September 30, 2018

Powerful Monodramas: Zender, Manoury and Schoenberg

The final scene of Strauss’s Salome almost touches the edges of this musical form; indeed, this scene is often performed outside its opera in concert so one might be persuaded this is where the twentieth century monodrama evolves into its own genre. Erwartung, Schoenberg’s epochal psychological musical drama from 1909, goes very much further than Strauss, however: It’s openly Expressionist, deeply psychoanalytical, ambiguous in its narrative, terrifying in its musical language and flickers between dream and nightmare.

The link between these two concerts given by the Philharmonia Orchestra was not in the slightest tenuous; indeed, a lot conjoined the music rather than distinctly separated it. Although almost a century of music exists between Erwartung and the two works by Zender and Manoury - written respectively in 2001 and 2004 - one was drawn back into the past - no matter how obliquely - even if the musical language often felt distinctly more advanced. Hans Zender’s Cabaret Voltaire, for example, uses a text by the Dadaesque poet Hugo Ball: The text itself is almost meaningless, a complete inversion of language, though as you listen to it occasionally you’re struck by its Germanic tone: “großgiga m’pfa habla horem”. There is a linguistic geometry to much of poetry; the entirely original vocabulary, the use of repetition, the combination of consonants or vowels in close proximity to one another (“bschigi bschigi” or “a-o-auma”) are themselves music. Hearing Zender’s Cabaret Voltaire was not unlike reading, or listening to, James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake.

Zender’s music, on the other hand, is distinctly ascetic, even spiky. Scored for a small chamber ensemble, this is music that coalesces around the consonantal hardness of the text; a cello or violin bow screeches or scratches against a string, a trombone is muted. The voice itself is treated in virtuosic terms - and it clearly requires a soloist calibrated to sing outside the standard operatic repertoire. Salome Kammer was simply breath-taking to listen to: The vocal acrobatics, the range and breadth of her dynamics, the sense that she has lived with this text were obvious. Only once in the entire work does Zender really plummet the depths of human emotions - in ‘Todenklage’ - and here the intensity and darkness of Kammer’s voice, as well as the soloists from the Philharmonia, really excelled in changing the atmosphere of the work.

I think Philippe Manoury’s Blackout is rather closer to Schoenberg’s Erwartung, both in its narrative and musical language. It tells the story of a woman who gets in a lift which then gets stuck during a power cut. As she waits in the darkness, her mind is forced into an emotional state of memory and dream. Manoury tells the story in real time over a period of twenty minutes - so, we get the rapid speed of the escalation of the lift contrasted with the slow-motion depiction of the narrator’s state of mind. Daniela Langer’s French text could be said to have its origins in Walter Grauman’s 1964 psychological thriller, Lady in a Cage, though the way she has written the text in prose-form suggests a nod towards the monodramas of Samuel Beckett.

Manoury writes for a slightly larger ensemble than Zender does but the expressionism is still there in spades. The febrile string writing, underscored by nervousness in the woodwind, dig deep into the psychological darkness of a mind in dream-mode. The music feels like elastic at times - it pulls between tempos that are fast and slow, and this is somewhat reflected in the narration of the text. A crackled recording of Ella Fitzgerald interjects. I don’t think this music requires the contralto Hilary Summers to use the full range of her quite remarkable voice, but she is never strained by the demands the music makes on her either. I found some of her French a little on the prosaic side, but she successfully navigated the internal psychology of the narrator’s mind to beautiful effect.

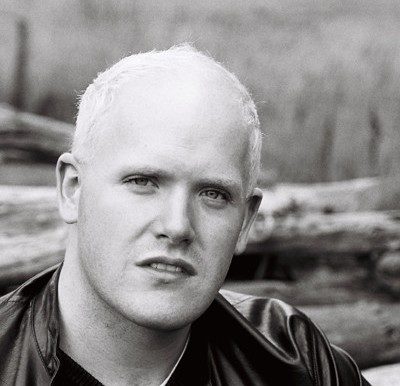

Esa-Pekka Salonen. Photo Credit: Minna Hatinen.

Esa-Pekka Salonen. Photo Credit: Minna Hatinen.

The Philharmonia Orchestra’s opening concert of their autumn season, conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen, placed Schoenberg’s Erwartung in the middle of their programme. Schoenberg has always played to Salonen’s strengths, and so it did here. He treats this work as one of the great pillars of Modernism and there is much in his conducting of it that brings out the psychosis, lamentation and darkness of this monodrama. The fluidity he brings to the score, over its half-hour span, is quite remarkable - the contours of the music are almost unbroken, even if the trajectory of the narration never is. The changes in tempo and meter are so perfectly judged you almost feel as if this is a musical form of linguistic stream-of-consciousness. There is, however, one powerful impression one is left with in a Salonen performance of this work, and it’s a somewhat ironic one. Erwartung is a towering affirmation of Expressionism, but Salonen draws playing of incredible beauty from the Philharmonia Orchestra it seems to stand in opposition to the work’s more powerful emotive strands. I’ve rarely heard such refined woodwind playing as we got here - but this has long been a hallmark of this orchestra. It wasn’t necessarily out of place, but this came close to bordering on Romanticism.

It was left to the soloist - the outstanding Angela Denoke (replacing at short notice Camilla Nyland) - to raise this performance to the quite exceptional. Denoke brings despair, fear, madness and complete immersion into the psychological confusion the narrative demands. Her timbre resonates with darkness and ambiguity, but get to the upper range of her voice and the angst is shattering. One of the difficulties of a concert performance of this piece is it can sometimes lack the dramatic element it needs - Denoke, however, is consumed on stage in front of an orchestra using the colours of her voice to convey the moonlit streets, dense woodland or meadows and paths. The voice is entirely an expression of what Schoenberg termed his “Angst-dream”.

I’m not sure the rest of the Philharmonia’s concert was quite as memorable. “Siegfried’s Death and Funeral March” from Götterdämmerung, if notable for some superlative brass playing (especially a quartet of splendid Wagner tubas) avoided the pitfall of being overly lugubrious but sacrificed some of the music’s clarity of orchestration - I missed the transparency in the harps (pretty much inaudible), and the woodwind phrasing wasn’t plaintive enough, though I think much of this was due to the orchestral balance being somewhat overwrought. It did, nevertheless, feel cohesively dramatic. I think the best - and probably the worst - one can say about Salonen’s Bruckner Sixth Symphony was that it was utterly unique. If the opening of the first movement barely touched on Bruckner’s Majestoso tempo, Salonen’s intention was to take the rest of it at a sprightly allegro. Even if the playing was largely razor-sharp rhythms weren’t, and string bowing was notably messy. Oddly, the Adagio was taken in tempo and it was a highpoint of the performance (Tom Blomfield’s oboe solo being exquisite). The Scherzo achieved a neat symmetry of balance - with a fluid Trio section - but come the Finale the performance fell out of tempo again. The coda was undeniable exciting, but this was an extraordinarily mysterious Bruckner Sixth in almost every sense.

Marc Bridle

Hans Zender: Cabaret Voltaire for voice and ensemble (UK premiere) - Salome Kammer (vocal artist); Philippe Manoury: Blackout - Monodrama for contralto and ensemble (UK premiere) - Hilary Summers (contralto), Philharmonia Orchestra soloists, Pierre-André Valade (conductor)

Purcell Room, London; 27th September 2018.

Wagner, Schoenberg, Bruckner - Angela Denoka (soprano), Philharmonia Orchestra, Esa-Pekka Salonen (conductor)

Royal Festival Hall, London; 27th September 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Salome_Kammer_CHF8224_RGB-full%20%281%29.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title= product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id=Above: Salome KammerPhoto credit: Christoph Hellhake

ENO's Salome both intrigues and bewilders

It’s not surprising that a twenty-first-century opera director might want to find ways of re-imagining Salome which do not simply reproduce fin-de-siècle obsessions and neuroses. Adena Jacobs’s new production for English National Opera eschews the quivering sensuousness of Flaubert, Huysmans, Moreau, Beardsley, Wilde, Klimt et al - overlooking, in so doing, Richard Strauss’s own chromatic writhing and lurid orchestrations - and replaces their visual and literary lavishness with defiant feminist imagery. Barbies and Bronies both take a bashing, as this insolent teenager in black leather hot pants gives as good a gaze as she gets, wielding a phallic baton in brutal defiance and steely self-definition.

Ella Ferris Pell - Salome. Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Ella Ferris Pell - Salome. Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Jacobs isn’t the first to attempt, as Lawrence Kramer puts it, ‘to appropriate the Salome complex on Salome’s behalf’. [1] Kramer draws attention to a portrait of Salome which the American artist Ella Ferris Pell exhibited in 1890 and which Bram Dijkstra reproduces on the cover of his book Idols of Perversity, citing Dijkstra’s suggestion that, ‘Pell's Salome makes a revolutionary statement by being nothing but the realistic portrait of a young, strong, radiantly self-possessed woman who looks upon the world around her with confidence … [Such a woman] was far more threatening, far more a visual declaration of defiance against the canons of male dominance than any of the celebrated vampires and viragoes created by turn-of-the-century intellectuals could ever have been.’

Dijkstra’s words largely seem to sum up the intentions of Jacobs and designer Marg Horwell in their feminist commandeering of Strauss’s opera, though of course the twenty-first-century context supplies its own particular imagery. We begin in near-darkness, Stuart Jackson’s Narraboth yearningly proclaiming his obsessive love for the beautiful princess of Judaea, surrounded by a crowd of fellow-fans and Instagram-followers who, confined within a roped-off enclave, await the arrival of their idol. Above is suspended what at first seems to be a fish-tank, though grainy glimpses of the sinuous movements of a woman bathing gradually come into semi-focus.

At last, Salome herself becomes visible through the blackness. She watches herself being watched. Given what will follow, perhaps she should have learned a lesson from the long list of troubled, contemporary ‘celebrities’ who have found, with sometimes tragic consequences, that though playing with one’s public personae gives illusions of control, it’s not so easy to exorcise patriarchy and find one’s authentic self.

David Soar (Jokanaan). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

David Soar (Jokanaan). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

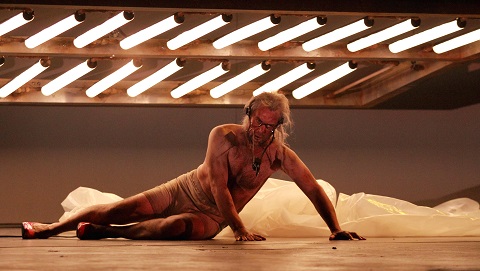

Indeed, out of the blackness, via a reverberant loud-speaker, come the stirring warnings of David Soar’s resonant and arresting Jokanaan. Allison Cook’s Salome is drawn like a fly to an electric zapper and descends to the Baptist’s den of incarceration. Only the feet of the filthy prisoner are visible, protruding from a grubby tarpaulin - presumably preventing the prophet from being fried alive by the fierce lights burning above him. His feet are crushed into shocking pink stilettos and his mouth, so feared by Herod, so fetishized by Salome, is magnified on the rear wall. When he staggers from beneath his protective sheet we see that a pin-hole camera is strapped to Jokanaan’s face - a sort of scold’s bridle - relaying projections of the potent orifice.

The portentous confrontation between redeemer and radical unfolds: as Salome luxuriates in her desires, Narraboth circles with a video camera - presumably for up-loading to YouTube - before killing himself. Slipping her feet into Jokanaan’s stilettos, Salome indulges in some necrophiliac writhing on the Syrian guard. She had unwound her clothing, to bare her flesh; now, Jokanaan unties the bandage on his wrist in order to shield his eyes from such debauchery.

Michael Colvin (Herod). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Michael Colvin (Herod). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

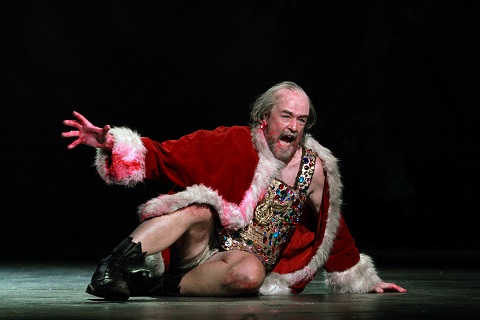

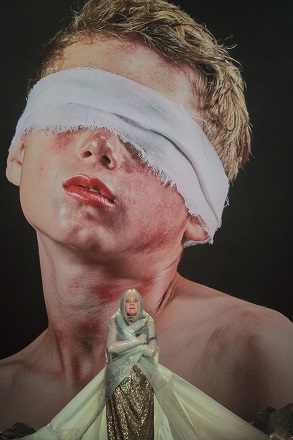

Leaving the prison to return to Herod’s ‘pleasure’ palace, we find the monarch frolicking with four nymphs in shiny nude leotards. Dressed in a be-jewelled wrestler’s suit, grubby boxer shorts and Santa coat, Michael Colvin is a ‘Mad King’ indeed. Desperate, debauched and deluded, he makes George III look a picture of mental and physical health. His ‘courtiers’ sit on the side-lines, aptly dressed in blue surgical gowns and gloves - they are going to have to do the clearing up, after all. Herod slithers in Narraboth’s blood; a rosy My Little Pony is decapitated, disembowelled and hoisted aloft, its mane hanging limply as its floral entrails spill across the stage. In the face of such dysfunctionality, the eloquent pleas of the Nazarenes (Robert Winslade Anderson and Adam Sullivan) are as impotent as the knock-kneed Herod. Herodias (Susan Bickley) wraps herself in a net-curtain which has been pulled down to reveal a blindfolded Saint Sebastian-cum-David Bowie.

Susan Bickley (Herodias). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Susan Bickley (Herodias). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

I confess that, by this point, I was suffering from an overload of the absurd. I hoped that some sense of ‘purpose’ or context would arise from the Dance of the Seven Veil’s and Salome’s final monologue: the still points at which Salome is the focus of our own voyeurism. Allison Cook is a terrific singing-actor and she has all the notes in her arsenal, if not quite the gloss that might outshine the instrumental excess.

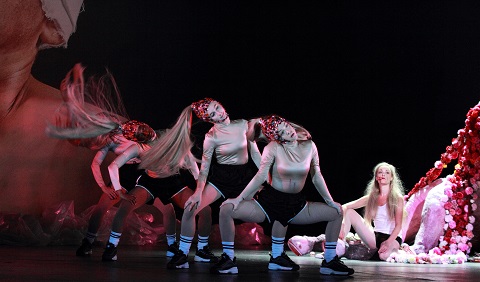

But, her Salome doesn’t so much as dance as pose languidly and grasp a baseball bat, appropriating phallic authority. Having discarded her Barbie-doll candy-pink sweatshirt and whipped off her blond wig to reveal a power-haircut, she slides up the pony’s belly and revels in its ripe intestines. Four dancers - Essex-scrapes, black football shorts, sequinned head-dresses - jerk and twerk.

Ensemble dancers and Allison Cook (Salome). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Ensemble dancers and Allison Cook (Salome). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Jacobs believes that the dance is not a ‘true unveiling or an expression of the soul. It is a dance constructed for Herod’s gaze … On this night, Salome subverts the dance for her own gain, she uses it to radicalise herself’. It is not mystical, she declares, but ‘an escalation of her power, a ritualistic dance for the head of Jokanaan, an act of ritual preparation.’ Well, the notion that women can subvert the patriarchal, scopophiliac gaze is nothing new; even Flaubert suggested that Salome usurped power, that her movements evaded male determination: ‘With her eyes half-closed she twisted her body backwards and forwards, making her belly rise and her breasts quiver, while her face remained expressionless and her feet never stopped moving … From her arms, her feet, and her clothes there shot out invisible fire.’ But, what if there is no ‘movement’: can her dance still empower? Though conductor Martyn Brabbins drew radiant silk and riotous sleaze from the ENO Orchestra, I was unable to make sense of the schism that opened between visual image and musical motion.

Having turned all male heads, Salome then topples them. And, it is the severed head - in Wilde’s play, this is a magisterial and monstrous Medusa - that ultimately draws our gaze. But, Jacobs doesn’t give us a head, only a lumpen white plastic bag. This makes a nonsense of the text and psychology of the monologue - ‘If you had looked at me, you would have loved me’, she sings to the severed gore, desperate to command Jokanaan’s gaze.

Allison Cook (Salome’s monologue). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Allison Cook (Salome’s monologue). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

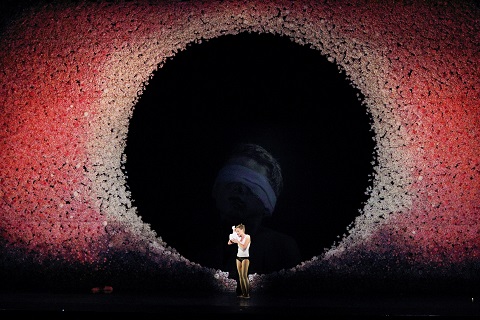

One thinks again of Pell’s portrait of Salome with its empty platter. Is this Jacobs’s design: if there is no head then our gaze remains fixed on Salome herself and thus the patriarchy does not re-exert its power? The director’s final image is equivocal: a flower-bordered black-hole, framing the bandage-eyed Bowie look-a-like; is this a mouth, a vulva, or what Elena Manafi (Senior Tutor/Programme Director PsychD In Psychotherapeutic and Counselling Psychology at the University of Surrey) describes in her programme article as ‘the abyss of the feminine’? Jacobs, it would appear, wants to turn Salome’s pathological narcissism into a ‘victory’, but her Salome is figuratively blinded by solipsism: and, spoiler alert, literally blinded by her mother’s hands which shroud her eyes from the truth that the lips she kisses are not Jokanaan’s - he’s still in the plastic bag - but Herodias’s own? Aren’t there enough Freudian threads in this tale already …

Allison Cook (Salome). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Allison Cook (Salome). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

This Salome ends as the protagonist places a phallic gun in her mouth. Manafi argues that ‘Destruction becomes a form of liberation’, and that although Salome’s attempts to master and manipulate the male gaze have been ‘nothing but mimicry’ of patriarchal dynamics, her final act is an ‘outburst of violence that constitutes her emancipation’. But, Jacobs and Manafi seem to have forgotten that there is a theatrical audience: she becomes a prey to our gaze. As scholar Peter Conrad has observed, ‘Salome ceases to be a character and becomes an image, and opera turns simultaneously into a symphonic poem, into a ballet, and into a painting’. [2]

Jacobs allows for equivocation. But Angela Carter did just this nearly forty years ago, in the stories of The Bloody Chamber where the fantastical allows women to embrace their inner ‘darkness’: some critics argue that the female ‘victims’ of Carter’s fairy-tales become gradually empowered by embracing desire and passion as a human animal, others that Carter envisages women’s sensuality simply as a response to male arousal and that her tales can only reproduce patriarchal values rather than modify or shatter them.

Jacobs gives us arresting and intriguing visual images, but her Salome is smorgasbord of ideas and theories. Narraboth’s blood and the pony’s entrails are too slippery to tie the tableaux together.

Claire Seymour

Richard Strauss: Salome

Salome - Allison Cook, Jokanaan - David Soar, Herod - Michael Colvin, Herodias - Susan Bickley, Narraboth - Stuart Jackson, Nazarenes - Robert Winslade Anderson/Adam Sullivan, Herodias’s Page - Clare Presland, Soldiers - Simon Shibambu/Ronald Nairne, A Cappadocian - Trevor Eliot Bowes, Slave - Ceferina Penny, Jews - Daniel Norman/ Christopher Turner/Amar Muchhala/Alun Rhys-Jenkins/Jonathan Lemalu; Director - Adena Jacobs, Conductor - Martyn Brabbins, Designer - Marg Horwell, Lighting Designer - Lucy Carter, Choreographer - Melanie Lane, Orchestra of English National Opera.

English National Opera, Coliseum, London; Friday 28th September 2018.

[1]

Lawrence Kramer, ‘Culture and musical hermeneutics: The Salome

complex’, Cambridge Opera Journal Vol.2, No.3 (November 1990):

269—94

[2] Peter Conrad, Romantic Opera and Literary Form (Berkeley, 1981), p.154.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore

September 29, 2018

In the Company of Heaven: The Cardinall's Musick at Wigmore Hall

Palestrina’s musical devotions to Saints Peter and Paul opened with the composer’s six-voice motet, Tu es Petrus, and the parody mass which it inspired. With just a single voice to each part, Carwood generated a strong sense of forward movement and exploited the vibrant luminosity that Palestrina’s ‘antiphonal’ effects create, as the three higher voices alternate with the three lower strands in the opening phrases - an effect which reappears in the movements of the mass. There was a gradual blossoming as the music drove towards the confident statement, ‘Et tibi dabo claves regni caelorum’ (And I will give you the keys to the kingdom of heaven), but the mood remained buoyant and fresh. Though the six ‘solo’ voices cannot produce a rich sonorous blend such as might swell around a Baroque basilica during a liturgical ritual, bathing the congregation in an inspiring wash of resonant fullness, the differentiation of the individual lines, each sung with strong character, enabled Carwood to subtly highlight individual lines and phrases, which simultaneously injected muscularity into the evolving polyphony, with the brightness of the soprano and alto adding further ‘uplift’.

The movements of the Mass were interspersed with Gregorian chants for the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul - Introitus, Alleluia Tu es Petrus, Offertorium - Constitues eos and Communio Tu es Petrus - sung by tenor and countertenor voices from the rear of Wigmore Hall.

The Cardinall’s Musick deliver their repertory directly and without affectation, and the six voices invited an intimacy that is entirely appropriate for Wigmore Hall. But, I could not help reflecting that this music might not be similarly apt for the venue; it was not intended for ‘performance’ but for participation, in a spiritual sense, and would not have been delivered in a ‘static’ manner but rather during the ritual processions and acts of the liturgy, the sound moving through the architectural spaces with wondrous and elevating impact.

That said, The Cardinall’s Musick sang the Mass with assurance and some sense of the spiritual engagement it was designed to inspire. The interweaving of the even lines of the Kyrie resolved into the purity of a shining cadential ‘eleison’, the SSA group within the ensemble conveying heaven-aspiring lucidity. A light flowing bass line in the Gloria created relaxed momentum, though I felt that in this and other of the longer movements, greater variety of dynamics and colour would have communicated a stronger response to the text. Carwood demonstrated clear insight into the formal structure of the movements though, producing a measured sense of acceleration in anticipation of the ‘Cum Sancto Spiritu’. And, the same flexibility was evident and put to good effect in the Credo; the expansiveness achieved with the phrase ‘Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto,/ Ex Maria virgine, et homo factus’ (And was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man) was powerful. In the Sanctus and Benedictus, the tender unfolding conveyed peace and assurance, and again the strong but sweet bass line illuminated ‘Hosanna in excelsis’ from below, with the voices finding surprisingly translucence with the pronouncement of the blessing itself. With the Agnus Dei came a lowering of tessitura, suggesting the arrival of a point of rest, which was reassuringly achieved in the six-voice echo of the ‘Ite missa est’ (the Mass is ended).

More Palestrina followed the interval, with Saint Paul taking his turn to be venerated in the composer’s ‘Magnus sanctus Paulus’. Here, the power of the full eight-voice ensemble made itself felt in the decorative floridity of the appeal, ‘Qui te elegit, ut digni efficiamur gratia Dei’ (so that we may be worthy by the grace of God); when repeated in the concluding episode, the muscular counterpoint, driven from the bottom, truly conveyed a striving to be ‘worthy’.

Saints Mark, Bartholomew and Andrew were honoured in music by composers who are not such household names. Giovanni Bassano was employed in Venice as a wind player and became leader of the instrumental ensemble at San Marco Basilica. The rich homophony of the close of his ‘O rex gloriae’ a5 (published 1598) resolved into a lovely fluid Alleluia which wound its way expressively through the syllables. The four-part ‘Sanctus Bartholomaeus’ (published 1586) of Jacob Handl was followed by Thomas Crecquillon’s ‘Andreas Christus famulus’ (1546). Little is known of Crecquillon’s life, though he was associated with the chapel of the Emperor Charles V for ten or more years from 1540 and was sufficiently esteemed for a major retrospective of his motets to be published after his death (c.1557). Crecquillon’s eight-voice motet ‘Andreas Christi famulus’ was composed for the annual meeting of the Order of the Golden Fleece in 1546 and was for a time judged to be the work of Cristóbal de Morales. Here, as the contrapuntal glories extended the compass, the tuning was less consistently secure. Moreover, in this less familiar repertory, the singers were understandably more score-bound and sometimes lacking in animation.

Sacred music from Spain in honour of the Virgin Mary concluded the programme. Tomás Luis de Victoria’s ‘Vidi speciosam’ a6 (1572) was beautifully sung. The gently restful repetitions - ‘Flores rosarum et lilia convallium’ (She was surrounded by roses and lilies of the valley) - conjured the sweet fragrance of the Virgin who ascends from streams of water, as beautiful as a dove. Here, the singers captured the drama and spirituality of music, moving through the sublime harmonic progressions with an animation sometimes lacking elsewhere. Carwood sat at the side during the four-voice ‘Virgo prundetissima’ (1555) of Francisco Guerrero, a prolific composer who was born in Seville in 1528.

Sebastián de Vivanco (c.1551-1622) was born in Ãvila at roughly the same time as Victoria and has been rather overshadowed by the latter’s achievements and renown. However, with the full complement of voices reassembled, The Cardinall’s Musick showed us that, while less experimental than Victoria, Vivanco could craft imposing counterpoint. The ‘Magnificat octavi toni’ (published 1607) accumulated majesty through the evolving parts, building to a series of statements of comfort and certainty: ‘Quia fecit mihi magna qui potens est’ (For he that is might has done great things for me), ‘Suscepit Israel puerum suum:/Recordatus misericordiae’ (Concerning Israel, his child: he remembered his mercifulness). The blending of voices in the final Gloria Patri et Filio was reassuringly resonant and firm.

Despite my minor misgivings about the partnership of repertory and context, this was a beautifully sung programme - and a well-conceived one too, engagingly introduced and explained by Andrew Carwood. The Cardinall’s Musick will present another opportunity to enter the company of heaven in January next year , returning to Wigmore Hall to perform works focusing on Mary Magdalene and other saints.

Claire Seymour

In the Company of Heaven : The Cardinall’s Musick (Andrew Carwood, director)

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina - Motet Tu es Petrus, Missa Tu es Petrus (interspersed with sections from Gregorian Chant Propers for the Feast of SS Peter and Paul), Magnus Sanctus Paulus a8; Giovanni Bassano - O Rex gloriae; Jacob Handl - Sanctus Bartholomeus; Thomas Crecquillon - Andreas Christi famulus; Tomás Luis da Victoria - Vidi speciosam; Francisco Guerrero - Virgo prudentissima; Sebastián de Vivanco - Magnificat octavi toni.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/The-Cardinall%E2%80%99s-Musick.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=In the Company of Heaven: The Cardinall’s Musick (director, Andrew Carwood) at Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: The Cardinall’s MusickSeptember 28, 2018

Roberto Devereux in San Francisco

Donizetti traversed these sordid histories in 8 years (from 1830-1838). It took San Francisco Opera 13 years (Joan Sutherland as Maria Stuarda in 1971, Monserrat Caballé as Elizabeth I in 1978, and Joan Sutherland as Anna Bolena in 1984). Of course a couple of years ago the mighty Met managed to mount the whole bloody history in a few mere months.

This is opera history and Donizetti’s queens are opera history, rather history according to opera. There is no question which history is more real and true — crumbling parchment documents and a few words etched in stone from long ago or the delicate intimacies and huge tantrums that flew off the War Memorial stage last night at the final (of six) performances of Roberto Devereux. Donizetti’s bel canto miraculously achieved the Apollonian ideal — raw emotion absorbed into high art.

Soprano Sondra Radvanovsky portrayed history’s most terrifying queen in terrifying intricacies of voice, high d’s surreally emerging from nowhere to cap thrilling ascents of tortured lines, then other moments of descending lines, stepwise and sorrowfully slow. La Radvanovsky’s Elizabeth is terrifying, a persona of monumental presence, of absolute authority terrorised by love, a persona that is fully aware of her regal power, exuding the pleasure of executing astonishingly difficult vocalism, and surely of holding the 3000 spectators in the War Memorial in her thrall.

And a persona willing to fully suffer the torment of losing those she most loves, Roberto Devereux whom she blindly loves and the woman Devereux loves, her confident Sara.

Russell Thomas as Devereux, Jamie Barton as Sara

Russell Thomas as Devereux, Jamie Barton as Sara

Elizabeth is hardly the only one to suffer. Sara’s husband, the Duke of Nottingham is Devereux’s best friend who must reconcile his love for and trust of his wife with his love and respect for his friend. Sara must reconcile her love for the queen with being her rival for Devereux’s love, and Devereux must reconcile his political and blatant personal betrayals of absolutely everyone with himself. So there is a lot to sing about.

And sing and suffer they do. After three hours of trying no one reconciled much of anything, to our very great pleasure. It was indeed an evening of bel canto! Italian conductor Riccardo Frizza established an unwavering dramatic pace that drove the betrayals and at the same time offered the protagonists all freedom to expand each moment of elation or despair and all gradations of joy and suffering in between. It was an all-too-rare conductorial achievement in parsing the emotional machinations of this difficult repertoire.

The voices of the protagonists were carefully matched. The all American cast was in prime vocal condition, and musical preparation was stylistically consistent. All voices were indeed beautiful, befitting the essence of bel canto. If the Radvanovsky sound is magisterial, mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton as Sara added the freshness of voice of a young woman in love. Tenor Russel Thomas as Roberto Devereux produces a limpid yet lush tenor sound throughout his full register, including its stratospheric tenorino reaches. In such company Adler Fellow Andrew Manea as the Duke of Nottingham strangely was not over parted. If his youth was obvious, his authority of presence, his command of style and use of his quite beautiful voice were formidable.

Sondra Radvanovsky as Elisabetta in final scene

Sondra Radvanovsky as Elisabetta in final scene

The well traveled production by British director Stephen Lawless belongs to Canadian Opera. Mr. Lawless took his cue from Donizetti’s quote of “God Save the Queen” in the overture to attempt to create levity, if not caricature of opera history. The surround was the galleries an Elizabethan theater indicating, I suppose, that we need not assume what we saw happen on the center stage acting platform was true or real, that it was, after all, only opera. There was a multitude of cute staging tricks that tried to keep us distanced from the distraught, often overwrought protagonists. They did not. We suffered.

That the production is not distinguished was of little importance to this evening. Mme. Radvanovsky grounded the production in high bel canto style that easily overcame all directorial conceits. This unique artist had the support of a well qualified cast. With Maestro Frizza we, right along with this distinguished cast, enjoyed a splendid evening of opera history.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Elisabetta: Sondra Radvanovsky; Roberto Devereux: Russell Thomas; Lord Cecil: Amitai Pati; Sir Walter Raleigh: Christian Pursell; Sara: Damie Barton; A page: Ben Brady; Duke of Nottingham: Andrew Manea; Nottingham’s servant: Igor Vieira. Chorus and Orchestra of San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Riccardo Frizza; Director: Stephen Laless; Set Designer: Benoit Dugardyn; Costume Designer: Ingeborg Bernerth; Lighting Designer: Christopher Akerlind. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, September 27, 2018

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Devereux_SF1.png

product=yes

product_title=Roberto Devereux San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Sondra Radvanovsky as Elisabetta I [All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

September 27, 2018

O18: Queens Tries Royally Hard

Subtitled as “The Ring Cycle of drag, tenors, and rock & roll, unfolding over three different nights,” I saw only the first, and was sated by the time Blythely After Hours came to a close with We Are the Champions sung in an Italian translation by Corrado Rovaris.

Starring one of the great operatic mezzos of our day, Stephanie Blythe uncompromisingly adapted the guise of star “tenor,” Blythely Oratonio. “He” begins the night singing upstage, back to us, intoning Pavarotti’s signature aria, Nessun dorma, in thundering chest tones, arms semaphoring, succeeding after a fashion, but somewhat hampered by initially tinny miking. (Daniel Perelstein’s sound design thereafter settled in to a good mix.)

When Mr. Oratonio finally turned to face us on the applause, “he” looked like Baba the Turk had wandered in from another opera. And it made me realize how much rather I would be hearing the mezzo in that or any other real opera role. Don’t get me wrong, Ms. Blythe, er um, I mean Mr. Blythely can sing the phone book with artistry and compelling delivery. And while she-as-he never slums stylistically essaying the copious pop material, neither does the performer ever quite consistently come into her own. For all her confident showmanship, the evening simply did not show off the magnificent richness of Stephanie Blythe’s potent instrument, with the insistent chest voice sharply pointed without turning over into her warm, womanly, not tenorly coloring.

To her great credit, the diva seems to be having a great time, one moment the complete esthete, another calculatedly vulgar, always engaged, ever energized to entertain us, and the vast majority of the audience was eating it up. Operatic tradition put-downs: big laugh. Singers’ ego disses: ha ha ha. Mezzo singing Vesti la giubba alternating with Send in the Clowns: how does she change gears like that?

Everyone did their level best to enliven and sustain the 90-minute goof. Rachel Camp (Bey) and Rob Tucker (Linda) were willing accomplices. A group of acolytes dubbed the Merepeople sang and cavorted gamely: Dane Allison, Messapotamia Lefae, Kathryn Raines, Bobby “Fabulous” Goodrich. Two of them chirped some agreeable interjected measures of the Flower Duet. Best of all, the vivacious guest star Brenda Rae wandered in to shuck her fur coat down to her bloody white Lucia gown, accompany herself on a Tori Amos song, and then sing counterpoint to Oratonio’s Faithfully with an operatically soaring The Winner Takes It All. A second guest appearance by Justin Vivian Bond was less assured, with a cue card having to be provided for her to get through her number.

Curiously for a festival that is top tier in every way, that sort of stumble occurred a couple times in the evening, with gentle prompts having to be provided to get things back on track. Indeed, the whole enterprise seemed to have the aura of a somewhat (intended?) slapdash, wee hours drag show. At the piano, the talented Daniel Kazemi provided excellent musical leadership and very satisfying arrangements. When he took off his suit jacket to reveal a leather vest and some toned biceps, the ripple through the audience told me exactly the hedonism and chicanery most were here for.

The inventive director John Jarboe mostly kept things moving at a good clip, and while the material he wrote (in tandem with the two stars) was a little loosey goosey, the pace at least was forward-looking, and he kept us from spending too long dwelling on one beat. Machine Dazzle’s costume and production was suitably Tacky Chic, and Drew Billiau lit the show with color and imagination.

Personally, in a slightly overlong evening of flimsy, jokey, pop material, I was hoping for more Blythe and less Blythely, more emphasis on her incomparable voice than her over-the-top assumed “persona.” That said, there are probably many satisfied customers who intend to come back to be similarly subjected to the second and third installments of the series: Fauréplay with Martha Graham Cracker, and Dito & Aeneas: Two Queens, One Night. As for me, Blythely After Hours was a good enough chuckle but I think for the moment I am queened out. . .

James Sohre

Queens of the Night, Blythely After Hours

Blythely Oratonio: Stephanie Blythe; Bey: Rachel Camp; Linda: Rob Tucker; Guest stars: Brenda Rae, Justin Vivian Bond; Merepeople: Dane Allison, Messapotamia Lefae, Kathryn Raines, Bobby “Fabulous” Goodrich; Writer/Director: John Jarboe; Music Direction/Arrangements: Daniel Kazemi; Costume/Production Design: Machine Dazzle; Lighting Design: Drew Billau; Sound Design: Daniel Perelstein

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Stephanie%20Blythe%20as%20Blythely%20Oratonio.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Blythely After Hours: Opera Philadelphia

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id= Above: Stephanie Blythe as Blythely Oratonio

O18 Magical Mystery Tour: Glass Handel

How to even describe it without your thinking I am as bonkers as the mad Lucia I had seen at the festival earlier in the day? Let’s start in the venue, the long Annenberg Court that is the antechamber to the awesome Barnes Foundation art collection. (A gratis visit to the art was included in the evening.)

A small square stage platform is set in the center of the space, backed by two - count ‘em - two orchestras, a larger rectangular platform to the left, a raised platform with a large blank canvas to the right, beyond which are a bank of monitor screens. Chairs are placed around the space, set within a grid defined by blue lines. Rows of curious-looking, multi-colored dollies are parked at the ready. What could this wide-ranging spread possibly add up to?

Well, quite a lot as it turns out. Star counter-tenor Anthony Roth Costanzo, Visionaire, and Cath Brittan have conspired to present an artistic “happening” where singing, dance, fine art, and video are presented simultaneously to saturate the senses and create a one of a kind, on the spot experience. The 60-minute communal performance is anchored by the substantial interpretive gifts of Mr. Costanzo, and he sings magnificently, unstintingly, soulfully, and with unerring distinction of style alternating between Handel and Glass arias.

Anthony Roth Costanzo in Glass Handel, costumed by Raf Simons for Calvin Klein. Photo Credit: Dominic M. Mercier.

Anthony Roth Costanzo in Glass Handel, costumed by Raf Simons for Calvin Klein. Photo Credit: Dominic M. Mercier.

Anthony’s pure, pointed vocalizing has gained a bit in vocal heft since last I heard him, without losing any of the haunting, spiritual quality that informs his entrancing tone. He is an uncommonly expressive interpreter, not so much singing the vocal lines as embodying them. His participation is not only seminal to the project, it rightly dominates and inspires it.

For the audacious concept is this: Three gifted dancers will simultaneously perform, and a renowned painter will create a work of art in immediate “reaction” or “interpretation” as the arias are being presented. Dance world’s lithe and athletic luminaries Patricia Delgado, David Hallberg, and Ricky Ubeda take turns cavorting tirelessly with practiced abandon on the second stage, nimbly executing Tony-winning Justin Peck’s evocative, impromptu-seeming choreography.

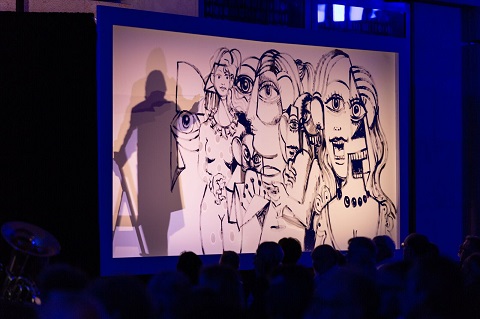

Artist George Condo enters during the opening Grand Parade of performers and supers to take his place behind the large framed canvas at the other stage. Back lit like a shadow box, Mr. Condo spends the hour in silhouette painting a huge, abstract, cubist-inspired sketch that eventually filled the space and seemed at times like a magical, highly refined Etch-a-Sketch. Further afield past this canvas, video monitors screened installations, especially created for the event.

George Condo paints live at Glass Handel. Photo Credit: Dominic M. Mercier.

George Condo paints live at Glass Handel. Photo Credit: Dominic M. Mercier.

But wait, there’s more. Last year’s festival featured a premier of the opera We Shall Not Be Moved. In a reversal, the mantra of Glass Handel was that we SHALL be moved. Literally, and it happily turns out figuratively. For you see, fresh-scrubbed, attractive young supers manned those special dollies, and methodically moved audience members between the three staging locations. From the downbeat, a people shifter would put the dolly in place, put a hand on the shoulder to signal the intent to move the chair, tilt back and wheel the chair to a different vantage point. This was repeated with audience members in sequence.

I began directly in front of the singer, then went to the dance area, then finished in the painting area. While each had a different dynamic, all the while I was able to still enjoy the other concurrent elements. The hypnotic parade of spectators was itself a calculated element in the “performance art” nature of the project. As the music surged in the climactic aria, as the final touches and tweaks were daubed on the painting, and as the trio of dancers finally all assembled as one, the resettled audience had taken a mightily impressive “journey.” Although each element was exciting, it has to be said the real energizing presence of the evening was the towering, generous, inspiring contribution from Mr. Costanzo, first among equals.

There was so much to take in, we almost took for granted the two separate instrumental groups, one superbly essaying the Baroque glories of Mr. Handel, and the other restlessly, luminously liming the harmonies and pulsing rhythms of Mr. Glass. All this flash and dazzle would not have been possible without the dynamic and stylistically adroit conducting by Maestro Corrado Rovaris.

The technical elements were of necessity simple but competent, with Brandon Stirling Baker’s even lighting design solving many if not all of the challenges in lighting that space. Anthony’s costumes were over-the-top creations, starting with a red satin bell-shaped robe, with enormous puff sleeves that tied at the neck with an enormous billowing bow, contrasted with purple gloves. He eventually peeled that off to reveal a blue satin ball gown/shift emblazoned with Glass Handel, ending in a sort of androgynous white nightgown covered with Condo-like squiggles.

Did I mention it was revealed that the counter-tenor was prankishly wearing red satin high heels with rhinestone stripes under all that? The dancers were provocatively clad in the briefest of red briefs, with irregular rows of long red, silver, and black fringe creating cascades of visual movement. Completing the production “look,” the supers sported red tops and black slacks, while the black clad orchestra was accessorized with draped, wide red lanyards around their necks. This scintillating costume plot was created by Calvin Klein Chief Creative Officer Raf Simons. Kudos as well to stage manager Betsy Ayer who kept things flowing seamlessly.

I commend all concerned for taking this enormous leap of faith, this mighty artistic risk. There is much about this that portended that it shouldn’t work, but it did, and brilliantly, a stunning evening. The performers and creators were lavished with cheering ovations that called them back again and again. I am cheering them still: Bravi tutti!

James Sohre

Glass Handel

Music of George Frideric Handel

And Philip Glass

Countertenor: Anthony Roth Constanzo; Dancers: Patricia Delgado, David Hallberg’ Ricky Ubeda; Painter: George Condo; Conductor: Corrado Rovaris; Production: Anthony Roth Constanzo, Visionaire, Cath Brittan; Costume Design: Calvin Klein, designed by Chief Creative Officer Raf Simons; Choreography: Justin Peck; Videos: James Ivory and Pix Talarico, Mark Romanek, Tilda Swinton and Sandra Kapp, Tianzhou Chen, Daniel Askill, Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari, Rupert Sanders, AES+F, Mickalene Thomas; Lighting Designer: Brandon Stirling Baker; Production Format: Ryan McNamara; Video Consultant: Adam Larsen; Stage Manager Betsy Ayer; Rehearsal Director: Miguel A. Castillo

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ricky%20Ubeda.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Glass Handel: Opera Philadelphia

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Ricky Ubeda

Photo credit: Dominic M. Mercier

September 26, 2018

Magic Lantern Tales: darkness, disorientation and delight from Cheryl Frances-Hoad

In 1668, the English scientist Robert Hooke published an article in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, in which he described the projection of transparent and opaque objects, illuminated by sunlight or candle. Two years earlier, and two weeks before the Fire of London, Samuel Pepys had purchased a lantern from the London optician John Reeves recording in his diary, “Comes by agreement Mr Reeves, bringing me a lanthorn, with pictures on glass, to make strange things appear on a wall, very pretty”. Camera obscuras, magic mirrors, Laterna Magica, Phantasmagoria; for millennia, people have been enchanting, terrifying and transfixing each other with projected lights and shadows, shapes and colours, spinning tales of wonder and terror.

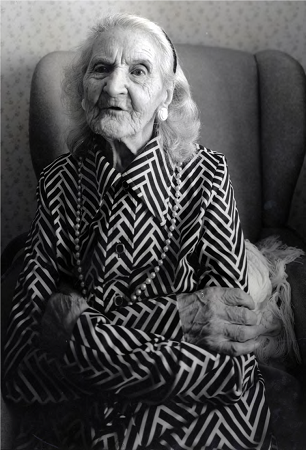

Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s forthcoming new recording, Magic Lantern Tales, similarly presents us a veritable son et lumière of musical light, colour, shapes and sounds. The cycle which gives the disc its title presents five poems from Ian McMillan’s collection Magic Lantern Tales (2014), written in response to interviews and documentary photographs by Ian Beesley. In 1994, Beesley was appointed artist-in-residence at the Moor Psychiatric Hospital in Lancaster, working on the unit specifically for the care of the extreme elderly, many of whom had been in the Moor for decades. H discovered a collection of old photographs in a chest of drawers, many of which were related to the First World War - soldiers in uniform, family gatherings, and weddings with the grooms in uniform - which had belonged to patients who had died in the hospital and who had no living relatives. Beesley describes these fading photographs as ‘a visual eulogy to forgotten lives’; they prompted him “to photograph and interview as many men and women who had experienced the First World War before it was too late”.

Lily Maynard. Photo Credit: Ian Beesley.

Lily Maynard. Photo Credit: Ian Beesley.

He and McMillan subsequently created a magic lantern show to present these personal narratives of the War by those who survived it. Now, Frances-Hoad has given musical expression to the stories of Lily Maynard (101), who told Beesley of her grief for her beloved, “We were thinking of getting married, when he went off to France , the Somme”; Harry Holmes (100), who was decorated for his bravery at Ypres when, whilst trying to retrieve wounded colleagues from no-man’s-land, he single-handedly captured five German soldiers; and Mabel Walsh (104), whose fiancé was killed in 1918 when struck in the head by a small piece of shrapnel, and who, like Lily, never married.

Nicky Spence. Photo Credit: Mardo Studio.

Nicky Spence. Photo Credit: Mardo Studio.

Frances-Hoad frames their memories with McMillan’s ‘Marching Through Time’, and so the cycle opens with a quiet but purposeful tolling, as pianist Sholto Kynoch summons Nicky Spence’s folk-tinged preface to the subsequent unfolding of the past, drawing the voice back to its anchor just as dissonant second and ninths reveal the narrator’s wish for release. Just over three minutes long, this is a marvellously crafted song which, through the expanding bare fifths and octaves in the accompaniment, the rhythmic and resonant intimation of military echoes, and the tense heightening of the vocal line, travels widely through time, place and emotions. The ascending line, “Stories rebuild just what wartime destroys”, spills intensely into a densely accompanied proclamation: “And a photograph is a kind of map.” Spence’s unaccompanied voice bursts with the anguished weight of memory, “That story lifting up the tentflap of history”. There is a subtle chromatic alteration in the repeated final line, “Stories as brittle as glass”, to which Spence adds timbral nuance, which is both beautiful and anguished. Such precise musical insight into the relationship between sound, sense and sensibility is characteristic of Frances-Hoad’s writing in all of the compositions recorded on this disc, and the results are deeply affecting.

The piano introduction to ‘Lily Maynard’ swings with a lovely lop-sided lilt, which is complemented by Spence’s warm, affectionate tone in the refrain, “Come on Lily, Let’s go walking”, and as the song and journey into memory proceed, so the enrichening of the piano’s harmony expresses first a sensuous passion, “Heating up the air something magical”, and then a pained portentousness, “And you pictured him in a trench/ Cowering and crying like a baby.” Spence’s repetitions of Lily’s name somehow seems both encouraging and tormenting, but the softness of the tenor’s head voice in the final refrain, “We’ll talk as we’re walking/ And pretend you’re young again,/ Lily”, follows Kynoch’s star-bound accompaniment into the air and we too are borne aloft on Lily’s dreams and memories.

Harry Holmes. Photo Credit: Ian Beesley.

Harry Holmes. Photo Credit: Ian Beesley.

‘The Ballad of Harry Holmes’, like ‘Lily Maynard’, evokes a war-time song, but now wistfulness is replaced by chirpy resilience, as Spence’s narrator launches with rollicking gusto into this tale of brave Harry who meets bombs, barbed wire and a bonfire-sky with the pragmatic refrain: “All O want when I get through this,/Is a stroll, and a pint, and a kiss.” The rattling spikiness and quirkiness of the piano’s ringing tattoo - which reappears in various guises through the tale - brings Britten to mind, as does the text-setting. Spence’s expansive, galloping laudation, “I guess Harry was a hero”, is halted by the half-spoken whisper, “don’t take me…”, uttered in the “stinking night” to the dark terror. Frances-Hoad whips us through an extraordinary panoply of fluctuation moods and emotions. A cockney voice yelps with joy, “Harry, it’s over!”; the perennial bird-song stills the bombs; Harry’s chest puffs with pride on his home streets of Bradford; Harry-the-decorator dismisses his Military Cross in Yorkshire brogue, “a medal’s just a gaudy lump of tin”; he and Harry Ramsden of chip-shop fame hatch plots to frequent the Crown Inn when Harry R’s wife objects to his ale glugging. Frances-Hoad paints vivid pictures of Harry’s life and at the close, when Spence reflects, “Now Harry’s tale has been told”, we feel that we’ve travelled with him through his adventures and that we know him well, and love him.

The rhythmic ambiguities of the destabilising piano ‘clock-ticking’ in ‘Mabel Walsh’ suggest the centenarian’s straddling and merging of past and present. The effect is heightened by the piano’s gentle inter-verse ringing, a motif which is drily reiterated at the close as we hear “the hourly chimes/ Struck silent by that bastard war”.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad.

There is more magic and memory, as well as strong characters and strange places, in the other substantial ‘cycle’ included on the disc: The Thought Machine, ten settings of poems from Kate Wakeling’s children’s collection, Moon Juice (2016), which was commissioned by the Oxford Lieder Festival. Frances-Hoad’s delight in the whimsical and wry is ever-present in these songs, as is her feeling for the sophistication of a child’s perspective and assimilation of the ‘weirdness of the world’. We are sucked into an echoing cosmic vastness by the piano’s low shudderings and high tremors in ‘Telescope’, and by the slow intertwining, intoning and swooping of the two vocal lines, expertly pitched and co-ordinated by Sophie Daneman and baritone Mark Stone. We glide along the “dizzy black” motorway in ‘Night Journey’, Kynoch’s accompaniment a swirling kaleidoscope of colours and lights that form fantastic shapes in Daneman’s imagination. The singers bring Skig the Warrior and Rita the Pirate to vibrant life - the former more coward than combatant, the latter a swashbuckling gold-grabber who pinches your money with panache, to the tune of a Paganini caprice. The Hamster Man runs round and round his wheel in a wild fury; The light-fingered Thief is cheekily brazen - he even filches the last word of the song. Daneman gleams and teases with mystery in ‘Moon’, with the singers race impressively through the tongue-twisting text of ‘Comet’. After we’ve been pounded, spun and ‘shaken’ in ‘Machine’, bell-chimes send us in search of the ‘Shadow Boy’ as Stone and Daneman smoothly and assuredly traverse the wide-spanning vocal lines, reaching higher and higher as the tentative child tries his hardest to brave the dark.

Sophie Daneman. Photo Credit: Sandra Lousada.

Sophie Daneman. Photo Credit: Sandra Lousada.

There are childhood experiences of a different kind in ‘Scenes from Autistic Bedtime’ which have their origins in a workshop for a projected chamber opera. The text was written by Stuart Murray, Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Leeds and author of Representing Autism (2008), and the three scenes share the opening line, “It is shower time. It is bedtime”, as well as a continuous, shape-shifting piano accompaniment of splashes, splutterings and stutterings, played by Alisdair Hogarth. Treble Edward Nieland sings the child’s short phrases with a directness and clarity that is at first at little unnerving against the unstable piano accompaniment, but we hear too his mother’s voice (Natalie Raybould), by turns anxious then weary, relieved then resigned, but always loving. And, in the second scene she joins her child’s shower-song, in which the soaring voices, warmly lyrical cello (Anna Menzies) and glorious vibraphone chiming (Beth Higham-Edwards) grow into a glowing, intense expression of creativity, joy and laughter. There is darkness and confusion, even the threat of violence, in the third section, but if these scenes are disorientating at times, they are also uplifting and communicate with a striking strength that is both emotive and visceral.

Sholto Kynoch. Photo Credit: Raphaelle Photography.

Sholto Kynoch. Photo Credit: Raphaelle Photography.

Frances-Hoad also conjures ‘alternative perspectives’ in Love Bytes: A Virtual Romance, in which ‘he’ (the cello) and ‘she’ (the vibraphone) articulate and enhance the strange conversation between two cyber-lovers, baritone Philip Smith and soprano Verity Wingate, who wonder just who exactly is on the end of the digital ‘line’. Frances-Hoad treads the fine line between a Walton-esque flippancy and the fragility of human connection and alienation; and, there is both wit and poignancy in their concluding reflection, “Perhaps it’s best/ We never meet at all”. Lament, an affecting setting of a text by Sir Andrew Motion, is sung with vivid emotional presence by mezzo-soprano Anna Huntley, accompanied by Hogarth. Hogarth also performs Invoke Now the Angels, conceived as a response to Britten’s Canticles I and II, which brings Wingate together with mezzo-soprano Sinéad O’Kelly and countertenor Collin Shay. This trio sing the a cappella A Song Incomplete, which sets text by Aristotle; Kynoch performs two short piano works, Star Falling and Blurry Bagatelle.

The works on this disc are varied in tone, context and form, but they are also consistent in the very visceral effects that they have upon the listener. Frances-Hoad’s Magic Lantern Tales disorientate and delight in equal measure.

Magic Lantern Tales is released on the Champs Hill label in November 2018.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Magic%20Lantern%20slide%20circa%201900s.png image_description= product=yes product_title=Magic Lantern Tales: a new recording by Cheryl Frances-Hoad (Champs Hill, CHRCD146) product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Magic Lantern slide c.1900A lunchtime feast of English song: Lucy Crowe and Joseph Middleton at Wigmore Hall

Where else to start but with Henry Purcell, as realised by Benjamin Britten. ‘Lord, what is man?’, one of Purcell’s divine hymns, setting Bishop William Fuller’s text and published in the second volume of the Harmonia Sacra in 1693, poses quite a weighty question for a lunchtime recital, and Middleton embraced its rhetorical power, issuing a sterling call-to-arms with a stabbing mordant deep from the darkness of the piano’s bass. Though her soprano has developed real weight and impact, Crowe could not quite match the incision of the drama that Britten shapes within the accompaniment’s flourishes, jangles and sudden gruff outbursts. A little challenged to find colour when the vocal line swooned low, Crowe did project the recitative-like line cleanly and with feeling, but what was missing was a symbiosis between sound and sense - at times I struggled to follow what the soprano was singing about even though I had the text before me. There was, however, a convincing progression through the tripping dance, ‘O for a quill drawn from your wing’, towards the concluding ‘Hallelujah’ in which Crowe flew brightly through the melismatic runs above the piano’s stamping praise.

I’d have liked a less emphatic ground bass in ‘O solitude’, though, and while Crowe’s soprano retains its beguiling purity of tone and crystalline sparkle, I did not find her phrasing consistently convincing. The singer-protagonist’s wonder at the trees, as fresh and green as ‘when their beauties first were seen’, rose with ethereal elation supported by Middleton’s delicate decorations, but in the subsequent reflection on the mountains whose ‘hard fate makes then endure/Such woes as only death can cure’, some unexpected dynamic fluctuations disrupted the indissolubility of the musical and semantic articulation of the text. Little of the theatre music or sacred music of John Weldon (1676-1736) is well-known, excepting the concluding work of Crowe and Middleton’s seventeenth-century triptych: the ‘Alleluia’ found in one source of Weldon’s anthem O Lord, rebuke me not, the latter’s renown being a consequence of its misattribution to Purcell and Britten’s subsequent realisation. Middleton found nuance and sensitivity in the piano’s engagement with the repetitive vocal phrases, and the latter were agilely negotiated by Crowe.

Over the rim of the moon (1918) by Britten’s contemporary Michael Head followed. The high piano chords which introduce ‘The ships of Arcady’ had a lovely swing, both gentle and propulsive like the ebb and flow of the moon-tugged tide, and Middleton conjured a Debussyian sea-scape of rippling wavelets. Crowe’s unmannered directness communicated strongly though a little more give and take would have drawn us in still further. In Francis Ledwidge’s final stanza, when the poet-narrator dreams of Arcady as he looks across the waves and pauses, alone, drifting slowly into reverie as he stares through the ‘misty filigree’, there is time in the music for lingering, but such opportunities for poetic reverie felt at little rushed at times. However, the soprano spanned the arching lines persuasively, both here and in the subsequent song, ‘Beloved’, where the melody often ranges high and low within a single phrase. Middleton’s octave doublings deepened the Romantic intensity of this brief but passionate ode to music, nature and love. In his introduction to Songs of the Field (1916), Lord Dunsany affectionately nicknamed Ledwidge, ‘the poet of the blackbird’, because of the frequency with which he returned to the bird’s artless song and the simple forms and language with which he represented its beauty. Crowe confirmed the aptness of this phrase through the sweet simplicity of manner and melody in ‘A blackbird singing’, though it was a pity that Ledwidge’s relaxed rhymes were again often indistinguishable. ‘Nocturne’ was an unsettling expression of the poet’s grief for his homeland which captured the melodic melancholy of Georgian wistfulness.

Head was the composer of more than 100 songs and, apart from a few well-known songs, we do not hear enough of them in the concert hall. The same might be said of John Ireland whose vocal compositions stand at the heart of his output and which were described by the scholar William Mann as ‘perhaps the most important between Purcell and Britten’; so, it was good to have five of Ireland’s songs at the centre of this programme - and, indeed, they inspired wonderfully communicative expression from Crowe and Middleton. The duo captured the philosophical depths and mysteries of Aldous Huxley’s poem, ‘The trellis’, in the timelessness of the piano’s initial quiet rocking which blossomed so richly, and in the searching lyricism of the vocal melodies which Crowe brought to a ravishing close, suggestive of the secret transfiguration of a poet enveloped by the ecstasy of love: ‘None but the flow’rs have seen/ Our white caresses/ Flow’rs and the bright-eyed birds.’ ‘My true love hath my heart’ rippled with sensuousness, and the performers communicated the spontaneity that Ireland evokes, as feelings well up and overspill. In contrast, they revealed the heart-ache that lies beneath the sparse economy of the composer’s setting of Christina Rossetti’s ‘When I am dead, my dearest’, creating a deep, quiet anguish from such simple means. The flowing naturalness of ‘If there were dreams to sell’ conveyed a gentler fatalism, but ‘Earth’s Call’ brought a concluding flood of sensuous, even dangerous, emotions. The piano writing here is tremendous, and Middleton relished the musical narrative, truly conjuring ‘every natural sound’.

The three settings from William Walton’s Façade that closed the recital programme did not seem Crowe’s natural territory, not least because Edith Sitwell did not merely provide Walton with his texts, but also influenced his musical setting, the rhythms of which were shaped by her own recitation of the poems which the composer notated. In Laughter in the Next Room (1948), Sitwell’s brother, Osbert, described the creative process: ‘I remember very well the rather long sessions, lasting for two or three hours, which my sister and the composer used to have, when together they read the words, she, going over them again and again, while he marked and accented them for his own guidance, to show where the precise stress and emphasis fell, the exact inflection or deflection.’ Crowe’s diction did not really do justice to such meticulous collaboration and the songs’ linguistic acrobatics, but she coped very well with the challenging oddities and angularities of Walton’s intonations and inflections. The three songs selected, ‘Daphne’, ‘Through Gilded Trellises’ and ‘Old Sir Faulk’, are all based on popular song - English, Spanish and American, respectively. Middleton’s accompaniment wriggled and writhed with Hispanic flair and Crowe blanched her tone effectively at the close of ‘Through Gilded Trellises’: ‘Ladies, Time dies!’ But, one felt, though, that the soprano needed to throw her innate poise and composure to the wind, in order to release the extravagance, eccentricity and sheer mad gaiety of Walton’s and Sitwell’s cryptic archness.

Crowe’s encores found her back on more comfortable and familiar ground. After an unaccompanied and beautifully elegiac performance of the Irish folk-song ‘She Moves through the Fair’, the soprano was joined by Middleton to take us ‘Down by the Salley Gardens’, as set by Britten, bringing the recital back to its beginnings. The two songs coloured this lunchtime presentation of glorious English song with a lovely Celtic tint.

Claire Seymour

Lucy Crowe (soprano), Joseph Middleton (piano)

Purcell - ‘Lord, what is man?’ (realised by Benjamin Britten), ‘O solitude, my sweetest choice’ (realised by Benjamin Britten); John Weldon - ‘Alleluia’ (realised by Benjamin Britten); Michael Head - Over the rim of the moon; Ireland - ‘The trellis’, ‘My true love hath my heart’, ‘When I am dead, my dearest’, ‘If there were dreams to sell’, ‘Earth's call’; Walton - three settings from Fa çade (‘Daphne’, ‘Through gilded trellises’, ‘Old Sir Faulk’)

Wigmore Hall, London; Monday 24th September 2018

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Crowe%20%C2%A9%20Marco%20Borggreve%2C%20harmonia%20mundi%20usa.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Lucy Crowe (soprano) and Joseph Middleton (piano): BBC Radio 3 lunchtime recital at Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Lucy CrowePhoto credit: Marco Borggreve

September 24, 2018

O18: Mad About Lucia

As the more “traditional” offering in the O18 Festival, director Laurent Pelly has nonetheless helmed a potent, uniquely stylized staging of this perennial favorite with a decidedly sinister underbelly. With more contemporary resonance than is comfortable, Pelly emphasizes the subjugation of Lucia, forced into a politically expedient marriage by a mentally and physically abusive brother.

Lucia’s squirm-inducing confrontation with Enrico, followed by the lying, emotional manipulation by Raimondo portend her descent into madness with brutal clarity. This Lucia is visibly troubled from the outset, and Pelly/Rae have developed a physical manifestation for the girl that makes us fear for her well-being, long before the wedding.

Lucia (soprano Brenda Rae) re-emerges at the wedding festivities, covered in Arturo’s blood. Photo Credit: Kelly & Massa.

Lucia (soprano Brenda Rae) re-emerges at the wedding festivities, covered in Arturo’s blood. Photo Credit: Kelly & Massa.

The luminous soprano Brenda Rae was a Donizettian’s dream, singing with poised limpid tone, savvy musical execution, and flawless coloratura. This was an utterly perfect match of artist to role. I was already convinced that no one is singing this famously difficult part better when I saw her do it in Santa Fe last summer. But unlike that flaccid staging, Pelly and Rae have collaborated to realize a staggering theatrical portrayal to match its musical eloquence.

Ms. Rae’s hapless heroine is afflicted with alarming physical tics, a slight stoop to the side, uncontrollable pumping of the fists and arms, as if fending off physical violence such as is visited upon her in her duet with her brother. Her consistency in maintaining this physicality was a motivic visual, informing us of how relentlessly her brother must brutalize her. It also inexorably builds in intensity after her unwarranted rejection by Edgardo, and her forced wedding to another patriarchal bully, Arturo. “That” she is going to snap is certain, even if “when” is not. It is to the great credit of all concerned that this thrice familiar story throbbed with emotional spontaneity.

Brenda Rae is a wonder in this repertoire. Her attractive lyric instrument has good bite and power, and she never needs to push to make her effects. Her intelligent delivery of the text invests each phrase with truth and empathy, and her unerring sense of line is a joy to hear. Florid passages are not only technically flawless but also theatrically vital. Her alluring tone is even from top to bottom, and her stage demeanor exudes star quality. There is no finer Lucia in her generation of young singers.

I am also an admirer of tenor Michael Spyres, his solid, rolling tenor possessed of uncommon beauty and vitality. Mr. Spyres has all the goods to succeed in the notoriously daunting role of Edgardo. He has an enviably good extension at the top of the staff, and if one or two of the highest reaches were slightly veiled, he knows just how to use his gifts, and knit them together to make a splendid impression. He has also gained in stage presence since last I saw him, presenting a dramatic persona that had an engaging natural ease.

Michael Spyres as Edgardo. Photo Credit: Kelly & Massa.

Michael Spyres as Edgardo. Photo Credit: Kelly & Massa.

As Raimondo, Christian Van Horn’s very first portentous utterance announced: “Star bass!” This lanky singer not only cuts a handsome figure but also sings with laser-focused, persuasive intensity. Already hailed as a prodigiously promising talent, on the basis of this overwhelming performance, I would say the promise has been fulfilled. The excellent baritone Troy Cook has such a self-centered character to portray as Enrico, and he immerses himself into it with such convitcion, it is almost hard to stop hating him long enough to realize he is singing superbly. Mr. Cook’s buzzy, responsive baritone is a thing of great beauty, with a rock solid technique, thrilling in the exposed climaxes.

The minor roles were cast from equal strength. Andrew Owens’ bright, steady tenor made the most of Arturo’s brief assignment; tenor Adrian Kramer was a suitably brash presence as Normanno, his solid vocalizing having a hint of baritonal richness; and Hannah Ludwig’s Alisa was served by an unusually plummy, opulent mezzo that made an especially notable contribution to the famous sextet. Elizabeth Braden’s exceptional chorus not only sang with stylish elan, but also executed the complicated staging with aplomb.

Corrado Rovaris knows his way around every note of this atmospheric score, and he paced the show with stylistic acumen. Maestro Rovaris has a keen sense of theatre and he flawlessly partners the orchestra with the singers, ebbing and flowing as they live the drama together. The ardent vitality in the pit supports the unfolding tragedy with a characterful presence.

Chantal Thomas is a frequent collaborator with Mr. Pelly, often with playful, jocose set designs. On this occasion Ms. Thomas has crafted an eerie, almost spectral look, setting the tale first on a set of foreboding snow-covered hills, with a non-descript stage high structure stage right that loomed with foreboding. After a moody lighted cabin appears behind the cloud-filled scrim during Regnava nell silenzio, the up right edifice revolves to form the basis of the homestead, with more and more scrim-and-skeletal-frame walls flying in, always cutting off Lucia and forcing her forward, eventually onto the apron.

In a brilliant decision, Mr. Pelly plays the wedding scene cramped onto that forward space, blocking by the inch, and reinforcing the fact that Lucia is fatally trapped in a familial web. The Wolf’s Crag scene opens Act Two in a desolate ruin that recollects the squarish structure that opened Act One. The main hall of Lucia’s madness is a startling coup de theatre, a massive solid red wall, cut high up with arrow slits, and dressed with a single wonky row of akimbo black chairs. A red carpet lines the hill from the massive doorway to the forestage. Masterful.

The show began with an hallucination, with Lucia appearing in her wedding dress atop the largest hill, only to recede as huntsmen peopled the scene. At the end, the male chorus returned to the hill to observe Edgardo’s demise as the snow took up again. Throughout, poor Lucia’s wandering faculties were underscored with startling touches. For example, Edgardo exits upstage in an overcoat during the love duet, leaving Lucia in a down right position, then reappears in shirtsleeves to complete her imagined version of the “happy ending” of the duet, now bathed in a surreal light. In her climactic cabaletta, Lucia climbs to stand, tottering on a chair. After she releases her final high note, her cry of death, she falls into a mosh pit of choristers who hoist her aloft into a blazing special, a bloodied white flower in a sea of oppression.

The hauntingly effective lighting design was by the always commendable Duane Schuler. Mr. Pelly served as his own costume designer and his muted, texture suits, overcoats, and court wear were handsomely stolid. David Zimmerman’s hair and make-up designs were effectively austere and there were even surreal streaks of primitive facial marks in one scene if my eyes did not deceive me.

I have seen many another accomplished production of this showpiece in my day, but none other quite gripped me by the collar and never let go like this one. O18’s Lucia di Lammermoor is a nonpareil melding of engrossing theatre and stunning music.

James Sohre

Donizetti: Lucia di Lammermoor

Lucia: Brenda Rae; Enrico: Troy Cook; Edgardo: Michael Spyres; Raimondo: Christian Van Horn; Arturo: Andrew Owens; Normanno: Adrian Kramer; Alisa: Hannah Ludwig; Conductor: Corrado Rovaris; Director and Costume Design: Laurent Pelly; Set Design: Chantal Thomas; Lighting Design: Duane Schuler; Wig and Make-up Design; David Zimmerman; Chorus Master: Elizabeth Braden

image=http://www.operatoday.com/OPLucia.jpg

image_description=O18 Lucia

product=yes

product_title=Lucia di Lammermoor, Opera Philadelphia Festival

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: The wedding guests catch Lucia (soprano Brenda Rae) as she collapses.

Photo credit: Kelly & Massa

O18 Poulenc Evening: Moins C’est Plus

… but more on that later.

I have to say Ms. Racette is giving a wholly committed, theatrically vivid, musically thrilling account as Elle in Francis Poulenc’s monodrama. The libretto is by Jean Cocteau, based on his own play. In the fifty-minute running time, Elle is having a last, difficult phone conversation with her former lover who is about to marry another woman. In an anguished attempt to stay the inevitable, the woman desperately processes the reality of her unrequited love.

There is no aspect of this complex “conversation” that eludes this fine performer. Her sudden shifts of temperament, her calculating tactics, her frightened outbursts as the phone disconnects, the occasional catch in the voice, her aching persistence, all combine to make as good a case for the somewhat repetitive script as possible. Moreover, Elle is a perfect vocal fit for Racette at this point in her illustrious career.

The conversational writing of the vast majority of the score is easily encompassed by her full-bodied soprano, the middle and lower registers “speaking” with a ripe presence, and the top congenially negotiated. In my recent encounters, her very top notes have sometimes been characterized by a more generous vibrato than in the past, but on this occasion the singing was wonderfully controlled in the upper reaches of Poulenc’s leaping phrases, and they were generously weighted with searing drama.

A take-no-prisoners performance of such accomplishment and artistry does not come along every day, and Patricia Racette’s traversal is a memorable marvel of this or any other festival. Her partner in music-making, pianist Christopher Allen proved a thrilling collaborator, finding orchestral colors in his virtuosic playing.

With the evening marketed as Ne quittez pas, this short piece was preceded by a noble attempt to fill out the program and create a “first act” based on Poulenc songs, piano works and a dash of Apollinaire, to “set up” the opera proper, and to provide a backstory for Elle’s predicament. What looked good on paper proved problematic in execution.

The premise is that it is past closing time at a nightclub-cum-cabaret, not unlike the Living Arts Theatre, the venue we are sitting in. A chain-smoking, brooding pianist (Mr. Allen) is being chided by the owner (Ames Adamson), who for some reason has a cockney accent, urging him to find new material for the house’s fading diva (presumably Elle whom we have yet to meet). The owner storms off and leaves the pianist to play some introspective Poulenc. And smoke. And smoke. And. Smoke.

Christopher Allen. Photo Credit: Dominic M. Mercier.

Christopher Allen. Photo Credit: Dominic M. Mercier.

There is a beating at the door that interrupts the pouty piano player. It is a hipster brother and sister team, Paul and Elizabeth/Lise, (Marc Bendavid and Mary Tuomanen ), hell-bent on upheaval and debauchery who have a handsome man (Le jeune homme) somewhat unwillingly in tow. They argue, they smash things, and the brother insists they play “The Game,” in which the young man must inexplicably do whatever bawdy act he is bid. None of these characters is likable, sympathetic, or appealing, although they are physically attractive. I looked at my watch. Twenty minutes have passed and not a note has been sung by anyone. Opera, anyone?

Finally, le jeune homme begins performing a series of rather randomly assembled Poulenc songs (they may have had an intended logic that eluded me). He started out performing intimate acts against his will, later giving in more eagerly to his fate. Edward Nelson performs his assignments with a most agreeable, burnished baritone, although a few of the uppermost notes were not without effort. Still, Mr. Nelson thereafter admirably performed an almost non-stop recital while being spun around, shoved, forced into various carnal positions, stripped to the waist, tied up, blindfolded, and man-(and woman-) handled. I sometimes wondered how he managed to sing at all, much less as mellifluously as he did. After sixty longish minutes, this “prequel” premise eventually limped to an end with a baffling lack of closure. The intermission chatter in my part of the house was marked by confusion, belying the clarity of set-up to which the venture aspired.

Not that there is not merit to be found in this concept. Director James Darrah is clearly talented. His varied and focused La voix humaine was a model of invention, unity of purpose, and honestly motivated emotions. In the first act however, Mr. Darrah seemed more intent on shocking than informing. That said, he used the space creatively, elicited brazen performances from the performers, got in our faces with fervent intent, and made undeniably bold choices. Too bad he didn’t also instill some heart and soul into the proceedings. The relentless abrasiveness was not helped by over amplifying the actors.