November 28, 2016

Gothic Schubert : Wigmore Hall, London

This recital will be one Lieder aficionados will remember for years. For 19th century Romantics, death was a source of endless fascination, much in the way that sex dominated the 20th century. Many songs in this programme are early works, some written when Schubert was as young as 14, and give an insight into his youthful psyche. Like most teenagers, before and since, he was intrigued by "the dark side". In a strict Catholic society, the Gothic Imagination gave a kind of legitimacy to dangerous, subversive emotions. The whole Romantic sensibility was a kind of Oedipal reaction against the paternalism of neo-Classical values. In these songs, we can hear young Schubert rebelling against his father, connecting to what we'd now call the subconscious.

In Ein Leichenfantasie D7 (1811) to a poem by Friedrich Schiller, a man is burying his son in a crypt. But why is the burial taking place in the dead of night. The son has a "Feuerwunde" penetrating his very soul with "Höllenschmerz". This death was not from natural causes. Suicide was a mortal sin. Schiller's meditation on the reversal of the natural order is sophisticated, the transits in the poem rather more elegant than Schubert's setting. In 1811, he was but still a child, so his transits between ideas are less elegant than Schiller's, but the ideas are original, if not completely coherent. Still, the song is an audacious tour de force lasting nearly 20 minutes, an undertaking that calls for finesse in performance. Eine Leichenfantasie exists in both baritone and tenor versions, though the former is better known, but it would have been asking too much of most audiences to hear both versions together in succession.

There were other sets of songs like Das war ich D174 a and b but the Kosegarten pairs, An Rosa I D315 (1815) and An Rosa II D 316 and the two Abends unter der Linde D235 and D237 (1816) benefited from the greater variety in the settings. The first Abends unter der Linde, for example, is more lyrical, the second more haunted, with its reference to the names of the poet's deceased children. Hence the value of a tenor/baritone recital highlighting contrasts in related pieces. There's clearly a good dynamic between Jackson and Farnsworth, which made the alternations flow together well. Their joint Lied (Ins stille Land) D403 (1816) was extremely impressive, the alternating voices capturing the lively flow of the music in typically Schubertian style, reaching "the land of rest" by vigorous images of movement, vividly depicted by Baillieu's expressive playing. Even with two very different songs, Lob des Tokayers D248 (1815)(Gabriele von Naumberg) and Punschlied 'Im Norden zu singen' D253 (1815) (Schiller) the flow between voices was enhanced by a very genuine sense of conviviality between Jackson and Farnsworth. Sincerity does matter in a genre like Lieder, which is so intense and so personal.

Sincerity matters, too, in strophic ballads like Der Vatermörder D10 (1811) to a poem by Gottlieb Conrad Pfeffel, in which a son kills his father. "Kein Wolf, kein Tiger, nein, Der Mensch allein, der Tiere Fürst, erfand den Vatermord allein, which makes an emotional point, though it's not borne out in nature. The text is maudlin. Having killed his father, the son wipes out a brood of fledgings whom he thinks were mocking him. Such melodrama might call for overblown declamation. Instead, Jackson sang sensitively: we must not laugh. The piano part thunders obsessively, suddenly slowing into watchful near silence, suggesting that the killer is insane, or at least as feral as the beasts of the woods. Like Eine Leuchenfantasie, Der Vatermörder is a teenage piece without much finesse, but Schubert treats it seriously, and so should we. This same emotional truth illuminated another pairing Der Einseidelei I and II, D393(1816) and D563 (1817) respectively. Both are settings of poems by Johann Gaudenz, Freiherr von Salis-Seewis, about hermits who live alone in nature: simple sentiments but not at all simplistic. Jackson's phrasing was sensual yet pure, suggesting that the hermit's choice was riches indeed. In Des Fräuleins Liebeslauchen D698 (1820) (Schlechta), a lovesick knight throws flowers to his ladylove. Jackson's naturalness of expression made us respect the knight, though his love might be in vain.

Jackson and Farnsworth are among the most promising English singers of their generation. I first heard Jackson sing a few songs in a private recital when he was only 22. Yet his voice is so distinctive that I immediately recognized it some years later when he sang at the Wigmore Hall/Kohn Foundation International Song Competition in 2011. Since then, he's developed extremely well, with a blossoming career in opera. Having worked in Stuttgart, his German is also more idiomatic than most English singers. Marcus Farnsworth won the Wigmore Hall/Kohn Foundation Song Competition in 2009 and appears in recital and on the BBC. James Baillieu is a well-known song accompanist and chamber player, who presented an 11-concert series at the Wigmore Hall last year.

This splendid programme, and performance, concluded with Schubert's Fischerweise D881 (1826) (Franz Xaver Freiherr von Schlechta) , a familiar favourite but rarely, if ever, heard with tenor and baritone sharing the honours. An inspired idea! The song moves briskly, with the piano playing jaunty rhythms "gleich den Wellen, und frei sein wie die Flut", which repeat in not quite matching pairs. With two singers, you can also hear how this duality is also embedded in the vocal line.The voices interact, like oars, pulling together. In the final strophe,words like "Die Hirtin" and "schlauer Wicht" are separated more clearly than is often the case, but this further emphasizes the choppy "waves" in the piano part and the concept of the sea as a metaphor for life. Meanwhile, on a bridge, a shepherdess coyly pretends to fish. The fisherman isn't fooled. "Den Fisch betrügst du nicht!"

Anne Ozorio

image=https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/Caspar_David_Friedrich_-_Graveyard_under_Snow_-_Museum_der_bildenden_K%C3%BCnste.jpg/256px-Caspar_David_Friedrich_-_Graveyard_under_Snow_-_Museum_der_bildenden_K%C3%BCnste.jpg

image_description: Caspar David Freidrich : Graveyard under snow (1826)

product=yes

product_title= Franz Schubert Lieder : Stuart Jackson, Marcus Farnsworth, James Baillieu, Wigmore Hall, London 24th November 2016

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=

November 26, 2016

Rusalka, AZ Opera

With water-reflected light bathing the stage, Water Nymph Rusalka and her sisters “swam” sitting on the backs of chairs and waving their arms much as Russian ballerinas do in The Dying Swan.

Their world was separated from the world of humanity by a forbidding white door. Water nymphs and wood sprites wore ethereal gowns that moved gracefully with them and allowed the audience to perceive them as denizens of a different realm. Melinda Whittington was a poignant, tragic Rusalka who enchanted the audience and brought them into her world with her moon song “Mesiku na nebi hlubokem” (“O moon high up in the sky”).

Sara Gartland and David Danholdt as Rusalka and The Prince

Sara Gartland and David Danholdt as Rusalka and The Prince

When Rusalka fell in love with the human Prince, her father, Vodnik, sung magnificently by Richard Paul Fink, warned her that no good could come of the match because humans are sinful. I wonder if Dvořák got his idea for Vodnik and the Three Wood Sprites from Wagner's Das Rheingold. Vocally, the combination of stentorian baritone and three high lyric voices was fascinating. Daveda Karanas was a human looking Ježibaba. With no pointed ears or other marks of an alien being, she wore a dress with a cut-out bustle that would have been quite fashionable in 1890s. She sang with dramatic vocal colors, but her characterization was rather bland.

Kevin Ray was a dramatic-voiced Prince whose character was bewildered by two women, Rusalka and the Foreign Princess, vying for his hand. Alexandra Loutsion was every inch the evil Foreign Princess and she sang with easily produced warm and resonant dramatic notes that made me wonder if she is a future Wagnerite. In this fairy tale, the Foreign Princess got the Prince’s ring and eventually shoved the social climbing water nymph back into her pond. That was a sad lesson, indeed, but one that must sometimes be learned.

Daveda Karanas and Sara Gartland as Ježibaba and Rusalka

Daveda Karanas and Sara Gartland as Ježibaba and Rusalka

Kevin Newell was a dutiful hunter, but The Gamekeeper in a scruffy wig and the cowardly but limber Kitchen Boy supplied the comic relief that kept Rusalka from being totally tragic opera. Henri Venanzi’s chorus never appeared in front of the curtain and I wondered why. He has a good group but they might have seemed too earthbound for nymphs or sprites.

Dvořák’s music is exquisite and Conductor Steven White presented it in all its liquid, translucent beauty. Although memorable, the moon song is not the only great piece in this opera. There are many other scenes of similar evocative lyricism. The duet between Rusalka and the Prince has been described as one of the most enchantingly nuanced in all opera. Rusalka is a work we need to hear again so that we can get to know and understand its melancholy charm. I hope it won’t be too long before a company in Arizona or Southern California again presents Rusalka. It’s well worth hearing more than once.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Conductor, Steven White; Stage Director, Joshua Borths; Set Design, Mark Halpin; Costume Design, Adriana Diaz; Lighting Design, Jeremy Dominik; Choreographer, Molly Lajoie; Rusalka, Melinda Whittington; The Prince, Kevin Ray; Vodnik, Richard Paul Fink; Ježibaba, Daveda Karanas; The Foreign Princess, Alexandra Loutsion; Wood Sprites: Katrina Galka, Lacy Sauter, and Mariya Kaganskaya; Gamekeeper, Joseph Lattanzi; Kitchen Boy, Alyssa Martin; The Hunter, Kevin Newell; Chorus Director, Henri Venanzi.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rusalka%20dress-14.png

image_description=Sara Gartland as Rusalka [Photo by Tim Trumble]

product=yes

product_title=Rusalka, AZ Opera

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Sara Gartland as Rusalka

Photos by Tim Trumble

November 25, 2016

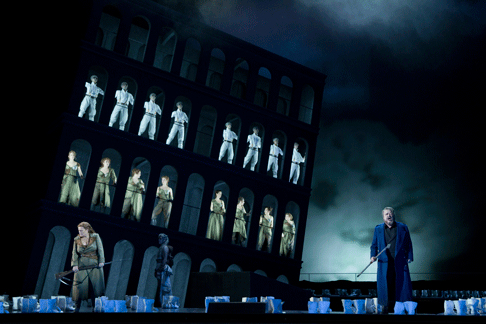

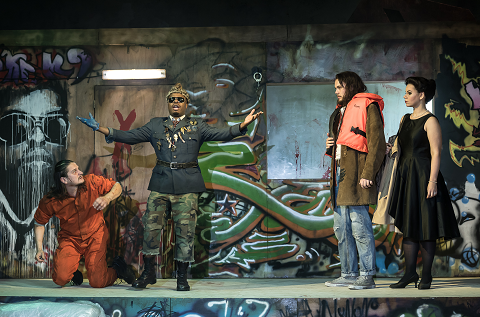

First new Ring Cycle in 40 Years, Leipzig

This spectacular musical experience by the Gewandhaus Orchestra (GO) enthralled the audience with engaging singers that included Markus Marquardt, Andreas Schager, Evgeny Nikitin, Christiane Libor, and Stefan Vinke and a superb supporting cast. This was a vocally dramatic thrill ride. If you’re a stickler for basic productions, you will be missing out on the terrific orchestra. This Ring Cycle is worth a trip to Germany.

That’s not to say there weren’t any problems. Sound effects clumsily missed their timing. Wotan didn’t catch his stagecall for Die Walküre’s Third Act, so everything needed to be stopped and restarted. But this made the communal experience all the more endearing and disarming: an intimate sharing experience of musical excellence for the audience. It was the strong cast and sublime Gewandhaus Orchestra that turned this Ring Cycle into an unforgettable experience.

Ulf Schirmer demonstrated why the GO can count itself to best orchestras of the world. With ceaseless intensity, Schirmer elevated Wagner’s luxuriant Romantic score to superlative heights with many goosebumps and hair raising moments. With a history of Herbert Blomstedt and Riccardo Chailly as past Principal Conductors, the development of such high quality German culture is evident. Now Andris Nelsons has made the GO his orchestra together with his Boston Symphony Orchestra. Overseeing both, he plans a partnership and festival. However at the Leipzig Oper, it is Schirmer who brilliantly conducts!

Simple but at times cluttered staging

After their collaboration on Tri Sestri by Peter Eötvös, Leipzig Oper’s General Music Director Ulf Schirmer approached Rosamund Gilmore for this Ring Cycle, starting with the premiere of Das Rheingold in 2013. Even if the staging had its convoluted moments, none were deal-breaking. The simple sets allowed for intensely sung drama to occur between the performers and kept an emphasis on the music.

Gilmore’s ballet background influenced her production. Throughout, the British choreographer included baffling modern dance for the “mythical elements” of Wagner’s world. I could have done without these distracting spasms. They showed up every evening, but it was not until their appearance in Siegfried’s forest setting that they finally seemed to fit in Gilmore’s world. Though what she turned Fafner the dragon into left me a bit confused in his giant appearance.

The stage involved geometrical structures and deconstructed buildings. The flashy Das Rheingold had the most interesting set: Carl Friedrich’s Oberle’s dynamically changing Escher-esque design with atmospheric lighting turned Nibelheim into a visually enflamed hell. He enriched the Rhine and the Rhinemaidens with aquatic projections.

Nicole Reichert‘s costumes added an elegant class to the gods. She made the Rhinemaidens look tantalising, and turned giants Fasolt and Fafner into convincing oafs. Her childish outfit for young Siegfried was a bit over the top, but Vinke pulled it off.

Superb vocals and orchestral excellence

In Das Rheingold, Tuomas Pursio convinced as the young Wotan, but Karin Lovelius’ stunning vocals as Fricka overpowered him. Pursio would have an impressive vocal revanche as the manipulating Gunther in Götterdämmerung. With her eerie vocal effects, Nicole Piccolomini had scene-stealing moments as Erda, though in her gothically glamorous dress she particularly dazzled in Siegfried. Jürgen Linn as Alberich carried a devious and resentful air that made him fully dislikable. His voice filled with a dark, hateful intonation. As Mime, Dan Karlström’s impressive voice clashed with more of Gilmore’s awkward choreography.

The vocal high point of the four nights was Andreas Schager’s boisterous Siegmund in his impassioned duet with Christiane Libor. Together they delivered great chemistry. With her vocal prowess, she held her own as Sieglinde. Though with his star wattage, Schager was the clear audience favorite; his curtain call led to an endless applause. Hanging on to every breath of the charismatic Schager, the young man next to me sat on the edge of his seat, equally captivated and swept away as I was, as Siegmund exclaimed his love for his sister. After Siegmund’s death, Schager’s absence left a void of glamour.

Later in Akt III, after he killed the momentum due to his missed stage cue, disrupting the thrilling energy of Schirmer’s electrifying “Flight of the Valkyries”, a commanding Markus Marquardt as Wotan made up for as much as he could in his father-daughter drama together with Eva Johansson’s Brünnhilde. Her emotion convinced, though she never quite reignited. This technical interruption resulted in a energetically challenged Third Act.

Die Walküre ruled with its thrilling female power. In Siegfried’s coming-of-age story Schirmer switched to Wagner’s testosterone drive. Bayreuth regular Stefan Vinke took a while to grow into his role as this young Siegfried. He delivered some great comedic timing on his puerile journey through the forest. He finally hit his stride in his interaction with Elisabet Strid’s sensitive Brünnhilde at the end. Their dynamic felt real and served as a disarming finale, leaving me with tears streaming down my face.

Götterdämmerung came with the stylish severity of the unhappily wealthy (here also alcoholic) siblings Gurtrune and Gunther. Wagner’s passionate interactions exploded on stage. Marika Schönberg turned Gurtrune into a hot mess, shivering in fear from Stockholm Syndrome in her relationship with her brother. Michael Reger as Hagen served showstopping moments.

But on this last night, it was Christiane Libor’s time to shine. She commanded the spotlight as she owned the role of Brünnhilde. Full of passion and despair, she captivated me with her convincing emotion and powerful voice. Mindblowing!

On these four consecutive evenings, Ulf Schirmer demonstrated conducting skills through his professorial discipline enriched by his deep passion and academic expertise. Every night, he kept a thrilling momentum going. Time became meaningless.

With “Siegfried’s Rhine Journey” and the “Funeral March” as monumental highlights, Schirmer produced the GO’s distinguished brilliance and electrifying depth. A crisp sound, lush textures, and an elucidating transparency kept the listener fully intoxicated. Even after the music ended it kept on going in my head. In fact, it was one of those rare life affirming musical experiences.

What more can I say to convince you to visit this Ring Cycle? After the invigorating Vorabend in the early evening, a hilarious scene occurred. Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony Orchestra made their debut at the Gewandhaus Hall right across from the Oper Leipzig. So after two and half hours of Wagner, a mass of music fanatics hurried across to be on time for Mahler’s Ninth Symphony. Such concentrated quality programming is not uncommon in the highly cultural Leipzig.

Don’t miss the Oper Leipzig’s Ring Cycle.

David Pinedo

For additional information: http://www.oper-leipzig.de/de/wagner

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Foto-20_Siegfried_12.04.15_%C2%A9Tom-Schulze.png image_description= product=yes product_title=First new Ring Cycle in 40 Years, Leipzig product_by=A review by David Pinedo product_id=Photos by Tom SchulzeSan Jose’s Beta-Carotene Rich Barber

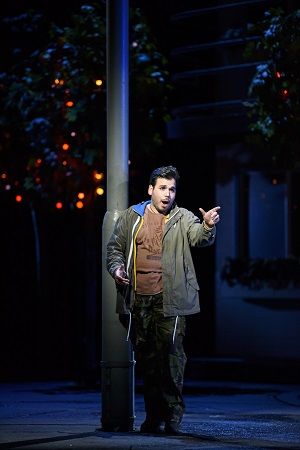

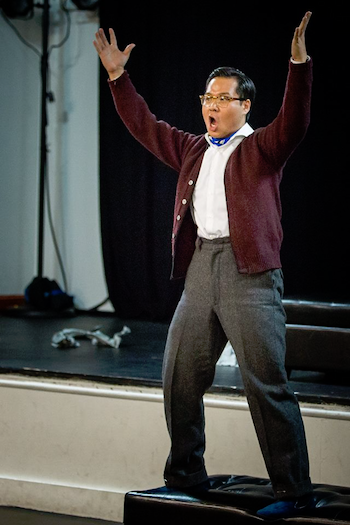

Inventive stage director Layna Chianakas cleverly started the homage to The Rabbit of Seville early on and carried the hijinks throughout the performance. As the orchestra launched into the jaunty up-tempo repeated chords of the overture, suddenly a silhouette of an enormous carrot appeared as a projection on the grand curtain, traveled across the front of it, and disappeared. Before you wondered if you could believe your eyes, another one appeared from the opposite side and did the same.

By then, we got it. The laughter and applause as we recognized the reference nearly drowned out the merry music-making in the pit (a taut, idiomatic reading led by Andrew Whitfield). The overture was “staged” with carrots dancing, parading and moving into positions suggesting the crossed swords of a family crest. With this cheeky beginning, the tone was set for a no holds barred romp.

The Count and Rosina

The Count and Rosina

Babatunde Akinboboye put his polished baritone on ample display as a winning Fiorello, serving immediate notice that the standard of the afternoon’s singing would match the ingenuity of the staging, and then some. Maestro Whitfield is also the Chorus Master and the men’s ensemble belied their disparate and ragtag look by offering meticulous harmonizing. We are all waiting Figaro’s signature entrance, of course, to experience one of the most familiar arias in all of operadom.

Brian James Myer delivered a true star turn in the title role. Factotum is too puny a word to describe Mr. Myer’s (dare I say ‘definitive’?) performance. I cannot recall encountering anyone in my many years of seeing this piece who exhibited anywhere near such a total command of the role, the style, the joyous abandon. His arsenal included an effortless stage demeanor, a thoroughly considered subtext, flawless comic timing, and a tirelessly wiry presence.

Brian’s evenly produced, appealing baritone may not be in the burly Milnes or Mattei vein, but it has plenty of ping and sass, with a warmly ingratiating tone that fills the house. Figaro is Brian James Myer’s first role assumption as a Resident Artist, and Opera San Jose can be very proud of their superlative choice in adding such a fine young talent to their roster. Nor was he alone in his accomplishments.

Kirk Dougherty (Almaviva) flirts with Renée Rapier (Rosina) in the Lesson Scene

Kirk Dougherty (Almaviva) flirts with Renée Rapier (Rosina) in the Lesson Scene

The OSJ talent roster has a deep bench and the remarkably versatile tenor Kirk Dougherty turned in another treasurable performance as Count Almaviva. Mr. Dougherty once again regales us with a honeyed voice that is pliable, beautifully produced, and consistently responsive. His forays into the upper reaches of the role are as comfortably negotiated as the characterful melismas.

The Count has several comic guises in this piece to be sure, and Kirk keeps his tone freely produced even as he colors it to suggest less aristocratic denizens of Seville. His beautifully delivered serenade benefitted from his skill at providing his own guitar accompaniment, a singular feat. Like his titular costar, he established his comic credentials early on, and the expository Figaro-Almaviva duet crackled with witty Rossinian interplay.

The radiant mezzo Renée Rapier immediately engaged our ears with a plush, ripe tonal beauty that announced her as a major discovery. In short order, she also captured our hearts with an especially assured Una voce poco fa. Her fresh, spontaneous reading of this thrice-familiar piece immediately established her credentials as a first tier Rosina. Ms. Rapier’s rich lower register was wedded to a solid middle and brilliant top, giving off coloratura sparks as demanded, and coy romantic heat when appropriate.

Brian James Myer as Opera San Jose's dynamic Barber of Seville

Brian James Myer as Opera San Jose's dynamic Barber of Seville

She, too, proved to be a well-rounded, richly complicated personality, and she found a variety of meaningful expression in her impersonation. Her comic sensibilities were a formidable component in the day’s success, and she clearly relished interacting and conspiring with her Figaro and Lindoro. Even though I knew it was coming, her spot on revelation that she has already written the love note that Figaro is prompting her to compose was so “right” that I barked a surprised laugh out loud. This cast was treating the audience to Barbiere as if for the first time, and we relished their sense of discovery.

The oily Music Master Basilio was well-served by the wonderfully suave basso voice of another Young Artist, Colin Ramsey. Allowing him to be honestly, unabashedly youthful was an inspired choice, and no comedy was lost by showcasing Mr. Ramsey’s gorgeously rolling tones, with their vibrant young sheen. A solidly delivered La calunnia has rarely been as pleasingly voiced, yet with all the necessary sinuous underpinnings.

Considering that Valerian Ruminski was undertaking the challenging part of Bartolo for the first time, he revealed much in his depiction of the devious curmudgeon. Mr. Ruminski has a smooth, orotund baritone, perhaps a bit too smooth for this volatile character. His was not (yet?) in the tradition of bloviating, blustering practitioners, but is a little (too?) smooth around the edges. His difficult rapid-fire patter was not always as precise as it may become. Still, his persona and physical stature are ideal for the role and he proved a competent player in the twisting plot. His outlandishly comic, brazenly mis-tuned aria in the Lesson Scene was alone worth the price of admission.

It would be hard to imagine a more committed and scene-stealing Berta than that embodied by the vivacious Teressa Foss. Too often this can be a throw-away part, but Ms. Foss played a deliciously willing accomplice in Rosina’s detention, with an apparent girly fixation on carrying stuffed animals, which increased in obsessive number as the show progressed. Teressa is also possessed of a laser-focused whiz-bang of a soprano voice, and her effortless flights above the staff were as admirable as they were totally unexpected. In the small role of the Sergeant, Sidney Ragland made every phrase count with a secure delivery

Valerian Ruminski's role debut as Bartolo

Valerian Ruminski's role debut as Bartolo

The physical production was all that could be wished. Matthew Antaky designed an unfussy, practical, attractive set that afforded plenty of opportunities for varied blocking, effective levels, and even a few surprises. The colorful exterior for the opening was wonderfully dressed with palm trees, profusions of flowers, Mediterranean tiles and a fountain. That gave way to a two-level interior with enough doors for a decent Feydeau farce.

Alyssa Oania is credited as being costume coordinator, which may mean she carefully selected the good-looking attire from stock. But Rosina’s well-styled burgundy dress and Spanish shawl seemed far too fetching not to have been created specifically for her, and Basilio’s accessories (including eyewear resembling designer goggles, prissy white hanky, fuschia jabot and matching striped socks) were brilliant touches. And were brilliantly copied for Almaviva’s phony teacher in Act Two.

A highly effective wig and make-up design complemented the dress, with Christina Martin providing excellent support. The gag of having Figaro distractedly tease Bartolo’s wig, not having realized the good Doctor has vacated it, was a memorable visual. And Basilio’s heavily made up doe eyes and high cheekbones made him look eerily like Lily Tomlin in drag. The bobbling, wobbling mustache for Almaviva’s drunken soldier was also a comic plus.

Kent Dorsey achieved a good deal with his diverse lighting design. In addition to even area washes and atmospheric gobos, Mr. Dorsey programmed a number of specialty spots that were helpful in creating a rhythm to the look and flow of the show. He alternated blackouts with spotlighting Figaro during his entrance aria, contributing to the cartoon-like sensibility that permeated the concept. Only the colored disco light effect at the end seemed slightly out of sync.

Teressa Foss's Berta loves animals

Teressa Foss's Berta loves animals

With all the key casting and technical positions filled with consummate professionals, it was arguably Maestro Whitfield and Director Chianakas who were the icing on the cake. Or the maple glaze on the carrots. Whitfield helmed a talented collective of solid strings, colorful winds, and punctuating brass that unified into an effective Rossinian arc. And Ms. Chianakas drew out richly detailed interplay onstage that was chockfull of revelatory ideas.

The uninhibited clowning by the choristers at the top, including some balletic goofs, was infectious and conveyed an expectation of what would follow. This included a dizzy moment with the Count and the Barber freezing as “statues” in the fountain to avoid detection by Bartolo, who is exiting his house. The removal of the ladder by some unseen force in the climactic scene was perfectly timed. I am not sure that Mr. Myer’s masterful Figaro needed help putting across his aria by the addition of three chorus girls extras sporting huge wigs studded with salon accouterments, but I appreciate the thought.

A far better thought was turning the storm into a psychological tempest, in which a dreaming Rosina presents a love letter to each of the other principals, then thinks better of it and tears the missives up one by one before returning to her sleep on the settee. A well-considered, serious moment in all the jollity.

But it was not long before those danged carrots were back with us, as a running gag that paid good dividends. Whether being played as musical instruments, tossed about the stage, or God knows what else, those orange veggies always brought us back to the source of this production’s comic inspiration.

So, what’s up Doc? A witty, slapstick celebration of an in-joke that was always characterized by well-calculated physical and intellectual humor, and married to an admirably first tier musical execution. In short, another solid achievement by the resourceful Opera San Jose.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Fiorello: Babatunde Akinboboye; Almaviva: Kirk Dougherty; Figaro: Brian James Myer; Bartolo: Valerian Ruminski; Rosina: Renée Rapier; Berta: Teressa Foss; Basilio: Colin Ramsey; Sergeant Sidney Ragland; Conductor/Chorus Master: Andrew Whitfield; Director: Layna Chianakas; Set Design: Matthew Antaky; Costume Coordinator: Alyssa Oania; Lighting Design: Kent Dorsey; Wig and Make-up Design: Christina Martin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/OSJ%20Count%20Basilio%20Figaro%20Rosina.png image_description=From left, Kirk Dougherty (Almaviva), Colin Ramsey (Basilio), Brian James Myer (Figaro), Renée Rapier (Rosina) [Photo by Pat Kirk] product=yes product_title=San Jose’s Beta-Carotene Rich Barber product_by=A review by James Sohre product_id=Above: From left, Kirk Dougherty (Almaviva), Colin Ramsey (Basilio), Brian James Myer (Figaro), Renée Rapier (Rosina)Photos by Pat Kirk

November 24, 2016

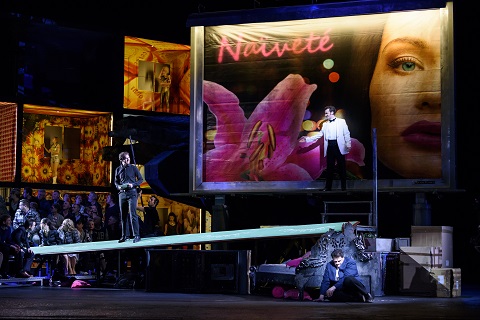

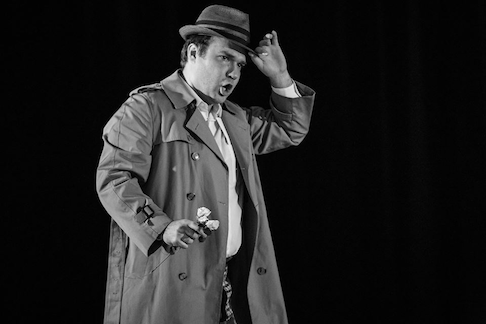

Manon Lescaut at Covent Garden

A crumbling freeway flyover juts jaggedly into a black nothingness. As Manon collapses into her desert surrounding, so the terrain itself sinks into abyss.

Puccini’s third opera was premiered in Turin on 1st February 1893 - just over a week before the first performance of Verdi’s Falstaff in Milan - and the work’s blending of obvious debts to Italian Ottocento lyric traditions and an engagement with Wagner’s innovative harmonic language ensured that it was an unqualified success, with contemporary critics declaring Puccini the foremost composer on the Italian scene.

However, to present-day audiences, Puccini’s opera can seem less an evolutionary development of the past, and more a strikingly modern statement. And, despite the undeniable beauty of the score, after its initial triumph the opera’s subsequent critical reception has at times been characterised by disquiet: a sense that there is something insalubrious and ‘not quite nice’ about the opera. Kent and his designer Paul Brown wholly embrace the dark side of Puccini, and drag his nineteenth-century good-time-girl-gone-bad into the modern world.

Their dystopian twilight zone is, however, somewhat at odds with the sensuous eroticism of Puccini’s score. Admittedly, when mired in the bleakness of Act 4, it is difficult to find a redemptive note in Manon’s demise - a death which she fights to the last: ‘No! non voglio morir …’ But, it is passion and not pointlessness which lies at the heart of this opera, and it is this essential ‘soul’ which Kent neglects. There is a gratuitous quality about Manon’s suffering; it signifies nothing but itself.

Fortunately, conductor Antonio Pappano is in the pit to restore the opera’s impassioned pulse and pump emotional life-blood through its veins. On the first night of the run, his crafting of the musico-dramatic ebbs, flows and lurches was masterly and utterly convincing. Pappano has an innate feeling for the long lines which expand so effortlessly. The constant shifts of mood seem entirely natural. The Prelude opened with a searing and slashing slash of the violins’ knife but before we knew it the mood had lightened and we were swept along by the rich busyness of the opening scene. The intermezzo between Acts 2 and 3 presented a stunning array of emotional colours and musical ambiences: there was a tremendously sense of spontaneity and directness, as Pappano plunged the depths of the drama. The ROH Orchestra held nothing back, but the playing was never anything but elegant. Indeed, one of the most striking features of the performance was that while the ostentatious romantic climaxes were relished there were moments of great delicacy too. The series of chords that open the final Act were an unnerving shudder of death; mid-way through this Act, the theme which represents the protagonists’ love - and which had blazed so triumphantly at the end of Act 3 - was heard again, a shimmering reprise, a symbol of a hope now faded and elusive.

ROH Chorus, Act 1. Photo credit: Bill Cooper

ROH Chorus, Act 1. Photo credit: Bill Cooper

Kent and Brown are more mundane, the brutality of their realism quashing any lingering romance. The square and inn of Amiens, the setting for Act 1, are jettisoned for a flashy apartment block and a gambling casino. Thus, a light-hearted evening gathering in the village - denim-clad teenagers whizz around atop wheelie bins and adolescents bounce about exuberantly led by Luis Gomes’ ebullient, open-hearted and warm-voiced Edmondo - is set against an iniquitous den of baize gaming tables and one-armed bandits, intermittently lit with a lavish glare by lighting designer Mark Henderson.

Luis Gomez as Edmondo. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Luis Gomez as Edmondo. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Manon arrives in a silver SUV, a picture of innocence in her floral frock. But, it’s but a short step from urban ingénue to Geronte’s peacock in a ‘golden cage’. And, in Act 2 Manon finds herself in an opulent but lurid boudoir of cerise and purple, in which time stands still and Manon herself is frozen as one of Geronte’s riches.

There is nothing intimate about this ‘private’ space which is the setting for Act 2; it’s a peep-show booth in which Manon preens her hair, applies her elaborate make-up, is pleasured by the lesbian Singer - a role ably sung by Emily Edmonds - and gyrates and squirms for the delectation of a posse of geriatric, masked voyeurs, who, with their backs to us, enjoy a soft-porn display during the Act 2 pastorale which a cameraman records on a hand-held camera - presumably for YouTube dissemination.

Levente Molnar as Lescaut, Sondra Radavanokvsy as Manon Lescaut. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Levente Molnar as Lescaut, Sondra Radavanokvsy as Manon Lescaut. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Kent’s trope, though, is not irrelevant. From her first entrance in Act 1, Manon is presented through the gaze of others, principally Des Grieux. When Lescaut’s cries to the Innkeeper catch his attention, he raises his eyes and sees Manon: the libretto tells us that ‘facendo un gesto di meraviglia, la osserva estatico’ (making a gesture of amazement, he looks at her ecstatically), and with a cry, ‘Dio! Quanto è bella’ (God! How beautiful she is), he hides from view in order to espy her. His gaze guides us; we first see Manon through the filter of Des Grieux’s rapture and wonder. Our gaze is bound with his and that of the other characters on stage, including the assembled line of dirty old men. In Kent’s reading, our ‘heroine’ is aware that all eyes are on her, and is complicit in the performance of her personae.

Yet, whether the director manages to turn Manon from a passive object of desire into an active subject who can manipulate her own identity within a prescribed system is another matter. Urging her to escape, Des Grieux cries ‘Bring only your heart’ as Manon stuffs Geronte’s jewels into a pillow case; her tardiness is her downfall - seemingly captivated by the room’s treasures she succumbs to its claustrophobic clutch and is arrested.

David Shipley as Sergeant, Nicholas Crawley as Naval Captain, Aleksandrs Antonenko as Des Grieux. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

David Shipley as Sergeant, Nicholas Crawley as Naval Captain, Aleksandrs Antonenko as Des Grieux. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

In Act 3 the dock-side square at Le Havre, through which the humiliated prisoners process on their way to deportation to the US, becomes in Kent’s hands the studio of a TV reality-show, compered not by a police sergeant but by a tuxedoed MC. The girls are taken to an Amsterdam-style red-light district where sex slaves are trafficked abroad by pimps.

And, though there are, during the proceedings, some front curtain projections of text from the 1731 novella by Abbé Prévost on which the opera is based, Puccini’s Act 4 crucially rejects the context provided by Prévost's narrative, and excludes the months of contentment spent by Manon and Des Grieux in New Orleans. So, Kent plunges us into misery - and pushes Des Grieux and Manon through a gaudy advertising hoarding onto a highway of broken dreams.

In the title role, Sondra Radvanovsky does not always appear a natural fit for Kent’s soft-porn star protagonist but her warm soprano wins our sympathy, and she crafts many a winning lyrical line, counter to the staging’s coldness. Radvanovsky acts and moves well. Her vibrato was quite wide and in the first two Acts she exhibited a tendency to slide onto notes - and struggled to hold onto the note when she’d got there - but she succeeded in conveying both the warmth and vulnerability of Puccini’s creation. Manon’s Act 4 peroration, ‘Sola, perduta, abbandonata’ - in which Puccini thrusts Manon into our prying gaze (in contrast to Prévost’s discretion) - was a touching rebellion against death and against the society which seeks to punish her. In Manon's last vocal moments, Radvanovsky found incredible, if waning, sweetness, ensuring that we understood the dreadful regrets of the dying woman. Radvanovsky crafted the arching cries, the fragmented contours, and the truncated repetitions, with acute theatrical insight and technical skill - she moved, indeed leapt, effortlessly, from the top to the bottom of her range.

Aleksandrs Antonenko as Des Grieux and Sondra Radanovsky as Manon Lescaut. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Aleksandrs Antonenko as Des Grieux and Sondra Radanovsky as Manon Lescaut. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Latvian tenor Aleksandrs Antonenko was vocally assured as Des Grieux; he fired his big guns with lyric aplomb - ‘Donna non vidi mai’ was impressively expansive - and if some of the risks he took at the top end did not come off, then at least he was impassioned in his essays, and his Act 4 emoting was superb. Antonenko is not equally assured across his range, but this helped to convey an impression that his Des Grieux combined vocal strength with vulnerability.

Eric Halfvarson as Geronte de Revoir. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Eric Halfvarson as Geronte de Revoir. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Eric Halvarson was a cunning Geronte de Revoir, not afraid to make an ugly sound if it served the drama. His elderly roué had strong dramatic presence, and the text was cleanly delivered. Levente Molnár was persuasive as Manon’s charming but unprincipled brother, Lescaut.

I left the theatre feeling that if Tosca was Puccini’s ‘shabby little shocker’, then Manon Lescaut was his depiction of shockingly cruel injustice.

Claire Seymour

Giacomo Puccini: Manon Lescaut

Manon Lescaut - Sondra Radvanovsky, Chevalier des Grieux - Aleksandrs Antonenko, Lescaut - Levente Molnár, Geronte de Revoir - Eric Halfvarson, Edmondo - Luis Gomes, Musician - Emily Edmonds, Dancing Master - Aled Hall, Singer - Emily Edmonds, Lamplighter - David Junghoon Kim, Sergeant - David Shipley, Naval Captain - Nicholas Crawley, Innkeeper - Thomas Barnard; Director - Jonathan Kent, Conductor - Antonio Pappano, Designer - Paul Brown, Lighting designer - Mark Henderson, Movement director - Denni Sayers, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Royal Opera Chorus.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Tuesday 22nd November 2016.

image= http://www.operatoday.com/cBC20161118_%20MANON_LESCAUT_0057_%20SONDRA%20RADVANOVSKY%20AS%20MANON%20LESCAUT%20c%20ROH.%20PHOTO%20BY%20BILL%20COOPER.jpg image_description=Manon Lescaut at Covent Garden product=yes product_title=Manon Lescaut at Covent Garden product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Sondra Radvanovksy (Manon)Photo credit: Bill Cooper

November 21, 2016

Fierce in War, dazzling in Peace: Joyce DiDonato at the Concertgebouw

Amsterdam was the second stop on DiDonato’s currently ongoing concert tour, which is coupled with her latest album and titled In War & Peace — Harmony through Music. Extensive preparation attested to how much this undertaking means for the singer. Each patron was handed a card with a heartfelt message from her, and an invitation to answer the question, posed in sixteen languages: “In the midst of chaos, how do you find peace?”. When the public trickled into the half-lit hall, DiDonato was already on the stage, where she remained the whole time, acting and interacting with her fellow performers. She has eloquently explained her goals for this project in the media: to find peace in a time of unfettered hate speech and violence, to rediscover hope smothered by despair. Whether her choice of music, atmospherically enhanced by lighting, video and dance, achieved this for her audience would depend on the individual, but no one could deny her impressive display of prowess and involvement. She is an artist at the zenith of her powers, wielding her technical tools with surgical skill and maximum expressive impact.

On the program were familiar Baroque gems, orchestral interludes performed by Il Pomo d’Oro, and two rediscovered arias by Neapolitan composers Leonardo Leo and Niccolò Jommelli. The concert was thematically split into two, War before and Peace after the break. In an asymmetrical gunmetal-colored gown, her face and neck livid with stylized wounds, DiDonato kicked off War with Handel’s aria “Scenes of Horror, Scenes of Woe” from Jephtha. She put such intensity into the dark premonitions that one wondered how she could sustain the pressure during successive numbers. She did. Surrounded by video projections and light effects suggesting explosions and aerial bombings, she was an ever-deepening vortex of emotion. During an orchestral arrangement of Gesualdo’s Tristis est anima mea, originally a vocal setting of Christ’s fearful prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane, DiDonato lay consumed by silent suffering. In Leo’s “Prendi quel ferro, o barbaro!” Andromache’s music swings back and forth from rapid rage to maternal tenderness. In the torridness of this aria and Handel’s “Pensieri, voi mi tormentate” from Agrippina, DiDonato drove her voice to its expressive limits. Her high notes were at times so piercing it seemed as if she were about to lose control. This was, however, just an illusion. In her fierceness she retained technical command, effortlessly stretching and embellishing Agrippina’s tortured lines. For the two mournful arias by Purcell and Handel, deeply saturated with feeling, Maxim Emelyanychev, leading from the harpsichord, scaled down the ensemble to a delicate whisper. It was the perfect accompaniment to the ghostly diminuendos on the repeated “remember me” of “When I Am Laid in Earth”. Never has Dido sounded so desperately close to death. Handel’s “Lascia ch’io pianga” was taken very slowly, closing the first half with a trace of hope symbolized by projected falling petals.

The theme of hope in captivity was picked up in the second part, Peace, with “They Tell Us that You Mighty Powers” from Purcell’s unfinished The Indian Queen. Singer and orchestra struck an ideally soothing tone in this charming, unadorned melody. DiDonato offered her antidote to violence and darkness dressed in liquid silver by Vivienne Westwood, having replaced her painted wounds with sprays of flowers. More than through the content, she administered the medicine through her musical brilliance, fully on display in the Handel arias. Ravishing tone in “Crystal Streams in Murmurs Flowing” from Susanna, dazzling coloratura in Cleopatra’s triumphant “Da tempeste il legno infranto”, and fabulous chirping and warbling in “Augelletti, che cantate” from Rinaldo, twinned with Anna Fusek’s baffling virtuosity on the recorder. Besides hope and joy, there was also remembrance. Manuel Palazzo danced a dignified solo to the hypnotically rippling chords of Arvo Pärt’s Da pacem Domine, composed after the 2004 Madrid train bombings in memory of the victims. Although Emelyanychev could have ratcheted up the exuberance in “Da tempeste”, as well as in the closing aria, Jommelli’s “Par che di Giubilo”, the musicians were otherwise exemplary — rhythmically even, shapely in phrasing and excellent in the obbligato solos. DiDonato acknowledged the richly earned ovation with an even more ebullient and vocally free reprise of the intricate Jommelli. After a short, grateful speech she then performed a deeply intimate, quietly hopeful “Morgen!” by Richard Strauss. On this extraordinary emotional journey, DiDonato spared neither herself nor her audience, and the rewards were great, truly great.

Jenny Camilleri

Performers and program:

Joyce DiDonato, mezzo-soprano; Ralf Pleger, director; Henning Blum, lighting, Manuel Palazzo, choreography and dance; Yousef Iskander, video; Il Pomo d’Oro, Maxim Emelyanychev, conductor and harpsichord.

Handel: “Scenes of Horror, Scenes of Woe” (from Jephtha, HWV 70); Leo: “Prendi quel ferro, o barbaro!” (from L'Andromaca); De Cavalieri: Sinfonia (from La rappresentatione di anima e di corpo); Purcell: Chacony in G minor, Z 730; Purcell: “When I Am Laid in Earth” (from Dido and Aeneas, Z 626); Handel: “Pensieri, voi mi tormentate” (from Agrippina, HWV 6); Gesualdo: Tristis est anima mea; Handel: “Lascia ch'io pianga mia cruda sorte” (from Rinaldo, HWV 7a); Purcell: “They Tell Us that You Mighty Powers” (from The Indian Queen, Z 630); Handel: Crystal Streams in Murmurs Flowing (from Susanna, HWV 66); Handel: “Da tempeste il legno infranto” (from Giulio Cesare in Egitto, HWV 17);

Pärt: Da pacem Domine; Handel: “Augelletti, che cantate” (from Rinaldo, HWV 7a); Jommelli: “Par che di Giubilo” (from Attilio Regolo); Strauss: “Morgen!”, Op. 27, no. 4.

Royal Concertgebouw, Amsterdam. Saturday, 19th November, 2016

image=http://www.operatoday.com/In_War_Peace_7.png image_description=Joyce DiDonato [Photo courtesy of http://inwarandpeace.com] product=yes product_title=Fierce in War, dazzling in Peace: Joyce DiDonato at the Concertgebouw product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Above: Joyce DiDonato [Photo courtesy of inwarandpeace.com]Walter Braunfels Orchestral Songs Vol 2

Walter Braunfels Orchestral Songs, Vol. 2, with Hansjörg Albrecht, this time conducting the Konzerthausorchester Berlin, with soloists Camilla Nylund, Genia Kühmeier and Ricarda Merbeth, an excellent companion to the outstanding Braunfels Orchestral Songs vol 1 (reviewed here).

Braunfels' Drei chinesiche Gesänge op 19 (1914) sets texts by Hans Bethge whose loose translations of Chinese poetry, Die chinesische Flöte (1907) had a huge influence, building on the mid-European fascination with the East, which dates back at least to Goethe. The East represented an alien aesthetic, something possibly purer and more mysterious. Hence the appeal to Jugendstil tastes and the new century's quest for new ideas and forms of expression. Braunfels's songs are not specifically"oriental", but evoke an attractive ambiguity, as if the forms of 19th century tonality were being gradually evoked from within. "Ein Jungling denkt an die Geliebte", in particular, seems to float in timeless space, evoking the moonlit night beside a pool where "ein feiner Windhauch küsst den blanken Speigel des Teiches" : a mood which Braunfels captures with great poise. The image will be familiar to anyone who knows Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde - the last line even refers to "der dunkeln Erde" - but Braunfels's treatment is very individual. The high tessitura of Camilla Nylund's voice complements the long, searching lines for the strings. Extremely refined.

In "Die Geliebte des Kreigers", dying diminuendos suggest the despair of the maiden as she thinks of her soldier, far away. The horns evoke the sound of a (European) battle and the rhythms the sound of galloping horses. It is somewhat reminiscent of Mahler, though the rest of the song is more turbulent, culminating in several climaxes, the final "dem mein Herz gehört!" a shout of anguish.

Braunfels' Romantisches Gesänge op 58 were completed by 1942, but some date back to 1918. The first, "Abendständchen", to a text by Clemens Brentano bears resemblance to the Bethge songs, but "Der Kranke", to a text by Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff, is altogether more individual. In "Ist der lebens Band mit scherz gelöset" (Brentano) the searching woodwinds and sliding vocal ellipses are echt Braunfels. "Der Pilot" (Eichendorff), with its rousing trumpet calls and choppy rhythms, is heroic, the second strophe swelling magnificently. "Liebe schwellet sanft die Segel" - the wind in the sails, propelling the boat forward. Nylund emphasizes the word "Morgen!", which Braunfels marks with a short pause.

With Die Gott minnende Seele op 53 (1935-6), we are firmly in Braunfels's characteristic territory, medievalism employed as disguise for dangerous modern thoughts, beating the Nazis at their own game. The poems are by Mechthilde von Magdeburg, a 13th century mystic. As so often in Braunfels, background matters. Mechthilde's writings, collected together as Das fließende Licht der Gottheit, were controversial because she criticized the Church hierarchy practices that didn't tally with the purity of faith. Had she lived 300 years later, she might have been a protestant, in every sense of the word. For Braunfels, living under the Third Reich, Mechthilde would have had more than mystical appeal. She could have been a prototype for Jeanne d’Arc - Szenen aus dem Leben der Heiligen Johanna op. 57. Please read my piece on Braunfels Jeanne d' Arc HERE

The magnificent introduction to Die Gott minnende Seele, with its haunting horn melody, prepares us for the dark richness of the vocal line to come. It feels like slipping through a time tunnel, for the text isn't poetry so much as prayer. In the first song, the same phrase repeats with pointed variation "O du giessender Gott in deiner Gabe, O du fliessendern Gott in deiner Minne!", the pattern recreated in the orchestration. Utter simplicity, yet great depth and sincerity. Gradually the pace quickens: sudden flashes in strings suggesting rapture, then a quiet humble ending "ohne dich mag ich nicht sein". An even lovelier melody sets the tone for the second song, where Genia Kühmeier sings the sprightly lines so they suggest excited palpitation. The song ends with the melody, this time on low winds and brass. There's something vernal and innocent in the "medievalism" in this cycle, where voice and orchestra interact, as if Mechthilde is singing to invisible voices: not a bad thing in a hostile world, and very Joan of Arc. When Kühmeier sings "Herre, Herre, wo soll ich hinlegen?" her voice flutters and the flute answers. A duet between birds, another Braunfels signature. This delicate fluttering is even more prominent in the last song "Eia, fröliche Anshauung" which begins with quasi-medieval pipes and develops into a merry dance. Mecthilde may be isolated, but she's happy. This wonderful, tightly constructed song cycle is a miniature masterpiece.

From a nun to an Egyptian queen: Braunfels's Der Tod der Kleopatra op 59 (1944). The harp suggests a lyre, and there are suggestions of bells but Braunfels know what's more important to Cleopatra: the man without whom she'd rather be dead. Braunfels marks this moment with an orchestral interlude, suggesting that Kleopatra is thinking about what really matters in life, not the trappings of wealth. This song runs nearly 10 minutes but proceeds in carefully marked stages, the point at which Kleopatra takes hold of the snake also highlighted by the orchestra.

Back to Bethge with Braunfels' Vier Japanische Gesänge op. 62 (1944-45) based on Bethge's Von der Liebe süß’ und bittrer Frucht In these songs, Braunfels doesn't even bother with fake japonisme, but treats each song on its own merits. Whatever the culture, human emotions remain the same. All four songs are dramatic art pieces, the third, "Trennung und Klage", particularly interesting, with the lovely dialogue between instruments in the orchestra, the strings suggesting night breezes "the Dämmerung den Mond". The singer here is Ricarda Merbeth. It's worth noting that Bethge, despite his interest in exotic cultures died only in 1946 and was a contemporary of Braunfels.

On this second recording of Braunfels's Orchestral Songs, Hansjörg Albrecht conducts the Konzerthausorchester Berlin, which doesn't have an ancient pedigree like the Staatskappelle Weimar on the first recording, but does have Braunfels connections. The orchestra, set up by the DDR to counterbalance the Berliner Philharmoniker, was conducted for many years by Kurt Sanderling, like Braunfels no friend of the Nazis, and by Lothar Zagrosek whose recording of Braunfels Die Vögel is outstanding. Quite frankly, unless you know Zagrosek you don't know Braunfels. DDR musical traditions weren't as dominated by commercial pressure as in the west, so they represent much deeper traditions.

In recent years there seems to have been an attempt to pigeonhole Braunfels as a "romantic" . When his Berlioz Variations were done at the Proms. the most interesting variations were cut so the piece came over like Hollywood pap. That might please some audiences but it's unfaithful to what Braunfels really stands for. In any case what passes for"romantic" bears no resemblance to Romanticism as the cultural revolution which reshaped European history and aesthetics. Although Sensucht was a typical Romantic meme, Romanticism as a movement was progressive, radical and very political. Although the notes for this recording are more focused than in the previous volume, they are too concerned with fitting Braunfels into a category, which is not the author's fault since she clearly knows Braunfels and his music, but may be marketing imperative. But what is so wrong with evaluating a composer on his own grounds, without having to force him into the straitjacket of categories? Why not listen to his music, as music, without preconditions? Braunfels is a good composer because he was himself, whatever the Reich around him might have wanted. The Nazis liked "romantic", backward-looking music, so re-branding Braunfels would be ironic. All the more we can thank Oehms Classics and Hansjörg Albrecht for bringing us Braunfels as Braunfels, revealing his true originality.

Anne Ozorio

image=https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c6/Braunfels-Walter-03(1920).jpg

image_description=Walter Braunfels

product=yes

product_title= Walter Braunfels : Orchestral Songs Vol 2,, Camilla Nylund, Genia Kühmeier and Ricarda Merbeth, Konzerthausorchester Berlin, Hansjörg Albrecht (conductor) Oehms Classics

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=

November 19, 2016

Simplicius Simplicissimus

Of those contemporary Bavarian composers who did not go into exile, Hartmann - in contrast to Richard Strauss, Hans Pfitzner and Carl Orff, among others - refused to cooperate with the National Socialist regime and retreated in a so-called ‘inner emigration’, composing works whose anti-militaristic stance and utopian socialism condemned them to silent obscurity until after the fall of the Third Reich.

I wonder, too, if Hartmann sensed how prophetic his epic (in both senses) tale of indiscriminate brutality would prove to be. Simplicius predicts that the peasants will rise up and slay the Governor and his court, and so the rebellion comes to pass. Hartmann, likewise, is often seen as a truth-teller who could foresee that the Nazi regime would be destroyed by external agents. A general protest against war and also a specific swipe at the social and political repressions of the Nazi era, Simplicius invites us to imagine that the composer saw the writing on the wall; and this oracular quality probably accounts for at least some of the interest in a work which, although undoubtedly gripping, is musically uneven.

By the mid-1930s, Hartmann (1905-63) had witnessed his own thirty years of war and social crisis: the sight of injured soldiers returning from the trenches of the First World War was followed by Hitler’s rise to power, with the unstoppable march towards a new world conflict that the latter seemed destined to bring about. Simplicius was dedicated to Hartmann’s brother, Richard, who had fled Germany in 1933. It was first heard on Bavarian Radio in April 1948 and staged the following year in Cologne. Hartmann later revised the work - eliminating the extended sections of spoken dialogue, expanding the orchestra forces and adding three symphonic interludes - and the second version was performed at Mannheim’s Nationaltheater in July 1957.

The libretto was written by Hermann Scherchen, Wolfgang Petzet and Hartmann himself, after Johann Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen’s novel Der abenteuerliche Simplicissimus which written in the aftermath of the Thirty Years War (1618-48) in what we know today as Germany, where the action takes place.

At the start a Narrator explains the social and political context, and draws attention to the figure of Simplicius Simplicissimus, an unworldly peasant boy who lazes away his days tending his parents’ sheep. The meaning of Simplicius’s dream about a tree whose branches are so overladen with people that its roots experience pain gradually becomes apparent to the young boy, and to us, as he experiences suffering at the hands of a Mercenary who evicts and kills his parents. Seeking refuge in a forest, Simplicius encounters a Hermit who tries to educate the naïve lad in the ways of the world. The Hermit’s death leaves Simplicius alone once more, and he is captured by soldiers who transport him to the Governor’s banqueting hall. The Governor, amused by the boy’s truth-telling, gives him the role of court jester. Asked to make a speech, Simplicius tells of his dream: the painful roots symbolise the oppressed who will rise up against their persecutors. In timely fashion, the peasants force their way into the hall and kill everyone apart from Simplicius. The Narrator reappears and closes the frame with a recapitulation of the opening.

Stephanie Corely. Photo credit: Robbie Jack.

Stephanie Corely. Photo credit: Robbie Jack.

Polly Graham’s production for Independent Opera pulls no punches. It is intense, utterly engaging and all the more impressive for the economical means with which it achieves its ends. The sparse black cube of the Lilian Bayless Studio at Sadler’s Wells is a fitting venue. Designer Nate Gibson’s split-level set recreates the particular while inferring the universal. Crates, cardboard boxes and household debris - including a child’s doll’s house that later is viciously, and symbolically, trampled by a marauding jack-boot - are scattered about a family attic of a war-torn house. Doors to the rear, and a large picture canvas upon which are projected barren vistas and a burning church, evoke a land beyond the attic walls, ravaged by pillage and war. Subsequently, a raised circle strewn with suitcases suggests the extent of the ensuing exile. The painting is up-ended at the start of the third and final scene: this is a world in moral anarchy. Ceri James’ lighting frequently leaves much of the stage in shadow, making the sudden splashes of brightness unsettling interlopers amid the general gloom. James projects menacing lupine silhouettes to press home that Simplicius, in his ignorance, equates his fear of the ‘Wolf’ that preys on the family sheep, with the pillaging soldiers.

At this performance, the third of four, Hartmann’s score was incisively articulated by players from the Britten Sinfonia, who are nestled on the right of the auditorium, clearly visible but snaking their way under the raised curving platform. With the percussion placed towards the rear of the under-stage area, the arsenal of bangs, thumps and clashes bounced with alarming resonance against the platform, creating a disconcerting nerviness.

William Dazeley. Photo credit: Max Lacome.

William Dazeley. Photo credit: Max Lacome.

In the long instrumental passages, the music often felt quite balletic, as it shaped the movement and mime. Hartmann’s scenes are essentially tableaux: there is spoken dialogue, declamatory singing and some songs, but these musical numbers illustrate rather than develop the dramatic action.

During the extensive orchestral prelude, Simplicius enters, innocently playing with simple toys, leafing through a book, chewing a sweet treat; a yearning Jewish melody, projected superbly by solo viola then solo cello, signalled the context. The string ensemble was fairly small, and at times a greater richness would have been desirable, but the lean textures and strongly shaped phrases were potent and immediate.

Hartmann’s score is highly allusive; if the overture seems almost an homage to Prokofiev, then Stravinsky, Borodin, Bach, even The Lord’s Prayer, get a look-in subsequently. This production made use of the 1957 revised score, with a few passages of the first version restored and some debt to Karl Peinkofer’s 1976 reduced percussion version. Conductor Timothy Redmond did not let one detail escape.

The palette ranged from Weill-like decadence to honest poignancy, by way of many an acerbic march. Perhaps the populist touches do not quite have Weill’s directness of communication but they make for animated eclecticism. There were moments of pastoralism, as when a flock of sheep rolld in the grass, chewing the cud, to the bucolic hues of a trio for bassoon, clarinet and oboe. The probing string counterpoint which accompanies the Hermit’s oration becomes a mis-harmonised Bach chorale, which Redmond crafted - as the pitch rose, repetitive fluttering motifs were introduced and a powerful accelerando took hold - into a stirring declaration.

Graham makes use of the whole auditorium. The characters - who are to some extent caricatures in the mould of Wozzeck’s parade of grotesques - traverse the two tiers of the set, wander around instrumentalists, enter from rear of arena; it’s disconcerting to find oneself almost face to face with spear-clutching marauders.

Matthew Durkan and Ensemble. Photo credit: Max Lacome.

Matthew Durkan and Ensemble. Photo credit: Max Lacome.

An ensemble of eight men form a flexible collective. Choreographed deftly by Michael Spencely, they are a flock of sheep, a band of mercenaries, gang rapists, a brigade of Hitler Youth. The Narrator’s opening dialogue is shared between them, and there is a Brechtian quality as they boom their pronouncements from different placements in the auditorium with chilling matter-of-factness: ‘In Anno Domini 1618, 12 million people lived in Germany … In Anno Domini 1848, only 4 million people lived in Germany.’

Stephanie Corley’s Simplicius was the embodiment of unaffected unselfconsciousness. In knee-length breeches and knitted tank-top she was every inch the 1930s school-boy. Corley veered convincingly from despair to ecstasy: her carefree songs, sensitive recitative and impassioned aria-moments were equally compelling. Singing with brightness and lustre, she evoked innocent optimism and candid feeling. Corley’s diction was superb too; indeed, the whole cast ensured that we heard every word of David Pountney’s piquant new translation, and for once the surtitles seemed unnecessary.

Emyr Wyn Jones’ Farmer states the opera’s core maxim, ‘The peasant plays a noble part/ He is the nation’s beating heart’, singing with a rich tone and full vibrato which imbue his words with passion. His pocket was picked by William Dazely’s hard-hearted Soldier, who swaggered arrogantly through Simplicius’s home shredding, if not burning, books, pillaging, razing, and dangling Simplicius by his feet in a painful hand-stand.

Adrian Thompson and Stephanie Corley. Photo credit: Max Lacome.

Adrian Thompson and Stephanie Corley. Photo credit: Max Lacome.

Adrian Thompson emerged from beneath the platform to give a show-stealing performance as the Hermit. His words of Christian compassion contrast with Simplicius’s unknowing purity of feeling. Singing with impressive steadiness of tone, Thompson grasped every opportunity to project intensity of feeling and the Hermit’s death scene swelled into a visionary oration of fervent spirituality.

So compelling was Thompson that it seemed a pity to insert an interval between the second and third scenes, thereby breaking the mood established by Thompson and Corley in the Hermit’s dying moments before the increasingly brutal final episode that sees Chiara Vinci as the Woman (a silent role) abused and raped. The words ‘Fornication … is a woman’s occupation’ mock her anguish unnervingly.

Marc le Brocq was garish and ghastly as the repugnant Governor, ridiculously conceited in salmon-pink doublet and white tights, terrifyingly deranged as he devoured the strips of meat lain across the Woman’s bare back and breasts with bestial relish: her flesh is meat, she is an animal - ‘This lady is a monkey’. Tristan Hambleton’s Sergeant and Matthew Durkan’s Captain ably completed the portraits of nastiness.

The closing moments raged as the unison ensemble, accompanied by violent percussion, bellowed a revolutionary song and the shocking facts which opened the opera were restated. By this point, we had witnessed a terrible history re-lived, and its images were hard to shake off as one left the theatre.

Claire Seymour

Simplicius - Stephanie Corley, Farmer - Emyr Wyn Jones, Soldier - William Dazely, Hermit - Adrian Thompson, Sergeant - Tristan Hambleton, Governor - Mark Le Brocq, Captain - Matthew Durkan, The Woman - Chiara Vinci, Ensemble (Tristan Hambleton, Emyr Wyn Jones, Nicholas Morris, Nicholas Morton, Bradley Smith, Adam Sullivan, Andrew Tipple, James Way); Director - Polly Graham, Conductor - Timothy Redmond, Designer - Nate Gibson, Light Designer - Ceri James, Projection Designer - Will Duke, Choreographer - Michael Spenceley, Britten Sinfonia.

Lilian Bayliss Studio, Sadler’s Wells, London; Thursday 17th November 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mark%20Le%20Brocq%2C%20Stephanie%20Corley.%20c.%20Robbie%20Jack.png image_description=Simplicius Simplicissimus, Independent Opera at Sadler’s Wells product=yes product_title=Simplicius Simplicissimus, Independent Opera at Sadler’s Wells product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Mark Le Brocq (Governor) and Stephanie Corley (Simplicius)

Photo credit: Robbie Jack

November 17, 2016

2017 Summer Festival at Lucerne

Who am I? The issue of identity illuminates the human condition in the present and through history in its relation to origin, homeland, faith, culture, and religion. How did we become the people we are? And how are we changed by our current environment? Paradigmatic answers to these questions can be found in the fates of such composers as Béla Bartók, Gustav Mahler, Sergei Prokofiev, and Dmitri Shostakovich. But they also come up in general for every musician involved in the international concert scene. Like nomads they travel around the world, performing today in New York and tomorrow in Tokyo. And the issue of identity is highly controversial, as we see in the case of refugees who are coming to Europe from war zones and who have to choose between the desire to integrate and the preservation of what is uniquely their own.

Click here for complete press release.

Lucia di Lammermoor at Lyric Opera of Chicago

The title role is performed by Albina Shagimuratova, who sang an excerpt from this opera at Millennium Park, Chicago several seasons ago. Lucia’s beloved Edgardo di Ravenswood is sung by Piotr Beczała and her brother, Lord Enrico Ashton, by Quinn Kelsey. A major company debut is scored by Adrian Sâmpetrean in the role of Raimondo, the chaplain and tutor to Lucia. The parts of Alisa, Normanno, and Lord Arturo Bucklaw are performed by Lindsay Metzger, Matthew DiBattista, and Jonathan Johnson. Enrique Mazzola makes his debut conducting these performances and the Chorus Master is Michael Black.

During the overture a plaid scrim, emphasizing Scottish family clans, covers the stage. The title of the opera appears in blood-red script at the base of the scrim. Slow tempi encouraged at first by Mr. Mazzola allow for an appreciation of orchestral detail and contrast which commences at the moment that characters begin to interact. Staged concepts are displayed in this production by means of a series of horizontal and vertical moving panels. In the first scene Normanno and his band of henchmen search fruitlessly through the stylized heather for evidence of an intruder on the Ashton lands. The entrance of Enrico and Raimondo identifies the suspected culprit as Edgardo di Ravenswood, enemy to Enrico and secret lover of the latter’s sister Lucia. The bright, excited projection of accusations by Mr. DiBattista’s Normanno gives fire to the troubled soul of Enrico. Mr. Kelsey embodies here the spirit of his self-descriptive line, “Io fremo” [“I seethe with rage”]. Throughout the balance of the scene Kelsey unleashes his lines with dramatic force, often giving preference to declamatory emphasis over a traditional bel canto line. His performance of “Cruda, funesta smania” [“Cruel, baneful torment”] exemplifies this approach to the character of Enrico. While incorporating some notable embellishments in the aria, he uses a dominant forte approach to various lines such as “amor sì perfido” [“such a perfidious love”]. Once the suspicion of Edgardo’s identity is indeed confirmed by the searching chorus, Raimondo makes the case for Lucia’s innocence. Already in this brief exchange Mr. Sâmpetrean demonstrates an admirably flexible, rich bass voice which he uses to good effect in character delineation. Enrico’s reaction to the news of Lucia’s suitor intensifies an earlier fury, shown here by Kelsey’s performance of the cabaletta “La pietade in suo favore” [“compassion for her”] with unrelenting determination.

The following scenes of the act introduce Lucia, her confidante Alisa, and Edgardo. The heroine’s initial aria, “Regnava nel silenzio” [“Ruled (the night) enveloped in silence”], is performed by Ms. Shagimuratova with careful shaping and a firm sense for legato; her narration of Lucia’s vision at the fountain matches the apprehension of the heroine with a tentative, dramatic approach. In the second piece, “Quando rapito in estasi” [“When enraptured, ecstatic”], as Lucia’s misgivings yield to the joy of her lover’s projected arrival, Shagimuratova incorporates florid decoration, an effective diminuendo, and at least the suggestion of a trill. Her interaction with Ms. Metzger’s supportive Alisa prepares for the emotional reception of Edgardo. When Mr. Beczała appears, sporting a contrasting red tartan, he states with forthright conviction his plan to leave the “patrie” by morning. Beczała’s emotional reaction to Lucia’s fear is here believably expressed by his forte pitches “il sangue mio” [“my blood”] and the chill with which he invests “m’odi e trema” [“listen to me and tremble”]. Although Edgardo must narrate here the conflict engendered by his father’s murder with his present love, Beczała does not depart from a lyrical flow. His continued urging leads to the mutual spousal vows and the exchange of rings. The duet “Verranno a te” [“(my sighs) will come to you”] is in these performances a vocal highpoint of the act with both singers moving from piano tenderness to heartfelt avowal of their affection before parting.

In Act II Enrico, Lucia, and Raimondo interact in several key scenes leading to the heroine’s subsequent transformation. In the first of these the production emphasizes the familial split by means of panels: Enrico is seated at his desk in the company of Normanno, while Lucia appears simultaneously in the garden outdoors next to the moonlit gnarled tree where she had earlier met her lover. Enrico’s troubled spirit is given an appropriately brooding release by Kelsey, who summarizes in a breathless flow the family’s precarious standing. Once he dispatches Normanno to carry out the plans for a wedding, Lucia is escorted into his writing chamber. The line “Appressati, Lucia” [“Come nearer, Lucia”] is uttered by Kelsey with a snake’s duplicity as he tries to reason with the young girl who already shows the librettist Cammarano’s “sintomi d’una alienazione mentale” [“signs of madness”]. Lucia sits stiffly in a period chair and refuses to consider her brother’s coaxing to save the family by marrying Lord Arturo Bucklaw. Once she is shown a forged letter written allegedly by her Edgardo, the girl is weakened further by the presumption of her lover’s inconstancy. As Kelsey comforts Lucia with an embrace, here both kneeling together, he rationalizes her “folle … perfido amore” [“foolish perfidious love”] with a strong sense of melodic line. In their duet, “Se tradirmi tu potrai” [“If you can betray me”] Shagimuratova displays excited vocalism yet begins to yield symbolically to Enrico by allowing him here to dominate their concluding lines. This shift is reinforced in Lucia’s subsequent duet with Raimondo. In this scene Mr. Sâmpetrean truly shines in his aria, “Ah, cedi, cedi!” [“Ah, relent!”], in which he uses carefully wrought embellishments in a progressively rising line as a means of convincing Lucia to yield to Enrico’s plan. Equally impressive are Sâmpetrean’s secure, lower register and his varied technique in the piece “Oh! qual gioia!” [“Oh, what joy!”] while he celebrates Lucia’s agreement.

At the start of the following scene the chorus welcomes Arturo Bucklaw as the savior of the troubled Ashton household. In his brief aria “Per poco fra le tenebre” [“For a short time in the darkness”] Mr. Johnson’s Arturo addresses Enrico with assurances for the future. Johnson’s attractive technique incorporates elegant legato phrasing and high pitches securely fixed to the significant line “amico, fratello e difensor” [“friend, brother, and protector”], all of which he swears to become. As soon as the document is signed, with still notable resistance by Lucia, her lover Edgardo bursts into the room. The renowned sextet as highlight toward the close of the act is here well blocked, such that individual performers are distinctly heard yet all blend sonorously in passages where vocal lines converge. Afterward, Mr. Beczała’s effective cry of “Maledetto sia l’istante” [“Cursed be the moment”], his judgement against Lucia’s presumed treachery, returns the act to a level of tension even higher than earlier.

The four vocal scenes of the final act are a direct result of this inflamed spirit of enmity and continued misunderstanding. At first Edgardo and Enrico face each other at Wolf’s Crag, estate of the unhappy lover. Although Enrico has sealed the marriage of his sister, his heart yet thirsts for revenge, “La vendetta mi parlava!” While each defends his family’s position, the two men agree to a duel at dawn. In their duet Kelsey returns to a dramatically rough edge to underscore vocally his character’s intent for the present, whereas Beczała’s flights into lyrical ardor latch more emotionally onto his father’s memory.

The following scene begins as celebration and ends with tragic consequences. At first the chorus dances and sings in jubilation at Lucia’s wedding; they are interrupted by Raimondo announcing tragedy from the bridal chamber, that Lucia has murdered her husband. In his aria “Dalle stanze ove Lucia” [“From the rooms where Lucia”] Sâmpetrean enunciates “quelle mura” [“into the chamber”] with quiet dignity as though in sympathy with a higher power. His imitation of Lucia’s query for her husband shifts to a confused intonation with a deeply rolled -rr- as he describes her demented smile [“un sorriso balenò”]. When joined by the chorus in praying for forgiveness from “heaven’s” wrath, Sâmpetrean holds an extended pitch on “ciel” long after the choral expression of shock subsides.

The following mad scene shows Shagimuratova at her best of this performance. With a face tinted white to emphasize her “pallor,” she incorporates multiple embellishments to illustrate the current deranged state of her character’s persona. Glides drifting upward, scales and roulades performed flawlessly, and individual pitches taken flat or sustained are a credible appeal to the “ciel clemente” [“merciful heaven”] where her delusion seeks happiness. The pendant to this magnificent vocal display is sung by Beczała in the final scene. He gives an equally virtuosic account of “Fra poco a me ricovero” [“Soon refuge for me”], where he modulates his voice to accommodate accusation with an ultimate tone of forgiveness. When Raimondo announces Lucia’s death, “È in cielo” [“She is in heaven”] with a flawless melisma on the final word, Edgardo can wait no longer. Perhaps the reaction to Lucia’s death before his own suicide is best expressed here by his coloring of the phrase “sì crude guerra” [“such cruel agony”] to describe the ultimate effect of selfish human strife on the most innocent of loves.

Lyric Opera is to be congratulated for assembling such a premiere cast to give a fresh interpretation to a repertoire staple.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/lucia-article-card.png

image_description=Albina Shagimuratova as Lucia [Photo courtesy of Lyric Opera of Chicago]

product=yes

product_title=Lucia di Lammermoor at Lyric Opera of Chicago

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=Above: Albina Shagimuratova as Lucia [Photo courtesy of Lyric Opera of Chicago]

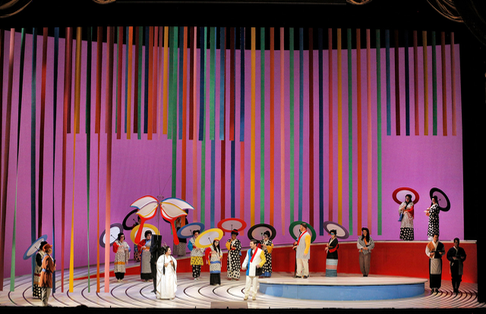

Akhnaten Offers L A Operagoers Both Ear and Eye Candy

Akhnaten or Akhenaten as his name is sometimes written, ruled Egypt for seventeen years, from a date near 1351 to a date near 1334 BCE. He and his queen, Nefertiti, were part of the eighteenth dynasty. Because composer Philip Glass and his librettists were researching so far back into history to tell his story, they could not answer many of the questions about events in his life. Thus, the opera is not historical. It is inspirational. Akhnaten tried to change his country’s religion from polytheism to a quasi-monotheism in which the Sun God ranked above all others.

On Saturday November 5, 2016, Los Angeles Opera presented the American premiere of Phelim McDermott’s spectacular production of Akhnaten, which had already been seen at English National Opera. Countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo was a perfect fit for the role of the religiously inclined pharaoh. Head shaven and body waxed, he looked the part of a magnificent ruler, and his clear, soaring tones were as smooth as freshly ironed silk. He seemed to produce his strong voice easily and he was not tired at the end of this very long role. Akhnaten was onstage almost all the time.

J'Nai Bridges as Nefertiti, Anthony Roth Costanzo as Akhnaten and Stacey Tappan as Queen Tye

J'Nai Bridges as Nefertiti, Anthony Roth Costanzo as Akhnaten and Stacey Tappan as Queen Tye