April 28, 2017

Shortlist Announced for 2017 Wigmore Hall/Kohn Foundation International Song Competition

Established in 1997, the biennial International Song Competition has grown to become one of the most significant platforms worldwide for recognising young talent in song recital, as part of Wigmore Hall’s longstanding commitment to celebrating the art form. This year’s shortlist features a diverse list of emerging performers aged 33 and under from the UK, Germany, USA, Australia, Belgium, China, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, New Zealand, Portugal, Serbia, Slovakia, and Switzerland - all on the verge of embarking on significant international careers.

Over a five-day period, the shortlisted duos will compete in front of a distinguished panel of jurors and Wigmore Hall audiences. They will also receive coaching and feedback from some of the foremost international song performers and experts. Between the rounds, talks, workshops and masterclasses by leading musical figures are also open to the public. The week culminates in a prize-giving ceremony, in which the overall winner receives £10,000. A Pianist’s Prize of £5,000 is also awarded, as well as the Jean Meikle Prize for the best Duo, and the Richard Tauber Prize for best interpretation of Schubert Lieder.

Past winners include British baritone Marcus Farnsworth, who now enjoys a busy international career, tenor Robin Tritschler (2nd prize winner in 2007) who is now a Signum recording artist, and 2009 Pianist’s Prize-winner James Baillieu, in great demand around the world.

Director of Wigmore Hall and chair of the jury John Gilhooly OBE says of the Competition:

‘There is a palpable excitement within the global singing community about the Wigmore Hall/Kohn Foundation International Song Competition, which offers an unrivalled platform for contestants to introduce their musical personalities and individual vocal qualities to an audience that appreciates and understands the countless imaginative insights that the repertoire requires. Song and Lieder are central to Wigmore Hall. As such, the International Song Competition forms an integral part of our work to recognise and encourage the next generation of great performers.’

Sir Ralph Kohn FRS

This year’s Competition celebrates the outstanding contribution of the late Sir Ralph Kohn FRS as one of its co-original founders. It is also a fitting tribute to this great man and his huge contribution to medical science, philanthropy and music.

More information about the 2017 Wigmore Hall/Kohn Foundation International Song Competition can be found on the Wigmore Hall website . A full list of events can be found here .

Over 180 perform in action-packed new work: Silver Birch

Appearing alongside top professional singers and orchestral players, they will perform as dancers, singers, actors and instrumentalists. Garsington Opera’s Artistic Director Douglas Boyd will conduct and collaborate with the dynamic female creative team of leading British composer Roxanna Panufnik, novelist and journalist Jessica Duchen (librettist), Creative Director of Garsington’s Learning and Participation programmeKaren Gillingham (director), movement directorNatasha Khamjani, vocal directorSuzi Zumpe, designerRhiannon Newman Brown and video designer Mischa Ying. Ying

Silver Birch , a People’s Opera, is a celebration of music, drama and poetry for all the family (aged 8+). It is a beautiful original story about courage and aspiration, centring on themes and issues of relationships and family ties which are tested when two boys go off to fight in a present-day war, while drawing upon Siegfried Sassoon’s poetry for echoes of the past. Sassoon was a regular visitor to Garsington Manor in Oxfordshire during the First World War, and his great-nephew is taking part in the adult company of Silver Birch. The all-female creative team comes together at a time when opera, like the entertainment industry overall, has become increasingly aware of a lack of gender parity across all sectors of the industry.

Roxanna Panufnik is one of Britain’s leading composers and daughter of Polish composer Andrezej Panufnik. She has written a wide range of pieces including opera, ballet, music theatre, choral works, chamber compositions and music for film and TV which are regularly performed all over the world and have been widely recorded.

Novelist and journalist Jessica Duchen has created a libretto which cleverly weaves together Siegfried Sassoon's poems and the testimony of a British soldier, who served recently in Iraq, to illustrate the human tragedies of conflicts past and present. “It is not only the fulfilment of a dream; this creative process, deeply collaborative at every level, has been entirely new to me, and it's one of the most exciting and rewarding experiences I've been lucky enough to encounter,” said Duchen. “The theme is the impact of war on soldiers and their families, tying together Siegfried Sassoon's World War I poetry and the experiences of those serving in modern warfare. It is designed to appeal to opera regulars and first-time attenders alike. It is fast paced and action packed; emotions run high and Roxanna Panufnik has written some incredibly beautiful music, as well as letting her hair down a bit in the battle scene!”

The Company has been selected from workshops and residencies throughout Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire where over 300 people were auditioned to take part. It includes a mix of 60 enthusiastic local adults, including 10 recruited from the military community. The 40 strong Youth Company aged between 10 and 20 come from over 25 different schools and colleges in Buckinghamshire and beyond, and the 50 youngsters forming the Primary Company from six local schools. Four child soloists share the key roles of siblings Leo and Chloe. With ideas created during the devising process by Sound and Music Consultant Jem Panufnik, a team of students from Cressex Community School will perform alongside the Sound Design team led by Glen Gathard and Foley artists from Pinewood Studios. In the orchestra pit, in partnership with Buckinghamshire Music Education Hub, a group of young local instrumentalists will have the opportunity to play specially written shadow parts, performing alongside the Garsington Opera Orchestra.

The professional roles will be performed by Sam Furness (Jack), Victoria Simmonds (Anna), Darren Jeffery (Simon), Bradley Travis (Sassoon), Sarah Redgwick (Mrs Morrell) andJames Way (Davey) with the Garsington Opera Orchestra.

Silver Birch will be performed on the main stage of Garsington Opera at Wormsley on 28, 29, 30 July, start time 7.30pm.

Tickets from £5 www.garsingtonopera.org Telephone 01865 361636

image= http://www.operatoday.com/Garsington.png image_description= product=yes product_title= product_by= product_id=April 25, 2017

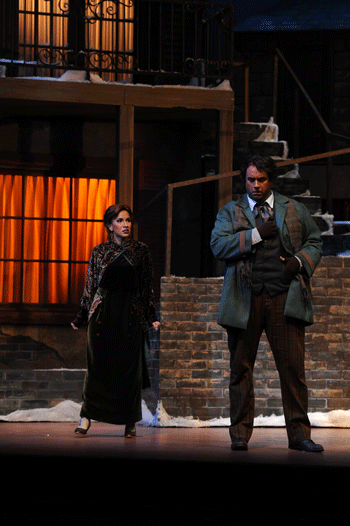

San Jose’s Bohemian Rhapsody

It is a rare pleasure to see a production that is peopled by actors that actually look like young, struggling artists. I recall many a version when some, even all of the main quartet of men sported waistline numbers that exceeded even their considerable ages. Not so here, with four male leads whose visual suitability and acting acumen were exceeded only by their consistently sublime vocalizing.

Resident tenor Kirk Dougherty, a company treasure, is rounding out his tenure with a heartfelt, full-throated, unfailingly honest Rodolfo. Mr. Dougherty is an economical actor, but every move has meaning, every phrase has a dramatic subtext, and he has that rare charismatic appeal that immediately engages an audience. His clear, plangent singing can soar above the orchestra with spine-chilling effect, or pare down to hushed introspection that makes his poet a fully realized, well-rounded character.

From left: Brian James Myer (Schaunard), Matthew Hanscomb (Marcello), Kirk Dougherty (Rodolfo), and Colin Ramsey (Colline)

From left: Brian James Myer (Schaunard), Matthew Hanscomb (Marcello), Kirk Dougherty (Rodolfo), and Colin Ramsey (Colline)

Baritone Matthew Hanscom has also contributed many enjoyable performances during his time with OSJ, but none have been more impressive than his beautifully rendered Marcello. Mr. Hanscom sports a big, burnished tone with plenty of buzz and sheen. As the painter, he displays a sense of arching line that is wonderfully controlled and highly satisfying. O Mimì, tu più non torni found colleagues Matt and Kirk in perfect sync, vocally and emotionally, and it was one highlight of many in the evening’s music-making.

Colin Ramsey’s participation always raises high expectations, since this talented young bass always brings assured singing and committed stage presence to every role. Mr. Ramsey does not disappoint, scoring a solid success with a wrenching, doleful Vecchia zimarra. Schaunard can sometimes blend into the garret since he has no solo or duet, but with the wiry, animated Brian James Myer in the part, there was plenty of high-viz stage business, and a richly detailed characterization. Mr. Myer deployed his well-schooled lyric baritone in excellent service to the role, singing with characterful presence.

Alone, all four of these outstanding leading men were merely ‘terrific.’ As a quartet of living, breathing, emotive, interactive playmates, they were ‘as good as it gets.’

Not that the distaff side wasn’t of a high caliber. Vanessa Becerra brought a silvery, well-projected soprano to the role of Musetta. Her appealing look and pert demeanor explored every aspect of the flirtatious coquette. And her easily produced lyricism fell agreeably on the ear. I only suggest that the talented Ms. Becerra might discover a little more genuine gravitas for the final act as she keeps exploring the role.

Vanessa Becerra (Musetta) and Matthew Hanscom (Marcello)

Vanessa Becerra (Musetta) and Matthew Hanscom (Marcello)

Sylvia Lee, who was such a successful Lucia earlier in the season, brought her laudable vocal gifts to the hapless Mimi. During her opening pages, she seemed a bit cautious, as if feeling her way through a role she wasn’t quite convinced was a good fit, and the parlando sections had a slight brittle quality. But once she could get above the staff, Ms. Lee’s approach loosened up, and she showed that all her limpid high notes were in fine estate, thank you very much.

As the evening progressed, her Mimi took on all of the required tragic stature, and her internalized feelings became fully realized in a characterization of tonal beauty and dramatic commitment. By opera’s end, the soprano seems to have convinced both herself and us that she is absolutely a worthy artist to portray the world famous singing seamstress.

Carl King was a relatively youthful Benoit, but his approach was appealing and infectious, and he sang the role with beauty of tone infused with humorous invention. Yungbae Yang intoned Parpignol’s lines with steady precision, and Vagarsh Martirosyan suffered amusingly as a buffo Alcindoro.

Joseph Marcheso conducted with a heady enthusiasm that was joyously urgent. With his cast and a large, responsive orchestra, he sometimes took familiar passages at a faster clip than traditional, but always to good effect. When it came to the expansive Puccini ‘money moments,’ the maestro elicited lustrous results, the kind of goose bump inducing music-making that characterizes the very best interpretations. Andrew Whitfield’s chorus sang cleanly and contributed all the gusto and atmosphere the piece requires.

The company has updated the setting to post-World War One Paris, almost always to interesting ends. Kim A. Tolman’s large-scale set design is a masterpiece of a Monmartr’ian Rubik’s Cube. It turns and repositions, and gets re-dressed and re-purposed with eye-popping results. Twice, the curtain reveal of a new setting garnered well-merited audience applause. Pamila Z. Gray’s lighting was effective in establishing indoor and outdoor locations and times of day, and her textured washes were complemented with good specials and isolated areas. The only rather abrupt cue was when the lovers’ candles went out in Act One. It suddenly got darker out of all proportion to the amount of illumination those two li’l ol’ candles could have been giving off.

The lavish, varied, masterful costume design was provided by Alina Bokovikova. The characters were greatly enhanced by her thoughtful attire, and the delineation of the denizens of the Paris street scene was an embarrassment of visual riches. Christina Martin contributed a thoughtful make-up and wig design, with a clever ‘hair’ effect. When Colline speaks in Act One of cutting his hair, he refers to his long scraggly beard. Sure enough, in Act Two, he is clean shaven. Very thoughtful detail in a production that is rife with such attention.

Michael Shell is a very gifted director who moves his cast through their story-telling with insightful precision. Whether moving crowds of people, or devising meaningful small-scale expressions of character relationships, he proves to be equally adept. One of his greatest skills is that Mr. Shell knows how to place singers in a relationship to the audience so that they are heard to maximum effect in the house. Another is that he devises blocking that unfolds with a natural simplicity and inevitability. I will never forget the moment when Mimi is on her deathbed and calls out the characters’ names one by one. They effortlessly glided into a stage picture of grieving solidarity that was so unerringly lovely that, damn if I am not tearing up again just thinking about it.

There are a few endearing oddities in this update that are mostly intriguing, or at least, not distracting. Colline has been blinded in the war, wears dark glasses, and carries a tapping cane. Schaunard is his attentive care-giver. And (spoiler alert:) ultimately revealed as somewhat more than that. The parade in Act II is a victory march imagined to be passing in the audience, with actors waving French and US flags. A banner in English seemed out of place. But even with these few well-intended ‘gilding of the lilies,’ this was a winning, thought provoking, lovingly rendered, treasurable La bohème.

Opera San Jose’s next season promises much. As this triumphant season closes with such a flourish, it will have much to live up to.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Rodolfo: Kirk Dougherty; Marcello: Matthew Hanscom; Colline: Colin Ramsey; Schaunard: Brian James Myer; Benoit: Carl King; Mimi: Sylvia Lee; Parpignol: Yungbae Yang; Musetta: Vanessa Becerra; Alcindoro: Vagarsh Martirosyan; Conductor: Joseph Marcheso; Director: Michael Shell; Set Design: Kim A. Tolman; Costume Design: Alina Bokovikova; Lighting Design: Pamila Z. Gray; Wig and Make-up Design: Christina Martin; Chorus Master: Andrew Whitfield

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rodolfo-Mimi.png

image_description=Kirk Dougherty (Rodolfo) and Sylvia Lee (Mimi) [Photo by Pat Kirk]

product=yes

product_title=San Jose’s Bohemian Rhapsody

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Kirk Dougherty (Rodolfo) and Sylvia Lee (Mimi)

Photos by Pat Kirk

Fine Traviata Completes SDO Season

Domingo’s costumes featured form fitting, slinky long gowns. In Act I, raven haired Violetta arrived in a town car wearing silver-tinged white. For Flora’s Act III party, Violetta wore sparkling black while Flora hosted in copper-trimmed splendor. The men sported perfectly coordinated formal wear of the era. Flora’s dancers performed in minimal metallic costumes that underscored the Egyptian lines of Kitty McNamee’s choreography.

Domingo’s scenic designs included iconic furniture for Act I, an autumn garden for Act II, a chic salon with shiny black and gold pillars holding up a balcony for Act III and a huge bed beneath a star-filled sky for the fulfillment of the tragedy in Act IV. Most of Alan Burrett’s lighting functioned well but there was a tiny light spill atop the shiny black proscenium.

Jesús Garcia is Alfredo Germont and Corinne Winters is Violetta Valéry

Jesús Garcia is Alfredo Germont and Corinne Winters is Violetta Valéry

Conductor David Agler, the artistic director of Ireland’s Wexford Festival, kept the orchestral accompaniment in propulsive mode with pleasant, appropriate tempi. Occasionally, he made a smaller voice difficult to hear, but I enjoyed his knowledgeable approach to the score. Chorus Master Bruce Stasyna’s group moved like individual couples as they sang their secure harmonies.

The Violetta, Corinne Winters, had no trouble being heard and she gave an engrossing rendition of her role. Winters’ interpretation showed the audience both the public glamor of the celebrated nineteenth century courtesan and the private tragedy of the real woman’s illness ending in death at the age of twenty-three. Winters displayed Violetta’s longing for a normal life in “A forse lui” (“Perhaps he’s the one”) but she soon tossed that aside with wonderful coloratura runs in “Sempre Libera” (“Always Free”).

Peabody Southwell is Flora Bervoix

Peabody Southwell is Flora Bervoix

Winters’ vocal and physical acting in the ensuing acts made her Violetta truly memorable. The recipient of undeserved insults in Act III, she became a tragic heroine in Act IV as she struggled to stand and dream of a life with Alfredo. Eventually, when she sang that love and understanding had come far too late, many audience members were in tears as the opera ended.

As Alfredo, tenor Jesús Garcia sang with bronzed tones. He was a stalwart consort for Winters, although he seemed to be plagued by allergy during his second act aria. Stephen Powell sang the often-ungrateful part of Alfredo’s custom-bound father, Germont. Powell’s large, resonant voice enchanted the San Diego operagoers, and they greeted his aria “Di Provenza il mar, il suol” (“The sea, the soil of Provence”) with momentous applause.

Stephen Powell is Alfredo Germont and Corinne Winters is Violetta Valéry

Stephen Powell is Alfredo Germont and Corinne Winters is Violetta Valéry

Peabody Southwell was an unusually dramatic Flora and Tasha Koontz sang beautifully as Annina. Kevin Langan’s distinctive bass sound defined the role of Dr. Grenvil, while the rich voices of Brenton Ryan, Scott Sikon, and Walter DuMelle filled out the roster of upper class partygoers. Solo Dancer Louis Williams seemed to defy gravity with his leaps, and he proved to be a skilled partner as he danced a mini pas de deux with each member of the corps de ballet.

It was a delight to again be in the Civic Theater where San Diego Opera has presented so many fine performances. Next season the company will present six shows: Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance, Puccini’s Turandot, and Catan’s Florencia in el Amazonas will be found at the Civic Theater while two chamber operas, Kaminsky’s As One and Piazzolla’s Maria de Buenos Aires, will be seen at the Joan B. Kroc and Lyceum Theaters. Finally, San Diego opera and the San Diego Symphony will get together for a concert starring René Barbera and Lise Lindstrom at Balboa Theater.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Violetta, Corinne Winters; Flora, Peabody Southwell; Der Grenvil, Kevin Langan; Gastone, Brenton Ryan; Marquis d'Obigny, Scott Sikon; Alfredo, Jesús Garcia; Baron Douphol, Walter DuMelle; Annina, Tasha Koontz; Giuseppe, Mario Rios; Giorgio Germont, Stephen Powell; Messenger, Michael Blinco; Servant, David Marshman; Conductor, David Agler; Director, Costume and Scenic Designer, Marta Domingo; Lighting Designer, Alan Burrett; Choreographer, Kitty McNamee; Wig and Makeup Designer, Stephen W. Bryant; Chorus Master, Bruce Stasyna.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/LaTraviata_041917_014.png

image_description=Corinne Winters is Violetta Valéry, flanked by the San Diego Opera Chorus [Photo by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz Johnson]

product=yes

product_title=Fine Traviata Completes San Diego Opera Season

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Corinne Winters is Violetta Valéry, flanked by the San Diego Opera Chorus

Photos by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz Johnson

The Exterminating Angel: compulsive repetitions and re-enactments

The Exterminating Angel - a co-production with the Salzburg Festival, The Metropolitan Opera and the Royal Danish Opera - was premiered to great acclaim at the 2016 Salzburg Festival, and most of the original stellar ensemble cast reprise their roles here at Covent Garden. The libretto is the result of a long collaboration between Adès and director Tom Cairns (according to the latter, work on the text started in 2009), and is based upon Luis Buñuel’s 1962 film El ángel exterminador, in which the Mexican surrealist lampoons a bunch of egocentric aristocrats who, gathering for a lavish post-opera dinner party, find themselves afflicted by a surreal curse. Despite the open door, they are inexplicably unable to leave the elegant dining room. Even as their conditions deteriorate, and hunger and desperation bring degradation, they cannot will themselves to cross the threshold. Outside, the servants - who, blessed with a sixth sense that scented the imminent danger, fled the mansion before the guests arrived - are disinclined to rescue their social betters.

Buñuel injects the carnivalesque with a dose of Sartre and a dash of Beckett. The inexact but excessive repetitions of his film reveal the solipsism and arrogance of these vain bourgeoisie who accuse the servants of being like rats deserting a ship, blaming them for their predicament rather than acknowledging their own lack of will. The tone is abstract and absurd, and the focus is on the ensemble rather than on individual protagonists, as Buñuel exposes the sterility of the ritual-like behaviour that structures daily life and social interaction.

Adès replaces Buñuel’s cinematic wit with musical parody and ingenuity, but the musical structures, macro and micro, confirm the film’s exposure of mankind’s obligation to repeat, even while the opportunity for individual musical expression offers emotional ‘close-ups’. The clamour of church bells which accompanies the audience’s arrival in the auditorium, heralds the exterminating angel is heard again at the opera’s close. The arrival of the guests is not only staged twice - as in the film - but is also built upon a passacaglia form, as if the aristocrats are stuck on a spiralling stairway, plummeting down into the abyss. In the final Act, as the guests seat themselves around the burning brazier to devour their feast of lamb (as Bach’s ‘Sheep May Safely Graze’ insouciantly but piquantly infiltrates the score), they slip back into the obsequious small talk of their opening dinner party in a futile attempt to re-establish social equilibrium, just as the quasi-waltz of Lucia’s Act 1 ‘ragout-aria’ lurches distortedly into ear-shot.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Many of the moments of musical ‘stillness’ are built upon variation forms. For example, the music of Blanca’s Act 1 aria - based on the children’s poem ‘Over the Sea’ by Chaim Bialik - takes the form of variations on the Ladino song ‘Lavaba la blanca niña’, intimating the vapid predictability of post-dinner discourse. Many of the arias make use of strophic forms, and frequent pedal points and ostinatos enhance the sense of overwhelming stasis, as such repetitive devices musically embody habitual bourgeois behaviour. Even the thundering interlude between Acts 1 and 2 - which alludes to Buñuel’s Drums of Calanda (1964) and the filmmaker’s native Calanda where, during Holy Week, the drums would resound for three days and three nights - develops from a repeating rhythmic motif.

The opera’s score is an ingenious re-enactment of the past in the present. But, in this work Adès’s characteristically and remarkably skilful parodic eclecticism does more than remind us that our experience of music is filtered through our memory of past musical experiences - from medieval song to modernism; here, such musical echoes imply own our entrapment. So, in Act II the ‘Fugue of Panic’ layers snatches of Strauss waltzes - and Adès imagines the latter as teasing and taunting, ‘Why don’t you stay a little longer? Don’t worry about what’s going on outside’ - as the artifice of which the waltz is a symbol, and upon which the guests’ sense of propriety is founded, is exposed as illusory.

There is no doubting Adès’s astonishing dexterity and perspicacity, nowhere more evident than in his inventive handling of the large orchestral forces, comprising piano, guitar and a whole arsenal of percussion. But, Buñuel’s black humour seems diluted; the ‘laughs’ - judging from the audience reaction at this performance - are primarily derived from recognition of musical echoes, which ironically makes Buñuel’s point.

Anne Sofie von Otter. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Anne Sofie von Otter. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Buñuel, irritated by attempts to psychologically ‘un-pick’ his film, retaliated, “I simply see a group of people who couldn’t do what they wanted to - leave a room”. (Luis Buñuel, My Last Breath, trans. Abigail Israel, 1984). Adès’s exterminating angel takes more tangible form. It is a supernatural or mythical force which takes possession of the guests and leads to what the composer describes as ‘an absence of will, of purpose, of action’. Musically, the angel is embodied by the nightmarish wail of the ondes martenot - the first time that Adès has used an electronic instrument in his music. At moments when the characters find themselves unable to act, or when they die, the return of this alien timbre reinforces their entrapment; it is a ‘voice’ that Adès describes as treacherously attractive and alluring, “like the sirens of Greek mythology, saying: ‘Stay!’”

Tom Cairns directs the large cast with meticulous attention to detail while Hildegard Bechtler’s set is sensibly sparse, dominated by an imposing, square proscenium which swivels like a Kafkaesque plot, denying the characters escape until the closing moments.

John Tomlinson (centre). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

John Tomlinson (centre). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The cast list reads like a family-tree of British singing-aristocracy, with John Tomlinson and Thomas Allen relishing their character roles as fusty doctor and lusty conductor respectively, while Christine Rice sings beautifully as the latter’s wife, Blanca, and Sally Matthews wins our sympathy as the bereaved Silvia de Ávila who in Act III pitifully cradles a dead sheep in her arms believing that her ‘Berceuse macabre’ is a lullaby for her son Yoli. Anne Sofie von Otter is brilliantly baffled as the old battle-axe, Leonora Palma, slipping painfully from reality in her Act 3 aria, a number which sets Buñuel’s 1927 poem ‘It Seems to Me Neither Good Nor Evil’ - a textual strategy that Cairns and Adès employ in several of the ‘aria moments’ to convey the characters’ mental states.

Iestyn Davies and Sally Matthews. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Iestyn Davies and Sally Matthews. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

In a parodic Baroque mad aria, Iestyn Davies (as Francisco) becomes wonderfully and woefully unhinged when he finds that there are no coffee spoons with which to stir his post-dinner beverage, and his sister-fixation with Matthews’ Silvia is convincingly conveyed - well as ‘convincing’ as surrealism can be. Sophie Bevan and Ed Lyon are a touching pair of lovers, Beatriz and Eduardo, remaining apart from the bourgeois vacuities and choosing to commit suicide, in the score’s most delicate duet - a veritable Liebestod, sung from within a suffocating closet - rather than to become victims of the exterminating angel.

Sophie Bevan and Ed Lyon. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Sophie Bevan and Ed Lyon. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Though I couldn’t hear a word she sang, Amanda Echalaz is a luscious-toned hostess, Lucia Marquesa de Nobile, and if Charles Workman, as her husband, scales the tenorial heights with aplomb, then Audrey Luna tops him, literally and figuratively, as Leticia Maynar - the opera singer whose performance in Lucia di Lammermoor ostensibly prompts the original gathering. Luna’s stratospheric peels are as ‘unreal’ as the ondes martenot’s eerie howl and perhaps it is no coincidence that Leticia, the so-called ‘Valkyrie’, who does not share the aristocratic pretensions of the other diners, is aligned with the otherness of the exterminating angel; for it is Leticia who first recognises their entrapment and it is she, at the close, who, with her strange quasi-medieval chanson, enables their ‘release’.

Audrey Luna. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Audrey Luna. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

At the end of El ángel exterminador, the characters are ‘freed’ by the re-enactment of the patterns of their imprisonment. The survivors go to the cathedral to mourn those who have been lost and give thanks for their own assumed emancipation, but as they seek solace in the passive church rituals they find themselves entrapped once more, the cathedral doors locked.

Adès and Cairns offer a different conclusion. The Chorus sing a line from the Requiem mass over and over in a chaconne that, it seems, could go on for ever. The score has no double-bar line to signal its close. The music simply stops in the present, presumably to continue for eternity. And, so, the opera is itself a ‘repetition’, or a ‘repetition with difference’, reprising Buñuel’s film and creating a discursive space between the media of film and opera.

Buñuel sometimes showed contempt for those who tried to pin down the ‘meaning’ of his films. A caption at the start of El ángel exterminador reads, ‘The best explanation of this film is that, from the standpoint of pure reason, there is no explanation’ and the film-maker declared, “This rage to understand, to fill in the blanks, only makes life more banal. If only we could find the courage to leave our destiny to chance, to accept the fundamental mystery of our lives, then we might be closer to the sort of happiness that comes with innocence”. ( My Last Sigh)

But, it is difficult to ignore the search for ‘meaning’. One might look to Buñuel’s own time: are the film’s aristocrats, marooned in their elitism while the populace protest outside, a metaphor for Franco’s Spanish regime, from which Buñuel was in exile in Mexico when he made the film? Is the film a nihilistic statement by one who had witnessed the catastrophes of the Spanish Civil War?

At the ‘close’ of Adès’s opera I found myself wondering to what extent he was playing musical games and how far he was - hilariously and terrifyingly - satirising our own lives.

Claire Seymour

Thomas Adès: The Exterminating Angel

Libretto: Tom Cairns, after Luis Buñuel and Luis Alcoriza

Leonora - Anne Sofie von Otter, Blanca - Christine Rice, Nobile - Charles Workman, Lucia - Amanda Echalaz, Raúl - Frédéric Antoun, Doctor - John Tomlinson, Roc - Thomas Allen, Francisco - Iestyn Davies, Eduardo - Ed Lyon, Leticia - Audrey Luna, Silvia - Sally Matthews, Beatriz - Sophie Bevan, Lucas - Hubert Francis, Enrique - Thomas Atkins, Señor Russell - Sten Byriel, Colonel - David Adam Moore, Julio - Morgan Moody, Pablo - James Cleverton, Meni - Elizabeth Atherton, Camila - Anne Marie Gibbons, Padre Sansón - Wyn Pencarreg, Yoli - Jai Sai Mehta; Director - Tom Cairns, Conductor - Thomas Adès, Set and costume designer - Hildegard Bechtler, Lighting designer - Jon Clark, Video designer - Tal Yarden, Choreographer - Amir Hosseinpour, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House (ondes martenot - Cynthia Millar, piano - Finnegan Downie Dear), Royal Opera Chorus (Chorus director - William Spaulding).

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Monday 24th April 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/170421_0813%20angel%20adj%20EXTERMINATING%20ANGEL%20PRODUCTION%20IMAGE%20%28C%29%20ROH.%20PHOTO%20BY%20CLIVE%20BARDA.jpg image_description=The Exterminating Angel, Royal Opera House product=yes product_title=The Exterminating Angel, Royal Opera House product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: The Exterminating AngelPhoto credit: Clive Barda

April 24, 2017

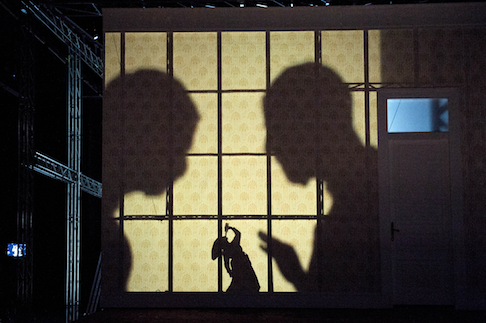

Dutch National Opera revives deliciously dark satire A Dog’s Heart

Soviet censorship nixed the publication of Mikhail Bulgakov's 1925 satirical novella, Heart of a Dog, on which Cesare Mazzonis based his libretto. Its plot, in which an eminent professor transplants a man’s pituitary gland and testicles into a scraggy stray dog, is an allegory of the foisting of Communist ideology on Russian society. Professor Preobrazhensky (his name is related to the word “transformation”) wants to rejuvenate the dog, Sharik. But instead of just perking up, Sharik starts becoming human, eventually transforming into Sharikov. This rude, lascivious menace turns the professor, his assistant Dr. Bormenthal, and their servants into nervous wrecks. Further galling the professor's life is Shvonder, his apartment building’s Head of the Residents’ Committee. He tries to shrink the professor's living space and gives Sharikov a job ridding the city of stray cats. When Sharikov's lying, befouling and sexual incontinence get out of control, the professor reverses the transplant, turning him back into an agreeable dog.

Scene from A Dog’s Heart

Scene from A Dog’s Heart

McBurney's staging, revived under Josie Baxter’s supervision, visually realizes the great divide between the professor, ensconced in his gold-and-white rooms, and the grey-clad proletarian masses he despises. Preobrazhensky, who dresses for dinner and enjoys fine wine and Italian opera, has to endure Shvonder and his workers droning Soviet hymns. By means of an enormous wall that slides backwards and forwards, the action moves from room to room or out onto the snowy streets. The wall also serves as a screen for projecting footage in 1920s Russian style. Every aspect of this darkly hilarious production, from prop to personage, is purposefully choreographed. It is difficult to decide which performance is more fascinating: Sharik the puppet dog and his four handlers using bunraku, a Japanese puppetry technique, or tenor Peter Hoare as the unmistakably canine Sharikov. Although the handlers are visible all the time, Sharik slinks, leaps and drools so naturally, that one forgets all about them. Hoare is so uninhibitedly feral that when Bormenthal wants to kill him, the audience sympathizes.

The cast, led by a commanding Sergei Leiferkus as the professor, is uniformly convincing. Baritone Ville Rusanen was a vocally excellent Bormenthal and bass Gennady Bezzubenkov a hair-raisingly sinister, string-pulling Big Boss. Only Hoare and the dog, however, could compete with the brilliant stage business. Some of the briefest scenes are the best, such as a dream sequence in which Sharikov embarrasses Preobrazhensky in front of his colleagues with a lewd song. The two operations also stand out — one comical, using shadow theatre, the second alarmingly gory. Besides moving like clockwork, the staging is deliciously illustrative, with cats swinging from the chandelier (more puppet wizardry) and pink monkey ovaries bobbing in green fluid.

Filipp Filippovitsj (Sergei Leiferkus), Poppenspelers, Bormenthal (Ville Rusanen) and Sjarikov (Peter Hoare)

Filipp Filippovitsj (Sergei Leiferkus), Poppenspelers, Bormenthal (Ville Rusanen) and Sjarikov (Peter Hoare)

Raskatov's angular score bravely extends the satirical operatic legacy of Dmitri Shostakovich (The Nose) and Alfred Schnittke ( Life with an Idiot), applying the same polystylistic idiom. However, unlike the staging, the score does not have a clear narrative. It supports and punctuates, rather than recounts. Raskatov creates a myriad sound effects and impressions by supplementing the traditional orchestra with, among others, a saxophone family, a balalaika, an electric guitar, a harpsichord and percussion galore. The Netherlands Chamber Orchestra under Martyn Brabbins adeptly evoked the plentiful flavors, which, alas, do not amount to an intriguing three-course dinner. The score’s strongest point is that it assigns each character a recognizable vocal style. Sharik has two voices, sometimes singing together: Nasty Sharik, soprano Elena Vassilieva growling into a megaphone, and Nice Sharik, plaintive countertenor Andrew Watts. Like his predecessors, Raskatov follows Russian speech rhythms, but his vocal means are limited in variation.

Filipp Filippovitsj (Sergei Leiferkus) & Bormenthal (Ville Rusanen) and Sjarikov (Peter Hoare)

Filipp Filippovitsj (Sergei Leiferkus) & Bormenthal (Ville Rusanen) and Sjarikov (Peter Hoare)

After a while, three main styles emerge. The men either huff in staccato syllables or repeat legato phrases in short ariosos, while the women shriek out notes with agonizing intervals. Alexey Sulimov whined efficaciously as killjoy Comrade Shvonder. Elena Vassilieva, Nasty Sharik, doubled as Darya the cook, who mostly reached for top notes or fished for bottom ones. As the excitable maid Zina, Nancy Allen Lundy’s chief task was to squeal out improbably high notes. Sharikov’s fiancée, soprano Sophie Desmars, suffered in jagged coloratura, then sang some warming-up vocal exercises. Raskatov's intentions and orchestral colors are thought through, and it is a shame that his score is not more distinguished. Some excerpts, such as the screaming duet between Darya and Zina, are so heavy-handed as to miss their caricatural point entirely. The music works best when decorating speech or escalating tension with whiplashing dissonant chords. If one doesn’t think of A Dog's Heart as an opera, the score is a highly effective soundtrack for a singular, special piece of theatre.

Jenny Camilleri

Cast and production information:

Professor Filipp Filippovich Preobrazhensky: Sergei Leiferkus; Ivan Arnoldovich Bormenthal: Ville Rusanen; Poligraf Poligrafovich Sharikov: Peter Hoare; Darya Petrovna/Voice of Nasty Sharik: Elena Vassilieva; Zina: Nancy Allen Lundy; Shvonder: Alexey Sulimov; Vyasemskaya/Voice of Nice Sharik: Andrew Watts; Big Boss/Fyodor/Paperboy: Gennady Bezzubenkov; Sharikov’s Fiancée: Sophie Desmars; First Patient/Provocateur: Alasdair Elliot; Second Patient: Annett Andriesen; Proletarians: Sophie Desmars, Andrew Watts, Alexey Sulimov, Piotr Micinski; Detective: Piotr Micinski. Director & Choreographer: Simon McBurney (revival supervised by Josie Baxter); Set Design: Michael Levine; Costume Design: Christina Cunningham; Lighting Design: Paul Anderson; Video: Finn Ross; Puppetry: Blind Summit Theatre (Mark Down, Nick Barnes); Movement: Toby Sedgwick. Conductor: Martyn Brabbins. Dutch National Opera Chorus, Netherlands Chamber Orchestra. Seen at Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam, on Saturday, 22 nd April 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/a_dogs_heart_17_306.png image_description=Sjarikov (Peter Hoare) [Photo by Monika Rittershaus] product=yes product_title=Dutch National Opera revives deliciously dark satire A Dog’s Heart product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Above: Sjarikov (Peter Hoare)Photos by Monika Rittershaus

April 22, 2017

A Chat With Italian Conductor Riccardo Frizza

He also tells us why some of Donizetti's masterworks are better known than others, although a number of his lesser known works are of equal merit.

Q: Where did you grow up?

RF: I was born in Brescia, in the Lombard region of Italy, and grew up in a countryside village about ten kilometers from the city. Although I wouldn’t call my family musical, I started piano lessons when I was five years old after playing a small toy, one that my parents had bought me for Christmas. After high school, I studied at the Giuseppe Verdi Conservatory in Milan and at the Accademia Chigiana in Siena. Later, I did graduate work in harmony, counterpoint and fugue in Milan, and conducting in Siena.

Q: Are there any artists or musicians from the past whose work has significantly influenced you?

RF: When I discovered the orchestra as an instrument, I was totally mesmerized and in love with Leonard Bernstein. Several masters of the Italian school, including Claudio Abbado and Riccardo Muti, subsequently influenced me. My most significant teachers were: composer Elisabetta Brusa, who taught me to be able to understand music, and conductor Gilberto Serembe, who taught me the basics and the necessities of conducting technique. Perhaps the most important thing I learned from them is that conducting is not just getting the orchestra to play together. It is the conductor’s responsibility to have musical ideas to present to the musicians, as well as to the listener. If you don’t have anything inside of yourself to express, nothing will pour forth from your conducting.

Q: What did you learn from your teachers that you especially want to pass on to the instrumentalists and singers with whom you work?

RF: Often, young conductors are afraid to be clear in conducting or are only focused on the beauty of the gesture. Thus, they forget the reason why they are on the podium: the music.

Q: Do you ever teach?

RF: I don’t teach anywhere on a regular basis because my activity as a performer doesn’t allow me to have a permanent position. It is also something I don’t want to do, at least at this point of my career. Perhaps I’ll change my mind in the future. I have to say that I love teaching conducting and I teach whenever my calendar gives me the time needed. Actually one of my ‘fellows’ was the recipient of the first prize at the Tokyo International Conducting Competition in 2015.

Q: What level of musicianship do you see in young American singers?

RF: Their level of musicianship is very high! You have such great universities, and the best music schools on the globe. Also, now it is much easier for the students to get information and knowledge. They can also travel to take master classes with the most important figures of the opera world. I think anyone with talent can emerge into the profession. Obviously, if you have a good income you can study in the best academies, but there are many public institutions where you can attend classes with superb teachers. There are examples of great artists, “stars,” such as Juan Diego Florez, Pretty Yende, and Lawrence Brownlee who advanced and became famous even though they did not have easy economic conditions.

Q: Please tell us something about your forthcoming performances:

RF: I love Chicago. I made my Lyric Opera debut in Kevin Newbury’s production of Vincenzo Bellini’s Norma and it was a memorable experience for me to be at this major music center. Lyric’s Norma was a co-production between Lyric, the Canadian Opera Company, the San Francisco Opera, and the Liceu in Barcelona. Norma is Bellini’s greatest opera and it is best known for the purity of the singing it requires.

I am conducting Rigoletto in Spain and it is one of my favorite scores. I call it Verdi’s perfect opera. It was the very first of the masterful operas Verdi composed. Dutch director Monique Wagemakers will stage Rigoletto at the Gran Teatre del Liceu of Barcelona. She did a wonderful job when she staged the same opera in Madrid a few years ago. Her production was minimal and had a modern set but her direction followed Verdi’s wishes exactly. Thoroughly introspective, this production permits all the psychological aspects of the characters to come through.

Q: Of equally great masterworks, why do you think some are better known than others?

RF: I think the fortune of some operas is related to the fame of the artists who interpret them. This is also one of the reasons why some titles are not famous. Try to think what Norma would be without Callas or Attila without Ramey. Those operas were not famous until opera companies staged them with stars in their leading roles. I hope to convince some modern stars to do more unusual repertoire.

Gaetano Donizetti’s works are not well enough understood. As an interpreter, I would like to present more of the rare titles of his catalogue. He is a genius too often forgotten and there is so much yet to be discovered. In the last two or three decades we have become familiar with some of Donizetti’s operas, particularly La Favorita and the Tudor trilogy: Anna Bolena, Maria Stuarda, and Roberto Devereux. However, I consider operas such as Maria di Rohan, Maria de Rudenz, Poliuto, and Dom Sebastien to be equally valuable masterpieces and they are not staged at all. In the future, I certainly hope major opera houses will stage them.

I have a special relationship with Venice’s Teatro La Fenice where I will be conducting Lucia di Lammermoor. The city of Venice is magical and the Fenice or Phoenix is one of the most beautiful opera houses in the world. The fact that there are no cars in the city and that people have to walk over the bridges and through the narrow streets makes the ambience more relaxed. One begins to understand how much less frenetic life was two centuries ago.

Francesco Micheli, who will stage a new production of Lucia at the Fenice, is one of the most interesting Italian directors of the new generation. Despite his youth, he is the artistic director of the Donizetti Festival in Bergamo. Francesco knows the Donizetti world very well and I’m really looking forward to working on this masterpiece beside him. The second reason I’m looking forward to Lucia is that Nadine Sierra will sing the title role. In my opinion, she is one of the most interesting sopranos of her generation.

During this summer, I will be at the Macerata Opera Festival in Italy conducting Aida. My last performances of Aida were in Seattle in 2010. I can’t wait to do this opera again because, after seven years, I can really prepare the score ex-novo. I consider myself a better musician than I was seven years ago. At least I have more experience and I have led many of Verdi’s operas in the meantime. The Arena Sferisterio in Macerata is a unique space unlike any other auditorium in the world. Seating over three thousand people, it is an open-air theater with a specific shape that provides a perfect acoustic.

About Aida, you should know that an overture exists. Verdi prepared it for the first night at La Scala, but withdrew it after a private performance that Franco Faccio conducted shortly before the Italian premiere.

Q: Who are some of the most valued singers of the past and why are their interpretations important?

RF: There are so many major figures who made the history of opera that I will limit my comments to just four: Callas, Pavarotti, Domingo, Sutherland. Each is an icon and we remember each for something special. Callas is considered to be the first modern singer because she was not only the greatest in vocal matters but she achieved the heights in acting. Her Norma is still thought to be without peer. Pavarotti is important because he was the master of the Italian school, which, unfortunately, is disappearing.

Placido Domingo has been the supreme Otello in my opinion. The way he went deeply into the interpretation both musically and dramatically is simply stunning. Dame Joan Sutherland was the first of her era to rediscover the bel canto repertoire, including the works of Donizetti, which I feel have been neglected.

Q: What recordings do you have out currently?

RF: I have so many. ITunes recently released Puccini’s La bohème, which we taped live at the Met two years ago with Kristine Opolais and Jean-Francois Borras.

Here’s an anecdote from my first studio recording. In Milan in 2003, we made Don Pasquale, which was Juan Diego Florez’s first bel canto recording. As you might know, this opera has a big introduction with a tremendously difficult trumpet solo. The producer told us to do an orchestra reading and prepare it for the take. We played it, and afterward, when I said we were ready to tape it, he answered they had gotten it already! They recorded the rehearsal and it was perfect. Very smart action: he removed the tension and the pressure of the difficult solo from the trumpet player.

Q: What do you see yourself doing five years from now?

RF: Exactly what I’m doing right now. I expect to be making music, traveling around the world and maybe starting to add some Wagner to my repertoire. It is time to discover scores such as Lohengrin and Die Meistersinger.

Q: Do you have any interesting hobbies like cooking, painting, or reading in three alphabets?

RF: I love cooking. It is my passion. My favorite is creating various types of risotto. I also like to discover the local cuisine of the countries where I’m working.

Q: Do you ever have time for a private life?

RF: I’m married to Spanish soprano Davinia Rodriguez and we have a five-year-old daughter. Since my wife is an opera singer, we are very often apart and it does not make our life easy. Sometimes it happens that we don’t see each other for more than two months. Doing the same job, however, gives us both an understanding of this lifestyle. We met during a production of L’elisir d’amore in 2005 and we have been a family since then. She’s a great artist and after her pregnancy her voice grew tremendously. She had to change the repertoire moving from coloratura to full lirico spinto. Recently, she had a huge success singing her first Lady Macbeth alongside Placido Domingo in a new production at Vienna's Theater an der Wien.

Sofia, our daughter, went to the opera for the first time when she was seven months old. In 2012, she attended the final dress rehearsal of L’elisir d’amore in Dresden at the Semperoper, but we had to take her out during the finale because she began to sing. She loves opera and she’s actually able to sing many arias.

I do suggest that kids be introduced to classical music even before they are born. During their pregnancies mothers should listen to classical music. It is very helpful for babies because they later recognize the music listened to in utero. We have had this experience with our daughter. For children, classical music should be as available as the food they eat, the toys they play with, and their mother’s smell. Then they will grow up with it as a part of their daily lives.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Frizza_Riccardo_JHenry%20Fair.png

image_description=Riccardo Frizza [Photo by J Henry Fair]

product=yes

product_title=A Chat With Italian Conductor Riccardo Frizza

product_by=An interview by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Riccardo Frizza [Photo by J Henry Fair]

Opera Rara: new recording of Bellini's Adelson e Salvini

Adelson e Salvini was the 24-year-old Bellini’s ‘graduation piece’, written in 1825 for the Real Collegio di Musica di San Sebastiano in Naples. Either the student singers at Bellini’s disposal were remarkably talented, or the young composer was intent on showing off his own prowess and the singers could do or die!

My review of Opera Rara’s concert performance contained a fairly lengthy account of the work’s origins, fortunes and revisions, as well as the literary source and plot. So, suffice it to say here that Andrea Leone Tottola’s libretto, set in seventeenth-century Ireland, unfolds as a somewhat disjointed series of scenes of melodramatic scuffles, infernos and emotional volte faces, in which Lord Adelson and the Italian painter Salvini are rivals for the heart of Nelly, the niece of the vengeful Colonel Struley. There is melodrama and incredulity aplenty: in a struggle to prevent Nelly being abducted by her uncle, Salvini fears he has killed his beloved and threatens to commit suicide; but, learning she is alive - and after several fake letters have add further convolution - Adelson ultimately marries Nelly, as Salvini renounces his love and promises to return after a year to claim his young pupil Fanny as his bride.

There is little of the prototype Sonnambula-limpidity evident in the student Bellini’s nascent musical arsenal, but Rossini’s fingerprints make a deep imprint, most impressionably in the music written for Salvini’s comic servant, Bonifacio, who makes his entrance with a Rossini patter aria - accompanied by a nonchalant flute which makes a paradoxically insouciant foil for the Figaro-esque bluster of the aggrieved, put-upon Bonifacio. Bass-baritone Maurizio Muraro makes much of the text and a strong musical personality emerges, but occasionally the pitch strays from dead-centre.

Muraro himself makes a good counterpart for Enea Scala’s over-wrought and initially vocally tense Salvini; as the latter begs ‘beguiling hope’ to abandon his heart, it’s hard to disagree with his servant’s conclusion that his master is ‘really off his head’ and ‘belongs in the madhouse’. Perhaps Salvini’s vapidity and vulnerability are the inevitable outcome of the ‘insane’ cabaletta which Bellini gives the tenor, before he’s had time to warm up his vocal cords, comprising twenty-six high Cs, four Ds, and a top E. The stratospheric ascents have more elegance than Scala can muster, but it’s understandable and forgivable that he sounds strained at times, and once he’s hit the targets, Scala reveals a polished technique and pleasing tone. His would-be grave-bound avowal of love for Nelly is heartbreakingly sincere, and is complemented by the poignancy of the oboe’s lyrical commentary and the urgency of the Opera Rara Chorus (directed by Eamonn Dougan).

Salvini’s Act 2 duet, ‘Torna, o caro, a questo seno', with Simone Alberghini’s patrician-toned Adelson is beautifully enriched by some lovely horn and woodwind playing while Scala’s more relaxed tenor whips slickly but ardently through the cascades of split loyalties; both singers exhibit tenderness in the passages in seductive thirds and sixths, forming a gentle blend. This number throbs with emotions unspoken, misinterpreted and misunderstood. And, if elsewhere Alberghini doesn’t consistently display the technical assurance, accuracy and nimbleness of his colleagues, his is a convincing contribution to the drama.

The opera was performed originally by an all-male cast, even though there are three female roles, and one wonders who sang Nelly’s romanza ‘Dopo l'oscuro nembo’ (later reshaped into Giulietta’s ‘Oh quante volte’ in I Capuleti e iMontecchi), and how. For, the melodic voluptuousness of this number is a beguiling intimation of where the ‘Swan of Catania’ was heading. The pathetic instrumental prelude passes slithering motifs from the depths of the bass to the heights of the woodwind, before pizzicato strings hook the sentiment and lead into the aria proper. Perhaps bel canto patterns inevitably lead one to make connections, but there seem to me to be more than a few foreshadowings - in the harmonic progressions and melodic sighs - of ‘Una furtiva lagrima’. Daniela Barcellona is able to hold back the full power of her mezzo, prioritising elegant elaboration over vocal emoting, while using her rich tone to convey Nelly’s romantic agonies.

David Soar’s Geronio impressed me at the Barbican Hall and continues to do so on this recording: he offers dark colour to the lighter toned Colonel Struley of Russian baritone Rodion Pogossov - who still brings some heft to the role - and the duet with which the dishonourable duo open Act 2 is engagingly characterised, with some strong string pizzicato adding extra parodic fierceness and bite. Mezzo-sopranos Kathryn Rudge (Fanny) and Leah-Marian Jones (Madam Rivers) complete the accomplished cast. The recitative is well-delivered, and given that most of the cast are native Italians, dialogue director Daniel Dooner must have had a fairly easy task.

Daniele Rustioni shows off his bel canto credentials, conducting with unflagging alertness to every dramatic and lyrical detail. The Sinfonia is typical: a weighty orchestral sound, supported by a strong bass, from which, by turns, punchy and poignant woodwind themes and, here, a cello solo emerge with clarity: somehow Rustioni combines power and translucence. We can hear Bellini’s drama, restlessness and redolent emotion. If occasionally a withdrawal of the sound seems to owe more to the engineers than to Rustioni’s interpretative dynamics, this is a very minor quibble.

The glossy accompanying booklet contains a detailed and informative essay, ‘Bellini’s Full Opera’, by Benjamin Walton; an account by co-editor Fabrizio Della Setta of the new critical edition which was prepared for this Opera Rara performance and recording; a synopsis in English, French, German and Italian; and, a full Italian libretto with English translation, the spoken text usefully differentiated by coloured ink.

This is another welcome Opera Rara addition to the forgotten repertory of the nineteenth century, and the company’s forthcoming plans are exciting.

Claire Seymour

Vincenzo Bellini: Adelson e Salvini, opera in 3 acts (1825)

Opera Rara

ORC56 [CD: 73:11; 79:52]

Lord Adelson - Simone Alberghini; Nelly - Daniela Barcellona, Salvini - Enea Scala, Bonifacio - Maurizio Muraro, Colonel Struley - Rodion Pogossov, Geronio - David Soar, Madama Rivers - Leah-Marian Jones, Fanny - Kathryn Rudge; conductor - Daniele Rustioni, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Opera Rara Chorus (chorus director - Eamonn Dougan)

Recorded in May 2016, BBC Maida Vale Studios, London.

April 20, 2017

Jonas Kaufmann : Mahler Das Lied von der Erde

A single voice in a song symphony created for two voices? Not many artists have the vocal range and heft to sustain 45 minutes at this intensity but Kaufmann achieves a feat that would defy many others. Das Lied von der Erde for one soloist is a remarkable experiment that's probably a one-off, but that alone is reason enough to pay proper attention.

The dichotomy between male and female runs like a powerful undercurrent through most of Mahler's work. It's symbolic. The "Ewig-wiebliche", the Eternal Feminine, represents abstract concepts like creativity, redemption and transcendence, fundamentals of Mahler's artistic metaphysics. Ignore it at the risk of denaturing Mahler! But there can be other ways of creating duality, not tied to gender. Witness the tenor/baritone versions, contrasting singers of the calibre of Schreier and Fischer-Dieskau. For Das Lied von der Erde, Mahler specified tenor and alto/mezzo, the female voice supplying richness and depth in contrast to the anguish of the tenor, terrified of impending death. This is significant, since most of Mahler's song cycles and songs for male voices are written for medium to low voices, and favour baritones. Tenors generally get short-changed, so this is an opportunity to hear how tenors can make the most of Mahler. .

Kaufmann is a Siegmund, not a Siegfried: his timbre has baritonal colourings not all can quite match. Transposing the mezzo songs causes him no great strain. His "Abschied" is finely balanced and expressive, good enough to be heard alone, on its own terms. What this single voice Das Lied sacrifices in dynamic contrast, it compensates by presenting Das Lied von der Erde as a seamless internal monologue. Though Mahler uses two voices, the protagonist is an individual undergoing transformation: Mahler himself, or the listener, always learning more, through each symphony. Thus the idea of a single-voice Das Lied is perfectly valid, emotionally more realistic than tenor/baritone. All-male versions work when both singers are very good, but a single-voice version requires exceptional ability. Quite probably, Kaufmann is the only tenor who could carry off a single-voice Das Lied.

With his background, Kaufmann knows how to create personality without being theatrical, an important distinction, since Das Lied von der Erde is not opera, with defined "roles", but a more personal expression of the human condition. This Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde is unusually intense, since the person involved emphatically does not want to die. The horns call, the orchestra soars, but Kaufmann's defiance rings with a ferocity most tenors might not dare risk. Wunderlich couldn't test this song to the limits the way Kaufmann does. Schreier, on the other hand, infused it with similar courage, outshining the mezzo and orchestra in his recording with Kurt Sanderling. This heroic, outraged defiance is of the essence, for the protagonist is facing nothing less than annihilation. Twenty years ago, when Kaufmann sang Das Lied with Alice Coote in Edinburgh, I hated the way he did this song, as if it was a drinking song. Now Kaufmann has its true measure, spitting out the words fearlessly, taking risks without compromise. No trace whatsoever of Mario Lanza! This reveals a side of Kaufmann which the marketing men pushing commercial product like the Puccini compilation will not understand, but enhances my respect for Kaufmann's integrity as a true artist.

After the outburst of "Das Trinklied", "Der Einsame im Herbst" is reflective, with Kaufmann's characteristic "smoky" timbre evoking a sense of autumnal melancholy. This is usually a mezzo song, so at a few points the highest notes aren't as pure as they might be, though that adds to the sense of vulnerability which makes this song so moving. "Von der Jugen" is a tenor song, though no surprises there. If Kaufmann's voice isn't as beautiful as it often is, he uses it intelligently. The arch of the bridge mirrored in the water is an image of reversal. Nothing remains as it was. In "Von der Schönheit" Mahler undercuts the image of maidens with energetic, fast-flowing figures in the orchestra. This song isn't "feminine". The protagonist is no longer one of the young bucks with prancing horses. He has other, more pressing things on his mind. "Der Trunkene im Frühling" usually marks the exit of the tenor, recapitulating "Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde". Though there are tender moments, such as the bird song and its melody, the mood is still not resigned. Kaufmann throws lines forcefully : "Der Lenz ist da!", "Am schrwarzen Firmament!" and, defiant to the end with "Laßt mich betrunken sein!"

Jonathan Nott conducts the Wiener Philharmoniker. creating an atmospheric "Abschied" with muffled tam tam, woodwinds, strings, harps, celeste and mandolin. Excellent playing, as you'd expect from this orchestra. Just as the first five songs form a mini-cycle, the "Abschied" itself unfolds in several stages, each transition marked by an orchestral interlude. The dichotomy now is not merely between voice types but between voice and orchestra: altogether more abstract and elevated. This final song is the real test of this Das Lied and Kaufmann carries it off very well. Now the tone grows ever firmer and more confident. There are mini-transitions even within single lines of text, such as the beautifully articulated "Er sprach....., seine Stimme war umflort...... Du, mein Freund". At last, resolution is reached. The ending is transcendant, textures sublimated and luminous. The protagonist has reached a new plane of consciousness not of this world. Kaufmann's voice takes on richness and serenity. He breathes into the words "Ewig....ewig" so the sound seems almost to glow. Utterly convincing. This isn't the prettiest Das Lied von der Erde on the market, but it wouldn't be proper Mahler if it were. It is much more important that it is psychologically coherent and musically valid. Too often, interesting performances are dismissed out of hand because they are different, but Kaufmann's Das Lied von der Erde definitely repays thoughtful listening.

Anne Ozorio

image=https://cdn.smehost.net/sonymusicmasterworkscom-45pressprod/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/613DMKJxRL._SS500.jpg

product=yes

product_title=Gustav Mahler : Das Lied von der Erde- Jonas Kaufmann, Weiner Philharmoniker, Jonathan Nott (conductor), Sony Classics

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=

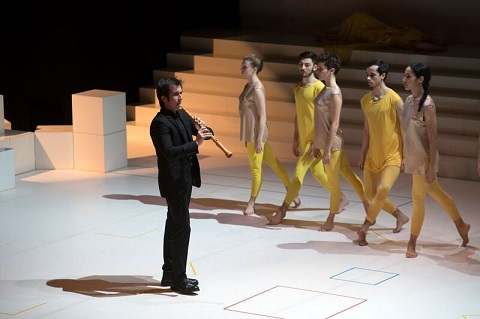

Garsington Opera For All

SCREENINGS ON BEACHES, RIVER BANKS AND PARKS

In each location a large-scale programme of education and outreach work is firmly integrated with the free public screenings and will provide ground-breaking opportunities for communities to be involved in creating, learning about, and performing opera. Semele will also have a free public screening as part of Oxford Festival of the Arts (1 July) and Garsington Opera's 2016 production of Tchaikovsky’sEugene Onegin will be screened this year at the Buckingham Film Place community cinema (17 June).

Opera for All is a programme which challenges expectation by uncovering the ingredients and foundation of opera - drama, music, story-telling and expressive emotion. In 2016 Opera for All worked with 25 schools, reached 1,000 young people, working directly with artists in residencies, and provided skills development for 50 teachers. Over 2,500 people attended the opera screenings. For the students in each location, the experience of working alongside a team of professional artists to create and perform their own pieces in response to the opera was transformative. For many it was their first experience of live professional singing and evaluation of the project has shown significant positive impact on confidence and social cohesion.

Opera for All is a three-year partnership project between Garsington Opera, the charitable trust Magna Vitae, and the Coastal Communities Alliance, and is supported by Arts Council England’s Strategic Touring Fund. As a result of this partnership an online network - the Coastal Culture Network - has been formed.

Semele - a love story in which the god Jupiter (performed by British tenor Robert Murray) is captivated by the beauty of the all-too-human Semele (sung by Heidi Stober making her UK debut). It features some of Handel’s most exquisitely beautiful music, with soaring choruses and splendid orchestral writing.

SCREENING DATES FOR SEMELE

SKEGNESS: Saturday 1 July, SO Festival

OXFORD: Saturday 1 July, Oxford Festival of the Arts

RAMSGATE: Saturday 22 July, Ramsgate Festival

BRIDGWATER: Saturday 29 July, Bridgwater Quayside Festival

GRIMSBY: Wednesday 11 October, Grimsby Auditorium

SCREENING DATE FOR EUGENE ONEGIN

BUCKINGHAM: Saturday 17 June, The Film Place

www.garsingtonopera.org ; www.operaforall.org

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Garsington.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title= product_by= product_id=April 15, 2017

María José Moreno lights up the Israeli Opera with Lucia di Lammermoor

A superlative cast for Lucia di Lammermoor set the house on fire. I was spellbound by Lucia’s madness like never before!

Based on Walter Scott’s novel set in the Lowlands of Scotland in 16th Century, Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor accounts the conflict between the Ravenwood and Ashton clans. For financial reasons, Enrico Ashton forces Lucia to marry the rich Arturo. However, Lucia loves her brother’s arch nemesis Edgardo Ravenwood.

Edgardo, whose family fortune the Ashtons stole, loves Lucia in return. But fate leads to tragedy: on her wedding night, Lucia kills her husband Arturo. This leads up to the mother of all madness scenes. Of course, Lucia dies and Edgardo stabs himself with the dagger to join her in heaven.

Before I tell just how mind-blowing this Lucia was, I should let you know about the opera trauma the last Lammermoor caused me. Last June, over in Cologne, director Eva-Maria Höckmayr thought it was a good idea to rearrange Walter Scott’s Scottish locale for a Nazi Germany setting at the end of the WWII. An incestuous relationship between Lucia and her brother Enrico Ashton added a sick and twisted dimension to this dark version of the Von Trapp family in full Nazi gear with, bizarrely, a Minotaur thrown in the mix.

I can hear you thinking, what the…? Hold on, it gets even better.

Edgardo is a Jew returning after the war to his family home in Germany: a set inspired by Mies van der Rohe’s villa Tageshund commissioned by Jewish industrialists. The Gestapo seized the building for operational use. Really, if you hadn’t read those programme notes, you would not have recognised the story. Long live Regietheater!

Half a year later at the Israeli Opera, Emilio Sagi’s Lucia di Lammermoor rekindled my love for Donizetti’s masterpiece, as I ended up mesmerised by María José Moreno’s Lucia. Her impressively delirious madness scene had me in a frenzy. With modesty and tender fragility, the Spanish coloratura proved explosive on stage. If you check her out in operabase you find she quite the specialist in this role. No doubt: she nails the character.

As Ms. Moreno sang “Il dolce suono mi colpì di sua voce”, she seemed the ideal Lucia --her vocal nuances as equally persuasive as her acting. Ms Moreno reached those insanely high notes with startling purity and moved from joy to horror in a convincing delirium. In one of those rare opera experiences, I leaned-in. My body gravitated forward as Moreno’s magnetic performance drew me in and kept me on the edge of my seat. Bafflingly beautiful.

In an historic castle setting with bedroom and great hall, Emilio Sagi’s staging complemented the singing with a simplistic elegance in red, black, and metallic hues. The luxurious textures of the costumes flowed to the music. The spacious staging allowed the singers to demand the spotlight. The IO brought Sagi’s 1999 production Lucia over from Oviedo’s Opera, and this is its second revival. It is very effective.

A sharply dressed up Israeli Opera Chorus by Imme Moller served as an additional backbone to the astounding soloists. The IOC, coached by Ethan Schmeisser, brought a sense of grandeur as the singers fuelled the spectacle with a thrilling energy.

Ms Moreno did not outshine Alexey Dolgov’s Edgardo. The Russian from the Bolshoy was her match. Their romantic chemistry filled the drama with tender love. In one of the most difficult tasks in opera, the follow up to Lucia’s madness aria, Dolgov kept the dramatic momentum moving, touching me deeply with Edgardo’s final aria “Tombe degli avi miei”. He earned that explosive applause.

This would have been the perfect introduction to an opera for any newcomer with its persuasively emotive vocals. The Israeli Opera clearly has a nose for casting. Each role role was performed admirably.

Mario Cassi proved a sonorous clashing combatant to Dolgov’s Edgardo during their conflict scene in the opening of the Second Act. Anat Czarny’s Alicia, Lucia’s companion, contrasted Moreno’s virtuous innocence with a darkly edged, wizened tone. As Arturo, Yosef Aridan’s voice fittingly dropped to the background during his interfering moments between Moreno and Dolgov’s fiery chemistry.

Daniele Callegari led the Israel Symphony Orchestra Rishon LeZion and served up Donizetti’s score with lush detail as the orchestra played with great intensity. Although no glass harmonium added to the estrangement of Lucia’s mad scene, Margalit Gafni on her flute did an excellently creepy job at enriching Ms. Moreno’s madness. During the haunting craziness, Mr. Callegari evoked an eeriness just as the expressionistic chills from a Fritz Lang film. By sheer coincidence several evenings earlier, I attended a screening of Metropolis with a new score performed live. In retrospect, it might have been a divination of this sublime afternoon.

As Dolgov’s Edgardo sang “The voice that penetrated my heart,” I felt indeed how Ms. Moreno’s incisive Lucia cut me deep. With such a voice Ms. Moreno could get away with diva attitude, but her thespian camaraderie became clear as she made sure all the performers joined in for the seemingly endless standing ovation. What a treasure she is!

David Pinedo

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Maria%20Jose%20Moreno%20All%20Rights%20Reserved.jpg

image_description=María José Moreno [Photo by Javier del Real]

product=yes

product_title=María José Moreno lights up the Israeli Opera with Lucia di Lammermoor

product_by=A review by David Pinedo

product_id=Above: María José Moreno [Photo by Javier del Real]

All other photos by Yossi Zwecker

April 14, 2017

Cinderella Enchants Phoenix

Stage Director Crystal Manich’s most amusing, well thought out production featured elegant tall building facades from Kentucky Opera that were easily turned around to produce different settings. Designer Kathleen Trott dressed Don Magnifico and his “ugly” daughters in clashing bright colors and textures. The sisters had huge feathers protruding from their coiffures. Don Ramiro and his entourage wore black and white, while the oppressed Angelina wore neutrals. The external settings were serene but the interiors, like their residents, had a great deal of agitation inside them.

Manich directed a group of principals, some of whom were familiar with their roles and had performed them many times. Others, who came from the Arizona Opera Marion Roose Pullin Studio, were singing them for the first time. Two of these young artists showed a great deal of promise. As Dandini, the valet, Joseph Lattanzi sang some incredible coloratura. So did Katrina Galka as Clorinda who sang many fiorature or vocal decorations in her character’s difficult, seldom-performed aria, “Sventurata mi credea” (“I thought I was unlucky”). The stepsisters were expected to create an atmosphere of hilarity. Galka’s Clorinda and Mariya Kaganskaya’s Tisbe kept the laughs coming.

Joseph Lattanzi, Alek Shrader, Daniela Mack, Mariya Kaganskaya, Stefano de Peppo and Katrina Glaka as Dandini, Don Ramiro, Angelina, Tisbe, Don Magnifico and Clorinda

Joseph Lattanzi, Alek Shrader, Daniela Mack, Mariya Kaganskaya, Stefano de Peppo and Katrina Glaka as Dandini, Don Ramiro, Angelina, Tisbe, Don Magnifico and Clorinda

Together, this group of fine artists produced a comic whole that will be remembered long after they have departed for their next engagements. As Angelina, Daniela Mack had a strong voice that cut through the orchestra instead of being heard over it, and featured a huge gleaming bloom above the staff. As Don Ramiro, Alek Shrader’s voice was more lyrical. He sang his long melodic lines with a delightfully sweet, open sound and impeccable coloratura.

Stefano de Peppo who has sung Don Magnifico around the world and across the United States, is known for his large, robust bass-baritone voice. It was fascinating to see him do this role in two different conceptions of the opera, last fall at San Diego Opera and this spring at Arizona Opera. The San Diego company performed a shorter, happier version that cut references to Don Magnifico having supported his household on Angelina’s inheritance. By including that information, Arizona Opera gave good reasons for the Don’s cruelty toward one of his daughters. Best of all, the longer version of the score allowed De Peppo to sing more of his incredibly accurate patter. As the tutor, Alidoro, Zachary Owen was a somewhat mysterious scholar who did not need magic to bring about the fairy tale’s happy ending.

Mariya Kaganskaya and Katrina Galka as Tisbe and Clorinda

Mariya Kaganskaya and Katrina Galka as Tisbe and Clorinda

Directed by Henri Venanzi, male members of AZ Opera chorus rendered their harmonious music in royal style. Conductor Dean Williamson's orchestra sounded a bit rough at the beginning of the overture and the singers’ opening lines were slightly off the beat. For the rest of the performance, however, stage and pit were in perfect coordination. I love Williamson’s version of this opera. Clorinda’s aria was a gem to be treasured. This performance of Cinderella was a delight for young and old alike. Both age groups were well represented in this enthusiastic audience.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Cinderella/Angelina, Daniela Mack; Don Ramiro, Alek Shrader; Dandini, Joseph Lattanzi; Don Magnifico, Stefano de Peppo; Clorinda, Katrina Galka; Tisbe, Mariya Kagankaya; Alidoro, Zachary Owen. Conductor, Dean Williamson; Stage Director, Crystal Manich, Costume Designer Kathleen Trott; Lighting Designer, Gregory Allen Hirsch; Chorus Master, Henri Venanzi.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Cinderella-5.png

image_description=Daniela Mack and Alek Shrader as Angelina and Don Ramiro [Photo by Tim Trumble]

product=yes

product_title=Cinderella Enchants Phoenix

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Daniela Mack and Alek Shrader as Angelina and Don Ramiro

Photos by Tim Trumble

LA Opera’s Young Artist Program Celebrates Tenth Anniversary

Sondra Radvanovsky opened the program with a rendition of the Bolero from Giuseppe Verdi’s I Vespri Siciliani, “Merce, dilette amiche” (“Thank you dear friends”). At first she seemed still to be warming up, but her voice soon attained its usual lustre and radiant qualities. Later, she sang a heart rending version of “Senza Mamma” (“without Mama”) from Giacomo Puccini’s Suor Angelica. She sang two duets with Domingo who was in marvelous voice for this auspicious occasion. They joined their voices in the revealing “Orfanella il tetto umile” (“An Orphan under a Humble Roof”) from Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra and the sophisticated “Lippen Schweigen” (“Silent Lips”) from Johann Strauss’s Die Fledermaus.

Although Diana Damrau and Nicholas Testé, who are currently appearing in LA Opera's production of The Tales of Hoffmann were expected to sing at the concert, their health issues did not allow it. However, with the profusion of talent available among the members of past and present LAO Young Artist Programs, the concert provided an excellent showcase.

Liv Redpath

Liv Redpath

Unlike most opera concerts, this program included ensembles. For the Rigoletto Quartet, “Bella figlia dell’amore” (“Beautiful Daughter of Love”), Kihun Yoon was a lyrical Rigoletto, Hyesang Park a refined Gilda, Joshua Guerrero a warm-voiced Duke and Renée Rapier an experienced Maddalena who did not fall for one word of the Duke’s flattery. A different group, consisting of Carlos Enrique Santelli, René Rapier, So Young Park, Michelle Siemens, Theo Hoffman, and Nicholas Brownlee, sang the smartly contrapuntal but rather slow moving sextet “Siete voi? . . . Questo è un nodo avvilupato” (“Is that you? This is a tangled knot”) from Gioachino Rossini’s Cinderella.

Duets abounded. First year program member Liv Redpath showed not only the beauty of her mid-sized voice but also a talent for comedy when she sang “Pronto io son” from Gaetano Donizetti’s Don Pasquale with equally talented program member Theo Hoffman. I can’t help thinking that one of Joshua Guerrero’s daydreams was to sing with Domingo. With robust tones, the young tenor and the tenor-turned-baritone sang “Au Fond du Temple Saint” from Georges Bizet’s The Pearlfishers.