May 28, 2017

A sunny L'elisir d'amore at the Royal Opera House

It’s the bank holiday weekend and the sun is shining, both here in London and over the wheat fields and haystacks of 1950s rural Italy as conjured by Laurent Pelly and designer Chantal Thomas for their 2007 production of L’elisir d’amore, which is back at the ROH for its fourth revival. Last time round, in 2014, the big draw was Bryn Terfel making his first essay at the role of the fraudulent quack. On this occasion, we had the opportunity to hear both exciting ‘newcomers’ to the House, with South African soprano Pretty Yende making her ROH debut, and familiar returnees, with Italian bass-baritone Alex Esposito stepping into the duplicitous doctor’s boots for his role debut.

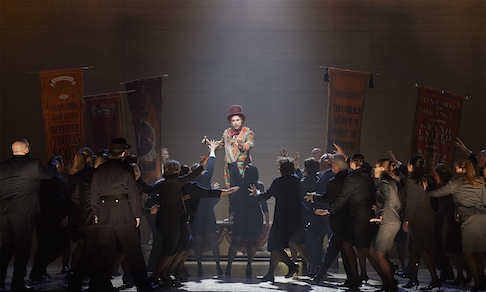

Alex Esposito (Dulcamara). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Alex Esposito (Dulcamara). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Three years ago, I described Terfel’s Dulcamara as ‘less sleazy smooth-operator and more grimy grease-ball’. Esposito’s swindler is even nastier: a veritable bruiser. Unshaven, dirty, with tattooed biceps and a contemptuous sneer, this Dulcamara’s dodginess couldn’t be hidden by designer shades and a scruffy white lab coat. No wonder the villagers scattered in advance of his arrival despite their excited chorus of expectation, but the strength of his call to his customers - ‘Udite, udite, o rustici’ - compelled, rather than charmed, them back. Esposito’s tone was wonderfully firm and strongly coloured. There was simply no arguing with his bullish self-promotion, as his side-kicks peered mischievously from beneath the dilapidated medic-truck watching their master humiliate and fleece his dupes. This Dulcamara could barely take the trouble to feign professionalism or concern, so gullible were the eager elixir-gulpers, and a grimy white ti-shirt poked out beneath the sleazy red suit he donned for the nuptial celebrations. In contrast, Esposito took great care with the text and the line; the grace notes in ‘lo son ricco’ were deliciously deft as the doctor made his pitch for Adina.

Pretty Yende’s Adina could look after herself though. Yende’s voice is plumper and more ample than the crystalline soprano of Lucy Crowe who took the part in 2014, and this gave Adina more obvious presence and self-possession: she pouted and posed with the panache of a 1950s Hollywood starlet. If Yende had any nerves on her first night at Covent Garden, she didn’t show them: her soprano was full and warm from the off, and she strolled through the arias with the ease, beauty and grace with which Adina lounged on the haystacks beneath a parasol. She was a feisty match for Liparit Avetisyan’s Nemorino in their Act 2 duet; the pause at the close was judged perfectly, allowing us to register the strength of the fiery emotions. But, Yende had the full measure of Adina’s heart and allowed her essential tenderness to shine through - as when revealing the extent of Nemorino’s delusions (he thinks because he worships her, she must return his love) to Belcore. Her Act 3 ‘Prendi, per me sei libero’ was absolutely exquisite, the coloratura roulades tumbling like jewels, the highest reaches clean and pure. It’s been quite a month for Yende: she’s won the International Achiever Award at the 23th annual South African Music Awards and her Sony Classical release, A Journey won the 2017 International Opera Award for Best Recording (Solo Recital). There will surely be many more such accolades.

Liparit Avetisyan (Nemorino). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Liparit Avetisyan (Nemorino). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Armenian tenor Avetisyan made his ROH debut earlier this season (as Alfredo Germont in Il traviata) and found himself back in the House following the withdrawal of the previously advertised Rolando Villazón took a while to warm up as Nemorino; initially a rather rapid vibrato made his tenor somewhat tight and he was occasionally just under the note. But, as the ‘elixir’ (a bottle of Bordeaux) worked its magic, so Avetisyan relaxed into the role, and his impish charm - he hoisted a bale aloft with nonchalant swagger, and his chirpy knee-and-elbow wiggle of glee raised a grin - was as winning as his appealing, pliable tenor. The big test was, as always, ‘Una furtive lagrima’, and Avetisyan sailed through; unaffected and focused, he let Donizetti’s expressive lyricism do the work and the aria cast its spell - time stood still as if the whole House held its breath.

Paolo Bordogna (Belcone) and Pretty Yende (Adina). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Paolo Bordogna (Belcone) and Pretty Yende (Adina). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Paolo Bordogna made an impressive ROH debut as a ridiculously pompous Belcore, accompanied by two ‘warriors’ whose mismatched heights and over-enthusiastic goose-stepping added to the preposterousness of their boss’s cocksure conceit. Bordogna enjoyed his character’s pretentiousness, adding some neat details - chest-thumping through a trill, hip-twisting when demanding that Adina ‘Name the day!’, and launching into some impressive acrobatic tumbles down the haystack. His zealousness was not neglected either: Bordogna seemed to have Adina in a head-lock at one point, from which she struggled to extricate herself.

Jette Parker young artist, Vlada Borovko, has impressed me in the past (see Oreste at Wilton's and JPYA Summer Performance 2016 ) and here she was a rich, vibrant Giannetta who relished the opportunity to play to the crowd when delivering the latest gossip about Nemorino - she’s got the news from the haberdasher, so it must be true.

The ROH Chorus occasionally found it difficult to pick up conductor Bertrand de Billy’s beat - the opening ensemble was a bit scruffy and de Billy’s zippy accelerando in the closing scene of Act 2 wrong-footed them for a while. But, they kept cool heads and were in fine voice; the blocking and acting was precise and nuanced. The overture felt a bit ‘solid’ and I’d have liked a bit more brightness and sparkle from the ROH Orchestra but the playing was, as always, accomplished.

This was a beguiling evening which got better and better as it went on. The cast were committed to the drama, and there was an occasional sense of spontaneity which added a charming freshness (though, reassuringly, Alfie the dog and the bicycling sweethearts were back). The dashes of realism - the piles of rotting tyres and wonky lampshade that frame the sets of Act 3, the louring clouds on the back-cloth that seem to threaten storms ahead - were outshone by Nemorino’s heart-warming love, optimism and belief. In uncertain times, it’s good to be reminded that sometimes hopes and dreams do come true.

Claire Seymour

Gaetano Donizetti: L’elisir d’amore

Adina - Pretty Yende, Nemorino - Liparit Avetisyan, Dulcamara - Alex Esposito, Belcore - Paolo Bordogna, Giannetta - Vlada Borovko; Director/Costume designer - Laurent Pelly, Revival director - Daniel Dooner, Conductor - Bertrand de Billy, Set designer - Chantal Thomas, Associate costume designer - Donate Marchand, Lighting designer - Joël Adam, Royal Opera Chorus (Concert Master - Peter Manning), Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Saturday 27th May 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/cBC20170525_L%27elisir_0187%20PRETTY%20YENDE%20AS%20ADINA%2C%20LIPARIT%20AVETISYAN%20AS%20NEMORINO%20c%20ROH.%20PHOTO%20BILL%20COOPER.jpg image_description=L’elisir d’amore, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product=yes product_title=L’elisir d’amore, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Pretty Yende as Adina and Liparit Avetisyan as NemorinoPhoto credit: Bill Cooper

May 24, 2017

Budapest Festival Orchestra: a scintillating Bluebeard

Not surprisingly, Béla Bartók was the fulcrum of the evening: but the programme was paradoxically both cohesive in spirit and diverse in medium. We enjoyed Bartók’s Hungarian Peasant Songs, presented with a decidedly Romantic slant, and an astonishingly transparent and detailed performance of the composer’s one-act opera Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, both of which were preceded by examples of the folk sources from which Bartók’s invention sprang.

I feared that the first half of the concert was in danger of turning into a lecture-recital, with the visceral experience of the music itself pushed aside by scholarly ethnographical explanation. And, by the time we reached the interval, my misgivings had not been entirely dispelled. Fischer began by offering a brief introductory account of Bartók’s ethnographic research and innovation, supplemented by some archive recordings. Then, we had the ‘live experience’ as folk singer Márta Sebestyén and three instrumentalists performed some of the folk songs that had so stimulated Bartók’s musical imagination in the early years of the twentieth century.

Sebestyén - confident, composed, wryly playful but absolutely honest - is a master of her material; she makes no concessions, her tone quite hard but direct, but she has a piercing gaze and was a captivating presence in her deep red dress. But, why on earth did the RFH not provide surtitles? For it’s difficult to respond and evaluate when one doesn’t have a clue what situation, action or emotion is being conveyed in song. Moreover, given that Sebestyén’s attire seemed to nod in the direction of ‘authenticity’, why were her fellow musicians - playing folk violin, viola and double bass - dressed in Western concert dress? (The sticky resin-capped fingerboards of András Szabó’s viola and Zsolt Fejérvári’s double bass seemed a droll rebuke to the context in which they were performing.) Perhaps I was alone in sensing an air of constriction: I wanted these performances to break out more exuberantly. In the song offered at the end of the first half, the toes of violinist István Kádar did indeed seem to be twitching as nimbly as his fingers, and Fejérvári’s snapping pizzicati and fingerboard-cracking slaps did suggest that the music would flourish with freedom in the bar afterwards. But, I felt this was an ‘experiment’ that did not quite come off.

Fischer’s reading of Bartók’s Hungarian Peasant Songs (1933) - an arrangement of 9 of the composer’s 15 Hungarian Songs for piano that date from twenty years earlier - emphasised the lyricism of the melodic writing and the richness of the orchestral colour. The opening unison was strikingly dense and opulent in tone and if the string playing was gloriously silky - and the players relished the characterful glissandi and harmonics, leader Violetta Eckhardt sometimes turning to smile at her section - woodwind and brass offered occasionally nasality to prevent the performance slipping into the syrupy folk nationalism of Brahms or Dvořák, and there were some darker colourings from the timpani and low brass. Fischer was simultaneously alert to the details and free in gesture: flicks and sways elicited precise responses by players who know their maestro well.

It was a real joy to experience such an attractive orchestral sound, but it was an extraordinarily vivid performance of Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, by turns crystalline and ample, that brought the concert alive. Fischer himself recited (from memory) the opening narration while simultaneously indicating the beat to the musicians behind him. As the conductor gradually tightened the psychological screw, the BFO made every single one of Bartók’s scintillating, brilliantly defined sonorities tell, from ecstasy - the gleaming blast of golden C Major at the opening of the fifth door - to tragedy: the pathetic, weeping undulations of the lake of tears revealed behind the sixth - ‘What is this water?’ Judith gasps, her incredulity tinted by celesta, harp and flutes.

Hungarian mezzo-soprano Ildikó Komlósi has - according to the programme - sung the role of the naïve, curious Judith over 150 times. I have heard her sing the role twice in the last two years: here at the RFH with Sir Willard White’s Bluebeard in a performance by the LPO conducted by Charles Dutoit; and at the Proms in 2016 (again with Dutoit, conducting the RPO, and alongside John Relyea as Bluebeard). This time, however, I missed the ‘freshness’ and ‘youthful excitement’ I found in these previous interpretations. Certainly, there was an assured sense of dramatic progression but Komlósi did not convince me that she was an impetuous young bride, and her mezzo is not as steady as it once was. That said, there was real poignancy in the quieter moments, as when arriving at the castle, the disconcerted Judith questions, ‘What no windows?’; and, the astonished horror of the realisation, ‘Your castle is crying!’ was equalled for delicate expressivity by the cellos’ oscillating string crossings. Komlósi has the power, too, to ride the orchestra tumult: her demand that Bluebeard open the doors was spine-chilling and, though at the bottom of her range, her insistence that she be given the keys and her observation that ‘Your castle’s walls are bloody’ were perturbingly penetrating.

Bass Krisztián Cser was a striking portrait of steely repressed emotion allied with an almost unwelcome recognition of power - ‘You see the extent of my Kingdom’ - and of his own capacity for violent domination. There were hints of vulnerability too: ‘Judith, Judith’ Cser cried, accompanied by a lovely cello solo, and at times the warm horns suggested heart-feeling submerged and suppressed.

The Budapest Festival Orchestra pride themselves in being one of Gramophone’s ‘top ten’ world orchestras. On the evidence of this stirring and disturbing performance, the accolade is fully deserved.

Claire Seymour

Ildikó Komlósi (mezzo-soprano), Krisztián Cser (bass), Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer (conductor).

Royal Festival Hall, London; Tuesday 23rd May 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/krisztiancserHerman%20P%C3%A9ter.jpg image_description=Budapest Festival Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall product=yes product_title=Budapest Festival Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall product_id= Above: Krisztián CserPhoto credit: Péter Herman

May 22, 2017

Elizabeth Llewellyn: Investec Opera Holland Park stages Puccini's La Rondine

‘There is a wonderful sense of style in her delivery, which sees her stand as a goddess, eternally elegant of bearing’, wrote one commentator. She returned to OHP the following year for more Mozart, performing Fiordiligi in Così fan tutte, a role which found her ‘in her element’ and forming a partnership with Julia Riley’s Dorabella which resulted ‘in a vocal blend of the utmost sweetness and beauty’ (Classical Source).

The intervening years have seen Llewellyn blossom and develop largely in European houses and she has been a fairly infrequent performer in the UK. So, it is with delight and great anticipation that we look forward to her return to Investec Opera Holland Park, to sing the role of Madga - the society-girl as free and flighty as a ‘swallow’, who falls in love with Ruggero but sacrifices her own happiness to save him ruin - in Puccini’s La Rondine.

I ask Llewellyn what ‘tempted’ her back to these shores and without a doubt the opportunity to perform the title role in one of the outliers in Puccini’s canon, but one which has become increasingly popular in recent years, was a compelling draw. Her operatic debut was in 2010 as Mimì in Jonathan Miller’s La bohème at ENO (in which I admired her ‘warm, generous’ soprano), and since then her voice has gained in weight and depth allowing her to take on the title role in Suor Angelica - ‘a sensational debut in the title role … [her] voice has a beguiling combination of duskiness and velvety warmth. ’ - and Giorgetta (Il tabarro) at Royal Danish Opera in 2015. She followed this with her first Tosca at Theater Magdeburg last year singing with members of what MDR Radio described as ‘a downright dream-cast’: ‘in the first place to mention is the English soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn who sings and plays a glowing, passionate Diva.’

Llewellyn describes herself as a lyric spinto and says that the role of Magda feels absolutely right for her voice at this time. La rondine is not ‘typical’ Puccini, though; after all, it’s a ‘comedy’ - presumably because no-one dies, jokes Llewellyn - though the lack of tragedy might seem to remove Puccini’s defining motif. But, there’s no lack of heart-wrenching and soul-wringing in La rondine; and it’s this reaching for emotional extremities which are at once both larger-than-life and yet so familiar to us all that Llewellyn seems to find so powerfully absorbing in Puccini.

La rondine has its share of tear-jerking moments but there’s plenty of comedy too, especially in the first two acts: it’s a sort of cross between La traviata (the jaded courtesan who finds and loses true love) and La bohème (bohemians in bustling bars), with a splash of Fledermaus (charming waltzes and even a fox-trot) thrown in. For, despite having vowed to his friend and agent, Angelo Eisner, that ‘an operetta is something I will never do’, in 1914 Puccini signed a contract with the Carltheater in Vienna to do just that. However, Llewellyn laughs that, having completed the first two acts, the composer seems to have decided enough was enough, and Act 3 (which Puccini revised twice) takes us to more familiar Puccinian terrain - prompting Llewellyn and Matteo Lippi, who sings Magda’s beloved Ruggero, to ‘breathe a sigh of relief’!

I ask Llewellyn what is distinctive about rehearsing and performing at OHP, and she is in no doubt that the fact that those responsible for the ‘decision-making’ are closely involved with the rehearsal process is a huge benefit to the singers, and helps to create a ‘family atmosphere’ in which old hands, new faces and returnees are equally welcomed and comfortable.

Llewellyn clearly enjoys being given freedom to explore and experiment. We discuss her roles for ENO - where she participated in the Opera Works training programme - and she speaks eagerly of her appearance as Micaëla in Calixto Bieito’s Carmen in 2012. In reviewing, this performance I remarked that, ‘This Micaëla is no innocent; in Act 1, she professes to bring a greeting from José’s mother, but bourgeois sentiment is manifestly and unashamedly discarded when, rather than offering a demure peck on the cheek, she grabs her José in a passionate embrace.’ Llewellyn explains that Bieito was adamant that she should play Micaëla not as a prepubescent ingénue but as a ‘real woman’ - no one would travel that far if they were not driven by, and determined to satisfy, their own desires - and she welcomed this interpretation, and the fact that she did not have to pretend to be a sixteen-year-old!

After ENO, opportunities in Europe beckoned, including her first Wagner (Elsa, Lohengrin) for Theatre Magdeburg, and Elvira (Don Giovanni) for Bergen National Opera. Alongside these emotionally and vocally weighty roles were lighter diversions, such as The Merry Widow for Cape Town Opera, which will surely stand her in good stead as she interprets Magda’s capriciousness.

And, Llewellyn hasn’t been entirely absent from British shores. Her performance as Amelia in English Touring Opera’s 2013 Simon Boccanegra was described by the Telegraph’s Rupert Christiansen as the element of the performance that ‘truly comes alive’: ‘Elizabeth Llewellyn’s Amelia shines brightly: as well as negotiating one of Verdi’s trickiest arias with elegant aplomb and crowning the wonderful Council Chamber ensemble with glory, she also makes the girl’s hopes and fears vivid, suggesting that innocent womanhood can point the way out of the mess that men have made of the world.’ No wonder her performance saw her nominated for ‘Singer of the Year’ in OpernWelt magazine that year.

There have been more unusual ventures too, such as last year’s The Iris Murder with the Hebrides Ensemble, a new chamber opera by Alasdair Nicolson and librettist John Gallas which was commissioned to mark the Hebrides Ensemble’s 25th birthday. Though she is not a regular performer of contemporary music, Llewellyn enormously valued being about to work with one of the foremost chamber music collectives in the UK which, under its artistic director and co-founder, cellist and conductor William Conway, has placed contemporary music at the heart of its repertoire.

Llewellyn is obviously an intelligent musician - thoughtful and discerning - and I ask her what led her to a career as a singer. Her Jamaican parents both enjoyed choral singing, but it was when her elder sister abandoned her piano lessons and the piano at home languished in silence, that Llewellyn’s appetite was stimulated. An accomplished pianist, she has a strong sense of the structural and harmonic architecture of the operas that she performs, which must sharpen her musico-dramatic judgment and acumen. She remarks that, in rehearsal, she always needs a musical context to fully inhabit the role: it’s no good being told ‘here’s your note’, she needs to know where that note has come from and where it’s going.

There is a quiet determination about Llewellyn. Her career has been one of steady growth and development, rather than stellar ascendancy, but she’s reaching the stage where she can take her time to choose the roles that are right for her, and she’s not without ambition. She’d love to singAida and some Strauss, possibly Rosenkavalier or Arabella, and maybe some more Wagner will beckon.

Before that, this autumn she returns to Copenhagen for more Puccini (Madame Butterfly), and 2018 will see Llewellyn make her US debut at Seattle Opera, singing Bess in Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, a role she seems surprised but delighted to have bagged.

First though, it is Puccini’s sophisticated but compromised Magda whom Llewellyn will bring to life. Puccini may have struggled with the work, calling it a ‘pig of an opera’, but the ephemerality of Magda’s love - which is destroyed from without by bourgeois morality and within by Magda’s indulgent sensuousness - will surely be made poignantly tangible by Llewellyn’s elegiac lyricism.

Soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn opens the Investec Opera Holland Park 2017 season as Magda in La rondine , 1-23 June.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Cosi2012%20162%20Fritz%20Curzon.jpg image_description=Investec Holland Park 2017 product=yes product_title=Investec Holland Park 2017 product_by=An interview with Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Elizabeth Llewellyn as Fiordiligi Così fan tutte, 2012Photo credit: Fritz Curzon

Sukanya: Ravi Shankar's posthumous opera

Will we add Anoushka Shankar/David Murphy to the Trivial Pursuit card-pack in future years? For they have guided and shaped Ravi Shankar’s last musical thoughts and sketches to fruition: the result being the opera, Sukanya, which has been performed on its premiere-tour in Leicester, Salford, Birmingham and finally here at the Royal Festival Hall in London.

When sitar-player and musical guru Shankar died in 2012 at the age of 92, he left behind sketches of an opera. A coincidental meeting of the personal and mythological had triggered the eighty-year-old musician’s operatic imagination. He discovered that his third wife, Sukanya Rajan (the mother of his daughter Anoushka Shankar, a renowned sitar-player in her own right) shared her name with a character in one his favourite tales from the ancient Sanskrit epic, the Mahābhārata, which recounts the story of a young woman who accidentally blinds an old sage, Chyavana, with whom she then falls in love and marries, and to whom she stays faithful despite the advances of two envious, roguish demi-gods. These Aswini Twins struggle to understand how a decrepit mortal can appeal to such youth and beauty. They put Sukanya to a test which she passes, and which proves redeeming.

Alok Kumar (Chyavana). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Alok Kumar (Chyavana). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Shankar’s sketches have been assembled and posthumously fleshed out by Anoushka Shankar and composer-conductor David Murphy. One can see that autobiographical resonances may have drawn Shankar to this tale but this staging of the work is anything but intimate. Director Suba Das’s sweeping, triple-staircase design raises and brings to the fore the soloists, dancers and Indian musicians, who make for a feast of colour against the black-clad BBC Singers ranged on the side-stairs and the London Philharmonic Orchestra nestled on the left and right of the stage below.

Rukmini Vijayakumar. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Rukmini Vijayakumar. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Visually, the collaborative outcome is a veritable feast. 59 Productions, led by Akhila Krishnan, and choreographer Aakash Odedra ensure that light, colour, movement - by turns sensuous and subdued - stimulate and provoke our sensual appetites. The kaleidoscopic diversity of the Indian sub-continent is conjured in all its mystery: from softly lit, pastel landscapes of rose pink and dusky grey, to jungles of emerald green and sun-drenched ochre plains whose colours blaze and dazzle. Digital animations seductively transport us from land to sky to sea, from the historic Mahābhārata to the present day.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The performance was described as ‘semi-staged’ but with so many bodies on stage the responsibility for conveying the progression of narrative mood was largely born by the silk-draped, be-jewelled dancers whose captivating whirls and leaps were astonishingly athletic, and whose elaborate hand and facial gestures were enchantingly expressive. The combination of classical Indian movement motifs and the evocative timbres conjured by the five Indian musicians (M. Balachandar, Rajkumar Misra, Parimal Sadaphal, Ashwani Shankar and Pirashanna Thevarajah) was by turns magical and invigorating. The opening sitar improvisation, penetrating the semi-darkness, immediately erased the present time and place; there was some remarkable rhythmic explosiveness from the tabla - enhanced by konnokol (percussive vocal singing), while the shehnai oboe injected an elegiac wistfulness.

Michel de Souza and Njabulo Madlala (Aswini Twins). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Michel de Souza and Njabulo Madlala (Aswini Twins). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The playing of the LPO was superb and David Murphy calmly and clearly held the large forces together. I was less convinced by the score itself though; and, it was difficult to know where Shankar ended and Murphy began. Some of the well-crafted orchestrations were effectively atmospheric and the familiar classical gestures and styles moved suavely along; but, West and East were placed side-by-side rather than integrated, and while the Indian elements seemed pungent and zestful, the Western fabric onto which the former were etched were harmonically and temporally repetitive. I appreciate that Murphy has striven to respect the conventions of raga in which improvisation on a set of given notes creates atmosphere and meaning through emphasis and articulation. But, the result was frequently somewhat banal minimalist mood-painting, occasionally enlivened by folk-inflections - at times, I was put in mind of Michael Nyman’s score for The Piano and of Enya’s multi-vocal fusion of Irish folk music and Rachmaninov-like Romantic rapture.

Keel Watson (King Sharyaati). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Keel Watson (King Sharyaati). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

More problematic still is Amit Chaudhuri’s libretto. I struggled to find the professed allusions to ‘Shakespeare, Tagore, T.S. Eliot and beyond’ amid its uncomfortable mix of poetic self-awareness and prosaic mundanity. It wasn’t helped by some awkward text-setting and unnatural verbal rhythms, though there were moments were word and music came together to create poignancy and honesty - as when Chyavana explains the mysteries of raga to Sukanya.

Fortunately, the cast offered strong vocal performances which pushed some of my misgivings temporarily aside. Bass-baritone Keel Watson was imposing and resonant as King Sharyaati while Njabulo Madlala and Michel de Souza, as the unscrupulous Aswini Twins, provided some much-needed mischief and lightness. Tenor Alok Kumar was convincing as Chyavana but it was soprano Susanna Hurrell who shone most brightly, her soaring lines glowing and warm, the pure tone blending beguiling with the Indian musical elements.

Susanna Hurrell (Sukanya). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Susanna Hurrell (Sukanya). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Sukanya has had a long gestation: Shankar’s earliest ideas for the work date from the mid-1990s and excerpts were presented at the Royal Opera House with the London Philharmonic Orchestra - with whom Shankar enjoyed a long relationship - in 2014. This premiere tour has taken the opera from The Curve in Leicester, to Symphony Hall Birmingham, to the Lowry in Sheffield, finally arriving at the Royal Festival Hall. The many musicians, artists and administrators who have collaborated to bring Sukanya to the stage are to be greatly credited and thanked.

In his work with the LPO - who followed the first European performance of Shankar’s Sitar Concerto No.2 in 1982 with the world premiere of his Symphony in 2010 - and in his historic collaborations with Yehudi Menuhin, Shankar never aimed for ‘fusion’. Indeed, the recording that he made with Menuhin is entitled ‘West Meets East’: Shankar aimed for interplay not amalgamation, and it was the conversation between idioms which was so spellbinding.

But, opera implies ‘synthesis’ and in Sukanya I did not feel that text and tone came together in expressive union. The layering of different aural and visual worlds was exciting, the result a vibrant, shifting, often mesmerising, mosaic. But, at the end my senses felt paradoxically over-stimulated and unsatisfied: it was hard to determine whence ‘meaning’ lay. This performance at the RFH was certainly a ‘spectacle’; I’m not so sure it was an opera.

Claire Seymour

Princess Sukanya - Susanna Hurrell, Chyavana - Alok Kuma, King Sharyaati - Keel Watson, Aswini Twins - Njabulo Madlala & Michel de Souza, Sukanya’s friend - Eleanor Minney; Director - Suba Das, Conductor/Arranger - David Murphy, Design - 59 Productions, Choreographer - Aakash Odedra, Lighting Designer - Matt Haskins, Aakash Odedra Dance Company, BBC Singers, London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Royal Festival Hall, London; Friday 19th May 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/cBC20170510_SUKANYA_0800%20SUKANYA%20PRODUCTION%20IMAGE%20%28C%29%20ROH.%20PHOTO%20BY%20BILL%20COOPER.jpg image_description=Sukanya at the Royal Festival Hall product=yes product_title=Sukanya at the Royal Festival Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: SukanyaPhoto credit: Bill Cooper

May 21, 2017

Cavalli's Hipermestra at Glyndebourne

Blood on white sheets usually denotes deflowered brides but in Giovanni Andrea Moniglia’s libretto, derived from Aeschylus’s Danaid trilogy, it’s a symbol of decapitated husbands. This libretto has many streams of tears and red rivers of blood.

Pre-curtain-up the nuptial signs seemed favourable. Just as Pippa Middleton was getting hitched to a moneyed financier in Berkshire so, amid the rolling Sussex Downs, 50 white-frocked brides were marrying 50 sheikhs, resplendent in red keffiyehs and designer shades, the couples parading their finery in the gardens of Glyndebourne. But, once inside the House, the front curtain confirmed that these were the soon-to-be-slaughtered betrotheds of Danao’s daughters.

Cavalli’s grandiose three-act festa teatrale is an example of a pan-European dramma regio musicale which, like Cavalli’s and Bissari’s Bradamante - which was performed at the royal palace in Milan in 1658 - celebrated the birth of Prince Philip Prosper, the Spanish Infanta. Hipermestra had in fact been completed four years before its June 1658 premiere; it had originally been commissioned to celebrate the birthday of the Grand Duchess Vittoria Della Rovere, wife of Ferdinand II de’Medici, in 1654, but the re-design of the Florentine Pergola theatre, together with organisation and financial difficulties - and the threat of plague - led to it being postponed and its dedicatee changed.

The opera conforms to what Ellen Rosand (in Opera in Seventeenth-Century Venice) describes as the ‘Faustini formula’ - after librettist Giovanni Faustini (1615-51): it narrates the history of ‘two pairs of lovers, surrounded by a variety comic characters, whose adventures involved separation and eventual reunion’.

Hipermestra (Emőke Baráth). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Hipermestra (Emőke Baráth). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

King Danao, chased from Libya by the 50 sons of his brother, Egitto, has fled to safety in Argos, of which he later becomes King. Informed by an oracle that he will lose his life at the hands of one of his nephews, he commands his own 50 daughters to wed their cousins and kill his would-be assassins in their marital beds. However, Danao’s eldest daughter, Hipermestra, has fallen in love with Linceo and, revealing the threat to his life, helps him escape; her betrayal leads to her imprisonment. Linceo returns with a vast army to free his wife and destroy Danao, but jealous desire - in the form of Arbante who covets Hipermestra and denies his own wife, Elisa - intervenes: false accusations of infidelity and apocalyptic carnage ensue. Believing Hipermestra to be faithless and dead, Linceo seeks solace with Elisa, but saved from self-sacrifice by a magical bird who scoops her up as she falls from a tower, Hipermestra is ultimately reunited with Linceo.

No expense was spared for the first performances of this opera. The sets were by Ferdinando Tacca (1619-1689) and the detailed drawings of Stefano della Bella’s costume sketches (see the British Museum online ), which specify particular fabrics, colours, embroidered lace and jewels, testify to the care lavished.

Hipermestra (Emőke Baráth). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Hipermestra (Emőke Baráth). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Stuart Nunn’s design and Giuseppe di Iorio’s lighting are similarly rich and detailed. Multiple locations in Acts 1 and 2 are framed within the angled black-gold colonnades and porticos of Danao’s Arabian palace. East mingles with West, and past with present, much like any modern Middle Eastern state, I guess. Natty cerise outfits are shrouded in black hijabs; underneath sombre thwabs, business suits and glinting tie-pins attest to wealth and power. Director Graham Vick and his design team do not strive for direct parallels with modern Arab states or Caliphates. But, the links between oil-rich dynasties and oppressive regimes is clear: the women, even when permitted to momentarily voice ideals, beliefs, hopes, and to express desires, are quickly wrapped up in veils and abayas.

Act 1 opens in Danao’s garden, as the King oversees a circular parade of nuptial couples through a white and pink hoop of balloons: it’s an Alice in Wonderland illusion, all red roses and sparkling gold fairy-lights; the multi-tiered wedding-cake topped with sugar-icing Byzantine domes.

Nunn economically recreates the characterless luxury of a 5-star hotel bedroom, the rhythmically ‘in tune’ laundry where the tumble driers spin away bloodshed, and the stark sand-dunes where the pumping oil-rigs figuratively spew up black-slimed money. The desert garage where Danao Oil provides a petrol oasis - complete with Coca-Cola vending machine - is gate-crashed by Linceo’s armoured war truck, which spectacularly catches fire in Act 2. While the design is detailed, Vick’s direction is fairly laissez-faire: there’s a lot of lamenting and hand/head-wringing, prowling and machine-gun swinging, but the ‘arias’ themselves - such as they exist: Cavalli’s score is dominated by fluid arioso in which recitative and aria are barely distinguishable - are fairly inert, enlivened principally by quirky design features.

One challenge for the modern director is Cavalli’s blend of broad comedy and tragedy, a clash of sensibilities which jarred with contemporary audiences - at least those prone to aesthetic philosophising. In 1700, Giovanni Crescimbeni, spokesperson for the Accademia ’d’Arcadia, complained of Cicognini’s Giasone that, ‘with unparalleled monstrosity’, it mixed kings and heroes with buffoons and servants, resulting in a ‘hodgepodge of characters that caused the utter ruin of the poetic rules’ (cited in Readying Cavalli's Operas for the Stage, Rosand). Such complaints about the amalgam of tragic elements with farce led to the reforms associated with the poet Metastasio, which resulted in the ‘rules’ of opera seria.

Vick just about controls the schizophrenic lurching between farce and tragedy. The threat of imbalance is most forcefully represented by Hipermestra’s nurse, Berenice - played exuberantly by a bearded Mark Wilde. A clear descendant of Monteverdi’s Iro (Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria) and the wily old nurses of the commedia dell’arte, Wilde’s Berenice is a sly, pragmatic opportunist who forms a comic foil to the lovers’ idealism, jealousy and yearning; urging Elisa and Hipermestra to grab sexual fulfilment when it is on offer, Berenice disparages fidelity and steadfastness in favour of fickle self-gratification.

With more than a dash of Les Dawson’s handbag-swinging dames, Wilde’s Berenice confirms Jane Glover’s assertion (in her 1978 monograph on Cavalli) that the commedia-derived characters are more strongly characterised musically than their ‘serious’ mistresses and masters. And, Wilde uses his pliant tenor to add some realism: perhaps Hipermestra would be better advised to accept the handsome general Arbante’s marriage proposal than continue to lament the warring Linceo’s absence.

Wilde is boisterous and raucous, shoving musicians aside and launching himself amid the instrumentalists for a comic romp bewailing that ‘youth is wasted on the young’: after filching William Christie’s skull-cap and fondling his pate, Wilde scribbled down his mobile number and thrust it into the hands of a front-row audience member, signalling that he’d be expecting a call …

The 10-player ensemble, drawn from the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, may be one of the smallest groups to accompany an opera at Glyndebourne, but they are in no way marginal to the action. Just as the singers prowl in their midst, they take to the stage, emphasising the fable-like quality of the opera. Nowhere is this fluidity more powerfully conveyed than at the start of Act 3 when, amid the ruins of Argos, a lone fiddler strikes up a musical call-to-arms: tentatively, the other musicians appeared, stepping over the blood-splattered bed, fractured furniture and collapsed columns to reassume their positions at the front of the stage. Anarchy is redeemed by culture, to misrepresent Matthew Arnold.

In the title role, Emőke Baráth seemed a little tentative initially, but her tone brightened and her voice relaxed. By the time we reached her Act 3 suicidal soliloquy she had mastered the move which Cavalli enacts in each lament from fragmented chromatic phrasing to more formal ‘aria’. Atop the broken walls of Argos, Baráth projected strongly. When she leapt to her ‘doom’, it was with startling alacrity that Juno’s peacock spooned up the falling suicide and bore her aloft to the lieto fine.

Linceo (Raffaele Pe) and Arbante (Benjamin Hulett). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Linceo (Raffaele Pe) and Arbante (Benjamin Hulett). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

At times I had difficulty reconciling the different vocal registers and colours with dramatic contexts. Raffaele Pe’s countertenor danced with light-weight frivolity when he and Hipermestra crawled out from beneath the frosted wedding cake; as he waited, with eager, self-preening lust, to consummate the marriage - teased for his haste - tenderness seemed lacking. And, in Act 3 Pe increasingly sounded hysterical rather than driven by hate-fuelled machismo: as the tessitura rose his voice sometimes lost strength and focus, and strayed sharp. But, these comments present an unduly negative portrait: overall, Pe captured the fervency and unpredictability which arises when devotion is undermined by disloyalty.

I admired Renato Dolcini’s Danao: a blend of Leontes and Lear, he is duped by oracle, demands duty from his daughter, and when defied disowns and punishes her - with scourges, chains and irons. Discovering that he has slaughtered the innocents while the guilty roam free, Dolcini was not afraid to give voice to growls and groans of self-castigation; finding that his daughter has betrayed him, he spat out plosive consonants of anger. Later, Dolcini conveyed the pathos of loss: no longer is he a father just a King, and soon he is not even that - like Lear, Danao finds his patriarchal and regal power dissolved, and with the advance of Linceo’s army anticipates ignominy and defeat.

Benjamin Hulett’s Arbante burns with Iago-like duplicity: the tenderness of his voice belies Arbante’s villainy. But, while Iago wants to destroy others, and what they covet, simply because they have a desire that he cannot recognise, in Act 3 Hullet reveals Arbante’s self-awareness with a lovely soft grain which he is not afraid to crack and strain when conveying recognition of his unredeemable evil. Ana Quintans is superb as Elisa, the glint to her soprano equal to the flash of Hipermestra’s redundant, disused knife.

Hipermestra (Emőke Baráth), Linceo (Raffaele Pe), Elisa (Ana Quintans) and Arbante (Benjamin Hulett). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Hipermestra (Emőke Baráth), Linceo (Raffaele Pe), Elisa (Ana Quintans) and Arbante (Benjamin Hulett). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

The last contemporary performance of Hipermestra took place in 1680 in Pisa in a commercial theatre, 8 years after Cavalli’s death, and the first modern performance since the 17th century took place in Utrecht, in August 2006, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the renowned Early Music Festival. Glyndebourne have done Cavalli and us all a service in giving us another chance to hear this detailed, contradictory work.

In the closing stages, one character sings - ‘I’m not sure if this love is wise or if it’s insane,/The more I think about it the less I understand.’ One might say the same about Cavalli’s opera itself. But, Glyndebourne, Vick, Nunn and Christie embrace the anarchy and in so doing tell us a lot about ourselves.

Claire Seymour

Francesco Cavalli: Hipermestra

Linceo - Raffaele Pe, Hipermestra - Emőke Baráth, Arbante - Benjamin Hulett, Elisa - Ana Quintans, Berenice - Mark Wilde, Danao - Renato Dolcini, Vafrino - Anthony Gregory, Arsace - David Webb, Alindo/Delmiro - Alessandro Fisher; Director - Graham Vick, Conductor - William Christie, Designer - Stuart Nunn, Lighting designer - Giuseppe Di Iorio, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (leader, Kati Debretzeni).

Glyndebourne Festival Opera; Saturday 20th May 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Hipermestra-Glyndebourne-993.png image_description=Hipermestra, Glyndebourne Festival Opera product=yes product_title=Hipermestra, Glyndebourne Festival Opera product_id= Above: Hipermestra (Emőke Baráth) and Elisa (Ana Quintans)Photo credit: Tristram Kenton

Dougie Boyd, Artistic Director of Garsington Opera: in conversation

On the day we meet, Boyd is dashing between rehearsals for two of this year’s productions: Semele, directed by Annilese Miskimmon, Artistic Director of Norwegian National Opera, and conducted by Jonathan Cohen who is making his Garsington Opera debut; and, John Cox’s production of Le nozze di Figaro which Boyd himself conducts.

Conversation quickly turns to Figaro, which Boyd describes as a ‘re-creation’ rather than a revival of Cox’s elegant, eighteenth-century production, first seen in 2005. It was time for Garsington to stage Figaro again, he says, but the more a ‘new’ version was contemplated, the more it seemed foolish to get rid of an ‘old’ staging, one which was and is much-loved. Boyd jokes that Garsington is being ‘cutting-edge’ in setting the work ‘in period’, when the trend is for updating and relocating - re-orientations which, if not carefully considered and delivered, can destroy the opera’s astonishing integrity of the union of music and drama. Cox’s production was last seen during the Festival’s final season at Garsington Manor in 2010 - Boyd conducted - and the wider stage and more professional technical facilities at Wormsley have necessitated alterations to the sets (their modular, reversible design has presumably proven fortuitously flexible), props and direction.

Figaro sees the return to Garsington of Joshua Bloom (Leporello, Don Giovanni, 2012) as Figaro and Jennifer France (Marzelline, Fidelio, 2014) as Susanna, with the baritone Duncan Rock and Canadian soprano Kirsten MacKinnon making their Garsington debuts as the Count and Countess. Glancing at this season’s cast lists and photographs on the rehearsal room wall, I remark that the quality and depth of Garsington’s casts and artistic teams seems to grow year on year; Boyd agrees that this artistic strength has developed in tandem with the increasing international recognition and repute of the Festival.

2017 also represents an adventurous increase in the number of operas and performances given. Previously the season would comprise three main operas; this year, four works will be staged and over thirty performances given. Boyd admits that such expansion comes with some risk, but is heartened by the advanced tickets tales, with many performances sold out and only limited availability remaining.

Alongside Semele and Figaro, Michael Boyd and Tom Piper (director and designer of last year’s acclaimed production of Eugene Onegin) re-unite for a new production of Pelléas et Mélisande, with Jac van Steen (Intermezzo, 2015) conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra in its Garsington debut. Audiences also have the opportunity to enjoy Martin Duncan’s exuberant 2011 production of Il turco in Italia, conducted by Rossini expert David Parry.

Then, in late July, there will be three performances of Silver Birch, a new commission from Roxanna Panufnik with a libretto by Jessica Duchen which draws upon Siegfried Sassoon’s poems and the testimony of a British soldier who served recently in Iraq to illustrate the human tragedies of conflicts past and present. Silver Birch, directed by Karen Gillingham, Creative Director of Garsington’s Learning and Participation programme and conducted by Boyd himself will bring together professional singers - those with sufficient talent to perform on the main Garsington stage, Boyd insists - and around 180 members of the local community, selected from local schools and organisations following auditions. Silver Birch follows 2013’s Road Rage by Richard Stilgoe and Orlando Gough, and clearly this sort of community celebration of music, poetry and dance will be an on-going part of Garsington’s commitment to increased participation and shared cultural experience. Indeed, Boyd is fervent in his belief in the Garsington ‘ethos’: that everyone should be welcome, and made to feel welcome, at Garsington, from the moment they enter the gates of the car park to the moment that they depart.

Boyd hopes that Silver Birch will help to build new audiences for the future and take opera to those for whom it is usually out of reach. Similarly, Garsington’s Opera for All series of screenings (a three-year partnership with the charitable trust Magna Vitae and the Coastal Communities Alliance, supported by Arts Council England’s Strategic Touring Fund) will take opera - via free public screenings of live performances of Semele - to coastal communities in Thanet, Grimsby, Skegness and Somerset, building on existing participation schemes. As one who survived adolescence in one such cultural desert, my operatic thirst slaked only - but gloriously so - by the energy and invention of Kent Opera - I can testify to the veracity of Boyd’s belief that such initiatives can ‘change lives’. The benefits are at least threefold, he argues: participation is increased; new audiences are stimulated; and Garsington gains further reach through such streaming. I ask if there are plans afoot for further cinema streaming, such as we have become accustomed to by the Met, the NT, Glyndebourne and others, and Boyd replies that its certainly something under consideration.

Last year’s Opera For All audiences enjoyed Michael Boyd’s Eugene Onegin and the venture forged further pathways when Garsington understudies gave a performance to an audience of local school students conducted by Boyd’s assistant conductor Jack Ridley; the production was then regularly screened on BBC Arts.

New collaborations are obviously an important part of Boyd’s vision for Garsington and recent years have seen exciting bonds formed with other artistic companies. In 2015, Boyd conducted Mendelssohn’s complete incidental music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream to accompany a performance of the play by the Royal Shakespeare Company, while last year saw a cast of over 50 dancers from Ballet Rambert and the Rambert School join 70 musicians on the Garsington stage for a grand scale performance of Haydn’s The Creation. The outcomes of such endeavours cannot be foreseen, but they offer new artistic approaches and fresh ideas, though Boyd notes that they cannot be ‘forced’ and must grow organically.

Boyd also hopes that Garsington’s productions will travel more widely in future. In 2014 Fidelio travelled to the concert hall of the Philharmonie de Paris for a semi-staged concert performance in November 2016, and on 27 June this season’s Figaro will be presented in the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées with the Orchestre de chambre de Paris. Co-productions may become a more regular feature at Garsington too. Next year, Boyd will conduct his first Strauss opera, Capriccio, directed by Tim Albery - a co-production with Santa Fe Opera.

The 2018 season will open with Die Zauberflöte, conducted by Christian Curnyn and directed by Netia Jones, both of whom will be making their Garsington debuts. And, the partnership with the Philharmonia Orchestra will continue when the orchestra returns for Bruno Ravella’s production of Falstaff under the baton of Richard Farnes. Garsington will present the world premiere of The Skating Rink by British composer David Sawer with a libretto - based on the short novel by Chilean author Roberto Bolaño - by award-winning playwright Rory Mullarkey. Commissioning and performing new work is obviously important to Boyd - to show that opera is not a ‘dead art form’ - and, given the recent successes of several new operas by British composers, such as Benjamin’s Written on Skin and Adès’ The Exterminating Angel, such work surely offers the opportunity to further raise Garsington’s international profile and impact.

When I ask Boyd about future programming plans, he is tight-lipped, beyond explaining the need to continue striking the right balance each season between new and old, familiar and unknown (though he doesn’t wish Garsington to focus unduly on ‘niche rarities’), operas with much work for the chorus and those without. But, he will divulge that he hopes that Capriccio is followed by more Strauss - perhaps Rosenkavalier - and that he’d like to see Garsington staging more Janáček, following the acclaimed 2014 production of The Cunning Little Vixen.

Boyd himself has had, and continues to have, a truly international career. He was a founding member of the Chamber Orchestra of Europe and principal oboe for 21 years, before taking up his first major conducting post as Music Director of the Manchester Camerata - alongside which he was a frequent visitor to the United States, as Artistic Partner of the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra in Minnesota for 6 years and Principal Guest Conductor of the Colorado Symphony. He’s retained his ties with Europe, too, spending 7 years as Music Director with Musikkollegium Winterthur, and since September 2015 has been Music Director of the Orchestre de chambre de Paris.

Those early years at the COE have planted deep-rooted musical values, and he often speaks of the ‘COE spirit’. When I ask him what he means by this, Boyd explains: members shared the belief that playing with the orchestra was not a job it was a privilege; that one played every performance as it if was one’s last; and that this commitment and passion was equalled by the search for musical excellence.

As Boyd races back to the rehearsal studio, I cannot imagine him approaching any musical endeavour or challenge in any other way.

Garsington Opera runs from 1 June - 30 July.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/160625_0055%20boyd%20adj.jpg product=yes product_title=Garsington Opera product_id= Above: Dougie Boyd (Artistic Director, Garsington Opera)May 20, 2017

I Fagiolini's Orfeo: London Festival of Baroque Music

Orfeo, first performed in 1607 at the Gonzaga court in Mantua is, in formal and stylistic terms, derived from earlier models: the madrigal, balletta, the intermedi, the pastoral tradition. But, it is also one of the boldest experiments: a favola in musica (a play in music) lasting 90 minutes, its units bound together by repeating ritornelli - an extraordinary conception in its day.

Robert Hollingworth directed a performance which urged us to remember what a thrilling occasion the first performance of Orfeo - in the Sala Nuova, 30 metres long and 7 metres wide, of the Gonzagas’ ducal palace in Mantua - must have been. But, his players and singers also made us aware of the musical roots of the opera, commencing the performance with a madrigal, a reminder of the aesthetics of the seconda prattica style - with its emphasis on melody over harmony, and the union of word and tone - from which opera sprung.

At first, I wondered at the appropriateness of adding a ‘preface’ to the ceremonial toccata with which the opera begins, but as the performance continued I appreciated the way the opening madrigal served to reinforce the lack of stylistic division between genres, as elements of the madrigal idiom appeared in the declamatory arioso, in the recitative and in the more discrete formal dances and songs. The latter, in which the voices came together in ensemble or chorus, were vivid portraits of joy and despair: the Act 1 balletta ‘Lasciate i monti’ skipped in pastoral sunshine, while the chorus of lamentation which closes Act 2 was weighted with despondent gloom.

The introductory toccata itself, a gloriously rich explosion of brass, immediately translated us to a world of courtly decorum and majesty. As the musicians took their seats - some in front of the stage, some behind and raised, replicating the placement which made the instrumentalists visible at the first performance - the singers processed in. Hollingworth, who had joined the madrigalists at the start, now took his position behind the organ, and it did not seem fanciful to envisage the hierarchically arranged horse-shoe configuration of the original audience, with the Duke elevated on a balustraded dais. The historical echoes must have been even more resonant when Tom Guthrie’s semi-staged production was first performed by these artists in 2015, in a ‘private’ performance for Martin Randall Travel in the scuola of San Giovanni Battista, Venice.

However, I’m not sure if simply having singers enter from the rear, or sing from the gallery, or assume a variety of positions on the platform really produces a performance which can be genuinely be described as ‘semi-staged’? I may be being unfair to Guthrie, though, for St John’s does not afford much opportunity for adventurous staging and the sight-lines are not good (so it wasn’t a good idea for La Musica to begin the Prologue seated on the floor, removed from view).

Monteverdi employs a large orchestra and the playing of I Fagiolini and The English Cornett & Sackbutt Ensemble was stylish and incredibly accomplished. Whether it was the piquant descant recorders colouring the repeating Act 1 balletta with squeals of delight; the rhapsodic theorbo of Eligio Quinteiro underscoring the emotions of the text; the fleet, feathery decorative echoes of violinists Bojan Čičič and Jorge Jimenez in Orfeo’s impassioned plea ‘Possente spirto’; or the blazing richness of the cornetts allied with the warm blend of sackbuts singing in consort, the instrumental playing was an integral element in the drama - commenting, reflecting, building tension, celebrating.

In the title role, Matthew Long wonderfully illustrated the rhetorical eloquence of Monteverdi’s ‘musical speech’. Initially I wondered if his tenor would acquire sufficient range of colour to convey the music’s emotional diversity, but in ‘Possente spirto’ he probed every word for nuance and shade, showing sensitive appreciation for the mannerist aesthetic in which the style takes the text as the point of departure. Long treated the declamatory rhythms with just the right touch of flexibility, the slightest looseness deepening the expressive gestures of the vocal melody. The way in which Long gradually opened Orfeo’s heart to the listener, creating ever more heart-tugging empathy, was very impressive. Rachel Ambrose-Evans sang with a clear, attractive tone, but her Euridice was less strongly defined dramatically.

I noted the vivacity of baritone Greg Skidmore’s response to situation and text when reviewing a recent concert by Ex Cathedra , and here, once again, Skidmore had considerable stage presence, distinguishing effectively between the Infernal Spirit and the Shepherd. Christopher Adams’ Carone plumbed cavernous depths complemented by the dark-toned trombones, while Charles Gibbs was a regal Pluto, patently enjoying the affectionate attentions of Clare Wilkinson’s expressive, elegant Proserpina.

Hollingworth was intensely involved in all aspects of the musical drama, moving from the organ to join a madrigal or chorus, returning to the keyboard to supplement the musical mood with a percussive adornment. He epitomised the relaxed flow of the performance as a whole, further emphasising the astonishing formal synthesis of Monteverdi’s innovative and marvellous opera.

Claire Seymour

Monteverdi:

Orfeo

I Fagiolini/The English Cornett & Sackbutt Ensemble

Robert Hollingworth (organ & director)

Thomas Guthrie (stage director)

Orfeo - Matthew Long, Euridice - Rachel Ambrose-Evans, Messenger/Silvia - Ciara Hendrick, Ninfa/Proserpina - Clare Wilkinson, Speranza/Shepherd - William Purefoy, Apollo/Shepherd - Nicholas Hurndall Smith, Caronte - Christopher Adams, Plutone/Shepherd - Charles Gibbs, Shepherd/Infernal Spirit Greg Skidmore.

St John’s Smith Square, London; Thursday 18th May 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/i_fagiolini_credit-russell-gilmour_website.jpg image_description=I Fagiolini and The English Cornett & Sackbutt Ensemble at the St John’s Smith Square product=yes product_title= I Fagiolini and The English Cornett & Sackbutt Ensemble at the St John’s Smith Square product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: I FagioliniPhoto credit: Russell Gilmour

May 18, 2017

The English Concert: a marvellous Ariodante at the Barbican Hall

Gone are the supernatural diversions and obfuscating sub-plots which complicate so many of Handel’s libretti. Here, Antonio Salvi, drawing upon Ariosto’s Orlando Jurioso, provides Handel with a blistering human drama of envy and evil, which hinges on the supposed infidelity of the Scottish Princess Ginevra who, loved by Polinesso, Duke of Albany, prefers the noble Ariodante.

Despite receiving only eleven performances during its first season in 1735, Ariodante has long been admired as one of Handel’s finest operas. The part of the hero Ariodante was written for Giovanni Carestini, who was renowned for his versatility, virtuosity and fully working three-octave range. Alice Coote - deputising in the European performances for the indisposed Joyce DiDonato who will resume the role for the American leg of the tour - matched Carestini’s fabled technique and sang with deep commitment: this Ariodante was an immensely sympathetic hero, and the emotional journey he experiences through the opera was laid bare.

In Act 1, Coote exuded regal confidence. Bold but dignified, Coote used her gloriously rich, bronzed mezzo to convey Ariodante’s serenity and certainty in ‘Quì d’amor’. As her lines floated freely, at times there was a rhapsodic quality to the tone, almost Mahlerian; but, later, when suspicion troubled her tranquillity, an urgency entered the strongly moulded arioso. She used the text brilliantly in her Act 2 aria, ‘Scherza infida’, communicating the bitterness, grief and devastation which spring from the imagined betrayal of her beloved Ginevra; lutenist William Carter wonderfully underscored Ariodante’s despair at the close. Having demonstrated incredible stamina in this long aria, Coote flew through the wide-ranging - literally and in terms of expressive breadth - and astoundingly virtuosic ‘Dopo notte’ in Act 3. She doesn’t make it look ‘easy’ - indeed, she sings with her whole body and almost deliberately seems to strive to convey the visceral intensity by making us notice the vocal and physical demands, further deepening our awe. Coote may have paired her stylish trousers with open-toed stilettos but, despite the flowing blond mane and the sensuousness of her mezzo, there was a convincing, and paradoxical, ‘masculinity’ about her anger. Or, perhaps it was just that gender seemed irrelevant in the face of such consuming despair and ecstasy.

Alice Coote as Ariodante. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Alice Coote as Ariodante. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Coote’s stunning vocalism held us transfixed but she was out-strutted by Sonia Prina’s dastardly Polinesso. Prina’s Iago-like persuasiveness and prowling were utterly compelling. Visually, the spikes, killer heels, tattoos and lace trousers over shorts were arresting, but the transgender attire was also entirely at one with the dramatic integrity and naturalness which Prina brought to the role. As she strode and slunk across the Barbican stage, she drew the eye, dominating the drama just as the scheming Polinesso coercively manipulates the naïve, Dalinda, toying with her affections so that she will carry out his ruse to make Ariodante believe that Ginevra is faithless.

Prina seemed less concerned with the actual sound produced than with the effect it could and would have - on Dalinda and the audience, equally. Some of the coloratura was less than clean and at the top there was an occasional harsh edge, but this mattered little, so thoughtful and dramatic was the phrasing - the rubato, the ornamentation, the dynamic variety. Prina allies rhetorical power with dramatic flexibility. Entirely off-score throughout the evening, she encouraged and supported her fellow cast members generously.

Christine Karg as Ginevra. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Christine Karg as Ginevra. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Christine Karg’s Ginevra was a cooler portrait of tender love and loyalty. In fact, despite her silky scarlet dress which stood out so strikingly amid the prevailing black, I felt Karg’s ‘ice maiden’ Ginevra would have benefited from greater musical contrasts. But technically she was flawless. Act 1’s ‘Vezze, lusinghe’ was poised and eloquent; Karg controlled the line expertly and her soprano had well-defined colour and a strong core. Ginevra’s quiet introspection was an asset, too, in ‘Il mio crudel martoro’; condemned as a whore by her father, the King of Scotland, Ginevra’s inner despair was palpable, immune to Dalinda’s consolatory solace. Karg may not have tapped the full emotional range that Handel offers, but this was a touching performance. And, her duets with Coote were affecting for the way that vocally and dramatically they seemed to draw the best from each other.

Mary Bevan, standing in at short notice for the indisposed Joélle Harvey, held her own impressively alongside the more experienced singers. Confident, characterful and with a nice range of colour, Bevan was a surprisingly spirited Dalinda. Her soprano was powerful in ‘Il primo ardor’, in which Dalinda deflects the smitten Lurcanio’s advances. Exulting in the reward promised her by Polinesso, at the bottom her voice acquired a mezzo-ish weight in ‘Se tanto piace al cor’. ‘Neghittosi or voi che fate?’ was a moving expression of regret and, reunited, Dalinda and David Portillo’s Lurcanio sang a beautiful final duet which was one of the highlights of the evening.

David Portillo as Lurcanio. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

David Portillo as Lurcanio. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Portillo had already impressed in Act 2’s revenge aria, ‘Il tuo sangue’, in which the tenor’s vocal athleticism served him well in passages of florid anger, where Carter again provided strongly accented support. Prior to that we had enjoyed Lurcanio’s warm profession of love, ‘Del mio sol vezzosi rai’, and admired Portillo’s lovely clean, even gentleness.

Matthew Brook played the King of Scotland as benign, cultivated patriarch, whose calm civility hides a deeper emotionalism which is distressingly released when he hears of his daughter’s supposed dishonour. A little more heft might have enhanced the regality, but the King’s disbelief was totally credibly and the pathos of his grief heart-rending. Bradley Smith sang the small, predominantly recitative, role of Odoardo with a sure sense of his character’s function in the drama.

Alice Coote, Harry Bicket, Christine Karg, Sonia Prina, Mary Bevan, David Portillo, Matthew Brook, Bradley Smith and The English Concert. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Alice Coote, Harry Bicket, Christine Karg, Sonia Prina, Mary Bevan, David Portillo, Matthew Brook, Bradley Smith and The English Concert. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Bicket directed the small forces of The English Concert with economy and precision: the barest, swiftest flick of the wrist was all that was needed to bring about a change of colour or to usher a detail to the fore. The instrumental sound was fairly light, though capable of poignancy as well as brightness; it provided the singers with an airy support, and space to project.

This was a ‘concert performance’ but many of the cast dispensed with scores and stands, and the dramatic interaction was sustained and animated. Shakespeare’s tale of jealous delusion ends in tragedy, but in Handel’s opera covetousness and resentment are defeated by love. And, the performance was a veritable triumph.

Harry Bicket and the English Concert return to the Barbican Hall in March 2018 to perform Handel’s Rinaldo, with Iestyn Davies in the title role.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Ariodante (concert performance)

The English Concert: Harry Bicket, conductor

Ariodante - Alice Coote, Ginevra - Christiane Karg, Dalinda - Mary Bevan, Polinesso - Sonia Prina, Lurcanio - David Portillo, King of Scotland - Matthew Brook, Odoardo - Bradley Smith.

Barbican Hall, London; Tuesday 16th May 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Prina%20and%20Bevan.jpg image_description=The English Concert at the Barbican Hall product=yes product_title=The English Concert at the Barbican Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Sonia Prina and Mary BevanPhoto credit: Robert Workman

May 14, 2017

Riel Deal in Toronto

Mr. Somers’ challenging three act opera, set to a text by Mavor Moore with the collaboration of Jacques Languirand, charts the fascinating history of Louis David Riel. Now a national hero, Riel helped found the province of Manitoba, and he championed the plight of the Métis indigenous prairie people, seeking to preserve their culture and rights as their homelands came under increasing encroachment by the Canadian government. He led two resistance movements against the political sphere of the first post-Confederation Prime Minister, Sir John A. MacDonald. Riel has attained the revered status of a folk hero.

This operatic treatment is no dusty, linear history lesson, far from it. The angular, pulsating, often jarring score mixes indigenous influences with classical music trends of its time, evoking the sonic world of Stockhausen, Boulez, Penderecki, Foss, and Xenakis. Although I came of age in that era and heard numerous such recordings, I never had the pleasure of experiencing compositions of this school in live performance. With Louis Riel, I made up for lost time.

(l-r) Russell Braun as Louis Riel, Alain Coulombe as Bishop Taché and Allyson McHardy as Julie Riel [Photo by Michael Cooper]

(l-r) Russell Braun as Louis Riel, Alain Coulombe as Bishop Taché and Allyson McHardy as Julie Riel [Photo by Michael Cooper]

A brilliant aural palette called for a virtuoso orchestra and demanded extremely wide-ranging vocal accomplishments. This was a riveting, engrossing immersion into a model of its genre. Not to say that there aren’t some dramaturgical hiccups in the episodic, presentational structure. But sweeping all before it is a haunting blend of a capella melismatic arias; disorienting percussive effects; searing brass stings; scraping, then soaring strings; flighty woodwind licks; and flawless choral work (Sandra Horst, Chorus Master). Under the assured, inspired baton of Maestro Johannes Debus, this added up to a pretty spectacular evening of first tier, nay, virtuosic music making.

But if there are three key elements to the evening’s success, they are: Russell Braun, Russell Braun, Russell Braun. (Did I mention Russell Braun?) The Canadian baritone is at the top of his game, and commands the stage with a nonpareil traversal of the title role. Tour de force is too puny a phrase to describe the magnitude of Mr. Braun’s achievement. He tears into the punishing role with a De Niro-like intensity and draws on a rock-solid vocal technique that he daringly pushes to its very limit.

This was the sort of “personal best” triumph that, like its subject, merits legendary status; an “I-was-there” performance that I will cherish as a gold standard of operatic excellence for years to come. I am a long time Russell Braun fan, and all his familiar strengths were on ample display: the pointed lyricism, the easy top, the smooth legato, the vibrant tone, the supreme control, the intelligent musicianship. What I could not have anticipated was the reserve of firepower he had at his command, and the heart-stopping emotional commitment that he was able to invest in this towering role assumption. His disjointed, unhinged, anguished Mad Scene that closed Act One was gut-wrenching its impact. The composer often crafts fiendishly high lying phrases for Riel that verge on Sprechstimme shrieks, and Russell negotiated them all with raw power. There is simply no aspect of the complicated vocal line or the complex characterization that eluded him. Unforgettable. Bravissimo divo!

(l-r) Jean-Philippe Fortier-Lazure as Father André, Everett Morrison as Wandering Spirit and Keith Klassen as Father Moulin [Photo by Michael Cooper]

(l-r) Jean-Philippe Fortier-Lazure as Father André, Everett Morrison as Wandering Spirit and Keith Klassen as Father Moulin [Photo by Michael Cooper]

He was decidedly not alone in his success. Please read the large cast list below, and please know that each and every one of this prodigiously gifted ensemble of Canadian singers made their solo appearances into a true star turn, wondrously sung and fervently acted. Moreover, their efforts congealed into a brilliant, evenly matched musical ensemble that would be envy of any opera company.

It may be odious to single out any of these players, but baritone James Westman was first among equals with his snide, snarling, overbearing, blustering, duplicitous Sir John A. MacDonald (think Donald Trump with high notes). Mr. Westman’s powerful, secure baritone has an easy high extension, and as he effortlessly rode wave after wave of cresting orchestral sound, he seemed more like the world’s next great Heldentenor in making. While most of the arias are given to Riel, his wife Marguerite has an extended solo to open Act III. Singing in Cree, virtually unaccompanied as she cradled their baby, soprano Simone Osborne lavished creamy tone and negotiated seamless register shifts in one of the opera’s longest, most accessible passages. This alluring, poised vocalist surely has a bright future.

Jean-Philipe Fortier-Lazure displayed a ringing tenor as Cartier, and Peter Barrett showed off a burnished baritone as Colonel Garnet Wolseley. The two of them collaborated with Mr. Westman for a gripping, argumentative trio, all tumbling phrases and shifting tonalities. Allyson McHardy brought a dusky, well-schooled mezzo to Riel’s mother Julie, and his sister Sara was well served by Joanna Burt’s agreeable soprano. The two women were especially fine as they urged Riel not to execute Thomas Scott, whose strident non-PC slurs were passionately delivered by Michael Colvin. Mr. Colvin’s characterful singing was exceeded only by the conviction of his acting. Although a slight graininess could creep into his extreme upper register when pressured, veteran bass Alain Coulombe created a sympathetic, tortured Bishop Taché.

Peter Hinton’s inventive staging could hardly have been bettered, as he seized on the concept of ritualizing the story telling. There was much use of religious prayer circles and other symbolic formations, all highly stylized and visually apt. Mr. Hinton had a willing story-telling partner in set designer Michael Gianfrancesco. Mr. Gianfrencesco gave him a minimalist marvel of a playing space, backed by an amphitheater of benches upstage, that could separate, elevate, you name it, and were revealed or enclosed at will by stage width flying dividers. False proscenium towers right and left completed the look, all of it handsomely executed in blond wood.

(centre) Andrew Love as Dr. Schultz [Photo by Michael Cooper]

(centre) Andrew Love as Dr. Schultz [Photo by Michael Cooper]

This simple design was then filled with all manner of carefully chosen pieces and effects including a roaring fire pit, falling snow, imposing desks, and lots and lots of chairs. The latter were inventively placed, sometimes up-ended, cradled as dead bodies, and even used as “stilts” for actors to tromp around the stage like menacing spiritual forces.

The success of Bonnie Beecher’s sumptuous lighting design cannot be over-praised. With such a sparse scenic realm, her beautifully crafted illumination was critical in delineating the shifting moods and locations. Of especial impact were the bands of color on the upstage cyclorama that were ravishing in well-calculated cross fades from red to azure to fuchsia and all shades in between.

The wide spectrum of Gillian Gallow’s costume design immeasurably helped identify the large cast of disparate characters, and made them readily identifiable to the audience in this sprawling narrative. Ms. Gallow’s skillful choices include garish tartan plaid suits for the Canadian officials. As the indigenous people are gradually absorbed into the general populace, they morph from the bright red garb that made them unique, to all black modern attire indistinguishable from that worn by the chorus. Santee Smith’s haunting ceremonial choreography was an important component in Mr. Hinton’s masterful directorial vision, with lithe Justin Many Fingers moving evocatively as the Buffalo Dancer.

Before I saw this piece I must confess, I did not know who Louis Riel was nor that, some years ago, Harry Somers composed a knotty, disturbing, soaring, compelling, illuminating, moving, unique piece of lyric theatre about a national hero who should have international recognition.

The rapt audience received the production with roaring enthusiasm, knowing they had just participated in an artistic adventure with a seldom-performed work that may not come along again. This profound production of Louis Riel may not send you out of the theatre with a tune in your ear, but it cannot help but have planted a new appreciation of a hero in your heart.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

The Activist: Cole Alvis; Folk Singer/Elzéar/Lagimodière/Court Clerk/Prison Guard: Jani Lauzon; William McDougal/Judge: Doug MacNaughton; British Soldier/Hudson’s Bay Scout/Father Moulin: Keith Klassen; Ambroise Lépine: Charles Sy; Thomas Scott: Michael Colvin; Joseph Delorme: Bruno Cormier; Janvier Ritchot: Jan Vaculik; Elzéar Goulet: Michael Downie; André Nault: Vanya Abrahams; Baptiste Lépine: Taras Chmil; Louis Riel: Russell Braun; Dr. Schultz: Andrew Love; Charles Mair: Thomas Glenn; O’Donaghue/a Fenian/B.B. Osler/a Prosecutor: Neil Craigshead; Bishop Taché: Alain Coulombe; Sir John A. MacDonald: James Westman; Donald Smith/Gen. Sir Frederick Middleton: Aaron Sheppard; Sir George-Étienne Cartier/Father André: Jean-Philipe Fortier-Lazure; Julie Riel (mother): Allyson McHardy; Sara Riel (sister): Joanna Burt; Colonel Garnet Wolseley: Peter Barrett; Marguerite Riel (wife): Simone Osborne; Gabriel Dumont: Andrew Haji; James Isbister: Clarence Frazer; Poundmaker: Billy Merasty; Louis Schmidt/Dr. François Roy: Bruno Roy; Wandering Spirit/War Chief of the Crees: Everett Morrison; F.X. Lemieux (lawyer): Dion Mazerolle; Buffalo Dancer: Justin Many Fingers; Conductor: Johannes Debus; Director: Peter Hinton; Set Design: Michael Gianfrancesco; Costume Design: Gillian Gallow; Lighting Design: Bonnie Beecher; Choreographer: Santee Smith; Chorus Master: Sandra Horst

image=http://www.operatoday.com/LouisRiel-SI-1272.png

image_description=Russell Braun as Louis Riel [Photo by Sophie I'anson]

product=yes

product_title=Riel Deal in Toronto

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Russell Braun as Louis Riel [Photo by Sophie I'anson]

Concert Introduces Fine Dramatic Tenor

The program opened with a dramatic rendition of the overture to Verdi’s La forza del destino. New to LA Opera, Bignamini’s interpretation included rough, loud chords at the opening followed by smooth legato playing in the overture’s more melodic sections. He drew a great variety of musical color from the ensemble and their sound often reminded me of multicolored Neapolitan ice cream. Thus, he notified California opera lovers that his interpretations are distinctive and architecturally strong.