December 22, 2017

New Cinderella SRO in San Jose

This was a stunning achievement from one so young, and announces a prodigious talent has entered the world of opera. The mere fact that Miss Deutscher has the concentration and skill to not only craft a two-and-a-half hour stage piece, but also to score it effectively for a full orchestra is nothing less than astonishing.

Ms. Deutscher has a fine ear for melody, although at this stage in her development, musical ideas are on the pleasantly generic, if tuneful side. Still, there was plenty of invention in the overlapping phrases in the duets and ensembles, and she has a real innate skill for comic invention. Vocal writing was grateful, and orchestral colors were richly layered, only lacking that final measure of detailed solo opportunities that might provide more musical commentary and depth.

Alma has absorbed many influences in her young life and they are readily apparent in this score: a bit of Wagner here, Rossini there, now Lehar, then Strauss (both of them). Indeed, with its light-hearted tone and copious dialogue, this felt at times like the best new operetta of 1895. While Cinderella is far too skillfully constructed to label it derivative, the composer is nonetheless currently speaking through a fresh pastiche of other composers’ voices. It will be intriguing to follow her development as she now matures and develops her own voice.

The young miss is also an accomplished keyboardist and violinist and while she performed nobly at select moments in the show, these extraneous passages seemed to me a somewhat cloying interruption. That said, the story of her youthful achievement has emphatically captured the public imagination, and the producers were perhaps wise to capitalize on it and give her max exposure since it resulted in added performances and SRO attendance.

Full cast, with Vanessa Becerra as Cinderella, and Jonas Hacker as Prince in foreground center. (Note, composer Alma Deutscher is in shot, performing organ on stage.)

Full cast, with Vanessa Becerra as Cinderella, and Jonas Hacker as Prince in foreground center. (Note, composer Alma Deutscher is in shot, performing organ on stage.)

If the “Alma Deutscher Experience” was the leading reason for the successful run, the second most extraordinary achievement was the musical execution, starting with a nonpareil cast of some of the country’s best singers. Vanessa Becerra was perfection in the title role, her silvery, secure soprano by turns radiant and touching. Ms. Becerra has such a warm, engaging presence that when she beams your heart leaps, and when she laments, your heart breaks. Vanessa’s extended, sorrowful scena late in Act I was ravishingly sung and deeply moving. This aria is the best, most emotionally specific writing of the evening, and this talented singer made the most of the opportunity.

Jonas Hacker’s sweetly appealing, freely produced lyric tenor was a fine complement to his co-star, with his slight, boyishly appealing stature proving very sympathetic. Nathan Stark not only brought his richly resounding bass to his portrayal of the aging King, but also unleashed an inventive barrage of comic business to the mix. As the over-taxed Minister, Brian Myer was Mr. Stark’s willing cohort in the comic antics, and the duo kept the audience rapt with attention. Curiously, while Mr. Myer is a winning baritone, well loved by the San Jose public, on this occasion he sang not one solo note! Never mind, Brian is one of the best actors in opera today and his Minister is another memorable portrayal.

The luxury casting continued with the spiteful stepfamily. Mary Dunleavy made hay with the mean-spirited Stepmother, offering such suavely spirited vocalizing and committed acting that we rejoiced that this celebrated Violetta Valery brought so much alluring, polished singing to this secondary role. It is fascinating that Stacey Tappan (Griselda) and Karen Mushegain (Zibaldona) could sing so beautifully while chewing mouthfuls of scenery as the stepsisters. While they conveyed unrestrained comic abandon, every piece of business was meticulously calculated. Moreover, Ms. Tappan’s crystalline, poised soprano, and Ms. Mushegain’s robust, shining mezzo were delectable to experience singly or in tandem.

As Emiline, Claudia Chapa is first seen in disguise as a beggar woman, then turns out to be the fairy godmother figure. Her first phrases did not seem to lie comfortably for her, with ascending figures that repeatedly bridged the break. Happily, Ms. Chapa came into her own in the finale of Act I, when her earthy, distinctive mezzo first caressed lush passages, then at last roared and soared. Alma’s sister Helena Deutscher had a scene stealing turn as a flower girl at the wedding. Andrew Whitfield’s well-schooled chorus performed admirably.

Continuing the incredible roster of major practitioners, internationally renowned conductor Jane Glover led a sensitive, responsive performance in the pit. Maestra Glover clearly relished the material and the sense of “occasion,” and her sure baton drew magical results from even the more naïve portions of the score.

The physical production was easily the most lavish I have yet experienced in San Jose. Steven Kemp’s sumptuous scenery was a riot of color and invention. Whether a backstage view of an opera auditorium, a coolly atmospheric forest of birches, the king’s handsome chambers, or the ornate ballroom with a massive, movable staircase, this was a triumphant use of the relatively limited stage space. Just when you thought the visual feast was over, the curtain rose on the final scene to reveal an imposing, stained glass windowed chapel replete with choir stalls and organ.

Matching Mr. Kemp’s over-the-top sets, costumer Johann Stegmeir seems to have been spared no expense in creating admirably detailed attire. Opulent court attire was rife with pastel and cream hues; pre-ball Cinderella, the disguised Prince, and the beggar woman were clothed in mostly earth-toned, roughly textured fabrics; the step-sisters were tastefully garish; and Stepmom was given an eye-popping red ball gown. No detail was overlooked, including well-considered footwear and characterful wigs. David Lee Cuthbert lit the proceedings with consummate skill, and his well-integrated projections were effectively complementary.

Director Brad Dalton devised effective stage pictures, practiced cleverly varied stage movement, and had the characters interact with broad clarity of purpose that carried to the top tier. He managed to not only enliven the proceedings, but also successfully kept the pace going in a rather-too-long evening. At this point in her acclaim, I am not sure how receptive Ms. Deutscher (and her family) are to having a seasoned eye shape the piece further, but there are opportunities to trim and focus that could make this charming first success be even more engaging.

At the end of the day, the total package of a young talent’s sensational burst to prominence, and a buoyant production of the highest professional standard combined to make this the once-in-a-lifetime opera-going event that had audiences standing and cheering. The Packard Humanities Institute and Opera San Jose should be justifiably proud of their achievement in presenting this high profile English language and US premiere.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Cinderella: Vanessa Becerra; Prince: Jonas Hacker; King: Nathan Stark; Griselda: Stacey Tappan; Zibaldona: Karin Mushegain; Stepmother: Mary Dunleavy; Emeline: Claudia Chapa; Minister: Brian Myer; Flower Girl: Helena Deutscher; Conductor: Jane Glover; Director: Brad Dalton; Set Design: Steven Kemp; Costume Design: Johann Stegmeir; Lighting and Projection Design: David Lee Cuthbert; Dance Director: Richard Powers; Chorus Master: Andrew Whitfield

image=http://www.operatoday.com/17dc_8299s.png

image_description=Jonas Hacker (Prince) and Vanessa Becerra (Cinderella) [Photo by Bob Shomler]

product=yes

product_title=New Cinderella SRO in San Jose

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Jonas Hacker (Prince) and Vanessa Becerra (Cinderella)

Photos by Bob Shomler]

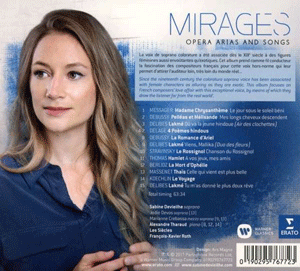

French orientalism : songs and arias, Sabine Devieilhe

A stunning "Ou va la jeune hindou"! (Bell song) from Delibes Lakmé. Devielhe's agile coloratura negotiates the challenges so gracefully that they seem almost effortless, flowing as fluidly as molten silver. The decorations sparkle - like bells - evoking emotions an innocent virgin cannot otherwise articulate. Lines float with a legato which seems inexhaustible, and dance with sensual rhythm. The natural freshness in Devieilhe's voice evokes Lakmé's purity without artifice. If Devieilhe is still quite young, that adds tender fragility to her portrayal. Listen also to the way the orchestra replicates exotic "oriental" sounds with western instruments. Les Siècles' background in period-inspired performance pays off handsomely. Also included here are a good "Viens, Malika" (with Marianne Crebassa) and "Tu m'as donné le plus doux rêve".

"Celle qui vient est plus belle" from Massenet Thaïs, and "!A vos jeux, mes amis" from Ambroise Thomas's Hamlet, indicating whee Devieilhe's career will develop. Berlioz La Mort d'Ophélie , Debussy La Romance d'Ariel and Charles Koechlin's Le Voyage show she's also promising in song, where Devieilhe is accompanied by Alexandre Tharaud. But there are other treasures, too. One of the many reasons why Roth and Les Siècles are so extraordinary is because they know their music history and make intelligent, perceptive connections. Thus they present, together, "La jour sous le soleil béni" from Messager's Madame Chrysanthėme, a French Madama Butterfly with "Mes longs cheveaux descendent" from Debussy Pelléas et Mélisande, a thoughtful juxtaposition which brings out the contrast between two almost contemporary pieces.

Still further reason to get this recording is that it includes Maurice Delage's Quatre Poėmes hindous. Delage (1879-1961) travelled to India, Indo-China and Japan, absorbing non-western musical form. Although there are several recordings of these songs, most aren't easy to come by except for Felicity Lott/Armin Jordan from 1995, so it's refreshing to hear Devieilhe with Roth and Les Siècles who are even more idiomatic than Jordan and the Kammerensemble de Paris. What gives this performance the edge is the orchestral playing. Les Siècles, with their extensive experience in Ravel and in unusual instruments, create the exotic sounds of the East of Delage's imagination so well that the songs have an almost authentic "Indian" flavour, even the one titled Lahore which is in fact a setting of Heinrich Heine's Ein Fichtenbaum steht einsam, also set by Grieg, Liszt, Delius and Stenhammer. In Delage's setting, cello, viola and harp are plucked like Indian string instruments, while the voice curls sensuously around. In the song Bénarès, we might think we hear tablas and Indian reeds, but we're actually hearing western instruments played by musicians who have endeavoured to understand what their Asian counterparts might do. When western composers discovered Asia, they opened new possibilities in western form. From The East to Debussy, to Stravinsky (whose Le Rossignol is also on this disc. Modern and ancient, in symbiosis. With Roth and Les Siècles: "The unexpected is always with us", to borrow a phrase from Luciano Berio, another Roth speciality.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/0190295767723.png

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Sabine Devieilhe—Mirages

product_by=Sabine Devieilhe, Jodie Devos, Marianne Crebassa, Alexandre Tharaud, Les Siecles, Francois-Xavier Roth

product_id=Erato 0190295740153 [CD]

price=$17.03

product_url=https://www.amazon.com/Mirages-Sabine-Devieilhe/dp/B075QX4RB2/ref=as_sl_pc_tf_til?tag=operatoday-20&linkCode=w00&linkId=1f94e3be909e8473a6f4fa120321272c&creativeASIN=B075QX4RB2

La Cenerentola in Lyon

Norwegian stage director Stefan Herheim and the Opéra de Lyon pulled out all the stops to create the biggest, most complicated Cenerentola you may ever encounter. Immensely gifted set designer Daniel Unger, with Mr. Herheim, offered a perspective of six superposed classical proscenium arches. Each leg revolved to become a street of working class row houses in forced perspective, each house with a chimney belching smoke. Immensely gifted video artists Torge Möller and Momme Hinrichs created the fairytale palace that appeared in many digital guises, and magical rainbows of flowers and gears as well.

Herheim, a quite respected and credentialed metteur en scène, began (and ended) with a contemporary janitor’s cart and a cleaning lady on a blank stage. A book fell from the lofts, she picked it up and read, a Baroque cloud descended, Giacomo Rossini emerged. Five elaborately costumed (18th century) actors frolicked onto the stage, the cleaning lady climbed into a fireplace that had magically descended, and emerged as a smoke smudged Cinderella. That was the overture.

There was no let up for the next 3 hours.

When astonishing scenic magic was not occurring a show curtain swooped down for the principals to frolic in front of. The hard selling comedians of the overture in their highly elaborated costumes executed highly exaggerated shtick. It was visually deafening.

Cinderella herself exposed some unusual bratty traits.

In Mr, Herheim’s avalanche of scenic gimmicks and fast and loud comic shtick, there were actually a few slightly amusing moments. The second act curtain rose revealing the conductor lounging on the stage smoking a joint, Tisbe and Clorinda had to order him into the pit. Dandini dropped his pants, broke off a piece of the stage lip and kicked it into the pit and then unceremoniously (his pants around this ankles) pushed the janitor’s-cart-now-royal-carriage off this stage. The best however was the enactment of the storm, the principals became the stagehands who would have created the scenic effects back when such effects were mechanical and hand operated.

All in all Mr. Herheim’s Cenerentola was a tsunami of mostly unrelated conceits.The real Cinderella of the evening was finally Rossini himself, sequestered irrevocably into the kitchen of tricks dreamed up by vainglorious regietheater.

(left to right) Katherine Aitken as Tisbe, Renato Girolami as Don Magnifico, Clara Meloni as Clorinda, Michèle Losier as la Cenerentola, Cyrille Dubois as Don Ramiro, Simone Alberghini as Alidoro, Nikolay Borchev as Dandini

(left to right) Katherine Aitken as Tisbe, Renato Girolami as Don Magnifico, Clara Meloni as Clorinda, Michèle Losier as la Cenerentola, Cyrille Dubois as Don Ramiro, Simone Alberghini as Alidoro, Nikolay Borchev as Dandini

A fine cast was sacrificed to the production. The singers gamely pulled off all the hard-sell antics, remaining always the stock vaudeville comedians they were supposed to be, their loud antics never betraying that they were accomplished musicians. A Golden Carriage ending might have been a dynamite “Non piu mesta.” As it was French mezzo Michèle Losier did not have the vocal clarity, point and bite to make the opera’s finale into the showpiece it is meant to be.

The scope of this Opera de Lyon / Oslo Opera production was evidently to show off the talents of Mr, Herheim and his team. This it most certainly did.

Stendal back in 1823 noted that the Trieste public found the production splendid. So did the Lyon public, evidenced by the opening night ovation.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Angelina aka Cenerentola: Michèle Losier; Don Ramiro: Cyrille Dubois; Dandini: Nikolay Borchev; Don Magnifico: Renato Girolami; Clorinda: Clara Meloni; Tisbe: Katherine Aitken; Alidoro: Simone Alberghini. Orchestre et Chœurs de l'Opéra de Lyon. Conductor: Stefano Montanari; Mise en scène: Stefan Herheim; Costumes: Esther Bialas; Lumières: Phoenix (Andreas Hofer); Dramaturgie: Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach: Vidéo: fettFilm (Momme Hinrichs, Torge Möller). Opéra de Lyon, December 15, 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Cenerentola_Lyon1.png

product=yes

product_title=Cenerentola in Lyon

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Renato Girolami as Rossini later known as Don Magnifico [All photos from the Opéra de Lyon website.]

December 21, 2017

Messiah, who?: The Academy of Ancient Music bring old and new voices together

Director Richard Egarr was a fizzing bundle of energy throughout the performance: swivelling swiftly from his wheeled piano-stool and leaping from his harpsichord to galvanise his 17-person chorus with swishing arm-sweeps, dynamically indicating rhythmic counterpoints and, sometimes extreme and always precisely nuanced, dynamic contrasts. The orchestra of the AAM were alert to every gesture. The overture eschewed the commonly heard double-dotting, Egarr also preferring a more legato bow stroke than we may be used to. The AAM’s playing was prevailingly fresh and spirited, though at times I felt that it was a little bottom-heavy, the organ dominating occasionally - perhaps the absence of oboes was a contributing factor?

I like my Messiahs to unfold like an opera, each number progressing segue into the next, the drama accruing compelling narrative and musical momentum. In this context, tenor Thomas Hobbs’ opening recitative and aria (‘Comfort Ye’ and ‘Every Valley’) felt a little too emphatic for my taste. But, not only did Egarr increasingly put his foot on the accelerator pedal often to thrilling effect - and it was fortunate that the Barbican audience quickly decided not to applaud each number - but Hobbs, too, came into his own in Part 2: ‘Thy rebuke’ really did evoke a heart broken, full of heaviness, while ‘Behold and see’ was assuaging, paradoxically urgent and soothing.

Countertenor Reginald Mobley took a little while to warm up. His voice has undoubted beauty and grace, but it rather lacked focus and weight in ‘But who may abide’, where the registral transitions felt cumbersome. But, the fluidity of ‘He shall feed his flock’ suited Mobley’s effortless lyricism perfectly. ‘He was despised’, sung absolutely off score, was one of the highpoints of the evening, and Mobley’s pointed vocal assertions were accompanied by a dry string timbre and bitter dotted rhythms in the energised central episode.

Christopher Purves gave us a powerfully vigorous ‘Why do the nations’, but one that was not consistently focused, and ‘The trumpet shall sound’, when pushed, strayed sharp - though trumpeter David Blackadder was compelling, combining mellifluousness and rhetoric with a truly beautiful sound. But, in Part 1, Purves’ ‘For behold, darkness shall cover the earth’ was richly foreboding, forming a pleasing complement to the later emotive frissons of ‘Behold, I tell you a mystery’.

Soprano Mary Bevan out-sang the chaps on this occasion, though! The soprano soloist in Messiah has to wait a long time for her first entry, but the recitative introducing us to the shepherds abiding in the fields was compelling and communicative. ‘Rejoice’ was relaxed and carefree, despite the technical demands, and conjured the drama of opera. In Part 2, ‘How beautiful’ spoke of simply, unsullied joy; ‘I know that my Redeemer’ was quite introspective but also persuasively assuring. Bevan’s soprano climbed high and sank low with ease and without disruption to timbre or tone. This was simply wonderful singing.

The real stars of the show, however, were the AAM chorus. When there are just seventeen singers there is nowhere to hide, but no safe haven was needed. If the combined voices couldn’t quite summon the majesty required in ‘Glory to God’, this was more than compensated for by their alacrity and agility in ‘And he shall purify’, in which waves of sound swelled and washed over us. The choral sequence at the start of Part 2 was wonderfully dramatic. We were provided with surtitles, but these were not necessary; soloists and chorus enunciated with clarity and bite, even when the lines danced lightly, as in ‘His Yolk is Easy’. ‘He trusted in God ’ seemed to trip along on tiptoe.

Egarr was able to indulge his whims in the choral numbers. In the first chorus, ‘And the Glory’, the phrases seemed occasionally foreshortened; ‘All We Like Sheep’ was characterised by idiosyncratic dynamic contrasts, and emphatic stress on particular words, such as ‘iniquity’. In the Hallelujah chorus Egarr didn’t ‘milk’ the fermata before the final cadence and seemed impatient to sweep forward with urgency. The homophonic mystery of ‘Since by Man’ tingled the spine, especially as the contrasting fast interludes raced ahead. The wall of resonant sound that pronounced the final ‘Amen’ belied the small forces.

Does Handel’s Messiah need to be made relevant for new, young audiences? I have to confess that, having spent my entire adult life endeavouring to share my artistic passions - musical, literary and visual - with learners young and old, and stubbornly resisting and denying the notion that art needs to be made relatable, my hackles tend to rise in the face of such terms. But, that’s an argument for another day …

This performance of Messiah was prefaced by Hannah Conway’s A Young Known Voice, a work collectively created after a series of workshops, Messiah Who?, in which young students aged 11-15 from various London schools had come together to explore their response to Handel’s work and create a new composition. The result was a palimpsest of Handel, negro spiritual, community anthem, declamatory rap and textual soundbite: a heady, and sometimes powerful and disconcerting mix. Text was whispered and proclaimed by the chorus, and members of the AAM chorus, and declaimed by young soloists who took bravely and assuredly took turns to come to the fore to make their voices heard.

There were startling juxtapositions: ‘Behold I tell you a mystery. It’s gone viral into all lands.’ ‘Death weighs upon our shoulder/ Until nothing is left. The trumpet shall sound and the dead shall be raised incorruptible.’ The unifying cry, ‘Hallelujah!’, was undercut by expressions of alienation, ‘We do not fit in the mould. We are seen as different. You’re not my child. Not my child.’

Conway - an experienced and undoubtedly skilful and empathetic leader of many such projects - said that she hoped the work would make us listen to Handel’s Messiah in a new way. Certainly, the young musicians who participated will undoubtedly remember the night they performed in the Barbican Hall - Mobley's presence and performance must have been an inspiration to some of the young participants - and who knows what artistic pathways such experiences may inspire them to follow.

One heckler, who objected to both Conway’s prefatory evangelism, as she urged us to ‘trust the younger generation’, and to the performance of A Young Known Voice itself, was - following some ‘Out, out!’ cries from nearby audience members - asked to leave by the Barbican Hall ushers. On my last visit to the Barbican Hall , just a few days before, the audience were dancing in the aisles; now they were being evicted from the stalls - Merry Christmas, indeed.

Occasionally, the text cut close to the bone, reminding us of the viciousness of rejection, estrangement and loneliness: ‘You are eight times more likely to be strip searched if you are black’; ‘shouts of Faggot and Queer only fed my fear.’ But, there was hope in the conclusion: ‘We are the future/ The newer generation/ We are the inspiration/ We will lead.’ One hopes that they are right.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Messiah

Academy of Ancient Music: Richard Egarr (director/harpsichord), Mary Bevan (soprano), Reginald Mobley (countertenor), Thomas Hobbs (tenor), Christopher Purves (baritone), Choir and Orchestra of AAM.

Messiah, Who? A Young Known Voice (Hannah Conway): La Retraite RC School, St Paul’s Way Trust School, Tri-Borough Music Hub, Westminster City School.

Barbican Hall, London; Thursday 20th December 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/AAM%20Messiah.jpg image_description=Messiah, Academy of Ancient Music, Barbican Hall product=yes product_title=Messiah, Academy of Ancient Music, Barbican Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: A Young Known VoicePhoto credit: AAM

December 19, 2017

The Golden Cockerel Bedazzles in Amsterdam

Rimsky-Korsakov’s last opera, which premiered in 1909, after his death, is a thinly veiled parody of tyrannical stupidity and callousness. Its composition, to a libretto by Vladimir Belski based on Pushkin, was prompted by the Russian Revolution of 1905. The bird of the title is a magic animal given by an Astrologer to Tsar Dodon to warn him of impending enemy attacks. Aleksandra Kubas-Kruk crowed beautifully as the Golden Cockerel, mostly from the balcony, her soprano slightly heavier than is usual in the role. Fearing hostility from Shemakha, Dodon sends his army eastward, led by his two doltish sons, who slay each other by mistake. The war ends when the Queen of Shemakha seduces Dodon and they get married. Then the Astrologer claims her as his price for the cockerel, and both he and the Tsar meet a sticky end. As if to soften the satirical edge, the Astrologer is resurrected to reassure the audience that they’ve just witnessed an illusion, and that only he and the Queen are real. This simple tale unfolds on a colorful orchestral tapestry, where the kingdom of blundering Dodon is contrasted with the tantalizing exoticism of Shemakha. Vasily Petrenko rendered the score like a master painter, as vivid in the delicate tracery of arpeggiated accompaniment as in the brass-heavy, showy parades. The Netherlands Radio Philharmonic responded to his sure-footed leadership by performing at their virtuosic best. There were superlative solos, including the recurring Astrologer’s bell motif and the satin ribbon of the Queen’s theme on the clarinet and fellow woodwinds. The prominent brass acquitted themselves with honors, but so did every other section.

Selfish Dodon, incompetent and indifferent towards his people, is an unsparing caricature of Tsar Nicolas II. But Rimsky-Korsakov also parodies the stylistic devices of the Mighty Handful, the five composers, including him, who collaborated to create a distinctly Russian musical language. Dodon’s self-absorbed monologue, the pompous military marches and the risible lamentations echo their serious counterparts in operas such as Boris Godunov. Veteran bass Maxim Mikhailov, singing, like the rest of the cast, from memory, was dramatically very persuasive. Vocally, however, he lacked freshness and volume and the orchestra frequently submerged him. Dodon’s howling for his dead sons, underscored by the chorus, was inaudible. Volume was also a problem for bass Oleg Tsibulko, whose General Polkan remained tethered to the stage. Housekeeper Amelfa does little more than plump pillows and prepare nightcaps, but Yulia Mennibaeva made her a contoured, vocally alluring character, a far cry from a hooty aging servant. Mennibaeva is billed as a mezzo-soprano, which would explain why her lowest notes in this contralto role were not seamlessly stitched to the rest of her voice. Tenor Viktor Antipenko, unswerving and trumpet-like, sang Tsarevich Gvidon. Andrei Bondarenko, starting out with a fidgety top, but then settling to produce a beautifully poised baritone, was Tsarevich Afron. With voices like these, it’s a shame the princes don’t survive beyond the first act, even though their stupidity is beyond belief.

The long encounter in Act 2 between Dodon and the heartless Queen of Shemakha is a bewitching example of Russian orientalism. Rimsky-Korsakov has fun with the orgiastic abandon of “foreign” rhythms in the vein of Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances. When the Queen forces Dodon to dance, he shambles clumsily while the music eggs him on with a punishing accellerando. There is little irony, however, in the Queen’s enticing songs, with their chromatic cascades and sparkling orchestral hues. Venera Gimadieva, who has sung the role on the opera stage, has everything it requires. Her soprano is pure silver, with a downy middle range, employed to devastating effect during her description of her naked body. Poor Dodon is defenceless against such weaponry. With her clear, full top notes and fluid coloratura, Gimadieva was spectacular in the opera’s hit aria, the “Hymn to the Sun”. It is striking that, after so many send-ups, the people grieve for their Tsar with a magnificent choral lament. Although their praise for him is ludicrous, the composer sympathizes with the nation and refrains from ridicule. With this touching final chorus the Netherlands Radio Choir topped a glowing, round-toned performance marked by subtle role differentiation. The women’s slave chorus was an aesthetic highlight. The Astrologer is a role for a tenor who can soar comfortably above the staff. Barry Banks did so outstandingly, up to the fearful high E natural in Act 3. He sang with plenty of panache, bracketing this frequently magical performance with a fittingly strong prologue and epilogue.

Jenny Camilleri

Cast and production information:

Tsar Dodon: Maxim Mikhailov, bass; Tsarevich Gvidon: Viktor Antipenko, tenor; Tsarevich Afron: Andrei Bondarenko, baritone; General Polkan: Oleg Tsibulko, bass; Amelfa, a housekeeper: Yulia Mennibaeva, mezzo-soprano; Astrologer: Barry Banks, tenor; Tsaritsa of Shemakha: Venera Gimadieva, soprano; Golden Cockerel: Aleksandra Kubas-Kruk, soprano; First Boyar, Alan Belk, tenor; Second Boyar, Lars Terray, bass. Netherlands Radio Choir, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra. Conductor: Vasily Petrenko. Heard at the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam on Saturday, 16 December 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Petrenko_Vasily_2013a_PC_Mark_McNulty_300.png image_description=Vasily Petrenko [Photo by Mark McNulty] product=yes product_title=The Golden Cockerel Bedazzles in Amsterdam product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Above: Vasily Petrenko [Photo by Mark McNulty]December 18, 2017

Mahler Das Lied von der Erde, London - Rattle, O'Neill, Gerhaher

Metamorphosen deals with annihilation, the symbolic death of civilisation. Das Lied von der Erde confronts annihilation but offers transcendance, through metamorphosis. Whether Rattle realisazed or not, the Massacre of Nanking started on this day, 80 years ago, one incident in a century of horrors. Music doesn't exist in a vacuum. It can enhance our sensitivity to what happens around us.

In Metamorphosen, Strauss overturns the cliché that strings are necessarily "romantic". His strings operate together like a chorale, in which the voices are too numb to articulate except through abstract sound. Hence the haunted sussurations, generating a haze of sound which both suggests and obscures meaning. The bombing of German opera houses was, to Strauss, symptomatic of a much wider trauma : the scenes of past triumphs literally going up in smoke. Rattle and the LSO strings defined the textures so well that the effect was almost claustrophobic : moments when the first violin rose above the density shone, illuminating the background. Rattle also, suggests how "modern" the piece is, with its subtleties and its Night and Fog ambiguity.

Simon O'Neill and Christian Gerhaher were the soloists in Das Lied von der Erde, an interesting combination since their voices are so different, and a choice which also intensified meaning. In performance, singers interact with each other, and with the orchestra, so a good choice of singers contributes to interpretation.

O'Neill is a Wagner tenor, capable of great force. He's also a singer who inhabits roles, bringing out the psychology of the characters he portrays. Wagner heroes aren't nice, or romantic, so the metallic quality in O'Neill's timbre works particularly well in suggesting inner conflict. Some of his keynote roles are Siegmund and Tannhäuser, men who have experienced life to the full. In "Das Trinklied von Jammer der Erde", the tenor does not want to die, and struggles against Fate. Defiantly, he raises his Gold'nen Pokale to drink himself insensate. Even when O'Neill sang the word "Das Firmament" he laced it with poisoned irony. The harsh truth is that apes will howl on abandoned graves. In Chinese culture where heritage is sacred, this image is horrific : the Id consuming the Ego, barbarity annihilating civilisation. When O'Neill sang the words "wild-gespenstische Gestalt", he spat them out with a savagery that showed how well he understood the context.

In contrast, Christian Gerhaher sang with serene smoothness, which worked well with O'Neill's intensity. " DasTrinklied vom Jammer der Erde" and "Der Abschied" form two pillars, between which the protagonist reflects upon his life. The voices don't operate in dialogue, but suggest different parts of the same persona, as does the mirror image of the half moon bridge reflected in the pond. Gerhaher had been singing for years before he shot to international stardom in Tannhäuser with an astonishingly beautiful "O du holdes Abendstern", still his signature role. Wolfram represents purity, the Wartburg tradition where battles are fought by song. Wolfram's a paragon, Tannhäuser raddled and cursed, but Elisabeth chose the bad boy, who had lived. Gerhaher is one of the finest Wolframs ever, but O'Neill, is an excellent Tannhäuser. In so many ways, this Das Lied von der Erde could have been Tannhäuser the Rematch, a level of meaning that's essential to understanding.

Das Lied von der Erde represents a traverse from life to sublimated afterlife. The images in this song symphony are pretty, but doomed. O'Neill established the right emotional tone, while Gerhaher's serenity acted a foil. The images in the text are pretty, but pointed. The young men will no longer prance on their horses as they did when young, the friends in the pavilion will part. Gerhaher's calm smoothness reminded me of Kuan Yin, the Goddess of Mercy, who salves troubled souls. Lotus blossoms dignify Kuan Yin in Chinese mythology. The roots grow in darkness and dirt, but the flowers grow towards the sun. The maidens pluck them because they are edible : a source of nutrition in every sense. Eventually the poet/protagonist is silenced, with only a bird (woodwind) as guide (like Siegfried). Then in Der Abschied the journey metamorphosed onto another level altogether. Gerhaher's singing here was exquisite, well modulated and even paced, the last words "ewig...ewig...ewig" expressed with depth and richness.

This Rattle/LSO Das Lied von der Erde was also outstanding because Rattle understood its structural architecture. The work is remarkably symmetric, dualities creating internal links within and between each section. The singers’ voices are paralleled by flute and oboe. The repeating refrain "Dunkel ist das Leben ist der Tod" connects to the much more esoteric "ewigs" with which the work ends. Each song ends with an emphatic break, which Rattle clearly marks, for each song closes a door and moves on. In "Der Abschied", there are multiple inner sections, interspersed with orchestral interludes which serve to mark transitions. Whatever is happening now is beyond the realm of words alone: like a kind of transition in which something is gradually distilled into a new plane of existence. Think about the Purgatorio in what would have been Mahler's tenth. A pulse like a heartbeat throbs in the early songs, which gradually resolves into the calm almost-breathing stillness in the end. It may be fashionable in some quarters to knock Rattle on principle because he's successful and famous, but that overlooks the fact that he has very strong musical instincts. And the LSO plays for him as if divinely inspired.

Anne Ozorio

image=https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/84/Rattle_BPH-Rittershaus1-Wikipedia.jpg

image_description=Sir Simon Rattle (photo: Monika Ritterhuas)

product=yes

product_title=Richard Strauss Metamorphosen, Gustav Mahler Das Lied von der Erde : Simon Rattle, London Symphony Orchestra, Simon O'Neill, Christian Gerhaher, Barbican Hall, London 13th December 2017

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Sir Simon Rattle (photo: Monika Ritterhuas)

December 17, 2017

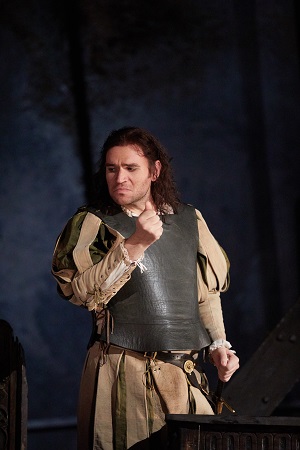

David McVicar's Rigoletto returns to the ROH

The first Act took a little time to settle. Alexander Joel led the ROH Orchestra through a pretty work-a-day reading of the overture in which some unfocused intonation seemed visually symbolised by the precariousness of Sofia Formia’s vulnerable Gilda, perched high on an extending platform, peering tragically into the gloom.

The ball scene was less divertissement than downright debauchery. McVicar leaves us in no doubt of the nature of Rigoletto’s role at the Duke’s licentious court: he provides ‘entertainment’ in the form of facilitating violent seduction and rape, and the assault on Monterone’s daughter - accompanied by hedonist whoops of the fornicating couples and avid voyeurs, and a vicious prod from Rigoletto’s staff - is played out for all to see. There’s no sense of a ‘dance’, though there’s plenty of movement, wild and ugly, as well as much intrusive noise, including the thump of Rigoletto’s crutches as they stab at the floor. Vale’s leaning, metallic wall - which swivels to reveal Rigoletto’s tumble-down shack - is a steely silver, an apt emblem of the emotional coldness and cruelty of this Renaissance den of iniquity, though Tanya McCallin’s costumes add some welcome colour.

Michael Fabiano (Duke of Mantua). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Michael Fabiano (Duke of Mantua). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

The sense that things might escalate out of control was exacerbated by disagreements about tempo between stage and pit, which created musical disequilibrium to match the dissolution of morals. Into this maelstrom, Michael Fabiano flung a roaring ‘Questa o quella’: there was no doubt of this Duke’s power and presence. But, the physical and vocal swagger which characterised Fabiano’s account became ever more coarse, loudness replacing legato: this Mantuan libertine was certainly a dissolute pleasure-seeker but there was little sensuality in Fabiano’s singing. There was a tendency to shout rather than seduce in ‘È il sol dell'anima’ and Fabiano seemed to make no attempt to imbue ‘Parmi veder le lagrime’ with aristocratic elegance; his Duke was a thug and his supposed sorrow merely superficial. I became increasingly puzzled by this interpretation as the performance proceeded.

Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Dmitri Platanias’s leather-clad, crutch-wielding hunchback lumbered and lurched like an aggressive stag-beetle, his crooked jester’s cap-and-bells jiggling grotesquely. Platanias baritone was hardened with anger, swelling with barely repressed rage. Platanias released this fury with fire in ‘Cortigiani, vil razza dannata’ when Gilda is abducted by the Duke’s courtiers; but, he seemed emotionally disengaged during the father-daughter duets, absorbed by his own suffering rather than consumed with obsessive paternal protectiveness. This Rigoletto seemed to take no responsibility for the tragedy which ensues, and thus garnered little sympathy.

Sofia Fomina (Gilda) and Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Sofia Fomina (Gilda) and Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Sofia Fomina has a big soprano and the top notes were powerfully projected, though a wide vibrato, particularly lower in the range, often caused the focus of the note to spread. However, dramatically the Russian soprano also seemed a little detached at times - I wasn’t convinced that this Gilda was intensely attracted to the Duke, overcome by unconscious, unfamiliar sexual desire - although Fomina’s commitment in the final scene was unstinting.

Andrea Mastroni was a fantastic Sparafucile, a man of the shadows, his evil understated but undoubtable: Mastroni’s sensitive, graded parlando in Act 1 told us all we needed to know. Nadia Krasteva’s richly coloured mezzo-soprano conveyed Maddalena’s voluptuousness and the Bulgarian singer acted persuasively. Several Jette Parker Young Artists acquitted themselves well - Francesca Chiejijna (Countess Ceprano), Dominic Sedgwick (Marullo) and Simon Shibambu (Count Ceprano). Despite his suit of armour, James Rutherford’s Monterone was disappointingly underpowered, his curse overshadowed by the general cacophony and depravity.

Andrea Mastroni (Sparafucile) and Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Andrea Mastroni (Sparafucile) and Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

When my colleague, Anne Ozorio, reviewed the 2012 revival of this production she admired the way McVicar ‘gets to the visceral drama’. I wouldn’t disagree with that … but, on this occasion, the bleakness that she notes was unremitting, as neither cast nor orchestra summoned the genuine, if fleeting, tenderness that tempers the machismo and malevolence.

This first performance in the run was dedicated to the memory of Russian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky.

Claire Seymour

Verdi: Rigoletto

Duke of Mantua - Michael Fabiano, Rigoletto - Dimitri Platanias, Gilda - Sofia Fomina, Sparafucile - Andrea Mastroni - Maddalena - Nadia Krasteva, Giovanna - Sarah Pring, Count Monterone - James Rutherford, Marullo - Dominic Sedgwick, Matteo Borsa - Luis Gomes, Count Ceprano - Simon Shibambu, Countess Ceprano - Francesca Chiejina, Giovanna - Sarah Pring, Page - Louise Armit, Court Usher - Olle Zetterström; Director - David McVicar, Conductor - Alexander Joel, Set designer - Michael Vale, Costume designer - Tanya McCallin, Lighting designer - Paule Constable, Movement director - Leah Hausman, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 14th December 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mark%20Douet%20production%20image.jpg image_description=Rigoletto, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product=yes product_title=Rigoletto, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: ROH Chorus and castPhoto credit: Mark Douet

December 16, 2017

Verdi Otello, Bergen - Stuart Skelton, Latonia Moore, Lester Lynch

Otello is one of Stuart Skelton's signature roles. He's matured into the part, singing with even morer depth and richness than before, negotiating the range fearlessly, for Otello is a hero who has achieved great deeds. Significantly though, a storm is brewing in the orchestra as he arrives in Cyprus in triumph. Skelton sang that "Esulate" like a roar, like a lion pre-emting danger. But what was most striking about Skelton's portrayal was its subtlety. His Otello is a man who has confronted overwhelming obstacles all his life and has no delusions about apparent success. When he does find the love he needed so much, his inner insecurities prove his undoing. His tragedy is that he's a good man, destroyed by those more venal than himself. "Fuggirmi io sol non so!" After Otello has killed Desdemona, Skelton's singing is coloured by such sincerity that, despite the crime, Otello is, for his last moments alive, revealed in his true nobility.

Skelton's Otello proves that make-up has nothing to do with artistry. We see the "real" face of Otello and feel his emotions direct. Blacking-up has been anathema in Britain and most of Europe for decades, and it should be. Blackface reinforces the idea that people are defined by outward appearance It may not have been racist in Shakespeare's time, but isn't acceptable now. Otello is an outsider, as is clear in the plot and in the music. No-one should need a caricature Darkie to understand the opera. So Bergen deserves absolute respect for giving us a white Otello and a black Desdemona - people are people, and equal, whatever the colour of their skin.

Latonia Moore is beautiful, in every sense. Her voice is lustrously pure. She creates Desdemona as a halo that glows with spiritual light, which is much more to the point of the opera. Desdemona is an almost visionary personality who sees the innate goodness in Otello and who is prepared to sacrifice herself for love. A soul sister of Gilda and Violetta Valéry. Moore is also sexy, suggesting Desdemona's love of life. The natural sensuality in her voice intensifies characterization, for Desdemona, like other Verdi heroines, isn't virginal though her moral strength elevates her saint-like self-denial. In the first Act, Moore was surrounded by the children's choruses, all of them looking, and sounding, angelic. One young girl looked like she had stars in her eyes - no wonder she was looking at Moore with genuine fondness. Though the staging was minimal, it serves to enhance Moore's artistry, Her dialogue with Hanna Hipp's Emilia was lucidly intimate. Curtains and bed linen don't create personality : good singing does. Incidentally Hanna Hipp sang Emilia at the Royal Opera House. I first heard her in student productions at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

I was looking forward to Lester Lynch's Iago, too, after his Lescaut in Baden-Baden, where he achieved a hugely impressive dynamic with Eva-Maria Westbroek. The pair interacted so well that they really felt like brother and sister, sparring and flirting. Manon wasn't the only rebel in that family. As Iago, Lynch generated similar energy, his voice curling with menace, key words darting forth with venom. Yet again, there's no reason why Iago "has" to be any particular race. Scumballs lurk anywhere.

This Bergen Otello is hard-hitting and emotionally secure,the orchestra playing with vigorous élan. A clean "northern" Otello (staging by Peter Mumford) and no worse for that. Otello is universal. It's not Mediterranean, nor Italian, nor Shakespearean but human drama, for all times and places.

Anne Ozorio

image=

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Giuseppe Verdi : Oterllo. Stuart Skelton, Latonia Moore, Lester Lynch, Vladimir Dmitruk, Remus Alazaroae, Jongmin Park, David Hansford, Hanna Hipp,

Ørjan Hartveit, Bergen Philharmonic Chorus, Edvard Grieg Kor, Collegiûm Mûsicûm Kor,

Bergen pikekor & Bergen guttekor, Chorus master Håkon Matti Skrede, Bergen Philharmoniuc Orchestra, conductoir : Edward Gardner 15th December 2017

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=

December 15, 2017

Temple Winter Festival: the Gesualdo Six

Startling us from our pre-concert chatter, the six singers, led by musical director Owain Park, commenced Brian Kay’s arrangement of the traditional carol at the east end of this glorious late 12th-century church, which was built by the Knights Templar. Then, leaving behind the impressive stained glass of the east windows, they processed through the rectangular chancel, resting in the pointed arch which connects Gothic and Norman parts of the church. The rhythmic tugs and sways of Gaudate were initially complemented by a virile timbre, though subsequent verses offered calmer contrast, before baritone Michael Craddock launched into his solo verse with a confident swagger worthy of a Chaucerian story-teller. A unison clarion rang the piece to a close.

The subsequent items were eloquently introduced by Park, who inspired evident confidence in his singers: his gestures were minimal but efficient; the singers’ eye-contact and obviously pleasure spoke tellingly.

The complex arrangement of Luther’s chorale , Nun Komm, der Heiden Heliand (Now come, saviour of the heathen) by Michael Praetorius throws many challenges at the performers and the Gesualdo Six chose to tackle these by emphasising the strength and character of the individual voices within the ensemble, in order to highlight the vigour of the counterpoint, although the intonation of the whole took a little while to settle.

These Cambridge choral scholars came together in 2014 for a performance of Gesualdo’s Tenebrae Responsories for Maundy Thursday in the chapel of Trinity College and so the Gesualdo Six was born. The English choral tradition and its extant institutions, in which the singers have learned their craft, seemed both an asset and limitation here, and throughout the programme. First, this music is clearly and persuasively ‘in the blood’; and there is an assured balance of blended mellifluousness with soloist narrative. But, diction was sacrificed to beauty of sound; consonants often disappeared, and vowels were bent into uniformity.

However, such consistency has its uses! The programme juxtaposed the traditional with the modern and the Gesualdo Six switched between the two with admirable ease. The sweetness of Jonathan Harvey’s The Annunciation was tempered by harmonic piquancy that seemed almost modal in flavour. Likewise, the exploratory chromatic inflections of Tallis’s Videte Miraculum spoke of modern concerns. In the former, solo voices fluently exchanged the melody, setting the words of Edwin Muir, against a gentle but firm background hum; and while, again, I’d have liked more textual definition - which would have given the contrast between homophony and counterpoint stronger meaning - the ‘deepening trance’ of the close was expertly crafted.

Praetorius’s arrangement of Es ist ein Ros Entsprungen offered more familiar musical fare, and an opportunity to enjoy the contrast of the crystalline countertenor solo of the outer verses with the richer hues of the lower voices, firmer of presence, in the middle verse. The crafting of the pianissimo fade into silence at the close was exquisite, symbolising infinity: ‘uns das verleith’. Park’s own On the Infancy of our Saviour was similarly beguiling, hovering in homophonic enunciation, then swelling with quasi-zealous melismatic rapture, though once again I wished for more textual definition. Francis Quarles’s sentimental images of childhood - of the ‘Saviour perking on thy knee!’, ‘nuzzling’ in virgin brest, with ‘spraddling limbs’, and going ‘diddle up and down the room’ - may be rooted in the pragmatic fact that he and his wife Ursula Woodgate had eighteen children, but such images are still whimsical and remarkable in the context of the virgin birth.

The Gesualdo Six repaired to the circular nave, beside the towering decorated spruce at the west end of Temple Church, for the linch-pin of the performance: Thomas Tallis’s Videte Miraculum, in which the plainchant is both woven into the texture and used to underpin the structure through solo reiteration. One could not fault the ease with which Park shaped the grand architecture of the contrapuntal branches, nor the evocation of awed reverence; but, I did feel that the ensemble needed a weightier bass. The countertenors exhibited the occasional tendency to drift sharp and Craddock and bass Sam Mitchell did not exert the gravitational pull to reign them in to an anchored centre - not that this is a criticism of the individual singers, but additional numbers would have helped.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s The Promised Light of Life followed - in what must have been an arrangement as the original is for TTBB: though who could complain when the countertenors’ soft, echoing ‘Christus’ summoned the silvery sheen of the ‘morning star’ which St Bede’s prayer celebrates. This was a hypnotic conjuring of peace and everlasting assurance.

The singers became compelling story-tellers in Herbert Howells’s Here is the little door. Parks relished the quasi-theatrical setting of Frances Chesterton’s ambivalent text: exaggerating the vocal vitality - ‘lift up that latch, of lift!’ - and the blazing sheen of ‘Our gift of finest gold’. But, there was real drama, and perhaps disquiet, in the juxtaposition of the ‘keen-edged sword’ of gold and the ‘Myrrh for the honoured happy dead’, while the withdrawal of sound with the line ‘Gifts for His children, terrible and sweet’ anticipated the awed reverence at the closing sight of ‘such tiny hands/ and Oh such tiny feet’.

William Byrd’s Vigilate shook us from wondrous contemplation, though: ‘Watch ye’! shuddered with rhythmic vibrancy and attack - ‘nescitis enim quando dominus domus veniat’ (for you know not when the lord of the house cometh). Park again exhibited a masterly command, conveyed unfussily, of the architectural majesty of this motet and the balancing of, and transitions between, different moods were expertly handled. The final cry - ‘omnibus dico: vigilante’ (I say to you all: Watch) - had me bristling with attentiveness.

Lawson’s arrangement of the traditional carol Veni, veni, Emmanuel was beautifully delivered, the varying combinations of ensemble and solo voices, and increasing harmonic complexity, executed with confident and consummate musicianship. Jonathan Rathbone’s setting of Thomas Hardy’s ‘The Oxen’ brought the concert to a close: the slow tempo, ambient humming, and flowering of homophony into more complex counterpoint, all pointed to the ambivalent hopefulness of Hardy’s verse. We were left with the tentative but expectant wish of the poet: ‘I should go with him in the gloom./ Hoping it might be so.’

Though the stunning venue and sonorous vocal ambience had combined to mesmeric effect, the noisy interruption of an overhead helicopter briefly forestalled the encore. But, the dulcet performance of Away in a Manger, which allowed us to enjoy the warmth and easy fluency of Sam Mitchell’s bass, briefly lulled us to forget the buses rattling down Fleet Street and the black cabs chuntering over Waterloo Bridge. This was a lovely festive musical banquet.

Gesualdo Six ’s first recording will be an album of English renaissance polyphony, due for release by Hyperion in spring of 2018.

Claire Seymour

The Gesualdo Six : Owain Park (director), Guy James & Alexander Chance (countertenors), Gopal Kambo & Josh Cooter (tenor), Michael Craddock (baritone), Sam Mitchell (bass).

Trad. arr. Brian Kay - Gaudete; Praetorius -Nun Komm, der Heiden Heiland à 6; Harvey -The Annunciation; Trad. German, harm. Praetorius -Es Ist ein’ Ros’ Entsprungen; Park - On the Infancy of our Saviour; Tallis - Videte Miraculum; Frances-Hoad - The Promised Light of Life; Howells -Here is the little door; Byrd - Vigilate; Trad. arr. Lawson - Veni, veni, Emmanuel; Rathbone - The Oxen.

Temple Church, London; Thursday 14th December 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Gesualdo-Six-by-Ash-Mills.jpg image_description=Gesualdo Six at Temple Church (Temple Winter Festival) product=yes product_title=Gesualdo Six at Temple Church (Temple Winter Festival) product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Gesualdo SixPhoto credit: Ash Mills

December 13, 2017

Mark Padmore and Mitsuko Uchida at the Wigmore Hall

Such thoughts were in my mind at the start of this recital by tenor Mark Padmore and pianist Mitsuko Uchida. As the musicians walked onto the Wigmore Hall platform and an expectant hush descended, I felt a wonderful sense of anticipation tinged with tension: the journey through the twenty-four songs of Winterreise is so familiar, and yet if, at the start of a performance, we know where we are heading we have no idea of how we are going to get there. Nor, paradoxically, what - emotionally, psychologically - our final destination will be.

On this occasion, it was not a journey during which we were buffeted by icy blasts which blew the hats from our heads. The rustling branches, raging streams, rattling chains and barking dogs were finely etched but seemed to herald from a world at one remove - a distant dreamscape into which Padmore and Uchida gently but irresistibly pulled us. As the embracing chill deepened and the wanderer’s tears froze upon the cold flakes of snow, we seemed to be travelling ever deeper into an ‘interior’ landscape of detachment and emptiness: time slowed, movement stilled, the ‘real’ world dissipated into imaginative introspection. When Padmore’s wanderer was lured by the will-o’-the-wisp into the deep rocky chasm, his indifference - ‘How to find a way out does not greatly concern me. I’m used to going astray’ (‘Wie ich einen Ausgang finder,/ Liegt nicht schwer mir in dem Sinn./Bin gewohnt das irregehen’) - was dangerously tempting and undeniable. After all, he sang, ‘Every path leads to one goal’ (’S fürht ja jeder Weg zum Ziel’).

Padmore and Uchida were perfect partners, as they coaxed us into an alienation which seemed to be quietly accepted rather than angrily resisted. Both perform with a delicacy and care that is underpinned by a core of steel. Padmore’s vocal control - the evenness of line and colour, the immaculate phrasing, the meticulous articulation of the text - was complemented by Uchida’s crystalline sculpting of the wintry mind-scape.

Indeed, at times the piano seemed to be bearing the emotional weight of the cycle, particularly as Padmore’s tenor became more withdrawn, almost blanched in the later songs. His soft head voice had an almost hypnotic beauty, beguiling us into the bewildered isolation of ‘Erstarrung’ (Numbness) - ‘Where shall I find a flower, where shall I find a green grass?’ (‘Wo find’ ich eine Blüte,/Wo find’ ich grünes Gras?’) - and making us feel both the pain of perplexed wretchedness in ‘Einsmakeit’ (Loneliness) and the comfort of a dream’s sanctuary in ‘Frühlingstraum’ (Dream of Spring). There was contrast, creating a sense of progression, between the shapely legato of the young man’s farewells to his ‘sweetest love’ in the opening song, and the shrouded pianissimos of the later songs. In ‘Täuschung’ (Delusion), Padmore’s ghostly tenor conjured a disturbing terror as the wanderer is lured from the path by the ‘garish guile’ of a dancing light which promises friendship and warmth beyond the ice and night.

But, there were moments where I missed vocal weight, particularly in the lower range, and variety of tone: in ‘Irrlicht’ (Will-o’-the-wisp) where the plunging vocal leaps and dark descent convey the wanderer’s submission to sorrow; in the desperate plea - ‘O crow, let me at last see faithfulness unto death!’ (Krähe, lass mich endliich she/Treue bis zum Grabe!’) at the close of ‘Die Krähe’.

Uchida synthesised the musical architecture and emotional trajectory, demonstrating a remarkable insight into the structural coherence of Schubert’s cycle, articulating the expressive details with wonderful judiciousness. The opening chords of ‘Gute Nacht’ were paradoxically both reticent and resolute, becoming almost imperceptibly more firm as the wanderer’s resolve hardens, pausing for the barest moment before the final stanza, where a prevailing tension in the piano’s tread, underlined by Padmore’s vocal intensification in the closing line, belied the deceptive shift to the major mode.

The limpidity of Uchida’s delineation of the frozen tears of ‘Gefrorne Trähe’; the coolness of the dark meandering at the start of ‘Erstarrung’; the perfectly judged triplets of ‘Auf dem Flusse’ intimating the murmuring currents beneath the stream’s silent surface; the incontestable blast at the opening of ‘Rückblick’ (A backward glance) which pushed the wanderer ever onwards: such masterful musical story-telling was both astonishing and utterly absorbing. In ‘Der Lindenbaum’ (The linden tree), the delicate breeze which nudged the branches at the start became a bitterer force at the close, the piano’s taut dotted rhythms seeming to stab cruelly at the wanderer in the final verse, taunting him with the promise of rest. Contrastingly, there seemed to be no pulse at all in the first two bars of ‘Irrlicht’, as if the piano’s four-notes came from ‘elsewhere’, an embodiment of the wander’s delusions.

The harmony of spirit between singer and pianist was compelling. In ‘Wasserflut’ (Flood), the rhythmic tension between voice and accompaniment was sensitively controlled, and Padmore’s heightening of the repeated last line of each stanza was underscored by the swelling of the piano’s richer chords and Uchida’s expressive shaping of the return to the minor key. ‘Frühlingstraum’ balanced frighteningly on the edge of an abyss, hovering between reality and fantasy, pausing in silence when the screaming ravens had woken the dreaming wanderer, before Uchida resumed the slow, rocking of the dream-world for which he longs - the battle for mental stability subtly but sharply dramatized in musical terms. The clarity of the interplay of voice and piano in ‘Der Wegweiser’ (The Signpost) made the piano’s left-hand ornaments speak eloquently beneath Padmore’s beautifully even high line, Uchida retreating to a barely-there pianissimo in the final verse as the wanderer gazes at the road he must travel and ‘from which no man has ever returned’ (Die noch Keiner ging zurück).

The performers’ vision cohered most powerfully in the final four songs. The slow sombreness of ‘Das Wirthaus’ (The inn) was thrust aside by the desperate wilfulness of ‘Muth’ (Courage), but it was the exquisite, gentle warmth - almost shocking after the preceding unrelenting coldness - of Uchida’s introductory phrase in ‘Die Nebensonnen’ (Phantom song) that was so striking; as was the way the yearning of the vocal line faded to quiet hopelessness, as the piano’s attempted assertiveness slipped into resignation. When Padmore asked the cycle’s final question, ‘Will you grind your hurdy-gurdy to my songs?’, slight warmth adding urgent need to the rising plea, Uchida’s reply - strong at first, then diminishing into silence - seemed to suggest that this wanderer would indeed find his peace ‘elsewhere’.

Claire Seymour

Mark Padmore (tenor), Mitsuko Uchida (piano)

Schubert: Winterreise D911

Wigmore Hall, London; Monday 11th December 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/MarkPadmore004web.jpg image_description=Mark Padmore and Mitsuko Uchida at the Wigmore Hall product=yes product_title=Mark Padmore and Mitsuko Uchida at the Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Mark PadmorePhoto credit: Marco Borggreve

December 12, 2017

Turandot in San Francisco

The David Hockney Turandot, with the John Adams / Peter Sellers Girls of the Golden West, the Vincent Boussard Manon and the Prague/Karlsruhe/SF shared Elektra were all fascinating in their mises en scène. Only La traviata of the five operas of the 2017 fall season (some of us remember when there were thirteen) suffered an outdated production, though it too had its merits — the three excellent principal singers and the masterful conducting of Nicola Luisotti.

In September the refurbished David Hockney 1992 Turandot burst once again onto the War Memorial Opera House stage in new intense colors for Puccini’s musically imagined Peking, the princess Turandot enacted in highest verismo terms by Austrian soprano Martina Serafin and the pit energized by the subtleties of Puccini’s score, conductor Luisotti having matured over his ten San Francisco years to join the ranks of the great conductors of Italian opera.

Leah Crocetto as Liu

Leah Crocetto as Liu

The Turandot casting evolved in three significant ways for the six November performances. The icy Princess was now sung in highest heroic terms by Swedish dramatic soprano Nina Stemme, the slave girl Liu was sung by former Adler Fellow Leah Crocetto who has achieved a now deserved diva status, and Calaf’s father Timur was sung fully and forcefully by American bass Soloman Howard, grounding this role dramatically into the Liu tragedy of Calaf’s ascension into the realm of high love.

Nina Stemme, the world’s reigning dramatic soprano, took us into the heady stratospheres of the soprano voice and kept us there beyond what we know can be humanly possible. The three riddles were hurled in intense colors and vocal luster, her defeat felt in surprisingly human terms, this superb artist like almost no other is able to be both human and super-human. The ascension to love in the Alfano finale took the human love she had discovered into the rarefied spheres of Romanticism’s spiritual union, this impossible Teutonic ideal rendered possible, finally, in the Puccini oeuvre where before it had never found, or even sought.

Leah Crocetto in her Adler days was perhaps prematurely cast as Liu in the 2011 SFO Turandot. Just now la Corcetto projected the musical and histrionic attributes of a fully arrived, mature artist. Gratefully she is willing to take risks, like her first act “Signore, ascolta!” sung pianissimo, knowing dramatically that it is a silent prayer. It was stunning even with this estimable artist rested on the lower edges of pitch tones. There were not issues at all with her third act “Tu che di gel sei cinta,” delivered with compassion and fervor. La Crocetto brought great dignity to Liu’s tragedy in studied, convincing and satisfying verismo terms.

If conductor Christopher Franklin fully supported these two remarkable artists in their vocal and dramatic subtleties he took the balance of the score to its most blatant terms, knocking out the intimacy of the Ping, Pang, Pong interplay in rhythmic force, and resorting to the latent bombast of both Puccini and Alfano whenever possible. Obvious effect was certainly achieved, a thoughtful realization of the musical and dramatic magic of the Puccini score was sacrificed.

The June revival of the San Francisco Opera’s 2011 Der Ring des Nibelungen will tell more about a perceived new sophistication of casting perspectives at San Francisco Opera. The casting of Evelyn Herlitzius as Brünnhilde is a great start.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Turandot: Nine Stimme; Calaf: Brian Jagde; Liù: Leah Crocetto; Timur: Soloman Howard; Ping: Joo Won Kang; Pang: Julius Ahn; Pong: Joel Sorensen; A Mandarin: Brad Walker; Emperor Altoum: Robert Brubaker. San Francisco Opera Chorus and Orchestra. Conductor: Nicola Luisotti; Production and Design: David Hockney; Director: Garnett Bruce; Costume Designer: Ian Falconer; Original Lighting Designer: Thomas J. Munn; Lighting Designer: Gary Marder; Choreographer: Lawrence Pech. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, November 6, 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/TurandotNov17_SFO1.png

product=yes

product_title=Turandot in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Nine Stimme as Turandot [All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

December 8, 2017

Daniel Michieletto's Cav and Pag returns to Covent Garden

But, in the event, this performance of Damiano Michieletto’s production of the verismo duo was so compelling that the December chill and Christmas sparkles of the Covent Garden piazza were utterly forgotten and for three hours we were in a village in south Italy, with its family bakery, shabby school hall, kitsch Easter parade, black-veiled mamas and flower-strewn madonnas.

In 2015 , I found the incessantly revolving set distracting and some of Michieletto’s gestures mannered; but, this time round (the first revival) I was absolutely persuaded. How to explain my change of heart? Perhaps it was that revival director Rodula Gaitanou seemed to have found a way to balance stylisation and naturalism in such a way that the movement of cast and chorus around the revolve, and the interweaving of motifs across the two operas, felt genuine and ‘real’. Just as, under the baton of conductor Daniel Oren, the ROH orchestra gave us an introductory tour of the emotional trajectory of Cavalleria, so the revolving set seemed to take us on a stroll through the town, and not just into its homes and houses but into the hearts and minds of its inhabitants.

Inside the Panificio bakery, with its sacks of flour stacked high beside the mechanical weighing scales, the trays of loaves sat waiting for the oven. The Catholic icon perched on a high shelf later found its way into the scuffed school hall where the performance of Pagliacci - advertised on the bakery wall - took place. The children scrabbling for panettone at the bakery window donned tinsel halos and papery wings to form an angelic Easter choir, and after the parade remained in costume to reappear on the cramped school stage in a choral prelude to Pagliacci. The ROH Chorus - as ever, in tremendous voice - wandered casually about the village, gathered in the square for a post-parade knees-up, assembled eagerly for the ensuing entertainment, all with complete naturalism.

There are some surreal and stylised moments too. When the devout villagers raise their candles and adjust their shrouds during the Easter hymn, the gaudy Madonna on the festive float seems to come to life, pointing an accusatory finger at the traumatised Santuzza. And, the meta-theatre of Pagliacci is emphasised not just by the interlocking jigsaw of Paolo Fantin’s set, which allows us to witness parallel action as fiction spills into fact, but also by Alessandro Carletti’s lighting contrasts which pit blinding strip lights against blackness, and a lurid green glow against a rosy-pink shimmer.

What really swept me to the Italian South, though, was the terrific singing of all involved. This was the first time that I have heard Latvian mezzo-soprano Elīna Garanča and I was struck by the expressive weight of her voice, which burst forth with power and punch - as if the betrayed Santuzza’s distress and dishonour were just too devastating to be contained, literally overwhelming her and all around her too. Indeed, the rich layers and grand plushness of her mezzo seemed almost too majestic for the unlucky lass in a dowdy cardigan, but I guess that’s what Mascagni’s music is telling us: that human emotions have no bounds or boundaries.

I remained unbeguiled by Michieletto’s decision to begin Cavalleria at its end, presenting us with a play of maternal grief as Mamma Lucia bends over the bloody body of Turiddu - a child’s red scooter-bike leaning on the street-lamp adds a touch of sentimentality - and I again found Elena Zilio’s histrionic head-clutching, body-convulsing and hand-wringing to be hyperbolic. But, elsewhere Zilio was a strong presence, physically and vocally, in the production - a true matriarch in every sense.

Mark S. Doss (Alfio/centre) and ROH Chorus. Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Mark S. Doss (Alfio/centre) and ROH Chorus. Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Mark S. Doss convincingly cast aside the relaxed confidence which Alfio displays when he rolls into town with a car boot full of fashionable wares - the tussle between two girls who fancy the same handbag is a neat touch - for dark-toned menace when he learns of Lola’s betrayal. Martina Belli returned to the latter role and her glossy mezzo-soprano gave the temptress real allure.

Carmen Giannattasio (Nedda) and Simon Keenlyside (Tonio). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Carmen Giannattasio (Nedda) and Simon Keenlyside (Tonio). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Also reappearing in her 2015 role, Carmen Giannattasio was a persuasive Nedda in Pagliacci, encompassing a gamut from shining ardour to a silvery whisper in her duet with Polish baritone Andrzej Filończyk’s warm-hued Silvio, and acting superbly when ‘Columbine’ is dragged by the raging Canio from harmless play-acting to murderous reality.

Simon Keenlyside injected a terrible hostility into the Prologue of Pagliacci. Alone in Nedda’s claustrophobic, starkly-lit backstage dressing-room, as he invited us to enjoy the ensuing drama, Tonio seemed to sneer with contempt at our gullibility and casual ignorance as he reminded us that what we were about to see involved real people with real emotions. And, Keenlyside made sure that the rejected hunch-back’s latent menace was evident throughout, despite Tonio’s shabbiness and shuffling: think Rigoletto meets Iago.

Elena Zilio (Mamma Lucia) and Bryan Hymel (Turridu). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Elena Zilio (Mamma Lucia) and Bryan Hymel (Turridu). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

It was American tenor Bryan Hymel, though, who stole the show. Cast as Turiddu, he also stepped into Canio’s shoes (family circumstances obliged the originally cast Fabio Sartori to withdraw from the first three performances), and proved equally compelling in both role debuts, holding nothing back despite the vocal, and expressive, demands. The confident, bright ring of his tenor was imbued with deeper, darker colours when Turridu was confronted by the vengeful Alfio, and in his farewell to Mamma Lucia, Hymel heartbreakingly conveyed the doomed Turridu’s honesty, self-knowledge and vulnerability. Canio’s account of the evening entertainment to come, at the start of Pagliacci, had a lyricism and power that hinted at terrifying tragic potential. And, indeed, Hymel continually ratcheted up the emotional thermometer until the mercury exploded in a blazing conclusion.

Tonio may have spoken the truth when he spat out his closing line, ‘La commedia è finita!’, but the impact of this double bill’s punch will surely be long-lasting.

Claire Seymour

Cavalleria Rusticana : Santuzza - Elīna Garanča, Turiddu - Bryan Hymel, Mamma Lucia - Elena Zilio, Alfio - Mark S. Doss, Lola - Martina Belli.

Pagliacci: Canio - Bryan Hymel, Tonio - Simon Keenlyside, Nedda - Carmen Giannattasio, Beppe - Luis Gomes, Silvio - Andrzej Filończyk, Two Villagers - Andrew O’Connor/Nigel Cliffe.

Director - Damiano Michieletto, Conductor - Daniel Oren, Set designs - Paolo Fantin, Costume designs - Carla Teti, Lighting design - Alessandro Carletti, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Royal Opera Chorus.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Wednesday 6th December 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Santuzza%20and%20madonna.jpg image_description=Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci at Covent Garden product=yes product_title=Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci at Covent Garden product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Elīna Garanča (Santuzza/left) and ROH ChorusPhoto credit: Catherine Ashmore

December 5, 2017

Manitoba Opera: Madama Butterfly

Last staged locally in April 2009, the three-show run directed by Winnipeg’s Robert Herriot also featured Tyrone Paterson leading the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra through Puccini’s rapturous score. The maestro also notably marked his own auspicious anniversary on the MO podium in November, beginning his tenure as the company’s music advisor/principal conductor 25 years ago conducting exactly this same work.

The three-act tragedy sung in Italian, and based on a libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa tells the tale of 15-year old Cio-Cio San (a.k.a. Madama Butterfly), who weds American naval officer B.F. Pinkerton based in Nagasaki, Japan. After he returns home to the U.S to find a “proper” American wife, she bears his son, little Sorrow, and awaits his return with tragic consequences.

The 150-minute production featured a particularly strong cast of principals. The first of those is world-renowned Tokyo-born soprano Hiromi Omura, who delivered a masterful performance as the young geisha in a role she debuted in 2004, and has now performed over 100 times. As she morphed from lovesick girl to noble young woman who dies for honour, her soaring, well-paced vocals in the notoriously difficult part were fully displayed from her opening “Ancora un passo or via—Spira sul mar,” until final “suicide aria” “Con onor muore.”

Omura also performed her highly anticipated aria “Un bel di vedremo” with limpid fragility and ringing high notes as sparkling as the starry night sky, trembling in anticipation for her husband’s ship to sail back into harbour that earned her spontaneous applause and cries of brava. However, it’s during her silent vigil as she awaits Pinkerton’s return during the exquisite “Humming Chorus” where Omura’s profoundly moving artistry spoke loudest, as seemingly every shade of raw, vulnerable emotion flashed across her face: from hope to fear; love to loss, lit beautifully by Bill Williams.

Her equal in every way, acclaimed Canadian lyric tenor David Pomeroy created a strapping, 19-year old Pinkerton, who swaggered through his opening aria “Dovunque al mondo” fueled by strains of the “Star Spangled Banner,” and chillingly proclaimed “America forever.” Pomeroy set sail on his own harrowing narrative arc with port stops along the way, including sweetly tender love duet with this new bride, “Viene la sera,” until becoming unmoored and wracked with remorse during Act III’s “Addio fiorito asil” sung with dramatic intensity.

It’s also a testament to Pomeroy’s powerhouse acting skills that he earned perhaps one of the greatest compliments during his opening night curtain call: boisterous boos from a clearly engaged, impassioned audience on their feet for his wholly believable characterization that the artist acknowledged with delight.

Baritone Gregory Dahl also brought subtle nuance to his role as US consul Sharpless, who urges Pinkerton to be cautious of Butterfly’s heart, and later becomes caught in the lovers’ downward spiral during trio “Io so che alle sue pene,” sung with Pinkerton and Suzuki as a well-balanced ensemble.

Suzuki, portrayed by Japanese-American mezzo-soprano Nina Yoshida Nelsen in her MO debut also crafted a dedicated maid and confidant, who harmonized seamlessly with Butterfly and strewed cherry blossom petals during “Flower Duet” “Scuoti quella fronda,” while infusing the culturally sensitive production with greater verisimilitude.

It’s always a joy seeing baritone David Watson onstage, who made every moment count as The Bonze. Kudos also to Quinn Ledlow (alternating with Ava Kilfoyle), who brought sweet innocence to little Sorrow, despite the evening’s late hour for a four-year old tot. Winnipeg baritone Mel Braun served double duty as the Commissioner and a Prince Yamadori, while mezzo-soprano Laurelle Jade Froese instilled Kate Pinkerton with dignified, sensitive compassion.

However, the production is not without flaw. Cio-Cio San—now Mrs. Pinkerton—remained resolutely Japanese in appearance, still dressed in a kimono during Acts II and III despite singing of her “American house” that visually weakened her character’s transformation. And marriage broker Goro, (tenor James McLennan), who machinates the nuptials between Pinkerton and Cio-Cio San appeared far too polite and at times overly pedestrian for a scheming plot driver.

Just as Cio-Cio San paints pictures of wisps of smoke with her voice during her iconic “Un bel di vedremo,” Herriot likewise uses the stage as a canvas for his creative ideas.