February 28, 2017

Matthias Goerne : Mahler Eisler Wigmore Hall

Goerne's programme was structured like a symphony, through which songs flowed in thoughtful combination, culminating in the Abschied from Das Lied von der Erde, revealed as a well-constructed miniature song cycle in its own right. Goerne is more than a superb singer. He's a true artist who illiuminates the musical logic that underlies Mahler's music.

Song is the voice of the human soul. With remarkable consistency, from beginning to end, Mahler's music poses questions about the purpose of human existence in the face of suffering and death, Nearly always, transcendance is found through creative renewal. Thus this programme began with Der Tamboursg'sell (1901), so well known that it symbolizes the whole Des Knaben Wunderhorn collection of songs. The drummer boy is young but he's being marched to the gallows, for reasons unknown. "Gute Nacht, Gute Nacht!" Goerne's tone rumbled with chilling darkness, as if haunted. Das irdische Leben (1892-3) followed, paired with Urlicht, in the piano song version, though it's better known as part of Mahler's Symphony no 2, sung by an alto. This was a thoughtful pairing. Das irdische Leben isn't just about child neglect, but opens onto wider issues like the nurturing of artists. In Urlicht, the protagonist refuses to be turned away, determined to reach its destiny. The song occurs at a critical point in the symphony, where the soul has passed through purgatory and is heading towards resurrection. In Goerne's programme, it is halted, temporarily, though we know there will be resolution. These first three songs thus form a kind of prologue for what is to follow.

Goerne has been singing Mahler for decades, though he hasn't recorded much, which is a loss to posterity as his Mahler is deeply thought through and perceptive. He's been singing Hanns Eisler even longer, since he grew up a child star in the DDR where Eisler's childrens' songs were well known He recorded Eisler's German Symphony op 50 (1957) with Lothar Zagrosek in 1995. Eisler's German Symphony is a song symphony, an "Anti-Fascist Cantata" setting poems by Brecht and Ignazio Silone. Goerne's recording of Eisler's Hollywood Songbook in 1998 is a masterpiece, easily eclipsing all others.and still remainsthe classic. At the Wigmore Hall, Goerne combined two specialities into a well-integrated whole, the Eialer songs functioning as middle movements expanding the themes in the Mahler songs.

Eisler wrote Hollywood Liederbuch while in exile in Hollywood, pondering on the nature of German culture and identity during the cataclysm that was the Third Reich. Although Eisler is often colonized by pop singers, these songs are serious art songs and include settings of Hölderlin and Heine and really need to be heard with singers like Goerne who can handle the tricky phrasing and vocal range with the understated finesse they need. These are songs of existential anguish, expressed obliquely because the pain they deal with is almost too hard to articulate. For this recital, Goerne chose songs set to some of Brecht's finest poetry, like Hotelzimmer 1942 where Brecht describes neatly arranged objects. But from a radio blare out "Die Seigesmeldungen meiner Feinde". Goerne flowed straight into An den kleinen Radioapparat, reinforcing the connection between the two songs so they flowed together as one larger piece. The piano parts are written with delicacy, suggesting the fragility of radio waves and the vulnerability of life itself.

Brecht, like Eisler, was a refugee, fleeing from persecution. After this first group of Eisler songs, Goerne placed Über den Selbstmord. The contrast was shocking. The mood changed from suppressed anxiety to outright horror. Goerne brought out the surreal malevolence, his voice rasping with menace. "Das ist gefährlich". The song is a deliberate reversal of Romantic imagery - bridges, moonlight, rivers - and sudden, unplanned suicide. Goerne sang the last phrase, letting his words hang, suspended "das uberträgliche Leben"....coming to a violent sudden end on the word "fort".

A brief respite when Goerne recited lines from Blaise Pascal, which Eisler set with minimal coloration to the Brecht Fünf Elegien, refined miniatures about daily life in Los Angeles, where everything seems normal. Three more songs of poisoned "normacly"- Ostersonntag, Automne californien and In die Frühe before a return to the grim reality of Der Sohn I and Die Heimkehr. Then again Brecht and Eisler overturn Romantic nostalgia. "Vor mir kommen die Bomber, Tödlicher Schwärme" and a horrific parody of a Homecoming hero. The songs in the Hollywood Liederbuch can be presented in any order, but Goerne arranged them here in a pattern which suggests deceptively light andantes cut short by brutal scherzi.

Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde progresses from frenzied denial to transfigured acceptance, expressed through a series of very distinctive songs. In this performance, context came from the songs that had come before, widening the panorama. Bethge's texts evoke China a thousand years past. Once again, many face what Brecht and Eisler went through. Hearing the Abschied in this context is uncomfortable, yet also uplifting, for it reminds us that the grass will grow again. Hearing the Abschied for piano also makes us focus on the structure of the song, and the way it, too, develops in a series of distinct stages, like a miniature song cycle, like Das Lied von der Erde itself, "wunderlich im Spiegelbilde".

The orchestral Das Lied von der Erde predicates on the tension between tenor and alto/mezzo, a typical Mahler contrast between unhappy man and redeeming female deity, but as a stand alone, the Abschied lends itself perfectly well to other voice types. Goerne thus resurrects the Abschied for baritones, connecting the songs of passage, whether they be passages through death or domicile. The message remains the same. The darker hues in Goerne's voice suggest strength and solidity, values which emphasize the earthiness of the imagery in the text. He sings gravitas yet the high notes are reached with grace and ease. At the moment he's singing particularly well, better even than when he recorded Eisler's Ernste Gesänge in 2013, also with songs from the Hollywood Songbook. Marcus Hinterhäuser's playing was exquisite, so elegant that he made the piano sound like pipa or erhu, revealing the refined, chamber music intimacy in the song that the orchestral versions don't often access. Although the piano/voice recording with Brigtte Fassbaender, Thomas Moser and Cyprien Katsaris has been around for years, there's no comparison whatsoever. At times I thought Hinterhäuser might be playing a new, cleaner edition of the score, since his playing was infinitely more beautiful and expressive. I suspect he's just a much better pianist, and he and Goerne have worked together a lot in recent years. As Hinterhäuser played the long non-vocal interludes, Goerne was visibly following the score, listening avidly. That's how good Lieder partnerships are made. As Goerne sang the last "Ewig....ewig...." I couldn't bear for the music to end.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.matthiasgoerne.com/fileadmin/alle/bilder/header/header1.jpg

product=yes

product_title= Gustav Mahler Wunderhorn Songs and Das Anschied from Das ied von der Erde, Hanns Eisler : Songs from the Hollywood Liederbook :. Matthias Goerne, Marcus Hinterhäuser, Wigmore Hall London, 24th February 2017

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id= Matthias Goerne, photo: Michael Kocyan

Oxford Lieder Festival 2017: Gustav Mahler and fin-de-siècle Vienna

Mahler’s choices of texts, wider artistic influences from literature to art to nature and folk music, his Jewish background in a conservative Catholic city, his encounter with Freud, his encouragement of other composers, and more, will all be explored over the fortnight.

Mahler’s Vienna will also be placed in a wider context, with tradition represented in the songs of Schubert and Beethoven; an exploration of Brahms’ glorious melodic gifts; an in-depth look at Richard Strauss; and music by Hugo Wolf, Alexander Zemlinsky, Erich Korngold, Joseph Marx and others.

A late-night salon will look ahead to the Second Viennese School, including several of Schoenberg’s seminal works. Study days, readings, screenings, workshops and more once again make for an exhilarating Festival that will illuminate the era.

Some of the world’s leading singers and instrumentalists will take part, including Ian Bostridge, Sarah Connolly,Katarina Karnéus, Angelika Kirchschlager,Mark Padmore, Roderick Williams, Imogen Cooper, the Doric String Quartet and members of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment.

Passes will be on sale from 1 March from www.oxfordlieder.com/01865

591276.

Full Passes: £600/£510. One-week Passes: £400/£340.

General booking opens 1 June 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/OLF%202017.jpg image_description=Oxford Lieder Festival 2017 product=yes product_title=Oxford Lieder Festival 2017 product_by= product_id=February 25, 2017

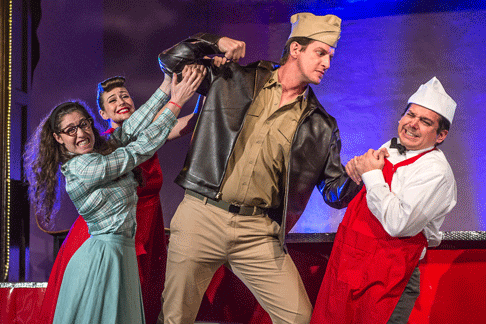

A Merry Falstaff in San Diego

Shakespeare created Falstaff to be an amusing companion to the young and somewhat frivolous Henry IV. Falstaff is gone when Henry becomes a serious ruler. Falstaff lives only for today and indulges in actions that members of the audience forego because they don’t want to deal with the consequences. San Diego Opera’s Falstaff, Roberto de Candia, sang with moderately sized burnished bronze tones. He gave a masterful interpretation of the lovable ‘drinking buddy’ who had no compunction about seducing married women. He even tried for two at once. Thus, the audience almost felt sorry for him but laughed vociferously when he had to hide in a laundry basket that ended up in the river.

Maureen McKay (Nannetta) and Johnathan Johnson (Fenton)

Maureen McKay (Nannetta) and Johnathan Johnson (Fenton)

Olivier Tambosi’s electric direction had Falstaff and his rollicking pals cavorting all over the wide Civic Theater stage even though designer Frank Philipp Schlössman placed the Garter Inn in a small area a few steps below stage level. The younger ladies were refined and demure, but Mistress Quickly was an earthy, Grandmotherly, arm twirling comic character.

San Diego Opera had built Schlössman’s three-sided, roofed wooden set for Chicago Lyric Opera, so it was a treat to have it back where it was born. It did a fine job of helping the voices resonate and throwing their sound out into the auditorium. Not only did the center section open up to form the Garter Inn, panels on the sides opened for various functions.

(L-R) Kirstin Chavez (Meg Page), Maureen McKay (Nannnetta), Ellie Dehn (Alice Ford), and Marianne Cornetti (Mistress Quickly)

(L-R) Kirstin Chavez (Meg Page), Maureen McKay (Nannnetta), Ellie Dehn (Alice Ford), and Marianne Cornetti (Mistress Quickly)

Schlössman’s costumes included jewel-toned silks for the ladies and the upper class men. For much of the opera, Falstaff and his friend wore what looked like rag pickers’ left-overs, but Sir John wore a new neon red suit with a prominent cod piece for his assignation.

Falstaff’s devil-may-care friends, Bardolfo and Pistola, sung by Simeon Esper and Reinhard Hagen were impressive, both vocally and physically. Marianne Cornetti is a trumpet-voiced mezzo who has sung in the world’s most important opera houses. She is a formidable comedienne, and her performance was enchanting. Her low tones are smooth as chocolate cream , so her ‘reverenzas’ were a special treat. Ellie Dehn who had sung Mozart and Puccini with San Diego Opera, was a clear toned Alice Ford who sang with an opulent, voluminous sound. I would love to hear her sing one of the lighter Richard Strauss roles.

Roberto de Candia as Falstaff and Ellie Dehn as Alice Ford

Roberto de Candia as Falstaff and Ellie Dehn as Alice Ford

As Nanetta, soprano Maureen McKay sang with crystalline tones. She and the Fenton, sweet-toned tenor Jonathan Johnson, were perfect young lovers with all the energy youth implies. Kirstin Chavez, who sang a sultry Carmen in Arizona, was a seductive Meg Page who sang with creamy tones. Joel Sorensen was a crafty Dr. Caius who sang his thankless role with character-driven tones. Conductor Daniele Callegari brought out many sonorities that are unique to late Verdi operas such as Don Carlo and Otello. His tempi always pressed forward and supported both the voices and the drama. Despite the presence of a large orchestra, he never covered any of the voices.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Dr. Caius, Joel Sorensen; Sir John Falstaff, Roberto de Candia; Bardolfo, Simeon Esper; Pistola, Reinhard Hagen; Meg Page, Kirstin Chavez; Alice Ford, Ellie Dehn; Mistress Quickly, Marianne Cornetti; Nanetta, Maureen McKay; Fenton, Jonathan Johnson; Ford, Troy Cook; Conductor, Daniele Callegari; Stage Director, Olivier Tamboi; Scenic and Costume Designer Frank Philipp Schlössman; Lighting Designer, Christine A. Binder; Chorus Master, Bruce Stasyna; Supertitles, Charles Arthur; Wig and Makeup Designer, Stephen W. Bryant; Production Stage Manager, Mary Yankee Peters; Stage Manager, Michael Janney; Diction Coach, Emanuela Patroncini.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/jkat_Falstaff_021617_150.png

image_description=Roberto de Candia is Falstaff [Photo by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz Johnson]

product=yes

product_title=A Merry Falstaff

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Roberto de Candia is Falstaff [Photo by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz Johnson]

New Production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute at Lyric Opera, Chicago

Several notable debuts contribute to the unqualified success of this production: Andrew Staples appears as Tamino in the initial part of the run, and Kathryn Lewek sings the Queen of the Night in all performances. Christiane Karg performs the role of Pamina and Adam Plachetka sings Papageno. The three ladies are Ann Toomey, Annie Rosen, and Lauren Decker; Sarastro is performed by Christof Fischesser. Mmes. Toomey and Decker and M. Fischesser also make their debuts at Lyric Opera in this production. Monostratos is sung by Rodell Rosel, and Diane Newman performs as Papagena. The set and costume designer is Dale Ferguson and lighting is by Damien Cooper. The Lyric Opera Orchestra is conducted by Rory Macdonald and the Lyric Opera Chorus is prepared by its Chorus Master Michael Black.

During the overture to the opera the premise of this ingenious production becomes apparent. When the curtain rises, a large, two-story house dominates the stage, whereas ample space is left for a performing area outside the dwelling. Some individual performers appear in the process of costuming, while the adults in 1960s dress are shown to their seats in several areas facing the house. Even at this moment at the beginning of the performance, one’s attention is variously lured to the performers, to those who are witness to the performance outside, and to those individuals inside the house rapt in their duties and visible through the windows of the large rotating structure. By the close of the overture the last person has been shown to a seat, those inside the house can watch from their unique vantage, and all attention is focused on the menacing chords accompanying Prince Tamino’s entrance - appreciated by both onstage audience and by us. In the role of Tamino Mr. Staples appears dressed as the Prince from Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, here fleeing a mock serpent manipulated from beneath by several of the children. As he cries for aid [“Zu Hilfe!”] with excellent German diction, Staples moves with nimble strides if only to fall into an exhausted faint. The three ladies, who vanquish the serpent and find Tamino, blend well sonically, while each retains her individual identity in the competition to remain standing guard over the “holder Jüngling” [“handsome youth”]. The curiosity evoked by this scene is enhanced in Lyric Opera’s staging: Tamino’s encounters first with the dragon and then with the victorious ladies both take place near the house’s porch; a trio of neighborhood adolescents looks down on the second action from an upper story. Our attention is drawn to both groups on the stage until the ladies vanish, Tamino awakens, and the bird-catcher Papageno arrives. In this latter role Mr. Plachetka acts naturally, his movements showing consonance with Mozart’s musical gestures. In the signature aria, “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja” [“I am the bird-catcher, that’s me”] Plachetka sings with a consistent legato, while he draws out phrases to give the effect of extending his net to encompass “alle Mädchen” [“all the girls”] as well. Plachetka’s interaction with Tamino allows here sufficient opportunity for boasting until the three ladies return and remind him of his subordinate position. Once the three ladies silence Papageno, they declare their association with the Queen of the Night and reveal to Tamino the portrait of her daughter. In his reaction, “Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön” [“This portrait is enchantingly beautiful”], Tamino is stricken immediately and concludes that his emotions must be a signal of love. When Staple asks if the “Feuer brennen” [“burning fire”] in his breast could be love, his voice rises magically on “die Liebe,” only to glide comfortably down on its repetition and realization that he must find the maiden. The same progression is exquisitely used by Staples in Tamino’s final lines with the repetition of “ewig wäre sie dann mein” [“she would then be mine forever”].

Once the three ladies announce the arrival of the Queen of the Night, a primitively ominous waft of smoke is visible from the doors of the second-story porch. The portal opens to reveal the Queen dressed in a fashion similar to her ladies yet with a higher collar and characteristic touches reminiscent of dominant, negative personalities in animated films made popular through the Disney studio. As Ms. Lewek’s demeanor and command of the role demonstrate, she is ideally cast to portray this pivotal figure. Not only are the top pitches produced effortlessly and as a natural extension of her voice, but Lewek also creates an unforgettable portrayal through vocal color and interpretive effect. Aside from conjoining her introductory verses by means of a faultless legato, Lewek’s emphatic trills on “all mein Glück verloren” [“lost”] depict a pronounced lament of deprivation. When singing here to Tamino of her daughter, Lewek’s vocal decoration and heartfelt flourishes inserted into “so sei sie dann auf ewig dein” [“she shall be yours forever”] create a fresh approach to the Queen’s manipulative character.

Andrew Staples, Ann Toomey, Annie Rosen, Lauren Decker, and Adam Plachetka

Andrew Staples, Ann Toomey, Annie Rosen, Lauren Decker, and Adam Plachetka

The exit of the Queen and subsequent reappearance of her ladies allows for several significant dramatic developments. As if part of a further adventure narrative, the ladies release Papageno from his enforced silence and present Tamino with the magic flute while delineating its special powers. In keeping with the spirit of this production, three of the neighborhood youths watching the action from an upper porch now function as the three “Knäbchen,” or genii, to guide Tamino and Papageno on their quest. In a scenic shift with a briskly delivered orchestral accompaniment Pamina, daughter of the Queen, attempts unsuccessfully to flee her guard Monostratos. At the entrance of Papageno, the captor flees while Pamina-costumed here to resemble Disney’s Snow White-discovers that this newcomer acts in the service of her mother. Once she recognizes his “gefühlvolles Herz” [“tender heart”], Pamina together with Papageno perform their sympathetic duet on the hope of forthcoming love. Ms. Karg’s bright, unforced voice glides through the arching melody of “Bei Männern welche Liebe fühlen” [“Men who feel the call of love”]; at the same time, Plachetka’s role interweaves a sonorous accompanying line so that both parts merge and end on the optimistic note of humans attaining “Gottheit” [“divinity”].

The start of the Finale brings Tamino led by his genii into the vicinity of the temple, for which the suburban house now functions. When left alone Tamino declares that his goal is pure, to save Pamina. Here Staples embellishes “Pamina retten” with a repeated melisma in his affirmative statement. Voices from within the house/temple warn him away until the Sprecher [Speaker] steps out to comfort the youth. Mr. Govertsen’s dialogue with Temino, in which the noble goodness of Sarastro is clarified, shows a masterful command of German intonation and dignity of delivery. Once Tamino hears from the male chorus concealed inside the house that Pamina is alive, he plays his flute in joyous response. As if in answer to the call, the children of the neighborhood parade beneath makeshift representations of animals - this to the delight of the adult audience onstage and to those watching the Lyric production. The rapid succession of scenes brings Pamina and Papageno to the temple, as Karg reminds her decidedly timid companion with clear top notes that “die Wahrheit” [“truth”] must be their guide. Sarastro’s men - adult denizens of the neighborhood - emerge from the front door of the house sporting white and gold robes. As Sarastro, Mr. Fischesser’s demeanor is both fatherly and dignified, his vocal range ideally suited to the role and his projection of low bass notes especially clear. As soon as Fischesser directs with rising pitches “Führt diese beiden Fremdlinge” [“Lead these two strangers”] into the house to further the instruction of Tamino and Papageno, Karg’s Pamina looks despondently at the front door as the act ends.

While the young characters are gradually tested and purified in the second act, sentiments are intensified and individual goals are ennobled or cast aside. At first, Sarastro’s men stand with horns in the second-story windows as he sings his appeal, “O Isis und Osiris,” asking for wisdom and strength to be granted by the gods to the two initiates. Once Tamino and Papageno receive instruction from Sarastro’s men, the house rotates to reveal Pamina asleep. At the arrival of her mother, an appeal for Tamino’s life is made, in reaction to which the Queen sings her second showpiece aria, “Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen” [“The vengeance of Hell boils in my heart”]. Lewek’s security of pitch and well-chosen decoration are here intensified, just as her character’s fury and resolve have grown over time. The subsequent vocal response of Sarastro balances the Queen’s suggested violence. When he intercedes to protect Pamina from the advances of Monostratos, Sarastro banishes the assailant and sings “In diesen heil’gen Hallen” [“In these sacred halls”]. Fischesser’s performance of this aria is a seamless praise of humanity and forgiveness, his sonorous and varied pitches on “Freundes Hand” [“hand of a friend”] and “Mensch zu sein” [“to be a human being”] acting as conclusory watchwords for both the initiates and the audience(s).

While Tamino bravely and Papageno reluctantly follow the tenets of Sarastro’s teaching, Pamina’s despair gradually intensifies. At first Karg laments her perceived abandonment with aching languor in “Ach, ich fühl’s” [“Ah, I feel it”]. When in the Finale Pamina considers suicide, she is dissuaded by the magical, glittery intervention of the three genii who communicate the love of her prince as a reward for patient trust. This final transformation concludes with both characters wrapped in white robes leading a procession about the house. The ending is a celebration of the spirit of Mozart’s music and the ingenuity of this production which brings it to a renewed level of humanity.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kathryn-Lewek_Andrew-Staples_THE-MAGIC-FLUTE_LYR161208_130_c.Todd-Rosenberg.png

image_description=Kathryn Lewek and Andrew Staples [Photo by Todd Rosenberg]

product=yes

product_title=New Production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute at Lyric Opera, Chicago

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=Above: Kathryn Lewek (Queen of the Night) and Andrew Staples (Tamino)

Photos by Todd Rosenberg

A Salome to Remember

On February 18, 2017, Los Angele Opera presented Richard Strauss’s Salome backed by a set originally designed by John Bury for Peter Hall’s 1986 production at the Music Center. Its newly refurbished version directed by David Paul featured a dark platform that held the necessary cistern. The sky was filled with clouds surrounding a pale moon that crept almost imperceptibly across the sky during the course of the opera. Sara Jean Tosetti’s costumes encased Salome in layers of jewel-toned chiffon, wrapped Herod and Herodias in bright brocades and clothed the soldiers in stiff, braid-trimmed jackets and skirts.

Allan Glassman (center front) as Herod, with Gabriele Schnaut (second from left) as Herodias [Photo by Larry Ho / LA Opera]

Allan Glassman (center front) as Herod, with Gabriele Schnaut (second from left) as Herodias [Photo by Larry Ho / LA Opera]

Issachah Savage, a promising young dramatic tenor, sang Narraboth’s lines with shining bronze tones. Reports of his Otello in Mexico make him a tenor to watch. As the Page, Katarzyna Sadej sang with a sweet sound that could barely be heard over the eighty-four-piece orchestra. Tómas Tómasson was a rough and rugged Jokanaan, physically and vocally. Unfortunately, he seemed to lack any semblance of romanticism that might have made him attractive to the teenage princess. Other cast members who added measurably to the value of this performance were: Nicholas Brownlee as the First Soldier and Kihun Yoon as the First Nazarene. Rodell Rosel, Josh Wheeker, Brian Michael Moore, Carlos Enrique Santelli, and Gabriel Vamvulecu were most energetic as the Five Jews.

Patricia Racette’s Salome is an impetuous teenage princess who interrupts the royal routine on a cloudy night by demanding to see her stepfather’s famous prisoner. Racette’s interpretation makes her Salome younger than the characters portrayed by many of her famous colleagues of the past. This princess plays mental games with Jochanaan and with Herod. Later, she plays a physical game with the gruesome, natural-looking head of the prophet. Having grown from lyric to dramatic status by way of Puccini and Verdi rather then Wagner, Racette’s voice has a different sound for Strauss than the ones we heard from Nilsson, Rysanek, or Mattila. Great Salomes can also come from the Italian dramatic tradition and Racette isn’t just a sex kitten. She has the dramatic vocal ability to surmount Strauss’s huge orchestra and project her silver-toned soprano throughout a huge hall.

Patricia Racette as Salome [Photo by Ken Howard / LA Opera]

Patricia Racette as Salome [Photo by Ken Howard / LA Opera]

Her character managed to tantalize Herod who was sure she could be satisfied with a large jewel or, at most, a small province to rule. Racette danced Peggy Hickey’s intricate, rhythmic choreography with four bare chested male dancers who lifted her on to their shoulders as she released veils. When they put her down, she snatched a cover from the prompter’s box and wrapped it around her body after the few seconds of its complete revelation.

As Herod, veteran tenor Allan Glassman was a most credible politician who wanted to be on the winning side of the religious debacle. Gabriele Schnaut was an officious, self-serving Herodias who did not intend to lose her position to anyone. When Herodias took the ring from Herod’s hand and relayed it to the executioner, the tetrarch momentarily lost his power. Salome had won for the few minutes she used to cavort with the head and sing her monumental Final Scene. Racette sang all the highs with lustrous tones and connected artistically with the score’s most difficult lows.

The most important aspect of the opera Salome is its huge orchestra and Richard Strauss’s opulent orchestration. One of the main reasons for attending Salome at Los Angeles Opera is James Conlon’s conducting. He brought out the composer’s leitmotifs and his symbolic use of musical color while engulfing listeners in the score’s unusual modulations, chromaticism, extended tonality, and tonal ambiguity. Best of all, Conlon did it without ever covering any of the principal singers. Salome will be at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion through March 19. If you are in the Los Angeles area you don’t want to miss it.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Conductor, James Conlon; Production, Peter Hall; Director, David Paul; Set Design, John Bury; Costume Design, Sara Jean Tosetti; Lighting Design, Duane Schuler; Choreographer, Peggy Hickey; Salome, Patricia Racette; John the Baptist, Tómas Tómasson; Herod, Allan Glassman; Herodias, Gabriele Schnaut; Narraboth, Issachah Savage; Page, Katarzyna Sądej; First Soldier, Nicholas Brownlee; Second Soldier, Patrick Blackwell; First Nazarene, Kihun Yoon; Second Nazarene, Theo Hoffman; First Jew, Rodell Rosel; Second Jew, Josh Wheeker; Third Jew, Brian Michael Moore; Slave / Fourth Jew, Carlos Enrique Santelli; Cappadocian / Fifth Jew, Gabriel Vamvulescu.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/sal_la_3535.png

image_description=Tomas Tomasson as John the Baptist and Patricia Racette as Salome [Photo by Ken Howard/LA Opera]

product=yes

product_title=A Salome to Remember

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Tomas Tomasson as John the Baptist and Patricia Racette as Salome [Photo by Ken Howard/LA Opera]

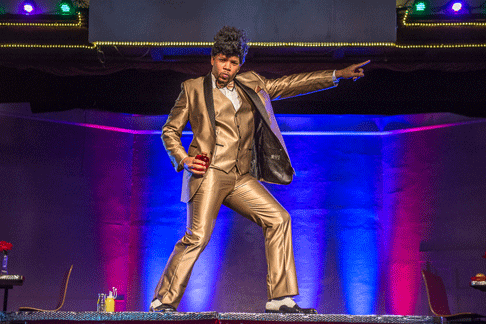

L’Elisir d’Amore Goes On Despite Storm

At seven PM, workers of every description were hooking lights up to a borrowed generator, running out for gasoline, arranging the setting on the specially built thrust stage, and putting hors d’oeuvres on patrons’ tables. Although the orchestra was behind the stage and there were no working monitors for the singers, shortly after eight o’clock the performance began.

Director Josh Shaw wrote: “The generator was noisy and it ran out of gas just a few minutes in. Before I could even get outside to refill it, the audience was lighting the stage with their cell phones. We carried on from there without a hitch and even decided to tempt fate and turn off the generator for Kyle Patterson's ‘Una furtiva lagrima,’ lighting him only with a few flashlights. It was magical. And the show ended without a blackout, but it didn't matter because the crowd was on its feet before the cast could even begin bows.”

Shaw’s bright, shiny red and white set placed the story in a smart 1950s diner where teenagers gathered and happily sipped sodas. His direction was full of edgy visual comedy that required no explanation and his surtitles translation told the story in the fifties slang of an Italian-American neighborhood.

Rocky Sellers as Dulcamara

Rocky Sellers as Dulcamara

Tenor Kyle Patteron was Nemorino, the good hearted, but short and pudgy soda jerk who loved the svelte, sophisticated village beauty. His goofy smile and easy physicality made him loveable, while his heartrending aria told the story not only of his character’s situation but also of this wonderfully exciting performance. As Adina, secure and stately soprano Amanda Kingston embodied all the attributes of a village belle, but she eventually recognized that her behavior might make her marry the wrong man. The possessor of a large and lustrous voice, she sang of the ‘Cruel Isolda’ with silvery tones.

Tall and lanky Andrew Potter was the conceited army recruiter, Belcore, who thought he was God’s gift to women. With his huge, all-encompassing bass voice and precise comic timing he nearly stole the show. Adina’s friend Gianetta, sung with gusto by Jenna Friedman, might have made him a loving wife, but he literally threw her over before stalking off to his next assignment.

Amanda Kingston as Adina, Andrew Potter as Belcore, Kyle Patteron as Nemorino, Jenna Friedman as Gianetta

Amanda Kingston as Adina, Andrew Potter as Belcore, Kyle Patteron as Nemorino, Jenna Friedman as Gianetta

Energetic bass, Rocky Sellers, was a doo-wop styled Dulcamara who disdained the finer points of literature but knew how to conn his mark, Nemorino, out of his last penny. Although Sellers currently lacks the experience and musical precision of Potter, he has an enormous talent for comedy that we can expect to enjoy for many years to come.

Conductor Nicholas Gilmore cut Donizetti’s score down to a ten-player extravaganza. It featured four string players along with flute, oboe, bassoon, and an occasionally overbearing trumpet. Gilmore’s light, airy but propulsive reading of the score captured both its comedy and its underlying sentiment.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Conductor and Orchestrator, Nicholas Gilmore; Director and Designer, Josh Shaw; Nemorino, Kyle Patterson; Adina, Amanda Kingston; Belcore, Andrew Potter; Dulcamara, Rocky Sellers; Gianetta, Jenna Friedman; Costumer, Maggie Green; Choreographer, Amy Lawrence.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Elixir-MARTHA-BENEDICT-Press-1-1.png

image_description=Rocky Sellers as Dulcamara, Amanda Kingston as Adina, Andrew Potter as Belcore, Kyle Patteron as Nemorino, Jenna Friedman as Gianetta [Photo by Martha Benedict]

product=yes

product_title=L’Elisir d’Amore Goes On Despite Storm

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Rocky Sellers as Dulcamara, Amanda Kingston as Adina, Andrew Potter as Belcore, Kyle Patteron as Nemorino, Jenna Friedman as Gianetta

All photos by Martha Benedict

Boris Godunov in Marseille

Only the frieze above the stage is said to remain of the original theater.

While the current theater does not have a pit of sufficient size to host full-scale Romantic orchestras (to compensate harps and percussion instruments are placed in the baignoires (boxes stage level) over the pit often resulting in bizarre acoustics. At the same time this opera house boasts an amazing stage/spectator rapport that may be unequalled anywhere in the world — words flowing from the stage are clearly audible with no loss of the clarity and volume of orchestral sound. This theater like no other offers the possibility of achieving the epitome of the operatic ideal.

There were fortunately a few splendid moments to be savored in the recent production of Mussorgsky’s 1969 (first version) Boris Godunov, notably the sly Boyar Shuisky fueling Boris’ fears with his description of the dead Dimitri, the old monk Pimen’s recounting of the miracle at Dimitri’s tomb (a blind man praying recovered his sight), and finally Boris admonitions to his son Feodor to rule justly, delivered in his dying breaths.

These moments occurred in the few, very few periods when the frenetic movement on the stage relaxed somewhat, when storytelling phobia quieted a bit, when the singers could remain still long enough to expound the Pushkin story in the glories of the play of Russian phonemes.

Italian conductor Paolo Arrivabeni well supported these successful soliloquies in a somewhat restrained reading of the score. Perhaps he was attempting to mitigate the scenic hyperventilation.

Marseille fielded a respectable cast to tell Mussorgsky’s story, most notably the Boris of Russian bass Alexey Tikhomirov who had replaced Ruggiero Raimondi in this same production from Liège in 2010. Mr. Tikhomirov is of imposing stature and imposing voice. He finds much subtlety in the Boris personage, and as well assumes much of the stature needed to illuminate such a conflicted ruler. Tenor Luca Lombardo brought a blatantly evil spirit into his character portrayal of Shuisky. Of the principles 44 year-old French bass Nicolas Courjal made the most effect as the old monk Pimen, illuminating the Boris/Dimitri mysteries in a beautiful and clear tonal language that filled the theater.

Nicolas Courjal as Pimen, Jean-Pierre Furlan as Gregory

Nicolas Courjal as Pimen, Jean-Pierre Furlan as Gregory

Mezzo Marie-Ange Todorovitch did double duty as the innkeeper and the Boris children’s nurse, both roles delivered with pleasurable linguistic gusto. Soprano Ludivine Bombert made beautiful sounds in her laments as Boris’ daughter Xenia. Bass Wenwei Zhang enacted a splendid Varlaam, the drunken friar.

More problematic were the roles of Boris’ son Feodor, nicely sung by diminutive mezzo Caroline Meng. For the role to achieve its full and intended effect it must be sung by a young boy. Tenor Jean-Pierre Furlan embodied a ribald, ambitious, rough-voiced Grigory — a nervous wreck. This Grigory was definitely not a subtle schemer who you might believe could rally revolutionary forces. The Innocent, sung by tenor Christophe Berry, was in strident tone and grotesquely staged body movements.

Dimitri, Czar of Russia 1605-1606, the final image of the Ionesco production of the 1869 Boris Godunov

Dimitri, Czar of Russia 1605-1606, the final image of the Ionesco production of the 1869 Boris Godunov

Stage director and designer Petrika Ionesco deconstructed a Russian Orthodox fresco into George Braque-like, i.e. cubistic shapes, adding solid blocks of colored lights in open places. Scene changes were long, noisy and off-putting in this two and one-half hour sitting (no intermission). Evidently Mr. Ionesco was taken by the intense poses he found in Russian frescos, poses that he induced his actors and the chorus to imitate. This came across as blatantly naive, caricatured acting in incessant movement. It was laughable until it became unwatchable.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Boris Godounov: Alexey Tikhomirov; Pimène: Nicolas Courjal; Gregori / Dimitri: Jean-Pierre Furlan; Chouisky: Luca Lombardo; Xénia: Ludivine Gombert; Fiodor: Caroline Meng; La Nourrice / L’Hôtesse: Marie-Ange Todorovitch; Varlaam: Wenwei Zhang; L’Innocent: Christophe Berry; Andrei Tchelkalov: Ventseslav Anastasov; Missail: Marc Larcher; Nikitch / Officier de Police: Julien Veronese; Mityukha: Jean-Marie Defpas. Orchestre et Chœur de l’Opéra de Marseille; Maîtrise des Bouches-du-Rhône. Conductor: Paolo Arrivabeni; Mise en scène / Décors Petrika Ionesco; Lumières: Patrick Méeus. Opéréa Municipal, Marseille, February 21, 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Boris_Marseille1.png

product=yes

product_title=Boris Godunov in Marseille

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Alexey Tiknomirov as Boris, Luca Lombardo as Shuisky [All photos by Christian Dresse, courtesy of the Opéra de Marseille]

Garsington Opera Announces Extended Season: 1 June to 30 July 2017

This year the festival offers Handel’s seductive masterpiece Semele, Debussy’s enigmatic Pelléas et Mélisande, Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro, Rossini’s Il turco in Italia and will conclude with Silver Birch, a large-scale work for a professional cast with local community participants of all ages, commissioned by Garsington Opera, from leading British composer Roxanna Panufnik and librettist Jessica Duchen. The JLT Group is the season’s sponsor for the fourth consecutive year. As part of the Garsington Opera for All programme, funded by Arts Council England and run in partnership with Magna Vitae, Semele will also be screened free of charge in Skegness, Ramsgate, Burnham-on-Sea and Grimsby.

Semele is a love story in which the god Jupiter is captivated by the beauty of the all-too-human Semele; these dramatic and colourful mythological characters inspired Handel’s most memorably beautiful arias. The title role will mark the British debut of American soprano Heidi Stober, an established favourite at some of the world’s most important opera houses, including San Francisco Opera, Deutsche Oper Berlin, the Vienna Staatsoper and the Metropolitan Opera, New York. Singing the pivotal role of Jupiter is Robert Murray with Christine Rice singing his spurned wife Juno. They are joined by Jurgita Adamonytė (Ino), David Soar (Cadmus & Somnus), South African countertenor Christopher Ainslie (Athamas) and Leonard Ingrams Foundation Award winner Llio Evans (Iris). Leading early music specialist Jonathan Cohen will conduct the Garsington Opera Orchestra and Chorus and Annilese Miskimmon, Artistic Director of Norwegian National Opera will direct, in collaboration with designer Nicky Shaw.

Pelléas et Mélisande, Debussy’s only opera, and often considered to be one of the most original in the history of music, is full of shimmering beauty creating a work of intense hypnotic allure. It will feature established French bass-baritone Paul Gay (Golaud) and two rising stars taking the title roles - Jonathan McGovern (Pelléas) and American soprano Andrea Carroll (Mélisande) making her British debut, with Brian Bannatyne-Scott (Arkel) and Susan Bickley (Geneviève). Jac van Steen returns (Strauss Intermezzo 2015) to conduct the Philharmonia Orchestra in its first year of partnership with Garsington Opera. Michael Boyd (director) together with Tom Piper (designer) return following their acclaimed production of Eugene Onegin last season.

Il turco in Italia will be a revival of Garsington Opera’s joyous 2011 production directed by Martin Duncan with designs by Francis O’Connor. Three members of the original cast return - Mark Stone as the poet Prosdocimo, Quirijn de Lang as the dashing Turk Selim, and Geoffrey Dolton as the devoted but dull husband Geronio. They are joined by renowned British soprano Sarah Tynan as the dazzling and flirtatious Fiorilla and rising star Katie Bray as Zaida. Italian tenor Luciano Botelho returns as the love-lorn Narciso. Rossini doyen David Parry will conduct the Garsington Opera Orchestra and Chorus in this glittering musical score.

John Cox’s legendary production of Le nozze di Figaro, first seen at Garsington Manor in 2005, will be recreated for the opera pavilion at Wormsley. Written at the height of his genius, this is one of Mozart’s finest works. Australian born Joshua Bloom (Leporello, Don Giovanni, 2012) will sing the title role with the exciting soprano Jennifer France (Leonard Ingrams Award winner) as Susanna. The Canadian singer Kirsten MacKinnon will make her UK debut as the Countess with Duncan Rock as the Count andMarta Fontanals-Simmons as Cherubino. Stephen Richardson (Bartolo), Janis Kelly (Marcellina), and Timothy Robinson (Basilio) join the vibrant young cast. Douglas Boyd will again conduct this highly acclaimed production with the Garsington Opera Orchestra and Chorus. In June the principals and chorus of Garsington Opera will travel to the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris to give a semi-staged concert performance of Figaro with the Orchestre de Chambre de Paris conducted by its Music Director Douglas Boyd.

Roxanna Panufnik ’s Silver Birch is a commission for Garsington Opera's Learning & Participation programme with Jessica Duchen as librettist. The production will see over 180 community participants aged 8-80, including recruits from the local military community, performing as dancers, singers, actors, instrumentalists, as well as student Foley artists from Cressex Community School under the guidance of Pinewood Studios Sound Designer Glen Gathard. They will perform alongside favourite Garsington professionals in the cast and orchestra. The story explores the extraordinary power of love within the devastating context of war and makes use of Siegfried Sassoon's poetry from WW1 (some of which was written while staying at Garsington Manor). The creative team isKaren Gillingham director, Rhiannon Newman Brown designer, and Garsington Opera’s Artistic Director Douglas Boyd joins them to conduct. The professional roles will be performed by Sam Furness (Jack), Victoria Simmonds (Anna), Darren Jeffery (Simon), Bradley Travis (Sassoon), Sarah Redgwick (Mrs Morrell) andJames Way (Davey) and the Garsington Opera Orchestra will be playing.

Garsington Opera: inside the auditorium.

Garsington Opera: inside the auditorium.

GARSINGTON OPERA AT WORMSLEY

For the Handel, Debussy, Rossini and Mozart operas, patrons are invited to arrive from 3.30pm to enjoy the gardens and deer park of the Wormsley Estate before performances begin in the early evening. Those arriving early are able to take a short trip in a vintage bus to the 18th century walled garden. On their return, they can enjoy traditional afternoon tea overlooking the cricket pitch, admire the spectacular views across the deer park and lake from the Champagne Bar, or stroll around the opera garden. In the long dinner interval patrons can dine in the elegant restaurant marquee overlooking the famous cricket ground or have a picnic by the lake, in the garden or in one of the private picnic tents. Performances resume as the evening light begins to fade and end by 10.15pm. A minibus service connects with High Wycombe station, a half hour train journey from London.

DIARY OF EVENTS AT WORMSLEY

Semele (new production) 1,3,9,15,24,30 June, 4 July start time 5.55pm

Le nozze di Figaro (recreation) 2,4,8,10,17 June, 3,6,9,11,14,16 July start time 5.25pm

Pelléas et Mélisande (new production) 16,18,22,25,27 June, 1,7 July start time 5.55pm

Il turco in Italia (revival) 26, 29 June, 2,5,8,10,13,15 July start time 5.55pm

Silver Birch (new commission) 28,29,30 July start time 7.30pm (no interval)

Tickets £135 - £200 including suggestion but non-obligatory donation of £70

Public booking opens 28 March www.garsingtonopera.org

Telephone 01865 361636

Photo credit: Clive Barda

Glyndebourne Festival 2017: White Cube artist Rachel Kneebone to exhibit new work

The exhibition takes place in the third year of a collaboration between

Glyndebourne and White Cube, and is housed in a state-of-the-art gallery

in the Glyndebourne gardens. It will be open to audiences throughout the

Festival which runs from 20 May to 27 August 2017.

Furthermore, an exhibition by Rachel Kneebone including her largest and

most ambitious single installation, 399 Days, can be seen at the

Victoria and Albert Museum from 1 April 2017 until early 2018.

Rachel Kneebone

Rachel Kneebone

‘399 Days’

(2012-13), Porcelain and mild steel (540 x 287 x 283 cm). © Rachel Kneebone. Photo © White Cube (Jack Hems).

Rachel Kneebone’s intricate porcelain sculptures address and question the

human condition: taking themes of renewal, transformation, the life cycle

and the experience of inhabiting the body.

Gus Christie, Executive Chairman of Glyndebourne, said: ‘A visit to

Glyndebourne has always been about more than opera, and in recent years

the experience has been further enhanced by exhibitions from some wonderful

artists on the White Cube roster. This year we’re delighted to be

exhibiting sculpture by Rachel Kneebone and I look forward to seeing the

pieces she has created.’

The 2017 Glyndebourne Festival opens with the UK’s first-ever production of Hipermestra, a rarely-performed work by the influential baroque

composer Francesco Cavalli. The team behind the production are director

Graham Vick and William Christie, a pioneer in the rediscovery of baroque

music who will conduct the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment.

Other Festival highlights include the world premiere of a brand new opera

based on Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the work of Australian composer

Brett Dean and Canadian librettist Matthew Jocelyn. The cast of outstanding

singers includes Allan Clayton, Barbara Hannigan and John Tomlinson.

The third new production of the season is Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito directed by Claus Guth and conducted by

Glyndebourne's Music Director Robin Ticciati.

The season is completed with revivals of Verdi’s La traviata,

Donizetti’s Don Pasquale and Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos.

La Traviata (2014). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

La Traviata (2014). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The Festival can once again be accessed on stage, on screen and online as

part of Glyndebourne’s efforts to make its operas available to broad

audiences. Three Festival productions will be screened in cinemas UK-wide

and broadcast for free online in partnership with Telegraph Media Group.

Public booking for Glyndebourne Festival 2017 opens online at 6.00pm on

Sunday 5 March. Tickets from £10. Visit glyndebourne.com.

Glyndebourne Festival 2017 runs from 20 May - 27 August 2017. View the trailer.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DB%20Rachel%20Kneebone%2009%20Mid_photographer%20David%20Bebber.jpg image_description=Glyndebourne Festival 2017 product=yes product_title=Glyndebourne Festival 2017 product_by= product_id=Above:Rachel KneebonePhoto credit: David Bebber

February 20, 2017

Bartoli a dream Cenerentola in Amsterdam

Bartoli has intimated in interviews that this European tour of a semi-staged La Cenerentola could be the last time she sings Cinderella, real name Angelina, one of her signature roles. Her bravura performance attested that she is still a vocally great Angelina. Physically she was completely credible as the mistreated stepdaughter whose unbridled optimism is rewarded with a spectacular change of fortune. Perhaps Bartoli should not hang up her glass slippers yet, though Rossini’s heroine loses none. Instead, Angelina gives the prince one of two matching bracelets, inviting him to find out who she is. La Cenerentola was composed for the 1817 Roman carnival and librettist Jacopo Ferretti made sure the papal censor would not be offended by women baring their feet. Neither is there a fairy godmother. The entirely nonmagical task of bringing Angelina and Prince Ramiro together is entrusted to the prince’s tutor, Alidoro. Instead of a cruel stepmother there is a self-regarding stepfather, the impoverished aristocrat Don Magnifico. Angelina falls in love with the prince while he is disguised as his valet, Dandini, which twists the plot and underlines her goodness — she refuses Dandini’s marriage proposal when he makes it disguised as the prince.

Happily, Rossini and Ferretti kept the viperish stepsisters. Sen Guo’s Clorinda needled with her incisive soprano and Irène Friedli lent the ungainly Tisbe her hooty mezzo. They shuffled to the ball as Fish and Fowl, hideously got up as a squamous mermaid and a fuzzy peacock. The costumes, from a 1992 production for Zurich by Cesare Lievi, were all over the place in terms of fashion eras. Claudia Blersh directed the singers around a squat sofa with minimal intervention. She scored a couple of comedic goals, but baritones Alessandro Corbelli and Carlos Chausson as Dandini and Don Magnifico provided the real humour. Corbelli’s voice is now dry and just a husk of its former self. His comedic inflection and phrasing, however, are impeccable. His Dandini was stylistically exemplary and hugely entertaining. Chausson, rich and sonorous, savoured every word of Don Magnifico’s splenetic recitatives and raced through his rat-a-tat patter with facility. In the hands of two such ace Rossini comedians, the duet “Un segreto d’importanza”, in which Dandini reveals his true identity to Magnifico, was a standout number. The chorus of the Monte-Carlo opera gave the third outstanding male performance, displaying great dynamic finesse and tonal shine.

Sounding constricted at first, bass Ugo Guagliardo as Alidoro took some time to find his vocal footing before revealing an attractive bass with limpid legato. Edgardo Rocha has an exquisite light lyric tenor and a flair for the Rossini idiom. It is a shame that his Prince Ramiro seemed restrained throughout most of the evening, both in volume and animation. Maybe he needed more theatrical direction than was available. He certainly can light up the stage, as he did during his showpiece aria "Sì, ritrovarla io giuro", singing ardently and hitting one silvery high C after another. Conductor Gianluca Capuano kept up a constant rhythmic momentum, building up the ensembles like a master patissier stacking a multitiered cake. Les Musiciens du Prince, of which Bartoli is artistic director, played with loads of pep, whipping up a robust storm in the Temporale, under flashing house lights. Even allowing for the wildness of period brass, there were several skidded entrances, but the beautiful woodwinds were a great asset and the orchestra as a whole kept the music fizzing.

Then there was Bartoli herself, whose task as the primadonna was to outshine all others, just like Cinderella at the ball. This she did. Bartoli’s voice has lost a little of the gleam of her younger years, but none of its distinctive colours or its stupefying agility. Her lower notes have deepened and her top A’s and B’s are as pinging as ever. Cinderella’s first words at the royal palace, a series of intricate runs spanning two octaves, were executed with breathtaking fluency. The glittering technique and infectious elation of the final rondo, “Nacqui all’affanno e al pianto” worked the audience up to a joyous roar. People cheered Bartoli in her ivory wedding dress as they would a real bride. The way she throws off her head-spinning runs is mightily impressive, but Bartoli also puts her heart and soul into every word. Her Angelina, far from being a dull goody two shoes, is disarmingly determined. In the end, one cheers her on not because she is a paragon of integrity, but because she is a real, suffering, hoping, rejoicing human being.

Jenny Camilleri

Cast and production information:

Angelina: Cecilia Bartoli, mezzo-soprano; Prince Ramiro: Edgardo Rocha, tenor; Dandini: Alessandro Corbelli, baritone; Don Magnifico: Carlos Chausson, baritone; Alidoro: Ugo Guagliardo, bass; Clorinda: Sen Guo, soprano; Tisbe: Irène Friedli, mezzo-soprano; Mise en scène: Claudia Blersh. Costume Design: Luigi Perego. Chœur de l’Opéra de Monte-Carlo, Les Musiciens du Prince. Conductor: Gianluca Capuano. Heard at the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, Wednesday, 15th February, 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/cecilia-bartoli-nc.png image_description=Cecilia Bartoli product=yes product_title=Bartoli a dream Cenerentola in Amsterdam product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Above: Cecilia BartoliWinterreise : a parallel journey

Pathetic fallacy, through art, articulates complex emotions. Often there is more truth in poetry than in straightforward prose. Each image stimulates a response from the protagonist: visuals are so integral to this cycle that it's perfectly reasonable that Winterreise has inspired so many different presentations. As we listen, we reaffirm the connection between Nature and art.

Matthew Rose's recording of Schubert Winterreise for Stone Records in 2012 is greatly admired. The authority in Rose's bass added savage grandeur, evoking the idea of a grand soul, brought down by fate. His Schwanengesang, also from Stone Records, is also rewarding. Live performance is subject to so many factors. A singer's instrument is his body, subject to the vicissitudes of life. So no single performance is be-all and end-all. Even though there were technical problems in the delivery, Rose is never boring. He's a born communicator, and those who know his voice and work hear things in context. Gary Matthewman gave Rose sensitive support. Winterreise is so well known that it can be a pleasure to follow the pianist. Very accomplished playing, with many good moments. Matthewman's pedalling let the piano sing. At the end of "Der Leiermann", the reverberations of the piano lingered, haunting, in the silence. A wonderful image, so true to meaning.

Because Winterreise lends itself so well to imagery, there have been numerous performances where visuals have added to impact. Some have been works of art in themselves, enhancing understanding and opening out new perspectives. For example, Ian Bostridge's Dark Mirror, a staging of Hans Zender's homage to Schubert at the Barbican, London, with Netia Jones's video projections drawing out disturbing depths. Please read my review here. And Matthias Goerne's Winterreise with pianist Markus Hinterhäuser at the Aix en Provence Festival with a background of projected images designed by Sabine Theunissen, directed by William Kentridge (Please read my review here). This included an image of the notorious "Hanging Tree" of the Thirty Years War, connecting the trauma of German history to the birth of the Romantic revolution. Schubert's Winterreise is so profound that it's pointless to decry interpretation. What matters is the nature of presentation.

This performance was illustrated by Victoria Crowe's paintings of winter, created over a 40-year period. Some of these, like the picture of a huge oak tree, bereft of leaves, against a blue background, were immediately familiar since they were used in the booklet for Rose and Matthewman's Winterreise recording for Stone Records. While some of the illustrations used were inspired by Winterreise, others had different origins,which perhaps explains why some connected to the songs better than others did. Crowe's work can be eerily beautiful, like the flowers springing from the ground, drafted with great skill. The crows in the painting used for "Die Krähe" hung awkwardly, a fault of the mechanical means of projection, rather than the quality of the image itself. Whatever technology was used, it wasn't particularly effective, doing no justice either to the music or to Crowe's art. Although Winterreise is so well known, many in the audience were immersed in the printed text, rather than paying attention. This performance deserved more attention.

Anne Ozorio

image=

product=yes

product_title= Schubert Winterreise : Matthew Rose, Gary Matthewman, Wigmore Hall London, 15th February 2017

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=

February 18, 2017

Anna Bolena in Lisbon

Just now, in this twenty-first century, it returned for five performances, its long absence(s) due to the 150 years the operatic public has preferred operas it finds dramatically more engaging.

Donizetti’s Anna Bolena (the first of his famous three queens) does however introduce a sense of real drama to opera, as his voices explore their personal passions in a flow that almost overrides the divisions of narrative into “numbers” i.e. separate musical pieces — this considered a first, Donizetti’s breakthrough. The passions are hugely powerful, most notably of course in the protagonist who is no longer loved, wrongfully accused and then, no longer a queen, a sore loser. It flows from her first startlingly difficult aria “Come, innocente Giovine” where she expounds that her position as queen is threatened, to her final cabaletta condemning the new queen, Jane Seymour as she, Anna, proudly marches to her beheading.

Elena Mosuc as Anna Bolena and Leonardo Cortellazzi as Percy

Elena Mosuc as Anna Bolena and Leonardo Cortellazzi as Percy

There were many, many more passions that are brilliantly laid out by Donizetti over the long, very long evening — by the queen-to-be Jane Seymour, Henry VIII, Percy (Anna’s former lover) and his friend Lord Rochefort (Anna’s brother), plus the page Smeton in seemingly countless arias and duets —the extraordinarily beautiful Act II duet of Percy and Lord Rochefort was indeed notable. Plus a plentitude of trios, quintets and finales with chorus.

It falls to the ambitious queen Anna Bolena to hold all this together by sheer force of artistry and personality. If 53 year-old Romanian/Swiss soprano Elena Mosuc seemed tentative in her first aria (the usual reaction of critics to this aria in performance) by the end of the opera she had found the histrionic and vocal depth and beauty of tone to thrill us first with her quiet, splendidly vocal reminiscences (usually said to be her madness) and then her full fury in “Coppia iniqua."

La Mosuc is an accomplished bel canto heroine of rich low notes, a full middle voice and beautiful high notes, notably a resplendent high E-flat that we heard over and over throughout the evening. You might wish for more dramatic heft and particularly for ornamentation that arises more naturally out of the vocal line, nonetheless her Anna Bolena was a satisfying tour de force.

Young American soprano Jennifer Holloway as Jane Seymour well held her own amidst a regional European cast, notably fine Italian tenor Leonardo Coretllazzi as Percy and Portuguese baritone Luis Rodrigues as Lord Rochefort. Turkish bass-baritone Burak Bilgili cut the imposingly wide figure of Henry VIII well enough without establishing a force of personality, histrionically or vocally to ground his participation in this passionately complicated (long) story.

Giampaolo Bisanti, music director of Bari’s Teatro Petruzzelli, led Teatro São Carlos’ willing orchestra, the house acoustic itself adding a roughness of tone that added a pleasing sense of times past to this old opera. This maestro, well traveled to Europe’s major stages in standard nineteenth century repertory, drove Donizetti’s music relentlessly seldom relaxing into the style and only rarely finding the soaring beauty of bel canto.

The 2007 production came from Verona’s Teatro Filarmonico, staged by Graham Vick and his designer Paul Brown. Mr. Vick based his staging on his assessment that the two women (Anna and Jane) use the bed to get themselves to the throne and the king (Henry VIII) uses the throne to get to the bed. Thus there was first a huge baldaquin bed, then later a huge sculpted head of blindfolded Justice followed by a huge (stage wide) sword that fell, and finally a crown of thorns, etc. — all unifying symbols to pull us through the numbers, which is to say fuse the musical pieces into a compelling narrative. A gratuitous visual quote was the enactment of the famous portrait of Henry VIII and Anna Bolena on horseback that hangs in London’s National Gallery.

No amount of staging or dramatic intelligence can obliterate the fact that this bel canto opera is purely and simply beautiful singing into which you must be able to immerse yourself, and that Donizetti’s first queen Anna Bolena will always sit uneasily if restlessly on the fringes of the repertory.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Henry VIII: Burak Bilgili; Annad Bolena: Elena Mosuc; Jane Seymour: Jennifer Holloway; Lord Rochefort: Luis Rodrigues; Lord Richard Percy: Leonardo Cortellazzi; Seeton: Lilly Jorstad; Sir Hervey: Marco Alves dos Santos. Chorus of the Teatro Nacional de Sao Carlos. Orquestra Sinfónica Portuguesa. Conductor: Giampaolo Bisanti; Stage Director: Graham Vick; Sets and Costumes: Paul Brown; Lighting: Giuseppe Di Iorio.Teatro São Carlos, Lisbon, Portugal, February 9, 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/AnnaBolena_Lisbon1.png

product=yes

product_title=Anna Bolena in Lisbon

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Elena Mosuc as Anna Bolena [All photos courtesy of Teatro São Carlos]

February 17, 2017

Oh, What a Night in San Jose

Happily, there is more than enough glory to go around. Certainly, substantial credit must go to director Michael Shell for having mastered all of the inherent staging challenges as he unlocked the profound riches of the piece that composer Kevin Puts and librettist Mark Campbell have crafted. Mr. Shell was well partnered in his pursuit by a design team operating at the top of its game.

Silent Night is based on the film Joyeux Noël, which captures a historical, spontaneous 1914 Christmas truce between partisan soldiers during World War One. Mr. Campbell’s affecting libretto follows personal journeys in three national camps, and is sung in English, German, and French, with some Italian and Latin (as the combatants pray together). Mr. Puts’ thrillingly eclectic score is at once character/culture-specific and embracingly universal. While much of the story takes place simultaneously in three battlefield trenches, there are important scenes in various localities that individualize the plight of the participants.

Set and projection designer Steven Kemp has wisely chosen to suggest locations, rather than attempting realism. Mr. Kemp’s most beautifully realized effect was to create three large wagons to serve as the bunkers for the Scots, Germans and French. These long but narrow platforms had a skeletal wooden enclosure “box” that was just tall enough to suggest a trench dug in the ground. The succinct look suggested at once a prison and an exposed asylum of emotionally conflicted warriors. This important major playing space was augmented by simple additions, a few period chairs here, a chandelier there, that simply conveyed the necessary place.

Colin Ramsey as Father Palmer and Mason Gates as Jonathan Dale

Colin Ramsey as Father Palmer and Mason Gates as Jonathan Dale

Pamela Z. Gray’s moody, varied lighting design contributed very effectively to transition us seamlessly from spot to spot, and to point up every nuanced situation. The opening sequence is but one example: As an opening operatic duet is sung in a “theatre,” the singing is interrupted by an announcement (sound design, Tom Johnson) to say that war has been declared. As the curtain rises, upstage wagons of low, rolling fields with denuded trees advance from upstage to the apron, as lighting transitions from warm stage illumination to the bleak, moonlit reality of a battlefield. These talented designers thereby successfully set the tone and the story-telling style for the whole evening. The diverse costumes from designer Melisssa Nicole Torchia brought welcome color and necessary visual coherence.

Given these creative choices, director Shell managed the large cast against this sprawling canvas with commendable focus and economy of gesture. The entire concept was choreographed with great specificity. The bunker wagons were on casters, able to be re-positioned for visual interest, and even used menacingly in a “circling the wagons” moment. The glory of this piece lies in following the individual narratives and Michael never lost sight of these human stories. He proved to have an uncanny knack for creating naturally evolving stage pictures, and a refined skill for directing our attention to just the right character. Together with a superb ensemble of singers, he fashioned an inevitable ebb and flow of memorable dramatic revelations.

Librettist Campbell stated that the central message is that “war is not sustainable when you come to know your enemy as a person.” The cast assembled for Silent Night have proven to be gifted ambassadors in that pursuit. Anchoring the show, and first among equals, Kirk Dougherty ably embodied the conflicted stage tenor, conscripted against his conscience, who is offered, then rejects command privilege. Singing with his usual burnished security and acted with honesty, Mr. Dougherty adds another memorable role to his growing resume. As his love interest, and essentially the only female role, Julie Adams was the radiant diva Anna Sorensen. Her rich, creamy, agile soprano was of the highest quality, the kind that prompts excited “who-is-she?” intermission chatter (and beyond). Ms. Adams is entrusted to deliver a beautifully judged battlefield prayer, and boy, deliver it she did with heart-stopping effect. You read it here: We will be hearing much more from her.

Kirk Dougherty as Nikolaus Sprink and Julie Adams as Anna Sorensen

Kirk Dougherty as Nikolaus Sprink and Julie Adams as Anna Sorensen

As the French Lieutenant Audebert, Ricardo Rivera found just the right scope for his particular odyssey. Having had to abandon his pregnant wife Madeleine (a cameo warmly sung by Ksenia Popova), he struggles to make sense of his role in the conflict. This is not only because of his own moral compass, but also owing to the overbearing exhortations of his General (authoritatively performed by Nathan Stark), who surprisingly also turns out to be his father. Mr. Rivera began the evening quite lyrically, with his sensitive, well-modulated intentions occasionally becoming a mite diffuse. But as the tensions heightened, Ricardo turned up the heat and produced ringing, mellifluous vocalizing.

While the opera has been crafted to avoid weighting the focus too much to one character or another, Ponchel is the work’s pièce de résistance. Is there a sunnier, more appealing character in the entire operatic canon? This simplistic Frenchman lives to spread joy and longs for nothing more than daily coffee with his beloved mother. Ponchel proves to be a perfect vehicle for the considerable talents of Brian James Myer. Handsome, charming, stage savvy, and with a polished baritone to boot, Mr. Myer threatens to steal every scene he is in. Ponchel’s “big moment” is one of the most touching in all lyric theatre, and Brian mined every ounce of detail and pathos from it.

Conversely, Mason Gates is charged with engaging us in the plight of the evening’s most embittered character, Scotsman Jonathan Dale. Having seen his brother killed in front of his eyes, he relies on equal parts denial and thirst for vengeance to fuel his actions. The creators use him as somewhat a symbol of a “justified,” blind hatred that fuel and sustain many tragic conflicts. Mr. Gates is a focused, involved actor, possessed of a secure, intense tenor that he is able to weight with a single-minded pain and purpose. He makes us understand the character’s anguish, all the while he disturbs us with his potent hatred. Matthew Hanscom’s imposing baritone brought kind-hearted authority to Lieutenant Gordon, and bass Colin Ramsey’s wondrously sung Father Palmer showed once again that this accomplished Resident Artist is one the company’s major assets. Kirk Eichelberger made a fine impression as the German Officer, his sonorous bass sporting as much secure swagger as his character’s demeanor.

Tenor Christopher Bengochea was smugly efficient as a hectoring Kronprinz, with Vital Rozynko making the most of his stage time deploying his characterful baritone in service of the irritating British Major. Kyle Albertson was a solid Lieutenant Horstmayer, and Branch Fields offered some attractive singing as Jonathan Dale’s felled brother William.

There is no amount of direction, design, scripting, hype, or earnest performances that can make a case for an operatic work that doesn’t “sing” with a beating heart. And here is where Silent Night soars. Composer Kevin Puts has taken Mark Campbell’s inspired words and found voice for an impressive array of styles and musical idioms. Classical opera is paraphrased, there are nods to neo-romanticism and atonality, Berg and Strauss are suggested, and there are uses of quasi-folk songs. But in his restless, ever-morphing sound palette, Mr. Puts has emphatically fused his artistic views of these diverse influences into his own unique statement of dramatically urgent, gratefully constructed vocal lines that are integrated into a virtuosic musical fabric.

The musical writing encompasses everything from solo bagpipe to chamber music to full symphonic outpourings. Mr. Puts has a real champion in conductor Joseph Marcheso, who elicited mesmerizing musical results from the pit and the stage. Additional kudos must go to Andrew Whitfield’s well-prepared chorus. The scoring demands impeccable solo and ensemble work alike from the large orchestra and they did not disappoint. Maestro Marcheso lovingly built an inevitably unfolding arc in a performance of constantly evolving and enriching musical delights.

Silent Night just may prove to be the first enduring operatic masterpiece of the century. Time and history will prove me right or wrong. But I can promise you this: there is no better case to be made for Silent Night than the production currently on view at the California Theatre.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Anna Sorensen: Julie Adams; Nikolaus Sprink: Kirk Dougherty; German Officer: Kirk Eichelberger; Jonathan Dale: Mason Gates; Father Palmer: Colin Ramsey; William Dale: Branch Fields; Madeleine Audebert: Ksenia Popova; Lt. Audebert: Ricardo Rivera; Ponchel: Brian James Myer; Lt. Gordon: Matthew Hanscom; Lt. Horstmayer: Kyle Albertson; French General: Nathan Stark: Kronpriz: Christopher Bengochea; British Major: Vital Rozynko; Conductor: Joseph Marcheso; Director: Michael Shell; Fight Director: Kit Wilder; Set and Projection Design: Steven Kemp; Costume Design: Melisssa Nicole Torchia; Lighting Design: Pamela Z. Gray; Sound Design: Tom Johnson; Make-up and Wig Design: Christina Martin; Chorus Master: Andrew Whitfield

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rivera%20and%20Myer.png

image_description=Brian James Myer as Ponchel and Ricardo Rivera as Lt. Audebert [Photo by Pat Kirk]

product=yes

product_title=Oh, What a Night in San Jose

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Brian James Myer as Ponchel and Ricardo Rivera as Lt. Audebert

Photos by Pat Kirk

Billy Budd in Madrid

And always mean at least something to everyone.

Case in point — the new Deborah Warner production of Billy Budd at the Teatro Real in Madrid where Billy is ambitious and assertive, where his nemesis Claggart is a sadistic brute and where his alter ego Captain Vere is a weak, uncertain young man. Mme. Warner does indeed make the case, sort of, that Billy Budd may be read in such light.

Forsaking the intrinsic naturalistic and psychological impressionism of Britten’s muse Mme. Warner and her designer Michael Levine created an expressionistic world, the specific location was an actual aircraft carrier of 1940’s rather than Britten’s man-of-war (frigate) of the 1790’s, both ships in fact named the HMS Indomitable. Thus the spaces were wide open, there were huge platforms that moved up and down. The copious ropes and webs were metaphors of human entanglement and imprisonment rather than the essential tools of sailors — the means they used to move their ship and their lives.

While the officers were of the 1940’s, the sailors, a massive number (possibly a hundred), were interpreted as grubby galley slaves (the rowers of the quick, old Mediterranean ships), forced to work (here usually scrubbing the decks) by brutes with clubs and whips.

Officers and sailors of the HMS Indomitable

Officers and sailors of the HMS Indomitable

There was impressive scenographic rhetoric, the deck of the aircraft carrier (the full stage) rose to reveal a hundred or so suspended hammocks (a reference to the 18th century), the suspended command bridge of the ship was swung back and forth in a brutally thwarted mutiny, and finally Billy Budd disappeared up a ladder into the fly-loft for the hanging (one heard the clicks of the safety lines being attached).

There was impressive musical rhetoric emanating from the pit as well, Teatro Real music director Ivor Bolton incising precise musical shapes from his excellent players. The flute solos of the Billy death oration eschewed the mystical pull of death, invoking instead nervousness and certainty. And the maestro brought the full, massive orchestral force to a shattering fortissimo that made the presaged death of Billy a truly huge, indeed monumental moment. His was an impressively powerful reading of the Britten score in detached, mannered moments rather than in a flow of emotional atmospheres.

Musically the effect was somewhat like the Janacek of Jenufa.

Billy Budd was sung by South African baritone Jacques Imrailo in a very physical performance. There were spine tingling moments like when he heaved himself up on a downstage rope to sing his farewell to his former ship the Rights o’Man, like the viper-strike punch that felled Claggart, and like the confident, frightening ascent to his death. It was a beautifully sung, total performance that alone was the soul of this evening.

Above: Captain Vere, below: Billy Budd

Above: Captain Vere, below: Billy Budd

There was, strikingly, no soul to be found in Captain Vere, sung by British tenor Toby Spence, and perhaps this was the intention of metteur en scène Deborah Warner. There was no intimation of the intense, human conflicts that torment Claggart, well sung by British bass Blindlay Sherratt but in absolutely one-dimensional tones.

The Teatro Real is one of the world’s major stages. The casting, mostly British, of Billy Budd was uniformly top notch, evidently fulfilling the needs and wishes of the production. The orchestra and chorus of the Teatro Real are estimable, its aspirations to producing fine opera were palpable. This Billy Budd is a co-production with Paris, Rome and Helsinki.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Billy Budd: Jacques Imbrailo; Edward Fairfax Vere: Toby Spence; John Claggart: Brindley Sherratt; Mr. Redburn: Thomas Oliemans; Mr. Flint: David Soar; Lieutenant Ratcliffe: Torben Jürgens; Red Whiskers: Christopher Gillet; Donald: Duncan Rock; Dansker: Clive Bayley; Un novicio: Sam Furness; Squeak: Francisco Vas; Bosun: Manel Esteve; Oficial primero: Gerardo Bullón; Oficial segundo: Tomeu Bibiloni; Amigo del novicio: Borja Quiza; Vigía: Jordi Casanova; Arthur Jones: Isaac Galán. Chorus and Orchestra of the Teatro Real. Conductor: Ivor Bolton; Stage Director: Deborah Warner; Set Design: Michael Levine; Costumes: Chloé Obolensky; Lighting: Jean Kalman; Choreography: Kim Brandstrup. Teatro Real, Madrid, February 12, 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/BillyBudd_Madrid1.png

product=yes

product_title=Billy Budd in Madrid

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Toby Spence as Captain Vere, Jacques Imrailo as Billy Budd [All photos courtesy of Teatro Real, copyright Javier del Real]

February 15, 2017

A riveting Nixon in China at the Concertgebouw

When it premiered in Houston in 1987 the American critics were divided about its merits, but the reception at its European premiere in Amsterdam the following year was unanimously enthusiastic. Adams’s account of Richard Nixon’s 1972 historic visit to the People’s Republic of China, told through the polychrome poetry of librettist Alice Goodman, has since claimed a place in the repertoire. Last Saturday’s performance at the Concertgebouw, led by conductor Kevin John Edusei, did full justice to all its key musical aspects: the tidal tug of its repeated motifs, its rhythmic adroitness and its reflective lyricism.