March 30, 2018

Fiona Shaw's The Marriage of Figaro returns to the London Coliseum

As the walls of the Almaviva abode revolve, constantly, we are whisked into the back-quarters - the kitchen, the boot-polishing room, the laundry - which underpin aristocratic luxury. It’s a sort of horizontal upstairs-downstairs of class divisions, as maids slyly observe mistresses’ misdemeanours and footmen feign indifference to aristocratic indiscretions. Figaro and Susanna plan the construction and placement of their wedding bed while a scullery maid scrubs the stairs; as the Count woos Susanna, a housemaid carries a basket of oranges through the room, head bowed but eyes and ears craning.

Shaw strives to create a sense of the busyness of the back-room personnel, whose labours ensure that the front-of-house is a portrait of tasteful tranquillity and aristocratic idleness. But, despite having seen this production in both 2011 and 2014, I still can’t fathom why so many of the Almavivas’ workforce are suffering from a sleep disorder, unless the aim is to show the inefficacy and impotence of the Count as master of the house. Even the gardener Antonio is encountered asleep in a chair: and, so, his leap from la-la-land to lambasting fury makes a nonsense of the idea that he has just come running from the flowerbeds, his anger at window-hopping page’s destruction of his gardenias throwing another spanner into the maelstrom of the Act 2 finale.

Revival director Peter Relton hasn’t injected much of a pick-me-up into the proceedings, but part of the blame for the slightly lackadaisical spirit that I felt on this occasion seemed to lie with Brabbins. The ENO Orchestra sounded decidedly messy at times - though things did tighten up in Acts 3 and 4 - and pit-stage coordination was often adrift (though subsequent performances in the run will surely improve in this regard). But, tempi felt perennially just a shade too slow, with soloists often seeming to be tugging at the bit. The action of the recitatives sometimes laboured and dragged, though that’s also a weakness of the production, for it makes heavy work of the dramatic business: the intrigues and mishaps simply don’t buzz, fizz and whirl.

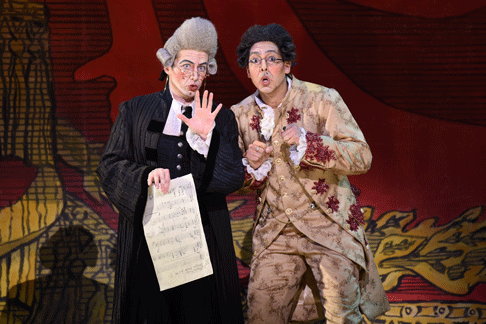

There are plentiful motifs, but they don’t always for mischief make. For example, Shaw has turned Basilio into a blind chorus-master (a variation on the piano-tuner stereotype I guess) which facilitates a few visual gags - incessant tapping of a white stick, the conducting of an invisible choir as the actual wedding chorus revolve off the set - but lost is the irony of such vicious lines as ‘What I said about the page, it was just a suspicion’ in the Act 1 trio, when Cherubino is discovered hiding and quaking in a trunk in Susanna’s room. Colin Judson sings with phrasing of curling obsequiousness and pertinently nasal piquancy but, deprived of his Act 4 aria, Basilio fades into the ‘foliage’ by Act 4.

Colin Judd (Basilio) and Ashley Riches (Count Almaviva). Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Colin Judd (Basilio) and Ashley Riches (Count Almaviva). Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

A few pre-curtain chuckles were garnered when a bedpost-carrying Figaro fiddled with an on-stage harpsichord, only to leap back in amazement when the keyboard seemed unilaterally to strike up the opera’s overture; but the gesture was less amusing when the Count repeated it with variations at the start of Act 3. And, the thumps and bumps (festive fireworks?) which accompanied the lengthy scene change before the final Act, as well as the vomiting in a flowerbed by an inebriant servant, were simply tiresome.

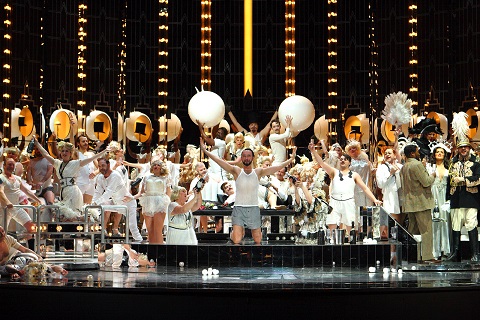

When the main ‘funny business’ of the first couple of Acts is some front-of-curtain shenanigans then things have gone awry, and there were times in Acts 1 and 2 when I had to remind myself that Figaro is an opera buffa. Fortunately, the arrival in Act 3 of Janis Kelly’s Marcellina, eager to claim the fulfilment of her marriage contract with Figaro only to discover that her ‘husband-to-be’ is her long-lost son, Rafaello, tipped the scales enchantingly, from to humdrum to humorous. Kelly, alongside Keel Watson’s bemused but beaming Doctor Bartolo, really did show how it’s done; and the comic duos’ esprit lifted the sharpness and sprightliness of the spat between Thomas Oliemans’ Figaro and Rhian Lois’ Susanna, resulting in an invigorating Act 3 sextet. One could only regret that Kelly, too, was deprived of her Act 4 aria.

Keel Watson (Doctor Bartolo) and Janis Kelly (Marcellina). Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Keel Watson (Doctor Bartolo) and Janis Kelly (Marcellina). Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Much of the appeal of this production derived from the appearance of several young singers in role debuts. Lois was the best of the bunch: ‘progressing’ from her WNO turn as Barbarina, she was a vibrant, nimble, quick-witted Susanna, animated both dramatically and vocally, who had no trouble getting the better of both the loyal but laborious Figaro and the fickle but foolish Count. ‘Deh vieni, non tardar’ was beautiful, Lois’ unadorned melodic sincerity proving a masterful counterfeit.

Ashley Riches both sang and acted superbly as the hapless Count, puffing out his chest, squaring his shoulders, striding imperiously in his black leather boots, but ever sporting an air of slight bafflement as to how everyone else seemed to be in the know. Riches’ recitatives were fluently and convincingly delivered and in ‘Vedrò mentr’io sospiro’ he used all of his vocal might and nuance to offer a momentarily persuasive riposte to the uncovered plotting of Susanna and Figaro.

Rhian Lois (Susanna) and Thomas Oliemans (Figaro). Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Rhian Lois (Susanna) and Thomas Oliemans (Figaro). Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Thomas Oliemans’ Figaro was a pleasant enough chap. The Dutch tenor has a relaxed manner and attractive voice, but I’d have liked a bit more vocal ebullience, and physical presence. I was impressed by Katie Coventry’s Cherubino: just the right amount of richness in the voice to suggest nascent sexual burgeoning but balanced by a lovely gamine gentleness which Coventry did not overplay.

Katie Coventry (Cherubino) and Rhian Lois (Susanna). Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Katie Coventry (Cherubino) and Rhian Lois (Susanna). Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

The appearance of Lucy Crowe making her role debut as Countess Almaviva was one of the big draws of this revival for me, but I left the Coliseum feeling slightly disappointed. We did have an occasional glimpse of the heavenly threads of Crowe’s high soprano, and her voice has become enriched with both new weight and fullness; but I felt that Crowe did not display the plushness of tone and colour required to communicate the Countess’s genuine distress and the pathos of her situation. She was able to soar over the ensemble, as in the Act 2 finale, but in the Countess’s two arias there was neither the enveloping luxuriousness nor the poignant eloquence to really win this listener over to the abused Countess’s cause. If the vocal characterisation seemed rather one-dimensional then Crowe also seemed not entirely comfortable dramatically: obviously attracted to Cherubino (she stroked his cheek during ‘Voi che sapete’), she later accepted her husband’s apologies at the close only to don modern dress and pick up her suitcase, heading, it seemed, for the marital exit. It may not have been Crowe’s fault, but the characterisation didn’t seem to add up.

Lucy Crowe (Countess Almaviva). Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Lucy Crowe (Countess Almaviva). Photo credit: Alastair Muir.

Shaw’s production tells the tale clearly - and given the nonsensical complexity of both libretto and back-story that in itself is no mean feat. Moreover, there are many vocal performances to enjoy in this revival. I think that my dissatisfactions come back to the production and design. The white-washed walls are lowered for Acts 3 and 4, opening up spaces which could be anything and anywhere. The cast may sport - at least until the close - period costumes, and oranges, flags and bull-fight motifs hint at a Sevillian setting, but the monochrome architecture and flowerless garden provide no context in which da Ponte’s larger-than-life characters can come to musical life and convincingly convey the human forgiveness which, in its concluding episode, Mozart’s opera so enchantingly and comfortingly espouses.

Claire Seymour

Mozart: The Marriage of Figaro

Count Almaviva - Ashley Riches, Countess Almaviva - Lucy Crowe, Susanna - Rhian Lois, Figaro - Thomas Oliemans, Cherubino - Katie Coventry, Marcellina - Janis Kelly, Doctor Bartolo - Keel Watson, Don Basilio - Colin Judson, Don Curzio - Alasdair Elliott, Antonio - Paul Sheehan, Barbarina - Alison Rose, Village Girls - Jane Read/Lydia Marchione; Director - Fiona Shaw, Conductor - Martyn Brabbins, Revival Director - Peter Relton, Designer - Peter McKintosh, Lighting Designer - Jean Kalman, Revival Lighting Designer - Mike Gunning, Movement Director - Kim Brandstrup, Video Designer - Steven Williams, Orchestra and Chorus of English National Opera.

English National Opera, London Coliseum; Thursday 29th March 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Alastair%20Muir.jpg image_description=The Marriage of Figaro: English National Opera, London Coliseum product=yes product_title=The Marriage of Figaro: English National Opera, London Coliseum product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above:The Marriage of FigaroPhoto credit: Alastair Muir

Lenten Choral Music from the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge

Not that I did, of course: I tended to go to my own chapel services more than others’; I also tended to prefer the services down the road at St John’s, less packed with tourists and thus seemingly less of a ‘concert’. I also preferred, in many ways, the more ‘Continental’ sound of St John’s to the typically ‘English’, whiter sound of King’s. Nevertheless, it was always quite an experience, first to set foot in that masterpiece of late Perpendicular Gothic – pay no heed to its cultured despisers, the same sort who will tell you that St Paul’s is a monstrous hybrid – gowned (and thus in slightly better seating than the non-Cambridge congregants), and to hear that celebrated choir, which, through radio and other recordings, I had known for so long before my time in the city that was essentially my home for fifteen years.

Ben Parry, an old boy from the choir and Assistant Director of Music at King’s, substituted for Stephen Cleobury, who was recovering from a bicycle accident. Parry certainly knew the choir and how to play to its strengths; it is difficult to imagine anyone having been disappointed, even in the almost diametrically opposed (to its echoing Chapel home) acoustic of Cadogan Hall. If some tempo choices, perhaps especially in the closing Brahms motets, seemed chosen more to help the boys than on ‘purely’ musical grounds, there is no great harm in that. The business of a collegiate (or other) choral foundation, after all, is far more than providing concert material; indeed, that is not really its business at all. Perhaps those works by Brahms, Warum ist das Licht gegeben? and Schaffe in mir, Gott, the latter a setting of part of Luther’s translation of the Miserere (Psalm 51), will have flowed more readily, especially in the relationship between different sections, and indeed have benefited from surer intonation, but there was much to enjoy, especially in their respective closing sections.

Two settings of the Stabat Mater, by Palestrina and Lassus, opened the concert’s two halves. Both were nicely shaded, without jarring (to my ears, without any) anachronism. The performance of the former imparted, when called upon, a real sense of ‘dec and can’ ( decani and cantoris) antiphony in a different setting. It perhaps sounded closer to Monteverdi than often one hears, less ‘white’ than I had expected. Whatever the Council of Trent’s suspicion of the poem, I was struck by the essential simplicity, however artful, of the music and by the guiding role of words. Lassus’s setting came across as darker, a little more Northern perhaps. (He was, after all, Kapellmeister in Munich.) Within the context of an undoubtedly ‘Anglican’ performance, full of tone yet not too full, the sound seemed – or maybe it was just my ears adjusting – to become a little more Italianate as time progressed.

Poulenc’s Quatre motets pour un temps de penitence offer a challenge, not least intonational, to any choir, and are more often heard with older (female) voices. In these forthright performances, there was – rightly, I think – no great attempt made to ape other performing traditions, but there was nevertheless sometimes a harshness, even perhaps, in the closing ‘Tristis est anima mea’, an anger, we do not necessarily associate with the choir. The shading of ‘Vinea mea electa’ was intelligent, fuller than Anglican reputation would have you believe. If intonation proved far from perfect, especially in the opening ‘Timor et tremor’, nor should one exaggerate; one always knew where the music and indeed the text were heading.

The music of Tallis and Byrd is home territory for King’s – albeit here without the trebles. Naturally, in their absence, countertenors came more strongly to the fore. Parry wisely made no attempt to do too much in terms of word-painting in the Tallis; the words speak for themselves, and did so here especially on the Lenten cries for ‘Ierusalem, Ierusalem’ to return to her God. The two Byrd motets offered, for me, the highlight of the concert. Without a hint of blandness or routine, there was simply – or not so simply – that ineffable sense of ‘rightness’, of ease with the music, the composer’s recusancy notwithstanding. Music and words spoke freely, in greatly satisfying performances. As we heard in both, ‘Sion deserta facta est, Jerusalem desolata est.’ And yet, there was comfort to be had, if not in the wilderness and desolation of Jerusalems heavenly and earthly, then in their artistic representation – which is doubtless as it should be.

Mark Berry

Programme:

Palestrina: Stabat Mater; Tallis:Lamentations of Jeremiah (Part 1); Poulenc:Quatre motets pour un temps de penitence; Lassus:Stabat Mater; Byrd: Ne irascaris, Domine;Civitas sancti tui; Brahms: Warum ist das Licht gegeben; Schaffe in mir, Gott. Choir of King’s College, Cambridge/Ben Parry (conductor). Cadogan Hall, London, Wednesday 21 March 2018

image=http://www.operatoday.com/choral-services-full-music-list-lent-2018-1.png image_description=Photo courtesy of King's College, Cambridge product=yes product_title=Lenten Choral Music from the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Photo courtesy of King's College, CambridgeA New Faust at Lyric Opera of Chicago

The role of Marguerite is sung by Aylin Pérez and that of her brother Valentin by Edward Parks. Siébel is performed by Annie Rosen, Marthe by Jill Grove, and Wagner is Emmett O’Hanlon. The performances are conducted by Emmanuel Villaume and the Lyric Opera Chorus is prepared by its Chorus Master Michael Black. This new production of Faust is designed by John Frame and directed by Kevin Newbury. Sets and costumes are designed by Vita Tzykun, projected imagery is designed by David Adam Moore, lighting by Duane Schuler, and wigs and makeup by Sarah Hatten.

The predominantly dark stage in the opening scene depicts a workroom or studio, interior windows are covered with drapes while ladders are placed near these channels to the exterior world. A small screen shows a video projection. As light begins to pervade the studio, a scrim rises, and attention is focused on the doddering movements of an elderly man. His resigned words beginning with “Rien” (“Nothing”) express dissatisfaction with an oppressive existence. Mr. Bernheims’ monologue continues with an impassioned statement on the vanity of Faust’s efforts until now. While applying a constant volume in vocal projection, Bernheim colors distinctly individual words, “Salut” and “destin,” by which Faust “greets” his purported final day when he plans to take poison and master his “destiny.” In response to Faust’s doubt in God’s help and his repeated curses, Bernheim’s final evocation forte to “Satan! à moi!” brings Méphistophélès out from behind a draped window. Mr. Van Horn’s entrance establishes this Satan as a master of all situations: his cool control and unyielding intrusion into the dramatic progression make him here a force that cannot be shut off. From the start, Van Horn’s supple voice lends even greater credibility to his characterization of the demonic force in nature. His performance throughout shows a remarkable command and ability to adapt his voice to varying dramatic needs. Van Horn’s emphasis here on “puissance” (“power”) is countered by Bernheim’s insistence on “la jeunesse” (“youth”) as a goal. Two innovations of this productions support the dramatic flow at this point and again in subsequent acts. The video projection of a woman moving through a natural setting captures Faust’s thoughts and desires of the moment. Once he commits his signature guaranteeing future service to Méphistophélès, Faust drinks the potion of youth and is transformed by a band of masked minions who appear henceforth in this production at strategic moments to carry out the devil’s bidding. “En route” (“Let us away”) is taken as a journey of discovery for Faust with Méphistophélès leading the path immediately into the public space and tavern starting in Act Two.

The drinking song is performed by a chorus dressed now in nineteenth-century garb; gradually soldiers wearing French uniforms from the time of Gounod drift onto the scene. At the entrance of Valentin attention is focused on the supervision of Marguerite during the brother’s forthcoming military absence. Mr. Parks performs the signature aria “Avant de quitter ces lieux” (“Before departing thee lands”) with a soldierly tone, while expressing lyrical warmth primarily in the middle section of the piece. His confrontation with Méphistophélès is facilitated by the masked assistants pushing stage center the table onto which the devil climbs to sing “Le veau d’or” (“The calf of gold”). Van Horn’s crisp intonation of the melodic line and his exciting delivery of the final verse, “Et Satan conduit le bal” (“And Satan leads the ball”) characterizes the unflagging power of this demonic force. During this first, extended scene of the act Faust lurks about and wanders among the citizens, students, and soldiers assembled, as though reinforcing Mr. Newbury’s program comments that “the whole story is in Faust’s imagination.” Once he reenters vocally in keeping with Gounod’s score, the protagonist persists in reminding Méphistophélès of his promise. As the crowd separates, Marguerite appears here in a solitary, seated pose. Ms. Pérez rebuffs Faust’s offer “pour faire le chemin” (“to escort you on your way”) with understated yet thoughtfully intoned lines. Once she is spirited away with the intercession of the minions, Bernheim declares fortissimo his affection for Marguerite. A stylized, projected image of Faust appears on the stage rear wall at the close.

Such emphasis on demonic control continues into the central Act Three. Through a scrim, village trees are gradually visible during the entr’acte as well as Van Horn’s Méphistophélès posed in contemplation with a lit cigarette. In delivering Siébel’s couplets of a lovelorn suitor’s devotion Ms. Rosen pours out cascades of sincere emotion while addressing the flowers to be left for Marguerite. Rosen’s attention to key lines and application of rubato communicate her character’s pivotal attempts to shield the heroine with innocent love. The final “doux baiser” (“tender kiss”) which Siébel hopes to send via the flowers is held by Rosen with an achingly extended pitch. Faust’s approach to Marguerite’s dwelling is, likewise, accompanied by his cavatina praising nature for its formation of Marguerite. Bernheim’s slightly nasal, reedy voice caresses the individual lines as he credits “Nature” for having developed this ideal. The repetition of “Salut” and Bernheim’s panegyric to Marguerite’s beauty is accomplished with seamless legato and shifts in color to indicate emotional intensity. During and after the iconic aria this production’s external visualization of a character’s feelings is displayed to good effect just as an image of large, colorful lilies is projected onto the stage, while Bernheim concludes with a sustained note Faust’s outpouring of devotion. Almost immediately the Satanic helpers bring a box of jewels and place it at a strategic locale near Marguerite’s dwelling. This cottage appears raised on stilts so that the helpers can crawl beneath the house and indicate their watchful temptation. In her performance of the “Roi de Thulé” Pérez sings with an introspective, wistful tone to capture the king’s fond memory of his departed wife. Her exquisite piano phrasing at the close forms a transition to the startled reaction of finding the box. Pérez begins the “Jewel Song” indeed softly with enthusiasm and vocal decoration building after she tries on a pair of earrings. This curiosity increases as one of Satan’s helpers emerges to hold up a mirror and thereby tempt Marguerite even further. The following quartet of Marthe and Méphistophélès, Marguerite and Faust is cleverly staged, so that the interests of both couples remain constant while they continue to perform from different focal points. Ms. Grove shines in the cameo tole of Marthe with both her singing and acting contributing comic relief and a motivation to further the plot. Yet the ultimate prod is here Méphistophélès, at whose urging Faust is now pushed by the minions into the arms of Marguerite.

The scenes of progressive emotional starkness in the remaining parts of the opera present Marguerite first with a callous Faust, then alone, and next as a penitent in church. In this latter scene the lighting on the stage rear suggests a religious interior when Marguerite sits on a bench. Positioned next to her, and clearly plaguing her conscience as symbol, Méphistophélès’s ringing statements accelerate as the orchestral volume swells. At the same time the lighting through a mock window now resembles the flames of hell. The chilling determination unleashed by Van Horn’s performance in this scene in church epitomizes the dramatic power communicated by this superb singer and actor. His facial expression etches a relentless force which dominates through to the inevitable conclusion. Marguerite’s faith will save her as declared, but Faust must pay for his transgressions. As an ironic reminder in the final scene of the opera in this production, Faust dons one of the sculpted masks to follow the others as henceforth one of the band of Méphistophélès.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/benjamin_bernheim_faust_t8a0811_c.cory_weaver_preview.png

image_description=Benjamin Bernheim [Photo © Cory Weaver]

product=yes

product_title=A New Faust at Lyric Opera of Chicago

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=Above: Benjamin Bernheim [Photo © Cory Weaver]

March 26, 2018

Netrebko rules at the ROH in revival of Phyllida Lloyd's Macbeth

Key scenes take place at night. The witches, who meet Macbeth ‘’ere the set of sun’, are, says Banquo, ‘ The instruments of darkness [who] tell us truths’. Lady Macbeth invokes darkness to help her to descend to hellish depths: ‘Come, thick night,/And pall thee in the dunnest smoke of hell,/That my keen knife see not the wound it makes,/Nor heaven peep through the blanket of the dark,/ To cry “Hold, hold!”’ While one would not doubt the transformative magic effected by Shakespeare’s text, it’s a play that seems less suited to a sun-lit staging on the broad platform of London’s Globe Theatre, say, than to the candle-lit intimacies of the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse which now sits alongside.

This might have been a matinee performance but Anthony Ward’s designs and Paule Constable’s lighting set for Phyllida Lloyd’s 2002 Macbeth, receiving its third revival at the ROH under revival director Daniel Dooner, certainly plunged us into an enveloping blackness. And, as we moved through murky vaults and weightily panelled castle rooms, strong contrasts of shrouding coal-blackness and concentrated brightness vividly evoked the claustrophobic darkness of the troubled mind - none more effectively than the dagger of light that streaks like a bolt of lightning across the floor as Macbeth contemplates regicide and its consequences. Even the cherished and acquired golden sceptre, for all its bright gleam, suffocates with hollow promise rather than liberates through ambition fulfilled: kingship is a gilded cage, sometimes a miniature casket, sometimes spinning throne room, but always sterile and unrewarding.

Anna Netrebko (Lady Macbeth). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Anna Netrebko (Lady Macbeth). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

However, Lloyd and Ward also successfully enlarge the vista at times, particularly with the arrival of Macduff’s and Malcolm’s armed soldiers in Act 4. In this way, Macbeth reverses the trajectory of Othello which moves from Venetian streets, the beaches of Cyprus, and rooms of state towards the terrible poignant intimacy of the bedchamber. And, there are some impressing visual images which cut through the prevailing gloom: the body of the executed traitor, Cawdor, splayed behind the battlefield; Duncan’s blood-stained corpse displayed in a glass coffin in the subterranean mausoleum where Banquo will meet his untimely end; Lady Macbeth’s bath - a marble sarcophagus into which she slips at the end of her first scene, thereby introducing the juxtaposition of blood and water which runs through the play and will be underscored when the bath returns in the sleep-walking scene.

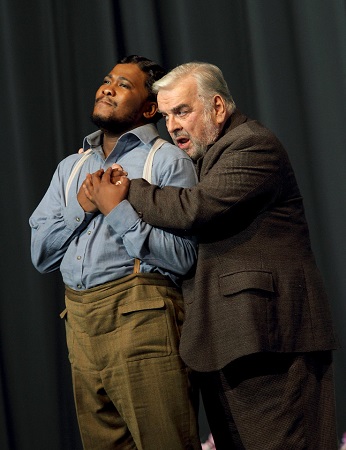

Ildebrando D’Arcangelo (Banquo). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Ildebrando D’Arcangelo (Banquo). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

I am less enamoured by Lloyd’s decision to make the witches not just the messengers of Fate but its very agents: they carry Macbeth’s letter from the battlefield to his wife; they open a trapdoor which enables Fleance to escape from the murderers who slay his father. Surely this undermines the very notion of Fate which needs no assisting interventions? More significantly, it conflicts with Shakespeare’s Queen’s conviction that her husband will wear ‘the golden round,/ Which fate and metaphysical aid doth seem/ To have thee crown'd withal’ [emphasis added]. And, in weakening Lady Macbeth’s own authority over her husband, the ambiguity of influence is destroyed: is it Fate, evil as embodied by the witches, his wife’s insatiable lust for power or Macbeth’s own ‘vaulting ambition’ that drives the inexorable tragedy. Verdi himself had described Lady Macbeth as ‘il demonio dominatore’ (the dominating demon … [who] controls everything’. [1]

Željko Lučić and witches chorus. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Željko Lučić and witches chorus. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Admittedly, Verdi’s opera is less interested in individual psychologies than Shakespeare’s play. Terrible acts are carried out, but the pace is swift and there’s not time for much self-scrutinising soul-raking. And, Lloyd uses the witches to create visual and dramatic coherence, as when their red turbans metamorphose into the military sashes sported by Macduff’s troops. Moreover, the branches from Birnam Wood which the soldiers clutch are the very staffs so roughly stamped into the ground by the witches in the opening chorus. The latter gesture and other choreographic exaggerations, such as the witches’ tortured writhing at the start of Act 3, sometimes border on pantomime. But, there are other effectively choreographed moments such as the monk-habited murderers killing of Banquo as he pays homage at Duncan’s tomb, and the staging of the banquet scene which spins with slippery unease - though Banquo’s ghost fails to make its present felt in the maelstrom.

I also remain unconvinced by the production’s intimation that it is the anguish of childlessness that drives the usurping couple. Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth has ‘given suck’ (though admittedly the Macbeth’s children don’t loom large in the play text); but, more importantly, she taunts the unmanly, wavering Macbeth with her own derision for feminine and maternal feeling and the fortitude of her purpose: ‘I … know/How tender 'tis to love the babe that milks me:/ I would, while it was smiling in my face, Have pluck’d my nipple from his boneless gums, /And dash’d the brains out,had I so sworn as you/ Have done to this.’

Lloyd’s reading seems to negate one of the most chilling images of the play. In Act 3, Macbeth’s imagined dreams of happy family life are briefly fulfilled by the witches who bring in a brood of children to perch upon the marriage bed, bearing them aloft like angels, only to snatch them away again and for the bed to divide, the schism between the couple - who remain onstage, asleep on their single beds as Malcolm’s troops gather - forever irreparable. But, it is surely guilt which isolates the couple? Verdi, unlike Shakespeare, has Lady Macbeth in on the plot to murder Banquo, but it’s hard to imagine that she kills herself - if indeed it is suicide that brings about her end - because she is not a mother.

If the conflicts of conscience are suggested by Constable’s contrasts of blackness and brightness, then conductor Antonio Pappano conjured equally striking chiaroscuro effects from the ROH orchestra. The pianissimo wind melody and violin whispers which begin the overture were brutally thrust aside by the loud heralding triplet motif of dark bassoons, trumpets and trombones; then, from the silence, crept the slightest, most tentative of violin forays, only for the strings to be obliterated by a tutti onslaught. So the battle of light and darkness went on, as vividly painted, and at times as shocking, as a Caravaggio biblical drama. Pappano also knows how to make something of Verdi’s rum-te-tum accompaniments, not quite, but almost, overcoming the disjuncture we sometimes feel between the surprisingly jaunty musical sound-world and what we imagine to be the unsettling maelstroms within the individuals’ psyches.

Anna Netrebko (Lady Macbeth). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Anna Netrebko (Lady Macbeth). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Of course, Verdi’s Macbeth needs a Queen who can reign over all, and the ROH was fortunate to have Anna Netrebko to draw in the crowds and preside vocally. I have to say that the icing on the cake of this theatrically imperial performance - which was throughout and at the final curtain vigorously and loudly lauded - would have been, for this listener at least, a little more pitch-precision and occasionally a less steely hardness. Netrebko’s Queen was reckless from her the first, storming wildly through ‘Vieni! T'affretta!’ with impetuous fire and undeniable wilfulness and in Act II’s ‘La luce langue’ (the 1865 revised Paris score was used) her implacable desire, bordering on insanity, could not be doubted. Netrebko’s soprano has tremendous weight - at the close of Act 2 she brilliantly and brazenly surmounted the choral majesty - and both sheen and darkness, and a whole host of other textures and colours in between. And, if I longed for a little more grace at times then my wish was fulfilled in the sleep-walking scene were such is the Russian soprano’s technique - already greatly in evidence in the tight trills of the brindisi - that she was able to bring together the conflicting voices of Lady Macbeth’s inner conscience - the disjointed fragments, the leaps between registers, the arioso which tantalisingly offers the all too brief consolation of cantabile lyricism - and she almost nailed the quiet Db peak at the close. Perhaps Netrebko’s acting was a little too self-conscious at times, but there’s no doubt that she created a lustrous-voiced Queen to please the composer who called for a Lady Macbeth who was ‘ugly and evil … [with] a diabolical quality’. [2]

Željko Lučić and Anna Netrebko. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Željko Lučić and Anna Netrebko. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Netrebko was reunited with baritone Željko Lučić with whom she appeared in Macbeth at the Met in 2014. Lučić’s warrior seemed psychologically wounded from the start, unnerved by the appearance of the witches and dominated by his wife, and he didn’t really plumb the depths of vaulting ambition nor convince me that there was any chemistry between the regal pair. But, Lučić’s baritone is mellow, if not velvety, and the line elegant. If the vocal vacillations of Act I’s ‘Due vaticini’ were not totally persuasive, and if the Serbian baritone had a tendency to be just below the note, then Act IV’s ‘Pietà, rispetto, amore’ was measured, powerful and true.

Yusif Eyvazov (Macduff). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Yusif Eyvazov (Macduff). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

All of the emphasis in Macbeth is on the central protagonists - Macduff is not an antagonist but a tenore comprimario and the murder of Lady Macduff and her children are excised (though Lloyd makes their presence felt briefly, when they make a hasty exit from the banquet) - but the ROH cast for this revival is uniformly strong and we enjoyed a beautiful exemplification of bel canto technique from Yusif Eyvazov (Macduff) and a strong performance by Jette Parker Young Artist Konu Kim as a reluctantly crowned Malcolm. I particularly liked the directness and sombre colour of Ildebrando D’Arcangelo’s Banquo, and as the Doctor and Lady-In-Waiting respectively, JPYA’s Simon Shibambu and Francesca Chiejina introduced the somnambulist in clearly enunciated recitative.

This may not be a ‘perfect’ Macbeth, if there can be such a thing, but the cast - from fictional monarch to minion - conjure Verdi’s and Shakespeare’s darkness powerfully and persuasively.

Claire Seymour

Giuseppe Verdi: Macbeth

Macbeth - Željko Lučić, Lady Macbeth - Anna Netrebko, Banquo - Ildebrando D'Arcangelo, Macduff - Yusif Eyvazov, Lady-in-waiting - Francesca Chiejina, Malcolm - Konu Kim, Doctor - Simon Shibambu, Fleance - Matteo di Lorenzo, Assassin - Olle Zetterström, First Apparition - John Morrissey, Second Apparition - Gaius Davey Bartlett, Third Apparition - Edward Hyde, Herald - Jonathan Coad; Director - Phyllida Lloyd, Conductor - Antonio Pappano, Designer - Anthony Ward, Lighting designer - Paule Constable, Choreography - Michael Keegan-Dolan, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Royal Opera Chorus (Concert Master - Sergey Levitin).

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Sunday 25th March 2018.

[1] Quoted in David Rosen and Andrew Porter, Verdi’s ‘Macbeth’: A Sourcebook (New York, 1984), p.99.

[2] Verdi, letter to Salvatore Cammarano, 23rd November 1848; trans. in Verdi’s ‘Macbeth’, p.67.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper

March 25, 2018

San Diego’s Ravishing Florencia

I had been hoping for years to catch up with a production of this acclaimed piece, but schedules have conflicted and life had intruded. Happily, I have made up for lost time, and the SDO mounting was so persuasive that I immediately vowed to seek out another performance of this masterwork at the earliest opportunity.

San Diego has long had a connection with the composer, having produced his Rappaccini’s Daughter (La hija de Rappaccini), the first work by a Mexican composer to be presented by a major opera house in the United States. The success of Rappaccini's Daughter brought Catán international attention, launching his musical career in the United States and sealing the commission of his next opera, Florencia en el Amazonas by the Houston Grand Opera .

In this local premiere, the piece was so lovingly mounted that it was clear the company was treating the work as the masterpiece it decidedly is. The lush score borrows stylistically from Puccini here, Debussy there, here a taste of Strauss, there a dash of Britten, but the unifying whole is peppered with Latin undertones and the voice is uniquely Catán’s.

Almost the entire plot unfolds on the deck of a ship sailing up the Amazon bound for Manaus. There, a legendary opera house awaits the return engagement of diva Florencia Grimaldi, performing a concert as she returns to her homeland to reunite with her lover Cristobal, a hunter of exotic butterflies. Her quest to rediscover her lover Cristobal is the whole driving force of the piece. Although she is traveling among other passengers in disguise, Florencia’s enigmatic persona drives the motivations of the other characters.

Elaine Alvarez as Florencia Grimaldi. Photo credit: J. Katarzyna Woronowicz.

Elaine Alvarez as Florencia Grimaldi. Photo credit: J. Katarzyna Woronowicz.

The music making was superlative, starting with the vocals. In the title role, Elaine Alvarez made a stunning impression. Her pliable spinto soprano easily encompassed every demand of three wide-ranging arias. The rich, pulsing tone was absolutely even throughout the wide-ranging part, and her alluring vocal presence anchored the performance with a poised, polished musical presence. Ms. Alvarez made us abundantly aware of why the public was in awe of her towering talents.

Every bit her equal, María Fernanda Castillo was a luminous Rosalba, her plush lyric soprano soaring above the staff to provide many of the evening’s most goose bump inducing moments. Ms. Castillo’s substantial soprano is tinged with pure gold and her sympathetic phrasing endeared her to the spectators. As her partner in romance, dashing Daniel Montenegro (Arcadio) provided exceedingly poised singing in equal measure. Mr. Montenegro is not only an ingratiating lyric tenor, but also has a winning way with a high-lying, pulsing phrase that made a fine impression. As the two love interests, the pair provided one of the evening’s highlights with a rhapsodic Act II duet.

Maria Fernanda Castillo as Rosalba and Daniel Montenegro was Arcadio. Photo credit: J. Katarzyna Woronowicz.

Maria Fernanda Castillo as Rosalba and Daniel Montenegro was Arcadio. Photo credit: J. Katarzyna Woronowicz.

Luis Alejandro Orozco was a galvanizing presence as Riolobo. Part narrator, part demigod, Mr. Orozo’s imposing baritone was a potent presence, and his shirtless strutting provided handsome eye candy for the opera glasses crowd.

As the bickering, dyspeptic married couple, Levi Hernandez (Alvaro) and Adriana Zabala (Paula) were alternately amusing, annoying, and ultimately, touching. Mr. Hernandez has a beefy baritone that communicates securely and sympathetically.

Ms. Zabala’s rather barbed opening pronouncements eventually morphed into some mellifluous phrases infused with deference and luminosity. Hector Vásquez was a solid presence as the stolid Capitán, his seasoned baritone ringing out with honesty and clarity. Chorus Master Bruce Stasyna’s well-schooled ensemble not only sang with glowing tone and dramatic fire, but also cleanly executed some inventive staging while doing it.

Conductor Joseph Mechavich worked wonders with the orchestra, mastering every harmonic surge and eliciting finely tuned detail from the pit. Maestro Mechavich also skillfully wed singers, dancers and instrumentalists into a seamless ensemble. He controlled the arc of the piece with refined skill, all the while he somehow magically made the outpouring of melodies and effects feel exuberantly spontaneous.

Luis Alejandro Orozco as Riolobo is joined by the San Diego Opera Chorus. Photo credit: J. Katarzyna Woronowicz.

Luis Alejandro Orozco as Riolobo is joined by the San Diego Opera Chorus. Photo credit: J. Katarzyna Woronowicz.

The handsome physical production originated at Indiana University, but seemed a perfect fit for the resources of the Civic Theatre. A forty-two-foot, double-decker riverboat dominates the stage as part of Mark Frederic Smith’s masterful set design. It begins at a pier in the opera’s first scene, with a boathouse structure framing the action. However, as the craft soon sets sail on the murky Amazon, the house flies away, and lush foliage droops artistically around the action.

The effect never becomes tiresome since the ship rotates on a turntable to reveal different, detailed perspectives of its construction. When the ship beaches in the storm, terraced riverbanks swing into place down left and right, and up right, which afford mystical river creatures to gambol and pose with enigmatic abandon.

Those “creatures” (aka the chorus and corps de ballet) were lavishly costumed by Linda Piano, who seems to have limitless imagination. The masks, fanciful accessories, painted body stockings and footwear were meticulously coordinated, and were complemented marvelously by Steven W. Bryant’s wacky, winning wig and make-up design. Ms. Piano also created lovely, character specific period wear for the diva Florencia, upper and lower-class guests, and laborers, greatly helping to define the relationships.

Todd Hensley’s brooding, ever-changing lighting design perfectly captured the emotional shifts in the plot, as well as the climate changes on the river. His choices of color filters were especially apt. Only two effects might have been improved upon: the storm lightning was tracked to look too predictable, and the overall threat of the turbulent storm (as heard in the music) was not realized with enough abandon. And the climactic moment of Florencia transforming into a butterfly went for too little. The unfurling of the costume, creating two wings, was a great start, but the rotating star gobo was a far cry from the coup de theatre that was called for. Think Defying Gravity, Wicked’s Act One closer, where the main character soars up to the wings as the black cloth of her cape spreads to fill the entire backdrop around her, and you get some idea of the jaw-dropping effect that might be needed.

Still, director/choreographer Candace Evans worked wonders with her resources, achieving moments that were beautifully judged for character revelations and dramatic insights. Ms. Evans deployed her assemblage of spirits with aplomb, creating a fine diversity of groupings and movement without ever creating a distraction. Indeed, she instilled a keen sense of dramatic focus was one the productions strong suits.

From the downbeat and the start of the engaging musical effects, to the ascendant metamorphosis that rang the curtain down, this was one memorable river journey I wished would never end.

James Sohre

Daniel Catán: Florencia en el Amazonas

Florencia Grimaldi: Elaine Alvarez; Rosalba: María Fernanda Castillo; Riolobo: Luis Alejandro Orozco; Arcadio: Daniel Montenegro; Capitán: Hector Vásquez; Alvaro: Levi Hernandez; Paula: Adriana Zabala; Sailor: Bernardo Bermudez; Conductor: Joseph Mechavich; Director/Choreographer: Candace Evans; Set Design: Mark Frederic Smith; Lighting Design: Todd Hensley; Costume Design: Linda Piano; Wig and Make-up Design: Steven W. Bryant; Chorus Master: Bruce Stasyna.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/FLORENCIA%20EN%20EL%20AMAZONAS.Photo%20J.%20Katarzyna%20Woronowicz%20Johnson.jpg image_description=Florencia en el Amazonas: San Diego Opera product=yes product_title=Florencia en el Amazona: San Diego Opera product_by=A review by James Sohre product_id= Above: Cast of Florencia en el AmazonasPhoto credit: J. Katarzyna Woronowicz

Samantha Hankey wins Glyndebourne Opera Cup

Mezzo-soprano Samantha Hankey, 25, from the USA, was crowned the overall winner, receiving £15,000 and the guarantee of a role within five years at one of the top opera houses represented on the competition jury. She also won the Media prize, chosen by a panel of opera critics and classical music journalists.

A native of Massachusetts, Hankey attended the Merola Opera Program in San Francisco and recently graduated from The Juilliard School. In 2017/18 she makes her debuts as Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia at Den Norske Opera, Siébel in Faust at Grand Théâtre de Genève, and her Carnegie Hall debut in Handel’s Messiah with Musica Sacra. She was Grand Finals winner of the 2017 Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions and first prize winner of the Dallas Opera Guild Competition.

‘I am honoured and humbled to be awarded the Glyndebourne Cup,’ she says. ‘The announcement left me speechless. This entire week has been incredible working with the staff at Glyndebourne and all who were involved in the competition, and it means so much to me to have been acknowledged as having something to say in interpreting Mozart’s music. I cannot say “thank you” enough for this honour”

Winning the Audience Prize, with a third of all votes cast by those in the auditorium who watched the final, was Kosovan soprano Elbenita Kajtazi, 27. Kajtazi as a young girl was forced to flee her home in war-torn Kosovo with her family, and live as a refugee in Albania. ‘Every time there would be a dangerous situation - the soldiers would come into our house or something like that - I would find a corner and sing to myself. Singing was my way to be able to feel safe,’ she recalls.

Elbenita Kajtazi and Dame Janet Baker Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Elbenita Kajtazi and Dame Janet Baker Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

On her win she commented: ‘The audience prize means that the audience loved me and what more could I ask for? I’m for the first time here in England and I get this kind of treat and I’m able to get in people’s hearts, this means the world to me.’ Kajtazi also took Third place.

Second place went to American soprano Jacquelyn Stucker, 28, currently a Jette Parker Young Artist at the Royal Opera House, where she recently performed the role of Frasquita in Barrie Kosky’s production of Carmen.

The Ginette Theano prize for most promising talent was awarded to American soprano Emily Pogorelc, 21. Pogorelc was the youngest competitor to reach the final and is currently entering her final year at the Curtis Institute of Music.

The prizes were presented by Dame Janet Baker, the competition’s honorary president who helped to adjudicate the final. The final of the Glyndebourne Opera Cup was broadcast live on Sky Arts, hosted by Chris Addison and Danielle de Niese.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Glyndebourne%20Cup%20winner.jpg image_description=The Glyndebourne Opera Cup 2018 product=yes product_title=The Glyndebourne Opera Cup 2018 product_by= product_id= Above: Samantha Hankey with Dame Janet BakerPhoto credit: Richard Hubert Smith

Handel's first 'Israelite oratorio': Esther at the London Handel Festival

In fact, Handel’s first ‘Israelite oratorio’, Esther, dates from Handel’s early years in London. Like Acis and Galatea, which the London Handel Festival had presented at St. John’s Smith Square a few days earlier, it was written for James Brydges (later Duke of Chandos) and thought to have been performed at Cannons, Brydges’ Middlesex estate, during 1718-20.

The libretto, which was probably fashioned by the poets Alexander Pope and John Arbuthnot, is a dramatic adaptation of the Old Testament narrative, in which the pious Esther acts to save the threatened Israelites from a pogrom at the hands of their Persian oppressors, and Jean Racine’s play Esther of 1688 (which had been seen in London in 1715 in an English paraphrase by Thomas Brereton), which emphasises the challenge to God’s authority and the divine salvation of the Israelite people. Musicologists and commentators have sought allegorical relevance in the affirmation of Jewish courage and conviction but have been as likely to suggest a parallel between the English Anglicans and the ‘Chosen People’ as to see the Jewish minority as representative of the English Catholics within a Protestant majority. When the worked received its ‘public’ premiere, in London in 1732, additional text by Samuel Humphreys enhanced the connection to the Hanoverians through implied compliments to George II and Queen Caroline.

This performance by the London Handel Orchestra at Wigmore Hall was stylishly directed by Adrian Butterfield, who fulfilled a dual role as violinist-conductor. In fact, with such an accomplished band of musicians before him, I wondered if Butterfield might not have relinquished his fiddle on this occasion; for, while the vocal standards were high, not all of the young soloists were equally adept at creating character and developing the narrative momentum. The numbers that were most successful were the choruses, when Butterfield laid his violin aside and stood to conduct, creating exciting drive and momentum.

Indeed, one might feel that Handel’s finest achievements in Esther are the choral sections: the contrasting joy - when the Jews rejoice that Esther, a believer, has become Queen - and despair, when they learn of Haman’s vicious decree that they should be annihilated; their confident assertion, ‘He comes!’, that God will defend them; and the magnificent triumphal chorus which closes the oratorio. Almost all of the soloists joined to form the choral ensemble, producing a lively, bright sound, with the strings’ generating zip and vigour and Darren Moore’s trumpet adding majesty and jubilance to the final triumph: ‘The Lord our enemy has slain’.

The instrumental contributions in the arias were no less affecting and accomplished. Stephen Mills’ relaxed, pure tenor was graciously accompanied by the violins’ gentle pizzicato and James Eastaway’s beautiful oboe obbligato, as the First Israelite expressed the people’s unwavering trust in ‘great Jehovah’, and Mills’ clean tone was equally well-suited to persuading us of the condemned Mordecai’s faith. The horns (Gavin Edwards and Clare Penkey) added relish to the glorification of Jehovah of the start of Act 3.

Best of the soloists was Erica Eloff as the eponymous saviour of the nation. The winner of the 2008 Handel Singing Competition, Eloff has impressed before ( Adriano in Siria , Elpidia ) and on this occasion I was struck by the extended range of colours that the South African soprano deployed to convey Esther’s love, fear, doubts and hopes. She really made the text count in Esther’s first air, capturing the deep sincerity of the queen’s prayer, and her angry dismissal of Haman’s ‘flatt’ring tongue’ left none in doubt of Esther’s inner strength, an impression which grew in the elaborated repetitions of the aria’s da capo. Eloff even managed a convincing ‘faint’ when Esther quakes in fear before Ahasverus as she pleads for Mordecai’s deliverance, before reviving to invite her lord to a banquet at which she intends to expose Haman’s vendetta with sufficient beauty of voice and manner to convince Ahasverus to submit to his wife’s entreaties.

As Ahasverus, William Wallace - in common with some of the other soloists - took a little while to judge the acoustic of Wigmore Hall, in which a capacity audience was seated. Initially he forced his tenor a little too much, but as Esther’s appeals worked their magic, Wallace’s voice relaxed and charmed in ‘O beauteous Queen’. Baritone Josep-Ramon Olivé colourfully revealed Haman’s vengeful exasperation in the oratorio’s opening aria, expressing his indignant fury with plenty of bluster, though a little less might have been more - the diction was rather muddy.

Timothy Morgan was also somewhat over-earnest as the First Priest of the Israelites, which affected his tuning at times, but Morgan’s counter-tenor is appealing, and he communicated with directness. As the Israelite Boy, Camilla Harris displayed a lovely sheen and graceful phrasing in her single aria, which was further enhanced by exquisite interplay from the pianissimo violins, flute (Rachel Brown) and harp (Frances Kelly). Tenors Ben Smith (Habdonah) and Laurence Kilsby (Officer/Second Israelite) completed the accomplished vocal ensemble.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Esther HWV50

London Handel Orchestra: director/violin - Adrian Butterfield.

Esther - Erica Eloff, Ahasverus - William Wallace, Haman - Josep-Ramon Olivé, Israelite Boy - Camilla Harris, Priest of the Israelites - Timothy Morgan, Mordecai/First Israelite - Stephen Mills, Habdonah - Ben Smith, Officer/Second Israelite - Laurence Kilsby.

Wigmore Hall, London; Thursday 22nd March 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Erica%20Eloff.jpg image_description=Esther: London Handel Festival, Wigmore Hall product=yes product_title=Esther: London Handel Festival, Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Erica EloffMarch 23, 2018

Probing Bernstein and MacMillan double bill in Amsterdam

Clemency is based on an episode in Genesis in which three strangers visit Abraham and Sarah. They promise that Sarah, who is childless and past her climacteric, will bear a son within a year, but also announce the obliteration of the sinful cities Sodom and Gomorrah. In Trouble in Tahiti, Sam and Dinah already have a son, Junior, and everything else they could wish for, but they can’t seem to muster any patience or tenderness for each other, let alone love. Both one-acters deal with barrenness, emotional and biological, and director Ted Huffman stages them symbolically in an empty swimming pool. For Trouble in Tahiti the well-lit pool is cluttered with furniture, accessories and everything money can buy. The soft pastels are then replaced by Clemency’s dim interior. All the stuff is gone, and the bottom of the pool is lined with leaves. Alex Brok lights Abraham and Sarah’s dining table with beams from above, as in paintings depicting visitations from heaven. Set and costume designers Elena Zamparutti and Gisella Cappelli use clean lines and make marked statements with color. Like the rest of the production team and cast, they are young artists with great promise.

In the pit, Duncan Ward conducted the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra with alertness and dash. Musically, the two works are worlds apart. Bernstein uses a wide orchestral palette for his feather-light jazzy tunes and swelling lyricism. MacMillan’s string-only orchestra sounds like an augmented string quartet. His dark, threatening score is imaginatively crafted, with frequent tempo switches and harmonies that toss and turn as in a fever. Perhaps because MacMillan’s chamber opera is the more operatic piece, Clemency was more musically successful. Both the musical theatre idiom and the language of Trouble challenged the singers, most of whom are not North American. Even the orchestra, despite some very accomplished playing, did not sound completely free. In particular, the singers in the jazz Trio that provides a running commentary on suburban vapidity seemed to be working a little too hard. They bravely aimed for, but missed, the called-for powder-puff, breathy effect.

Theatrically, they fleshed out the plot by playing the invisible characters in the opera, such as Dinah’s psychiatrist. Dressed as clowns, they remained constantly onstage, ineffectually trying to direct Sam and Dinah to act like an American dream couple. Sebastià Peris i Marco sang Sam with a lovely, soft-grained baritone. A more assured attack on the words would have given his character more defined contours, especially in Sam’s anthem for alpha manhood and jockhood “There’s a law”. Soprano Turiya Haudenhuyse gave a winning performance as Dinah. Haudenhuyse is not only an expressive singer, but also an inherently natural actress who easily takes possession of the stage. Richly colored at the center and pliant throughout, her voice is a special instrument. For the hit number “What a movie”, Huffman put her on a flower swing, the visual high point of the evening. He dealt with the cultural appropriation and misattribution in Dinah’s plot summary by labeling the scene “Mom sees a racist movie”. The staging was chock-full of such entertaining and insightful touches, but was marred by live black-and-white video of the performers, distractingly out of sync with their movements. Whether this was on purpose or not, the video was superfluous. The libretto makes it clear enough that the silver screen is, for Sam and Dinah, both an ideal to strive for and a form of escapism.

Everything worked in Clemency and it will be among the best productions of DNO’s current season. Resonant bass-baritone Frederik Bergman hijacked the public’s attention with the first, full-bodied notes of Abraham’s Chant, and the rest of the performance followed suit. The orchestra rendered the tense score with horrific splendor. The five excellent soloists, whose voices blended with and overlaid each other perfectly, moved with studied purpose. Soprano Jenny Stafford was a penetrant Sarah, a heroine in a psychological thriller falling to pieces bit by bit. Lucas van Lierop, Stefan Kennedy and Alexander de Jong were the Triplets, the polite visitors who turn out to be suicide bombers on their way to destroy the Twin Towns, an echo of the Twin Towers. Taking his cue from MacMillan’s dissonant warnings, Huffman reveals the travelers’ ambivalent nature much earlier. Their annunciation plays out as a macabre ritual as they put Sarah on the table and lay their hands on her intrusively. From then on the tension started mounting and never let up.

Jenny Camilleri

Cast and production information:

Leonard Bernstein: Trouble in Tahiti

Dinah: Turiya Haudenhuyse; Sam: Sebastià Peris i Marco; The Trio: Kelly Poukens, Lucas van Lierop and Dominic Kraemer; Junior (Actor): Jasper Fleischmann.

James MacMillan: Clemency

Sarah: Jenny Stafford; Abraham: Frederik Bergman; The Triplets: Lucas van Lierop, Stefan Kennedy and Alexander de Jong.

Director: Ted Huffman; Set Design: Elena Zamparutti; Costume Design: Gisella Cappelli; Lighting Design: Alex Brok; Video: Pierre Martin; Conductor: Duncan Ward. Netherlands Chamber Orchestra.

Seen at the De Meervaart Theatre, Amsterdam, on Thursday, 22nd of March 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DNO_troubleintahiti_1600x900.png image_description=Photo courtesy Dutch National Opera & Ballet product=yes product_title=Probing Bernstein and MacMillan double bill in Amsterdam product_by=Review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Photo courtesy Dutch National Opera & BalletDon Carlos in Lyon

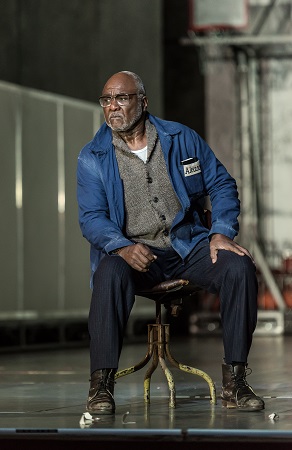

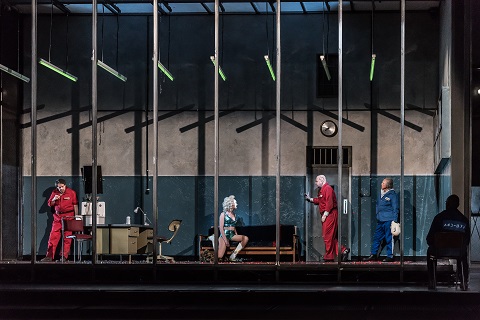

Mr. Honoré has reduced his Lyon Don Carlos to some sort of obscure theater metaphor. Thus basic scenic accoutrements and machines of an empty stage are the environments wherein the complexities of Phillip II’s filicide, uxoricide and amicicide unfold.

For the Fontainebleau forest there were some theatrical drapes and a dense, very dense fog of choking theatrical fog and not very much theatrical light. For Saint-Just there was another plane of theatrical drape and not much light, but there was a stage floor trap open to somewhere below. The masquerade was an orgy, theatrical drapes moving back and forth, hide and seek, peeking at couplings (sexual) certainly not that public during the Spanish Inquisition.

For the auto-da-fe the stage became an old raw wood theater, the Spanish court, the Flemish supplicants, and the Madrid populace stuffed into a side wall of boxes, the heretics (four total) were twitching architectural detail. Phillip II’s bedroom was a variation of the raw wood theater structure whose side boxes served to hint at cloister for the Grand Inquisitor. The stage was an empty black box for Rodrigo’s death in Carlos’ cell.

The Auto-da-fé

The Auto-da-fé

Back in Saint-Just the floor trap was again open to allow the entrance of incarnate Carlo V ashes in the form of a sort of walking cherub with a lighted breast plate. There was a scenic coup de theatre to let us know something had happened (what?) when a panel of drapes fell to the floor revealing a huge, seated blue madonna.

The evening was divided into two two-hour segments. At first we sat patiently during the lengthy minutes it took to cobble, and re-cobble together these set changes, and then impatiently in disbelief at such conceptual, indeed abusive ineptitude.

The edition was cobbled together as well. Among other machinations a part of the ballet was restored. Given that Ferrando had showered before his tryst with Fiordiligi back in Aix we knew a water feature would come. Voilà! The four soon to be immolated heretics fought and frolicked under an inexplicable shower of water as the ballet music chugged on. These four dancers appeared a final time laid out in Phillip II’s study during his famous soliloquy.

Two of the four heretics in the shower

Two of the four heretics in the shower

Mr. Honoré embellished his concept by confining Princess Eboli to a wheel chair. French mezzo Eve-Maud Hubeaux is a lyric mezzo whose presence is non-threatening even without a broken leg. Her Eboli was of an engaging comic energy. French baritone Stéphane Degout is a quite lyric baritone as well, conferring a youthful naïveté on Rodrigue (Posa) that precluded a poetic gravitas we might expect from the opera’s one sympathetic personage. The easy energy of these two performers made them audience favorites.

Russian tenor Sergei Romanovsky carved a plausible Don Carlos, his light lyric voice responding to this character’s presumed epilepsy, though his swoon before Elisabeth found none of its magic. But this Don Carlos could not plausibly challenge his father. British soprano Sally Matthews has a significant wobble in her low and medium register evoking a maternal rather than romantic presence. She did find some convincing phrasing in her high voice that made her "Toi qui suis la néant" (Tu che la vanita) one of the few dramatic successes of the evening.

Italian bass Michele Pertusi as well captured some of the sublimity of phrasing in Phillip II’s "Elle ne m'aime pas" (Ella giammai m'amò) though the dignity of this scene dissolved into a dry anger that permeated his character start to finish. Italian bass Roberto Scandiuzzi was a warm voiced, bland Grand Inquisitor, though the night before he had created a dynamic Banquo in Macbeth.

With the conceptual, directorial and casting malaise of the production it was difficult to access the contribution of the pit to the evening. The Opéra de Lyon orchestra put forth some beautiful sounds, notably in the strings. Conductor Daniele Rustioni did indeed support the few successful moments of the evening with stylistic precision.

It was a long, very long, too long evening in Lyon.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Philippe II: Michele Pertusi; Don Carlos: Sergey Romanovsky; Rodrigue, marquis de Posa: Stéphane Degout; Le Grand Inquisiteur: Roberto Scandiuzzi; Un Moine: Patrick Bolleire; Elisabeth de Valois: Sally Matthews; La Princesse Eboli: Eve-Maud Hubeaux; Thibault, page d’Elisabeth: Jeanne Mendoche; Une Voix d'en haut: Caroline Jestaedt; Le Comte de Lerme: Yannick Berne; Un Héraut royal: Didier Roussel; Députés flamands:Dominique Beneforti, Charles Saillofest, Antoine Saint-Espes, Paolo Stupenengo, Denis Boirayon, Thibault Gerentet. Orchestre, Chœurs et Studio de l'Opéra de Lyon. Conductor: Daniele Rustioni; Mise en scène: Christophe Honoré; Décors: Alban Ho Van; Costumes: Pascaline Chavanne; Lumières: Dominique Bruguière; Chorégraphie: Ashley Wright. Opéra de Lyon, March 16, 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DonCarlos_Lyon1.png

product=yes

product_title=Don Carlos in Lyon

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Eboli (in wheelchair) and Elisabeth at masquerade [All photos copyright Jean-Louis Hernandez, courtesy of Opéra de Lyon]

March 21, 2018

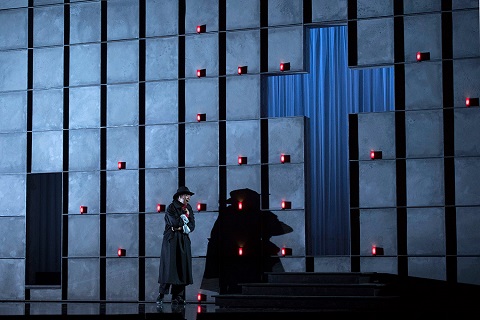

Macbeth in Lyon

It’s a hard stretch of imagination indeed to connect the dynastic intrigue of Verdi’s opera (and this is Shakespeare’s play) with money hungry stock trading witches. Nonetheless the high tech trading room provided a rich backdrop of arbitrary decor — binary numbers flashing on countless monitors, the myriad screens morphing into interpretive pop television images from time to time, the entire back wall of the white stage box becoming a gigantic TV screen of surveillance camera images of the opera’s murders, its apparitions, and the TV reportage of Occupy Wall St.

All this was simply the counterpoint of passionate pursuit of riches to an intense Freudian drama playing out center stage, Lady Macbeth nurturing the ambitions of her husband Macbeth with her idea of a realpolitik — the simple elimination of competing parents and their progeny. These acts evolved into the couple’s shared moral and physical sterility that precluded all possibility of creating their own succession.

Lady Macbeth and Macbeth, above is negative projection of soon-to-be-murdered Duncan's rooms

Lady Macbeth and Macbeth, above is negative projection of soon-to-be-murdered Duncan's rooms

Stage director Ivo van Hove defied Verdi’s wishes for a Lady Macbeth of ugly voice and overt madness by creating a full breasted, nurturing Lady Macbeth of powerful, even beautiful voice to match her fully confident if morally hesitant and certainly beautifully voiced husband. Mr. Van Hove further defied Verdi (and Shakespeare) by ultimately joining husband and wife into one tortured being, Macbeth shadowing and suffering with Lady Macbeth in her final moments of torture. His ultimate spousal compassion was his strangulation of Lady Macbeth.

This was not the blood and thunder Verdi of political action, it was a Verdi of bel canto, two tortured beings singing themselves into a complicity of mutual understanding that was to become their destruction. It was the stuff of high tragedy.

Conductor Daniele Rustioni found the precise balance between beautiful singing and stinging feeling countered from time to time with Verdi’s interwoven compassionate flute and oboe solos. Mo. Rustioni worked unrelentingly with Azerbaidjan baritone Elchin Azizov, a fine singer and a gifted actor, and Italian soprano Susanna Branchini, a physically and musically elegant singer to find and musically achieve this latent, and very real human tragedy.

Macbeth and Lady Macbeth

Macbeth and Lady Macbeth

Director van Hove wittily introduced a silent, observant black janitress who cleaned up the messes left on stage — the trader/witches’ printouts, Lady Macbeth’s bloody rags, the thrown chairs — and generally replaced the grim emotional residue with a stoic calm. She was a pointed, sarcastic comment on big money.

Director van Hove’s chorus scenes were masterfully configured, the chorus of female witches spread around the edges of the huge white box stage, its disembodied sound coming together in occasional center stage groupings. Of particular effect was the staging of the chorus of Scottish refuges, here something like later day East Coast flower children, who emerged in solo movements to animate individual suffering.

The opera’s triumphal chorus was a Occupy Wall Street camp bacchanal of live TV coverage including an gigantic cameo of beautifully sung lines by Macduff, Russian Arseny Yakovlev. There were splendid takes of cocky young Malcolm, the new king, sure to soon become, together with the balance of the Occupy Wall Street demonstrators, as greedy as Mr. and Mrs. Macbeth.

And such inevitable domestic tragedies to begin anew.

Maybe Mr. Van Hove did not have this resolution in mind when he created this production in the aftermath of the 2008 financial markets crisis and the 2011 demonstrations. But his fine production has discovered unexpected new resonance.

It was a splendid evening of beautifully produced opera.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Macbeth: Elchin Azizov: Lady Macbeth: Susanna Branchini; Banco: Roberto Scandiuzzi; Macduff: Arseny Yakovlev; Médecin: Patrick Bolleire; Malcolm: Louis Zaitoun. Chorus and orchestra of the Opéra de Lyon. Conductor: Daniele Rustioni: Mise en scène: Ivo van Hove; Décors et lumières: Jan Versweyveld; Costumes: Wojciech Dziedzic; Vidéo: Tal Yarden. Opéra de Lyon, March 15, 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Macbeth_Lyon1.png

product=yes

product_title=Macbeth in Lyon

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Arseny Yakovlev as Macduff (live projection) and Occupy Wall St. demonstrators [All photos copyright Stofleth, courtesy of Opéra de Lyon]

An Interview with Soprano Lisette Oropesa

Staged in conjunction with Joffrey Ballet Chicago, the production features both dance and singing. Since Oropesa sings with silver tones and moves as gracefully as a dancer, she is a natural for the part.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. I went to several different schools growing up, and got to know lots of different people. We attended church on Sundays, and my mom was the junior choir director there. That's where I got my major start in singing in public, as I sang solos almost every week. I started playing the flute as a “tween” as well, and have many wonderful memories of being in band and orchestra.

Did you study piano? Other instruments? Guitar?

Yes I studied the flute formally for about 10 years, and I do play some piano by ear, as well as guitar!

Lisette Oropesa as Eurydice [Photo © Ken Howard]

Lisette Oropesa as Eurydice [Photo © Ken Howard]

When did you see your first opera?

My mom, Rebeca Oropesa, was a singer so I saw operas that she was in. I think my first was La Traviata when she was singing Violetta. The first opera I was ever in was Hansel and Gretel, at the Baton Rouge Opera, in which I played one of the gingerbread children. I saw very littls opera on TV, but we heard it on the Met radio broadcasts, which my grandpa diligently recorded every week. He had an extensive collection of recordings that he accumulated for many years. So yes, I heard my fair share!

Does that treasure trove of broadcast recordings still exist?

Sadly, a lot of it was destroyed in Hurricane Katrina years ago, but my grandparents still do have a lot.

Are there any artists or musicians from the past whose work has significantly influenced you?

My mom was a big fan of Anna Moffo growing up, so I heard her voice and artistry a lot. My grandfather had a beautiful tenor voice so we heard a lot from the three tenors, too. My mom would always discuss their voices, including which ones we liked best in which repertoire.

Who were your most important teachers?

My mom was my first real teacher and she still gives me a lot of help with my singing. My voice teacher in my university years as well as now, is Robert Grayson at Louisiana State University. My New York based voice teacher is Bill Schumann. They are the people I trust the most and get the most advice from.

What did you learn from your teachers that you would like to see passed on to the next generation of artists?

There are lots, but one of the most important things I learned from them that I do use daily, and pass on, is the International Phonetic Alphabet! It's so important to know your vowel sounds and be able to us them across all languages.

Do you teach?

I don’t teach private students but I have taught a few master classes and given voice lessons at the university level.

Have you won any big competitions?

Yes! I won the Metropolitan Opera Competition, The George London Award, the Loren Zachary Society Vocal Competition, as well as prizes at the Richard Tucker Foundation and Operalia.

Did you attend one or more young artist programs?

Yes, I attended the Lindemann Young Artist Development Program at the Met from 2005 to 2008. It was like conservatory training in the setting of a real opera house. I had coachings, language classes, studied roles, took voice lessons, and movement classes. I was at the Met all the time seeing how the incredible opera house runs. We got to see every single final dress rehearsal so we got to enjoy a lot of productions and learn from the best!

Lisette Oropesa as Gretel [Photo © Marty Sohl]

Lisette Oropesa as Gretel [Photo © Marty Sohl]

What kind of role best suits your voice?

I have said no to roles that are too high or too heavy. I feel that the best roles for me are lyric coloratura parts, a few Mozart and Handel roles, and a few French parts that are on the lyric end of true coloratura.

Which are your favorite roles?

I enjoy singing Violetta in La Traviata and Lucia di Lammermoor

the most. I like these roles because they are very fulfilling musically and dramatically. They are the epitome of bel canto and a true showcase for the soprano. They are also great characters to play because they both have incredible stories, and difficult circumstances. They live in an unfair society which dictates a lot of their struggle. I love playing both of these characters very much.

What important performances do you have coming up this season and next?

I've got debuts coming up that I'm excited about, such as the one at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro. I will sing the title role in Rossini's Adina and I will make my debut at the Teatro la Fenice in Venice as La Traviata. I'm also really excited to be returning to the Paris Opera for L'Elisir d'Amore. It's my role debut.

How do you feel about the emergence of the stage director as a major force in opera?

I have learned a lot of incredible things about performance from stage directors, both for acting and movement, as well as interpretation. They are often like psychologists and can read you at the deepest level. I feel that I have done my best work because of directors who bring out those depths in all of us in the cast and we all inspire each other.

What recordings do you have out?

I released my first album, officially, last year. It's called Within/Without. It's available on iTunes and via my website; here's the link to it. https://lisetteoropesa.bandcamp.com/album/within-without

I did a Spanish set of Obradors, along with music by: Schubert, Haydn, Mendelssohn, Poulenc, and Barber, plus Meyerbeer for my encore aria.

Do you have other recordings coming out in the near future?

I'm working on releasing some more recital repertoire as downloadable tracks online.

What do you see yourself doing five years from now?

Hopefully the same things I'm doing now but with a few more new roles sprinkled in, such as Juliette, Puritani, and Manon.

How much modern technology do you use in your work?

Not that much really, I still use paper scores, highlighters, pencil and paper, and a piano. I do record myself with my iphone, marking through any hard bits in a part so I can memorize them. I also listen to recordings but I don't really rely heavily on them.

How do you feel about downloads replacing compact discs?

For opera recordings I'm thrilled to have so many resources available online! There is is a wonderful wealth of music out there available for us as singers. I have been bringing CDs to my recitals and it's nice for people to be able to walk away with a copy if they want one. I am also working to get the album available in opera gift shops. It's at the Met, Los Angeles Opera, Dutch National Opera, and Glyndebourne.

Do you ever have time for a private life?

Yes, my wonderful husband Steven travels with me and we have made our work homogeneous. He's a web developer, and his skills with technology have been irreplaceable in producing my recordings, creating and maintaining my website, photos, social media, and videos. We run together and cook together, and really are so happy in this life. He loves traveling and has found his stride in this career path with me. I'm so lucky!

Do you have any interesting hobbies?

Yes we love cooking, running, wine, and good old fashioned debate. We are vegan so we cook all kinds of incredible dishes from all different types of cuisines. Our favorites are Indian curries. We love to drink Burgundy wines, or wines from the state of Oregon such as Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. When we debate it's usually about big philosophical ideas that have no right or wrong answer. We try to solve the world's problems.

Maria Nockin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Oropesa_Homa.png

image_description=Lisette Oropesa [Photo © Jason Homa]

product=yes

product_title=An Interview with Soprano Lisette Oropesa

product_by=By Maria Nockin

product_id=Lisette Oropesa [Photo © Jason Homa]

Barber of Seville Is Fun in Tucson

The Washington National Opera and Opera Omaha. His sets were replete with perspective, flowing red curtains painted on flat canvas, and three chandeliers that could be raised and lowered at will. No designer was credited for the attractive soft colored eighteenth century costumes.

The cast was entirely made up of young singers and the stage director was Joshua Borths, Arizona Opera’s director of education and community engagement. Borths kept everyone on stage in constant motion. Six non-singing actors playing servants and townspeople kept the movement constant even when the singers were rendering major arias. However, their antics drew a profusion of laughs from the Sunday matinee audience.

Baritone Jared Bybee was a sophisticated Figaro who seemed totally at home in his part and delivered his lines with the panache expected of the town hero. Without a padded costume to make him seem portly, bass baritone Calvin Griffin looked much too young and vital to be cast as the aging Dr. Bartolo. He sang with a young man’s energy, but his fast patter lines were lacking in volume.

Having heard a mezzo Rosina at Opera Santa Barbara on Friday evening, it was interesting to hear a soprano sing the role on Sunday Afternoon in Tucson. Katrina Galka was a kittenish, feminine Rosina who had no intention of marrying her elderly guardian. Best of all, she sang her coloratura lines clearly with silvery tones and great attention to Rossinian style. Tenor Anthony Ciaramitaro sang with a relatively large voice that was flexible enough to sing Rossini’s runs and decorations with ease. I am looking forward to hearing both Galka and Ciaramitaro again.

Stephanie Sanchez, a most amusing Berta with commanding low tones, thought Don Basilio would make her a good husband. The Don, played by Zachary Owen, thought otherwise, however, and he seemed much more interested in his men friends. A limber and energetic performer, Owen sang his venomous aria with good diction but was hard to hear in its faster passages.

Jared Porter, Dale Dreyfoos and Jeffrey Stevens were amusing and helpful as Fiorello, Ambrogio, and the Notary while Daniel Prunaru was a serious Officer who pointed out class differences in that time and place. The men of Henri Venanzi’s chorus sang and cavorted wonderfully in this full-blooded rendition of Rossini’s most famous comic opera.