December 24, 2016

Les Troyens at Lyric Opera of Chicago

In the first part of the opera the role of Cassandra is performed by Christine Goerke, in the second part that of Queen Dido of Carthage by Susan Graham; the role of Aeneas spanning both parts of the opera is sung by Brandon Jovanovich. Chorebus, fiancé of Cassandra, features Lucas Meachem; Anna and Narbal, sister of Dido and the latter’s minister, are performed by Okka von der Damerau and by Christian Van Horn. In the first part the roles of Priam and Hecuba, rulers of Troy, and the ghost of Hector, their son fallen in battle, are taken by David Govertsen, Catherine Martin, and Bradley Smoak. Ascanius, son of Aeneas, and Helenus, son of Priam, are sung by Annie Rosen and Corey Bix. The role of Panthus, those of a Trojan soldier and of a Greek captain are performed by Philip Horst, Takaoki Onishi, and by Patrick Guetti. In the second part of the opera the lyrical roles of Iopas and Hylas are sung by Mingjie Lei and by Jonathan Johnson. This new production is directed by Tim Albery with sets and costumes by Tobias Hoheisel. Lighting design and choreography are by David Finn and by Helen Pickett, the latter in her debut with this company. Sir Andrew Davis conducts the Lyric Opera Orchestra and Michael Black is the Chorus Master.

The Lyric Opera of Chicago production makes use of a stylized, rotating wall - punctuated by entrance panels and a staircase - and ingenious lighting to adapt the staging to both parts of the opera. At the same time the five acts in Berlioz’s score, each neatly divisible into two parts, match the seamless transformation of the stage throughout. At the start of the first part, “The Taking of Troy,” Cassandra embodies a dominant force atop the moving wall. As Ms. Goerke’s Cassandra gazes wild-eyed on the chorus of assembled Trojans, her presence has no effect on the citizens mistakenly celebrating their liberation from the Greeks. It is indeed against this foe that Cassandra unleashes her impassioned warning. Goerke hurls herself into the role while displaying a spectrum of emotional shifts; she communicates both portent and tenderness by means of voice and physical gesture. Once the crowd of happy Trojans deserts Cassandra, who had expressed her painful fear by clutching her stomach, Goerke shivers while pronouncing the “dessein fatal” [“dread plan”] hidden by the Greeks. Despite her vision of Hector’s ghost [“l’ombre d’Hector”], neither the people nor the King will heed repeated warnings [“tu ne veux rien comprendre”], both thoughts singled out by Goerke with searing top notes. A softer, lyrical intonation accompanies the shift of emotional focus to her betrothed Chorèbe. Here Goerke sings - as though in a happy, distant milieu - of the expected loss “de doux rêves de tendresse” [“of tender dreams of happiness”]. Just as she slips into this emotional reverie, Chorèbe enters to greet his beloved. Called back into the present Cassandra recoils from her lover’s greeting. Mr. Meachem’s projection and polished legato urging Cassandra to seek “ton âme rassurée” [“calm for your soul”] is followed by a dramatic, sustained pitch coaxing from her “un doux rayon d’espoir” [“a sweet ray of hope”]. Rather than feel solace, Cassandra’s dread intensifies with rapid notes intoned by Goerke on the “livre du destin” [“book of fate”] in which she sensed a forthcoming “fleuve de sang” [“river of blood”]. Chorèbe attempts to paint a contrasting, benevolent picture of nature which Meachem traces with rising, emotional pitches on “soufle de la brise [“breeze’s soft breath”] and on “joyeux oiseaux” [“joyful birds”]. Once Cassandra accepts with resignation his refusal to save himself by leaving, Goerke sings a chillingly shocking declaration that their nuptial bed is prepared by death “pour demain” [“for tomorrow”]. As the couple leaves, the royal family appears for the funeral rites accorded to Hector, celebrated in pantomime with choral commentary and emphasizing here, with appropriate irony, “destin” [“fate”] once again. Orchestral accompaniment directed by Davis tracing the movements of the widow Andromache are especially effective with the somber line of the oboe following her path toward King Priam as she holds the hand of her orphaned son.

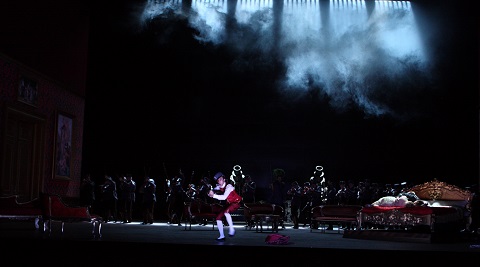

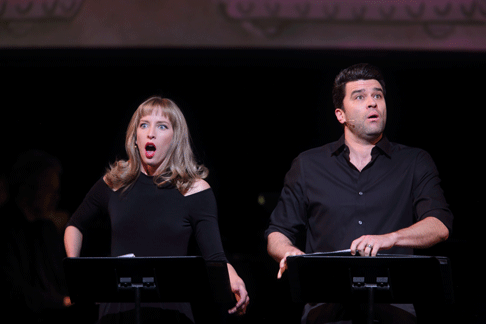

Scene from Les Troyens

Scene from Les Troyens

While the royal couple are surrounded by onlookers, Aeneas rushes into the court to announce the horrifying fate of Laocoön: the priest had thrown a javelin at the wooden horse left behind by the Greeks and was, in turn, ensnared and devoured by “serpents monstrueux” [“sea monsters”]. Aeneas’s precipitate entrance and excited message are delivered ideally by Mr. Jovanovich whose bright top notes and excellent French diction define his character convincingly. In the subsequent concerted passage Jovanovich’s projection remains equally impressive accompanying the urgent, unforced lines sung by Ms. Rosen as his son Ascanius. Alone and perched again atop the city’s wall Cassandra levels judgements on the Trojans’ foolishness as the horse is pushed into the city. In Lyric Opera’s production, the movement of the horse is illustrated by a giant equestrian shadow progressing across the brightly lit city’s walls. The end of the first act features Cassandra following with resignation the horse’s arrival within the walls as Goerke hurls out the phrase “les débris de Troie” [‘the ruins of Troy”] with a shocking dramatic top note on the final word.

In the second act concluding the first part of Les Troyens Aeneas sleeps fitfully while the sounds of distant fighting are rendered by the orchestra. The ghost of Hector, disheveled and covered with grime, enters to stand at the foot of Aeneas’s cot. When the protagonist awakes to face the shade, Jovanovich’s startled reaction matches the shifting chords in the orchestra. Upon asking after Hector’s intent Mr. Smoak replies with deep, resonant pitches on the hopeless collapse of the city and offers the repeated advice “Va, cherche l’Italie … [“Go, seek Italy…”] before he fades from sight. Before he is able to heed the stern admonition of Hector, Aeneas responds to the urgent calls of Panthus and Chorèbe to defend the Trojan citadel. At this point in Lyric Opera’s production the heroism written into the role of Berlioz’ Aeneas rises gloriously as Jovanovich sings the line “Tentons de nous défendre” [“Let us strive to defend ourselves”] with his voice arching above the chorus on the final word. Soon afterward, when grouped alone with the Trojan women, Cassandra announces that Chorèbe is dead and that Troy will presently no longer exist. Her reciprocal exchange with the chorus of Trojan women calls up the horror of potential captivity, beneath “la loi brutale des vainqueurs” [“the brutal law of the victors”], colored by Goerke with a shudder as her voice skids into the lower register. The chorus echoes her resolve to die rather than accept subjugation. When Mr. Guetti’s Greek captain bursts into their midst, he can simply marvel at their “noble transport” [“magnificent fervor”]; as the second Greek detachment announces Aeneas’s escape with the sacred treasure, the defiant women perform their self-sacrifice.

In the second part of the opera, “The Trojans at Carthage,” action proceeds from vantage points of the earlier wall, transformed now into a series of differing structures from the first part of the opera. While the Carthaginians sing of their festive day, Dido looks out from a window at the upper recesses of the building. Once the chorus sings its anthem and praise of Dido, the queen enters with her sister Anna and the court adviser Narbal. The personality and concerns of each character are gradually revealed by the performers in Lyric Opera’s production during the course of Act III. Ms. Graham demonstrates her close association with the role of Dido while she musters the people’s resolve and inspires the “chers Tyiens” [“dear Tyrians”] to continue their efforts at settlement. Just as she will later hear from the court poet Iopas, the queen now sings of the fecundity of the land and the labors that bring products from afar. Graham’s rising embellishments on “où s’éveille l’aurore” [“where the sun rises”] evokes an optimistic, public exterior yet cloaks any personal thoughts and emotions. Only when Dido speaks in privacy with Anna are her inner misgivings revealed. Ms. von der Damerau’s opulent, flexible vocal line forms not only a foil to Graham’s increasing apprehensions but she also assumes a truly developed characterization of her own. While Graham muses with melancholy on her “étrange tristesse” [“strange sadness”], her sister sings assuredly and repeatedly “Vous aimerez, ma soeur” [“You will love again, my sister”]. Von der Damerau’s lilting voice is matched by bodily gesture, both of these encouraging Dido’s openness to emotional adventure. The conclusion of the sisters’ duet unites both voices on the “trouble” [“unease”] in Dido’s heart which will determine her future.

Political and military concerns predominate at the entrance of Aeneas and the Trojans. Graham emphasizes the queen’s hospitality by welcoming the expatriates with moving declamation on “qui connut la souffrance” [“one who has known suffering”]. The introduction of the Trojans sung by Ascanius coincides with Narbal’s entrance to announce the approaching military danger of Iarbas leading the Numidians against Carthage. In the role of Narbal Christian Van Horn propels the act forward in his ominous description of the Numidian foe. Van Horn’s projection and fluid line are an ideal instrument to awaken Dido’s concerns for her people. His effective delivery forms a bridge to Aeneas declaring “Permettez aux Troyens de combattre avec vous!” [“Permit the Trojans to fight alongside you!”], intoned by Jovanovich with clarion top notes. Before departing to fight for Carthage, the father Aeneas asks that Dido protect his son. Into these lines Jovanovich injects a tender balance to the heroic preparedness that characterize his demeanor for battle.

At the start of Act IV the image of the sleeping queen approached by Aeneas, the forest, and the projections of a waterfall reveal symbolically the developing love between the protagonists. In a subsequent exchange Anna continues her light-hearted tone while Narbal cautions for the future. Although he admits that the Numidian enemy has been repulsed, he fears that the queen neglects her duties as exemplary figure. Van Horn inserts a troubled, distended tone into describing the “chasses … festins” [“hunts … feasts”] to which Dido now dedicates herself despite the “destin” [“fate”] of Italy being inexorably part of Aeneas’ future. In his aria, “De quels revers?” [“What disasters?”], Van Horn’s voice imparts an ominous warning, as though a pendant to that of Cassandra’s in the first part of the opera. His heartfelt legato in describing the ambivalent nature of Jupiter, “dieu de l’hospitalité” [“God of hospitality”], is countered by von der Damerau in her florid decoration of “Carthage est triumphante.” The subsequent ballet is staged as an entertainment set up by Anna with both dancers and observers attired in semi-formal wear reminiscent of the 1930s. With the protagonists seated as audience in a semi-circle of chairs, Aeneas places his arm about the shoulder of Dido in a natural embrace. As though instinctively in need of a familiar voice from the court, Dido asks Iopas to sing his “poème des champs” [“poem of the fields”]. Mr. Lei assumes the center of the court’s stage to perform “Ô blonde Cérès.” Lei’s song is light and natural, with supple embellishments and use of rubato at strategic moments in the text. Lei’s high pitches are unforced and extend the vocal decoration with elegance. Despite the beauty of his song Dido remains restless and asks Aeneas to recount further his previous wanderings. As the collected principals admire the twilight, Aeneas encourages Dido to forget the past sadness and heed the “brise caressante” [“gentle breeze”]. When the stage revolves, the two remain alone to sing “Nuit d’ivresse” [“Night of rapture”], performed by Graham and Jovanovich with layers of sensual decoration and softly extended, repeated lines. Upon their departure, the voice of Hector echoes the call “Italie!”

The final act of Les Troyens contrasts, in the main, sharply with the tender moments of the preceding. Here the two major parts place a rift between, on the one hand, Aeneas and his calling, and on the other, the isolation of Dido. At the start of Act V Hylas is perched in an upper window of the wall whence he sings “Vallon sonore” [“Echoing vale”], his plaintive wish to return to the homeland. Mr. Johnson captures the spirit of Hylas with an arching, lyrical line, some of the concluding pitches held as if endlessly. When he asks the eternal sea to rock him gently on her mighty breast [“Berce mollement”], Johnson’s voice evokes the movement of a comforting swell. The remaining parts of the act depart with dramatic force from this wistful introduction. Aeneas interacts with the chorus of soldiers and the spirits of Troy to a self-reconciliation of duty. In his “Inutiles regrets” [“Futile regrets”] Jovanovich remains in control of his character’s destiny while hurling out dramatic laments such as “Rien n’a pu la toucher” [“Nothing moved her”], as he describes his attempts to rationalize departing to the stricken Dido. In his realization that he must confront the queen one last time Jovanovich releases the word “désespoir” [“despair”] with shattering finality. During their final moments together Graham’s repetition of “Tu pars” [“You are leaving”] renders her positive yet uncomprehending sentiments, before she curses Aeneas and his gods. In the final scene Graham summons the power of the deserted queen to give a multifaceted depiction of Dido’s shifting emotions. Here Graham’s transitions in vocal color trace a line from vengeance to fear to resignation, ending on “Je vais mourir” [“I am going to die”]. In the company of Anna she stabs herself while looking to the possible future of her people. Graham sings the name “Annibal!” [“Hannibal!”] forte as the word ROMA appears in majuscule on the wall. This dignified conclusion reveres the spirit of Berlioz in a vocally and dramatically flawless production at Lyric Opera of Chicago.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Christine%20Goerke_LES%20TROYENS_LYR161109_0040_c.Todd%20Rosenberg.png image_description=Christine Goerke as Cassandre [Photo by Todd Rosenberg courtesy of Lyric Opera of Chicago] product=yes product_title=Les Troyens at Lyric Opera of Chicago product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino product_id=Above: Christine Goerke as CassandrePhotos by Todd Rosenberg courtesy of Lyric Opera of Chicago

Merry Christmas, Stephen Leacock

The four-show production held December 1 – 3 at the Canadian Mennonite University’s Laudamus Auditorium featured Weisensel, who also penned Vancouver Opera’s acclaimed “Stickboy” in 2014 leading the five-piece string orchestra, including two celli.

Set during the height of the Great War, the one-act, through-composed opera directed by Donna Fletcher is based on the beloved Canadian writer’s short story, where an author — Leacock — struggles to pen a Christmas tale while inundated with horrific daily headlines. An all-knowing spirit, Time, and a shell-shocked Father Christmas help him realize that his writing will only help bring joy to a wounded world.

Winnipeg-born, now Toronto-based James McLennan as Leacock, who also recently performed as Bardolfo in Manitoba Opera’s Falstaff first declaims, “The spirit, the beauty, the joy is gone,” with his tenor voice clear and even. He brought requisite angst to his title role, moving through initial despondency to ultimate hope and renewal.

The cast also included two local artists: Rachel Landrecht (and Weisensel’s real-life wife), who sensitively crafted a benevolent Time. Her expressive soprano matched equally by her warm stage presence were immediately apparently during her opening aria, “I am the spirit of Time.”

Winnipeg baritone Matthew Pauls created a shaggy, heart-breaking Father Christmas, who staggers into Leacock’s den with his sack of torn, soaked books and asks for schnapps to blunt his pain. His begging of Time to “Give me back my children” rang with sorrow.

The opera proved at its best during the fuller trios, including its emotional climax. When the ensemble sings, “Children are the future,” greater dramatic impact is created by virtue of close-knit harmonies and vocal counterpoint. Also strong were the more textural sections, including the strings’ pizzicato accompaniment that afforded more opportunity to hear the individual singers in Weisensel’s compact, often densely written orchestrations.

Fletcher’s skillful direction successfully navigated the logistics of the postage-stamp sized stage, with Sean McMullen’s homey set wisely lent greater visual depth by Aiden Ritchie’s archival video projections of harrowing trench warfare and images of embattled children.

Balance issues proved, at times, challenging, with the two male singers at risk for becoming obfuscated whenever the higher strings came into play. The narrative’s central plot device, a relatively tiny wooden toy horse that gets mended with beeswax, thus becoming a metaphor for hope and healing, did not read as effectively as with a larger prop.

Still, kudos to TLOC for choosing this opera as one of its two seasonal offerings. And its proud, ongoing support of homegrown talent continues to be its own gift to the city’s lively arts community, not just during Yuletide but indeed, all year long.

Holly Harris

The Little Opera Company, Canadian Mennonite University, Laudamus Auditorium, Winnipeg, Manitoba CANADA

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Christmas%20Stephen%20Leacock-2.png image_description=Merry Christmas, Stephen Leacock [Photo by Darryl Neustaedter Barg] product=yes product_title=Merry Christmas, Stephen Leacock product_by=A review by Holly Harris product_id=Photos by Darryl Neustaedter BargDecember 23, 2016

Bampton Classical Opera 2017

Having seen La grotta di Trofonio - at Bampton Deanery in July and St John’s Smith Square in the autumn - I concluded that ‘this trip to Trofonio’s Grotto unearthed some real magic’.

Bampton first explored Salieri’s operatic oeuvre in 2003; their production of Falstaff - also the first performance of the opera in the UK - was described by Opera magazine as ‘Thirty-one scenes of sheer joy’. So, the news that the company will return to the composer’s archive for their 2017 summer production, The School of Jealousy (La scuola de’ gelosi) - the first UK performances since the late 18th century - certainly whets the appetite. The production will be designed and directed by Jeremy Gray and conducted by Anthony Kraus, Assistant Head of Music at Opera North. The English translation will be by Gilly French.

Salieri was Imperial Court Composer and Kapellmeister in Vienna for so many years that Beethoven referred to him as the Pope of Music. Haydn staged and conducted several of Salieri’s operas at the Esterhazy court theatre including La scuola de Gelosi in 1780-81; the opera was perhaps Salieri’s greatest success.

Matthew Stiff as Trofonio (BCO 2015). Photograph courtesy of Bampton Classical Opera.

Matthew Stiff as Trofonio (BCO 2015). Photograph courtesy of Bampton Classical Opera.

Setting a sharply cynical libretto by Caterino Mazzolà, this opera buffa was written in Venice and first performed at the Teatro San Moisè in 1778. Later revised by the composer and with some textual adjustments by Lorenzo da Ponte, the opera made an enormous impact at the Burgtheater in Vienna in 1783.

The great success in Vienna of La scuola de’ gelosi almost certainly inspired Da Ponte and Mozart to create La scuola degli amanti which eventually became known by its alternative title Così fan tutte and there are many narrative parallels between the two. In both fidelity and honesty are tested by means of dangerous games and deceits, and the manipulative Lieutenant in Gelosi is a counterpart to Don Alfonso.

La scuola de’ gelosi was performed widely across Europe - from London to St Petersburg - for several decades, and was praised warmly by Goethe. The work was selected to inaugurate the Emperor Joseph II’s new Italian opera troupe in Vienna in 1783, with an outstanding cast including Nancy Storace (later one of Mozart’s favourite sopranos and the first Susanna) as the Countess, and Francesco Benucci (later Figaro and Guglielmo) as Blasio. It was the first of Salieri’s works to be performed in London, in 1786: The Herald judged, ‘it is the first lyric drama that may be termed strictly good, whether we advert to the poem itself, the music, or the performance’ and the Morning Post called it a ‘masterly composition’ that ‘does great honour to Salieri, whose reputation as a composer must rise infinitely in the musical world, from this very pleasing specimen of his abilities’. For the performances in 1780 at the court theatre at Esterháza, Haydn composed two insertion arias.

La scuola de’ gelosi is enjoying a current revival across Europe, including performances in 2017 in Florence and Vienna. L’arte del mondo have recently released a recording for Deutsche Harmonia Mundi Deutsche Harmonia Mundi. Bampton has also selected the work to mark the bicentenary of the death of Nancy Storace in 1817.

2017 will also see the third Bampton Young Singers’ Competition which takes place in the autumn.

The School of Jealousy will be performed at:

The Deanery Garden, Bampton, Oxfordshire: 21, 22 July

The Orangery Theatre, Westonbirt School, Glos: 28 August

St John’s Smith Square, London: date to be confirmed

Further details of Bampton Classical Opera’s production, including casting, will be announced in due course: www.bamptonopera.org

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Nicholas%20Merryweather%20and%20Aoife%20O%27Sullivan.jpg image_description=Bampton Classical Opera 2017 product=yes product_title=Bampton Classical Opera 2017 product_by=A preview by Claire Seymour product_id= Nicholas Merryweather and Aoife O’Sullivan in La grotta di Trofonio, Bampton Classical Opera 2015Photograph courtesy of Bampton Classical Opera

The nature of narropera?

While the majority of well-known operas probably have a cast of seven or so major roles, the grand operas of the nineteenth century swelled the ranks considerably. And, there are no limits. Jonathan Dove’s 2015 Monster in the Maze - jointly commissioned by the London Symphony Orchestra, the Berliner Philharmoniker and the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence - involved 350 singers: children, teenagers and adults; amateurs and professionals.

Opera comes in all shapes and sizes, as do the venues where it has been performed: from the Gonzaga’s ducal palace that witnessed the first performance of Monteverdi’s Orfeo in 1607 to the the Bayreuth Festspielhaus which opened in 1876 with three performances of the complete Ring cycle. Nowadays one is just as likely to see opera performed in amulti-story car-park, a disused warehouse, a North London pub, or even on the beach.

Haydn Rawstron’s opera company, Narropera, have reinvented the genre once again. Narropera pares down the operatic experience to its essentials. There are just three performers, the Narropera Trio. There is a singer (Rawstron’s wife, the versatile soprano, Dorothee Jansen, whose career has taken her to venues such as La Scala, Bayreuth, and the Wigmore Hall) who represents several different characters. Then, a violinist (or rather, one of three violinists, depending on where in the world the company are performing) weaves the vocal lines together and or adopts the vocal lines of an actual character of the story. These two are joined by a pianist (Rawstron himself), who both provides the musical structure and serves as a narrator, filling in the ‘story’ between the singer’s arias.

The emphasis, as one might imagine from the company’s name, is on narrative. But, while the opera may be ‘pared down’ to 90 minutes or so of uninterrupted story-telling, there is no lessening of the musical quality or experience. The intimacy of the chamber form and context creates an immediacy and directness. Knowledgeable listeners may hear afresh and discover new details; those unfamiliar with the work, or even new to opera itself, will be beguiled by a story clearly told through words and music.

Rawstron, a New Zealander, read music and was organ scholar at Christ Church, Oxford, before working at the Oldenburg State Theatre and developing a career in opera in Germany. Later, he established a successful agency for opera singers, conductors and stage directors, developing and managing the international careers of performers such as Anne Schwanewilms, Katarina Dalayman, Hillevi Martinpelto, Kathleen Kuhlmann, Birgitta Svenden, Renate Behle, Robert Gambill, Rainer Trost, Klaus Florian Vogt, Benjamin Bruns, Eike Wilm Schulte, Kristinn Sigmundsson, Willy Decker, Andreas Homoki, Göran Järvefelt, Heinz Wallberg, Arnold Östman, among others. When he retired in 2009, Rawstron wished to return to performing. As he puts, it ‘Out of that desire has evolved narropera’.

Dorothee Jansen.

Dorothee Jansen.

Rawstron explains the concept of narropera: ‘Whereas opera is understandably inflexible given the numerous forces that require coordinating, narropera’s chamber-music trio-presentation and its story-telling/singing interaction allow for considerable flexibility and creativity, not only in the preparation of the individual narroperas, but also in terms of a certain improvisation in actual performance. […] It is not necessary for the public to bring any special knowledge to narropera performances, neither of the opera being performed nor of opera in general […] the opera fan and the opera novice share in the same clarity and at the end of a narropera performance there is a great deal less difference between that which the fan and the novice respectively knows about the opera they have just experienced, and frankly that is just how it should be.’ This short interview confirms Rawstron’s creative spirit and commitment to the genre.

The company was created in response to the 2010-11 Canterbury earthquakes which damaged or destroyed many of the region’s cultural and performance venues, leaving the area without theatre, opera house or concert hall. Initially planned as a ‘stop-gap entertainment’, the first narropera - an adaptation of Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro - was performed at the Old Tai Tapu Road-based Lansdown House near Christchurch in early 2013, by Rawstron, Jansen and violinist Jan van den Berg. Narropera has out-lived those early intentions, however, and Rawstron and Jansen have not only established an annual festival at Lansdown but have also exported the concept to Germany, England and the Isle of Man.

The current format evolved gradually during the three years leading to that first narropera performance. First, Rawstron mounted a series of programmes, entitled Caccini to Puccini, which charted four centuries of Italian bel canto. Each programme presented arias from twelve different Italian composers metaphorically ‘holding hands’ through the centuries, and each aria programme came with a narration, setting the arias in their historical context, with a literal text translation preceding each aria.

Dorothee Jansen and Hanns Heinz Odenthal.

Dorothee Jansen and Hanns Heinz Odenthal.

The popularity of these performances encouraged Rawstron to expand the format to encompass the presentation of whole operas. Eighteenth-century Italian works proved well-suited to the concept, and Handel and Mozart have been the mainstay of the company’s repertory. Handel’s aria cycle, Neun deutsche Arien, setting poems by B. H. Brockes, followed that first Figaro. Since then, the composer’s Giulio Cesare and a ‘medley’ - wryly entitled Handeling the Old Testament - presenting ten arias from five of Handel’s oratorios (Esther, Athalia, Saul, Samson and Jephtha) with accompanying biblical stories to link the arias, have followed.

Mozart has been represented by La clemenza di Tito, Don Giovanni and, most recently in 2016, Così van tutte. Moreover, Rawstron comments that once created, the narroperas ‘evolve’ in subsequent performances: ‘For instance, we have added three additional pieces to the overall musical component of Don Giovanni, one extra piece in Figaro and made various changes to the narrative texts of both.’

Floriane Peycelon who has recently joined the Narropera Trio as the company’s UK-based violinist.

Floriane Peycelon who has recently joined the Narropera Trio as the company’s UK-based violinist.

A review in the Manx Independent of the company’s Così at Peel’s Centenary Centre in October 2016, by Dr Peter Litman, the director of music at Peel Cathedral, captures the flavour of a Narropera performance: ‘Rawstron’s ability to weave the complex tapestry of plot with the music of Mozart was quite mesmerising. Soprano Dorothee Jansen displayed both a beauty and dexterity, effortlessly moving between head and chest voice, and playing out her various roles through compelling facial expression. Having an intimate feel -rather like a soiree in a grand house in a lost era I was surprised by how much Jansen brought the plot of the opera to life drawing the audience into the story, even though she was singing in Italian. […] Joining the singer and pianist, Hanns Heinz Odenthal’s silvery violin complemented the voice like lace icing, and gave us a real sense of chamber performance. […] The diverse talents of Rawstron as a dramatic reader provided not only entertainment but gave real depth and accessibility to the plot during the narrations. He presented himself as impresario and performer and we were amazed at the fluidity and ease with which he could move from wistful storytelling to the piano.’

There have already been four narropera performances in the Isle of Man, nearly twenty performances in the UK and three in Germany (includingLe nozze di Figaro at the festival Musica Bayreuth), while the remaining performances have been in New Zealand, home to Lansdown Summer, an indoor festival of narropera presented in a magical heritage setting in rural Christchurch. In October 2016 Narropera gave its 50th performance since Rawstron and Jansen invented the new genre, at Eastwell Manor near Ashford, in Kent.

The 4th Narropera Festival takes place at Lansdown in February/March 2017, where the company will perform a new narropera derived from Weber’s Der Freischütz. It will have its UK premiere in spring 2017.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mozart%20Narropera%20Trio%2C%20German%20artists%20Dorothee%20Jansen%20%28soprano%29%20and%20Hanns%20Heinz%20Odenthal%20%28violin%29%20and%20Cantabrian%20Haydn%20Rawstron%20%28piano%20and%20narrator%29.jpg image_description=Narropera product=yes product_title=Narropera product_by=An article by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Hanns Heinz Odenthal, Dorothee Jansen and Haydn Rawstron.December 22, 2016

A Christmas Festival: La Nuova Musica at St John's Smith Square

Artistic director Stephen Layton must have been delighted to entice such stellar musical forces to come together to celebrate the festive season. Contributing to the seasonal riches, this heart-warming performance by David Peter Bates’ La Nuova Musica revelled in splendid settings for the soprano voice by way of the festive cantatas of J.S. Bach and two characterful classical sacred works.

Bates is an energetic stage presence. He conveys, reassuringly, a persuasive conviction: one immediately senses that when he sets off, Bates knows exactly where he is heading and how he plans to get there. That said, however clear one’s vision - and however accomplished the musicians at one’s command - to capture the innate grandeur of the work sufficient forces are required.

J.S. Bach’s cantata Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland I BVW61 (Now come, Saviour of the heathens) was composed for the first Sunday in Advent and first performed in Weimar in 1714. The titular chorus of the cantata introduces the Lutheran hymn but the adventurous young composer combines it with a regal overture that would not have sounded out of place in the Versailles of Louis XIV.

La Nuova Musica is - at least, it was on this occasion - a svelte ensemble: a chorus of just 8 singers, accompanied by 17 instrumentalists led stylishly and assuredly by Madeleine Easton. Bates drew robust, finely dotted rhythms - in the French manner - shifting fluidly through the changes from common to triple time. Both strings and chorus produced clean lines, but some of the necessary majesty and heft was missing.

Simon Wall has a light tenor, which is not in itself problematic, but the account of the miracle of Christ’s birth presented in the following recitative and aria (‘Komm, Jesu, komm zu deiner Kirche’ - Come, Jesus, come to Your church) also lay uncomfortably low in his voice - more apt for a baritone, perhaps? - and Wall’s fairly weak projection, and indistinct enunciation, could not do justice to the animated Italianate style or the spiritual glories recounted. The violins’ melody was full and rich, but I found Joseph McHardy’s organ unsympathetically heavy.

In the subsequent recitative, ‘Siehe, ich stehe’, Christ knocks on the doors of the faithful. The pizzicato summons was fittingly eerie and bass James Arthur sang with focus and sensitivity. It is the soprano soloist who answers this call and opens her heart to the Saviour: Augusta Herbert sang the final, delicate aria with expressive warmth, sweet simplicity and a lovely colouring at the top. The phrase ‘Bin ich gleich nur Staub’ (Even though I am only dust and earth) slowed expressively, and cellist Alexander Rolton made the first of many telling, intelligent and reflective contributions during the evening.

In the final chorus, Bach introduces another Christmas song, ‘Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern’ (How beautifully shines the morning start), to celebrate and welcome Christ. This chorus needs to drive with head-strong vigour to the close and eight voices are simply not enough to generate the requisite passionate rush of fervour.

The arrival of soprano Lucy Crowe for Bach’s cantata Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen! BWV51 (Praise God in every land!) marked a distinct change of gear and increase in engine power. Crowe confirmed not just how vibrantly expressive her voice is - astonishing diverse in colour for a light lyric soprano, deliciously fluid in the coloratura flourishes, but always centred and possessing just the right weight - but also the supreme assurance with which she marries technical skill and innate musicianship. She can both sing and interpret the text; means and method serve the message perfectly.

Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen! is a work of Bach’s Leipzig years - it was first performed in 1730 - and its numbers all offer jubilant and direct praise to God. In the first aria, a perfect balance was achieved between Crowe, David Blackadder’s gleaming, lithe natural trumpet, and Easton’s spirited solo violin contributions; as the trio engaged in long coloraturas Bates judiciously managed the tutti interruptions.

The ensuing recitative, ‘Wir beten zu dem Tempel an’ (We pray at your temple), was an expressive arioso, complemented by some beautiful string playing and thoughtful organ continuo. The aria ‘Höchster, mache deine Güte (Highest, renew Your goodness) was fresh of tone, but introspective of spirit; Crowe span the long lines seamlessly and glossily. A busy vigour resumed in the chorale, ‘Sei Lob und Preis mit Ehren’ (Glory, and praise with honour), in which we enjoyed more stylish violin playing (from Easton and Miki Takahashi) as they wound expressively around the soprano line supported by Rolton’s sensitive cello underpinning. The exuberant ‘Amen’ with which cantata concludes sparkled: Crowe’s ornaments glittered fetchingly.

Mozart’s Exultate Jubilate K165 opened the second half of the concert. Crowe relished the operatic and theatrical qualities of this motet which, reportedly, the adolescent Mozart rushed out just in time to meet a deadline for castrato Venanzio Rauzzini’s scheduled performance at the Church of San Antonio on 17 January 1773, even though during the preceding weeks singer and composer were both involved in performances of Mozart’s Lucio Silla which opened in Milan on 26 December 1772.

The ‘motet’ exhibits no hint of compromise, though, and Crowe drew visible delight from the exquisite craft with which Mozart showcases the solo soprano voice. Every note was placed with absolute precision, the line was beautifully clean, ornaments - such as the exquisite trill that issued the invitation ‘Let the heavens sing forth with me’ at the close of the first aria - were finely wrought and tasteful. The slower middle section was dignified and eloquent, while the gorgeously molten lines of the Andante ‘Tu virginum corona’ (You, o crown of virgins) ran gleefully into the concluding Alleluia. In a letter to his mother in 1773, whilst on tour, Mozart wrote that ‘a composition should fit a singer’s voice like a well-tailored dress’: Crowe fitted so neatly into its seams and sequins that it might have been made for her.

Haydn’s Missa Sancti Nicolai, one of comparatively few choral works that he wrote before he was fifty, concluded the programme. Although this is a fairly light-spirited work - probably intended for the Feast of St Nicholas which was also the name day of Haydn’s patron, Prince Nicolaus Esterházy - Bates made the most of the mass’s drama. He ensured that the orchestral prelude was tense and exciting, and that the pairing of the voices in the Kyrie created momentum; the Credo was pulsing and exuberant, with fleetly rushing cello lines beneath complex vocal conversations, though Bates deftly drew breath for the slow minor key quartet in which the birth and death of Christ is reverentially declaimed. But, there was gravity and composure in the Sanctus; and the lyrical reflectiveness of the Agnus Dei, made more piquant by Haydn’s surprising dissonances, offered a serious counterweight, as the mass lilted gently to a close.

Claire Seymour

La Nuova Musica: David Peter Bates (harpsichord & director), Lucy Crowe (soprano), David Blackadder (trumpet).

J.S. Bach - Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland BWV62, Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen BWV51; Mozart -Exsultate Jubilate K165; Haydn - Missa Sancti Nicolai.

St John’s Smith Square, London; Monday 19th December 2016.

image= http://www.operatoday.com/Lucy%20Crowe%20Sussie%20Ahlburg.jpg image_description=La Nuova Musica at St John’s Smith Square product=yes product_title=La Nuova Musica at St John’s Smith Square product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Lucy CrowePhoto credit: Sussie Ahlburg

December 19, 2016

Fleming's Farewell to London: Der Rosenkavalier at the ROH

For this ‘new’ production at the Royal Opera House, Canadian director Robert Carsen - as he did in Salzburg in 2004 - updates the action from Hofmannsthal’s mid-eighteenth century, before Enlightenment was superseded by Revolution and Terror, to the time of the opera’s composition, during the troubled years leading up to World War I.

The curtain rises tantalisingly slowly on designer Paul Steinberg’s Act 1 set, to reveal the formal grandeur of a nineteenth-century Vienna which is tottering through the increasingly unstable years of the early twentieth. Through the imposing doors of the Marschallin’s chamber emerges Alice Coote’s Octavian, in crumpled night-shirt; flinging his leg swaggeringly across the arm of a plush Beidermeier sofa in the antechamber, the young Count enjoys a post-coital cigarette, before Renée Fleming’s Marie Thérèse appears, drawing him back into her den of sexual intimacy.

Renée Fleming (Marschallin). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Renée Fleming (Marschallin). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Peeling back the façade, Carsen and Steinberg present us with the first of three wide-screen vistas. The angled brocaded walls of the bedchamber span the stage. The focus, naturally, is the bed itself, larger than most studio apartments in present-day London. The polished parquet floors and plush red pelmets are reminiscent of the rococo luxury of Hofmannsthal’s original locale; the walls are decorated with portraits of men of measure and might - it’s clearly a man’s world.

Beyond a door to the rear lie a series of connective antechambers and corridors. Later, when the anxious Marschallin requests that Octavian be summoned back, so that she can remedy her remissness in failing to bestow her departing lover with a kiss, a dozen footmen appear in a flash, anxiously insisting that they had done their best, but failed, to waylay the Count’s impulsive departure. Silent servants appear throughout the scene, to move a chair, hold a salver, or re-position a platter. When the curtain falls on this opening Act, one senses the overwhelming responsibility borne by those charged with sustaining the identity of a city which, at the crossroads of Europe and the centre of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, has been crumbling for years.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Act 2 takes us to Herr von Faninal’s nouveau riche mansion. He’s an arms-dealer so it’s fitting that this act is all about regiments: of servants and seamstresses, of dancing duos, of Ochs’ menacing Prussian retainers. The highly ornamented interior of the Marschallin’s mansion is replaced by a more modern, monochrome palette. There’s an elegant simplicity about the black and white marble floor tiles, while a mustard-toned Grecian frieze tells historic tales of war and plunder. Not cultural artefacts but two giant cannons - destined for the battlefields of Flanders? - are the centre-piece of Faninal’s modish interior. When Sophie and Octavian seek respite from the maelstrom of Ochs’ marauding servants, their hiding place - they nestle between the two grey guns - ominously belies the romance. And, sure enough, Ochs’ nasties return: the choreography (Philippe Giraudeau) of their vicious humiliation of Sophie is superb.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

As in Salzburg, Carsen replaces Act 3’s usual rustic inn with a gaudy brothel managed by a male ‘madam’. We begin, like the opening, with a façade; for all the gilt paint and flock wallpaper, the series of doors through which scantily clad women beckon and beguile, recalls the soulless sex-selling of ENO’s recent Don Giovanni. This is a world of decadent debauchery; at one wonderfully wry moment, a near-naked man wanders casually and indifferently through the dissipation as Ochs cries in disbelief, ‘Was war denn das?’ (‘What was that?’). And, Ochs’ temptress, ‘Mariandel’, is no shrinking violet - sporting a blue satin dressing gown atop a cerise corset, she dreams up indecencies for Ochs that are played out in the neon windows - straight from Amsterdam’s red light district - whose vices push aside the classical paintings of naked majas, nymphs and Venuses.

Alice Coote (Octavian/Mariandel) and Matthew Rose (Baron Ochs). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Alice Coote (Octavian/Mariandel) and Matthew Rose (Baron Ochs). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

It’s an odd place for the Marschallin to find herself; and the second half of the Act doesn’t quite convince. She should be above such crudeness and coarseness; and, she knows it. The Murphy bed - confidently flipped down by Mariandel - is again the site of most of the action, as Sophie and Octavian, bathed in a red glow, canoodle fervently, as the Marschallin graciously, with quiet resignation, accepts that the two youngsters are in love.

Renée Fleming (Marschallin). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Renée Fleming (Marschallin). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

This production was unofficially promoted as Fleming’s London swansong, and there was an autumnal air which straddled real life and theatre. Aided by Brigitte Reiffenstuel’s gorgeous costumes, Fleming had undeniable stage presence. But, while her bitter-sweet reflections about transience and the relentlessness of Time avoided a cloying sentimentality, Fleming did not really communicate the Marschallin’s inner life. Her musings needed to be projected more strongly. She can still glide through a phrase with lovely sweetness and style, and the bloom and lustre are not lost, but they can’t be sustained. And, Fleming knows this: she saved herself for the big moments, and at times her soprano seemed too reticent to hold Strauss’s ardency. The last 20 minutes of Act 1 saw her tone and timbre recede - the Marschallin’s psychological fragility seemed vocally laid bare. Yet, Fleming showed that she could still yield the magic: when she gave the silver rose presentation box to her young page for him to take to Octavian, she spun a line of wonderful silky sheen, a delicious musical anticipation of the formal courtship ritual to come. Conductor Andris Nelsons seemed to quell the orchestral boisterousness and pace in sensitivity to Fleming (in contrast, in the ensembles he was less judicious and the voices sometimes struggled to compete) and this further lowered the temperature at times, though during this Act 1 finale Nelsons encouraged some exquisite playing from the woodwind, adding to the sense of introspection.

Sophie Bevan (Sophie von Faninal) and Alice Coote (Octavian). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Sophie Bevan (Sophie von Faninal) and Alice Coote (Octavian). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Alice Coote sang the marathon role of Octavian with enormous commitment - some may have found her young Count a touch too uninhibited - and acted well. Occasionally petulant and over-sensitive to slights to his amour propre, this Octavian was more than a match for Matthew Rose’s menacing Ochs. Even when upset by Marschallin’s honest prophesying, Octavian summoned his stature, and with a sharp, click of the heels made an authoritative exit, not a young man to let the public face of masculine command slip. There was a discrepancy, however, between the heaviness and occasional lack of focus of Coote’s lower register and the rich brightness of her top, and vocally her performance did not feel entirely controlled, but she blended beautifully in the ensembles and overall this was a persuasive performance.

Sophie Bevan sang her namesake’s soaring phrases with ease, and considerable strength; this Sophie was by turns furiously feisty and - particularly in the final duet - charmingly innocent. But, Bevan could not offer the slithers of silvery caress that we have come to expect. I longed for ‘Wie himmlische, nicht irdische’ to linger, just a fraction longer. But, perhaps this was not Bevan’s fault; for though Nelsons often took things fairly steadily, the presentation of the rose felt far too precipitous. Dressed not head-to-toe in silver, but in military black and white, Octavian fairly charged through the ranks of ceremonial onlookers. Behind the enchanted young lovers, pairs of dancers swirled in stylised fashion during the duet which should seem to hold Time still and refute the evidence of the opera, and of life, that the clock’s cannot be stopped. The purple light which bathed the scene was not enough to transport and translate, and was quickly superseded by the white glare of reality during the ensuing tête-à-tête, and later by the lurid green gleam which accompanied Ochs’ pompous arrival.

Sophie Bevan (Sophie von Faninal). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Sophie Bevan (Sophie von Faninal). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Matthew Rose’s Baron was a revelation. I have never heard Rose sing with such elegance and beauty of tone. Writing in 1942, Strauss recalled the first performances of Der Rosenkavalier and offered some hints to performers, noting that Ochs was not, as ‘most basses have presented him’, ‘a disgusting vulgar monster with a repellent mask and proletarian manners’, but rather ‘a rustic beau of thirty-five, who is after all a member of the gentry […] He is at heart a cad, but outwardly still so presentable that Faninal does not refuse him at first sight.’ Carsen and Rose seem to have heeded the composer’s advice. Dressed in the stiff military uniform of a Prussian office, this Ochs was no lumbering bucolic buffoon but a threatening lecher, accompanied by a rifle-toting platoon. Angry at Sophie’s rejection and obvious distaste, Ochs threw her dismissively to the floor. The resonance and charm of Rose’s voice was an unnerving but rewarding counterfoil to Ochs’ confident menace.

Carsen offers many inventive gestures, quirky details that tickle the imagination but never go too far, and in the secondary roles the cast are characterful. As the Italian Singer, a matinée idol in white suit and hat, Giorgio Berrugi blasted his way through his aria with a little too much bombast, but did a good impression of Caruso, effusively handing out his latest gramophone recording. The conspiratorial manoeuvring of Annina (Helene Schneiderman) and Valzacchi (Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke) is well-choreographed, as is Alasdair Elliot’s spirited abandon as the cross-dressing brothel owner. Jochen Schmeckenbecher bullied and badgered blusteringly as Faninal, while Scott Connor’s Police Commissioner was a smooth-operator, coolly departing with the Marschallin at the close - her next inamorato, perhaps.

Helene Schneiderman (Annina) and Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke (Valzacchi). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Helene Schneiderman (Annina) and Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke (Valzacchi). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

In the pit the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House were fervent but occasionally a little ragged under Nelsons’ baton. Certainly he fired the players up in the graphically pictorial prelude - indeed, the horns let rip with a little too much vigour at the expense of control, and more punch than blend at times. But, there was too often a lack of finesse.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Conventionally, the opera’s whimsical coda consists of a playful dash by the page Mohammed back into the bedroom to search for Sophie’s lost handkerchief. Instead, Carsen slides back the slanting walls of the garish bawdy house and opens up the expanse of the ROH stage, to reveal a row of ghostly soldiers, headed by the Feldmarschall and with a green-turbaned Prophet in their midst. Faninal’s cannons, shrouded in mist, point towards the slaughter-grounds of WW1. The grey platoons fall, in slow motion. The outsized Silver Rose may have sparkled like Swarovski crystal but its dazzle was clearly deceptive. The frisky pastimes of the bordello are over; it seems that future field manoeuvres offer Octavian only an early grave.

Claire Seymour

Richard Strauss: Der Rosenkavalier

Marschallin - Renée Fleming, Octavian - Alice Coote, Sophie von Faninal - Sophie Bevan, Baron Ochs - Matthew Rose, Faninal - Jochen Schmeckenbecher, Valzacchi - Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke, Annina - Helene Schneiderman, Italian Singer - Giorgio Berrugi, Marschallin’s Major Domo - Samuel Sakker, Faninal’s Major Domo - Thomas Atkins, Marianne/Noble Widow - Miranda Keys, Innkeeper - Alasdair Elliott, Police Inspector - Scott Conner, Notary - Jeremy White, Milliner - Kiera Lyness, Animal Seller - Luke Price, Doctor - Andrew H. Sinclair, Boots - Jonathan Fisher, Noble Orphans -Katy Batho, Deborah Peake-Jones, Andrea Hazell, Lackey/Waiters - Andrew H. Sinclair, Lee Hickenbottom, Dominic Barrand, Bryan Secombe, Mohammed - James Wintergrove, Leopold - Atli Gunnarsson; Director - Robert Carsen, Conductor - Andris Nelsons, Set designer - Paul Steinberg, Costume designer - Brigitte Reiffenstuel, Lighting designers - Robert Carsen and Peter van Praet, Choreographer - Philippe Giraudeau, Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House (Concert Master - Sergey Levitin)

Saturday 17th December 2016; Royal Opera House.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/0737%20MATTHEW%20ROSE%20AS%20BARON%20OCHS%2C%20REN%C3%89E%20FLEMING%20AS%20THE%20MARSCHALLIN%20c%20ROH.%20PHOTO%20CATHERINE%20ASHMORE.jpg product=yes product_title=Der Rosenkavalier at the Royal Opera House product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Matthew Rose (Baron Ochs) and Renée Fleming (Marschallin)Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore

December 14, 2016

Loft Opera’s Macbeth: Go for the Singing, Not the Experience

It was worth the wander, though, upon arriving to the venue, the MAST Chocolate Factory in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The space was “wow”-inducing and perfectly shabby chic, lit by the glow of the neon Brooklyn Brewery sign that indicated where one could get some craft brew to enjoy with their craft opera.

As the opera began, at least on the surface level, the venue worked well. The acoustics were a bit cathedral-like, but it allowed the singers and orchestra to envelope the audience in an eerie wash of sound. The faded brick wall used as the backdrop of the majority of the opera appropriately hinted at a crumbling castle, with large brick archways that were likely windows some time ago. Later in the opera, these arches are lit in a very fine effect that greatly enhanced the psychological drama of the scene.

Speaking of lighting, it was remarkably well done, used not only to indicate atmosphere but also to provide projections that illustrated the mental unwind of Macbeth, or served as flashbacks to emotionally fraught backstory. Projections can be tricky, as the use of this type of technology can sometimes err on disruptive rather than enriching, but these were subtle, well designed, and enhanced the mood of the scenes.

Perhaps I also enjoyed the lighting because it was one of the only aspects of the opera I was actually able to see fully. There’s partial-view seating, and then there’s 10-percent view seating, which is what the majority of the audience outside of the first ten rows was treated to. This unique space was difficult to work with, certainly, but the addition of a few platforms onstage would have made the difference between an evening of awe and an evening of frustration. Multiple major duets and arias occurred with the singers sitting, kneeling, or lying on the floor, the performers completely obscured to the majority of the audience.

By the end of the opera, I was barely even watching the stage because it was a fruitless exercise. The annoyance of the people around me was unmistakable, with people giving up on their seat and standing on benches to try to get a glimpse of what was happening.

Of what I could see, many of the directorial decisions were confusing and detrimental to the heart of the story. There was a montage at the beginning indicating that Lady Macbeth lost her child before the start of the play, because it’s not enough that a woman is ruthlessly ambitious because she’s ruthlessly ambitious—she needs softening by motherhood and some kind of tragic motivation for her bloodlust. Similarly, not one duet goes by where Macbeth wasn’t driven mad with lust by Lady Macbeth’s plans of vengeance (and high notes), performing an awkward from-the-back breast grab that reduces their deviousness to some kind of sexual kink that’s activated by murder plans.

That being said, the musicians made the evening worthwhile and handled some of the more baffling staging decisions very well. The four principles were very finely cast, each filling their role naturally with ease—not a small feat for such vocally and dramatically challenging roles as these.

Craig Irvin as Macbeth has a hugely rich and dark baritone that fills the space but moves with ease, allowing him for some stunning messa di voce moments and a real sense of vulnerability lurking beneath the murderous façade. He’s appropriately brooding but portrays determination to stay fixed to his murderous path, and neither voice nor dramatics falter through a difficult three-hour opera. Indeed, his last aria is one of his most stunning moments, a commendable feat after the demands of the singing of the first three acts.

Elizabeth Baldwin as Lady Macbeth sings a role few would dare with pizazz and effortlessness. She embodies Lady Macbeth completely, her voice sparkling through her coloratura passages and her upper range clear and easy. A lingering high note at the end of her aria in Act II caused awe and delight to ripple through the audience, yet Baldwin does all of it completely naturally. Her mad scene was haunting, the final climax echoing through the rafters with unnerving beauty.

Kevin Thompson (Banco) has excellent control over an enormous instrument, and gives an exceptional performance with appropriate gravitas. Peter Scott Drackley as MacDuff brings the performance to an awestruck standstill with his exquisitely sung Act IV aria. He cuts a fine figure throughout the performance, with an intense stage presence even in absence of any singing. Ashley Curling as Dama fills out a small role with a committed performance and gorgeously blossoming high notes.

The orchestra fared quite well with a full, rounded sound that fills the space suitably. The coordination between the orchestra and the chorus was the most noticeable sloppiness of the night, the two regularly getting mismatched by half a beat, but it may very well have just been the nature of the overly live performance space. The chorus is small for Verdi but blends nicely, especially the women’s chorus.

There was something missing in the overall scope of the production, besides the obvious sightline issues. Perhaps it was an immediacy, or an authenticity, that as audience members, we hope for in a stripped-down production, especially when sitting so close to the playing space. Many moments felt quintessentially “opera-y” and detracted from the thoughtfulness the singers were so committed to providing.

That being said, Macbeth is an ambitious opera, and for the excellent singing alone, it’s worth a try. There aren’t many venues where such fine singing could be heard in this mammoth of a Verdi composition, and at least you get to go on an adventure to get there.

Alexis Rodda

image=http://www.operatoday.com/LoftOpera1.png image_description=Craig Irvin as Macbeth and Elizabeth Baldwin as Lady Macbeth [Photo by Robert Altman] product=yes product_title=Loft Opera’s Macbeth: Go for the Singing, Not the Experience product_by=A review by Alexis Rodda product_id=Above: Craig Irvin as Macbeth and Elizabeth Baldwin as Lady MacbethPhotos by Robert Altman

December 12, 2016

A clipped Walküre in Amsterdam

Presumably, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, foremost in the land and one of the best in the world, could not muster the budget for a complete Walküre — a worrisome fact, if this was indeed the case. Second, it would have cost nothing extra to include the names of the Valkyries next to the singers’ names in the programme, instead of just their voice type. On a more positive note, congratulations are in order to mezzo-soprano Alexandra Petersamer, who sang Rossweisse after having stepped in for an indisposed Petra Lang as Kundry in Act I of Parsifal at the Dutch National Opera. The original replacement, Elena Pankratova, whose flight had been delayed, sang the rest of the role.

Michael Volle [Photo by Wilfried Hösl]

Michael Volle [Photo by Wilfried Hösl]

Petersamer and her lower-voiced sisters were fine assets in this flight of Valkyries. Among the sopranos, Allison Oakes as Gerhilde stood out with her large, prepossessing sound. Jumping immediately into Act III of Die Walküre means that we find ourselves in the midst of winged goddesses whooping in the air as they carry fallen warriors to Valhalla. Meanwhile, their sister Brünnhilde is carrying their human half-sister Sieglinde to safety, fleeing their father Wotan’s anger. Sieglinde is pregnant by Siegmund, her twin brother. Brünnhilde, ignoring Wotan’s orders, tried to save Siegmund’s life, but Wotan had him killed, punishing him for adultery and incest. Wotan must now also chastise Brünnhilde, his favourite, who carried out his true wish as a father, but must succumb to his will as chief god.

Conductor Valery Gergiev muted the first bars of the Ride of the Valkyries to create the illusion of distance, then suddenly they were upon us with a huge sound surge. Gergiev delivered in big moments such as this one, but did not maintain consistent tension throughout the performance. The exchange between the Valkyrie huntresses was flagging before Christine Goerke as Brünnhilde entered to charge it up. It is not uncommon in Wagner for the orchestra to steal the show, but this evening belonged to the soloists. There was nothing really amiss with Gergiev’s conducting, but neither was there much cause for elation. He seemed to be content to let the RCO produce beautiful sounds, which, of course, they did. The low woodwind solos keened gorgeously at Brünnhilde and Wotan’s farewell, and the Magic Fire Music glistened splendidly. Gergiev’s articulation, however, lacked psychological incisiveness. Wotan’s anger was stated rather than expressed, and the orchestra never reflected Brünnhilde’s terror of becoming mortal, locked in a deep sleep encircled by fire.

Tamara Wilson [Photo courtesy of Columbia Artists Management Inc.]

Tamara Wilson [Photo courtesy of Columbia Artists Management Inc.]

Happily, the three main soloists brought enough theatrical passion to make the performance take off. Soprano Tamara Wilson created a vulnerable, bruised Sieglinde, her opening phrases darkened with deepest grief. Lithe and shining, her voice then soared ecstatically in “O hehrstes Wunder!”. Wilson’s impressive brief appearance was a tantalizing glimpse into what she could do with the complete role. Her laser-like sound contrasted thrillingly with Goerke’s broad, complex soprano. Young and energetic, her Brünnhilde turned incredulously wide-eyed when pleading with Wotan in “War es so schmählich”. One really believed she was his somewhat spoiled favourite. Goerke’s unique instrument is dark and rich at the bottom and vastly opulent in the middle, tapering off into a focused top with a quick vibrato. It is a voice of many metals and minerals, and she wielded it expertly. The Amsterdam audience was lucky to get a slice of her Brünnhilde, as well as a taste of Michael Volle’s deluxe Wotan. With a baritone on the lighter side of the Wotan spectrum, Volle sang Brünnhilde to sleep in an impossibly tender, almost erotic, “Der Augen leuchtendes Paar”. At the other extreme, his seething rage while chasing his renegade daughter was tremendous. Volle’s clear German diction is pure bliss. Add to that a lustrous legato, natural theatrical instincts and a first-class instrument, and it is easy to see why he is one of the best operatic interpreters of our time.

Innovation in the concert hall is most welcome, but illustrator Tjarko van der Pol’s repetitious animation added little at best. At worst, it was a maddening distraction. Animated on a loop, drawings of the characters appeared each time they sang — a superfluous labelling exercise. The Valkyries were shields with facial features, gyrating rotors and limbs swinging back and forth. Sieglinde was a Venus of Willendorf with a clock face, and Wotan had a giant eye for a head, stuck on a tree trunk neck. These designs would look great on T-shirts and other Ring Cycle merchandise, but their spare, quasi-naïf style was totally incongruous with Wagner’s elaborate sonic world.

Jenny Camilleri

Cast and production information:

Brünnhilde: Christine Goerke (soprano); Wotan: Michael Volle (baritone); Sieglinde: Tamara Wilson (soprano); Valkyries: Christiane Kohl (soprano), Allison Oakes (soprano), Dara Hobbs (soprano), Stephanie Houtzeel (mezzo-soprano), Julia Rutigliano (mezzo-soprano), Alexandra Petersamer (mezzo-soprano), Simone Schröder (alto), Nadine Weissmann (alto); Tjarko van der Pol, animation. Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. Conductor: Valery Gergiev. Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, Friday, 9th December 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Goerke.png image_description=Christine Goerke [Photo courtesy of http://www.christinegoerke.com] product=yes product_title=Soloists help lift off clipped Walküre in Amsterdam product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Above: Christine Goerke [Photo courtesy of christinegoerke.com]A Leonard Bernstein Delight

With Faith Prince as wisecracking Ruth and Nikki M. James as sexy Eileen, Wonderful Town was a fabulous concert that told a story of the “good old days” in Greenwich Village with singing, dancing, and updated jokes.

In the nineteen thirties, Ruth McKenney wrote of the adventures she and her sister Eileen had in New York City. Although they lived in a damp, mold infested Greenwich Village basement for a mere six months, Ruth’s stories of that time have fascinated readers and listeners for three quarters of a century. She first published her tales in the New Yorker, but in 1938 they appeared in book form as My Sister Eileen and the book became a play and movie. In 1953, when Leonard Bernstein added music to Betty Comden and Adolph Green’s lyrics, Ruth McKenney’s tales of life in New York became Wonderful Town. That was the version of the story that Los Angeles Opera audiences saw on December 2, 2016.

Julia Aks (Helen) and Ben Crawford (Wreck)

Julia Aks (Helen) and Ben Crawford (Wreck)

Director David Lee enabled his artists to tell their story in a realistic manner even though their space was severely limited. The projected scenery, consisting of varied watercolor paintings of a remembered Greenwich Village, could be seen over the heads of the cast, chorus, and orchestra. There was always some movement within these Hana S. Kim projections. Although there were no trees to be seen, shadows of their leaves continually moved on buildings at the behest of soft breezes. From my time in the Village I don’t remember any green fire escapes, but they were charming to see onstage. Projected names such as “Christopher Street” were in the iconic font seen on the cover of the magazine, The New Yorker.

Wonderful Town is the first of three Los Angeles Opera presentations of Bernstein musicals, the last of which will be in 2018, the one-hundredth anniversary of the composer’s birth. The story was still set in the nineteen-thirties and Faith Prince was the street-smart Ruth, a role originally played by Rosalind Russell. In the role of Eileen, originally played by Edie Adams, Nikki M. James was as cute as a kitten. Some things never change and Eileen got the attention of every man, onstage and off, even though it was Ruth who wrote the stories for posterity. Both Prince and James created memorable characters and sang with admirable diction.

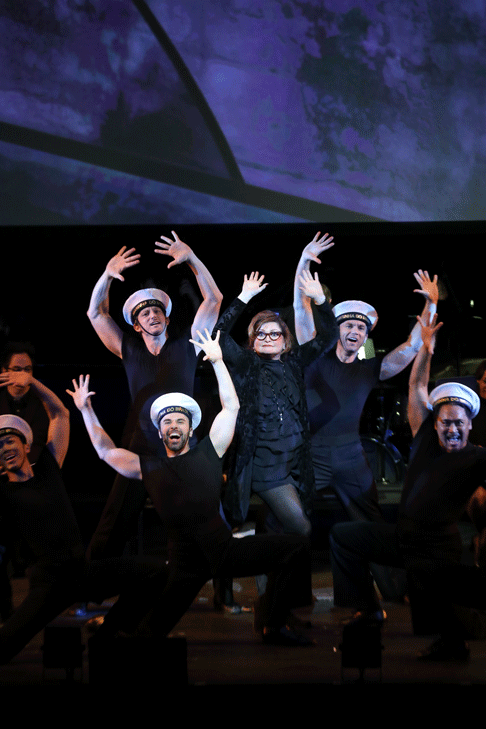

Faith Prince as Ruth Sherwood, with the dancers of Wonderful Town

Faith Prince as Ruth Sherwood, with the dancers of Wonderful Town

Nineteen fifties musicals were known for their dance scenes and Wonderful Town was no exception. I was amazed at how much dancing Peggy Hickey’s troupe could fit into a minimum of space afforded them with orchestra, chorus and soloists on stage. The Navy Yard Conga was the whipped cream on a fabulous dessert and James’s cartwheels were the topmost cherry.

One of the stars of this show was the orchestra under the leadership of Grant Gershon who conducted with crisp, forward pressing tempi and took a minute to dance on the podium. Quite a few of its twenty-seven instrumentalists played more than one instrument, too, so the audience heard the sound of a full compliment of musicians. The rhythms were captivating. Bernstein said, “Music can name the unnameable and communicate the unknowable.” It can also keep on communicating for decades after the demise of its composer.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Book, Joseph Fields and Jerome Chodorov; Original Stories, Ruth McKenney; Music, Leonard Bernstein; Lyrics, Betty Comden and Adolph Green; Adaptation for Concert Performance, David Lee; Ruth, Faith Prince; Eileen, Nikki M. James; Tour Guide, Speedy Valenti, Rexford and other characters, Roger Bart; Mr. Appopolous, Tony Abbatemarco; Officer Lonigan, Brian Michael Moore; Wreck, Ben Crawford; Helen, Julia Aks; Violet, Elizabeth Zharoff; Robert Baker, Marc Kudich; Daniel and Associate Editor, Theo Hoffman; Frank Lippincott, Jared Gertner; Sean, Carlos Enrique Santelli; Pat, Josh Wheeker; Conductor, Grant Gershon; Director, David Lee; Choreographer, Peggy Hickey; Projection Design, Hana S. Kim; Lighting Design, Azra King-Abadi; Musical Preparation, Jeremy Frank and Miah Im.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Wonderful-Town_16207-0302.png image_description=Nikki M. James as Eileen Sherwood [Photo: Craig T. Mathew / LA Opera] product=yes product_title=A Leonard Bernstein Delight product_by=A review by Maria Nockin product_id=Above: Nikki M. James as Eileen SherwoodPhotos by Craig T. Mathew / LA Opera

December 7, 2016

An English Winter Journey

Baritone and pianist are both experienced exponents of Schubert’s Winterreise, having performed the work, in Williams’ case, in both German and English, and in Drake’s case with numerous internationally renowned singers. This Temple Song Series recital was musically rewarding, intellectually stimulating and emotionally fulfilling in equal measure.

The poems by Wilhelm Müller which Schubert set in 1828 are vivified by the sublime gothic imagery of Romantic excess. Mary Shelley’s ‘everlasting ices of the north’ - where the snows descend upon Victor Frankenstein as he obsessively seeks the monster of his own creation, ‘ cursed by some devil and carr[ying] about with me my eternal hell’ - are the Wanderer’s home.

The language, musical and poetic, of the songs selected by Williams and Drake is, predominantly, more nostalgic and elegiac. As Williams noted in an engaging opening address, the music of Ivor Gurney and the poetry of Thomas Hardy recur frequently in their chosen sequence. This is less the language of radical revolution than pensive reflection on a passing age and the lamented loss of erstwhile values. But, alongside the wistful contemplations of the poets and composers of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, Williams and Drake gave us some contemporary songs that served to create an ongoing temporal narrative.

Müller’s poems rove through diverse, destabilising emotional fields: from energy to listlessness; idealism to sensuality; penetrating bitterness to dry irony. And, Schubert’s settings glisten with sonic imagery. The selection of songs presented by Williams and Drake both reflect and develop these predecessors. Williams described the process of assembling the sequence as one of ‘free association’.

Some songs presented a natural parallel to Schubert and Müller. The steady perambulation of Schubert’s opening song, ‘Gute Nacht’, was emulated here by the dry tread of Robert Louis Stephenson’s vagabond, as dramatized by Vaughan Williams. Vocal flourishes such the animation of the end of the first verse - ‘ There’s the life for me’ - and the dark colouring of the subsequent plea - ‘All I ask, the heaven above/And the road below me’ - confirmed the vitality of Williams’ delivery. And, his sensitivity to dynamic nuance was utterly persuasive, the veiled final stanza culminating in a more laboured plea, ‘All I ask, is the heaven above/ And the road below me’.

Müller’s ‘Die Wetterfahne’, in which the weathervane creaks in the shifting wind, was evocatively matched by Shakespeare’s ‘Blow, blow, thou winter wind’ as set by Roger Quilter; here the detailed eddying of blast and breeze in Drake’s accompaniment was immensely stirring, and Williams’ baritone shivered: ‘Freeze, freeze, thou bitter sky’. Amid the well-known fare, there were wonderful rarities. Madeleine Dring’s ‘Weep you no more, sad fountains’ (Anon.) was a magical lullaby, the gentle eloquence of both voice and piano utterly beguiling. There was stirring theatre too. Finzi’s setting of Hardy’s ‘At Middle-Field gate in February roved through the fog as Drake’s even, easy touch became emotively mired in the ‘clammy and clogging’ ploughland, rocking dissonantly, as Williams effectively modulated his vocal tone.

Schubert’s ‘Der Lindenbaum’ is a reminder of happier days, luring the poet-narrator towards a rest he ultimately rejects, though its appeal echoes in retrospect: ‘Here you would find peace.’ Its complement here, Vaughan Williams’ setting of William Barnes’ ‘Linden Lea’, surged lyrically forward, undemonstrative but direct. The image of ‘cloudless sunshine overhead’ was injected by Williams with a warmth and expansion that was deeply consoling; there was pleasing self-assurance in the quickening step of the final stanza, though a sudden withdrawal before the final three lines of lingering allegiance - ‘Or take again my homeward road/ To where, for me, the apple tree/ Do lean down low in Linden Lea’ - was moving.

The turbulence hidden by the frozen landscape as evoked by Müller in ‘Auf dem Flusse’ was recalled in Hubert Parry’s setting of Langdon Elwyn Mitchell’s ‘Nightfall in winter’. The piano prelude dripped chillingly, icy drops falling from wintry branches, and Williams’ baritone was gently hushed: ‘Cold is the air/ The woods are bare/ And brown’. But, later, the piano’s ethereal swirling conjured emotional unrest of Williams’ statement - sustained, growing in strength - that ‘The night is come’. Ivor Gurney’s ‘On the Downs’ (John Masefield), which followed segue, had rhetorical force, while in Finzi’s eerie setting of Thomas Hardy’s ‘In the mind’s eye’, the phantom of Hardy’s first wife, Emma, was as false and deceiving as the Will o’ the Wisp of Schubert’s ‘Irrlicht’. Only with the certainty that ‘She abides with me’ did Williams’ baritone acquire a fuller warmth, and the piano’s echoing repetitions of the vocal line in the final verse confirmed the eternal presence of Emma’s ghostly form. Gurney’s ‘Sleep’ (John Fletcher) was introspective but, in the enriched final plea, ‘O let my joyes have some abiding’, deeply earnest; I was impressed by the way the restrained evenness of the piano accompaniment made its own telling impact.

In Schubert’s ‘Frühlingstraum’ the wanderer dreams of springtime and love but wakes to a numbing darkness and the shrieking of ravens. George Butterworth’s setting of Housman’s ‘Bredon Hill’ began with the vibrant ringing of bells as Williams sang brightly of happy memories. But thoughts of air-born larks, Sunday gatherings and ‘springing thyme’ gave way to more sombre reflections on love and loss. In the final stanza Williams responded to the tolling beckoning with the plummeting acquiescence, ‘I hear you’, and a dark confirmation, ‘I will come’. Williams’ technical assurance in Gurney’s ‘The folly of being comforted’ (Yeats) allowed him to communicate both loneliness and the hope that Time would make ‘her beauty over again’. Any sense of consolation, however, was swept aside by the pained disintegration of the closing lines - ‘O heart! O heart! If she’d but turn her head,/ You’d know the folly of being comforted.’

The clanging dissonances of the journeying railway carriage in Britten’s ‘Midnight on the Great Western’ were an onomatopoeic match for the post-horn of Schubert’s ‘Die Post’, and it was to Thomas Hardy that Drake and Williams turned again to engage with the draining despondency of ‘Die Krähe’ (The Crow) and ‘Letzte Hoffnung’ (Last Hope). The dreamy melodiousness of Judith Weir’s setting of ‘The Darkling Thrush’ was punctuated by harp-like flourishes in the piano part which prompted the voice to tremulous enrichment and hope, as the thrush’s ‘full-hearted evensong/ Of joy illimited’ was heard. Drake’s introduction to Gerald Finzi’s ‘The too short time’ seeped limpidly but Williams’ penetrating focus animated the poetry, and the piano surged with momentum into the second stanza’s vision of sunlight that ‘goes on shining/ As if no frost were here’. These two Hardy settings were preceded by Williams’ own setting of Blake’s ‘The Angel’, where the gentle brushes of the piano established a compelling pulse for the unaccompanied folk-like melody which highlighted the intent communicativeness of Williams’ baritone.

In Vaughan Williams’ ‘Whither must I wander?’ (Robert Louis Stevenson) Williams’ strong lower register had a demotic directness that was persuasive and enthralling. He again proved himself a natural storyteller in Butterworth’s ‘The lads in their hundreds’ (Housman), singing with an absorbing directness of expression which made its point about the lads who ‘will die in their glory and never be old’ without undue sentimentality. Britten’s rhythmically sprung setting of Walter de la Mare’s ‘Autumn’ conjured a sad, troubling wind, redolent of the stormy swirls of Schubert’s ‘Der stürmische Morgen’.

The closing songs of the sequence acquired a disturbing urgency. The despairing supplication at the end of Britten’s ‘Before Life and After’ (Hardy) - ‘How long, how long?’ will it be ‘Ere nescience shall be reaffirmed’ - gave way to the ceaseless wandering in the ‘unfathomable deep forest’ of Gurney’s ‘Lights Out’ (Edward Thomas). Williams found courage in Tippett’s appeal, ‘Come unto these yellow sands’ (Shakespeare); the baritone relished the drama of Tippett’s word-setting: ‘The watch dogs bark;/ Bow-wow,/ Hark hark!’ The piano’s speculative rovings opened Britten’s ‘I wonder as I wander’ (Anon.) and Drake repeatedly vivified the details of the largely unaccompanied vocal line. The open vista of the ending, ‘I wonder as I wander out under the sky’, was closed only by the chords which commenced the following, final song - Gurney’s setting of John Masefield’s ‘By a bierside’. Williams had saved his strongest vocal presence for this closing song: his baritone was true and penetrating, ‘It is most grand to die’, while Drake’s postlude was filled with fury, majesty and, ultimately, sadness, the final notes seeming to call to us from beyond the grave.

Williams has an innately relaxed baritone and an open-hearted demeanour. His diction was exemplary and his alertness to textual nuance impressive. The low platform and semi-circular configuration in Middle Temple Hall encouraged a closeness and warmth between performers and listeners. Seated to the central fore, I often felt that Williams was singing directly and intently to me alone.

Claire Seymour

An English Winter Journey: Roderick Williams (baritone) and Julius Drake (piano)