January 30, 2017

Falstaff in Genoa

Both earlier productions designed by his long time operatic scenic collaborator Margarita Palli.

This Luca Ronconi Falstaff production was first seen in Bari in 2013 (then in Naples and Florence). It is designed by Tiziano Santi, normally a collaborator in Ronconi’s non-operatic theater projects. Santi’s set is nothing more than walls of blank canvases, including the show curtain itself, against which walls Verdi’s gigantic comedy takes place. It is minimalist staging, the scenes traveling presentationally back and forth across downstage. Finally it was a purely verbal Falstaff, staged so the we heard every word uttered both by the voice on the stage and by Verdi’s orchestra in the pit. And we clearly saw every word lived by the opera’s protagonists.

29 year-old, wunderkind conductor Andrea Battistoni was in the pit engaging the hyper alive Genoa orchestra with the stage, magnifying the “Falstaff immenso! enorme Falstaff!” announced by Sir John Falstaff into monumental proportion, driving the punctuating cadences to every last one of Verdi’s intended exclamation points, delighting in the sweet, fleeting encounters of the young lovers, encouraging the female chatter and indulging the Italian male cuckold fetish to its absolute maximum. It was a conducting tour de force, sparks still flying from the tip of his baton (stick still in-hand) at his stage bow.

Ford's tractor, Fenton extreme left, Ford in hat with feather extreme right

Ford's tractor, Fenton extreme left, Ford in hat with feather extreme right

The Genoa cast of January 28 found a distinctly Mediterranean bias for Ronconi’s simple English farm life — The Italiano Alberto Mastromarino as Falstaff, Brazilian born, Spain finished baritone Rodrigo Esteves as Ford, Serbian born and trained Nenad Čiča as Fenton, Livorno born Valentina Boi as Alice. Plus two Russian born artists who have become Italian artists — Anastasia Boldyreva as Dame Quickly and Daria Kovalenko as Nanetta. Add to these the bevy of Italian male buffo character roles that were plumbed to perfection in the inimitable Italian buffo tradition.

Interestingly this was the second cast, singing two of the five performances, but you could not imagine or wish for more finished performances. Sir John Falstaff was of believable girth, of quick spirit and of powerful voice. You could, for moments from time to time, even believe that this Falstaff was an honest predator and not simply a caricature of delusion. He quibbled with Ford as an equal, triggering Rodrigo Estives, a very smart-looking, too handsome farmer, to go-off-the-deep-end in forceful hyper-baritonal terms. Note that the Ford disguise was dark glasses and, wittily, a pillow stuffed under his jacket to add girth. Fenton was dressed in bibbed denim trousers, the classic piece-of-straw chewin’ farm hand, tenor Nenad Čiča’s “Dal labro il canto estasiato vola” exquisitely wrought in tenorial flight.

The Alice Ford of Valentina Boi was ever so slightly maternal, her ample lyric voice buoying the fracas of female voices in Ronconi’s barnyard (sketched by nothing more than four geese in a line), pedaling on and off on fantastical antique bicycles with her daughter, Nanetta, sung by Daria Kovalenko in her little-girl operetta-like voice. Anastasia Boldyreva found the richness of tone to vocally convey Verdi’s satiric Quickly, yet it was the voice of a real woman (and gratefully not a cameo appearance by a famous over-the-hill diva). Meg Page did what she always does — stayed out of the way except when needed.

The upside down oak tree

The upside down oak tree

It was perfect theater, well until Act III when the Herne, the Hunter’s Oak inexpicably flew in upside down and dramatically the carefully entwined threads lost direction. Focus was further diluted by Nanetta’s anemic delivery of “Sul fil d’un soffio etesio.” It is possible that the slight musical insecurities inherent to a second cast noticed throughout the evening became more pronounced. We were left musically and dramatically adrift until finally the 10 protagonists walked across the stage apron to sit on the lip and deliver Falstaff’s immense and enormous fugue “Tutto nel mondo è burla, l’uomo è nato burlone” directly under the conductor’s baton. It was indeed Verdi’s 10 voiced fugal joke as never before, his response maybe to Wagner’s 50 voiced Meistersinger riot and certainly a bit of well-meaning one-upmanship to the great ensembles of Rossini himself.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Sir John Falstaff: Alberto Mastromarino; Ford: Rodrigo Esteves; Fenton: Nenad Čiča; Dottor Cajus: Cristiano Olivieri; Bardolfo: Marcello Nardis; Pistola: Mihailo Šljivić; Mrs. Alice Ford: Valentina Boi; Nannetta: Daria Kovalenko; Mrs. Quickly: Anastasia Boldyreva; Mrs. Meg Page: Manuela Custer. Chorus and Orchestra of the Teatro Carlo Felice. Conductor: Andrea Battistoni; Production: Luca Ronconi; Stage Director: Marina Bianchi; Scenery: Tiziano Santi; Lighting: A. J. Weissbard. Teatro Carlo Felice, Genoa, Italy, January 28, 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Falstaff_Genoa1.png

product=yes

product_title=Falstaff at Teatro Carlo Felice

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Valentina Boi as Alice, Alberto Mastromarino as Falstaff [All photos courtesy of Teatro Carlo Felice

January 26, 2017

Traviata in Seattle

The exact proportions of the blend in any given staging would of course vary according to the character of the work in question. Le comte Ory, whatever else it is, is frivolous entertainment, and received a hyper-frivolous staging, with doll-like puppets gamboling in a toy-store window setting. Nabucco, whatever else it is, is achingly serious drama, and got a suitably solemn approach.

La traviata is quite a different matter. There are literally dozens of productions available for remounting, most of them fairly bland, set up to frame conventional notions about Verdi’s pathbreaking music drama, with thought, if employed at all, goes into decorative details

For his Traviata, Lang chose to revive Peter Konwitschny’s 2011 Graz staging, which was quickly taken up at the English National Opera and just as quickly revived there.

Corinne Winters (Violetta) and Joshua Dennis (Alfredo)

Corinne Winters (Violetta) and Joshua Dennis (Alfredo)

Seeing the Seattle Opera staging beside the Graz original on video, makes it perfectly clear that Konwitschny, as proudly high-handed in his approach the the operatic classics as any director living, requires the most meticulous adherence to his own instructions. I don’t think I saw a moment or movement on the McCaw Hall stage which varied by a hair from what’s to be seen in the live video.

It was nevertheless revelatory seeing this stereotyped staging in full. Choices which once were puzzling to me now seem explicable, moments I thought I grasped now seemed odder when viewed in context.

The most successful directorial intervention is playing all four scenes without a break. Traviata is a remarkably short opera considering the dramatic range covered, and if a soprano is willing to submit herself to such unrelenting exertions, the audience’s hour and fifty minutes in their seats are amply recompensed in the continuing tension of the drama.

But two other major interventions damage the overall impression badly, which suffers badly from the unshifting point of view of a theater seat. Konwitschny sees Alfredo Germont as a . . . a what? A dweeb? A geek? Not, externally at least, a passionately romantic nature: This Alfredo wears cardigan sweaters, horn-rimmed spectacles, in never seen without a book even while being introduced to a famous courtesan whom he has long worshiped from afar. Franco Corelli would have been hard-put to overcome this handicap; and Joshua Dennis is too honorable to work against it.

Maya Lahyani (Flora) and Corinne Winters (Violetta) [Photo by Jacob Lucas]

Maya Lahyani (Flora) and Corinne Winters (Violetta) [Photo by Jacob Lucas]

The second interventions begins promisingly but veers fatally off-course. Speaking about Traviata as a work, Aidan Lang rightly identifies the first scene of act two as the dramatic and emotional heart of the opera and Germont père as the most crucial character. Where, on the spectrum from paternal love to cold calculation, sincere appeal to relentless manipulation, does his heart lie?

Konwitschny’s approach renders him an utter enigma. Weston Hunt uses a warm, enveloping voice and his imposing physical bulk to present a classic troubled father. Even the director’s decision to bring Alfredo’s (much) younger sister on stage to reinforce the father’s appeal to the honor of his family (and loss to her marital prospects) seems defensible.

Then, in one gesture, the who picture collapses. Pestered by the child while making a point, Germont strikes her savagely across the face, knocking her to the floor. Then, while Violetta (and the audience) stare at him in horror, suavely continues his appeal.

The violence recurs, with as little motivation and effect as before. Violetta cuddles the child protectively but hands her passively back to Germont in agreeing to his terms for abandoning Alfredo. The contradiction created by Germont’s action engulfs her as well. To the end of the scene nothing that happens makes sense.

Eliana Harrick (Germont's Daugher) and Corinne Winters (Violetta)

Eliana Harrick (Germont's Daugher) and Corinne Winters (Violetta)

From this point onward oddity and bizarrerie intrude more and more deeply. The movement of the chorus in the first scene at Violetta’s party was stylized to the point of parody; in the second scene of act twotheir behavior goes beyond the parodic as they first constantly parade across the stage during Alfredo’s encounter with Violetta before collapsing to the floor in a heap and crawling off the stage on their bellies during the celestial prelude to act three.

After this, one barely asks why Doctor Duphol is wearing a party hat covered with green glitter when he comes to attend Violetta. Cause and effect are no longer a consideration. For me, the little has was the last straw. I suddenly saw the show as a conventional, even routine walk through of a masterpiece, the spare stand-and-deliver blocking dotted with conspicuous peculiarities to distract from the lack of contact between the players and lack of development within them.

The fearless soprano Marliss Petersen, in almost constant close-up, punches right though this inertia in the Graz video. On the McCaw stage, bare and draped in interminable red, Corinne Winters can’t escape the chill of the void, the clichés of her costuming (black Lulu wig in scene one, Doris Day ditto in scene 2 . . .), the hollowness of the dramaturgy. Her effort is nonetheless heroic. I hope that she is better supported by the new production of Jenůfa here which opens in late February. With little emotion and next to no serious thought, this Traviata doesn’t meet the ambitions declared for the company by its director and board.

Roger Downey

image=http://www.operatoday.com/170110_Traviata_pn_-1779.png image_description=Corinne Winters (Violetta) [Photo by Philip Newton] product=yes product_title=Traviata in Seattle product_by=A review by Roger Downey product_id=Above: Corinne Winters (Violetta)Photos by Philip Newton

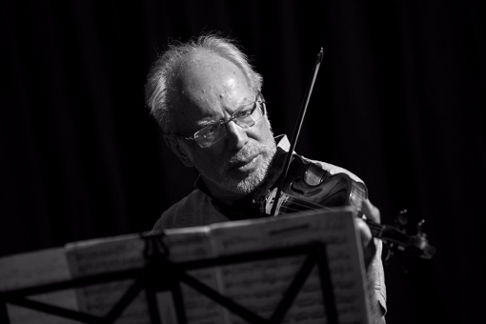

When Performance Gets Political: A Brooklyn Concert Benefiting the ACLU

However, after Trump suggested he may defund the National Endowment for the Arts, politics have become deeply personal for artists across the nation and the world. A group of New York-based classical musicians have decided to make their voice heard in an eclectic concert featuring solo voices and instruments, cleverly named “PiaNO” to indicate the lack of piano and also the “no” that resounds so clearly from dissenters of the Trump administration’s values and proposed policies.

“The election left me and many of my loved ones feeling scared and powerless. However, as an artist, I also felt fired up and ready to do something for my community,” says Chelsea Feltman, soprano, of her involvement with PiaNO.

Soprani Elise Brancheau, Chelsea Feltman, and Katya Gruzglina will sing, while Timothy Leonard, David Rocca, Charlotte Nicholas, and Christian Berrigan, will play cello, bassoon, violin, and guitar, respectively. The evening is presented by the Vertical Player Repertory, founded by Judith Barnes, and all proceeds from the concert will go to support the New York chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

“I have been a longtime supporter of the ACLU for the work they do to protect civil rights throughout the US, and this seemed like a tangible to use my skills to contribute to their cause,” says Feltman.

The program includes a mix of unusually programmed pieces: Bist du bei mir (attributed to J.S. Bach, but actually from an opera by Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel), Philtrum, a contemporary composition by Andrew Hsu and poet Taije Silverman, I Never Saw Another Butterfly by Lori Laitman, which sets poetry written by children killed in the Holocaust, and Suite for Violin and Voice by Heitor Villa-Lobos, a set pairing violin and voice inspired by Portuguese folk melodies.

Feltman says of the programming, “We wanted to feature music from across genres. We also had ideas of the program being easily portable and reprisable, so not bound to a space with grand piano (or any piano!)!”

Soprano Elise Brancheau says, “Not being bound to a traditional format has been incredibly freeing. We were able to choose repertoire based on musicians who wanted to be involved.”

This celebration of songs across culture and time will oscillate between the whimsical and the melancholy, and will represent many voices, including those of the artists who feel now is a time for action.

Feltman underlined the need for artists to take action, saying, “Even if you don’t raise money, art in itself brings healing to communities, promotes sympathy, and is an important tool in affecting societal change. Don’t wait for someone to present you with an opportunity; go out there and make it happen.”

PiaNo will have one performance Saturday, January 28th at 7 PM at Behind the Door, 219 Court Street in Brooklyn, NY. Tickets are $20 ($10 with student ID) and all proceeds will go to benefit the New York Chapter of the ACLU. Tickets can be found at: http://songswithoutpiano.brownpapertickets.com/

Alexis Rodda

image=http://www.operatoday.com/piaNO_logo.gif image_description= product=yes product_title=When Performance Gets Political: A Brooklyn Concert Benefiting the ACLU product_by=Commentary by Alexis Rodda product_id=January 25, 2017

Wagner at the Deutsche Oper Berlin Part II: Kasper Holten’s angelic Lohengrin

Holten’s vision turns out a facilitating backdrop to put Wagner’s musical cosmos on a pedestal. From the Orchestra of the DOB, Alex Kober coaxed an electrifying momentum burning with brilliance in the musical details of Wagner’s early masterpiece. The evening flew by.

Act I opens with a shooting star on the hanging backdrop. The meandering fog making its way lowly across the stage during the slow-burning, lusciously misty Overture, evoked my memory of the cloak of morning fog covering Lake Lucerne during my Swiss adventure to Tribschen, where Wagner composed Lohengrin around 1850. I can’t imagine a better way to open this opera. And this was just the beginning.

Annette Dasch conquered the audience with her stunning portrayal of Elsa von Brabant. She captivated from the moment she appeared on stage. Dasch endowed Elsa with a chastity and devotion, which she reflected with ferocious virtue in her voice. She equally convinced in her growing panic and doubt concerning the true name of her savior and husband, Lohengrin.

In Act II, the slim beams with green light vertically erected on stage, I associated with the Northern Lights, from where, I imagined, Ortrud drew her powers. Elisabete Matos sang sinisterly brooding and highly vindictive. Her voice resonated all the envy Ortrud requires. Matos proved a scene stealer as Ortrud manipulated Telramund into her scheme to seed doubt in Elsa about Lohengrin’s origin. An intimidating and threatening tone permeated Wolfgang Koch’s angerful Telramund.

The light and darkness, Elsa’s innocent virtue and Ortrud’s jealousy and cunning, could not have been more strongly reflected than in the contrasting timbres of Dasch and Matos.

Dasch proved a riveting actress on all fronts. Rich in sound, convincingly emotional, and absolutely glamourous. What a voice! What great acting! I was absolutely enamoured by her.

Slightly superheroic with swan (or angel?) wings on his back, Peter Seiffert put on an honourable and warmhearted Lohengrin. Jesper Kongshaug’s lighting and smoking effects added explosive dramatic energy during Seiffert’s showstopping first appearance as Lohengrin...but no swan to be seen except for the wings on his back.

In the Third Act when he reveals he is Parsifal’s son, Lohengrin radiated nobly, almost saintly. Is Holten’s Lohengrin an angel as well? Yet even with his divine voice, Seiffert could not compete with Dasch's starpower. Still, above all, their synergy surged in romance and despair during their wedding night duet.

Holten’s ideas had some drawbacks. Gottfried’s role felt absently unexamined. At the front of the stage, his body was outlined as if at a modern crime scene. At the end, Ortrud redrew the lines emphatically provocative. It served as a continual reminder of Gottfried’s death.

After the glorious Bridal Chorus, during the wedding night, Holten’s strange inclusion of a one-person wedding bed with one pillow, that turned out to be Gottfried’s coffin covered by a white sheet with the corpse of Gottfried. In an unforeseen twist Holten seems to suggest that Ortrud was right. Elsa killed Gottfried? So there was no swan? Is Lohengrin then an angel?

Whatever these mysteries for interpretation, they certainly didn’t impede any of the musical drama.

In two last minute replacements, Günther Groissböck sang with a majesty that seemed to be emanating from every fibre of his body. His dashing and virtuous demeanor made for an excellent King Heinrich. Equally impressive as substitute was Markus Brück as Announcer of the King. However brief his moments, Brück owned the stage with his grounded voice as if he was the actual lead character.

With Alex Kober, the Orchestra of the DOB’s luscious strings carried on Wagner’s fast-paced drive. From the balconies or from high up in the wings, the brilliance from the brass and pulsating percussion resonated in Wagner’s majestic passages, providing spectacular moments in Act III.

In addition, under Kober the solos flashed, more so than in the powerful and thickened texture of Runnicles’s Parsifal. Then again, Lohengrin has the lighter touch of a younger Richard, whereas his last opera has a much consuming score. Runnicles optimized the power of Parsifal’s length that forces the listener to travel deeper into Wagner’s intoxicating musical cosmos.

This was just the DOB in the Fall. If you at their programming this spring, they cast the best Wagner singers (including, Herlitzius and Westbroek) for the final two performances of its current production of Ring Cycle in April. You can still catch in this Lohengrin in February.

While for the newcomers, a visit to Tannhäuser or Der fliegende Holländer should be a highly encouraging introduction to Wagner’s world.

If you can’t make it to Bayreuth, when it comes to frequent and consistent Wagnerian vocal extravagance, the Deutsche Oper is the place to be in Berlin.

David Pinedo

Heard December 11, 2016, Deutsch Oper Berlin.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lohengrin_MLieberenz4207.png image_description=[Photo by Marcus Lieberenz] product=yes product_title=Wagner at the Deutsche Oper Berlin Part II: Kasper Holten’s angelic Lohengrin product_by=A review by David Pinedo product_id=Photos by Marcus LieberenzWagner at the Deutsche Oper Berlin Part I: Stölzl’s Psychedelic Parsifal

Donald Runnicles led Parsifal, and Alex Kober took care of Lohengrin. The stagings were not by the same director nor in any way connected. Still, it felt pleasantly familiar to return to DOB with the rich sound of the orchestra and the superior singers musically connecting the connections of Wagner’s father and son mythology. I preferred Holten’s Lohengrin straightforward staging rather than Stölzl’s convoluted, though intellectually stimulating, madness in Parsifal. The shortcomings or excesses on stage barely mattered against the superlative musical experience.

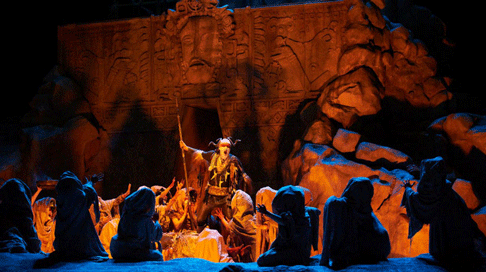

Premiering in 2012, Stölzl’s psychedelic Parsifal trip visualizes in three tableaux vivants the gruesome sides to religion. Far from the healing timelessness usually experienced during Wagner’s last opera, Stölzl’s merging of different narratives with Wagner’s already convoluted mythology made for some tricky confusion.

Was Stölzl trying to approach Wagner’s Parsifal with a tongue-in-cheek angle? Klaus Florian Vogt, dressed like John Travolta in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, seemed to be on a hallucinatory experience through space and time. Kathi Maurer’s anachronistic, yet stylish, black suit made this Parsifal totally out of place in Stölzl’s historical settings.

In Act I, Parsifal ends up at Jesus’s Crucifixion. At first I thought Kundry might have doubled for Mary Magdalene, but then her laughter confused me. And were the Knights of the Grail here Crusaders?

The dying Amfortas was accompanied by a dimly lit stage. Stumbling on Mount Golgotha as if he jumped out of a time warp, Vogt’s lithe tenor voice brightened up the stage that, together with Ulrich Niepel’s mood altering lighting, effectively purified the gruesome biblical scene. The profoundly impressive Choirs of the DOB closed Act I, and made up for Stölzl’s taxing affairs on stage.

In the Second Act, we move on to Aztec times, where Klingsor appears to be Chief of the tribe. We get another human sacrifice. Here the electrifying Flower Maidens turn out to be cannibals after Parsifal. Kundry with her scream saves Parsifal. He kills Klingsor with the spear. By now I had given up on disentangling Stölzl’s historical superimpositions on Wagner’s cosmos. I let myself just be swept away in Runnicles’s blissful momentum of Wagnerian opium.

In Act III, I think we are in the present. A minescape forms the setting of the baptizing of Kundry; the death of Amfortas by Parsifal; and finally, the worshipping of the new King. For practitioners of intellectual masturbation, a second viewing might be necessary to dissect all the overlapping layers. But the singers were impeccable and nonetheless convinced dramatically in Stölzl’s mindbending adaption.

Vogt appears late in Act I, which really belonged to Thomas Johannes Meyer’s regally sung Amfortas and Daniela Sindram’s Kundry. But when Vogt appeared he sang with his famous lyricism. His voice melted beautifully into Runnicles’s rich texture. He moved me to tears, basking in the glow of the DOB Orchestra, in his finale song about the spear.

Daniele Sindram dosed Kundry with the perfect amount of frenzy without any overacting. In Act II in her interactions with Parsifal, she moved impressively from the motherly care to the seductive attempts as lover. A commanding presence, Sindram generated captivating chemistry with Vogt.

Andrew Harris’s old Titurel walked with shaky fragility, but he sang with with noble strength. Derek Walton's flamboyant Klingsor brought enough creepy ambiguity for his sexless character. The rest of the supporting cast sang pretty much flawlessly adding to the glorious vocal experience.

The specific religious scenery of Stölzl’s production does undercut Wagner’s already complex mythology. But with first class singers, Stölzl’s changes (to some perhaps heretical) are quickly forgiven. Most of all, the Orchestra of the DOB reflected Principal Conductor Runnicles’s mastery of Wagner’s work.

David Pinedo

Seen October 30, 2016, Deutsche Oper Berlin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/PARSIFAL_3MB1082_MatthiasBaus.png image_description= [Photo by Matthias Baus] product=yes product_title=Wagner at the Deutsche Oper Berlin Part I: Stölzl’s Psychedelic Parsifal product_by=A review by David Pinedo product_id=Photos by Matthias BausJanuary 24, 2017

Donna abbandonata: Temple Song Series

The last time I saw her perform she was magnificent as a spurned Elvira, all fury and frenzy, in Richard Jones’ Don Giovanni at ENO. On this occasion, at Middle Temple Hall, she conjured the despondency and desperation of a deserted Cretan princess, rustic lasses from Galicia and Italy, and an elegant Parisian whose love affair is callously ended by a fraught, fragmented telephone call.

This was a technically and emotionally taxing programme, which called for extremes of euphoria and despair, and considerable stamina. Two solo dramas framed five songs by Ravel that, despite their relative brevity, did not allow Rice to take her foot off the emotive pedal. Drake was, as ever, a composed, unobtrusive but unwaveringly intent partner.

Haydn’s dramatic solo cantata, Arianna a Naxos, went down well with London audiences when it was performed in February 1791 by the castrato Gasparo Pacchierotti, with Haydn accompanying on the harpsichord. In the dignified, ornate introduction to the first recitative - which depicts Ariadne’s dawn awakening - Drake captured something of the crispness and melodic clarity of this instrument, though his close observance of Haydn’s dynamic and expressive markings, most particularly in the gentle in-between phrase commentaries, suggested the expressive character of the fortepiano, with its soft, light tone and vibrant sforzandos.

Rice made much of the variety of Haydn’s dramatic modulations, moving from sleepy appeals to the absent Theseus - her hand caressing her cheek in dreamy remembrance - to heightened frustration. Initially her vibrato was quite wide, giving Arianna’s impassioned cries a plum-rich tone but adversely affecting the centring of the pitch. However, in the succeeding aria, ‘Dove sei, mio bel tesoro?’ (Where are you, my beloved?), the sensuousness of her mezzo came into its own as, with earnest solemnity, she begged the Gods to allow her beloved to return to her. Rice shaped the fragmented vocal line well, as Arianna’s growing anxiety was underpinned by harmonic twists to and from the minor mode, culminating in punchy piano punctuations heralding the second recitative section, ‘Ma, a chi parlo?’ (But to whom am I speaking?). A whispered pianissimo diminished fragilely, as the Echo mocked her pleas; then, warmth conveyed hope - ‘Poco da me lontano esser egli dovria’ (He cannot be far from me). The span of the vocal part is not wide and the piano accompaniment offers detailed depiction - of Arianna’s ascent to the cliff-top, of the wind and waves that carry away her agitated words - but Drake never overpowered the vocal line as the tempi chopped and changed, and silence alternated with dramatic rhetoric.

Having witnessed her lover’s departure, and overcome with despair, Rice’s frail reflections, ‘A chi mi volgo?’ (To whom can I turn?), were ironically decorated by the piano, the slightest delay of the off-beat semi-quavers brilliantly conveying the pulsations of Arianna’s trembling heart. Then, having recovered her nobility and strength for the concluding aria, ‘Ah, che morir vorrei’ (Ah, how I long to die), Rice exploded in anger and grief - a woman scorned, vitalised by passion and anguish.

Rice’s ability to encompass and move between a variety of dramatic moods was put to good effect in Ravel’s Chants populaires, as was the mezzo’s linguistic dexterity. Singing with directness and strong character, she shifted easily from the bright bucolic simplicity of the ‘Chanson française’, which somehow managed to seem both naïve and knowing, to the intensity of the ‘Chanson italienne’, whose extravagant outbursts and plummeting lament - ‘Chiamo l’amore mio, nun m’arrisponde!’ (I call my love, no one answers!) - consolidated the evening’s theme. I loved the ‘Cancion española’, which combined sultry heat with a ‘La la’ refrain of dreamy coolness. Rice relished the rich Yiddishisms of the ‘Chanson hébraïque’, modifying her mezzo for the young Mejerke’s reply to his father in the final line of each stanza, and the performers’ following this stirring exchange with Ravel’s Kaddisch - a worshipful prayer of exaltation to conclude the first half of the recital.

Julius Drake. Photo credit: Sim Canetty-Clarke.

Julius Drake. Photo credit: Sim Canetty-Clarke.

After such riches, I keenly anticipated Poulenc’s 1958 opera La Voix humaine. But, while the performance was consummately accomplished, with singer and pianist in unwavering accord, I wondered whether the decision not to re-print the libretto in the programme was a wise one. Cocteau’s 1927 play on which the opera is based depicts a tumultuous telephone conversation between an unstable young woman, Elle, and her former lover. Richard Stokes’ synopsis deftly and eloquently outlined the traumatic twists and turns of their altercation, but one needed a facility in the French language in advance of my own if one was to follow the precise emotional trajectory of the interchange. Such clarity of context is surely crucial given that the conversation ranges from outright lies to recollections of love letters, from revelations and confessions to garbled nonsense, and is constantly interrupted by the intrusions of the operator and other callers, wrong-numbers and disconnections.

Stokes explains the omission of the libretto text in a programme note, suggesting that, ‘To fully experience the emotional force of this great work, it’s crucial for the audience not only to hear but also see the heroine’s commotion’. I certainly agree that Rice, using an infinite array of gesture, posture and facial expression to suggest impending nervous collapse and suicidal despair, was an utterly gripping stage presence, whose wretchedness and decline was painfully absorbing.

But, without some clearly defined ‘signposts’, it was hard to wholly grasp the dramatic and emotional structure of the whole. Poulenc’s opera starts at fever pitch and escalates from there. And, while Rice’s registral range was as impressive as her ability to project with ease and gleaming clarity the highest vocal motif, there was, particularly towards the close, less variety of colour than I’d have expected. Moreover, if we do not know exactly what Elle is saying, how can we conceive of the unheard respondents whose absent words so powerfully invite imaginative reconstruction and thus draw us into the drama?

Rice sang from the score and there was no ‘staging’. Nor was any needed. But, I questioned, too, the absence of the telephone that is almost a second character in the work. This is not a monologue: all of Elle’s words are, in effect, addressed to the telephone. It is a conduit to other characters whose voices we never hear. It is her physical companion: she caresses it and entwines it around her. In the end, she goes to bed with the receiver and seems to strangle herself with its cord. In this way, Cocteau shows how the notorious French telephone system of the period when the opera was written impedes communication and relationships, exacerbates Elle’s hopelessness, and increases the poignancy of her loneliness. Interesting, Cocteau - who gave Poulenc strict instructions about the design and staging of the opera - insisted that he should not create a true bedroom, but a bedroom ‘asleep with remembering’: a room which contained just a woman and the phone she holds ‘like a revolver’.

But, such digressions and reflections should not detract from the quality of the performance itself, which was a powerful psychological portrait of anguish and anger, hope and loss of heart, culminating in drained resignation. Rice showed once again what an astonishing singing actress she is: her flexible mezzo coped effortlessly with the shifting vocal contours and the rapid vacillations of short snatches. When the music blossomed into lyricism, the beauty of the vocal sound was touched with a rawness, which spoke powerfully in the unaccompanied utterances.

Once again, Drake’s attentiveness, precision and ability to convey precise moods through colour, weight and sustain, was astonishing. Never once did he seem to be ‘accompanying’; rather, his disjointed gestures echoed Elle’s psychological disintegration, while the piano’s more lyrical expansions seemed to offer nostalgic glimpses of the past.

One may at times have missed the sumptuousness of Poulenc’s orchestration (the composer notes at the beginning of the score, ‘The entire work should be bathed in the greatest orchestral sensuality’), but there was no lack of feeling at the close, as Rice descended from hysterical heights to crushed futility: ‘Je t’aime, je t’aime … t’aime.’

Claire Seymour

Christine Rice (mezzo-soprano), Julius Drake (piano)

Haydn - Arianna a Naxos Hob.XXVIb:2; Ravel -Chants Populaires and Kaddisch; Poulenc/Cocteau - La Voix Humaine

Middle Temple Hall, London; Monday 23rd January 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Christine_Rice_%28c%29_Patricia_Taylor_WEB-480.jpg image_description=Christine Rice product=yes product_title=Temple Song Series, Middle Temple Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Christine RicePhoto credit: Patricia Taylor

January 22, 2017

Fortepiano Schubert : Wigmore Hall

For this recital, he was joined by Georg Nigl, an Austrian baritone, who once was a soprano soloist with the Wiener Sängerknaben. Perhaps that background shaped Nigl's finely detailed approach, which suited Staier's restrained but expressive style. In a programme focused on mainly early Schubert, the balance was nicely poised.

Early Schubert, though, isn't always showcase material, except perhaps to devotees, who relish it dearly. Schubert's Andenken D99 (1814) will always be outshone by Beethoven's setting of the same poem, though on its own terms it's a delicate piece of youthful innocence. Nigl and Staier presented a set of six Schubert settings of Friedrich Matthisson (1767-1831) which Schubert set between 1813 and 1814, almost certainly being aware of Beethoven' settings of Matthisson. Schubert's admiration for Beethoven knew no bounds, but, apart from Andenken, he was cautious enough to set poems other than those Beethoven chose. The Matthisson songs Nigl and Staier performed included lively spook tales like Die Schatten D50, Geistenähe D100 and Der Geistertanz D116, but the rather more sophisticated poetry of Der Abend (Purpur malt die Tannenhügel.) D108 inspired a lyricism which clearly suggests Schubert's idiomatic style.

The Matthisson settings were followed by six settings of Ludwig Heinrich Christoph Hölty (1748-1760), whom Brahms was to set so well. Schubert's Hölty settings include An den Mond D193, but here we heard the lovely Die Mainacht D194 (1815), Frühlingslied D398 (1816), and Die Knabenzeit D400 (1816) where the instrumental line dances with cheerful vigour. Staier's playing was meticulously lucid, never over-dominant, and responsive to Nigl, who has an attractive voice but may have been unwell. He looked flushed. We all get sick sometimes, and singers are no different. At moments his voice filled out well. The words "Freud' ist überall" from Erntelied D 424 (1816) soared nicely, suggesting how Nigl might sound when on form.

With Abschied "Über die Berg zieht fort" D475 (1816) after the interval, Nigl's voice at last blossomed. The song is dear to him, as he said after the recital, repeating it with even greater poise as an encore. The gentle cadences in this song revealed the richness of Nigl's voice at the lower end of his register. Staier shaped the delicate triplets and firm single chords with plangent finesse. Staier's recording of Schubert's Mayrhofer songs with Christoph Prégardien , made in 2001, is still an essential choice for any Schubert lover, so it was interesting to hear him with Nigl, who, though a baritone, has a lighter timbre than many. Apart from Abschied and Nachstück D D672 (1819), Staier and Nigl performed Orest und Tauris D548 (1817) Erlafsee D685 (1817) and Beim Winde D669 (1819). Staier also recorded Schubert Seidl settings with Prégardien, so it was a delight to hear him again, now with Nigl, in old favourites like Der Wanderer am Mond D870 (18126) Das Zügenglöcklein D 871 (1826), Am Fester D878 (1826) and Irdisches Glück D 866/4 (1828). These late songs, though technically demanding, are also easier on the ear than some of the early songs, thus always welcome.

Nigl and Staier concluded with two settings of Franz von Schober, Schubert's raffish companion, Genügsamkeit D143 (1815) and Schiffers Schiedelied D 910 (1827), the driving "ocean waves" in the piano part sounding rather livelier on fortepiano than they would on some keyboards. Heavy pedalling makes heavy weather ! The singer shouldn't drown. Neither song is a masterpiece, though they are worth knowing. As a friend observed "Genügsamkeit" doesn't mean "contentment" but a double edged feeling of having "enough"to be happy with, though you wouldn't mind having more.

Anne Ozorio

image=https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4e/FortepianoByMcNultyAfterWalter1805.jpg/256px-FortepianoByMcNultyAfterWalter1805.jpg

product=yes

product_title= Schubert Lieder; Andreas Staier, Georg Nigl, Wigmore Hall, London 18th January 2017

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=

Baroque at the Edge: London Festival of Baroque Music, 12-20 May 2017

Artistic Director Lindsay Kemp said: “This year’s two anniversary composers come from opposite ends of the Baroque era, which got me thinking about ways in which musical styles and tastes change over time. At times such as the transition from Renaissance to Baroque around 1600, and from Baroque to Classical around 1750, change can come quickly and different styles end up jostling with each other. These corners of music history, and the whole idea of blurred edges and crossed boundaries, is what has given us our Festival theme this year.”

This year there are 13 concerts over 9 days, with highlights including Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 from the stellar partnership of Belgian vocal ensemble Vox Luminis and the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra; the Pergolesi Stabat mater with Early Opera Company under Christian Curnyn with soloists Lucy Crowe and Tim Mead; Telemann’s cantataIno with Florilegium and Elin Manahan Thomas; Monteverdi'sOrfeo with I Fagiolini and Robert Hollingworth; Handel’s Jephtha with the Holst Singers and the Academy of Ancient Music under Stephen Layton; string-ensemble music by Biber, Schmelzer and Fux from Swiss ensemble Les Passions de l’Ame (with Turkish percussion!); and a harpsichord recital (entitled ‘Le Vertigo’) by Jean Rondeau.

Monteverdi’s iconic Vespers of 1610 is a classic example of a work at the edge, juxtaposing the newest musical techniques of the early Baroque with the older methods of the Renaissance. Ultimately this makes it not just a work of stylistic reconciliation but also one of unparalleled expressive richness. On Sunday 14 May at 7.30pm, this glorious music will be performed by two top-class ensembles, both of whom have made strong impressions at the Festival in the past: Belgian vocal ensembleVox Luminis and the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, coming together for the first time for this project.

Like the Vespers, Monteverdi’s first opera Orfeo has one foot in the world of Baroque vocal expression and the other in Renaissance traditions, in this case those of court entertainment and madrigal. But it is also music history’s first great opera, a work of power, depth and beauty that never ceases to enthral. Written for Monteverdi's own regular vocal ensemble, it will be performed on Thursday 18 May at 7.45pm at St John's Smith Square by Monteverdi masters I Fagiolini in their 30th anniversary year, with the brilliant Matthew Long as the virtuosic demi-God of singing, and a full cast of singers with a strong background in Monteverdi's secular and sacred music. Directed by Robert Hollingworth, it is given in an imaginative semi-staging by Thomas Guthrie that was first performed by I Fagiolini in Venice in 2015.

Opening this year's festival on Friday 12 May at 7.30pm at St John's Smith

Square is the Early Opera Company, under the musical

direction of Christian Curnyn, with

Pergolesi’s exquisite and profoundly moving Stabat mater, with

soprano Lucy Crowe and countertenorTim Mead as soloists. Pergolesi was one of the 18 th century’s most influential and admired composers, and did

much to power the stylistic transition from the Baroque to the Classical

style in music. Curnyn and his superb ensemble also include more music from

the late Baroque cutting edge with fire-cracker modernistic orchestral

pieces by WF and CPE Bach.

On Saturday 13 May at 4pm at St Peter's Eaton Square, rising virtuoso Jean Rondeau (‘One of the most natural performers one is likely to hear on a classical music stage these days … a master of his instrument.’ Washington Post) explores the flamboyant, poetic and compelling fantasy world of the French harpsichord repertoire, with character pieces, preludes and dances music by two of its most brilliant exponents, Jean-Philippe Rameau and Pancrace Royer.

On the evening of Saturday 13 May at 7.00pm at St John's Smith Square, leading British ensemble Florilegium focus on one of 2017’s great anniversary composers, Georg Philipp Telemann. Their concert puts Telemann the man of the High Baroque up against Telemann the progressive with two works from his final decade, including a powerful late masterpiece, the extraordinary and dramatic cantata Ino. This work is rarely heard in concert so this is an exceptional opportunity to experience it sung by Elin Manahan Thomas. Before it Florilegium perform one of the enduring favourites of the Baroque concerto repertoire - Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 5.

The London Festival of Baroque Music's annual visit to Westminster Abbey on Tuesday 16 May at 7pm honours Bach’s late masterpiece, his Mass in B Minor, compiled and adapted in his final years from earlier works and seemingly devised as a summation of his life’s work as a composer of sacred music. From joy to grief, celebration to supplication and triumph to penitence this is one the great monuments of Western music. It will be performed by The Choir of Westminster Abbey and St James's Baroque under James O'Donnell.

Swiss string ensemble Les Passions de l’Ame give their UK full concert debut on Wednesday 17 May at 7.30pm at St John's Smith Square, under their violinist director Meret Lüthi. Their programme is entitled ‘Edge of Europe’, and presents string music from 17th-century Austria, at that time Christian Europe’s interface with the Ottoman Empire. The music, by Schmelzer, Biber, Fux and Walther is imaginative and often quirky, enhanced in Les Passions de l’Ame’s performance by the colourful addition of Turkish percussion.

There’s another meeting of cultures in the 9.30pm ‘Late o’Clock Baroque’ concert on Saturday 13 May at St John’s Smith Square, when harpsichordist Jean Rondeau makes his second appearance of the Festival, this time in the company of lutenist Thomas Dunford and classical Persian percussionist Keyvan Chemirani. All three musicians are superb improvisers, and in a project they have entitled ‘Jasmin Toccata’ they meld Persian percussion and Baroque instruments in imaginative transformations of European masters such as Scarlatti and Purcell and major composers from the Persian tradition. The result (in their words) is ‘a vivid toccata that echoes the sensuality of Jasmin’.

The Festival’s focus on young artists continues this year with three more Future Baroque lunchtime concerts at St John’s Smith Square featuring some of the best new talent on the Baroque music scene. This year there are concerts by two instrumental groups: Ensemble Molière in a programme of music by Telemann and his French friends Blavet, Guignon and Forqueray (Friday 12 May at 1.05pm); and Ensemble Hesperi, who will be introducing us to music from 18 th-century Scotland (Wednesday 17 May at 1.05pm). The third and final concert is a solo harpsichord recital by Nathaniel Mander, who will perform works by English composers from Byrd to JC Bach (Friday 19 May at ).

On Friday 19 May at

The Festival ends on Saturday 20 May at 7.00pm at St John’s Smith Square with a performance of Handel’s last, and in many people’s opinion best, dramatic oratorio Jephtha. Stephen Layton conducts the Holst Singers, the Academy of Ancient Music and a fine cast of young singers led by Nick Pritchard as the Israelite warrior who lives to regret a rash vow to God.

In addition to these concerts, the Festival also features 'Sing Baroque', a special amateur choral workshop with conductor Robert Howarth on Sunday 14 May at

To quote Lindsay Kemp again: “As ever it has been enormous fun to create a Festival around an unusual theme, one that allows us to programme rarely heard but deserving music alongside familiar works that reveal themselves in new and particular contexts. It shows just how deep, complex and varied Baroque music can be!”

http://www.lfbm.org.uk/

For further information please contact:

Jo Carpenter Music PR Consultancy jo@jocarpenter.com

image= http://www.operatoday.com/LFBM.jpg image_description=Baroque at the Edge, London Festival of Baroque Music, 12-20 May 2017 product=yes product_title=Baroque at the Edge, London Festival of Baroque Music, 12-20 May 2017 product_by= product_id=OPERA RARA AUCTION: online auction for opera lovers worldwide

Lots which are anticipated to get opera aficionados’ hearts racing include LPs and posters signed by Dame Joan Sutherland, rare Maria Callas recordings and a selection of 19th-century opera posters hand-picked from Opera Rara’s extraordinary archive. Opera Rara’s Music Director Sir Mark Elder, together with stars from recent recordings including Spyres, El-Khoury and Ermonela Jaho have also offered their time to the highest bidder. Other prizes which will attract opera collectors’ attentions include prints of 19th-century opera sensations Pauline Viardot and the Grisi sisters as well as signed photographs by singers including Bruce Ford and Valerie Masterson.

The brain-child of Patric Schmid and Don White - who together collected the items on auction - Opera Rara has been in the business of bringing back forgotten operatic repertoire since its conception in the early 1970’s, with the operas of the Italian bel canto repertory being a particular focus. Future CD releases include Bellini’s first opera Adelson e Salvini in February conducted by Daniele Rustioni; two discs of bel canto arias with Michael Spyres and Joyce El-Khoury in July; and Rossini’s Semiramide in September featuring Sir Mark Elder conducting the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment with Russian soprano Albina Shagimuratova in the title role.

Click here for full information about the online auction and the gala dinner on 7 February.

For further information: moe@macbethmediarelations.co.uk

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Don%20Quichotte.jpg image_description=Opera Rara online auction, 17 January - 7 Feburary product=yes product_title=Opera Rara online auction, 17 January - 7 Feburary product_by= product_id=Above: Opera poster from 1910 advertising the first Paris production of Massenet’s Don Quichotte at the Théâtre Lyrique Municipal (Gaîté)January 18, 2017

MOZART 250: the year 1767

The music of the 11-year-old Mozart did not, however, dominate this performance at the Wigmore Hall. For while the prodigious feats of the musical wunderkind were certainly feted across Europe at this time - when he was just 6 years old, Francis I of Vienna referred to him as ‘ein kleine hexenmeister’ (a little master-wizard) - there was still some way to go before the teenager would find his mature creative voice. The programme was instead a smorgasbord of arias, secular and sacred, by composers both renowned and relatively obscure, set alongside three of Mozart’s adolescent offerings. The talented young singers who joined Page and his period-instrument orchestra struggled to make something meaningful of the multi-flavoured mix of miniatures.

There were some strong performances to admire, though, and some little-known treasures to enjoy, not least the duetting of soprano Gemma Summerfield and Emilia Benjamin’s viola da gamba in ‘Frena le belle lagrime’ from Carl Friedrich Abel’s opera Sifari. This pasticcio, on which Abel collaborated with Baldassare Galuppi and Johann Christian Bach, was presented on 5 March 1767 at the King’s Theatre Haymarket as a benefit performance for the celebrated castrato Tommaso Guarducci, with Abel - a skilled viola da gamba and viol player - himself playing the solo part. The text of the aria is taken from Metastasio’s L’eroe cinese.

Summerfield’s well-shaped line and variety of colour aptly conveyed the protagonist’s attempt to resist the flood of ‘soft affections’ and the ‘throbs’ of love which the tears of the beholden inspire, and she varied the vocal nuance to match Abel’s unusual modulations. Voice and viola da gamba trilled consonantly at the close of the first section; perhaps more elaborate vocal ornamentation would have enlivened later verses? Benjamin’s preludes and solo commentaries were eloquent but frequently, even though the strings were muted, the viola da gamba struggled to be heard. More animation in the second section, which was accompanied by alert pizzicato, might have generated greater dramatic interest.

Summerfield opened the evening’s vocal items with an aria by a composer unfamiliar to me: Florian Leopold Gassmann. Appointed to succeed Gluck as ballet composer in Vienna in 1763, and the teacher of Salieri, Gassmann was principally admired - by such 18th-century musicians as Burney, Gerber and Mozart - for his comic operas, which received performances in places as far apart as Naples, Lisbon, Vienna and Copenhagen. Amore e Psiche, which was first performed on 5 October 1767 to celebrate the ill-fated marriage of Archduchess Maria Josepha to King Ferdinand of Naples, reflects the influence of Gluck’s operatic ‘reforms’ of the early 1760s. ‘Bella in un vago viso’ - in which Zephyrus tries to reassure Apollo, who is alarmed by the disappearance of the weeping bride-to-be Psyche, with the dubious argument that women are prettier when they cry than when they smile - has a full complement of woodwind, and Page made much of the appealing interplay between voice and accompaniment. Summerfield again crafted a warm, fluid line, but she seemed a little hesitant at times and ‘pick-ups’ and tempi did not always feel settled and secure.

Bass-baritone Ashley Riches joined Summerfield after the interval for Mozart’s cantata, Grabmusik, which is reported to have been composed when the young prodigy, suspected of putting his name to works penned by his father, was shut away by the Prince of Salzburg with just some manuscript paper for company and told to prove his compositional prowess. The resulting work is believed to be this cantata, which was first performed in Salzburg Cathedral on 7 April 1767. It takes the form of an earnest dialogue between a departed Soul, which feels guilt for Christ’s death, and an Angel who offers absolution. Riches’ recitative was anguished and expressive; he handled the difficult coloratura with assurance, snarling at the bitterness of death, and his first aria was as fiery as a revenge aria - running through roulades, plummeting thunderously. The flexibility of the line was fore-grounded by some lucid string playing. Summerfield’s consolatory air - originally intended to be sung by a boy - was characteristically eloquent, imbued with gravity. The pair blended well in their duet, Riches accepting the Angel’s instruction with a gentleness of tone which conveyed resigned content.

Riches’ solo aria was ‘Sopra quel capo indegno’ from J.C. Bach’s Carattaco, the fourth of the five operas that he wrote for London and which was heard at the King’s Theatre shortly before Sifari. In this aria Teomanzio rages against the perfidious Queen Cartismandua, whose deceit has led to the Britons’ defeat at the hands of the Romans. Riches, impressively ‘off score’, was grandoliquent without straying into bombast.

Haydn’s Stabat Mater was one of the first sacred works that he composed in his new position as Kapellmeister of the Esterházy court; Riches and tenor Stuart Jackson presented two of its movements. The orchestral drama of ‘Flammis orci ne succendar’ vividly conjured the flames of hell and showcased Riches’ extensive registral range; ‘Vidit suum’, by contrast, allowed us to enjoy the sweet softness of Jackson’s voice, his phrases being poignantly echoed by the strings. In contrast, it was a dry tremolando that set the scene for the urgent recitative which precedes Gluck’s ‘No, crudel; non posso vivere’, in which Admeto laments the self-sacrifice Alceste has made in order to save his life. Jackson was precise but his tone was somewhat unvarying, and at times the projection seemed forced.

In the two orchestral works presented the instrumental playing was robust and dynamic, though occasionally rough-edged. Arne’s three-movement first symphony was rhythmically lithe and energised by the strings’ impressive bustling and swirling. After some insecure intonation at the start of the opening Allegro, Mozart’s Symphony No.6 settled into a charming, colourful Andante whose lyrical nature signaled its origins: it is an adaptation of a duet from Mozart’s first opera Apollo and Hyacinthus (1766), ‘Natus cadit’, which Summerfield and Jackson performed with grace and fluency to provide an unusually gentle close to the programme.

More substantial Mozart juvenilia will follow later this year. Classical Opera will present two of Mozart’s works from 1767 at St John’s Smith Square: a new production of Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebots which they recorded in 2013, and a fully staged Apollo and Hyacinthus alongside a staging of the Grabmusik. In addition, the company will return to the Wigmore Hall to perform Mozart’s first four keyboard concertos - composed between April and June 1767 - with South African fortepianist Kristina Bezuisdenhout. A new recording with Sophie Bevan, Perfido!, featuring concert arias by Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven will also be released in May.

Claire Seymour

Classical Opera: Ian Page - conductor, Gemma Summerfield - soprano, Stuart Jackson - tenor, Ashley Riches - bass-baritone.

Mozart: Symphony No.6 in F major K43; Gassmann: ‘Bella in un vago viso’ (from Amore e Psiche); Gluck ‘No, crudel, non posso vivere’ (fromAlceste); J.C. Bach: ‘Sopra quell capo indegno’ (from Carattaco); Abel: ‘Frena le belle lagrime’ (from Sifari); Mozart: Grabmusik K42; Haydn: No.6 Vidit suum, No.11 Flammis orci (from Stabat Mater HXXbis; Arne: Symphony No.1 in C major; Mozart: ‘Natus cadit atque Deus’ (from Apollo et Hyacinthus K38)

Wigmore Hall, London; Tuesday 17th January 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ian%20Page%20Ben%20Ealovega.jpg image_description=Classical Opera Company: MOZART 250 product=yes product_title= Classical Opera Company: MOZART 250 product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Ian PagePhoto credit: Ben Ealovega

January 17, 2017

Monteverdi, Masters and Poets - Imitation and Emulation

Vincenzo Giustiniani’s account (in his Discorso sopra la musica, c.1630) of the technical accomplishments and elegant stylisation of the concerto delle donne who performed at the Ferrarese court of during the late sixteenth-century, might equally describe the vocal refinement and rich expressiveness demonstrated by the soloists of Les Arts Florissants during this concert of music inspired by the poetry of Torquato Tasso and Giovanni Battista Guarini.

Between 2011 and 2015, Paul Agnew and Les Arts Florissants undertook the enormous challenge of performing and recording the eight Books of Claudio Monteverdi’s madrigals. Here, with Monteverdi’s Mantuan years as the focus, the six singers performed madrigals drawn from the composer’s first five Books, juxtaposed with settings of the same texts by those whose example and influence shaped Monteverdi’s response to the vivid images, ruminative conceits and passionate exultations of the poetry.

Ferrara and Mantua were startling vibrant cultural centres under the courtly patronage of Alfonso II d’Este and Vincenzo Gonzaga respectively. Vincenzo, who succeeded his father Guglielmo in September 1587, seems to have relished the lively social and artistic milieu cultivated by Alfonso and his wife, Margherita Gonzaga, which contrasted with the more austere court at Mantua. It was at Ferrara that he gained a grounding in the literary and musical arts, and formed friendships with Tasso and Guarini. There was an animated interplay of musical forces between Ferrara and Mantua - one might describe it as a sort of ‘cultural espionage’ as the courtly performers vied with each other with regard to technique and timbre - and the 1580s witnessed a flourishing of artistic experimentation at Mantua which resulted in startling, novel forms and styles of singing and theatre.

The soloists of Les Arts Florissants, led by tenor and director Paul Agnew, demonstrated full and effortless command of the new vocal techniques that were described by Caccini in the Introduction to Le nuove musiche of 1602, and which embody the philosophical ambitions of what was termed the seconda prattica: that is, the ornamented declamatory style in which the music was governed by the sentiments of the text. This justified the freer treatment of dissonance, but equally, composers sought texts that expressed extremes of emotion, and attentively squeezed every drop of feeling from the individual words.

The performers’ technical ease, expressive finesse and dramatic directness were equally striking. Every phrase had individuality, animation and shapeliness; cadences were thoughtfully effected, with dynamic shading and judicious ornament. The vocal blend was beguiling, but from tranquil or comforting timbral consonances, individual voices pushed assertively forward: by turns angry, despairing, pleading, accusatory. Theatricality predominated: the singers were very much off score, facing the audience, turning towards each other; bowing, swaying, smiling, frowning. In assertive episodes the words quite literally seemed to leap and dance, but the diction was no less clear in the more subdued passages. Chromatic twists and contortions were savoured and wherever the modulations strayed, the intonation remained true. Dissonances and suspensions were allowed to linger, where it was shrewd to do so. Time and again, Miriam Allan’s soprano rose with radiant purity above the other voices; she was joined by Hannah Morrison - who sang with directness and animation - and Lucille Richardot to form a gleaming efflorescence of colour - recalling the famed ‘Three Ladies of Ferrara’, Laura Peverara, Anna Guarini and Livia d’Arco, who starred at the Ferrarese could during these years. Tenor Sean Clayton formed a supple, soft-grained complement to Agnew’s declamatory energy and forthrightness. At the bottom Cyril Costanzo was warm-toned and as steady as a rock, an anchor for the roving, contending explorations and elaborations above.

The ensemble began with three settings of paired texts in which Tasso’s ‘Ardi e gela à tua voglia’ (You can burn or freeze as you wish) formed a riposte to Guarini’s ‘Ardo sì ma no t’amo’ (Yes, I burn but I don’t love you). Such intertextual references became increasingly common in cinquecento secular polyphony and these two texts were the first such pair in what was to become a prominent tradition.

Orazio Vecchi’s Guarini setting (à 6) was characterised by restlessness though there was self-composure in the penultimate line, ‘Perch’ho già sano il core’ (for already I have healed my heart). Tasso’s riposte grew into furious outbursts when the protagonist scorned the lover’s suffering - full textures being reserved for key lines of text. The personas in the poem seemed to be represented by contrasting high and low voices, creating drama and rhetoric, especially with repetitions of ‘E se l’amor fu vano’ (and if love was in vain). Marc’Antonio Ingegneri is known to have taught Monteverdi, when he was maestro di cappella of the cathedral in Cremona during the 1580s. His five-voice setting unfolded Guarini’s accusations more gently, while Tasso’s contemptuous rejection was communicated by energetic counterpoint and an assertive high tenor line. Monteverdi himself exchanges a contralto for a tenor, in a vibrant setting (from the First Book) in which the high soprano line shone brightly, and which seemed to teem with real human emotion. Also from the First Book, ‘Baci soavi e cari’ (Sweet, precious kisses (SSATB)) swelled with bittersweet suspensions; the female trio slowed with exquisite delicacy for the declaration, ‘O dolcissime rose/ In voi tutto ripose’ (Everything rests in you, softest of roses).

In ‘Dolcemente dormiva la mia Clori’ (My Cloris was sleeping sweetly (SSTTB), from the Second Book of 1590), Costanzo’s sure bass was a firm foundation for the twisting progressions which follow the serene opening portrait of the sleeping nymph. The expansive ‘Non si levav’ancor l’alba novella’ (The new day had not yet dawned (SSATB)) emerged hesitantly from a beautiful pianissimo as the upper voices held long notes above the lower voices moving lines - a gesture which Monteverdi borrowed from Luca Marenzio’s setting of the same text. Surprisingly this did not precede Monteverdi’s madrigal, Agnew preferring Marenzio’s ‘Non vidi mai dopo notturna pioggia’ with its meandering depiction of the ‘wandering stars’ which evade the poet-speaker’s vision and its plummeting image of weariness, as the spirit finds rest from pain. Both ‘Non si levav’ancor’ and ‘Se tu mi lassi, perfida, tuo danno’ (If you leave me, faithless one, it’s your loss!) were enlivened by vivacious points of imitations and canzonetta-like rhythms.

Before the interval, the music of Giaches de Wert was introduced. In 1565 the Gonzaga family appointed Wert maestro di cappella at the recently completed ducal chapel of Santa Barbara and he remained in this role until 1592. Monteverdi thus spent his earliest years at Mantua during Wert's final ones. During the 1570s increasing involvement with the Este court at Ferrara brought Wert into close contact with Tasso and Guarini, as is evidenced his seventh book of madrigals (1577) whose settings of the poets’ epic verse are dramatic and full of theatrical contrasts. ‘Vezzosi augelli’ (Joyous birds) comes from the eighth book (1586): the fleetly running upper parts - a hallmark of madrigals written for the concerto delle donne and imitated by composers such as Benedetto Pallavicino and Monteverdi himself - demanded great precision and virtuosity from the three female singers, while Costanzo, too, skilfully met the florid challenges of the close. Wert’s detailed response to the text is echoed in Monteverdi’s ‘Ecco mormorar l’onde’ (Hear the murmuring waves), in which Tasso’s tight images trigger picturesque musical gestures. The two birds which ‘gently sing’ were beautifully represented by the falling soprano voices, their unison descent blossoming into a joyful exclamation at the sight of dawn. ‘O primavera, gioventù de l’anno’ (O springtime, youth of the year (SSATB)) from Book Three featured an extraordinary sequence of suspensions at the close which was supported with gentle but focused understatement by Costanzo.

After the interval, the drama of Wert’s ‘Forsennata gridava’ - forcefully directed by Agnew, especially at the close - was complemented by the rhetorical explosiveness of Monteverdi’s ‘Vattene, pur crudel’ (Go, wicked man, (Book Three)) in which the individual voices emerged from the texture with striking insistence, building towards the collective assertiveness of the final stanza, and the final, weighty oratorical gesture, ‘Invendicata ancor piango,/ e m’assido’ (do I, still unavenged, weep and implore?). ‘Ch’io non t’ami’ (à 6) was a highlight of the evening, with the singers creating an exciting sense of innovation and newness - a hint of the radicalism to come. Such radicalism was represented by ‘Ah, dolente partita!’ which, though published in the Fourth Book which followed ten years after the Third, had first appeared in an anthology in 1597 just two years after Wert’s setting. While the debt of the younger composer to the elder is evident - in general and particular terms (Monteverdi’s pairing of the sopranos pays homage to Wert’s setting) - Monteverdi’s risk-taking now takes flight: Wert’s thirds are replaced by biting dissonances, and the descent, ‘La pena de la morte’ (the pain of death) in Wert’s setting is taken up and repeated compulsively to convey excessive suffering.

We closed, as we began, with three settings of the same text: Guarini’s ‘Cruda Amarilli’ (Cruel Amaryllis). The strange intervallic dissonances and varying meters of Benedetto Pallavicino (1600), were followed by Wert’s powerfully surging lines - the rolling r’s were articulated with startling incisiveness and bite. The vivid freedom of Monteverdi’s response to Guarini’s Il pastor fido brought the programme to a close. It was this madrigal, which opened the Fifth Book of 1605 which provoked criticism from the polemist Artusi, who attacked Monteverdi’s use of dissonance. In fact, Monteverdi’s dissonances seem tamer than Artusi’s accusations of harmonic ‘wrong-doing’ suggest: what was made apparent here, though, was the expressive humanity of Monteverdi’s setting. Orfeo was just two years ahead, and the soloists of Les Arts Florissants showed us that the notion of opera as a ‘drama in music’, a depiction of human psychology is writ large in this musical embodiment of Mirtillo’s complaint: ‘Poi che col dir t’offendo,/ I’ mi morrò tacendo’ (Since I offend you with my words, I shall die in silence).

Claire Seymour

Monteverdi: Masters and Poets - Imitation and Emulation:

Soloists of Les Arts Florissants: Paul Agnew - director, tenor, Miriam Allan & Hannah Morrison - soprano, Lucile Richardot - contralto, Sean Clayton - tenor, Cyril Costanzo - bass

Vecchi - ‘Ardo sì, ma non t’amo’; Ingegneri - ‘Ardo sì, ma non t’amo’; Monteverdi - ‘Ardo sì, ma non t’amo’, ‘Baci soavi e cari’, ‘Dolcemente dormiva la mia Clori’; Marenzio - ‘Non vidi mai dopo notturna pioggia’; Monteverdi - ‘Non si levav'ancor l'alba novella’, ‘Se tu mi lasci, perfida, tuo danno’; Wert - ‘Vezzosi augelli’; Monteverdi - ‘Ecco mormorar l'onde’, ‘O primavera, gioventú dell'anno’; Wert - ‘Forsennata gridava’; Monteverdi - ‘Vattene pur, crudel, con quella pace’, ‘Ch’io t'ami e t'ami più de la mia vita’; Wert - ‘Ah dolente partita’; Monteverdi - ‘Ah dolente partita’, ‘Piagne e sospira, e quando i caldi raggi’; Pallavicino - ‘Cruda Amarilli’; Wert - ‘Cruda Amarilli’; Monteverdi - ‘Cruda Amarilli’.

Wigmore Hall, London; 16th January 2017. image=http://www.operatoday.com/Paul%20Agnew%20photo%20credit%20Denis%20Rouvre.jpg image_description=Les Arts Florissants at the Wigmore Hall product=yes product_title=Les Arts Florissants at the Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Paul AgnewPhoto credit: Denis Rouvre

Visionary Wagner - The Flying Dutchman, Finnish National Opera

Holten connects Der fliegende Holländer to Der Meistersinger von Nürnberg and even to Parsifal by bringing out sub-texts on artistic creativity and metaphysics. And what amazing theatre this is, too, and very sensitive to the abstract cues in the music.

Just as the Overture begins quietly with woodwinds, we encounter The Dutchman (Johan Reuter) in a contemplative mood. He's in a studio, possibly a painter who makes portraits. A woman is lying on his bed. Model, lover or muse, we don't now, but as tempi increase, and the orchestra swells like the ocean, Reuter moves outside, exposed to the elements of the storm that is breaking. Huge figures loom over him, suggesting storm clouds and crashing waves. Darkened figures scurry past, like the cross- currents in the score. Back in his studio, the Dutchman is confronted by female dancers, who writhe as the music does, tantalizing him yet pulling away. The Overture reaches a crescendo, then decelerates. We glimpse the private Dutchman, as Reuter's face contorts in agony. He's having a panic attack. Far more moving, and human, than Dutchman-as-Demon.

Daland (Gregory Frank) and his crew have survived the storm unscathed. Unlike The Dutchman, Daland is a public person, who likes status and wealth. Here, he's in what might be an art gallery reception, where the rich pose. They don't actually "do" art. Amidst this sophistication, the Steuermann's song seems unsettling, too sincere and too simple to fit in with the pretentious setting. But so it should be, for the Steersman (Tuomas Katajala) represents earthier values. Significantly, in the libretto, Daland passes responsibility for his ship to the lowly sailor. "Gefahr ist nicht, doch gut ist's, wenn du wachst." He doesn't realize that the Dutchman has quietly entered the party unnoticed. Low winds and brass moan, and suddenly the Dutchman materializes and the crowd clears. "Der Frist is um", sings Reuter. Gold means nothing. "Ew'ge Vernichtung, nimm mich auf!" with intense agony. The party crowd repeat the phrase, but still don't get the full import. Daland thinks he's been through the same storm. If only he's paid attention to the music Wagner wrote around the Dutchman! He doesn't even realize what he might be letting his daughter in for. The Dutchman brings out a portrait. Drums beat in the orchestra, but Daland's laying around with his i-pad, oblivious.

The women are seen spinning, their movements reflecting the circular figures in the music though their cheerful singing parodies the infinitely grimmer cycles the Dutchman has to keep repeating. Pottery classes are middle class, producing nice objects, not necessarily functional, or artistic. Senta (Camilla Nylund) has her sights on greater things. She grabs the clay on her wheel and squishes it up into a shape that vaguely suggests a penis, reminding us that sexuality, in some form or other, is implicit in the true meaning of this opera. Shen then dons a white painter suit and paints with huge, dramatic brush strokes as she sings her keynote monologue, without missing a beat or inflection in her singing: quite a feat. The other women look on, uncomprehending. It's interesting how Wagner sets their chorus as quasi-religious chorale. Nylund jumps bodily into the painting, getting dirty. The women grab their bags, preparing to flee. Mary, (Sari Nordqvist), the only woman with individual flair, pays attention. When Erik (Mika Pojhonen) comes with roses, he flinches. Hes a land person not someone who faces the open seas. The Steersman's song is exquisitely beautiful because he lives: Erik's music is sincere, but dreams are the only time he lives in the imagination.

Senta and the Dutchman meet, and gradually their music builds up towards intense passion. In this production, we see their connection grow as the Dutchman sees a painting Senta's created. He takes out his camera, in deep appreciation. The use of a revolving stage allows the action to flow, marking the subtle gradations in their relationship. Eventually, the Dutchman and Senta end up, embracing tenderly in bed, but almost immediately the Sailors' chorus intrudes upon their dream This time, the innocent song sounds frantic, the rhythm clipped with near ostinato violence. Alcohol fuelled sexuality and fundamental antagonism between the living and the dead. This isn't a party in the normal sense. Senta sleeps on, but the Dutchman has been through this before. The nightmare's coming back, as it does every seven years. The ghostly chorus surround the bed, their faces masked and menacing, flashing their phones, to blind the Dutchman. When he's encircled, they point at him accusingly. This staging also emphasizes the way the Norwegian chorus parallel the chorus of the Dutchman's crew, and both adapt the Steersman's tune in brutal new ways. The village women dance with the Dutchman, but their coldness has a Flower Maiden surrealism. He tries to make sense by painting on them, as an artist does, but he's doomed, pursued by the singing, the music and the storm that's building up. Demonic lighting effects, sharp angles match visuals to music Modern technology can whip up cosmic storms of truly metaphysical force.

The music stills, for a moment, and the Dutchman wakes. Senta's still there, asleep. Has he broken the curse. Erik enters, scolding, showing Senta clips of their happy past on his i-phone. . For the Dutchman, the nightmare descends again. "Verloren! Ach! Verloren! Ewig verlornes Heil!" The Dutchman sets sail, in his mind. Everything's turning in dizzying circles: we see closeups of Reuter's face as if taken from a small handheld, projected across the entire stage. "Du kennst mich nicht, du ahnst nicht, wer ich bin!". Reality disintegrates. Do we see the Dutchman shoot himself We know he cannot die. But suddenly we're back in the art gallery, Senta is showing an installation she's made in which the Dutchman's last moments are preserved forever on endless tape loop. Has the Dutchman sacrificed his dreams to save Senta? Or has Senta sacrificed herself, after all, to redeem him? Nylund turns away from the crowd, and we see her, "as" Reuter, her features contorted in agony, as if her soul were disintegrating within. Is the Dutchman free, or has the curse fallen on Senta in his place ? A tantalizing but brilliant ending, which suggests that being creative is a vocation, where vision matters. Sacrifice and redemption, through art. Holten's Der fliegende Holländer is true Wagner.

Watch this production, conducted for the Finnish National Opera by John Fiore, on Opera Platform until 17th February.

Anne Ozorio

image=

product=yes

product_title= Richard Wagner : The Flying Dutchman, Finnish National Opera

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=

January 16, 2017

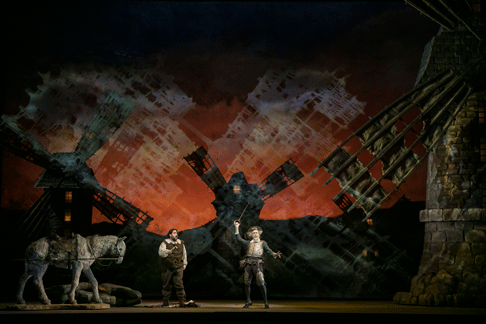

Don Quichotte at Chicago Lyric

The lead was portrayed definitively by Ferruccio Furlanetto; in the roles of Dulcinée and Sancho, Clémentine Margaine and Nicola Alaimo, both featured in their debuts with the company, made equally strong impressions. Additional courtiers and rival suitors for the affections of Dulcinée — Pedro, Garcias, Rodriguez, and Juan — were portrayed by Diana Newman, Lindsay Metzger, Jonathan Johnson, and Alec Carlson. The roles of servants were sung by Takaoki Onishi and Emmett O’Hanlon, while the chief of the bandits was Bradley Smoak. This production from San Diego Opera was directed at Lyric Opera of Chicago by Matthew Ozawa with sets and costumes by Ralph Funicello and Missy West; the lighting designer was Chris Maravich. The Lyric Opera Orchestra was conducted by Sir Andrew Davis, and the Lyric Opera Chorus was directed by its Chorus Master Michael Black.

At the start of each act throughout this production a quote from Cervantes’ Don Quijote appears on a scrim as a generalized introduction to the action about to unfold. Since the source for Massenet’s librettist Henri Cain was a 1904 stage play by Jacques Le Lorrain, taking inspiration from Cervantes, these citations help to return the operatic material to its ultimate novelistic origins. The first of these quotes, shown during the overture, describes the protagonist being “captive of Dulcinée, ” based on a passage from part I of Cervantes’ text. A child, seated on the stage and holding a book while reading, is also now seen just before the start of the action as a further reminder of the work’s origins in literature. The first scene approximates a Spanish courtyard while protagonists and chorus wear costumes with touches of late Renaissance style. Before Dulcnée can step onto her balcony overlooking the courtyard, the chorus cries our “Alza!” and “Vivat Dulcinée!” as a prelude to the four suitors singing of their desire to see her. As if in response to these entreaties Dulcinée appears and takes up the cry “Alza!” in her opening aria, “Quand la femme a vingt ans” [“When a woman is twenty years of age”]. Ms. Margaine performs an elaborate melisma on this word before launching into her thoughts on a young woman’s emotional needs and risks. Margaine’s warm, flexible mezzo voice sings comfortably in Dulcinée’s range, her embellishments adding to the tantalizing appeal of the character.

Nicola Alaimo and Ferruccio Furlanetto

Nicola Alaimo and Ferruccio Furlanetto