April 30, 2018

La concordia de’ pianeti: Imperial flattery set to Baroque splendor in Amsterdam

La concordia de’ pianeti was commissioned to celebrate the name day of Elizabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, mother of Empress Maria Theresa and grandmother of Queen Marie Antoinette of France. In November 1723 she and her husband, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, were returning to Vienna from Prague, where they had been crowned monarchs of Bohemia. During a stop in Znojmo, Moravia, Caldara, who was employed by the emperor, conducted the open-air premiere for the imperial couple. La concordia de’ pianeti is more of a secular cantata than a one-act opera. Its plot, such as it is, consists of the god Mercury persuading six other gods that “Elisa”, the empress, possesses qualities equal, or even superior, to theirs, thus deserving deification. Each of the seven gods and goddesses is associated with a heavenly body: Apollo with the sun, Saturn and Venus with the eponymous planets, and so on. Their final agreement on Elisa’s unsurpassable wonderfulness corresponds to the harmony of the spheres, hence the title. At one point the lunar goddess Diana scoffs that she’d like to see Elisa hunting boar and deer as skillfully as herself. Unfortunately, this tantalizing diversion in the plot never happens. As the gods concede Elizabeth’s supremacy one by one, the obsequious puffery reaches ridiculous proportions. The deities eulogize Elizabeth’s spotlessness, beauty and, most insistently, her fertility, ad nauseam. The empress, who was under immense pressure to produce a male heir, was pregnant with a boy at the time, but later had a miscarriage.

Given the qualitative chasm separating the words and the music, this performance by the Baroque ensemble La Cetra under Andrea Marcon, would have been better off without subtitles. But Caldara’s ornate score certainly deserved to be rescued from obscurity in 2014. Four trumpets and a set of timpani festoon the introduction. The laudatory choruses, plushly sung by the La Cetra chorus, set a celebratory mood. Conducting deftly but unhurriedly, Marcon maintained a festive pace throughout. The arias are eminently hummable, often danceable, the melodies set off with brilliant instrumental colors, and there were plenty of opportunities for the excellent musicians to show off their virtuosity. The two lutenists supplied springy rhythms and the principal trumpet elegantly dueled with Marte (Mars) in one of his arias. At full strength, the orchestra, with its warm and vibrant strings, threatened to swamp the smaller voices.

All seven soloists are to be commended for trying to inject some theatre into the empty, repetitive flattery, and succeeding to an extent by dint of their personalities. Vocally, they offered between them an impressive variety of qualities. Countertenor David Hansen sang Apollo, a role created by the star castrato Carestini, with a gauzy middle voice that opened up into a full, clarion top. Carlos Mena made an assertive Marte (Mars). Mena’s countertenor is idiosyncratic, with surprisingly dark low notes. He glided through the contrasting hues of his registers with agility and appealing swagger. Both Hansen and Mena had enough volume to hold their own against the orchestra, as did bass Luca Tittoto. As Saturno, Tittoto combined power with comely phrasing. Verónica Cangemi was a charmingly combative Diana. All the gods get two arias, except for Venere (Venus), who gets three, and Cangemi’s thin-topped soprano sounded at its best in her second aria, which made full use of its warm, upper middle band. Lovers of smooth, evenly produced voices could sit back and enjoy Emiliano Gonzalez Toro as Mercurio, Christophe Dumaux as Giove (Jupiter) and Delphine Galou as Venere. With modestly sized voices, they each spun out ribbons of unblemished coloratura. Galou’s mellow mezzo-soprano, Dumaux’s patrician countertenor and Gonzalez Toro’s bright tenor differentiated their characters in a way the stilted text never could. Above all, everyone on the podium projected great pleasure in performing this effulgent music, and the audience responded with appreciative enthusiasm.

Jenny Camilleri

Cast and production information:

Venere - Delphine Galou, mezzo-soprano; Diana - Verónica Cangemi, soprano; Giove - Christophe Dumaux, countertenor; Apollo - David Hansen, countertenor; Marte - Carlos Mena, countertenor; Mercurio - Emiliano Gonzalez Toro, tenor; Saturno - Luca Tittoto, bass. Conductor - Andrea Marcon. La Cetra Barockorchester & Vokalensemble Basel. Heard at the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, on Saturday, 28th of April, 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Elisabeth_Christine_of_Braunschweig_Wolfenbuettel.png image_description=Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel [Source: Wikipedia] product=yes product_title=La concordia de’ pianeti: Imperial flattery set to Baroque splendor in Amsterdam product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Above: Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel [Source: Wikipedia]Kathleen Ferrier Awards Final 2018

The six twenty-minute programmes were, naturally, eclectic and international though, ranging from Mozart to Mussorgsky, from Puccini to Poulenc, from Rossini to Ravel. Soprano Nardus Williams had the challenge of opening the proceedings, with accompanist Jȃms Coleman. Currently studying at the International Opera School at the Royal College of Music, where she is the sole recipient of the Kiri Te Kanawa Scholarship, this summer Williams will be a Jerwood Young Artist at Glyndebourne Festival Opera, before joining the Houston Grand Opera Studio in September. On this occasion, however, nerves seemed to get the better of her: she struggled at times to control her intonation and a rather fast, prominent vibrato made the tone somewhat shrill. Williams looked a little tense in her opening item, ‘Come scoglio’, and her delivery was rather four-square, though Coleman’s light-touch add some rhythmic vitality. Indeed, this seemed a rather ambitious choice as Williams doesn’t yet have the strength and focus at the bottom to convincingly assail the aria’s highs and lows with equal presence. Strauss’s ‘Cäcilie’ was more consistently sumptuous and I was again impressed by Coleman’s judicious accompaniment and sensitive dynamics.

Two French items allowed Williams to reveal the power of her voice, as she soared through the closing phrase of Fauré’s ‘Fleur jetée’ with sustained strength and crested the climaxes in Charpentier’s ‘Depuis le jour’ (from Louise) with a shimmering frisson. I’m not sure the French idiom is Williams’ natural territory though: the projection was a little too forthright and the diction less than clear. The soprano was most at home in Barber’s lyrical ‘Saint Ita’s Vision’, where she thoughtfully shaped both the declamatory recitative and the changing contours of the ensuing lullaby to convey the mother’s changing emotions, delicately supported by the gently placed spread chords of the accompaniment.

Bass-baritone Samuel Carl fairly bounded onto the Wigmore Hall platform and displayed a strong theatrical instinct throughout his programme with pianist Soohong Park. ‘I rage … O ruddier than the cherry’, from Handel’s Acis and Galatea, in which the smitten cyclops, Polyphemus, expresses both his jealousy and passion for the sea nymph Galatea, was strongly characterised and full of varied colours. Carl was attentive to the text, the gaping descent of his ‘capacious mouth’ prompting a chuckle from the capacity audience and the sincerity of his love captured by the floating glide with which he worshipped ‘Sweet Galatea’s beauty’. Park summoned an eerie darkness at the start of Mussorgsky’s ‘Trepak’ (from Songs and Dances of Death), in which the bass-baritone again used his voice to explore diverse moods, from sweetness to mystery, belligerence to indifference. The rhetoric was powerful but Carl wasn’t afraid to diminish his voice and make us listen hard.

Through these first two items, I wondered if at times the ‘theatricality’ wasn’t a little too ‘busy’, even distracting, and in John Ireland’s perennially popular ‘Sea-fever’ more stillness and focus would have been advantageous in capturing the effortless gentility of the folk-like idiom. Carl was in his element in Leporello’s ‘Madamina, il catalogo è questo’ (from Don Giovanni), flourishing a ‘little red book’ from his inside pocket to taunt the imagined Elvira, but while he certainly inhabited the character and drama, Carl paid insufficient attention to the rhythmic tautness and to the shaping of the phrase endings. Overall, though, this was a confident, entertaining and engaging sequence.

The finalists are required to include at least one song in English. Contralto Stephanie Wake-Edwards tackled three, beginning with ‘Never so weary’ from A Midsummer Night’s Dream in which Hermia, her pride wounded by Helena’s insults and her heart pained by Lysander’s apparent betrayal, wanders alone in the wood before sleep overcomes her. I was impressed by the manner in which Wake-Edwards used her rich, well-focused contralto to immediately establish character and mood, and the ensemble between the contralto and pianist Thormod Rønning Kvam in the recitative was flawless. Well-centred intonation and carefully crafted phrasing created a somnolent ‘strangeness’ in the ensuing aria. The warm flowering of harmonic colour in the piano accompaniment at the start of Richard Strauss’s ‘Das Rosenband’ was welcome after the cool intimacy of Britten’s nocturnal woods and although Wake-Edwards didn’t always have the full measure of the expansiveness of Strauss’s melody, there were signs of an incipient Straussian plumpness and flush, particularly at the close when ‘Paradise bloomed about us’.

Wake-Edwards returned to Britten with Lucretia’s ‘Flower Song’ from The Rape of Lucretia, written for Kathleen Ferrier who performed the title role at Glyndebourne in 1946. The aria is sung by the shamed Lucretia the morning after she has been raped by Tarquinius. Ronald Duncan’s text presents the rather questionable proposition that while flowers are always ‘chaste’, all women are ‘debauched’ by ‘vanity or flattery’: ‘Women bring to every man/The same defection’. Dubious tenets aside, the aria is one of beautiful melodic sincerity and here the piano bass line provided a sure anchor for Wake-Edwards clean, round vocal tone. She certainly acts with her voice, but here and in Elgar’s ‘Sea slumber-song’ which closed her programme, I felt that at times the contralto pulled the words around a little too much, distorting and elongating vowels into somewhat odd shapes. However, she made a good attempt to capture the languor of the French prose in Ravel’s account of the innate regality of the peacock, as he awaits his bride, in Ravel’s ‘Le paon’ from the musical menagerie, Histoires Naturelles. Kvam made much of Elgar’s wonderful piano sonorities and gently rocking lilt, and if I’d have liked Wake-Edwards to make more of the dynamic contrasts and deepen the shine of the melodic line, then she demonstrated that her contralto certainly has a secure and wide compass, as she plummeted resonantly, ‘on the shadowy sand’.

After a short interval, soprano Josephine Goddard and pianist Elliot Launn invited us on a journey, opening their programme with a gorgeous and utterly absorbing performance of Duparc’s ‘L’invitation au voyage’ in which the soprano spun the high line with a silvery gleam above Launn’s delicately trickling accompaniment. Here, again, was the vocal elegance I admired when I saw Goddard perform the role of Adolfo in the 2017 London Handel Festival production of Faramondo , and the well-shaped melodism that Goddard demonstrated as Helena in A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Royal College of Music earlier this year was again in evidence in Mimì’s ‘Donde lieta uscí’ in which strength of line was complemented by an appealing ‘freedom’ in the voice. Goddard controlled both dynamics and tone effectively, injecting a lovely flush of colour at the close, when the dying Mimì offers Rodolfo her pink bonnet as a memento of her love.

Launn’s steady, precise and gently articulated piano chords contributed greatly to a well-structured rendition of the ‘Nocturne’ from Britten’s 1937 song-cycle On this Island, in which the simple melodic line was expertly controlled and shaped creating a wonderfully serene image of the world sleeping as the globe spins ‘through night’s caressing grip’. Goddard coolly negotiated the sometimes surprising harmonic twists of the song, making much of the dissonance at the close, ‘Calmly till the morning break,/ Let him lie,’ before slipping easefully into the final cadence, ‘then gently wake’. Written for Peter Pears, and more commonly sung by the tenor voice, this song perhaps acquired even greater serenity from the sweetness of Goddard’s soprano. Rosalinde’s homeland reminiscences, from Johann Strauss junior’s Die Fledermaus), swept us from soothing slumber to champagne-fuelled masquerade. The aria ranges high and deep, but the soprano soared smoothly and evening through the melodic arcs. Goddard’s German was also excellent, and she paced the growing exuberance of the Csárdás perfectly, gradually ratcheting up the tempo and allowing the ‘Hungarian Countess’s’ high spirits free rein at the close. The Wigmore Hall audience loved it.

William Thomas (bass): Kathleen Ferrier Awards 2018, First Prize.

William Thomas (bass): Kathleen Ferrier Awards 2018, First Prize.

William Thomas and pianist Michael Pandya adopted a more sombre tone at the start of their sequence of Russian, French, Italian and English songs, but the dark whispering of the Dawn to the Heavens - ‘I love thee well’ - at the opening of Rachmaninov’s ‘Utro’ (Morning) was no less striking. Thomas has a ‘real’ bass voice: full and ringing right at the bottom; layers of colour that blend smoothly and thickly; sonorous roundness without heaviness. Rachmaninov’s vocal line is quite austere in this early song, but Thomas injected interest into the fairly narrow melodic compass and limited gestures, capturing the gravity which derives from the careful intonation of the language and the intensity of the text’s romantic imagery. Pandya cherished the delicate pianism. In Poulenc’s ‘Mazurka’ from Mouvements du Coeur the duo offered a masterclass in how to build through a strophic form. Thomas displayed evenness across the range and a lyricism which brought depth of character to the melodic lines which present a series of disparate images.

Thomas demonstrated his adaptability and diversity in Don Basilio’s ‘La calunnia è un venticello’ (from Il barbiere di Siviglia), capturing every ounce of Basilio’s delight in cruelly baiting Bartolo with tales of Rosina’s faithlessness, of his suave self-confidence as he admires his own chicanery, and of his inflated egoism as he imagines the whirlwind of vicious gossip he will conjure and the resulting apocalyptic downfall of his intended victim. There was no loss of musicality as the patter picked up pace, once again showing intelligent appreciation of the architecture of the form, and the text was consistently idiomatic and clear.

Thomas proved himself not just a good actor, but a persuasive storyteller too, in Mussorgsky’s setting of Mephistopheles’s ‘Song of the flea’, delivering a darkly devilish account of the lavish attention bestowed by a king on his pet flea, to the detriment of his court and at the expense of his aristocratic courtiers’ comfort. Pandya’s accompaniment was full of drama, too, adding to the quasi-operatic scale. And, in the final item, Katie Moss’s ‘The floral dance’, the slightest freedom in the placement of the second beat in the triple-time lilt creating a lovely carefree air fitting for this bucolic celebration of spring’s arrival. With a skilfully controlled accelerando, Thomas conveyed the genuine ardour of youthful passion as every Cornish lad grabbed a girl by the waist and whisked her off, kissing and dancing: ‘Up and down, around the town/ Hurrah! For the Cornish Floral Dance.’

Catriona Hewitson and Eleanor Kornas had had a long wait, but the Scottish-born soprano and her accompanist made a confident start to their programme with Annette’s ‘Einst träumte … Trübe Augen’ from Weber’s Der Freischütz. Hewitson crafted the arioso effectively and her light, clean soprano had a thrilling glossiness as Annette recounted her cousin’s fervent prayer: ‘Susanna, Margaret! Susanna, Margaret!’ The running passages of the ensuing aria were unforced and free, and Kornas’s lively responsiveness contributed to a very communicative performance. Supported by the piano’s soft textures and gentle lilt, the effortlessness of Hewitson’s vocal ascents in Schumann’s ‘Stille Tränen’ was impressive; she floated to the top easily and with gracefulness, though I’d have liked her to have made more of the text.

Two songs by Poulenc were beguilingly idiomatic though. The title of ‘C’, or Cé’, is taken from the name of a commune in France, ‘The Bridges of Cé’, which had been the site of many historic battles - something that was surely in Poulenc’s mind when he set Louis Aragon’s text during WW2. Hewitson and Kornas had the full measure of the song’s shifting complexities of harmony and rhythm - which match the historic sweep encompassed by Aragon’s surreal sequence of images - and the challenging pedalling and dense accompanying chords proved no impediment to limpidity. The quiet wistfulness at the close was broken by the more bitter chain of absurd images - ‘pimps in kits’, ‘sly fellows hindered by long noses’, ‘drowned corpses that float beneath bridge’ - which depict life during the Nazi Occupation, in ‘Fêtes galantes’. A lighter spirit was evoked by Mozart’s ‘Deh vieni, no tardar’, in which Susanna, in league with the Countess, sings a seductive song to lure the Count to a nocturnal meeting. The artless simplicity of the vocal line was beautifully captured by Hewitson, but though the light clarity was fittingly enticing, this aria is many-layered, and the innate passion in Susanna’s pleas was missing. For Figaro has learned of the planned assignation and is listening in; and Susanna knows it - her promise to ‘wreathe your brow in roses’ is both a tease and a vow, and the sincerity of the latter needs to be felt too. But, Hewitson’s directness and lightness was just perfect for Liza Lehmann’s ‘If no one ever marries me’ which closed the Competition with delicately wry humour.

The six young singers all acquitted themselves well and provided considerable musical pleasure. No doubt we will be seeing much more of them in the future. The Jury - Elaine Padmore OBE, John Mark Ainsley, Malcolm Martineau OBE, Joan Rodgers CBE and David Syrus - awarded the following prizes.

First Prize: William Thomas

Second Prize: Josephine Goddard

Ferrier Loveday Song Prize: Catriona Hewitson

Help Musicians UK Accompanist’s Prize: Michael Pandya

Claire Seymour

Nardus Williams (soprano), Jȃms Coleman* (piano): Mozart - ‘Temeraro! … Come scoglio’ (from Così fan tutte ); Barber -‘Saint Ita’s vision’; Fauré - ‘Fleur jetée’; Charpentier - ‘Depuis le jour’ (from Louise); R. Strauss - ‘Cäcilie’

Samuel Carl (bass-baritone), Soohong Park (piano): Handel - ‘I rage … O ruddier than the cherry’ (fromAcis and Galatea); Mussorgsky - ‘Trepak’ (from Songs and Dances of Death); Ireland - ‘Sea-fever’; Mozart - ‘Madamina, il catalogo è questo’ (from Don Giovanni)

Stephanie Wake-Edwards (contralto), Thormod R ønning Kvam* (piano): Britten - ‘Puppet? Why so? … Never so weary (from A Midsummer Night’s Dream); R. Strauss - ‘Das Rosenband’; Britten - ‘Flowers bring to every year (from The Rape of Lucretia); Ravel - ‘Le paon’ (from Histoires Naturelles); Elgar - ‘Sea slumber-song (from Sea Pictures)

Josephine Goddard (soprano), Elliot Launn* (piano): Duparc - ‘L’invitation au voyage’; Puccini - ‘Donde lieta uscí’ (fromLa bohème); Britten - ‘Nocturne’ (fromOn this Island); J. Strauss II - ‘Klänge der Heimat’ (from Die Fledermaus)

William Thomas (bass), Michael Pandya* (piano): Rachmaninov - ‘Utro’ (Morning); Poulenc - ‘Mazurka’ (from Mouvements du Coeur); Rossini - ‘La calunnia è un venticello’ (from Il barbiere di Siviglia); Mussorgsky - ‘Pesnya Mefistofelya o blokhe (Song of the flea)’; Moss - ‘The Floral Dance’

Catriona Hewitson (soprano), Eleanor Kornas* (piano): Weber - ‘Einst tr äumte … Trübe Augen’ (from Der Freischütz); Schumann - ‘Stille Tränen’ (Zwölf Gedichte von Jusinus Kerner); Mozart - ‘Giunse alfin il momento … Deh vieni, no tardar’ (fromLe nozze di Figaro); Poulenc - ‘C’, ‘Fêtes galantes’ ( Deux poèmes de Louis Aragon); Lehmann - ‘If no one ever marries me’ (from The Daisy Chain)

* denotes pianist competing for the Accompanist’s Prize

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ferrier%20Award%20winners%202018.jpg image_description=Kathleen Ferrier Awards 2018, Wigmore Hall product=yes product_title=Kathleen Ferrier Awards 2018, Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Catriona Hewitson, Josephine Goddard, William Thomas and Michael Pandya (Kathleen Ferrier Award prize winners, 2018)April 29, 2018

Affecting and Effective Traviata in San Jose

Violetta Valery is regarded as an Everest of operatic soprano roles and Amanda Kingston proved more than up to the climb. Ms. Kingston has a supple, agile, alluring instrument that is more than capable of meeting the legendary challenges of the part, namely the flights of impetuous coloratura in Act I; the midrange conversational passages that give way to spinto outbursts in Act II; the weighty pathos and then the limpid lyricism of Acts III and IV. Vocally, the singer has all these effects in her arsenal, and she has a lovely presence that is majestic and assured. The San Jose public has been blessed to have an artist of her caliber on their opera stage this season.

Violetta, like Carmen, is a complex persona, sometimes enigmatic, often unpredictable, and endlessly malleable to the interpreter’s individual gifts. Amanda’s two strongest assets are her rock solid, searing flights above the staff that filled the auditorium with plangent, vibrant sound; and her heart-breaking pathos with which she imbued the self-sacrificial moments. She clearly understands and communicates the text, and there is not a note out of place in here secure technique that is even from top to bottom.

If there is one thing I wish this fine artist could invest in her already accomplished portrayal it is a method of communicating the heroine’s extreme physical frailty. Moments of temporary (and ultimately fatal) physical lapses were a bit too robustly ‘present’; intelligently rendered but missing that final tragically hollow color that can haunt the viewer’s heart. I have no doubt that the prodigiously talented Amanda Kingston is capable of this final dimension, which will further enhance what is already one of the best sung Violetta’s on display anywhere.

Violetta (Amanda Kingston) is comforted by Flora Bervoix (Christina Pezzarossi) and Sr. Grenvil (Colin Ramsey).

Violetta (Amanda Kingston) is comforted by Flora Bervoix (Christina Pezzarossi) and Sr. Grenvil (Colin Ramsey).

Dane Suarez is perhaps the most effortlessly boyish Alfredo I have yet seen, and he communicates his helpless romantic (and sexual) infatuation with Violetta with honesty and abandon. His fresh faced, puppy dog approach made him stand out from the other jaded men in Violetta’s circle, and made us understand why Violetta might be attracted to his impetuous sincerity and handsome naiveté.

Mr. Suarez has an appealing, substantial tenor, which he deployed with considerable nuance. Although he sang sturdily throughout the evening, he found his most solid vocal footing in the sardonic phrases and recriminating outbursts in Act III, where he poured out highly charged high notes that were riveting in their intensity. When Dane affected the boyish sweetness earlier on, the gears were sometimes on display as he worked (albeit successfully) to reign in his sizable tone, and to color it youthfully. In the future, he might pay attention to not letting his voice get off the breath since some crooning phrase ends drooped just under the pitch. Still, his total emotional investment in pursuing and later, comforting Violetta proved heart rending.

Veteran baritone Trevor Neal was an imposing Giorgio Germont, his physical stature and orotund baritone impressively illuminating the character. Verdi gives Germont some of the opera’s best music and a wonderful theatrical arc, and Mr. Neal took full advantage of the opportunity. His sonorous, mellifluous delivery was marked by beautifully shaped phrases and incisive theatrical insights. Although Trevor’s secure instrument is otherwise totally hooked up, he uncharacteristically had a few passing encounters with a bit of a rasp on topmost G-flats. Small matter, when this fine interpreter dominated his every scene.

As usual, OSJ invested the smaller roles with its usual high standard of meticulous casting. Mason Gates put his fine lyric tenor to good service as Gastone. Baritone Philip Skinner was a memorable, firm-voiced Baron Douphol. Christina Pezzarossi made a notable impression as Flora, with her resonant, smoky mezzo providing ample pleasure. Erin O’Meally’s poised, silvery soprano was well suited to Annina’s gentle phrases. Baritone Babatunde Akinboboye was agile of voice and playful of demeanor as a cavorting Marchese d’Obigny. In true luxury casting bass-baritone Colin Ramsey, who has successfully assumed a number of major roles at OSJ, was a firm-toned Doctor Grenvil.

In the pit, Dennis Doubin whipped up a sprightly, propulsive reading, after the shimmering strings opened the performance with a luminous reading of the prologue. Maestro Doubin led a secure, idiomatically correct rendition that eschewed indulgence in the oom-pah segments of this middle-Verdi opus. Conversely, he luxuriated in the expansive melodies that comprise much of the work. The conductor elicited a cleanly detailed account of Verdi’s masterpiece, even as he lived the drama in admirable collaboration with his vocal soloists. Andrew Whitfield’s well prepared chorus proved a considerable asset in the evening’s success.

Director Shawna Lucy has staged an efficient, cogent presentation that pushes all the right buttons, managing the large populated scenes with skill and imagination, highlighting select minor dramas played out between choristers. She also creates meaningful interactions with her principals, and underscores all the major emotional beats. Shawna gets excellent results from the chorus, and the re-imagined gypsy and toreador choruses in Act III were fresh and topical. The #metoo movement was even meaningfully evoked when, late in Act III, the chorus courtesans suddenly reject male domination in solidarity with Violetta, and forcibly extricate themselves from unwanted relationships. Ms. Lucy was assisted by choreographer Michelle Klaers D’Alo

Eric Flatmo has designed a workable unit set that consists of a raked platform stage left, with a sunken playing space stage right, all of which gets repurposed each act, with telling different set pieces and looks. A large picture window upstage reveals the Eiffel tower, with the exception of Act II when a pastoral setting is projected. Beginning with a copper toned look, this paneled environment's shifting appearance proved a highly effective playing space.

Elizabeth Poindexter’s lavish and character specific costumes provided a sumptuous visual component, abetted by Christina Martin’s comprehensive wig and make-up design. Pamila Z. Gray devised a moody and comprehensive lighting design, with good use of area washes and designated specials.

As this memorable season comes to an end, Opera San Jose has announced their varied slate for 2018-2019 which includesThe Abduction from the Seraglio, Pagliacci, Moby Dick and Madama Butterfly.

James Sohre

Verdi: La traviata

Violetta Valery: Amanda Kingston; Flora Bervoix: Christina Pezzarossi; Annina: Erin O’Meally; Alfredo Germont: Dane Suarez; Giorgio Germont: Trevor Neal; Gastone: Mason Gates; Baron Douphol: Philip Skinner; Marchese d’Obigny: Babatunde Akinboboye; Doctor Grenvil: Colin Ramsey; Giuseppe: Kevin Gino; Guest: Noah DeMoss; Messenger: Lazo Mihajlovich; Conductor: Dennis Doubin; Director: Shawna Lucey; Choreographer: Michelle Klaers D’Alo; Set Design: Eric Flatmo; Costume Design: Elizabeth Poindexter; Lighting Design: Pamila Z. Gray; Wig and Make-up Design: Christina Martin; Chorus Master: Andrew Whitfield

image=http://www.operatoday.com/chorus%20of%20revelers%20surrounds%20Flora%20Bervoix.jpg image_description=San Jose Opera, La traviata product=yes product_title=San Jose Opera, La traviata product_by=A review by James Sohre product_id= Above: The chorus of revelers surrounds Flora Bervoix (Christina Pezzarossi) in Act IIIApril 27, 2018

Brahms Liederabend

That set came last in this Wigmore Hall recital from Goerne and Alexander Schmalcz. Whilst it is difficult to imagine anyone having been seriously disappointed by the performance heard, I do not think it came close to matching a performance I heard last year in Salzburg from Goerne with Daniil Trifonov . Before hastening to judgement, however, I should caution that the fault did not necessarily lie with the pianist. Here, as indeed throughout, Schmalcz gave estimable accounts of Brahms’s musical structures, duly suggestive of both how they complement and how they do not the ways of the verbal texts. ‘Denn est gehet dem Menschen’ was perhaps the strongest performance here, offering a true sense of having reached the beginning of the end, finality clear even in the fury of its central stanza; ‘Es fährt alles an einen Ort…’. Echoes from Ein deutsches Requiem, always apparent, were perhaps more than usually so here. However, during the second and fourth songs in particular, a hectoring quality to Goethe’s performance, sometimes apparent earlier too, seemed to go a little too far in the role of the verbal Preacher (be it that of Ecclesiastes or St Paul). In the latter and final song, ‘Wenn ich met Menschen,’ there was a sense of the music never quite having settled; it seemed unduly complicated, as if minds of singer and pianist had not truly come together.

The Neun Lieder und Gesänge, op.32, fared much better. Why we do not hear these songs more often I really do not know. Perhaps it is simply that Brahms is still thought of more as an instrumental than a vocal composer. Surely the autobiographical element – Graham Johnson once suggested considering the set as a Komponistenliebe sequel to Schumann’s Dichterliebe – should attract. Above all, though, the sheer musical – and musico-dramatic – quality should. Wagner’s was not the only way. Schubert often hovered in the background, more oppressively than benignly, the opening ‘Wie raft ich mich auf in der Nacht’ suggestive almost of a retelling of the night of ‘Der Doppelgänger’, from a different, related person’s standpoint, several years later. Indeed that fabled ‘lateness’ of Brahms, however much it may stand in need of deconstruction , seemed, not inappropriately, present throughout this dark night’s proceedings. That is not to say that darkness was unvaried; it nevertheless predominated, still more so in the following ‘Nicht mehr zu dir zu gehen’. ‘Ich schleich umher’ offered different forms of repression, repression remaining the operative word, however. Two August von Platen storms ensued, prior to a true sense of reckoning in another setting of that same poet, ‘Du sprichst, dass ich mich täuschte’, almost as if this were the cycle’s – if indeed a cycle it be – peripeteia. Hafiz, translated by Georg Friedrich Daumer followed, in three songs, the first two exquisitely bitter in their ‘Süsse’ (‘sweetness’, as the first has it) – or should that be the other way around? Blissful in its quiet ecstasy, ‘Wie bist du meine Königin’ seemed to hark back to Schubert’s ‘Du bist die Ruh’, without abdicating its ‘late’ knowledge that it would prove impossible to return.

Five Heine settings came in between. (There was no interval.) ‘Sommerabend’ benefited from especially fine piano voicing, as if shadowing the vocal line, a Doppelgänger to it, which in a way it is, yet not only in a ‘purely musical’ way. ‘Mondenschein’ proved in turn a moonlit Doppelgänger to its predecessor. The exquisite drowsiness of death and recollection, quite without hope of an after-life or any other ‘beyond’, came to us in the deathly ‘Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht’. An intermezzo-like reading – from both artists – of ‘Es schauen die Blumen’ was followed by a somewhat hectoring ‘Meerfahrt’. Perhaps that was the point – up to a point. Sometimes, however, as Heine might have advised, there are other forms of preparation than rage.

Mark Berry

Programme:

Neun Lieder und Gesänge , op.32; Sommerabend, op.85 no.1; Mondenschein, op.85 no.2; Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht, op.96 no.1;Es schauen die Blumen, op.96 no.3; Meerfahrt, op.96 no.4; Vier ernste Gesänge, op.96 no.4. Matthias Goerne (baritone)/Alexander Schmalcz (piano). Wigmore Hall, London, Thursday 26 April 2018

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Goerne.jpg image_description=Matthias Goerne product=yes product_title=Brahms Liederabend product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Matthias GoerneAngel Blue in La Traviata

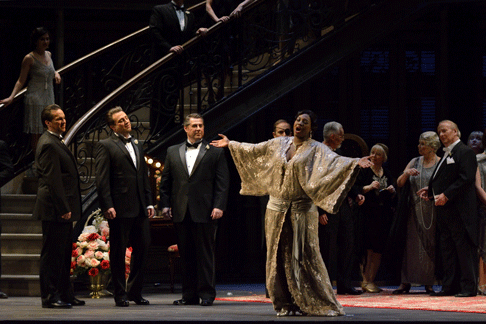

However rising American superstar soprano Angel Blue, notably marking her Canadian debut with Manitoba Opera from April 14th -20 th, 2018 also ensured that the timeless classic became a lesson in nobility and grace even against the dying of the light, as witnessed through the lens of her ill-fated heroine Violetta.

The 45-year old company closed its season with Giuseppe Verdi’s three-act masterpiece sung in Italian (with English surtitles), based on Francesco Maria Piave’s libretto, in turn inspired by Alexandre Dumas's play, La Dame aux Camélias. MO principal conductor Tyrone Paterson led the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra throughout the 19 th century composer’s iconic score with aplomb.

Last staged here in 2008, the 170-minute show (including two intermissions) directed by Montreal’s Alain Gauthier (MO debut) is notably the first offering co-produced by a consortium of five Canadian opera companies, including: MO, Edmonton Opera, Pacific Opera Victoria, Vancouver Opera and L’Opéra de Montréal, with the (mostly) re-cast production slated for each of the five respective cities throughout next season.

Typically set in the 1850s, this particular staging transports the story to 1920s Paris, with Violetta’s character, originally a courtesan dying of consumption, a.k.a. tuberculosis, inspired by real-life American cabaret dancer Josephine Baker, whose risqué performances lit up the “City of Light” during the Roaring Twenties.

However in the end, this noble premise ultimately becomes a moot point (albeit the decadent, art-deco sets and fringed flapper costumes created by Christina Poddubiuk, and built by Edmonton Opera and Pacific Opera Victoria, respectively, provide serious eye candy). Any allusion to Baker quickly slips away, with the Los Angeles-born Blue, a protégé of Placido Domingo praised by the New York Times as “the clear star” during her Metropolitan Opera debut as Mimi in Puccini’s La Bohème last September (and also sings the lead character with Toronto’s Canadian Opera Company in April 2019), and performs Violetta during her Royal Opera House Covent Garden premiere in January 2019, firmly stamping this role as her own.

Her luscious vocals were immediately apparent as she made her first grand entrance down the sweeping, wrought iron staircase, bathing the ear in shimmering beauty while always perfectly controlled and consistent throughout her expansive range, including her knack for shading her uppermost notes to a barely-there pianissimo.

But Blue’s vocal gifts are matched equally by her innate acting skills, with her nuanced portrayal seemingly growing more luminous with each passing scene. She begins her emotional trajectory as a bon vivant who gaily sings of life’s pleasures, morphing before our eyes into a woman of honour who sacrifices her own happiness in the name of love.

Her delivery of opera’s quintessential ode to freedom, “ Sempre Libera” nearly stopped the show with her character growing more defiant, even punctuating her own vocal line by slamming her champagne bottle at one point, that provided fascinating sub-text. She capped her aria with an enthralling final high E-flat; made even more astounding when delivered lying nearly horizontal on her velvety chaise longue while swilling bubbly.

Another highlight – of many – came during Act III, in which her Violetta grows increasingly desperate as death whispers at the door. Her heartrending “Addio del passato,” sung while tenderly cradling her former cabaret bustier like a babe in arms, followed by a deeply moving duet “Partigi, o cara” sung with Newfoundland-born tenor Adam Luther’s Alfredo elicited sobs in the opening audience, as further testament of her empathic compassion for her character.

Luther in his MO debut also possesses magnetic stage power, as dashing as a matinée idol unafraid to dig into his role, crafted as a passionate hothead in love with Violetta. He also proved a real-life hero for soldiering on despite being under the weather on opening night (as announced from the stage after the first intermission), that nonetheless played havoc in his upper range during Act II’s “ De' miei bollenti spiriti...O mio rimorso,” and did not allow him to fully project at all times.

Despite these challenges, Luther still displayed buttery smooth phrasing in Act I’s “Un dì, felice, eterea" sung with Blue including ringing high notes, and it’s a credit to his artistry he can still sound so good when not at his vocal best. And in a curious, “life-imitates-art way,” his subdued vocals mirrored the dying Violetta’s faltering utterances, viscerally bonding their characters as organically, simpatico lovers.

Another standout proved to be Canadian baritone James Westman as Alfredo’s father Germont, with his booming voice immediately establishing his imperious character during Act II’s “ Di Provenza il mar, il suol,” as well as showcasing his resonant, expressive vocals. He then proceeded to peel back the emotional onion layers of his character, showing us he is not a villain, but hapless victim of societal norms and expectations, until finally wracked by remorse at the end as he realizes Violetta’s inner goodness.

The all-Canadian cast – save for Blue – also included Violetta’s faithful dresser Annina sung by mezzo-soprano Shannon Unger (MO debut), who made every moment of her relatively brief stage time count, as did tenor Michael Barrett’s Gastone and baritone Andrew Love’s eye-patched Baron Douphol, who squires Violetta to Flora (mezzo-soprano Barbara King, MO debut), and the Marquis d’Obigny’s (baritone Howard Rempel) party.

It’s a joy to see Winnipeg baritone David Watson back onstage – this time as Doctor Grenvil - who always adds gravitas whether performing comedic or tragic fare.

The 40-member Manitoba Opera Chorus proved in its usual fine fettle, prepared by chorus master Tadeusz Biernacki notably celebrating his 35th year with MO, including their rousing opening number, “ Libiamo ne’lieti calici,” popularly known as “The Drinking Song” sung with gusto.

Several curious directorial choices included having the female chorus members, garbed in their flapper finery, performing unison choreography that evoked more a country line-dance hootenanny than free-spirited gypsy twirls during Flora’s party scene. The women’s subsequent donning of bullhorns to their male counterparts’ puffed-up, machismo matadors (wearing crisp tuxedos) also just felt plain bizarre – with any presumed parallels attempted to being made between gay Parisian nightlife and life-and-death bullrings lost in translation. Designer Kevin Lamotte’s unusually dim lighting during this scene helped mitigate the oddness of it all, and once we got past this section, proved highly effective, including several stunning, stylized lighting effects highlighting Blue and her series of white costumes visually underscoring her character’s purity of heart.

Just as there is inherent risk involved when offering edgy new contemporary operas – and this company has been there, done that – there’s also peril when producing an audience-pleasing favourite that can teeter towards predictability. This production happily marries a fresh take with a more traditional approach, but in the end, it is Blue’s show – surely one of this generation’s great opera artists in the making - with Winnipeggers now able to proudly boast, “I saw her when.”

As expected, the artists received a standing ovation with loud cries of bravo and prolonged applause by the clearly moved crowd.

Holly Harris

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Angel-Blue-%28Violetta%29%2C-MB-Opera%2C-La-Traviata%2C-2018%2C-Photo---R.-Tinker.png image_description= product=yes product_title=Angel Blue in La Traviata product_by=A review by Holly Harris product_id=Above: Angel Blue as ViolettaPhotos by R. Tinker

April 25, 2018

Matthias Goerne and Seong-Jin Cho at Wigmore Hall

But, this programme at Wigmore Hall, simultaneously a paean to and epitome of the spirit of late-Romantic ‘sehnsucht’ - aching yearning, wistful sorrow, poignant reminiscence and bitter-sweet loss - threatened to not just to take one’s breath away but to transport one away to a world where the static emotional weight might overwhelm and consume the very spirit of life.

Goerne and his young accompanist, Seong-Jin Cho, opened their recital, ten minutes after the advertised start time, with Hugo Wolf’s Drei Gedichte von Michelangelo (1897). These were among Wolf’s last compositions and the three songs are suffused with the weary melancholy of unattainable love - as the celebrated painter, sculptor and poet works by candlelight and reflects on the painful disjuncture between the artistic creativity which bestows fulfilment and longevity, and human relationships that are fractured by failure and loss.

At times, such as at the close of ‘Wohl denk’ ich oft’ (I often recall), Goerne summoned oratorical grandeur - ‘Genannt in Lob und Tadel bin ich heute/ Und, dass ich da bin, wissen alle Leute!’ (Today my name is praised and censured, and the entire world knows that I exist!) - and there was quiet resignation as the voice plummeted at the close of ‘Alles endet, was entstehet’ (All must end that has beginning). Moreover, though the tempi were languorous and the spirit laden - ‘Ziemlich getragen, schwermütig’ (sombre and depressed), ‘Langsam und getragen’ (slow and grave), and ‘Sehr langsam und ruhig’ (very slow and calm) being Wolf’s instructions - an angry energy whipped through ‘Fühlt meine Seele’ (Is it the longed-for light of God) when the poet-speaker’s memories were stirred by rays from heaven which storm the heart.

But, the prevailing mood, here and throughout the recital, was one of weary defeat. In these Wolf songs, Goerne’s baritone was decidedly bass-baritonal in register and colour, and Cho complemented these hues with dark, sombre, intensely responsive introductions and postludes.

Immediately apparent, also, was the intense sensibility and strong independent voice of Cho - whose international career was kick-started by his Gold Medal success at the 2015 Chopin Competition in Warsaw. The two-bar unison which prefaces the first song was remarkably and compellingly nuanced; the low semi-tonal murmuring of the second lied evoked both mystery and fear. Cho isn’t afraid to take his time; nor to eke every ounce from a mezza voce line. Though the lid of the Wigmore Steinway was fully raised, not once did Cho make his presence improperly felt. It was to his credit that, while such painstaking expressivity might have further burdened the music with torpid solipsism, the effect was in fact invigorating - the piano preludes, postludes and dialogues injecting light and life into the sober sequence of lieder.

Seong-Jin Cho. Photo credit: Harold Hoffmann.

Seong-Jin Cho. Photo credit: Harold Hoffmann.

The Wolf songs were followed by eight songs by Hans Pfiztner (1869-1949), a composer whose opportunistic relationship with the Nazi regime has probably attracted more attention that his music. The lieder presented here certainly demonstrated Pfitzner’s Schumann-esque sensitivity to text. But, despite Goerne’s ability to heighten individual words and phrases - ‘Ich liebe dich’, first intensified then, at the close, diminished in ‘Sehnsucht’ (Longing); ‘Doch schöner ist deiner Augen Schein’ (but prettier still are your shining eyes) in ‘Es glänzt so schön die sinkende Sonne’ - the overwhelming mood was one of a down-dragging lethargy. Admittedly, this allowed us to enjoy the grainy beauty of Goerne’s lower, bassy, register - as in the final stanza of ‘Ist der Himmer darum im Lenz so blau?’ (Is the sky so blue in spring?) - alongside his effortless elision of the musical phrases.

Again, Cho was an independent voice; the piano part did not so much complement or enhance as articulate its own strong narrative. Surges upwards from the bass in ‘Sehnsucht’; exquisite textural clarity in ‘Wasserfahrt’ (Sea voyage); wonderful expansiveness at the opening of ‘Es glänab so schön die sinkende Sonne (The setting sun shines so prettily); fluent third-based movement in ‘An die Mark’ (To the March of Brandenburg), which expressed the wonder of the speaker, ‘dreaming like dark eyes, in an eternal yearning for spring’s realm’. These features gripped one’s attention just as the light-fingered but niggling clarity of the postlude to ‘Stimme der Sehnsucht’ (Voice of longing) was affecting.

After the interval, Goerne returned to songs he knows well: Wagner’s Wesendock Lieder which are more commonly heard sung by the female voice, but for which the baritone made a compelling case for transposition. If in ‘Der Engel’ (The angel) Goerne’s ‘fervent prayer’ conjured an airy expansive which lifted him and us heavenward, then Cho’s delicate accompaniment and playout was truly celestial. There was a vocal strength and urgency in ‘Stehe stille!’ (Stand still!) which was balanced by the piano’s self-regarding busyness, and which transmuted to a transfiguring pianissimo as with remarkably purity and earnestness, Goerne proclaimed, ‘Erkennt der Mensch des Ew’gen Spur/ Und lost dein Rätsel, heil’ge Natur! (then men perceives Eternity’s footprint, and solves your riddle, Holy Nature!).

The meandering of ‘Im Treibhaus’ (In the greenhouse, a study for Tristan and Isolde) was delicately shaped, Goerne’s middle range effortlessly focused, the lower part of his voice viscerally affecting. The clarity of line and immaculate intonation at the close was stunning. ‘Schmerzen’ (Agonies) opening with a bitter-sweet smear of harmonic and vocal anguish; in ‘Träume’ (Dreams, study for Tristan and Isolde) Cho’s accompaniment pulsed through the harmonic sequence before extinguishing itself in dissonance with astonishing delicacy, and the slightest sequence of expressive ‘delays’ in the piano postlude spoke of an exquisitely alert sensibility.

Five songs by Richard Strauss - again these lieder are more often associated with the female voice but were convincingly transposed here - moving from youthful dreams to fading dusk, closed the recital. In ‘Traum durch die Dämmerung’ (Dream into dusk) the ‘lilt’ was just sufficiently present to be persuasive, and Goerne floated the final phrase into the divine light - ‘blaues, mildes Licht’ - of heaven’s glow. Cho’s delicate arpeggiated chords at the start of ‘Morgen!’ (Tomorrow!) offered both hope and poignant resignation, and the oscillating dissonances of ‘Ruhe, meine Seele!’ (Rest, my soul!) were paradoxically troubling; here, Goerne’s strengthening, then softening, of the voice was expertly controlled, as was the translucent beauty of the image - ‘Und ich geh’ mit Einer, die mich lieb hat’ (I walk with one who loves me) - at the heart of ‘Freundlich Vision’ (A pleasant vision).

I’m not sure if it was his intent, but in compiling this idiosyncratically undeviating and unalleviated programme, Goerne almost seemed to be issuing a sombre challenge to his audience: if you want to experience the beauty and truth of these songs, then listen, come, follow me into the hinterland where this ‘truth’ exists. He beckoned us into the a strange world - a world of shadows, sensibility, quietude, sweet sorrow - never more so than in the final lied, ‘Abendrot’ from the Four Last Songs (1948). The gleam and frailty of Cho’s extended postlude was otherworldly.

But, I’m not sure that we were entirely transported. This was a strangely ‘distanced’ performance, in which the communication that is at the essence of a lieder recital was both tantalisingly and teasingly present, but just out of reach. Goerne read many of the songs from the printed scores positioned on a music stand to his right, and his gaze was at other times directly into the belly of the piano, to the floor, towards an imagined horizon. At the close, he stood still and silent as Cho’s piano postlude trickled away. For a moment, I imagined that the audience might simply, silently creep away, leaving Goerne and Cho transfixed in that hinterland to which they had summonsed us - the musicians, like Keats and all the Romantics poets, subsumed within an artistic immersiveness which is both necessary and dangerous.

But, no; the frames which, as Virginia Woolf knew, separate, so frustratingly, art and life, were re-established. Goerne’s fractional glance towards his accompanist served, like Keats’s ‘Forlorn! the very word is like a bell/ To toll me back from thee to my sole self!’, to bring us all back to the present. The spell was broken, the applause began. But the slight disquiet lingered.

Claire Seymour

Matthias Goerne (baritone), Seong-Jin Cho (piano)

Wolf - Drei Gedichte von Michelangelo; Pfitzner - ‘Sehnsucht’ Op.10 No.1, ‘Wasserfahrt’ Op.6 No.6, ‘Es glänzt so schön die sinkende Sonne’ Op.4 No.1, ‘Ist der Himmel darum im Lenz so blau’ Op.2 No.2, ‘An die Mark’ Op.15 No.3, ‘Abendrot’ Op.24 No.4, ‘Nachts’ Op.26 No.2, ‘Stimme der Sehnsucht’ Op.19 No.1; Wagner - Wesendonck Lieder; Richard Strauss - ‘Traum durch die Dämmerung’ Op.29 No.1, ‘Morgen’ Op.27 No.4, ‘Ruhe, meine Seele’ Op.27 No.1, ‘Freundliche Vision’ Op.48 No.1, ‘Im Abendrot’ from Four Last Songs.

Wigmore Hall, London; Tuesday 24th April 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Goerne.jpg image_description=Matthias Goerne and Seong-Jin Cho at Wigmore Hall, London product=yes product_title=Matthias Goerne and Seong-Jin Cho at Wigmore Hall, London product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Matthias GoerneMaria Callas: Tosca 1964: A film by Holger Preusse

This disc might well be worth the price alone just to see the film of Act II, still rather grainy, but sounding rather better than I have heard it before, because it is just such an extraordinary artistic achievement. The Zeffirelli/Callas/Gobbi Tosca is, like Schnabel’s Beethoven or Gericault’s Raft of Medusa, imperfection in art raised to the level of genius.

Renzo Mongiardino’s sets and Marcel Escoffier’s costumes - which have been so influential in dictating the historical settings of so many Tosca’s since, not least Jonathan Kent’s at Covent Garden, last staged this January - give an epic, Romantic realism to the opera that are fundamental to its success, and quality, as opera on film. In lesser hands, it might come across as melodramatic; in fact, the combination of Zeffirelli, Callas and Gobbi gives us something that is searing, powerful and often ravishing. Beyond its value as art, the film is important because it preserves one of the very few examples, and certainly the most significant visual document, of Maria Callas in a staged performance.

Callas’s voice, even in her prime in the early 1950s, was never particularly prone to beauty, but she was often mercurial - and she totally absorbs the role of Tosca. There is no denying that there is unevenness at the very top of the register but, as Jürgen Kesting points out in the documentary about this legendary production, Callas spends much of Act II “permanently screaming her lungs out”. “Doing that with calm reason, or cold precision, requires extraordinary self-control”, Kesting adds, and this is the apotheosis of Callas’s Tosca. Callas’s darker voice, the steadiness of her mid-tones and lower register, the deeper psychological impact her singing conveys, the humanity that is a hallmark of her vocal complexion, the brilliance of the coloratura, makes her Tosca more haunting than is usual. It’s often suggested that Maria Callas disliked the role of Tosca; there is some truth in this, though I’ve always thought it was closer to suggest she approached the part with the darkness and despair she brought to Verdi heroines like Lady Macbeth, Desdemona or Elisabetta. I think if one’s keystone for a performance of a great Tosca is a sumptuous vocal legato and a ravishing top-note, one should probably ignore Callas altogether and opt instead for Caballé or Leontyne Price.

Tito Gobbi, too, has had his detractors over the years. Some find his assumption of Scarpia, especially vocally, to be hectoring and loud, though even a decade after his recording with Maria Callas and Victor de Sabata he was still capable of astonishing vocal power and had lost none of his Italianate elegance when it comes to phrasing. This is by no means the subtlest performance of the role - the voice is huge, even cavernous - but I find the seismic, stentorian power of his baritone compelling and even in 1964 much of the part of Scarpia was still very comfortably within his range. I have heard many singers take on the role of Scarpia who are under-powered, or bass-baritones who struggled with the upper range of the role - and none who would probably use their bare hands to extinguish smouldering flames because his Tosca got too close to a candle, as Callas did during one of the 1964 performances. Perhaps only Taddei, Raimondi and Ramey have come close to embracing Gobbi’s domination of the part of Scarpia since the early-to-mid 1960s, though even these great singers struggled when their Tosca wasn’t a great one.

Holger Preusse’s documentary, Maria Callas: Tosca 1964 is, in many ways, a peculiar film. It tries to be two things and doesn’t really succeed in being either. On the one hand, it’s a critical commentary on the performance of Act II itself; on the other, it is a sociological documentary on the themes of fame, marriage, love, gossip - a Greek Tragedy whose subject has become the narrative for a celluloid piece of tabloid newsreel. The problem I had with much of the film is that editorial decisions resulted in people being interviewed either being asked the wrong questions (or, no questions at all) resulting in opinions that were either meaningless, or plain bizarre. Rufus Wainwright’s statement that Act II “is my favourite music in the opera” tells us everything about Wainwright but nothing about Callas. I found completely pointless the German fashion designer, Wolfgang Joop, suggesting that were Callas alive today she would be “resurrected” as Lady Gaga rather than Madonna. It’s the kind of statement, once heard or read, that one can’t, unfortunately, erase from the mind. The narrative of Callas’s failed relationship with Aristotle Onasis, her mental and physical decline, her struggle with weight loss, and withdrawal from the opera stage are recycled ad nauseum - though offer nothing new. As Brian McMaster reminds us, people queued in the freezing January weather, even taking to sleeping overnight outside Covent Garden for almost a week, to get hold of tickets - much as they had done over a decade earlier for Toscanini’s Philharmonia Orchestra concerts at the Royal Festival Hall. The Internet has rather changed the functionality of booking for opera performances today - but even if it hadn’t, I can’t imagine there are artists with the selling-power to turn the pavement of the Royal Opera House into a make-shift shelter.

More interesting are the musical insights into Act II. Jürgen Kesting is surely right to suggest that the “second act is torture chamber music”, something which Thomas Hampson alludes to as well, particularly in his succinct description of the role of Scarpia as almost definitively captured here by Gobbi. I think there is a general consensus that both Callas and Gobbi were beyond their best - but it matters not the slightest. Kristine Opolais views this as the greatest Tosca she has ever seen and go beyond the individual criticisms of the singing and focus on the bigger picture and it’s difficult not to reach the same conclusion.

Anna Prohaska’s comment that Callas’s voice “goes beyond the outer limits of beauty” is echoed by Rolando Villazón who, perhaps more critical than most of those interviewed here, described Callas’s technique as “not at all impeccable”. He’s just as critical of Gobbi - but concedes that the “fusion” of these two unique singers together brings out an unusual humanity. Thomas Hampson describes the magic between them both as “magnetism” and adds: “What they had in common (Callas and Gobbi) was that you listened to the people - characters - they were singing”. For Antonio Pappano the magic of Callas and Gobbi had less to do with their vocal command of the roles and more with their stage presence. “Great singers sing through their eyes - Callas and Gobbi sing through their eyes as well their physical movements”. It’s one of the more revealing comments because this is a Tosca you simply become drawn into watching; the chemistry between these two artists is so spellbinding. Jürgen Kesting draws attention to the lascivious gesture of Gobbi caressing Callas’s arm with his quill and states, quite correctly, that it is “beautifully acted by them both”. McMaster is still astonished today by the sight of Gobbi stamping his feet, with the cellar door suddenly opening and Cioni’s heroic tenor emerging from it. Half a century after it was staged, everything about this Tosca is as fresh and compelling as the day it was first seen.

There is no information suggesting the film of Act II has in any way been remastered for Blu-ray - and I’m not sure I really detect any improvement over picture quality in the DVD copy I already own. It does, however, continue to have a distinctive vintage feel to it, with darkness and shadows depicted intuitively, and the heavily “Gothic” nature of the production - or “lurid”, as Antonio Pappano describes it - still magnificently captured, even if it clearly feels much older than the year in which it was filmed. It’s hugely atmospheric, however, the black and white film perhaps doing so much more than colour would have for the billowing grey tones of the smouldering fire place and the shadows cast by the multiple candles. Whether a major opera company would even get away with a production that looks such a fire risk as this one is highly debatable today. I do think there is some minor clarity in audio, however, and this is really only noticeable in the tonal range of the voices.

Whether the documentary will be of much interest will really depend on your enthusiasm for all things Callas. I’m not sure it adds much to our understanding of the singer, and only marginally to the production and performance of Act II itself.

Marc Bridle

Maria Callas: Tosca 1964

A Film by Holger Preusse; filmed in HD. Picture Format: 1080i, 16:9. Sound Format: PCM Stereo; Subtitles Documentary: English, German, French, Korean, Japanese; Subtitles Opera: Italian (original language), English, German, French, Korean, Japanese; Region Code: 0; Total Time: 97 minutes [Documentary: 52 minutes/Opera 45 minutes]; C Major 745104 Blu-ray;

Bonus: Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924): Tosca (Second Act)

Maria Callas (Tosca); Renato Cioni (Cavardossi); Tito Gobbi (Scarpia); Robert Bowman (Spoletta); Dennis Wicks (Sciarrone); The Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House Covent Garden; Conducted by Carlo Felice Cillario; Stage Designer and Director, Franco Zeffirelli; Costumes, Marcel Escoffier; Scenery, Renzo Mongiardino; Lighting, Franco Zeffirelli and William Bundy; Filmed at Covent Garden 9th February 1964. image=http://www.operatoday.com/Callas.jpg image_description=Maria Callas: Tosca 1964; a film by Holger Preusse product=yes product_title=Maria Callas: Tosca 1964; a film by Holger Preusse product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id=

Philip Venables: 4.48 Psychosis

Not until Bellini’s I Puritani and Donizetti’s Lucia Di Lammermoor did the gender disparity between the more masculine mania and the feminisation of the melancholic become obscured. It was only at the beginning of the Twentieth Century that opera ceased to treat madness and insanity as the apex of the operatic mad scene, and more the full-scale development of its psychological development throughout the entire span of an opera, as we get in Strauss’s Elektra and Berg’s Wozzeck. With Strauss and Berg, the psychological opera is born.

Philip Venables’s 4.48 Psychosis, drawn from the final full-scale play of Sarah Kane, is something of a mythological beast. Of all Kane’s dramatic works, it is the one that comes closest to opera because, of all her theatrical pieces, it is the one that least fits the description of a modern play. Written without a dramatis personae, it appears on the page as a monologue, often seeming to fully scale the heights of stream of consciousness in the way the words drench the pages. It’s unusually poetic, too. The words have a soaring, literary beauty to them that are muscular, but intensely musical: “the capture/the rupture/the rapture/of a soul… a solo symphony”.

4.48 Psychosis has often been viewed, because Kane killed herself so soon after it was completed, as a suicide note - and the unusual structure of the work has probably cemented this idea as much as any other. However, this is a piece of drama that blazes with historical awareness of its art form, much as Venables’s treatment of the text does so as music. Just as Kane embraces the Theatre of the Absurd of Artaud and Ionescu, and even Beckett, so Venables looks to the example of a composer like Berg: there are the veins of palpably dense serialism for the violas, the sudden orchestral flare-ups on the baritone saxophones, the stark, yet rather tenebrous, orchestration, the symmetry of two spatially separated percussionists. The threads of this music can be surprisingly dark, almost as if they are describing the moment a mind fragments. Venables has been careful to create a symbiotic balance between the music and the words of Kane’s canvas - so, the percussionists tap out their notes like Morse code, but there is a rhythm and tempo to the music that frames the meaning of the text. Every part of Kane’s vast monologue is composed for - so even full-stops and question-marks are given a musical equivalent, such as a buzzer or a bell. There are hammers and saws which articulate the inner voices of a psychotic mind in its bleakest moments of despair.

Kane herself said that “performance is visceral” and the experience of seeing 4.48 Psychosis, I think, need not necessarily be wedded to one’s own experience of mental illness; for many, however, it will resemble it. Whilst it is primarily about psychiatric disintegration, it is also about love, albeit the loss of love: “cut out my tongue/tear out my hair/cut off my limbs/but leave me my love”. Psychosis is an internal civil war, and this production doesn’t shirk from confronting that conflict. The use of an ensemble cast - often singing in unison - seeks to define psychosis through multiple voices and personalities, but it also somewhat catalyses mental illness into distinct sections. You watch from the point of view as the victim, as the lover, as a doctor. That love should be unrequited is connected to the depression experienced: “I cannot go on I cannot fucking go on without expressing this terrible so fucking awful physical aching fucking longing I have for you. And I cannot believe I feel this for you and that you feel nothing. Do you feel nothing?” That “love” is in some respects a bond between the patient and their doctor - and it is certainly implied as such in this production where the role of a doctor figure is given some prominence. But Kane is scathing about the relationship - and of modern medicine. Zopiclone, Melleril and Lofepramine are prescribed to restore sanity, but are withdrawn because of the side-effects; in the end, they simply become the tools of suicide.

Gweneth-Ann Rand. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Gweneth-Ann Rand. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Given the power of Kane’s source material - and the sheer beauty of her prose - so little needs to be done to develop the libretto for dramatic purposes. It rather stands on its own. From a musical point of view, the monologue and fragments of speech probably assume greater vocal colour and describe more devastatingly the unrelenting despair and “black snow” of mental decline if taken by an ensemble of voices than if by a single voice - as they are in Erwartung, for example. Culturally, mania, insanity and suicide are often questionable - but here the production embraces them, even if the salient effects of it are to present it in traumatic terms. Ted Huffman’s production, with its slabs of grey and nakedly-shone glass doors, is almost entirely vacant - like a mind that has already collapsed into despair. Colours are entirely neutral. Against the grey walls are typed out parts of Kane’s play. Despite the utter barrenness of the production, which works on its own terms, it constantly threw up literary allusions: Biblical words, and references to Judaism, recalled Sylvia Plath’s lampshades made of skin, and the final scene with the body lying on the table reminded me of TS Eliot’s “When the evening is spread out against the sky/Like a patient etherized upon a table” from The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock. Neither Plath, nor Eliot, escaped the devastation of mental illness either.

Lucy Hall, Gweneth-Ann Rand and Lucy Schaufer. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Lucy Hall, Gweneth-Ann Rand and Lucy Schaufer. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

I don’t think one can praise the singing of the Gwyneth-Ann Rand enough. She sang not only beautifully, but with considerable power and raw emotion. When she sang “I REFUSE I REFUSE I REFUSE LOOK AWAY FROM ME” you really believed in her complete isolation and her rejection. It was an utterly devastating moment. She was ably supported by Lucy Schaufer, Rachel Lloyd, Susanna Hurrell, Lucy Hall and Samantha Price - all of whom, as an ensemble, were superbly well-matched. The hive-like nature of the singing, with the singers rotating the roles of the patient and doctor, gave added complexity to the voice shadows. Richard Baker, conducting CHROMA, who were on outstanding form, brought a huge amount of kaleidoscopic detail to the score. This is music that is deceptively well-balanced - constrained enough, given the unorthodox orchestration, not to overwhelm the singers, but powerful enough in scenes such as the 100-steps, where the music takes on the sounds of computer game music, to be both gripping and sound menacing. That this music should sound both so rhythmic and yet so flexible was something of a bonus.

There is enough black humour in this production (though it’s sometimes hard to see it) to offset the impression its subject matter might be otherwise. In part, the assumption has always been that 4.48 Psychosis is Sarah Kane’s bleakest work because it is so inextricably linked to her own suicide. It is certainly the case that internal dimensions of the play’s narrative, such as they are, define the very premise of manic psychosis - and in particular, Kane’s description of madness from waking up repeatedly at 4.48, morning after morning. Venables and Huffman have given us a very different perspective on this work than one might expect to see in the theatre; though, if nothing else, Venables’s 4.48 Psychosis is simply the most recent, and perhaps most graphic, example of psychological opera.

At Lyric Hammersmith 26th, 28th, 30th April, 2nd, 4th May 2018

Marc Bridle

Philip Venables: 4.48 Psychosis based on the play by Sarah Kane

Singers: Gwyneth-Ann Rand/Lucy Schaufer/Rachel Lloyd/Susanna Hurrell/Lucy Hall/Samantha Price

Conductor: Richard Baker/CHROMA; Director: Ted Huffman; Designer: Hannah Clark; Lighting: D.M.Wood; Video: Pierre Martin; Sound: Sound Intermedia

Royal Opera Production at Lyric Hammersmith; 24th April 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Psychosis%20production%20image%20Stephen%20Cummiskey.jpg image_description=4.48 Psychosis: ROH at Lyric Hammersmith product=yes product_title=4.48 Psychosis: ROH at Lyric Hammersmith product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id=4.48 Psychosis: ROH at Lyric HammersmithPhoto credit: Stephen Cummiskey

Hubert Parry and the birth of English Song

New from SOMM recordings, the second volume from Hubert Parry's English Lyrics. Between 1874 and 1918, Parry wrote 74 songs in twelve collections, all titled "English Lyrics", two sets of which were published after his death. As Jeremy Dibble, Parry scholar and biographer writes,"The generic title of English Lyrics symbolised more than purely the setting of English poetry (but) also an artistic manifesto and advocacy of the English tongue as a force for musical creativity shaped by the language's inherent accent, syntax, scansion, and assonance".

German and French composers were quick to recognise how poetry could develop art song, and even set a great deal of Shakespeare (in translation and adaptation). Parry's interest in English lyrics opened new frontiers for British music. The prosperity of late Victorian and early Edwardian London fuelled the growth of audiences with sophisticated tastes, many of whom travelled and were up to date with music in mainland Europe. The splendid art nouveau interior of the Wigmore Hall attests to this golden age. Until 1914, it was the Bechstein Hall, connected to the Bechstein piano company who supplied pianos - and European music - to audiences beyond the choral society/oratorio market.

The first SOMM volume of Parry English Lyrics focused on settings of Shakespeare, Herrick, Beaumont and Fletcher, Sidney et al (Please read more here). In this second volume, the emphasis is on poets of the 19th century, some of whom were "modern", ie contemporaries of Parry himself. A thoughtful choice, for this reinforces the connection to art song in Europe. Parry's setting of Percy Bysshe Shelley's O World, O Life, O Time respects the declamatory nature of the poem, well expressed by Sarah Fox. There are two settings of Lord Byron When we two were parted and There be none of Beauty's daughters, the latter inspiring a particularly rich piano lovely vocal complemented by a rich piano part, which sets off the crispness in the vocal line, ideal for the distinctive "English tenor" style, highlighting consonants, eliding vowels, sharpening impact.

Not all English tenors are "English tenors" but here we can hear how the style connects to syntax and expressiveness. In Bright Star!, a setting of John Keats, James Gilchrist rolls his "r's", and breathes into longer phrases like "or else the swoon of death" shaping each word carefully in the line. Listen to the way he sings "swoon", drawing out the vowel, the sound of which is echoed by the piano, played by Andrew West. In Dream Pedlary, (If there were dreams to sell) to a poem by Thomas Lovell Beddoes, Gilchrist's voice curls around the words, adding magical frisson.

Harry Plunket Greene who was to become Parry's son-in-law, premiered many of Parry's songs for baritone. Perhaps Parry created these songs for Plunket Greene's agile voice and down-to-earth delivery. It's certainly no surprise that Roderick Williams is easily the finest baritone in English song, since he sings with a natural directness which communicates almost as if singer and listener were in conversation, which is ideal for English song, where the floridness of, say, an Italianate style would not work. Also, his voice is not pitched too low, but lends itself to flexiblity and brightness, which suits the English syntax. It's almost impossible to know English song without having heard Williams, whose experience in this field is unequalled. Compare Williams in two songs: Thomas Ford's And yet I love her till I die, an early 17th century air, and Love is a bable, a quasi-folk song. In the first Williams is correct and courtly, in the second, his innate warmth adds sincerity to the wry humour in the song. In Parry's two settings of poems by George Meredith, Marian and Dirge in the Woods, Williams captures the rollicking, open air energy in the songs. In What part of dread Eternity?, to a text which may be Parry's own, Williams's voice darkens forcefully, taking on the solemn tone of the poem.

This recording includes the whole ninth set of Parry's English Lyrics, (1908) settings of seven songs by Mary Coleridge (1861-1907). If the poems are fairly slight, Parry's treatment makes the most of what Jeremy Dibble has called their "lack of ostentation". The songs are simple but dignified homilies. Sarah Fox sings them with lucid purity, reflecting their almost Brahmsian reserve. Elsewhere on this recording, she sings lyrical pieces like Proud Maisie (Walter Scott) and A Welsh Lullaby (John Ceiriog Hughes), a poet popular in 19th century Wales.

Anne Ozorio

image=

image_description=SOMM Records SOMMCD270

product=yes

product_title=Sir Hubert Parry : Twelve Sets of English Song vol II, Sarah Fox, James Gilchrist, Roderick Williams, Andrew West.

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=SOMM Records SOMMCD270

price=

product_url=

April 24, 2018

Soprano Nadine Sierra Wins the 2018 Beverly Sills Artist Award

The $50,000 award, the largest of its kind in the United States, is given to extraordinarily gifted singers between the ages of 25 and 40 who have already appeared in featured solo roles at the Met. The award, given in honor of Beverly Sills, was established in 2006 by an endowment gift from the late Agnes Varis, a managing director on the Met board. In 2009 Sierra became the youngest ever winner of the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions and has gone on to make her mark at the Met with memorable performances in Verdi’s Rigoletto, and Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro, Idomeneo and Don Giovanni. In the Met’s 2018-19 season, Sierra will reprise the role of Gilda in Rigoletto.

Met General Manger Peter Gelb presented Sierra with the award today, saying: “Nadine is a most deserving recipient. I’m sure that Beverly would have been pleased with our choice.”

The Sills Award was created to help further recipients’ careers, including funding for voice lessons, vocal coaching, language lessons, related travel costs, and other professional assistance. Sills, who passed away in 2007, was well known as a supporter and friend to developing young artists, and this award continues her legacy as an advocate for rising singers. The 29-year-old Sierra is the 13th recipient of the award, following baritone Nathan Gunn in 2006, mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato in 2007, tenorMatthew Polenzani in 2008, bass John Relyea in 2009, soprano Susanna Phillips in 2010, mezzo-soprano Isabel Leonard in 2011, soprano Angela Meade in 2012, tenor Brian Hymel in 2013, tenor Michael Fabiano in 2014, baritoneQuinn Kelsey in 2015, sopranoAilyn Pérez in 2016, and mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton in 2017.

Nadine Sierra said: “This award is a true gift to singers because it honors not only a beautiful artist in Beverly Sills, but treasures the legacy she left behind. It's not enough to say that I'm honored to be receiving it, but more that I feel incredibly humbled. Opera can and should belong to anyone who has the pleasure of witnessing its timeless beauty. I believe Ms. Sills, through all of her achievements and generosity of sharing this music with people around the world for many decades, would certainly agree. I'm very thankful to the Metropolitan Opera for selecting me as the recipient of such a meaningful and empowering award.”

Nadine Sierra made her Met debut in 2015 as Gilda in Verdi’s Rigoletto. She followed that with three Mozart roles at the Met: Zerlina in Don Giovanni, her role and Live in HD debuts as Ilia in Idomeneo, and earlier this season, her role debut as Susanna in Le Nozze di Figaro. She made her professional debut with Palm Beach Opera while still a teenager, in her home state of Florida. She studied in New York at Mannes College of Music and was an Adler Fellow with San Francisco Opera. She made her debut at San Francisco Opera in 2011 as Juliet/Barbara in the world premiere of Christopher Theofanidis'sHeart of a Soldier. Recent engagements include Gilda in Rigoletto (La Scala, Milan, Chorégies d'Orange, Opéra Bastille, Seattle Opera), Lucia in Lucia di Lammermoor (La Fenice, Venice, San Francisco Opera, Zürich Opera), Zerlina inLe Nozze di Figaro (Paris Opera), Tytania in A Midsummer Night's Dream and Norina in Don Pasquale (Valencia), Musetta in La Bohème, Countess Almaviva in Le Nozze di Figaro and Pamina in Die Zauberflöte (San Francisco Opera), Flavia Gemmira inEliogabalo (Paris Opéra) and Nannetta in Falstaff (Staatsoper Berlin). In June she sings the role of Norina in Donizetti's Don Pasquale (Paris Opéra). She is the winner of the Marilyn Horne Foundation Vocal Competition, the 2017 Richard Tucker Award Winner, and has recently signed a record contract with Deutsche Grammophon/Universal.

Contact: Lee Abrahamian / Tim McKeough

(212) 870-7457 labrahamian@metopera.org / tmckeough@metopera.org

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Idomeneo_2328-s.png image_description=Nadine Sierra as Ilia in Mozart's Idomeneo. Photo: Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera product=yes product_title=Soprano Nadine Sierra Wins the 2018 Beverly Sills Artist Award product_by=Press release by Metropolitan Opera product_id=Above: Nadine Sierra as Ilia in Mozart's Idomeneo. Photo: Marty Sohl/Metropolitan OperaApril 19, 2018

European premiere of Unsuk Chin’s Le Chant des enfants des étoiles, with works by Biber and Beethoven

Any connections between the first and second halves were not necessarily explicit; this was not an overtly didactic programme (nothing wrong with that, of course). Nevertheless, I fancied I could hear certain pitches, certain turns of phrases, perhaps even certain rhythms, in both; and even if I could not, contrasts fascinated enough.