May 30, 2018

Feverish love at Opera Holland Park: a fine La traviata opens the 2018 season

Indeed, the lingering damp of the summer storms which had rattled and racketed London throughout the day might have led to fears that the audience might be at risk of joining Violetta behind the black curtain which was laboriously closed during the overture, to enshroud the circular ante-room to the far-right of the stage.

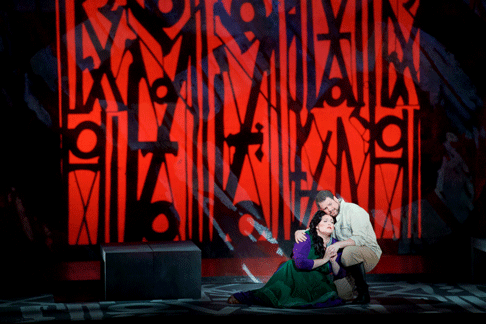

It is a delight to see Gaitanou and her designer Cordelia Chisholm making a virtue rather than an issue of the extensive breadth of the Opera Holland Park stage. Rather than force us to swivel our vision back and forth across the expanse with the agility of a tennis-match crowd - as was the case with Marie Lambert’s scenographically inventive-cum-hyperactive production of Zazà last year - or push the action to a narrow fore-stage strip, as did Oliver Platt last season when directing Don Giovanni , Gaitanou and Chisholm have created a gracious sweep of reflective glass and decorous greenery: a single set which serves equally well as society salon or country chateau. As the strains of the overture unfurl, a footman refreshes the bouquets and un-drapes a chaise-longue. The curtained circle is first boudoir then conservatory; at the close, quasi-brothel then death chamber.

Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Photo credit: Robert Workman.

The lack of scenic fuss sharpens the dramatic clarity and colours are similarly simple and striking. In Act 1 Violetta is helped into a gleaming white gown by her maid Annina, (Ellie Edmonds) the dazzling purity of which sets off the blood-splatters which result from her heart-rending hacking. In the final Act, a black dress signals her doom, while Simon Corder’s garish lighting overwhelms the day-light lucidity with the ghoulish purple excess of Flora’s party. The orangery doors come into their own in this last Act: half-open, they admit both lurid light and tumbling crowds of raucous revellers - the Opera Holland Park Chorus in fine voice.

In the title role, Lauren Fagan proves as adept as Gaitanou and Chisholm at commanding the breadth of the OHP stage. Her soprano has real gloss, her coloratura is shaped with expressive grace and her stage presence is gripping. ‘Sempre libera’ was gleefully carefree, sparkling with agility and diamantine shine. Fagan strides the stage with unwavering composure and even her death-approaching agonies have elegiac elegance.

Many will have been thrilled by Matteo Desole’s ringing and pinging but I found his Alfredo, although technically very assured, to be lacking in emotional resonance. There were a few intonation wobbles at the start - understandable, given that this was the first night in an unfamiliar venue, and things quickly settled - but Desole has only two volume switches, loud and very loud, and despite the bel canto ease, the unalleviated boom was wearisome. This Alfredo seemed emotionally disengaged, an impression exacerbated in Act 2 when he was more interested in rearranging the potted plants in his country conservatory than in living the sentiments of his aria. Despite these misgivings, I can’t deny that Desole’s voice carries effortlessly and his legato phrasing is luxurious - no mean virtues in this venue.

Matteo Desole as Alfredo. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Matteo Desole as Alfredo. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Stephen Gadd’s Germont is unbendingly bourgeois and stern, though he clearly comes to recognise Violetta’s courtesy and good manners, and despite some occasional lack of firmness vocally Germont’s confrontation with Violetta in Act 2 is one of the most dramatically convincing and compelling episodes of the drama, as Alfredo’s father pushes his son’s concubine relentlessly towards sacrificial renunciation. In ‘Di Provenza il mar’, Germont’s nostalgic reminiscence feels entirely sincere.

Lauren Fagan as Violetta and Stephen Gadd as Giorgio Germont. Photo credit: Ali Wright.

Lauren Fagan as Violetta and Stephen Gadd as Giorgio Germont. Photo credit: Ali Wright.

Though the spotlight shines firmly on the central, fraught triangle, the minor roles all make their mark, for the unfussy staging gives them room to find their ground and occupy it. Laura Woods is a minxy Flora, her voice full of colour and lushness; Charne Rochford as Gastone and Nicholas Garrett’ as Douphol define their characters well.

Although the overture sounded somewhat thin and lacking in sentiment, conductor Matthew Kofi Waldren encouraged ever more responsive playing from the City of London Sinfonia and the precision of the playing in the final Act was complemented by impassioned warmth. Waldren doesn’t hang about and that only serves to enhance the sure dramatic thrust established by Gaitanou and Chisholm.

Lauren Fagan as Violetta and Nicholas Garrett as Barone Douphol. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Lauren Fagan as Violetta and Nicholas Garrett as Barone Douphol. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

In the closing scene, the reflections in Chisholm’s glass evoke fore-shadowings of Violetta’s ghostly form - as if she is haunting the stage even while she still struggles to draw her last, irregular, painful breaths. The recording of shallow consumptive breathlessness echoes disturbingly in the memory.

Despite the Parisian partying and pleasures, Gaitanou’s La traviata is permeated with the shadows of disease and death. Fagan’s Violetta is both frail and fervent; the fever of love and illness burn with equal intensity. It’s a paradoxically uplifting blend.

Claire Seymour

Violetta - Lauren Fagan, Alfredo - Matteo Desole, Giorgio Germont - Stephen Gadd, Flora - Laura Woods, Annina - Ellie Edmonds, Gastone - Charne Rochford, Barone Douphol - Nicholas Garrett, Marchese d’Obigny - David Stephenson, Dottore Grenvil - Henry Grant Kerswell, Giuseppe - Robert Jenkins Flora's Servant - Ian Massa-Harris, Messenger Alistair Sutherland; Director - Rodula Gaitanou, Conductor - Matthew Kofi Waldren, Designer - Cordelia Chisholm, Lighting Designer - Simon Corder, Movement Director - Steve Elias, City of London Sinfonia and the Opera Holland Park Chorus.

Opera Holland Park, London; Tuesday 29th May 2018

Image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lauren%20Fagan%20as%20Violetta%20with%20Anina%20Act%201.jpg image_description=Il Traviata, Opera Holland Park 2018 product=yes product_title=Il Traviata, Opera Holland Park 2018 product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Lauren Fagan as Violetta and Ellie Edmonds as AnninaPhoto credit: Robert Workman

The Devil, Greed, War, and Simple Goodness: Ostrčil’s Jack’s Kingdom

Otakar Ostrčil was a prominent Czech composer who has fallen into obscurity. His dates, 1879-1935, span a key moment in the history of Central Europe, for it was in 1918 that the Czech lands became part of the new country of Czechoslovakia, independent of Austrian rule. In the preceding decades, Czech writers and artists had often attempted to define a national identity for themselves, as can be heard in many works of Smetana and Dvořák. When national statehood arrived, composers took one of several paths: some modeled their work on trends within the European musical mainstream (e.g., symphonic poems in the manner of Liszt or Strauss; or neoclassicism in the manner of Stravinsky and some of Les Six), while others continued to explore ways of sounding distinctive and different, for example by writing vocal music and opera using Czech texts based on Slavic folk legends. The whole story is further enriched by the fact that Prague had a substantial German-speaking population (including many Jews), and even a German opera house, the New German Theater, which is now known—after a number of name changes—as The Prague State Opera.

Ostrčil, who established himself early on as a conductor and composer, served as the music director at the Prague National Opera (i.e., the Czech-speaking house) from 1920 till his death at the age of 56. He was greatly admired for the precision of his conducting and for the open-minded welcome he gave to a wide range of repertoire, from the comic operas of Auber to a work for which he was roundly chastised in the press: Berg’s Wozzeck. His 1933 recording of Smetana’s The Bartered Bride was at one point released on CD by Naxos but seems to have been withdrawn, perhaps for contractual reasons.

Ostrčil wrote a number of successful orchestral works and operas. Honzovo Království was the last of his operas, and the present recording is a re-release of a superlative recording made in 1954. The opera was a great success at its premiere in 1934, but Ostrčil died four months later, possibly in part because of overwork. (The often-contentious Czech musical scene during the first half of the twentieth century comes vividly to life in two scholarly books that, I should confess, I had a hand in getting published: Opera and Ideology in Prague, by Brian Locke—no relation to me!—and Bedřich Smetana: Myth, Music, and Propaganda, by Kelly St. Pierre.)

In Honzovo Království (which has been variously translated as “Johnny’s Kingdom” or “Jack’s Kingdom”), Ostrčil distinguishes himself from most Western composers by basing the libretto on “Ivan the Fool,” a quasi-folktale published in 1886 by a fellow Slav, Leo Tolstoy. The story tells of four siblings whom the Devil tries to manipulate for his own nefarious purposes. Ivan, though seemingly dim-witted, is the one who manages to out-maneuver the Devil. He ends up establishing a kingdom in which there are no wars, and people who do physically demanding labor are the first to be served dinner, whereas intellectuals and nobles (people with soft, pale hands) have to be content with whatever is left over.

Ostrčil’s librettist, Jiří Mařánek, gave the story a specifically Czech twist, in part by renaming the characters: most notably, Ivan becomes Honza, a figure clearly derived from the character in many Czech folk tales known as “Hloupý Honza,” i.e., Dull Jack. (The name Honza, like Hans in German, derives from Johannes.) Honza’s brothers are now called Ondřej (i.e., Andrew) and, a bit oddly, Ivan. The fourth sibling, a mute sister, is omitted. Honza comes across here as similar to another powerfully effective simpleton in Czech culture: the title figure in Jaroslav Hašek’s novel The Good Soldier Schweik (1921-23).

The opera is compact, taking, in this recording, only 107 minutes. The basic style reminds me at times of mid-career Prokofiev (e.g., The Prodigal Son) or the motoric ensemble scenes in Weill’s Mahagonny. On a basic musicodramatic level, the work follows certain Wagnerian procedures that had become normative for many Western European opera composers in the intervening half-century. In general, the melodic lines are conversational, requiring clear enunciation more than long-phrased breathing. There are exceptions, though, mainly in lyrical passages for Honza, the Princess (CD 2, track 3), and the slippery, multi-faceted Devil. I might recommend to enterprising lyric tenors Honza’s soliloquy that opens Scene 2.

Continuity is provided by several recurring themes and by richly elaborated interludes between scenes. (For example, the orchestral description, in Act 2, of the sadness that has gripped the kingdom because—as the Constable has just explained in spoken words—the princess is mysteriously ill: begin at 0’50”.) Passages of spoken dialogue over orchestral music, a technique known in the opera world as melodrama, depart forcefully from the Wagnerian model and help emphasize the modesty and directness of the folk-like story. (Melodrama was a technique particularly cultivated by Ostrčil’s teacher, Zdeněk Fibich.) The spirits of hell converse with the devil from all parts of the theater, using megaphones. On the recording, their speaking voices—they are trying to cook up a war in Honza’s peaceable kingdom—are made even creepier by some simple electronic reverb. (The YouTube track begins with a symphonic interlude; the conversation begins at 2’13”.)

This recording, apparently the only one that Honzovo Království has ever been granted, was made in the Prague radio studios in 1954 and was released on LP by Supraphon. (It can be heard entire, in many segments, at YouTube, but they are not arranged in any recognizable sequence.) The performance under Jiráček is vivid and presumably reflects the extensive series of staged performances that the work had received in the Czech and Slovak lands up to that point. The work was first heard in Brno, in 1934, then in Ostrava, and from 1935 onward in Prague. It was given in German in 1937 in the aforementioned German-language opera house in Prague.

The reissue of this recording on CD was made possible, according to a note in the booklet, by Astrid Štúrová-Kočí, presumably the daughter of baritone Přemysl Kočí . The latter performs the role of the Devil splendidly—acting and singing all at once, all the way through, with witty understatement rather than Boris Christoff-like overemphasis. The CD release coincides, surely not by chance, with the hundredth anniversary of Kočí’s birth. What a wonderful tribute to the memory of someone who was a major artist in Soviet-era Czechoslovakia. The Czech Radio website (radioteka.cz) offers for sale, on CD or as a download, a Czech-language performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni with Kočí in the title role.

The other cast members come across just as vividly, including Otava, who sang his role here (Ondřej) at the opera’s first Prague production, 17 years earlier. In the meantime, Czechoslovakia had experienced almost unimaginable turbulence: occupation by the Nazis, mass deportations for forced labor in Germany, persecution of political resisters, the systematic murder of most of the Jewish population, and, in the post-war years, the expulsion of most of the German population and the beginnings of what would be four decades of repressive Communist dictatorship. I can barely imagine the many different ways that this anti-war opera may have resonated for Czechs and Slovaks in 1954.

The best-known of the singers is the tenor Ivo Žídek , in the title role. We hear him at age 28; he had been singing leading roles since 18 and would continue to expand his repertory, and to perform and record internationally, at the highest level, until age 59. His singing nicely balances secure vocal production with a serene characterization and touches of humor.

Indeed, the singing from the whole cast is light and clear, with little trace of the “Slavic wobble” that I find tiresome in many recordings from further east (e.g., Russia and Bulgaria). The spoken roles seem to be taken by professional actors: they are superbly done. The orchestra and chorus play and sing alertly. Occasionally the woodwind and brass sections are not perfectly tuned, or the brass blare a bit. The various solos for wind instruments and for violin are nicely characterized. The sound quality is high-quality mid-1950s mono: clear, no distortion, but with the orchestra a bit recessed instead of richly surrounding the voices. Essay, synopsis (with helpful track numbers), and libretto, in Czech and (mostly comprehensible) English. I would say that it is time for a more modern recording, allowing us to appreciate the power and wit of the orchestral writing more. (And of course some live performances, either on stage or in concert.) But, if the vocal performances did not show the detail and insight that they do in this recording, I suspect the work wouldn’t come across half as well as it does here.

The second CD is filled out with a recording of Ostrčil’s fascinating fourteen-section set of Variations for Orchestra, Op. 24 (1928), entitled “Křížová cesta,”which is translated on the CD box as “Calvary.” Other sources list the work’s title as “Golgotha.” Closer English approximations would be “The Way of the Cross” or “The Stations of the Cross.”

This mono recording of the Variations, by the Czech Philharmonic under Václav Neumann in 1957, may have been the work’s first. (Like the opera, it is available on YouTube in segments. Here is the opening: “The Son of Man Is Condemned to Death.”) The sessions took place in Dvořák Hall, in the famous 1886 building called the Rudolfinum. The 1100-seat hall has fine acoustics—reflected in the good clear sound—and is the home of the Czech Philharmonic (and of many Prague Spring events). A stereo recording, likewise by the Czech Philharmonic under Neumann, was released on CD in 1990 and re-released in 1995. Carl Bauman, in the American Record Guide, at first found the work “bombastic” but, upon re-listening, discovered “various beauties” in it (March/April 1995). Each of the work’s fourteen short sections is headed with a descriptive phrase describing a moment from Christ’s last days, beginning with his being condemned to death and ending with his entombment. The booklet essay suggests that Ostrčil identified with Christ because of how he himself had suffered for the art he loved.

The musicologist Martin Nedbal informs me that there have been, for centuries now, “Calvary hills” constructed throughout Europe, including several in what used to be Czechoslovakia. A Calvary hill often consists of a cross (or three crosses) on a hill, and other markers and chapels on the way toward the hill, for pilgrims who wish to reenact and ponder Jesus’s last journey.

I found the 31-minute-long piece continuously engaging, especially when I remembered to keep in mind the titles over each of the fourteen sections: for example, in section 4, Jesus meets his mother Mary (Mahlerian sorrow, beginning with the strings alone and then broadening out) and, in section 7, he collapses for a second time under the weight of the Cross (much thrust and intensity, full orchestra). The work follows the traditional list of 14 Stations (some based on medieval legends), not the more carefully scripture-derived versions authorized by Pope John Paul II in 1991 and by Pope Benedict in 2007 (which purge, for example, the episode of Saint Veronica wiping Jesus’s face with her veil—Ostrčil’s section 6).

I am not sure I’ve yet fully grasped the variation process here, aside from a very noticeable rising motive that begins most of the fourteen sections. I was more aware of the expressive contrasts from one section to another. Still, I look forward to listening again to this remarkable case of a programmatic orchestral work that conveys a message at once religious and highly personal.

I continue to be surprised to find so many fine, even exciting musical works that are floating “out there” yet rarely, if ever, get performed in North America. I am grateful daily to Thomas Edison and his followers who perfected the medium that gives me so much joy and emotional gratification—including these two works by a composer who was to me, until now, just a name in books.

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and the second is also available as an e-book.

‡ Click here for a review of Laci Boldemann’s Black Is White, Said the Emperor. Click here for a review of Ravel’s L’enfant et les sortilèges.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/0099925422424.png image_description=Supraphon SU 4224 product=yes product_title=Otakar Ostrčil: Honzovo Království, opera; and “Calvary” Variations, for orchestra product_by=Jaroslava Vymazalová (Princess), Ivo Žídek (Honza), Přemysl Kočí (Devil), Josef Celerin (Father), Antonín Votava (Ivan), Zdeněk Otava (Ondřej), Jaroslav Veverka (King), Milada Jirásková (Ivan’s wife), Ludmila Hanzalíková (Ondřej’’s wife). Prague Radio Symphony and Chorus, conducted by Václav Jiráček (in the opera); Czech Philharmonic, conducted by Václav Neumann (in the Variations) product_id=Supraphon SU 4224 [2 CD] price=$19.99 product_url=https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0718YX88Q/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=operatoday-20&camp=1789&creative=9325&linkCode=as2&creativeASIN=B0718YX88Q&linkId=35bc9963c52b790defc8d190bf742113May 29, 2018

Iestyn Davies and Fretwork bring about a meeting of the baroque and the modern

All of Davies’ astute musicianship, technical expertise and expressive sensitivity was in evidence in Purcell’s song, compressed within four minutes of exquisite musical rhetoric. The twists and leaps of the ascending ground bass were articulated with lyricism as Davies let the descending melodic phrases fall silkily. His care with the text was both exemplary and thoughtful: a frisson on ‘beguile’ in the first phrase was transferred to the repetitions of ‘for all’ in the second. The snakes dropped from Alecto’s head as if slipping into cold water. The reiterated pledge of the closing phrase was dusted with a dash of piquancy by the upwards appoggiatura at the final cadence and by the suggestive lingering of the voice, the slightest vocal resonance persisting beyond the viols’ silence.

Interested readers can turn to my recent interview with Iestyn Davies for his (and my) thoughts about the musical threads that tether the baroque and minimalism together across three hundred years of changing musical forms and language, as well as for details about the origins and first performances of the works by Nyman included in this programme.

In her programme article, Alexandra Coghlan suggests that, although they share a ‘common vocabulary’, what distinguishes Bach and Purcell, say, from minimalists such as Glass and Nyman, is the use to which the composers put such means: that is, the repetitions of a Purcellian ground bass result in an intensification of emotion whereas the gyrations of minimalism serve ‘to strip away emotional as well as musical landmarks, to nullify, to hypnotise’.

I think that in some contexts this is probably true. But, this concert suggested that a more nuanced comparative relationship and dialogue is at work: that it is ‘time’, or rather the dialectic between timelessness and movement, which is at the core of both baroque and minimalist idioms, but that composers from these respective eras explore and articulate concepts of rest and unrest, stillness and progress, in different ways. Emotion, and its intensification, is present in both idioms, but the arousal of such emotion is achieved by contrasting methods of manipulating repetitive structures - whether structural, harmonic or motivic - as these features engage with other musical elements.

Or, as Iestyn Davies himself put it, with more directness, both Purcell and Nyman seem to contrive to deliberately make us aware of the passing of time. The works performed here certainly seemed to exemplify the way that Purcell’s emotional intensification and rhetorical ‘progression’ is effected by what I previously described as ‘ever more complex, nuanced elaboration, and more radical re-interpretation of harmonic structures and inferences’, while Nyman’s music acquires accumulating intensity, and restlessness, through amendments - sometimes unexpected - to the ‘episodic reiterations’ which results in forward movement of a sometimes physically shuddering nature.

The programme was framed by two works by Nyman for countertenor and viols. The seven short metaphysical epigrams, ‘To Music’, by Robert Herrick which Nyman sets in the form of a continuous unfolding in No Time in Eternity, immediately foreground the seventeenth-century representation of music as something active, with the power to effect varied change - by turns redemptive and destructive, enchanting and decadent. ‘Begin to charm’ is the initial, repeated cry, as the poet calls upon Music to first ‘melt me into tears’, then ‘make my spirits frantic’ and finally ‘make me smooth as balm and oil again’. Davies instantly cast an Orphic spell. The purity of his countertenor as he reiterated the opening word, ‘Begin’, set against the quiet, dark graininess of the viols’ gently propelling rhythmic gesture, and the intensification of chromatic false relations, beautifully embodied the sensual impact of Herrick’s ‘silvery strain’.

And aptly too, for, as the title implies, Herrick is concerned with the human, the ‘body’, rather than with the ethereal: ‘By hours we all live here;/ In Heaven is known/ No spring of time, or time’s succession.’ Herrick’s text emphasises the seventeenth-century concern with the unequal relationship between the music of the world and the music of the spheres on which it is based. The cold sparsity of the viol textures and voice-viol unisons in ‘Things Mortal Still Mutable’ emphasised the dangers that uncertainty and change bring to man, who is set on ‘icy pavements’, as well as the inevitable progression of musical phrase upon musical phrase. I was struck, too, by the clarity and shapeliness of Nyman’s melodic definition in ‘The Definition of Beauty’ - ‘Beauty no other thing is than a beam/Flashed out between the middle and extreme.’ - and by Davies’ diction and eloquence here. The epigrammatic fragment conjured in my mind the text-setting of Benjamin Britten, particularly the early works such as Hymn to St Cecilia, another poetic mediation on the nature of music and its power: ‘Translated Daughter, come down and startle/Composing mortals with immortal fire.’

Nyman’s Self-Laudatory Hymn of Inanna and her Omnipotence - written for and first performed by Fretwork and James Bowman - drew forth contrasting but complementary skills from Davies and Fretwork. Sustained high declamatory utterances, relentless octave leaps, melismatic unpredictability, excursions into the singer’s lowest register which emphasise Inanna’s princely status - ‘He has given me lordship’: all these musical elements captured the power-hungry egoism of the Sumerian Queen, the ancient goddess of love, sensuality, fertility, procreation and war - and all were effortless despatched by Davies. Fretwork added drama to the rhetorical pronunciations of identity and self-belief: shimmering upper viols and brusque pizzicato sweeps; folk-like circulatory gestures which whipped up energy in the middle voices; driving repeated groups of semi-quavers; unison crystallisations of the self-belief confirmed by forceful repetitions, ‘is mine’.

In two songs ‘If’ and ‘Why’, written by Nyman to texts by Roger Pulvers for inclusion in director Seiya Araki’s 1995 animated film, The Diary of Anne Frank, even these supreme musicians could not quite overcome the banality of Pulvers’ texts which express a child-like hope - ‘I’d blink my eyes/And wave my arms./I’d wish a wish to stop all harm’ - but whose anaphoric pleas (‘Tell me why, somebody … Why people can not love./ Why people hate all day and night/ […] Why adults fight over God/Why adults fight over colour/ Why adults go to war.’) have the ring of a collective classroom poetry project. That said, the looseness of the musicians’ crafting of Nyman’s ostinatos, which slip between time signatures and across varied phrase lengths, added some thought-provoking depth to the general consonant sweetness.

More interesting was Nyman’s Music after a while for viol consort, receiving its world premiere, for it offered a direct dialogue between present and past. Nyman begins with a sort of retrograde inversion variant on Purcell’s ground, the semitone falling rather than rising, before leaping up a fourth (not a fifth), and the distortions are further exacerbated by the irregularity of the rhythmic values in contrast to Purcell’s steady progression. The result is an increased frustration, as the motif seems to fight against itself rather than simply accumulate intensity as it moves forward. Gradually, the rhythmic figuration and syncopated tension increase, and the drama derived from growing the harmonic complexity and revolving deep bass line was enhanced by the delicious airiness of the viol players’ bow strokes which seemed to fly and float across the strings. Purcell’s ground, in its original form, increasingly made its presence felt, though it had to fight through chromatic obstacles and fast viol figures in the upper voices to sustain itself, and such dialogues resulted in rhythmic disjunctions which were eventually subdued into unisons and steadiness of pulse. This was a thrilling conversation between a ghostly voice and a present scribe.

However, the highlight of the concert was, inevitably perhaps, the beauty of Davies’ countertenor - for which I don’t really have the words, which is probably as it should be. Purcell’s ‘An Evening Hymn’ had closed the first part of the recital with hypnotic reverie. The encore was ‘O Solitude’, the 28 ground-bass repetitions of which - of infinite expressive variety, imaginative re-interpretation, formal flexibility - surely issue a challenge to any composer, baroque or minimalist. It’s hard, too, to imagine a text - Antoine Girard Saint-Amand’s ‘O que j’ayme la solitude!’, translated by Purcell’s contemporary, Katherine Philip - more diametrically opposed to the self-aggrandising oratory of the Sumerian warrior-Queen which had preceded it. Davies, accompanied initially by lute-mimicking pizzicatos then by graceful viol interweaving, was Orpheus Britannicus indeed.

Claire Seymour

Iestyn Davies (countertenor), Fretwork (Asako Morikawa, Joanna Levine, Sam Stadlen, Emily Ashton, Richard Boothby)

Michael Nyman - No Time in Eternity; Purcell - Two Fantazias in four parts, ‘Music for a While’; Nyman - Music after a while; Purcell - ‘An Evening Hymn’; Nyman - Balancing the Books, The Diary of Anne Frank (‘If’, ‘Why’); Purcell - Fantazy in four parts and Fantazy upon one note (1680); Nyman - Self-Laudatory Hymn of Inanna and her Omnipotence.

Milton Court Concert Hall, London; Monday 28th May 2018.

Image=http://www.operatoday.com/%C2%A9Chris%20Sorensen_4.jpg image_description=Iestyn Davies and Fretwork at Milton Court Concert Hall, 28th May 2018 product=yes product_title=Iestyn Davies and Fretwork at Milton Court Concert Hall, 28th May 2018 product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Iestyn DaviesPhoto credit: Chris Sorensen

May 27, 2018

BLACK OPERA: HISTORY, POWER, ENGAGEMENT

From the University of Illinois Press:

image=http://www.operatoday.com/9780252083570_med.png image_description=BLACK OPERA: HISTORY, POWER, ENGAGEMENT product=yes product_title=BLACK OPERA: HISTORY, POWER, ENGAGEMENT product_by=By Naomi André product_id=ISBN: 978-0-252-08357-0 (paper) price=$27.95 product_url=https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0252083571/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=operatoday-20&camp=1789&creative=9325&linkCode=as2&creativeASIN=0252083571&linkId=9520633c597f6b6ec8006d5d7d4b29b4From classic films like Carmen Jones to contemporary works like The Diary of Sally Hemmings and U-Carmen eKhayelitsa, American and South African artists and composers have used opera to reclaim black people's place in history.

Naomi André draws on the experiences of performers and audiences to explore this music's resonance with today's listeners. Interacting with creators and performers, as well as with the works themselves, André reveals how black opera unearths suppressed truths. These truths provoke complex, if uncomfortable, reconsideration of racial, gender, sexual, and other oppressive ideologies. Opera, in turn, operates as a cultural and political force that employs an immense, transformative power to represent or even liberate.

Viewing opera as a fertile site for critical inquiry, political activism, and social change, Black Opera lays the foundation for innovative new approaches to applied scholarship.

May 26, 2018

Works by Beethoven and Gerald Barry

The first half, however, put one in mind of that proverbial, clichéd curate’s egg. Adès walked onto the stage and apologetically informed us that two works had been added to the programme. Nothing wrong with that, although Beethoven hardly requires apology. The first was his Six Ecossaises, WoO 83, which many of us will recall from childhood piano lessons. Adès’s performance proved a curious mixture of the reticent – as though he would rather be playing the dances at home – and the heavy-handed. It became more flexible, to good effect, as it went on. Ultimately, though, little was made of these charming miniatures, whether individually or as a whole.

An die ferne Geliebte followed, Adès continuing to show a good deal of reticence, for most of the time very much the ‘accompanist’. Allan Clayton offered a sincere, verbally attentive performance until the final song, in which he sounded curiously harsh of tone, even hectoring. Still, there was a good deal to savour, for instance a true hint of sadness at the close of the fifth stanza of ‘Es kehret der Maien’. Adès seemed to come into his own as the cycle progressed. If he still came across as shadowing the singer at the beginning of ‘Leichte Segler in den Höhen’, his shaping of a minor-mode phrase at the end of the third stanza – ‘Klagt ihr, Vöglein, meine Qual’, offered just the sort of touching insight I had hoped he would bring to the music of a composer with whom he is not so obviously associated. The transition to the next song, ‘Diese Wolken in den Höhen’ was also skilfully handled.

The second additional work was In questa tomba oscura, WoO 133, Beethoven’s setting of a poem by Giuseppe Carpani, amongst other things an early biographer of Haydn (and royalist spy!) This proved a duly haunting performance of a song whose text has a man visit the grave of his beloved, albeit from the standpoint of the latter, who reproaches her lover for not having thought more of her whilst she was alive. Perhaps again Adès might have brought out the piano part more strongly. Beethoven’s harmonies nevertheless told – and there is much to be said for understatement. Clayton clearly relished its challenges, heightening without overstating its curious drama.

‘Curious’ is certainly a word to be applied to Lewis Carroll, and to Gerald Barry, let alone to their combination in Jabberwocky , commissioned and premiered by Britten Sinfonia in 2012. The idea of performing its nonsense words in French and German translation is typically brilliant – and makes just as much (non)sense as the original. Clayton’s declamatory performance perhaps inevitably put one in mind of Barry’s brilliant operatic comedy, The Importance of Being Earnest. Alex Wide’s bizarre horn flourishes added another level to the studiously inexplicable entertainment unfolded. The song – should one call it a ‘song’? – seemed, almost in spite of itself, to grow, even to develop. And then it was over.

Additional wind players joined the ensemble after the interval for Beethoven’s Quintet for piano and wind instruments, op.16. It was the sheer gorgeousness of their sonorities that struck me first – and Beethoven at his most Mozartian (or, his tragedy, post-Mozartian). Balance with the piano here sounded much improved; there was greater impetus to the performance too. This is music that needs plenty of space, a grandeur of scale if you will, as well as chamber intimacy; it received both. The second movement was again well paced, its post-Mozartian sadnesses again given space to breathe, yet also to progress. Here, Adès could prove a little indulgent, his solo rubati occasionally puzzling; in concert, however, everything delighted. The hunting finale again summoned up Mozart’s ghost – as opposed to Haydn’s ebullience. Yet, quite rightly, not all was subtlety, not all was interiority. That balance and others were finely judged, in a performance of almost tiggerish enthusiasm.

Mark Berry

Programme:

Beethoven: Six Ecossaises, WoO 83; An die ferne Geliebte, op.98; In questa tomba obscura, WoO 133; Gerald Barry: Jabberwocky; Beethoven: Quintet in E-flat major, op.16. Allan Clayton (tenor); Alex Wide (horn); Timothy Rundle (oboe); Joy Farrall (clarinet); Sarah Burnett (bassoon); Thomas Adès (piano). Milton Court Concert Hall, London, Wednesday 23 May 2018

image=http://www.operatoday.com/beethoven.png image_description=Ludwig van Beethoven product=yes product_title=Works by Beethoven and Gerald Barry product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Ludwig van BeethovenMay 24, 2018

The Moderate Soprano : Q&A with Nancy Carroll and Roger Allam

What interested you about the play and taking on the role?

RA : In the first version of the play when John Christie comes on he’s described as short, fat, bald and wearing lederhosen and I thought, ‘That’s the part for me, I have to play that role’. So there’s that kind of infantile appeal of dressing up and changing one’s appearance as you can see [he says this while having his bald cap put on], that has always been an element of the appeal of acting to me. Maybe after this I’m giving it a break though [laughs]. But actually, it was getting to know the story both through the play and reading a biography of John Christie which was something I knew nothing about at all. I didn’t know how it was founded, I certainly knew nothing about how they kind of lucked out completely when the three probably best people in the world were escaping Nazi Germany, and came to work at Glyndebourne. And for me it became very clear that there was a real thing about standards, they really built and maintained standards. Whatever you feel about the ‘snobs on the lawn’ aspect of it, they raised the bar, I think, for everyone else.

NC : For me, it was telling a story about a woman who pushed her husband forward and just got on with it and even Gus Christie who currently runs the festival knows very little about his grandmother. She died in 1952 before he was born and all the stories are about his grandfather but very little is known about her. And indeed, for me as an actress to play a part that skips between 1934 and 1952 when that person was in two very, very different states is a fantastic acting challenge and that’s what interested me. And also, as a post-Brexit story the fact that this quintessentially English treasure was actually set up by two extraordinary Germans and an Austrian – as a message to the leaders of Brexit, I think it’s quite an important one…

So there’s the story of Glyndebourne as an institution…

RA : And I was also drawn in by John Christie as a character, he was the most extraordinary man. Deeply and naturally eccentric but also someone who wanted to do good, you know. I mean, in 1911 when he was 29 he had a car – when there weren’t that many cars on the road – a Daimler, and he took a trip to Bayreuth and he took two friends, two Eton schoolmasters, with him and there were no car ferries then of course, so the car was put on a barge and the barge was towed by a ferry and the three men sat in the car on the barge going across the channel and then drove to Bayreuth. I mean, it’s just rather wonderful. And he had a building company, he had an organ company, he installed electricity in Glyndebourne…

NC : I think he had an entrepreneurial, scientific mind and although he believed in hierarchy in so many ways, he also did extraordinary things, like he created a library for his staff at Glyndebourne because he believed that information and education should be for everybody…

Yes, his idea of opera as public service is an interesting one.

NC : But then it was always… in Italy, in Germany – it was popular music. It’s only in this country that we’ve created this sort of… it’s like Shakespeare really… you know it sometimes seems to before the educated and higher classes, which is nonsense. Shakespeare, although he was middleclass, was an actor working in theatres, in London, around the country, and they were playing to people, to every single class, it’s how it should be. It’s beautiful music – why should it be for one set of people and not another?

Nancy Carroll and Roger Allam at Glyndebourne [Photo © Piers Foley]

Nancy Carroll and Roger Allam at Glyndebourne [Photo © Piers Foley]

You visited the Glyndebourne archive when preparing for the role. What was interesting about that, what did you uncover?

NC : It was interesting to see lots of photographs of them, between 1934 and 1952 and the difference in her physicality, because she was in so much pain by then. But the photographs that I found fascinating were the 1934 ones when they were completely in their element and the kids were small – and when she was pregnant with their second child, they looked idyllically happy. And then 1952 he was still thriving and she was obviously much more sort of, held, and then 1962 when he was very ill he grew a big beard because he couldn’t shave any more…

RA : Also the difference in the building, the expanding opera house, so that every year from 1934 you look at the photographs, something has been added so that by the 1960’s they’d done lots of extensions, put in many rehearsal and dressing rooms, they put a gallery in the theatre… I think it ended up seating about 800 and started off at around 300. And the current building was built in the 90’s…

NC : The thing I loved in the second rehearsal period is that we were visited by John Cox who had assisted Carl Ebert and who was able to give us first hand knowledge of what it was like in its heyday. He said it was incredibly moving how committed everybody was and what an extraordinary ethos they had, which was very much the work of John Christie, of the two of them really -the family had an incredible ethos of creating a safe haven for singers, where they had these long rehearsal periods, and people were invited to stay in the family home and were treated as family. Everybody who was there felt incredibly loyal to the place, and John Christie had this incredible loyalty to people. So, he couldn’t have experienced that without going there and seeing this…. It was incredibly moving. And I think this is what the place inspires, it’s what the dream inspires.

Did you get to hear Audrey Mildmay singing?

NC : I heard Audrey Mildmay singing and that was just beautiful and it was really lovely to read some of her reviews from 1934, 1935, 1936 and everybody would always comment on the delicate honesty of her voice which in the play Rudolf Bing describes as Ausstrahlung, which is this essence, something about her which radiated, something from deep inside her that came out in her voice – but it didn’t have the power to fill a bigger space which is why Christie refers to her as a moderate soprano. There was this lack of power but actually the quality of the voice was very, very beautiful, and it was lovely to hear that. And one of the things I loved was seeing her travelling with her trunk when she was touring with the Carl Rosa company before she married John. There’s something about playing somebody who existed like that…

You mentioned you heard recordings of John Christie too…

RA : Yes, it was very useful to hear his voice but I can’t represent it accurately on stage because it would be too slow, as he was much older then, so I have to kind of invent something, but I invented it with the knowledge of what his voice sounded like when he was older which was great. And it was also great to be in Glyndebourne to soak up the atmosphere of the place.

So overall, a story worth telling?

NC: I think the main thing is it’s a fantastic story and so unexpected. The way that David [Hare] has written it… I think it comes to the audience almost like a stream of consciousness. Bob Crowley calls it a memory play but that suggests a gentleness and it’s not a gentle story. It’s robust and it’s about people passionately trying to make art. And I think that’s what interested David as well, as somebody who from a very young age worked against the odds to tell stories that he felt needed to be told and show the other side of the argument. It’s a beautiful thing and it comes at an audience from so many different angles so that at the end of two hours you’ve formed a picture, but it’s not a linear one – and that’s what makes it so interesting.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Glyndebourne-archives.png image_description=Nancy Carroll and Roger Allam product=yes product_title=The Moderate Soprano : Q&A with Nancy Carroll and Roger Allam product_by=An interview by Mahima Luna product_id=Above: Nancy Carroll and Roger AllamLe Concert Royal de la Nuit - Ensemble Correspondances

Le Concert Royal de la Nuit was a statement so extravagant that it stunned the unruly Court into submission. As an artistic manifesto, it set out visions of what music, theatre, visual arts and dance might achieve. From Le Concert Royal de la Nuit, we can trace the origins of the arts as we know them today, not only in France, but in European culture as whole, with implications so wide that they are still felt today. Sébastien Daucé and Ensemble Correspondances made an acclaimed recording a few years back, and have been performing it in semi-staged productions, with dancers. No wonder St John's Smith Square was almost sold out!

The original Concert Royal de la Nuit ran over 13 hours,from dusk to dawn, though there were breaks for feasting and rest. For practical purposes, this version comes in four Veilles (Watches) and 67 individual parts, ending with a Grand Ballet, running around 2 1/2 hours. But what variety ! There are pieces for different groupings from soloist with orchestra to full ensemble, scenes of high drama and moments of quiet contemplation, marking the transition from night to day. At the beginning, the beating of a single drum, a reminder that the pulse of music is rhythm, and that life itself marches to a rhythm that is greater than any individual. Despite the glories that are to come, pastoralism - and war - are never far away. As King, Louis XIV represented idealized virtues of manliness and refinement, strength and benevolence. The dances at court were structured displays, and dance itself a form of physical fitness and mental discipline. This idea of orderly logic would flow through to design, philosophy, and much more.

But Nature remains present. Like the gardens which Louis XIV would layout at Versailles, nature is contained in defined formal patterns, but in the woods surrounding, nature runs free. A hibou calls (a small archaic pipe) marking the descent into night. "Languissante clarté", the first Récit, in which The Night reveals herself, a showpiece for Lucile Richardot, who projected the long, flowing legato so it seemed to fill the hall like moonlight. Behind her, murmuring low strings, sussurating like creatures of the night.Richardot has amazing timbre and range, her voice so expressive that she can "act" with her voice, though here she uses hand gestures reminiscent of those used in drawings of the original performance, an inportant consideration given that Le concert royal was meant to unify visual and aural art. This was followed by pieces marking the passing of "Hours" (soprano and small groups) and vignettes depicting huntsmen, gypsies and peasants, all well characterized.

The shades of darkness descend in the second Veille, and Venus appears, risen fully formed from the sea. This is a pointed reference to Louis XIV, taking command at the age of 14, throwing off the authority of Cardinals and courtiers. Though the Three Graces sang the praises of Venus, the connections must have been obvious. Thus choruses of Italians and Spaniards (rivals of the French) praise "unvanquished France", united behind the leadership of Louis "Le plus Grand des Monarques", as Venus herself declared. If the Moon symbolizes purity, Hercules symbolizes manly heroism. The Third Veille is a panorama where countertenor, bass, and male and female voices interact with orchestral interludes, replete with dramatic sound effects (instruments suggesting wind and thunder). The contrast between countertenor and bass was particularly vivid, performed here with great brio, the orchestra equally animated. Greek Gods, witches and figures from Antiquity emerge but the real subject is clearly Louis the King. Venus and Juno have extended récits which acknowledge opposition but posit that a strong, benevolent ruler can triumph. The "love" here means love for an absolute King. Also extremely effective, the trio of male voices in the Chorus of Brooks and Breezes, "Dormi, dormi, o Sonno, dormi". The last Veille describes Orpheus's entry into the Underworld. Hero as he is, he cannot defy the laws of Life and Death. Night symbolizes sleep, dreams and submission, to Fate, Time and Nature. Then Apollo appears, promising the retun of "mio figlio", the sun and Spring.

This set the context for the Grand Ballet, where Louis XIV himself appeared, garbed in golden splendour as the Sun, his headress emanating rays of light."Depuis que j'ouvre l'Orient" the récit of Aurore - beautifully sung and phrased by tenor, "jamais si pompeuse et si fiere......Le Soleil qui me suit c'est le jeune LOUIS". The Chorus, representing the Planets hail the king. Now the orchestra burst forth with full enegy, percussion announcing the triumphal procession of the King into centre stage. The rhythmic energy of these orchestral interludes suggests that Louis XIV was an accomplished athlete - nothing wimpy about that dancing. Hercules and Beauty (baritone and soprano) united to sing of "Altro gallico Alcide orso d'affecto". Cosmic forces indeed! Glorious final chorus, "All'impero d'Amore hi non cederà, S'à lui cede il valore d'ogni deità". The effect must have dazzled the Court of Louis XIV, blinding them into silence. Le Concert Royal de la Nuit marks the start of music, theatre, dance and opera as we know them now, but also marked a turning point in French history. Ensemble Correspondances have been performing Le Concert Royal de la Nuit in staged performance, complete with dancers, in recent years (premiering in Caen), so let's hope a miracle happens and we might get to see it in London. (William Christie and Les Arts Florissants have done a shortened unstaged version but with dancers). Until, then, give thanks and praise to Saint John's Smith Square and above all to the London Festival, of Baroque Music who had the courage to sponsor this remarkable series. Support their commitment and dedication !

Anne Ozorio

image=https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/97/Louis_XIV_habill%C3%A9_en_soleil.jpg/256px-Louis_XIV_habill%C3%A9_en_soleil.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

title=

product_by=Le Concert Royal de la Nuit : Ensemble Correspondances, Sébastien Daucé, London Baroque Festival, St John's Smith Square, London. 19th May 2018 A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Louis XIV, Le Roi Soliel

May 23, 2018

Voices of Revolution – Prokofiev, Exile and Return

The Philharmonia’s ‘Voices of Revolution’ concert series, programmed in the wake of celebrations for the hundredth anniversary of the October Revolution, reached its climax with a performance of Prokofiev’s Cantata for the Twentieth Anniversary of that revolution. First, however, we heard two highly contrasted works by the composer from 1917 itself: the much shorter cantata, Seven, they are Seven, and the First Violin Concerto (on whose material he had begun work two years earlier).

Seven, they are Seven (Semero ikh) received an exhilirating performance under Vladimir Ashkenazy, conductor of the entire series, joined by the equally fine David Butt Philip, Philharmonia Voices, and Crouch End Festival Chorus. Talk about starting in medias res! Here was a Russianised hymn to Mesopotamian paganism such as few of us, however feverish our imaginations, might otherwise have imagined, albeit with a materialist, nihilist bent the performers could not and should not shake off: the Scythian Suite rendered choral and, somehow, both more and less austere. Prokofiev’s clamour for a spirit world in which he clearly did not believe – hints of something later in the programme, or not? – looked forward to The Fiery Angel, and perhaps even beyond. Perhaps, though, the deepest, darkest music came with the relative hush towards the close: ‘Spirit of Heaven, conjure them’.

That Silver Age dying away into nothing seemed apt preparation for the Violin Concerto’s celebrated silver opening. ‘Febrile’ is a word I am sure I overuse. It is difficult, however, not to resort to it in describing Pekka Kuusisto’s performance, full of the most intense – perhaps, for some, too intense? – variegation in articulation and phrasing. Unfashionably, I have always preferred the concerto’s G minor successor; if this performance did not change my mind, it came closer than most and, indeed, seemed almost to highlight what the two works have in common rather than what distinguishes them. Moreover, its side-slipping harmonic progressions, especially in the first movement, seemed almost to incite metrical equivalents. The second movement proved truly a twentieth-century scherzo, with the musical – and technical – consequences implied. Bitter-sweet lyricism and much else one could imagine, whether a priori or a posteriori, characterised the finale. Kuusisto’s despatch of Prokofiev’s double-stopping was despatched with almost diabolically casual ease, he and Ashkenazy shaping and characterising the movement to a tee. Kuusisto’s encore improvisation on a Russian folksong, ‘Midnight in Moscow’, was perhaps for fans only – but he clearly, far from unreasonably, has a good few of them.

Then came the Cantata grand finale. Ashkenazy seems to have had it about right in an interview with The Daily Telegraph – remember when that was still occasionally a serious newspaper? – in 2003, telling Geoffrey Norris that the composer had ‘kind of welcomed what was happening in Russia and wanted to see the brighter side. He didn't want to see the tragedy. With this welcome back into his country, he felt he should do what the country wanted him to do.’ More specifically concerning the Cantata, Ashkenazy continued, ‘it wasn't … an obligation ... Some people say that he wanted to mock, but I don't think so. It's a great piece, one of his greatest achievements. His attitude was just to go along with the general flow.’ It is a fascinating piece, certainly; I am not entirely convinced that it was one of his greatest achievements, but it is far, far too good not to hear. And how the world has moved on since that interview: bar a few irreconcilables on the Right, we are mostly communists again now, albeit of very different stripes, from ‘fully automated luxury queer space’ to something a little more traditionally Stalinist. If the point, as Marx maintained in his Theses on Feuerbach, as heard here, were not just, as philosophers had done, to interpret the world, but to change it, then the progress socialism has made in just the last few years augurs well indeed. It still seems a little odd, perhaps, to watch a Festival Hall full of Home Counties concert-goers, celebrating Leninism, but none of them seemed to have a problem with doing so. Good for them, for who, in what is also Marx 200 year, is not now in some sense a Marxist? At any rate, surely none of us would have the grimly negative imagination – or perhaps you would? – to dream up a neoliberal cantata celebrating, say, Hayek, Thatcher, and May: perhaps one of those curious ‘Hecklers’ who once disrupted Birtwistle performances? Trump, perhaps, albeit in a gaudier, more ironic fashion: perhaps a commission for Helmut Lachenmann. As for a Blairite Third Way…

The opening sounded as if a socialist realist-ish Boris Godunov, the Philharmonia brass commendably ‘Russian’ in tone, albeit without raucousness. Whether that lack of roughness were an entirely good thing one may wonder; it is certainly Ashkenazy’s way. Listening afterwards, for instance, to Valery Gergiev in Rotterdam, I found more variety, perhaps something deeper, but it would be churlish to complain unduly, in what remained a highly accomplished performance. For Prokofiev’s late (late for him, that is) modernistic fragmentation retained degrees both of revolutionary disconcertion and of traditional grounding: surely Beethoven’s Ninth in the cellos that prepare the way for the choral entry: ‘massive’ here in every respect. Frozen, then thawing strings seemed also to pave the way for the ‘patriotic’ world soon to come, of Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible. Russia or socialism? You decide – or rather, Stalin will. Factory metal resounded, a reminder, perhaps of Mosolov, heard earlier in the series?

The lack of belief, in a strict sense, is quite different here from that of Shostakovich, and sounded as such. Whatever we think of the latter composer as ‘dissident’ or anything else, Prokofiev’s personality, musical and political, was of a very different nature, as side-slipping as those harmonies, which is not to impute cynicism, but perhaps to return us to Ashkenazy’s observations. (He, after all, unlike most of us, lived in the USSR.) And, just as in the Violin Concerto, Cinderella called too. There are no straight lines to draw in Prokofiev’s career; he did not come to write as he later did only on account of ‘external’ pressures. For there was belief of a sort: on hearing ‘We vow to you, Comrade Lenin…’ we did – if only, to quote Ashkenazy, ‘kind of’, at least whilst in thrall to Prokofiev’s stream of consciousness. Deafening: almost. Extraordinary: certainly.

Mark Berry

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sergei_Prokofiev_circa_1918_over_Chair_Bain.png image_description=Sergei Prokofiev, 1918 [Source: Wikipedia] product=yes product_title=Voices of Revolution – Prokofiev, Exile and Return product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Sergei Prokofiev, 1918 [Source: Wikipedia]Charpentier Histoires sacrées, staged - London Baroque Festival

Religion as theatre : and why not ? Like the architecture and ornamentation in baroque churches, devotional art served faith. Although St John's Smith Square was built in the less florid Northern Baroque style, Huguet's production transformed it, so it glowed. It felt as if we had stepped into a painting by Caravaggio or Velázquez.

Charpentier's Histoires sacrées have their roots both in sacred oratorio and in the mystery plays of the Middle Ages. Charpentier's audiences were well versed in biblical and liturgical texts, so they could appreciate these "stories" told with sophistication. At the heart of this programme were three histoires - Judith ou Béthulie libérée H.391, Madeleine en larmes H.343 and Cécile Vierge et Martyre H.397, framed by Ô Sacrement de Piété H.274, as prelude, Au parfum de tes onguents H.510) as interlude and Sous l’abri de ta miséricorde H.28 as postlude. This formal structure connects the three central characters, each of them a strong woman : Judith kills the Assyrian Holofernes who persecutes the Hebrews, Magdalena sings of her love for Christ and St Cecilia is martyred because she will not renounce her faith. Their stories are told through dramatic recitative, interspersed with choral and instrumental commentary and spoken narrative. While Judith's story is the most developed, with many sections and variations, the others have individual character. Magdalena's relatively short song is introduced by the vocal interlude, which mentions "scented oils", thus enhancing, figuratively, her odour of sanctity. The section about St Cecilia is bright and defiant, like the flames which devour the saint’s body, but not her soul. Towards the conclusion, the harpsichord, breaking from continuo, sings in joyous cadenza.

Although the text was in Latin, the stories themselves aren't hard to follow, and the work as a whole is propelled by vibrant musical logic, flowing freely from superb performances by the whole Ensemble Correspondances team. Modern performances of Charpentier's Histoires sacrées were pioneered some years ago by Gérard Lesni and Il Seminario Musicale but there is still much more in this rich vein to be discovered. Sébastien Daucé and Ensemble Correspondances present these three histoires with flair, enhanced immeasurably by Vincent Huguet's production. Huguet, who worked with Patrice Chéreau, understands the innate human drama in these narratives, though they may be expressed in stylized form. Large objects that resemble rockfaces, such as we see in 17th century depictions of biblical scenes, including symbolic olive trees. The idea that painting, or art, should be "realistic" is actually quite recent, and didn't apply in Charpentier's time. The simplicity of the sets also means that they can be moved quickly and quietly, without interrupting the flow of performance. Colours are added by lighting effects. Thoughtfully, the designers made use of the configuration of the building itself, using one of the high windows behind the stage to let light shine in "from above" as so often happens in devotional painting. As daylight faded to night, nature itself became part of the narrative. The singer's movements also reflected those in religious painting - hands raised and pointed, directing attention away from the singers as themselves to the stories being told. Altogether a remarkable experience. How fortunate we were that Sébastien Daucé has brought top quality, cutting edge performance practice to London.

Anne Ozorio

image=https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b2/Caravaggio_Judith_Beheading_Holofernes.jpg/400px-Caravaggio_Judith_Beheading_Holofernes.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

title= Marc-Antione Charpentier : Histoires sacrées - Ensemble Correspondances, Sébastien Daucé, St John';s Smith Square, London Festival of Baroque Music, 17th May 2018

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Caravaggio : Judith beheading Holofernes

May 22, 2018

No Time in Eternity: Iestyn Davies discusses Purcell and Nyman

In fact, Purcell and Nyman are not ‘musical strangers’. Nyman’s soundtrack for Peter Greenaway’s 1982 film The Draftsman’s Contract had drawn on Purcellian grounds - the composer is credited on the album as ‘music consultant’ - and the original Michael Nyman Band, formed in 1976, comprised instruments old and new: rebecs, sackbuts and shawms were heard alongside a banjo, electric bass and saxophone.

The Milton Court concert programme was curated by Fretwork’s Richard Boothby, Iestyn Davies explains, and includesThe Self-Laudatory Hymn of Inanna and Her Omnipotence (1992) , written for and first performed by Fretwork and James Bowman. The text - a translation of an ancient Near-Eastern hymn - is characterised by repetitions of the Sumerian Queen of Heaven’s sweeping exaltations of self-praise. The more recent No Time in Eternity - settings of seven short poems by the 17th-century metaphysical poet, Robert Herrick - was commissioned in 2014 by another viol consort, Ensemble Céladon, and countertenor Paulin Bündgen, and first performed by them in 2016.

There are further reflections on the musical and historical past in Nyman’s Balancing the Books, commissioned for the 250th anniversary of Bach’s death and loosely based on ideas drawn from the 48 Preludes and Fugues, and in the songs ‘If’ and ‘Why’, written to texts by Roger Pulvers and for inclusion in director Seiya Araki’s animated film, The Diary of Anne Frank (1995). Alongside Purcell’s ‘Evening Hymn’ and several of the composer’s fantasias for viol, a work which intimates a direct ‘conversation’ between past and present, Nyman’s Music after a While, completes the programme.

Christina Pluhar and L’Arpeggiata have previously woven the baroque, folk and jazz into a seamless tapestry; can minimalism be interlaced into the mix? I ask Iestyn Davies what forms and methods might create dialogue between the music of Purcell and Nyman? He remarks the similarity between the lucidity of the composers’ approaches to the setting of the English language, and also the repetitive structures that provide both architectural foundations and developmental impetus; both composers seem to contrive to deliberately make us aware of the passing of time. Certainly, I am often struck by the paradoxical presence of both somewhat rarefied gravity and accumulating rhetorical passion in the works of both composers, but I wonder if the ‘forward movement’ to which Iestyn refers is created by rather different means: that is, while Purcell’s repetitions are characterised by ever more complex, nuanced elaboration, and more radical re-interpretation of harmonic structures and inferences, Nyman effects forward ‘shifts’ by amending episodic reiterations - or, as Iestyn puts it, we are often ‘jolted’ by unanticipated interruptions to the revolving patterns.

I heard Iestyn Davies and Fretwork perform at Kings Place in December 2015 when I found the textural and timbral interplay of the viol consort and the countertenor voice compelling. The latter’s purity and limpidity and the gentle grain and refinement of the instrumental ensemble make interesting bedfellows. I ask Iestyn what he finds stimulating and challenging about performing with Fretwork - does one try to become the sixth voice in the viol consort? - and he surprises me with a detailed, sensitive and informed description of the contrast between the articulation, and thus the emphasis and phrasing, that results from the performance technique and practicalities of playing the viol. And, he notes the way this can surprise a performer who might more frequently perform a particular song with lute or string accompaniment. To exemplify, he hums the first few notes of the ground bass of Purcell’s ‘Music for a While’ and illustrates - gesturally and vocally - the way in which the viol-player’s bow-hold results in a ‘pushed’ rather than ‘pulled’ stroke, and so shapes the way the ground’s rising progressions are crafted and accented. He is no less precise and discerning when responding to my query whether performing with stringed-instrument accompaniments presents particular tuning problems to singers, explaining with astuteness and clarity the way in which a singer perceives the sung sound from both within and without, and the subsequent significance that the size and acoustic nature of the performing environment can have. He refers to a recent performance of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice to illustrate some of the challenges, noting that the delicacy of the strings’ texture in the quiet passage which follows ‘Che farò’ can make the harmony difficult to discern, and drawing a parallel with the shifting interplay of the viol voices within the consort - when performing at the less familiar pitch of A=430, for example.

Reflecting on repertoire, I note that the countertenor’s lot is essentially one of ‘old and new’ with a couple of centuries missing in between, but Iestyn reminds me that in June he will perform a programme of Purcell, Mendelssohn, Schumann and Quilter with soprano Carolyn Sampson and pianist Joseph Middleton at Wigmore Hall (drawing on their 2017 album, Lost is My Quiet ). And, then there is Schubert, specifically Die schöne Müllerin which I heard the countertenor perform at Middle Temple Hall with pianist Julius Drake in July last year. A recording of Florean Boesch singing a Schubert lied and a telephone call from Drake stirred Iestyn’s initial interest: after further consideration and investigation, Die schöne Müllerin - with a less broad registral range than other of Schubert’s cycles and a prevailingly ‘youthful’ spirit - seemed ‘do-able’. Though evidently very satisfied with the performance at Temple - and justifiably so; not only did both musicians’ technical and expressive performances provide much to admire, I was impressed too by the ‘imaginative psychological portrait that Davies and Drake created, and by the convincing coherence of the narrative arc of the sequence’ - Iestyn seems in no hurry to repeat the experience!

Instead, in July he returns to Glyndebourne to reprise his role as David in Barrie Kosky’s production of Handel’s Saul; he speaks eagerly about revisiting some of the dramatic challenges which Kosky poses and looks forward to the freshness that an entirely new cast will bring to the production. Kosky’s Saul was first seen in 2015, the year that also saw Iestyn treading the theatrical boards alongside Mark Rylance in Claire van Kampen’s Farinelli and the King, which originated at the Globe Theatre and subsequently transferred to the West End, and then to Broadway in 2017. Iestyn seems unbothered by the travel demands which modern-day singers faced, and looks forward to returning to New York in November this year - where last autumn he appeared at the Met in Thomas Adès The Exterminating Angel (seen at the ROH in April 2017) - to perform the role of Terry Rutland in Nico Muhly’s Marnie.

When I ask what is on his repertoire/role ‘wish-list’, apart from observing that Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is infinitely rewarding, Iestyn is pragmatic, open-minded and positive - he describes himself as a ‘fatalist’. He explains that the path to ‘star’ status was neither unclouded nor straight: he had been a ‘good’ treble at St John’s College Cambridge, but at eighteen it was not necessarily evident that he would be a ‘good countertenor’. Both Wells Cathedral - where he sang each Tuesday during his final year at school, and then as a full-time choral scholar during his gap year before university - and the London conservatoires, to which he applied post Cambridge Archaeology studies, did not instantly open their doors. Moreover, he has a healthily rational and reasonable attitude to decisions made and past triumphs and failures: one can’t have regrets. If he had studied at Eton, as his mother had wished, and not attended the school at which she was a deputy head, his experiences would have been ‘different’, but would they necessarily have been ‘better’ or the outcome more advantageous?

Iestyn speaks sensitively and intelligently, too, about the identification of the singer with their voice - by singers themselves and listeners alike. He remarks that while he wants to sing as long as he is able to perform at the highest level, when the time comes to stop there will be other things in life: one is not born a singer, and alongside performing there is simply being a ‘human being’ too. I find his observations about this merging of voice and identity fascinating, and agree that it is the ‘uniqueness’ of the singer’s sound which is so captivating; while there are some instrumentalists whose tone is instantly recognisable, the singing voice presents not just an interpretation of a particular piece of music, rather it is the visceral embodiment of it - and it can feel as if it is literally touching the heart. Iestyn remarks that this is as true of singers who have had a classical training, and those in other genres who have not, and notes that the speaking voice does not exert the same mesmeric sway.

I’ve no doubt, though, that on 28th May at Milton Court Concert Hall, Iestyn Davies and Fretwork will entrance us once more.

Claire Seymour

Image=http://www.operatoday.com/Iestyn-Davies%20Marco%20Borggreve.jpg image_description=Iestyn Davies and Fretwork perform Purcell and Nyman at Milton Court Theatre, 28th May 2018 product=yes product_title=Iestyn Davies and Fretwork perform Purcell and Nyman at Milton Court Theatre, 28th May 2018 product_by=An interview with Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Iestyn DaviesPhoto credit: Marco Borggreve

May 21, 2018

Aïda in Seattle: don’t mention the war!

Despite all that, the production was greeted with general applause from audience and critics alike as a sensitive and thoughtful updating of Verdi’s 1871 grand opera. (Read my Opera Today colleague James Sohre’s review here .)

What a difference four years can make. The Zambello Aïda which opened in San Francisco in 2016 was graced by the same kind of multi-culty, anti-violence program notes that accompanied Glimmerglass’s. But the ideological edge had vanished. True, Radamès gave a Fascist salute at the climax of the Triumphal scene; but that edgy moment had vanished by the time the show arrived at the Kennedy Center last year.

Further softenings ensued before touch-down in Seattle: what we saw wouldn’t have troubled a 1950 audience, apart from the absence of elephants.

Elena Gabouri (Amneris) and Daniel Sumegi (Ramfis). [Photo by Jacob Lucas]

Elena Gabouri (Amneris) and Daniel Sumegi (Ramfis). [Photo by Jacob Lucas]

War and its agonies had been pretty much painted over, rendering Verdi’s stuffy but memorable opera as anodyne as a Midwestern Christian college musical: at the cost, granted, of depriving it of any dramatic impact at all.

That left us with half a dozen of Verdi’s most memorable tunes to occupy us for three and a half hours. We were diverted (or not) strictly to the extent the performers were capable of overcoming the incoherence of the staging and the faint but pervasive aroma of bad faith.

Most prepossessing of the Saturday evening cast I saw was David Pomeroy as Radamès. His voice is not particularly beautiful or powerful, but his stamina convinces one he could go on popping off ringing high As and Bs all night, and his youthful, open demeanor earns necessary sympathy for one of the most clueless heroes in the whole repertory.

Alfred Walker scored points for his dignity and dramatic declamation as the heroine’s prisoner father Amonasro. The same goes for bass Daniel Sumegi as the high priest Ramfis, towering over everybody else like the very incarnation of high dudgeon.

Alexandra LoBianco (Aida) and David Pomeroy (Radamès). [Photo by Jacob Lucas]

Alexandra LoBianco (Aida) and David Pomeroy (Radamès). [Photo by Jacob Lucas]

As the title character Alexandra Lobianco sang the tender music of acts three and four with sweetness and warmth; in the first two acts, she was inaudible whenever the orchestra rose above mezzo piano. Burdened with silent-movie heroine make-up and blocking which kept her hovering timidly on the edge of the action, she seemed feebleness personified. It seemed impossible that fierce divas like Leontyne Price and Birgit Nilsson could have achieved fame in such a mousy role.

No such doubt could be felt in Elena Gabouri’s Amneris, Aïda’s rival for the hero’s love. Amneris is a severly conflicted woman; Gabouri made her a thoroughly disagreeable one as well. Her first appearance, marching around Egyptian military HQ and blaring with bad temper, set the tone for her whole performance.

John Fiore appears to be a “singer’s friend” type of opera conductor, giving telegraphic cues and pacing generously, at the cost of dramatic tension Jessica Lang’s choreography, most prominent in the Triumphal scene, is pretty, graceful, and cloying.

“Cloy” doesn’t cover the substitution of a covey of red-beret-wearing Cub Scouts for the libretto’s dancing Moorish slave-boys. They also feature in the climax of the Triumphal scene, along with a blizzard of gilded-vinyl confetti. Cute kids and confetti: that’s what I’ll remember from this production. Whatever the political incorrectness of Verdi’s original, it didn’t deserve this.

Roger Downey

Cast and production information:

Ramfis: Daniel Sumegi; Radames: David Pomeroy; Amneris: Elena Gabouri; Aida: Alexandra Lobianco; King: Clayton Brainerd; Messenger: Eric Neuville; High Priestess: Marcy Stonikas; Amonasro: Alfred Walker; Stage Director: E. Lauren Meeker, after the original staging by Francesca Zambello; Set Design: Michael Yeargen; Projections hangings, set pieces: RETNA (Marquis Duriel Lewis); Costumes: Anita Yavich; Lighting Design: Mark McCullough and Peter W. Mitchell; Choreographer: Jessica Lang; Chorus Master: John Keene. Seattle Opera Orchestra, John Fiore, conductor.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/180502_Aida_DR.1_-1608.png image_description=Alexandra LoBianco (Aida). Jacob Lucas photo product=yes product_title=Aïda in Seattle: don’t mention the war! product_by=A review by Roger Downey product_id=Above: Alexandra LoBianco (Aida). [Photo by Jacob Lucas]May 20, 2018

Glyndebourne Festival Opera 2018 opens with Annilese Miskimmon's Madama Butterfly

Miskimmon has shifted the action forward to the 1950s in order, she explains, to use the ‘fake GI bride industry’ that was kick-started by the 1945 War Brides Act and the 1952 Immigration Act, which enabled American serviceman to bring foreign brides home to the US to underline the darkness of the power, to underline the exploitative darkness of the power dynamic between Lieutenant B.F. Pinkerton and Cio-Cio-San.

So, the action begins in the ugly office of Gozo’s ‘marriage-broker’ business - though the catalogues of oriental beauties from which the GI’s make their choice and the clanging chink of silver in the cash register suggests that ‘brothel’ might be a more apt term. Designer Nicky Shaw evokes a drab seediness: higgledy-piggledy filing cabinets are illuminated by the intermittent flash of red and blue neon - ‘Hotel’, ‘Tattoo’ - and as cheap confetti is strewn brusquely over the conveyor belt of brides, the strings’ violent stabs in the overture take on a discomforting resonance. Flip-charts spin and cine-reels roll, instructing Eastern ingénues how to be a good American wife and embark on a journey to a new life in the US, where they can live the Dream. There is a disturbing double displacement: the Americans have callously colonised Nagasaki, and then coerced and lured the Japanese into their own world. Nowhere is this more apparent than when Cio-Cio-San is forced by her new husband to fling her wedding bouquet over her shoulder, as confused as the wedding guests who dart aside to avoid its fall.

Olga Busuioc (Cio-Cio-San, left), Joshua Guerrero (Lieutenant B.F. Pinkerton, left), Carlo Bosi (Goro, rear). Photo credit: Robbie Jack.

Olga Busuioc (Cio-Cio-San, left), Joshua Guerrero (Lieutenant B.F. Pinkerton, left), Carlo Bosi (Goro, rear). Photo credit: Robbie Jack.

It leaves a horrid taste of merciless mercantilism, which makes Miskimmon’s point. More problematic is that the shift of locale makes a nonsense of the libretto’s frequent references to the house on which Pinkerton has just taken out a 999-year lease. An estate agent’s cardboard model is an attempt at remedy: and, the miniature abode does underline that paper walls can be shifted just as easily as deeds can be undone and knots tied torn asunder. It’s all a game - Pinkerton lounges insouciantly with his feet on Gozo’s desk - and Cio-Cio-San is a plaything, a doll. This ‘unreality’ is emphasised during the marriage ceremony by the division of the stage, as the bored US contingent lean impatiently, stage-left, while opposite, Cio-Cio-San’s family strive to earnestly engage in the ‘ceremony’.