June 30, 2018

An ambitious double-bill by the Royal College of Music

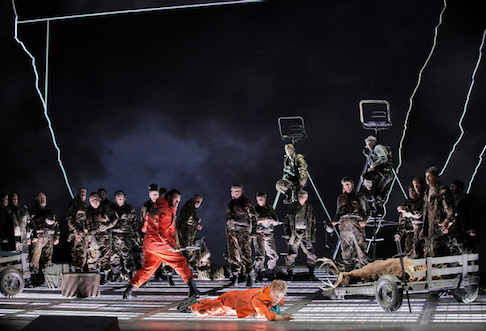

On Monday, ENO and Regent’s Park Theatre’s production of Britten’s The Turn of the Screw, invited us to ponder Jamesian ambiguities and the moral and psychological chasms which open up when appearance and reality, feeling and knowing, become confused. Subsequently, this double-bill by the Royal College of Music International Opera School trod a similarly equivocal line between imaginative fancies, both teasing and threatening, and cold pragmatic reality.

The unknowable evil of James’s ghosts and the unfathomable horror of the ‘cry of the beast’ which lurches through the fog towards the three lighthouse keepers at the close of Peter Maxwell Davies’s The Lighthouse conjure similar psychological and paranormal mysteries. But, the ‘nightmares’ presented by Huw Watkins and librettist David Harsent in their forty-five-minute opera, The Locked Room, are of a more prosaic, if no less tragic and disturbing, nature.

Ella Foley faces the misery of a loveless marriage and the frustrations of bourgeois life. Married to the boorish Stephen - a mobile-phone clutching businessman who’s desperate to seal a crucial City deal - Ella retreats into poetry; namely, the work of Ben Pascoe. The poet, Ella is astonished to learn from Susan, the owner of the Sussex home that she and Stephen are renting, has a permanent lease on a single room in their cottage - a room which the poet insists remains locked when he is absent. Retreating from her husband’s insensitivity, and violence, Ella enters into an imagined conversation with Pascoe; she is distressed to find that he has visited the house while she was out, but seeing that the poet has left his coat on the chair, she fantasises his return, and their subsequent spiritual and physical union.

The Locked Room was first seen in 2012 at the Edinburgh Festival and has subsequently been produced in the ROH’s Linbury Theatre, by Music Theatre Wales, and more recently by Staatsoper Hamburg. The libretto is ‘loosely’ based upon a short story by Thomas Hardy, ‘The Imaginative Woman’. ‘Loosely’ is an apt word; in fact, the programme booklet did not mention Hardy at all, director Stephen Unwin preferring instead to describe the opera as an ‘Ibsenite drama’. And, indeed, there is something of The Doll’s House, in the painful discrepancy between Ella’s expectations, hopes and desires and her practical situation.

But, Hardy’s story, while exposing the marriage of Ella and William Marchmill to be characterised by evasion and self-deception, and symptomatic of the nineteenth-century belief that matrimony was an exemplification of the ‘necessity of getting life-leased at all cost’, is as much a Romantic tale as a ‘modern’ one. Marriage is shown to be a tragically inadequate means of realising the aspirations of the individual’s creative, imaginative inner life. And, it is this absence of fulfilment which gives the short story its power.

In Hardy’s tale, this absence is represented by the elusiveness of the poet, Robert Trewe, who never actually materialises in the text, beyond Ella’s dreaming. We never see, nor hear directly from Trewe. As with The Turn of the Screw and The Lighthouse, it is the stubborn refusal of the ‘text’ to yield its secrets that is at the root of the narrative power. Trewe’s room in the Wessex boarding house where the Marchmills are lodged is not locked and Ella appropriates this room, ‘because [his] books are here’. A would-be poet herself, she is envious of the success and renown of his passionate and pessimistic verses, which seem so much stronger than her own feeble lines.

Despite frequent intimations that he might pass by the house, Robert Trewe never visits the Marchmill abode, though this does not prevent Ella indulging in a quasi-sexual encounter with his photograph, futilely seeking out the poet’s own lodging in a ‘lonely spot’ nearby. Eventually, she pens Trewe a note of admiration, signed as her alias John Ivy, which receives a short, polite response but initiates a regular, terse correspondence, and she is able to manoeuvre a possible meeting with the poet, inviting him to visit when he is in the vicinity. The meeting never occurs, and when Ella learns, shortly afterwards, that the depressive has killed himself, Ella - though the mother of three and pregnant with a fourth child - contemplates suicide. In the end, she dies in childbirth; some years later the resemblance of the boy to the photograph of Trewe which William finds among her possessions when preparing for his second marriage, triggers jealous suspicions and rejection of the faultless child.

I offer this summary of Hardy’s story not because I believe that Harsent is obliged in any way to reproduce his literary model without imaginative intervention and adaptation, but because it highlights one of the weaknesses arising from the changes that he has made. While their music-drama is taut and tense, Harsent and Watkins decision to present us with the living, breathing Ben Pascoe - an alcoholic depressive who makes use of Susan’s sexual services (“Is it me or the sex”, he asks; “The sex,” she replies), destroys the essence of the emotional tragedy: the corporeal manifestation of the imagined soul-mate - wearing turned-up jeans and a scarf tightly wounded around his neck - over-powers the delicate equivocation of the tale.

Transferring the tale to the modern-day seems to rob the characters of some of their fullness of depiction and thus further reduces the moral ambiguity. For example, Stephen seems too one-dimensional and crude. Hardy’s William may be uncultivated and indifferent to Ella’s needs and desires, but he is not cruel; Hardy describes him as ‘equable’ and ‘usually kind and tolerant to her’. Harsent’s Stephen rapes his wife - and Watkins provides the expected percussive assault. Hardy also shows that Ella, too, contributes to the sterility of their marriage: she is a ‘votary of the muse … shrinking humanely from detailed knowledge of her husband’s [gun-making] trade’ which she considers ‘sordid and material’. Her imaginativeness is not harmless; rather, it is tragically destructive, for William and their child as much as for herself. Harsent’s Ella seems entirely removed from any moral scrutiny. She does not die; instead, the heavily pregnant Ella, standing beside the gravestone of Pascoe, rejects her husband and retreats from the reality of marriage into her own imaginative cocoon.

It’s partly a consequence of the up-dating of the tale, but another problem, for me at least, is that the libretto is too prosaic, given that it is the imaginative faculty, as symbolise by poetry, that Hardy both celebrates and critiques, within the context nineteenth-century marriage. Like Strauss, in Capriccio, Hardy is essentially asking, what is poetry for? Stephen does ask Ella this question directly, but it’s not a question that the opera itself really attempts to answer; the score seems often to be quite detached from the drama ensuing on stage. Stephen is glued to his mobile phone and frets about deals that may “come good” or “tank”, ranting, “Jesus Christ! What a day I’ve had.” - though, Harsent’s quip that business is simply a matter of “telling the right lie at the right time” rings all too true.

These misgivings aside, Watkins’ score is a beautiful patterned tapestry of understated sentiment and colour - burbling woodwind, string harmonics, lyrical utterances from the horns - with occasional outbursts of violence from the growling brass. It was played with accomplishment by the RCM instrumentalists under Michael Rosewell.

And, the cast of four produced dramatically focused and confidently sung performances. Thomas Erlank swaggered belligerently as the crude financier, Stephen, singing with forthrightness and directness, while Theodore Platt did well to make Ben Pascoe a more sympathetic character than the text might suggest. Lauren Joyanne Morris delivered Susan’s quiet aria assuredly. Beth Moxon delivered Ella’s short, declamatory lines with conviction and fluency, while managing to make Ella appear convincingly troubled and ‘lost’.

The staging was minimal, perhaps by economic necessity rather than choice, but the central door which stood defiantly against a plain lit-backdrop of blue sea-sky was an effective motif, one which put me in mind of another ‘locked room’ - that at the heart of Britten’s Owen Wingrave, which presents another Jamesian mystery with a tragic denouement. Less pleasing was the incessant shifting about of assorted chairs - garden benches, arm-chairs, sofas - that were wheeled or carried briskly on and off stage by headset-wearing, black-clad RCM stage-hands. It didn’t enhance the depiction of the imaginative life.

Hannah Wolfe’s designs for The Lighthouse were similarly economical but more evocative and inventive. Particularly effective was the transition, in the opening Act, from the courtroom -represented by three chairs placed before the front-curtain from which the officers gave their disturbing evidence to the National Lighthouse Board - to the evocation of the locale of their account: a transition effected by the half-lifting of the curtain to reveal the foot of the lighthouse tower, swirling in mist and shadows, at the centre of which three unoccupied chairs, over-turned buckets, dangling ropes and lanterns, and other debris intimated unexplained disappearance and fear. Subsequently, as the officers ‘re-enacted’ their discovery of the abandoned island, and the curtain rose fully, we became increasingly immersed in their experience, only to be swiftly returned to the present with the announcement of the open verdict and the return to the front-stage courtroom.

Unwin and Wolfe couldn’t quite generate genuine, gripping horror in the opera’s final moments; there was plenty of mist and some shadow-inducing lighting, but the shifting shapes on the streaked back-drop and the sudden blaze of red light didn’t have me on the edge of my seat. That was not the fault of the three singers, though, who in both guises - officers and light-house keepers - performed with tremendous commitment, intensity and flair. Richard Pinkstone’s Act 1 narration was deeply engaging, and he brought a similarly affecting tone to his Act 2 song about a mysterious lover, imbuing the song with aching despair and distress. As Blazes, James Atkinson was certainly a fiery spirit, his falsetto flashes indicating psychological imbalance and anger in equal measure. Timothy Edlin thundered Arthur’s Salvation Army hymns of damnation and redemption with passion and rhetorical fervour. The playing of the RCM instrumentalists matched the tautness of the unfolding drama, as Rosewell dug deep into Maxell Davies’s striking sound-palette.

Overall, this was a characteristically ambitious and polished double-bill by the Royal College of Music International Opera School.

Claire Seymour

Huw Watkins:

The Locked Room

Susan Wheeler - Lauren Joyanne Morris, Ella Foley - Beth Moxon, Stephen

Foley - Thomas Erlank, Ben Pascoe - Theodore Platt.

Peter Maxwell Davies: The Lighthouse

Sandy/Officer 1 - Richard Pinkstone, Blazes/Officer 2 - James Aitkinson,

Arthur/Voices of the Cards/Officer 3 - Timothy Edlin.

Director - Stephen Unwin, Conductor - Michael Rosewell, Designer - Hannah Wolfe, Lighting Designer - Ralph Stokeld.

The Britten Theatre, Royal College of Music, London; Wednesday 27 th June 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Locked%20Room.jpg image_description=The Locked Room and The Lighthouse: Royal College of Music International Opera School product=yes product_title=The Locked Room and The Lighthouse: Royal College of Music International Opera School product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Theodore Platt (Ben Pascoe) Beth Moxon (Ella Foley), Thomas Erlank (Stephen Foley), and Lauren Joyanne Morris (Susan Wheeler)June 29, 2018

POP Uncorks Bubbly Rossini Vintage

Whether the assembled patrons were loyal POP-eragoers, or eager Italian comic opera enthusiasts, it was demonstrably clear they were already expecting a good time. Happily, La Gazetta did not disappoint.

The plot is fast, loose, and occasionally illogical. A wealthy Neapolitan merchant arrives at the Aquila Hotel in Paris with his marriageable daughter in tow. Don Pomponio has anonymously placed an ad in newspapers far and wide that he will entertain “applications” to wed his attractive offspring, Lisetta. Unbeknownst to the Don, the girl is already (somehow) secretly in love with the owner of the Aquila, Filippo.

In parallel stories, a well-to-do playboy (Alberto) is ready to marry somebody/anybody who will have him. After Lisetta rejects him by falsely claiming she is already wed, Alberto instantly pursues Doralice, improbably and instantly winning her hand, since she has arrived looking for a husband.

With more comic twists and contortions than a Feydeau farce, Doralice is manipulated by her hectoring, aging dad, Anselmo. Tossed into the mix for no real reason are two extraneous personages: the meddling Madama la Rose (a blasé woman of luxury) and her inexplicably fey traveling companion Monsu Traversen. Got all this so far?

Well, you can now forget about it pretty much completely since the characters’ motivations, intentions, and emotional trajectories seem to turn on a dime (or a Euro). Giuseppe Palomba’s libretto (adapted from Goldoni’s Il matrimonio per concorso) serves only to approximate relationships and calculate conflicts that can then explode in an outpouring of delectable solos and ensembles. All the beloved trademark Rossinian musical effects are on ample display: dizzying coloratura, stratospheric melodic flights, tongue-twisting patter, intricately interwoven ensembles, heady crescendi, and ample variety.

Rossini notoriously “borrowed” from his own other works throughout his storied career, thus La Gazzetta has the same overture as La Cenerentola, part of an Act One Finale from Il barbiere di Sivigilia, a scrap or two from L’Italiana in Algieri, and unless my ears deceived me, some limpid phrases from Semiramide. If nothing in La Gazzetta is as effective as the set pieces in the master’s more familiarly celebrated works, there is still plenty to tickle the ear and even tug at the heart.

Armando Contreras (Phillipo) and E. Scott Levin (Don Pompoonio). Photo credit: Martha Benedict.

Armando Contreras (Phillipo) and E. Scott Levin (Don Pompoonio). Photo credit: Martha Benedict.

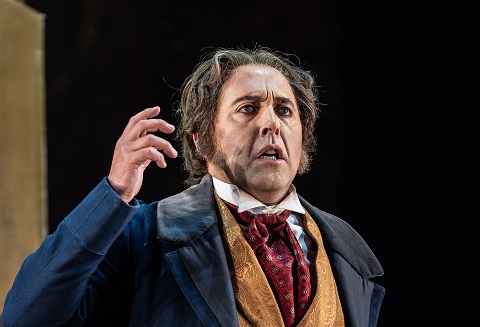

Don Pomponio’s entrance aria was one notably well-crafted solo piece, and E. Scott Levin made the most of the vocal opportunity. Mr. Levin has a sturdy, malleable bass-baritone, and he wields it with precision and authority. He has just the right look for this rich buffo role, although the requisite blustery musical temperament took a bit of time to catch up. After a somewhat “controlled” beginning, he capably eased into more abandoned comic effects, both visual and vocal.

Another memorable moment was Alberto’s plangent Act Two aria, which was suavely, tenderly delivered by tenor Kyle Patterson. Mr. Patterson’s earnest, boyish presence also characterized his exceedingly pleasant singing, complete with accurate, rapid-fire coloratura, which whizzed about effortlessly throughout the range. If Kyle slightly veils his very top notes, they were nevertheless delivered with enough panache to elicit one of the evening’s most enthusiastic ovations.

Messrs. Levin and Patterson also contributed notably to a flashy, rhythmically complex, stuttering trio, ably joined by Armando Contreras (Phillipo). Mr. Contreras is possessed of a strapping baritone, which he deploys with unerring musicianship and fine dramatic understanding. Armando’s complete command of copious, Dandini-esque melismatic passages was commendable for its fiery accuracy and conviction. This same trio also ignited a goofy charisma between the three performers who brought the house down with uninhibited hip bumps, daftly synchronized semaphoric gestures, and flat out unrestrained good singing.

Rachel Policar (Lisetta). Photo credit: Martha Benedict.

Rachel Policar (Lisetta). Photo credit: Martha Benedict.

On the distaff side, Rachel Policar scored a considerable success as the complicated, conflicted daughter-for-sale, Lisetta. Ms. Policar cuts a petite, slender figure on the stage, and her silvery soprano is in the very light lyric Fach. But don’t underestimate her power to communicate spitfire moments, as she zings out roulades and acuti with effortless aplomb. In her main aria, she manages not only a bravura display of florid singing, but does it all while being toted and hoisted around by four chorus boys, at one point being held aloft in a full-flying split. Do not try this at home!

Molly Clementz displayed a plummy mezzo as the man-hunting Doralice. Ms. Clementz has a wonderfully rich tone, gleaming top notes, and a vibrant lower register. While she is not yet quite wholly immersed in the specific Rossinian tradition of presentation, hers is still already an enjoyable role traversal. As Doralice’s manipulative father Anselmo, veteran Phil Meyer’s commanding bass rolled forth with domineering, characterful results.

Mezzo-soprano Jessie Shulman and baritone Scott Ziemann perhaps did all they could in the (for me) extraneous throwaway roles of Madama La Rose and Monsu Traversen, respectively. In these under-written parts, Ms. Shulman nevertheless had effective moments above the staff when she mustered some real oomph to propel her distinctive, diffuse vocal quality. For all Mr. Ziemann’s animated mincing and limp-wristed tic’s, his singing did not match his physical commitment. What I heard was attractive, but I did not always hear him.

The industrious chorus of eight was called upon to do the work of eighty, and man, did they deliver the goods! Whether singing with full-throated abandon, or executing Amy Lawrence’s relentless choreography, or quick-changing costumes numerous times, this energetic group never flagged in their coordinated concentration.

Photo credit: Scott Ziemann (Monsu Traversen), Jessie Shulman (Madama La Rose), and Kyle Patterson (Alberto). Photo credit: Martha Benedict.

Photo credit: Scott Ziemann (Monsu Traversen), Jessie Shulman (Madama La Rose), and Kyle Patterson (Alberto). Photo credit: Martha Benedict.

Director Josh Shaw has invested the proceedings with enough good comic ideas for at least three productions. Designer Josh Shaw has set the show in 1960’s Paris, with eye-popping set elements and brilliant uses of color which add to the manic feel. The hotel lobby is on the main stage with an up center platform backed by four large cutout diamonds, with the check-in desk looming down stage left. The action spills over to house right, onto a platform dressed as the hotel bar.

As visually appealing as is the total look, it felt more like Retro Vegas than 60’s Paris Chic. That said, Maggie Green’s witty profusion of costumes added immeasurably to ground the concept. By the ending tableau with everyone cavorting in glitzy, sparkling, faux Turkish floor show attire, okay, okay, I might just stretch to imagine we could indeed be reveling in the Lido or Moulin Rouge “in the day.”

One promising design element was the well-intended lighting. The prolific and effective use of color did not quite compensate for the recurring dark spots, or infrequent delayed cues. In the bar, there were five stools used for the beautifully performed, rediscovered quintet, but one of the characters was in the dark for the whole segment. Perhaps an instrument was out? This should be an easy adjustment to make for future performances.

Mr. Shaw has fashioned a take-no-prisoners approach to the staging, which was rife with clever touches. The use of revolving chairs was a recurring theme, likewise a kick line or ten. Unison gestures were repeated, inverted, subtracted, added and inverted again. While all of this was meticulously executed, I felt there could have been moments of stillness that would have added variety. During a particularly unrelenting frenzied passage I found myself wanting to say: “Don’t just do something, stand there!” I got my wish in Act II when the material lent itself to a more measured presentation.

Brooke deRosa conducted with stylistic acumen, in a reduced orchestration of her own creation. In spite of the sprawling playing space and the supreme challenge of the musical complexities, Maestra deRosa commanded her forces with admirable precision. While the ten instrumentalists displayed good individual talent and a conscientious approach, at the premiere they experienced a few scrappy ensemble moments. Too, they sometimes ran out of aural steam in musical playoffs. Perhaps reordering their placement behind the set, putting the strings forward and the winds in the rear would even out the sound a bit more.

To the cheering, capacity audience, none of this nitpicking mattered, of course. The crowd was fully engaged from first to last. In addition to the charming performance, the opera-going experience included table seating, a charcuterie platter, and a bottle of wine. Pacific Opera Project has evidently hit on a winning formula for a night out, serving up food, drink and an operatic discovery in equal measure.

POP will be broadcasting the final performance (Saturday, July 7 at 8:00 pm PDT) on Facebook Live.

James Sohre

Rossini: La Gazzetta

Don Pomponio: E. Scott Levin; Lisetta: Rachel Policar; Phillipo: Armando Contreras; Alberto: Kyle Patterson; Doralice: Molly Clementz; Madama La Rose: Jessie Shulman; Monsu Traversen: Scott Ziemann; Anselmo: Phil Meyer; Conductor: Brooke deRosa; Director and Designer: Josh Shaw; Choreographer: Amy Lawrence; Costume Designer: Maggie Green; Continuo: Zach Neufeld

Image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rachel%20Policar%20%28Lisetta%29%2C%20E.%20Scott%20Levin%20%28Don%20Pomponio%29%2C%20Kyle%20Patterson%20%28Alberto%29%2C%20Armando%20Contreras%20%28Fillipo%29%2C%20Molly%20Clementz%20%28Doralice%29.jpg

image_description=La Gazetta, Pacific Opera Project

product=yes

product_title=La Gazetta, Pacific Opera Project

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id= Above: Rachel Policar (Lisetta), E. Scott Levin (Don Pomponio), Kyle Patterson (Alberto), Armando Contreras (Fillipo), Molly Clementz (Doralice)

Photo credit: Martha Benedict

Dangerous Liasions : Music and dance in the French Baroque

More than 40 extracts, primarily from Lully and Rameau, were chosen to form a highly original compilation, unfolding in thematic sequence : Idyllic Delight, Seduction, a Ballet des Fleurs, Vexation, Loss and Despair, Frolics and Mischief, with Reconciliation, the happy ending. It's quite an achievement to put together more than 40 disparate extracts so they flow together naturally, yet with much variety. Like Le Concert Royal de la Nuit, (more here) this cohered well, an excellent summary of style and content. Much admiration is due to the OAE's Principal Flute Lisa Beznosiuk, who curated this with the support of an OAE team and Hubert Hazebroucq, who choreographed the dancing in period style. This was also an exercise in French declamatory song style, with period (not modern) pronunciation, so credit is due, too, to soloists Anna Dennis and Nick Pritchard. Conducted by John Butt, the OAE were in vivacious form : a delightful two and a half hours which passed all too quickly.

Like a prologue to a drama, the OAE began with Lully's Overture from Le Triomphe de L'Amour, followed by six miniatures, four from Lully's Thésée (1675) "Aimons tout nous y convie, on aime ici sans danger". Notice the archaic language, which did mater, since it complemented the stylised, idealised sentiments in the text, and in this context reminded us that the world of the baroque needs to be understood on its own terms. Thus the dancing, very different to what we take for granted today. Like the art of fencing, dance prepared young noblemen with skills much needed in Court circles : physical fitness, mental discipline, alertness to strategy and form and an awareness of elegant presentation. Thus the stances - hands and feet held at angles, foot positions which would have developed formidable muscles, enabling the dancer to control his position until he was ready to execute swift, decisive changes. The formal patterns of dance also reflected concepts of social and cosmic order, the individual functioning as part of an ensemble.

Hazebroucq's choreography is based on extensive archival research but also on the relationship between dance and music, so fundamental to the baroque aesthetic. Lully didn't conduct with a staff for nothing : he was (literally) beating time, creating a percussive foundation for music that was made to be moved to. Hence the vigorous rhythms and exuberance, at times reminiscent of military marches and fanfares. Period instruments pack an earthy punch, horns and percussion evoking instruments from even more archaic times, complementing the baroque fascination with classical antiquity. The stringed instruments, plucked or bowed, added variety and character, sometimes providing continuo, or embarking on flights of inventiveness. Seeing the dancers move in close relation to the music enhanced understanding of the musical logic.

Thoughtfully, this Liaisons Dangereuses (like the novel that is told in letters, not narrative), interleaved an extract from Lully's Les Noces de Village (1663),between the pieces from Lully's Thésée. Philinte and Climene are idealised shepherd and shepherdess, more personable than the more stylised, abstract evocations of love in Thésée. This also served to show that court dance, even when inspired by pastoral fantasy, was not folk dance but far more sophisticated. The second section, "Seduction", combined extracts from André Campra's L'Europe Galante (1697) and Lully's Le Bourgeois Genthilhomme (1670),, the vaguely "Spanish" allusions adding exotic spice, to the dancing as much as to the music. In the Interlude, a "Ballet des Fleurs" , the dancers enacted an allegory in which three figures interact as lovers and rivals, eventually finding reconciliation. This is an allegory in music, too, combining Gavottes and Airs sourced from Rameau's Les Indes Galantes and Lully's Atys (1676), allowing the dancers ample room for elegant, intricate patterns of movement. The section "Vexation" was based on Lully's Armide (1686), where the sorceress Armide tries to seduce Renaud. Anna Dennis was particularly impressive in this splendid role with Nick Pritchard her foil, dancers in black, the orchestra conjuring up a storm..

The section "Loss and Despair" began with the Prelude from Charpentier's Orphée descendant aux enfers (1684) setting the scene. An extract from Lully's Ballet royal de la Naissance de Venus (1665) prepared the way for Orpheus "Tu ne la pendras point, hélas, pour me le rendre" and Proserpine's "Courage Orphée, étale ici les plus grands charmes", also from Charpentier's La descent d'Orphee aux Enfers depict the Underworld. But love itself does not die. Venus (Anna Dennis) sang "Amiable Vainqueur" from Campra's Hésione (1700), neatly connecting the Orpheus legend with a tragédie en musique with characters from other parts of classical mythology. "Love that is strong enough can "Désarmer le Dieu de la Guerre: le Dieu de la Tonnere" evoked by the wind machines, crashes of percussion and baleful brass in the orchestra. After the tumult, fantasy and fun. From Rameau's Platée (1745) a satire, and a parody from Jean-Joseph Mouret's Les Amours de Ragonde (1714) In the former, the gods squabble, causing invertebrates and mortals to fall in unrequited love. In the latter, couples end up mismatched. Colin, who ends up wed to his would be mother in law sings mock peasant dialect "Je ne songeons qu'uà bien aimer, je rougirions d'être volage". Warped humour, the opposite of idealised courtly love, but an opportunity to see the dancers imitate folksy jigs and "exotic" dances. But all is resolved in the final tableau, Reconciliation. Eglé and Mercury sort out their differences in a dialogue from Rameau's Les Fêtes d'Hébé (1739) and Calatée, Mercure, Zoroaster and Amelite sort out theirs in Rameau's Zoroastre (1739).

Anne Ozorio

image=https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f6/Armide_Lully_by_Saint-Aubin.jpg/512px-Armide_Lully_by_Saint-Aubin.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

title=

product_by=Dangerous Liasions : The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Anna Dennis, Nick Pritchard, Les Corps Éloquents (Hubert Hazebrouq, choreographer), Queen Elizabeth hall, London. 26th June 2018. A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: -Armide_Lully_by_Saint-Aubin

June 27, 2018

Lessons in Love and Violence at the Holland Festival: Impressive in parts

Dutch National Opera, one of the work’s seven (!) co-producers, is hosting the production. Benjamin’s new opus impresses with its orchestral texture and the production boasts deluxe visuals and top-drawer performances. But Crimp’s dialogue renders the characters elusive and the score loses theatrical momentum after a strong first half.

Lessons is loosely based on Christopher Marlowe’s historical play Edward II. The plot’s motor is the King’s politically disastrous relationship with his despised favorite, Piers Gaveston. Crimp distills the drama around four main characters: the King, Queen Isabel, Gaveston and the rebel lord Mortimer. After masterminding Gaveston’s death, Mortimer teams up with Isabel to depose the King in favor of his son. The boy king then brutally repays Mortimer for his lessons in ruthless statesmanship. Split into seven scenes, the plot explores the conflict between personal relationships and the responsibilities of power. The libretto specifies different locations, but director Katie Mitchell stages every scene in the King’s bedroom. The handsome set, decorated with Francis Bacon paintings, a reference to Edward’s patronage of the arts, and a tropical aquarium, shifts to reveal different angles of the room. It looks wonderful, but anchoring the plot in a single space has an alienating effect. Mitchell creates further emotional distance between the stage and the public by casting the royal children as constant observers, although this could be Crimp’s directive. Sleek-voiced tenor Samuel Boden as the Boy and Ocean Barrington-Cook, eloquent in the silent role of the Girl, are privy to the most intimate and lacerating interactions between their parents, Gaveston and Mortimer. Seeing them observe and absorb their dubious lessons turns us spectators into clinical observers.

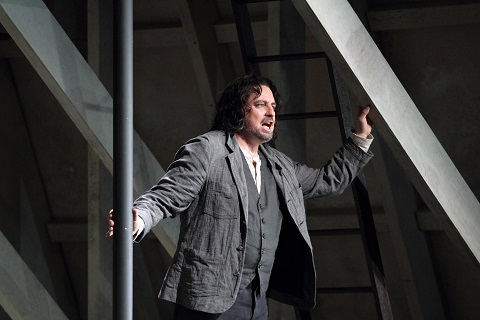

Crimp’s conversations also seem designed to discourage emotional involvement. His pairs of questions and answers sound like wisps of Socratic dialogue. Feelings are hinted at, personalities remain undeveloped. Stéphane Degout’s baritone flowed like dark honey but his words never conveyed who the King really is. He is in thrall to his controlling lover Gaveston, but why? That Isabel emerges as the most clearly delineated character is certainly thanks to Barbara Hannigan’s consummate artistry, but also because her high-lying music, tailored to Hannigan’s strengths, has a distinctive imprint. One of the opera’s best scenes is the nocturnal duet between Isabel and the King. Gaveston has been killed and their relationship has reached its breaking point. Hannigan’s penetrant soprano twisting up into florid hysteria above Degout’s mellifluous misery presented a striking contrast to the prevalent bas-relief of singing imitating speech rhythms. Benjamin gives most of the big, dissonant climaxes to the orchestra. Several of these come, predictably after a while, in the interludes that facilitate scene changes. A most welcome exception was the tautly constructed vocal ensemble as Mortimer has Gaveston seized at a private entertainment. The mix of high and low voices within the orchestral cyclone was the dramatic high point of the performance.

Another big ensemble would have made the suffering of the population more palpable. Instead, two soloists emerge from a crowd of actors and plead with Isabel, who responds by provokingly dissolving a pearl in vinegar, à la Cleopatra. However fierce their interventions, soprano Jennifer France and mezzo-soprano Krisztina Szabó could not, on their own, convey nation-wide unrest. Since the whole plot hinges on the political consequences of what goes on in the King’s bed, those bedroom walls cried to be knocked down by a huge chorus. While the singing only sporadically reflects the savagery of the violence, and the little love in evidence, the writing for the orchestra is highly dramatic. Benjamin stirs up an atmosphere doused in cold sweat, with threatening strings and rumbling brass. Low instruments predominate, resonating in a deep, multilevel darkness, with the occasional flute darting about in short neurotic figures. Only the composer can say if the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic produced the sounds he had in mind, but they seemed concentrated and responsive to his conducting. The orchestral fabric sounded rich and vibrant throughout, from the bare eeriness of the cimbalom and harp to the density of the looming string figures.

Since the best scenes occur in the first half, the rest suffers by comparison. In spite of accomplished performances, especially from the excellent Peter Hoare as Mortimer, the appearance of an insane pretender to the throne made little impact. The Madman, bass-baritone Andri Björn Róbertsson, and everyone else, seemed to be repeating the same vocal patterns used earlier. Two short monologues slow things down without adding any insight. First Gaveston, sung by Gyula Orendt, appears to the King looking like himself, although he is, in fact, Death, and summarizes the events we’ve just witnessed. Orendt’s slim baritone did not project enough foreboding to justify this exposition. In the final scene the Boy does the same thing all over again. After several big orchestral crescendos, the ending is a musical anticlimax – a surprising musical device, but also something of a dramatic comedown. There are many fine elements in Lessons in Love and Violence. It feels unfair that the whole does not equal the best of its parts.

Jenny Camilleri

George Benjamin: Lessons in Love and Violence

King - Stéphane Degout; Isabel - Barbara Hannigan; Gaveston/Stranger - Gyula Orendt; Mortimer - Peter Hoare; Boy/Young King - Samuel Boden; Girl - Ocean Barrington-Cook; Witness 1/Singer 1/ Woman 1 - Jennifer France; Witness 2/Singer 2/ Woman 2 - Krisztina Szabó; Witness 3/Madman - Andri Björn Róbertsson. Director - Katie Mitchell; Set and Costume Designer - Vicki Mortimer; Lighting Designer - James Farncombe; Movement - Joseph Alford. Conductor - George Benjamin. Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra. Seen at Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam, on Monday, 25th of June, 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lessons-in-Love-and-Violence.png image_description=Scene from Lessons in Love and Violence [Photo © Hans van den Bogaard] product=yes product_title=Lessons in Love and Violence at the Holland Festival: Impressive in parts product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Above: Scene from Lessons in Love and Violence [Photo © Hans van den Bogaard]June 26, 2018

The Turn of the Screw: ENO at Regent's Park Theatre

The spiky shards and rusting scaffold of the attic of designer Soutra Gilmour’s gothic summer-house point their confrontational fingers towards the thick green tree-tops and ever-darkening sky above the ‘woodland auditorium’. The house is a potent symbol of the neglect of which the children’s guardian is guilty, and of the moral danger to which this ethical irresponsibility exposes his two charges. Indeed, there’s physical danger too, for the set is formed of twisting ladders, roof-top perches and planked pathways which skirt and lead down to the tangled canes beside the imagined lake - bringing to my mind the reed beds of Snape Maltings, though beside the River Alde the whispering swoosh of the wind and the cool cry of the curlew have none of the aura of decay and peril that the rustling leaves and fleeting bird-song conjure here.

Director Timothy Sheader, the artistic director of Regent’s Park Theatre, leaves us in no doubt of the presence of evil and menace - the dilapidated piano and lop-sided chalk-board embedded in the undergrowth seem to undermine the notion that the children are to receive any ethical or educational instruction at Bly - but he might perhaps have been wise to have paid more heed to Henry James’s own words, ‘Make [the reader] think the evil, make him think it for himself, and you are released from weak specifications’ (‘Preface’ to the Turn of the Screw).

For, it’s the withholding of knowledge and certainty, the prevalence of secrets, the refusal to elucidate ‘meaning’ which makes James’s novella so chillingly disconcerting. It’s true that Britten does ‘fill in’ some of James’s gaps, particularly in determining that the ghosts should sing (and surely they should, if they are to be a driving musico-dramatic force and not simply Freudian intimations or projections of the Governess’s psycho-neurosis). While James was concerned with ‘causing the situation to reek with the air of Evil’ rather than with ‘having my apparitions correct’, according to Lord Harewood, Britten was adamant that the haunting should be ‘real’ rather than a product of the Governess’s paranoia. But, it’s hard to believe that the composer imagined that his ghosts would walk amongst the seated audience, undeniably corporeal.

. Daniel Alexander Sidhom as Miles. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

. Daniel Alexander Sidhom as Miles. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Sheader risks inciting the criticism which The Times made of the 1954 premiere in Venice: that the ghosts were ‘two too solid stage villains’. This Quint is a solid physical presence whose rugged vulgarity is emphasised by an ugly red wig and beard. Moreover, his first calls to Miles, which emanate from the top-rear of the auditorium, are too firm and present - a consequence of the amplification of this production which frequently shatters the music’s inherent intimations and subtleties and upsets the balance between singers and instrumentalists. I missed the unearthly beauty of Quint’s vocal arabesques, as audience heads swivelled and strained to see from whence the strong voice arose: the point is, surely, that it springs unbidden but welcome from an unexplained shadow world - its presence heralded by the ornamental gestures, pentatonic sweeps and exotic colourings of the scene’s instrumental preface. It doesn’t help that a scene titled ‘At Night’ takes place in sun-drenched daylight (despite the shifting of the original start time to achieve a more ambient coincidence of narrative and setting). I began to reflect on Deborah Warner’s ROH production, twenty years ago now, when Ian Bostridge’s creepy, even ghastly, Quint emerged from the dense, mist-ensconced thickets, and it was hard to know what was real or imagined, inside or outside.

Miss Jessel was similarly corporeal - and, heavily pregnant, presumably by Quint (as is hinted in James’s tale when Mrs Grose tells the Governess that despite their difference in rank and position, there was ‘everything’ between them, and that, after that ‘She couldn’t have stayed. Fancy it here - for a Governess!’). Heavily made up, with gothic eye-shadows, draped in heavy green and purple which seems stained with pond-weed, her hands mud-streaked, this former governess looked as if she had been dredged up from lake in which she might have drowned.

. Elen Willmer and Daniel Alexander Sidhom as Flora and Miles. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

. Elen Willmer and Daniel Alexander Sidhom as Flora and Miles. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Some of Sheader’s ‘realism’ is effective, mostly that which pertains to the characterisation and relationship of the two children, Miles and Flora. Mischievous and boisterously fun-loving, they prepare for their new ward’s arrival by exuberantly practising their bows of greeting - and emptying flower-pots on their heads and drawing on the misty window panes. Gradually their games become ‘darker’, as they taunt each other with worms, race about and venture into the night with a confident abandon that might easily escalate into the violence of Lord of the Flies.

Sheader establishes their strong identification with the two ghosts: Miles puffs nonchalantly on a toy pipe; Flora plays with her long plait that imitates Miss Jessel’s fairy-tale, knee-length rope of hair. Wiping away the Latin conjugations which his Governess wishes him to practise, Miles draws two smiling stick-men, one large, one small, a none too subtle suggestion of allegiance.

When the letter arrives informing her that Miles has been dismissed from his school - a ‘shocking’, ‘unclean’ place, James’s Governess infers - she burns it; later, Miles carries out his own nocturnal immolation - what ‘shameful’ items does he incinerate? - and it is at this point that Quint calls to him, prompting young Miles to whip off his clean white suit and don a scruffy shirt, presumably once belonging to Quint. As Quint joins him on the lake-side platform, Miles hugs his chest, leaps and swirls, and grins with glee: certainly, freedom, discovery and fulfilment are what Quint offers - “In me secrets and half-formed desires meet. […] I am the hidden life that stirs when the candle is out.” - but Sheader seems to state with no ambiguity that it is sexual initiation that Miles is proffered and covets.

The earliest critics did not like this scene: Colin Mason, writing in The Guardian (15th Septembherer 1954), decried the expansion of the ‘episode with Miles on the lawn at night’ into ‘a quartet in which the relationship between the children and the ghosts is made crudely explicit’. In fact, here, Elen Willmer’s Flora shows great discipline in avoiding catching Miss Jessel’s eye as her former governess lunges towards her, coming centimetres within touching distance (librettist Myfanwy Piper’s stage directions indicate that Flora should ‘silently and deliberately turns around to face the audience away from Miss Jessel’). And, more successfully, in Act 2 Scene 6, ‘The Piano’, Quint arrogantly places a music-score on the piano and then reclines against the instrument, only raising himself to turn to a new page in the music, as Miles performs his parodic recital - leaving us in no doubt whose tune Miles is singing, whose song he imitates.

. Elgan Llŷr Thomas as Peter Quint and Anita Watson as The Governess, with Daniel Alexander Sidhom and Elen Willmer as Miles and Flora. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

. Elgan Llŷr Thomas as Peter Quint and Anita Watson as The Governess, with Daniel Alexander Sidhom and Elen Willmer as Miles and Flora. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Just as the relationships between the children and ghosts seem unequivocally real and intense, so the suggestiveness of the instrumental parts is lost owing to the amplification of the musicians. Seated within the ruined glass-house, there is an opportunity for the musicians to serve as ghostly presences, intimated by elusive, often erotic, lyricism; but, the over-amplification sends percussive thumps, the horn’s statement of the ‘screw theme’, and the delicate traceries of harp and celeste in ‘At Night’, booming around the auditorium. And, as dusk finally falls, two hanging lights within the glass-house illuminate the players with all too clear definition.

There are two casts for the nine performances. It is common to assign a single tenor to perform the Prologue and the role of Peter Quint - Peter Pears took both roles at the first performance - which has the advantage of further increasing the ambiguity of James’s tale. Here, William Morgan and Elgan Llŷr Thomas sing both parts but take only one each in any one performance, switching roles with the changing casts. On this occasion, Morgan opened proceedings, delivering the Prologue in casual modern dress from amid the audience stalls, and extending a relaxed invitation into the narrative, though one that seemed too detached from the piano accompaniment which articulates the motifs of the ensuing musical narrative. Notwithstanding the aforementioned over-emphatic presence that results from the amplification, Llŷr Thomas’s muscular, firmly defined tenor captured Quint’s viciousness and angry resentment; he was similarly imposing physically - no wonder Miles was idolatrous and intimidated in equal measure. Elin Pritchard’s Miss Jessel was more other-worldly, and the luxurious richness of her soprano hinted at forbidden, transgressive passions; the scene in which she intrudes into the schoolroom and places herself at the Governess’s desk was frighteningly threatening.

. Anita Watson and Elin Pritchard as The Governess and Miss Jessel. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

. Anita Watson and Elin Pritchard as The Governess and Miss Jessel. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

As the Governess, Anita Watson sang with a beautifully sweet tone and finely, entrancingly nuanced phrasing; her words - there were no surtitles though copies of the libretto were supplied - were as crystalline as her conception of her own ‘mission’. But, while there was a strong sense of the Governess’s growing fear, I did not feel that this deluded ‘innocent’ was aware of her own culpability in the ensuing tragedy - this surely necessary if her final line, “What have we done between us?”, is to make sense? She should be firmly centred in a morally ambiguous middle-ground, but here seemed rather too sympathetic, against the obvious malevolence of the ghosts. And, Mrs Grose, sung with impressive musical composure and dramatic credibility by Janis Kelly, seemed to share this sympathy with the potential hysterical Governess, appearing never to challenge her even when it is implied that it is the Governess who terrifies Flora, not Miss Jessel at all, as the young girl begs Mrs Grose, “Cruel, horrible, hateful, nasty! We don’t want you! Take me away, take me away from her!”

Daniel Alexander Sidhom and Elen Willmer were tremendous as Miles and Flora; their expressive faces and utterly natural acting made the children believably and worryingly unpredictable and ‘uncontrollable’, beneath the veneer of polite conventions and mores, and their vocal lines were confidently and persuasively delivered.

Perhaps this review hasn’t fully conveyed the strong narrative propulsion of this production: while it may lack the suggestive inference of the most subtle and ghostly readings of the score, it is sincere, attentive to detail and tells the tale clearly. The singing is superb and one sensed that every member of the capacity audience was spellbound if not spooked. I just wish that Sheader had avoided some of James’s ‘weak specifications’ and trusted in the equivocal erotic suggestiveness of Britten’s music.

Claire Seymour

Britten: The Turn of the Screw

Prologue - William Morgan, Peter Quint - Elgan Llŷr Thomas, Governess - Anita Watson, Mrs Grose - Janis Kelly, Miss Jessel - Elin Pritchard, Miles - Daniel Sidhom, Flora - Elen Willmer; Director - Timothy Sheader, Conductor - Toby Purser, Designer - Soutra Gilmour, Movement Director - Jenny Ogilvie, Lighting Designer - Jon Clark, Sound Designer - Nick Lidster for Autograph, Season Associate Director (Voice) - Barbara Houseman, Fight Director - Paul Benzing, Orchestra of English National Opera.

Regent’s Park Theatre, London; Monday 25th June 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/AW%20Gov.jpg image_description=The Turn of the Screw: ENO & Regent’s Park Theatre product=yes product_title=The Turn of the Screw: ENO & Regent’s Park Theatre product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Anita Watson (The Governess)Photo credit: Johan Persson

June 25, 2018

Die Entführung aus dem Serail at The Grange

Kiandra Howarth sang as fine a Konstanze as I have heard, Christine Schäfer included, coloratura clear and meaningful, line finely spun. Humanity breathed into her character was Mozart’s - yet hers too. Daisy Brown’s spirited Blonde offered virtues similar yet far from identical; there was no difficulty in distinguishing the two soprano roles, style and delivery complementary yet distinctive. Much the same might be said of the two tenors, Ed Lyon and Paul Curievici. Lyon’s dignified, yet heartfelt Belmonte and Curievici’s quicksilver Pedrillo offered complementary nobilities, alert to distinctions of social order whilst also suggesting that they - we too - should not be bound by them. And so, in the case of duets and ensembles, indeed of questions and responses, the vocal ingredients were prepared, ready to blend, yet also to retain their individual flavours: which they did. Jonathan Lemalu’s Osmin offered similar virtues from ‘outside’ the charmed European circle, as it were: more contrast, than complement. All handled dialogue well - even if it suffered, as still more did the rest, from a ‘translation’ into English, often very loose indeed, by David Parry: a translation apparently more concerned to draw attention to itself with ‘amusing’ rhymes than to permit the drama to unfold.

Alas, there was little to cheer in the rest. The strange decision to translate - there were English titles - was one thing; more seriously, John Copley’s new (?!) production seemed stuck in a misremembered 1950s. An Entführung, sorry Abduction, for Brexit? There was certainly little in the way of diversity amongst the audience. More bizarrely, it registered not a jot that this is an Orientalist opera concerned with a purported clash between European and Ottoman civilisations; such was neither portrayed nor deconstructed. Nor, however, was anything put in place of that admittedly problematical clash. We saw neither an exploration of what human ‘love’ might or might not mean, as in Calixto Bieito’s Berlin staging or Stefan Herheim’s exhilarating total reinvention of the work - minus the Pasha - for Salzburg, nor any sense of the dark sadomasochism (‘Martern aller Arten…’) both directors and others have explored. I am not sure I could imagine anything less erotic if I tried - and I certainly do not intend to try.

It was as if this were just a terribly unfunny comedy chosen for an end-of-term school play: nothing to scare away the parents, yet nothing to attract them either. The æsthetic, such as it was, seemed very much ‘school play’ - unironically so. It was not so much that Copley had no concept, nor a question of ‘traditionalism’ or otherwise; it was about a fruitless search for drama ending in watching some people in vaguely ‘exotic’ costumes walk around a stage. Even David McVicar’s determinedly anodyne production for Glyndebourne seemed deep by comparison. One at least had the sense that McVicar might, for the sake of ‘entertainment’, have been knowingly evading the issues rather than remaining blissfully unaware of them. This might have been directed by Andrea Leadsom, although not #asamother.

Jean-Luc Tingaud’s conducting proved no more revealing. Mostly hard-driven, with occasional arbitrary slowing (presumably for ‘expression’), it again had one wondering what the fuss might all be about when it came to the operas of Mozart. (My companion, a highly experienced and reflective opera-goer, commented that, had this been her first encounter, it would most likely also have been her last.) On the occasions that the woodwind of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra managed to break a little free, they sounded delectable. Again, however, the drama remained entirely vocal.

Mark Berry

Mozart: Die Entführung aus dem Serail, KV 384

Pasha Selim: Alexander Andreou; Konstanze: Kiandra Howarth; Blonde: Daisy Brown; Belmonte: Ed Lyon; Pedrillo: Paul Curievici; Osmin: Jonathan Lemalu. Director: John Copley; Designs: Tim Reed; Lighting: Kevin Treacy. Grange Festival Chorus (chorus master: Tom Primrose)/Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/Jean-Luc Tingaud (conductor).

The Grange, Northington, Hampshire, 24 June 2018

Image=http://www.operatoday.com/Alexander%20Andreou%20%28Pasha%20Selim%29_The%20Abduction%20from%20the%20Seraglio_The%20Grange%20Festival%202018%20%C2%A9Simon%20Annand%20%281%29.jpg image_description=Die Entführung aus dem Serail:The Grange Festival 2018 product=yes product_title=Die Entführung aus dem Serail:The Grange Festival 2018 product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id= Above: Alexander Andreou (Pasha Selim)Photo credit: Simon Annand

June 24, 2018

Cave: a new opera by Tansy Davies and Nick Drake

Does the nature of a venue shape one’s experience of a work, or is it inconsequential? Obviously, there are practical factors that may influence one’s response - the acoustic, sight-lines, distance between audience and performers, even the degree of physical comfort or discomfort - and external atmosphere can certainly seep and diffuse into one’s inner experience. Lowering skies over a whipped up North Sea, the bite of a brisk breeze and the salty tang of the ocean might melt away the years between a present-day fishing town and George Crabbe’s early nineteenth-century Borough.

I mention these matters because Cave, a new opera by Tansy Davies, with a libretto by Nick Drake, produced by the London Sinfonietta in association with The Royal Opera, led me to reflect on issues relating to site-specific performances, such as the relationship between musical and architectural form, the dialogue between form and function, the potential longevity of works designed for specific places.

Mark Padmore as Man. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Mark Padmore as Man. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

It’s hard to imagine a more fitting venue in which to present Cave than Printworks, the former south-east London home of a newspaper printing-press which has been transformed into an events venue comprising six cavernous spaces, arranged over multiple levels connected by a corridor-maze. It was once Western Europe’s largest print facility, spread over 119,200 square feet, and entering into its vastness - the cathedral-like ceilings arch up into infinite darkness, strange slippery echoes take one unawares, lights starkly challenge and shadows flicker hauntingly - was slightly disorientating. The walls had been hung with shifting white fabric and a river of floor-lights guided us through the darkness into this immersive twilight zone, the very fabric of which seemed woven into Cave, a near-future dystopia of post-apocalypse barrenness and loneliness.

Drake’s libretto - or perhaps poem would be a better term - is set in a world devastated by climate change and communicates the grief of a father who enters an underground spirit world in a quest to connect with his daughter, Hannah, who is ‘lost’. Dead or simply missing, it’s not clear. Indeed, uncertainty seems the only certainty in this half-world. As Davies explained in a recentinterview, “ Cave is about Skin. The skin between life and death, the skin between humans and animals, the relationship between father and daughter. The cave goes through several phases of being imagined by the father whose lost his daughter and he’s remembering her. There’s a sense of things being apparently there, but not there. Half-there you might say.”

Subsumed into the darkness of the cave, the father reminisces on the world’s tragic tipping-point and mourns ‘the extinction of colour’. His dreams of re-birth, of enchanted forests, are severed by the roar of war-planes. Shadows tower threateningly as he is engulfed by a hysterical fear which destroys language, until one shadow transforms into a tree which provides peace and shelter. And, it is here, through memory, that he re-connects with Hannah, whose tattooed arm attests to her ‘courage’ as clearly as her words convey the certainty of her faith in regeneration. When she departs, a storm breaks, literally and in his heart, but the water is restorative and forms a running river which bears him into the future, to “begin again/ With your voice/ In mine -”

Mark Padmore as Man. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Mark Padmore as Man. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Cave was inspired by visits which the composer and librettist made to the Cave of Niaux in Southern France, on the floor of which is a dry river bed, which led them to explore the historic significance of caves for humans, as ritual and communal spaces for sharing culture and knowledge. If there is no ‘plot’ in a traditional sense, and equivocation and liminality are at the opera’s core, then there is certainly a clear ‘message’, that nature is a healing force in the face of human suffering and despair. Davies comments, “Cave is also about the relationship we have with nature. The performance isn’t just about grief and loss. It’s about gaining through wisdom.”

It’s a message that was communicated too in Davies and Drake’s first collaboration, Between Worlds (premiered at the Barbican in 2015), a similarly poetic drama which placed the events of 9/11 within human experience and suffering. Occasionally, though, Drake’s ecological evangelism is expressed with a little too much blunt ideological fervour. Hannah avows, “I want to do something/ About the disaster we’ve made”, just as Davies declares that she and Drake “both want to try and achieve a better world”, genuinely worthy sentiments which might seem naively idealistic, just as Hannah’s condemnation of “This insane exploitation/ Of people and Nature -/ For what? So we can have 4x4s?/ And holidays in the sun/ And peaches in winter?” and her ‘solution’, “We have to imagine/ A humbler way to belong together -”, seems simplistic in the face of the depth and complexity of modern-day challenges.

Despite this, director Lucy Bailey’s presentation of this one-hour opera was as compelling as Davies’ score, which crept delicately and hauntingly above and around the audience, was hypnotically beautiful. Designer Mike Britton placed the audience on tiers which stretched along an extended central galley, a mulchy undergrowth of chippings and mud, the ends of which were bathed in lighting designer Jack Knowles’ mood-changing colours. Shadows shifted and loomed, before slipping into the surrounding darkness.

Mark Padmore as Man. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Mark Padmore as Man. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Conductor Geoffrey Paterson and six members of the London Sinfonietta were assembled at one end, from which floated Davies’ delicately embroidered sound-scape. As the low resonations of the bass clarinet and contra-bassoon swirled around the harp’s high pure intonations, embraced by electronic stutterings and swoons, it was as if Printworks had become a repository of a primordial language which was both intuitive and imaginative, brutal and beautiful. I’m not sure that the music ‘articulated’ the words in any direct way but it powerfully evoked another world, beyond words, as Davies herself described: “In Cave we discover a portal into an ancient belief-system where humans understood life through interacting with nature much more.”

More than the music’s drama and delicacy, though, it was the performance of tenor Mark Padmore as the questing protagonist which made Cave so gripping. Padmore’s commitment, vocal and physical, was astonishingly intense and unwavering, from his first dishevelled entrance, clutching a briefcase which he would later set alight, to the transfiguration of his departure via the lost river. Whether lyricising or crooning, speaking or howling, clapping or whistling, every utterance was delivered with care and sensitivity; and, the purity of his voice was immensely touching, creating credibility and empathy for a character whose situation and intent might seem distanced from our own experiences. One could only admire the stamina and focus required to sustain this throughout the man’s soul-changing experiences - which included stripping off his tatty suit, being drenched by the storm, and curling up in the damp compost.

Elaine Mitchener as Hannah. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Elaine Mitchener as Hannah. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

As Hannah and the ‘Voice’ which echoes through the cave and in the man’s memory, mezzo-soprano Elaine Mitchener demonstrated vocal versatility, smoothly stretching across registral leaps, her enunciation of the short, often speech-like melodic fragments fluent and natural. Akilah Mantock danced gracefully as the young Hannah who runs through the man’s memories.

Emerging from the enveloping intimacy of this performance and stepping onto the mundane streets of Canada Water, still sunlit in the early evening, was as unsettling as entering Printworks’ vast cavern had been one hour earlier. Davies describes her creative engagement with the venue as being like ‘playing a duet with the space’; site and sound had truly communicated as one.

Claire Seymour

Tansy Davies: Cave (with a libretto by Nick Drake)

Mark Padmore (tenor), Elaine Mitchener (mezzo-soprano), Akilah Mantock (young Hannah); Lucy Bailey (director), Geoffrey Paterson (conductor), Mike Britton (designer), Jack Knowles (lighting designer), Sarah Dowling (movement director), Sound Intermedia (sound design), London Sinfonietta (Timothy Lines - clarinet/bass clarinet, John Orford - contra-bassoon, Michael Thompson - horn, Jonathan Morton - violin, Enno Senft - double bass, Helen Tunstall - harp).

Printworks, London; Wednesday 20th June 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Cave%20production%20image%20%28C%29%20London%20Sinfonietta%20and%20ROH.%20Photo%20by%20Manuel%20Harlan.jpg image_description=Cave: London Sinfonietta & The Royal Opera House product=yes product_title=Cave: London Sinfonietta & The Royal Opera House product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Cave at PrintworksPhoto credit: Manuel Harlan

June 23, 2018

Götterdämmerung in San Francisco

The Zambello Ring is big, and particularly Götterdämmerung is huge. There is a lot of video — Wagner’s musical interludes are always fully illustrated. Some of this surprisingly successful video was newly created for this revival by S. Katy Tucker, earlier created videos were by Jan Hartley.

There is a lot of architecture — abandoned warehouse buildings of some post-industrial era, monumental civic structures, crumbling elevated cement roadways, there are tons of plastic bottles that litter a dried up river bed. In this re-mounting of the 2011 San Francisco Ring the sets designed by Michael Yeargan have become fully absorbed into the telling of the saga, and fully achieve Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwert where words and music are one with sight, an achievement to be savored as it is indeed rare.

The Donald Runnicles Ring is big, well exploiting the full resources of the eighty-nine players of the admirable San Francisco Opera Orchestra. Seated on the left side of the theater the magnitude of sound flowed gloriously across the expanse of the theater to fully absorb me into its myriad of leitmotivic detail and massive ensemble. The Wagnerian Rhine, its reality and its myth, was fully present in the Runnicles reading.

The signature image of the Götterdämmerung is the massive computer mother board and the three norns who plug and replug cables until one snaps in the famous orchestral clap and we enter the pitiful world of the Gibichungs (FYI fourth century Burgandians) whose leader is the unmarried Gunter, his sister Gutrune is also unmarried. Alberich’s son Hagen manipulates these two weak creatures into disastrous marriages to further his goal of becoming lord of the ring and possessor of the massive hoard of gold.

Hagen kills Siegfried. The Ring production costume designer is Catherine Zuber.

Hagen kills Siegfried. The Ring production costume designer is Catherine Zuber.

San Francisco Opera’s house bass Andrea Silvestrelli sang Hagen. Mr. Silvestrelli’s extraordinary height plus his dark, rough and powerful voice gave a strong presence to this cunning personnage who cruelly orchestrates the marital disasters. Though you might wish for more elegance of sound and subtlety of character, Mr. Silverstrelli certainly did the job, playing the role to the hilt.

San Francisco Opera house baritone Brian Mulligan sang Gunter. Mr. Mulligan possesses a very beautiful, Italianate voice without supplying a persuasive presence. This worked for establishing a certain character for Gunter though you might have wished for a less lyric voice and a more forward personality. Mr. Mulligan did succeed in making Gunter pathetic, evoking my reluctant sympathies for such a weakness.

We first encountered mezzo soprano Jamie Barton as a contemptuous Fricka. In Götterdämmerung she sings Waltraute, Brünnhilde’s valkyrie sister who comes to Brünnhilde to beg her to return the ring to the Rhine, to break its curse and perhaps save the gods. It is our last reference to Wotan before his annihilation in the opera’s last moments. Unfortunately Mlle. Barton was unable to achieve the angst and the gravitas that might have moved Brünnhilde to save her father. The complexity of the pathos of this scene were lost in its pallid reading.

Siegfried and his two brides. Gutrune (right) sung by Melissa Citro

Siegfried and his two brides. Gutrune (right) sung by Melissa Citro

Soprano Iréne Theorin perservered through it all. In firm Brünnhilde character she ferociously denounced her marriage to Gunter, and together with Hagan and Gunter she swore revenge on Siegfried, this spectacular marriage scene set in the monumental architecture of the Gibichung Hall. She remained in equal vocal radiance for her immolation. Tenor Daniel Brenna’s Siegfried perservered through it all to make, finally, his scene with the Rhine maidens one of the memorable moments of the entire Ring. Maestro Runnicles brought earth shattering pathos to Siegfried’s death, freezing for eternity the complex emotions of this climactic moment.

After much sublime poetry over sixteen or so hours of one of the finest Rings I have ever seen, the immolation of Brünnhilde and the gods of Valhalla was strangely prosaic. Inexplicably, or maybe as victimized sisters Gutrune, Siegfried’s wife, stood by Brünnhilde’s during the valkerie's invocation to the ravens (unseen) to fly to Valhalla. The female chorus joined the Rhine maidens and Gutrune on stage for Brünnhilde’s horseless immolation. The radiant calm of the Ring’s final music was captured by the Rhine maidens energetically swirling great swathes of gold cloth.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Brunnhilde: Irene Thorin; Siegfried: Daniel Brenna; Gunther: Brian Mulligan; Hagen: Andrea Silvestrelli; Waltraute: Jamie Barton; Gutrune: Melissa Citro; Alberich: Falk Struckmann; First Norn: Ronnita Miller; Second Norn: Jamie Barton; Third Norn: Sarah Cambidge; Woglinde: Stacey Tappan; Wellgunde: Lauren McNeese; Flosshilde: Renée Tatum. Chorus and orchestra of the San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Donald Runnicles; Production/Stage Director: Francesca Zambello; Associate Director: Laurie Feldman; Choreographer: Denni Sayers; Set Designer: Michael Yeargan; Costume Designer: Catherine Zuber; Lighting Designer: Mark McCullough; Projections: Jan Hartley. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, June 17, 2018..

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Gotterdammerung_SF1.png

product=yes

product_title=Gotterdammerung in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Alberich appearing to Hagen in a dream [All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

Siegfried in San Francisco

Though dubbed the “American” Ring there is nothing specifically American about this Siegfried except maybe the Siegfried — Wisconsin born Daniel Brenna, a veteran of the Washington D.C. Ring who has sung Siegfried in Budapest, Karlsruhe and Dijon as well.

In this Ring we relate to Wagner’s greedy dwarfs Alberich and his brother Mime perhaps as gypsies more than anything else, though for San Franciscans they might also be the classic, wily homeless (not unlike some of those on my block). They were Wagner’s Jews.

Mime’s dilapidated caravan (a gypsy image) is in a truly desolate setting, thus we know Mime is a loner, all the better to protect Siegfried, his ticket to the gold he covets. The Mime of American tenor David Cangelosi is slinking, garrulous and bubbling over with deceit — just perfect.

Falk Struckmann as Alberich, David Cangelosi as Mime

Falk Struckmann as Alberich, David Cangelosi as Mime

Mime’s bleak landscape is the only nature in the Zambello Ring beyond a few video references. There are no horses, there are no ravens, no forest bird, but there is Siegfried’s bear who playfully gallops onstage chased by his playmate Siegfried. The two creatures epitomize Wagner’s vision of unspoiled nature, and for Zambello tenor Brenner embodies a perfect portrait of wide and bright-eyed American innocence.

Of youthful visage and fine young voice tenor Brenna well embodied Wagner’s ideal of pure and indeed powerful nature. This innocence served him well through his almost joyful murders of Fafner and Mime and prepared him for his monumentally guileless encounters with the god Wotan and Wotan's once immortal daughter Brünnhilde.

Bass baritone Greer Grimsley’s heroic Wotan wanders through Siegfried’s industrially littered world in search of its and his destiny, the outcome he himself has willed to Siegfried. He encounters Siegfried’s protector Mime, and he encounters his arch rival Alberich, known to us since the initial moments of Das Rheingold in the personnage of Falk Struckmann, an imposing German bass baritone who is also known as a Wotan. As Alberich Mr. Struckmann's currency is gold, Wotan’s contracts forgotten.

Greer Grimsley as the Wanderer, Daniel Brenna as Siegfried

Greer Grimsley as the Wanderer, Daniel Brenna as Siegfried

Wotan encounters Brunnhilde’s mother Erde in a scene where he completely loses his cool, and finally Wotan encounters Siegfried who shatters his creator's spear into which is imbued all social order. In all these encounters Grimsley’s Wotan exploits a humanity that is profoundly tragic and richly heroic, knowing finally that he himself has willed his destruction. And tenor Brenna musters the magnitude of innocent force to equal Grimsley’s resigned humanity in this spellbinding scene created by these two gifted actors.

The Forest Bird is no bird but rather a simple human creature who normally might have been Siegfried’s first love. Destiny however leads Siegfried to Brünnhilde. This final scene of the opera is spellbinding as well, playing on the youthful and direct voice of Siegfried in contrast to the powerful, mature voice of Wotan’s fallen daughter Brünnhilde, Swedish soprano Iréne Theorin. If at first the disparity of vocal production in this climactic scene is musically jarring, upon reflection it brilliantly sets up the tensions that will obsess us for the last, lengthy installment of the Ring.

A Ring given truly rich life by conductor Donald Runnicles and the San Francisco Opera Orchestra.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Mime: David Cangelosi; Siegfried: Daniel Brenna; Brünnhilde: Iréne Theorin; Wotan: Greer Grimsley; Alberich: Falk Struckmann; Fafner: Raymond Aceto; Forest Bird: Stacey Tap;pan; Erda: Ronnita Miller. San Francisco Opera Orchestra. Conductor: Donald Runnicles; Production/Stage Director: Francesca Zambello; Associate Director: Laurie Feldman; Choreographer: Denni Sayers; Set Designer: Michael Yeargan; Costume Designer: Catherine Zuber; Lighting Designer: Mark McCullough; Projections: Jan Hartley. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, June 15, 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Siegfried_SF1.png

product=yes

product_title=Siegfried in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Daniel Brenna as Siegfried [All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

Boris Godunov in San Francisco

Though the Symphony billed the program as semi-staged for all intents and purposes it is fully staged. There is scenery or what purports to be in this digital age (this also happens across the street). There are lights and costumes and make-up. There is a stage on two levels. Reduced San Francisco Symphony forces (the string count [and personnel] is not specified in the program booklet — maybe 12/10/8/6/5) were stuffed in between in a sort of pit.

More accurate billing would have defined the production as a compromised staging, given that nothing functioned very well, sacrificing the contributions of the pit players of a major symphony orchestra and the imposing presence of imported Russian singers among the generally high-level cast.

Perhaps the four towers that support a lighting-grid circle are recycled from staged production to staged production at the Symphony thus alleviating what must be the breath-taking cost of trying to mount an opera production in a symphony hall. Lighting, rather lack of effective lighting was the most problematic technical issue of the evening.

There was a huge cyclorama — a semi-architectural, jagged backdrop — behind the orchestra and stage platforms onto which unrelenting video images were projected. There were cutouts to reveal the San Francisco Symphony Chorus seated in the stage terrace (amphitheater) behind the orchestra platform, the voices of the Russian populace. The projections onto the huge backdrop attempted grandeur — sometimes nature, sometimes specific colorful Russian architecture, sometimes interpretive color blotches, sometimes black shadows on blank white.

Stage director James Darrah employed six ninja-like action facilitators who were often, but not always, carefully choreographed. These six were sometimes joined by another 12 or so supers to constitute more specific though soundless Russian souls. The ninja’s participation was sometimes abstract and sometimes descriptive, like the lengthy, bloody downstage center brutalizations of a captured boyar (aristocrat) and two Jesuits.

It was complex staging that attempted to adapt Mussorgsky’s sprawling drama to an essentially non theatrical space.

The event was certainly envisioned to be magnificent, and it was in spite of itself. After all it is magnificent music, and San Francisco Symphony music director Michael Tilson Thomas of course made the most of it. Two loge boxes were conscripted to hold ranks of Russian bells that rang forth gloriously when called upon. A solo trumpet sounded an imposing fanfare from the first tier. These moments of unleashed sonic grandeur encased Mussorgsky’s grand choruses as well as the vaguely connected scenes of private discussions and of Boris’ raving. The extended intimacy of these solo voice scenes required that the SF Symphony’s virtuoso players become accompanists. And that they did, like an overly careful sometimes precious accompanist at a lieder recital.

There were two genuine Russian basses, the Boris of Stanislav Trofimov of St. Petersburg’s Marinsky Theater and the Pimen of Maxim Kuzmin-Karavaev of the Novaya Opera Theatre Moscow. Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov is about words, about the Russian language and about the Russian soul. The Russian bass epitomizes these qualifications as no other voice. Both Mr. Trofimov and Mr. Kuzmin-Karavaev are excellent specimens.

There were three genuine Russian tenors, the intense Grigory (the Pretender) of Sergei Skorokhodov of the Marinsky Theatre and the harsh, very harsh Shuisky of Yevgeny Akimov, a veteran of the Marinsky and all of the world’s major stages, and the very sweetly sung Holy Fool of Stanislav Mostovoy of the Bolshoi Theatre.

The home team included San Francisco Opera’s Catherine Cook and Philip Skinner as the Innkeeper and Nikitich (a police officer) respectively who well held their own amidst the Russians. Of particular note was the Shchelkalov of American baritone Aleksey Bogdanov who made the opera’s momentous announcements in convincingly Russian voice.

It is always said that the protagonist of Boris Godunov is its chorus of suffering Russians. The San Francisco Symphony Chorus brought true beauty of style and edge of tone to its cultured and earnest concert choir voice, well defining its role as a musical protagonist. Though of course the real protagonists of the drama are Russian basses — the suffering czar Boris and the hermit Pimen, the chronicler of his reign.

Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas held all of this together with great aplomb and with obvious understanding, respect and affection for this great monument of Russian art.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Stanislav Trofimovbass (Boris Godunov), Eliza Bonet Mezzo-soprano (Fyodor), Jennifer Zetlan Soprano (Xenia), Silvie Jensen Mezzo-soprano (Nurse), Yevgeny Akimov Tenor (Prince Shuisky), Aleksey Bogdanov Baritone (Andrei Shchelkalov), Maxim Kuzmin-Karavaev Bass (Pimen), Sergei Skorokhodov Tenor (Grigory), Vyacheslav Pochapsk yBass (Varlaam), Ben Jones Tenor (Missail), Catherine Cook Mezzo-soprano (Innkeeper), Stanislav Mostovoy Tenor (Holy Fool), Philip Skinner Bass (Nikititsch), Chung-Wai Soong Bass (Mityukha). Pacific Boychoir, Andrew Brown, Director; San Francisco Symphony Chorus, Ragnar Bohlin Director; San Francisco Symphony, Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor. Stage Director: James Darrah, Lighting Design: Pablo Santiago; Video: Adam Larsen; Scenic and Costume Design: cameron Jaye Mock. Davis Hall, San Francisco, June 14, 2018)

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Boris_SFS1.png image_description=Photo by Christian Dresse courtesy of the Opéra de Marseille product=yes product_title=Boris Godunov in San Francisco product_by=A review by Michael Milenski product_id=Above: Stanislav Trofimovbass as Boris GodunovPhotos by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Symphony.

June 19, 2018

Garsington Opera transfers Falstaff from Elizabeth pomp to Edwardian pompousness

Setting Verdi’s opera in the era of the suffragettes’ campaigning and Edward Elgar’s paean to ‘Englishness’ - the composer’s symphonic study Falstaff Op.68 was premiered in 1913 - neatly promotes pertinent ‘issues’ but also dilutes, a little, the immediate comic impact of the out-size peer of the realm, Sir John Falstaff.

Designer Giles Cadle has been eager, it seems, and unlike the opera’s eponymous protagonist, to stick within his budget. While Falstaff is pestered in his attic garret by a gothic, disembodied hand which thrusts an unpaid bill - for “Six chickens: six shillings. Thirty bottles of sherry: two pounds. Three turkeys ... Two pheasants. An anchovy ...” - through the floor boards, Cadle presents us with a cardboard cut-out set which allows us to take in a long and short perspective of Windsor’s castle and forest, and to enter some interior dwellings.