October 31, 2016

The Tallis Scholars: Josquin's Missa Di dadi

The practice of basing both secular and sacred polyphonic compositions on cantus firmi exemplifies this referential symbolism and Josquin’s Missa Di dadi intensifies the use of aural and visual stimuli from the secular world in the service of the sacred to an extreme degree. The liking of French medieval society for dice games - legislation against which was stringent during the period - would seem at first glance, however, to be at odds with the purpose of the liturgy: gain without effort was akin to usury, and we might imagine that any musical reference or association was intended in only the darkest of humorous veins. Phillips links Josquin’s composition to the Milan of the Sforzas, a known ‘hot-house of gambling during the fifteenth century’, and speculates that the composer possibly ‘joined in with this fashion, at court and in private’. There’s an added ‘gamble’ in that there is some doubt as to whether the Missa Di dadi is a genuine part of Josquin’s oeuvre at all.

Whatever the conjectures, what is certain is that the tenor line of Robert Morton’s three-part rondeau ‘N’aray je jamais mieulx que j’ay’ provides the cantus firmus, and this aural dimension is enriched by the ‘dadi’ (the Italian for ‘dice’) which appear in the tenor part, signalling proportionality of form - symmetry in the Gloria and Credo, unpredictability in the Sanctus. For example, the Gloria is preceded by a pair of dice reading four and one, indicating to the tenor that the notes of the chanson need to be quadrupled in length to fit with the other parts. [1]

This recording of Josquin’s Missa Di dadi, on the Gimell label, is the sixth album (of a projected nine) in The Tallis Scholars’ project to record all of Josquin’s masses. Phillips explains the rationale behind the endeavour: ‘I chose to record all Josquin’s masses partly because The Tallis Scholars have been associated with his music for their entire career, and partly because his masses make the best possible project. 19 masses over nine discs is manageable - where Palestrina’s 107 masses is not - while their scoring sets them apart in Josquin’s output. Nowhere else did he concentrate so specifically on four-part chamber-music-like writing, yet every Mass has its own individual sound world.

‘I realised that in his masses Josquin had created a set of pieces of unique quality, designed to explore all the potential within the form, as Beethoven later did with the symphony. I wanted to gather them all together for the first time, so that the public can appreciate the scope of Josquin’s genius.’

From the first notes of the Kyrie, The Tallis Scholars summon an acoustic richness which is invigorating and dynamic. The balance between unity of ensemble and the characterisation of individual lines is exemplary. As pairs and groups of voices move apart and come together, with meticulous precision, even bare fifths have a tension which is released in the succeeding movement of voices. Close-voiced part-writing converges on unisons which then flower into searching vocal flourishes. Listening to the first Kyrie, one admires the way that the voices enter in turn, adding weight and depth; from the first there is a stylish confidence in the delivery - epitomised by the purity and focus of the final chord of this section.

The Christe frees individual voices within the polyphonic texture; one is able to focus on the melodic and motivic development of any particular vocal line while remaining always aware of the symphony of whole. Kyrie II is more ecstatic, with greater rhythmic vitality and a wider registral range; the bass is especially rich in this movement, and the warm major-key resolution conjures the jubilant effect of a resounding organ.

The Gloria is notable for the seamless movement from chant to polyphony. Rhythmic points gain impetus through repetition and there is a bracing contrast between rich harmony and unisons at cadences. The setting of ‘Domine Deus, Rex caelestis’ is sparser of texture and darker in tone; and while ‘Domine Fili unigenite’ descends still further into barer realms, the addition of the upper voices in the ‘Domine Deus, Agnus Dei’ and the greater floridity of the melodic line lifts the spirit of the music once more. In the ‘Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere’ we can appreciate what Phillips means when he speaks of Josquin’s exploitation of the full potential of the four-part texture and mass form: the overall blend of voices seems to soften here, but distinction is still made between homophonic and polyphonic passages, with solo voices drawn forth, leading to a euphoric climax.

A lovely firm bass in the Credo forms a sure foundation above which the lighter tenors and altos can take flight. The contrapuntal points in the Crucifixus take on a harder ‘edge’ initially but as the lines become increasingly elaborate they acquire, almost imperceptibly, a mesmerising richness: the emotive mellifluousness is intensely spiritual, but the homophonic episodes too have great vibrancy.

The freedom and expansiveness of the Sanctus is immediately evident, while the Agnus Dei - especially the second of the three sections - has a refreshing transparency. This is a tremendous performance of the Missa Di dadi which showcases Josquin at both his most intimate and theatrical.

The disc also includes Josquin’s ‘Missa une mousse de Biscaye’ - a work thought to be the composer’s earliest Mass setting, dating from 1473-75, and in which there is the same sense of a composer exploring all the possible techniques and forms available to him. Typically, the mass is based on a secular tune - one with a French and Basque text (Biscay is a province in the Basque region of northern Spain). The French ‘mousse’ is derived from the Castilian ‘moza’ meaning ‘a lass’, and the original song presents a dialogue between a young man, speaking in French, and a Basque girl, who replies to all his amorous proposals with the puzzling refrain ‘Soaz, soaz, ordonarequin’.

The Tallis Scholars’ enunciation of the text of both masses is characteristically precise and clear. The music of the ‘Missa une mousse de Biscaye’ wanders quite waywardly through an unusually diverse harmonic palette - perhaps evoking the mis-communication of the lovers in the original song? - but the singers’ intonation is always true and the progressions sure. Long vocal lines are effortlessly spun, and individual parts come together to form strikingly plush bodies of sound.

The ensemble brings drama and intensity to the mass. The ‘Qui sedes ad dexterum Patris’ drives forward with rhythmic cogency and the sound is bright and energising; the singers create grandeur and spaciousness in the ‘Credo in unum Deum’ and expand confidently into the ‘Et iterum venturus est’. Similarly, after the stillness of the initial setting of ‘Sanctus’ there is persuasive movement into the ‘Pleni sunt caeli’, which in turn swells into a majestic first ‘Hosanna’ where the light-footed bass line and strong cadence bring a sense of joy.

The Tallis Scholars’ first album in this Josquin series won the Gramophone Record of the Year Award in 1987 and this new addition continues the ensemble’s masterly exploration of the way the composer’s music reconciles the earthly and the liturgical.

The album is available on CD and from iTunes in their “Mastered for iTunes” format. It is also available in a variety of high resolution Stereo and Surround Sound Download formats from the Gimell website at www.gimell.com.

Claire Seymour

Josquin Masses: Di dadi; Une mousse de Biscaye.

The Tallis Scholars, directed by Peter Phillips.

Gimell CDGIM 048 (CD: 71.13)

[1] Michael Long presents a comprehensive and persuasive account of the function and meaning of the dice in ‘Symbol and Ritual in Josquin’s Missa di Dadi’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol.42, No.1. (Spring, 1989): 1-22.

October 27, 2016

San Diego Opera Presents Charming Cinderella

On Saturday, October 22, San Diego Opera opened its main stage season with Rossini’s comic opera, Cinderella (La Cenerentola). I saw the performance on the following Tuesday. Lindy Hume’s production had already worked it intrinsic magic in Australia, New Zealand, and Leipzig, Germany but this was its first run of performances in the United States. Hume is the artistic director of Opera Queensland in Brisbane, Australia.

Her stage direction makes use of almost every kind of comedy that can be invoked on the opera stage and she kept varying each artist’s movements so that nothing was ever repeated. If a member of the audience looked away for even a moment he missed something. Dan Potra, who designed The Barber of Seville for Houston Grand Opera created the designs for Cinderella’s scenery and costumes.

The curtain opens upon a wall of library shelves. In this version of the opera, Don Magnifico, the father of Cinderella and ugly sisters Tisbe and Clorinda, owns a general store. He and his daughters live above it. The store contains all sorts of items, both useful and imaginative. Other scenes are denoted with appropriate decor. Potra’s costumes ranged from clownish togs for Magnifico and the ugly sisters, to a red velvet suit for Dandini as the false prince and a gorgeous dark blue ball gown for soon-to-be Princess Angelina.

Scenic and Costume Designer, Dan Potra

Scenic and Costume Designer, Dan Potra

For all this fun and games, Egyptian-born bass-baritone Ashraf Sewailam as the prince’s tutor, Alidoro, was the only straight man. He sang with stentorian dark tones and maintained a singular dignity throughout the evening. In many ways, the charismatic presence of this artist kept the production centered and allowed the comedy to go on around him.

Lauren McNeece was a sweet Cinderella whose sisters bullied her constantly and whose father denied her paternity. For most of the opera she sang with a sweet lyrical sound. At the finale, however, she let loose and sang her high notes with unfettered full rich tones that I never suspected she had hidden all along. As her future husband, Don Ramiro, David Portillo negotiated his difficult coloratura line with exquisite grace and delightful lyricism. Right now, the opera world is blessed with tenors who can sing coloratura and it is a joy to see them spread their wings and fly with the most complicated Rossini roles.

Susannah Biller and Alissa Anderson were the “ugly” sisters Clorinda and Tisbe. They were always amusing and they earned a few laughs with their antics. Most importantly, they were never strident, a difficult feat in those roles. Either of them could be the next Angelina. Italian bass Stefano de Peppo is a gifted commedian and a past master of the fast “patter” that many of Rossini’s comic roles demand. Already dressed for laughs, he made Magnifico real by ever-so-lightly underplaying the part.

Although Los Angeles Opera Young Artist Program alumnus José Adán Pérez was already well known in Southern California, this was his San Diego Opera debut. He was a no-holds-barred Dandini who wanted Cinderella for himself. He sang with an opulent light baritone sound as he made his character realize that although he was a high level servant, he was a servant nonetheless.

Chorus Master Bruce Stasyna made his debut directing the all male ensemble who sometimes danced and at other times goose stepped as an amusing group of serving men and whiskered “women.” Gary Thor Wedow conducted the San Diego Symphony Orchestra in a well-paced translucent reading of Rossini’s elegant score. Patrons heard a multiplicity of interesting sonorities from the lower as well as the higher and brighter-sounding instruments. It was good to be back at the Civic Theatre and to realize that San Diego Opera is again on a firm footing in its community. I look forward to the chamber opera, Soldier Songs, next month and to more main stage productions in 2017.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Cast and Production Information:

Conductor, Gary Thor Wedow; Director, Lindy Hume; Scenic and Costume Designer, Dan Potra; Lighting Designer, Matthew Marshall; Wig and Makeup Designer, Stephen Bryant; Chorus Master, Bruce Stasyna; Pianist, Catherine Miller; Movement Coach, Bernadette Torres; Supertitles, Lindy Hume and Navelle French; Clorinda, Susannah Biller; Tisbe, Alisa Anderson; Cinderella/Angelina, Lauren McNeece; Alidoro, Ashraf Sewailam; Don Magnifico, Stefano de Peppo; Don Ramiro, David Portillo; Dandini, José Adán Pérez.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Cinderella_Nochlin3.png

product=yes

product_title=La cenerentola in San Diego

product_by=A review by Marua Nockin

product_id=Above: Lauren McNeecey as Cinderella [All photos by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz Johnson, courtesy of San Diego Opera]

October 26, 2016

Macbeth, LA Opera

The Chandler audience saw the opera in the usual manner from across the orchestra pit to wherever they were seated. The park audience saw the singers so closely that they could observe their characterizations via the tiniest changes in facial expressions. Thus, the artists had to play to both the theater and HD audiences. They mingled large and small gestures so as to give each audience its due.

Opera is very different when audience members can look into a singer’s eyes and see what his character is contemplating. For opera singers and stage directors, high definition transmission is a new world. With Placido Domingo as Macbeth and Ekaterina Semenchuk as Lady Macbeth the HD audience could watch the characters’ mental machinations grow into actions. Domingo’s interpretation of the title character was as affecting as that of any fine Shakespearian actor. He was a pliable Macbeth who needed his wife to help him plan his path through life. In this production, he could even be considered her victim. For Domingo, Macbeth is a baritone role that rides comfortably on his voice and allows him to act the great Shakespearian role for which he is aptly suited. He goes from jubilant thane and insecure king to soulless death at the hand of Macduff after Lady Macbeth’s demise.

Placido Domingo (center) as Macbeth and Ekaterina Semenchuk (left) as Lady Macbeth

Placido Domingo (center) as Macbeth and Ekaterina Semenchuk (left) as Lady Macbeth

Semenchuk has a huge voice with a beautiful timbre. Verdi said he wanted an ugly voice for Lady Macbeth, but her gorgeous tones were most welcome, especially since she bestowed her vocal jewels more freely at this performance than she did at the performance I reviewed for Opera Today on September 22nd. This Lady was a calculating courtier who had no qualms about murder and could inspire her husband to act the part of a host when all he saw was the ghost of the murdered Banquo. At the same time, she included all the bel canto coloratura and trills that the young Verdi wrote for this early opera. Both Domingo and Semenchuk gave us a fine combination of early seventeenth century acting and early nineteenth century singing.

Ildebrando D'Arcangelo was a thought-provoking Banquo who sang with bronzed stentorian tones. Tenor Joshua Guerrero sang Macduff with the resonant golden notes that have made him an up-and-coming matinee idol. He has a sizeable voice and a secure technique so he is not restricted to light roles Having been raised in the South Gate area, he garnered wild applause from the park audience.

Although no tickets were required at South Gate Park, Los Angeles Opera personnel were at the entrance to greet opera goers and show them where to set up blankets, chairs, and picnic baskets. They even had blankets for anyone who needed them. There were food trucks in the area and a few ice cream vendors. Many families brought their children and I enjoyed watching the little girl in front of me introduce her Barbie Doll to opera. The mother of an older boy told me he had read the Macbeth Comic Book in preparation for the show.

Since most of the people in the South Gate area speak Spanish, the on-screen titles were in both Spanish and English. Perhaps we can have that at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion soon. It was a beautiful evening with a full moon and even the songs of night birds. Los Angeles Opera gave us magnificent show that I hope draws many new enthusiasts to the opera house.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Conductor, James Conlon; Director, Darko Tresnjak; Co-Scenic Designers, Darko Tresnjak and Colin McGurk; Costume Designer, Suttirat Anne Larlarb; Lighting Design, Matthew Richards; Projection Design, Sean Nieuwenhuis; Chorus Director Grant Gershon; Macbeth, Plácido Domingo; Lady Macbeth, Ekaterina Semenchuk; Banquo, Ildebrando D'Arcangelo; Macduff, Joshua Guerrero; Malcolm, Josh Wheeker; Lady-in-Waiting, Summer Hassan; Doctor / First Apparition, Theo Hoffman; Second Apparition, Liv Redpath; Third Apparition, Isaiah Morgan; Fight Director, Steve Rankin; Climbing Consultant, Daniel Lyons.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/KA1_279.jpg

image_description=Ekaterina Semenchuk as Lady Macbeth and Placido Domingo as Macbeth [Photo: Karen Almond / LA Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Macbeth in Los Angeles’ South Gate Park

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Ekaterina Semenchuk as Lady Macbeth and Placido Domingo as Macbeth

Photos: Karen Almond / LA Opera

COC’d Up Ariodante

Mr. Jones and team have taken the courtly setting of the piece Handel wrote and displaced it from a medieval palace to a remote 1960’s Scottish island ”kingdom.” And although the King is still a character, the updated “realm” consists of a massive, unattractive setting that is one large part community meeting hall and one small part private residence. Well, “residence” in the sense that Ginerva’s bedroom and a cramped, ill-used “foyer” were all that were seen other than the rather primitive common room.

From the numbingly ugly bedroom wallpaper, to the floating doorknobs that open/close non-existent “doors,” to the confusing configuration of entrances, this was a depressing, intentionally dull atmosphere, meant to convey a mandated routine and an oppressive societal structure. Set designer ULTZ was also responsible for the drab, purposefully provincial costumes. The attire was at times confusing (chorus women were dressed as men but danced as women), at best functional (such as the wedding gown that gets passed around), and at worst, defeating (the titular prince looks like a hang-dog village simpleton). Although the whole dwelling was covered with a realistic ceiling which prevented down-lighting, Mimi Jordan Sherin provided an admirable lighting design that featured evenly produced washes and meaningful area illumination.

So what was this concept all about? Some program ink was taken up justifying Ginerva as the main focus (Handel be damned), pursuing a rather heavy-handed subtext that she is forced into assuming the limiting woman’s role that society demands of her. To that end, Duke Polinesso was repurposed as a hypocritical evangelist who is in actuality an unrestrained sexual predator. More program notes expounded about Ibsen and Strindberg as some sort of inspiration for this interpretation, but that was not born out by inconsistent staging choices.

The ensemble (singing well under Sandra Horst’s tutelage) was treated more like a Greek chorus than anything those Scandinavian writers might have inspired. Often (make that “too often”) the chorus would enter or exit in single file, as if in some unspoken ritual that involved moving the wooded chairs on, off, and around stage like a poor man’s bus-and-truck tour of Grand Hotel. When they tired of that, they moved the heavy table to and fro. And characters certainly did not behave realistically, clambering over, on and under furniture as they ignored each other and sought merely to create different visual levels.

Characters that were said to be “asleep” had their eyes wide open, those said to be “kneeling” were standing, those hailed as being “together” were apart, well, you get the idea. Just like in a slam-bang, authentic Hedda Gabler, right? You can only stage against the text so many times before an audience tunes out. As if this weren’t enough, puppets were added to comment on the action at the ends of each act.

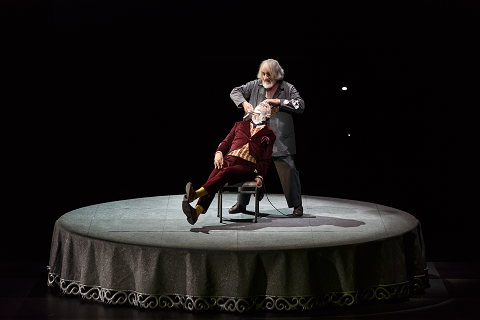

A scene with puppets

A scene with puppets

Without meaning to insult anyone’s appeal in any way, it is telling that the puppets are actually more engaging than the live singers. The marionette enactment of marriage and family life at the end of One was a breath of delightful whimsy. But then came the thudding scenario at the end of Two in which mini-“Ginerva” was tarted up as a red-pumped, street-walking pole dancer. I am not making this up. The show ended with an Instant Replay of the end of One’s marital bliss, except with the real Ginerva packing a suitcase and leaving: the scene, the set, the show. The actress walked down off the raised set onto the front apron (unobserved by anyone else on stage), and made some odd gesture(s) as if to tell the follow-spot operator to kill her light. What ‘that’ meant prompted much discussion as patrons exited the theatre. No one in earshot understood it, but then I am not sure “understanding” Ariodante was what this staging was about. Talking about it was enough.

I will say that taken on its own terms, it was all of a piece. Within its dramatic suppositions, character relationships were clear, the plot was clear enough, and given the highly accomplished musical execution, the oddities were mostly forgivable even as they were often unhelpful. The completely unsavory take on Polinesso did neither the show nor the cross-dressing performer any favors. We should have a love-hate relationship with this character, but there was such an “ick” factor in the brutal rape scene that it was impossible to connect with the talented singer. Sigh.

Johannes Weisser as the King of Scotland, Jane Archibald as Ginevra, Alice Coote as Ariodante,

Johannes Weisser as the King of Scotland, Jane Archibald as Ginevra, Alice Coote as Ariodante,

Which returns us now to “sumptuously sung.” COC has spared no effort in assembling a veritable Dream Team of Handelians to sweep almost all of this before it. Alice Coote is at the top her considerable game in the title role, with every perfectly judged phrase confirming the impression that she has few (any?) equals in this Fach. Not only does Ms. Coote have a ripe, rich tone, but she also negotiates page after page of ungodly rapid coloratura with trip hammer accuracy. In addition to the fire, sass and brass she brings to such explosive passages, this talented artist can turn on a dime and offer limpid, affecting, introspective stretches of poised, hushed beauty.

I first encountered the equally thrilling soprano Jane Archibald in Semele with this same company, and as jaw-dropping as was that performance, she has only grown even finer in the interim. As Ginevra, Ms. Archibald summons a luxuriant tone, an unerring technique, and a compelling delivery to prove every inch a match for her Ariodante. When Alice and Jane duet late in the show, their almost mystic melismas tumbling over each other in haunting beauty, you got the impression this perfection was not meant merely for human ears.

In the trouser role of Polinesso, Varduhi Abrahamyan sported a creamy, responsive mezzo that was enormously pleasing, and admirably agile. Ms. Abrahamyan sang splendidly and went through the directed motions of sexual aggression with consistent commitment. Pity that her very real vocal achievement got eclipsed by a repugnant character concept. I will dearly look forward to encountering this wonderful singer in a happier situation. Dalinda was embodied by the assured soprano Ambur Braid portraying an endearing character, in this case made more sympathetic by the “concept.” Her subservient, sometimes cowering demeanor drew us in, and was well complemented by her secure, idiomatic singing. Impressive throughout, she was especially potent as she unleashed any number of gleaming phrases at full throttle.

At first, the role of Lurcanio seems like an after thought, even as winningly sung by Owen McCausland. Mr. McCausland made a good impression in his first aria, sharing a mellow, well-modulated tenor, albeit with a hint or two of strain at the very top. As the performance progressed, everything settled into place as he went from strength to strength, and assumed a progressively more integral role in the story. Young Aaron Sheppard had few lines as Odoardo, but served notice that his is a talent of good promise.

Among this roster of exceptional, almost exclusively Canadian principals, Norwegian Johannes Weisser was the King of Scotland. Mr. Weisser’s melismas were accurate enough, to be sure, but his bass is decidedly on the dry side, and he simply lacked the warm gravitas that would benefit the role.

Music Director Johannes Debus was conducting his first Handel but you would never have known it, given his total command of the style and his embrace of the dramatic possibilities. Maestro Debus proved to be a meticulous partner, not only with the accomplished singers but also with the dramatic intent of the composer and yes, even the director. His pacing of the evening was miraculous, making a long score fly by with a vibrant, informed reading.

Given the realities of having to produce popular bread-and-butter titles, COC is to be commended for not only programming this less accessible Handel opus, but then also challenging its patrons further with such a gritty re-interpretation. It is to the great credit of all concerned that the rapt audience willingly embraced the journey.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Ariodante: Alice Coote; Ginerva: Jane Archibald; Dalinda: Ambur Braid; Polinesso: Varduhi Abrahamyan; Lurcanio: Owen McCausland; King of Scotland: Johannes Weisser; Odoardo: Aaron Sheppard; Conductor: Johannes Debus; Director: Richard Jones; Set and Costume design: ULTZ; Lighting Design: Mimi Jordan Sherin; Choreographer: Lucy Burge; Puppetry Director and Design: Finn Caldwell; Chorus Master: Sandra Horst

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sohre_COC1.png

product=yes

product_title=Ariodante at Canadian Opera Company, Toronto

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Jane Archibald as Ginevra [All photos copyright Michael Cooper, courtesy of Canadian Opera Company]

October 24, 2016

Jamie Barton at the Wigmore Hall

But, it wasn’t all plain sailing. Prefaced by Baillieu’s grandiose and statuesque introduction, Barton launched bravely into the first song, ‘Cuando tan hermosa os miro’ (When I gaze on thy great beauty) from Joaquín Turina’s Homenaje a Lope de Vega Op.90; and, the first phrase was gorgeously rapturous of tone and supremely floated, yet also wayward with regard to pitch. Perhaps it was nerves, but the note just drifted out of control. But, it didn’t really matter; Barton had such an instinct sense of the song’s drama and sensuality that her vocal allure carried the day. The trio of songs which form Turina’s homage to one of Spain’s truly great literary figures are surely among the composer’s best work; and, if there was some uncharacteristic unsteadiness at the start, there was also considerable nobility.

The subsequent song ‘Si con mis deseos’ (If by my desires) was more intimate, however, the change of mood signalled by Baillieu’s quiet, murmuring introduction. Lack of familiarity with the Hall’s dimensions and acoustic was an issue here, though; reflecting that ‘Y mis dulces emploes/ Celebrara Sevilla’ (my sweet employments would be celebrated by Seville), Barton’s mezzo bloomed to operatic dimensions - but the Wigmore Hall is not the Met, nor the Coliseum. In contrast, the delicacy of the conclusion, with its imagery of turtle doves and bridal beds was beguiling, but again the wide vibrato led the pitch astray. The final song of the trilogy, ‘Al val de Fuente Ovenuja’ (Into the vale of Fuente Ovejuna), was notable for the narrative fluency which Baillieu created. Barton imbued these songs with smokiness and sensuality but drama was not always equalled by secure vocal discipline.

It was a different story in the sequence of songs by Johannes Brahms. Barton made her Proms debut in 2015 with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment conducted by Marin Alsop in Brahms’ Alto Rhapsody, a performance of great focus and dignity which confirmed her status - suggested by her performance at the Cardiff competition - as an important interpreter of this composer’s music. The beauty of the phrasing was remarkable, and was complemented in ‘Ständchen’ (Serenade) by Baillieu’s initial lightness of touch and subsequent depth of sentiment. ‘Meine Liebe is grün’ (My love’s as green as the lilac bush) had a compelling rhythmic motion; ‘Unbewegte laue Luft’ (Motionless mild air) was trancelike and transparent - Barton withholding her mezzo to a mere whisper, but releasing some warmth mid-song to question, ‘Sollten nicht auch deine Brust/ Sehnlichere Wünsche heben?’ (Should not your breast too heave with more passionate longing).

It was Antonín Dvořák’s Op.55 Gypsy Songs which finally released the dusky voluptuousness so beloved of Barton’s mezzo; each phrase was invigorated by colour and shade. Moreover, Barton’s ability to switch between emotional registers, and vocal styles, while still retaining the coherence of the sequence was evident. Several of the songs confirmed the power and richness of Barton’s lower register, and the idiomatic Czech pronunciation (as far as I am qualified to judge!) was impressive. Indeed, it’s worth noting that Barton sang in five languages in this recital: Spanish, German, Czech, English and Finnish.

The first song, ‘My songs rings with love to me again’ was notable for the relaxed interplay of voice and piano. The anxious cry ‘Aj!’ was the springboard for the passionate song of death which followed. ‘A les je tichý kolem kol’ (And all the wood is silent all around) was one of the highpoints of the recital; Baillieu’s falling arpeggios dripped with aching languor and there was a veiled quality to both the vocal line and the accompaniment that, while injected with greater definition as the song progressed, suggested a world beyond. In contrast, in the familiar ‘When my old mother taught me to sing’ Barton’s mezzo soared ecstatically but the slow tempo tempered the rapture with yearning. The final three songs of the sequence danced with theatricality.

After the interval we roved into less familiar territory, but Barton’s confidence in conveying the musical and narrative threads of the Charles Ives’ songs presented made this listener feel entirely at home. Commenting on her Cardiff programme, Barton has explained her inclusion of Ives’ work, including ‘The Housatonic at Stockbridge’: “I very, very pointedly, desperately wanted to do an American composer because I was representing the U.S. So I built a set around that.” There was a sort of intellectual distance to the first Ives’ song, ‘The Things Our Fathers Loved’, but this was refreshing after the subjective passion of the Brahms and Dvořák songs heard before. Ives’ setting of Rupert Brooke’s ‘Grantchester’ (1920) drifting wistfully, but I’m not sure that the allusive parodic impact of Ives’ quotation of Debussy’s Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune - with the lines ‘Nature there or Earth or such./ And clever modern men have seen/ A Faun a-peeping through the green’ -really registered.

‘Immortality’ built to a fearful and aggressive climax; the piano’s syncopated freedoms in the aforementioned ‘The Housatonic at Stockbridge’ were beguiling and Baillieu summoned an artist’s palette at the close. Indeed, the unassuming Baillieu’s contribution to the emotional and communicative impact of this recital should not be overlooked: especially given that Barton told us that her accompanist had spent much of the previous day in hospital - something to do with ‘a walnut’ was her explanation!

‘The Cage’ stemmed from a visit Charles Ives made with several friends to the Central Park Zoo, where they saw a leopard pacing restlessly back and forth in its cage. Reading the text I was reminded of Ted Hughes’ two poems, ‘The Jaguar’ and ‘Second Glance at a Jaguar’, and although Ives’ song is much more epigrammic than Hughes’ poetry I was surprised that the audience seemed to find this song funny rather than sharing my disquiet at its uncanny claustrophobia. ‘Old Home Day’ provided a folksy playout, albeit it one tinged with tempering nostalgia.

Six songs by Sibelius closed the programme, and enabled us to enjoy the glossy voluptuous of Barton’s mezzo. There was pointed attentiveness to the text: a steeliness in ‘Svarta rosor’ (Black roses) when the rancour and pain instigated by the roses thorns are alluded too; an enriching of the tone and wonderfully profound registral descent with the reference to the ‘mournful lay’ at the close of ‘Säv, säv, susa’ (Sigh, rushes, sigh). ‘Flickan kom ifråsin älskings möte (The girl came from her lover’s tryst) was a veritable operatic drama of Verdian proportions.This recital was supported by the American Friends of Wigmore Hall and there was a large partisan presence in the Hall who delighted in Barton’s encores, ‘Never Never Land’ from Peter Pan, and Ernest Charles’s ‘When I Have Sung My Songs’. She held the audience in the palm of her hands; playful but pert, when challenged by an audience member to sing Eboli’s Act 4 aria ‘O don fatale’ from Verdi’s Don Carlos for her second encore, Barton’s rejoinder was ‘You sing Eboli!’ Barton was awarded Best Young Singer at the International Opera Awards in 2014; this performance suggested that her natural home is the opera house rather than the recital hall. How long will it be before Barton conquers triumphantly not just Cardiff but the London, and European, opera stage?

Claire Seymour

Jamie Barton - mezzo-soprano, James Baillieu - piano

Joaquín Turina: Homenaje a Lope de Vega Op.90, Johannes Brahms: ‘Ständchen’ Op.106 No.1, ‘Meine Liebe ist grün’ Op.63 No.5, ‘Unbewegte laue Luft’ Op.57 No.8, ‘Von ewiger Liebe’ Op.43 No.1; Antonín Dvořák Gypsy Songs Op.55; Charles Ives ‘The things our fathers loved’, ‘Grantchester’, ‘Immortality’, ‘The Housatonic at Stockbridge’, ‘The Cage’, ‘Old Home Day’; Jean Sibelius: ‘Svarta rosor’ (Black rose) Op.36 No.1, ‘Säv, säv, susa’ (Reed, reed, rustle) Op.36 No.4, ‘Flickan kom ifrån sin älsklings möte’ Op.37 No.5, Marssnön Op.36 No.5, ‘Var det en dröm?’ Op.37 No.4

Wigmore Hall, London; Sunday 23rd October 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Jamie%20Barton.jpg image_description=Jamie Barton’s Wigmore Hall debut product=yes product_title=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Jamie BartonAnd London Burned: in conversation with Raphaela Papadakis

The London-based soprano met with me to talk about this exciting new opera. Librettist Sally O’Reilly, who worked with Rogers on The Virtues of Things which was premiered at the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Studio Theatre last year, has woven together stories from The Great Fire, the flames of which were ignited shortly after midnight on Sunday 2nd September 1666 at the bakery of Thomas Farynor in Pudding Lane, in the east of the City of London. The Fire raged for three days, fanned by unseasonably strong easterly winds, destroying much of the City and eventually reaching The Temple, about a mile and a quarter to the west. King Charles II put his younger brother James, Duke of York, in charge of fire-fighting and rescue operations; James and his men probably did more than anyone to help stop the spread of the fire and they extinguished the last flames on the roof of Inner Temple Hall on Wednesday 5th September.

Rogers and O’Reilly seek to tell both the City’s tale and those of its dwellers. The opera - which is directed by Sinéad O’Neill, a regular Assistant Director at Glyndebourne - has a cast of five and Papadakis is joined by a team of rising stars and award-winning young singers: Gwilym Bowen, Alessandro Fisher, Aoife O’Sullivan, and Andrew Rupp.

Papadakis plays ‘London’ itself, at times moving among its citizens, the diverse populous being conjured by three singers who take on multiple roles. Then, there is a young Lawyer who finds himself torn between allegiances and values: as the flames devour Inner Temple, his private yearning to preserve the beautiful historical Temple battles with his duty to observe the edict which demands that the building be pulled down in order to prevent the Fire from spreading further. The Lawyer’s regret provides a poignant counterpart to the climactic events of the inferno itself. Papadakis remarks that the period design (by Kitty Callister) is complemented by more abstract elements; and, that the unfolding stories reveal much about human nature. At first, Londoners find the Fire a curiosity rather than a threat; then, as its fury escalates, panic begins to grow. To prevent an exodus, which would deprive the fire-fighters of desperately needed manpower, the Duke of York prohibits the population from leaving the City; the citizens in turn look for someone to blame for the catastrophe which has been unleased upon them - and turn upon the foreigners in their midst.

One thing that Papadakis has found revealing is the way that the opera shows the Fire to be simultaneously destructive and creative, viciously razing vast swathes of the city but also clearing away the old - including the rampant plague and the rats upon which the disease was born - and making way for the seeds of new beginnings.

And London Burned will be conducted by Christopher Stark, co-Artistic Director of the RPS Award Winning Multi-Story Orchestra which made its debut at the Proms this summer. The opera is scored for two cellos, two horns - Papadakis describes their distorted cries as the darkness in the opera - and two clarinets, plus organ; the latter will be played by Roger Sayer, the Organist and Director of Music of the Temple Church. Papadakis has found Matt Rogers’ approach to text-setting particularly interesting; she observes that the words are quite ‘drawn out’, the rhythms and syllables perhaps more elongated than would at first seem natural, but she believes that this will allow the text to be clearly heard by the audience, particularly in the Temple Church acoustic.

Raphaela Papadakis. Photo credit: Ben Ealovega.

Raphaela Papadakis. Photo credit: Ben Ealovega.

Papadakis is supported by City Music Foundation, an organisation which uses its position and contacts with the City of London’s institutions to provide young musicians with the opportunities, tools and networks to develop a successful and rewarding career in music. The soprano is excited to be benefitting from the experiences that the two-year programme offers, not least the opportunity to meet and perform with internationally acclaimed musicians such as pianist Roger Vignoles and soprano Joan Rodgers. Such experiences are not just musically inspiring but can also help musicians develop their repertoire and make new contacts, as Papadakis has found, describing her discovery of new music suggested to her by Rodgers.

And, it’s not just the musical experiences that CMF has provided that Raphaela finds enriching, motivating and valuable; it’s the practical ones too. CMF’s unique two-year programme also includes business mentoring as well as professional development workshops covering topics such as managing finances, tax and pensions, copyright and contracts, presentation and interview skills, and publicity strategies - aspects of professional musical life which are not always part of conservatoires’ postgraduate training programmes.

Finally, CMF musicians are supported in devising, organising, funding and promoting a bespoke musical project to help them develop a unique niche and selling point. Papadakis’ project involves commissioning, producing, performing and promoting a double bill of new operas which will explore links between music and mental health. Following workshops, the operas will be performed in the autumn of 2017 and Papadakis hopes to take this new music into unconventional venues, extending opera’s reach and impact.

Papadakis is clearly busy with diverse projects and engagements. Last week she performed two ‘pop-up’ recitals at the Oxford Lieder Festival, in the city’s Ashmolean Museum, with the Gildas String Quartet. The musicians presented Aribert Reimann’s arrangements of songs by Schumann, Brahms and Mendelssohn for voice and string quartet, and Papadakis explains how she is intrigued by the dialogue that Reimann creates between the voice, which presents the songs’ melodies more or less in their original form, and the specially composed instrumental intermezzi which make use of subtle, evolving references to thematic material from the song as points of interpretative departure. The players will reprise this programme of Reimann’s works again at the SongMakers Festival in Sheffield in November.

But, this week Papadakis’ focus is on London, as final rehearsals get underway for the premiere of And London Burned on Thursday 27th October in the Temple Church - one of the most historic and beautiful churches in London. This artistic recreation of momentous past events, which have in turn shaped the present-day city, will undoubtedly create its own piece of history.

Tickets are available from https://www.templemusic.org/main-events/ and more information, including audio tracks of Rogers’ music and the director’s blog, at https://www.templemusic.org/shop/and-london-burned-performance1/ .

Raphaela Papadakis http://raphaelapapadakis.com/

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/0787%20CMF%20Sept2015%20Raphaela%20Papadakis%20Ben%20Ealovega.jpg image_description=And London Burned product=yes product_title=And London Burned product_by=An interview with Raphaela Papadakis, by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Raphaela PapadakisPhoto credit: Ben Ealovega

Toronto: Bullish on Bellini

Perhaps you cannot be blamed if you prefer your Druid tale to be more concerned with the love triangle that propels the story but love be damned, it cannot be denied that Director Kevin Newbury conspired with his set designer David Korins to keep impending violence in the forefront.

Mr. Korins has devised a playing environment that begins life as an armory, with heavy stone walls festooned with all manner of ancient weaponry. But hold on, he wants to have it both ways, so the huge double door flies away revealing rows of pale tree trunks, that tie in to the visual of the huge, severed, bare white tree that is suspended horizontally up center. Two enormous bull heads flank the upstage false proscenium, hovering ominously as symbols of the preferred sacrificial animal of Druid rites.

A gentle snow falls but rather than suggesting serenity it conveys a barrenness, a void of passion that would prove all too prophetic. And problematic. Significant scenic additions to this playing environment included a rolling, rustic, two-tiered wagon that may have wandered in out of an English Mystery Play. It existed solely to allow Oroveso and Norma a method of gaining focus by mounting the second level to address the populace like a politician working partisan supporters.

The immolation

The immolation

And then there is . . .the bull. A giant, Trojan-horse-cum-bull made of rude wooden slats and set on a wheeled platform rolls on up right in the final scene to become the funeral pyre. Handsome enough as a sculpture, it was in the wrong place at the wrong time, first stealing, then lacking focus; proving awkward for Pollione and Norma to access; and decidedly unfrightening. As the “pyre” starts burning, it is safely and neatly contained along the front edge of the platform, clearly unthreatening, and it fires up well before the lovers can scramble into place for the effect. So, the big finish fizzled and amounted to just a lotta overwrought “bull.”

Jessia Jahn’s costumes had just the right primitive look along with a commendable variety. She made especially beautiful choices for Adalgisa, alluring in a simple blue gown, and Norma, radiant in sumptuous gold attire and blond wig. By making Norma look totally foreign to the rest of the citizenry, it was easy to believe that her “otherness” contributed to her veneration as a priestess. Duane Schuler is a renowned lighting designer whose his effects did not disappoint. Although some of the sudden color washes (red, green, etc.) seemed bluntly executed, they were obviously in collegial support of some rather blunt directorial choices.

Not that Kevin Newbury’s theatrical guidance did not have good intentions and some fresh ideas. Crowd management and motivation of group entrances/exits were well conceived overall, with only one instance of awkwardness when the chorus (and Oroveso) were left without a motivated focus. The smaller ensembles contained so many moments of meaningful interaction that it seemed a shame that there were also conspicuous lapses with characters upstaging each other, while doing their best to get out of the way of the focal singer.

Norma began the show on stage holding a torch aloft, a nice premonition of her fate, although it did deprive her of Bellini’s star entrance later in the scene. I liked the Druid “salute,” a “dap” variation on the sign of the cross that was well incorporated and conveyed a fine sense of communal religious observances. I was less persuaded by manufactured bits like having a group of female supers cross the stage bearing black stools just prior to the first Norma-Adalgisa duet, and being persuaded to leave two stools en route stage left so that the two soloists could “sit and chat.” It also rang false that those two leads casually folded the children’s blankets and played with their toys during the conclusion of their second duet! There is a bit more at stake at that point than tidying up the nursery like giggly schoolgirls.

If the staging sometimes called attention to itself, the performers were able to maintain musical integrity and make a solid case for Bellini’s masterpiece. In the pit, Stephen Lord led a robust, refined account of the score and the players responded with real, purposeful dramatic fire. The splendid cello solo was but one of many instrumental high points, and the entire ensemble excelled under Maestro Lord’s knowing baton.

The role of Norma is a “big sing” of course, and world star Sondra Radvanovksy more than fulfilled expectations. Is there anyone in the business that has a firmer command of her technique than Ms. Radvanovsky? She knows what she wants to do, what she can do, and has the wisdom to know the difference. And in an age when many voices sound somewhat anonymous, her instrument is recognizable and uniquely personal.

The soprano is never heard to better advantage than when she is ravishing us with beautifully controlled filigrees of pianissimo passages. Caballe, Sills and Scotto were past mistresses of this effect, and I would be hard pressed to name any current performer who is Sondra’s equal at this intense, hushed soft singing. It is when she presses harder that her tone can come to grief, with high notes that are admirably secure nonetheless taking on an occasional harsh, metallic tinge.

Still, the diva performs with total mastery of her art, both musically and theatrically. If her turn as Norma is not quite the complete triumph it may become, it is owing to a certain cerebral calculation of effects which are meticulously judged but somewhat wanting in spontaneity and emotional honesty. I have seen Ms. Radvanovksy be incredibly moving and genuine on past occasions, but on this night I was more aware of her consummate craft than her personal commitment.

Sondra Radvanovsky as Norma, Isabel Leonard as Adalgisa

Sondra Radvanovsky as Norma, Isabel Leonard as Adalgisa

We are spoiled by the perfection of legendary Norma-Adalgisa match-ups like Sutherland-Horne, Callas-Cossotto, Caballe-Verrett, or presently, Meade-Barton. It has to be said the luminous Isabel Leonard is a very affecting Adalgisa, and her plush, throbbing mezzo-soprano is thing of refined beauty indeed. Ms. Leonard is such a sympathetic presence, her bearing at once determined and contrite, that I wish she had been a better vocal match for her co-star. Her rounded, suave delivery had all the requisite coloratura at her command, but explosive phrases were executed within the vocabulary of her own distinctive, gentler firepower. The duets were always well-coordinated and cleanly managed, only at odds in tonal approach.

Russell Thomas proved to be an engrossing Pollione, his burnished, meaty tenor caressing plangent phrases one minute and hurling out riveting declamations the next. I had enjoyed Mr. Thomas some years ago as a promising Hoffmann, but nothing could have prepared me for the assertive star turn he provided in Norma. He is deservedly maturing into a major artist on the international scene. Dimitry Ivashchenko was a sturdy Oroveso, although his ample bass could turn hard when pushed for dramatic volume rather than deployed for musical finesse.

Young Charles Sy had pleasing tone to spare as he put his well-schooled tenor in good service of Flavio’s several scenes. Aviva Fortunata made a highly favorable impression, her attractive, substantial soprano imbuing each of Clotilde’s phrases with such real quality that it reminds us the great Sutherland once herself made quite an impression in this secondary role.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Oroveso: Dimitry Ivashchenko; Pollione: Russell Thomas; Flavio: Charles Sy; Norma: Sondra Radvanovsky; Adalgisa: Isabel Leonard; Clotilde: Aviva Fortunata; Conductor: Stephen Lord; Director: Kevin Newbury; Set Design: David Korins; Costume Design: Jessica Jahn; Lighting Design: Duane Schuler; Chorus Master: Sandra Horst.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sohre_COC4.png

product=yes

product_title=Norma at the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Sondra Radvanovsky as Norma [All photos copyright Michael Cooper, courtesy of the Canadian Opera Company]

October 23, 2016

Arizona Opera’s Sapphire Celebration

Sapphire is the stone that represent forty-five years and at Arizona Opera’s Sapphire Celebration patrons wore blues, dark and light, brilliant and matte fabrics, with deep toned genuine or sparkling faux jewels.

Conductor Ari Pelto opened the program with a slightly rough rendition of Mozart’s overture to The Abduction from the Seraglio. Everything fell into place, however, when Mistress of Ceremonies Frederica von Stade joined Marion Roose Pullin Studio Artist Alyssa Martin in the soaring melodic duet from the same composer’s The Marriage of Figaro, “Che soave zeffiretto,” (“A gentle zephir”). The second vocal selection echoed the company’s first opera from 1972, Rossini’s The Barber of Seville, as Martin blended her mellifluous voice with that of suave young baritone Joseph Lattanzi in the Act I Scene 2 duet: “Tu non m’inganni” (“You don’t deceive me”).

Arizona Opera has a fine chorus directed by Henri Venanzi and its members showed their abillity to set a scene and elicit emotional responses with their rendition of “Patria Oppressa” (“Oppressed Fatherland”) from Verdi’s Macbeth. Later, they would show us a sunnier scene with their rendition of a chorus from Mascagni’s verismo opera, Cavalleria Rusticana.

Daniel Montenegro is a fine young tenor who gave an excellent rendition of “La donna è mobile,” (“Woman is Fickle”) from Verdi’s Rigoletto, reminding us all that “locker room talk” is as old as mankind. Montenegro and soprano Laquita Mitchell then sang the universally loved duet from the first act of Puccini’s La bohème that began “O suave fanciulla.” As is usually done in a staged version of the opera, they took the final note off stage.

Craig Verm scaled down his sizeable baritone sound to match the lyric tones of Andrew Stenson for the duet “Au fond du temple saint” (“Into the holy temple”) from Bizet’s The Pearlfishers. Verm followed it with the burnished bronze tones of “O Nadir, Tendre ami” (“O Nadir, dear friend”) while Stenson followed their duet with the plaintive aria ‘Una furtive lagrima” (“A furtive tear”) from Donizetti’s The Elixir of Love.

Before the intermission, Arizona Opera celebrated its success with a duet the company had never before performed. Baritone Joseph Lattanzi and bass-baritone Zachary Owen joined their strong, virile voices with the orchestra’s brass to sing the gracefully melodic “Suoni la tromba” (“Sound the trumpet”) from Bellini’s I Puritani. The company then brought the first half of the concert to a delightful end with the sextet from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. Rachele Gilmore was the deranged bride and her final high note was simply glorious.

After the intermission, Laquita Mitchell and Thomas Cannon caused vocal sparks to fly as they sang a dramatic duet from Verdi’s Aida. In it, the Ethiopian king convinces his daughter to ask her Egyptian lover to commit treason and reveal the route by which Egyptian forces will march to Ethiopia.

As the evening wore on, the fare became a bit lighter. Coloratura soprano Rachele Gilmore and mezzo Mariya Kaginskaya sang a tuneful duet from Delibes’ Lakme about flowers blooming on a riverbank. Then Mistress of Ceremonies Frederica von Stade pretended to have drunk just one too many in a riotously funny version of “Ah, quel diner” from Offenbach’s La Perichole. Rachele Gilmore responded with her version of the mechanical doll from the same composer’s The Tales of Hoffmann.

Soprano Laquita Mitchell returned with an icy aria from Puccini’s Turandot and baritone Thomas Cannon countered with the universally loved “O du mein holder Abendstern” (“O you my blessed Evening Star”) from Wagner’s Tannhäuser.

Over the past decades, von Stade has sung myriad performances of Zerlina in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. Here she sang the duet “La ci darem la mano” (“Give me your hand”) with every baritone on the program and it was a delight to watch. Crowning the evening was a rendition of “Make Our Garden Grow” from Leonard Bernstein’s Candide, featuring everyone not already onstage. The audience was thoroughly enthused and the sounds of applause were enormous. We will have to wait five more years for Arizona Opera’s fiftieth anniversary, but I guarantee it will be a fantastic celebration.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Conductor, Ari Pelto; Stage Director, Joshua Borths; Scenic Designer, Anthony Diaz; Chorus Master, Henri Venanzi; Master of Ceremonies, Frederica von Stade; Sopranos: Rachele Gilmore, Laquita Mitchell; Mezzo-sopranos: Alyssa Martin, Mariya Kaginskaya; Tenors: Andrew Stenson, Daniel Montenegro; Baritones: Craig Verm, Thomas Cannon, Joseph Lattanzi; Bass-baritone, Zachary Owen.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/woolfe2-von_stade_frederica_eric_melear_0.png

image_description=Frederica von Stade [Photo by Eric Melear]

product=yes

product_title=Arizona Opera’s Sapphire Celebration

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Frederica von Stade [Photo by Eric Melear]

The Nose: Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

Nikolai Gogol’s logic-defying tale of a runaway nose is magnificent in its extravagant absurdity. But, when Collegiate Assessor Kovalov awakens one morning to find his olfactory proboscis has mysteriously gone AWOL and launches a madcap search for his errant sniffer, it is more than his sense of smell that he is desperate to retrieve. His Nose, inflated in size, status and ego, is now a ‘self’ in its own right; indeed, it has stolen Kovalov’s own sense of ‘self’. He appeals for help to a wide range of state institutions - police, medicine and media: he places an advertisement in the newspaper, “I am giving you an announcement … about my own nose: which means almost about me myself …”

Ambitious, pretentious - a petty poseur - Kovalov has not known his place, and now he has none. This is the ‘dark side’ of ‘The Nose’, but it is not an angle which is illuminated with any great intensity by director Barrie Kosky’s new production of Shostakovich’s modernist operatic romp currently being staged at the Royal Opera House (the first production of the 1928 opera in the House). Kosky does, however, give us a virtuosic vaudeville which makes for an entertaining, if not electrifying, evening. Gogol’s hapless protagonist is a vain, flirtatious bureaucrat whose lust for status among the proto-bourgeois milieu is displayed in his casual amorous dalliances (he uses the military rank of ‘Major’ to impress women) and his obsession with his visual appearance - and its continual display during his daily strolls on Nevsky Boulevard. He awakens one morning to find that his nose has inexplicably vanished. Offended by its ‘owner’s’ habit of allowing the filthy barber Ivan Iakovlevitch to take his nose in his stinking hands when he soaps Kovalov’s cheeks, during his bi-weekly shaves, the Nose makes a bid for independence and embarks on a two-week spree of psychological revenge. Martin Winkler as Kovalov, John Tomlinson as Ivan Iakovlevitch © ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Martin Winkler as Kovalov, John Tomlinson as Ivan Iakovlevitch © ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The Nose first turns up in a loaf of bread, baked for breakfast by Iakovlevitch’s wife. Discarded in disgust, it then takes on a life of its own. Tormented by the thought of parading along the fashionable Nevsky Prospect sans nose, Kovalov sets off in pursuit, chasing his missing sensory appendage through the streets to the market place and the cathedral; he seeks help from the state and from science but the institutions fail to assist him. And, when the Nose has been tracked down, arrested and returned, the Doctor actually encourages Kovalov to sell the Nose to him in order to make it available for the benefit of modern science and medicine, and his own pocket: “As for the nose, I advise you to put it in a jar of alcohol … then you’ll get decent money for it. I’ll even buy it myself, if you don’t put too high a price on it.”

Shostakovich was in his early twenties when he wrote his first opera, The Nose. He had entered the Leningrad Conservatory in 1919 and graduated in 1925. These were years of multifarious literary and musical manifestos among the cultural avant-garde in Russia and with its deliberately disordered chronology and symbolic distortions of events, it’s easy to see why Gogol’s absurdist satire appealed to the young composer, offering as it does ample opportunity for experimentation with new musical idioms but also allowing for a re-interpretation of the Russian society of the past. At its first fully-staged appearance, the opera was billed as an ‘experimental performance’ by the Artistic Council of Maly Theatre in Leningrad, who feared that some of proletarian audience might be ‘bewildered by the complexity and modernism of the musical medium’. And, Shostakovich does give us a riot of idioms, acrobatic vocalism and kaleidoscopic orchestration, along with a cast of almost 80 individual roles who perform a helter-skelter medley of scenes which race randomly and irrationally through umpteen St Petersburg locales with cinematic slickness. Sung and spoken dialogues alternate with diverse orchestral episodes, the latter serving as satirical embodiments of the dramatic events which ensue as Kovalov runs wildly through the streets in search of his nose, with all its social, and cultural potential. © ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

© ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Shostakovich’s daring musical comedy doesn’t always come off but the bravura bluster of the opera’s theatrical drum-rolls has been ingeniously exploited by Kosky and his set and lighting designer Klaus Grünberg. Wisely, they do not over-complicate things, and instead allow Buki Shiff’s gaudy, exuberant costumes and choreographer Otto Pichler’s vaudeville absurdities to serve as a coloristic complement to Shostakovich’s chaotic, often deliberately cacophonous, score. The garish spectacle is set against a black-grey-white backdrop scheme. Grünberg has placed a proscenium circle within the ROH’s fourth wall, creating a spy-hole through which we can observe, from the safe distance of ‘reality’, the ensuing anarchy. Circular platforms and a few props allow for some suggestion of place but otherwise the ‘city’ is abstract. Gradually any hints of realism are consumed by the escalating nightmare: these small private ‘spaces’ grow in size and become huge circus-rings around which gather a mindless human collective which witnesses the nose-less, near-naked Kovalov’s public disgrace and scandal with rabid relish. The dissident body-part becomes synonymous with personal humiliation.

The cast of The Nose © ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The cast of The Nose © ROH. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Occasionally, as Kosky gives free rein to the lunacy, there’s a risk of absurdity blunting satire and the whole thing falling off the precipice into farce - some scenes have too much of a Keystone-Cops-capers whiff about them - but Pickler does give us some terrific set pieces. The sacred tranquillity of Kazan Cathedral is shattered when a bevy of belles whip off their fur coats to reveal basques and fishnets and, to a percussion interlude, enact an unbridled physical paean to the giant Nose-God - a sort of black parody of Stravinsky’s Rite. A Tiller-girl line of outsized noses gives us a dazzling tap-dance spectacle which, judging from the guffaws, tickled the audience’s ribs. And, we don’t need Freud to tell us that the nose is a symbol of Kovalov’s fears of lost virility - indeed, Madame Podtotshina mistakes the Nose for a sexual rival of Kovalov - and there’s the requisite phallic imagery to suggest an impotence complex.

But, Kosky takes a couple of wrong turns. Gogol’s protagonist laments, “How can I do without such a conspicuous part of the body? It’s not like some little toe that I can put in a boot and no one will see it’s not there.” And, herein lies a related problem for a director: how to show a missing nose when the singer performing the role clearly has one? Kosky’s solution is to give the entire cast extra-large prosthetic noses - in the director’s words, a nose ‘that morphs an anti-Semitic Nazi cartoon nose with a bit of Barbra Streisand’s nose’ - and to give the nose-denuded Kovalov a circus-clown red conk. But, as the surreal commotion escalates, this only serves to emphasise the farcical at the expense of the potentially subversive. Then, Shostakovich’s Nose is sung by a high tenor but Kosky chooses to separate the Nose from its Voice. The Nose, which grows from animatronic mouse-dimensions to huge tap-dancing colossus, is performed by a boy dancer, Ilan Galkoff - who rightly received a hugely appreciative reception. But, this deprives the opera of one of Gogol’s most powerful scenes, when Kovalov, the preening careerist, is astonished to come across his Nose in the guise of a high-ranking official - a gentleman, as Gogol tells us, in a “gold-embroidered uniform with a big standing collar; he had kidskin trousers on; at his side hung a sword. From his plumed hat it could be concluded that he belonged to the rank of state councillor”. ‘Major’ Kovalov derides the poor, boasts about his fortune and status, and is fixated with image: he misses his nose because its loss inhibits his social climb. So, he summons his courage to confront the Nose with the fact that it is really his nose, but receives - aptly - just a sneer: “You are mistaken, my dear sir. I am by myself. Besides, there can be no close relationship between us. Judging by the buttons on your uniform, you must serve in a different department.” Kosky jettisons this crucial element of the original tale: Kovalov’s dream of personal advancement is destroyed by the personal part that defines his ‘self’ - his Nose has cut itself off to spite its owner’s face. Amid all the wit and hyperactivity, though, there are moments of stillness, and Martin Winkler in the title role is almost single-handedly responsible for the redeeming interjections of bathos amid the bedlam. The moment when having been summarily dismissed by the newspaper officials when he tries to place a classified ad about his missing nose is laden with real anguish, and Winkler - despite - made us pity Kovalov in his shame and anguish, lending this loathsome, lecherous narcissist an almost tragic dimension. This was a tremendously committed, brave performance from Winkler, one that makes the show. Winkler is partnered by John Tomlinson’s shrewd triple-embodiment as the barber Iakovlevitch, the Newspaper Office Clerk and the Doctor. The production opens with a chilling visual image of Iakovlevitch sharpening his knife on his leather belt, and it’s clear that the barber, who is utterly indifferent to his own distasteful odours, is the main suspect implicated in the disappearance of the Nose. As his scolding wife, Praskovya Ossipovna, Rosie Aldridge pounced with fiery anger to demand that her husband remove the offending olfactory adjunct from her house; she negotiated the unalleviated high register - perfect for her foul language and nagging - with aplomb, her voice penetrating but never ear-splitting. Alexander Kravets is an experienced ‘Nose-ist’: he has taken the title role (at the Aix en Provence Festival and Opéra de Lyon) and appeared as the District Police Inspector (at Staatsoper Berlin, Opéra de Lausanne, Dutch National Opera, and the Met). Here, he conjured piercing sounds as the embodiment of the state police, quite literally a bureaucrat shouting - though never nasally! - at the top of his voice. Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke was splendid as Ivan, Kovalov’s servant, and intoned his balalaika song with melancholy tinged with tongue-in-cheek irony. Ailish Tynan floated the Mourning Woman’s lament in the cathedral with grace and feeling, and Susan Bickley was assured and engaging as the Old Countess. Shostakovich described the orchestra score as an ‘uninterrupted symphonic current’ and conductor Ingo Metzmacher made the individual exclamations and ensemble interjections, which form a backdrop to the various on-stage conversations with the Nose, transparent and biting. We were treated to a deluge of contrapuntal textures and wonderful sounds which at times struck an (intentionally) satirical discord with absurdity on stage The opera is performed in a new English translation by David Pountney. While it has many admirable drolleries, I found the mis-accentuation of the text a bit galling at times. Shostakovich produced his own libretto from Gogol, in collaboration with Yevgeny Zamyatin, Georgy Ionin, and Alexander Preis, expanded the brief original with borrowings from other works by Gogol and a smattering of Dostoevsky. As he changed the narrative to direct speech, Shostakovich insisted that he aimed to achieve ‘a musicalisation of [the] words’ pronunciation’, and that described the vocal parts as building on ‘conversational intonations’. The vivid grotesqueness of Shostakovich’s theatrical satire was undoubtedly influenced by the work of Vsevolod Emilievich Meyerhold. Though the opera ends with an ensemble which reinforces how pointless the story is - it doesn’t benefit the motherland, and has no moral value - Kosky risks reducing the opera to meaningless absurdities. One might take a moment to remember the Book of Matthew and to consider its relevance to Gogol’s tale: “If your right eye offends you (skandalidzei se), pluck it out and cast it from you; for it is more profitable for you that one of your members perish, than for your whole body to be cast into hell.” Claire Seymour Shostakovich: The Nose Platon Kuzmitch Kovalov - Martin Winkler, Ivan Iakovlevitch/Clerk/Doctor - John Tomlinson, Ossipovna/Vendor - Rosie Aldridge, District Inspector - Alexander Kravets, Angry Man in the Cathedral - Alexander Lewis, Ivan - Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke, Iaryshkin - Peter Bronder, Old Countess - Susan Bickley, Pelageya Podtotshina - Helene Schneiderman, Podtotshina’s daughter - Ailish Tynan, Ensemble (Daniel Auchincloss, Paul Carey Jones, Alasdair Elliott, Alan Ewing, Hubert Francis, Sion Goronwy, Njabulo Madlala, Charbel Mattar, Samuel Sakker, Michael J. Scott, Nicholas Sharratt, David Shipley, Jeremy White, Simon Wilding, Yuriy Yurchuk); Director - Barrie Kosky, Conductor - Ingo Metzmacher, Set and lighting designer - Klaus Grünberg, Costume designer - Buki Shiff, Choreographer - Otto Pichler, Translator - David Pountney, Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 20th October 2016. image=http://www.operatoday.com/The_Nose_0041%20THE%20NOSE%20AT%20ROYAL%20OPERA%20HOUSE%20%C2%A9%20ROH.%20PHOTO%20BY%20BILL%20COOPER.png image_description=The Nose, Covent Garden product=yes product_title=The Nose, Covent Garden product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: The Nose at the Royal Opera HousePhoto credit: Bill Cooper

October 22, 2016

The Source, an Important New Stage Work

More oratorio than opera, The Source is as new as today’s headlines. Doten’s libretto is taken from the United States Army field reports, diplomatic cables, and short bits of sound from miscellaneous sources. In 2010, Bradley (now Chelsea) Manning gave the military materials to Wikileaks and its media partners. It was the outing of these papers, many of which were labeled secret, that resulted in this soldier being sentenced to serve thirty-five years in prison.

Doten humanized selected passages from the huge array of material and has allowed the listener to grasp some of the human cost of war, not only to Iraqi and Afghani citizens but to the press and American soldiers as well. One of the outside quotations he uses is from Steven Hawking: “And how insignificant and accidental human life is in it.” Although Hawking may not have been speaking of Middle East war, his thoughts on the insignificance of life are what The Source conveys with sensitivity as it invites its audience to enjoy Hearne’s enchanting musical fabric. Listeners may have come for the news-oriented show, but they leave with an appreciation for the fine artistry demonstrated by composer and librettist in their construction of this most interesting piece.

Hearne’s instrumental music combines the sonorities of a string quartet, in this case violin, viola, cello and bass, with keyboard, guitar, and drums. To the mix, he added electronics and a vocal quartet. The electronic sounds include snippets from recordings including Clay Aiken’s rendition of Kurt Weill’s “Mack the Knife,” the Dixie Chicks’ “Easy Silence,” and Dinah Washington’s interpretation of Jerome Kern’s “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” Hearne also used clips from interviews and occasionally a bit of electronic distortion. With these varied entries, he created a huge sonic tapestry that envelops his listeners in a multi-layered score combining classical string sounds sometimes played col legno (by the wooden side of the bow) with jazz rhythms and the previously mentioned electronics.

From this seemingly dry military material, Doten selected lyrical passages that came to life with Hearne’s creative soundscape. The twelve sections of the score reminded me of the Stations of the Cross. Doten and Hearne dramatized a dozen poignant musical snapshots of the horrors of war and its effects, both long and short term.

Director Daniel Fish had the audience seated on folding chairs on a level lower than the orchestra, which was behind a semi-transparent screen. Half the chairs faced the orchestra and half faced away from it, but there were screens on all four “walls” framing the space. At the post-performance Talk Back, we learned that the faces of people seen on the screens were relating to the presentation's final, musically unaccompanied combat video. The singers, all of whom were miked, sat among the onlookers. Garth MacAleavey designed the sound and Philip White was the vocal processing engineer. Doten and Hearne’s theater piece is revolutionary in its use of libretto material, it’s staging, and above all in the music from the fecund mind of Ted Hearne. Anyone in Los Angeles this week should definitely see The Source.

Maria Nockin

Cast and creative team information:

Composer, Ted Hearne; Librettist, Mark Doten; Director, Daniel Fish; Produced by Beth Morrison Projects; Production Design, Jim Findlay; Video Design, Jim Findlay and Daniel Fish; Music Director, Nathan Koci; Lighting Design, Christopher Kuhl; Costume Deign, Terese Wadden; Sound Design, Garth MacAleavey; Vocal Processing Engineer, Philip White; Assistant Director, Ashley Tata; Stage Manager, Jason Kaiser; Video Engineer, Keith Skretch; Sound Engineer, Nick Tipp; Vocalists: Mellissa Hughes, Samia Mounts, Isaiah Robinson, Jonathan Woody; Cover Vocalist, Martin Bakari; Keyboard, Nathan Koci; Violin, Courtney Orlando; Viola, Anne Lanzilotti; Cello, Leah Coloff; Guitar, Taylor Levine; Bass, Greg Chudzig; Drums, Ron Wiltrout.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/the-source.png

image_description=The Source

product=yes

product_title=The Source, an Important New Stage Work

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=

October 21, 2016

Věc Makropulos in San Francisco

Strange programming at San Francisco Opera. While these October performances of Janacek’s penultimate opera do mark the 50th anniversary of its American premiere (at SFO in November 1966) one might have wished for a change of opera — not theme. For one of many examples we might have had Janacek’s last opera — From the House of the Dead instead, a surpassing masterpiece that has yet to find its way to San Francisco.

But dismiss that thought. In many ways this seems like the first time we will have witnessed this strange Slavic comedy here in San Francisco, given a convergence of factors — notably a comedienne of such dimension that we were irrevocably and directly present at the final collapse and total disintegration of a 337 year-old woman, and, strangely, the absence of a star conductor, leaving us with the raw, unfiltered power of the Janacek orchestral specter. It was an evening of monumental art.

There will be many of us San Franciscans who recall the veritable Who’s Who of Makropulos Case personages over the past 50 years — the Paul Hager production of 1966 with the forever mourned Marie Collier (our Tosca when Maria Callas was not), the 1976 remount of the same sets but with legendary Anna Silja directed by the young David Pountney, conducted by Ernő Dohnányi, the 1993 remount of the same cloth painted sets now staged by legendary soprano Elisabeth Söderström and conducted by famed Janacek champion Charles Mackerras. Then finally in 2010 a new production. French born, Germany based director Olivier Tambosi created a vehicle for the powerhouse presence of Karita Mattila conducted by esteemed Janacek interpreter Jiří Bělohlávek.

Nadja Michael as Emilia Marty, Stephen Powell as Baron Jaroslav Prus

Nadja Michael as Emilia Marty, Stephen Powell as Baron Jaroslav Prus

But it has taken Leipzig born, Berlin based, American educated (IU) Nadja Michael to realize the Emilia Marty (formerly Elina Makropulos et al) in deepest and truest and most vivid essence on the War Memorial stage, aided in no small way by stage director Tambosi in this remount of his turntable, solid-walled production. The lithographic scenic texture grounded the storytelling in timelessness — even with the naive, gratuitous real time clock. The concentrated playing areas forced the action into high theatrical pitch, and the lighting burned through the threads of time with maximum intensity.

Soprano Nadja Michael was one with her costumes and platinum wig, brilliant quotations from historic haute couture, teasing where high fashion crosses into theater (and cinema) and visa versa. Her costumes gave free flow to the supple physical contortions she effected, that took us to a confusion of the real with the irreal, blurring human and the supernatural. Mme. Michael possesses a strong voice and riveting presence that dissolved into moral exhaustion and the finality of her existence.

The death of Emilia Marty, Elina Makropolus, et al

The death of Emilia Marty, Elina Makropolus, et al

But neither the men in her life nor the young singer aspiring to this artistic immortality had the size of personality or voice to illuminate much less confront the very complicated machinations of the plot. I wanted bigger, more important characters to effect the musical gestures of love and longing, hopelessness and realization that Janacek develops in all of his operas. It is possible that this pallid humanity was exaggerated by the naïveté of the conducting. Young St. Petersberg conductor Mikhail Tatarnikov permitted the primary, primitive motions of Janacek’s orchestral continuum to illuminate the diva but the maestro all but ignored the complex world in which she existed. As well, and disappointingly the young maestro did not achieve the shattering orchestral climaxes that would ordinarily cap each of the acts.

Given the conducting perhaps the supporting characters did not have a chance. Tenor Charles Workman as Berti missed the soaring climaxes of the hapless, incestuous lover, tenor Brenton Ryan, a participant in the L.A. Opera young artist program, does not yet have the chops to muster the intensity of compulsive infatuation. Joel Sorensen brought sharp brittleness to the role of the law clerk Vitek, and as well I found an unwanted caricature in the role of the aspiring singer Kristina, performed by Adler Fellow Julia Adams. As Gregor’s lawyer, Dr. Kolenaty, and Gregor’s opponent, Baron Prus, baritones Dale Travis and Stephen Powell left me wishing for more powerful voices and personages.

Nonetheless it was an exhilarating evening at San Francisco Opera.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Emilia Marty: Nadja Michael; Albert Gregor: Charles Workman; Baron Jaroslav Prus: Stephen Powell; Dr. Kolenatý; Dale Travis; Vitek: Joel Sorensen; Kristina: Julie Adams;

Count Hauk-Sendorf: Matthew O’Neill; Janek: Brenton Ryan; A Cleaning Woman/A Chambermaid: Zanda Svede; A Stagehand: Brad Walker. Chorus and orchestra of the San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Mikhail Tatarnikov; Stage Director: Olivier Tambosi;

Production Designer: Frank Philipp Schlössmann; Lighting Designer: Duane Schuler. War Memorial Opera House, October 18, 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Makropulos_SF1.png

product=yes

product_title=The Makropulos Case at San Francisco Opera

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Nadja Michael as Emilia Marty [All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

October 20, 2016