August 31, 2018

Prom 64: Verdi’s Requiem

If the text is religious, the music can seem apocalyptic, coruscating, relentless - and even agnostic. Hans von Bülow, even before he had heard the work, described it as “Verdi’s latest opera, though in ecclesiastical costume”, and for some (though not Brahms), this view remains a valid one. But the scale of this requiem, and the miracle of its orchestration and vocal writing, rather prove the opposite: Where else, except perhaps in Mahler’s Resurrection, does the power of trumpets, on-stage, and antiphonally off-stage, take you towards the precipice of religious cataclysm? In what other sacred work does the timpani sound like a hammer against an anvil? And is there a darker, more sonorous, and bleaker, ‘Amen’ than the one that Verdi writes at the close of his ‘Dies Irae’?

Great performances of Verdi’s Requiem are rare in my experience. They fall short for all kinds of reasons - and yes, the worst do treat this work as an opera. The young Columbian conductor, Andrés Orozco-Estrada, making his Proms debut with this work - as Lorin Maazel had done almost fifty years ago - clearly sees Verdi’s work in very sacred terms. This was in no sense a hard-edged, or even driven, performance in the Solti mould - but nor was it one that lingered over phrases to the point of paralysis as Maazel was wont to do in his later years. That is not to say that Orozco-Estrada doesn’t take time to illuminate details of orchestration. The woodwind phrasing was luscious, for example - but given this conductor’s ear for ravishing sonorities in a work like Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben this didn’t overly surprise me.

It’s difficult to sustain drama and tension in this piece for almost ninety minutes but for most of that span Orozco-Estrada managed to do just that. The ‘Dies Irae’ was taken in almost a single arc and the impact of it was entirely memorable. He brings a younger man’s sense of terror to this music rather than the more usual sense of prophecy than someone like Giulini did. Those indelible piccolos almost seemed to stab themselves through the orchestra like blades, the bass drum thundered, the trombones erupted into pyroclastic clouds of sound. This was a ‘Dies Irae’ with fire scorching like an inferno, the horror of the Day of Wrath painted from the ink of Verdi’s music. But there was room for great luminosity, too: bassoons were sculpted, not just phrased, flutes fluttered like angels. The ‘Agnus Dei’ had an ethereal beauty to it, and this is a conductor who can shape a pianissimo with breath-taking transparency.

Lise Davidsen. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Lise Davidsen. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

None of this would have been possible without his soloists or choir, however. Of all the great choral works, Verdi’s Requiem is the most difficult to cast well and this one did much better than most. The Norwegian soprano, Lise Davidsen, I sometimes felt was a touch hard-edged. This isn’t the most obviously beautiful, or creamy, soprano and the sheer steeliness of her voice sometimes felt too harsh. I think anyone who was familiar with Margaret Price in this work would have found her rather cold - even shrill. But where it mattered the accuracy of her singing, the brilliance of her upper register and the ability to scale her dynamics was stunning. She definitely took some time to get into her stride; the ‘Introit and Kyrie’ wasn’t as assured as I’d have liked, but she undoubtedly became more secure as the performance developed. Indeed, her ‘Libera me’ was a tour de force: exquisite strength, imperious high notes and a pianissimo that was ravishing. This is a voice that doesn’t just cut through the orchestra like a sabre; it rises effortlessly above it as well.

The mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly, replacing the indisposed Karen Cargill, was magnificent. The voice is rich, yet the tone is so burnished as well, and no-one who heard her sing would have been unmoved by the depth she brought to her part. Perhaps the voice isn’t huge - and certainly it didn’t have the dramatic impact that Lise Davidsen summoned at times - but the pairing of these two voices was symbiotic. The Ukrainian tenor, Dmytro Popov, is that rare thing: A true Verdian tenor. His ‘Ingemisco’, so often a point of anti-climax in a performance of Verdi’s Requiem, was staggering. The top notes ring out with a steady evenness that is as disciplined as it is stentorian, and yet that brightness of tone belies a really deep, unquivering lower register that is granitic. Short of stature - it was difficult from where I was sat in the stalls to see him above his music stand - the voice has huge presence. The Polish bass, Tomasz Konieczny, brought the strength and terror of Wotan to his ‘Confutatis’. Again, here was a singer who didn’t just sing his part; he brought a wealth of vocal colour and heroic range to it. Konieczny’s voice is rock-solid at the bottom, the final line of his ‘Confutatis’ - ‘Gere curam mei finis’ - so sonorous you felt it would split the heavens apart. This isn’t just a voice that has strength, however; it abounds in lyricism, too.

Tomasz Konieczny. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Tomasz Konieczny. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Both the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and its chorus, were fully equal to the demands of Verdi’s score. This was a performance where neither the orchestra, nor the chorus, overwhelmed the other. It wasn’t the weightiest sounding Verdi Requiem I can remember; in fact, it projected a feeling of period performance being both highly disciplined and strongly incisive. Indeed, balances were so in harmony with each other you often felt the whole requiem was like a slow, blossoming flower. Moments like the opening of the ‘Introit and Kyrie’ were exquisitely poetic, defined by playing that was almost inaudible, barely above the level of a ghostly whisper; yet, on the other hand, the ‘Sanctus’, with its double fugue and double chorus, was a triumph of vocal clarity.

This was a sublime concert, magnificently performed and interpreted, and a very notable Proms debut from its young Columbian conductor.

Marc Bridle

Prom 64: Verdi, Requiem

Lise Davidsen (soprano) - Sarah Connolly (mezzo-soprano) - Dmytro Popov (tenor) - Tomasz Konieczny (bass) - London Philharmonic Choir (Neville Creed, Chorus-master) - London Philharmonic Orchestra - Andrés Orozco-Estrada (conductor)

Royal Albert Hall, London, 30th August 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Prom64%20Connolly.jpg image_description=Prom 64: Verdi’s Requiem, London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Andrés Orozco-Estrada product=yes product_title=Prom 64: Verdi’s Requiem, London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Andrés Orozco-Estrada product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id= Above: Sarah ConnollyPhoto credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou

Prom 62: Petrenko and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic - one concert, two stellar sopranos

And, the performances by Romanian soprano Adela Zaharia and Swedish soprano Miah Persson in this Prom, with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Vasily Petrenko, were certainly satisfying, completely and complementarily.

However, the music that they performed did not hit similar heights. Persson’s Straussian credentials were polished at Garsington this summer where her role debut performance as the Countess in Tim Albery’s production of Capriccio was unanimously acclaimed. Gold, silver and pearl: the adjectives bandied about by the critics suggested that the Three Kings had come to Wormsley. But, such effulgence was retrospectively justified by the sumptuousness, gracefulness and purity with which Persson floated - with glorious freedom, suppleness and coloristic range - through the four songs selected here.

Slightly reduced in forces after the interval, the RLPO glistened with the excited heart-flutterings of a love-inflamed adolescent at the start of ‘Ständchen’ (Serenade) - indeed, Persson’s impassioned impetuosity evoked the palpitating ardours of a Cherubino. After the sweet reflectiveness of the first two stanzas of ‘Das Bächlein’ (The Brooklet), the final verse had a wonderful sense of new energy and confident purposefulness, lifted too by the exuberant spiralling in the orchestral texture. In ‘Morgen!’ (Tomorrow!), Persson crafted the vocal line with simple but pure delicacy, her melody embraced by leader Thelma Handy’s eloquent violin solo as the delicious rubatos of the heaven-aspiring harp and the deep resonance of the bass pizzicatos provided a fulfilling accompaniment. There was a ripening of emotion with the declamatory “Stumm warden wir uns in die Augen schauen” (We shall look mutely into each other’s eyes), and Petrenko exploited the harmonic tensions in the sustained chords until feeling overflowed in the final duet of solo violin and harp; Petrenko dared to diminuendo to a whisper and then to nothing, and then still further into silence. The glories of ‘Zueignung’ were over all too soon; the intensification and apotheosis of the third stanza were thrilling.

Miah Persson. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Miah Persson. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Throughout, Persson’s lovely vocal sheen held the Proms audience in still wonderment and joy, though, if one were to quibble, perhaps the soprano might have paid a little more attention to Strauss’s word-painting. There was an occasional verbal-coloristic frisson, as in as ‘Ständchen’, when the dusk fell beneath the linden trees - “Unter den Lindenbaumen” - and Persson’s rich rolling of the ‘r’ - “Und die Rose, wenn sie am Morgen erwacht” - made the flower glow with the night’s rapture; and Strauss’s cadential falling appoggiaturas were discerningly articulated. More of such details would have raised a very fine performance still higher. But, the final phrase of ‘Zueignung’ said it all: “habe Dank!” Be thanked, indeed.

Persson was replacing Diana Damrau who had withdrawn owing to illness, and Damrau had also been the intended soloist in Iain Bell’s Aurora, a BBC co-commission with the RLPO, written for Damrau with whom Bell has collaborated frequently. It fell instead to Romanian soprano Adela Zaharia to present the world premiere. Operalia 2017 winner Zaharia, making her Proms debut here, won acclaim when she stood in for an ailing Damrau last December in Munich, when the latter withdrew from the first performance of the run of Lucia di Lammermoor at the Bayerische Staatsoper. Bell’s exploration of the coloristic mystery and majesty of the aurora borealis was well served by the ease of Zaharia’s flights into the stratosphere; the darkness and strength of her tone in the middle and lower ranges; and by the powerful muscularity, allied with subtle flexibility, of her soprano, which breezed easily over the varied orchestral textures. Such qualities did much to sustain a narrative arc and expressive focus through the three linked movements of Bell’s nocturnal probing and wonderment. Zaharia worked hard to imbue the vocalise of the first movement, ‘Dusk to Darkness: First Glimmers’, with expressive weight and intent, her voice flickering and glittering over orchestral intimations of coming night, beginning coolly and then accruing warmth, to glow with the luminescent strength of the sky’s display of dancing of electrons and photons. She slithered provocatively and fierily - and with impressive precision - through the frolics of ‘Night-time: Lights Come Out to Play’, rising exuberantly to climactic vocal peaks and soaring over the flourishes of full-textured orchestral playfulness. In ‘Dead of Night: Phantom Shadows’, her florid outbursts were delivered with deceptive ease, untroubled by the aggressiveness of the orchestra’s rhythmic repetitions, brassy challenges and percussive onslaughts. And, in the closing stages, as the sustained low pedal dissipated into the ether, Zaharia shaped the voice’s final declaration of the supremacy of light most beautifully.

Vasily Petrenko. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Vasily Petrenko. Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

The work itself, I found less convincing. Bell certainly knows how to exploit orchestral timbres and how to tint textures with flashes of colour, light and tactility. The ear was teased with myriad gestures; one could never anticipate from whence or which instrumental voice would speak, sing, stutter or demand, then disappear back into the shimmering mass. Petrenko shaped the evolving hues and episodes with a sure sense of pace and atmosphere, and, particularly in the central movement, ensured that we appreciated the teasing dialogues between voice and orchestra, in a manner of a ‘traditional’ concerto. But, it’s difficult to sustain a sense of expressive focus through twenty minutes of vocalise, however inventive the instrumental effects; and, in a work centring on colour and conflict, it’s a pity that harmony played a less significant role in Bell’s pictorial arsenal. Overall, what I missed most was the mythic poetry of the aurora borealis, though I certainly hope that we get another chance to hear Zaharia perform in the UK soon.

The vocal items were framed by two exuberant scores in which Petrenko inspired some committed and virtuosic playing from the RLPO. Elgar’s In the South opened the Prom with a blast of Mediterranean heat, sunshine and out-of-doors joie de vivre, though it was the tenderness of the strings’ playing during the episode depicting the shepherd’s pastoral idyll - a lovely, warm viola solo from Catherine Marwood - which was most stirring. Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra allowed the RLPO to demonstrate their individual and collective prowess. The Introduzione offered contrasts of blackness and brightness to complement Bell’s night-time vistas, while the snareless side-drum was an exacting master in Giuoco delle coppie. The central Elegia was somewhat restrained, and Petrenko thus did not emphasis the characteristic arch-structure of the work, but the extremes of decorum and boorishness were entertainingly exploited in the Intermezzo interrotto, while in the Finale: Presto Petrenko threw the orchestral caution to the wind in spectacular style. We needed the gentle beauty of the RLPO’s encore - Rachmaninov song, ‘Zdes’ khorosho’ (All is well here), transcribed for orchestra by the orchestra’s principal horn, Timothy Jackson - to remind us that, indeed, all was well.

Claire Seymour

Prom 62: Miah Persson (soprano), Adela Zaharia (soprano), Vasily Petrenko (conductor), Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra

Elgar - In the South (Alassio); Iain Bell - Aurora (BBC co-commission: world premiere); Richard Strauss - ‘Ständchen’, ‘Das Bächlein’, ‘Morgen!’, ‘Zueignung’; Bartók - Concerto for Orchestra

Royal Albert Hall, London; Wednesday 29th August 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Zaharia.jpg image_description=Prom 62: Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Vasily Petrenko product=yes product_title=Prom 62: Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Vasily Petrenko product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Adela ZahariaPhoto credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou

August 27, 2018

A brilliant celebration of Bernstein & co. from Wallis Giunta at Cadogan Hall

But, in what genre, who would hazard a guess, given Giunta’s evident passion and affinity for, and accomplishment within, anything from opera to blues, art song to jazz, music theatre to cabaret? On the evidence of this Chamber Prom, the mezzo-soprano doesn’t simply sing, she truly performs: every textual line is inhabited vocally, gesturally, physically, and the characters to which she gives voice, spirit and presence are immediately, viscerally and compelling ‘real’. Her tone - high, middle, or low - is simply gorgeous, though it was the full, flickering hues of the middle that I found most stunning; and, if in this recital, Giunta didn’t have to call upon an enormously extended range, then she was even from top to bottom, and seemed happy to slip out of her natural comfort-zone when music and drama called - and to incorporate all manner of spoken and sung sounds, sound-effects and percussive gestures as the repertoire demanded.

The English texts of the songs by Bernstein and his contemporaries, and also that set by Bushra el-Turk (b.1982) whose BBC commission offered us a song inspired by and in homage to Bernstein, were crisply enunciated, no matter how racy the rhythms or tongue-twisting the consonants. Indeed, versatility might be considered the quintessence of Giunta’s art, and in this regard she seems to have found the perfect accompanist in Michael Sikich, whose studies at the Aspen Music Festival and School, the Schubert Institute in Baden, and with Peter Bithell and Julius Drake at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, where he received the Piano Accompaniment Prize, have been complemented by mentoring in jazz piano by Barry Green at the GSMD and working as a bandleader and pianist for the jazz group Cut Time. Such experience and range resulted here in accompaniments characterised by a soft but sure touch, precise but animated rhythms, and a latent friskiness that always supported and never overpowered the singer.

In Aaron Copland’s ‘Pastorale’ (composed in 1921, first performed the following year, but not published until 1979), Giunta’s silvery tone effortlessly served the simple beauty of the unornamented melodic line. The setting of Edward Powys Mather’s ‘Song’ (translated from the Kafiristan) eschews any ‘eastern’ mannerism, instead fore-grounding the innocence faith in the joy that love can bring, a quality evinced by Giunta’s floating octave rise: “Since you love me and I love you/ The rest matters not.” The song seems to speak of a belief in ideal love, which is given a sensual twisty in the dusky harmonies of the closing repetition, “I love you”, and of a heavenly bliss which here was exquisitely captured by Sikich’s three pianissimo notes at the close, which dissolved gently into the air.

Perhaps Giunta tapped into her Irish roots in ‘Sea-Snatch’; it’s an ancestry she shares with the composer of the Hermit Songs Op.29, Samuel Barber, who in this song set lines from Sean O’Faolain’s poem - in which the poet cries out to heaven as the sea brings turmoil and death. As the wind consumed and swallowed the ailing poet, and the ship’s timber was devoured by “crimson fire”, Giunta’s melismatic appeal to “O King of the starbright Kingdom of Heaven!” burned with fervour and stirring potency. In contrast, in ‘The Monk and His Cat’ Giunta purred with the self-satisfied contentment of the theological scholar who finds peace and fulfilment in the company of his “white Pangur”.

Two songs by Marc Blitzstein let Giunta off the leash. Though her hands were clasped, as if in prayer, for the opening self-introduction by the “Victorian and modest maid”, the subsequent revelation that, despite her neatness and discreteness, what she really loves is “LECHERY/ Simple LECHERY”, released wry and riotous emotions and Giunta relished the lascivious ‘maid’s’ indiscretions and confessions - I was put in mind of the insouciant defiance and rejection of archetype of Thomas Hardy’s ‘Ruined Maid’. The opening reflections of ‘Stay in My Arms’ were poignant and Giunta suggested a universal relevance beyond the song’s romantic confines: “In this great city, is there no peaceful, pretty place where noise is not?/ A little quiet, somewhere amid this riot, would help things a lot.” The subsequent varied sentiments of the unfolding stanzas were vividly communicated.

Sondheim’s ‘The Miller’s Son’, from A Little Night Music, seems purposefully designed to trip up the singer who dares to tackle it - “It’s a wink and a wiggle/ And a giggle on the grass/ And I’ll trip the light fandango./ A pinch and a diddle/ In the middle of what passes by.” - but Giunta sailed through as if it were a breeze, literally enacting every gesture from the “flings of confetti” to the “rustle in the hay”.

The mezzo-soprano exhibited similar adeptness as an enunciator in the opening four Bernstein songs which form La bonne cuisine. She pattered pianississimo through Émile Dumont’s recipe for ‘Plum Pudding’, her clarity showcased here and in the following ‘Queues de Boeuf’ by Sikich’s finely etched unison accompaniments. ‘Tavouk Gueunksis’ lilted louchely to an oriental pulse and tint, Sikich’s percussive ostinati clattering edgily, while the instructions how to cook a ‘Rabbit at Top Speed’ had a purposefully, sometimes manic, drive, coupled with occasional lyrical expanse à la Candide. Giunta displayed a flawless control not just of enunciation but also of intonation and rhythm, and she crowned her vocal-culinary demonstration with a flamboyant air kiss: “mix them together … and serve!”

Bushra El-Turk’s ‘Crème Brûlée on a Tree’ was even more visually demonstrative and Giunta didn’t let her need for a score here - the rest of the recital was sung from memory - inhibit her one iota; indeed, I longed to know whether the facial tics, slaps, claps, puffed and pouting cheeks, shoulder twitches and nose-pinching had been prescribed by El-Turk or were Giunta’s own invention. Spoken text, whooping repetitions and explosive commands directed at Sikich - who lurched finely through the perfected custard’s jiggles and wobbles - were capped with the nonchalant declaration: “You’ll notice a few nooks and crannies on the surface. That’s fine.” I suspect that a few brave singers may attempt to show their own gastronomic prowess in encores to come …

On Saturday evening we’d had the opportunity, courtesy of John Wilson and the LSO, to enjoy Bernstein’s On the Town , the foundations of which were laid in the 1944 ballet Fancy Free. Set in a bar, the ballet had opened with a juke box playing the blues number ‘Big Stuff’ - a song subsequently recorded by Billie Holiday. Giunta’s middle-range had a wonderful silky warmth which was complemented by Sikich’s lazy, unassuming accompaniment; and, with the nous of a doyenne of musical theatre, the mezzo’s final statement, “it may be that you’re the guy”, diminished with sensual invitation, as her unwavering gaze pierced the Cadogan Hall audience.

There was a Bernstein ‘novelty’ too: Conch Town, Bernstein’s never-published 1941 ballet - which would provide material for both Fancy Free and West Side Story - in a two-piano and percussion form as completed by Tom Owen and Nigel Simeone in 2009, and here receiving its UK premiere. Sikich was joined by pianist Iain Farrington, timpani (and sometime tambourine player) Owen Gunnell and percussionist Toby Kearney, and the quartet convincingly shaped the dance episodes, conveying a sense of an evolving narrative during which two beat-bending rhythmic ideas maintained a toe-tapping presence. The 3+3+2+2+2 pattern, announced quite sparsely and unobtrusively, with a gentle Cuban tint, might have alerted listeners to the forthcoming appearance of this motif in a more well-known melodic guise, explicated in an anecdote by Stephen Sondheim about the composition of West Side Story: ‘Lenny came back from a vacation in Puerto Rico and said that he'd come across a wonderful dance rhythm called the huapango, and he said, “And I have an idea for a tune.” And he went to the piano and he started going “Ya-ta-ta ya-ta-ta tum-tum-tum” with the idea of alternating between six and three, six and three ... And, many years later, a friend of mine found in a box of Lenny's papers an unproduced ballet he’d written called Conch Town [composed in 1941], and the friend said, “Look on page 17.” And there, on page 17, was “Ya-ta-ta ya-ta-ta tum-tum-tum.” He made up that whole story so he could use that old tune and, of course, I fell for it.’ [1]

The pianos’ running melodies chased each other with a propelling sway, and a contrasting section of similar-motion chains provided a temporary still centre above with Sikich’s high right hand indulged Bernstein’s melodic explorations with quasi-improvisatory grace. The musical editors demonstrated attention to orchestrational detail worthy of the originator, the climax of the ‘America’ prototype being coloured with a tambourine flourish - produced successively by hand, one timpani sticks and, at the last, two.

Giunta and Sikich closed their recital with Bernstein’s ‘What a Movie’ (from the opera Trouble in Tahiti which the composer later adapted into A Quiet Place): the perfect medium for the singer to confirm both her operatic and music theatre instincts. She acted with aplomb - as ‘Dinah’ lamented the banality of the “Technicolor twaddle” she’d endured, and imagined real ‘trouble in Tahiti’ - and relished the declamatory, lyrical and explosive vocalism equally.

Sondheim provided the encore: ‘Send in the Clowns’. As Giunta seemed to quickly brush aside a tear, I glanced around the Cadogan Hall. She wasn’t the only one.

Claire Seymour

Proms Chamber Music 7: Wallis Giunta (mezzo-soprano), Michael Sikich (piano)

Bernstein - ‘La bonne cuisine’; Bushra El-Turk - ‘Crème Brûlée on a Tree’ (BBC commission, world premiere); Bernstein - Fancy Free ‘Big Stuff’, ‘Conch Town’ (completed by Tom Owen and Nigel Simeone, UK premiere); Copland - ‘Pastorale’; Barber - ‘Sea Snatch’ (from Hermit Songs Op.29), ‘The Monk and His Cat’; Marc Blitzstein - ‘Modest Maid’, ‘Stay in My Arms’; Sondheim - ‘The Miller’s Son’ (fromA Little Night Music); Bernstein - ‘What a Movie!’ (from Trouble in Tahiti).

Cadogan Hall, London; Monday 27th August 2018.

[1]

Recounted in Andrew Milner, ‘More Insights from Sondheim’, The Sondheim Review, Summer 2012: 41.

Photo credit: Dario Acosta

August 26, 2018

Porgy and Bess in Seattle

I am delighted that Mr. Sohre's review is only a click away. It frees me to register a strongly differing opinion. I found the staging not only ugly to look at but ill-serving of the work itself.

The setting of Porgy and Bess is a row of tenement dwellings abutting a steamy, stormy channel of the Atlantic Ocean on the southern side of the city of Charleston, South Carolina. To present this shabby but exotic locale this production provides something resembling a Motel 6 composed of rusty corrugated sheet metal, shut off from the natural and human world by a towering sliding door of the same material.

The interior of this container is illuminated for the most part by an undifferentiated wash of rust-colored light, varied from time to time by mustard and vinegar overtones. The color palette could not be better devised to wash out the varied black skin tones of the cast. In a work which is the very definition of "an ensemble opera," the performers face an uphill struggle to make their characters distinct.

The blocking of the action renders their effort even more difficult by keeping the ensemble lined up like an oratorio chorus, letting individuals step forward for individual turns only to fade back into the murk. When the hurricane blows in act two, it batters the tin box, but no physical emotional wind sweeps through the people inside it: they are inert as Neolithic standing stones.

I am certain that the show Mr. Sohre saw in Cooperstown looked a lot different. The Alice Busch Theater is a state-of- the-art jewel box seating fewer than 900 people; Marion McCaw Hall in Seattle is more than three times as large, and its acoustics vary not just row to row, but seat to seat.

There's no way, no matter how sensitively mounted, this production could come across with equal weight in these two halls.

Nonetheless, this is very much recognizable as a Zambello production. She is not so much a "concept" director as a conceptual magpie. Her shows are like theatrical pull-aparts composed of half a dozen contrasting doughs: slice of life, presentational, Broadway-glitzy, expressionistic, according to whatever seems to work at the moment.

In her Aïda here this season (also originating at Glimmerglass), she offered everything from static, stand-and- deliver Stivanello to hokey Broadway hoe-down side by side in the triumphal scene. Much the same kind of megillah pervades the long picnic sequence and final scenes of Porgy.

By the time the show's over (divided into two exhausting hour-plus-long acts instead of the original three), the lingering impression is of intermittent glories (like the mighty Mary Elizabeth Williams' "My Man Done Gone") and lovely flashes (like the cameos of Ibidunni Ojikutu and Ashley Faatoalia as Strawberry Woman and Crabman) embedded in trudging routine.

The principals do their best under these dire conditions.

Lester Lynch sings Crown with grinding menace, but his costume makes him look less a brutal longshoreman than a suburban daddy longing to get his feet up in the Barcalounger. Elizabeth Llewellyn, a debutante Bess,

doesn't seem comfortable with the tessitura of the role (she's known best in England for her Butterfly and Rondine), but she's painfully believable as the helpless creature and blazes up in her (wholly inappropriate) Apache dance with the veteran Sportin' Life of Jermaine Smith.

Kevin Short's Porgy is grandly sung, but he's hampered from the git-go by his striking size and the sorry modern tendency to minimize the character's disability. Heyward's Porgy was crippled from birth and unable to walk at all; Short's Porgy uses (and sometimes forgets to use) a single crutch. He looks and sounds more than a match for his nemesis Crown, leaving the central conflict of the opera utterly implausible. When a Porgy could obviously lay out his opponent with one blow of his crutch, what's left of the story?

A gentle suggestion for my reader: Heyward's original novel is easily accessible on line. To read it is to appreciate for the first time what a marvel of compression the Porgy libretto is: very nearly as fine as the unforgettable songs Gershwin wrote for it.

Roger Downey

Cast and production information:

Kevin Short (Porgy); Elizabeth Llewellen (Bess); Lester Lynch (Crown); Jermaine Smith (Sportin' Life); Mary Elizabeth Williams (Serena); Brandie Sutton (Clara); Edward Graves (Robbins); Martin Bakari (Honeyman). Original production: Francesca Zambello, reproduction by Garnett Bruce. Scenic design: Peter J. Davidson; Lighting: Mark McCullough; Costumes: Paul Tazewell, assistant Loren Shaw; Choreography: Eric Sean Fogel; Chorus master: John Keene. Conductor: John DeMain, members of the Seattle Symphony Orchestra.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/180808_PorgyBess_DR%202252_PN.png image_description=© Philip Newton product=yes product_title=Porgy and Bess in Seattle product_by=A review by Roger Downey product_id=Above: Porgy & Bess [Photo © Philip Newton]John Wilson takes the Prommers out On the Town

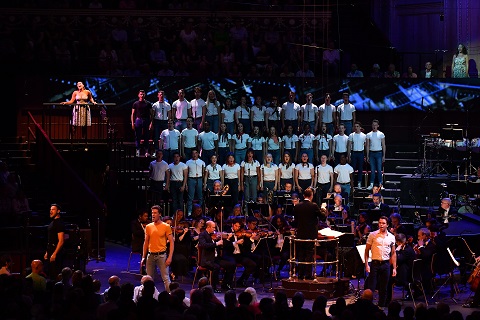

John Wilson is rapidly becoming an essential ingredient in the Proms season recipe. It’s hard to imagine a year going by without the conductor and his eponymous orchestra entertaining us with a performance or two characterised by slick professionalism, musical precision and kinetic energy. He and his band have already contributed to the BBC’s Bernstein 100 celebrations with a sassy performance of the concert version of West Side Story earlier this month. For his second Proms appearance this year, Wilson teamed up with the LSO, a jaunty cast and the bright-voiced students of ArtsEd for a night on the town that whizzed by with jazzy high-jinks and ear-pleasing appeal.

So, before the praise, the provisos. First, On the Town was a theatrical adaptation of Bernstein and Robbin’s previous collaboration: the thirty-minute ballet, Fancy Free, which had triumphed at the Met. The New York Times headline on 19th April 1944 had read, ‘Ballet by Robbins Called Smash Hit’, and critic John Martin hailed score and choreography: ‘The music by Leonard Bernstein utilizes jazz in about the same proportion that Robbins’ choreography does. It is not in the least self- conscious about it, but takes it as it comes. It is a fine score, humorous, inventive and musically interesting. The whole ballet, performance included, is just exactly ten degrees north of terrific.’ When the romantic adventures of three wide-eyed sailors who find themselves with twenty-four hours to kill in New York - “a helluva town” - before their ship leaves its berth in Brooklyn Navy Yard was transformed into a Broadway show, the narrative was largely dance-driven, as attested by the large proportion of the score of On the Town that is taken up by instrumental interludes which accompany and articulate the balletic narrative.

Indeed, subsequently, when MGM bought the film rights to On the Town, producer Arthur Freed excised most of Bernstein’s songs. Will Friedwald suggests that director Gene Kelly’s ‘primary motivation as one of the film’s stars was to dance to Bernstein’s superlative ballet music; as a first-time director, he apparently didn't feel he had the clout to make the case for the rest of the original score. Neither did Comden and Green--who were importuned to write substitute songs with MGM stalwart Roger Edens--and, remarkably, neither did Sinatra. Betty Comden later told me, in 1994, “Frank said that the only reason he agreed to do the movie was so that he could sing ‘Lonely Town,’” a number that never made it to the film.’ [1]

Kerry Shale. Photo Credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

Kerry Shale. Photo Credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

Robbins’ choreography may not be extant, but dance remains integral to the dynamism of the plot and the stylistic expressivity of the musical milieu. The absence of physical embodiment of the narrative in this Proms concert performance was a major hindrance, for the dance binds together the nineteen episodic scenes that carry us across New York. Some attempt at redress was made with the inclusion of a narrator, the experienced Kerry Shale, who, lyric book nestled in the crook of his arm, proved a confident story-teller, suavely linking the musical numbers; but Shale’s larger-than-life delivery only confirmed the problem, particularly in Act 2 when dance numbers predominate over song.

John Wilson. Photo Credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

John Wilson. Photo Credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

Second, the BBC engineers really do need to modify the ear-splitting amplification of the Proms’ musical theatre presentations. I think the volume and reverb switches were turned down after the first twenty minutes or so, but perhaps my ears, simply and sadly, just became accustomed to the head-churning echoes. The spoken dialogue was particularly deafening initially; and single-line contributions from soloists in the ArtsEd Chorus thundered over the LSO with the stridency of a regimental Sergeant Major.

There were some unintended benefits of the absence of a choreographic narrative though, chiefly that in the extensive instrumental interludes the spotlight was thrown on the music itself: the easeful flow of Bernstein’s poly-stylistic integration and the LSO’s precisely etched delivery of the composer’s jazz, blues and Broadway-vernacular cocktail. Perhaps there was a little less swing and sassiness than we are customarily treated to courtesy of the John Wilson Orchestra: others may disagree, but to my ears the brass didn’t have quite enough raspy brashness and the violin tone, while clear and singing, needed a bit more luscious Broadway schmaltz. In Gabey’s ‘Lonely Town’, Wilson’s left hand went into overdrive in an effort to coax a syrupy sheen and emotive vibrato from the LSO violins, but after the interval he seemed more restrained. That said, individual players and sections - particularly the woodwind and trumpets - played with a precision that highlighted the order and clarity of Bernstein’s musical language and form, no matter the sense of freedom and free will that it conjures. Jazz specialist, saxophonist Howard McGill, tugged the heart-strings. And, nestled at the rear was an inner band of piano (Elizabeth Burley, showing how to honky-tonk), drum-kit, brass and amplified double bass (one rhythm-invigored Laurence Ungless, I think), that brought some brazen vigour to the proceedings.

Students from ArtsEd. Photo Credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

Students from ArtsEd. Photo Credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

I had not been that impressed by the students of ArtsEd during the Proms’ concert version of West Side Story but here the young singers were much more impressively marshalled, choreographically and vocally, and, as city crowds, night club revellers, they had a firmer narrative role too. Uncredited individuals put in fine solo turns: in Act 2, Diana Dream’s parodic blues number, ‘I Wish I Was Dead’, successful trod the fine line between glamorous celebration and satirical parody. The three sailors who appeared in the organ gallery at the close to begin their own twenty-four hours ‘on the town’, delivered their closing salute with military panache and pride.

Stage director Martin Duncan made good use of the Hall’s walkways and stairwells; and the panel frieze offered vistas of New York - its arching, aspiring bridges, the underbelly of the metro, the red lights of its night-life. When Ozzie and the voracious anthropologist Claire de Loone enjoyed their amorous assignation amid the dinosaur fossils, the collapsing animation - complemented by acrobatics from the xylophone player, who simultaneously juggled rattle and whistle - raised the loudest laugh of the night.

The cast demonstrated a unanimous appreciation of Bernstein’s blend of the comedic and the serious. Much is frivolous, but it shouldn’t be flippant. Claire Moore staggered on her red stilettos in stupendous inebriation but we knew she would not topple, and her message to Siena Kelly’s fresh-voiced Ivy Smith - let your artistic dreams and goals be your guiding light, not your romantic whims - spoke surely of the feminist ambitions of the 1940s. Barnaby Rea revealed a terrifically focused low bass as the First Workman in the opening moments and was a sympathetic Judge Pitkin.

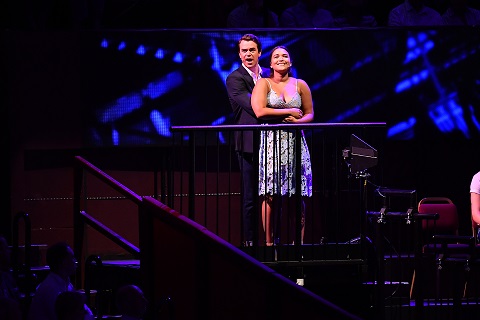

Nadim Naaman (Ozzie) and Celinde Schoenmaker (Claire de Loone). Photo Credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

Nadim Naaman (Ozzie) and Celinde Schoenmaker (Claire de Loone). Photo Credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

Nadim Naaman’s Ozzie was fittingly over-the-top without being ridiculously overblown. As Chip, Fra Fee winced with naïve gaucheness when rampant taxi cab driver Hildy launched herself upon him, in their disorderly duet, ‘Come Up To My Place’. Nathaniel Hackmann was an earnest Gabey, singing ‘Lonely Town’ with open-hearted warmth and ‘Lucky To Be Me’ with guileless honesty, but he did not neglect the humour of Gabey’s desperate trawl ‘in search of his gal’ in Act 2.

But, the male characters are largely ‘types’, and it’s the women who, more individualised and independent of spirit, who hog the spotlight. As Hildy Esterhazy, Louise Dearman was assertively but harmlessly predatory, ready to drive a cab or rustle up a cordon bleu dinner with equal élan if it would win her a man. Dearman gave an invigorating rendition of ‘I Can Cook Too’, all brassy assurance with a light-hearted patina, avowing breathlessly that she could “make a magazine cover” and be a “wonderful lover”, as well as “hit the high Cs” - and she did. Celinde Schoenmaker’s more ‘operatic’ Claire de Loone was similarly in command but, despite her tight trouser-suit, more obviously sensual, though Schoenmaker’s beautifully sweet, floating leaps to the top suggested sincerity too.

Fra Fee (Chip) Louise Dearman (Hildy) and Photo Credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

Fra Fee (Chip) Louise Dearman (Hildy) and Photo Credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

If there was one thing missing, it was the very real sadness and shadows that surely reverberate through the quartet, ‘Some Other Time’, when Chip and Hildy, Ozzie and Claire realise that their day of hunting for their soul mate is over and that they must soon return to their ship and sail off to war, and perhaps to their deaths: “When you're in love/ Time is precious stuff -- /Even a lifetime isn’t enough.”

Claire Seymour

Prom 57: Bernstein - On the Town (concert version)

Barnaby Rea (First Workman/Judge Pitkin), Nadim Naaman (Ozzie), Fra Fee (Chip), Nathaniel Hackmann (Gabey), Siena Kelly (Ivy Smith), Louise Dearman (Hildy), Celinde Schoenmaker (Claire de Loone), Claire Moore (Madame Dilly); John Wilson (conductor), Martin Duncan (stage director), London Symphony Orchestra, Students from ArtsEd.

Royal Albert Hall, London; Saturday 25th August 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/On%20the%20Town%20Prom%2057.jpg image_description=On the Town : BBC Prom 57, London Symphony Orchestra conducted by John Wilson product=yes product_title=On the Town : BBC Prom 57, London Symphony Orchestra conducted by John Wilson product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Cast of On the TownPhoto credit: BBC/Mark Allan

August 25, 2018

The Barber of Seville

at the Rossini Opera Festival

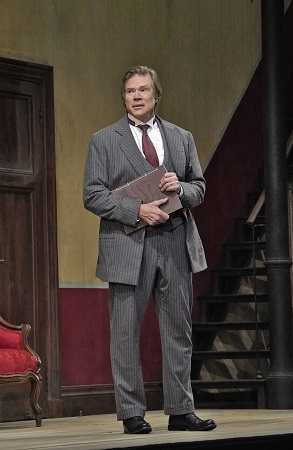

And the best it was, though Canadian born Europe based conductor Yves Abel had some formidable competition for being the star of the show, namely 88 year old Pier Luigi Pizzi who staged it. In turn Signor Pizzi was upstaged by Italian baritone Davide Luciano, Seville’s factotum Figaro. But even he disappeared into the shadows when Russian tenor Maxim Mironov cut loose with his brilliant “Cessa di piu resistere,” that closes the show.

Never has the patter been more cuttingly precise at breakneck speed than when Italian bass baritone Pietro Spagnoli unleashed his “A un doctor della mia sorte” nor has the malicious pleasure of “La calunnia è un venticello” been more indulged than when intoned by Italian bass Michele Pertusi.

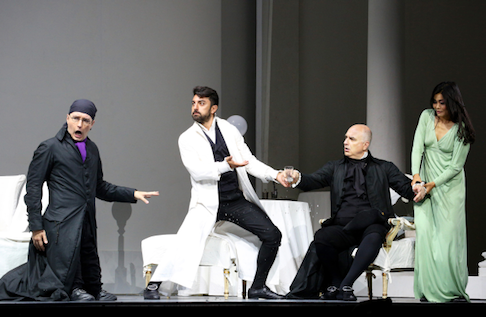

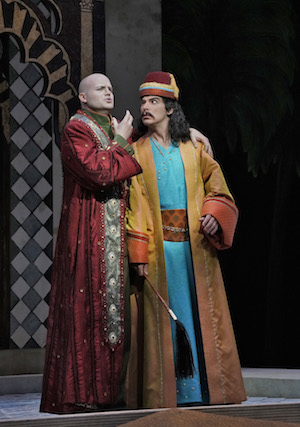

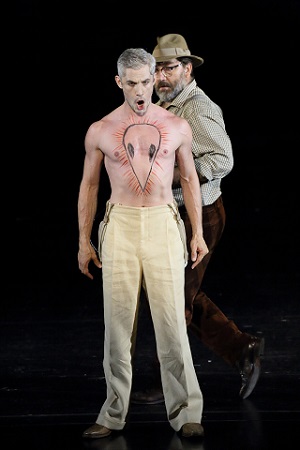

Michele Pertusi as Basilio, Pietro Spagnoli as Bartolo

Michele Pertusi as Basilio, Pietro Spagnoli as Bartolo

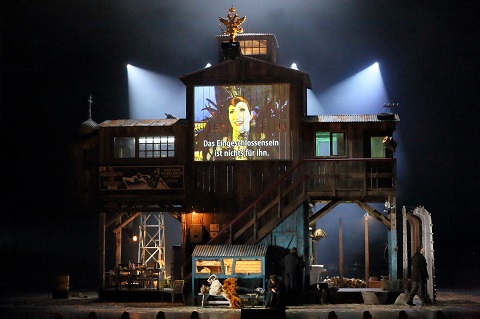

That Rossini himself became the true star of the show can only be credited to stage director Pizzi who stripped the comedy of any specific scenic context using only a white box, anonymous white architecture, white furniture, a visual technique that thrust his actors and Rossini’s singers into high relief. The octogenarian stage director instilled an energy of personality into this production that effected the comic process — the triumph of youth over age — in monumental terms. It was the all too rare proof that Il barbiere is indeed one of the repertoire’s greatest masterpieces.

The overwhelming atmosphere of the production was that of youth, from Fiorello, sung by Venetian baritone William Corrò, to Almaviva and to Rosina, sung by splendid Japanese mezzo soprano Aya Wakizono, and finally, and even most of all to Figaro who stripped to his culottes, jumped into the fountain and then did a beefcake parade along the catwalk fronting the orchestra pit regaling us with his “Largo al factotum!”

None of this possible, of course, without conductor Abel who propelled Rossini’s numbers onto plateaux of lyricism that bordered on delirium. Of greater accomplishment was perhaps the pacing the maestro imposed on Rossini’s parade of blockbuster numbers, allowing us to savor each of them to the fullest but leaving us resource to sink ourselves into the opera’s two gigantic finales.

There was virtually no comic schtick (sight gags) in Pizzi’s production, the innate charm of each of its virtuoso singers needing no embellishment to create character. Except the music lesson scene which itself is nothing but schtick, and usually annoying. Director Pizzi solved this in simple strokes. There was no piano. Fiorello mimicked a cello for “L’inutil precauzione” conducted by Almaviva disguised as a dwarf. When it was Bartolo’s turn to show how to sing Sig. Spagnoli leapt into falsetto soprano!

Almaviva disguised as dwarf music teacher [shoes on knees], Figaro, Basilio and Rosina

Almaviva disguised as dwarf music teacher [shoes on knees], Figaro, Basilio and Rosina

Note that before the performance I had spotted three little people among the spectators. Hopefully they enjoyed the comedy of such travesty (Almaviva had shoes on his knees) made transparent when Almaviva jumped to his feet from time to time when Bartolo wasn’t looking).

Not to forget that the storm was nothing more than the throes of fever that overtook Rosina when she thought Lindoro was betraying her, reinforcing stage director Pizzi’s firm commitment to comedy of character.

Esteemed Italian character mezzo soprano Elena Zilio sang Berta, sharing the tasks of Ambrogio, charmingly and broadly played by actor Armando de Ceccon, with little more to do that just be there to answer the door and bring in the laundry. Sig.ra Zilio’s “aria di sorbetto” “il vechhiotto cerca moglie” was met with huge applause. Note that in Rossini times sorbet was hawked near the end of a performance where such secondary arias were placed.

Sig. Pizzi directed, designed both sets and costumes, and designed the lighting with his associate Massimo Gasparon. The elegance of the costume design — abstracted formal wear in black and white, with Rosina in various solid colors — well served the elegance of the singing.

In his formative years Pier Luigi Pizzi worked as a designer with Giorgio Strehler and Luca Ronconi, incorporating much of mid-twentieth century Italian avant garde into his theatrical vocabulary. He made his Pesaro Rossini Opera Festival debut in 1982 with Tancredi. During the 1980’s as well he both designed and directed productions at San Francisco Opera, notably Simon Boccanegra, Semiramide and Orlando Furioso (though these credits are not included on Wikipedia). His productions have appeared in all of the world’s major theaters.

The male chorus of the Teatro Ventidio Basso (an historic opera house in Ascoli Piceno, a town halfway between Pesaro and Rome) was the raucous police force. The Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale Della RAI (Italian Radio/Television) were the polished collaborators of maestro Abel.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Il Conte d’Almaviva: Marim Mironov; Bartolo: Pietro Spagnoli; Rosina: Aya Wakizono; Figaro: David Luciano; Basilio: Michele Pertusi; Berta: Elena Zilio; Fiorello/Ufficiale: William Corrò. Chorus of the Teatro Ventidio Basso, Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI. Conductor: Yves Abel; Regia, Scene e Costumi: Pier Luigi Pizzi; Regista collaboratore e Luci: Massimo Gasparon. Arena Adriatica, Pesaro, August 19, 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Barber2_Pesaro1.png

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Il barbiere di Siviglia at the 2018 Pesaro Festival

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Maxim Mironov as Almaviva, Davide Luciano as Figaro [All photos by Studio Amati Bacciardi, courtesy of the Rossini Opera Festival, Pesaro]

August 23, 2018

Saul, Glyndebourne Festival

Although the production raised questions at times, with what some purists may decry as gimmicks, the performance overall presented a dark and searching exploration of the themes of power, age, love and loss. Here was a highly enjoyable and memorable examination of the human condition.

Taking its narrative from the First Book of Samuel, Handel’s oratorio – first performed in 1739 – explores the descent of King Saul, where respect for young David (who has just slain Goliath) rapidly turns to hateful jealousy of the younger man’s popularity. Glyndebourne’s revival of Barrie Kosky’s 2015 production for the Festival brought more than a streak of tragedy: here was an emotionally compelling performance full of instrumental and vocal colour.

Countertenor Iestyn Davies took the role of David, who alongside the lustrous singing of tenor Allan Clayton – who played Jonathan, King Saul’s son – provided the soloistic highlights of the evening. In the First Act, Davies provided moments of genuinely heart-stopping beauty, the lyrical power of his voice evident when the orchestra suddenly cut out, leaving the countertenor sustaining a single note on a crescendo. With masterly awareness of dynamics coupled with a silky upper register, Davies displayed a vocal control few can match. Captivating. Allan Clayton was similarly expressive, again especially striking when the texture was most exposed; there were moments when the orchestra fell silent, leaving Clayton singing quietly alone, his voice full of lyrical warmth. This was music-making of the most controlled, sensitive and nuanced degree.

Topping off a superb cast, German baritone Markus Brück played King Saul in what is his Glyndebourne debut, alongside Handelian soprano Karina Gauvin as Merab, Saul’s daughter. Brück’s voice was richly expressive, bringing out the darker colours in this most troubled of characters. Although the libretto, in my eyes at least, hardly portrays a character of great psychological complexity – the King declines to madness within the blink of an eye, hardly the nuanced depiction of madness and decline in Shakespeare’s King Lear – Brück presented a character full of emotional contrasts with a voice similarly replete with juxtaposing colours. Gauvin was equally impressive, her duet with Davies at the opening of Act 3 full of urgency.

Also in particularly fine form were The Glyndebourne Chorus, whose voices provided both musical and dramatic delight; at the point in which Saul is confronting his madness explicitly, The Chorus stride right up to the edge of the stage, feet from the audience, their powerful singing dominating the space in an effective recreation of the voices swirling through the monarch’s mind. With Kosky’s creative use of space and The Chorus’s dramatic projection of their voices, this was a supreme example of how imaginative production and performance can combine to create the most vivid portrayal of a text. The Glyndebourne Chorus’s forceful fortissimo singing and vivid characterisation were one of the highlights of the evening.

The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment conducted by Handel expert Laurence Cummings were also brimming with energy. The opening was full of bounce, whilst a consistently transparent texture allowed us to hear every delightful imitation in Handel’s intricate scoring. One of Saul’s unique points is its orchestration, with trombones evoking sackbuts, playing alongside kettledrums (which Handel borrowed from the Tower of London, no less), harp and carillon (a keyboard-glockenspiel). The score is therefore packed to the brim with colour, and Cummings made plentiful use of this, pointedly emphasising specific moments of instrumental contrast, most notably the tenderness of a theorbo (played by David Miller) accompanying the scene in which a declining Saul is cradled by Allan Clayton’s Jonathan.

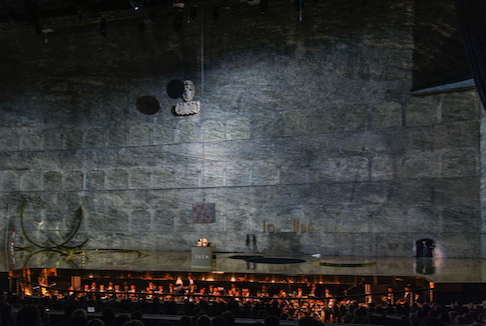

Michal (Anna Devin) and dancers

Michal (Anna Devin) and dancers

The production itself memorably played on the theme of light and dark, with effective use of stage lighting; the spotlight at the very start gently grew so as to expose the severed head of Goliath on stage, whilst later on the all-white tablecloths that dominated the stage dazzled the audience with light, perhaps a comment on Saul’s growing emotional blindness. A production highlight was the set for the final act, where hundreds of candles lined the stage, only to be gently extinguished by the chorus; this warm orange glow slowly reduced to darkness, Kosky’s staging here was a poignant moment of visual poetry.

However, if I am to make any criticism of this fine evening, it was that at times the production gave way to what some purists might decry as gimmickry; six dancers would rush onto the stage, sometimes after moments of exquisite emotional tenderness, and start gyrating at the edge of the stage. Although it brought a few laughs from the audience, I wondered whether the frequency of these interruptions was necessary, with the dancers breaking the flow of the narrative and wrecking the emotional tenderness that made many of the scenes so striking. Similarly distracting was the regularity of the shrieks and screams from the chorus, which – although a superb way of evoking the distress and the very humanity of the characters onstage – came so frequently that they detracted from their power. One scream would be striking, but ten or eleven become plain distractions.

Despite this small criticism, to the production’s credit, Kosky’s minimalism brought us back to the world of Ancient Greek tragedy, most appropriate for this Lear-like narrative; in having minimal distractions on stage in the way of set design, Kosky allowed us to focus on the human beings that are at the centre of this tragedy. Such an exposed stage drew greater sympathy from the audience because, when Saul was sat alone with just his closest family near him, his isolation was made painfully clear. Kosky appears to find that the inherent drama in Handel’s oratorios – even if they are not strictly operas, they are operatic by nature – is suited to the similarly dramatic nature of Greek theatre.[*] The influence of Greek Tragedy reminds us that, whilst this story is taken from the Bible, there are numerous parallels to Tragic plays and theatre in its progression, something Kosky’s production magnified with great effect.

An evening full of horror, delight, humour and despair all at once, this was an emotionally compelling and beautifully-performed evening. They say that a tragic story can be cathartic; no wonder everyone emerged from the theatre so full of life. An excellent evening.

Jack Pepper [†]

Editor’s Notes:

[*] According to Grout & Williams, “Wearied by the material difficulties and discouraged by the waning fortunes of opera, Handel had already begun in the 1730s to turn his attention to composing oratorios: Saul and Israel in Egypt were performed by the end of that decade, and in the following years came some of the other masterpieces by which the composer is best known today.” (p. 187)

[†] Jack, who has written for Opera Today, was invited by Glyndebourne to review their production of Saul as part of an initiative to engage younger writers in opera and opera criticism.

Photos © Bill Cooper

1818 Rossini

at the 2018 Rossini Opera Festival

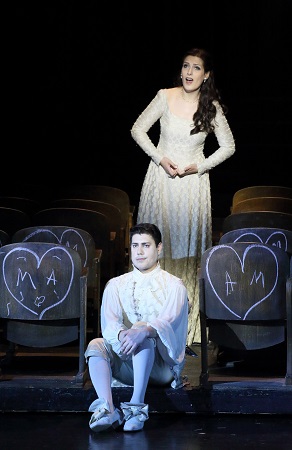

A bit of a success in its time, Ricciardo e Zoraida soon disappeared to be resurrected only in 1990 by the Rossini Festival (that unquestioningly does all Rossini). Improbable as it may seem just now in Pesaro it attracted two major singers, Juan Diego Flórez as Ricciardo and South African soprano Pretty Yende as Zoraida, even though each has but one aria the entire evening.

The story is a generic, old style chivalric tale — exotic tyrant wishes to marry a damsel loved by a Christian knight, slightly complicated by a father who has his own ideas. Compared to the great Rossini tragedies of this same (Naples) period it is of slight dramaturgical interest, and therefore of lesser musical challenge for Rossini.

Its musical lines are however exquisitely Rossini, starting with the overture’s extended and quite lovely clarinet and horn solos followed by a brilliant flute display, brazenly interrupted from time to time by a raucous military band — a first use of stage musicians by Rossini, and quite startling indeed.

The African tyrant Agorante was sung by Russian bari-tenore Sergey Romanovsky whose darkly colored tenor voice soared with easy heft to the required high C’s, simultaneously sculpting elaborate coloratura in his lengthy aria. It was his one and only aria, an auspicious inauguration of this evening of spectacular vocal fireworks.

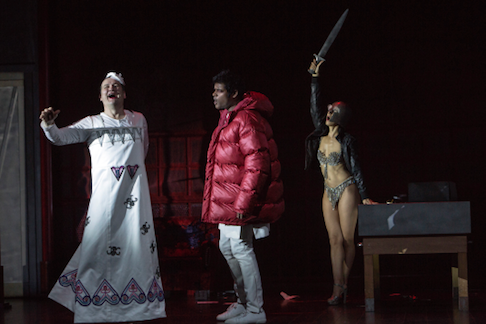

Front row Juan Diego Flórez, Sergey Romanovsky, Xabier Anduaga as Ernesto (a Christian ambassador). Back row Sofia Mchedlishvili as Fatima (Zoraide's confidant), Martiniana Antonie as Elmira, Victoria Yarovaya as Zomira (Agorante's wife); Pretty Yende (in gold gown)

Front row Juan Diego Flórez, Sergey Romanovsky, Xabier Anduaga as Ernesto (a Christian ambassador). Back row Sofia Mchedlishvili as Fatima (Zoraide's confidant), Martiniana Antonie as Elmira, Victoria Yarovaya as Zomira (Agorante's wife); Pretty Yende (in gold gown)

If Pretty Yende seemed vocally tentative in her initial scenes — a duet with the tyrant’s current wife, Zomira, becoming a trio by adding the lovesick tyrant Agorante — it was perhaps because she was simply coping with a dramatically awkward situation (the other woman), exacerbated when Ricciardo unexpectedly showed up. She did hold her own in their extended duet.

But by the time la Yende, her stage father Ircano and Ricciardo got rescued from the tyrant’s clutches she was in magnificent voice and delivered her one aria with ultimate virtuoso aplomb. Though Rossini had embedded his usual soprano showpiece finale within the larger finale (in which the Christian forces overwhelmed those of Agorante and everyone forgave everyone), the glories of her shining high notes (well above the staff) lingered and the energy of her coloratura endured earning her an ovation at the curtain calls that well surpassed the ovation awarded to Juan Diego Flórez for his splendid Ricciardo.

Tenorissimo Flórez had great opportunity to show off his high C’s and his impeccable fioratura while imbuing his character with the welcomed notion that we didn’t have to take any of this too seriously, that after all this Rossini opera was meant to be about singing and that he can do, as everyone knows.

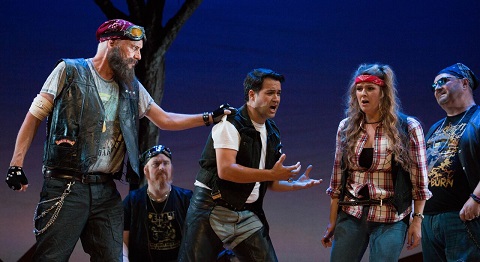

The production was staged by French director Marshall Pynkoski, a specialist in Baroque and proto-Romantic opera. Thus the staging was highly formalized in static stage pictures. Action when demanded was in the abstract choreography of five ballerinas and six male dancers — there were pompous entrances by the tyrant, preparations for beheadings, and a great battle among other, lesser activities. The extensive choreography was created by Jeanette Lajeunesse Zingg (Mr. Pynkoski’s wife).

An entrance of Agorante with ballet

An entrance of Agorante with ballet

Mr. Pynkoski did avail himself of the “close-up” technique so effectively used by director Pier Luigi Pizza in the Rossini Festival’s ad hoc 1200-seat theater inside Pesaro’s massive Adriatic Arena. Singers are brought outside the proscenium onto a catwalk fronting the orchestra pit, thus eliminating all scenic and musical context. The direct contact of these superb Rossini singers with the audience was an awesome experience.

Canadian set designer Gerard Gauci, a collaborator of Mr. Pynkoski at Versaille’s Opéra Atelier offered backdrops of painted canvas in monumental shapes and somber color. Appropriate period costumes were created by Michael Gianfrancesco, a Canadian colleague of Mr. Gauci. Neither sets nor costumes, nor Mr. Pynkoski’s staging for that matter, succeeded in finding the indulgent smile we might confer on such a precious literary relic.

Italian conductor Giacomo Sagripanti presided over the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI. The young maestro set the elegant musical level of the evening in the overture, finding its caressing lines, encouraging the excellent solo playing, stoically tolerating the noisy stage band, then providing Rossini’s richly colored foundation for some of Rossini’s loveliest vocal lines. The maestro’s tempi kept the easy energy needed to sustain ornamental singing and at the same time drive the opera’s substantial ensembles to maximum effect.

It is not hard to fathom why Giachino Rossini returned to the very simple one-act semi-serious farsa form of his youth after creating his four magnificent character comedies, as well as coping with libretti based on Shakespeare and Sir Walter Scott among other literary luminaries for his Neapolitan tragedies — he was paid to do it (but that’s another story)!

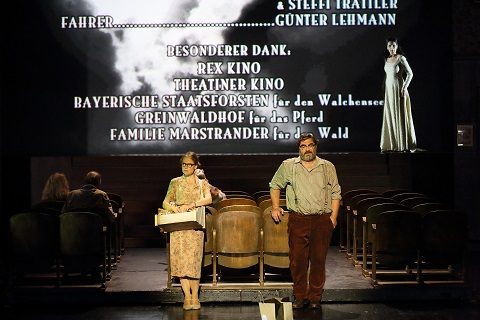

Adina is the essentially the same story as Ricciardo e Zoraide. An older Persian caliph has taken a fancy to a beautiful prisoner of his seraglio and is about to marry her. Her former fiancé Selimo appears, whom she has believed to be dead after the shipwreck that separated them. The lovers hatch plans to escape with the help of Mustafa, the palace gardener. Ali, servant and confident of the caliph becomes aware or the plot. It fails. But as it turns out Adina is the long lost daughter of the caliph, thus Selimo need not be executed.

There are little complications to sing about. Selimo feels betrayed by Adina who is about to marry the caliph. Adina respects the caliph and is grateful to him for rescuing her. Adina believes Selimo to have been executed and is distraught.

Rossini actually recycled much of Adina’s music from his early operas and even borrowed musical material from other composers. Nonetheless Adina is still the musically mature Rossini, the vocal lines boast his ultimate sophistication. There is a splendid quartet near the end of great effect, plus a robust, exciting finale (with Adina’s splendid “Dove sono? Ancora respiro?”) composed especially for this operatic stepchild, the two pieces alone making the evening worthwhile.

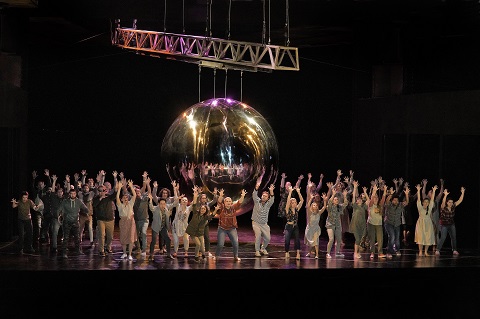

Lisette Oropesa (center) with chorus of the Teatro della Fortuna M Agostini

Lisette Oropesa (center) with chorus of the Teatro della Fortuna M Agostini

Adina was sung by New Orleans born soprano Lisette Oropesa well known to L.A. and Met audiences as Lucia. An able Rossini singer as well, she did find the singerly excitement of her final aria. Her fiancé Selimo was ably sung by South African tenor Levy Sekgapane whose aria “Giusto ciel, che i dubbi miei tu conosci” is really a beautiful duet with English horn, attesting Rossini’s mature orchestral sophistication. The caliph was sung by Italian baritone Vito Priante, bringing the energy of his usual big-house Figaro to the caliph’s lone aria “D’intorno il Serraglio.” Completing the small farsa cast were character singers Matteo Macchioni as Ali who dutifully delivered his “aria di sorbetto” (a secondary singer’s small aria near the end of an opera) and Davide Giangregorio as Mustafa.

That the singers in this new production made little impression can be attributed to its metteur en scène, Rosetta Cucchi. Sig.a Cucchi is a pianist once associated with the Rossini Festival. Turned provincial opera house stage director she is now on the artistic staff of Ireland’s Wexford Festival. This Adina is a shared production with that festival.

Rather than allowing Rossini’s farsa process to work naturally, allowing its singers to expose Rossini’s prototype characters, this director imposed a blinding, supposedly comic environment (saturated pinks, blues and greens for the decor) that overwhelmed mere Rossini.

The stage was dominated by one huge scenic image — a three tiered wedding cake with the bride and groom statuette on the top (who were real people echoing the ins and outs of the farsa action).

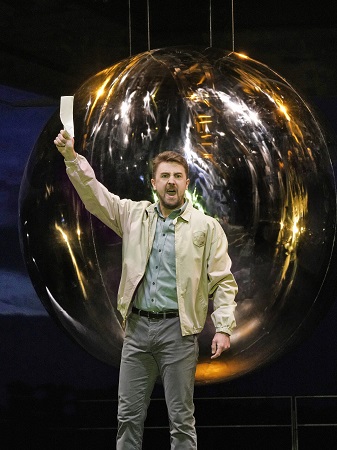

Live groom and bride statuette

Live groom and bride statuette

When the caliph wasn’t in a gold lame suit jacket for the wedding that never happened he was in a bubble bath singing his aria. Adina herself was accompanied by two mincing acolytes in short pink dresses. Selimo got off a bit easier appearing in a simple frocked shirt and gold vest as did his gardener sidekick who donned a straw hat adorned with foliage as well. The caliph’s henchmen threatened the lovers with colorful toy Uzis. There was not a turban or eunuch in sight.

A protege of Venezuela’s famed “Sistema” and now music director of Venice’s La Fenice, young (33 years old) conductor Diego Matheuz gave a fine account of this minor Rossini score, respecting the current performance practices that favor stylistically informed singers. The Orchestra Sinfonica G. Rossini, resident orchestra of Le Marche’s historic theaters (Pesaro, Fano, Jesi and Pergola) performed at its usual high level. The male chorus of the Teatro della Fortuna M Agostini in Fano (a small city 12 kilometres south of Pesaro) did its best to fulfill stage director Cucchi’s idea of what fun is not.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Ricciardo e Zoraide Agorante: Sergey Romanovsky; Zoraide: Pretty Yende; Ricciardo: Juan Diego Flórez; Ircano Nicola Ulivieri; Zomira: Victoria Yarovaya; Ernesto: Xabier Anduaga; Fatima: Sofia Mchedlishvili; Elmira: Martiniana Antonie; Zamorre: Ruzil Gatin. Chorus of Teatro Ventidio Basso, Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI. Conductor: Giacomo Sagripanti; Metteur en scène: Marshall Pynkoski; Coreografie: Jeannette Lajeunesse Zingg; Scene: Gerard Gauci; Costumi: Michael Gianfrancesco; Luci: Michelle Ramsay. Arena Adriatico, Pesaro, August 20, 2018.

Adina Califo: Vito Priante; Adina: Lisette Oropesa; Selimo: Levy Sekgapane; Alì: Matteo Macchioni; Mustafà: Davide Giangregorio. Chorus of the Teatro Della Fortuna M. Agostini, Orchestra Sinfonica G. Rossini. Conductor: Diego Matheuz; Metteur 3n scène: Rosetta Cucchi; Scene: Tiziano Santi; Costumi: Claudia Pernigotti; Luci: Daniele Naldi. Teatro Rossini, Pesaro, August 18, 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ricciardo_Pesaro1.png

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=The 1818 Rossini at the 2018 Pesaro Festival

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Juan Diego Flórez as Ricciardo, Sergey Romanovsky as Agorante [Photos by Studio Amati Bacciardi, courtesy of the Rossini Opera Festival, Pesaro]

London Bel Canto Festival: Aprile Millo at Cadogan Hall

Over the years, ‘diva’ has become interchangeable with ‘prima donna’, with both terms connoting a female singer who is distinguished by the magnitude of her vocal prowess and her personal aura, both of which astonish, seduce and mesmerise. More recently, diva has often been used pejoratively, with associations of bad tempers, unreliable behaviour and narcissism.

In her London solo recital debut, legendary soprano Aprile Millo - whose official website is titled ‘The Golden Voiced Diva’ - reminded us of the original meaning of the term. For the devoted fans who had eagerly gathered in Cadogan Hall, Millo certainly is a ‘goddess’ - indeed, a critic once described her, memorably and pertinently, as the “High Priestess of that old-time operatic religion”. She also demonstrated why she is so revered by devotees of the bel canto repertory. Millo has a gorgeously rich voice of enormous power, which she uses judiciously, swelling with ease to fill the Hall but holding back to coax us into the sentiments the song. Her soprano is unfailingly supported, even across its wide range. The beauty of the sound is paramount, and the phrasing is unfailingly gracious and elegant, but there is no lack of expression and communication with the audience. It’s no surprise that her fans revere her as the upholder of vocal traditions and a successor to former bel canto heavyweights such as vocal heavyweights such as Renata Tebaldi and Rosa Ponselle.

It seems incredible that after a career spanning more than thirty years, during which Millo has performed at the Metropolitan Opera House more than 180 times, in 15 different roles, as well as in countless opera houses from San Francisco to Vienna, Milan to Moscow, Rio de Janeiro to Tokyo, the soprano had not previously appeared on the Covent Garden stage or in the capital. What finally brought her to London was the invitation to give a masterclass and perform the closing concert of the second London Bel Canto Festival (6-22 August), an international music festival and academy which, in the words of scholar, tenor and founding Director Ken Querns Langley, focuses on “the development of young singers and the reinvigoration of bel canto”. This year, students attended masterclasses by Millo, Bruce Ford and Nelly Miricioiu, before presenting a Young Artists Concert at Cadogan Hall.

Aprile Millo.

Aprile Millo.

Hailed as ‘a new Verdi star’ when she stepped in to replace the indisposed Anna Tomowa-Sintow in Simon Boccanegra at the Met in December 1984, Millo has made Verdi’s major roles the centre of her career in the theatre and on disc, though her performances of Puccini and verismo have been equally lauded. Millo’s programme, therefore, might have been expected to have comprised ‘old favourites’, but the soprano had some surprises in store. She didn’t simply give the fans what they wanted, she gave them what they didn’t know that they wanted.

Millo, born in New York, has Italian and Irish ancestry, and this was reflected in her programme. The first half focused on nineteenth-century Italian repertoire. We had some Bellini and Verdi, but not well-known arias, rather ‘studies’ - ‘La Ricordanza’, a study of ‘Qui la voce’ from La sonnambula, and ‘Insolitaria Stanza’, a study for Leonore’s ‘Tacea la notte’ from Il trovatore - as well as Donizetti’s ‘Me voglio fà na casa’ from Soirées d’automne à l’Infrascata. And, there were songs, arias and scenes by Paulo Tosti, Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari and Lincinio Refice among others. After the interval, Millo travelled more widely, incorporating Rachmaninov and Massenet, in memory of Dmitri Hvorostovsky, two songs by Richard Strauss dedicated to the memory of Simonetta Puccini (the composer’s grand-daughter), and following these with some traditional English and Irish folksongs, some of which were accompanied by harpist Merynda Adams.

Given that in her repertoire choices Millo was straying off-the-beaten-track, it was a little surprising that no texts were provided, or at the least some brief indication of the context and/or content of each aria. From the start of her career, Millo has made known her disapproval of surtitles, telling The Washington Post in 1990 that, ‘They distract from the performers’ ability to weave the story, to make it believable and make it understood. You spend a lot of money on costumes and scenery, and then you divide attention with a piece of paper at the top of the proscenium. It makes no sense. Opera has survived this long without it.”

However, the sequence might perhaps have had a clearer narrative if the audience had had a more precise indication of what Millo was singing about. She describes her programme as “the story of a relationship in Italian songs … there are different songs for how it goes” and explains that “at one point the audience will decide whether the relationship is a success or whether it’s not. And It’s a bit of audience participation”. And, so Stefano Donaudy’s ‘O del mio amato ben’ (from 36 Arie di Stile Antico) marked ‘Falling in Love’, Paulo Tosti’s concert aria ‘Non t’amo più’ marked the ‘First Quarrel’ and both Frank Bridge’s Frank Bridge’s ‘Love went a-riding’, and ‘Cara la mia Venezia’ from Il campiello by Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari necessitated ‘A Decision’.

I particularly enjoyed the light-hearted simplicity of Donizetti’s ‘Me voglio fà na casa’ (I want to build a house), in which pianist Inseon Lee accompanied with charming insouciance as Millo rose with an effortless legato to the sustained high passages. Millo relished the drama of Bridge’s ‘Love went a riding’, and both singer and accompanist were equal to the verismo heights of ‘Grazie, sorelle’, the death and transfiguration scene from Refice’s Saint Cecilia, Lee getting her fingers around the mass of ‘orchestral’ detail with aplomb. It was a treat to hear these and other unfamiliar works, such as Tosti’s ‘Sogno’ and ‘Ideale’ (‘The Dream of Love’ and ‘The Honeymoon’, respectively, in Millo’s narrative); in these salon songs, Millo soared through the arching lines with grandeur, sensuality and compelling dramatic presence.

Perhaps those familiar with the chosen songs, or Italian speakers in the audience, could discern the development of a romance, but in the second part of the recital there was less sense of a binding narrative, and perhaps this was because Millo herself seemed on slightly less comfortable ground. There was no lack of vocal sheen, power and expressivity, but the songs in Russian, French and German require a vocal style different to the glorious weight and effortless scope of Millo’s natural bel canto. Strauss’s ‘Allerseelen’ and ‘Zueignung’, for example, had a vibrant intensity which seemed to overpower the long-breathed silkiness of the vocal writing. In the folk-songs, Millo made little attempt to modify her vocal colour, singing ‘The Rose of Tralee’ and ‘Danny Boy’ with rich lustre and a potent vibrato, but while some purists may have demurred I found her commitment to these songs to be compelling and the ‘art-song’ manner made them seem personal and honest to the singer - indeed, in her prefatory remarks she mentioned memories of her mother singing to her when she was a child.

For her final item, Millo returned to ‘home territory’, inviting baritone Jeffrey Carl to join her on the platform to perform ‘Ciel, mio padre’ from Aida (dedicated to the memory of Rita Saponaro Patene). The singers, performing from memory, immediately created a persuasive dramatic context and presented a vivid, impassioned and emotionally driven scena. Needless to say, her fans loved it, jumping to their feet and whooping their delight.

From the first, Millo engaged in a relaxed fashion with her audience, in banter and through song, revealing her humour, directness and passion. Everything was done with style, panache and a flourish - Millo even managed to make the putting on of her spectacles a ‘grand’ gesture! - and the intent to communicate, engage and entertain was evident and sustained. We were far from the hushed gentility of Wigmore Hall and I was a little surprised to find myself so absorbed by Millo’s presence and performance. At the close, I felt somewhat exhausted emotionally - and I guess this was what the soprano intended. She had drawn us into the songs and the stories, suspending our disbelief by the power of her singing and of song. When Rossini retired from the opera world in 1858, he reportedly lamented the state of contemporary Italian singing, “Alas for us, we have lost our bel canto”. Here, Millo showed that the bel canto tradition is in fact very much alive.

Claire Seymour

London Bel Canto Festival: April Millo (soprano), Inseon Lee (piano), Jeffrey Carl (baritone), Merynda Adams (harp)

Donaudy - ‘O del mio amato ben’ (from 36 Arie di Stile Antico), Tosti - ‘Sogno’, Donizetti - ‘Me voglio fà na casa’ (from Soir ées d’automne à l’Infrascata), Tosti - ‘Ideale’, ‘Non t’amo più’, Bridge - ‘Love went a-riding’, Wolf-Ferrari ‘Cara la mia Venezia’ (from Il campiello), Bellini - ‘La Ricordanza’ (a study of ‘Qui la voce’ from La sonnambula), Verdi - ‘Insolitaria Stanza’ (a study for Leonore’s ‘Tacea la notte’ fromIl trovatore), Refice - ‘Grazie, sorelle’ (fromSaint Cecilia), Rachmaninov - ‘Ne poy, krasavitsa, pri mne’ (from 6 Romances Op.4), Massenet - ‘Elegie’, Richard Strauss - ‘Allerseelen’, ‘Zueigning’ (from 8 Gedichte aus ‘Letzte Bl ätter Op.10), C.W.Glover - ‘The Rose of Tralee’, Mrs George D Presentis - ‘The Kerry Dance’, ‘Bendeemer Stream’, ‘Danny Boy’, Verdi - ‘Ciel, mio padre!’ (from Aida).

Cadogan Hall, London; Tuesday 21st August 2018. image=http://www.operatoday.com/londonbelcanto-festival%20%281%29.jpg image_description=London Bel Canto Festival: Aprile Millo at Cadogan Hall product=yes product_title=London Bel Canto Festival: Aprile Millo at Cadogan Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=

August 22, 2018

PROM 51 - Wagner, Strauss and a Nørgård UK premiere

We had music from the end of two composers’ careers, poised against music from the early period of another, and yet there was considerable overlap, even symmetry, to be heard. Nørgård’s Third might steal, like a magpie, from any number of contemporary and classical idioms - and for a European symphony it acknowledges elements of American music, too - but it also abounds in a harmonic, even polyphonic, language, that would have been fully recognisable to both Wagner and Strauss.

The concert opened with the Prelude to Act I of Wagner’s Parsifal. Thomas Dausgaard is one of those interesting conductors who sets very fluid, some might argue hasty, tempos for almost all the works he conducts and yet the effect tends to be rather the opposite. It’s a skilful art for a conductor to have, and it worked beautifully for the Wagner. I’ve always thought this particular prelude from a Wagner opera the most difficult to bring off in concert - one recalls Nietzsche’s quote that this music “is the sort of thing to be found in Dante, and nowhere else” - and most performances do seem to sink into some kind of Dantesque quagmire. The best, on the other hand, tend to treat the music with great suppleness, looking inwards rather than being self-consciously controlled or over-grandiose. It’s true that the strings of the BBCSSO didn’t always have the lushness or depth of tone one might have craved, but the brass were magnificent, peerlessly golden-hued, and were careful to phrase their notes. There is a thin line in this music between playing that is refined and tinged with beauty - and playing that simply seems civilized. Dausgaard very much drew the former from his orchestra, even in the Prelude’s most powerful moments, such as the ‘Faith’ theme. This was a performance that managed to achieve tension, depth and spirituality.

I’m not really sure that Strauss’s Vier Letze Lieder, sung by the Swedish soprano Malin Byström, really managed to demonstrate her artistry as a singer, nor the sheer greatness of these songs: this was a performance that was both understated, and all but swallowed whole by the cathedral that is the Albert Hall. Here we have music of ravishing humanity that is born from the destruction and annihilation of a Germany - and Europe - in ruin; music that is unashamedly late Romantic, music that refuses to embrace the brutalism and atonality that would seduce other European composers post-1945 attempting to draw a line under that very culture that had been implicated in the terror of war and the Holocaust. But these are songs that also look forward, even if the music doesn’t: they are about rebirth and renewal, a reflection on decay and the past. They are about serenity and love; life and death.

Although there can be no doubt whatsoever that Strauss had in mind these songs should be sung by a soprano, it’s much less clear what kind of soprano voice he was writing for. The composer specifically asked for Kirsten Flagstad to give the premiere, though it would be crude to suggest this is the only kind of sound he imagined; the orchestration, and even the settings of the poems by Hesse and Eichendorff, don’t easily sit with one type of soprano as decades of performance have revealed. ‘Frühling’ can be a notable problem - and it was here. Byström’s dark, tenebrous voice felt notably chilly, even distant. I found the lack of colour a little unappealing, this song’s curving lines less a barometer of the season in which it’s set, more a prelude towards the rest of the cycle. She didn’t settle into ‘September’ either - again, there was nothing really distinctive about the intricate vocal writing - Byström rarely brought an expansiveness to the text; a tendency to clip phrases only made us more aware of the beautiful phrasing of individual instruments, especially the horn writing - played outstandingly well here.