February 27, 2018

Dialogues de Carmélites at the Guildhall School: spiritual transcendence and transfiguration

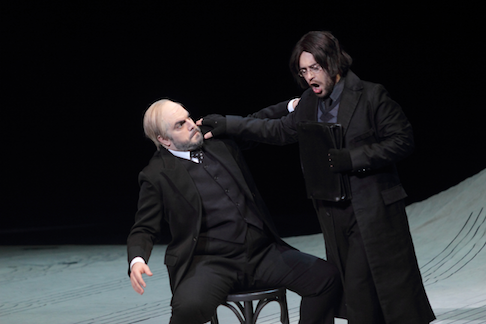

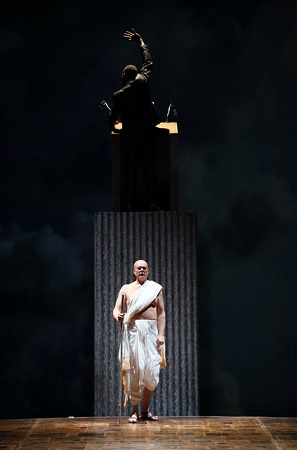

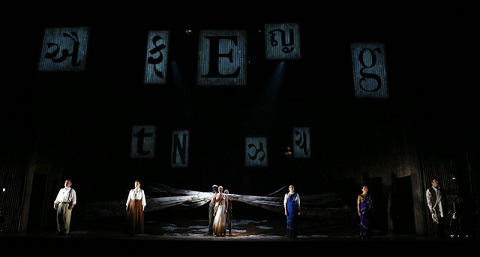

This new production which Martin Lloyd-Evans has devised for the postgraduate opera students at the Guildhall School may share some of Carsen’s and his designer Michael Levine’s visual minimalism but it is altogether a calmer, more intimate affair. Lloyd-Evans, conductor Dominic Wheeler and the young cast pay great respect to this challenging work: it is no mean feat to sustain a pretty well unrelievedly intense mood for so long, so effectively.

The production team achieve this through a combination of period-specific detail, simple iconographic statements by designer takis, and Robbie Butler’s striking lighting design, which work collectively to both link the tableaux-like episodes of Poulenc’s narrative and allow space for symbolic gesture. Poulenc’s Stravinkian ostinatos injected momentum into the unfolding rituals. Admittedly, though, spiritual serenity can be achieved at the expense of inflamed passions, and some of the crowd scenes fell a little flat, lacking a palpable sense of menace and terror.

And, though the Guildhall School tackled Poulenc’s opera just seven years ago, it does seem a strange choice for a student production given that there are so few roles for the men - and for those chaps taking those roles that do exist there is not much time to establish credibility of character - and that even the plentiful prioresses are seldom individualised. Moreover, the grandeur of the choral scenes might seem to require more forces and funds than the average music college can muster.

Commissioned in 1953 by La Scala, Dialogues des Carmélites is based on a play by Georges Bernanos which dramatises the experiences of a neurotically anxious young aristocrat, Blanche de la Force, who, in search of spiritual peace and safety, leaves her family home at the beginning of the French Revolution to join the Carmelite order in Compiègne. But, the convent walls cannot keep out Revolutionary convictions. Blanche and her fellow sisters are arrested and while she initially flees from the oath of martyrdom that they have all taken under the guidance of the formidable Mère Marie, as her sisters embrace the ultimate sacrifice, Blanche returns to take her place at the scaffold.

What seems important, and what Lloyd-Evans and takis clearly appreciate, is that this is not an opera about the French Revolution. Indeed, I can’t find, or write myself, a better explanation of what the opera is ‘ about’ than this ‘explanation’ by Donald Spoto’s explanation in Opera News fifteen years ago:

‘It is rather a series of nearly classical dialogue-scenes in which issues and questions of deeply human and religious significance are set forth, explored and clarified. The key to its complex of ideas is to be found in certain matters of the faith that claimed the loyalties of Poulenc and of Georges Bernanos, whose lifelong motto was set forth at the end of his novel Journal d’un Curé de Campagne (Diary of a Country Priest, 1936): “Tout est grâce” - everything is grace.’ [1]

This concept is powerfully embodied in one line in the libretto, when the Le Prieure warns the overly fervent, naively self-righteous Blanche, who is seeking to enter the order, ‘Prayer alone justifies our existence .... we are bound to it day and night’. These words may be difficult for a non-believer to understand or empathise with, but they underpin the opera, and Lloyd-Evans’ production. The musical set-pieces of observance - the Qui Lazarum, Ave Verum Corpus and Salve Regine - are architectural linchpins in the unfolding sequence of tableaux through which the spiritual journeys of Blanche and Mère Marie is conveyed. During the performance I was reminded of the words of one of my colleagues, Anne Ozorio, who, writing of the last GSMD production in 2011 observed that, ‘Dialogues des Carmélites … unfolds as a series of disconnected tableaux, like the Stations of the Cross. This structure is significant, for Poulenc is connecting the nun’s journey to the guillotine to Christ’s journey to the cross. The narrative is deliberately stylized to emphasize the spiritual and moral implications of the plot. It’s not simple narrative.’

Various hanging flats - interior walls, marble edifices, grilles that evoke both confessional chambers and prison gates (and when florally decorated, garden trellises) - slide, diverge and re-form, at one point forming an air-borne Crucifix, and ultimately coalesce as a granite headstone memorialising the life of Blanche de la Force. The subtle movement and prevailing stillness expressed an unassailable spiritual nobility.

Claire Lees (Soeur Constance); Jake Muffett (1er Officer); Meriel Cunningham (Mere Gerald); Michael Vickers (Le Marquis); Eva Gheorghiu (Soeur Felicite). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Claire Lees (Soeur Constance); Jake Muffett (1er Officer); Meriel Cunningham (Mere Gerald); Michael Vickers (Le Marquis); Eva Gheorghiu (Soeur Felicite). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Lucy Anderson’s Blanche was fittingly unbalanced and febrile, and if at first, in the scene with Michael Vicker’s luxuriously costumed Marquis de la Force, her broad vibrato diffused the focus of the tone, then later, when paradoxically attired in humble habit, the rich layers of her soprano blossomed with lyric intensity. I was pleased, too, that the oft-cut spoken scene, which links the final conversation between Marie and Blanche and the assembling of the nuns in their prison cell, was retained. Blanche’s street encounter with citizens who tell her of the arrest of the nuns and are astonished by the emotive response of this ‘servant’ who declares she has never been to Compiègne, is pivotal to her remorseful acceptance of her place beside her sisters at the scaffold.

Chloë Latchmore’s Mère Marie was superbly acted and sung. She movingly conveyed the spiritual misunderstandings that this fervent but sometimes misguided nun must face, and her struggle to truly understand the new prioress’s guidance that, ‘It is not up to us to decide whether our names will later appear in a list of martyrs’ was deeply affecting. Latchmore has a strong middle voice but can also project convincingly at the top, whatever the dynamic; this was an utterly convincing vocal and dramatic performance.

Georgia Mae Bishop threw her all into the Prioress’s all too human fears of death (though the quasi-Gothic blue/black eye-shadow was perhaps a supernatural step too far). Claire Lees captured Sister Constance’s gaiety and unpretentious spiritual vision. The French diction of the entire cast was exemplary.

Dominic Wheeler’s direction of the Guildhall School's instrumentalists reminded me how sympathetic and helpful Poulenc’s orchestral writing is to the voices: at times the orchestral fabric becomes a huge organ-like tapestry, supporting their arioso lines. Elsewhere, the strings in particular conjured an almost Tchaikovskian lyricism and ardency, while finely delineated woodwind playing was complemented by warm and pretty reliable horns.

With the first UK performance of Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking (at the Barbican Hall last Tuesday) fresh in my mind, the obvious narrative parallels with Poulenc’s opera seemed strong. But, in Dialogues, the spiritual mysteries are in the music itself, something which to me seemed lacking in Heggie’s score, and Wheeler did much to communicate the ambiguities and conflicts.

Much, of course, rests upon the opera’s final scene. Some might have wished for more melodrama than Lloyd-Evans offered, but, for me, this opera is about sacrifice - a journey through fear of death to faith in martyrdom - and this needs no grand gestures. Earlier in the opera, the second prioress confronts the Revolutionary Officer who comes to arrest the nuns, and who taunts their readiness to remove their religious habits: ‘Your uniform does not make you a soldier.’ And, while Lloyd-Evans’ closing gesture pays a nod to the opening image of Carsen’s production - of neatly folded habits decorously arrayed across the ROH stage - as each of the nuns stepped forward and placed her brown habit on the ground, and the shocking swishing of the guillotine sent shudders through the instrumental texture, we understood that this humble ‘offering’ was a sign of spiritual serenity and transcendence.

Claire Seymour

Poulenc: Dialogues de Carmélites

Blanche - Lucy Anderson, Le Chevalier/Premier Commissaire - Daniel Mullaney, L’Aumônier - Eduard Mas Bacardit, Le Marquis - Michael Vickers, Premier Officer - Jake Muffet, Le Prieure/Mère Jeanne - Georgia Mae Bishop, Soeur Constance - Claire Lees, Mère Marie - Chloë Latchmore, La seconde Prieure - Michelle Alexander, Soeur Mathilde - Lucy McAuley, Deuxième Commissaire/Theirry/M.Javelinot/Le Geôlier - Bertie Watson; director - Martin Lloyd-Evans, conductor - Dominic Wheeler, scenography and costume designer - takis, lighting designer - Robbie Butler.

Guildhall School of Music and Drama, Silk Street, London; Monday 26 th February 2018.

[1] Donald Spoto, ‘Dialogue on Carmélites II: A Roman Catholic's Perspective’, Opera News, Jan 2003, Vol. 67, Issue 7.

Photo credit: Clive Barda

'B & B’ in a new key

But as any scientist will tell you, an experiment that fails is as invaluable as one which comes off. As such, again, Seattle’s show is quite a success. We now have strong evidence that a number of plausible approaches to“fixing” B&B just don’t work.

The overarching problem with opéra comique today, even in France, is its incorporation of substantial passages of spoken dialogue. The theater for which almost all the traditional Parisian opéras comiques were written contained 1,100 seats. The newly-restored house, which opened in April 2017, only 100 more.

The Susan Brotman Auditorium of Seattle’s Marion McCaw Hall seats 2,900: more than 260% larger. A human voice, no matter how well-trained, cannot be understood from its stage without amplification. Even with amplification, the performers’ diction must be perfect to be comprehended, and the disproportion between great big voices and the tiny figures producing them creates a sense of eerie alienation rather than intimacy.

So: bottom line—B&B doesn’t fit this room and never will. But Seattle Opera’s production team couldn’t accept that. They wanted to do the show, period. And they convinced themselves that with enough tweaks and kludges it could be made to fit.

Tweak number one: the spoken dialogue is amplified, with just the effect it always has on the operatic stage: a clumsy jolt to the ear every time the music starts or stops.

Tweak number two: the opera is performed in English throughout, only the sung portion is supertitled, which only emphasizes how poorly one understands the dialogue when the mikes come back on.

Tweak number three: the perfectly serviceable dialogue Berlioz himself created to span the scenes between numbers with scraps of gen-yew-ine 100% Shakespeare, whose words can be hard to follow when spoken at speedby fine actors in an auditorium designed for spoken theater.

Not content with those additional challenges, they have restored scenes and characters cut by Berlioz, requiring an additional half-dozen speaking actors and 20 minutes more dialogue, most of it dry and expository. The only character Berlioz invented for his version, the tedious music master Somarone, is rendered somewhat less tiresome by giving him comic lines taken from Shakespeare’s constable Dogberry. To smooth the bits where the talk gets to be too much even for the innovators, they innovate some more, suturing in music from other Berlioz works including little tune-clips for underscoring.

Entire cast (singers and actors)

Entire cast (singers and actors)

Overall it is a triumph of artistic perversity, and the physical production amplifies the torment for all concerned, with a stage-filling M.C. Escheresque assemblage of industrial-strength staircases leading to landings with no function. Sicily’s torrid Messina has never looked chillier.

Considering the unnecessary handicaps imposed on them, it’s a wonder the performers manage to survive at all. But Shakespeare’s play, and the characters of the squabbling titular lovers, are apparently indestructible; assoon as they are in charge, you can feel the musing audience come alive again. The laughs are real, not forced; the drama soars.

As the secondary pair of lovers Hero and Claudio, carried their weight but set no fires. Laura Tatulescu, a notably saturnine Despina in Seattle Opera’s recent Così, was a little colorless dramatically, even for the colorless-virgin character she was playing, but she sang appealingly, especially in the duet with her companion Ursule (Avery Amereau, a superb supporting performance). Craig Verm, the boisterous-bro Ferrando of Seattle Così, contributed fine vocalism to his ensemble numbers but was strangely subdued as Hero’s jealous lover; even with the advantage of an interpolated revenge number (from Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini) he seemed utterly unengaged with the role.

Andrew Owens (Benedict), Marvin Grays (Leonato), Craig Verm (Claudio), and Daniel Sumegi (Don Pedro)

Andrew Owens (Benedict), Marvin Grays (Leonato), Craig Verm (Claudio), and Daniel Sumegi (Don Pedro)

But like the play, the whole show depends in the end onthe two principal singers’ gifts, and on Sunday afternoon we had a pair of pippins. Andrew Owens, bushy of beard and bouncy of demeanor, sings Bénédict’s busy, declarative music with brio; he has a sharp comic sense which enlivens his every scene. Most astonishingly, when forced by the director to climb the eternal stairs backwards, does it with élan.

Hanna Hipp, a Rossinian mezzo with the chops to take on Strauss’s Composer in Ariadne auf Naxos, was queen of the evening. Her sung and spoken English a model for everyone else on stage, her character, sprightly, furious, and rueful by turns, never let the moment down and bumped up the energy whenever it sagged.

The unobtrusive accompaniment of conductor Ludovic Morlot provided the most important support for the whole evening. The departing music director of the Seattle Symphony has particularly excelled in French repertory, and he excelled equally with the idiosyncratic chiaroscuro of Berlioz’ orchestration and the firmly traditional structure pacing of his arioso.

I’m glad to have had a second chance to see B&B live (the first was one streamed from Glyndebourne last summer). And though this ambitious remodeling turned out about as unsatisfactory as can be imagined, I feel I’ve learned two things about the piece. It is viable; but even in French we need to recognize that in opera houses as large as most in America, an all-sung version it the only way to go. I’m sure that Carmen was wonderful in its original opéra comique form; but does anyone really want to go back to regularly performing the original?

I don’t believe it. And if that’s the case, can’t we consider setting the spoken parts of B&B as “accompanied recitative,” as Ernest Giuiraud did for Bizet’s work? Isn’t there enough vocal music by Berlioz to allow a gifted pasticheur material for matching? What a shame we didn’t ask Stephen Sondheim to take a look at the job years ago.

Roger Downey

Cast and production information:

Cast (singing roles only): Daniel Sumegi (Don Pedro); Kevin Burdette (Somarone); Avery Amereau (Ursule); Craig Verm (Claudio); Laura Tatulescu (Hero); Andrew Owens (Bénédict); Hanna Hipp (Béatrice).Conductor: Ludovic Morlot; Stage director: John Langs; Scenography: Matthew Smucker; Lighting: Connie Yun; Costumes: Deborah Trout. John Keene: chorus

image=http://www.operatoday.com/B&B_Seattle1.png

product=yes

product_title=Béatrice et Bénédict at Seattle Opera

product_by=A review by Roger Downey

product_id=Above: Andrew Owens as Bénédict), Hanna Hipp as Béatrice [All photos copyright Jacob Lucas, courtesy of Seattle Opera]

February 26, 2018

Songs for Nancy: Bampton Classical Opera celebrate legendary soprano, Nancy Storace

Anglo-Italian soprano Ann Selina (Nancy) Storace (1765-1817) was renowned for her vocal prowess and remarkable stage presence, enjoying a glittering career across Europe. Recruited for Emperor Joseph II’s new Italian opera company, she dazzled audiences in 18th-century Vienna and enthralled the leading composers of the day; not least one Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart who created the role of Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro specifically for her.

Nancy’s father, Stefano, originally from Naples, was a professional double bass player in London and Dublin. He recognized the talent exhibited by his eight-year-old daughter, who could sing sweetly and sight-read effortlessly, and nurtured her precocity - perhaps, some have suggested, at the price of a long-lived career. In August 1773, she appeared in Hampshire with the violinist Ximenez, and their concert was so successful that a repeat was demanded. (So, Stefano left his young daughter alone in Southampton, while he travelled to Worcester to perform in the Three Choirs Festival!) [1]

Stefano arranged for Nancy to study in London with the Italian castrato and composer Venanzio Rauzzini (1746-1810) and, at the age of eleven, she took a minor role in his opera, L’ali d’amo. Two years later, she and her parents travelled to Italy to join her brother Stephen, a composer, and immediately she impressed in Naples and Florence. She was not yet sufficiently wise to the profession’s games and pitfalls, however, and found herself sacked from the Florentine Pergola Theatre, after she offended the castrato Luigi Marchesi whose vocal tricks she dared to effortlessly imitate.

The Storaces travelled to Lucca, Leghorn (where she met life-long friend, the Irish tenor Michael Kelly), Milan, Parma and Venice. Success, and wealth, seemed hers for the taking. An Imperial talent scout, Count Durazzo, snapped her up (along with Kelly) and Nancy found herself installed as prima donna of opera buffa at Emperor Joseph II’s Burgtheatre. By 1782, at the age of just seventeen, she was undoubtedly a European star.

Nancy’s ambitious mother encouraged her to marry the wealthy violinist and music scholar, John Abraham Fisher, who was more than twice her age. Fisher’s threatening, violent behaviour led the Emperor to order his exile, and thereafter there was much speculation about Nancy’s private life - was she the mistress of Mozart, or even the Emperor? In February 1787, following a quarrel between Kelly and a Bohemian officer, and Stephen Storace’s drunken antics at a ball, the Storace clan returned to London. Nancy had caught the eye of the young English aristocratic Lord Barnard, and after they had travelled homeward together he attended the performance which marked her return to London: a royal gala performance of Paisiello’s Gli schiavi per amore (The slave of love) at the King’s Theatre Haymarket on 24th April 1787 London, that was attended by the Prince of Wales. Yet, just three months later, Barnard had deserted Nancy and married.

She maintained a discrete liaison with the Jewish tenor John Braham, nine years her junior, with whom she toured Europe in 1797. Although they could not marry (as Fisher was still living, until 1806), they set up house and a son, William Spencer Harris Braham, was born on 3rd May 1802.

Anna Selina Storace (c.1790) by Benjamin Van der Gucht (1753-1794) from the Collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Anna Selina Storace (c.1790) by Benjamin Van der Gucht (1753-1794) from the Collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

During these years, Nancy’s voice was beginning to fade and, while her acting abilities continued to be praised, in 1801 the Times noted that her voice was ‘occasionally affected by a little hoarseness’; the same year the Chronicle suggested that ‘she would do more … if she attempted to do less’. [2] Nancy retired in 1808: her farewell to the stage was her brother’s No Sing, No Supper, alongside her old friend Kelly. Her relationship with Braham deteriorated - he eloped at end of 1815 with Sophie Wright, who had been a close friend of the couple - and she died in 1817 in Dulwich.

So, was Nancy was one of the 18th century’s operatic darlings? Or, as one scholar has suggested, was she ‘exploited not only by theater managers and impresarios, but by family and friends as well, who used her for their own purposes.’ [3]

Bampton Classical Opera marks the bicentenary of Nancy’s death with a fascinating concert of music associated with her, including arias sung by sopranos Jacquelyn Stucker, currently a Jette Parker Young Artist at the Royal Opera (whose roles this season include Azema ( Semiramide ), Countess Ceprano (Rigoletto) and Frasquita ( Carmen )) and Rhiannon Llewellyn, who sang the role of the Countess in the company’s production of Salieri’s The School of Jealousy last year. The performance will be conducted by Andrew Griffiths, a graduate of The Royal Opera’s JPYA Programme. The concert brings together a number of significant works with which Nancy was linked.

Alessandro Fisher (Count) and Rhiannon Llewellyn (Countess) in Salieri’s The School of Jealousy, Bampton Classical Opera, 2017.

Alessandro Fisher (Count) and Rhiannon Llewellyn (Countess) in Salieri’s The School of Jealousy, Bampton Classical Opera, 2017.

I spoke with both Jacquelyn and Rhiannon as they prepared to inhabit the legendary soprano’s shoes. I was interested in whether young singers training today are taught about, or consider, past singers and historic contexts? For example, if one is learning the role of Susanna, does one reflect on the first performance and the role’s initial interpreter?

Jacquelyn explained that, while she could not speak for all young singers, “looking up the soprano who premiered a role that interests me is how I discover new repertoire, particularly for Baroque and Classical works. I do think that the way we sing now is different from the way singers would sing in the past - for example, the most powerful part of a soprano’s voice in Handel’s heyday was right in the middle of the staff, which is why the A sections of his da capo arias always feature a cadence right in the middle of the soprano vocal range. Ask most sopranos singing now about their middle voice (myself included!), and I’m willing to bet that you’ll get a variety of responses: an eye-roll, a shrug, perhaps some self-effacing laughter.

“And, here’s why: in terms of modern technique, it can really be a temperamental part of the voice, whereas the voice at the top of the staff is much more secure for sopranos [which also, she explains, relates to how instruments and orchestras have changed]. To address this, sopranos now often ornament these final cadences into the highest parts of their range - it’s in the spirit of what Handel intended, but it accommodates modern technique. So, I think taking a few minutes to be aware of the singer who created a role is always wise as an awareness of what has been done before can serve to inform our own choices. However, times and expectations and techniques have changed apropos how we study and listen to and execute works in the Western canon, and the only way to possibly add something to the larger artistic discourse is to use our unique voices to declaim the text as truthfully and as diligently as we can.”

Jacquelyn Stucker. Photo courtesy of IMG Artists.

Jacquelyn Stucker. Photo courtesy of IMG Artists.

Obviously ‘career paths’ are very different today … but, I wondered whether the challenges that singers such as Storace faced bore any resemblance to the hurdles that young professionals today have to climb? Interestingly, both Jacquelyn and Rhiannon were keen to emphasise some of the factors and circumstances that had stayed the same or changed only a little. For Jacquelyn, “Performing new music is a huge part of my professional life, and it sounds like it was an important part of Nancy’s as well! This programme of music written especially for Nancy Storace has reaffirmed for me how important it is for singers of any generation to collaborate with living composers and perform new music. In my experience, composers enjoy writing music that singers want to sing, that feels good to sing - seeing how Haydn, Stephen Storace, Salieri, and Mozart all achieved this within their own musical language only reaffirms for me how productive and creative the composer-singer relationship can be.”

Interestingly, Jacquelyn is currently preparing for a solo recital presented through the Jette Parker Young Artist Programme which comprises three large works: one UK premiere, one European premiere, and one world premiere - and, two of the three composers featured on the concert are travelling to London from the US to attend the recital. The recital is entitled Fragments of Life: Songs of Loss, of Memory, of What Happens Next, and Jacquelyn’s excitement at being able to bring works by Federico Favali, John Harbison, and Mark Kilstofte to the London music scene is clear. The performance is at 1pm at St. Clement Danes on The Strand on Monday 26 th March, and admission is free - “And, really, when else would you get to hear a world premiere on your lunch break?”

Is the need for present-day singers to ‘promote’ themselves via social media etc. actually quite similar to Stefano’s promotion of his daughter, albeit in different contexts? And, Nancy was propelled into the limelight at such an early age: not so different from some modern child-stars, perhaps?

Jacquelyn remarked, “I cannot even imagine the pressure she must have been under! I also read that she had a unique and vibrant personality, so a part of me thinks she was, even at such a tender age, up for the challenge of being in the public eye for a significant part of her adolescence.

“My perspective on this subject is heavily influenced by my experience as a singer trained in the United States, but I do think there is a similar pressure on singers now to promote themselves: get the ‘right’ headshots, make a ‘proper’ website, matriculate into the ‘posh’ YAPs - to curate a public image, a brand, a pedigree. In my opinion, there is less pressure to do this here in the UK, but there is significantly more pressure to really say something artistically in a powerful way every time you open your mouth to sing. There is also more demanded of singers in terms of their dramatic ability. I fully admit that my view of this profession is more narrow than I’d like it to be, but these are the honest impressions I have based on working in both of these countries. Truth be told, I’m grateful for both approaches to modern professionalism. I think they are essential to becoming a well-rounded modern performer-entrepreneur, which is the global expectation at large, as I perceive it, for young singers.”

Rhiannon Llewellyn.

Rhiannon Llewellyn.

Then there’s the question of needing to travel to develop and nurture a budding career. While it must have been much more taxing in a practical, and financial, sense in the eighteenth century, it never ceases to amaze me how singers today seem to have to whizz, exhaustingly, around the globe at the drop of an audition-invitation.

Rhiannon agreed that there are some similarities but noted that one essential difference is that to travel to from London to Vienna in the late-eighteenth century was no casual enterprise: one needed not inconsiderable money and time. The Storaces’ journey to Europe took months of planning and fundraising. And, once you had arrived, you stayed put. Nowadays, singers are constantly receiving last minute calls to travel to Oslo or Zurich or further afield to undertake auditions, the outcomes of which are uncertain. “It sometimes feels as if one is constantly gambling.”

Storace and Cornetti are really just ‘names from history’ today; audiences have little knowledge of or familiarity with their music. As a singer, is there a difference in the way that one prepares such repertoire? Jacquelyn observed, “My approach to repertoire is always the same no matter if the piece is well-known or not: I always start with the most complicated element, which is (based on the repertoire I tend to sing) either the words or the rhythms. I always like to cmemorize the poems and speak them to myself constantly. (It drives my husband totally crazy.) Then, I work out the notes as much as I can away from the piano. Sight-singing the vocal part helps it stick in my brain better, for some reason - I think it helps me work out how the piece is organized, and understanding form is how I memorize pieces. I like having one approach for everything I sing - it makes assimilating music much faster; I have a technique that works, and I apply it every time. It took me a few years to figure out my method, but this has worked for me over the past three years.”

One among many of the less familiar and more intriguing works on Bampton’s Storace programme is the cantata Per la ricuperata salute di Ofelia, which, I think, is receiving its first full performance since it was presented with harpsichord accompaniment in 2016 , following the rediscovery of a printed score from 1785 in the archives of the Czech national music.

The title of the cantata (‘For the recovered health of Ophelia’), for which Lorenzo Da Ponte wrote the libretto, derives from the work’s origins. It was designed to celebrate Storace’s recovery after a ‘vocal crisis’ at the age of nineteen forced the singer to retreat from the stage for four months. Chancellor describes how, in June 1785, Nancy suddenly lost her voice at the beginning of the premiere performance of her brother's opera Gli sposi malcontenti: ‘Though it was then tactfully rumored that this resulted from the emotional stress of an unhappy marriage, it is much more credible that the strain of being eight months pregnant—her child died soon after birth the following month—and the added stress of an appearance before the emperor and the Duke of York, then on a state visit, while she was suffering from a throat infection, were the real causes of the disaster.’ [4] Her return to the stage seems to have brought about a collaboration between composers, Salieri and Mozart (and the little-known Cornetti), so often considered bitter rivals.

Stephen Storace.

Stephen Storace.

Jacquelyn considers the music of Per la ricuperata salute di Ofelia as “anything but dramatic or florid, in my opinion! It is balanced, it embraces simplicity, and it has a bit of a wide compass in the vocal line, much in the way ‘Deh, vieni’ [which she is also performing in the Bampton programme] does. In practising this work, I’ve decided that its charm lies in how exposed it is for the singer, and how well the singer can simply sing a beautiful legato line.

Interesting, Rhiannon makes similar observations about another contemporary ‘hit’, written especially for Nancy by Martin y Soler: ‘Dolce mu parve un di’ from Una cosa rara, finding the aria lyrical and sensuous. Jacquelyn also remarks that ‘Deh, vieni’ and the role of Susanna in general “does not sit particularly high in the voice - which is what Nancy was known for, from what I’ve read”. Rhiannon - who has recently been singing the role of the Countess in Figaro, with The Merry Opera Company, similarly finds ‘Porgi amor’ beautiful but quite low-lying. She added: “Look at the roles she sang! Despina is a pretty, party-girl, who doesn’t take things too seriously. I think that this was Nancy … it was, and is, okay to be a little irreverent at times!”

Jacquelyn agreed, “I am of the opinion that Susanna [Figaro] was modelled more after Nancy’s personality than her instrument, and I think that’s kind of fantastic. Whether or not this is accurate, I love thinking that a composer would write a piece for a singer as a human being with a voice and not just a voice with a personality attached.” Similarly, Rhiannon suggested that the music written for her confirms that Nancy Storace must have first and foremost been a terrific actress - this might explain some of the vocal writing, which is almost “nonsensical at times!”

Mozart’s ‘Ch’io mi scordi di te’ was written for Nancy’s farewell concert in Vienna which took place on 23rd February 1787 (with Mozart playing the piano obbligato part). I asked Jacquelyn if she sensed her predecessor’s vocal strengths and qualities in this concert aria? Is this aria, and the role of Susanna, a ‘tribute to her talent’?

“Absolutely. Nancy was known earlier in her career for her amazing high notes, but she must have had, in the later stages of her singing life, truly remarkable command over her lower passaggio (which is, for us lighter sopranos, a tricky part of the voice). This concert aria also places the text in the middle of the voice, which means articulating the words is much easier than in other concert arias Mozart wrote. Because of this, it’s clear to me that Nancy must have been a dynamic performer with an unshakeable commitment to text. She definitely left some big shoes to fill, but I love knowing that Mozart wrote this amazing music for a spitfire of a woman who also happened to be an amazing musician.”

Claire Seymour

Bampton Classical Opera, Songs for Nancy: St John’s Smith

Square, 7th March 2018, 7.30pm

Jacquelyn Stucker and Rhiannon Llewellyn (sopranos), Andrew Griffiths

(conductor and piano), CHROMA

Concert programme: Sarti - Fra i due litiganti il terzo gode, Overture; Mozart - Le nozze di Figaro, ‘Giunse al fin il momento … Deh vieni’; Stephen Storace - No song, no supper, Overture & ‘With lowly suit’; Salieri - La scuola de’ gelosi, Overture & ‘Or ei con Ernestina … Ah sia già de’ miei sospiri’; Haydn - Cantata, Miseri noi, misera patri & Symphony No.83 (‘The Hen’); Martin y Soler - Una cosa rara, ‘Dolce mi parve un di’; Mozart, Salieri, Cornetti - Cantata, Per la ricuperata di Ofelia; Mozart -‘Ch’io mi scordi di te’ K505.

[1] See V.E. Chancellor, ‘Nancy Storace: Mozart’s Susanna’, The Opera Quarterly, Volume 7, Issue 2, 1 July 1990: 104-124.

[2] Isabelle Putnam Emerson, Five Centuries of Women Singers (Praeger, 2005)

[3] Chancellor, op.cit., p.105.

[4] Chancellor, op.cit., p.107.

February 25, 2018

Tenebræ Responsories

recording by Stile Antico

The varied programming is the disc’s greatest strength, with the inclusion of a six-voice motet and excerpts from the Lamentations showing a mindfulness to provide listeners with textural and harmonic contrast. However, this is a competitive market, with a critically acclaimed recording from Tenebrae under Nigel Short, not to mention a warm and thick-textured account by The Sixteen under Harry Christophers. This new release brings plenty of imagination in the programme, but the performances of the Responsories themselves - whilst engaging and persuasive - may struggle to add anything over their competitors.

The Responsories are all about darkness; in the 16th-century in which Victoria was writing, the service would have concluded in total darkness, as the candles representing Christ, the Disciples and the three Marys were gradually extinguished during the service (‘Tenebrae’ is the Latin for darkness). Stile Antico convey the bleakness of the text well, using men’s voices alone in ‘Tenebrae factae sunt’ and ‘Aestimatus sum’; the darker hue of the bass singers is particularly striking here, conveying the pain and despair of the text. Indeed, it is a tradition that, in performance, a selection of the Responsories for upper voices are instead performed by the lower ones; whilst enabling a more vivid portrayal of the text, it also allows for contrast with the SATB scoring of the other Responsories.

Contrast is vital in the Responsories, as a danger of Victoria’s setting is monotony; all eighteen Responsories use the same mode, and similar three or four-part textures. Thus, the reversion to male-only voices for two of the Responsories creates an edifying contrast that makes it more comfortable to listen to the full disc in one sitting. Further contrast is created by the admirable inclusion of Victoria’s six-voice motet ‘O Domine Jesu Christe’ at the end of the disc, in which the more adventurous harmonies provide an interesting snapshot into the broader musical language of this Renaissance master. Equally interesting is how the disc intersperses excerpts from the Lamentations readings, sung to a plainchant setting; given that the broader Liturgy in which the Responsories appear would have been dominated by plainchant, such works provide a useful context for Victoria’s polyphonic Responsories. Such variety creates an imaginative and elegant programme that is perfectly enjoyable in a single sitting.

Contrast within the Responsories themselves is, however, slightly lacking. A mezzo forte dominates the Responsories, with the portrayal of the “innocent lamb” in ‘Eram quasi agnus innocens’ finding much the same dynamic as the presentation of the “hanged man” in ‘Amicus Meus’. Surely greater nuance could be found between these two starkly opposed images, connotations and emotions? Although one mood pervades all eighteen Responsories, the text includes some striking oppositions, contrasting good with evil, and peace with violence. Such varied images - even if united by a common emotion - deserve more nuanced treatment.

Within individual Responsories, too, there lacks dynamic subtlety; although ‘Una hora’ opens with a delicate hush courtesy of a solo voice, as soon as the choir enters, one yearns for greater dynamic nuance. Such gradations are only more important given how the text sustains a single mood.

Having said this, Stile Antico perform with great clarity of diction and purity of line. Take, for instance, the immediate solo opening of ‘Una hora’; the plaintive simplicity of the solo line contrasts with the distracting vibrato of the soloist in Schola Antiqua’s 2005 recording. However, this section also provides a useful example of how, like the disc more broadly, this new release offers a pleasant reading but nothing that adds a great deal to its numerous rivals; Ensemble Corund feature a striking crescendo on the opening note of ‘Una hora’, something that maintains the purity of the line but also imbues it with greater dramatism and weight. Both Tenebrae and Stile Antico opt for stillness instead, which communicates melancholy but arguably at the expense of drama.

Stile Antico’s acoustic allows for greater clarity and delineation of lines in ‘Animam meam dilectam’, in comparison to Tenebrae. Such a keen sense of interweaving voices is vital given that the Responsories form part of a much longer liturgy, the majority of which would have been performed to plainchant; as such, Victoria’s polyphony would have provided noticeable contrast within the broader liturgy, a fact that Stile Antico are keen to emphasise through their own clarity of line and texture.

The programming of this release is its greatest strength, with the inclusion of excerpts from the Lamentations readings as well as the concluding motet providing both engaging contrast and useful context for the Responsories as part of a longer liturgy. The performances are dark and powerful, with the use of lower voices alone for selected Responsories a striking way of illustrating the darker texts. However, the relative dynamic uniformity of the Responsories reduces the dramatic power of the text. Overall, these are engaging performances, but with strong competition from Tenebrae in particular, they are a pleasant alternative, if not a game-changer.

Jack Pepper

Recordings:

Nigel Short, Tenebrae, 2013, Signum Classics

Harry Christophers, The Sixteen, 2011, Coro

Juan Carlos Asensio, Schola Antiqua, 2005, Glossa

Stephen Smith, Ensemble Corund, 2006, Dorian Recordings

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Pepper_Tenebrae.png

product=yes

product_title=Tomas Luis de Victoria : Tenebrae Responsories : Stile Antico

product_by=A review by Jack Pepper

product_id=Harmonia Mundi HMM902272

Digital Release: March 9, 2018

CD Release: April 13, 2018

Mahler Symphony no 9, Daniel Harding SRSO

A graceful first movement, respecting the marking andante comodo "comfortable pace". The harp and strings here have a mellow richness which enhances the gentle rhythmic pulse. For "pulse" this is, suggesting the human body at rest, calmly breathing. Gradually the palpitations build up towards expansive outbursts, as if invigorated by the flow of life. When silence descends, marked by timpani ans strident brass, the effect is chilling. The harp ruminates, and the steady pace resumes. The music flares up again : tension, alarm and a spiralling descent into darkness, and a wall of mournful winds and brasses. Yet again, though, steadiness prevails. Celli and bassoons lead the way ahead. Harding shapes the flow by highlighting the fanfares, so the undertow can be heard without undue exaggeration. Now, when relative silence returns, the mood is pure and calm: the high, clear pitch of the woodwinds is exquisite, evoking, perhaps, memories of summer, a typical Mahler touch.

Thus we are prepared for the second movement, marked "Etwas täppisch und sehr derb".(rustic, simple, earthy). Why Ländler in a symphony some still associate with death ? Ländler are danced by peasants who till the soil, who know that seasons change and that harvests return after fallow times. This movement is much more than folklore : it connects to the theme of change and rebirth that runs through so much of Mahler's work. The Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra plays with gusto, Harding gauging their strengths. There's humour here and impish high jinks. The spirit of Pan awakes ! Thus the lively leaps ans swirls, the flow of the first movement returning in exuberant form. The pace whips up, propelled along with force, yet once again, the dance returns, for dance, like Nature, moves in rhythmic cycles. The movement ends with a smile - a deft, piping little figure.

The Rondo in the third movement was vigorously animated. The pace is now near-frenzy, strings and winds flying free, though steady beat can still be heard in the lower voices. Nonetheless, though the spirit may be wild, Harding doesn't lose shape. We hear the violin emerge, its way lit by harp. In the tumult, the swaying palpitations of the first movement revive in burlesque parody. Indeed, much of this symphony is like dance, motifs returning in guises. Two slow movements at each end, taken slow, encasing two fast-moving inner movements.

If the first movement was comodo, the last is stately, even majestic in its sweep. The strings take charge, lifting above and away from the orchestra, much in the way that birds take flight above the earth. Their line shimmers, undimmed, though the sound is rich. Bassoons moan, suggesting depth, which intensifies the heights the strings are striving towards. The leader plays a keening, soaring line at a tessitura so high it's almost ethereal. The "pulse" of the first movement is back, now transfigured, no longer bodily but spiritual. At the end, sounds become so pure that they dissolve, as if beyond human hearing.

Although this was the last symphony Mahler completed, there is no evidence that he was contemplating his own death. From what we now know about his life, from the events of his life, and also from what we have of what was to be his Tenth Symphony, he wasn't just looking backward any more than in so many other of his works where death is vanquished by new life. It is significant that when Harding, aged 20, was Claudio Abbado's chosen assistant in Berlin, he was given the Tenth to study, at a period when many conductors were still performing only the first movement. Learning a composer back to front is not a bad thing, especially a composer like Mahler whose work forms a huge trajectory from beginning to to end, where an understanding of overall structure makes a huge difference.

Following on from the recent livestream of Mahler's Symphony no 8 reviewed http://www.operatoday.com/content/2018/02/mahler_symphony.php in Opera Today, this recording helps make connections between Mahler's four last works, two of which are purely orchestral, two of which employ voice to intensify orchestral colour.

Anne Ozorio

image=https://images-eu.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51mdk7PCaML._SS500.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Gustav Mahler : Symphony no 9 : Daniel Harding, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchesta

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Harmonia Mundi HMM902258

price=

product_url=https://www.amazon.co.uk/Mahler-Swedish-Orchestra-Daniel-Harding/dp/B0791HK52R/ref=sr_1_1?s=music&ie=UTF8&qid=1519558816&sr=8-1&keywords=harding+mahler+9

February 22, 2018

A newly discovered song by Alma Mahler

One of those ‘lost’ songs, Einsamer Gang (Lonely Walk), has recently been discovered and will be given its UK premiere performances by Rozanna Madylus and Counterpoise at the Wagner 1900 conference in Oxford (April) and at the Newbury Spring Festival (May).

Einsamer Gang is one of three songs composed by Alma Mahler in 1899-1900 and was written before her lessons with Alexander Zemlinsky and before her introduction to Gustav Mahler. The other two, Leise weht ein erstes Blühn and Kennst du meine Nächte?, were published by the American scholar Susan Filler in 2000, but Einsamer Gang was tracked down by Deborah Calland and Barry Millington in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, at the University of Pennsylvania. They have made a performing edition of the song for these concerts and plan to publish it in The Wagner Journal later in the year

Rozanna Madylus and John Tomlinson in The Art of Love. Photo credit: Tony Nandi.

Rozanna Madylus and John Tomlinson in The Art of Love. Photo credit: Tony Nandi.

Einsamer Gang , a touchingly evocative and personal setting of a poem by Leo Greiner, expressive of Alma’s almost suicidal loneliness and depression at this period, will form part of the sequence The Art of Love: Alma Mahler’s Life and Music, which features also music by Gustav Mahler, Zemlinsky and Wagner. In the second part of these concerts, Counterpoise will perform Kokoschka’s Doll with Sir John Tomlinson, for whom it was written last year by John Casken. The painter Oskar Kokoschka had a brief but tempestuous love-affair with Alma Mahler, following which he commissioned a life-size doll of her which he took to parties and other public events. The text of this new work describes the events as seen through the eyes of Kokoschka as an older man, evoking the passions unleashed by the affair, against the background of the physical and psychological traumas suffered by Kokoschka in the First World War. The score weaves the texts into a musical fabric that references fin-de-siècle Vienna (including the music of Wagner and Alma Mahler) while being of our own time.

Kokoschka’s Doll and The Art of Love , incorporating Einsamer Gang, will be performed at:

Holywell Music Room, Oxford, Tuesday 10 April, 8.30pm

Corn Exchange, Newbury, Wednesday 16 May, 7.30pm

The press on last year’s performances of Kokoschka’s Doll : ‘Tomlinson’s titanic, heart-rending performance’ (Daily Telegraph ), ‘the incomparable John Tomlinson’, ‘a compelling dramatic presence’ ( Guardian), ‘magnificent’ (Opera), ‘riveting’ (Seen and Heard International)

For further information see:

www.counterpoise.org.uk/projects.php;

www.music.ox.ac.uk/wagner-190;

www.newburyspringfestival.org.uk

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Alma%20Maria%20Schindler%20%28Alma%20Mahler%29%2C%201899.jpg

image_description=Kokoschka’s Doll and The Art of Love: performances by Counterpoise in Oxford and Newbury

product=yes

product_title=Kokoschka’s Doll and The Art of Love: performances by Counterpoise in Oxford and Newbury

product_by=

product_id= Above: Alma Maria Schindler (Alma Mahler), 1899

Of Animals and Insects: a musical menagerie at Wigmore Hall

The programme opened with a perennial favourite, Schubert’s ‘Die Forelle’ (The trout) and Middleton and Riches immediately made evident their concern, which was sustained throughout the recital, to communicate the narrative of their chosen songs - through motivic word-painting, vocal nuance, diversity of tone and dramatic presence. Middleton delicately conjured the slithering scales and flapping tail of the capricious fish, while Riches’ strong, forth-right projection conveyed the fisherman’s determination to land his catch.

This was beautiful and vivid characterisation. And, ‘Der Alpenjäger’ (The alpine huntsman) was similarly engaging. Riches relished, here and elsewhere, the opportunity to embody different characters and their energetic debates, aiming for comic contrast between the floating appeals of a mother who wishes her son to stay at home to tend the lambs and the insistent protests of the young adventurer who yearns to set out on his quest for the gazelle. Riches’ buoyant baritone brought to mind an image of the eager hazelnut gatherer in Wordsworth’s ‘Nutting’, sallying forth ‘in the eagerness of boyish hope … Tricked out in proud disguise of cast-off weeds’! The duo exploited the way Schubert’s rhythmic structure tells the tale, culminating in the stately pronouncements of the Spirit of the Mountain who intervenes - here with a sonorous gravity worthy of Sarastro - to protect the trembling gazelle. And, alert to every expressive dimension, Riches injected a little tenderness and pathos into the god’s final plea, ‘The earth has room for all; why do you persecute my herd?’ (‘Raum für alle hat die Erde,/Was verfolgst du meine Herde?’)

Riches works hard with his texts, and - as was evident during his vibrant performance in Purcell’s King Arthur with the Academy of Ancient Music at the Barbican Hall recently - he is not afraid to prioritise textual meaning over beauty of line to deepen the expressive meaning, though there is plentiful lyrical mellifluousness too. I was impressed by the directness and impact of his diction in the three German lieder. But, while he certainly took care (perhaps too much?) with the enunciation in the sequence of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Gallic songs that followed, his French is less idiomatic and this did affect the vocal phrasing, as occasionally Riches’ tendency to emphasise particular syllables disrupted the evenness of the syllabic scansion that is inherent in the language and reflected in the melodic and rhythmic settings.

I think, too, that this repertory is not Riches’ natural territory; his voice is full and strong, and while he did make a good attempt to ‘lighten’ the tone, the result did not feel entirely ‘natural’. The landscape of Fauré’s ‘Le papillon et la fleur’ (The butterfly and the flower) is a world away from Schubert’s forest foraging and it took Riches a little while to settle into the new terrain, but the wry reflections of the young man troubled by the contesting attractions of his lover’s lips and the rose-coloured ladybird resting on her snow-white neck, in Saint-Saëns’ ‘La coccinelle’, were engagingly delivered, Riches swooning into romantic reverie at the parodic close. Middleton’s atmospheric accompaniment added much to the sentimental hyperbole of Massenet’ quasi-operatic ‘La mort de la cigale’ (Death of the cicada), and here Riches exercised satisfying control during the extended vocal phrases and flowed lightly through the melismas of the central section.

One wonders why the French seem to have had such a ‘thing’ for insects, for Ravel, too, included an homage to the cricket (‘Le grillon’) in his Histoires naturelle (1906). Here, Middleton’s tremulous pointillism was delicately and delightfully evocative and what was really impressive about this song was the way the duo maintained rhythmic momentum, and a beguiling narrative, despite the fragmentary vocal line and seemingly ‘static’ piano gestures. It is the birds rather than the beetles that Ravel truly celebrates though, and none more than the peacock (‘Le paon’), whose pomp and pride rang from Middleton’s introductory bars with the brightness of the feathered eyes of the bird’s train, which was itself brandished with a startling pianistic flourish at the close. Some critics have suggested that Ravel is indulging in self-portraiture, here, painting a picture of the fin de siècle artist-cum-dandy, and this performance made that reading a convincing one. I admired Riches’ memory in this song - indeed, in all of Ravel’s set of five, for the texts are lengthy and often prosaic, with subtly shifting meters. He made a good effort to make the words ‘live’ in both ‘Le martin-pêcheur’ (The kingfisher), in which Middleton’s grave tone conveyed the bird’s regal status and demeanour, and in the account, in ‘La pintade’ (The guinea-fowl), of the quarrelsome nature of a farmer’s querulous hen.

Riches’ had shown his comfort and flair in the musical theatre idiom during the LSO’s Bernstein Anniversary celebrations at the Barbican Hall, before Christmas, when he was displayed a cocksure swagger and vibrant Yankee drawl in Bernstein’s Wonderful Town. And, while this recital did not, as then, end with Riches leading the audience in a conga down Wigmore Hall’s aisles, the final item of the programme, Vernon Duke’s Ogden Nash’s Musical Zoo, did give him liberty to don his Flanders-and-Swann hat, indulge his instinct for showmanship and celebrate the piquant wit of Vernon Duke’s musical embodiments of the brief portraits which form Ogden Nash’s bestiary. I have to confess that this repertoire is not really my cup of tea (I tend to the view that the poetry isn’t worth reading, let alone setting to music, but many will, for good reasons, disagree!). But, Riches rattled off the zoological roster with panache, and his poise and pronunciation were admirable. He couldn’t resist going down to the farm one more time: his encore, ‘I Bought Me A Cat’ from Copland’s Old American Songs was a noisy and nonsensical, and fittingly ‘natural’, end to a charming recital.

This recital can be heard for one month following the performance on BBC iPlayer.

Claire Seymour

Ashley Riches (bass-baritone), Joseph Middleton (piano)

Franz Schubert - ‘Die Forelle’ D550, ‘Die Vögel’ D691, ‘Der Alpenjäger’ D588; Fauré - ‘Le papillon et la fleur’ Op.1 No.1; Saint-Saëns - ‘La coccinelle’; Massenet - ‘La mort de la cigale’; Ravel -Histoires naturelles; Vernon Duke - Ogden Nash's Musical Zoo.

Wigmore Hall, London; Monday 19th February 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ASHLEY-EDITED-HIGH-RES-15-of-37-1024x683.jpg image_description=Ashley Riches and James Middleton at Wigmore Hall product=yes product_title=Ashley Riches and James Middleton at Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Ashley RichesPhoto courtesy of Askonas Holt

February 18, 2018

Hugo Wolf, Italienisches Liederbuch

Wolf, one might say, was an Austrian composer, which is or at least was certainly to say also a German composer; yet he was born in Windischgrätz, now Slovenj Gradec. Both names for what was long a Styrian town refer to the Slovene or Wendish Graz, to distinguish it from the larger Graz. And so on, and so forth. Mitteleuropaïsch is more than a collection of disparate identities; it is an identity in itself. It certainly was in the Austrian Empire in which Wolf was born, and it certainly was in the Dual Monarchy in which he grew up. Moreover, northern Italy had long been part, to varying extents, and depending on who was, of that identity too. So too, however, had a romanticised German idea of ‘Italy’, of the Mediterranean, of the South. Look to Goethe and Liszt, for instance - or to Paul Heyse’s selection and translations of songs, as set by Wolf (not greatly, or indeed at all, to Heyse’s pleasure).

What one can say is that this idealised ‘Italy’, Tuscan rispetti and Venetian vilote could only have come from without the Italian lands. If ‘German’ constitutes at least as multifarious a multitude of sins as ‘Italian’, these songs remain very much a German evocation of lightness, of sunlight, of serenades, of a ‘love’ that is rarely, if ever that of German Romanticism, although it may well be viewed through that prism. All three performers at this Barbican recital understood that, I think: both intuitively and intellectually. At any rate, the tricky balance between Italian ‘light’, in more than one sense, and German ‘prism’ seemed almost effortlessly communicated - however much art had been required to convey such an impression.

The songbook is not a song-cycle, so to speak of ‘reordering’ is perhaps slightly misleading. At any rate, the ordering selected made good sense, grouping the book’s forty-six little songs into four groups, which, if not exactly narratives of their own, made sense as scenes or, if you will, scenas. One made connections as and when one wished; nothing was forced, much as in the music and the performances themselves. Diana Damrau and Jonas Kaufmann opted, boldly yet not too boldly, for a staginess alive to the humour, or at least to the potential for humour without sending anything up or otherwise trying to turn the songs into something they are not. Helmut Deutsch, in general the straight man, perhaps had the ultimate moment of humour, in his piano evocation of a hapless violinist (‘Wie lange schon war immer mien Verlangen), Damrau having ambiguously prepared the way, at least in retrospect, with a lightly wienerisch account. Deutsch provided an excellent sense of structure throughout: non-interventionist perhaps, but none the worse for that. Damrau and Kaufmann, after all, were intended to be the ‘stars’ here.

In general, but only in general, Damrau’s performances - roughly alternating, yet with a few exceptions - were knowing, whilst Kaufmann’s were lovelorn. Such is the order of things in this ‘German Italy’. Metaphysics, when they reared their head - more in Wolf than in Heyse - tended to be the tenor’s. Was he right to make relatively little of them? I am not sure that right or wrong makes much sense here. Perhaps it is all, or mostly, in inverted commas anyway. There were a few occasions when I found Kaufmann, especially during the first half, somewhat generalised, but such generality remains a very superior form: more baritonal still than I can recall having heard him, yet with an ardent, show-stopping tenor, even upper-case Tenor, that puts one in mind, just in time, of his Walther (‘Ihr seid die Allerschönste’) or his Bacchus (‘Nicht länger kann ich singen’). And Damrau was perfectly capable of responding, of singing about his singing, as for instance, in ‘Mein Liebster singt am Haus’, to which Kaufmann’s ‘Ein Ständchen Euch zu bringen’ came as the perfect response, and so on. Piano and voice together in the latter song conveyed to near perfection the shallow yet genuine sexual impetuosity of youth. (Or is that just what older people think?) The lightness of a wastrel’s self-pity in ‘O wüsstest du, wie viel ich deinetwegen,’ was likewise finely judged. So too was the cruelty of his beloved in ‘Du denkst mit einem Fädchen’.

Yet, as the two archetypes, stereotypes, call them what you will, drew closer towards the end of the first half, there was genuine affection too, or so one thought. The rocking piano in ‘Nun lass uns Frieden schliessen’ suggested, without unnecessary underlining, a peace perhaps all the more interesting, or at least characteristic, for its lack of interest in passing all understanding. For, as that half had climaxed with an acknowledged role for Wolf’s Lisztian Romantic inheritance, so the piano harmonies of the second half took up from that half-destination, taking us somewhere new, briefly darker (the austere Doppelgänger flirtation of ‘Wir haben beide lange Zeit geschweiegen’) and ultimately, once again, ‘lighter’, yet perhaps never truly ‘light’. Sweetness of death (‘Sterb’ ich, so hüllt in Blumen meine Glieder’) intervened, yet was it but an act, the commedia dell’arte perhaps, or, as the Marschallin would soon have it, ‘eine wienerische Maskerad[e]’. Increasingly, neither party wished truly to resist, whilst making great play of doing so: on stage as well as in music. An air of Straussian sophistication became more marked, without ever shading into mere cynicism. If the ‘girl’ were always going to win, that was as it ‘should’ be. There were enough qualifications, or potential alternative paths and readings, though, to make one wonder. And then to wonder - ‘lightly’ or no - why one was wondering at all.

Mark Berry

Diana Damrau (soprano), Jonas Kaufmann (tenor), Helmut Deutsch (piano).

Barbican Hall, London; Friday 16 February 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Damrau_Kaufmann_Barrbican_1272.jpg image_description=Jonas Kaufmann and Diana Damrau perform Wolf’s Italienisches Liederbuch as part of the Barbican Presents 2017-18 season in the Barbican Hall on 16th February 2018. product=yes product_title=Jonas Kaufmann and Diana Damrau perform Wolf’s Italienisches Liederbuch as part of the Barbican Presents 2017-18 season in the Barbican Hall on 16th February 2018. product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id= Above: Helmut Deutsch, Diana Damrau and Jonas KaufmannPhoto credit: Mark Allan/Barbican

San Jose’s Dutchman Treat

First, the company has chosen to tell the story and serve the composition, rather than impose a concept and serve themselves. It was a “first” for me to ever see real spinning wheels in the spinning scene! No kidding. I have seen, oh, let’s see, Senta in a spinning class at a fitness center, ladies spinning ship’s helms, and ladies just spinning themselves in circles. What a breath of fresh (sea) air to see such a beautifully straightforward rendering of Wagner’s intentions. That is not to say there wasn’t plenty of vibrant creativity on display.

Steven C. Kemp has designed a setting that is effectively modular, all the while framing it in a handsome fixed unit. An imposing upstage wall is flanked by angled walls stage left and right, all richly textured with planking. That wooden look, suggestive of a ship’s deck is carried over to the stage floor, this entire construction forming a sort of reflective shell that greatly enhanced the acoustic.

Gustav Andreassen as Daland

Gustav Andreassen as Daland

Walls can fly and retract, allowing for the addition of other scenic elements: the upstage row of windows in the spinning room, Daland’s merchant ship down right, rustic tables and benches for the revelry in the final scene. That this simplicity worked so well owes a great debt to the sumptuous, variegated lighting design by David Lee Cuthbert and especially the superlative projection design by Ian Wallace.

Wagner often envisioned stage effects without workable ideas to execute them, and in this case a spectral ship with ghostly, singing passengers must appear on cue; Senta must sacrifice her life with a suicidal leap into the roiling sea; and the Dutchman’s redemption must be visualized. It is to this talented team’s credit, that all of these challenges were persuasively met with uncommonly apt choices. If Wagner had know technical possibilities like this could be achieved, he would have undoubtedly come up with even more brainstorms!

Johann Stegmeir has provided a splendid array of costumes that were homey, comfortable, and definitive of their character’s stations in life. The pleasing silhouette of Senta’s lovely gown was matched by the effectiveness of its rich blue sheen. The folk nature of the chorus attire allowed Mr. Steigmeier to indulge in some careful use of color. Conversely, he applied more austerity to the Dutchman’s look, managing to make him look mysteriously appealing, without becoming grotesquely sinister. As always Christina Martin’s wig and make-up design was so “right” that we almost take it for granted.

Joseph Marcheso drew wondrous playing from his orchestra, with the banks of strings luxuriating in the lush writing. The winds were similarly characterful and stylistically secure. The brass provided exciting accents, with the horns nailing the familiar opening statement of the overture. Maestro Marcheso paced the evening with skill and obvious enjoyment and he drew impressive results that the most celebrated houses would take pride in. He also proved to be a highly capable partner with a cadre of exciting vocalists.

If this performance is any evidence, bass-baritone Noah Bouley is a rising star that seems poised to become the next Dutchman “of choice.” There is nothing about the taxing role that eludes him. Mr. Bouley has a robust, rolling tone that is well-supported and responsive to his every interpretive nuance. His rich vocalizing and well-considered musical journey resulted in a potent, cathartic performance.

Kerriann Otaño as Senta

Kerriann Otaño as Senta

Kerriann Otaño’s engaging, rich soprano has the heft and beauty that makes hers a memorable Senta. Just listen to the variety of color she brings to her opening aria, and revel in its specificity and pliability. Ms. Otaño has the technique and musical intelligence to not only limn the introspective moments with ravishing beauty, but also ride the amassed orchestra with thrilling focus and power.

Gustav Andreassen brings a meaty, buzzy bass-baritone to the role of Daland. He is more youthful then some interpreters of this paternal role, but the sheer power of his utterance and the mellifluous tonal production fell gratefully on the ear. Derek Taylor was a splendid Erik, his steely, substantial tenor filling the house with poised phrasings.

Fresh-voiced Mason Gates successfully brought his well-schooled tenor and youthful exuberance to the role of the Steersman, and he made the most of his featured solos. The role of Mary is often doled out to veteran singers in their twilight years (Astrid Varnay, anyone?). Not so in San Jose. Nicole Birkland was easily the most impressive Mary I have yet heard, her prime, plummy mezzo filling the California Theatre with warm, expressive sound. Andrew Whitfield’s precise, robust chorus covered themselves in glory, easily giving the best performance I have ever heard from this talented ensemble.

In another first for me, San Jose performed the work in three acts, rather than the usual one long act that has been my experience. Well, sort of. While the first act had a proper intermission, and while the act curtain rang down after act two, the last two acts did nonetheless utilize the musical bridge that connects the last two thirds of the piece.

All that being said, there is no denying that Opera San Jose has presented a Flying Dutchman of such accomplishment that it could put itself firmly on the map for Wagner enthusiasts. Wunderbar!

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Steersman: Mason Gates; Daland: Gustav Andreassen; The Dutchman: Noel Bouley; Senta: Kerriann Otaño; Mary: Nicole Birkland; Erik: Derek Taylor; Conductor: Joseph Marcheso; Director: Brad Dalton; Set Design: Steven C. Kemp; Costume Design: Johann Stegmeir; Lighting Design: David Lee Cuthbert; Projection Design: Ian Wallace; Wig and Make-up Design: Christina Martin; Chorus Master: Andrew Whitfield

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Dutchman_SanJose2.png

product=yes

product_title=San Jose Dutchman Treat

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Noel Bouley as the Dutchman [All photos copyright Pat Kirk, courtesy of Opera San Jose].

February 16, 2018

Mortal Voices: the Academy of Ancient Music at Milton Court

On the one hand, a musician’s survival depended on patronage: wealthy individuals, and the institutes of state and Church, put their hands in their pockets and enabled budding young composers to learn their craft, and geniuses to get on with the business of composing masterpieces. On the other, the reflected glory - reputation for cultural discernment and refinement, social status among the wealthy elite - derived from works composed on demand was worth paying for.

Handel arrived in Rome in 1707 and one of his patrons was Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni who, each Wednesday, held concerts in his Palazzo della Cancelleria, directed by Corelli. Some think that Handel’s solo cantata, ‘Ah! che troppo ineguali’, may have been commissioned by Ottoboni; others that the commission came in 1708 from Cardinal Colonna, in celebration of the feast of the Madonna del Carmine. Whatever and whoever, the Church clearly had a hand in the composition: the text is religious, but non-liturgical, the brief recitative and short aria comprising a supplication to the Queen of Heaven to send peace down to earth - most likely a response to the War of the Austrian Succession in which the Papal States were then engaged.

Canadian soprano Keri Fuge, who won second prize in the 2011 Handel Singing Competition, seemed a little tense during the recitative, and took a while to gage the dimensions of the Milton Court Concert Hall. But, the slight shrillness and over-emphatic accents had gone by the time Fuge reached the da capo repeat, and though she employed what I thought was a rather wide vibrato, she summoned a noble eloquence which matched the sentiments of the accompaniment provided by members of the Academy of Ancient Music, directed by Christian Curnyn who made much of the expressive contrast between the high shine of the violins and the low sonorous of the bass strings and organ.

Fuge was joined by countertenor Tim Mead for Handel’s duet-cantata ‘Il Duello Amoroso’, which was composed in 1708 for Marquis Francesco Maria Ruspoli, a member of the Arcadian Academy. It presents a stand-off between a love-sick Arcadian shepherd, Daliso, and the scornful and supercilious Amarilli. Handel’s setting is characteristically playful: when Daliso threatens to subdue the teasing nymph, ‘either by force or inclination or resentment before the enticing pains of death come’, Amarilli doesn’t bat an eyelid: ‘No more! I would have you satisfy the wicked desire that torments you; unfeeling man, come! Why delay? Take the blade and strike it into this heart.’ The humiliated Daliso retreats and demands that she return his heart only to be further emasculated: ‘you do not have the torch that can kindle my flame.’

Keri Fuge.

Keri Fuge.

The menuetto of the three-part overture was delicately wry, but Mead initially seemed quietly crestfallen even stoical, rather than indignant and resentful, about his rejection. That said, his countertenor was agile and light, then sensuously legato, in the two parts of his opening aria, and later he summoned a simple plaintiveness - ‘Is it better to hear many times promises of love but not when they may be fulfilled?’ - which was complemented by some finely phrased violin-playing from the AAM. Fuge was more ‘on score’ and this, as well as Mead’s tendency to prioritise mellifluous beauty over dramatic impact, did temper the dramatic frisson between the pair. But, Amarilli’s cruelty was evident in a slight edge to the voice and in the pointed echoes between soprano and violins, though as the temptress’s fury rose so Fuge’s focus and intonation became less consistent. The showdown was spirited with Mead summoning an angry pride, expressed through vivid adornment - ‘Sì, sì, lasciami ingrate’ (Very well, leave me alone, heartless girl) - his bitterness highlighted by the contrast between the high vocal line and low-pitched accompaniment of cellos, bass and continuo.

Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater - commissioned by the Brotherhood of the Vergine dei dolori in Naples, in 1736 - followed after the interval, with the original vocal ensemble reduced to just two voices. I’m not sure of the wisdom of this slimming down of the vocal sound: in the opening duet, the poignant suspensions did not register as emphatically or with the immediacy that one might expect. Moreover, despite their concerted efforts to blend their voices, particularly in the duet ‘Sancta mater, istud agas’ (Holy mother, pierce me through), Fuge’s soprano was often dominant.

That said, the soprano aria ‘Vidit suum dulcem natum’ (She beheld her gentle child) which lies lower in the voice was very affecting, unfolding quietly and lyrically above hesitant accompanying phrases. And, the fugal duet, ‘Fac ut ardeat cor meum’ (Make me feel as thou has felt), generated fervency and passion.

Mead’s aria, ‘Fac ut portem Christi mortem’ was beautifully sung and his strong technique - well-crafted phrasing, assured breath control, impressive trills - apparent; the orchestral unisons added rhetorical weight.

In the final duet, ‘Quando corpus morietur’ (While my body here decays), the violas and celli shuddered with a suffering that was more tender than tragic. One was reminded of the question asked by Jean Frangois Marmontel in the Mercure de France (September 1778): ‘Does it not cause tears to fall?’ And as the vocal lines wound around each other the resultant dissonances made for a delicate but affecting statement of anguish and faith.

In this concert, The Academy of Ancient Music confirmed their status as perhaps the finest period-instrument ensemble performing today, not least with the fleet-footed performance of Corelli’s Concerto Grosso Op.6 No.1 in D major that opened the programme. The antiphonal placement of the violins created drama and excitement - there was some wonderfully seamless interplay between both section-leaders, Bojan Čičić and Rebecca Livermore, and the full violin ranks, particularly in the second Allegro. And, Curnyn drew a warm, full sound from his fairly small ensemble, Alastair Ross’s organ providing sonorous depth, particularly in the slow movements. The upper string players were standing throughout the concert which encouraged vitality and freedom - lead viola Alexandru-Mihai Bota exhibited surprising balletic nimbleness, despite his height! - but it was a pity that cellist Joseph Crouch was rather ‘buried’ amid the ensemble, for his contributions to the concertante episodes were beautifully dulcet yet incisive. The facility of all conveyed a virtuosic ease which, at the final cadence, cohered into a closing gesture of graciousness and taste.

Claire Seymour

Keri Fuge (soprano), Tim Mead (counter-tenor), Christian Curnyn (director, harpsichord), Academy of Ancient Music.

Corelli - Concerto Grosso Op.6 No.1 in D major, Handel - Cantatas HWV230 ‘Ah! Che troppo ineguali’ and HWV82 ‘Il Duello Amoroso’, Pergolesi - Stabat Mater.

Milton Court, London; Thursday 15th February 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tim%2BMead_May%2B2013_166bw_%28c%29%2BBenjamin%2BEalovega.jpg image_description=Mortal VoicesAcademy of Ancient Music at Milton Court Concert Hall product=yes product_title=Mortal VoicesAcademy of Ancient Music at Milton Court Concert Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Tim MeadPhoto credit: Benjamin Ealovega

Glyndebourne Opera Cup 2018: semi-finalists announced

The singers will be competing for one of 10 places in the final on 24 March, which will be broadcast live on Sky Arts. The overall winner will receive £15,000 and the guarantee of a role within five years at one of the top opera houses represented on the competition jury.

Fourteen nationalities are represented among the semi-finalists, reflecting the international scope of the competition. The countries represented are Austria, Canada, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Guatemala, Ireland, Kosovo, Mexico, Poland, the UK, Ukraine, and the USA.

The backgrounds of the semi-finalists are as varied as their nationalities. Among them are soprano Elbenita Kajtazi (26), who as a young girl was forced to flee her home in war-torn Kosovo with her family, and live as a refugee in Albania. She fell in love with opera after watching clips of Maria Callas on YouTube. Soprano Francesca Chiejina (27), born in Lagos, Nigeria, had first planned to be a doctor before she caught the singing bug, as had her fellow semi-finalist, Canadian tenor Charles Sy (26). American bass baritone Cody Quattlebaum (24) was a chef for six years before he decided to commit to his musical career. Further details about the contestants will be revealed in an hour-long Glyndebourne Opera Cup documentary to be broadcast on Sky Arts on Thursday 22 March.

The Glyndebourne Opera Cup focuses on a different single composer or strand of the repertoire. In 2018 the featured composer is Mozart and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment will accompany the singers at the final.

The full list of semi-finalists is:

Adèle Charvet

24, mezzo-soprano (France)

Francesca Chiejina

27, soprano (USA)

Jorge Espino

26, baritone (Mexico)

Adriana Gonzalez

26, soprano (Guatemala)

Samantha Hankey

24, mezzo-soprano (USA)

Elbenita Kajtazi

26, soprano (Kosovo)

Dmytro Kalmuchyn

24, baritone (Ukraine)

Aurora Marthens

25, soprano (Finland)

Mirjam Mesak

27, soprano (Estonia)

Denis Milo

27, baritone (Germany)

Jake Muffett

24, baritone (UK)

Diana Newman

28, soprano (USA)

Gemma Ní Bhriain

25, mezzo-soprano (Ireland)

Alexandra Nowakowski

25, soprano (USA/Poland)

Eléonore Pancrazi

27, mezzo-soprano (France)

Emily Pogorelc

21, soprano (USA)

Cody Quattlebaum

24, bass-baritone (USA)

Anita Rosati

24, soprano (Austria)

Carl Rumstadt

25, baritone (Germany)

Jacquelyn Stucker 28, soprano (USA)

Jack Swanson

24, tenor (USA)

Charles Sy

26, tenor (Canada)

Hubert Zapiór

23, baritone (Poland)

A further heat will take place nearer the semi-final for a small number of contestants who had qualified for the competition but for reasons of illness were unable to attend one of the preliminary rounds, so it is possible that one or two additional names will be added to the list at a later date.

‘Glyndebourne enjoys a long held reputation for finding and nurturing new talent,’ says Gus Christie, Glyndebourne’s Executive Chairman. ‘It is with this in mind that I look forward to welcoming all of the competitors to the inaugural Glyndebourne Opera Cup semi-final on 22 March.

‘These talented young singers will have the opportunity to perform on the Glyndebourne stage, sing in front of a TV audience and ultimately have the chance of winning a cash prize and even a major operatic role. I wish them all the very best of luck and am delighted that Glyndebourne is able to showcase this new generation of singers on our stage.’

Sebastian F. Schwarz, Chair of The Glyndebourne Opera Cup jury, says, ‘These young singers piqued our curiosity; they revealed engaging artistic personalities and promising, beautiful instruments, and they demonstrated superior technical and musical skills.’