August 31, 2016

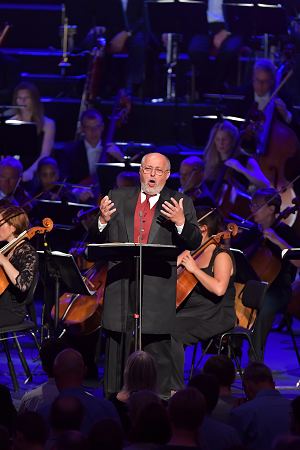

Prom 60: Bach and Bruckner

Keen though I was to hear the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra in Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony, for he principal attraction for me, and for a good part of the audience, was in any case the extremely rare opportunity to hear a Bach cantata played by mainstream performers - especially, so it seemed, when the soloist was Christian Gerhaher. According to the programme, there had only been two previous such opportunities to hear Ich habe genug at the Proms: in 1956 and in 1962, with Heinz Rehfuss and Hermann Prey as soloists, both enticing prospects indeed. Ian Bostridge performed the version for high voice (with flute obbligato, rather than oboe, and period instruments) in 2000.

As it was, Philippe Jordan, heedless of the size of the hall, opted for a very small orchestra (oboe, strings 6.4.3.2.1, chamber organ) and, perhaps more to the point, insisted throughout that the strings play in very subdued fashion. An advantage of smaller forces can often be a greater willingness to play out, but not here. It is a reflective work, of course, and does not need to sound like Mahler (or Bruckner), but the approach nevertheless seemed perverse; I can imagine it might have worked better on the radio. The opening aria was taken at a ‘flowing’ tempo, which is to say considerably faster than would ‘traditionally’ have been the case. On its own terms, it worked well enough, but memories of, say, John Shirley-Quirk with Neville Marriner, or Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (with various conductors) were anything but effaced. Gerhaher’s use of head-voice, moreover, left this listener at least longing for something deeper, darker. There was certainly greater resolution, though, upon the da capo. His diction, whether in arias or recitatives, was impeccable. Bernhard Heinrichs’s oboe playing was unfailingly musical, very much a second ‘voice’. ‘Schlummert ein’ was again relatively swift, although I felt Gerhaher might have done more with the words without coming anywhere near over-emphasis. And Jordan’s pauses seemed excessive: disruptive more than anything else. The following recitative offered much more in the way of verbal emphasis, as did, to a lesser extent, the final aria, ‘Ich freue mich auf meinen Tod’. Here I was rather taken with the swift tempo, which engendered something of a spirit of defiance.

Jordan seemed very much to have rethought ‘traditional’ approaches to Bruckner, but to rather more successful effect. Once past a rocky opening - devoid of mystery, and of much else too, not helped by an onslaught of coughing - we heard some fine playing indeed from the young players of the GMYO: first strings, then the oboe soloist, and so on. The first movement was taken pretty fast, but not unrelievedly so. Intriguingly pointillistic woodwind matched well string pizzicato playing, and added to a sense of provisionality; this was no ‘cathedral in sound’ of cliché. There was, moreover, a strong sense of development: necessary here to avoid a sense of mere repetition. And there was a sense of intimacy too: not the constraint of the Bach performance, but something penetrating deeper, to the very essence of the musical lines. The moment of return was duly awe-inspiring: what a wonderful orchestra this is! Was the approach too fragmentary, though? Perhaps, perhaps not. It was certainly interesting. There was no wanting of power in the coda.

The scherzo opened with a lightness that was far from non-committal, more Mendelssohnian perhaps. Response thereto was anything but light, although one could certainly hear Bruckner as an heir to Schubert (his Ninth Symphony in particular). Perhaps it was a little too driven, but it was certainly not dull. There was occasional insecurity concerning pulse, though. The trio was full of incident, proving both urgent and, occasionally, a little languorous. I liked its range. The finale developed the sense of late Romantic hypertension. There was nothing comfortable to this view of Bruckner, which was all to the good. Both the virtues and the drawbacks of the previous movements endured. Jordan proved, however, especially able in highlighting the contrasting nature in the musical material. Moments of crisis registered; much, it seemed, was at stake. The close was blissful, Schubertian.

Mark Berry

Prom 60: Bach and Bruckner

Bach: Cantata: ‘Ich habe genug’, BWV 82; Bruckner: Symphony No.9 in D minor. Christian Gerhaher (baritone); Bernhard Heinrichs (oboe); Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra; Philippe Jordan (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, Tuesday 30 August 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Prom%2060.png image_description=Prom 60, Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra conducted by Philippe Jordan product=yes product_title= Prom 60, Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra conducted by Philippe Jordan product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Philippe Jordan conducting the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra in Bruckner's Ninth Symphony

Photo credit: Mark Allan/BBC.

August 30, 2016

Prom 57: Semyon Bychkov conducts the BBCSO

Larcher does not consider it a piece of programme music, though, and there seems no reason to doubt him. Or, to put it another way, if we can consider Strauss’s Alpine Symphony, the third work on the night’s programme, as a symphony, there is no reason why we should not this.

It certainly felt like a symphony, not just on account of its four movements, but also their character and their relationship to one another. The first movement opened with a sense of pent-up energy being released, in very fast, highly rhythmic music, that material alternating with slower passages, in which tension is maintained, perhaps even increased, by various means including bass pedals. Without being ‘process music’, musical processes were very much to the fore, both, it seemed in the work, and in the excellent performance from the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Bychkov. Distorted - and sometimes not distorted - tonalities mapped out its space; they were not, perhaps, without nostalgia, but a nostalgia that did not shade into pastiche. A huge orchestral cry of agony - it was difficult not to think of the opening Adagio to Mahler’s Tenth Symphony, both with respect to similarity and difference - made its point, whether ‘programmatic’ or not. Henze, coincidentally or otherwise, sometimes came to mind too. A final descent left us wondering into what we were descending. The chorale-like opening to the succeeding Adagio inevitably brought Austro-German tradition once again to mind; for this really did feel like something akin to a ‘traditional’ slow movement, with a ‘traditional’ symphonic dialectic. Accordion and wind were often prominent, there seeming something to be fundamental about their timbres to the work. Vibraphone and piano duetting also caught the ear’s attention, likewise percussion more generally (as indeed in the first movement). Scalic movement in both directions was a particular concern too.

The third movement sounded not entirely unlike a post-Brahmsian scherzo, with a touch of Stravinskian rhythmic insistence (although not always). The strange repetition of a chord - heard 140 times, apparently! - paradoxically seemed to increase tension, as much as any increase in volume and/or tempo. Then, at the end, a strange little Austrian dance fragment (a Ländler?) suggested neo-Mahlerian affinity to and alienation from Nature. The slow introduction to the finale seemed both connected to and yet something that had moved on from the world of the slow movement. Chorale music again soon flowered. The fast ‘main’ section showed an analogous (perhaps) affinity with the first movement. Again, it proved highly rhythmical and especially concerned with musical process; perhaps even the material itself was similar. In essence, this was a ‘traditional’ moto perpetuo, which then dissolved into a slow coda, which clearly spoke of sadness, shading into desolation. Apparent resolution (disconcertingly close, to my ears, to the world of Arvo Pärt, bells and all) was, mercifully, questioned at the last.

Having spent the previous week or so in Bayreuth, I had the opportunity with the Wesendonck-Lieder, here in Felix Mottl’s familiar orchestration, to begin to ween myself off Wagner for a little while. There is nothing wrong with Mottl’s version, but I could not help wishing that Henze’s had instead been chosen; on the other hand, Mottl’s intimations of Strauss had their own logic in this particular context. Making her Proms debut, Elisabeth Kulman, always an admirable artist, proved a fine choice as soloist: the ‘instrumental’ quality to her voice adding, in a typically Wagnerian dialectic, to the blend of words and music.

‘Der Engel’, opening, sounded very much as a Lied, as it should, even if one with undeniable ‘operatic’ connections. Tristan und Isolde was inescapably close at times, but not repressively so. Kulman’s word-led approach here and elsewhere reminded us of Wagner’s priorities here (not so in Tristan, of course). The angelic, almost Straussian quality to the orchestra was judged to perfection by Bychkov and his players. ‘Stehe still!’ had a different character: more dramatic, with vocal delivery taking us closer to the world of Die Walküre, never more so than in the first half of the final stanza, eye drinking blissfully from eye, and so forth. (Think of Wotan and Brünnhilde, if you will.) Bychkov took his time, quite rightly, and the conclusion proved properly radiant. ‘Im Treibhaus’ took us to Tristan-land proper, yet still with an element of distance; this is a song with its own concerns, not an excerpt. Kulman’s vocal colouring proved just the thing, very much with its own instrumental quality, as mentioned above. There was some especially wonderful viola playing - both solo and as a section - to enjoy too, likewise woodwind playing of Tristan-esque malevolence. ‘Schmerzen’ had a not un-Straussian autumnal glow to it, albeit on a smaller scale. Finally, ‘Träume’ returned us from autumn to a summer evening, its opening pregnant with Tristan-esque possibility, disciplined by the words and their implied structuring capability. Balm and eroticism proved two sides of the same Wagnerian coin.

Strauss’s giant symphonic poem had the second half to itself. Bychkov’s reading flowed beautifully, sometimes quickly indeed; at the same time, he was not remotely afraid to hold back where necessary. If the opening sections were perhaps a little too closely defined in themselves, that should not be exaggerated. The Night in which the work opens was clear, directed: no lazy murkiness here. The BBC SO’s strings sounded voluptuous indeed as our journey gathered pace. Off-stage, Tannhäuser-plus horns thrilled: not just ‘materially’, but with a Nietzschean sense that that materiality might also too be spiritual. This is a symphony, after all, for the Anti-Christ. The forest proved darkly inviting, Bychkov alert to the detail of its beauties, without ever lapsing into pedantry. A post-Mozartian grace to the meadows was especially welcome, offering both contrast to and context for the Zarathustra-like grandeur and ambiguity to the greatest climax of all. As darkness began to fall, before the storm itself, tension could be felt, just as, or almost as, in ‘real life’. So too could the force of the storm, albeit with the detachment of an audience member rather than an actual participant. It was, inevitably, though the Epilogue (Karajan once claimed to conduct the work for this alone) that brought tears to the eyes, exquisite woodwind playing an especial joy. It lingered, as it must: never quite enough, for Strauss is just as sure a dramatist here as in his operas. After which, the darkness into which his world was falling, as is ours.

Mark Berry

Prom 57: Thomas Larcher: Symphony No.2, ‘Cenotaph’ (UK premiere); Wagner (orch. Felix Mottl): Wesendonck-Lieder; Strauss: Eine Alpensinfonie, Op.64. Elisabeth Kulman (mezzo-soprano); BBC Symphony Orchestra/Semyon Bychkov (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, Sunday 28 August.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kulman_01.png image_description=Prom 57, BBCSO conducted by Semyon Bychkov product=yes product_title=Prom 57, BBCSO conducted by Semyon Bychkov product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Elisabeth KulmanPhoto credit: Julia Wesely.

August 29, 2016

40 minutes with Barbara Hannigan...in rehearsal

Without knowing what’s on the programme. For tonight’s edition with Berg and Gershwin, the queue outside went around the building. A huge interest! Inside, folks were arguing over seats. A disgruntled elderly couple planted themselves demonstratively on the reserved press seats next to me. They did not budge—I wouldn’t have either. That’s what you get when Barbara Hannigan performs!

The “Singing Conductor” shared her great musicianship with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra (MCO) in an insightful, albeit slightly haphazard, rehearsal for the concert the next day. The first part of that programme would also include Debussy’s Syrinx, singing Sibelius (Luonnotar), and a Haydn symphony. But tonight Hannigan performed the second half of that programme with a bit of Alban Berg’s Lulu Suite and most excitingly offered a sneakpeak of Bill Elliott’s adaptation of Gershwin’s Crazy Girl, specifically tailored for the Prima Donna. Elliott won a Tony for working on the orchestration for Christopher Wheeldon’s An American in Paris.

The rehearsal was a rehearsal, so I shouldn’t comment on the music...but it was great! What was more interesting was the insights into Hannigan’s collaborative spirit. She truly is rare jewel. The Lucerner Saal, a smaller venue within the marvelous structure of the Kultur und Kongresszentrum Luzern (KKL), made for an intimate experience that stimulated a dialogue between Hannigan’s wit and the audience’s laughter. Whispering kids full of curiosity added an additional giddy dimension.

On bare feet and in jeans with a casual but focused air, the virtuosa opened with a segment from Berg’s Lulu Suite. Having sung this role often, she knows all the tone rows of Berg’s characters, thus prepared to conduct this piece with dramatic perspective, but She did not sing. Instead she demonstrated her conducting skills were not just a gimmick and revealed an authentic talent. As extended extremities, her sinewy, muscular yoga arms became her batons. She performed the part of the piece where Dr. Schön’s in-love son Alwa meets Lulu right after she is released out of prison. Highly dramatic and very engrossing. Berg’s feverish music fit the humid summer heat arising from the lake.

Around the same time Berg was writing Lulu, Gershwin composed Crazy Girl. Hannigan recounted how the American composer supposedly was too shy to perform his music in front of the Austrian composer at a Vienna party. To which Berg responded: “Music is music”. Bill Elliott’s orchestration of Gershwin’s songs strangely resonated Berg’s atonality. I would have never associated the two with each other, if I had not heard them in this context: Gershwin like never before. It was a pity I could not stay next evening’s official premiere of Elliott’s Berg-echoing orchestration of “I’ve Got Rhythm”, “Embraceable You”, and “But not for me”.

Hannigan has a slightly dansant conducting style, natural and in tune with the music. Nothing overtly theatrical. With her fabulous voice and North-American intonation she brought Gershwin’s character immediately to life. Her sighs gave the songs authenticity. “Mister, listen to the the rhythm of my heartbeat” she sang. How poetic as conductor!

During this rehearsal, Hannigan revealed her collaborative spirit. She frequently requested feedback from the MCO’s musicians and strategically asked the saxophonist for a crescendo so she could recognize her cue: “The problems is, I cannot look at the my score then”. Her insistence on feedback resulted in great synergy: “Can I just hear that one, but without me?”.

The big reveal in Elliot’s orchestration was the sudden choral singing of the Mahler Chamber Orchestra as back-up to the Maestra. They really seemed to enjoy this part. Certainly an unforgettable rehearsal.

I highly recommend the intimate setting of the 40 min. series. A terrific place to bring small children.

David Pinedo

image=http://www.operatoday.com/160822_40min4_mco_hannigan_c_patrick_huerlimann_lucerne_festival_4.png image_description=Barbara Hannigan product=yes product_title=40 minutes with Barbara Hannigan...in rehearsal product_by=A review by David Pinedo product_id=Above: Barbara HanniganAugust 27, 2016

Prom 54 - Mozart's Last Year with the Budapest Festival Orchestra

Conductor Iván Fischer was having nothing to do with melancholy portentousness at this Prom with the Budapest Festival Orchestra, however, preceding the Mass’s dignity and darkness with two of the composer’s more sunny compositions from the final year of his life, 1791.

It’s not often that a double-bass player takes centre stage at the Royal Albert Hall. But, Zsolt Fejérvári - the Budapest Festival Orchestra’s principal double bass player since 1994 - found himself in just such a spotlight, alongside bass Hanno Müller-Brachmann (replacing, at short notice, the indisposed Neal Davies), before an expectant audience.

The concert aria ‘Per questa bella mano’ was probably composed for two members of Emanuel Schikaneder’s company at the Freihaus-Theater auf der Wieden in Vienna: the composer and singer Franz Xaver Gerl - who would become Mozart’s first Sarastro - and the double bass player, Friedrich Pischelberger. The text is a light-weight trifle - ‘By this beautiful hand, by these lovely eyes, I promise, my love, that I will never love another’ - but Mozart coats the fripperies with melodic sweetness and orchestral freshness.

Fejérvári exhibited a warm tone, investing the sound with vibrancy. His bowing was agile and fluent in the racing scales, while the challenging double-stopped passages were well-tuned and rich - no mean feat given that the Viennese violone for which the concert aria was written was rather different from the modern double bass, and the tuning pattern adopted by eighteenth-century virtuosi such as Pischelberger (so-called Viennese tuning, F1 -A1-D-F#-A) makes both the arpeggios built on the original natural harmonic series and the extended double stopping challenging on a modern instrument. Fejérvári inserted an idiomatic cadenza and engaged cheerily with the vocal line, as if raising a wry eyebrow at the singer’s more indulgent sentimentalities.

Zsolt Fejérvári (double bass) and Hanno Müller-Brachmann (bass) with Iván Fischer (conductor) and the Budapest Festival Orchestra. Photo Credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Zsolt Fejérvári (double bass) and Hanno Müller-Brachmann (bass) with Iván Fischer (conductor) and the Budapest Festival Orchestra. Photo Credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Müller-Brachmann (who has performed this concert aria recently with the BFO) had trouble settling the pitch in the opening phrases of the introductoryAndante, but later revealed a sonorous low register, if not always a full weight, and a well-rounded tone. The exuberance he brought to the Allegro revealed why his Papageno has won acclaim, and in the imperious vocal rises he demonstrated a strong, centred baritonal top. The Budapest Festival Orchestra, which Fischer co-founded in 1983 with his fellow Hungarian conductor Zoltán Kocsis, accompanied with precision and delicacy, the flute ‘duetting’ elegantly at times with the solo double bass. Fischer established a lovely lilt in the Andante, and expressive string vibrato and phrasing was complemented by lucid woodwind and honeyed horns.

The BFO were joined by clarinettist Ákos Ács, the orchestra’s principal clarinet since 1999, for Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto in A, which Ács performed on the longer, more mellow-toned basset clarinet - the instrument for which Mozart composed the concerto. The orchestral playing remained fresh and transparent of texture, and Ács’s unassuming melodiousness, supple phrasing and rhythmic buoyancy were refreshing. The sound was clean and airy, the phrasing full of grace, and Ács employed a variety of articulations, nicely contrasting flowing slurs with tripping, articulated runs. But, somehow the concerto didn’t quite sparkle. The opening of the second movement Adagio was phrased sensitively by all, but the tempo felt needlessly hurried and Ács didn’t make enough of the dynamic contrasts or fully exploit the expressive weight of the instrument’s lower register. The Rondo, Allegro began at a lick but lost momentum, and the later restatements of the theme thus didn’t invoke the joyous ebullience that they can and should. For that we had to wait for the klezmer-style encore, ‘Sholem-Alekhem, Rov Feidman’ (Peace be upon you, Rabbi Feidman), by the Hungarian clarinettist Bela Kovacs - which Ács, with the complicity of the BFO, seemed to begin in the wings and which induced faux surprise and disdain from Fischer.

In a recent interview-article in The Guardian (interview) Fischer made it clear that what he wants above all in his music-making with the BFO is to avoid a sense of routine: “We work with intensity and in a very personal way. It is more like the way a string quartet works. I don’t say to the principal cellist: ‘Please a little softer.’ I would say: ‘Come on Peter, what the hell are you doing?’ It’s a different communication, much more personal. I immediately notice when their level of focus or concentration is not what it should be. I work much more like a theatre director would work with actors.”

There was nothing at all ‘routine’ about Fischer’s reading of the Requiem: tempos, stage placements and the overall expressive sentiment were all highly individual, verging on the eccentric. Fischer’s reading was not without interest but many of his choices eventuated inherent problems that were not entirely overcome in performance.

The first note of surprise was instigated by the spatial arrangement of the musicians and singers. The 24 singers of the Collegium Vocale Gent were dispersed among the BFO players, seated at orchestral desks as if members of an instrumental section; the woodwind formed an inner circle in front of the strings, while the brass were ranged in an arc behind. Given the fairly small forces, Fischer would seem to be aiming for a seamless fusion of vocal and instrumental sound - a worthy ambition, but one which hit a few problems.

I’d be surprised if the singers could actually hear each other: each member of the Collegium Vocale Gent was essentially a soloist, or part of duo, and though the individual lines of the choral numbers were sung with beautiful tone and crisp rhythms, at times ensemble and balance were awry. It may have depended upon where one was seated in the RAH - and perhaps the effect on live radio (BBC iPlayer), aided by well-placed BBC microphones, was more effective - but for this listener the two tenors at the rear and the two sopranos at front-left were acoustically privileged. At times, the dispersion of the sound was exciting and embracing. But, some of the contrapuntal writing, especially in the opening movements, was messy, and the majestic power, and terror, of the full choral pronouncements in the Dies Irae and the Confutatis (pity the fiddles whose right arms must have almost flown out of their sockets so precipitous was Fischer’s tempo - hysterical rather than horrified - in the former) felt diluted.

The BFO principal violinist had a trying task leading an orchestra many of whose members must have had difficulty in seeing her (and perhaps in gaining a clear sight-line of Fischer himself, when the desks of singers stood for the choral numbers). Ensemble both within and between sections was poor in places, even though the orchestra was chamber-sized, and the intense focus that might be summoned from smaller forces was absent. This was a pity because it was clear that each phrase was shaped with extreme care by Fischer and that the players understood his intent: the fragmented stage-positioning meant that it was challenging for them to produce the desired effect as a synchronised ensemble.

Fischer did conjure some theatricality, without melodrama, whizzing through the movements, which often succeeded each other segue; indeed, Fischer seemed to be driving through an ‘operatic’ scenario so fast that I began to wonder if the BFO were booked on a 10.30pm flight back to Hungary. Road traffic signs warn that ‘Speed kills’: and this is a caution worth heeding. The score’s dramatic gestures did not have time to tell, dotted rhythms seemed bouncy rather tremorous with tension. I winced when we were cheated of the tender beauty of the Recordare: the initial dialogue between the cellos and clarinet was as impetuous as a 100-meters Olympic final and the singers had neither melodic breadth nor spaciousness of breath to shape the glorious layering of the vocal lines - regrettable given the apparent, though fleeting, unified blending of the quartet of solo voices.

The pervasive sobriety of the Tuba miriam was also denied us but trombonist Balázs Szakszon admirably coped with the technical challenges of performing one of the repertoire’s most well-known orchestral solos at the urgent tempo chosen by Fischer. Similarly, the soul-worrying cries, ‘Rex’, at the start of the Rex tremendae majestatis (O King of awful majesty) did not have time to register the terror that the text implies.

Then, having created seemingly unstoppable, even accelerating, momentum, Fischer slammed on the brakes before both the Offertorum and the Sanctus: the long silences implied that the Proms’ audience - perennially the most attentive and focused of listeners - was comprised of naughty children of whom absolute silence and stillness were demanded before the performance would recommence.

Fischer did find some sad delicacy in the Lacrimosa which pleasingly did not drip with sentiment: the string sighs were expressive rather than effusive, and were complemented by lovely pianissimos from the Collegium Vocale Gent, with the woodwind solos allowed to speak tellingly.

The four soloists - seated to rear, and in the midst, of the orchestra - gave performances of varying impact. Soprano Lucy Crowe tended to dominate the ensembles, but this was not her fault, her voice simply soared with wonderful clarity: her solo statements had a lofting intensity and richness which was utterly heart-winning. When I saw Barbara Kozelj sing with the Academy of Ancient Music at the Barbican Hall last October, in Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria (review), I commented that the mezzo-soprano’s Penelope was a ‘still oasis of stoical forbearance’; and Kozelj didn’t seem any more inclined to join in the breakneck haste here. She shaped her solo and ensemble contributions with chastening elegance and restraint, and her tone had a soulful focus which Fischer was not disposed to indulge.

Müller-Brachmann was again resonant but the intonation problems which tempered his earlier aria reappeared at the start of the Tuba miriam; tenor Jeremy Ovenden was at home with the prevalent theatrical urgency but his tone was occasionally protrusive in the ensembles.

I’m not averse to innovation and a fresh look at familiar musical friends. But, there are some works of art that don’t need to be tinkered with, especially if nothing new is revealed.

Claire Seymour

Prom 54 - Mozart: Aria ‘Per questa bella mano’ K.612, Clarinet Concerto in A major K.622, Requiem in D minor K.626 (compl. Süssmayr).

Lucy Crowe (soprano), Barbara Kozelj (mezzo-soprano), Jeremy Ovenden (tenor), Hanno Müller-Brachmann (bass), Ákos Ács (clarinet), Zsolt Fejérvári (double bass), Iván Fischer (conductor), Budapest Festival Orchestra, Collegium Vocale Gent.

Royal Albert Hall, London; Friday 26th August 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Prom%2054%20Budapest%20Festival%20Orchestra%20Fischer.png image_description=Prom 54, Budapest Festival Orchestra conducted by Iván Fischer product=yes product_title= Prom 54, Budapest Festival Orchestra conducted by Iván Fischer product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Iván Fischer conducting the Budapest Festival Orchestra and Collegium Vocale Gent.Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

August 26, 2016

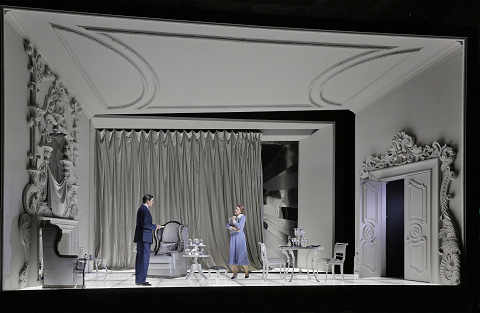

High Voltage Tosca in Cologne

This dramatic production engaged with fine vocals and an exhilarating choir. With his vocal gravitas, Samuel Youn as Scarpia dominated the stage. The Te Deum made for one of the more epically scaled opera scenes I witnessed this season. The director moved the opera from Puccini’s originally intended 1800 to the end of WW II in fascist Italy. It wasn’t too farfetched after Lucia yesterday, so I didn’t mind. The idea of history repeating seemed acceptable.

While the audience sits down, the priest is already preparing mass. Choir members pray in the pews. Thilo Reinhardt’s staging already invites intimate audience involvement. Bombs drop and explode around the church. Once in awhile the stage would reverberate. Luke Stoker carried the role of Catholic priest here with conviction and his singing kept me focused.

In a flashy pink dress, Ingela Brimberg as Floria had a highly charged voice and the required dramatic flair to enrich the thespian nature of her character. Her vibrant voice phrased her passage with great urgency. In “Vissi d’arte” she reached all her notes resonantly. Her voice went the distance. Disappointing chemistry with Lance Ryan’s Mario made their scenes only mildly sensual, especially in their love duet “Qual'occhio”.

Ms. Brimberg cast a bit of a shadow with her ardor. I expected Mr. Ryan to give back more. I did not get carried away by his “Recondita armonia”. In his interactions with Angelotti, he was also overshadowed by the revolutionary zeal in Lucas Singer’s engrossing voice. Still, I was quite taken by Mr. Ryan’s “E lucevan le stelle” in Act III. His drama skills convinced.

The star of the evening, Youn intimidated as his powerfully authoritarian Scarpia commanded the stage. His voice resonated with grounding depth with a devious, even bitter, character. He made this role his own. The opera is worth seeing just for him and that marvelous Te Deum with banners and inflamed torches held by the superlative choir. A truly exhilarating climax to Act I amplified by the contrast with the preceding intimacy.

Claude Schnitzler made the Gurzenich Orchester Koln have moments of brilliance with colorful woodwinds. The strings carried a great depth. He propelled Puccini’s musical momentum forward as the singers kept firing up their voices. Schnitzler balanced all the dynamic vocal forces bringing out all the violence, power, and passion in the Italian composer’s score.

The Chor of Oper Koln enriched the staging with an impressive sonority dosed with a surging energy. Reinhardt’s incorporation of the individual singers proved highly effective. Exhilarating to hear the choir’s members engage so vigorously. They brought grandeur to this production. The vocal intensity invigorated Paul Zoller’s simple set, meant to elevate the vocal drama.

It was remarkable to see two similarly dislocated productions, one over the top and uneven; the other properly balanced and vocally superb. Oper Koln’s Tosca captivates and leaves an epic impression. Even though it is not set in the time that Puccini ascribed, this Tosca hit her notes very high.

David Pinedo

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tosca_Cologne.png image_description=Ingela Brimberg as Tosca and Lance Ryan as Cavaradossi [Photo © Klaus Lefebvre] product=yes product_title=High Voltage Tosca in Cologne product_by=A review by David Pinedo product_id=Above: Ingela Brimberg as Tosca and Lance Ryan as Cavaradossi [Photo © Klaus Lefebvre]August 22, 2016

Haitink at the Lucerne Festival

So it was with great expectations that I came to hear him perform with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra and its assembly of superb musicians. However, after tonight’s performance it became clear, that the octogenarian conductor has lost much of his vigor and grip. Haitink’s masterful technique to sustaining suspense from beginning to end lacked, resulting in more than a few moments of monotony. Still, this is Bernard Haitink! So even if he is not performing as he used to, he is still more awesome than most conductors. The performance included several exhilarating, hair raising passages.

In the opening Allegro moderato, Haitink generated a thick, rich sound from the strings that he never let go. Lucas Macias Navarro (Assistant Conductor, Orchestre de Paris), a former soloist at the Royal Concertgebouw, where he has performed under Haitink, made his oboe passages sound ever so delicate against the backdrop of this lush texture.

In between Bruckner’s lengthy movements, Haitink was able to take a moment on the chair behind him to regenerate. The Scherzo was full of buoyant optimism. The flute solos by Chiara Tonelli (from the Mahler Chamber Orchestra) enjoyed vibrancy. Raymond Curfs (Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra) made his timpani roar, though Haitink made sure never too loudly. In the Trio, the Dutch conductor, and longtime citizen of Lucerne, kept a steady tension going.The elegance of the dreamy harp (a rare usage by Bruckner) contrasted sharply with the horns and trumpets. Slowly and deliberately with minimal direction, Haitink brought to life Bruckner’s heft.

In the third movement, the symphony lost its intensity. Haitink used to be a master at Bruckner’s and Mahler’s Feierlich passages. He would generate and sustain a slow burning suspense throughout an entire symphony, but here is grip was missing. The person next to me let out a deep, seemingly impatient, sigh--the third movement did feel a bit tiresome. On the other hand, the chemistry between oboist and flautist produced playful contrasts in their duets.

The energetic surge at the beginning of the final movement woke up the audience again. Thrillingly bellicose sounded the triumphing Brass. The Wagner tubas added to their glow. The dark timbres of the bassoons offered their distinct shades. Haitink’s minimal conducting here generated an awesome intensity that made for a stupendous finale. He intended to elongate the delicate tension after the last note of the symphony, but an eager audience broke the silence too soon and erupted in a feverish ovation.

David Pinedo

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Haitink_Lucerne.png image_description=Bernard Haitink [Photo by Peter Fischli/Lucerne Festival] product=yes product_title=Haitink at the Lucerne Festival product_by=A review by David Pinedo product_id=Above: Bernard Haitink [Photo by Peter Fischli/Lucerne Festival]BBC Prom 45 - Janáček: The Makropulos Affair

For Emilia Marty is much more than a diva. She's the embodiment of a universal life force that transcends time and place. Emilia Marty is one of Janáček's

Dangerous Women (read more here) who live life to the full

and change those around them, and who symbolize freedom. Yet, ultimately, freedom comes at a price.

Bass-baritone Gustáv Beláček (Dr Kolenatý) at the BBC Proms 2016. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou

Bass-baritone Gustáv Beláček (Dr Kolenatý) at the BBC Proms 2016. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou

The Overture opens like an expansive panorama. Belohlávek's generous style suggested warm, glowing colours, adding richness to Janáček's energetic rhythms,

underlining the contrast with the claustrophobic litigation that's drained the Prus and Gregor clans for centuries. Tense, jerky figures in the orchestra.

The lines of Dr Kolenatý (Gustáv Beláček) are long and ponderous; Mattila's timbre is lustrous, but she's astute enough to make Emilia Marty's short, sharp

lines bristle, but suddenly softens gently. She knows more about the forebears of Albert Gregor (Aleš Briscein) than he does. Mattila's emotional range is

as extensive as her vocal range: her singing was extraordinarily subtle. In the Second Act, Mattila manages to convey even more complex feelings. She's

tender towards Baron Prus (Svatopluk Sem) and his son Janek (Aleš Vorácek). She understands what Emilia Marty must have felt when she sees how Kristina

(Eva Šterbová), the aspiring young singer, fancies Janek. But there's still something in EM that drives men mad. "Ha ha ha", she laughs, as if she didn't

care.

Tenor Jan Ježek as Count Hauk-Šendorf at the BBC Proms 2016. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou

Tenor Jan Ježek as Count Hauk-Šendorf at the BBC Proms 2016. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou

The point cannot have been lost on Janáček himself. whose best years came late. Significantly, Count Hauk-Šendorf (Jan Ježek) is written for the same Fach

as the protagonist in The Diary of One who Disappeared, which marked the composer's true creative breakthrough. Hauk thinks Emilia Marty is the

girl he loved 50 years before, a gypsy, an outsider beyond the pale of polite society. "I left everything behind, everything with her". The song cycle, the

opera and the composer's private life are thus linked. Kamila Stösslová, Janáček's muse but not mistress, was also a "chula negra" (a dusky beauty). Hauk

sings "It's an ugly business, being old" and wants to run off to Spain with Emilia, since making love keeps you young. Emilia packs her bags, but Hauk's

doctor intervenes. Hauk's been insane since he lost his gypsy. Like Emilia, he laughs in hollow, mechanical tones, more tragic than funny.

This throws sinister light on the scene in which EM reveals her past, as Elian Macgregor, as Eugenia Montez, as Ekaterina Myshkin and as Elina Makropulos,

whose father invented the potion that's kept her young for 337 years. That's the "Věc Makropulos", the formula that disrupts the natural cycle of life. The

opera ends with a kind of Mad Scene, where Janáček's music explodes into manic, yet oddly logical frenzy. To EM, the explanation makes perfect sense.

Trumpets blare, the tuba howls, the strings whizz like demons. Emilia blasphemes. "You believe in humanity, in greatness, in love!", she sings, "There's

nothing more we could wish for!". A small chorus (the men of the BBC Singers) appeared, singing responses in a parody of a Mass. Mattila's too good to

screech but manages to show how EM unwinds, like a broken toy. She wants Kristina to take the formula, and be famous. But Kristina is much too down to

earth to fall for it.

Jirí Belohlávek was Chief Conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra for many years, concurrently with his role as Chief of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, which he brought to London earlier this year for Janáček Jenůfa. (Read my review here.)

(L-R) Eva Štĕrbová, Jan Vacík, Gustáv Beláček, Kartia Mattila, Aleš Briscein and Svatopluk Sem perform under the direction of Jiří Bĕlohlávek at the BBC Proms 2016. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou

(L-R) Eva Štĕrbová, Jan Vacík, Gustáv Beláček, Kartia Mattila, Aleš Briscein and Svatopluk Sem perform under the direction of Jiří Bĕlohlávek at the BBC Proms 2016. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou

The BBC SO rose to the

occasion for this Prom, welcoming Belohlávek with wonderfully lively playing. They learned much in their "Belohlávek Years" and haven't forgotten. His

rapport with his singers and players was almost palpable. None of us will make age 337, but the message, as such, is not so much how long you live but how

well you live. As Janáček wrote to Stösslová, after attending the Karel Čapek play on which the opera is based, "We are happy because we know that our life

isn't long. So it's necessary to make use of every moment, to use it properly". Belohlávek is looking frail these days, though his conducting is still full

of fire. As I watched, I thought how wonderful it was to be able to hear him again. I hope he realizes how much he's appreciated!

Anne Ozorio

BBC Prom 45 - Leoš Janáček: The Makropulos Affair (Věc Makropulos)

Emilia Marty, Karita Mattila (soprano); Albert Gregor, Aleš Briscein (tenor); Dr Kolenatý, Gustáv Belácek (bass-baritone); Vítek, Jan Vacík (tenor); Kristina, Vitek's daughter, Eva Šterbová (soprano); Baron Jaroslav Prus, Svatopluk Sem (baritone); Janek, Aleš Vorácek (tenor); Count Hauk-Šendorf, Jan Ježek (tenor); Stage Technician, Jiri Klecker (baritone); Cleaning Woman, Yvona Škvárová (contralto); Chambermaid, Jana Hrochová-Wallingerová (contralto); Jirí Belohlávek, conductor; Kenneth Richardson, stage director; BBC Singers (men's voices), BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Royal Albert Hall, London, 19th August 2016.

Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou

August 21, 2016

Two Tales of Offenbach: Opera della Luna at Wilton's Music Hall

And, where better to perform these exuberant burlesques than Wilton’s Music Hall - the earliest surviving Grand Music Hall, set in the historic East End of London.

Founded by Clarke in 1994, Opera della Luna has garnered well-deserved praise for its zany, zippy productions of operatta, comic opera and pantomime. Its touring productions might notionally be ‘small-scale’ - performed by a troupe of actor-singers, without chorus, and accompanied by a small orchestral ensemble - but there’s nothing ‘miniature’ about their ambition or their theatrical impact.

Charmed as we are by Offenbach’s full-scale operatic gems - such Les Contes d'Hoffmann, Orphée aux enfers and La vie parisienne - we often forget that he was the composer of some 90 operettas, more than 50 of which comprise just a single act. Sometimes employing a full cast and chorus, elsewhere just two singers, they ranged from brief curtain-raisers to hour-long works, and reveal Offenbach’s delight in farce, fantasy, cloak-and-dagger melodrama and the exotic.

Having striven in vain to get his work performed at the Opéra-Comique and other lyric theatres in Paris, in 1855 at the age of 35, Offenbach obtained a license to open a small wooden theatre in the Champs Elysees - the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens - for the performance of one-act pieces typically comprising a brief orchestral prelude followed by half-dozen or so solos and duets.

Railing against the dull pretentiousness of the operatic fare on offer at the Opéra-Comique, Offenbach promoted the tiny new theatre which had lain empty between two trees on the Champs-Élysées, declaring: ‘In an opera which lasts only three quarters of an hour, in which only four characters are allowed and an orchestra of at most thirty persons is employed, one must have ideas and tunes that are as genuine as hard cash.’ The same might be said of a modern-day independent opera company - particularly in the absence of much ‘hard cash’ in the form of government support for artistic innovation and accomplishment.

Fortunately, Clarke is a cornucopia of ideas and theatrical masterstrokes. These two productions overflow with a glut of side-splitting gimmicks and gags. The guffaws came thick and fast from the first, and did not stop. Clarke appreciates the affection with which Offenbach lays bare human eccentricities, delusions and shortcomings. And, with a knowing nudge-wink which steers just the right side of vulgarity and excess, the director shows that he is genuinely fond of these preposterous characters while at the same time nailing their bizarre flaws and foibles.

Croquefer lampoons the violent immorality of the Crusades and sends up the arrogant affectations of medieval knighthood. Croquefer, ‘an immodest and faithless knight’, has imprisoned Peasblossom, the daughter of his arch-enemy, Rattlebone. Their enmity has lasted for 23 years, financially ruining Croquefer and depriving Rattlebone of arm, leg and tongue. Yet the latter remains a formidable, fear-inducing opponent, and Croquefer swallows his last weapon, his beloved sword of Toledo, willing to accept an inglorious peace.

He orders his nephew, Headstrong, to guard their hostage. From her cell, Peasblossom recognises her guard as her beloved, and in their ensuing love-duet they dream of running off together to Paris, imagining the delights they will enjoy at the Opéra. When Rattlebone arrives, Croquefer gives him a choice: either he must permit Peasblossom to become Croquefer’s wife, or she will be killed. To evade this fate, Peasblossom and her amour poison the wine and plot to murder the two adversaries, who are preparing to do battle. As the duel commences, the spiked drinks take effect and the sword-play is interrupted for a swift dash to the thrones-turned-commodes. The violent purgation returns both Croquefer’s sword and Rattlebone’s tongue to their owners. Differences are settled, Croquefer begs the audience’s indulgence - and the composer and librettist of the piece (or in this case, conductor Toby Purser) are dragged off to the asylum!

The exposed bricks of Wilton’s, shrouded in wafting smoke, were a fitting back-drop for Croquefer’s dilapidated black tower which thrust up into a storm-cloud strewn sky. Elroy Ashmore’s economical set designs had a Gothic edge - the arms of Croquefer’s throne curling out like grotesque hands - which was complemented by Nic Holdridge’s bold lighting design.

Attired in leather breeches and sporting straggly black locks, Carl Sanderson made an immediate impression as the eponymous villain - self-important, blustering and snarling, and equipt with a powerful tenor with which to lament the disintegration of his once-modish castle. He was aided with apt ineptitude by Caroline Kennedy’s goofy Fireball - a cross-between the Artful Dodger and a circus clown. Eager to please, Kennedy shone with feverish excitement as she peered through her telescope at the advancing Rattlebone, or lined up model Crusaders to imitate the beleaguered Croquefer’s diminished army. The role of Fireball was originally composed for tenor, but Kennedy’s bright, sweet-toned soprano added freshness and air to the macho mix, especially in the spirited Trio in which Headstrong’s eagerness for combat encourages Croquefer to renew his struggle against his foe.

Anthony Flaum’s lovely lyric tenor blended melodiously with Lynsey Docherty’s ingénue Peasblossom in their mock-dramatic love duet, as they scaled the parodic heights of Offenbach’s comedic quotations from the hits of the day: Jacques Halévy’s La Juive and Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable and Les Huguenots.

Offenbach and his librettists cocked-a-snook at the Parisian authorities, evading the regulation forbidding more than four characters to appear on stage at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, by making their fifth character a mute who has sacrificed his tongue in his battles with the Saracens, and whose contribution to the final quintet is limited to grunts and howls. One-armed and one-legged, Paul Featherstone staggered valiantly and lop-sidedly on crutches, worn down by his over-size helmet and basket of placards as he sought to rescue his captive daughter. He and Sanderson had plenty of fun during the pantomime-joust and sword-fights (choreography, Jenny Arnold), their perfectly timed faux-amateurism paradoxically highly polished and professional.

Known as the ‘Mozart of the Champs-Élysées’ and the ‘Napoleon of the operetta’ - and living in Paris under Napoleon III, a time when few in society, from high to low, were really what they claimed to be - in some ways Offenbach’s whole life was a mask-wearing charade, and it’s no surprise that so many of his characters do nothing but pretend to be what they are not. Offenbach’s The Isle of Tulipatan takes this role-playing to a new level of Wildean absurdity. A double-en travesti farce of identity-crisis and quid pro quo, in which Nature triumphs over human presumption and foolishness, this ‘bouffonerie’ takes place ‘at 25,000 kilometres from Nanterre, 473 years before the invention of the chamber pot’.

On the island of Tulipatan, King Cacatois XXII is unaware that his only son, Alexis - whose gentle disposition dismays him - is in fact biologically, his daughter, disguised as such by his wife who refused to have another attempt at producing the heir to the throne so craved for by her husband. Coincidentally, in order to avoid her child being conscripted into the army, Theodorine, the wife of the Duke’s steward, Field Marshall Rhomboid, has also deceived her husband: their daughter, Hermosa, is in fact a boy, because the anxious mother could not bear the thought of losing him to military service. Alexis and Hermosa are engaged to be married but their ignorance of their true sex spawns a string of misunderstandings until self-awakening and gender-realignment ensue, to the satisfaction of all. But, not before a multitude of farcical opportunities which neither Offenbach nor Clarke neglect to exploit to the full.

Carl Sanderson (Field Marshall Romboid) and Caroline Kennedy (Prince Alexis). Photo Credit: Jeff Clarke.

Carl Sanderson (Field Marshall Romboid) and Caroline Kennedy (Prince Alexis). Photo Credit: Jeff Clarke.

Caroline Kennedy’s emerald-frock-coated Prince Alexis delivered ‘his’ sentimental romance on the death of his pet bird with bell-like purity, touching sincerity, not a hint of mockery and just the right amount of mawkishness. After the tomfooleries of Croquefer, Kennedy really showed her dramatic range here using her voice and face most expressively. Her naïve curiosity when faced with the veracity of her femininity - ironically dressed in a green and purple gown with black Doc Martins - was heart-winning.

Costumer Isobel Fellow supplemented the absurdities of the plot with costumes of garish complementary hue and Hermosa’s lurid pink frock with zebra accessories made for a wonderfully incongruous clash with the swaggering sentiments of Hermosa’s military song. This was a terrific performance from Flaum who, in drag, seemed to have taken inspiration from the late Les Dawson’s pantomime-dame arm-folding, hand-bag clutching and gurning grimaces.

Anthony Flaum (Hermosa) and Carl Sanderson (Field Marshall Romboid). Photo Credit: Jeff Clarke.

Anthony Flaum (Hermosa) and Carl Sanderson (Field Marshall Romboid). Photo Credit: Jeff Clarke.

Ashmore’s crenellated tower had been stripped of its battlements to reveal the crimson and gold flock-wallpaper of Rhomboid’s shabby-chic chateaux: a fitting setting for Lynsey Docherty’s Theodorine who had clearly wandered off the set of Ab Fab and whose lugubrious inebriation would have given Edina a good run for her money. Docherty’s insouciant indifference when she sweetened the Duke’s tea with a sugar-lump salvaged from his foot-bath was priceless.

Carl Sanderson’s Field Marshall and Paul Featherstone’s Duke were once again a superb double-act: their performances were full of vitality. Featherstone minced with ludicrous pomposity, resplendent in red velvet knickerbockers and diamond-patterned stockings. This was Alice in Wonderland meets Oscar Wilde: the Knave of Hearts had somehow found himself in The Importance of Being Earnest. Featherstone may have ‘delivered’ his numbers - a political satire with animal imitations, and a tongue-in-cheek ‘bacarolle’ - rather than sung them, but that didn’t lessen their spiciness or éclat.

Offenbach’s two scores may not be sparkling with musical invention - indeed, sometimes the music seemed to play second fiddle to the farcical comedy - but the composer had an innate flair for heightening theatrical comedy with a catchy tune and a touch of musical twinkle, and the nine instrumentalists played the score with evident enjoyment and vibrancy. Purser kept things whipping along, but judiciously allowed the cast to make the comic moments tell.

In any case, Clarke’s playful improprieties and droll rhyming couplets could turn even the most mundane melody into a memorable ear-tickler: “So here’s a happy ending to our curious farce/ A tale of gender-bending in the upper class.” In this delicious double-bill, Clarke entwined madness and merriment, and coated both with tenderness: quite simply, irresistible.

Claire Seymour

Jacques Offenbach: Croquefer, or The Last of the Paladins (1857)

Libretto: Adolphe Jaime and Etienne Trefeu

New English Version: Jeff Clarke - first performance July 23 2016

First performance: Theatre des Bouffes-Parisiens, February 12, 1857

Croquefer, Carl Sanderson; Fireball (Boutefeu), Caroline Kennedy; Headstrong (Ramasse-ta-Tête), Anthony Flaum; Rattlebone (Mousse-à-Mort), Paul Featherstone; Peasblossom, (Fleur-de-Soufre), Lynsey Docherty.

Jacques Offenbach:

The Isle of Tulipatan

Libretto: Henri Chivot and Alfred Duru

New English Version: Jeff Clarke - first performance July 23 2016

First performance: Theatre des Bouffes-Parisiens September 13 1868

Cacatois XXII, Duke of Tulipatan, Paul Featherstone; Prince Alexis, his son, Caroline Kennedy; Field Marshall Rhomboid, Carl Sanderson; Theodorine, his wife, Lynsey Docherty; Hermosa, his daughter, Anthony Flaum.

Director, Jeff Clarke; Conductor, Toby Purser; Set Designer, Elroy Ashmore; Costume Designer, Isobel Pellow; Lighting Designer, Nic Holdridge; Choreographer, Jenny Arnold; Orchestra of Opera della Luna.

Wilton’s Music Hall, London; Friday 19th August 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Anthony%20Flaum%20%28Headstrong%29%20and%20Caroline%20Kennedy%20%28Fireball%29.png image_description=Opera della Luna at Wilton’s Music Hall product=yes product_title=Opera della Luna at Wilton’s Music Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Anthony Flaum (Headstong) and Caroline Kennedy (Fireball)Photo credit: Jeff Clarke.

August 19, 2016

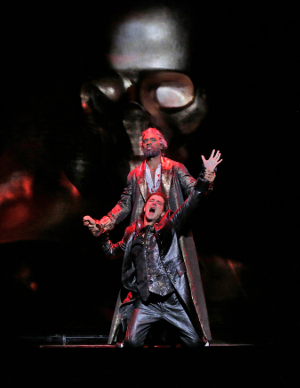

Britten Untamed! Glyndebourne: A Midsummer Night's Dream

The First Act takes place in dense forest, at night, when nothing is as it might seem. Do we see trees or projections thereof, or both? What do the shadows

conceal, even when the moon slips fleetingly through clouds? John Bury's designs are immortal because they are so abstract, and surprisingly ‘modern’,

though they ostensibly resemble the well-known Victorian painting by John Noel Paton - another reversal of visual imagery. Since Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream operates on so many simultaneous levels, the one thing to be wary of is literal realism.

How Britten must have relished the opportunities to express in music what could not be said in words. Like Shakespeare, Britten was poking fun at a world

that mistakes power for virtue and convention for truth. Theseus and Hippolyta - ancient Greeks in Elizabethan costume - sneer at the Mechanical's play.

But perhaps the joke is on them. A Bergomask before bedtime might just have unforeseen consequences. Britten's Gloriana was long misunderstood by

audiences who took it at face value. A Midsummer Night’s Dream, written barely seven years later, has an infinitely superior plot and the music is

much more sophisticated, but there are parallels. And in A Midsummer Night's Dream there are levels which would have had personal resonance for

the composer.

Jakub Hrůša's conducting is so idiomatic that we can almost feel the caustic bite of Britten's humour, while also feeling the pain that lies beneath the

surface. Britten's score sparkles with variety. Figures shape shift as swiftly as they are delineated, Elizabethan forms pop up from the endlessly elusive

and very contemporary stream of consciousness. Hrůša doesn't smooth over the spikiness, but keeps the pace animated, so the orchestral playing seems to fly

free, like the Fairies - the Elementals to the earthbound Mechanicals. The moments of reverie glowed, the lower woodwinds and brass breathing ominous

mystery. The London Philharmonic Orchestra seemed to shine for Hrůša, even more than they usually do. Perhaps Hrůša brought insight from having conductedRusalka and The Cunning Little Vixen at Glyndebourne in the past, two operas which also have close affinity with A Midsummer Night's Dream. Hrůša seems to intuit how pertinent the variety in the score is to the meaning of the opera. Everything changes at the

turn of a point, themes transform, like magic, nothing can be taken for granted. Because Hrůša got such alert, taut playing from the orchestra, he could

bring out the innate anarchy beneath Britten's elegantly defined orchestration. Orchestrally, this was an exceptionally vivid performance, so strong that

it will live in the memory.

Matthew Rose (centre) as Bottom, with the Mechanicals. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Matthew Rose (centre) as Bottom, with the Mechanicals. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

The cast, acting as well as singing, were of an equally high order. Matthew Rose first sang Bottom ten years ago. Now, he's matured and so has his characterization of the part, which will probably now be hard for anyone else to improve upon. Bottom is Everyman but no fool. Rose's voice carries authority, which is why his friends turn to him as leader. Even with the head of an ass, and his bottom in the air, Rose makes the part dignified and sympathetic. Rose makes the ‘donkey’ wheeze in Bottom's lines sound so natural that, even in the palace in the final Act, a bit of donkey-ese breaks through irreverently. Even his body movements worked in synch. Equally strongly cast were the

Mechanicals - David Soar (Quince), Sion Goronwy (Snug), William Dazeley (Starveling), Anthony Gregory (Flute) and Colin Judson (Snout). In ensemble, they

were superb, singing and speaking as if to the manner born. In the play, and in the opera they are much more significant than Theseus (Michael Sumuel) and

Hippolyta (Claudia Huckle).

As Oberon, Tim Mead's high, sharp timbre dripping malevolence, reversing the more usual baroque stereotype of counter tenor as hero. He towered over

Kathleen Kim, as Tytania. Good visual casting, reflecting the power play between them. Kim, though, was no submissive. She sang forcefully and with élan -

no surprise that she's a Glyndebourne favourite. Oberon's hair was styled in two peaks, resembling the ears of an ass. Wonderfully subtle touch. The

lovers, Lysander (Benjamin Hulett), Hermia (Elisabeth DeShong), Helena (Kate Royal) and Demetrius (Duncan Rock) were also well cast, DeShong creating

Hermia's feisty, strong-willed personality with particular definition.

David Evans (Puck) and Tim Mead (Oberon). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

David Evans (Puck) and Tim Mead (Oberon). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

But Puck is the agent of insurrection, upon which the plot turns, and particularly symbolic for Britten himself. Puck is not a singing part, but David

Evans stole the show, quite an achievement for an actor stepping in at short notice, into a part that's so demanding that it's notoriously difficult to

cast. Britten dreamed that it could be played by a young athlete whose voice was beginning to break: a changeling between two worlds, a Britten innocent on

the cusp of corruption. Tadzio, with a voice. And what a voice! Evans is cheeky and shrill like a boy, yet also rebellious and assertive like someone

passing into his teens, though he looks younger. He also projects with great force, while respecting the curious rhythm in the text. Evans runs up and down

stage, sailing into space on a guy rope, popping in and out of the scenery, without missing a note. Did Britten identify with Puck, who could get away with

things a nice, obedient boy like Young Ben could not? And yet Puck is a tragic figure, not so much because he doesn't belong but because his freedom cannot

last. Will he be sucked into Oberon's sick games? Evans will grow up, but this moment of glory will live with him for the rest of his life.

Catch this Glyndebourne A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Anne Ozorio

Britten: A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Theseus (Michael Sumuel), Hippolyta (Claudia Huckle), Tim Mead (Oberon), Kathleen Kim (Tytania), David Evans (Puck), Benjamin Hulett (Lysander), Elisabeth DeShong (Hermia), Kate Royal (Helena) and Duncan Rock (Demetrius), Matthew Rose (Bottom), David Soar (Quince), Sion Goronwy (Snug), William Dazeley (Starveling), Anthony Gregory (Flute) and Colin Judson (Snout); Director, Peter Hall; Conductor, Jakub Hrůša, Designer, John Bury; London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Glyndebourne Festival Opera; August 16, 2016

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bottom%20and%20Tytania%20.png image_description=Glyndebourne Festival Opera: A Midsummer Night’s Dream product=yes product_title= Glyndebourne Festival Opera: A Midsummer Night’s Dream product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio product_id=Above: Matthew Rose as Bottom, Kathleen Kim as TytaniaPhoto credit: Robert Workman, Glyndebourne Festival Opera

August 18, 2016

Salzburg encores

Opera in concert is a tradition at the Salzburg Festival. The format of such endeavors is however puzzling, at least based on the concert performances (three) of Manon Lescaut in early August. Basic expectations of such events might assume that musical values would be paramount since there would not be the distraction of staging. This was not the case of this Manon Lescaut.

Instead it was a showcase for Anna Netrebko, and that alone of course validates the programming. However such a centerpiece could surely give incentive to the festival to build a cast around such vocal splendor that might strive toward some degree of high, finished art.

The assembled cast included Algerian born, Moscow trained, Franco-Corelli-finished tenor Yusif Eyvazov as Des Grieux (who happens to be Mme. Netrebko’s husband), and Mexican baritone Armando Piña as Manon’s brother Lescaut. Piña, a fine young singer, is a Resident Artist, i.e. student at Philadelphia’s prestigious finishing school for opera singers, the Academy of Vocal Arts. Geronte was sung by 66 year-old bass-baritone Carlos Chausson who has made a distinguished career singing the repertory’s well-known buffo roles.

Rather than the singers sitting in chairs with music stands and scores while waiting their turn to sing the Salzburg concert format elicits actual staging, if minimal. Singers entered and exited much as staging instruction in the score might tell them. Roles were acted, singers moved as if staged. It did not arrive at what the French call a mise en espace (there was no lighting or costumes) nor was it a concert.

The staging, probably improvised by the singers, was on the stage apron therefore the conductor, Marco Armiliato and the Munich Rundfunkorchester were behind the singers. Mo. Armiliato had no visual contact with the singers, nor did the singers ever communicate with him. Apparently at ease with standard Manon Lescaut routine this maestro never felt the need even to look over his shoulder.

Forty-five year old Anna Netrebko, in good physical and perfect vocal shape, appeared in a huge black gown discretely studded with black sequins, i.e. concert dress that made her entrances and a few hurried exits cumbersome indeed. Mr. Eyvazov wore some sort of ethnic coat of maybe Slavic, maybe Turkic inspiration that indeed set him apart, the balance of the performers wore formal concert dress.

Portraying a teenage girl was of course out of the question for Mme. Netrebko under the circumstances, and she did not really shine as an artist until Manon’s death. It was spellbinding. Though of course she was a star the entire evening and that is why we were there. Mr. Eyvazoy delivered the first act deploying the tenorial vocal and histrionic attitudes that are long out of fashion, the stuff of caricature. He rose valiantly and with a degree of artistic honesty to the occasion of Manon’s deportation — well rewarded by applause. Without proper costuming and wig Mr. Piña’s well coached singing disappeared into little more than a reading of the role to support the exploits of the tenor and soprano. In the midst of these two powerful, youthful male voices Mr. Chausson’s performance seemed small indeed. The only performance of the evening that seemed appropriate for what a Salzburg Festival concert opera might be was that of the Dance Master, fancily performed by young German tenor Patrick Vogel.

András Schiff and page turner with set for Children's Corner puppet ballet

András Schiff and page turner with set for Children's Corner puppet ballet

Hungarian pianist András Schiff, one of the world’s established concert artists, slickly played Robert Schumann’s youthful Papillons (Op. 2) of about 16 minute duration, and then played Claude Debussy’s Children’s Corner, a suite of about 17 minutes duration that Debussy composed for a piano teaching method book. For this piece Mr. Schiff used the music. Both pieces are well within the reach of advanced piano students. Surely I am not alone in wishing Mr. Schiff’s program had been from the major, virtuoso repertory.

The piano was then pushed to one side exposing puppet show contraptions. Mr. Schiff returned to perform the same two pieces, accompanying a mise en scène for each, executed by four puppeteers operating a variety of puppets.

For the Schumann’s Papillons there were characters of the novel Flegeljahre (Adolescent Years) by a writer named “Jean-Paul,” this novel the inspiration for these 12 brief pieces. Essentially the well-organized Walt wins the girl, having competed with his impetuous brother Vult for her attentions. This mise en scène was imagined by puppeteer Thomas Reichert. It was premiered in 2014 in Calgary, Canada.

Debussy amplified his Children’s Corner suite for piano into a full-scale puppet ballet for children with orchestra, La Boite à joujoux. The ballet was recast in 2010 in Ittigen, Switzerland by puppeteer Hinrich Horstkotte to fit Debussy’s original Children’s Corner for piano. The characters are Pulcinella, Golliwog — a late nineteenth century black faced puppet, evidently not a politically incorrect issue in Austria — for Debussy’s famed Golliwog’s Cakewalk, and a Soldier, plus lots of mechanical intervention of the toy box set contraption and dramatic participation by the four, obviously accomplished, black dressed puppeteers.

The evening was appreciated by the audience who apparently did not care that it was gratuitous use of the talents of Andràs Schiff.

Michael Milenski

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Salzburg_Salzburg1.png

product=yes

product_title=Encores in Salzburg

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Anna Netrebko as Manon, Yusif Eyvazov as Des Grieux [All photos copyright Marco Borrelli courtesy of the Salzburg Festival]

August 17, 2016

Leah Crocetto at Santa Fe

Since Crocetto had a major success as Anna in Rossini’s Maometto II in 2012, she opened the recital with an aria from that composer's Semiramide, a tour de force for both singer and pianist. Rossini wrote Semiramide for his wife, Isabella Colbran, who was known for her accurate dramatic coloratura. “Bel raggio lusinghier” is the opera’s major aria and in Santa Fe both artists performed it with exquisite articulation.

I wonder if these artists knew that Angela Meade had sung the same three Richard Strauss songs, Zueignung, Morgen, and Cäcilie, in the same hall a few days earlier. In any case, they are wonderful songs and both Crocetto and Meade sang them with exquisite grace. In all probability the Rachmaninov segment that included Zdes khorosho (How fair this place), Ne poy kravitsa pri mne (Don’t sing, my beauty), and Otrivok iz A. Musset (An excerpt from Alfred de Musset), brought many art song lovers to the recital. Here Crocetto proved her ability to put the text over when even the most frequent concertgoers might not know the meaning of the Russian words. Listening to her vocal colors, one could think of being in a majestic natural setting with with a lover. The message of the second song served to remind listener of past homes and the last song invited the audience to empathize with Musset’s hopeless lover.

In 1838, when Franz Liszt and Marie d’Agoult stayed in Italy they read Petrarch’s works together and the readings inspired the composition of Three Petrarch Sonnets. In Pace non trovo (I can’t find peace) the lyrics are replete with extreme contrasts, so Liszt expressed them with forward-looking harmonies and constant agitation. Crocetto and Sanikidze made the urgency of the poet’s love real to their twenty-first century audience. The second song, Benedetto sia l’giorno (Blessed be the day) was quite appropriate in this uniquely beautiful old hall far from the crowds and commercialism of a less appreciative city. Toward the end of I vidi in terra (On earth revealed), Petrarch wrote a line that describes much of this recital: “So sweet a concert made as ne’er was given mortal ear.” Crocetto’s high notes are extraordinary; her middle range is warm, and her chest tones remind the listener of singers we can now only hear on records.

For their finale, Crocetto and Sanikidze offered an aria from Carlisle Floyd’s opera Susannah: “Ain’t it a Pretty Night?” Crocetto's phrasing was regal, her diction understandable, and her tones luscious. During this selection and every other work on this program, Sanikidze partnered her with exquisite playing. Since the soprano had sung jazz earlier in her career, her encores included Jerome Kern’s All the Things You Are and “My Heart Is So Full of You” from Frank Loesser’s The Most Happy Fella.

This summer, Performance Santa Fe presented recitals by Daniel Okulitch and Keri Alkema with pianists Glen Roven and Joe Illick; Angela Meade with Illick, Leah Crocetto with Tamara Sanikidze, as well as Joshua Hopkins and Ben Bliss with Illick. We can expect them to have a similarly fine roster next season.

Maria Nockin

Program:

Rossini: Semiramide “Bel raggio lusinghier” R. Strauss: Zueignung, Morgen, Cäcilie Rachmaninov: How Fair this Place, Don’t Sing to Me, my Beauty, Why is my Sick Heart Beating so Frantically? Liszt: Three Petrach Sonnets Floyd: Susannah, “Ain’t it a Pretty Night?”

Encores:

Kern: All the Things You Are; Loesser: The Most Happy Fella, “My Heart Is So Full of You”.

Scottish Rite Center, Santa Fe; August 4, 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Crocetto%20Faye%20Fox.png image_description=Leah Crocetto at Sante Fe product=yes product_title=Leah Crocetto at Sante Fe product_by=A review by Maria Nockin product_id=Above: Leah CrocettoPhoto credit: Faye Fox.

Angela Meade at Sante Fe

Performance Santa Fe presents recitals by artists in town to perform at Santa Fe Opera. The Scottish Rite Center is a Masonic temple built in 1912 containing an intimate theater. It houses a fully outfitted stage with a painted back drop and scrims created with the kind of fine workmanship seldom seen in today’s theatrical settings. On July 31, 2016, against the ethereal beauty of this setting, soprano Angela Meade and pianist Joe Illick gave a recital offering both opera and art songs ranging in origin from early nineteenth century Europe to mid twentieth century America. Many in the audience probably remembered Meade’s recent excellent portrayal of Norma at Los Angeles Opera.

Wearing a dress with a black top and a red and black printed skirt, Meade and the black-clad Illick began their program with an emotion-filled rendition of the aria “Io son l’umile ancella” (“I am the humble servant”) from Francesco Cilea’s infrequently performed opera Adriana Lecouvreur. It showed Meade’s ability to immediately grasp the psyche of her audience in her capable hands.

They continued with three of the five songs Franz Liszt composed in the early eighteen forties to texts by Victor Hugo: Enfant, si j’étais roi (Child, if I were King), Oh, Quand je dors (Oh! When I sleep), and Comment, disaient ils (How, they asked). In the first song Meade sang a magnificent messa di voce, swelling to a fortissimo and diminishing to the finest thread of sound. A quick look at the text of Quand je dors tells the reader that it’s about dreaming of a lover. Meade and Illick’s opulent tones soon made the meaning clear. In Comment disaient ils Meade and Illick again showed the smoothness of their combined, well-nurtured lyricism. The soprano also demonstrated a full range of dynamics and the perfect trill we heard in Norma.

Angela Meade. Photo Credit: Dario Acosta.Vincenzo Bellini, the composer of Norma, wrote songs such as the familiar, melodic Vaga Luna and the less well-known but equally interesting Ma rendi pur contento. Neither song is “Casta Diva”, but Meade sang both with gorgeous tone and saved her golden age operatic ability for the next aria: “Pace, pace mio dio” from Giuseppe Verdi’s La Forza del Destino. Forza is no longer in the usual repertoire because big juicy voices like that of Zinka Milanov are hard to come by. A major opera company needs to revive Forza for Meade because she sings that aria magnificently and international audiences should be able to hear her perform it with orchestra. If there had been an intermission, I think it would have been placed at this juncture. Unfortunately, at this recital there was no chance to mingle and get acquainted with other Santa Fe concertgoers.

Meade’s singing of Marietta’s bittersweet “Glück das mir verblieb” (“Joy that remains with me”) from Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s 1920 opera Die Tote Stadt left listeners contemplating the lost loves of their own lives as the artists left the stage. Illick and Meade returned to render thoughtful interpretations of three well-known songs by Richard Strauss: Zueignung and Allerseelen from Op 10, and Cäcilie from Op. 27.

For their finale, the artists performed “Ebben? Ne andro lontana” (“Well, then? I’ll go father away”) from Alfredo Catalani’s 1892 Alpine opera that ends in an avalanche, La Wally. Actually, Catalani had written the aria as a separate work but added it to the opera before its premiere. Maria Callas made the aria famous with her recording, but Meade’s rendition showed what a more voluminous voice could do for this piece. At its end she was greeted with a huge wave of applause. When we listen to Meade, we begin to know the sound of golden age singing.

Maria Nockin

Program:

Cilea: Adriana Lecouvreur, “Io son l’umile ancella.” Liszt: Enfant, Si j’étais roi, Oh! Quand je dors, Comment disaient ils Bellini: Vaga Luna, Ma rendi pur contento Verdi: La forza del destino, “Pace, pace mio Dio.” Korngold: Die tote Stadt, "Mariettas Lied" . R. Strauss: Zueignung, Allerseelen, Cäcilie Catalani: La Wally, “Ebben? Ne andro lontana.”

Scottish Rite Center, Sante Fe; July 31, 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Angela_Meade__credit_Faye_Fox.png image_description=Angela Meade at Sante Fe product=yes product_title=Angela Meade at Sante Fe product_by=A review by Maria Nockin product_id=Above: Angela MeadePhoto credit: Faye Fox.

August 16, 2016

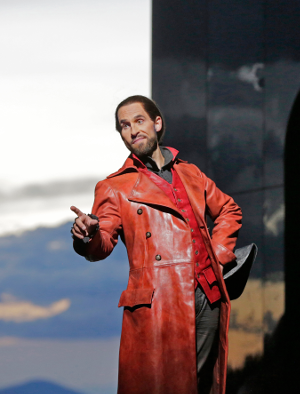

Turco in Italia in Pesaro

That’s Gioachino Rossini and Federico Fellini in Pesaro’s historic Teatro Rossini. Italian director Davide Livermore (that’s lee-vair-MOR-aye) unabashedly re-wrote Fellini’s Lo scieco bianco (The White Sheik) and 8 1/2 as Rossini’s Il Turco in Italia, or maybe it’s the other way around. All your favorite characters were present: the sheik himself, Guido (Marcello Mastroiani) as the film director, the whore Saraghina, the priest(s) and cardinal, the glamorous mistress(s), the bearded lady, the showgirls, and probably many more characters you and I may have forgotten since the 1960’s.

Rossini’s world became Fellini’s and Fellini’s world became Rossini’s. Prosdocimo’s play got written (with a lot of help from his actors), and Fellini’s film got made. Davide Livermore brought it all together adding the perfect physical comic schtick that matched up perfectly with the musical pace of Rossini’s masterpiece. And was funny to boot, sometimes really funny, like the mute Saraghina’s dominatrix relationship with the tenor priest Narciso.

Paolo Spagnolo as Prosdocimo in Act I costume, Pietro Adaini as Albazar, Cecilia Molinari as Saida with members of the Chorus of the Teatro della Fortuna M. Agostini

Paolo Spagnolo as Prosdocimo in Act I costume, Pietro Adaini as Albazar, Cecilia Molinari as Saida with members of the Chorus of the Teatro della Fortuna M. Agostini

Surprisingly all this was not too much, given that Rossini’s librettist Felice Romani had already complicated a really simple comic situation with an absurdist pre-Pirandello intuition, like the metatheatrical Six Charactors. Just as Fellini’s films are laden with images that abstractly create a real world that is imaginary so does Livermore’s opera, a world that we feel and understand but that would take volumes to define. Finally Livermore lays out Rossini’s mixture of error and truth in the same way as had Fellini.

Like some of the American film critics of the time (1963) opined the film 8 1/2 misses touching the heart or moving the spirit, that it’s structure is incomprehensible, and finally that it was a plain out fiasco. This of course can be said of Livermore’s masterful staging. It was far more an intellectual game than a honest rendering of comic and sentimental truths of Rossini’s opera.

Roman born, Juilliard trained opera coach turned conductor Speranza Scappucci was in the pit with the Filarmonica Gioachino Rossini. This brilliant young conductor provided the control needed to keep the bedlam on the stage comprehensible. It was solid music making, with the possibility of inspired music making far beyond what could be expected or even wanted. Her tempos were moderate, patter was measured, the Rossini “boil” or ‘buzz” was never fully achieved, and the unique Rossini joy of singing was absent. But the event was about Fellini, and it was spectacular.

The question looms — what was the understanding and pleasure of those (few) of later generations sitting in Teatro Rossini for whom Fellini films are not part of their general culture?

Erwin Schrott as Selim recognizing Cecilia Molinari as Zaida in Act I

Erwin Schrott as Selim recognizing Cecilia Molinari as Zaida in Act I

The greatest charm of the evening was the sheik Selim, sung by Uruguay born, Italian trained baritone Erwin Schroit [FYI former partner of Anna Netrebko] who had no more to do than walk onto the stage to steal the show. He reinforced the physical mannerisms of Fellini's White Sheik with powerful voice, simply making the world turn about him. This made it all the more fun for Prosdocimo to try to lay out his comedy, which veteran Italian baritone Pietro Spagnoli did with equal panache and volume, if not with such overwhelming charm.