October 30, 2018

Boston Early Music Festival Chamber Opera to Present Caccini’s Alcina

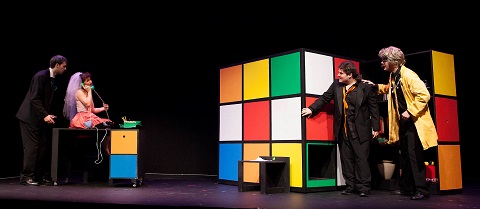

Cambridge, MA – The GRAMMY Award-winning Boston Early Music Festival Chamber Opera Series returns on Thanksgiving weekend with an all-new production of the first opera by a woman composer, Francesca Caccini’s Alcina. Alcina is a brilliant entertainment, full of wit, magic, and drama, with a demanding title role first sung by the composer herself. The production will receive four performances: Saturday, November 24 and Sunday, November 25 in Boston, and Monday, November 26 and Tuesday, November 27 in New York City.

“Women have been shaping the world of opera from the very beginning, and we at BEMF are excited to present a new production of the first opera by a female composer, Francesca Caccini’s 1625 La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola d’Alcina ,” offers Executive Director Kathleen Fay. “As more and more women are finding their voice in opera, whether as artists, producers, patrons, or composers, it is exciting to be reminded that this is not a new phenomenon. We have been here for nearly 400 years already, and we are only getting started!”

This groundbreaking work is brought to life by the all-star BEMF Vocal and Chamber Ensembles in a magnificent production featuring gorgeous costumes and elegant period staging. Led by BEMF’s GRAMMY-winning Musical Directors Paul O’Dette and Stephen Stubbs and Stage Director Gilbert Blin, the directorial team also features Concertmaster Robert Mealy, Dance Director Melinda Sullivan, Costume Designer Anna Watkins, and Executive Producer Kathleen Fay. The dynamic cast of 15 singers features many BEMF favorites, including Canadian soprano Shannon Mercer (Alcina), praised for “ the lyric beauty and surprising power of her voice” ( Salt Lake Tribune); tenor Colin Balzer (Ruggiero), a frequent guest of BEMF’s Centerpiece Opera productions and recordings; and mezzo-soprano Kelsey Lauritano (Melissa), who made her début with the BEMF Orchestra at the June 2017 Festival. These superb vocalists appear alongside the twelve-member BEMF Chamber Ensemble.

A contemporary of Monteverdi and a colleague of Galileo, Francesca Caccini came of age in Florence during the earliest years of opera as an art form. Both a composer and a performer, she was one of the most important musical figures at the Medici court during the regency of Christina of Lorraine and Maria Maddalena. In 1625, amid this time of female leadership, she created Alcina, the first opera by a woman composer and among the first Italian operas performed outside of Italy. Adapted from Ludovico Ariosto’s 16th-century epic poem Orlando furioso, the sorceress Alcina stands at the center of a struggle between illusion and destiny as the valiant Melissa strives to save the warrior Ruggiero and liberate the captives Alcina has transformed into plants and trees to ornament her island.

ARTISTS:

Boston Early Music Festival Chamber Opera Series

Paul O’Dette & Stephen Stubbs, Musical Directors

Gilbert Blin, Stage Director

Robert Mealy, Concertmaster

Melinda Sullivan, Dance Director

Anna Watkins, Costume Designer

Kathleen Fay, Executive Producer

Boston Early Music Festival Vocal Ensemble

Shannon Mercer, Alcina

Colin Balzer, Ruggiero

Kelsey Lauritano, Melissa

Teresa Wakim, Margot Rood, Sonja DuToit Tengblad, Danielle Sampson, Sophie

Michaux, Mindy Ella Chu, Jason McStoots, Brian Giebler, David Evans, David

McFerrin, Ian Pomerantz & Daniel Fridley

Boston Early Music Festival Chamber Ensemble

Paul O’Dette & Stephen Stubbs, chitarrone & Baroque guitar

Robert Mealy & Julie Andrijeski, violin

Sarah Darling, viola

Erin Headley, Christel Thielmann & Laura Jeppesen, viola da gamba

Kathryn Montoya & Héloïse Degrugillier, recorder

Maxine Eilander, Baroque harp

Michael Sponseller, organ, regal & harpsichord

WHEN:

Saturday, November 24, 2018 at 8pm

Sunday, November 25, 2018 at 3pm

New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall, 30 Gainsborough Street,

Boston, MA

Monday, November 26, 2018 at 7:30pm

Tuesday, November 27, 2018 at 7:30pm

Gilder Lehrman Hall at the Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Avenue at 36th Street, New York, NY

PROGRAM: Francesca Caccini’s Alcina

TICKETS: Tickets for the Boston performances are priced at $25, $45, $55, $75, and $125 each, and can be purchased at www.BEMF.org and 617-661-1812; as well as through the Jordan Hall Box Office located at 30 Gainsborough Street in Boston and by telephone at 617-585-1260; a $5 discount for students, seniors, and groups is available by calling 617-661-1812. Subscription discounts are available with the purchase of three or more programs on the 2018-2019 Season.

Tickets for the New York performance are priced at $55 for Morgan members and $65 for non-members, and can be purchased at www.themorgan.org/bemf and at 212-685-0008 ext. 560.

ASSOCIATED EVENTS:

There will be a Pre-Opera Talk with members of the directorial team one hour prior to each performance in Boston, and one half-hour prior to each performance in New York.

RESOURCES:

Download artist photos: http://www.bemf.org/pages/press/images.htm

BEMF’s 2018–2019 Season Press Release: http://www.bemf.org/pages/press/071618_1819season.htm

ABOUT THE BEMF CHAMBER OPERA SERIES:

Hailed by the Boston Globe for “vivid performances,” since 2008 the BEMF Chamber Opera Series has taken the internationally acclaimed musicianship, scholarship, and direction showcased in BEMF’s fully staged Festival operas and focused it on small-scale works in intimate productions each Thanksgiving weekend. Two productions from the Chamber Opera Series have also been presented on tour across North America: Handel’s Acis and Galatea in 2011 and Charpentier’s La Descente d’Orphée aux Enfers and La Couronne de Fleurs in 2014. BEMF’s studio recording of Charpentier’sLa Descente d’Orphée aux Enfers and La Couronne de Fleurs was awarded the 2015 GRAMMY Award for Best Opera Recording.

ABOUT THE MORGAN LIBRARY & MUSEUM:

The Morgan Library & Museum began as the private library of financier Pierpont Morgan, one of the preeminent collectors and cultural benefactors in the United States. Today, more than a century after its founding, the Morgan serves as a museum, independent research library, musical venue, architectural landmark, and historical site. Located at Madison Avenue and 36th Street, its collection includes world-renowned collections of drawings, literary and historical manuscripts, musical scores, medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, printed books, photography, and ancient near Eastern seals and tablets. Gilder Lehrman Hall, designed by renowned architect Renzo Piano, was opened by the Morgan in May 2006, and seats 264 people, providing a uniquely intimate concert venue. This marks the Boston Early Music Festival’s 13th season of concerts at the Morgan Library & Museum.

ABOUT THE BOSTON EARLY MUSIC FESTIVAL:

Recognized as the preeminent early music presenter and Baroque opera producer in North America, the Boston Early Music Festival (BEMF) has been credited with securing Boston’s reputation as “America’s early music capital” ( The Boston Globe). Founded in 1981, BEMF offers diverse programs and activities, including one GRAMMY Award-winning and four GRAMMY Award-nominated opera recordings, an annual concert series that brings early music’s brightest stars to the Boston and New York concert stages, and a biennial week-long Festival and Exhibition recognized as the “world’s leading festival of early music” ( The Times, London). The 20th Boston Early Music Festival will take place from June 9–16, 2019, and feature the fully staged North American premiere of Agostino Steffani’s Orlando as the Centerpiece Opera. BEMF’s Artistic Leadership includes Artistic Directors Paul O’Dette and Stephen Stubbs, Opera Director Gilbert Blin, Orchestra Director Robert Mealy, and Dance Director Melinda Sullivan.

The 2018-2019 Boston Early Music Festival Concert Series is presented with support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, National Endowment for the Arts, WGBH Radio Boston, and Harpsichord Clearing House, as well as a number of generous foundations and individuals from around the world.

For more information, images, press tickets, or to schedule an interview, please contact Kathleen Fay at 617-661-1812 or email kathy@bemf.org.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/BEMF%20Versailles%20Chamber%20Opera%20-%20Kathy%20Wittman%20credit.jpg image_description=Photo by Kathy Wittman courtesy of Boston Early Music Festival Chamber Opera product=yes product_title=Boston Early Music Festival Chamber Opera to Present Caccini’s Alcina product_by=Press release by Boston Early Music Festival Chamber Opera product_id=Photos by Kathy Wittman courtesy of Boston Early Music Festival Chamber OperaOctober 28, 2018

Complementary Josquin masses from The Tallis Scholars

For, Peter Phillips, the Tallis Scholars’ founder (in 1973) and director, has chosen to pair the Missa Gaudeamus, based on the introit ‘Gaudeamus omnes in Domine’, with the Missa L’ami Baudichon which draws upon a secular song, notable for its textual lewdness: a reference to female genitalia in the French language text is excised in the only source to present the text, now held in Verona.

In his CD liner note, Phillips explains that the Gaudeamus cantus firmus is associated with All Saint’s Day from which it derives it liturgy, a view proposed - not without dispute by other scholars - by Willem Elders in his Studien zur Symbolik in der Musik der alten Niederlander (1968) and Symbolic Scores: Studies in the Music of the Renaissance (1995).

Further, the Missa Gaudeamus, which is assumed to date from the composer’s middle period of the mid 1480s (though it is documented only in Petrucci’s first book of masses in 1502), is said by Elders to be permeated by ‘hidden’ and mystical numerical ‘codes’. These will probably be seldom detectable or of little import to the listener. What will undoubtedly strike the ear more emphatically is the resonant ambience of the initial articulation of the chant - the engineers having exploited the sonorous acoustic of the College of Merton College Oxford - which, cascading in inspiring echoes from the Chapel’s walls, windows and alcoves seems designed to inspire the fervent, flowing drive of the Kyrie and subsequent movements.

Josquin seldom states the whole chant, excepting the Gloria and Credo where it is embellished in the tenor; instead, snatches of the first six notes which are characterised by an aspiring, invigorating ascending leap of a ‘pure’ 5th, infiltrate the music, sometimes suggesting a sweeping, spacious expanse, sometimes ‘filled in’ with stepwise melodic movement.

The effect is a homogeny of gesture - and on this recording, of timbre, dynamics and mood also - which at times exerts a hypnotic, magnetic tug and elsewhere seems a little unalleviated. This listener was swept up in the mellifluous precision - of intonation, vocal entries, rhythmic interplay - and forward drive of the Tallis Scholars’ committed rendition, Phillips adopting swift tempi and pushing fervently onwards. But, I longed at times for a little more dynamic contrast, both within and between phrases, and timbral variety. The latter comes not through expressive or devotional interpretation but only when Josquin reduces and varies his forces: most notably in the Sanctus and Benedictus where the light and airy three-voice (SAB) ‘Pleni sunt caeli’ takes off in the first ‘Hosanna in excelsis’, as if a multitude have been inspired to ecstatic worship by such lucid devotion. Similarly, the sparse counterpoint of the Benedictus, which intimates a gravity sometimes absent elsewhere, is followed by a second ‘Hosanna’ of secure and assuring faith. Likewise, the dynamic cross-rhythms of the opening Kyrie are succeeded by the ambiguous, fervently rhapsodic weak-beat entries of the Christe, before being cleansed by the sparser textures of the second Kyrie episode.

Not every such opportunity for such contrast is taken up: the ‘Qui tollis’, following the vibrant Gloria, opens with the two lower voices moving in slower rhythmic values, but Phillips pushes ever forwards. I think that a little more spaciousness and pause for reflection would, occasionally, have been advantageous, though it’s certainly the case that the excited ebb and flow of voices in the Gloria creates real ardency and energy, and the move from duple to triple meter for the concluding ‘Cum Sancto spiritu’ and ‘Amen’ is wonderfully persuasive and uplifting.

It is the Credo that is most compelling, though, as Josquin floods the voices with florid but elegant developments of the cantus firmus and pushes the higher three voices ever upwards; again, I’d have liked a little more spaciousness here - for example during the textural contrasts of the repetitions of ‘omnia secula’, where the relentlessness can obscure the rhetorical power of individual utterances - though it is true that the overlapping entries have a mesmeric power. And, as ‘Et resurrexit’ in the ‘Et incarnatus’ episode pushes forward one feels that sound is prioritised over text. ‘Et unam sanctum’ follows with barely a pause or breath, though Phillips does permit and welcome, enrichening broadening in the final Amen.

The overall vocal balance is controlled, though the soprano entries sometimes sound rather too dominant (interestingly, Elders notes, the discantus part of the Missa Gaudeamus, in common with Josquin’s two other Masses in honour of Our Lady, is written wholly in the G clef, suggesting the use of boys’ voices). Moreover, the flattening of particular pitches within the modes does not seem to be a consistently applied principle.

But, Phillips structures the Agnus Dei persuasively: the second repetition of the text - sung by the overlapping, intertwining, dialoguing soprano and alto soloists - is a lovely palette cleanser for the final, sombre statement in which the alto descends to serious depths, carried downwards by the same scalic motifs which raise up the heaven-bound soprano.

There’s nothing very heaven-bound, one might think, about the Missa L’ami Baudichon: in pre-7th century French ‘baud’ means joyful and it is commonly assumed that ‘Baudichon’ is the nickname for a ‘lusty swaggering youth’. But, if the text derives from the secular, the music seems to strive for the divine and infinite. This is usually considered to be one of the earliest of Josquin’s Mass settings, although the attribution has been doubted: David Fallows, for example, has suggested that the extensive duos are more indicative of Dufay’s writing than that of Josquin, concluding (in his 2009 book), ‘I really do not believe this can be a work of Josquin: logic aside, it simply feels to me wrong, even though it has more than its fair share of truly marvellous moments’.

And, ‘marvellous moments’ there are in plenty. The richness of resounding organ stops seems to lift the start of the Kyrie, the simple descending melody - not unlike ‘Three Blind Mice’ - borne aloft with a broadness and expanse missing in the Missa Gaudeamus. And, the Tallis Scholars seem inspired to more emotive and visceral expression. The vibrantly rolled ‘r’ in ‘Christe’ evinces real human devotion and passion, and the strong colour and energy of the bass line seems to lift the other voices: the sopranos have a lovely brightness and freshness, while the inner voices move with joyful vigour.

This sense of aspiration and confidence continues in the Gloria, where initially the soprano and bass lines endeavour in complementary fashion, as if contouring the expanse of the heavenly spheres. When they are joined by the alto and tenor, the full choir radiates real human energy - all its glories and imperfections. The lack of elaborate contrapuntal (and numerical?) argument between the alto and bass in the ‘Qui Tollis’ is direct and affecting, and seems to inspire the singers to inject more individual colour into their respective lines, creating greater dynamic variety and a lively conversation. The ‘Cum sancto spiritu’ which closes the Gloria is invigorating and visceral in timbre, while the wide vistas of the Credo rove and roam, rhythmically energised, modally inflected.

Two duos articulate the ‘Et incarnatus’ and ‘Crucifixus’ - by ST then AB respectively - before all four voices join together for ‘Et resurrexit’: and here, the opening bare fifth and subsequent homophonic richness are almost rudely confident and direct, though such features give way to lighter, tripping, decorative interjections, around the tenor’s bold, almost defiant, long-held notes. The Sanctus is similarly confident - harmonically and texturally ambitious - and resonantly sung. And, the experimentation and exploration in ‘Pleni sunt’ which temporally pits two in soprano against three in alto and inflects the invigorating lines with modal nuance, is responded to by all four voices with joyful brightness: ‘Hosanna’ indeed.

One might suggest that these two Masses are the work of different composers, but Phillips comments of the two ‘sound worlds: the one intensely worked, the other joyful, bright, easy-going’: ‘I would say genius on this scale knows no rules.’

This recording of Missa Gaudeamus and Missa L’ami Baudichon by the Tallis Scholars is released on 2nd November by Gimell.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Gimell%20Josquin.jpg image_description=Gimmell CDGIM 050 product=yes product_title=Josquin Masses – Missa Gaudeamus and Missa L’ami Baudichon product_by=The Tallis Scholars, directed by Peter Phillips product_id=Gimmell CDGIM 050 [CD] price=$19.98 product_url=https://amzn.to/2Q0doD2

Piotr Beczała – Polish and Italian art song, Wigmore Hall London

The two parts of the programme reflected two aspects of Beczała's artistic persona. As an opera singer, he has sung in Italian, German, French, Russian, Czech and Polish. The Italian songs he chose for this occasion showed the dramatic possibilities in art song - art song for opera singers, vehicles for technique and expressiveness. The programme began with three songs from 36 Arie di stile antico by Stefano Donaudy (1879-1925), a Sicilian contemporary of Puccini's, which were taken up soon after publication by singers like Caruso and Tito Schipa. Beczała's crisp diction made Freschi luoghi, prati aulenti sparkle, contrasting well with the darker O del mio amato ben. Followed by four songs from 8 rispetti by Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari (1876-1948). Although Ottorino Respighi wrote operas, he also composed a substantial body of orchestral and chamber music. The songs on this programme thus represent an approach to art song which favours the more private, personal medium of voice and piano. The songs of Paolo Tosti (1846-1916)served as a bridge between Donaudy and Wolf-Ferrari and Respighi.

The second part of the programme focused on Beczała's Polish roots. Throughout his career, he has made a point of promoting Poland's rich musical heritage. He sang The Shepherd in Karol Szymanowski's Król Roger in the 2003 Warsaw production, and has also done many of the composer’s songs for male voice. For this Wigmore Hall recital Beczała chose Szymanowski's Sześć pieśni (Six Songs), his op 2, completed when he was still a student, aged 18. Significantly, all are also settings of living poets, contemporaries of the composer. Although Szymanowski was to make his name as a cosmopolitan sophisticate, these songs show that his Polish identity went deep. The texts here were by Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer (1860-1940) . Przerwa-Tetmajer was both a nationalist and modernist, given that Secessionism and Symbolism were forces for renewal, all over Europe. Each of these poems is brief, but the imagery is so concentrated that meaning is left deliberately elusive. The first two songs, in a minor key, are autumnal, but the strong piano part suggests resolve. In both songs, rise the image of a woman who may no longer exist. With the third song, We mgłach (In the Mist) the vocal line curves mysteriously, like the mists and streams in the evening cool. What's happening ? "Bez dna, bez dna! bez granic!" sings Majzner, (No bottom, no bottom, without borders!). In dreams, the poet hears mysterious voices calling . In the last song, Pielgrzym, the line rises, swelling with hope. "Gdziekolwiek zwrócę krok, wszędzie mi jedno, na północ pójdę, czyli na południe", (Everywhere I turn, from the north I will go south) Immediately one thinks of the Persian Song of the Night in Szymanowski’s Symphony no 3 and in the Shepherd in the opera Król Roger whose singing changes the King's life.

Mieczław Karłowicz (1876-1909) and Szymanowski were influenced by the Young Poland movement, a literary and artistic aesthetic not dissimilar to the Secession in Munich and Vienna, but with specifically nationalist elements. Pointedly, Beczała and Deutsch paired the early Szymanowski songs with Karłowicz's settings of poems by the same Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer . Indeed, both set the same text, Czasem, gdy długo na pół sennie marżę (Sometimes when long I drowsily dream) which describes a strange, disembodied voice, heard in a dream. "I do not know if this is love, or death, that sings" . The piano part in Karłowicz's version is particularly sophisticated, suggesting perhaps Liszt or Chopin, though the style is distinctively fin de siècle. In Na spokojnnym, ciemnym morzu (On the calm, dark sea) (op3 no 4 1896) the poet imagines sinking into oblivion. "Let me revel in Nothingness". In recitals, reading the text while listening is not a good idea. You might get the words, but you cut yourself off from nuance and musical truth. Much, much better to concentrate on singer and pianist and use your intuition. Because Beczała and Deutsch are so very good at what they do, intuitive listening was surprisingly accurate. The moody piano part suggested strange dissonance, and the edge in Beczała's voice suggested psychic anomie. The stillness in W wieczorną ciszę (In the calm of the evening) (op3 no 8) is ominous. Again, the poet disassociates from the world. perishing "in the dark emptiness". The Przerwa-Tetmajer texts are so surreal that they evoke very fine expression from Karłowicz. Ironically, the composer died young, killed while skiing in the mountains.

Also from Karłowicz's op 3 are the songs Przed nocą wieczną (Before eternal night) and Zaczarowana królewna (The Enchanted Princess) settings respectively of Zygmunt Krasinski and Adam Asnyk, receiving relatively more straightforward treatment from the composer, but as evocatively performed by Beczała and Deutsch. Beczała has appeared in several Polish operas, including Stanisław Monicuisko's Halka and Straszny dwór (The Haunted Manor) - please read about that here. After the intensity of the very beautiful Karłowicz songs, the Monicuisko songs were rather more down to earth. Monicuisko (1819-1872) reflected an earlier aesthetic than that of Karłowicz : more nationalistic, closer to Smetana than to the world at the turn of the 20th century. Thus robust songs about sweethearts and spinning wheels, complete with atmospheric piano figures, and Polna różyczka so vividly sung by Beczała that it was instantly recognizable as a setting of Goethe's Heidenröslein, without needing translation. Then Monicuisko's Krawkowiaczek (The Krakow Boy) who fools around but loves only Halka. For an encore, another wonderful Karłowicz song The Golden years of Childhood. "It's my favourite" said Beczała : almost as well crafted as the Przerwa-Tetmajer songs but warmer and cheerier.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Beczala-Piotr.jpg

image_description=Piotr Beczała [Photo by Johannes Ifkovits]

product=yes

product_title= Piotr Beczała, Helmut Deutsch, Polish and Italian art songs, Wigmore Hall, London, 22nd October 2018

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Piotr Beczała [Photo by Johannes Ifkovits]

Soloists excel in Chelsea Opera Group's Norma at Cadogan Hall

The young Richard Wagner, writing in Heinrich Laube’s Zeitung für die elegante Welt during the 1830s, suggested that German composers should look to learn from the Italians, and particular from the flowing vocal melodies and bel canto expressiveness of Bellini, whom he affectionately nicknamed ‘the gentle Sicilian’. Perhaps less surprisingly, Tchaikovsky, having read the first biography of Bellini, wrote to a friend, “I have always felt great sympathy towards Bellini. When I was still a child the emotions which his graceful melodies, always tinged with melancholy, awakened in me were so strong that they made me cry”.

Despite being standard repertory fare in the 1950s and ’60s, subsequently Norma fell out of favour, perhaps because of the fearsome demands it makes upon the soprano brave enough to embody the titular Druid priestess in all her roles - leader, mother, lover. 2016 was, though, ‘ Norma year’ in London, with ENO staging their first ever production of Bellini’s bel canto masterpiece in February and the ROH presenting the first production at Covent Garden for almost 30 years in September.

Now, Chelsea Opera Group, who tackled Bellini’s I Capuleti e I Montecchi in 2014, have mounted a concert performance of Norma. And, if I had any doubts about the wisdom of this repertoire choice, not just because of the challenging writing for the soloists but also because the choruses, though energetic, are not great in number, then these were immediately and absolutely swept away by the stunning performances of the principals - two of whom, like conductor Dane Lam, have Australian origins or links - at Cadogan Hall.

Sopranos who are equipped to follow in the path of Guiditta Pasta, Lilli Lehmann, Rosa Ponselle, Callas and Joan Sutherland, to name but a few illustrious exponents of the role, may be rare, but Helena Dix is undoubtedly one of those with the vocal and expressive qualities to climb to the summit of this operatic Everest. The star of Wexford Festival Opera’s award-winning 2013 production of Jacopo Foroni’s Cristina, Regina di Svezia , her lyric soprano is silky and soars effortlessly. As Cristina, Dix’s poise and dignity were much in evidence in the ceremonial scenes and she brought such gravitas and authority to her role here, establishing the emotional profundity and maturity of the Druid priestess. She was a noble presence, by turns vulnerable and authoritative, her utterances sincere but also at times portentous. We saw a relaxed and caring Norma, in her duet when Adalgisa at the start of Act 2, when the women come together in feminine unity. Her maternal love and distress touched our hearts as she pleaded with her father, Oroveso, to spare her children from suffering and shame after her death.

Dix alternates her chest and head voice with ease and has a lovely clean-edged tone. She softened it beautifully for ‘Casta diva’, demonstrating stunning power, control and expansiveness of breath, to offer the requisite nuance. In the florid cabaletta, though, the Australian soprano released her voice in rapturous flights, gleaming lightly. Elsewhere, Norma’s anger drew forth a full, weighty sound which quelled both Adalgisa and Pollione in the trio at the close of Act 1, while tenderness was served by her beautiful pianissimo. She had the stamina to build towards the fortitude and sense of duty which dominate the close, and if Dix seemed to tire a little at start of Act 2 - some of the phrasing was ‘choppier’ - then she may have simply been saving herself for the final scena.

After Norma’s opening scene, I feared that we would not have an Adalgisa who could match Dix’s vocal authority. I need not have worried: Elin Pritchard’s rich soprano conveyed all the emotional urgency and vacillation of the youthful Adalgisa, who is not burdened with such vast responsibilities but who is driven by overpowering passions. The persuasive characterisation of Pritchard’s Adalgisa was enhanced by the fact that she had learnt the part well enough to sing almost entirely off-score throughout. I’ve seen two of Pritchard’s recent performances, and her Adalgisa confirmed her impressive dramatic and vocal range. It’s hard to imagine a role more different to the motorbike-obsessed Marie in Opera della Luna’s production of Donizetti’s The Daughter of the Regiment at Wilton’s Music Hall this summer; and, if she had had no trouble ascending to Marie’s high Es, then the luxurious richness of her middle register which had been so strongly in evidence during her performance as Miss Jessel in Regent Park’s The Turn of Screw once again made its mark. One sensed every atom of Adalgisa’s passion, anguish and guilt during this terrific performance.

I first enjoyed Christopher Turner’s firm lyric tenor in two of Bampton Classical Opera’s recent productions: Salieri's La grotta di Trofonio in 2015 and Gluck's Philémon e Baucis the following year. Currently performing in ENO’s Salome , here Turner was an unusually sympathetic Pollione, overcome by genuine strength of feeling, suffering rather than imposing cruelty on other. From the first, this Roman knew that he had been consumed by a higher force that could not be resisted, whatever tragedy would consequently and inevitably befall him and those he loved. In his opening cavatina, ‘Meco all’altar di Venere’, Turner’s recounting of Pollione’s terrifying dream was paradoxically both remorseful and determined. The tenor avoided over-exaggeration or mannerism but made good use of a convincingly Italianate ring and a ‘sob’ which was occasionally an effective, piercing frisson through the lyricism.

Australian-American bass Joshua Bloom was a thunderous Oroveso, sounding sonorously and magisterially from amid the Chorus: no Druid would surely dare to ignore Oroveso’s instruction to look out for the rising moon (‘Ite sul colle, O Druidi’), but Bloom effectively lifted his song from the choral sound, and allowed it to be re-subsumed. Despite the literal distance between father and daughter, the emotional threads that tie Norma and Oroveso were powerfully communicated at the close of Act 2. The minor roles of Pollione’s friend Flavio and Norma’s confidante Clotilde, were sung very competently by Adam Music and Claire Pendleton respectively.

And, so, what of the Chelsea Opera Group Chorus? Though the tenors were fairly few in number, the combined male forces made a vigorous and wholesome sound, and the full Chorus essayed a stirring War Hymn, invigorated by the relaxed and encouraging gestures of their conductor, Dane Lam. I was impressed by the fluid drama that Lam crafted; accelerations and changes of tempo were clearly and deftly indicated by the left-hander, and if the Orchestra of Chelsea Opera Group didn’t always follow his precise commands instantly, then Lam was untroubled and simply worked effectively to wind them up to the mark he had set. He conjured a true sense of grandeur and tragic intensity at the musical and dramatic climaxes, as well as tenderness in the intimate moments. His efforts were rewarded with solid orchestral playing: there was some expressive cello lyricism and in general the strings were much less ragged than they have sometimes been during past COG performances that I’ve attended. There was a real sense, too, that the instrumentalists were listening to the singers, and some particularly note-worthy flute playing from Ben Pateman. Tuning was generally good, though less secure in the quieter, slower passages where horns and brass were sometimes imprecise; and, I’d have liked more confident and forthright playing from across the whole woodwind section, to give their contributions more telling presence.

Perhaps inevitably, during this concert performance, in which the soloists were so striking and compelling, it was the passages of emotional intimacy that held sway over the vast national and religious conflicts. But, this was a good account of this quintessential bel canto gem, one which whetted my appetite for COG’s next two ventures into the rarer parts of the repertoire in the spring and summer of 2019 - Mefistofele by Boito in March and Anton Rubinstein’s The Demon - which will both be performed at the Queen Elizabeth Hall.

Claire Seymour

Bellini: Norma

Norma - Helena Dix, Adalgisa - Elin Pritchard, Pollione - Christopher Turner, Oroveso - Joshua Bloom, Flavio - Adam Music, Clotilde - Claire Pendleton; Conductor - Dane Lam, Chelsea Opera Group Chorus and Orchestra.

Cadogan Hall, London: Saturday 27th October 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/helena-dix-cr-Grzegorz-Monkiewicz-800px.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Norma, Chelsea Opera Group at Cadogan Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Helena Dix (Norma)Photo credit: Grzegorz Monkiewicz

October 27, 2018

Handel's Serse: Il Pomo d'Oro at the Barbican Hall

But, the present-day doesn’t have a monopoly on narcissistic premiers and princes, and many historical prototypes seem to find their way into opera librettos of Baroque opera seria. Watching Argentine countertenor Franco Fagioli’s Serse, King of Persia, huff and puff, rant and rave, swagger and bluster during Il Pomo d’Oro’s concert performance at the Barbican Hall (which followed performances in Lubljana, Vienna and Paris), it was perhaps fitting that the image of Donald Trump’s baby blimp, which floated over the streets of London during the President recent UK visit, came to mind. For Handel’s Serse certainly is tragi-comic, to the chagrin of contemporary commentators such as Charles Burney: “One of the worst that Handel ever set to music”, bemoaned the music historian after the premiere of the opera at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket, on 15 th April 1738.

It’s worth remembering, though, that Burney was imposing the eighteenth-century taste for the repetitions and excesses ofopera seria on a libretto that had its roots in the seventeenth century - having been adapted by an unknown author from Silvio Stampiglia’s libretto for Giovanni Bononcini’s 1694 opera, Stampiglia’s text having itself been based on Nicolò Minato’s version of the Persian King’s antics for Francesco Cavalli in 1654. And, that the structures of the text set by Handel implied not an inexorable succession of rigid da capo arias but rather, as Handel supplies, a sequence of short airs of varied forms, which follow one another swiftly, often without ritornelli and little recitative.

Burney may have lamented the serio-comic tone of Handel’s Serse, but it was the “buffoonery” that he believed resulted in “feeble writing” which Il Pomo d’Oro frequently brought to the fore, sometimes at the expense of the music elegance of the score, and overlooking that Handel’s ironic twists on opera seria conventions and structures are more often witty and whimsical than rowdy or histrionic.

Fagioli encouraged us to mock Serse’s peevishness, infantilism and narcissism, thereby weakening our sense of the very real danger that such tyrants pose. The loyal Amastre was dismissed as a “perpetual nuisance” by the foot-stamping King in a frustrated fury, and when the upright Ariodate - whose own integrity prevented him from reading between the lines - took Serse at his word and betrothed his daughter, Romilda, to the wrong royal brother, I half expected a full-on ‘Red Queen’ hissy fit, “Off with his head!”, from the enraged monarch whose romantic plans had been thwarted.

The pace of Il Pomo d’Oro’s near-complete performance of the opera was fast, the dramatic flow of the seventeenth-century libretto structure pushed almost to excess. Musically there were benefits, the rapid sequence of songs seeming to spring spontaneously from the unfolding dramatic situations. But, the haste risked further undermining the ‘serious’ dimension of the drama and, given that the performers were in modern concert dress, perpetuating the perennial confusions and complications of the seria web of gender-crossing and disguise. The towering Jimmy Choo stiletto boots donned by Arsamene, sung by mezzo-soprano Vivica Genaux, and the ‘soldier’s uniform’ sported by Delphine Galou’s Amastre - a long black cardigan over a sparkling, back-less evening gown, might have had uninitiated audience members scratching their heads as to who was who, related to whom, on what basis their schemes and stratagems had been borne.

Despite this, although billed as a concert performance, the cast made a concerted effort to communicate the action, often singing confidently off-score, and carrying off the carefully choreographed exits and entrances. Moreover, not a single person present in the Barbican Hall could surely have failed to be bowled over by Fagioli’s dramatic commitment and acrobatic musical accomplishments. This was a truly ‘lived’ performance, physically and vocally. The soprano-like punch and precision at the top; the striking agility which spun reams and curlicues on a single, long breath; the ability to leap with accuracy and evenness across wide expanses - even venturing down into his bass voice before leaping back to his shining countertenor; all such feats were mesmerising.

‘Se bramate’ and, most especially, ‘Crude furie’ were electrified by explosive elaborations and ornamentations. Though such extravagance was undoubtedly impressive, initially I felt that the pyrotechnics resulted in a distortion of the phrasal, cadential and formal balance; but, the technical daring was, by the close, simply hypnotic - a thrilling, breath-taking expression of the King’s solipsistic immaturity. Perhaps Fagioli was striving to embody the overweening arrogance not just of the Persian premier but also of the role’s first interpreter, the soprano castrato Caffarelli - described by his teacher, Porpora, as “the greatest singer Italy had ever produced”, who was notoriously unpredictable and even served a spell in prison for assault. If so, he succeeded in resurrecting the castrato’s temper and tantrums, even if he did not revive the legendary refinement of Caffarelli’s liquid legato which Handel exploited in his slower airs. ‘Ombra mai fù’, though pure of tone, felt rather rushed, and the pathos of line in ‘It core spera e teme’ was lost in the floridity of the ornamentation. A little more simplicity at times would have bestowed equal weight on the sincerity of Handel’s music as on the drama’s comic excesses.

Fagioli’s exhilarating performance was far from being the only vocal delectation of the evening. As Romilda, Inga Kalna repeatedly coaxed beauty and expanse from Handel’s phrasing: that she had plenty of power in reserve enabled her to spin the most gossamer piano threads, as when expressing her love in ‘Nemmen con l’ombre’, and if there was a danger that such gestures might become a mechanical mannerism, then Kalna balanced delicacy with a sonorous, creamy tone which was effortlessly projected, most especially in ‘Chi cede al furore’, and flashes of fire in her vigorous Act 3 duet-argument with Genaux’s Arsamene, ‘Troppo oltraggi la mia fede, alma fiera’.

Genaux’s lower register did not project as well as her soprano range, but she offered much stylish singing and her performance grew progressively in stature. In so persuasively articulating the contrast between the pained pathos of ‘Quella che tutta fé’ and the impassioned hurt of ‘Sì, la voglio’, Genaux made Arsamene’s suffering one of the more convincingly tangible ‘human’ experiences of the evening.

Contralto Delphine Galou gave a similarly tasteful and composed performance as Amastre, and if the gentle warmth of her voice didn’t always carry effectively across the Hall, she showed terrific agility in her vengeful ‘Saprà delle mie offese’ in Act 1, and grace of line in the sparsely accompanied final cavatina, ‘Cagion son io’.

Much of the evening’s warmest humour came courtesy of the mischievous, insouciant wilfulness of Francesca Aspromonte’s Atalanta and the Mozartian directness of Biagio Pizzuti’s Elviro. Aspromonte’s lovely rich tone made this Atalanta a more sympathetic and forgivable character than is sometimes the case. Resourceful and resilient, despite her stated romantic intentions Atalanta could not resist ‘vocally flirting’ with leader Evgeny Sviridov, who was more than happy to respond with his own brief serenade, and at the close she shrugged off the failure of her romantic stratagems, declaring herself ready to look for love elsewhere - and catching the opportunistic Elviro’s eye in the process.

Pizzuti almost stole the show in a minor role to which he brought terrific comic presence - and considerable vocal style. Disguised, somewhat improbably, as a flower seller, in a flamboyant purple head-scarf, and a little encumbered by his large music score and plastic bouquet, Pizzuti was an engaging stooge, creeping around the instrumentalists, hamming wickedly to Katrin Laza’s colourful bassoon playing; his final aria, ‘Del mio cara baco amabile’, was a smooth and suave paean to Bacchanalian indulgence and relaxed revelry. Andreas Wolf’s Ariodate was no less impressive: his powerful, focused bass sailed through the vocal phrases with easy projection, terrific diction and even tone. It was quite a feat for Wolf to convey both the warrior’s haplessness amid the amorous machinations off the battlefield and his accomplishment at manoeuvres in the field. One could truly sympathise when his exasperated expression conveyed all of his exhaustion and incredulity: Oh, for the quiet life of soldiering!

This was a meticulous prepared performance. Director Maxim Emelyanychev was an almost hyperactive and vigorously gestural guide, striving unceasingly to coax the most energetic tone from his small band of instrumentalists and precisely pointing the minutest of accents, swells and surges. In command of every detail, he gave encouragement with whole body, scarcely seeming to have time to be seated at the keyboard. Perhaps it was the small numbers, but I didn’t always find sufficient brightness or variety in the instrumental timbre, though the playing was technically assured and there was a lovely lightness to the dance-like accompaniments, as well as effective dynamic range and contrast.

As the inevitable and improbable lieto fine ran its course, Elviro sat to the side with head in hands, and issued a snide, noisy yawn. Ironically, through the three hours of music, there was nothing at all in the vocal and instrumental performances that might induce such an exhalation. This was an exciting, entertaining romp through the rough, the ridiculous and the romantic, brought to a calming close by Romilda’s sweet, and infectious, air, ‘Caro voi siete’.

Il Pomo d’Oro return to the Barbican Hall in May 2019 to perform Handel’s Agrippina with Joyce DiDonato in title role and Fagioli as Nerone. Don’t miss it.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Serse (concert performance)

Il Pomo d’Oro ; Maxim Emelyanychev (director/harpsichord), Franco Fagioli (Serse), Vivica Genaux (Arsamene), Delphine Galou (Amastre), Inga Kalna (Romilda), Francesca Aspromonte (Atalanta), Biagio Pizzuti (Elviro), Andreas Wolf (Ariodate)

Barbican Hall, London; Friday 26th October 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Franco%20Fagioli.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Serse, Il Pomo d’Oro, Barbican Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Franco FagioliOctober 26, 2018

Dutch touring Tosca is an edge-of-your-seat thriller

The plot of Tosca is as time- and location-specific as they come. The action takes place in Rome in June 1800, as news of Napoleon’s victory at Marengo reaches the city, then in the hands of his enemies. Chief of police and reactionary baddie Scarpia is hounding opera diva Floria Tosca and her freethinking revolutionary lover, the painter Cavaradossi. Scarpia wants her for himself and him dead. In the libretto’s source, Victorien Sardou’s play La Tosca, none of the protagonists is actually Roman. Tosca, Cavaradossi and Scarpia, are, respectively, Veronese, French and Sicilian. However, Rome is ingrained in the score, which sweeps over its vistas picking up its sounds, most famously its bells. Conductor David Parry rendered the orchestral cityscapes with broad, brilliant brushstrokes. In a performance brimming with energy, the Orkest van het Oosten played for him with the exuberance of a light-refracting fountain. It was easy to forgive a few intonation slips when the lovers’ passion burned with such fever and the chords of death came down so shudderingly.

Director Harry Fehr tenuously hangs on to the place, but lets go of the time particulars. His characters live in a repressive police state in an indeterminate present. The three well-known Roman sites of the libretto become anonymous locations drained of color. Brightness is reserved for Tosca’s wardrobe, and the one crowd scene in church, when costume designer Yannis Thavoris puts on an impressive display of clerical vestments. Thanks to the canny use of video, all three acts are set in Scarpia’s police headquarters, where he keeps the whole city under surveillance. John Bishop’s lighting suggests office dreariness without assaulting the eye with unremitting starkness. In Acts 1 and 3 the singers are doubled by pre-filmed footage of themselves on the surveillance screens. CCTV cameras catch Cavaradossi trying to help his friend Angelotti avoid capture, Scarpia fanning Tosca’s jealousy and, finally, Cavaradossi’s execution. Inevitably, there are disjunctures when the video doesn’t exactly mirror what the singers are doing live. But, instead of being distracting, these discrepancies intensify the oppressive atmosphere. In Act 2, Cavaradossi’s torture and Scarpia’s sexual assault on Tosca actually take place at the police headquarters. The screen is then ingeniously used to show a televised broadcast of Tosca singing a cantata with the choir, usually only heard offstage. It all plays out like a nail-biting thriller.

Fehr has a firm grip on the singers’ direction and they did him proud. Phillip Rhodes neither looked nor sounded like a vindictive sleazeball, which is precisely why his well-groomed, outwardly respectable Scarpia was so chilling. His supple baritone always sounded noble, effortlessly rising to the thundering Te Deum finale. Only at the end of “Già mi dicon venal”, when Scarpia pounces on Tosca, did Rhodes allow a tinge of vulgarity into his voice. His Scarpia was a textbook assimilated sociopath. Noah Stewart was an outstanding Cavaradossi, his svelte, sunlit tenor switching from caressing to clarion as required. He attacked his top notes cleanly and fearlessly, most successfully the sustained high B natural on “La vita mi costasse”. Soprano Kari Postma does not have the warmly Italianate sound usually associated with Tosca. Her metallic top rockets confidently out of a rich middle range, whose slightly veiled quality sometimes clouded her words. Yet she was an admirable Tosca, temperamental yet poised, inflecting each phrase with intelligence. Regrettably, her beautifully shaped “Vissi d’arte” was marred by a timing mishap with the pit.

Curiously, Postma had more chemistry, if that’s the correct term, with Scarpia than with Cavaradossi. In his khaki Bermudas, Stewart’s Cavaradossi looked like he was barely out of art school, while Postma was all urban sophistication. Not every woman can carry off a canary-yellow coat like she did. Still, they made the relationship wholly credible, and, although very different in timbre, their duetting voices produced an exciting cocktail. In Act 2, however, Postma and Rhodes scorched the set with their dance of hatred and lust. Her fierce, clear-headed stabbing of the police chief in his swivel chair brought the act to a hair-raising end. All supporting roles were at the very least adequately cast. Baritone Oleksandr Pushniak as the sacristan and soprano Bernadeta Astari as the shepherd boy, here transformed into a night-time cleaner, stood out with their lovely singing. Consensus Vocalis and the children’s choir further enhanced this punchy Tosca, which continues to tour until the 13th of November, 2018.

Jenny Camilleri

Cast and production information:

Floria Tosca: Kari Postma; Mario Cavaradossi: Noah Stewart; Scarpia: Phillip Rhodes; Cesare Angelotti: Roman Ialcic; Sacristan: Oleksandr Pushniak; Spoletta: Michael J. Scott; Sciarrone: Simon Wilding; A jailer: Alexander de Jong; Shepherd Boy: Bernadeta Astari. Director: Harry Fehr; Set and Costume Design: Yannis Thavoris; Lighting Design: John Bishop; Video: Silbersalz Film. Conductor: David Parry. Consensus Vocalis. Tosca Children’s Choir. Het Orkest van het Oosten. Seen at the Zuiderstrandtheater, The Hague, on Thursday, 25th of October, 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/KariPostma.jpg image_description=Kari Postma product=yes product_title=Dutch touring Tosca is an edge-of-your-seat thriller product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Above: Kari PostmaDavid Alden's fine Lucia returns to ENO

Historic conflicts and losses loom in the form of sepia ancestral portraits which glare impenetrably and accusingly from the crumbling walls of Ravenswood Castle, complemented by the prurient faces of the hypocritical observers who peer through the gaping windows at the familial abuse within. Lucia, too, is trapped in the past of her own childhood: a fragile, whimsical doll-woman, she is infantilised by her incestuous and paederastic brother, Enrico, while her own retreats into juvenile fantasy and memory cannot save her from the sadistic, even psychotic, adults who manipulate and manhandle her.

Lester Lynch (Enrico) and ENO Chorus. Photo credit: John Snelling.

Lester Lynch (Enrico) and ENO Chorus. Photo credit: John Snelling.

Alden has moved the action to the mid-nineteenth century, and designer Charles Edwards’ dilapidated mansion resembles a decaying boarding school worthy of the bleakest Victorian novel: dark, damp and decrepit, with Lucia the lone sleeper in the chilly dormitory at the start of Act 1. Indeed, the opening image brought Jane Eyre’s experiences at Lowood School to mind - Enrico would certainly give Mr Brocklehurst a run for his money in the cruelty stakes - and this wasn’t the only literary comparison that seemed pertinent during the performance. This Lucia is an ‘inmate’, imprisoned in a mental asylum, and the insane are her jailors. When Enrico ties her to her bed with a skipping rope in their Act 2 confrontation, I was put in mind of the “atrocious” former nursery at the top of the house, with its barred windows, nailed down bedstead, iron rings in the walls, and peeling wallpaper - “repellant, almost revolting; a smouldering, unclean yellow” - in which the narrator of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper finds herself similarly imprisoned by her oppressive husband.

Lester Lynch (Enrico) and Sarah Tynan (Lucia). Photo credit: John Snelling.

Lester Lynch (Enrico) and Sarah Tynan (Lucia). Photo credit: John Snelling.

When Lucia, teetering on the edge of mental crisis from the first, succumbs absolutely to insanity, her mad display seems to provide the observing crowd with delectation and delight. Her bloody self-destruction doesn’t seem so much an ‘escape’ through a madness that evades the understanding and structures of her oppressors, but more a submission to an unavoidable destiny. Dressed like a doll, she resembles Carroll’s Alice - an image strengthened when Arturo arrives, posing elegantly in a pristine suit, and looking rather like the White Rabbit. But, her only comfort, a fluffy toy, is brutally torn apart by her brother; and, unlike Alice, Lucia will find no wonderland through Ravenswood’s looking-glasses or wardrobes - just fusty piles of ancestral documents. This child-woman has been assaulted by Enrico, manipulated by Raimondo, rejected by the deceived Edgardo, defiled by Arturo (one presumes); the last drop of her innocence is destroyed when she is forced to watch Edgardo’s demise.

Alden sustains the trope of the gaze which objectifies - Lucia is after all the ultimate commodity, her body the material means by which Enrico will pay off the family debts, her sacrifice designed to ensure the survival of the house and family name - through imagery of the theatre and performance. We first see Lucia seated at the foot of a curtained proscenium and, when the curtain is drawn back, her confrontations - romantic and deadly - will take place upon its stage. At the close, the theatre swivels and we are taken behind the scenes, unavoidably complicit in the gaze of the male chorus who sit in the on-stage audience ranks, alongside the dead Lucia, surrounded by the framed photographs which have now become gravestones.

Eleazar Rodríguez (Edgardo) and Sarah Tynan (Lucia). Photo credit: John Snelling.

Eleazar Rodríguez (Edgardo) and Sarah Tynan (Lucia). Photo credit: John Snelling.

The ENO Chorus were in splendid voice, and Alden’s blocking (revival movement director, Maxine Braham) emphasised the rigidity of the social manacles which enchain Lucia. Lined up in dour grey, with sour scowls, their condemnatory weight was crushing. It was hard though to imagine such a joyless crowd engaging in revelry after the wedding of Lucia and Arturo, and, indeed, Alden and lighting designer Adam Silverman (revival lighting director, Andrew Cutbush) keep the party shrouded in shadows which means that Raimondo’s arrival with the news of Arturo’s death and Lucia’s demise doesn’t make such a strong dramatic impact as it would were the entertainments colourfully contrasted with the behind-scenes tragedy.

American tenor Lester Lynch was an imposing Enrico: self-righteous, solipsistic and frighteningly sadistic - a huge presence and a resounding voice, with clear diction. Lynch and Clive Bayley’s malicious, manipulative Raimondo were a deeply disturbing double-act, Bayley emphasising the cruelty of the pastor through his aggressive demeanour and thunderous delivery.

Clive Bayley (Raimondo). Photo credit: John Snelling.

Clive Bayley (Raimondo). Photo credit: John Snelling.

I found Eleazar Rodríguez’s heroic assaults on Edgardo’s soaring phrases in Act 1 a little too hefty, but he found a true bel canto flexibility subsequently, making a gleaming contribution to the Sextet, and convincingly conveying Edgardo’s anger and hurt in the face of Lucia’s supposed betrayal. Michael Colvin’s lighter tenor offered a pleasing contrast, and he displayed lovely colour and vocal grace as Arturo. The role was a better fit for Colvin than his recent essay as Herod in Adena Jacobs’ Salome and it felt a pity that Alden doesn’t foreground Arturo more. Alisa is also often pushed into the shadows, though Sarah Pring gave a fine performance, vocally and dramatically; to extend the Jane Eyre parallel, she reminded me of Grace Poole, a figure of mystery residing in the half-light and hinterland.

Sarah Tynan (Lucia). Photo credit: John Snelling.

Sarah Tynan (Lucia). Photo credit: John Snelling.

Sarah Tynan, making her role debut in the title role, was in a class of her own. Her light soprano conjured a delicate Lucia, fey and vulnerable; her voice stayed relaxed even as it climbed and her coloratura - she omitted the cadenza in the mad scene - was not decorative but truly expressive of Lucia’s battered and suffering soul - beautifully phrased, controlled, spacious, the dreamy wistfulness enhanced by the glass harmonica.

Conductor Stuart Stratford led a superb performance by the ENO Orchestra: stark swipes of instrumental colour never over-powered the singers, the pace was dramatic but not precipitous, the tension sustained.

Alden’s 2008 production , reprised once before in 2010 was ENO’s first staging of Lucia di Lammermoor. It was, and is, a terrific addition to the company’s repertoire, especially when in the hands of such a splendid team of singers and musicians.

Claire Seymour

Donizetti: Lucia di Lammermoor

Lucia - Sarah Tynan, Enrico - Lester Lynch, Edgardo - Eleazar Rodríguez, Arturo - Michael Colvin, Raimondo - Clive Bayley, Alisa - Sarah Pring, Normanno - Elgan Llŷr Thomas; Director - David Alden, Conductor - Stuart Stratford, Set designer - Charles Edwards, Costume designer - Brigitte Reiffenstuel, Lighting designer - Adam Silverman, Revival lighting designer - Andrew Cutbush, Movement director - Claire Glaskin, Revival movement director - Maxine Braham, Orchestra and Chorus of English National Opera.

English National Opera, London Coliseum; Thursday 25th October 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lucia%20and%20Arturo%20.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Lucia di Lammermoor, ENO product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Sarah Tynan (Lucia), Michael Colvin (Arturo)Photo credit: John Snelling

October 25, 2018

Verdi's Requiem at the ROH

Indeed, Verdi was a vociferous participant in the conflict between Church and State, and, at this stage of his life, was probably agnostic. The death of Alessandro Manzoni - the poet and novelist whom the composer venerated, and whose I promessi sposi (1827), a patriotic text which was a forerunner in the development of a unified Italian language, is customarily considered to be a symbol of the Italian risorgimento - prompted Verdi to return to and revise the ‘Libera me’ that he had composed for the planned Rossini commemoration. A letter which the composer penned to Clara Maffei on day of Manzoni’s funeral, declared: ‘Now it is all ended! And with him ends the purest, the most holy, the highest of our glories!’ David Rosen (in the Cambridge Music Handbook to the Requiem) remarks Verdi’s mixture of nostalgia and pessimism, and suggests that ‘in bidding farewell to Manzoni, Verdi was also writing a “Requiem for the Risorgimento” and marking a passing of a whole generation and a whole tradition’.

This performance at the Royal Opera House of Verdi’s Requiem fulfilled several functions, and these were also not without political inference and context. As conductor Antonio Pappano explained in his opening address, the performance celebrated the awarding of the Royal Charter fifty years ago to what was then known as the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden; and, as Armistice day approaches, it commemorated the end of WWI and remembered those who died in that conflict. Pappano also urged us to remember the recent passing of the soprano, Montserrat Caballé.

This performance was not a religious ritual though, but, it was one of emotive, spiritual, as well as dramatic, impact and import. The ROH stage was crowded, the House’s Orchestra raised from the pit and the Chorus assembled behind - and, perhaps, pushed a little too far from the four soloists arrayed at the front of the stage. Not all of the choral text was communicated clearly and directly, and the Chorus members took a little while to get into their stride: the basses’ opening ‘Te decet hymnus’ was a little cloudy - just as, later, the closing fugue was a little flabby. But, the ROH Chorus made their mark when it counted. A fortissimo ‘Rex tremendae majestatis’ from the basses was countered by a wonderfully graded quiet response from the divided tenors. The double choir opening of the Sanctus also seemed rather woolly, perhaps because the singers were set so far back on the stage, but the ladies were light and precise in the subsequent counterpoint, carried aloft by springy string pizzicatos and deliciously light staccato motoring quavers which later swelled into roaring chromatic arcs.

Pappano conjured both operatic intensity and contemplative intimacy; notably, this was a spaciousness interpretation which offered time for apt reflection, though I didn’t feel that Pappano fully sustained the dramatic tension throughout the 90 minutes: the Lacrymosa seemed ponderous, the entry of the choir and percussion here, rather weighty. But, there was much orchestral and soli playing to admire. The muted celli sighed, barely a whisper, at the start, intimating terror, expectation and drama. The first ‘Requiem aeternam’ strove to obey Verdi’s instruction - il più piano possible: there was a sense of restrained weeping, a reverential hush.

The wrath of the Dies Irae was a terrifying energy: one admired the accuracy of the strings’ tumbling somersaults, the thunderous portentousness of timpani and bass drum, the punches from the horns and brass that hit with a full, fat fist, as well as the lovely solos subsequently from the clarinet and bassoon. The tricky opening of the Offertorio, for celli and woodwind, combined rhetoric and intimacy.

At the front of the stage the spotlight shone on the four young soloists, most especially on Lise Davidsen - in between ROH Ring cycles - who was deputising for the indisposed Krassimira Stoyanova. But, whatever the soloists individual merits, there was a real sense of the quartet working and communicating together, collectively. The trio ‘Quaerans me, sedisti lassus’ in the Dies Irae was full of penitence and relief - ‘You have saved me, by enduring the cross’ - and the quartet, ‘Hostias et preces tibi’ at the close of the Offertorio had the delicacy of a madrigal with respect to the placement of the parlando text.

And, so, to Davidsen’s performance. One of my colleagues commented on her participation in the Requiem at this summer’s Proms , admiring the ‘accuracy of her singing, the brilliance of her upper register and the ability to scale her dynamics’, and judged her ‘Libera me’ to be ‘a tour de force: exquisite strength, imperious high notes and a pianissimo that was ravishing. This is a voice that doesn’t just cut through the orchestra like a sabre; it rises effortlessly above it as well.’ - sentiments with which I concur absolutely after this performance. There is such astonishing power and steel, on show and seemingly in reserve, that it takes one’s breath away. Thus, one marvels that Davidsen can float such effortless arcs of gleaming sound: her entry in the Kyrie seemed to lift the music from its roots - Pappano’s tempo was definitely on the un poco side of animando - like a magnet, brightening and elevating the ensemble sound. She used vibrato judiciously and varied the tone expressively: there was a lovely sincerity at the start of the Recordare, above the cello’s easy lilt, and a well-judged warming of the tone as the phrases broadened. In the Libera me one could palpably feel the heat of the flame as she flung ‘Dum veneris judicare saeculum per ignem’ (When You come to judge the world by fire) into the firmament; she was complemented by some splendid bassoon playing here, though the strings could have been even more fragile. The expansive breadth of Davidsen’s phrasing made the explosive interruption of the Dies irae reprise all the more theatrical; the return of ‘Requiem aeternam’ pierced like a moonbeam through the soft darkness of the low-pitched chorus - perpetual light might indeed shine on them and us. Verdi asks for a pppp dynamic for the high Bb, rather optimistically perhaps, but I did wonder about the appropriateness of Davidsen’s crescendo through the sustained summit.

American mezzo Jamie Barton was Davidsen’s equal with regard to sonic impact, and perhaps surpassed her in expressive nuance. Her entry in the Dies irae, ‘Liber scriptus proferetur’, was crystalline, and when repeated subsequently, stirring and powerful. Barton has an innate instinct for the drama that resides within the vocal phrase: ‘Judex ergo, cum sedebit’ floated aloft the resonant chordal brass before plummeting an octave, the sound delving into our hearts and souls. Her ‘Recordare Jesu pie’ was gentle and sincere; ‘Lacrymosa dies illa’ was poised against the sobbing throb of the strings. Davidsen and Barton intertwined sensuously in ‘Salve me’, though I’m not sure Verdi’s pianissimo was observed. And, the Agnus Dei was perfectly tuned and composed, though subsequently marred by some wayward and missing flute entries.

Frenchman Benjamin Bernheim offered a tender tenor in ‘Ingemisco, tanquam reus’ (I groan, like the sinner I am) conveying a sense of the frailty of man, and unfolded the narrative persuasively building to his plea, on a secure high B, ‘Statuens in parte dextra’ (Let me stand at your right hand). Hungarian bass Gábor Bretz made less theatrical or emotive impact. Despite the spooky, spiky lower strings accompaniment, his entry ‘Mors stupebit’ felt rather distant, and the emphatic statement in the Dies Irae, ‘Confutatis maledictis’, was surely not con forza? But elsewhere, Bretz displayed a lovely legato line, and real elegance and nobility - as in ‘Oro supplex et acclinis’ (Bowed down in supplication I beg You); and, in the Lacrymosa he offered a softness of tone against the crystalline sheen of Barton.

At the close, Pappano dared to hold the silence: a time for deep reflection.

This ROH’s performance of Verdi’s Requiem was broadcast live on BBC Radio.

Claire Seymour

Verdi: Requiem

Lise Davidsen (soprano), Jamie Barton (mezzo-soprano), Benjamin Bernheim (tenor), Gábor Bretz (bass), Antonio Pappano (conductor), Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Tuesday 23rd October 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lise%20Davidsen.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Verdi: Requiem, Royal Opera House, 23rd October 2018 product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Lise DavidsenPhoto credit: Florian Katolay

October 24, 2018

Wexford Festival 2018

Not a bad 10th birthday present for the House, which opened in 2008 and was designated Ireland’s National Opera House in 2014, and one which this year’s Festival confirmed is greatly deserved.

Opening night offered a double dose of verismo viciousness and violence: a compelling alternative to Cav & Pag. Born in 1864, Leoni studied alongside Puccini and Mascagni at the Milan Conservatoire under the supervision of Amilcare Ponchielli and Cesare Dominicetti. When he emigrated in London in 1892, aged 28, Londoners took the Milanese composer of operas, sacred works and ballads to their hearts. “Signor Leoni, although a foreigner, has … proved himself a better friend to the cause of English music than most people seem inclined to admit,” wrote ‘G.H.C.’ in the Observer on 7th November 1909, and his view seems to have been shared by many, if contemporary newspaper reports and letter pages are anything to go by.

Correspondents praised Leoni’s instigation of the foundation of the Queen’s Hall Choral Society, of which he became conductor, and admired his endeavours “to inspire his chorus with a genial, warm Southern enthusiasm […] the general effect produced is keen and musicianly in the best sense of the word”. After a performance of Leoni’s oratorio Golgotha at the Queen’s Hall in 1911 one enthusiast, James Bernard Fagan, expressed the somewhat florid opinion that “Mr Leoni has done for sacred music what Francis of Assisi did for Christianity, bidding us look for the spirit of God not in cold, gloomy, formless abstractions on remote unscalable heights, but down on the warm earth - in trees and in flowers and in running waters, in the birds and in the beasts, and in the hearts of men”.

There’s not much evidence of “the spirit of God” in L’oracolo ( The Oracle) which premiered at Covent Garden on 28th June 1905, conducted by André Messager and with Antonio Scotti playing the vicious and venal Cim-Fen. Set in an opium den in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Camille Zanoni’s libretto - based on a Chinese-American story, The Cat and the Cherub, by Chester Bailey Fernald - is swift and sensational. It crams villainy and viciousness, kidnapping and stabbing, strangulation and insanity into its sixty minutes. Its personnel include gamblers and fortune-tellers, drug addicts and reprobates, as well as chattering choruses of children and vendors. The action takes us through the seedy back-streets of 1900 Chinatown, down alley-ways which are choked by the San Francisco fog and the festering stench of the running drains, and teaming with caterwauling costermongers. The opium dens of ‘Hatchet Row’ are ruled by Cim-Fen, a merciless cut-throat who wields his knife with slickness and a smile.

Leon Kim and Joo Won Kang. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Leon Kim and Joo Won Kang. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

The eponymous Oracle predicts that two people will die, and murder follows murder with chilling speed and inevitability. When San-Lui discovers that Cim-Fen has kidnapped the child of the wealthy merchant Hu-Tsin - in a ploy to win the hand of Hu-Tsin’s niece, Ah-Joe, by heroically ‘rescuing’ the infant - Cim-Fen despatches his love rival with an efficient single hatchet-blow to the back of the head. Uin-San-Lui’s father, Uin-Scî, may be of philosophical bent, but that doesn’t stop him displaying his own thuggish resourcefulness and expertise in seeking vengeance. When the blade that he has plunged into Cim-Fen’s back fails in its fatal intent, Uin-Scî calmly winds his son’s killer’s plait around his neck and with delicate deliberation proceeds to strangle him. So peacefully occupied in quiet conversation do the pair appear, seated side-by-side on a bench, that a passing policemen notices nothing amiss.

Director Rodula Gaitanou and designer Cordelia Chisholm leave us in no doubt of the squalor and sadism of life in the ghetto. Dimly lit by Paul Hackenmueller, Chisholm’s set is dominated by a towering, three-story brick edifice which revolves to reveal the business premises of Dr Uin-Scî, a Chinese herbalist, the imposing entrance to the domestic quarters of Hu-Tsin, and the red-lit steps which descend into the bowels of Cim-Fen’s opium den. We are swirled along with the chattering Chinese inhabitants through the network of grimy alleyways. A corner street-light illuminates the coarseness and brutality of the gamblers, drug-takers and drinkers departing Cim-Fen’s den: knives flash in the lamp-light gloom, fists lash out, grievances are born and nurtured. Even the festive spectacle of a Chinese New Year Dragon Procession doesn’t alleviate the shabby sleaziness: the festooning red balloons can’t hide the shabbiness of the parading wagons, and the arching Dragon dips and dives menacingly, glaring with a mean, sharp-toothed stare.

Much of the success of L’oracolo was due to Scotti’s championing of the opera at the Met, where he persuaded General Manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza to present the work in 1915. It became a star vehicle for Scotti - often paired with Cavalleria Rusticana, Pagliacci, L’Amico Fritz and even La boh ème - until 1933, when the 55th performance of the opera served as the Italian baritone’s farewell to the house. Here, Joo Won Kang was entrusted with embodying the repugnant Cim-Fen, and his baritone was darkly aggressive at the bottom, richly coloured in the middle and firm of weight throughout. As Uin-San-Lui, Sergio Escobar provided complementary lightness and beauty, his tenor ringing brightly at the top, though there was little chemistry between Escobar and Elisabetta Farris’s Ah-Joe. But, if their voices didn’t blend with sufficiently powerful rhapsodic intimacy in the duet which is ended by Cim-Fen’s plunging knife, then the gentle beauty of Farris’s soprano did win our pity for the suffering girl, though Gaitanou did little to suggest that Ah-Joe’s grief was followed by mental derangement.

Sergio Escobar and Elisabetta Farris. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Sergio Escobar and Elisabetta Farris. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Leon Kim was superb as Uin-Scî, his grave and authoritative manner never concealing the sincerity of his love or integrity of his belief: the bereaved father’s appeal to the ‘Supreme Divinity of the Western Sky’ to reveal his son’s assassin was both chilling in its implications and compelling in its genuinely human motivation. The role of Hu-Tsin was commandingly sung by Benjamin Cho, while Louise Innes acted and sang convincingly as Hua-Quî, nurse to the kidnapped Hu-Cî. The latter was portrayed with infectious spiritedness by Cillian McCamley, who yawned cheekily during the adults’ rituals and sprinted around mischievously before he was imprisoned by Cim-Fen, first a garbage bin, then down the coal chute.

Conductor Francesco Cilluffo - who led Mascagni’s Isabeau impressively at Opera Holland Park this summer - had the measure of the score’s melodrama and pace, finding both stirring passion and moments of lightness, and the Orchestra of Wexford Festival Opera painted the diverse local colours with vividness and energy. There was especially fine playing from the lower strings, particularly during Uin-Scî’s retributive prayer and vow.

Despite the unalleviated ruthlessness and savagery which Leoni and Zanoni dish up, Gaitanou obviously felt there was room for more. Leon Kim’s Chinese herbalist did not consider throttling-by-pigtail to be sufficient punishment for his son’s murderer: instead, he exercised a ritual disembowelment of the barely-breathing Cim-Fen, slicing through clothes, peeling back skin and plunging his hand into the cut-throat criminal’s chest - should we have been in doubt, by the close the latter really was ‘heartless’. And, though the libretto ends with Uin-Scî’s vengeful actions undiscovered, here the clinical killer immediately confessed his crime to the passing policeman, crossing his wrists to indicate that the cuff-links should be clicked into place. The result was not the resumption of ‘normal’ life with which the original concludes, but the unbalancing of the scales of justice.

After the interval, Chisholm’s set was deftly transformed - out with the herbalist and in with Valentino’s cobbler’s shop, the Bella Napoli café replacing the opium den, and laden washing-lines adding to the authenticity of the milieu in the second Act - in order to transfer us from San Francisco’s Chinatown at the turn of the century to New York’s Little Italy in the 1950s. There are no knifings or strangulations in Umberto Giordano’s Mala vita but, like L’oracolo, for a relatively small-scale drama the large-scale musical climaxes pull no emotional punches and hit the theatrical bull’s-eye. Librettist Nicola Daspuro’s lurid tale of Neapolitan low-life - based on a play by Salvatore Di Giacomo and Goffredo Cognetti, which was itself derived from Giacomo’s 1888 short story Il voto (The vow) - was a success at its premiere in Rome’s Teatro Argentina in February 1892, and also surprisingly well-received when, translated into German, it was subsequently presented in Germany and Austria. But, Mala vita didn’t go down so well with the Neapolitans, who were less appreciative of Giordano’s ‘veristic’ - in their eyes, insulting - depiction of the ‘wretched lives’ endured in Naples’ ugly alleyways and slum dwellings.

The opera takes us into what Matilde Serao, the author of Il ventre di Napoli (1884), described as ‘the bowels of Naples’. Vito, who works in a dye-house, believes that the tuberculosis that afflicts him, rather than being an inevitable consequent of the chemicals and fumes he ingests each day, is a punishment from God for his misdemeanours - including his affair with Amalia, of which only her coachman husband Annetiello seems unaware. In hope of a cure and divine forgiveness, Vito vows to give up Amalia and marry a prostitute, thereby saving the fallen woman from a life of degradation and his own soul from damnation. News of his vow travels fast through the slum alleyways and when Cristina drops a rose from her brothel window onto the passing Vito’s shoulders, she is chosen as his path to redemption - to the brothel-regular Annetiello’s amusement and Amalia’s anger. The latter confronts Cristina, and Vito, unable to resist Amalia’s wiles and charms, ditches Cristina along with his plans for physical and moral improvement, leaving Cristina to lament that Jesus obviously didn’t want her to be redeemed after all.

Chorus of Mala vita. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Chorus of Mala vita. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

The expansive anguished and impassioned outbursts of the three protagonists stand out against the musical ‘backdrop’ provided by Giordano of everyday neighbourhood goings-on, and the Wexford Festival Chorus sang, and danced, with real spirit and vivacity. Gaitanou blocked the ensemble scenes more successfully than in L’oracolo, where occasionally the narrow street-strip at the front of the stage seemed crowded and the Dragon procession felt less than fluid. In contrast, the traditional Piedigrotta procession and festivities were vividly animated: the tarantella sprang ebulliently as the Neapolitan folk songs rang out colourfully, the snaking lines of revellers intertwined dexterously, and the children practised their dance-steps at the side of the stage. Similarly, the Chorus captured the intensity of the community’s belief in popular local superstitions during the opening vow scene.

Sergio Escobar and Chorus. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Sergio Escobar and Chorus. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Escobar was able to tap all the warm lyricism of his tenor and did his best to make Vito’s lurches from fervent prayer to ardent romance convincing, as he switched from devout consumptive to devious charmer in the blink of an eye. The characterisation is largely conveyed through the three main duets which bring Vito and Cristina together in Act 1, Amalia and Cristina into confrontation in Act 2 and subsequently reunite Amalia and Vito, and Escobar was well-partnered by both Dorothea Spilger’s Amalia and Francesca Tiburzi’s Cristina. Spilger was a powerful presence especially in Act 2, which Amalia dominates, communicating all of Amalia’s selfishness, recklessness and wilfulness. Her mezzo-soprano is powerful and focused, and in the lunchtime recital which she gave the following day, in St Iberius’s Church, she revealed its full range of colour, vibrancy and intensity, the dense layers of the bottom being complemented by strikingly intense and pure top notes. Spilger moved effortlessly between high and low, too, and her presentation of songs by Brahms, Schumann and Richard Strauss, and an aria from Lehár’s Zigeunerliebe, confirmed her flawless technique and assurance, and dramatic range.

Dorothea Spilger and Francesca Tiburzi. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Dorothea Spilger and Francesca Tiburzi. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.