September 30, 2017

Aida opens the season at ENO

Of McDermott’s Satyagraha in 2010, one of my colleagues wrote, ‘There are so many amazing images in this production that it’s hard to take them all in at once’. Here, it’s more a case of there are so many diverse visual images that it’s hard to make them come together in any coherent way.

The sets do establish an ‘epic’ mood: coarse-grained rock textures suggest monumental edifices and set off Pollard’s striking fabrics, face-paint and fabulous headdresses (topped with antlers in Act 2!). Bruno Poet’s lighting design is one of the best things about the production. On the poster advertising this opening production of ENO’s 2017/18 season, a blade of light slices through darkness, bouncing off granite to bathe a standing woman, who gazes aloft as if in supplication, in a cone of light. A similar triangle of red dissects the black drop which confronts us at the start, gradually widening and opening up a small geometric space on the wide Coliseum stage. Throughout, Poet sculpts his light like sliding walls, to create mystery. Sometimes diagonal rays sear across the stage; at other times subtle mists shimmer.

Latonia Moore (Aida). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Latonia Moore (Aida). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

A prevailing hieroglyph - the ‘breadcone’, designating a ‘gift’ or ‘offering’ - evokes a pyramid. But, that’s just about the only hint of Egypt we get. For, while the visuals are spectacular, they don’t help to ‘tell the story’, and there is no coherent sense of context. A programme article explains McDermott’s thoughts about the period setting, which he describes as ‘a slight mash up’: ‘It’s not ancient and it’s not modern. I’m not dissing the past, but we’ve got modern battle gear and yet priests and temple dancers too. It’s its own world, like a dream which is not real but has its own logic and you can do anything with that as long as you stay within the logic.’

The allusions are indeed eclectic, but I’m not sure I could recognise their ‘logic’. Radamès first appears wearing a gilt braided blue tunic, topped with fur pelisse, worthy of a Napoleonic Hussar, but in the fateful tomb he has ditched his uniform for a grubby grey shirt. The participants in the sacred ritual which prepares the Egyptian general for battle against the Ethiopians seem to have been modelled on the semi-clad women who sit behind the windows of Amsterdam’s red-light district, while the celebrants at the victory procession sport an array of outlandish 30s-style outfits. The priestesses of Isis who await the wedding of Amneris and Radamès look like they have borrowed their red robes from Margaret Atwood’s Handmaids. Amneris herself seems to have got trapped in an outsize origami confection.

Eleanor Dennis (High Priestess), Robert Winslade Anderson (Ramfis) and members of Mimbre. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Eleanor Dennis (High Priestess), Robert Winslade Anderson (Ramfis) and members of Mimbre. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Within this smorgasbord of references there is little sense of who the protagonists are, of the love triangle between them, or of the context which pits their love against their loyalty. Static visual images have taken priority over the development of character and relationship. There is scarcely any convincing interaction. The programme offers an account of McDermott’s rehearsal methods: he has encouraged his cast to ‘explore three options: stand still, move forward, or move backwards’.

Most seem to have plumped for the first option. Singers barely look at each other or engage physically; instead, on the whole they stand stock still, facing the audience. Basil Twist’s beautiful silks flutter and billow but the only other movement on stage comes from the dancers and acrobats of Mimbre, who entertain Amneris when she prepares to welcome home Radamès by tumbling light-footedly or forming geometric human sculptures. In the triumphal scene, some of the latter look so complex and potentially precarious that perhaps they should come with a warning, ‘don’t try this at home’.

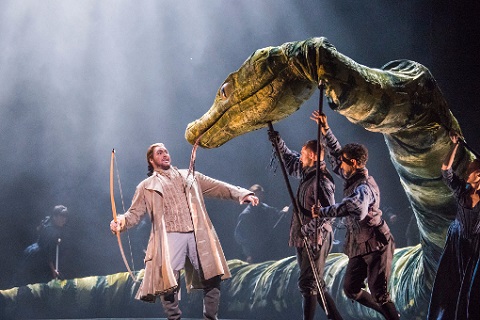

Gwyn Hughes Jones (Radamès), members of Mimbre and ENO Chorus. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Gwyn Hughes Jones (Radamès), members of Mimbre and ENO Chorus. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

We have no elephants, but there is some flag-waving and coffin-carrying - and, some terrific trumpet playing from the six onstage players whose gorgeously warm tone glows with an energy that is missing among the artfully positioned but static throng. Indeed, the ENO orchestra play consistently well for Canadian conductor Keri-Lynn Wilson who balances vigour and refinement, injects tension effectively and conjures exoticism and magic at the start of Act 3. The enlarged ENO Chorus produced some beautiful hushed, reverential singing in Act 1.

Latonia Moore (Aida). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Latonia Moore (Aida). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

ENO is fortunate in that they have an eponymous Ethiopian princess whose glorious soprano gleams with an intensity to match Poet’s beams of light. American Latonia Moore is simply fabulous: she soars above the rest of the cast - literally and figuratively. When she commenced ‘Ritorna vincitor’, she made one immediately sit up and listen: for the first time we had persuasive, genuine human emotion, and as the performance developed she showed that from the gentlest pianissimo to the plushest fortissimo she could make us believe unwaveringly in Aida’s devotion, defiance, despair and dignity. ‘O patria mia’ was infused with strength and sincerity, and if she seemed a little nervous about the top C that could be forgiven. In Aida’s duet with Amneris, Moore’s soprano blazed radiantly and effortlessly.

Gwyn Hughes Jones’s tenor has plenty of ringing vibrancy. His Radamès is a plausible soldier and makes a confident entrance, sustaining the final Bb well in ‘Celeste Aida’. Even more shine at the top might help to convince us of his passion for Aida and give fervour to his confrontation with Amneris, but Jones has the stamina for the role and the Tomb Scene intimacy is moving, the poignancy of the lovers’ short-lived reunion deepened by the presence of Amneris, watching from above.

Mimbre and Michelle DeYoung (Amneris). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Mimbre and Michelle DeYoung (Amneris). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

As Amneris, mezzo Michelle DeYoung seemed to be struggling. Certainly, her Act 1 costume was ‘larger-than-life’ but vocally DeYoung was too ragged and unfocused to convey the tragic princess’s conflicted emotions. It didn’t help that some distorted vowels made the clunky English translation even more cumbersome. De Young’s characterisation was unmodulated and somewhat superficial, though her voice did relax and begin to bloom in the Judgement Scene.

Eleanor Dennis was poised and imperious as the High Priestess, and Robert Winslade Anderson (deputising for the indisposed Brindley Sherratt) and Matthew Best were more than competent as Ramfis and the (white-suited?) Egyptian King respectively. Musa Ngqungwana’s Amonasro wasn’t quite imposing enough; a bit more patriarchal authority was needed.

Whatever misgivings there may be about McDermott’s ‘logic’, if there’s one reason to see this show, it’s the opportunity to hear Moore in a role she has sung to great acclaim many times, including at the Met and the ROH, for her performance confirms her as a lirico spinto of great distinction.

Claire Seymour

Verdi: Aida

Aida - Latonia Moore, Amneris - Michelle DeYoung, Radamès - Gwyn Hughes Jones, Ramfis - Robert Winslade Anderson, Amonasro - Musa Ngqungwana, King - Matthew Best, High Priestess - Eleanor Dennis, Messenger - David Webb; Director - Phelim McDermott, Conductor - Keri-Lynn Wilson, Designer - Tom Pye, Lighting designer - Bruno Poet, Costume designer - Kevin Pollard, Silk effects choreographer - Basil Twist, Movement director - Lina Johansson, Chorus movement - Elaine Tyler-Hall, ENO Orchestra and Chorus, Mimbre Skills Ensemble.

English National Opera, Coliseum, London; Thursday 28th September 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ENO%20Aida%20Cast%20and%20Chorus%20%28c%29%20Tristram%20Kenton.jpg image_description=Aida: English National Opera product=yes product_title=Aida: English National Opera product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: ENO Cast and ChorusPhoto credit: Tristram Kenton

September 28, 2017

La Traviata in San Francisco

Romanian soprano Aurelia Florian sings Violetta in all ten performances (through October 17). She is young and pretty, her voice is strong and rich throughout all registers, and her high notes are splendid (she does not take the optional high E flat in the “Sempre libera”). Verdi famously wanted a real woman for this role, a woman who could actually suffer. Mme. Florian does indeed suffer, if as a heroine of opera’s coming verismo. In Verdian terms la Florian’s Violetta is far from the proto-verismo of his delicate Desdemona, hers is more his decisive Lady Macbeth.

Most of all Mme. Florian greatly pleases us as an excellent singer. That she is also a suffering mid 19th century courtesan is less compelling.

Alfredo, the Brazilian tenor Atalla Ayan, is an excellent singer as well. His voice is wonderfully even throughout its registers, its tone more decisive than rich. He offers his arias with a vocal enthusiasm that is infectious, easily projecting his vibrant emotions.

Atalla Ayan as Alfredo, Aurelia Floria as Violetta

Atalla Ayan as Alfredo, Aurelia Floria as Violetta

In the first act both singers easily found their characters, Violetta seated alone in her grand salon to contemplate her “Ah fors’è lui,” then to burst onto her balcony to deliver its antithesis, Alfredo, behind the scene, grandly intoning his ardor.

The second act became difficult, the complex turns of the plot demand subtle development of character and emotion, here the actors were exploiting the fine movement of their voices, leaving the unfolding tragedy to find its own way. The loss of dramatic focus was most evident in the Germont of young Polish baritone Artur Ruciński. Mr. Ruciński is an extraordinary singer, able to gloriously project text in musical line, providing enormous satisfaction to his listeners. But he did not achieve the warmth and maturity and the deep humanity of this sympathetic, honest man trapped in provincial morality.

The Copley production in this fifth edition staged by Shawna Lucey became clumsy in the gambling scene, the chorus and ballet cumbersome, and the showdown (Alfredo humiliating Violetta) pallid. Without having deepened and exploited the opera’s personalities the death scene read as incidental.

Artur Ruciński as Germont

Artur Ruciński as Germont

Meanwhile conductor Nicola Luisotti was finding every palpitation of emotion in the score, the strings of the San Francisco Opera orchestra choking with emotion in the overture, the clarinet solo unabashedly sobbing while Violetta writes her note to Alfredo, the enormity of the tragedy welling up in the death scene, the finality of death hammered in the final, magnificent roll of the tympani.

In concert with the truly excellent singing the magnificence of the Luisotti orchestra trapped this evening into inexplicable musical and dramatic frigidity.

As Verdi wished (and was initially denied) the Copley production sets the action in 1852 or so. Verdi wanted the contemporary moment. Of course it is now 2017. Our contemporary moment is of great complexity, and of a breadth far beyond the concerns of Verdi. It is a fascinating question how to stage a timeless work of art in a production that recognizes, respects and exploits the artistic and moral accomplishment of the intervening 150 or so years.

This production marked the first time supertitles were used for La traviata at San Francisco Opera. The supertitles were created by Jerry Sherk (SFO’s then production manager, now legendary). They tell the story simply and easily in the abstract manner of supertitles of that era. It is time to create new supertitles for future productions that echo the rhythms of the phrases as they are sung.

It should be mentioned that sloppy masking in the first act allowed an annoying, blinding light from a stage manager’s desk to escape into the house.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Violetta Valery: Aurelia Floria; Alfredo Germont: Atalla Ayan; Giorgio Germont: Arthur Rucinski; Flor Bervoix: Renee Rapier; Gastone: Amitai Pati; Baron Douphon: Philip Skinner; Doctor Grenvil: Anthony Reed; Marquis d’Obigny: Andrew G. Manea; Annina: Amina Edris. Chorus and Orchestra of the San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Nicola Luisotti; Production: John Copley; Stage Director: Shawna Lucey; Set Designer: John Conklin; Lighting Designer: Gary Marder; Choreogorapher: Carola Zertuche; Costume Designer: David Walke. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, September 26, 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Traviata17_SFO1.png

product=yes

product_title=La Traviata in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Aurelia Florian as Violetta [All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

September 26, 2017

The Judas Passion: Sally Beamish and David Harsent offer new perspectives

Librettist David Harsent notes that there is no doubt that Judas’s betrayal led to Christ’s death, but begs us to ask, what did Judas believe was his ‘purpose’? After all, if he had not ‘fulfilled’ this role, chosen or predetermined, mankind would not have been saved. David Harsent professes that his own aim was to ‘write Judas out of hell’, ‘to set him before an audience and bring him to a new judgment’.

Beamish and Harsent purport to present the Passion story from the perspective of Judas Iscariot, but this is not really what they do. Or rather, at times do they seem to offer Judas’s understanding of his role, but this is set against a single question which is reiterated and rephrased throughout - ‘Does Judas choose, or is he chosen to betray Christ?’ Moreover, ‘Do we following the callings of our own heart - or the callings of whatever voice we choose to name, God’s voice, or the Devil’s’?

In accordance with this ambiguity, the Devil and God sing in rhythmic unison: countertenor Christopher Field and bass William Gaunt were designated both roles. As Mary Magdalene relates, ‘And the Devil went into Judas, the Devil or God’.

Indeed, ambiguity prevails. There is little to distinguish between any of the protagonists, other than Christ, Judas and Mary Magdalene, and in fact towards the close the former two men are intimated to be kindred. The entire cast are dressed in black and individuals such as Peter (bass Dingle Yandell) and the two Thieves (tenor Hugo Hymas and bass Jonathan Brown) emerge from and are reintegrated into the Chorus (which is at times split in two). I guess the idea is that the players in the drama could be anyone, historic or present, involved by chance in momentous events, powerless to change the course of mankind’s predetermined narrative.

There are no philosophical musings which might essay an answer at the posed questions; as I’ve suggested above, at times the libretto seems to suggest that there is no question to answer. In the opening scene, Judas is a reluctant participant when asked to name his price for betraying Jesus: ‘I do it because I must […] I do it because it fell to me. His hand on mine’; words that are repeated time and again, through to the final scene. And, unlike the other disciples who probe, ‘Is it me?’, he stays silent at the Last Supper. God and the Devil declare in rhythmic unison, ‘He is chosen … the man is already chosen’. In his programme article, Harsent refers to an extant Gospel of Judas, dated at 3 or 4 CE, ‘a Gnostic text found in Middle Egypt around 1978’ which was published in 2006 and from which he takes a single line: when Jesus calls the disciples to him none save Jesus can hold his gaze, ‘whereupon Jesus tells Judas: “You are the best of them, for you will free me of the man who clothes me.”’ From this, Harsent suggest we may infer that ‘Judas was born to the task’.

Perhaps the potential philosophical complexities cannot be satisfactorily pursued within a simple dramatic form? Beamish’s Passion is not really an opera, despite the involvement of a ‘stage director’, Peter Thomson, or an oratorio; nor is it a ‘Passion’ in the mould of Bach, despite the baroque instrumentation (strings, lute, flutes plus a very twentieth-century percussion collection), the use of polyphonic forms (canons, fugues) and recitative- and aria-like episodes, and the incorporation of fragments of the St Matthew Passion.

I was at first put in mind of Britten’s Church Parables: indebted to Japanese noh plays, they present drama and stage movement with a similar slow-motion solemnity to that adopted by Thomson. Progressively, though, Britten’s Rape of Lucretia seemed a closer model: it also has a framing Male and Female Chorus - the latter role here is represented by Mary Magdalene - who sometimes intervene in the action and present abstract ethical and philosophical sentiments. So, Harsent’s opening male Chorus denounce Judas, ‘Better that man had not been born who sold his soul, who gave himself up to Satan, who bartered the Son of Man, who made a deal with darkness’, while Britten’s Male and Female Chorus tell us that ‘We’ll view these human passions and these years/ Through eyes which once have wept with Christ’s own tears.’

The problem with Harsant’s libretto is that it becomes predictable, and often seems to follow its biblical model. More imaginative engagement with the Passion stories can be found in John Adams’ and Peter Sellars’ The Gospel According to Mary which presents the story of the Passion through the eyes of those whose tales are usually unheard: Mary Magadalen, her sister Martha and their brother Lazarus. And, there are several recent literary explorations, notably Colm Tóibín’s The Testament of Mary.

Moreover, though it is evocative at times, I found Beamish’s score pretty predictable too. The writing for the chorus is largely declamatory, and incorporates some Chassidic chanting, but there is little variety of timbre or manner. There is effective writing for the strings - alternating glacial ethereality with pungent chordal and pizzicato stabs - and the flutes and lute offer delicacy and grace. But, the strident natural horns and trumpets, as the cock crows, were all too foreseeable. Similarly, the percussive effects, such as real hammers, whips and nails alongside slapsticks to provide an aural complement for the text’s uncomfortable imagery - ‘on his head a cap of thorns driven hard into the skin’; ‘with ropes and winches and hammer and nails and flesh, They nailed him, then hauled him up’ - and the centre-piece ‘Judas Chime’ constructed from 30 ‘pieces of silver’ are pictorial but unsubtle.

The inclusion of the figure of Mary Magdalene - sung with radiance and fierce focus by Mary Bevan - is one of the strengths of the libretto and score. Magdalene is the only figure on stage at the close, and her final question, ‘If he can’t be saved, who can be saved? If he can’t be forgiven, who can be forgiven?’, is provocative and penetrating. Not only does this inclusion of a female role provide timbral and registral contrast, but the role of Mary Magdalene also offers a more objective, calmer perspective on the events that we witness unfold. She comments in the past tense, as the participants enact their roles in the present (though this effective distinction is blurred at times, as when Mary interacts with Peter in the denial scene).

Mary’s vocal line also incorporates expressive melisma in contradistinction to the prevailing syllabic motion of the other parts, most effectively in ‘Who Do You Say I Am?’, when she reminds us that though the Chorus tell of Jesus’s reputation as a ‘prophet’ and ‘man of miracles’, there were those who called him blasphemer, fool, lawbreaker. When the Chorus accuse Christ of ‘Blasphemy!’ and throw their shrill demands, ‘Crucify him!’, Mary reminds us of the miracles performed.

Brendan Gunnell’s Judas pins us with a penetrating upper register that is as captivating as his stern stare. There is a moving moment when the angularity of the melodic intervals - ‘My face on these coins, my name on them. For all time: my face, my name’ - gives way to the stillness of repeated pitch, ‘his blood’. I was confused, though, as to why Judas, in Harsent’s words, ‘in effect - stands in for Pilate’ in the scene when Christ is brought before the Roman prefect of Judaea: Judas is, as the syllabic chanting of his name in the opening scene reinforces, a Jew; Pilate is not. And, why does Judas/Pilate sometimes speak his own words, while at other times they are reported by Mary, as if retrospectively?

Roderick Williams struck the right balance between serenity and suffering, as Jesus. It must have been quite an emotional shift taking on this role in between his embodiment of Mozart’s bird-catcher at the Royal Opera House , though both dramas involve much magic and miracle. Williams’ delivery suggested both gravitas and humanity. In the second scene, ‘The Last Supper’, he stood at the rear, forcing the Chorus to turn towards him and subtly implicating us as members of his audience; in ‘The Agony in the Garden’ he stood at the front, fixing us with an intent gaze.

There are some moments of affecting dramatic intensity. Towards the close, Jesus and Judas stand at the rear of the stage, backs turned (to indicate their dying and death), and sing together, ‘My God, why are you lost to me?’. But, the incisiveness of the moment is lost as Judas slips back into what might be seen as self-justifying repetition (though, as I’ve suggested, the ethical questions are not truly explored): ‘What I did I was chosen to do. What I have I was asked to give. What I lost I was told to lose. My only purpose, his death and mine.’

I felt that there was a dissipation of intellectual intensity towards the close, as the text slipped towards sentimental abstractions. When Mary and the Chorus sing, ‘His death … our salvation … this and only this.’, I felt we were back in Lucretia territory - specifically Ronald Duncan’s dreadfully woolly epilogue: ‘Is it all? Is all this suffering and pain,/ Is it in vain? … Is this all loss? Are we lost? … Is it all? Is this it all?’

The noble Classical columns of St John’s Smith Square should have provided the perfect setting for The Judas Passion (the work had been premiered the previous evening in Saffron Walden), and it was pleasing to see the church nave full for this performance of a challenging new work. However, SJSS’s sightlines are poor and seated to the rear I struggled to sustain my view of and engagement with Thomson’s stage action. Fortunately, the cast’s diction was uniformly good for it was not possible to read the libretto, usefully provided, in the dimmed lighting, and the two surtitle screens were obscured by the imposing pillars.

At the close, the Devil and God pronounce, ‘Chosen for this: born to this: his only purpose …’ A troubling statement, and one which Beamish and Harsent reiterate but do not really interrogate.

Claire Seymour

Sally Beamish: The Judas Passion

Mary Magdalene - Mary Bevan, Brendan Gunnell - Judas, Roderick Williams - Christ; Orchestra and Choir of the Age of Enlightenment: Nicholas McGegan (conductor), Peter Thomson (stage director).

St John’s Smith Square, London; Monday 25th September 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/3251-sallybeamish___credit__ashley_coombes.jpg image_description=The Judas Passion: St John’s Smith Square product=yes product_title=The Judas Passion: St John’s Smith Square product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Sally BeamishPhoto credit: Ashley Coombes

September 25, 2017

Choral at Cadogan: The Tallis Scholars open a new season

This, and the striking opening of the first piece, Palestrina’s motet Laudate pueri, set me ruminating about nature of an ‘ensemble sound’, and although the following tangential digression might be a little indulgent, it is not irrelevant to my experience and review of the music performed.

The Tallis Scholars’ website lists the following six personnel as ‘The Singers’: soprano Amy Haworth (who first sang with the group in 2005), soprano Emma Walshe (2010), alto Caroline Trevor (1982), tenor Steven Harrold (1993) and basses Robert Macdonald (1994) and Tim Scott Whiteley (2007), only four of whom were performing on this occasion. Any long-standing ensemble, instrumental or vocal, will inevitably have a flexible constitution over time: indeed, Harrold’s first sustained spell was from 1996 to 2001 (in 1998 he replaced John Potter in the Hilliard Ensemble, the members of which remained unchanged from then until the group disbanded in 2014) and has recently re-joined the Tallis Scholars. And, the distinctive and defining ‘sound’ of a group will principally be shaped by the predilections and practices of its director or conductor. Peter Philips founded The Tallis Scholars in 1973 and has now appeared in almost 2000 concerts with the ensemble.

However, on this occasion I found that some individual voices were more conspicuously discernible than I had expected and that, particularly in the first half of the concert, The Tallis Scholars did not always coalesce the imitative polyphony into a homogenous sonority, or capture the ‘impersonal’, transcendent beauty of music which is designed to sound, literally, as if it comes from another ‘world’, the heavens.

Perhaps, it was simply that these are early days in the new season; I wondered how much time the group had had to rehearse (some eyes were at times quite wedded to the score) and the works performed did represent some of the rarer reaches of this repertory. But, at the risk of being accused of ‘nit-picking’, I felt that even visually the ensemble did not consistently present a ‘united front’. In other contexts, I have admired bass Greg Skidmore’s relaxed engagement with the music sung (indeed, I drew attention to this quality during a recent performance by Ex Cathedra here at the Cadogan Hall) but on this occasion his tendency to use only one hand to hold the score suggested a casual insouciance which sometimes jarred with the more formal comportment of most of the other singers.

Digression over. But, such thoughts were in my mind during what was a festive but not particularly reverential performance of Palestrina’s Laudate pueri, in which the tuning took a while to settle and the high soprano and tenor lines were often very prominent (admittedly the textures of this motet are constantly changing), but which also shone warmly when the text praised the Lord ‘high above all nations … his glory above the heavens’, reflecting Palestrina’s magnificent ‘architecture’.

The singers’ rearranged their semi-circle in descending pitch order after the ‘double choir’ position adopted for the opening motet, and the gentle soprano and alto entries at the start of the first part of Palestrina’s Virgo prudentissima did create an air of wonder and veneration. As the other voices joined the seven-part polyphony, there was a calm fluency and ease. Philips’ gestures were small but guided the ensemble skilfully towards the culminating cadences, although there was a sense of ‘searching’ for the intonation of the final cadence.

The more decorative melodic style and exploratory dissonances of Monteverdi’s Messa a quattro voci da cappella of 1650 seemed to suit The Tallis Scholars better. The text repetitions of the Kyrie had a stirring cumulative energy, though I’d have liked a few more consonants, especially from the sopranos. In the Gloria there was a vivacious sense of release as the homophonic ‘Gratias agimus tibi’ blossomed into vibrant polyphony, ‘propter magnam gloriam tuam’ (We give thanks to thee for thy great glory), and the declaration ‘Quoniam tu solus Sanctus’ (For thou only art Holy) inspired a fresh impetus, before coming to rest with an ‘Amen’ of assured contentment.

The Credo’s opening address to the almighty Father, ‘Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible’, was wonderfully lucid, leading to a cadential statement, ‘by whom all things were made’, which was reverently hushed. Reflection on Christ’s suffering and death at the hands of Pontius Pilate prompted some striking dissonances in the inner voices, but the ensuing major key and melismatic ascents brightly conveyed joy at the resurrection. After the Credo’s extended and florid ‘Amen’, the basses’ slow stepwise descent established a soothing serenity at the start of the Sanctus but the ‘Hosanna’ had a vigour and warmth that overflowed into the following Benedictus. At the close of the Agnus Dei, though, stillness and peace were restored.

Despite Cadogan Hall’s ecclesiastical origins (it opened in 1907 as a New Christian Science Church designed by Robert Fellowes Chisholm) its acoustic is rather drier than that of the Venetian churches where Monteverdi’s masses would have first been heard, but The Tallis Scholars were successful in bringing their ten voices together to evoke a spatial magnificence and magnitude. It was a pity, therefore, that some felt it necessary or appropriate to applaud between the movements of the Mass.

After the interval, there was a crowd-pleaser, Allegri’s Miserere (in its ‘top C’ version) for which tenor Simon Wall climbed to the gallery above the stage to deliver the cantor’s phrases, while four singers placed in a balcony at the rear provided antiphonal interaction with the SSATB group on the platform. The timbre was quite light of weight, and the pristine tone of the soprano’s top Cs - perfectly tuned - rang beautifully, although some of the decorative flourishes felt a little rushed in descent (and some unfortunate coughing in the Hall disturbed the tranquillity so deftly sculpted by Philips).

Gesualdo’s O vos omnes and Aestimatus sum (Tenebrae Responsories for Holy Saturday) offered the composer’s customary harmonic twists and turns, and the semitone movement in the inner parts at the chordal start of O vos omnes did unsettle the intonation, but there was a wealth of colour and varied dynamic contrasts in this sombre performance, and a moving progression from darkness to light with the request ‘et videte dolorum meum’ (look upon my sorrow). The text of Aestimatus sum speaks of descending into the darkest pit and Philips gave us real drama: the running bass provided strong direction at the start, and pictorial flourishes in the final section, while a torturously curling dissonance resolved securely to suggest release, ‘inter mortuos liber’ (free among the dead).

Four of Monteverdi’s motets closed the programme. The word-painting was rendered clearly: the chromatic descent at the start of the five-part Crucifixus was sharply defined and darkly lamenting to convey Christ’s suffering and burial, while the long-held notes which open Adoramus te suggested awestruck devotion before flowering into a spirited blessing, ‘benedicimus tibi’. Monteverdi was no less ‘experimental’ than Gesualdo in his harmonic journeyings, and the major/minor sleights of hand in the latter motet were expressive and well-controlled; the final plea, ‘Miserere nobis’, had a focused sincerity. Domine, ne in furore had terrific rhetorical energy but closed with a poignant softness, ‘led tu, Domine, usquequo?’ (but, Lord, how long?).

These Monteverdi motets had been preceded by the well-known eight-part Crucifixus by Antonio Lotti (1667-1740). The rich, pungent blend of the opening seemed almost to mimic the organ which would have originally accompanied the singers, as the suspensions piled up and the inner voices wound through the dissonances.

Like Allegri, Lotti is known principally for one work, this Crucifixus (which actually forms part of a longer work, the Credo in F for choir and orchestra from the Missa Sancti Christophori). Ever keen to explore musical by-ways Philips selected another of the composer’s Crucifixuses, this time in ten parts, for his encore. I’m not a great fan of encores, especially when a programme has been thoughtfully designed, as this one clearly had: I’d have preferred to go out with the joyful repetitions of Cantate Domine ringing in my ears. ‘Cantate et exultate et psallite/ in cithara et voce psalmi’ (Sing and exult and rejoice with the lyre and the voice of psalmody) seemed to sum things up nicely.

Claire Seymour

The Tallis Scholars - Peter Phillips (director), Amy Haworth, Emma Walshe, Emily Atkinson and Charlotte Ashley (sopranos), Caroline Trevor and Helen Charlston (altos), Steven Harrold and Simon Wall (tenors), Simon Whitely and Greg Skidmore (bass).

Palestrina - Laudate pueri, Virgo prudentissima; Monteverdi - Messa a quattro voci da cappella; Allegri - Miserere; Gesualdo - O vos omnes, Aestimatus sum ; Lotti - Crucifixus (à 8); Monteverdi - Crucifixus, Adoramus te, Domine ne in furore, Cantate Domine.

Cadogan Hall, London; Friday 22nd September 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tallis%20Scholars%20Nick%20Rutter.jpg image_description=Choral at Cadogan: The Tallis Scholars directed by Peter Philips product=yes product_title=Choral at Cadogan: The Tallis Scholars directed by Peter Philips product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: The Tallis Scholars with Peter Philips (centre)Photo credit: Nick Rutter

September 24, 2017

Stars of Lyric Opera 2017, Millennium Park, Chicago

The Lyric Opera Orchestra and the Lyric Opera Chorus, under the direction of Sir Andrew Davis and Michael Black respectively, provided excellent accompaniment. Indeed, several of the selections showcased the talents of both groups as a significant part of this preview.

Individual segments of the evening’s program were introduced with prefatory comment by Anthony Freud, General Director of Lyric Opera. After a brisk performance of the overture to Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro, Lauren Snouffer sang Susanna’s recitative and aria, “Giunse alfin il momento … Deh, vieni, non tardar” [“At last the moment approaches … O, come, do not delay”] from Act IV of the opera. Ms. Snouffer’s approach to both introductory lines and the aria shows her command of a wide vocal range. Her voice descends to well-enunciated low notes and rises naturally to a top piano emphasis on “e il mondo tace” [“and the world is still”], both extremes joined with comfortable legato phrasing. Snouffer’s final repeat of “Vieni” toward the close is held with endless urgency as an expression of Susanna’s emotional yearning.

Starting with the second selection individual arias and ensembles focused, in large part, on operas that will be produced in the coming season. From Verdi’s Rigoletto Matthew Polenzabi sang the Duke’s aria, “La donna è mobile” [“Women are fickle”]; he also participated in the Act III quartet, “Un dì, se ben rammentomi … Bella figlia dell’amore” [“One day, if I remember rightly … Fairest daughter of love”], along with J’nai Bridges, Andriana Chuchman, and Anthony Clark Evans. In the first selection Polenzani displayed a practiced diminuendo where appropriate as well as lush variation on the word “pensier.” At times, his notes produced forte were unnecessarily magnified by the system of amplification, an aspect not quite as noticeable in the following quartet. Here the rising and falling lyrical lines sung by Mmes. Bridges and Chuchman were interwoven to suggest the contradictory personalities caught up in a web of love, intrigue, and betrayal.

The brief, touching aria for Liù, “Tu, che di gel sei cinta” [“You who are enclosed in ice“] from Puccini’s Turandot introduced Lyric Opera of Chicago audiences to the voice of Janai Brugger, who will sing this role in January performances of the opera. Brugger’s sense of the role’s pathos was communicated deeply just as top pitches before the final “più” in “Per non vederlo più” [“And I’ll never see him more!”] hung in near magical suspension. Two solo pieces from Charles Gounod’s Faust were presented by Evans and Brugger. The siblings Marguerite and Valentin play vital parts in Gounod’s Faustian adaptation with each character expressing personality or narrative function through an aria. Mr. Evans struck an immediate, heroic pose in his performance of “Avant de quitter ces lieux” [“Before taking leave of these lands”], in which he prays for Marguerite’s protection during his absence in battle. Evans’s performance of the rising line to imitate the spirit of his prayer shows a natural vocal bloom and consistent legato in approach. His repeat of the thematic opening was varied nicely and ended with an authoritative forte pitch. Brugger’s “Jewel Song” from Faust captured the fascination of the innocent maiden, an approach using sensitive modulations in expression and volume, an effective trill, and a dramatically rising close.

The Lyric Opera Chorus sang two excerpts, one from last season’s Eugene Onegin and one from I Puritani in its forthcoming roster. The precise articulation and adaptability of the Chorus under Mr. Black’s direction were evident in these two pieces. In both selections, the Chorus’s responses to public scenes were projected as further comment on orchestral accompaniment.

The final two numbers in the first part of this concert were drawn from Act III of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Orphée et Eurydice, with which Lyric Opera will open its 2017-18 season in a new production and collaboration with the Joffrey Ballet. Since the French version of Gluck’s opera will be performed this season, the role of Orphée is here sung by a tenor. Dmitry Korchak performed the noted aria, “J’ai perdu mon Eurydice” [“I have lost my Eurydice”] in spirited voice, at times singing flat to underscore the lament. The line “Quels tourments déchirent mon Coeur!” [“What torments tear apart my heart!”] showed admirable decoration, yet his consistent volume could be modified to suggest greater subtlety in emotional reaction. In the trio, “L’Amour triomphe” [“Amor triumphs”], Korchak was joined by Chuchman and Snouffer who will also perform in the new production. The joy of the resuscitated heroine and the god of Love were proclaimed by the women with appropriate lyrical beauty as the Chorus rounded out the final words.

The second part of the evening’s program included several excerpts to be featured soon as well as some from Lyric Opera’s recent repertoire. Ms. Chuchman sang a striking performance of Norina’s “So anch’io la virtù magica” [“I also know the magic virtue”], indeed this showpiece was one of several highlights of the evening. Chuchman’s instinctive use of rubato at select moments and words chosen for melismatic embellishment were not only authentic bel canto singing but also an etching of the character’s persona whom she portrayed. The selections from Massenet’s Werther included the tenor aria, “Pourquoi me réveiller” and Charlotte’s “Laisse couler mes larmes” [“Allow my tears to flow”], the second piece sung by J’nai Bridges. Ms. Bridges is especially adept at introducing emotional urgency into her portrayals by varying a note’s intensity and pure sound. Here she projected the complexity of Charlotte’s soul-searching by means of such effective sonic extension on several pitches.

The crowd-pleasing duet from Bizet’s Les Pêcheurs de perles was certainly well liked on this occasion as Polenzani and Evans sang at their best, even introducing head tones as a means to vary the higher pitches. The final two selections previewed the new production of Wagner’s Die Walküre which will open later this fall. First Davis conducted the orchestral version of the “Ride of the Valkyries” which, as shown in this exciting performance, functions vividly on a concert’s program. Eric Owens sang Wotan’s solo “Leb’wohl” [“Farewell”] from the conclusion of the opera. Extended notes were held impressively, as the orchestra played more and more softly to suggest the Walküre’s gradual slumber. As a foretaste of much more to come, the final two excerpts augur well for Lyric Opera’s new production of Die Walküre and for the balance of the coming season.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Stars-of-lyric-opera-millennium-park-2017.png

image_description=Stars of Lyric Opera 2017, Millennium Park, Chicago

product=yes

product_title=Stars of Lyric Opera 2017, Millennium Park, Chicago

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=

A Verlaine Songbook

Today, singers and their pianists are often more willing also to explore repertory by composers who are much less well known. Furthermore, a CD can carry much more music than the typical LP. Carolyn Sampson—an established light soprano—here offers an entire, well-stocked disc of Verlaine settings by no fewer than ten composers: the inevitable (but always welcome!) Debussy and Fauré, but also Saint-Saëns, Chausson, Ravel, Reynaldo Hahn, Charles Bordes, Déodat de Séverac, Joseph Szulc, and Régine Wieniawski Poldowski (daughter of the famous violinist).

This does not produce a scattershot effect because several cycles or sets are recorded entire (Debussy’s Fêtes galantes, series 1, and Ariettes oubliées; and Fauré’s La bonne chanson). Also, the songs of Poldowski are grouped together, as are those of Hahn. The single songs by Ravel, Szulc, et al., thus come as refreshment after a group of tracks by one composer.

Another element of coherence: a number of the songs use the same text as some other song on the disc. There is much fascination in observing how Saint-Saëns, for example, fills “C’est l’extase langoureuse” with a lively accompaniment emphasizing ecstasy whereas Debussy’s setting emphasizes languor. And, for extra fun, certain images recur from poem to poem, in different contexts: moonlight, nightingale, musical note-names (“do-mi-sol”), and so on.

Roger Nichols’s booklet-essay gives much insight into the different composers’ approaches to each poem. The translations, by William Jewson, of the often-laconic song texts are as clear as can be without adding many words of explanation.

People who already know the Debussy and Fauré songs recorded here may well be delighted, as I was, to discover how responsive the other composers were to this poet’s evocative verses. Hahn, Poldowski, Séverac, and Szulc produce what are, in many ways, quite conservative settings. (Szulc would go on to write musical comedies.) But conservative need not mean routine. Szulc’s setting of “Clair de lune” captures the dreamy mood of the text beautifully, as does Poldowski’s somewhat Schumannesque “En sourdine” (“Calmes dans le demi-jour”). Poldowski’s “Mandoline” (“Les donneurs de sérénades”) evokes the atmosphere of commedia dell’arte no less effectively than do the famous settings by Fauré and Debussy. And there are poetically apt echoes of church style in a song by Bordes and the closing number of the disc, by Séverac. As for the master composers, I will confine myself here to mentioning the sole Ravel song: “Sur l’herbe,” which I had never encountered before, is a wonderful “slice of life” song in his magical pseudo-Spanish style.

This was my first time hearing Sampson. She is a light, flexible soprano, a bit like Sylvia McNair or Kathleen Battle. She commands a wide range of techniques, from straight tone to rich vibrato, and from super-legato singing and controlled portamento to a semi-spoken lightness. She can file her voice down to a slender but well-supported thread. Some of the singing is among the most beautiful that my ears have ever been privileged to receive: for example, in Chausson’s “Apaisement” (“La lune blanche”)—which is one of several tracks from the CD that can be heard on YouTube —and Hahn’s “L’heure exquise” (“Votre âme est un paysage choisi”).

Sampson receives superb support from Joseph Middleton, who is director of the Leeds Lieder Festival and a professor at the Royal Academy of Music. I was often enchanted by the ways in which the pianist responds to the changing imagery in the texts and to shifts in harmony and figuration.

The same performers’ previous CD for BIS, Fleurs (likewise including some songs by “lesser” composers), was rapturously received by record critics (including Erin Heisel, in American Record Guide, September/October 2015). I foresee a similarly positive response to this marvelously well thought-out CD, which nicely reminds us that many lesser-known composers from the past have written at least a few pieces that can gratify performers and listeners alike today.

Warning: at first I listened to some tracks from this Verlaine disc on the CD player in my car. Sampson's loud high notes often came across as harsh; the echo, annoying. I wonder if this was a side-product of it being a compatible SACD disc. (This is the first SACD disc I have tried listening to.) At home, on good equipment, the whole disc is as exquisite as (Verlaine might say) the glow of moonlight on russet grass.

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). The first is now available in paperback, and the second soon will be (and is also available as an e-book).

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Verlaine_Songbook.png image_description=A Verlaine Songbook product=yes product_title=A Verlaine Songbook product_by=Carolyn Sampson, soprano; Joseph Middleton, piano. product_id=BIS-2233 [SACD] price=$14.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=2225586

Die Zauberflöte at the ROH: radiant and eternal

As we journey from the dungeon-esque darkness of the Queen’s nocturnal demesne towards the gleaming sun-disc which bathes the final chorus in the luminosity of enlightenment, a Dantesque night is truly turned into day.

However, in 2013 , I found the performance, while elegant and slickly choreographed, ‘disappointingly lacklustre’ and missing the sparkle of ‘simple youthful vitality and dreamy enchantment’. Reflecting again, perhaps some of my disenchantment derived from a perceived imbalance, on that occasion, between allegory and artifice.

For, while some lines of the opera’s libretto are based on sources used by the Freemasons, whose symbolism scholars have sometimes purloined in order to argue that a hidden masonic allegory underpins the opera’s quests and initiation rituals, in fact many of the magical and ‘marvellous’ episodes derive from earlier operas, pantomimes and comic plays that would have been well known to the audiences at Schikaneder’s the Theater auf der Wieden, and I am of the view that any elements of ‘freemasonry’ that are present are far less important than those of fairy-tale.

Mauro Peter (Tamino). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Mauro Peter (Tamino). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

During this performance, however, as the giant segments of the serpent wiggled and waggled, expertly manipulated by the puppeteers, and the marble columns of hallowed halls slid imperiously into dignified place as the orrery spun in heliocentric harmony, it was the opera’s human concerns that seemed more compelling than any abstruse philosophising.

And, for this more harmonious union of folky comedy and high seriousness, we have Roderick Williams’ effortlessly warm-voiced Papageno to thank. Williams is a seasoned bird-catcher having taken the role in several productions, including Nicholas Hytner’s ENO long-lived production and Tim Supple’s ‘grungy’ Flute at Opera North. But, even so, this Papageno has some way to go before his earns his stripes as master of the aviary. Outwitted by a puppet goose - I remember, too, an ‘incident’ with some recalcitrant real-life doves at ENO! - he eventually learns his own tricks, making the Priest’s feet (Harry Nicolls) dance to Papageno’s tune in ‘Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen’. Williams evinces an easy physicality which never drifts into farce and heaps of appealing guilelessness: who would not be touched by fellow-feeling when this Papageno humbly voices his simple desire for love and happiness? His cheek and charm certainly earn the bird-catcher his perky Papagena-in-pink, though one suspects that he will have trouble preventing Christina Gansch’s sassy slapper from fluttering her feathers from time to time.

Roderick Williams (Papageno) and Mauro Peter (Tamino). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Roderick Williams (Papageno) and Mauro Peter (Tamino). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Williams’ expert comic timing was matched by that of Peter Bronder’s Monostatos. There was a ‘nasty’ edgy to this villain’s lasciviousness which, together with the masked beasts and vultures, suggested a darker vein in the pantomime.

Several of the cast are making their Covent Garden debuts and this was a significant incentive to see this revival. In particular, I was very keen to hear French soprano Sabine Devieilhe scale the Queen of the Night’s stratospheric peaks, having greatly admired her performance as Bellezza in Handel’s Il trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno at Aix-en-Provence in 2016. And, she didn’t disappoint: ‘O zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn’ was absolutely secure and clean-toned, but ‘Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen’ simply took my breath away. I’m not sure how such a glacial tone can intimate ‘warmth’ or fullness, but somehow Devieilhe managed not just to hit the top Fs but to shape and soften them.

Sabine Devieilhe (Queen of the Night). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Sabine Devieilhe (Queen of the Night). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

I’d previously been impressed too when I heard Australian soprano Siobhan Stagg sing in Keith Warner’s ROH production of Luigi Rossi's Orpheus at the Sam Wanamaker Theatre at Shakespeare’s Globe in 2015, noting that she combined ‘a ravishing tone with pinpoint accuracy.’ The purity and richness of Stagg’s tone were put to good effect in her interpretation of Pamina’s gentle innocence, for she infused the lovely sound with a firm glint which suggested that beneath Pamina’s naivety lie integrity and resilience. ‘Ach, ich fühl’s’ was unsentimental but deeply communicative, though I wondered whether Stagg would have liked conductor Julia Jones to have taken her foot of the pedal slightly - the aria followed rather precipitously from the preceding aria although Stagg’s poise steadied the ship.

Roderick Williams (Papageno) with Siobhan Stagg (Pamina). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Roderick Williams (Papageno) with Siobhan Stagg (Pamina). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Mauro Peter’s Tamino might have had a little more ruggedness, but the Swiss singer has a lyric tenor of great beauty and the polished artistry of his phrasing and his careful diction certainly made his ‘princely’ mien convincing: ‘Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön’ was tenderly love-struck. I found that Finnish bass Mika Kares lacked the sonorous weight needed to convey Sarastro’s authoritative sobriety - though I note that those who saw earlier performances in the run disagreed.

The three boys - James Fernandes, Oliver Simpson and Jayden Tejuoso - struck just the right balance between real boyish charm and pure otherworldliness. Their three voices blended beautifully to form a single gleaming thread of innocence and light; if one shut one’s eyes, one really could believe that they had descended from celestial realms. But, their interventions, preventing tragedy, were genuinely human. The three Ladies were less consistent, Rebecca Evans, Angela Simkin (a Jette Parker Young Artist) and Susan Platts coming adrift at times in terms of timbre and temperament, and, occasionally, tuning.

Jones’ tempos were swift. As in 2013, I wished for a more spacious composure at times for the opera presents both fury and sobriety, but I enjoyed the ROH Orchestra’s sure sense of period style.

Revival directors Thomas Guthrie and Angelo Smimmo (movement) have made a good job of polishing the ROH’s silverware and McVicar’s production continues to shine. At the closing curtain, Macpherson’s sun-disc seemed a perfect metaphor for Mozart’s opera: radiant and eternal.

The Magic Flute runs in repertory at the Royal Opera House until 14 October.

Claire Seymour

Mozart: Die Zauberflöte

Tamino - Mauro Peter; First Lady - Rebecca Evans; Second Lady - Angela Simkin; Third Lady - Susan Platts; Papageno - Roderick Williams; Queen of the Night - Sabine Devieilhe; Pamina - Siobhan Stagg; Monostatos - Peter Bronder; First Boy - James Fernandes; Second Boy - Oliver Simpson; Third Boy - Jayden Tejuoso; Speaker of the Temple - Darren Jeffery; Sarastro - Mika Kares; First Priest - Harry Nicoll; Second Priest - Donald Maxwell; Pagagena - Christina Gansch; First Man in Armour - Thomas Atkins; Second Man in Armour - Sion Shibambu; Director - David McVicar, Conductor - Julia Jones; Revival Director - Thomas Guthrie, Designer - John Macfarlane; Lighting Designer - Paule Constable, Movement Director - Leah Hausman, Revival Movement Director - Angelo Smimmo, Royal Opera Chorus (Chorus Director, William Spaulding), Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Wednesday 20th September 2017.

image= http://www.operatoday.com/Flute%20production%20image.jpg image_description=Die Zauberflöte at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product=yes product_title=Die Zauberflöte at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: The closing scene.Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton

September 23, 2017

Fantasy in Philadelphia: The Wake World

This world premiere of a spellbinding new one-act opera was inspired by Aleister Crowley's fairy tale of the same name. Crowley was a larger-than-life British persona, a prolific poet, recreational drug user, magician, bisexual, and founder of his own cultist religion. The company chose to present the work in the long Annenberg Hall of the Barnes Foundation, a massively important collection of Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and early Modern masterpieces.

Dr. Albert C. Barnes was an American chemist, art collector, educator, and writer.

After growing up in a rough and tumble Philly neighborhood, Barnes earned a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania, amassing his fortune by co-developing Argyrol, a silver nitrate antiseptic. Along the way, he managed to procure one of the world's finest collections of late 19th- and early 20th-century art and create the Barnes Foundation, an educational institution dedicated to promoting the appreciation of fine art and horticulture.

While a student at Curtis, composerHertzberg spent a good deal of time at the Institute, and sensed a link between Barnes’ logic of eccentric groupings and mystical symbols on display in his “palace of art,” and Crowley’s elusive visionary tale of Lola and her chaotic, surreal quest to meet and wed her Fairy Prince on the way to a transcendent awakening.

The audience was allowed ample time before the show to experience the stunning collection and begin to absorb a mystique that characterizes the puzzling arrangement of the sequence of images. About 30 minutes prior to the performance, your peripheral vision catches a creature passing through the gallery. Then another. Some are in colorful unitards with skullcaps and faces painted to match. Others might be a fairy princess, a prince, two cranky old clowns. All of them float silently among us, gazing at and being inspired by the art. They become part of the exhibition itself and equally worthy of scrutiny and admiration, thanks to the fanciful costumes designed by the Terese Wadden.

Man of the Blue House (bass-baritone James Osby Gwathney, Jr.)

Man of the Blue House (bass-baritone James Osby Gwathney, Jr.)

Eventually the creatures lead us to the great room where we assemble, mostly standing all around a very long runway of elevated platforms. This is the stage proper but much more is in store. The creatures are silently walking, no, gliding among us. And then. . .WHAM! A crashing whack of the bass drum ricochets through the room like a gunshot. And if that didn’t make us perk up. . .WHAM! Another. And another. And then with a wordless layering of vocal sounds, chants, organ like intonements, the cast among us began a musical journey that was an unparalleled delight.

Director R.B. Schlather has realized this otherworldly rite of passage as miraculously executed immersive theatre. In the ritual opening as the voices threaten to reach Nirvana, we “get” that we are encouraged to move around the room as the opera unfolds and a parade begins around the runway like pilgrims at Mecca. When the action begins at one end of the platform and surges to the center, viewers surge with it, not only changing the dynamic of the relationship between “audience” and “actor,” but also the spatial relationship of the audience itself.

I have never seen this sort of interplay work so well, engaging without being demanding, spontaneous yet rehearsed within an inch of its life. Since there is no scenery other than the assembled cast and audience, Jax Messenger’s minimal lighting design contributed some beautiful effects, not least of which was the surprising, almost blinding back light effect that comes from an unexpected place at a crucial dramatic moment. David Zimmerman’s spot on make-up and wig design beautifully complemented Ms. Wadden’s costumes.

The central role of Lola is a big, complicated sing and soprano Maeve Höglund was triumphant. Ms. Höglund has a solid technique wedded to a rich, alluring soprano that can climb the heights with an easy sheen. She is called upon to execute extreme emotional states, and whether hurling out angular accusations, or musing introspectively, her responsive instrument was a joy to hear. It does not hurt that she is also pretty as a princess and utterly at ease in her stage demeanor.

The Fairy Prince (mezzo-soprano Rihab Chaieb), Lola (soprano Maeve Höglund)

The Fairy Prince (mezzo-soprano Rihab Chaieb), Lola (soprano Maeve Höglund)

In the trouser role of the Fairy Prince, Rihab Chaieb matched her co-star strength for strength. Her smoky, beguiling mezzo was poised and pliant, and she cut an exotic, authoritative figure as the swaggering royal. Ms. Chaieb is a first rate musician who ably met the considerable musical demands set out for her, including an easy sensuality in her caressing manner with any number of loving, arched phrases.

Soprano Jessica Beebe made the most of her solo time as Luna/Hecate, regaling us with ample tonal beauty and shimmering delivery. George Rose Somerville was totally invested into his garrulous portrayal of Morbus, and John David Miles hectored with conviction as Pestilitas. The sirens Parthenope (soprano Rebecca Myers), Ligeia (soprano Veronica Chapman-Smith), and Leucosia (mezzo-soprano Joanna Gates) intertwined their polished voices with radiant beauty. James Osby Gwathney, Jr.’s well-modulated bass-baritone made a substantial impression as Man of the Blue House. As the collective ensemble, Palace of Names, the Opera Philadelphia Chorus was superb, offering dramatic commitment as well as ravishing vocalizing.

Holding all of this together was the masterful conductor Elizabeth Braden. The musical execution was faultless, no mean feat with her forces spread across a sixty foot runway and throughout the audience. Maestra Braden found just the right balance between her exceptional instrumentalists and the vocal forces, and made a compelling case for Mr. Hertzberg’s evocative score. There are hints of Debussy, echoes of Strauss, reminiscences of Penderecki, but at the end of the day his is a unique style, and he writes gratefully and inventively for the voice.

But The Wake World not only sings, it soars. Mysterious. Challenging. Moody. Risky. Enriching. What an inspiring night in the theatre.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

The Wake World

Music and Libretto by David Hertzberg

Lola: Maeve Höglund; Fairy Prince: Rihab Chaieb; Parthenope: Rebecca Myers; Ligeia: Veronica Chapman-Smith; Leucosia: Joanna Gates; Luna/Hecate: Jessica Beebe; Morbus: George Rose Somerville; Pestilitas: John David Miles; Giant/BoneMan/Man in the Azure Coat/Man of the Blue House: James Osby Gwathney, Jr.; Palace of Names: Opera Philadeplhia Chorus; Conductor: Elizabeth Braden; Director: R.B. Schlather; Costume Design: Terese Wadden; Lighting Design: Jax Messenger; Wig and Make-up Design: David Zimmerman

image=http://www.operatoday.com/WakeWorld_OT1.png

product=yes

product_title=The Wake World at Opera Philadelphia

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Maeve Höglund as Lola [All photos copyright Dominic M. Mercier, courtesy of Opera Philadelphia]

September 22, 2017

A Mysterious Lucia at Forest Lawn

Conductor Isaac Selya and his orchestra of twenty-seven played the overture with its emotion-inducing harp music as the red sun slipped behind the mountains, leaving orange clouds and purple shadows to introduce the mysteries of night. Director and Designer Josh Shaw used three levels backed by rough walls that resembled ancient ruins as the basis for each scene. Maggie Green’s costumes involved a variety of tartans that evoked the mystique of historical Scotland.

The opera opened with a fight between Lucia Ashton’s relatives and their Ravenswood opponents. Enrico Ashton, Lucia’s brother, sung by Daniel Scofield, won this skirmish, but the war was nowhere near over. Enrico vented his fury in magnificent song at the idea of his sister falling in love with the family’s sworn enemy, Edgardo of Ravenswood. Scofield was only one of the stars of this show who had large, resonant Italianate voices. Tenor Nathan Granner as Edgardo matched him note for note.

Jacqueline Marshall’s beautiful harp music announced Lucia’s arrival at the fountain where she waited for Edgardo. Bevin Hill was a full service Lucia who hit all the notes at the right times and was able to deal with all the technical aspects of the role. Not every tone was beautiful, however. Following Lucia’s description of the spectre in the fountain, it emerged in the form of a wraith-like dancer who followed the soprano throughout the opera as a prime indicator of her mental state.

When Edgardo, who does not know that his messages to Lucia have been intercepted or that she has been told he loves another, arrived and found her marrying Arturo, he and the guests sang a magnificent sextet. Enrico and Edgardo sang of their fears for Lucia, and she took over the melody. Lyric bass-baritone Nicholas Boragno as Raimondo, the man of God, wondered about an evil end to the situation. Bridegroom Arturo, sung by lyric tenor William Grundler, and Lucia’s companion, Alisa, sung by mezzo-soprano Danielle Bond, sang of their fear for the future. Each character sang about this fatal day in the exquisitely blended sonorities that form the opera’s dramatic lynchpin.

Because Forest Lawn closes its gates on both spectres and living beings alike at ten o’clock, this performance had to skip the Wolf’s Crag Scene in which Enrico challenges Edgardo to a duel. Act III opened on Lammermoor Castle with the guests enjoying copious food and drink. All are shocked when Raimondo tells them that Lucia has murdered Arturo.

Appearing dazed, Lucia wore a blood-stained gown and held a dagger in one hand as she sang her Mad Scene accompanied by the flutes of Eve Bañuelos and Michelle Huang. Hill sang with great control but her character was mentally in another world. At the end of this pièce de resistance Lucia fell to the floor, lifeless. Later, in the Ravenswood graveyard, Edgardo hears the bell tolling her death. Stabbed through the heart, he leaves this unhappy world singing of the future he and Lucia will have together in Heaven. Although the story was sad, the performance was enthralling with audience members humming Donizetti’s tunes as they wound their way down the mountain that is Forest Lawn.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Director and Designer, Josh Shaw; Conductor, Isaac Selya; Company Manager, Mari Sullivan; Stage Manager, Carson Gilmore; Costumes, Maggie Green; Fight Director and Choreographer, Aubrey Trujillo-Scarr; Fight Captain and Choreographer, Elias Scarr; Lucia, Bevin Hill; Edgardo, Nathan Granner; Enrico, Daniel Scofield; Raymond, Nicholas Boragno; Arturo, William Grundler; Alisa, Danielle Bond; Norman, Robert Norman.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lucia-Press-4.png

image_description=Bevin Hill as Lucia and Nathan Granner as Edgardo [Photo by Martha Benedict]

product=yes

product_title=A Mysterious Lucia at Forest Lawn

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Bevin Hill as Lucia and Nathan Granner as Edgardo

Photos by Martha Benedict

This is Rattle: Blazing Berlioz at the Barbican Hall

If Simon Rattle can achieve such excellence in the cramped confines of the Barbican Hall, imagine how Britain's cultural life would be transformed if a world class concert hall with state of the art facilities were built. The arts are central to the nation's economy and prestige. Britain cannot afford to slip.

As Rattle has said, the London Symphony Orchestra have the potential to do a lot more repertoire, given the chance. Berlioz The Damnation of Faust is an extravagant work. The stage was crowded with performers, and the volume projected into the shoebox that is the Barbican Hall threatened at times to overwhelm. On the BBC Radio 3 re broadcast and on medici.tv the sound balance might be better, but the live experience was intoxicating, despite the acoustic. Wisely, Rattle held his forces back, emphasizing instead the intricate orchestration and textures that make this piece so exciting. It is a sprawling drama, whose theatrical effects are embedded in the music. In Berlioz's time audiences didn't need literal realism. They paid attention to the music. This performance was so vivid that the Barbican Hall seemed transformed as if by magic, as Berlioz's music came alive.

Faust, the old scholar, watches peasants dancing in the countryside. "Tra la la , Haha ha!" sing the chorus. It is Easter. Spring has come. Nature blossoms. Christ has risen. Dare Faust dream of rejuvenation? Bryan Hymel sang Faust, the rich, ringing warmth in his voice bringing colour to the role. Hymel then injected chill fear. "Hélas! doux chants du ciel, pourquoi dans sa poussière Réveiller le maudit? ". Faust is no fool: he already senses the immensity of what is to come.

A Faust as strong as Hymel needs an equally singular Méphistophélès. Christopher Purves provided an authoritative counterbalance. The expressiveness in Hymel's voice contrasted with the authority in Purves's voice and his purposeful enunciation. The way Purves sang "Ô pure émotion!" showed how Méphistophélès had sized Faust up. A strong Brander, too, in Gabor Bretz. Though the part isn't big, it's important, for Brander is to the students what Méphistophélès is to Faust. The chorus sang lines that swayed from side to side, as drinkers do. But an undercurrent of violence runs through the merriment. Purves sings the Song of the Flea but the drunks think it's funny. In the Voici des roses, Purves suggested the thoughtful side of Méphistophélès.'s character: low winds and strings evoking melancholy. The devil is dangerous because he understands human sensitivity, and uses that to manipulate. Perhaps Méphistophélès is a kind of Oberon, for Faust is lulled into a dream by a magical flute melody, later taken up by the strings, and the songs of gnomes and sylphs. A magical scene which owes much to Mendelssohn.

For Faust, a reverie of love. For the students, mindless delusion as they march off to war. Hymel's aria "Merci, doux crépuscule! " was a star turn, beautifully articulated, glowing with feeling. The phrase "Que j’aime ce silence," glowed beautifully, followed by a deeply felt "et comme je respire Un air pur!" The orchestra responded in kind, with transparently delicate textures. When Méphistophélès. butts in, a violin plucks a banal ditty, like a student with a lute. But Faust is made of far finer stff, as is Marguerite. Karen Cargill sang the Song of the King of Thule with sincerity. The song is a paean to fidelity, loyalty so strong it defies death. Garlanded by viola and cellos, it's anothe moment of "silence" where Méphistophélès and the world cannot reach.

Berlioz's The Damnation of Faust owes as much to Shakespeatre as to Goethe. In the magical Evocation, fireflies dance, piccolos playing bright figures augmented by darker hued winds and strings. Textures as transparent as these need this kind of definition There was humour, too, in the trombones and tuba, which not every orchestra can carry off as well as the LSO. Purves curled his tongue around the final words, with the menace of a snake, for now Faust and Marguerite have their encounter. Hymel's " Ange adoré" glowed resplendently, and his cry "Marguerite est à moi!" scaled the heights. But the world intrudes. After fast paced exchanges, the lovers are torn apart. The cross currents between soloists, choirs and orchestra were very well defined.

Then, back to solitude. Cargill's Romance showed her at her finest. matched by evocative oboe accompaniment. Although some incarnations of Faust emphasize the God/Devil angles in the legend, Berlioz was very much a Romantic, for whom Nature was an alternative diety. Thus, the importance of the Invocation. Hymel sang the aria Nature immense, impénétrable et fière, with such fervour it seemed an act of faith. But Fast is doomed. Méphistophélès and Faust set off on horses that fly through the sky, defying the laws of Nature. Wailing woodwinds, and a frenzied pace in the orchestra, tensely plucked pizzicato. The children's voices screamed "Ah!" and the tubas wailed pounding staccato, Now, Méphistophélès has little need for formal language. "Hop! Hop!" screamed Purves. My flesh creeped, thinking of the "Hop Hop" at the end of Wozzeck. The men's chorus walked on stage, among the orchestra, singing their demonic chorus: skat lyrics before the term was invented, interspersed with machine-gun staccato. Are the demons the students and soldiers?

"Hosana!" sang the choirs at the back of the stage. Harps sggested angels, and the palpitating, ascending rhythms, the flapping of wings, or the image of water (as opposed to the fires of hell). And then the children's choirs filed into the auditorium, illuminating the darkness with their high, pure voices. Like a miracle!

Anne Ozorio

Hector Berlioz: The Damnation of Faust

Sir Simon Rattle, London Symphony Orchestra, Bruyan Hymel, Christopher Purves, Karen Cargill, Gabor Bretz, London Symphony Chorus (concertmaster Simon Halsey) Tiffin School Choirs (concert master James Day).

Barbican Hall, London. Sunday 17th September 2017

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rattle%20photo.jpg image_description=This is Rattle: Sir Simon Rattle and the London Symphony Orchestra perform Hector Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust at the Barbican Hall product=yes product_title=This is Rattle: Sir Simon Rattle and the London Symphony Orchestra perform Hector Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust at the Barbican Hall product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio product_id=Above: Sir Simon RattleSeptember 20, 2017

Moved Takes on Philadelphia Headlines

That is marketing shorthand for Philadelphia Opera Festival 2017, and in longhand, this is a nonpareil, landmark event.

Never was this more evident than at the world premiere of We Shall Not Be Moved, a musically compelling and deeply moving new piece of lyric theatre by composer Daniel Bernard Roumain and librettist Marc Bamuthi Joseph.

Five North Philly teens are on the run to avoid arrest after unintended involvement in several tragic incidents. They seek refuge in the abandoned house that served as the headquarters for the MOVE organization, where a 1985 standoff with police infamously ended with citizens dead and a neighborhood destroyed. As this disparate, self-defined family takes refuge, they unexpectedly find inspiration in the ghosts who linger in the historic residence. Their initial fear transforms first into resistance, then destiny.

Family Stand and the OGs come to live in an abandoned home on Osage Avenue. Photo by Dominic M. Mercier

Family Stand and the OGs come to live in an abandoned home on Osage Avenue. Photo by Dominic M. Mercier

Mr. Roumain’s genre-defying score is not only often earthy but also just as frequently ethereal, and seems poised to freely move between the two extremes. He is equally at home writing in classical style, injecting jazz riffs, or hunkering down into pulsing R&B, but this score is filtered through a unique lens of self-invention. Mr. Joseph’s edgy libretto blends poetry, prosedy, spoken word, street slang, and rap into a masterful expressive vocabulary that often seems a laser-focused response to current race relation headlines.

A third collaborator is the renowned director, choreographer, dramaturge and dancer Bill T. Jones who completes the triumvirate responsible for this piece he calls “ambitiously interdisciplinary.” Mr. Jones brings together contemporary movement, video projection, staggeringly powerful stage pictures and deeply explored characterization to unite his abundantly talented cast, crew and creative team.

Lauren Whitehead, a noted spoken word performer and writer brings her substantial gifts to the role of Un/Sung, the central teenage figure, narrator, and surrogate mother whose determined journey binds the other family to her. Lauren holds her own with her operatically trained colleagues, singing with secure sincerity. As her counterpart, the policewoman Glenda, luminous mezzo Kirstin Chavez turns in a galvanizing performance. As her assured, tough love authority is reduced to a legal predicament not of her making, Ms. Chavez invests her character with intense, conflicted duality. And, Lisa is possessed of a particularly attractive mezzo, for which the composer provided some of his most urgent and limpid phrases. Hers was a touching and beautifully crafted portrayal.

The gifted counter-tenor John Holiday threatens to walk away with any show he is in. On this occasion, Mr. Holiday deploys his distinctively pointed, high-flying instrument to not only cry out some R&B licks that challenge Mariah Carey, but he also reined in his sassy delivery to create a heartbreaking, internalized impersonation as a bullied trans man. I will not soon forget the tears that fell in the audience as John sang pitiably about his binding himself at peril of bullying to become who is, and not the gender he was born to.

West Philly cop Glenda (mezzo-soprano Kirstin Chávez) asks Un/Sung (spoken word artist Lauren Whitehead) why her and her brothers are not in school. Photo by Dave DiRentis

Powerhouse bass-baritone Aubrey Allicock commanded the stage as John Henry, prowling the perimeter with restless purpose and howling out jazz licks with obvious delight. His middle and upper range have acquired an admirably burnished sheen over time, and his legit operatic phrases were fulsome and fearsome. John Mack was played by Adam Richardson, handsome and sympathetic of presence, who sang with a characterful, grainy, immensely appealing lyric baritone. Daniel Shirley rounded out the family as John Little, able to color his smooth lyric tenor to suggest real danger and aggression.

As soloists, these fine artists were commendable. As an ensemble, they were perfection. Thanks to Mr. Jones, this group of accomplished pros sang together, loved together, danced together and suffered together, forming the beating heart that was key to this production’s total success. They were ably abetted in their excellence by four tireless, omnipresent dancers as the OG’s (ghosts) who inhabit the historic sacrificial grounds. These lithe, expressive, generous artists provided a writhing, body slamming, break dancing commentary on every nuance of the unfolding drama and they are: Michael Bishop, Duane Lee Holland, Jr., Tendayi Kuumba and Caci Cole Pritchett.

Their choreographed contribution to the evening’s triumph included moving around Matt Saunders’ modular set pieces. Mr. Saunders has provided four flexible mobile wall units and a couple of simple stair and platform pieces that are chameleon-like and able to transform into any number of configurations and locales. Since they are white, they are amazingly receptive to Mr. Cousineau’s inspired projection design, which occasionally found dancers behind scrim panels being mirrored by dancer images on the screens in front of them. The sacrificial immolation effect was mesmerizing and shattering in its intensity.

Liz Prince’s costume design kept things simple but her attire really helped define the characters, and her white hoody riff for the ghosts was urban inspired. Robert Wierzel’s lighting successfully complemented the projections, always enhancing the look, never interfering. David Zimmerman’s tasteful sound design was effective without calling attention to itself.

While this was a monumental collaboration of many individual efforts, at the end of the day, Bill T. Jones was probably the overriding component in its success. I believe his assured melding of all the elements in this challenging new piece, and his artistic vision propelled We Shall Not Be Moved from the merely excellent to the profound. We “were” moved. Future audiences “will” be moved. How could anyone “not” be moved by Opera Philadelphia’s towering, musically engaging, emotionally wrenching achievement?

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

We Shall Not Be Moved

Music by Daniel Bernard Roumain

Libretto by Marc Bamuthi Joseph

Un/Sung: Lauren Whitehead; Glenda: Kirstin Chavez; John Blue: John Holiday; John Little: Daniel Shirley; John Mack: Adam Richardson; John Henry: Aubrey Allicock; OG: Michael Bishop; OG: Duane Lee Holland, Jr.; OG: Tendayi Kuumba; OG: Caci Cole Pritchett; Voice of the Reporter: Pat Ciarocchi; Caller: Mike J. Dees; Conductor: Viswa Subbaraman; Director/Choreographer/Dramaturge: Bill T. Jones; Set Design: Matt Saunders; Costume Design: Liz Prince: Lighting Design: Robert Wierzel; Projection Design: Jorge Cousineau; Sound Design: David Zimmerman

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Moved_OT1.png

product=yes