July 30, 2017

Sirens and Scheherazade: Prom 18

For his largest and longest work to date, Sirens, Swedish composer Anders Hillborg has turned to Homer’s account of Odysseus being bound to his ship’s mast so that he might hear the eponymous enchanters’ song but resist its lure - and thus avoid the fate of the shipwrecked sailors who have been enticed to their doom on the rocky coast of the sirens’ island. Commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic and first performed in 2011, Sirens was receiving its UK première in this Prom the theme of which was heroics on the high seas.

Homer does not name his sirens but he does give their number as two, and Hillborg’s work is scored for two solo sopranos, mixed chorus and large orchestra. The roles of the mantic temptresses, who with increasing desperation attempt to mesmerise Odysseus with their song, were taken by Swedish sopranos Hannah Holgersson and Ida Falk Winland, who recorded Sirens with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Swedish Radio Choir and Eric Ericson Chamber Choir, conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen, on the BIS label in 2015. Here, the sopranos were joined by the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus under the American conductor James Gaffigan, who was making his Proms debut.

It’s always tempting to identify what is described as a ‘Nordic’ sound - what we imagine as a musical embodiment of the cool stillness and spaciousness of the landscape - and Hillborg’s spectral whispers, chord clusters, sustained harmonies and minimalist gestures might encourage one to use this label. We hear weeping winds; strain after the highest-lying violins; feel dark, unearthly tremors.

Hillborg has stated that the challenge was to create music that was simultaneously irresistibly beautiful and unnervingly menacing. Certainly, both the sensuous and the uneasiness deepened with the entry of the chorus whose floating cries and whistles reverberated around the hall. Time and movement seemed suspended, as if we were falling into a void. Textures would accumulate, as the sound mass seemed almost to tremble; then an individual instrumental voice would pierce through, a ghostly presence. A high ringing ‘whine’ was produced by the percussionists’ fingers, sliding along the edge of two glasses.

Hannah Holgersson. Photo credit: Mats Oscarsson.

Hannah Holgersson. Photo credit: Mats Oscarsson.

Winland took the higher of the two solo parts, her soprano rising above the massed sound with crystalline purity and sheen, but Holgersson’s lower lying melodies communicated with equal impact and strength, and the two singers’ voices blended persuasively.

There is no doubt that Sirens is intoxicating. I felt like Odysseus himself, hypnotised and compelled to submit to the sonic beauty of Hillborg’s score. The dreamlike ambience is dangerously destabilising: are the voices Odysseus hears real or imagined?

What was less satisfying was the absence of any definition in the delivery of the text - essentially this was wordless vocalise - with the result that the work had no clear narrative character, though Gaffigan did convey the musical structure’s sense of accumulating danger. Moreover, the text is a combination of Homer, translated into English, and Hillborg, but the latter’s anachronistic contributions sit uncomfortably against Homer’s poetry: ‘Breathe them, hear them, plunge into them. Drown in their sweetness, We’d love to turn you on.’

At the end of Homer’s episode, the sirens declare, ‘No life on earth can be hid from our dreaming … We will take you to the crack between the worlds’. Sirens drifts ambiguously into silence: has Odysseus sailed on, and the defeated sirens perished, or has he succumbed?

The concert opened with the swashbuckling swagger of the overture of Erich Korngold’s score for the 1940s classic film The Sea Hawk in which Errol Flynn played ‘Geoffrey Thorpe’, the fictional Elizabethan privateer who commanded marauding raids against the Spanish fleets to fill the coffers of the English treasury. (At the time, commentators noted parallels between the film and the contemporary political situation: with Hitler-like condescension, King Philip of Spain declares that he will only cease his conquests when the entire world is under his dominion, while the Elizabethan courts policy of appeasement raised similarities with Chamberlain.)

The BBCSO brass provided lots of bite and brilliance but Gaffigan balanced the punchy derring-do with nostalgic warmth in the more lyrical episodes, the solo flute singing sweetly above expressive cello support, and guest leader Sarah Christian providing an eloquent violin solo.

The sea stories after the interval came courtesy of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade in which Gaffigan drew stylish, disciplined playing from the BBCSO. But while the rhythmic lilt was persuasive, and the colours clearly defined, I expected the oriental rhetoric to be delivered with rather more flamboyance, as the music swept through Sinbad’s exploits on the open seas and the swirling Festival of Baghdad. The brassy climax was fittingly rousing, though, after which the solo violin brought the evening’s story-telling to a close and the ship returned home to calm waters.

Claire Seymour

Korngold: The Sea Hawk - overture; Anders Hillborg: Sirens; Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade - symphonic suite (Op.35)

Hannah Holgersson (soprano), Ida Falk Winland (soprano), James Gaffigan (conductor), BBC Symphony Chorus, BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Royal Albert Hall, London; Friday 28th July 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ida%20Falk%20Winland%201%20-%20foto%20Tilo%20Stengel.jpg image_description=Sirens and Scheherazade, Prom 18 product=yes product_title=Sirens and Scheherazade, Prom 18 product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Ida Falk WinlandPhoto credit: Tilo Stengel

July 29, 2017

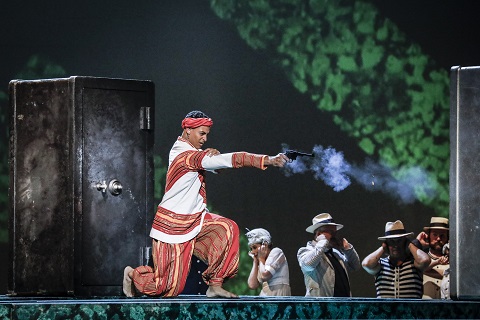

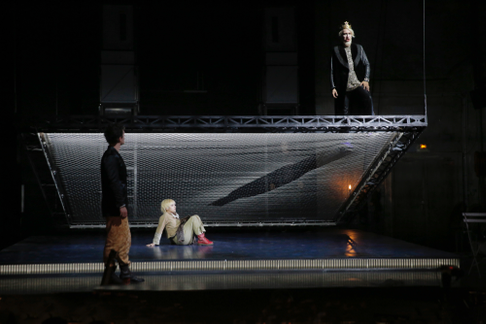

Discovering Gounod’s Cinq Mars: Another Rarity Success for Oper Leipzig

After Leipzig’s sensational production last year of Wagner’s early work Die Feen, the only current staging in opera, I returned to this optimistic German city for Gounod’s Cinq Mars, or here renamed Der Rebell des Königs. While Gounod’s music packs less thrills than his Faust or even Roméo et Juliette, the vocal and dramatic chemistry in this production certainly did not disappoint and made the trip more than worthwhile.

Gounod based his 1877 Cinq Mars on Alfred de Vigny’s historical novel about Marquis Henri de Cinq Mars’s failed attempt at rebellion against Richelieu, the manipulative Catholic Cardinal advising King Louis XIII. The libretto was written by Paul Poirson and Louis Gallet, who also wrote Massenet’s Thaïs, and some lesser known works by Bizet and Saint-Saëns.

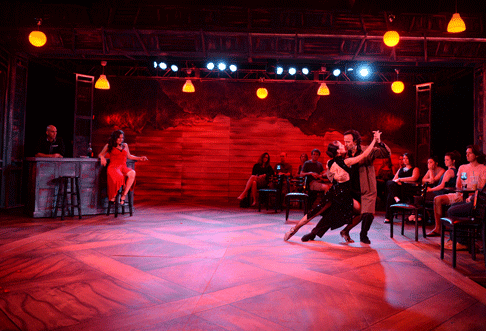

Anthony Pilavachi created a traditional tableaux vivants, faithful to most of the directions in the libretto. Markus Meyer’s costume design from that time and painting frame set, a frame within a frame, worked well. The pictures added to the inauthentic portrayal of ourselves as we tread into the social spheres, in this case the King’s court. All the world is still a stage.

To turn this into a true grand opera, Gounod added an impossible romance between Henri and a princess and included a delightful ball scene in the second act, humorously choreographed by Julia Grunwald. The Leipzig Ballet put on an entertaining, pastoral dance scene that offered some levity and witty moments provoking laughter amongst the audience.

As Henri de Cinq Mars and Princess Marie de Gonzague, who for political reasons must wed the Polish King, the stars of the evening Mathias Vidal and Fabienne Conrad led with passionately romantic chemistry an excellent cast. At the end of Act I and Act III, their duets received boisterous applause. In the final act, Vidal, right before Cinq Mars’s death, channelled the glamorous dramatics of Jonas Kaufmann: his singing produced deeply moving emotions to which the audience responded with the loudest bravi.

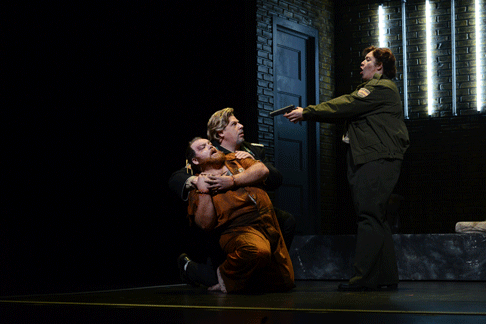

Vidal and Conrad in an impossible romance

Vidal and Conrad in an impossible romance

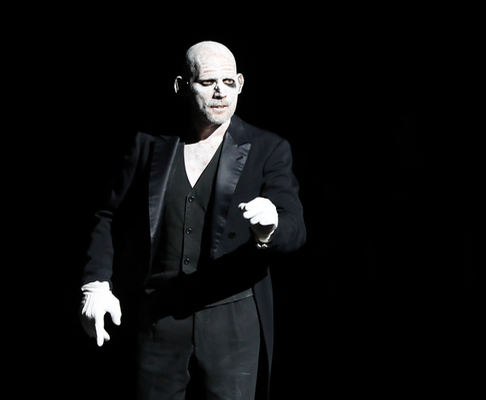

As head of Richelieu’s network of spies, Mark Schnaible created Father Joseph with the necessary religious villainy. He conveyed enough sickening contempt to remind me of a corrupted satanic Catholic. Toxic in the worst of ways. At the curtain call, for one moment he almost seem to rouse some boos, Schnaible was that successful at his antagonism.

The supporting roles were all well cast. As the pistol whip Marion Delorme, coloratura Danae Kontora stole each scene. Delorme hosts the party during which the ballet occurred. Not only did she carry her scenes with charm and wit, her voice commanded the stage and almost eclipsed Ms Conrad. Together with Delorme’s mischievous counterpart Ninon de Lenclos (an entertaining Sandra Maxheimer), the two devious ladies dazzled and brought out overtop flamboyance in their coquette scenes in the second act.

Amongst the supporting men, Jonathan Michie as Conseiller de Thou impressed the most. Always caring and forewarning towards his best friend Henri. In Act I, he particularly charmed in his bromance, although some of their funny French shenanigans were lost in translation. Later Michie demonstrated his vulnerability in his protection over Cinq Mars, before his friend’s tragic ending. Jeffery Krueger and Sébastien Soules, also contributed remarkably as de Montmort and de Fontrailles.

The cast and choir in Cinq Mars

The cast and choir in Cinq Mars

Alessandro Zuppardo prepped the Choir of the Oper Leipzig who provided indispensable energy. They offered great momentum in the beginning as they drew the audience into the story. They also engaged in lovely theatrics on stage in the frivolity at the ball in the Act II. Above all, the German choir authentically conveyed French patriotism in rousing moments.

David Reiland (from Opéra Théâtre de Saint-Étienne) conducted the Gewandhaus with much verve, never overshadowing the soloists. His pace created a continuous momentum which he led through each act. I was never bored with this composition by Gounod.

While Cinq Mars didn’t reach the epic grandeur of Leipzig’s early Wagner Die Feen, this production should be seen by any opera aficionado who wants to be treated to Gounod’s excellently executed, unrecognised work. It will be performed several more times in early 2018.

David Pinedo

Cast and production information:

Prinzessin Marie de Gonzague: Fabienne Conrad; Marion Delorme: Danae Kontora; Ninon de L'Enclos/ Ein Schäfer: Sandra Maxheimer; Marquis de Cinq-Mars: Mathias Vidal; De Montmort/ Der polnische Botschafter: Jeffery Krueger; Conseiller de Thou: Jonathan Michie; Vicomte de Fontrailles: Sébastien Soules; Pater Joseph: Mark Schnaible; Der König von Frankreich: Randall Jakobsh; Eustache: Jean-Baptiste Mouret; De Montrésor: Joshua Morris; De Brienne: Artur Mateusz Garba; Gewandhaus Orchestra, Conductor: David Reiland; Director: Anthony Pilavachi; Set and Costumes: Markus Meyer; Choreographer Julia Grunwald; Chorus master; Alessandro Zuppardo; Dramaturge: Elisabeth Kühne, at Oper Leipzig, May 27, 2017

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Der_Rebell_des_Konigs_Cinq_Mars_Ensemble_Premiere_20517Tom_Schulze.jpg

product=yes

product_title=Gounod's Cinq Mars at Oper Leipzig

product_by=A review by David Pinedo

product_id=Above: A traditional staging in Leipzig [All photos by Tom Schulze]

July 28, 2017

Detlev Glanert : Requiem for Hieronymus Bosch

It helps that the paintings are so much part of popular culture that everyone recognizes his images of extreme excess. Bosch’s people wear medieval dress, but their actions depict the subconscious, the ‘Id’ and existential guilt in operation, centuries before the concepts of psychology found expression in formal language.

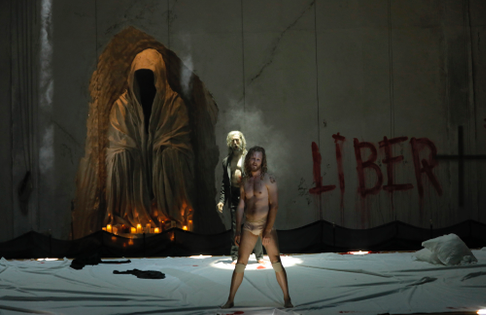

Like Carnina Burana, Glanert’s Requiem is highly dramatic music theatre, adapting the cataclysmic dreamscapes of Bosch’s paintings into music of extremes as lurid as Bosch’s images. Glanert’s Requiem unfolds in 18 episodes, rather like panels in a medieval triptych. This gives the piece structure, making it easy to follow. The teeming, sprawling panoramas Bosch depicts could plausibly be depicted in sound, but that would probably be asking too much of most audiences. Like Bosch, though, Glanert’s piece replicates extremes. Literally heaven and hell, for the premise is the judgement Bosch faces after death. Thus the standard elements of a Requiem Mass are interleaved with the Seven Deadly Sins, the acrid flames of hellfire whipping against the smoke of incense.

A harsh Voice (David Wilson-Johnson, narrating) calls from above “Hieronymus Bosch!” Immediately we spring to attention. Bells ring,. Throbbing, rushing figures in the choral line, suggesting the doomed hordes we see in Bosch’s paintings. The orchestral lines veer wildly, lit by screaming brass, the chorus screaming to crescendo. Suddenly the forces fragment and, from the silence, a slow, low penitential intonation. An abstract ‘Requiem Aeternam’, the choral line flowing ambiguously, in almost microtonal haze. like smoke. In ‘Gluttony’ the bass (the aptly named Christof Fischesser) sings of food, his lines circular and rotund. The text may be in Latin, but the meaning is clear. The choir responds with the long, thin lines of an ‘Absolve Domine’, reinforced by ‘Wrath’ with tenor (Gerhard Siegel) and a ‘Dies Irae’ which ends with a vivid orchestral flourish. Another demon, ‘Envy’, fights back. Soprano Aga Mikolaj’s fluid, curving lines mimic the lines in the “heavenly” chorus— imitation is a sign of envy!

But the serene ‘Juste judex’ prevails. But where are we? The organ solo (Leo van Doeselaar) lets rip with a frenzy that suggests a cathedral organ hijacked by ‘Satan’. Despite the extremes of volume and tempi, the lines between heaven and hell are, tellingly, blurred. In ‘Sloth’, the soprano sings langorously, joined in sensuous duet by the mezzo (Ursula Hesse von den Steinen). ‘Pride’, ‘Lust’ and ‘Avarice’ appear, but the balance shifts towards the big guns : Full choir, offstage choir, and orchestra in increasingly full throttle : listen for the jazzy culmination of the ‘Domine Jesu Christe’. and the funky trumpet that heralds the ‘Agnus Dei’.

With the ‘Libera Me’ and ‘Peccatum’, we are in Carmina Burana territory, bursting forth in a blaze, the earthly chorus in raucuous flow, augmented by brass and percussion and the offstage chorus singing of ‘lux perpetua’. Big forces. But is might right? Glanert’s Requiem ends ‘In Paradisium’, here the ‘Voice from Above’ recites lines from the Book of Revelation. Apocalyptic visions, marking the end of the world and of time. Now, when the Voice screams “Hieronymus!”, he doesn’t add a demonic epithet. With an unearthly low hum, the choir sings of the chorus angelorum that brings eternal rest.

Glanert’s Requiem for Hieronymus Bosch was commissioned to celebrate Bosch’s 500th anniversary, and premiered in Sint Janskathedraal, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, in April 2016. So it’s a public piece rather than a work of inward inspiration. It must be great fun to perform, without being particularly demanding, technically or interpretively. It could, in theory, be performed elsewhere, much as Carmina Burana is, these days. It is admirably performed on this world premiere recording made in November 2016 with the top-notch Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, conducted by Markus Stenz.

Glanert was one of Hans Werner Henze’s few disciples. Henze’s political beliefs influenced his music, though he never sacrificed high artistic and intellectual standards. Glanert is a man of the theatre, too, with a more earthy sense of humour than Henze had, though that quirkiness isn’t too obvious. When the ENO did Glanert’s opera Caligula, London audiences just couldn’t get it. (Please read HERE what I wrote about Caligula, which I first heard in Frankfurt). In this Bosch Requiem, Glanert again mixes grotesque with irony. Just as the vastness of Carmina Burana appealed to Nazi taste, the vastness of this Requiem veers on parody. Will it be loved for its vulgarity or its irony? Just as the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch reveal the viewer, Glanert’s Requiem reveals the listener.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/rco_glanert_requiembosch.png image_description=RCO 17005 product=yes product_title=Detlev Glanert : Requiem for Hieronymus Bosch. Markus Stenz, Royal Concertgebouw Amsterdam. product_by= A review by Anne Ozorio product_id=RCO 17005 [CD] price=€ 12.99 product_url=https://www.jpc.de/jpcng/classic/detail/-/art/detlev-glanert-requiem-fuer-hieronymus-bosch/hnum/7384097

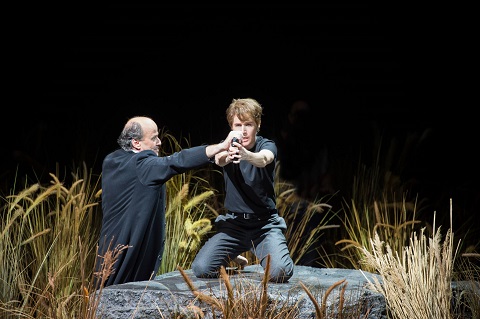

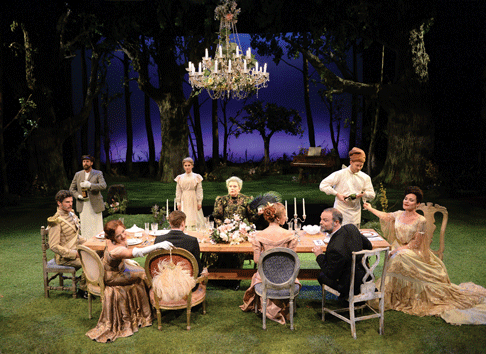

A new La clemenza di Tito at Glyndebourne

Guth’s and designer Christian Schmidt’s concept is more sentimental than Imperial, but not without relevance and effect. During the overture - brisk and airy under Robert Ticciati’s guidance - we enter a world of whimsy, as a digital projection unfolds the adventures of two young boys playing amid the woods and beside the lake in a rural idyll with more than a hint of resemblance to Glyndebourne’s own grounds. The faux chivalry of sword-fights with sticks takes a more sinister turn when the boys stalk wildlife, one with catapult a-ready. A shot is slung, and a bloodied magpie is the result - a betrayal of trust and of nature.

Unfortunately, first-night flickers and blackouts made the visuals even more distracting from the musical prelude than might have been the case; and, it’s not immediately clear that these two lads are the adolescent Tito and Sesto, whose friendship will be so tensely tested in the ensuing operatic narrative. This is not just a matter of realism - Richard Croft’s Tito looking at least one generation ahead of Anna Stéphany’s Sesto - but also because there is no clear link between the on-screen Elysian fields and the post-eruption ashes of the land of Vesuvian shadows which form half of the set. It is only in Act 2, when the conflicted Tito must decide the traitorous Sesto’s fate, that the parallels crystallise: the two young boys escape from the digital celluloid and clamber through the rough reed beds, ghostly representatives of disloyalty and division, who haunt their subsequent selves with disturbing memories.

Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

There is nothing Imperial about Schmidt’s split set: ravaged undergrowth - presumably the foothills of the recently erupted Vesuvius, as lava rocks and odds bits of furniture lay strewn - is juxtaposed with a grim, grey modern corporate milieu which lies hidden above until the black projection screen is lifted. There’s a lot of up and down, and upstairs/downstairs, but Olaf Winter’s gloomy lighting is atmospheric and apposite, emphasising the dullness and inertia of Tito’s political relationships and his own disaffection with a power dependent on fear.

Guth’s Personenregie is not always credible. Vitellia cries ‘Come here and embrace me,’ as she wanders off in the opposite direction from the infatuated Sesto; ‘Come near me!’ Tito demands, as he and Sesto walk backwards towards each other (tentatively, across an obstacle-strewn set - which ironically almost wrong-footed some the production team during the curtain calls), bump into each other and then lurch apart. When Sesto refuses to divulge the reasons for his treason, Tito threatens his beloved friend with a sickle, then uses it to scythe clumps of reeds which he clutches to his chest. There is much synchronised choral semaphoring from the ‘men in grey suits’ (both the gents and ladies of the Glyndebourne Chorus being thus attired).

Vitellia (Alice Coote), Sesto (Anna Stéphany) and Publio (Clive Bayley). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Vitellia (Alice Coote), Sesto (Anna Stéphany) and Publio (Clive Bayley). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Fortunately, there is some excellent singing to distract us from the irritating visuals. The withdrawal of the pregnant Kate Lindsay led Anglo-French mezzo-soprano Anna Stéphany - originally intended for the role of Annio - to step into Sesto’s shoes and her performance was simply stunning. I missed Stéphany’s much-lauded Marschallin at the ROH (where I saw a performance by the first cast), but I did admire her capricious Serse in the Early Opera Company’s performance of Handel’s opera at St John’s Smith Square last November. And, once again it was a true delight to enjoy her exquisitely styled phrasing and expressive coloratura. The challenges of ‘Parto, parto, ma tu, ben mio’ were met with ease, and the coloratura was sweet-toned, as if overflowing with Sesto’s love for both Vitellia and Tito - a love which was reflected in the beautifully played basset clarinet obbligato. ‘Deh, per questo istante solo’, in which Sesto declares himself deserving of death, vowing to take all the guilt upon himself, was equally moving. Impressively, Stéphany made the role dramatically credible too, plausibly treading the fine line between idealistic self-sacrifice and all-consuming passion - a task made more difficult in a production where it was not evident why anyone would fall so unreservedly under the erotic spell of Vitellia.

The vengeful daughter of a deposed emperor who abuses Sesto’s love to gain power and become Empress, Alice Coote’s Vitellia is clear ‘a baddie’ - a gun-toting chain-smoker, she even has a purple coat. Less femme fatale than a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown, this vituperative Vitellia seems to slide into hysteria, even psychosis, when she holds a pistol to Sesto’s head to convince him to murder Tito. No one could accuse Coote of lack of commitment and this was a heroic effort, but she was vocally taxed by a role which frequently lies too high for her mezzo. In ‘Deh, se piacer mi vuoi’ she pushed her voice hard, as Vitellia dreams of being Empress, but the result was sometimes squally. In the revelatory ‘Non più di fiore’, however, we finally enjoyed Coote’s lovely full, burnished lower register, as Vitellia is enlightened, recognising the error of her ways. We, too, were ‘enlightened’, as the aria was sung with the house lights on - another technical hitch, or designed to suggest spiritual illumination in contrast to the prevailing moral darkness?

Tito (Richard Croft) and Sesto (Anna Stéphany). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Tito (Richard Croft) and Sesto (Anna Stéphany). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

American tenor Richard Croft, following the withdrawal of Steve Davislim, was a benevolent patriarch, singing with soft-grained lyricism and fluency, although he wasn’t entirely comfortable at the top and had a tendency to be ponderous in the recitatives. This Tito was deeply tormented by the dilemmas he faced, as his innate compassion clashed with the magisterial demands of office, but he lacked a certain aristocracy - an imperial nobility which is essential if the qualms caused by his high-mindedness are to ring true. Tito is magnanimous, but he is not meek. Moreover, by placing Tito’s quasi-infatuation with Sesto centre-stage, the production neglected the political context for the drama: it was not clear why Tito must banish Berenice - we see her depart bearing two suitcases - whom he loves but whom his nation will not accept as Empress, nor why having initially chosen Servilia as her replacement, she too is rejected in favour of Vitellia.

Servilia (Joélle Harvey). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Servilia (Joélle Harvey). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Joélle Harvey, who made a strong impression here in La finta giardiniera three year ago, sang with stylishness and delicacy as Servilia, giving depth to the slight role and pleading for Sesto’s life with heart-moving earnestness in her final aria. Annio, the role originally intended for Stéphany, was beautifully sung by Canadian mezzo-soprano Michèle Losier who captured all of Annio’s loyalty and honesty.

The playing of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment was tender and spacious, though the ceremonial numbers might have had a little more regality. Ticciati sensitively gave his singers the time they needed, but there was occasional loss of momentum in the recitatives with too many longueurs and silences. Ashok Gupta (fortepiano) and Luise Buchberger (cello), raised in the pit, were not once unsettled by the hiatuses, however.

Some have seen La clemenza di Tito as a homage to Leopold II, whose coronation as King of Bohemia the opera was commissioned to celebrate; others, as a warning to pre-Revolutionary European rulers of the dangers of the abuse of power. Certainly, contemporary political tensions remind us of the need for leaders who will ensure the safety and security of nations, as emphasised perhaps in the closing moments of this production when Clive Bayley’s dark-voiced Publio - the unsettling, manipulative commander of the Praetorian Guard - came out of the shadows to assume the reins of power.

Another self-conscious directorial gesture, perhaps; but the superb cast ensured that the sincerity which is at the heart of this opera was preserved.

Claire Seymour

Mozart: La clemenza di Tito

Vitellia - Alice Coote, Sesto - Anna Stéphany, Annio - Michèle Losier, Publio - Clive Bayley, Tito - Richard Croft, Servilia - Joélle Harvey, Children - Rupert Wade and Logan Bradley; director - Claus Guth, conductor - Robin Ticciati, designer - Christian Schmidt, lighting designer - Olaf Winter, video designer - Arian Andiel, dramaturg - Ronny Dietrich, movement director - Ramses Sigl, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Glyndebourne Chorus (chorus master, Jeremy Bines).

Glyndebourne Festival Opera; Wednesday 26th July 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Chorus%20and%20Tito.jpg image_description=La clemenza di Tito, Glyndebourne Festival Opera product=yes product_title=La clemenza di Tito, Glyndebourne Festival Opera product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Tito (Richard Croft) and the Glyndebourne ChorusPhoto credit: Monika Rittershaus

July 23, 2017

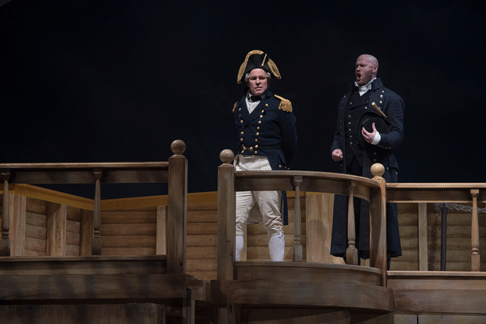

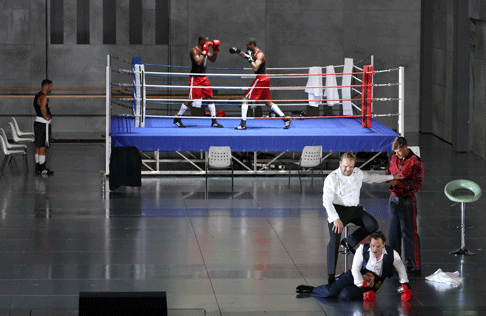

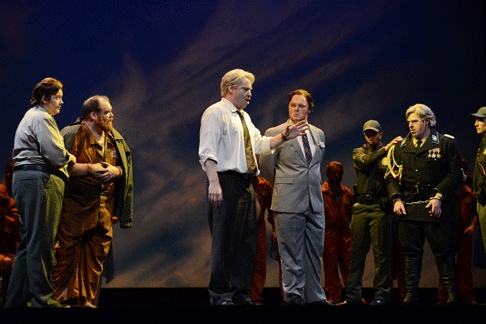

Prom 9: Fidelio lives by its Florestan

Given that the opera celebrates both individual freedom and the spirit of collectivism - ‘A brother has come to seek his brothers, to help them, if he can, with all his heart,’ sings Don Fernando, as he delivers his gracious king’s order to ‘dispel the evil cloud of darkness’ which has enveloped the populace and the prisoners - it must have seemed an apt choice of work, exemplifying the very principles upon which the Arab-Israeli project was founded.

Indeed, Fidelio can seem more an expression of ideas and ideals than a drama about the lives of credible, three-dimensional individuals. As such, it might lend itself more readily to concert performance than to theatrical staging, and it was the former that we were offered at the Royal Albert Hall in a performance by a cast of international soloists, the BBC Philharmonic and the singers of Orfeón Donostiarra, under the baton of Juanjo Mena.

Fidelio - which falls between several stools: opéra comique, ‘rescue opera’ (or, in German, Befreieungsgeschichte) and Singspiel - is often described as a ‘problem opera’ and one of its sticking points is how to treat the spoken dialogue. On this occasion, the spoken German was amplified, which created a disjuncture between the various sections which form the whole and served to confirm that only one of the cast had the vocal power required to reach the furthest corners of the RAH. The dramatic veracity of the opera was also weakened by the failure of the soloists, by and large, to interact with each other - despite the fact that they were all (with the understandable exception of James Creswell, deputising for the indisposed Brindley Sherratt) singing from memory.

These minor misgivings, however, were unequivocally redeemed by the performance of Stuart Skelton as Florestan, once again contributing in utterly compelling fashion to the Proms’ Beethoven offerings following his memorable performance in Missa Solemnis last year. There can be few operas where the catalyst of the dramatic action is silenced for the entire first half of the work; but, this means that by the time Act 2 commences, with Leonore/Fidelio fervently embarked on her rescue mission, we are in a state of high expectation when we finally encounter the shackled Florestan, languishing alone in the prison’s furthest, darkest, dankest cell.

The BBC Philharmonic’s Act 2 orchestral prelude was cleanly and expressively executed, the instability of the rhythmic fragmentations and violent outbursts coalescing in the timpani’s disturbing tritone; but, nothing could fully prepare for the almost existential anguish of Skelton’s opening utterance, ‘Gott, welch Dunkel heir!’ (Oh, God! How dark it is!), the first word swelling with searing courage and defiance, and then depleting, an emblem of Florestan’s fading strength and hope. The declaration that ‘Doch gerecht ist Gottes Wille!’ (God’s will is just!) was assertive; the acceptance, ‘Das Mass der Leiden steht bei dir’ (He has decreed the measure of my suffering) was, despite the vehement melismatic twist, even and resigned.

Florestan’s liberator - his wife Leonore, disguised as ‘Fidelio’ - was Ricarda Merbeth, who delivered a vocal performance which was secure and disciplined, but who seemed reluctant to dare to complement her careful vocal delivery with dramatic commitment. Leonore has a lot of persuading to do. She must first don a male disguise with sufficient credibility to divert the affections of Marzelline from her light-hearted lover, Jaquino; then, she must insinuate her way into her husband’s prison by winning her ‘prospective father-in-law’s’ trust, and convince prison guard Rocco to allow her to accompany him to the cells. Surely, Fidelio would at least need to look at those whom she seeks to dupe? But, time and time again - despite the efforts of Louise Alder’s open-hearted, responsive Marzelline to engage with her new beloved - Merbeth stared straight ahead, as if oblivious and immune to such attempts. This was most frustrating in the Act 2 ‘Melodram’ in which Fidelio descends to Florestan’s cavern and must convince Rocco to employ ‘him’ as his assistant in the arduous task of digging the long-confined Florestan’s grave.

That said, Merbeth’s vocal performance was solid, the tone rich and rounded, if sometimes filled out with what I felt to be an overly wide vibrato, and the role’s wide range caused no problems. In Leonore’s Act 1 aria, ‘Abscheulicher!’ (Monster!) the ungainly angularity of the vocal line and the rapid runs and arpeggios - essentially instrumental in nature - were used to create urgency and to convey the heroine’s struggle.

Creswell’s Rocco might have displayed more ‘oafishness’ but all credit to the bass for this show-saving performance: Rocco’s ‘gold aria’ was a model of bourgeois proselyting, and Creswell’s phrasing was eloquent throughout. Detlef Roth’s Pizarro was a bit underwhelming; he needed darker vocal hues to convey the prison governor’s malice and bluster, and to justify the heckling of this reprehensible on-stage character - oh when will UK audience’s cease this undignified practice? - which greeted Roth at his ‘curtain call’. (Mena stepped forward and whispered in Roth’s ear - presumably to explain that the hoots were not a sign of audience disapproval of his singing but rather a relic of pantomime heckling.)

Louise Alder (Marzelline). Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Louise Alder (Marzelline). Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

The younger soloists didn’t always have the heft for the venue but gave intelligent, vocally assured performances. Louise Alder seems to have limitless stamina and a musical memory as cavernous as Florestan’s cell: following recent performances in the Cardiff Singer of the World Final, and as Sophie in WNO’s Der Rosenkavalier, at the RAH she brought Marzellina to life, and the contrast between her crystalline soprano and Merbeth’s plumper, darker voice was effective. (The following evening, Alder stepped in at the last moment to replace the indisposed Andrei Bondarenko at the Wigmore Hall, where she’d performed earlier in the month in a recital entitled ‘Schubert and Women’s Voices’.)

As Jaquino, Benjamin Hulett was a vocally attractive partner for Alder and he imbued the spoken text with sensitivity and dignity. His opening duet with Alder, ‘Jetzt Schätzchen’ (Yes, sweetheart), made for an effectively sunny contrast to the Hadean depths of Florestan’s underworld to come.

As Don Fernando, David Soar was alone in being able to (almost) match Skelton’s projection, but he was more than a mere mouthpiece for royal authority and his addresses to the people conveyed genuine benevolence and fellow-feeling. As always, Soar gave an intelligent, considered performance.

The men of Orfeón Donostiarra were solicitous rather than revolutionary in tone in ‘O welche Lust’, and this helped Mena achieve textual clarity through the Act 1 finale. Similarly, the voices of the individual prisoners - Andrew Masterson (First Prisoner) and Timothy Bagle (Second Prisoner) - were given space to emerge from the mass. For the final chorus, the men, in evening dress, were joined by the women, in white, and we seemed to step even further into the realms of oratorio.

Wilhelm Furtwängler’s notes for his 1950 Salzburg production of the opera declared, ‘Fidelio is a Mass, not an opera - its emotions touch the borders of religion. […] After all we have experienced and suffered in recent times, this religious faith has never seemed so essential as it does today. … This is what constitutes the unique power and grandeur of Fidelio. […] What Beethoven was trying to express in Fidelio cannot be encompassed by any form of historical classification but extends beyond the narrow limits of a musical composition - it touches the heart of every human being and will always appeal directly to the conscience of Europe.’ Furtwängler’s words carried the momentous burden of the losses and atrocities of WW2, but the shadows cast by crimes against humanity are no less lowering today. Mena refrained from hammering home heavy-handed didacticism; but I did feel that, however ‘noble’, this performance lacked dramatic intensity.

Claire Seymour

Beethoven: Fidelio

Juanjo Mena (conductor), BBC Philharmonic, Orfeón Donostiarra.

Florestan - Stuart Skelton, Leonore - Ricarda Merbeth, Rocco - James Creswell,Marzelline - Louise Alder, Jaquino - Benjamin Hulett, Don Pizarro - Detlef Roth, Don Fernando - David Soar.

Royal Albert Hall, London; Friday 21st July 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Prom-9-CR_BBC-Chris-Christodoulou_7.jpg image_description=Fidelio, Prom 9 product=yes product_title=Fidelio, Prom 9 product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou

July 21, 2017

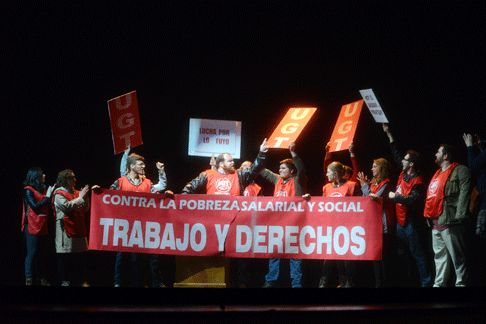

The Merchant of Venice: WNO at Covent Garden

Polish pianist and composer André Tchaikowsky, born in November 1935, had experienced the ghettos of Warsaw as a child; he was also a homosexual. One imagines that the discriminatory divisions and brutal biases of The Merchant of Venice struck a personal chord; that, paradoxically, he empathised with both the experience of the despised Jewish moneylender, Shylock, and with the latter’s nemesis, the refined Venetian, Antonio, whose melancholy has oft been accredited to his frustrated homosexual love for Bassanio - a love which other Venetians in the play mock: ‘You look not well, signor Antonio’, smirks the garrulous Gratiano.

Martin Wölfel (Antonio) and Mark Le Brocq (Bassiano). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Martin Wölfel (Antonio) and Mark Le Brocq (Bassiano). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Tchaikowsky’s opera was completed in 1978. He offered it to ENO, when the company was under Lord Harewood’s directorship and David Pountney was artistic director, but in 1982 it was rejected and Tchaikowsky, seriously ill with cancer, died shortly afterwards at the age of 46. It remained unperformed until Pountney, by then artistic director of the Bregenz Festival in Austria, commissioned performances, directed by Keith Warner, for the 2013 festival. WNO’s performances of this production in Cardiff in September last year brought the opera to the UK for the first time.

In Shakespeare’s day, Venice was considered an eclectic model of democratic republicanism, international trade, maritime prowess, Renaissance art and, as in Ben Jonson’s Volpone, corruption and vice. But, Shakespeare largely ignores these stereotypes and focuses on the city’s cultural divisions and conflicts (a pattern repeated in Othello). The ‘City of Love’, he suggests, is intoxicated by hatred.

WNO cast. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

WNO cast. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Keith Warner’s production emphasises not just the prevailing persecution and prejudice but also the motives which fuel them: in this case, mercantile ruthlessness and envy. Ashley Martin-Davis’ handsome designs take us to the underbelly of Venice’s leisured glamour: its bank vaults. There are none of the magnificent ‘argosies with portly sail’ - emblems of the trading wealth that paid for the city’s opulent piazzas, buildings and art - that dominate the conversation at the start of Shakespeare’s play. Venice’s commerce depended upon the finance made available by Jewish usurers, and so the Jews were ‘tolerated’ not out of humanitarianism but because of mercantile necessity.

Warner and Martin-Davis take us directly into the city’s counting houses: sturdy strong-boxes form the very fabric of Shylock’s house. The set’s mobile walls rotate slickly, spinning us through a world of ceaseless commercial transaction. The action is updated to the Edwardian era - a period during which the cosmopolitan Jewish elite, from the highest echelons of the likes of the Rothschilds to the middle-class financiers, seemed largely integrated into London society, until the start of WW1 released previously repressed hostility. Warner and Martin-Davis thus ignore the gondoliers and visual riches of the Rialto, just as Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice ignores the local colour and opulence, to focus on the Venetians’ self-justifying persecution of the stereotyped ‘alien’.

John O’Brien’s libretto largely follows Shakespeare’s plot and imports much text - too much? - verbatim. There are some unexpected omissions, though. The absence of Bassanio’s description of Portia - ‘a lady richly left;/ And she is fair, and, fairer than that word,/ Of wondrous virtues: sometimes from her eyes/ I did receive fair speechless messages’ - with its alliterative dreaminess, deprives the spendthrift’s request for a loan of its romantic validation: after all, he is asking his homosexual admirer for money that the latter does not have so that he can pursue his female beloved. Then, when Shylock commands Jessica to lock the doors of his house in his absence, the usurer’s detestation of music - of the ‘vile squealing pf the wry-necked fife’, the ‘shallow foppery’ that shall not enter his ‘sober house’ - is excised; it seems strange to omit an opportunity to exploit the text for characterisation, given the operatic context - after all, Shakespeare’s villains are never lovers of music. But, then, I suppose something has to go.

Tchaikowsky employs a lyrical vocal idiom which often has much grace - as in Portia’s ‘quality of mercy’ monologue - and rhetorical impact, as in Shylock’s vociferous self-vindication, ‘I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes?’, which is moved, with dramatic effectiveness, from the Act 3 street scene in which Shylock spits his exculpation at Solanio and Salarino to the court-room denouement, where his audience is the Venetian state itself. But, the arioso lines often drift and overall the opera feels too wordy. One wishes that O’Brien had been more adventurous, re-ordering and revising in order to create ‘anew’, in the manner of a Boito, as there is a danger that the music becomes simply illustration - an enabling medium for the presentation of the play, rather than a work in its own right. Even Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream - which was similarly faithful to the original, adding just one line of ‘explanatory’ text (‘compelling thee to marry with Demetrius’) and in which the lovers’ music can suffer from the same plaint - has the unsettling eeriness of Oberon’s countertenor magic, the elevation of ‘Bottom’s Dream’ and, not least, the wonders of Britten’s score to suggest new meanings.

Musically, here, there is a predominant debt to Berg and, while not particularly memorable, the score serves the tenser dramatic moments adequately. However, the languorous lyricism of Belmont evades Tchaikowsky. Both Lorenzo’s final-act eulogy to music and the entire second Act - which feels like an extended scherzo, in which the divertissements are supplemented by an on-stage (here, side-box) Renaissance consort of two recorders, oboe d’amore, oboe da caccia, two bassoons, lute, tabor and harpsichord - lack the requisite ‘poetry’.

Wade Lewin (Prince of Morocco). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Wade Lewin (Prince of Morocco). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Warner offers a contrast to the dark Venetian drama of the opening act and stages the Act 2 Belmont scenes within a box-hedge maze, a bird’s-eye view of which is artfully relayed on a video back-drop. The easy luxury, sense of sexual freedom (at one point Portia pins Nerissa down in what seems a lesbian embrace), frequent interpolation of musical allusion and set-piece (‘Tell Me Where Is Fancy Bred?’ is delivered by a Dietrich-style diva in white top hat and tails) and the maze itself, put me in mind of Kenneth Branagh’s 1993 film of Much Ado About Nothing. But, the flippancy feels excessive: the caskets are held in three cumbersome safes, reminding us of the ugly, mercenary motivation behind the suitors’ quests, but the riddle scenes are hyperbolic - the gun-toting Moroccan prince leaps acrobatically and resorts to an outsize detonator to gain entry into the gold casket - and disproportionate, disrupting the dramatic flow.

Lionel Friend conducts with attentiveness to the details of the score - the orchestra is large - and does a good job at keeping stage and pit in balance and coordination. The instrumental interlude following the court-room scene was beautifully played, a poignant representation of Shylock’s defeat and, Warner suggests, death: for Shylock seems to succumb fatally to his shame and humiliation, his ghost rising during the moonlit meeting of Lorenzo and Jessica, to haunt his daughter’s betrothment and betrayal.

African American baritone Lester Lynch is cast as Shylock, his race adding to the alienation signalled by his gabardine and skull-cap amid the prevailing Edwardian urbanity. Lynch’s voice glows with pride and hatred, while the contortions of the tuba, bass clarinet and counter-bassoon convey his self-destructive bitterness. There seems little to redeem him: in the trial scene, he pulls on his rubber gloves like an amateur surgeon, eager for his ‘pound of flesh’, deaf to the warnings of the Duke of Venice - nobly sung by Miklós Sebestyén - that ‘victory’ will bring Shylock only vilification.

Lauren Michelle’s Jessica may toss her father’s treasure chests through the casements with overly enthusiastic gusto into the sheets held below by Lorenzo’s Christian friends, but she must fight her own battles to overcome prejudice. Michelle coped well with the high melismatic lines which, crystalline, rose above the scornful reception she meets at Belmont and deepened our sympathy still further.

Sarah Castle was superb as Portia. Her strong diction allowed Portia’s words to penetrate to the back of the stalls, giving the feisty proto-feminist further stature, while her phrasing was stylish. Its elegance was equalled by Mark Le Brocq whose high-lying lines conveyed all of Bassanio’s levity and heedlessness. Verena Gunz’s animated Nerissa and David Stout’s tactless Gratiano made a well-matched pair. Only Martin Wölffel disappointed: Tchaikowsky’s decision to cast Antonio as a counter-tenor (presumably to emphasise his homosexuality - Antonio surprises Bassanio with an impetuous kiss when the latter embarks for Belmont to woo Portia) may be questionable, but by any measure Wölffel lacked power and definition, and the English text was indistinguishable.

Verena Gunz (Nerissa), David Stout (Gratiano), Bruce Sledge (Lorenzo) and Sarah Castle (Portia). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Verena Gunz (Nerissa), David Stout (Gratiano), Bruce Sledge (Lorenzo) and Sarah Castle (Portia). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Warner’s production opens and closes with an image of Antonio on the psychiatrist’s couch. The final gesture - Antonio hurls an object at Shylock’s ghost, silhouetted against the moon - is presumably designed to suggest that the therapy isn’t working, unable to overcome the depth and perpetuation of hatred, but if so it seems redundant. More importantly, it subverts or at least alters the balance of the ending of Shakespeare’s romantic comedy, in which love and loyalty defeat malice and cruelty. That said, Warner does consistently emphasise the darker aspects of Shakespeare’s tale and at the close of this production the scales of justice are still crookedly weighted with intolerance and bigotry.

Claire Seymour

André Tchaikowsky:

The Merchant of Venice

Co-production of the Bregenzer Festspiele, Austria, the Adam Mickiewicz

Institute as part of the Polska Music programme & Teatr Wielki, Warsaw/

Shylock - Lester Lynch, Antonio - Martin Wölfel, Lorenzo - Bruce Sledge, The Duke of Venice - Miklós Sebestyén, Bassanio - Mark Le Brocq, Solanio - Gary Griffiths, Salerio - Simon Thorpe, Gratiano - David Stout, Jessica - Lauren Michelle, Portia - Sarah Castle, Nerissa - Verena Gunz, Prince of Aragon/Freud - Juliusz Kubiak, Prince of Morocco - Wade Lewin, A Boy - Fiona Harrison-Wolfe, Woman one - Amanda Baldwin, Woman two - Helen Jarmany; Director - Keith Warner, Conductor - Lionel Friend, Designer - Ashley Martin-Davis, Original Lighting Designer - Davy Cunningham (realised by Ian Jones), Movement Director - Michael Barry, Associate Director - Amy Lane, WNO Orchestra and Chorus (Chorus Master - Robert Pagett).

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Wednesday 19th July 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Martin%20Wolfel%20%28Antonio%29%20and%20Lester%20Lynch%20%28Shylock%29-%20WNO%27s%20the%20Merchant%20of%20Venice-%20photo%20credit%20Johan%20Persson-%202708.jpg image_description=The Merchant of Venice, WNO at the Royal Opera House product=yes product_title=The Merchant of Venice, WNO at the Royal Opera House product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Martin Wölfel (Antonio) and Lester Lynch (Shylock)Photo credit: Johan Persson

July 20, 2017

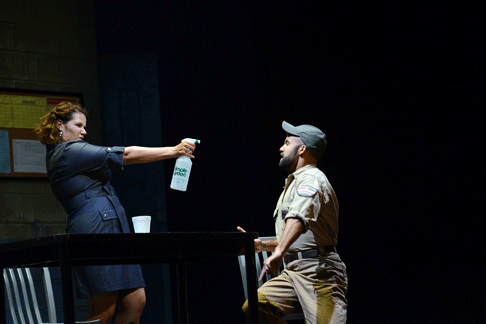

Leoncavallo's Zazà at Investec Opera Holland Park

And, fittingly so. For, in 1900, eight years after Leoncavallo had drawn back the curtain on the tawdrier side of theatre life in Pagliacci , and at the time when audiences were lapping up the self-sacrifice of Tosca - a well-known singer, adored by her public, redeemed by the beauty of her voice from a life of poverty or religious devotion - Zazà confirms the contemporary fascination (on-going?) with back-stage lives which combined luxury and glamour with lurid domestic soap-opera.

Indeed, the parade of performers with which Lambert opens the opera - stage-hands, Pierrots, cloaked magicians, drag artists, tutu-ed ballerinas, cabaret divas, acrobats, aerial artistes, a theatre troupe decked in full Renaissance garb - have their verismo roots in the itinerant comedians of Pagliacci, the traveling performers of Mascagni'sIris, and the professional actors in Cilèa’s Adriana Lecouvreur.

Lambert makes clear that this is an all-singing/all-dancing, show-must-go-on world, whose glitzy frontage is stained by a grittier reality. Ironically, it was a world with which Leoncavallo himself would later become familiar as, to supplement the royalties from Pagliacci, in his later years the composer toured Europe and North America, conducting condensed versions of his own opera. When he arrived in London in September 1911, a music-hall arrangement Pagliacci at the Hippodrome was announced as ‘The Sensation of the Century’: ‘Signor Leoncavallo’s appearance in person to conduct his own condensed version of his own Pagliacci, and bringing his own company with him, is an event of a unique character in the history of variety theatres.’ A media circus, indeed.

Reviewing Opera Rara’s superb concert performance of Zazà at the Barbican in 2015, I remarked that, ‘Perhaps a fully staged production is necessary to do justice to Zazà’s melodramatic excesses’. (My review contained a stage history and synopsis, to which readers might be directed.)

Louise Winter as Anaide and Michael Bradley as Augusto. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Louise Winter as Anaide and Michael Bradley as Augusto. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Lambert certainly holds nothing back scenographically in the first Act, making use of the whole span of the OHP stage to offer us a revue performance (-within the performance), a stage-crew at their labours, a working-class café-chantant, Zazà’s dressing-room-cum-bedroom, and an external staircase and platform where thespians and dancers gather to practise their art.

If that sounds a lot to take in, it is. I appreciate that it’s a milieu that we are intended to absorb, not a landscape whose every detail we should laboriously note; but, it seems a pity when dancers are practising at the barre, or show-girls are fanning bubbles, or Long John Silver is strutting his stuff, to ignore these details. Particularly so when central and peripheral events intertwine: when the protagonists’ music provides the rhythm and form for those performing in the stage’s marginal arenas; or where Zazà’s seductive flirtations are mirrored by erotic couplings at the fringe. But, without mimicking a Centre Court audience watching a thrilling rally swing back and forth, it’s impossible to take in and link up everything, and ultimately the hyperactivity - all wonderfully detailed and authentic - distracts from the central focus.

Act 2 puts the spotlight on Zazà’s dressing-room itself, all powder puffs, pillows and strewn underwear, while Act 3 transports us to the caddish Dufresne’s Parisian dwelling, which the family are preparing to leave. Trunks and cases are piled high, making the apartment appropriately spiritless but also making a nonsense of some of the text: as when Dufresne complains that his little desk, like his heart, is covered with clutter, when there isn’t a bureau in sight as all the furniture is swathed in white sheets. But, the bareness effectively complements the tightening of the dramatic intensity and focus in this Act.

Anne Sophie Duprels excels in the title role, demonstrating a dramatic range that matches her vocal commitment. Geraldine Farrar, the Met’s biggest star in 1920, and for whom the company staged Zazà, said that the role depended ‘altogether on the true, convincing interpretation of the heroine by the singer ... The singer who can make her audience feel that the emotions she is portraying are real, can make the figure live in voice and action, must always carry the part to success.’ (cited in Frederick H. Martens, The Art of the Prima Donna and Concert Singer). And, Duprels certainly lived up to this high threshold.

Anne Sophie Duprels as Zazà and Joel Montero as Milio. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Anne Sophie Duprels as Zazà and Joel Montero as Milio. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

The ‘heroine’ does not have formal arias as such, rather long musical monologues that hit peaks of passion and pique though which Duprels swelled gloriously. She has warmth in the middle range, and if occasionally her soprano becomes a little harsh as the voice climbs, the singer makes Leoncavallo’s somewhat indistinctive melodies speak. They take on a declamatory quality in the sense of an on-going conversation: Zazà’s voice will be heard - indeed, it is only quietened by the ‘angelic’ calm of Defresne’s daughter Totò, charmingly played by Aida Ippolito, whose spoken words alternate with Zazà’s plaintive sung reflections on the injustice of life and recognition that she must give up hopes of a future with Dufresne.

Duprels captured all of Zazà’s precariousness - her brassiness, her wit, her volatility, her vulnerability - and did not allow the drama to lapse into melodramatic sentimentality. In fact, she seemed at times to emphasise Zazà’s self-preserving flintiness. She smeared on red lipstick as she dismissively reminded her inebriate mother - whose idiosyncrasies were richly mined by Louise Winter - that living by the matriarch’s rules led to ruinous poverty, an accusation rendered sharper by Anaide’s obvious concern for her daughter, as she picked up her stockings from the floor and laid them carefully on the bed.

There was humour too, though, as Zazà donned Brünnhilde’s helmet to ‘rescue’ the furious peg-legged pirate she’d left stranded on stage, when missing her cue as Dufresne swept her off her feet. Duprels also conveyed a strong relationship with her long-suffering dresser, Natalya, a role sung with sensitivity and acted with nuance by Ellie Edmonds. Edmonds conveyed Natalya’s genuine love for her mistress, just as Duprels’ dependence on her employee-friend was plain to see.

Aida Ippolito as Totò, Anne Sophie Duprels as Zazà, and Ellie Edmonds as Natalia. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Aida Ippolito as Totò, Anne Sophie Duprels as Zazà, and Ellie Edmonds as Natalia. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Some of the best singing of the night came from Richard Burkhard’s Cascart; ‘Zaza, piccola zingara’ was tender, firm of tone and carefully phrased. If only Zazà had heard the loyalty and affection in her former lover’s voice then she might have heeded his warnings and spared herself suffering …

The minor roles - the starry revue artiste, Floriana (Johane Ansell), James Cleverton’s Bussy, a writer, impresario Courtois (Charne Rochford), stage manager Duclou (Eddie Wade), and Michael Bradley’s Augusto, a waiter - were persuasively sung and though their contributions were often quite brief, the direction was detailed and lively.

Richard Burkhard as Cascart and Anne Sophie Duprels as Zazà. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Richard Burkhard as Cascart and Anne Sophie Duprels as Zazà. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

As Zazà’s weak-willed, selfish deceiver, Milio Dufresne, Joel Montero seemed out of sorts. Though he produced a stirring tone at times, there were a lot of rough edges and the intonation was hit-and-miss and wavering.

Peter Robinson and the City of London Sinfonia made much of the brash colours and popular-song rhythms of Act 1, and brought out the more nuanced instrumental detail of the latter acts. This was disciplined, stylish playing.

When Farrar - who had a large following of idolising young women, nicknamed ‘Gerry-flappers’ - bid farewell to the stage in the title role of Leoncavallo’s opera, she was festooned with balloons and flowers, hailed with banners, ‘Hurrah, Farrar! Farrar Hurrah!’, eulogised in speeches of devotion, and paraded up Broadway in an open top car (as reported in Music Journal, October 1965).

Dream and reality, art and life: Zazà struggles to recognise the distinction between a world that can be created on a theatre stage and a life that must be lived. Perhaps it is ever thus. But, as Tosca learned that integrity is more than important than life, by the close Zazà has learned that integrity is more important than love.

Claire Seymour

Leoncavallo: Zazà

Zazà - Anne Sophie Duprels, Milio - Joel Montero, Anaide - Louise Winter, Cascart - Richard Burkhard, Bussy - James Cleverton, Floriana - Johane Ansell, Natalia - Ellie Edmonds, Courtois - Charne Rochford, Duclou - Eddie Wade, La Signora Dufresne - Joanna Marie Skillett, Marco - Oliver Brignall, Augusto - Michael Bradley, Totò Dufresne - Aida Ippolito, Claretta - Alexandra Stenson, Simona - Charlotte Hewett; Director - Marie Lambert, Conductor - Peter Robinson, Designer - Alyson Cummins, Costume Designer - Camille Assaf, Lighting Director - Mark Jonathan, Choreographer - Danilo Rubeca, City of London Sinfonia, Opera Holland Park Chorus.

Investec Opera Holland Park; Tuesday 18th July 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Johane%20Ansell%20as%20Floriana%2C%20Anne%20Sophie%20Duprels%20as%20Zaz%C3%A0%2C%20James%20Cleverton%20as%20Bussy%20.jpg image_description=Zazà at Investec Opera Holland Park product=yes product_title=Zazà at Investec Opera Holland Park product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Johane Ansell as Floriana, Anne Sophie Duprels as Zazà, James Cleverton as Bussy and the Opera Holland Park ChorusPhoto credit: Robert Workman

July 19, 2017

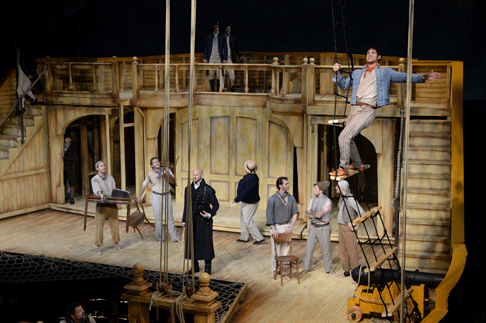

McVicar’s Enchanting but Caliginous Rigoletto in Castle Olavinlinna at Savonlinna Opera Festival

With his traditional staging and dress, McVicar brings to life the grotesqueries of a Renaissance libertine court. Due to the censors of the time, Verdi had to relocate Rigoletto in Italian Mantua, but he based his opera on Victor Hugo’s “The King's Amusement” that recounts the life of libertine King Francois I. The lighting and ambience of McVicar's adaptation was hauntingly eerie, even though some of the singers couldn’t master the Castle’s acoustics. Mostly, though, the Finnish soloists offered the greatest quality in singing.

Manolov proved a sensational Rigoletto spanning a wide spectrum emotion. As a giant hunchback on crutches and covered in black leather, he appeared more a monstrosity than a court jester. Manolov sang full-blooded about his despair in his desire for his daughter’s safety, or of his anger towards the Duke and his court (unleashing a fury for kidnapping his daughter in “Cortigiani, vil razza dannata”). Before he is cursed by him, Manolov delivered biting wit in his rant against Monterone.

Juha Pikkarainen performed Manterone with deep, rounded sonority, especially in his grand entrance through one of Olavinlinna’s side portals. In the beginning, Pikkarainen easily overshadowed Lahaj’s Duke of Mantua.

In the beginning, Rame Lahaj’s Duke of Mantua worried me. As McVicar’s display of libertine syphilitic licentiousness (with young men howling like rabid dogs and coïtus coerced on Monterone’s daughter) took over the stage during the overture, the orchestra in full force led by Philippe Auguin, overpowered Lahaj’s voice. His “Questo o quella” lacked body and was almost inaudible; he failed to hold his own amongst the terrific choir (in scattered sexual acrobatics on stage). I was worried I was in for some poor singing tonight.

Lahaj and Manolov as Mantua and Rigoletto amused by the court's licentiousness

Lahaj and Manolov as Mantua and Rigoletto amused by the court's licentiousness

But I was wrong, Lahaj seemed to be saving his voice for his solos later and for his duets with Gilda. During his “La donna è mobile” in the Final Act, with Auguin toning down the orchestra's volume, he sang decently, yet it still not was the Verdi showstopper I was hoping for. On the other hand, in his vocals with Gilda he managed sensitive dramatic chemistry during the quieter orchestral passages.

Lahaj and Takala in sensitive romantic chemistry

Lahaj and Takala in sensitive romantic chemistry

Gilda's “Caro Nome” put Tuuli Takala’s lyrical coloratura up to full display. Her high notes were so pure and radiated innocence. Even when the speedboats jetted over the lake outside and disrupted her singing, Takala would amp her vibrato not letting anything interfere in her declarations of love to her father or the Duke. As Giovanna, Merja Mäkäla offered beautifully grounded contrasts to Takala’s transparent vocals.

Manolov and Takala made an excellent pairing as Rigoletto and Gilda, in their father and daughter relationship. Their duets made believable and deeply moving. In their chemistry, two singing actors created great drama.

Manolov and Takala as father and daughter

Manolov and Takala as father and daughter

In supporting roles, Mika Kares contributed cunning intelligence to the assassin Sparafucile’s character. He performed wickedly together with a devilish Katarina Giotas as the conniving Maddalena, the sister Sparafucile emphatically pimps out in McVicar’s direction. Juha Riihimäki as Borsa and Jussi Merikanto as Marullo both sang decently. Though similarly to Lahaj, they also had some issues with the choir and orchestra’s force in Verdi’s music.

A magical moment occurred, during the storm in Act III. As lightning flashed brightly over the stage, a cold draft flowed through Castle Olavinlinna. As it passed the nape of my neck, right before the orchestra burst into a roaring tempest, it raised the hair on my arms and covered my back in goosebumps. A palpable tension hung in the air. Such moments make the castle such a thrilling locations for the right production.

After Manolov bowed over his dying Gilda at the end, and acknowledged Monterone with: “The Curse!”, the audience exploded in cheers. Yes the Finnish talent of this production received the applause (and loud stamping) it deserved. McVicar’s production proved a perfect fit for the Castle Olavinlinna.

David Pinedo

Cast and production information:

Duke of Mantua: Rame Lahaj; Gilda: Tuuli Takala; Rigoletto: Kiril Manolov; Giovanna: Merja Mäkelä; Sparafucile: Mika Kares; Maddalena: Katerina Giotas; Monterone: Juha Pikkarainen; Ceprano: Mikko Järviluoto; Countess Ceprano: My Johansson; Marullo: Jussi Merikanto; Borsa: Juha Riihimäki; Court usher: Roman Chervinko; Savonlinna Opera Festival Orchestra and Choir; Conductor: Philippe Auguin; Stage director: David McVicar; Stage design and costumes: Tanya McCallin; Lighting designer: David Finn; Movement director: Jo Meredith; Chorus master: Matti Hyökki; Olavinlinna Castle, Savonlinna Opera Festival, July 10, 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/_I2I7222.jpg

product=yes

product_title=Verdi's Rigoletto at Savonlinna

product_by=A review by David Pinedo

product_id=Above: Rigoletto at the Court in Olavinlinna [All photos by Soila Puurtinen, Itä-Savo]

July 18, 2017

Jette Parker Young Artists Summer Performance at Covent Garden

There are plenty of ‘on-a-budget’ opera companies who regularly show that a lot can be made of not very much, so the scanty set and properties in the first-half sequence - a few chairs and tables, a dozen champagne glasses, a bucket of cherries - were not in themselves a problem. Matthew Mulberry’s lighting design was economical and effective. The Byronic gloom of Jacopo Foscari’s prison cell was effectively conjured by a single hanging lamp; Prince Charmant’s palace bathed in a pink glow, while a cooler blue illumed Arabella’s fraught exchange with Mandrynka.

The direction, however, was minimal and too often the singers seemed to be ‘hanging about’ wondering where to move next, singing straight to the house, or into the wings or back-cloth, rather than at or to each other, even though each of the first-half items presents an intimate, charged exchange. The diction was also, generally, poor with almost no discernible distinction between Italian and French.

David Junghoon Kim and Vlada Borovko. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

David Junghoon Kim and Vlada Borovko. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Fortunately, there were several names that have become well-known over the last year or two from their performances in minor roles in the House, and engagements elsewhere, and their appearances in more substantial fare were eagerly anticipated. Opening the programme with the Act II duet from Verdi’s I due Foscari, Vlada Borovko confirmed my previous impression (not least in last year’s JPYA performance and most recently in the ROH’s L'elisir d'amore ) that she is a soprano of dramatic power and commanding presence, well equipped to master Verdi’s surging vocal lines. She was a stirring Lucrezia, comforting David Junghoon Kim’s Foscari when he learns of his exile and conveying the full fierceness of Lucrezia’s love for her husband and fiery scorn for the scheming clique, the Council of Ten. Later, when the ensemble came together for the end of Act 2 of Don Giovanni, Borovko displayed similar concentration and intensity in Donna Anna’s ‘Non mi dir’.

Junghoon Kim’s acting has improved markedly during his time as a JPYA - as his recent engagement with Grange Park Opera confirmed - and here he was convincing as the tortured Foscari who is being tormented by delirious visions of the ghost of the decapitated mercenary, Carmagnola. He sang with clean, appealing tone, though he might have employed a wider dynamic range.

The tenor hasn’t yet quite got the refinement that Rossini’s music calls for and he seemed less comfortable decked up in habit and wimple as ‘Sister Colette’ - the disguised Count Ory who falls into the trap set for him by his page, Isolier, and finds himself in a darkened bedroom making advances to the latter rather than the object of his unwelcome affections, Countess Adèle. Comic timing is not Junghoon Kim’s forte, and it didn’t help that the staging of this trio - which Berlioz described as the composer’s ‘absolute masterpiece’ - lacked a certain jeu d’esprit, the only (mild) chuckles coming from the somewhat clichéd wriggling under the duvet and climbing under the bed.

The trio of singers didn’t ‘play off’ one another with sufficient zip, and conductor James Hendry let the tempo lag, failing to show how the orchestral rhythms point up the dramatic charm and wit. The enunciation of the French text was weak, but there was some attractive singing from Angela Simkin whom I admired in the title role of Oreste at Wilton’s Music Hall in 2016, and who displayed a firm technique and vocal gleam as Isolier. This followed her stylish appearance as Prince Charmant in Massenet’s love-at-first-sight duet, ‘Toi qui m’es apparue’, alongside Kate Howden’s Cendrillon. Howden, standing in at short notice for the indisposed Emily Edmonds, did well to shape Massenet’s lines with simple elegance. She coped well at the top and her fresh sound blended pleasingly with Simkin’s slightly fuller mezzo.

Cendrillon. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Cendrillon. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Soprano Francesca Chiejina was the third of Rossini’s comic threesome but she needed rather more vocal presence to communicate Adèle’s impish sense of fun. Chiejina had appeared a little tentative in her earlier guise as Suzel in the ‘Cherry Duet’ from L’amico Fritz - another comic gem which fell rather flat, missing the sparkle which imbues Mascagni’s trifling operetta - and her intonation strayed a little at the start. She has a sweet tone but doesn’t always project with enough dramatic vigour. As Fritz, Thomas Atkins did impress, however. Atkins studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, and when I heard him sing Florindo in the 2015 production of Wolf-Ferrari’s Le donne curiose I remarked his ‘incipient Italianate gleam’, a quality which has now bloomed nicely. His ‘Il mio tesoro’ in the post-interval Don Giovanni episode was the highlight of the evening, revealing a well-supported lyric tenor and an ability to imbue a character who can seem weak-willed and ineffectual with convincing strength and integrity.

Francesca Chiejina and Thomas Atkins. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Francesca Chiejina and Thomas Atkins. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The other first-half item was the final duet from Strauss’s Arabella. As ever with Strauss, the writing lies quite high and Jennifer Davis, as the eponymous aristocrat, scaled the peaks but could not colour them with the requisite silvery tone, and this deprived this exquisite reconciliation scene of its transcendence. A similar heft, and tonal hardness, was apparent in Elvira’s ‘Mi Tradì’.

Jennifer Davis and Gyula Nagy. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Jennifer Davis and Gyula Nagy. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Perhaps it’s hard to invest the foolish Mandryka with any real credibility but Hungarian baritone Gyula Nagy needed a bit more focus to supplement the warmth of his sound in order to capture the dignity of the close. The absence of a staircase down which Arabella famously glides to her lover - to make the formalised gesture of offering the glass of water that signals her willingness to be her betrothed’s wife - was understandable and forgivable; what was less acceptable, however, was the lack of any convincing engagement between the reunited lovers.

Director Gerard Jones had put more thought and effort into the staging of the final scenes of Don Giovanni, and it paid off, as the simple set - a white-walled chapel where the Commendatore’s ebony coffin served as an unavoidable reminder of the Don’s dastardly deeds and impending doom - brought the singers together with more dramatic involvement and integration. Haegee Lee, who joins the JPYA scheme next season, took the role of Zerlina - intended for Edmonds and acted by Alicia Frost - singing from the side and revealing a good sense of Mozartian style which bodes well for her appearance as Papagena in the ROH’s new staging of Die Zauberflöte, directed by David McVicar, in the autumn. Simon Shibambu was a stentorian Commendatore but softened his tone effectively when doubling up as Masetto. Gyula Nagy was a fittingly disreputable Giovanni, and interacted well with David Shipley’s rich-hued Leporello.

Simon Shibambu and Gyula Nagy. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Simon Shibambu and Gyula Nagy. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

This staging gave Don Giovanni the last laugh. After the moralising finale and departure of the ‘victors’, the coffin in which Giovanni had been entombed raised its lid, and the chancer seized his opportunity, scampering off with a look which hinted, ‘I’ll be back’. So, too, will many of these young singers in the forthcoming ROH season, alongside six new Young Artists: Haegee Lee and fellow soprano Jacquelyn Stucker, mezzo-soprano Aigul Akhmetshina, tenor Konu Kim, baritone Dominic Sedgwick and stage director Noa Naamat.

Further details of the ROH autumn season can be found at http://www.roh.org.uk/seasons/2017-18/autumn .

Claire Seymour

Verdi: I due Foscari, Act II (duet)

Conductor - David Syrus; Lucrezia Contarini - Vlada Borovko, Jacopo Foscari

- David Junghoon Kim,

Massenet: Cendrillon, Act II (duet - ‘Toi qui m’es apparue’)

Conductor - Matthew Scott Rogers, Cendrillon - Kate Howden, Prince - Angela

Simkin

Mascagni: L’amico Fritz, Act I (duet)

Conductor: David Syrus, Suzel - Francesca Chiejina, Fritz - Thomas Atkins

Strauss: Arabella, Act III (final duet)

Conductor - David Syrus, Arabella - Jennifer Davis, Mandryka - Gyula Nagy

Rossini: Le Comte Ory, Act II (‘A la faveur de cette nuit

obscure’)

Conductor - James Hendry, Countess Adèle de Formoutiers - Francesca

Chiejina, Isolier - Angela Simkin, Count Ory - David Junghoon Kim

Mozart: Don Giovanni, Act II

Conductor - David Syrus, Fortepiano continuo - Nick Fletcher, Donna Anna -

Vlada Borovko, Donna Elvira - Jennifer Davis, Zerlina - Haegee Lee, Don

Ottavio - Thomas Atkins,Don Giovanni - Gyula Nagy, Leporello - David

Shipley, Masetto/Commendatore - Simon Shibambu, Ensemble - Francesca

Chiejina, Angela Simkin, David Junghoon Kim.

Director - Gerard Jones, Lighting designer - Matthew Mulberry, Movement - Anjali Mehra.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Sunday 16th July 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ANGELA%20SIMKIN%2C%20DAVID%20JUNGHOON%20KIM%2C%20FRANCESCA%20CHIEJINA%20%28C%29%20ROH.%20PHOTO%20BY%20CLIVE%20BARDA.jpg image_description=JPYA Summer Performance, Royal Opera House product=yes product_title=JPYA Summer Performance, Royal Opera House product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: David Junghoon Kim, Francesca Chiejina and Angela Simkin in a scene from Comte OryPhoto credit: Clive Barda

July 17, 2017

A Falstaff Opera in Shakespeare’s Words: Sir John in Love

The three operas bear distinctive titles: Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor, by Otto Nicolai; Verdi’s Falstaff; and Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Sir John in Love. Of these, only Vaughan Williams’s was composed to an English text. Thus it has the special merit of allowing singers and listeners to relish Shakespeare’s actual words.

The British firm Lyrita has recently released a studio recording made in 1956 by the cast that, I assume, was currently performing the work at Sadler’s Wells. (Sadler’s Wells Opera, in London, would later be renamed the English National Opera.) Three of the singers had performed these same roles at Sadler’s Wells during the work’s first run of performances there (1946). One of them—Roderick Jones, the Falstaff—had sung in the opening night of the 1946 production and thus, as one says, had “created” the role.

The opera’s actual first, tryout staging had taken place seventeen years earlier at the Royal College of Music. During the years between that student production and the Sadler’s Wells premiere, Vaughan Williams added several notable passages to the score that enrich it greatly.

The CD recording under review was made in the BBC studios in 1956 and broadcast at the time, apparently with narrative explanations between the scenes. (Only one of those spoken links is included in this release, just enough to give a bit of period flavor.) Fortunately, many important BBC broadcasts of important works and performances were recorded by a devoted listener, Richard Itter, at his home on high-quality equipment . Sir John in Love is one of a number of these that are now being released for the first time—with permission from the BBC and the musicians’ union.

The recording is the third commercial release of Sir John in Love to reach the market, though it was the first of them to have been recorded. The other two are likewise studio recordings, but in stereo. One, on EMI (1975), is conducted by Meredith Davies, with Raimund Herincx as Falstaff; the other, on Chandos (2001), is conducted by Richard Hickox, with Donald Maxwell as Falstaff. April Milazzo, in American Record Guide, praised the Chandos recording (November/December 2001 issue), but she regretted that Maxwell showed little heft or personality in the title role. (Click here to get a sense of Maxwell’s rather placid take on the role.) I have listened to excerpts from that recording and find it often entrancing, mainly because one can hear so much more detail in the orchestra than on the 1956 recording reviewed here. The 1975 EMI recording also has many merits. (Click here for the final scene of the opera as heard in the 1975 EMI recording featuring Herincx. The scene begins with a prelude that Vaughan Williams would later expand and publish as a separate orchestral piece: the Fantasia on “Greensleeves.”)

But the belatedly released historic radio-broadcast recording from 1956 may well be the best point of entry for anyone who is unfamiliar with the opera, for it vividly conveys the interplay between the characters and between characters and chorus.

Opera lovers familiar with Verdi’s Falstaff will find that this work takes a refreshingly different tack. Vaughan Williams prepared the libretto himself, and skillfully. We get to experience many lively interchanges involving secondary characters who are absent from, or greatly downsized in, Boito’s libretto for Verdi, including Shallow, Slender, Peter Simple, and Dr. Caius.

Vaughan Williams also made the libretto more music-friendly by having various of the characters, or sometimes the chorus, sing folk-like numbers using poems and song texts from Shakespeare’s time—e.g., by Ben Jonson and Philip Sidney. He also sometimes integrated entire tunes from the time. The various “song” numbers are extraordinarily well integrated: for example, Mistress Page sings an extended snatch of the folksong “Greensleeves” while awaiting a visit from Falstaff, who then announces his arrival with his usual self-importance by continuing her song. There are, at several points in the opera, witty references in the orchestra to the well-known and, for this opera, aptly worded folk song “John, Come Kiss Me Now.” The chorus often participates actively, sometimes aligning itself with one or another character.

On those occasions when a situation in Sir John in Love is closely parallel to one in Verdi’s Falstaff, Vaughan Williams handles it no less expertly, though differently: for example, Mistress Page and Mistress Ford have fun reading Falstaff’s letters to each of them in canon, something Verdi did not choose to do.

The monophonic sound is extremely well engineered, as one would expect from a BBC radio broadcast. One hardly needs to look at the libretto to follow the main thrust of what people are singing. The singers generally show healthy vocal production and clear enunciation. Standouts include a young Owen Brannigan in the small role of the Host of the Garter Inn (a role he had sung in the 1946 season) and a consistently lovely and intelligent-sounding April Cantelo as Ann Page—one understands why several men in the play are attracted to her!

James Johnston had played Fenton during the opera’s first season at Sadler’s Wells, and he sings it here with clarity and power, clearly enjoying a tenor role that is more substantial than the idealized teenager that Verdi created as his Fenton. This eager lover is an appropriate match for Vaughan Williams’s Ann Page, who is herself more substantial than Verdi’s lighter-than-air Nanetta.

I found myself looking forward to the occasions when contralto Pamela Bowden, as Mistress Quickly, would next enter the scene and take command of the proceedings. John Cameron invests Ford with a splendid, Germont-quality baritone and eloquent acting skills that help one sympathize with this, in some ways, unsavory character. As for Roderick Jones, I kept forgetting that I was hearing a singer at all: each utterance seemed so true to character. How lucky for us that Jones’s reading of the title role got broadcast and “captured”!

( Click here for numerous excerpts from the 1956 recording. )

(And click here for the entire scene in Act 2, in that same recording, in which Master Ford, husband of Alice Ford but pretending to be a certain “Master Brook,” comes to make an offer to John Falstaff. The offer is that Falstaff, in exchange for some money from “Master Brook,” will seduce Mistress Ford “between ten and eleven” that same morning in order to cuckold Master Ford—i.e., the very man who, disguised to Falstaff, is making the offer. The whole plan is of course a trap for Sir John, set by Ford, his wife, and others. The dramatic effect in this recorded scene is so specifically conveyed by John Cameron, Roderick Jones, and the orchestra under Stanford Robinson that one can imagine the whole scene in one’s inner eye.)