into marrying her. While Act III is a bit convoluted dramatically, Bertman directs it with a lighthearted approach. The Astrologer demands the bride during Dodon’s wedding to her, but the Tsar kills the him. Then the bird kills Dodon. In the epilogue, the Astrologer leaves the audience with the message that everyone on stage was unreal, except for the Tsarita and him. Make of that what you will.

Bertman’s Act I opens with Tsar Dodon, his two dunces of sons, and his general in a hottub. The buffoonery of the royals and the incapacitated state of General Polkan set the farcical tone for the rest of the evening. These rampant drunks mix beer and vodka, while brawling and flashing each other. Their behavior starts to make sense, once Tsar Dodon acts the most devious: he feeds the unconscious General milk from a baby bottle. Bertman included many of these suggestive moments that served as provocative comedy..

The highlights of the evening occurred in Act II. On a comical level, Bertman’s production made the audience laugh many times, and Antonina Vesina enchanted with her irresistible vocal acrobatics, especially in the “Hymn to the Sun”. She seemed to sustain her endless high notes without any effort. Her vocal prowess is enough reason to go see this production. The Tsarita’s knowing looks at the audience created some tongue-in-cheek moments.

In several highly rhythmic passages, in which the Russian male temperament seemed to echo, Statsenko kept up with the fast pace and demonstrated intense stamina. The Russian baritone truly impressed in Rimsky-Korsakov’s vocal demands, while delivering plenty of comedy during his seduction by the Tsarina.

In Act III, the Tsar and his entourage return from Shemakha--in this case with lots of tax free shopping from Paris. Bertman creates a vibrant tableaux vivant with the choir in high gear and a full parade. Renée Morloc demonstrated great comedic timing as Amelfa, the Tsar’s secretary. A rich voluptuous voice with a hint of mischief. With turbo blond hair on top of her head and a big caboose, she played off Stetsenko in highly comedic sexual innuendo. In act III, an exasperated Amelfa devours the now roasted cockerel; Morloc proved herself priceless in this scene.

As golden cockerel, Eva Bodorova dressed up in flashy golden costume that would easily seem at home in a Las Vegas show. The man behind me gasped “geil”, a common German word to describe the titillating. Her golden tenue reflected light as she appeared from the sides of the balcony. With her commanding and crisp voice, she drew all the attention to her.

Unrecognisable in his wig and wizarding tenue (one of the imaginative and detailed costumes by Ene-Liss Semper), Cornel Frey offered a creepy, enigmatic air to the Astrologer's voice. Roman Hoza and Corby Welch sang decently. Their mere presence on stage as Tsar’s bumbling offspring added to the political commentary on royal heritage.

Conductor Alex Kober continued to propel the narrative forward in Act III through well paced momentum in the Dusseldorfer Symphoniker. Rimsky-Korsakov’s score consists of lots of exotic colours from the woodwinds. His Sheherazade often came to mind.

In great detail, the conductor punctuated Bertman’s comedy, amplifying the hilarity on stage. Kober effectively balanced the orchestra and the singer, while allowing the choir, prepared by Edward Kurig, to burst with invigorating energy. Although the Russian language was hard to discern.

With a surprising amount of laughs, flashy scenery, and some vocally breathtaking moments, Bertman’s Golden Cockerel comes highly recommended.

David Pinedo

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Der_goldene_Hahn_09_FOTO_HansJoergMichel.png image_description=Scene from The Golden Cockerel [Photo by Hans Jörg Michel] product=yes product_title=The Golden Cockerel in Düsseldorf product_by=A review by David Pinedo product_id=Above: Scene from The Golden CockerelPhoto by Hans Jörg Michel

April 23, 2016

San Diego Opera Presents a Tragic Madama Butterfly

They added color and texture to the setting and placed the scene amid the beauty of a Japanese spring. Cio-Cio San’s red wedding kimono was a beautiful work of art, but many more of Anibal Lapiz’s costumes appeared in soft shades reminiscent of Japanese watercolor paintings. Even the usually flamboyant, swaggering Prince Yamadori wore muted colors.

Latonia Moore was a credible, poignant Butterfly who brought the geisha’s tragedy home. She has a creamy lyric voice that resounded with beauty of tone throughout the auditorium and her phrases were delivered with a quality of tone well suited to the expression of their meaning. Her acting was believable and her characterization of the abandoned young wife became totally convincing. Every woman in the audience could relate Butterfly’s plight to memories of waiting for the phone to ring.

Romanian tenor Teodor Ilincăi has a robust voice with pleasing qualities and the right amount of heft for Pinkerton. He was virile, charming, even ardent, but uncomprehending in the first act when the voices of tenor and soprano blended with great intensity. Later, he showed real horror at what his actions brought about. Baritone Anthony Clark Evans is completing his second year at the Lyric Opera of Chicago’s prestigious Ryan Opera Center. He was a dignified Sharpless who sang with burnished bronze sonorities.

J'Nai Bridges is Suzuki, Anthony Clark Evans is Sharpless and Teodor Ilincai (background) is B.F. Pinkerton

J'Nai Bridges is Suzuki, Anthony Clark Evans is Sharpless and Teodor Ilincai (background) is B.F. Pinkerton

As is usual with San Diego Opera, committed fine artists inhabited the smaller roles. J’Nai Bridges was a caring and compliant Suzuki. Joseph Hu was a thoroughly amusing Goro, Scott Sikon a frightening Bonze, and Bernardo Bermudez a pretentious Yamadori. As Pinkerton’s American wife, Kate, Katerzina Sadej, had no idea of the actual situation until she saw Butterfly. Charles Prestinari’s chorus added musical color to the scenes in which they sang. Because the second and third acts were joined, we heard some of the very beautiful music that Puccini wrote as part of the opera’s first version that depicts the night before Pinkerton returns to the home he kept for Cio-Cio San.

The San Diego Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Yves Abel performed Puccini’s score with impressive dramatic qualities. His tempi were sometimes a bit slow, but he brought out the immense pathos of Puccini’s score. This Butterfly left many patrons weeping tears of sympathy. I left the theater thinking of C. S. Lewis’s comment, "Tragedy is more important than love. Out of all human events, it is tragedy alone that brings people out of their own petty desires and into awareness of other humans' suffering.”

Maria Nockin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/jkwMButterfly_041316_123.png

image_description=Latonia Moore is Cio-Cio San and Teodor Ilincai is B.F. Pinkerton. [Photo by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz]

product=yes

product_title=San Diego Opera Presents a Tragic Madama Butterfly

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Latonia Moore is Cio-Cio San and Teodor Ilincai is B.F. Pinkerton

Photos by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz

Simon Rattle conducts Tristan und Isolde

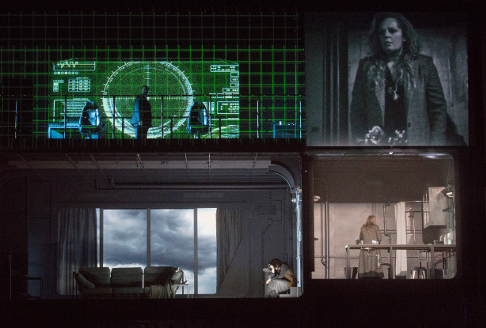

In a letter to Mathilde Wesendonck, Richard Wagner writes about Tristan und Isolde: “I would call my art....the art of transformation. The masterful point in this work is certainly the great scene of the second act”. This sums up Mariusz Treliński’s technically mind blowing Tristan und Isolde. The stage in the first act transforms through highly complex engineering, while the second act was one of the most dazzling, Romantic opera settings I have witnessed. With Simon Rattle at the helm of his Berliner Philharmoniker, the performance resulted in a superlatively transformative experience; however much exhausting in Act III, you would not want to miss it for the world. And with the Herculean Eva-Maria Westbroek as Isolde, the performance in Baden-Baden became an unforgettable memory.

Video projections of a ship at sea during a storm complemented the Prelude in its metaphor for Tristan and Isolde’s tempestuous emotions. At the same time, that ship could have been Captain Rattle’s Berliner. From the opening, the BPO played with astounding intensity. I immediately realised I was in for a very privileged journey.

As Maestro Rattle unfolded Wagner’s luscious tapestry, he ceaselessly generated a resounding depth from his strings. Wagner’s swooning romance and erotic tension overflowed in full force. Dense in texture the leitmotifs resonated deeply. Sir Simon sustains such captivating suspense without interruption that as a listener it was impossible not to feel included in his musical universe. And one cannot forget the men of the Philharmonia Chorus Vienna, who from the pit jolted the piece with their generous energy. In addition, the Festspielhaus greatly amplified the level of musical detail and intensity with its transparent and enveloping acoustics.

As the first act opens, we see a highly complex staging of a military naval vessel. Dark metallic colours dominate. What little light there is, reflects into the audience. The set by Boris Kudlička and Marc Heinz’s lighting impressed as through complex engineering the stage switched its focus: covering three floors, the deck, the stairwell, the Captain’s quarter’s below, and Isolde’s room at the centre.

The stage functioned like a comic book panel that was each time covered and lit from different angles. Through spy footage, Bartek Macias’s videos of Isolde from different angles projected her on the ever changing stage. Although it sounds like too much, this might be true in the end, but for now the energetic dynamics on stage enthralled.

From the bat Ms. Westbroek dazzled dominating the stage: her voice full of violent distrust, as Treliński makes his Isolde a femme fatale before she has fallen in love. The Dutch Diva convinced both in that capacity, as well later as the enamored Isolde later, when her vibrato conquered all.

In Act I, dressed in black, she smokes, drinks, and even slaps Melot, played deviously by Roman Sadnik. Sarah Connolly transformed for Braegene into a persuasive secretary (spectacles and all) highly involved, with a dark but affectionate tone that contrasted Ms. Westbroek in the best of ways. Together they created a sound to behold.

The second act was one of the most memorable opera moments I have had. On stage we see the ship‘s wheelhouse that throughout rotates as the action takes place, eventually establishing the setting for the love duet. But for the Northern Lights morphing around behind the two lovers, all is darkness. The flux of those green lights certainly symbolized the transformative nature of this experience and gave this production a feeling cosmic grandeur.

As Tristan and Isolde breathed in darkness with the Northern Lights in the background, the Berliner’s music gained the foreground and Skelton and Westbroek launched into a captivating “O sink hernieder, Nacht der Liebe”. While Mr Skelton never reached the voluminous vocal heights of Ms. Westbroek, he compensated with authentic sensitivity, including even some glass eyed moments. I imagine Wagner would have loved to witness such indulgent and thoughtfully atmospheric moods for his Gesamtkunstwerk.

Each excessively budgeted production reaches a tipping point. At some point it all becomes too much to absorb. Here it occurred in the final act, when everything turns strangely static. The glaring metallic reflections tortured the audience’s vista; as if trying to keep you awake, but with agitating results.

A sullen ambience emerged and a lone hospital bed made for Kurnewal and Tristan’s interaction. As a brotherly Kurnewal, Michael Nagy commanded the stage, even vocally upstaging Mr. Skelton. Still no matter the musical excellence, a nagging dread permeated the first part of the third act.

With the memory of young Tristan in a broken down home in a projection of a forest, Treliński’s applied psychology felt unnecessary and the video excessively taxed the experience of the third act. Perhaps he wanted to slow down the momentum before Isolde’s Liebestod, but the pause in momentum made it quickly clear how consuming the first two acts had already been.

When she returned, Eva-Maria impressively reignited the musical momentum. For “Das Wiedersehen” she stormed onto the stage creating such an impetus with her electrifying voice. Even more impressively, she brought back the preceding intoxication. Her “Liebestod” closed the evening with such persuasive power, leaving me exhausted, drained, but profoundly changed by the overall experience.

The audience responded with a mighty applause and bravas for Ms Westbroek and Sir Simon, while expected boos met Treliński and his team (this is Tristan und Isolde after all). The staging ended up a bit too extravagant with all its excessive sensory stimulation, but the rendition was superlative in its musical execution. This co-production with Shanghai and Warsaw opera houses, opens the Met’s new season in September...also with Simon Rattle at the helm.

David Pinedo

Cast and production information:

Eva-Maria Westbroek (Isolde); Stuart Skelton (Tristan); Sarah Connolly (Brangäne); Michael Nagy Bass (Kurwenal); Stephen Milling (König Marke); Thomas Ebenstein (Shepherd, Sailor); Roman Sadnik (Melot); Simon Stricker (Steersman). Rundfunkchor Berlin, Simon Halsey (Chorus Master). Berliner Philharmoniker, Sir Simon Rattle (Conductor).

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Femme%20Fatale%20Act%20I.png image_description=Scene from Act I [Photo by Monika Rittershaus] product=yes product_title=Simon Rattle conducts Tristan und Isolde product_by=A review by David Pinedo product_id=Above: Scene from Act IPhotos by Monika Rittershaus

April 20, 2016

San Jose’s Smooth Streetcar Ride

“Lavish” may not be quite the right word, for while Brad Dalton’s direction and scenery were mightily effective, they were daringly spare. The orchestra is placed upstage behind a simple platform that juts out toward the audience over the usual pit. This creates an immediacy that allows director Dalton to make every gesture connect. Every nuance of character relationship has a visceral impact.

On that playing space, designer Dalton has simply added a host of wooden straight back chairs, a kitchen table, a double bed, a trunk, and a few simple props. It is difficult, nay dangerous, to be this simple, but the risk paid off in spades. These homely set pieces were endlessly re-configured in all manner of interesting patterns by a mute “Greek chorus” of particularly attractive, buff and (many) shirtless young men.

This conceit was quite a brilliant theatrical effect. The young men represent Blanche’s multiple past partners, and they often accompany her, distract her, dog her, and define her. They are not omnipresent, but their appearances were very well-calculated, none more so than when they surrounded Blanche and Stanley as he raped her down center stage. Forming a semi-circular barricade with their backs to the audience, torsos bared, they pulsated down and up as one to suggest the mounting fervor of the sex act.

Matthew Hansom (Stanley) and Ariana Strahl (Blanche)

Matthew Hansom (Stanley) and Ariana Strahl (Blanche)

The fluidity of the set piece placement also allowed for great variety in the blocking and the visual impact was heightened exponentially. It didn’t matter that the table was not always in the same place, or the bed, or the trunk, or the imagined doorways. The effect was as unsettled as Blanche’s emotional state. The usual two story set was deftly suggested by having Eunice simply stand on a chair and “yell down” from the second story when required. Mr. Dalton’s direction was a model of creativity and restraint.

The only final scenic element was a bare bulb hanging off right center. This is needed for the paper lantern to temporarily cover it, serving as a potent Tennessee Willams metaphor: hiding the truth under pretty trappings. Capitalizing on that basic “illumination,” David Lee Cuthbert conjured up a bewitching and moody lighting design that not only partnered beautifully with Mr. Dalton’s concept but also greatly magnified its impact. Mr. Cuthbert’s meticulous blending of area lighting, specials, gobo effects, and the judicious use of follow spots was really quite splendid.

Johann Stegmeir’s costume design was also well considered, especially for the men and secondary women. For Blanche, Mr. Stegmeir made her more glamorous than usual, in fact, was she too attractive? The “usual” design renditions of this classic script at least hint at decay, faded glory, and a slightly moldy New Orleans, its Old World allure fraying around the edges. With the minimalistic set elements, the one place this milieu might have been conjured was in the costumes. The attire was wonderfully constructed and carefully selected, but might have been more characterful.

In the pivotal role of Blanche DuBois, Ariana Strahl was a real star presence. This is arguably one of the most complex roles in the English language theatrical canon, and Ms. Strahl did not shrink from its mighty challenges. She sings it beautifully, with a ringing soprano possessed of considerable beauty, assured technique, even production throughout the range, and consummate musicianship. Every move she made was motivated by the drama, and ably conveyed the script as musicalized by Mr. Previn.

What Ariana does not embody just yet is the haunted quality that permeates her being, the barely suppressed emotional turmoil, and the encroaching dementia that informs her practiced deceptions. Yes, Blanche needs all of that, and then she must sing demanding music, too! Ms. Strahl is young, she is highly gifted and smart, attractive and empathetic, so there is no doubt she will grow into this part and fully discover its many facets. She deserves to have many more outings as Ms. DuBois.

Stacey Tappan was nigh unto perfection as Blanche’s simpler sister Stella Kowalski. Her silvery soprano was captivating and shimmering. Her easy delivery of the top register was matched by a well-focused tone, which found an exciting presence in the middle range where much of the ‘conversational’ vocal writing lives. She was wholly believable in her blind love and physical attraction to her husband Stanley.

While the two male leads sang powerfully and made impeccable vocal impressions, they were physically miscast. Opera San Jose has a wonderful roster of resident artists who serve effectively in a wide variety of roles all season long. However, this can result in the occasional odd match-up. The accomplished baritone Matthew Hanscomb has the perfect physique for the sympathetic role of Mitch, the lovable, slightly hangdog teddy bear. Unfortunately, Mitch is a tenor role. Stanley needs an animal allure, an effortless sexual appeal. While Mr. Hanscomb sang the part with power, insight, and flawless delivery, no matter how much he committed to suspending his own disbelief that he was a chick magnet, he couldn’t suspend mine.

Conversely, the rather lumpy good-boy Mitch was here impersonated by the handsome, trim, preppy tenor that is Kirk Dougherty. Again, a terrific vocalist, in total command of his considerable resources, showing off a total understanding of what he is singing, and pouring his heart out as he regales us with a honeyed, attractive lyric instrument. But when the script requires him to say he is out of shape, and that he weighs “190 pounds,” well Mr. Dougherty does not look as though he could tip that scale even soaking wet in several layers of winter clothing. Still, these two men are real company assets, and within their own physical realities, they give their all to the commendable ensemble effort.

Xavier Prado did double duty with a nicely sung Young Collector, and as a ghostly presence as Blanche’s young husband who killed himself. Cabiria Jacobsen was a brazen and appropriately shrewish Eunice Hubbell, and she clearly relished her bitchy pronouncements. Michael Boley was an amusing and firm-voiced Steve Hubbell, a perfect foil to Ms. Jacobsen’s domineering spouse. Teressa Foss was a fine presence as both the Old Relative and the stern Nurse. Silas Elash proved a solid Doctor and ably held his own in the crucial denouement.

In her poignant aria, Blanche urges “I want magic!” Conductor Ming Luke seemed to have answered her demand, and he made a significant case for Previn’s uneven score. Even at times it seems the writing is all effect and little substance, Maestro Ming paid that no never mind, and plumbed the score for all it was worth and occasionally, more. The absolute commitment to the idiomatic jazz licks is integral to the success of the sound and throughout, the accomplished orchestra responded with a reading of sensitive conviction and cumulative power. Exposed instrumental solos were exceptionally pleasing, especially the sinuous trombone phrases.

Ming Luke managed to make an unfamiliar piece accessible to a willing public, he forged a reading that had a logical dramatic/musical arc, and he commanded all his forces in a taught ensemble effort.

Opera San Jose’s impressive A Streetcar Named Desire should be required viewing for all who care about adventurous programming and first-class stagecraft.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Young Collector: Xavier Prado; Blanche DuBois: Ariana Strahl; Eunice Hubbell: Cabiria Jacobsen; Stella Kowalski: Stacey Tappan; Old Relative: Teressa Foss; Stanley Kowalski: Matthew Hanscom; Harold “Mitch” Mitchell: Kirk Dougherty; Steve Hubbell: Michael Boley; Nurse: Teressa Foss; Doctor: Silas Elash; Conductor: Ming Luke; Director: Brad Dalton; Set Design: Brad Dalton; Costume Design: Johann Stegmeir; Lighting Design: David Lee Cuthbert; Wig and Make-up Design: Vicky Martinez.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Streetcar5.png image_description=Stacey Tappan as Stella Kowalski product=yes product_title=San Jose’s Smooth Streetcar Ride product_by=A review by James Sohre product_id=Above: Stacey Tappan as Stella KowalskiApril 18, 2016

Roméo et Juliette: Dutch National Opera and Ballet seal merger with leaden Berlioz

To mark their recent merger, the Dutch National Opera and Ballet companies are collaborating as equal partners for the first time. Last season, DNO presented Sasha Waltz's choreographed opera L’Orfeo, which was favourably received. But while her Monteverdi was dramatically lucid and moving, this Roméo et Juliette, which premiered in 2007 at the Opéra Bastille, is inchoate and emotionally hollow. The music, rich in thematic tracery, willingly lends itself to Tanztheater’s fusion of dance, movement and drama. The plot lacks linearity and only one of the three vocal soloists plays a character, Friar Laurence. He only appears in the final cantata, to harangue the warring Capulets and Montagues, a double chorus, into a peace treaty. The orchestra takes on the main roles. Rather than retelling Shakespeare, Berlioz tried to capture his genius in music that is both wonderfully descriptive and wrenchingly evocative. There is the clink and glint of clashing rapiers in the opening fugue, and profound longing in Roméo seul, which contains the seed of Wagner’s Tristan chord. The great love scene is achingly beautiful and Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech is transliterated into the flitting filigree of the Scherzo.

Igone de Jongh as Juliette and James Stout as Romeo

Igone de Jongh as Juliette and James Stout as Romeo

Choreography could have fleshed out the plot and complemented the orchestral characterization. This staging, however, is vague, emotionally dormant and at times utterly wrong-headed. It is very handsome visually, thanks to Bernd Skodzig’s black and cream costumes, which understatedly reference the Isreali-Palestinian conflict. Specific characters are assigned, but it was difficult to tell who was who. Romeo’s lovingly teasing friends, Mercutio and Benvolio (Bastiaan Stoop and Peter Leung), were the most clearly drawn individuals. Dancing barefoot, the cast deftly executed the jerky, twitchy steps, linking their bodies into sinuous chains. At first they were confined to an inclined platform, one of two white surfaces forming what could be taken for a book. The reduced space precluded runs and spectacular jumps and some of the sequences became repetitious. Attempts at humour fell flat. The Capulets scoffed their banquet like hogs at a trough and the dances at the ball were irritating nervous tics. The drunken guests walked tortuously home like puppet zombies. None of this was funny. Once the ramp was hoisted up, opening the book, the choreography became more spacious. But then, puzzlingly, the music paused. Romeo danced his desperation unaccompanied, trying to scale a smooth wall.

At least James Stout, moving in short, energetic bursts, got a chance to give Romeo an emotional profile, as opposed to Igone de Jongh as Juliet. She is a slender dancer who moves in long, fluids line, but, limited to sudden jumps and propeller arms, she was all elbows and other angles. During the balcony scene there was no hint of chemistry between the lovers. They kept gingerly running away from each other and then colliding amicably. Juliet was directed as a worldly-wise girl for whom the secret meeting is mildly rebellious fun — hardly the state of mind that would motivate elopement, feigned death and suicide. Ironically, Ms De Jongh was most graceful and tender as a sleeping corpse, when the mourners gently lifted and swung Juliet at her funeral.

Failing to compensate for the theatrical aridness, the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra under Kazushi Ono sounded under-rehearsed in a grey, matted performance. The usually excellent woodwinds lacked expression and the brass skidded in harshly over and over again. After a tentative Introduction, a leaden Prologue was somewhat relieved by Alisa Kolosova’s full-bodied mezzo-soprano — a thing of beauty, despite undifferentiated diction and a vibrato that widens slightly on the top notes. Tenor Benjamin Bernheim then delivered a snappy, bright-toned Scherzetto. After that, dullness had the upper hand until the poignant funeral dirge by the Dutch National Opera Chorus. Even they, affected by the general malaise, were no more than efficiently competent most of the time. Diffuse orchestral phrasing marred Romeo’s melancholy pages and the enthralling love scene was, just like the pas de deux, devoid of lyricism. The Mab music buzzed aimlessly like a fly trapped in a jar. Applauding politely, the audience only cheered for bass-baritone Paul Gay, maybe because he shook it from its torpor with his resounding “Silence!”. It was a slight shock when he came out in a black sarong, belatedly revealing that the athletic Vito Mazzeo, in identical garb, was, in fact, his dancing counterpart. Mr. Gay sang persuasively, with a firmly anchored lower range, and he and the chorus provided a confident, if not exactly rousing, finale. Here’s hoping that the next joint venture by the National Opera and Ballet will be more fortunate that this one.

Jenny Camilleri

Casts and production information:

Singers Mezzo-soprano: Alisa Kolosova; Tenor: Benjamin Bernheim; Friar Laurence (bass-baritone): Paul Gay. Dancers Roméo: James Stout; Juliette: Igone de Jongh; Friar Laurence: Vito Mazzeo. Dutch National Opera Choir, Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra. Conductor: Kazushi Ono; Director and Choreographer: Sasha Waltz; Set Designers: Pia Maier Schriever, Thomas Schenk, Sasha Waltz; Costume Designer: Bernd Skodzig: Lighting Designer: David Finn. Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam, Friday, 15th April 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Romeo1.png

product=yes

product_title=Roméo et Juliette in Amsterdam

product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri

product_id=Above: Dancers Igone de Jongh as Juliette and James Stout as Roméo [All photos copyright Monika Rittershaus, courtesy Dutch National Opera and Ballet]

April 14, 2016

Donizetti : Lucia di Lammermoor, Royal Opera House

And, perhaps he was wise to be wary as the graphic sex, sadism and barbarism of director Katie Mitchell’s recent production of Sarah Kane’s Cleansed at the National Theatre reportedly caused some audience-members to faint with revulsion and others to flounce out in disgust. Having now seen Mitchell’s Lucia, I wouldn’t be surprised if Holten’s cautionary announcement was not simply designed to generate some interest - for the production itself offers little, though the cast is uniformly impressive.

As the eponymous heroine, Diana Damrau deserves credit for her committed engagement with the physical and psychological extremes of Mitchell’s devising while successfully negotiating Donizetti’s high-wire vocal lines. She didn’t have much plushness or power at the top, but Damrau sang with precision, observing all the details in the mad scene’s disintegrating roulades and spiky staccatos, and holding nothing back in conveying Lucia’s distress - it was good to hear the glass-harmonica’s uncanny whistles too. Earlier in the opera, Damrau had delivered an eerily coloured entrance aria, and she convincingly portrayed the anger and resentment felt by Mitchell’s protagonist - who is more feisty than feminine. But, she didn’t have the strength or warmth to make her presence felt in the sextet.

Charles Castronovo was an ardent, lyrical Edgardo; the American-Italian tenor’s phrasing was refined and he displayed both fullness in the middle range and clarity up high. Castronovo also has a handsome stage presence and was fittingly heroic. Some of the best singing of the night came from Ludovic Tézier as Enrico; his baritone is strong but he uses it with subtlety. The Wolf’s-Crag confrontation between the two enemies was exciting and vigorously sung. Rachael Lloyd, as Alisa, and Taylor Stayton, in the thankless role of Arturo, made a solid contribution.

‘A pure and magnificent tragic romance’ was the critical response of Blackwood’s Magazine to Walter Scott’s novel when it was published in 1819. The novel overflows with the immoderations of Gothic romance - witches, madwomen, Byronic heroes, star-crossed lovers, derelict castles, public disgrace, financial ruin and ominous prophecies - and, burdened by familial, political and psychological fractures, its over-emotional heroine submits to insanity and goes on a murderous rampage. Donizetti and his librettist Salvadore Cammarano were not ones to miss an opportunity for violent contrasts and tragic excess and give us a veritable bel canto soap opera.

Katie Mitchell is not that interested in either Scott’s Bride of Lammermoor or Donizetti’s opera, though. She has a different story to tell, a ‘feminist take’ (‘My focus is 100% on the female characters’) set in the 1830s (updated from the novel’s early-17th-century setting), the decade in which Donizetti’s opera was first seen in Naples and as Mitchell notes, the decade which was ‘a very important period for feminism with the Brontës and all those amazing women like Mary Anning who were early feminists, fossil-hunters and scientists’.

Mitchell’s Lucia is a frustrated proto-feminist, trapped in an oppressive male world, whose refusal to endure a life of passive self-denial and duty results in her cruel and bloody demise. This is not such a radical reading. The mad-scene has been variously interpreted, sometimes as the beautiful but futile expression of female passivity and entrapment, elsewhere as a convention-breaking proclamation of self-determination.

However, while it’s true that in the 19th century, madness, both ‘real’ and ‘operatic’, was stereotypically a ‘female malady’, I feel that Mitchell goes too far in her assertion of the work’s ‘cultural meaning’. And, in her endeavour to fill in all the ‘gaps’ and provide us with an unambiguous account of ‘what Lucia does while the male characters are singing about her’, she loads the action with extraneous imagined action.

So, as the guests gather to celebrate the nuptial union of the two families, on the other side of the stage we see Lucia and her maid murder Lucia’s husband of just a few minutes. And, they take an awful long time to do so, for he’s a disobliging victim who survives attempted suffocation, prolonged stabbing and a hatchet to the head and ekes out his death-shakes as long as possible - completely distracting one’s attention from the ‘scripted’ plot being presented alongside.

Then, as if murdering one’s husband would not be enough to send one crazy, Mitchell invents a further reason for Lucia’s insanity: a miscarriage - or self-induced abortion? - which causes Lucia to lose enough blood to drown the entire Ashton and Ravenswood clans. It is disconcerting and uncomfortable to watch, but mental breakdown is disturbing too and Donizetti’s depiction of it is sufficient to stir our disquiet.

As for the reported erotic excesses of the production, the characters did seem to be eternally engaged in taking off their clothes, though they exposed little flesh and the nocturnal assignation of Edgardo and Lucia (fully clothed in men’s attire) in the Lammermoor gardens involved an excruciatingly clichéd ‘sex-scene’ of cartoonish gaucheness. Presumably it was more potent than it looked for in the following scene Lucia rushed to the water closet apparently in the throes of morning sickness, which raised a chuckle in the stalls.

Vicky Mortimer’s set divides the ROH stage into two, fairly shallow rooms. Centre-stage is given, literally and figuratively, to a partition wall. Bedchamber is juxtaposed with bathroom, boudoir with billiard room. The eye doesn’t really know where to settle, and as much of the business occurs towards the far edges of the stage, there’s a danger that ‘crucial’ action is missed.

Lucia’s mental wanderings are almost outdone for grimness by an itinerant interloper - the portentous ghost whom Lucia sees of a girl killed by a jealous Ravenswood ancestor - whom Mitchell introduces in almost every scene. And, the set - admittedly detailed and sumptuous, and naturalistically lit by Jon Clark - is small and cluttered. In Act 2, in the billiard room there is almost no room for ROH Chorus to stand, let alone move.

It’s a rare evening when the ROH Orchestra receive a lukewarm reception, but conductor Daniel Oren’s stately tempos and unresponsive, rigid beat didn’t lift the performances from the pit above the work-a-day.

Thank goodness for Castronovo’s terrific performance in the final scene, where despite the visual distraction of Lucia slitting her wrists in the bathtub next door, Castronovo sang with truly affecting tenderness. Despite Mitchell’s assertion that the focus of this production ‘is 100% on the female characters’ it was Sir Edgardo di Ravenswood who stole the show.

Claire Seymour

Donizetti: Lucia di Lammermoor

Lucia - Diana Damrau, Enrico Ashton - Ludovic Tézier, Egardo - Charles Castronovo, Normando - Peter Hoare, Alisa - Rachael Lloyd, Raimondo Bidebent - Kwangchul Youn, Arturo Bucklaw - Taylor Stayton; Director - Katie Mitchell, Designer - Vicki Mortimer, Lighting Designer - Jon Clark, Movement Director and Associate Director - Joseph Alford, Fight Directors - Rachel Bown-Williams and Ruth Cooper-Brown.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London

Monday 11th April 2016

image=

image_description=

product=yesD F

product_title=

product_by= Donizetti :Lucia di Lammermoor, Royal Opera House, London 11th April 2016. A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above

April 12, 2016

Five Reviews of Regina at Maryland Opera Studio

For as long as Marc Blitzstein had been writing music, he was determined to create socially conscious art that was accessible to a broad audience. Much of his early career was devoted to writing workers’ songs for the American Communist Party. When he started composing musical theater works Blitzstein stayed true to his leftist politics, setting texts that focused on working-class Americans and confronted issues such as capitalism, minority politics, and labor rights. His earliest works had limited, if any, success. In 1929 he began work on The Travelling Salesman, a “colloquial” opera that follows an everyman on his journey to become President of the United States, but Blitzstein abandoned the project not two years later. His 1937 pro-union musical The Cradle Will Rock made headlines only because of its bizarre premiere. The work was ready to be staged on Broadway, but at the last minute the federal government pulled the rug out from under the production, prohibiting venues from hosting the musical for fear of its overtly Communist message. In defiance, Blitzstein performed the musical anyway at a smaller theater, playing a piano reduction alone onstage while cast members sang their lines from seats in the audience.

Then in 1946, in the wake of his successful Airborne Symphony, Blitzstein received a commission to write a musical theater work to be performed by the Boston Symphony at Tanglewood. Here at last was an opportunity to write a large-scale, genuinely American work for a high-profile institution; the first step was to find a suitable libretto. Discussing ideas with his then-lover Bill Hewitt, Blitzstein broached the possibility of adapting the work of a friend and playwright, Lillian Hellman. The two had collaborated in the past, and Blitzstein was currently providing incidental music for her play, Another Part of the Forest. When Hewitt suggested adapting the play’s sequel, The Little Foxes, for the operatic stage, Blitzstein was immediately enthusiastic and enlisted Hellman for the project.

Set in postbellum Alabama, Another Part of the Forest follows the corruption of a working-class family who cheat their way into fortune, but succumb to lies, greed, and emotional abuse. Unbeknownst to most of his family, Marcus Hubbard, the family patriarch, acquires money by exploiting his fellow townspeople during the Civil War. He abuses his wife and his three children, Ben, Oscar, and Regina. Regina wishes to escape the small town with her wealthy lover, John Bagtry, but is prevented from doing so by her father. Ben, the eldest son, learns of his father’s lewd wartime dealings and uses the information to blackmail him, effectively dethroning him, and asserts control over the family. He arranges for both of his siblings to marry into money: Regina to banker Horace Giddens, and Oscar to John Bagtry’s sister, Birdie (and to her family’s valuable land.) Ben remains single and presides over the family property, monitoring the activities of Ben and Regina.

The Little Foxes finds the Hubbards twenty years later in the same Alabama town, now involved in their own questionable business practices. Regina and her brothers are visited by Mr. Marshall, an entrepreneur from Chicago who is looking to invest in the family’s plantation. Ben and Oscar have their share of the deal ready; Regina must first convince her sick husband, Horace, to agree and—if she can—manipulate her brothers into allotting to her a larger share of the profit. Regina is the operatic setting of their story: at once intriguing and repulsive, and in Blitzstein’s words, full of “greed and glamor.”

Horace (Daren Jackson) greeting his brother-in-law

Horace (Daren Jackson) greeting his brother-in-law

Nick Olcott’s staging of Regina with the Maryland Opera Studio at the University of Maryland, College Park is true to the original setting, including period-appropriate costumes and an exaggerated drawl that places us undoubtedly in the Deep South. An especially challenging aspect of this opera is its inclusion of sung text, spoken words over music, and plain speech. The cast handles this with apparent ease, alternating seamlessly between speech and song without interrupting the flow of dialogue. Conductor Craig Kier expertly navigates through the opera’s wide variety of musical styles, ranging from ragtime to waltzes, and gives a convincing musical performance despite the orchestra’s frequent struggles with intonation.

Regina’s title character is ruthless and heartless from the very first scene, when she stamps out the joyful singing and dancing of her daughter, Zan, and her servants, Cal and Addie, while an onstage band plays ragtime music. Regina was sung by mezzo-soprano Louisa Waycott on Thursday, April 7 and Nicole Levesque on Sunday, April 10. Waycott portrays a reserved but calculating Regina, showing brief moments of vulnerability that remind us of her character’s humanity. This occasional softness, however, is balanced aurally by her appropriately steely tone, and an upper register that cuts through the orchestral texture like a knife. Levesque sings with dramatic intensity that matches her delightfully cold-blooded, haughty Regina. Here is a character who takes great pleasure in her own cruelty, sneering at her daughter and delivering her nastiest lines with an ingratiating smile. Her smoky middle register accents Regina’s insatiable lust for money, power, and “things.” Each singer inspires a slightly different reaction from her fellow cast members, yielding two unique but equally provocative performances.

Soprano Laynee Dell Woodward breathes life into the dismal household by imbuing the long-suffering Birdie with a complex inner life. She calls attention to Birdie’s relationships with Zan and Horace, her nostalgia for her childhood home, and her love for music, resulting in one of the most interesting characters in the opera. Woodward’s tone is sweet and effortless, and her shimmering high register is showcased in her Act I vocalise, which she modifies from the original score to incorporate a stunning high F6.

Bass-baritone Daren Jackson is a commanding presence in the role of Horace Giddens from the moment he appears onstage. His physical poise and is mirrored by his rich timbre and the natural ease with which he projects in his low register. He joins Birdie, Zan, and Addie at the opening of Act III for a charming performance of the lighthearted “Rain Quartet,” the only silver lining to the dark final act. In this quartet, Horace stands up from his wheelchair and proclaims, “Some people eat all the earth, some people stand around and watch while they eat.” Jackson delivers this line, a biblical allusion, with authority and stateliness, and there is no doubt that his words embody the true spirit of Regina.

Baritones Anthony Eversole and Mark Wanich play against one another brilliantly in their respective roles as Oscar and Ben Hubbard. Eversole exaggerates Oscar’s volatility; he is temperamental, abusive toward Birdie, and bitter about his longstanding subservience to his brother. Wanich plays Ben with humor and irreverence, often providing his scenes with much-needed comic relief.

Soprano Chelsea Davidson convincingly portrays Zan’s loss of childlike innocence as she is slowly exposed to the horrors of her family’s legacy. Davidson sings with a silvery tone that highlights Zan’s youth; at the same time she is able to consistently project to the back of the hall, reminding us that although Zan is young, she is far from powerless.

Through no fault of the directors or cast, certain scenes in the opera are simply too busy, musically and visually. One such instance is the end of Act II when the Hubbards, gathered on a balcony, have a heated argument while a raucous party carries on in the parlor below. For all the singers’ efforts, it is virtually impossible to hear the conversation over the din of singing, dancing, stomping party guests; were it not for the surtitles, the audience would miss a great deal of important dialogue. Olcott’s solution of visually separating the family from their guests is a creative one, but in reality the dancing is distracting and the Hubbards appear distant and out of focus.

There is a fruitful discussion to be had regarding Regina’s themes of unadulterated greed and inhumanity in light of America’s shifting social milieu. At the time of the work’s premiere in the mid-twentieth century, Regina’s actions were meant to be shocking, callous, and evil; in fact, the opera’s working title was A Bitch in the House. Today’s audience, however, might look back at Regina as a product of her environment. Perhaps the reason that she lies, cheats, and steals is not due to pure selfishness and malice; perhaps she is a woman who has been controlled by male relatives her entire life, and is ready to escape her arranged marriage by any means necessary.

However one chooses to interpret Regina, the Maryland Opera Studio puts on an entertaining and engaging production that initiates dialogue about power and materialism. Through it, we may observe how far America has come, and just how far it has to go. The production closes on Saturday, April 16th.

Rachel Ace

On Friday, April 8th, 2016, the Maryland Opera Studio debuted Marc Blitzstein’s Regina at the Kay Theatre of The Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center (University of Maryland, College Park). Set in the early twentieth-century rural South, the show centers around Regina Hubbard Giddens and her conniving brothers’ plot to secure a business deal at the expense of their community. The family drama explores the abuse, manipulation, and betrayal within the Hubbard clan in their effort to maximize their family fortune. By presenting this lesser-known title that condemns capitalism and greed while exposing both individual and institutionalized racism, director Nick Olcott and conductor Craig Kier make a strong statement on our current political climate regarding class and racial inequality and prove that student opera need not be toothless or apolitical.

Marc Blitzstein, Regina’s composer and librettist, was no stranger to controversy and politics. An outspoken leftist and homosexual, the composer aligned himself philosophically and politically with German artists Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill. Blitzstein first successful theatrical work, 1937 The Cradle Will Rock, was a product of their influence: its allegorical plot promotes steelworkers unions and attacks American corporate corruption. Even more successful was Blitzstein’s English-language adaptation of Weill and Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera, which also offers a progressive political critique of society. Due to his leftist art and politics, Blitzstein was subpoenaed by the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1950s to testify about his affiliation with the Communist Party; the composer was ultimately blacklisted.

Blitzstein’s Regina has been problematic since its conception. The composer based his opera on Lillian Hellman’s sophisticated 1939 drama, The Little Foxes. Hellman, known for being difficult and possessive about her work, was an influential force in the compositional process and often angled for changes in Blitzstein’s drafts. Her notes consistently repudiated the composer's interpretations of Southern culture and her characters. Additionally, the playwright often sent conflicting critiques to Blitzstein about adhering too close to the original text or drifting too far away from it. As a result, Regina was plagued by constant revisions up until its opening week in 1949. Thereafter Blitzstein and others continued to make changes for subsequent revivals; most recent mountings of the opera often cut the score to omit problematic racial stereotypes. Consequently, a standard, definitive version of the opera does not exist in score or recording.

This season, the Maryland Opera Studio provides its own unique version of Regina by presenting the opera’s racial subtext through “alternative” casting, where originally black characters are played by white actors and vice versa. This manifests most prominently with the casting of Daren Jackson, a black bass, as Horace, the sympathetic white patriarch, and Alexandra Christoforakis, a white mezzo-soprano, as Addie, the black mammy. Both singers give stunning performances that capture the emotional essence of these characters. And, despite this alternative casting in its ensemble and chorus, the production continues to engage with the racial prejudices of the time period depicted in the opera. Student productions often confront limited options with respect to race-conscious casting, and MSO’s tactful approach and awareness of its implication, complete with a public roundtable on the topic of race and art, offers a model for other student studios and professional companies.

As with the casting, Diana Chun’s set design presents an alternative concept of Regina’s home and world. The gilded Southern mansion’s strong slanted angles, floating golden picture frames, and grand serpentine staircase suggest opulence, while highlighting something sinister about the Hubbard family. This abstract set design is well-balanced with both realist lighting and period costumes. Lighting designer Max Doolittle’s ability to simulate an evening sky or a rainy afternoon through the center-stage “mega-window” is breathtaking. Tyler Gunther’s costuming is best represented during the party scene in Act II. The pale pastels of the chorus’s evening gowns offer an intriguing contrast to the black and gold color scheme of the set. Taken together, I was pleased with the unique and well executed design elements that enhanced the story without becoming a distraction.

Unfortunately, Craig Kier’s pit orchestra cannot claim the same success, as at times its dominating sound obstructed vocal performances and story-driving dialog. This is not to say their performance was anything less than stellar. The transitional music was captivating, and the chorus of Act II and ensemble performances throughout were clear and well balanced. Regrettably, however, many scenes of spoken dialog and occasional arias were muffled beneath the orchestra.

The members of the opera chorus were skilled in both singing and acting. The party scene at the end of Act II offered comic relief, as various members of the chorus expressed about their catty distrust of the Hubbard-Giddens family while being uncontrollably transfixed by the decadence of Regina’s party. Though, much like the pit orchestra, their wild dancing during the gallop chorus distracted from the action during a pivotal moment in the story.

The opening-night student cast was mostly strong and near-professional. Mezzo-soprano Louisa Waycott led as the dangerous titular character Regina. Though consistently good throughout, her best moments were in the first half of the show, particularly in the scene leading up to the aria “The Best Thing of All.” Additionally, her monotone orders to Cal, the house servant, as Regina prepares for her party at the beginning of Act II showcased Waycott’s lighter comic abilities. Unfortunately, the mezzo-soprano’s acting never truly expressed the hues of Regina’s darker side. This was especially evident in the cold scenes between her and Horace; Regina’s commanding and distasteful lines such as “I’ll be waiting [for you to die]” and “I’ll be lucky again [when you die]” lacked the authentic toxicity I was expecting from a femme fatale.

Bass Daren Jackson, playing Regina’s compassionate and moral husband Horace, gave a fabulous vocal and acting performance, providing the audience with a sincere character arch in a fraction of stage time compared to other characters. His solo “Consider the Rain” in the spectacular Rain Quartet at the beginning of Act III delicately articulated the ethical dimension of the plot withheld up until that point.

Chelsea Davidson showcased her lovely soprano voice as Zane, the young naive daughter of Regina and Horace, yet it was often covered by the pit orchestra. Her acting favored the lighter aspects of her character, while her fraught confrontations with Regina, especially at the end, seemed slightly stilted.

As for Regina’s deceitful brothers, baritone Anthony Eversole was commanding in the role of Oscar, whereas Mark Wanich was less convincing as the older and wiser Ben. Their two acting styles were nearly identical, brutish and loud, which unfortunately made for a stale drama in many of their scenes.

The strongest and most consistently natural performance was that of soprano Laynee Dell Woodward’s Birdie, Regina’s sad, endearing alcoholic sister-in-law. On a technical level, Woodward was stunning: her coloratura arpeggios in Act I were spot-on, and her descant in Act II added a favorable light aura to “Addie’s Blues”. Both her recitative and arias were fabulous and enrapturing, starting within the first ten minutes of the opera with her entrance scene and aria “Music, Music, Music.” In almost every scene involving Birdie, Woodward’s acting captured the audience's undivided attention with meticulously chosen gestures and vulnerable expressions that carried an intense gravitational pull. A high point of the entire opera was “Birdie’s Aria” in Act III, in which the character declares: “I drink!” Due to Woodward's commanding presence, this seemingly sideline moment presented much more drama than Regina’s climactic high C “I’ll be waiting!” in the finale of Act II, despite the efforts of staging and intense lighting for the latter. This may be a coloratura-soprano bias, but just as Woodward’s notes soared above the others’ in the ensemble, so did her enchanting performance as Birdie.

Overall, director Nick Olcott and conductor Craig Kier presented a winning production of this out-of-the-canon opera. Both cast and crew rose to the occasion to present a show that is both thought-provoking and entertaining. Issues of race and class are at the forefront of this production, and MSO’s team takes on these themes in respectful and innovative ways. Though there are still some areas to improve, particularly the balance of the pit orchestra with the ensemble, I highly suggest seeing MSO’s Regina, as this period piece allows its audience to reflect on the timely themes of greed and injustice while imagining the bright futures for its strong student performers and designers. The production closes on Saturday, April 16th.

William Gonzales