March 29, 2017

The "Lost" Songs of Morfydd Owen

Though she was not part of the male English Establishment, Owen needs no special pleading. Her music stands on its own merits, highly individual and original. Her work was published in the Welsh Hymnal even before she graduated and moved to London, where she moved in Bohemian, arty circles with the likes of D H Lawrence, Ezra Pound and Prince Yusupov, one of the conspirators who assassinated Rasputin. What might she have achieved, had she lived longer, or continued to develop in an international milieu ? Tŷ Cerdd have produced an intriguing collection of her piano pieces and songs, performed by Elin Manahan Thomas and Brian Ellsbury. Definitely a recording worth getting, for Owen's music is exquisite, enhanced by good performances. Buy it HERE from Tŷ Cerdd, who also supply scores.

In his notes, Brian Ellsbury writes "One of the fascinations of (Owen's) compositions is the plethora of contrast, often simply between major and minor, melancholy and joy.....the juxtaposition of a self conscious gaucheness and sophistication - the cosy homely feel of Welsh harmony suddenly layered with unexpectedly complex and deft modulations and almost modern jazz-like harmony,"

Owen's setting of William Blake's Spring (1913) is joyously energetic. "Little boy, full of joy, little girl, sweet and small" Manahan Thomas's lithe, bright soprano perfectly captures the spirit of youth. In The Lamb (1914) Evans subtly underpins the deceptive innocence with richer, more contemplative undertones, never overloading the lines with pathos. Sophisticated, yet pristine. In contrast, Tristesse (1915) with dramatic, exclamatory crescendi, very much in the surreal spirit of Maeterlinck, though the text is Alfred de Musset. More hyperactive than Debussy, as exotic as Ravel, this is an unusually unsettling song that suggests not romance but fervid imagination.

A selection of pieces for piano, some like the Rhapsody in C sharp major and Maida Vale, discovered in unpublished manuscript. The miniature Little Eric (1915) is barely a minute long yet vividly idiosyncratic while Tal y Llyn (1916) is confidently lyrical with a jaunty central motif - witty contrasts of tempi. Strong chords alternate with lively figures in Prelude in E minor (1914), contrasting well with the early (1910) Sonata for Piano in E minor, which is more diffuse.

The Four Flowers Songs - Speedwell, Daisy's Song, To Violets and God Made a Lovely Garden were written over a period of seven years, Speedwell (1918) being among Owen's last completed works. A speedwell is a weed, but cheerful and perky, but here it dreams grand dreams. In a way, this song might encapsulate Owen's idiom, lending seeming insouciance with great inner strength. God made a Lovely Garden (1917) reveals Owen's gift for melody, expressed with sincerity, not sentimentality.

A long, pensive piano introduction opens Gweddi y Pechadur (1913), the only Welsh language song on this disc. Although neither texts nor translations are included with this recording, the clarity of Owen's setting displays the innate beauty of the language, a "singing language" if ever there was one, and a good reason why non-speakers should study the song. It is a dignified lament, in minor key. To Our Lady of Sorrows ((1912) is a miniature scena, in which the Mater Dolorosa contemplates the body of Christ. Like Gweddiy Pechadur, its lines descend to diminuendo, but the last line packs a punch. Suddenly, the Mother isn't a religious icon, but an ordinary, human woman. A sudden leap up the scale, and passionate mellisma on the word "Baby" and an equally sudden hushed, hollow descent on the words "is dead".

Photographs show that Morfydd Owen was a beauty with dark hair and eyes, to match what might have been an intense, passionate personality. She had love affairs, requited or unrequited, but after a courtship of only six weeks, married Ernest Jones, the psychiatrist, and acolyte of Sigmund Freud. Perhaps Owen needed a father figure, despite her talent and acclaim: she wasn't independently wealthy. Jones didn't encourage her career, and she seems to have been unhappy. In September 1918, the couple went on holiday in Wales, where Owen died suddenly in uncertain circumstances. This recording concludes with In the Land of Hush-a-bye, with words by Eos Gwalia "The Nightingale of Wales", aka Gaynor Rowlands (1883-1906), a Welsh actress who lived in London, who, like Morfydd Owen, died young from complications after surgery. The song is simple, yet charming, and includes Owen's characteristic use of sudden leaps within a phrase. At the end, Manahan Thomas holds the last word for several measures until it fades into silence.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://discoverwelshmusic.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Morfydd-Owen-POLI-CD-cover.jpg

product=yes

product_title= Morfydd Owen : Portrait of a Lost Icon - Elin Manaham Thomas, Brian Ellsbury. Tŷ Cerdd - promoting the music of Wales

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=

March 28, 2017

Enchanting Tales at L A Opera

The performing version of the work was conceived and directed by Marta Domingo based on the integral edition of the opera edited by Michael Kaye and Jean-Christophe Keck. There are different versions of this opera because Offenbach died several months before its premiere and some work had to be completed by others.

Giovanni Agostinucci’s heavily detailed set and costumes placed the stories in their original locales and gave the audience a fascinating stage picture to contemplate. Alan Burrett’s lighting design pointed out pictures on the walls, one of which looked like Mozart. An operagoer might have to see this production more than once to get all the meaning out of it.

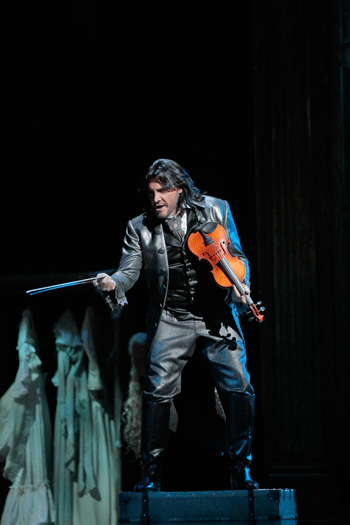

Nicolas Teste as Dr. Miracle

Nicolas Teste as Dr. Miracle

Marta Domingo’s direction gave each character both motivations and expressive activities and she showed that her artistic ability has grown considerably over the last decade. Having sung the title role all over the world, Placido Domingo now leads this opera with a knowledge few conductors can approximate. His tempi were inviting and despite dealing with a singer in the orchestra pit as well as a full cat onstage, the result was a unified whole.

Vittorio Grigòlo sang the title role of Hoffmann with a great deal of panache, creating different aspects of the character in each scene. In the prologue he gives an amusing imitation of the fictional Kleinzach. In Act I he dons rose colored glasses that make him think Olympia is a young girl instead of a roughly assembled automaton as he sings the romance “Ah! vivre deux!” (“Ah! To live together!”) with inviting lyrical tones. With each new love his desire seemed more intense, and it was more difficult for him to deal with rejection, so by the Epilogue, he has lost his grip on reality. Only then did his muse remind him that poetry is empowered by tears, not contentment.

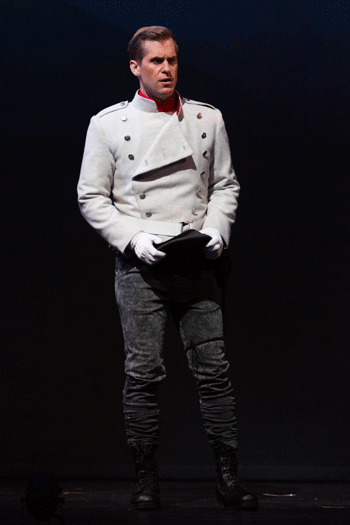

Kate Aldrich as Giulietta and Kate Lindsey as Nicklausse

Kate Aldrich as Giulietta and Kate Lindsey as Nicklausse

Offenbach expected all Hoffmann’s love interests, Olympia, Giulietta, Antonia, and Stella, all to be sung by one soprano. Diana Damrau intended to do that, but for health reasons, she eventually relinquished Olympia, the doll, to So Young Park and Giulietta, the Venetian courtesan, to Kate Aldrich. Park was an incredibly energetic magic doll who sang about "Les oiseaux dans la charmille" (“The Birds in the Arbor”) with sweet, stratospheric notes. Aldrich sang the courtesan with a creamy sound but her acting was anything but subtle. Damrau’s Antonia was both technically exquisite and visually heartrending. Even her dying breath was a perfect trill. Stella does not have much to sing, but her demeanor told us that she would never again embrace Hoffmann. I hope someday Damrau will return to Los Angeles and sing all four heroines. When her health is good, she is most certainly capable of showing Angelinos various facets of characterization with these roles.

So Young Park as Olympia

So Young Park as Olympia

French bass-baritone Nicholas Testé was to sing all four villains, but became ill the last minute. Thus, an American counterpart, Wayne Tigges, flew in to sing the roles from the orchestra pit while Testé acted them onstage. Most amazing was Tigges’s ability to blend into the ensembles when he could not see the other singers. He is most certainly an incredibly able artist.

Kate Lindsey has sung The Muse/Nicklausse all over the world but last night she outdid herself. Not only was her character the voice of reason, she did an imitation of Olympia that had the audience laughing out loud. Lindsey is a subtle artist but there is deep thought behind her characterizations. French buffo tenor Christophe Mortagne also brought out peals of laughter when Frantz, one of his four servants, attempts serious dance. As tavern owner Luther, Korean baritone Kihun Yoon sang with robust tones that easily filled the hall. Rodell Rosel was a self-important Spalanzani who looked much like one of Offenbach’s contemporaries, Richard Wagner.

Diana Damrau as Stella (with, at rear left, Kihun Yoon as Luther and Christophe Mortagne as Andres)

Diana Damrau as Stella (with, at rear left, Kihun Yoon as Luther and Christophe Mortagne as Andres)

If there was a slight weak link, it was the chorus, which seemed to be slightly off the beat when they entered. Hopefully that, and the other problems mentioned here will be fixed by the second performance.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Conductor, Placido Domingo; Director, Marta Domingo; Scenery and Costume Designer, Giovanni Agostinucci; Lighting Designer, Alan Burrett; Chorus Director, Grant Gershon; Choreographer, Kitty McNamee; Fight Director, Ed Douglas; Prompter, Nino Sanikidze; Hoffmann, Vittorio Grigòlo; Nicklause/ Muse of Poetry, Kate Lindsey; Lindorf/Coppelius/Dapertutto/Dr. Miracle, Nicholas Testé/Wayne Tigges; Olympia, So Young Park; Giulietta, Kate Aldrich; Antonia/Stella, Diana Damrau; Andres/Cochinille/ Pitichinaccio/Frantz, Christophe Mortagne; Luther, Kihun Yoon; Hermann, Theo Hoffmann; Nathanael, Brian Michael Moore; Spalanzani, Rodell Rosel; Bass Voice, Reid Bruton; Schlémil, Daniel Armstrong; Crespel, Nicholas Brownlee; Voice of Antonia’s Mother, Sharmay Musacchio.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/hoff_0644.png

image_description=Vittorio Grigolo as Hoffmann and Christophe Mortagne as Frantz [Photo by Ken Howard / LA Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Enchanting Tales at L A Opera

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Vittorio Grigolo as Hoffmann and Christophe Mortagne as Frantz

Photos by Ken Howard / LA Opera

Ermonela Jaho in a stunning Butterfly at Covent Garden

When I saw Jaho at the Barbican in November 2015, in Opera Rara’s semi-staged performance of Leoncavallo’s Zazà I was wowed by the ‘incredible commitment and vocal allure’ that the Albanian soprano displayed as the charismatic chanteuse from the backstreets. Here, similarly, she lived and breathed the role of the culturally and sexually exploited naïf. Her voice may be quite light for a part that demands great stamina and strength, but the power of her stage presence and vocal impact was simply breath-taking. Soft, silky, sensuous, her soprano throbbed with love. The gentleness of her pianissimo captured the tragic naivety of Cio-Cio-San’s misperception of reality. Jaho has a command of phrasing that imbues every melodic line with dramatic meaning. The Act 1 love duet for Cio-Cio-San and Pinkerton soared with a passion so fierce that it seemed almost shocking, coming from one so slight and mild. ‘Un bel dì’ was unbearably sweet, Jaho’s voice a tender wisp, as faint as the puff of smoke she longs to see on the horizon. In Act 1 Butterfly charmed Pinkerton and all; in the second she was resolute through heartbreak; and in the final Act she sank into terrible desolation with dignity.

Marcelo Puente (Pinkerton), Ermonela Jaho (Cio-Cio-San). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Marcelo Puente (Pinkerton), Ermonela Jaho (Cio-Cio-San). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Leiser and Caurier focus less on Cio-Cio-San’s cruel exploitation and abandonment and more on her selfless love; this truly is a fragile Butterfly, not a playful or feisty one, and physically Jaho captures all of her grace and delicacy of her airborne namesake, fluttering and hovering with feathery lightness. The floating sleeves of her silk furisode curve and glide; her long black tresses, or taregami, drape sensuously across her form.

Jaho wholly embodied the delicate sensibility that flinches from danger even as it embraces it. The newly married Butterfly shrinks from Pinkerton: ‘They say that in your country, if a butterfly is caught by man, he’ll pierce its heart with a needle and then leave it to perish!’ But, at the close, her frail wings broken, it is Cio-Cio-San’s own ornamental kaiken that delivers the fatal impalement. When, illumined by pale moonlight, the sakura petals tumbled from the outstretched branches of the lone tree, the tragic pathos was almost overwhelming.

Ermonela Jaho (Cio-Cio-San). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Ermonela Jaho (Cio-Cio-San). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

This was the third time that I have seen this production ( review 2015 ) and I found that my seat in the Amphitheatre offered new visual experiences. The more distant perspective made Christian Fenouillat’s faraway vistas, visible through and beyond the sliding shoji screens, acquire an air of whimsical romance, while the blue-pink mist, or shūyū, which drifts through the ornamental garden infused Butterfly’s entrance with fairy-tale romance. Similarly, the criss-crossing shards of coloured light at the close of Act 1 created an even more penetrating sense of restlessness and disorientation, while, the jarring complementary colours of the lighting scheme seemed to suggest both a dreamy otherworldliness and a disturbing unease.

Marcelo Puente (Pinkerton). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Marcelo Puente (Pinkerton). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Marcelo Puente looked the part as Lieutenant B.F. Pinkerton, though he lacked the leering arrogance more common among interpreters - indeed, the ‘boos for the baddie’ at the curtain call seemed even more inappropriate than usual. Despite some initial graininess in Act 1 and a little strain at the top, by the end-of-act duet Puente had settled into what was a strong performance, if a little stiff dramatically.

Making her ROH debut American mezzo-soprano Elizabeth DeShong exhibited a wonderfully glossy lower register as a fierce, loyal Suzuki, animated of manner and voice; Carlo Bosi’s self-important, guileful Goro suffered the sharp end of her tongue. I’d like to see much more of DeShong at the ROH.

Carlo Bosi (Goro), Elizabeth DeShong (Suzuki). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Carlo Bosi (Goro), Elizabeth DeShong (Suzuki). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Returning, like Bosi, to reprise their 2015 roles, Jeremy White as the Bonze and Yuriy Yurchuk as Yamadori contributed to the consistent high musical and dramatic standards. White harangued stentoriously; Yurchuk made Yamadori a figure of noble pride. Scott Hendricks was a fairly light-weight Sharpless but interacted well with Jaho. Jette Parker Young Artist Emily Edmonds sang Kate Pinkerton with accomplishment.

Scott Hendricks (Sharpless). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Scott Hendricks (Sharpless). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Expertly propelling the drama along with surefooted ease and naturalness, Sir Antonio Pappano made yet another remarkably vigorous contribution in the pit, pushing the surging climaxes to their peaks and allowing the tender moments to speak for themselves.

This is a stunning Butterfly. Grab a ticket if you can, or catch it in cinemas when it is broadcast live on Thursday 30th March: http://www.roh.org.uk/showings/madama-butterfly-live-2017

Claire Seymour

Puccini: Madame Butterfly

Cio-Cio-San - Ermonela Jaho, Lieutenant B.F. Pinkerton - Marcelo Puente, Sharpless - Scott Hendricks, Goro - Carlo Bosi, Suzuki - Elizabeth DeShong, Bonze - Jeremy White, Kate Pinkerton - Emily Edmonds, Imperial Commissioner - Gyula Nagy, Prince Yamadori - Yuriy Yurchuk; Directors - Moshe Leiser and Patrice Caurier, Conductor - Antonio Pappano, Set designer - Christian Fenouillat, Costume designer - Agostino Cavalca, Lighting designer - Christophe Forey, Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Monday 27th March

2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ERMONELA%20JAHO%20AS%20CIO-CIO-SAN%20%28C%29%20ROH.%20PHOTO%20BILL%20COOPER.jpg

image_description=Madame Butterfly, Royal Opera House, London

product=yes

product_title=Madame Butterfly, Royal Opera House, London

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Ermonela Jaho (Cio-Cio-San)

Photo credit: Bill Cooper

March 27, 2017

Brave but flawed world premiere: Fortress Europe in Amsterdam

The number of migrants trying to reach Europe by sea is already picking up, as it does every year. Putting their lives in the hands of unscrupulous smugglers, scores of them will drown. The ones who reach European shores will face years of uncertainty in asylum centers and hostility from nativists and nationalists who feel threatened by them. Librettist Jonathan West, informed by the writings of Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer, bravely tackles the most salient aspects of the European migrant crisis. The libretto is economical and purposeful in the beginning, but loses momentum halfway through. Tsoupaki’s atmospheric score contains some involving scenes, but is ultimately too circuitous to be fully convincing.

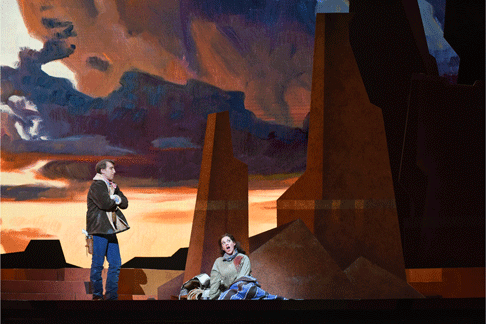

Totally up to the mark, on the other hand, are the cast and production. Director Floris Visser keeps things clear and to the point. Costumes and set are unfussy. On a rotating stage, sharp rocks denote a Greek island and a large door is the gateway to Europe. The drowning chorus wears life jackets sent over from Lesbos by an NGO that works with migrants. Soprano Rosemary Joshua sang Europa, an old woman living in Brussels. She is the mouthpiece of the current anti-immigrant sentiment shaping the European political landscape. With meticulous singing and crisp enunciation, Joshua created a focused portrait of a woman clinging to the past and terrified of the present. Her hankering for Old Europe is poetically expressed through the myth of Europa, the Phoenician princess who dreamed of two continents, Asia and an unnamed continent, fighting over her. The next morning she was carried away across the sea to Crete by Zeus disguised as a beautiful white bull. Europa gave Zeus sons and her name to her new home.

A scene from Fortress Europe

A scene from Fortress Europe

Political tensions over the influx of migrants are explored in conversations between Europa and her son Frans, a politician. Tenor Erik Slik sank his teeth wholeheartedly into this role in an emotionally charged and vocally assertive performance. Frans, a progressively sympathetic figure, is torn between his political mandate to guard European borders and his empathy for the refugees. While Europa recalls her youthful romance with phrases curling into melismas, Frans reminds her that even she once washed up in Europe from foreign shores. Mother and son fight over granting asylum to Amar, a Syrian who is the sole survivor of a catastrophic crossing. Europa refuses him entry, destroying him. Bass-baritone Yavuz Arman İşleker sang Amar with much vocal beauty and dignity. His slight Turkish accent added to the complexity of the topic under scrutiny. Amar’s re-enactment of the drowning with the chorus of migrants was the emotional peak of the opera. The excellent Netherlands Student Chamber Choir supplied young, vibrato-light voices for the spectral chorus. Singing a haunting Arab folk song, they fell silent one by one, shedding their life jackets onto a forlorn heap.

Conductor Bas Wiegers led the seven-strong Asko|Schönberg ensemble with confidence. The oboe and cor anglais had the lion’s share of the solos, in languid Eastern scales and plaintive keening. Tsoupaki is free with musical idioms, braiding passages for string quartet with Greek Orthodox hymns and Arab melodies. A harp evokes nostalgia and percussion crescendos mark dramatic events, while sound effects recreate wind and waves. Lucid orchestral colors suggest an exposed beach or the glade where Europa gives herself to Zeus. The problem is that Tsoupaki’s vocal writing is rhythmically repetitive and her melodies tenuous. Ariosos for the soloists begin promisingly, but end up where they started without evolving. The percussion flare-ups lose their impact through overuse. She passes over the opportunity to write a lively ensemble scene when journalists cross-examine Frans about his immigration policy. The entire press conference is spoken, and very well too, but it is too long.

Wordiness, successfully avoided during the trenchant phone conversations between mother and son, mars their final confrontation. They become megaphones for pro- and anti-immigration arguments and the music is not inventive enough to sustain interest. Amar’s tragic end is a horrific climax, but it arrives to late. Fortress Europe is the first installment of a trilogy about sociopolitical bushfires called Sign of the Times, produced by a company called Opera Trionfo. Dutch National Opera is collaborating on the project and this world premiere was part of their annual Opera Forward Festival. Musically, this ninety-minute work never reaches the boiling point required by its subject matter, but its best moments and the high quality of the performance makes one curious about its sequels.

Jenny Camilleri

Cast and production information:

Europa: Rosemary Joshua, soprano; Frans, the politician: Erik Slik, tenor; Amar, the refugee: Yavuz Arman İşleker, bass-baritone. Director: Floris Visser; Set and Costume Design: Dieuweke van Reij; Lighting Design: Alex Brok. Composer: Calliope Tsoupaki; Libretto: Jonathan West; Conductor: Bas Wiegers. Netherlands Student Chamber Choir, Asko|Schönberg. Seen at the Rabozaal, Stadsschouwburg, Amsterdam, Wednesday, 22nd March 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/17.03.19-1117.png image_description=A scene from Fortress Europe [Photo by Hans van den Bogaard] product=yes product_title=Brave but flawed world premiere: Fortress Europe in Amsterdam product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Above: A scene from Fortress EuropePhotos by Hans van den Bogaard

New Sussex Opera: A Village Romeo and Juliet

The company makes a fair job of the task too. There is much to admire and enjoy in this production, but ultimately an overly complicated design scheme impedes rather than assists dramatic momentum. Moreover, at the E.M. Forster at Tonbridge School the cast struggled both to create credible characters and relationships, and to communicate the text with sufficiently clarity.

To be fair, the singers may not be entirely to blame. Delius concentrates on the opera’s central lovers - Sali and Vrenchen - and the other characters are only lightly sketched. There is little to differentiate them musically and, in any case, the characters’ vocal lines are shaped by harmonic imperatives rather than given individual melodic identity. Furthermore, the lovers themselves are more ‘emblems’ - of, paradoxically, both childhood innocence and, in the opera’s final moments, consuming passion - than ‘real’ figures. The composer seems to have been more concerned with what might be termed the ‘emotional landscape’, as evoked by the instrumental preludes that precede each of the six scenes.

Moreover, the E.M. Forster Theatre itself did not prove the most sympathetic venue for opera. The auditorium is fairly small, and there is no pit, which meant that the audience were seated very close to the orchestra - the excellent 24-piece Kantanti Ensemble - which served to distance the action. It did not help that conductor Lee Reynolds, who displayed enormous sensitivity to Delius’s musical rhetoric and no small skill in guiding and encouraging his instrumentalists, is himself rather tall. It was hard to avoid the visual distraction in the centre of one’s vision and focus on the stage action, particularly as the stage drapes at the rear of the stage further hindered the projection of the vocal lines.

The playing of Kantanti Ensemble was one of the strengths of the performance. Although Reynolds occasionally allowed his players a bit too much free rein, it was a treat to hear the textural and melodic delicacies. Tom Pollock’s horn playing was superb (he can be forgiven for tiring a little towards the close), and he was matched by Sacha Rattle doubling on clarinet and bass clarinet; the double basses’ tone was deliciously dark and there was some explosive drama from timpanist Will Renwick. If the sixteen string players inevitably could not generate a luxuriant stream of sound, then the accuracy of their playing was impressive, and leader Beatrice Philips offered sure, sweet-toned solos.

Kirsty Taylor-Stokes and Luke Sinclair. Photo credit: Robert Knights.

Kirsty Taylor-Stokes and Luke Sinclair. Photo credit: Robert Knights.

Director Susannah Waters and her design team told Delius’ tale clearly. The composer’s libretto, drawn from a short story by Gottfried Keller, reprises Shakespeare’s themes of family feuds and doomed love. Two farmers, Marti and Manz, contest the narrow strip of wild land that separates their fields and which is owned by the Dark Fiddler who, as an illegitimate son, cannot inherit. Though prohibited by their fathers, during the bitter dispute that bankrupts both farms, Sali and Vrenchen meet secretly. Friendship blossoms into love, while their fathers surreptitiously encroach onto the fallow land, inch by inch. The Dark Fiddler reappears and cautions that they should beware the time when the land is no longer a haunt of birds and animals, a warning which presages the tragedy that unfolds.

Anna Driftmier’s set is evocative. At the rear, distressed windmills flap and whirl, beside denuded tree trunks; in this barren world, one can imagine why the two farmers stake their claim for the wild pasture. However, Driftmier’s design - while ingenious - is over-complicated: the persistent choreographed re-arrangement of wooden planks and slats - they form pathways, platforms and are assembled into raised frames to suggest homes and bridges - must have caused the community chorus, effectively reduced to stage-hands, no end of trouble in rehearsal. It’s just as well that the chorus don’t have an awful lot of musical business but they sang warmly and with confidence in the marriage scene, though the communal festivities were a bit stiff.

New Sussex Opera Chorus (The Fair). Photo credit: Robert Knights.

New Sussex Opera Chorus (The Fair). Photo credit: Robert Knights.

While the chorus effected the set transitions slickly, their complicated reshuffles could not help but be a distraction during the instrumental episodes. In the fairground setting of Scene 5 the necessary manoeuvring undermined the tense jollity of the scene, though the garish costumes were a welcome splash of colour emphasising the fickle unpredictability of this uncanny world. Even the famous ‘Walk to Paradise Garden’ was not spared: we witnessed a dumb show as Sali forged a stepping-stone conduit, stopping on their arduous journey to remove one boot and bathe his foot in a stream. And, in truth, despite the strong greens, purples, reds of Jai Morjaria’s lighting design, which created an eerie otherness, the plywood boxes and boards never looked like anything other than very real Ikea bookcases.

Tenor Luke Sinclair was buoyant and managed the high tessitura well, conveying Sali’s irrepressible impetuousness, while Kirsty Taylor-Stokes’ richly coloured mezzo and full vibrato suggested the ardour blossoming in the innocent Vrenchen’s heart, and captured her despair at the start of Scene 4. Ian Beadle’s baritone needed more nuance and portentous resonance to capture the Dark Fiddler’s enigmatic air; Beadle was all too amiable, but his song in praise of the ‘Vagabond wind’ was appealingly sung.

Ian Beadle. Photo credit: Robert Knights.

Ian Beadle. Photo credit: Robert Knights.

Geoffrey Moses (Marti) and Robert Gildon (Manz) established the context and their characters deftly at the start, though Moses’ diction was weak at times and I found Gildon’s bass a little tense and occasionally unfocused. As the Young Sali and Young Vrenchen, Alex Edwards and Nell Parry were sadly over-powered (a case for a mic?); Edwards was almost inaudible, while Parry had to strain to rise above the instrumental texture.

Robert Gildon and Alex Edwards. Photo credit: David James.

Robert Gildon and Alex Edwards. Photo credit: David James.

The final moments of the opera were absorbing and well-crafted. When the lovers are recognised at the fair, Sali suggests that they should go to the Paradise Garden where they find the Dark Fiddler and his entourage drinking and carousing. Rather than submit to the temptations of his hedonistic life, they choose to drift down river in a gradually submerging boat, resigned to the Tristan-esque double suicide that must follow. I think that the ‘wrist-slashing’ would have been best left to the imagination, but the final tableau was artfully lit in a gleam of ultramarine, and superbly paced by Reynolds.

This was an admirably ambitious production, but given the demands of performing such a musically and dramatically challenging work in five different venues one couldn’t help feel that a more minimalist staging might have more effectively focused attention on the internal drama - the power passions and dreams that are embodied in Delius’ score - which develops in the village lovers’ hearts and minds.

There are three further performances: on Tuesday 28th March at Cadogan Hall, London; and on Friday 31st March at the Stag Theatre, Sevenoaks, and on Sunday 2nd April at the Devonshire Park Theatre, Eastbourne.

Claire Seymour

Delius: A Village Romeo and Juliet

Sali - Luke Sinclair, Vrenchen - Kirsty Taylor-Stokes, The Dark Fiddler - Ian Beadle, Manz - Rob Gildon, Marti - Geoffrey Moses; Young Sali - Alex Edwards; Young Vrenchen - Nell Pary; Wild Girl - Georgia Cudby; Director - Susannah Waters Conductor - Lee Reynolds, Designer - Anna Driftmier, Lighting designer - Jai Morjaria, New Sussex Opera Chorus, Kantanti Ensemble.

E.M. Forster Theatre, Tonbridge School; Sunday 26th March 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sali-and-Vrenchen-3-RK.jpg image_description=New Sussex Opera, A Village Romeo and Juliet product=yes product_title=New Sussex Opera, A Village Romeo and Juliet product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Kirsty Taylor-Stokes and Luke SinclairPhoto credit: Robert Knights

March 26, 2017

Cast announced for Bampton Classical Opera's 2017 production of Salieri's The School of Jealousy

Setting a sharply cynical libretto by Caterino Mazzolà, this opera buffa was written in Venice and first performed at the Teatro San Moisè in 1778. It was selected to inaugurate the Emperor Joseph II’s new Italian opera troupe at the Burgtheater in Vienna in 1783, with an outstanding cast including the star English soprano Nancy Storace (later one of Mozart’s favourite sopranos and the first Susanna) as the Countess, and Francesco Benucci (later Figaro and Guglielmo) as Blasio. Salieri revised the score for these performances including new arias specially for Nancy Storace, and the librettist Lorenzo da Ponte added some textual adjustments. The opera made a huge impact and became one of the highlights of Storace’s career.

La scuola de’ gelosi was performed widely across Europe - from London to St Petersburg - for several decades, and was praised warmly by Goethe. The opera’s great success in Vienna almost certainly inspired Da Ponte and Mozart to create La scuola degli amanti which eventually became known by its alternative title Così fan tutte and there are many narrative parallels between the two. In both fidelity and honesty are tested by means of dangerous games and deceits, and the manipulative Lieutenant in Gelosi is a counterpart to Don Alfonso.

It was the first of Salieri’s works to be performed in London, in 1786: The Herald judged “it is the first lyric drama that may be termed strictly good, whether we advert to the poem itself, the music, or the performance” and the Morning Post called it a “masterly composition” that “does great honour to Salieri, whose reputation as a composer must rise infinitely in the musical world, from this very pleasing specimen of his abilities”. For performances in 1780 at the court theatre at Esterháza, Haydn composed two insertion arias.

La scuola de’ gelosi is enjoying a current revival across Europe, including performances this year in Florence and Vienna and a recording by L’arte del mondo on Deutsche Harmonia Mundi. Bampton has also selected the work to mark the bicentenary of the death of Nancy Storace in 1817.

Plot outline

The Count Bandiera is a skilful philanderer, but takes a big risk when he invites Ernestina, wife of a pathologically jealous businessman, out on a shopping trip. A decidedly non-PC visit to a madhouse, fortune-telling gypsies and the lessons taught by paintings are just some of the bizarre situations encountered in this scintillating comedy of marital dis-harmony.

Cast

Countess Rhiannon Llewellyn (soprano)

Ernestina Nathalie Chalkley (soprano)

Carlotta Kate Howden (mezzo-soprano)

Count Alessandro Fisher (tenor)

Tenente Thomas Herford (tenor)

Blasio Matthew Sprange (baritone)

Lumaca Samuel Pantcheff (baritone)

Bampton Classical Opera was founded in 1993 by its artistic directors, Gilly French and Jeremy Gray, and stages less familiar works from the late Classical period, many of which might not otherwise be heard. The performances are of the highest musical quality, yet are relaxed and welcoming with fresh and accessible English translations, and can be enjoyed even by those with little opera experience. The company also provides valuable performance opportunities for the country’s finest young professional singers, and hosts a Young Singers’ Competition every two years.

Bampton Classical Opera stages productions in rural venues in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire as well as regularly in London at St John’s Smith Square. Other significant venues and festivals have included Wigmore Hall and Purcell Room, Buxton Festival, Cheltenham Festival and Theatre Royal Bath. Amongst their many performances have been UK premières of Bertoni Orfeo, Marcos Portugal The Marriage of Figaro, Paer Leonora, BendaRomeo and Juliet, Gluck Il Parnaso confuso,Philemon and Baucis, Salieri Falstaff and La grotta di Trofonio.

The delightful Deanery Garden at Bampton provides a charming and picturesque venue for open-air opera, with an excellent natural acoustic. Westonbirt School is a spectacular Victorian mansion, with extensive Grade I listed gardens: the performances take place in the Orangery Theatre. Audiences are encouraged to bring their own garden chairs and enjoy a pre-performance or interval picnic.

St John’s Smith Square is the most historic of London’s concert halls and provides an outstanding and appropriately eighteenth-century setting for this performance.

The School of Jealousy performances, with free pre-performance talks:

The Deanery Garden, Bampton, Oxfordshire OX18 2LL

7.00 pm Friday 21 and Saturday 22 July

The Orangery Theatre, Westonbirt School, near Tetbury, Gloucestershire GL8

8QG

5.00 pm Monday 28 August

St John’s Smith Square, London SW1P 3HA

7.00 pm Tuesday 12 September

La voix humaine: Opera Holland Park at the Royal Albert Hall

For this performance of Poulenc’s one-woman emotional roller-coaster, La voix humaine (1959), Opera Holland Park ventured indoors, into the genteel setting of the Elgar Room at the Royal Albert Hall. The room is not a large one and some of the sell-out crowd may have found their sightlines somewhat restricted as Marie Lambert’s intense, taut direction placed French soprano Anne Sophie Duprels at the centre of a slightly raised platform, often kneeling, crouching or reclining.

But, the intimacy of the setting, together with Duprels’ astonishing presence and impact, more than made up for any visual impediment. Duprels’ tour de force also helped mitigate the drabness of the design. Given the nature of this one-off excursion to the RAH, allowance can be made for adopting a limited staging, especially for a work that in fact needs no staging at all (except perhaps a single property, the telephone itself, which is almost a second character) to make its emotional and dramatic impact).

But, Lambert’s fluctuating lighting was distracting. And, the dilapidated plywood bedstead, daubed with blue paint splashes, did little to evoke Parisian chic. Nor did it suggest the bedroom ‘asleep with remembering’ which contains just a woman and the telephone that she clutches, ‘like a revolver’, as Cocteau demanded when instructing Poulenc about the design and staging of the opera in 1959. However, the blue cord of the telephone was a subtle but powerful visual image: Duprels’ ultramarine fingernails suggested it was delivering an intravenous infusion of a blue barbiturate, sedating and hypnotising the anxiety-fuelled woman, as she slipped ever nearer to sleep, or suicide.

Fortunately, Duprels’ performance pushed any concerns aside. As ‘Elle’, the lonely woman who makes a desperate telephone call to the lover who has abandoned her, she spanned an enormous emotional spectrum from terror to tremulous hope, from existential despair to excitement. We hear just one side of the conversation but, through careful pacing of the silences and nuanced repetitions of others’ words, Duprels was able to evoke a world beyond the forlorn bedroom, thereby deepening her own alienation from normal human interaction and exchange. As her attempted tête-à-tête was continually disrupted by wrong-numbers, disconnections, crossed-wires and an intrusive operator, Elle’s inner distress became a palpable but unspoken inner cry for help, ‘Can you hear me?’

Anne Sophie Duprels. Photo credit: Alex Brenner.

Anne Sophie Duprels. Photo credit: Alex Brenner.

Cocteau’s 1930 play grew out extreme personal crisis: addicted to opium, he was in the midst of a turbulent affair with a young writer, Jean Desbordes, who eventually abandoned Cocteau for a woman and joined the French Resistance movement, suffering a torturous death at the hands of the Gestapo. Poulenc, in the 1950s, was also suffering private distress, depression and drug addiction following the death of his partner Lucien Roubert. Though the work, in both dramatic and operatic form, conveys the universal experience of grief for a lost love, there is a crypto-homosexual insinuation in Elle’s quasi-masochistic sensibility which recalls the plays of Tennessee Williams.

Cocteau does not seem particularly sympathetic towards his protagonist. Her lies are barefaced - she is wearing his favourite dress (in Lambert’s production she is draped in an unflattering, dirty, crumpled beige night-shirt); she has spent the day with her best friend, Marthe, when in fact she hasn’t left the room; she’s coping well, even though she later confesses she has tried to take her own life just the evening before.

But, as Elle recollected old love letters and rambled incoherently - almost a caricature of emotional neediness - Duprels managed to draw sympathy for the suffering women, despite her histrionics and melodrama. The moment when Elle discovers that her lover’s mendacity equals her own was full of pathos. We infer that he is calling her from his apartment, and when the line suddenly goes dead, she re-dials, only to be answered by the servant Joseph. Duprels’ reiteration of Joseph’s words, ‘Monsieur is not in and will not be returning home tonight’, was laden with tragic realisation and recognition.

Duprels confirmed that she is a tremendous singing actress. Not surprisingly, every word of the French text was audible and she had a sure sense of how to accommodate her voice to the small venue. She conjured an enormous variety of vocal colour and tone: at times whispering, speaking, crooning, then flowering in full blown lyrical ecstasy, gleaming at the top, breathless and dusky below. As she tried vainly to win her lover back with nostalgic remembrance, her voice was caressing, but when pain and pride broke through Duprels exposed Elle’s bitterness, introducing a shrill stridency or hardness of tone. Her physical commitment to the role was consummate, the final moments of Elle’s breakdown gripping and troubling.

Pascal Rogé was an attentive, detailed and discreet accompanist, powerfully interjecting with angular, jabbing motifs to portray the climactic peaks of Elle’s nervous disintegration, but elsewhere delicately hinting at wistful memories of tenderness or expanding lyrically to convey past passions.

Duprels demonstrated just how powerful a musico-dramatic experience she could create with limited means and time. I greatly admired Duprels’ performance last year in Mascagni’s in Iris and her performance here certainly whets the appetite for this year’s season at Holland Park, where in July she will be reunited with Lambert in a new production of Leoncavallo’s Zazà whose eponymous ‘heroine’ - a chanteuse raised from the backstreets to the bright lights - runs her own gamut from fervent passion to dejected self-pity.

Claire Seymour

Poulenc: La voix humaine

Anne Sophie Duprels (soprano), Pascal Rogé (piano)

Opera Holland Park, Elgar Room, Royal Albert Hall, London; Wednesday 22nd March 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Anne%20Sophie%20Duprels%202%20%28c%29%20Alex%20Brenner.jpg image_description=Opera Holland Park, La voix humaine product=yes product_title=Opera Holland Park, La voix humaine product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Anne Sophie DuprelsPhoto credit: Alex Brenner

March 21, 2017

London Handel Festival: Handel's Faramondo at the RCM

The pseudo-historical plot is an almost unfathomable cat’s-cradle of intrigues, misalliances and mistaken identities. The King of the Franks, Faramondo has killed Sveno, the son of Gustavo, the Cimbrian King. The latter swears vengeance but when his knife is poised above Clotilde, Faramondo’s sister, Gustavo promptly falls in love with his prisoner, who is herself in an amorous dalliance with Alfonso, Gustavo’s other son. Meanwhile, Gustavo’s daughter, Rosimonda, whom he dangles as a prize to would-be avengers, has fallen in mutual love with Faramondo, but struggles with her split allegiances - and against Faramondo’s rival for her heart, Gernando.

The result: amorous stalemate. Lovely aria follows lovely aria as the protagonists, often alone on stage, bewail the deadlock. As degeneracy ensues, it’s not always clear where enmity and loyalty dwell. It’s really no surprise when - in Trovatore fashion - Sveno turns out not to have been Sveno after all, but Childerico, the son of Gustavo’s ambitious general Teobaldo who swapped the babes at birth.

Despite the torturous and dramatically encumbering narrative knots, the score is full of fine features: incisive sinfonie (one for each act); beautiful melodies; lively, springy rhythms; interesting - often quite sparse - instrumental colouring; and arias that contrast emotional excitement with lyrical breadth. Handel reduced the recitative in Gasparini’s version of the opera - which had already considerably sliced Zeno’s original libretto - to the barest of minimums but, given that there is no real ‘action’, this is not a hindrance to a dramatic comprehensibility that is already stretched to the limits.

When Göttingen Händel-Festspiele director Laurence Cummings conducted the opera at the June 2014 Festival he and his director, Paul Curran, opted wisely to dispense with historical ‘veracity’ and shifted the action to a mafioso gangland in the mid-twentieth century. For this collaboration between the London Handel Festival and the Royal College of Music’s International Opera School director William Relton and designer Cordelia Chisholm retain the Scorsese-inspired setting and add a dash of West Side Story in the form of rival gangs of knife-wielding ganstas and hoods.

Faramondo is the leather-clad leader of one band of thugs, Gernando heads a rival clan of glue-sniffing skinheads, while Gustavo is a sharp-suited casino magnate. We’re in a twilight zone. Blood oaths bind the members of Gustavo’s Family and flick knives flash in the stark glare of the strip lights on every seedy corner. Casting a patina of glamour over this sordid underworld are the sultry lights and glitter balls of Gustavo’s wine bar. At one point, Rosimonda - glitzy in gold lamé - spins a star turn in front of the mic to entertain the gamblers.

Ida Ränzlöv. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Ida Ränzlöv. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

There’s plenty of ‘business’, much of it clever, some of it overly fussy, nearly all of it irrelevant to what is being sung, or even felt. The da capo repeats are supplemented not with melodic ornamentation but with excessive alcohol and drug consumption. Faramondo’s mobsters swig from bottles of beer, he gulps from a hip-flask, and having emptied the used glasses on the tables of Gustavo’s, Clotilde grabs a bottle and lets the bubbles flow. Rosimonda drags agitatedly on a cigarette, while Gernando fuels his da capo with a deep inhalation of solvents. Nifty use of a cross curtain, which allows for swift changes of locale, keeps things swinging along.

After a vibrant overture from the London Handel Orchestra led by Oliver Webber, the cast took a little while to settle. There were some slips of intonation and stage-pit timing in the opening few numbers, the coloratura was sometimes rather muddy and I don’t think I heard a trill characterised by the requisite evenness, accuracy of tuning and speed in the first Act. That’s not to suggest that the singing was bad - there was much colour and charm - just that a certain polish was lacking.

Fortunately, the singers found their feet subsequently. In the title role, however, mezzo soprano Ida Ränzlöv was in a class of her own from the start. There is a real richness to Ränzlöv’s sound and a vividness of tone; she demonstrated a natural feeling for the Handelian phrase, delivering the coloratura with effortless seamlessness and crafting a fine cantabile. Ränzlöv also demonstrated dramatic range and - in this opera, no mean feat - credibility, conveying both Faramondo’s vicious streak and an underlying tenderness.

Similarly, Beth Moxon convincing captured the conflicted Rosimonda’s inner battle with desire and duty. The only thing she seemed certain about, as she strutted and fretted back and forth, compulsively chain-smoking, was her disdain for Gernando. Rosimonda’s vengeance aria bristled, but her final aria charmed and calmed.

< Timothy Morgan. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Timothy Morgan. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

The few ensembles of Acts 2 and 3 contain some of the finest music of the opera; the cheerful intertwining of the central lovers mezzos at the end of Act 2 offered hope for resolution, although Clotilde and Adolfo shared a more muted moment at the start of the final Act.

Soprano Harriet Eyley sparkled as a gamine Clotilde. Josephine Goddard was her hopelessly love-struck suitor; though Goddard’s soprano has vocal elegance, her Jimmy Krankie wig did not add to her dignity.

New Zealand baritone Kieran Ryaner was a dark-voiced Gustavo but though he could call on significant weight and power his coloratura was not always finely focused; countertenor Timothy Morgan relished Gernando’s unsavoury sleaziness. Baritone Harry Thatcher was a confident Teobaldo and Lauren Morris made her mark as the diffident nerd Childerico, even though the role has no arias.

With revenge, restitution and realignment all satisfactorily effected, Faramondo’s final aria led into a spirited chorus. But, while the protagonists sang of Virtue’s merits, the villainy continued, as Faramondo’s heavies despatched the victims of Gustavo’s lingering resentment and rancour: a quick flick of an efficient knife and off they went, dragged feet first. In Relton’s eyes, there is no distinction between those with morals and those without. I guess they are all Goodfellas.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Faramondo

Faramondo - Ida Ränzlöv, Clotilde - Harriet Eyley, Gustavo - Kieran Rayner, Rosimonda - Beth Moxon, Adolfo - Josephine Goddard, Gernando - Timothy Morgan, Teobaldo - Harry Thatcher, Childerico - Lauren Morris; Director - William Relton, Conductor - Laurence Cummings, Designer - Cordelia Chisholm, Lighting designer - Kevin Treacy, London Handel Orchestra.

Britten Theatre, Royal College of Music, London; Monday 20th March 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kieran-Rayner-Gustavo-Harriet-Eyley-ClotildeFaramondo-London-Handel-Festival-Credit-Chris-Christodoulou-536x357.jpg image_description=London Handel Festival, Faramondo product=yes product_title=London Handel Festival, Faramondo product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Kieran Rayner and Harriet EylesPhoto credit: Chris Christodoulou

Brahms A German Requiem, Fabio Luisi, Barbican London

The Barbican Centre is built over the remains of a much older London, which still exists in hidden corners. During the week, the metropolis is manic, but on a Sunday night, a quiet calm descends, and once more you can feel the presence of the past amid the high tech towers and traffic. Under the Barbican Hall itself was Three Herring Court, where my companion's ancestors lived in extreme poverty. An atmospheric way in which to experience Brahms German Requiem, which commemorates the endurance of the human spirit across boundaries of time and place. Not for nothing did Brahms blend together verses from the Old and New Testaments, evidence of an upbringing steeped in North German Lutheran tradition, even though he rejected conventional piety, and lived much of his life in staunchly Catholic Vienna. .

The voices of the London Symphony Chorus rose beautifully from the hushed opening chords. "Selig sind, die da Lied tragen", for those who go forth weeping bearing precious seed will return "Mit Freuden und bringen ihre Garben". Death is a not an end, but a process. With Sir Simon Rattle as Music Director of the LSO, Londoners get another advantage : Simon Halsey, Rattle's choral counterpart through the years at Birmingham and in Berlin. The LSO Chorus sounded luminous, voices carefully blended. If anything, the LSO Chorus sounded even richer in the second movement Denn alles Fleisch es ist wie Gras though this brought the orchestra to the fore. The "march" theme was particularly well defined, with a good sense of surge underlying the solemn, deliberate pace, so when the lyrical motif appeared, it suggested light and hope. The fanfare at the end of the movement was understated but confident.

Simon Keenlyside sang the baritone part, which he has taken many times before. Experience showed. Brahms quotes Psalm 9 (verses 4 to 7), where a man contemplates his fate : humility is of the essence, surrounded as he is by the tumult in the orchestra. Yet the assured, unforced timbre of Keenlyside's singing highlighted the inner strength that comes from faith, whatever the source of that faith. When the chorus joined in, the protagonist was no longer alone, in every sense. Perhaps for this reason the song with soprano (Julia Kleiter) Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit was added, for it is a moment of illumination, before the mood turns sombre yet again. The solemn processional of the second movement echoes in the sixth. Forceful chords from the orchestra, and a blazing fanfare of brass, strings and percussion, and the chorus in full swell , for momentous changes are to come. The trumpets rang out, as in the Book of Revelation, a trumpet will herald the End of Time, when the dead of past ages will be raised to life again. Keenlyside's voice rang out "Wir werden verwandelt werden" and the chorus entered, forcefully "Hölle, wo ist dein Sieg!" A thunderous finale, after which it took some moments to recover.

Fabio Luisi and the London Symphony Orchestra were impressive, and their Schubert Symphony no 8 was excellent, well poised and stylish. But the full honours went to the London Symphony Chorus, for Brahms's German Requiem is one of the high points in the choral repertoire. "Selig sind die Toten.....daß sie ruhen von ihrer Arbeit". Rich, fulsome playing from the LSO, luminous singing from the LSO Chorus. The German Requiem concluded in transcendance.

Anne Ozorio

image=https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/Johannes_Brahms_portrait.jpg/256px-Johannes_Brahms_portrait.jpg

product=yes

product_title= Schubert:Symphony no 8 "The Unfinished", Brahms A German Requiem, Fabio Luisi, London Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Chorus, Simon Keenlyside, Julia Kleiter, Barbican Hall London, 19th March 2017

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Johannes Brahms

March 19, 2017

Káťa Kabanová in its Seattle début

The immediately preceding production of Seattle Opera’s 2016-17 season had been the much-traveled Traviata from the atelier of Peter Konwitschny, and the show’s rather coarse updating and arbitrary dramaturgy had not gone down at all well with the company’s conservative but sophisticated audience. Was this to be another evening of mannered, second-hand Regietheater? The immense bare black box confronting the house as we entered was not promising: even the supertitle screen looked more like a stage-wide guillotine than a refuge for the eyes of the Czech-impaired among us.

Nicky Spence (Tichon) and Maya Lahyani (Varvara)

Nicky Spence (Tichon) and Maya Lahyani (Varvara)

Well, Regietheater it was, but of the engaged, engaging audience-friendly kind. As the music began, the marvelous American dramatic soprano Melody Moore stood center-stage, impaled in a column of searing white light. Then around her, images familiar to most of the audience began to fill the box: the rosy brown basalt cliffs of an Eastern Washingotn river valley; a white picket fence complete with red-flagged mailbox by the gate; townsfolk strolling in high-1940’s Sunday-go-to-meeting gear; finally, a broadspread American flag descending to complete the thoroughly Normal Rockwell picture.

The visuals of Mark Howett and Genevieve Blanchett’s deft production did not remain so Grant-Woody American Gothic (though the tschochke-choked home the heroine shares with her cringing husband and horrible mother-in-law could easily host that master’s Daughters of the American Revolution). Projections of roiling waters, clouds of crows began to invade the scene as the dream of childish bliss Kàt’a recounts to her bobby-soxer sister-in-law fade away. Stark lighting contrasts both isolate and link the performers.

Victoria Livengood (Kabanicha)

Victoria Livengood (Kabanicha)

Kàt’a’s dreams are the key to look and dramaturgy of Patrick Nolan’s production. The danger for an updated, Americanized Kàt’a is implausibility: how can the love even of a timid small-town girl and a feckless rich boy be thwarted so thoroughly the era when Rosalind Russell, Ginger Rogers, and Betty Grable are setting the tone for young American girls’ behavior every weekend at the movie palace?

But this Kàt’a isn’t just a dreamer: she’s all dreamer. When life hands her lemons like mom-in-law Kabanicha (Victoria Livengood, a church lady who doesn’t mind a smoke, drink, or cuddle behind closed doors) and husband Tichon (Nicky Spence, a boozy bullpup without a bite) she incorporates them as dream enemies, and finds a dream prince handy in the form of Boris, (Joseph Dennis), lollygagging and at loose ends in the provinces

Ms. Moore is a mature woman and Dennis is a young man, but the mismatch in ages only accents the absurd of their relationship, while their voices, more sumptuous and powerful than those of the second cast’s Corinne Winters and Scott Quinn give them ever greater emotional clout as the drama deepens.

Joseph Dennis (Boris) and Melody Moore (Katya)

Joseph Dennis (Boris) and Melody Moore (Katya)

The power of the production is mightily enhanced from the pit. When a show is this well sung and acted throughout, it’s easy to forget the challenge for non-Czech singers in this repertory. I have no idea if a Czech speaker would find their delivery “authentic,” but they convinced me completely, and their attack and confidence can only be the result of the conducting of Oliver von Dohnànyi.

His is one of the proudest names of the last century in Central Europe. I do not know if Von Dohnànyi is related to the great musicians and statesmen whose name he shares, but his artistry is worthy of his name. Seattle Opera and Seattle audiences are lucky to have him.

They are also fortunate in the rest of the cast. The thoughtless young lovers Varvara and Kudrjas are taken in both casts by Maya Lahyani and Joshua Kohl in rather genre-generic musical-comedy second-couple fashion, but both sing very well; Nicky Spence and Stefan Skafarowsky make the most of their tiny roles. look forward to seeing them all in future productions.

Above all, let’s have Janacek Bring back: It’s been more than 25 year since we saw Cunning Little Vixen. Thanks to this fine show and above all to maestro von Dohnanyi, we’re prapared for The Macropolos Affair and From the House of the Dead!

Roger Downey

Cast and production information:

Conductor: Oliver von Dohnanyi. Kàt’a: Melody Moore/Corinne Winters; Boris: Joseph Dennis/Scott Quinn; Kabanicha: Victoria Livengood; Kudrjas: Joshua Kohl; Varvara: Maya Lahyani; Tichon: Nicky Spence; Dikoi: Stefan Skafarowsky; Glasha: Jennifer Cross; Feklusha: Susan Salas; Kuligin: Joseph Lattanzi. Seattle Opera chorus and Orchestra. Director: Patrick Nolan; Production design: Genevieve Blanchett; Lighting and digital effects: Mark Howett.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/17_Katya_JL_052.png image_description=Melody Moore (Katya) [Photo by Jacob Lucas] product=yes product_title=Káťa Kabanová in its Seattle début product_by=A review by Roger Downey product_id=Above: Melody Moore (Katya) [Photo by Jacob Lucas]All other photos by Philip Newton

March 18, 2017

Bampton Classical Opera Young Singers’ Competition 2017

The previous winners were mezzo-soprano Anna Starushkevych (2013) and soprano Galina Averina (2015). Bampton Classical Opera has a reputation for its commitment to young talent and a number of singers who have appeared on the Bampton stage have gone on to work with national companies such as The Royal Opera, English National Opera and Opera North.

The first round of the Bampton Classical Opera Young Singers’ Competition 2017 (closed sessions) will take place on 28 and 29 October in London. The public final will take place in the Holywell Music Room, Oxford, on Sunday 19 November at 6pm. Judges for the competition will be two renowned British singers: tenor Bonaventura Bottone and mezzo-soprano Jean Rigby.

Competitors can apply by downloading an application form and information document from www.bamptonopera.org or on request by emailing ysc@bamptonopera.org

Applications opened on 1 March 2017 and the entry deadline is 11 August 2017.

First prize £1,500 - Second prize £500. For the first time there will also be a £500 Accompanists’ Prize.

The winner of the first Young Singers’ Competition in 2013 was Ukrainian mezzo-soprano Anna Starushkevych and British soprano Rosalind Coad was the runner-up.

Since then Anna Starushkevych performed the role of Erato in Gluck’s Il Parnaso confuso and the title role in Bertoni’s Orfeo (UK première) for Bampton Classical Opera, both during summer 2014. In summer 2015 she sang the role of Ofelia in Salieri’s La grotta di Trofonio , also for the company. She is one of the soloists on a new Resonus Classics CD of song cycles by Pavel Haas, including the world première recording of Fata Morgana. Later this year Anna will sing the role of Matilda in Handel’s Ottone at both the Beaune Festival and Theater an der Wien.

Rosalind Coad was a Scottish Opera Emerging Artist from 2014-15 and sang a number of roles for the company. Currently she is covering the role of Mélisande in Pelléas et Mélisande for Scottish Opera. Other performances have included Gianetta (L’Elisir d’Amore) and Clotilde (Norma) for Opera Holland Park. She sang the role of Daughter in the Bampton Classical Opera concert performance of Maurice Greene’s Jephtha in 2014.

In the Young Singers’ Competition 2015 Russian soprano Galina Averina won first prize and Welsh soprano Céline Forrest was the runner-up.

Since the competition Galina Averina sang the role of Atalanta ( Serse) for English Touring Opera in 2016. She is currently singing Pamina for Mid-Wales Opera, and will be performing at the London Handel Festival. She will be taking part in the young artists programme at this year’s Aix-en-Provence Festival and will return to English Touring Opera for next season’s autumn and spring tours.

Céline Forrest studied at the National Opera Studio in 2015/2016. Her opera training took her to Opera North and Welsh National Opera, where she worked with Graham Vick and Elaine Kidd. Recently she covered the role of Jessica in Welsh National Opera’s The Merchant of Venice by Tchaikowsky. She is currently working on the role of Mina in Verdi’s Aroldo for UCOpera.

This competition is open UK residents aged between 21 and 32 on 19 November, 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Anna%20Starushkevych.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Bampton Classical Opera Young Singers’ Competition 2017 product_by= product_id=Above: Anna StarushkevychFestival Mémoires in Lyon

Le Couronnement de Poppée

Klaus Michael Grüber's production of L'incoronazione di Poppea comes from the Aix Festival of 2000. The design was by visual artist/painter Gilles Aillaud (1928-2005), Grüber's frequent collaborator at West Berlin's Schaubühne (and opera houses in Berlin and elsewhere). It was a prestigious cast, Grenoble's Les Musiciens du Louvre in the pit with Marc Minkowski.

I remember being bored, very bored. For me, then, there was no hint of mythic-in-the-making.

Just now in Lyon's 870 seat Théâtre National Populaire it indeed became mythic, brought there not solely by messieurs Gruber and Aillaud, but also and possibly because of the Les Nouveaux Caractères (a French early music ensemble) and principally its conductor Sébastien d'Hérin, and the fourteen Solistes du Studio de l'Opéra de Lyon (its young artists program). We, all of us -- the cast and audience -- were enthralled.

Conductor d'Hérin drove the music of the words, Monteverdi's dramatic genius bursting into dramatic phrases, with the double continuo of Les Nouveaux Caractères melding a myriad of colors into the Monteverdi's unfettered catalogue of affects. It was never mere musical color, it was always word and phrase, a relentless concentration of affects from beginning to end.

Conductor d'Héron evoked a flowing sensuality of sound, and an obsessive drive that never allowed Poppea and Nerone's ambitions to falter, culminating in the sublime love duet where Grüber's actors cross and cross and finally line-up on the most abrupt and corrupt ending of all opera.

Josefine Göhmann as Poppea [Poppea photos copyright Jean-Louis Fernandez, courtesy of the Opera de Lyon]

Josefine Göhmann as Poppea [Poppea photos copyright Jean-Louis Fernandez, courtesy of the Opera de Lyon]

Director Grüber was a disciple of Giorgio Strehler. He bases much of what he does on Strehler's minimalistic principles and physical theater convictions. Gruber creates a theatrical language of abstractions, both in positioning and posturing. It is entirely presentational, eschewing all sense of an actual world, remaining always an imaginary, artistic world where the word itself is the only reality. Designer Aillaud's flat scenery visually embraces Grüber's artistic spaces to the fullest.

Without the distraction of famous artists attempting to realize such arcane abstractions, we entered this theatrical world through the willing young singers of the Opéra de Lyon's studio, who without exception gave total performances. Especially effective were the Nerone of Lithuanian mezzo Laura Zigmantaite and German/Chilean soprano Josefine Göhmann who were the only of Grüber's actors required to realize a constant plasticity of simultaneous gestural and musical movement -- a kind of emotional puppetry. Both were consummate performers.

Laura Zigmantaite as Nerone, Oliver Johnston as Lucano

Laura Zigmantaite as Nerone, Oliver Johnston as Lucano

Excellent as well were the Seneca of Polish bass Pawel Kolodziej and the Ottavia of Finnish mezzo Elli Vallinoja. There were many memorable scenes, among them the spellbinding duet as Nerone expounds the sensual splendors of Poppea to his poet friend Lucano, sung by English tenor Oliver Johnston. And as well every scene with Poppea's nurse Arnalta, sung by French tenor André Gass.

Much praise for the success of this revival must be attributed to stage director Ellen Hammer, a directorial collaborator of Klaus Michael Grüber throughout his career. Mme. Hammer however in her program booklet remarks reveals herself needlessly pretentious as well as condescending to these superb young artists.

Cast and Production Information Poppea: Josefine Göhmann; Drusilla / Virtu: Emilie Rose Bry; Nerone: Laura Zigmantaite; Ottone: Aline Kostrewa; Arnalta: André Gass; Damigella: Amore Rocio Perez; Fortuna / Valletto: Katherine Aitken; Famigliare / Pallade: James Hall; Famigliare / Mercurio / Soldato: Brenton Spiteri; Littore / Liberto: Pierre Héritier; Ottavia: Elli Vallinoja; Seneca: Pawel Kolodziej; Lucano / Soldato Oliver Johnston; Famigliare Aaron O'Hare. Orchestra: Les Nouveaux Caractères. Conductor: Sébastien d'Hérin; Mise en scène: Klaus Michael Grüber; Revival director: Ellen Hammer; Décors: Gilles Aillaud; Re-creater of sets: Bernard Michel; Costumes: Rudy Sabounghi; Lighting: Dominique Borrini. Théâtre National Populaire, Lyon, France, March 16, 2017.

Elektra

By definition any Ruth Berghaus production is mythic, and not just because this mega famous stage director was intimately associated with Bertolt Brecht's Berliner Ensemble and his (and East Germany's) didactic Epic Theater. Mme. Berghaus thinks and acts in epically scaled proportions.

Like her early mentor Walter Felsenstein (founder of East Berlin's Komische Oper), Mme. Berghaus insisted on an equal balance of the musical and theatrical elements of opera. This in the light of "regietheater" (which she more or less founded) wherein the director is free to modify period, locale, even the story itself to didactic ends. At the same time the music and text (usually) are sacrosanct, and must not be altered.

All this plays out brilliantly in this 1986 production of Elektra from Dresden's Semperoper, where it remained in the repertoire until 2012. The orchestra sits, dramatically, on the stage! The Semperoper pit simply could not accommodate Strauss's 49 winds and percussion players, plus strings (only 50 in Lyon -- a minimum number, and certainly the Opéra Nouvel's pit would burst even with that number). [Note that there exists a much used reduced orchestration of Elektra for approximately 70 total players.]

Strauss deemed that an expanded orchestra is necessary to create the colors necessary to his telling of this Greek tragedy, thus it becomes an absolute necessity for a Berghaus production. With this outsized orchestra needing to sit on the stage Elektra's cellar could only perch above the orchestra. So Mme. Berghaus simply transforms Elektra's prison into a perch from which the sisters see a world beyond their imprisonment and terror, and from which they search their salvation in the person of their brother Oreste who will murder his and their mother.

It becomes therefore perfect Brechtian Epic Theater -- theater as a catalyst for change and renewal. With the orchestra on yhe stage displacing traditional operatic staging convention the primary Brechtian precept was present -- distancing the spectator (and I indeed struggled with this distance) from the work of art in order that he might understand, and presumably act on its message rather than to be absorbed into its world.

These many years later, and in a different and far advanced social and political structure I struggled to transform such didactic theater into contemporary art. For me however it remained very much a period piece, evoking impotent nostalgia for the avant-garde of the ephemeral ideals of a failed world, and a longing for real, contemporary avant-garde operatic art.

This Lyon revival was very well cast, and convincingly conducted. It was a quite powerful if cold experience.

Cast and Production Information Elektra: Elena Pankratova; Clytemnestre: Lioba Braun; Chrysothémis: Katrin Kapplusch; Egisthe: Thomas Piffka; Oreste: Christof Fischesser; Le précepteur d'Oreste: Bernd Hofmann; La confidente de Clytemnestre: Pascale Obrecht; La porteuse de traine: Marie Cognard; Un Jeune serviteur: Patrick Grahl; Un Vieux serviteur: Paul-Henry Vila; La Surveillante Christina Nilsson. Orchestra of the Opera de Lyon; Solistes du Studio de l'Opera de Lyon. Conductor: Hartmut Haenchen; Mise en scène: Ruth Berghaus; Revival stage director: Katharina Lang; Décors: Hans Dieter Schaal; Costumes: Marie-Luise Strandt; Lumières: Ulrich Niepel. Opera Nouvel, Lyon, France, March 17, 2017.

Tristan et Isolde

East Germany's and now Germany's most famous playwright after Bertold Brecht is Heiner Müller. His staging of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde was a part of the 1993 Bayreuth Festival, and is his only staging of an opera. Though a prolific playwright and dramaturg becoming finally the artistic director of the Berliner Ensemble, he himself staged few plays and then only in the last 15 years of his life.

Unlike Brecht or Ruth Berghaus theater for Müller is not didactic, nor does he promote social or political agenda (though it may be referenced). Rather he introduced multiple perspectives into his theater works, destroying linear storytelling and, in fact, drama itself in search of abstracted associations. In this sense Müller defined theatrical post-modernism for his generation.

It is no surprise then that Müller chose to stage Tristan und Isolde, composed as it is of three protagonists (including King Mark) whose life situations intersect only at brief moments of action, but whose personal dramas, or traumas are powerful and poetic, and associate only by chance.

Müller's collaborator for the Tristan production was avant-garde designer Erick Wonder who with Müller locked the opera's lengthy monologues in a huge, closed box. Theater's "fourth wall" was in fact an often visible scrim, referenced early in the evening by Isolde placing her hands directly on the [not merely imaginable, but quite real] fourth wall to indicate its boundary and, in fact, significantly, the box's separation from the audience itself.

The famed love scene of the second act was realized as two simultaneous monologues, the lovers met by placing their hands on an imaginary wall that isolated each from the other. The dreamy intensity of the love duet was rendered by the protagonists kneeling side by side, in separate prayers to love.

Ann Petersen sings the "Liebestod"

Ann Petersen sings the "Liebestod"

The stage box became Tristan's decaying chateau in the delirium, its floor now strewn with dead leaves, Tristan resting in a dilapidated easy chair. Blocks of intense color, first red then gold heralded Isolde who shed several cloaks to deliver, finally her "Liebestod" in a golden gown, motionless, breaking through the fourth wall at last, singing directly to us.

The squares of color, large and small, throughout the opera -- on the walls, floor and ceiling -- visually created the suggestion of separated emotional spaces, reinforcing the abstractions of the dramatic spaces of the protagonists. The staging itself kept each of the protagonists in oblique, abstractly linear movement, intersecting only in the rare moments of action. If nothing else the production itself made a splendid evening of abstract visual art, and this alone was sufficient to propel it to mythic status.

Separating the protagonists, isolating each in a unique space placed enormous responsibility on its artists to create individual theatrical and musical worlds -- it is certainly a very difficult requirement, and it may simply have demanded too much. If hopefully this responsibility was fulfilled in Bayreuth back in 1993 it was not just now in Lyon. On the stage the singers were left helplessly on their own, conductor Hartman Haenchen absorbed in a quite detailed reading of Wagner's score, a reading that excluded the sweep of sensual poetry, the dynamic force of poetic delirium and the depth of tragic, Romantic love.

After the orchestral excesses of Ruth Bergman's Elektra, the Opéra de Lyon opted for 69 players in the pit (who indeed sounded like many more), whose apparent artistry was welcome indeed in this otherwise frustrating evening.

Cast and Production Information Tristan: Daniel Kirch; Isolde: Ann Petersen; Roi Marke: Christof Fischesser; Kurwenal: Alejandro Marco-Buhrmester; Melot: Thomas Piffka; Brangäne: Eve-Maud Hubeaux; Le Jeune Matelot / Le Berger: Patrick Grahl; Un timonier: Paolo Stupenengo. Chorus and Orchestra of the Opera de Lyon. Direction musicale: Hartmut Haenchen; Mise en scène: Heiner Müller; Réalisation de la mise en scène: Stephan Suschke; Décors: Erich Wonder; Recréation des décors: Kaspar Glarner; Costumes: Yohji Yamamoto; Lumières: Manfred Voss; Recréation des lumières: Ulrich Niepel. Opera Nouvel, Lyon, France, March 18, 2017.

Michael Milenski

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Elektra_Lyon1.png

product=yes

product_title=Festival Mémoires (Poppea, Elektra, Tristan) in Lyon

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Elena Pankratova as Elektra, Christof Fischesser as Oreste [Elektra and Tristan photos copyright Stofleth, courtesy of the Opéra de Lyon]

Handel's Partenope: surrealism and sensuality at English National Opera

Silvio Stampiglia’s libretto contains the requisite amorous knots endured by classical kings and queens. Partenope, the founding Queen of Naples, is courted by three royal lovers: Arsace, Prince of Corinth, who is first in line for Partenope’s affections; the affectatious Armindo, Prince of Rhodes; and Emilio, Prince of Cumae, who, spurned by the Queen, determines to make war not love. Arsace’s abandoned fiancée, Rosmira, disguises herself as Eurimene in order to pursue her betrayer, and becomes Partenope’s fourth suitor.

ENO Cast. Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

ENO Cast. Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

Director Christopher Alden largely ignores the historic context and plumps instead for ‘Partenope the sailor-serenading siren’ who, so the myth goes, cast ashore on the Neapolitan coast after throwing herself into the sea in her despair at not having been able to sing Ulysses to his death. Alden and his excellent design team - Andrew Lieberman (set), Jon Morrell (costume), Adam Silverman (lighting) - set the action in a Parisian salon of the 1920s at the height of Surrealism. Ironically, ‘Partenope’ means ‘virgin’ in Greek, for it’s the bedroom which is the battleground here.

The Surrealists sought to overthrow society’s ‘rules’ and demolish its reliance on ‘rational thought’. Their philosophy - as summed up by artist-at-the-helm, André Breton - might seem potentially risky for a director seeking to untangle the libretto and offer a credible context: ‘thought expressed in the absence of any control exerted by reason, and outside all moral and aesthetic considerations.’

Tapping the subconscious and liberating the creative power of the unconscious mind could prove profitable though. Alden turns Partenope into Nancy Cunard, in whose art deco apartment various artists gather to drink, play cards, tap dance, twirl batons, distastefully prat about with gas marks and bayonets, graffiti the pristine white walls with Matisse-squiggles and lewd symbols, and pay ardent homage to their hostess. A spectacular sweeping staircase is a death-trap to the inebriated, and if the hedonists don’t slip on the banana skins that are literally thrown around the stage then there’s the risk of getting locked in the lavatory (toilets dominate the second Act, complementing the smutty colloquialisms of Amanda Holden’s translation). By Act 3, the sharp suits of Act 1 have been abandoned for pyjamas and various states-of-undress.

ENO cast. Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

ENO cast. Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

Emilio is now photographer Man Ray. I presume that the photographs that he obsessively snaps - of artfully piled bodies and kinky indulgences - are designed to ‘expose’ the protagonists to reality. In Act 3 Emilio climbs a ladder and slowly assembles a collage-mural: what starts off looking like a monochrome of Matisse’s ‘The Snail’ is revealed as Man Ray’s 1934 ‘Nude Bent Forward’.

The design is certainly chic and Silverman’s chameleon-like lighting is superbly evocative. But, there’s no clear raison d’être. Handel’s humour is underpinned by honesty: even Partenope’s desire is sincere, if itinerant, and Armindo values fidelity - as he sings (in Holden’s words), in ‘Nobil core, che ben ama’: ‘Faithful lovers wisely ponder/ that if fancy never wanders,/ they’ll achieve a life sublime./ Constancy’s a thing to cherish;/ truthful love need never perish/ e’en until the end of time.’

Alden’s concept is not true to such avowals. His is a world of artifice: sophisticated but superficial. There’s a lack of emotional engagement between his characters, and twixt them and us: we simply don’t care about their urbane game-playing.

Rupert Charlesworth (Emilio) and Sarah Tynan (Partenope). Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

Rupert Charlesworth (Emilio) and Sarah Tynan (Partenope). Photo credit: Donald Cooper.