October 29, 2017

Richard Jones's Rodelinda returns to ENO

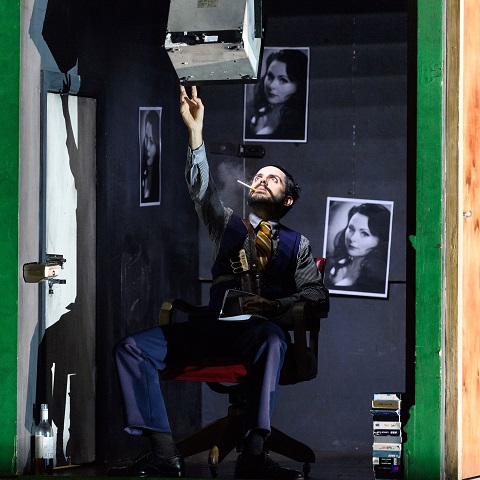

An indignant sense of unjust usurpation was probably just as prevalent in Hanoverian London - that is, among those Jacobites who sought to re-establish a Stuart monarchy. But, despite the large map of Milan which looms from the wall of the political headquarters in Jones’s production, there is little sense of ‘specificity’ of geography or ideology. Instead, we find ourselves in a mid-twentieth-century mobster-land - dimly lit, ugly, bleak. Characters - a steadfast but resourceful wife; a conflicted villain; a noble, self-knowing ‘deliverer’ - take precedence over locale or period which, given the striking musical portraits created by Handel, is fitting.

For Acts 1 and 2, Jeremy Herbert’s set divides the wide Coliseum stage in two. Stage left is a dingy incarceration cell where Rodelina - whose husband Bertarido, King of Milan, has been ousted from the throne by the iniquitous Grimoaldo who nurtures amorous aims and claims upon his rival’s wife - languishes in grief, with her son Flavio. The grimy prison houses an array of surveillance cameras and telescreens worthy of an Orwellian dystopia. In the panelled office of state, stage right, the supplanting despots pour over the transmitted images of their captives with voyeuristic slathering; when, that is, they are not eagerly destroying iconic images of the rightful King and decorating the walls with their own visual propaganda. The split stage is most powerfully deployed at the close of Act 2, when the reunited beloveds are forced to sing to each other, first through a dividing wall, then separated by a central corridor, before the rooms left and right slide torturously away from each other, cruelly entrenching their severance. The emotional segregation of the characters is further exacerbated in the final act, when horizontal partitions isolate individuals with only their own emotional crises and inadequacies for company.

Rodelinda end of Act 2. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Rodelinda end of Act 2. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Rodelinda has one of Handel’s least convoluted plots. Nicholas Haym’s libretto, adapted from a text by Antonio Salvi, presents Rodelinda’s fidelity to her ‘dead’ husband (he has faked his own demise to both spy on his grieving wife and surprise his usurpers), Grimoaldo’s inner conflict (he is torn between genuine desire for Rodelinda and a lust for absolute power), and Bertarido’s honour. There are a couple of ‘grotesques’: Eduige, Bertarido’s sister, who is rejected by Grimoaldo, and the brutish thug Garibaldo who makes overtures to Eduige in the hope of gaining the throne for himself. In the end, ‘right’ triumphs over rapacity.

Jones (as revived by Donna Stirrup) and Herbert offer plentiful visual, aural and choreographic details, with varying degrees of relevance and effectiveness. Some will welcome and others lament the aural verisimilitude: the door slamming, foot stamping, pained wailing that punctures the exquisite music. The notion of fidelity which is at the heart of the opera is represented visually by a recurring tattooing motif and some blood-letting: one of the closing images of Act 3 is of a huge forearm, tattooed in gilt with the name ‘Rodelina’, lying askew in the sand beside a giant fist clutching a broken-off sword hilt: ‘Ozymandias’ meets Planet of the Apes.

Jones essays some humorous counterpoints to the prevailing tragic gloom, but they don’t all hit the mark. During the overture, three turning treadmills propel the characters into the dramatic maelstrom, but it’s not so far from such cartoon capers to the farce of Keystone Kops. Indeed, subsequently, when the loyal but ineffectual Unulfo (beautifully sung by Christopher Lowrey), fleeing from his aggressors, spins and swirls along and off the treadmill with the grace of a ballerina, one wonders if he’s auditioning for English National Ballet.

Christopher Lowrey. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Christopher Lowrey. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Sometimes, mockery undermines a strong dramatic point, as when Flavio’s rabid gesticulations present a violent charade to Grimoaldo which swerves our attention from the fact that, in daring the tyrant to kill her son - an act which will confirm his dastardliness but which she believes him too cowardly to fulfil - Rodelinda proves herself an equal Machiavellian. Similarly, when she dances a tense tango with Grimoaldo and then taunts him, ‘I loathe you’, the bathos prompted a (surely unintended) chuckle. By Act 3, when Unulfo is accidentally wounded by the imprisoned Bertarido and staggers through the final act - ‘Don’t worry, it won’t be fatal’ - the comic drollery has the upper hand over potentially tragic conflict. One wishes that Jones had had faith that Handel’s own penchant for irony would be sufficient.

The cast are, fortunately, superb, many reprising their roles from the first run. Rebecca Evans captures all of Rodelinda’s dolorous grief and self-examination, untroubled by the heights from which so many of Handel’s phrases start, then fall lamentingly. She imbues her soprano with freshness and warmth to convey the depth of her love for Bertarido, and their Act 2 duet is a musical and emotional peak of the performance.

Rebecca Evans. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Rebecca Evans. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Tim Mead surprised me with the impact and strength of his performance as the exiled King; his always expressive countertenor seems to have found new fullness and depth, and he persuasively communicated Bertarido’s sincerity and self-belief. Bertarido’s aria of despair when he believes that Rodelinda has forsaken him was utterly compelling, sung beneath the fluorescent illuminations of a cocktail bar - the motif was perhaps a nod towards David Alden’s 2004/05 Munich/San Francisco 1930s film noir infused production which presented a similar neon sign, ‘Bar’, at the start of Act 2, above seedy backstreets.

Juan Sancho and Tim Mead. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Juan Sancho and Tim Mead. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Juan Sancho was striking as Grimoaldo; though his tenor is quite light, he made genuine the villain’s inner conflict - between his desire for power and his desire for Rodelinda. The aria in which he reflects on his dilemma - if he has Bertarido killed, he will retain his power but will lose all hope of persuading Rodelinda to marry him; if he frees Bertarido, he will lose both Rodelinda and, most probably, the throne - achieved the seemingly impossible task of arousing some small sympathy for the rogue. Here, though, one problem of Amanda Holden’s crisp translation was emphasised; the English text is sometimes too sparse to convey the inferences of the original Italian. In his self-doubt, Grimoaldo compares his complicated torment to the simple life he imagines a shepherd to lead; the comparison, and the lilting rhythms of the aria which suggest the peace offered by the pastoral, are entirely authentic within an eighteenth-century context, but the rather blunt translation raised an awkward laugh.

Juan Sancho. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Juan Sancho. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Susan Bickley’s Eduige was sparky and larger-than-life - a bit too Mrs Slocombe (Are You Being Served) for my liking, but the role was well sung. Neal Davies was a terrifically rough-edged Garibaldo without ever sinking into pantomime mode. Actor Matt Casey is given a lot to do, more than Handel probably intended, in the silent role of Flavio, and almost suggested psychopathic tendencies equal to those of his captor.

Susan Bickley and Rebecca Evans. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Susan Bickley and Rebecca Evans. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Conductor Christian Curnyn guided his instrumentalists through an elegant, attentive reading of the score - there was some lovely, prominent woodwind playing - but it felt at little sedate at times; Act 2, in particular, needed more dramatic impetus.

Handel provides the expected lieto fine, as all sing in praise of the sun which warms the land and brings peace and harmony; but Jones, characteristically, has one final twist up his sleeve. Whether you like this production may well depend on whether you delight in such pouting and piquancy; but, if you enjoy superb Handelian singing then you should get yourself along to the Coliseum before the run finishes on 15th November .

Claire Seymour

Handel: Rodelinda

Rodelinda - Rebecca Evans, Bertarido - Tim Mead, Flavio - Matt Casey, Grimoaldo - Juan Sancho, Eduige - Susan Bickley, Garibaldo - Neal Davies, Unulfo - Christopher Lowrey; director - Richard Jones, revival director - Donna Stirrup, conductor - Christian Curnyn, set designer - Jeremy Herbert, costume designer - Nicky Gillibrand, lighting designer - Mimi Jordan Sherin, choreographer - Sarah Fahie, video designer - Steven Williams, fight director - Bret Yount.

English National Opera, London Coliseum; Thursday 26th October 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ENO-1718-Rodelinda-Matt-Casey-Rebecca-Evans-Tim-Mead-Juan-Sancho-c-Jane-Hobson.jpg image_description=Rodelinda, English National Opera product=yes product_title=Rodelinda, English National Opera product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Matt Casey, Rebecca Evans, Tim Mead and Juan SanchoPhoto credit: Jane Hobson

October 28, 2017

Amusing Old Movie Becomes Engrossing New Opera

In it he replaced the spoken words of the film with recitative, arioso, aria, and an occasional orchestral interlude, the building blocks of opera. Technically, it was not an easy job because Morganelli’s music had to fit into the exact timings of the film.

In April 2015, when Los Angeles Opera asked Morganelli to arrange Hercules vs. Vampires for showing in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, he revised it saying, "I completely re-orchestrated the score to take advantage of a bigger orchestra.” He added, "There was about 10 minutes that I was honestly not happy with, so I completely tossed it and wrote new material." Arizona Opera presented Hercules vs. Vampires in its new version on October 21, 2017 at Phoenix’s Symphony Hall.

In the opera, Hercules visits Acalia where blonde and beautiful Princess Dianara should have become queen after the recent death of her father, the king. However, her evil uncle Lycos has put the young woman under a spell and she is too weak to rule. Hercules, played by body builder Reg Park, consults Medea for advice and she tells him he needs to obtain a golden apple from the Hesperides and a living stone from Hades.

Francis Giacobini as Telemachus and George Ardisson as the incredibly handsome Theseus join Hercules on the journey. Eventually they have to sleep and the queen of the Hesperides captures them. Hercules climbs a gigantic tree and grabs the apple but Telemachus and Theseus end up in the clutches of the murderous Procrustes. Hercules saves them and opens up the portal to Hades where the living stone is surrounded by boiling lava.

Having fallen into the lava, Theseus wakes up in the Underworld where he meets Persephone, a brunette almost as charming as Dianara. They fall in love and he hides her on the ship that will take him back home. Eventually, Persephone erases Theseus memories of their love and returns to the Underworld taking the living stone with her. Hercules kills Lycos and saves Dianara as the opera ends.

Although the acting and stage decor in the film were a bit old fashioned, the singing was as new and fresh as a rosebud. I particularly loved Lacy Sauter’s dramatic Dianara and Katrina Galka’s silvery coloratura. As Persephone, Stephanie Sanchez sang velvet tones. Jarrett Porter was a commanding Hercules who faced monsters with commanding robust sound.

Anthony Ciaramitaro was a lyrical Theseus and Justin Carpenter a collegial Kyros. Paul Nicosia was a warm-toned Telemachus while bass-baritones Zachary Owen and Brent Michael Smith broadcast their evil-sounding pronouncements across the wide movie landscape.

Lately audiences are seeing a great many mixtures of opera and film. From full length opera movies, to snippets of film projected into live opera, and new scores for classic films, the mélange works and opera companies are reveling in it. Meanwhile, movie composer Patrick Morganelli is writing an opera that we can hope to experience live in a year or so. It’s all good theater for us to enjoy.

Maria Nockin

Movie Cast/Opera Cast, and Production Information:

Hercules, Reg Par/Jarett Porter, baritone; King Lico, Christopher Lee/Zachery Owen, bass-baritone; Dianara, Leonora Ruffo/Lacy Sauter, soprano; Theseus, George Ardisson/ Anthony Ciaramitaro, tenor; Aretusa, Marisa Belli/Katrina Galka, soprano; Medea, Gaia Germani/Katrina Galka, soprano; Helena, Rosalba Neri/Katrina Galka, soprano; Persephone, Ida Galli, Stephanie Sanchez, mezzo-soprano; Kyros, Mino Doro/Justin Carpenter, tenor, Telemachus, Franco Giacobini/Paul Nicosia, tenor; Procrustes, Brent Michael Smith, bass-baritone; Composer, Patrick Morganelli; Conductor, Shawn Galvin; Lighting, Gregory Allen Hirsch.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Herc.png

image_description=Hercules vs. Vampires [Image courtesy of Arizona Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Amusing Old Movie Becomes Engrossing New Opera

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Hercules vs. Vampires [Image courtesy of Arizona Opera]

Rigoletto at Lyric Opera of Chicago

Notable performances are also given by Matthew Polenzani as the Duke of Mantua and by Rosa Feola as Rigoletto’s daughter Gilda. The siblings Maddalena and Sparafucile are portrayed by Zanda Švēde and Alexander Tsymbalyuk. Count Monterone, Borsa, Count and Countess Ceprano, Marullo, Giovanna, and a page are sung by Todd Thomas, Mario Rojas, Alan Higgs, Whitney Morrison, Takaoki Onishi, Lauren Decker, and Diana Newman. Debut performances at Lyric Opera of Chicago are being given by Mmes. Feola, Švēde, and Morrison as well as by Messrs. Tsymbalyuk, Rojas, and Higgs. The Lyric Opera Orchestra is conducted by Marco Armiliato, and the Chorus Master is Michael Black. The production is owned by San Francisco Opera and is given under the direction of E. Loren Meeker.

During the orchestral prelude the dramatic tensions in Verdi’s score are revealed by the set design and the positioning of characters. A Renaissance courtyard is suggested by buildings framing either side of the stage. Doorways open out onto the courtyard - which will also function as the interior space of the Duke’s residence - allowing for fluid movements in multiple scenes. As the brass sound ominously, Mr. Kelsey’s Rigoletto emerges from a backdrop reddish glow surrounded by both his professional and domestic environments. While Rigoletto stares blankly forward, the audience is permitted a brief view of the Duke positioned behind Rigoletto with two women of the court in ornate costume. Gradually the light fades on the latter three characters, and the jester dons his fool’s costume and cap. At the conclusion of the prelude, courtiers stream out of the lateral doorways, a backdrop of arches descends, and the lively atmosphere of the Duke’s immoral residence prevails now as an interior.

The brief, first scene of Act One showcasing the Duke’s personality is staged with rapid movement. Interchanges with the courtiers concerning future conquests lead to the Duke’s aria, “Questa o quella” [“This woman or that one”]. Mr. Polenzani sings this aria with emphasis on his character’s determination, ending verses with frequent sustained, top notes; here a greater application of legato could bind the individual lines into an even more credible image. While the Duke searches for the Countess Ceprano, Rigoletto weaves about athletically and comments on the atmosphere of debauchery. Mr. Kelsey’s striking facial expressions and kinetic postures speak for a complete involvement in the role of jester. Kelsey’s voice rises in defiance when threatened by Ceprano, and he declares himself untouchable as “del Duca un protetto” (“a favorite of the Duke”). Once the courtiers conspire with Ceprano to exact revenge on the fool, Count Monterone enters demanding an audience. Mr. Thomas is appropriately stentorian as the nobleman seeking justice for a father’s grief. When Monterone is detained and led away from the court, Polenzani and Kelsey diverge in their reactions, the Duke showing indifference to the nobleman’s curse while the jester is now serious and shaken.

The transition to Rigoletto’s conversation with an assassin at the start of the following scene shows an effective maneuver of the stage. By means of corresponding lighting and blocking, the Duke’s court becomes a dim deserted street with a single, cloaked figure positioned in a doorway. As Rigoletto proceeds homeward, he is lost in thought, still musing on the powerful curse of Monterone. During his change out of jester’s clothing, performed significantly away from the setting of home, the assassin begins a conversation while elaborating on his murderous offer. Mr. Tsymbalyuk’s vibrant and even vocal delivery in describing his practice with Maddalena plants an unforgettable seed in Rigoletto’s complex of thoughts, as if invigorating Kelsey’s cry in his sustained note on “Quel vecchio maledivami!” (“The old man cursed me!”). While shrugging off such concerns from his public life at the court, Rigoletto opens the gate to his private sphere with the baritone’s voice here swelling defiantly to insist “Ah no, è follia!” Rigoletto’s domestic scene with his daughter Gilda shows Kelsey blending singing and acting in a convincing display of protective concern. Ms. Feola’s light voice seems at first especially comfortable in the middle range while she projects in her character both innocence and anticipation. During the course of the touching duet with her father the soprano shows a wider range and greater emotional color. Kelsey stands behind Gilda as a shield while softening top notes to emphasize his paternal affection. Feola’s understated approach gains intensity until the moment of Rigoletto’s departure, nearly coinciding with the arrival of the Duke. In the subsequent duet both singers embellish their lines to indicate a growing emotional attachment. Feola’s expressive delivery of “miei vergini sogni” captures the developing love which has invaded her “maiden dreams,” just as Polenzani intones “fama e gloria” as worthless attributes compared to this new love. At the sounds of Ceprano and other courtiers arriving outside for the planned abduction, the Duke takes leave preparing for lyrical and dramatic highlights that bring the act to a close. First, Gilda’s musing on the alleged name of the Duke in “Caro nome” (“Beloved name”) furnishes the soprano great opportunity for vocal and dramatic display. Feola uses aspirated notes at the start to inject a tone of anticipation into her admission of the quickened pulse of her heart (“festi primo palpitar”). Feola binds phrases gracefully and shows admirable breath control while acting the part of infatuated maiden. Trills are suggested, and top notes are sung cautiously, while phrases are sufficiently varied to create a convincing image. Perhaps the most striking moment in the ensuing drama begins after Rigoletto’s return in the darkness. The courtiers reveal a plan to abduct the wife of Ceprano while concealing their actual goal. Rigoletto is blindfolded and dons a mask so that he assists by holding a ladder to permit access unknowingly to his own home. Only Gilda’s belated cries alert the jester to his mistaken collusion. Kelsey’s portrayal of Rigoletto’s participation is remarkable primarily because of the silently delivered bodily movements and poses. His assumption of the character’s physical impairment is ever-present while he holds the ladder, yet an exaggerated grin of mistaken mischief remains visible beneath the mask. For several heartbreaking moments Kelsey stands alone, gripping the ladder in self-satisfaction, until the offstage cries of his daughter shatter the jester’s domestic world forever.

At the start of Act Two the Duke’s aria enumerating conflicting emotions on loss and recovery is given every possible shade of nuance by Polenzani. His gentle piano notes and introduction of wistful phrasing diminuendo characterize what the Duke feels he no longer possesses. Only after the conspirators reveal their prey does the Duke’s personality revert to the triumph of conquest, a tone invested with lively, vocal decoration in Polenzani’s reprise. The jester’s subsequent appeal to the courtiers that his daughter be released, “Cortigiani,” counts as one of the great baritone solo arias composed by Verdi. Kelsey sings this piece as an anguished lament tinged with desperation when he confronts the falsely trusted Marullo for information on Gilda. Stage lighting in the final moments of this aria emphasizes Rigoletto’s isolation from the courtiers, standing in dim recess, while Kelsey’s voice blooms with emotion on the last “Signori … pietate!” (“My lords … have pity!”). Once Gilda is returned to her father, she confesses the details of her growing infatuation with the nobleman. Tempos in “Tutte le feste” (“On all the holy days”) are taken slowly to encourage Feola’s delineation of a gradual, inescapable affection. In the concluding duet between father and child Kelsey and Feola sing truly as equal voices, the father swearing revenge, while Gilda begs that the Duke be forgiven. The final chilling top note is indeed shared dramatically, yet Kelsey’s ominous “Vendetta di quest’ anima” (“Revenge from my heart”) resounds even longer at the close.

The ensemble pieces of Act Three show in this production Rigoletto’s humble dwelling transformed on stage into the space for Sparafucile’s lair. Gilda and Rigoletto remain outside while the Duke enters and demonstrates, in his approach to Maddalena, the betrayal of Gilda’s innocent love. Polenzani’s performance of “La donna è mobile” (“Women are fickle”) captures the Duke’s swagger ideally, line and top notes securely in place, and with volume modulated throughout the piece to excellent effect. The following quartet (“Bella figlia dell’ amore” [“Fair daughter of love”]) between the pairs outside and inside of Sparfucile’s “rustica osteria” depends, as here, on a mastery of balance among the four singers. Ms. Švēde’s lush and deep repeat of “Ah! Rido ben di core” (“That really makes me laugh”) contrasts notably with Feola’s arching line recognizing betrayal. Gilda’s ultimate decision to sacrifice herself by taking the place of the Duke in her father’s murderous pact with Sparafucile becomes here an inevitable consequence of Rigoletto’s actions and the “maledizione.” (“curse”). Gilda’s love and innocence will remain, at best, as a memory.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Quinn%20Kelsey_RIGOLETTO_LYR171004_175_c.Todd%20Rosenberg.png

image_description=Quinn Kelsey [Photo © Todd Rosenberg]

product=yes

product_title=Rigoletto at Lyric Opera of Chicago

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=Above: Quinn Kelsey [Photo © Todd Rosenberg]

Wexford Festival Opera 2017

Battered by Hurricane Ophelia during the preceding weekend, this south-east tip of Ireland had suffered power cuts lasting several days, leading to disrupted and abandoned dress rehearsals and countless administrative complications and obstacles. With the power still down just a day before curtain-up on the 66th Wexford Opera Festival, there must have been doubts whether there would be an Opening Night at all. As it was, only the fireworks fell victim to the prevailing gusts and hail (and have been rescheduled for the closing celebrations). This Festival, the tenth in the National Opera House, promised much and did not disappoint, although the hits did not always come from the quarters that one might have expected.

Jacopo Foroni (1825-58) has given Wexford one of its biggest successes in recent years: Stephen Medcalf’s 2013 production of the composer’s Cristina, regina di Svezia garnered great accolades from audiences and critics, and became the deserving winner of the ‘Best Rediscovered Work’ category at the 2014 International Opera Awards. It’s not surprising, therefore, that Artistic Director David Agler has decided to plunder Foroni’s slender operatic catalogue in search of another winner. In the event, Margherita, Foroni’s first opera (composed in 1848 when he was in his early twenties), is no match for Cristina’s musical invention, remarkably coloristic orchestration, stirring characterisation and dramatic persuasiveness; but, it is melodically rich, balances vivacity and comic drollery with theatrical tension, and was given a slick and entertaining presentation by director Michael Sturm and set/costume designer Stefan Rieckhoff.

Giorgio Giachetti’s libretto, based upon Eugène Scribe’s op éra-comique, Marguerite (originally intended to for François-Adrien Boieldieu), has a characterful cast, a central story of frustrated love, and rather too many subplots. Roberto uses his connections to the newly appointed mayor, Ser Matteo, to badger the pretty Margherita, a rich orphan, to marry him. Margherita, however, is in love with the soldier Ernesto; when the latter’s regiment returns from the wars, Ernesto’s sister Giustina begins to plan the forthcoming nuptials. Her preparations are disrupted, however, when Ernesto’s cap is found at a ‘crime scene’ and he is accused of having attacked Count Rodolfo, his colonel, and is arrested; in fact, he was trying to help the Count avoid a duel arising from his own amorous entanglements. With Ernesto holed up in the town gaol, Roberto seizes his chance to bully Margherita: he will engineer her lover’s release if she agrees to marry him. To save Ernesto from the scaffold, she submits to this demand. At a timely moment, Count Rodolfo re-appears and reveals that Ernesto is innocent; the latter is freed but is dismayed to learn that Margherita has proved faithless, until Giustina enlightens him and the lovers are reunited. At which point, the Count once again saves the day when he recognises Roberto as his assailant: the marriage contract is declared null and void, and Roberto is carted off to prison leaving the villagers to sing in praise of the strength of true love.

The cast of Margherita.

The cast of Margherita.

Rieckhoff’s set, fronted by a semi-transparent drop which adds detail and perspective to the street-corner interchange, cobble-stone piazza and imposing façade of the Church of the Blessed Virgin and Martyrs behind, ingeniously conjures post-WW2 Italy. The girls’ frocks and the chaps’ shirts are a clatter of primary colours as they whizz about on bicycles, gather in the piazza to welcome home the troops, dance and cavort during a celebratory street party, and jostle in the town-hall court-room. Sturm’s choreography is excellent: despite the fact that the stage is often crowded, there is never clutter or stasis, only naturalistic energy and movement. And, he is ably aided by the neat shifts and transformations of Rieckhoff’s set: a tree descends and the backcloth is bathed in night-blue light to evoke a ruined castle; a square of patterned wallpaper is lowered to create an intimate bedroom interior; the chorus nonchalantly carry chairs, beds and tables on and off, creating merry-go-round scene-changes. And, the Wexford Festival Chorus were in fine voice (on 20th October), particularly in the first 20 minutes or so, during which the drama unfolds in a swiftly moving sequence of ensemble scenes (although thereafter Foroni has a tendency to mimic Verdi in rum-te-tum mode).

As the eponymous beauty, Alexandra Volpe revealed a mezzo-soprano that can convey both integrity and mischief: reunited with Ernesto she removes her stocking suspender to adorn his hat with a memento of her love. Margherita’s extended Act 2 aria was a highpoint of the evening: Volpe used the layers of velvety warmth in her voice to make us feel the maligned, sacrificial innocent’s suffering; she was complemented by a beautiful violin obbligato. Giuliana Gianfaldoni was a lively counterpart as the breezy Giustina, relishing her role as the community’s source of gossip and direction. Gianfaldoni’s soprano has enormous power and clarity; and, just when I was beginning to find these qualities a little unalleviated, she reduced her voice to the most exquisite wisp of a pianissimo in the Act 2 duet with Margherita.

Giuliana Gianfaldoni.

Giuliana Gianfaldoni.

Andrew Stenson was a little ‘wooden’ as Ernesto, but perhaps that’s the nature of the role; his tenor was bright and true, however, and one could feel his delight when he nailed the top Cs beautifully in his Act 2 aria, poised on the scaffold, anticipating an undeserved, tragic end. Yuriy Yurchuk gave a masterclass in how, with scant time and space, to inject a role with a profundity not immediately apparent in the action, or indeed the score. Count Rodolfo’s Act 1 aria was both nuanced and psychologically weighty.

As Ser Matteo, the fittingly named Matteo d’Apolito milked the overture-accompanying mime to amusing effect, wandering insouciantly into the piazza swinging a leather briefcase from which he pulled a flask of piping hot coffee and a newspaper, settling himself comfortably into a chair to declare, as the townsfolk celebrated his new appointment, that he’s the perfect job: he intends to stroll, eat and drink and do nothing! The Mayor’s Act 1 duet with his scheming nephew Roberto is engagingly choreographed with both d’Apolito and Filippo Fontana’s indignant Roberto indulging in a panoply of deft comic gestures. Fontana has shown us his comic nous before at Wexford ( Cagnoni - Don Bucefalo ; Nino Rota - Il Capello Di Paglia Di Firenza ) and it’s clear from this performance that he continues to sharpen his skills and his ability to darken his bass as required.

Conductor Timothy Myers kept things bustling along, even when the score lacked originality, and the Wexford Festival Orchestra entered into the spirit of the drama with lightly enunciated playing that was punctuated by exuberant dramatic motifs. At the close, the greying long-johns and vests which had dangled from the overhead clothes’-line at the start were substituted by a primary-coloured fashionable array - all wars, of state and of love, are truly over.

Another, perhaps the biggest, enticement of this Wexford Festival was the prospect of hearing Lise Davidsen sing the title role in Fiona Shaw’s production of Cherubini’s Medea, for which the Norwegian soprano had whetted our appetites at the Wigmore Hall earlier this year. Davidsen was, as anticipated, a towering force blending epic fury, violence and indecision. Sadly, her statuesque grandeur and gravity did not really find a happy home in Shaw’s ‘concept’ of the opera, in which the mundane outweighed the mythic and petulance triumphed over perspicacity.

Lise Davidsen.

Lise Davidsen.

Shaw seems to have striven to wipe the slate clean of her own, acclaimed theatrical interpretations and embodiments of Euripides’ tragedy: indeed, in an interview reproduced in the Festival programme book she remarks, ‘It’s useful to have Euripides in the hinterland, but I’m starting from scratch, without preconceptions.’ Nothing wrong with that, but alarm bells started ringing when I read that Shaw, anxious not to let her experience of performing (during 2001-03) Deborah Warner’s vision of the play (for which Shaw received the Evening Standard Award for Best Actress and a Tony nomination), had decided to delegate the determining of the visual ‘concept’ to designer Annemarie Woods - do not visual and narrative elements go hand-in-hand?; and, that initial plans had involved turning the preparations for Jason and Glauce’s wedding, which form Act 1, into a ‘hen night’. This idea and setting had then been jettisoned in favour of a gymnasium. And, because the aftermath of the French Revolution was at the forefront of Shaw’s mind - the opera was premiered in 1797 - the obsessive fitness fanatics cum wedding guests swapped their lycra for mock-eighteenth-century hoops, silks, flounces and wigs.

It sounded, and subsequently looked in realisation, somewhat random - and almost entirely trivial. Myths are not simply ‘history’ or ‘stories’; nor is myth a singular mode of thought. Watching this production, I was put in mind of Claude Lévi-Strauss’s remark that myths ‘get thought in man unbeknownst to him’. Surely, there must be some pattern of conceptual thought evident as the mythic tale unfolds? But, Shaw and Woods gave us simply gimmicks, hyperactivity and frippery. Having filled the gym with a display of exercise and rowing machines, they deemed it imperative that all of them be used, incessantly, creating constant visual distraction from the establishment of character and narrative. Champagne was quaffed with abandon. When Medea entered, spoiling the engagement party, she squirted detergent at Creon in a pique of anger, contempt and frustration: perhaps, a single gesture of this nature would have made its mark, but when kitchen-cleaner spray becomes the perennial weapon of choice, disenchantment ensues.

Acts 2 and 3 are set in a dingy bedsit/children’s bedroom which is dominated by a huge rock - described by Shaw as ‘representing the problem of the failure of Jason and Medea’s marriage’ - on which the ghost of Medea’s dead brother is splayed. Volcanic passions, perhaps? This accident-trap is later draped with a red wedding-carpet … only for a cleaner to appear with a carpet-sweeper, thereby puncturing any sense of dignity and regality. As Medea contemplates her revenge she bounces a basket-ball and essays a shot at the hoop - it seems fitting that she misses the target.

Some potentially interesting pathways are opened up at the start. During the overture, Medea’s children play a mime-game which, along with a few words on the house curtain and some childish drawings and squiggles on a white front-drop, fills in the ‘back-story’ - the murder of Medea’s brother, the theft of the Golden Fleece. The latter is given a Damien Hirst-treatment: a glass rectangular box containing the formaldehyde pelt is wheeled on, it’s brown-paper wrapping peeled away for the children’s delectation. Subsequently, however, it’s just a sheepskin rug to be carelessly tossed around.

Thankfully, the cast provided vocal splendour to assuage the visual mish-mash. Davidsen used every inch of her height and every ounce of her vocal heft to convey the all-encompassing force of Medea’s aggrievement, grief and conviction. She was a still centre amid blustery stage business. At times, I questioned the wisdom of such seemingly relentless vocal capaciousness, wondering whether a little less might have been more; but, then the Norwegian soprano turned up the volume still further - what for most would be an effort and an extreme is, for Davidsen, entirely natural. And, she did not neglect Cherubini’s lyricism; moreover, she balanced Medea’s nobility with her very human hesitancy. Davidsen worked hard to make us understand why Medea behaves as she does; the pathos of her final murderous act, the smothering of her children, was deepened when she dragged their pitiful bodies onto the rock, to prevent Jason claiming possession of his dead children. In a different production this would have been a towering performance in all dimensions.

As Medea’s slave, Neris, Raffaella Lupinacci really impressed, singing her Act 2 aria with a haunting penetration which suspended the dramatic haste; her mezzo is beautifully appealing - one wondered how Medea could resist Neris’ pleas, full of both sadness and affection, for her to leave the city of Corinth. Ruth Iniesta’s Glauce was appropriately wary and disturbed in Act 1; Iniesta has an alert lyric soprano, and displayed vocal assuredness, well-centred intonation and strong projection.

Sergey Romanovsky held his own against Davidsen in the two duets for Jason and Medea, finding an almost baritonal colour to match the soprano’s vocal strength. Adam Lau had just the right balance of weight and flexibility as King Creon and - despite his mundane garb - established a regal presence. The children were excellent, never once slipping out of character and, when murdered, lying still with almost unnatural self-discipline for ones so young!

Lise Davidsen, Rioch Kinsella, Anthony Kenna.

Lise Davidsen, Rioch Kinsella, Anthony Kenna.

Cherubini’s opera is a tragédie lyrique: a noble and elevated drama presented in arias, spoken dialogue (in French), and with opportunities for choruses and ballet. But, in recent times it has become best known to us in the bastardised form performed by Maria Callas: an Italian version, with the original dialogue replaced by the recitatives which Franz Lachner composed thirteen years after Cherubini’s death in 1842. Conductor Stephen Barlow declared their intention to do Cherubini’s original ‘lean, sharp and elegantly classical articulations’ justice: and, the orchestral playing was indeed incisive and pointed, though having adopted the Italian version, the decision to include the odd line or two of spoken dialogue ‘when we believe this is justified - including an extended melodrama of dialogue spoken against and over music when the marriage ceremony is happening offstage’ produced questionable results, tending to hold up the dramatic momentum.

The third of Wexford’s 2017 productions, Franco Alfano’s Risurrezione (1904), rather slipped under the radar in the lead-up to the Festival but, for this listener at least, it was the ‘hit’ of the trio. Best known for his role in completing Puccini’s Turandot, and languishing in the shadow of Puccini and other verismo masters such as Mascagni, Alfano is in fact the composer of nine operas, of which Risurrezione was his first major success. He was in his mid-twenties, making a living writing ballets for the Folies-Bergère, when he read Tolstoy’s novel, Resurrection. Two friends, Camillo Traversi and Cesare Hanau, helped him devise a libretto and five months later the opera was completed.

Each of the four acts centres around an encounter between Prince Dimitri and Katiusha; the latter has been taken into Sofia Ivanovna’s house as a young girl, and has spent her childhood growing up beside her ward’s nephew, under the condescending eye of the servants. When Dimitri returns home, he seduces and then abandons Katiusha; finding herself pregnant and evicted from Ivanovna’s home - ‘contaminated goods’ - she waits at a train station for her beloved, hoping that he will return and redeem her. Espying him with a woman on his arm, she disappears into the snowy night. In Act 3 we learn that she has become a prostitute; wrongly convicted of murder she is awaiting transportation to Siberia when she is visited in prison by Dimitri who, assailed by guilt (he had been on the jury that convicted Katiusha), vows to make amends. Learning that the son she bore has died, the Prince offers to marry her, but the drunken, debauched Katiusha seems beyond redemption. Act 4 takes place in Siberia: Dimitri arrives bearing a pardon for Katiusha but she chooses to marry Simonson, a fellow prisoner, while admitting her unwavering love for Dimitri. Despite his own misery, Dimitri rejoices in Katiusha’s spiritual ‘resurrection’.

Whereas Tolstoy’s novel had, inevitably, a strong political dimension - a critique of the ills inflicted by Russia’s ruling elite - the opera focuses not on the spiritual and ethical rebirth of the noble Prince Dmitri [Nekludoff] but on the fall and redemption of the young girl whom he seduces and abandons - a spiritual ‘resurrection’ may prove discomforting and dissatisfying for the modern viewer. When Katiusha avowed her love for the man who has condemned her to a life of degeneracy, punishment and terrible suffering, her words - ‘You have always been so good to me’ - incited incredulity and irritation in this observer. The Prince has secured her pardon and given her a ‘free choice’: they are now united by their mutual love … but, still, such victimhood sticks in the throat! The final image offered to us by director Rosetta Cucchi and designer Tiziano Santi - a sun-drenched field of wheat in which Katiusha and her younger alter ego, the embodiment of lost innocence who has shadowed Katiusha throughout the drama, dance with freedom and joy - was just too saccharine for my taste, though probably true to Alfano’s conception. One can imagine Janáček being drawn to Tolstoy’s tale - but he’d have engineered a different ending …

On the whole, though, Santi’s sets are persuasive and emotionally probing. The red-glowing warmth of the Russian reception room of Act 1, in which Katiusha is beguiled by Dimitri’s deceitful charming, is replaced by the chill starkness of the lamplit bench on the station platform in Act 2. Impatient passengers loiter and bustle beside glimpses of train track and beneath the oversize clock - an emblem of the terribly slow passing of time experienced by the desperate, though still hopeful, Katiusha. One might have longed for Dimitri and his female acquaintance to have been held for just a fraction longer in Katiusha’s vision, to impress the pain of her abandonment and rejection. But, there was no doubting the biting nip in the air. A black box lined with rows of labour-desks recreated the brutal inhumanity of a Russian prison with discomforting realism in Act 3; one could almost feel the cold gusts piercing through the white cracks. No wonder the condemned women - superbly embodied by the Wexford Festival Chorus - found solace in cigarettes and vodka. Act 4 took us to the white wastes of Siberia, where the pitiless cold cleanses away all past lives and identities.

Much of the success of this production was due to Anne Sophie Duprels’ unwavering commitment in the role of Katiusha. Twice, recently, I have admired Duprels’ unstinting vocal and theatrical integrity ( La Voix humaine ; Zazà ) and here she again excelled and astonished. Scarcely absent from the stage, she encompassed the challenging vocal and dramatic range of the role with assurance, spiralling from gauche impressionability to incipient passion, from abysmal desolation to transcendental ecstasy. Alongside the heart-rending cries and virulent ripostes, Duprels floated some exquisite pianos. She balanced radiance with harshness, and fortitude with vulnerability. This was true singing-acting: no wonder Duprels looked exhausted, overcome and elated in equal measure at the close.

Anne Sophie Duprels and Chorus.

Anne Sophie Duprels and Chorus.

At times the drama struck me as Hardy-esque: Katiusha is a sort of hybrid of Madame Butterfly, Pushkin’s Tatiana and Hardy’s Tess; even the opera’s ‘happy ending’ seems a parallel of the uncomfortable marriage of Angel Clare and Liza-Lu at the close of Tess of the d’Urbervilles. So, it seemed fitting when tenor Gerard Schneider first entered, debonair in boots, breeches and blue frock-coat, looking unnervingly like a cross between Terence Stamp’s Sergeant Troy and Leigh Lawson’s Alec Stokes-d’Urberville! Schneider sang with honeyed warmth - in fact, so beautiful was his tone that at times it was difficult to remember that Dimitri has behaved with selfish, reckless irresponsibility. Perhaps that’s the point: Schneider just about pulled off the difficult task of making us feel some sympathy for the abusing aristocrat; after all, as he says when he finds Katiusha in prison, debauched, degenerated, utterly ‘spoiled’, it is his Calvary that begins here too.

Gerard Schneider and Anne Sophie Duprels.

Gerard Schneider and Anne Sophie Duprels.

Given that he had only moments to establish Simonson’s character, baritone Charles Rice gave an astonishingly captivating performance as the compassionate prisoner and his Act 4 aria was incredibly moving. Louise Innes (Sofia Ivanovna), Veta Pilipenko (Korableva/Vera) and, especially, Henry Grant Kerswell (Kritzloff/Contadino) were all dramatically persuasive. Romina Tomasoni made a strong impression as Ivanovna’s supercilious housekeeper, Matrena Pavlovna, and as Katuishka’s confidante, Anna. Her performance was all the more admirable given that Tomasoni had stepped in at short notice just a few hours before to replace the indisposed Andrew Stenson, presenting a stunningly vibrant lunchtime recital in St Iberius Church. Tomasoni’s programme ranged from a Vivaldi lament and Handel’s ‘Lascia ch’io pianga’ (Almira), which showcased her idiomatic and expressive ornamentation, through embodiments of Cherubino, Charlotte (Werther), Carmen and Rosina ( Il barbiere). But, it was Canteloube’s Chants d’Auvergne - suavely phrased with imperceptible registral shifts and richly layered tone - which brought the house down: I don’t think I’ve ever seen a singer performing a lunchtime recital at Wexford receive a standing ovation before the final item.

Although one feels the shadow of Puccini resting on Alfano’s score, the composer undoubtedly had an unerring instinct for the telling melodic motif which could push down the dramatic and emotional accelerator - often to the floor! - and under conductor Francesco Cilluffo the WFO played with impassioned richness and deep, vibrant colour. At the close, I would happily have gone back to the beginning for a repeat performance.

Wexford also offered us the customary three Short Works (performed in Clayton Whites Hotel) and, again, one couldn’t confidently place a bet where the riches might lie. Perhaps the most enticing proposition was Andrew Synnott’s new double bill of two of Joyce’s stories from Dubliners, ‘Counterparts’ and ‘The Boarding House’, directed by Annabelle Comyn and designed by Paul O’Mahony. (This is a co-production with Opera Theatre Company which will be performed at the Samuel Beckett Theatre, Dublin, 9th-11th November.) The performance I attended (20 th October) received a very warm, appreciative reception, and my own slight misgivings probably stemmed from my familiarity with the literary texts. But, any operatic adaptation inevitably necessitates alterations and shifts in emphasis, and both design and delivery were strong.

Joyce’s ‘Counterparts’ focuses on the economic and emotional stagnation that results from meaningless, repetitive working-life in early-twentieth-century Dublin. The title refers to the endless/pointless copying of legal documents undertaken by those such as the protagonist, Farrington, an infinite repetition that is echoed in the ‘rounds’ that are bought in the public house after work each evening, paradoxically, to assuage the Dubliners’ paralysis. O’Mahony’s clever set shifted almost imperceptibly from the claustrophobic office where Farrington is bullied and humiliated by his superior, Mr Alleyne, to the public house where he is humbled by the arm-wrestler, Weathers, the typewriters whipped from the marble topped tables and replaced by a tumble of glasses and bottles.

Cormac Lawlor was superb as Farrington: comically incompetent, pitifully vulnerable, shamefully irresponsible, tragically aggressive. Left alone in the office at the end of the day, Farrington’s lament about his lack of opportunity and money was especially probing; pathetically, he pawns his watch to buy the alcohol on which he is dependent, but which will not even provide him with the solace of inebriation. Arthur Riordan has adapted Joyce’s text and isolates particular phrases and lines to good effect: Farrington’s ‘Blast him!’ is rather over-used, but the protagonist’s riposte to his domineering employer’s question, ‘Do you think me an utter fool?’ - ‘I don’t think sir, that that’s a fair question to put to me’ - is effectively employed to create a vibrant ensemble of disdainful reflection.

Dubliners.

Dubliners.

Andrew Gavin was a striking Mr Alleyne, pomposity and puerility embodied; and Gavin - like all the cast, taking multiple roles - needed barely moments, just a change of jacket, a loosening of tie, to transform himself into Farrington’s drinking partner, O’Halloran. Gavin had performed earlier that day alongside soprano Sinead Campbell, in a lunchtime programme, The Thomas Moore Songbook, compiled, presented and accompanied by Una Hunt, which showcased diverse settings of Moore’s songs, from authentic folk ballads to art songs by composers ranging from Stanford to Duparc. Gavin was at his best in Schumann’s Venetian airs, drawn from the composer’s Myrthen cycle, where the tenor’s strong sense of line and articulate diction was showcased; Campbell’s performance of Duparc’s ‘Élégie’ impressively negotiated the song’s wide range, extended phrases and sustained tones.

The need to alleviate the prevailingly male vocal roles in ‘Counterparts’ was accomplished by casting soprano Anna Jeffers as Weathers, a portrait of masculine conceit and arrogance, a role which she carried off with aplomb. Emma Nash was a vibrant presence as the rich client Mrs Delacour, the flirtatious barmaid, and as Farrington’s vulnerable, pyjama-clad son Tom who, having let the fire go out in his mother’s absence (she is at chapel), earns a beating from his father. Rory Beaton’s lighting was appropriately discomforting at this point. There was, however, little sense of Joyce’s bitter critique of Catholicism at the close, a significant dimension of the story, when Tom tells his father that if he stops beating him, he will say a Hail Mary for him.

Synnott’s score - for piano and string quartet - to some extent mimics Joyce’s representation of ‘paralysis’, comprising as it does a mosaic of ostinato fragments, assembled like a jig-saw; any one of which may be dramatically illustrative but which, together, do not really form a coherent whole. The text setting is Britten-esque which some effective rhythmic displacements, but multi-syllabic words tend to be rushed; when we need to hear the text, the accompaniment is appropriately and effectively reduced to a medley of sustained strings, piano chord punctuations and pizzicato interjections.

There was one major change to the narrative of ‘The Boarding House’ which significantly altered the perspective and satire, and reduced the ironic weight of the ending. In this story, unusually, Joyce takes us to a world dominated and organised by women: Mrs Mooney, a butcher’s daughter, is, Joyce tells us ‘a determined woman’: her husband ‘drank, plundered the till, ran headlong into debt’, and when he ‘went for his wife with the cleaver’, Mrs Mooney ‘went to the priest and got a separation from him with care of the children’. O’Mahony attests to Mrs Mooney’s background via the carcasses, cleavers and hand-saws that hang behind the glass, replacing the whiskey bottles of ‘Counterparts’; and the carving knife that rests menacing alongside the hunk of dinner-time meat tells its own tale. But, the libretto does not fully convey Mrs Mooney’s striking power, as a woman, in a patriarchal, Catholic society - a power which has led her to self-determination.

Synnott and O’Mahony turn Mrs Mooney’s son, Jack, into our ‘narrator’ - a self-confessed cad who is, in his own words, as quick with his wits as he is with his mitts; but Jack doesn’t inform us of Mrs Mooney’s rapacious intent to marry her daughter off to one of their unsuspecting boarders - a Mr Doran, who is ‘not rakish or loud-voiced like the others’ - by demanding ‘reparation’ for the deflowerment of her daughter. Joyce presents marriage as a ‘trap’, sprung by a conniving mother and her daughter on a sober young man; whereas the opera presents Mrs Mooney as oppressive and disapproving of her daughter, Joyce makes clear that Polly has been nudged towards her fate by her mother. Mr Doran agrees to marry the girl he has, almost inadvertently, kissed, out of concern for conventional morality and fear of losing a lucrative position - not, as in the opera, because he fears the reprobation of his family. ‘[H]is instinct urged him to remain free’ and he ‘had a notion he was being had’, but he cannot face the realities and risks of action - he is another of Joyce’s paralysed Dubliners. At the close of Joyce’s tale, Polly has convinced herself that marriage will bring her happiness; at the close of the opera, recognising her husband-to-be’s sadness, she is served up like a sacrificial lamb. She is, in Joyce’s tale, sacrificed at the altar of her mother’s greed, but she does not realise it; hence, Synnott and Riordan deprive the tale of its most painful irony.

Despite this, we are again presented with a striking, swift dramatic skewering of pretence and hypocrisy. Anna Jeffers was a fearsome Mrs Mooney, Emma Nash a charming blend of ingenue and seductive opportunist. By repeatedly seating ‘Bob’ [Doran] (Andrew Gavin) with his back to the audience - as during Mrs Mooney’s interrogation of her daughter, or when Polly urges Doran to resolve the dilemma - Comyn mimics the reticence of Joyce’s narrator in revealing Doran’s feelings. The boot of Jack Mooney on the kitchen table was, I felt, an unnecessarily aggressive presence; the threat to Mr Doran’s public reputation at work and within the Church - Joyce tells us that ‘he had been employed for thirteen years in a great Catholic wine-merchant’s office’ and that the ‘recollection of his confession of the night before was a cause of acute pain to him’ - is sufficient to make a man of Mr Doran’s conformist inclinations cower. Overall, though, these were compelling dramatic vignettes: perhaps they might benefit from expansion - each story seems to hold a wealth of nuance and inference, worthy of a more extended treatment.

Rossini’s La Scala di seta (The Silken Ladder), a one-act farsa comica in fifteen scenes, is mostly known to audience for its spirited overture, and its panoply of secret rendezvous and mistaken identities promised more insouciant entertainment the following afternoon. Written in 1812 when the composer was only 20 years old, the opera’s plot and characters are rooted in the commedia tradition. Giulia, an opera singer, has secretly married Dorvil, against her guardian Dormont’s wishes, and each night lets down the eponymous silken ladder so that he may climb into her room. Dormont wishes his charge to marry Blansac; his old retainer, Germano, spies on the amorous intriguers. Much misunderstanding and meddling ensue but eventually Giulio tricks Blansac into falling for her cousin Lucilla and all ends well.

Luca Dalbosco’s over-elaborate set - more bordello than back-stage boudoir, with countless ladders draped in silk, a chaise-longue and an over-laden dressing-table crammed onto the platform - made things even more complicated than they need have been, and potentially treacherous for the cast. The overture (played by music director Tina Chang, who had accompanied Tomasoni with similar unassuming accuracy and grace just a few hours earlier), was neatly dramatised by director Nathan Troup. Germano (Filippo Fontana), crept in bearing the diva’s flowers and chocolates, and finding the latter to his distaste hastily shoved a half-eaten sweet back into the box before Giulia’s (Galina Bakalova) arrival. Bakalova donned a towering wig and passed through the stage curtain erected stage left, to perform to a posse of adoring fans whose slow-motion clapping and rose-throwing was visible through the open curtain. This swiftly established where the egos and eccentricities lay, but thereafter the crowded platform proved impractical for deft comic gesture. There were not many laughs to be had and it did not help that Rory Beaton’s red-hued, dim lighting seemed to cast a patina of grey over the characters, though perhaps that was just a peculiarity of the angle from which I was viewing the action.

The cast were rather uneven. Best of the bunch was Fontana, whose Germano was a mixture of drollery and dunceness. The role comprises a lot of recitative and here, and in the numerous duets with Giulia, Fontana proved himself a strong singer-actor; he had to wait a while for his aria moment, but when it came ‘Amore Dolcemente’ was full of lyric charm and accurately sung, with firm, full tone. Chase Hopkin’s Dormant was also a strong, convincing presence (despite being lumbered with a silly, spiralling goatee) and Cecilia Gaetani made much of the small role of Lucilla singing her aria, ‘Sento talor nell’anima’, with grace and clarity.

As Giulia, Bakalova acted with spirit and sparkle, but her soprano was often shrill and hard; she whipped through the coloratura precisely, but did not win our sympathy for the flustered diva. Ji Hyun Kim struggled with Dorvil’s ardent tenor aria, ‘Vedro qual Sommo Incanto’; the dynamics were unsubtle, the intonation strayed, and the bravura section went entirely adrift. I’ve heard and enjoyed the Korean tenor’s performances at the ROH, where he was a Jette Parker Young Artist, many times, so perhaps this was just a case of first-performance nerves.

Some of the ensembles were ragged, but the finale scene, which saw the entire cast tied up with the silken ladder before they wriggled free from Dormant’s clutches and accusations, bubbled nicely. Overall, though, the production fell rather flat. Thank goodness for Fontana who, despite Germano’s incompetence, proved an utterly safe pair of hands at the core of the drama.

That just left Rigoletto to complete the trio of Short Works. One might be forgiven for agreeing with director Roberto Recchia who, in his programme note, wrote of this most well-known of Verdi’s operas, ‘What is left to be said by the poor director?’ But, that would be to under-estimate Recchia who has proved year after year at Wexford that he can be relied on to distil the essence of a work and communicate it to the audience with precision, focus and impact. Here, his answer to his own question was pertinent: ‘Maybe nothing, if not digging as deep as possible into every character.’ And, Recchia was ably aided by his talented cast, most particularly by his hunch-backed, vengeful jester.

Together with his stage/costume designer, Dalbosco, and lighting designer, Beaton, Recchia offered a masterclass in just how much can be achieved with minimal means: and, the Act 3 Quartet was the pinnacle of such discerning visual and dramatic conception. Prevailing shadows and swirling mist conjured a sinister mien, which was intensified by the menacing carnival masks donned by the Duke’s courtiers - a threatening band of vicious rabble-rousers - and Rigoletto himself. Just two black blocks were required to evoke the ducal palace, raising Aidan Coburn’s preening Duke of Mantua to a position of worshipful elevation. As Recchia says, we all know ‘what happens’: and he foreshadowed the tragic outcome of Monterone’s curse in the opening visual image - a body-bag centre-forestage, over which a distraught figure bowed in grief before lifting his burden and bearing it through the curtain at the rear. The subsequent reprise of this image was replete with pain and pathos.

Occasionally I felt that Music Director Giorgio D’alonzo pushed the tempo along a little too impetuously in the ensembles; but, the pared-down performance, lasting 90 minutes, told a clear tale and the singers were well cast. Coburn has plentiful bright ring and rattled off ‘La donna è mobile’ with confidence and éclat. Thomas D Hopkinson was a forceful presence as Monterone, his dreadful bitterness apparent in the dark hues of Hopkinson’s bass. Toni Nežić has quite a light-weight voice for Sparafucile, but it’s an appealing sound and he acted convincingly; this was no cardboard cut-out villain, but a three-dimensional, conflicted rogue who retained some small sense of moral integrity. As Maddalena, Veta Pilipenko revealed a richly coloured full mezzo-soprano; when she begged Sparafucile to spare the Duke’s life it was easy to believe that she was motivated by genuine love. The minor roles - Giovanna (Vivien Conacher), Count Ceprano (Malachy Frame), Matteo Borsa (Simon Chalford Gilkes) and Marullo (Steven Griffin) were all more than competently filled.

Giuliana Gianfaldoni was the vocal and visual embodiment of ‘goodness’; Gilda’s love for her father was fiercely communicated; her silky, pure soprano caressed ‘Caro nome’, and the ornamentation was angelically clean and sweet. But, it was Charles Rice’s Rigoletto who held the audience rapt; this was a tremendously committed performance, as detailed vocally as it was dramatically. This Rigoletto held his crooked body at an angle from his condescending tormentors; masked or not, his face was bent slightly downwards - he never allowed himself to catch their eyes. Every word was clear and made to serve the characterisation. Rice’s baritone is full of different hues and textures, and we heard them all; perhaps a little more light and shade in terms of dynamics might have been the icing on the cake, but who could fault such a committed, captivating performance? Rice looked both overjoyed and overcome at the close; he fully deserved his ovation.

And so my 2017 Wexford Festival drew to a close all too quickly, with only the thought of next year’s programme to cheer me up! In 2018, once again eschewing German repertoire, David Agler has chosen to present a double bill of Saint-Saëns’La Princesse Jaune and Franco Leoni’s L’oracolo, Dinner at Eight by William Bolcom, and the original version of Gounod’s Faust.

Claire Seymour

Foroni: Margherita (20th October)

Conte Rodolfo - Yuriy Yurchuk, Ser Matteo - Matteo d’Apolito, Margherita -

Alessandra Volpe, Ernesto - Andrew Stenson, Giustina - Giuliana

Gianfaldoni, Roberto - Filippo Fontana, Gasparo - Ji Hyun Kim; Director -

Michael Sturm, Conductor - Timothy Myers, Set and Costume Designer - Stefan

Rieckhoff, Lighting Designer - D.M. Wood.

Alfano: Risurrezione (21st October)

Prince Dimitri - Gerard Schneider, Katiusha - Anne Sophie Duprels, Simonson

- Charles Rice, Governanate/Anna - Romina Tomasoni, Sofia Ivanovna - Louise

Innes; Director - Rosetta Cucchi, Conductor - Francesco Cilluffo, Set

Designer - Tiziano Santi, Costume Designer - Claudia Pernighotti, Lighting

Designer - D.M. Wood.

Cherubini: Medea (22nd October)

Medea - Lise Davidsen, Glauce - Ruth Iniesta, Neris - Raffaella Lupinacci,

Jason - Sergey Romanovsky, King Creon - Adam Lau; Director - Fiona Shaw,

Conductor - Stephen Barlow, Set and Costume Designer - Annemarie Woods,

Assistant Director - Ella Marchment, Lighting Designer - D.M. Wood,

Choreographer - Kim Brandstrup.

Synnott: Dubliners (20th October)

Polly/Mrs Delacour/Barmaid/Tom - Emma Nash, Mother/Weathers - Anna Jeffers,

Bob/Alleyne/O'Halloran - Andrew Gavin, Jack/Flynn - David Howes, Higgins -

Peter O' Donohue, Farrington - Cormac Lawlor; Stage Director - Annabelle

Comyn, Music Director - Andrew Synnott, Set Designer - Paul O'Mahony,

Costume Designer - Joan O'Clery, Lighting Designer - Rory Beaton.

Rossini: La Scala di seta (21st October)

Dormont - Chase Hopkins, Giulia - Galina Bakalova, Lucilla - Cecilia

Gaetani, Dorvil - Ji Hyun Kim, Blansac - Nicholas Morton, Germano - Filippo

Fontano; Stage Director - Nathan Troup, Music Director - Tina Chang, Stage

& Costume Designer - Luca Dalbosco, Lighting Designer - Rory Beaton.

Verdi: Rigoletto (22nd October)

Rigoletto - Charles Rice, Gilda - Giuliana Gianfaldoni, Duke of Mantua -

Aidan Coburn, Sparafucile - Toni Nežić, Maddalena - Veta Pilipenko,

Giovanna - Vivien Conacher, Count Ceprano - Malachy Frame, Matteo Borsa -

Simon Gilkes, Count Monterone - Thomas D Hopkinson, Marullo - Steven

Griffin; Stage Director - Roberto Recchia, Music Director - Giorgio

D’alonzo, Stage & Costume Director - Luca Dalbosco, Lighting Designer -

Rory Beaton.

Photo credit: all images by Clive Barda

October 26, 2017

The Genius of Purcell: Carolyn Sampson and The King's Consort at the Wigmore Hall

Framed at the centre of the platform by bass violist Reiko Ichise and theorbo player Lynda Sayce, with violinists Cecilia Bernardini and Huw Daniel to right and left, and Robert King’s harpsichord and chamber organ to the rear, Sampson looked and sounded the epitome of elegance and expressiveness. Her smoothly polished soprano is a perfect fit for Purcell’s melodic fecundity. The tone was clear as a bell, the diction superb: the words seemed to float on the melody. And, the purity and easefulness of Sampson’s sound production is wonderfully suited to Purcell’s rhythmic shifts and quirks which were pliantly absorbed into the flowing phrases. Moreover, while Sampson’s tone is unblemished it is never colourless: she imbued the clean line with judicious expressive radiance.

The programme alternated some of Purcell’s ‘greatest hits’ with instrumental sonatas, largely drawn from the Ten Sonatas in Four Parts that Purcell’s wife, Frances, published in 1697, two years after her husband’s untimely death. The first and third of the composer’s three settings of Colonel Henry Heveningham’s ‘If music be the food of love’ bookended the performance. In the 1692 setting, Purcell often assigns two notes to each syllable and Sampson flowed freely through the relaxed vocal line, accompanied by bass viol, theorbo and harpsichord. The third setting, dating from three years later, is more extravagant and elated, and here Sampson’s melismatic elaborations had a delightful ‘slipperiness’ which captured the poet-speaker’s excited appeals; the latter were echoed in Ichise’s vivacious but eloquent bass viol line.

The tempo of ‘Music for a while’ seemed to me to be fairly swift and the angular ground bass unfurled with compelling forward motion as it searched for new harmonic terrain and then retreated to home ground in an unceasing exploratory cycle. Similarly, the vocal line seemed to be perpetually striving towards something just out of reach, the small leaping motifs creating energy and brightness. When the peaks are reached many of the vocal phrases slip down scalically, and the flowing tempo helped Sampson create a fluid, silky vocal line and to integrate the shifts of register into a sinuous whole which was enriched by plangent instrumental suspensions.

The text for ‘Not all my torments can your pity move’ is just four lines long, but Purcell manages to traverse a wide emotional landscape. Above the grave, slow-moving bass line, Sampson sang with recitative-like freedom at the start, flourishing through Purcell’s melismatic rhetoric in the opening line to convey the anguish of the rejected poet-speaker’s unrequited love, a biting pain which seems to deepen with the extended, more angular repetition. The contrasting simplicity of the monosyllabic directness of ‘your scorn’ was thus a more pressing assertion of an angry despair which overflowed in the impassioned excess of ‘increases with my love’. ‘Yet to the grave I will my sorrow bear’ sank to the depths, yet Sampson’s voice remained full of emotive weight; and, while there was vigour in the hopeful repetition of ‘I love’, the final melisma was a cry of desolation. This was wonderfully dramatic, communicative singing.

Ichise’s ground bass again created a fluent momentum in ‘O! fair Cedaria’, which complemented the freedom and grace of Sampson’s opening melisma, while the gracefulness of the soprano’s ornamentation was an exquisite embodiment of the ‘beauty and charms’ which shine so dangerously from Cedaria’s visage. Again, lovely interaction between voice and bass viol created a beguiling lyrical rhetoric, suggestive of the enslavement of one who ‘Unless I may your favour have/[cannot] one moment live’, an almost delightful torture which was emphasised by the major/minor harmonic tensions and the sustained sequences played by the organ and theorbo which underpin the final magical vocal descent.

Such cares were swept aware by the unadorned purity and melodicism of ‘Fairest Isle’, in which the two violins provided invigorating inter-verse reflections, the two fiddlers injecting freshness and life through interesting bowing which created a sense of airiness and lift, above the lightly tripping harpsichord. King chose the chamber organ to accompany ‘O solitude’ but there was no sense of ‘heaviness’, particularly as Sampson’s isolated single-syllable utterances were so perfectly placed and the rises in the vocal line were infused with a frisson of brightness. She withdrew to an enchantingly delicate pianissimo, though, when reflecting on her own ‘fancy’ - ‘I hate it for that reason too,/Because it needs must hinder me/From seeing and from serving thee’ - and the tierce de Picardie in the final phrase, ‘O solitude, O how I solitude adore’, evoked the self-reflective indulgence of the poet-speaker.

‘Incassum Lesbia, incassum rogas’ (In vain, Lesbia, do you beseech me), written following the death of Queen Mary in December 1694, was a highlight of the recital. In the framing recitative-like sections Purcell employs every rhetorical harmonic and rhythmic gesture in his arsenal to communicate unassuageable grief. Sampson relished the dissonant cries and sobs, which were paradoxically both sweet and sorrowful, a dualism complemented by the instrumental swings between major and minor harmonies. In contrast, the central aria ‘En nymphas! En pastores!’ (Lo, the nymphs, lo the shepherds) lilted flowingly, and the dark colours which saturated the final lines were assuaged by the warmth and stability of the final image of the Queen’s ‘star’, which ‘Shines on in the heavens’.

The final item, ‘If love’s a sweet passion’, was given persuasive direction by the bass viol and enlivened by the contributions of the two violins. We had had the opportunity to enjoy the instrumentalists’ conversation in the Sonatas which had intervened between the vocal numbers. The King’s Consort combined precision and flexibility, creating varied textures and timbres within single sonatas. Yet, even when the harmonic dissonances created density there was a prevailing lightness which allowed the interplay between instruments to come to the fore, as in the Allegro of the Trio Sonata in G minor, or the Canzona of the Sonata of Four Parts in A minor. Elsewhere, there was a seamless blending, as in the beautiful evenness and serenity of the Largo which closes the Sonata in D Minor. The instrumentalists did not overlook even the slightest harmonic nuance, and guided unobtrusively by King used Purcell’s myriad harmonic devices and discordances - the yearning suspensions of theLargo of the Sonata in B minor were particularly telling - to create rhythmic impetus and build coherent forms from diverse parts.

The Sonata in F major which opened the second half of the concert was especially appealing, with second violinist Huw Daniel making a lively contribution in the Canzona and ensuing Grave, the violins’ dialogue creating a sense of ‘theatre’ - fitting for a work commonly known as the ‘Golden’ Sonata. Here, too, the bass viol line was full of vigour and freedom; indeed, King reminded us in a programme note that the sonatas had initially been written in three parts but that a separate basso continuo part had been added - for ‘the Organ or Harpsecord’ - which strengths the harmonic foundations of the sonatas and enhances the chromatic colouring so characteristic of the composer’s harmonic language.

The full house at the Wigmore Hall were warmly appreciative at the close, and when King disturbed the symmetry of the WH florist’s platform adornments, plucking a red bloom to bestow upon the unassuming Sampson, the gesture seemed an appropriate mirror of our own gratitude and admiration.

Claire Seymour

The Genius of Purcell : The King’s Consort - Carolyn Sampson (soprano), Cecilia Bernardini & Huw Daniel (violins), Reiko Ichise (bass viol), Lynda Sayce (theorbo), Robert King (harpsichord & chamber organ)

Henry Purcell: Sonata of Four Parts in A minor Z804, ‘If music be the food of love’ (first setting), ‘Music for a while’, Trio Sonata in G minor Z780, ‘Not all my torments’, ‘O! Fair Cedaria’, Sonata of Four Parts in D minor Z805, ‘Fairest Isle’, Sonata of Four Parts in F Major Z810, ‘O solitude, my sweetest choice’, Sonata of Four Parts in G minor Z807 (Adagio), ‘Incassum Lesbia’ (The Queen’s Epicedium), Sonata of Four Parts in B minor Z809, ‘If music be the food of love’ (third setting), ‘If love’s a sweet passion’.

Wigmore Hall, London; Wednesday 25th October 2017

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Carolyn%20Sampson%20credit-Marco-Borggreve.jpg

image_description=The Genius of PurcellCarolyn Sampson and The King’s Consort at the Wigmore Hall

product=yes

product_title=The Genius of Purcell: Carolyn Sampson and The King’s Consort at the Wigmore Hall

product_by=Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Carolyn Sampson

Photo credit: Marco Borggreve

October 23, 2017

Opera Rara - How to Rescue a Lost Opera

Opera Rara - How to Rescue a Lost Opera from Opera Rara on Vimeo.

October 18, 2017

Hans Werner Henze : Kammermusik 1958

A landmark recording because it reflects the Scharoun Ensemble's years of experience with Henze and his music. Their relationship began in 1983, shortly after the ensemble was formed. Kammermusik 1958 is one of their signature pieces. "It soon became clear" they write "that the composer's interpretation of Kammermusik 1958 was freer than the written score. Henze took some tempi more slowly, which resulted in more songful, indeed quite romantic music". This performance is outstanding, more assured and more idiomatic than the original recording made in November 1958 with Peter Pears and Julian Bream. Though Henze himself conducted that premiere, he was young, still very much in thrall to Britten, Pears and their cliquey circles. As Henze developed, he became himself, finding the freer, more poetic approach this recording honours. Obviously the first recording is part of the archive, but this new performance opens horizons: very much in the spirit of the poetry of Hölderlin's text and of Henze's mature work. This performance also uses Henze's 1963 revision of the score.

Kammermusik 1958 is also a landmark because it represents a period in which Henze made a creative breakthrough. It connects to the sensuality of Undine and to the esoteric Being Beauteous, but also explores ideas which Henze would develop in later years. The piece begins with a horn call, which is repeated more quietly, as if in response — a deliberate reference to Britten's Serenade for tenor, horn and strings. Almost immediately, though, Henze breaks into new territory — long, shimmering lines that seem to stretch into endless space. The clarinet leads, like the call of a shepherd's flute sounding out over distance.

From this evolves the first song with its long, arching lines that rise expansively, accompanied by guitar. The text is abstract, almost impressionistic in its evocation of colour and mood. "In lieblicher Blue blühet mit dem metallenen Dache der Kirchtum." Hölderlin in his tower, singing to the moon, Andrew Staples and Jürgen Ruck, eternal troubadours. Hölderlin's poetry fascinates modern composers.This particular hymn has also been set by Wilhelm Killmayer and Julian Anderson (whose version will be heard 21/10/17 at the Barbican.) Staples's singing is pristine, for "Reinheit aber ist auch Schönheit". Two Tentos for solo guitar frame the second song in which Henze sets another section of Hölderlin's hymn. Innen aus verschiedenem entsteht, where the poet connects humble mankind with the vastness of the universe. "als der Mensch, der heisset ein Bild der Gottheit". Ruck's playing creates intimacy, cradling the song with protective warmth. It also recreates the flowing rhythms of Tento I which Henze titled "Du schönes Bächlein", a reference to images in the text, which resurface in the third song, where the pace picks up. Staples sings the phrase "Du schönes Bächlein" with minimal accompaniment, as if the poet were transfixed by a vision.

As the voice falls silent, the ensemble emerge in a short Sonata for the ensemble, brisk, turbulent figures that seem to have a life of their own. "Möcht ich ein Komet sein?" Staples sings. Key phrases like "eine schöne Jungfrau" deliciously savoured. The final line "Myrten aber gibt es in Greichenland" shone with intense light, for this epitomizes Hölderlin's concepts of beauty, from the ideals of antiquity far into the future. For Henze, the guitar is more than a “Mediterranean" device. It connects to the lute of Orpheus and all that implied in classical mythology. An inventive cadenza, where the strings dance and cor and bassoon moan, until strong chords in ensemble introduce the next song, "Wenn einer in den Spiegel siehet". which flows with great freedom, as if the clarity of the mirror were drawing ideas into sharper focus. The tento for guitar, which follows, is titled "Sohn Laios" which connects to the references to Oedipus in this and the final song, "Wie Bäche reißt des Ende von Etwas mich dahin". Henze creates a stream of consciousness, weaving text, music, ideas and images together in a stream that's at once elusive yet intriguing. Hölderlin contemplates the destiny of suffering. "Leben ist Tod , und Tod ist auch ein Leben". Long, plaintive vocal lines,yet oddly affirmative, merging into a beautiful wind melody, which might suggest ancient flutes. Horn, cor, bassoon and contrabass create mysterious atmosphere, lightened by strings. This last Epilogue, added by Henze in1963, is extraordinarily moving, very "inwards", true to Hölderlin and his visionary imagination. In the notes, Jürgen Ruck comments on the connections between the Oedipus legend and Henze's socio-political views and his work in music theatre. In some ways, the Oedipus theme might also apply to other things in Henze's life, including his relationship to Britten.

The Scharoun Ensemble Berlin paired this Henze Kammermusik 1958 with Henze's Neue Volkslieder und Hirtengesänge (183/1996) for Bassoon, Guitar and String Trio. Excellent choice, for these extend the idea of Arcadian "Shepherd" songs and fit well with Hölderlin. These songs were premiered by the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin in 1997, presumably with Henze himself in attendance.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/7198_t.png image_description=Tudor 7198 [CD] product=yes product_title=Hans Werner Henze : Kammermusik 1958, Neue Volkslieder und Hirtengesänge product_by=Andrew Staples, Tenor; Markus Weidmann, Fagott; Jürgen Ruck, Gitarre; Scharoun Ensemble Berlin. Daniel Harding, Dirigent product_id=Tudor 7198 [CD] price=€15.99 product_url=https://www.jpc.de/jpcng/classic/detail/-/art/neue-volkslieder-und-hirtengesaenge/hnum/6882747

October 15, 2017

Written on Skin: the Melos Sinfonia take George Benjamin's opera to St Petersburg