January 29, 2018

Brent Opera: Nabucco

When a small company does what we deem to be a big piece, normally endowed with a 50-strong chorus, 70 orchestra and camels in abundance, disbelief hangs in the air before the first down beat, but this production proved that Nabucco can work with a chorus of 19 and a piano. The other big challenge with Verdi is finding a Verdi baritone, in this case 2 and even though Verdi bills one of them as a bass, he slips in the high odd note which is just out of reach. This problem was skilfully tackled by the Musical Director James Williams who deftly but sympathetically kept going almost carrying the singers along with him – and it was in everyone’s interest that he was only in charge of an upright piano rather than a blazing orchestra.

Without resources for a set, a further pro was the lovely setting of St Andrew’s Church and bearing in mind the libretto is based on the biblical books of Jeremiah and Daniel this seemed fitting. Stage designer Leah Sams seemingly had an easy time although her arch, cleverly lit by Nigel Lewis to depict city walls, a cell door etc worked well.

Brent Opera has been going for nearly 100 years (2021) and is a free for all to audition. The regulars in the company are of a certain age and this proved to be another pro for the chorus which cleverly ranged in age down to 2 children (and a fake babe in arms) – when they sang the famous "Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves", " Va, pensiero, sull'ali dorate " / "Fly, thought, on golden wings", it was an authentically moving moment and with the odd good voice in the mix, the sound was pretty impressive too.

Fears aligned Nabucco doesn’t have to be staged in Verona or Earls Court. It’s a psychological drama with a cast of 8, about the Jews when they were being exiled from their homeland by the Babylonian King Nabucco. A romantic and political plot are played out with the strong message that good will conquer evil, and this point was clearly delivered by director Ptolemy Christie. Having portrayed Nabucco as a maniacal nutcase using his cruel daughter Abigaille as a side-kick vindictively abusing the Jews, the revelation of his prayers to the God of Israel pledging to convert at the end of the opera, were all the more poignant. Christie systematically characterizes his characters. Zaccaria, the High Priest decently sung by Steven East clad in an almost winged cloth top is Jesus – good, kind, generous, while Abigaille sung bravely by Elisabeth Poirel is the root of all evil, bagging the crown, tossing her father in prison and torturing Jews. These portrayals work across the cast and chorus and make it believable in a way you didn’t think would be possible. Sofia Celenza’s Anna (only one line sadly) shines out both dramatically and vocally.

Clever old Brent Opera booking Williams and Christie – they’re the real deal and produced an evening of great entertainment.

Louise Flind

image=http://www.operatoday.com/4632364052_525x348.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Brent Opera: Nabucco product_by=A review by Louise Flind product_id=LPO: Das Rheingold

One can envy the practice of many German orchestras, which play for both opera house and symphony hall, but envy does not necessarily take us very far. (Actually, as Alberich will show us, it does, but perhaps not in the best direction.) In a closer-to-ideal world, admitted Vladimir Jurowski in the programme, there would have been a theatrical production, but the Ring ‘would be the end of Glyndebourne as a venue – it would simply fall apart if we tried to squeeze the orchestra into the pit!’ Why an achievement to perform it, though? Because Wagner’s dramas offer a standing rebuke to neoliberalism. It is not that there is any lack of ‘demand’; look how performances, especially in Wagner-starved Britain, will often sell out within a few minutes. But however great the demand, they will not ‘pay for themselves’. They are a communal undertaking, explicitly intended and functioning as heirs, political, social, religious, and dramatic – the distinctions make no sense – to the Attic tragedy of Aeschylus and Sophocles. (For more on that, please click here .)

Robert Hayward as Alberich with Lucie Špičková, Rowan Hellier and Sofia Fomina

Robert Hayward as Alberich with Lucie Špičková, Rowan Hellier and Sofia Fomina

Moreover, for the London Philharmonic Orchestra to give such an outstanding orchestral performance, in what must be the first time many of its players will have performed the score, is again cause for thanks and rejoicing. The LPO strings could hardly have proved more protean, the variegation of their tone a challenge to many an opera orchestra, that variegation surely born in part of Jurowski’s strenuous demands. Detail was present and vivid to what sometimes seemed a well-nigh incredible decree. For instance, the brass spluttering as Alberich floundered in the Rhine, for instance, looked forward suggestively to Strauss’s critics in Ein Heldenleben . If the anvils did not sound as they might in one’s head, when do they ever? That was no fault of the excellent nine players on three sides of the stage. The Prelude sounded – and, given the pipes behind the stage – unusually organ-like: not just the timbres, but also the insistence on the E-flat pedal, quite beyond any I can recall previously having heard. Such was the revealing side of Jurowski’s tight leash and rhythmic (harmonic rhythm included) exactitude, Bruckner coming strongly to mind.

And yet, as so often, Jurowski himself proved too unyielding, almost Toscanini-like, if on a lower voltage. His again was quite an achievement, given that this was the first time he had conducted the score. There is no reason to think that subsequent performances will not reap rewards. By the same token, however, it would be idle to think that this compared to a Daniel Barenboim or a Bernard Haitink, although it certainly knocked spots off the incoherent incompetence Wagner generally suffers under Haitink’s successor at Covent Garden . To Londoners who hear little or nothing else, this would rightly be a cause for rejoicing. Moreover, the sometimes almost caricatured formalism of Jurowski’s approach – I wondered at times whether he had been reading Alfred Lorenz! – was not without its rewards. Was structure, however, too clarified, even simplified? For every revealing instance of opposition between different varieties of thematic material – Fricka’s disruptive, recitative-like ‘Wotan, Gemahl’, for instance, amidst Wotan’s orchestral dreaming of Valhalla – there were at least two passages that were distinctly subdued, almost as if concerned that the orchestra would threaten audibility of the singers. (It never did, by the way.) It was wonderful to hear so much harp detail as the gods crossed the rainbow bridge, and there is certainly good, Feuerbachian dramatic reason to emphasis the unreal beauty of the fortress and the path thereto. It need not, though, and surely should not come at the expense of its sacerdotal power. Novelistic, almost domesticated narrative sometimes threatened, in a dialectical turn, the integrity of musico-dramatic form. Yes, this is epic, yet it is anything but undisciplined. Das Rheingold, however, is a very difficult work to bring off: in some ways more so than the subsequent Ring dramas. Even Barenboim has sometimes erred a little too much towards Neue Sachlichkeit here. That there was a good deal to engage with critically, however, the foregoing merely illustrative, suggests that Jurowski’s Wagner is and will continue to be something to take seriously.

London Philharmonic Orchestra, cast and conductor, Vladimir Jurowski curtain call

London Philharmonic Orchestra, cast and conductor, Vladimir Jurowski curtain call

Vocally, as will almost always be the case, the bag was mixed. I could not resist the sense that, to a certain extent, at least Matthias Goerne’s Wotan was a little too much reliant on stock emotionally stunted sociopathy. Only towards the end, after the arrival of Anna Larsson’s typically excellent Erda, did he seem more truly ruminative. That is a crucial moment, of course, in his road towards Schopenhauerian conversion, but Wotan is never merely a figure of force. ‘Nicht durch Gewalt!’ is, after all, his injunction to Donner. Robert Hayward’s Alberich went awry a few too many times; at his best, however, he proved darkly impressive. The giant pair of Matthew Rose and Brindley Sherratt also duly impressed as Fasolt and Fafner, the lovelorn brother genuinely moving, the sheer malevolence of Fafner at and after his death chilling indeed. Vsevolod Grivnov and Adrian Thompson offered detailed, dramatically alert ‘character tenor’ portrayals of Loge and Mime respectively, Allan Clayton’s light, bright-toned Froh a proper contrast. Michelle DeYoung’s Fricka, often imperious, was sometimes a little on the wobbly side, but there was little harm done in that respect, nor in the not dissimilar case of Lyubov Petrova’s cleanly sung Freia. Above all, there was a fine, almost Mozartian sense of conversation in passages of much dramatic to-and-fro. If only there had been a little more conventional drama. There nevertheless remained much to admire – and far from only because it happened at all.

Mark Berry

Cast and production information:

Woglinde: Sofia Fomina; Wellgunde: Rowan Hellier; Flosshilde: Lucie Špicková; Freia: Lyubov Petrova; Fricka: Michelle DeYoung; Erda: Anna Larsson; Froh: Allan Clayton; Loge: Vsevolod Grivnov; Wotan: Matthias Goerne; Donner: Stephen Gadd; Fasolt: Matthew Rose; Fafner: Brindley Sherratt; Mime: Andrew Thompson; Alberich: Robert Hayward. Consultant: Ted Huffman; Deputy Stage Manager: Katie Thackeray; Lighting: Malcolm Rippeth. London Philharmonic Orchestra/Vladimir Jurowski. Royal Festival Hall, London, Saturday 27 January 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Matthias%20Goerne%20and%20Michelle%20deYoung%20in%20LPO%27s%20Das%20Rheingold%20c.%20Simon%20Jay%20Price.png image_description=Matthias Goerne and Michelle deYoung in LPO's Das Rheingold c. Simon Jay Price. product=yes product_title=LPO: Das Rheingold product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Matthias Goerne and Michelle deYoungPhotos © Simon Jay Price

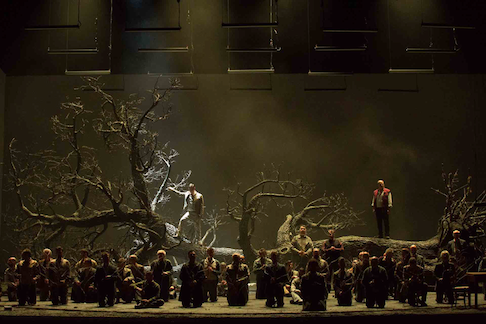

William Tell in Palermo

The Palermitani, evidently less offended by abject sexual violence, tolerated the production’s humiliation and rape of a young woman without remark (having tacitly accepted as well Hunding’s gang rape of Sieglinde in last year’s Ring). Not that Damiano Micheletto’s William Tell production was not resolutely booed at this opening night of the Teatro Massimo’s one-hundred-twenty-first season. It was indeed.

It was a relaxed, festive evening at the Teatro Massimo, a red carpet runner ushering the very well-dressed audience past two magnificently uniformed guards at the entrance, shining swords at their sides. Never mind the heavy police presence in the piazza in anticipation of a demonstration (unrealized) against such extravagance.

At the hour the performance was to begin an announcement was made delaying the beginning by one-half hour due to a strike of some sort. No one minded as it was a very social evening, the animated conversations would have been hard to interrupt anyway.

Guillaume Tell, Rossini’s French style grand opera can be a very long evening (five hours plus in a recent Rossini Opera Festival production). In Palermo just now it was reduced to a bit over four hours, the act one marriage ballets were sacrificed, plus other less prominent sections.

Dmitry Korchak as Arnold (in white light), Roberto Frontali as William Tell (in red vest)

Dmitry Korchak as Arnold (in white light), Roberto Frontali as William Tell (in red vest)

The Michieletto production reduced Rossini’s spectacle to bare bones — an illustrated comic book story (projected from time to time) was its cornice from which a surrogate William Tell emerged to cement William Tell’s patriotic resolve at crucial moments. Rossini’s quite specifically human, and complicated storytelling was transformed in Palermo into a ceremonial hymn to liberty, told in three bold strokes, Gesler’s thugs tore out the tree of peasant life (Gesler is the tyrant villain). The tree lay dead on the stage until William Tell eradicated Gesler. A new tree was planted as the Swiss peasants celebrated their emancipation from tyranny.

The effect of the production, and it was considerable, was exponentially increased by the expansive conducting of Teatro Massimo’s music director Gabriele Ferro. His tempos were indeed deliberate, elaborating the ceremonial tone of the production, the flights of lyricism were reduced to the beautiful sounds of the overture’s flute solo and to the splendidly voiced fisherman’s song that opens the first act.

After this it was all business. The chorus of Swiss peasants was grimly seated at regimented tables to grimly celebrate love, marriage and the harvest. William Tell got right to work liberating them through his heroic resolve, abetted by the heroic courage of his son Jemmy and the stoicism of his wife Hedwige. The murdered Melcthal’s son Arnold came to his senses and swore to avenge his father (though William Tell actually did all the work), not without the help of the Hapsburg princess Mathilda whom he loved.

Done.

The chorus and the principals then let Rossini’s final hymn to liberty soar, and it was spine tingling. The gigantic dead tree magically lifted (grand opera is famous for spectacular scenic effects, and this was just that) to allow a young boy to pass under with a sapling that he planted down stage center.

Roberto Frontali as William Tell

Roberto Frontali as William Tell

The Micheletto production was given vibrant life by an excellent cast whose voices and personae seconded its conceptual intentions. Baritone Roberto Frontali (San Francisco Opera’s recent Scarpia and L.A. Opera’s recent Falstaff) brought sharp edge to William Tell, no longer Rossini’s father figure he was far more a warrior. Soprano Anna Maria Sarra as William Tell’s son Jemmy was not diminutive, rather she was full-sized both vocally and morally, a warrior who mimed a child's movement.

Arnold, rendered impotent by love was sung by Russian tenor Dmitry Korchak in fine French and fine Rossini style. He was in love with Mathilde, the Hapsburg princess sung by Tbilisi (Georgia) born Nino Machaidze, a soprano of ample voice and great charm who negotiated her bit of fioritura with ease and to good effect.

William Tell’s stolid friend Walter Furst, sung by bass Marco Spotti, remained in the shadows, helping when called upon. Albanian mezzo Enkelejda Shkoza made Tell’s wife Hedwige a strong, purposeful presence supporting her husband and son, and a strong, purposeful voice in the upper registers of Rossini’s large ensembles, in Palermo executed with requisite magnificence.

The villain Gesler was delivered in high caricature by bass Luca Tittoto, underscoring the Italianate nature of this French evening (after all we were in Palermo!). Tenor Matteo Mezzaro, Gesler’s lieutenant Rodolphe, managed infectious charm in his nefarious duties.

The splendid first act’s fisherman’s song was sung by Sicilian tenor Enea Scala for the opening night performance only. He will sing Arnold in the final two of this eight performance run — the dynamic will be greatly changed. As the fisherman he and Enkelejda Shkoza were the only carryovers from the Covent Garden cast.

The orchestra and chorus of the Teatro Massimo seccured the solid artistic level of the evening, proving again that this Palermo theater is among the finest in Italy.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Guillaume Tell: Roberto Frontali; Arnold: Dmitry Korchak; Walter Furst: Marco Spotti; Melcthal: Emanuele Cordaro; Jemmy: Anna Maria Sarra; Gesler: Luca Tittoto; Rodolphe: Matteo Mezzaro; Ruodi: Enea Scala; Leuthold: Paolo Orecchia; Mathilde: Nino Machaidze; Hedwige: Enkelejda Shkoza; Un chasseur: Cosimo Diano. Chorus and Orchestra of the Teatro Massimo. Conductor: Gabriele Ferro; Metteur en scène: Damiano Michieletto; Scene designer: Paolo Fantin; Costumes: Carla Teti; Lighting: Alessandro Carletti. Teatro Massimo, Palermo, January 23, 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tell_Palermo1.png

product=yes

product_title=Guillaume Tell in Palermo

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Anna Maria Sarra as Jemmy, Matteo Mezzaro as Rodolphe [first two photos copyright Rosellina Garbo, third photo copyright Franco Lannini, al photos courtesy of Teatro Massimo]

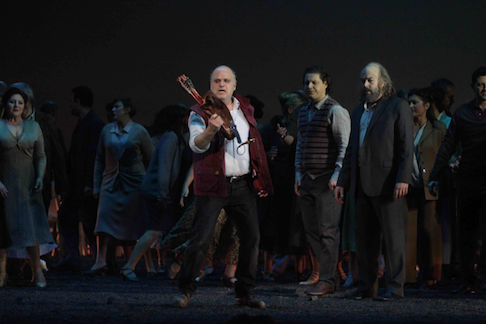

The Bandits in Rome

And to this day “Tu del mio Carlo al seno” and its cabaletta remain a showpiece for sopranos, not to mention the “Parea mi che sorto da lauto convito” that is a blockbuster showpiece for baritones. There is even a greater amount of splendid music for tenor, starting with the opera’s initial scene “O mio castel paterno” that creates the situation that will result in the brutal murder of the soprano.

Just now in Rome the tenor Carlo, yearning for his childhood home, was sequestered up on some sort of rolling scaffold on the side of the stage for this first scene (and most of the opera), but upon learning that his father has disinherited him he vowed to remain in a band of robbers who plunder the countryside (and in this production brutally rape women). The robbers rose magically on one of Teatro Costanzi’s famous full stage elevators and he agreed to become their leader.

Carlo (Stefano Secco) becoming leader of Verdi's bandits

Carlo (Stefano Secco) becoming leader of Verdi's bandits

Meanwhile we learn that the baritone had deceived the tenor. The tenor had not been disinherited after all, he could in fact have renounced his dissolute life and returned home. The problem now becomes the tenor’s sworn loyalty to his band of robbers, not to mention that the soprano from his former upright life loves him. Unfortunately the conniving baritone wants to marry her. So there was a lot to sing about.

The metteur en scène of this new production was popular 57 year-old Italian actor and voiceover artist (for dubbing films) Massimo Popolizio. Mr. Popolizio made his directorial debut only last year with Author Miller’s 1968 play The Price. Mr. Popolizio is said to have based his staging of The Bandits on the popular U.S. TV series Game of Thrones. Maybe this explains the several scenes of gratuitous gang rape. Unlike the well developed threads of Game of Thrones, Mr. Popolizio left Verdi’s admittedly worst libretto without a discernible story line. We will never know from Mr. Popolizio why Carlo (the tenor) murdered Amalia (the soprano) just after their ardent declaration of love.

It was an an evening about singing, not about theater. After overcoming quite deserved opening night nerves the mostly Italian cast sang stylishly. Unfortunately tenor Stefano Secco (San Francisco’s 2014 Pinkerton) as Schiller’s questionable hero Carlo did not deliver the opening scene with sufficient pizazz to impress the audience which, despite his intense and eloquent (though small scale) delivery of the third act, awarded him vociferous boos at the final bows.

Twenty-nine year old ingenue diva Roberta Mantegna, a recent graduate of Rome Opera’s new young artist program, negotiated Amalia’s treacherous outpourings with knowing aplomb, belying the fact that this was her debut in a major role on a major stage. Additional maturity of voice will add effect to her Amalia.

Francesco (Artur Ruciński) beginning “Parea mi che sorto da lauto convito”

Francesco (Artur Ruciński) beginning “Parea mi che sorto da lauto convito”

Polish baritone Artur Ruciński, San Francisco Opera’s recent Germont, gave an impressive account of the repentant Francesco’s big scene, his fine diction finding its intimacy rather than its bravura. The role of Massimiliano, Carlo and Francesco’s feeble father, was competently delivered by ubiquitous bass Ricardo Zanellato.

Conductor Roberto Abbado exhibited little affection for early Verdi, and had no patience for attempting ensemble in the extended scenes with the male chorus.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Massimiliano: Riccardo Zanellato; Carlo: Stefano Secco; Francesco: Artur Ruciński; Amalia: Roberta Mantegna; Arminio: Saverio Fiore; Moser: Dario Russo; Rolla: Pietro Picone. Orchestra and Chorus of the Teatro dell’opera di Roma. Conductor: Roberto Abbado; Metteur en scène: Maurizio Popolizio; Set designer: Sergio Tramonti; Costumres: Silvia Aymonino; Lighting: Robert Venturi. Video: Luca Brinchi and Daniele Spanò. Teatro Costanzi. Rome, January 21, 2018

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bandits_Rome1.png

product=yes

product_title=I masnadieri in Rome

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Roberta Mantegna as Amalia, Carlo Secco as Carlo [All photos copyright Yasuko Kageyama courtesy of Teatro dell'Opera di Roma]

January 28, 2018

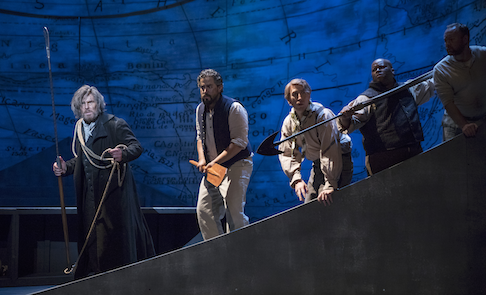

Utah’s New Moby Dick Sets Sail

The original premier’s set design by Robert Brill seemed to me not only definitive, but almost inextricable from the work’s success. Problem is that only the largest, most solvent companies could accommodate its demands.

The new, streamlined version on display in Salt Lake City not only keeps all of the fluid changes and atmospheric background for the monumental story, but actually also improves the stature of the work. With fewer eye-catching bells and whistles in the visuals, the ear is freed to pay closer attention to the bells and whistles in the score, and I was surprised how much richer I found Mr. Heggie’s accomplishment to be. More on the success of the design will follow.

I wholly admired the original conception, but on this occasion I came to believe this is the composer’s finest work to date. The score is wonderfully colored; the sea effects are sometimes lulling, sometimes wrenching; vocal writing is grateful and characterful; and the imposing, monumental, goose bump-inducing orchestral and choral writing that sweeps listeners along to the shattering climax are effectively balanced with moments of camaraderie and infectious humor.

Conductor Joseph Mechavich displayed equal flair for both the rhapsodic and intimate extremes in this varied score, and he shaped the evening’s musical arc with a firmly controlled reading. It helps that he has a seasoned ensemble of players under his baton, playing with a polish and unity of purpose that comes from having full-time employment as an orchestra. This fine band is one of the few in America that are employed 52 weeks a year and that approach pays big dividends in musical quality and cohesiveness.

Maestro Mechavich is aided mightily by Michaella Calzaretta’s superb choral preparation. Her large chorus was flawless in tonal beauty, dramatic engagement, and clarity of diction, even when performing busy stage movement. The musical excellence carried over to the principal singers who proved a top tier collective of singing actors.

Roger Honeywell doesn’t so much sing the role of Captain Ahab as inhabit it. Mr. Honeywell prides himself on being a committed actor first, and a suave vocalist second. In many of my memorable experiences viewing his performances, he has struck a bargain and offered tonal beauty and theatrical fire in equal measure. In this role assumption, Roger tilts the scale decidedly to the dramatic side, coloring his substantial, heroic tenor with ire, fanaticism and fateful determination.

While this makes for chilling dramatic effects, there are times that the voice turns hard, or even a mite unsteady. I have no doubt that this is his intent. His anguished, raspy moans as he dozes, are emitted with a huskiness of vocal production that would send most singers into apoplexy. But there is no question that Roger Honeywell, with his perfect diction and total emotional investment anchored (pun intended) the show.

As Starbuck, the strapping baritone David Adam Moore threatened to run off with the vocal honors. His beautiful, easily produced tone was even throughout the range, and his sensitive phrasing and dramatic understanding made a most appealing case for this sympathetic character. He found his equal in Joshua Dennis’ polished, mellifluously sung Greenhorn. Mr. Dennis’ well-schooled lyric tenor is not exceptionally large, but it is so well focused, and so limpidly produced that he made a resounding impression. He also embodied real pathos in his moving final scene.

Musa Ngqungwana brought a winning persona and orotund, rolling bass-baritone to the exotic character Queequeg. He not only impressed with his distinctive solo moments, but also made solid contributions in his touching duets with Mr. Dennis’ Greenhorn. Indeed the two created a magical, infectious relationship that was most appealing, and the major subplot in the story.

Joseph Gaines turned in his usual high quality performance as Flask, marked by a well-defined characterization, a good sense of fun, and a securely deployed tenor. His buddy, Stubb was enthusiastically impersonated by Craig Irvin, who showed off a shining, meaty baritone that was steady even as he was called upon to simultaneously do a sprightly jig. Indeed both Mssrs. Gaines and Irvin were delightfully fleet of foot in their animated performances.

The sole female voice, serving the role of the boy Pip, was the vibrant soprano Jasmine Habersham. The diminutive performer was suitably juvenile and her well-controlled, silvery tone had an alluring presence. Perhaps her voice is too “womanly” to utterly convince as the hapless lad, but this was an impressive role assumption, delivered with fierce commitment. Jesús Vicente Murillo did admirable double duty as Captain Gardiner and a Spanish Sailor; Babatunde Akinboboye made the most of his stage time as Daggoo; and the role of Tashtego was well-served by Keanu Aiono-Netzler. Anthony Buck was the firmly intoned Nantucket Sailor.

As impressive as all of these demonstrably fine singers were singly, they were most remarkable for their impressive ensemble work, thanks to inspired direction from Kristine McIntyre. Ms. McIntyre thrives on large cast extravaganzas, managing to move masses of singers meaningfully about the playing space, all the while effectively focusing attention on solo moments as required. She crafted richly detailed character relationships, and seemed to effortlessly manufacture one telling stage picture after another.

Having recently marveled at her Billy Budd at Des Moines Metro Opera, I am wondering if she is entering the nautical phase of her career? What’s next Kristine? Pinafore? Dutchman? I would sail well out of my way to see anything this talented director undertakes. She is especially adept at synchronized gestures, steps, and percussive effects, and there were many potent passages of unison group movement, with effective choreography incorporated by Daniel Charon.

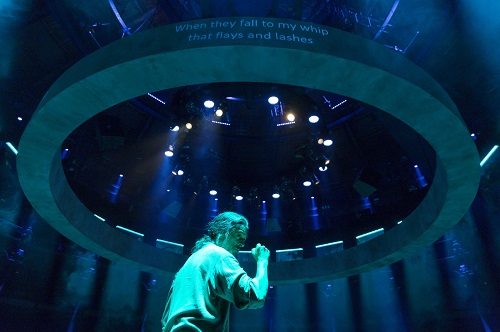

Set designer Erhard Rom is celebrated not only for his artistic gifts but also for mounting attractive multiple sets with economy of means. His evocative, practical solutions here are praiseworthy indeed. Mr. Rom has borrowed a page from Wieland Wagner and placed a disc/platform center stage. Decorated with what suggests a compass, it spins to create multiple effects, with stairs, sleeping cubicles, and even a prow.

A large totem of a mast, with a perilous looking crow’s nest dominates the visuals dead center. The backdrop looks like someone took an old nautical map and subjected it to an imaginative paper cutting. The resulting silhouette with its swooping dip in the top center and large panoramic “window” suggests a colosseum. It turns out that opening can be closed by four separate panels, a device masterfully used in various combinations.

Mr. Rom meets the other requirements of varying locations by adding or subtracting furniture, angular insets flown in and out, and simple set pieces like the whaling boat. The grand drape not only sets the mood with its depiction of turbulent waves but is used for a startlingly good effect near opera’s end.

Lighting Designer Marcus Dilliard has provided one superb effect after another, from an azure starry sky to the fiery glow below deck to the mottled light of late afternoon to a gathering storm to a stylized whale hunt. Mr. Dilliard’s general washes always create just the right ambience, and his use of tightly focused areas and specials was highly proficient. Jessica Jahn’s spot-on costume design and Yancy J. Quick’s comprehensive wig and make-up design completed the look by so ably defining the characters and their stations.

The one important moment neither the original design nor this one fully mastered was the critical climactic moment of Ahab’s fateful confrontation with the whale. Rom, McIntyre, Dilliard and company have definitely come very very close. I will not spoil the surprise but I can say a truly menacing suggestion of the killer whale comes about in a surprising fashion. Ahab is suitably terrified, the music churns, the tension builds inexorably and then. . .the scenery takes an easy way out.

Still, this was such a stunning achievement full of so many memorable components, that it is easy to predict this winningly re-imagined Moby Dick will have a long and full run on national and world stages.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Captain Ahab: Roger Honeywell; Greenhorn: Joshua Dennis; Starbuck: David Adam Moore; Queequeg: Musa Ngqungwana; Flask: Joseph Gaines; Stubb: Craig Irvin; Pip: Jasmine Habersham; Captain Gardiner/Spanish Sailor: Jesús Vicente Murillo; Daggoo: Babatunde Akinboboye; Tashtego: Keanu Aiono-Netzler; Nantucket Sailor: Anthony Buck; Conductor: Joseph Mechavich; Director: Kristine McIntyre; Set Design: Erhard Rom; Costume Design: Jessica Jahn; Lighting Design: Marcus Dilliard; Choreographer: Daniel Charon; Wig and Make-up Design: Yancey J. Quick; Chorus Master: Michaella Calzaretta

image=http://www.operatoday.com/UtahOpera_1801-8326.png

image_description=Photo © Utah Opera/Dana Sohm

product=yes

product_title=Utah’s New Moby Dick Sets Sail

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Photos © Utah Opera/Dana Sohm

January 24, 2018

Bevan and Drake travel to 1840s Leipzig

As soprano Sophie Bevan explained to me recently ( The Schumanns at home ), Drake had selected four songs to represent each of five of the Schumanns’ illustrious international guests, and the hosts themselves. At the start of the evening, he invited us to imagine ourselves at a musical soirée in the Schumanns’ piano nobile apartment, being entertained by some of the cultural elite of the mid-nineteenth century. As Schumann himself said of musical life in Leipzig, ‘What an abundance of great works of art were produced for us last winter! How many distinguished artists charmed us with their art!’

With such a cornucopia of lieder from which to choose, one wonders how Drake settled upon his selections. Certainly, one could discern distinctive musical ‘voices’, and it was interesting to hear Clara Schumann’s gentle melodising beside Chopin’s folk-tinted melancholy, or Liszt’s blending of fervent human passion and reverent spirituality. And, as the lieder weaved from German to Polish and back again, with diversions into French and even English, a truly international conversation unfolded. But, there was variety of expressive range within the song-quartets, too. Moreover, Bevan had remarked that many of these songs were new to her, and many were also new to me and so the programme offered numerous fresh discoveries and delights.

This was a very engaging recital, both performers communicating with directness and sincerity. Despite the ‘newness’ of the material, Sophie Bevan was impressively ‘off score’ for many of the songs and took evident care to capture the spirit of each lied through the manner of performance.

She seemed a little nervous at the start of the recital, which was her debut at Middle Temple Hall, but still conveyed the tender intimacy of the opening quartet of songs by Clara Schumann. The textural repetitions, fairly low register and narrow range of ‘Liebst du um Schönheit’ (If you love for beauty) delicately draw us into the conversation; ‘Sie liebten sich beide’ (They loved each other) was more emotionally heightened but closed with a rueful, sweet-toned whisper, ‘Sie waren läbgst gestorben/Und wußten es selber kaum.’ (They died a long time ago and hardly knew it themselves.) ‘Der Mond kommt still gegangen’ (The moon rises silently) revealed the subtleties of Clara Schumann’s harmonic inventiveness and pianistic writing; Drake traversed sensitively from the relaxed chords of the opening to the more intense piano postlude. But, if the first three songs had shared a quiet serenity, then ‘Am Strand’ revealed a more turbulent expressive mode which allowed Bevan’s soprano to blossom ecstatically in conclusion: as she called to the spirits to murmur tidings of her beloved, the piano’s softening response duly obliged.

The lieder by Clara Schumann and the fours songs by Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel that followed led me to wish that performers would more regularly embrace the sizeable song repertory by such women composers. Fanny Mendelssohn wrote 249 songs, more than twice as many as her brother Felix, and ‘Frühling’, with its bubbling, trilling piano part, frequent wide vocal leaps and rapturous blooming at the close revealed an audacious, exuberant approach to song-writing. The harmonic explorations of ‘Warum sind denn die Rosen so blaß’ (Why are all the roses so pale?) were similarly responsive to the text, as the wandering phrases seemed to echo the unanswered questions of Heine’s poem. Again, Drake’s discerning selections offered expressive range, the tenderness of ‘Nachtwanderer’, contrasting with the powerful epiphanies of ‘Bergeslust’ (Mountain rapture).

One of the strengths of Bevan’s performance of these opening songs was the lack of artifice and the sincerity of her engagement with the texts, and I felt that this quality came even more to the fore in the four songs by Felix Mendelssohn. She seemed to relax, perhaps because the songs are more familiar, and ‘Die liebende schreibt’ (The beloved writes) was sensuous and impassioned. Songs by a mandolin-playing page, by rustling pond reeds and by a coven of witches ensued, and Bevan and Drake moved smoothly from the jaunty spiritedness of ‘Pagenlied’, through the richness and resignation of ‘Schilflied’, to the darkness and defiance of ‘Hexenlied’.

In the first of four songs selected from Chopin’s Polish Songs Op.74, the mazurka-like ‘Śliczny chlopiec’ (Handsome lad), Drake immediately established an insouciant air, employing a playful rubato. His fluent pianism imbued these songs with conviction and drama, most particularly in ‘Wojak’ (The warrior), summoning a crisp vision of a galloping steed whose impatience was equalled his war-mongering master’s elated urgency. At the close, after a momentary stay, man and beast sped onto the bloody battlefield and disappeared over the horizon, the piano diminishing with wonderful control.

Given that these are Chopin’s only contribution to the vocal repertoire, it’s perhaps surprising that the Op.74 songs are not performed more regularly; until, that is, one reflects on the fact that there are probably few singers who would avow to being fluent in, or familiar with, Polish. Bevan pronounced the text with care and suppleness but did not have quite enough declamatory confidence to capture the dramatic intensity of the texts (two of which are anonymous, with additionally one each by Chopin's contemporaries, Stefan Witwicki and Bohdan Zaleski). That said, ‘Dumka’ had a poignant Slavic sorrow and Bevan’s pianissimos were touching and perfectly tuned, while the narrative of the Lithuanian song (‘Piosnka litewska’) unrolled naturally, Drake’s staccatos giving life to the dialogue and Bevan displaying rich vocal quality in the lower register.

Drake is the curator of Hyperion’s ongoing project to record Liszt’s complete songs (to date four volumes have been released) - a worthy and necessary endeavour, given that even lieder enthusiasts may be unaware that Liszt composed any songs other than ‘Die Loreley’. Here, the pianist made miniature tone poems of the accompaniments, sparking and trickling with transparency in ‘Die stille Wasserrose’ (The silent water-lily), and conjuring the majesty of Cologne cathedral in ‘Im Rhein, im schönen Strome’ (In the Rhine, the beautiful river). Best of all was the brooding concentration of the introduction to ‘Der du von dem Himmel bist’ (You who come from heaven).

Bevan revealed a strong feeling for the Romantic sensibility in this sequence, and the vocal range with which to express it. Often her soprano descended quite low, as at the openings of ‘Die stille Wasserrose’ and ‘Im Rhein’, and she used vocal colour to imbue these songs with a quasi-spiritual ambience. Elsewhere, such as at the contemplative close of ‘Ihr Glocken von Marling’ (Bells of Marling), the mood was ethereal, and the high melody at the end of ‘Im Rhein’, which floated above Drake’s low pianissimo accompaniment, shimmered with reverence for ‘Our beloved Lady’. In contrast, ‘Der du von dem Himmel bist’ was impelled by anxious but irresistible urgency and intensity, attaining rapturous transcendence in the final, surging line, ‘Komm, ach komm in meine Brust!’ (Come, ah come into my breast!).

Bevan showed a similar affinity for a distinctly French sensibility in Berlioz’s ‘Chant de bonheur’ (Song of bliss), in which the melodic line freely hovered between song and recitative, and was matched by the rhythmic flexibility of Drake’s accompaniment. ‘Petit oiseau’ had classical, even ‘antique’, elegance and Bevan’s piano invitation, ‘Viens écouter ses chants touchants’ (Come and listen to his moving song) was focused and compelling. ‘Adieu Bessy’, a setting of a poem by Thomas Moore (one of one of nine composed in 1829 to translation by Berlioz’s friend, Thomas Gounet), possessed rhetorical weight despite the sweetness of the vocal line; ‘Zaïde’ was propelled by Drake’s insistent rhythmic motifs and the ecstatic, fluctuating colours of Bevan’s soprano.

Four songs by Robert Schumann brought the soirée to a close. Bevan mastered the vocal expanse of ‘Widmung’ (Dedication), the melodic line unfolding lyrically above the fervent murmurings and motions of the piano accompaniment. Again, she showed that her lower register has real focus and presence, falling with the change of mood - ‘Du bist die Ruh, du bist der Frieden’ (You are repose, you are peace) - as, paradoxically, tension was injected by the three against two rhythmic dialogue between piano and voice. ‘Die Einsiedler’ (The hermit), too, benefitted from an even vocal line, while the final song, ‘Aufträge’ (Messages) burbled excitedly propelled by an intoxicating lyrical and poetic impulse.

Claire Seymour

Sophie Bevan (soprano), Julius Drake (piano)

Clara Schumann - ‘Liebst Du um Schönheit’, ‘Sie liebten sich beide’, ‘Der Mond kommt still gegangen’, ‘Am Strande’; Fanny Mendelssohn - ‘Frühling’, ‘Warum sind den die Rosen so blaß’, ‘Nachtwanderer’, ‘Bergeslust’; Felix Mendelssohn - ‘Die Liebende schreibt’, ‘Pagenlied’, ‘Schilflied’, ‘Hexenlied’; Frédéric Chopin - ‘Śliczny chlopiec’, ‘Dumka’, ‘Piosnka litewska’, ‘Wojak’; Franz Liszt - ‘Die stille Wasserrose’, ‘Ihr Glocken von Marling’, ‘Im Rhein, im schönen Strome’, ‘Der du von dem Himmel bist’; Hector Berlioz - ‘Chant du Bonheur’, ‘Petit oiseau’, ‘Farewell, Bessy’, ‘Zaïde’; Robert Schumann - ‘Widmung’, ‘Muttertraum’, ‘Der Einsiedler’, ‘Aufträge’.

Middle Temple Hall, London; Monday 22nd January 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Schumann%20house%20Leipzig.jpg image_description=The Schumanns at home, Temple Song 2018 product=yes product_title=The Schumanns at home, Temple Song 2018 product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: The Schumann Haus in LeipzigJanuary 23, 2018

The Chalk Circle in Lyon

Der Kreiderkreis or The Chalk Circle or Le Circle de Craie in French (1931) is the seventh of Zemlinsky’s eight operas (A Florentine Tragedy [1916] is the fifth, The Dwarf [1921] is the sixth, the unfinished Le Roi Candaule is the eighth). This Lyon production is the French premiere of The Chalk Circle.

Zemlinski’s The Chalk Circle is realized in masterful musical strokes, the late Romanticism and its destruction that surrounded Zemlinsky is fully assimilated into a finished style that floats faultlessly from the grotesque to the sublime, through cruelty and hopelessness to generosity and redemption. The.exotic tones of the ancient Orient and the new American world plus extended tracts in the actual spoken language finished the sophisticated soundscape of this tumultuous German political era. It was a unique music that mesmerized the opening night audience.

Director Richard Brunel found this sound world in ephemeral white images that merely suggested architecture. He dressed his actors in colors and periods that spoke to and of the wealth, power and corruption of the early twentieth century and to our current moment and to these early moments of the Chinese twenty-first century as well. He dissolved morality play abstractions into very specific and intense human scenes incorporating a large number of silent actors and even a live horse. The horse was white of course, and as the white snowflakes of the full stage snowstorm it too purified the heroine Haitang in her impossible plight.

Ma’s number one wife Yu-Pei overhears Haitong’s reunion with her brother Ling and hatches her plot to frame Haitang for infidelity.

Ma’s number one wife Yu-Pei overhears Haitong’s reunion with her brother Ling and hatches her plot to frame Haitang for infidelity.

The story is simple. A maiden sold into sex slavery is saved first by a villain she then purifies by giving him an heir. Accused of killing this husband by his number one wife she is again saved, now by the emperor of China himself who discerns her purity when she refuses to inflict violence on her child by wrenching it from a circle drawn by chalk. Among the splendidly staged scenes was her initial house of joy encounter with the young noble who later became emperor. It made startling effect indeed as circles of white light moved and bounced in pleasure and innocence.

Director Brunel knows however that such purity and innocence is doomed. He is not duped by the happy morality of the Chinese play. Brunel’s heroine we learn in the split second before final blackout has only imagined this happy ending. This extended delirious love duet with the emperor was but a flash in the moments before she is executed by the forces of an unjust world.

It was a production of purely human dimension executed in exquisite theatrical taste.

The cast, primarily Germanic language singers, was perfection, physically and vocally finding the depths of purity and depravity in the humanity of the characters of this ancient morality play. Conductor Lothar Koenigs created a vibrant presence for Zemlinsky’s score.

Haitang (in red) refuses to subject her child to the violence of a physical struggle. The emperor in light tan coat looks on.

Haitang (in red) refuses to subject her child to the violence of a physical struggle. The emperor in light tan coat looks on.

Soprano Ilse Eerens beautifully exploited every nuance of emotion felt by Haitang, convincingly traversing Zemlinsky’s quick shifts through fear, resolve, tenderness and ecstasy. Her first love, Prince Pao, the young noble later emperor sung by Stephan Rügamer, was of stentorian tone, her brother Tschang-Ling, sung by baritone Lauri Vasar was, as Haitang, a voice of sweetness and human understanding. Haitang’s husband Ma, a tax collector, sung by bass Martin Winkler was rough and raspy. His divorce lawyer Tchao, sung by baritone Zachary Altman matched the menacing warmth of his lover mezzo soprano Nicola Beller Carbone who as Ma’s number one wife was the opera’s villain. As the judge, Tchou-Tchou, at the murder trail character tenor Stefan Kurt gave terrifying presence to the corruption of power as character singer Paul Kaufman created the shocking depravity of German cabaret as the Chinese house of joy.

The French production team was metteur en scène Richard Brunel; set designer Anouk Dell’Aiera; costumer Benjamin Moreau; lighting designer Christian Pinaud and video by Fabienne Gras.

Michael Milenski

Opéra Nouvel, Lyon, January 20, 2018

image=http://www.operatoday.com/3-LeCercleDeCraie2-%C2%AEJeanLouisFernandez020%203.png

image_description=Prince Pao and Haitang falling in love [Photos copyright Jean Louis Fernandez courtesy of the Opéra de Lyon]

product=yes

product_title=The Chalk Circle in Lyon

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Prince Pao and Haitang falling in love

All photos copyright Jean Louis Fernandez courtesy of the Opéra de Lyon

January 21, 2018

Jonathan Miller’s “Così” strikes gold again

Richard Wagner’s grandson Wieland is usually given credit for sowing the seeds of Regietheater “(director’s theater”) with his Bayreuth Parsifal of 1951.

Wieland’s experiment generated ferocious outrage from Wagner traditionalists. But when today we look at his designs and read reviews of his staging it all looks mercifully mild: an honest attempt at fulfilling grandpa’s dream of “total theater” (Gesamtkunstwerk) by implementing the pre-war scenic dreams of English visionary Gordon Craig.

But as the decades rolled on and fury turned first to respect and even reverence, younger directors drew a dangerous conclusion. An outraged audience became a touchstone of artistic seriousness. By the time Hans Neuenfels presented his audience a cleaning lady Aïda and mirrored the Frankfurt audience itself as jaded witnesses to the Triumphal March in 1981, the lesson had been learned: Skandal macht Karriere: outrage gets you attention—and jobs. By the turn of the century, when he forced his Salzburg Fiordiligi Karita Mattila to sing her big aria Come scoglio while wrangling two leather queens on leashes, critica response was downright indulgent: Oh ,those directors, what scamps they can be!

I am happy to report that no leather queens were harmed in Seattle Opera’s staging of the same opera: even happier to report that Jonathan Miller’s ageing production of Cosi fan tutte—first mounted at London’s Royal Opera more than three decades ago—is as fresh as daisy, lively as a puppy, and as to the point as a slap in the face.

Sir Jonathan’s enduring concept for Così, presented with equal success here just over 10 years ago ? The same which has guided his long list of constantly revived, consistently successful productions: Ignore surfaces; take emotions seriously, even the most superficial and silly; above all, take seriously what the composer and librettist are saying with every word and note. When this production fails to do so, when it plays just for laughs instead of truth of feeling—and it fails sadly often in the first act—you can feel the momentum slacken even as you laugh out loud.

Fortunately, there is one person on stage who never lets you off with just a laugh. Our Fiordiligi is Marina Costa-Jackson, who first stepped on the professional stage in 2015 in the traditional debut soprano role of Musetta. A year later she was “covering” the role for the Met; 2016 brought in quick succession Violetta, (Cologne), Micaëla (Paris), and Adalgisa (Dallas)—an incredibly steep ascent.

With the formidable Fiordiligi she takes on a role all but made for her vocally. The low As and high B flats that the composer put in to tease the freakish range of the lady who first essayed the role are not totally up to par, but they will become more secure with time. More important is that, three years out of the conservatory, Ms. Costa-Jackson captures Fiordiligi’s soul.

The name means “lily-flower”, and she convinces you the woman who bears it really longs for purity, chastity, fidelity. She’s not a tragic character: she’s too pampered, weak, human for that. But her discovery of her own frailty is enough to give the whole wind-up plot of Cosi a depth of feeling it wouid not otherwise have. She even succeeds in one of the risky gags that punctuate act one: a mid-aria false exit that rouses a hearty laugh only enriches her character more.

Her colleagues on stage all have far less onerous dramatic tasks to play, and acquit themselves with honor. Costa-Jackson’s sister Ginger is a delicious Dorabella, as quintessential and lovable an airhead as Alicia’s Silverstone’s immortally Clueless Cher. Kevin Burdett’s scheming Don Alfonso brings an agreeable whiff of brimstone to the role, reminiscent of the genial Ray Walston’s Mr. Applegate in the musical Damn Yankees. Finnish tenor Tuomas Katajala’s Ferrando is the perfect hangdog “hero’s friend,” while Guglielmo, the hero himself (in his own mind at least) is played to self-satisfied perfection by “bari-hunk” Craig Verm, who must find it relaxing for once to be allowed to remain fully-dressed for the entire length of a perfomance.

Click here for audio playlist.

Laura Tatulescu plays Don Alfonso’s paid co-conspirator as an agreeably bitter little pill. I wish Harry Fehr and Cythia Savage (re-mounter and costume designer respectively) could have been a little more consistently contemporary about her costuming in the disguise scenes; they’re sadly old-fashioned-stagey and unfunny.

Did I mention all these people can sing? And, saints preserve us, act? Without their eyes constantly seeking the conductor’s baton like dogs waiting for a stick to be thrown? On the dangerous vast stage dictated by McCaw Hall’s layout, this is a near miracle of ensemble in itself.

But such miracles don’t happen without a master hand in the pit, and after a few disquieting moments during the overture Paul Daniels takes utter self-effacing charge of affairs, with wonderfully judged tempi and subtle moment-by-moment balance between orchestra and stage. To see, again and again, an auditorium full of heads nodding happily as they recognize the rueful truth of the unfolding tale, is to wish you could somehow say: “That’s right: trust your instincts: If it feels that good, it must be that good. Never mind “concepts”, contemporary, topical. timely or not. Only truth and artistry conjoined feel like this. Accept no substitutes.

Through January 27th

Roger Downey

Cast and production information:

Marina Costa-Jackson (Fiordiligi), Ginger Costa-Jackson (Dorabella), Tuomas Katajala (Ferrando), Craig Verm (Guglielmo), Kevin Burdette (Don Alfonso), Laura Tatulescu (Despina). Paul Daniel (conductor), Harry Fehr (director), Sir Jonathan Miller (original stage directorand designer), Neil Peter Jampolis (lighting), Cynthis Savage (costumes), Jonathan Dean (English surtitles). Orchestra and Chorus of the Seattle Opera. Marion Oliver McCaw Hall, Seattle January 14th, 2018

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Cosi_06_cropped.png image_description=© Tuffer product=yes product_title=Jonathan Miller’s “Così” strikes gold again product_by=A review by Roger Downey product_id=Images © TufferTucson Desert Song Festival Presents Artists from the Met and Arizona Opera

Held at the University of Arizona, artists and patrons also enjoy in the warm Sonoran Desert climate where flowers bloom in January and February. The festival’s sixth year features a celebration of the life and music of Leonard Bernstein who would have been one hundred years old in 2018.

On January 17, the festival presented a recital by Metropolitan Opera mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson Cano and collaborative pianist Christopher Cano who is Head of Music and Director of the Marion Roose Pullin Opera Studio at Arizona Opera. Upon entering, the audience was greeted with a wonderfully well organized program that included song texts in the original languages and excellent English translations by the singer herself. Also the lights were never too low for members of the audience to read translations as Jennifer Cano sang them.

The Canos opened their program with three selections from Joseph Canteloube’s Chants d’Auvergne: “L’Antouéno” (“Anthony”), “La delaïssádo” (The Deserted Girl”), and “Lou Coucut” (“The Cuckoo”). Cantaloube’s collection is made up folk songs from the Auvergne region of France that he arranged for voice and orchestra between 1923 and 1930. The songs are sung in Occitan, (also known as Provençal or Languedoc). Occitan speakers communicate officially in French, but they still use the dialect for local purposes.

Clad in black silk trimmed with lace, in the first song, russet haired Jennifer Cano charmed “Anthony” into taking her to the fair. She sings of getting a cow but will only let him have its horns. Then she made us commiserate with the sad young girl whose lover never comes to meet her. The evening star finds “The Deserted Girl” in a place so many of us have been, alone in the dark of night. “The Cuckoo” drew us out of the sad mood with its cheery song, however, even though we had to imagine him singing in the cooler forests of France. Christopher Cano’s virtuosity had been evident during each of these pieces. He brought out sonorities not always heard in a piano accompaniment and his articulation was comparable to many of the finest solo pianists. This was one of the rare vocal recitals where it was important to sit on the keyboard side of the house.

For their second group the Canos’ performed Antonín Dvořák’s Ziguenerlieder (“Gypsy Songs”), a set of seven songs set to texts by Czech poet Adolph Heyduk. Heyduk translated some of his poems into German so Dvořák could set them to music for popular Vienna Opera tenor Gustav Walter. For many people of European extraction, these songs bring back memories of childhood. "Als die alte Mutter" (“Songs My Mother Taught Me”) could frequently be heard not only in Prague and Vienna but in many American cities during the years following World War II. It was a treat to hear it sung by members of a new generation who carefully detailed all its hidden meanings.

The Canos’ idiomatic rendition of Manuel de Falla’s 1914 composition, Siete Canciones Populares Españolas (“Seven Popular Spanish Songs”) concluded the first half of the program. De Falla composed some songs in styles representing particular areas of Spain such as Murcia and Asturias. Other songs tell of the vagaries of love. The Canos presented each piece as a precious jewel in an individual setting. I particularly loved the beautifully expressed meanings, both sung and unsung, in the “Jota,” a dance from Aragon.

After the intermission, the Canos presented songs in English by Samuel Barber, Leonard Bernstein and Jonathan Dove. In 1935, when Barber won the Prix de Rome, he composed music for three poems about love and lovers from James Joyce’s 1907 Chamber Music. In each, Barber allows his music to follow the poetic speech pattern. The first and last songs of the low voice edition are in the key of A minor while the middle song is a minor third lower. Sung and played by the Canos, they dazzled listeners with a kaleidoscope of gorgeous sound colors.

Three Songs from West Side Story with texts by Stephen Sondheim have increased meaning when we contemplate them as a memorial to a great composer. With “One Hand One Heart” the artists spoke of unity. Onstage there was complete unity of singer and pianist during the entire evening. Christopher and Jennifer Cano seemed to breathe together and each was able to anticipate the other’s moves. In “Somewhere” they expressed common longing for a place that could appreciate people who care and create. In the less familiar “I Have a Love” they spoke of love as the most important aspect of life.

London born Jonathan Dove has composed opera, choral works, plays, films, chamber and orchestral music. Over the years he has arranged a number of operas for British companies. Three Tennyson Songs is a short song cycle composed in 2011 for Canadian baritone Philippe Sly. In it the poet first sends a swallow to tell his lady of his love. Day breaks upon a still wakeful lover and “The Sailor-Boy” obeys his unquenchable desire to spend his life riding the high seas.

Although the nearest bay is a hundred miles away, the Canos brought its beauty and its thrill to the desert with their ability to project musical images into the minds of their audience. When they finished presenting these songs, there was a great thunder of applause from this excellent audience, which only applauded at the end of each group. After several forays before the curtain they gave their single encore: John Jacob Niles’ "Go 'Way From My Window," and the audience departed slowly with tunes from this excellent recital still running around in their brains.

Maria Nockin

Program:

Joseph Cantaloube, Selections from Chants d’Auvergne; Antonín Dvořák, Gypsy Songs; Manuel deFalla, Siete Canciones Populares Españolas; Samuel Barber, Three Songs, Op 10; Leonard Bernstein, Three Songs from West Side Story; Jonathan Dove, Three Tennyson Songs.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Canos.png

image_description=Christopher Cano and Jennifer Johnson Cano. [Photo by Lisa Mazzucco]

product=yes

product_title=Tucson Desert Song Festival

product_by=A recital by Jennifer Johnson Cano, mezzo-soprano, and Christopher Cano, piano

product_id=Above: Christopher Cano and Jennifer Johnson Cano. [Photo by Lisa Mazzucco]

January 20, 2018

The Schumanns at home: Temple Song 2018

During the next four years, this was where Schumann composed many of his important compositions, including the three string quartets and the ‘Spring Symphony’. In the first year of their marriage alone, the Liederjahr, over 150 songs tumbled from Robert’s pen, expressive of his love for his new wife, and his happy hopes for their future together.

As Clara gained renown as a concert pianist - alongside bearing eight children and managing the household finances - Robert’s reputation as a composer, and as editor and publisher of the New Journal of Music (Neue Zeitschrift für Musik) which he had founded in 1834, flourished. In autumn 1840, the journal published an extensive article about musical life in Leipzig during the winter of 1839-40:

‘One must confess that in this Leipzig, which nature treats so shabbily, German music blooms to such a degree that - without seeming immodest - it can easily compete with the richest and largest fruit- and flower gardens of other cities. What an abundance of great works of art were produced for us last winter! How many distinguished artists charmed us with their art!’

The Schumanns’ home became a meeting place for such artists - composers, poets, writers, performers - from all parts of Europe. Many of these visits were described in a journal, the Ehetagebuch (marriage journal), in which, alternating weekly, the couple kept a record of their daily activities and of their emotional lives. They noted their thoughts about the music they studied, played, composed and heard, and composed ‘character studies of significant artists with whom we are in close contact’. The list of distinguished guests included Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn, Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, Frédéric Chopin, Johannes Brahms, Richard Wagner, William Sterndale Bennett, Heinrich Heine, Hans-Christian Andersen, the pianist/composer Adolph Henselt, and the young pianists Amalie Rieffel and Harriet Parrish, among many others.

In October 1840, Clara wrote to her friend Dr Adolf Keferstein,

‘We have so many musical pleasures now that our life is truly blissful. [Bohemian composer and pianist] Moscheles was here last week … and we gave soirées in our homes. It was a frantic time, something different every day. Now he has gone and we are awaiting [Norwegian violinist] Ole Bull about whom I am very curious.’ [1]

Surely there can have been no other residence in Leipzig from which so much music poured.

Sophie Bevan. Photo credit: Sussie Ahlburg.

Sophie Bevan. Photo credit: Sussie Ahlburg.

Katharine Armitage’s play, Duet (seen at Wilton’s Music Hall in 2016), took us into Poppe’s coffeehouse in Leipzig, where Robert Schumann and Clara Wieck became engaged; interweaving original text and songs by both composers, Armitage allowed Robert’s and Clara’s ‘voices’ to be heard directly, their struggle for self-expression embodied in song.

Now, Sophie Bevan and Julius Drake have prepared a lieder recital which will to transport us from the Middle Temple Hall to 1840s Leipzig: specifically, to an imagined concert party at the Schumanns’ home, at which the hosts and a selection of their celebrated guests will be each represented by four songs.

Sophie Bevan explains to me that the recital programme was proposed by Julius Drake, who curates the Temple Song series, ‘Julius Drake and Friends’: “Julius asked if I’d be interested, and I was keen to try it as I wanted to learn some new songs; songs that may be less well-known by very famous composers.” When I ask if there were any particular songs that ‘spoke’ to her most powerfully, Sophie’s delight in these new songs is immediate and infectious: “Not really! They are all wonderful songs, and each has a particular ‘something special’ about them. That’s why I think they’ve been chosen. Each song needs to speak to the audience on first hearing!”

Julius Drake. Photo credit: Sim Canetty-Clarke.

Julius Drake. Photo credit: Sim Canetty-Clarke.

I’m interested to see that the programme begins with songs by Clara Schumann (née Wieck) and Fanny Hensel (née Mendelssohn). One of the most popular and acclaimed books about classical music in the last couple of years, Anna Beer’s Sounds and Sweet Airs: The Forgotten Women of Classical Music, celebrates the achievements of eight women - Francesca Caccini, Barbara Strozzi, Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, Marianna Martines, Fanny Hensel, Clara Schumann, Lili Boulanger, and Elizabeth Maconchy - who challenged ideological conventions and restraints, and dared to compose for public consumption.

But, while Clara bravely defied her father’s wishes to marry Robert, she was less forthright about her own music, writing before her marriage, ‘A woman must not wish to compose — there never was one able to do it’. Perhaps she was disheartened by her husband’s remark, when she commented on his music: ‘You are wrong, little Clara … If you think you could do it better, that would be as if a painter, for example, wanted to make a tree better than God.’ Fanny, Felix’s older sister, persisted with her compositions but was similarly dissuaded from publishing her work by her brother and father.

Sophie tells me that this is the first time she has sung songs by these nineteenth-century women: “It’s been very challenging learning it all. I’m hoping I’ll get to perform them all again and again. It’s always hard learning a brand-new programme and making it your own. As for Fanny’s and Clara’s songs, they are beautiful and intelligent and every bit the equal of their male contemporaries’ songs. Felix Mendelssohn was even known to pass off Fanny’s songs as his own. I suppose if people sang them more often, then they would more likely to become part of the mainstream lieder repertoire. I know I will certainly ask my future students to learn them.”

I ask Sophie is she feels that the songs are expressive of the character of their composer: “I think the individual language (the harmonic language and the style of song-writing) is discernible in the four representative songs of each composer. They’re naturally all different. I ’m not particularly trying to communicate character (in the sense of the individual composer at the imagined concert party) - just trying to let the beauty and style of each composer speak for itself.”

So, on Monday evening we will enjoy songs by another of the pioneers of Romanticism, Frédéric Chopin. Robert Schumann, who was born in the same year, followed Chopin’s progress from afar, but in October 1836, the two men spent, in Schumann’s words, an ‘unforgettable day’ together when Chopin past through Leipzig. Sophie remarks that the four songs by Chopin pose further new challenges: “I’ve never sung in Polish before and it’s totally different from anything I’ve done before. So many consonants to fit in a very short space of time!”

Berlioz and Robert Schumann had corresponded throughout the late 1830s and early 1840s, about performances of Berlioz’s music in Leipzig and the Euterpe Society of Leipzig’s awarding of their Diploma to Berlioz in March 1838. In 1840 the Neue Zeitschrift began to republish articles by Berlioz which were appearing in Paris journals. However, the first meeting of the two men did not take place until January 1843, when Mendelssohn invited Berlioz to Leipzig. When he visited the Schumanns’ home on 27 February, Berlioz was unwell; Clara reported that she found him ‘cold’. Perhaps, as they had no shared language, the Schumanns and Berlioz found it easier to communicate through the music that was undoubtedly on that occasion.

In 1839, Robert published his first essay on Franz Liszt - a review of the Grand études, which had been composed two years earlier - in which he suggested that Liszt’s virtuosity outshone his compositional talent. But, in imagining the Études in performance, Robert evoked sublime, magisterial imagery to convey Liszt’s power in harnessing the titanic forces present in the music, and he professed himself to be eagerly anticipating the day when Liszt might perform these Études in Leipzig. When Liszt eventually gave his first Leipzig recital, in 1840, Schumann pronounced his achievement to be superhuman: ‘He played like a god.’

I wonder if any of the songs that Sophie and Julius are to perform might seem to be ‘in dialogue’ with each other? “Not intentionally, by the composers themselves; however, I often like to create some sort of narrative in my mind to help with the learning process. For instance, maybe a path through a character’s life involving new love, then pain and suffering etc.”

There is certainly much love, pain and suffering in the Benjamin Britten’s opera, Gloriana. In April, Sophie will take the role of Lady Penelope Rich, in a new production by David McVicar in Madrid - the first time Gloriana has been performed in the city - conducted by Ivor Bolton, the Musical Director of the Teatro Real. Sophie is “looking forward to being in Madrid again - a wonderful city and opera house. I love singing Britten and can’t wait to have a new role under my belt. I have no idea what David McVicar is planning for this production, or what challenges he will have in store, but as far singing the role is concerned, so far, it seems pretty easy-going. She doesn’t have too much to sing and when she does it’s great stuff. Maybe I’ll change my mind once we get going with rehearsals!”

In February, Sophie will tackle more new repertory, by Stravinsky and Ravel, when she joins with the Nash Ensemble at the Wigmore Hall as they continue their series, The Friend Connection .

But, first there is a soirée chez Schumanns to enjoy, in which composers, musicians and poets of the past will meet again - much like characters in Robert Schumann’s Carnaval which Anthony Tommasini, the chief music critic for The New York Times, described as ‘a portrait gallery of Schumann’s friends (real and imagined), love interests, musical heroes (including Chopin) and adversaries.’

Sophie Bevan and Julius Drake spoke to Katie Derham on BBC Radio 3’s In Tune on Thursday 18th January, and performed four songs from their Temple song programme: ‘Liebst du um Schonheit’ (Clara Schumann), ‘Muttertraum’ (Robert Schumann), ‘Warum sind denn die Rosen so blass’ (Fanny Mendelssohn) and ‘Schilflied’ (Felix Mendelssohn). [The broadcast is available until Saturday 17 th February 2018.]

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/clara-robert-schumann.jpg image_description=Sophie Bevan and Julius Drake will perform ‘The Schumanns at home’: Temple Song, 22nd January 2018, Middle Temple Hall product=yes product_title=Sophie Bevan and Julius Drake will perform ‘The Schumanns at home’: Temple Song, 22nd January 2018, Middle Temple Hall product_by= product_id= Above: Clara and Robert SchumannJanuary 17, 2018

Bartók’s Duke Bluebeard’s Castle at the Barbican

Duke Bluebeard didn’t really get much international exposure until the 1950s - it premiered in France in 1950, New York in 1952 and London in 1957. Bartók certainly calls for a large orchestra, but even he would have been impressed by the sheer scale of the one fielded by the National Youth Orchestra for their performance at the Barbican - some 160 musicians.

The scale of the orchestral forces required, even in a standard performance, underpins much of the work’s psychological layers and its musical narrative. This isn’t an opera where the stage is overly important, hence why it’s usually performed in concert rather than in the opera house. It can undeniably seem a static work, and this was even the case in concert here, but it remains a magnificent opera nevertheless. You cannot escape the minor second in this opera - it’s everywhere. Like a knife being twisted in slowly, inch-by-inch, Bartók evokes sadness and despair, shock and danger through fluctuating musical scenes that while sounding dissonant (and in this performance they were grounded in phenomenally charged beacons of brilliance) they remain largely tonal. You get Judith’s “blood motif”, but you’re also aware of the sheer tonality of passages that breathe throughout Door Three and then the massive, blazing major triads that herald the opening of the Fifth Door, one of the greatest pieces Bartók ever composed.

It was perhaps not surprising that Sir Mark Elder brought an element of early Schoenberg and Wagner (Siegfried came to mind) in this performance. It was notably expansive, with some broad tempos - but this worked allowing the scale of the opera to unfold very grandly. There was something very Gothic about this castle, a touch lurid perhaps, almost as if one could touch the blood running through it - helped by some glorious string playing and some febrile and nervous, but assured, wind playing, that if it at first suggested more Hammer Horror was always authentically Bartókian. The Seventh Door was menacing and brooding, perhaps a little darker than we might normally hear - but with twelve double basses there was no shortage of depth of tone here. The First Door had thrown up a potential problem which was how successfully the two singers, Rinat Shaham, the mezzo-soprano, singing Judith, and Robert Hayward, as Bluebeard, would tackle the large orchestra. Ms Shaham in particular sounded a touch overwhelmed at the beginning of the opera (in fact, I initially thought the voice too high for the part) but she proved more than able to fight against the massed forces of the National Youth Orchestra, and her bottom range was often sumptuous. I still came away from this performance largely preferring a darker, more tenebrous, voice such as Christa Ludwig or Birgit Nilsson in the role of Judith but after the initial problems and inertia of Ms Shaham’s “crimson sunrise” in Door One she adequately played the part. She was a little too stuck to her score but was expressive enough with her hands and body to give Judith some humanity. Mr Hayward was rich and powerful and found it easy to ride above the orchestra. Daisy Evans’ direction of the opera, with its coils of alternating light switching colours, was sparse, but effective.

A brief mention of the first half of the concert, if only because it showed how ineffective a conductor can be, or perhaps something else entirely. Liadov’s The Enchanted Lake was quite superbly done, in fact it was exquisite, showing exactly what a huge orchestra can do in shaping dynamics. Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice was probably the least magical performance I’ve heard in the concert hall. But perhaps it’s just wrong to think of Dukas’ piece like this: it is, after all, dark, sinister and rather terrifying. In an age of Harry Potter, Walt Disney is much more difficult to bring off, it seems.

Marc Bridle

Bela Bartók: Duke Bluebeard’s Castle

Sir Mark Elder (conductor), Robert Hayward (bass-baritone), Rinat Shaham (mezzo-soprano), Daisy Evans (director), National Youth Orchestra.

Barbican Hall, London: Sunday 7th January 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bluebeard%20Elder%20NYO.jpg image_description=Mark Elder and the National Youth Orchestra perform Duke Bluebeard’s Castle at the Barbican Hall product=yes product_title=Mark Elder and the National Youth Orchestra perform Duke Bluebeard’s Castle at the Barbican Hall product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id= Above: Mark Elder and the National Youth Orchestra perform Duke Bluebeard’s Castle with Rinat Shaham (mezzo-soprano) and Robert Hayward (bass-baritone) (at the Nottingham Theatre Royal)Photo credit: Tracey Whitefoot

January 16, 2018

Puccini’s Tosca at the Royal Opera House

Century old power struggles between artists and lovers and authoritarian rulers may be set in Jonathan Kent’s 1800, but the austerity of food riots, street-brawls that end in bloody knifings, mass imprisonments, deportations and executions resonate century’s later in different times and different places.

The very static nature of the production seems to reiterate this inaction, just as Paul Brown’s designs distance almost everyone except the main actors from everyone else. In Act One, for example, the celebrants of the Te Deum are not just nearer God, in the sense they are above everyone else, they are also behind gilded bars. This is religion as an exclusive and very pious celebration. When we come to Act Two, and Scarpia’s opulent quarters, deliberately angled to magnify their size, and a statue that recalls the Commendatore in Don Giovanni, a bookcase masks a door that leads downwards towards torture chambers. The idea we are moving from heaven towards hell couldn’t be more transparent.

It’s arguable this Tosca is just too darkly lit at times. It feels oppressive. The tenebrous shroud that sits like decades of peat and dust is undeniably impressive at times, especially when it highlights shadows. Scarpia descending the staircase before the Te Deum in Act one is one such example - giving a fleeting glimpse of a 1930s black and white swashbuckler movie. There are hints of sepia and chrome. But in Act Two, especially at the very opening of it, it can make both Floria and Scarpia almost invisible as if they have become absorbed into the scenery like part of a Roman frieze. One doesn’t really notice the candlelight gradually becoming extinguished as Act Two reaches its glorious conclusion - and by the time Floria places two candles besides Scarpia’s lifeless body there isn’t enough light to really emphasise the curdling red of his murder. It’s all rather pallid.

Adrianne Pieczonka (Floria Tosca). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Adrianne Pieczonka (Floria Tosca). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

If the staging and production itself of this Tosca are memorable, the casting of it has some acute problems. Adrianne Pieczonka is absolutely mesmerising in the title role. Here we have a soprano who has the lyrical qualities of someone like Mirella Freni at her very best, but with the dramatic heft to make the voice ride effortlessly over the orchestra, which Freni couldn’t always do live. The power and ease with which Ms Pieczonka was able to sustain her high register without the trace of a wobble was always notable, though I found her Act Two strangely underwhelming. A tendency to clip her higher notes at the point rather than ride them generally made some of her singing in Act Two seem rushed, which was unfortunate, notably in her extended duets with Scarpia. This became all the more obvious when she gave such a glorious performance of “Vissi d’arte’. The tenor, Joseph Calleja, as Cavaradossi, also struggled at times. His voice sounded small and often opaque. Having said that, he is unquestionably a masterful interpreter of what he actually sings and no singer on the evening came closer to getting as musically close to what Puccini demanded of his singer. One particular line just leaps out from the entire evening - “le belle forme disciogliea dai veli!”… the final pianissimo was one of the most breath-taking I have heard any tenor sing live in an opera house. Most disappointing of all was Gerald Finley’s Baron Scarpia. Here we have a singer who looks the part, but that is as far as it goes. With his barely concealed malevolence, he cuts a dashing figure, but the voice is hugely underpowered for the role. Aled Hall, as Spoletta, and Simon Shibambu as Angelotti, were both fine.

The Israeli conductor, Dan Ettinger, was rarely inspired in a score that is dripping with inspiration. Although the playing by the orchestra was perfectly fine, nor was it lush enough to capture the opulence that breathes from every pore of this opera. There was some very notable horn playing, though largely this rather felt like the ninth revival for much of the orchestra as well. This is a Tosca that looks impressive, but feels like it needs a reboot.

From 18th January until 3rd March 2018. Performance 7th February relayed in cinemas live around the world.

Marc Bridle

Puccini: Tosca

Adrianne Pieczonka (Tosca), Joseph Caleja (Cavaradossi), Gerald Fiinley (Baron Scarpia), Aled Hall (Spoletto), Simon Shibambu (Angelotti), Jeremy White (Sacristan) Jihoon Kim (Sciarrone). Dan Ettinger (conductor), Jonathan Kent (director), Paul Brown (designer), Mark Henderson (lighting), Orchestra and Chorus of Royal Opera House Covent Garden

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; 15th January 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/GERALD%20FINLEY%20AS%20BARON%20SCARPIA%20%28C%29%20ROH.%20PHOTO%20BY%20CATHERINE%20ASHMORE.jpg image_description=Tosca, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product=yes product_title=Tosca, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id= Above:Gerald Finley (Baron Scarpia)Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore

ROH Announces 2018 Jette Parker Young Artists

The 2018 Jette Parker Young Artists are:

Chilean soprano, Yaritza Véliz

Chinese mezzo-soprano, Hongni Wu

American countertenor, Patrick Terry

Argentinean baritone, Germán E Alcántara

Scottish-Iranian bass-baritone, Michael Mofidian