July 29, 2018

Götterdämmerung in Munich

It is also an odd thing, perhaps, to start as well as to end with Götterdämmerung, although that oddness may well be overstated. Wagner’s initial intention was, after all, to write a single drama on the death of Siegfried; after a certain point in the formulation of theRing project, much of what had been written as Siegfrieds Tod remained as Götterdämmerung. Might one even be able to recapture something of that initial intent, relying on the narrations here as they might originally have been conceived? Perhaps - and it is surely no more absurd intrinsically to watch - and to listen to - one of the Ring dramas than it is to one part of the Oresteia . On the other hand, a Götterdämmerung conceived as a one-off - whether in simple terms or as part of a series such as that presented some time ago by Stuttgart, each by a different director, glorying in rather than apologising for disjuncture and incoherence - will perhaps be a different thing from this. Anyway, we have what we have, and I can only speak of what I have seen and heard.

In that respect, I am afraid, this Götterdämmerung proved sorely disappointing - especially, although not only, as staging. Indeed, the apparent vacuity of the staging combined with what seemed a distinctly repertoire approach - yes, I know there will always be constraints upon what a theatre can manage - combined to leave me resolutely unmoved throughout. This did not seem in any sense to be some sort of post-Brechtian strategy, a parallel to where parts at least of Frank Castorf’s now legendary Bayreuth Ring started out - if not, necessarily, always to where they ended up. I distinctly had the impression that what acting we saw had come from a largely excellent cast. Is that at least an implicit criticism of the revival direction? Not necessarily. I know nothing of how what few rehearsals I suspect there were had been organised. I could not help but think, though, that once again Wagner’s wholesale rejection - theoretical and, crucially, practical too - of the ideology and practices of ‘normal’ theatres had once again been vindicated. This, after all, is the final day of a Bühnenfestspiel. At one point, he even wrote of post-revolutionary performances in a temporary theatre on the banks of the Rhine, after which it and the score would be burnt. Did he mean that? At the time, he probably did, just as we mean all sorts of things at the time we might not actually do in practice. Nevertheless, his rejection of everyday practice points us to an important truth concerning his works. As Pierre Boulez, whilst at work on the Ring at Bayreuth, put it: ‘Opera houses are often rather like cafés where, if you sit near enough to the counter, you can hear waiters calling out their orders: “One Carmen! And one Walküre! And one Rigoletto!”’ What was needed, Boulez noted approvingly, ‘was an entirely new musical and theatrical structure, and it was this that he [Wagner] gradually created’. Bayreuth, quite rightly, remains the model; Bayreuth, quite wrongly, remains ignored by the rest of the world.

Chorus. Photo credit: Wilfried Hösl.

Chorus. Photo credit: Wilfried Hösl.

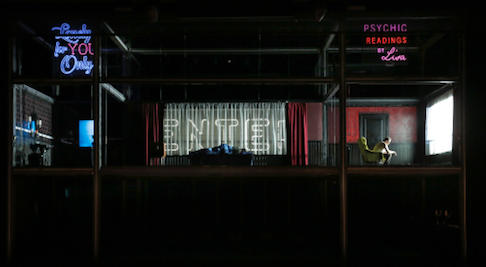

Such unhelpfulness out of the way, what did we have? Details of

Kriegenburg’s staging seem to borrow heavily - let us say, pay homage to -

from other productions. The multi-level, modern-office-look set is not

entirely unlike that for Jürgen Flimm’s (justly forgotten) Bayreuth

staging. Brünnhilde arrives at the Gibichung Court with a paper bag over

her head, although it is sooner shed than in Richard Jones’s old Covent

Garden Ring. I shall not list them all, but they come across here,

without much in the way of conceptual apparatus, more as clichés than

anything else. Are they ironised, then? Not so far as I could tell. I liked

Siegfried’s making his way through a baffling - to him - crowd of

consumers, as he entered into the ‘real world’, images from advertising and

all. Alas, the idea did not really seem to lead anywhere.

A euro figure (€) is present; perhaps it has been before. First, somewhat

bafflingly, it is there as a rocking horse for Gutrune; again, perhaps

there is a backstory to that. Then, it seems to do service - not a bad

idea, this - as an unclosed ring-like arena for some of the action,

although it is not quite clear to me why it does at some times and not at

others. Presumably this is the euro as money rather than as emblematic

hate-figure for the ‘euroscepticism’ bedevilling Europe in general and my

benighted country in particular. (That said, I once had the misfortune to

be seated in front of Michael Gove and ‘advisor’, whose job appeared to be

to hold Gove’s jacket, at Bayreuth; so who knows?) There also seems to be a

sense of Gutrune as particular victim, an intriguing sense, although again

it is only intermittently maintained. Doubtless her behaviour earlier on,

drunk, hungover, posing for selfies with the vassals, might be ascribed to

her exploitation by the male society; here, however, it comes perilously

close to being repeated on stage rather than criticised. That she is left

on stage at the end, encircled by a group of actors who occasionally come

on to ‘represent’ things - the Rhine during Siegfried’s journey, for

instance - is clearly supposed to be significant. I could come up with

various suggestions why that might be so; I am not at all convinced,

however, that any of them would have anything to do with the somewhat

confused and confusing action here.

. Hans-Peter König (Hagen) and Markus Eiche (Gunther). Photo credit: Wilfried Hösl.

. Hans-Peter König (Hagen) and Markus Eiche (Gunther). Photo credit: Wilfried Hösl.

Kirill Petrenko led a far from negligible account of the score, which, a few too many orchestral fluffs aside - it nearly always happens in Götterdämmerung, for perfectly obvious reasons - proved alert to the Wagnerian melos. It certainly marked an advance upon the often hesitant work I heard from him in the Ring at Bayreuth. However, ultimately, it often seemed - to me - observed rather than participatory, especially during the Prologue and First Act. The emotional and intellectual involvement I so admired in, for instance, his performances of Tannhäuser and Die Meistersinger here in Munich was not so evident. Perhaps some at least of that dissatisfaction, however, was a matter of the production failing to involve one emotionally at all. The Munich audience certainly seemed more appreciative than I, so perhaps I was just not in the right frame of mind.

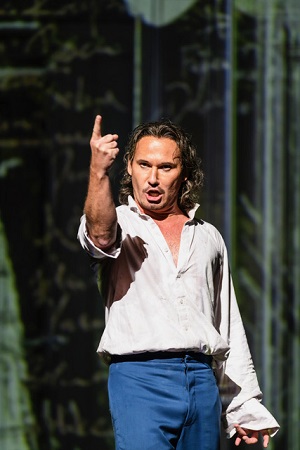

Much the same might be said of the singing. Nina Stemme’s Brünnhilde redeemed itself - as well, perhaps, as the world - in the third act, recovering some of that sovereign command we know, admire, even love, although even here I could not help but reflect how surer her performance at the 2013 Proms under Daniel Barenboim had been. There is nothing wrong with using the prompter; that is what (s)he is there for, as Strauss’s Capriccio M. Taupe might remind us. Stemme’s - and not only Stemme’s - persistent resort thereto, however, especially when words were still sometimes confused, was far from ideal during the first and second acts. Stefan Vinke ploughed through the role of Siegfried, often heroically, sometimes with a little too grit in the voice, yet with nothing too much to worry about. It was not a subtle portrayal, but then, what would a subtle Siegfried be?

Nina Stemme (Brünnhilde) and Okka von der Damerau (Norn). Photo credit: Wilfried Hösl.

Nina Stemme (Brünnhilde) and Okka von der Damerau (Norn). Photo credit: Wilfried Hösl.

Some might have found Hans-Peter König a little too kindly of voice as Hagen; I rather liked the somewhat avuncular persona, with a hint of concealment. Again, there was no doubting his ability to sing the role. Markus Eiche and Anna Gabler were occasionally a little small of voice and, in Eiche’s case, presence as his half-siblings, but there remained much to admire: Gabler’s whole-hearted embrace of that reimagined role, for one thing. Okka von der Damerau made for a wonderfully committed, concerned Waltraute: as so often, the highlight of the first act. John Lundgren’s darkly insidious Alberich left one wanting more, much more. The Rhinemaidens and Norns were, without exception, excellent. I especially loved the contrasting colours - Jennifer Johnson’s contralto-like mezzo in particular - and blend from the latter in the opening scene. If there are downsides to repertory systems, casting from depth as here can prove a distinct advantage. Choral singing was of the highest standard too.

If only the production, insofar as I could tell, had had more to say and

more to bring these disparate elements together. Without the modern look,

it might often as well have been Robert Lepage or Otto Schenk.

Mark Berry

Richard Wagner, Götterdammerung

Siegfried: Stefan Vinke; Gunther: Markus Eiche; Hagen: Hans-Peter König;

Alberich: John

Lundgren; Brünnhilde: Nina Stemme; Gutrune, Third Norn: Anna Gabler;

Waltraute, First

Norn: Okka von der Damerau; Woglinde: Hanna-Elisabeth Müller; Wellgunde:

Rachael Wilson; Flosshilde, Second Norn: Jennifer Johnston; Third Norn: Anna

Gabler. Director: Andreas Kriegenburg; Revival Director: Georgine Balk; Set Designs: Harald

B. Thor; Costumes: Andrea Schraad; Lighting: Stefan Bolliger; Choreography: Zenta

Haerter; Dramaturgy: Marion Tiedtke, Olaf A. Schmitt. Bavarian State Opera Chorus

and Extra Chorus (chorus master: Sören Eckhoff)/Bavarian State Orchestra/Kirill

Petrenko (conductor). Nationaltheater, Munich, Friday 27 July

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Siegfried%20%28Stefan%20Vinke%29%2C%20Hagen%20%28Hans-Peter%20K%C3%B6nig%29%2C%20Br%C3%BCnnhilde%20%28Nina%20Stemme%29.jpg

image_description=Götterdammerung, Munich Festival Opera

product=yes

product_title=Götterdammerung, Munich Festival Opera

product_by=A review by Mark Berry

product_id= Above: Siegfried (Stefan Vinke), Hagen (Hans-Peter König), Brünnhilde (Nina Stemme)

Photo credit: Wilfried Hösl

July 28, 2018

A celebration of Parry at the BBC Proms

Hubert Parry's hope-filled symphonic masterpiece, Symphony No. 5 (Symphonic Fantasia '1912') from 1912 was paired with three works written in the shadow of the war, Vaughan Williams' The Lark Ascending and Pastoral Symphony, and Gustav Holst’s Ode to Death, none of them obviously war inflected but each piece affected by their composer's wartime experience. This year is also the centenary of Parry's death, and as well his symphony the concert also included his large-scale anthem, Hear my words, ye people. Tai Murray was the violin soloist in the Lark Ascending, with Francesca Chiejina (soprano) and Ashley Riches (bass) soloists in the Parry anthem.

Parry's fifth (and last) symphony was premiered at the Queen's Hall in London in December 1912. It consists of four linked movements; that each movement has a title ('Stress', 'Love', 'Play', 'Now') suggests the work's tone-poem like character, and this is emphasised by the way Parry has labelled the various themes ('Brooding thought', 'Tragedy', 'Wrestling Thought' etc). As a symphonist, we can hear Parry's debt to Elgar, to Brahms and to Liszt but we should also remember that Elgar the symphonist owed something to Parry. Parry's writing, whilst having a sound akin to Elgar, lacks the latter composer's sheer grandiloquence and the fifth symphony is a thoughtful and in many ways poetic work.

The first movement opens with a theme which Parry labelled 'Brooding thought' and it brooded indeed as the slow introduction developed restlessly into an 'Allegro' with Elgarian overtones (or perhaps we should say that Elgar has Parry overtones!). The orchestra made a fine, mellow sound, with much ebb and flow of detail, moments of calm and thrilling drama. The second movement included a lovely duet for bass clarinet and solo cello (evidently the bass clarinet was one of Parry's most favourite instruments), and also a remarkably noble tune. Yet the movement did not progress in an obvious fashion, and there was a remarkable amount of complexity in the detail whilst at the end everything simply subsided into the scurrying delight and perky rhythms of the third movement. This had a delightful, country-dance style trio featuring the horns. The finale brought thoughts of Elgar again, but with a more rumbustious quality to the big tune. Parry gives this a terrific development, which strives to a triumphant close. Throughout, Brabbins and the orchestra played the music as if they had known it for ever, with lovely string phrasing and fine woodwind solos.

This was followed by a far more familiar work, RVW's Lark Ascending with the American violinist Tai Murray. From the opening with its hushed strings, and Murray's bare-there solo, it was clear that she took a very particular view of the work. Her solo line, all elegant fine-grained sound, seemed to go on for ever and throughout the piece tempos were relaxed (without ever being over-done) and Murray emphasised the time-less, contemplative nature of the piece rather than worrying about the descriptive natural detail. This is, in fact, all apiece with the modern view of the work as arising out of RVW's war-time experiences (it was written originally in 1914 and revised in 1920). The middle section had greater vitality, with a clarity and transparency to the orchestral contribution, but then we relaxed into a truly magical ending.

After the interval we had Parry's Hear my words, ye people for choir, brass, organ, solo soprano (Francesca Chiejina) and bass solo (Ashley Riches). Originally written for the Diocesan Choral Festival at Salisbury Cathedral in 1894, the work alternates between full chorus and semi-chorus, with sections for the soloists. It started with an organ peroration (from Adrian Partington on the Royal Albert Hall organ) and throughout the organ part was important, hardly accompanying and rather commenting though there were times when it seemed rather too prominent in the mix in the hall. The soloists were placed quite far back, and neither completely felt present enough in the hall though both sang confidently. All in all, the piece rather failed to hang together, the individual sections never coalescing into a significant work, and this was emphasised by the final section when we suddenly jumped into a memorable tune which became a well-known hymn tune.

Thankfully, Holst's Ode to death was a richer and subtler piece. Premiered in 1919, it arose out of Holst's war-time experiences with the YMCA in Salonica and Istanbul. A setting of Walt Whitman for chorus and orchestra, Holst matches the individual tone of the different verses yet melds the whole into a unique piece. The opening sounded aetherial with transparent scoring when, listening to the words ('Come lovely and soothing death/Undulate round the world, serenely arriving'), we might have expected something more elegiac. This is Holst in The Planets mode (in fact written just before in 1914-1916 and premiered in 1918), and for all the richness of the harmony there was a certain coolness particularly arising out of Holst's fondness for bitonality. In the 'Dark mother always gliding near with soft feet', Holst's writing almost suggests a march, yet the material is hardly martial and Brabbins really brought out the work's subtle poetry. Holst the mystic emerged in the 'Lost in the loving floating ocean', a truly remarkable passage, whilst the concluding section with its bitonality and otherworldly tension, was truly eerie.

This was the work's first performance at The Proms, and I have not heard it live since I sang in a performance with the University chorus as a student in 1974. It is puzzling why such a rich, fascinating work, a secular requiem in all but name, is not better known.

The final work in the programme was another deceptive one. It is fatally easy to fall back on Peter Warlock's satirical comment ' like a cow looking over a gate', yet the piece had its origins in the First World War, and the landscape being evoked is wartime France. This is another contemplative meditation on war, rather than an angry striving. It is worth remembering that another British First World War participant, Sir Arthur Bliss, produced his Morning Heroes after the war, another thoughtful, troubling work.

There is little fast or loud music in RVW's symphony, yet it is full of expressive and passionate moments. The opening movement was quietly concentrated, with quite a flowing tempo and the music gradually building in layers. Brabbins beautifully controlled the ebb and flow of ideas, constantly keeping the music moving yet revealing a lot of detail in the orchestra. As drama progressed, he and the orchestra relished the lush textures and brought out a surprising amount of passion. The second movement opened with a melancholy horn call (again we had bitonality as a profoundly expressive device), creating an eerie moment. The concentrated texture of the orchestral playing was broken by the atmospheric off-stage natural trumpet, creating a moment where time was suspended. The vigorous scherzo was remarkably rumbustious, with pastoral flute passages and an English country dance on the brass, all mixed into something characteristic of RVW. Then suddenly it turns into a perky English country dance. The final movement includes a wordless soprano, off-stage, here Francesca Chiejina who sang with a very rich timbre and create sound which was very present in the hall, there was nothing aetherial about this soprano she was a full-blooded woman (RVW's wife talked about this passaged being about 'that essence of summer where a girl passes singing' and this was a flesh and blood girl). This solo unleashed complex passions in the orchestra, leading to a magical ending where the soprano solo reappears, then evaporates leaving just a high violin note.

This was a fine and thoughtful concert which paired the music of Parry with that of the younger generation of English composers and giving us the more thoughtful side of English music from the 1910s and 1920s.

Robert Hugill

Prom 17: Hubert Parry - Symphony No.5; Ralph Vaughan Williams -The Lark Ascending; Hubert Parry - Hear my words, ye people; Gustav Holst - Ode to Death; Ralph Vaughan Williams - Pastoral Symphony (No.3)

Tai Murray (violin), Francesca Chiejina (soprano), Ashley Riches (bass-baritone), Adrian Partington (organ)

BBC National Chorus of Wales, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Martyn Brabbins (conductor)

Royal Albert Hall, London; Friday 27th July 2018

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ashley%20Riches.jpg image_description=Prom 17: Martyn Brabbins with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and the BBC National Chorus of Wales product=yes product_title= Prom 17: Martyn Brabbins with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and the BBC National Chorus of Wales product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id= Above: Ashley RichesPhoto credit: BBC/Mark Allan

July 26, 2018

Oxford Lieder Festival 2018: The Grand Tour - A European Journey in Song

A celebration of European song will be the focus of the 2018 Oxford Lieder Festival (12th - 27th October) and will showcase the familiar masterpieces of the song repertoire while exploring wider cultural influences from Finland to the south of Spain and from Dublin to Moscow. The great masters of the German Lied brush shoulders with composers from Carl Nielsen to Ester Magi to Lili Boulanger. Fascinating talks and study events will illuminate music, art and literature across the continent. A series of ‘language labs’ explore language and poetry from Polish to Czech to Estonian.

International stars including Louise Alder (15 Oct), Toby Spence (16 Oct), Kai Rüütel (17 Oct), James Gilchrist (19 Oct), Camilla Tilling (20 Oct), Christoph Prégardien (21 Oct), Benjamin Appl (22 Oct), Sarah Connolly (22 Oct), Véronique Gens (24 Oct), Thomas Oliemans (25 Oct) and Kate Royal (26 Oct) appear alongside exceptional young artists, including the winners of the Kathleen Ferrier Awards, the Wigmore Hall International Song Competition and, in a new collaboration with Heidelberger Frühling, Das Lied. The lunchtime series includes concerts of Polish, Hungarian and Italian songs, and there is a rich programme of chamber music in the rush-hour series, including music from the Baltic states, Russia and France.

A day-long event focuses on Scandinavian song, with performances given by native-speaking singers from all the Nordic countries (20 Oct). There will be a day devoted to Claude Debussy on the centenary of his death, including a recital with leading French pianist Anne Le Bozec and two of the brightest emerging French singers: Marie-Laure Garnier and Jean-Christophe Lanièce (13 Oct). An evening in Spain features soprano Lorena Paz Nieto and British/Catalan mezzo Marta Fontanals-Simmons, as well as Spanish violin music, a Spanish wine tasting and Flamenco (18 Oct). A range of events mark the 100th anniversary of the death of Hubert Parry taking a fresh look at his significance for English song.

Other highlights include the opening concert (12 Oct) with Sophie Bevan, Kitty Whateley, James Gilchrist and Marcus Farnsworth performing works including Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Serenade to Music, and the closing concert (27 Oct) with the thrilling Irish mezzo Tara Erraught and BBC New Generation Artist Ashley Riches performing Schumann’sMyrthen. Robert Holl and Graham Johnson perform Winterreise (14 Oct) and the exciting new ensemble Schubert & Co. present an uplifting Schubertiade (23 Oct).

Tickets and festival passes visit www.oxfordlieder.co.uk / 01865 591276.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Oxford%20lieder%20logo.jpg image_description=Oxford Lieder Festival, 12th - 27th October 2018: The Grand Tour - A European Journey in Song product=yes product_title=Oxford Lieder Festival, 12th - 27th October 2018: The Grand Tour - A European Journey in Song product_by= product_id=July 25, 2018

Angelika Kirchschlager's first Winterreise

Similarly, men are often the voice of choice in female roles where an element of strangeness is to the fore, such as Birtwistle’s Snake Priestess (The Minotaur) and Britten’s Madwoman (Curlew River). Theatre, too, is gender-neutral these days, and Glenda Jackson can be King Lear just as Mark Rylance can become Cleopatra.

But, what of the recital hall? Where the solo lieder singer has no dramatic role to embody and where the poet so often seems to have identified intensely with the poetic persona for whose voice the singer is an expressive conduit?

I put this question to Austrian mezzo-soprano Angelika Kirchschlager, before her performance of Schubert’s Winterreise at Middle Temple Hall , with pianist Julius Drake. She sensibly pointed out that in the opera house, the travesti roles make a positive and essential contribution, androgyny being integral to the dramatic and musical design, and also to the ‘entertainment’. But, art song is not entertainment: it is both delicate and powerful; it forces one to reflect on and to integrate ideas and emotions; it issues challenges of a political and personal nature. “There is always something humming beneath the surface.”

I wondered if, while we are unperturbed by a woman embodying, say, the lovesick travelling journeyman in Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen or Schubert’s Ganymede, there is something unique about Winterreise, Wilhelm Müller’s poems being too ‘confessional’ to permit the crossing of gender lines? Angelika explained that she believes Winterreise communicates human experience, rather than an explicitly male or female perspective. She described the song-cycle as “a journey to the inside of a human being”, a spiral ever deeper into loneliness as the male persona becomes increasing cut off from the world, unable to find his place, ever more lost. “A man or a woman can do that journey.”

And, why not? Female singers including Elisabeth Schumann, Lois Marshall, Christa Ludwig and Brigitte Fassbaender have all performed or recording Winterreise. After thirty years of singing opera and lieder, and ten years of teaching, Angelika hoped that it would come up some day. “It is the ultimate challenge in lieder. A complex masterpiece for which I have so much respect.” The exploration of the cycle’s psychology and parameters is obviously something that the mezzo-soprano has relished.

When I questioned whether a male singer could sing Schumann’s Frauenliebe und Leben, Angelika replied, “No. Because the songs communicate uniquely female experience. No man can ever know what it is to love as a woman, to marry, to become a mother.” Schumann’s songs tell of a woman’s daily life, whereas in Winterreise only the first song, ‘Gute Nacht’, is connected to the real world, and through the rest of the cycle the persona travels ever further into nature and away from people.

Angelika told me that she feels the influence of Schubert’s own life experiences in these songs - practical problems arranging concerts, with women, money, illness - and that the cycle expresses feelings of helplessness about where life can go. She also believes that the winter traveller’s journey into isolation and introspection has begun long before the first song commences; that he had suffered before, and that the cycle resumes a long process of separation. “Why is he leaving? We don’t know and can only speculate. But, I try to keep out lament; not to cry unless it is in the songs, and to focus on other emotional aspects. He is rushing away, and he just keeps on going.” Interestingly, Angelika remarked that after more than a year of learning the song-cycle, she felt that she was getting into the mind of a man, encountering problems which she recognised from the experiences of men whom she knew.

I was surprised when Angelika revealed that she has never heard Winterreise performed live before, and I asked her how she has been preparing for her own first performance of the cycle. She listened to recordings of single songs - “thinking about how creative I could be,” she said, with a laugh - and then explored the texts, looking for connections between Schubert’s harmonies and the texts. Schubert’s textual annotations were comprehensive, and she commented, “you don’t have to do anything, just find out what Schubert wants to tell us”. As she advises her students, if you just sing what you feel, it will be your music but not the composer’s.

We discussed some of the practicalities such as the choice of keys and transposition. Angelika’s choices are entirely her own, drawing on the original version and those for medium and low voice. She carefully considered the connections between songs, asking herself whether she wanted progressions to seem “weird” or natural, whether to retain links or to break them. Having gone through numerous sets of possibilities, changing the key relationships over and over, she has settled on her fifth version!

We talked, too, of vocal technique and colour, and Angelika emphasised that the absence of contrast between the chest and head voice for women has a marked effect. Schubert may have written a particularly high passage for tenor, anticipating the softness and colour of the head voice, and so a woman’s performance will inevitably be different. I raised the matter of the ‘distance’ between the vocal line and piano, the former higher in pitch than usual, and the latter lower as a result of the transposition, and Angelika reflected that perhaps this increases the sense of the traveller’s alienation and loneliness.

I wondered whether the close proximity of the audience at Temple Church presented challenges, but Angelika laughed again: “I like the audience close! I’ve sung in venues where they’ve been much closer. It means the audience cannot escape! I don’t want to sing in a dark auditorium where the audience are anonymous: they must be part of it, they are 50% of the evening.”

At the end of our conversation, Angelika spoke with passion. “There can never be a right or wrong Winterreise. There are simply always more aspects of the cycle to explore and each new interpretation is a positive contribution to the work’s life. A ‘solution’, there can never be. But the essential thing is to be faithful to the music and that will ensure that the singer is faithful to Schubert’s genius.”

With such thoughts in mind, I settled into the pew at Temple Church and listened to the urgent but light tread of Julius Drake’s piano introduction to ‘Gute Nacht’, and was immediately struck by this traveller’s intensity: the fixity of Angelika Kirchschlager’s stare as she seemed to reach for a distant point, beyond the horizon, was riveting. There was steely purpose, here: ‘Was soll ich länger wellen/ Bis man mich treib’ hinaus?’ (Why should I wait longer for them to drive me out?) pushed forward, with defiant determination. There was tension and turbulence too - in the unruly trembling of Drake’s weathervane in the following song, and in the traveller’s heart - but in these opening songs it was restrained, almost repressed, occasionally retreating into numbness, or, as in the final stanza of ‘Gefrorne Tränen’, momentarily relaxing and finding warm release: ‘Als wolltet ihr zerschmelzen/Des ganzen Winters Eis’ (As if you would melt/All this winter’s ice).

Dreams of ‘Der Lindenbaum’ transported the traveller far from the present, but the tenderness of the vision only emphasised the vulnerability of the voyager. This was less a ‘narration’ than a drama, as Kirchschlager communicated emotion openly and directly. Though her artistry was ever evident, the mezzo-soprano seemed to render these art songs into pure feeling, almost folk-like in their honesty, often singing with little vibrato and using vocal heightening and nuance with care and thoughtfulness. Flashes of brightness - passion, anger, pain - were thus all the more telling. The slow tempo of ‘Wasserflut’ suggested the traveller’s ‘lostness’, though the heatedness of the burning tears reminded us of his anguish; Drake’s tip-toeing accompaniment in ‘Auf dem Flusse’ took us deeper into a dream-scape, before we were wrenched back to reality by the traveller’s agonized questioning as he gazes into the stream at the close of the song - ‘Ob’s unter seiner Rinde/ Wohl auch so reißend schwillt?’ (Is there such a raging torment beneath its surface too?) - the agitation spilling over into restless ‘Rückblick’ (A backward glance).

It was the lurch in Drake’s skittish accompaniment at the start of ‘Irrlicht’ (Will-o’-the-wisp) which signalled a shift to a darker, dangerous psychological landscape. Ironically, the terrible unfulfillment of the traveller’s searching was communicated by Kirchschlager’s beautifully warm lower range and her effortless transitions between registers. She seemed to physically inhabit the tiredness of ‘Rast’, though Drake’s steady accompaniment was cruelly impassive; the sudden freshness and vigour of ‘Frühlingstraum’ (Dream of Spring), was troubled by deep, unpredictable currents. Always the tension was kept in check, though the threat of disintegration seemed ever imminent, and contrasts between the lassitude of ‘Einsamkeit’ (Loneliness) and the frantic haste of ‘Die Post’ were disquieting. The delicacy of the close of ‘Der greise Kopf’ was frightening, and it was no surprise when it was shattered by the piano’s tormented circlings in ‘Die Krähe’ (The crow).

‘Letzte Hoffnung’ (Last hope) followed segue, another irrevocable staging-post on a journey into existential solitude. The final songs accrued a gripping dramatic force, which relaxed slightly as Kirchschlager lightened her voice to capture the hallucinations of ‘Täuschung’ (Delusion) but then exerted its grip as she hardened the sound to convey the traveller’s obsessive intensity in ‘Der Wegweiser’ (The signpost): ‘Eine Straße muß ich gehen,/ Die noch keener ging zurück.’ (One road I must travel, form which no man has ever returned.) The arrival at the inn (‘Das Wirthaus’) seemed to bring some comfort and relief, but the courage of ‘Mut’, as the vocal line flashed with fire, bordered on madness and the low piano bass in ‘Die Nebensonnen’ (Phantom suns) seemed to draw the traveller ever deeper into his own obsessions and fixations. The encounter with ‘Der Leiermann’ offered no solace: subdued, still, the music and the traveller seemed to slip away, elsewhere.

The sustained focus and intensity of this performance of Winterreise was astonishing and almost hypnotic. During our conversation, Angelika had been keen to point out that this is first time that she has performed Winterreise, and that her interpretation will undoubtedly develop. The next stop is the Vienna Staatsoper, where she and Julius Drake will perform the cycle in October. This is just the beginning of her own musical journey.

Claire Seymour

Angelika Kirchschlager (mezzo-soprano), Julius Drake (piano)

Temple Church, London; Tuesday 24th July 2018.

Photo credit: Nikolaus Karlinsky

John Storgårds takes the BBC Philharmonic on a musical journey at the BBC Proms

Just as there was a variety of composers, there was a variety of performance standards; to the extent that it did not take too much to guess where the rehearsal time had been spent. The Wagner Meistersinger Overture was a casualty in this regard, the legato articulation of the opening and the very soft-sticked timpani basically offering Wagnerian sludge. On the plus side, the BBC Philharmonic’s sound is deeper, more burnished in the lower registers these days, the eight double-basses a real presence, and there were plenty of excellent individual contributions, most notably the tuba (Christopher Evans) and, in fact, the brass section in general, but there was a somnambulistic aspect to the performance that seemed markedly against the spirit of the music.

The excellent soprano Elizabeth Watts proved something of a turning-point in the concert’s trajectory, bringing superb shaping to each of the four Schubert/Liszt songs. The meeting of Schubert with Liszt’s unmistakable voice in the orchestrations is fascinating, and the performances were vibrant. Capturing the dark, stormy energy of Die junge Nonne, D828, to perfection, the BBC Philharmonic provided the perfect backdrop to Watts’ rich, resonant voice. Watts’ diction here, and throughout, was exemplary, not a syllable getting eaten up by the vastness of the Albert Hall. Her voice is free, allowing her to convey peace as well as anger inNonne; and how strong, too, is her lower register. The famous Gretschen am Spinnrade (D118) opened with a tapestry of strings over which Watts spun the drama of the young girl’s infatuation. Schubert’s great gift for simplicity came to the fore in Lied der Mignon, D877/3 (which included a lovely solo cello contribution from Peter Dixon); Watt’s superbly free voice once more soared. One of the most famous of Schubert songs, Erlkönig, found Watts acting the various parts of father, son and Erlking physically as well as vocally, thinning her voice for the son; filling it for the Erlking (and how delightful are Liszt’s woodwind additions to “Du liebes Kind”).

The idea of contrast and variety in this concert was massively confirmed by including Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s Symphony in One Movement of 1947-51, heard in its 1953 revision (in which Zimmermann cuts the organ part of the original). The piece began with an existential cry; forthcoming textures were vibrant with dark energy. The sureness of the performance indicated careful rehearsal, the angst-ridden march rhythms, laden, heavy, contrasted strongly with woodwind passages of Zimmermann meeting Mendelssohn in terms of lightness. Block chords were superbly balanced by the conductor. No easy piece to listen to (or play), this performance seemed to sum up what the Proms is all about, introducing music of huge value to large audiences.

The second half held two contrasting pieces. Schubert’s “Wanderer” Fantasy arranged for piano and orchestra by Liszt rubbing shoulders with Sibelius’ miraculous, seeming stream-of-consciousness yet in fact exquisitely structured, Seventh Symphony. Louis Lortie was the fine soloist (playing a beautifully toned and prepared Bösendorfer) in a performance of the Schubert “Wanderer’ Fantasy of terrific verve. The violin semiquavers at he opening in the violins were supremely together, setting the tone for the orchestral discipline on evidence throughout the performance. Lortie was technically commanding throughout, but he also found just the right depth for the prayer-like opening to the slow movement. Ländler rhythms lilted beautifully from all. This was a wonderful performance of this rarely-heard arrangement (the last time it was heard at the Proms, for example, was 1986, with the great Jorge Bolet as soloist).

Finally, Sibelius’ fabulous one-movement Seventh Symphony of 1924. The BBC Philharmonic trombones were tasked with Sibelius’ potent, noble theme that recurs at salient points, and delivered with beautifully creamy tone and a well considered sense of balance. Consonances or near-consonances glowed from within, and Storgårds ensured a real sense of organic unfolding; more, even. The BBC Philharmonic perfectly captures Sibelius’ stark, sometimes forbidding, landscape. Monumental brass, light wind in the scherzo-like Vivacissimo and superbly together strings all contributed to this stunning performance, the crowning brass (the Elgarian term ‘nobilmente’ sprung to mind) glowing.

Quite a musical journey over the course of the evening, then; and quite right that the Sibelius should be its crowning glory.

Colin Clarke

PROM 14: Elizabeth Watts (soprano), Louis Lortie (piano), BBC Philharmonic/John Storgårds

Wagner: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg - Overture; Schubert/Liszt: ‘Die junge Nonne’, ‘Gretschen am Spinnrade’, ‘Lied der Mignon’, ‘Erlkönig’; Zimmermann - Symphony in One Movement; Schubert/Liszt - Fantasy in C, ‘Wanderer’, D760; Sibelius - Symphony No.7

Royal Albert Hall, London; 24th July 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Elizabeth%20Watts.jpg image_description=PROM 14: BBC Philharmonic/John Storgårds (conductor), Elizabeth Watts (soprano), Louis Lortie (piano) product=yes product_title=PROM 14: BBC Philharmonic/John Storgårds (conductor), Elizabeth Watts (soprano), Louis Lortie (piano) product_by=A review by Colin Clarke product_id= Above: Elizabeth WattsPhoto credit: Marco Borggreve

July 24, 2018

Heavenly choruses - Mahler 8th at the BBC Proms

In music, quality comes before quantity, so many performances scale down the numbers for the sake of the music. But the Royal Albert Hall was created for extravagant choral spectaculars In this vast barn of a building, it's possible to do things with Mahler's 8th that couldn't be done elsewhere. Most of the 6000-strong audience will remember this Prom for years to come. For starters, the Royal Albert Hall is in itself a form of theatre: the dome, the atmosphere, the sense of communal anticipation and the sheer visual impact of seeing the choristers file into their places. All eight rows of the choir stalls were packed, with another row of singers above that still. Across the entire breadth of the hall, two rows of young singers dressed in white. And right at the heart, the Royal Albert Hall organ so majestic that it sustain the whole powerful experience.

With its unconventional structure and eclectic meaning, Mahler's 8th still remains perplexing for many. Why are the two parts so different ? How do they work? Nearly every good performsnce can offer insight. Under Søndergård, the BBC NOW is at a peak but the glory of this performance was built on the choral forces he had to hand - the BBC National Chorus of Wales (Adrian Partington, chorus master), the BBC Symphony Chorus (Neil Ferris) and the London Symphony Chorus (Simon Halsey) with the Southend Boys' Choir and Southend Girls' Choir (Roger Humphreys). Halsey was chorus master of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and of the Berlin Philharmonic before his present post, and Partington, one of the stalwarts of the Three Choirs Festival (which starts next weekend) has conducted Mahler 8 before, at Gloucester Cathedral. Thus the exceptional coherence in the singing : hundreds of individuals operating in unison, negotiating the swift changes with precision, keeping lines fluid and clean. In a symphony that predicates on images of illumination, this clarity is important. Most impressive of all was the stillness these massed voices managed to achieve in the quieter passages. Though the nickname "Symphony of a Thousand" predisposes listeners to expect overwhelming volume, the critical passages are marked by hushed refinement, the "poetical thoughts" of spiritual refinement. Hearing hundreds of voices singing quietly, tenderly and yet in unison was very moving. They even seemed to synchronize turning their pages.

Tamara Wilson. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Tamara Wilson. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

The First Part of this symphony is based on an ancient latin hymn about the Pentecost. Divine fire descends upon the Apostles, inspiring them to go forth on their mission to spread Enlightenment. Hence the direct attack with which "Veni creator spiritus!" was executed , creating an aural force field n which the soloists voices were embedded. Though the soloists - Tamara Wilson, Camilla Nylund, Marianne Beate Kielland, Claudia Huckle, Joélle Harvey, Simon O'Neill, Quinn Kelsey and Morris Robinson - stand at the front of the platform where they can be heard, they are primus inter pares - first among equals - operating as an extension of the chorus and orchestra.

In the Second Part of this Symphony, Mahler was inspired by Goethe's Faust, where Faust is redeemed by divine grace. The soloists are named but they operate as stages in the transformation,: they aren't acting out roles as if in an opera. Take the names too literally and miss the esoteric spirituality, where ego is sublimated for a higher purpose. The variety in the voice types reflects human diversity,. I liked the balance between O'Neill's earnest fervour and Kelsey's rich tone, anchored by Robinson's bass. These parts also operate in musical terms suggesting movement upwards and downwards, on simultaneous planes, also pertinent to meaning. The women's voices supply the Das Ewig-wiebliche, the "Eternal Feminine". This dichotomy between male and female, creator and muse, is central to Mahler's later work. The chorus of Blessed boys operates in parellel. "Wir werden früh entfernt von Lebenchören", They too, have been reborn by an act of faith, but how cheeky and childlike they are, like th child in Mahler Symphony no 4.

Quinn Kelsey. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Quinn Kelsey. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

The vocal music in Mahler's 8th inevitably draws attention, and deservedly so. Thus the absolute importance of the silence that follows the ecstasy with which the first part ends. It represents a transition, bridging the two disparate parts, cleansing away what has gone before, settingb the scene for what is to come. But in many ways, the whole Symphony pivots on the first part of the Second Part where the orchestra alone speaks. Søndergård approached it with restraint, letting the detail shine. Pizzicato figures suggest tentative footseps entering the new territory evoked by sweeping strings, called forward by horn and flutes. The Chorus and echo repeat the pattern, marking the transition. Throughout the symphony, details were respected, so individual instruments like flutes, celesta and harps could be heard despite the size of the forces around them. Some conductors achieve much more luminous purity, but Søndergård made the most of generous choral resources at his disposal, which played to the strengths of the Royal Albert Hall.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mahler%20Prom%20BBC%20CC.jpg

image_description=Gustav Mahler: Symphony no 8 Thomas Søndergård, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, BBC National Chorus of Wales, BBC Symphony Chorus, London Symphony Chorus, Southend Boys' Choir, Southend Girls' Choir, Tamara Wilson, Camilla Nylund, Marianne Beate Kielland, Claudia Huckle, Joélle Harvey, Simon O'Neill, Quinn Kelsey, Morris Robinson, BBC Prom 11 - 22nd July 2018

product=yes

product_title=Gustav Mahler: Symphony no 8 Thomas Søndergård, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, BBC National Chorus of Wales, BBC Symphony Chorus, London Symphony Chorus, Southend Boys' Choir, Southend Girls' Choir, Tamara Wilson, Camilla Nylund, Marianne Beate Kielland, Claudia Huckle, Joélle Harvey, Simon O'Neill, Quinn Kelsey, Morris Robinson, BBC Prom 11 - 22nd July 2018

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Photo credit: BBC Proms/Chris Christodoulou

July 22, 2018

Beyond Gilbert and Sullivan: Edward Loder’s Raymond and Agnes and the Apotheosis of English Romantic Opera

It thus comes as a surprise to many opera lovers to learn that, before Gilbert and Sullivan teamed up in 1871, Britain had its own distinctive school of serious opera. This is conventionally referred to as English Romantic opera: it made its first appearance in 1834, continued to be produced into the 1860s, and the best-known examples were performed well into the twentieth century. It was strongly influenced by both German (especially Weber) and Italian (mainly Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti) models, but it also had distinctively British elements. The most important of these was the ballads, generally not too difficult to sing, which were designed to become hit songs outside the opera house – British composers were much more dependent on the sale of sheet music than their Continental rivals.

English Romantic opera had been almost completely forgotten when Richard Bonynge made a landmark recording of Michael William Balfe’s The Bohemian Girl in 1991. This was the obvious place to start a revival, for The Bohemian Girl was the most successful of all these operas. Inspired by Bonynge’s example, other operas from this period have since been revived and recorded. Bonynge himself has recorded William Vincent Wallace’s Lurline and Balfe’sSatanella. There have also been recordings of Balfe’s The Maid of Artois, Wallace’s Maritana, and – a favourite of this writer – George Alexander Macfarren’s Robin Hood. Alongside these have appeared George Biddlecombe’s standard study, English Opera from 1834 to 1864 (1994), and books on Balfe, Wallace, and Edward Loder. All this would have been quite unthinkable before 1990.

Most of these recordings have been met with surprise and delight by critics astonished at the fact that such impressive operas from the pre-Gilbert and Sullivan era even existed. Yet until now it has been impossible to listen to the work that critics have increasingly highlighted as the finest of all the English Romantic operas: Edward Loder’s Raymond and Agnes of 1855. Biddlecombe wrote of this as having ‘a quality of invention and dramatic power that raises it to an unusual position in English nineteenth-century opera’. Nigel Burton, in The Grove Dictionary of Opera, goes even further, emphasising the ‘surprising emotional intensity’, ‘the sense of drama and depth of musical characterization … close to Verdi’, which makes Loder ‘the foremost composer of serious British opera in the early Victorian period’.

In 1855, Raymond and Agnes was premiered at the Theatre Royal, Manchester, where Loder had been musical director since 1851. It enjoyed considerable success there, but when a London production was organised four years later, it was something of a disaster, thanks to the very poor quality of the performance. Loder (1809–65) was by that time suffering from the mental illness which painfully afflicted his final years, and was unable to promote his own work adequately. Thus this extraordinary opera disappeared from sight and was more or less unheard of for a century.

Edward James Loder, c. 1836 [Print, after an oil painting, in possession of Janet Snowman]

Edward James Loder, c. 1836 [Print, after an oil painting, in possession of Janet Snowman]

Then in 1963, Nicholas Temperley discovered a vocal score and immediately recognised Raymond and Agnes as a lost masterpiece. He organised a staged performance at Cambridge in 1966, and as word got out about just how good the opera was, critics travelled from all over the country to see it. They were all impressed. Charles Osborne wrote that he ‘was bowled over by Raymond and Agnes. Its intensity, and Loder’s gift for melody and musical characterization, were indeed Verdian and marvellously exciting.’ Andrew Porter called Loder a genius, John Warrack dubbed the Act 2 quintet ‘magnificent’ and Stanley Sadie thought it ‘would not disgrace middle‑period Verdi’.

After all the excitement in 1966, one might suppose that Raymond and Agnes could not be forgotten again. Yet it was. The problem was that in the 1960s, no libretto was thought to survive, and Temperley’s production was a speculative recreation of the opera based on the sung music. Although the BBC did broadcast a radio version in 1967, there was too much uncertainty about the opera for recording companies, or professional opera companies, to show interest. And so, once more, the dust gradually settled.

Finally, though, in the last decade there has been a steady movement toward reviving Raymond and Agnes in the form of a professional recording. A copy of the libretto, as used in London in 1859, has been located, and musicologist Valerie Langfield has spent years creating a definitive performance edition. When Retrospect Opera, the British charity, was founded in 2014, their first goal was to record Raymond and Agnes. It has been a crowdfunded project, with over 200 donations coming in from all over the world. Richard Bonynge was the obvious conductor to turn to, and a studio recording under his baton was made in October 2017. It is being released this summer complete with a sumptuous booklet containing the full libretto and three authoritative essays.

It must be confessed that the title, Raymond and Agnes, does not raise the same degree of interest as The Bohemian Girl or Robin Hood. It can sound prudishly ‘Victorian’. But this is very misleading. The title was in existence long before the opera, having been given to various works derived from Matthew ‘Monk’ Lewis’s classic Gothic novel, The Monk (1796), which had much the same impact in the 1790s as Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho had in the 1960s, fascinating, horrifying and appalling people. The Monk contains several intertwined stories – that of the lovers Raymond and Agnes is just one of them, and when that part of the story began to be treated as an independent work, it was called, unimaginatively, Raymond and Agnes. Loder’s librettist, Edward Fitzball, adapted this time-tested story, enlarging and complicating it with elements drawn from Lewis’s play, The Castle Spectre (1797), and Weber’s Der Freischütz.

The plot is very intricate, no doubt; the listener needs to make some effort to understand what is happening. It is also improbable in the extreme. But it is full of intensely dramatic situations and inspired Loder’s greatest music. Although Raymond and Agnes does contain some of the ballads that the Victorians demanded, it is in no sense a ‘ballad opera’. Its musical core is found in the duets and ensembles, composed with a Verdian level of force and conviction. The three central characters, Raymond (tenor), Agnes (soprano) and their sinister nemesis, the Baron of Lindenberg (bass-baritone), are brought together in various combinations and with every variety of emotion, from the most passionate youthful love to the profoundest hate, from tender gratitude to remorseless revenge. These scenes are orchestrated with a mastery unprecedented in nineteenth-century English opera, and make the strongest possible case for taking pre-Gilbert and Sullivan works seriously.

In Loder’s youth, Weber was making his huge impact on English opera, first with the sensationally successful adaptations of Der Freischütz (one of them made by Fitzball) in 1824, then with Oberon two years later. Weber seems to have been, enduringly, Loder’s greatest inspiration, and it is certainly not fanciful to imagine these German Romantic operas giving him his sense of vocation. By 1827, young Loder was studying music in Germany with Ferdinand Ries, and in 1834, when his own operatic career commenced, he introduced himself to the British public as ‘a German Student in music’. Unlike Balfe, with his mainly Italian influences, Loder wanted to create an English Romantic opera that could stand beside and claim kinship with the works of Weber and his German followers. Raymond and Agnes, with a story appropriately set long ago in a Romantic Germany of forest and castle, represents a most satisfying fulfilment of this goal.

Retrospect Opera’s recording of Raymond and Agnes can be ordered directly through their website ( www.retrospectopera.org.uk ), as well as through standard music retailers.

David Chandler

image=http://www.operatoday.com/R%26A_front_cover.jpg image_description=Raymond and Agnes by Edward Loder {Retrospect Opera RO005 [2CDs]} product=yes product_title=Beyond Gilbert and Sullivan: Edward Loder’s Raymond and Agnes and the Apotheosis of English Romantic Opera product_by=Commentary by David Chandler product_id=Retrospect Opera RO005 [2CDs] price=£17.95 product_url=http://www.retrospectopera.org.uk/CD_SALES/CD_Sales_R&A.htmlJuly 19, 2018

A Donizetti world premiere: Opera Rara at the Royal Opera House

L’Ange de Nisida is one of the middle knots in a cat’s-cradle of sources. In 1838, frustrated by the obduracy of the Italian censors, Donizetti moved to Paris and within just a few months his operas were being acclaimed in all the capitals major theatres. Les Martyrs (a revision of Poliuto, which had been disallowed from the Neapolitan stage) was admired at L’Opéra, which had also commissioned Le Duc d’Albe; La Fille du régiment had a successful premiere at the Opéra-Comique; a French version, prepared by Donizetti, ofLucia di Lammermoor opened at the Théâtre de la Renaissance in August 1839. No wonder Berlioz complained that Donizetti’s presence in Paris was a ‘véritable guerre d’invasion’.

The success of Lucia led the Théâtre de la Renaissance to commission a new work with a libretto by Alphonse Royer and Gustave Vaëz - L'Ange de Nisida. Donizetti putLe Duc d’Albe on hold and began work on L’Ange de Nisida, drawing on the score of Adelaide, an incomplete opera semiseria. The bankruptcy of the Théâtre de la Renaissance put a spanner in the works, though; ever the pragmatist, Donizetti drafted in Eugene Scribe to re-work the libretto, set about adapting the score of L’Ange de Nisida, added a little music from Le Duc d’Alba, and La Favorite was born. The latter was premiered on 2nd December 1840 at L’Opéra, while L’Ange de Nisida was condemned to nearly two decades of silence and obscurity.

10 years of painstaking detective and re-construction work by Italian musicologist Candida Mantica have brought the 800-page score back to life. Mantica has shown that press reports from La France musicale and La Revue et Gazette musicale, dating from February 1839, confirm that not only was the opera complete, but that rehearsals were underway and that the Théâtre de la Renaissance had prepared a mise-en-scène. The scholar argues that the reconstruction of L’Ange de Nisida (from the autograph score of La Favorite and other materials in the Bibliothèque nationale de France) illuminates Donizetti’s creative process, enables comparison of the dramatic and musical characteristics of French and Italian genres at this time, and offers information about the history of Théâtre de la Renaissance. [1]

Set in 1470 in Nisida and Naples, L’Ange de Nisida serves up the standard elements of opera semiseria - a tragic love-triangle and a comic strand. It also makes one rue, ‘If only they’d talked about things’, for the characters are all sure of their own plans and ignorant of those of others, and the result of their misconceptions is muddle and misery.

Leone de Casaldi, exiled from the army after a duel, flees to Nisida, an island off the Neapolitan coast. He yearns to see his beloved Sylvia who, unbeknown to Leone, is the mistress of King Fernand of Naples and is much admired by his people. Sylvia, annoyed at being lured to Naples from her native Andalusia with the promise of a husband only to become a mere paramour, keeps both admirers at arm’s length. Don Gaspar, Chamberlain to the King, meets Leone, learns of his need for refuge and starts meddling. In brief: Leone lands up in gaol before Sylvia’s pleas gain his release; the King’s plan to wed Sylvia is scuppered when a monk appears brandishing a Papal Bull threatening to send Sylvia to a convent if the King defies Rome and marries her; and Don Gaspar comes up with a plan by which Leone will marry Sylvia, then be banished so that the King can keep Sylvia as his mistress. After various mix-ups, the deceptions are discovered, and Leone decides to become a monk. Sylvia, near death, follows him to beg forgiveness for doubting his fidelity, but when they attempt to flee she expires at his feet.

Joyce El-Khoury (Sylvia), David Junghoon Kim (Leone) and Sir Mark Elder. Photo credit: Russell Duncan (Opera Rara/ROH).

Joyce El-Khoury (Sylvia), David Junghoon Kim (Leone) and Sir Mark Elder. Photo credit: Russell Duncan (Opera Rara/ROH).

Mark Elder’s commitment and concentration were noteworthy. There was not the smallest motif in the choral or orchestral parts that was not carefully, lovingly gestured and nurtured. The balance between soloists and orchestra was superb, especially as the ROH Orchestra had been released from the nether regions and placed on stage. Elder made sure that the imaginative woodwind colours registered, allowing us to enjoy not only Donizetti’s orchestrations but also those of Martin Fitzpatrick who has fleshed out some of the sketchy passages in the sources. Both Chorus and Orchestra demonstrated an excellent appreciation of style and a feeling for the dramatic character of the piece, and Elder’s energy was unflagging throughout the two and a half hours of music.

As the Chancellor puffed up with his own self-importance and misguided assurance of his Machiavellian nous, Laurent Naouri squeezed ever dramatic drop from the role of Don Gaspar; energised, colourful, attentive to the text and nimble in the patter, Naouri made a considerable contribution to the theatrical impact of this concert staging. Act Three is full of musico-dramatic interest, and Naouri’s duet with Vito Priante’s King Ferdinand, was a highlight of the evening, as he sought to back-track on his plan when he realised that Leone was truly in love with Sylvia.

I have to confess that David Junghoon Kim, a former Jette Parker Young Artist, has not impressed me overly in the past, singing competently and sometimes acting a little stiffly. But, I’m now prepared to eat my words: this was a tremendous performance which revealed a sure sense of bel canto idiom and a powerful tenor with plenty of penetrating presence. His phrasing was elegant, from his first avowals of love to his bitter rejection of the King, when Leone learns of Don Gaspar’s manoeuvrings and throws down the sword that he had previously put at the King’s service. The tenor went from strength to strength, growing in dramatic confidence as the action progressed. As the machinating monk who thwarts the amorous intrigues, Evgeny Stavinsky was also superb, revealing a lovely warm bass.

Joyce El-Khoury seemed a little out of sorts as Sylvia. She looked and sounded hesitant initially, and her tone never really found its shine or coloration. Though she sang with discerning shapeliness of phrase in the Act 3 cabaletta - in which she laments Leone’s apparent, but mistaken, dishonour - the following cabaletta (adapted from Maria di Rohan, owing to a gap in the sources), was lacking in fluency and clarity.

While the first three Acts were fully engaging, Donizetti seems rather to have lost his way a little in Act 4, where the extended quiet, plaintive duet for Leone and Sylvia resulted in a dissipation of dramatic energy and, for this listener at least, lessened the emotive impact of the tragedy. But, we are indebted to Opera Rara for yet another ‘first’ and for their courage, commitment and stamina in pursuing the rare and vanished in this repertoire.

L’Ange de Nisida is repeated on 21st July. A live live recording will be made for release in 2019, marking the company’s 25 th complete opera recording by the composer and Sir Mark Elder’s ninth Donizetti title for Opera Rara.

Claire Seymour

Donizetti: L’ange de Nisida (Libretto by Alphonse Royer and

Gustave Vaëz)

Opera Rara: Conductor - Mark Elder

Sylvia - Joyce El-Khoury, Leone de Casaldi - David Junghoon Kim, King

Fernand of Naples - Vito Priante, Don Gaspar - Laurent Naouri, Monk -

Evgeny Stavinsky, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Royal Opera Chorus.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; Wednesday 18th July 2018.

[1] Candida Mantica, ‘From Lucia de Lammermoor to L’Ange de Nisida, 1839-1840: Gaetano Donizetti at the Théâtre de la Renaissance’, Revue Belge de Musicologie/Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Muziekwetenschap , 2012, Vol.66, pp.167-179.

Photo credit: Russell Duncan (Opera Rara/ROH)

July 18, 2018

A stellar Ariadne auf Naxos at Investec Opera Holland Park

This co-production between Investec Opera Holland Park and Scottish Opera adds further bifocal perspectives. Antony McDonald’s production was originally staged in spring, behind the scenes of the mansion belong to ‘the richest man in Glasgow’, and now the director and designer has brought the show from north to south, morphing the Scottish pile into South Kensington’s Holland Park House.

The rival operatic and vaudeville troupes are cooped up in tatty trailers either side of the lawn, the burlesque comedians, circus artists and MC taking the air on the top of their grass-bound motorhome, the diva and her tenor lounging in a curtained caravan.

Julia Sporsén (Composer), Jennifer France (Zerbinetta) [Photo credit: Ali Wright]

The Prologue antics are rather frantic as Stephen Gadd’s deliciously poker-faced Music Teacher receives and rebuffs the news - delivered in broad Glaswegian brogue by Eleanor Bron’s Party-Planner (aka the Major Domo) - that his protégé’s classical-themed opera will need to be synchronised with the burlesque troupe’s acrobatics if the money-man’s pyrotechnic coda is to be lit by 9pm. The colloquial quips of Helen Cooper’s English translation help Strauss’s conversational idiom to skip along, but the acoustics of Opera Holland Park’s dome defeated Bron, and sadly I for one struggled to make sense of her spoken text (for which there were no surtitles - a pity, in an unforgiving venue).

Seria and buffa elements were confrontational rather than cohesive - perhaps that’s how it should be - but Julia Sporsén’s Composer brought disparate parts into a cohesive whole, with her Schubertian-Straussian paean an die Musik. Sporsén’s soprano shone and thrilled and both her declaration that music is a holy art and her interactions with Zerbinetta were genuinely touching. Jennifer France’s Dietrich-like, dynamic Zerbinetta may have thought she was engaging in mild flirtation, but her heart was clearly hooked by the Composer’s soulful sincerity and artistic and romantic integrity. And, here McDonald has added another piquant twist, making the Composer a woman - given that Sporsén sported a blue suit and the only hint of femininity was dark underwear showing through her white polka-dot blouse, some in the audience may have been confused -thereby adding a touch of spice to the androgynous aromas of Strauss’s original travesti interactions.

The gender-switch also means that it is a woman who has penned the tale of Ariadne’s love, loyalty and loss, subtly shifting the sympathies of the perspective. When Mardi Byers appears at the start of Act 2 and lingers beside a grand dining-table, abandoned mid-meal - taking a glug of red wine from a half-filled glass, gazing forlornly at an un-cut tiered cake - it’s hard not to see a hint of Miss Haversham’s Satis House mausoleum, spacious and handsome but in which ‘every discernible thing in it was covered with dust and mould, and dropping to pieces’, the most prominent object being ‘a long table with a tablecloth spread on it, as if a feast had been in preparation when the house and the clocks all stopped together’.

Daniel Norman (Scaramuccio), Jennifer France (Zerbinetta), Lancelot Nomura (Truffaldino) and Elgan Llŷr Thomas (Brighella). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Daniel Norman (Scaramuccio), Jennifer France (Zerbinetta), Lancelot Nomura (Truffaldino) and Elgan Llŷr Thomas (Brighella). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Dickens jilted bride ‘laid the whole place waste, as you have seen it, and she has never since looked upon the light of day’, and so this Ariadne stares yearning at the coffin which she longs to make her final resting place, sooner rather than later. Only the dulcet urgings of the three nymphs keep her from the abyss. Elizabeth Cragg (Naiad), Laura Zigmantaite (Dryad) and Lucy Hall (Echo) resembled the Queen of the Night’s Three Ladies in their gorgeous frocks, with bat-like trains, of white-grey-black: veritable bridesmaids-in-decay.

McDonald doesn’t quite keep seria and buffa in balance, and the vaudeville troupe threaten to up-stage the classical in Act 2, especially when they take a rest from the show-casing their spectacular circus skills - not one spinning china-plate fell - and they grab the wedding-cake from the table and flick through a book of Greek myths. Circus skills director Joe Dieffenbacher has mentored his tutees expertly and Alex Otterburn (Harlequin), Daniel Norman (Scaramuccio), Lancelot Nomura (Truffaldino) and Elgan Llŷr Thomas (Brighella) form a compelling vocal and kinetic ensemble. And, to be honest, it’s a relief, after several recent productions, to have a vaudeville troupe who are more Berlin satire than barbershop saccharinity.

Kor-Jan Dusseljee (Bacchus) and Mardi Byers (Ariadne). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Kor-Jan Dusseljee (Bacchus) and Mardi Byers (Ariadne). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

The arrival of Kor-Jan Dusseljee’s stentorian Bacchus - high notes sometimes a little overly ear-piercing but still remarkably true and firm - marked a shift in the dramatic dynamic from triviality to transcendence. Byers didn’t negotiate every phrase with Straussian suavity, but there were rich colours and honest emotions, and this Ariadne’s torment and troubles were palpably evident. In their final duet, she and Dusseljee effected the necessary translation and quickly the busy preliminaries to their romantic apotheosis were forgotten as they drew us into their unearthly paradise. It was at this moment too that conductor Brad Cohen, who had presided over an impressive account of Strauss’s sumptuous music up to this point, seemed to become totally absorbed, his arms swirling and sweeping all sumptuously into Strauss’s musical magic.

Jennifer France (Zerbinetta). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Jennifer France (Zerbinetta). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

But the real transcendence was to be found elsewhere. When Strauss began setting Hofmannsthal’s libretto he said that he envisaged Zerbinetta as the leading role, and he told his librettist that he would be writing the part for a high coloratura soprano - Ariadne was originally to be a contralto - advising Hofmannsthal to listen to Selma Kurz, the first Zerbinetta, singing arias from La sonnambula or Lucia di Lammermoor if he wanted to get a feel for the idiom. And, so it was that Jennifer France was the true Sirius in a stellar show, delivering her vocal acrobatics with astonishing athleticism, precision and expressive nuance, all the while performing a teasing strip-show. Languor and assertiveness were wonderfully melded in sensual sublimity. It was hard to tell who enjoyed it most: France or the mesmerised audience.

And, it was France who held our attention in the closing moments. With Ariadne and Bacchus united in divine devotion, one by one the other characters crept in to witness the denouement and take their bows. Sporsén’s Composer was the last, and her arrival drew Zerbinetta from her embrace with Harlequin: it was the women’s love that had the last word. A love celebrated by a fountain of fireworks - an hour late, at 10pm, but still a fitting accolade for Investec Holland Park’s vocally stunning Strauss debut.

Claire Seymour

Richard Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos

The Prima Donna/Ariadne - Mardi Byers, The Tenor/Bacchus - Kor-Jan Dusseljee, Zerbinetta - Jennifer France, Harlequin - Alex Otterburn, Scaramuccio - Daniel Norman, Truffaldino - Lancelot Nomura, Brighella - Elgan Llŷr Thomas, The Party Planner - Eleanor Bron, The Professor of Composition - Stephen Gadd , The Composer - Julia Sporsén, The Producer - Jamie MacDougall, Naiad - Elizabeth Cragg, Dryad - Laura Zigmantaite, Echo - Lucy Hall , Wig Master - Thomas Humphreys, Butler - Trevor Bowes, Officer - Oliver Brignall; Director/Designer - Antony McDonald, Conductor - Brad Cohen, Lighting Designer - Wolfgang Göbbel, Choreographer - Lucy Burge, Circus Skills Director - Joe Dieffenbacher, Prologue Translation - Helen Cooper, City of London Sinfonia.

Investec Opera Holland Park, South Kensington, London; Tuesday 17 th July, 2018.

Photo credit: Robert Workman

PROM 5: Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande

That the semi-staging probably rescued the evening from large-scale failure - as many semi-staging’s do - had much to do with focussing the drama of this opera rather tightly. It was largely beautifully acted, with some of the symbolism and mystery of the text much less micro-managed than in a full-scale production of the opera.

I think Sinéad O’Neil’s staging is mostly admirable. It would have been easy to have done very little, but she does quite the reverse. Some scenes are certainly more compelling than others - Golaud’s hair-pulling scene, with Mélisande writhing as if bound to a stake, is rather monstrously done. Golaud, from one of the choir stalls, acts just like a malevolent puppet-master. The end of Act III, where Golaud persuades Yniold to spy into the windows of the tower, was genuinely rather terrifying - indeed, it’s reasonably rare to find any production where the tension between these two characters seems to fit with the music Debussy wrote but it does here. Pelléas and Golaud wandering through the castle dungeons only worked through careful lighting but it was magnificently sepulchral nevertheless. On the downside, interior scenes looked and felt cluttered and had the unintended effect of making one feel everyone had fallen on very hard times; it often felt like downstairs at Downton Abbey. Importing the original productions hefty over-reliance on hand gestures, especially the perpetual covering of eyes, became slightly grating; one often felt one was trying to read sign language. Often there’s so much going on it’s against the very synthesis of the music itself. Much of this opera, for better or worse, is about stillness and that’s a concept that the staging really didn’t appreciate.

Brindley Sherratt (Arkel), John Chest (Pelléas), Karen Cargill (Geneviève). Photo credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Brindley Sherratt (Arkel), John Chest (Pelléas), Karen Cargill (Geneviève). Photo credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

I did find the casting a problem. Debussy attached great significance to the libretto of this opera - indeed, the rhythms of the words are quite meticulously designed to be heard in this opera - so it was disappointing that so much of the sung French was so opaque. It had little to do with the fact that the hall sometimes swallowed voices, or they simply disappeared, rather that it wasn’t a particularly refined cast. In one sense this is a rather misty, or ethereal opera, and the lack of detail in the voices rather added to this. Karen Cargill’s Geneviève, for example, was luxury casting - but she was so velvety, so vocally secure that she rather forgot to bring any sense of mystery or depth to her character. Christopher Purves, as Golaud, seemed a tad one dimensional to me. This is perhaps the most vividly drawn character in the entire opera, but that was entirely irrelevant here. What we got was someone who acted beautifully but sang as if Golaud was entirely driven by anger and violence; the fact Purves felt the need to dominate the orchestra again suggested a lack of depth - this is a man possessed by raging jealousy, too, and innately virile; it didn’t come across that way. John Chest’s Pelléas began a little nervously - some of his A flats were flaky - but of all the male leads he was the most successful at pitching the balance between rhythm and concept - and his singing became notably more passionate during the evening. If the voice had been a little frayed earlier on, it was notably more secure by the time of his death. Christina Gansch’s Mélisande was girlish enough, but the blandness of the voice, and the lack of nuance, left me wondering why this particular Golaud and Pelléas would be involved with her at all. Only Chloé Briot’s Yniold - the sole native French speaker among this cast - was really a success at getting to grips with the text, and also doing something meaty with her role.

Christopher Purves (Golaud), Chloé Briot (Yniold). Photo credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Christopher Purves (Golaud), Chloé Briot (Yniold). Photo credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

The undisputed highlight of the evening was the playing of the London Philharmonic Orchestra. I’ve rarely - if ever - heard this score better played. The LPO is becoming one of the great opera orchestras: time and time again, I found the detail a revelation, the internal instrumental voices, the clarity of phrasing and the impeccable balance of tone and colour remarkable. The woodwind, especially, have such flexibility they can almost do anything asked of them. I think one can certainly quibble with Robin Ticciati’s approach to the opera itself - and this was certainly reflected in the LPO’s overall sound. At times I did feel as if I was listening to Parsifal rather than Pelléas et Mélisande - the Wagnerian inferences are certainly in Debussy’s score but sometimes you wondered if Ticciati thought it was Klingsor wielding the sword rather than Golaud. The strings, too, sounded heavy at times - but what a wonderful, spellbinding richness of sound it was. Ticciati took a somewhat majestic view of the score, too, less overtly sensuous than some, certainly less French, but he can whip up tension and terror when it’s needed but there are also beautifully seductive, dark-hued moments too. It certainly won’t appeal to everyone, and sometimes borders on being self-indulgent, but the tightrope he walks is just narrowly a viable one.

The tightrope that Glyndebourne’s semi-staged production walked wasn’t entirely a successful one, but very few productions of this magnificent opera manage to make a complete success of it. Not the most satisfying Pelléas, but a ravishing orchestral feast I won’t soon forget.

Marc Bridle

Prom 5: Debussy, Pelléas et Mélisande (semi-staging based on production by Stefan Herheim)

Golaud - Christopher Purves, Mélisande - Christina Gansch, Geneviève - Karen Cargill, Arkel - Brindley Sherratt, Pelléas - John Chest, Yniold - Chloé Briot. Sinéad O’Neill; conductor - Robin Ticciati, London Philharmonic Orchestra, The Glyndebourne Chorus.

Royal Albert Hall, London; Tuesday 17th July 2018.

Available on BBC iPlayer for 30 days.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Debussy%20Pelleas.jpg image_description=Pelléas et Mélisande, Glyndebourne Festival Opera at the BBC Proms product=yes product_title=Pelléas et Mélisande, Glyndebourne Festival Opera at the BBC Proms product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id= Above: Christina Gansch (Mélisande, Christopher Purves (Golaud), Pelléas (John Chest)Photo credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou

July 17, 2018

Thought-Provoking Concert in Honor of Bastille Day

“We wanted this recital to be beautiful even when the political climate is so ugly,” said Jones, of the choice of French-song centered evening.

And beauty the sopranos did indeed present with a highly ambitious, challenging program that included Benjamin Britten, Gabriel Fauré, Viktor Ullman, and a world premiere by composer Martha Sullivan.

Elise Brancheau began the program with Les Illuminations, op. 18 by Benjamin Britten. Brancheau oscillated between coy gaiety and deep desperation in order to illustrate the pathos of poetry imbued with pastoral playfulness and perverse paintings of human freakishness. Martin Néron played the at-times perversely cheerful stylings of Britten with aplomb, supporting Brancheau in a display of skillful duetting. Brancheau navigated the difficult cycle with incredible breath control, musical sensibility, and a shimmering instrument seemingly unphased by the music’s many vocal challenges.

Brancheau’s performance of the world premiere of Lunaire by Martha Sullivan also proved a success.

“The collaboration came about by chance,” said Brancheau of her partnership with Sullivan. “She [Sullivan] reached out to me and said she had always wanted to set these poems [by Albert Giraud].”

Sullivan’s music is lyric and sweeping, and clearly displays her knowledge of the soprano voice. The piano moves between complex harmonies while repeating haunting leitmotifs that linger in the mind long after each musical phrase has ended. The vocal line deftly illustrates the eeriness of each of Giraud’s poems with frequent moments of musical word painting, supported by a thrusting piano part that almost evokes a more sinister Debussy.

Shannon Jones collaborated with pianist Keith Chambers to present Cinq Melodies “de Venise” by Gabriel Fauré. Jones brought a lush and sensual interpretation to Fauré’s songs. Her second selection, a set of Viktor Ullman songs setting the poetry of Louïse Labé, displayed the full depth and range of Jones as a singer, as well as Chambers as a pianist. Jones sang through two songs of unrelentingly high tessitura with clear and striking vocal timbre, while Chambers ripped through the difficult piano accompaniment with nearly unbelievable ease.

Ullman was a striking and poignant choice by Jones, who said of the composer, “He and his works are a reminder of what we stand to lose if we look at people as a race versus a being.”