July 31, 2016

Prom 20: Berlioz, Romeo and Juliet

Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette was inspired by the ‘supreme drama’ of the composer’s life when, in 1827, he first saw the actress Harriet Smithson performing with Charles Kemble’s theatrical troupe in Paris. The score is suffused with passion and tenderness: for Smithson, who five years later would become his wife; for the playwright, whose ‘poetic thread whose golden tracery enfolds his marvellous ideas’ left Berlioz stunned, penetrated by ‘Shakespearean fire’; and for Juliet, Ophelia and Desdemona whose tragic pathos became inextricably fused with his love for Smithson - leading Berlioz to write to a friend in 1833, in anticipation of seeing Smithson again, ‘I am mad, dearest I am dead! Sweetest Juliet! my life, my soul, my heart, all, all, ’tis the heaven, oh!!!!!! … parle donc, mon orchestre’.

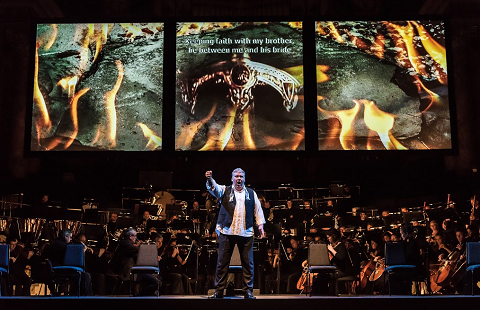

Gardiner, who recorded the work with these ensembles in 1998, summoned a performance from his large forces which was similarly flushed with sensitivity and care, supported by the conductor’s encyclopaedic familiarity with the score’s richly variegated details. He made sure that we recognised just how remarkable Berlioz’s independence and invention truly are, and he gave us some novelties too, reinstating the second Prologue, after the Queen Mab Scherzo and before the Capulets’ Convoi funèbre upon the discovery of Juliet’s death, which itself included inserted material setting the Requiem mass.

For those who are still inclined to associate Berlioz, that most misunderstood of composers, with massive musical tempests, dissonant disturbances, and platoons of brass and percussion, this performance will have been a revelation. Not for nothing did his Treatise on Orchestration establish his reputation as a master of instrumentation and the founder of the modern orchestra. We had a full battery here including five trombones, four bassoons, ophicleide and enough percussion instruments to keep six players busy. But, while he made the most of the dramatic climaxes, subtlety was Gardiner’s watchword. He showed that the work is ‘monumental’ not because of the sheer size of sound conjured, but because of the meticulousness of the way the kaleidoscopic ‘narrative’ details are married with formal necessities in a work where volume is superseded by sonority.

In his preface to the score, Berlioz made it clear that he viewed the work as ‘a symphony, and not a concert opera’, believing that Romeo’s meditation, the Capulets’ ball the Scène d’amour could be better depicted without the limiting specificity of words. Of the three solo voices, only the bass - who takes the role of Friar Lawrence in the Finale - embodies an individual character, and it is the ‘symphonic’ music which bears the burden of expression and dramatic development.

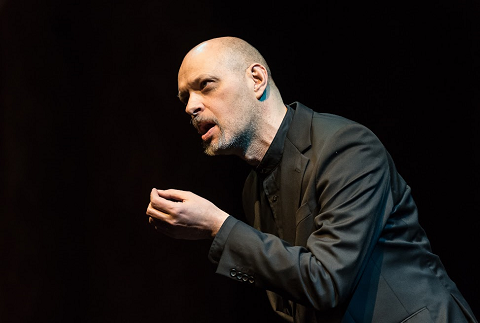

Sir John Eliot Gardiner conducts. Photo Credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Sir John Eliot Gardiner conducts. Photo Credit: Chris Christodoulou.

The Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique gave us a stirring performance and a wide expressive palette. The brass had a dark coloration which was perfect for establishing the stature of the tragedy at the start and the full, homophonic chords of the trombones, horns and ophicleide were menacing in depicting the hot anger of the Prince who subdues the muttering of the rowdy rabble-rousers in Verona’s streets. There was scrupulous attention to the strings’ timbre and articulation with only light vibrato employed; in particular, Gardiner repeatedly quelled the sound to the barest whisper, the bows barely brushing the string but the large complement of players ensuring that the merest breaths of sound had softness and fullness. Cello and double bass pizzicatos were by turn astonishing agile - there must have been some sore right fore-fingers as Berlioz puts the players through their paces - and beguilingly harp-like. String tremolos shivered, shimmered and glimmered. Spiccatos were as light as butterflies’ wings, and the muted saltato bows combined with chattering woodwind, harp harmonics and the ting of antique cymbals in the Queen Mab scherzo to magical effect.

In the ball scene the high-registered strings and woodwind brought radiance and vivacity to the celebration. Berlioz’s woodwind divulge the protagonists’ hearts: oboist Michael Niesemann painted a sensuous portrait of Juliet as she lives in Romeo’s erotic fantasy while in the Part 3 Scène d’amour softly sustained horns, and clarinet and cor anglais in octaves sang beautifully above the exquisite richness of the quiet divided strings.

There were a few slips, mind. Gardiner set off at a recklessly frenetic pace, and while the period-instruments’ tone added an authentic touch of roughness to the patrician rioting, it was a bit too fast and furious, even disordered, and we weren’t able to enjoy the full originality of Berlioz’s rhythmic conversations in the Allegro fugato.

Gardiner did not always judge the acoustic effectively either. Yes, Berlioz does distinguish between p, pp and ppp - but surely he did want us to hear the notes he’d written? At times the diminuendos drew the delicacies into niente, and I doubt those seated in the furthest reaches of the Hall, and standing in the Gallery, could hear some of the most fragile details, including the cheeky chimes of the antique symbols which close Queen Mab - which is a pity as the percussion player had walked to the front of the stage to deliver them.

Another aspect of the performance that gave me pause for thought was the ‘choreography’. The stage began bare of singers and the Monteverdi Choir semi-chorus walked onto the stage during Part 1 to deliver their expressive narration - sung with meditative beauty and exemplary French phrasing, and accompanied by harp, cor anglais and obbligato cello - to set the dramatic scene. Placed in front of Gardiner, at the very front of the stage (middle to left) they were conducted by an unnamed conductor who was standing in the Arena. (I've subsequently learned that this was Dinis Sousa.) This seemed unnecessarily fussy (the conductor was kept busy, racing up to the Gallery for the off-stage chorus of Young Capulets) and became more irritating when the semi-chorus then walked off stage during the Prince’s stern intervention, distracting us from the tragic overtones of the brass’s disapproving dismissal of the bickering citizens.

The sense of disruption was unfortunately made worse by noisy late-comers at the opening of Part 2: with so much shuffling, seat-banging and fidgeting, Romeo seemed far from ‘alone’ as the strings descended through the chromatic, ppp, sinuous line which embodies the young lover’s melancholy solitude - and Gardiner’s determination that the strings should diminish to the point of vanishing didn’t help. Later, during the funeral cortege, the National Youth Choir of Scotland literally brought the sombre procession to life, walking onto the raked choir-seating - in perfectly rehearsed formation but with less than silent footsteps - just as the accumulating textures and harmonies in the orchestra developed their fugal lament.

But, these were minor blots in a performance that on the whole cohered impressively, aided by some fine singing from three French soloists. Mezzo-soprano Julie Boulianne brought star-quality to her Act 1 narration with the semi-chorus: her rich voice had real presence and weight in the Hall, even in the most intimate and understated melodic gestures, and the long vocal lines unwound compellingly.

Jean-Paul Fouchécourt (who performed on the 1998 recording) used his agile high tenor and strong colour to good effect in the Part 1 Scherzetto in which the tenor mocks Romeo’s love. Bass-baritone Laurent Naouri presented the heartfelt, honourable pleas of Friar Laurence in beautifully elegant French declamation and found a nobility of line that gave moral stature to the recitative in which he unveils the truth. He was a little lacking in weight, however, and at times was almost overwhelmed by the angry choral condemnations of the duplicitous cleric. The young voices of the NYCS were vibrant if rather polite, but the strength of the choral finale - the women’s voices eventually joining those of the men, added a sort of beneficent glow - gave conviction to Berlioz’s apparent intent that at the final reckoning reconciliation triumphs over tragedy.

In its communication of Berlioz’s intense individualism and subjectivity, and obsessive feeling, this performance was truly Romantic.

Claire Seymour

Berlioz: Romeo and Juliet (sung in French)

Julie Boulianne (soprano), Jean-Paul Fouchécourt (tenor), Laurent Naouri (bass-baritone), Sir John Eliot Gardiner (conductor), Monteverdi Choir, National Youth Choir of Scotland (chorus-master, Christopher Bell), Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique (leader, Kati Debretzeni).

Royal Albert Hall, London; Saturday 30th July 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Julie%20Boulianne%20Christodoulou.png

image_description=Prom 20: Berlioz, Romeo and Juliet

product=yes

product_title=Prom 20: Berlioz, Romeo and Juliet

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Julie Boulianne, with the Monteverdi Choir

Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou

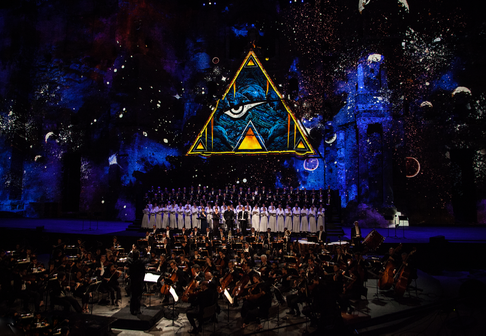

Prom 18: Mahler, Symphony No.3

He showed that again here, and how - with a London Symphony Orchestra on outstanding form. Haitink did not seem to offer a particular point of view on the work, but nor did he conduct with anonymity: something that could, on occasion, prove a problem in this music, during his later years, for Claudio Abbado - or at least a problem for me. Rather, one had a sense, even though one knew it to be unfounded, even nonsensical, that this was somehow the music ‘itself’ we were hearing.

Haitink opened the first movement briskly, but the opening phrase’s subsiding both told of possibilities ahead in this movement and beyond (the prefigurement of the fourth movement’s ‘O Mensch’ as clear, as telling, as I can recall). There was no doubt that this was a march: how could there be with the LSO drummers on such magnificent form? But there was far more to the LSO’s performance than military might: this was Mahler with great warmth and unanimity of attack. It was post-Wagnerian Mahler, with equal emphasis on the ‘post-’ and the ‘Wagner’. The huge orchestra notwithstanding, Mahler’s ability to conjure up a miraculous array of chamber ensembles - always, be it noted, directed by Haitink - never ceased to amaze. When those phantasmagorical flutes began their chorale-like passage - and, again, when it returned - Haitink held the tempo back slightly, hinting perhaps that summer marching in might not all be good; it might even be bad, although undoubtedly irresistible, as leader Carmine Lauri’s sinuous solo suggested. The gravity of the trombones seemed to reach back across the centuries, past Mozart’s Requiem, to ancient (relatively speaking) Habsburg equale. Tempi shifted with infinite subtlety; this was no ‘look at me, the conductor’ Mahler, for Haitink wanted us to look at Mahler. Marching onward, the woodwind in particular seemed almost to threaten metamorphosis into the deathly marionettes of the Sixth Symphony; equally crucial, though, that metamorphosis never happened. For this was marching that could be enjoyed too, almost as if we were paying a decidedly non-Marschallin like visit to the Prater. But then, there came disintegration: it was not just, or even principally shattering; it was perhaps closer to Mendelssohnian exhaustion. Attempts at rejuvenation or resuscitation were thereby rendered all the more ambiguous. The loudest offstage percussion I can recall (up in the Gallery, I think) heralded the recapitulation: it was as before, yet utterly transformed. And how the differences in the material were now revealed - or, so it seemed, revealed themselves! The end, when it came, was not lingered over; whatever Haitink may be, he is no sentimentalist. There was, indeed, a touch of Haydn to it.

Bernard Haitink conducting the London Symphony Orchestra. Photo Credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Bernard Haitink conducting the London Symphony Orchestra. Photo Credit: Chris Christodoulou.

A graceful oboe solo (Oliver Stankiewicz) and gracious second violins’ response set the tone for the second movement. Except soon it became clear that it had not; it was not long before unease set in, from within the music, nothing appliqué. Indeed, there was as much unease in ‘beauty’, whatever that might be, as in dissonant corrosion thereof. Thematic profusion seemed almost to rival Mozart - and this music is perhaps still more difficult to hold together. (So many conductors, often praised to the rafters, fail here.) Haitink’s rubato was expertly judged: again there was nothing self-regarding to it, but rather it always made a musical point; so did his ritenuti. He revealed to us all manner of connections, intra- and extra-musical, whether intentionally or otherwise. Not the least of them was the sweetness, inviting yet not without malignance, of Alt-Wien, that malignance ever more present towards the close.

We heard, almost stepped into, a city dweller’s countryside in the third movement: its nightmares as well as its dreams. This was, it seemed, Mahler exploring the terrain of Hänsel und Gretel, only with more overt nastiness. Internal coherence was just as striking: at times, we seemed close to Webern’s Bach. Until, that is, we could not be more distant from it. Cross-rhythms were as disconcerting as those of Brahms, whatever the gulf that might otherwise separate the two composers (in both of whose music Haitink has long excelled). The trumpet’s presentiments of the posthorn solos have never registered so strikingly to me. And how wondrous that sounded, from afar, in Nicholas Betts’s flugelhorn rendition. Again, there was more than a hint of modernist Mendelssohn. Above all, though, it moved: with dignity, with nobility, rather than pleading for us, Bernstein-like, to shed tears. Instrumental scurrying also had something of A Midsummer Night’s Dream to it: Mendelssohn and Shakespeare. With that ‘Nocturne’ in mind, it seemed especially fitting that the French horns as well as the posthorn should have us hold our collective breath once again. We flitted around a weird liminal zone, combining Webern and Mendelssohn; on reflection, is that not often what Mahler is? A hint of balletic Tchaikovsky was swiftly banished by parodic ‘triumph’. And then, everything, or so it seemed, was to be heard that had gone before: together and eternally separate, alienated.

Sarah Connolly brought equal sincerity and subtlety to her vocal part in ‘O Mensch!’ Indeed the different colourings of the first statement of those words and her repetition of them spoke volumes; likewise the ensuing ‘Gib acht!’ The orchestral backdrop, if one can call it that, sounded again close to Webern in its shifting colours. Haitink’s strength of symphonic purpose was, however, quite different in nature (which is not, of course, to imply that Webern has not strength of purpose!) I have heard more contralto-like performances, but there was no denying the excellence of Connolly’s blend of Wort and Ton, nor the strength of the emotional response provoked. Indeed, perhaps not coincidentally, given her recent performances of the role, there was something Brangäne-like to her warnings, the deepness of Nietzschean midnight already in danger of disruption.

Bernard Haitink, Sarah Connolly and the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Photo Credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Bernard Haitink, Sarah Connolly and the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Photo Credit: Chris Christodoulou.

The boys’ calls of ‘Bimm bamm’ - I have heard dull people decry this wondrous moment as ‘silly’, when nothing could stand further from the truth -came as a fifth-movement, quite heavenly wake-up call from such Tristan-esque reverie. Connolly, intriguingly, continued to warn; it was certainly not only Haitink who understood how the two movements are connected. The women’s chorus and the LSO stood somewhere in between: mediators, perhaps even sainted mediators.

Quiet, infinite warmth marked the hymnal intensity of the LSO strings at the opening of the finale. I thought of - and felt - Communion. ‘What God tells me’, indeed! There was an almost Nono-like imperative to listen, as the strings spoke to us not just corporately, not just sectionally (what viola playing!) but, so one fancied, from individual desks and individual positions at those desks too. Fragility and strength were partners as the movement gathered pace, as something or Something revealed itself or Itself. There was, moreover, a well-nigh Beethovenian benevolence of spirit, albeit more vulnerable, to be experienced, perhaps even a little neurosis aufgehoben. And how Haitink guided the unfolding of that long line of unendliche Melodie; how he and his players communicated that echt-Romantic Innigkeit, so close to Schumann and yet alienated from him as modernity must be! For there was a Lied-like simplicity to what we heard and felt. This is difficult music, but its difficulty is accessible to anyone with a heart - and a mind. Unlike, alas, the idiot who disrupted the silence-that-never-was by shouting ‘Yeahhhhhhhhh!’ How can people be quite so inconsiderate? Still, that was an irritation rather than a catastrophe; the performance, both then and in recollection, rose far, far above it.

Mark Berry

Sarah Connolly (mezzo-soprano); Tiffin Boys’ Choir (chorus master: James Day); London Symphony Chorus (chorus master: Simon Halsey); London Symphony Orchestra/Bernard Haitink (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, 29 July 2016.

image= http://www.operatoday.com/Prom%2018%20Sarah%20Connolly%20Chris%20Christodoulou.png image_description= Prom 18: Mahler, Symphony No.3 product=yes product_title=Prom 18: Mahler, Symphony No.3 product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Sarah ConnollyPhoto credit: Chris Christodoulou

Munich Opera Festival Baroque Concert: Music from the Court of Louis XIV

Music from the court of Louis XIV covers, after all, a good number of years, the king having reigned between 1643 and 1715. The works by Marais and Couperin at the close were probably the latest, both dated 1711, four years before Louis’s death. Rather to my surprise, although not without exception, it was the first half that proved more compelling as a performance to me. Perhaps that was partly a matter of having tired a little; although this repertory certainly interests me, I can lay no claim to great expertise. One has to listen intently to appreciate its subtleties and its variety, just as one does with, say, the music of Luigi Nono. Maybe, then, I am - perhaps unusually - more accustomed to listening to Nono.

For there was certainly variety in the programming, within its chronological and courtly framework. Its French title - ‘Au bord d’une fontaine - Airs et Brunettes’ - alluded nicely not only to one of the Charpentier works and implicitly to Versailles itself, but also to the celebrated 1721 collection of songs arranged for flute by Jacques Hotteterre, ‘ Airs et brunettes a deux et trois dessus pour les flutes traversieres tirez des meilleurs autheurs, anciens et modernes, ensembles les airs de Mrs. Lambert, Lully, De Bousset, &c les plus convenables a la flute traversiere seule, ornez d'agremens par Mr. Hotteterre Ie Romain et recueillis par M. ++++.’ And so, rather than arrangements, we heard ‘originals’, mostly vocal, with Claire Lefilliâtre as soprano, but with instrumental interludes, from viola de gamba (Friederike Heumann), theorbo (Fred Jacobs), and the two instruments in concert. We also heard a couple of recitations, Lefilliâtre reading from Corneille and La Fontaine.

What I think I missed most of all, especially during the second half, was something more outgoing in Lefilliâtre’s vocal performances. Now there is much to be gained from intimacy, which I valued greatly in the vocal music of Etienne Moulinié and Michel Lambert in particular, and not all of this music, indeed not much of it, is ‘operatic’, whether in a seventeenth- or a more modern sense. By the same token, however, there were times when, despite trying to listen as I could, I missed a greater sense of variation both within and between pieces.

The Italianate style of some of the first-half performances - more than once, I thought of Cavalli - initially surprised me, until I reflected on Cavalli’s own Ercole armante, commissioned by Mazarin for the 1662 wedding of Louis to Marie-Thérèse. As the harpsichordist Luke Green reminded me afterwards, the roots go back further, however: to the influence of Marie de’ Medici. Such tendencies are not absent, of course, even in Charpentier and Couperin; not only did I miss them being brought to the vocal foreground more strongly, however; I missed much of what made those composers different, more modern. Their music looks forward to Rameau as well as back to the earlier years of Louis’s reign. A further oddity was the inconsistency in Lefilliâtre’s ‘historical’ pronunciation, whether in the declamatory Corneille or the vocal items. I have no particularly strong feelings either way about the practice as such, whether in my own language or another, but it was unclear to me why some word endings should be pronounced and others not. Details matter in most music, but they certainly do here. Diction and intonation could sometimes be a little wayward too.

There was, though, a moving sincerity to Lefilliâtre’s performances at their best - enhanced for me by the warmth of the church acoustic, although others . Tales of love and death - are they not often one and the same? - drew one in. So too, very much, did not only the ‘accompaniments’ but the instrumental items. Heumann’s gamba playing proved her not only mistress of her instrument but above all a deeply sensitive musician, responding to it just as a fine pianist would to Chopin. The pieces from Marais’s Pièces de viole sounded not only as justly acclaimed summits of this still little-known (at least beyond certain circles) repertory, but as instrumental music fully fit to hold its own with more celebrated successors. Likewise Jacobs’s theorbo playing, pulse always clear, and for that reason capable of meaningful rather than arbitrary modification. I do not think I had heard the music of Robert de Visée before; it emerged in Jacobs’s hands as something clearly worthy of further exploration. And that, whatever certain reservations regarding vocal performances, is surely the point.

Mark Berry

Etienne Moulinié: Si mes soupirs sont indiscrets; Bien que l’Amour; O che gioia; Charles Hurel: Prélude; Nicolas Hotman: Allemande; Pierre Corneille: Psyché: ‘A peine je vous vois’; Michel Lambert: Ombre de mon amant;Vos mépris chaque jour; Sieur de Sainte-Colombe - Les Couplets; Sébastien le Camus: Laissez durer la nuit;Ah! Fuyons ce dangereux séjour; Amour, cruel Amour; Michel Lambert - Rochers, vous êtes sourds; Robert de Visée: Prélude;La Mascarade: Rondeau; Chaconne; Jean de La Fontaine - Fables, Livre XII, 14: ‘L’Amour et la Folie’; Charpentier - Profitez du printemps; Celle qui fait tout mon tourment; Au bord d’une fontaine; Sans frayeur dans de bois; Marin Marais - Pièces de viole, 3ème livre: Prélude and Grand ballet; Couperin - Zéphire, modère en ces lieux. Claire Felliâtre (soprano); Friederike Heumann (viola da gamba); Fred Jacobs (theorbo). Klosterkirche St Anna im Lehel, Munich, Monday 25 July 2016.

image= http://www.operatoday.com/Claire%20Lefilliatre.png image_description=Munich Opera Festival Baroque Concert product=yes product_title=Munich Opera Festival Baroque Concert product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Claire LefilliâtrePhoto credit: Sébastien Brohier

July 29, 2016

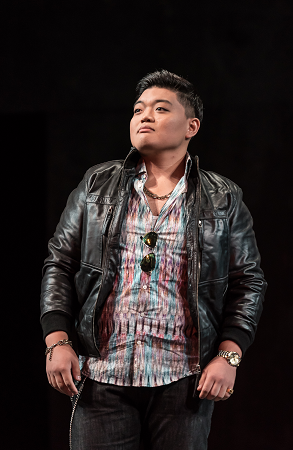

Les Indes galantes, Bavarian State Opera

Yet, whilst there has been much Handel, Monteverdi, Cavalli, et al., in recent years, the French Baroque in general and Rameau’s music in particular seem to have been a closed book - as so often in the world outside France. Let us leave aside for the moment debates concerning whether ‘Baroque’ should be a suitable designation, merely noting that Rameau’s music seems to have provoked the word’s first artistic usage. An anonymous letter to the Mercure de France, occasioned by the 1733 Paris premiere of the composer’s first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie, printed in the Mercure de France, dismissed the opera’s novelty as ‘du barocque’; its melody was incoherent, its harmony unduly dissonant, and its metre chaotic.

[Click here for a review of a streamed performance of this production.]

That was certainly not how Rameau sounded on this occasion, quite the contrary. Indeed, I should not have minded a little more truculence - if not incoherence! - from Ivor Bolton’s conducting. Its fluency was admirable, but I could not help notice - and, at times, become a little tired by - a tendency remarked upon by a friend beforehand: namely the conductor’s penchant for turning everything into a dance. There is much dance music, of course, in this opéra-ballet, but that is not to say that everything must be. I know that many ‘authenticke’ musicians will argue to the contrary, even, God help us, in Gluck and Mozart, but the declamatory French of Rameau’s recitatives - here, admirably, indeed often thrillingly, supported by a continuo group involving Luke Green (harpsichord), Fred Jacobs and Michael Fremiuth (theorbo), and Werner Matzke (cello) - is not necessarily to be confined to them. The ravishing airs, duets, and above all, ensembles, would have benefited, at least to my ears, from greater - dare I say, quoting the writer to the Mercure de France, more ‘chaotic’? - variation.

That said, and that said perhaps at too great a length, there was otherwise much to relish from the Munich Festival Orchestra. Even I did not find myself missing modern instruments. (This is, I learned afterwards, the Dresden Festival Orchestra on location.) Indeed, the woodwind in particular very much offered their own, splendidly Gallic justification. Moreover, strings (twelve violins, five violas, seven cellos, two bass viols, one violone) were certainly not parsimonious with their vibrato, quite from it; this was an enlightened as well as an Enlightened performance from all concerned. Rameau’s love of orchestral sound, its implications for Gluck and, via him, for Mozart too (think of Idomeneo!) was vividly and, above all, dramatically, communicated.

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s direction, choreography included, treads a

judicious line between various competing elements. If I were a little surprised

that Munich chose this Rameau work as its first - for me, a tragédie

lyrique, such as Hippolyte, would have been a more obviously

compelling choice - then the voguish (for the 1730s, that is!) amalgam of opera

and ballet offered opportunities to ravish other of the senses too.

Cherkaoui’s dancers never disappointed, their movements - do these people

have no bones in their bodies? - not merely responsive to the music, to the

drama, but intensifying its possibilities, above all visual-dramatic tension at

points of decision. If one wished to visualise a Rameau flute line, for

instance, one could have done far worse than watch the movement on stage.

Without pressing his point too far, Cherkaoui probes what might hold this

prologue and four entrées - as in Rameau’s definitive version -

together. Opening in a classroom, the teacher, Hébé, leading her children in

conjugation of French verbs, the unified drama takes them - and us - on a tour

of different civilisations, and shows them, not the war personified by Bellone,

often to have as much to teach us as we have to teach them. That is not to say

that Rameau’s work, still less Louis Fuzelier’s libretto, can or

should be understood in twenty-first century terms; however, its ambiguity, its

insistence upon asking ‘who actually is the barbarian here?’

reminds us that we - and, looking at the world around us, how could we doubt

this? - have no monopoly on multicultural virtue.

Yet there are differences too. The homosexual love denied by the Incan Huescar (here in European clerical carb) in Cherbaouki’s funeral-turned-wedding setting for the second entrée also finds its fulfilment; L’Amour, for us today, does not discriminate, heterosexual and homosexual love are, ultimately, after a struggle, equally valued. Moreover, for an English visitor, more than unusually embarrassed by his nationality at the moment, Munich’s ecumenism offered hope that Europe and indeed the world beyond it will survive. National flags, favoured by Bellone and a visiting American President, are not banished, but there is a vision of something greater to be glimpsed, in the European flags - and, indeed, in the exquisite blue and yellow of many of the children’s outfits. (The Kinderstaterie of the Bavarian State Opera were well trained and delightful in their roles.) And so, the young men who forsake Hébé and Europe for the ‘Indies’ (an all-purpose, ‘exotic’ Orientalism or Occidentalism!), learn through experience that conflict is not the way to prosper; the realisation of the peace-pipe ceremony at the close strikingly fulfils the work’s strikingly internationalist sentiment, dancers and vocalists as one.

The singing was, without exception, wonderful. Words were as clear as Rameau’s lines, whether in solo, duet, ensemble, or choral numbers. The Balthasar-Neumann Chor was certainly not the least impressive aspect of the performance. Lisette Oropesa and Ana Quintans set the scene splendidly in the Prologue, Hébé and L’Amour carefully differentiated, with Goran Jurić a strikingly successful general-in-drag. Tareq Nazmi’s sensitive bass offered wisdom and humanity; Cherbaouki’s skilful comparison between the roles of Osman and Ali was given sympathetic life, as were other such doublings of roles (more than mere doublings). Mathias Vidal and Anna Prohaska shone likewise as Carlos/Damon and Phani/Fatime. Both imparted depth in lightness, and lightness in depth, as graceful on stage as of voice. Cyril Auvity’s unerringly stylish tenor, François Lis’s deep yet never bluff bass, and Elsa Benoit’s sparkling yet variegated soprano offered other highlights; so too did the highly attractive chiaroscuro of John Moore’s baritone. Above all, there was a true sense of collaboration, rendering the performance as well as the work substantially more than the sum of its parts. As we once hoped - and perhaps may one day hope again - for a Europe too often divided, indeed torn apart, by Bellone…

Mark Berry

Cast and production details:

Hébé, Zima: Lisette Oropesa; Bellone: Goran Jurić; L’Amour/Zaïre: Ana Quintans; Osman, Ali: Tareq Nazmi; Emilie: Elsa Benoit; Valère, Tacmas: Cyril Auvity; Huascar, Alvar: François Lis; Phani, Fatime: Anna Prohaska; Carlos, Damon: Mathias Vidal; Adario: John Moore. Dancers: Navala ‘Niku’ Chaudhari, Kazutomi ‘Tzuki’ Kozuki, Jason Kittelberger, Denis ‘Kouné’ Kuhnert, Elias Lazaridis, Nicola Leahey, Shintaro Oue, James Vu Anh Pham, Acacia Schachte, Patrick Williams ‘Twoface’ Seebacher’, Jennifer White, Ema Yuasa. Director, Choreography: Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui (director, choreography); Set designs: Anna Viebbrock; Costumes: Greta Goiris; Lighting: Michael Bauer; Dramaturgy: Antonio Cuenca Ruiz, Miron Hakenbeck (dramaturgy); Choreographic Assistance: Jason Kittelberger. Balthasar-Neumann-Chor, Freiburg (chorus master: Detlef Bratschke)/Munich Festival Orchestra/Ivor Bolton (conductor). Prinzregententheater, Munich, Sunday 24 July 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Les%20Indes%20Galantes.png image_description=Les Indes galante, Bavarian State Opera product=yes product_title=Les Indes galates , Bavarian State Opera product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Elsa Benoit (Emilie) and Dancers of the Eastman CompanyPhoto credit: Wilfried Hösl

July 28, 2016

Don Giovanni, Bavarian State Opera

At any rate, whilst not every aspect might have been the ‘very best ever’ - how could it be? - all was of a very high standard, and much was truly outstanding. I even began to think that the wretched ‘traditional’ Prague-Vienna composite version might for once be welcome; it was not, yet, given the distinction of the performances, the dramatic loss was less grievous than on almost any other occasion I have experienced.

If Daniel Barenboim’s Furtwänglerian reading in Berlin in 2007 remains the best conducted of my life, there was nothing whatsoever to complain about in James Gaffigan’s direction of the score. It was certainly a far more impressive performance than a Vienna Figaro last year, which led me to wonder how much was to be ascribed to other factors, not least the truly dreadful production; perhaps, on the other hand, Don Giovanni is just more Gaffigan’s piece. The depth and variegation of the orchestral sound was second, if not quite to none, than only to Barenboim’s Staatskapelle Berlin. This was far and away the best Mozart playing I have heard in Munich. Even if the alla breve opening to the Overture were not taken as I might have preferred, and certain rather rasping brass concerned me at the opening, I find it difficult to recall anything much to complain about after that; nor do I have any reason to wish to try. Tempi were varied, well thought out, and above all considered in relation to one another. Terror and balm were equal partners: on that night in Munich, we certainly needed them to be.

This was, I think, Stephan Kimmig’s first opera staging, first seen in 2009. I shall happily be corrected, but I am not aware of anything since. If so, that is a great pity, for the intelligence of which I have heard tell in his ‘straight’ theatre productions - alas, I have yet to see any of them - is certainly manifest here. There are, above all, two things with which an opera staging cannot survive: a strong sense of theatre and a strong sense of intellectual and dramatic coherence. Equally desirable is, of course, at least something of an ear for music, and coordination between pit, voices, and stage action seemed to me splendidly realised too.

A perennial lament of mine concerning Don Giovanni productions concerns refusal or inability to understand it as a thoroughly religious work. Here, there is certainly some sense of sin; its relationship to atheistic heroism is, just as it should be, complex. And the reappearance of the Commendatore and (excellent) chorus at the end, some, including the Stone Guest himself, in clerical garb, reminded us, without pushing the matter, that authority is at least partly religious here. There are other forms of authority too - Don Ottavio’s ever-mysterious reference to the authorities perhaps intrigues us more than it should, or perhaps not - and they are also represented: military berets, business suits, and so forth. A libertine offends far more than the Church; and of course, the Church as an institution has always been many things in addition to Christian (to put it politely).

Katja Haß’s set designs powerfully, searchingly evoke the liminality of Da Ponte’s, still more Mozart’s Seville. The drama is not merely historical, although it certainly contains important historical elements. But above all, there is a labyrinth - one I am tempted to think of as looking forward to operas by Berg, even Birtwistle, perhaps even the opera that Boulez never wrote - in which all manner of masquerading may take place. Social slippage and dissolution - above all the chameleon-like abilities of the (anti-)hero - need such possibilities, which are present here, in abundance, in a setting that both respects traditional dramatic unities and renders them properly open to development. A warehouse, containers revolving, opening and closing, changing and remaining the same, provides the frame. Yet we are never quite sure what will be revealed, languages of graffiti transforming, never quite cohering, Leporello’s catalogue - and, more to the point, its implications - foreseen, shadowed, recalled. There is butchery - literally - to be seen in the carcasses from which the Commendatore emerges. There is glitzy - too glitzy - glamour in the show Giovanni puts on to dazzle the peasantfolk; but it does its trick, coloured hair and all.

And there is an Old Man, observer and participant, sometimes there, sometimes not. Everyman? The nobleman, had he outstayed his welcome, not accepted the invitation? He is clearly disdained, even humiliated (what a contrast, we are made to think, almost despite ourselves, between his naked body and the raunchy coupling - or more - around him). That is, when he is seen at all: and that is, quite rightly, as much an indictment of the audience as of the characters onstage. Part of what we are told, it seems, is that this is a drama of the young, who have no need of the elderly. Not for nothing, or so I thought, did Alex Esposito’s Leporello exaggerate his caricatured sung response to Giovanni’s elderly women.

It is, then, an open staging: suggestive rather than overtly didactic. In a drama overflowing with ideas, that is no bad thing at all. Coherence is, whatever I might have implied above, always relative; the truest of consistency will often if not always come close to the dead hand of the Commendatore. For this was a staging that had me question my initial assumptions: again, something close to a necessity for intelligent theatre. (I assume that the bovine reactions from a few in the stalls were indicative of a desire for anything but.)

If religion lies at the heart of the opera, too little acknowledged, perhaps at least a little too little here too, then so does sex. Sorry, ‘Against Modern Opera Productions’, but there you have it; this really is not an opera for you, but then what is? Don Giovanni and Don Giovanni ooze - well, almost anything and everything you want and do not want them to. They certainly did here, which is in good part testament to this superlative cast. Erwin Schrott’s Giovanni may be a known quantity - I have certainly raved about it before, more than once - but it was no less welcome and no less impressive for that. ‘Acting’ and singing were as one. He held the stage as strongly as I have ever seen - which means very strongly indeed - and his powers of seduction were as strong as I have ever seen - which means, as I said… His partnership with Esposito’s Leporello was both unique and yet typical of the dynamically drawn relationships between so many of the characters on stage. Leporello was clearly admiring, even envious of his master; their changing, yet not quite, of clothes and identities was almost endlessly absorbing its erotic, yet disconcerting charge. Esposito brought as wide a range of expressive means to his delivery of the text as any Leporello, Schrott included, I remember. Their farewell was truly shocking, Giovanni picking up his quivering servant from the floor, kissing him for several spellbinding seconds, then wiping his mouth clean on his sleeve and spitting contemptuously on the floor. It was time finally to accept the Commendatore’s invitation, issued with grave, deep musicality by the flawless, excellent Ain Anger.

I had seen Pavol Breslik as Don Ottavio before. There could have been no doubting the distinction of his performance in Berlin, under Barenboim, although neither artist was helped by the non-production of Peter Mussbach. Here, however, Breslik presented, in collaboration with the production, perhaps the most fascinating Ottavio I have seen - and no, that is not intended as faint praise. This was a smouldering counterpart to Giovanni, unable to keep his hands off Donna Anna, and frankly all over her during her second-act aria. Their pill-popping - he supplied the pills - opened up all manner of possibilities, not least given the frank sexuality of their, and particularly his, reactions. The beauty of Breslik’s tone, silken-smooth in his arias, added an almost Così fan tutte-like agony to the violent proceedings. In Albina Shagimuratova, we heard a Donna Anna of the old school: big-boned, yet infinitely subtle, her coloratura a thing of wonder. Combined with the uncertainty of her character’s development - again, most intriguingly so - this was again a performance both physically to savour and intellectually to relish.

So too was that the case with Dorothea Röschmann’s Donna Elvira. Her portrayal - Kimmig’s portrayal - would certainly not have pleased, at least initially, those for whom this is in large part a misogynistic work. (It seems to me that they misunderstand some, at least, of what is going on, but that is an argument for another time, and I am only too well aware that it is not necessarily a claim that I, as a man, should be advancing anything other than tentatively.) Downtrodden, yet beautifully sung, in the first act, she nevertheless came into her defiant own in the second, above all through the most traditionally operatic of means: sheer vocal splendour. What a ‘Mi tradì’ that was!

Eri Nakamura gave the finest performance I have heard from her as Zerlina, seemingly far more at home in Mozart than when I heard her at Covent Garden. This was a Zerlina who both knew and did not know what she was doing - as a character, of course, not as a performance. And finally, Brandon Cedel’s portrait in wounded, affronted, unconscious yet responsive masculinity proved quite a revelation: I do not think any Masetto has made me think so much about his role in the drama. Nor can I think, offhand, of any Masetto so dangerously attractive - again, like Ottavio, in some sense an aspirant Giovanni, but one still more incapable of being so. Morally, of course, that is to the character’s credit - but in this most ambiguous of operas, and in this most fruitfully ambiguous of productions, one was never quite sure.

Mark Berry

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Don Giovanni

Don Giovanni: Erwin Schrott; Commendatore: Ain Anger; Donna Anna: Albina Shagimuratova; Don Ottavio: Pavol Breslik; Donna Anna: Dorothea Röschmann; Leporello: Alex Esposito; Zerlina: Eri Nakamura; Masetto: Brandon Cedel; Old Man: Ekkehard Bartsch. Director: Stephan Kimmig; Set Designs: Katja Haß; Costumes: Anja Rabes; Video: Benjamin Krieg; Lighting: Reinhard Traub; Dramaturgy: Miron Hakenbeck: Chorus of the Bavarian State Opera (chorus master: Stellario Fagone)/Bavarian State Orchestra/James Gaffigan (conduct0r). Nationaltheater, Munich, Saturday 23 July 2016.

image= http://www.operatoday.com/Erwin-Schrott_Don-Giovanni_c-Wilfried-H%C3%B6sl.jpg image_description=Don Giovanni, Bavarian State Opera product=yes product_title=Don Giovanni, Bavarian State Opera product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Erwin Schrott as Don GiovanniPhoto credit: Wilfried Hösl.

A dance to life in Munich’s Indes galantes

Such to my mind was the world premiere of Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s staging of Rameau’s Les indes galantes for this summer’s opera festival at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich.

M. Cherkaoui, a Belgian of Moroccan descent, has been dancing since he was 13; he won his first major prize as a performer when he was 21 and has received awards for his choreography—the Kouros in 2009, two Oliviers (in ’11 and 14) with almost monotonous regularity. He is a handsome, personable, articulate media magnet, whose work, immediately accessible seamlessly blends classical steps, modern dance intensity, and street moves.

He is also an insanely talented choreographer, probably the most gifted and distinctive to emerge since the American Mark Morris burst onto the international dance scene on the stage of Belgium’s Theatre de la Monnaie a quarter century ago. With his first operatic staging, he has established himself a master of this most difficult of dramatic arts, and done so with a work from the French opera-ballet repertory, arguably the most challenging form for a stage director or choreographer in all the lyric theater repertory.

The society that gave birth to the French operatic repertory is as dead-and-gone as Akhnaten’s Egypt. The grandeurs and absurdities of Parisian grand opéra swept away the huge repertory of tragèdie lyrique and comèdie ballet and all but ground to dust the performing tradition upon which the depended. The “comeback” of this repertory over the last 40 years is even more astonishing in light of the plain fact, widely recognized though rarely acknowledged, that many revivals of works of the period 1660–1750 productions have succeeded on purely musico-dramatic grounds, with their huge choreographic element either unsupportive of or actively discordant with the overall experience.

John Moore (Adario), Lisette Oropesa (Hébé/Zima), Tänzer der Compagnie Eastman, Antwerpen

John Moore (Adario), Lisette Oropesa (Hébé/Zima), Tänzer der Compagnie Eastman, Antwerpen

There are good reasons that so many of these stagings found themselves so artistically conflicted. The most powerful choreographic trends of the period, particularly in the Francophone nations of Europe, were indifferent to or actively hostile toward the old values of grace and musicality in dance: rough, spasmodic, angular, abstract movement was all but compulsory for a dance-maker to be considered serious and important.

Anybody who has come to love the dance-operas of Lully, Charpentier, and Rameau can also recall the embarrassment, anger, and boredom occasioned by stagings in which dance and music and drama were, if not in open war, at most grudging and awkward collaborators.

And the same lovers of this repertory can recall moments when suddenly the warfare ceased: when all the elements melted together and if only for a little while, released the intoxicating perfume of this art at its most elevated.

It is fitting that M. Cherkaoui hails from the anti-beauty heartland of modern dance. His work in Les indes galantes embraces every dance fashion and trend of the last 40 years and harmonizes them because he’s not thinking about them but about the ever-passing moment of the music. His movement exalts the human figure, celebrates human interaction, energizes the stage picture from back wall to apron, wing to wing, flies to floor.

M. Cherkaoui’s approach to librettist Louis Fuzilier’s string of loosly-connected illustrations of true love in exotic climes is to melt them together, retaining the amorous spirit but making the individual tales of pasha and slave-girl, Inca prince and temple-maiden etc. fragments floating on a continuous spate of images.

The setting is a drably furnished école élémentaire: uniformed students in their battered desks, informative maps and charts on the wall, hard-working teachers and staff going about the pedestrian essentials of creating new citizens for France.

And that is the only moment is the show that might be called pedestrian. Rameau’s music blows through this space, suggesting and supporting a flickering series of visions of a world in flux, peoples displaced, cultures in conflict. The overall effect is to portray a universal struggle for stability, safety, repose. And at every moment the tone is set by Rameau. The movement seems only the inevitable consequence: the touchstone of great choreography in any age.

Ana Quintans (L’Amour/Zaire), Cyril Auvity (Valère), Anna Prohaska (Phani/Fatime), Tareq Nazmi (Osman/Ali), Tänzer der Compagnie Eastman, Antwerpen

Ana Quintans (L’Amour/Zaire), Cyril Auvity (Valère), Anna Prohaska (Phani/Fatime), Tareq Nazmi (Osman/Ali), Tänzer der Compagnie Eastman, Antwerpen

The use of contemporary popular dance forms is not new in this repertory: José Montalvo’s 2004 staging of Rameau’s Les paladins for the Châtelet was non-stop hip-hop, visually dazzling but utterly failing to provide anything but dazzle.

The difference from the Munich Indes galantes could not be more striking. Cherkaoui has found a movement synthesis which moves: the dazzle is just a delightful extra. What seems at first a high-handed way with the dramaturgy of the work proves to be the best way I have ever encountered in this repertory to break through to its enduring essence.

I believe that soon this exemplary staging—all hail the Bavarian State Opera for its courage and dedication in mounting it—will soon be seen as a milestone in the revival of French baroque theater on a par with the 1987 Atys of Jean-Marie Villégier and William Christie. One of the commonest tropes of Baroque dramaturgy is the ever-troubled alliance between the arts of music and dance (the first act of the Molière-Lully Bourgeois gentilhomme is the locus classicus). M. Cherkaoui appears like a god from the flies to join their hands once more after too long a divorce.

Roger Downey

Cast and production details:

Musikalische Leitung

Ivor

Bolton

Inszenierung und Choreographie Sidi

Larbi Cherkaoui

Bühne Anna

Viebrock

Kostüme Greta

Goiris

Licht Michael

Bauer

Dramaturgie Antonio

Cuenca , Miron

Hakenbeck

Chor Detlef

Bratschke

Hébé Lisette

Oropesa

Bellone Goran

Jurić

L'Amour Ana

Quintans

Osman Tareq

Nazmi

Emilie Elsa

Benoit

Valère Cyril

Auvity

Huascar François

Lis

Phani Anna

Prohaska

Don Carlos Mathias

Vidal

Tacmas Cyril

Auvity

Ali Tareq

Nazmi

Zaire Ana

Quintans

Fatime Anna

Prohaska

Damon Mathias

Vidal

Don Alvaro François

Lis

Zima Lisette

Oropesa

Adario John

Moore

Tänzerinnen Jennifer

White ,

Niku Navala Chaudhari,Acacia

Schachte,Ema

Yuasa, Nicola

Leahey

Tänzer Elias

Lazaridis ,

Kazutomi “Tsuki” Kozuki,Shintaro

Oue,Patrick

Williams "Twoface" Seebacher,Denis

Kooné,James

Vu Anh Pham, Jason

Kittelberger

Tänzer der Compagnie Eastman, Antwerpen

Balthasar-Neumann-Chor, Freiburg

Münchner Festspielorchester

Photos courtesy of Bayerische Staatsoper

July 26, 2016

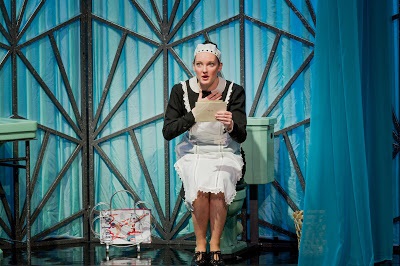

Il barbiere di Siviglia, Glyndebourne Festival Opera at the Proms

Annabel Arden's production, designed by Joanna Parker, was adapted by Sinead O'Neill. Enrique Mazzola conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra, placed to the rear of the stage, with Danielle de Niese as Rosina, Alessandro Corbelli as Dr Bartolo, Taylor Stayton as Count Almaviva, Björn Bürger as Figaro, Christophoros Stamboglis as Don Basilio, Janis Kelly as Berta, Huw Montague Rendall as Fiorello and Adam Marsden as an Officer, plus the men of the Glyndebourne Chorus.

I have not seen Annabel Arden's production at Glyndebourne, but Sinead O'Neill had successfully created a vibrant and all-encompassing staging (there was little that was semi- about it) which involved both the orchestra and conductor. The evening was full of laugh out loud moments which seemed to fill the Royal Albert Hall (no mean feat with a comedy designed for a far smaller space).

The problem was that Arden seemed to have taken her cue from the staging of the Act One finale. In most productions I have seen, this is given in a highly stylised and choreographed manner. It was no different here, Arden (and director of movement Toby Sedgwick) created an almost hyper-active physical commentary on the music, creating a very funny ensemble. But Arden transferred this style to the whole opera, each solo and each ensemble was highly choreographed and the whole evening became a long sequence of physical theatre. The addition of three actors to the cast (Tommy Luther, Maxime Nourissat and Jofre Caraben van der Meer) emphasised this as the three were rarely absent from the stage, either as carnival figures in the opening and closing scenes or as three extra servants in Doctor Bartolo's house

I have great admiration for the performers because all concerned brought off the conception superbly, combining fine musicianship with brilliant theatre. The problem for me was that somewhere along the line, Rossini's sense of character seemed to disappear. One of the reasons why the opera has remained so popular is that Rossini manages to combine a sense of fun with a real feeling of drama so that the comedy and the music arise out of the situation. By the end of the opera I was no clearer who these characters really were. For all Taylor Stayton's charm in performance, without a feeling of dramatic context we had little idea who the Count really was.

To take a couple of examples. In the Act One where the Count first encounters Figaro (a scene culminating in the duet 'All'idea di quel metallo') we received no sense of the social hierarchy, that Figaro had once worked for the Count. Instead Björn Bürger and Taylor Stayton interacted as equals. And in the climactic Act Two trio when Figaro and the Count climb up the ladder into Rosina's room in order to rescue her, Rossini sends up opera seria convention so that the Count and Rosina have a classically structured duet complete with the necessary repeats, whilst Figaro must wait impatiently on the sidelines hurrying them up and sending up their music. Here all three performers were highly physical and we had no sense of the two worlds meeting.

Danielle de Niese (Rosina), Christophoros Stamboglis (Don Basilio), Alessandro Corbelli (Dr Bartolo), Björn Bürger (Figaro) and Taylor Stayton (Count Almaviva). Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Danielle de Niese (Rosina), Christophoros Stamboglis (Don Basilio), Alessandro Corbelli (Dr Bartolo), Björn Bürger (Figaro) and Taylor Stayton (Count Almaviva). Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

For all its use of Alberto Zedda's critical edition, and the presence of a forte piano in the continuo, this was a rather traditional version of the opera. The Count did not get his final aria, alas, and Rosina was sung by a soprano (rather than mezzo-soprano) complete with the alternative aria 'Ma forse, ahimè' in Act Two.

Changing Rosina from mezzo-soprano to soprano usually means the character moves from rich-voiced spitfire to pert charm. Danielle de Niese successfully re-made the role in her own image, using her lustrous eyes to great expressive effect and emphasising both Rosina's great personal charm and her physical attraction. De Niese also seems to have got first go at the dressing up box, with a series of striking costumes. Overall, I felt that Danielle de Niese's Rosina was perhaps a little too pleased with herself and we could have done with more of the spitfire. 'Una voce poco fa' was sung with confident style though the aria sat a little low in De Niese's voice and could have done with an upward transposition. As it was, on the repeat her ornamentation pushed the tessitura up significantly. De Niese has a great sense of style in this music, but her execution of the fioriture was a little uneven. Sometimes she produced passages of pin-sharp coloratura such as the duet with Björn Bürger's Figaro, but too often her delivery was rather vaguer in outline and lacked the sense of precise detail which was ideal in the role. 'Ma forse, ahimè' which was written by Rossini for a soprano and which prizes line over coloratura, De Niese really showed what she can do.

Taylor Stayton made a highly personable Count Almaviva, combining physical charms with a strong technique. His opening aria 'Ecco, ridente in cielo' demonstrated a slim-line tenor which he used elegantly, with a superbly confident sense of style in the ornamentation. My only real complaint was that we could have done with a greater variety of colour. Stayton showed himself capable of lyric beauty too in the Count's second serenade. He had a nice sense of comic timing in the disguise scenes, and in the Act Two trio with De Niese and Björn Bürger, Stayton and De Niese really made the Count and Rosina's duet sparkle, adding some rather steamy action.

Björn Bürger as Figaro and Alessandro Corbelli as Dr Bartolo. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Björn Bürger as Figaro and Alessandro Corbelli as Dr Bartolo. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Björn Bürger was a name that was new to me; he is a young German baritone and is a member of the ensemble at Opera Frankfurt. He has an attractive, narrow-bore baritone which he used with great bravura and a lovely ease at the top of the range. His 'Largo as factotum' combined musical elan with a great sense of character, as well as being very funny. Bürger confidently combined a highly physical performance with a musically appealing one. This was a Figaro who seemed easily in control, yet Bürger's Figaro was also a delight to listen to.

Alessandro Corbelli is a veteran as Doctor Bartolo, and his combination of comic timing and musical felicity was effortless. He had the audience in the palm of his hand whenever he was on stage, yet there was no pulling of focus, this was very much an ensemble performance. Perhaps his performance was a little more one-sided than usual, thanks to the highly physical nature of the production, this was a Doctor Bartolo who was very funny throughout, and there was less of the sense of feeling sorry for the old fool that can happen in some performances. But there was so much to delight, whether it was the over-done charm in the arietta 'Quando mi sei vicina' or his lovely way with the recitative.

Christophoros Stamboglis was somewhat disappointing as Don Basilio. His tuning was not ideal in his calumny aria, but then transferring from Glyndebourne Opera House to the Royal Albert Hall with minimal rehearsal cannot be easy. He made Don Basilio delightfully pompous, and though 'La calunnia' was also somewhat effortful, he brought the piece to a great climax.

Janis Kelly was rather luxury casting as Berta, and she made her single aria into a wonderfully show-stopping number. Huw Montague Rendall and Adam Marsden (both from the Glyndebourne Chorus) contributed strong performances as Fiorello and the Officer.

This was very much an ensemble production, and the cast's sense of communal timing and great physicality made it a lovely piece of theatre. The recitative was done very vividly, though sometimes I would have liked a greater feeling of pace. The continuo from Alessandro Amoretti and Pei-Jee Ng was supportive without drawing attention to itself.

Enrique Mazzola and the London Philharmonic Orchestra gave a suavely characterful account of the overture, though it was not the most comically pointed of performances. Here and elsewhere Mazzola seemed to rather like a lot of percussion (mainly drum) in the mix. Throughout the evening the balance was not ideal and though the orchestra was behind the singers, there were too many moments when the balance favoured the orchestra.

The high musical values of the production make it well worth seeking out on BBC iPlayer (where it will be around for 30 days), but in the theatre the over-busyness of the production became a little too much and I felt rather self-defeating. In the end though, I had to admire the entire cast for their energy and commitment, and the superb way they combined the physical with the musical.

Robert Hugill

Rossini: Il barbiere di SivigliaRosina: Danielle de Niese, Dr Bartolo: Alessandro Corbelli, Count Almvaviva: Taylor Stayton, Figaro: Björn Bürger, Don Basilio: Christophoros Stamboglis, Berta: Janis Kelly, Fiorello: Huw Montague Rendall, Office: Adam Marsden, actors: Tommy Luther, Maxime Nourissat, Jofre Caraben van der Meer, original director: Annabel Arden, conductor: Enrique Mazzola, designer: Joanna Parker, stage director: Sinead O’Neill, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Glyndebourne Chorus.

Glyndebourne Festival Opera at the BBC Proms at the Royal Albert Hall, London; 25 July 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Danielle%20Niese%20Figaro%20Glyndebourne%20Prom.png image_description=Il barbiere di Siviglia, Glyndebourne Festival Opera at the Proms product=yes product_title=Il barbiere di Siviglia, Glyndebourne Festival Opera at the Proms product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id=Above: Danielle de Niese as RosinaPhoto credit: Chris Christodoulou

July 25, 2016

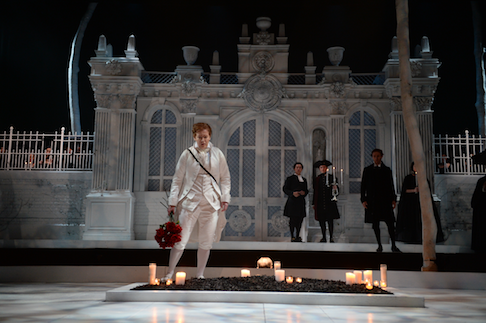

Béatrice and Bénédict at Glyndebourne

Laurent Pelly’s new production for Glyndebourne is certainly capricious: updated to a vague and varying period during the first half of the 20th century, the costumes embrace Edwardian elegance, ’40s Dior ‘new look’ radicalism, and de Gaullian militarism. But, Pelly’s surreal, monochrome hinterland, constructed of wedding-gift boxes - a sort of posh ‘cardboard city’ - from which characters emerge like jacks-in-the-box, offers none of the golden warmth of Shakespeare’s Sicily.

Instead, we have a ‘Fifty (at least) Shades of Grey’ palette worthy of a Farrow & Ball marketing catalogue. At the opening, when the Chorus burst from two large boxes and fling forth a joyful sicilienne to celebrate the arrival of peace, even their vigorously flapping Tricolores are tint-less, deprived of their revolutionary colour symbolism. Arriving at the wedding ceremony which concludes the opera, the guests look as if they’ve been dragged down a Dickensian chimney-stack.

Colour, as Pelly explains, ‘emerges from the music’, but his design and concept betray no awareness of the Sicilian balminess that is built into the score by way of the distinctive orchestration and native dance rhythms. There is no bitterness in Berlioz’s opera but Pelly gives us a storm-cloud back-drop which offers no intimation that the apparently imminent tempest will give way to the clear blue skies of nuptial bliss. Visually, this production presents not a ‘merry war’ but mirthless gloom.

Pelly imagines the bickering protagonists as ‘two rebellious people who refuse to fit into a mould and live in a “box”’, and the characters as ‘puppets’ within a ‘slightly unreal social ritual’. But, how are we to believe in these characters? The romantic dilemmas and dramas, conflicts and conciliations, of Beatrices and Benedicks have been box-office sure-fire hits since Shakespeare created his originals precisely because we can empathise with their emotional upheavals and appeasements.

Pelly puts all his eggs in one basket - or, dare I say it, box. The Glyndebourne Chorus - in wonderful voice - clamber in and out of these boxes, which Pelly conceives as containers of, and conduits to, conformity and domesticity. But more direction is needed for an opera which has hardly any plot - even though its spoken dialogue is drawn directly from Shakespeare - and the arias of which are largely static. The incessant re-arranging of the towers of teetering boxes assumes the choreographic complexity of a shipping dock in a busy freight port, but the human interplay gets lost in the carousel of cartons and chests.

In this opera, so much depends upon Béatrice, and how she is dramatically conceived: fortunately, Stéphanie d’Oustrac (last year’s Carmen) blends Gallic hauteur with elegance of wit and attire, and possesses a mezzo which can explode fierily, brood portentously and float contemplatively.

She made her mark dramatically in Act 1, but it was not until her Act II aria, ‘Il m’en souvient’, in which Béatrice recognises the nature and extent of her hitherto repressed feelings, that the range of d’Oustrac’s vocal expression was fully exhibited: tenderness sat side-by-side with strength, though the sound was never forced; there was diversity of colour and an impressive sense of the long line of Berlioz’s phrases. As the armour protecting her heart was pierced by Cupid’s stubborn arrow, d’Oustrac conveyed Béatrice’s real sense of fear: where will the release of repressed sentiments lead her? When the truth revealed itself, the shocked Béatrice grabbed a chair to defend herself from the alarming emotional onslaught - a melodramatic gesture which was at once comical, charming and touching. Then, as the off-stage wedding hymn wafted dreamily, d’Oustrac was a portrait of contemplative serenity as graceful supernumeraries balletically removed the detritus of the incompetent music-master Somarone’s feast in a beguiling silent charade around the seated dreamer. Yet, Béatrice’s impetuosity was as much a part of her submission as of her opposition: she recklessly dashed off a signature on the wedding contract which tied her in matrimonial subservience, embracing love as impulsively as she had resisted the amorous dart.

Paul Appleby as Bénédict and Stéphanie d’Outrac as Béatrice. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Paul Appleby as Bénédict and Stéphanie d’Outrac as Béatrice. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

As Bénédict, American tenor Paul Appleby just about held his own in the face of d’Oustrac’s dramatic intensity, parrying her acerbic verbal thrusts with pointedness, if not much clout in Act 1. At times he seemed under-directed: Bénédict lurked unresponsively when he overheard his buddies speaking of Béatrice’s love for him. But, if Appleby demonstrated little sense of French style, his tenor is sweet-toned, ardent and flexible, and he offered masculine arrogance a-plenty. Bénédict’s exuberant aria, ‘Ah! je vais l’aimer,’ was vigorous and clear. Unfortunately, in Act 1 the skirmishes between the sceptical pair lacked an enervating frisson, though there were some piquant touches, as when, ordered to leave by her contra-amour, Béatrice stomped off in the opposite direction. But, as the proportion of music to spoken dialogue increased in Act 2, the rapport between the warring lovers became more absorbing, and the final Scherzo-Duetti, ‘Oui, pour aujourd’hui la trêve est signée; Nous redeviendrons ennemis demain’ (Yes, for today a truce is signed, We’ll become enemies again tomorrow) was delightfully sparky.

Sophie Karthäuser, replacing Hélène Guilmette, took a while to settle into the role of Héro, and didn’t capture the excitement or splendour of her Act 1 aria ‘Je vais le voir, je vais le voir!’ But, the end-of-act moonlit serenade, ‘Nuit paisible et sereine!’, in which she was partnered by Katarina Bradić's dulcet Ursule, was exquisite. I was torn between admiring Pelly’s coup de théâtre, as the two excited girls drew back the walls of yet another box to reveal a Dior wedding gown bathed in golden light - some colour at last to counter the pitch-black sky and glaring pendant globes of ‘star-light’ - and regretting that the visual spectacle distracted, and detracted, from the poignant mingling of pain and pleasure in Héro’s heart as she contemplates the bitter-sweetness of true love.

Katarina Bradić as Ursule and Sophie Karthäuser as Héro. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Katarina Bradić as Ursule and Sophie Karthäuser as Héro. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Berlioz replaces Shakespeare’s Dogberry with the asinine music-master Somarone, and the latter’s involvement in the wedding plans is perhaps better integrated into the action than the Master of the Watch’s malapropisms and mishaps. Lionel Lhote was a portrait of puffed-up, pedantic mediocrity, and his exhibitionism injected some much needed levity, if at times it strayed into farce - Somarone’s drinking song, ‘Le vin de Syracuse, Accuse, Une grande chaleur’, ended with a perfectly-timed exit atop the banqueting table, narrowly avoiding decapitation. As Lhote conducted his grotesque epithalamium with pompous self-absorption, flinging out furious commands at the orchestra and urging his singers to ‘milk the ecstasy’, the musical jokes reminded us of the artifice of the plot.

Philippe Sly has little to do as Claudio - except provide Héro with her sole topic of conversation - but his warm baritone made a strong contribution to the Act 1 trio, and Frédéric Caton was an authoritative Don Pedro. As Léonato, Georges Bigot was characteristic of all the cast in delivering the French text idiomatically.

Lionel Lhote (Somarone), Frédéric Caton (Don Pedro) and Philippe Sly (Claudio). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Lionel Lhote (Somarone), Frédéric Caton (Don Pedro) and Philippe Sly (Claudio). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Replacing Robin Ticciati (who is recovering from back surgery), Antonello Manacorda made an auspicious Glyndebourne début in the pit. The overture didn’t quite tease and delight as it should, but once things got going he revealed a sure sense of the nuance and detail of Berlioz’s gossamer score.

Berlioz concluded that the opera shows us that ‘madness is better than stupidity’. Béatrice’s conversion is inspired not, as in Shakespeare’s play, by Bénédict’s defence of Héro’s honour and virtue but by Love - ‘a torch, a flame, a will o’the wisp, coming from no one knows where, gleaming then vanishing from sight, to the distraction of our souls’. Perhaps Pelly’s surrealism does capture this sense of strangeness, but while the singing offers much joy, visually this defeat of romantic scepticism is a melancholy affair.

Claire Seymour

Béatrice et Bénédict continues until 27th August: http://www.glyndebourne.com/tickets-and-whats-on/events/2016/beatrice-et-benedict/

The performance on 9th August will be screened in cinemas and online: http://www.glyndebourne.com/tickets-and-whats-on/events/2016/watch-beatrice-et-benedict/

Hector Berlioz: Béatrice et Bénédict

Béatrice - Stéphanie d’Oustrac, Bénédict - Paul Appleby, Héro - Sophie Karthäuser (23, 27, 30 July; 3, 5, 9 August; Anne-Catherine Gillet will sing Héro on 12, 15, 19, 22, 25, 27 August), Claudio - Philippe Sly, Somarone - Lionel Lhote, Don Pedro - Frédéric Caton, Ursule - Katarina Bradić; Director - Laurent Pelly, Conductor - Antonello Manacorda, Set Designer - Barbara de Limburg, Costume Designer - Laurent Pelly, Lighting Designer - Duane Schuler, Dialogue adapted by Agathe Mélinand, London Philharmonic Orchestra, The Glyndebourne Chorus.

Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Saturday 23 July 2016.

image= http://www.operatoday.com/BandB1.png

image_description=Béatrice and Bénédict, Glyndebourne

product=yes

product_title=Béatrice and Bénédict, Glyndebourne

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Stéphanie d’Oustrac as Béatrice

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

July 24, 2016

Der fliegende Holländer, Bavarian State Opera

Although the Bavarian State Opera eschewed Wagner’s Tristan-esque revision - rightly, in my view, that working better for Tannhäuser than The Flying Dutchman - this was not Götterdämmerung. Moreover, the end, as we experienced it, came more as silence and alienation than a whimper; close, then, but probably not quite the same. More important still, in retrospect - hindsight was inescapable on this particular occasion - the real catastrophe, or rather news of it, came after the end of the performance, the ‘real world’, as is far too often the case at the moment, offering the keenest of tragedy. So perhaps I should start again; I shall not, however, since I should like to start at the end, indeed feel compelled to do so, lest tales of Mrs Lincoln and her critique of the evening’s dramatic proceedings hover too close for comfort. For this was an evening - thank God - never to be repeated, one that even the most ambitious of stage directors would have struggled to envisage, let alone to create. Without in any sense wishing to minimise Peter Konwitschny’s achievement in this typically arresting, provocative, yet ultimately deeply, if not unrelievedly, sympathetic production, only Karlheinz Stockhausen, and before him Richard Wagner himself, might have come anywhere near this - and even then, not so very near.

The music stopped, then, just before the final bars; the lights fell. Silence fell too, the singers looking uneasily at each other: splendidly acted, I remember thinking. Then, following that caesura - inevitable memories of Konwitschny’s celebrated Meistersinger, even for those of us who only heard tell - we heard the final bars, albeit from what sounded like a distant, wind-up gramphone. I even wondered whether it might have been Konwitschny père’s recording, rendered more ancient, not that that matters. Redemption, then, was undercut not only by Wagner’s Tristan-less ending. (I am skating over the more complex issues of earlier versions, but that is not really the point here.) It was ironised - few directors manage to ironise Wagner successfully; Konwitschny does - by hearing it as something we all knew, all expected, were more or less hearing in our heads anyway, and yet then did not hear as we should. It was a little like King Marke’s appearance in Die Meistersinger: meaningful, consequential, a modernist rather than a post-modernist quotation.

Then we spilled out onto the Max-Joseph-Platz, quite unaware of Munich’s terrorist lockdown. My telephone had no reception; I could not contact a friend, to see whether he had been there or not. (It later transpired that he had not.) Many of my fellow opera-leavers seemed puzzled. We could not, for instance, enter a restaurant on the other side of the square; although a few people in there were eating, the doors were locked. Whilst trying to find out what was going on, I eventually received a call from my father, to check that I was safe; he began to explain, and armed police came into view. I learned after that those who were less quick on their feet than I had been were unable to leave the Nationaltheater for quite some time. I, however, had little choice but to try to walk back to where I was staying, armed police and other advisors pointing me and others first in one direction, then in another, often seeming to disagree with each other. Meanwhile, so far as I was aware - this was not the case, but it was what everyone seemed to think at the time - the U-Bahn was closed, since one of several gunmen (there was, of course, only one) had gone down there, armed. Walking past Odeonsplatz station was a little frightening, then; but it was the eeriness of the evacuated beer festival in the square - when I had walked to the opera, it had been full of beer, music, Dirndls, Lederhosen - that, if anything, chilled more. Having spoken to my brother too, I made it back to my host’s, who filled me in on events unfolded and unfolding - and immediately poured me a much-needed drink.

I learned much later that what I ‘should’ have seen and heard - Barry Millington had sent me his review of the production, but I had not read it at the time - was Senta, clearly furious with the Dutchman for not having trusted enough, setting one of the quayside barrels ablaze and mount her own act of terror. The explosion I ‘should’ have heard - unlike Wagner’s music, I did not know it - never came; darkness and alienation, nevertheless curiously, chillingly effective, did. No wonder so many onstage ‘acted’ confused; they had not, it seems, been acting at all. Presumably many had suspected a technical problem. The Bavarian State Opera had, it seems, decided to pull the explosion. For those in the know, was this perhaps a bit like ‘hearing’ Mahler’s missing third hammer-blow in the Sixth Symphony? (Thank goodness this was not a Mahler evening: that really would have been too much.) And so, the business of interpreting, reinterpreting, a particularised version of Konwitschny’s staging - never, let us hope, to be repeated - truly got under way; or at least it did in the odd couple of seconds between replying to anxious Facebook and Twitter messages from friends. (Why, they wondered, had I not replied? Most of them had no idea, of course, that I had been in the theatre for nearly two-and-a-half hours, without an interval.) I shall never forget the non-bang and the gramophone whimper, nor the further step our wretched world made towards Götterdämmerung.

Let me turn, though, to what I had seen and heard before. My memory and my experience are doubtless coloured by the ‘other’ events of that night. Nevertheless, what I saw and heard was impressive indeed, on its own terms. Our friends at Against Modern Opera Productions - how chilling it was to see, that very night, them railing, as if Hitler had never fallen, against ‘degenerate’ artists - might even have liked, had they not seen the word ‘Konwitschny’, the realistic designs from Johannes Leiacker, with which the mise-en-scène opens. For it is a (German) Romantic, even Gothic landscape that provides the backdrop. Apart from anything else, this is a ghost story: every one of us, every society, is overwhelmed by ghosts from our pasts. So too, of course, is opera. Nevertheless, ships are definitely ships; the sea and sky are definitely the sea and sky. The Dutchman’s crew, moreover, are most definitely Golden Age Dutchmen. The painterliness is, in one sense at least, ironic. AMOP would not have ‘got’ that; representations and their deconstruction would have gone unnoticed, uncomprehended. They would surely, though, have noticed the heightened venality not only of Daland, but his crew too (modern Norwegians, but as yet, not with an overwhelming Wagnerian clash between ghostly visitors and the ‘present’). Daland’s pockets of a few golden chains; the Steersman crowns himself with a golden crown; the other lads eagerly join in the bonanza: there is much jewellery to be had from the new ship’s Cardillac-like cargo, unless, as one of Wagner’s less-eagerly acknowledged forebears might have advised him, ‘L’or est une chimère’. A chimera of another variety haunts the Dutchman: the Angel in white who visits the stage. This Dutchman is a man, with sexual fantasies of his own; they distract him, pave the way for tragedy; they lead us to the second act.

Our opera-as-Pegida acquaintances would certainly have started screaming degeneracy, at the deliberate scenic contrast when the curtain rose upon that act. This is a swish health club, in which the wheels that spin are those on the exercise bicycles. Mary leads the class, the girls engaged in the uneasy camaraderie and rivalry of the mindless heteronormative pursuit for an ‘ideal’ physical form to please ‘the’ men they have either hooked or would like to hook. (Or is it the other way round?) Spinning, one might say, takes more than one guise: old visiting new, new visiting old; connections abound. Senta does not fit in; she arrives late for the class, and is far more interested in her Romantic painting. Erik is a creepy yet impatient voyeur: no mere innocent he. Yet it is Senta’s disruptive presence, encouraged by the reappearing Angel, that ultimately, prophetically, proves the turning point. It sets in process the Brechtian - house lights on - lecture to the audience she and the Dutchman give at the close of the act. ‘Romantic love? Yeah, right…’ Everything, then, is set up to fail, as it increasingly does during the third act, modernity and caricatured Old Dutchmen engaging in violent combat, the past, as it so often is, victorious - not least because the present refuses to learn from it. And then - well, you have heard the rest. Explosion there comes - on this occasion, came there not.