November 30, 2017

Girls of the Golden West in San Francisco

John Adams’ eighth opera takes his now astonishing sonic and dramatic vocabulary to ever greater depths, creating, ultimately, shattering climax to the lives of seven early Californians, their stories, as construed by librettist Peter Sellars, unfolding both in their own words and in the words of poets and slaves in American history. The real protagonist of Girls of the Golden West is however the corpus of the 49er miners who pursue riches above all else and their inalienable right to the gold of the California mountains.

Girls of the Golden West, as staged by Peter Sellars, is an apt prelude to San Francisco Opera’s forthcoming Der Ring des Nibelungen (it’s essentially the same story). But far more than a prelude it stands on its own as the artistic exploration of the human and social forces of the American post-industrial era (Wagner’s Ring is of the industrial world), insisting that we inherit from these miners a collective guilt for destroying the hopes and lives of people of color — black, brown and yellow, and, yes, even poor Joe Cannon from Missouri (white). It is of epic proportion though it takes a mere three hours compared to the sixteen hours of Wagner’s epic when both finally arrive at a moment of purification.

The minor Joe in the whorehouse, with whore Ah Sing, and corp de ballet whores

The minor Joe in the whorehouse, with whore Ah Sing, and corp de ballet whores

But Sellars’ Girls of the Golden West goes dramatically beyond its philosophic purpose, immersing us in Adams’ musical worlds of each of its characters. Dame Shirley is an actress from New England who plays Lady Macbeth to the down-on-luck miner Clarence’s Macbeth inciting the miners to lynch Ned Peters, a black slave turned teamster. Joe Cannon’s Sally back home in Missouri marries a butcher, on the rebound he marries a Chinese whore, Josefa is the beautiful Latina lure to attract the miners to the bar where Ramón is the croupier.

Act I is an idyll of perfect life inasmuch as life may be dreamt to be in this beautiful if rough, ugly world. In Act II these worlds are brutally vanquished in music that relentlessly throbs in powerful pulses, punctuated with bursts of tone that cannot be placed.

This bit of California history is real, in the real words of its historical actors, and thus alien to history or myth as usually imagined by opera where elaborated human situations are acted by invented human psyches. Composer Adams composes music to these real words that create art songs, an extended series of songs that you know and feel to be a cycle of some sort. There is a rare duet or two, six or so magnificent male choruses, several ballets (a respectful bow to grand opera), an occasional orchestral interlude. But there is no dialogue and there is no real story.

It is beautiful music of profound lyricism that is fiendishly difficult to sing, thus adding to the atmosphere of art that liberates this Girls of the Golden West from its imposed moral reprimand.

The Sellars production plays on the minimal, the literal and the naive. Scenic designer David Gropman ignores masking, thus there is no illusion. We know what we see is theater, and only that. Against an upstage gold drape stagehands walk on and off with props now and then. Visual quotes from rustic melodrama fly in and out. There is a huge stump and slice of a sacrificed California redwood. Costume designer Rita Ryack stays literal to the period, adding naive concept to dancers’ costumes. Choreographer John Heginbotham too played the naive against the en point classical technique exploits of the four women of the corps de ballet and particularly for the spider dance of prima ballerina Lorena Feijóo as the famed Lola Montez.

Josefa in the act of murdering Joe

Josefa in the act of murdering Joe

But finally it was the words, and nothing but words, discretely if significantly amplified by sound designer Mark Grey. Amplification served to add heroic dimension to the voices most notably to mezzo-soprano J’Nai Bridges as Josefa Segovia and baritone Elliot Madore as Ramón, these two roles the focus of the Sellars’ romantic tragedy — and it was sublime. Bass-baritone Davóne Tines as Ned Peters as the former slave was the moral focus, drawing a character of immense stature. Tenor Paul Appleby was the driven miner Joe Cannon who with soprano Hye Jung Lee as the Chinese whore Ah Sing created the grittiness and hopelessness of the gold rush free-for-all in their go-for-it-all performances.

Finally the soul of the opera was found in the performance of bass-baritone Ryan McKinny as Joe’s friend Clarence who wielded Lady Macbeth’s knife, forever transforming the lives of the opera’s victims, and in the end, perhaps, embodying the opera’s spiritual redemption (if there was one). The opera’s redeemer was Dame Shirley sung by soprano Julia Bullock who saw all, and as Lady Macbeth motivated all. Mlle. Bullock found the amplitude of emotional tone to observe, live and understand the tragedies of Downieville, by now a mere gold rush relic in the high Sierras, never letting us forget that these are real people with real names as was she (note that skin color was not always consistent with character).

These unique artists responded perfectly to the John Adams musical world, as did the spectacular accomplishment of the men of the San Francisco Opera chorus, all mastering the daunting score in what seemed to be a perfect performance (the fourth of eight). Conductor Grant Gershon took the San Francisco Opera Orchestra to the magnificent heights of the Adams score, in sometimes mind and heart boggling amplified fortes.

Surely this is composer John Adams’ masterpiece. It is understood that the masterful Peter Sellars setting of the opera is but one of the infinite possibilities for stagings of the Sellars libretto and Adams score.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Dame Shirley: Julia Bullock; Ned Peters: Davóne Tines; Joe Cannon: Paul Appleby; Ah Sing: Hye Jung Lee; Clarence Ryan McKinny; Josefa Segovia: J’Nai Bridges; Ramón: Elliott Madore; Lola Montez: Lorena Feijóo. Chorus and Orchestra of the San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Grant Gershon; Stage director: Peter Sellars; Set designer: David Gropman; Costume designer; Rita Ryack; Lighting designer: James F. Ingalls; Sound designer: Mark Grey; Choreographer: John Heginbotham. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, November 29, 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/GirlsWest_SFO1.png

product=yes

product_title=Girls of the Golden West in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera.

DiDonato is superb in Semiramide at Covent Garden

Even with some customary cuts, there are over three and a half hours of music, stretching the attention span of most modern audiences. So, some enticing ‘crowd-pullers’ are required, and the ROH served them up in the form of a prima donna non plus ultra, a star-studded cast, and a staging by David Alden that emphasises the Shakespearean scale of the opera’s moral complexities and emotional conflicts.

Crime and punishment, guilt and retribution are at the heart of Semiramide. The opera, which is based on Voltaire’s play Sémiramis, is driven by an innocent hero’s quest for revenge and a guilty anti-heroine’s desire for redemption. The sins of the protagonists rival the most heinous misdeeds to be found in mythic Greek tragedy, and a Freudian would have a field-day with a plot whose deviancies include Oedipal attraction and matricide.

The eponymous Queen of Babylon may be the builder of the wondrous Hanging Gardens, but her wickedness must be purged if her kingdom of Assyria is to be renewed. She has murdered her husband, Nino, and now rules alongside her accomplice and lover, Assur. Forced to name her heir, she chooses the swashbuckling soldier Arsace to whom she is attracted but who, unbeknown to Semiramide, is in fact her long-lost son. In any case, Arsace shares with Assur and Prince Idremo an infatuation with Princess Azema. It takes the divine/supernatural intervention of the gods and a ghost to ensure justice is delivered.

Reviewing Opera Rara’s concert performance of Semiramide at the Royal Albert Hall - one of the highlights of the 2016 Proms season - I commented that ‘a concert staging of the opera was perfectly apt’, given that Rossi’s libretto relates a drawn-out mission to avenge an assassination which has taken place years before while the perpetrators of the crime are essentially in the hands of the gods. Director David Alden opts for a monumentalism which reflects the epic nature of the protagonists’ emotional maelstrom, and which is complemented by chiaroscuro effects (lighting by Michael Bauer) that enhance the air of intrigue and secrecy. But, the vastness and majesty of Paul Steinberg’s swivelling, lowering, expanding sets, while making the most of the massive extent of the ROH stage, don’t do much to pep up the drama.

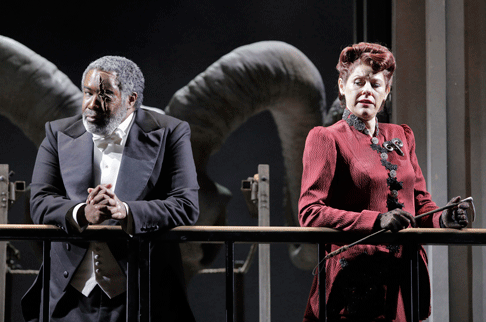

Cast, Act 1. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Cast, Act 1. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

We may not be in Babylon, but we seem to be in the modern-day Middle East. Tyranny is not geography-specific though, so there are allusions - through iconographic propaganda; drab utilitarian locales juxtaposed with richly-hued ceramic mosaics; a cornucopia of marvellously detailed costumes (Buki Shiff has conjured a dressing-up box of every child’s dreams); and choreographic stylisation (Beate Vollack) - to the Soviet Union, North Korea and south-east Asia, as well as to caliphates of yore and now. There are turbaned Turks, shuffling Islamic priests and women in burkas, alongside embroidered Mughal robes and modern business suits. Alden’s general concern seems to be the trouble that brews when politics meets religion, but there’s no clearly articulated ‘argument’, political or otherwise.

Joyce DiDonato (Semiramide) and Michele Pertusi (Assur). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Joyce DiDonato (Semiramide) and Michele Pertusi (Assur). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

There are, however, visual and gestural motifs a-plenty. The ROH Chorus - in tremendous voice and offering some seriousness to complement the splendour - sport a fabulous array of costumes and wave i-Pads and hymn-books with equal fervour. The High Priest of the Magi, Oreo, is kitted out with some natty pink-tinted shades. There’s a small child clutching a stuffed-toy horse who drifts, then rolls, around the stage. Assur has more medals on his uniform than Prince Philip, while Princess Azema - whose future will be determined by others - is confined inside a gold lama straight-jacket and afflicted by, alternately, arm-flailing fits and catatonia; moreover, her feet seem to have been bound Chinese-style, as she has to be fireman-lifted on and off the stage. The smoke-swirling resurrection of Nino’s ghost (acted by John O’Toole) owes more to Bram Stoker than to Hamlet; well, that will teach Semiramide for disrespectfully plonking her goblet of red wine on her dead husband’s coffin.

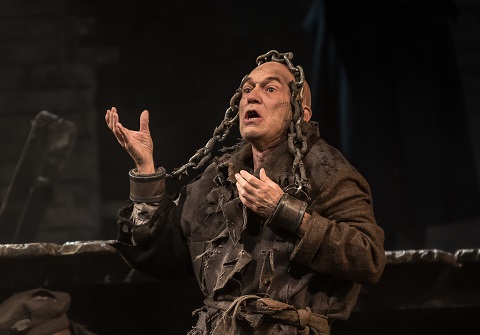

John O’Toole (Nino’s ghost). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

John O’Toole (Nino’s ghost). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

In the opening scene, the citizens, who are celebrating the anticipated announcement by their Queen of the identity of the next King, assemble at the feet of a huge, pedestalled statue: the prophet Baal has been replaced by a modern-day dictator, though there are distinct shades of Ozymandios. Later we get the full picture, in the form of enormous wall-paintings of a royal clan who bear a disconcerting resemblance to the US First Family. In one looming portrait, the King raises an arm à la Statue of Liberty while the Alpine view evokes the Romantic questing of Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog - though, facing us, he’s not really inviting us to explore his vision, but showing us what he has already conquered.

Semiramide is an opera in which the Queen’s redemption is necessary for the renewal of her state, and fortunately for this production, it is itself redeemed by some fabulous singing, not least by Joyce DiDonato in the title role. What struck me most was what a perceptive, intelligent and thoughtful singing-actress DiDonato is. She can rattle off the pyrotechnics and infuse the Queen’s lines with beguiling lyricism; but she does so much more than this. She shapes each tiny gesture into meaningful musical utterances which communicate every iota of Semiramide’s distress, desire and dilemma. She moves from whispered pianissimo to rich projection with startling control, and her vocal and dramatic performance perfectly accords with the visual ‘progression’. The Queen’s emotions are initially confined by black turban and veil; she then declares her regality in resplendent red and gold, topped with a sparkling crown; finally, her inner life is revealed as her dark tresses tumble over her midnight-blue silk nightdress in her bedroom colloquy with Assur. DiDonato’s understanding of her character - and how to communicate it - and her utter commitment are reason alone to see this production.

Daniela Barcellona (Arsace). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Daniela Barcellona (Arsace). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

In 2016, at the RAH, I found Daniela Barcellona’s interpretation of the role of Arsace impressively focused and profound. Here, she was less consistently in command: her voice retained its agility and dusky beauty, and there could be no doubting her dramatic presence and boldness, but at the bottom her mezzo seemed less focused this time around. That said, the two mezzos formed a stunningly affective blend in their numerous duets, and here Barcellona’s lyrical flights really did convey inner feeling and enlarge the emotional field.

The ladies didn’t entirely steal the show, though. Lawrence Brownlee is a superb Rossinian stylist, and it was a pity that we were not treated to both of Idreno’s arias. The tenor’s high excursions and expansive phrasing were as effortless as his dramatic presentation of this minor role was confident and credible - a good thing, too, when some Bollywood garlands and gallivanting threatened to reduce this Mughal raja to ridicule.

Lawrence Brownlee (Idreno). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Lawrence Brownlee (Idreno). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Assur’s mad scene was delivered with dark passion allied with accuracy by Michele Pertusi. Pertusi’s Assur is no pantomime villain: the Italian bass offered a nuanced characterisation which conveyed a complex psychology expressed through dynamic and tonal variety. In Pertusi’s and DiDonato’s Act 2 duet, their mutually destructive anger and rivalry was laid brutally bare.

All credit to Jacquelyn Stucker for her forbearance, trussed up as Princess Azema was inside gilded shackles. She sang with directness and clear tone, and it was good to see this Jette Parker Young Artist partnered by two other young singers on the ROH scheme: South Korean tenor Konu Kim (Mitrane) and South African bass Simon Shibambu (Voice of Nino’s Ghost). Due to illness, Hungarian bass Bálint Szabó was unable to sing the role of Oroe and he was replaced by Simon Wilding.

Jacquelyn Stucker (Azema). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Jacquelyn Stucker (Azema). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

In the pit, Pappano aimed for and achieved pin-point precision and definition: it was clear from the overture, and from the horns’ beautifully shaped first theme, that lightness would prevail, and Pappano remained sympathetic to his singers throughout while evidently having the structural measure of the sprawling score. But, even Pappano couldn’t keep the momentum raging through a first Act lasting nearly 2 hours, although Act 2 did turn up the intensity.

Alden seems to have been intent on injecting irony into Rossini’s seria drama, but the singers ensured that the emotional depths of the opera were unfolded. And, DiDonato’s contribution cannot be underestimated: she balanced fire, fear and fatalism with astonishing conviction and credibility.

Claire Seymour

Rossini: Semiramide

Semiramide - Joyce DiDonato, Assur - Michele Pertusi, Arsace - Daniela Barcellona, Idreno - Lawrence Brownlee, Azema - Jacquelyn Stucker, Oroe - Simon Wilding, Mitrane - Konu Kim, Nino's Ghost - Simon Shibambu; Director - David Alden, Conductor - Antonio Pappano, Set designer - Paul Steinberg, Costume designer - Buki Shiff, Lighting designer - Michael Bauer, Choreographer - Beate Vollack, Orchetra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; Tuesday 28th November 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Pertusi%20Assur%20and%20iconography.jpg image_description=Semiramide at Covent Garden product=yes product_title=Semiramide at Covent Garden product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Michele Pertusi (Assur) and ROH castPhoto credit: Bill Cooper

November 29, 2017

Hans Werner Henze Choral Music

Calling these "choral" works is a misnomer, since Henze writes so well for vocal ensemble that the voices move as a unity and as individuals, like a parallel orchestra, voices interacting with instruments. Such are the densities of vocal interaction in Orpheus Behind the Wire that Henze can dispense with orchestra altogether. SATB form is stretched with such refinement that the voices are almost microparted, in 12 part a capella. The voices of the SWR Vokalensemble are so perfectly balanced that the singing seems to flow seamlessly, the rich textures, enhanced with great depth.

That sense of flowing movement is significant, for Orpheus Behind the Wire was created to be danced to. Fluid movements, subtle changes which suggest constant evolution. This is music as Greek sculpture, form as clearly defined as muscles carved in marble, or the folds of garments on statues frozen mid-flow. The progress across the five songs is formal, yet elegant and deliberate, as stylized as Greek art. The text was written in 1978 by Edward Bond, and re-tells the story of Orpheus's journey to the Underworld in search of Eurydice with a modern twist : the idea of individuals caught up in situations beyond human control. Orpheus can never unite with Eurydice, but will forever remain alone and alienated from the world around him. When Henze splits the four vocal groups into twelve individual voices, he unites meaning with musical form.

An otherworldy hum underpins the first song, What was hell like?, the vocal line shimmering on several levels. "No echo came from my music". The words “silence, silence" repeated like an echo spreading into empty distance. Orpheus and Eurydice cannot travel together, but the physical death of one means the spiritual death of the other. Thus the long lines reaching out, but not connecting. Undulating lines, where words are broken into particles and scattered, like dust in the wind, "silenced, silenced". This is deliberate irony. The singing is pitch perfect and beautifully modulated but the sentences are hard to make out, for this is the Underworld, where shadows deceive. In Hades, meaning is shrouded. By breaking up the vocal line, Henze is using sound to capture the ambiguity. Like Orpheus we must pay attention and feel our way.

Orpheus grows old, "more strings on this lyre than hairs on my head", but he is not free. Occasionally the men's voices dominate, but the mood is troubled. At last, something stirs. "Pressed" the voices sing on an upbeat, "by the weight of the world". Now tense, more anguished figures, a multiplicity of voices, their lines wavering in tumult. The text draws hope that "somewhere the starving have taken bread/from those who argue the moral of guns/ in assemblies guarded by guns". When the poor no longer shiver in rags, "Then I hear music of Orpheus, of Triumph ! of Freedom!". In the dense layers of texture, the exact words aren't easy to make out, but that might be for the reason that freedom is not yet at hand, meaning must remain occluded, secretive, literally "Behind the Wire".

In Lieder von einer Insel, Henze recalled his close friendship with Ingeborg Bachmann. She wriote the poems in the summer of 1953, when the pair had escaped to Italy, symbol of the "golden South" celebrated by Goethe and so many other northerners before and since. Bachmann's poems are sunlit, but haunted : "Schattenfrüchte fallen von der Wanden". Henze's setting is dominated by celli, trombone and double bass, long, keening lines that suggest darkness. The voices sing in unison, the range of timbres creating a rich lustre. The double bass leads the celli into a solemn dance. The central song, Einmal muss das Fest ja kommen, resembles a festive procession, led by trombone and portative, a small portable organ with connotations of the Middle Ages, extended by simple percussion. The male and female voices separate, singing alternate lines, the vocal parts then alternating with instrumental. The effect of a medieval celebration. But what celebration ? perhaps a brief Carneval before a period of mourning. ? "...die Krater nicht rühn!" Henze sets the men’s voices in the fourth song almost as plainchant, the women's voice high and piping like choirboys. Whoever leaves the island cannot return unless rituals are performed. The mood is sinister : the trombone wails, the portative groans. The final song is deceptively simple, though the images are apocalyptic. "es ist ein Strom unter der Erde, der sengt das Gebein". And we shall bear witness. When Henze set Bachmann's poems, she still had ten years to live, but he knew the dreams they'd had were doomed.

Based on translations of early French poetry, Henze's Fünf Madrigales is a lively mix of mock medievalism and modernism. He was only 21, just emerging from a youth in which music had to conform to Nazi taste. Although it's an early work, we can already hear Henze's distinctive personality in embryo.

Anne Ozorio

mage=

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Hans Werner Henze : Lieder von einer Insel, Orpheus Behind the Wire, Funf Madrigaleby= SWR Vokalensemble, Ensemble Modern, Marcus Creed

product_id=SWR Classic SWR19049CD[CD]

price=

product_url=

November 28, 2017

Philippe Jaroussky and Ensemble Artaserse at the Wigmore Hall

Jaroussky and Ensemble Artaserse - the period instrument ensemble that he co-founded in 2002 - offered a wonderful Handel-fest/feast at the Wigmore Hall, following the release of their Handel Album last month on the Erato/Warner Classics label. In the liner notes to that disc, Jaroussky comments that although ‘it’s only in the last few years that I’ve been able to play the big Handel roles on stage … I wanted to choose a selection of arias from less well-known operas’. And, so, alongside arias from Radamisto, we had a selection which dipped into the lesser-known waters of Tolomeo, Flavio, Siroe (kings of Egypt, Longobardi and Persia respectively) and Imeneo.

Handel is, in every sense, a ‘man of the theatre’, and this concert was structured into quasi-operatic sequences of arias and instrumental items that, performed segue, carried us through varied moods in discrete groups. Occasionally the juxtapositions were startling, even a little disconcerting, but they created a vitalism that surged through the sequences. ‘Theatricality’ was at the heart of this recital. After accompanying the ensemble onto the platform at the start, Jaroussky retreated, returning during the archlute’s striking prefaces, or during improvised instrumental bridges, or - in the case of Radamisto’s ‘Vile! se mi dai vita’ - bursting passionately through the players during the accompanied recitative.

Jaroussky’s effortless lyricism and dulcet tone have long been acclaimed, but his countertenor has now acquired an increasing weight and diversity of colour, and the aria choices seemed designed to show-case this, with rapid and rage-fired numbers outweighing those of limpidity and lament. The seductive slipperiness of the voice across and between ranges remains, though, as does the ease with which it pours smoothly through the extended coloratura that Handel spins - as in ‘Se parla nel mio cor’ from Guistino.

While Jaroussky had the resonance to penetrate through the vibrant instrumental accompaniments, his voice is not necessarily best suited to Handel’s ‘rage arias’. His vocal agility impressed, but he couldn’t quite capture Radamisto’s burning outrage when he is condemned by the tyrannous Tiridate (‘Vile! se mi dai vita’), despite the turbulent, quasi-percussive string fire; but there was melodic nuance and a shining melisma expressing confident defiance. In contrast, ‘Ombra cara’ from the same opera, was a peak of unaffected beauty: every note, every phrase was perfectly shaped and controlled, Jaroussky’s vocal shading ever-alert to the major/minor coloration and chromatic nuances in the instrumental accompaniment.

Flavio, re de’ Longobardi framed the programme, and the opening aria, ‘Bel contento’, conveyed all of the protagonist’s impetuous joy as Guido expresses his delight at his forthcoming marriage to Emilia. Jaroussky’s lower range pulsed with varied colours and matched the strings’ sprightly dotted rhythms. The voice surged through the triplets as if overflowing with content, and the da capo elaborations were both idiomatic and enriching, particularly as the expansion of range showcased the bright purity of Jaroussky’s upper voice. Handel’s heroic roles were composed for Senesino, who was renowned for the projection of his messa di voce, and his alto timbre must have been quite different to Jaroussky’s light soprano-light colour.

A beguiling solo by concert-master Raul Orellana seemed to invite Jaroussky back onto the platform for Tirinto’s beautiful ‘Se potessero i sospir’ miei’ from Imeneo - an aria which borrows from David’s ‘O Lord, whose mercies numberless’ from Saul, which Handel was composing simultaneously. The sweetness of the quiet close of the B-section, as Tirinto prays that his beloved Rosmene will return safely, was simply magical, and with the gentility of the final cadence and trill Jaroussky really did seem, as Tirinto sings, to ‘breathe out every sigh in my heart’. Best of all was Tolomeo’s ‘Stille amare, gia vi sento’ from Tolomeo, in which both players and singer were astonishingly responsive to Handel’s extraordinary depth and range of expression. In the recitative, Marc Wolff’s enticing archlute made the cup of poison seem as sweet as honey, while the strings’ brusque down bows urged him to drink. The intensity of the vocal line at the end of the recitative was salved by the light, trilling quavers of the upper strings - ‘bitter drops’ which, paradoxically, ease Tolomeo’s pain as he approaches death, his acceptance finding expression through Jaroussky’s wonderful lyricism and ornamentation.

The instrumental items were as ‘theatrical’ as the arias. Ensemble Artaserse have a tonal brightness and vitality of articulation which makes the ear sit up, and their risk-taking musical rhetoric rivals that of Fabio Biondi’s Europe Galante. Whether there are twenty or three instrumentalists, playing the sound is airy and buoyant - bow strokes rose and hovered far above the string - but the tone quality has a real ‘bite’. Tempi were generally on the swift side. There was no languorous lingering in the Adagio from the Concerto Grosso in C (incorporated into the 1736 ode Alexander’s Feast), which showcased the strongly defined meatiness of Nicolas André’s bassoon line complemented by the richly coloured resonance of Guillaume Cuiller’s oboe.

Drama was sought, and found, in each diverse movement - in the gritty down bow strokes at the start of the Grave from the C minor Concerto Grosso, in the beautiful song for cello and oboe in the Largo from the Bb concerto Op.3 No.2, in the fugal intensity of the Allegro ma non troppo from the sixth of the Op.6 set. But, such drama was balanced with delicacy in the Largo from the Op.6 No.2 concerto; and, having generally emphasised the incisive individualism of the parts, the instrumentalists blended in plush, warm, layers in the Largo from the Concerto Grosso in A minor Op.6 No.4. The Sinfonia from Solomon flashed by with such brio and brightness that it was as if we were hearing the celebratory announcement of the arrival of the Queen of Sheba for the first time: one could image the Queen floating in triumphantly on the shimmering sheen of sound.

This was a generous concert but - judging from the players’ smiles, and their physical and musical responsiveness to each other throughout - the musicians were enjoying the music-making as much as we were; and, so, we had three encores - two from Serse, including that enduring favourite ‘Ombra mai fu’, and ‘Pena tiranna’ from Amadigi di Gaula in which bassoonist André and oboist Cuiller joined Jaroussky at the front of the platform for a sarabande of exquisite intimacy and grace.

Claire Seymour

Philippe Jaroussky (countertenor), Ensemble Artaserse

Handel: Radamisto HWV12 - Overture; Flavio, re di Longobardi HWV16 - ‘Son pur felice al fine … Bel contento già gode quest’alma’; Concerto Grosso in G Op.6 No.1 HWV319 (Allegro); Concerto Grosso in C HWC318 (Alexander’s Feast); Siroe, re di Persia HWV24 - ‘Son stanco, ingiusti Numi … Deggio morire, o stelle’; Sinfonia from Solomon ( Arrival of the Queen of Sheba); Concerto Grosso in C minor Op.6 No.8 HWV326 (Grave); Imeneo HWV41 - ‘Se potessero i sospir miei’; Concerto Grosso in A minor Op.6 No.4 HWV322 (Largo and Allegro); Radamisto - ‘Vieni, d'empietà mostro … Vile! Se mi dai vita’; Concerto Grosso in F Op.6 No.2 HWV320 (Largo); Giustino HWV37 - ‘Chi mi chiama alla gloria? … Se parla nel mio cor’; Concerto Grosso in F Op.6 No.6 HWV320 (Allegro ma non troppo); Concerto Grosso in Bb Op.3 No.2 HWV 313 (Largo); Tolomeo HWV25 - ‘Inumano fratel, barbara madre … Stille amare, già vi sento’; Concerto Grosso in A minor Op.6 No.4 (Larghetto affetuoso and Allegro); Radamisto - ‘Ombra cara di mia sposa’; Concerto Grosso in G Op.3 No.3 HWV315 (Adagio); Flavio, re di Longobardi - ‘Privarmi ancora … Rompo i lacci, e frango i dardi’.

Wigmore Hall, London; Sunday 26th November 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Jaroussky%20%28C%29%20Simon%20Fowler.jpg

image_description=Philippe Jaroussky and Ensemble Artaserse at the Wigmore Hall

product=yes

product_title=Philippe Jaroussky and Ensemble Artaserse at the Wigmore Hall

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id= Above: Philippe Jaroussky

Photo credit: Simon Fowler

November 24, 2017

La Rondine Takes Flight in San Jose

Not only was the performance musically rewarding, the piece was also staged with genuine care and fidelity to the composer’s intentions. General Director and (on this occasion) set designer Larry Hancock seems to have his finger firmly on the pulse of his constituency’s preferences. The happy result is that his period scenery is visually luxurious and vibrantly colorful, all the while it exudes a distinctively Old World appeal. That is not to suggest it is in any sense “dated,” just winsomely “accurate.”

The handsomely paneled, burgundy-curtained drawing room of Act I yields to a wrought ironed revelry of a popular Parisian bar in Act II, before making way for a serene seaside haven in Act III, replete with a profusion of many-hued flowers. Mr. Hancock’s appealing settings were ably complemented by Elizabeth Pointdexter’s sumptuous costumes, which were not only richly detailed, but also particularly characterful in defining the station of the dramatis personae. In tandem with Ms. Pointdexter, Christina Martin was in command of the effective wig and make-up design, which ably completed the “look.”

Kent Dorsey has contributed a particularly subtle, beautifully judged lighting design. The discreet shifts in intensity and color captured the vacillating emotional state of the leading characters. Mr. Kent also used creditable deployment of specials, including understated implementation of follow spot effects.

Act II Quartet with (from l) Mason Gates (Prunier), Elena Galván (Lisette), Amanda Kingston (Magda) and Jason Slayden (Ruggero)

Act II Quartet with (from l) Mason Gates (Prunier), Elena Galván (Lisette), Amanda Kingston (Magda) and Jason Slayden (Ruggero)

Director Candace Evans has devised an unfussy, dramatically apt staging with effective traffic patterns and groupings, which underscored meaningful character relationships; and she made commendable use of the entire playing space. Occasionally, Ms. Evans might let an actor wander a bit unmotivated to make use of a different stage area, but I always appreciated her thoughtful quest for variety and her intelligent sense of dramatic focus. Michelle Klaers created the sprightly choreography that enlivened Act II.

But no matter how successful the physical production, no one should come out of Puccini humming the scenery or the staging, so I can gladly report that the musical virtues were nothing less than top tier.

As the enigmatic, evasive “swallow” of the title, Amanda Kingston presented a Magda that embodied all that one could wish in this part. First, she is a statuesque beauty with a glowing, poised stage presence. More important, Ms. Kingston is a Puccinian dream of a singer with a plush, vibrant top voice characterized by creamy, luxuriant tone that is even throughout the range. Her vocal appeal is such that I mentally made a list of all the heroines I would love to hear her lavish with her artistry. Moreover, Amanda has an easy, unforced demeanor that is highly engaging. Her treatment of the famous Doretta’s Song in Act I was ravishing in its aural beauty.

As Ruggero, the physically handsome presence of Jason Slayden represented a one-two punch of effective casting. And he sings, too! Ruggero does not have much to do in Act I, and Mr. Slayden’s rather reserved presence and slightly hard-edged beginning (marked by a rather rapid vibrato) did not allow him at first to show off his interpretive gifts. However, this accomplished tenor quickly made up for lost time.

In Act II, Jason was all boyish charm and he poured on the vocal allure, solidly claiming his status as co-equal co-star with exuberant tone and arching phrases. Act III is largely his showcase, and here he rose to convincing heights with full-throated declarations that rang out in the house with impassioned conviction. The Dynamic Duo of Kingston and Slayden made quite an unassailable case for this neglected opus.

Nor were they alone in their accomplishment. The entertaining tenor Mason Gates was quite an irresistible Prunier, honeyed of voice, bewigged of presence, and assured of theatrical delivery. As his foil, the animated soprano Elena Galván was a silver-voiced, spunky actress who accurately hit each and every one of her musical and dramatic marks. Mr. Gates and Ms. Galván contributed mightily to the soaring Act II quartet (with Magda and Ruggero), helping to make it a true highlight of the evening.

Trevor Neal intoned a mellifluous Rambaldo, his imposing stature and smooth baritone a real asset to the production. Maya Kherani (Yvette); Teressa Foss (Suzy) and especially Katharine Gunnink (Bianca) contributed memorable turns. Babatunde Akinboboye was the firm-voiced Rabbonier, and Dane Suarez the poised Gobin.

In the pit, Andrew Whitfield inspired an idiomatic reading, marked by lush playing from the banks of strings and accents from the winds and brass that were by turns insightful, playful, and dramatic. Maestro Whitfield implemented a detailed, propulsive path for this lesser known piece that made a substantial case for Puccini’s talents in general and La Rondine in particular. His baton ably elicited the abundant colors in the score and he inspired a sweep and expanse that were inevitably very touching.

In short, Opera San Jose has served up such a totally satisfying, stylistically convincing rendition, it made me think La Rondine might yet join the ranks of vintage Puccini.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Yvette: Maya Kherani; Bianca: Katharine Gunnink; Prunier: Mason Gates; Magda: Amanda Kingston; Lisette: Elena Galván; Suzy: Teressa Foss; Rambaldo: Trevor Neal; Gobin: Dane Suarez; Ruggero: Jason Slayden; Rabbonier: Babatunde Akinboboye; Conductor: Andrew Whitfield; Director: Candace Evans; Set Design: Larry Hancock; Costume Design: Elizabeth Pointdexter; Lighting Design: Kent Dorsey; Wig and Make-up Design: Christina Martin; Choreographer: Michelle Klaers D’Alo

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Amanda-Kingson-as-Magda.png

image_description=Amanda Kingston as Magda [Photo by Pat Kirk]

product=yes

product_title=La Rondine Takes Flight in San Jose

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Amanda Kingston as Magda

Photo by Pat Kirk

Bettina Smith, Norwegian Mezzo, in Songs by Fauré and Debussy

Impressive that Bettina Smith (who is, like her pianist, a Norwegian) handles the French texts so well. Still, I noticed some approximate pronunciations: she often forgets to pronounce certain s’s as z’s, the soft g can come a sh, and ou (i.e., oo) sometimes turns into o. Smith’s vibrato is mostly under good control, but the brief passages of coloratura in Fauré’s “Clair de Lune” are not tossed off with ease. Her mezzo-soprano voice broadens wonderfully at the top, especially at high volumes. At the bottom, it is often a bit light. Is she singing these songs in keys that are a little low for her (which thus helps the top notes be well within her grasp)?

On a more interpretive level, the singer is often emotionally neutral. There are few shadings to indicate specific tones of voice: regret, humor, passion. The singer responds to the text mainly by becoming louder or softer, or by speeding up or slowing down a little, and this is done at the level of entire long phrases and sentences, rarely individual words. The touching conclusion of “C’est l’extase”—“tout bas” (“soft and low”)—here becomes merely two more words for Smith to sing in her nice, solid fashion. Her pianist shows high skill but, at least in this repertoire, little independent imagination.

This shortcoming is most apparent in the least well-known set: a true cycle by Fauré that amounts to a kind of mini-opera for Eve, the world’s first woman. I cannot help but wonder if Smith (or, indeed, Røttingen) has thought about the many fascinating aspects of the ten poems that Fauré selected out of a much longer collection by Charles van Lerberghe. For one thing, Eve, in Fauré’s cycle, has an intriguing relationship with what seems to be the primary more-or-less-male figure in her life: God, about whom the world’s first woman sings in an intimate, even sensual manner (e.g., songs 4 and 7). Smith and Rottingen’s straightforward approach—and their high competence on a purely musico-technical level, which I do not mean in any way to disparage—can be heard on YouTube in the minute-long song 3 of the cycle, “Roses ardentes.”

There are numerous recordings of these works that I know, or suspect, provide more variety in the emission of the voice and greater attention to the subtleties of the poetry. I have either read high praise of, or have sampled with pleasure on YouTube, recordings of the Eve cycle by Elly Ameling, Jan De Gaetani, Barbara Hendricks, Irma Kolassi, Nathalie Stutzmann (who is a native French-speaker), and Dawn Upshaw. Upshaw is pure and gripping, with superb support from pianist Gilbert Kalish. The pioneering and highly responsive recording by Phyllis Curtin and Ryan Edwards (1964) is still available on VAI 1186, and the long first song from the Curtin/Edwards recording is on YouTube, revealing the great soprano’s admirable combination of warmth and control.

The booklet-essay for the present CD alternates trenchant observations and hyperbolic generalizations. I was delighted to find full texts and translations, from Graham Johnson and Richard Stokes’s first-rate A French Song Companion.

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). The first is now available in paperback, and the second soon will be (and is also available as an e-book).

image=http://www.operatoday.com/F%C3%AAtes_Galantes.png image_description=Lawo LWC1116 [CD] product=yes product_title=Fêtes Galantes: Songs by Debussy and Fauré product_by=Bettina Smith, mezzo-soprano; Einar Røttingen, piano. product_id=Lawo LWC1116 [CD] price=$16.81 product_url=https://www.amazon.com/Fetes-Galantes-BETTINA-RØTTINGEN-EINAR/dp/B01N3LVT3X/ref=as_sl_pc_tf_til?tag=operatoday-20&linkCode=w00&linkId=f8e91745e84d3545dceed1e22fd4d146&creativeASIN=B01N3LVT3X

Clonter Opera Gala

It was billed as an evening for newcomers and it delivered, dazzling them with a line-up of classy young singers, a world-class repetiteur and a slickly staged set of pieces. But it also worked for the aficionados in that the chosen pieces were certainly known yet not only Boheme and Butterfly, but also Rodelinda and Cendrillon – my only gripe was there was one too many in each half although you couldn’t fault the pianist Robin Humphreys who, along with director Lissa Lorenzo kept the action moving swiftly between the numbers. It was a cleverly crafted programme, and the arias flowed neatly on from one another with Lorenzo, acting as compere, announcing them in groups - the first lot involving kings and queens, she dubbed ‘Game of Thrones.’

Whenever Clonter is unearthed from its Northern roots, it rightly receives huge commendation for its work, namely paving the way between music schools and the big wide world by running courses where a singer can learn a role and perform it publicly. This is not such an original idea any more with opera houses themselves running young singers’ programmes. However, it was back in 1974, when Jeffery Lockett, a young singer himself at the time, invited Abbey Opera Group to perform in his barn. Possibly because of his own experience, Clonter’s residential artistic programme was born and due to his tireless audition process and talent for spotting young artists, Clonter has since been on the operatic map.

Last night’s talent didn’t disappoint. A line-up of three girls and two boys, they sang arias and duets, with skilfully light staging by Lorenzo. Working with the repertoire and these artists, Lorenzo paired them perfectly for duets. Tall Catalan tenor Eduard Mas Bacardit and tiny Spanish soprano Lorena Paz Nieto were authentically delightful in Breton’s La Verbena de la Paloma, while the more Northern (Anglo-Scottish) baritone Thomas Humphreys and Estonian soprano Mirjam Mesak were well matched in Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci and (even better) Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma. The lonesome mezzo Bianca Andrew opened the evening in a show-stopping red halter neck gown with ‘Nobles Seigneurs, Salut!’ from Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots – aptly French bearing in mind the mirrored Louis Quatorze setting, her softly-rounded mezzo is intrinsically suited to this music, and she has an easy upper register and with her boyish good looks she’d be a gorgeous Cherubino. Interestingly a scout from the Royal Opera House’s young artist programme was at the concert.

This is an exposed venue for young artists as well as being a boomy one. Mirjam Mesak initially sang Ilia’s ‘Padre! germani! addio!’ from Mozart’s Idomeneo impressively having no problem with the tessitura as her voice lies high, but there’s an edge to the sound - as the evening wore on, she got louder and louder and really only came back into her own in the musical numbers – she’d be an exciting Donna Anna and even a Constanze. Her fellow soprano Lorena Paz Nieto has a smaller voice and sang Tornami a vagheggiar from Handel’s Alcina cleanly and crisply but again her inbuilt projection nearly played against her in close proximity, but she has huge charm and vitality on stage. The baritone Thomas Humphreys took some time to settle and by aria four, the sublime Ideale by Tosti, he was velveteen in tone. The one to watch in my book was the tenor Eduard Mas Bacardit who opened with the beautiful Fatty inferno…… ‘Pastorello d’un povero amento’ from Handel’s Rodelinda and sang meltingly legato lines – he’s a clean almost pretty sounding tenor with a firm Italianate tone, a natural stage presence and is quite easy on the eye too….

They ended with ‘The Saga of Jenny’ from Weill’s Lady in the Dark again choregraphed lightly by Lorenzo but ‘musical’ enough so they repeated the finale in true musical style – a hat’s off moment to a great evening.

Louise Flind

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Clonter_Gala.png image_description=Clonter Opera Gala [Photo by Jack Thompson] product=yes product_title=Clonter Opera Gala product_by=A review by Louise Flind product_id=Above: Clonter Opera Gala [Photo by Jack Thompson]Étienne-Nicolas Méhul: Uthal

Or they avoid the problem by not performing the work at all. The French operatic tradition, in particular, is full of important works with spoken dialogue that we rarely get to see on stage: some comic (e.g., by Auber or Adam), others serious (e.g., by Cherubini or, as here, Méhul).

Recording a little-known work, whether in the studio or during a performance, can give performers a chance to find out whether it retains enough vitality to speak to present-day listeners. I am currently reviewing two works with spoken dialogue and will soon post them here: Hérold’s Le pré aux clercs, a long-loved French opéra-comique whose tone alternates between giddy and grim; and, most unusually, an Italian work: De Giosa’s comic opera Don Checco. (The latter recording was actually made during a staged performance, apparently quite a successful one.)

Here we have the first fully satisfactory modern recording of the one-act opera Uthal (1806) by Étienne-Nicolas Méhul (1763-1817). This work has long been praised for its unusual treatment of the orchestra, but performances have been few. An LP of a BBC studio performance from 1972 was once available on a pirate LP; it can now be retired.

The opera’s story comes from the writings of “Ossian,” a bard purported to have lived in southern Scotland in the third century. The Ossian epics were beloved in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, even after it became known that they were, to a significant degree, inventions by a Scottish poet named James Macpherson, not (as Macpherson had at first claimed) translations from Gaelic originals. In Méhul’s opera we meet Malvina, her aged father Larmor, and her husband Uthal, who has deposed Larmor. There is much mention of Fingal, the people’s leader; many of us still recognize that brave warrior’s name through the other standard title for Mendelssohn’s “Hebrides” Overture: “Fingal’s Cave.” The libretto was written by J. B. de Saint-Victor, largely in classical alexandrines (rhymed verses consisting of six-plus-six syllables, as in the great tragedies of Corneille and Racine).

The many intriguing musical moments include an arioso for Malvina (track 9) in which orchestral fragments of the tramp-tramp of the warriors (who have just left the stage) can still be heard; the first chorus of bards, to which Malvina then overlays an entirely different melody (track 10); and the soliloquy aria for Uthal upon his long-awaited first appearance, halfway through the work (track 12). One senses here an opera composer who is never content to provide music in an automatic, conventional manner—and one from whom Berlioz, who likewise loved to layer disparate musical materials on top of one another, learned a lot.

Another intriguing moment: a solo cello, in high register, threads its quiet way through that aria of Uthal’s, playing long notes that form the melodic core of his vocal line, which has been somewhat more elaborated by the composer to allow for extra syllables in the text. (The vocal lines throughout the opera are on the plain and direct side, with nary a hint of coloratura.)

The singers here all have steady and attractive voices and sing their texts persuasively. They speak the dialogues well, though with a very wide dynamic range: I had to turn the volume up for some patches of whispering and then turn it down again when a character became agitated or insistent, or when the singing returned. But this complaint is also a compliment: the performers take the work seriously and make sure to convey the drama at every turn. And of course one can skip the dialogue tracks (clearly marked in the track list) and go from musical number to musical number.

My favorite singer here is Karine Deshayes, whom I have previously praised in Rossini arias and as the pagan queen in Félicien David’s 1859 opera Herculanum. Jean-Sébastien Bou sings beautifully as the father, though his lowest notes lack fullness, as was also true when he played another heroine’s father: in Lalo and Coquard’s La Jacquerie. The much-recorded tenor Yann Beuron—his voice still firm at 48—conveys well the resoluteness of the title character Uthal.

Christophe Rousset’s early-instrument group plays with spirit, accuracy, and much tonal variety. The orchestration is somewhat dark, because Méhul excluded the violins: instead, he called for a larger-than-usual viola section and divided it into two parts to provide the top lines of the string choir. (Brahms would similarly do without violins in his orchestral Serenade No. 2 and in the first movement of the German Requiem.) The absence of violins is frequently relieved by many other interesting instrumental effects. We often hear two very woodsy flutes, colorful stopped notes from two unvalved horns, and glinting arpeggios from two light-toned period harps. Passages of tremolo for the string sections are full of energy and impulse. The chorus (men only) is small but spirited and nearly always clear in pitch. The solo singers playing Ullin and four other bards—cousins, in a sense, to Oroveso and the druids in Bellini’s Norma—have only a little to sing, but they do it superbly.

The small book that comes with the CD contains excellent essays and background readings in French and English (including substantial passages by the composer, the librettist, and three nineteenth-century critics, one of them being Berlioz); the libretto is likewise given in both languages. The alexandrine lines are broken up into shorter ones on the page. This inadvertently disguises the verse meter and the rhyme schemes. But a reader, once alerted, should be easily able to restore mentally the original layout. Translations throughout are straightforward but occasionally too literal to be immediately clear.

The performance materials were prepared, and the recording funded, by the Center for French Romantic Music, located at the Palazzetto Bru Zane (Venice). The recording sessions took place in the Versailles-palace opera house, whose acoustics have long been admired. The Center’s website offers one track from the CD—Uthal’s cello-aria discussed above—plus a video interview with the conductor. An informative interview with the conductor can be seen on YouTube (with snippets from the recording). And YouTube offers track 18, in which the bards calmly of glorious battles from the past, while Malvina keeps interrupting them as the sounds of actual battle increase offstage, pitting her husband against her father, increase offstage. The published score can be downloaded at IMSLP.org.

I urge anyone who has a fondness for Cherubini’s Médée (or Medea, as it is known in its more usual Italianized version) to get to know this work by Méhul. You are in for an hour of pleasant surprises in the areas of melody, harmony, orchestral color, musico-dramatic cogency, and Napoleonic-era cultural mythology.

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). The first is now available in paperback, and the second soon will be (and is also available as an e-book).

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Uthal.png image_description=Ediciones Singulares ES1026 [CD] product=yes product_title=Étienne-Nicolas Méhul: Uthal product_by=Karine Deshayes (Malvina), Yann Beuron (Uthal), Jean-Sébastien Bou (Larmor), Sébastien Droy (Ullin), Philippe-Nicolas Martin, Reinoud Van Mechelen, Aravazd Sargsyan, Jacques-Greg Belobo (bards). Les Talens Lyriques, Choeur de Chambre de Namur, conducted by Christophe Rousset. product_id=Ediciones Singulares ES1026 [CD] price=$34.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldownname_id1=7997&name_role1=1&bcorder=1&comp_id=626341

A New Anna Moffo?: The Debut Disc of Aida Garifullina

She was clearly well trained in her native Tatarstan and then in Nuremberg and Vienna. She won first prize in the Operalia competition (2013), and has already sung at major European opera houses in Russian roles. She is scheduled to make her Metropolitan Opera debut in 2019.

The repertoire she has chosen here displays her strengths. She sings Russian arias and songs by Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Rachmaninov, the Russian popular song known in English as “Midnight in Moscow,” and two folk songs: a Cossack lullaby and (in her native Tatar) “Allüki.”

She starts the CD off with two French arias: “Juliette’s Waltz Song” from Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette and the “Bell Song” from Delibes’s Lakmé. She transposes the latter down a bit to suit her voice, which is not the stratospheric type of soprano that has often been associated with the role, though she can certainly sing normal high notes with ease. Her French pronunciation is approximate: the mute e is too open, and I did not notice a single nasal vowel. She also did little in those two arias to color individual words—the focus is far more on producing a beautifully even string of pearl-like notes.

Garifullina says in the booklet that she took the recordings of Anna Moffo as one of her main models, and she has chosen well. I hope she continues to grow as a singer, mastering the art of performing in other languages and responding more to the meanings of individual words and phrases—but without losing the astounding perfection of vocal production that is on display here.

The orchestra is sometimes a bit in the background. Various orchestrators are credited for the songs she chose to sing (e.g., Rachmaninov’s “Lilacs”), and their work is mostly capable and inoffensive. But I disliked Paul Bateman’s reorchestration of the “Song of India” (from Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sadko): why not just let us hear what Rimsky-Korsakov wrote, since this is already an opera aria, not a song with piano? Bateman had the not-brilliant idea of making the orchestration more elaborate in the second strophe. It’s somewhat distracting and unnecessary.

Far more distracting, I find, is Paul Campbell’s lush arrangement of the Tatar folk song. Campbell seems to have taken as a model what Joseph Canteloube did with the famous Chants d’Auvergne: a cushion of string sound, swooshing harps, soft arpeggios in the woodwinds, and so on. If you like the Canteloube songs (I have never had the patience for them), then here’s a Tatar equivalent.

Complete texts in the original languages, plus good translations into French, German, and English. The CD’s table of contents is a little confusing: the layout could give the inadvertent impression that Rachmaninov wrote the Tatar song and the Cossack lullaby.

You can sample all the tracks at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2tMPAqWICoE. YouTube also has a video version of Garifullina doing the Gounod (with fake applause at the end). One way or the other, I suggest that you listen to her: she offers some of the most beautiful singing I have heard in years.

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). The first is now available in paperback, and the second soon will be (and is also available as an e-book).

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Aida_Garifullina.png image_description=Decca 478 8305 [CD] product=yes product_title=A New Anna Moffo?: The Debut Disc of Aida Garifullina product_by=Aida Garifullina, soprano. ORF Radio-Symphonieorchester Wien, conducted by Cornelius Meister. product_id=Decca 478 8305 [CD] price=$10.69 product_url=https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B017MZSLJW/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=operatoday-20&camp=1789&creative=9325&linkCode=as2&creativeASIN=B017MZSLJW&linkId=061820c306fd3a9ba7ff49498d5083c4

A New Die Walküre at Lyric Opera of Chicago

The mortal twins Siegmund and Sieglinde are Brandon Jovanovich and Elisabet Strid. Hunding is sung by Ain Anger and Fricka by Tanja Ariane Baumgartner. The sisters of Brünnhilde are portrayed by Whitney Morrison, Alexandra LoBianco, Catherine Martin, Lauren Decker, Laura Wilde, Deborah Nansteel, Zanda Švēde, and Lindsay Ammann. The Lyric Opera Orchestra is conducted by its music director Sir Andrew Davis. The production is directed by David Pountney with scenery by Johan Engels and by Robert Innes Hopkins, costumes by Marie-Jeanne Lecca, and lighting by Fabrice Kebour. Mmes. Strid and LoBianco and M. Anger make their debut at Lyric Opera of Chicago in this production.

As the curtain rises Wotan appears briefly while holding his spear of authority and justice. During the orchestral introduction the ash tree, into which Wotan had previously plunged his sword, descends onto the stage into the midst of Hunding’s dwelling. Figures representing the three Norns and assistants push Hunding’s domestic table into place; Sieglinde, now alone, moves about, held by an extended chain attached to the tree. As a door at stage rear opens, Siegmund stumbles into the presumed haven. Visibly worn by battle, Mr. Jovanovich utters the lines “Hier muss ich rasten!” (“I have to recover here!”) with a gasp of desperate hope. Ms. Strid’s reaction shows an immediate sympathy for the weakened man seeking refuge. Her vocal color and range are ideal in portraying Sieglinde’s solicitous curiosity and her subsequent statements to Siegmund describing her own plight. From low pitches on “ihn muss ich fragen” (“I must find out where he’s from”) to the higher, palpable emotion with which she sings “noch schwillt ihm der Atem” (“I hear him still breathing”), Strid invests her lines with an anticipation matching the introductory tone set by Jovanovich. The refreshment of water once provided is followed by a lush orchestral performance of the love motif under Davis’s taught direction. In Sieglinde’s identification of home and self as “Hundings Eigen” (“belonging to Hunding”) Strid’s words are fraught with tension. Once both characters drink from the mead-vessel, Jovanovich’s voice blooms with noble color in describing his flight from the pursuit of “Misswende” (“ill fate”). In response to Sieglinde’s tentative yet clear invitation, the hero names himself “Wehwalt” and declares with assured resolve, “Hunding will ich erwarten” (“I intend to await Hunding here”). At the close of the scene each character sits alone at the base of a tower positioned on opposite sides of the stage, an indication of burgeoning attraction stunted by the domestic atmosphere and spirit of Hunding.

The entrance of Hunding, the lord and husband, injects a tone of caution and formality into the closed interior of the dwelling. Mr. Anger’s deep, resonant intonation emphasizes Hunding’s suspicion while asking after Siegmund and later during his visual comparison of the guest to Sieglinde. After reassurances of the law of hospitality, expressed by Anger with rich vibrato, Siegmund is encouraged to name himself. Upon complying, Siegmund also volunteers the story of his youth in the forest together with his father Wolfe. Here Jovanovich sings excited pitches on “Zwillingsschwester” (“twin sister”), then drifts to a piano lament at “kaum habe ich sie gekannt” (“I scarcely knew her”) when narrating the disappearance of both mother and sister. While telling of Siegmmund’s progressive isolation from father Wolfe and from potential friend or wife, Jovanovich sings the final line explaining his name with a hushed delivery of “Wehwalt … des Wehes walte’ ich nur” (“Wehwalt … only sadness was ascribed to me”). After describing his battle against a cruel race that tried to force a maiden into marriage, Siegmund’s extended pitches on “Friedmund - nicht heisse!” (“not called - Friedmund!”) identify him as Hunding’s enemy. From this point forward, the focus shifts from the past to an imminent struggle with future consequences. Anger’s chilling notes on “Sippenblut” (“clan’s blood”), and his vow to avenge it against the hero “Wehwalt,” prompts several violent movements. He throws his wife to the floor and demands from her his evening draught. Before departing grimly from the scene, Hunding casts a battle-axe into the communal table.

Eric Owens and Tanja Ariane Baumgartner

Eric Owens and Tanja Ariane Baumgartner

In the final scene of Act I Siegmund searches desperately for a weapon with which to counter Hunding’s threat. The dramatic cries of “Wälse! Wälse! Wo ist dein Schwert?” (Wälse! Wälse! Where is your sword?”) become endlessly held pitches by Jovanovich until the light of the glowing weapon catches his eye. When Sieglinde returns to the hearth, she indicates that Hunding has been drugged and that Siegmund should escape. Strid’s highly dramatic declamation of the narrative “Der Männer Sippe” (“My husband’s kinsmen”) becomes a catalyst for emotional and scenic development. Siegmund embraces her and reveals his love, whereupon the door at stage rear opens revealing the wonders of a springtime scene. During their subsequent duet spontaneous displays of genuine affection are here a natural extension of love through song. These displays render believable Jovanovich’s emotional declaration “Heiligster Minne höchste Not” (“Holiest love in highest need”) when he prepares to pull the sword Notung from the ash tree. As a joint impulse and with the future in mind the two principals escape from the confines of Hunding’s dwelling onto the spring heather, where their physical love is consummated.

The start of Act II in this production is ultimately bound to the previous space, yet now from the perspective of the immortal beings. The brief opening introduces Wotan and Brünnhilde, the latter giddy as she trips through the spring heath. The stage then assumes horizontal division with Wotan appearing on an upper level and Brünnhilde remaining below. The expected battle between Siegmund and Hunding fills Mr. Owens’s voice with rich excitement, as he instructs Brünnhilde to stand by Siegmund (“dem Wälsung kiese sie Sieg” [“let her assure victory for the Wälsung”]). Ms. Goerke in turn acquiesces with equivalent excitement and the exemplary performance of her repeated “Hojotoho!” with decorative trills inserted after each cry. Yet the mood of adventure fades just as Goerke reports with a decidedly expressive frown that Fricka approaches. Two central doors on Wotan’s raised station open, enabling Fricka - dressed similar to Wotan in formal attire befitting rank - to emerge from her chariot and demand an audience from her husband. In the role of Wotan’s wife and protector of marriage, Ms. Baumgartner assumes at once the position of a goddess slighted. She presents details of the infraction with deep resonant pitches, then rises vocally to emotional outbursts against the incestuous union at “ich klage!” (“I accuse”) and “Geschwister sich liebten?” (“the siblings as lovers?”). Despite Owens’s passionate defense of the twins’ innocent love, accompanied again by the orchestral spring motif, this Fricka reminds him imperiously of his own less than faithful treatment of marital vows. When Baumgartner demands that the sword, with a telling emphasis on “zauberstark” (“associated with magic”) be taken back, Wotan’s plan for the hero is clearly halted. She continues to press her case against Siegmund until Owens asks, with his voice descending to a statement of deep resignation, “Was verlangst du?” (“What must I do?”). His final words to Fricka, “Nimm den Eid!” (“Take my oath!”) capture decisiveness here and the duty of Brünnhilde to intercede in recovering Fricka’s honor.

The following scenes of Act II are admirably staged in natural progression. Wotan’s balcony descends so that he stands on Brünnhilde’s level to meet her return. In his intimate exchange with Brünnhilde, Owens narrates as “unaugesprochen,” with the hush of privacy, the story of the ring, Erda, and the Walküren. Wotan’s voice shakes with emotion as Owens declares forte that he seeks only “das Ende” (“the ending”) to what he has caused. Despite his daughter’s protests Wotan threatens chastisement if Brünnhilde does not assure the victory of Hunding. The stage platform lifts Wotan again to the elevation of his power while Brünnhilde realizes, beset with gloom below, her task.

Siegmund and Sieglinde appear in flight from Hunding’s wrath. Despite his encouragement to continue, Sieglinde relates her hysterical fears from dreams of the sword breaking in battle. Jovanovich’s tender replies of “Schwester” (“Sister”) coax her into a fitful sleep. Brünnhilde’s approach bearing shield and cloak is greeted by Siegmund as “schön und ernst” (“beautiful and somber”). When Goerke informs him with ceremonial dignity that she has come as a messenger of death to ensure his entrance into Walhall, the hero asks if he will find there his father and be joined by Sieglinde. At the denial of this second hopeful request, Jovanovich replies with grim resolution, “… folg ich dir nicht” (“ … I shall not follow you there”). Goerke then circles the stage through the air on an elevated steed perched on a crane manipulated from below. Despite her emotional supplications to consider honor and “ewige Wonne” (“eternal joy”) as a slain hero, Siegmund refuses to ignore his companionship of Sieglinde. The Walküre’s declaration that she can understand the hero’s suffering is expressed here with moving empathy, leading to her ultimate defiance of Wotan’s will. When Goerke announces with searing determination “Beschlossen ist’s” (“It is decided”), the course of the remaining action is set. In his final address to Sieglinde Jovanovich incorporates achingly soft melismatic phrases into what becomes a touching farewell. Battle horns accompany a transformation of scene: Wotan and Fricka appear on the towers at opposite sides of the stage, with Siegmund and Hunding on raised platforms closer to the center. When Wotan allows Siegmund’s sword to shatter, causing his death at the hand of Hunding, Fricka’s will is complete. With Owens calling excitedly for Brünnhilde’s punishment, the orchestra swells to accompany Fricka’s contented smile as she gazes, at stage center, upon Wotan’s spear of justice.

The musical and dramatic excitement of the opening scene of Act III is imaginatively staged and costumed. The Walküre sisters appear variously on elevated horses, reminiscent of Brünnhilde’s steed, and at work on stage level, while they prepare or direct the transport of fallen heroes to the honor of Walhall. When Brünnhilde appears shielding Sieglinde, Goerke utters her line “Schützt mich!” (“Protect me!”) with frantic appeal. Before the arrival of Wotan, she is able to transform Sieglinde’s desperation into thoughts of her future child and an escape into the forest. During the following scene the sisters attempt to conceal Brünnilde before Wotan’s wrath. Instead they become witnesses to his public condemnation of the favored child. Here Owens delivers Wotan’s address with powerful declamation in his pronouncement that she will no longer fill his drinking horn in Walhall. Indeed she is, with Owens’s dramatically conclusive pitch, “verbannt” (“banished”).

In the opera’s last scene, the Walküren have retreated at Wotan’s command and left father and daughter alone for the reckoning of punishment. The emotionally wrenching dialogue between the two principal singers is here sung and acted by Goerke and Owens as an ultimate, moving confrontation. When Goerke declares, with sustained top pitches, that in her way she remained loyal to Wotan, Owens concedes with resignation that duty forced him to change his resolve. In their simple clasp of hands both figures show here the inevitable resolution of the story. Brünnhilde, now as a mortal, is surrounded by the bridal fire to be discovered only by the bravest hero. The masterfully played orchestral conclusion seals this unforgettable production.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Christine-Goerke_Brandon-Jovanovich_Elisabet-Strid_DIE-WALK%C3%9CRE_37A5218_c.Cory-Weaver.png

image_description=Christine Goerke, Brandon Jovanovich, and Elisabet Strid [Photo by Cory Weaver]

product=yes

product_title=A New Die Walküre at Lyric Opera of Chicago

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=Above: Christine Goerke, Brandon Jovanovich, and Elisabet Strid

Photos by Cory Weaver

November 22, 2017

As One a Haunting Success in San Diego

This relatively new one act opera (music by Laura Kaminsky, book by Mark Campbell and Kimberly Reed) has become the most often performed contemporary work in recent years for several reasons. First, it is a wholly engrossing character study as it traces the topical, personal, transgender journey of “Hannah.”

Second, it achieves a luminous and absorbing effect with absolute economy of means, requiring only two singers, a string quartet, suggested scenery, and simple costumes. It is an opera producer’s dream that is also a spectator’s wonder.

Hannah Before and Hannah After are compellingly sung and impersonated by baritone Kelly Markgraf and mezzo-soprano Blythe Gaissert. As Hannah evolves from being trapped in a male body to embracing the woman she is, the two perform seamlessly together, to coin a phrase, “as one.”

Mr. Markgraf (Before) has a beautifully rich and well-modulated vocal delivery. He can thunder out pain that rings off the back wall one minute, and then break your heart with hushed, intense phrases of melting beauty the next. He is somewhat slight in stature, but looms large in stage presence and a total emotional investment.

Ms. Gaissert (After) matches her co-star in complete conviction, breathtaking musicality, and vocal allure. She is afforded a complex, riveting final scena of rage and frustration and doubt and acceptance that highlighted every one of her substantial vocal gifts. Blythe has a beautiful sheen in her well-schooled instrument and deploys an even delivery throughout the wide-ranging writing.

Director Kyle Lang has choreographed stage movement that is fluid and restless when possible, and wondrously still and reflective when appropriate. His varied use of the simple floor plan of a few steps and adjoining platforms is notable for its profound simplicity. Moreover, as the music intertwines the two beings, Mr. Lang visually embodies this with carefully considered, dance-inspired interplay between the singing duo.

He is well served by filmmaker and videographer Kimberly Reed who has collaborated fruitfully with set designer Jonathan Gilmer to devise a handsome backdrop of hanging screens. Projected on these are images of Hannah’s life experiences that accomplish the feat of being informative without being distracting. Ingrid Helton’s honest costumes provide just the right look, especially in her choice to have the actors and onstage musicians barefoot. That simple touch conveyed a subtle feeling that somehow primal truths were being addressed.

Pride of place for the physical production must go to Christopher Rynne for his accomplished lighting design. Not only did Mr. Rynne make potent use of well-focused specials, but he (and the director) were also not afraid to incorporate an intriguing use of shadows. Since Hannah’s life developed in a series of shadowy denials, having the soloists occasionally be on the edge of the light, or in and out of it, was telling.

Conductor Bruce Stasyna wrought a demonstrative performance from his small band of mighty performers. The Hausmann String Quartet played superbly under Maestro Stasyna’s assured baton, and their ensemble with the singers was musically and dramatically flawless. The conductor and two of the players were even called upon to play cameo roles in the action, which they accomplished with aplomb.

Ms. Kaminsky, Mr. Campbell and Ms. Reed have crafted a beautiful, informed work that might have been pulled out of today’s headlines. While its framework is somewhat that of a themed song cycle, with brief pauses after set pieces, the entire artistic team admirably keeps the tension, interest, and emotional honesty urgently tumbling forward throughout the eighty-minute duration.

I can’t imagine a better case being made for As One than San Diego Opera‘s haunting, lovingly mounted production.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Hannah Before: Kelly Markgraf; Hannah After: Blythe Gaissert; The Hausmann String Quartet, Violins: Isaac Allen, Bram Goldstein; Viola: Angela Choong; Cello: Alex Greenbaum; Conductor: Bruce Stasyna; Director: Kyle Lang; Filmmaker/Videographer: Kimberly Reed; Set Design: Jonathan Gilmer; Costume Design: Ingrid Helton; Lighting Design: Christopher Rynne

image=http://www.operatoday.com/KarliCadel_SDOpera_AsOne_4421.png

image_description=Scene from As One [Photo by Karli Cadel courtesy of San Diego Opera]

product=yes

product_title=As One a Haunting Success in San Diego

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Scene from As One [Photo by Karli Cadel courtesy of San Diego Opera]

OLF: Songs by Tchaikovsky, Anton Rubinstein, Rachmaninov and Georgy Sviridov

The rich and sensuous timbres of Ukrainian baritone Andrei Bondarenko, coupled with the consistently sensitive and elegant piano accompaniment of Gary Matthewman, made this a highly enjoyable recital.

The themes confronting us were heavy; life, death, doomed love and loneliness dominated the programme, with a sprinkling of nature and alcohol for good measure. However, whilst the programme was weighted with songs of melancholy and regret, Bondarenko was never afraid to show a lighter side, presenting a work in each half of the evening that lightened the pensive sound-world of the surrounding works.

The second half of the evening consisted of a dozen Tchaikovsky songs, songs which – despite the fact Tchaikovsky, as the programme acknowledges, looked down on them – form a key part of the Russian song repertoire. Bondarenko expertly conveyed the anguished soul at the core of these works, frequently displaying a powerful higher register that was equally capable of dropping to a delicate piano in the space of a bar; this was clear in Solovej (The Nightingale), where he brilliantly evoked the unjust power of “evil folk” in separating the narrator from his “fair maid”, only to rein in the undeniable force of his voice for the hushed whisperings of “a grave for me”. The interpretation at times lacked the sense of the sinister – the menace, the harshness, the coldness – that the texts conveyed. However, Bondarenko’s warmth worked well for Moj Genij, Moj Angel, Moj Drug (My Genius, My Angel, My Friend), the earliest surviving song by the composer; he dealt admirably with the higher leaps of “my friend” and “you bestow”, with the slightest hint of portamento adding an extra level of expressive power. What seemed most impressive to the audience, however, was the sheer power of Bondarenko’s voice, projecting the louder dynamics with great force and richness. The insistent fortissimo reached towards the end of the vocal line of Otchego (Why?), a setting of Heine, formed a great contrast to the quiet opening verse, whilst Matthewman deftly brought the dynamics back to a delicate softness for the extended piano postlude.

Indeed, Matthewman’s piano accompaniment was consistently elegant and sensitive, never overpowering the baritone nor afraid to raise the dynamics or reinforce a prominent countermelody. The biting dissonances of the major seventh chord in the introduction to Primiren’e (Reconciliation) makes clear Tchaikovsky’s sense of imperfect and pained happiness, taking “solace on the couch of suffering”; the composer’s extensive use of interludes and postludes showcased Matthewman’s soaring lyricism and heartfelt feeling, the richly romantic piano writing ruminating upon the words of the singer. Matthewman’s sensitive presentation of the insistently repeating single note that closes Snova, Kak Prezhde (Again, As Before, Alone) was profoundly moving, the sense of tolling bells not far away.

But melancholic reflection and sweeping lyricism were not the only qualities on display; lightening the heavy atmosphere of introspection was Don Juan’s Serenade, a bravura piece embodying Don’s endless romantic escapades. Despite a consistently rapid tempo, both Bondarenko and Matthewman maintained a superb sense of control, the baritone beautifully broadening the speed momentarily at the line “Fight them to the death”, as if to draw our attention to the histrionic force of Don Juan’s words. Similarly, Matthewman’s virtuosity was on full display with Tchaikovsky’s rapid runs, which the pianist captured with an energetic bounce and finesse. The delicate ending – brought about with great control and no slackening of tempo – was enjoyed by all.